User login

Medicare beneficiaries in hospice care get better care, have fewer costs

Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries suffering from poor-prognosis cancer who received hospice care were found to have lower rates of hospitalizations, admissions to intensive care units, and invasive procedures than those who did not receive hospice care, according to a study published in JAMA.

“Our findings highlight the potential importance of frank discussions between physicians and patients about the realities of care at the end of life, an issue of particular importance as the Medicare administration weighs decisions around reimbursing physicians for advance care planning,” said Dr. Ziad Obermeyer of the emergency medicine department at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and his associates.

In a matched cohort study, Dr. Obermeyer and his colleagues examined the records of 86,851 patients with poor-prognosis cancer – such as brain, pancreatic, and metastatic malignancies – using a nationally representative, 20% sample of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries who died in 2011. Of that group, 51,924 individuals (60%) entered hospice care prior to death, with the median time from first diagnosis to death being 13 months (JAMA 2014;312:1888-96).

The researchers then matched patients in hospice vs. nonhospice care, using factors such as age, sex, region, time from first diagnosis to death, and baseline care utilization. Each sample group consisted of 18,165 individuals, with the non–hospice-care group acting as the control. The median hospice duration for the hospice group was 11 days.

Dr. Obermeyer and his associates discovered that hospice beneficiaries had significantly lower rates of hospitalization (42%), intensive care unit admission (15%), invasive procedures (27%), and deaths in hospitals or nursing facilities (14%), compared with their nonhospice counterparts, who had a 65% rate of hospitalization, a 36% rate of intensive care unit admission, a 51% rate of invasive procedures, and a 74% rate of deaths in hospitals or nursing facilities.

Furthermore, the authors found that nonhospice beneficiaries had a higher rate of health care utilization, largely for acute conditions that were not directly related to their cancer, and higher overall costs. On average, costs for hospice beneficiaries were $62,819, while costs for nonhospice beneficiaries were $71,517.

“Hospice enrollment of 5 to 8 weeks produced the greatest savings; shorter stays produced fewer savings, likely because of both hospice initiation costs, and need for intensive symptom palliation in the days before death,” Dr. Obermeyer and his coauthors wrote. “Cost trajectories began to diverge in the week after hospice enrollment, implying that baseline differences between hospice and nonhospice beneficiaries were not responsible for cost differences,” they added.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Although the study by Obermeyer et al. adds to the evidence regarding hospice care for patients with poor-prognosis cancer, several caveats should be considered. An important threat to the validity of this study was that the unobserved difference in preferences for aggressive care may explain the observed cost savings. Rightfully, the authors acknowledge this and other limitations, such as restriction of the study population to patients with cancer, exclusion of Medicare beneficiaries with managed care and non-Medicare patients, and reliance only on claims-based information for risk adjustments, Dr. Joan M. Teno and Pedro L. Gozalo, Ph.D., both of the Brown University School of Public Health, Providence, R.I., wrote in an editorial accompanying the study.

The findings from this study raise several important policy issues, they said. If hospice saves money, should health care policy promote increased hospice access? Perhaps an even larger policy issue involves the role of costs and not quality in driving U.S. health policy in care of the seriously ill and those at the close of life (JAMA 2014;312:1868-69).

The pressing policy issue in the United States involves not only patients dying of poor-prognosis cancers, but patients with noncancer chronic illness for whom the costs of prolonged hospice stays exceed the potential savings from hospitalizations. Even in that policy debate, focusing solely on expenditures is not warranted. That hospice or hospital-based palliative care teams save money is ethically defensible only if there is improvement in the quality of care and medical decisions are consistent with the informed patient’s wishes and goals of care.

Dr. Teno is a professor at the Brown University School of Public Health. Dr. Gozalo is an associate professor at the university.

Although the study by Obermeyer et al. adds to the evidence regarding hospice care for patients with poor-prognosis cancer, several caveats should be considered. An important threat to the validity of this study was that the unobserved difference in preferences for aggressive care may explain the observed cost savings. Rightfully, the authors acknowledge this and other limitations, such as restriction of the study population to patients with cancer, exclusion of Medicare beneficiaries with managed care and non-Medicare patients, and reliance only on claims-based information for risk adjustments, Dr. Joan M. Teno and Pedro L. Gozalo, Ph.D., both of the Brown University School of Public Health, Providence, R.I., wrote in an editorial accompanying the study.

The findings from this study raise several important policy issues, they said. If hospice saves money, should health care policy promote increased hospice access? Perhaps an even larger policy issue involves the role of costs and not quality in driving U.S. health policy in care of the seriously ill and those at the close of life (JAMA 2014;312:1868-69).

The pressing policy issue in the United States involves not only patients dying of poor-prognosis cancers, but patients with noncancer chronic illness for whom the costs of prolonged hospice stays exceed the potential savings from hospitalizations. Even in that policy debate, focusing solely on expenditures is not warranted. That hospice or hospital-based palliative care teams save money is ethically defensible only if there is improvement in the quality of care and medical decisions are consistent with the informed patient’s wishes and goals of care.

Dr. Teno is a professor at the Brown University School of Public Health. Dr. Gozalo is an associate professor at the university.

Although the study by Obermeyer et al. adds to the evidence regarding hospice care for patients with poor-prognosis cancer, several caveats should be considered. An important threat to the validity of this study was that the unobserved difference in preferences for aggressive care may explain the observed cost savings. Rightfully, the authors acknowledge this and other limitations, such as restriction of the study population to patients with cancer, exclusion of Medicare beneficiaries with managed care and non-Medicare patients, and reliance only on claims-based information for risk adjustments, Dr. Joan M. Teno and Pedro L. Gozalo, Ph.D., both of the Brown University School of Public Health, Providence, R.I., wrote in an editorial accompanying the study.

The findings from this study raise several important policy issues, they said. If hospice saves money, should health care policy promote increased hospice access? Perhaps an even larger policy issue involves the role of costs and not quality in driving U.S. health policy in care of the seriously ill and those at the close of life (JAMA 2014;312:1868-69).

The pressing policy issue in the United States involves not only patients dying of poor-prognosis cancers, but patients with noncancer chronic illness for whom the costs of prolonged hospice stays exceed the potential savings from hospitalizations. Even in that policy debate, focusing solely on expenditures is not warranted. That hospice or hospital-based palliative care teams save money is ethically defensible only if there is improvement in the quality of care and medical decisions are consistent with the informed patient’s wishes and goals of care.

Dr. Teno is a professor at the Brown University School of Public Health. Dr. Gozalo is an associate professor at the university.

Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries suffering from poor-prognosis cancer who received hospice care were found to have lower rates of hospitalizations, admissions to intensive care units, and invasive procedures than those who did not receive hospice care, according to a study published in JAMA.

“Our findings highlight the potential importance of frank discussions between physicians and patients about the realities of care at the end of life, an issue of particular importance as the Medicare administration weighs decisions around reimbursing physicians for advance care planning,” said Dr. Ziad Obermeyer of the emergency medicine department at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and his associates.

In a matched cohort study, Dr. Obermeyer and his colleagues examined the records of 86,851 patients with poor-prognosis cancer – such as brain, pancreatic, and metastatic malignancies – using a nationally representative, 20% sample of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries who died in 2011. Of that group, 51,924 individuals (60%) entered hospice care prior to death, with the median time from first diagnosis to death being 13 months (JAMA 2014;312:1888-96).

The researchers then matched patients in hospice vs. nonhospice care, using factors such as age, sex, region, time from first diagnosis to death, and baseline care utilization. Each sample group consisted of 18,165 individuals, with the non–hospice-care group acting as the control. The median hospice duration for the hospice group was 11 days.

Dr. Obermeyer and his associates discovered that hospice beneficiaries had significantly lower rates of hospitalization (42%), intensive care unit admission (15%), invasive procedures (27%), and deaths in hospitals or nursing facilities (14%), compared with their nonhospice counterparts, who had a 65% rate of hospitalization, a 36% rate of intensive care unit admission, a 51% rate of invasive procedures, and a 74% rate of deaths in hospitals or nursing facilities.

Furthermore, the authors found that nonhospice beneficiaries had a higher rate of health care utilization, largely for acute conditions that were not directly related to their cancer, and higher overall costs. On average, costs for hospice beneficiaries were $62,819, while costs for nonhospice beneficiaries were $71,517.

“Hospice enrollment of 5 to 8 weeks produced the greatest savings; shorter stays produced fewer savings, likely because of both hospice initiation costs, and need for intensive symptom palliation in the days before death,” Dr. Obermeyer and his coauthors wrote. “Cost trajectories began to diverge in the week after hospice enrollment, implying that baseline differences between hospice and nonhospice beneficiaries were not responsible for cost differences,” they added.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries suffering from poor-prognosis cancer who received hospice care were found to have lower rates of hospitalizations, admissions to intensive care units, and invasive procedures than those who did not receive hospice care, according to a study published in JAMA.

“Our findings highlight the potential importance of frank discussions between physicians and patients about the realities of care at the end of life, an issue of particular importance as the Medicare administration weighs decisions around reimbursing physicians for advance care planning,” said Dr. Ziad Obermeyer of the emergency medicine department at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and his associates.

In a matched cohort study, Dr. Obermeyer and his colleagues examined the records of 86,851 patients with poor-prognosis cancer – such as brain, pancreatic, and metastatic malignancies – using a nationally representative, 20% sample of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries who died in 2011. Of that group, 51,924 individuals (60%) entered hospice care prior to death, with the median time from first diagnosis to death being 13 months (JAMA 2014;312:1888-96).

The researchers then matched patients in hospice vs. nonhospice care, using factors such as age, sex, region, time from first diagnosis to death, and baseline care utilization. Each sample group consisted of 18,165 individuals, with the non–hospice-care group acting as the control. The median hospice duration for the hospice group was 11 days.

Dr. Obermeyer and his associates discovered that hospice beneficiaries had significantly lower rates of hospitalization (42%), intensive care unit admission (15%), invasive procedures (27%), and deaths in hospitals or nursing facilities (14%), compared with their nonhospice counterparts, who had a 65% rate of hospitalization, a 36% rate of intensive care unit admission, a 51% rate of invasive procedures, and a 74% rate of deaths in hospitals or nursing facilities.

Furthermore, the authors found that nonhospice beneficiaries had a higher rate of health care utilization, largely for acute conditions that were not directly related to their cancer, and higher overall costs. On average, costs for hospice beneficiaries were $62,819, while costs for nonhospice beneficiaries were $71,517.

“Hospice enrollment of 5 to 8 weeks produced the greatest savings; shorter stays produced fewer savings, likely because of both hospice initiation costs, and need for intensive symptom palliation in the days before death,” Dr. Obermeyer and his coauthors wrote. “Cost trajectories began to diverge in the week after hospice enrollment, implying that baseline differences between hospice and nonhospice beneficiaries were not responsible for cost differences,” they added.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Medicare beneficiaries with poor-prognosis cancer who received hospice care had lower rates of hospitalization, ICU admission, and invasive procedures than those who did not.

Major finding: Of those receiving hospice care, 42% were admitted to the hospital vs. 65% of those not receiving hospice care.

Data source: Matched cohort study of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Palliative tumor removal extends survival

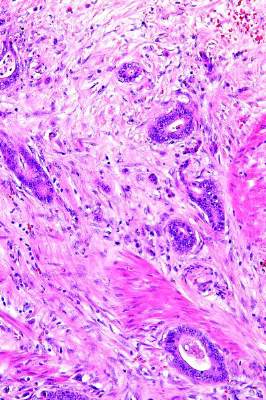

Palliative resection of the primary tumor actually extends survival in patients with metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma, according to a report published online Nov. 4 in Annals of Surgery.

In what the investigators described as the first population-based study to assess trends in cancer-specific and overall survival among U.S. patients who did or did not undergo palliative removal of the primary tumor, the resection consistently conferred statistically significant and clinically meaningful survival benefits among 37,793 patients treated during a 12-year period.

“There is a heated debate in the medical and surgical oncology community regarding whether or not an asymptomatic primary tumor should be removed in patients with unresectable, synchronous cancer metastases,” wrote Dr. Ignazio Tarantino of the department of surgery, Kantonsspital St. Gallen (Switzerland) and the department of general, abdominal, and transplant surgery, University of Heidelberg (Germany) and his associates.

Current National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend against palliative surgery in this setting, primarily because of evidence that leaving the primary tumor in situ seldom leads to life-threatening complications such as bleeding or bowel obstruction, while resection can cause complications and is not strictly necessary in terminally ill patients. But given these new findings of a significant survival benefit, “the dogma that [such tumors] never should be resected ... must be questioned,” the investigators wrote.

Dr. Tarantino and his associates analyzed Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data for 23,004 patients (60.9% of the total study population) who underwent primary tumor resection and 14,789 (39.1%) who did not. The percentage of patients who had the surgery steadily declined throughout the study period.

Palliative removal of the primary tumor was a significant protective factor for overall survival (HR of death, 0.49) and for cancer-specific survival (HR of cancer death, 0.49) in both the primary data analysis and a proportional hazard regression analysis.

Patients undergoing resection tended to be younger and healthier than those who did not have the procedure, so the researchers performed a propensity-score matching analysis to account for baseline differences between the two study groups. After adjustment for numerous potential confounders, palliative primary tumor resection continued to exert a significant protective effect for overall and cancer-specific survival, with HRs of 0.40 and 0.39, respectively. The survival benefit also persisted, with identical hazard ratios, in two further sensitivity analyses of the data, Dr. Tarantino and his associates noted (Ann. Surg. 2014 Nov. 4 [doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000860]).

The mechanism by which palliative resection imparts a survival benefit is not yet known, they added.

Major advances in systemic treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer were achieved during the study period, and survival improved accordingly across both groups of patients over time. “Because of the improvement in systemic treatment, we anticipated that the differences in survival between the subsets of patients who did and who did not undergo palliative primary tumor resection would decrease over time. However – against our a priori hypothesis – our analysis demonstrates the contrary,” the investigators noted.

No financial or material support was provided for this study. Dr. Tarantino and his associates reported having no financial disclosures.

Palliative resection of the primary tumor actually extends survival in patients with metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma, according to a report published online Nov. 4 in Annals of Surgery.

In what the investigators described as the first population-based study to assess trends in cancer-specific and overall survival among U.S. patients who did or did not undergo palliative removal of the primary tumor, the resection consistently conferred statistically significant and clinically meaningful survival benefits among 37,793 patients treated during a 12-year period.

“There is a heated debate in the medical and surgical oncology community regarding whether or not an asymptomatic primary tumor should be removed in patients with unresectable, synchronous cancer metastases,” wrote Dr. Ignazio Tarantino of the department of surgery, Kantonsspital St. Gallen (Switzerland) and the department of general, abdominal, and transplant surgery, University of Heidelberg (Germany) and his associates.

Current National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend against palliative surgery in this setting, primarily because of evidence that leaving the primary tumor in situ seldom leads to life-threatening complications such as bleeding or bowel obstruction, while resection can cause complications and is not strictly necessary in terminally ill patients. But given these new findings of a significant survival benefit, “the dogma that [such tumors] never should be resected ... must be questioned,” the investigators wrote.

Dr. Tarantino and his associates analyzed Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data for 23,004 patients (60.9% of the total study population) who underwent primary tumor resection and 14,789 (39.1%) who did not. The percentage of patients who had the surgery steadily declined throughout the study period.

Palliative removal of the primary tumor was a significant protective factor for overall survival (HR of death, 0.49) and for cancer-specific survival (HR of cancer death, 0.49) in both the primary data analysis and a proportional hazard regression analysis.

Patients undergoing resection tended to be younger and healthier than those who did not have the procedure, so the researchers performed a propensity-score matching analysis to account for baseline differences between the two study groups. After adjustment for numerous potential confounders, palliative primary tumor resection continued to exert a significant protective effect for overall and cancer-specific survival, with HRs of 0.40 and 0.39, respectively. The survival benefit also persisted, with identical hazard ratios, in two further sensitivity analyses of the data, Dr. Tarantino and his associates noted (Ann. Surg. 2014 Nov. 4 [doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000860]).

The mechanism by which palliative resection imparts a survival benefit is not yet known, they added.

Major advances in systemic treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer were achieved during the study period, and survival improved accordingly across both groups of patients over time. “Because of the improvement in systemic treatment, we anticipated that the differences in survival between the subsets of patients who did and who did not undergo palliative primary tumor resection would decrease over time. However – against our a priori hypothesis – our analysis demonstrates the contrary,” the investigators noted.

No financial or material support was provided for this study. Dr. Tarantino and his associates reported having no financial disclosures.

Palliative resection of the primary tumor actually extends survival in patients with metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma, according to a report published online Nov. 4 in Annals of Surgery.

In what the investigators described as the first population-based study to assess trends in cancer-specific and overall survival among U.S. patients who did or did not undergo palliative removal of the primary tumor, the resection consistently conferred statistically significant and clinically meaningful survival benefits among 37,793 patients treated during a 12-year period.

“There is a heated debate in the medical and surgical oncology community regarding whether or not an asymptomatic primary tumor should be removed in patients with unresectable, synchronous cancer metastases,” wrote Dr. Ignazio Tarantino of the department of surgery, Kantonsspital St. Gallen (Switzerland) and the department of general, abdominal, and transplant surgery, University of Heidelberg (Germany) and his associates.

Current National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend against palliative surgery in this setting, primarily because of evidence that leaving the primary tumor in situ seldom leads to life-threatening complications such as bleeding or bowel obstruction, while resection can cause complications and is not strictly necessary in terminally ill patients. But given these new findings of a significant survival benefit, “the dogma that [such tumors] never should be resected ... must be questioned,” the investigators wrote.

Dr. Tarantino and his associates analyzed Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data for 23,004 patients (60.9% of the total study population) who underwent primary tumor resection and 14,789 (39.1%) who did not. The percentage of patients who had the surgery steadily declined throughout the study period.

Palliative removal of the primary tumor was a significant protective factor for overall survival (HR of death, 0.49) and for cancer-specific survival (HR of cancer death, 0.49) in both the primary data analysis and a proportional hazard regression analysis.

Patients undergoing resection tended to be younger and healthier than those who did not have the procedure, so the researchers performed a propensity-score matching analysis to account for baseline differences between the two study groups. After adjustment for numerous potential confounders, palliative primary tumor resection continued to exert a significant protective effect for overall and cancer-specific survival, with HRs of 0.40 and 0.39, respectively. The survival benefit also persisted, with identical hazard ratios, in two further sensitivity analyses of the data, Dr. Tarantino and his associates noted (Ann. Surg. 2014 Nov. 4 [doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000860]).

The mechanism by which palliative resection imparts a survival benefit is not yet known, they added.

Major advances in systemic treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer were achieved during the study period, and survival improved accordingly across both groups of patients over time. “Because of the improvement in systemic treatment, we anticipated that the differences in survival between the subsets of patients who did and who did not undergo palliative primary tumor resection would decrease over time. However – against our a priori hypothesis – our analysis demonstrates the contrary,” the investigators noted.

No financial or material support was provided for this study. Dr. Tarantino and his associates reported having no financial disclosures.

Key clinical point: Palliative removal of the primary tumor extends survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer.

Major finding: Palliative resection of the primary tumor was a significant protective factor for overall survival (HR of death, 0.49) and for cancer-specific survival (HR of cancer death, 0.49) in both the primary data analysis and a proportional hazard regression analysis.

Data source: A population-based study of the duration of survival in 23,004 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer who had palliative removal of the primary tumor and 14,789 who did not during a 12-year period.

Disclosures: No financial or material support was provided for this study. Dr. Tarantino and his associates reported having no disclosures.

‘Co-rounding’ decreases patient length of stay

BOSTON – When a palliative care oncologist partners with a medical oncologist on everyday rounds and in everyday practice on an inpatient floor, both patients and the clinicians who provide their care benefit from the arrangement, an oncologist reports.

At Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C., where palliative care is integrated with medical oncology on an inpatient oncology ward, the “co-rounding” model is associated with improvements in quality outcomes, improved nursing and physician satisfaction, and increased collaboration and communication, said Dr. Richard F. Riedel of the medical center.

In a study comparing the periods before and after implementation of the co-rounding model, lengths of stay and 7- and 30-day readmission rates were significantly shorter with co-rounding.

“I’d like to think that decreased resource utilization through decreased ICU transfer rates and decreased readmissions will result in a cost savings that would certainly justify putting a second provider up on an inpatient ward,” he said at the Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium.

The co-rounding model was introduced at Duke in 2011. Under this system, a medical oncologist and palliative care oncologist meet three times daily with house staff, fellows, and other team members to discuss the care of all patients on the unit. They decide which physician will oversee care of which patient. Patients who have high symptom burdens, for example, might be assigned to the palliative care physician. The physicians and staff go on rounds together with support staff, including internal medicine house staff, physician assistants, and pharmacists, allowing both formal and “curbside” consultations about how best to manage each patient.

“Critical to the success of this model is open communication and collaboration. We have three points where we meet throughout the day, and we emphasize to our colleagues that we are one team – we do not work in silos,” Dr. Riedel said.

Before and after

To see whether the co-rounding model was really, as they thought, a better way of doing business, Dr. Riedel and his colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of all patients admitted to the solid tumor inpatient service before the intervention – 731 patients admitted from September 2008 through June 2010 – compared with 783 admitted from September 2011 through June 2012, in the first year of co-rounding.

They found that co-rounding was associated with a significantly lower mean length of stay (4.51 days pre-intervention to 4.16 post, P =.02), and in both 7-day and 30-day readmission rates (12.1% vs. 9.3%, P <.0001, and 32.1% vs 28.3%, P = .048, respectively).

Although there were numerically fewer ICU transfers post intervention, this difference was not significant. Similarly, there was a trend, albeit nonsignificant, toward more hospice referrals under co-rounding.

When the researchers surveyed registered nurses who worked in the unit during both periods, they found that most agreed that adding a palliative care specialist improved quality of care, allowed for earlier goals-of-care discussions with patients, improved the involvement of nurses in care planning, reduced stresses on the staff, and improved symptom management.

Importantly, the improvements came without making rounds take longer or detracting from any appropriate focus on oncologic care, the authors found.

Medical oncology faculty who had rounded at least 2 weeks under the new regimen were surveyed, and they uniformly reported that the palliative care providers added a valuable skill set, that palliative care was a necessary component of cancer care, and that the rounding experience was more enjoyable. They also agreed that palliative care is different from hospice care, and said they felt that the discussion of hospice for those patients with incurable disease did not come too soon in the course of care,

“Importantly, the majority of physicians felt that they learned some new ways to manage symptoms, and I can tell you that I certainly have. I’m a medical oncologist, I’m not a palliative-care trained physician,” Dr. Riedel said.

He acknowledged that the study was limited by its retrospective design and the lack of a patient satisfaction component. Also, the intervention occurred at a single large academic medical center, and involved a smaller physician-to-patient ratio that could have confounded results.

The symposium was cosponsored by AAHPM, ASCO, ASTRO, and MASCC.

Why is this study important? The researchers show that this model has modified a health care quality outcome, and that’s always very important. When we in the field change some quality outcome, that is something to further explore. They carefully measured the satisfaction of physicians and nurses, and that’s not always something we pay attention to. We can do a wonderful efficacy study, and then everybody hates doing it, and we shelve it, and nobody else does it. So seeing that people really like doing this is important.

Dr. Eduardo Bruera, the invited discussant, is with the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Why is this study important? The researchers show that this model has modified a health care quality outcome, and that’s always very important. When we in the field change some quality outcome, that is something to further explore. They carefully measured the satisfaction of physicians and nurses, and that’s not always something we pay attention to. We can do a wonderful efficacy study, and then everybody hates doing it, and we shelve it, and nobody else does it. So seeing that people really like doing this is important.

Dr. Eduardo Bruera, the invited discussant, is with the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Why is this study important? The researchers show that this model has modified a health care quality outcome, and that’s always very important. When we in the field change some quality outcome, that is something to further explore. They carefully measured the satisfaction of physicians and nurses, and that’s not always something we pay attention to. We can do a wonderful efficacy study, and then everybody hates doing it, and we shelve it, and nobody else does it. So seeing that people really like doing this is important.

Dr. Eduardo Bruera, the invited discussant, is with the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

BOSTON – When a palliative care oncologist partners with a medical oncologist on everyday rounds and in everyday practice on an inpatient floor, both patients and the clinicians who provide their care benefit from the arrangement, an oncologist reports.

At Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C., where palliative care is integrated with medical oncology on an inpatient oncology ward, the “co-rounding” model is associated with improvements in quality outcomes, improved nursing and physician satisfaction, and increased collaboration and communication, said Dr. Richard F. Riedel of the medical center.

In a study comparing the periods before and after implementation of the co-rounding model, lengths of stay and 7- and 30-day readmission rates were significantly shorter with co-rounding.

“I’d like to think that decreased resource utilization through decreased ICU transfer rates and decreased readmissions will result in a cost savings that would certainly justify putting a second provider up on an inpatient ward,” he said at the Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium.

The co-rounding model was introduced at Duke in 2011. Under this system, a medical oncologist and palliative care oncologist meet three times daily with house staff, fellows, and other team members to discuss the care of all patients on the unit. They decide which physician will oversee care of which patient. Patients who have high symptom burdens, for example, might be assigned to the palliative care physician. The physicians and staff go on rounds together with support staff, including internal medicine house staff, physician assistants, and pharmacists, allowing both formal and “curbside” consultations about how best to manage each patient.

“Critical to the success of this model is open communication and collaboration. We have three points where we meet throughout the day, and we emphasize to our colleagues that we are one team – we do not work in silos,” Dr. Riedel said.

Before and after

To see whether the co-rounding model was really, as they thought, a better way of doing business, Dr. Riedel and his colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of all patients admitted to the solid tumor inpatient service before the intervention – 731 patients admitted from September 2008 through June 2010 – compared with 783 admitted from September 2011 through June 2012, in the first year of co-rounding.

They found that co-rounding was associated with a significantly lower mean length of stay (4.51 days pre-intervention to 4.16 post, P =.02), and in both 7-day and 30-day readmission rates (12.1% vs. 9.3%, P <.0001, and 32.1% vs 28.3%, P = .048, respectively).

Although there were numerically fewer ICU transfers post intervention, this difference was not significant. Similarly, there was a trend, albeit nonsignificant, toward more hospice referrals under co-rounding.

When the researchers surveyed registered nurses who worked in the unit during both periods, they found that most agreed that adding a palliative care specialist improved quality of care, allowed for earlier goals-of-care discussions with patients, improved the involvement of nurses in care planning, reduced stresses on the staff, and improved symptom management.

Importantly, the improvements came without making rounds take longer or detracting from any appropriate focus on oncologic care, the authors found.

Medical oncology faculty who had rounded at least 2 weeks under the new regimen were surveyed, and they uniformly reported that the palliative care providers added a valuable skill set, that palliative care was a necessary component of cancer care, and that the rounding experience was more enjoyable. They also agreed that palliative care is different from hospice care, and said they felt that the discussion of hospice for those patients with incurable disease did not come too soon in the course of care,

“Importantly, the majority of physicians felt that they learned some new ways to manage symptoms, and I can tell you that I certainly have. I’m a medical oncologist, I’m not a palliative-care trained physician,” Dr. Riedel said.

He acknowledged that the study was limited by its retrospective design and the lack of a patient satisfaction component. Also, the intervention occurred at a single large academic medical center, and involved a smaller physician-to-patient ratio that could have confounded results.

The symposium was cosponsored by AAHPM, ASCO, ASTRO, and MASCC.

BOSTON – When a palliative care oncologist partners with a medical oncologist on everyday rounds and in everyday practice on an inpatient floor, both patients and the clinicians who provide their care benefit from the arrangement, an oncologist reports.

At Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C., where palliative care is integrated with medical oncology on an inpatient oncology ward, the “co-rounding” model is associated with improvements in quality outcomes, improved nursing and physician satisfaction, and increased collaboration and communication, said Dr. Richard F. Riedel of the medical center.

In a study comparing the periods before and after implementation of the co-rounding model, lengths of stay and 7- and 30-day readmission rates were significantly shorter with co-rounding.

“I’d like to think that decreased resource utilization through decreased ICU transfer rates and decreased readmissions will result in a cost savings that would certainly justify putting a second provider up on an inpatient ward,” he said at the Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium.

The co-rounding model was introduced at Duke in 2011. Under this system, a medical oncologist and palliative care oncologist meet three times daily with house staff, fellows, and other team members to discuss the care of all patients on the unit. They decide which physician will oversee care of which patient. Patients who have high symptom burdens, for example, might be assigned to the palliative care physician. The physicians and staff go on rounds together with support staff, including internal medicine house staff, physician assistants, and pharmacists, allowing both formal and “curbside” consultations about how best to manage each patient.

“Critical to the success of this model is open communication and collaboration. We have three points where we meet throughout the day, and we emphasize to our colleagues that we are one team – we do not work in silos,” Dr. Riedel said.

Before and after

To see whether the co-rounding model was really, as they thought, a better way of doing business, Dr. Riedel and his colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of all patients admitted to the solid tumor inpatient service before the intervention – 731 patients admitted from September 2008 through June 2010 – compared with 783 admitted from September 2011 through June 2012, in the first year of co-rounding.

They found that co-rounding was associated with a significantly lower mean length of stay (4.51 days pre-intervention to 4.16 post, P =.02), and in both 7-day and 30-day readmission rates (12.1% vs. 9.3%, P <.0001, and 32.1% vs 28.3%, P = .048, respectively).

Although there were numerically fewer ICU transfers post intervention, this difference was not significant. Similarly, there was a trend, albeit nonsignificant, toward more hospice referrals under co-rounding.

When the researchers surveyed registered nurses who worked in the unit during both periods, they found that most agreed that adding a palliative care specialist improved quality of care, allowed for earlier goals-of-care discussions with patients, improved the involvement of nurses in care planning, reduced stresses on the staff, and improved symptom management.

Importantly, the improvements came without making rounds take longer or detracting from any appropriate focus on oncologic care, the authors found.

Medical oncology faculty who had rounded at least 2 weeks under the new regimen were surveyed, and they uniformly reported that the palliative care providers added a valuable skill set, that palliative care was a necessary component of cancer care, and that the rounding experience was more enjoyable. They also agreed that palliative care is different from hospice care, and said they felt that the discussion of hospice for those patients with incurable disease did not come too soon in the course of care,

“Importantly, the majority of physicians felt that they learned some new ways to manage symptoms, and I can tell you that I certainly have. I’m a medical oncologist, I’m not a palliative-care trained physician,” Dr. Riedel said.

He acknowledged that the study was limited by its retrospective design and the lack of a patient satisfaction component. Also, the intervention occurred at a single large academic medical center, and involved a smaller physician-to-patient ratio that could have confounded results.

The symposium was cosponsored by AAHPM, ASCO, ASTRO, and MASCC.

AT THE PALLIATIVE CARE IN ONCOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point: A system of joint rounding of medical oncologists with palliative care specialists improved patient outcomes.

Major finding: Length of stay on an impatient solid tumor oncology unit decreased by 8% after the co-rounding model was introduced.Data source: Retrospective cohort analysis comparing 731 patients treated under the standard model of care, and 783 treated under the co-rounding model.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Duke University Medical Center. Dr. Riedel disclosed ties with several companies, but none were relevant to the study. Dr. Bruera reported having no disclosures.

Automated support eases hospice patient, caregiver burden

BOSTON – An automated system for monitoring the symptoms of patients in home hospice and supporting their caregivers with coaching can both improve patient comfort and relieve at least some of the stress on the caregiver, said investigators in a pilot program.

In a prospective, randomized controlled trial, caregivers assigned to symptom care by phone, in which they received automated coaching tailored to the specific situation, had better overall vitality, and the patients they cared for had less fatigue and anxiety than caregiver-patient pairs assigned to usual care, reported Dr. Kathi Mooney, professor of nursing at the University of Utah College of Nursing, Salt Lake City.

“The family inclusion in hospice care, the philosophy around that, offers the opportunity to extend PROs [patient-reported outcomes] to FCROs, family caregiver reported outcomes. We call that an opportunity to use electronic monitoring to monitor a family,” she said at the Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium.

Dr. Mooney and her colleagues have previously reported on the use of automated symptom monitoring for support of patients undergoing ambulatory chemotherapy. In the current study, she described its application in home-based end-of-life care to support both the patient and the caregiver.

The investigators recruited 319 cancer patient/caregiver dyads from 12 hospices in Illinois, Massachusetts, Oregon, and Utah. The mean age of the patients was 72 years, and the mean age of caregivers was 59 years.

The caregivers were randomly assigned either to the symptom care by phone (SCP) system or to usual care. The SCP system is an automated system in which caregivers phone in to report the patient’s symptoms and their own levels of stress, anxiety, etc., and receive automated responses based on the severity of symptoms and number of days reported without relief. The system offers both patient care and self-care strategies, and identifies and reinforces issues that should be addressed by contacting the hospice team. At the end of the call, the data are sent to the nurse, including alerts to matters that require prompt attention.

Caregivers in each group made daily automated monitoring calls to report 1 or more of 11 patient symptoms and 5 caregiver symptoms on a 0-10 scale, and to report the patient’s and their own distress about the symptoms.

“We have developed algorithms to provide just-in-time, tailored suggestions related to the pattern that they have reported,” Dr. Mooney said.

Data reported by caregivers in the control (usual care) group were recorded but not acted upon, whereas data reported by those in the SCP intervention group triggered the automated coaching and hospice nurse alerts for moderate to severe symptoms.

“People in the usual care group understood that they were just contributing symptom information, and they were told on every call and at consent that if they had any concerns to call their hospice nurse,” Dr. Mooney said.

For clinicians, the automated system triggers an alert at preset thresholds of severity (4-10), as well as trend alerts. Hospice nurses have online and mobile access to the alert website, where they can view a report of symptoms over the previous 24 hours, and review graphs of symptoms over time to see trends. The nurses were instructed to log that they had seen the alert and what their planned action was, which was left to their professional judgment.

The average length of the calls was 7 minutes, 4 seconds for the usual care group, and 7 minutes, 59 seconds for the intervention group. Control group caregivers completed 59% of expected calls, and those in the intervention group completed 64%.

Reported symptoms present in more than 50% of patients included fatigue (88.8%), pain (60.2%), eating/drinking problems (76.6%), difficulty thinking (69.6%), anxiety (67.6%), negative mood (67.3%), bowel problems (61%), and trouble sleeping (58.3%).

Among caregivers, 73.3% reported fatigue, 66.7% anxiety, 61% trouble sleeping, and 57.1% negative mood.

In a mixed-effects model looking at caregiver vitality – a composite of caregiver symptoms – the authors found that the severity of symptoms in the usual care group increased steadily over the course of hospice care, out to at least 91 days. In contrast, the severity of symptoms among caregivers in the SCP group rose only slightly. The between-group difference was significant (P < .001).

Similarly, among patients the overall symptom severity scores were lower for those in the intervention group than for controls (P =.03). Additionally, the onset of benefit, defined as time to the first symptom-free day, was significantly earlier among patients in the SCP group (P < .02)

Patterns of patient and fatigue during the last 8 weeks of life also favored the symptom-care intervention, Dr. Mooney noted.`

Invited discussant Dr. Michael H. Levy, vice chair of medical oncology and director of the pain and palliative care program at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, commented that the SCP system “is interesting, but it’s very expensive, the impact is limited, and it’s challenging to export.”

He noted that for a palliative care support system to be implemented successfully, it would need to be reproducible and applicable to a wide range of health care systems.

The symposium was cosponsored by AAHPM, ASCO, ASTRO, and MASCC.

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Mooney and Dr. Levy reported having no relevant disclosures.

BOSTON – An automated system for monitoring the symptoms of patients in home hospice and supporting their caregivers with coaching can both improve patient comfort and relieve at least some of the stress on the caregiver, said investigators in a pilot program.

In a prospective, randomized controlled trial, caregivers assigned to symptom care by phone, in which they received automated coaching tailored to the specific situation, had better overall vitality, and the patients they cared for had less fatigue and anxiety than caregiver-patient pairs assigned to usual care, reported Dr. Kathi Mooney, professor of nursing at the University of Utah College of Nursing, Salt Lake City.

“The family inclusion in hospice care, the philosophy around that, offers the opportunity to extend PROs [patient-reported outcomes] to FCROs, family caregiver reported outcomes. We call that an opportunity to use electronic monitoring to monitor a family,” she said at the Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium.

Dr. Mooney and her colleagues have previously reported on the use of automated symptom monitoring for support of patients undergoing ambulatory chemotherapy. In the current study, she described its application in home-based end-of-life care to support both the patient and the caregiver.

The investigators recruited 319 cancer patient/caregiver dyads from 12 hospices in Illinois, Massachusetts, Oregon, and Utah. The mean age of the patients was 72 years, and the mean age of caregivers was 59 years.

The caregivers were randomly assigned either to the symptom care by phone (SCP) system or to usual care. The SCP system is an automated system in which caregivers phone in to report the patient’s symptoms and their own levels of stress, anxiety, etc., and receive automated responses based on the severity of symptoms and number of days reported without relief. The system offers both patient care and self-care strategies, and identifies and reinforces issues that should be addressed by contacting the hospice team. At the end of the call, the data are sent to the nurse, including alerts to matters that require prompt attention.

Caregivers in each group made daily automated monitoring calls to report 1 or more of 11 patient symptoms and 5 caregiver symptoms on a 0-10 scale, and to report the patient’s and their own distress about the symptoms.

“We have developed algorithms to provide just-in-time, tailored suggestions related to the pattern that they have reported,” Dr. Mooney said.

Data reported by caregivers in the control (usual care) group were recorded but not acted upon, whereas data reported by those in the SCP intervention group triggered the automated coaching and hospice nurse alerts for moderate to severe symptoms.

“People in the usual care group understood that they were just contributing symptom information, and they were told on every call and at consent that if they had any concerns to call their hospice nurse,” Dr. Mooney said.

For clinicians, the automated system triggers an alert at preset thresholds of severity (4-10), as well as trend alerts. Hospice nurses have online and mobile access to the alert website, where they can view a report of symptoms over the previous 24 hours, and review graphs of symptoms over time to see trends. The nurses were instructed to log that they had seen the alert and what their planned action was, which was left to their professional judgment.

The average length of the calls was 7 minutes, 4 seconds for the usual care group, and 7 minutes, 59 seconds for the intervention group. Control group caregivers completed 59% of expected calls, and those in the intervention group completed 64%.

Reported symptoms present in more than 50% of patients included fatigue (88.8%), pain (60.2%), eating/drinking problems (76.6%), difficulty thinking (69.6%), anxiety (67.6%), negative mood (67.3%), bowel problems (61%), and trouble sleeping (58.3%).

Among caregivers, 73.3% reported fatigue, 66.7% anxiety, 61% trouble sleeping, and 57.1% negative mood.

In a mixed-effects model looking at caregiver vitality – a composite of caregiver symptoms – the authors found that the severity of symptoms in the usual care group increased steadily over the course of hospice care, out to at least 91 days. In contrast, the severity of symptoms among caregivers in the SCP group rose only slightly. The between-group difference was significant (P < .001).

Similarly, among patients the overall symptom severity scores were lower for those in the intervention group than for controls (P =.03). Additionally, the onset of benefit, defined as time to the first symptom-free day, was significantly earlier among patients in the SCP group (P < .02)

Patterns of patient and fatigue during the last 8 weeks of life also favored the symptom-care intervention, Dr. Mooney noted.`

Invited discussant Dr. Michael H. Levy, vice chair of medical oncology and director of the pain and palliative care program at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, commented that the SCP system “is interesting, but it’s very expensive, the impact is limited, and it’s challenging to export.”

He noted that for a palliative care support system to be implemented successfully, it would need to be reproducible and applicable to a wide range of health care systems.

The symposium was cosponsored by AAHPM, ASCO, ASTRO, and MASCC.

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Mooney and Dr. Levy reported having no relevant disclosures.

BOSTON – An automated system for monitoring the symptoms of patients in home hospice and supporting their caregivers with coaching can both improve patient comfort and relieve at least some of the stress on the caregiver, said investigators in a pilot program.

In a prospective, randomized controlled trial, caregivers assigned to symptom care by phone, in which they received automated coaching tailored to the specific situation, had better overall vitality, and the patients they cared for had less fatigue and anxiety than caregiver-patient pairs assigned to usual care, reported Dr. Kathi Mooney, professor of nursing at the University of Utah College of Nursing, Salt Lake City.

“The family inclusion in hospice care, the philosophy around that, offers the opportunity to extend PROs [patient-reported outcomes] to FCROs, family caregiver reported outcomes. We call that an opportunity to use electronic monitoring to monitor a family,” she said at the Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium.

Dr. Mooney and her colleagues have previously reported on the use of automated symptom monitoring for support of patients undergoing ambulatory chemotherapy. In the current study, she described its application in home-based end-of-life care to support both the patient and the caregiver.

The investigators recruited 319 cancer patient/caregiver dyads from 12 hospices in Illinois, Massachusetts, Oregon, and Utah. The mean age of the patients was 72 years, and the mean age of caregivers was 59 years.

The caregivers were randomly assigned either to the symptom care by phone (SCP) system or to usual care. The SCP system is an automated system in which caregivers phone in to report the patient’s symptoms and their own levels of stress, anxiety, etc., and receive automated responses based on the severity of symptoms and number of days reported without relief. The system offers both patient care and self-care strategies, and identifies and reinforces issues that should be addressed by contacting the hospice team. At the end of the call, the data are sent to the nurse, including alerts to matters that require prompt attention.

Caregivers in each group made daily automated monitoring calls to report 1 or more of 11 patient symptoms and 5 caregiver symptoms on a 0-10 scale, and to report the patient’s and their own distress about the symptoms.

“We have developed algorithms to provide just-in-time, tailored suggestions related to the pattern that they have reported,” Dr. Mooney said.

Data reported by caregivers in the control (usual care) group were recorded but not acted upon, whereas data reported by those in the SCP intervention group triggered the automated coaching and hospice nurse alerts for moderate to severe symptoms.

“People in the usual care group understood that they were just contributing symptom information, and they were told on every call and at consent that if they had any concerns to call their hospice nurse,” Dr. Mooney said.

For clinicians, the automated system triggers an alert at preset thresholds of severity (4-10), as well as trend alerts. Hospice nurses have online and mobile access to the alert website, where they can view a report of symptoms over the previous 24 hours, and review graphs of symptoms over time to see trends. The nurses were instructed to log that they had seen the alert and what their planned action was, which was left to their professional judgment.

The average length of the calls was 7 minutes, 4 seconds for the usual care group, and 7 minutes, 59 seconds for the intervention group. Control group caregivers completed 59% of expected calls, and those in the intervention group completed 64%.

Reported symptoms present in more than 50% of patients included fatigue (88.8%), pain (60.2%), eating/drinking problems (76.6%), difficulty thinking (69.6%), anxiety (67.6%), negative mood (67.3%), bowel problems (61%), and trouble sleeping (58.3%).

Among caregivers, 73.3% reported fatigue, 66.7% anxiety, 61% trouble sleeping, and 57.1% negative mood.

In a mixed-effects model looking at caregiver vitality – a composite of caregiver symptoms – the authors found that the severity of symptoms in the usual care group increased steadily over the course of hospice care, out to at least 91 days. In contrast, the severity of symptoms among caregivers in the SCP group rose only slightly. The between-group difference was significant (P < .001).

Similarly, among patients the overall symptom severity scores were lower for those in the intervention group than for controls (P =.03). Additionally, the onset of benefit, defined as time to the first symptom-free day, was significantly earlier among patients in the SCP group (P < .02)

Patterns of patient and fatigue during the last 8 weeks of life also favored the symptom-care intervention, Dr. Mooney noted.`

Invited discussant Dr. Michael H. Levy, vice chair of medical oncology and director of the pain and palliative care program at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, commented that the SCP system “is interesting, but it’s very expensive, the impact is limited, and it’s challenging to export.”

He noted that for a palliative care support system to be implemented successfully, it would need to be reproducible and applicable to a wide range of health care systems.

The symposium was cosponsored by AAHPM, ASCO, ASTRO, and MASCC.

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Mooney and Dr. Levy reported having no relevant disclosures.

Key clinical point: An automated symptoms-reporting system lowered the burden of symptoms for patients in home hospice and their caregivers.

Major finding: Caregiver vitality, a composite of caregiver symptoms, was significantly better among those assigned to the intervention.

Data source: Prospective randomized trial in 319 patient-caregiver dyads from 12 hospices in four states.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Mooney and Dr. Levy reported having no relevant disclosures.

The dilemma of using drugs of questionable benefit

Recently, an article in JAMA Internal Medicine suggested that more than 50% of nursing home patients with advanced dementia are on “medications of questionable benefit.” The study went on to define those drugs as memantine, cholinesterase inhibitors, and statins.

Shocker, huh?

“Questionable benefit” is in the eyes of the beholder. Two of the above drugs have FDA indications for advanced dementia (statins for dyslipidemia), so you could argue there’s nothing “questionable” about it. The FDA says we can do it, so we will.

Right, but we all use drugs off label in this business without hesitation. So why should we think twice about using them on label?

It’s a valid point. Why do we prescribe these drugs to advanced dementia patients? How many of you have actually seen meaningful clinical benefit with them in this group, not just graphed points on a detail piece?

I use them, too, but I try to lower expectations with patients and their families. If all they see are direct-to-consumer ads, they’ll think this is a cure. Nope.

The fact is that the best we can do today is to slow progression ... somewhat. So if they’re already in end-stage disease, why bother? At some point, trying to keep these patients alive becomes more of an emotional torture for their families. All of us have seen these patients. How many of us want to live like that? I’m going to say none.

So, if their use in this population is “questionable,” I have to question why we do it at all.

This is where medicine gets hazy. On one side are those who claim that anyone with end-stage dementia should be treated with comfort care only. On the other are those who argue we need to do everything possible to keep them alive (usually politicians, not doctors). But most people are in a gray middle.

There’s also a big difference between what we can do and what we should do. This point, unfortunately, is often lost in the complex web of patient care. Advanced dementia patient = memantine + cholinesterase inhibitor. Medicine becomes a flowchart rather than a thinking specialty.

Then there’s the families. None of us wants to destroy hope. So we go with “Well, let’s try this medicine and see what happens.” It is, admittedly, easier than saying “I have nothing that will make a meaningful difference.” People see these advertised and want to believe these magical drugs will fix what ails grandma.

There’s also nursing staff, leaving Post-It notes on the chart that say “Patient has Alzheimer’s disease. Do you want to start Aricept?” I see that here and there, too. I think most of us okay it, because it’s easier than saying “What’s the point?”

Hiding in the background is, lastly, the specter of a malpractice suit. Even if the patient is beyond you making them worse, there’s always another neurologist out there willing to testify (for a fee) that by not prescribing these drugs, you fell beneath the standard of care.

The practice of using these drugs in end-stage dementia is indeed questionable. But the possible answers, and the dilemmas they put us in, often lead to doing what’s possible instead of simply necessary.

And when that happens, the only ones who benefit are the legal profession and drug companies.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Recently, an article in JAMA Internal Medicine suggested that more than 50% of nursing home patients with advanced dementia are on “medications of questionable benefit.” The study went on to define those drugs as memantine, cholinesterase inhibitors, and statins.

Shocker, huh?

“Questionable benefit” is in the eyes of the beholder. Two of the above drugs have FDA indications for advanced dementia (statins for dyslipidemia), so you could argue there’s nothing “questionable” about it. The FDA says we can do it, so we will.

Right, but we all use drugs off label in this business without hesitation. So why should we think twice about using them on label?

It’s a valid point. Why do we prescribe these drugs to advanced dementia patients? How many of you have actually seen meaningful clinical benefit with them in this group, not just graphed points on a detail piece?

I use them, too, but I try to lower expectations with patients and their families. If all they see are direct-to-consumer ads, they’ll think this is a cure. Nope.

The fact is that the best we can do today is to slow progression ... somewhat. So if they’re already in end-stage disease, why bother? At some point, trying to keep these patients alive becomes more of an emotional torture for their families. All of us have seen these patients. How many of us want to live like that? I’m going to say none.

So, if their use in this population is “questionable,” I have to question why we do it at all.

This is where medicine gets hazy. On one side are those who claim that anyone with end-stage dementia should be treated with comfort care only. On the other are those who argue we need to do everything possible to keep them alive (usually politicians, not doctors). But most people are in a gray middle.

There’s also a big difference between what we can do and what we should do. This point, unfortunately, is often lost in the complex web of patient care. Advanced dementia patient = memantine + cholinesterase inhibitor. Medicine becomes a flowchart rather than a thinking specialty.

Then there’s the families. None of us wants to destroy hope. So we go with “Well, let’s try this medicine and see what happens.” It is, admittedly, easier than saying “I have nothing that will make a meaningful difference.” People see these advertised and want to believe these magical drugs will fix what ails grandma.

There’s also nursing staff, leaving Post-It notes on the chart that say “Patient has Alzheimer’s disease. Do you want to start Aricept?” I see that here and there, too. I think most of us okay it, because it’s easier than saying “What’s the point?”

Hiding in the background is, lastly, the specter of a malpractice suit. Even if the patient is beyond you making them worse, there’s always another neurologist out there willing to testify (for a fee) that by not prescribing these drugs, you fell beneath the standard of care.

The practice of using these drugs in end-stage dementia is indeed questionable. But the possible answers, and the dilemmas they put us in, often lead to doing what’s possible instead of simply necessary.

And when that happens, the only ones who benefit are the legal profession and drug companies.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Recently, an article in JAMA Internal Medicine suggested that more than 50% of nursing home patients with advanced dementia are on “medications of questionable benefit.” The study went on to define those drugs as memantine, cholinesterase inhibitors, and statins.

Shocker, huh?

“Questionable benefit” is in the eyes of the beholder. Two of the above drugs have FDA indications for advanced dementia (statins for dyslipidemia), so you could argue there’s nothing “questionable” about it. The FDA says we can do it, so we will.

Right, but we all use drugs off label in this business without hesitation. So why should we think twice about using them on label?

It’s a valid point. Why do we prescribe these drugs to advanced dementia patients? How many of you have actually seen meaningful clinical benefit with them in this group, not just graphed points on a detail piece?

I use them, too, but I try to lower expectations with patients and their families. If all they see are direct-to-consumer ads, they’ll think this is a cure. Nope.

The fact is that the best we can do today is to slow progression ... somewhat. So if they’re already in end-stage disease, why bother? At some point, trying to keep these patients alive becomes more of an emotional torture for their families. All of us have seen these patients. How many of us want to live like that? I’m going to say none.

So, if their use in this population is “questionable,” I have to question why we do it at all.

This is where medicine gets hazy. On one side are those who claim that anyone with end-stage dementia should be treated with comfort care only. On the other are those who argue we need to do everything possible to keep them alive (usually politicians, not doctors). But most people are in a gray middle.

There’s also a big difference between what we can do and what we should do. This point, unfortunately, is often lost in the complex web of patient care. Advanced dementia patient = memantine + cholinesterase inhibitor. Medicine becomes a flowchart rather than a thinking specialty.

Then there’s the families. None of us wants to destroy hope. So we go with “Well, let’s try this medicine and see what happens.” It is, admittedly, easier than saying “I have nothing that will make a meaningful difference.” People see these advertised and want to believe these magical drugs will fix what ails grandma.

There’s also nursing staff, leaving Post-It notes on the chart that say “Patient has Alzheimer’s disease. Do you want to start Aricept?” I see that here and there, too. I think most of us okay it, because it’s easier than saying “What’s the point?”

Hiding in the background is, lastly, the specter of a malpractice suit. Even if the patient is beyond you making them worse, there’s always another neurologist out there willing to testify (for a fee) that by not prescribing these drugs, you fell beneath the standard of care.

The practice of using these drugs in end-stage dementia is indeed questionable. But the possible answers, and the dilemmas they put us in, often lead to doing what’s possible instead of simply necessary.

And when that happens, the only ones who benefit are the legal profession and drug companies.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Assessing and Addressing Psychosocial Distress in Veterans Living With Cancer

A multidisciplinary group of content experts from the New Mexico VA Health Care System explored the current state of cancer-related psychosocial distress and developed a standardized process to improve assessment and access to cancer related distress care. The DISTRESS (Distress Initial Survivorship Tool Recommended Evaluation through Surgical Service) system was developed and incorporated into the CPRS Cancer Survivorship Care Plan, creating permanent data within the medical record.

"Over 700 veterans at the Albuquerque VA have prostate cancer and no one was monitoring them consistently," Janice Schwartz, RN, OCN, said. "We designed a tool so veterans can come in, see their physician, and manditorily be assessed."

To learn more, watch the video or read the full abstract from Schwartz's poster presentation.

A multidisciplinary group of content experts from the New Mexico VA Health Care System explored the current state of cancer-related psychosocial distress and developed a standardized process to improve assessment and access to cancer related distress care. The DISTRESS (Distress Initial Survivorship Tool Recommended Evaluation through Surgical Service) system was developed and incorporated into the CPRS Cancer Survivorship Care Plan, creating permanent data within the medical record.

"Over 700 veterans at the Albuquerque VA have prostate cancer and no one was monitoring them consistently," Janice Schwartz, RN, OCN, said. "We designed a tool so veterans can come in, see their physician, and manditorily be assessed."

To learn more, watch the video or read the full abstract from Schwartz's poster presentation.

A multidisciplinary group of content experts from the New Mexico VA Health Care System explored the current state of cancer-related psychosocial distress and developed a standardized process to improve assessment and access to cancer related distress care. The DISTRESS (Distress Initial Survivorship Tool Recommended Evaluation through Surgical Service) system was developed and incorporated into the CPRS Cancer Survivorship Care Plan, creating permanent data within the medical record.

"Over 700 veterans at the Albuquerque VA have prostate cancer and no one was monitoring them consistently," Janice Schwartz, RN, OCN, said. "We designed a tool so veterans can come in, see their physician, and manditorily be assessed."

To learn more, watch the video or read the full abstract from Schwartz's poster presentation.

Psychiatrists embrace growing role in palliative care

Palliative care often involves the treatment of depression and anxiety, along with pain relief and managing lack of appetite, areas that are familiar ground for psychiatrists.

So are psychiatrists a natural addition to the palliative care team? Dr. Dean Schuyler of Charleston, S.C., says yes.

For the last 4 years, Dr. Schuyler has worked alongside three internists, a social worker, a chaplain, and other providers, as part of the palliative care team working at the Ralph H. Johnson Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Charleston. He uses cognitive therapy to counsel patients at the VA’s attached community living center, where many patients receive end-of-life care, as well as the medical center’s oncology and geriatric clinics.

When talking to patients at the end of life, Dr. Schuyler focuses on their mindset. For instance, when he visits with veterans with a terminal diagnosis, he always asks them about their plans. The answer, for most patients, is “I’m here to die.” But a week later, after meeting with a recreational therapist, patients typically have a plan, whether it’s a project with woodworking, or art, or writing.

Sometime during that week, the patient’s mindset changes, Dr. Schuyler said.

“It seems sort of obvious to me that cognitive therapy would have a role here. If you deal with their thoughts, can you help them? I think that applying this theory to these patients at this point makes an enormous amount of sense,” he said.

But Dr. Schuyler said engaging patients at the end of life can be accomplished in many ways. For instance, Dr. William S. Breitbart of Memorial Sloan Kettering in New York has written about a model of meaning-centered group psychotherapy that can help patients at the end of life. And Dr. Harvey Max Chochinov of the University of Manitoba has advanced the concept of dignity therapy.

While Dr. Schuyler’s role was unusual 4 years ago, the role for psychiatrists in palliative care is expanding today.

Dr. Scott A. Irwin, director of palliative care psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego Health System, said there is a range of ways for psychiatrists to be involved in palliative care. Some psychiatrists work as consultants to a palliative care team, providing expertise on the psychosocial elements of care. A smaller number of psychiatrists are embedded within front-line teams.

Dr. Irwin said he sees embedding psychiatrists as the most-effective model, because this approach gives the care team a well-rounded range of knowledge, with experts on physical symptom control and in psychosocial areas. For some patients, the psychiatrist’s role will be small, but it’s important to have someone there to make differential diagnoses that distinguish between normal reactions and those needing higher-level intervention, such as a patient with normal grief vs. major clinical depression, he said.

“By being part of the team, I make the palliative care clinicians better, and they make me better,” said Dr. Irwin, who also serves as director of patient and family support services at the the university’s Moores Cancer Center. “And the patient care, which is the focus, is better than it could be if we were just working in parallel.”

But some obstacles lie within the embedded model. For example, Dr. Irwin said, even though a growing number of psychiatrists are interested in getting involved, they sometimes get pushback from the specialists on the palliative care team. At the same time, he has heard from palliative care physicians who say they want to add psychiatrists to the team but can’t find anyone with the time or interest to do it.

Despite those challenges, Dr. Irwin is optimistic that psychiatry will have an expanded role in palliative care.

One reason is that addressing psychiatric needs through palliative care can help hospitals reduce costs for some of their most complex patients by reducing unnecessary readmissions, trips to emergency departments, and decreasing lengths of stay in the hospital.

“If we continue down this path toward quality measures and the value equation, we’ll see this more and more, because palliative care and psychiatric care, separately and together, are a huge part of increasing quality while decreasing costs for health care,” Dr. Irwin said.

Another factor that could increase the prevalence of psychiatry in palliative care is board certification, said Dr. Maria I. Lapid, a geriatric psychiatrist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

Dr. Lapid, who is board certified in hospice and palliative medicine through the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology, said the availability of board certification probably will push psychiatrists to play a bigger role in providing palliative care. In all, 10 boards under the umbrella of the American Board of Medical Specialties offer some form of hospice and palliative medicine certification, which she said will contribute to making palliative care “truly interdisciplinary.”

For hospitals that want to add psychiatry to their palliative care services but are being stymied by the workforce shortage, other options, such as telepsychiatry, are available, said Dr. Andrew E. Esch, an internist and palliative care specialist in Tampa, Fla., and a consultant with the Center to Advance Palliative Care.

When Dr. Esch was the medical director for the palliative care program at Lee Memorial Health System in Fort Myers, Fla., the system didn’t have the funding to recruit and hire a psychiatrist for the palliative care program, even if one could have been found. So Lee Memorial partnered with the psycho-oncologists at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. For a set fee, Lee Memorial was able to call Massachusetts General about difficult patients and get real-time consults.

“I think there’s going to be a lot of opportunities for innovation in the future,” Dr. Esch said.

Palliative care often involves the treatment of depression and anxiety, along with pain relief and managing lack of appetite, areas that are familiar ground for psychiatrists.

So are psychiatrists a natural addition to the palliative care team? Dr. Dean Schuyler of Charleston, S.C., says yes.