User login

Phase 3 COVID-19 vaccine trials launching in July, expert says

The race to develop a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is unlike any other global research and development effort in modern medicine.

According to Paul A. Offit, MD, there are now 120 Investigational New Drug applications to the Food and Drug Administration for these vaccines, and researchers at more than 70 companies across the globe are interested in making a vaccine. The Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) has awarded $2.5 billion to five different pharmaceutical companies to make a vaccine.

“The good news is that the new coronavirus is relatively stable,” Dr. Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said during the virtual Pediatric Dermatology 2020: Best Practices and Innovations Conference. “Although it is a single-stranded RNA virus, it does mutate to some extent, but it doesn’t look like it’s going to mutate away from the vaccine. So, this is not going to be like influenza virus, where you must give a vaccine every year. I think we can make a vaccine that will last for several years. And we know the protein we’re interested in. We’re interested in antibodies directed against the spike glycoprotein, which is abundantly present on the surface of the virus. We know that if we make an antibody response to that protein, we can therefore prevent infection.”

Some research groups are interested in developing a whole, killed virus like those used in the inactivated polio vaccine, and vaccines for hepatitis A virus and rabies, said Dr. Offit, who is a member of Accelerating COVID-19 Technical Innovations And Vaccines, a public-private partnership formed by the National Institutes of Health. Other groups are interested in making a live-attenuated vaccine like those for measles, mumps, and rubella. “Some are interested in using a vectored vaccine, where you take a virus that is relatively weak and doesn’t cause disease in people, like vesicular stomatitis virus, and then clone into that the gene that codes for this coronavirus spike protein, which is the way that we made the Ebola virus vaccine,” Dr. Offit said. “Those approaches have all been used before, with success.”

Novel approaches are also being employed to make this vaccine, including using a replication-defective adenovirus. “That means that the virus can’t reproduce itself, but it can make proteins,” he explained. “There are some proteins that are made, but most aren’t. Therefore, the virus can’t reproduce itself. We’ll see whether or not that [approach] works, but it’s never been used before.”

Another approach is to inject messenger RNA that codes for the coronavirus spike protein, where that genetic material is translated into the spike protein. The other platform being evaluated is a DNA vaccine, in which “you give DNA which is coded for that spike protein, which is transcribed to messenger RNA and then is translated to other proteins.”

Typical vaccine development involves animal models to prove the concept, dose-ranging studies in humans, and progressively larger safety and immunogenicity studies in hundreds of thousands of people. Next come phase 3 studies, “where the proof is in the pudding,” he said. “These are large, prospective placebo-controlled trials to prove that the vaccine is safe. This is the only way whether you can prove or not a vaccine is effective.”

“Some companies may branch out on their own and do smaller studies than that,” he said. “We’ll see how this plays out. Keep your eyes open for that, because you really want to make sure you have a fairly large phase 3 trial. That’s the best way to show whether something works and whether it’s safe.”

The tried and true vaccines that emerge from the effort will not be FDA-licensed products. Rather, they will be approved products under the Emergency Use Authorization program. “Ever since the 1950s, every vaccine that has been used in the U.S. has been under the auspices of FDA licensure,” said Dr. Offit, who is also professor of pediatrics and the Maurice R. Hilleman professor of vaccinology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “That’s not going to be true here. The FDA is involved every step of the way but here they have a somewhat lighter touch.”

A few candidate vaccines are being mass-produced at risk, “meaning they’re being produced not knowing whether these vaccines are safe and effective yet or not,” he said. “But when they’re shown in a phase 3 trial to be safe and effective, you will have already produced it, and then it’s much easier to roll it out to the general public the minute you’ve shown that it works. This is what we did for the polio vaccine back in the 1950s. We mass-produced that vaccine at risk.”

Dr. Offit emphasized the importance of managing expectations once a COVID-19 vaccine gets approved for use. “Regarding safety, these vaccines will be tested in tens of thousands of people, not tens of millions of people, so although you can disprove a relatively uncommon side effect preapproval, you’re not going to disprove a rare side effect preapproval. You’re only going to know that post approval. I think we need to make people aware of that and to let them know that through groups like the Vaccine Safety Datalink, we’re going to be monitoring these vaccines once they’re approved.”

Regarding efficacy, he continued, “we’re not going know about the rates of immunity initially; we’re only going to know about that after the vaccine [has been administered]. My guess is the protection is going to be short lived and incomplete. By short lived, I mean that protection would last for years but not decades. By incomplete, I mean that protection will be against moderate to severe disease, which is fine. You don’t need protection against all of the disease; it’s hard to do that with respiratory viruses. That means you can keep people out of the hospital, and you can keep them from dying. That’s the main goal.”

Dr. Offit closed his remarks by noting that much is at stake in this effort to develop a vaccine so quickly and that it “could go one of two ways. We could find that the vaccine is a lifesaver, and [that] we can finally end this awful pandemic. Or, if we cut corners and don’t prove that the vaccines are safe and effective as we should before they’re released, we could shake what is a fragile vaccine confidence in this country. Hopefully, it doesn’t play out that way.”

The race to develop a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is unlike any other global research and development effort in modern medicine.

According to Paul A. Offit, MD, there are now 120 Investigational New Drug applications to the Food and Drug Administration for these vaccines, and researchers at more than 70 companies across the globe are interested in making a vaccine. The Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) has awarded $2.5 billion to five different pharmaceutical companies to make a vaccine.

“The good news is that the new coronavirus is relatively stable,” Dr. Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said during the virtual Pediatric Dermatology 2020: Best Practices and Innovations Conference. “Although it is a single-stranded RNA virus, it does mutate to some extent, but it doesn’t look like it’s going to mutate away from the vaccine. So, this is not going to be like influenza virus, where you must give a vaccine every year. I think we can make a vaccine that will last for several years. And we know the protein we’re interested in. We’re interested in antibodies directed against the spike glycoprotein, which is abundantly present on the surface of the virus. We know that if we make an antibody response to that protein, we can therefore prevent infection.”

Some research groups are interested in developing a whole, killed virus like those used in the inactivated polio vaccine, and vaccines for hepatitis A virus and rabies, said Dr. Offit, who is a member of Accelerating COVID-19 Technical Innovations And Vaccines, a public-private partnership formed by the National Institutes of Health. Other groups are interested in making a live-attenuated vaccine like those for measles, mumps, and rubella. “Some are interested in using a vectored vaccine, where you take a virus that is relatively weak and doesn’t cause disease in people, like vesicular stomatitis virus, and then clone into that the gene that codes for this coronavirus spike protein, which is the way that we made the Ebola virus vaccine,” Dr. Offit said. “Those approaches have all been used before, with success.”

Novel approaches are also being employed to make this vaccine, including using a replication-defective adenovirus. “That means that the virus can’t reproduce itself, but it can make proteins,” he explained. “There are some proteins that are made, but most aren’t. Therefore, the virus can’t reproduce itself. We’ll see whether or not that [approach] works, but it’s never been used before.”

Another approach is to inject messenger RNA that codes for the coronavirus spike protein, where that genetic material is translated into the spike protein. The other platform being evaluated is a DNA vaccine, in which “you give DNA which is coded for that spike protein, which is transcribed to messenger RNA and then is translated to other proteins.”

Typical vaccine development involves animal models to prove the concept, dose-ranging studies in humans, and progressively larger safety and immunogenicity studies in hundreds of thousands of people. Next come phase 3 studies, “where the proof is in the pudding,” he said. “These are large, prospective placebo-controlled trials to prove that the vaccine is safe. This is the only way whether you can prove or not a vaccine is effective.”

“Some companies may branch out on their own and do smaller studies than that,” he said. “We’ll see how this plays out. Keep your eyes open for that, because you really want to make sure you have a fairly large phase 3 trial. That’s the best way to show whether something works and whether it’s safe.”

The tried and true vaccines that emerge from the effort will not be FDA-licensed products. Rather, they will be approved products under the Emergency Use Authorization program. “Ever since the 1950s, every vaccine that has been used in the U.S. has been under the auspices of FDA licensure,” said Dr. Offit, who is also professor of pediatrics and the Maurice R. Hilleman professor of vaccinology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “That’s not going to be true here. The FDA is involved every step of the way but here they have a somewhat lighter touch.”

A few candidate vaccines are being mass-produced at risk, “meaning they’re being produced not knowing whether these vaccines are safe and effective yet or not,” he said. “But when they’re shown in a phase 3 trial to be safe and effective, you will have already produced it, and then it’s much easier to roll it out to the general public the minute you’ve shown that it works. This is what we did for the polio vaccine back in the 1950s. We mass-produced that vaccine at risk.”

Dr. Offit emphasized the importance of managing expectations once a COVID-19 vaccine gets approved for use. “Regarding safety, these vaccines will be tested in tens of thousands of people, not tens of millions of people, so although you can disprove a relatively uncommon side effect preapproval, you’re not going to disprove a rare side effect preapproval. You’re only going to know that post approval. I think we need to make people aware of that and to let them know that through groups like the Vaccine Safety Datalink, we’re going to be monitoring these vaccines once they’re approved.”

Regarding efficacy, he continued, “we’re not going know about the rates of immunity initially; we’re only going to know about that after the vaccine [has been administered]. My guess is the protection is going to be short lived and incomplete. By short lived, I mean that protection would last for years but not decades. By incomplete, I mean that protection will be against moderate to severe disease, which is fine. You don’t need protection against all of the disease; it’s hard to do that with respiratory viruses. That means you can keep people out of the hospital, and you can keep them from dying. That’s the main goal.”

Dr. Offit closed his remarks by noting that much is at stake in this effort to develop a vaccine so quickly and that it “could go one of two ways. We could find that the vaccine is a lifesaver, and [that] we can finally end this awful pandemic. Or, if we cut corners and don’t prove that the vaccines are safe and effective as we should before they’re released, we could shake what is a fragile vaccine confidence in this country. Hopefully, it doesn’t play out that way.”

The race to develop a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is unlike any other global research and development effort in modern medicine.

According to Paul A. Offit, MD, there are now 120 Investigational New Drug applications to the Food and Drug Administration for these vaccines, and researchers at more than 70 companies across the globe are interested in making a vaccine. The Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) has awarded $2.5 billion to five different pharmaceutical companies to make a vaccine.

“The good news is that the new coronavirus is relatively stable,” Dr. Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said during the virtual Pediatric Dermatology 2020: Best Practices and Innovations Conference. “Although it is a single-stranded RNA virus, it does mutate to some extent, but it doesn’t look like it’s going to mutate away from the vaccine. So, this is not going to be like influenza virus, where you must give a vaccine every year. I think we can make a vaccine that will last for several years. And we know the protein we’re interested in. We’re interested in antibodies directed against the spike glycoprotein, which is abundantly present on the surface of the virus. We know that if we make an antibody response to that protein, we can therefore prevent infection.”

Some research groups are interested in developing a whole, killed virus like those used in the inactivated polio vaccine, and vaccines for hepatitis A virus and rabies, said Dr. Offit, who is a member of Accelerating COVID-19 Technical Innovations And Vaccines, a public-private partnership formed by the National Institutes of Health. Other groups are interested in making a live-attenuated vaccine like those for measles, mumps, and rubella. “Some are interested in using a vectored vaccine, where you take a virus that is relatively weak and doesn’t cause disease in people, like vesicular stomatitis virus, and then clone into that the gene that codes for this coronavirus spike protein, which is the way that we made the Ebola virus vaccine,” Dr. Offit said. “Those approaches have all been used before, with success.”

Novel approaches are also being employed to make this vaccine, including using a replication-defective adenovirus. “That means that the virus can’t reproduce itself, but it can make proteins,” he explained. “There are some proteins that are made, but most aren’t. Therefore, the virus can’t reproduce itself. We’ll see whether or not that [approach] works, but it’s never been used before.”

Another approach is to inject messenger RNA that codes for the coronavirus spike protein, where that genetic material is translated into the spike protein. The other platform being evaluated is a DNA vaccine, in which “you give DNA which is coded for that spike protein, which is transcribed to messenger RNA and then is translated to other proteins.”

Typical vaccine development involves animal models to prove the concept, dose-ranging studies in humans, and progressively larger safety and immunogenicity studies in hundreds of thousands of people. Next come phase 3 studies, “where the proof is in the pudding,” he said. “These are large, prospective placebo-controlled trials to prove that the vaccine is safe. This is the only way whether you can prove or not a vaccine is effective.”

“Some companies may branch out on their own and do smaller studies than that,” he said. “We’ll see how this plays out. Keep your eyes open for that, because you really want to make sure you have a fairly large phase 3 trial. That’s the best way to show whether something works and whether it’s safe.”

The tried and true vaccines that emerge from the effort will not be FDA-licensed products. Rather, they will be approved products under the Emergency Use Authorization program. “Ever since the 1950s, every vaccine that has been used in the U.S. has been under the auspices of FDA licensure,” said Dr. Offit, who is also professor of pediatrics and the Maurice R. Hilleman professor of vaccinology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “That’s not going to be true here. The FDA is involved every step of the way but here they have a somewhat lighter touch.”

A few candidate vaccines are being mass-produced at risk, “meaning they’re being produced not knowing whether these vaccines are safe and effective yet or not,” he said. “But when they’re shown in a phase 3 trial to be safe and effective, you will have already produced it, and then it’s much easier to roll it out to the general public the minute you’ve shown that it works. This is what we did for the polio vaccine back in the 1950s. We mass-produced that vaccine at risk.”

Dr. Offit emphasized the importance of managing expectations once a COVID-19 vaccine gets approved for use. “Regarding safety, these vaccines will be tested in tens of thousands of people, not tens of millions of people, so although you can disprove a relatively uncommon side effect preapproval, you’re not going to disprove a rare side effect preapproval. You’re only going to know that post approval. I think we need to make people aware of that and to let them know that through groups like the Vaccine Safety Datalink, we’re going to be monitoring these vaccines once they’re approved.”

Regarding efficacy, he continued, “we’re not going know about the rates of immunity initially; we’re only going to know about that after the vaccine [has been administered]. My guess is the protection is going to be short lived and incomplete. By short lived, I mean that protection would last for years but not decades. By incomplete, I mean that protection will be against moderate to severe disease, which is fine. You don’t need protection against all of the disease; it’s hard to do that with respiratory viruses. That means you can keep people out of the hospital, and you can keep them from dying. That’s the main goal.”

Dr. Offit closed his remarks by noting that much is at stake in this effort to develop a vaccine so quickly and that it “could go one of two ways. We could find that the vaccine is a lifesaver, and [that] we can finally end this awful pandemic. Or, if we cut corners and don’t prove that the vaccines are safe and effective as we should before they’re released, we could shake what is a fragile vaccine confidence in this country. Hopefully, it doesn’t play out that way.”

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY 2020

Daily Recap: Transgender patients turn to DIY treatments; ACIP plans priority vaccine groups

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

Ignored by doctors, transgender patients turn to DIY treatments

Without access to quality medical care, trans people around the world are seeking hormones from friends or through illegal online markets, even when the cost exceeds what it would through insurance. Although rare, others are resorting to self-surgery by cutting off their own penis and testicles or breasts.

Even with a doctor’s oversight, the health risks of transgender hormone therapy remain unclear, but without formal medical care, the do-it-yourself transition may be downright dangerous. To minimize these risks, some experts suggest health care reforms such as making it easier for primary care physicians to assess trans patients and prescribe hormones or creating specialized clinics where doctors prescribe hormones on demand.

Treating gender dysphoria should be just like treating a patient for any other condition. “It wouldn't be acceptable for someone to come into a primary care provider’s office with diabetes” and for the doctor to say “‘I can't actually treat you. Please leave,’” Zil Goldstein, associate medical director for transgender and gender non-binary health at the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center in New York City. Primary care providers need to see transgender care, she adds, “as a regular part of their practice.” Read more.

ACIP plans priority groups in advance of COVID-19 vaccine

Early plans for prioritizing vaccination when a COVID-19 vaccine becomes available include placing critical health care workers in the first tier, according to Sarah Mbaeyi, MD, MPH, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

A COVID-19 vaccine work group is developing strategies and identifying priority groups for vaccination to help inform discussions about the use of COVID-19 vaccines, Dr. Mbaeyi said at a virtual meeting of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

Based on current information, the work group has proposed that vaccine priority be given to health care personnel, essential workers, adults aged 65 years and older, long-term care facility residents, and persons with high-risk medical conditions.

Among these groups “a subset of critical health care and other workers should receive initial doses,” Dr. Mbaeyi said. Read more.

‘Nietzsche was wrong’: Past stressors do not create psychological resilience.

The famous quote from the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, “That which does not kill us makes us stronger,” may not be true after all – at least when it comes to mental health.

Results of a new study show that individuals who have a history of a stressful life events are more likely to develop PTSD and/or major depressive disorder (MDD) following a major natural disaster than their counterparts who do not have such a history.

The investigation of more than a thousand Chilean residents – all of whom experienced one of the most powerful earthquakes in the country’s history – showed that the odds of developing postdisaster PTSD or MDD increased according to the number of predisaster stressors participants had experienced.

“At the clinical level, these findings help the clinician know which patients are more likely to need more intensive services,” said Stephen L. Buka, PhD. “And the more trauma and hardship they’ve experienced, the more attention they need and the less likely they’re going to be able to cope and manage on their own.” Read more.

High-impact training can build bone in older women

Older adults, particularly postmenopausal women, are often advised to pursue low-impact, low-intensity exercise as a way to preserve joint health, but that approach might actually contribute to a decline in bone mineral density, researchers report.

Concerns about falls and fracture risk have led many clinicians to advise against higher-impact activities, like jumping, but that is exactly the type of activity that improves bone density and physical function, said Belinda Beck, PhD, professor at the Griffith University School of Allied Health Sciences in Southport, Australia. But new findings show that high-intensity resistance and impact training was a safe and effective way to improve bone mass.

“Once women hit 60, they’re somehow regarded as frail, but that becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy when we take this kinder, gentler approach to exercise,” said Vanessa Yingling, PhD. Read more.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

Ignored by doctors, transgender patients turn to DIY treatments

Without access to quality medical care, trans people around the world are seeking hormones from friends or through illegal online markets, even when the cost exceeds what it would through insurance. Although rare, others are resorting to self-surgery by cutting off their own penis and testicles or breasts.

Even with a doctor’s oversight, the health risks of transgender hormone therapy remain unclear, but without formal medical care, the do-it-yourself transition may be downright dangerous. To minimize these risks, some experts suggest health care reforms such as making it easier for primary care physicians to assess trans patients and prescribe hormones or creating specialized clinics where doctors prescribe hormones on demand.

Treating gender dysphoria should be just like treating a patient for any other condition. “It wouldn't be acceptable for someone to come into a primary care provider’s office with diabetes” and for the doctor to say “‘I can't actually treat you. Please leave,’” Zil Goldstein, associate medical director for transgender and gender non-binary health at the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center in New York City. Primary care providers need to see transgender care, she adds, “as a regular part of their practice.” Read more.

ACIP plans priority groups in advance of COVID-19 vaccine

Early plans for prioritizing vaccination when a COVID-19 vaccine becomes available include placing critical health care workers in the first tier, according to Sarah Mbaeyi, MD, MPH, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

A COVID-19 vaccine work group is developing strategies and identifying priority groups for vaccination to help inform discussions about the use of COVID-19 vaccines, Dr. Mbaeyi said at a virtual meeting of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

Based on current information, the work group has proposed that vaccine priority be given to health care personnel, essential workers, adults aged 65 years and older, long-term care facility residents, and persons with high-risk medical conditions.

Among these groups “a subset of critical health care and other workers should receive initial doses,” Dr. Mbaeyi said. Read more.

‘Nietzsche was wrong’: Past stressors do not create psychological resilience.

The famous quote from the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, “That which does not kill us makes us stronger,” may not be true after all – at least when it comes to mental health.

Results of a new study show that individuals who have a history of a stressful life events are more likely to develop PTSD and/or major depressive disorder (MDD) following a major natural disaster than their counterparts who do not have such a history.

The investigation of more than a thousand Chilean residents – all of whom experienced one of the most powerful earthquakes in the country’s history – showed that the odds of developing postdisaster PTSD or MDD increased according to the number of predisaster stressors participants had experienced.

“At the clinical level, these findings help the clinician know which patients are more likely to need more intensive services,” said Stephen L. Buka, PhD. “And the more trauma and hardship they’ve experienced, the more attention they need and the less likely they’re going to be able to cope and manage on their own.” Read more.

High-impact training can build bone in older women

Older adults, particularly postmenopausal women, are often advised to pursue low-impact, low-intensity exercise as a way to preserve joint health, but that approach might actually contribute to a decline in bone mineral density, researchers report.

Concerns about falls and fracture risk have led many clinicians to advise against higher-impact activities, like jumping, but that is exactly the type of activity that improves bone density and physical function, said Belinda Beck, PhD, professor at the Griffith University School of Allied Health Sciences in Southport, Australia. But new findings show that high-intensity resistance and impact training was a safe and effective way to improve bone mass.

“Once women hit 60, they’re somehow regarded as frail, but that becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy when we take this kinder, gentler approach to exercise,” said Vanessa Yingling, PhD. Read more.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

Ignored by doctors, transgender patients turn to DIY treatments

Without access to quality medical care, trans people around the world are seeking hormones from friends or through illegal online markets, even when the cost exceeds what it would through insurance. Although rare, others are resorting to self-surgery by cutting off their own penis and testicles or breasts.

Even with a doctor’s oversight, the health risks of transgender hormone therapy remain unclear, but without formal medical care, the do-it-yourself transition may be downright dangerous. To minimize these risks, some experts suggest health care reforms such as making it easier for primary care physicians to assess trans patients and prescribe hormones or creating specialized clinics where doctors prescribe hormones on demand.

Treating gender dysphoria should be just like treating a patient for any other condition. “It wouldn't be acceptable for someone to come into a primary care provider’s office with diabetes” and for the doctor to say “‘I can't actually treat you. Please leave,’” Zil Goldstein, associate medical director for transgender and gender non-binary health at the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center in New York City. Primary care providers need to see transgender care, she adds, “as a regular part of their practice.” Read more.

ACIP plans priority groups in advance of COVID-19 vaccine

Early plans for prioritizing vaccination when a COVID-19 vaccine becomes available include placing critical health care workers in the first tier, according to Sarah Mbaeyi, MD, MPH, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

A COVID-19 vaccine work group is developing strategies and identifying priority groups for vaccination to help inform discussions about the use of COVID-19 vaccines, Dr. Mbaeyi said at a virtual meeting of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

Based on current information, the work group has proposed that vaccine priority be given to health care personnel, essential workers, adults aged 65 years and older, long-term care facility residents, and persons with high-risk medical conditions.

Among these groups “a subset of critical health care and other workers should receive initial doses,” Dr. Mbaeyi said. Read more.

‘Nietzsche was wrong’: Past stressors do not create psychological resilience.

The famous quote from the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, “That which does not kill us makes us stronger,” may not be true after all – at least when it comes to mental health.

Results of a new study show that individuals who have a history of a stressful life events are more likely to develop PTSD and/or major depressive disorder (MDD) following a major natural disaster than their counterparts who do not have such a history.

The investigation of more than a thousand Chilean residents – all of whom experienced one of the most powerful earthquakes in the country’s history – showed that the odds of developing postdisaster PTSD or MDD increased according to the number of predisaster stressors participants had experienced.

“At the clinical level, these findings help the clinician know which patients are more likely to need more intensive services,” said Stephen L. Buka, PhD. “And the more trauma and hardship they’ve experienced, the more attention they need and the less likely they’re going to be able to cope and manage on their own.” Read more.

High-impact training can build bone in older women

Older adults, particularly postmenopausal women, are often advised to pursue low-impact, low-intensity exercise as a way to preserve joint health, but that approach might actually contribute to a decline in bone mineral density, researchers report.

Concerns about falls and fracture risk have led many clinicians to advise against higher-impact activities, like jumping, but that is exactly the type of activity that improves bone density and physical function, said Belinda Beck, PhD, professor at the Griffith University School of Allied Health Sciences in Southport, Australia. But new findings show that high-intensity resistance and impact training was a safe and effective way to improve bone mass.

“Once women hit 60, they’re somehow regarded as frail, but that becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy when we take this kinder, gentler approach to exercise,” said Vanessa Yingling, PhD. Read more.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Don't Let the Bedbugs Bite: An Unusual Presentation of Bedbug Infestation Resulting in Life-Threatening Anemia

To the Editor:

A 61-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a rash on the right leg, generalized pruritus, and chest pain. The patient described intermittent exertional pressure-like chest pain over the last few days but had no known prior cardiac history. He also noted worsening edema of the right leg with erythema. Three months prior he had been hospitalized for a similar presentation and was diagnosed with cellulitis of the right leg. The patient was treated with a course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and permethrin cream for presumed scabies and followed up with dermatology for the persistent generalized pruritic rash and cellulitis. At that time, he was diagnosed with stasis dermatitis with dermatitis neglecta and excoriations. He was educated on general hygiene and treated with triamcinolone, hydrophilic ointment, and pramoxine lotion for pruritus. He also was empirically treated again for scabies.

At the current presentation, preliminary investigation showed profound anemia with a hemoglobin level of 6.2 g/dL (baseline hemoglobin level 3 months prior, 13.1 g/dL). He was subsequently admitted to the general medicine ward for further investigation of severe symptomatic anemia. A medical history revealed moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, xerosis, and fracture of the right ankle following open reduction internal fixation 6 years prior to admission. There was no history of blood loss, antiplatelet agents, or anticoagulants. He was on disability and lived in a single-room occupancy hotel. He did not report any high-risk sexual behaviors or abuse of alcohol or drugs. He actively smoked 1.5 packs of cigarettes per day for the last 30 years. He denied any allergies.

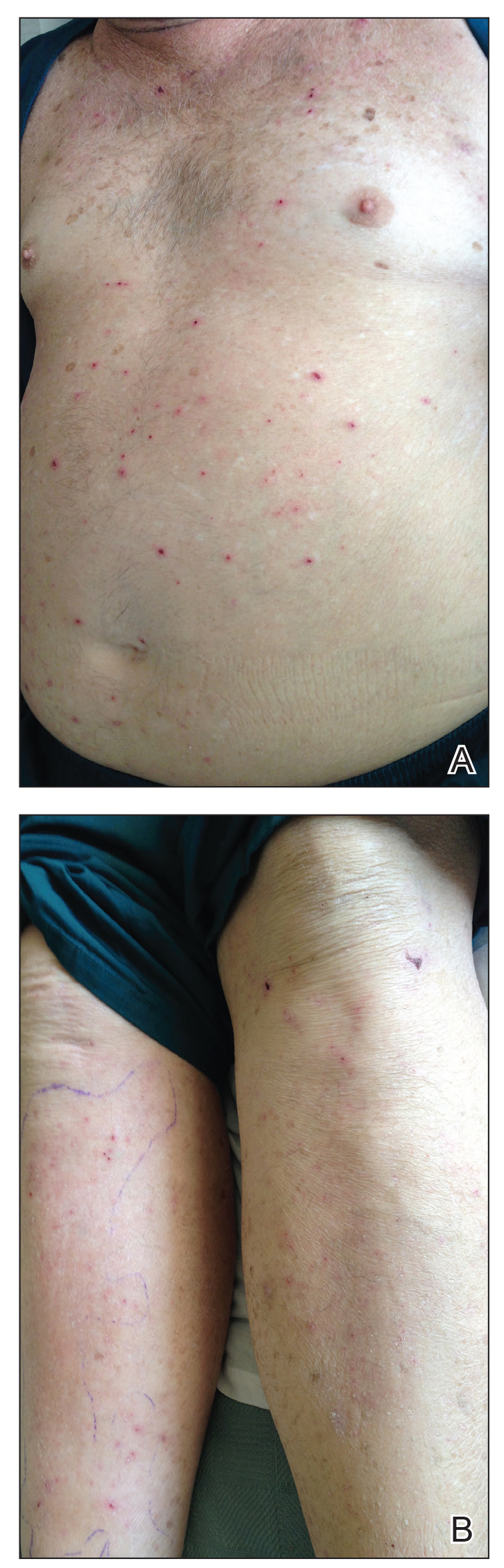

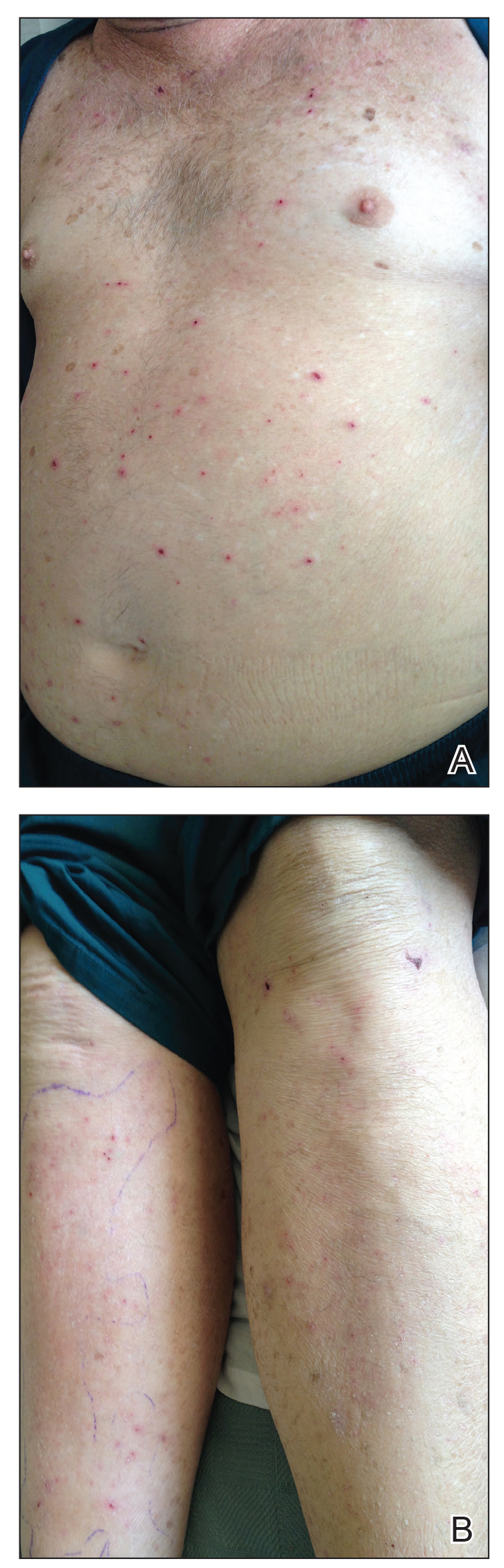

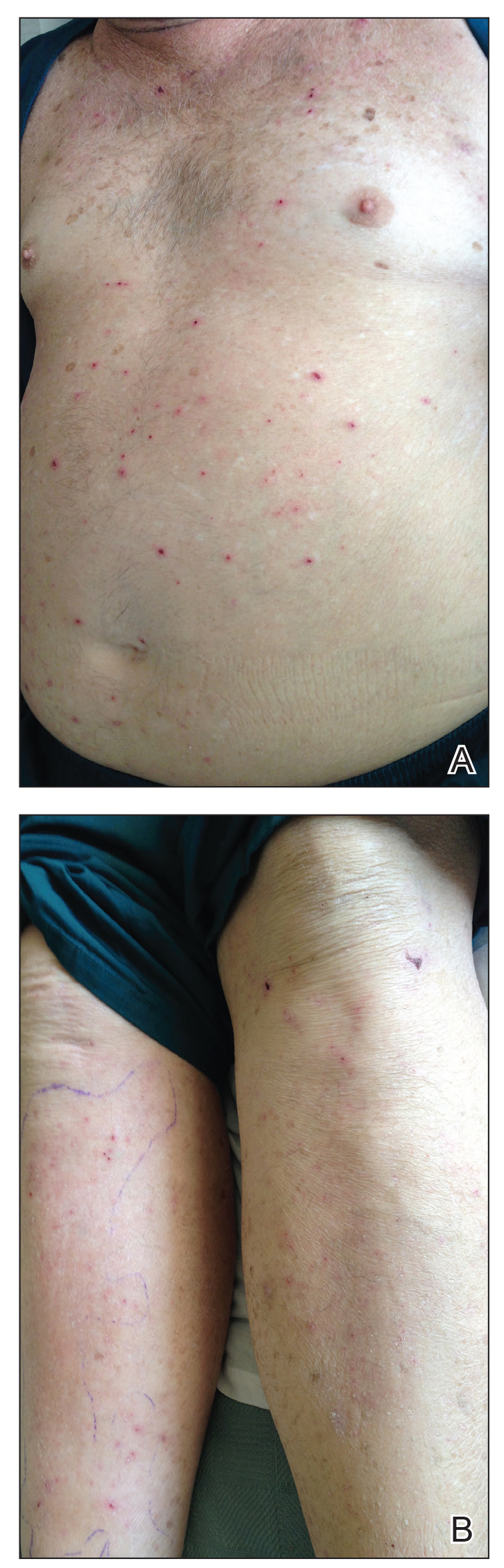

Physical examination revealed the patient was afebrile, nontoxic, disheveled, and in no acute distress. He had anicteric sclera and pale conjunctiva. The right leg appeared more erythematous and edematous compared to the left leg but without warmth or tenderness to palpation. He had innumerable 4- to 5-mm, erythematous, excoriated papules on the skin (Figure). His bed sheets were noted to have multiple rusty-black specks thought to be related to the crusted lesions. Physical examination was otherwise unremarkable.

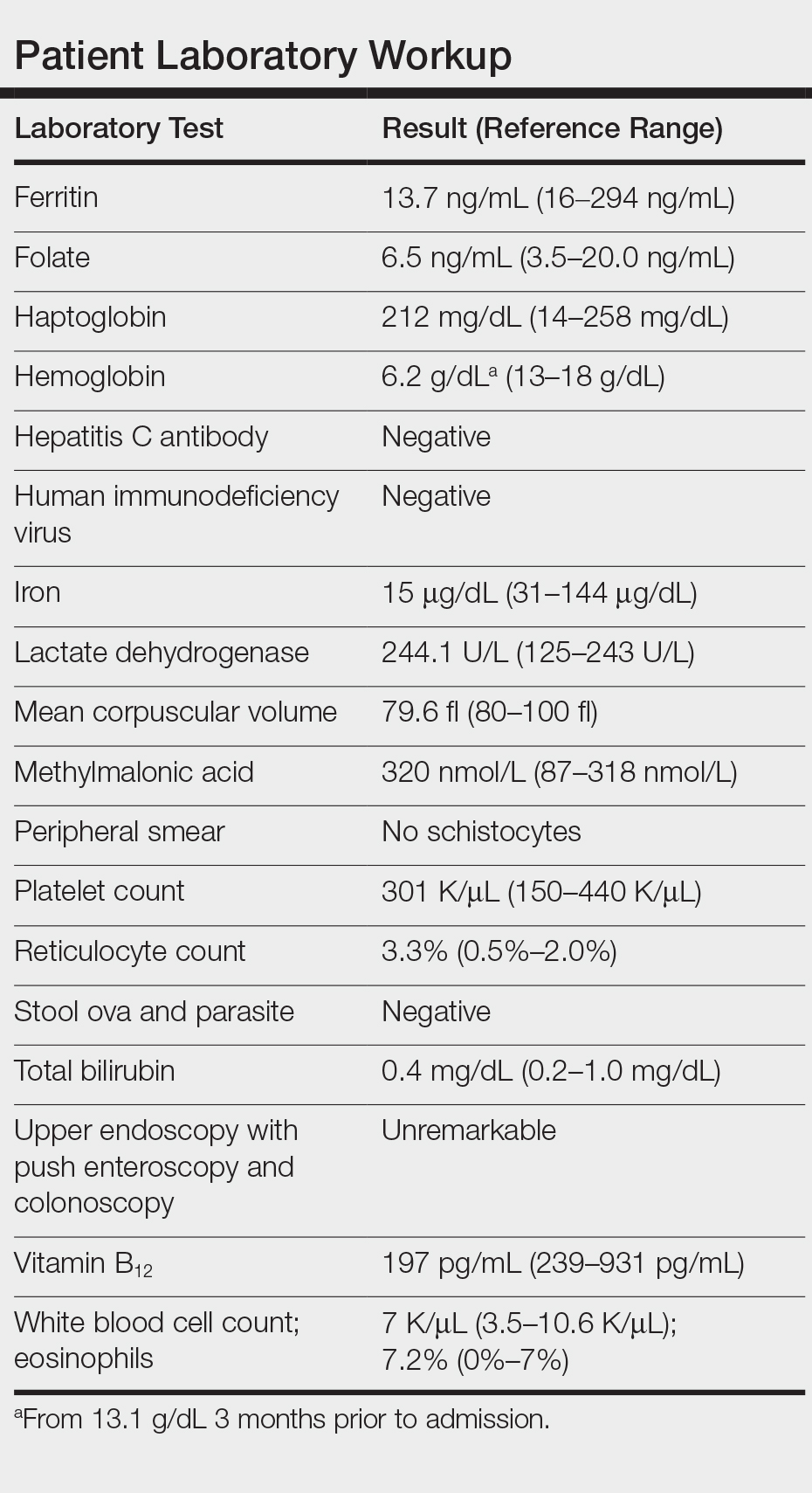

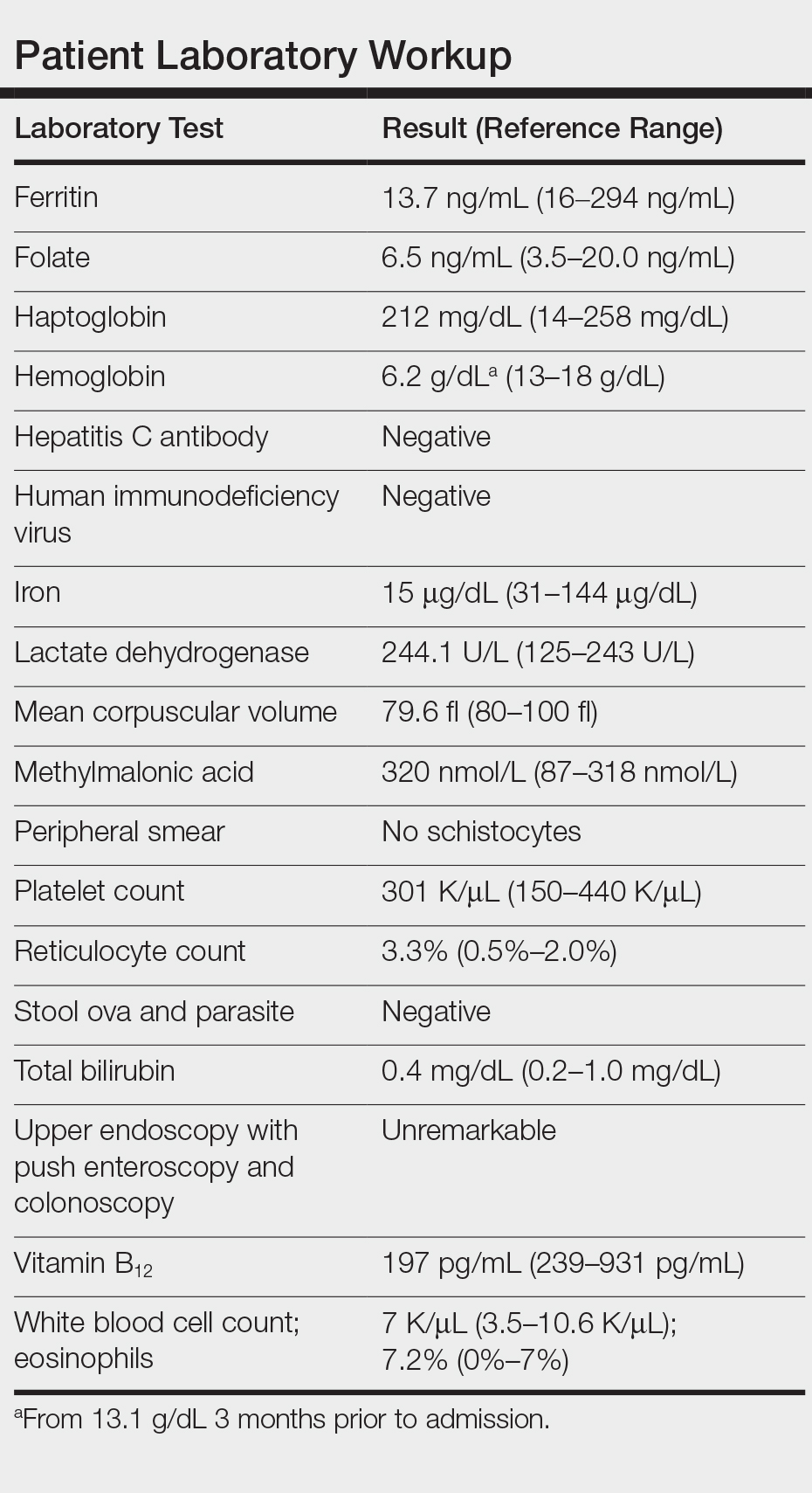

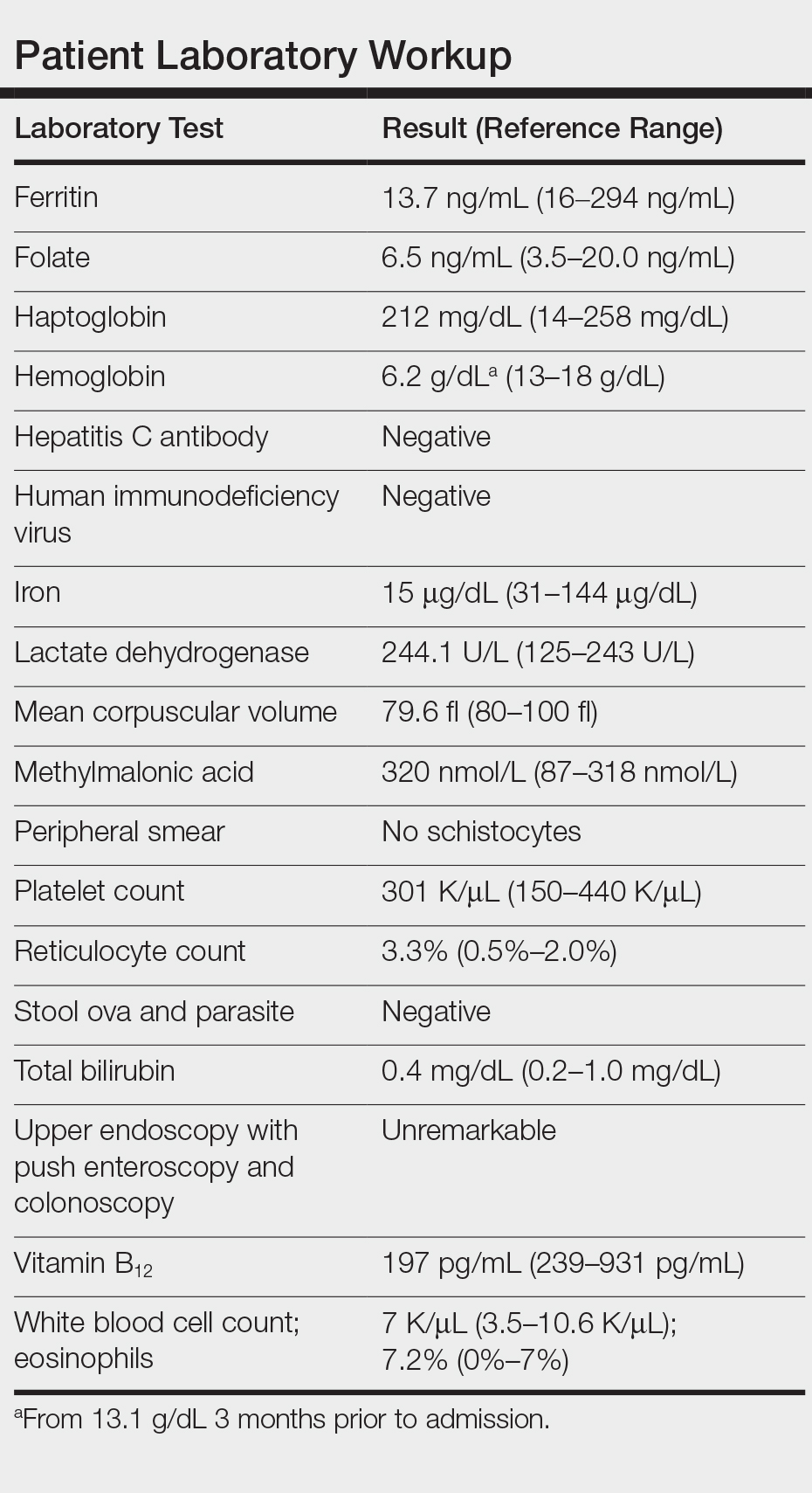

Laboratory workup revealed severe iron-deficiency anemia without any evidence of hemolysis, marrow suppression, infection, or immune compromise (Table). He had a vitamin B12 deficiency (197 pg/mL [reference range, 239-931 pg/mL]), but we felt it was very unlikely to be responsible for his profound, sudden-onset microcytic anemia. Further evaluation for occult bleeding revealed an unremarkable upper endoscopy with push enteroscopy and colonoscopy. An alternate etiology of the anemia could not be identified.

Subsequently, he reported multiple pruritic bug bites sustained at the hotel room where he resided and continued to note pruritus while hospitalized. Pest control inspected the hospital room and identified bedbugs, Cimex lectularius, among his belongings. Upon further review, his clothes and walker were found to be completely infested with these organisms in different stages of development. Treatment included blood transfusions, iron supplementation, and environmental control of the infested living space both in the hospital and at his residence, with subsequent resolution of symptoms and anemia. Two weeks following discharge, the patient no longer reported pruritus, and his hemoglobin level had returned to baseline.

Over the last decade there has been an exponential resurgence in C lectularius infestations in developed countries attributed to increasing global travel, growing pesticide resistance, lack of public awareness, and inadequate pest control programs. This re-emergence has resulted in a public health problem. Although bedbugs are not known to transmit infectious diseases, severe infestation can result in notable dermatitis, iron-deficiency anemia from chronic blood loss, superinfection, allergic reactions including anaphylaxis in rare cases, and psychologic distress.

Iron-deficiency anemia caused by excessive bedbug biting in infants and children has been documented as early as the 1960s.1 Our knowledge of severe anemia due to bedbug infestation is limited to only 4 cases in the literature, according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms bedbugs anemia and cimex anemia.1-4 All cases reported bedbug infestations involving personal clothing, belongings, and/or living spaces. Patient concerns at presentation ranged from lethargy and fatigue with pruritic rash to chest pain and syncope with findings of severe microcytic or normocytic anemia (hemoglobin level, 5-8 g/dL). All cases were treated supportively with blood transfusion and iron supplementation, with hemoglobin recovery after several weeks. Environmental extermination also was required to prevent recurrence.1-4 Given that each bedbug blood meal is on average 7 mm3, one would have to incur a minimum of 143,000 bites to experience a blood loss of 1 L.3

The differential diagnosis for a patient with generalized pruritus should be broad and includes dermatologic conditions (eg, xerosis, atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, urticaria, dermatophytosis, lichen simplex chronicus, psoriasis, scabies, pediculosis corporis and pubis, other arthropod bites, bullous pemphigoid), systemic disorders (eg, renal disease, diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, cholestasis, human immunodeficiency virus), malignancy, connective tissue disease, medication side effects, and psychogenic and neuropathic itch.

The diagnosis of C lectularius infestation is confirmed by finding the wingless, reddish brown, flat and ovular arthropod, with adult lengths of 4 to 7 mm, approximately the size of an apple seed.5-11 Bedbugs typically are active at night and feed for 3 to 10 minutes. After their feed or during the day, bedbugs will return to their nest in furniture, mattresses, beds, walls, and floors. Bedbug bites appear as small clusters or lines of pruritic erythematous papules with a central hemorrhagic puncta. Other cutaneous symptoms include isolated pruritus, papules, nodules, and bullous eruptions.7 Additional signs of bedbug infestation include black fecal stains in areas of inhabitation as well as actual bedbugs feeding during the day due to overcrowding.

Treatment of pruritic localized cutaneous reactions is supportive and includes antipruritic agents, topical steroids, topical anesthetics, antihistamines, or topical or systemic antibiotics for secondary infections.5-11 Systemic reactions, including anaphylaxis, are treated with epinephrine, antihistamines, and/or corticosteroids, while severe anemia is treated supportively with blood transfusions and iron supplementation.5-11 To prevent reoccurrence, environmental control in the form of nonchemical and chemical treatments is crucial in controlling bedbug infestations.5-11

This case highlights the relevance of a rare but notable morbidity associated with bedbug infestation and the adverse effects of bedbugs on public health. This patient's living situation in a single-room occupancy hotel, poor hygiene, and possible cognitive impairment from his multiple medical conditions may have increased his risk for extreme bedbug infestation. With a good history, physical examination, proper inspection of the patient's belongings, and provider awareness of this epidemic, the severity of this patient's anemia may have been circumvented on the prior hospital admission and follow-up office visit. Once such an infestation is confirmed, a multidisciplinary approach including social work assistance, health services, and pest control is needed to appropriately treat the patient and the environment. Methods in preventing and managing this growing public health problem include improving hygiene, avoiding secondhand goods, and increasing awareness in the identification and proper elimination of bedbugs.5-7

- Venkatachalam PS, Belavady B. Loss of haemoglobin iron due to excessive biting by bed bugs. a possible aetiological factor in the iron deficiency anaemia of infants and children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1962;56:218-221.

- Pritchard MJ, Hwang SW. Severe anemia from bedbugs. CMAJ. 2009;181:287-288.

- Paulke-Korinek M, Széll M, Laferl H, et al. Bed bugs can cause severe anaemia in adults. Parasitol Res. 2012;110:2577-2579.

- Sabou M, Imperiale DG, Andrés E, et al. Bed bugs reproductive life cycle in the clothes of a patient suffering from Alzheimer's disease results in iron deficiency anemia. Parasite. 2013;20:16.

- Studdiford JS, Conniff KM, Trayes KP, et al. Bedbug infestation. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:653-658.

- Goddard J, deShazo R. Bed bugs (Cimex lectularis) and clinical consequences of their bites. JAMA. 2009;301:1358-1366.

- Bernardeschi C, Le Cleach L, Delaunay P, et al. Bed bug infestation. BMJ. 2013;346:f138.

- Silvia Munoz-Price L, Safdar N, Beier JC, et al. Bed bugs inhealthcare settings. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33:1137-1142.

- Huntington MK. When bed bugs bite. J Fam Pract. 2012;61:384-388.

- Delaunay P, Blanc V, Del Giudice P, et al. Bedbugs and infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:200-212.

- Doggett SL, Dwyer DE, Penas PF, et al. Bed bugs: clinical relevance and control options. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:164-192.

To the Editor:

A 61-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a rash on the right leg, generalized pruritus, and chest pain. The patient described intermittent exertional pressure-like chest pain over the last few days but had no known prior cardiac history. He also noted worsening edema of the right leg with erythema. Three months prior he had been hospitalized for a similar presentation and was diagnosed with cellulitis of the right leg. The patient was treated with a course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and permethrin cream for presumed scabies and followed up with dermatology for the persistent generalized pruritic rash and cellulitis. At that time, he was diagnosed with stasis dermatitis with dermatitis neglecta and excoriations. He was educated on general hygiene and treated with triamcinolone, hydrophilic ointment, and pramoxine lotion for pruritus. He also was empirically treated again for scabies.

At the current presentation, preliminary investigation showed profound anemia with a hemoglobin level of 6.2 g/dL (baseline hemoglobin level 3 months prior, 13.1 g/dL). He was subsequently admitted to the general medicine ward for further investigation of severe symptomatic anemia. A medical history revealed moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, xerosis, and fracture of the right ankle following open reduction internal fixation 6 years prior to admission. There was no history of blood loss, antiplatelet agents, or anticoagulants. He was on disability and lived in a single-room occupancy hotel. He did not report any high-risk sexual behaviors or abuse of alcohol or drugs. He actively smoked 1.5 packs of cigarettes per day for the last 30 years. He denied any allergies.

Physical examination revealed the patient was afebrile, nontoxic, disheveled, and in no acute distress. He had anicteric sclera and pale conjunctiva. The right leg appeared more erythematous and edematous compared to the left leg but without warmth or tenderness to palpation. He had innumerable 4- to 5-mm, erythematous, excoriated papules on the skin (Figure). His bed sheets were noted to have multiple rusty-black specks thought to be related to the crusted lesions. Physical examination was otherwise unremarkable.

Laboratory workup revealed severe iron-deficiency anemia without any evidence of hemolysis, marrow suppression, infection, or immune compromise (Table). He had a vitamin B12 deficiency (197 pg/mL [reference range, 239-931 pg/mL]), but we felt it was very unlikely to be responsible for his profound, sudden-onset microcytic anemia. Further evaluation for occult bleeding revealed an unremarkable upper endoscopy with push enteroscopy and colonoscopy. An alternate etiology of the anemia could not be identified.

Subsequently, he reported multiple pruritic bug bites sustained at the hotel room where he resided and continued to note pruritus while hospitalized. Pest control inspected the hospital room and identified bedbugs, Cimex lectularius, among his belongings. Upon further review, his clothes and walker were found to be completely infested with these organisms in different stages of development. Treatment included blood transfusions, iron supplementation, and environmental control of the infested living space both in the hospital and at his residence, with subsequent resolution of symptoms and anemia. Two weeks following discharge, the patient no longer reported pruritus, and his hemoglobin level had returned to baseline.

Over the last decade there has been an exponential resurgence in C lectularius infestations in developed countries attributed to increasing global travel, growing pesticide resistance, lack of public awareness, and inadequate pest control programs. This re-emergence has resulted in a public health problem. Although bedbugs are not known to transmit infectious diseases, severe infestation can result in notable dermatitis, iron-deficiency anemia from chronic blood loss, superinfection, allergic reactions including anaphylaxis in rare cases, and psychologic distress.

Iron-deficiency anemia caused by excessive bedbug biting in infants and children has been documented as early as the 1960s.1 Our knowledge of severe anemia due to bedbug infestation is limited to only 4 cases in the literature, according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms bedbugs anemia and cimex anemia.1-4 All cases reported bedbug infestations involving personal clothing, belongings, and/or living spaces. Patient concerns at presentation ranged from lethargy and fatigue with pruritic rash to chest pain and syncope with findings of severe microcytic or normocytic anemia (hemoglobin level, 5-8 g/dL). All cases were treated supportively with blood transfusion and iron supplementation, with hemoglobin recovery after several weeks. Environmental extermination also was required to prevent recurrence.1-4 Given that each bedbug blood meal is on average 7 mm3, one would have to incur a minimum of 143,000 bites to experience a blood loss of 1 L.3

The differential diagnosis for a patient with generalized pruritus should be broad and includes dermatologic conditions (eg, xerosis, atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, urticaria, dermatophytosis, lichen simplex chronicus, psoriasis, scabies, pediculosis corporis and pubis, other arthropod bites, bullous pemphigoid), systemic disorders (eg, renal disease, diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, cholestasis, human immunodeficiency virus), malignancy, connective tissue disease, medication side effects, and psychogenic and neuropathic itch.

The diagnosis of C lectularius infestation is confirmed by finding the wingless, reddish brown, flat and ovular arthropod, with adult lengths of 4 to 7 mm, approximately the size of an apple seed.5-11 Bedbugs typically are active at night and feed for 3 to 10 minutes. After their feed or during the day, bedbugs will return to their nest in furniture, mattresses, beds, walls, and floors. Bedbug bites appear as small clusters or lines of pruritic erythematous papules with a central hemorrhagic puncta. Other cutaneous symptoms include isolated pruritus, papules, nodules, and bullous eruptions.7 Additional signs of bedbug infestation include black fecal stains in areas of inhabitation as well as actual bedbugs feeding during the day due to overcrowding.

Treatment of pruritic localized cutaneous reactions is supportive and includes antipruritic agents, topical steroids, topical anesthetics, antihistamines, or topical or systemic antibiotics for secondary infections.5-11 Systemic reactions, including anaphylaxis, are treated with epinephrine, antihistamines, and/or corticosteroids, while severe anemia is treated supportively with blood transfusions and iron supplementation.5-11 To prevent reoccurrence, environmental control in the form of nonchemical and chemical treatments is crucial in controlling bedbug infestations.5-11

This case highlights the relevance of a rare but notable morbidity associated with bedbug infestation and the adverse effects of bedbugs on public health. This patient's living situation in a single-room occupancy hotel, poor hygiene, and possible cognitive impairment from his multiple medical conditions may have increased his risk for extreme bedbug infestation. With a good history, physical examination, proper inspection of the patient's belongings, and provider awareness of this epidemic, the severity of this patient's anemia may have been circumvented on the prior hospital admission and follow-up office visit. Once such an infestation is confirmed, a multidisciplinary approach including social work assistance, health services, and pest control is needed to appropriately treat the patient and the environment. Methods in preventing and managing this growing public health problem include improving hygiene, avoiding secondhand goods, and increasing awareness in the identification and proper elimination of bedbugs.5-7

To the Editor:

A 61-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a rash on the right leg, generalized pruritus, and chest pain. The patient described intermittent exertional pressure-like chest pain over the last few days but had no known prior cardiac history. He also noted worsening edema of the right leg with erythema. Three months prior he had been hospitalized for a similar presentation and was diagnosed with cellulitis of the right leg. The patient was treated with a course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and permethrin cream for presumed scabies and followed up with dermatology for the persistent generalized pruritic rash and cellulitis. At that time, he was diagnosed with stasis dermatitis with dermatitis neglecta and excoriations. He was educated on general hygiene and treated with triamcinolone, hydrophilic ointment, and pramoxine lotion for pruritus. He also was empirically treated again for scabies.

At the current presentation, preliminary investigation showed profound anemia with a hemoglobin level of 6.2 g/dL (baseline hemoglobin level 3 months prior, 13.1 g/dL). He was subsequently admitted to the general medicine ward for further investigation of severe symptomatic anemia. A medical history revealed moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, xerosis, and fracture of the right ankle following open reduction internal fixation 6 years prior to admission. There was no history of blood loss, antiplatelet agents, or anticoagulants. He was on disability and lived in a single-room occupancy hotel. He did not report any high-risk sexual behaviors or abuse of alcohol or drugs. He actively smoked 1.5 packs of cigarettes per day for the last 30 years. He denied any allergies.

Physical examination revealed the patient was afebrile, nontoxic, disheveled, and in no acute distress. He had anicteric sclera and pale conjunctiva. The right leg appeared more erythematous and edematous compared to the left leg but without warmth or tenderness to palpation. He had innumerable 4- to 5-mm, erythematous, excoriated papules on the skin (Figure). His bed sheets were noted to have multiple rusty-black specks thought to be related to the crusted lesions. Physical examination was otherwise unremarkable.

Laboratory workup revealed severe iron-deficiency anemia without any evidence of hemolysis, marrow suppression, infection, or immune compromise (Table). He had a vitamin B12 deficiency (197 pg/mL [reference range, 239-931 pg/mL]), but we felt it was very unlikely to be responsible for his profound, sudden-onset microcytic anemia. Further evaluation for occult bleeding revealed an unremarkable upper endoscopy with push enteroscopy and colonoscopy. An alternate etiology of the anemia could not be identified.

Subsequently, he reported multiple pruritic bug bites sustained at the hotel room where he resided and continued to note pruritus while hospitalized. Pest control inspected the hospital room and identified bedbugs, Cimex lectularius, among his belongings. Upon further review, his clothes and walker were found to be completely infested with these organisms in different stages of development. Treatment included blood transfusions, iron supplementation, and environmental control of the infested living space both in the hospital and at his residence, with subsequent resolution of symptoms and anemia. Two weeks following discharge, the patient no longer reported pruritus, and his hemoglobin level had returned to baseline.

Over the last decade there has been an exponential resurgence in C lectularius infestations in developed countries attributed to increasing global travel, growing pesticide resistance, lack of public awareness, and inadequate pest control programs. This re-emergence has resulted in a public health problem. Although bedbugs are not known to transmit infectious diseases, severe infestation can result in notable dermatitis, iron-deficiency anemia from chronic blood loss, superinfection, allergic reactions including anaphylaxis in rare cases, and psychologic distress.

Iron-deficiency anemia caused by excessive bedbug biting in infants and children has been documented as early as the 1960s.1 Our knowledge of severe anemia due to bedbug infestation is limited to only 4 cases in the literature, according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms bedbugs anemia and cimex anemia.1-4 All cases reported bedbug infestations involving personal clothing, belongings, and/or living spaces. Patient concerns at presentation ranged from lethargy and fatigue with pruritic rash to chest pain and syncope with findings of severe microcytic or normocytic anemia (hemoglobin level, 5-8 g/dL). All cases were treated supportively with blood transfusion and iron supplementation, with hemoglobin recovery after several weeks. Environmental extermination also was required to prevent recurrence.1-4 Given that each bedbug blood meal is on average 7 mm3, one would have to incur a minimum of 143,000 bites to experience a blood loss of 1 L.3

The differential diagnosis for a patient with generalized pruritus should be broad and includes dermatologic conditions (eg, xerosis, atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, urticaria, dermatophytosis, lichen simplex chronicus, psoriasis, scabies, pediculosis corporis and pubis, other arthropod bites, bullous pemphigoid), systemic disorders (eg, renal disease, diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, cholestasis, human immunodeficiency virus), malignancy, connective tissue disease, medication side effects, and psychogenic and neuropathic itch.

The diagnosis of C lectularius infestation is confirmed by finding the wingless, reddish brown, flat and ovular arthropod, with adult lengths of 4 to 7 mm, approximately the size of an apple seed.5-11 Bedbugs typically are active at night and feed for 3 to 10 minutes. After their feed or during the day, bedbugs will return to their nest in furniture, mattresses, beds, walls, and floors. Bedbug bites appear as small clusters or lines of pruritic erythematous papules with a central hemorrhagic puncta. Other cutaneous symptoms include isolated pruritus, papules, nodules, and bullous eruptions.7 Additional signs of bedbug infestation include black fecal stains in areas of inhabitation as well as actual bedbugs feeding during the day due to overcrowding.

Treatment of pruritic localized cutaneous reactions is supportive and includes antipruritic agents, topical steroids, topical anesthetics, antihistamines, or topical or systemic antibiotics for secondary infections.5-11 Systemic reactions, including anaphylaxis, are treated with epinephrine, antihistamines, and/or corticosteroids, while severe anemia is treated supportively with blood transfusions and iron supplementation.5-11 To prevent reoccurrence, environmental control in the form of nonchemical and chemical treatments is crucial in controlling bedbug infestations.5-11

This case highlights the relevance of a rare but notable morbidity associated with bedbug infestation and the adverse effects of bedbugs on public health. This patient's living situation in a single-room occupancy hotel, poor hygiene, and possible cognitive impairment from his multiple medical conditions may have increased his risk for extreme bedbug infestation. With a good history, physical examination, proper inspection of the patient's belongings, and provider awareness of this epidemic, the severity of this patient's anemia may have been circumvented on the prior hospital admission and follow-up office visit. Once such an infestation is confirmed, a multidisciplinary approach including social work assistance, health services, and pest control is needed to appropriately treat the patient and the environment. Methods in preventing and managing this growing public health problem include improving hygiene, avoiding secondhand goods, and increasing awareness in the identification and proper elimination of bedbugs.5-7

- Venkatachalam PS, Belavady B. Loss of haemoglobin iron due to excessive biting by bed bugs. a possible aetiological factor in the iron deficiency anaemia of infants and children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1962;56:218-221.

- Pritchard MJ, Hwang SW. Severe anemia from bedbugs. CMAJ. 2009;181:287-288.

- Paulke-Korinek M, Széll M, Laferl H, et al. Bed bugs can cause severe anaemia in adults. Parasitol Res. 2012;110:2577-2579.

- Sabou M, Imperiale DG, Andrés E, et al. Bed bugs reproductive life cycle in the clothes of a patient suffering from Alzheimer's disease results in iron deficiency anemia. Parasite. 2013;20:16.

- Studdiford JS, Conniff KM, Trayes KP, et al. Bedbug infestation. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:653-658.

- Goddard J, deShazo R. Bed bugs (Cimex lectularis) and clinical consequences of their bites. JAMA. 2009;301:1358-1366.

- Bernardeschi C, Le Cleach L, Delaunay P, et al. Bed bug infestation. BMJ. 2013;346:f138.

- Silvia Munoz-Price L, Safdar N, Beier JC, et al. Bed bugs inhealthcare settings. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33:1137-1142.

- Huntington MK. When bed bugs bite. J Fam Pract. 2012;61:384-388.

- Delaunay P, Blanc V, Del Giudice P, et al. Bedbugs and infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:200-212.

- Doggett SL, Dwyer DE, Penas PF, et al. Bed bugs: clinical relevance and control options. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:164-192.

- Venkatachalam PS, Belavady B. Loss of haemoglobin iron due to excessive biting by bed bugs. a possible aetiological factor in the iron deficiency anaemia of infants and children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1962;56:218-221.

- Pritchard MJ, Hwang SW. Severe anemia from bedbugs. CMAJ. 2009;181:287-288.

- Paulke-Korinek M, Széll M, Laferl H, et al. Bed bugs can cause severe anaemia in adults. Parasitol Res. 2012;110:2577-2579.

- Sabou M, Imperiale DG, Andrés E, et al. Bed bugs reproductive life cycle in the clothes of a patient suffering from Alzheimer's disease results in iron deficiency anemia. Parasite. 2013;20:16.

- Studdiford JS, Conniff KM, Trayes KP, et al. Bedbug infestation. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:653-658.

- Goddard J, deShazo R. Bed bugs (Cimex lectularis) and clinical consequences of their bites. JAMA. 2009;301:1358-1366.

- Bernardeschi C, Le Cleach L, Delaunay P, et al. Bed bug infestation. BMJ. 2013;346:f138.

- Silvia Munoz-Price L, Safdar N, Beier JC, et al. Bed bugs inhealthcare settings. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33:1137-1142.

- Huntington MK. When bed bugs bite. J Fam Pract. 2012;61:384-388.

- Delaunay P, Blanc V, Del Giudice P, et al. Bedbugs and infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:200-212.

- Doggett SL, Dwyer DE, Penas PF, et al. Bed bugs: clinical relevance and control options. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:164-192.

Practice Points

- There has been a resurgence in bedbug (Cimex lectularius) infestations in developed countries.

- Although rare, anemia due to bedbug infestation should be considered in patients presenting with anemia and a widespread pruritic papular eruption.

- A thorough history and physical examination are essential to prevent a delay in diagnosis and avoid a costly and unnecessary workup.

- Successful treatment requires a multidisciplinary approach, which includes medical management, social services, and pest control.

How racism contributes to the effects of SARS-CoV-2

It’s been about two months since I volunteered in a hospital in Brooklyn, working in an ICU taking care of patients with COVID-19.

Everyone seems to have forgotten the early days of the pandemic – the time when the ICUs were overrun, we were using FEMA ventilators, and endocrinologists and psychiatrists were acting as intensivists.

Even though things are opening up and people are taking summer vacations in a seemingly amnestic state, having witnessed multiple daily deaths remains a part of my daily consciousness. As I see the case numbers climbing juxtaposed against people being out and about without masks, my anxiety level is rising.

A virus doesn’t discriminate. It can fly through the air, landing on the next available surface. If that virus is SARS-CoV-2 and that surface is a human mucosal membrane, the virus makes itself at home. It orders furniture, buys a fancy mattress and a large high definition TV, hangs art on the walls, and settles in for the long haul. It’s not going anywhere anytime soon.

Even as an equal opportunity virus, what SARS-CoV-2 has done is to hold a mirror up to the healthcare system. It has shown us what was here all along. When people first started noticing that underrepresented minorities were more likely to contract the virus and get sick from it, I heard musings that this was likely because of their preexisting health conditions. For example, commentators on cable news were quick to point out that black people are more likely than other people to have hypertension or diabetes. So doesn’t that explain why they are more affected by this virus?

That certainly is part of the story, but it doesn’t entirely explain the discrepancies we’ve seen. For example, in New York 14% of the population is black, and 25% of those who had a COVID-related death were black patients. Similarly, 19% of the population is Hispanic or Latino, and they made up 26% of COVID-related deaths. On the other hand, 55% of the population in New York is white, and white people account for only 34% of COVID-related deaths.

Working in Brooklyn, I didn’t need to be a keen observer to notice that, out of our entire unit of about 20-25 patients, there was only one patient in a 2-week period who was neither black nor Hispanic.

As others have written, there are other factors at play. I’m not sure how many of those commentators back in March stopped to think about why black patients are more likely to have hypertension and diabetes, but the chronic stress of facing racism on a daily basis surely contributes. Beyond those medical problems, minorities are more likely to live in multigenerational housing, which means that it is harder for them to isolate from others. In addition, their living quarters tend to be further from health care centers and grocery stores, which makes it harder for them to access medical care and healthy food.

As if that weren’t enough to put their health at risk, people of color are also affected by environmental racism . Factories with toxic waste are more likely to be built in or near neighborhoods filled with people of color than in other communities. On top of that, black and Hispanic people are also more likely to be under- or uninsured, meaning they often delay seeking care in order to avoid astronomic healthcare costs.

Black and Hispanic people are also more likely than others to be working in the service industry or other essential services, which means they are less likely to be able to work from home. Consequently, they have to risk more exposures to other people and the virus than do those who have the privilege of working safely from home. They also are less likely to have available paid leave and, therefore, are more likely to work while sick.

With the deck completely stacked against them, underrepresented minorities also face systemic bias and racism when interacting with the health care system. Physicians mistakenly believe black patients experience less pain than other patients, according to some research. Black mothers have significantly worse health care outcomes than do their non-black counterparts, and the infant mortality rate for Black infants is much higher as well.

In my limited time in Brooklyn, taking care of almost exclusively black and Hispanic patients, I saw one physician assistant and one nurse who were black; one nurse practitioner was Hispanic. This mismatch is sadly common. Although 13% of the population of the United States is black, only 5% of physicians in the United States are black. Hispanic people, who make up 18% of the US population, are only 6% of physicians. This undoubtedly contributes to poorer outcomes for underrepresented minority patients who have a hard time finding physicians who look like them and understand them.

So while SARS-CoV-2 may not discriminate, the effects it has on patients depends on all of these other factors. If it flies through the air and lands on the mucosal tract of a person who works from home, has effective health insurance and a primary care physician, and lives in a community with no toxic exposures, that person may be more likely to kick it out before it has a chance to settle in. The reason we have such a huge disparity in outcomes related to COVID-19 by race is that a person meeting that description is less likely to be black or Hispanic. Race is not an independent risk factor; structural racism is.

When I drive by the mall that is now open or the restaurants that are now open with indoor dining, my heart rate quickens just a bit with anxiety. The pandemic fatigue people are experiencing is leading them to act in unsafe ways – gathering with more people, not wearing masks, not keeping a safe distance. I worry about everyone, sure, but I really worry about black and Hispanic people who are most vulnerable as a result of everyone else’s refusal to follow guidelines.

Dr. Salles is a bariatric surgeon and is currently a Scholar in Residence at Stanford (Calif.) University. Find her on Twitter @arghavan_salles.

It’s been about two months since I volunteered in a hospital in Brooklyn, working in an ICU taking care of patients with COVID-19.

Everyone seems to have forgotten the early days of the pandemic – the time when the ICUs were overrun, we were using FEMA ventilators, and endocrinologists and psychiatrists were acting as intensivists.

Even though things are opening up and people are taking summer vacations in a seemingly amnestic state, having witnessed multiple daily deaths remains a part of my daily consciousness. As I see the case numbers climbing juxtaposed against people being out and about without masks, my anxiety level is rising.

A virus doesn’t discriminate. It can fly through the air, landing on the next available surface. If that virus is SARS-CoV-2 and that surface is a human mucosal membrane, the virus makes itself at home. It orders furniture, buys a fancy mattress and a large high definition TV, hangs art on the walls, and settles in for the long haul. It’s not going anywhere anytime soon.

Even as an equal opportunity virus, what SARS-CoV-2 has done is to hold a mirror up to the healthcare system. It has shown us what was here all along. When people first started noticing that underrepresented minorities were more likely to contract the virus and get sick from it, I heard musings that this was likely because of their preexisting health conditions. For example, commentators on cable news were quick to point out that black people are more likely than other people to have hypertension or diabetes. So doesn’t that explain why they are more affected by this virus?

That certainly is part of the story, but it doesn’t entirely explain the discrepancies we’ve seen. For example, in New York 14% of the population is black, and 25% of those who had a COVID-related death were black patients. Similarly, 19% of the population is Hispanic or Latino, and they made up 26% of COVID-related deaths. On the other hand, 55% of the population in New York is white, and white people account for only 34% of COVID-related deaths.

Working in Brooklyn, I didn’t need to be a keen observer to notice that, out of our entire unit of about 20-25 patients, there was only one patient in a 2-week period who was neither black nor Hispanic.

As others have written, there are other factors at play. I’m not sure how many of those commentators back in March stopped to think about why black patients are more likely to have hypertension and diabetes, but the chronic stress of facing racism on a daily basis surely contributes. Beyond those medical problems, minorities are more likely to live in multigenerational housing, which means that it is harder for them to isolate from others. In addition, their living quarters tend to be further from health care centers and grocery stores, which makes it harder for them to access medical care and healthy food.

As if that weren’t enough to put their health at risk, people of color are also affected by environmental racism . Factories with toxic waste are more likely to be built in or near neighborhoods filled with people of color than in other communities. On top of that, black and Hispanic people are also more likely to be under- or uninsured, meaning they often delay seeking care in order to avoid astronomic healthcare costs.

Black and Hispanic people are also more likely than others to be working in the service industry or other essential services, which means they are less likely to be able to work from home. Consequently, they have to risk more exposures to other people and the virus than do those who have the privilege of working safely from home. They also are less likely to have available paid leave and, therefore, are more likely to work while sick.

With the deck completely stacked against them, underrepresented minorities also face systemic bias and racism when interacting with the health care system. Physicians mistakenly believe black patients experience less pain than other patients, according to some research. Black mothers have significantly worse health care outcomes than do their non-black counterparts, and the infant mortality rate for Black infants is much higher as well.

In my limited time in Brooklyn, taking care of almost exclusively black and Hispanic patients, I saw one physician assistant and one nurse who were black; one nurse practitioner was Hispanic. This mismatch is sadly common. Although 13% of the population of the United States is black, only 5% of physicians in the United States are black. Hispanic people, who make up 18% of the US population, are only 6% of physicians. This undoubtedly contributes to poorer outcomes for underrepresented minority patients who have a hard time finding physicians who look like them and understand them.

So while SARS-CoV-2 may not discriminate, the effects it has on patients depends on all of these other factors. If it flies through the air and lands on the mucosal tract of a person who works from home, has effective health insurance and a primary care physician, and lives in a community with no toxic exposures, that person may be more likely to kick it out before it has a chance to settle in. The reason we have such a huge disparity in outcomes related to COVID-19 by race is that a person meeting that description is less likely to be black or Hispanic. Race is not an independent risk factor; structural racism is.

When I drive by the mall that is now open or the restaurants that are now open with indoor dining, my heart rate quickens just a bit with anxiety. The pandemic fatigue people are experiencing is leading them to act in unsafe ways – gathering with more people, not wearing masks, not keeping a safe distance. I worry about everyone, sure, but I really worry about black and Hispanic people who are most vulnerable as a result of everyone else’s refusal to follow guidelines.

Dr. Salles is a bariatric surgeon and is currently a Scholar in Residence at Stanford (Calif.) University. Find her on Twitter @arghavan_salles.

It’s been about two months since I volunteered in a hospital in Brooklyn, working in an ICU taking care of patients with COVID-19.

Everyone seems to have forgotten the early days of the pandemic – the time when the ICUs were overrun, we were using FEMA ventilators, and endocrinologists and psychiatrists were acting as intensivists.

Even though things are opening up and people are taking summer vacations in a seemingly amnestic state, having witnessed multiple daily deaths remains a part of my daily consciousness. As I see the case numbers climbing juxtaposed against people being out and about without masks, my anxiety level is rising.

A virus doesn’t discriminate. It can fly through the air, landing on the next available surface. If that virus is SARS-CoV-2 and that surface is a human mucosal membrane, the virus makes itself at home. It orders furniture, buys a fancy mattress and a large high definition TV, hangs art on the walls, and settles in for the long haul. It’s not going anywhere anytime soon.

Even as an equal opportunity virus, what SARS-CoV-2 has done is to hold a mirror up to the healthcare system. It has shown us what was here all along. When people first started noticing that underrepresented minorities were more likely to contract the virus and get sick from it, I heard musings that this was likely because of their preexisting health conditions. For example, commentators on cable news were quick to point out that black people are more likely than other people to have hypertension or diabetes. So doesn’t that explain why they are more affected by this virus?

That certainly is part of the story, but it doesn’t entirely explain the discrepancies we’ve seen. For example, in New York 14% of the population is black, and 25% of those who had a COVID-related death were black patients. Similarly, 19% of the population is Hispanic or Latino, and they made up 26% of COVID-related deaths. On the other hand, 55% of the population in New York is white, and white people account for only 34% of COVID-related deaths.

Working in Brooklyn, I didn’t need to be a keen observer to notice that, out of our entire unit of about 20-25 patients, there was only one patient in a 2-week period who was neither black nor Hispanic.

As others have written, there are other factors at play. I’m not sure how many of those commentators back in March stopped to think about why black patients are more likely to have hypertension and diabetes, but the chronic stress of facing racism on a daily basis surely contributes. Beyond those medical problems, minorities are more likely to live in multigenerational housing, which means that it is harder for them to isolate from others. In addition, their living quarters tend to be further from health care centers and grocery stores, which makes it harder for them to access medical care and healthy food.

As if that weren’t enough to put their health at risk, people of color are also affected by environmental racism . Factories with toxic waste are more likely to be built in or near neighborhoods filled with people of color than in other communities. On top of that, black and Hispanic people are also more likely to be under- or uninsured, meaning they often delay seeking care in order to avoid astronomic healthcare costs.

Black and Hispanic people are also more likely than others to be working in the service industry or other essential services, which means they are less likely to be able to work from home. Consequently, they have to risk more exposures to other people and the virus than do those who have the privilege of working safely from home. They also are less likely to have available paid leave and, therefore, are more likely to work while sick.

With the deck completely stacked against them, underrepresented minorities also face systemic bias and racism when interacting with the health care system. Physicians mistakenly believe black patients experience less pain than other patients, according to some research. Black mothers have significantly worse health care outcomes than do their non-black counterparts, and the infant mortality rate for Black infants is much higher as well.

In my limited time in Brooklyn, taking care of almost exclusively black and Hispanic patients, I saw one physician assistant and one nurse who were black; one nurse practitioner was Hispanic. This mismatch is sadly common. Although 13% of the population of the United States is black, only 5% of physicians in the United States are black. Hispanic people, who make up 18% of the US population, are only 6% of physicians. This undoubtedly contributes to poorer outcomes for underrepresented minority patients who have a hard time finding physicians who look like them and understand them.