User login

Vaccinations in certain combinations may slightly increase febrile seizure risk

There is an increased risk of febrile seizures when children receiving certain recommended vaccinations at the same time, but that risk is low, a study found.

Dr. Jonathan Duffy from the Immunization Safety Office of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and his colleagues followed up on a study that showed an increased risk of febrile seizures in children vaccinated with a trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV3) and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) at the same time during the 2010-2011 influenza season.

The investigators wanted to assess the effect of administering other common childhood vaccines with IIV3 on the risk for febrile seizures so they examined chart records of potential cases of febrile seizures in those aged 6-23 months from the Vaccine Safety Datalink. The data were collected between the 2006-2007 through 2010-2011 influenza seasons.

The search yielded 333 chart-confirmed cases of febrile seizures. To examine the safety of each recommended vaccination administered alone or in combination, the cases were divided into two groups, one to serve as a risk interval group (n = 103) for febrile seizures on days 0 to 1 postvaccination; and one control interval comparison group (n = 230) with febrile seizures 14-20 days postvaccination. The multivariable model used for the study indicated that IIV3, PCV, and DTaP-containing vaccines were most often associated with febrile seizures in the risk interval group, but that only PCV7 showed an independent increased risk of febrile seizures (incidence rate ratio, 1.98) after the model was adjusted to strip out concomitantly administered vaccines.

Although increased risks of febrile seizures were detected for these three combinations, the overall risk of febrile seizures was quite low, on the order of 10, 24, and 38 per 100,000 vaccinated children at 6, 12, and 15 months, respectively, for the triple concomitant administration in the risk interval.

The risk of febrile seizures also was higher after receiving three different combinations of concomitantly-administered vaccinations, IIV3 plus PCV (IRR, 3.50), IIV3 plus DTaP (IRR, 3.50), and IIV3 plus PCV plus DTaP (IRR, 5.00).

“Our results suggest that the risk of [febrile seizure] is increased after certain combinations of vaccines, but the absolute risk of [febrile seizure] after these combinations is small,” Dr. Duffy and his associates noted in Pediatrics (2016;138[1]:e20160320).

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the study. Dr. Naleway and Dr. Klein reported receiving research funding/support from multiple industry sources. The remaining authors reported no financial disclosures.

Concomitant administration of influenza, DTaP, and pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) vaccines was associated with febrile seizures at a rate of up to 30 in 100,000 children immunized. This would result in one child, at most, who would be expected to experience a febrile seizure caused by the concomitant administration of these vaccines in the first 2 years of life over a 5-10 year period in an average pediatric practice, based on a patient base including 1,000 children younger than 5 years of age, which would include 3-500 patients between 6 and 24 months of age annually.

Does this mean we should stop giving these vaccines together or stop giving them at all? We say, emphatically, no.

Febrile seizures, although frightening to parents, rarely have any long-term sequelae. The risk from these diseases far outweigh the risk from the vaccines.

This study, conducted by the Vaccine Safety Datalink, and others like it, are important as we engage in dialogue with parents about the risks and benefits of vaccines.

These comments are excerpted from a commentary by Dr. Mark H. Sawyer of the University of California, San Diego, department of pediatrics and Rady Children’s Hospital, also in San Diego. Dr. Geoff Simon of Nemours duPont Pediatrics, Wilmington, Del., and Dr. Carrie Byington of the department of pediatrics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City. Dr. Sawyer and Dr. Simon are members of and Dr. Byington is the chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Disease. Dr. Byington has intellectual property in and receives royalties from BioFire Diagnostics; Dr. Sawyer and Dr. Simon indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article. Funded by the National Institutes of Health. (Pediatrics. 2016 Jun 6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0976 ).

Concomitant administration of influenza, DTaP, and pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) vaccines was associated with febrile seizures at a rate of up to 30 in 100,000 children immunized. This would result in one child, at most, who would be expected to experience a febrile seizure caused by the concomitant administration of these vaccines in the first 2 years of life over a 5-10 year period in an average pediatric practice, based on a patient base including 1,000 children younger than 5 years of age, which would include 3-500 patients between 6 and 24 months of age annually.

Does this mean we should stop giving these vaccines together or stop giving them at all? We say, emphatically, no.

Febrile seizures, although frightening to parents, rarely have any long-term sequelae. The risk from these diseases far outweigh the risk from the vaccines.

This study, conducted by the Vaccine Safety Datalink, and others like it, are important as we engage in dialogue with parents about the risks and benefits of vaccines.

These comments are excerpted from a commentary by Dr. Mark H. Sawyer of the University of California, San Diego, department of pediatrics and Rady Children’s Hospital, also in San Diego. Dr. Geoff Simon of Nemours duPont Pediatrics, Wilmington, Del., and Dr. Carrie Byington of the department of pediatrics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City. Dr. Sawyer and Dr. Simon are members of and Dr. Byington is the chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Disease. Dr. Byington has intellectual property in and receives royalties from BioFire Diagnostics; Dr. Sawyer and Dr. Simon indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article. Funded by the National Institutes of Health. (Pediatrics. 2016 Jun 6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0976 ).

Concomitant administration of influenza, DTaP, and pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) vaccines was associated with febrile seizures at a rate of up to 30 in 100,000 children immunized. This would result in one child, at most, who would be expected to experience a febrile seizure caused by the concomitant administration of these vaccines in the first 2 years of life over a 5-10 year period in an average pediatric practice, based on a patient base including 1,000 children younger than 5 years of age, which would include 3-500 patients between 6 and 24 months of age annually.

Does this mean we should stop giving these vaccines together or stop giving them at all? We say, emphatically, no.

Febrile seizures, although frightening to parents, rarely have any long-term sequelae. The risk from these diseases far outweigh the risk from the vaccines.

This study, conducted by the Vaccine Safety Datalink, and others like it, are important as we engage in dialogue with parents about the risks and benefits of vaccines.

These comments are excerpted from a commentary by Dr. Mark H. Sawyer of the University of California, San Diego, department of pediatrics and Rady Children’s Hospital, also in San Diego. Dr. Geoff Simon of Nemours duPont Pediatrics, Wilmington, Del., and Dr. Carrie Byington of the department of pediatrics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City. Dr. Sawyer and Dr. Simon are members of and Dr. Byington is the chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Disease. Dr. Byington has intellectual property in and receives royalties from BioFire Diagnostics; Dr. Sawyer and Dr. Simon indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article. Funded by the National Institutes of Health. (Pediatrics. 2016 Jun 6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0976 ).

There is an increased risk of febrile seizures when children receiving certain recommended vaccinations at the same time, but that risk is low, a study found.

Dr. Jonathan Duffy from the Immunization Safety Office of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and his colleagues followed up on a study that showed an increased risk of febrile seizures in children vaccinated with a trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV3) and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) at the same time during the 2010-2011 influenza season.

The investigators wanted to assess the effect of administering other common childhood vaccines with IIV3 on the risk for febrile seizures so they examined chart records of potential cases of febrile seizures in those aged 6-23 months from the Vaccine Safety Datalink. The data were collected between the 2006-2007 through 2010-2011 influenza seasons.

The search yielded 333 chart-confirmed cases of febrile seizures. To examine the safety of each recommended vaccination administered alone or in combination, the cases were divided into two groups, one to serve as a risk interval group (n = 103) for febrile seizures on days 0 to 1 postvaccination; and one control interval comparison group (n = 230) with febrile seizures 14-20 days postvaccination. The multivariable model used for the study indicated that IIV3, PCV, and DTaP-containing vaccines were most often associated with febrile seizures in the risk interval group, but that only PCV7 showed an independent increased risk of febrile seizures (incidence rate ratio, 1.98) after the model was adjusted to strip out concomitantly administered vaccines.

Although increased risks of febrile seizures were detected for these three combinations, the overall risk of febrile seizures was quite low, on the order of 10, 24, and 38 per 100,000 vaccinated children at 6, 12, and 15 months, respectively, for the triple concomitant administration in the risk interval.

The risk of febrile seizures also was higher after receiving three different combinations of concomitantly-administered vaccinations, IIV3 plus PCV (IRR, 3.50), IIV3 plus DTaP (IRR, 3.50), and IIV3 plus PCV plus DTaP (IRR, 5.00).

“Our results suggest that the risk of [febrile seizure] is increased after certain combinations of vaccines, but the absolute risk of [febrile seizure] after these combinations is small,” Dr. Duffy and his associates noted in Pediatrics (2016;138[1]:e20160320).

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the study. Dr. Naleway and Dr. Klein reported receiving research funding/support from multiple industry sources. The remaining authors reported no financial disclosures.

There is an increased risk of febrile seizures when children receiving certain recommended vaccinations at the same time, but that risk is low, a study found.

Dr. Jonathan Duffy from the Immunization Safety Office of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and his colleagues followed up on a study that showed an increased risk of febrile seizures in children vaccinated with a trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV3) and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) at the same time during the 2010-2011 influenza season.

The investigators wanted to assess the effect of administering other common childhood vaccines with IIV3 on the risk for febrile seizures so they examined chart records of potential cases of febrile seizures in those aged 6-23 months from the Vaccine Safety Datalink. The data were collected between the 2006-2007 through 2010-2011 influenza seasons.

The search yielded 333 chart-confirmed cases of febrile seizures. To examine the safety of each recommended vaccination administered alone or in combination, the cases were divided into two groups, one to serve as a risk interval group (n = 103) for febrile seizures on days 0 to 1 postvaccination; and one control interval comparison group (n = 230) with febrile seizures 14-20 days postvaccination. The multivariable model used for the study indicated that IIV3, PCV, and DTaP-containing vaccines were most often associated with febrile seizures in the risk interval group, but that only PCV7 showed an independent increased risk of febrile seizures (incidence rate ratio, 1.98) after the model was adjusted to strip out concomitantly administered vaccines.

Although increased risks of febrile seizures were detected for these three combinations, the overall risk of febrile seizures was quite low, on the order of 10, 24, and 38 per 100,000 vaccinated children at 6, 12, and 15 months, respectively, for the triple concomitant administration in the risk interval.

The risk of febrile seizures also was higher after receiving three different combinations of concomitantly-administered vaccinations, IIV3 plus PCV (IRR, 3.50), IIV3 plus DTaP (IRR, 3.50), and IIV3 plus PCV plus DTaP (IRR, 5.00).

“Our results suggest that the risk of [febrile seizure] is increased after certain combinations of vaccines, but the absolute risk of [febrile seizure] after these combinations is small,” Dr. Duffy and his associates noted in Pediatrics (2016;138[1]:e20160320).

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the study. Dr. Naleway and Dr. Klein reported receiving research funding/support from multiple industry sources. The remaining authors reported no financial disclosures.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: The concomitant administration of certain childhood vaccinations may slightly increase the risk of febrile seizures.

Major finding: Although the risk of febrile seizures in the population studied was low in general, it was higher for those receiving concomitantly-administered IIV3 plus PCV, IIV3 plus DTaP, and IIV3 plus PCV plus DTaP.

Data sources: Vaccine Safety Datalink repository of vaccine safety research and surveillance.

Disclosures: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the study. Dr. Naleway and Dr. Klein reported receiving research funding/support from multiple industry sources. The remaining authors reported no financial disclosures.

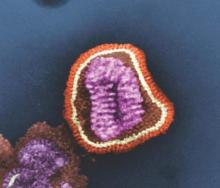

2015-2016 flu season slower and milder than past 3 years

The 2015-2016 flu season was less severe than the last three seasons, with a lower hospitalization rate and fewer pediatric deaths.

Cases of influenza appeared later in the season that typically seen, and activity didn’t peak until March, Stacy L. Davlin, Ph.D., wrote in the June 10 issue of the Morbidity and Mortality report (MMWR 2016; 22:567-75)

“During the most recent 18 influenza seasons, only two other seasons have peaked in March (2011-2012 and 2005-2006),” wrote Dr. Davlin, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta. This serves as a reminder that influenza can and does occur outside the traditionally expected season, and that clinicians shouldn’t discount the possibility of flu when a patient presents with typical symptoms.

“Although summer influenza activity in the United States typically is low, influenza cases and outbreaks have occurred during summer months, and clinicians should remain vigilant in considering influenza in the differential diagnosis of summer respiratory illnesses,” Dr. Davlin said.

The most common influenza virus of the last season was A(H1N1), which accounted for about half of cases in those aged 5-24 years, and about 70% of cases in those younger than 5 years and those 65 years and older.

Three novel viruses were seen as well: variants of A(H1N1), A(H1N2), and A(H3N2). The A(H1N1) variant occurred in a Minnesota resident who lived and worked in an area of swine farming, but who denied direct contact with pigs. The A(H3N2) variant occurred in a New Jersey resident who reported visiting a farm shortly before symptom onset. There was no evidence of human-to-human transmission. Both recovered fully without hospitalization. The A(H1N2) variant occurred in a Minnesota resident who was hospitalized but who recovered. This person was not interviewed so no possible source of infection was identified.

The CDC tested 2,408 viral specimens for susceptibility to antiviral medications. Among the 2,193 A(H1N1) specimens, less than 1% were resistant to oseltamivir and peramivir. All were susceptible to zanamivir. However, the testing found persistent high levels of resistant to amantadine and rimantadine in the A viruses. Amantadine is not effective on the B strains at all. Therefore, CDC does not recommend the use of amantadine as an anti-influenza medication.

Reports of influenza first exceeded the 2.1% baseline level in the week ending Dec. 26, 2015, according to the U.S. Outpatient Influenza-Like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet). They remained elevated for the next 17 weeks, with a peak of 3.6% of all outpatient visits in the week ending March 12. From October 2015-April 2016, the overall hospitalization rate for influenza-like illness was 31 per 100,000. This was highest in those aged 65 years and older (85/100,000), and lowest in those aged 5-17 years (10/100,000). About 92% of adults hospitalized for flu-like illness had at least one underlying medical comorbidity, including obesity (42%), cardiovascular disease (40%), and metabolic disorders (38%). Almost half of children (48%) also had medical comorbidities, including asthma or other reactive airway disease (22%) and neurologic disorders (18%).

CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics Mortality Surveillance System found that the percentage of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza peaked at 8% during the week ending March 19. This is slightly lower than the death rate seen in the last 5 years, which ranged from 9% in 2011-2012 to 11% in 2012-2013.

Of this season’s deaths, 74 occurred in children. The mean and median ages of these patients were 7 years and 6 years, respectively; the range was 2 months-16 years. This total was lower than that recorded in any of the past three influenza seasons: 171 pediatric deaths in 2012-2013, 111 in 2013-2014, and 148 in 2014-2015.

Dr. Davlin also announced the Food and Drug Administration’s recommendations for composition of the 2016-2017 influenza vaccine.

Trivalent vaccines should contain an A/California/7/2009 (H1N1) pdm09-like virus, an A/Hong Kong/4801/2014 (H3N2)-like virus, and a B/Brisbane/60/2008-like virus (B/Victoria lineage). Quadrivalent vaccines, which have two influenza B viruses, should include the viruses recommended for the trivalent vaccines, as well as a B/Phuket/3073/2013-like virus (B/Yamagata lineage).

“The vaccine viruses recommended for inclusion in the 2016-2017 Northern Hemisphere influenza vaccines are the same vaccine viruses that were chosen for inclusion in 2016 Southern Hemisphere seasonal influenza vaccines,” Dr. Davlin noted. “These vaccine recommendations were based on a number of factors, including global influenza virologic and epidemiologic surveillance, genetic and antigenic characterization, antiviral susceptibility, and the availability of candidate vaccine viruses for production.”

As a CDC employee, Dr. Davlin had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

The 2015-2016 flu season was less severe than the last three seasons, with a lower hospitalization rate and fewer pediatric deaths.

Cases of influenza appeared later in the season that typically seen, and activity didn’t peak until March, Stacy L. Davlin, Ph.D., wrote in the June 10 issue of the Morbidity and Mortality report (MMWR 2016; 22:567-75)

“During the most recent 18 influenza seasons, only two other seasons have peaked in March (2011-2012 and 2005-2006),” wrote Dr. Davlin, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta. This serves as a reminder that influenza can and does occur outside the traditionally expected season, and that clinicians shouldn’t discount the possibility of flu when a patient presents with typical symptoms.

“Although summer influenza activity in the United States typically is low, influenza cases and outbreaks have occurred during summer months, and clinicians should remain vigilant in considering influenza in the differential diagnosis of summer respiratory illnesses,” Dr. Davlin said.

The most common influenza virus of the last season was A(H1N1), which accounted for about half of cases in those aged 5-24 years, and about 70% of cases in those younger than 5 years and those 65 years and older.

Three novel viruses were seen as well: variants of A(H1N1), A(H1N2), and A(H3N2). The A(H1N1) variant occurred in a Minnesota resident who lived and worked in an area of swine farming, but who denied direct contact with pigs. The A(H3N2) variant occurred in a New Jersey resident who reported visiting a farm shortly before symptom onset. There was no evidence of human-to-human transmission. Both recovered fully without hospitalization. The A(H1N2) variant occurred in a Minnesota resident who was hospitalized but who recovered. This person was not interviewed so no possible source of infection was identified.

The CDC tested 2,408 viral specimens for susceptibility to antiviral medications. Among the 2,193 A(H1N1) specimens, less than 1% were resistant to oseltamivir and peramivir. All were susceptible to zanamivir. However, the testing found persistent high levels of resistant to amantadine and rimantadine in the A viruses. Amantadine is not effective on the B strains at all. Therefore, CDC does not recommend the use of amantadine as an anti-influenza medication.

Reports of influenza first exceeded the 2.1% baseline level in the week ending Dec. 26, 2015, according to the U.S. Outpatient Influenza-Like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet). They remained elevated for the next 17 weeks, with a peak of 3.6% of all outpatient visits in the week ending March 12. From October 2015-April 2016, the overall hospitalization rate for influenza-like illness was 31 per 100,000. This was highest in those aged 65 years and older (85/100,000), and lowest in those aged 5-17 years (10/100,000). About 92% of adults hospitalized for flu-like illness had at least one underlying medical comorbidity, including obesity (42%), cardiovascular disease (40%), and metabolic disorders (38%). Almost half of children (48%) also had medical comorbidities, including asthma or other reactive airway disease (22%) and neurologic disorders (18%).

CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics Mortality Surveillance System found that the percentage of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza peaked at 8% during the week ending March 19. This is slightly lower than the death rate seen in the last 5 years, which ranged from 9% in 2011-2012 to 11% in 2012-2013.

Of this season’s deaths, 74 occurred in children. The mean and median ages of these patients were 7 years and 6 years, respectively; the range was 2 months-16 years. This total was lower than that recorded in any of the past three influenza seasons: 171 pediatric deaths in 2012-2013, 111 in 2013-2014, and 148 in 2014-2015.

Dr. Davlin also announced the Food and Drug Administration’s recommendations for composition of the 2016-2017 influenza vaccine.

Trivalent vaccines should contain an A/California/7/2009 (H1N1) pdm09-like virus, an A/Hong Kong/4801/2014 (H3N2)-like virus, and a B/Brisbane/60/2008-like virus (B/Victoria lineage). Quadrivalent vaccines, which have two influenza B viruses, should include the viruses recommended for the trivalent vaccines, as well as a B/Phuket/3073/2013-like virus (B/Yamagata lineage).

“The vaccine viruses recommended for inclusion in the 2016-2017 Northern Hemisphere influenza vaccines are the same vaccine viruses that were chosen for inclusion in 2016 Southern Hemisphere seasonal influenza vaccines,” Dr. Davlin noted. “These vaccine recommendations were based on a number of factors, including global influenza virologic and epidemiologic surveillance, genetic and antigenic characterization, antiviral susceptibility, and the availability of candidate vaccine viruses for production.”

As a CDC employee, Dr. Davlin had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

The 2015-2016 flu season was less severe than the last three seasons, with a lower hospitalization rate and fewer pediatric deaths.

Cases of influenza appeared later in the season that typically seen, and activity didn’t peak until March, Stacy L. Davlin, Ph.D., wrote in the June 10 issue of the Morbidity and Mortality report (MMWR 2016; 22:567-75)

“During the most recent 18 influenza seasons, only two other seasons have peaked in March (2011-2012 and 2005-2006),” wrote Dr. Davlin, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta. This serves as a reminder that influenza can and does occur outside the traditionally expected season, and that clinicians shouldn’t discount the possibility of flu when a patient presents with typical symptoms.

“Although summer influenza activity in the United States typically is low, influenza cases and outbreaks have occurred during summer months, and clinicians should remain vigilant in considering influenza in the differential diagnosis of summer respiratory illnesses,” Dr. Davlin said.

The most common influenza virus of the last season was A(H1N1), which accounted for about half of cases in those aged 5-24 years, and about 70% of cases in those younger than 5 years and those 65 years and older.

Three novel viruses were seen as well: variants of A(H1N1), A(H1N2), and A(H3N2). The A(H1N1) variant occurred in a Minnesota resident who lived and worked in an area of swine farming, but who denied direct contact with pigs. The A(H3N2) variant occurred in a New Jersey resident who reported visiting a farm shortly before symptom onset. There was no evidence of human-to-human transmission. Both recovered fully without hospitalization. The A(H1N2) variant occurred in a Minnesota resident who was hospitalized but who recovered. This person was not interviewed so no possible source of infection was identified.

The CDC tested 2,408 viral specimens for susceptibility to antiviral medications. Among the 2,193 A(H1N1) specimens, less than 1% were resistant to oseltamivir and peramivir. All were susceptible to zanamivir. However, the testing found persistent high levels of resistant to amantadine and rimantadine in the A viruses. Amantadine is not effective on the B strains at all. Therefore, CDC does not recommend the use of amantadine as an anti-influenza medication.

Reports of influenza first exceeded the 2.1% baseline level in the week ending Dec. 26, 2015, according to the U.S. Outpatient Influenza-Like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet). They remained elevated for the next 17 weeks, with a peak of 3.6% of all outpatient visits in the week ending March 12. From October 2015-April 2016, the overall hospitalization rate for influenza-like illness was 31 per 100,000. This was highest in those aged 65 years and older (85/100,000), and lowest in those aged 5-17 years (10/100,000). About 92% of adults hospitalized for flu-like illness had at least one underlying medical comorbidity, including obesity (42%), cardiovascular disease (40%), and metabolic disorders (38%). Almost half of children (48%) also had medical comorbidities, including asthma or other reactive airway disease (22%) and neurologic disorders (18%).

CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics Mortality Surveillance System found that the percentage of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza peaked at 8% during the week ending March 19. This is slightly lower than the death rate seen in the last 5 years, which ranged from 9% in 2011-2012 to 11% in 2012-2013.

Of this season’s deaths, 74 occurred in children. The mean and median ages of these patients were 7 years and 6 years, respectively; the range was 2 months-16 years. This total was lower than that recorded in any of the past three influenza seasons: 171 pediatric deaths in 2012-2013, 111 in 2013-2014, and 148 in 2014-2015.

Dr. Davlin also announced the Food and Drug Administration’s recommendations for composition of the 2016-2017 influenza vaccine.

Trivalent vaccines should contain an A/California/7/2009 (H1N1) pdm09-like virus, an A/Hong Kong/4801/2014 (H3N2)-like virus, and a B/Brisbane/60/2008-like virus (B/Victoria lineage). Quadrivalent vaccines, which have two influenza B viruses, should include the viruses recommended for the trivalent vaccines, as well as a B/Phuket/3073/2013-like virus (B/Yamagata lineage).

“The vaccine viruses recommended for inclusion in the 2016-2017 Northern Hemisphere influenza vaccines are the same vaccine viruses that were chosen for inclusion in 2016 Southern Hemisphere seasonal influenza vaccines,” Dr. Davlin noted. “These vaccine recommendations were based on a number of factors, including global influenza virologic and epidemiologic surveillance, genetic and antigenic characterization, antiviral susceptibility, and the availability of candidate vaccine viruses for production.”

As a CDC employee, Dr. Davlin had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

FROM THE MMWR

Key clinical point: The last flu season peaked later, and killed fewer people than the last three seasons.

Major finding: The overall death rate was 31/100,000, with a peak of 8% occurring in March.

Data source: Numbers were drawn from CDC databases and other national influenza surveillance programs.

Disclosures: As a CDC employee, Dr. Davlin had no financial disclosures.

Time of day matters for flu vaccine administration in older adults

A simple and cost-neutral manipulation of the timing of flu vaccine administration – vaccinating older adults in the morning – may improve protection from the influenza virus, according to a study published in Vaccine.

Anna C. Phillips, PhD, of the School of Sport, Exercise, and Rehabilitation Sciences at the University of Birmingham (England), and her associates assessed the change in antibody titers to three vaccine influenza strains (A/H1N1, A/H3N2, and B) from prevaccination to one month postvaccination in a non-blinded cluster-randomized trial of 276 adults aged 65 or older receiving vaccinations in the morning or afternoon between October 28, 2011 and November 12, 2013. Because diurnal variations in immune cell responses and/or levels of hormones with immune modifying properties, such as cortisol or inflammatory cytokines, may provide an advantageous period for vaccination responses to occur, their levels were analyzed at baseline to identify relationships with antibody responses (Vaccine. 2016 May;34[24]:2679-85. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.032).

The study results indicated significant effects of time of day on the A/H1N1 and B strain antibody responses, but not for the A/H3N2 strain. More specifically, morning vaccinations produced greater antibody responses for the A/H1N1 and B strains as compared with those vaccinated in the afternoon, while the A/H3N2 strain antibody responses did not differ between morning and afternoon administration. Furthermore, both men and women were equally likely to show these effects.

Given their known diurnal rhythms, expected significant differences between groups were found for cortisol, the cortisol:cortisone ratio, corticosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and androstenedione. However, none of the measured steroid hormone or cytokine levels showed any relationship between the time of day and antibody responses.

Dr. Phillips and her associates said that the strength of their study was its first-of-a-kind, large-scale randomized design for the assessment of different times of vaccination, which provided evidence for the enhancement of the antibody responses to the influenza vaccine following morning administration. Limitations included the inability to reach the recruitment goal of 400 participants over three years, which may have reduced the statistical power of the study.

The study was funded by a Medical Research Council Lifelong Health and Wellbeing Collaborative Research Grant to the University of Birmingham. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A simple and cost-neutral manipulation of the timing of flu vaccine administration – vaccinating older adults in the morning – may improve protection from the influenza virus, according to a study published in Vaccine.

Anna C. Phillips, PhD, of the School of Sport, Exercise, and Rehabilitation Sciences at the University of Birmingham (England), and her associates assessed the change in antibody titers to three vaccine influenza strains (A/H1N1, A/H3N2, and B) from prevaccination to one month postvaccination in a non-blinded cluster-randomized trial of 276 adults aged 65 or older receiving vaccinations in the morning or afternoon between October 28, 2011 and November 12, 2013. Because diurnal variations in immune cell responses and/or levels of hormones with immune modifying properties, such as cortisol or inflammatory cytokines, may provide an advantageous period for vaccination responses to occur, their levels were analyzed at baseline to identify relationships with antibody responses (Vaccine. 2016 May;34[24]:2679-85. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.032).

The study results indicated significant effects of time of day on the A/H1N1 and B strain antibody responses, but not for the A/H3N2 strain. More specifically, morning vaccinations produced greater antibody responses for the A/H1N1 and B strains as compared with those vaccinated in the afternoon, while the A/H3N2 strain antibody responses did not differ between morning and afternoon administration. Furthermore, both men and women were equally likely to show these effects.

Given their known diurnal rhythms, expected significant differences between groups were found for cortisol, the cortisol:cortisone ratio, corticosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and androstenedione. However, none of the measured steroid hormone or cytokine levels showed any relationship between the time of day and antibody responses.

Dr. Phillips and her associates said that the strength of their study was its first-of-a-kind, large-scale randomized design for the assessment of different times of vaccination, which provided evidence for the enhancement of the antibody responses to the influenza vaccine following morning administration. Limitations included the inability to reach the recruitment goal of 400 participants over three years, which may have reduced the statistical power of the study.

The study was funded by a Medical Research Council Lifelong Health and Wellbeing Collaborative Research Grant to the University of Birmingham. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A simple and cost-neutral manipulation of the timing of flu vaccine administration – vaccinating older adults in the morning – may improve protection from the influenza virus, according to a study published in Vaccine.

Anna C. Phillips, PhD, of the School of Sport, Exercise, and Rehabilitation Sciences at the University of Birmingham (England), and her associates assessed the change in antibody titers to three vaccine influenza strains (A/H1N1, A/H3N2, and B) from prevaccination to one month postvaccination in a non-blinded cluster-randomized trial of 276 adults aged 65 or older receiving vaccinations in the morning or afternoon between October 28, 2011 and November 12, 2013. Because diurnal variations in immune cell responses and/or levels of hormones with immune modifying properties, such as cortisol or inflammatory cytokines, may provide an advantageous period for vaccination responses to occur, their levels were analyzed at baseline to identify relationships with antibody responses (Vaccine. 2016 May;34[24]:2679-85. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.032).

The study results indicated significant effects of time of day on the A/H1N1 and B strain antibody responses, but not for the A/H3N2 strain. More specifically, morning vaccinations produced greater antibody responses for the A/H1N1 and B strains as compared with those vaccinated in the afternoon, while the A/H3N2 strain antibody responses did not differ between morning and afternoon administration. Furthermore, both men and women were equally likely to show these effects.

Given their known diurnal rhythms, expected significant differences between groups were found for cortisol, the cortisol:cortisone ratio, corticosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and androstenedione. However, none of the measured steroid hormone or cytokine levels showed any relationship between the time of day and antibody responses.

Dr. Phillips and her associates said that the strength of their study was its first-of-a-kind, large-scale randomized design for the assessment of different times of vaccination, which provided evidence for the enhancement of the antibody responses to the influenza vaccine following morning administration. Limitations included the inability to reach the recruitment goal of 400 participants over three years, which may have reduced the statistical power of the study.

The study was funded by a Medical Research Council Lifelong Health and Wellbeing Collaborative Research Grant to the University of Birmingham. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Key clinical point: Vaccinating older adults in the morning may improve protection from the influenza virus.

Major finding: Antibody responses to two of three influenza strains were higher when vaccinations were administered in the morning.

Data sources: Participants aged 65 years or older, recruited from 24 Primary Care General Practices within the West Midlands (England), vaccinated in the morning or afternoon between 2011 and 2013.

Disclosures: The study was funded by a Medical Research Council Lifelong Health and Wellbeing Collaborative Research Grant to the University of Birmingham. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

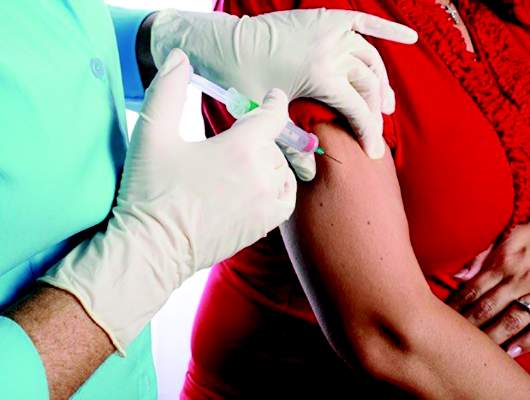

Maternal flu shot offers far-reaching protection

WASHINGTON – The influenza vaccine is highly recommended for pregnant women, protecting the woman, the newborn, and even the fetus, according to Dr. Sonja Rasmussen.

Multiple prospective and retrospective studies have shown that the inactivated influenza shot is safe and effective for pregnant women. And not only does it confer a transient passive immunity upon the newborn, the vaccine also guards against the dangers the flu poses to fetuses, she said at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Among the benefits seen with the flu shot are healthier birth weights, less preterm birth, and a much lower risk of birth defects that are associated with maternal fever in the first trimester, said Dr. Rasmussen, director of public health information dissemination at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Fever in the first trimester doubles the risk of neural tube defects in the fetus,” said Dr. Rasmussen. She cited a 2014 meta-analysis that found increased risks of other fetal anomalies associated with first trimester flu: hydrocephaly (odds ratio, 5.74), congenital heart defects (OR, 1.56), cleft lip (OR, 3.12), limb abnormalities (OR, 2.03) and digestive system defects (OR, 1.72) (Hum Reprod. 2014 Apr;29[4]:809-23).

“We don’t know if these are more due to the hyperthermia of fever or to the flu virus crossing the placenta,” she said. “But we do know these are real risks.”

Newborns come with an immature immune system that takes a while to get ramped up. In the first 6 months of life, they’re especially vulnerable to communicable illnesses, and they can become severely ill and even die from flu, Dr. Rasmussen said. A new study of nearly 250,000 mother-child pairs confirmed that maternal vaccination reduces the risks of flu hospitalization by more than 80% in infants younger than 6 months (Pediatrics. 2016 May 2. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2360).

For most women, the understanding that a flu shot protects their baby before and after birth is good enough reason to get one, Dr. Rasmussen said, but the benefits for the woman are extremely important. “Pregnant women experience a lot of changes in immune function and heart and lung function that increase the risk for complications from influenza. In prior pandemics, we have seen pregnant women at an increased risk of severe illness, hospitalization, and death.”

She cited data from the 2009 H1N1 epidemic that showed that 5% of those who died from H1N1 flu were pregnant women, despite the fact that they represented only 1% of the U.S. population (JAMA. 2010;303[15]:1517-25).

Despite the well-documented benefits and reassuring safety data, flu vaccine coverage remains suboptimal for pregnant women, Dr. Rasmussen said. The most recent CDC data suggest that just half of pregnant women were immunized in 2014-2015, a rate that has remained steady since 2012.

The most effective way to boost this number, Dr. Rasmussen suggested, is to stress to women that the vaccine protects both the fetus and newborn from a potentially fatal illness. “We know that a large number of babies and children die of influenza every year,” she said. “The biggest motivator for moms is their desire to protect their baby – much more so than protecting themselves.”

Dr. Rasmussen reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – The influenza vaccine is highly recommended for pregnant women, protecting the woman, the newborn, and even the fetus, according to Dr. Sonja Rasmussen.

Multiple prospective and retrospective studies have shown that the inactivated influenza shot is safe and effective for pregnant women. And not only does it confer a transient passive immunity upon the newborn, the vaccine also guards against the dangers the flu poses to fetuses, she said at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Among the benefits seen with the flu shot are healthier birth weights, less preterm birth, and a much lower risk of birth defects that are associated with maternal fever in the first trimester, said Dr. Rasmussen, director of public health information dissemination at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Fever in the first trimester doubles the risk of neural tube defects in the fetus,” said Dr. Rasmussen. She cited a 2014 meta-analysis that found increased risks of other fetal anomalies associated with first trimester flu: hydrocephaly (odds ratio, 5.74), congenital heart defects (OR, 1.56), cleft lip (OR, 3.12), limb abnormalities (OR, 2.03) and digestive system defects (OR, 1.72) (Hum Reprod. 2014 Apr;29[4]:809-23).

“We don’t know if these are more due to the hyperthermia of fever or to the flu virus crossing the placenta,” she said. “But we do know these are real risks.”

Newborns come with an immature immune system that takes a while to get ramped up. In the first 6 months of life, they’re especially vulnerable to communicable illnesses, and they can become severely ill and even die from flu, Dr. Rasmussen said. A new study of nearly 250,000 mother-child pairs confirmed that maternal vaccination reduces the risks of flu hospitalization by more than 80% in infants younger than 6 months (Pediatrics. 2016 May 2. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2360).

For most women, the understanding that a flu shot protects their baby before and after birth is good enough reason to get one, Dr. Rasmussen said, but the benefits for the woman are extremely important. “Pregnant women experience a lot of changes in immune function and heart and lung function that increase the risk for complications from influenza. In prior pandemics, we have seen pregnant women at an increased risk of severe illness, hospitalization, and death.”

She cited data from the 2009 H1N1 epidemic that showed that 5% of those who died from H1N1 flu were pregnant women, despite the fact that they represented only 1% of the U.S. population (JAMA. 2010;303[15]:1517-25).

Despite the well-documented benefits and reassuring safety data, flu vaccine coverage remains suboptimal for pregnant women, Dr. Rasmussen said. The most recent CDC data suggest that just half of pregnant women were immunized in 2014-2015, a rate that has remained steady since 2012.

The most effective way to boost this number, Dr. Rasmussen suggested, is to stress to women that the vaccine protects both the fetus and newborn from a potentially fatal illness. “We know that a large number of babies and children die of influenza every year,” she said. “The biggest motivator for moms is their desire to protect their baby – much more so than protecting themselves.”

Dr. Rasmussen reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – The influenza vaccine is highly recommended for pregnant women, protecting the woman, the newborn, and even the fetus, according to Dr. Sonja Rasmussen.

Multiple prospective and retrospective studies have shown that the inactivated influenza shot is safe and effective for pregnant women. And not only does it confer a transient passive immunity upon the newborn, the vaccine also guards against the dangers the flu poses to fetuses, she said at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Among the benefits seen with the flu shot are healthier birth weights, less preterm birth, and a much lower risk of birth defects that are associated with maternal fever in the first trimester, said Dr. Rasmussen, director of public health information dissemination at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Fever in the first trimester doubles the risk of neural tube defects in the fetus,” said Dr. Rasmussen. She cited a 2014 meta-analysis that found increased risks of other fetal anomalies associated with first trimester flu: hydrocephaly (odds ratio, 5.74), congenital heart defects (OR, 1.56), cleft lip (OR, 3.12), limb abnormalities (OR, 2.03) and digestive system defects (OR, 1.72) (Hum Reprod. 2014 Apr;29[4]:809-23).

“We don’t know if these are more due to the hyperthermia of fever or to the flu virus crossing the placenta,” she said. “But we do know these are real risks.”

Newborns come with an immature immune system that takes a while to get ramped up. In the first 6 months of life, they’re especially vulnerable to communicable illnesses, and they can become severely ill and even die from flu, Dr. Rasmussen said. A new study of nearly 250,000 mother-child pairs confirmed that maternal vaccination reduces the risks of flu hospitalization by more than 80% in infants younger than 6 months (Pediatrics. 2016 May 2. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2360).

For most women, the understanding that a flu shot protects their baby before and after birth is good enough reason to get one, Dr. Rasmussen said, but the benefits for the woman are extremely important. “Pregnant women experience a lot of changes in immune function and heart and lung function that increase the risk for complications from influenza. In prior pandemics, we have seen pregnant women at an increased risk of severe illness, hospitalization, and death.”

She cited data from the 2009 H1N1 epidemic that showed that 5% of those who died from H1N1 flu were pregnant women, despite the fact that they represented only 1% of the U.S. population (JAMA. 2010;303[15]:1517-25).

Despite the well-documented benefits and reassuring safety data, flu vaccine coverage remains suboptimal for pregnant women, Dr. Rasmussen said. The most recent CDC data suggest that just half of pregnant women were immunized in 2014-2015, a rate that has remained steady since 2012.

The most effective way to boost this number, Dr. Rasmussen suggested, is to stress to women that the vaccine protects both the fetus and newborn from a potentially fatal illness. “We know that a large number of babies and children die of influenza every year,” she said. “The biggest motivator for moms is their desire to protect their baby – much more so than protecting themselves.”

Dr. Rasmussen reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ACOG 2016

Flu vaccination cut hospitalizations in heart failure patients

FLORENCE, ITALY – Influenza vaccination of heart failure patients cut their rate of hospitalization for cardiovascular disease by nearly a third during the year following vaccination in a study of more than 59,000 British heart failure patients.

Influenza vaccination of heart failure patients also cut their rate of hospitalization for respiratory infections by a statistically significant 16% during the year following vaccination, Dr. Kazem Rahimi said at a meeting held by the Heart Failure Association of the ESC.

“In the absence of randomized trials, this [observational] study of 59,202 heart failure patients provides the most compelling evidence to date for the protective effect of influenza vaccination on hospital admissions,” said Dr. Rahimi, a cardiologist and epidemiologist who is deputy director of the George Institute for Global Health at the University of Oxford (England).

The analysis also showed that influenza vaccination of heart failure patients had no significant effect on all-cause hospitalizations.

Dr. Rahimi and his associates analyzed electronic health records from primary and secondary care settings in England during 1990-2013, from which they identified 59,202 heart failure patients with records for at least 1 year of influenza vaccination and at least 1 year without vaccination. The patients averaged 75 years old and were divided equally among women and men.

To control for potential confounding factors, they used a self-control model in which hospitalizations for each heart failure patient during the year following an influenza vaccination were compared with an adjacent year for that same patient when no vaccination occurred.

The results showed that the incidence of hospitalizations for cardiovascular diseases fell by a statistically significant 30% in the year following an influenza vaccination, compared with one or more adjacent years without vaccination. The protection again hospitalization was strongest during the second month following vaccination and then gradually waned over the ensuing year; by about 10 months following vaccination the protection effect had disappeared.

The study also looked at influenza vaccine uptake by heart failure patients through the 24-year period examined. During that time, the vaccination uptake rate rose from a low of less than 10% in 1990 to a peak rate of just over 60% in 2006, after which the rate gradually declined to a rate of just under 50% in 2013. Dr. Rahimi attributed the rise in uptake during the period from 1990 to 2006 in part to incentives that primary care physicians in England began receiving to administer influenza vaccine to their patients. “Higher uptake of annual vaccination in heart failure patients may help alleviate the burden of influenza-related hospital admissions,” he said.

Dr. Rahimi had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The main problem with observational studies is confounding, and the observational studies done until now that had looked at the protective role of influenza vaccination in heart failure patients had not been very convincing. Dr. Rahimi and his associates performed a high-quality study that adds to the evidence and underlines recommendations for influenza vaccination of heart failure patients. Their study was very large, and it used a self-control approach to adjust for potential confounding. I think they did their best to eliminate confounding.

|

Dr. Arno W. Hoes |

The newly released, updated guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure recommend annual vaccination of heart failure patients against influenza and pneumococcal disease. The data reported by Dr. Rahimi also document that only about half of heart failure patients in England currently receive an annual influenza vaccine. That percentage needs to increase.

Dr. Arno W. Hoes is professor of clinical epidemiology at the University Medical Center in Utrecht, the Netherlands. He made these comments as designated discussant for the study. He had no disclosures.

The main problem with observational studies is confounding, and the observational studies done until now that had looked at the protective role of influenza vaccination in heart failure patients had not been very convincing. Dr. Rahimi and his associates performed a high-quality study that adds to the evidence and underlines recommendations for influenza vaccination of heart failure patients. Their study was very large, and it used a self-control approach to adjust for potential confounding. I think they did their best to eliminate confounding.

|

Dr. Arno W. Hoes |

The newly released, updated guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure recommend annual vaccination of heart failure patients against influenza and pneumococcal disease. The data reported by Dr. Rahimi also document that only about half of heart failure patients in England currently receive an annual influenza vaccine. That percentage needs to increase.

Dr. Arno W. Hoes is professor of clinical epidemiology at the University Medical Center in Utrecht, the Netherlands. He made these comments as designated discussant for the study. He had no disclosures.

The main problem with observational studies is confounding, and the observational studies done until now that had looked at the protective role of influenza vaccination in heart failure patients had not been very convincing. Dr. Rahimi and his associates performed a high-quality study that adds to the evidence and underlines recommendations for influenza vaccination of heart failure patients. Their study was very large, and it used a self-control approach to adjust for potential confounding. I think they did their best to eliminate confounding.

|

Dr. Arno W. Hoes |

The newly released, updated guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure recommend annual vaccination of heart failure patients against influenza and pneumococcal disease. The data reported by Dr. Rahimi also document that only about half of heart failure patients in England currently receive an annual influenza vaccine. That percentage needs to increase.

Dr. Arno W. Hoes is professor of clinical epidemiology at the University Medical Center in Utrecht, the Netherlands. He made these comments as designated discussant for the study. He had no disclosures.

FLORENCE, ITALY – Influenza vaccination of heart failure patients cut their rate of hospitalization for cardiovascular disease by nearly a third during the year following vaccination in a study of more than 59,000 British heart failure patients.

Influenza vaccination of heart failure patients also cut their rate of hospitalization for respiratory infections by a statistically significant 16% during the year following vaccination, Dr. Kazem Rahimi said at a meeting held by the Heart Failure Association of the ESC.

“In the absence of randomized trials, this [observational] study of 59,202 heart failure patients provides the most compelling evidence to date for the protective effect of influenza vaccination on hospital admissions,” said Dr. Rahimi, a cardiologist and epidemiologist who is deputy director of the George Institute for Global Health at the University of Oxford (England).

The analysis also showed that influenza vaccination of heart failure patients had no significant effect on all-cause hospitalizations.

Dr. Rahimi and his associates analyzed electronic health records from primary and secondary care settings in England during 1990-2013, from which they identified 59,202 heart failure patients with records for at least 1 year of influenza vaccination and at least 1 year without vaccination. The patients averaged 75 years old and were divided equally among women and men.

To control for potential confounding factors, they used a self-control model in which hospitalizations for each heart failure patient during the year following an influenza vaccination were compared with an adjacent year for that same patient when no vaccination occurred.

The results showed that the incidence of hospitalizations for cardiovascular diseases fell by a statistically significant 30% in the year following an influenza vaccination, compared with one or more adjacent years without vaccination. The protection again hospitalization was strongest during the second month following vaccination and then gradually waned over the ensuing year; by about 10 months following vaccination the protection effect had disappeared.

The study also looked at influenza vaccine uptake by heart failure patients through the 24-year period examined. During that time, the vaccination uptake rate rose from a low of less than 10% in 1990 to a peak rate of just over 60% in 2006, after which the rate gradually declined to a rate of just under 50% in 2013. Dr. Rahimi attributed the rise in uptake during the period from 1990 to 2006 in part to incentives that primary care physicians in England began receiving to administer influenza vaccine to their patients. “Higher uptake of annual vaccination in heart failure patients may help alleviate the burden of influenza-related hospital admissions,” he said.

Dr. Rahimi had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

FLORENCE, ITALY – Influenza vaccination of heart failure patients cut their rate of hospitalization for cardiovascular disease by nearly a third during the year following vaccination in a study of more than 59,000 British heart failure patients.

Influenza vaccination of heart failure patients also cut their rate of hospitalization for respiratory infections by a statistically significant 16% during the year following vaccination, Dr. Kazem Rahimi said at a meeting held by the Heart Failure Association of the ESC.

“In the absence of randomized trials, this [observational] study of 59,202 heart failure patients provides the most compelling evidence to date for the protective effect of influenza vaccination on hospital admissions,” said Dr. Rahimi, a cardiologist and epidemiologist who is deputy director of the George Institute for Global Health at the University of Oxford (England).

The analysis also showed that influenza vaccination of heart failure patients had no significant effect on all-cause hospitalizations.

Dr. Rahimi and his associates analyzed electronic health records from primary and secondary care settings in England during 1990-2013, from which they identified 59,202 heart failure patients with records for at least 1 year of influenza vaccination and at least 1 year without vaccination. The patients averaged 75 years old and were divided equally among women and men.

To control for potential confounding factors, they used a self-control model in which hospitalizations for each heart failure patient during the year following an influenza vaccination were compared with an adjacent year for that same patient when no vaccination occurred.

The results showed that the incidence of hospitalizations for cardiovascular diseases fell by a statistically significant 30% in the year following an influenza vaccination, compared with one or more adjacent years without vaccination. The protection again hospitalization was strongest during the second month following vaccination and then gradually waned over the ensuing year; by about 10 months following vaccination the protection effect had disappeared.

The study also looked at influenza vaccine uptake by heart failure patients through the 24-year period examined. During that time, the vaccination uptake rate rose from a low of less than 10% in 1990 to a peak rate of just over 60% in 2006, after which the rate gradually declined to a rate of just under 50% in 2013. Dr. Rahimi attributed the rise in uptake during the period from 1990 to 2006 in part to incentives that primary care physicians in England began receiving to administer influenza vaccine to their patients. “Higher uptake of annual vaccination in heart failure patients may help alleviate the burden of influenza-related hospital admissions,” he said.

Dr. Rahimi had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT HEART FAILURE 2016

Key clinical point: When heart failure patients received an influenza vaccination, their rate of hospitalization for cardiovascular disease and for respiratory infection fell significantly during the year following vaccination.

Major finding: Cardiovascular hospitalizations fell by 30% in the year following influenza vaccination, compared with adjacent years with no vaccination.

Data source: Review of electronic health records for 59,202 heart failure patients in England during 1990-2013.

Disclosures: Dr. Rahimi had no disclosures.

Seasonal flu holding strong in New Jersey

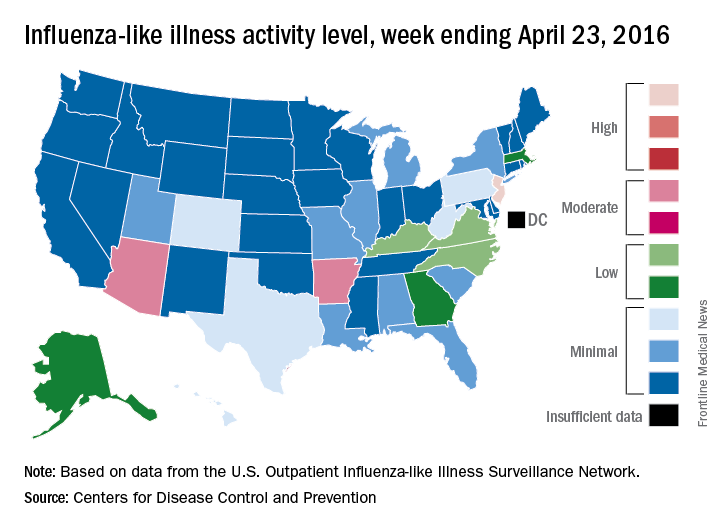

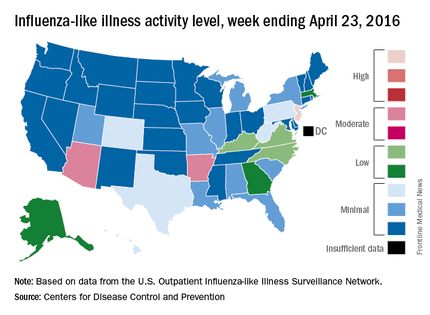

The 2015-2016 seasonal influenza virus has gotten hold of New Jersey and just won’t let go, according to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For the week ending April 23, 2016, influenza-like illness (ILI) activity in the United States remained at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale for the 11th consecutive week, even as the country’s overall proportion of outpatient visits for ILI dropped to 2.0%, which is below the national baseline of 2.1%, the CDC reported.

Two other states – Arizona and Arkansas – joined New Jersey in bucking the trend of decreasing ILI activity, as both moved up to level 7 and the high end of the “moderate” range. Arizona had been at level 5 the week before, while Arkansas was at level 4. No other state was above level 5 for the most recent week, and 27 states were at level 1, data from the CDC’s Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet) show.

Four flu-related pediatric deaths were reported during the week ending April 23, only one of which occurred that week. The total number of pediatric deaths rose to 60 for the 2015-2016 season, with 27 states and Puerto Rico reporting deaths so far, the CDC noted.

The CDC also reported a cumulative influenza-associated hospitalization rate for the season of 29.8 such hospitalizations per 100,000 population. This data was based on 8,239 laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations reported between October 1, 2015 and April 23, 2016. The highest rate of hospitalization was among adults aged 65 years or older (79.6 per 100,000 population), followed by adults aged 50-64 (43.1 per 100,000 population) and children aged 0-4 years (40.5 per 100,000 population). Among all hospitalizations, 6,254 (75.9%) were associated with influenza A, 1,905 (23.1%) with influenza B, 41 (0.5%) with influenza A and B co-infection, and 39 (0.5%) had no virus type information.

The 2015-2016 seasonal influenza virus has gotten hold of New Jersey and just won’t let go, according to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For the week ending April 23, 2016, influenza-like illness (ILI) activity in the United States remained at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale for the 11th consecutive week, even as the country’s overall proportion of outpatient visits for ILI dropped to 2.0%, which is below the national baseline of 2.1%, the CDC reported.

Two other states – Arizona and Arkansas – joined New Jersey in bucking the trend of decreasing ILI activity, as both moved up to level 7 and the high end of the “moderate” range. Arizona had been at level 5 the week before, while Arkansas was at level 4. No other state was above level 5 for the most recent week, and 27 states were at level 1, data from the CDC’s Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet) show.

Four flu-related pediatric deaths were reported during the week ending April 23, only one of which occurred that week. The total number of pediatric deaths rose to 60 for the 2015-2016 season, with 27 states and Puerto Rico reporting deaths so far, the CDC noted.

The CDC also reported a cumulative influenza-associated hospitalization rate for the season of 29.8 such hospitalizations per 100,000 population. This data was based on 8,239 laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations reported between October 1, 2015 and April 23, 2016. The highest rate of hospitalization was among adults aged 65 years or older (79.6 per 100,000 population), followed by adults aged 50-64 (43.1 per 100,000 population) and children aged 0-4 years (40.5 per 100,000 population). Among all hospitalizations, 6,254 (75.9%) were associated with influenza A, 1,905 (23.1%) with influenza B, 41 (0.5%) with influenza A and B co-infection, and 39 (0.5%) had no virus type information.

The 2015-2016 seasonal influenza virus has gotten hold of New Jersey and just won’t let go, according to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For the week ending April 23, 2016, influenza-like illness (ILI) activity in the United States remained at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale for the 11th consecutive week, even as the country’s overall proportion of outpatient visits for ILI dropped to 2.0%, which is below the national baseline of 2.1%, the CDC reported.

Two other states – Arizona and Arkansas – joined New Jersey in bucking the trend of decreasing ILI activity, as both moved up to level 7 and the high end of the “moderate” range. Arizona had been at level 5 the week before, while Arkansas was at level 4. No other state was above level 5 for the most recent week, and 27 states were at level 1, data from the CDC’s Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet) show.

Four flu-related pediatric deaths were reported during the week ending April 23, only one of which occurred that week. The total number of pediatric deaths rose to 60 for the 2015-2016 season, with 27 states and Puerto Rico reporting deaths so far, the CDC noted.

The CDC also reported a cumulative influenza-associated hospitalization rate for the season of 29.8 such hospitalizations per 100,000 population. This data was based on 8,239 laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations reported between October 1, 2015 and April 23, 2016. The highest rate of hospitalization was among adults aged 65 years or older (79.6 per 100,000 population), followed by adults aged 50-64 (43.1 per 100,000 population) and children aged 0-4 years (40.5 per 100,000 population). Among all hospitalizations, 6,254 (75.9%) were associated with influenza A, 1,905 (23.1%) with influenza B, 41 (0.5%) with influenza A and B co-infection, and 39 (0.5%) had no virus type information.

Neuraminidase inhibition titer a better predictor of influenza protection

Neuraminidase inhibition (NAI) titer is a better predictor of protection against influenza infection than hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) titer, according to new research, which could have implications for future flu vaccine development.

Investigators at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, performed a healthy volunteer challenge study with a wild-type 2009 A(H1N1)pdm influenza A challenge virus at the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, Md., to evaluate two groups of participants with HAI titers of greater than 1:40 and less than 1:40. The primary objective was to determine whether participants with HAI titers of greater than 1:40 were less likely to develop mild to moderate influenza disease after intranasal inoculation

In a multiple regression analysis, researchers evaluated the independent effects of both HAI and NAI titers on four diseases severity measures. In all measures – duration of shedding (HAI: P = .164; NAI: P less than .001), duration of symptoms (HAI: P = .497; NAI: P = .011), number of symptoms (HAI: P = .533; NAI: P less than .001), and symptom severity score (HAI: P = .906; NAI: P less than .001) – increasing NAI titers showed a statistically significant independent effect of decreasing severity, while HAI titers showed no significant independent effect on any of the disease severity measures examined.

When grouped by baseline NAI titers, those participants with high titers (greater than or equal to 1:40) had only minimal increases in NAI after challenge, but unlike HAI titer, every cohort with a low NAI titer had a rise in NAI titer after challenge, regardless of the outcome.

“These data further suggest that NAI titer may play a more significant role as a correlate of protection than previously thought and that the role of neuraminidase immunity should be considered when studying influenza susceptibility after vaccination and as a critical target in future influenza vaccine platforms,” Dr. Jeffery K. Taubenberger of the NIAID and his coauthors concluded.

This study was the first time the current “gold standard” for evaluating influenza vaccines – a protective HAI titer of greater than 1:40 – has been evaluated in a well-controlled healthy volunteer challenge since the cutoff was established, and the first time NAI titer has been identified in a controlled trial to be an independent predictor of a reduction in all aspects of influenza. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Read the full study in mBio (doi: 10.1128/mBio.00417-16).

Neuraminidase inhibition (NAI) titer is a better predictor of protection against influenza infection than hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) titer, according to new research, which could have implications for future flu vaccine development.

Investigators at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, performed a healthy volunteer challenge study with a wild-type 2009 A(H1N1)pdm influenza A challenge virus at the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, Md., to evaluate two groups of participants with HAI titers of greater than 1:40 and less than 1:40. The primary objective was to determine whether participants with HAI titers of greater than 1:40 were less likely to develop mild to moderate influenza disease after intranasal inoculation

In a multiple regression analysis, researchers evaluated the independent effects of both HAI and NAI titers on four diseases severity measures. In all measures – duration of shedding (HAI: P = .164; NAI: P less than .001), duration of symptoms (HAI: P = .497; NAI: P = .011), number of symptoms (HAI: P = .533; NAI: P less than .001), and symptom severity score (HAI: P = .906; NAI: P less than .001) – increasing NAI titers showed a statistically significant independent effect of decreasing severity, while HAI titers showed no significant independent effect on any of the disease severity measures examined.

When grouped by baseline NAI titers, those participants with high titers (greater than or equal to 1:40) had only minimal increases in NAI after challenge, but unlike HAI titer, every cohort with a low NAI titer had a rise in NAI titer after challenge, regardless of the outcome.

“These data further suggest that NAI titer may play a more significant role as a correlate of protection than previously thought and that the role of neuraminidase immunity should be considered when studying influenza susceptibility after vaccination and as a critical target in future influenza vaccine platforms,” Dr. Jeffery K. Taubenberger of the NIAID and his coauthors concluded.

This study was the first time the current “gold standard” for evaluating influenza vaccines – a protective HAI titer of greater than 1:40 – has been evaluated in a well-controlled healthy volunteer challenge since the cutoff was established, and the first time NAI titer has been identified in a controlled trial to be an independent predictor of a reduction in all aspects of influenza. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Read the full study in mBio (doi: 10.1128/mBio.00417-16).

Neuraminidase inhibition (NAI) titer is a better predictor of protection against influenza infection than hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) titer, according to new research, which could have implications for future flu vaccine development.

Investigators at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, performed a healthy volunteer challenge study with a wild-type 2009 A(H1N1)pdm influenza A challenge virus at the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, Md., to evaluate two groups of participants with HAI titers of greater than 1:40 and less than 1:40. The primary objective was to determine whether participants with HAI titers of greater than 1:40 were less likely to develop mild to moderate influenza disease after intranasal inoculation

In a multiple regression analysis, researchers evaluated the independent effects of both HAI and NAI titers on four diseases severity measures. In all measures – duration of shedding (HAI: P = .164; NAI: P less than .001), duration of symptoms (HAI: P = .497; NAI: P = .011), number of symptoms (HAI: P = .533; NAI: P less than .001), and symptom severity score (HAI: P = .906; NAI: P less than .001) – increasing NAI titers showed a statistically significant independent effect of decreasing severity, while HAI titers showed no significant independent effect on any of the disease severity measures examined.

When grouped by baseline NAI titers, those participants with high titers (greater than or equal to 1:40) had only minimal increases in NAI after challenge, but unlike HAI titer, every cohort with a low NAI titer had a rise in NAI titer after challenge, regardless of the outcome.

“These data further suggest that NAI titer may play a more significant role as a correlate of protection than previously thought and that the role of neuraminidase immunity should be considered when studying influenza susceptibility after vaccination and as a critical target in future influenza vaccine platforms,” Dr. Jeffery K. Taubenberger of the NIAID and his coauthors concluded.

This study was the first time the current “gold standard” for evaluating influenza vaccines – a protective HAI titer of greater than 1:40 – has been evaluated in a well-controlled healthy volunteer challenge since the cutoff was established, and the first time NAI titer has been identified in a controlled trial to be an independent predictor of a reduction in all aspects of influenza. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Read the full study in mBio (doi: 10.1128/mBio.00417-16).

FROM MBIO

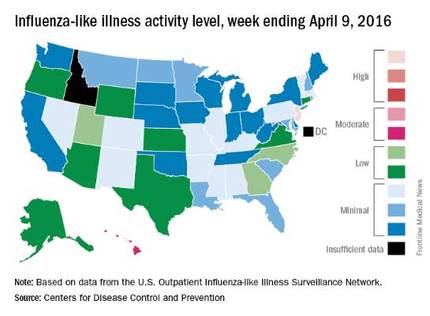

U.S. flu activity down again, except in New Jersey

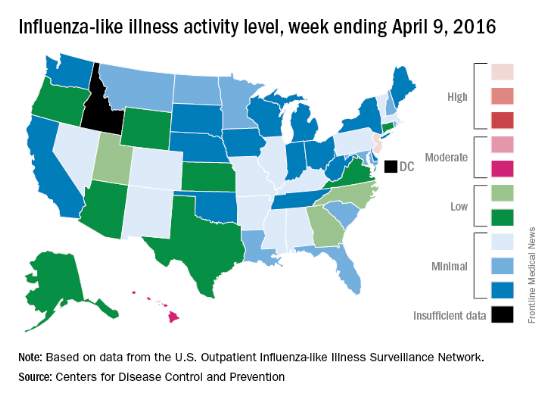

Overall activity of influenza-like illness (ILI) in the United States continued to fall, but New Jersey took a turn for the worse during the week ending April 9, 2016, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

New Jersey’s ILI activity level went from 8 the previous week to 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale. For the week ending April 9, it was the only U.S. state in the “high” range, with Hawaii the next highest at level 6 – the only state in the “moderate” range, the CDC reported.

Nationwide, the proportion of outpatient visits for ILI was 2.1%, which is at the national baseline of 2.1% and down from 2.5% the week before. That number has now dropped for 4 consecutive weeks since hitting a season high of 3.7% for the week ending March 12. The CDC also reported a cumulative rate of 26.6 influenza-associated hospitalizations per 100,000 population.

Ten flu-related pediatric deaths were reported during the week, of which only one occurred during the week. A total of 50 flu-related pediatric deaths have been reported during the 2015-2016 season, the CDC said. The overall proportion of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza was below the system-specific threshold in the National Center for Health Statistics Mortality Surveillance System, but above the system-specific threshold in the 122 Cities Mortality Reporting System.

Overall activity of influenza-like illness (ILI) in the United States continued to fall, but New Jersey took a turn for the worse during the week ending April 9, 2016, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

New Jersey’s ILI activity level went from 8 the previous week to 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale. For the week ending April 9, it was the only U.S. state in the “high” range, with Hawaii the next highest at level 6 – the only state in the “moderate” range, the CDC reported.

Nationwide, the proportion of outpatient visits for ILI was 2.1%, which is at the national baseline of 2.1% and down from 2.5% the week before. That number has now dropped for 4 consecutive weeks since hitting a season high of 3.7% for the week ending March 12. The CDC also reported a cumulative rate of 26.6 influenza-associated hospitalizations per 100,000 population.

Ten flu-related pediatric deaths were reported during the week, of which only one occurred during the week. A total of 50 flu-related pediatric deaths have been reported during the 2015-2016 season, the CDC said. The overall proportion of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza was below the system-specific threshold in the National Center for Health Statistics Mortality Surveillance System, but above the system-specific threshold in the 122 Cities Mortality Reporting System.

Overall activity of influenza-like illness (ILI) in the United States continued to fall, but New Jersey took a turn for the worse during the week ending April 9, 2016, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

New Jersey’s ILI activity level went from 8 the previous week to 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale. For the week ending April 9, it was the only U.S. state in the “high” range, with Hawaii the next highest at level 6 – the only state in the “moderate” range, the CDC reported.

Nationwide, the proportion of outpatient visits for ILI was 2.1%, which is at the national baseline of 2.1% and down from 2.5% the week before. That number has now dropped for 4 consecutive weeks since hitting a season high of 3.7% for the week ending March 12. The CDC also reported a cumulative rate of 26.6 influenza-associated hospitalizations per 100,000 population.

Ten flu-related pediatric deaths were reported during the week, of which only one occurred during the week. A total of 50 flu-related pediatric deaths have been reported during the 2015-2016 season, the CDC said. The overall proportion of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza was below the system-specific threshold in the National Center for Health Statistics Mortality Surveillance System, but above the system-specific threshold in the 122 Cities Mortality Reporting System.

ED bedside flu test accurate across flu seasons