User login

Few states fully support HCV prevention, treatment

The prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) varies considerably by state, and the same can be said for the state laws and policies attempting to decrease that prevalence, according to an assessment by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

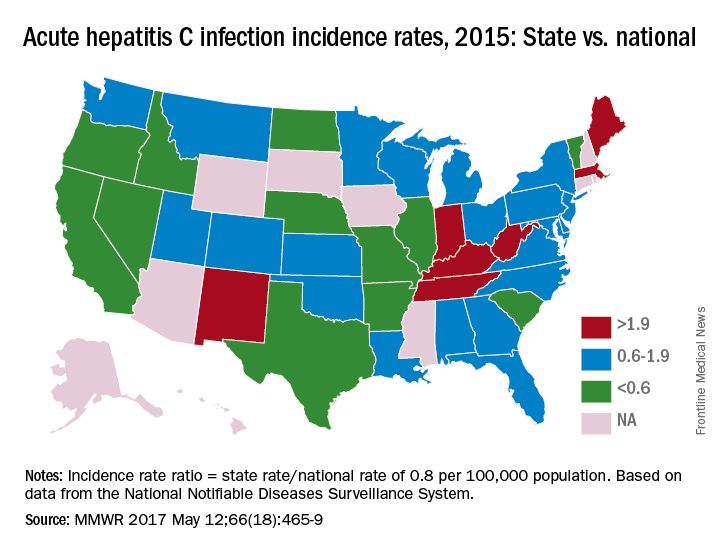

In 2015, incidence of acute HCV infection exceeded the national average of 0.8 per 100,000 population in 17 states, including seven with rates that at least doubled it, the report noted. New HCV infections have increased in recent years despite curative therapies “and known preventive measures to interrupt transmission.”

The U.S. incidence of HCV jumped by 294% from 2010 to 2015, and “this increase in acute cases of HCV is largely attributed to injection drug use,” the CDC investigators said. Since state laws and policies affect access to HCV preventive and treatment measures, the researchers reviewed laws related to access to clean needles and policies on Medicaid fee-for-service treatment.

Only three states – Massachusetts, New Mexico, and Washington – had a comprehensive (all three were considered “more comprehensive”) set of prevention laws and a permissive treatment policy, the investigators said, while also noting that two of the three – Massachusetts and New Mexico – were among the states with acute HCV rates that were at least twice the national average.

“Although the costs of HCV therapies have raised budgetary issues for state Medicaid programs in the past, the costs of HCV treatment have declined in recent years, increasing the cost-effectiveness of treatment, particularly among persons who inject drugs and who might serve as an ongoing source of transmission to others,” the report concluded.

The analysis examined three types of laws on access to clean needles and syringes: authorization of exchange programs, the scope of drug paraphernalia laws, and retail sale of needles and syringes. Each law was assessed for five elements, including authorization of syringe exchange statewide or in selected jurisdictions and exemption of needles or syringes from the definition of drug paraphernalia.

For the accompanying map (see “Acute hepatitis C infection incidence rates, 2015: State vs. national”), each state’s acute HCV incidence rate for 2015 was divided by the national rate to determine the incidence rate ratio, with data unavailable for 10 states.

AGA Resource

The AGA HCV Clinical Service Line offers tools to help you become more efficient, understand quality standards and improve the process of care for patients. Read more at http://www.gastro.org/patient-care/conditions-diseases/hepatitis-c.

The prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) varies considerably by state, and the same can be said for the state laws and policies attempting to decrease that prevalence, according to an assessment by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

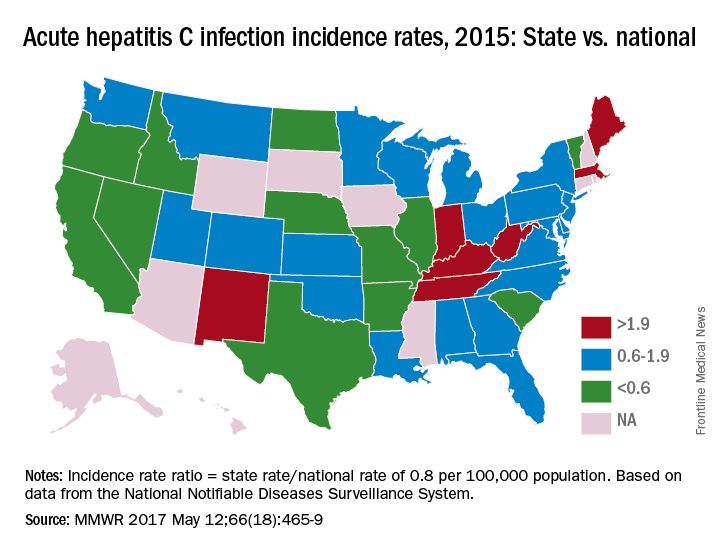

In 2015, incidence of acute HCV infection exceeded the national average of 0.8 per 100,000 population in 17 states, including seven with rates that at least doubled it, the report noted. New HCV infections have increased in recent years despite curative therapies “and known preventive measures to interrupt transmission.”

The U.S. incidence of HCV jumped by 294% from 2010 to 2015, and “this increase in acute cases of HCV is largely attributed to injection drug use,” the CDC investigators said. Since state laws and policies affect access to HCV preventive and treatment measures, the researchers reviewed laws related to access to clean needles and policies on Medicaid fee-for-service treatment.

Only three states – Massachusetts, New Mexico, and Washington – had a comprehensive (all three were considered “more comprehensive”) set of prevention laws and a permissive treatment policy, the investigators said, while also noting that two of the three – Massachusetts and New Mexico – were among the states with acute HCV rates that were at least twice the national average.

“Although the costs of HCV therapies have raised budgetary issues for state Medicaid programs in the past, the costs of HCV treatment have declined in recent years, increasing the cost-effectiveness of treatment, particularly among persons who inject drugs and who might serve as an ongoing source of transmission to others,” the report concluded.

The analysis examined three types of laws on access to clean needles and syringes: authorization of exchange programs, the scope of drug paraphernalia laws, and retail sale of needles and syringes. Each law was assessed for five elements, including authorization of syringe exchange statewide or in selected jurisdictions and exemption of needles or syringes from the definition of drug paraphernalia.

For the accompanying map (see “Acute hepatitis C infection incidence rates, 2015: State vs. national”), each state’s acute HCV incidence rate for 2015 was divided by the national rate to determine the incidence rate ratio, with data unavailable for 10 states.

AGA Resource

The AGA HCV Clinical Service Line offers tools to help you become more efficient, understand quality standards and improve the process of care for patients. Read more at http://www.gastro.org/patient-care/conditions-diseases/hepatitis-c.

The prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) varies considerably by state, and the same can be said for the state laws and policies attempting to decrease that prevalence, according to an assessment by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

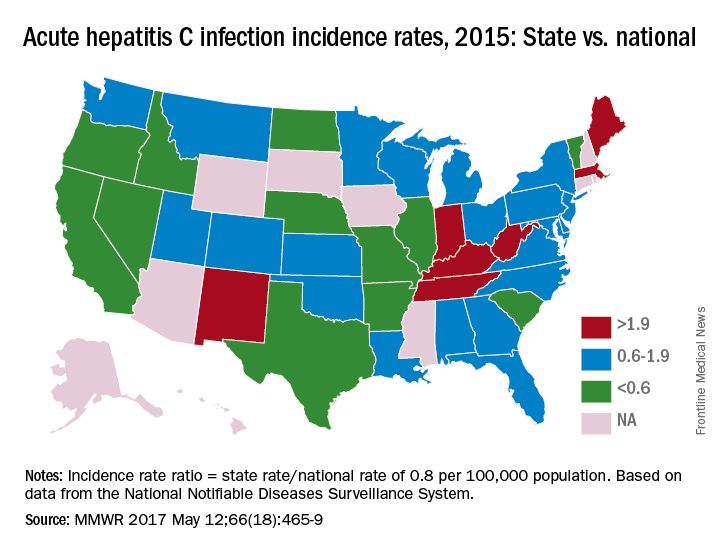

In 2015, incidence of acute HCV infection exceeded the national average of 0.8 per 100,000 population in 17 states, including seven with rates that at least doubled it, the report noted. New HCV infections have increased in recent years despite curative therapies “and known preventive measures to interrupt transmission.”

The U.S. incidence of HCV jumped by 294% from 2010 to 2015, and “this increase in acute cases of HCV is largely attributed to injection drug use,” the CDC investigators said. Since state laws and policies affect access to HCV preventive and treatment measures, the researchers reviewed laws related to access to clean needles and policies on Medicaid fee-for-service treatment.

Only three states – Massachusetts, New Mexico, and Washington – had a comprehensive (all three were considered “more comprehensive”) set of prevention laws and a permissive treatment policy, the investigators said, while also noting that two of the three – Massachusetts and New Mexico – were among the states with acute HCV rates that were at least twice the national average.

“Although the costs of HCV therapies have raised budgetary issues for state Medicaid programs in the past, the costs of HCV treatment have declined in recent years, increasing the cost-effectiveness of treatment, particularly among persons who inject drugs and who might serve as an ongoing source of transmission to others,” the report concluded.

The analysis examined three types of laws on access to clean needles and syringes: authorization of exchange programs, the scope of drug paraphernalia laws, and retail sale of needles and syringes. Each law was assessed for five elements, including authorization of syringe exchange statewide or in selected jurisdictions and exemption of needles or syringes from the definition of drug paraphernalia.

For the accompanying map (see “Acute hepatitis C infection incidence rates, 2015: State vs. national”), each state’s acute HCV incidence rate for 2015 was divided by the national rate to determine the incidence rate ratio, with data unavailable for 10 states.

AGA Resource

The AGA HCV Clinical Service Line offers tools to help you become more efficient, understand quality standards and improve the process of care for patients. Read more at http://www.gastro.org/patient-care/conditions-diseases/hepatitis-c.

FROM MMWR

‘Rich pipeline’ of novel NASH treatments being studied

AMSTERDAM – There is a “very, very rich pipeline” of drugs being developed for the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), Jean-François Dufour, MD, the head of hepatology and director of the University Clinic for Visceral Surgery and Medicine at the University of Berne (Switzerland) said at the International Liver Congress.

“We have many therapeutic options [under investigation],” Dr. Dufour noted at the Congress, which is sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL). These include drugs that target metabolic homeostasis, insulin resistance, inflammation, oxidative stress, or fibrosis (Liver Int. 2017 May;37:634-47).

In fact, there is such a range of options that target different pathways, from fatty acid and bile acid synthesis to the early and late stages of fibrosis, that it is very likely that these drugs will be used in combination, Dr. Dufour observed as he gave an overview of the current trials that are underway in NASH.

There are currently five ongoing multicenter phase III trials being undertaken with four drugs. First, there is the REGENERATE trial with Intercept’s farnesoid X receptor obeticholic acid(Ocaliva). This is a placebo-controlled trial comparing two daily doses of obeticholic acid (10 and 25 mg) on top of the standard of care. The trial will recruit just over 2,000 patients with biopsy-proven stage 2-3 NASH fibrosis, and the primary endpoint is the resolution of NASH without fibrosis worsening or improvement in fibrosis without worsening of NASH at week 72.

Second there is the RESOLVE-IT trial with Genfit’s peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha/delta agonist elafibranor. This randomized, double-blind trial hopes to recruit 2,000 patients with biopsy-proven NASH stage 1-3 fibrosis and will compare elafibranor 120 mg given once a day with placebo. The primary endpoint is the resolution of NASH without worsening of fibrosis at week 72.

Next, Tobira Therapeutics’ C-C chemokine receptor type 2 and 5 antagonist cenicriviroc is being studied in the AURORA trial. Again, recruiting around 2,000 patients is the target, but this time with stage 2-3 biopsy-proven NASH fibrosis. Cenicriviroc will be given daily at a dose of 150 mg and will be compared against placebo. The primary endpoint is the improvement of fibrosis by one or more stage with no worsening of steatohepatitis at 1 year.

Finally, there are the STELLA 3 and STELLA 4 trials with Gilead’s apoptosis signal-regulated kinase-1 inhibitor selonsertib. Target accrual in both studies is 800 patients with STELLA 3 recruiting patients with stage-3 NASH fibrosis and STELLA 4 recruiting those with compensated cirrhosis from NASH. Both trials will compared two daily doses of selonsertib (6 mg and 18 mg) versus placebo. The primary endpoints are the improvement of at least one or more fibrosis stage with no worsening of steatohepatitis at 48 weeks and event-free survival at week 240.

In addition, there are at least 20 phase 2b and 2a studies looking at a variety of other novel drugs with different therapeutic targets, Dr. Dufour said, and during separate presentations at the congress, results of several early trials with novel drugs being tested for NASH were given.

Eric J. Lawitz, MD, reported the promising results of a “proof of concept” open-label study in which the safety and efficacy of 12 weeks’ treatment with the oral acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) inhibitor, GS-0976, was examined in 10 patients with a clinical diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

“ACC catalyzes the rate-limiting step in de novo hepatic lipogenesis (DNL),” which is an underlying pathologic process in NASH, Dr. Lawitz, who is vice president of scientific and research development at the Texas Liver Institute, San Antonio, observed.

He reported that 12 weeks’ treatment with the ACC inhibitor GS-0976 suppressed DNL by 29%, compared with baseline (P = .022). There was also a 43% decrease in hepatic steatosis from baseline to 12 weeks (P = .006), as measured by the magnetic resonance imaging–proton-density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF), and a nonsignificant 9% reduction in liver stiffness measured using magnetic resonance elastography (MRE).

Two markers of fibrosis and cell death (TIMP-1 and CK18) were also improved, he said, noting that overall, the drug was well tolerated, bar a trend to an increase in triglycerides and reduction in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol that needs further follow up.

“There is a placebo-controlled phase II trial of GS-0976 in patients with NASH that is ongoing,” Dr. Lawitz said. Results of two phase II studies presented during the late-breaking abstracts session at the meeting showed similar promising results could be achieved with drugs mimicking the activity of different fibroblast growth factors.

“Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) is a nonmitogenic hormone produced in the liver that is an important regulator of energy metabolism,” said Arun J. Sanyal, MD, who presented the findings of a study with the FGF21 inhibitor BMS-986036.

”From a NASH perspective, it improves insulin sensitivity and by doing that, decreases lipogenesis, and it also has been shown to have some antifibrotic effects,” Dr. Sanyal of Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, added.

FGF21 has a short half-life, however, and BMS-986036 is a recombinant human analog of this hormone that could potentially allow it to be given up to once weekly.

The study involved 74 patients with stage 1-3 biopsy-proven NASH fibrosis and a hepatic fat fraction of 10% or greater measured by MRI-PDFF. Patients were randomized to treatment with BMS-986036 at subcutaneously administered doses of 10 mg given once daily or 20 mg given once weekly or to placebo for 16 weeks.

A significant reduction in the hepatic fat fraction was seen in patients treated with both the once-daily and once-weekly regimen of the active treatment relative to placebo, with absolute changes from baseline of –6.8% (P = .008) and –5.2% (P = .0004), respectively, and just –1.3% for placebo.

“Results suggest that BMS-986036 had beneficial effects on steatosis, liver injury, and fibrosis in NASH,” said Dr. Sanyal, who also noted that there were no deaths and no signal that there could be any safety concerns.

NGM282 is another recombinant human analog mimicking the action of an FGF, this time FGF19, and early data also suggest that it also reduces hepatic steatosis and key biomarkers of NASH. Dr. Stephen Harrison, MD, the medical director of Pinnacle Clinical Research in Live Oak, reported data on 82 patients with stage 1-3 NASH fibrosis who had been treated with NGM-282 3 mg or 6 mg subcutaneously once a day or placebo for 12 weeks.

“The primary endpoint [decrease in absolute liver fat content greater than or equal to 5%] was met in 79% of NGM-282-treated subjects, with over one-third of subjects achieving normalization of liver fat content with 12 weeks of therapy,” Dr. Harrison reported.

“There were significant and rapid reductions in multiple markers that are relevant to the resolution of NASH and improvement in fibrosis,” Dr. Harrison added.

One serious adverse event of acute pancreatitis occurred in a patient treated with FGF19, which was possibly thought to be treatment related, but otherwise adverse events were generally mild and included gastrointestinal effects such as diarrhea and nausea, and injection site reactions.

“These data strongly support the continued development of NGM282 in NASH,” Dr. Harrison said.

During his presentation at a symposium session on current and future approaches to NAFLD and NASH, Dr. Dufour was keen to point out that a combination of diet and exercise remains central to managing patients with NASH.

“We should not forget, that the first line of discussion with these patients should be about changing their lifestyles.” Improving diet and exercise is something that everybody can do, he said, it is widely available and inexpensive, associated with few side effects and can produce good results.

However, convincing some patients can be difficult and those with a low acceptance to lifestyle changes often prefer to take medication. That is likely to come at a cost, not just in terms of money but there are likely to be some side effects, and, of course, efficacy in NASH is yet to be proven in many cases, Dr. Dufour said.

Dr. Dufour disclosed he had been part of a number of advisory committees or received speaking and teaching fees from a host of pharmaceutical companies, many of whom have an interest in the development of treatments for NASH.

Gilead Sciences supported the study reported by Dr. Lawitz and he disclosed receiving research grants or other support from the company, as well as several other pharmaceutical companies.

The study presented by Dr. Sanyal was financed by Bristol-Myers Squibb and he disclosed research funding was provided to his institution. Dr. Sanyal also disclosed receiving research support and consulting fees from multiple other pharmaceutical companies.

Dr. Harrison acknowledged receiving research funding from and acting as a consultant to NGM Bio, who sponsored the study he presented. He also disclosed acting as an adviser or speaker, and receiving grants from other pharmaceutical companies in the past 12 months.

AMSTERDAM – There is a “very, very rich pipeline” of drugs being developed for the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), Jean-François Dufour, MD, the head of hepatology and director of the University Clinic for Visceral Surgery and Medicine at the University of Berne (Switzerland) said at the International Liver Congress.

“We have many therapeutic options [under investigation],” Dr. Dufour noted at the Congress, which is sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL). These include drugs that target metabolic homeostasis, insulin resistance, inflammation, oxidative stress, or fibrosis (Liver Int. 2017 May;37:634-47).

In fact, there is such a range of options that target different pathways, from fatty acid and bile acid synthesis to the early and late stages of fibrosis, that it is very likely that these drugs will be used in combination, Dr. Dufour observed as he gave an overview of the current trials that are underway in NASH.

There are currently five ongoing multicenter phase III trials being undertaken with four drugs. First, there is the REGENERATE trial with Intercept’s farnesoid X receptor obeticholic acid(Ocaliva). This is a placebo-controlled trial comparing two daily doses of obeticholic acid (10 and 25 mg) on top of the standard of care. The trial will recruit just over 2,000 patients with biopsy-proven stage 2-3 NASH fibrosis, and the primary endpoint is the resolution of NASH without fibrosis worsening or improvement in fibrosis without worsening of NASH at week 72.

Second there is the RESOLVE-IT trial with Genfit’s peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha/delta agonist elafibranor. This randomized, double-blind trial hopes to recruit 2,000 patients with biopsy-proven NASH stage 1-3 fibrosis and will compare elafibranor 120 mg given once a day with placebo. The primary endpoint is the resolution of NASH without worsening of fibrosis at week 72.

Next, Tobira Therapeutics’ C-C chemokine receptor type 2 and 5 antagonist cenicriviroc is being studied in the AURORA trial. Again, recruiting around 2,000 patients is the target, but this time with stage 2-3 biopsy-proven NASH fibrosis. Cenicriviroc will be given daily at a dose of 150 mg and will be compared against placebo. The primary endpoint is the improvement of fibrosis by one or more stage with no worsening of steatohepatitis at 1 year.

Finally, there are the STELLA 3 and STELLA 4 trials with Gilead’s apoptosis signal-regulated kinase-1 inhibitor selonsertib. Target accrual in both studies is 800 patients with STELLA 3 recruiting patients with stage-3 NASH fibrosis and STELLA 4 recruiting those with compensated cirrhosis from NASH. Both trials will compared two daily doses of selonsertib (6 mg and 18 mg) versus placebo. The primary endpoints are the improvement of at least one or more fibrosis stage with no worsening of steatohepatitis at 48 weeks and event-free survival at week 240.

In addition, there are at least 20 phase 2b and 2a studies looking at a variety of other novel drugs with different therapeutic targets, Dr. Dufour said, and during separate presentations at the congress, results of several early trials with novel drugs being tested for NASH were given.

Eric J. Lawitz, MD, reported the promising results of a “proof of concept” open-label study in which the safety and efficacy of 12 weeks’ treatment with the oral acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) inhibitor, GS-0976, was examined in 10 patients with a clinical diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

“ACC catalyzes the rate-limiting step in de novo hepatic lipogenesis (DNL),” which is an underlying pathologic process in NASH, Dr. Lawitz, who is vice president of scientific and research development at the Texas Liver Institute, San Antonio, observed.

He reported that 12 weeks’ treatment with the ACC inhibitor GS-0976 suppressed DNL by 29%, compared with baseline (P = .022). There was also a 43% decrease in hepatic steatosis from baseline to 12 weeks (P = .006), as measured by the magnetic resonance imaging–proton-density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF), and a nonsignificant 9% reduction in liver stiffness measured using magnetic resonance elastography (MRE).

Two markers of fibrosis and cell death (TIMP-1 and CK18) were also improved, he said, noting that overall, the drug was well tolerated, bar a trend to an increase in triglycerides and reduction in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol that needs further follow up.

“There is a placebo-controlled phase II trial of GS-0976 in patients with NASH that is ongoing,” Dr. Lawitz said. Results of two phase II studies presented during the late-breaking abstracts session at the meeting showed similar promising results could be achieved with drugs mimicking the activity of different fibroblast growth factors.

“Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) is a nonmitogenic hormone produced in the liver that is an important regulator of energy metabolism,” said Arun J. Sanyal, MD, who presented the findings of a study with the FGF21 inhibitor BMS-986036.

”From a NASH perspective, it improves insulin sensitivity and by doing that, decreases lipogenesis, and it also has been shown to have some antifibrotic effects,” Dr. Sanyal of Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, added.

FGF21 has a short half-life, however, and BMS-986036 is a recombinant human analog of this hormone that could potentially allow it to be given up to once weekly.

The study involved 74 patients with stage 1-3 biopsy-proven NASH fibrosis and a hepatic fat fraction of 10% or greater measured by MRI-PDFF. Patients were randomized to treatment with BMS-986036 at subcutaneously administered doses of 10 mg given once daily or 20 mg given once weekly or to placebo for 16 weeks.

A significant reduction in the hepatic fat fraction was seen in patients treated with both the once-daily and once-weekly regimen of the active treatment relative to placebo, with absolute changes from baseline of –6.8% (P = .008) and –5.2% (P = .0004), respectively, and just –1.3% for placebo.

“Results suggest that BMS-986036 had beneficial effects on steatosis, liver injury, and fibrosis in NASH,” said Dr. Sanyal, who also noted that there were no deaths and no signal that there could be any safety concerns.

NGM282 is another recombinant human analog mimicking the action of an FGF, this time FGF19, and early data also suggest that it also reduces hepatic steatosis and key biomarkers of NASH. Dr. Stephen Harrison, MD, the medical director of Pinnacle Clinical Research in Live Oak, reported data on 82 patients with stage 1-3 NASH fibrosis who had been treated with NGM-282 3 mg or 6 mg subcutaneously once a day or placebo for 12 weeks.

“The primary endpoint [decrease in absolute liver fat content greater than or equal to 5%] was met in 79% of NGM-282-treated subjects, with over one-third of subjects achieving normalization of liver fat content with 12 weeks of therapy,” Dr. Harrison reported.

“There were significant and rapid reductions in multiple markers that are relevant to the resolution of NASH and improvement in fibrosis,” Dr. Harrison added.

One serious adverse event of acute pancreatitis occurred in a patient treated with FGF19, which was possibly thought to be treatment related, but otherwise adverse events were generally mild and included gastrointestinal effects such as diarrhea and nausea, and injection site reactions.

“These data strongly support the continued development of NGM282 in NASH,” Dr. Harrison said.

During his presentation at a symposium session on current and future approaches to NAFLD and NASH, Dr. Dufour was keen to point out that a combination of diet and exercise remains central to managing patients with NASH.

“We should not forget, that the first line of discussion with these patients should be about changing their lifestyles.” Improving diet and exercise is something that everybody can do, he said, it is widely available and inexpensive, associated with few side effects and can produce good results.

However, convincing some patients can be difficult and those with a low acceptance to lifestyle changes often prefer to take medication. That is likely to come at a cost, not just in terms of money but there are likely to be some side effects, and, of course, efficacy in NASH is yet to be proven in many cases, Dr. Dufour said.

Dr. Dufour disclosed he had been part of a number of advisory committees or received speaking and teaching fees from a host of pharmaceutical companies, many of whom have an interest in the development of treatments for NASH.

Gilead Sciences supported the study reported by Dr. Lawitz and he disclosed receiving research grants or other support from the company, as well as several other pharmaceutical companies.

The study presented by Dr. Sanyal was financed by Bristol-Myers Squibb and he disclosed research funding was provided to his institution. Dr. Sanyal also disclosed receiving research support and consulting fees from multiple other pharmaceutical companies.

Dr. Harrison acknowledged receiving research funding from and acting as a consultant to NGM Bio, who sponsored the study he presented. He also disclosed acting as an adviser or speaker, and receiving grants from other pharmaceutical companies in the past 12 months.

AMSTERDAM – There is a “very, very rich pipeline” of drugs being developed for the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), Jean-François Dufour, MD, the head of hepatology and director of the University Clinic for Visceral Surgery and Medicine at the University of Berne (Switzerland) said at the International Liver Congress.

“We have many therapeutic options [under investigation],” Dr. Dufour noted at the Congress, which is sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL). These include drugs that target metabolic homeostasis, insulin resistance, inflammation, oxidative stress, or fibrosis (Liver Int. 2017 May;37:634-47).

In fact, there is such a range of options that target different pathways, from fatty acid and bile acid synthesis to the early and late stages of fibrosis, that it is very likely that these drugs will be used in combination, Dr. Dufour observed as he gave an overview of the current trials that are underway in NASH.

There are currently five ongoing multicenter phase III trials being undertaken with four drugs. First, there is the REGENERATE trial with Intercept’s farnesoid X receptor obeticholic acid(Ocaliva). This is a placebo-controlled trial comparing two daily doses of obeticholic acid (10 and 25 mg) on top of the standard of care. The trial will recruit just over 2,000 patients with biopsy-proven stage 2-3 NASH fibrosis, and the primary endpoint is the resolution of NASH without fibrosis worsening or improvement in fibrosis without worsening of NASH at week 72.

Second there is the RESOLVE-IT trial with Genfit’s peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha/delta agonist elafibranor. This randomized, double-blind trial hopes to recruit 2,000 patients with biopsy-proven NASH stage 1-3 fibrosis and will compare elafibranor 120 mg given once a day with placebo. The primary endpoint is the resolution of NASH without worsening of fibrosis at week 72.

Next, Tobira Therapeutics’ C-C chemokine receptor type 2 and 5 antagonist cenicriviroc is being studied in the AURORA trial. Again, recruiting around 2,000 patients is the target, but this time with stage 2-3 biopsy-proven NASH fibrosis. Cenicriviroc will be given daily at a dose of 150 mg and will be compared against placebo. The primary endpoint is the improvement of fibrosis by one or more stage with no worsening of steatohepatitis at 1 year.

Finally, there are the STELLA 3 and STELLA 4 trials with Gilead’s apoptosis signal-regulated kinase-1 inhibitor selonsertib. Target accrual in both studies is 800 patients with STELLA 3 recruiting patients with stage-3 NASH fibrosis and STELLA 4 recruiting those with compensated cirrhosis from NASH. Both trials will compared two daily doses of selonsertib (6 mg and 18 mg) versus placebo. The primary endpoints are the improvement of at least one or more fibrosis stage with no worsening of steatohepatitis at 48 weeks and event-free survival at week 240.

In addition, there are at least 20 phase 2b and 2a studies looking at a variety of other novel drugs with different therapeutic targets, Dr. Dufour said, and during separate presentations at the congress, results of several early trials with novel drugs being tested for NASH were given.

Eric J. Lawitz, MD, reported the promising results of a “proof of concept” open-label study in which the safety and efficacy of 12 weeks’ treatment with the oral acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) inhibitor, GS-0976, was examined in 10 patients with a clinical diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

“ACC catalyzes the rate-limiting step in de novo hepatic lipogenesis (DNL),” which is an underlying pathologic process in NASH, Dr. Lawitz, who is vice president of scientific and research development at the Texas Liver Institute, San Antonio, observed.

He reported that 12 weeks’ treatment with the ACC inhibitor GS-0976 suppressed DNL by 29%, compared with baseline (P = .022). There was also a 43% decrease in hepatic steatosis from baseline to 12 weeks (P = .006), as measured by the magnetic resonance imaging–proton-density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF), and a nonsignificant 9% reduction in liver stiffness measured using magnetic resonance elastography (MRE).

Two markers of fibrosis and cell death (TIMP-1 and CK18) were also improved, he said, noting that overall, the drug was well tolerated, bar a trend to an increase in triglycerides and reduction in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol that needs further follow up.

“There is a placebo-controlled phase II trial of GS-0976 in patients with NASH that is ongoing,” Dr. Lawitz said. Results of two phase II studies presented during the late-breaking abstracts session at the meeting showed similar promising results could be achieved with drugs mimicking the activity of different fibroblast growth factors.

“Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) is a nonmitogenic hormone produced in the liver that is an important regulator of energy metabolism,” said Arun J. Sanyal, MD, who presented the findings of a study with the FGF21 inhibitor BMS-986036.

”From a NASH perspective, it improves insulin sensitivity and by doing that, decreases lipogenesis, and it also has been shown to have some antifibrotic effects,” Dr. Sanyal of Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, added.

FGF21 has a short half-life, however, and BMS-986036 is a recombinant human analog of this hormone that could potentially allow it to be given up to once weekly.

The study involved 74 patients with stage 1-3 biopsy-proven NASH fibrosis and a hepatic fat fraction of 10% or greater measured by MRI-PDFF. Patients were randomized to treatment with BMS-986036 at subcutaneously administered doses of 10 mg given once daily or 20 mg given once weekly or to placebo for 16 weeks.

A significant reduction in the hepatic fat fraction was seen in patients treated with both the once-daily and once-weekly regimen of the active treatment relative to placebo, with absolute changes from baseline of –6.8% (P = .008) and –5.2% (P = .0004), respectively, and just –1.3% for placebo.

“Results suggest that BMS-986036 had beneficial effects on steatosis, liver injury, and fibrosis in NASH,” said Dr. Sanyal, who also noted that there were no deaths and no signal that there could be any safety concerns.

NGM282 is another recombinant human analog mimicking the action of an FGF, this time FGF19, and early data also suggest that it also reduces hepatic steatosis and key biomarkers of NASH. Dr. Stephen Harrison, MD, the medical director of Pinnacle Clinical Research in Live Oak, reported data on 82 patients with stage 1-3 NASH fibrosis who had been treated with NGM-282 3 mg or 6 mg subcutaneously once a day or placebo for 12 weeks.

“The primary endpoint [decrease in absolute liver fat content greater than or equal to 5%] was met in 79% of NGM-282-treated subjects, with over one-third of subjects achieving normalization of liver fat content with 12 weeks of therapy,” Dr. Harrison reported.

“There were significant and rapid reductions in multiple markers that are relevant to the resolution of NASH and improvement in fibrosis,” Dr. Harrison added.

One serious adverse event of acute pancreatitis occurred in a patient treated with FGF19, which was possibly thought to be treatment related, but otherwise adverse events were generally mild and included gastrointestinal effects such as diarrhea and nausea, and injection site reactions.

“These data strongly support the continued development of NGM282 in NASH,” Dr. Harrison said.

During his presentation at a symposium session on current and future approaches to NAFLD and NASH, Dr. Dufour was keen to point out that a combination of diet and exercise remains central to managing patients with NASH.

“We should not forget, that the first line of discussion with these patients should be about changing their lifestyles.” Improving diet and exercise is something that everybody can do, he said, it is widely available and inexpensive, associated with few side effects and can produce good results.

However, convincing some patients can be difficult and those with a low acceptance to lifestyle changes often prefer to take medication. That is likely to come at a cost, not just in terms of money but there are likely to be some side effects, and, of course, efficacy in NASH is yet to be proven in many cases, Dr. Dufour said.

Dr. Dufour disclosed he had been part of a number of advisory committees or received speaking and teaching fees from a host of pharmaceutical companies, many of whom have an interest in the development of treatments for NASH.

Gilead Sciences supported the study reported by Dr. Lawitz and he disclosed receiving research grants or other support from the company, as well as several other pharmaceutical companies.

The study presented by Dr. Sanyal was financed by Bristol-Myers Squibb and he disclosed research funding was provided to his institution. Dr. Sanyal also disclosed receiving research support and consulting fees from multiple other pharmaceutical companies.

Dr. Harrison acknowledged receiving research funding from and acting as a consultant to NGM Bio, who sponsored the study he presented. He also disclosed acting as an adviser or speaker, and receiving grants from other pharmaceutical companies in the past 12 months.

Key clinical point: Lots of new approaches to treating nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are being investigated, some with phase III trials underway.

Major finding: Hepatic steatosis was significantly reduced by the GS-0976, BMS-986036, and NGM282.

Data source: An expert review and three early-phase studies testing of the safety and efficacy of novel NASH treatments.

Disclosures: Dr. Dufour disclosed he had been part of a number of advisory committees or received speaking and teaching fees from a host of pharmaceutical companies, many of whom have an interested in the development of treatments for NASH. Gilead Sciences supported the study reported by Dr. Lawitz and he disclosed receiving research grants or other support from the company, as well as several other pharmaceutical companies. The study presented by Dr. Sanyal was financed by Bristol-Myers Squibb and he disclosed research funding was provided to his institution. Dr. Sanyal also disclosed receiving research support and consulting fees from multiple other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Harrison acknowledged receiving research funding from and acting as a consultant to NGM Bio, who sponsored the study he presented. He also disclosed acting as an adviser or speaker and receiving grants from other pharmaceutical companies in the past 12 months.

VIDEO: Indomethacin slashes post-ERCP pancreatitis risk in primary sclerosing cholangitis

CHICAGO – Rectal indomethacin reduced by 90% the risk of post-procedural pancreatitis in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis.

The anti-inflammatory has already been shown to reduce the risk of acute pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in a general population, Nikhil Thiruvengadam, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week®. Now, his retrospective study of almost 5,000 patients has shown the drug’s benefit in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), who are at particularly high risk of pancreatitis after the procedure.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“A prior history of PEP and a difficult initial cannulation were significant risk factors for developing PEP,” he said. “Indomethacin significantly reduced this risk, and our findings suggest that future prospective trials studying pharmacological prophylaxis of PEP – including rectal indomethacin – should be powered to be able detect a difference in PSC patients, and they should be included in such studies.”

In 2016 Dr. Thiruvengadam and his colleagues showed that rectal indomethacin significantly reduced the risk of PEP by about 65% in a diverse group of patients, including those with malignant biliary obstruction (Gastroenterology. 2016;151:288–97). The new study used an expanded patient-cohort but focused on patients with PSC, as they require multiple ERCPs for diagnosis and stenting of strictures and cholangiocarcinoma screening and thus may be more affected by post-procedural pancreatitis.

The study comprised 4,764 patients who underwent ERCP at the University of Pennsylvania from 2007-2015; of these, 200 had PSC. Rectal indomethacin was routinely administered to patients beginning in June 2012. The primary outcome of the study was post-ERCP pancreatitis. The secondary outcome was the severity of post-ERCP pancreatitis.

PEP was about twice as common in the PSC group as in the overall cohort (6.5% vs. 3.8%). Moderate-severe PEP also was twice as common (4% vs. 2%).

Dr. Thiruvengadam broke down the cohort by indication for ERCP. These included PSC as well as liver transplant, choledocholithiasis, benign pancreatic disease, bile leaks, and ampullary adenoma. PSC patients had the highest risk of developing PEP – almost 3 times more than those without the disorder (OR 2.7).

Among PSC patients, age, gender, and total bilirubin were not associated with increased risk. A history of prior PEP increased the risk by 17 times, and a difficult initial cannulation that required a pre-cut sphincterotomy increased it by 15 times.

“Interestingly, dilation of a common bile duct stricture reduced the odds of developing PEP by 81%,” Dr. Thiruvengadam said.

He then examined the impact of rectal indomethacin on the study subjects. Overall, PEP developed in 5% of those who didn’t receive indomethacin and 2% of those who did. In the PSC group, PEP developed in 11% of those who didn’t get indomethacin and less than 1% of those who did.

Indomethacin was particularly effective at preventing moderate-severe PEP, Dr. Thiruvengadam noted. In the overall cohort, moderate-severe PEP developed in 3% of unexposed patients compared to 0.6% of those who received the drug. The difference was more profound in the PSC group: None of those treated with indomethacin developed moderate-severe PEP, which occurred in 9.3% of the unexposed group.

Generally, patients who have previously undergone a sphincterotomy are at lower risk for PEP, Dr. Thiruvengadam said, and this was reflected in the findings for the overall group: PEP developed in 3% of the untreated patients and 0.5% of the treated patients. Post-sphincterotomy patients with PSC, however, were still at an increased risk of PEP. Indomethacin significantly mitigated this – no patient who got the drug developed PEP, compared with 10.5% of those who didn’t get it.

A series of regression analyses confirmed the consistency of these findings. In an unadjusted model, rectal indomethacin reduced the risk of post-ERCP PEP by 91% in patients with PSC. A model that adjusted for common bile duct brushing, type of sedation, and common bile duct dilation found a 90% risk reduction. Another model that controlled for classic risk factors for PEP (age, gender, total bilirubin, history of PEP, pancreatic duct injection and cannulation, and pre-cut sphincterotomy) found a 94% risk reduction.

“We additionally performed a propensity score matched analysis to account for potential unmeasured differences between the two cohorts, and it also confirmed the results found and demonstrated that indomethacin significantly reduced the odds of developing PEP by 89%,” Dr. Thiruvengadam said.

He had no financial conflicts of interest to disclosures.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

CHICAGO – Rectal indomethacin reduced by 90% the risk of post-procedural pancreatitis in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis.

The anti-inflammatory has already been shown to reduce the risk of acute pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in a general population, Nikhil Thiruvengadam, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week®. Now, his retrospective study of almost 5,000 patients has shown the drug’s benefit in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), who are at particularly high risk of pancreatitis after the procedure.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“A prior history of PEP and a difficult initial cannulation were significant risk factors for developing PEP,” he said. “Indomethacin significantly reduced this risk, and our findings suggest that future prospective trials studying pharmacological prophylaxis of PEP – including rectal indomethacin – should be powered to be able detect a difference in PSC patients, and they should be included in such studies.”

In 2016 Dr. Thiruvengadam and his colleagues showed that rectal indomethacin significantly reduced the risk of PEP by about 65% in a diverse group of patients, including those with malignant biliary obstruction (Gastroenterology. 2016;151:288–97). The new study used an expanded patient-cohort but focused on patients with PSC, as they require multiple ERCPs for diagnosis and stenting of strictures and cholangiocarcinoma screening and thus may be more affected by post-procedural pancreatitis.

The study comprised 4,764 patients who underwent ERCP at the University of Pennsylvania from 2007-2015; of these, 200 had PSC. Rectal indomethacin was routinely administered to patients beginning in June 2012. The primary outcome of the study was post-ERCP pancreatitis. The secondary outcome was the severity of post-ERCP pancreatitis.

PEP was about twice as common in the PSC group as in the overall cohort (6.5% vs. 3.8%). Moderate-severe PEP also was twice as common (4% vs. 2%).

Dr. Thiruvengadam broke down the cohort by indication for ERCP. These included PSC as well as liver transplant, choledocholithiasis, benign pancreatic disease, bile leaks, and ampullary adenoma. PSC patients had the highest risk of developing PEP – almost 3 times more than those without the disorder (OR 2.7).

Among PSC patients, age, gender, and total bilirubin were not associated with increased risk. A history of prior PEP increased the risk by 17 times, and a difficult initial cannulation that required a pre-cut sphincterotomy increased it by 15 times.

“Interestingly, dilation of a common bile duct stricture reduced the odds of developing PEP by 81%,” Dr. Thiruvengadam said.

He then examined the impact of rectal indomethacin on the study subjects. Overall, PEP developed in 5% of those who didn’t receive indomethacin and 2% of those who did. In the PSC group, PEP developed in 11% of those who didn’t get indomethacin and less than 1% of those who did.

Indomethacin was particularly effective at preventing moderate-severe PEP, Dr. Thiruvengadam noted. In the overall cohort, moderate-severe PEP developed in 3% of unexposed patients compared to 0.6% of those who received the drug. The difference was more profound in the PSC group: None of those treated with indomethacin developed moderate-severe PEP, which occurred in 9.3% of the unexposed group.

Generally, patients who have previously undergone a sphincterotomy are at lower risk for PEP, Dr. Thiruvengadam said, and this was reflected in the findings for the overall group: PEP developed in 3% of the untreated patients and 0.5% of the treated patients. Post-sphincterotomy patients with PSC, however, were still at an increased risk of PEP. Indomethacin significantly mitigated this – no patient who got the drug developed PEP, compared with 10.5% of those who didn’t get it.

A series of regression analyses confirmed the consistency of these findings. In an unadjusted model, rectal indomethacin reduced the risk of post-ERCP PEP by 91% in patients with PSC. A model that adjusted for common bile duct brushing, type of sedation, and common bile duct dilation found a 90% risk reduction. Another model that controlled for classic risk factors for PEP (age, gender, total bilirubin, history of PEP, pancreatic duct injection and cannulation, and pre-cut sphincterotomy) found a 94% risk reduction.

“We additionally performed a propensity score matched analysis to account for potential unmeasured differences between the two cohorts, and it also confirmed the results found and demonstrated that indomethacin significantly reduced the odds of developing PEP by 89%,” Dr. Thiruvengadam said.

He had no financial conflicts of interest to disclosures.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

CHICAGO – Rectal indomethacin reduced by 90% the risk of post-procedural pancreatitis in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis.

The anti-inflammatory has already been shown to reduce the risk of acute pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in a general population, Nikhil Thiruvengadam, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week®. Now, his retrospective study of almost 5,000 patients has shown the drug’s benefit in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), who are at particularly high risk of pancreatitis after the procedure.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“A prior history of PEP and a difficult initial cannulation were significant risk factors for developing PEP,” he said. “Indomethacin significantly reduced this risk, and our findings suggest that future prospective trials studying pharmacological prophylaxis of PEP – including rectal indomethacin – should be powered to be able detect a difference in PSC patients, and they should be included in such studies.”

In 2016 Dr. Thiruvengadam and his colleagues showed that rectal indomethacin significantly reduced the risk of PEP by about 65% in a diverse group of patients, including those with malignant biliary obstruction (Gastroenterology. 2016;151:288–97). The new study used an expanded patient-cohort but focused on patients with PSC, as they require multiple ERCPs for diagnosis and stenting of strictures and cholangiocarcinoma screening and thus may be more affected by post-procedural pancreatitis.

The study comprised 4,764 patients who underwent ERCP at the University of Pennsylvania from 2007-2015; of these, 200 had PSC. Rectal indomethacin was routinely administered to patients beginning in June 2012. The primary outcome of the study was post-ERCP pancreatitis. The secondary outcome was the severity of post-ERCP pancreatitis.

PEP was about twice as common in the PSC group as in the overall cohort (6.5% vs. 3.8%). Moderate-severe PEP also was twice as common (4% vs. 2%).

Dr. Thiruvengadam broke down the cohort by indication for ERCP. These included PSC as well as liver transplant, choledocholithiasis, benign pancreatic disease, bile leaks, and ampullary adenoma. PSC patients had the highest risk of developing PEP – almost 3 times more than those without the disorder (OR 2.7).

Among PSC patients, age, gender, and total bilirubin were not associated with increased risk. A history of prior PEP increased the risk by 17 times, and a difficult initial cannulation that required a pre-cut sphincterotomy increased it by 15 times.

“Interestingly, dilation of a common bile duct stricture reduced the odds of developing PEP by 81%,” Dr. Thiruvengadam said.

He then examined the impact of rectal indomethacin on the study subjects. Overall, PEP developed in 5% of those who didn’t receive indomethacin and 2% of those who did. In the PSC group, PEP developed in 11% of those who didn’t get indomethacin and less than 1% of those who did.

Indomethacin was particularly effective at preventing moderate-severe PEP, Dr. Thiruvengadam noted. In the overall cohort, moderate-severe PEP developed in 3% of unexposed patients compared to 0.6% of those who received the drug. The difference was more profound in the PSC group: None of those treated with indomethacin developed moderate-severe PEP, which occurred in 9.3% of the unexposed group.

Generally, patients who have previously undergone a sphincterotomy are at lower risk for PEP, Dr. Thiruvengadam said, and this was reflected in the findings for the overall group: PEP developed in 3% of the untreated patients and 0.5% of the treated patients. Post-sphincterotomy patients with PSC, however, were still at an increased risk of PEP. Indomethacin significantly mitigated this – no patient who got the drug developed PEP, compared with 10.5% of those who didn’t get it.

A series of regression analyses confirmed the consistency of these findings. In an unadjusted model, rectal indomethacin reduced the risk of post-ERCP PEP by 91% in patients with PSC. A model that adjusted for common bile duct brushing, type of sedation, and common bile duct dilation found a 90% risk reduction. Another model that controlled for classic risk factors for PEP (age, gender, total bilirubin, history of PEP, pancreatic duct injection and cannulation, and pre-cut sphincterotomy) found a 94% risk reduction.

“We additionally performed a propensity score matched analysis to account for potential unmeasured differences between the two cohorts, and it also confirmed the results found and demonstrated that indomethacin significantly reduced the odds of developing PEP by 89%,” Dr. Thiruvengadam said.

He had no financial conflicts of interest to disclosures.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

AT DDW

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The anti-inflammatory reduced the risk in these patients by 90%.

Data source: A retrospective study of 4,764 patients with PSC who underwent ERCP at a single institution, Disclosures: Dr. Thiruvengadam had no financial disclosures.

Genetic test predicts cirrhosis outcomes

CHICAGO – Cirrhosis patients with the rs738409 CG/GG genotype experienced worse outcomes, including a slower recovery of encephalopathy, ascites, and bilirubin, compared with those without this CG/GG genotype, based on data from a prospective study. The findings were presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Most patients with hepatitis C virus–associated cirrhosis do well after treatment with direct-acting antiviral agents to achieve a sustained virologic response, according to Winston Dunn, MD, of Kansas University Medical Center, Kansas City, and his colleagues.

However, patients with decompensated cirrhosis may have a range of outcomes, and, to help predict treatment success, Dr. Dunn and his colleagues examined the possible genetic role of the rs738409 Single Nucleotide Polymorphism of Patatin-like Phospholipase Domain Containing 3 gene.

The researchers assessed 30 adults with Child-Pugh (CPT) Class B or C cirrhosis caused by HCV infection who underwent interferon-free, direct-acting antiviral therapy and achieved sustained virologic response. They collected DNA from each patient using a cheek swab. The study population included 16 patients with a CC genotype, 11 with CG, and 3 with GG.

They measured changes in CPT scores and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores from before DAA treatment to 12 weeks after treatment. Baseline scores were similar among all patients, as were demographic characteristics, although patients with the rs738409 CC genotype averaged a higher body-mass index 35 kg/m2, vs. 29 kg/m2 (P = 0.03).

After 12 weeks, 13 of 16 patients with the CC genotype (81 %) had improved CPT scores, and 8 patients (50%) had improved MELD scores by at least 1 point. None had worsened CPT or MELD scores. By contrast, 5 of 14 patients with CG/GG genotype (36%) had improved CPT scores, and 4 (29%) had improved MELD scores by at least 1 point; 3 patients (21%) had worsened CPT scores and 4 (29%) had worsened MELD scores by at least 1 point.

Overall, patients in the CG/GG groups showed a 1.7-point higher delta CPT score and a 2.3-point higher delta MELD score after adjusting for confounding variables, compared with patients with CC after adjusting for confounding variables.

The study findings were limited by small numbers and prospective design, and the genetic test is not yet widely available, Dr. Dunn said. However, “Our results will help target patients for liver transplant evaluation based on individual genetic risk factors,” the researchers said.

The study was funded by the Frontiers Pilot and Collaborative Studies Funding Program. Dr. Dunn had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

CHICAGO – Cirrhosis patients with the rs738409 CG/GG genotype experienced worse outcomes, including a slower recovery of encephalopathy, ascites, and bilirubin, compared with those without this CG/GG genotype, based on data from a prospective study. The findings were presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Most patients with hepatitis C virus–associated cirrhosis do well after treatment with direct-acting antiviral agents to achieve a sustained virologic response, according to Winston Dunn, MD, of Kansas University Medical Center, Kansas City, and his colleagues.

However, patients with decompensated cirrhosis may have a range of outcomes, and, to help predict treatment success, Dr. Dunn and his colleagues examined the possible genetic role of the rs738409 Single Nucleotide Polymorphism of Patatin-like Phospholipase Domain Containing 3 gene.

The researchers assessed 30 adults with Child-Pugh (CPT) Class B or C cirrhosis caused by HCV infection who underwent interferon-free, direct-acting antiviral therapy and achieved sustained virologic response. They collected DNA from each patient using a cheek swab. The study population included 16 patients with a CC genotype, 11 with CG, and 3 with GG.

They measured changes in CPT scores and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores from before DAA treatment to 12 weeks after treatment. Baseline scores were similar among all patients, as were demographic characteristics, although patients with the rs738409 CC genotype averaged a higher body-mass index 35 kg/m2, vs. 29 kg/m2 (P = 0.03).

After 12 weeks, 13 of 16 patients with the CC genotype (81 %) had improved CPT scores, and 8 patients (50%) had improved MELD scores by at least 1 point. None had worsened CPT or MELD scores. By contrast, 5 of 14 patients with CG/GG genotype (36%) had improved CPT scores, and 4 (29%) had improved MELD scores by at least 1 point; 3 patients (21%) had worsened CPT scores and 4 (29%) had worsened MELD scores by at least 1 point.

Overall, patients in the CG/GG groups showed a 1.7-point higher delta CPT score and a 2.3-point higher delta MELD score after adjusting for confounding variables, compared with patients with CC after adjusting for confounding variables.

The study findings were limited by small numbers and prospective design, and the genetic test is not yet widely available, Dr. Dunn said. However, “Our results will help target patients for liver transplant evaluation based on individual genetic risk factors,” the researchers said.

The study was funded by the Frontiers Pilot and Collaborative Studies Funding Program. Dr. Dunn had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

CHICAGO – Cirrhosis patients with the rs738409 CG/GG genotype experienced worse outcomes, including a slower recovery of encephalopathy, ascites, and bilirubin, compared with those without this CG/GG genotype, based on data from a prospective study. The findings were presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Most patients with hepatitis C virus–associated cirrhosis do well after treatment with direct-acting antiviral agents to achieve a sustained virologic response, according to Winston Dunn, MD, of Kansas University Medical Center, Kansas City, and his colleagues.

However, patients with decompensated cirrhosis may have a range of outcomes, and, to help predict treatment success, Dr. Dunn and his colleagues examined the possible genetic role of the rs738409 Single Nucleotide Polymorphism of Patatin-like Phospholipase Domain Containing 3 gene.

The researchers assessed 30 adults with Child-Pugh (CPT) Class B or C cirrhosis caused by HCV infection who underwent interferon-free, direct-acting antiviral therapy and achieved sustained virologic response. They collected DNA from each patient using a cheek swab. The study population included 16 patients with a CC genotype, 11 with CG, and 3 with GG.

They measured changes in CPT scores and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores from before DAA treatment to 12 weeks after treatment. Baseline scores were similar among all patients, as were demographic characteristics, although patients with the rs738409 CC genotype averaged a higher body-mass index 35 kg/m2, vs. 29 kg/m2 (P = 0.03).

After 12 weeks, 13 of 16 patients with the CC genotype (81 %) had improved CPT scores, and 8 patients (50%) had improved MELD scores by at least 1 point. None had worsened CPT or MELD scores. By contrast, 5 of 14 patients with CG/GG genotype (36%) had improved CPT scores, and 4 (29%) had improved MELD scores by at least 1 point; 3 patients (21%) had worsened CPT scores and 4 (29%) had worsened MELD scores by at least 1 point.

Overall, patients in the CG/GG groups showed a 1.7-point higher delta CPT score and a 2.3-point higher delta MELD score after adjusting for confounding variables, compared with patients with CC after adjusting for confounding variables.

The study findings were limited by small numbers and prospective design, and the genetic test is not yet widely available, Dr. Dunn said. However, “Our results will help target patients for liver transplant evaluation based on individual genetic risk factors,” the researchers said.

The study was funded by the Frontiers Pilot and Collaborative Studies Funding Program. Dr. Dunn had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

FROM DDW

Key clinical point: Genotyping patients with advanced cirrhosis from HCV could help predict improvement and determine fitness for liver transplants.

Major finding: The rs738409 CG/GG genotype was associated with a 1.7-point higher delta CPT score, a 2.3 -point higher delta MELD score, and slower recovery of encepholpathy, ascites, and bilirubin, compared with those without this CG/GG genotype.

Data source: A prospective study of 35 adults with cirrhosis caused by HCV infection.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Frontiers Pilot and Collaborative Studies Funding Program.

Fibrate could offer additional option for primary biliary cholangitis

AMSTERDAM – Patients with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) who are not responding to first-line therapy with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) may benefit from the addition of bezafibrate, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study findings have suggested.

Almost one-third of the 50 patients who were treated with bezafibrate in addition to UDCA in the 2-year, phase III BEZURSO study met the primary endpoint for response, compared with none of the 50 patients in the control arm of the study.

The findings, presented as a late-breaking abstract at the International Liver Congress, sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), could be practice changing for a population of patients who have relatively few treatment options.

Although obeticholic acid was recently approved as a second-line treatment in combination with UDCA for PBC, one of the side effects of obeticholic acid is that it can cause pruritus, which is one of the symptoms of the condition as well. It can be tricky to explain to patients that there is a treatment but that this treatment might also increase their symptoms, Dr. Corpechot observed.

Between October 2012 and December 2014, mostly female patients (more than 92%), mean age 53 years, who were being treated with UDCA were recruited at 21 centers in France. For inclusion in the study, patients had to have an inadequate biochemical response to UDCA, which was defined by the Paris-2 criteria of an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) or an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of more than 1.5 times the upper limit of normal (ULN), or a total bilirubin level of more than 17 micromol/L.

Patients were randomized to continue UDCA treatment (13-15 mg/kg per day) with or without the addition of bezafibrate, given as a 400-mg daily dose.

The primary endpoint was a complete biochemical response as defined by normal serum levels of total bilirubin, ALP, aminotransferases, albumin, and a normal prothrombin time at 2 years. The hypothesis was that 40% of the patients in the bezafibrate group and only 10% of patients in the UDCA group would reach this primary endpoint. The actual percentages were 30% and 10% (P less than .0001).

A significantly higher (67% vs. 0%) percentage of patients treated with the fibrate versus UDCA also achieved a normal serum ALP by 2 years, Dr. Corpechot reported, with a significant decrease seen by the third month of treatment.

The mean changes in all the biochemical parameters tested from baseline to the end of the study comparing the bezafibrate group with the control group were a respective –14% and +18% (P less than .0001) for total bilirubin, –60% and 0% for ALP (P less than .0001), –36% and 0% for alanine aminotransferase (P less than .0001), –8% and +8% for AST (P less than .05), –38% and +7% for gamma-glutamyl transferase (P less than .0001), 0% and –3% for albumin (P less than .05), and –16% and 0% for cholesterol (P less than .0001).

Other significant findings favoring the fibrate therapy were a significantly (–75% vs. 0%, P less than .01) decreased itch score (assessed with a visual analog scale) and a significantly lower (–10% vs. +10%, P less than .01) liver stiffness (assessed by transient elastography) at 2 years.

Importantly, the frequency of adverse events, including serious adverse events, did not differ significantly between the two groups.

Fibrates could thus offer a well tolerated and cheaper alternative, as they are already widely used in clinical practice, although they are not licensed for PBC treatment at the current time.

Dr. Tacke, professor of medicine in the department of gastroenterology, metabolic diseases and intensive care medicine at University Hospital Aachen, Germany, also noted that bezafibrate was a drug that “had been on the market for a very long time,” and was very inexpensive in comparison to obeticholic acid and, importantly, seemed to be very well tolerated in the study.

“One question the community will want to know is whether [bezafibrate] is as effective as obeticholic acid in the second-line treatment of PBC,” Dr. Tacke said. This is a question only a head-to-head study can answer and also it is not possible to say whether other fibrates may have the same benefit as bezafibrate as seen in this trial.

Although the study included only 100 patients, this was a relatively large study considering the disease area and that most patients given the primary treatment of UDCA will do well on it, Dr. Tacke acknowledged in an interview.

“What I like about this study is that they treated patients for 2 years and bezafibrate was given as an add-on treatment, so nobody was at risk for not receiving the UDCA, and they saw a very stable and solid improvement in the parameters studied,” Dr. Tacke said.

EASL launched new guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of PBC to coincide with the meeting, which state that patients should be treated with UDCA for 1 year and then their biochemical response to treatment should assessed to see if they might need additional treatment. “Up to now, the second-line treatment recommended is obeticholic acid but off-label therapy is mentioned,” Dr. Tacke said.

He noted that there were small, nonrandomized studies with two fibrates – bezafibrate and fenofibrate – that have shown “very encouraging” results but that the current findings suggested that bezafibrate therapy may be an alternative, well-tolerated treatment option for patients failing to respond to standard UDCA therapy that could well be added into the guidelines when they are next revised.

The BEZURSO study was an investigator-led trial sponsored by the Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris. Dr. Corpechot disclosed financial relationships with Arrow Génériques, Intercept Pharma France, Mayoly-Spindler. Dr. Tacke had nothing to disclose.

AMSTERDAM – Patients with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) who are not responding to first-line therapy with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) may benefit from the addition of bezafibrate, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study findings have suggested.

Almost one-third of the 50 patients who were treated with bezafibrate in addition to UDCA in the 2-year, phase III BEZURSO study met the primary endpoint for response, compared with none of the 50 patients in the control arm of the study.

The findings, presented as a late-breaking abstract at the International Liver Congress, sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), could be practice changing for a population of patients who have relatively few treatment options.

Although obeticholic acid was recently approved as a second-line treatment in combination with UDCA for PBC, one of the side effects of obeticholic acid is that it can cause pruritus, which is one of the symptoms of the condition as well. It can be tricky to explain to patients that there is a treatment but that this treatment might also increase their symptoms, Dr. Corpechot observed.

Between October 2012 and December 2014, mostly female patients (more than 92%), mean age 53 years, who were being treated with UDCA were recruited at 21 centers in France. For inclusion in the study, patients had to have an inadequate biochemical response to UDCA, which was defined by the Paris-2 criteria of an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) or an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of more than 1.5 times the upper limit of normal (ULN), or a total bilirubin level of more than 17 micromol/L.

Patients were randomized to continue UDCA treatment (13-15 mg/kg per day) with or without the addition of bezafibrate, given as a 400-mg daily dose.

The primary endpoint was a complete biochemical response as defined by normal serum levels of total bilirubin, ALP, aminotransferases, albumin, and a normal prothrombin time at 2 years. The hypothesis was that 40% of the patients in the bezafibrate group and only 10% of patients in the UDCA group would reach this primary endpoint. The actual percentages were 30% and 10% (P less than .0001).

A significantly higher (67% vs. 0%) percentage of patients treated with the fibrate versus UDCA also achieved a normal serum ALP by 2 years, Dr. Corpechot reported, with a significant decrease seen by the third month of treatment.

The mean changes in all the biochemical parameters tested from baseline to the end of the study comparing the bezafibrate group with the control group were a respective –14% and +18% (P less than .0001) for total bilirubin, –60% and 0% for ALP (P less than .0001), –36% and 0% for alanine aminotransferase (P less than .0001), –8% and +8% for AST (P less than .05), –38% and +7% for gamma-glutamyl transferase (P less than .0001), 0% and –3% for albumin (P less than .05), and –16% and 0% for cholesterol (P less than .0001).

Other significant findings favoring the fibrate therapy were a significantly (–75% vs. 0%, P less than .01) decreased itch score (assessed with a visual analog scale) and a significantly lower (–10% vs. +10%, P less than .01) liver stiffness (assessed by transient elastography) at 2 years.

Importantly, the frequency of adverse events, including serious adverse events, did not differ significantly between the two groups.

Fibrates could thus offer a well tolerated and cheaper alternative, as they are already widely used in clinical practice, although they are not licensed for PBC treatment at the current time.

Dr. Tacke, professor of medicine in the department of gastroenterology, metabolic diseases and intensive care medicine at University Hospital Aachen, Germany, also noted that bezafibrate was a drug that “had been on the market for a very long time,” and was very inexpensive in comparison to obeticholic acid and, importantly, seemed to be very well tolerated in the study.

“One question the community will want to know is whether [bezafibrate] is as effective as obeticholic acid in the second-line treatment of PBC,” Dr. Tacke said. This is a question only a head-to-head study can answer and also it is not possible to say whether other fibrates may have the same benefit as bezafibrate as seen in this trial.

Although the study included only 100 patients, this was a relatively large study considering the disease area and that most patients given the primary treatment of UDCA will do well on it, Dr. Tacke acknowledged in an interview.

“What I like about this study is that they treated patients for 2 years and bezafibrate was given as an add-on treatment, so nobody was at risk for not receiving the UDCA, and they saw a very stable and solid improvement in the parameters studied,” Dr. Tacke said.

EASL launched new guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of PBC to coincide with the meeting, which state that patients should be treated with UDCA for 1 year and then their biochemical response to treatment should assessed to see if they might need additional treatment. “Up to now, the second-line treatment recommended is obeticholic acid but off-label therapy is mentioned,” Dr. Tacke said.

He noted that there were small, nonrandomized studies with two fibrates – bezafibrate and fenofibrate – that have shown “very encouraging” results but that the current findings suggested that bezafibrate therapy may be an alternative, well-tolerated treatment option for patients failing to respond to standard UDCA therapy that could well be added into the guidelines when they are next revised.

The BEZURSO study was an investigator-led trial sponsored by the Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris. Dr. Corpechot disclosed financial relationships with Arrow Génériques, Intercept Pharma France, Mayoly-Spindler. Dr. Tacke had nothing to disclose.

AMSTERDAM – Patients with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) who are not responding to first-line therapy with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) may benefit from the addition of bezafibrate, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study findings have suggested.

Almost one-third of the 50 patients who were treated with bezafibrate in addition to UDCA in the 2-year, phase III BEZURSO study met the primary endpoint for response, compared with none of the 50 patients in the control arm of the study.

The findings, presented as a late-breaking abstract at the International Liver Congress, sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), could be practice changing for a population of patients who have relatively few treatment options.

Although obeticholic acid was recently approved as a second-line treatment in combination with UDCA for PBC, one of the side effects of obeticholic acid is that it can cause pruritus, which is one of the symptoms of the condition as well. It can be tricky to explain to patients that there is a treatment but that this treatment might also increase their symptoms, Dr. Corpechot observed.

Between October 2012 and December 2014, mostly female patients (more than 92%), mean age 53 years, who were being treated with UDCA were recruited at 21 centers in France. For inclusion in the study, patients had to have an inadequate biochemical response to UDCA, which was defined by the Paris-2 criteria of an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) or an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of more than 1.5 times the upper limit of normal (ULN), or a total bilirubin level of more than 17 micromol/L.

Patients were randomized to continue UDCA treatment (13-15 mg/kg per day) with or without the addition of bezafibrate, given as a 400-mg daily dose.

The primary endpoint was a complete biochemical response as defined by normal serum levels of total bilirubin, ALP, aminotransferases, albumin, and a normal prothrombin time at 2 years. The hypothesis was that 40% of the patients in the bezafibrate group and only 10% of patients in the UDCA group would reach this primary endpoint. The actual percentages were 30% and 10% (P less than .0001).

A significantly higher (67% vs. 0%) percentage of patients treated with the fibrate versus UDCA also achieved a normal serum ALP by 2 years, Dr. Corpechot reported, with a significant decrease seen by the third month of treatment.

The mean changes in all the biochemical parameters tested from baseline to the end of the study comparing the bezafibrate group with the control group were a respective –14% and +18% (P less than .0001) for total bilirubin, –60% and 0% for ALP (P less than .0001), –36% and 0% for alanine aminotransferase (P less than .0001), –8% and +8% for AST (P less than .05), –38% and +7% for gamma-glutamyl transferase (P less than .0001), 0% and –3% for albumin (P less than .05), and –16% and 0% for cholesterol (P less than .0001).

Other significant findings favoring the fibrate therapy were a significantly (–75% vs. 0%, P less than .01) decreased itch score (assessed with a visual analog scale) and a significantly lower (–10% vs. +10%, P less than .01) liver stiffness (assessed by transient elastography) at 2 years.

Importantly, the frequency of adverse events, including serious adverse events, did not differ significantly between the two groups.

Fibrates could thus offer a well tolerated and cheaper alternative, as they are already widely used in clinical practice, although they are not licensed for PBC treatment at the current time.

Dr. Tacke, professor of medicine in the department of gastroenterology, metabolic diseases and intensive care medicine at University Hospital Aachen, Germany, also noted that bezafibrate was a drug that “had been on the market for a very long time,” and was very inexpensive in comparison to obeticholic acid and, importantly, seemed to be very well tolerated in the study.

“One question the community will want to know is whether [bezafibrate] is as effective as obeticholic acid in the second-line treatment of PBC,” Dr. Tacke said. This is a question only a head-to-head study can answer and also it is not possible to say whether other fibrates may have the same benefit as bezafibrate as seen in this trial.