User login

Post-COVID fatigue, exercise intolerance signal ME/CFS

A new study provides yet more evidence that a significant subset of people who experience persistent fatigue and exercise intolerance following COVID-19 will meet diagnostic criteria for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

Data from the prospective observational study of 42 patients with “post-COVID-19 syndrome (PCS),” including persistent fatigue and exercise intolerance, suggest that a large proportion will meet strict diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS, including the hallmark postexertional malaise (PEM). Still others may experience similar disability but lack duration and/or severity requirements for the diagnosis.

Moreover, disease severity and symptom burden were found similar in those with ME/CFS following COVID-19 and in a group of 19 age- and sex-matched individuals with ME/CFS that wasn’t associated with COVID-19.

“The major finding is that ME/CFS is indeed part of the spectrum of the post-COVID syndrome and very similar to the ME/CFS we know after other infectious triggers,” senior author Carmen Scheibenbogen, MD, acting director of the Institute for Medical Immunology at the Charité University Medicine Campus Virchow-Klinikum, Berlin, told this news organization.

Importantly, from a clinical standpoint, both diminished hand-grip strength (HGS) and orthostatic intolerance were common across all patient groups, as were several laboratory values, Claudia Kedor, MD, and colleagues at Charité report in the paper, published online in Nature Communications.

Of the 42 with PCS, including persistent fatigue and exercise intolerance lasting at least 6 months, 19 met the rigorous Canadian Consensus Criteria (CCC) for ME/CFS, established in 2003, which require PEM, along with sleep dysfunction, significant persistent fatigue, pain, and several other symptoms from neurological/cognitive, autonomic, neuroendocrine, and immune categories that persist for at least 6 months.

Of the 23 who did not meet the CCC criteria, 18 still experienced PEM but for less than the required 14 hours set by the authors based on recent data. The original CCC had suggested 24 hours as the PEM duration. Eight subjects met all the Canadian criteria except for the neurological/cognitive symptoms. None of the 42 had evidence of severe depression.

The previously widely used 1994 “Fukuda” criteria for ME/CFS are no longer recommended because they don’t require PEM, which is now considered a key symptom. The more recent 2015 Institute (now Academy) of Medicine criteria don’t define the length of PEM, the authors note in the paper.

Dr. Scheibenbogen said, “Post-COVID has a spectrum of syndromes and conditions. We see that a subset of patients have similar symptoms of ME/CFS but don’t fulfill the CCC, although they may meet less stringent criteria. We think this is of relevance for both diagnostic markers and development of therapy, because there may be different pathomechanisms between the subsets of post-COVID patients.”

She pointed to other studies from her group suggesting that inflammation is present early in post-COVID (not yet published), while in the subset that goes on to ME/CFS, autoantibodies or endothelial dysfunction play a more important role. «At the moment, it’s quite complex, and I don’t think in the end we will have just one pathomechanism. So I think we’ll need to develop various treatment strategies.”

Asked to comment on the new data, Anthony L. Komaroff, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, senior physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, and editor in chief of the Harvard Health Letter, told this news organization, “This paper adds to the evidence that an illness with symptoms that meet criteria for ME/CFS can follow COVID-19 in nearly half of those patients who have lingering symptoms. This can occur even in people who initially have only mild symptoms from COVID-19, although it is more likely to happen in the people who are sickest when they first get COVID-19. And those who meet criteria for ME/CFS were seriously impaired in their ability to function, [both] at work and at home.”

But, Dr. Komaroff also cautioned, “the study does not help in determining what fraction of all people who are infected with SARS-CoV-2 go on to develop a condition like ME/CFS, nor how long that condition will last. It is crucial that we get answers to these questions, as the impact on the economy, the health care system, and the disability system could be substantial.”

He pointed to a recent report from the Brookings Institution (2022 Aug 24. “New data shows long Covid is keeping as many as 4 million people out of work” Katie Bach) “finding that “long COVID may be a major contributor to the shortage of job applicants plaguing many businesses.”

Biomarkers include hand-grip strength, orthostatic intolerance, lab measures

Hand-grip strength, as assessed by 10 repeat grips at maximum force and repeated after 60 minutes, were lower for all those meeting ME/CFS criteria, compared with the healthy controls. Hand-grip strength parameters were also positively correlated with laboratory hemoglobin measures in both PCS groups who did and didn’t meet the Canadian ME/CFS criteria.

A total of three patients with PCS who didn’t meet ME/CFS criteria and seven with PCS who met ME/CFS criteria had sitting blood pressures of greater than 140 mm Hg systolic and/or greater than 90 mm Hg diastolic. Five patients with PCS – four who met ME/CFS criteria and one who didn’t – fulfilled criteria for postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Orthostatic hypotension was diagnosed in a total of seven with PCS, including one who did not meet ME/CFS criteria and the rest who did.

Among significant laboratory findings, mannose-binding lectin deficiency, which is associated with increased infection susceptibility and found in only about 6% of historical controls, was found more frequently in both of the PCS cohorts (17% of those with ME/CFS and 23% of those without) than it has been in the past among those with ME/CFS, compared with historical controls (15%).

There was only slight elevation in C-reactive protein, the most commonly measured marker of inflammation. However, another marker indicating inflammation within the last 3-4 months, interleukin 8 assessed in erythrocytes, was above normal in 37% with PCS and ME/CFS and in 48% with PCS who did not meet the ME/CFS criteria.

Elevated antinuclear antibodies, anti–thyroid peroxidase antibodies, vitamin D deficiencies, and folic acid deficiencies were all seen in small numbers of the PCS patients. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 1 levels were below the normal range in 31% of all patients.

“We must anticipate that this pandemic has the potential to dramatically increase the number of ME/CFS patients,” Dr. Kedor and colleagues write. “At the same time, it offers the unique chance to identify ME/CFS patients in a very early stage of disease and apply interventions such as pacing and coping early with a better therapeutic prognosis. Further, it is an unprecedented opportunity to understand the underlying pathomechanism and characterize targets for specific treatment approaches.”

Dr. Scheibenbogen and Dr. Komaroff reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study provides yet more evidence that a significant subset of people who experience persistent fatigue and exercise intolerance following COVID-19 will meet diagnostic criteria for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

Data from the prospective observational study of 42 patients with “post-COVID-19 syndrome (PCS),” including persistent fatigue and exercise intolerance, suggest that a large proportion will meet strict diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS, including the hallmark postexertional malaise (PEM). Still others may experience similar disability but lack duration and/or severity requirements for the diagnosis.

Moreover, disease severity and symptom burden were found similar in those with ME/CFS following COVID-19 and in a group of 19 age- and sex-matched individuals with ME/CFS that wasn’t associated with COVID-19.

“The major finding is that ME/CFS is indeed part of the spectrum of the post-COVID syndrome and very similar to the ME/CFS we know after other infectious triggers,” senior author Carmen Scheibenbogen, MD, acting director of the Institute for Medical Immunology at the Charité University Medicine Campus Virchow-Klinikum, Berlin, told this news organization.

Importantly, from a clinical standpoint, both diminished hand-grip strength (HGS) and orthostatic intolerance were common across all patient groups, as were several laboratory values, Claudia Kedor, MD, and colleagues at Charité report in the paper, published online in Nature Communications.

Of the 42 with PCS, including persistent fatigue and exercise intolerance lasting at least 6 months, 19 met the rigorous Canadian Consensus Criteria (CCC) for ME/CFS, established in 2003, which require PEM, along with sleep dysfunction, significant persistent fatigue, pain, and several other symptoms from neurological/cognitive, autonomic, neuroendocrine, and immune categories that persist for at least 6 months.

Of the 23 who did not meet the CCC criteria, 18 still experienced PEM but for less than the required 14 hours set by the authors based on recent data. The original CCC had suggested 24 hours as the PEM duration. Eight subjects met all the Canadian criteria except for the neurological/cognitive symptoms. None of the 42 had evidence of severe depression.

The previously widely used 1994 “Fukuda” criteria for ME/CFS are no longer recommended because they don’t require PEM, which is now considered a key symptom. The more recent 2015 Institute (now Academy) of Medicine criteria don’t define the length of PEM, the authors note in the paper.

Dr. Scheibenbogen said, “Post-COVID has a spectrum of syndromes and conditions. We see that a subset of patients have similar symptoms of ME/CFS but don’t fulfill the CCC, although they may meet less stringent criteria. We think this is of relevance for both diagnostic markers and development of therapy, because there may be different pathomechanisms between the subsets of post-COVID patients.”

She pointed to other studies from her group suggesting that inflammation is present early in post-COVID (not yet published), while in the subset that goes on to ME/CFS, autoantibodies or endothelial dysfunction play a more important role. «At the moment, it’s quite complex, and I don’t think in the end we will have just one pathomechanism. So I think we’ll need to develop various treatment strategies.”

Asked to comment on the new data, Anthony L. Komaroff, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, senior physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, and editor in chief of the Harvard Health Letter, told this news organization, “This paper adds to the evidence that an illness with symptoms that meet criteria for ME/CFS can follow COVID-19 in nearly half of those patients who have lingering symptoms. This can occur even in people who initially have only mild symptoms from COVID-19, although it is more likely to happen in the people who are sickest when they first get COVID-19. And those who meet criteria for ME/CFS were seriously impaired in their ability to function, [both] at work and at home.”

But, Dr. Komaroff also cautioned, “the study does not help in determining what fraction of all people who are infected with SARS-CoV-2 go on to develop a condition like ME/CFS, nor how long that condition will last. It is crucial that we get answers to these questions, as the impact on the economy, the health care system, and the disability system could be substantial.”

He pointed to a recent report from the Brookings Institution (2022 Aug 24. “New data shows long Covid is keeping as many as 4 million people out of work” Katie Bach) “finding that “long COVID may be a major contributor to the shortage of job applicants plaguing many businesses.”

Biomarkers include hand-grip strength, orthostatic intolerance, lab measures

Hand-grip strength, as assessed by 10 repeat grips at maximum force and repeated after 60 minutes, were lower for all those meeting ME/CFS criteria, compared with the healthy controls. Hand-grip strength parameters were also positively correlated with laboratory hemoglobin measures in both PCS groups who did and didn’t meet the Canadian ME/CFS criteria.

A total of three patients with PCS who didn’t meet ME/CFS criteria and seven with PCS who met ME/CFS criteria had sitting blood pressures of greater than 140 mm Hg systolic and/or greater than 90 mm Hg diastolic. Five patients with PCS – four who met ME/CFS criteria and one who didn’t – fulfilled criteria for postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Orthostatic hypotension was diagnosed in a total of seven with PCS, including one who did not meet ME/CFS criteria and the rest who did.

Among significant laboratory findings, mannose-binding lectin deficiency, which is associated with increased infection susceptibility and found in only about 6% of historical controls, was found more frequently in both of the PCS cohorts (17% of those with ME/CFS and 23% of those without) than it has been in the past among those with ME/CFS, compared with historical controls (15%).

There was only slight elevation in C-reactive protein, the most commonly measured marker of inflammation. However, another marker indicating inflammation within the last 3-4 months, interleukin 8 assessed in erythrocytes, was above normal in 37% with PCS and ME/CFS and in 48% with PCS who did not meet the ME/CFS criteria.

Elevated antinuclear antibodies, anti–thyroid peroxidase antibodies, vitamin D deficiencies, and folic acid deficiencies were all seen in small numbers of the PCS patients. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 1 levels were below the normal range in 31% of all patients.

“We must anticipate that this pandemic has the potential to dramatically increase the number of ME/CFS patients,” Dr. Kedor and colleagues write. “At the same time, it offers the unique chance to identify ME/CFS patients in a very early stage of disease and apply interventions such as pacing and coping early with a better therapeutic prognosis. Further, it is an unprecedented opportunity to understand the underlying pathomechanism and characterize targets for specific treatment approaches.”

Dr. Scheibenbogen and Dr. Komaroff reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study provides yet more evidence that a significant subset of people who experience persistent fatigue and exercise intolerance following COVID-19 will meet diagnostic criteria for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

Data from the prospective observational study of 42 patients with “post-COVID-19 syndrome (PCS),” including persistent fatigue and exercise intolerance, suggest that a large proportion will meet strict diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS, including the hallmark postexertional malaise (PEM). Still others may experience similar disability but lack duration and/or severity requirements for the diagnosis.

Moreover, disease severity and symptom burden were found similar in those with ME/CFS following COVID-19 and in a group of 19 age- and sex-matched individuals with ME/CFS that wasn’t associated with COVID-19.

“The major finding is that ME/CFS is indeed part of the spectrum of the post-COVID syndrome and very similar to the ME/CFS we know after other infectious triggers,” senior author Carmen Scheibenbogen, MD, acting director of the Institute for Medical Immunology at the Charité University Medicine Campus Virchow-Klinikum, Berlin, told this news organization.

Importantly, from a clinical standpoint, both diminished hand-grip strength (HGS) and orthostatic intolerance were common across all patient groups, as were several laboratory values, Claudia Kedor, MD, and colleagues at Charité report in the paper, published online in Nature Communications.

Of the 42 with PCS, including persistent fatigue and exercise intolerance lasting at least 6 months, 19 met the rigorous Canadian Consensus Criteria (CCC) for ME/CFS, established in 2003, which require PEM, along with sleep dysfunction, significant persistent fatigue, pain, and several other symptoms from neurological/cognitive, autonomic, neuroendocrine, and immune categories that persist for at least 6 months.

Of the 23 who did not meet the CCC criteria, 18 still experienced PEM but for less than the required 14 hours set by the authors based on recent data. The original CCC had suggested 24 hours as the PEM duration. Eight subjects met all the Canadian criteria except for the neurological/cognitive symptoms. None of the 42 had evidence of severe depression.

The previously widely used 1994 “Fukuda” criteria for ME/CFS are no longer recommended because they don’t require PEM, which is now considered a key symptom. The more recent 2015 Institute (now Academy) of Medicine criteria don’t define the length of PEM, the authors note in the paper.

Dr. Scheibenbogen said, “Post-COVID has a spectrum of syndromes and conditions. We see that a subset of patients have similar symptoms of ME/CFS but don’t fulfill the CCC, although they may meet less stringent criteria. We think this is of relevance for both diagnostic markers and development of therapy, because there may be different pathomechanisms between the subsets of post-COVID patients.”

She pointed to other studies from her group suggesting that inflammation is present early in post-COVID (not yet published), while in the subset that goes on to ME/CFS, autoantibodies or endothelial dysfunction play a more important role. «At the moment, it’s quite complex, and I don’t think in the end we will have just one pathomechanism. So I think we’ll need to develop various treatment strategies.”

Asked to comment on the new data, Anthony L. Komaroff, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, senior physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, and editor in chief of the Harvard Health Letter, told this news organization, “This paper adds to the evidence that an illness with symptoms that meet criteria for ME/CFS can follow COVID-19 in nearly half of those patients who have lingering symptoms. This can occur even in people who initially have only mild symptoms from COVID-19, although it is more likely to happen in the people who are sickest when they first get COVID-19. And those who meet criteria for ME/CFS were seriously impaired in their ability to function, [both] at work and at home.”

But, Dr. Komaroff also cautioned, “the study does not help in determining what fraction of all people who are infected with SARS-CoV-2 go on to develop a condition like ME/CFS, nor how long that condition will last. It is crucial that we get answers to these questions, as the impact on the economy, the health care system, and the disability system could be substantial.”

He pointed to a recent report from the Brookings Institution (2022 Aug 24. “New data shows long Covid is keeping as many as 4 million people out of work” Katie Bach) “finding that “long COVID may be a major contributor to the shortage of job applicants plaguing many businesses.”

Biomarkers include hand-grip strength, orthostatic intolerance, lab measures

Hand-grip strength, as assessed by 10 repeat grips at maximum force and repeated after 60 minutes, were lower for all those meeting ME/CFS criteria, compared with the healthy controls. Hand-grip strength parameters were also positively correlated with laboratory hemoglobin measures in both PCS groups who did and didn’t meet the Canadian ME/CFS criteria.

A total of three patients with PCS who didn’t meet ME/CFS criteria and seven with PCS who met ME/CFS criteria had sitting blood pressures of greater than 140 mm Hg systolic and/or greater than 90 mm Hg diastolic. Five patients with PCS – four who met ME/CFS criteria and one who didn’t – fulfilled criteria for postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Orthostatic hypotension was diagnosed in a total of seven with PCS, including one who did not meet ME/CFS criteria and the rest who did.

Among significant laboratory findings, mannose-binding lectin deficiency, which is associated with increased infection susceptibility and found in only about 6% of historical controls, was found more frequently in both of the PCS cohorts (17% of those with ME/CFS and 23% of those without) than it has been in the past among those with ME/CFS, compared with historical controls (15%).

There was only slight elevation in C-reactive protein, the most commonly measured marker of inflammation. However, another marker indicating inflammation within the last 3-4 months, interleukin 8 assessed in erythrocytes, was above normal in 37% with PCS and ME/CFS and in 48% with PCS who did not meet the ME/CFS criteria.

Elevated antinuclear antibodies, anti–thyroid peroxidase antibodies, vitamin D deficiencies, and folic acid deficiencies were all seen in small numbers of the PCS patients. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 1 levels were below the normal range in 31% of all patients.

“We must anticipate that this pandemic has the potential to dramatically increase the number of ME/CFS patients,” Dr. Kedor and colleagues write. “At the same time, it offers the unique chance to identify ME/CFS patients in a very early stage of disease and apply interventions such as pacing and coping early with a better therapeutic prognosis. Further, it is an unprecedented opportunity to understand the underlying pathomechanism and characterize targets for specific treatment approaches.”

Dr. Scheibenbogen and Dr. Komaroff reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NATURE COMMUNICATIONS

Prior psychological distress tied to ‘long-COVID’ conditions

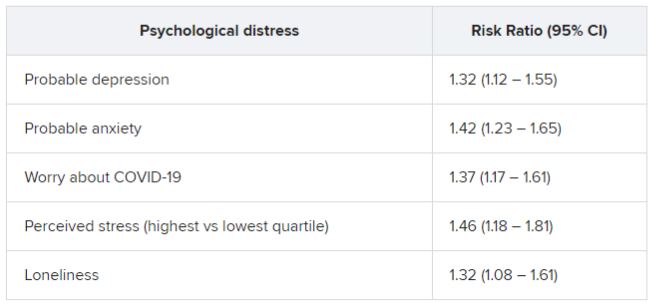

In an analysis of almost 55,000 adult participants in three ongoing studies, having depression, anxiety, worry, perceived stress, or loneliness early in the pandemic, before SARS-CoV-2 infection, was associated with a 50% increased risk for developing long COVID. These types of psychological distress were also associated with a 15% to 51% greater risk for impairment in daily life among individuals with long COVID.

Psychological distress was even more strongly associated with developing long COVID than were physical health risk factors, and the increased risk was not explained by health behaviors such as smoking or physical comorbidities, researchers note.

“Our findings suggest the need to consider psychological health in addition to physical health as risk factors of long COVID-19,” lead author Siwen Wang, MD, postdoctoral fellow, department of nutrition, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, said in an interview.

“We need to increase public awareness of the importance of mental health and focus on getting mental health care for people who need it, increasing the supply of mental health clinicians and improving access to care,” she said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

‘Poorly understood’

Postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (“long COVID”), which are “signs and symptoms consistent with COVID-19 that extend beyond 4 weeks from onset of infection” constitute “an emerging health issue,” the investigators write.

Dr. Wang noted that it has been estimated that 8-23 million Americans have developed long COVID. However, “despite the high prevalence and daily life impairment associated with long COVID, it is still poorly understood, and few risk factors have been established,” she said.

Although psychological distress may be implicated in long COVID, only three previous studies investigated psychological factors as potential contributors, the researchers note. Also, no study has investigated the potential role of other common manifestations of distress that have increased during the pandemic, such as loneliness and perceived stress, they add.

To investigate these issues, the researchers turned to three large ongoing longitudinal studies: the Nurses’ Health Study II (NSHII), the Nurses’ Health study 3 (NHS3), and the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS).

They analyzed data on 54,960 total participants (96.6% women; mean age, 57.5 years). Of the full group, 38% were active health care workers.

Participants completed an online COVID-19 questionnaire from April 2020 to Sept. 1, 2020 (baseline), and monthly surveys thereafter. Beginning in August 2020, surveys were administered quarterly. The end of follow-up was in November 2021.

The COVID questionnaires included questions about positive SARS-CoV-2 test results, COVID symptoms and hospitalization since March 1, 2020, and the presence of long-term COVID symptoms, such as fatigue, respiratory problems, persistent cough, muscle/joint/chest pain, smell/taste problems, confusion/disorientation/brain fog, depression/anxiety/changes in mood, headache, and memory problems.

Participants who reported these post-COVID conditions were asked about the frequency of symptoms and the degree of impairment in daily life.

Inflammation, immune dysregulation implicated?

The Patient Health Questionnaire–4 (PHQ-4) was used to assess for anxiety and depressive symptoms in the past 2 weeks. It consists of a two-item depression measure (PHQ-2) and a two-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-2).

Non–health care providers completed two additional assessments of psychological distress: the four-item Perceived Stress Scale and the three-item UCLA Loneliness Scale.

The researchers included demographic factors, weight, smoking status, marital status, and medical conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, asthma, and cancer, and socioeconomic factors as covariates.

For each participant, the investigators calculated the number of types of distress experienced at a high level, including probable depression, probable anxiety, worry about COVID-19, being in the top quartile of perceived stress, and loneliness.

During the 19 months of follow-up (1-47 weeks after baseline), 6% of respondents reported a positive result on a SARS-CoV-2 antibody, antigen, or polymerase chain reaction test.

Of these, 43.9% reported long-COVID conditions, with most reporting that symptoms lasted 2 months or longer; 55.8% reported at least occasional daily life impairment.

The most common post-COVID conditions were fatigue (reported by 56%), loss of smell or taste problems (44.6%), shortness of breath (25.5%), confusion/disorientation/ brain fog (24.5%), and memory issues (21.8%).

Among patients who had been infected, there was a considerably higher rate of preinfection psychological distress after adjusting for sociodemographic factors, health behaviors, and comorbidities. Each type of distress was associated with post-COVID conditions.

In addition, participants who had experienced at least two types of distress prior to infection were at nearly 50% increased risk for post–COVID conditions (risk ratio, 1.49; 95% confidence interval, 1.23-1.80).

Among those with post-COVID conditions, all types of distress were associated with increased risk for daily life impairment (RR range, 1.15-1.51).

Senior author Andrea Roberts, PhD, senior research scientist at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, noted that the investigators did not examine biological mechanisms potentially underlying the association they found.

However, “based on prior research, it may be that inflammation and immune dysregulation related to psychological distress play a role in the association of distress with long COVID, but we can’t be sure,” Dr. Roberts said.

Contributes to the field

Commenting for this article, Yapeng Su, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, called the study “great work contributing to the long-COVID research field and revealing important connections” with psychological stress prior to infection.

Dr. Su, who was not involved with the study, was previously at the Institute for Systems Biology, also in Seattle, and has written about long COVID.

He noted that the “biological mechanism of such intriguing linkage is definitely the important next step, which will likely require deep phenotyping of biological specimens from these patients longitudinally.”

Dr. Wang pointed to past research suggesting that some patients with mental illness “sometimes develop autoantibodies that have also been associated with increased risk of long COVID.” In addition, depression “affects the brain in ways that may explain certain cognitive symptoms in long COVID,” she added.

More studies are now needed to understand how psychological distress increases the risk for long COVID, said Dr. Wang.

The research was supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institutes of Health, the Dean’s Fund for Scientific Advancement Acceleration Award from the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, the Massachusetts Consortium on Pathogen Readiness Evergrande COVID-19 Response Fund Award, and the Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service funds. Dr. Wang and Dr. Roberts have reported no relevant financial relationships. The other investigators’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Su reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

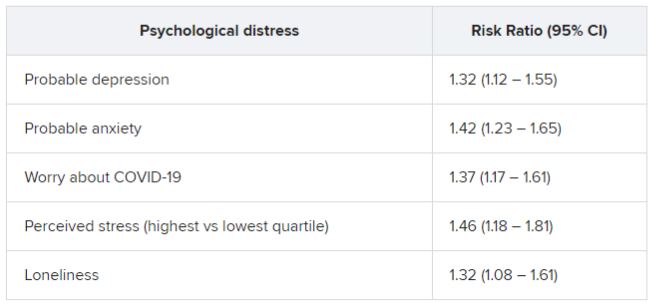

In an analysis of almost 55,000 adult participants in three ongoing studies, having depression, anxiety, worry, perceived stress, or loneliness early in the pandemic, before SARS-CoV-2 infection, was associated with a 50% increased risk for developing long COVID. These types of psychological distress were also associated with a 15% to 51% greater risk for impairment in daily life among individuals with long COVID.

Psychological distress was even more strongly associated with developing long COVID than were physical health risk factors, and the increased risk was not explained by health behaviors such as smoking or physical comorbidities, researchers note.

“Our findings suggest the need to consider psychological health in addition to physical health as risk factors of long COVID-19,” lead author Siwen Wang, MD, postdoctoral fellow, department of nutrition, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, said in an interview.

“We need to increase public awareness of the importance of mental health and focus on getting mental health care for people who need it, increasing the supply of mental health clinicians and improving access to care,” she said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

‘Poorly understood’

Postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (“long COVID”), which are “signs and symptoms consistent with COVID-19 that extend beyond 4 weeks from onset of infection” constitute “an emerging health issue,” the investigators write.

Dr. Wang noted that it has been estimated that 8-23 million Americans have developed long COVID. However, “despite the high prevalence and daily life impairment associated with long COVID, it is still poorly understood, and few risk factors have been established,” she said.

Although psychological distress may be implicated in long COVID, only three previous studies investigated psychological factors as potential contributors, the researchers note. Also, no study has investigated the potential role of other common manifestations of distress that have increased during the pandemic, such as loneliness and perceived stress, they add.

To investigate these issues, the researchers turned to three large ongoing longitudinal studies: the Nurses’ Health Study II (NSHII), the Nurses’ Health study 3 (NHS3), and the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS).

They analyzed data on 54,960 total participants (96.6% women; mean age, 57.5 years). Of the full group, 38% were active health care workers.

Participants completed an online COVID-19 questionnaire from April 2020 to Sept. 1, 2020 (baseline), and monthly surveys thereafter. Beginning in August 2020, surveys were administered quarterly. The end of follow-up was in November 2021.

The COVID questionnaires included questions about positive SARS-CoV-2 test results, COVID symptoms and hospitalization since March 1, 2020, and the presence of long-term COVID symptoms, such as fatigue, respiratory problems, persistent cough, muscle/joint/chest pain, smell/taste problems, confusion/disorientation/brain fog, depression/anxiety/changes in mood, headache, and memory problems.

Participants who reported these post-COVID conditions were asked about the frequency of symptoms and the degree of impairment in daily life.

Inflammation, immune dysregulation implicated?

The Patient Health Questionnaire–4 (PHQ-4) was used to assess for anxiety and depressive symptoms in the past 2 weeks. It consists of a two-item depression measure (PHQ-2) and a two-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-2).

Non–health care providers completed two additional assessments of psychological distress: the four-item Perceived Stress Scale and the three-item UCLA Loneliness Scale.

The researchers included demographic factors, weight, smoking status, marital status, and medical conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, asthma, and cancer, and socioeconomic factors as covariates.

For each participant, the investigators calculated the number of types of distress experienced at a high level, including probable depression, probable anxiety, worry about COVID-19, being in the top quartile of perceived stress, and loneliness.

During the 19 months of follow-up (1-47 weeks after baseline), 6% of respondents reported a positive result on a SARS-CoV-2 antibody, antigen, or polymerase chain reaction test.

Of these, 43.9% reported long-COVID conditions, with most reporting that symptoms lasted 2 months or longer; 55.8% reported at least occasional daily life impairment.

The most common post-COVID conditions were fatigue (reported by 56%), loss of smell or taste problems (44.6%), shortness of breath (25.5%), confusion/disorientation/ brain fog (24.5%), and memory issues (21.8%).

Among patients who had been infected, there was a considerably higher rate of preinfection psychological distress after adjusting for sociodemographic factors, health behaviors, and comorbidities. Each type of distress was associated with post-COVID conditions.

In addition, participants who had experienced at least two types of distress prior to infection were at nearly 50% increased risk for post–COVID conditions (risk ratio, 1.49; 95% confidence interval, 1.23-1.80).

Among those with post-COVID conditions, all types of distress were associated with increased risk for daily life impairment (RR range, 1.15-1.51).

Senior author Andrea Roberts, PhD, senior research scientist at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, noted that the investigators did not examine biological mechanisms potentially underlying the association they found.

However, “based on prior research, it may be that inflammation and immune dysregulation related to psychological distress play a role in the association of distress with long COVID, but we can’t be sure,” Dr. Roberts said.

Contributes to the field

Commenting for this article, Yapeng Su, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, called the study “great work contributing to the long-COVID research field and revealing important connections” with psychological stress prior to infection.

Dr. Su, who was not involved with the study, was previously at the Institute for Systems Biology, also in Seattle, and has written about long COVID.

He noted that the “biological mechanism of such intriguing linkage is definitely the important next step, which will likely require deep phenotyping of biological specimens from these patients longitudinally.”

Dr. Wang pointed to past research suggesting that some patients with mental illness “sometimes develop autoantibodies that have also been associated with increased risk of long COVID.” In addition, depression “affects the brain in ways that may explain certain cognitive symptoms in long COVID,” she added.

More studies are now needed to understand how psychological distress increases the risk for long COVID, said Dr. Wang.

The research was supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institutes of Health, the Dean’s Fund for Scientific Advancement Acceleration Award from the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, the Massachusetts Consortium on Pathogen Readiness Evergrande COVID-19 Response Fund Award, and the Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service funds. Dr. Wang and Dr. Roberts have reported no relevant financial relationships. The other investigators’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Su reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

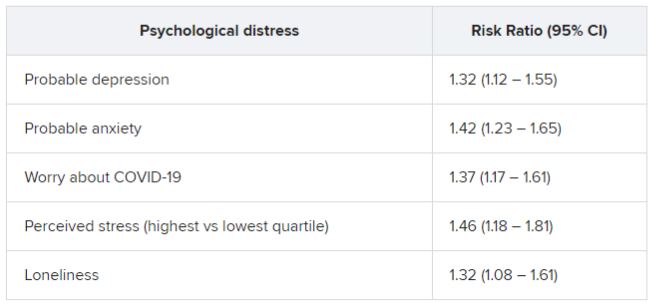

In an analysis of almost 55,000 adult participants in three ongoing studies, having depression, anxiety, worry, perceived stress, or loneliness early in the pandemic, before SARS-CoV-2 infection, was associated with a 50% increased risk for developing long COVID. These types of psychological distress were also associated with a 15% to 51% greater risk for impairment in daily life among individuals with long COVID.

Psychological distress was even more strongly associated with developing long COVID than were physical health risk factors, and the increased risk was not explained by health behaviors such as smoking or physical comorbidities, researchers note.

“Our findings suggest the need to consider psychological health in addition to physical health as risk factors of long COVID-19,” lead author Siwen Wang, MD, postdoctoral fellow, department of nutrition, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, said in an interview.

“We need to increase public awareness of the importance of mental health and focus on getting mental health care for people who need it, increasing the supply of mental health clinicians and improving access to care,” she said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

‘Poorly understood’

Postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (“long COVID”), which are “signs and symptoms consistent with COVID-19 that extend beyond 4 weeks from onset of infection” constitute “an emerging health issue,” the investigators write.

Dr. Wang noted that it has been estimated that 8-23 million Americans have developed long COVID. However, “despite the high prevalence and daily life impairment associated with long COVID, it is still poorly understood, and few risk factors have been established,” she said.

Although psychological distress may be implicated in long COVID, only three previous studies investigated psychological factors as potential contributors, the researchers note. Also, no study has investigated the potential role of other common manifestations of distress that have increased during the pandemic, such as loneliness and perceived stress, they add.

To investigate these issues, the researchers turned to three large ongoing longitudinal studies: the Nurses’ Health Study II (NSHII), the Nurses’ Health study 3 (NHS3), and the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS).

They analyzed data on 54,960 total participants (96.6% women; mean age, 57.5 years). Of the full group, 38% were active health care workers.

Participants completed an online COVID-19 questionnaire from April 2020 to Sept. 1, 2020 (baseline), and monthly surveys thereafter. Beginning in August 2020, surveys were administered quarterly. The end of follow-up was in November 2021.

The COVID questionnaires included questions about positive SARS-CoV-2 test results, COVID symptoms and hospitalization since March 1, 2020, and the presence of long-term COVID symptoms, such as fatigue, respiratory problems, persistent cough, muscle/joint/chest pain, smell/taste problems, confusion/disorientation/brain fog, depression/anxiety/changes in mood, headache, and memory problems.

Participants who reported these post-COVID conditions were asked about the frequency of symptoms and the degree of impairment in daily life.

Inflammation, immune dysregulation implicated?

The Patient Health Questionnaire–4 (PHQ-4) was used to assess for anxiety and depressive symptoms in the past 2 weeks. It consists of a two-item depression measure (PHQ-2) and a two-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-2).

Non–health care providers completed two additional assessments of psychological distress: the four-item Perceived Stress Scale and the three-item UCLA Loneliness Scale.

The researchers included demographic factors, weight, smoking status, marital status, and medical conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, asthma, and cancer, and socioeconomic factors as covariates.

For each participant, the investigators calculated the number of types of distress experienced at a high level, including probable depression, probable anxiety, worry about COVID-19, being in the top quartile of perceived stress, and loneliness.

During the 19 months of follow-up (1-47 weeks after baseline), 6% of respondents reported a positive result on a SARS-CoV-2 antibody, antigen, or polymerase chain reaction test.

Of these, 43.9% reported long-COVID conditions, with most reporting that symptoms lasted 2 months or longer; 55.8% reported at least occasional daily life impairment.

The most common post-COVID conditions were fatigue (reported by 56%), loss of smell or taste problems (44.6%), shortness of breath (25.5%), confusion/disorientation/ brain fog (24.5%), and memory issues (21.8%).

Among patients who had been infected, there was a considerably higher rate of preinfection psychological distress after adjusting for sociodemographic factors, health behaviors, and comorbidities. Each type of distress was associated with post-COVID conditions.

In addition, participants who had experienced at least two types of distress prior to infection were at nearly 50% increased risk for post–COVID conditions (risk ratio, 1.49; 95% confidence interval, 1.23-1.80).

Among those with post-COVID conditions, all types of distress were associated with increased risk for daily life impairment (RR range, 1.15-1.51).

Senior author Andrea Roberts, PhD, senior research scientist at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, noted that the investigators did not examine biological mechanisms potentially underlying the association they found.

However, “based on prior research, it may be that inflammation and immune dysregulation related to psychological distress play a role in the association of distress with long COVID, but we can’t be sure,” Dr. Roberts said.

Contributes to the field

Commenting for this article, Yapeng Su, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, called the study “great work contributing to the long-COVID research field and revealing important connections” with psychological stress prior to infection.

Dr. Su, who was not involved with the study, was previously at the Institute for Systems Biology, also in Seattle, and has written about long COVID.

He noted that the “biological mechanism of such intriguing linkage is definitely the important next step, which will likely require deep phenotyping of biological specimens from these patients longitudinally.”

Dr. Wang pointed to past research suggesting that some patients with mental illness “sometimes develop autoantibodies that have also been associated with increased risk of long COVID.” In addition, depression “affects the brain in ways that may explain certain cognitive symptoms in long COVID,” she added.

More studies are now needed to understand how psychological distress increases the risk for long COVID, said Dr. Wang.

The research was supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institutes of Health, the Dean’s Fund for Scientific Advancement Acceleration Award from the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, the Massachusetts Consortium on Pathogen Readiness Evergrande COVID-19 Response Fund Award, and the Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service funds. Dr. Wang and Dr. Roberts have reported no relevant financial relationships. The other investigators’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Su reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

How do you live with COVID? One doctor’s personal experience

Early in 2020, Anne Peters, MD, caught COVID-19. The author of Medscape’s “Peters on Diabetes” column was sick in March 2020 before state-mandated lockdowns, and well before there were any vaccines.

She remembers sitting in a small exam room with two patients who had flown to her Los Angeles office from New York. The elderly couple had hearing difficulties, so Dr. Peters sat close to them, putting on a continuous glucose monitor. “At that time, we didn’t think of COVID-19 as being in L.A.,” Dr. Peters recalled, “so I think we were not terribly consistent at mask-wearing due to the need to educate.”

“Several days later, I got COVID, but I didn’t know I had COVID per se. I felt crappy, had a terrible sore throat, lost my sense of taste and smell [which was not yet described as a COVID symptom], was completely exhausted, but had no fever or cough, which were the only criteria for getting COVID tested at the time. I didn’t know I had been exposed until 2 weeks later, when the patient’s assistant returned the sensor warning us to ‘be careful’ with it because the patient and his wife were recovering from COVID.”

That early battle with COVID-19 was just the beginning of what would become a 2-year struggle, including familial loss amid her own health problems and concerns about the under-resourced patients she cares for. Here, she shares her journey through the pandemic with this news organization.

Question: Thanks for talking to us. Let’s discuss your journey over these past 2.5 years.

Answer: Everybody has their own COVID story because we all went through this together. Some of us have worse COVID stories, and some of us have better ones, but all have been impacted.

I’m not a sick person. I’m a very healthy person but COVID made me so unwell for 2 years. The brain fog and fatigue were nothing compared to the autonomic neuropathy that affected my heart. It was really limiting for me. And I still don’t know the long-term implications, looking 20-30 years from now.

Q: When you initially had COVID, what were your symptoms? What was the impact?

A: I had all the symptoms of COVID, except for a cough and fever. I lost my sense of taste and smell. I had a horrible headache, a sore throat, and I was exhausted. I couldn’t get tested because I didn’t have the right symptoms.

Despite being sick, I never stopped working but just switched to telemedicine. I also took my regular monthly trip to our cabin in Montana. I unknowingly flew on a plane with COVID. I wore a well-fitted N95 mask, so I don’t think I gave anybody COVID. I didn’t give COVID to my partner, Eric, which is hard to believe as – at 77 – he’s older than me. He has diabetes, heart disease, and every other high-risk characteristic. If he’d gotten COVID back then, it would have been terrible, as there were no treatments, but luckily he didn’t get it.

Q: When were you officially diagnosed?

A: Two or 3 months after I thought I might have had COVID, I checked my antibodies, which tested strongly positive for a prior COVID infection. That was when I knew all the symptoms I’d had were due to the disease.

Q: Not only were you dealing with your own illness, but also that of those close to you. Can you talk about that?

A: In April 2020, my mother who was in her 90s and otherwise healthy except for dementia, got COVID. She could have gotten it from me. I visited often but wore a mask. She had all the horrible pulmonary symptoms. In her advance directive, she didn’t want to be hospitalized so I kept her in her home. She died from COVID in her own bed. It was fairly brutal, but at least I kept her where she felt comforted.

My 91-year-old dad was living in a different residential facility. Throughout COVID he had become very depressed because his social patterns had changed. Prior to COVID, they all ate together, but during the pandemic they were unable to. He missed his social connections, disliked being isolated in his room, hated everyone in masks.

He was a bit demented, but not so much that he couldn’t communicate with me or remember where his grandson was going to law school. I wasn’t allowed inside the facility, which was hard on him. I hadn’t told him his wife died because the hospice social workers advised me that I shouldn’t give him news that he couldn’t process readily until I could spend time with him. Unfortunately, that time never came. In December 2020, he got COVID. One of the people in that facility had gone to the hospital, came back, and tested negative, but actually had COVID and gave it to my dad. The guy who gave it to my dad didn’t die but my dad was terribly ill. He died 2 weeks short of getting his vaccine. He was coherent enough to have a conversation. I asked him: ‘Do you want to go to the hospital?’ And he said: ‘No, because it would be too scary,’ since he couldn’t be with me. I put him on hospice and held his hand as he died from pulmonary COVID, which was awful. I couldn’t give him enough morphine or valium to ease his breathing. But his last words to me were “I love you,” and at the very end he seemed peaceful, which was a blessing.

I got an autopsy, because he wanted one. Nothing else was wrong with him other than COVID. It destroyed his lungs. The rest of him was fine – no heart disease, cancer, or anything else. He died of COVID-19, the same as my mother.

That same week, my aunt, my only surviving older relative, who was in Des Moines, Iowa, died of COVID-19. All three family members died before the vaccine came out.

It was hard to lose my parents. I’m the only surviving child because my sister died in her 20s. It’s not been an easy pandemic. But what pandemic is easy? I just happened to have lost more people than most. Ironically, my grandfather was one of the legionnaires at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia in 1976 and died of Legionnaire’s disease before we knew what was causing the outbreak.

Q: Were you still struggling with COVID?

A: COVID impacted my whole body. I lost a lot of weight. I didn’t want to eat, and my gastrointestinal system was not happy. It took a while for my sense of taste and smell to come back. Nothing tasted good. I’m not a foodie; I don’t really care about food. We could get takeout or whatever, but none of it appealed to me. I’m not so sure it was a taste thing, I just didn’t feel like eating.

I didn’t realize I had “brain fog” per se, because I felt stressed and overwhelmed by the pandemic and my patients’ concerns. But one day, about 3 months after I had developed COVID, I woke up without the fog. Which made me aware that I hadn’t been feeling right up until that point.

The worst symptoms, however, were cardiac. I noticed also immediately that my heart rate went up very quickly with minimal exertion. My pulse has always been in the 55-60 bpm range, and suddenly just walking across a room made it go up to over 140 bpm. If I did any aerobic activity, it went up over 160 and would be associated with dyspnea and chest pain. I believed these were all post-COVID symptoms and felt validated when reports of others having similar issues were published in the literature.

Q: Did you continue seeing patients?

A: Yes, of course. Patients never needed their doctors more. In East L.A., where patients don’t have easy access to telemedicine, I kept going into clinic throughout the pandemic. In the more affluent Westside of Los Angeles, we switched to telemedicine, which was quite effective for most. However, because diabetes was associated with an increased risk of hospitalization and death from COVID, my patients were understandably afraid. I’ve never been busier, but (like all health care providers), I became more of a COVID provider than a diabetologist.

Q: Do you feel your battle with COVID impacted your work?

A: It didn’t affect me at work. If I was sitting still, I was fine. Sitting at home at a desk, I didn’t notice any symptoms. But as a habitual stair-user, I would be gasping for breath in the stairwell because I couldn’t go up the stairs to my office as I once could.

I think you empathize more with people who had COVID (when you’ve had it yourself). There was such a huge patient burden. And I think that’s been the thing that’s affected health care providers the most – no matter what specialty we’re in – that nobody has answers.

Q: What happened after you had your vaccine?

A: The vaccine itself was fine. I didn’t have any reaction to the first two doses. But the first booster made my cardiac issues worse.

By this point, my cardiac problems stopped me from exercising. I even went to the ER with chest pain once because I was having palpitations and chest pressure caused by simply taking my morning shower. Fortunately, I wasn’t having an MI, but I certainly wasn’t “normal.”

My measure of my fitness is the cross-country skiing trail I use in Montana. I know exactly how far I can ski. Usually I can do the loop in 35 minutes. After COVID, I lasted 10 minutes. I would be tachycardic, short of breath with chest pain radiating down my left arm. I would rest and try to keep going. But with each rest period, I only got worse. I would be laying in the snow and strangers would ask if I needed help.

Q: What helped you?

A: I’ve read a lot about long COVID and have tried to learn from the experts. Of course, I never went to a doctor directly, although I did ask colleagues for advice. What I learned was to never push myself. I forced myself to create an exercise schedule where I only exercised three times a week with rest days in between. When exercising, the second my heart rate went above 140 bpm, I stopped until I could get it back down. I would push against this new limit, even though my limit was low.

Additionally, I worked on my breathing patterns and did meditative breathing for 10 minutes twice daily using a commercially available app.

Although progress was slow, I did improve, and by June 2022, I seemed back to normal. I was not as fit as I was prior to COVID and needed to improve, but the tachycardic response to exercise and cardiac symptoms were gone. I felt like my normal self. Normal enough to go on a spot packing trip in the Sierras in August. (Horses carried us and a mule carried the gear over the 12,000-foot pass into the mountains, and then left my friend and me high in the Sierras for a week.) We were camped above 10,000 feet and every day hiked up to another high mountain lake where we fly-fished for trout that we ate for dinner. The hikes were a challenge, but not abnormally so. Not as they would have been while I had long COVID.

Q: What is the current atmosphere in your clinic?

A: COVID is much milder now in my vaccinated patients, but I feel most health care providers are exhausted. Many of my staff left when COVID hit because they didn’t want to keep working. It made practicing medicine exhausting. There’s been a shortage of nurses, a shortage of everything. We’ve been required to do a whole lot more than we ever did before. It’s much harder to be a doctor. This pandemic is the first time I’ve ever thought of quitting. Granted, I lost my whole family, or at least the older generation, but it’s just been almost overwhelming.

On the plus side, almost every one of my patients has been vaccinated, because early on, people would ask: “Do you trust this vaccine?” I would reply: “I saw my parents die from COVID when they weren’t vaccinated, so you’re getting vaccinated. This is real and the vaccines help.” It made me very good at convincing people to get vaccines because I knew what it was like to see someone dying from COVID up close.

Q: What advice do you have for those struggling with the COVID pandemic?

A: People need to decide what their own risk is for getting sick and how many times they want to get COVID. At this point, I want people to go out, but safely. In the beginning, when my patients said, “can I go visit my granddaughter?” I said, “no,” but that was before we had the vaccine. Now I feel it is safe to go out using common sense. I still have my patients wear masks on planes. I still have patients try to eat outside as much as possible. And I tell people to take the precautions that make sense, but I tell them to go out and do things because life is short.

I had a patient in his 70s who has many risk factors like heart disease and diabetes. His granddaughter’s Bat Mitzvah in Florida was coming up. He asked: “Can I go?” I told him “Yes,” but to be safe – to wear an N95 mask on the plane and at the event, and stay in his own hotel room, rather than with the whole family. I said, “You need to do this.” Earlier in the pandemic, I saw people who literally died from loneliness and isolation.

He and his wife flew there. He sent me a picture of himself with his granddaughter. When he returned, he showed me a handwritten note from her that said, “I love you so much. Everyone else canceled, which made me cry. You’re the only one who came. You have no idea how much this meant to me.”

He’s back in L.A., and he didn’t get COVID. He said, “It was the best thing I’ve done in years.” That’s what I need to help people with, navigating this world with COVID and assessing risks and benefits. As with all of medicine, my advice is individualized. My advice changes based on the major circulating variant and the rates of the virus in the population, as well as the risk factors of the individual.

Q: What are you doing now?

A: I’m trying to avoid getting COVID again, or another booster. I could get pre-exposure monoclonal antibodies but am waiting to do anything further until I see what happens over the fall and winter. I still wear a mask inside but now do a mix of in-person and telemedicine visits. I still try to go to outdoor restaurants, which is easy in California. But I’m flying to see my son in New York and plan to go to Europe this fall for a meeting. I also go to my cabin in Montana every month to get my “dose” of the wilderness. Overall, I travel for conferences and speaking engagements much less because I have learned the joy of staying home.

Thinking back on my life as a doctor, my career began as an intern at Stanford rotating through Ward 5B, the AIDS unit at San Francisco General Hospital, and will likely end with COVID. In spite of all our medical advances, my generation of physicians, much as many generations before us, has a front-row seat to the vulnerability of humans to infectious diseases and how far we still need to go to protect our patients from communicable illness.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Anne L. Peters, MD, is a professor of medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and director of the USC clinical diabetes programs. She has published more than 200 articles, reviews, and abstracts; three books on diabetes; and has been an investigator for more than 40 research studies. She has spoken internationally at over 400 programs and serves on many committees of several professional organizations.

Early in 2020, Anne Peters, MD, caught COVID-19. The author of Medscape’s “Peters on Diabetes” column was sick in March 2020 before state-mandated lockdowns, and well before there were any vaccines.

She remembers sitting in a small exam room with two patients who had flown to her Los Angeles office from New York. The elderly couple had hearing difficulties, so Dr. Peters sat close to them, putting on a continuous glucose monitor. “At that time, we didn’t think of COVID-19 as being in L.A.,” Dr. Peters recalled, “so I think we were not terribly consistent at mask-wearing due to the need to educate.”

“Several days later, I got COVID, but I didn’t know I had COVID per se. I felt crappy, had a terrible sore throat, lost my sense of taste and smell [which was not yet described as a COVID symptom], was completely exhausted, but had no fever or cough, which were the only criteria for getting COVID tested at the time. I didn’t know I had been exposed until 2 weeks later, when the patient’s assistant returned the sensor warning us to ‘be careful’ with it because the patient and his wife were recovering from COVID.”

That early battle with COVID-19 was just the beginning of what would become a 2-year struggle, including familial loss amid her own health problems and concerns about the under-resourced patients she cares for. Here, she shares her journey through the pandemic with this news organization.

Question: Thanks for talking to us. Let’s discuss your journey over these past 2.5 years.

Answer: Everybody has their own COVID story because we all went through this together. Some of us have worse COVID stories, and some of us have better ones, but all have been impacted.

I’m not a sick person. I’m a very healthy person but COVID made me so unwell for 2 years. The brain fog and fatigue were nothing compared to the autonomic neuropathy that affected my heart. It was really limiting for me. And I still don’t know the long-term implications, looking 20-30 years from now.

Q: When you initially had COVID, what were your symptoms? What was the impact?

A: I had all the symptoms of COVID, except for a cough and fever. I lost my sense of taste and smell. I had a horrible headache, a sore throat, and I was exhausted. I couldn’t get tested because I didn’t have the right symptoms.

Despite being sick, I never stopped working but just switched to telemedicine. I also took my regular monthly trip to our cabin in Montana. I unknowingly flew on a plane with COVID. I wore a well-fitted N95 mask, so I don’t think I gave anybody COVID. I didn’t give COVID to my partner, Eric, which is hard to believe as – at 77 – he’s older than me. He has diabetes, heart disease, and every other high-risk characteristic. If he’d gotten COVID back then, it would have been terrible, as there were no treatments, but luckily he didn’t get it.

Q: When were you officially diagnosed?

A: Two or 3 months after I thought I might have had COVID, I checked my antibodies, which tested strongly positive for a prior COVID infection. That was when I knew all the symptoms I’d had were due to the disease.

Q: Not only were you dealing with your own illness, but also that of those close to you. Can you talk about that?

A: In April 2020, my mother who was in her 90s and otherwise healthy except for dementia, got COVID. She could have gotten it from me. I visited often but wore a mask. She had all the horrible pulmonary symptoms. In her advance directive, she didn’t want to be hospitalized so I kept her in her home. She died from COVID in her own bed. It was fairly brutal, but at least I kept her where she felt comforted.

My 91-year-old dad was living in a different residential facility. Throughout COVID he had become very depressed because his social patterns had changed. Prior to COVID, they all ate together, but during the pandemic they were unable to. He missed his social connections, disliked being isolated in his room, hated everyone in masks.

He was a bit demented, but not so much that he couldn’t communicate with me or remember where his grandson was going to law school. I wasn’t allowed inside the facility, which was hard on him. I hadn’t told him his wife died because the hospice social workers advised me that I shouldn’t give him news that he couldn’t process readily until I could spend time with him. Unfortunately, that time never came. In December 2020, he got COVID. One of the people in that facility had gone to the hospital, came back, and tested negative, but actually had COVID and gave it to my dad. The guy who gave it to my dad didn’t die but my dad was terribly ill. He died 2 weeks short of getting his vaccine. He was coherent enough to have a conversation. I asked him: ‘Do you want to go to the hospital?’ And he said: ‘No, because it would be too scary,’ since he couldn’t be with me. I put him on hospice and held his hand as he died from pulmonary COVID, which was awful. I couldn’t give him enough morphine or valium to ease his breathing. But his last words to me were “I love you,” and at the very end he seemed peaceful, which was a blessing.

I got an autopsy, because he wanted one. Nothing else was wrong with him other than COVID. It destroyed his lungs. The rest of him was fine – no heart disease, cancer, or anything else. He died of COVID-19, the same as my mother.

That same week, my aunt, my only surviving older relative, who was in Des Moines, Iowa, died of COVID-19. All three family members died before the vaccine came out.

It was hard to lose my parents. I’m the only surviving child because my sister died in her 20s. It’s not been an easy pandemic. But what pandemic is easy? I just happened to have lost more people than most. Ironically, my grandfather was one of the legionnaires at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia in 1976 and died of Legionnaire’s disease before we knew what was causing the outbreak.

Q: Were you still struggling with COVID?

A: COVID impacted my whole body. I lost a lot of weight. I didn’t want to eat, and my gastrointestinal system was not happy. It took a while for my sense of taste and smell to come back. Nothing tasted good. I’m not a foodie; I don’t really care about food. We could get takeout or whatever, but none of it appealed to me. I’m not so sure it was a taste thing, I just didn’t feel like eating.

I didn’t realize I had “brain fog” per se, because I felt stressed and overwhelmed by the pandemic and my patients’ concerns. But one day, about 3 months after I had developed COVID, I woke up without the fog. Which made me aware that I hadn’t been feeling right up until that point.

The worst symptoms, however, were cardiac. I noticed also immediately that my heart rate went up very quickly with minimal exertion. My pulse has always been in the 55-60 bpm range, and suddenly just walking across a room made it go up to over 140 bpm. If I did any aerobic activity, it went up over 160 and would be associated with dyspnea and chest pain. I believed these were all post-COVID symptoms and felt validated when reports of others having similar issues were published in the literature.

Q: Did you continue seeing patients?

A: Yes, of course. Patients never needed their doctors more. In East L.A., where patients don’t have easy access to telemedicine, I kept going into clinic throughout the pandemic. In the more affluent Westside of Los Angeles, we switched to telemedicine, which was quite effective for most. However, because diabetes was associated with an increased risk of hospitalization and death from COVID, my patients were understandably afraid. I’ve never been busier, but (like all health care providers), I became more of a COVID provider than a diabetologist.

Q: Do you feel your battle with COVID impacted your work?

A: It didn’t affect me at work. If I was sitting still, I was fine. Sitting at home at a desk, I didn’t notice any symptoms. But as a habitual stair-user, I would be gasping for breath in the stairwell because I couldn’t go up the stairs to my office as I once could.

I think you empathize more with people who had COVID (when you’ve had it yourself). There was such a huge patient burden. And I think that’s been the thing that’s affected health care providers the most – no matter what specialty we’re in – that nobody has answers.

Q: What happened after you had your vaccine?

A: The vaccine itself was fine. I didn’t have any reaction to the first two doses. But the first booster made my cardiac issues worse.

By this point, my cardiac problems stopped me from exercising. I even went to the ER with chest pain once because I was having palpitations and chest pressure caused by simply taking my morning shower. Fortunately, I wasn’t having an MI, but I certainly wasn’t “normal.”

My measure of my fitness is the cross-country skiing trail I use in Montana. I know exactly how far I can ski. Usually I can do the loop in 35 minutes. After COVID, I lasted 10 minutes. I would be tachycardic, short of breath with chest pain radiating down my left arm. I would rest and try to keep going. But with each rest period, I only got worse. I would be laying in the snow and strangers would ask if I needed help.

Q: What helped you?

A: I’ve read a lot about long COVID and have tried to learn from the experts. Of course, I never went to a doctor directly, although I did ask colleagues for advice. What I learned was to never push myself. I forced myself to create an exercise schedule where I only exercised three times a week with rest days in between. When exercising, the second my heart rate went above 140 bpm, I stopped until I could get it back down. I would push against this new limit, even though my limit was low.

Additionally, I worked on my breathing patterns and did meditative breathing for 10 minutes twice daily using a commercially available app.

Although progress was slow, I did improve, and by June 2022, I seemed back to normal. I was not as fit as I was prior to COVID and needed to improve, but the tachycardic response to exercise and cardiac symptoms were gone. I felt like my normal self. Normal enough to go on a spot packing trip in the Sierras in August. (Horses carried us and a mule carried the gear over the 12,000-foot pass into the mountains, and then left my friend and me high in the Sierras for a week.) We were camped above 10,000 feet and every day hiked up to another high mountain lake where we fly-fished for trout that we ate for dinner. The hikes were a challenge, but not abnormally so. Not as they would have been while I had long COVID.

Q: What is the current atmosphere in your clinic?

A: COVID is much milder now in my vaccinated patients, but I feel most health care providers are exhausted. Many of my staff left when COVID hit because they didn’t want to keep working. It made practicing medicine exhausting. There’s been a shortage of nurses, a shortage of everything. We’ve been required to do a whole lot more than we ever did before. It’s much harder to be a doctor. This pandemic is the first time I’ve ever thought of quitting. Granted, I lost my whole family, or at least the older generation, but it’s just been almost overwhelming.

On the plus side, almost every one of my patients has been vaccinated, because early on, people would ask: “Do you trust this vaccine?” I would reply: “I saw my parents die from COVID when they weren’t vaccinated, so you’re getting vaccinated. This is real and the vaccines help.” It made me very good at convincing people to get vaccines because I knew what it was like to see someone dying from COVID up close.

Q: What advice do you have for those struggling with the COVID pandemic?

A: People need to decide what their own risk is for getting sick and how many times they want to get COVID. At this point, I want people to go out, but safely. In the beginning, when my patients said, “can I go visit my granddaughter?” I said, “no,” but that was before we had the vaccine. Now I feel it is safe to go out using common sense. I still have my patients wear masks on planes. I still have patients try to eat outside as much as possible. And I tell people to take the precautions that make sense, but I tell them to go out and do things because life is short.

I had a patient in his 70s who has many risk factors like heart disease and diabetes. His granddaughter’s Bat Mitzvah in Florida was coming up. He asked: “Can I go?” I told him “Yes,” but to be safe – to wear an N95 mask on the plane and at the event, and stay in his own hotel room, rather than with the whole family. I said, “You need to do this.” Earlier in the pandemic, I saw people who literally died from loneliness and isolation.

He and his wife flew there. He sent me a picture of himself with his granddaughter. When he returned, he showed me a handwritten note from her that said, “I love you so much. Everyone else canceled, which made me cry. You’re the only one who came. You have no idea how much this meant to me.”

He’s back in L.A., and he didn’t get COVID. He said, “It was the best thing I’ve done in years.” That’s what I need to help people with, navigating this world with COVID and assessing risks and benefits. As with all of medicine, my advice is individualized. My advice changes based on the major circulating variant and the rates of the virus in the population, as well as the risk factors of the individual.

Q: What are you doing now?

A: I’m trying to avoid getting COVID again, or another booster. I could get pre-exposure monoclonal antibodies but am waiting to do anything further until I see what happens over the fall and winter. I still wear a mask inside but now do a mix of in-person and telemedicine visits. I still try to go to outdoor restaurants, which is easy in California. But I’m flying to see my son in New York and plan to go to Europe this fall for a meeting. I also go to my cabin in Montana every month to get my “dose” of the wilderness. Overall, I travel for conferences and speaking engagements much less because I have learned the joy of staying home.

Thinking back on my life as a doctor, my career began as an intern at Stanford rotating through Ward 5B, the AIDS unit at San Francisco General Hospital, and will likely end with COVID. In spite of all our medical advances, my generation of physicians, much as many generations before us, has a front-row seat to the vulnerability of humans to infectious diseases and how far we still need to go to protect our patients from communicable illness.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Anne L. Peters, MD, is a professor of medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and director of the USC clinical diabetes programs. She has published more than 200 articles, reviews, and abstracts; three books on diabetes; and has been an investigator for more than 40 research studies. She has spoken internationally at over 400 programs and serves on many committees of several professional organizations.

Early in 2020, Anne Peters, MD, caught COVID-19. The author of Medscape’s “Peters on Diabetes” column was sick in March 2020 before state-mandated lockdowns, and well before there were any vaccines.

She remembers sitting in a small exam room with two patients who had flown to her Los Angeles office from New York. The elderly couple had hearing difficulties, so Dr. Peters sat close to them, putting on a continuous glucose monitor. “At that time, we didn’t think of COVID-19 as being in L.A.,” Dr. Peters recalled, “so I think we were not terribly consistent at mask-wearing due to the need to educate.”

“Several days later, I got COVID, but I didn’t know I had COVID per se. I felt crappy, had a terrible sore throat, lost my sense of taste and smell [which was not yet described as a COVID symptom], was completely exhausted, but had no fever or cough, which were the only criteria for getting COVID tested at the time. I didn’t know I had been exposed until 2 weeks later, when the patient’s assistant returned the sensor warning us to ‘be careful’ with it because the patient and his wife were recovering from COVID.”

That early battle with COVID-19 was just the beginning of what would become a 2-year struggle, including familial loss amid her own health problems and concerns about the under-resourced patients she cares for. Here, she shares her journey through the pandemic with this news organization.

Question: Thanks for talking to us. Let’s discuss your journey over these past 2.5 years.

Answer: Everybody has their own COVID story because we all went through this together. Some of us have worse COVID stories, and some of us have better ones, but all have been impacted.

I’m not a sick person. I’m a very healthy person but COVID made me so unwell for 2 years. The brain fog and fatigue were nothing compared to the autonomic neuropathy that affected my heart. It was really limiting for me. And I still don’t know the long-term implications, looking 20-30 years from now.

Q: When you initially had COVID, what were your symptoms? What was the impact?

A: I had all the symptoms of COVID, except for a cough and fever. I lost my sense of taste and smell. I had a horrible headache, a sore throat, and I was exhausted. I couldn’t get tested because I didn’t have the right symptoms.

Despite being sick, I never stopped working but just switched to telemedicine. I also took my regular monthly trip to our cabin in Montana. I unknowingly flew on a plane with COVID. I wore a well-fitted N95 mask, so I don’t think I gave anybody COVID. I didn’t give COVID to my partner, Eric, which is hard to believe as – at 77 – he’s older than me. He has diabetes, heart disease, and every other high-risk characteristic. If he’d gotten COVID back then, it would have been terrible, as there were no treatments, but luckily he didn’t get it.

Q: When were you officially diagnosed?

A: Two or 3 months after I thought I might have had COVID, I checked my antibodies, which tested strongly positive for a prior COVID infection. That was when I knew all the symptoms I’d had were due to the disease.

Q: Not only were you dealing with your own illness, but also that of those close to you. Can you talk about that?

A: In April 2020, my mother who was in her 90s and otherwise healthy except for dementia, got COVID. She could have gotten it from me. I visited often but wore a mask. She had all the horrible pulmonary symptoms. In her advance directive, she didn’t want to be hospitalized so I kept her in her home. She died from COVID in her own bed. It was fairly brutal, but at least I kept her where she felt comforted.