User login

Long COVID & Chronic Fatigue: The Similarities are Uncanny

An estimated two million people in England and Scotland were experiencing symptoms of long COVID as of March 2024, according to the Office for National Statistics. Of these, 1.5 million said the condition was adversely affecting their day-to-day activities.

As more research emerges about long COVID, some experts are noticing that its trigger factors, symptoms, and causative mechanisms overlap with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

ME/CFS is characterized by severe fatigue that does not improve with rest, in addition to pain and cognitive problems. One in four patients are bed- or house-bound with severe forms of the condition, sometimes experiencing atypical seizures, and speech and swallowing difficulties.

Despite affecting around 250,000 people in the UK and around 2 million people in the European Union (EU), it is a relatively poorly funded disease research area. Increased research into long COVID is thus providing a much-needed boost to ME/CFS research.

“What we already know about the possible causation of ME/CFS is helping research into the causes of long COVID. At the same time, research into long COVID is opening up new avenues of research that may also be relevant to ME/CFS. It is becoming a two-way process,” Dr. Charles Shepherd, honorary medical adviser to the UK-based ME Association, told this news organization.

While funding remains an issue, promising research is currently underway in the UK to improve diagnosis, treatment, and understanding of the pathology of ME/CFS.

Viral Reactivation

Dr. David Newton is research director at ME Research UK. “Viral infection is commonly reported as a trigger for [ME/CFS, meaning that the disease] may be caused by reactivation of latent viruses, including human herpes viruses and enteroviruses,” he said.

Herpes viruses can lie dormant in their host’s immune system for long periods of time. They can be reactivated by factors including infections, stress, and a weakened immune system, and may cause temporary symptoms or persistent disease.

A 2021 pilot study found that people with ME/CFS have a higher concentration of human herpesvirus 6B (HHV-6B) DNA in their saliva, and that concentration correlates with symptom severity. HHV-6B is a common virus typically contracted during infancy and childhood.

A continuation of this research is now underway at Brunel University to improve understanding of HHV-6B’s role in the onset and progression of ME/CFS, and to support the development of diagnostic and prognostic markers, as well as therapeutics such as antiviral therapies.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Dr. Shepherd explained that there is now sound evidence demonstrating that biochemical abnormalities in ME/CFS affect how mitochondria produce energy after physical exertion. Research is thus underway to see if treating mitochondrial dysfunction improves ME/CFS symptoms.

A phase 2a placebo-controlled clinical trial from 2023 found that AXA1125, a drug that works by modulating energy metabolism, significantly improved symptoms of fatigue in patients with fatigue-dominant long COVID, although it did not improve mitochondrial respiration.

“[The findings suggest] that improving mitochondrial health may be one way to restore normal functioning among people with long COVID, and by extension CFS,” study author Betty Raman, associate professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Oxford, told this news organization. She noted, however, that plans for a phase III trial have stalled due to insufficient funding.

Meanwhile, researchers from the Quadram Institute in Norwich and the University of East Anglia are conducting a pilot study to see if red light therapy can relieve symptoms of ME/CFS. Red light can be absorbed by mitochondria and is used to boost energy production. The trial will monitor patients remotely from their homes and will assess cognitive function and physical activity levels.

Gut Dysbiosis

Many studies have found that people with ME/CFS have altered gut microbiota, which suggests that changes in gut bacteria may contribute to the condition. Researchers at the Quadram Institute will thus conduct a clinical trial called RESTORE-ME to see whether fecal microbiota transplants (FMT) can treat the condition.

Rik Haagmans is a research scientist and PhD candidate at the Quadram Institute. He told this news organization: “Our FMT studies, if effective, could provide a longer lasting or even permanent relief of ME/CFS, as restoring the gut microbial composition wouldn’t require continuous medication,” he said.

Biobank and Biomarkers

Europe’s first ME/CFS-specific biobank is in the UK and is called UKMEB. It now has more than 30,000 blood samples from patients with ME/CFS, multiple sclerosis, and healthy controls. Uniquely, it includes samples from people with ME/CFS who are house- and bed-bound. Caroline Kingdon, RN, MSc, a research fellow and biobank lead at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, told this news organization that samples and data from the UKMEB have been provided to research groups all over the world and have contributed to widely cited literature.

One group making use of these samples is led by Fatima Labeed, PhD, senior lecturer in human biology at the University of Surrey. Dr. Labeed and her team are developing a diagnostic test for ME/CFS based on electrical properties in white blood cells.

“To date, studies of ME/CFS have focused on the biochemical behavior of cells: the amount and type of proteins that cells use. We have taken a different approach, studying the electrical properties,” she explained to this news organization.

Her research builds on initial observations from 2019 that found differences in the electrical impedance of white blood cells between people with ME/CFS and controls. While the biological implications remain unknown, the findings may represent a biomarker for the condition.

Using blood samples from the UKMEB, the researchers are now investigating this potential biomarker with improved techniques and a larger patient cohort, including those with mild/moderate and severe forms of ME/CFS. So far, they have received more than 100 blood samples and have analyzed the electrical properties of 42.

“Based on the results we have so far, we are very close to having a biomarker for diagnosis. Our results so far show a high degree of accuracy and are able to distinguish between ME/CFS and other diseases,” said Dr. Labeed.

Genetic Test

Another promising avenue for diagnostics comes from a research team at the University of Edinburgh led by Professor Chris Ponting at the university’s Institute of Genetics and Cancer. They are currently working on DecodeMe, a large genetic study of ME using data from more than 26,000 people.

“We are studying blood-based biomarkers that distinguish people with ME from population controls. We’ve found a large number — including some found previously in other studies — and are writing these results up for publication,” said Ponting. The results should be published in early 2025.

The Future

While research into ME/CFS has picked up pace in recent years, funding remains a key bottleneck.

“Over the last 10 years, only £8.05m has been spent on ME research,” Sonya Chowdhury, chief executive of UK charity Action for ME told this news organization. She believes this amount is not equitably comparable to research funding allocated to other diseases.

In 2022, the UK government announced its intention to develop a cross-government interim delivery plan on ME/CFS for England, however publication of the final plan has been delayed numerous times.

Dr. Shepherd agreed that increased funding is crucial for progress to be made. He said the biggest help to ME/CFS research would be to end the disparity in government research funding for the disease, and match what is given for many other disabling long-term conditions.

“It’s not fair to continue to rely on the charity sector to fund almost all of the biomedical research into ME/CFS here in the UK,” he said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

An estimated two million people in England and Scotland were experiencing symptoms of long COVID as of March 2024, according to the Office for National Statistics. Of these, 1.5 million said the condition was adversely affecting their day-to-day activities.

As more research emerges about long COVID, some experts are noticing that its trigger factors, symptoms, and causative mechanisms overlap with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

ME/CFS is characterized by severe fatigue that does not improve with rest, in addition to pain and cognitive problems. One in four patients are bed- or house-bound with severe forms of the condition, sometimes experiencing atypical seizures, and speech and swallowing difficulties.

Despite affecting around 250,000 people in the UK and around 2 million people in the European Union (EU), it is a relatively poorly funded disease research area. Increased research into long COVID is thus providing a much-needed boost to ME/CFS research.

“What we already know about the possible causation of ME/CFS is helping research into the causes of long COVID. At the same time, research into long COVID is opening up new avenues of research that may also be relevant to ME/CFS. It is becoming a two-way process,” Dr. Charles Shepherd, honorary medical adviser to the UK-based ME Association, told this news organization.

While funding remains an issue, promising research is currently underway in the UK to improve diagnosis, treatment, and understanding of the pathology of ME/CFS.

Viral Reactivation

Dr. David Newton is research director at ME Research UK. “Viral infection is commonly reported as a trigger for [ME/CFS, meaning that the disease] may be caused by reactivation of latent viruses, including human herpes viruses and enteroviruses,” he said.

Herpes viruses can lie dormant in their host’s immune system for long periods of time. They can be reactivated by factors including infections, stress, and a weakened immune system, and may cause temporary symptoms or persistent disease.

A 2021 pilot study found that people with ME/CFS have a higher concentration of human herpesvirus 6B (HHV-6B) DNA in their saliva, and that concentration correlates with symptom severity. HHV-6B is a common virus typically contracted during infancy and childhood.

A continuation of this research is now underway at Brunel University to improve understanding of HHV-6B’s role in the onset and progression of ME/CFS, and to support the development of diagnostic and prognostic markers, as well as therapeutics such as antiviral therapies.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Dr. Shepherd explained that there is now sound evidence demonstrating that biochemical abnormalities in ME/CFS affect how mitochondria produce energy after physical exertion. Research is thus underway to see if treating mitochondrial dysfunction improves ME/CFS symptoms.

A phase 2a placebo-controlled clinical trial from 2023 found that AXA1125, a drug that works by modulating energy metabolism, significantly improved symptoms of fatigue in patients with fatigue-dominant long COVID, although it did not improve mitochondrial respiration.

“[The findings suggest] that improving mitochondrial health may be one way to restore normal functioning among people with long COVID, and by extension CFS,” study author Betty Raman, associate professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Oxford, told this news organization. She noted, however, that plans for a phase III trial have stalled due to insufficient funding.

Meanwhile, researchers from the Quadram Institute in Norwich and the University of East Anglia are conducting a pilot study to see if red light therapy can relieve symptoms of ME/CFS. Red light can be absorbed by mitochondria and is used to boost energy production. The trial will monitor patients remotely from their homes and will assess cognitive function and physical activity levels.

Gut Dysbiosis

Many studies have found that people with ME/CFS have altered gut microbiota, which suggests that changes in gut bacteria may contribute to the condition. Researchers at the Quadram Institute will thus conduct a clinical trial called RESTORE-ME to see whether fecal microbiota transplants (FMT) can treat the condition.

Rik Haagmans is a research scientist and PhD candidate at the Quadram Institute. He told this news organization: “Our FMT studies, if effective, could provide a longer lasting or even permanent relief of ME/CFS, as restoring the gut microbial composition wouldn’t require continuous medication,” he said.

Biobank and Biomarkers

Europe’s first ME/CFS-specific biobank is in the UK and is called UKMEB. It now has more than 30,000 blood samples from patients with ME/CFS, multiple sclerosis, and healthy controls. Uniquely, it includes samples from people with ME/CFS who are house- and bed-bound. Caroline Kingdon, RN, MSc, a research fellow and biobank lead at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, told this news organization that samples and data from the UKMEB have been provided to research groups all over the world and have contributed to widely cited literature.

One group making use of these samples is led by Fatima Labeed, PhD, senior lecturer in human biology at the University of Surrey. Dr. Labeed and her team are developing a diagnostic test for ME/CFS based on electrical properties in white blood cells.

“To date, studies of ME/CFS have focused on the biochemical behavior of cells: the amount and type of proteins that cells use. We have taken a different approach, studying the electrical properties,” she explained to this news organization.

Her research builds on initial observations from 2019 that found differences in the electrical impedance of white blood cells between people with ME/CFS and controls. While the biological implications remain unknown, the findings may represent a biomarker for the condition.

Using blood samples from the UKMEB, the researchers are now investigating this potential biomarker with improved techniques and a larger patient cohort, including those with mild/moderate and severe forms of ME/CFS. So far, they have received more than 100 blood samples and have analyzed the electrical properties of 42.

“Based on the results we have so far, we are very close to having a biomarker for diagnosis. Our results so far show a high degree of accuracy and are able to distinguish between ME/CFS and other diseases,” said Dr. Labeed.

Genetic Test

Another promising avenue for diagnostics comes from a research team at the University of Edinburgh led by Professor Chris Ponting at the university’s Institute of Genetics and Cancer. They are currently working on DecodeMe, a large genetic study of ME using data from more than 26,000 people.

“We are studying blood-based biomarkers that distinguish people with ME from population controls. We’ve found a large number — including some found previously in other studies — and are writing these results up for publication,” said Ponting. The results should be published in early 2025.

The Future

While research into ME/CFS has picked up pace in recent years, funding remains a key bottleneck.

“Over the last 10 years, only £8.05m has been spent on ME research,” Sonya Chowdhury, chief executive of UK charity Action for ME told this news organization. She believes this amount is not equitably comparable to research funding allocated to other diseases.

In 2022, the UK government announced its intention to develop a cross-government interim delivery plan on ME/CFS for England, however publication of the final plan has been delayed numerous times.

Dr. Shepherd agreed that increased funding is crucial for progress to be made. He said the biggest help to ME/CFS research would be to end the disparity in government research funding for the disease, and match what is given for many other disabling long-term conditions.

“It’s not fair to continue to rely on the charity sector to fund almost all of the biomedical research into ME/CFS here in the UK,” he said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

An estimated two million people in England and Scotland were experiencing symptoms of long COVID as of March 2024, according to the Office for National Statistics. Of these, 1.5 million said the condition was adversely affecting their day-to-day activities.

As more research emerges about long COVID, some experts are noticing that its trigger factors, symptoms, and causative mechanisms overlap with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

ME/CFS is characterized by severe fatigue that does not improve with rest, in addition to pain and cognitive problems. One in four patients are bed- or house-bound with severe forms of the condition, sometimes experiencing atypical seizures, and speech and swallowing difficulties.

Despite affecting around 250,000 people in the UK and around 2 million people in the European Union (EU), it is a relatively poorly funded disease research area. Increased research into long COVID is thus providing a much-needed boost to ME/CFS research.

“What we already know about the possible causation of ME/CFS is helping research into the causes of long COVID. At the same time, research into long COVID is opening up new avenues of research that may also be relevant to ME/CFS. It is becoming a two-way process,” Dr. Charles Shepherd, honorary medical adviser to the UK-based ME Association, told this news organization.

While funding remains an issue, promising research is currently underway in the UK to improve diagnosis, treatment, and understanding of the pathology of ME/CFS.

Viral Reactivation

Dr. David Newton is research director at ME Research UK. “Viral infection is commonly reported as a trigger for [ME/CFS, meaning that the disease] may be caused by reactivation of latent viruses, including human herpes viruses and enteroviruses,” he said.

Herpes viruses can lie dormant in their host’s immune system for long periods of time. They can be reactivated by factors including infections, stress, and a weakened immune system, and may cause temporary symptoms or persistent disease.

A 2021 pilot study found that people with ME/CFS have a higher concentration of human herpesvirus 6B (HHV-6B) DNA in their saliva, and that concentration correlates with symptom severity. HHV-6B is a common virus typically contracted during infancy and childhood.

A continuation of this research is now underway at Brunel University to improve understanding of HHV-6B’s role in the onset and progression of ME/CFS, and to support the development of diagnostic and prognostic markers, as well as therapeutics such as antiviral therapies.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Dr. Shepherd explained that there is now sound evidence demonstrating that biochemical abnormalities in ME/CFS affect how mitochondria produce energy after physical exertion. Research is thus underway to see if treating mitochondrial dysfunction improves ME/CFS symptoms.

A phase 2a placebo-controlled clinical trial from 2023 found that AXA1125, a drug that works by modulating energy metabolism, significantly improved symptoms of fatigue in patients with fatigue-dominant long COVID, although it did not improve mitochondrial respiration.

“[The findings suggest] that improving mitochondrial health may be one way to restore normal functioning among people with long COVID, and by extension CFS,” study author Betty Raman, associate professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Oxford, told this news organization. She noted, however, that plans for a phase III trial have stalled due to insufficient funding.

Meanwhile, researchers from the Quadram Institute in Norwich and the University of East Anglia are conducting a pilot study to see if red light therapy can relieve symptoms of ME/CFS. Red light can be absorbed by mitochondria and is used to boost energy production. The trial will monitor patients remotely from their homes and will assess cognitive function and physical activity levels.

Gut Dysbiosis

Many studies have found that people with ME/CFS have altered gut microbiota, which suggests that changes in gut bacteria may contribute to the condition. Researchers at the Quadram Institute will thus conduct a clinical trial called RESTORE-ME to see whether fecal microbiota transplants (FMT) can treat the condition.

Rik Haagmans is a research scientist and PhD candidate at the Quadram Institute. He told this news organization: “Our FMT studies, if effective, could provide a longer lasting or even permanent relief of ME/CFS, as restoring the gut microbial composition wouldn’t require continuous medication,” he said.

Biobank and Biomarkers

Europe’s first ME/CFS-specific biobank is in the UK and is called UKMEB. It now has more than 30,000 blood samples from patients with ME/CFS, multiple sclerosis, and healthy controls. Uniquely, it includes samples from people with ME/CFS who are house- and bed-bound. Caroline Kingdon, RN, MSc, a research fellow and biobank lead at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, told this news organization that samples and data from the UKMEB have been provided to research groups all over the world and have contributed to widely cited literature.

One group making use of these samples is led by Fatima Labeed, PhD, senior lecturer in human biology at the University of Surrey. Dr. Labeed and her team are developing a diagnostic test for ME/CFS based on electrical properties in white blood cells.

“To date, studies of ME/CFS have focused on the biochemical behavior of cells: the amount and type of proteins that cells use. We have taken a different approach, studying the electrical properties,” she explained to this news organization.

Her research builds on initial observations from 2019 that found differences in the electrical impedance of white blood cells between people with ME/CFS and controls. While the biological implications remain unknown, the findings may represent a biomarker for the condition.

Using blood samples from the UKMEB, the researchers are now investigating this potential biomarker with improved techniques and a larger patient cohort, including those with mild/moderate and severe forms of ME/CFS. So far, they have received more than 100 blood samples and have analyzed the electrical properties of 42.

“Based on the results we have so far, we are very close to having a biomarker for diagnosis. Our results so far show a high degree of accuracy and are able to distinguish between ME/CFS and other diseases,” said Dr. Labeed.

Genetic Test

Another promising avenue for diagnostics comes from a research team at the University of Edinburgh led by Professor Chris Ponting at the university’s Institute of Genetics and Cancer. They are currently working on DecodeMe, a large genetic study of ME using data from more than 26,000 people.

“We are studying blood-based biomarkers that distinguish people with ME from population controls. We’ve found a large number — including some found previously in other studies — and are writing these results up for publication,” said Ponting. The results should be published in early 2025.

The Future

While research into ME/CFS has picked up pace in recent years, funding remains a key bottleneck.

“Over the last 10 years, only £8.05m has been spent on ME research,” Sonya Chowdhury, chief executive of UK charity Action for ME told this news organization. She believes this amount is not equitably comparable to research funding allocated to other diseases.

In 2022, the UK government announced its intention to develop a cross-government interim delivery plan on ME/CFS for England, however publication of the final plan has been delayed numerous times.

Dr. Shepherd agreed that increased funding is crucial for progress to be made. He said the biggest help to ME/CFS research would be to end the disparity in government research funding for the disease, and match what is given for many other disabling long-term conditions.

“It’s not fair to continue to rely on the charity sector to fund almost all of the biomedical research into ME/CFS here in the UK,” he said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Almost 10% of Infected Pregnant People Develop Long COVID

Almost 1 in 10 pregnant people infected with COVID-19 end up developing long COVID, according to a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Researchers at University of Utah Health looked at the medical records of more than 1500 people who got COVID-19 while pregnant and checked their self-reported symptoms at least 6 months after infection, according to a news release from the school.

The scientists discovered that 9.3% of those people reported long COVID symptoms, such as fatigue and issues in their gut.

To make sure those long COVID symptoms were not actually symptoms of pregnancy, the research team did a second analysis of people who reported symptoms more than 12 weeks after giving birth. The risk of long COVID was about the same as in the first analysis.

“It was surprising to me that the prevalence was that high,” Torri D. Metz, MD, vice chair for research of obstetrics and gynecology at the school and co-leader of the study, said in the release. “This is something that does continue to affect otherwise reasonably healthy and young populations.”

The school said this is the first study to look at long COVID risks in pregnant people. Previous research found other dangers for pregnant people who get COVID, such as a higher chance of hospitalization or death, or complications such as preterm birth.

In the general population, research shows that 10%-20% of people who get COVID develop long COVID.

Dr. Metz said healthcare providers need to remain alert about long COVID, including in pregnant people.

“We need to have this on our radar as we’re seeing patients. It’s something we really don’t want to miss. And we want to get people referred to appropriate specialists who treat long COVID,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Almost 1 in 10 pregnant people infected with COVID-19 end up developing long COVID, according to a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Researchers at University of Utah Health looked at the medical records of more than 1500 people who got COVID-19 while pregnant and checked their self-reported symptoms at least 6 months after infection, according to a news release from the school.

The scientists discovered that 9.3% of those people reported long COVID symptoms, such as fatigue and issues in their gut.

To make sure those long COVID symptoms were not actually symptoms of pregnancy, the research team did a second analysis of people who reported symptoms more than 12 weeks after giving birth. The risk of long COVID was about the same as in the first analysis.

“It was surprising to me that the prevalence was that high,” Torri D. Metz, MD, vice chair for research of obstetrics and gynecology at the school and co-leader of the study, said in the release. “This is something that does continue to affect otherwise reasonably healthy and young populations.”

The school said this is the first study to look at long COVID risks in pregnant people. Previous research found other dangers for pregnant people who get COVID, such as a higher chance of hospitalization or death, or complications such as preterm birth.

In the general population, research shows that 10%-20% of people who get COVID develop long COVID.

Dr. Metz said healthcare providers need to remain alert about long COVID, including in pregnant people.

“We need to have this on our radar as we’re seeing patients. It’s something we really don’t want to miss. And we want to get people referred to appropriate specialists who treat long COVID,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Almost 1 in 10 pregnant people infected with COVID-19 end up developing long COVID, according to a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Researchers at University of Utah Health looked at the medical records of more than 1500 people who got COVID-19 while pregnant and checked their self-reported symptoms at least 6 months after infection, according to a news release from the school.

The scientists discovered that 9.3% of those people reported long COVID symptoms, such as fatigue and issues in their gut.

To make sure those long COVID symptoms were not actually symptoms of pregnancy, the research team did a second analysis of people who reported symptoms more than 12 weeks after giving birth. The risk of long COVID was about the same as in the first analysis.

“It was surprising to me that the prevalence was that high,” Torri D. Metz, MD, vice chair for research of obstetrics and gynecology at the school and co-leader of the study, said in the release. “This is something that does continue to affect otherwise reasonably healthy and young populations.”

The school said this is the first study to look at long COVID risks in pregnant people. Previous research found other dangers for pregnant people who get COVID, such as a higher chance of hospitalization or death, or complications such as preterm birth.

In the general population, research shows that 10%-20% of people who get COVID develop long COVID.

Dr. Metz said healthcare providers need to remain alert about long COVID, including in pregnant people.

“We need to have this on our radar as we’re seeing patients. It’s something we really don’t want to miss. And we want to get people referred to appropriate specialists who treat long COVID,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Cold or Flu Virus May Trigger Relapse of Long COVID

researchers have found.

In some cases, they may be experiencing what researchers call viral interference, something also experienced by people with HIV and other infections associated with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

Clinical studies on the issue are limited, but patients, doctors, and researchers report many people who previously had long COVID have developed recurring symptoms after consequent viral infections.

Viral persistence — where bits of virus linger in the body — and viral reactivation remain two of the leading suspects for Yale researchers. Viral activation occurs when the immune system responds to an infection by triggering a dormant virus.

Anecdotally, these flare-ups occur more commonly in patients with long COVID with autonomic dysfunction — severe dizziness when standing up — and other symptoms of ME/CFS, said Alba Azola, MD, a Johns Hopkins Medicine rehabilitation specialist in Baltimore, Maryland, who works with patients with long COVID and other “fatiguing illnesses.”

At last count, about 18% of those surveyed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said they had experienced long COVID. Nearly 60% of those surveyed said they had contracted COVID-19 at least once.

Dr. Azola said that very afternoon she had seen a patient with the flu and a recurrence of previous long COVID symptoms. Not much data exist about cases like this.

“I can’t say there is a specific study looking at this, but anecdotally, we see it all the time,” Dr. Azola said.

She has not seen completely different symptoms; more commonly, she sees a flare-up of previously existing symptoms.

David Putrino, PhD, is director of rehabilitation innovation for the Mount Sinai Health System in New York City. He treats and studies patients with long COVID and echoes what others have seen.

Patients can “recover (or feel recovered) from long COVID until the next immune challenge — another COVID infection, flu infection, pregnancy, food poisoning (all examples we have seen in the clinic) — and experience a significant flare-up of your initial COVID infection,” he said.

“Relapse” is a better term than reinfection, said Jeffrey Parsonnet, MD, an infectious diseases specialist and director of the Dartmouth Hitchcock Post-Acute COVID Syndrome Clinic, Lebanon, New Hampshire.

“We see patients who had COVID-19 followed by long COVID who then get better — either completely or mostly better. Then they’ve gotten COVID again, and this is followed by recurrence of long COVID symptoms,” he said.

“Every patient looks different in terms of what gets better and how quickly. And again, some patients are not better (or even minimally so) after a couple of years,” he said.

Patients Tell Their Stories

On the COVID-19 Long Haulers Support Facebook group, many of the 100,000 followers ask about viral reactivation. Delainne “Laney” Bond, RN, who has battled postinfection chronic illness herself, runs the Facebook group. From what she sees, “each time a person is infected or reinfected with SARS-CoV-2, they have a risk of developing long COVID or experiencing worse long COVID. Multiple infections can lead to progressive health complications.”

The posts on her site include many queries about reinfections. A post from December included nearly 80 comments with people describing the full range of symptoms. Some stories relayed how the reinfection symptoms were short lived. Some report returning to their baseline — not completely symptom free but improved.

Doctors and patients say long COVID comes and goes — relapsing-remitting — and shares many features with other complex multisystem chronic conditions, according to a new National Academy of Sciences report. Those include ME/CFS and the Epstein-Barr virus.

As far as how to treat, Dr. Putrino is one of the clinical researchers testing antivirals. One is Paxlovid; the others are drugs developed for the AIDS virus.

“A plausible mechanism for long COVID is persistence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in tissue and/or the reactivation of latent pathogens,” according to an explanation of the research on the PolyBio Institute website, which is involved with the research.

In the meantime, “long COVID appears to be a chronic condition with few patients achieving full remission,” according to a new Academy of Sciences report. The report concludes that long COVID recovery can plateau at 6-12 months. They also note that 18%-22% of people who have long COVID symptoms at 5 months are still ill at 1 year.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

researchers have found.

In some cases, they may be experiencing what researchers call viral interference, something also experienced by people with HIV and other infections associated with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

Clinical studies on the issue are limited, but patients, doctors, and researchers report many people who previously had long COVID have developed recurring symptoms after consequent viral infections.

Viral persistence — where bits of virus linger in the body — and viral reactivation remain two of the leading suspects for Yale researchers. Viral activation occurs when the immune system responds to an infection by triggering a dormant virus.

Anecdotally, these flare-ups occur more commonly in patients with long COVID with autonomic dysfunction — severe dizziness when standing up — and other symptoms of ME/CFS, said Alba Azola, MD, a Johns Hopkins Medicine rehabilitation specialist in Baltimore, Maryland, who works with patients with long COVID and other “fatiguing illnesses.”

At last count, about 18% of those surveyed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said they had experienced long COVID. Nearly 60% of those surveyed said they had contracted COVID-19 at least once.

Dr. Azola said that very afternoon she had seen a patient with the flu and a recurrence of previous long COVID symptoms. Not much data exist about cases like this.

“I can’t say there is a specific study looking at this, but anecdotally, we see it all the time,” Dr. Azola said.

She has not seen completely different symptoms; more commonly, she sees a flare-up of previously existing symptoms.

David Putrino, PhD, is director of rehabilitation innovation for the Mount Sinai Health System in New York City. He treats and studies patients with long COVID and echoes what others have seen.

Patients can “recover (or feel recovered) from long COVID until the next immune challenge — another COVID infection, flu infection, pregnancy, food poisoning (all examples we have seen in the clinic) — and experience a significant flare-up of your initial COVID infection,” he said.

“Relapse” is a better term than reinfection, said Jeffrey Parsonnet, MD, an infectious diseases specialist and director of the Dartmouth Hitchcock Post-Acute COVID Syndrome Clinic, Lebanon, New Hampshire.

“We see patients who had COVID-19 followed by long COVID who then get better — either completely or mostly better. Then they’ve gotten COVID again, and this is followed by recurrence of long COVID symptoms,” he said.

“Every patient looks different in terms of what gets better and how quickly. And again, some patients are not better (or even minimally so) after a couple of years,” he said.

Patients Tell Their Stories

On the COVID-19 Long Haulers Support Facebook group, many of the 100,000 followers ask about viral reactivation. Delainne “Laney” Bond, RN, who has battled postinfection chronic illness herself, runs the Facebook group. From what she sees, “each time a person is infected or reinfected with SARS-CoV-2, they have a risk of developing long COVID or experiencing worse long COVID. Multiple infections can lead to progressive health complications.”

The posts on her site include many queries about reinfections. A post from December included nearly 80 comments with people describing the full range of symptoms. Some stories relayed how the reinfection symptoms were short lived. Some report returning to their baseline — not completely symptom free but improved.

Doctors and patients say long COVID comes and goes — relapsing-remitting — and shares many features with other complex multisystem chronic conditions, according to a new National Academy of Sciences report. Those include ME/CFS and the Epstein-Barr virus.

As far as how to treat, Dr. Putrino is one of the clinical researchers testing antivirals. One is Paxlovid; the others are drugs developed for the AIDS virus.

“A plausible mechanism for long COVID is persistence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in tissue and/or the reactivation of latent pathogens,” according to an explanation of the research on the PolyBio Institute website, which is involved with the research.

In the meantime, “long COVID appears to be a chronic condition with few patients achieving full remission,” according to a new Academy of Sciences report. The report concludes that long COVID recovery can plateau at 6-12 months. They also note that 18%-22% of people who have long COVID symptoms at 5 months are still ill at 1 year.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

researchers have found.

In some cases, they may be experiencing what researchers call viral interference, something also experienced by people with HIV and other infections associated with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

Clinical studies on the issue are limited, but patients, doctors, and researchers report many people who previously had long COVID have developed recurring symptoms after consequent viral infections.

Viral persistence — where bits of virus linger in the body — and viral reactivation remain two of the leading suspects for Yale researchers. Viral activation occurs when the immune system responds to an infection by triggering a dormant virus.

Anecdotally, these flare-ups occur more commonly in patients with long COVID with autonomic dysfunction — severe dizziness when standing up — and other symptoms of ME/CFS, said Alba Azola, MD, a Johns Hopkins Medicine rehabilitation specialist in Baltimore, Maryland, who works with patients with long COVID and other “fatiguing illnesses.”

At last count, about 18% of those surveyed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said they had experienced long COVID. Nearly 60% of those surveyed said they had contracted COVID-19 at least once.

Dr. Azola said that very afternoon she had seen a patient with the flu and a recurrence of previous long COVID symptoms. Not much data exist about cases like this.

“I can’t say there is a specific study looking at this, but anecdotally, we see it all the time,” Dr. Azola said.

She has not seen completely different symptoms; more commonly, she sees a flare-up of previously existing symptoms.

David Putrino, PhD, is director of rehabilitation innovation for the Mount Sinai Health System in New York City. He treats and studies patients with long COVID and echoes what others have seen.

Patients can “recover (or feel recovered) from long COVID until the next immune challenge — another COVID infection, flu infection, pregnancy, food poisoning (all examples we have seen in the clinic) — and experience a significant flare-up of your initial COVID infection,” he said.

“Relapse” is a better term than reinfection, said Jeffrey Parsonnet, MD, an infectious diseases specialist and director of the Dartmouth Hitchcock Post-Acute COVID Syndrome Clinic, Lebanon, New Hampshire.

“We see patients who had COVID-19 followed by long COVID who then get better — either completely or mostly better. Then they’ve gotten COVID again, and this is followed by recurrence of long COVID symptoms,” he said.

“Every patient looks different in terms of what gets better and how quickly. And again, some patients are not better (or even minimally so) after a couple of years,” he said.

Patients Tell Their Stories

On the COVID-19 Long Haulers Support Facebook group, many of the 100,000 followers ask about viral reactivation. Delainne “Laney” Bond, RN, who has battled postinfection chronic illness herself, runs the Facebook group. From what she sees, “each time a person is infected or reinfected with SARS-CoV-2, they have a risk of developing long COVID or experiencing worse long COVID. Multiple infections can lead to progressive health complications.”

The posts on her site include many queries about reinfections. A post from December included nearly 80 comments with people describing the full range of symptoms. Some stories relayed how the reinfection symptoms were short lived. Some report returning to their baseline — not completely symptom free but improved.

Doctors and patients say long COVID comes and goes — relapsing-remitting — and shares many features with other complex multisystem chronic conditions, according to a new National Academy of Sciences report. Those include ME/CFS and the Epstein-Barr virus.

As far as how to treat, Dr. Putrino is one of the clinical researchers testing antivirals. One is Paxlovid; the others are drugs developed for the AIDS virus.

“A plausible mechanism for long COVID is persistence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in tissue and/or the reactivation of latent pathogens,” according to an explanation of the research on the PolyBio Institute website, which is involved with the research.

In the meantime, “long COVID appears to be a chronic condition with few patients achieving full remission,” according to a new Academy of Sciences report. The report concludes that long COVID recovery can plateau at 6-12 months. They also note that 18%-22% of people who have long COVID symptoms at 5 months are still ill at 1 year.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Long COVID Can’t Be Solved Until We Decide What It Is

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I want to help people suffering from long COVID as much as anyone. But we have a real problem. In brief, we are being too inclusive. The first thing you learn, when you start studying the epidemiology of diseases, is that you need a good case definition. And our case definition for long COVID sucks. Just last week, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) issued a definition of long COVID with the aim of “improving consistency, documentation, and treatment.” Good news, right? Here’s the definition: “Long COVID is an infection-associated chronic condition that occurs after SARS-CoV-2 infection and is present for at least 3 months as a continuous, relapsing and remitting, or progressive disease state that affects one or more organ systems.”

This is not helpful. The symptoms can be in any organ system, can be continuous or relapsing and remitting. Basically, if you’ve had COVID — and essentially all of us have by now — and you have any symptom, even one that comes and goes, 3 months after that, it’s long COVID. They don’t even specify that it has to be a new symptom.

And I have sort of a case study in this problem today, based on a paper getting a lot of press suggesting that one out of every five people has long COVID.

We are talking about this study, “Epidemiologic Features of Recovery From SARS-CoV-2 Infection,” appearing in JAMA Network Open this week. While I think the idea is important, the study really highlights why it can be so hard to study long COVID.

As part of efforts to understand long COVID, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) leveraged 14 of its ongoing cohort studies. The NIH has multiple longitudinal cohort studies that follow various groups of people over time. You may have heard of the REGARDS study, for example, which focuses on cardiovascular risks to people living in the southern United States. Or the ARIC study, which followed adults in four communities across the United States for the development of heart disease. All 14 of the cohorts in this study are long-running projects with ongoing data collection. So, it was not a huge lift to add some questions to the yearly surveys and studies the participants were already getting.

To wit: “Do you think that you have had COVID-19?” and “Would you say that you are completely recovered now?” Those who said they weren’t fully recovered were asked how long it had been since their infection, and anyone who answered with a duration > 90 days was considered to have long COVID.

So, we have self-report of infection, self-report of duration of symptoms, and self-report of recovery. This is fine, of course; individuals’ perceptions of their own health are meaningful. But the vagaries inherent in those perceptions are going to muddy the waters as we attempt to discover the true nature of the long COVID syndrome.

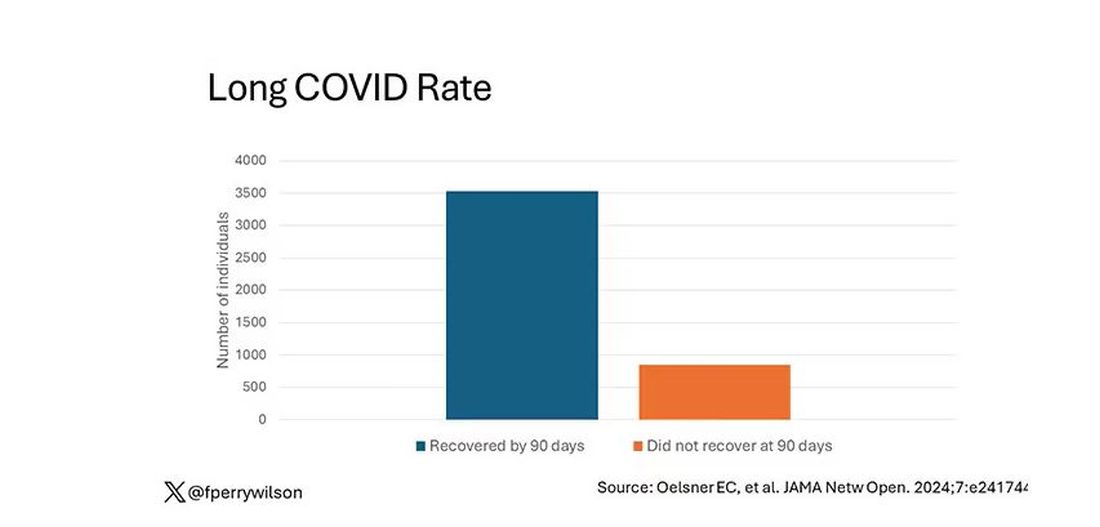

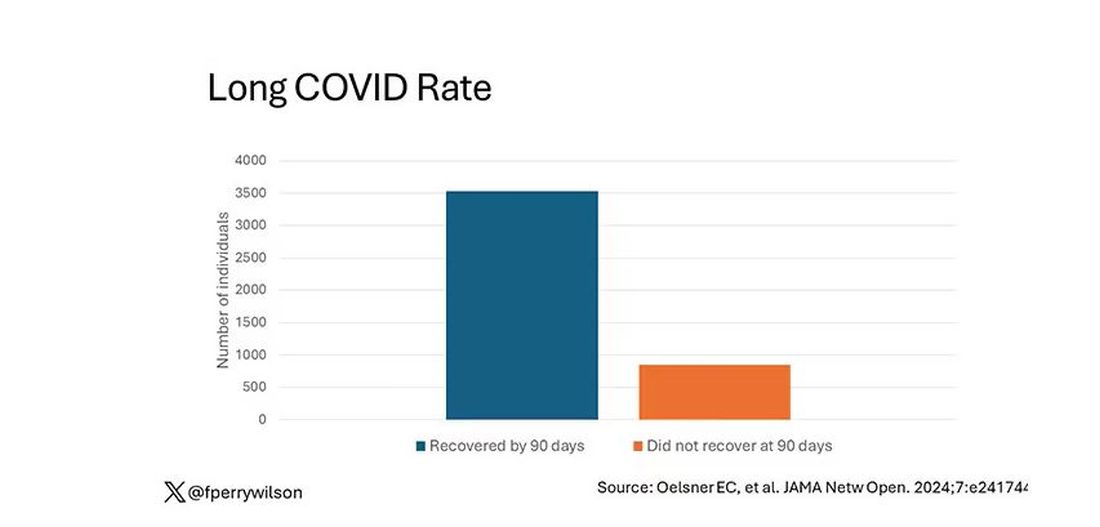

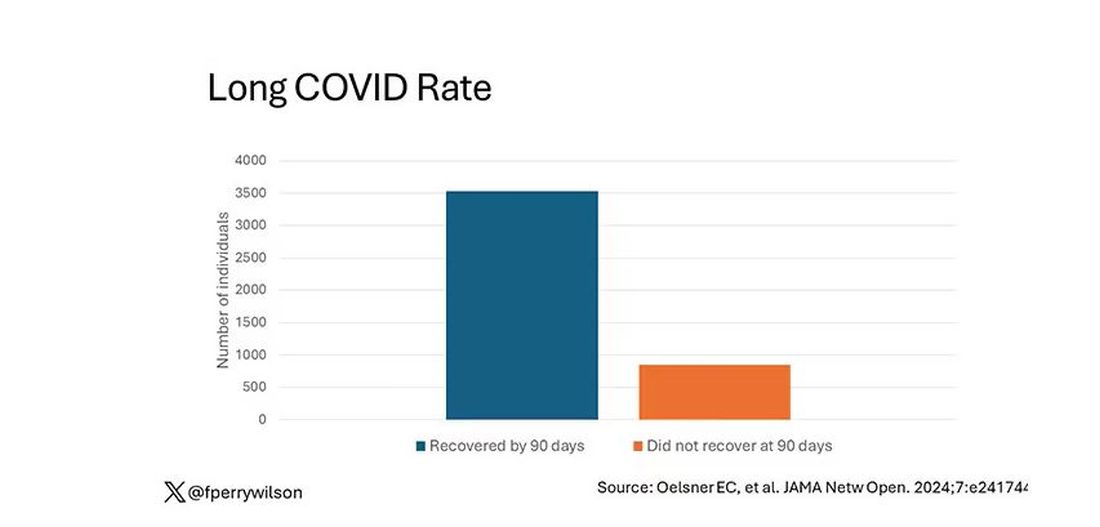

But let’s look at some results. Out of 4708 individuals studied, 842 (17.9%) had not recovered by 90 days.

This study included not only people hospitalized with COVID, as some prior long COVID studies did, but people self-diagnosed, tested at home, etc. This estimate is as reflective of the broader US population as we can get.

And there are some interesting trends here.

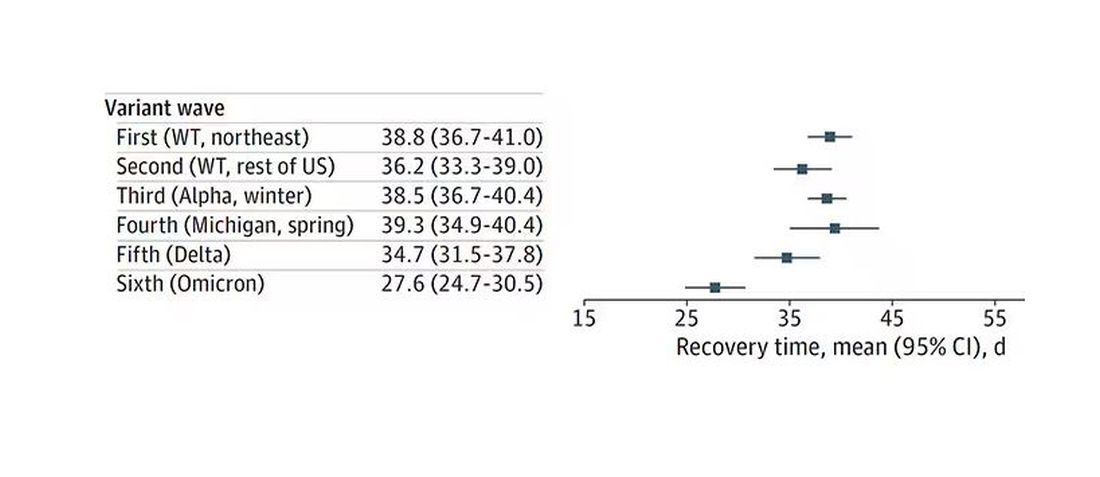

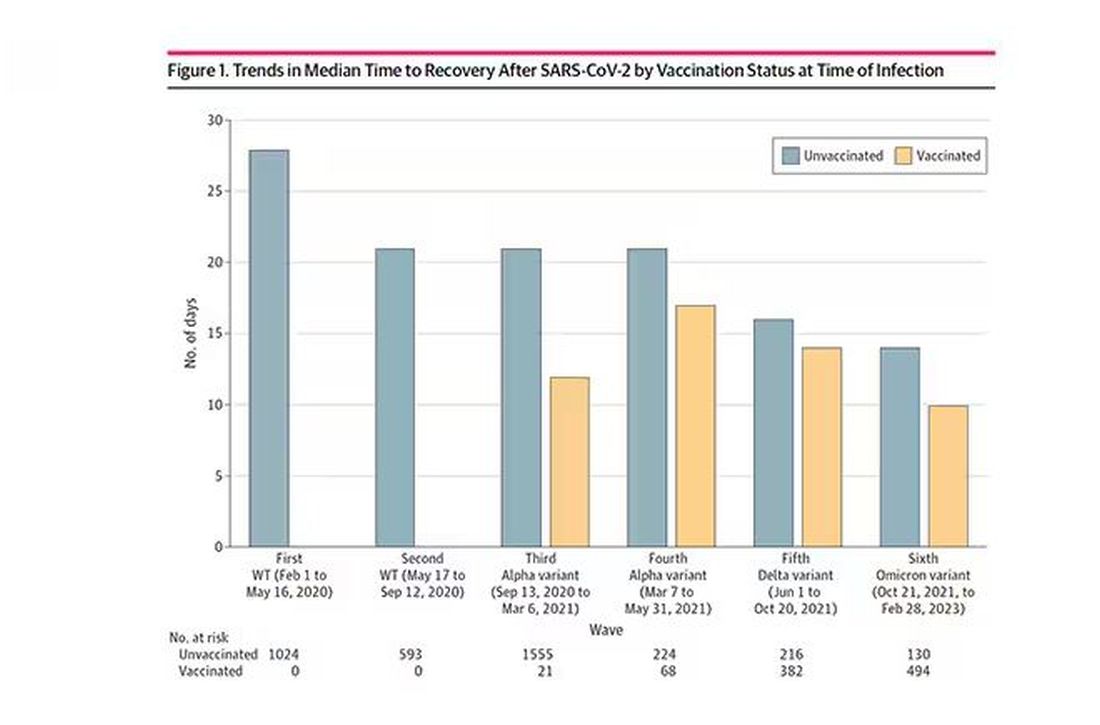

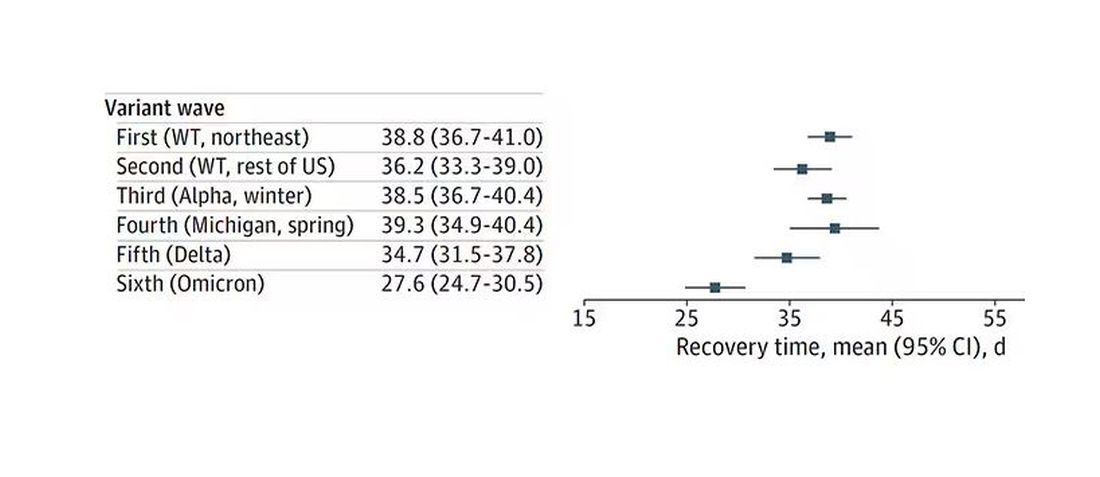

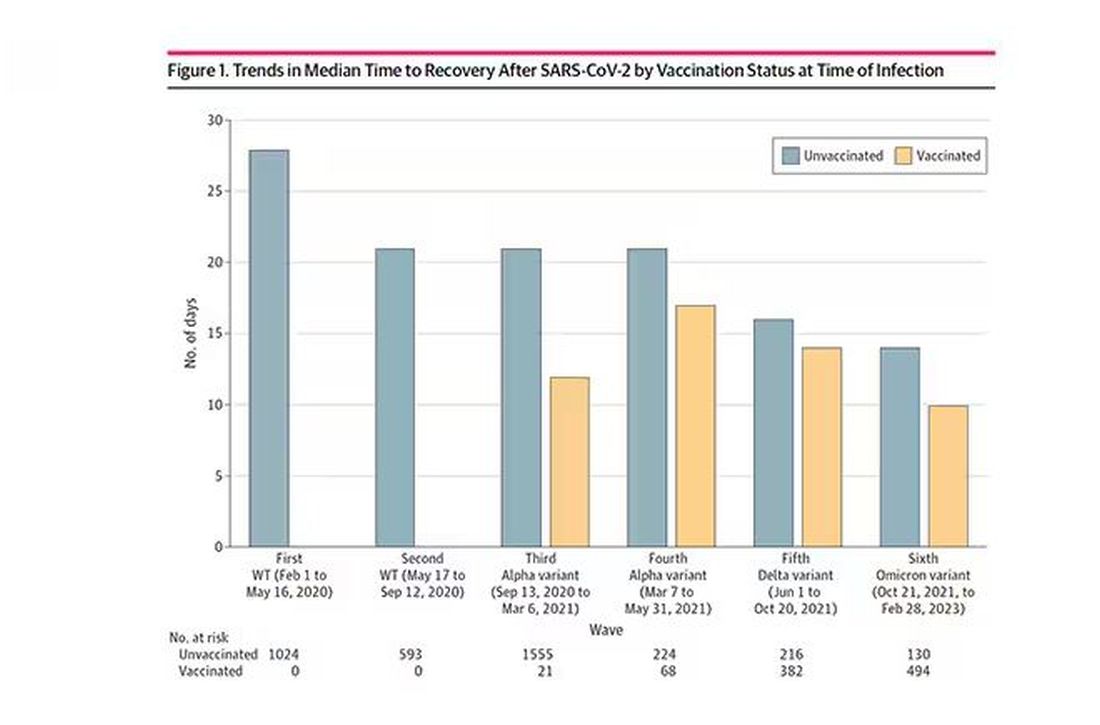

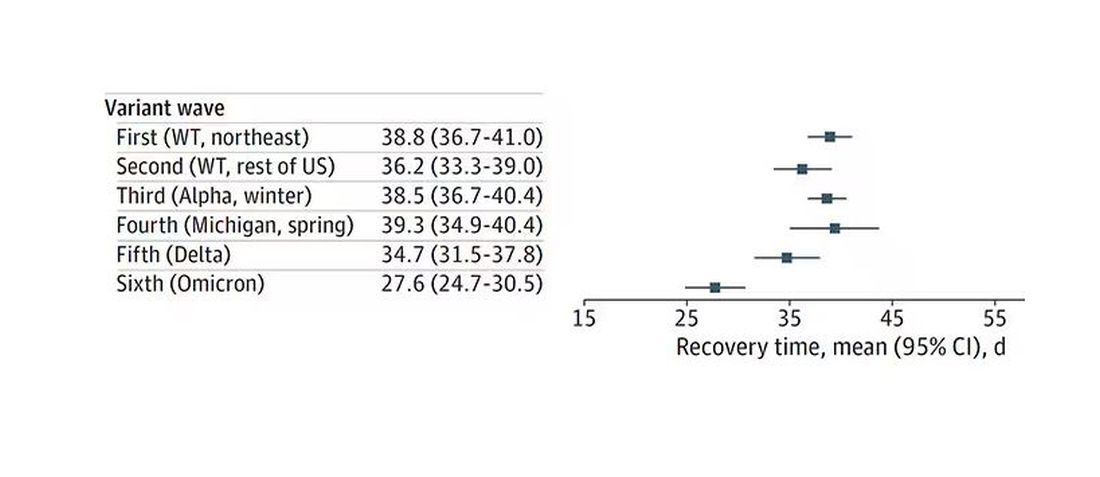

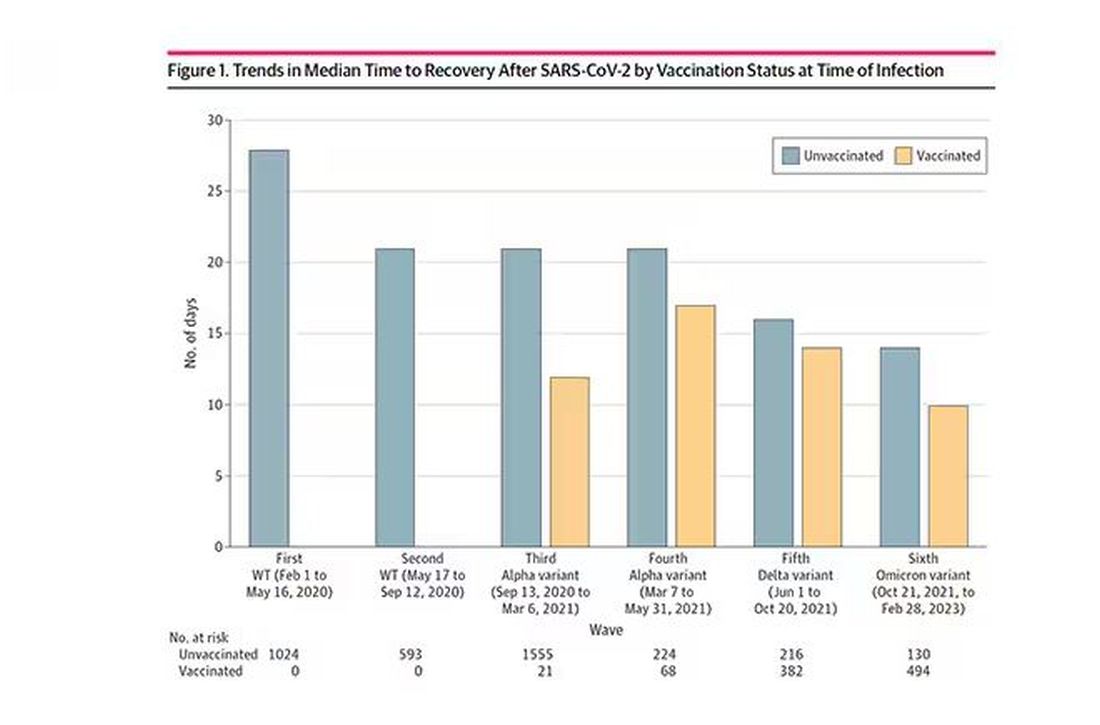

Recovery time was longer in the first waves of COVID than in the Omicron wave.

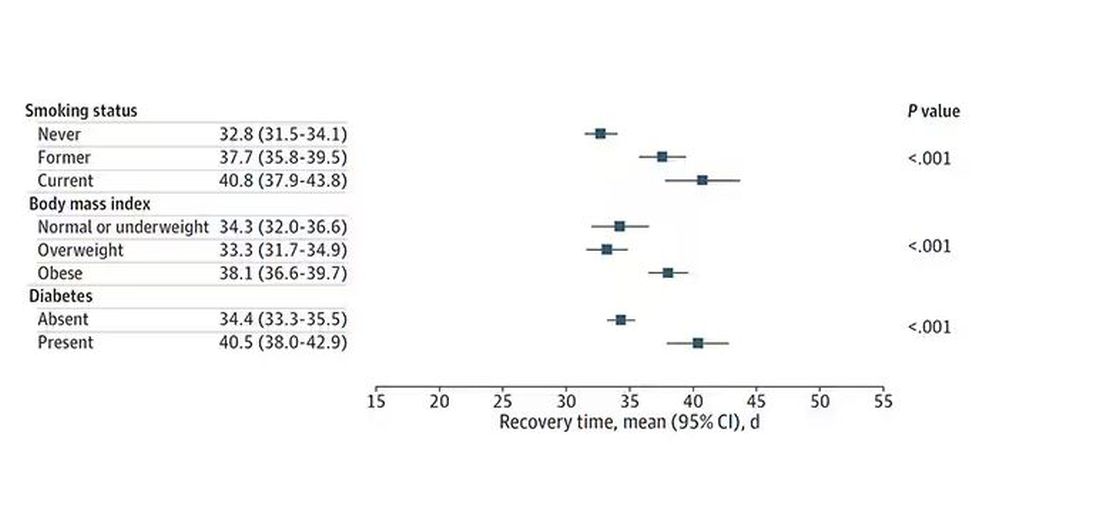

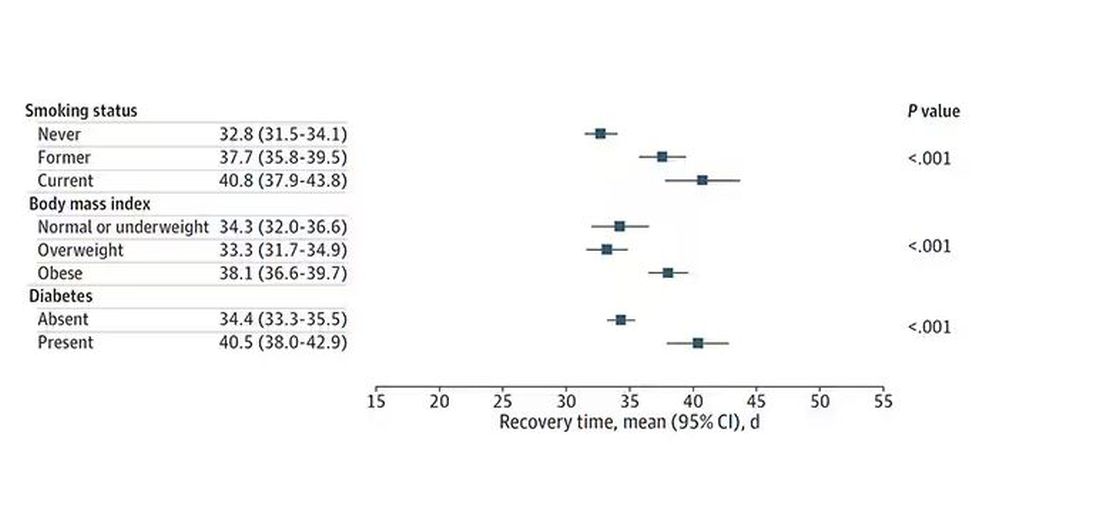

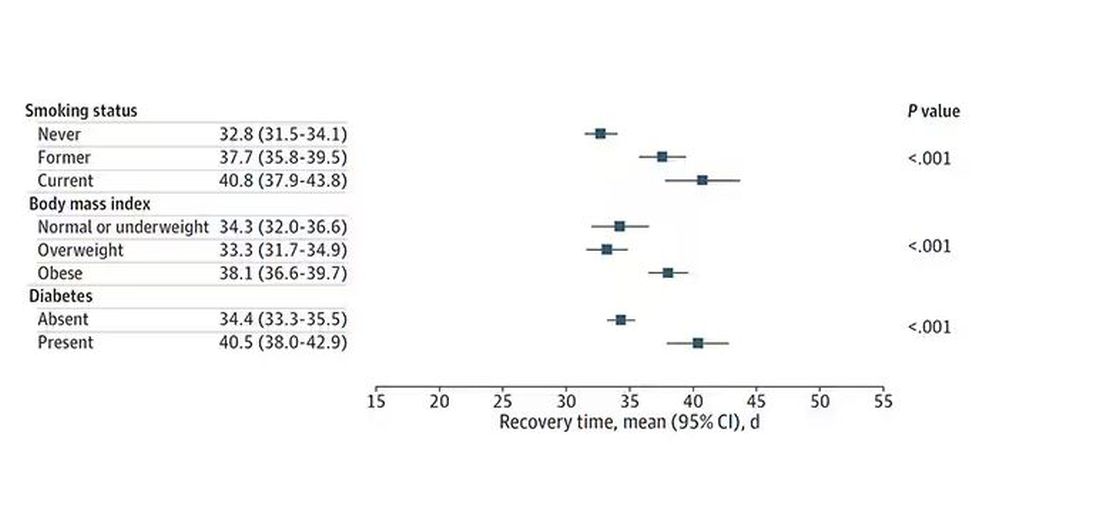

Recovery times were longer for smokers, those with diabetes, and those who were obese.

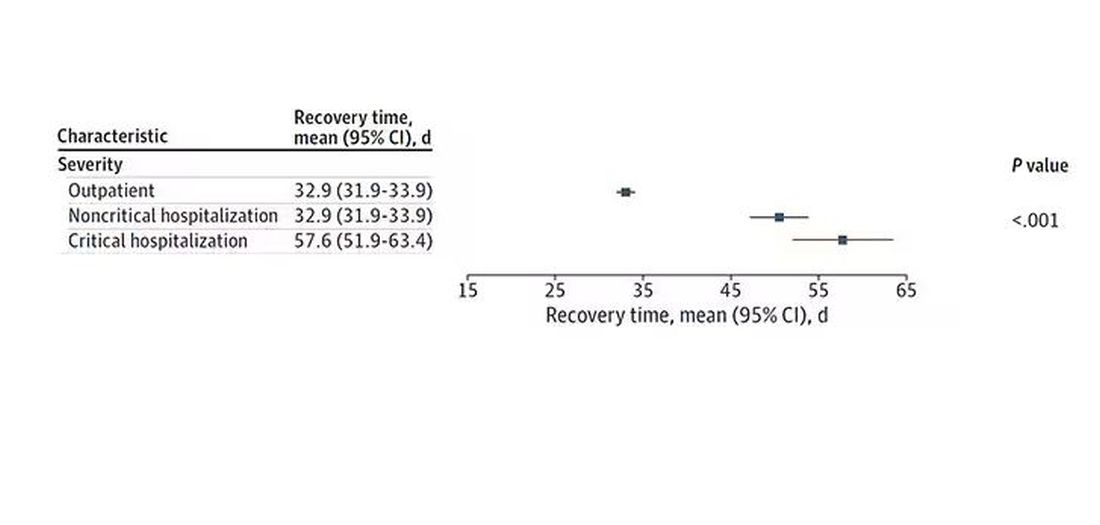

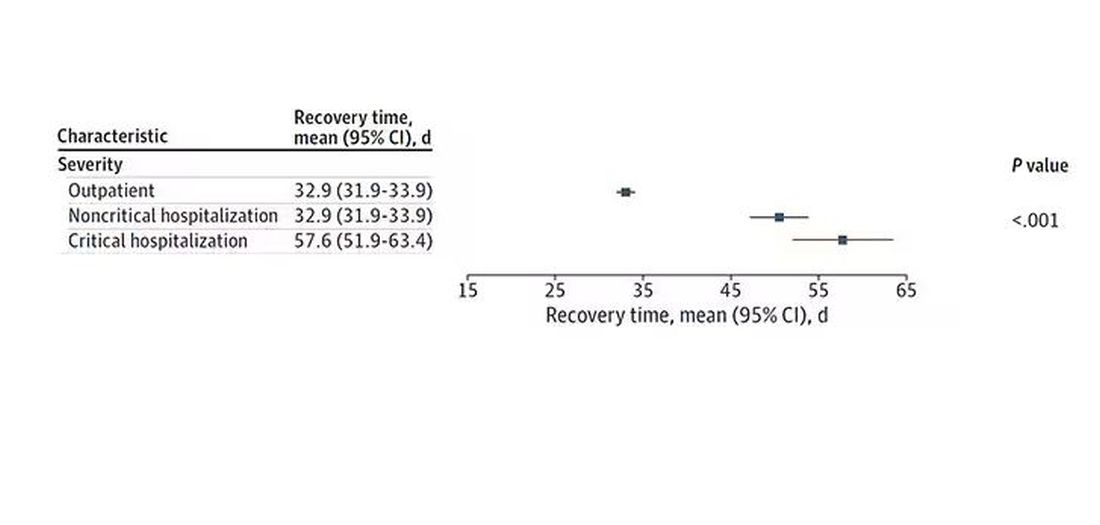

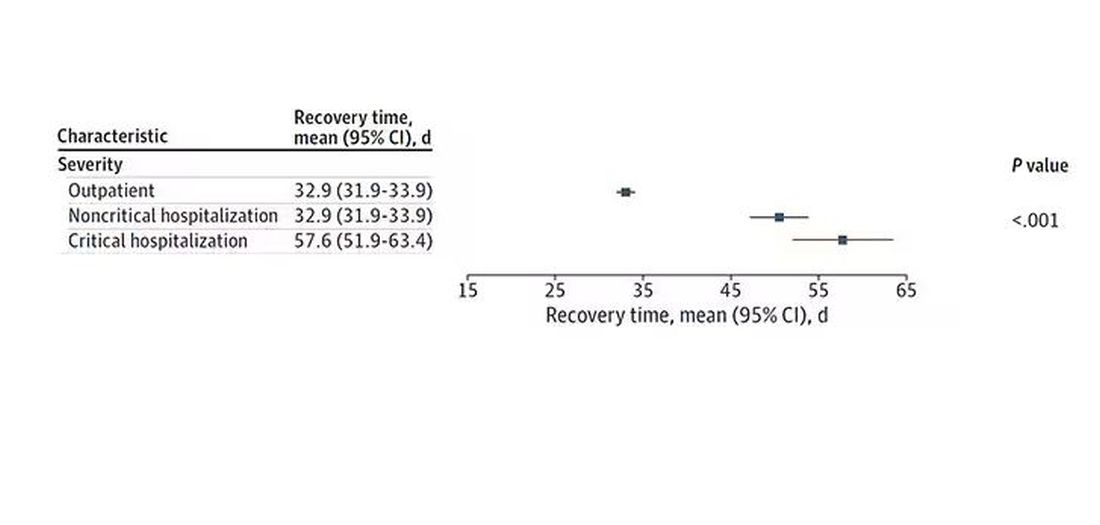

Recovery times were longer if the disease was more severe, in general. Though there is an unusual finding that women had longer recovery times despite their lower average severity of illness.

Vaccination was associated with shorter recovery times, as you can see here.

This is all quite interesting. It’s clear that people feel they are sick for a while after COVID. But we need to understand whether these symptoms are due to the lingering effects of a bad infection that knocks you down a peg, or to an ongoing syndrome — this thing we call long COVID — that has a physiologic basis and thus can be treated. And this study doesn’t help us much with that.

Not that this was the authors’ intention. This is a straight-up epidemiology study. But the problem is deeper than that. Let’s imagine that you want to really dig into this long COVID thing and get blood samples from people with it, ideally from controls with some other respiratory virus infection, and do all kinds of genetic and proteomic studies and stuff to really figure out what’s going on. Who do you enroll to be in the long COVID group? Do you enroll anyone who says they had COVID and still has some symptom more than 90 days after? You are going to find an awful lot of eligible people, and I guarantee that if there is a pathognomonic signature of long COVID, not all of them will have it.

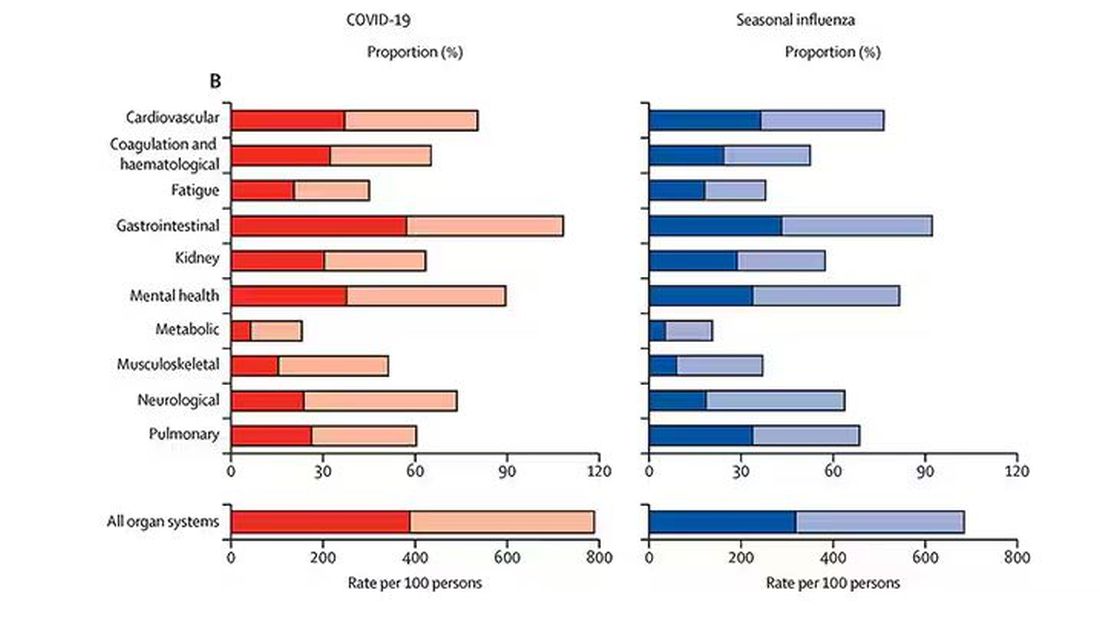

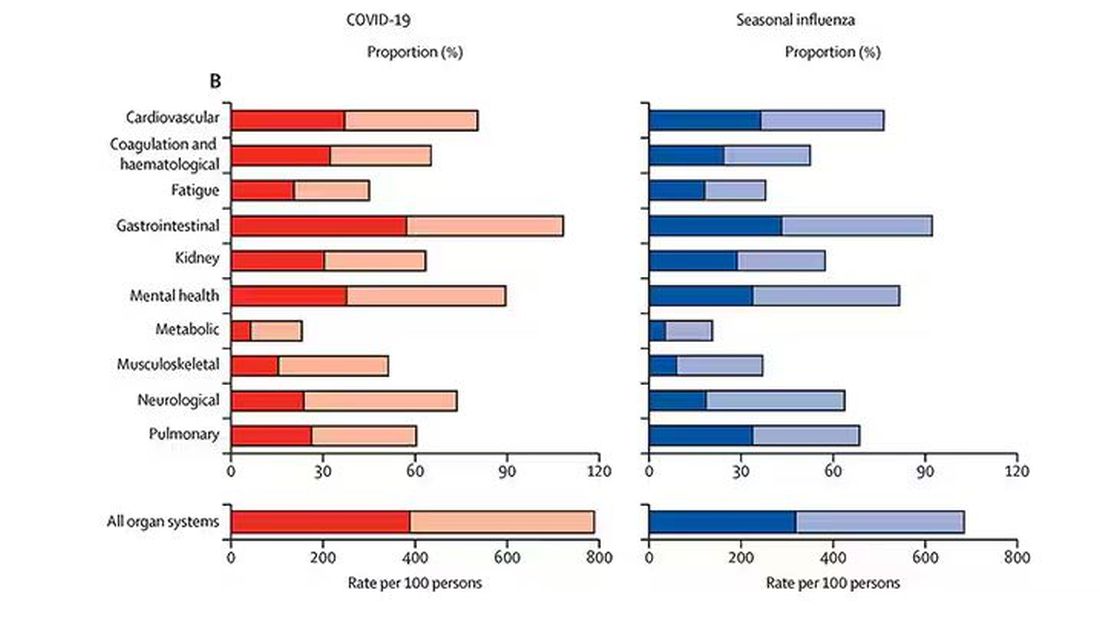

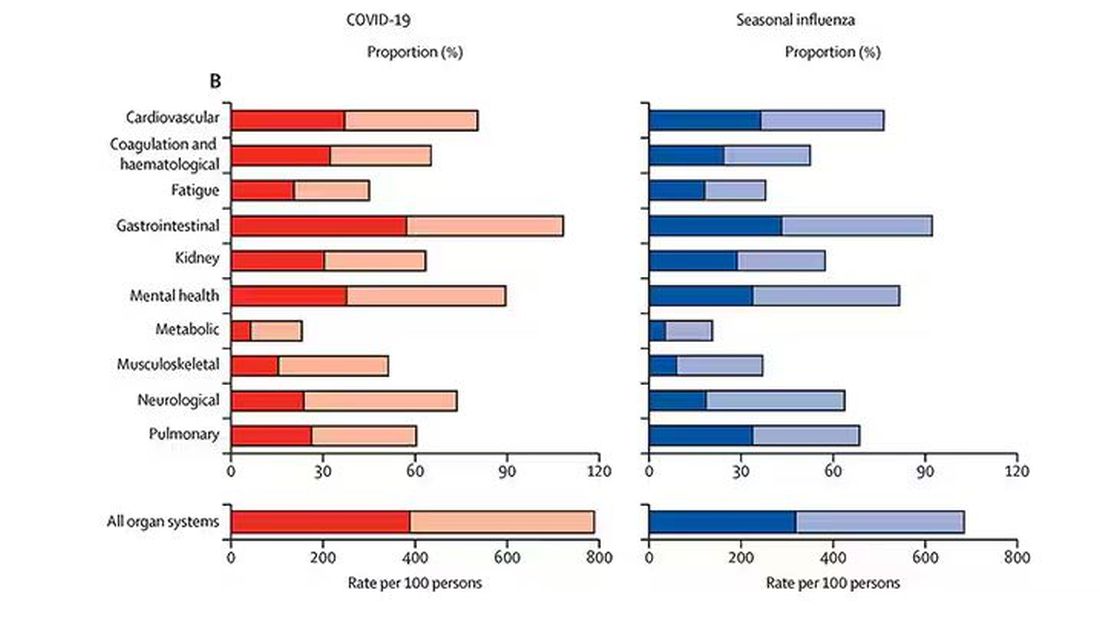

And what about other respiratory viruses? This study in The Lancet Infectious Diseases compared long-term outcomes among hospitalized patients with COVID vs influenza. In general, the COVID outcomes are worse, but let’s not knock the concept of “long flu.” Across the board, roughly 50% of people report symptoms across any given organ system.

What this is all about is something called misclassification bias, a form of information bias that arises in a study where you label someone as diseased when they are not, or vice versa. If this happens at random, it’s bad; you’ve lost your ability to distinguish characteristics from the diseased and nondiseased population.

When it’s not random, it’s really bad. If we are more likely to misclassify women as having long COVID, for example, then it will appear that long COVID is more likely among women, or more likely among those with higher estrogen levels, or something. And that might simply be wrong.

I’m not saying that’s what happened here; this study does a really great job of what it set out to do, which was to describe the patterns of lingering symptoms after COVID. But we are not going to make progress toward understanding long COVID until we are less inclusive with our case definition. To paraphrase Syndrome from The Incredibles: If everyone has long COVID, then no one does.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I want to help people suffering from long COVID as much as anyone. But we have a real problem. In brief, we are being too inclusive. The first thing you learn, when you start studying the epidemiology of diseases, is that you need a good case definition. And our case definition for long COVID sucks. Just last week, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) issued a definition of long COVID with the aim of “improving consistency, documentation, and treatment.” Good news, right? Here’s the definition: “Long COVID is an infection-associated chronic condition that occurs after SARS-CoV-2 infection and is present for at least 3 months as a continuous, relapsing and remitting, or progressive disease state that affects one or more organ systems.”

This is not helpful. The symptoms can be in any organ system, can be continuous or relapsing and remitting. Basically, if you’ve had COVID — and essentially all of us have by now — and you have any symptom, even one that comes and goes, 3 months after that, it’s long COVID. They don’t even specify that it has to be a new symptom.

And I have sort of a case study in this problem today, based on a paper getting a lot of press suggesting that one out of every five people has long COVID.

We are talking about this study, “Epidemiologic Features of Recovery From SARS-CoV-2 Infection,” appearing in JAMA Network Open this week. While I think the idea is important, the study really highlights why it can be so hard to study long COVID.

As part of efforts to understand long COVID, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) leveraged 14 of its ongoing cohort studies. The NIH has multiple longitudinal cohort studies that follow various groups of people over time. You may have heard of the REGARDS study, for example, which focuses on cardiovascular risks to people living in the southern United States. Or the ARIC study, which followed adults in four communities across the United States for the development of heart disease. All 14 of the cohorts in this study are long-running projects with ongoing data collection. So, it was not a huge lift to add some questions to the yearly surveys and studies the participants were already getting.

To wit: “Do you think that you have had COVID-19?” and “Would you say that you are completely recovered now?” Those who said they weren’t fully recovered were asked how long it had been since their infection, and anyone who answered with a duration > 90 days was considered to have long COVID.

So, we have self-report of infection, self-report of duration of symptoms, and self-report of recovery. This is fine, of course; individuals’ perceptions of their own health are meaningful. But the vagaries inherent in those perceptions are going to muddy the waters as we attempt to discover the true nature of the long COVID syndrome.

But let’s look at some results. Out of 4708 individuals studied, 842 (17.9%) had not recovered by 90 days.

This study included not only people hospitalized with COVID, as some prior long COVID studies did, but people self-diagnosed, tested at home, etc. This estimate is as reflective of the broader US population as we can get.

And there are some interesting trends here.

Recovery time was longer in the first waves of COVID than in the Omicron wave.

Recovery times were longer for smokers, those with diabetes, and those who were obese.

Recovery times were longer if the disease was more severe, in general. Though there is an unusual finding that women had longer recovery times despite their lower average severity of illness.

Vaccination was associated with shorter recovery times, as you can see here.

This is all quite interesting. It’s clear that people feel they are sick for a while after COVID. But we need to understand whether these symptoms are due to the lingering effects of a bad infection that knocks you down a peg, or to an ongoing syndrome — this thing we call long COVID — that has a physiologic basis and thus can be treated. And this study doesn’t help us much with that.

Not that this was the authors’ intention. This is a straight-up epidemiology study. But the problem is deeper than that. Let’s imagine that you want to really dig into this long COVID thing and get blood samples from people with it, ideally from controls with some other respiratory virus infection, and do all kinds of genetic and proteomic studies and stuff to really figure out what’s going on. Who do you enroll to be in the long COVID group? Do you enroll anyone who says they had COVID and still has some symptom more than 90 days after? You are going to find an awful lot of eligible people, and I guarantee that if there is a pathognomonic signature of long COVID, not all of them will have it.

And what about other respiratory viruses? This study in The Lancet Infectious Diseases compared long-term outcomes among hospitalized patients with COVID vs influenza. In general, the COVID outcomes are worse, but let’s not knock the concept of “long flu.” Across the board, roughly 50% of people report symptoms across any given organ system.

What this is all about is something called misclassification bias, a form of information bias that arises in a study where you label someone as diseased when they are not, or vice versa. If this happens at random, it’s bad; you’ve lost your ability to distinguish characteristics from the diseased and nondiseased population.

When it’s not random, it’s really bad. If we are more likely to misclassify women as having long COVID, for example, then it will appear that long COVID is more likely among women, or more likely among those with higher estrogen levels, or something. And that might simply be wrong.

I’m not saying that’s what happened here; this study does a really great job of what it set out to do, which was to describe the patterns of lingering symptoms after COVID. But we are not going to make progress toward understanding long COVID until we are less inclusive with our case definition. To paraphrase Syndrome from The Incredibles: If everyone has long COVID, then no one does.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I want to help people suffering from long COVID as much as anyone. But we have a real problem. In brief, we are being too inclusive. The first thing you learn, when you start studying the epidemiology of diseases, is that you need a good case definition. And our case definition for long COVID sucks. Just last week, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) issued a definition of long COVID with the aim of “improving consistency, documentation, and treatment.” Good news, right? Here’s the definition: “Long COVID is an infection-associated chronic condition that occurs after SARS-CoV-2 infection and is present for at least 3 months as a continuous, relapsing and remitting, or progressive disease state that affects one or more organ systems.”

This is not helpful. The symptoms can be in any organ system, can be continuous or relapsing and remitting. Basically, if you’ve had COVID — and essentially all of us have by now — and you have any symptom, even one that comes and goes, 3 months after that, it’s long COVID. They don’t even specify that it has to be a new symptom.

And I have sort of a case study in this problem today, based on a paper getting a lot of press suggesting that one out of every five people has long COVID.

We are talking about this study, “Epidemiologic Features of Recovery From SARS-CoV-2 Infection,” appearing in JAMA Network Open this week. While I think the idea is important, the study really highlights why it can be so hard to study long COVID.

As part of efforts to understand long COVID, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) leveraged 14 of its ongoing cohort studies. The NIH has multiple longitudinal cohort studies that follow various groups of people over time. You may have heard of the REGARDS study, for example, which focuses on cardiovascular risks to people living in the southern United States. Or the ARIC study, which followed adults in four communities across the United States for the development of heart disease. All 14 of the cohorts in this study are long-running projects with ongoing data collection. So, it was not a huge lift to add some questions to the yearly surveys and studies the participants were already getting.

To wit: “Do you think that you have had COVID-19?” and “Would you say that you are completely recovered now?” Those who said they weren’t fully recovered were asked how long it had been since their infection, and anyone who answered with a duration > 90 days was considered to have long COVID.

So, we have self-report of infection, self-report of duration of symptoms, and self-report of recovery. This is fine, of course; individuals’ perceptions of their own health are meaningful. But the vagaries inherent in those perceptions are going to muddy the waters as we attempt to discover the true nature of the long COVID syndrome.

But let’s look at some results. Out of 4708 individuals studied, 842 (17.9%) had not recovered by 90 days.

This study included not only people hospitalized with COVID, as some prior long COVID studies did, but people self-diagnosed, tested at home, etc. This estimate is as reflective of the broader US population as we can get.

And there are some interesting trends here.

Recovery time was longer in the first waves of COVID than in the Omicron wave.

Recovery times were longer for smokers, those with diabetes, and those who were obese.

Recovery times were longer if the disease was more severe, in general. Though there is an unusual finding that women had longer recovery times despite their lower average severity of illness.

Vaccination was associated with shorter recovery times, as you can see here.

This is all quite interesting. It’s clear that people feel they are sick for a while after COVID. But we need to understand whether these symptoms are due to the lingering effects of a bad infection that knocks you down a peg, or to an ongoing syndrome — this thing we call long COVID — that has a physiologic basis and thus can be treated. And this study doesn’t help us much with that.

Not that this was the authors’ intention. This is a straight-up epidemiology study. But the problem is deeper than that. Let’s imagine that you want to really dig into this long COVID thing and get blood samples from people with it, ideally from controls with some other respiratory virus infection, and do all kinds of genetic and proteomic studies and stuff to really figure out what’s going on. Who do you enroll to be in the long COVID group? Do you enroll anyone who says they had COVID and still has some symptom more than 90 days after? You are going to find an awful lot of eligible people, and I guarantee that if there is a pathognomonic signature of long COVID, not all of them will have it.

And what about other respiratory viruses? This study in The Lancet Infectious Diseases compared long-term outcomes among hospitalized patients with COVID vs influenza. In general, the COVID outcomes are worse, but let’s not knock the concept of “long flu.” Across the board, roughly 50% of people report symptoms across any given organ system.

What this is all about is something called misclassification bias, a form of information bias that arises in a study where you label someone as diseased when they are not, or vice versa. If this happens at random, it’s bad; you’ve lost your ability to distinguish characteristics from the diseased and nondiseased population.

When it’s not random, it’s really bad. If we are more likely to misclassify women as having long COVID, for example, then it will appear that long COVID is more likely among women, or more likely among those with higher estrogen levels, or something. And that might simply be wrong.

I’m not saying that’s what happened here; this study does a really great job of what it set out to do, which was to describe the patterns of lingering symptoms after COVID. But we are not going to make progress toward understanding long COVID until we are less inclusive with our case definition. To paraphrase Syndrome from The Incredibles: If everyone has long COVID, then no one does.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

National Academies Issue New Broad Definition of Long COVID

A new broadly inclusive definition of long COVID from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) has been developed with the aim of improving consistency, documentation, and treatment for both adults and children.

According to the 2024 NASEM definition of long COVID issued on June 11, 2024, “Long COVID is an infection-associated chronic condition that occurs after SARS-CoV-2 infection and is present for at least 3 months as a continuous, relapsing and remitting, or progressive disease state that affects one or more organ systems.”

People with long COVID may present with one or more of a long list of symptoms, such as shortness of breath, rapid heartbeat, extreme fatigue, post-exertional malaise, or sleep disturbance and with single or multiple diagnosable conditions, including interstitial lung disease, arrhythmias, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), diabetes, or autoimmune disorders. The condition can exacerbate preexisting health conditions or present as new ones.

The definition does not require laboratory confirmation or other proof of initial infection. Long COVID can follow SARS-CoV-2 infection of any severity, including asymptomatic infections, whether or not they were initially recognized.

Several working definitions and terms for long COVID had previously been proposed, including those from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, but no common definition or terminology had been established.

The new definition was developed at the request of the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response and the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH). It was written by a multi-stakeholder panel convened by NASEM, which recommended that the new definition be universally adopted by the federal government, clinical societies and associations, public health practitioners, clinicians, payers, the drug industry, and others using the term long COVID.

Recent surveys suggest that approximately 7% of Americans have experienced or are experiencing long COVID. “It’s millions of people,” panel chair Harvey V. Fineberg, MD, president of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, told this news organization.

The new definition “does not erase the problem of clinical judgment ... But we think this definition has the real advantage of elevating to the clinician’s mind the real likelihood in the current environment of prevalence of this virus that a presenting patient’s strange symptoms are both real and maybe related as an expression of long COVID,” Dr. Fineberg noted.

One way this new definition differs from previous ones such as WHO’s, he said, is “they talk about a diagnosis of exclusion. One of the important points in our definition is that other diagnosable conditions like ME/CFS or POTS can be part of the picture of long COVID. They are not alternative. They are, in fact, an expression of long COVID.”

Indeed, the NASEM report also introduces the term infection-associated chronic condition (IACC). This was important, Dr. Fineberg said, “because it’s the larger family of conditions of which long COVID is a part. It emphasizes a relatedness of long COVID to other conditions that can follow from a variety of infections. We also adopted the term ‘disease state’ to convey the seriousness and reality of this condition in the lives of patients.”

Comments on New Definition

In a statement provided to this news organization, Lucinda Bateman, MD, and Brayden Yellman, MD, co-medical directors of the Bateman-Horne Center in Salt Lake City, said that “describing long COVID as an IACC ... not only meets the NASEM goal of allowing clinicians, researchers, and public health officials to meaningfully identify and serve all persons who suffer illness or disability in the wake of a SARS-CoV-2 infection, but also draws direct comparison to other known IACC’s (such as ME/CFS, post-treatment Lyme, POTS) that have been plaguing many for decades.”

Dr. Fineberg noted another important aspect of the NASEM report: “Our definition includes an explicit statement on equity, explaining that long COVID can affect anyone, young and old, different races, different ages, different sexes, different genders, different orientations, different socioeconomic conditions ... This does not mean that every single person is at equal risk. There are risk factors, but the important point is the universal nature of this as a condition.”

Two clinical directors of long COVID programs who were contacted by this news organization praised the new definition. Zijian Chen, MD, director of Mount Sinai’s Center for Post-COVID Care, New York, said that it’s “very similar to the definition that we have used for our clinical practice since 2020. It is very important that the broad definition helps to be inclusive of all patients that may be affected. The inclusion of children as a consideration is important as well, since there is routinely less focus on children because they tend to have less disease frequency ... The creation of a unified definition helps both with clinical practice and research.”

Nisha Viswanathan, MD, director of the long COVID program at the University of California, Los Angeles, said: “I think they left it intentionally broad for the medical practitioner to not necessarily use the definition to rule out individuals, but to perhaps use more of a clinical gestalt to help rule in this diagnosis ... I think this definition is providing clarity to health care providers on what exactly would be falling under the long-COVID diagnosis header.”

Dr. Viswanathan also said that she anticipates this definition to help patients make their case in filing disability claims. “Because long COVID has not previously had a good fleshed-out definition, it was very easy for disability providers to reject claims for patients who continue to have symptoms ... I actually think this might help our patients ultimately in their attempt to be able to have the ability to care for themselves when they’re disabled enough to not be able to work.”

Written into the report is the expectation that the definition “will evolve as new evidence emerges and the understanding of long COVID matures.” The writing committee calls for reexamination in “no more than 3 years.” Factors that would prompt a reevaluation could include improved testing methods, discovery of medical factors and/or biomarkers that distinguish long COVID from other conditions, and new treatments.

Meanwhile, Dr. Fineberg told this news organization, “If this definition adds to the readiness, awareness, openness, and response to the patient with long COVID, it will have done its job.”

Dr. Fineberg, Dr. Bateman, Dr. Yellman, Dr. Viswanathan, and Dr. Chen have no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A new broadly inclusive definition of long COVID from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) has been developed with the aim of improving consistency, documentation, and treatment for both adults and children.

According to the 2024 NASEM definition of long COVID issued on June 11, 2024, “Long COVID is an infection-associated chronic condition that occurs after SARS-CoV-2 infection and is present for at least 3 months as a continuous, relapsing and remitting, or progressive disease state that affects one or more organ systems.”

People with long COVID may present with one or more of a long list of symptoms, such as shortness of breath, rapid heartbeat, extreme fatigue, post-exertional malaise, or sleep disturbance and with single or multiple diagnosable conditions, including interstitial lung disease, arrhythmias, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), diabetes, or autoimmune disorders. The condition can exacerbate preexisting health conditions or present as new ones.

The definition does not require laboratory confirmation or other proof of initial infection. Long COVID can follow SARS-CoV-2 infection of any severity, including asymptomatic infections, whether or not they were initially recognized.

Several working definitions and terms for long COVID had previously been proposed, including those from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, but no common definition or terminology had been established.

The new definition was developed at the request of the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response and the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH). It was written by a multi-stakeholder panel convened by NASEM, which recommended that the new definition be universally adopted by the federal government, clinical societies and associations, public health practitioners, clinicians, payers, the drug industry, and others using the term long COVID.

Recent surveys suggest that approximately 7% of Americans have experienced or are experiencing long COVID. “It’s millions of people,” panel chair Harvey V. Fineberg, MD, president of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, told this news organization.

The new definition “does not erase the problem of clinical judgment ... But we think this definition has the real advantage of elevating to the clinician’s mind the real likelihood in the current environment of prevalence of this virus that a presenting patient’s strange symptoms are both real and maybe related as an expression of long COVID,” Dr. Fineberg noted.

One way this new definition differs from previous ones such as WHO’s, he said, is “they talk about a diagnosis of exclusion. One of the important points in our definition is that other diagnosable conditions like ME/CFS or POTS can be part of the picture of long COVID. They are not alternative. They are, in fact, an expression of long COVID.”

Indeed, the NASEM report also introduces the term infection-associated chronic condition (IACC). This was important, Dr. Fineberg said, “because it’s the larger family of conditions of which long COVID is a part. It emphasizes a relatedness of long COVID to other conditions that can follow from a variety of infections. We also adopted the term ‘disease state’ to convey the seriousness and reality of this condition in the lives of patients.”

Comments on New Definition

In a statement provided to this news organization, Lucinda Bateman, MD, and Brayden Yellman, MD, co-medical directors of the Bateman-Horne Center in Salt Lake City, said that “describing long COVID as an IACC ... not only meets the NASEM goal of allowing clinicians, researchers, and public health officials to meaningfully identify and serve all persons who suffer illness or disability in the wake of a SARS-CoV-2 infection, but also draws direct comparison to other known IACC’s (such as ME/CFS, post-treatment Lyme, POTS) that have been plaguing many for decades.”

Dr. Fineberg noted another important aspect of the NASEM report: “Our definition includes an explicit statement on equity, explaining that long COVID can affect anyone, young and old, different races, different ages, different sexes, different genders, different orientations, different socioeconomic conditions ... This does not mean that every single person is at equal risk. There are risk factors, but the important point is the universal nature of this as a condition.”

Two clinical directors of long COVID programs who were contacted by this news organization praised the new definition. Zijian Chen, MD, director of Mount Sinai’s Center for Post-COVID Care, New York, said that it’s “very similar to the definition that we have used for our clinical practice since 2020. It is very important that the broad definition helps to be inclusive of all patients that may be affected. The inclusion of children as a consideration is important as well, since there is routinely less focus on children because they tend to have less disease frequency ... The creation of a unified definition helps both with clinical practice and research.”

Nisha Viswanathan, MD, director of the long COVID program at the University of California, Los Angeles, said: “I think they left it intentionally broad for the medical practitioner to not necessarily use the definition to rule out individuals, but to perhaps use more of a clinical gestalt to help rule in this diagnosis ... I think this definition is providing clarity to health care providers on what exactly would be falling under the long-COVID diagnosis header.”

Dr. Viswanathan also said that she anticipates this definition to help patients make their case in filing disability claims. “Because long COVID has not previously had a good fleshed-out definition, it was very easy for disability providers to reject claims for patients who continue to have symptoms ... I actually think this might help our patients ultimately in their attempt to be able to have the ability to care for themselves when they’re disabled enough to not be able to work.”

Written into the report is the expectation that the definition “will evolve as new evidence emerges and the understanding of long COVID matures.” The writing committee calls for reexamination in “no more than 3 years.” Factors that would prompt a reevaluation could include improved testing methods, discovery of medical factors and/or biomarkers that distinguish long COVID from other conditions, and new treatments.

Meanwhile, Dr. Fineberg told this news organization, “If this definition adds to the readiness, awareness, openness, and response to the patient with long COVID, it will have done its job.”

Dr. Fineberg, Dr. Bateman, Dr. Yellman, Dr. Viswanathan, and Dr. Chen have no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A new broadly inclusive definition of long COVID from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) has been developed with the aim of improving consistency, documentation, and treatment for both adults and children.

According to the 2024 NASEM definition of long COVID issued on June 11, 2024, “Long COVID is an infection-associated chronic condition that occurs after SARS-CoV-2 infection and is present for at least 3 months as a continuous, relapsing and remitting, or progressive disease state that affects one or more organ systems.”

People with long COVID may present with one or more of a long list of symptoms, such as shortness of breath, rapid heartbeat, extreme fatigue, post-exertional malaise, or sleep disturbance and with single or multiple diagnosable conditions, including interstitial lung disease, arrhythmias, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), diabetes, or autoimmune disorders. The condition can exacerbate preexisting health conditions or present as new ones.

The definition does not require laboratory confirmation or other proof of initial infection. Long COVID can follow SARS-CoV-2 infection of any severity, including asymptomatic infections, whether or not they were initially recognized.