User login

Turning the Cancer Research Problem Into an Opportunity

Turning the Cancer Research Problem Into an Opportunity

The War on Cancer, declared by President Richard Nixon some 50 years ago, has been canceled during the second Trump administration in 2025 — so saith The New York Times Sunday magazine cover story on September 14, 2025. This war seems now to be best described as "The War on Cancer Research."

To our horror and disbelief, we've witnessed the slow but persistent drift of much of the United States citizenry away from science and the sudden and severe movement of the US government to crush much medical research. But it is not as if we were not warned.

In August 2024, on these pages and without political bias, I urged Medscape readers to pay attention to Project 2025. A great deal of what we as a population are now experiencing was laid out as a carefully constructed plan.

What is surprising is the cruel ruthlessness of the "move fast and break things" approach, taken with little apparent concern about the resultant human tragedies (workforce and patients) and no clear care about the resulting fallout. As we've now learned, destroying something as grand as our cancer research enterprise can be accomplished very quickly. Rebuilding it is certain to be slow and difficult and perhaps can never be accomplished.

In this new anti-science, anti-research, and anti-researcher reality, what can we now do?

First and foremost, we must recognize that the war on cancer is not over. Cancer is not canceled, even if much of the US government's research effort/funding has been. Those of us in medicine and public health often speak in quantification of causes of death of our populations. As such, I'll remind Medscape readers that cancer afflicts some 20 million humans worldwide each year, killing nearly 10 million. Although two-thirds of Americans diagnosed with a potentially lethal malignancy are cured, cancer still kills roughly 600,000 Americans each year. Cancer has been the second most frequent cause of death of Americans for 75 years.

Being inevitable and immutable, death itself is not the enemy. We all die. Disease, disability, pain, and human suffering are the real enemies of us all. Cancer maims, pains, diabetes, and torments some 20 million humans worldwide each year. That is a huge humanitarian problem that should be recognized by individuals of all creeds and backgrounds.

With this depletion of our domestic government basic and applied cancer research program, what can we do?

- Think globally and look to the international scientific research enterprises — relying on them, much as they have relied on us.

- Defend the universal importance of reliable and available literature on medical science.

- Continue to translate and apply the vast amount of available published research in clinical practice and publish the results.

- Urge private industries to expand their research budgets into areas of study that may not produce quickly tangible positive bottom-line results.

- Remind the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (for whom chronic diseases seem paramount) that cancer is the second leading American chronic disease by morbidity.

- Redouble efforts of cancer prevention, especially urging the FDA to ban combustible tobacco and strive more diligently to decrease obesity.

- Appeal to our vast philanthropic universe to increase its funding of nonprofit organizations active in the cancer investigation, diagnosis, and management space.

One such 501c3 organization is California-based Cancer Commons. (Disclosure: I named it in 2010 and serve as its editor in chief).

A commons is a space shared by a community to use for the common interest. As we originally envisioned it, a cancer commons is an open access internet location where individuals and organizations (eg, corporations, universities, government agencies, philanthropies) will voluntarily share their data to work together to defeat the common enemy of humans: cancer.

On September 8, 2025, Cancer Commons was the 15th annual Lundberg Institute Lecturer at the Commonwealth Club of California in San Francisco. At the lecture, Cancer Commons founder (and long-term survivor of metastatic malignant melanoma), Jay Martin "Martin" Tenenbaum, PhD, spoke of the need for a cancer commons and the founder's vision. Emma Shtivelman, PhD, the long-time compassionate chief scientist, described some of the thousands of patients with advanced cancer that she has helped — all free of charge. And newly named CEO Clifford Reid, MBA, PhD, used his entrepreneurial prowess to envision an ambitious future.

Cancer Commons has always focused on patients with cancer who are beyond standards of curative care. As Cancer Commons evolves, it anticipates focusing on patients with cancer who are beyond National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines. The organization intends to greatly expand its 1000 patients per year with "high touch" engagement with PhD clinical scientists to many thousands by including artificial intelligence. It plans to extend its N-of-One approach to create new knowledge — especially regarding the hundreds of drugs that are FDA-approved for use in treating cancer but have not been further assessed for the utility in actually treating patients with cancer.

The war on cancer is not over. It remains a persistent foe that causes immense disability, pain, and human suffering. With government support depleted, the burden now shifts to the private sector and philanthropic organizations, such as Cancer Commons, to serve as the new vital infrastructure in the fight for a cure. Now, we must redouble our efforts to ensure that these research endeavors are supported if the US government will not do its part.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The War on Cancer, declared by President Richard Nixon some 50 years ago, has been canceled during the second Trump administration in 2025 — so saith The New York Times Sunday magazine cover story on September 14, 2025. This war seems now to be best described as "The War on Cancer Research."

To our horror and disbelief, we've witnessed the slow but persistent drift of much of the United States citizenry away from science and the sudden and severe movement of the US government to crush much medical research. But it is not as if we were not warned.

In August 2024, on these pages and without political bias, I urged Medscape readers to pay attention to Project 2025. A great deal of what we as a population are now experiencing was laid out as a carefully constructed plan.

What is surprising is the cruel ruthlessness of the "move fast and break things" approach, taken with little apparent concern about the resultant human tragedies (workforce and patients) and no clear care about the resulting fallout. As we've now learned, destroying something as grand as our cancer research enterprise can be accomplished very quickly. Rebuilding it is certain to be slow and difficult and perhaps can never be accomplished.

In this new anti-science, anti-research, and anti-researcher reality, what can we now do?

First and foremost, we must recognize that the war on cancer is not over. Cancer is not canceled, even if much of the US government's research effort/funding has been. Those of us in medicine and public health often speak in quantification of causes of death of our populations. As such, I'll remind Medscape readers that cancer afflicts some 20 million humans worldwide each year, killing nearly 10 million. Although two-thirds of Americans diagnosed with a potentially lethal malignancy are cured, cancer still kills roughly 600,000 Americans each year. Cancer has been the second most frequent cause of death of Americans for 75 years.

Being inevitable and immutable, death itself is not the enemy. We all die. Disease, disability, pain, and human suffering are the real enemies of us all. Cancer maims, pains, diabetes, and torments some 20 million humans worldwide each year. That is a huge humanitarian problem that should be recognized by individuals of all creeds and backgrounds.

With this depletion of our domestic government basic and applied cancer research program, what can we do?

- Think globally and look to the international scientific research enterprises — relying on them, much as they have relied on us.

- Defend the universal importance of reliable and available literature on medical science.

- Continue to translate and apply the vast amount of available published research in clinical practice and publish the results.

- Urge private industries to expand their research budgets into areas of study that may not produce quickly tangible positive bottom-line results.

- Remind the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (for whom chronic diseases seem paramount) that cancer is the second leading American chronic disease by morbidity.

- Redouble efforts of cancer prevention, especially urging the FDA to ban combustible tobacco and strive more diligently to decrease obesity.

- Appeal to our vast philanthropic universe to increase its funding of nonprofit organizations active in the cancer investigation, diagnosis, and management space.

One such 501c3 organization is California-based Cancer Commons. (Disclosure: I named it in 2010 and serve as its editor in chief).

A commons is a space shared by a community to use for the common interest. As we originally envisioned it, a cancer commons is an open access internet location where individuals and organizations (eg, corporations, universities, government agencies, philanthropies) will voluntarily share their data to work together to defeat the common enemy of humans: cancer.

On September 8, 2025, Cancer Commons was the 15th annual Lundberg Institute Lecturer at the Commonwealth Club of California in San Francisco. At the lecture, Cancer Commons founder (and long-term survivor of metastatic malignant melanoma), Jay Martin "Martin" Tenenbaum, PhD, spoke of the need for a cancer commons and the founder's vision. Emma Shtivelman, PhD, the long-time compassionate chief scientist, described some of the thousands of patients with advanced cancer that she has helped — all free of charge. And newly named CEO Clifford Reid, MBA, PhD, used his entrepreneurial prowess to envision an ambitious future.

Cancer Commons has always focused on patients with cancer who are beyond standards of curative care. As Cancer Commons evolves, it anticipates focusing on patients with cancer who are beyond National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines. The organization intends to greatly expand its 1000 patients per year with "high touch" engagement with PhD clinical scientists to many thousands by including artificial intelligence. It plans to extend its N-of-One approach to create new knowledge — especially regarding the hundreds of drugs that are FDA-approved for use in treating cancer but have not been further assessed for the utility in actually treating patients with cancer.

The war on cancer is not over. It remains a persistent foe that causes immense disability, pain, and human suffering. With government support depleted, the burden now shifts to the private sector and philanthropic organizations, such as Cancer Commons, to serve as the new vital infrastructure in the fight for a cure. Now, we must redouble our efforts to ensure that these research endeavors are supported if the US government will not do its part.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The War on Cancer, declared by President Richard Nixon some 50 years ago, has been canceled during the second Trump administration in 2025 — so saith The New York Times Sunday magazine cover story on September 14, 2025. This war seems now to be best described as "The War on Cancer Research."

To our horror and disbelief, we've witnessed the slow but persistent drift of much of the United States citizenry away from science and the sudden and severe movement of the US government to crush much medical research. But it is not as if we were not warned.

In August 2024, on these pages and without political bias, I urged Medscape readers to pay attention to Project 2025. A great deal of what we as a population are now experiencing was laid out as a carefully constructed plan.

What is surprising is the cruel ruthlessness of the "move fast and break things" approach, taken with little apparent concern about the resultant human tragedies (workforce and patients) and no clear care about the resulting fallout. As we've now learned, destroying something as grand as our cancer research enterprise can be accomplished very quickly. Rebuilding it is certain to be slow and difficult and perhaps can never be accomplished.

In this new anti-science, anti-research, and anti-researcher reality, what can we now do?

First and foremost, we must recognize that the war on cancer is not over. Cancer is not canceled, even if much of the US government's research effort/funding has been. Those of us in medicine and public health often speak in quantification of causes of death of our populations. As such, I'll remind Medscape readers that cancer afflicts some 20 million humans worldwide each year, killing nearly 10 million. Although two-thirds of Americans diagnosed with a potentially lethal malignancy are cured, cancer still kills roughly 600,000 Americans each year. Cancer has been the second most frequent cause of death of Americans for 75 years.

Being inevitable and immutable, death itself is not the enemy. We all die. Disease, disability, pain, and human suffering are the real enemies of us all. Cancer maims, pains, diabetes, and torments some 20 million humans worldwide each year. That is a huge humanitarian problem that should be recognized by individuals of all creeds and backgrounds.

With this depletion of our domestic government basic and applied cancer research program, what can we do?

- Think globally and look to the international scientific research enterprises — relying on them, much as they have relied on us.

- Defend the universal importance of reliable and available literature on medical science.

- Continue to translate and apply the vast amount of available published research in clinical practice and publish the results.

- Urge private industries to expand their research budgets into areas of study that may not produce quickly tangible positive bottom-line results.

- Remind the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (for whom chronic diseases seem paramount) that cancer is the second leading American chronic disease by morbidity.

- Redouble efforts of cancer prevention, especially urging the FDA to ban combustible tobacco and strive more diligently to decrease obesity.

- Appeal to our vast philanthropic universe to increase its funding of nonprofit organizations active in the cancer investigation, diagnosis, and management space.

One such 501c3 organization is California-based Cancer Commons. (Disclosure: I named it in 2010 and serve as its editor in chief).

A commons is a space shared by a community to use for the common interest. As we originally envisioned it, a cancer commons is an open access internet location where individuals and organizations (eg, corporations, universities, government agencies, philanthropies) will voluntarily share their data to work together to defeat the common enemy of humans: cancer.

On September 8, 2025, Cancer Commons was the 15th annual Lundberg Institute Lecturer at the Commonwealth Club of California in San Francisco. At the lecture, Cancer Commons founder (and long-term survivor of metastatic malignant melanoma), Jay Martin "Martin" Tenenbaum, PhD, spoke of the need for a cancer commons and the founder's vision. Emma Shtivelman, PhD, the long-time compassionate chief scientist, described some of the thousands of patients with advanced cancer that she has helped — all free of charge. And newly named CEO Clifford Reid, MBA, PhD, used his entrepreneurial prowess to envision an ambitious future.

Cancer Commons has always focused on patients with cancer who are beyond standards of curative care. As Cancer Commons evolves, it anticipates focusing on patients with cancer who are beyond National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines. The organization intends to greatly expand its 1000 patients per year with "high touch" engagement with PhD clinical scientists to many thousands by including artificial intelligence. It plans to extend its N-of-One approach to create new knowledge — especially regarding the hundreds of drugs that are FDA-approved for use in treating cancer but have not been further assessed for the utility in actually treating patients with cancer.

The war on cancer is not over. It remains a persistent foe that causes immense disability, pain, and human suffering. With government support depleted, the burden now shifts to the private sector and philanthropic organizations, such as Cancer Commons, to serve as the new vital infrastructure in the fight for a cure. Now, we must redouble our efforts to ensure that these research endeavors are supported if the US government will not do its part.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Turning the Cancer Research Problem Into an Opportunity

Turning the Cancer Research Problem Into an Opportunity

Cancer Treatment 101: A Primer for Non-Oncologists

The remaining 700,000 or so often proceed to chemotherapy either immediately or upon cancer recurrence, spread, or newly recognized metastases. “Cures” after that point are rare.

I’m speaking in generalities, understanding that each cancer and each patient is unique.

Chemotherapy

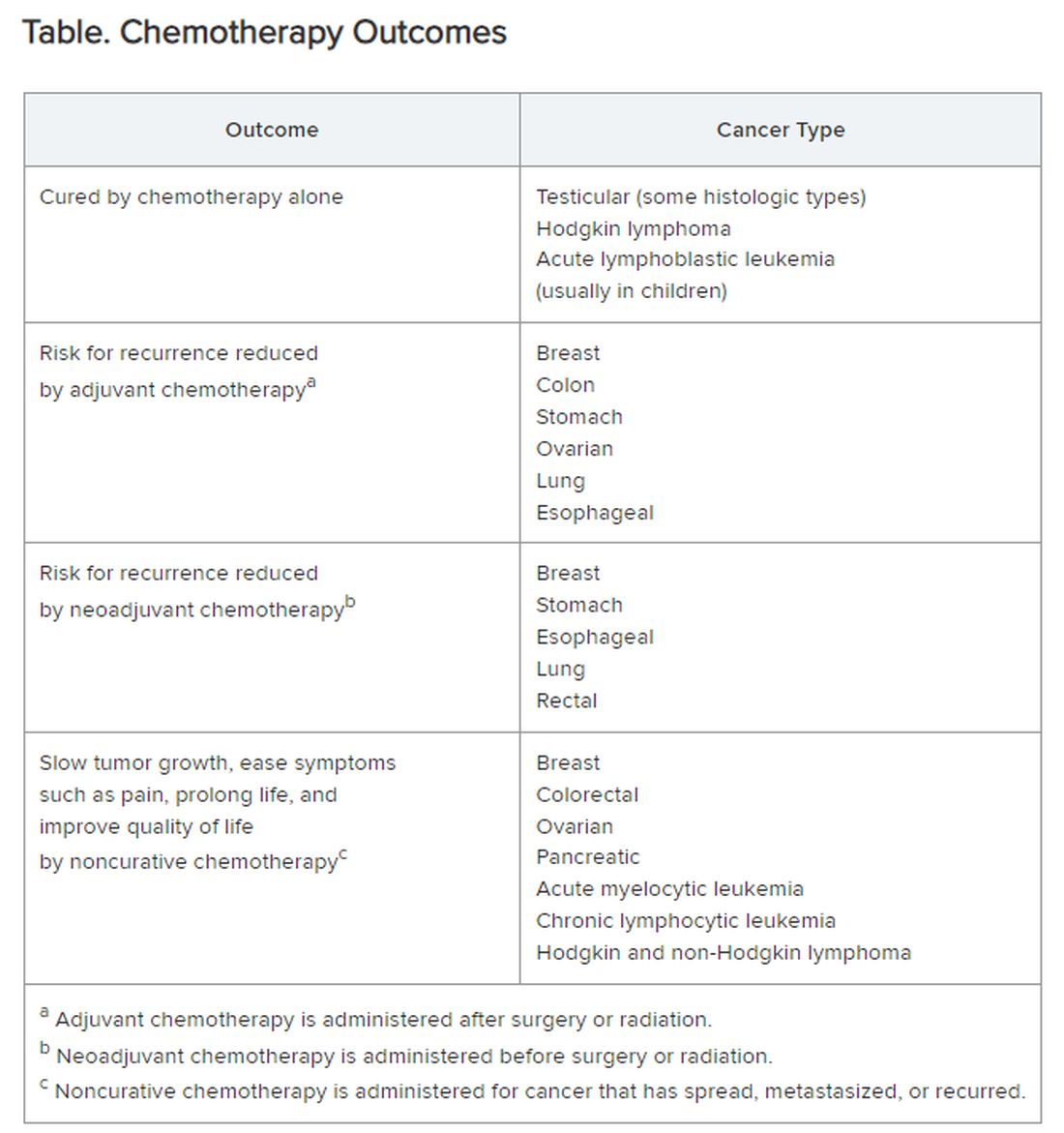

Chemotherapy alone can cure a small number of cancer types. When added to radiation or surgery, chemotherapy can help to cure a wider range of cancer types. As an add-on, chemotherapy can extend the length and quality of life for many patients with cancer. Since chemotherapy is by definition “toxic,” it can also shorten the duration or harm the quality of life and provide false hope. The Table summarizes what chemotherapy can and cannot achieve in selected cancer types.

Careful, compassionate communication between patient and physician is key. Goals and expectations must be clearly understood.

Organized chemotherapeutic efforts are further categorized as first line, second line, and third line.

First-line treatment. The initial round of recommended chemotherapy for a specific cancer. It is typically considered the most effective treatment for that type and stage of cancer on the basis of current research and clinical trials.

Second-line treatment. This is the treatment used if the first-line chemotherapy doesn’t work as desired. Reasons to switch to second-line chemo include:

- Lack of response (the tumor failed to shrink).

- Progression (the cancer may have grown or spread further).

- Adverse side effects were too severe to continue.

The drugs used in second-line chemo will typically be different from those used in first line, sometimes because cancer cells can develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs over time. Moreover, the goal of second-line chemo may differ from that of first-line therapy. Rather than chiefly aiming for a cure, second-line treatment might focus on slowing cancer growth, managing symptoms, or improving quality of life. Unfortunately, not every type of cancer has a readily available second-line option.

Third-line treatment. Third-line options come into play when both the initial course of chemo (first line) and the subsequent treatment (second line) have failed to achieve remission or control the cancer’s spread. Owing to the progressive nature of advanced cancers, patients might not be eligible or healthy enough for third-line therapy. Depending on cancer type, the patient’s general health, and response to previous treatments, third-line options could include:

- New or different chemotherapy drugs compared with prior lines.

- Surgery to debulk the tumor.

- Radiation for symptom control.

- Targeted therapy: drugs designed to target specific vulnerabilities in cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy: agents that help the body’s immune system fight cancer cells.

- Clinical trials testing new or investigational treatments, which may be applicable at any time, depending on the questions being addressed.

The goals of third-line therapy may shift from aiming for a cure to managing symptoms, improving quality of life, and potentially slowing cancer growth. The decision to pursue third-line therapy involves careful consideration by the doctor and patient, weighing the potential benefits and risks of treatment considering the individual’s overall health and specific situation.

It’s important to have realistic expectations about the potential outcomes of third-line therapy. Although remission may be unlikely, third-line therapy can still play a role in managing the disease.

Navigating advanced cancer treatment is very complex. The patient and physician must together consider detailed explanations and clarifications to set expectations and make informed decisions about care.

Interventions to Consider Earlier

In traditional clinical oncology practice, other interventions are possible, but these may not be offered until treatment has reached the third line:

- Molecular testing.

- Palliation.

- Clinical trials.

- Innovative testing to guide targeted therapy by ascertaining which agents are most likely (or not likely at all) to be effective.

I would argue that the patient’s interests are better served by considering and offering these other interventions much earlier, even before starting first-line chemotherapy.

Molecular testing. The best time for molecular testing of a new malignant tumor is typically at the time of diagnosis. Here’s why:

- Molecular testing helps identify specific genetic mutations in the cancer cells. This information can be crucial for selecting targeted therapies that are most effective against those specific mutations. Early detection allows for the most treatment options. For example, for non–small cell lung cancer, early is best because treatment and outcomes may well be changed by test results.

- Knowing the tumor’s molecular makeup can help determine whether a patient qualifies for clinical trials of new drugs designed for specific mutations.

- Some molecular markers can offer information about the tumor’s aggressiveness and potential for metastasis so that prognosis can be informed.

Molecular testing can be a valuable tool throughout a cancer patient’s journey. With genetically diverse tumors, the initial biopsy might not capture the full picture. Molecular testing of circulating tumor DNA can be used to monitor a patient’s response to treatment and detect potential mutations that might arise during treatment resistance. Retesting after metastasis can provide additional information that can aid in treatment decisions.

Palliative care. The ideal time to discuss palliative care with a patient with cancer is early in the diagnosis and treatment process. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care; it isn’t just about end-of-life. Palliative care focuses on improving a patient’s quality of life throughout cancer treatment. Palliative care specialists can address a wide range of symptoms a patient might experience from cancer or its treatment, including pain, fatigue, nausea, and anxiety.

Early discussions allow for a more comprehensive care plan. Open communication about all treatment options, including palliative care, empowers patients to make informed decisions about their care goals and preferences.

Specific situations where discussing palliative care might be appropriate are:

- Soon after a cancer diagnosis.

- If the patient experiences significant side effects from cancer treatment.

- When considering different treatment options, palliative care can complement those treatments.

- In advanced stages of cancer, to focus on comfort and quality of life.

Clinical trials. Participation in a clinical trial to explore new or investigational treatments should always be considered.

In theory, clinical trials should be an option at any time in the patient’s course. But the organized clinical trial experience may not be available or appropriate. Then, the individual becomes a de facto “clinical trial with an n of 1.” Read this brief open-access blog post at Cancer Commons to learn more about that circumstance.

Innovative testing. The best choice of chemotherapeutic or targeted therapies is often unclear. The clinician is likely to follow published guidelines, often from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

These are evidence based and driven by consensus of experts. But guideline-recommended therapy is not always effective, and weeks or months can pass before this ineffectiveness becomes apparent. Thus, many researchers and companies are seeking methods of testing each patient’s specific cancer to determine in advance, or very quickly, whether a particular drug is likely to be effective.

Read more about these leading innovations:

SAGE Oncotest: Entering the Next Generation of Tailored Cancer Treatment

Alibrex: A New Blood Test to Reveal Whether a Cancer Treatment is Working

PARIS Test Uses Lab-Grown Mini-Tumors to Find a Patient’s Best Treatment

Using Live Cells from Patients to Find the Right Cancer Drug

Other innovative therapies under investigation could even be agnostic to cancer type:

Treating Pancreatic Cancer: Could Metabolism — Not Genomics — Be the Key?

High-Energy Blue Light Powers a Promising New Treatment to Destroy Cancer Cells

All-Clear Follow-Up: Hydrogen Peroxide Appears to Treat Oral and Skin Lesions

Cancer is a tough nut to crack. Many people and organizations are trying very hard. So much is being learned. Some approaches will be effective. We can all hope.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief, Cancer Commons, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The remaining 700,000 or so often proceed to chemotherapy either immediately or upon cancer recurrence, spread, or newly recognized metastases. “Cures” after that point are rare.

I’m speaking in generalities, understanding that each cancer and each patient is unique.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy alone can cure a small number of cancer types. When added to radiation or surgery, chemotherapy can help to cure a wider range of cancer types. As an add-on, chemotherapy can extend the length and quality of life for many patients with cancer. Since chemotherapy is by definition “toxic,” it can also shorten the duration or harm the quality of life and provide false hope. The Table summarizes what chemotherapy can and cannot achieve in selected cancer types.

Careful, compassionate communication between patient and physician is key. Goals and expectations must be clearly understood.

Organized chemotherapeutic efforts are further categorized as first line, second line, and third line.

First-line treatment. The initial round of recommended chemotherapy for a specific cancer. It is typically considered the most effective treatment for that type and stage of cancer on the basis of current research and clinical trials.

Second-line treatment. This is the treatment used if the first-line chemotherapy doesn’t work as desired. Reasons to switch to second-line chemo include:

- Lack of response (the tumor failed to shrink).

- Progression (the cancer may have grown or spread further).

- Adverse side effects were too severe to continue.

The drugs used in second-line chemo will typically be different from those used in first line, sometimes because cancer cells can develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs over time. Moreover, the goal of second-line chemo may differ from that of first-line therapy. Rather than chiefly aiming for a cure, second-line treatment might focus on slowing cancer growth, managing symptoms, or improving quality of life. Unfortunately, not every type of cancer has a readily available second-line option.

Third-line treatment. Third-line options come into play when both the initial course of chemo (first line) and the subsequent treatment (second line) have failed to achieve remission or control the cancer’s spread. Owing to the progressive nature of advanced cancers, patients might not be eligible or healthy enough for third-line therapy. Depending on cancer type, the patient’s general health, and response to previous treatments, third-line options could include:

- New or different chemotherapy drugs compared with prior lines.

- Surgery to debulk the tumor.

- Radiation for symptom control.

- Targeted therapy: drugs designed to target specific vulnerabilities in cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy: agents that help the body’s immune system fight cancer cells.

- Clinical trials testing new or investigational treatments, which may be applicable at any time, depending on the questions being addressed.

The goals of third-line therapy may shift from aiming for a cure to managing symptoms, improving quality of life, and potentially slowing cancer growth. The decision to pursue third-line therapy involves careful consideration by the doctor and patient, weighing the potential benefits and risks of treatment considering the individual’s overall health and specific situation.

It’s important to have realistic expectations about the potential outcomes of third-line therapy. Although remission may be unlikely, third-line therapy can still play a role in managing the disease.

Navigating advanced cancer treatment is very complex. The patient and physician must together consider detailed explanations and clarifications to set expectations and make informed decisions about care.

Interventions to Consider Earlier

In traditional clinical oncology practice, other interventions are possible, but these may not be offered until treatment has reached the third line:

- Molecular testing.

- Palliation.

- Clinical trials.

- Innovative testing to guide targeted therapy by ascertaining which agents are most likely (or not likely at all) to be effective.

I would argue that the patient’s interests are better served by considering and offering these other interventions much earlier, even before starting first-line chemotherapy.

Molecular testing. The best time for molecular testing of a new malignant tumor is typically at the time of diagnosis. Here’s why:

- Molecular testing helps identify specific genetic mutations in the cancer cells. This information can be crucial for selecting targeted therapies that are most effective against those specific mutations. Early detection allows for the most treatment options. For example, for non–small cell lung cancer, early is best because treatment and outcomes may well be changed by test results.

- Knowing the tumor’s molecular makeup can help determine whether a patient qualifies for clinical trials of new drugs designed for specific mutations.

- Some molecular markers can offer information about the tumor’s aggressiveness and potential for metastasis so that prognosis can be informed.

Molecular testing can be a valuable tool throughout a cancer patient’s journey. With genetically diverse tumors, the initial biopsy might not capture the full picture. Molecular testing of circulating tumor DNA can be used to monitor a patient’s response to treatment and detect potential mutations that might arise during treatment resistance. Retesting after metastasis can provide additional information that can aid in treatment decisions.

Palliative care. The ideal time to discuss palliative care with a patient with cancer is early in the diagnosis and treatment process. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care; it isn’t just about end-of-life. Palliative care focuses on improving a patient’s quality of life throughout cancer treatment. Palliative care specialists can address a wide range of symptoms a patient might experience from cancer or its treatment, including pain, fatigue, nausea, and anxiety.

Early discussions allow for a more comprehensive care plan. Open communication about all treatment options, including palliative care, empowers patients to make informed decisions about their care goals and preferences.

Specific situations where discussing palliative care might be appropriate are:

- Soon after a cancer diagnosis.

- If the patient experiences significant side effects from cancer treatment.

- When considering different treatment options, palliative care can complement those treatments.

- In advanced stages of cancer, to focus on comfort and quality of life.

Clinical trials. Participation in a clinical trial to explore new or investigational treatments should always be considered.

In theory, clinical trials should be an option at any time in the patient’s course. But the organized clinical trial experience may not be available or appropriate. Then, the individual becomes a de facto “clinical trial with an n of 1.” Read this brief open-access blog post at Cancer Commons to learn more about that circumstance.

Innovative testing. The best choice of chemotherapeutic or targeted therapies is often unclear. The clinician is likely to follow published guidelines, often from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

These are evidence based and driven by consensus of experts. But guideline-recommended therapy is not always effective, and weeks or months can pass before this ineffectiveness becomes apparent. Thus, many researchers and companies are seeking methods of testing each patient’s specific cancer to determine in advance, or very quickly, whether a particular drug is likely to be effective.

Read more about these leading innovations:

SAGE Oncotest: Entering the Next Generation of Tailored Cancer Treatment

Alibrex: A New Blood Test to Reveal Whether a Cancer Treatment is Working

PARIS Test Uses Lab-Grown Mini-Tumors to Find a Patient’s Best Treatment

Using Live Cells from Patients to Find the Right Cancer Drug

Other innovative therapies under investigation could even be agnostic to cancer type:

Treating Pancreatic Cancer: Could Metabolism — Not Genomics — Be the Key?

High-Energy Blue Light Powers a Promising New Treatment to Destroy Cancer Cells

All-Clear Follow-Up: Hydrogen Peroxide Appears to Treat Oral and Skin Lesions

Cancer is a tough nut to crack. Many people and organizations are trying very hard. So much is being learned. Some approaches will be effective. We can all hope.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief, Cancer Commons, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The remaining 700,000 or so often proceed to chemotherapy either immediately or upon cancer recurrence, spread, or newly recognized metastases. “Cures” after that point are rare.

I’m speaking in generalities, understanding that each cancer and each patient is unique.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy alone can cure a small number of cancer types. When added to radiation or surgery, chemotherapy can help to cure a wider range of cancer types. As an add-on, chemotherapy can extend the length and quality of life for many patients with cancer. Since chemotherapy is by definition “toxic,” it can also shorten the duration or harm the quality of life and provide false hope. The Table summarizes what chemotherapy can and cannot achieve in selected cancer types.

Careful, compassionate communication between patient and physician is key. Goals and expectations must be clearly understood.

Organized chemotherapeutic efforts are further categorized as first line, second line, and third line.

First-line treatment. The initial round of recommended chemotherapy for a specific cancer. It is typically considered the most effective treatment for that type and stage of cancer on the basis of current research and clinical trials.

Second-line treatment. This is the treatment used if the first-line chemotherapy doesn’t work as desired. Reasons to switch to second-line chemo include:

- Lack of response (the tumor failed to shrink).

- Progression (the cancer may have grown or spread further).

- Adverse side effects were too severe to continue.

The drugs used in second-line chemo will typically be different from those used in first line, sometimes because cancer cells can develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs over time. Moreover, the goal of second-line chemo may differ from that of first-line therapy. Rather than chiefly aiming for a cure, second-line treatment might focus on slowing cancer growth, managing symptoms, or improving quality of life. Unfortunately, not every type of cancer has a readily available second-line option.

Third-line treatment. Third-line options come into play when both the initial course of chemo (first line) and the subsequent treatment (second line) have failed to achieve remission or control the cancer’s spread. Owing to the progressive nature of advanced cancers, patients might not be eligible or healthy enough for third-line therapy. Depending on cancer type, the patient’s general health, and response to previous treatments, third-line options could include:

- New or different chemotherapy drugs compared with prior lines.

- Surgery to debulk the tumor.

- Radiation for symptom control.

- Targeted therapy: drugs designed to target specific vulnerabilities in cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy: agents that help the body’s immune system fight cancer cells.

- Clinical trials testing new or investigational treatments, which may be applicable at any time, depending on the questions being addressed.

The goals of third-line therapy may shift from aiming for a cure to managing symptoms, improving quality of life, and potentially slowing cancer growth. The decision to pursue third-line therapy involves careful consideration by the doctor and patient, weighing the potential benefits and risks of treatment considering the individual’s overall health and specific situation.

It’s important to have realistic expectations about the potential outcomes of third-line therapy. Although remission may be unlikely, third-line therapy can still play a role in managing the disease.

Navigating advanced cancer treatment is very complex. The patient and physician must together consider detailed explanations and clarifications to set expectations and make informed decisions about care.

Interventions to Consider Earlier

In traditional clinical oncology practice, other interventions are possible, but these may not be offered until treatment has reached the third line:

- Molecular testing.

- Palliation.

- Clinical trials.

- Innovative testing to guide targeted therapy by ascertaining which agents are most likely (or not likely at all) to be effective.

I would argue that the patient’s interests are better served by considering and offering these other interventions much earlier, even before starting first-line chemotherapy.

Molecular testing. The best time for molecular testing of a new malignant tumor is typically at the time of diagnosis. Here’s why:

- Molecular testing helps identify specific genetic mutations in the cancer cells. This information can be crucial for selecting targeted therapies that are most effective against those specific mutations. Early detection allows for the most treatment options. For example, for non–small cell lung cancer, early is best because treatment and outcomes may well be changed by test results.

- Knowing the tumor’s molecular makeup can help determine whether a patient qualifies for clinical trials of new drugs designed for specific mutations.

- Some molecular markers can offer information about the tumor’s aggressiveness and potential for metastasis so that prognosis can be informed.

Molecular testing can be a valuable tool throughout a cancer patient’s journey. With genetically diverse tumors, the initial biopsy might not capture the full picture. Molecular testing of circulating tumor DNA can be used to monitor a patient’s response to treatment and detect potential mutations that might arise during treatment resistance. Retesting after metastasis can provide additional information that can aid in treatment decisions.

Palliative care. The ideal time to discuss palliative care with a patient with cancer is early in the diagnosis and treatment process. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care; it isn’t just about end-of-life. Palliative care focuses on improving a patient’s quality of life throughout cancer treatment. Palliative care specialists can address a wide range of symptoms a patient might experience from cancer or its treatment, including pain, fatigue, nausea, and anxiety.

Early discussions allow for a more comprehensive care plan. Open communication about all treatment options, including palliative care, empowers patients to make informed decisions about their care goals and preferences.

Specific situations where discussing palliative care might be appropriate are:

- Soon after a cancer diagnosis.

- If the patient experiences significant side effects from cancer treatment.

- When considering different treatment options, palliative care can complement those treatments.

- In advanced stages of cancer, to focus on comfort and quality of life.

Clinical trials. Participation in a clinical trial to explore new or investigational treatments should always be considered.

In theory, clinical trials should be an option at any time in the patient’s course. But the organized clinical trial experience may not be available or appropriate. Then, the individual becomes a de facto “clinical trial with an n of 1.” Read this brief open-access blog post at Cancer Commons to learn more about that circumstance.

Innovative testing. The best choice of chemotherapeutic or targeted therapies is often unclear. The clinician is likely to follow published guidelines, often from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

These are evidence based and driven by consensus of experts. But guideline-recommended therapy is not always effective, and weeks or months can pass before this ineffectiveness becomes apparent. Thus, many researchers and companies are seeking methods of testing each patient’s specific cancer to determine in advance, or very quickly, whether a particular drug is likely to be effective.

Read more about these leading innovations:

SAGE Oncotest: Entering the Next Generation of Tailored Cancer Treatment

Alibrex: A New Blood Test to Reveal Whether a Cancer Treatment is Working

PARIS Test Uses Lab-Grown Mini-Tumors to Find a Patient’s Best Treatment

Using Live Cells from Patients to Find the Right Cancer Drug

Other innovative therapies under investigation could even be agnostic to cancer type:

Treating Pancreatic Cancer: Could Metabolism — Not Genomics — Be the Key?

High-Energy Blue Light Powers a Promising New Treatment to Destroy Cancer Cells

All-Clear Follow-Up: Hydrogen Peroxide Appears to Treat Oral and Skin Lesions

Cancer is a tough nut to crack. Many people and organizations are trying very hard. So much is being learned. Some approaches will be effective. We can all hope.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief, Cancer Commons, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

You Can’t Spell ‘Medicine’ Without D, E, and I

Please note that this is a commentary, an opinion piece: my opinion. The statements here do not necessarily represent those of this news organization or any of the myriad people or institutions that comprise this corner of the human universe.

Some days, speaking as a long-time physician and editor, I wish that there were no such things as race or ethnicity or even geographic origin for that matter. We can’t get away from sex, gender, disability, age, or culture. I’m not sure about religion. I wish people were just people.

But race is deeply embedded in the American experience — an almost invisible but inevitable presence in all of our thoughts and expressions about human activities.

In medical education (for eons it seems) the student has been taught to mention race in the first sentence of a given patient presentation, along with age and sex. In human epidemiologic research, race is almost always a studied variable. In clinical and basic medical research, looking at the impact of race on this, that, or the other is commonplace. “Mixed race not otherwise specified” is ubiquitous in the United States yet blithely ignored by most who tally these statistics. Race is rarely gene-specific. It is more of a social and cultural construct but with plainly visible overt phenotypic markers — an almost infinite mix of daily reality.

Our country, and much of Western civilization in 2024, is based on the principle that all men are created equal, although the originators of that notion were unaware of their own “equity-challenged” situation.

Many organizations, in and out of government, are now understanding, developing, and implementing programs (and thought/language patterns) to socialize diversity, equity, and inclusion (known as DEI) into their culture. It should not be surprising that many who prefer the status quo are not happy with the pressure from this movement and are using whatever methods are available to them to prevent full DEI. Such it always is.

The trusty Copilot from Bing provides these definitions:

- Diversity refers to the presence of variety within the organizational workforce. This includes aspects such as gender, culture, ethnicity, religion, disability, age, and opinion.

- Equity encompasses concepts of fairness and justice. It involves fair compensation, substantive equality, and addressing societal disparities. Equity also considers unique circumstances and adjusts treatment to achieve equal outcomes.

- Inclusion focuses on creating an organizational culture where all employees feel heard, fostering a sense of belonging and integration.

I am more than proud that my old domain of peer-reviewed, primary source, medical (and science) journals is taking a leading role in this noble, necessary, and long overdue movement for medicine.

As the central repository and transmitter of new medical information, including scientific studies, clinical medicine reports, ethics measures, and education, medical journals (including those deemed prestigious) have historically been among the worst offenders in perpetuating non-DEI objectives in their leadership, staffing, focus, instructions for authors, style manuals, and published materials.

This issue came to a head in March 2021 when a JAMA podcast about racism in American medicine was followed by this promotional tweet: “No physician is racist, so how can there be structural racism in health care?”

Reactions and actions were rapid, strong, and decisive. After an interregnum at JAMA, a new editor in chief, Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, PhD, MD, MAS, was named. She and her large staff of editors and editorial board members from the multijournal JAMA Network joined a worldwide movement of (currently) 56 publishing organizations representing 15,000 journals called the Joint Commitment for Action on Inclusion and Diversity in Publishing.

A recent JAMA editorial with 29 authors describes the entire commitment initiative of publishers-editors. It reports JAMA Network data from 2023 and 2024 from surveys of 455 editors (a 91% response rate) about their own gender (five choices), ethnic origins or geographic ancestry (13 choices), and race (eight choices), demonstrating considerable progress toward DEI goals. The survey’s complex multinational classifications may not jibe with the categorizations used in some countries (too bad that “mixed” is not “mixed in” — a missed opportunity).

This encouraging movement will not fix it all. But when people of certain groups are represented at the table, that point of view is far more likely to make it into the lexicon, language, and omnipresent work products, potentially changing cultural norms. Even the measurement of movement related to disparity in healthcare is marred by frequent variations of data accuracy. More consistency in what to measure can help a lot, and the medical literature can be very influential.

A personal anecdote: When I was a professor at UC Davis in 1978, Allan Bakke, MD, was my student. Some of you will remember the saga of affirmative action on admissions, which was just revisited in the light of a recent decision by the US Supreme Court.

Back in 1978, the dean at UC Davis told me that he kept two file folders on the admission processes in different desk drawers. One categorized all applicants and enrollees by race, and the other did not. Depending on who came to visit and ask questions, he would choose one or the other file to share once he figured out what they were looking for (this is not a joke).

The strength of the current active political pushback against the entire DEI movement has deep roots and should not be underestimated. There will be a lot of to-ing and fro-ing.

French writer Victor Hugo is credited with stating, “There is nothing as powerful as an idea whose time has come.” A majority of Americans, physicians, and other healthcare professionals believe in basic fairness. The time for DEI in all aspects of medicine is now.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief of Cancer Commons, disclosed having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Please note that this is a commentary, an opinion piece: my opinion. The statements here do not necessarily represent those of this news organization or any of the myriad people or institutions that comprise this corner of the human universe.

Some days, speaking as a long-time physician and editor, I wish that there were no such things as race or ethnicity or even geographic origin for that matter. We can’t get away from sex, gender, disability, age, or culture. I’m not sure about religion. I wish people were just people.

But race is deeply embedded in the American experience — an almost invisible but inevitable presence in all of our thoughts and expressions about human activities.

In medical education (for eons it seems) the student has been taught to mention race in the first sentence of a given patient presentation, along with age and sex. In human epidemiologic research, race is almost always a studied variable. In clinical and basic medical research, looking at the impact of race on this, that, or the other is commonplace. “Mixed race not otherwise specified” is ubiquitous in the United States yet blithely ignored by most who tally these statistics. Race is rarely gene-specific. It is more of a social and cultural construct but with plainly visible overt phenotypic markers — an almost infinite mix of daily reality.

Our country, and much of Western civilization in 2024, is based on the principle that all men are created equal, although the originators of that notion were unaware of their own “equity-challenged” situation.

Many organizations, in and out of government, are now understanding, developing, and implementing programs (and thought/language patterns) to socialize diversity, equity, and inclusion (known as DEI) into their culture. It should not be surprising that many who prefer the status quo are not happy with the pressure from this movement and are using whatever methods are available to them to prevent full DEI. Such it always is.

The trusty Copilot from Bing provides these definitions:

- Diversity refers to the presence of variety within the organizational workforce. This includes aspects such as gender, culture, ethnicity, religion, disability, age, and opinion.

- Equity encompasses concepts of fairness and justice. It involves fair compensation, substantive equality, and addressing societal disparities. Equity also considers unique circumstances and adjusts treatment to achieve equal outcomes.

- Inclusion focuses on creating an organizational culture where all employees feel heard, fostering a sense of belonging and integration.

I am more than proud that my old domain of peer-reviewed, primary source, medical (and science) journals is taking a leading role in this noble, necessary, and long overdue movement for medicine.

As the central repository and transmitter of new medical information, including scientific studies, clinical medicine reports, ethics measures, and education, medical journals (including those deemed prestigious) have historically been among the worst offenders in perpetuating non-DEI objectives in their leadership, staffing, focus, instructions for authors, style manuals, and published materials.

This issue came to a head in March 2021 when a JAMA podcast about racism in American medicine was followed by this promotional tweet: “No physician is racist, so how can there be structural racism in health care?”

Reactions and actions were rapid, strong, and decisive. After an interregnum at JAMA, a new editor in chief, Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, PhD, MD, MAS, was named. She and her large staff of editors and editorial board members from the multijournal JAMA Network joined a worldwide movement of (currently) 56 publishing organizations representing 15,000 journals called the Joint Commitment for Action on Inclusion and Diversity in Publishing.

A recent JAMA editorial with 29 authors describes the entire commitment initiative of publishers-editors. It reports JAMA Network data from 2023 and 2024 from surveys of 455 editors (a 91% response rate) about their own gender (five choices), ethnic origins or geographic ancestry (13 choices), and race (eight choices), demonstrating considerable progress toward DEI goals. The survey’s complex multinational classifications may not jibe with the categorizations used in some countries (too bad that “mixed” is not “mixed in” — a missed opportunity).

This encouraging movement will not fix it all. But when people of certain groups are represented at the table, that point of view is far more likely to make it into the lexicon, language, and omnipresent work products, potentially changing cultural norms. Even the measurement of movement related to disparity in healthcare is marred by frequent variations of data accuracy. More consistency in what to measure can help a lot, and the medical literature can be very influential.

A personal anecdote: When I was a professor at UC Davis in 1978, Allan Bakke, MD, was my student. Some of you will remember the saga of affirmative action on admissions, which was just revisited in the light of a recent decision by the US Supreme Court.

Back in 1978, the dean at UC Davis told me that he kept two file folders on the admission processes in different desk drawers. One categorized all applicants and enrollees by race, and the other did not. Depending on who came to visit and ask questions, he would choose one or the other file to share once he figured out what they were looking for (this is not a joke).

The strength of the current active political pushback against the entire DEI movement has deep roots and should not be underestimated. There will be a lot of to-ing and fro-ing.

French writer Victor Hugo is credited with stating, “There is nothing as powerful as an idea whose time has come.” A majority of Americans, physicians, and other healthcare professionals believe in basic fairness. The time for DEI in all aspects of medicine is now.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief of Cancer Commons, disclosed having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Please note that this is a commentary, an opinion piece: my opinion. The statements here do not necessarily represent those of this news organization or any of the myriad people or institutions that comprise this corner of the human universe.

Some days, speaking as a long-time physician and editor, I wish that there were no such things as race or ethnicity or even geographic origin for that matter. We can’t get away from sex, gender, disability, age, or culture. I’m not sure about religion. I wish people were just people.

But race is deeply embedded in the American experience — an almost invisible but inevitable presence in all of our thoughts and expressions about human activities.

In medical education (for eons it seems) the student has been taught to mention race in the first sentence of a given patient presentation, along with age and sex. In human epidemiologic research, race is almost always a studied variable. In clinical and basic medical research, looking at the impact of race on this, that, or the other is commonplace. “Mixed race not otherwise specified” is ubiquitous in the United States yet blithely ignored by most who tally these statistics. Race is rarely gene-specific. It is more of a social and cultural construct but with plainly visible overt phenotypic markers — an almost infinite mix of daily reality.

Our country, and much of Western civilization in 2024, is based on the principle that all men are created equal, although the originators of that notion were unaware of their own “equity-challenged” situation.

Many organizations, in and out of government, are now understanding, developing, and implementing programs (and thought/language patterns) to socialize diversity, equity, and inclusion (known as DEI) into their culture. It should not be surprising that many who prefer the status quo are not happy with the pressure from this movement and are using whatever methods are available to them to prevent full DEI. Such it always is.

The trusty Copilot from Bing provides these definitions:

- Diversity refers to the presence of variety within the organizational workforce. This includes aspects such as gender, culture, ethnicity, religion, disability, age, and opinion.

- Equity encompasses concepts of fairness and justice. It involves fair compensation, substantive equality, and addressing societal disparities. Equity also considers unique circumstances and adjusts treatment to achieve equal outcomes.

- Inclusion focuses on creating an organizational culture where all employees feel heard, fostering a sense of belonging and integration.

I am more than proud that my old domain of peer-reviewed, primary source, medical (and science) journals is taking a leading role in this noble, necessary, and long overdue movement for medicine.

As the central repository and transmitter of new medical information, including scientific studies, clinical medicine reports, ethics measures, and education, medical journals (including those deemed prestigious) have historically been among the worst offenders in perpetuating non-DEI objectives in their leadership, staffing, focus, instructions for authors, style manuals, and published materials.

This issue came to a head in March 2021 when a JAMA podcast about racism in American medicine was followed by this promotional tweet: “No physician is racist, so how can there be structural racism in health care?”

Reactions and actions were rapid, strong, and decisive. After an interregnum at JAMA, a new editor in chief, Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, PhD, MD, MAS, was named. She and her large staff of editors and editorial board members from the multijournal JAMA Network joined a worldwide movement of (currently) 56 publishing organizations representing 15,000 journals called the Joint Commitment for Action on Inclusion and Diversity in Publishing.

A recent JAMA editorial with 29 authors describes the entire commitment initiative of publishers-editors. It reports JAMA Network data from 2023 and 2024 from surveys of 455 editors (a 91% response rate) about their own gender (five choices), ethnic origins or geographic ancestry (13 choices), and race (eight choices), demonstrating considerable progress toward DEI goals. The survey’s complex multinational classifications may not jibe with the categorizations used in some countries (too bad that “mixed” is not “mixed in” — a missed opportunity).

This encouraging movement will not fix it all. But when people of certain groups are represented at the table, that point of view is far more likely to make it into the lexicon, language, and omnipresent work products, potentially changing cultural norms. Even the measurement of movement related to disparity in healthcare is marred by frequent variations of data accuracy. More consistency in what to measure can help a lot, and the medical literature can be very influential.

A personal anecdote: When I was a professor at UC Davis in 1978, Allan Bakke, MD, was my student. Some of you will remember the saga of affirmative action on admissions, which was just revisited in the light of a recent decision by the US Supreme Court.

Back in 1978, the dean at UC Davis told me that he kept two file folders on the admission processes in different desk drawers. One categorized all applicants and enrollees by race, and the other did not. Depending on who came to visit and ask questions, he would choose one or the other file to share once he figured out what they were looking for (this is not a joke).

The strength of the current active political pushback against the entire DEI movement has deep roots and should not be underestimated. There will be a lot of to-ing and fro-ing.

French writer Victor Hugo is credited with stating, “There is nothing as powerful as an idea whose time has come.” A majority of Americans, physicians, and other healthcare professionals believe in basic fairness. The time for DEI in all aspects of medicine is now.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief of Cancer Commons, disclosed having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Long COVID: Another Great Pretender

Has COVID replaced syphilis as the great imitator? At the turn of the 20th century, Sir William Osler was quoted as saying, “He who knows syphilis knows medicine.”

If you have any doubts about the “imitator” analogy, simply use any broad search engine or AI portal and enter “what is the differential diagnosis of primary syphilis, or secondary syphilis, or tertiary syphilis?” A plethora of diseases across many body systems appears.

Another Great Pretender?

Did you or do you now have long COVID? How do you know? Do you even know what long COVID is? How would you diagnosis it?

When asked about long COVID, this is what large language model source bard.google.com had to say:

Long COVID, also known as post-COVID conditions or PASC, is a complex condition that can occur in people who have had COVID-19, even if their initial illness was mild or even asymptomatic. It’s characterized by a wide range of symptoms that can last for weeks, months, or even years after the initial infection.

Symptoms of long COVID can include: fatigue, shortness of breath, brain fog (trouble thinking or concentrating), loss of smell or taste, sleep problems, muscle pain, joint pain, headache, dizziness, depression or anxiety, heart palpitations, gastrointestinal problems.

Duh!!! It reads much like a continuation of the symptoms of acute COVID. Bard continued:

The exact cause of long COVID is still unknown, but there are several theories. One possibility is that the virus itself can damage organs and tissues, leading to ongoing symptoms. Another possibility is that the immune system’s response to the virus can continue to cause inflammation even after the virus is gone.

Human intelligence source Wikipedia says this:

Long COVID or long-haul COVID is a group of health problems persisting or developing after an initial COVID-19 infection. Symptoms can last weeks, months or years and are often debilitating. The World Health Organization defines long COVID as starting three months after infection, but other definitions put the start of long COVID at four weeks.

Highly varied, including post-exertional malaise (symptoms made worse with effort), fatigue, muscle pain, shortness of breath, chest pain, and cognitive dysfunction (brain fog).

Acute COVID to Long COVID

The World Health Organization estimates that 36 million people in the European region have developed long COVID in the first 3 years of the pandemic. That›s a lot.

We all know that the common signs and symptoms of acute COVID-19 include fever or chills, a dry cough and shortness of breath, feeling very tired, muscle or body aches, headache, loss of taste or smell, sore throat, congestion, runny nose, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Except for the taste and smell findings, every one of these symptoms or signs could indicate a different virus infection or even some type of allergy. My point is the nonspecificity in this list.

Uncommon signs and symptoms of acute COVID include a flat skin rash covered with small bumps, discolored swollen areas on the fingers and toes (COVID toes), and hives. The skin of hands, wrists, or ankles also can be affected. Blisters, itchiness, rough skin, or pus can be seen.

Severe confusion (delirium) might be the main or only symptom of COVID-19 in older people. This COVID-19 symptom is linked with a high risk for poor outcomes, including death. Pink eye (conjunctivitis) can be a COVID-19 symptom. Other eye problems linked to COVID-19 are light sensitivity, sore eyes, and itchy eyes. Acute myocarditis, tinnitus, vertigo, and hearing loss have been reported. And 1-4 weeks after the onset of COVID-19 infection, a patient may experience de novo reactive synovitis and arthritis of any joints.

So, take your pick. Myriad symptoms, signs, diseases, diagnoses, and organ systems — still present, recurring, just appearing, apparently de novo, or after asymptomatic infection. We have so much still to learn.

What big-time symptoms, signs, and major diseases are not on any of these lists? Obviously, cancer, atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases, obesity, bone diseases, and competitive infections. But be patient; the lingering effects of direct tissue invasion by the virus as well as a wide range of immunologic reactions may just be getting started. Mitochondrial damage, especially in muscles, is increasingly a pathophysiologic suspect.

Human diseases can be physical or mental; and in COVID, that twain not only meet but mix and mingle freely, and may even merge into psychosoma. Don’t ever forget that. Consider “fatigue.” Who among us, COVID or NOVID, does not experience that from time to time?

Or consider brain fog as a common reported symptom of COVID. What on earth is that actually? How can a person know they have brain fog, or whether they had it and are over it?

We need one or more lab or other diagnostic tests that can objectively confirm the diagnosis of long COVID.

Useful Progress?

A recent research paper in Science reported intriguing chemical findings that seemed to point a finger at some form of complement dysregulation as a potential disease marker for long COVID. Unfortunately, some critics have pointed out that this entire study may be invalid or irrelevant because the New York cohort was recruited in 2020, before vaccines were available. The Zurich cohort was recruited up until April 2021, so some may have been vaccinated.

Then this news organization came along in early January 2024 with an article about COVID causing not only more than a million American deaths but also more than 5000 deaths from long COVID. We physicians don’t really know what long COVID even is, but we have to sign death certificates blaming thousands of deaths on it anyway? And rolling back the clock to 2020: Are patients dying from COVID or with COVID, according to death certificates?Now, armed with the knowledge that “documented serious post–COVID-19 conditions include cardiovascular, pulmonary, neurological, renal, endocrine, hematological, and gastrointestinal complications, as well as death,” CDC has published clear and fairly concise instructions on how to address post-acute COVID sequelae on death certificates.

In late January, this news organization painted a hopeful picture by naming four phenotypes of long COVID, suggesting that such divisions might further our understanding, including prognosis, and even therapy for this condition. Among the clinical phenotypes of (1) chronic fatigue–like syndrome, headache, and memory loss; (2) respiratory syndrome (which includes cough and difficulty breathing); (3) chronic pain; and (4) neurosensorial syndrome (which causes an altered sense of taste and smell), overlap is clearly possible but isn›t addressed.

I see these recent developments as needed and useful progress, but we are still left with…not much. So, when you tell me that you do or do not have long COVID, I will say to you, “How do you know?”

I also say: She/he/they who know COVID know medicine.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Has COVID replaced syphilis as the great imitator? At the turn of the 20th century, Sir William Osler was quoted as saying, “He who knows syphilis knows medicine.”

If you have any doubts about the “imitator” analogy, simply use any broad search engine or AI portal and enter “what is the differential diagnosis of primary syphilis, or secondary syphilis, or tertiary syphilis?” A plethora of diseases across many body systems appears.

Another Great Pretender?

Did you or do you now have long COVID? How do you know? Do you even know what long COVID is? How would you diagnosis it?

When asked about long COVID, this is what large language model source bard.google.com had to say:

Long COVID, also known as post-COVID conditions or PASC, is a complex condition that can occur in people who have had COVID-19, even if their initial illness was mild or even asymptomatic. It’s characterized by a wide range of symptoms that can last for weeks, months, or even years after the initial infection.

Symptoms of long COVID can include: fatigue, shortness of breath, brain fog (trouble thinking or concentrating), loss of smell or taste, sleep problems, muscle pain, joint pain, headache, dizziness, depression or anxiety, heart palpitations, gastrointestinal problems.

Duh!!! It reads much like a continuation of the symptoms of acute COVID. Bard continued:

The exact cause of long COVID is still unknown, but there are several theories. One possibility is that the virus itself can damage organs and tissues, leading to ongoing symptoms. Another possibility is that the immune system’s response to the virus can continue to cause inflammation even after the virus is gone.

Human intelligence source Wikipedia says this:

Long COVID or long-haul COVID is a group of health problems persisting or developing after an initial COVID-19 infection. Symptoms can last weeks, months or years and are often debilitating. The World Health Organization defines long COVID as starting three months after infection, but other definitions put the start of long COVID at four weeks.

Highly varied, including post-exertional malaise (symptoms made worse with effort), fatigue, muscle pain, shortness of breath, chest pain, and cognitive dysfunction (brain fog).

Acute COVID to Long COVID

The World Health Organization estimates that 36 million people in the European region have developed long COVID in the first 3 years of the pandemic. That›s a lot.

We all know that the common signs and symptoms of acute COVID-19 include fever or chills, a dry cough and shortness of breath, feeling very tired, muscle or body aches, headache, loss of taste or smell, sore throat, congestion, runny nose, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Except for the taste and smell findings, every one of these symptoms or signs could indicate a different virus infection or even some type of allergy. My point is the nonspecificity in this list.

Uncommon signs and symptoms of acute COVID include a flat skin rash covered with small bumps, discolored swollen areas on the fingers and toes (COVID toes), and hives. The skin of hands, wrists, or ankles also can be affected. Blisters, itchiness, rough skin, or pus can be seen.

Severe confusion (delirium) might be the main or only symptom of COVID-19 in older people. This COVID-19 symptom is linked with a high risk for poor outcomes, including death. Pink eye (conjunctivitis) can be a COVID-19 symptom. Other eye problems linked to COVID-19 are light sensitivity, sore eyes, and itchy eyes. Acute myocarditis, tinnitus, vertigo, and hearing loss have been reported. And 1-4 weeks after the onset of COVID-19 infection, a patient may experience de novo reactive synovitis and arthritis of any joints.

So, take your pick. Myriad symptoms, signs, diseases, diagnoses, and organ systems — still present, recurring, just appearing, apparently de novo, or after asymptomatic infection. We have so much still to learn.

What big-time symptoms, signs, and major diseases are not on any of these lists? Obviously, cancer, atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases, obesity, bone diseases, and competitive infections. But be patient; the lingering effects of direct tissue invasion by the virus as well as a wide range of immunologic reactions may just be getting started. Mitochondrial damage, especially in muscles, is increasingly a pathophysiologic suspect.

Human diseases can be physical or mental; and in COVID, that twain not only meet but mix and mingle freely, and may even merge into psychosoma. Don’t ever forget that. Consider “fatigue.” Who among us, COVID or NOVID, does not experience that from time to time?

Or consider brain fog as a common reported symptom of COVID. What on earth is that actually? How can a person know they have brain fog, or whether they had it and are over it?

We need one or more lab or other diagnostic tests that can objectively confirm the diagnosis of long COVID.

Useful Progress?

A recent research paper in Science reported intriguing chemical findings that seemed to point a finger at some form of complement dysregulation as a potential disease marker for long COVID. Unfortunately, some critics have pointed out that this entire study may be invalid or irrelevant because the New York cohort was recruited in 2020, before vaccines were available. The Zurich cohort was recruited up until April 2021, so some may have been vaccinated.

Then this news organization came along in early January 2024 with an article about COVID causing not only more than a million American deaths but also more than 5000 deaths from long COVID. We physicians don’t really know what long COVID even is, but we have to sign death certificates blaming thousands of deaths on it anyway? And rolling back the clock to 2020: Are patients dying from COVID or with COVID, according to death certificates?Now, armed with the knowledge that “documented serious post–COVID-19 conditions include cardiovascular, pulmonary, neurological, renal, endocrine, hematological, and gastrointestinal complications, as well as death,” CDC has published clear and fairly concise instructions on how to address post-acute COVID sequelae on death certificates.

In late January, this news organization painted a hopeful picture by naming four phenotypes of long COVID, suggesting that such divisions might further our understanding, including prognosis, and even therapy for this condition. Among the clinical phenotypes of (1) chronic fatigue–like syndrome, headache, and memory loss; (2) respiratory syndrome (which includes cough and difficulty breathing); (3) chronic pain; and (4) neurosensorial syndrome (which causes an altered sense of taste and smell), overlap is clearly possible but isn›t addressed.

I see these recent developments as needed and useful progress, but we are still left with…not much. So, when you tell me that you do or do not have long COVID, I will say to you, “How do you know?”

I also say: She/he/they who know COVID know medicine.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Has COVID replaced syphilis as the great imitator? At the turn of the 20th century, Sir William Osler was quoted as saying, “He who knows syphilis knows medicine.”

If you have any doubts about the “imitator” analogy, simply use any broad search engine or AI portal and enter “what is the differential diagnosis of primary syphilis, or secondary syphilis, or tertiary syphilis?” A plethora of diseases across many body systems appears.

Another Great Pretender?

Did you or do you now have long COVID? How do you know? Do you even know what long COVID is? How would you diagnosis it?

When asked about long COVID, this is what large language model source bard.google.com had to say:

Long COVID, also known as post-COVID conditions or PASC, is a complex condition that can occur in people who have had COVID-19, even if their initial illness was mild or even asymptomatic. It’s characterized by a wide range of symptoms that can last for weeks, months, or even years after the initial infection.

Symptoms of long COVID can include: fatigue, shortness of breath, brain fog (trouble thinking or concentrating), loss of smell or taste, sleep problems, muscle pain, joint pain, headache, dizziness, depression or anxiety, heart palpitations, gastrointestinal problems.

Duh!!! It reads much like a continuation of the symptoms of acute COVID. Bard continued:

The exact cause of long COVID is still unknown, but there are several theories. One possibility is that the virus itself can damage organs and tissues, leading to ongoing symptoms. Another possibility is that the immune system’s response to the virus can continue to cause inflammation even after the virus is gone.

Human intelligence source Wikipedia says this:

Long COVID or long-haul COVID is a group of health problems persisting or developing after an initial COVID-19 infection. Symptoms can last weeks, months or years and are often debilitating. The World Health Organization defines long COVID as starting three months after infection, but other definitions put the start of long COVID at four weeks.

Highly varied, including post-exertional malaise (symptoms made worse with effort), fatigue, muscle pain, shortness of breath, chest pain, and cognitive dysfunction (brain fog).

Acute COVID to Long COVID