User login

Extremely preterm infants fare better with corticosteroid and magnesium combo

Children born before 27 weeks’ gestation had lower combined risk of death or severe neurodevelopmental impairment when exposed to antenatal corticosteroids and magnesium sulfate together, compared with exposure of either or neither therapy, according to a prospective observational study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“If there is sufficient time to administer antenatal corticosteroids, there should similarly be sufficient time to administer magnesium sulfate,” wrote Samuel J. Gentle, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and colleagues. “Given the lower rate of severe neurodevelopmental impairment or death in children exposed to both antenatal corticosteroids and magnesium sulfate in the present study, compared with those exposed to antenatal corticosteroids alone, increasing the rates of magnesium sulfate exposure through quality improvement or other interventions may improve infant outcomes.”

Although previous randomized controlled trials had shown neurologic benefits of each therapy independently in preterm children, few data exist on extremely preterm children, the authors noted. They also pointed out differences in the findings when they analyzed neurodevelopmental outcomes and death separately.

“Whereas exposure to both therapies was associated with a lower rate of death, exposure to magnesium sulfate in addition to antenatal corticosteroids was not associated with a lower rate of severe neurodevelopmental impairment or components of severe neurodevelopmental impairment including Bayley scores, bilateral hearing impairment, and cerebral palsy,” Dr Gentle and his coauthors wrote.

The researchers used prospectively collected data from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network Generic Database to track 3,093 children born extremely preterm – from 22 weeks 0 days to 26 weeks 6 days – during 2011-2014.

The researchers compared outcomes of death or severe neurodevelopmental impairment when the children were 18-26 months of corrected age based on whether they had been exposed to antenatal corticosteroids alone (betamethasone or dexamethasone) or antenatal corticosteroids in addition to magnesium sulfate. Severe neurodevelopmental impairment included “severe cerebral palsy, motor or cognitive composite score less than 70 on the Bayley-III exam, bilateral blindness, or bilateral severe functional hearing impairment with or without amplification.”

The researchers also looked at severe neurodevelopmental impairment and death among children with only magnesium sulfate exposure or with no exposure to steroids or magnesium.

In the study population, 73% of infants had been exposed to both therapies, 16% had been exposed to only corticosteroids, 3% to only magnesium sulfate, and 8% to neither therapy.

“Importantly, a larger proportion of mothers unexposed to either therapy, compared with both therapies, received high school or less education or had no maternal private health insurance which may suggest health inequity as a driver for antenatal therapy exposure rates,” Dr. Gentle and associates noted.

Children whose mothers received corticosteroids and magnesium had a 27% lower risk of severe neurodevelopmental impairment or death, compared with those whose mothers only received corticosteroids (adjusted odds ratio, 0.73). Just over a third of children exposed to both interventions (36%) had severe neurodevelopmental impairment or died, compared with 44% of those exposed only to steroids.

Similarly, corticosteroids and magnesium together were associated with approximately half the risk of death or severe neurodevelopmental impairment, compared with magnesium alone (aOR, 0.49) and 34% lower risk, compared with neither therapy (aOR 0.66).

When the researchers uncoupled the outcomes, severe neurodevelopmental impairment rates were similar among all exposure groups, but rates of death were lower among those who received both therapies than among those who received just one or neither therapy.

“The therapeutic mechanism for neuroprotection in children exposed to magnesium sulfate is unclear but may result from neuronal stabilization or anti-inflammatory properties,” Dr. Gentle and colleagues said.

They also compared rates in the exposure groups of grade 3-4 intracranial hemorrhage, which has been linked to poor neurodevelopmental outcomes in extremely preterm children.

“The rate of grade 3-4 intracranial hemorrhage did not differ between children exposed to both antenatal corticosteroids and magnesium sulfate and those exposed to antenatal corticosteroids alone,” they said. “These findings further support data from randomized controlled trials showing benefit for antenatal corticosteroids but not for magnesium sulfate.”

They further noted a Cochrane Review that found significantly reduced risk of severe or any intracranial hemorrhage among children exposed to antenatal corticosteroids. No similar reduction in intracranial hemorrhage occurred in a separate Cochrane Review of antenatal magnesium sulfate trials.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. One author is a consultant for Mednax who has received travel funds. Another author disclosed Catholic Health Professionals of Houston paid honorarium for an ethics talk he gave.

SOURCE: Gentle SJ et al. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003882.

Children born before 27 weeks’ gestation had lower combined risk of death or severe neurodevelopmental impairment when exposed to antenatal corticosteroids and magnesium sulfate together, compared with exposure of either or neither therapy, according to a prospective observational study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“If there is sufficient time to administer antenatal corticosteroids, there should similarly be sufficient time to administer magnesium sulfate,” wrote Samuel J. Gentle, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and colleagues. “Given the lower rate of severe neurodevelopmental impairment or death in children exposed to both antenatal corticosteroids and magnesium sulfate in the present study, compared with those exposed to antenatal corticosteroids alone, increasing the rates of magnesium sulfate exposure through quality improvement or other interventions may improve infant outcomes.”

Although previous randomized controlled trials had shown neurologic benefits of each therapy independently in preterm children, few data exist on extremely preterm children, the authors noted. They also pointed out differences in the findings when they analyzed neurodevelopmental outcomes and death separately.

“Whereas exposure to both therapies was associated with a lower rate of death, exposure to magnesium sulfate in addition to antenatal corticosteroids was not associated with a lower rate of severe neurodevelopmental impairment or components of severe neurodevelopmental impairment including Bayley scores, bilateral hearing impairment, and cerebral palsy,” Dr Gentle and his coauthors wrote.

The researchers used prospectively collected data from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network Generic Database to track 3,093 children born extremely preterm – from 22 weeks 0 days to 26 weeks 6 days – during 2011-2014.

The researchers compared outcomes of death or severe neurodevelopmental impairment when the children were 18-26 months of corrected age based on whether they had been exposed to antenatal corticosteroids alone (betamethasone or dexamethasone) or antenatal corticosteroids in addition to magnesium sulfate. Severe neurodevelopmental impairment included “severe cerebral palsy, motor or cognitive composite score less than 70 on the Bayley-III exam, bilateral blindness, or bilateral severe functional hearing impairment with or without amplification.”

The researchers also looked at severe neurodevelopmental impairment and death among children with only magnesium sulfate exposure or with no exposure to steroids or magnesium.

In the study population, 73% of infants had been exposed to both therapies, 16% had been exposed to only corticosteroids, 3% to only magnesium sulfate, and 8% to neither therapy.

“Importantly, a larger proportion of mothers unexposed to either therapy, compared with both therapies, received high school or less education or had no maternal private health insurance which may suggest health inequity as a driver for antenatal therapy exposure rates,” Dr. Gentle and associates noted.

Children whose mothers received corticosteroids and magnesium had a 27% lower risk of severe neurodevelopmental impairment or death, compared with those whose mothers only received corticosteroids (adjusted odds ratio, 0.73). Just over a third of children exposed to both interventions (36%) had severe neurodevelopmental impairment or died, compared with 44% of those exposed only to steroids.

Similarly, corticosteroids and magnesium together were associated with approximately half the risk of death or severe neurodevelopmental impairment, compared with magnesium alone (aOR, 0.49) and 34% lower risk, compared with neither therapy (aOR 0.66).

When the researchers uncoupled the outcomes, severe neurodevelopmental impairment rates were similar among all exposure groups, but rates of death were lower among those who received both therapies than among those who received just one or neither therapy.

“The therapeutic mechanism for neuroprotection in children exposed to magnesium sulfate is unclear but may result from neuronal stabilization or anti-inflammatory properties,” Dr. Gentle and colleagues said.

They also compared rates in the exposure groups of grade 3-4 intracranial hemorrhage, which has been linked to poor neurodevelopmental outcomes in extremely preterm children.

“The rate of grade 3-4 intracranial hemorrhage did not differ between children exposed to both antenatal corticosteroids and magnesium sulfate and those exposed to antenatal corticosteroids alone,” they said. “These findings further support data from randomized controlled trials showing benefit for antenatal corticosteroids but not for magnesium sulfate.”

They further noted a Cochrane Review that found significantly reduced risk of severe or any intracranial hemorrhage among children exposed to antenatal corticosteroids. No similar reduction in intracranial hemorrhage occurred in a separate Cochrane Review of antenatal magnesium sulfate trials.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. One author is a consultant for Mednax who has received travel funds. Another author disclosed Catholic Health Professionals of Houston paid honorarium for an ethics talk he gave.

SOURCE: Gentle SJ et al. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003882.

Children born before 27 weeks’ gestation had lower combined risk of death or severe neurodevelopmental impairment when exposed to antenatal corticosteroids and magnesium sulfate together, compared with exposure of either or neither therapy, according to a prospective observational study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“If there is sufficient time to administer antenatal corticosteroids, there should similarly be sufficient time to administer magnesium sulfate,” wrote Samuel J. Gentle, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and colleagues. “Given the lower rate of severe neurodevelopmental impairment or death in children exposed to both antenatal corticosteroids and magnesium sulfate in the present study, compared with those exposed to antenatal corticosteroids alone, increasing the rates of magnesium sulfate exposure through quality improvement or other interventions may improve infant outcomes.”

Although previous randomized controlled trials had shown neurologic benefits of each therapy independently in preterm children, few data exist on extremely preterm children, the authors noted. They also pointed out differences in the findings when they analyzed neurodevelopmental outcomes and death separately.

“Whereas exposure to both therapies was associated with a lower rate of death, exposure to magnesium sulfate in addition to antenatal corticosteroids was not associated with a lower rate of severe neurodevelopmental impairment or components of severe neurodevelopmental impairment including Bayley scores, bilateral hearing impairment, and cerebral palsy,” Dr Gentle and his coauthors wrote.

The researchers used prospectively collected data from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network Generic Database to track 3,093 children born extremely preterm – from 22 weeks 0 days to 26 weeks 6 days – during 2011-2014.

The researchers compared outcomes of death or severe neurodevelopmental impairment when the children were 18-26 months of corrected age based on whether they had been exposed to antenatal corticosteroids alone (betamethasone or dexamethasone) or antenatal corticosteroids in addition to magnesium sulfate. Severe neurodevelopmental impairment included “severe cerebral palsy, motor or cognitive composite score less than 70 on the Bayley-III exam, bilateral blindness, or bilateral severe functional hearing impairment with or without amplification.”

The researchers also looked at severe neurodevelopmental impairment and death among children with only magnesium sulfate exposure or with no exposure to steroids or magnesium.

In the study population, 73% of infants had been exposed to both therapies, 16% had been exposed to only corticosteroids, 3% to only magnesium sulfate, and 8% to neither therapy.

“Importantly, a larger proportion of mothers unexposed to either therapy, compared with both therapies, received high school or less education or had no maternal private health insurance which may suggest health inequity as a driver for antenatal therapy exposure rates,” Dr. Gentle and associates noted.

Children whose mothers received corticosteroids and magnesium had a 27% lower risk of severe neurodevelopmental impairment or death, compared with those whose mothers only received corticosteroids (adjusted odds ratio, 0.73). Just over a third of children exposed to both interventions (36%) had severe neurodevelopmental impairment or died, compared with 44% of those exposed only to steroids.

Similarly, corticosteroids and magnesium together were associated with approximately half the risk of death or severe neurodevelopmental impairment, compared with magnesium alone (aOR, 0.49) and 34% lower risk, compared with neither therapy (aOR 0.66).

When the researchers uncoupled the outcomes, severe neurodevelopmental impairment rates were similar among all exposure groups, but rates of death were lower among those who received both therapies than among those who received just one or neither therapy.

“The therapeutic mechanism for neuroprotection in children exposed to magnesium sulfate is unclear but may result from neuronal stabilization or anti-inflammatory properties,” Dr. Gentle and colleagues said.

They also compared rates in the exposure groups of grade 3-4 intracranial hemorrhage, which has been linked to poor neurodevelopmental outcomes in extremely preterm children.

“The rate of grade 3-4 intracranial hemorrhage did not differ between children exposed to both antenatal corticosteroids and magnesium sulfate and those exposed to antenatal corticosteroids alone,” they said. “These findings further support data from randomized controlled trials showing benefit for antenatal corticosteroids but not for magnesium sulfate.”

They further noted a Cochrane Review that found significantly reduced risk of severe or any intracranial hemorrhage among children exposed to antenatal corticosteroids. No similar reduction in intracranial hemorrhage occurred in a separate Cochrane Review of antenatal magnesium sulfate trials.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. One author is a consultant for Mednax who has received travel funds. Another author disclosed Catholic Health Professionals of Houston paid honorarium for an ethics talk he gave.

SOURCE: Gentle SJ et al. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003882.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Vitamin D intake among U.S. infants has not improved, despite guidance

with breastfed infants less likely to have adequate levels than formula-fed infants, according to results of a study.

The American Association of Pediatrics has recommended since 2008 that breastfeeding babies under 1 year of age receive 400 IU of vitamin D supplementation daily, usually in the form of drops, to prevent rickets. For formula-fed infants, the AAP recommends that infants be fed one liter of formula daily, as formulas must contain 400 IU of vitamin D per liter.

A study looking at caregiver-reported dietary data through 2012 suggested that the guideline was having little impact, with only 27% of U.S. infants considered to be getting adequate vitamin D. The same researchers have now updated those findings with data through 2016 to report virtually no improvement over time. For their research, published in Pediatrics, Alan E. Simon, MD, of the National Institutes of Health in Rockville, Md., and Katherine A. Ahrens, PhD, of the University of Southern Maine in Portland, analyzed data for 1,435 infants aged 0-11 months. All data were recorded during 2009-2016 as part of the ongoing National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Overall, 27% of infants in the study were considered likely to meet the guidelines. Among nonbreastfeeding infants, 31% were deemed to have adequate levels, compared with 21% of breastfeeding infants (P less than .01).

Parents’ income and education affected infants’ likelihood of meeting guidelines. Breastfeeding infants in families with incomes above 400% of the federal poverty level were twice as likely to meet guidelines (31% vs. 14%-16% for lower income brackets, P less than .05). Babies from families whose head of household had a college degree had a 26% likelihood of having enough vitamin D, compared with less than 11% of those in whose parents had less than a high school education (P less than .05). Babies from families with private insurance also had a better chance of meeting guidelines, compared with those with public insurance (24% vs. 13%; P less than .05).

Ethnicity was seen as affecting vitamin D intake only insofar as some groups had more formula use than breastfeeding. The only ethnic or racial subgroup in the study that saw more than 40% of infants likely to meet guidelines was nonbreastfeeding infants of Asian, American Indian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or multiracial parentage, with 46% considered to have adequate vitamin D levels. This group makes up 6% of the infant population in the United States.

“Reasons for low rates of meeting guidelines in the United States and little improvement over time are not fully known,” Dr. Simon and Dr. Ahrens wrote in their analysis. “One factor may be that the impact of low vitamin D in infancy is not highly visible to physicians because rickets is an uncommon diagnosis in the United States.” They noted that recent studies from Canada, where public health officials have done more to promote supplementation, have shown rates of adequate vitamin D in breastfeeding babies to be as high as 90%.

The researchers listed among limitations of their study the fact that the data source, NHANES, captured nutrition information only for the previous 24 hours; that it relied on parental report, and did not confirm serum levels of vitamin D; and that it was possible that cow’s milk – which is not recommended before age 1 but frequently given to older infants anyway – could be a hidden source of vitamin D that was not taken into consideration.

In an editorial comment, Jaspreet Loyal, MD, and Annette Cameron, MD, of Yale University in New Haven, Conn., faulted “a combination of inconsistent prescribing by clinicians and poor adherence to the use of a supplement by parents of infants … further complicated by a lack of awareness of the consequences of vitamin D deficiency in infants among the public” for the low adherence to guidelines in the United States, compared with other countries.

Also, the editorialists noted, the dropper used to administer liquid supplements has been associated with “inconsistent precision” and concerns about infants gagging on the liquid. More research is needed to better understand “prescribing patterns, barriers to adherence by parents of infants, and alternate strategies for vitamin D supplementation to inform novel public health programs in the United States,” they wrote.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study, and Dr. Ahrens is supported by a faculty development grant from the Maine Economic Improvement Fund. The researchers declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Loyal and Dr. Cameron disclosed no funding and no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Simon AE and Ahrens KA. Pediatrics 2020 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3574; Loyal J and Cameron A. Pediatrics. 2020 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0504.

with breastfed infants less likely to have adequate levels than formula-fed infants, according to results of a study.

The American Association of Pediatrics has recommended since 2008 that breastfeeding babies under 1 year of age receive 400 IU of vitamin D supplementation daily, usually in the form of drops, to prevent rickets. For formula-fed infants, the AAP recommends that infants be fed one liter of formula daily, as formulas must contain 400 IU of vitamin D per liter.

A study looking at caregiver-reported dietary data through 2012 suggested that the guideline was having little impact, with only 27% of U.S. infants considered to be getting adequate vitamin D. The same researchers have now updated those findings with data through 2016 to report virtually no improvement over time. For their research, published in Pediatrics, Alan E. Simon, MD, of the National Institutes of Health in Rockville, Md., and Katherine A. Ahrens, PhD, of the University of Southern Maine in Portland, analyzed data for 1,435 infants aged 0-11 months. All data were recorded during 2009-2016 as part of the ongoing National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Overall, 27% of infants in the study were considered likely to meet the guidelines. Among nonbreastfeeding infants, 31% were deemed to have adequate levels, compared with 21% of breastfeeding infants (P less than .01).

Parents’ income and education affected infants’ likelihood of meeting guidelines. Breastfeeding infants in families with incomes above 400% of the federal poverty level were twice as likely to meet guidelines (31% vs. 14%-16% for lower income brackets, P less than .05). Babies from families whose head of household had a college degree had a 26% likelihood of having enough vitamin D, compared with less than 11% of those in whose parents had less than a high school education (P less than .05). Babies from families with private insurance also had a better chance of meeting guidelines, compared with those with public insurance (24% vs. 13%; P less than .05).

Ethnicity was seen as affecting vitamin D intake only insofar as some groups had more formula use than breastfeeding. The only ethnic or racial subgroup in the study that saw more than 40% of infants likely to meet guidelines was nonbreastfeeding infants of Asian, American Indian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or multiracial parentage, with 46% considered to have adequate vitamin D levels. This group makes up 6% of the infant population in the United States.

“Reasons for low rates of meeting guidelines in the United States and little improvement over time are not fully known,” Dr. Simon and Dr. Ahrens wrote in their analysis. “One factor may be that the impact of low vitamin D in infancy is not highly visible to physicians because rickets is an uncommon diagnosis in the United States.” They noted that recent studies from Canada, where public health officials have done more to promote supplementation, have shown rates of adequate vitamin D in breastfeeding babies to be as high as 90%.

The researchers listed among limitations of their study the fact that the data source, NHANES, captured nutrition information only for the previous 24 hours; that it relied on parental report, and did not confirm serum levels of vitamin D; and that it was possible that cow’s milk – which is not recommended before age 1 but frequently given to older infants anyway – could be a hidden source of vitamin D that was not taken into consideration.

In an editorial comment, Jaspreet Loyal, MD, and Annette Cameron, MD, of Yale University in New Haven, Conn., faulted “a combination of inconsistent prescribing by clinicians and poor adherence to the use of a supplement by parents of infants … further complicated by a lack of awareness of the consequences of vitamin D deficiency in infants among the public” for the low adherence to guidelines in the United States, compared with other countries.

Also, the editorialists noted, the dropper used to administer liquid supplements has been associated with “inconsistent precision” and concerns about infants gagging on the liquid. More research is needed to better understand “prescribing patterns, barriers to adherence by parents of infants, and alternate strategies for vitamin D supplementation to inform novel public health programs in the United States,” they wrote.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study, and Dr. Ahrens is supported by a faculty development grant from the Maine Economic Improvement Fund. The researchers declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Loyal and Dr. Cameron disclosed no funding and no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Simon AE and Ahrens KA. Pediatrics 2020 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3574; Loyal J and Cameron A. Pediatrics. 2020 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0504.

with breastfed infants less likely to have adequate levels than formula-fed infants, according to results of a study.

The American Association of Pediatrics has recommended since 2008 that breastfeeding babies under 1 year of age receive 400 IU of vitamin D supplementation daily, usually in the form of drops, to prevent rickets. For formula-fed infants, the AAP recommends that infants be fed one liter of formula daily, as formulas must contain 400 IU of vitamin D per liter.

A study looking at caregiver-reported dietary data through 2012 suggested that the guideline was having little impact, with only 27% of U.S. infants considered to be getting adequate vitamin D. The same researchers have now updated those findings with data through 2016 to report virtually no improvement over time. For their research, published in Pediatrics, Alan E. Simon, MD, of the National Institutes of Health in Rockville, Md., and Katherine A. Ahrens, PhD, of the University of Southern Maine in Portland, analyzed data for 1,435 infants aged 0-11 months. All data were recorded during 2009-2016 as part of the ongoing National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Overall, 27% of infants in the study were considered likely to meet the guidelines. Among nonbreastfeeding infants, 31% were deemed to have adequate levels, compared with 21% of breastfeeding infants (P less than .01).

Parents’ income and education affected infants’ likelihood of meeting guidelines. Breastfeeding infants in families with incomes above 400% of the federal poverty level were twice as likely to meet guidelines (31% vs. 14%-16% for lower income brackets, P less than .05). Babies from families whose head of household had a college degree had a 26% likelihood of having enough vitamin D, compared with less than 11% of those in whose parents had less than a high school education (P less than .05). Babies from families with private insurance also had a better chance of meeting guidelines, compared with those with public insurance (24% vs. 13%; P less than .05).

Ethnicity was seen as affecting vitamin D intake only insofar as some groups had more formula use than breastfeeding. The only ethnic or racial subgroup in the study that saw more than 40% of infants likely to meet guidelines was nonbreastfeeding infants of Asian, American Indian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or multiracial parentage, with 46% considered to have adequate vitamin D levels. This group makes up 6% of the infant population in the United States.

“Reasons for low rates of meeting guidelines in the United States and little improvement over time are not fully known,” Dr. Simon and Dr. Ahrens wrote in their analysis. “One factor may be that the impact of low vitamin D in infancy is not highly visible to physicians because rickets is an uncommon diagnosis in the United States.” They noted that recent studies from Canada, where public health officials have done more to promote supplementation, have shown rates of adequate vitamin D in breastfeeding babies to be as high as 90%.

The researchers listed among limitations of their study the fact that the data source, NHANES, captured nutrition information only for the previous 24 hours; that it relied on parental report, and did not confirm serum levels of vitamin D; and that it was possible that cow’s milk – which is not recommended before age 1 but frequently given to older infants anyway – could be a hidden source of vitamin D that was not taken into consideration.

In an editorial comment, Jaspreet Loyal, MD, and Annette Cameron, MD, of Yale University in New Haven, Conn., faulted “a combination of inconsistent prescribing by clinicians and poor adherence to the use of a supplement by parents of infants … further complicated by a lack of awareness of the consequences of vitamin D deficiency in infants among the public” for the low adherence to guidelines in the United States, compared with other countries.

Also, the editorialists noted, the dropper used to administer liquid supplements has been associated with “inconsistent precision” and concerns about infants gagging on the liquid. More research is needed to better understand “prescribing patterns, barriers to adherence by parents of infants, and alternate strategies for vitamin D supplementation to inform novel public health programs in the United States,” they wrote.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study, and Dr. Ahrens is supported by a faculty development grant from the Maine Economic Improvement Fund. The researchers declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Loyal and Dr. Cameron disclosed no funding and no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Simon AE and Ahrens KA. Pediatrics 2020 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3574; Loyal J and Cameron A. Pediatrics. 2020 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0504.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Progress report: Elimination of neonatal tetanus

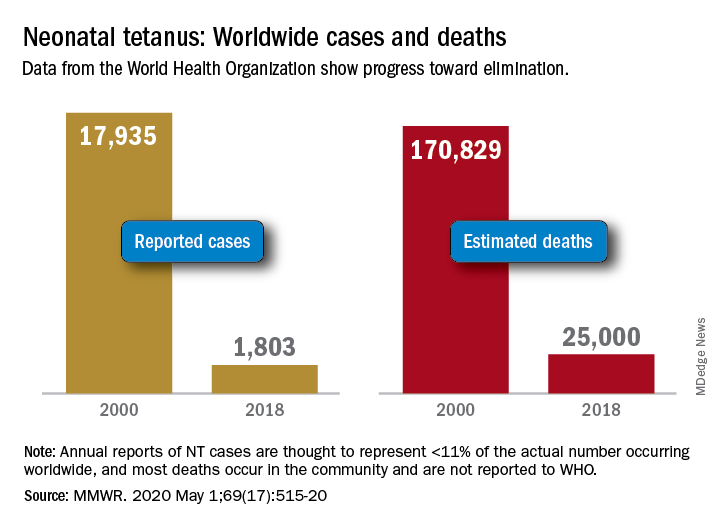

Worldwide cases of neonatal tetanus fell by 90% from 2000 to 2018, deaths dropped by 85%, and 45 countries achieved elimination of maternal and neonatal tetanus (MNT), according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Despite this progress, some countries that achieved elimination are still struggling to sustain performance indicators; war and insecurity pose challenges in countries that have not achieved MNT elimination,” Henry N. Njuguna, MD, of the CDC’s global immunization division, and associates wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Other worldwide measures also improved from 2000 to 2018: and the percentage of deliveries attended by a skilled birth attendant increased from 62% during 2000-2005 to 81% in 2013-2018, they reported.

The MNT elimination initiative, which began in 1999 and targeted 59 priority countries, immunized approximately 154 million women of reproductive age with at least two doses of tetanus toxoid–containing vaccine from 2000 to 2018, the investigators wrote, based on data from the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund.

With 14 of the priority countries – including Nigeria, Pakistan, and Yemen – still dealing with MNT, however, numerous challenges remain, they noted. About 47 million women and their babies are still unprotected, and 49 million women have not received tetanus toxoid–containing vaccine.

This lack of coverage “can be attributed to weak health systems, including conflict and security issues that limit access to vaccination services, competing priorities that limit the implementation of planned MNT elimination activities, and withdrawal of donor funding,” Dr. Njuguna and associates wrote.

SOURCE: Njuguna HN et al. MMWR. 2020 May 1;69(17):515-20.

Worldwide cases of neonatal tetanus fell by 90% from 2000 to 2018, deaths dropped by 85%, and 45 countries achieved elimination of maternal and neonatal tetanus (MNT), according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Despite this progress, some countries that achieved elimination are still struggling to sustain performance indicators; war and insecurity pose challenges in countries that have not achieved MNT elimination,” Henry N. Njuguna, MD, of the CDC’s global immunization division, and associates wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Other worldwide measures also improved from 2000 to 2018: and the percentage of deliveries attended by a skilled birth attendant increased from 62% during 2000-2005 to 81% in 2013-2018, they reported.

The MNT elimination initiative, which began in 1999 and targeted 59 priority countries, immunized approximately 154 million women of reproductive age with at least two doses of tetanus toxoid–containing vaccine from 2000 to 2018, the investigators wrote, based on data from the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund.

With 14 of the priority countries – including Nigeria, Pakistan, and Yemen – still dealing with MNT, however, numerous challenges remain, they noted. About 47 million women and their babies are still unprotected, and 49 million women have not received tetanus toxoid–containing vaccine.

This lack of coverage “can be attributed to weak health systems, including conflict and security issues that limit access to vaccination services, competing priorities that limit the implementation of planned MNT elimination activities, and withdrawal of donor funding,” Dr. Njuguna and associates wrote.

SOURCE: Njuguna HN et al. MMWR. 2020 May 1;69(17):515-20.

Worldwide cases of neonatal tetanus fell by 90% from 2000 to 2018, deaths dropped by 85%, and 45 countries achieved elimination of maternal and neonatal tetanus (MNT), according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Despite this progress, some countries that achieved elimination are still struggling to sustain performance indicators; war and insecurity pose challenges in countries that have not achieved MNT elimination,” Henry N. Njuguna, MD, of the CDC’s global immunization division, and associates wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Other worldwide measures also improved from 2000 to 2018: and the percentage of deliveries attended by a skilled birth attendant increased from 62% during 2000-2005 to 81% in 2013-2018, they reported.

The MNT elimination initiative, which began in 1999 and targeted 59 priority countries, immunized approximately 154 million women of reproductive age with at least two doses of tetanus toxoid–containing vaccine from 2000 to 2018, the investigators wrote, based on data from the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund.

With 14 of the priority countries – including Nigeria, Pakistan, and Yemen – still dealing with MNT, however, numerous challenges remain, they noted. About 47 million women and their babies are still unprotected, and 49 million women have not received tetanus toxoid–containing vaccine.

This lack of coverage “can be attributed to weak health systems, including conflict and security issues that limit access to vaccination services, competing priorities that limit the implementation of planned MNT elimination activities, and withdrawal of donor funding,” Dr. Njuguna and associates wrote.

SOURCE: Njuguna HN et al. MMWR. 2020 May 1;69(17):515-20.

FROM MMWR

AAP issues guidance on managing infants born to mothers with COVID-19

“Pediatric cases of COVID-19 are so far reported as less severe than disease occurring among older individuals,” Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, a neonatologist and chief of the section on newborn pediatrics at Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, and coauthors wrote in the 18-page document, which was released on April 2, 2020, along with an abbreviated “Frequently Asked Questions” summary. However, one study of children with COVID-19 in China found that 12% of confirmed cases occurred among 731 infants aged less than 1 year; 24% of those 86 infants “suffered severe or critical illness” (Pediatrics. 2020 March. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702). There were no deaths reported among these infants. Other case reports have documented COVID-19 in children aged as young as 2 days.

The document, which was assembled by members of the AAP Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Section on Neonatal Perinatal Medicine, and Committee on Infectious Diseases, pointed out that “considerable uncertainty” exists about the possibility for vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from infected pregnant women to their newborns. “Evidence-based guidelines for managing antenatal, intrapartum, and neonatal care around COVID-19 would require an understanding of whether the virus can be transmitted transplacentally; a determination of which maternal body fluids may be infectious; and data of adequate statistical power that describe which maternal, intrapartum, and neonatal factors influence perinatal transmission,” according to the document. “In the midst of the pandemic these data do not exist, with only limited information currently available to address these issues.”

Based on the best available evidence, the guidance authors recommend that clinicians temporarily separate newborns from affected mothers to minimize the risk of postnatal infant infection from maternal respiratory secretions. “Newborns should be bathed as soon as reasonably possible after birth to remove virus potentially present on skin surfaces,” they wrote. “Clinical staff should use airborne, droplet, and contact precautions until newborn virologic status is known to be negative by SARS-CoV-2 [polymerase chain reaction] testing.”

While SARS-CoV-2 has not been detected in breast milk to date, the authors noted that mothers with COVID-19 can express breast milk to be fed to their infants by uninfected caregivers until specific maternal criteria are met. In addition, infants born to mothers with COVID-19 should be tested for SARS-CoV-2 at 24 hours and, if still in the birth facility, at 48 hours after birth. Centers with limited resources for testing may make individual risk/benefit decisions regarding testing.

For infants infected with SARS-CoV-2 but have no symptoms of the disease, they “may be discharged home on a case-by-case basis with appropriate precautions and plans for frequent outpatient follow-up contacts (either by phone, telemedicine, or in office) through 14 days after birth,” according to the document.

If both infant and mother are discharged from the hospital and the mother still has COVID-19 symptoms, she should maintain at least 6 feet of distance from the baby; if she is in closer proximity she should use a mask and hand hygiene. The mother can stop such precautions until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, and it is at least 7 days since her symptoms first occurred.

In cases where infants require ongoing neonatal intensive care, mothers infected with COVID-19 should not visit their newborn until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, her respiratory symptoms are improved, and she has negative results of a molecular assay for detection of SARS-CoV-2 from at least two consecutive nasopharyngeal swab specimens collected at least 24 hours apart.

“Pediatric cases of COVID-19 are so far reported as less severe than disease occurring among older individuals,” Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, a neonatologist and chief of the section on newborn pediatrics at Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, and coauthors wrote in the 18-page document, which was released on April 2, 2020, along with an abbreviated “Frequently Asked Questions” summary. However, one study of children with COVID-19 in China found that 12% of confirmed cases occurred among 731 infants aged less than 1 year; 24% of those 86 infants “suffered severe or critical illness” (Pediatrics. 2020 March. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702). There were no deaths reported among these infants. Other case reports have documented COVID-19 in children aged as young as 2 days.

The document, which was assembled by members of the AAP Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Section on Neonatal Perinatal Medicine, and Committee on Infectious Diseases, pointed out that “considerable uncertainty” exists about the possibility for vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from infected pregnant women to their newborns. “Evidence-based guidelines for managing antenatal, intrapartum, and neonatal care around COVID-19 would require an understanding of whether the virus can be transmitted transplacentally; a determination of which maternal body fluids may be infectious; and data of adequate statistical power that describe which maternal, intrapartum, and neonatal factors influence perinatal transmission,” according to the document. “In the midst of the pandemic these data do not exist, with only limited information currently available to address these issues.”

Based on the best available evidence, the guidance authors recommend that clinicians temporarily separate newborns from affected mothers to minimize the risk of postnatal infant infection from maternal respiratory secretions. “Newborns should be bathed as soon as reasonably possible after birth to remove virus potentially present on skin surfaces,” they wrote. “Clinical staff should use airborne, droplet, and contact precautions until newborn virologic status is known to be negative by SARS-CoV-2 [polymerase chain reaction] testing.”

While SARS-CoV-2 has not been detected in breast milk to date, the authors noted that mothers with COVID-19 can express breast milk to be fed to their infants by uninfected caregivers until specific maternal criteria are met. In addition, infants born to mothers with COVID-19 should be tested for SARS-CoV-2 at 24 hours and, if still in the birth facility, at 48 hours after birth. Centers with limited resources for testing may make individual risk/benefit decisions regarding testing.

For infants infected with SARS-CoV-2 but have no symptoms of the disease, they “may be discharged home on a case-by-case basis with appropriate precautions and plans for frequent outpatient follow-up contacts (either by phone, telemedicine, or in office) through 14 days after birth,” according to the document.

If both infant and mother are discharged from the hospital and the mother still has COVID-19 symptoms, she should maintain at least 6 feet of distance from the baby; if she is in closer proximity she should use a mask and hand hygiene. The mother can stop such precautions until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, and it is at least 7 days since her symptoms first occurred.

In cases where infants require ongoing neonatal intensive care, mothers infected with COVID-19 should not visit their newborn until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, her respiratory symptoms are improved, and she has negative results of a molecular assay for detection of SARS-CoV-2 from at least two consecutive nasopharyngeal swab specimens collected at least 24 hours apart.

“Pediatric cases of COVID-19 are so far reported as less severe than disease occurring among older individuals,” Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, a neonatologist and chief of the section on newborn pediatrics at Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, and coauthors wrote in the 18-page document, which was released on April 2, 2020, along with an abbreviated “Frequently Asked Questions” summary. However, one study of children with COVID-19 in China found that 12% of confirmed cases occurred among 731 infants aged less than 1 year; 24% of those 86 infants “suffered severe or critical illness” (Pediatrics. 2020 March. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702). There were no deaths reported among these infants. Other case reports have documented COVID-19 in children aged as young as 2 days.

The document, which was assembled by members of the AAP Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Section on Neonatal Perinatal Medicine, and Committee on Infectious Diseases, pointed out that “considerable uncertainty” exists about the possibility for vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from infected pregnant women to their newborns. “Evidence-based guidelines for managing antenatal, intrapartum, and neonatal care around COVID-19 would require an understanding of whether the virus can be transmitted transplacentally; a determination of which maternal body fluids may be infectious; and data of adequate statistical power that describe which maternal, intrapartum, and neonatal factors influence perinatal transmission,” according to the document. “In the midst of the pandemic these data do not exist, with only limited information currently available to address these issues.”

Based on the best available evidence, the guidance authors recommend that clinicians temporarily separate newborns from affected mothers to minimize the risk of postnatal infant infection from maternal respiratory secretions. “Newborns should be bathed as soon as reasonably possible after birth to remove virus potentially present on skin surfaces,” they wrote. “Clinical staff should use airborne, droplet, and contact precautions until newborn virologic status is known to be negative by SARS-CoV-2 [polymerase chain reaction] testing.”

While SARS-CoV-2 has not been detected in breast milk to date, the authors noted that mothers with COVID-19 can express breast milk to be fed to their infants by uninfected caregivers until specific maternal criteria are met. In addition, infants born to mothers with COVID-19 should be tested for SARS-CoV-2 at 24 hours and, if still in the birth facility, at 48 hours after birth. Centers with limited resources for testing may make individual risk/benefit decisions regarding testing.

For infants infected with SARS-CoV-2 but have no symptoms of the disease, they “may be discharged home on a case-by-case basis with appropriate precautions and plans for frequent outpatient follow-up contacts (either by phone, telemedicine, or in office) through 14 days after birth,” according to the document.

If both infant and mother are discharged from the hospital and the mother still has COVID-19 symptoms, she should maintain at least 6 feet of distance from the baby; if she is in closer proximity she should use a mask and hand hygiene. The mother can stop such precautions until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, and it is at least 7 days since her symptoms first occurred.

In cases where infants require ongoing neonatal intensive care, mothers infected with COVID-19 should not visit their newborn until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, her respiratory symptoms are improved, and she has negative results of a molecular assay for detection of SARS-CoV-2 from at least two consecutive nasopharyngeal swab specimens collected at least 24 hours apart.

Reports suggest possible in utero transmission of novel coronavirus 2019

Reports of three neonates with elevated IgM antibody concentrations whose mothers had COVID-19 in two articles raise questions about whether the infants may have been infected with the virus in utero.

The data, while provocative, “are not conclusive and do not prove in utero transmission” of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), editorialists cautioned.

“The suggestion of in utero transmission rests on IgM detection in these 3 neonates, and IgM is a challenging way to diagnose many congenital infections,” David W. Kimberlin, MD, and Sergio Stagno, MD, of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at University of Alabama at Birmingham, wrote in their editorial. “IgM antibodies are too large to cross the placenta and so detection in a newborn reasonably could be assumed to reflect fetal production following in utero infection. However, most congenital infections are not diagnosed based on IgM detection because IgM assays can be prone to false-positive and false-negative results, along with cross-reactivity and testing challenges.”

None of the three infants had a positive reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test result, “so there is not virologic evidence for congenital infection in these cases to support the serologic suggestion of in utero transmission,” the editorialists noted.

Examining the possibility of vertical transmission

A prior case series of nine pregnant women found no transmission of the virus from mother to child, but the question of in utero transmission is not settled, said Lan Dong, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University in China and colleagues. In their research letter, the investigators described a newborn with elevated IgM antibodies to novel coronavirus 2019 born to a mother with COVID-19. The infant was delivered by cesarean section February 22, 2020, at Renmin Hospital in a negative-pressure isolation room.

“The mother wore an N95 mask and did not hold the infant,” the researchers said. “The neonate had no symptoms and was immediately quarantined in the neonatal intensive care unit. At 2 hours of age, the SARS-CoV-2 IgG level was 140.32 AU/mL and the IgM level was 45.83 AU/mL.” Although the infant may have been infected at delivery, IgM antibodies usually take days to appear, Dr. Dong and colleagues wrote. “The infant’s repeatedly negative RT-PCR test results on nasopharyngeal swabs are difficult to explain, although these tests are not always positive with infection. ... Additional examination of maternal and newborn samples should be done to confirm this preliminary observation.”

A review of infants’ serologic characteristics

Hui Zeng, MD, of the department of laboratory medicine at Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University in China and colleagues retrospectively reviewed clinical records and laboratory results for six pregnant women with COVID-19, according to a study in JAMA. The women had mild clinical manifestations and were admitted to Zhongnan Hospital between February 16 and March 6. “All had cesarean deliveries in their third trimester in negative pressure isolation rooms,” the investigators said. “All mothers wore masks, and all medical staff wore protective suits and double masks. The infants were isolated from their mothers immediately after delivery.”

Two of the infants had elevated IgG and IgM concentrations. IgM “is not usually transferred from mother to fetus because of its larger macromolecular structure. ... Whether the placentas of women in this study were damaged and abnormal is unknown,” Dr. Zeng and colleagues said. “Alternatively, IgM could have been produced by the infant if the virus crossed the placenta.”

“Although these 2 studies deserve careful evaluation, more definitive evidence is needed” before physicians can “counsel pregnant women that their fetuses are at risk from congenital infection with SARS-CoV-2,” Dr. Kimberlin and Dr. Stagno concluded.

Dr. Dong and associates had no conflicts of interest. Their work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Project and others. Dr. Zeng and colleagues had no relevant financial disclosures. Their study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and Zhongnan Hospital. Dr. Kimberlin and Dr. Stagno had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Dong L et al. JAMA. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4621; Zeng H et al. JAMA. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4861.

Reports of three neonates with elevated IgM antibody concentrations whose mothers had COVID-19 in two articles raise questions about whether the infants may have been infected with the virus in utero.

The data, while provocative, “are not conclusive and do not prove in utero transmission” of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), editorialists cautioned.

“The suggestion of in utero transmission rests on IgM detection in these 3 neonates, and IgM is a challenging way to diagnose many congenital infections,” David W. Kimberlin, MD, and Sergio Stagno, MD, of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at University of Alabama at Birmingham, wrote in their editorial. “IgM antibodies are too large to cross the placenta and so detection in a newborn reasonably could be assumed to reflect fetal production following in utero infection. However, most congenital infections are not diagnosed based on IgM detection because IgM assays can be prone to false-positive and false-negative results, along with cross-reactivity and testing challenges.”

None of the three infants had a positive reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test result, “so there is not virologic evidence for congenital infection in these cases to support the serologic suggestion of in utero transmission,” the editorialists noted.

Examining the possibility of vertical transmission

A prior case series of nine pregnant women found no transmission of the virus from mother to child, but the question of in utero transmission is not settled, said Lan Dong, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University in China and colleagues. In their research letter, the investigators described a newborn with elevated IgM antibodies to novel coronavirus 2019 born to a mother with COVID-19. The infant was delivered by cesarean section February 22, 2020, at Renmin Hospital in a negative-pressure isolation room.

“The mother wore an N95 mask and did not hold the infant,” the researchers said. “The neonate had no symptoms and was immediately quarantined in the neonatal intensive care unit. At 2 hours of age, the SARS-CoV-2 IgG level was 140.32 AU/mL and the IgM level was 45.83 AU/mL.” Although the infant may have been infected at delivery, IgM antibodies usually take days to appear, Dr. Dong and colleagues wrote. “The infant’s repeatedly negative RT-PCR test results on nasopharyngeal swabs are difficult to explain, although these tests are not always positive with infection. ... Additional examination of maternal and newborn samples should be done to confirm this preliminary observation.”

A review of infants’ serologic characteristics

Hui Zeng, MD, of the department of laboratory medicine at Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University in China and colleagues retrospectively reviewed clinical records and laboratory results for six pregnant women with COVID-19, according to a study in JAMA. The women had mild clinical manifestations and were admitted to Zhongnan Hospital between February 16 and March 6. “All had cesarean deliveries in their third trimester in negative pressure isolation rooms,” the investigators said. “All mothers wore masks, and all medical staff wore protective suits and double masks. The infants were isolated from their mothers immediately after delivery.”

Two of the infants had elevated IgG and IgM concentrations. IgM “is not usually transferred from mother to fetus because of its larger macromolecular structure. ... Whether the placentas of women in this study were damaged and abnormal is unknown,” Dr. Zeng and colleagues said. “Alternatively, IgM could have been produced by the infant if the virus crossed the placenta.”

“Although these 2 studies deserve careful evaluation, more definitive evidence is needed” before physicians can “counsel pregnant women that their fetuses are at risk from congenital infection with SARS-CoV-2,” Dr. Kimberlin and Dr. Stagno concluded.

Dr. Dong and associates had no conflicts of interest. Their work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Project and others. Dr. Zeng and colleagues had no relevant financial disclosures. Their study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and Zhongnan Hospital. Dr. Kimberlin and Dr. Stagno had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Dong L et al. JAMA. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4621; Zeng H et al. JAMA. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4861.

Reports of three neonates with elevated IgM antibody concentrations whose mothers had COVID-19 in two articles raise questions about whether the infants may have been infected with the virus in utero.

The data, while provocative, “are not conclusive and do not prove in utero transmission” of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), editorialists cautioned.

“The suggestion of in utero transmission rests on IgM detection in these 3 neonates, and IgM is a challenging way to diagnose many congenital infections,” David W. Kimberlin, MD, and Sergio Stagno, MD, of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at University of Alabama at Birmingham, wrote in their editorial. “IgM antibodies are too large to cross the placenta and so detection in a newborn reasonably could be assumed to reflect fetal production following in utero infection. However, most congenital infections are not diagnosed based on IgM detection because IgM assays can be prone to false-positive and false-negative results, along with cross-reactivity and testing challenges.”

None of the three infants had a positive reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test result, “so there is not virologic evidence for congenital infection in these cases to support the serologic suggestion of in utero transmission,” the editorialists noted.

Examining the possibility of vertical transmission

A prior case series of nine pregnant women found no transmission of the virus from mother to child, but the question of in utero transmission is not settled, said Lan Dong, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University in China and colleagues. In their research letter, the investigators described a newborn with elevated IgM antibodies to novel coronavirus 2019 born to a mother with COVID-19. The infant was delivered by cesarean section February 22, 2020, at Renmin Hospital in a negative-pressure isolation room.

“The mother wore an N95 mask and did not hold the infant,” the researchers said. “The neonate had no symptoms and was immediately quarantined in the neonatal intensive care unit. At 2 hours of age, the SARS-CoV-2 IgG level was 140.32 AU/mL and the IgM level was 45.83 AU/mL.” Although the infant may have been infected at delivery, IgM antibodies usually take days to appear, Dr. Dong and colleagues wrote. “The infant’s repeatedly negative RT-PCR test results on nasopharyngeal swabs are difficult to explain, although these tests are not always positive with infection. ... Additional examination of maternal and newborn samples should be done to confirm this preliminary observation.”

A review of infants’ serologic characteristics

Hui Zeng, MD, of the department of laboratory medicine at Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University in China and colleagues retrospectively reviewed clinical records and laboratory results for six pregnant women with COVID-19, according to a study in JAMA. The women had mild clinical manifestations and were admitted to Zhongnan Hospital between February 16 and March 6. “All had cesarean deliveries in their third trimester in negative pressure isolation rooms,” the investigators said. “All mothers wore masks, and all medical staff wore protective suits and double masks. The infants were isolated from their mothers immediately after delivery.”

Two of the infants had elevated IgG and IgM concentrations. IgM “is not usually transferred from mother to fetus because of its larger macromolecular structure. ... Whether the placentas of women in this study were damaged and abnormal is unknown,” Dr. Zeng and colleagues said. “Alternatively, IgM could have been produced by the infant if the virus crossed the placenta.”

“Although these 2 studies deserve careful evaluation, more definitive evidence is needed” before physicians can “counsel pregnant women that their fetuses are at risk from congenital infection with SARS-CoV-2,” Dr. Kimberlin and Dr. Stagno concluded.

Dr. Dong and associates had no conflicts of interest. Their work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Project and others. Dr. Zeng and colleagues had no relevant financial disclosures. Their study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and Zhongnan Hospital. Dr. Kimberlin and Dr. Stagno had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Dong L et al. JAMA. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4621; Zeng H et al. JAMA. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4861.

FROM JAMA

Despite strict controls, some infants born to mothers with COVID-19 appear infected

Despite implementation of strict infection control and prevention procedures in a hospital in Wuhan, China, according to Lingkong Zeng, MD, of the department of neonatology at Wuhan Children’s Hospital, and associates.

Thirty-three neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 were included in the study, published as a research letter in JAMA Pediatrics. Of this group, three neonates (9%) were confirmed to be infected with the novel coronavirus 2019 at 2 and 4 days of life through nasopharyngeal and anal swabs.

Of the three infected neonates, two were born at 40 weeks’ gestation and the third was born at 31 weeks. The two full-term infants had mild symptoms such as lethargy and fever and were negative for the virus at 6 days of life. The preterm infant had somewhat worse symptoms, but the investigators acknowledged that “the most seriously ill neonate may have been symptomatic from prematurity, asphyxia, and sepsis, rather than [the novel coronavirus 2019] infection.” They added that outcomes for all three neonates were favorable, consistent with past research.

“Because strict infection control and prevention procedures were implemented during the delivery, it is likely that the sources of [novel coronavirus 2019] in the neonates’ upper respiratory tracts or anuses were maternal in origin,” Dr. Zeng and associates surmised.

While previous studies have shown no evidence of COVID-19 transmission between mothers and neonates, and all samples, including amniotic fluid, cord blood, and breast milk, were negative for the novel coronavirus 2019, “vertical maternal-fetal transmission cannot be ruled out in the current cohort. Therefore, it is crucial to screen pregnant women and implement strict infection control measures, quarantine of infected mothers, and close monitoring of neonates at risk of COVID-19,” the investigators concluded.

The study authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Zeng L et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0878.

Despite implementation of strict infection control and prevention procedures in a hospital in Wuhan, China, according to Lingkong Zeng, MD, of the department of neonatology at Wuhan Children’s Hospital, and associates.

Thirty-three neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 were included in the study, published as a research letter in JAMA Pediatrics. Of this group, three neonates (9%) were confirmed to be infected with the novel coronavirus 2019 at 2 and 4 days of life through nasopharyngeal and anal swabs.

Of the three infected neonates, two were born at 40 weeks’ gestation and the third was born at 31 weeks. The two full-term infants had mild symptoms such as lethargy and fever and were negative for the virus at 6 days of life. The preterm infant had somewhat worse symptoms, but the investigators acknowledged that “the most seriously ill neonate may have been symptomatic from prematurity, asphyxia, and sepsis, rather than [the novel coronavirus 2019] infection.” They added that outcomes for all three neonates were favorable, consistent with past research.

“Because strict infection control and prevention procedures were implemented during the delivery, it is likely that the sources of [novel coronavirus 2019] in the neonates’ upper respiratory tracts or anuses were maternal in origin,” Dr. Zeng and associates surmised.

While previous studies have shown no evidence of COVID-19 transmission between mothers and neonates, and all samples, including amniotic fluid, cord blood, and breast milk, were negative for the novel coronavirus 2019, “vertical maternal-fetal transmission cannot be ruled out in the current cohort. Therefore, it is crucial to screen pregnant women and implement strict infection control measures, quarantine of infected mothers, and close monitoring of neonates at risk of COVID-19,” the investigators concluded.

The study authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Zeng L et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0878.

Despite implementation of strict infection control and prevention procedures in a hospital in Wuhan, China, according to Lingkong Zeng, MD, of the department of neonatology at Wuhan Children’s Hospital, and associates.

Thirty-three neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 were included in the study, published as a research letter in JAMA Pediatrics. Of this group, three neonates (9%) were confirmed to be infected with the novel coronavirus 2019 at 2 and 4 days of life through nasopharyngeal and anal swabs.

Of the three infected neonates, two were born at 40 weeks’ gestation and the third was born at 31 weeks. The two full-term infants had mild symptoms such as lethargy and fever and were negative for the virus at 6 days of life. The preterm infant had somewhat worse symptoms, but the investigators acknowledged that “the most seriously ill neonate may have been symptomatic from prematurity, asphyxia, and sepsis, rather than [the novel coronavirus 2019] infection.” They added that outcomes for all three neonates were favorable, consistent with past research.

“Because strict infection control and prevention procedures were implemented during the delivery, it is likely that the sources of [novel coronavirus 2019] in the neonates’ upper respiratory tracts or anuses were maternal in origin,” Dr. Zeng and associates surmised.

While previous studies have shown no evidence of COVID-19 transmission between mothers and neonates, and all samples, including amniotic fluid, cord blood, and breast milk, were negative for the novel coronavirus 2019, “vertical maternal-fetal transmission cannot be ruled out in the current cohort. Therefore, it is crucial to screen pregnant women and implement strict infection control measures, quarantine of infected mothers, and close monitoring of neonates at risk of COVID-19,” the investigators concluded.

The study authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Zeng L et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0878.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Arsenic levels in infant rice cereal are down

according to test results released by the Food and Drug Administration.

In April 2016, the FDA issued draft guidance calling for manufacturers of the product to reduce the level of arsenic in their cereals by establishing an action level of arsenic of 100 mcg/kg or 100 parts per billion.

Seventy-six percent of samples of infant rice cereal tested in 2018 had levels of arsenic at or below 100 parts per billion versus 47% of samples tested in 2014, according to a statement from the FDA. In 2011-2013, an even lower percentage of samples tested contained amounts of inorganic arsenic at or below the FDA’s current action level for this element, whose consumption has been associated with cancer, skin lesions, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes.

The 2018 data is based on the testing of 149 samples of infant white and brown rice cereal samples.

“Results from our tests show that manufacturers have made significant progress in ensuring lower levels of inorganic arsenic in infant rice cereal,” Susan Mayne, PhD, director of the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, said in the FDA statement.

“Both white rice and brown rice cereals showed improvement in meeting the FDA’s 100 ppb proposed action level, but the improvement was greatest for white rice cereals, which tend to have lower levels of inorganic arsenic overall,” according to the statement.

according to test results released by the Food and Drug Administration.

In April 2016, the FDA issued draft guidance calling for manufacturers of the product to reduce the level of arsenic in their cereals by establishing an action level of arsenic of 100 mcg/kg or 100 parts per billion.

Seventy-six percent of samples of infant rice cereal tested in 2018 had levels of arsenic at or below 100 parts per billion versus 47% of samples tested in 2014, according to a statement from the FDA. In 2011-2013, an even lower percentage of samples tested contained amounts of inorganic arsenic at or below the FDA’s current action level for this element, whose consumption has been associated with cancer, skin lesions, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes.

The 2018 data is based on the testing of 149 samples of infant white and brown rice cereal samples.

“Results from our tests show that manufacturers have made significant progress in ensuring lower levels of inorganic arsenic in infant rice cereal,” Susan Mayne, PhD, director of the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, said in the FDA statement.

“Both white rice and brown rice cereals showed improvement in meeting the FDA’s 100 ppb proposed action level, but the improvement was greatest for white rice cereals, which tend to have lower levels of inorganic arsenic overall,” according to the statement.

according to test results released by the Food and Drug Administration.

In April 2016, the FDA issued draft guidance calling for manufacturers of the product to reduce the level of arsenic in their cereals by establishing an action level of arsenic of 100 mcg/kg or 100 parts per billion.

Seventy-six percent of samples of infant rice cereal tested in 2018 had levels of arsenic at or below 100 parts per billion versus 47% of samples tested in 2014, according to a statement from the FDA. In 2011-2013, an even lower percentage of samples tested contained amounts of inorganic arsenic at or below the FDA’s current action level for this element, whose consumption has been associated with cancer, skin lesions, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes.

The 2018 data is based on the testing of 149 samples of infant white and brown rice cereal samples.

“Results from our tests show that manufacturers have made significant progress in ensuring lower levels of inorganic arsenic in infant rice cereal,” Susan Mayne, PhD, director of the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, said in the FDA statement.

“Both white rice and brown rice cereals showed improvement in meeting the FDA’s 100 ppb proposed action level, but the improvement was greatest for white rice cereals, which tend to have lower levels of inorganic arsenic overall,” according to the statement.

Pediatrics Board Review: Neonatal Seizures

Authors: Shavonne L. Massey, MD and Hannah C. Glass, MDCM, MAS

Test your knowledge of this topic HERE.

Seizures are among the most common signs of neurologic dysfunction in the neonatal period.1 Seizures in the neonate most often represent acute injury to the central nervous system, and, less commonly, are the initial presentation of an epilepsy syndrome. During childhood, the highest risk of seizure is in the first year of life, and within that first year the highest risk is in the neonatal period, which is defined as up to 28 days out of the womb or ≤ 44 weeks’ gestation for preterm neonates.2

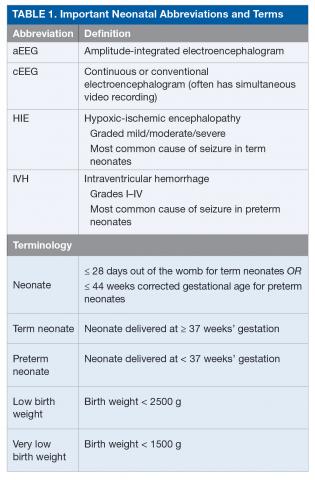

Seizures in neonates are associated with adverse short- and long-term outcomes, and the seizures themselves may result in additional brain injury.3–8 These adverse outcomes can lead to financial, social, and emotional costs to the patient and caregivers. As studies have linked seizure burden and outcome, it is important to quickly recognize, diagnose, and treat seizures in neonates. Because clinical identification of seizures is not reliable and seizures in neonates often do not have an apparent clinical correlate, neuromonitoring techniques should be used to accurately diagnose and manage neonatal seizures.9 Table 1 lists common neonatal abbreviations and terms used in this article.

Epidemiology

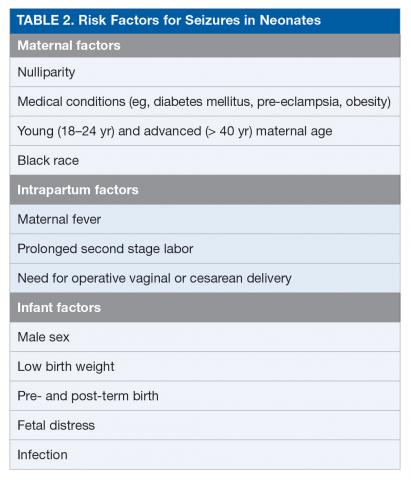

Seizures are among the most common conditions encountered in the neonatal neurocritical care unit.1 The population-based incidence of seizures in neonates ranges from approximately 1 to 5 per 1000 live births in term neonates (≥ 37 weeks’ gestation), but these estimates are based largely on clinical detection of abnormal movements suspected to be seizure, and the actual incidence of electrographic seizures is not known.10 The incidence of seizures is reported to be up to 10-fold higher in preterm (< 37 weeks’ gestation) and low-birth-weight (< 2500 g at birth) neonates, with estimated incidence inversely proportionate to both gestational age and birth weight.2 The estimated incidence of seizure is 20 per 1000 live births in neonates and up to 57 per 1000 live births in low-birth-weight preterm neonates.2,11,12 Table 2 outlines potential risk factors for neonatal seizures.13,14

Etiology

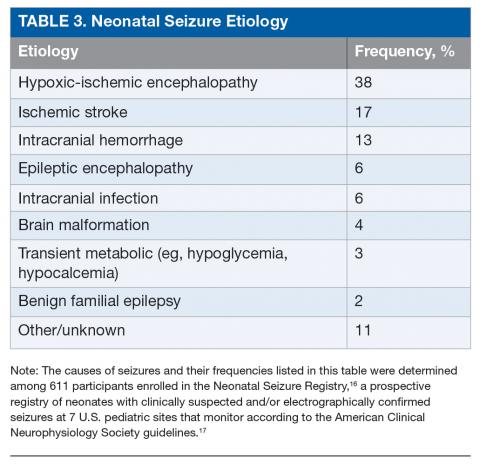

The most common etiology of seizures in neonates is hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE). Altogether the acute symptomatic causes, which also include ischemic stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, and, less commonly, infection or transient metabolic abnormalities, account for more than 75% of neonatal seizures (Table 3).15,16 Collectively, the neonatal-onset epilepsies (due to genetic epileptic encephalopathies, benign familial seizures, or brain malformations) comprise a small but important cause of neonatal seizures.16 It is important to distinguish acute symptomatic causes from neonatal-onset epilepsies, since the approach to diagnosis, management, and antiseizure medication choice will differ. Transient metabolic causes of seizures (eg, hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, and hyponatremia) rarely cause seizure in a tertiary care setting, but must be investigated emergently as correction will often be the only treatment needed.

Test your knowledge of this topic: Board Review Questions

Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy

HIE is the most common cause of seizures in neonates.15,18,19 Neonates with HIE present with encephalopathy and indicator(s) of a perinatal event (eg, placental abruption, umbilical cord dysfunction), which may include low Apgar scores, acidotic pH, and/or need for advanced resuscitation.20 Seizure onset is typically within the first 24 hours after birth.21,22 Therapeutic hypothermia (which is standard of care for neonates ≥ 36 weeks’ gestation with moderate to severe HIE) has been shown to reduce seizures, but approximately 50% of treated neonates have electrographic seizures nonetheless.23 For this reason, continuous brain monitoring is recommended.17

Ischemic Stroke

The incidence of perinatal arterial ischemic stroke is approximately 10 to 20 per 100,000 live births.24,25 The left middle cerebral artery territory is the most common location of injury, and therefore right-sided hemiclonic seizures (especially in a well-appearing neonate) are a common initial presentation. The etiology is thought to be embolism from the placenta or umbilical cord. Maternal risk factors for arterial stroke include infertility, preeclampsia, prolonged rupture of membranes, and chorioamnionitis.25,26 Infant risk factors are congenital cardiac abnormalities (and especially need for balloon atrial septostomy), systemic and intracranial infection, thrombophilia, and male sex.26,27 Venous strokes occur most commonly in the setting of illnesses, including dehydration and sepsis.28

Intracranial Hemorrhage

Intracranial hemorrhage into the parenchyma or extra-axial spaces, most commonly intraventricular and subarachnoid, can cause seizures (small subdural hemorrhages are common and rarely symptomatic). Intraventricular hemorrhage is the most common cause of seizures in preterm neonates.12,29 Parenchymal hemorrhages may be due to trauma, vascular malformation, cerebral sinovenous thrombosis, or coagulopathy, although in a large proportion, the cause is unknown.30,31

Central Nervous System Infections

Congenital and postnatal central nervous system infections are a rare cause of seizures in neonates. Infection can be acute or chronic and viral (eg, herpes simplex virus, parechovirus, and disseminated enterovirus) or bacterial (eg, group B streptococcus and Escherichia coli).

Brain Malformations

Brain malformations (eg, polymicrogyria, holoprosencephaly, schizencephaly, and lissencephaly, among others) may cause epilepsy with onset in the neonatal period. Neonates with brain malformations can also have seizures due to comorbid HIE and/or electrolyte disturbances or hypoglycemia due to pituitary dysfunction.16

Neonatal-Onset Genetic Epilepsy Syndromes