User login

More research needed on how fetal exposure affects later development

The number of genes in humans seems inadequate to account for the diversity seen in people. While maternal and paternal factors do play a role in the development of offspring, increased attention is being paid to the forces that express these genes and the impact they have on the health of a person, including development of psychiatric conditions, according to Dolores Malaspina, MD.

Epigenetics, or changes that occur in a fetal phenotype that do not involve changes to the genotype, involve factors such as DNA methylation to control gene expression, histone modification or the wrapping of genes, or the silencing and activation of certain genes with noncoding RNA-associated factors, said Dr. Malaspina of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

When this occurs during pregnancy, “the fetus does not simply develop from a genetic blueprint of the genes from its father and mother. Instead, signals are received throughout the pregnancy as to the health of the mother and signals about the environment,” she said in a virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

There is an evolutionary advantage to this so-called survival phenotype. “If, during the pregnancy, there’s a deficit of available nutrition, that may be a signal to the fetus that food will be scarce. In the setting of food scarcity, certain physiological adaptations during development can make the fetus more likely to survive to adulthood,” Dr. Malaspina said at the meeting, presented by Global Academy for Medical Education. But a fetus programmed to adapt to scarcity of food may also develop cardiovascular disease, metabolic disease, or mortality later in life if the prediction of scarce nutrition proved incorrect.

This approach to thinking about the developmental origins of health and disease, which examines how prenatal and perinatal exposure to environmental factors affect disease in adulthood, has also found a link between some exposures and psychiatric disorders. The most famous example, the Dutch Hunger Winter Families Study, found an increased risk of schizophrenia among children born during the height of the famine (Int J Epidemiol. 2007 Dec;36[6]:1196-204). During the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 (the Six-Day War), which took place in June, the fetuses of mothers who were pregnant during that month had a higher risk of schizophrenia if the fetus was in the second month (relative risk, 2.3; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-4.7) or third month (RR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.2-5.2) of fetal life during June 1967, Dr. Malaspina and associates wrote (BMC Psychiatry. 2008 Aug 21;8:71).

“The key aspect is the ascertainment of individuals during a circumscribed period, the assessment and then the longitudinal follow-up,” she said. “Obviously, these are not easy studies to do, but enough of them have been done such that for the last decade at least, the general population should be aware of the developmental origins of health and disease.”

Maternal depression is another psychiatric condition that can serve as a prenatal exposure to adversity. A recent review found that children of women with untreated depression were 56% more likely to be born preterm and 96% more likely to have a low birth weight (Pediatr Res. 2019 Jan;85[2]:134-45). “Preterm birth and early birth along with low birth weight, these have ramifying effects throughout life, not only on neonatal and infant mortality, but on developmental disorders and lifetime morbidity,” she said. “These effects of maternal depression withstand all sorts of accounting for other correlated exposures, including maternal age and her medical complications or substance use.”

“The modulation of mood and affect can affect temperament and affect mental health. Studies exist linking maternal depression to autism, attention-deficit disorder, developmental delay, behavioral problems, sleep problems, externalizing behavior and depression, showing a very large effect of maternal depression on offspring well-being.”

To complicate matters, at least 15% of women will experience major depression during pregnancy, but of these, major depression is not being addressed in about half. Nonpharmacologic interventions can include cognitive-behavioral therapy and relaxation practices, but medication should be considered as well. “There’s an ongoing debate about whether antidepressant medications are harmful for the offspring,” she said. However, reviews conducted by Dr. Malaspina’s group have found low evidence of serious harm.

“My summary would be the depression itself holds much more evidence for disrupting offspring health and development than medications,” Dr. Malaspina said. “Most studies find no adverse birth effects when they properly controlled accounting for maternal age and the other conditions and other medications.”

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Malaspina reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

The number of genes in humans seems inadequate to account for the diversity seen in people. While maternal and paternal factors do play a role in the development of offspring, increased attention is being paid to the forces that express these genes and the impact they have on the health of a person, including development of psychiatric conditions, according to Dolores Malaspina, MD.

Epigenetics, or changes that occur in a fetal phenotype that do not involve changes to the genotype, involve factors such as DNA methylation to control gene expression, histone modification or the wrapping of genes, or the silencing and activation of certain genes with noncoding RNA-associated factors, said Dr. Malaspina of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

When this occurs during pregnancy, “the fetus does not simply develop from a genetic blueprint of the genes from its father and mother. Instead, signals are received throughout the pregnancy as to the health of the mother and signals about the environment,” she said in a virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

There is an evolutionary advantage to this so-called survival phenotype. “If, during the pregnancy, there’s a deficit of available nutrition, that may be a signal to the fetus that food will be scarce. In the setting of food scarcity, certain physiological adaptations during development can make the fetus more likely to survive to adulthood,” Dr. Malaspina said at the meeting, presented by Global Academy for Medical Education. But a fetus programmed to adapt to scarcity of food may also develop cardiovascular disease, metabolic disease, or mortality later in life if the prediction of scarce nutrition proved incorrect.

This approach to thinking about the developmental origins of health and disease, which examines how prenatal and perinatal exposure to environmental factors affect disease in adulthood, has also found a link between some exposures and psychiatric disorders. The most famous example, the Dutch Hunger Winter Families Study, found an increased risk of schizophrenia among children born during the height of the famine (Int J Epidemiol. 2007 Dec;36[6]:1196-204). During the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 (the Six-Day War), which took place in June, the fetuses of mothers who were pregnant during that month had a higher risk of schizophrenia if the fetus was in the second month (relative risk, 2.3; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-4.7) or third month (RR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.2-5.2) of fetal life during June 1967, Dr. Malaspina and associates wrote (BMC Psychiatry. 2008 Aug 21;8:71).

“The key aspect is the ascertainment of individuals during a circumscribed period, the assessment and then the longitudinal follow-up,” she said. “Obviously, these are not easy studies to do, but enough of them have been done such that for the last decade at least, the general population should be aware of the developmental origins of health and disease.”

Maternal depression is another psychiatric condition that can serve as a prenatal exposure to adversity. A recent review found that children of women with untreated depression were 56% more likely to be born preterm and 96% more likely to have a low birth weight (Pediatr Res. 2019 Jan;85[2]:134-45). “Preterm birth and early birth along with low birth weight, these have ramifying effects throughout life, not only on neonatal and infant mortality, but on developmental disorders and lifetime morbidity,” she said. “These effects of maternal depression withstand all sorts of accounting for other correlated exposures, including maternal age and her medical complications or substance use.”

“The modulation of mood and affect can affect temperament and affect mental health. Studies exist linking maternal depression to autism, attention-deficit disorder, developmental delay, behavioral problems, sleep problems, externalizing behavior and depression, showing a very large effect of maternal depression on offspring well-being.”

To complicate matters, at least 15% of women will experience major depression during pregnancy, but of these, major depression is not being addressed in about half. Nonpharmacologic interventions can include cognitive-behavioral therapy and relaxation practices, but medication should be considered as well. “There’s an ongoing debate about whether antidepressant medications are harmful for the offspring,” she said. However, reviews conducted by Dr. Malaspina’s group have found low evidence of serious harm.

“My summary would be the depression itself holds much more evidence for disrupting offspring health and development than medications,” Dr. Malaspina said. “Most studies find no adverse birth effects when they properly controlled accounting for maternal age and the other conditions and other medications.”

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Malaspina reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

The number of genes in humans seems inadequate to account for the diversity seen in people. While maternal and paternal factors do play a role in the development of offspring, increased attention is being paid to the forces that express these genes and the impact they have on the health of a person, including development of psychiatric conditions, according to Dolores Malaspina, MD.

Epigenetics, or changes that occur in a fetal phenotype that do not involve changes to the genotype, involve factors such as DNA methylation to control gene expression, histone modification or the wrapping of genes, or the silencing and activation of certain genes with noncoding RNA-associated factors, said Dr. Malaspina of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

When this occurs during pregnancy, “the fetus does not simply develop from a genetic blueprint of the genes from its father and mother. Instead, signals are received throughout the pregnancy as to the health of the mother and signals about the environment,” she said in a virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

There is an evolutionary advantage to this so-called survival phenotype. “If, during the pregnancy, there’s a deficit of available nutrition, that may be a signal to the fetus that food will be scarce. In the setting of food scarcity, certain physiological adaptations during development can make the fetus more likely to survive to adulthood,” Dr. Malaspina said at the meeting, presented by Global Academy for Medical Education. But a fetus programmed to adapt to scarcity of food may also develop cardiovascular disease, metabolic disease, or mortality later in life if the prediction of scarce nutrition proved incorrect.

This approach to thinking about the developmental origins of health and disease, which examines how prenatal and perinatal exposure to environmental factors affect disease in adulthood, has also found a link between some exposures and psychiatric disorders. The most famous example, the Dutch Hunger Winter Families Study, found an increased risk of schizophrenia among children born during the height of the famine (Int J Epidemiol. 2007 Dec;36[6]:1196-204). During the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 (the Six-Day War), which took place in June, the fetuses of mothers who were pregnant during that month had a higher risk of schizophrenia if the fetus was in the second month (relative risk, 2.3; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-4.7) or third month (RR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.2-5.2) of fetal life during June 1967, Dr. Malaspina and associates wrote (BMC Psychiatry. 2008 Aug 21;8:71).

“The key aspect is the ascertainment of individuals during a circumscribed period, the assessment and then the longitudinal follow-up,” she said. “Obviously, these are not easy studies to do, but enough of them have been done such that for the last decade at least, the general population should be aware of the developmental origins of health and disease.”

Maternal depression is another psychiatric condition that can serve as a prenatal exposure to adversity. A recent review found that children of women with untreated depression were 56% more likely to be born preterm and 96% more likely to have a low birth weight (Pediatr Res. 2019 Jan;85[2]:134-45). “Preterm birth and early birth along with low birth weight, these have ramifying effects throughout life, not only on neonatal and infant mortality, but on developmental disorders and lifetime morbidity,” she said. “These effects of maternal depression withstand all sorts of accounting for other correlated exposures, including maternal age and her medical complications or substance use.”

“The modulation of mood and affect can affect temperament and affect mental health. Studies exist linking maternal depression to autism, attention-deficit disorder, developmental delay, behavioral problems, sleep problems, externalizing behavior and depression, showing a very large effect of maternal depression on offspring well-being.”

To complicate matters, at least 15% of women will experience major depression during pregnancy, but of these, major depression is not being addressed in about half. Nonpharmacologic interventions can include cognitive-behavioral therapy and relaxation practices, but medication should be considered as well. “There’s an ongoing debate about whether antidepressant medications are harmful for the offspring,” she said. However, reviews conducted by Dr. Malaspina’s group have found low evidence of serious harm.

“My summary would be the depression itself holds much more evidence for disrupting offspring health and development than medications,” Dr. Malaspina said. “Most studies find no adverse birth effects when they properly controlled accounting for maternal age and the other conditions and other medications.”

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Malaspina reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM FOCUS ON NEUROPSYCHIATRY 2020

Health disparity: Race, mortality, and infants of teenage mothers

according to a new analysis from the National Center for Health Statistics.

In 2017-2018, overall mortality rates were 12.5 per 100,000 live births for infants born to Black mothers aged 15-19 years, 8.4 per 100,000 for infants born to White teenagers, and 6.5 per 100,000 for those born to Hispanic teens, Ashley M. Woodall, MPH, and Anne K. Driscoll, PhD, of the NCHS said in a data brief.

Looking at the five leading causes of those deaths shows that deaths of Black infants were the highest by significant margins in four, although, when it comes to “disorders related to short gestation and low birth weight,” significant may be an understatement.

The rate of preterm/low-birth-weight deaths for white infants in 2017-2018 was 119 per 100,000 live births; for Hispanic infants it was 94 per 100,000. Among infants born to Black teenagers, however, it was 284 deaths per 100,000, they reported based on data from the National Vital Statistics System’s linked birth/infant death file.

The numbers for congenital malformations and accidents were closer but still significantly different, and with each of the three most common causes, the rates for infants of Hispanic mothers also were significantly lower than those of White infants, the researchers said.

The situation changes for mortality-cause No. 4, sudden infant death syndrome, which was significantly more common among infants born to White teenagers, with a rate of 91 deaths per 100,000 live births, compared with either black (77) or Hispanic (44) infants, Ms. Woodall and Dr. Driscoll said.

Infants born to Black teens had the highest death rate again (68 per 100,000) for maternal complications of pregnancy, the fifth-leading cause of mortality, but for the first time Hispanic infants had a higher rate (36) than did those of White teenagers (29), they reported.

according to a new analysis from the National Center for Health Statistics.

In 2017-2018, overall mortality rates were 12.5 per 100,000 live births for infants born to Black mothers aged 15-19 years, 8.4 per 100,000 for infants born to White teenagers, and 6.5 per 100,000 for those born to Hispanic teens, Ashley M. Woodall, MPH, and Anne K. Driscoll, PhD, of the NCHS said in a data brief.

Looking at the five leading causes of those deaths shows that deaths of Black infants were the highest by significant margins in four, although, when it comes to “disorders related to short gestation and low birth weight,” significant may be an understatement.

The rate of preterm/low-birth-weight deaths for white infants in 2017-2018 was 119 per 100,000 live births; for Hispanic infants it was 94 per 100,000. Among infants born to Black teenagers, however, it was 284 deaths per 100,000, they reported based on data from the National Vital Statistics System’s linked birth/infant death file.

The numbers for congenital malformations and accidents were closer but still significantly different, and with each of the three most common causes, the rates for infants of Hispanic mothers also were significantly lower than those of White infants, the researchers said.

The situation changes for mortality-cause No. 4, sudden infant death syndrome, which was significantly more common among infants born to White teenagers, with a rate of 91 deaths per 100,000 live births, compared with either black (77) or Hispanic (44) infants, Ms. Woodall and Dr. Driscoll said.

Infants born to Black teens had the highest death rate again (68 per 100,000) for maternal complications of pregnancy, the fifth-leading cause of mortality, but for the first time Hispanic infants had a higher rate (36) than did those of White teenagers (29), they reported.

according to a new analysis from the National Center for Health Statistics.

In 2017-2018, overall mortality rates were 12.5 per 100,000 live births for infants born to Black mothers aged 15-19 years, 8.4 per 100,000 for infants born to White teenagers, and 6.5 per 100,000 for those born to Hispanic teens, Ashley M. Woodall, MPH, and Anne K. Driscoll, PhD, of the NCHS said in a data brief.

Looking at the five leading causes of those deaths shows that deaths of Black infants were the highest by significant margins in four, although, when it comes to “disorders related to short gestation and low birth weight,” significant may be an understatement.

The rate of preterm/low-birth-weight deaths for white infants in 2017-2018 was 119 per 100,000 live births; for Hispanic infants it was 94 per 100,000. Among infants born to Black teenagers, however, it was 284 deaths per 100,000, they reported based on data from the National Vital Statistics System’s linked birth/infant death file.

The numbers for congenital malformations and accidents were closer but still significantly different, and with each of the three most common causes, the rates for infants of Hispanic mothers also were significantly lower than those of White infants, the researchers said.

The situation changes for mortality-cause No. 4, sudden infant death syndrome, which was significantly more common among infants born to White teenagers, with a rate of 91 deaths per 100,000 live births, compared with either black (77) or Hispanic (44) infants, Ms. Woodall and Dr. Driscoll said.

Infants born to Black teens had the highest death rate again (68 per 100,000) for maternal complications of pregnancy, the fifth-leading cause of mortality, but for the first time Hispanic infants had a higher rate (36) than did those of White teenagers (29), they reported.

Parental refusal of neonatal therapy a growing problem

according to an update at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine virtual. This finding indicates the value of preparing policies and strategies to guide parents to appropriate medical decisions in advance.

“Elimination of nonmedical exceptions to vaccinations and intramuscular vitamin K made it into two of the AAP [American Academy of Pediatrics] top 10 public health resolutions, most likely because refusal rates are going up,” reported Ha N. Nguyen, MD, of the division of pediatric hospital medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Importantly, state laws differ. For example, erythromycin ointment is mandated in neonates for prevention of gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum in many states, including New York, where it can be administered without consent, according to Dr. Nguyen. Conversely, California does not mandate this preventive therapy even though the law does not offer medico-legal protection to providers if it is not given.

“There is a glaring gap in the way the [California] law was written,” said Dr. Nguyen, who used this as an example of why protocols and strategies to reduce risk of parental refusal of neonatal therapies should be informed by, and consistent with, state laws.

Because of the low levels of vitamin K in infants, the rate of bleeding within the first few months of life is nearly 2%, according to figures cited by Dr. Nguyen. It falls to less than 0.001% with administration of intramuscular vitamin K.

Families who refuse intramuscular vitamin K often state that they understand the risks, but data from a survey Dr. Nguyen cited found this is not necessarily true. In this survey, about two-thirds knew that bleeding was the risk, but less than 20% understood bleeding risks included intracranial hemorrhage, and less than 10% were aware that there was potential for a fatal outcome.

“This is a huge piece of the puzzle for counseling,” Dr. Nguyen said. “The discussion with parents should explicitly involve the explanation that the risks include brain bleeds and death.”

Although most infant bleeds attributed to low vitamin K stores are mucocutaneous or gastrointestinal, intracranial hemorrhage does occur, and these outcomes can be devastating. Up to 25% of infants who experience an intracranial hemorrhage die, while 60% of those who survive have some degree of neurodevelopmental impairment, according to Dr. Nguyen.

Oral vitamin K, which requires multiple doses, is not an appropriate substitute for the recommended single injection of the intramuscular formulation. The one study that compared intramuscular and oral vitamin K did not prove equivalence, and no oral vitamin K products have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Nguyen reported.

“We do know confidently that oral vitamin K does often result in poor adherence,” she said,

In a recent review article of parental vitamin K refusal, one of the most significant predictors of refusal of any recommended neonatal preventive treatment was refusal of another. According to data in that article, summarized by Dr. Nguyen, 68% of the parents who declined intramuscular vitamin K also declined erythromycin ointment, and more than 90% declined hepatitis B vaccine.

“One reason that many parents refuse the hepatitis B vaccine is that they do not think their child is at risk,” explained Kimberly Horstman, MD, from Stanford University and John Muir Medical Center in Walnut Creek, Calif.

Yet hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, which is asymptomatic, can be acquired from many sources, including nonfamily contacts, according to Dr. Horstman.

“The AAP supports universal hepatitis B vaccine within 24 hours of birth for all infants over 2,000 g at birth,” Dr. Horstman said. In those weighing less, the vaccine is recommended within the first month of life.

The risk of parental refusal for recommended neonatal preventive medicines is higher among those with more education and higher income relative to those with less, Dr. Nguyen said. Other predictors include older maternal age, private insurance, and delivery by a midwife or at a birthing center.

Many parents who refuse preventive neonatal medications do not fully grasp what risks they are accepting by avoiding a recommended medication, according to both Dr. Nguyen and Dr. Horstman. In some cases, the goal is to protect their child from the pain of a needlestick, even when the health consequences might include far more invasive and painful therapies if the child develops the disease the medication would have prevented.

In the case of intramuscular vitamin K, “we encourage a presumptive approach,” Dr. Nguyen said. Concerns can then be addressed only if the parents refuse.

For another strategy, Dr. Nguyen recommended counseling parents about the need and value of preventive therapies during pregnancy. She cited data suggesting that it is more difficult to change the minds of parents after delivery.

Echoing this approach in regard to HBV vaccine, Dr. Horstman suggested encouraging colleagues, including obstetricians and community pediatricians, to raise and address this topic during prenatal counseling. By preparing parents for the recommended medications in the prenatal period, concerns can be addressed in advance.

The health risks posed by parents who refuse recommended medications is recognized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Both Dr. Horstman and Dr. Nguyen said there are handouts from the CDC and the AAP to inform parents of the purpose and benefit of recommended preventive therapies, as well as to equip caregivers with facts for effective counseling.

according to an update at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine virtual. This finding indicates the value of preparing policies and strategies to guide parents to appropriate medical decisions in advance.

“Elimination of nonmedical exceptions to vaccinations and intramuscular vitamin K made it into two of the AAP [American Academy of Pediatrics] top 10 public health resolutions, most likely because refusal rates are going up,” reported Ha N. Nguyen, MD, of the division of pediatric hospital medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Importantly, state laws differ. For example, erythromycin ointment is mandated in neonates for prevention of gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum in many states, including New York, where it can be administered without consent, according to Dr. Nguyen. Conversely, California does not mandate this preventive therapy even though the law does not offer medico-legal protection to providers if it is not given.

“There is a glaring gap in the way the [California] law was written,” said Dr. Nguyen, who used this as an example of why protocols and strategies to reduce risk of parental refusal of neonatal therapies should be informed by, and consistent with, state laws.

Because of the low levels of vitamin K in infants, the rate of bleeding within the first few months of life is nearly 2%, according to figures cited by Dr. Nguyen. It falls to less than 0.001% with administration of intramuscular vitamin K.

Families who refuse intramuscular vitamin K often state that they understand the risks, but data from a survey Dr. Nguyen cited found this is not necessarily true. In this survey, about two-thirds knew that bleeding was the risk, but less than 20% understood bleeding risks included intracranial hemorrhage, and less than 10% were aware that there was potential for a fatal outcome.

“This is a huge piece of the puzzle for counseling,” Dr. Nguyen said. “The discussion with parents should explicitly involve the explanation that the risks include brain bleeds and death.”

Although most infant bleeds attributed to low vitamin K stores are mucocutaneous or gastrointestinal, intracranial hemorrhage does occur, and these outcomes can be devastating. Up to 25% of infants who experience an intracranial hemorrhage die, while 60% of those who survive have some degree of neurodevelopmental impairment, according to Dr. Nguyen.

Oral vitamin K, which requires multiple doses, is not an appropriate substitute for the recommended single injection of the intramuscular formulation. The one study that compared intramuscular and oral vitamin K did not prove equivalence, and no oral vitamin K products have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Nguyen reported.

“We do know confidently that oral vitamin K does often result in poor adherence,” she said,

In a recent review article of parental vitamin K refusal, one of the most significant predictors of refusal of any recommended neonatal preventive treatment was refusal of another. According to data in that article, summarized by Dr. Nguyen, 68% of the parents who declined intramuscular vitamin K also declined erythromycin ointment, and more than 90% declined hepatitis B vaccine.

“One reason that many parents refuse the hepatitis B vaccine is that they do not think their child is at risk,” explained Kimberly Horstman, MD, from Stanford University and John Muir Medical Center in Walnut Creek, Calif.

Yet hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, which is asymptomatic, can be acquired from many sources, including nonfamily contacts, according to Dr. Horstman.

“The AAP supports universal hepatitis B vaccine within 24 hours of birth for all infants over 2,000 g at birth,” Dr. Horstman said. In those weighing less, the vaccine is recommended within the first month of life.

The risk of parental refusal for recommended neonatal preventive medicines is higher among those with more education and higher income relative to those with less, Dr. Nguyen said. Other predictors include older maternal age, private insurance, and delivery by a midwife or at a birthing center.

Many parents who refuse preventive neonatal medications do not fully grasp what risks they are accepting by avoiding a recommended medication, according to both Dr. Nguyen and Dr. Horstman. In some cases, the goal is to protect their child from the pain of a needlestick, even when the health consequences might include far more invasive and painful therapies if the child develops the disease the medication would have prevented.

In the case of intramuscular vitamin K, “we encourage a presumptive approach,” Dr. Nguyen said. Concerns can then be addressed only if the parents refuse.

For another strategy, Dr. Nguyen recommended counseling parents about the need and value of preventive therapies during pregnancy. She cited data suggesting that it is more difficult to change the minds of parents after delivery.

Echoing this approach in regard to HBV vaccine, Dr. Horstman suggested encouraging colleagues, including obstetricians and community pediatricians, to raise and address this topic during prenatal counseling. By preparing parents for the recommended medications in the prenatal period, concerns can be addressed in advance.

The health risks posed by parents who refuse recommended medications is recognized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Both Dr. Horstman and Dr. Nguyen said there are handouts from the CDC and the AAP to inform parents of the purpose and benefit of recommended preventive therapies, as well as to equip caregivers with facts for effective counseling.

according to an update at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine virtual. This finding indicates the value of preparing policies and strategies to guide parents to appropriate medical decisions in advance.

“Elimination of nonmedical exceptions to vaccinations and intramuscular vitamin K made it into two of the AAP [American Academy of Pediatrics] top 10 public health resolutions, most likely because refusal rates are going up,” reported Ha N. Nguyen, MD, of the division of pediatric hospital medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Importantly, state laws differ. For example, erythromycin ointment is mandated in neonates for prevention of gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum in many states, including New York, where it can be administered without consent, according to Dr. Nguyen. Conversely, California does not mandate this preventive therapy even though the law does not offer medico-legal protection to providers if it is not given.

“There is a glaring gap in the way the [California] law was written,” said Dr. Nguyen, who used this as an example of why protocols and strategies to reduce risk of parental refusal of neonatal therapies should be informed by, and consistent with, state laws.

Because of the low levels of vitamin K in infants, the rate of bleeding within the first few months of life is nearly 2%, according to figures cited by Dr. Nguyen. It falls to less than 0.001% with administration of intramuscular vitamin K.

Families who refuse intramuscular vitamin K often state that they understand the risks, but data from a survey Dr. Nguyen cited found this is not necessarily true. In this survey, about two-thirds knew that bleeding was the risk, but less than 20% understood bleeding risks included intracranial hemorrhage, and less than 10% were aware that there was potential for a fatal outcome.

“This is a huge piece of the puzzle for counseling,” Dr. Nguyen said. “The discussion with parents should explicitly involve the explanation that the risks include brain bleeds and death.”

Although most infant bleeds attributed to low vitamin K stores are mucocutaneous or gastrointestinal, intracranial hemorrhage does occur, and these outcomes can be devastating. Up to 25% of infants who experience an intracranial hemorrhage die, while 60% of those who survive have some degree of neurodevelopmental impairment, according to Dr. Nguyen.

Oral vitamin K, which requires multiple doses, is not an appropriate substitute for the recommended single injection of the intramuscular formulation. The one study that compared intramuscular and oral vitamin K did not prove equivalence, and no oral vitamin K products have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Nguyen reported.

“We do know confidently that oral vitamin K does often result in poor adherence,” she said,

In a recent review article of parental vitamin K refusal, one of the most significant predictors of refusal of any recommended neonatal preventive treatment was refusal of another. According to data in that article, summarized by Dr. Nguyen, 68% of the parents who declined intramuscular vitamin K also declined erythromycin ointment, and more than 90% declined hepatitis B vaccine.

“One reason that many parents refuse the hepatitis B vaccine is that they do not think their child is at risk,” explained Kimberly Horstman, MD, from Stanford University and John Muir Medical Center in Walnut Creek, Calif.

Yet hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, which is asymptomatic, can be acquired from many sources, including nonfamily contacts, according to Dr. Horstman.

“The AAP supports universal hepatitis B vaccine within 24 hours of birth for all infants over 2,000 g at birth,” Dr. Horstman said. In those weighing less, the vaccine is recommended within the first month of life.

The risk of parental refusal for recommended neonatal preventive medicines is higher among those with more education and higher income relative to those with less, Dr. Nguyen said. Other predictors include older maternal age, private insurance, and delivery by a midwife or at a birthing center.

Many parents who refuse preventive neonatal medications do not fully grasp what risks they are accepting by avoiding a recommended medication, according to both Dr. Nguyen and Dr. Horstman. In some cases, the goal is to protect their child from the pain of a needlestick, even when the health consequences might include far more invasive and painful therapies if the child develops the disease the medication would have prevented.

In the case of intramuscular vitamin K, “we encourage a presumptive approach,” Dr. Nguyen said. Concerns can then be addressed only if the parents refuse.

For another strategy, Dr. Nguyen recommended counseling parents about the need and value of preventive therapies during pregnancy. She cited data suggesting that it is more difficult to change the minds of parents after delivery.

Echoing this approach in regard to HBV vaccine, Dr. Horstman suggested encouraging colleagues, including obstetricians and community pediatricians, to raise and address this topic during prenatal counseling. By preparing parents for the recommended medications in the prenatal period, concerns can be addressed in advance.

The health risks posed by parents who refuse recommended medications is recognized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Both Dr. Horstman and Dr. Nguyen said there are handouts from the CDC and the AAP to inform parents of the purpose and benefit of recommended preventive therapies, as well as to equip caregivers with facts for effective counseling.

FROM PHM 2020

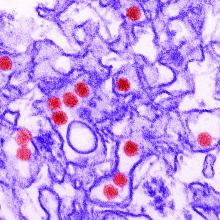

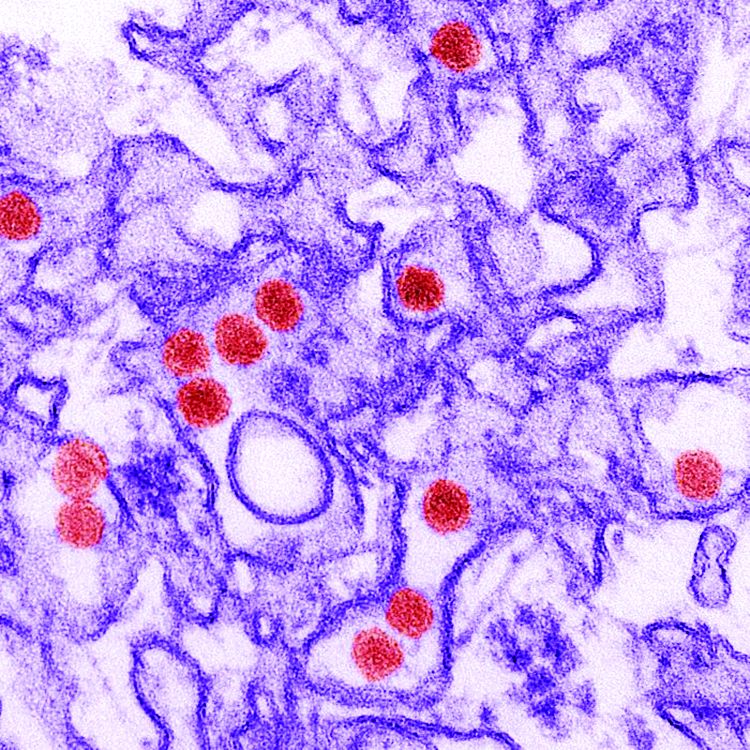

Small NY study: Mother-baby transmission of COVID-19 not seen

according to a study out of New York-Presbyterian Hospital.

“It is suggested in the cumulative data that the virus does not confer additional risk to the fetus during labor or during the early postnatal period in both preterm and term infants,” concluded Jeffrey Perlman, MB ChB, and colleagues in Pediatrics.

But other experts suggest substantial gaps remain in our understanding of maternal transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

“Much more needs to be known,” Munish Gupta, MD, and colleagues from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an accompanying editorial.

The prospective study is the first to describe a cohort of U.S. COVID-19–related deliveries, with the prior neonatal impact of COVID-19 “almost exclusively” reported from China, noted the authors. They included a cohort of 326 women who were tested for SARS-CoV-2 on admission to labor and delivery at New York-Presbyterian Hospital between March 22 and April 15th, 2020. Of the 31 (10%) mothers who tested positive, 15 (48%) were asymptomatic and 16 (52%) were symptomatic.

Two babies were born prematurely (one by Cesarean) and were isolated in negative pressure rooms with continuous positive airway pressure. Both were moved out of isolation after two negative test results and “have exhibited an unremarkable clinical course,” the authors reported.

The other 29 term babies were cared for in their mothers’ rooms, with breastfeeding allowed, if desired. These babies and their mothers were discharged from the hospital between 24 and 48 hours after delivery.

“Visitor restriction for mothers who were positive for COVID-19 included 14 days of no visitation from the start of symptoms,” noted the team.

They added “since the prepublication release there have been a total of 47 mothers positive for COVID-19, resulting in 47 infants; 4 have been admitted to neonatal intensive care. In addition, 32 other infants have been tested for a variety of indications within the unit. All infants test results have been negative.”

The brief report outlined the institution’s checklist for delivery preparedness in either the operating room or labor delivery room, including personal protective equipment, resuscitation, transportation to the neonatal intensive care unit, and early postresuscitation care. “Suspected or confirmed COVID-19 alone in an otherwise uncomplicated pregnancy is not an indication for the resuscitation team or the neonatal fellow,” they noted, adding delivery room preparation and management should include contact precautions. “With scrupulous attention to infectious precautions, horizontal viral transmission should be minimized,” they advised.

Dr. Perlman and associates emphasized that rapid turnaround SARSCoV-2 testing is “crucial to minimize the likelihood of a provider becoming infected and/or infecting the infant.”

Although the findings are “clearly reassuring,” Dr. Gupta and colleagues have reservations. “To what extent does this report address concerns for infection risk with a rooming-in approach to care?” they asked in their accompanying editorial. “The answer is likely some, but not much.”

Many questions remain, they said, including: “What precautions were used to minimize infection risk during the postbirth hospital course? What was the approach to skin-to-skin care and direct mother-newborn contact? Were restrictions placed on family members? Were changes made to routine interventions such as hearing screens or circumcisions? What practices were in place around environmental cleaning? Most important, how did the newborns do after discharge?”

The current uncertainty around neonatal COVID-19 infection risk has led to “disparate” variations in care recommendations, they pointed out. Whereas China’s consensus guidelines recommend a 14-day separation of COVID-19–positive mothers from their healthy infants, a practice supported by the American Academy of Pediatrics “when possible,” the Italian Society of Neonatology, the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, and the Canadian Paediatric Society advise “rooming-in and breastfeeding with appropriate infection prevention measures.”

Dr. Gupta and colleagues pointed to the following as at least three “critical and time-sensitive needs for research around neonatal care and outcomes related to COVID-19”:

- Studies need to have much larger sample sizes and include diverse populations. This will allow for reliable measurement of outcomes.

- Descriptions of care practices must be in detail, especially about infection prevention; these should be presented in a way to compare the efficacy of different approaches.

- There needs to be follow-up information on outcomes of both the mother and the neonate after the birth hospitalization.

Asked to comment, Lillian Beard, MD, of George Washington University in Washington welcomed the data as “good news.”

“Although small, the study was done during a 3-week peak period at the hottest spot of the pandemic in the United States during that period. It illustrates how delivery room preparedness, adequate personal protective equipment, and carefully planned infection control precautions can positively impact outcomes even during a seemingly impossible period,” she said.

“Although there are many uncertainties about maternal COVID-19 transmission and neonatal infection risks ... in my opinion, during the after birth hospitalization, the inherent benefits of rooming in for breast feeding and the opportunities for the demonstration and teaching of infection prevention practices for the family home, far outweigh the risks of disease transmission,” said Dr. Beard, who was not involved with the study.

The study and the commentary emphasize the likely low risk of vertical transmission of the virus, with horizontal transmission being the greater risk. However, cases of transplacental transmission have been reported, and the lead investigator of one recent placental study cautions against complacency.

“Neonates can get infected in both ways. The majority of cases seem to be horizontal, but those who have been infected or highly suspected to be vertically infected are not a small percentage either,” said Daniele de Luca, MD, PhD, president-elect of the European Society for Pediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care (ESPNIC) and a neonatologist at Antoine Béclère Hospital in Clamart, France.

“Perlman’s data are interesting and consistent with other reports around the world. However, two things must be remembered,” he said in an interview. “First, newborn infants are at relatively low risk from SARS-CoV-2 infections, but this is very far from zero risk. Neonatal SARS-CoV-2 infections do exist and have been described around the world. While they have a mild course in the majority of cases, neonatologists should not forget them and should be prepared to offer the best care to these babies.”

“Second, how this can be balanced with the need to promote breastfeeding and avoid overtreatment or separation from the mother is a question far from being answered. Gupta et al. in their commentary are right in saying that we have more questions than answers. While waiting for the results of large initiatives (such as the ESPNIC EPICENTRE Registry that they cite) to answer these open points, the best we can do is to provide a personalised case by case approach, transparent information to parents, and an open counselling informing clinical decisions.”

The study received no external funding. Dr. Perlman and associates had no financial disclosures. Dr. Gupta and colleagues had no relevant financial disclosures. Neither Dr. Beard nor Dr. de Luca had any relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Perlman J et al. Pediatrics. 2020;146(2):e20201567.

according to a study out of New York-Presbyterian Hospital.

“It is suggested in the cumulative data that the virus does not confer additional risk to the fetus during labor or during the early postnatal period in both preterm and term infants,” concluded Jeffrey Perlman, MB ChB, and colleagues in Pediatrics.

But other experts suggest substantial gaps remain in our understanding of maternal transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

“Much more needs to be known,” Munish Gupta, MD, and colleagues from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an accompanying editorial.

The prospective study is the first to describe a cohort of U.S. COVID-19–related deliveries, with the prior neonatal impact of COVID-19 “almost exclusively” reported from China, noted the authors. They included a cohort of 326 women who were tested for SARS-CoV-2 on admission to labor and delivery at New York-Presbyterian Hospital between March 22 and April 15th, 2020. Of the 31 (10%) mothers who tested positive, 15 (48%) were asymptomatic and 16 (52%) were symptomatic.

Two babies were born prematurely (one by Cesarean) and were isolated in negative pressure rooms with continuous positive airway pressure. Both were moved out of isolation after two negative test results and “have exhibited an unremarkable clinical course,” the authors reported.

The other 29 term babies were cared for in their mothers’ rooms, with breastfeeding allowed, if desired. These babies and their mothers were discharged from the hospital between 24 and 48 hours after delivery.

“Visitor restriction for mothers who were positive for COVID-19 included 14 days of no visitation from the start of symptoms,” noted the team.

They added “since the prepublication release there have been a total of 47 mothers positive for COVID-19, resulting in 47 infants; 4 have been admitted to neonatal intensive care. In addition, 32 other infants have been tested for a variety of indications within the unit. All infants test results have been negative.”

The brief report outlined the institution’s checklist for delivery preparedness in either the operating room or labor delivery room, including personal protective equipment, resuscitation, transportation to the neonatal intensive care unit, and early postresuscitation care. “Suspected or confirmed COVID-19 alone in an otherwise uncomplicated pregnancy is not an indication for the resuscitation team or the neonatal fellow,” they noted, adding delivery room preparation and management should include contact precautions. “With scrupulous attention to infectious precautions, horizontal viral transmission should be minimized,” they advised.

Dr. Perlman and associates emphasized that rapid turnaround SARSCoV-2 testing is “crucial to minimize the likelihood of a provider becoming infected and/or infecting the infant.”

Although the findings are “clearly reassuring,” Dr. Gupta and colleagues have reservations. “To what extent does this report address concerns for infection risk with a rooming-in approach to care?” they asked in their accompanying editorial. “The answer is likely some, but not much.”

Many questions remain, they said, including: “What precautions were used to minimize infection risk during the postbirth hospital course? What was the approach to skin-to-skin care and direct mother-newborn contact? Were restrictions placed on family members? Were changes made to routine interventions such as hearing screens or circumcisions? What practices were in place around environmental cleaning? Most important, how did the newborns do after discharge?”

The current uncertainty around neonatal COVID-19 infection risk has led to “disparate” variations in care recommendations, they pointed out. Whereas China’s consensus guidelines recommend a 14-day separation of COVID-19–positive mothers from their healthy infants, a practice supported by the American Academy of Pediatrics “when possible,” the Italian Society of Neonatology, the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, and the Canadian Paediatric Society advise “rooming-in and breastfeeding with appropriate infection prevention measures.”

Dr. Gupta and colleagues pointed to the following as at least three “critical and time-sensitive needs for research around neonatal care and outcomes related to COVID-19”:

- Studies need to have much larger sample sizes and include diverse populations. This will allow for reliable measurement of outcomes.

- Descriptions of care practices must be in detail, especially about infection prevention; these should be presented in a way to compare the efficacy of different approaches.

- There needs to be follow-up information on outcomes of both the mother and the neonate after the birth hospitalization.

Asked to comment, Lillian Beard, MD, of George Washington University in Washington welcomed the data as “good news.”

“Although small, the study was done during a 3-week peak period at the hottest spot of the pandemic in the United States during that period. It illustrates how delivery room preparedness, adequate personal protective equipment, and carefully planned infection control precautions can positively impact outcomes even during a seemingly impossible period,” she said.

“Although there are many uncertainties about maternal COVID-19 transmission and neonatal infection risks ... in my opinion, during the after birth hospitalization, the inherent benefits of rooming in for breast feeding and the opportunities for the demonstration and teaching of infection prevention practices for the family home, far outweigh the risks of disease transmission,” said Dr. Beard, who was not involved with the study.

The study and the commentary emphasize the likely low risk of vertical transmission of the virus, with horizontal transmission being the greater risk. However, cases of transplacental transmission have been reported, and the lead investigator of one recent placental study cautions against complacency.

“Neonates can get infected in both ways. The majority of cases seem to be horizontal, but those who have been infected or highly suspected to be vertically infected are not a small percentage either,” said Daniele de Luca, MD, PhD, president-elect of the European Society for Pediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care (ESPNIC) and a neonatologist at Antoine Béclère Hospital in Clamart, France.

“Perlman’s data are interesting and consistent with other reports around the world. However, two things must be remembered,” he said in an interview. “First, newborn infants are at relatively low risk from SARS-CoV-2 infections, but this is very far from zero risk. Neonatal SARS-CoV-2 infections do exist and have been described around the world. While they have a mild course in the majority of cases, neonatologists should not forget them and should be prepared to offer the best care to these babies.”

“Second, how this can be balanced with the need to promote breastfeeding and avoid overtreatment or separation from the mother is a question far from being answered. Gupta et al. in their commentary are right in saying that we have more questions than answers. While waiting for the results of large initiatives (such as the ESPNIC EPICENTRE Registry that they cite) to answer these open points, the best we can do is to provide a personalised case by case approach, transparent information to parents, and an open counselling informing clinical decisions.”

The study received no external funding. Dr. Perlman and associates had no financial disclosures. Dr. Gupta and colleagues had no relevant financial disclosures. Neither Dr. Beard nor Dr. de Luca had any relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Perlman J et al. Pediatrics. 2020;146(2):e20201567.

according to a study out of New York-Presbyterian Hospital.

“It is suggested in the cumulative data that the virus does not confer additional risk to the fetus during labor or during the early postnatal period in both preterm and term infants,” concluded Jeffrey Perlman, MB ChB, and colleagues in Pediatrics.

But other experts suggest substantial gaps remain in our understanding of maternal transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

“Much more needs to be known,” Munish Gupta, MD, and colleagues from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an accompanying editorial.

The prospective study is the first to describe a cohort of U.S. COVID-19–related deliveries, with the prior neonatal impact of COVID-19 “almost exclusively” reported from China, noted the authors. They included a cohort of 326 women who were tested for SARS-CoV-2 on admission to labor and delivery at New York-Presbyterian Hospital between March 22 and April 15th, 2020. Of the 31 (10%) mothers who tested positive, 15 (48%) were asymptomatic and 16 (52%) were symptomatic.

Two babies were born prematurely (one by Cesarean) and were isolated in negative pressure rooms with continuous positive airway pressure. Both were moved out of isolation after two negative test results and “have exhibited an unremarkable clinical course,” the authors reported.

The other 29 term babies were cared for in their mothers’ rooms, with breastfeeding allowed, if desired. These babies and their mothers were discharged from the hospital between 24 and 48 hours after delivery.

“Visitor restriction for mothers who were positive for COVID-19 included 14 days of no visitation from the start of symptoms,” noted the team.

They added “since the prepublication release there have been a total of 47 mothers positive for COVID-19, resulting in 47 infants; 4 have been admitted to neonatal intensive care. In addition, 32 other infants have been tested for a variety of indications within the unit. All infants test results have been negative.”

The brief report outlined the institution’s checklist for delivery preparedness in either the operating room or labor delivery room, including personal protective equipment, resuscitation, transportation to the neonatal intensive care unit, and early postresuscitation care. “Suspected or confirmed COVID-19 alone in an otherwise uncomplicated pregnancy is not an indication for the resuscitation team or the neonatal fellow,” they noted, adding delivery room preparation and management should include contact precautions. “With scrupulous attention to infectious precautions, horizontal viral transmission should be minimized,” they advised.

Dr. Perlman and associates emphasized that rapid turnaround SARSCoV-2 testing is “crucial to minimize the likelihood of a provider becoming infected and/or infecting the infant.”

Although the findings are “clearly reassuring,” Dr. Gupta and colleagues have reservations. “To what extent does this report address concerns for infection risk with a rooming-in approach to care?” they asked in their accompanying editorial. “The answer is likely some, but not much.”

Many questions remain, they said, including: “What precautions were used to minimize infection risk during the postbirth hospital course? What was the approach to skin-to-skin care and direct mother-newborn contact? Were restrictions placed on family members? Were changes made to routine interventions such as hearing screens or circumcisions? What practices were in place around environmental cleaning? Most important, how did the newborns do after discharge?”

The current uncertainty around neonatal COVID-19 infection risk has led to “disparate” variations in care recommendations, they pointed out. Whereas China’s consensus guidelines recommend a 14-day separation of COVID-19–positive mothers from their healthy infants, a practice supported by the American Academy of Pediatrics “when possible,” the Italian Society of Neonatology, the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, and the Canadian Paediatric Society advise “rooming-in and breastfeeding with appropriate infection prevention measures.”

Dr. Gupta and colleagues pointed to the following as at least three “critical and time-sensitive needs for research around neonatal care and outcomes related to COVID-19”:

- Studies need to have much larger sample sizes and include diverse populations. This will allow for reliable measurement of outcomes.

- Descriptions of care practices must be in detail, especially about infection prevention; these should be presented in a way to compare the efficacy of different approaches.

- There needs to be follow-up information on outcomes of both the mother and the neonate after the birth hospitalization.

Asked to comment, Lillian Beard, MD, of George Washington University in Washington welcomed the data as “good news.”

“Although small, the study was done during a 3-week peak period at the hottest spot of the pandemic in the United States during that period. It illustrates how delivery room preparedness, adequate personal protective equipment, and carefully planned infection control precautions can positively impact outcomes even during a seemingly impossible period,” she said.

“Although there are many uncertainties about maternal COVID-19 transmission and neonatal infection risks ... in my opinion, during the after birth hospitalization, the inherent benefits of rooming in for breast feeding and the opportunities for the demonstration and teaching of infection prevention practices for the family home, far outweigh the risks of disease transmission,” said Dr. Beard, who was not involved with the study.

The study and the commentary emphasize the likely low risk of vertical transmission of the virus, with horizontal transmission being the greater risk. However, cases of transplacental transmission have been reported, and the lead investigator of one recent placental study cautions against complacency.

“Neonates can get infected in both ways. The majority of cases seem to be horizontal, but those who have been infected or highly suspected to be vertically infected are not a small percentage either,” said Daniele de Luca, MD, PhD, president-elect of the European Society for Pediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care (ESPNIC) and a neonatologist at Antoine Béclère Hospital in Clamart, France.

“Perlman’s data are interesting and consistent with other reports around the world. However, two things must be remembered,” he said in an interview. “First, newborn infants are at relatively low risk from SARS-CoV-2 infections, but this is very far from zero risk. Neonatal SARS-CoV-2 infections do exist and have been described around the world. While they have a mild course in the majority of cases, neonatologists should not forget them and should be prepared to offer the best care to these babies.”

“Second, how this can be balanced with the need to promote breastfeeding and avoid overtreatment or separation from the mother is a question far from being answered. Gupta et al. in their commentary are right in saying that we have more questions than answers. While waiting for the results of large initiatives (such as the ESPNIC EPICENTRE Registry that they cite) to answer these open points, the best we can do is to provide a personalised case by case approach, transparent information to parents, and an open counselling informing clinical decisions.”

The study received no external funding. Dr. Perlman and associates had no financial disclosures. Dr. Gupta and colleagues had no relevant financial disclosures. Neither Dr. Beard nor Dr. de Luca had any relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Perlman J et al. Pediatrics. 2020;146(2):e20201567.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Ob.gyns. struggle to keep pace with changing COVID-19 knowledge

In early April, Maura Quinlan, MD, was working nights on the labor and delivery unit at Northwestern Medicine Prentice Women’s Hospital in Chicago. At the time, hospital policy was to test only patients with known COVID-19 symptoms for SARS-CoV-2. Women in labor wore N95 masks, but only while pushing – and practitioners didn’t always don proper protection in time.

Babies came and families rejoiced. But Dr. Quinlan looks back on those weeks with a degree of horror. “We were laboring a bunch of patients that probably had COVID,” she said, and they were doing so without proper protection.

She’s probably right. According to one study in the New England Journal of Medicine, 13.7% of 211 women who came into the labor and delivery unit at one New York City hospital between March 22 and April 2 were asymptomatic but infected, potentially putting staff and doctors at risk.

Dr. Quinlan already knew she and her fellow ob.gyns. had been walking a thin line and, upon seeing that research, her heart sank. In the middle of a pandemic, they had been racing to keep up with the reality of delivering babies. But despite their efforts to protect both practitioners and patients, some aspects slipped through the cracks. Today, every laboring patient admitted to Northwestern is now tested for the novel coronavirus.

Across the country, hospital labor and delivery wards have been working to find a careful and informed balance among multiple competing interests: the safety of their health care workers, the health of tiny and vulnerable new humans, and the stability of a birthing mother. Each hospital has been making the best decisions it can based on available data. The result is a patchwork of policies, but all of them center around rapid testing and appropriate protection.

Shifting recommendations

One case study of women in a New York City hospital during the height of the city’s surge found that, of seven confirmed COVID-19–positive patients, two were asymptomatic upon admission to the obstetrical service, and these same two patients ultimately required unplanned ICU admission. The women’s care prior to their positive diagnosis had exposed multiple health care workers, all of whom lacked appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), the study authors wrote. “Further, five of seven confirmed COVID-19–positive women were afebrile on initial screen, and four did not first report a cough. In some locations where testing availability remains limited, the minimal symptoms reported for some of these cases might have been insufficient to prompt COVID-19 testing.”

As studies like this pour in, societies continue to update their recommendations accordingly. The latest guidance from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists came on July 1. The group suggests testing all labor and delivery patients, particularly in high-prevalence areas. If tests are in short supply, it recommends prioritizing testing pregnant women with suspected COVID-19 and those who develop symptoms during admission.

At Northwestern, the hospital requests patients stay home and quarantine for the weeks leading up to their delivery date. Then, they rapidly test every patient who comes in for delivery and aim to have results available within a few hours.

The hospital’s 30-room labor and delivery wing remains reserved for patients who test negative. Those with positive COVID-19 results are sent to a 6-bed COVID labor and delivery unit elsewhere in the hospital. “We were lucky we had the space to do that, because smaller community hospitals wouldn’t have a separate unused unit where they could put these women,” Dr. Quinlan said.

In the COVID unit, women deliver without a support person – no partner, doula, or family member can join. Doctors and nurses wear full PPE and work only in that ward. And because some research shows that pregnant women who are asymptomatic or presymptomatic may develop symptoms quickly after starting labor with no measurable illness, Dr. Quinlan must decide on a case-by-case basis what to do, if anything at all.

Delaying an induction could allow the infection to resolve or it could result in her patient moving from presymptomatic disease to full-blown pneumonia. Accelerating labor could bring on symptoms or it could allow a mother to deliver safely and get out of the hospital as quickly as possible. “There is an advantage to having the baby now if you feel okay – even if it’s alone – and getting home,” Dr. Quinlan said.

The hospital also tests the partners of women who are COVID-19 positive. Those with negative results can take the newborn home and try to maintain distance until the mother is no longer symptomatic.

In different parts of the country, hospitals have developed different approaches. Southern California is experiencing its own surge, but at the Ronald Reagan University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center there still haven’t been enough COVID-19 patients to warrant a separate labor and delivery unit.

At UCLA, staff swab patients when they enter the labor and delivery ward — those who test positive have specific room designations. For both COVID-19–positive patients and women who progress faster than test results can be returned, the goals are the same, said Rashmi Rao, MD, an ob.gyn. at UCLA: Deliver in the safest way possible for both mother and baby.

All women, positive or negative, must wear masks during labor – as much as they can tolerate, at least. For patients who are only mildly ill or asymptomatic, the only difference is that everyone wears protective gear. But if a patient’s oxygen levels dip, or her baby is in distress, the team moves more quickly to a cesarean delivery than they’d do with a healthy patient.

Just as hospital policies have been evolving, rules for visitors have been constantly changing too. Initially, UCLA allowed a support person to be present during delivery but had to leave immediately following. Now, each new mother is allowed one visitor for the duration of their stay. And the hospital suggests that patients who are COVID-19 positive recover in separate rooms from their babies and encourages them to maintain distance from their infants, except when breastfeeding.

“We respect and understand that this is a joyous occasion and we’re trying to keep families together as much as possible,” Dr. Rao said.

Care conundrums

How hospitals protect their smallest charges keeps changing too. Reports have been circulating about newborns being taken away from COVID-19-positive mothers, especially in marginalized communities. The stories have led many to worry they’d be forcibly separated from their babies. Most hospitals, however, leave it up to the woman and her doctors to decide how much separation is needed. “After delivery, it depends on how someone is feeling,” Dr. Rao said.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that mothers who are COVID-19–positive pump breast milk and have a healthy caregiver use that milk, or formula, to bottle-feed the baby, with the new mother remaining 6 feet away from the child as much as she can. If that’s not possible, she should wear gloves and a mask while breastfeeding until she has been naturally afebrile for 72 hours and at least 1 week removed from the first appearance of her symptoms.

“It’s tragically hard,” said Dr. Quinlan, to keep a COVID-19–positive mother even 6 feet away from her newborn baby. “If a mother declines separation, we ask the acting pediatric team to discuss the theoretical risks and paucity of data.”

Until recently, research indicated that SARS-CoV-2 wasn’t being transmitted through the uterus from mothers to their babies. And despite a recent case study reporting transplacental transmission between a mother and her fetus in France, researchers still say that the risk of transference is low. To ensure newborn risk remains as low as possible, UCLA’s policy is to swab the baby when he/she is 24 hours old and keep watch for signs of infection: increased lethargy, difficulty waking, or gastrointestinal symptoms like vomiting.

Transmission via breast milk has also, to date, proven relatively unlikely. One study in The Lancet detected the novel coronavirus in breast milk, although it’s not clear that the virus can be passed on in the fluid, says Christina Chambers, PhD, a professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Chambers is studying breast milk to see if the virus or antibodies to it are present. She is also investigating how infection with SARS-CoV-2 impacts women at different times in pregnancy, something that’s still an open question.

“[In] pregnant women with a deteriorating infection, the decisions are the same you would make with any delivery: Save the mom and save the baby,” Dr. Chambers said. “Beyond that, I am encouraged to see that pregnant women are prioritized to being tested,” something that will help researchers understand prevalence of disease in order to better understand whether some symptoms are more dangerous than others.

The situation is evolving so quickly that hospitals and providers are simply trying to stay abreast of the flood of new research. In the absence of definitive answers, they are using the information available and adjusting on the fly. “We are cautiously waiting for more data,” said Dr. Rao. “With the information we have we are doing the best we can to keep our patients safe. And we’re just going to keep at it.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In early April, Maura Quinlan, MD, was working nights on the labor and delivery unit at Northwestern Medicine Prentice Women’s Hospital in Chicago. At the time, hospital policy was to test only patients with known COVID-19 symptoms for SARS-CoV-2. Women in labor wore N95 masks, but only while pushing – and practitioners didn’t always don proper protection in time.

Babies came and families rejoiced. But Dr. Quinlan looks back on those weeks with a degree of horror. “We were laboring a bunch of patients that probably had COVID,” she said, and they were doing so without proper protection.

She’s probably right. According to one study in the New England Journal of Medicine, 13.7% of 211 women who came into the labor and delivery unit at one New York City hospital between March 22 and April 2 were asymptomatic but infected, potentially putting staff and doctors at risk.

Dr. Quinlan already knew she and her fellow ob.gyns. had been walking a thin line and, upon seeing that research, her heart sank. In the middle of a pandemic, they had been racing to keep up with the reality of delivering babies. But despite their efforts to protect both practitioners and patients, some aspects slipped through the cracks. Today, every laboring patient admitted to Northwestern is now tested for the novel coronavirus.

Across the country, hospital labor and delivery wards have been working to find a careful and informed balance among multiple competing interests: the safety of their health care workers, the health of tiny and vulnerable new humans, and the stability of a birthing mother. Each hospital has been making the best decisions it can based on available data. The result is a patchwork of policies, but all of them center around rapid testing and appropriate protection.

Shifting recommendations

One case study of women in a New York City hospital during the height of the city’s surge found that, of seven confirmed COVID-19–positive patients, two were asymptomatic upon admission to the obstetrical service, and these same two patients ultimately required unplanned ICU admission. The women’s care prior to their positive diagnosis had exposed multiple health care workers, all of whom lacked appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), the study authors wrote. “Further, five of seven confirmed COVID-19–positive women were afebrile on initial screen, and four did not first report a cough. In some locations where testing availability remains limited, the minimal symptoms reported for some of these cases might have been insufficient to prompt COVID-19 testing.”

As studies like this pour in, societies continue to update their recommendations accordingly. The latest guidance from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists came on July 1. The group suggests testing all labor and delivery patients, particularly in high-prevalence areas. If tests are in short supply, it recommends prioritizing testing pregnant women with suspected COVID-19 and those who develop symptoms during admission.

At Northwestern, the hospital requests patients stay home and quarantine for the weeks leading up to their delivery date. Then, they rapidly test every patient who comes in for delivery and aim to have results available within a few hours.

The hospital’s 30-room labor and delivery wing remains reserved for patients who test negative. Those with positive COVID-19 results are sent to a 6-bed COVID labor and delivery unit elsewhere in the hospital. “We were lucky we had the space to do that, because smaller community hospitals wouldn’t have a separate unused unit where they could put these women,” Dr. Quinlan said.

In the COVID unit, women deliver without a support person – no partner, doula, or family member can join. Doctors and nurses wear full PPE and work only in that ward. And because some research shows that pregnant women who are asymptomatic or presymptomatic may develop symptoms quickly after starting labor with no measurable illness, Dr. Quinlan must decide on a case-by-case basis what to do, if anything at all.

Delaying an induction could allow the infection to resolve or it could result in her patient moving from presymptomatic disease to full-blown pneumonia. Accelerating labor could bring on symptoms or it could allow a mother to deliver safely and get out of the hospital as quickly as possible. “There is an advantage to having the baby now if you feel okay – even if it’s alone – and getting home,” Dr. Quinlan said.

The hospital also tests the partners of women who are COVID-19 positive. Those with negative results can take the newborn home and try to maintain distance until the mother is no longer symptomatic.

In different parts of the country, hospitals have developed different approaches. Southern California is experiencing its own surge, but at the Ronald Reagan University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center there still haven’t been enough COVID-19 patients to warrant a separate labor and delivery unit.

At UCLA, staff swab patients when they enter the labor and delivery ward — those who test positive have specific room designations. For both COVID-19–positive patients and women who progress faster than test results can be returned, the goals are the same, said Rashmi Rao, MD, an ob.gyn. at UCLA: Deliver in the safest way possible for both mother and baby.

All women, positive or negative, must wear masks during labor – as much as they can tolerate, at least. For patients who are only mildly ill or asymptomatic, the only difference is that everyone wears protective gear. But if a patient’s oxygen levels dip, or her baby is in distress, the team moves more quickly to a cesarean delivery than they’d do with a healthy patient.

Just as hospital policies have been evolving, rules for visitors have been constantly changing too. Initially, UCLA allowed a support person to be present during delivery but had to leave immediately following. Now, each new mother is allowed one visitor for the duration of their stay. And the hospital suggests that patients who are COVID-19 positive recover in separate rooms from their babies and encourages them to maintain distance from their infants, except when breastfeeding.

“We respect and understand that this is a joyous occasion and we’re trying to keep families together as much as possible,” Dr. Rao said.

Care conundrums

How hospitals protect their smallest charges keeps changing too. Reports have been circulating about newborns being taken away from COVID-19-positive mothers, especially in marginalized communities. The stories have led many to worry they’d be forcibly separated from their babies. Most hospitals, however, leave it up to the woman and her doctors to decide how much separation is needed. “After delivery, it depends on how someone is feeling,” Dr. Rao said.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that mothers who are COVID-19–positive pump breast milk and have a healthy caregiver use that milk, or formula, to bottle-feed the baby, with the new mother remaining 6 feet away from the child as much as she can. If that’s not possible, she should wear gloves and a mask while breastfeeding until she has been naturally afebrile for 72 hours and at least 1 week removed from the first appearance of her symptoms.

“It’s tragically hard,” said Dr. Quinlan, to keep a COVID-19–positive mother even 6 feet away from her newborn baby. “If a mother declines separation, we ask the acting pediatric team to discuss the theoretical risks and paucity of data.”

Until recently, research indicated that SARS-CoV-2 wasn’t being transmitted through the uterus from mothers to their babies. And despite a recent case study reporting transplacental transmission between a mother and her fetus in France, researchers still say that the risk of transference is low. To ensure newborn risk remains as low as possible, UCLA’s policy is to swab the baby when he/she is 24 hours old and keep watch for signs of infection: increased lethargy, difficulty waking, or gastrointestinal symptoms like vomiting.