User login

Core behaviors enhance communication about neonatal death

Clinicians can improve communications with parents during neonatal end-of-life situations by adopting key behaviors such as sitting down to talk to parents and using the infant’s name, according to data from a simulation study.

“Empirical evidence regarding communication with parents during and after a child’s critical instability or death is scarce,” wrote Marie-Hélène Lizotte, MD, of Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte-Justine, Montréal, and colleagues. Noting that realistic simulation has been shown to help clinicians improve their communication skills, the investigators recruited clinicians to participate in a simulated unsuccessful neonatal resuscitation to identify behaviors associated with optimal parent communication.

Behaviors associated with high scores for clinicians deemed “good communicators” included introducing themselves to parents, using the infant’s name (if known), sitting down to speak to parents, not leaving the infant alone on the bed after death, and allowing time for silence, the researchers reported in Pediatrics.

The investigators presented the video simulations to evaluators, including clinicians and bereaved parents. In the simulation, a term infant was born after an emergency cesarean delivery for fetal distress and died after an unsuccessful attempt at resuscitation. A manikin infant was programmed to remain pulseless, and two actors played the roles of the parents in the video.

Evaluators scored the videos for overall performance and for communication with the parent actors during and after the resuscitation.

Overall, parent evaluators and parent actors agreed with clinicians on what actions exemplified optimal communication in about 81% of evaluations. Discrepancies were mainly related to the language participants used related to death, as some parent evaluators said they had trouble understanding certain sentences or found them insensitive, such as “her heart never came back” and “allowing natural death.”

A total of 31 participants were recruited for the simulation, including 15 pediatric residents, 5 neonatal fellows, 3 neonatologists, 3 neonatal nurse practitioners, and 5 transport and resuscitation team providers. Videos of the simulations were examined by 21 evaluators, including bereaved parents, the parent actors, a neonatologist, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, a psychologist, and a respiratory therapist. There were 651 evaluations.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of a single center, use of videos for evaluations, and the use of a single infant-resuscitation scenario, the researchers noted. The results were strengthened, however, by the large number of evaluations, and they support the core behaviors as “a skeleton on which to build additional skills with practice and training” with attention to cultural differences in their application, such as recognizing that infants are not named until after birth in some cultures, they said.

The existing literature on strategies for providing empathy and support to parents facing the death of a child is limited, but this simulation study provides a design model to help address this issue, Chris Feudtner, MD, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia wrote in an accompanying editorial. “Overall, this study, in terms of design and methodologic rigor, is a great advance toward answering our key question: how to best support parents in such circumstances,” he said.

Dr. Feudtner said that he would divide the clinician behaviors into two groups. The first, “Calm kind politeness,” includes acknowledging the parents, introducing themselves, using the infant’s name, and remaining calm. The second set of behaviors, which he called “Skillful situational leadership,” includes preparing parents for the resuscitation activities and providing verbal milestones that prepared them for the fatal outcome.

“Picking up on a metaphor offered by the authors of the study, training and repetitive drills on these specific behaviors cannot be emphasized enough because they are not only the skeleton of excellent communication; they are likely also the muscles, the heart, and even the soul,” he concluded.

The study was supported by a grant from the Fonds de Recherche en Santé du Québec and the Medical Education Grant from Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte-Justine. The researchers and Dr. Feudtner reported no financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Lizotte M-H et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1925; Feudtner C. Pediatrics. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3116.

Clinicians can improve communications with parents during neonatal end-of-life situations by adopting key behaviors such as sitting down to talk to parents and using the infant’s name, according to data from a simulation study.

“Empirical evidence regarding communication with parents during and after a child’s critical instability or death is scarce,” wrote Marie-Hélène Lizotte, MD, of Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte-Justine, Montréal, and colleagues. Noting that realistic simulation has been shown to help clinicians improve their communication skills, the investigators recruited clinicians to participate in a simulated unsuccessful neonatal resuscitation to identify behaviors associated with optimal parent communication.

Behaviors associated with high scores for clinicians deemed “good communicators” included introducing themselves to parents, using the infant’s name (if known), sitting down to speak to parents, not leaving the infant alone on the bed after death, and allowing time for silence, the researchers reported in Pediatrics.

The investigators presented the video simulations to evaluators, including clinicians and bereaved parents. In the simulation, a term infant was born after an emergency cesarean delivery for fetal distress and died after an unsuccessful attempt at resuscitation. A manikin infant was programmed to remain pulseless, and two actors played the roles of the parents in the video.

Evaluators scored the videos for overall performance and for communication with the parent actors during and after the resuscitation.

Overall, parent evaluators and parent actors agreed with clinicians on what actions exemplified optimal communication in about 81% of evaluations. Discrepancies were mainly related to the language participants used related to death, as some parent evaluators said they had trouble understanding certain sentences or found them insensitive, such as “her heart never came back” and “allowing natural death.”

A total of 31 participants were recruited for the simulation, including 15 pediatric residents, 5 neonatal fellows, 3 neonatologists, 3 neonatal nurse practitioners, and 5 transport and resuscitation team providers. Videos of the simulations were examined by 21 evaluators, including bereaved parents, the parent actors, a neonatologist, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, a psychologist, and a respiratory therapist. There were 651 evaluations.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of a single center, use of videos for evaluations, and the use of a single infant-resuscitation scenario, the researchers noted. The results were strengthened, however, by the large number of evaluations, and they support the core behaviors as “a skeleton on which to build additional skills with practice and training” with attention to cultural differences in their application, such as recognizing that infants are not named until after birth in some cultures, they said.

The existing literature on strategies for providing empathy and support to parents facing the death of a child is limited, but this simulation study provides a design model to help address this issue, Chris Feudtner, MD, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia wrote in an accompanying editorial. “Overall, this study, in terms of design and methodologic rigor, is a great advance toward answering our key question: how to best support parents in such circumstances,” he said.

Dr. Feudtner said that he would divide the clinician behaviors into two groups. The first, “Calm kind politeness,” includes acknowledging the parents, introducing themselves, using the infant’s name, and remaining calm. The second set of behaviors, which he called “Skillful situational leadership,” includes preparing parents for the resuscitation activities and providing verbal milestones that prepared them for the fatal outcome.

“Picking up on a metaphor offered by the authors of the study, training and repetitive drills on these specific behaviors cannot be emphasized enough because they are not only the skeleton of excellent communication; they are likely also the muscles, the heart, and even the soul,” he concluded.

The study was supported by a grant from the Fonds de Recherche en Santé du Québec and the Medical Education Grant from Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte-Justine. The researchers and Dr. Feudtner reported no financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Lizotte M-H et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1925; Feudtner C. Pediatrics. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3116.

Clinicians can improve communications with parents during neonatal end-of-life situations by adopting key behaviors such as sitting down to talk to parents and using the infant’s name, according to data from a simulation study.

“Empirical evidence regarding communication with parents during and after a child’s critical instability or death is scarce,” wrote Marie-Hélène Lizotte, MD, of Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte-Justine, Montréal, and colleagues. Noting that realistic simulation has been shown to help clinicians improve their communication skills, the investigators recruited clinicians to participate in a simulated unsuccessful neonatal resuscitation to identify behaviors associated with optimal parent communication.

Behaviors associated with high scores for clinicians deemed “good communicators” included introducing themselves to parents, using the infant’s name (if known), sitting down to speak to parents, not leaving the infant alone on the bed after death, and allowing time for silence, the researchers reported in Pediatrics.

The investigators presented the video simulations to evaluators, including clinicians and bereaved parents. In the simulation, a term infant was born after an emergency cesarean delivery for fetal distress and died after an unsuccessful attempt at resuscitation. A manikin infant was programmed to remain pulseless, and two actors played the roles of the parents in the video.

Evaluators scored the videos for overall performance and for communication with the parent actors during and after the resuscitation.

Overall, parent evaluators and parent actors agreed with clinicians on what actions exemplified optimal communication in about 81% of evaluations. Discrepancies were mainly related to the language participants used related to death, as some parent evaluators said they had trouble understanding certain sentences or found them insensitive, such as “her heart never came back” and “allowing natural death.”

A total of 31 participants were recruited for the simulation, including 15 pediatric residents, 5 neonatal fellows, 3 neonatologists, 3 neonatal nurse practitioners, and 5 transport and resuscitation team providers. Videos of the simulations were examined by 21 evaluators, including bereaved parents, the parent actors, a neonatologist, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, a psychologist, and a respiratory therapist. There were 651 evaluations.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of a single center, use of videos for evaluations, and the use of a single infant-resuscitation scenario, the researchers noted. The results were strengthened, however, by the large number of evaluations, and they support the core behaviors as “a skeleton on which to build additional skills with practice and training” with attention to cultural differences in their application, such as recognizing that infants are not named until after birth in some cultures, they said.

The existing literature on strategies for providing empathy and support to parents facing the death of a child is limited, but this simulation study provides a design model to help address this issue, Chris Feudtner, MD, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia wrote in an accompanying editorial. “Overall, this study, in terms of design and methodologic rigor, is a great advance toward answering our key question: how to best support parents in such circumstances,” he said.

Dr. Feudtner said that he would divide the clinician behaviors into two groups. The first, “Calm kind politeness,” includes acknowledging the parents, introducing themselves, using the infant’s name, and remaining calm. The second set of behaviors, which he called “Skillful situational leadership,” includes preparing parents for the resuscitation activities and providing verbal milestones that prepared them for the fatal outcome.

“Picking up on a metaphor offered by the authors of the study, training and repetitive drills on these specific behaviors cannot be emphasized enough because they are not only the skeleton of excellent communication; they are likely also the muscles, the heart, and even the soul,” he concluded.

The study was supported by a grant from the Fonds de Recherche en Santé du Québec and the Medical Education Grant from Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte-Justine. The researchers and Dr. Feudtner reported no financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Lizotte M-H et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1925; Feudtner C. Pediatrics. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3116.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Clinicians who took steps such as sitting down and using the infant’s name were seen by parents as good communicators.

Major finding: Evaluators of a simulation agreed 81% of the time on defining optimal communication.

Study details: The data come from a simulation study of 31 participants and 21 evaluators and a total of 651 evaluations.

Disclosures: The study was supported in part by the Fonds de Recherche en Santé du Québec and the Medical Education Grant from Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte-Justine. The researchers and editorialist said they had no financial conflicts.

Source: Lizotte M-H et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1925; Feudtner C. Pediatrics. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3116.

Infant deaths from birth defects decline, but some disparities widen

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

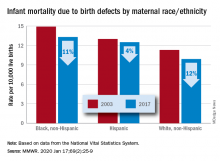

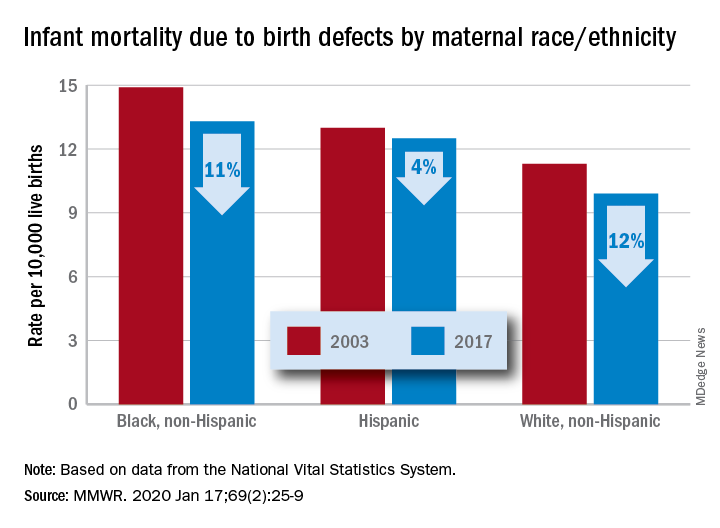

The total rate of IMBD dropped from 12.2 cases per 10,000 live births in 2003 to 11 cases per 10,000 in 2017, with decreases occurring “across the categories of maternal race/ethnicity, infant sex, and infant age at death,” Lynn M. Almli, PhD, of the CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities and associates wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Rates were down for infants of white non-Hispanic, black non-Hispanic, and Hispanic mothers, but disparities among races/ethnicities persisted or even increased. The IMBD rate for infants born to Hispanic mothers, which was 15% higher than that of infants born to white mothers in 2003, was 26% higher by 2017. The difference between infants born to black mothers and those born to whites rose from 32% in 2003 to 34% in 2017, the investigators reported.

The disparities were even greater among subgroups of infants categorized by gestational age. From 2003 to 2017, IMBD rates dropped by 20% for infants in the youngest group (20-27 weeks), 25% for infants in the oldest group (41-44 weeks), and 29% among those born at 39-40 weeks, they said.

For moderate- and late-preterm infants, however, IMBD rates went up: Infants born at 32-33 weeks and 34-36 weeks each had an increase of 17% over the study period, Dr. Almli and associates noted, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

“The observed differences in IMBD rates by race/ethnicity might be influenced by access to and utilization of health care before and during pregnancy, prenatal screening, losses of pregnancies with fetal anomalies, and insurance type,” they wrote, and trends by gestational age “could be influenced by the quantity and quality of care for infants born before 30 weeks’ gestation, compared with that of those born closer to term.”

Birth defects occur in approximately 3% of all births in the United States but accounted for 20% of infant deaths during 2003-2017, the investigators wrote, suggesting that “the results from this analysis can inform future research into areas where efforts to reduce IMBD rates are needed.”

SOURCE: Almli LM et al. MMWR. 2020 Jan 17;69(2):25-9.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The total rate of IMBD dropped from 12.2 cases per 10,000 live births in 2003 to 11 cases per 10,000 in 2017, with decreases occurring “across the categories of maternal race/ethnicity, infant sex, and infant age at death,” Lynn M. Almli, PhD, of the CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities and associates wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Rates were down for infants of white non-Hispanic, black non-Hispanic, and Hispanic mothers, but disparities among races/ethnicities persisted or even increased. The IMBD rate for infants born to Hispanic mothers, which was 15% higher than that of infants born to white mothers in 2003, was 26% higher by 2017. The difference between infants born to black mothers and those born to whites rose from 32% in 2003 to 34% in 2017, the investigators reported.

The disparities were even greater among subgroups of infants categorized by gestational age. From 2003 to 2017, IMBD rates dropped by 20% for infants in the youngest group (20-27 weeks), 25% for infants in the oldest group (41-44 weeks), and 29% among those born at 39-40 weeks, they said.

For moderate- and late-preterm infants, however, IMBD rates went up: Infants born at 32-33 weeks and 34-36 weeks each had an increase of 17% over the study period, Dr. Almli and associates noted, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

“The observed differences in IMBD rates by race/ethnicity might be influenced by access to and utilization of health care before and during pregnancy, prenatal screening, losses of pregnancies with fetal anomalies, and insurance type,” they wrote, and trends by gestational age “could be influenced by the quantity and quality of care for infants born before 30 weeks’ gestation, compared with that of those born closer to term.”

Birth defects occur in approximately 3% of all births in the United States but accounted for 20% of infant deaths during 2003-2017, the investigators wrote, suggesting that “the results from this analysis can inform future research into areas where efforts to reduce IMBD rates are needed.”

SOURCE: Almli LM et al. MMWR. 2020 Jan 17;69(2):25-9.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The total rate of IMBD dropped from 12.2 cases per 10,000 live births in 2003 to 11 cases per 10,000 in 2017, with decreases occurring “across the categories of maternal race/ethnicity, infant sex, and infant age at death,” Lynn M. Almli, PhD, of the CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities and associates wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Rates were down for infants of white non-Hispanic, black non-Hispanic, and Hispanic mothers, but disparities among races/ethnicities persisted or even increased. The IMBD rate for infants born to Hispanic mothers, which was 15% higher than that of infants born to white mothers in 2003, was 26% higher by 2017. The difference between infants born to black mothers and those born to whites rose from 32% in 2003 to 34% in 2017, the investigators reported.

The disparities were even greater among subgroups of infants categorized by gestational age. From 2003 to 2017, IMBD rates dropped by 20% for infants in the youngest group (20-27 weeks), 25% for infants in the oldest group (41-44 weeks), and 29% among those born at 39-40 weeks, they said.

For moderate- and late-preterm infants, however, IMBD rates went up: Infants born at 32-33 weeks and 34-36 weeks each had an increase of 17% over the study period, Dr. Almli and associates noted, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

“The observed differences in IMBD rates by race/ethnicity might be influenced by access to and utilization of health care before and during pregnancy, prenatal screening, losses of pregnancies with fetal anomalies, and insurance type,” they wrote, and trends by gestational age “could be influenced by the quantity and quality of care for infants born before 30 weeks’ gestation, compared with that of those born closer to term.”

Birth defects occur in approximately 3% of all births in the United States but accounted for 20% of infant deaths during 2003-2017, the investigators wrote, suggesting that “the results from this analysis can inform future research into areas where efforts to reduce IMBD rates are needed.”

SOURCE: Almli LM et al. MMWR. 2020 Jan 17;69(2):25-9.

FROM MMWR

Cognitive problems after extremely preterm birth persist

Cognitive and neuropsychological impairment associated with extremely preterm (EP) birth persists into young adulthood, according to findings from the 1995 EPICure cohort.

Of note, intellectual impairment increased significantly after the age of 11 years among 19-year-olds in the cohort of individuals born EP, Helen O’Reilly, PhD, of the Institute for Women’s Health at University College London and colleagues reported in Pediatrics.

Neuropsychological assessment to examine general cognitive abilities, visuomotor abilities, prospective memory, and certain aspects of executive functioning and language in 127 cases and 64 term-born controls showed significantly lower scores across all tests in those born EP.

Impairment in at least one neuropsychological domain was present in 60% of EP birth cases (compared with 21% of controls), with 35% having impairment in at least four domains. Most deficits occurred in general cognitive function and/or visuomotor abilities.

Further, and those with cognitive impairment at 11 years were at increased risk of deficit at 19 years (RR, 3.56), even after adjustment for sex and socioeconomic status, the authors wrote.

None of the term-born controls had a cognitive impairment at 11 years, and two (3%) had impairment at 19 years.

Studies of adults born very preterm have revealed that these individuals are at risk for neuropsychological impairment, but the extent of such impairment in individuals with EP birth, defined as birth before 26 weeks’ gestation, had not previously been studied in the long term.

Assessments in the EPICure cohort of individuals born EP in 1995 previously showed scores at 1.1-1.6 standard deviations lower on measures of general cognitive function, compared with standardized norms and/or term-born controls, at age 2.5, 6, and 11 years, Dr. O’Reilly and colleagues explained.

The current findings indicate that general cognitive and neuropsychological functioning problems associated with EP birth persist and can increase into early adulthood, and they “highlight the need for early and ongoing neuropsychological and educational assessment in EP children to ensure these children receive appropriate support in school and for planned educational pathways,” the investigators concluded.

In an accompanying editorial, Louis A. Schmidt, PhD, and Saroj Saigal, MD, of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., wrote that these findings “provide compelling evidence for persistent effects of cognitive impairments” in individuals born EP.

They highlighted three lessons from the study:

- It is important to control for anxiety in future studies like this “to eliminate potential confounding influences of anxiety when examining performance-based measures in the laboratory setting,” as individuals born EP are known to exhibit anxiety.

- Group heterogeneity also should be considered, as all survivors of prematurity are not alike.

- Measurement equivalency should be established between groups.

With respect to the latter, “although many of the measures used by O’Reilly et al. have been normed, issues of measurement invariance have not been established between EP and control groups on some of the measures reported,” Dr. Schmidt and Dr. Saigal wrote, noting that “many other studies [also] fail to consider this fundamental measurement property.”

“Considering issues of measurement equivalency is of critical importance to ensuring unbiased interpretations of findings,” they added, concluding that the findings by O’Reilly et al. represent an important contribution and confirm findings from many prior studies of extreme prematurity, which “informs how we effectively manage these problems.”

“As the percentage of preterm birth continues to rise worldwide, coupled with reduced morbidity and mortality, and with more EP infants reaching adulthood, there is a need for prospective, long-term outcome studies of extreme prematurity,” Dr. Schmidt and Dr. Saigal added.

The study was funded by the Medical Research Council United Kingdom. The authors reported having no relevant financial disclosures. The editorial by Dr. Schmidt and Dr. Saigal, who also reported having no relevant financial disclosures, was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

SOURCES: O’Reilly H et al. Pediatrics. 2020;145(2):e20192087; Schmidt LA, Saigal S. Pediatrics. 2020;145(2):e20193359.

Cognitive and neuropsychological impairment associated with extremely preterm (EP) birth persists into young adulthood, according to findings from the 1995 EPICure cohort.

Of note, intellectual impairment increased significantly after the age of 11 years among 19-year-olds in the cohort of individuals born EP, Helen O’Reilly, PhD, of the Institute for Women’s Health at University College London and colleagues reported in Pediatrics.

Neuropsychological assessment to examine general cognitive abilities, visuomotor abilities, prospective memory, and certain aspects of executive functioning and language in 127 cases and 64 term-born controls showed significantly lower scores across all tests in those born EP.

Impairment in at least one neuropsychological domain was present in 60% of EP birth cases (compared with 21% of controls), with 35% having impairment in at least four domains. Most deficits occurred in general cognitive function and/or visuomotor abilities.

Further, and those with cognitive impairment at 11 years were at increased risk of deficit at 19 years (RR, 3.56), even after adjustment for sex and socioeconomic status, the authors wrote.

None of the term-born controls had a cognitive impairment at 11 years, and two (3%) had impairment at 19 years.

Studies of adults born very preterm have revealed that these individuals are at risk for neuropsychological impairment, but the extent of such impairment in individuals with EP birth, defined as birth before 26 weeks’ gestation, had not previously been studied in the long term.

Assessments in the EPICure cohort of individuals born EP in 1995 previously showed scores at 1.1-1.6 standard deviations lower on measures of general cognitive function, compared with standardized norms and/or term-born controls, at age 2.5, 6, and 11 years, Dr. O’Reilly and colleagues explained.

The current findings indicate that general cognitive and neuropsychological functioning problems associated with EP birth persist and can increase into early adulthood, and they “highlight the need for early and ongoing neuropsychological and educational assessment in EP children to ensure these children receive appropriate support in school and for planned educational pathways,” the investigators concluded.

In an accompanying editorial, Louis A. Schmidt, PhD, and Saroj Saigal, MD, of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., wrote that these findings “provide compelling evidence for persistent effects of cognitive impairments” in individuals born EP.

They highlighted three lessons from the study:

- It is important to control for anxiety in future studies like this “to eliminate potential confounding influences of anxiety when examining performance-based measures in the laboratory setting,” as individuals born EP are known to exhibit anxiety.

- Group heterogeneity also should be considered, as all survivors of prematurity are not alike.

- Measurement equivalency should be established between groups.

With respect to the latter, “although many of the measures used by O’Reilly et al. have been normed, issues of measurement invariance have not been established between EP and control groups on some of the measures reported,” Dr. Schmidt and Dr. Saigal wrote, noting that “many other studies [also] fail to consider this fundamental measurement property.”

“Considering issues of measurement equivalency is of critical importance to ensuring unbiased interpretations of findings,” they added, concluding that the findings by O’Reilly et al. represent an important contribution and confirm findings from many prior studies of extreme prematurity, which “informs how we effectively manage these problems.”

“As the percentage of preterm birth continues to rise worldwide, coupled with reduced morbidity and mortality, and with more EP infants reaching adulthood, there is a need for prospective, long-term outcome studies of extreme prematurity,” Dr. Schmidt and Dr. Saigal added.

The study was funded by the Medical Research Council United Kingdom. The authors reported having no relevant financial disclosures. The editorial by Dr. Schmidt and Dr. Saigal, who also reported having no relevant financial disclosures, was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

SOURCES: O’Reilly H et al. Pediatrics. 2020;145(2):e20192087; Schmidt LA, Saigal S. Pediatrics. 2020;145(2):e20193359.

Cognitive and neuropsychological impairment associated with extremely preterm (EP) birth persists into young adulthood, according to findings from the 1995 EPICure cohort.

Of note, intellectual impairment increased significantly after the age of 11 years among 19-year-olds in the cohort of individuals born EP, Helen O’Reilly, PhD, of the Institute for Women’s Health at University College London and colleagues reported in Pediatrics.

Neuropsychological assessment to examine general cognitive abilities, visuomotor abilities, prospective memory, and certain aspects of executive functioning and language in 127 cases and 64 term-born controls showed significantly lower scores across all tests in those born EP.

Impairment in at least one neuropsychological domain was present in 60% of EP birth cases (compared with 21% of controls), with 35% having impairment in at least four domains. Most deficits occurred in general cognitive function and/or visuomotor abilities.

Further, and those with cognitive impairment at 11 years were at increased risk of deficit at 19 years (RR, 3.56), even after adjustment for sex and socioeconomic status, the authors wrote.

None of the term-born controls had a cognitive impairment at 11 years, and two (3%) had impairment at 19 years.

Studies of adults born very preterm have revealed that these individuals are at risk for neuropsychological impairment, but the extent of such impairment in individuals with EP birth, defined as birth before 26 weeks’ gestation, had not previously been studied in the long term.

Assessments in the EPICure cohort of individuals born EP in 1995 previously showed scores at 1.1-1.6 standard deviations lower on measures of general cognitive function, compared with standardized norms and/or term-born controls, at age 2.5, 6, and 11 years, Dr. O’Reilly and colleagues explained.

The current findings indicate that general cognitive and neuropsychological functioning problems associated with EP birth persist and can increase into early adulthood, and they “highlight the need for early and ongoing neuropsychological and educational assessment in EP children to ensure these children receive appropriate support in school and for planned educational pathways,” the investigators concluded.

In an accompanying editorial, Louis A. Schmidt, PhD, and Saroj Saigal, MD, of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., wrote that these findings “provide compelling evidence for persistent effects of cognitive impairments” in individuals born EP.

They highlighted three lessons from the study:

- It is important to control for anxiety in future studies like this “to eliminate potential confounding influences of anxiety when examining performance-based measures in the laboratory setting,” as individuals born EP are known to exhibit anxiety.

- Group heterogeneity also should be considered, as all survivors of prematurity are not alike.

- Measurement equivalency should be established between groups.

With respect to the latter, “although many of the measures used by O’Reilly et al. have been normed, issues of measurement invariance have not been established between EP and control groups on some of the measures reported,” Dr. Schmidt and Dr. Saigal wrote, noting that “many other studies [also] fail to consider this fundamental measurement property.”

“Considering issues of measurement equivalency is of critical importance to ensuring unbiased interpretations of findings,” they added, concluding that the findings by O’Reilly et al. represent an important contribution and confirm findings from many prior studies of extreme prematurity, which “informs how we effectively manage these problems.”

“As the percentage of preterm birth continues to rise worldwide, coupled with reduced morbidity and mortality, and with more EP infants reaching adulthood, there is a need for prospective, long-term outcome studies of extreme prematurity,” Dr. Schmidt and Dr. Saigal added.

The study was funded by the Medical Research Council United Kingdom. The authors reported having no relevant financial disclosures. The editorial by Dr. Schmidt and Dr. Saigal, who also reported having no relevant financial disclosures, was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

SOURCES: O’Reilly H et al. Pediatrics. 2020;145(2):e20192087; Schmidt LA, Saigal S. Pediatrics. 2020;145(2):e20193359.

FROM PEDIATRICS

AED exposure from breastfeeding appears to be low

, according to a study published online ahead of print Dec. 30, 2019, in JAMA Neurology. The results may explain why previous research failed to find adverse neurodevelopmental effects of breastfeeding in infants whose mothers are undergoing AED treatment, said the authors.

“The results of this study add support to the general safety of breastfeeding by mothers with epilepsy who take AEDs,” wrote Angela K. Birnbaum, PhD, professor of experimental and clinical pharmacology at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, and colleagues.

Investigators measured infants’ blood AED concentrations

To date, medical consensus about the safety of breastfeeding while the mother is taking AEDs has been elusive. Researchers have investigated breast milk concentrations of AEDs as surrogate markers of AED concentrations in children. Breast milk concentrations, however, do not account for differences in infant pharmacokinetic processes and thus could misrepresent AED exposure in children through breastfeeding.

Dr. Birnbaum and colleagues sought to measure blood concentrations of AEDs in mothers with epilepsy and the infants that they breastfed to achieve an objective measure of AED exposure through breastfeeding. They examined data collected from December 2012 to October 2016 in the prospective Maternal Outcomes and Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (MONEAD) study. Eligible participants were pregnant women with epilepsy between the ages of 14 and 45 years whose pregnancies had progressed to fewer than 20 weeks’ gestational age and who had IQ scores greater than 70 points. Participants were followed up throughout pregnancy and for 9 months post partum. Children were enrolled at birth.

The investigators collected blood samples from mothers and infants who were breastfed at the same visit, which occurred at between 5 and 20 weeks after birth. The volume of ingested breast milk delivered through graduated feeding bottles each day and the total duration of all daily breastfeeding sessions were recorded. For infants, blood samples were collected from the plantar surface of the heel and stored as dried blood spots on filter paper. The study’s primary endpoint was the percentage of infant-to-mother concentration of AEDs. Concentrations of AEDs in infants at less than the lower limit of quantification were assessed as half of the lower limit.

Exposure in utero may be greater than exposure through breast milk

In all, the researchers enrolled 351 pregnant women with epilepsy into the study and collected data on 345 infants. Two hundred twenty-two (64.3%) of the infants were breastfed, and 146 (42.3%) had AED concentrations available. After excluding outliers and mothers with missing concentration data, Dr. Birnbaum and colleagues included 164 matching infant-mother concentration pairs in their analysis (i.e., of 135 mothers and 138 infants). Approximately 52% of the infants were female, and their median age at blood collection was 13 weeks. The mothers’ median age was 32 years. About 82% of mothers were receiving monotherapy. The investigators found no demographic differences between groups of mothers taking various AEDs.

Sixty-eight infants (49.3%) had AED concentrations that were less than the lower limit of quantification. AED concentration was not greater than the lower limit of quantification for any infants breastfed by mothers taking carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, valproic acid, or topiramate. Most levetiracetam (71.4%) and zonisamide (60.0%) concentrations in infants were less than the lower limit of quantification. Most lamotrigine concentrations in infants (88.6%) were greater than the lower limit of quantification.

The median percentage of infant-to-mother concentration was 28.9% for lamotrigine, 5.3% for levetiracetam, 44.2% for zonisamide, 5.7% for carbamazepine, 5.4% for carbamazepine epoxide, 0.3% for oxcarbazepine, 17.2% for topiramate, and 21.4% for valproic acid. Multiple linear regression models indicated that maternal concentration was significantly associated with lamotrigine concentration in infants, but not levetiracetam concentration in infants.

“Prior studies at delivery demonstrated that umbilical-cord concentrations were nearly equal to maternal concentrations, suggesting extensive placental passage to the fetus,” wrote Dr. Birnbaum and colleagues. “Therefore, the amount of AED exposure via breast milk is likely substantially lower than fetal exposure during pregnancy and appears unlikely to confer any additional risks beyond those that might be associated with exposure in pregnancy, especially given prior studies showing no adverse neurodevelopmental effects of breastfeeding while taking AEDs.”

The investigators acknowledged several limitations of their research, including the observational design of the MONEAD study. The amount of AED in participants’ breast milk is unknown, and the investigators could not calculate relative infant dosages. Only one blood sample was taken per infant, thus the results may not reflect infants’ total exposure over time.

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the National Institute of Child Health and Development funded the research. The authors reported receiving research support from various pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Birnbaum AK et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Dec 30. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.4443.

, according to a study published online ahead of print Dec. 30, 2019, in JAMA Neurology. The results may explain why previous research failed to find adverse neurodevelopmental effects of breastfeeding in infants whose mothers are undergoing AED treatment, said the authors.

“The results of this study add support to the general safety of breastfeeding by mothers with epilepsy who take AEDs,” wrote Angela K. Birnbaum, PhD, professor of experimental and clinical pharmacology at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, and colleagues.

Investigators measured infants’ blood AED concentrations

To date, medical consensus about the safety of breastfeeding while the mother is taking AEDs has been elusive. Researchers have investigated breast milk concentrations of AEDs as surrogate markers of AED concentrations in children. Breast milk concentrations, however, do not account for differences in infant pharmacokinetic processes and thus could misrepresent AED exposure in children through breastfeeding.

Dr. Birnbaum and colleagues sought to measure blood concentrations of AEDs in mothers with epilepsy and the infants that they breastfed to achieve an objective measure of AED exposure through breastfeeding. They examined data collected from December 2012 to October 2016 in the prospective Maternal Outcomes and Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (MONEAD) study. Eligible participants were pregnant women with epilepsy between the ages of 14 and 45 years whose pregnancies had progressed to fewer than 20 weeks’ gestational age and who had IQ scores greater than 70 points. Participants were followed up throughout pregnancy and for 9 months post partum. Children were enrolled at birth.

The investigators collected blood samples from mothers and infants who were breastfed at the same visit, which occurred at between 5 and 20 weeks after birth. The volume of ingested breast milk delivered through graduated feeding bottles each day and the total duration of all daily breastfeeding sessions were recorded. For infants, blood samples were collected from the plantar surface of the heel and stored as dried blood spots on filter paper. The study’s primary endpoint was the percentage of infant-to-mother concentration of AEDs. Concentrations of AEDs in infants at less than the lower limit of quantification were assessed as half of the lower limit.

Exposure in utero may be greater than exposure through breast milk

In all, the researchers enrolled 351 pregnant women with epilepsy into the study and collected data on 345 infants. Two hundred twenty-two (64.3%) of the infants were breastfed, and 146 (42.3%) had AED concentrations available. After excluding outliers and mothers with missing concentration data, Dr. Birnbaum and colleagues included 164 matching infant-mother concentration pairs in their analysis (i.e., of 135 mothers and 138 infants). Approximately 52% of the infants were female, and their median age at blood collection was 13 weeks. The mothers’ median age was 32 years. About 82% of mothers were receiving monotherapy. The investigators found no demographic differences between groups of mothers taking various AEDs.

Sixty-eight infants (49.3%) had AED concentrations that were less than the lower limit of quantification. AED concentration was not greater than the lower limit of quantification for any infants breastfed by mothers taking carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, valproic acid, or topiramate. Most levetiracetam (71.4%) and zonisamide (60.0%) concentrations in infants were less than the lower limit of quantification. Most lamotrigine concentrations in infants (88.6%) were greater than the lower limit of quantification.

The median percentage of infant-to-mother concentration was 28.9% for lamotrigine, 5.3% for levetiracetam, 44.2% for zonisamide, 5.7% for carbamazepine, 5.4% for carbamazepine epoxide, 0.3% for oxcarbazepine, 17.2% for topiramate, and 21.4% for valproic acid. Multiple linear regression models indicated that maternal concentration was significantly associated with lamotrigine concentration in infants, but not levetiracetam concentration in infants.

“Prior studies at delivery demonstrated that umbilical-cord concentrations were nearly equal to maternal concentrations, suggesting extensive placental passage to the fetus,” wrote Dr. Birnbaum and colleagues. “Therefore, the amount of AED exposure via breast milk is likely substantially lower than fetal exposure during pregnancy and appears unlikely to confer any additional risks beyond those that might be associated with exposure in pregnancy, especially given prior studies showing no adverse neurodevelopmental effects of breastfeeding while taking AEDs.”

The investigators acknowledged several limitations of their research, including the observational design of the MONEAD study. The amount of AED in participants’ breast milk is unknown, and the investigators could not calculate relative infant dosages. Only one blood sample was taken per infant, thus the results may not reflect infants’ total exposure over time.

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the National Institute of Child Health and Development funded the research. The authors reported receiving research support from various pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Birnbaum AK et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Dec 30. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.4443.

, according to a study published online ahead of print Dec. 30, 2019, in JAMA Neurology. The results may explain why previous research failed to find adverse neurodevelopmental effects of breastfeeding in infants whose mothers are undergoing AED treatment, said the authors.

“The results of this study add support to the general safety of breastfeeding by mothers with epilepsy who take AEDs,” wrote Angela K. Birnbaum, PhD, professor of experimental and clinical pharmacology at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, and colleagues.

Investigators measured infants’ blood AED concentrations

To date, medical consensus about the safety of breastfeeding while the mother is taking AEDs has been elusive. Researchers have investigated breast milk concentrations of AEDs as surrogate markers of AED concentrations in children. Breast milk concentrations, however, do not account for differences in infant pharmacokinetic processes and thus could misrepresent AED exposure in children through breastfeeding.

Dr. Birnbaum and colleagues sought to measure blood concentrations of AEDs in mothers with epilepsy and the infants that they breastfed to achieve an objective measure of AED exposure through breastfeeding. They examined data collected from December 2012 to October 2016 in the prospective Maternal Outcomes and Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (MONEAD) study. Eligible participants were pregnant women with epilepsy between the ages of 14 and 45 years whose pregnancies had progressed to fewer than 20 weeks’ gestational age and who had IQ scores greater than 70 points. Participants were followed up throughout pregnancy and for 9 months post partum. Children were enrolled at birth.

The investigators collected blood samples from mothers and infants who were breastfed at the same visit, which occurred at between 5 and 20 weeks after birth. The volume of ingested breast milk delivered through graduated feeding bottles each day and the total duration of all daily breastfeeding sessions were recorded. For infants, blood samples were collected from the plantar surface of the heel and stored as dried blood spots on filter paper. The study’s primary endpoint was the percentage of infant-to-mother concentration of AEDs. Concentrations of AEDs in infants at less than the lower limit of quantification were assessed as half of the lower limit.

Exposure in utero may be greater than exposure through breast milk

In all, the researchers enrolled 351 pregnant women with epilepsy into the study and collected data on 345 infants. Two hundred twenty-two (64.3%) of the infants were breastfed, and 146 (42.3%) had AED concentrations available. After excluding outliers and mothers with missing concentration data, Dr. Birnbaum and colleagues included 164 matching infant-mother concentration pairs in their analysis (i.e., of 135 mothers and 138 infants). Approximately 52% of the infants were female, and their median age at blood collection was 13 weeks. The mothers’ median age was 32 years. About 82% of mothers were receiving monotherapy. The investigators found no demographic differences between groups of mothers taking various AEDs.

Sixty-eight infants (49.3%) had AED concentrations that were less than the lower limit of quantification. AED concentration was not greater than the lower limit of quantification for any infants breastfed by mothers taking carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, valproic acid, or topiramate. Most levetiracetam (71.4%) and zonisamide (60.0%) concentrations in infants were less than the lower limit of quantification. Most lamotrigine concentrations in infants (88.6%) were greater than the lower limit of quantification.

The median percentage of infant-to-mother concentration was 28.9% for lamotrigine, 5.3% for levetiracetam, 44.2% for zonisamide, 5.7% for carbamazepine, 5.4% for carbamazepine epoxide, 0.3% for oxcarbazepine, 17.2% for topiramate, and 21.4% for valproic acid. Multiple linear regression models indicated that maternal concentration was significantly associated with lamotrigine concentration in infants, but not levetiracetam concentration in infants.

“Prior studies at delivery demonstrated that umbilical-cord concentrations were nearly equal to maternal concentrations, suggesting extensive placental passage to the fetus,” wrote Dr. Birnbaum and colleagues. “Therefore, the amount of AED exposure via breast milk is likely substantially lower than fetal exposure during pregnancy and appears unlikely to confer any additional risks beyond those that might be associated with exposure in pregnancy, especially given prior studies showing no adverse neurodevelopmental effects of breastfeeding while taking AEDs.”

The investigators acknowledged several limitations of their research, including the observational design of the MONEAD study. The amount of AED in participants’ breast milk is unknown, and the investigators could not calculate relative infant dosages. Only one blood sample was taken per infant, thus the results may not reflect infants’ total exposure over time.

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the National Institute of Child Health and Development funded the research. The authors reported receiving research support from various pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Birnbaum AK et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Dec 30. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.4443.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

High infantile spasm risk should contraindicate sodium channel blocker antiepileptics

BALTIMORE – “This is scary and warrants caution,” said senior investigator and pediatric neurologist Shaun Hussain, MD, a pediatric neurologist at Mattel Children’s Hospital at UCLA. Because of the findings, “we are avoiding the use of voltage-gated sodium channel blockade in any child at risk for infantile spasms. More broadly, we are avoiding [them] in any infant if there is a good alternative medication, of which there are many in most cases.”

There have been a few previous case reports linking voltage-gated sodium channel blockers (SCBs) – which include oxcarbazepine, carbamazepine, lacosamide, and phenytoin – to infantile spasms, but they are still commonly used for infant seizures. There was some disagreement at UCLA whether there really was a link, so Dr. Hussain and his team took a look at the university’s experience. They matched 50 children with nonsyndromic epilepsy who subsequently developed video-EEG confirmed infantile spasms (cases) to 50 children who also had nonsyndromic epilepsy but did not develop spasms, based on follow-up duration and age and date of epilepsy onset.

The team then looked to see what drugs they had been on; it turned out that cases and controls were about equally as likely to have been treated with any specific antiepileptic, including SCBs. Infantile spasms were substantially more likely with SCB exposure in children with spasm risk factors, which also include focal cortical dysplasia, Aicardi syndrome, and other problems (HR 7.0; 95%; CI 2.5-19.8; P less than .001). Spasms were also more likely among even low-risk children treated with SCBs, although the trend was not statistically significant.

In the end, “we wonder how many cases of infantile spasms could [have been] prevented entirely if we had avoided sodium channel blockade,” Dr. Hussain said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

With so many other seizure options available – levetiracetam, topiramate, and phenobarbital, to name just a few – maybe it would be best “to stay away from” SCBs entirely in “infants with any form of epilepsy,” said lead investigator Jaeden Heesch, an undergraduate researcher who worked with Dr. Hussain.

It is unclear why SCBs increase infantile spasm risk; maybe nonselective voltage-gated sodium channel blockade interferes with proper neuron function in susceptible children, similar to the effects of sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 1 mutations in Dravet syndrome, Dr. Hussain said. Perhaps the findings will inspire drug development. “If nonselective sodium channel blockade is bad, perhaps selective modulation of voltage-gated sodium currents [could be] beneficial or protective,” he said.

The age of epilepsy onset in the study was around 2 months. Children who went on to develop infantile spasms had an average of almost two seizures per day, versus fewer than one among controls, and were on an average of two, versus about 1.5 antiepileptics. The differences were not statistically significant.

The study looked at SCB exposure overall, but it’s possible that infantile spasm risk differs among the various class members.

The work was funded by the Elsie and Isaac Fogelman Endowment, the Hughes Family Foundation, and the UCLA Children’s Discovery and Innovation Institute. The investigators didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Heesch J et al. AES 2019. Abstract 2.234.

BALTIMORE – “This is scary and warrants caution,” said senior investigator and pediatric neurologist Shaun Hussain, MD, a pediatric neurologist at Mattel Children’s Hospital at UCLA. Because of the findings, “we are avoiding the use of voltage-gated sodium channel blockade in any child at risk for infantile spasms. More broadly, we are avoiding [them] in any infant if there is a good alternative medication, of which there are many in most cases.”

There have been a few previous case reports linking voltage-gated sodium channel blockers (SCBs) – which include oxcarbazepine, carbamazepine, lacosamide, and phenytoin – to infantile spasms, but they are still commonly used for infant seizures. There was some disagreement at UCLA whether there really was a link, so Dr. Hussain and his team took a look at the university’s experience. They matched 50 children with nonsyndromic epilepsy who subsequently developed video-EEG confirmed infantile spasms (cases) to 50 children who also had nonsyndromic epilepsy but did not develop spasms, based on follow-up duration and age and date of epilepsy onset.

The team then looked to see what drugs they had been on; it turned out that cases and controls were about equally as likely to have been treated with any specific antiepileptic, including SCBs. Infantile spasms were substantially more likely with SCB exposure in children with spasm risk factors, which also include focal cortical dysplasia, Aicardi syndrome, and other problems (HR 7.0; 95%; CI 2.5-19.8; P less than .001). Spasms were also more likely among even low-risk children treated with SCBs, although the trend was not statistically significant.

In the end, “we wonder how many cases of infantile spasms could [have been] prevented entirely if we had avoided sodium channel blockade,” Dr. Hussain said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

With so many other seizure options available – levetiracetam, topiramate, and phenobarbital, to name just a few – maybe it would be best “to stay away from” SCBs entirely in “infants with any form of epilepsy,” said lead investigator Jaeden Heesch, an undergraduate researcher who worked with Dr. Hussain.

It is unclear why SCBs increase infantile spasm risk; maybe nonselective voltage-gated sodium channel blockade interferes with proper neuron function in susceptible children, similar to the effects of sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 1 mutations in Dravet syndrome, Dr. Hussain said. Perhaps the findings will inspire drug development. “If nonselective sodium channel blockade is bad, perhaps selective modulation of voltage-gated sodium currents [could be] beneficial or protective,” he said.

The age of epilepsy onset in the study was around 2 months. Children who went on to develop infantile spasms had an average of almost two seizures per day, versus fewer than one among controls, and were on an average of two, versus about 1.5 antiepileptics. The differences were not statistically significant.

The study looked at SCB exposure overall, but it’s possible that infantile spasm risk differs among the various class members.

The work was funded by the Elsie and Isaac Fogelman Endowment, the Hughes Family Foundation, and the UCLA Children’s Discovery and Innovation Institute. The investigators didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Heesch J et al. AES 2019. Abstract 2.234.

BALTIMORE – “This is scary and warrants caution,” said senior investigator and pediatric neurologist Shaun Hussain, MD, a pediatric neurologist at Mattel Children’s Hospital at UCLA. Because of the findings, “we are avoiding the use of voltage-gated sodium channel blockade in any child at risk for infantile spasms. More broadly, we are avoiding [them] in any infant if there is a good alternative medication, of which there are many in most cases.”

There have been a few previous case reports linking voltage-gated sodium channel blockers (SCBs) – which include oxcarbazepine, carbamazepine, lacosamide, and phenytoin – to infantile spasms, but they are still commonly used for infant seizures. There was some disagreement at UCLA whether there really was a link, so Dr. Hussain and his team took a look at the university’s experience. They matched 50 children with nonsyndromic epilepsy who subsequently developed video-EEG confirmed infantile spasms (cases) to 50 children who also had nonsyndromic epilepsy but did not develop spasms, based on follow-up duration and age and date of epilepsy onset.

The team then looked to see what drugs they had been on; it turned out that cases and controls were about equally as likely to have been treated with any specific antiepileptic, including SCBs. Infantile spasms were substantially more likely with SCB exposure in children with spasm risk factors, which also include focal cortical dysplasia, Aicardi syndrome, and other problems (HR 7.0; 95%; CI 2.5-19.8; P less than .001). Spasms were also more likely among even low-risk children treated with SCBs, although the trend was not statistically significant.

In the end, “we wonder how many cases of infantile spasms could [have been] prevented entirely if we had avoided sodium channel blockade,” Dr. Hussain said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

With so many other seizure options available – levetiracetam, topiramate, and phenobarbital, to name just a few – maybe it would be best “to stay away from” SCBs entirely in “infants with any form of epilepsy,” said lead investigator Jaeden Heesch, an undergraduate researcher who worked with Dr. Hussain.

It is unclear why SCBs increase infantile spasm risk; maybe nonselective voltage-gated sodium channel blockade interferes with proper neuron function in susceptible children, similar to the effects of sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 1 mutations in Dravet syndrome, Dr. Hussain said. Perhaps the findings will inspire drug development. “If nonselective sodium channel blockade is bad, perhaps selective modulation of voltage-gated sodium currents [could be] beneficial or protective,” he said.

The age of epilepsy onset in the study was around 2 months. Children who went on to develop infantile spasms had an average of almost two seizures per day, versus fewer than one among controls, and were on an average of two, versus about 1.5 antiepileptics. The differences were not statistically significant.

The study looked at SCB exposure overall, but it’s possible that infantile spasm risk differs among the various class members.

The work was funded by the Elsie and Isaac Fogelman Endowment, the Hughes Family Foundation, and the UCLA Children’s Discovery and Innovation Institute. The investigators didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Heesch J et al. AES 2019. Abstract 2.234.

REPORTING FROM AES 2019

Newborns’ maternal protection against measles wanes within 6 months

according to new research.

In fact, most of the 196 infants’ maternal measles antibodies had dropped below the protective threshold by 3 months of age – well before the recommended age of 12-15 months for the first dose of MMR vaccine.

The odds of inadequate protection doubled for each additional month of age, Michelle Science, MD, of the University of Toronto and associates reported in Pediatrics.

“The widening gap between loss of maternal antibodies and measles vaccination described in our study leaves infants vulnerable to measles for much of their infancy and highlights the need for further research to support public health policy,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote.

The findings are not surprising for a setting in which measles has been eliminated and align with results from past research, Huong Q. McLean, PhD, MPH, of the Marshfield (Wis.) Clinic Research Institute and Walter A. Orenstein, MD, of Emory University in Atlanta wrote in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2019 Nov 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2541).

However, this susceptibility prior to receiving the MMR has taken on a new significance more recently, Dr. McLean and Dr. Orenstein suggested.

“In light of increasing measles outbreaks during the past year reaching levels not recorded in the United States since 1992 and increased measles elsewhere, coupled with the risk of severe illness in infants, there is increased concern regarding the protection of infants against measles,” the editorialists wrote.

Dr. Science and colleagues tested serum samples from 196 term infants, all under 12 months old, for antibodies against measles. The sera had been previously collected at a single tertiary care center in Ontario for clinical testing and then stored. Measles has been eliminated in Canada since 1998.

The researchers randomly selected 25 samples for each of eight different age groups: up to 30 days old; 1 month (31-60 days); 2 months (61-89 days); 3 months (90-119 days); 4 months; 5 months; 6-9 months; and 9-11 months.

Just over half the babies (56%) were male, and 35% had an underlying condition, but none had conditions that might affect antibody levels. The conditions were primarily a developmental delay or otherwise affecting the central nervous system, liver, or gastrointestinal function. Mean maternal age was 32 years.

To ensure high test sensitivity, the researchers used the plaque-reduction neutralization test (PRNT) to test for measles-neutralizing antibodies instead of using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) because “ELISA sensitivity decreases as antibody titers decrease,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote. They used a neutralization titer of less than 192 mIU/mL as the threshold for protection against measles.

When the researchers calculated the predicted standardized mean antibody titer for infants with a mother aged 32 years, they determined their mean to be 541 mIU/mL at 1 month, 142 mIU/mL at 3 months (below the measles threshold of susceptibility of 192 mIU/mL) , and 64 mIU/mL at 6 months. None of the infants had measles antibodies above the protective threshold at 6 months old, the authors noted.

Children’s odds of susceptibility to measles doubled for each additional month of age, after adjustment for infant sex and maternal age (odds ratio, 2.13). Children’s likelihood of susceptibility to measles modestly increased as maternal age increased in 5-year increments from 25 to 40 years.

Children with an underlying conditions had greater susceptibility to measles (83%), compared with those without a comorbidity (68%, P = .03). No difference in susceptibility existed between males and females or based on gestational age at birth (ranging from 37 to 41 weeks).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices permits measles vaccination “as early as 6 months for infants who plan to travel internationally, infants with ongoing risk for exposure during measles outbreaks and as postexposure prophylaxis,” Dr. McLean and Dr. Orenstein noted in their editorial.

They discussed the rationale for various changes in the recommended schedule for measles immunization, based on changes in epidemiology of the disease and improved understanding of the immune response to vaccination since the vaccine became available in 1963. Then they posed the question of whether the recommendation should be revised again.

“Ideally, the schedule should minimize the risk of measles and its complications and optimize vaccine-induced protection,” Dr. McLean and Dr. Orenstein wrote.

They argued that the evidence cannot currently support changing the first MMR dose to a younger age because measles incidence in the United States remains extremely low outside of the extraordinary outbreaks in 2014 and 2019. Further, infants under 12 months of age make up less than 15% of measles cases during outbreaks, and unvaccinated people make up more than 70% of cases.

Rather, they stated, this new study emphasizes the importance of following the current schedule, with consideration of an earlier schedule only warranted during outbreaks.

“Health care providers must work to maintain high levels of coverage with 2 doses of MMR among vaccine-eligible populations and minimize pockets of susceptibility to prevent transmission to infants and prevent reestablishment of endemic transmission,” they concluded.

The research was funded by the Public Health Ontario Project Initiation Fund. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures. The editorialists had no external funding and no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Science M et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Nov 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0630.

according to new research.

In fact, most of the 196 infants’ maternal measles antibodies had dropped below the protective threshold by 3 months of age – well before the recommended age of 12-15 months for the first dose of MMR vaccine.

The odds of inadequate protection doubled for each additional month of age, Michelle Science, MD, of the University of Toronto and associates reported in Pediatrics.

“The widening gap between loss of maternal antibodies and measles vaccination described in our study leaves infants vulnerable to measles for much of their infancy and highlights the need for further research to support public health policy,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote.

The findings are not surprising for a setting in which measles has been eliminated and align with results from past research, Huong Q. McLean, PhD, MPH, of the Marshfield (Wis.) Clinic Research Institute and Walter A. Orenstein, MD, of Emory University in Atlanta wrote in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2019 Nov 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2541).

However, this susceptibility prior to receiving the MMR has taken on a new significance more recently, Dr. McLean and Dr. Orenstein suggested.

“In light of increasing measles outbreaks during the past year reaching levels not recorded in the United States since 1992 and increased measles elsewhere, coupled with the risk of severe illness in infants, there is increased concern regarding the protection of infants against measles,” the editorialists wrote.

Dr. Science and colleagues tested serum samples from 196 term infants, all under 12 months old, for antibodies against measles. The sera had been previously collected at a single tertiary care center in Ontario for clinical testing and then stored. Measles has been eliminated in Canada since 1998.

The researchers randomly selected 25 samples for each of eight different age groups: up to 30 days old; 1 month (31-60 days); 2 months (61-89 days); 3 months (90-119 days); 4 months; 5 months; 6-9 months; and 9-11 months.

Just over half the babies (56%) were male, and 35% had an underlying condition, but none had conditions that might affect antibody levels. The conditions were primarily a developmental delay or otherwise affecting the central nervous system, liver, or gastrointestinal function. Mean maternal age was 32 years.

To ensure high test sensitivity, the researchers used the plaque-reduction neutralization test (PRNT) to test for measles-neutralizing antibodies instead of using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) because “ELISA sensitivity decreases as antibody titers decrease,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote. They used a neutralization titer of less than 192 mIU/mL as the threshold for protection against measles.

When the researchers calculated the predicted standardized mean antibody titer for infants with a mother aged 32 years, they determined their mean to be 541 mIU/mL at 1 month, 142 mIU/mL at 3 months (below the measles threshold of susceptibility of 192 mIU/mL) , and 64 mIU/mL at 6 months. None of the infants had measles antibodies above the protective threshold at 6 months old, the authors noted.

Children’s odds of susceptibility to measles doubled for each additional month of age, after adjustment for infant sex and maternal age (odds ratio, 2.13). Children’s likelihood of susceptibility to measles modestly increased as maternal age increased in 5-year increments from 25 to 40 years.

Children with an underlying conditions had greater susceptibility to measles (83%), compared with those without a comorbidity (68%, P = .03). No difference in susceptibility existed between males and females or based on gestational age at birth (ranging from 37 to 41 weeks).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices permits measles vaccination “as early as 6 months for infants who plan to travel internationally, infants with ongoing risk for exposure during measles outbreaks and as postexposure prophylaxis,” Dr. McLean and Dr. Orenstein noted in their editorial.

They discussed the rationale for various changes in the recommended schedule for measles immunization, based on changes in epidemiology of the disease and improved understanding of the immune response to vaccination since the vaccine became available in 1963. Then they posed the question of whether the recommendation should be revised again.

“Ideally, the schedule should minimize the risk of measles and its complications and optimize vaccine-induced protection,” Dr. McLean and Dr. Orenstein wrote.

They argued that the evidence cannot currently support changing the first MMR dose to a younger age because measles incidence in the United States remains extremely low outside of the extraordinary outbreaks in 2014 and 2019. Further, infants under 12 months of age make up less than 15% of measles cases during outbreaks, and unvaccinated people make up more than 70% of cases.

Rather, they stated, this new study emphasizes the importance of following the current schedule, with consideration of an earlier schedule only warranted during outbreaks.

“Health care providers must work to maintain high levels of coverage with 2 doses of MMR among vaccine-eligible populations and minimize pockets of susceptibility to prevent transmission to infants and prevent reestablishment of endemic transmission,” they concluded.

The research was funded by the Public Health Ontario Project Initiation Fund. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures. The editorialists had no external funding and no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Science M et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Nov 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0630.

according to new research.

In fact, most of the 196 infants’ maternal measles antibodies had dropped below the protective threshold by 3 months of age – well before the recommended age of 12-15 months for the first dose of MMR vaccine.

The odds of inadequate protection doubled for each additional month of age, Michelle Science, MD, of the University of Toronto and associates reported in Pediatrics.

“The widening gap between loss of maternal antibodies and measles vaccination described in our study leaves infants vulnerable to measles for much of their infancy and highlights the need for further research to support public health policy,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote.

The findings are not surprising for a setting in which measles has been eliminated and align with results from past research, Huong Q. McLean, PhD, MPH, of the Marshfield (Wis.) Clinic Research Institute and Walter A. Orenstein, MD, of Emory University in Atlanta wrote in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2019 Nov 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2541).

However, this susceptibility prior to receiving the MMR has taken on a new significance more recently, Dr. McLean and Dr. Orenstein suggested.

“In light of increasing measles outbreaks during the past year reaching levels not recorded in the United States since 1992 and increased measles elsewhere, coupled with the risk of severe illness in infants, there is increased concern regarding the protection of infants against measles,” the editorialists wrote.

Dr. Science and colleagues tested serum samples from 196 term infants, all under 12 months old, for antibodies against measles. The sera had been previously collected at a single tertiary care center in Ontario for clinical testing and then stored. Measles has been eliminated in Canada since 1998.

The researchers randomly selected 25 samples for each of eight different age groups: up to 30 days old; 1 month (31-60 days); 2 months (61-89 days); 3 months (90-119 days); 4 months; 5 months; 6-9 months; and 9-11 months.

Just over half the babies (56%) were male, and 35% had an underlying condition, but none had conditions that might affect antibody levels. The conditions were primarily a developmental delay or otherwise affecting the central nervous system, liver, or gastrointestinal function. Mean maternal age was 32 years.

To ensure high test sensitivity, the researchers used the plaque-reduction neutralization test (PRNT) to test for measles-neutralizing antibodies instead of using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) because “ELISA sensitivity decreases as antibody titers decrease,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote. They used a neutralization titer of less than 192 mIU/mL as the threshold for protection against measles.

When the researchers calculated the predicted standardized mean antibody titer for infants with a mother aged 32 years, they determined their mean to be 541 mIU/mL at 1 month, 142 mIU/mL at 3 months (below the measles threshold of susceptibility of 192 mIU/mL) , and 64 mIU/mL at 6 months. None of the infants had measles antibodies above the protective threshold at 6 months old, the authors noted.

Children’s odds of susceptibility to measles doubled for each additional month of age, after adjustment for infant sex and maternal age (odds ratio, 2.13). Children’s likelihood of susceptibility to measles modestly increased as maternal age increased in 5-year increments from 25 to 40 years.

Children with an underlying conditions had greater susceptibility to measles (83%), compared with those without a comorbidity (68%, P = .03). No difference in susceptibility existed between males and females or based on gestational age at birth (ranging from 37 to 41 weeks).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices permits measles vaccination “as early as 6 months for infants who plan to travel internationally, infants with ongoing risk for exposure during measles outbreaks and as postexposure prophylaxis,” Dr. McLean and Dr. Orenstein noted in their editorial.

They discussed the rationale for various changes in the recommended schedule for measles immunization, based on changes in epidemiology of the disease and improved understanding of the immune response to vaccination since the vaccine became available in 1963. Then they posed the question of whether the recommendation should be revised again.

“Ideally, the schedule should minimize the risk of measles and its complications and optimize vaccine-induced protection,” Dr. McLean and Dr. Orenstein wrote.

They argued that the evidence cannot currently support changing the first MMR dose to a younger age because measles incidence in the United States remains extremely low outside of the extraordinary outbreaks in 2014 and 2019. Further, infants under 12 months of age make up less than 15% of measles cases during outbreaks, and unvaccinated people make up more than 70% of cases.

Rather, they stated, this new study emphasizes the importance of following the current schedule, with consideration of an earlier schedule only warranted during outbreaks.

“Health care providers must work to maintain high levels of coverage with 2 doses of MMR among vaccine-eligible populations and minimize pockets of susceptibility to prevent transmission to infants and prevent reestablishment of endemic transmission,” they concluded.

The research was funded by the Public Health Ontario Project Initiation Fund. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures. The editorialists had no external funding and no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Science M et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Nov 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0630.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Infants’ maternal measles antibodies fell below protective levels by 6 months old.

Major finding: Infants were twice as likely not to have protective immunity against measles for each month of age after birth (odds ratio, 2.13).

Study details: The findings are based on measles antibody testing of 196 serum samples from infants born in a tertiary care center in Ontario.

Disclosures: The research was funded by the Public Health Ontario Project Initiation Fund. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Science M et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Nov 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0630.