User login

Renal failure in HCV cirrhosis

A 54-year-old man with a history of cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has had a progressive decline in kidney function. He was diagnosed with hepatitis C 15 years ago; he tried interferon treatment, but this failed. He received a transjugular intrahepatic shunt 10 years ago after an episode of esophageal variceal bleeding. He has since been taking furosemide and spironolactone as maintenance treatment for ascites, and he has no other medical concerns such as hypertension or diabetes.

Two weeks ago, routine laboratory tests in the clinic showed that his serum creatinine level had increased from baseline. He was asked to stop his diuretics and increase his fluid intake. Nevertheless, his kidney function continued to decline (Table 1), and he was admitted to the hospital for further evaluation.

On admission, he appeared comfortable. He denied recent use of any medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics, and diuretics, and he had no genitourinary symptoms. His temperature was normal, blood pressure 170/90 mm Hg, pulse rate 72 per minute, and respiratory rate 16. His skin and sclerae were not jaundiced; his abdomen was not tender, but it was grossly distended with ascites. He also had +3 pedal edema (on a scale of 4) extending to both knees. The rest of his physical examination was unremarkable. Results of further laboratory tests are shown in in Table 2.

Ultrasonography of the liver demonstrated cirrhosis with patent flow through the shunt, and ultrasonography of the kidneys showed that both were slightly enlarged with increased cortical echogenicity but no hydronephrosis or obstruction.

EXPLORING THE CAUSE OF RENAL FAILURE

1. Given this information, what is the likely cause of our patient’s renal failure?

- Volume depletion

- Acute tubular necrosis

- Hepatorenal syndrome

- HCV glomerulopathy

Renal failure is a common complication in cirrhosis and portends a higher risk of death.1 The differential diagnosis is broad, but a systematic approach incorporating data from the history, physical examination, and laboratory tests can help identify the cause and is essential in determining the prognosis and proper treatment.

Volume depletion

Volume depletion is a common cause of renal failure in cirrhotic patients. Common precipitants are excessive diuresis and gastrointestinal fluid loss from bleeding, vomiting, and diarrhea. Despite having ascites and edema, patients may have low fluid volume in the vascular space. Therefore, the first step in a patient with acute kidney injury is to withhold diuretics and give fluids. The renal failure usually rapidly reverses if the patient does not have renal parenchymal disease.2

Our patient did not present with any fluid losses, and his high blood pressure and normal heart rate did not suggest volume depletion. And most importantly, withholding his diuretics and giving fluids did not reverse his renal failure. Thus, volume depletion was an unlikely cause.

Acute tubular necrosis

The altered hemodynamics caused by cirrhosis predispose patients to acute tubular necrosis. Classically, this presents as muddy brown casts and renal tubular epithelial cells on urinalysis and as a fractional excretion of sodium greater than 2%.1 However, these microscopic findings lack sensitivity, and patients with cirrhosis may have marked sodium avidity and low urine sodium excretion despite tubular injury.3

This diagnosis must still be considered in patients with renal failure, especially after an insult such as hemorrhagic or septic shock or intake of nephrotoxins. However, because our patient did not have a history of any of these and because his renal failure had been progressing over weeks, acute tubular necrosis was considered unlikely.

Hepatorenal syndrome

Hepatorenal syndrome is characterized by progressive renal failure in the absence of renal parenchymal disease. It is a functional disorder, ie, the decreased glomerular filtration rate results from renal vasoconstriction, which in turn is due to decreased systemic vascular resistance and increased compensatory activity of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis and of antiduretic hormone release (Figure 1).

Hepatorenal syndrome often occurs in patients with advanced liver disease. These patients typically have a hyperdynamic circulation (systemic vasodilation, low blood pressure, and increased blood volume) with a low mean arterial pressure and increased renin and norepinephrine levels. Other frequent findings include hyponatremia, low urinary sodium excretion (< 2 mmol/day), and low free water clearance,4 all of which mark the high systemic levels of antidiuretic hormone and aldosterone.

Importantly, while hepatorenal syndrome is always considered in the differential diagnosis because of its unique prognosis and therapy, it remains a diagnosis of exclusion. The International Ascites Club5 has provided diagnostic criteria for hepatorenal syndrome:

- Cirrhosis and ascites

- Serum creatinine greater than 1.5 mg/dL

- Failure of serum creatinine to fall to less than 1.5 mg/dL after at least 48 hours of diuretic withdrawal and volume expansion with albumin (recommended dose 1 g/kg body weight per day up to a maximum of 100 g per day)

- Absence of shock

- No current or recent treatment with nephrotoxic drugs

- No signs of parenchymal kidney disease such as proteinuria (protein excretion > 500 mg/day), microhematuria (> 50 red blood cells per high-power field), or abnormalities on renal ultrasonography.

While these criteria are not perfect,6 they remind clinicians that there are other important causes of renal insufficiency in cirrhosis.

Clinically, our patient had no evidence of a hyperdynamic circulation and was instead hypertensive. He was eunatremic and did not have marked renal sodium avidity. His pyuria, proteinuria (his protein excretion was approximately 1.9 g/day as determined by urine spot protein-to-creatinine ratio), and results of ultrasonography also suggested underlying renal parenchymal disease. Therefore, hepatorenal syndrome was not the likely diagnosis.

HCV glomerulopathy

Intrinsic renal disease is likely, given our patient’s proteinuria, active urine sediment (ie, containing red blood cells, white blood cells, and protein), and abnormal findings on ultrasonography. In patients with HCV infection and no other cause of intrinsic kidney disease, immune complex deposition leading to glomerulonephritis is the most common pattern.7 Despite the intrinsic renal disease, fractional excretion of sodium may be less than 1% in glomerulonephritis. Hypertension in a patient such as ours with cirrhosis and renal insufficiency raises suspicion for glomerular disease, as hypertension is unlikely in advanced cirrhosis.8

Glomerulonephritis in patients with cirrhosis is often clinically silent and may be highly prevalent; some studies have shown glomerular involvement in 55% to 83% of patients with cirrhosis.9,10 This increases the risk of end-stage renal disease, and the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guideline recommends that HCV-infected patients be tested at least once a year for proteinuria, hematuria, and estimated glomerular filtration rate to detect possible HCV-associated kidney disease.11 According to current guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) , detection of glomerulonephritis in HCV patients puts them in the highest priority class for treatment of HCV.12

HISTOLOGIC FINDINGS

Because of the high likelihood of glomerulopathy, our patient underwent renal biopsy.

2. What is the classic pathologic finding in HCV kidney disease?

- Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis

- Crescentic glomerulonephritis

- Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

- Membranous glomerulonephritis

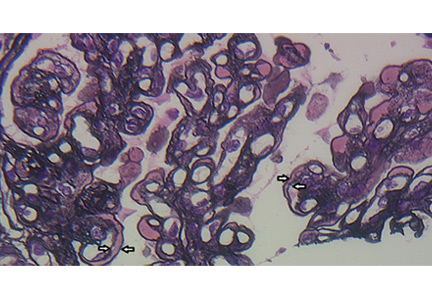

A number of pathologic patterns have been described in HCV kidney disease, including membranous glomerulonephritis, immunoglobulin A nephropathy, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. However, by far the most common pattern is type 1 membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis.13 (Types 2 and 3 are much less common, and we will not discuss them here.) In type 1, light microscopy shows increased mesangial cells and thickened capillary walls (lobular glomeruli), staining of the basement membrane reveals double contours (“tram tracking”) or splitting due to mesangial deposition, and immunofluorescence demonstrates immunoglobulin G and complement C3 deposition. All of these findings were seen in our patient (Figure 2, Figure 3).

Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis in patients with HCV is most commonly associated with cryoglobulins, a mixture of monoclonal or polyclonal immunoglobulin (Ig) M that have antiglobulin (rheumatoid factor) activity and bind to polyclonal IgG. They reversibly precipitate at less than 37°C, (98.6°F), hence their name. Only 50% to 70% of patients with cryoglobulinemic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis have detectable serum cryoglobulins; however, kidney biopsy may show globular accumulations of eosinophilic material and prominent hypercellularity due to infiltration of glomerular capillaries with mononuclear and polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

Noncryoglobulinemic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis is also found in patients with HCV infection. Its histologic features are similar, but on biopsy, there is less prominent leukocytic infiltration and no eosinophilic material. Although the pathogenesis of glomerulonephritis in HCV infection is poorly understood, it is thought to result from deposition of circulating immune complexes of HCV, anti-HCV, and rheumatoid factor in the glomeruli.

3. What laboratory finding is often seen in membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis?

- Positive cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

- serum complement Low levels

- Antiphospholipase A2 receptor antibodies

Cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody is seen in granulomatosis with polyangiitis, while antiphospholipid A2 receptor antibodies are seen in idiopathic membranous nephritis.

Low serum complement levels are frequently found in membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. It is believed that immune complex deposition leads to glomerular damage through activation of the complement pathway and the subsequent influx of inflammatory cells, release of cytokines and proteases, and damage to capillary walls. When repair ensues, new mesangial matrix and basement membrane are deposited, leading to mesangial expansion and duplicated basement membrane.14

In cryoglobulinemic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, the complement C4 level is often much lower than C3, but in noncryoglobulinemic forms C3 is lower. A mnemonic to remember nephritic syndromes with low complement levels is “hy-PO-CO-MP-L-EM-ents”; PO for postinfectious, CO for cryoglobulins, MP for membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, L for lupus, and EM for embolic.

BACK TO OUR PATIENT

In addition to kidney biopsy, we tested our patient for serum cryoglobulins, rheumatoid factor, and serum complements. Results from these tests (Table 3), in addition to the lack of cryoglobulins on his biopsy, led to the conclusion that he had noncryoglobulinemic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis.

WHO SHOULD RECEIVE TREATMENT FOR HCV?

4. According to the current IDSA/AASLD guidelines, which of the following patients should not receive direct-acting antiviral therapy for HCV?

- Patients with HCV and only low-stage fibrosis

- Patients with decompensated cirrhosis

- Patients with a glomerular filtration rate less than 30 mL/minute

- None of the above—nearly all patients with HCV infection should receive treatment for it

While certain patients have compelling indications for HCV treatment, such as advanced fibrosis, severe extrahepatic manifestations of HCV (eg, glomerulonephritis, cryoglobulinemia), and posttransplant status, current guidelines recommend treatment for nearly all patients with HCV, including those with low-stage fibrosis.12

Patients with Child-Pugh grade B or C decompensated cirrhosis, even with hepatocellular carcinoma, may be considered for treatment. Multiple studies have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of direct-acting antiviral drugs in this patient population. In one randomized controlled trial,15 the combination of ledipasvir, sofosbuvir, and ribavirin resulted in high sustained virologic response rates at 12 weeks in patients infected with HCV genotype 1 or 4 with advanced liver disease, irrespective of transplant status (86% to 89% of patients were pretransplant). Sustained virologic response was associated with improvements in Model for End-Stage Liver Disease and Child-Pugh scores largely due to decreases in bilirubin and improvement in synthetic function (ie, albumin).

Similarly, even patients with a glomerular filtration rate less than 30 mL/min are candidates for treatment. Those with a glomerular filtration rate above 30 mL/min need no dosage adjustments for the most common regimens, while regimens are also available for those with a rate less than 30 mL/min. Although patients with low baseline renal function have a higher frequency of anemia (especially with ribavirin), worsening renal dysfunction, and more severe adverse events, treatment responses remain high and comparable to those without renal impairment.

The Hepatitis C Therapeutic Registry and Research Network (HCV-TARGET) is conducting an ongoing prospective study evaluating real-world use of direct-acting antiviral agents. The study has reported the safety and efficacy of sofosbuvir-containing regimens in patients with varying severities of kidney disease, including glomerular filtration rates less than 30 mL/min). The patients received different regimens that included sofosbuvir. The regimens were reportedly tolerated, and the rate of sustained viral response at 12 weeks remained high.16

The efficacy of direct-acting antiviral agents for HCV-associated glomerulonephritis remains to be studied but is promising. Earlier studies found that antiviral therapy based on interferon alfa with or without ribavirin can significantly decrease proteinuria and stabilize renal function.17–20 HCV RNA clearance has been found to best predict renal improvement.

OUR PATIENT’S COURSE

Unfortunately, our patient’s kidney function declined further over the next 3 months, and he is currently on dialysis awaiting simultaneous liver and kidney transplant.

- Ginès P, Schrier RW. Renal failure in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1279–1290.

- Mackelaite L, Alsauskas ZC, Ranganna K. Renal failure in patients with cirrhosis. Med Clin North Am 2009; 93:855–869.

- Wadei HM, Mai ML, Ahsan N, Gonwa TA. Hepatorenal syndrome: pathophysiology and management. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 1:1066–1079.

- Gines A, Escorsell A, Gines P, et al. Incidence, predictive factors, and prognosis of the hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis with ascites. Gastroenterology 1993; 105:229–236.

- Salerno F, Gerbes A, Ginès P, Wong F, Arroyo V. Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. Gut 2007; 56:1310–1318.

- Watt K, Uhanova J, Minuk GY. Hepatorenal syndrome: diagnostic accuracy, clinical features, and outcome in a tertiary care center. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97:2046–2050.

- Graupera I, Cardenas A. Diagnostic approach to renal failure in cirrhosis. Clin Liver Dis 2013; 2:128–131.

- Dash SC, Bhowmik D. Glomerulopathy with liver disease: patterns and management. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 2000; 11:414–420.

- Arase Y, Ikeda K, Murashima N, et al. Glomerulonephritis in autopsy cases with hepatitis C virus infection. Intern Med 1998; 37:836–840.

- McGuire BM, Julian BA, Bynon JS, et al. Brief communication: glomerulonephritis in patients with hepatitis C cirrhosis undergoing liver transplantation. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144:735–741.

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of hepatitis C in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 2008; 109:S1–S99.

- American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. www.hcvguidelines.org/. Accessed July 10, 2016.

- Lai KN. Hepatitis-related renal disease. Future Virology 2011; 6:1361–1376.

- Sethi S, Fervenza FC. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis—a new look at an old entity. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1119–1131.

- Charlton M, Everson GT, Flamm SL, et al; SOLAR-1 Investigators. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for treatment of HCV infection in patients with advanced liver disease. Gastroenterology 2015; 149:649–659.

- Saxena V, Koraishy FM, Sise ME, et al; HCV-TARGET. Safety and efficacy of sofosbuvir-containing regimens in hepatitis C-infected patients with impaired renal function. Liver Int 2016; 36:807–816.

- Feng B, Eknoyan G, Guo ZS, et al. Effect of interferon alpha-based antiviral therapy on hepatitis C virus-associated glomerulonephritis: a meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27:640–646.

- Bruchfeld A, Lindahl K, Ståhle L, Söderberg M, Schvarcz R. Interferon and ribavirin treatment in patients with hepatitis C-associated renal disease and renal insufficiency. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003; 18:1573–1580.

- Rossi P, Bertani T, Baio P, et al. Hepatitis C virus-related cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis. Long-term remission after antiviral therapy. Kidney Int 2003; 63:2236–2241.

- Alric L, Plaisier E, Thebault S, et al. Influence of antiviral therapy in hepatitis C virus associated cryoglobulinemic MPGN. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 43:617–623.

A 54-year-old man with a history of cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has had a progressive decline in kidney function. He was diagnosed with hepatitis C 15 years ago; he tried interferon treatment, but this failed. He received a transjugular intrahepatic shunt 10 years ago after an episode of esophageal variceal bleeding. He has since been taking furosemide and spironolactone as maintenance treatment for ascites, and he has no other medical concerns such as hypertension or diabetes.

Two weeks ago, routine laboratory tests in the clinic showed that his serum creatinine level had increased from baseline. He was asked to stop his diuretics and increase his fluid intake. Nevertheless, his kidney function continued to decline (Table 1), and he was admitted to the hospital for further evaluation.

On admission, he appeared comfortable. He denied recent use of any medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics, and diuretics, and he had no genitourinary symptoms. His temperature was normal, blood pressure 170/90 mm Hg, pulse rate 72 per minute, and respiratory rate 16. His skin and sclerae were not jaundiced; his abdomen was not tender, but it was grossly distended with ascites. He also had +3 pedal edema (on a scale of 4) extending to both knees. The rest of his physical examination was unremarkable. Results of further laboratory tests are shown in in Table 2.

Ultrasonography of the liver demonstrated cirrhosis with patent flow through the shunt, and ultrasonography of the kidneys showed that both were slightly enlarged with increased cortical echogenicity but no hydronephrosis or obstruction.

EXPLORING THE CAUSE OF RENAL FAILURE

1. Given this information, what is the likely cause of our patient’s renal failure?

- Volume depletion

- Acute tubular necrosis

- Hepatorenal syndrome

- HCV glomerulopathy

Renal failure is a common complication in cirrhosis and portends a higher risk of death.1 The differential diagnosis is broad, but a systematic approach incorporating data from the history, physical examination, and laboratory tests can help identify the cause and is essential in determining the prognosis and proper treatment.

Volume depletion

Volume depletion is a common cause of renal failure in cirrhotic patients. Common precipitants are excessive diuresis and gastrointestinal fluid loss from bleeding, vomiting, and diarrhea. Despite having ascites and edema, patients may have low fluid volume in the vascular space. Therefore, the first step in a patient with acute kidney injury is to withhold diuretics and give fluids. The renal failure usually rapidly reverses if the patient does not have renal parenchymal disease.2

Our patient did not present with any fluid losses, and his high blood pressure and normal heart rate did not suggest volume depletion. And most importantly, withholding his diuretics and giving fluids did not reverse his renal failure. Thus, volume depletion was an unlikely cause.

Acute tubular necrosis

The altered hemodynamics caused by cirrhosis predispose patients to acute tubular necrosis. Classically, this presents as muddy brown casts and renal tubular epithelial cells on urinalysis and as a fractional excretion of sodium greater than 2%.1 However, these microscopic findings lack sensitivity, and patients with cirrhosis may have marked sodium avidity and low urine sodium excretion despite tubular injury.3

This diagnosis must still be considered in patients with renal failure, especially after an insult such as hemorrhagic or septic shock or intake of nephrotoxins. However, because our patient did not have a history of any of these and because his renal failure had been progressing over weeks, acute tubular necrosis was considered unlikely.

Hepatorenal syndrome

Hepatorenal syndrome is characterized by progressive renal failure in the absence of renal parenchymal disease. It is a functional disorder, ie, the decreased glomerular filtration rate results from renal vasoconstriction, which in turn is due to decreased systemic vascular resistance and increased compensatory activity of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis and of antiduretic hormone release (Figure 1).

Hepatorenal syndrome often occurs in patients with advanced liver disease. These patients typically have a hyperdynamic circulation (systemic vasodilation, low blood pressure, and increased blood volume) with a low mean arterial pressure and increased renin and norepinephrine levels. Other frequent findings include hyponatremia, low urinary sodium excretion (< 2 mmol/day), and low free water clearance,4 all of which mark the high systemic levels of antidiuretic hormone and aldosterone.

Importantly, while hepatorenal syndrome is always considered in the differential diagnosis because of its unique prognosis and therapy, it remains a diagnosis of exclusion. The International Ascites Club5 has provided diagnostic criteria for hepatorenal syndrome:

- Cirrhosis and ascites

- Serum creatinine greater than 1.5 mg/dL

- Failure of serum creatinine to fall to less than 1.5 mg/dL after at least 48 hours of diuretic withdrawal and volume expansion with albumin (recommended dose 1 g/kg body weight per day up to a maximum of 100 g per day)

- Absence of shock

- No current or recent treatment with nephrotoxic drugs

- No signs of parenchymal kidney disease such as proteinuria (protein excretion > 500 mg/day), microhematuria (> 50 red blood cells per high-power field), or abnormalities on renal ultrasonography.

While these criteria are not perfect,6 they remind clinicians that there are other important causes of renal insufficiency in cirrhosis.

Clinically, our patient had no evidence of a hyperdynamic circulation and was instead hypertensive. He was eunatremic and did not have marked renal sodium avidity. His pyuria, proteinuria (his protein excretion was approximately 1.9 g/day as determined by urine spot protein-to-creatinine ratio), and results of ultrasonography also suggested underlying renal parenchymal disease. Therefore, hepatorenal syndrome was not the likely diagnosis.

HCV glomerulopathy

Intrinsic renal disease is likely, given our patient’s proteinuria, active urine sediment (ie, containing red blood cells, white blood cells, and protein), and abnormal findings on ultrasonography. In patients with HCV infection and no other cause of intrinsic kidney disease, immune complex deposition leading to glomerulonephritis is the most common pattern.7 Despite the intrinsic renal disease, fractional excretion of sodium may be less than 1% in glomerulonephritis. Hypertension in a patient such as ours with cirrhosis and renal insufficiency raises suspicion for glomerular disease, as hypertension is unlikely in advanced cirrhosis.8

Glomerulonephritis in patients with cirrhosis is often clinically silent and may be highly prevalent; some studies have shown glomerular involvement in 55% to 83% of patients with cirrhosis.9,10 This increases the risk of end-stage renal disease, and the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guideline recommends that HCV-infected patients be tested at least once a year for proteinuria, hematuria, and estimated glomerular filtration rate to detect possible HCV-associated kidney disease.11 According to current guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) , detection of glomerulonephritis in HCV patients puts them in the highest priority class for treatment of HCV.12

HISTOLOGIC FINDINGS

Because of the high likelihood of glomerulopathy, our patient underwent renal biopsy.

2. What is the classic pathologic finding in HCV kidney disease?

- Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis

- Crescentic glomerulonephritis

- Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

- Membranous glomerulonephritis

A number of pathologic patterns have been described in HCV kidney disease, including membranous glomerulonephritis, immunoglobulin A nephropathy, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. However, by far the most common pattern is type 1 membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis.13 (Types 2 and 3 are much less common, and we will not discuss them here.) In type 1, light microscopy shows increased mesangial cells and thickened capillary walls (lobular glomeruli), staining of the basement membrane reveals double contours (“tram tracking”) or splitting due to mesangial deposition, and immunofluorescence demonstrates immunoglobulin G and complement C3 deposition. All of these findings were seen in our patient (Figure 2, Figure 3).

Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis in patients with HCV is most commonly associated with cryoglobulins, a mixture of monoclonal or polyclonal immunoglobulin (Ig) M that have antiglobulin (rheumatoid factor) activity and bind to polyclonal IgG. They reversibly precipitate at less than 37°C, (98.6°F), hence their name. Only 50% to 70% of patients with cryoglobulinemic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis have detectable serum cryoglobulins; however, kidney biopsy may show globular accumulations of eosinophilic material and prominent hypercellularity due to infiltration of glomerular capillaries with mononuclear and polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

Noncryoglobulinemic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis is also found in patients with HCV infection. Its histologic features are similar, but on biopsy, there is less prominent leukocytic infiltration and no eosinophilic material. Although the pathogenesis of glomerulonephritis in HCV infection is poorly understood, it is thought to result from deposition of circulating immune complexes of HCV, anti-HCV, and rheumatoid factor in the glomeruli.

3. What laboratory finding is often seen in membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis?

- Positive cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

- serum complement Low levels

- Antiphospholipase A2 receptor antibodies

Cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody is seen in granulomatosis with polyangiitis, while antiphospholipid A2 receptor antibodies are seen in idiopathic membranous nephritis.

Low serum complement levels are frequently found in membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. It is believed that immune complex deposition leads to glomerular damage through activation of the complement pathway and the subsequent influx of inflammatory cells, release of cytokines and proteases, and damage to capillary walls. When repair ensues, new mesangial matrix and basement membrane are deposited, leading to mesangial expansion and duplicated basement membrane.14

In cryoglobulinemic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, the complement C4 level is often much lower than C3, but in noncryoglobulinemic forms C3 is lower. A mnemonic to remember nephritic syndromes with low complement levels is “hy-PO-CO-MP-L-EM-ents”; PO for postinfectious, CO for cryoglobulins, MP for membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, L for lupus, and EM for embolic.

BACK TO OUR PATIENT

In addition to kidney biopsy, we tested our patient for serum cryoglobulins, rheumatoid factor, and serum complements. Results from these tests (Table 3), in addition to the lack of cryoglobulins on his biopsy, led to the conclusion that he had noncryoglobulinemic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis.

WHO SHOULD RECEIVE TREATMENT FOR HCV?

4. According to the current IDSA/AASLD guidelines, which of the following patients should not receive direct-acting antiviral therapy for HCV?

- Patients with HCV and only low-stage fibrosis

- Patients with decompensated cirrhosis

- Patients with a glomerular filtration rate less than 30 mL/minute

- None of the above—nearly all patients with HCV infection should receive treatment for it

While certain patients have compelling indications for HCV treatment, such as advanced fibrosis, severe extrahepatic manifestations of HCV (eg, glomerulonephritis, cryoglobulinemia), and posttransplant status, current guidelines recommend treatment for nearly all patients with HCV, including those with low-stage fibrosis.12

Patients with Child-Pugh grade B or C decompensated cirrhosis, even with hepatocellular carcinoma, may be considered for treatment. Multiple studies have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of direct-acting antiviral drugs in this patient population. In one randomized controlled trial,15 the combination of ledipasvir, sofosbuvir, and ribavirin resulted in high sustained virologic response rates at 12 weeks in patients infected with HCV genotype 1 or 4 with advanced liver disease, irrespective of transplant status (86% to 89% of patients were pretransplant). Sustained virologic response was associated with improvements in Model for End-Stage Liver Disease and Child-Pugh scores largely due to decreases in bilirubin and improvement in synthetic function (ie, albumin).

Similarly, even patients with a glomerular filtration rate less than 30 mL/min are candidates for treatment. Those with a glomerular filtration rate above 30 mL/min need no dosage adjustments for the most common regimens, while regimens are also available for those with a rate less than 30 mL/min. Although patients with low baseline renal function have a higher frequency of anemia (especially with ribavirin), worsening renal dysfunction, and more severe adverse events, treatment responses remain high and comparable to those without renal impairment.

The Hepatitis C Therapeutic Registry and Research Network (HCV-TARGET) is conducting an ongoing prospective study evaluating real-world use of direct-acting antiviral agents. The study has reported the safety and efficacy of sofosbuvir-containing regimens in patients with varying severities of kidney disease, including glomerular filtration rates less than 30 mL/min). The patients received different regimens that included sofosbuvir. The regimens were reportedly tolerated, and the rate of sustained viral response at 12 weeks remained high.16

The efficacy of direct-acting antiviral agents for HCV-associated glomerulonephritis remains to be studied but is promising. Earlier studies found that antiviral therapy based on interferon alfa with or without ribavirin can significantly decrease proteinuria and stabilize renal function.17–20 HCV RNA clearance has been found to best predict renal improvement.

OUR PATIENT’S COURSE

Unfortunately, our patient’s kidney function declined further over the next 3 months, and he is currently on dialysis awaiting simultaneous liver and kidney transplant.

A 54-year-old man with a history of cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has had a progressive decline in kidney function. He was diagnosed with hepatitis C 15 years ago; he tried interferon treatment, but this failed. He received a transjugular intrahepatic shunt 10 years ago after an episode of esophageal variceal bleeding. He has since been taking furosemide and spironolactone as maintenance treatment for ascites, and he has no other medical concerns such as hypertension or diabetes.

Two weeks ago, routine laboratory tests in the clinic showed that his serum creatinine level had increased from baseline. He was asked to stop his diuretics and increase his fluid intake. Nevertheless, his kidney function continued to decline (Table 1), and he was admitted to the hospital for further evaluation.

On admission, he appeared comfortable. He denied recent use of any medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics, and diuretics, and he had no genitourinary symptoms. His temperature was normal, blood pressure 170/90 mm Hg, pulse rate 72 per minute, and respiratory rate 16. His skin and sclerae were not jaundiced; his abdomen was not tender, but it was grossly distended with ascites. He also had +3 pedal edema (on a scale of 4) extending to both knees. The rest of his physical examination was unremarkable. Results of further laboratory tests are shown in in Table 2.

Ultrasonography of the liver demonstrated cirrhosis with patent flow through the shunt, and ultrasonography of the kidneys showed that both were slightly enlarged with increased cortical echogenicity but no hydronephrosis or obstruction.

EXPLORING THE CAUSE OF RENAL FAILURE

1. Given this information, what is the likely cause of our patient’s renal failure?

- Volume depletion

- Acute tubular necrosis

- Hepatorenal syndrome

- HCV glomerulopathy

Renal failure is a common complication in cirrhosis and portends a higher risk of death.1 The differential diagnosis is broad, but a systematic approach incorporating data from the history, physical examination, and laboratory tests can help identify the cause and is essential in determining the prognosis and proper treatment.

Volume depletion

Volume depletion is a common cause of renal failure in cirrhotic patients. Common precipitants are excessive diuresis and gastrointestinal fluid loss from bleeding, vomiting, and diarrhea. Despite having ascites and edema, patients may have low fluid volume in the vascular space. Therefore, the first step in a patient with acute kidney injury is to withhold diuretics and give fluids. The renal failure usually rapidly reverses if the patient does not have renal parenchymal disease.2

Our patient did not present with any fluid losses, and his high blood pressure and normal heart rate did not suggest volume depletion. And most importantly, withholding his diuretics and giving fluids did not reverse his renal failure. Thus, volume depletion was an unlikely cause.

Acute tubular necrosis

The altered hemodynamics caused by cirrhosis predispose patients to acute tubular necrosis. Classically, this presents as muddy brown casts and renal tubular epithelial cells on urinalysis and as a fractional excretion of sodium greater than 2%.1 However, these microscopic findings lack sensitivity, and patients with cirrhosis may have marked sodium avidity and low urine sodium excretion despite tubular injury.3

This diagnosis must still be considered in patients with renal failure, especially after an insult such as hemorrhagic or septic shock or intake of nephrotoxins. However, because our patient did not have a history of any of these and because his renal failure had been progressing over weeks, acute tubular necrosis was considered unlikely.

Hepatorenal syndrome

Hepatorenal syndrome is characterized by progressive renal failure in the absence of renal parenchymal disease. It is a functional disorder, ie, the decreased glomerular filtration rate results from renal vasoconstriction, which in turn is due to decreased systemic vascular resistance and increased compensatory activity of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis and of antiduretic hormone release (Figure 1).

Hepatorenal syndrome often occurs in patients with advanced liver disease. These patients typically have a hyperdynamic circulation (systemic vasodilation, low blood pressure, and increased blood volume) with a low mean arterial pressure and increased renin and norepinephrine levels. Other frequent findings include hyponatremia, low urinary sodium excretion (< 2 mmol/day), and low free water clearance,4 all of which mark the high systemic levels of antidiuretic hormone and aldosterone.

Importantly, while hepatorenal syndrome is always considered in the differential diagnosis because of its unique prognosis and therapy, it remains a diagnosis of exclusion. The International Ascites Club5 has provided diagnostic criteria for hepatorenal syndrome:

- Cirrhosis and ascites

- Serum creatinine greater than 1.5 mg/dL

- Failure of serum creatinine to fall to less than 1.5 mg/dL after at least 48 hours of diuretic withdrawal and volume expansion with albumin (recommended dose 1 g/kg body weight per day up to a maximum of 100 g per day)

- Absence of shock

- No current or recent treatment with nephrotoxic drugs

- No signs of parenchymal kidney disease such as proteinuria (protein excretion > 500 mg/day), microhematuria (> 50 red blood cells per high-power field), or abnormalities on renal ultrasonography.

While these criteria are not perfect,6 they remind clinicians that there are other important causes of renal insufficiency in cirrhosis.

Clinically, our patient had no evidence of a hyperdynamic circulation and was instead hypertensive. He was eunatremic and did not have marked renal sodium avidity. His pyuria, proteinuria (his protein excretion was approximately 1.9 g/day as determined by urine spot protein-to-creatinine ratio), and results of ultrasonography also suggested underlying renal parenchymal disease. Therefore, hepatorenal syndrome was not the likely diagnosis.

HCV glomerulopathy

Intrinsic renal disease is likely, given our patient’s proteinuria, active urine sediment (ie, containing red blood cells, white blood cells, and protein), and abnormal findings on ultrasonography. In patients with HCV infection and no other cause of intrinsic kidney disease, immune complex deposition leading to glomerulonephritis is the most common pattern.7 Despite the intrinsic renal disease, fractional excretion of sodium may be less than 1% in glomerulonephritis. Hypertension in a patient such as ours with cirrhosis and renal insufficiency raises suspicion for glomerular disease, as hypertension is unlikely in advanced cirrhosis.8

Glomerulonephritis in patients with cirrhosis is often clinically silent and may be highly prevalent; some studies have shown glomerular involvement in 55% to 83% of patients with cirrhosis.9,10 This increases the risk of end-stage renal disease, and the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guideline recommends that HCV-infected patients be tested at least once a year for proteinuria, hematuria, and estimated glomerular filtration rate to detect possible HCV-associated kidney disease.11 According to current guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) , detection of glomerulonephritis in HCV patients puts them in the highest priority class for treatment of HCV.12

HISTOLOGIC FINDINGS

Because of the high likelihood of glomerulopathy, our patient underwent renal biopsy.

2. What is the classic pathologic finding in HCV kidney disease?

- Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis

- Crescentic glomerulonephritis

- Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

- Membranous glomerulonephritis

A number of pathologic patterns have been described in HCV kidney disease, including membranous glomerulonephritis, immunoglobulin A nephropathy, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. However, by far the most common pattern is type 1 membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis.13 (Types 2 and 3 are much less common, and we will not discuss them here.) In type 1, light microscopy shows increased mesangial cells and thickened capillary walls (lobular glomeruli), staining of the basement membrane reveals double contours (“tram tracking”) or splitting due to mesangial deposition, and immunofluorescence demonstrates immunoglobulin G and complement C3 deposition. All of these findings were seen in our patient (Figure 2, Figure 3).

Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis in patients with HCV is most commonly associated with cryoglobulins, a mixture of monoclonal or polyclonal immunoglobulin (Ig) M that have antiglobulin (rheumatoid factor) activity and bind to polyclonal IgG. They reversibly precipitate at less than 37°C, (98.6°F), hence their name. Only 50% to 70% of patients with cryoglobulinemic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis have detectable serum cryoglobulins; however, kidney biopsy may show globular accumulations of eosinophilic material and prominent hypercellularity due to infiltration of glomerular capillaries with mononuclear and polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

Noncryoglobulinemic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis is also found in patients with HCV infection. Its histologic features are similar, but on biopsy, there is less prominent leukocytic infiltration and no eosinophilic material. Although the pathogenesis of glomerulonephritis in HCV infection is poorly understood, it is thought to result from deposition of circulating immune complexes of HCV, anti-HCV, and rheumatoid factor in the glomeruli.

3. What laboratory finding is often seen in membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis?

- Positive cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

- serum complement Low levels

- Antiphospholipase A2 receptor antibodies

Cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody is seen in granulomatosis with polyangiitis, while antiphospholipid A2 receptor antibodies are seen in idiopathic membranous nephritis.

Low serum complement levels are frequently found in membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. It is believed that immune complex deposition leads to glomerular damage through activation of the complement pathway and the subsequent influx of inflammatory cells, release of cytokines and proteases, and damage to capillary walls. When repair ensues, new mesangial matrix and basement membrane are deposited, leading to mesangial expansion and duplicated basement membrane.14

In cryoglobulinemic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, the complement C4 level is often much lower than C3, but in noncryoglobulinemic forms C3 is lower. A mnemonic to remember nephritic syndromes with low complement levels is “hy-PO-CO-MP-L-EM-ents”; PO for postinfectious, CO for cryoglobulins, MP for membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, L for lupus, and EM for embolic.

BACK TO OUR PATIENT

In addition to kidney biopsy, we tested our patient for serum cryoglobulins, rheumatoid factor, and serum complements. Results from these tests (Table 3), in addition to the lack of cryoglobulins on his biopsy, led to the conclusion that he had noncryoglobulinemic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis.

WHO SHOULD RECEIVE TREATMENT FOR HCV?

4. According to the current IDSA/AASLD guidelines, which of the following patients should not receive direct-acting antiviral therapy for HCV?

- Patients with HCV and only low-stage fibrosis

- Patients with decompensated cirrhosis

- Patients with a glomerular filtration rate less than 30 mL/minute

- None of the above—nearly all patients with HCV infection should receive treatment for it

While certain patients have compelling indications for HCV treatment, such as advanced fibrosis, severe extrahepatic manifestations of HCV (eg, glomerulonephritis, cryoglobulinemia), and posttransplant status, current guidelines recommend treatment for nearly all patients with HCV, including those with low-stage fibrosis.12

Patients with Child-Pugh grade B or C decompensated cirrhosis, even with hepatocellular carcinoma, may be considered for treatment. Multiple studies have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of direct-acting antiviral drugs in this patient population. In one randomized controlled trial,15 the combination of ledipasvir, sofosbuvir, and ribavirin resulted in high sustained virologic response rates at 12 weeks in patients infected with HCV genotype 1 or 4 with advanced liver disease, irrespective of transplant status (86% to 89% of patients were pretransplant). Sustained virologic response was associated with improvements in Model for End-Stage Liver Disease and Child-Pugh scores largely due to decreases in bilirubin and improvement in synthetic function (ie, albumin).

Similarly, even patients with a glomerular filtration rate less than 30 mL/min are candidates for treatment. Those with a glomerular filtration rate above 30 mL/min need no dosage adjustments for the most common regimens, while regimens are also available for those with a rate less than 30 mL/min. Although patients with low baseline renal function have a higher frequency of anemia (especially with ribavirin), worsening renal dysfunction, and more severe adverse events, treatment responses remain high and comparable to those without renal impairment.

The Hepatitis C Therapeutic Registry and Research Network (HCV-TARGET) is conducting an ongoing prospective study evaluating real-world use of direct-acting antiviral agents. The study has reported the safety and efficacy of sofosbuvir-containing regimens in patients with varying severities of kidney disease, including glomerular filtration rates less than 30 mL/min). The patients received different regimens that included sofosbuvir. The regimens were reportedly tolerated, and the rate of sustained viral response at 12 weeks remained high.16

The efficacy of direct-acting antiviral agents for HCV-associated glomerulonephritis remains to be studied but is promising. Earlier studies found that antiviral therapy based on interferon alfa with or without ribavirin can significantly decrease proteinuria and stabilize renal function.17–20 HCV RNA clearance has been found to best predict renal improvement.

OUR PATIENT’S COURSE

Unfortunately, our patient’s kidney function declined further over the next 3 months, and he is currently on dialysis awaiting simultaneous liver and kidney transplant.

- Ginès P, Schrier RW. Renal failure in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1279–1290.

- Mackelaite L, Alsauskas ZC, Ranganna K. Renal failure in patients with cirrhosis. Med Clin North Am 2009; 93:855–869.

- Wadei HM, Mai ML, Ahsan N, Gonwa TA. Hepatorenal syndrome: pathophysiology and management. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 1:1066–1079.

- Gines A, Escorsell A, Gines P, et al. Incidence, predictive factors, and prognosis of the hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis with ascites. Gastroenterology 1993; 105:229–236.

- Salerno F, Gerbes A, Ginès P, Wong F, Arroyo V. Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. Gut 2007; 56:1310–1318.

- Watt K, Uhanova J, Minuk GY. Hepatorenal syndrome: diagnostic accuracy, clinical features, and outcome in a tertiary care center. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97:2046–2050.

- Graupera I, Cardenas A. Diagnostic approach to renal failure in cirrhosis. Clin Liver Dis 2013; 2:128–131.

- Dash SC, Bhowmik D. Glomerulopathy with liver disease: patterns and management. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 2000; 11:414–420.

- Arase Y, Ikeda K, Murashima N, et al. Glomerulonephritis in autopsy cases with hepatitis C virus infection. Intern Med 1998; 37:836–840.

- McGuire BM, Julian BA, Bynon JS, et al. Brief communication: glomerulonephritis in patients with hepatitis C cirrhosis undergoing liver transplantation. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144:735–741.

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of hepatitis C in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 2008; 109:S1–S99.

- American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. www.hcvguidelines.org/. Accessed July 10, 2016.

- Lai KN. Hepatitis-related renal disease. Future Virology 2011; 6:1361–1376.

- Sethi S, Fervenza FC. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis—a new look at an old entity. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1119–1131.

- Charlton M, Everson GT, Flamm SL, et al; SOLAR-1 Investigators. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for treatment of HCV infection in patients with advanced liver disease. Gastroenterology 2015; 149:649–659.

- Saxena V, Koraishy FM, Sise ME, et al; HCV-TARGET. Safety and efficacy of sofosbuvir-containing regimens in hepatitis C-infected patients with impaired renal function. Liver Int 2016; 36:807–816.

- Feng B, Eknoyan G, Guo ZS, et al. Effect of interferon alpha-based antiviral therapy on hepatitis C virus-associated glomerulonephritis: a meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27:640–646.

- Bruchfeld A, Lindahl K, Ståhle L, Söderberg M, Schvarcz R. Interferon and ribavirin treatment in patients with hepatitis C-associated renal disease and renal insufficiency. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003; 18:1573–1580.

- Rossi P, Bertani T, Baio P, et al. Hepatitis C virus-related cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis. Long-term remission after antiviral therapy. Kidney Int 2003; 63:2236–2241.

- Alric L, Plaisier E, Thebault S, et al. Influence of antiviral therapy in hepatitis C virus associated cryoglobulinemic MPGN. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 43:617–623.

- Ginès P, Schrier RW. Renal failure in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1279–1290.

- Mackelaite L, Alsauskas ZC, Ranganna K. Renal failure in patients with cirrhosis. Med Clin North Am 2009; 93:855–869.

- Wadei HM, Mai ML, Ahsan N, Gonwa TA. Hepatorenal syndrome: pathophysiology and management. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 1:1066–1079.

- Gines A, Escorsell A, Gines P, et al. Incidence, predictive factors, and prognosis of the hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis with ascites. Gastroenterology 1993; 105:229–236.

- Salerno F, Gerbes A, Ginès P, Wong F, Arroyo V. Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. Gut 2007; 56:1310–1318.

- Watt K, Uhanova J, Minuk GY. Hepatorenal syndrome: diagnostic accuracy, clinical features, and outcome in a tertiary care center. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97:2046–2050.

- Graupera I, Cardenas A. Diagnostic approach to renal failure in cirrhosis. Clin Liver Dis 2013; 2:128–131.

- Dash SC, Bhowmik D. Glomerulopathy with liver disease: patterns and management. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 2000; 11:414–420.

- Arase Y, Ikeda K, Murashima N, et al. Glomerulonephritis in autopsy cases with hepatitis C virus infection. Intern Med 1998; 37:836–840.

- McGuire BM, Julian BA, Bynon JS, et al. Brief communication: glomerulonephritis in patients with hepatitis C cirrhosis undergoing liver transplantation. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144:735–741.

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of hepatitis C in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 2008; 109:S1–S99.

- American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. www.hcvguidelines.org/. Accessed July 10, 2016.

- Lai KN. Hepatitis-related renal disease. Future Virology 2011; 6:1361–1376.

- Sethi S, Fervenza FC. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis—a new look at an old entity. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1119–1131.

- Charlton M, Everson GT, Flamm SL, et al; SOLAR-1 Investigators. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for treatment of HCV infection in patients with advanced liver disease. Gastroenterology 2015; 149:649–659.

- Saxena V, Koraishy FM, Sise ME, et al; HCV-TARGET. Safety and efficacy of sofosbuvir-containing regimens in hepatitis C-infected patients with impaired renal function. Liver Int 2016; 36:807–816.

- Feng B, Eknoyan G, Guo ZS, et al. Effect of interferon alpha-based antiviral therapy on hepatitis C virus-associated glomerulonephritis: a meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27:640–646.

- Bruchfeld A, Lindahl K, Ståhle L, Söderberg M, Schvarcz R. Interferon and ribavirin treatment in patients with hepatitis C-associated renal disease and renal insufficiency. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003; 18:1573–1580.

- Rossi P, Bertani T, Baio P, et al. Hepatitis C virus-related cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis. Long-term remission after antiviral therapy. Kidney Int 2003; 63:2236–2241.

- Alric L, Plaisier E, Thebault S, et al. Influence of antiviral therapy in hepatitis C virus associated cryoglobulinemic MPGN. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 43:617–623.

Newer Insulin Glargine Formula Curbs Nocturnal Hypoglycemia

NEW ORLEANS – Insulin glargine 300 U/mL provided comparable glycemic control to that seen with insulin glargine 100 U/mL and consistently reduced the risk of nocturnal hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes, regardless of their renal function, results from a large post hoc meta-analysis showed.

The EDITION I, II, and III studies showed that over a period of 6 months, Gla-300 provided comparable glycemic control to Gla-100 with less hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. However, “renal impairment increases the risk of hypoglycemia in people with type 2 diabetes, and may limit glucose-lowering therapy options,” Javier Escalada, M.D., said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “Therefore, it may be more challenging to manage diabetes in this population than in people with normal renal function.”

Dr. Escalada of the department of endocrinology and nutrition at Clinic University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain, and his associates set out to investigate the impact of renal function on hemoglobin A1c reduction and hypoglycemia in a post hoc meta-analysis of 2,468 patients aged 18 years and older with type 2 diabetes who were treated with Gla-300 or Gla-100 for 6 months in the EDITION I, II, and III studies. Treatment consisted of once-daily evening doses of Gla-300 or Gla-100 titrated to a fasting self-measured plasma glucose of 80-100 mg/dL. Patients were classified by their renal function as having moderate loss (30 to less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m3; 399 patients), mild loss (60 to less than 90; 1,386 patients), or normal function (at least 90; 683 patients).

Outcomes of interest were change in HbA1c from baseline to month 6, and the percentages of patients achieving an HbA1c target of lower than 7.0% and lower than 7.5% at month 6. The researchers also assessed the cumulative number of hypoglycemic events, the relative risk of at least one confirmed or severe hypoglycemic event, and the nocturnal and at any time event rate per participant year.

Slightly more than half of participants (56%) had a baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate of 60 to less than 90 mL/min per 1.73 m3. Dr. Escalada reported that noninferiority for HbA1c reduction was shown for Gla-300 and Gla-100 regardless of renal function, and that evidence of heterogeneity of treatment effect across subgroups was observed (P = .46). However, the risk of confirmed or severe hypoglycemia was significantly lower for nocturnal events in the Gla-300 group, compared with the Gla-100 group (30% vs. 40% overall, respectively), while the risk of anytime hypoglycemia events in a 24-hour period was comparable to or lower in the Gla-300 group, compared with the Gla-100 group. Renal function did not affect the lower rate of nocturnal or anytime hypoglycemia. “Severe hypoglycemia was rare, and renal function did not affect the rate of severe events,” he said.

The trial was sponsored by Sanofi. Dr. Escalada disclosed that he is a member of the advisory panel for Sanofi and for Merck Sharp & Dohme. He is also a member of the speakers bureau for both companies as well as for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk.

NEW ORLEANS – Insulin glargine 300 U/mL provided comparable glycemic control to that seen with insulin glargine 100 U/mL and consistently reduced the risk of nocturnal hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes, regardless of their renal function, results from a large post hoc meta-analysis showed.

The EDITION I, II, and III studies showed that over a period of 6 months, Gla-300 provided comparable glycemic control to Gla-100 with less hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. However, “renal impairment increases the risk of hypoglycemia in people with type 2 diabetes, and may limit glucose-lowering therapy options,” Javier Escalada, M.D., said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “Therefore, it may be more challenging to manage diabetes in this population than in people with normal renal function.”

Dr. Escalada of the department of endocrinology and nutrition at Clinic University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain, and his associates set out to investigate the impact of renal function on hemoglobin A1c reduction and hypoglycemia in a post hoc meta-analysis of 2,468 patients aged 18 years and older with type 2 diabetes who were treated with Gla-300 or Gla-100 for 6 months in the EDITION I, II, and III studies. Treatment consisted of once-daily evening doses of Gla-300 or Gla-100 titrated to a fasting self-measured plasma glucose of 80-100 mg/dL. Patients were classified by their renal function as having moderate loss (30 to less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m3; 399 patients), mild loss (60 to less than 90; 1,386 patients), or normal function (at least 90; 683 patients).

Outcomes of interest were change in HbA1c from baseline to month 6, and the percentages of patients achieving an HbA1c target of lower than 7.0% and lower than 7.5% at month 6. The researchers also assessed the cumulative number of hypoglycemic events, the relative risk of at least one confirmed or severe hypoglycemic event, and the nocturnal and at any time event rate per participant year.

Slightly more than half of participants (56%) had a baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate of 60 to less than 90 mL/min per 1.73 m3. Dr. Escalada reported that noninferiority for HbA1c reduction was shown for Gla-300 and Gla-100 regardless of renal function, and that evidence of heterogeneity of treatment effect across subgroups was observed (P = .46). However, the risk of confirmed or severe hypoglycemia was significantly lower for nocturnal events in the Gla-300 group, compared with the Gla-100 group (30% vs. 40% overall, respectively), while the risk of anytime hypoglycemia events in a 24-hour period was comparable to or lower in the Gla-300 group, compared with the Gla-100 group. Renal function did not affect the lower rate of nocturnal or anytime hypoglycemia. “Severe hypoglycemia was rare, and renal function did not affect the rate of severe events,” he said.

The trial was sponsored by Sanofi. Dr. Escalada disclosed that he is a member of the advisory panel for Sanofi and for Merck Sharp & Dohme. He is also a member of the speakers bureau for both companies as well as for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk.

NEW ORLEANS – Insulin glargine 300 U/mL provided comparable glycemic control to that seen with insulin glargine 100 U/mL and consistently reduced the risk of nocturnal hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes, regardless of their renal function, results from a large post hoc meta-analysis showed.

The EDITION I, II, and III studies showed that over a period of 6 months, Gla-300 provided comparable glycemic control to Gla-100 with less hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. However, “renal impairment increases the risk of hypoglycemia in people with type 2 diabetes, and may limit glucose-lowering therapy options,” Javier Escalada, M.D., said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “Therefore, it may be more challenging to manage diabetes in this population than in people with normal renal function.”

Dr. Escalada of the department of endocrinology and nutrition at Clinic University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain, and his associates set out to investigate the impact of renal function on hemoglobin A1c reduction and hypoglycemia in a post hoc meta-analysis of 2,468 patients aged 18 years and older with type 2 diabetes who were treated with Gla-300 or Gla-100 for 6 months in the EDITION I, II, and III studies. Treatment consisted of once-daily evening doses of Gla-300 or Gla-100 titrated to a fasting self-measured plasma glucose of 80-100 mg/dL. Patients were classified by their renal function as having moderate loss (30 to less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m3; 399 patients), mild loss (60 to less than 90; 1,386 patients), or normal function (at least 90; 683 patients).

Outcomes of interest were change in HbA1c from baseline to month 6, and the percentages of patients achieving an HbA1c target of lower than 7.0% and lower than 7.5% at month 6. The researchers also assessed the cumulative number of hypoglycemic events, the relative risk of at least one confirmed or severe hypoglycemic event, and the nocturnal and at any time event rate per participant year.

Slightly more than half of participants (56%) had a baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate of 60 to less than 90 mL/min per 1.73 m3. Dr. Escalada reported that noninferiority for HbA1c reduction was shown for Gla-300 and Gla-100 regardless of renal function, and that evidence of heterogeneity of treatment effect across subgroups was observed (P = .46). However, the risk of confirmed or severe hypoglycemia was significantly lower for nocturnal events in the Gla-300 group, compared with the Gla-100 group (30% vs. 40% overall, respectively), while the risk of anytime hypoglycemia events in a 24-hour period was comparable to or lower in the Gla-300 group, compared with the Gla-100 group. Renal function did not affect the lower rate of nocturnal or anytime hypoglycemia. “Severe hypoglycemia was rare, and renal function did not affect the rate of severe events,” he said.

The trial was sponsored by Sanofi. Dr. Escalada disclosed that he is a member of the advisory panel for Sanofi and for Merck Sharp & Dohme. He is also a member of the speakers bureau for both companies as well as for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Newer insulin glargine formula curbs nocturnal hypoglycemia

NEW ORLEANS – Insulin glargine 300 U/mL provided comparable glycemic control to that seen with insulin glargine 100 U/mL and consistently reduced the risk of nocturnal hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes, regardless of their renal function, results from a large post hoc meta-analysis showed.

The EDITION I, II, and III studies showed that over a period of 6 months, Gla-300 provided comparable glycemic control to Gla-100 with less hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. However, “renal impairment increases the risk of hypoglycemia in people with type 2 diabetes, and may limit glucose-lowering therapy options,” Javier Escalada, M.D., said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “Therefore, it may be more challenging to manage diabetes in this population than in people with normal renal function.”

Dr. Escalada of the department of endocrinology and nutrition at Clinic University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain, and his associates set out to investigate the impact of renal function on hemoglobin A1c reduction and hypoglycemia in a post hoc meta-analysis of 2,468 patients aged 18 years and older with type 2 diabetes who were treated with Gla-300 or Gla-100 for 6 months in the EDITION I, II, and III studies. Treatment consisted of once-daily evening doses of Gla-300 or Gla-100 titrated to a fasting self-measured plasma glucose of 80-100 mg/dL. Patients were classified by their renal function as having moderate loss (30 to less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m3; 399 patients), mild loss (60 to less than 90; 1,386 patients), or normal function (at least 90; 683 patients).

Outcomes of interest were change in HbA1c from baseline to month 6, and the percentages of patients achieving an HbA1c target of lower than 7.0% and lower than 7.5% at month 6. The researchers also assessed the cumulative number of hypoglycemic events, the relative risk of at least one confirmed or severe hypoglycemic event, and the nocturnal and at any time event rate per participant year.

Slightly more than half of participants (56%) had a baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate of 60 to less than 90 mL/min per 1.73 m3. Dr. Escalada reported that noninferiority for HbA1c reduction was shown for Gla-300 and Gla-100 regardless of renal function, and that evidence of heterogeneity of treatment effect across subgroups was observed (P = .46). However, the risk of confirmed or severe hypoglycemia was significantly lower for nocturnal events in the Gla-300 group, compared with the Gla-100 group (30% vs. 40% overall, respectively), while the risk of anytime hypoglycemia events in a 24-hour period was comparable to or lower in the Gla-300 group, compared with the Gla-100 group. Renal function did not affect the lower rate of nocturnal or anytime hypoglycemia. “Severe hypoglycemia was rare, and renal function did not affect the rate of severe events,” he said.

The trial was sponsored by Sanofi. Dr. Escalada disclosed that he is a member of the advisory panel for Sanofi and for Merck Sharp & Dohme. He is also a member of the speakers bureau for both companies as well as for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk.

NEW ORLEANS – Insulin glargine 300 U/mL provided comparable glycemic control to that seen with insulin glargine 100 U/mL and consistently reduced the risk of nocturnal hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes, regardless of their renal function, results from a large post hoc meta-analysis showed.

The EDITION I, II, and III studies showed that over a period of 6 months, Gla-300 provided comparable glycemic control to Gla-100 with less hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. However, “renal impairment increases the risk of hypoglycemia in people with type 2 diabetes, and may limit glucose-lowering therapy options,” Javier Escalada, M.D., said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “Therefore, it may be more challenging to manage diabetes in this population than in people with normal renal function.”

Dr. Escalada of the department of endocrinology and nutrition at Clinic University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain, and his associates set out to investigate the impact of renal function on hemoglobin A1c reduction and hypoglycemia in a post hoc meta-analysis of 2,468 patients aged 18 years and older with type 2 diabetes who were treated with Gla-300 or Gla-100 for 6 months in the EDITION I, II, and III studies. Treatment consisted of once-daily evening doses of Gla-300 or Gla-100 titrated to a fasting self-measured plasma glucose of 80-100 mg/dL. Patients were classified by their renal function as having moderate loss (30 to less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m3; 399 patients), mild loss (60 to less than 90; 1,386 patients), or normal function (at least 90; 683 patients).

Outcomes of interest were change in HbA1c from baseline to month 6, and the percentages of patients achieving an HbA1c target of lower than 7.0% and lower than 7.5% at month 6. The researchers also assessed the cumulative number of hypoglycemic events, the relative risk of at least one confirmed or severe hypoglycemic event, and the nocturnal and at any time event rate per participant year.

Slightly more than half of participants (56%) had a baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate of 60 to less than 90 mL/min per 1.73 m3. Dr. Escalada reported that noninferiority for HbA1c reduction was shown for Gla-300 and Gla-100 regardless of renal function, and that evidence of heterogeneity of treatment effect across subgroups was observed (P = .46). However, the risk of confirmed or severe hypoglycemia was significantly lower for nocturnal events in the Gla-300 group, compared with the Gla-100 group (30% vs. 40% overall, respectively), while the risk of anytime hypoglycemia events in a 24-hour period was comparable to or lower in the Gla-300 group, compared with the Gla-100 group. Renal function did not affect the lower rate of nocturnal or anytime hypoglycemia. “Severe hypoglycemia was rare, and renal function did not affect the rate of severe events,” he said.

The trial was sponsored by Sanofi. Dr. Escalada disclosed that he is a member of the advisory panel for Sanofi and for Merck Sharp & Dohme. He is also a member of the speakers bureau for both companies as well as for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk.

NEW ORLEANS – Insulin glargine 300 U/mL provided comparable glycemic control to that seen with insulin glargine 100 U/mL and consistently reduced the risk of nocturnal hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes, regardless of their renal function, results from a large post hoc meta-analysis showed.

The EDITION I, II, and III studies showed that over a period of 6 months, Gla-300 provided comparable glycemic control to Gla-100 with less hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. However, “renal impairment increases the risk of hypoglycemia in people with type 2 diabetes, and may limit glucose-lowering therapy options,” Javier Escalada, M.D., said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “Therefore, it may be more challenging to manage diabetes in this population than in people with normal renal function.”

Dr. Escalada of the department of endocrinology and nutrition at Clinic University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain, and his associates set out to investigate the impact of renal function on hemoglobin A1c reduction and hypoglycemia in a post hoc meta-analysis of 2,468 patients aged 18 years and older with type 2 diabetes who were treated with Gla-300 or Gla-100 for 6 months in the EDITION I, II, and III studies. Treatment consisted of once-daily evening doses of Gla-300 or Gla-100 titrated to a fasting self-measured plasma glucose of 80-100 mg/dL. Patients were classified by their renal function as having moderate loss (30 to less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m3; 399 patients), mild loss (60 to less than 90; 1,386 patients), or normal function (at least 90; 683 patients).

Outcomes of interest were change in HbA1c from baseline to month 6, and the percentages of patients achieving an HbA1c target of lower than 7.0% and lower than 7.5% at month 6. The researchers also assessed the cumulative number of hypoglycemic events, the relative risk of at least one confirmed or severe hypoglycemic event, and the nocturnal and at any time event rate per participant year.

Slightly more than half of participants (56%) had a baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate of 60 to less than 90 mL/min per 1.73 m3. Dr. Escalada reported that noninferiority for HbA1c reduction was shown for Gla-300 and Gla-100 regardless of renal function, and that evidence of heterogeneity of treatment effect across subgroups was observed (P = .46). However, the risk of confirmed or severe hypoglycemia was significantly lower for nocturnal events in the Gla-300 group, compared with the Gla-100 group (30% vs. 40% overall, respectively), while the risk of anytime hypoglycemia events in a 24-hour period was comparable to or lower in the Gla-300 group, compared with the Gla-100 group. Renal function did not affect the lower rate of nocturnal or anytime hypoglycemia. “Severe hypoglycemia was rare, and renal function did not affect the rate of severe events,” he said.

The trial was sponsored by Sanofi. Dr. Escalada disclosed that he is a member of the advisory panel for Sanofi and for Merck Sharp & Dohme. He is also a member of the speakers bureau for both companies as well as for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Insulin glargine 300 U/mL provided glycemic control comparable to insulin glargine 100 U/mL, but it reduced the risk of nocturnal hypoglycemia by a greater margin, regardless of renal function.

Major finding: The risk of confirmed or severe hypoglycemia was significantly lower for nocturnal events in the Gla-300 group, compared with the Gla-100 group (30% vs. 40% overall, respectively), while the risk of anytime hypoglycemia events in a 24-hour period was comparable to or lower in the Gla-300 group, compared with the Gla-100 group.

Data source: A post hoc meta-analysis of 2,468 patients aged 18 years and older with type 2 diabetes who were treated with Gla-300 or Gla-100 for 6 months in the EDITION I, II, and III studies.

Disclosures: The trial was sponsored by Sanofi. Dr. Escalada disclosed that he is a member of the advisory panel for Sanofi and for Merck Sharp & Dohme. He is also a member of the speakers bureau for both companies as well as for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk.

Blood pressure targets

To the Editor: I read with great interest the article by Thomas et al, “Interpreting SPRINT: How low should you go?”1

Hypertension is the most prevalent modifiable risk factor, affecting almost one in every three people in the United States.2 Moreover, only half of people with hypertension have their blood pressure under control to the current standard of lower than 140/90 mm Hg.2 The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) tested a lower goal systolic pressure, ie, less than 120 mm Hg, and found it more beneficial than the standard goal of less than 140 mm Hg.3

A drawback of SPRINT that Thomas et al did not address in their interpretation of the trial is that the two study groups were not homogeneous in terms of the antihypertensive drugs used. Antihypertensive drugs do not only lower blood pressure—some of them have additional pleiotropic effects, making their use more advantageous in special situations. For example, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) blockers—ie, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists—are disease-modfying drugs in heart failure, as are certain beta-blockers.4 The cardiovascular benefit seen in the intensive-treatment group in SPRINT compared with the standard-therapy group was primarily due to a reduction in heart failure (a 38% relative risk reduction, P = .0002),3 for which RAAS blockers and beta-adrenergic blocking drugs have been shown consistently to be beneficial. But the intensive- and standard-therapy groups were not homogeneous in terms of the use of RAAS blockers and beta-blockers.

So, was the cardiovascular benefit attained in the intensive-treatment group in SPRINT due to the benefit of lower blood pressure or to the drugs used?

- Thomas G, Nally JV, Pohl MA. Interpreting SPRINT: how low should you go? Cleve Clin J Med 2016; 83:187–195.

- Nwankwo T, Yoon SS, Burt V, Gu Q. Hypertension among adults in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011–2012. NCHS Data Brief 2013 Oct;(133):1–8.

- SPRINT Research Group; Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:2103–2116.

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2013; 128:e240–e327.

To the Editor: I read with great interest the article by Thomas et al, “Interpreting SPRINT: How low should you go?”1

Hypertension is the most prevalent modifiable risk factor, affecting almost one in every three people in the United States.2 Moreover, only half of people with hypertension have their blood pressure under control to the current standard of lower than 140/90 mm Hg.2 The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) tested a lower goal systolic pressure, ie, less than 120 mm Hg, and found it more beneficial than the standard goal of less than 140 mm Hg.3

A drawback of SPRINT that Thomas et al did not address in their interpretation of the trial is that the two study groups were not homogeneous in terms of the antihypertensive drugs used. Antihypertensive drugs do not only lower blood pressure—some of them have additional pleiotropic effects, making their use more advantageous in special situations. For example, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) blockers—ie, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists—are disease-modfying drugs in heart failure, as are certain beta-blockers.4 The cardiovascular benefit seen in the intensive-treatment group in SPRINT compared with the standard-therapy group was primarily due to a reduction in heart failure (a 38% relative risk reduction, P = .0002),3 for which RAAS blockers and beta-adrenergic blocking drugs have been shown consistently to be beneficial. But the intensive- and standard-therapy groups were not homogeneous in terms of the use of RAAS blockers and beta-blockers.

So, was the cardiovascular benefit attained in the intensive-treatment group in SPRINT due to the benefit of lower blood pressure or to the drugs used?

To the Editor: I read with great interest the article by Thomas et al, “Interpreting SPRINT: How low should you go?”1