User login

Look for nephrotoxicity in adult survivors of childhood cancer

LAS VEGAS – Adult survivors of childhood cancer treated with high-dose cisplatin or high-dose ifosfamide are at markedly increased risk for chronic renal impairment, according to a large Dutch study with a median 18.3-year follow-up.

Long-term treatment-related nephrotoxicity was also seen in the adult survivors of childhood cancer who underwent unilateral nephrectomy combined with abdominal radiation therapy.

"This study is perhaps a warning to us when we’re seeing these adult survivors of childhood cancer in clinic, particularly if they have a history of ifosfamide or cisplatin use, to pay closer attention to the development of chronic kidney disease so they can be managed better in the future," Dr. Anushree C. Shirali said at a meeting sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation.

Drug-induced acute kidney injury is a common event during cancer therapy. Its mechanisms and treatments are well studied. In contrast, the long-term nephrotoxicity of the powerful therapies used in treating childhood cancers has received much less scrutiny. But it’s an increasingly relevant issue because childhood cancer survival rates have improved substantially. Indeed, as the Dutch investigators observed, today 1 in 570 young adults is a childhood cancer survivor (Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013;8:922-9).

Dr. Shirali, a nephrologist at Yale University in New Haven, Conn., highlighted the Dutch study of 763 adult survivors of childhood cancer because of its unusually long and complete follow-up. The investigators included nearly 90% of all adult survivors treated at Erasmus University in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, during 1964-2005.

High-dose ifosfamide was associated with a 6.2-fold greater likelihood of an increased urinary beta2-microglobulin/creatinine ratio indicative of persisting tubular dysfunction, compared with cancer survivors not receiving that therapy. High-dose cisplatin was associated with a 5.2-fold increased risk of albuminuria. The estimated glomerular filtration rate in adult survivors who had received high-dose ifosfamide was 88 mL/min per 1.73 m2, significantly lower than the 98 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in others. Similarly, patients who had received high-dose cisplatin had an average estimated glomerular filtration rate of 83 mL/min per 1.73 m2, compared with 101 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in survivors not treated with high-dose cisplatin.

In contrast to ifosfamide, its isomer cyclophosphamide was not associated with long-term nephrotoxicity; neither was carboplatin, a cisplatin analogue, or methotrexate. Although methotrexate is known to cause acute nephrotoxicity, this phenomenon appears to be completely reversible, since methotrexate-treated, long-term cancer survivors didn’t develop tubular or glomerular dysfunction.

This long-term study was supported by the Dutch Kidney Foundation. Dr. Shirali, who was not involved in the study, reported having no financial conflicts.

LAS VEGAS – Adult survivors of childhood cancer treated with high-dose cisplatin or high-dose ifosfamide are at markedly increased risk for chronic renal impairment, according to a large Dutch study with a median 18.3-year follow-up.

Long-term treatment-related nephrotoxicity was also seen in the adult survivors of childhood cancer who underwent unilateral nephrectomy combined with abdominal radiation therapy.

"This study is perhaps a warning to us when we’re seeing these adult survivors of childhood cancer in clinic, particularly if they have a history of ifosfamide or cisplatin use, to pay closer attention to the development of chronic kidney disease so they can be managed better in the future," Dr. Anushree C. Shirali said at a meeting sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation.

Drug-induced acute kidney injury is a common event during cancer therapy. Its mechanisms and treatments are well studied. In contrast, the long-term nephrotoxicity of the powerful therapies used in treating childhood cancers has received much less scrutiny. But it’s an increasingly relevant issue because childhood cancer survival rates have improved substantially. Indeed, as the Dutch investigators observed, today 1 in 570 young adults is a childhood cancer survivor (Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013;8:922-9).

Dr. Shirali, a nephrologist at Yale University in New Haven, Conn., highlighted the Dutch study of 763 adult survivors of childhood cancer because of its unusually long and complete follow-up. The investigators included nearly 90% of all adult survivors treated at Erasmus University in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, during 1964-2005.

High-dose ifosfamide was associated with a 6.2-fold greater likelihood of an increased urinary beta2-microglobulin/creatinine ratio indicative of persisting tubular dysfunction, compared with cancer survivors not receiving that therapy. High-dose cisplatin was associated with a 5.2-fold increased risk of albuminuria. The estimated glomerular filtration rate in adult survivors who had received high-dose ifosfamide was 88 mL/min per 1.73 m2, significantly lower than the 98 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in others. Similarly, patients who had received high-dose cisplatin had an average estimated glomerular filtration rate of 83 mL/min per 1.73 m2, compared with 101 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in survivors not treated with high-dose cisplatin.

In contrast to ifosfamide, its isomer cyclophosphamide was not associated with long-term nephrotoxicity; neither was carboplatin, a cisplatin analogue, or methotrexate. Although methotrexate is known to cause acute nephrotoxicity, this phenomenon appears to be completely reversible, since methotrexate-treated, long-term cancer survivors didn’t develop tubular or glomerular dysfunction.

This long-term study was supported by the Dutch Kidney Foundation. Dr. Shirali, who was not involved in the study, reported having no financial conflicts.

LAS VEGAS – Adult survivors of childhood cancer treated with high-dose cisplatin or high-dose ifosfamide are at markedly increased risk for chronic renal impairment, according to a large Dutch study with a median 18.3-year follow-up.

Long-term treatment-related nephrotoxicity was also seen in the adult survivors of childhood cancer who underwent unilateral nephrectomy combined with abdominal radiation therapy.

"This study is perhaps a warning to us when we’re seeing these adult survivors of childhood cancer in clinic, particularly if they have a history of ifosfamide or cisplatin use, to pay closer attention to the development of chronic kidney disease so they can be managed better in the future," Dr. Anushree C. Shirali said at a meeting sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation.

Drug-induced acute kidney injury is a common event during cancer therapy. Its mechanisms and treatments are well studied. In contrast, the long-term nephrotoxicity of the powerful therapies used in treating childhood cancers has received much less scrutiny. But it’s an increasingly relevant issue because childhood cancer survival rates have improved substantially. Indeed, as the Dutch investigators observed, today 1 in 570 young adults is a childhood cancer survivor (Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013;8:922-9).

Dr. Shirali, a nephrologist at Yale University in New Haven, Conn., highlighted the Dutch study of 763 adult survivors of childhood cancer because of its unusually long and complete follow-up. The investigators included nearly 90% of all adult survivors treated at Erasmus University in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, during 1964-2005.

High-dose ifosfamide was associated with a 6.2-fold greater likelihood of an increased urinary beta2-microglobulin/creatinine ratio indicative of persisting tubular dysfunction, compared with cancer survivors not receiving that therapy. High-dose cisplatin was associated with a 5.2-fold increased risk of albuminuria. The estimated glomerular filtration rate in adult survivors who had received high-dose ifosfamide was 88 mL/min per 1.73 m2, significantly lower than the 98 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in others. Similarly, patients who had received high-dose cisplatin had an average estimated glomerular filtration rate of 83 mL/min per 1.73 m2, compared with 101 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in survivors not treated with high-dose cisplatin.

In contrast to ifosfamide, its isomer cyclophosphamide was not associated with long-term nephrotoxicity; neither was carboplatin, a cisplatin analogue, or methotrexate. Although methotrexate is known to cause acute nephrotoxicity, this phenomenon appears to be completely reversible, since methotrexate-treated, long-term cancer survivors didn’t develop tubular or glomerular dysfunction.

This long-term study was supported by the Dutch Kidney Foundation. Dr. Shirali, who was not involved in the study, reported having no financial conflicts.

AT SCM 14

Key clinical point: Today 1 in 570 young adults is a childhood cancer survivor, and many are on the road to chronic kidney disease.

Major finding: Adult survivors of childhood cancer treated with high-dose cisplatin or high-dose ifosfamide had a significantly lower estimated glomerular filtration rate than those who were not.

Data source: This was a retrospective, single-center study involving 763 adult survivors of childhood cancer with a median 18.3 years of follow-up.

Disclosures: This long-term study was supported by the Dutch Kidney Foundation. Dr. Shirali, who was not involved in the study, reported having no financial conflicts.

High total and LDL cholesterol levels increased risk of chronic kidney disease

MELBOURNE – Elevated total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in patients with coronary heart disease were significantly associated with an increased risk of chronic kidney disease, according to a retrospective analysis of data from two large, randomized, controlled trials.

Data presented at the World Congress of Cardiology 2014 showed total cholesterol levels above 240 mg/dL were associated with a significant 78% increase in the risk of chronic kidney disease, while LDL cholesterol greater than 190 mg/dL was associated with a 72% increase in risk.

Elevated non–high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and the ratio of total cholesterol to HDL cholesterol were both associated with elevated risk of chronic kidney disease, but reduced HDL cholesterol and the ratio of apolipoprotein B/apolipoprotein A did not significantly affect risk.

Dyslipidemia is present in around 60% of patients with chronic kidney disease, noted presenter Dr. Prakash Deedwania, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. Previous studies in patients with coronary heart disease and chronic kidney disease also have shown that statins have a renoprotective effect.

However, Dr. Deedwania said there has been little exploration of the impact of baseline lipid parameters on renal function.

"We have found that there is a significant increase in not only the prevalence but also the morbidity and mortality in people with chronic kidney disease with coronary events and other cardiovascular events," Dr. Deedwania said in an interview.

Using data from the Treating to New Targets (TNT) study and Incremental Decrease in End Points Through Aggressive Lipid Lowering (IDEAL) study, in which patients were treated with either atorvastatin or simvastatin, researchers were able to examine the relationship between baseline lipoprotein parameters and kidney function in a combined cohort of more than 19,000 patients with coronary heart disease.

"That showed very good relationship between total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol with progressive decline in renal function, which then helped me explain what I had observed earlier in terms of improvement in kidney function in early-stage patients with statins," Dr. Deedwania said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the World Heart Federation.

The relationship between lipoprotein parameters and chronic kidney disease persisted even after adjustment for age, body mass index, smoking status, diabetes history and status, hypertension, and treatment assignment.

The study defined chronic kidney disease as an estimated glomerular filtration rate below 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2. However, Dr. Deedwania said no patients achieved stage 4 kidney disease, and all eGFR measurements fell between 45 and 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

The analysis used a relatively early definition of kidney disease as the outcome of interest, observed session chair Dr. Vlado Perkovic, professor of medicine at the University of Sydney (Australia).

Dr. Deedwania later said he believed the key was to focus on early-stage interventions rather than waiting until the disease progressed and suggested some interventional trials had failed to achieve an effect because they were done in more advanced patients.

The researchers declared a range of speakers fees, consultancies, and honoraria from the pharmaceutical industry; two of the authors were employees of Pfizer.

MELBOURNE – Elevated total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in patients with coronary heart disease were significantly associated with an increased risk of chronic kidney disease, according to a retrospective analysis of data from two large, randomized, controlled trials.

Data presented at the World Congress of Cardiology 2014 showed total cholesterol levels above 240 mg/dL were associated with a significant 78% increase in the risk of chronic kidney disease, while LDL cholesterol greater than 190 mg/dL was associated with a 72% increase in risk.

Elevated non–high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and the ratio of total cholesterol to HDL cholesterol were both associated with elevated risk of chronic kidney disease, but reduced HDL cholesterol and the ratio of apolipoprotein B/apolipoprotein A did not significantly affect risk.

Dyslipidemia is present in around 60% of patients with chronic kidney disease, noted presenter Dr. Prakash Deedwania, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. Previous studies in patients with coronary heart disease and chronic kidney disease also have shown that statins have a renoprotective effect.

However, Dr. Deedwania said there has been little exploration of the impact of baseline lipid parameters on renal function.

"We have found that there is a significant increase in not only the prevalence but also the morbidity and mortality in people with chronic kidney disease with coronary events and other cardiovascular events," Dr. Deedwania said in an interview.

Using data from the Treating to New Targets (TNT) study and Incremental Decrease in End Points Through Aggressive Lipid Lowering (IDEAL) study, in which patients were treated with either atorvastatin or simvastatin, researchers were able to examine the relationship between baseline lipoprotein parameters and kidney function in a combined cohort of more than 19,000 patients with coronary heart disease.

"That showed very good relationship between total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol with progressive decline in renal function, which then helped me explain what I had observed earlier in terms of improvement in kidney function in early-stage patients with statins," Dr. Deedwania said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the World Heart Federation.

The relationship between lipoprotein parameters and chronic kidney disease persisted even after adjustment for age, body mass index, smoking status, diabetes history and status, hypertension, and treatment assignment.

The study defined chronic kidney disease as an estimated glomerular filtration rate below 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2. However, Dr. Deedwania said no patients achieved stage 4 kidney disease, and all eGFR measurements fell between 45 and 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

The analysis used a relatively early definition of kidney disease as the outcome of interest, observed session chair Dr. Vlado Perkovic, professor of medicine at the University of Sydney (Australia).

Dr. Deedwania later said he believed the key was to focus on early-stage interventions rather than waiting until the disease progressed and suggested some interventional trials had failed to achieve an effect because they were done in more advanced patients.

The researchers declared a range of speakers fees, consultancies, and honoraria from the pharmaceutical industry; two of the authors were employees of Pfizer.

MELBOURNE – Elevated total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in patients with coronary heart disease were significantly associated with an increased risk of chronic kidney disease, according to a retrospective analysis of data from two large, randomized, controlled trials.

Data presented at the World Congress of Cardiology 2014 showed total cholesterol levels above 240 mg/dL were associated with a significant 78% increase in the risk of chronic kidney disease, while LDL cholesterol greater than 190 mg/dL was associated with a 72% increase in risk.

Elevated non–high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and the ratio of total cholesterol to HDL cholesterol were both associated with elevated risk of chronic kidney disease, but reduced HDL cholesterol and the ratio of apolipoprotein B/apolipoprotein A did not significantly affect risk.

Dyslipidemia is present in around 60% of patients with chronic kidney disease, noted presenter Dr. Prakash Deedwania, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. Previous studies in patients with coronary heart disease and chronic kidney disease also have shown that statins have a renoprotective effect.

However, Dr. Deedwania said there has been little exploration of the impact of baseline lipid parameters on renal function.

"We have found that there is a significant increase in not only the prevalence but also the morbidity and mortality in people with chronic kidney disease with coronary events and other cardiovascular events," Dr. Deedwania said in an interview.

Using data from the Treating to New Targets (TNT) study and Incremental Decrease in End Points Through Aggressive Lipid Lowering (IDEAL) study, in which patients were treated with either atorvastatin or simvastatin, researchers were able to examine the relationship between baseline lipoprotein parameters and kidney function in a combined cohort of more than 19,000 patients with coronary heart disease.

"That showed very good relationship between total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol with progressive decline in renal function, which then helped me explain what I had observed earlier in terms of improvement in kidney function in early-stage patients with statins," Dr. Deedwania said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the World Heart Federation.

The relationship between lipoprotein parameters and chronic kidney disease persisted even after adjustment for age, body mass index, smoking status, diabetes history and status, hypertension, and treatment assignment.

The study defined chronic kidney disease as an estimated glomerular filtration rate below 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2. However, Dr. Deedwania said no patients achieved stage 4 kidney disease, and all eGFR measurements fell between 45 and 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

The analysis used a relatively early definition of kidney disease as the outcome of interest, observed session chair Dr. Vlado Perkovic, professor of medicine at the University of Sydney (Australia).

Dr. Deedwania later said he believed the key was to focus on early-stage interventions rather than waiting until the disease progressed and suggested some interventional trials had failed to achieve an effect because they were done in more advanced patients.

The researchers declared a range of speakers fees, consultancies, and honoraria from the pharmaceutical industry; two of the authors were employees of Pfizer.

AT WCC 2014

Key clinical point: Patients with high total cholesterol levels or high LDL cholesterol may be at risk for chronic kidney disease.

Major finding: Total cholesterol levels above 240 mg/dL are associated with a significant 78% increase in the risk of chronic kidney disease among patients with coronary heart disease, while LDL cholesterol greater than 190 mg/dL was associated with a 72% increase in risk.

Data source: Retrospective analysis of data from more than 19,000 patients enrolled in two randomized, controlled trials of statin therapy in patients with coronary heart disease.

Disclosures: Researchers declared a range of speakers fees, consultancies, and honorariums from the pharmaceutical industry; two authors were employees of Pfizer.

FDA Approves Blood Test for Membranous Glomerulonephritis

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a noninvasive test to determine whether a chronic kidney disease is caused by an autoimmune disease or another cause such as infection.

The EUROIMMUN Anti- PLA2R IFA blood test detects an antibody that is specific to primary membranous glomerulonephritis (pMGN). MGN, a chronic kidney disease, damages the glomeruli; it can lead to kidney failure and transplant. Symptoms include swelling, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and an increased predisposition to blood clots.

The condition mostly affects white men. It occurs in 2 of every 10,000 people and is more common after age 40, according to the National Library of Medicine. Risk factors include cancers, especially lung and colon cancer; exposure to toxins, including gold and mercury; infections, including hepatitis B, malaria, syphilis, and endocarditis; certain medications, including penicillamine, trimethadione, and skin-lightening creams; and systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Graves’ disease, and other autoimmune disorders.

"Treatment of MGN depends on the underlying cause of the disease," said Alberto Gutierrez, Ph.D., director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, in a statement. "This test can help patients get a timely diagnosis for their MGN and aid with earlier treatment."

Test manufacturer EUROIMMUN US submitted data that compared 275 blood samples from patients with presumed pMGN, with 285 samples from patients diagnosed with other kidney diseases including secondary MGN (sMGN) and autoimmune diseases. The test detected pMGN in 77% of the presumed pMGN samples, and gave a false-positive result in less than 1% of the other samples.

The diagnostic test helped distinguish pMGN from sMGN in most of the patients.

The FDA said that the test should not be used alone to diagnose pMGN, but that patients’ symptoms and other laboratory test results should also be considered. A kidney biopsy is required for confirmation, according to the FDA.

On Twitter @aliciaault

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a noninvasive test to determine whether a chronic kidney disease is caused by an autoimmune disease or another cause such as infection.

The EUROIMMUN Anti- PLA2R IFA blood test detects an antibody that is specific to primary membranous glomerulonephritis (pMGN). MGN, a chronic kidney disease, damages the glomeruli; it can lead to kidney failure and transplant. Symptoms include swelling, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and an increased predisposition to blood clots.

The condition mostly affects white men. It occurs in 2 of every 10,000 people and is more common after age 40, according to the National Library of Medicine. Risk factors include cancers, especially lung and colon cancer; exposure to toxins, including gold and mercury; infections, including hepatitis B, malaria, syphilis, and endocarditis; certain medications, including penicillamine, trimethadione, and skin-lightening creams; and systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Graves’ disease, and other autoimmune disorders.

"Treatment of MGN depends on the underlying cause of the disease," said Alberto Gutierrez, Ph.D., director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, in a statement. "This test can help patients get a timely diagnosis for their MGN and aid with earlier treatment."

Test manufacturer EUROIMMUN US submitted data that compared 275 blood samples from patients with presumed pMGN, with 285 samples from patients diagnosed with other kidney diseases including secondary MGN (sMGN) and autoimmune diseases. The test detected pMGN in 77% of the presumed pMGN samples, and gave a false-positive result in less than 1% of the other samples.

The diagnostic test helped distinguish pMGN from sMGN in most of the patients.

The FDA said that the test should not be used alone to diagnose pMGN, but that patients’ symptoms and other laboratory test results should also be considered. A kidney biopsy is required for confirmation, according to the FDA.

On Twitter @aliciaault

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a noninvasive test to determine whether a chronic kidney disease is caused by an autoimmune disease or another cause such as infection.

The EUROIMMUN Anti- PLA2R IFA blood test detects an antibody that is specific to primary membranous glomerulonephritis (pMGN). MGN, a chronic kidney disease, damages the glomeruli; it can lead to kidney failure and transplant. Symptoms include swelling, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and an increased predisposition to blood clots.

The condition mostly affects white men. It occurs in 2 of every 10,000 people and is more common after age 40, according to the National Library of Medicine. Risk factors include cancers, especially lung and colon cancer; exposure to toxins, including gold and mercury; infections, including hepatitis B, malaria, syphilis, and endocarditis; certain medications, including penicillamine, trimethadione, and skin-lightening creams; and systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Graves’ disease, and other autoimmune disorders.

"Treatment of MGN depends on the underlying cause of the disease," said Alberto Gutierrez, Ph.D., director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, in a statement. "This test can help patients get a timely diagnosis for their MGN and aid with earlier treatment."

Test manufacturer EUROIMMUN US submitted data that compared 275 blood samples from patients with presumed pMGN, with 285 samples from patients diagnosed with other kidney diseases including secondary MGN (sMGN) and autoimmune diseases. The test detected pMGN in 77% of the presumed pMGN samples, and gave a false-positive result in less than 1% of the other samples.

The diagnostic test helped distinguish pMGN from sMGN in most of the patients.

The FDA said that the test should not be used alone to diagnose pMGN, but that patients’ symptoms and other laboratory test results should also be considered. A kidney biopsy is required for confirmation, according to the FDA.

On Twitter @aliciaault

Rituximab yielded long-term benefit in lupus nephritis

PARIS – Treatment with rituximab in patients with refractory lupus nephritis was associated with significant long-term improvement in symptoms, histology, and laboratory markers in a prospective study.

Over a median follow-up period of 18 months (interquartile range, 12-36 months), the drug normalized proteinuria and was associated with a median reduction in glucocorticoid use of 28 mg/day, according to Dr. Maria Tsanyan of the Nasonova Research Institute of Rheumatology, Moscow.

She and her colleagues followed 60 patients with refractory lupus nephritis who had a median age of 26 years and median disease duration of 37.5 months. At baseline, the patients’ median glomerular filtration rate was 46 mL/min, and their median amount of proteinuria was 1.83 g/day. A total of 14 patients (23%) had nephrotic syndrome.

All patients had failed prior therapy. These treatments included high-dose glucocorticoids (45%), pulsed high-dose glucocorticoid and cyclophosphamide (90%), mycophenolate mofetil (17%), azathioprine (7%), hydroxychloroquine (17%), and cyclosporine A (8%).

Treatment with rituximab varied according to clinical status and response. The initial doses were 1,000 mg in 25 patients and 2,000 mg in 30 patients. Five patients did not receive a full initial course of rituximab because of the development of end-stage renal disease, including four who received only 500 mg and one who received 1,500 mg.

Most (37) required more than one course: 21 needed two courses, 11 needed three, 4 needed four courses, and 1 received five courses of the drug.

In response to an audience member’s question about the basis on which the investigators decided to re-treat patients with rituximab, Dr. Tsanyan said that they tried to achieve complete responses in patients with disease exacerbation or partial response at 6 months or 12 months after the initial dose.

Based on the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus International Collaborating Clinics renal activity/response exercise criteria, 58% had a complete response, 22% had a partial response, 12% were nonresponders, and 8% died of acute renal failure. Overall, 28% of patients had an exacerbation of disease during treatment.

There was no difference in response between patients who received 1,000 mg and 2,000 mg rituximab, she said at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology.

By 6 months of treatment, the median Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K) score had decreased from 20 to 4. This improvement held at 12 months. By 42 months, the median score had dropped to 2. By SLEDAI-2K index, 50% were considered to be complete responders, 30% partial responders, and 12% nonresponders.

Antibodies to double-stranded DNA fell from a mean of 67.7 U/mL at baseline to 34.5 U/mL at 42 months. Daily glucocorticoid use dropped from 35 mg to 7.5 mg.

C3 and C4 complement components also improved. C3 rose from 0.7 to 0.98 g/L, and C4 from 0.1 g/L to 0.24 g/L. Daily proteinuria fell from 1.6 g/day to 0.01 g/day and serum total protein rose from 59 g/L to 72 g/L.

Sixteen patients had renal biopsies both at baseline and at the end of their follow-up period. Of 14 patients who had World Health Organization class IV nephritis at baseline, 5 were unchanged, 3 moved to class III, 5 to class II, and 1 to class I. Two class III patients improved to class I.

There were 13 adverse events, all of which occurred during the first 3 months of rituximab therapy. These included pneumonia (4), aspergillosis (1), bronchitis (1), cystitis (2), shingles (3), furunculosis (1) and pityriasis versicolor (1).

Dr. Tsanyan did not have any financial disclosures.

PARIS – Treatment with rituximab in patients with refractory lupus nephritis was associated with significant long-term improvement in symptoms, histology, and laboratory markers in a prospective study.

Over a median follow-up period of 18 months (interquartile range, 12-36 months), the drug normalized proteinuria and was associated with a median reduction in glucocorticoid use of 28 mg/day, according to Dr. Maria Tsanyan of the Nasonova Research Institute of Rheumatology, Moscow.

She and her colleagues followed 60 patients with refractory lupus nephritis who had a median age of 26 years and median disease duration of 37.5 months. At baseline, the patients’ median glomerular filtration rate was 46 mL/min, and their median amount of proteinuria was 1.83 g/day. A total of 14 patients (23%) had nephrotic syndrome.

All patients had failed prior therapy. These treatments included high-dose glucocorticoids (45%), pulsed high-dose glucocorticoid and cyclophosphamide (90%), mycophenolate mofetil (17%), azathioprine (7%), hydroxychloroquine (17%), and cyclosporine A (8%).

Treatment with rituximab varied according to clinical status and response. The initial doses were 1,000 mg in 25 patients and 2,000 mg in 30 patients. Five patients did not receive a full initial course of rituximab because of the development of end-stage renal disease, including four who received only 500 mg and one who received 1,500 mg.

Most (37) required more than one course: 21 needed two courses, 11 needed three, 4 needed four courses, and 1 received five courses of the drug.

In response to an audience member’s question about the basis on which the investigators decided to re-treat patients with rituximab, Dr. Tsanyan said that they tried to achieve complete responses in patients with disease exacerbation or partial response at 6 months or 12 months after the initial dose.

Based on the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus International Collaborating Clinics renal activity/response exercise criteria, 58% had a complete response, 22% had a partial response, 12% were nonresponders, and 8% died of acute renal failure. Overall, 28% of patients had an exacerbation of disease during treatment.

There was no difference in response between patients who received 1,000 mg and 2,000 mg rituximab, she said at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology.

By 6 months of treatment, the median Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K) score had decreased from 20 to 4. This improvement held at 12 months. By 42 months, the median score had dropped to 2. By SLEDAI-2K index, 50% were considered to be complete responders, 30% partial responders, and 12% nonresponders.

Antibodies to double-stranded DNA fell from a mean of 67.7 U/mL at baseline to 34.5 U/mL at 42 months. Daily glucocorticoid use dropped from 35 mg to 7.5 mg.

C3 and C4 complement components also improved. C3 rose from 0.7 to 0.98 g/L, and C4 from 0.1 g/L to 0.24 g/L. Daily proteinuria fell from 1.6 g/day to 0.01 g/day and serum total protein rose from 59 g/L to 72 g/L.

Sixteen patients had renal biopsies both at baseline and at the end of their follow-up period. Of 14 patients who had World Health Organization class IV nephritis at baseline, 5 were unchanged, 3 moved to class III, 5 to class II, and 1 to class I. Two class III patients improved to class I.

There were 13 adverse events, all of which occurred during the first 3 months of rituximab therapy. These included pneumonia (4), aspergillosis (1), bronchitis (1), cystitis (2), shingles (3), furunculosis (1) and pityriasis versicolor (1).

Dr. Tsanyan did not have any financial disclosures.

PARIS – Treatment with rituximab in patients with refractory lupus nephritis was associated with significant long-term improvement in symptoms, histology, and laboratory markers in a prospective study.

Over a median follow-up period of 18 months (interquartile range, 12-36 months), the drug normalized proteinuria and was associated with a median reduction in glucocorticoid use of 28 mg/day, according to Dr. Maria Tsanyan of the Nasonova Research Institute of Rheumatology, Moscow.

She and her colleagues followed 60 patients with refractory lupus nephritis who had a median age of 26 years and median disease duration of 37.5 months. At baseline, the patients’ median glomerular filtration rate was 46 mL/min, and their median amount of proteinuria was 1.83 g/day. A total of 14 patients (23%) had nephrotic syndrome.

All patients had failed prior therapy. These treatments included high-dose glucocorticoids (45%), pulsed high-dose glucocorticoid and cyclophosphamide (90%), mycophenolate mofetil (17%), azathioprine (7%), hydroxychloroquine (17%), and cyclosporine A (8%).

Treatment with rituximab varied according to clinical status and response. The initial doses were 1,000 mg in 25 patients and 2,000 mg in 30 patients. Five patients did not receive a full initial course of rituximab because of the development of end-stage renal disease, including four who received only 500 mg and one who received 1,500 mg.

Most (37) required more than one course: 21 needed two courses, 11 needed three, 4 needed four courses, and 1 received five courses of the drug.

In response to an audience member’s question about the basis on which the investigators decided to re-treat patients with rituximab, Dr. Tsanyan said that they tried to achieve complete responses in patients with disease exacerbation or partial response at 6 months or 12 months after the initial dose.

Based on the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus International Collaborating Clinics renal activity/response exercise criteria, 58% had a complete response, 22% had a partial response, 12% were nonresponders, and 8% died of acute renal failure. Overall, 28% of patients had an exacerbation of disease during treatment.

There was no difference in response between patients who received 1,000 mg and 2,000 mg rituximab, she said at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology.

By 6 months of treatment, the median Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K) score had decreased from 20 to 4. This improvement held at 12 months. By 42 months, the median score had dropped to 2. By SLEDAI-2K index, 50% were considered to be complete responders, 30% partial responders, and 12% nonresponders.

Antibodies to double-stranded DNA fell from a mean of 67.7 U/mL at baseline to 34.5 U/mL at 42 months. Daily glucocorticoid use dropped from 35 mg to 7.5 mg.

C3 and C4 complement components also improved. C3 rose from 0.7 to 0.98 g/L, and C4 from 0.1 g/L to 0.24 g/L. Daily proteinuria fell from 1.6 g/day to 0.01 g/day and serum total protein rose from 59 g/L to 72 g/L.

Sixteen patients had renal biopsies both at baseline and at the end of their follow-up period. Of 14 patients who had World Health Organization class IV nephritis at baseline, 5 were unchanged, 3 moved to class III, 5 to class II, and 1 to class I. Two class III patients improved to class I.

There were 13 adverse events, all of which occurred during the first 3 months of rituximab therapy. These included pneumonia (4), aspergillosis (1), bronchitis (1), cystitis (2), shingles (3), furunculosis (1) and pityriasis versicolor (1).

Dr. Tsanyan did not have any financial disclosures.

AT THE EULAR CONGRESS 2014

Key clinical point: Rituximab delivered long-term results for patients with refractory lupus nephritis.

Major finding: During a median follow-up period of 18 months, the drug normalized proteinuria, improved glomerular filtration rate, and was associated with a median steroid reduction of 28 mg/day.

Data source: An open-label, prospective study of 60 patients with refractory lupus nephritis.

Disclosures: Dr. Maria Tsanyan had no financial disclosures.

Hyponatremia linked to osteoporosis, fragility fractures

CHICAGO – Hyponatremia quadruples the risk of osteoporosis and fragility fractures, according to a retrospective database study presented at the joint meeting of the International Congress of Endocrinology and the Endocrine Society.

A team from Georgetown University in Washington matched 30,517 patients diagnosed with osteoporosis to 30,517 controls for age, race, sex, and how long they had been in the database of the MedStar Health System, which serves Baltimore and Washington.

The investigators found that patients with chronic hyponatremia – at least two sodium values below 135 mmol/L at least 1 year apart – were far more likely to be later diagnosed with osteoporosis (adjusted odds ratio, 3.99). Recent hyponatremia – at least one value below 135 mmol/L in the previous 30 days – also increased the risk (aOR, 3.08). In contrast, glucocorticoid use, a known osteoporosis risk factor, was associated with a far lower risk (aOR, 1.4), the team reported in a poster session at the meeting.

The researchers had similar results when they matched 46,256 patients with fragility fractures to 46,256 without: The fracture risk was substantially increased in patients with chronic hyponatremia (aOR, 4.71) and recent hyponatremia (aOR, 3.08). A previous diagnosis of osteoporosis – again, a known risk factor – increased the risk only moderately (aOR, 1.8).

The severity of hyponatremia played a role, too; patients with at least one value below 125 mmol/L had the highest risk for osteoporosis and fragility fractures.

The findings were all statistically significant.

"The results of this study support the hypothesis that hyponatremia is a significant and clinically important risk factor for both osteoporosis and bone fractures in inpatients and outpatients," the team concluded.

"We were surprised by the odds ratios and how strong a factor this was. Right now, hyponatremia is not an indication for bone mineral density [testing] because it’s never been considered to be a risk factor. It ought to be added as an indication. Patients with hyponatremia beyond an isolated single event should be evaluated for their bone density and fracture risk" no matter their age or sex, said senior investigator Dr. Joseph Verbalis, chief of the division on endocrinology and metabolism at Georgetown.

Based on the findings, "we [speculate] that early treatment of hyponatremia will prevent progression of bone disease and decrease fracture risk," and perhaps even obviate the need for bisphosphonates. "It’s an implication that needs to be followed up with definitive studies," he said.

Chronic hyponatremia increases osteoclast proliferation and activity, while recent hyponatremia reduces reaction time and makes it less likely people will catch themselves if they stumble. Elderly people are most at risk, either from overzealous salt restriction, sodium-depleting drugs like thiazide diuretics, or the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;15(Suppl3):S208-S215).

The mean age of subjects in the osteoporosis analysis was about 75 years, and almost 90% were women. In the fragility fracture analysis, the mean age was about 60 years, and just over half the subjects were women.

Among the roughly 3 million patients the team initially sampled at the start of their work, there was a more than twofold increase in the prevalence of osteoporosis in hyponatremic (4.6%) vs. nonhyponatremic (1.8%) subjects, and a similar increase in vertebral or long-bone fractures (9.5% vs. 3.7%).

Dr. Verbalis is a consultant, investigator, speaker, and adviser for Otsuka, the maker of the hyponatremia drug tolvaptan. He is also a consultant for Cornerstone Therapeutics and Ferring Pharmaceuticals. The study had no outside funding.

CHICAGO – Hyponatremia quadruples the risk of osteoporosis and fragility fractures, according to a retrospective database study presented at the joint meeting of the International Congress of Endocrinology and the Endocrine Society.

A team from Georgetown University in Washington matched 30,517 patients diagnosed with osteoporosis to 30,517 controls for age, race, sex, and how long they had been in the database of the MedStar Health System, which serves Baltimore and Washington.

The investigators found that patients with chronic hyponatremia – at least two sodium values below 135 mmol/L at least 1 year apart – were far more likely to be later diagnosed with osteoporosis (adjusted odds ratio, 3.99). Recent hyponatremia – at least one value below 135 mmol/L in the previous 30 days – also increased the risk (aOR, 3.08). In contrast, glucocorticoid use, a known osteoporosis risk factor, was associated with a far lower risk (aOR, 1.4), the team reported in a poster session at the meeting.

The researchers had similar results when they matched 46,256 patients with fragility fractures to 46,256 without: The fracture risk was substantially increased in patients with chronic hyponatremia (aOR, 4.71) and recent hyponatremia (aOR, 3.08). A previous diagnosis of osteoporosis – again, a known risk factor – increased the risk only moderately (aOR, 1.8).

The severity of hyponatremia played a role, too; patients with at least one value below 125 mmol/L had the highest risk for osteoporosis and fragility fractures.

The findings were all statistically significant.

"The results of this study support the hypothesis that hyponatremia is a significant and clinically important risk factor for both osteoporosis and bone fractures in inpatients and outpatients," the team concluded.

"We were surprised by the odds ratios and how strong a factor this was. Right now, hyponatremia is not an indication for bone mineral density [testing] because it’s never been considered to be a risk factor. It ought to be added as an indication. Patients with hyponatremia beyond an isolated single event should be evaluated for their bone density and fracture risk" no matter their age or sex, said senior investigator Dr. Joseph Verbalis, chief of the division on endocrinology and metabolism at Georgetown.

Based on the findings, "we [speculate] that early treatment of hyponatremia will prevent progression of bone disease and decrease fracture risk," and perhaps even obviate the need for bisphosphonates. "It’s an implication that needs to be followed up with definitive studies," he said.

Chronic hyponatremia increases osteoclast proliferation and activity, while recent hyponatremia reduces reaction time and makes it less likely people will catch themselves if they stumble. Elderly people are most at risk, either from overzealous salt restriction, sodium-depleting drugs like thiazide diuretics, or the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;15(Suppl3):S208-S215).

The mean age of subjects in the osteoporosis analysis was about 75 years, and almost 90% were women. In the fragility fracture analysis, the mean age was about 60 years, and just over half the subjects were women.

Among the roughly 3 million patients the team initially sampled at the start of their work, there was a more than twofold increase in the prevalence of osteoporosis in hyponatremic (4.6%) vs. nonhyponatremic (1.8%) subjects, and a similar increase in vertebral or long-bone fractures (9.5% vs. 3.7%).

Dr. Verbalis is a consultant, investigator, speaker, and adviser for Otsuka, the maker of the hyponatremia drug tolvaptan. He is also a consultant for Cornerstone Therapeutics and Ferring Pharmaceuticals. The study had no outside funding.

CHICAGO – Hyponatremia quadruples the risk of osteoporosis and fragility fractures, according to a retrospective database study presented at the joint meeting of the International Congress of Endocrinology and the Endocrine Society.

A team from Georgetown University in Washington matched 30,517 patients diagnosed with osteoporosis to 30,517 controls for age, race, sex, and how long they had been in the database of the MedStar Health System, which serves Baltimore and Washington.

The investigators found that patients with chronic hyponatremia – at least two sodium values below 135 mmol/L at least 1 year apart – were far more likely to be later diagnosed with osteoporosis (adjusted odds ratio, 3.99). Recent hyponatremia – at least one value below 135 mmol/L in the previous 30 days – also increased the risk (aOR, 3.08). In contrast, glucocorticoid use, a known osteoporosis risk factor, was associated with a far lower risk (aOR, 1.4), the team reported in a poster session at the meeting.

The researchers had similar results when they matched 46,256 patients with fragility fractures to 46,256 without: The fracture risk was substantially increased in patients with chronic hyponatremia (aOR, 4.71) and recent hyponatremia (aOR, 3.08). A previous diagnosis of osteoporosis – again, a known risk factor – increased the risk only moderately (aOR, 1.8).

The severity of hyponatremia played a role, too; patients with at least one value below 125 mmol/L had the highest risk for osteoporosis and fragility fractures.

The findings were all statistically significant.

"The results of this study support the hypothesis that hyponatremia is a significant and clinically important risk factor for both osteoporosis and bone fractures in inpatients and outpatients," the team concluded.

"We were surprised by the odds ratios and how strong a factor this was. Right now, hyponatremia is not an indication for bone mineral density [testing] because it’s never been considered to be a risk factor. It ought to be added as an indication. Patients with hyponatremia beyond an isolated single event should be evaluated for their bone density and fracture risk" no matter their age or sex, said senior investigator Dr. Joseph Verbalis, chief of the division on endocrinology and metabolism at Georgetown.

Based on the findings, "we [speculate] that early treatment of hyponatremia will prevent progression of bone disease and decrease fracture risk," and perhaps even obviate the need for bisphosphonates. "It’s an implication that needs to be followed up with definitive studies," he said.

Chronic hyponatremia increases osteoclast proliferation and activity, while recent hyponatremia reduces reaction time and makes it less likely people will catch themselves if they stumble. Elderly people are most at risk, either from overzealous salt restriction, sodium-depleting drugs like thiazide diuretics, or the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;15(Suppl3):S208-S215).

The mean age of subjects in the osteoporosis analysis was about 75 years, and almost 90% were women. In the fragility fracture analysis, the mean age was about 60 years, and just over half the subjects were women.

Among the roughly 3 million patients the team initially sampled at the start of their work, there was a more than twofold increase in the prevalence of osteoporosis in hyponatremic (4.6%) vs. nonhyponatremic (1.8%) subjects, and a similar increase in vertebral or long-bone fractures (9.5% vs. 3.7%).

Dr. Verbalis is a consultant, investigator, speaker, and adviser for Otsuka, the maker of the hyponatremia drug tolvaptan. He is also a consultant for Cornerstone Therapeutics and Ferring Pharmaceuticals. The study had no outside funding.

AT ICE/ENDO 2014

Key clinical point: Early treatment of hyponatremia may one day prove to slow the progression of osteoporosis and reduce the need for bisphosphonates.

Major finding: In patients with chronic hyponatremia, the adjusted odds ratio for developing osteoporosis was 3.99, compared with those without.

Data Source: Retrospective case-control study involving more than 150,000 subjects.

Disclosures: Dr. Verbalis is a consultant, investigator, speaker, and adviser for Otsuka, the maker of the hyponatremia drug tolvaptan. The study had no outside funding.

Trial of sirukumab for lupus nephritis falls flat

PARIS – The investigational interleukin-6 blocker sirukumab provided no benefit to patients with lupus nephritis but put them at a very high risk of developing a serious infection in a small, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Based on the study results, the study sponsor, Janssen, has shut down its program for the lupus nephritis indication, Dr. Ronald van Vollenhoven said at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology.

"While a few patients did experience a reduction in proteinuria, we had an unacceptably high rate of adverse events," said Dr. van Vollenhoven, chief of the Unit for Clinical Therapy Research, Inflammatory Diseases, at the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm. "Based on these findings, we will not be advancing any further investigation of sirukumab for patients with active lupus nephritis."

The company continues to develop the drug for rheumatoid arthritis.

In the trial, 21 patients received intravenous sirukumab 10 mg/kg once every 4 weeks for 24 weeks, and 4 received placebo. During the trial and a 16-week safety observation follow-up period, 48% of those who took the investigational IL-6 blocker developed a serious adverse event, including infections serious enough to require hospital admission.

While not specifying the infections, which occurred in 10 patients, Dr. van Vollenhoven noted that five patients taking the drug discontinued it because of adverse events, which included Haemophilus influenzae pneumonia, elevated liver enzymes, anaphylactic reaction after the first dose, worsening nephritis, and severe neutropenia.

Overall, 19 patients completed the study. In addition to the five who quit because of adverse events, one additional patient withdrew voluntarily. All had active lupus nephritis of about 50 months’ duration, with a mean daily proteinuria of more than 2 g; about a third of the group had nephrotic proteinuria. The mean Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 was about 16. All were taking concomitant mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine.

At the end of the treatment period, there was no significant between-group difference in proteinuria, Dr. van Vollenhoven said. Four of those in the active group experienced at least a 50% reduction in proteinuria over baseline, while none of those in the placebo group experienced this change. However, this difference was not statistically significant. There were no significant changes in the patient or physical global assessment for either group.

Serious adverse events occurred in 48% of those taking the drug, including serious infections (30%) as well as renal/urinary (19%), blood (9.5%), and gastrointestinal (9.5%) events. None occurred in the placebo group.

Among patients in the sirukumab group, there was one grade 4 lymphocytopenia, one grade 4 neutropenia, and two grade 3 neutropenias. One patient had a grade 2 liver enzyme elevation.

Dr. van Vollenhoven was on the study steering committee and is a consultant and speaker for Janssen, as well as other drug manufacturers. Four coauthors are employees of Janssen.

PARIS – The investigational interleukin-6 blocker sirukumab provided no benefit to patients with lupus nephritis but put them at a very high risk of developing a serious infection in a small, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Based on the study results, the study sponsor, Janssen, has shut down its program for the lupus nephritis indication, Dr. Ronald van Vollenhoven said at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology.

"While a few patients did experience a reduction in proteinuria, we had an unacceptably high rate of adverse events," said Dr. van Vollenhoven, chief of the Unit for Clinical Therapy Research, Inflammatory Diseases, at the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm. "Based on these findings, we will not be advancing any further investigation of sirukumab for patients with active lupus nephritis."

The company continues to develop the drug for rheumatoid arthritis.

In the trial, 21 patients received intravenous sirukumab 10 mg/kg once every 4 weeks for 24 weeks, and 4 received placebo. During the trial and a 16-week safety observation follow-up period, 48% of those who took the investigational IL-6 blocker developed a serious adverse event, including infections serious enough to require hospital admission.

While not specifying the infections, which occurred in 10 patients, Dr. van Vollenhoven noted that five patients taking the drug discontinued it because of adverse events, which included Haemophilus influenzae pneumonia, elevated liver enzymes, anaphylactic reaction after the first dose, worsening nephritis, and severe neutropenia.

Overall, 19 patients completed the study. In addition to the five who quit because of adverse events, one additional patient withdrew voluntarily. All had active lupus nephritis of about 50 months’ duration, with a mean daily proteinuria of more than 2 g; about a third of the group had nephrotic proteinuria. The mean Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 was about 16. All were taking concomitant mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine.

At the end of the treatment period, there was no significant between-group difference in proteinuria, Dr. van Vollenhoven said. Four of those in the active group experienced at least a 50% reduction in proteinuria over baseline, while none of those in the placebo group experienced this change. However, this difference was not statistically significant. There were no significant changes in the patient or physical global assessment for either group.

Serious adverse events occurred in 48% of those taking the drug, including serious infections (30%) as well as renal/urinary (19%), blood (9.5%), and gastrointestinal (9.5%) events. None occurred in the placebo group.

Among patients in the sirukumab group, there was one grade 4 lymphocytopenia, one grade 4 neutropenia, and two grade 3 neutropenias. One patient had a grade 2 liver enzyme elevation.

Dr. van Vollenhoven was on the study steering committee and is a consultant and speaker for Janssen, as well as other drug manufacturers. Four coauthors are employees of Janssen.

PARIS – The investigational interleukin-6 blocker sirukumab provided no benefit to patients with lupus nephritis but put them at a very high risk of developing a serious infection in a small, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Based on the study results, the study sponsor, Janssen, has shut down its program for the lupus nephritis indication, Dr. Ronald van Vollenhoven said at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology.

"While a few patients did experience a reduction in proteinuria, we had an unacceptably high rate of adverse events," said Dr. van Vollenhoven, chief of the Unit for Clinical Therapy Research, Inflammatory Diseases, at the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm. "Based on these findings, we will not be advancing any further investigation of sirukumab for patients with active lupus nephritis."

The company continues to develop the drug for rheumatoid arthritis.

In the trial, 21 patients received intravenous sirukumab 10 mg/kg once every 4 weeks for 24 weeks, and 4 received placebo. During the trial and a 16-week safety observation follow-up period, 48% of those who took the investigational IL-6 blocker developed a serious adverse event, including infections serious enough to require hospital admission.

While not specifying the infections, which occurred in 10 patients, Dr. van Vollenhoven noted that five patients taking the drug discontinued it because of adverse events, which included Haemophilus influenzae pneumonia, elevated liver enzymes, anaphylactic reaction after the first dose, worsening nephritis, and severe neutropenia.

Overall, 19 patients completed the study. In addition to the five who quit because of adverse events, one additional patient withdrew voluntarily. All had active lupus nephritis of about 50 months’ duration, with a mean daily proteinuria of more than 2 g; about a third of the group had nephrotic proteinuria. The mean Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 was about 16. All were taking concomitant mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine.

At the end of the treatment period, there was no significant between-group difference in proteinuria, Dr. van Vollenhoven said. Four of those in the active group experienced at least a 50% reduction in proteinuria over baseline, while none of those in the placebo group experienced this change. However, this difference was not statistically significant. There were no significant changes in the patient or physical global assessment for either group.

Serious adverse events occurred in 48% of those taking the drug, including serious infections (30%) as well as renal/urinary (19%), blood (9.5%), and gastrointestinal (9.5%) events. None occurred in the placebo group.

Among patients in the sirukumab group, there was one grade 4 lymphocytopenia, one grade 4 neutropenia, and two grade 3 neutropenias. One patient had a grade 2 liver enzyme elevation.

Dr. van Vollenhoven was on the study steering committee and is a consultant and speaker for Janssen, as well as other drug manufacturers. Four coauthors are employees of Janssen.

AT THE EULAR CONGRESS 2014

Key clinical point: Janssen has discontinued its investigation of sirukumab for lupus nephritis.

Major finding: Almost half of those who took sirukumab developed a serious adverse event, including infections requiring hospitalization.

Data source: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 21 patients.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Janssen. Dr. van Vollenhoven was on the study steering committee and is a consultant and speaker for the company, as well as other drug manufacturers. Four coauthors are employees of Janssen.

More than half of older women have experienced incontinence

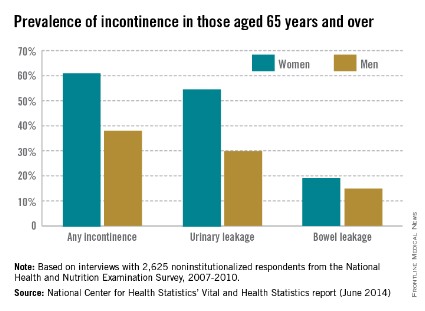

Among noninstitutionalized Americans aged 65 years and older, 61.2% of women and 38% of men experience at least occasional urinary or bowel incontinence, the National Center for Health Statistics reported.

Data from the 2007-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) show that 54.8% of women and 29.9% of men had urinary leakage at least a few times a month, while 19.2% of women and 14.9% of men had accidental bowel leakage of mucus, liquid stool, or solid stool at least one to three times a month, according to the NCHS (Vital Health Stat. 2014;3[36]).

Among women aged 65-74 years, 60.6% had some type of incontinence, compared with 61.9% of women aged 75 years and over. The difference was larger for men, however, with 34.1% of those aged 65-74 years reporting incontinence, compared with 42.4% of men aged 75 years and over, the report showed.

The NHANES data are based on in-home interviews with a nationally representative sample of 2,625 respondents.

Among noninstitutionalized Americans aged 65 years and older, 61.2% of women and 38% of men experience at least occasional urinary or bowel incontinence, the National Center for Health Statistics reported.

Data from the 2007-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) show that 54.8% of women and 29.9% of men had urinary leakage at least a few times a month, while 19.2% of women and 14.9% of men had accidental bowel leakage of mucus, liquid stool, or solid stool at least one to three times a month, according to the NCHS (Vital Health Stat. 2014;3[36]).

Among women aged 65-74 years, 60.6% had some type of incontinence, compared with 61.9% of women aged 75 years and over. The difference was larger for men, however, with 34.1% of those aged 65-74 years reporting incontinence, compared with 42.4% of men aged 75 years and over, the report showed.

The NHANES data are based on in-home interviews with a nationally representative sample of 2,625 respondents.

Among noninstitutionalized Americans aged 65 years and older, 61.2% of women and 38% of men experience at least occasional urinary or bowel incontinence, the National Center for Health Statistics reported.

Data from the 2007-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) show that 54.8% of women and 29.9% of men had urinary leakage at least a few times a month, while 19.2% of women and 14.9% of men had accidental bowel leakage of mucus, liquid stool, or solid stool at least one to three times a month, according to the NCHS (Vital Health Stat. 2014;3[36]).

Among women aged 65-74 years, 60.6% had some type of incontinence, compared with 61.9% of women aged 75 years and over. The difference was larger for men, however, with 34.1% of those aged 65-74 years reporting incontinence, compared with 42.4% of men aged 75 years and over, the report showed.

The NHANES data are based on in-home interviews with a nationally representative sample of 2,625 respondents.

Debate continues on antibiotic prophylaxis for UTIs in children with reflux

ORLANDO – Antibiotic prophylaxis was shown in the recently published RIVUR trial to halve the risk of recurrent febrile urinary tract infection in infants and young children with vesicoureteral reflux. Conversely, a meta-analysis of six controlled trials concluded there is little to no benefit of antibiotic prophylaxis in this population.

The conflicting data highlight the ongoing debate regarding the best approach for preventing and managing febrile urinary tract infections (UTIs) in children with vesicoureteral reflux (VUR).

The RIVUR (Randomized Intervention for Children with Vesicoureteral Reflux) trial findings, which were published in May in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed that among children with VUR who were aged 2-71 months, 2 years of treatment with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole halved the risk of febrile or symptomatic UTI recurrence (N. Eng. J. Med. 2014;370:2367-76). The difference between those who received prophylaxis and those who did not emerged early and increased over the 2-year study period, Dr. Saul Greenfield said during an update on the trial results at the annual meeting of the American Urological Association.

"The magnitude of treatment effect warrants serious consideration of prophylaxis in these children. We also feel that these results warrant reconsideration of the recent guideline recommendations by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2011 ... advising against evaluation of children with a VCUG [voiding cystourethrogram] after their first UTI," said Dr. Greenfield, director of pediatric urology at Women and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo, N.Y. and one of the RIVUR investigators.

That AAP recommendation was based on a number of studies that showed no benefit from antibiotic prophylaxis in children with VUR, which suggests there is little value in diagnosing VUR (Pediatrics 2011;28:595-610).

In fact, a meta-analysis of six controlled trials, which also was presented at the AUA meeting, suggested that the benefit of antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing febrile UTIs in children with VUR is small at best, and evidence to support its use is lacking.

Pooled data for 986 patients included in the trials showed that in 417 with dilating VUR, the risk of recurrent febrile UTI was 22.46% in those who received antibiotics, and 29.79% in controls. The relative risk of treatment failure with antibiotic prophylaxis was 0.75, and the absolute risk reduction was 7.33%, Dr. José Netto reported.

The number needed to treat to prevent one UTI was 13.64, according to Dr. Netto of State University of Feira de Santana in Brazil.

In 515 patients with nondilating VUR, the risk of febrile UTI was 5.31% in patients who received prophylactic antibiotics, and 6.09% in those who did not. The relative risk of treatment failure was 0.87, and the absolute risk reduction was 0.78%. The number needed to treat was 129, Dr. Netto said.

The studies included in the meta-analysis were published prior to August 2013. Only one was placebo-controlled. Patients included in the study included 663 girls (67.2%), and the median age of all patients was 21 months.

The studies all used co-trimoxazole in standard doses, and three of the six also used co-amoxiclav or nitrofurantoin as alternative treatments.

Antibiotic prophylaxis is often used in children with VUR, but several recent studies have failed to demonstrate the usefulness of this approach with respect to reducing the risk of febrile UTI, Dr. Netto said, noting that the studies included heterogeneous populations with distinct grades of VUR and varying rates of recurrent UTI.

Based on the current findings, it remains uncertain whether antibiotic prophylaxis reduces the risk of febrile UTI in children with VUR, although it is possible – given the differences seen between those with dilating VUR and those with nondilating VUR – that specific subgroups of children with dilating VUR may benefit from prophylaxis, he concluded.

The conflicting findings between this meta-analysis, and the RIVUR trial underscore the importance of ongoing evaluation of antibiotic prophylaxis.

"The best ways to prevent and treat febrile urinary tract infections in children with VUR are still very much up for discussion," Dr. Anthony Atala, W.H. Boyce Professor and chair of the urology department at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, N.C., said in an AUA press statement.

"Examining and reexamining the AAP guidelines and practices that guide our work are critical to better understand the condition and improve the lives of those children who are living with the condition each day," said Dr. Atala, who is also director of the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

Dr. Atala reported serving in a leadership position at Plureon Corp. Dr. Greenfield and Dr. Netto reported having no disclosures.

ORLANDO – Antibiotic prophylaxis was shown in the recently published RIVUR trial to halve the risk of recurrent febrile urinary tract infection in infants and young children with vesicoureteral reflux. Conversely, a meta-analysis of six controlled trials concluded there is little to no benefit of antibiotic prophylaxis in this population.

The conflicting data highlight the ongoing debate regarding the best approach for preventing and managing febrile urinary tract infections (UTIs) in children with vesicoureteral reflux (VUR).

The RIVUR (Randomized Intervention for Children with Vesicoureteral Reflux) trial findings, which were published in May in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed that among children with VUR who were aged 2-71 months, 2 years of treatment with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole halved the risk of febrile or symptomatic UTI recurrence (N. Eng. J. Med. 2014;370:2367-76). The difference between those who received prophylaxis and those who did not emerged early and increased over the 2-year study period, Dr. Saul Greenfield said during an update on the trial results at the annual meeting of the American Urological Association.

"The magnitude of treatment effect warrants serious consideration of prophylaxis in these children. We also feel that these results warrant reconsideration of the recent guideline recommendations by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2011 ... advising against evaluation of children with a VCUG [voiding cystourethrogram] after their first UTI," said Dr. Greenfield, director of pediatric urology at Women and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo, N.Y. and one of the RIVUR investigators.

That AAP recommendation was based on a number of studies that showed no benefit from antibiotic prophylaxis in children with VUR, which suggests there is little value in diagnosing VUR (Pediatrics 2011;28:595-610).

In fact, a meta-analysis of six controlled trials, which also was presented at the AUA meeting, suggested that the benefit of antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing febrile UTIs in children with VUR is small at best, and evidence to support its use is lacking.

Pooled data for 986 patients included in the trials showed that in 417 with dilating VUR, the risk of recurrent febrile UTI was 22.46% in those who received antibiotics, and 29.79% in controls. The relative risk of treatment failure with antibiotic prophylaxis was 0.75, and the absolute risk reduction was 7.33%, Dr. José Netto reported.

The number needed to treat to prevent one UTI was 13.64, according to Dr. Netto of State University of Feira de Santana in Brazil.

In 515 patients with nondilating VUR, the risk of febrile UTI was 5.31% in patients who received prophylactic antibiotics, and 6.09% in those who did not. The relative risk of treatment failure was 0.87, and the absolute risk reduction was 0.78%. The number needed to treat was 129, Dr. Netto said.

The studies included in the meta-analysis were published prior to August 2013. Only one was placebo-controlled. Patients included in the study included 663 girls (67.2%), and the median age of all patients was 21 months.

The studies all used co-trimoxazole in standard doses, and three of the six also used co-amoxiclav or nitrofurantoin as alternative treatments.

Antibiotic prophylaxis is often used in children with VUR, but several recent studies have failed to demonstrate the usefulness of this approach with respect to reducing the risk of febrile UTI, Dr. Netto said, noting that the studies included heterogeneous populations with distinct grades of VUR and varying rates of recurrent UTI.

Based on the current findings, it remains uncertain whether antibiotic prophylaxis reduces the risk of febrile UTI in children with VUR, although it is possible – given the differences seen between those with dilating VUR and those with nondilating VUR – that specific subgroups of children with dilating VUR may benefit from prophylaxis, he concluded.

The conflicting findings between this meta-analysis, and the RIVUR trial underscore the importance of ongoing evaluation of antibiotic prophylaxis.

"The best ways to prevent and treat febrile urinary tract infections in children with VUR are still very much up for discussion," Dr. Anthony Atala, W.H. Boyce Professor and chair of the urology department at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, N.C., said in an AUA press statement.

"Examining and reexamining the AAP guidelines and practices that guide our work are critical to better understand the condition and improve the lives of those children who are living with the condition each day," said Dr. Atala, who is also director of the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

Dr. Atala reported serving in a leadership position at Plureon Corp. Dr. Greenfield and Dr. Netto reported having no disclosures.

ORLANDO – Antibiotic prophylaxis was shown in the recently published RIVUR trial to halve the risk of recurrent febrile urinary tract infection in infants and young children with vesicoureteral reflux. Conversely, a meta-analysis of six controlled trials concluded there is little to no benefit of antibiotic prophylaxis in this population.

The conflicting data highlight the ongoing debate regarding the best approach for preventing and managing febrile urinary tract infections (UTIs) in children with vesicoureteral reflux (VUR).

The RIVUR (Randomized Intervention for Children with Vesicoureteral Reflux) trial findings, which were published in May in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed that among children with VUR who were aged 2-71 months, 2 years of treatment with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole halved the risk of febrile or symptomatic UTI recurrence (N. Eng. J. Med. 2014;370:2367-76). The difference between those who received prophylaxis and those who did not emerged early and increased over the 2-year study period, Dr. Saul Greenfield said during an update on the trial results at the annual meeting of the American Urological Association.

"The magnitude of treatment effect warrants serious consideration of prophylaxis in these children. We also feel that these results warrant reconsideration of the recent guideline recommendations by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2011 ... advising against evaluation of children with a VCUG [voiding cystourethrogram] after their first UTI," said Dr. Greenfield, director of pediatric urology at Women and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo, N.Y. and one of the RIVUR investigators.

That AAP recommendation was based on a number of studies that showed no benefit from antibiotic prophylaxis in children with VUR, which suggests there is little value in diagnosing VUR (Pediatrics 2011;28:595-610).

In fact, a meta-analysis of six controlled trials, which also was presented at the AUA meeting, suggested that the benefit of antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing febrile UTIs in children with VUR is small at best, and evidence to support its use is lacking.

Pooled data for 986 patients included in the trials showed that in 417 with dilating VUR, the risk of recurrent febrile UTI was 22.46% in those who received antibiotics, and 29.79% in controls. The relative risk of treatment failure with antibiotic prophylaxis was 0.75, and the absolute risk reduction was 7.33%, Dr. José Netto reported.

The number needed to treat to prevent one UTI was 13.64, according to Dr. Netto of State University of Feira de Santana in Brazil.

In 515 patients with nondilating VUR, the risk of febrile UTI was 5.31% in patients who received prophylactic antibiotics, and 6.09% in those who did not. The relative risk of treatment failure was 0.87, and the absolute risk reduction was 0.78%. The number needed to treat was 129, Dr. Netto said.

The studies included in the meta-analysis were published prior to August 2013. Only one was placebo-controlled. Patients included in the study included 663 girls (67.2%), and the median age of all patients was 21 months.

The studies all used co-trimoxazole in standard doses, and three of the six also used co-amoxiclav or nitrofurantoin as alternative treatments.

Antibiotic prophylaxis is often used in children with VUR, but several recent studies have failed to demonstrate the usefulness of this approach with respect to reducing the risk of febrile UTI, Dr. Netto said, noting that the studies included heterogeneous populations with distinct grades of VUR and varying rates of recurrent UTI.

Based on the current findings, it remains uncertain whether antibiotic prophylaxis reduces the risk of febrile UTI in children with VUR, although it is possible – given the differences seen between those with dilating VUR and those with nondilating VUR – that specific subgroups of children with dilating VUR may benefit from prophylaxis, he concluded.

The conflicting findings between this meta-analysis, and the RIVUR trial underscore the importance of ongoing evaluation of antibiotic prophylaxis.

"The best ways to prevent and treat febrile urinary tract infections in children with VUR are still very much up for discussion," Dr. Anthony Atala, W.H. Boyce Professor and chair of the urology department at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, N.C., said in an AUA press statement.

"Examining and reexamining the AAP guidelines and practices that guide our work are critical to better understand the condition and improve the lives of those children who are living with the condition each day," said Dr. Atala, who is also director of the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

Dr. Atala reported serving in a leadership position at Plureon Corp. Dr. Greenfield and Dr. Netto reported having no disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AUA ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: It remains unclear whether antibiotic prophylaxis is beneficial for febrile UTI in children with vesicoureteral reflux.

Major finding: In the RIVUR trial, antibiotic prophylaxis halved the risk of recurrent UTI; in the meta-analysis, prophylaxis was associated with only small benefit.

Data source: The randomized controlled RIVUR trial of 607 children, and a meta-analysis of six controlled studies involving 986 children.

Disclosures: Dr. Atala reported serving in a leadership position at Plureon Corp. Dr. Greenfield and Dr. Netto reported having no disclosures.