User login

Psychological/neuropsychological testing: When to refer for reexamination

The evolution of illness prevention, diagnosis, and treatment has involved an increased appreciation for the clinical utility of longitudinal assessment. This has included the implementation of screening evaluations for high base rate medical conditions, such as cancer, that involve considerable morbidity and mortality.

Unfortunately, the mental health professions have been slow to embrace this approach. Baseline assessment with psychological/neuropsychological screening tests and more comprehensive test batteries to clarify diagnostic status and facilitate treatment planning is far more the exception than the rule in mental health care. This seems to be the case despite the strong evidence supporting this practice as well as multiple surveys indicating that psychiatrists and other physicians report a high level of satisfaction with the findings and recommendations of psychological/neuropsychological test reports.1-3

There is a substantial literature that reviews the relative indications and contraindications for initial psychological/neuropsychological test evaluations.4-7 However, there is a paucity of clinical and evidence-based information regarding criteria for follow-up assessment. Moreover, there are no consensus guidelines to inform decision-making regarding this issue.

In general, good clinical practice for baseline assessment and reexamination should include administration of both psychological and neuropsychological tests. Based on clinical experience, this article addresses the relative indications and contraindications for psychological/neuropsychological test reassessment of adults seen in psychiatric care. It also outlines suggested time frames for such reevaluations, based on the patient’s clinical status and circumstances.

Why are patients not referred for reassessment more often?

There are several reasons patients are not referred for follow-up testing, beginning with the failure, at times, of the psychologist to state in the recommendations section of the test report whether a reassessment is indicated, under what circumstances, and within what time frame. Empirical data is lacking, but predicated on clinical experience, even when a strong and unequivocal recommendation is made for reassessment, only a very small percentage of patients are seen for follow-up evaluation.

There are numerous reasons why this occurs. The patient and/or the psychiatrist may overlook or forget about the recommendation for reassessment, particularly if it was embedded in a lengthy list of recommendations and the suggested time frame for the reassessment was several years away. The patient and the psychiatrist may decide against going forward with a reexamination, for a variety of substantive reasons. The patient might decline, against medical advice, to be retested. The patient may fail to make or keep an appointment for the follow-up reexamination. The patient might leave treatment and become lost to follow-up. The patient might not be able to find an appropriate psychologist. The insurance company may decline to authorize follow-up testing.8

Indications for reevaluation

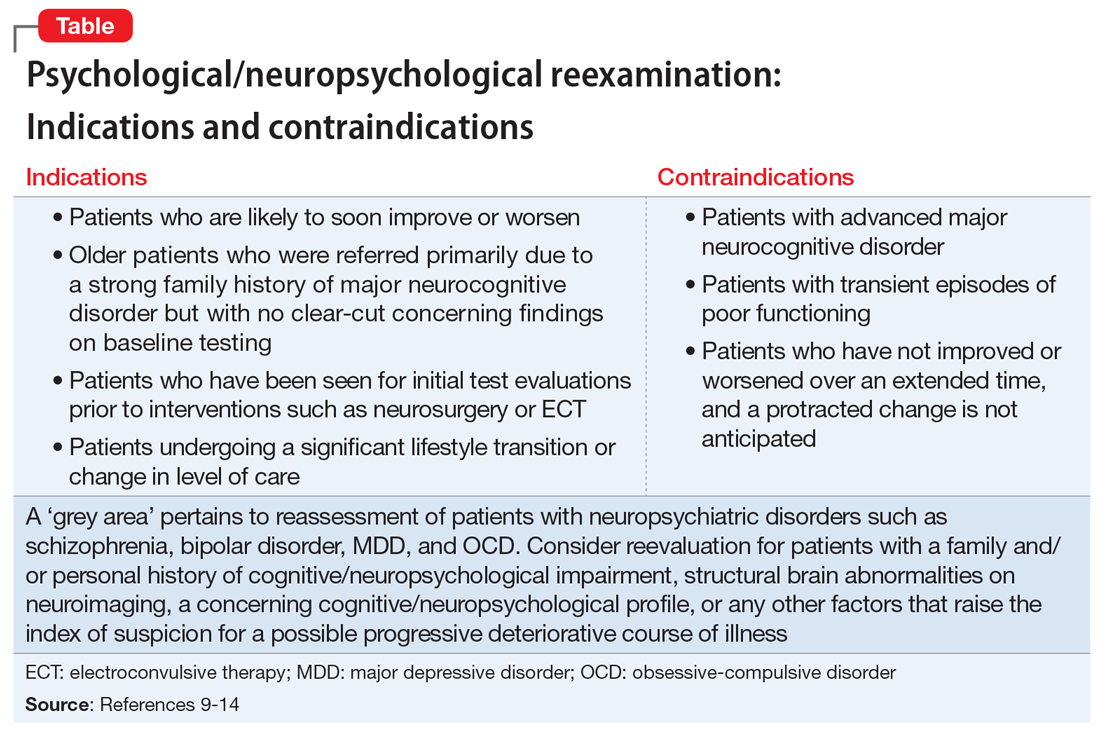

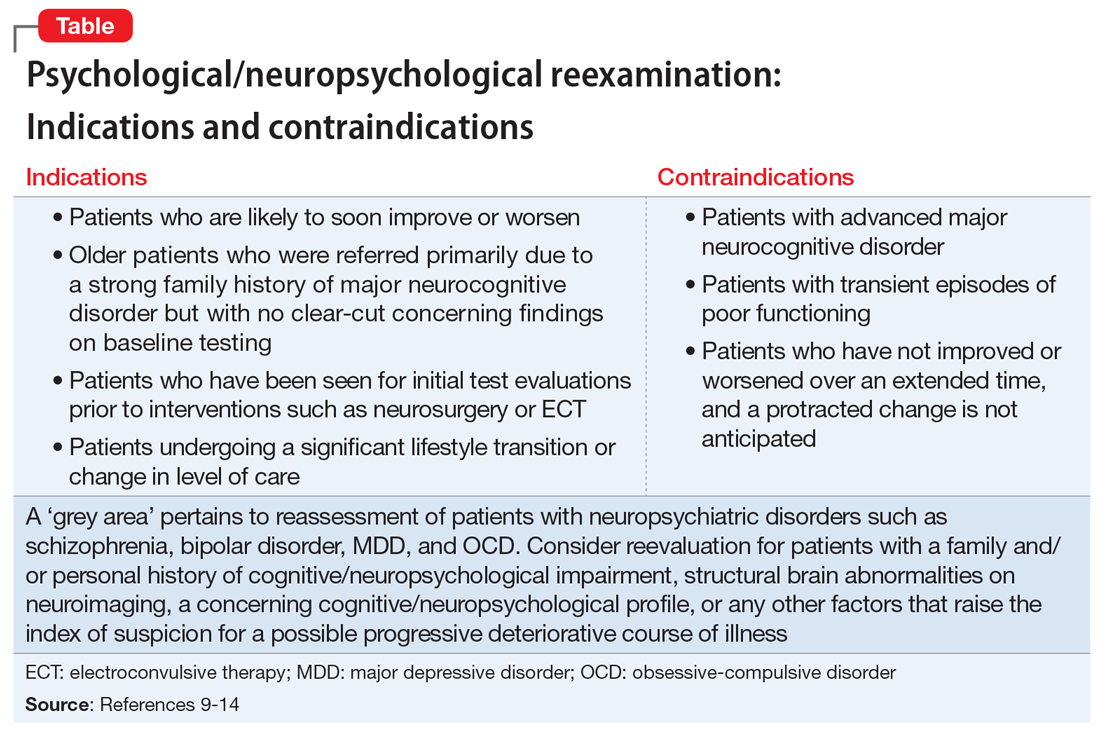

Follow-up testing generally is indicated in the following circumstances:

Patients who are likely to soon improve or worsen. Reassessment is indicated when, based on the initial evaluation, the patient has been identified as having a neuropsychiatric disorder that is likely to improve or worsen over the next year or 2 due to the natural trajectory of the condition and the degree to which it may respond to treatment.

Continue to: Patients who are likely...

Patients who are likely to improve include those with mental status changes referable to ≥1 medical and/or neuropsychiatric factors that are considered at least partially treatable and reversible. Patients who fall within this category include those who have mild to moderately severe head trauma or stroke, have a suspected or known medication- or substance-induced altered mental status, appear to have depression-related cognitive difficulties, or have an initial or recurrent episode of idiopathic psychosis.

Patients whose conditions can be expected to worsen over time include those with a mild neurocognitive disorder or major neurocognitive disorder of mild severity that is considered referable to a progressive neurodegenerative illness such as Alzheimer’s disease based on family and personal history, their psychometric test profile, and other factors, including findings from positron emission tomography scanning.

Older patients who were referred primarily due to a strong family history of major neurocognitive disorder but with no clear-cut concerning findings on baseline testing warrant reevaluation in the event of the emergence of significant cognitive and/or psychiatric symptoms and/or a functional decline since the baseline examination.

Patients who have been seen for initial test evaluations prior to interventions such as neurosurgery (including psychosurgery), electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), transcranial magnetic stimulation, cognitive rehabilitation, etc.

Patients undergoing a substantial transition. Reevaluation is appropriate for a broad range of patients experiencing difficulties when undergoing a significant lifestyle transition or change in level of care. This includes patients considering a return to school or work after a prolonged absence due to neuropsychiatric illness, or for whom there are questions regarding the need for a change in their level of everyday care. The latter includes patients who are returning to home care from assisted living, or transferring from home-based services to assisted living or a skilled nursing facility.

Continue to: What about patients with psychiatric disorders?

What about patients with psychiatric disorders? A “grey area” pertains to reassessment of patients with neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Patients with these conditions often have high rates of cognitive/neuropsychological impairment on baseline testing, even when they appear to be improving from a psychiatric perspective, are reasonably stable, and may even be in remission.9-12

These deficits are frequently a mix of pre-illness, prodromal, and early-stage illness– related neurocognitive difficulties that, for the most part, remain stable over time. That said, there is emerging evidence of worsening cognitive change over time following a first episode of psychosis for some patients with schizophrenia.13

In general, reevaluation should be considered for patients with a family and/or personal history of cognitive/neuropsychological impairment, structural brain abnormalities on neuroimaging, a concerning cognitive/neuropsychological profile, or any other factors that raise the index of suspicion for a possible progressive deteriorative course of illness.13,14

Patients with personality disorders who have had a baseline psychometric evaluation do not clearly warrant reassessment unless they develop medical and/or psychosocial difficulties that are often linked to problematic personality traits/patterns and that result in significant and persistent mental status changes. For example, reassessment might be indicated for a patient with borderline personality disorder who has new-onset or worsening cognitive and/or psychiatric complaints/symptoms after sustaining a head injury while intoxicated and embroiled in a domestic conflict triggered by anger and fears related to abandonment and separation.

Reevaluation also should be considered when a patient with a personality disorder has had a baseline assessment and subsequently completes an intensive, long-term treatment program that is likely to improve their clinical status. In this context, retesting may help document these gains. Examples of such programs/services include residential psychiatric and/or substance abuse care, object relational/psychodynamically-based psychotherapy, an extended course of dialectical behavioral therapy, or a related coping skills/distress tolerance psychotherapy.

Continue to: Contraindications for reassessment

Contraindications for reassessment

Retesting generally is not indicated in the following circumstances:

Patients with advanced major neurocognitive disorder. Reassessment is not indicated for such patients when there are no new questions regarding diagnosis, prognosis, level of care, and/or related disposition issues.

Patients with transient episodes of poor functioning. For the most part, reassessment is not helpful for patients with well-established diagnoses and treatment plans who, based on their history, experience time-limited, recurrent episodes of poor functioning and then reliably return to their baseline with ongoing psychiatric care. This includes patients with borderline personality disorder and other personality difficulties with histories of transient decompensation in response to psychosocial and psychodynamic triggers.

Patients who do not improve or worsen over time. Reassessment is not indicated when there has been no clear, sustained improvement or worsening of a patient’s clinical status over an extended time, and a protracted change is not anticipated. In this situation, reassessment is unlikely to yield clinically useful information beyond what is already known or meaningfully impact case formulation and treatment planning.

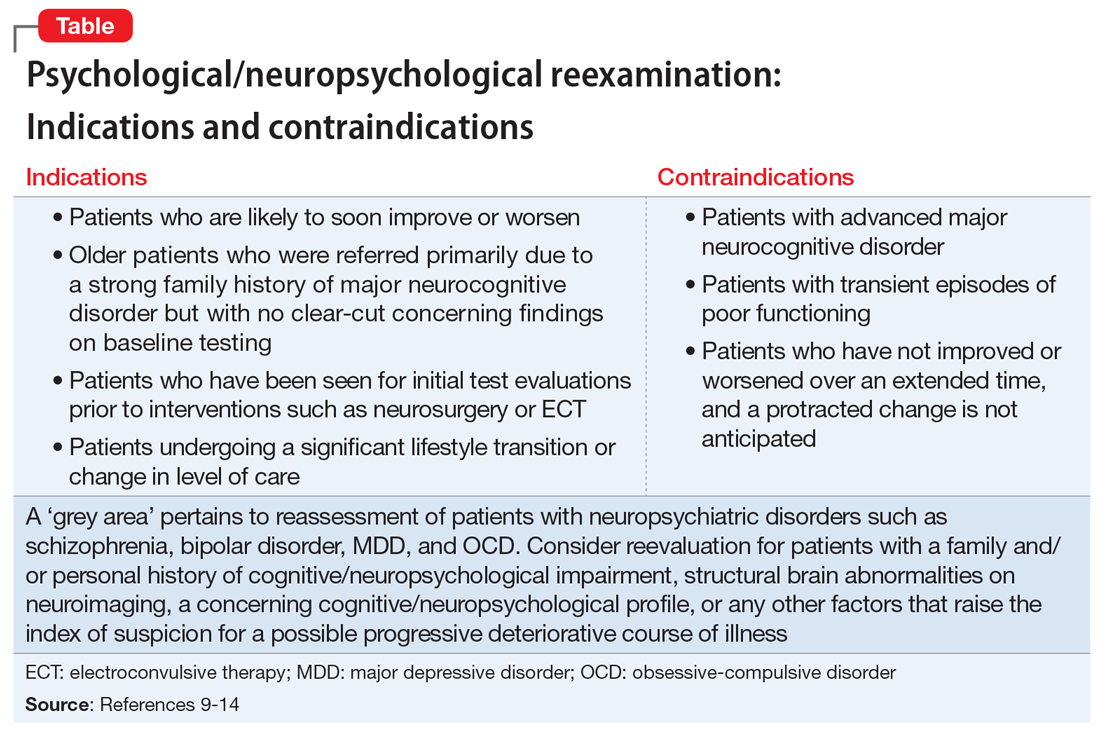

The Table9-14 summarizes the relative indications and contraindications for psychological/neuropsychological reexamination.

Continue to: Time frames for reassessment

Time frames for reassessment

Time frames for retesting vary considerably depending on factors such as diagnostic status, longitudinal course, treatment parameters, and recent/current life circumstances.

While empirical data is lacking regarding this matter, based on clinical experience, reevaluation in 18 to 24 months is generally appropriate for patients with neuropsychiatric conditions who are likely to gradually improve or slowly worsen over this time. Still, reexamination can be sooner (within 12 to 18 months) for patients who have experienced a more rapid and steep negative change in clinical status than initially anticipated.

For most patients with major mental illness, reexamination in 3 to 5 years is probably a reasonable time interval, barring a poorly understood and clinically significant negative change in functioning that warrants a shorter time frame. This suggested time frame would allow for sufficient time to better gauge improvement, stability, or deterioration in functioning and whether the reason(s) for referral have evolved. On the other hand, this time interval is somewhat arbitrary given the lack of empirical data. Therefore, on a case-by-case basis, it would be helpful for psychiatrists to consult with their patients and preferably with the psychologist who completed the baseline evaluation to determine a reasonable interval between assessments.

For patients who have undergone long-term/intensive treatment, reassessment in 3 or 6 months to as long as 1 year after the patient completes the program should be considered. Patients who undergo medical interventions such as neurosurgery or ECT—which can be associated with short-term, at least partially reversible negative effects on mental status—reassessment usually is most helpful when initiated as one or more screening level examinations for several weeks, followed by a comprehensive psychometric reassessment at the 3- to 6-month mark.

Suggestions for future research

Additional research is needed to ascertain the attitudes and opinions of psychiatrists and other physicians who use psychometric test data regarding how psychologists can most effectively communicate a recommendation for reassessment in their reports and clarify the ways psychiatrists can productively address this issue with their patients. Survey research of this kind should include questions about the frequency with which psychiatrists formally refer patients for retesting, and estimates of the rate of follow-through.

Continue to: It also would be desirable...

It also would be desirable to investigate factors that may facilitate follow-through with recommendations for reassessment, or, conversely, identify reasons that psychiatrists and their patients may decide to forgo reassessment. It would be important to try to obtain information regarding the optimum time frames for such reevaluation, depending on the patient’s circumstances and other variables. Evidence-based data pertaining to these issues would contribute to the development of consensus guidelines and a standard of care for psychological/neuropsychological test reevaluation.

Bottom Line

Only a very small percentage of patients referred for follow-up psychological/ neuropsychological test reevaluation actually undergo reexamination. Such retesting may be most helpful for certain patient populations, such as those who are likely to soon improve or worsen, were referred based on a family history of major cognitive disorder but have no concerning findings on baseline testing, or are undergoing a substantial life transition.

Related Resources

- Thom R, Farrell HM. Neuroimaging in psychiatry: potentials and pitfalls. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(12):27-28;33-34.

- Papakostas GI. Cognitive symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder and their implications for clinical practice. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(1):8-14.

- American Board of Professional Neuropsychology. https://abn-board.com

1. Schroeder RW, Martin PK, Walling A. Neuropsychological evaluations in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(2):101-198.

2. Bucher MA, Suzuki T, Samuel DB. A meta-analytic review of personality traits and their associations with mental health treatment outcomes. Clin Psychol Rev. 2019;70:51-63.

3. Pollak J. Feedback to the psychodiagnostician: a challenge for assessment psychologists in independent practice. Independent Practitioner: The community of psychologists in independent practice. 2020;40,6-9.

4. Pollak J. To test or not to test: considerations before going forward with psychometric testing. The Clinical Practitioner. 2011;6:5-10.

5. Schwarz L, Roskos PT, Grossberg GT. Answers to 7 questions about using neuropsychological testing in your practice. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):33-39.

6. Zucchella C, Federico A, Martini A, et al. Neuropsychological testing. Pract Neurol. 2018;18(3):227-237.

7. Moller MD, Parmenter BA, Lane DW. Neuropsychological testing: a useful but underutilized resource. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):40-46,51.

8. Pollak J. Psychodiagnostic testing services: the elusive quest for clinicians. Clinical Psychiatry News. Published October 18, 2019. Accessed July 8, 2021. https://www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/210439/schizophrenia-other-psychotic-disorders/psychodiagnostic-testing-services

9. Mesholam-Gately RI, Giuliano AJ, Goff KP, et al. Neurocognition in first episode schizophrenia: a meta- analytic review. Neuropsychology. 2009;23(3):315-336.

10. Lam RW, Kennedy SH, McIntyre RS et al. Cognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder: effects on psychosocial functioning and implications for treatment. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(12):649-654.

11. Szmulewicz AG, Samamé C, Martino DJ, et al. An updated review on the neuropsychological profile of subjects with bipolar disorder. Arch Clin Psychiatry. 2015;42(5):139-146.

12. Shin NY, Lee TY, Kim, E, et al. Cognitive functioning in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2013;44(6):1121-1130.

13. Zanelli J, Mollon J, Sandin S, et al. Cognitive change in schizophrenia and other psychoses in the decade following the first episode. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(10):811-819.

14. Mitleman SA, Buchsbaum MS. Very poor outcome schizophrenia: clinical and neuroimaging aspects. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19(4):345-357.

The evolution of illness prevention, diagnosis, and treatment has involved an increased appreciation for the clinical utility of longitudinal assessment. This has included the implementation of screening evaluations for high base rate medical conditions, such as cancer, that involve considerable morbidity and mortality.

Unfortunately, the mental health professions have been slow to embrace this approach. Baseline assessment with psychological/neuropsychological screening tests and more comprehensive test batteries to clarify diagnostic status and facilitate treatment planning is far more the exception than the rule in mental health care. This seems to be the case despite the strong evidence supporting this practice as well as multiple surveys indicating that psychiatrists and other physicians report a high level of satisfaction with the findings and recommendations of psychological/neuropsychological test reports.1-3

There is a substantial literature that reviews the relative indications and contraindications for initial psychological/neuropsychological test evaluations.4-7 However, there is a paucity of clinical and evidence-based information regarding criteria for follow-up assessment. Moreover, there are no consensus guidelines to inform decision-making regarding this issue.

In general, good clinical practice for baseline assessment and reexamination should include administration of both psychological and neuropsychological tests. Based on clinical experience, this article addresses the relative indications and contraindications for psychological/neuropsychological test reassessment of adults seen in psychiatric care. It also outlines suggested time frames for such reevaluations, based on the patient’s clinical status and circumstances.

Why are patients not referred for reassessment more often?

There are several reasons patients are not referred for follow-up testing, beginning with the failure, at times, of the psychologist to state in the recommendations section of the test report whether a reassessment is indicated, under what circumstances, and within what time frame. Empirical data is lacking, but predicated on clinical experience, even when a strong and unequivocal recommendation is made for reassessment, only a very small percentage of patients are seen for follow-up evaluation.

There are numerous reasons why this occurs. The patient and/or the psychiatrist may overlook or forget about the recommendation for reassessment, particularly if it was embedded in a lengthy list of recommendations and the suggested time frame for the reassessment was several years away. The patient and the psychiatrist may decide against going forward with a reexamination, for a variety of substantive reasons. The patient might decline, against medical advice, to be retested. The patient may fail to make or keep an appointment for the follow-up reexamination. The patient might leave treatment and become lost to follow-up. The patient might not be able to find an appropriate psychologist. The insurance company may decline to authorize follow-up testing.8

Indications for reevaluation

Follow-up testing generally is indicated in the following circumstances:

Patients who are likely to soon improve or worsen. Reassessment is indicated when, based on the initial evaluation, the patient has been identified as having a neuropsychiatric disorder that is likely to improve or worsen over the next year or 2 due to the natural trajectory of the condition and the degree to which it may respond to treatment.

Continue to: Patients who are likely...

Patients who are likely to improve include those with mental status changes referable to ≥1 medical and/or neuropsychiatric factors that are considered at least partially treatable and reversible. Patients who fall within this category include those who have mild to moderately severe head trauma or stroke, have a suspected or known medication- or substance-induced altered mental status, appear to have depression-related cognitive difficulties, or have an initial or recurrent episode of idiopathic psychosis.

Patients whose conditions can be expected to worsen over time include those with a mild neurocognitive disorder or major neurocognitive disorder of mild severity that is considered referable to a progressive neurodegenerative illness such as Alzheimer’s disease based on family and personal history, their psychometric test profile, and other factors, including findings from positron emission tomography scanning.

Older patients who were referred primarily due to a strong family history of major neurocognitive disorder but with no clear-cut concerning findings on baseline testing warrant reevaluation in the event of the emergence of significant cognitive and/or psychiatric symptoms and/or a functional decline since the baseline examination.

Patients who have been seen for initial test evaluations prior to interventions such as neurosurgery (including psychosurgery), electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), transcranial magnetic stimulation, cognitive rehabilitation, etc.

Patients undergoing a substantial transition. Reevaluation is appropriate for a broad range of patients experiencing difficulties when undergoing a significant lifestyle transition or change in level of care. This includes patients considering a return to school or work after a prolonged absence due to neuropsychiatric illness, or for whom there are questions regarding the need for a change in their level of everyday care. The latter includes patients who are returning to home care from assisted living, or transferring from home-based services to assisted living or a skilled nursing facility.

Continue to: What about patients with psychiatric disorders?

What about patients with psychiatric disorders? A “grey area” pertains to reassessment of patients with neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Patients with these conditions often have high rates of cognitive/neuropsychological impairment on baseline testing, even when they appear to be improving from a psychiatric perspective, are reasonably stable, and may even be in remission.9-12

These deficits are frequently a mix of pre-illness, prodromal, and early-stage illness– related neurocognitive difficulties that, for the most part, remain stable over time. That said, there is emerging evidence of worsening cognitive change over time following a first episode of psychosis for some patients with schizophrenia.13

In general, reevaluation should be considered for patients with a family and/or personal history of cognitive/neuropsychological impairment, structural brain abnormalities on neuroimaging, a concerning cognitive/neuropsychological profile, or any other factors that raise the index of suspicion for a possible progressive deteriorative course of illness.13,14

Patients with personality disorders who have had a baseline psychometric evaluation do not clearly warrant reassessment unless they develop medical and/or psychosocial difficulties that are often linked to problematic personality traits/patterns and that result in significant and persistent mental status changes. For example, reassessment might be indicated for a patient with borderline personality disorder who has new-onset or worsening cognitive and/or psychiatric complaints/symptoms after sustaining a head injury while intoxicated and embroiled in a domestic conflict triggered by anger and fears related to abandonment and separation.

Reevaluation also should be considered when a patient with a personality disorder has had a baseline assessment and subsequently completes an intensive, long-term treatment program that is likely to improve their clinical status. In this context, retesting may help document these gains. Examples of such programs/services include residential psychiatric and/or substance abuse care, object relational/psychodynamically-based psychotherapy, an extended course of dialectical behavioral therapy, or a related coping skills/distress tolerance psychotherapy.

Continue to: Contraindications for reassessment

Contraindications for reassessment

Retesting generally is not indicated in the following circumstances:

Patients with advanced major neurocognitive disorder. Reassessment is not indicated for such patients when there are no new questions regarding diagnosis, prognosis, level of care, and/or related disposition issues.

Patients with transient episodes of poor functioning. For the most part, reassessment is not helpful for patients with well-established diagnoses and treatment plans who, based on their history, experience time-limited, recurrent episodes of poor functioning and then reliably return to their baseline with ongoing psychiatric care. This includes patients with borderline personality disorder and other personality difficulties with histories of transient decompensation in response to psychosocial and psychodynamic triggers.

Patients who do not improve or worsen over time. Reassessment is not indicated when there has been no clear, sustained improvement or worsening of a patient’s clinical status over an extended time, and a protracted change is not anticipated. In this situation, reassessment is unlikely to yield clinically useful information beyond what is already known or meaningfully impact case formulation and treatment planning.

The Table9-14 summarizes the relative indications and contraindications for psychological/neuropsychological reexamination.

Continue to: Time frames for reassessment

Time frames for reassessment

Time frames for retesting vary considerably depending on factors such as diagnostic status, longitudinal course, treatment parameters, and recent/current life circumstances.

While empirical data is lacking regarding this matter, based on clinical experience, reevaluation in 18 to 24 months is generally appropriate for patients with neuropsychiatric conditions who are likely to gradually improve or slowly worsen over this time. Still, reexamination can be sooner (within 12 to 18 months) for patients who have experienced a more rapid and steep negative change in clinical status than initially anticipated.

For most patients with major mental illness, reexamination in 3 to 5 years is probably a reasonable time interval, barring a poorly understood and clinically significant negative change in functioning that warrants a shorter time frame. This suggested time frame would allow for sufficient time to better gauge improvement, stability, or deterioration in functioning and whether the reason(s) for referral have evolved. On the other hand, this time interval is somewhat arbitrary given the lack of empirical data. Therefore, on a case-by-case basis, it would be helpful for psychiatrists to consult with their patients and preferably with the psychologist who completed the baseline evaluation to determine a reasonable interval between assessments.

For patients who have undergone long-term/intensive treatment, reassessment in 3 or 6 months to as long as 1 year after the patient completes the program should be considered. Patients who undergo medical interventions such as neurosurgery or ECT—which can be associated with short-term, at least partially reversible negative effects on mental status—reassessment usually is most helpful when initiated as one or more screening level examinations for several weeks, followed by a comprehensive psychometric reassessment at the 3- to 6-month mark.

Suggestions for future research

Additional research is needed to ascertain the attitudes and opinions of psychiatrists and other physicians who use psychometric test data regarding how psychologists can most effectively communicate a recommendation for reassessment in their reports and clarify the ways psychiatrists can productively address this issue with their patients. Survey research of this kind should include questions about the frequency with which psychiatrists formally refer patients for retesting, and estimates of the rate of follow-through.

Continue to: It also would be desirable...

It also would be desirable to investigate factors that may facilitate follow-through with recommendations for reassessment, or, conversely, identify reasons that psychiatrists and their patients may decide to forgo reassessment. It would be important to try to obtain information regarding the optimum time frames for such reevaluation, depending on the patient’s circumstances and other variables. Evidence-based data pertaining to these issues would contribute to the development of consensus guidelines and a standard of care for psychological/neuropsychological test reevaluation.

Bottom Line

Only a very small percentage of patients referred for follow-up psychological/ neuropsychological test reevaluation actually undergo reexamination. Such retesting may be most helpful for certain patient populations, such as those who are likely to soon improve or worsen, were referred based on a family history of major cognitive disorder but have no concerning findings on baseline testing, or are undergoing a substantial life transition.

Related Resources

- Thom R, Farrell HM. Neuroimaging in psychiatry: potentials and pitfalls. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(12):27-28;33-34.

- Papakostas GI. Cognitive symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder and their implications for clinical practice. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(1):8-14.

- American Board of Professional Neuropsychology. https://abn-board.com

The evolution of illness prevention, diagnosis, and treatment has involved an increased appreciation for the clinical utility of longitudinal assessment. This has included the implementation of screening evaluations for high base rate medical conditions, such as cancer, that involve considerable morbidity and mortality.

Unfortunately, the mental health professions have been slow to embrace this approach. Baseline assessment with psychological/neuropsychological screening tests and more comprehensive test batteries to clarify diagnostic status and facilitate treatment planning is far more the exception than the rule in mental health care. This seems to be the case despite the strong evidence supporting this practice as well as multiple surveys indicating that psychiatrists and other physicians report a high level of satisfaction with the findings and recommendations of psychological/neuropsychological test reports.1-3

There is a substantial literature that reviews the relative indications and contraindications for initial psychological/neuropsychological test evaluations.4-7 However, there is a paucity of clinical and evidence-based information regarding criteria for follow-up assessment. Moreover, there are no consensus guidelines to inform decision-making regarding this issue.

In general, good clinical practice for baseline assessment and reexamination should include administration of both psychological and neuropsychological tests. Based on clinical experience, this article addresses the relative indications and contraindications for psychological/neuropsychological test reassessment of adults seen in psychiatric care. It also outlines suggested time frames for such reevaluations, based on the patient’s clinical status and circumstances.

Why are patients not referred for reassessment more often?

There are several reasons patients are not referred for follow-up testing, beginning with the failure, at times, of the psychologist to state in the recommendations section of the test report whether a reassessment is indicated, under what circumstances, and within what time frame. Empirical data is lacking, but predicated on clinical experience, even when a strong and unequivocal recommendation is made for reassessment, only a very small percentage of patients are seen for follow-up evaluation.

There are numerous reasons why this occurs. The patient and/or the psychiatrist may overlook or forget about the recommendation for reassessment, particularly if it was embedded in a lengthy list of recommendations and the suggested time frame for the reassessment was several years away. The patient and the psychiatrist may decide against going forward with a reexamination, for a variety of substantive reasons. The patient might decline, against medical advice, to be retested. The patient may fail to make or keep an appointment for the follow-up reexamination. The patient might leave treatment and become lost to follow-up. The patient might not be able to find an appropriate psychologist. The insurance company may decline to authorize follow-up testing.8

Indications for reevaluation

Follow-up testing generally is indicated in the following circumstances:

Patients who are likely to soon improve or worsen. Reassessment is indicated when, based on the initial evaluation, the patient has been identified as having a neuropsychiatric disorder that is likely to improve or worsen over the next year or 2 due to the natural trajectory of the condition and the degree to which it may respond to treatment.

Continue to: Patients who are likely...

Patients who are likely to improve include those with mental status changes referable to ≥1 medical and/or neuropsychiatric factors that are considered at least partially treatable and reversible. Patients who fall within this category include those who have mild to moderately severe head trauma or stroke, have a suspected or known medication- or substance-induced altered mental status, appear to have depression-related cognitive difficulties, or have an initial or recurrent episode of idiopathic psychosis.

Patients whose conditions can be expected to worsen over time include those with a mild neurocognitive disorder or major neurocognitive disorder of mild severity that is considered referable to a progressive neurodegenerative illness such as Alzheimer’s disease based on family and personal history, their psychometric test profile, and other factors, including findings from positron emission tomography scanning.

Older patients who were referred primarily due to a strong family history of major neurocognitive disorder but with no clear-cut concerning findings on baseline testing warrant reevaluation in the event of the emergence of significant cognitive and/or psychiatric symptoms and/or a functional decline since the baseline examination.

Patients who have been seen for initial test evaluations prior to interventions such as neurosurgery (including psychosurgery), electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), transcranial magnetic stimulation, cognitive rehabilitation, etc.

Patients undergoing a substantial transition. Reevaluation is appropriate for a broad range of patients experiencing difficulties when undergoing a significant lifestyle transition or change in level of care. This includes patients considering a return to school or work after a prolonged absence due to neuropsychiatric illness, or for whom there are questions regarding the need for a change in their level of everyday care. The latter includes patients who are returning to home care from assisted living, or transferring from home-based services to assisted living or a skilled nursing facility.

Continue to: What about patients with psychiatric disorders?

What about patients with psychiatric disorders? A “grey area” pertains to reassessment of patients with neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Patients with these conditions often have high rates of cognitive/neuropsychological impairment on baseline testing, even when they appear to be improving from a psychiatric perspective, are reasonably stable, and may even be in remission.9-12

These deficits are frequently a mix of pre-illness, prodromal, and early-stage illness– related neurocognitive difficulties that, for the most part, remain stable over time. That said, there is emerging evidence of worsening cognitive change over time following a first episode of psychosis for some patients with schizophrenia.13

In general, reevaluation should be considered for patients with a family and/or personal history of cognitive/neuropsychological impairment, structural brain abnormalities on neuroimaging, a concerning cognitive/neuropsychological profile, or any other factors that raise the index of suspicion for a possible progressive deteriorative course of illness.13,14

Patients with personality disorders who have had a baseline psychometric evaluation do not clearly warrant reassessment unless they develop medical and/or psychosocial difficulties that are often linked to problematic personality traits/patterns and that result in significant and persistent mental status changes. For example, reassessment might be indicated for a patient with borderline personality disorder who has new-onset or worsening cognitive and/or psychiatric complaints/symptoms after sustaining a head injury while intoxicated and embroiled in a domestic conflict triggered by anger and fears related to abandonment and separation.

Reevaluation also should be considered when a patient with a personality disorder has had a baseline assessment and subsequently completes an intensive, long-term treatment program that is likely to improve their clinical status. In this context, retesting may help document these gains. Examples of such programs/services include residential psychiatric and/or substance abuse care, object relational/psychodynamically-based psychotherapy, an extended course of dialectical behavioral therapy, or a related coping skills/distress tolerance psychotherapy.

Continue to: Contraindications for reassessment

Contraindications for reassessment

Retesting generally is not indicated in the following circumstances:

Patients with advanced major neurocognitive disorder. Reassessment is not indicated for such patients when there are no new questions regarding diagnosis, prognosis, level of care, and/or related disposition issues.

Patients with transient episodes of poor functioning. For the most part, reassessment is not helpful for patients with well-established diagnoses and treatment plans who, based on their history, experience time-limited, recurrent episodes of poor functioning and then reliably return to their baseline with ongoing psychiatric care. This includes patients with borderline personality disorder and other personality difficulties with histories of transient decompensation in response to psychosocial and psychodynamic triggers.

Patients who do not improve or worsen over time. Reassessment is not indicated when there has been no clear, sustained improvement or worsening of a patient’s clinical status over an extended time, and a protracted change is not anticipated. In this situation, reassessment is unlikely to yield clinically useful information beyond what is already known or meaningfully impact case formulation and treatment planning.

The Table9-14 summarizes the relative indications and contraindications for psychological/neuropsychological reexamination.

Continue to: Time frames for reassessment

Time frames for reassessment

Time frames for retesting vary considerably depending on factors such as diagnostic status, longitudinal course, treatment parameters, and recent/current life circumstances.

While empirical data is lacking regarding this matter, based on clinical experience, reevaluation in 18 to 24 months is generally appropriate for patients with neuropsychiatric conditions who are likely to gradually improve or slowly worsen over this time. Still, reexamination can be sooner (within 12 to 18 months) for patients who have experienced a more rapid and steep negative change in clinical status than initially anticipated.

For most patients with major mental illness, reexamination in 3 to 5 years is probably a reasonable time interval, barring a poorly understood and clinically significant negative change in functioning that warrants a shorter time frame. This suggested time frame would allow for sufficient time to better gauge improvement, stability, or deterioration in functioning and whether the reason(s) for referral have evolved. On the other hand, this time interval is somewhat arbitrary given the lack of empirical data. Therefore, on a case-by-case basis, it would be helpful for psychiatrists to consult with their patients and preferably with the psychologist who completed the baseline evaluation to determine a reasonable interval between assessments.

For patients who have undergone long-term/intensive treatment, reassessment in 3 or 6 months to as long as 1 year after the patient completes the program should be considered. Patients who undergo medical interventions such as neurosurgery or ECT—which can be associated with short-term, at least partially reversible negative effects on mental status—reassessment usually is most helpful when initiated as one or more screening level examinations for several weeks, followed by a comprehensive psychometric reassessment at the 3- to 6-month mark.

Suggestions for future research

Additional research is needed to ascertain the attitudes and opinions of psychiatrists and other physicians who use psychometric test data regarding how psychologists can most effectively communicate a recommendation for reassessment in their reports and clarify the ways psychiatrists can productively address this issue with their patients. Survey research of this kind should include questions about the frequency with which psychiatrists formally refer patients for retesting, and estimates of the rate of follow-through.

Continue to: It also would be desirable...

It also would be desirable to investigate factors that may facilitate follow-through with recommendations for reassessment, or, conversely, identify reasons that psychiatrists and their patients may decide to forgo reassessment. It would be important to try to obtain information regarding the optimum time frames for such reevaluation, depending on the patient’s circumstances and other variables. Evidence-based data pertaining to these issues would contribute to the development of consensus guidelines and a standard of care for psychological/neuropsychological test reevaluation.

Bottom Line

Only a very small percentage of patients referred for follow-up psychological/ neuropsychological test reevaluation actually undergo reexamination. Such retesting may be most helpful for certain patient populations, such as those who are likely to soon improve or worsen, were referred based on a family history of major cognitive disorder but have no concerning findings on baseline testing, or are undergoing a substantial life transition.

Related Resources

- Thom R, Farrell HM. Neuroimaging in psychiatry: potentials and pitfalls. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(12):27-28;33-34.

- Papakostas GI. Cognitive symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder and their implications for clinical practice. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(1):8-14.

- American Board of Professional Neuropsychology. https://abn-board.com

1. Schroeder RW, Martin PK, Walling A. Neuropsychological evaluations in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(2):101-198.

2. Bucher MA, Suzuki T, Samuel DB. A meta-analytic review of personality traits and their associations with mental health treatment outcomes. Clin Psychol Rev. 2019;70:51-63.

3. Pollak J. Feedback to the psychodiagnostician: a challenge for assessment psychologists in independent practice. Independent Practitioner: The community of psychologists in independent practice. 2020;40,6-9.

4. Pollak J. To test or not to test: considerations before going forward with psychometric testing. The Clinical Practitioner. 2011;6:5-10.

5. Schwarz L, Roskos PT, Grossberg GT. Answers to 7 questions about using neuropsychological testing in your practice. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):33-39.

6. Zucchella C, Federico A, Martini A, et al. Neuropsychological testing. Pract Neurol. 2018;18(3):227-237.

7. Moller MD, Parmenter BA, Lane DW. Neuropsychological testing: a useful but underutilized resource. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):40-46,51.

8. Pollak J. Psychodiagnostic testing services: the elusive quest for clinicians. Clinical Psychiatry News. Published October 18, 2019. Accessed July 8, 2021. https://www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/210439/schizophrenia-other-psychotic-disorders/psychodiagnostic-testing-services

9. Mesholam-Gately RI, Giuliano AJ, Goff KP, et al. Neurocognition in first episode schizophrenia: a meta- analytic review. Neuropsychology. 2009;23(3):315-336.

10. Lam RW, Kennedy SH, McIntyre RS et al. Cognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder: effects on psychosocial functioning and implications for treatment. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(12):649-654.

11. Szmulewicz AG, Samamé C, Martino DJ, et al. An updated review on the neuropsychological profile of subjects with bipolar disorder. Arch Clin Psychiatry. 2015;42(5):139-146.

12. Shin NY, Lee TY, Kim, E, et al. Cognitive functioning in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2013;44(6):1121-1130.

13. Zanelli J, Mollon J, Sandin S, et al. Cognitive change in schizophrenia and other psychoses in the decade following the first episode. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(10):811-819.

14. Mitleman SA, Buchsbaum MS. Very poor outcome schizophrenia: clinical and neuroimaging aspects. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19(4):345-357.

1. Schroeder RW, Martin PK, Walling A. Neuropsychological evaluations in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(2):101-198.

2. Bucher MA, Suzuki T, Samuel DB. A meta-analytic review of personality traits and their associations with mental health treatment outcomes. Clin Psychol Rev. 2019;70:51-63.

3. Pollak J. Feedback to the psychodiagnostician: a challenge for assessment psychologists in independent practice. Independent Practitioner: The community of psychologists in independent practice. 2020;40,6-9.

4. Pollak J. To test or not to test: considerations before going forward with psychometric testing. The Clinical Practitioner. 2011;6:5-10.

5. Schwarz L, Roskos PT, Grossberg GT. Answers to 7 questions about using neuropsychological testing in your practice. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):33-39.

6. Zucchella C, Federico A, Martini A, et al. Neuropsychological testing. Pract Neurol. 2018;18(3):227-237.

7. Moller MD, Parmenter BA, Lane DW. Neuropsychological testing: a useful but underutilized resource. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):40-46,51.

8. Pollak J. Psychodiagnostic testing services: the elusive quest for clinicians. Clinical Psychiatry News. Published October 18, 2019. Accessed July 8, 2021. https://www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/210439/schizophrenia-other-psychotic-disorders/psychodiagnostic-testing-services

9. Mesholam-Gately RI, Giuliano AJ, Goff KP, et al. Neurocognition in first episode schizophrenia: a meta- analytic review. Neuropsychology. 2009;23(3):315-336.

10. Lam RW, Kennedy SH, McIntyre RS et al. Cognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder: effects on psychosocial functioning and implications for treatment. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(12):649-654.

11. Szmulewicz AG, Samamé C, Martino DJ, et al. An updated review on the neuropsychological profile of subjects with bipolar disorder. Arch Clin Psychiatry. 2015;42(5):139-146.

12. Shin NY, Lee TY, Kim, E, et al. Cognitive functioning in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2013;44(6):1121-1130.

13. Zanelli J, Mollon J, Sandin S, et al. Cognitive change in schizophrenia and other psychoses in the decade following the first episode. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(10):811-819.

14. Mitleman SA, Buchsbaum MS. Very poor outcome schizophrenia: clinical and neuroimaging aspects. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19(4):345-357.

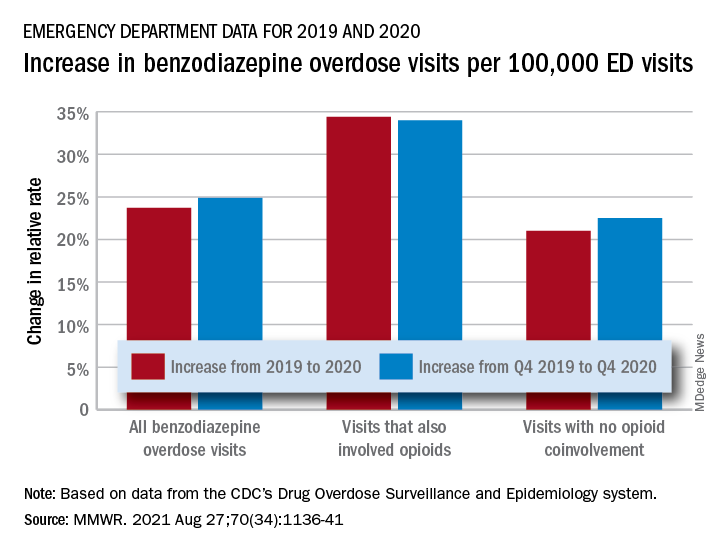

EDs saw more benzodiazepine overdoses, but fewer patients overall, in 2020

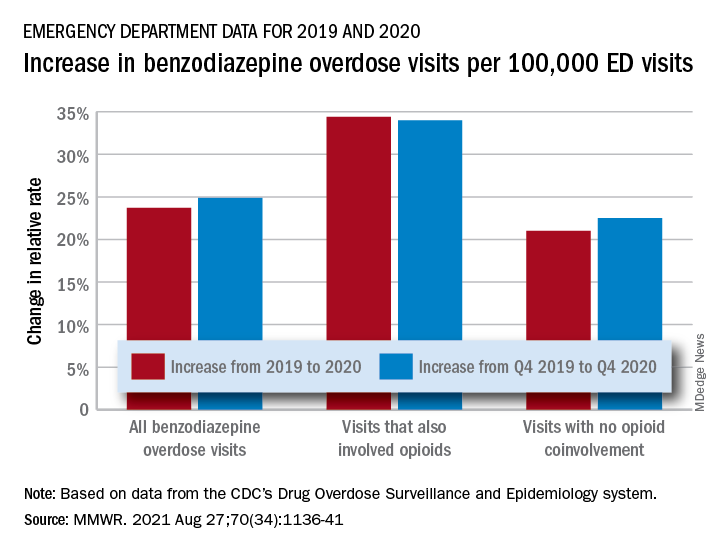

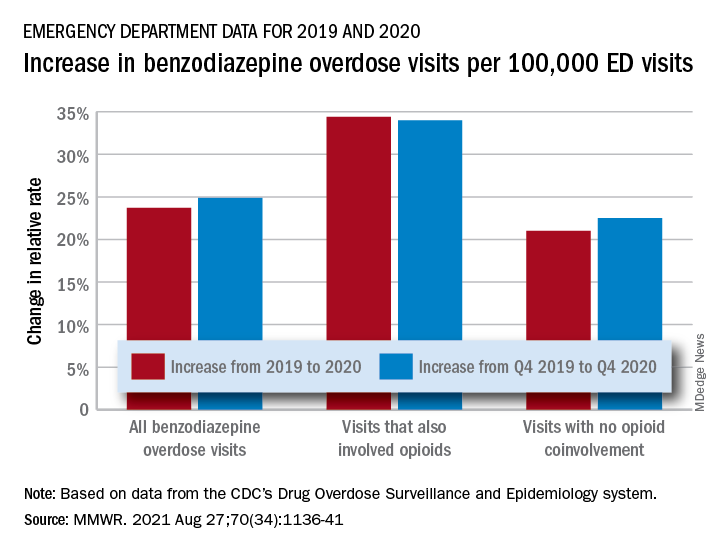

In a year when emergency department visits dropped by almost 18%, visits for benzodiazepine overdoses did the opposite, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The actual increase in the number of overdose visits for benzodiazepine overdoses was quite small – from 15,547 in 2019 to 15,830 in 2020 (1.8%) – but the 11 million fewer ED visits magnified its effect, Stephen Liu, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The rate of benzodiazepine overdose visits to all visits increased by 23.7% from 2019 (24.22 per 100,000 ED visits) to 2020 (29.97 per 100,000), with the larger share going to those involving opioids, which were up by 34.4%, compared with overdose visits not involving opioids (21.0%), the investigators said, based on data reported by 32 states and the District of Columbia to the CDC’s Drug Overdose Surveillance and Epidemiology system. All of the rate changes are statistically significant.

The number of overdose visits without opioid coinvolvement actually dropped, from 2019 (12,276) to 2020 (12,218), but not by enough to offset the decline in total visits, noted Dr. Liu, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control and associates.

The number of deaths from benzodiazepine overdose, on the other hand, did not drop in 2020. Those data, coming from 23 states participating in the CDC’s State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System, were available only for the first half of the year.

In those 6 months, The first quarter of 2020 also showed an increase, but exact numbers were not provided in the report. Overdose deaths rose by 22% for prescription forms of benzodiazepine and 520% for illicit forms in Q2 of 2020, compared with 2019, the researchers said.

Almost all of the benzodiazepine deaths (93%) in the first half of 2020 also involved opioids, mostly in the form of illicitly manufactured fentanyls (67% of all deaths). Between Q2 of 2019 and Q2 of 2020, involvement of illicit fentanyls in benzodiazepine overdose deaths increased from almost 57% to 71%, Dr. Liu and associates reported.

“Despite progress in reducing coprescribing [of opioids and benzodiazepines] before 2019, this study suggests a reversal in the decline in benzodiazepine deaths from 2017 to 2019, driven in part by increasing involvement of [illicitly manufactured fentanyls] in benzodiazepine deaths and influxes of illicit benzodiazepines,” they wrote.

In a year when emergency department visits dropped by almost 18%, visits for benzodiazepine overdoses did the opposite, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The actual increase in the number of overdose visits for benzodiazepine overdoses was quite small – from 15,547 in 2019 to 15,830 in 2020 (1.8%) – but the 11 million fewer ED visits magnified its effect, Stephen Liu, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The rate of benzodiazepine overdose visits to all visits increased by 23.7% from 2019 (24.22 per 100,000 ED visits) to 2020 (29.97 per 100,000), with the larger share going to those involving opioids, which were up by 34.4%, compared with overdose visits not involving opioids (21.0%), the investigators said, based on data reported by 32 states and the District of Columbia to the CDC’s Drug Overdose Surveillance and Epidemiology system. All of the rate changes are statistically significant.

The number of overdose visits without opioid coinvolvement actually dropped, from 2019 (12,276) to 2020 (12,218), but not by enough to offset the decline in total visits, noted Dr. Liu, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control and associates.

The number of deaths from benzodiazepine overdose, on the other hand, did not drop in 2020. Those data, coming from 23 states participating in the CDC’s State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System, were available only for the first half of the year.

In those 6 months, The first quarter of 2020 also showed an increase, but exact numbers were not provided in the report. Overdose deaths rose by 22% for prescription forms of benzodiazepine and 520% for illicit forms in Q2 of 2020, compared with 2019, the researchers said.

Almost all of the benzodiazepine deaths (93%) in the first half of 2020 also involved opioids, mostly in the form of illicitly manufactured fentanyls (67% of all deaths). Between Q2 of 2019 and Q2 of 2020, involvement of illicit fentanyls in benzodiazepine overdose deaths increased from almost 57% to 71%, Dr. Liu and associates reported.

“Despite progress in reducing coprescribing [of opioids and benzodiazepines] before 2019, this study suggests a reversal in the decline in benzodiazepine deaths from 2017 to 2019, driven in part by increasing involvement of [illicitly manufactured fentanyls] in benzodiazepine deaths and influxes of illicit benzodiazepines,” they wrote.

In a year when emergency department visits dropped by almost 18%, visits for benzodiazepine overdoses did the opposite, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The actual increase in the number of overdose visits for benzodiazepine overdoses was quite small – from 15,547 in 2019 to 15,830 in 2020 (1.8%) – but the 11 million fewer ED visits magnified its effect, Stephen Liu, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The rate of benzodiazepine overdose visits to all visits increased by 23.7% from 2019 (24.22 per 100,000 ED visits) to 2020 (29.97 per 100,000), with the larger share going to those involving opioids, which were up by 34.4%, compared with overdose visits not involving opioids (21.0%), the investigators said, based on data reported by 32 states and the District of Columbia to the CDC’s Drug Overdose Surveillance and Epidemiology system. All of the rate changes are statistically significant.

The number of overdose visits without opioid coinvolvement actually dropped, from 2019 (12,276) to 2020 (12,218), but not by enough to offset the decline in total visits, noted Dr. Liu, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control and associates.

The number of deaths from benzodiazepine overdose, on the other hand, did not drop in 2020. Those data, coming from 23 states participating in the CDC’s State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System, were available only for the first half of the year.

In those 6 months, The first quarter of 2020 also showed an increase, but exact numbers were not provided in the report. Overdose deaths rose by 22% for prescription forms of benzodiazepine and 520% for illicit forms in Q2 of 2020, compared with 2019, the researchers said.

Almost all of the benzodiazepine deaths (93%) in the first half of 2020 also involved opioids, mostly in the form of illicitly manufactured fentanyls (67% of all deaths). Between Q2 of 2019 and Q2 of 2020, involvement of illicit fentanyls in benzodiazepine overdose deaths increased from almost 57% to 71%, Dr. Liu and associates reported.

“Despite progress in reducing coprescribing [of opioids and benzodiazepines] before 2019, this study suggests a reversal in the decline in benzodiazepine deaths from 2017 to 2019, driven in part by increasing involvement of [illicitly manufactured fentanyls] in benzodiazepine deaths and influxes of illicit benzodiazepines,” they wrote.

FROM MMWR

FDA OKs IV Briviact for seizures in kids as young as 1 month

All three brivaracetam formulations (tablets, oral solution, and IV) may now be used. The approval marks the first time that the IV formulation will be available for children, the company said in a news release.

The medication is already approved in the United States as monotherapy and adjunctive therapy in adults with epilepsy.

In an open-label follow-up pediatric study, an estimated 71.4% of patients aged 1 month to 17 years with partial-onset seizures remained on brivaracetam therapy at 1 year, and 64.3% did so at 2 years, the company reported.

“We often see children with seizures hospitalized, so it’s important to have a therapy like Briviact IV that can offer rapid administration in an effective dose when needed and does not require titration,” Raman Sankar, MD, PhD, distinguished professor and chief of pediatric neurology, University of California, Los Angeles, said in the release.

“The availability of the oral dose forms also allows continuity of treatment when these young patients are transitioning from hospital to home,” he added.

Safety profile

Dr. Sankar noted that with approval now of both the IV and oral formulations for partial-onset seizures in such young children, “we have a new option that helps meet a critical need in pediatric epilepsy.”

The most common adverse reactions with brivaracetam include somnolence and sedation, dizziness, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting. In the pediatric clinical trials, the safety profile for pediatric patients was similar to adults.

In the adult trials, psychiatric adverse reactions, including nonpsychotic and psychotic symptoms, were reported in approximately 13% of adults taking at least 50 mg/day of brivaracetam compared with 8% taking placebo.

Psychiatric adverse reactions were also observed in open-label pediatric trials and were generally similar to those observed in adults.

Patients should be advised to report these symptoms immediately to a health care professional, the company noted.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

All three brivaracetam formulations (tablets, oral solution, and IV) may now be used. The approval marks the first time that the IV formulation will be available for children, the company said in a news release.

The medication is already approved in the United States as monotherapy and adjunctive therapy in adults with epilepsy.

In an open-label follow-up pediatric study, an estimated 71.4% of patients aged 1 month to 17 years with partial-onset seizures remained on brivaracetam therapy at 1 year, and 64.3% did so at 2 years, the company reported.

“We often see children with seizures hospitalized, so it’s important to have a therapy like Briviact IV that can offer rapid administration in an effective dose when needed and does not require titration,” Raman Sankar, MD, PhD, distinguished professor and chief of pediatric neurology, University of California, Los Angeles, said in the release.

“The availability of the oral dose forms also allows continuity of treatment when these young patients are transitioning from hospital to home,” he added.

Safety profile

Dr. Sankar noted that with approval now of both the IV and oral formulations for partial-onset seizures in such young children, “we have a new option that helps meet a critical need in pediatric epilepsy.”

The most common adverse reactions with brivaracetam include somnolence and sedation, dizziness, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting. In the pediatric clinical trials, the safety profile for pediatric patients was similar to adults.

In the adult trials, psychiatric adverse reactions, including nonpsychotic and psychotic symptoms, were reported in approximately 13% of adults taking at least 50 mg/day of brivaracetam compared with 8% taking placebo.

Psychiatric adverse reactions were also observed in open-label pediatric trials and were generally similar to those observed in adults.

Patients should be advised to report these symptoms immediately to a health care professional, the company noted.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

All three brivaracetam formulations (tablets, oral solution, and IV) may now be used. The approval marks the first time that the IV formulation will be available for children, the company said in a news release.

The medication is already approved in the United States as monotherapy and adjunctive therapy in adults with epilepsy.

In an open-label follow-up pediatric study, an estimated 71.4% of patients aged 1 month to 17 years with partial-onset seizures remained on brivaracetam therapy at 1 year, and 64.3% did so at 2 years, the company reported.

“We often see children with seizures hospitalized, so it’s important to have a therapy like Briviact IV that can offer rapid administration in an effective dose when needed and does not require titration,” Raman Sankar, MD, PhD, distinguished professor and chief of pediatric neurology, University of California, Los Angeles, said in the release.

“The availability of the oral dose forms also allows continuity of treatment when these young patients are transitioning from hospital to home,” he added.

Safety profile

Dr. Sankar noted that with approval now of both the IV and oral formulations for partial-onset seizures in such young children, “we have a new option that helps meet a critical need in pediatric epilepsy.”

The most common adverse reactions with brivaracetam include somnolence and sedation, dizziness, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting. In the pediatric clinical trials, the safety profile for pediatric patients was similar to adults.

In the adult trials, psychiatric adverse reactions, including nonpsychotic and psychotic symptoms, were reported in approximately 13% of adults taking at least 50 mg/day of brivaracetam compared with 8% taking placebo.

Psychiatric adverse reactions were also observed in open-label pediatric trials and were generally similar to those observed in adults.

Patients should be advised to report these symptoms immediately to a health care professional, the company noted.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ACST-2: Carotid stenting, surgery on par in asymptomatic patients

Carotid artery stenting (CAS) and carotid endarterectomy (CEA) provided comparable outcomes over time in asymptomatic patients receiving good medical therapy in the largest trial to date of what to do with severe carotid artery narrowing that is yet to cause a stroke.

Among more than 3,600 patients, stenting and surgery performed by experienced physicians involved a 1.0% risk for causing disabling stroke or death within 30 days.

The annual rate of fatal or disabling strokes was about 0.5% with either procedure over an average 5 years’ follow-up – essentially halving the annual stroke risk had neither procedure been performed, according to Alison Halliday, MD, principal investigator of the Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial-2 (ACST-2).

The results were reported Aug. 29 in a Hot Line session at the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology and published simultaneously online in The Lancet.

Session chair Gilles Montalescot, MD, Sorbonne University, Paris, noted that ACST-2 doubled the number of randomly assigned patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis studied in previous trials, “so, a huge contribution to the evidence base in this field and apparently good news for both revascularization techniques.”

Thirty-day and 5-year outcomes

The trial was conducted in 33 countries between January 2008 and December 2020, enrolling 3,625 patients (70% were male; mean age, 70 years) with carotid stenosis of at least 60% on ultrasonography, in whom stenting or surgery was suitable but both the doctor and patient were “substantially uncertain” which procedure to prefer.

Among the 1,811 patients assigned to stenting, 87% underwent the procedure at a median of 14 days; 6% crossed over to surgery, typically because of a highly calcified lesion or a more tortuous carotid than anticipated; and 6% had no intervention.

Among the 1,814 patients assigned to surgery, 92% had the procedure at a median of 14 days; 3% crossed over to stenting, typically because of patient or doctor preference or reluctance to undergo general anesthesia; and 4% had no intervention.

Patients without complications who had stenting stayed on average 1 day less than did those undergoing surgery.

During an earlier press briefing, Dr. Halliday highlighted the need for procedural competency and said doctors had to submit a record of their CEA or CAS experience and, consistent with current guidelines, had to demonstrate an independently verified stroke or death rate of 6% or less for symptomatic patients and 3% or lower for asymptomatic patients.

The results showed the 30-day risk for death, myocardial infarction (MI), or any stroke was 3.9% with carotid stenting and 3.2% with surgery (P = .26).

But with stenting, there was a slightly higher risk for procedural nondisabling strokes (48 vs. 29; P = .03), including 15 strokes vs. 5 strokes, respectively, that left patients with no residual symptoms. This is “consistent with large, recent nationally representative registry data,” observed Dr. Halliday, of the University of Oxford (England).

For those undergoing surgery, cranial nerve palsies were reported in 5.4% vs. no patients undergoing stenting.

At 5 years, the nonprocedural fatal or disabling stroke rate was 2.5% in each group (rate ratio [RR], 0.98; P = .91), with any nonprocedural stroke occurring in 5.3% of patients with stenting vs. 4.5% with surgery (RR, 1.16; P = .33).

The investigators performed a meta-analysis combining the ACST-2 results with those of eight prior trials (four in asymptomatic and four in symptomatic patients) that yielded a similar nonsignificant result for any nonprocedural stroke (RR, 1.11; P = .21).

Based on the results from ACST-2 plus the major trials, stenting and surgery involve “similar risks and similar benefits,” Dr. Halliday concluded.

Discussant Marco Roffi, MD, University Hospital of Geneva, said, “In centers with documented expertise, carotid artery stenting should be offered as an alternative to carotid endarterectomy in patients with asymptomatic stenosis and suitable anatomy.”

While the trial provides “good news” for patients, he pointed out that a reduction in the sample size from 5,000 to 3,625 limited the statistical power and that enrollment over a long period of time may have introduced confounders, such as changes in equipment technique, and medical therapy.

Also, many centers enrolled few patients, raising the concern over low-volume centers and operators, Dr. Roffi said. “We know that 8% of the centers enrolled 39% of the patients,” and “information on the credentialing and experience of the interventionalists was limited.”

Further, a lack of systematic MI assessment may have favored the surgery group, and more recent developments in stenting with the potential of reducing periprocedural stroke were rarely used, such as proximal emboli protection in only 15% and double-layer stents in 11%.

Friedhelm Beyersdorf, MD, University Hospital of Freiburg, Germany, said that, as a vascular surgeon, he finds it understandable that there might be a higher incidence of nonfatal strokes when treating carotid stenosis with stents, given the vulnerability of these lesions.

“Nevertheless, the main conclusion from the entire study is that carotid artery treatment is extremely safe, it has to be done in order to avoid strokes, and, obviously, there seems to be an advantage for surgery in terms of nondisabling stroke,” he said.

Session chair Dr. Montalescot, however, said that what the study cannot address – and what was the subject of many online audience comments – is whether either intervention should be performed in these patients.

Unlike earlier trials comparing interventions to medical therapy, Dr. Halliday said ACST-2 enrolled patients for whom the decision had been made that revascularization was needed. In addition, 99%-100% were receiving antithrombotic therapy at baseline, 85%-90% were receiving antihypertensives, and about 85% were taking statins.

Longer-term follow-up should provide a better picture of the nonprocedural stroke risk, with patients asked annually about exactly what medications and doses they are taking, she said.

“We will have an enormous list of exactly what’s gone on and the intensity of that therapy, which is, of course, much more intense than when we carried out our first trial. But these were people in whom a procedure was thought to be necessary,” she noted.

When asked during the press conference which procedure she would choose, Dr. Halliday, a surgeon, observed that patient preference is important but that the nature of the lesion itself often determines the optimal choice.

“If you know the competence of the people doing it is equal, then the less invasive procedure – providing it has good long-term viability, and that’s why we’re following for 10 years – is the more important,” she added.

The study was funded by the UK Medical Research Council and Health Technology Assessment Programme. Dr. Halliday reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Carotid artery stenting (CAS) and carotid endarterectomy (CEA) provided comparable outcomes over time in asymptomatic patients receiving good medical therapy in the largest trial to date of what to do with severe carotid artery narrowing that is yet to cause a stroke.

Among more than 3,600 patients, stenting and surgery performed by experienced physicians involved a 1.0% risk for causing disabling stroke or death within 30 days.

The annual rate of fatal or disabling strokes was about 0.5% with either procedure over an average 5 years’ follow-up – essentially halving the annual stroke risk had neither procedure been performed, according to Alison Halliday, MD, principal investigator of the Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial-2 (ACST-2).

The results were reported Aug. 29 in a Hot Line session at the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology and published simultaneously online in The Lancet.

Session chair Gilles Montalescot, MD, Sorbonne University, Paris, noted that ACST-2 doubled the number of randomly assigned patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis studied in previous trials, “so, a huge contribution to the evidence base in this field and apparently good news for both revascularization techniques.”

Thirty-day and 5-year outcomes

The trial was conducted in 33 countries between January 2008 and December 2020, enrolling 3,625 patients (70% were male; mean age, 70 years) with carotid stenosis of at least 60% on ultrasonography, in whom stenting or surgery was suitable but both the doctor and patient were “substantially uncertain” which procedure to prefer.

Among the 1,811 patients assigned to stenting, 87% underwent the procedure at a median of 14 days; 6% crossed over to surgery, typically because of a highly calcified lesion or a more tortuous carotid than anticipated; and 6% had no intervention.

Among the 1,814 patients assigned to surgery, 92% had the procedure at a median of 14 days; 3% crossed over to stenting, typically because of patient or doctor preference or reluctance to undergo general anesthesia; and 4% had no intervention.

Patients without complications who had stenting stayed on average 1 day less than did those undergoing surgery.

During an earlier press briefing, Dr. Halliday highlighted the need for procedural competency and said doctors had to submit a record of their CEA or CAS experience and, consistent with current guidelines, had to demonstrate an independently verified stroke or death rate of 6% or less for symptomatic patients and 3% or lower for asymptomatic patients.

The results showed the 30-day risk for death, myocardial infarction (MI), or any stroke was 3.9% with carotid stenting and 3.2% with surgery (P = .26).

But with stenting, there was a slightly higher risk for procedural nondisabling strokes (48 vs. 29; P = .03), including 15 strokes vs. 5 strokes, respectively, that left patients with no residual symptoms. This is “consistent with large, recent nationally representative registry data,” observed Dr. Halliday, of the University of Oxford (England).

For those undergoing surgery, cranial nerve palsies were reported in 5.4% vs. no patients undergoing stenting.

At 5 years, the nonprocedural fatal or disabling stroke rate was 2.5% in each group (rate ratio [RR], 0.98; P = .91), with any nonprocedural stroke occurring in 5.3% of patients with stenting vs. 4.5% with surgery (RR, 1.16; P = .33).

The investigators performed a meta-analysis combining the ACST-2 results with those of eight prior trials (four in asymptomatic and four in symptomatic patients) that yielded a similar nonsignificant result for any nonprocedural stroke (RR, 1.11; P = .21).

Based on the results from ACST-2 plus the major trials, stenting and surgery involve “similar risks and similar benefits,” Dr. Halliday concluded.

Discussant Marco Roffi, MD, University Hospital of Geneva, said, “In centers with documented expertise, carotid artery stenting should be offered as an alternative to carotid endarterectomy in patients with asymptomatic stenosis and suitable anatomy.”

While the trial provides “good news” for patients, he pointed out that a reduction in the sample size from 5,000 to 3,625 limited the statistical power and that enrollment over a long period of time may have introduced confounders, such as changes in equipment technique, and medical therapy.

Also, many centers enrolled few patients, raising the concern over low-volume centers and operators, Dr. Roffi said. “We know that 8% of the centers enrolled 39% of the patients,” and “information on the credentialing and experience of the interventionalists was limited.”

Further, a lack of systematic MI assessment may have favored the surgery group, and more recent developments in stenting with the potential of reducing periprocedural stroke were rarely used, such as proximal emboli protection in only 15% and double-layer stents in 11%.

Friedhelm Beyersdorf, MD, University Hospital of Freiburg, Germany, said that, as a vascular surgeon, he finds it understandable that there might be a higher incidence of nonfatal strokes when treating carotid stenosis with stents, given the vulnerability of these lesions.

“Nevertheless, the main conclusion from the entire study is that carotid artery treatment is extremely safe, it has to be done in order to avoid strokes, and, obviously, there seems to be an advantage for surgery in terms of nondisabling stroke,” he said.

Session chair Dr. Montalescot, however, said that what the study cannot address – and what was the subject of many online audience comments – is whether either intervention should be performed in these patients.

Unlike earlier trials comparing interventions to medical therapy, Dr. Halliday said ACST-2 enrolled patients for whom the decision had been made that revascularization was needed. In addition, 99%-100% were receiving antithrombotic therapy at baseline, 85%-90% were receiving antihypertensives, and about 85% were taking statins.

Longer-term follow-up should provide a better picture of the nonprocedural stroke risk, with patients asked annually about exactly what medications and doses they are taking, she said.

“We will have an enormous list of exactly what’s gone on and the intensity of that therapy, which is, of course, much more intense than when we carried out our first trial. But these were people in whom a procedure was thought to be necessary,” she noted.

When asked during the press conference which procedure she would choose, Dr. Halliday, a surgeon, observed that patient preference is important but that the nature of the lesion itself often determines the optimal choice.

“If you know the competence of the people doing it is equal, then the less invasive procedure – providing it has good long-term viability, and that’s why we’re following for 10 years – is the more important,” she added.

The study was funded by the UK Medical Research Council and Health Technology Assessment Programme. Dr. Halliday reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Carotid artery stenting (CAS) and carotid endarterectomy (CEA) provided comparable outcomes over time in asymptomatic patients receiving good medical therapy in the largest trial to date of what to do with severe carotid artery narrowing that is yet to cause a stroke.

Among more than 3,600 patients, stenting and surgery performed by experienced physicians involved a 1.0% risk for causing disabling stroke or death within 30 days.

The annual rate of fatal or disabling strokes was about 0.5% with either procedure over an average 5 years’ follow-up – essentially halving the annual stroke risk had neither procedure been performed, according to Alison Halliday, MD, principal investigator of the Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial-2 (ACST-2).

The results were reported Aug. 29 in a Hot Line session at the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology and published simultaneously online in The Lancet.

Session chair Gilles Montalescot, MD, Sorbonne University, Paris, noted that ACST-2 doubled the number of randomly assigned patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis studied in previous trials, “so, a huge contribution to the evidence base in this field and apparently good news for both revascularization techniques.”

Thirty-day and 5-year outcomes

The trial was conducted in 33 countries between January 2008 and December 2020, enrolling 3,625 patients (70% were male; mean age, 70 years) with carotid stenosis of at least 60% on ultrasonography, in whom stenting or surgery was suitable but both the doctor and patient were “substantially uncertain” which procedure to prefer.

Among the 1,811 patients assigned to stenting, 87% underwent the procedure at a median of 14 days; 6% crossed over to surgery, typically because of a highly calcified lesion or a more tortuous carotid than anticipated; and 6% had no intervention.

Among the 1,814 patients assigned to surgery, 92% had the procedure at a median of 14 days; 3% crossed over to stenting, typically because of patient or doctor preference or reluctance to undergo general anesthesia; and 4% had no intervention.

Patients without complications who had stenting stayed on average 1 day less than did those undergoing surgery.

During an earlier press briefing, Dr. Halliday highlighted the need for procedural competency and said doctors had to submit a record of their CEA or CAS experience and, consistent with current guidelines, had to demonstrate an independently verified stroke or death rate of 6% or less for symptomatic patients and 3% or lower for asymptomatic patients.