User login

Program decreased seizure frequency for people with epilepsy

NEW ORLEANS – A self-management program that focused on medication adherence, sleep, nutrition, and stress reduction was associated with decreased seizures and improved quality of life for adults with epilepsy.

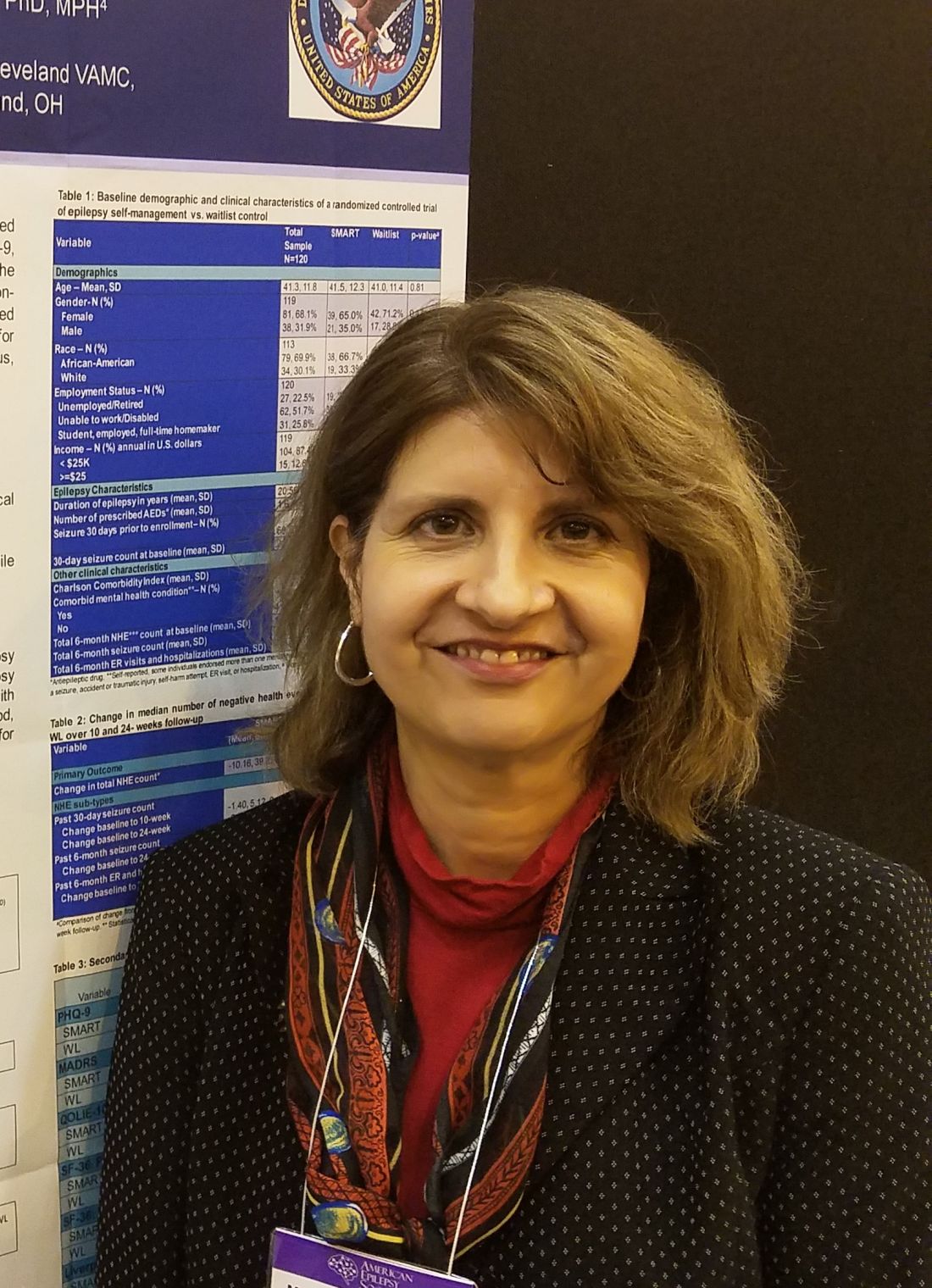

SMART (Self‐management for people with epilepsy and a history of negative health events) also was associated with improved depression scores and overall quality of life measures in participants, compared with a wait-listed control group, Martha Sajatovic, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“I believe what we’re seeing is a result of improved self-management,” said Dr. Sajatovic, the Willard Brown Chair in Neurological Outcomes Research at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. “This is multimodal, including better medication adherence, which in turn is related to better communication with the clinician. For example, if patients are not sleeping well or their medicine makes them nauseated or they experience sexual dysfunction, we encourage them to talk to their docs about what they can live with, and what they can’t.”

Presented as a poster during the meeting, the SMART study was also published in Epilepsia.

SMART is an 8-week online educational program delivered by a nurse educator and a “peer educator,” a person with epilepsy who has had at least three negative health events. The first session is an in-person visit during which the team gets acquainted and discusses goals. The remaining sessions are self-paced and delivered on computer tablets provided by the investigators.

SMART didn’t just focus on the physical issues of living with epilepsy, Dr. Sajatovic said in an interview. Sessions also discussed the stigma still associated with the disorder, and myths that unnecessarily inflate perceptions. Discussions include goal setting, epilepsy complications and how to manage them, the importance of good sleep hygiene, problem-solving skills, nutrition and substance abuse, exercise, and how to deal with medication side effects.

“One thing we really stressed was sharing information in a way that was accessible to all patients and fostered self-motivation,” she said. “Most of our participants had never been in a program like this before. It was very empowering for many.”

The researchers chose participants who were socioeconomically challenged for this project; 88% made less than $25,000 per year and 74% were unemployed. The mean age of participants was 41 years, 70% were black, and most had been living with epilepsy at least half of their life. About 70% lived alone, and 70% had experienced at least one seizure within the month before enrolling. Mental health comorbidities were common; 69% had depression, 32% had anxiety, and 13% had PTSD.

The study enrolled 120 people, who were evenly divided between the intervention group and the wait-list group. The primary outcome was the change in total negative health events from baseline to the study’s end. Negative health events were seizures and ED or hospital admissions for any other causes including attempts at self-harm, falls, and accidents.

Secondary outcomes included changes in depression scores as measured by the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale and the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire. Quality of life was measured using the 10-item Quality of Life in Epilepsy; functional status was measured using the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey.

At baseline, the total mean 6-month negative health events count was 15, with 13 events being seizures. The other events were hospital or ED visits for other reasons.

At the end of the study, the intervention group experienced a significant mean decrease of 10 fewer negative health events, compared with a decrease of 2 in the wait-listed group. This was largely driven by a mean of 7.8 fewer seizures in the active group, compared with a decrease of about 1.0 in the wait-listed group. The 6-month ER and hospitalization counts did not significantly change.

Among the secondary outcomes, depression, overall health, and quality of life all improved significantly in the intervention group, compared with the wait-listed group. The intervention group also had significant decreases in depression measures and improvements in daily function measures, Dr. Sajatovic said.

“It was so gratifying to see this. Most of our participants had never been in a program like this before. It was a chance for them to take control of their epilepsy, instead of simply having it control them,” she said.

This study was supported by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Sajatovic had no financial disclosures related to this presentation.

SOURCE: Sajatovic M et al.

NEW ORLEANS – A self-management program that focused on medication adherence, sleep, nutrition, and stress reduction was associated with decreased seizures and improved quality of life for adults with epilepsy.

SMART (Self‐management for people with epilepsy and a history of negative health events) also was associated with improved depression scores and overall quality of life measures in participants, compared with a wait-listed control group, Martha Sajatovic, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“I believe what we’re seeing is a result of improved self-management,” said Dr. Sajatovic, the Willard Brown Chair in Neurological Outcomes Research at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. “This is multimodal, including better medication adherence, which in turn is related to better communication with the clinician. For example, if patients are not sleeping well or their medicine makes them nauseated or they experience sexual dysfunction, we encourage them to talk to their docs about what they can live with, and what they can’t.”

Presented as a poster during the meeting, the SMART study was also published in Epilepsia.

SMART is an 8-week online educational program delivered by a nurse educator and a “peer educator,” a person with epilepsy who has had at least three negative health events. The first session is an in-person visit during which the team gets acquainted and discusses goals. The remaining sessions are self-paced and delivered on computer tablets provided by the investigators.

SMART didn’t just focus on the physical issues of living with epilepsy, Dr. Sajatovic said in an interview. Sessions also discussed the stigma still associated with the disorder, and myths that unnecessarily inflate perceptions. Discussions include goal setting, epilepsy complications and how to manage them, the importance of good sleep hygiene, problem-solving skills, nutrition and substance abuse, exercise, and how to deal with medication side effects.

“One thing we really stressed was sharing information in a way that was accessible to all patients and fostered self-motivation,” she said. “Most of our participants had never been in a program like this before. It was very empowering for many.”

The researchers chose participants who were socioeconomically challenged for this project; 88% made less than $25,000 per year and 74% were unemployed. The mean age of participants was 41 years, 70% were black, and most had been living with epilepsy at least half of their life. About 70% lived alone, and 70% had experienced at least one seizure within the month before enrolling. Mental health comorbidities were common; 69% had depression, 32% had anxiety, and 13% had PTSD.

The study enrolled 120 people, who were evenly divided between the intervention group and the wait-list group. The primary outcome was the change in total negative health events from baseline to the study’s end. Negative health events were seizures and ED or hospital admissions for any other causes including attempts at self-harm, falls, and accidents.

Secondary outcomes included changes in depression scores as measured by the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale and the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire. Quality of life was measured using the 10-item Quality of Life in Epilepsy; functional status was measured using the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey.

At baseline, the total mean 6-month negative health events count was 15, with 13 events being seizures. The other events were hospital or ED visits for other reasons.

At the end of the study, the intervention group experienced a significant mean decrease of 10 fewer negative health events, compared with a decrease of 2 in the wait-listed group. This was largely driven by a mean of 7.8 fewer seizures in the active group, compared with a decrease of about 1.0 in the wait-listed group. The 6-month ER and hospitalization counts did not significantly change.

Among the secondary outcomes, depression, overall health, and quality of life all improved significantly in the intervention group, compared with the wait-listed group. The intervention group also had significant decreases in depression measures and improvements in daily function measures, Dr. Sajatovic said.

“It was so gratifying to see this. Most of our participants had never been in a program like this before. It was a chance for them to take control of their epilepsy, instead of simply having it control them,” she said.

This study was supported by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Sajatovic had no financial disclosures related to this presentation.

SOURCE: Sajatovic M et al.

NEW ORLEANS – A self-management program that focused on medication adherence, sleep, nutrition, and stress reduction was associated with decreased seizures and improved quality of life for adults with epilepsy.

SMART (Self‐management for people with epilepsy and a history of negative health events) also was associated with improved depression scores and overall quality of life measures in participants, compared with a wait-listed control group, Martha Sajatovic, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“I believe what we’re seeing is a result of improved self-management,” said Dr. Sajatovic, the Willard Brown Chair in Neurological Outcomes Research at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. “This is multimodal, including better medication adherence, which in turn is related to better communication with the clinician. For example, if patients are not sleeping well or their medicine makes them nauseated or they experience sexual dysfunction, we encourage them to talk to their docs about what they can live with, and what they can’t.”

Presented as a poster during the meeting, the SMART study was also published in Epilepsia.

SMART is an 8-week online educational program delivered by a nurse educator and a “peer educator,” a person with epilepsy who has had at least three negative health events. The first session is an in-person visit during which the team gets acquainted and discusses goals. The remaining sessions are self-paced and delivered on computer tablets provided by the investigators.

SMART didn’t just focus on the physical issues of living with epilepsy, Dr. Sajatovic said in an interview. Sessions also discussed the stigma still associated with the disorder, and myths that unnecessarily inflate perceptions. Discussions include goal setting, epilepsy complications and how to manage them, the importance of good sleep hygiene, problem-solving skills, nutrition and substance abuse, exercise, and how to deal with medication side effects.

“One thing we really stressed was sharing information in a way that was accessible to all patients and fostered self-motivation,” she said. “Most of our participants had never been in a program like this before. It was very empowering for many.”

The researchers chose participants who were socioeconomically challenged for this project; 88% made less than $25,000 per year and 74% were unemployed. The mean age of participants was 41 years, 70% were black, and most had been living with epilepsy at least half of their life. About 70% lived alone, and 70% had experienced at least one seizure within the month before enrolling. Mental health comorbidities were common; 69% had depression, 32% had anxiety, and 13% had PTSD.

The study enrolled 120 people, who were evenly divided between the intervention group and the wait-list group. The primary outcome was the change in total negative health events from baseline to the study’s end. Negative health events were seizures and ED or hospital admissions for any other causes including attempts at self-harm, falls, and accidents.

Secondary outcomes included changes in depression scores as measured by the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale and the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire. Quality of life was measured using the 10-item Quality of Life in Epilepsy; functional status was measured using the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey.

At baseline, the total mean 6-month negative health events count was 15, with 13 events being seizures. The other events were hospital or ED visits for other reasons.

At the end of the study, the intervention group experienced a significant mean decrease of 10 fewer negative health events, compared with a decrease of 2 in the wait-listed group. This was largely driven by a mean of 7.8 fewer seizures in the active group, compared with a decrease of about 1.0 in the wait-listed group. The 6-month ER and hospitalization counts did not significantly change.

Among the secondary outcomes, depression, overall health, and quality of life all improved significantly in the intervention group, compared with the wait-listed group. The intervention group also had significant decreases in depression measures and improvements in daily function measures, Dr. Sajatovic said.

“It was so gratifying to see this. Most of our participants had never been in a program like this before. It was a chance for them to take control of their epilepsy, instead of simply having it control them,” she said.

This study was supported by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Sajatovic had no financial disclosures related to this presentation.

SOURCE: Sajatovic M et al.

REPORTING FROM AES 2018

Key clinical point: Patients with epilepsy had fewer seizures and improved quality of life after 6 months of participation in a program that teaches self-management techniques.

Major finding: The intervention group had a mean of 7.8 fewer seizures, compared with their baseline count during the 6-month study.

Study details: The prospective study randomized 120 people to either the intervention group or a wait-list group.

Disclosures: This study was supported by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Sajatovic reported no financial disclosures related to this presentation.

Source: Sajatovic M et al. AES

SUDEP risk may change over time

, based on study results presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Based on 3 years of data collected from over 12,000 people with epilepsy, 27.0% who had been at high risk (three or more generalized tonic-clonic seizures [GTCs] per year) at baseline moved out of the high-risk category. In addition, 32.5% at medium risk (one to two GTCs per year) at baseline changed categories. Finally, 7.0% in the low-risk category (no GTC seizures in the last year) at baseline moved to a higher-risk category.

“An individual’s risk [of SUDEP] is not set in stone,” said Neishay Ayub, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, who presented the data at the meeting. “Our findings support the recommendation that for people with epilepsy who have ongoing generalized tonic-clonic seizures, the goal of treatment is to reduce GTCs and thereby lower SUDEP risk.”

A 2017 practice guideline summary from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society identified the presence and frequency of GTCs and absence of seizure freedom as risk factors for SUDEP. Using these measures, Dr. Ayub and colleagues sought to stratify patients according to their risk of SUDEP and monitor how risk changed over time. They collected information about more than 1.4 million seizures that occurred from December 2007 to February 2018 in 12,402 users of the electronic diary Seizure Tracker.

For each user, the researchers calculated the number of generalized seizures for each year since the initial seizure diary entry. They categorized each user as being at low, medium, or high risk of SUDEP during each year. Low risk was defined as no generalized seizures in a year. Medium risk was defined as one or two generalized seizures in a year. High risk was defined as three or more generalized seizures in a year.

“The next step would be to see if we can confirm this patient-reported data with an objective study to determine when seizures did or did not occur,” said Daniel Goldenholz, MD, PhD, also of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and senior author of the study. “For example, assessing information using new FDA [Food and Drug Administration]-approved wearable seizure tracker devices could give us a more comprehensive picture.”

The study was funded by the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston.

SOURCE: Ayub N et al. AES 2018, Abstract 2.158.

, based on study results presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Based on 3 years of data collected from over 12,000 people with epilepsy, 27.0% who had been at high risk (three or more generalized tonic-clonic seizures [GTCs] per year) at baseline moved out of the high-risk category. In addition, 32.5% at medium risk (one to two GTCs per year) at baseline changed categories. Finally, 7.0% in the low-risk category (no GTC seizures in the last year) at baseline moved to a higher-risk category.

“An individual’s risk [of SUDEP] is not set in stone,” said Neishay Ayub, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, who presented the data at the meeting. “Our findings support the recommendation that for people with epilepsy who have ongoing generalized tonic-clonic seizures, the goal of treatment is to reduce GTCs and thereby lower SUDEP risk.”

A 2017 practice guideline summary from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society identified the presence and frequency of GTCs and absence of seizure freedom as risk factors for SUDEP. Using these measures, Dr. Ayub and colleagues sought to stratify patients according to their risk of SUDEP and monitor how risk changed over time. They collected information about more than 1.4 million seizures that occurred from December 2007 to February 2018 in 12,402 users of the electronic diary Seizure Tracker.

For each user, the researchers calculated the number of generalized seizures for each year since the initial seizure diary entry. They categorized each user as being at low, medium, or high risk of SUDEP during each year. Low risk was defined as no generalized seizures in a year. Medium risk was defined as one or two generalized seizures in a year. High risk was defined as three or more generalized seizures in a year.

“The next step would be to see if we can confirm this patient-reported data with an objective study to determine when seizures did or did not occur,” said Daniel Goldenholz, MD, PhD, also of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and senior author of the study. “For example, assessing information using new FDA [Food and Drug Administration]-approved wearable seizure tracker devices could give us a more comprehensive picture.”

The study was funded by the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston.

SOURCE: Ayub N et al. AES 2018, Abstract 2.158.

, based on study results presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Based on 3 years of data collected from over 12,000 people with epilepsy, 27.0% who had been at high risk (three or more generalized tonic-clonic seizures [GTCs] per year) at baseline moved out of the high-risk category. In addition, 32.5% at medium risk (one to two GTCs per year) at baseline changed categories. Finally, 7.0% in the low-risk category (no GTC seizures in the last year) at baseline moved to a higher-risk category.

“An individual’s risk [of SUDEP] is not set in stone,” said Neishay Ayub, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, who presented the data at the meeting. “Our findings support the recommendation that for people with epilepsy who have ongoing generalized tonic-clonic seizures, the goal of treatment is to reduce GTCs and thereby lower SUDEP risk.”

A 2017 practice guideline summary from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society identified the presence and frequency of GTCs and absence of seizure freedom as risk factors for SUDEP. Using these measures, Dr. Ayub and colleagues sought to stratify patients according to their risk of SUDEP and monitor how risk changed over time. They collected information about more than 1.4 million seizures that occurred from December 2007 to February 2018 in 12,402 users of the electronic diary Seizure Tracker.

For each user, the researchers calculated the number of generalized seizures for each year since the initial seizure diary entry. They categorized each user as being at low, medium, or high risk of SUDEP during each year. Low risk was defined as no generalized seizures in a year. Medium risk was defined as one or two generalized seizures in a year. High risk was defined as three or more generalized seizures in a year.

“The next step would be to see if we can confirm this patient-reported data with an objective study to determine when seizures did or did not occur,” said Daniel Goldenholz, MD, PhD, also of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and senior author of the study. “For example, assessing information using new FDA [Food and Drug Administration]-approved wearable seizure tracker devices could give us a more comprehensive picture.”

The study was funded by the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston.

SOURCE: Ayub N et al. AES 2018, Abstract 2.158.

REPORTING FROM AES 2018

Key clinical point: Yearly patient risk assessments for sudden unexpected death in epilepsy are advisable.

Major finding: About 7% of people with no generalized tonic-clonic seizures in the last year at baseline moved to a higher-risk category.

Study details: An analysis of self-reported seizures by 12,402 users of Seizure Tracker.

Disclosures: The Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, funded the study.

Source: Ayub N et al. AES 2018, Abstract 2.158.

Depression is linked to seizure frequency in patients with epilepsy

NEW ORLEANS –

The conclusion comes from a study of 120 people with epilepsy, 62 of whom had at least moderate depression based on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). The Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM-R), Quality of Life in Epilepsy (QOLIE-10) and Charlson Comorbidity Index were used to assess patients’ health literacy, quality of life, and medical comorbidity, respectively

Among demographic characteristics, only inability to work was significantly associated with depression severity. Higher 30-day seizure frequency, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder were correlated with more severe depression severity. Medical comorbidity was not associated with increased risk of depression.

Identifying and treating psychiatric comorbidities should be part of the management of patients with epilepsy, said Martha X. Sajatovic, MD, director of the Neurological and Behavioral Outcomes Center at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, who presented the data. “Following up to ensure they receive treatment is vital, because it can truly change patient outcomes and help them achieve their best quality of life.”

The study findings are consistent with those of previous research indicating that people with symptoms of depression are more likely to have more frequent seizures and decreased quality of life, said Dr. Sajatovic.

“Health care providers should screen their epilepsy patients for depression, but they shouldn’t stop there,” she advised. “A person may have depressive symptoms that don’t reach the level of depression but should be assessed for other types of mental health issues that could easily be overlooked.”

Patients with epilepsy should respond to the PHQ-9 annually, or more frequently, if warranted, she added.

“It’s important that people with epilepsy who have depression or other mental health issues get treatment such as cognitive behavioral therapy and medication,” said Dr. Sajatovic. “Even being in a self-management program helps, because the better they are at self management, the less likely they are to suffer negative health effects.”

This study was supported by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention SIP 14-007 1U48DP005030.

SOURCE: Kumar N et al. AES 2018, Abstract 1.371.

NEW ORLEANS –

The conclusion comes from a study of 120 people with epilepsy, 62 of whom had at least moderate depression based on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). The Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM-R), Quality of Life in Epilepsy (QOLIE-10) and Charlson Comorbidity Index were used to assess patients’ health literacy, quality of life, and medical comorbidity, respectively

Among demographic characteristics, only inability to work was significantly associated with depression severity. Higher 30-day seizure frequency, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder were correlated with more severe depression severity. Medical comorbidity was not associated with increased risk of depression.

Identifying and treating psychiatric comorbidities should be part of the management of patients with epilepsy, said Martha X. Sajatovic, MD, director of the Neurological and Behavioral Outcomes Center at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, who presented the data. “Following up to ensure they receive treatment is vital, because it can truly change patient outcomes and help them achieve their best quality of life.”

The study findings are consistent with those of previous research indicating that people with symptoms of depression are more likely to have more frequent seizures and decreased quality of life, said Dr. Sajatovic.

“Health care providers should screen their epilepsy patients for depression, but they shouldn’t stop there,” she advised. “A person may have depressive symptoms that don’t reach the level of depression but should be assessed for other types of mental health issues that could easily be overlooked.”

Patients with epilepsy should respond to the PHQ-9 annually, or more frequently, if warranted, she added.

“It’s important that people with epilepsy who have depression or other mental health issues get treatment such as cognitive behavioral therapy and medication,” said Dr. Sajatovic. “Even being in a self-management program helps, because the better they are at self management, the less likely they are to suffer negative health effects.”

This study was supported by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention SIP 14-007 1U48DP005030.

SOURCE: Kumar N et al. AES 2018, Abstract 1.371.

NEW ORLEANS –

The conclusion comes from a study of 120 people with epilepsy, 62 of whom had at least moderate depression based on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). The Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM-R), Quality of Life in Epilepsy (QOLIE-10) and Charlson Comorbidity Index were used to assess patients’ health literacy, quality of life, and medical comorbidity, respectively

Among demographic characteristics, only inability to work was significantly associated with depression severity. Higher 30-day seizure frequency, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder were correlated with more severe depression severity. Medical comorbidity was not associated with increased risk of depression.

Identifying and treating psychiatric comorbidities should be part of the management of patients with epilepsy, said Martha X. Sajatovic, MD, director of the Neurological and Behavioral Outcomes Center at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, who presented the data. “Following up to ensure they receive treatment is vital, because it can truly change patient outcomes and help them achieve their best quality of life.”

The study findings are consistent with those of previous research indicating that people with symptoms of depression are more likely to have more frequent seizures and decreased quality of life, said Dr. Sajatovic.

“Health care providers should screen their epilepsy patients for depression, but they shouldn’t stop there,” she advised. “A person may have depressive symptoms that don’t reach the level of depression but should be assessed for other types of mental health issues that could easily be overlooked.”

Patients with epilepsy should respond to the PHQ-9 annually, or more frequently, if warranted, she added.

“It’s important that people with epilepsy who have depression or other mental health issues get treatment such as cognitive behavioral therapy and medication,” said Dr. Sajatovic. “Even being in a self-management program helps, because the better they are at self management, the less likely they are to suffer negative health effects.”

This study was supported by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention SIP 14-007 1U48DP005030.

SOURCE: Kumar N et al. AES 2018, Abstract 1.371.

REPORTING FROM AES 2018

Key clinical point: Identification and treatment of psychiatric comorbidities are appropriate components of epilepsy management.

Major finding: Half of participants in a randomized, controlled trial had depression of at least moderate severity.

Study details: Researchers analyzed data from a trial of 120 people with epilepsy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by a grant from the CDC SIP 14-007 1U48DP005030.

Source: Kumar N et al. Abstract 1.371.

Enzyme-inducing AEDs may raise vitamin D dose requirements

NEW ORLEANS – Patients taking enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) may require a clinically meaningful increase in their vitamin D doses to achieve the same 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) plasma levels as patients taking nonenzyme-inducing AEDs, based on a retrospective chart review presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

While patients receiving either type of AED had similar average 25(OH)D levels in the study (32.0 ng/mL in the enzyme-inducing AED group and 33.2 ng/mL in the noninducing AED group), those in the enzyme-inducing group required 1,587 U/day to meet the goal – a 409-unit increase in dose, compared with the 1,108 U/day dose taken by patients in the nonenzyme-inducing group.

“Patients taking enzyme-inducing AEDs may benefit from more intensive monitoring of their vitamin D supplementation, and clinicians should anticipate this likely pharmacokinetic interaction,” said Barry E. Gidal, PharmD, professor of pharmacy and neurology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, and his colleagues.

Researchers have suggested that enzyme-inducing AEDs may affect CYP450 isoenzymes, increase vitamin D metabolism, and reduce 25(OH)D plasma levels. “It follows … that a potential pharmacokinetic interaction could exist between enzyme-inducing AEDs and oral formulations of vitamin D used for supplementation,” the investigators said.

To test the hypothesis, Dr. Gidal and his colleagues reviewed the charts of patients with epilepsy who were on any AED regimen and were prescribed vitamin D at William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin, between January 2013 and September 2017.

The researchers grouped patients by those using enzyme-inducing AEDs and those taking noninducing AEDs. Patients who were taking AEDs in both categories were placed in the enzyme-inducing AED group. Patients with malabsorptive conditions and patients using calcitriol were excluded from the analysis.

Data included AEDs used, prescription and over-the-counter vitamin D use, 25(OH)D plasma concentration, renal function, age, gender, and ethnicity. Patients’ 25(OH)D levels were measured using a chemiluminescence immunoassay, and a minimum 25(OH)D plasma level of 30 ng/mL was the therapeutic goal.

The multivariant analysis was adjusted for potentially confounding variables including 25(OH)D concentration, over-the-counter vitamin D use, chronic kidney disease, age, gender, and ethnicity.

The analysis included 1,113 observations from 315 patients, and 263 of the observations (23.6%) were in the enzyme-inducing AED group. The enzyme-inducing group and noninducing groups were mostly male (90.5% and 91.8%, respectively) and similar in average age (65.9 and 61.4 years, respectively). Variables were evenly distributed between the groups, with the exceptions of chronic kidney disease, which was less common in the enzyme-inducing group (6.1% vs. 13.8%), and ethnicity (78.7% Caucasian in the enzyme-inducing group vs. 87.7% Caucasian in the noninducing group). The most common enzyme-inducing AED was phenytoin (50.6%), followed by carbamazepine (31.9%), phenobarbital (14.1%), oxcarbazepine (6.8%), primidone (1.9%), and eslicarbazepine (0.8%).

Dr. Gidal reported honoraria from Eisai, Sunovion, Lundbeck, and GW Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Gidal BE et al. AES 2018, Abstract 1.315.

NEW ORLEANS – Patients taking enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) may require a clinically meaningful increase in their vitamin D doses to achieve the same 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) plasma levels as patients taking nonenzyme-inducing AEDs, based on a retrospective chart review presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

While patients receiving either type of AED had similar average 25(OH)D levels in the study (32.0 ng/mL in the enzyme-inducing AED group and 33.2 ng/mL in the noninducing AED group), those in the enzyme-inducing group required 1,587 U/day to meet the goal – a 409-unit increase in dose, compared with the 1,108 U/day dose taken by patients in the nonenzyme-inducing group.

“Patients taking enzyme-inducing AEDs may benefit from more intensive monitoring of their vitamin D supplementation, and clinicians should anticipate this likely pharmacokinetic interaction,” said Barry E. Gidal, PharmD, professor of pharmacy and neurology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, and his colleagues.

Researchers have suggested that enzyme-inducing AEDs may affect CYP450 isoenzymes, increase vitamin D metabolism, and reduce 25(OH)D plasma levels. “It follows … that a potential pharmacokinetic interaction could exist between enzyme-inducing AEDs and oral formulations of vitamin D used for supplementation,” the investigators said.

To test the hypothesis, Dr. Gidal and his colleagues reviewed the charts of patients with epilepsy who were on any AED regimen and were prescribed vitamin D at William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin, between January 2013 and September 2017.

The researchers grouped patients by those using enzyme-inducing AEDs and those taking noninducing AEDs. Patients who were taking AEDs in both categories were placed in the enzyme-inducing AED group. Patients with malabsorptive conditions and patients using calcitriol were excluded from the analysis.

Data included AEDs used, prescription and over-the-counter vitamin D use, 25(OH)D plasma concentration, renal function, age, gender, and ethnicity. Patients’ 25(OH)D levels were measured using a chemiluminescence immunoassay, and a minimum 25(OH)D plasma level of 30 ng/mL was the therapeutic goal.

The multivariant analysis was adjusted for potentially confounding variables including 25(OH)D concentration, over-the-counter vitamin D use, chronic kidney disease, age, gender, and ethnicity.

The analysis included 1,113 observations from 315 patients, and 263 of the observations (23.6%) were in the enzyme-inducing AED group. The enzyme-inducing group and noninducing groups were mostly male (90.5% and 91.8%, respectively) and similar in average age (65.9 and 61.4 years, respectively). Variables were evenly distributed between the groups, with the exceptions of chronic kidney disease, which was less common in the enzyme-inducing group (6.1% vs. 13.8%), and ethnicity (78.7% Caucasian in the enzyme-inducing group vs. 87.7% Caucasian in the noninducing group). The most common enzyme-inducing AED was phenytoin (50.6%), followed by carbamazepine (31.9%), phenobarbital (14.1%), oxcarbazepine (6.8%), primidone (1.9%), and eslicarbazepine (0.8%).

Dr. Gidal reported honoraria from Eisai, Sunovion, Lundbeck, and GW Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Gidal BE et al. AES 2018, Abstract 1.315.

NEW ORLEANS – Patients taking enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) may require a clinically meaningful increase in their vitamin D doses to achieve the same 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) plasma levels as patients taking nonenzyme-inducing AEDs, based on a retrospective chart review presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

While patients receiving either type of AED had similar average 25(OH)D levels in the study (32.0 ng/mL in the enzyme-inducing AED group and 33.2 ng/mL in the noninducing AED group), those in the enzyme-inducing group required 1,587 U/day to meet the goal – a 409-unit increase in dose, compared with the 1,108 U/day dose taken by patients in the nonenzyme-inducing group.

“Patients taking enzyme-inducing AEDs may benefit from more intensive monitoring of their vitamin D supplementation, and clinicians should anticipate this likely pharmacokinetic interaction,” said Barry E. Gidal, PharmD, professor of pharmacy and neurology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, and his colleagues.

Researchers have suggested that enzyme-inducing AEDs may affect CYP450 isoenzymes, increase vitamin D metabolism, and reduce 25(OH)D plasma levels. “It follows … that a potential pharmacokinetic interaction could exist between enzyme-inducing AEDs and oral formulations of vitamin D used for supplementation,” the investigators said.

To test the hypothesis, Dr. Gidal and his colleagues reviewed the charts of patients with epilepsy who were on any AED regimen and were prescribed vitamin D at William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin, between January 2013 and September 2017.

The researchers grouped patients by those using enzyme-inducing AEDs and those taking noninducing AEDs. Patients who were taking AEDs in both categories were placed in the enzyme-inducing AED group. Patients with malabsorptive conditions and patients using calcitriol were excluded from the analysis.

Data included AEDs used, prescription and over-the-counter vitamin D use, 25(OH)D plasma concentration, renal function, age, gender, and ethnicity. Patients’ 25(OH)D levels were measured using a chemiluminescence immunoassay, and a minimum 25(OH)D plasma level of 30 ng/mL was the therapeutic goal.

The multivariant analysis was adjusted for potentially confounding variables including 25(OH)D concentration, over-the-counter vitamin D use, chronic kidney disease, age, gender, and ethnicity.

The analysis included 1,113 observations from 315 patients, and 263 of the observations (23.6%) were in the enzyme-inducing AED group. The enzyme-inducing group and noninducing groups were mostly male (90.5% and 91.8%, respectively) and similar in average age (65.9 and 61.4 years, respectively). Variables were evenly distributed between the groups, with the exceptions of chronic kidney disease, which was less common in the enzyme-inducing group (6.1% vs. 13.8%), and ethnicity (78.7% Caucasian in the enzyme-inducing group vs. 87.7% Caucasian in the noninducing group). The most common enzyme-inducing AED was phenytoin (50.6%), followed by carbamazepine (31.9%), phenobarbital (14.1%), oxcarbazepine (6.8%), primidone (1.9%), and eslicarbazepine (0.8%).

Dr. Gidal reported honoraria from Eisai, Sunovion, Lundbeck, and GW Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Gidal BE et al. AES 2018, Abstract 1.315.

REPORTING FROM AES 2018

Key clinical point: Enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs affect vitamin D dose requirements.

Major finding: Patients taking enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs require a higher daily dose of vitamin D, compared with patients taking noninducing antiepileptic drugs (1,587 U/day vs. 1,108 U/day).

Study details: A retrospective chart review of data from 315 patients treated at a Veterans Affairs hospital.

Disclosures: Dr. Gidal reported honoraria from Eisai, Sunovion, Lundbeck, and GW Pharmaceuticals..

Source: Gidal BE et al. AES 2018, Abstract 1.315.

Teenagers with epilepsy may benefit from depression screening

NEW ORLEANS – Referral to a mental health provider is adequate for most patients with moderately severe symptoms of depression, but some patients may require active intervention during the clinical visit, said the researchers.

“We know that depression is more common in people with epilepsy, compared to the general population, but there is less information about depression in children and teens than adults, and little is known about the factors that increase the likelihood of depressive symptoms,” said Hillary Thomas, PhD, a pediatric psychologist at Children’s Medical Center in Dallas. “Depression screening should be routine at epilepsy treatment centers and can identify children and teens who would benefit from intervention.”

Following 2015 guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology, the Comprehensive Epilepsy Center at Children’s Health System in Dallas developed a behavioral health screening protocol for teens with epilepsy. The center aims to identify patients with depressive symptoms and ensure that they are referred to appropriate behavioral health practitioners. Clinicians also review the screening data and seizure variables for their potential implications for clinical care. Researchers at the center also seek to elucidate the relationship between depressive symptoms and seizure diagnosis and treatment.

As part of the protocol, Dr. Thomas and her colleagues administer the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (adolescent version) to all patients aged 15-18 years during their visit to the epilepsy clinic. Patients with intellectual disability or other factors that prevent them from providing valid responses are excluded. If a patient’s PHQ-9 score indicates at least moderately severe depressive symptoms, or if he or she reports suicidal ideation, clinicians follow a specific response protocol that includes providing referrals, encouraging follow-up with the patient’s current mental health provider, and obtaining a suicide risk assessment from a psychologist or social worker. After the screener is completed, clinicians retrieve demographic and clinical data (e.g., seizure diagnosis, medication, number of clinic or emergency department visits) from the patient’s medical record and include them in a database for subsequent analysis.

Dr. Thomas and her colleagues presented data from 394 youth with epilepsy whom they had screened. Patients’ mean age was 16 years, and half of the population was female. The study population had rates of depression similar to those identified in previous studies, said Dr. Thomas. Approximately 87% of patients had minimal or mild depressive symptoms, and 8% had moderately severe depressive symptoms. Furthermore, 5% of the patients reported suicidal ideation or previous suicide attempt. Several of the patients with suicidal ideation had a current mental health provider, and the others required an in-clinic risk assessment. Overall, 13% of the population required behavioral health referral or intervention. When the researchers conducted chi-squared analysis, they found no significant association between seizure type and depression severity.

“Our results don’t mean that only 13% of the teens with epilepsy had depressive symptoms,” said Susan Arnold, MD, director of the Comprehensive Epilepsy Center and a coauthor of the study. “They indicate the significant percentage of teens whose level of depressive symptoms warranted behavioral health referrals or further evaluation or even intervention during a clinic visit. Health care providers need to be vigilant about continually screening children and teens for depression.” As part of each patient’s comprehensive care, epilepsy treatment centers should provide psychosocial teams that include social workers or psychologists, she added.

The investigators plan to continue analyzing the data for specific depression symptoms that are most common in teens. These symptoms could be the basis for developing additional resources for families, such as lists of warning signs and guides to symptom management, as well as group therapy and support groups.

SOURCE: Thomas HM et al. Abstract 1.388.

NEW ORLEANS – Referral to a mental health provider is adequate for most patients with moderately severe symptoms of depression, but some patients may require active intervention during the clinical visit, said the researchers.

“We know that depression is more common in people with epilepsy, compared to the general population, but there is less information about depression in children and teens than adults, and little is known about the factors that increase the likelihood of depressive symptoms,” said Hillary Thomas, PhD, a pediatric psychologist at Children’s Medical Center in Dallas. “Depression screening should be routine at epilepsy treatment centers and can identify children and teens who would benefit from intervention.”

Following 2015 guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology, the Comprehensive Epilepsy Center at Children’s Health System in Dallas developed a behavioral health screening protocol for teens with epilepsy. The center aims to identify patients with depressive symptoms and ensure that they are referred to appropriate behavioral health practitioners. Clinicians also review the screening data and seizure variables for their potential implications for clinical care. Researchers at the center also seek to elucidate the relationship between depressive symptoms and seizure diagnosis and treatment.

As part of the protocol, Dr. Thomas and her colleagues administer the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (adolescent version) to all patients aged 15-18 years during their visit to the epilepsy clinic. Patients with intellectual disability or other factors that prevent them from providing valid responses are excluded. If a patient’s PHQ-9 score indicates at least moderately severe depressive symptoms, or if he or she reports suicidal ideation, clinicians follow a specific response protocol that includes providing referrals, encouraging follow-up with the patient’s current mental health provider, and obtaining a suicide risk assessment from a psychologist or social worker. After the screener is completed, clinicians retrieve demographic and clinical data (e.g., seizure diagnosis, medication, number of clinic or emergency department visits) from the patient’s medical record and include them in a database for subsequent analysis.

Dr. Thomas and her colleagues presented data from 394 youth with epilepsy whom they had screened. Patients’ mean age was 16 years, and half of the population was female. The study population had rates of depression similar to those identified in previous studies, said Dr. Thomas. Approximately 87% of patients had minimal or mild depressive symptoms, and 8% had moderately severe depressive symptoms. Furthermore, 5% of the patients reported suicidal ideation or previous suicide attempt. Several of the patients with suicidal ideation had a current mental health provider, and the others required an in-clinic risk assessment. Overall, 13% of the population required behavioral health referral or intervention. When the researchers conducted chi-squared analysis, they found no significant association between seizure type and depression severity.

“Our results don’t mean that only 13% of the teens with epilepsy had depressive symptoms,” said Susan Arnold, MD, director of the Comprehensive Epilepsy Center and a coauthor of the study. “They indicate the significant percentage of teens whose level of depressive symptoms warranted behavioral health referrals or further evaluation or even intervention during a clinic visit. Health care providers need to be vigilant about continually screening children and teens for depression.” As part of each patient’s comprehensive care, epilepsy treatment centers should provide psychosocial teams that include social workers or psychologists, she added.

The investigators plan to continue analyzing the data for specific depression symptoms that are most common in teens. These symptoms could be the basis for developing additional resources for families, such as lists of warning signs and guides to symptom management, as well as group therapy and support groups.

SOURCE: Thomas HM et al. Abstract 1.388.

NEW ORLEANS – Referral to a mental health provider is adequate for most patients with moderately severe symptoms of depression, but some patients may require active intervention during the clinical visit, said the researchers.

“We know that depression is more common in people with epilepsy, compared to the general population, but there is less information about depression in children and teens than adults, and little is known about the factors that increase the likelihood of depressive symptoms,” said Hillary Thomas, PhD, a pediatric psychologist at Children’s Medical Center in Dallas. “Depression screening should be routine at epilepsy treatment centers and can identify children and teens who would benefit from intervention.”

Following 2015 guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology, the Comprehensive Epilepsy Center at Children’s Health System in Dallas developed a behavioral health screening protocol for teens with epilepsy. The center aims to identify patients with depressive symptoms and ensure that they are referred to appropriate behavioral health practitioners. Clinicians also review the screening data and seizure variables for their potential implications for clinical care. Researchers at the center also seek to elucidate the relationship between depressive symptoms and seizure diagnosis and treatment.

As part of the protocol, Dr. Thomas and her colleagues administer the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (adolescent version) to all patients aged 15-18 years during their visit to the epilepsy clinic. Patients with intellectual disability or other factors that prevent them from providing valid responses are excluded. If a patient’s PHQ-9 score indicates at least moderately severe depressive symptoms, or if he or she reports suicidal ideation, clinicians follow a specific response protocol that includes providing referrals, encouraging follow-up with the patient’s current mental health provider, and obtaining a suicide risk assessment from a psychologist or social worker. After the screener is completed, clinicians retrieve demographic and clinical data (e.g., seizure diagnosis, medication, number of clinic or emergency department visits) from the patient’s medical record and include them in a database for subsequent analysis.

Dr. Thomas and her colleagues presented data from 394 youth with epilepsy whom they had screened. Patients’ mean age was 16 years, and half of the population was female. The study population had rates of depression similar to those identified in previous studies, said Dr. Thomas. Approximately 87% of patients had minimal or mild depressive symptoms, and 8% had moderately severe depressive symptoms. Furthermore, 5% of the patients reported suicidal ideation or previous suicide attempt. Several of the patients with suicidal ideation had a current mental health provider, and the others required an in-clinic risk assessment. Overall, 13% of the population required behavioral health referral or intervention. When the researchers conducted chi-squared analysis, they found no significant association between seizure type and depression severity.

“Our results don’t mean that only 13% of the teens with epilepsy had depressive symptoms,” said Susan Arnold, MD, director of the Comprehensive Epilepsy Center and a coauthor of the study. “They indicate the significant percentage of teens whose level of depressive symptoms warranted behavioral health referrals or further evaluation or even intervention during a clinic visit. Health care providers need to be vigilant about continually screening children and teens for depression.” As part of each patient’s comprehensive care, epilepsy treatment centers should provide psychosocial teams that include social workers or psychologists, she added.

The investigators plan to continue analyzing the data for specific depression symptoms that are most common in teens. These symptoms could be the basis for developing additional resources for families, such as lists of warning signs and guides to symptom management, as well as group therapy and support groups.

SOURCE: Thomas HM et al. Abstract 1.388.

REPORTING FROM AES 2018

Key clinical point: Screening children with epilepsy regularly for depression may be advisable.

Major finding: About 13% of patients screened required referral or intervention.

Study details: Prospective study of 394 patients with epilepsy.

Disclosures: The investigators have no disclosures and received no funding for this study.

Source: Thomas HM et al. Abstract 1.388.

Acute flaccid myelitis has unique MRI features

Acute flaccid myelitis appears to present most commonly as asymmetric weakness after respiratory viral infection and has distinctive MRI features that could help with early diagnosis.

In a paper published in JAMA Pediatrics, researchers presented the results of a retrospective case series of 45 children who were diagnosed between 2012 and 2016 with acute flaccid myelitis, or “pseudo polio,” using the Centers for Disease Control’s case definition.

Matthew J. Elrick, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his coauthors came up with a set of reproducible and distinctive features of acute flaccid myelitis. These were the presence of a prodromal fever or viral syndrome; weakness in a lower motor neuron pattern involving one or more limbs, neck, face, and/or bulbar muscles; supportive evidence either from MRI, nerve conduction studies, or cerebrospinal fluid; and the absence of objective sensory deficits, supratentorial white matter, cortical lesions greater than 1 cm in size, encephalopathy, elevated cerebrospinal fluid without pleocytosis, or any other alternative diagnosis.

The researchers commented that, while the CDC case definition has helped with epidemiologic surveillance of acute flaccid myelitis, it may also pick up children with acute weakness caused by other conditions such as transverse myelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, ischemic myelopathy, and other myelopathies.

To identify clinical features that might help differentiate patients with acute flaccid myelitis, the researchers attempted to see how many alternative diagnoses were captured in the CDC case definition.

The patients in their study all presented with acute flaccid paralysis in at least one limb and with either an MRI showing a spinal cord lesion spanning one or more spinal segments but largely restricted to gray matter or pleocytosis of the cerebrospinal fluid. The researchers divided the cases into those who also met a well-defined alternative diagnosis – who they categorized as “acute flaccid myelitis with possible alternative diagnosis” (AFM-ad) – and those who were categorized as “restrictively defined AFM” (rAFM). Overall, 34 patients were classified as rAFM and 11 as AFM-ad.

Those in the rAFD group nearly all had asymmetric onset of symptoms, while those in the AFM-ad group were more likely to experience bilateral onset in their lower extremities, “reflecting the pattern of symptoms often seen in other causes of myelopathy such as transverse myelitis and ischemic injury,” the authors noted.

While both groups often presented with decreased muscle tone and reflexes, this was more likely to evolve to increased tone or hyperreflexia in the AFM-ad group. Patients with AFM-ad were also more likely to experience impaired bowel or bladder function.

On MRI, lesions were mostly or completely restricted to the spinal cord gray matter in patients with rAFM or to involve the dorsal pons. These patients did not have any supratentorial brain lesions.

Patients in the rAFM category also had lower cerebrospinal fluid protein values than those in the AFM-ad category, but this was the only cerebrospinal fluid difference between the two groups.

All patients categorized as having rAFM had an infectious prodrome – such as viral syndrome, fever, congestion, and cough – compared with 63.6% of the patients categorized as AFM-ad. The pathogen was identified in only 13 of the rAFM patients, and included 5 patients with enterovirus D68, 2 with unspecified enterovirus, 2 with rhinovirus, 2 with adenovirus, and 2 with mycoplasma. Of the three patients in the AFM-ad group whose pathogen was identified, one had an untyped rhinovirus/enterovirus and mycoplasma, one had a rhinovirus B, and one had enterovirus D68.

“These results highlight that the CDC case definition, while appropriately sensitive for epidemiologic ascertainment of possible AFM cases, also encompasses other neurologic diseases that can cause acute weakness,” the authors wrote. However, they acknowledged that acute flaccid myelitis was still poorly understood and their own definition of the disease may change as more children are diagnosed.

“We propose that the definition of rAFM presented here be used as a starting point for developing inclusion and exclusion criteria for future research studies of AFM,” they wrote.

The study was supported by Johns Hopkins University, the Bart McLean Fund for Neuroimmunology Research, and Project Restore. Two authors reported funding from private industry outside the submitted work and five reported support from or involvement with research and funding bodies.

SOURCE: Elrick MJ et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov 30. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4890.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) initially presents subtly, complicating its diagnosis. Children present with a rapid onset of weakness that is associated with a febrile illness, which can be respiratory, gastrointestinal, or with symptoms of hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Given the lack of effective treatments, early diagnosis and monitoring are essential for mitigating the risk of respiratory decline and long-term complications.

While patient history and physical examination can provide clues to the presence of AFM, confirming the diagnosis requires lumbar puncture and MRI of the spinal cord. On MRI, diagnostic confirmation will come from findings of longitudinal, butterfly-shaped, anterior horn–predominant T2 and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensities of the central gray matter.

Patients with suspected AFM should be hospitalized because they can rapidly deteriorate to the point of respiratory compromise, particularly those with upper extremity and bulbar weakness.

Sarah E. Hopkins, MD, is from the division of neurology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; Matthew J. Elrick, MD, PhD, is from the department of neurology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore; and Kevin Messacar, MD, is from the department of pediatrics at the Children’s Hospital Colorado. These comments are taken from an accompanying viewpoint (JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov 30. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4896). Dr. Messacar reported support from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious and Dr. Hopkins reported support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) initially presents subtly, complicating its diagnosis. Children present with a rapid onset of weakness that is associated with a febrile illness, which can be respiratory, gastrointestinal, or with symptoms of hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Given the lack of effective treatments, early diagnosis and monitoring are essential for mitigating the risk of respiratory decline and long-term complications.

While patient history and physical examination can provide clues to the presence of AFM, confirming the diagnosis requires lumbar puncture and MRI of the spinal cord. On MRI, diagnostic confirmation will come from findings of longitudinal, butterfly-shaped, anterior horn–predominant T2 and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensities of the central gray matter.

Patients with suspected AFM should be hospitalized because they can rapidly deteriorate to the point of respiratory compromise, particularly those with upper extremity and bulbar weakness.

Sarah E. Hopkins, MD, is from the division of neurology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; Matthew J. Elrick, MD, PhD, is from the department of neurology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore; and Kevin Messacar, MD, is from the department of pediatrics at the Children’s Hospital Colorado. These comments are taken from an accompanying viewpoint (JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov 30. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4896). Dr. Messacar reported support from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious and Dr. Hopkins reported support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) initially presents subtly, complicating its diagnosis. Children present with a rapid onset of weakness that is associated with a febrile illness, which can be respiratory, gastrointestinal, or with symptoms of hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Given the lack of effective treatments, early diagnosis and monitoring are essential for mitigating the risk of respiratory decline and long-term complications.

While patient history and physical examination can provide clues to the presence of AFM, confirming the diagnosis requires lumbar puncture and MRI of the spinal cord. On MRI, diagnostic confirmation will come from findings of longitudinal, butterfly-shaped, anterior horn–predominant T2 and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensities of the central gray matter.

Patients with suspected AFM should be hospitalized because they can rapidly deteriorate to the point of respiratory compromise, particularly those with upper extremity and bulbar weakness.

Sarah E. Hopkins, MD, is from the division of neurology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; Matthew J. Elrick, MD, PhD, is from the department of neurology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore; and Kevin Messacar, MD, is from the department of pediatrics at the Children’s Hospital Colorado. These comments are taken from an accompanying viewpoint (JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov 30. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4896). Dr. Messacar reported support from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious and Dr. Hopkins reported support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Acute flaccid myelitis appears to present most commonly as asymmetric weakness after respiratory viral infection and has distinctive MRI features that could help with early diagnosis.

In a paper published in JAMA Pediatrics, researchers presented the results of a retrospective case series of 45 children who were diagnosed between 2012 and 2016 with acute flaccid myelitis, or “pseudo polio,” using the Centers for Disease Control’s case definition.

Matthew J. Elrick, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his coauthors came up with a set of reproducible and distinctive features of acute flaccid myelitis. These were the presence of a prodromal fever or viral syndrome; weakness in a lower motor neuron pattern involving one or more limbs, neck, face, and/or bulbar muscles; supportive evidence either from MRI, nerve conduction studies, or cerebrospinal fluid; and the absence of objective sensory deficits, supratentorial white matter, cortical lesions greater than 1 cm in size, encephalopathy, elevated cerebrospinal fluid without pleocytosis, or any other alternative diagnosis.

The researchers commented that, while the CDC case definition has helped with epidemiologic surveillance of acute flaccid myelitis, it may also pick up children with acute weakness caused by other conditions such as transverse myelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, ischemic myelopathy, and other myelopathies.

To identify clinical features that might help differentiate patients with acute flaccid myelitis, the researchers attempted to see how many alternative diagnoses were captured in the CDC case definition.

The patients in their study all presented with acute flaccid paralysis in at least one limb and with either an MRI showing a spinal cord lesion spanning one or more spinal segments but largely restricted to gray matter or pleocytosis of the cerebrospinal fluid. The researchers divided the cases into those who also met a well-defined alternative diagnosis – who they categorized as “acute flaccid myelitis with possible alternative diagnosis” (AFM-ad) – and those who were categorized as “restrictively defined AFM” (rAFM). Overall, 34 patients were classified as rAFM and 11 as AFM-ad.

Those in the rAFD group nearly all had asymmetric onset of symptoms, while those in the AFM-ad group were more likely to experience bilateral onset in their lower extremities, “reflecting the pattern of symptoms often seen in other causes of myelopathy such as transverse myelitis and ischemic injury,” the authors noted.

While both groups often presented with decreased muscle tone and reflexes, this was more likely to evolve to increased tone or hyperreflexia in the AFM-ad group. Patients with AFM-ad were also more likely to experience impaired bowel or bladder function.

On MRI, lesions were mostly or completely restricted to the spinal cord gray matter in patients with rAFM or to involve the dorsal pons. These patients did not have any supratentorial brain lesions.

Patients in the rAFM category also had lower cerebrospinal fluid protein values than those in the AFM-ad category, but this was the only cerebrospinal fluid difference between the two groups.

All patients categorized as having rAFM had an infectious prodrome – such as viral syndrome, fever, congestion, and cough – compared with 63.6% of the patients categorized as AFM-ad. The pathogen was identified in only 13 of the rAFM patients, and included 5 patients with enterovirus D68, 2 with unspecified enterovirus, 2 with rhinovirus, 2 with adenovirus, and 2 with mycoplasma. Of the three patients in the AFM-ad group whose pathogen was identified, one had an untyped rhinovirus/enterovirus and mycoplasma, one had a rhinovirus B, and one had enterovirus D68.

“These results highlight that the CDC case definition, while appropriately sensitive for epidemiologic ascertainment of possible AFM cases, also encompasses other neurologic diseases that can cause acute weakness,” the authors wrote. However, they acknowledged that acute flaccid myelitis was still poorly understood and their own definition of the disease may change as more children are diagnosed.

“We propose that the definition of rAFM presented here be used as a starting point for developing inclusion and exclusion criteria for future research studies of AFM,” they wrote.

The study was supported by Johns Hopkins University, the Bart McLean Fund for Neuroimmunology Research, and Project Restore. Two authors reported funding from private industry outside the submitted work and five reported support from or involvement with research and funding bodies.

SOURCE: Elrick MJ et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov 30. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4890.

Acute flaccid myelitis appears to present most commonly as asymmetric weakness after respiratory viral infection and has distinctive MRI features that could help with early diagnosis.

In a paper published in JAMA Pediatrics, researchers presented the results of a retrospective case series of 45 children who were diagnosed between 2012 and 2016 with acute flaccid myelitis, or “pseudo polio,” using the Centers for Disease Control’s case definition.

Matthew J. Elrick, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his coauthors came up with a set of reproducible and distinctive features of acute flaccid myelitis. These were the presence of a prodromal fever or viral syndrome; weakness in a lower motor neuron pattern involving one or more limbs, neck, face, and/or bulbar muscles; supportive evidence either from MRI, nerve conduction studies, or cerebrospinal fluid; and the absence of objective sensory deficits, supratentorial white matter, cortical lesions greater than 1 cm in size, encephalopathy, elevated cerebrospinal fluid without pleocytosis, or any other alternative diagnosis.

The researchers commented that, while the CDC case definition has helped with epidemiologic surveillance of acute flaccid myelitis, it may also pick up children with acute weakness caused by other conditions such as transverse myelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, ischemic myelopathy, and other myelopathies.

To identify clinical features that might help differentiate patients with acute flaccid myelitis, the researchers attempted to see how many alternative diagnoses were captured in the CDC case definition.

The patients in their study all presented with acute flaccid paralysis in at least one limb and with either an MRI showing a spinal cord lesion spanning one or more spinal segments but largely restricted to gray matter or pleocytosis of the cerebrospinal fluid. The researchers divided the cases into those who also met a well-defined alternative diagnosis – who they categorized as “acute flaccid myelitis with possible alternative diagnosis” (AFM-ad) – and those who were categorized as “restrictively defined AFM” (rAFM). Overall, 34 patients were classified as rAFM and 11 as AFM-ad.

Those in the rAFD group nearly all had asymmetric onset of symptoms, while those in the AFM-ad group were more likely to experience bilateral onset in their lower extremities, “reflecting the pattern of symptoms often seen in other causes of myelopathy such as transverse myelitis and ischemic injury,” the authors noted.

While both groups often presented with decreased muscle tone and reflexes, this was more likely to evolve to increased tone or hyperreflexia in the AFM-ad group. Patients with AFM-ad were also more likely to experience impaired bowel or bladder function.

On MRI, lesions were mostly or completely restricted to the spinal cord gray matter in patients with rAFM or to involve the dorsal pons. These patients did not have any supratentorial brain lesions.

Patients in the rAFM category also had lower cerebrospinal fluid protein values than those in the AFM-ad category, but this was the only cerebrospinal fluid difference between the two groups.

All patients categorized as having rAFM had an infectious prodrome – such as viral syndrome, fever, congestion, and cough – compared with 63.6% of the patients categorized as AFM-ad. The pathogen was identified in only 13 of the rAFM patients, and included 5 patients with enterovirus D68, 2 with unspecified enterovirus, 2 with rhinovirus, 2 with adenovirus, and 2 with mycoplasma. Of the three patients in the AFM-ad group whose pathogen was identified, one had an untyped rhinovirus/enterovirus and mycoplasma, one had a rhinovirus B, and one had enterovirus D68.

“These results highlight that the CDC case definition, while appropriately sensitive for epidemiologic ascertainment of possible AFM cases, also encompasses other neurologic diseases that can cause acute weakness,” the authors wrote. However, they acknowledged that acute flaccid myelitis was still poorly understood and their own definition of the disease may change as more children are diagnosed.

“We propose that the definition of rAFM presented here be used as a starting point for developing inclusion and exclusion criteria for future research studies of AFM,” they wrote.

The study was supported by Johns Hopkins University, the Bart McLean Fund for Neuroimmunology Research, and Project Restore. Two authors reported funding from private industry outside the submitted work and five reported support from or involvement with research and funding bodies.

SOURCE: Elrick MJ et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov 30. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4890.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Acute flaccid myelitis has distinct features that can distinguish it from other similar conditions.

Major finding: Asymmetric onset of symptoms and MRI signature can help distinguish acute flaccid myelitis from alternative diagnoses.

Study details: A retrospective case series in 45 children diagnosed with acute flaccid myelitis.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Johns Hopkins University, the Bart McLean Fund for Neuroimmunology Research, and Project Restore. Two authors reported funding from private industry outside the submitted work and five reported support from or involvement with research and funding bodies.

Source: Elrick MJ et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov 30. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4890.

Stroke, arterial dissection events reported with Lemtrada, FDA says

Instances of stroke and arterial dissection in the head and neck have been reported in some multiple sclerosis patients soon after an infusion of alemtuzumab (Lemtrada), according to a safety announcement issued by the Food and Drug Administration on Nov. 29.

Since the FDA approved alemtuzumab in 2014 for relapsing forms of MS, 13 cases of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke or arterial dissection have been reported worldwide via the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System, but “additional cases we are unaware of may have occurred,” the FDA said in the announcement.

Most of the patients who developed stroke or arterial lining tears showed symptoms within a day of taking the medication, although one patient reported symptoms three days after treatment. The drug is given via intravenous infusion and is generally reserved for patients with relapsing MS who have not responded adequately to other approved MS medications, according to the FDA.

Symptoms include sudden onset of the following: severe headache or neck pain; numbness or weakness in the arms or legs, especially on only one side of the body; confusion or trouble speaking or understanding speech; vision problems in one or both eyes; and dizziness, loss of balance, or difficulty walking.

As a result of the reports, the FDA has updated the drug label prescribing information and the patient Medication Guide to reflect these risks, and added the risk of stroke to the medication’s existing boxed warning.

Health care providers should remind patients of the potential for stroke and arterial dissection at each treatment visit and advise them to seek immediate medical attention if they experience any of the symptoms reported in previous cases. “The diagnosis is often complicated because early symptoms such as headache and neck pain are not specific,” according to the agency, but patients complaining of such symptoms should be evaluated immediately.

Alemtuzumab was also approved in May 2001 for treating B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) under the brand name Campath. The FDA will update the Campath label to reflect the new warnings and risks.

Instances of stroke and arterial dissection in the head and neck have been reported in some multiple sclerosis patients soon after an infusion of alemtuzumab (Lemtrada), according to a safety announcement issued by the Food and Drug Administration on Nov. 29.

Since the FDA approved alemtuzumab in 2014 for relapsing forms of MS, 13 cases of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke or arterial dissection have been reported worldwide via the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System, but “additional cases we are unaware of may have occurred,” the FDA said in the announcement.

Most of the patients who developed stroke or arterial lining tears showed symptoms within a day of taking the medication, although one patient reported symptoms three days after treatment. The drug is given via intravenous infusion and is generally reserved for patients with relapsing MS who have not responded adequately to other approved MS medications, according to the FDA.

Symptoms include sudden onset of the following: severe headache or neck pain; numbness or weakness in the arms or legs, especially on only one side of the body; confusion or trouble speaking or understanding speech; vision problems in one or both eyes; and dizziness, loss of balance, or difficulty walking.

As a result of the reports, the FDA has updated the drug label prescribing information and the patient Medication Guide to reflect these risks, and added the risk of stroke to the medication’s existing boxed warning.

Health care providers should remind patients of the potential for stroke and arterial dissection at each treatment visit and advise them to seek immediate medical attention if they experience any of the symptoms reported in previous cases. “The diagnosis is often complicated because early symptoms such as headache and neck pain are not specific,” according to the agency, but patients complaining of such symptoms should be evaluated immediately.

Alemtuzumab was also approved in May 2001 for treating B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) under the brand name Campath. The FDA will update the Campath label to reflect the new warnings and risks.

Instances of stroke and arterial dissection in the head and neck have been reported in some multiple sclerosis patients soon after an infusion of alemtuzumab (Lemtrada), according to a safety announcement issued by the Food and Drug Administration on Nov. 29.

Since the FDA approved alemtuzumab in 2014 for relapsing forms of MS, 13 cases of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke or arterial dissection have been reported worldwide via the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System, but “additional cases we are unaware of may have occurred,” the FDA said in the announcement.

Most of the patients who developed stroke or arterial lining tears showed symptoms within a day of taking the medication, although one patient reported symptoms three days after treatment. The drug is given via intravenous infusion and is generally reserved for patients with relapsing MS who have not responded adequately to other approved MS medications, according to the FDA.