User login

New Classifications and Emerging Treatments in Brain Cancer

- Sokolov AV et al. Pharmacol Rev. 2021;73(4):1-32. doi:10.1124/pharmrev.121.000317

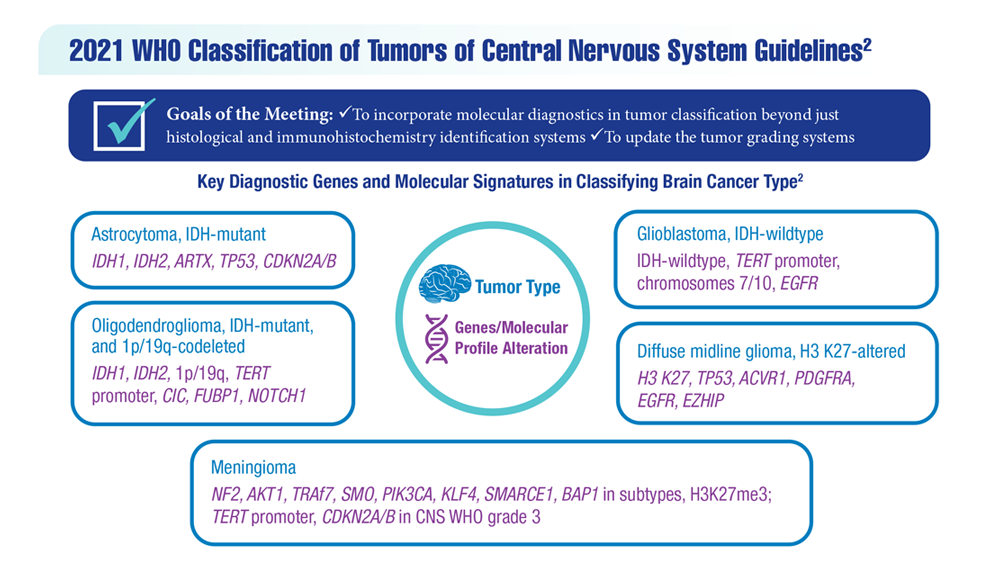

- Louis DN et al. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(8):1231-1251. doi:10.1093/neuonc/noab106

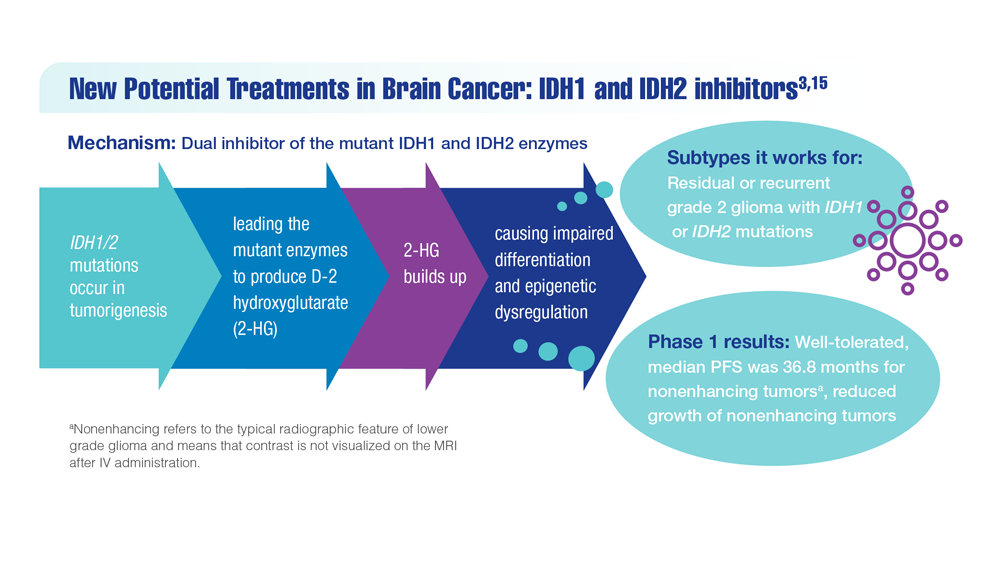

- Mellinghoff IK et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(16):4491-4499. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-0611

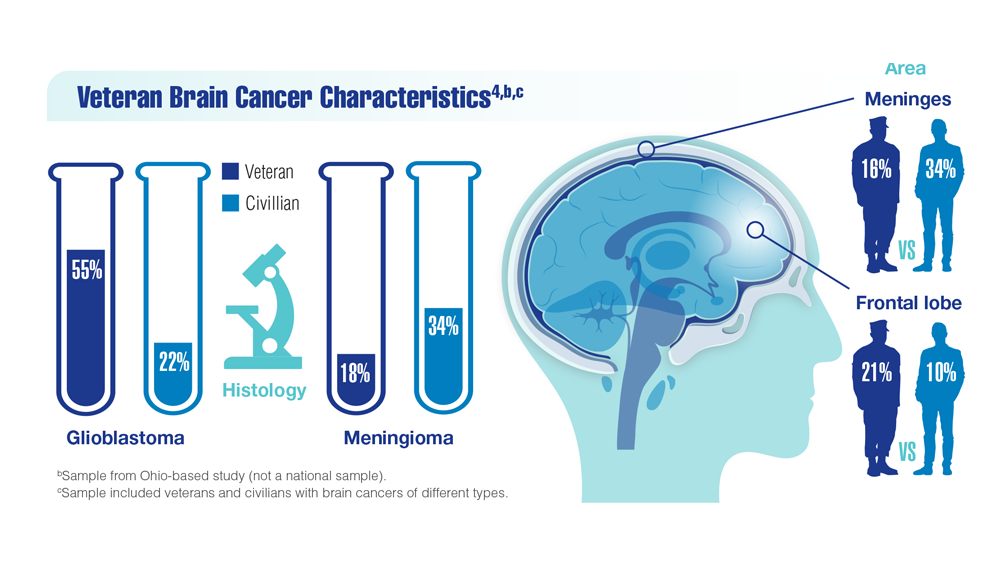

- Woo C et al. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2021;5:985-994. doi:10.1200/CCI.21.00052

- Study of vorasidenib (AG-881) in participants with residual or recurrent grade 2 glioma with an IDH1 or IDH2 mutation (INDIGO). ClinicalTrials.gov. Updated May 17, 2022. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04164901

- Servier's pivotal phase 3 indigo trial investigating vorasidenib in IDH-mutant low-grade glioma meets primary endpoint of progression-free survival (PFS) and key secondary endpoint of time to next intervention (TTNI) (no date) Servier US. March 14, 2023. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://www.servier.us/serviers-pivotal-phase-3-indigo-trial-meets-primary-endpoint

- Nehra M et al. J Control Release. 2021;338:224-243. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.08.027

- Hersh AM et al. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(19):4920. doi:10.3390/cancers14194920

- Shoaf ML, Desjardins A. Neurotherapeutics. 2022;19(6):1818-1831. doi:10.1007/s13311-022-01256-1

- Bagley SJ, O’Rourke DM. Pharmacol Ther. 2020;205:107419. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.107419

- Batich KA et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(20):5297-5303. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1082

- Lin J et al. Cancer. 2020;126(13):3053-3060. doi:10.1002/cncr.32884

- Barth SK et al. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;50(pt A):22-29. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2017.07.012

- VA and partners hope APOLLO program will be leap forward for precision oncology. US Department of Veteran Affairs. May 1, 2019. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://www.research.va.gov/currents/0519-VA-and-partners-hope-APOLLO-program-will-be-leap-forward-for-precision-oncology.cfm

- Konteatis Z et al. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2020;11(2):101-107. doi:10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00509

- Sokolov AV et al. Pharmacol Rev. 2021;73(4):1-32. doi:10.1124/pharmrev.121.000317

- Louis DN et al. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(8):1231-1251. doi:10.1093/neuonc/noab106

- Mellinghoff IK et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(16):4491-4499. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-0611

- Woo C et al. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2021;5:985-994. doi:10.1200/CCI.21.00052

- Study of vorasidenib (AG-881) in participants with residual or recurrent grade 2 glioma with an IDH1 or IDH2 mutation (INDIGO). ClinicalTrials.gov. Updated May 17, 2022. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04164901

- Servier's pivotal phase 3 indigo trial investigating vorasidenib in IDH-mutant low-grade glioma meets primary endpoint of progression-free survival (PFS) and key secondary endpoint of time to next intervention (TTNI) (no date) Servier US. March 14, 2023. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://www.servier.us/serviers-pivotal-phase-3-indigo-trial-meets-primary-endpoint

- Nehra M et al. J Control Release. 2021;338:224-243. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.08.027

- Hersh AM et al. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(19):4920. doi:10.3390/cancers14194920

- Shoaf ML, Desjardins A. Neurotherapeutics. 2022;19(6):1818-1831. doi:10.1007/s13311-022-01256-1

- Bagley SJ, O’Rourke DM. Pharmacol Ther. 2020;205:107419. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.107419

- Batich KA et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(20):5297-5303. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1082

- Lin J et al. Cancer. 2020;126(13):3053-3060. doi:10.1002/cncr.32884

- Barth SK et al. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;50(pt A):22-29. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2017.07.012

- VA and partners hope APOLLO program will be leap forward for precision oncology. US Department of Veteran Affairs. May 1, 2019. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://www.research.va.gov/currents/0519-VA-and-partners-hope-APOLLO-program-will-be-leap-forward-for-precision-oncology.cfm

- Konteatis Z et al. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2020;11(2):101-107. doi:10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00509

- Sokolov AV et al. Pharmacol Rev. 2021;73(4):1-32. doi:10.1124/pharmrev.121.000317

- Louis DN et al. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(8):1231-1251. doi:10.1093/neuonc/noab106

- Mellinghoff IK et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(16):4491-4499. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-0611

- Woo C et al. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2021;5:985-994. doi:10.1200/CCI.21.00052

- Study of vorasidenib (AG-881) in participants with residual or recurrent grade 2 glioma with an IDH1 or IDH2 mutation (INDIGO). ClinicalTrials.gov. Updated May 17, 2022. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04164901

- Servier's pivotal phase 3 indigo trial investigating vorasidenib in IDH-mutant low-grade glioma meets primary endpoint of progression-free survival (PFS) and key secondary endpoint of time to next intervention (TTNI) (no date) Servier US. March 14, 2023. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://www.servier.us/serviers-pivotal-phase-3-indigo-trial-meets-primary-endpoint

- Nehra M et al. J Control Release. 2021;338:224-243. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.08.027

- Hersh AM et al. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(19):4920. doi:10.3390/cancers14194920

- Shoaf ML, Desjardins A. Neurotherapeutics. 2022;19(6):1818-1831. doi:10.1007/s13311-022-01256-1

- Bagley SJ, O’Rourke DM. Pharmacol Ther. 2020;205:107419. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.107419

- Batich KA et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(20):5297-5303. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1082

- Lin J et al. Cancer. 2020;126(13):3053-3060. doi:10.1002/cncr.32884

- Barth SK et al. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;50(pt A):22-29. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2017.07.012

- VA and partners hope APOLLO program will be leap forward for precision oncology. US Department of Veteran Affairs. May 1, 2019. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://www.research.va.gov/currents/0519-VA-and-partners-hope-APOLLO-program-will-be-leap-forward-for-precision-oncology.cfm

- Konteatis Z et al. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2020;11(2):101-107. doi:10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00509

Medical cannabis does not reduce use of prescription meds

TOPLINE:

, according to a new study published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

METHODOLOGY:

- Cannabis advocates suggest that legal medical cannabis can be a partial solution to the opioid overdose crisis in the United States, which claimed more than 80,000 lives in 2021.

- Current research on how legalized cannabis reduces dependence on prescription pain medication is inconclusive.

- Researchers examined insurance data for the period 2010-2022 from 583,820 adults with chronic noncancer pain.

- They drew from 12 states in which medical cannabis is legal and from 17 in which it is not legal to create a hypothetical randomized trial. The control group simulated prescription rates where medical cannabis was not available.

- Authors evaluated prescription rates for opioids, nonopioid painkillers, and pain interventions, such as physical therapy.

TAKEAWAY:

In a given month during the first 3 years after legalization, for states with medical cannabis, the investigators found the following:

- There was an average decrease of 1.07 percentage points in the proportion of patients who received any opioid prescription, compared to a 1.12 percentage point decrease in the control group.

- There was an average increase of 1.14 percentage points in the proportion of patients who received any nonopioid prescription painkiller, compared to a 1.19 percentage point increase in the control group.

- There was a 0.17 percentage point decrease in the proportion of patients who received any pain procedure, compared to a 0.001 percentage point decrease in the control group.

IN PRACTICE:

“This study did not identify important effects of medical cannabis laws on receipt of opioid or nonopioid pain treatment among patients with chronic noncancer pain,” according to the researchers.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Emma E. McGinty, PhD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

LIMITATIONS:

The investigators used a simulated, hypothetical control group that was based on untestable assumptions. They also drew data solely from insured individuals, so the study does not necessarily represent uninsured populations.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. McGinty reports receiving a grant from NIDA. Her coauthors reported receiving support from NIDA and the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, according to a new study published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

METHODOLOGY:

- Cannabis advocates suggest that legal medical cannabis can be a partial solution to the opioid overdose crisis in the United States, which claimed more than 80,000 lives in 2021.

- Current research on how legalized cannabis reduces dependence on prescription pain medication is inconclusive.

- Researchers examined insurance data for the period 2010-2022 from 583,820 adults with chronic noncancer pain.

- They drew from 12 states in which medical cannabis is legal and from 17 in which it is not legal to create a hypothetical randomized trial. The control group simulated prescription rates where medical cannabis was not available.

- Authors evaluated prescription rates for opioids, nonopioid painkillers, and pain interventions, such as physical therapy.

TAKEAWAY:

In a given month during the first 3 years after legalization, for states with medical cannabis, the investigators found the following:

- There was an average decrease of 1.07 percentage points in the proportion of patients who received any opioid prescription, compared to a 1.12 percentage point decrease in the control group.

- There was an average increase of 1.14 percentage points in the proportion of patients who received any nonopioid prescription painkiller, compared to a 1.19 percentage point increase in the control group.

- There was a 0.17 percentage point decrease in the proportion of patients who received any pain procedure, compared to a 0.001 percentage point decrease in the control group.

IN PRACTICE:

“This study did not identify important effects of medical cannabis laws on receipt of opioid or nonopioid pain treatment among patients with chronic noncancer pain,” according to the researchers.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Emma E. McGinty, PhD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

LIMITATIONS:

The investigators used a simulated, hypothetical control group that was based on untestable assumptions. They also drew data solely from insured individuals, so the study does not necessarily represent uninsured populations.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. McGinty reports receiving a grant from NIDA. Her coauthors reported receiving support from NIDA and the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, according to a new study published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

METHODOLOGY:

- Cannabis advocates suggest that legal medical cannabis can be a partial solution to the opioid overdose crisis in the United States, which claimed more than 80,000 lives in 2021.

- Current research on how legalized cannabis reduces dependence on prescription pain medication is inconclusive.

- Researchers examined insurance data for the period 2010-2022 from 583,820 adults with chronic noncancer pain.

- They drew from 12 states in which medical cannabis is legal and from 17 in which it is not legal to create a hypothetical randomized trial. The control group simulated prescription rates where medical cannabis was not available.

- Authors evaluated prescription rates for opioids, nonopioid painkillers, and pain interventions, such as physical therapy.

TAKEAWAY:

In a given month during the first 3 years after legalization, for states with medical cannabis, the investigators found the following:

- There was an average decrease of 1.07 percentage points in the proportion of patients who received any opioid prescription, compared to a 1.12 percentage point decrease in the control group.

- There was an average increase of 1.14 percentage points in the proportion of patients who received any nonopioid prescription painkiller, compared to a 1.19 percentage point increase in the control group.

- There was a 0.17 percentage point decrease in the proportion of patients who received any pain procedure, compared to a 0.001 percentage point decrease in the control group.

IN PRACTICE:

“This study did not identify important effects of medical cannabis laws on receipt of opioid or nonopioid pain treatment among patients with chronic noncancer pain,” according to the researchers.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Emma E. McGinty, PhD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

LIMITATIONS:

The investigators used a simulated, hypothetical control group that was based on untestable assumptions. They also drew data solely from insured individuals, so the study does not necessarily represent uninsured populations.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. McGinty reports receiving a grant from NIDA. Her coauthors reported receiving support from NIDA and the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Lean muscle mass protective against Alzheimer’s?

Investigators analyzed data on more than 450,000 participants in the UK Biobank as well as two independent samples of more than 320,000 individuals with and without AD, and more than 260,000 individuals participating in a separate genes and intelligence study.

They estimated lean muscle and fat tissue in the arms and legs and found, in adjusted analyses, over 500 genetic variants associated with lean mass.

On average, higher genetically lean mass was associated with a “modest but statistically robust” reduction in AD risk and with superior performance on cognitive tasks.

“Using human genetic data, we found evidence for a protective effect of lean mass on risk of Alzheimer’s disease,” study investigators Iyas Daghlas, MD, a resident in the department of neurology, University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview.

Although “clinical intervention studies are needed to confirm this effect, this study supports current recommendations to maintain a healthy lifestyle to prevent dementia,” he said.

The study was published online in BMJ Medicine.

Naturally randomized research

Several measures of body composition have been investigated for their potential association with AD. Lean mass – a “proxy for muscle mass, defined as the difference between total mass and fat mass” – has been shown to be reduced in patients with AD compared with controls, the researchers noted.

“Previous research studies have tested the relationship of body mass index with Alzheimer’s disease and did not find evidence for a causal effect,” Dr. Daghlas said. “We wondered whether BMI was an insufficiently granular measure and hypothesized that disaggregating body mass into lean mass and fat mass could reveal novel associations with disease.”

Most studies have used case-control designs, which might be biased by “residual confounding or reverse causality.” Naturally randomized data “may be used as an alternative to conventional observational studies to investigate causal relations between risk factors and diseases,” the researchers wrote.

In particular, the Mendelian randomization (MR) paradigm randomly allocates germline genetic variants and uses them as proxies for a specific risk factor.

MR “is a technique that permits researchers to investigate cause-and-effect relationships using human genetic data,” Dr. Daghlas explained. “In effect, we’re studying the results of a naturally randomized experiment whereby some individuals are genetically allocated to carry more lean mass.”

The current study used MR to investigate the effect of genetically proxied lean mass on the risk of AD and the “related phenotype” of cognitive performance.

Genetic proxy

As genetic proxies for lean mass, the researchers chose single nucleotide polymorphisms (genetic variants) that were associated, in a genome-wide association study (GWAS), with appendicular lean mass.

Appendicular lean mass “more accurately reflects the effects of lean mass than whole body lean mass, which includes smooth and cardiac muscle,” the authors explained.

This GWAS used phenotypic and genetic data from 450,243 participants in the UK Biobank cohort (mean age 57 years). All participants were of European ancestry.

The researchers adjusted for age, sex, and genetic ancestry. They measured appendicular lean mass using bioimpedance – an electric current that flows at different rates through the body, depending on its composition.

In addition to the UK Biobank participants, the researchers drew on an independent sample of 21,982 people with AD; a control group of 41,944 people without AD; a replication sample of 7,329 people with and 252,879 people without AD to validate the findings; and 269,867 people taking part in a genome-wide study of cognitive performance.

The researchers identified 584 variants that met criteria for use as genetic proxies for lean mass. None were located within the APOE gene region. In the aggregate, these variants explained 10.3% of the variance in appendicular lean mass.

Each standard deviation increase in genetically proxied lean mass was associated with a 12% reduction in AD risk (odds ratio [OR], 0.88; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.82-0.95; P < .001). This finding was replicated in the independent consortium (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.83-0.99; P = .02).

The findings remained “consistent” in sensitivity analyses.

A modifiable risk factor?

Higher appendicular lean mass was associated with higher levels of cognitive performance, with each SD increase in lean mass associated with an SD increase in cognitive performance (OR, 0.09; 95% CI, 0.06-0.11; P = .001).

“Adjusting for potential mediation through performance did not reduce the association between appendicular lean mass and risk of AD,” the authors wrote.

They obtained similar results using genetically proxied trunk and whole-body lean mass, after adjusting for fat mass.

The authors noted several limitations. The bioimpedance measures “only predict, but do not directly measure, lean mass.” Moreover, the approach didn’t examine whether a “critical window of risk factor timing” exists, during which lean mass might play a role in influencing AD risk and after which “interventions would no longer be effective.” Nor could the study determine whether increasing lean mass could reverse AD pathology in patients with preclinical disease or mild cognitive impairment.

Nevertheless, the findings suggest “that lean mass might be a possible modifiable protective factor for Alzheimer’s disease,” the authors wrote. “The mechanisms underlying this finding, as well as the clinical and public health implications, warrant further investigation.”

Novel strategies

In a comment, Iva Miljkovic, MD, PhD, associate professor, department of epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh, said the investigators used “very rigorous methodology.”

The finding suggesting that lean mass is associated with better cognitive function is “important, as cognitive impairment can become stable rather than progress to a pathological state; and, in some cases, can even be reversed.”

In those cases, “identifying the underlying cause – e.g., low lean mass – can significantly improve cognitive function,” said Dr. Miljkovic, senior author of a study showing muscle fat as a risk factor for cognitive decline.

More research will enable us to “expand our understanding” of the mechanisms involved and determine whether interventions aimed at preventing muscle loss and/or increasing muscle fat may have a beneficial effect on cognitive function,” she said. “This might lead to novel strategies to prevent AD.”

Dr. Daghlas is supported by the British Heart Foundation Centre of Research Excellence at Imperial College, London, and is employed part-time by Novo Nordisk. Dr. Miljkovic reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators analyzed data on more than 450,000 participants in the UK Biobank as well as two independent samples of more than 320,000 individuals with and without AD, and more than 260,000 individuals participating in a separate genes and intelligence study.

They estimated lean muscle and fat tissue in the arms and legs and found, in adjusted analyses, over 500 genetic variants associated with lean mass.

On average, higher genetically lean mass was associated with a “modest but statistically robust” reduction in AD risk and with superior performance on cognitive tasks.

“Using human genetic data, we found evidence for a protective effect of lean mass on risk of Alzheimer’s disease,” study investigators Iyas Daghlas, MD, a resident in the department of neurology, University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview.

Although “clinical intervention studies are needed to confirm this effect, this study supports current recommendations to maintain a healthy lifestyle to prevent dementia,” he said.

The study was published online in BMJ Medicine.

Naturally randomized research

Several measures of body composition have been investigated for their potential association with AD. Lean mass – a “proxy for muscle mass, defined as the difference between total mass and fat mass” – has been shown to be reduced in patients with AD compared with controls, the researchers noted.

“Previous research studies have tested the relationship of body mass index with Alzheimer’s disease and did not find evidence for a causal effect,” Dr. Daghlas said. “We wondered whether BMI was an insufficiently granular measure and hypothesized that disaggregating body mass into lean mass and fat mass could reveal novel associations with disease.”

Most studies have used case-control designs, which might be biased by “residual confounding or reverse causality.” Naturally randomized data “may be used as an alternative to conventional observational studies to investigate causal relations between risk factors and diseases,” the researchers wrote.

In particular, the Mendelian randomization (MR) paradigm randomly allocates germline genetic variants and uses them as proxies for a specific risk factor.

MR “is a technique that permits researchers to investigate cause-and-effect relationships using human genetic data,” Dr. Daghlas explained. “In effect, we’re studying the results of a naturally randomized experiment whereby some individuals are genetically allocated to carry more lean mass.”

The current study used MR to investigate the effect of genetically proxied lean mass on the risk of AD and the “related phenotype” of cognitive performance.

Genetic proxy

As genetic proxies for lean mass, the researchers chose single nucleotide polymorphisms (genetic variants) that were associated, in a genome-wide association study (GWAS), with appendicular lean mass.

Appendicular lean mass “more accurately reflects the effects of lean mass than whole body lean mass, which includes smooth and cardiac muscle,” the authors explained.

This GWAS used phenotypic and genetic data from 450,243 participants in the UK Biobank cohort (mean age 57 years). All participants were of European ancestry.

The researchers adjusted for age, sex, and genetic ancestry. They measured appendicular lean mass using bioimpedance – an electric current that flows at different rates through the body, depending on its composition.

In addition to the UK Biobank participants, the researchers drew on an independent sample of 21,982 people with AD; a control group of 41,944 people without AD; a replication sample of 7,329 people with and 252,879 people without AD to validate the findings; and 269,867 people taking part in a genome-wide study of cognitive performance.

The researchers identified 584 variants that met criteria for use as genetic proxies for lean mass. None were located within the APOE gene region. In the aggregate, these variants explained 10.3% of the variance in appendicular lean mass.

Each standard deviation increase in genetically proxied lean mass was associated with a 12% reduction in AD risk (odds ratio [OR], 0.88; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.82-0.95; P < .001). This finding was replicated in the independent consortium (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.83-0.99; P = .02).

The findings remained “consistent” in sensitivity analyses.

A modifiable risk factor?

Higher appendicular lean mass was associated with higher levels of cognitive performance, with each SD increase in lean mass associated with an SD increase in cognitive performance (OR, 0.09; 95% CI, 0.06-0.11; P = .001).

“Adjusting for potential mediation through performance did not reduce the association between appendicular lean mass and risk of AD,” the authors wrote.

They obtained similar results using genetically proxied trunk and whole-body lean mass, after adjusting for fat mass.

The authors noted several limitations. The bioimpedance measures “only predict, but do not directly measure, lean mass.” Moreover, the approach didn’t examine whether a “critical window of risk factor timing” exists, during which lean mass might play a role in influencing AD risk and after which “interventions would no longer be effective.” Nor could the study determine whether increasing lean mass could reverse AD pathology in patients with preclinical disease or mild cognitive impairment.

Nevertheless, the findings suggest “that lean mass might be a possible modifiable protective factor for Alzheimer’s disease,” the authors wrote. “The mechanisms underlying this finding, as well as the clinical and public health implications, warrant further investigation.”

Novel strategies

In a comment, Iva Miljkovic, MD, PhD, associate professor, department of epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh, said the investigators used “very rigorous methodology.”

The finding suggesting that lean mass is associated with better cognitive function is “important, as cognitive impairment can become stable rather than progress to a pathological state; and, in some cases, can even be reversed.”

In those cases, “identifying the underlying cause – e.g., low lean mass – can significantly improve cognitive function,” said Dr. Miljkovic, senior author of a study showing muscle fat as a risk factor for cognitive decline.

More research will enable us to “expand our understanding” of the mechanisms involved and determine whether interventions aimed at preventing muscle loss and/or increasing muscle fat may have a beneficial effect on cognitive function,” she said. “This might lead to novel strategies to prevent AD.”

Dr. Daghlas is supported by the British Heart Foundation Centre of Research Excellence at Imperial College, London, and is employed part-time by Novo Nordisk. Dr. Miljkovic reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators analyzed data on more than 450,000 participants in the UK Biobank as well as two independent samples of more than 320,000 individuals with and without AD, and more than 260,000 individuals participating in a separate genes and intelligence study.

They estimated lean muscle and fat tissue in the arms and legs and found, in adjusted analyses, over 500 genetic variants associated with lean mass.

On average, higher genetically lean mass was associated with a “modest but statistically robust” reduction in AD risk and with superior performance on cognitive tasks.

“Using human genetic data, we found evidence for a protective effect of lean mass on risk of Alzheimer’s disease,” study investigators Iyas Daghlas, MD, a resident in the department of neurology, University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview.

Although “clinical intervention studies are needed to confirm this effect, this study supports current recommendations to maintain a healthy lifestyle to prevent dementia,” he said.

The study was published online in BMJ Medicine.

Naturally randomized research

Several measures of body composition have been investigated for their potential association with AD. Lean mass – a “proxy for muscle mass, defined as the difference between total mass and fat mass” – has been shown to be reduced in patients with AD compared with controls, the researchers noted.

“Previous research studies have tested the relationship of body mass index with Alzheimer’s disease and did not find evidence for a causal effect,” Dr. Daghlas said. “We wondered whether BMI was an insufficiently granular measure and hypothesized that disaggregating body mass into lean mass and fat mass could reveal novel associations with disease.”

Most studies have used case-control designs, which might be biased by “residual confounding or reverse causality.” Naturally randomized data “may be used as an alternative to conventional observational studies to investigate causal relations between risk factors and diseases,” the researchers wrote.

In particular, the Mendelian randomization (MR) paradigm randomly allocates germline genetic variants and uses them as proxies for a specific risk factor.

MR “is a technique that permits researchers to investigate cause-and-effect relationships using human genetic data,” Dr. Daghlas explained. “In effect, we’re studying the results of a naturally randomized experiment whereby some individuals are genetically allocated to carry more lean mass.”

The current study used MR to investigate the effect of genetically proxied lean mass on the risk of AD and the “related phenotype” of cognitive performance.

Genetic proxy

As genetic proxies for lean mass, the researchers chose single nucleotide polymorphisms (genetic variants) that were associated, in a genome-wide association study (GWAS), with appendicular lean mass.

Appendicular lean mass “more accurately reflects the effects of lean mass than whole body lean mass, which includes smooth and cardiac muscle,” the authors explained.

This GWAS used phenotypic and genetic data from 450,243 participants in the UK Biobank cohort (mean age 57 years). All participants were of European ancestry.

The researchers adjusted for age, sex, and genetic ancestry. They measured appendicular lean mass using bioimpedance – an electric current that flows at different rates through the body, depending on its composition.

In addition to the UK Biobank participants, the researchers drew on an independent sample of 21,982 people with AD; a control group of 41,944 people without AD; a replication sample of 7,329 people with and 252,879 people without AD to validate the findings; and 269,867 people taking part in a genome-wide study of cognitive performance.

The researchers identified 584 variants that met criteria for use as genetic proxies for lean mass. None were located within the APOE gene region. In the aggregate, these variants explained 10.3% of the variance in appendicular lean mass.

Each standard deviation increase in genetically proxied lean mass was associated with a 12% reduction in AD risk (odds ratio [OR], 0.88; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.82-0.95; P < .001). This finding was replicated in the independent consortium (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.83-0.99; P = .02).

The findings remained “consistent” in sensitivity analyses.

A modifiable risk factor?

Higher appendicular lean mass was associated with higher levels of cognitive performance, with each SD increase in lean mass associated with an SD increase in cognitive performance (OR, 0.09; 95% CI, 0.06-0.11; P = .001).

“Adjusting for potential mediation through performance did not reduce the association between appendicular lean mass and risk of AD,” the authors wrote.

They obtained similar results using genetically proxied trunk and whole-body lean mass, after adjusting for fat mass.

The authors noted several limitations. The bioimpedance measures “only predict, but do not directly measure, lean mass.” Moreover, the approach didn’t examine whether a “critical window of risk factor timing” exists, during which lean mass might play a role in influencing AD risk and after which “interventions would no longer be effective.” Nor could the study determine whether increasing lean mass could reverse AD pathology in patients with preclinical disease or mild cognitive impairment.

Nevertheless, the findings suggest “that lean mass might be a possible modifiable protective factor for Alzheimer’s disease,” the authors wrote. “The mechanisms underlying this finding, as well as the clinical and public health implications, warrant further investigation.”

Novel strategies

In a comment, Iva Miljkovic, MD, PhD, associate professor, department of epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh, said the investigators used “very rigorous methodology.”

The finding suggesting that lean mass is associated with better cognitive function is “important, as cognitive impairment can become stable rather than progress to a pathological state; and, in some cases, can even be reversed.”

In those cases, “identifying the underlying cause – e.g., low lean mass – can significantly improve cognitive function,” said Dr. Miljkovic, senior author of a study showing muscle fat as a risk factor for cognitive decline.

More research will enable us to “expand our understanding” of the mechanisms involved and determine whether interventions aimed at preventing muscle loss and/or increasing muscle fat may have a beneficial effect on cognitive function,” she said. “This might lead to novel strategies to prevent AD.”

Dr. Daghlas is supported by the British Heart Foundation Centre of Research Excellence at Imperial College, London, and is employed part-time by Novo Nordisk. Dr. Miljkovic reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM BMJ MEDICINE

Discontinuing Disease-Modifying Therapies in Nonactive Secondary Progressive MS:Review of the Evidence

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an immune-mediated demyelinating disorder. There are 2 broad categories of MS: relapsing, also called active MS; and progressive MS. Unfortunately, there is no cure for MS, but disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) can help prevent relapses and new central nervous system lesions in people living with active MS. For patients with the most common type of MS, relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), DMTs are typically continued for decades while the patient has active disease. RRMS will usually transition to secondary progressive MS (SPMS), which can present as active SPMS or nonactive SPMS. The latter is the type of MS most people with RRMS eventually experience.

A 2019 study estimated that nearly 1 million people in the United States were living with MS.1 This population estimate indicated the peak age-specific prevalence of MS was 55 to 64 years. Population data demonstrate improved mortality rates for people diagnosed with MS from 1997 to 2012 compared with prior years.2 Therefore, the management of nonactive SPMS is an increasingly significant area of need. There are currently no DMTs on the market approved for nonactive SPMS, and lifelong DMTs in these patients are neither indicated nor supported by evidence. Nevertheless, the discontinuation of DMTs in nonactive SPMS has been a long-debated topic with varied opinions on how and when to discontinue.

The 2018 American Academy of Neurology (AAN) guideline recommends that clinicians advise patients with SPMS to discontinue DMT use if they do not have ongoing relapses (or gadolinium-enhanced lesions on magnetic resonance imaging activity) or have not been ambulatory (Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS] ≥ 7) for ≥ 2 years.3 In recent years, there has been increased research on nonactive SPMS, specifically on discontinuation of DMTs. This clinical review assesses the recent evidence from a variety of standpoints, including the effect of discontinuing DMTs on the MS disease course and quality of life (QOL) and the perspectives of patients living with MS. Based on this evidence, a conversation guide will be presented as a framework to aid with the clinician-patient discussion on discontinuing MS DMTs.

Disease Modifying Therapies

Roos and colleagues used data from 2 large MS cohorts: MSBase and Observatoire Français de la Sclérose en Plaques (OFSEP) to compare high-efficacy vs low-efficacy DMT in both active and nonactive SPMS.4 In the active SPMS group, the strength of DMTs did not change disability progression, but high-efficacy DMTs reduced relapses better than the low-efficacy DMTs. On the other hand, the nonactive SPMS group saw no difference between DMTs in both relapse risk and disability progression. Another observational study of 221 patients with RRMS who discontinued DMTs noted that there were 2 independent predictors for the absence of relapse following DMT discontinuation: being aged > 45 years and the lack of relapse for ≥ 4 years prior to DMT discontinuation.5 Though these patients still may have been classified as RRMS, both these independent predictors for stability postdiscontinuation of DMTs are the typical characteristics of a nonactive SPMS patient.

Pathophysiology may help explain why DMT discontinuation seems to produce no adverse clinical outcomes in people with nonactive SPMS. Nonactive SPMS, which follows after RRMS, is largely correlated with age. In nonactive SPMS, there is less B and T lymphocyte migration across the blood-brain barrier. Furthermore, a lifetime of low-grade inflammation during the RRMS phase results in axonal damage and declined repair capacity, which produces the predominance of neurodegeneration in the nonactive SPMS disease process.6 This pathophysiologic difference between active and nonactive disease not only explains the different symptomatology of these MS subtypes, but also could explain why drugs that target the inflammatory processes more characteristic of active disease are not effective in nonactive SPMS.

Other recent studies explored the impact of age on DMT efficacy for patients with nonactive SPMS. A meta-analysis by Weidman and colleagues pooled trial data across multiple DMT classes in > 28,000 patients.7 The resulting regression model predicted zero efficacy of any DMT in patients who are aged > 53 years. High-efficacy DMTs only outperformed low-efficacy DMTs in people aged < 40.5 years. Another observational study by Hua and colleagues saw a similar result.8 This study included patients who discontinued DMT who were aged ≥ 60 years. The median follow-up time was 5.3 years. Of the 178 patients who discontinued DMTs, only 1 patient had a relapse. In this study, the age for participation provided a higher likelihood that patients included were in nonactive SPMS. Furthermore, the outcome reflects the typical presentation of nonactive SPMS where, despite the continuation or discontinuation of DMT, there was a lack of relapses. When comparing patients who discontinued DMTs with those who continued use, there was no significant difference in their 25-foot walk times, which is an objective marker for a more progressive symptom seen in nonactive MS.

The DISCOMS trial (NCT03073603) has been completed, but full results are not yet published. In this noninferiority trial, > 250 patients aged ≥ 55 years were assessed on a variety of outcomes, including relapses, EDSS score, and QOL. MS subtypes were considered at baseline, and subgroup analysis looking particularly at the SPMS population could provide further insight into its effect on MS course.

Quality of Life

Whether discontinuation of DMTs is worth considering in nonactive SPMS, it is also important to consider the risks and burdens associated with continuation. Medication administration burdens come with all MS DMTs whether there is the need to inject oneself, increased pill burden, or travel to an infusion clinic. The ever-rising costs of DMTs also can be a financial burden to the patient.9 All MS DMTs carry risks of adverse effects (AEs). These can range from a mild injection site reaction to severe infection, depending on the DMT used. Many of these severe AEs, such as opportunistic infections and cancer, have been associated with either an increased risk of occurrence and/or worsened outcomes in older adults who remain on DMTs, particularly moderate- to high-efficacy DMTs, such as sphingosine-1- phosphate receptor modulators, fumarates, natalizumab, alemtuzumab, cladribine, and anti-CD20 antibodies.10 In a 2019 survey of 377 patients with MS, 63.8% of respondents ranked safety as the most important reason they would consider discontinuing their DMTs.11 In addition, a real-world study comparing people with nonactive SPMS who continued DMTs vs those who discontinued found that discontinuers reported better QOL.8

Conversation Guide for Discontinuing Therapies

The 2019 survey that assessed reasons for discontinuation also asked people with nonactive SPMS whether they thought they were in a nonactive disease stage, and what was their likelihood they would stop DMTs.11 Interestingly, only 59.4% of respondents self-assessed their MS as nonactive, and just 11.9% of respondents were willing to discontinue DMTs.11 These results suggest that there may be a need for patient education about nonactive SPMS and the rationale to continue or discontinue DMTs. Thus, before broaching the topic of discontinuation, explaining the nonactive SPMS subtype is important.

Even with a good understanding of nonactive SPMS, patients may be hesitant to stop using DMTs that they previously relied on to keep their MS stable. The 2019 survey ranked physician recommendation as the third highest reason to discontinue DMTs.11 Taking the time to explain the clinical evidence for DMT discontinuation may help patients better understand a clinician’s recommendation and inspire more confidence.

Another important aspect of DMT discontinuation decision making is creating a plan for how the patient will be monitored to provide assurance if they experience a relapse. The 2019 survey asked patients what would be most important to them for their management plan after discontinuing DMT; magnetic resonance imaging and neurologic examination monitoring ranked the highest.11 The plan should include timing for follow-up appointments and imaging, providing the patient comfort in knowing their MS will be monitored and verified for the relapse stability that is expected from nonactive SPMS. In the rare case a relapse does occur, having a contingency plan and noting the possibility of restarting DMTs is an integral part of reassuring the patient that their decision to discontinue DMTs will be treated with the utmost caution and individualized to their needs.

Lastly, highlighting which aspects of MS treatment will continue to be a priority in nonactive SPMS, such as symptomatic medication management and nonpharmacologic therapy, is important for the patient to recognize that there are still opportunities to manage this phase of MS. There are many lifestyle modifications that can be considered complementary to medical management of MS at any stage of the disease. Vascular comorbidities, such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes, have been associated with more rapid disability progression in MS.12 Optimized management of these diseases may slow disability progression, in addition to the benefit of improved outcomes of the vascular comorbidity. Various formats of exercise have been studied in the MS population. A meta-analysis of aerobic, resistance, and combined exercise found benefits in these formats on health-related QOL.13

Many dietary strategies have been studied in MS. A recent network meta-analysis reviewed some of the more commonly studied diets, including low-fat, modified Mediterranean, ketogenic, anti-inflammatory, Paleolithic, intermittent fasting, and calorie restriction vs a usual diet.14 Although the overall quality of evidence was low, the Paleolithic and modified Mediterranean showed greater reductions in fatigue, as well as increased physical and

As with any health care decision, it is important to involve the patient in a joint decision regarding their care. This may mean giving the patient time to think about the information presented, do their own research, talk to family members or other clinicians, etc. The decision to discontinue DMT may not happen at the same appointment it is initially brought up at. It may even be reasonable to revisit the conversation later if discontinuation is not something the patient is amenable to at the time.

Conclusions

There is high-quality evidence that discontinuing DMTs in nonactive SPMS is not a major detriment to the MS disease course. Current literature also suggests that there may be benefits to discontinuation in this MS subtype in terms of QOL and meeting patient values. Additional research particularly in the nonactive SPMS population will continue to improve the knowledge and awareness of this aspect of MS DMT management. The growing evidence in this area may make discontinuation of DMT in nonactive SPMS a less-debatable topic, but it is still a major treatment decision that clinicians must thoroughly discuss with the patient to provide high-quality, patient-centered care.

1. Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Campbell JD, et al. The prevalence of MS in the United States: a population-based estimate using health claims data. Neurology. 2019;92(10):e1029-e1040. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000007035

2. Lunde HMB, Assmus J, Myhr KM, Bø L, Grytten N. Survival and cause of death in multiple sclerosis: a 60-year longitudinal population study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(8):621-625. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2016-315238

3. Rae-Grant A, Day GS, Marrie RA, et al. Practice guideline recommendations summary: disease-modifying therapies for adults with multiple sclerosis: report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2018;90(17):777-788. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000005347

4. Roos I, Leray E, Casey R, et al. Effects of high- and low-efficacy therapy in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2021;97(9):e869-e880. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000012354

5. Bsteh G, Feige J, Ehling R, et al. Discontinuation of disease-modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis - clinical outcome and prognostic factors. Mult Scler. 2017;23(9):1241-1248. doi:10.1177/1352458516675751

6. Musella A, Gentile A, Rizzo FR, et al. Interplay between age and neuroinflammation in multiple sclerosis: effects on motor and cognitive functions. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:238. Published 2018 Aug 8. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2018.00238

7. Weideman AM, Tapia-Maltos MA, Johnson K, Greenwood M, Bielekova B. Meta-analysis of the age-dependent efficacy of multiple sclerosis treatments. Front Neurol. 2017;8:577. Published 2017 Nov 10. doi:10.3389/fneur.2017.00577

8. Hua LH, Harris H, Conway D, Thompson NR. Changes in patient-reported outcomes between continuers and discontinuers of disease modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis over age 60. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;30:252-256. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2019.02.028

9. San-Juan-Rodriguez A, Good CB, Heyman RA, Parekh N, Shrank WH, Hernandez I. Trends in prices, market share, and spending on self-administered disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis in Medicare part D. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(11):1386-1390. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2711

10. Schweitzer F, Laurent S, Fink GR, et al. Age and the risks of high-efficacy disease modifying drugs in multiple sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2019;32(3):305-312. doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000000701

11. McGinley MP, Cola PA, Fox RJ, Cohen JA, Corboy JJ, Miller D. Perspectives of individuals with multiple sclerosis on discontinuation of disease-modifying therapies. Mult Scler. 2020;26(12):1581-1589. doi:10.1177/1352458519867314

12. Marrie RA, Rudick R, Horwitz R, et al. Vascular comorbidity is associated with more rapid disability progression in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2010;74(13):1041-1047. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d6b125

13. Flores VA, Šilic´ P, DuBose NG, Zheng P, Jeng B, Motl RW. Effects of aerobic, resistance, and combined exercise training on health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2023;75:104746. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2023.104746

14. Snetselaar LG, Cheek JJ, Fox SS, et al. Efficacy of diet on fatigue and quality of life in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized trials. Neurology. 2023;100(4):e357-e366. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000201371

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an immune-mediated demyelinating disorder. There are 2 broad categories of MS: relapsing, also called active MS; and progressive MS. Unfortunately, there is no cure for MS, but disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) can help prevent relapses and new central nervous system lesions in people living with active MS. For patients with the most common type of MS, relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), DMTs are typically continued for decades while the patient has active disease. RRMS will usually transition to secondary progressive MS (SPMS), which can present as active SPMS or nonactive SPMS. The latter is the type of MS most people with RRMS eventually experience.

A 2019 study estimated that nearly 1 million people in the United States were living with MS.1 This population estimate indicated the peak age-specific prevalence of MS was 55 to 64 years. Population data demonstrate improved mortality rates for people diagnosed with MS from 1997 to 2012 compared with prior years.2 Therefore, the management of nonactive SPMS is an increasingly significant area of need. There are currently no DMTs on the market approved for nonactive SPMS, and lifelong DMTs in these patients are neither indicated nor supported by evidence. Nevertheless, the discontinuation of DMTs in nonactive SPMS has been a long-debated topic with varied opinions on how and when to discontinue.

The 2018 American Academy of Neurology (AAN) guideline recommends that clinicians advise patients with SPMS to discontinue DMT use if they do not have ongoing relapses (or gadolinium-enhanced lesions on magnetic resonance imaging activity) or have not been ambulatory (Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS] ≥ 7) for ≥ 2 years.3 In recent years, there has been increased research on nonactive SPMS, specifically on discontinuation of DMTs. This clinical review assesses the recent evidence from a variety of standpoints, including the effect of discontinuing DMTs on the MS disease course and quality of life (QOL) and the perspectives of patients living with MS. Based on this evidence, a conversation guide will be presented as a framework to aid with the clinician-patient discussion on discontinuing MS DMTs.

Disease Modifying Therapies

Roos and colleagues used data from 2 large MS cohorts: MSBase and Observatoire Français de la Sclérose en Plaques (OFSEP) to compare high-efficacy vs low-efficacy DMT in both active and nonactive SPMS.4 In the active SPMS group, the strength of DMTs did not change disability progression, but high-efficacy DMTs reduced relapses better than the low-efficacy DMTs. On the other hand, the nonactive SPMS group saw no difference between DMTs in both relapse risk and disability progression. Another observational study of 221 patients with RRMS who discontinued DMTs noted that there were 2 independent predictors for the absence of relapse following DMT discontinuation: being aged > 45 years and the lack of relapse for ≥ 4 years prior to DMT discontinuation.5 Though these patients still may have been classified as RRMS, both these independent predictors for stability postdiscontinuation of DMTs are the typical characteristics of a nonactive SPMS patient.

Pathophysiology may help explain why DMT discontinuation seems to produce no adverse clinical outcomes in people with nonactive SPMS. Nonactive SPMS, which follows after RRMS, is largely correlated with age. In nonactive SPMS, there is less B and T lymphocyte migration across the blood-brain barrier. Furthermore, a lifetime of low-grade inflammation during the RRMS phase results in axonal damage and declined repair capacity, which produces the predominance of neurodegeneration in the nonactive SPMS disease process.6 This pathophysiologic difference between active and nonactive disease not only explains the different symptomatology of these MS subtypes, but also could explain why drugs that target the inflammatory processes more characteristic of active disease are not effective in nonactive SPMS.

Other recent studies explored the impact of age on DMT efficacy for patients with nonactive SPMS. A meta-analysis by Weidman and colleagues pooled trial data across multiple DMT classes in > 28,000 patients.7 The resulting regression model predicted zero efficacy of any DMT in patients who are aged > 53 years. High-efficacy DMTs only outperformed low-efficacy DMTs in people aged < 40.5 years. Another observational study by Hua and colleagues saw a similar result.8 This study included patients who discontinued DMT who were aged ≥ 60 years. The median follow-up time was 5.3 years. Of the 178 patients who discontinued DMTs, only 1 patient had a relapse. In this study, the age for participation provided a higher likelihood that patients included were in nonactive SPMS. Furthermore, the outcome reflects the typical presentation of nonactive SPMS where, despite the continuation or discontinuation of DMT, there was a lack of relapses. When comparing patients who discontinued DMTs with those who continued use, there was no significant difference in their 25-foot walk times, which is an objective marker for a more progressive symptom seen in nonactive MS.

The DISCOMS trial (NCT03073603) has been completed, but full results are not yet published. In this noninferiority trial, > 250 patients aged ≥ 55 years were assessed on a variety of outcomes, including relapses, EDSS score, and QOL. MS subtypes were considered at baseline, and subgroup analysis looking particularly at the SPMS population could provide further insight into its effect on MS course.

Quality of Life

Whether discontinuation of DMTs is worth considering in nonactive SPMS, it is also important to consider the risks and burdens associated with continuation. Medication administration burdens come with all MS DMTs whether there is the need to inject oneself, increased pill burden, or travel to an infusion clinic. The ever-rising costs of DMTs also can be a financial burden to the patient.9 All MS DMTs carry risks of adverse effects (AEs). These can range from a mild injection site reaction to severe infection, depending on the DMT used. Many of these severe AEs, such as opportunistic infections and cancer, have been associated with either an increased risk of occurrence and/or worsened outcomes in older adults who remain on DMTs, particularly moderate- to high-efficacy DMTs, such as sphingosine-1- phosphate receptor modulators, fumarates, natalizumab, alemtuzumab, cladribine, and anti-CD20 antibodies.10 In a 2019 survey of 377 patients with MS, 63.8% of respondents ranked safety as the most important reason they would consider discontinuing their DMTs.11 In addition, a real-world study comparing people with nonactive SPMS who continued DMTs vs those who discontinued found that discontinuers reported better QOL.8

Conversation Guide for Discontinuing Therapies

The 2019 survey that assessed reasons for discontinuation also asked people with nonactive SPMS whether they thought they were in a nonactive disease stage, and what was their likelihood they would stop DMTs.11 Interestingly, only 59.4% of respondents self-assessed their MS as nonactive, and just 11.9% of respondents were willing to discontinue DMTs.11 These results suggest that there may be a need for patient education about nonactive SPMS and the rationale to continue or discontinue DMTs. Thus, before broaching the topic of discontinuation, explaining the nonactive SPMS subtype is important.

Even with a good understanding of nonactive SPMS, patients may be hesitant to stop using DMTs that they previously relied on to keep their MS stable. The 2019 survey ranked physician recommendation as the third highest reason to discontinue DMTs.11 Taking the time to explain the clinical evidence for DMT discontinuation may help patients better understand a clinician’s recommendation and inspire more confidence.

Another important aspect of DMT discontinuation decision making is creating a plan for how the patient will be monitored to provide assurance if they experience a relapse. The 2019 survey asked patients what would be most important to them for their management plan after discontinuing DMT; magnetic resonance imaging and neurologic examination monitoring ranked the highest.11 The plan should include timing for follow-up appointments and imaging, providing the patient comfort in knowing their MS will be monitored and verified for the relapse stability that is expected from nonactive SPMS. In the rare case a relapse does occur, having a contingency plan and noting the possibility of restarting DMTs is an integral part of reassuring the patient that their decision to discontinue DMTs will be treated with the utmost caution and individualized to their needs.

Lastly, highlighting which aspects of MS treatment will continue to be a priority in nonactive SPMS, such as symptomatic medication management and nonpharmacologic therapy, is important for the patient to recognize that there are still opportunities to manage this phase of MS. There are many lifestyle modifications that can be considered complementary to medical management of MS at any stage of the disease. Vascular comorbidities, such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes, have been associated with more rapid disability progression in MS.12 Optimized management of these diseases may slow disability progression, in addition to the benefit of improved outcomes of the vascular comorbidity. Various formats of exercise have been studied in the MS population. A meta-analysis of aerobic, resistance, and combined exercise found benefits in these formats on health-related QOL.13

Many dietary strategies have been studied in MS. A recent network meta-analysis reviewed some of the more commonly studied diets, including low-fat, modified Mediterranean, ketogenic, anti-inflammatory, Paleolithic, intermittent fasting, and calorie restriction vs a usual diet.14 Although the overall quality of evidence was low, the Paleolithic and modified Mediterranean showed greater reductions in fatigue, as well as increased physical and

As with any health care decision, it is important to involve the patient in a joint decision regarding their care. This may mean giving the patient time to think about the information presented, do their own research, talk to family members or other clinicians, etc. The decision to discontinue DMT may not happen at the same appointment it is initially brought up at. It may even be reasonable to revisit the conversation later if discontinuation is not something the patient is amenable to at the time.

Conclusions

There is high-quality evidence that discontinuing DMTs in nonactive SPMS is not a major detriment to the MS disease course. Current literature also suggests that there may be benefits to discontinuation in this MS subtype in terms of QOL and meeting patient values. Additional research particularly in the nonactive SPMS population will continue to improve the knowledge and awareness of this aspect of MS DMT management. The growing evidence in this area may make discontinuation of DMT in nonactive SPMS a less-debatable topic, but it is still a major treatment decision that clinicians must thoroughly discuss with the patient to provide high-quality, patient-centered care.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an immune-mediated demyelinating disorder. There are 2 broad categories of MS: relapsing, also called active MS; and progressive MS. Unfortunately, there is no cure for MS, but disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) can help prevent relapses and new central nervous system lesions in people living with active MS. For patients with the most common type of MS, relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), DMTs are typically continued for decades while the patient has active disease. RRMS will usually transition to secondary progressive MS (SPMS), which can present as active SPMS or nonactive SPMS. The latter is the type of MS most people with RRMS eventually experience.

A 2019 study estimated that nearly 1 million people in the United States were living with MS.1 This population estimate indicated the peak age-specific prevalence of MS was 55 to 64 years. Population data demonstrate improved mortality rates for people diagnosed with MS from 1997 to 2012 compared with prior years.2 Therefore, the management of nonactive SPMS is an increasingly significant area of need. There are currently no DMTs on the market approved for nonactive SPMS, and lifelong DMTs in these patients are neither indicated nor supported by evidence. Nevertheless, the discontinuation of DMTs in nonactive SPMS has been a long-debated topic with varied opinions on how and when to discontinue.

The 2018 American Academy of Neurology (AAN) guideline recommends that clinicians advise patients with SPMS to discontinue DMT use if they do not have ongoing relapses (or gadolinium-enhanced lesions on magnetic resonance imaging activity) or have not been ambulatory (Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS] ≥ 7) for ≥ 2 years.3 In recent years, there has been increased research on nonactive SPMS, specifically on discontinuation of DMTs. This clinical review assesses the recent evidence from a variety of standpoints, including the effect of discontinuing DMTs on the MS disease course and quality of life (QOL) and the perspectives of patients living with MS. Based on this evidence, a conversation guide will be presented as a framework to aid with the clinician-patient discussion on discontinuing MS DMTs.

Disease Modifying Therapies

Roos and colleagues used data from 2 large MS cohorts: MSBase and Observatoire Français de la Sclérose en Plaques (OFSEP) to compare high-efficacy vs low-efficacy DMT in both active and nonactive SPMS.4 In the active SPMS group, the strength of DMTs did not change disability progression, but high-efficacy DMTs reduced relapses better than the low-efficacy DMTs. On the other hand, the nonactive SPMS group saw no difference between DMTs in both relapse risk and disability progression. Another observational study of 221 patients with RRMS who discontinued DMTs noted that there were 2 independent predictors for the absence of relapse following DMT discontinuation: being aged > 45 years and the lack of relapse for ≥ 4 years prior to DMT discontinuation.5 Though these patients still may have been classified as RRMS, both these independent predictors for stability postdiscontinuation of DMTs are the typical characteristics of a nonactive SPMS patient.

Pathophysiology may help explain why DMT discontinuation seems to produce no adverse clinical outcomes in people with nonactive SPMS. Nonactive SPMS, which follows after RRMS, is largely correlated with age. In nonactive SPMS, there is less B and T lymphocyte migration across the blood-brain barrier. Furthermore, a lifetime of low-grade inflammation during the RRMS phase results in axonal damage and declined repair capacity, which produces the predominance of neurodegeneration in the nonactive SPMS disease process.6 This pathophysiologic difference between active and nonactive disease not only explains the different symptomatology of these MS subtypes, but also could explain why drugs that target the inflammatory processes more characteristic of active disease are not effective in nonactive SPMS.

Other recent studies explored the impact of age on DMT efficacy for patients with nonactive SPMS. A meta-analysis by Weidman and colleagues pooled trial data across multiple DMT classes in > 28,000 patients.7 The resulting regression model predicted zero efficacy of any DMT in patients who are aged > 53 years. High-efficacy DMTs only outperformed low-efficacy DMTs in people aged < 40.5 years. Another observational study by Hua and colleagues saw a similar result.8 This study included patients who discontinued DMT who were aged ≥ 60 years. The median follow-up time was 5.3 years. Of the 178 patients who discontinued DMTs, only 1 patient had a relapse. In this study, the age for participation provided a higher likelihood that patients included were in nonactive SPMS. Furthermore, the outcome reflects the typical presentation of nonactive SPMS where, despite the continuation or discontinuation of DMT, there was a lack of relapses. When comparing patients who discontinued DMTs with those who continued use, there was no significant difference in their 25-foot walk times, which is an objective marker for a more progressive symptom seen in nonactive MS.

The DISCOMS trial (NCT03073603) has been completed, but full results are not yet published. In this noninferiority trial, > 250 patients aged ≥ 55 years were assessed on a variety of outcomes, including relapses, EDSS score, and QOL. MS subtypes were considered at baseline, and subgroup analysis looking particularly at the SPMS population could provide further insight into its effect on MS course.

Quality of Life

Whether discontinuation of DMTs is worth considering in nonactive SPMS, it is also important to consider the risks and burdens associated with continuation. Medication administration burdens come with all MS DMTs whether there is the need to inject oneself, increased pill burden, or travel to an infusion clinic. The ever-rising costs of DMTs also can be a financial burden to the patient.9 All MS DMTs carry risks of adverse effects (AEs). These can range from a mild injection site reaction to severe infection, depending on the DMT used. Many of these severe AEs, such as opportunistic infections and cancer, have been associated with either an increased risk of occurrence and/or worsened outcomes in older adults who remain on DMTs, particularly moderate- to high-efficacy DMTs, such as sphingosine-1- phosphate receptor modulators, fumarates, natalizumab, alemtuzumab, cladribine, and anti-CD20 antibodies.10 In a 2019 survey of 377 patients with MS, 63.8% of respondents ranked safety as the most important reason they would consider discontinuing their DMTs.11 In addition, a real-world study comparing people with nonactive SPMS who continued DMTs vs those who discontinued found that discontinuers reported better QOL.8

Conversation Guide for Discontinuing Therapies

The 2019 survey that assessed reasons for discontinuation also asked people with nonactive SPMS whether they thought they were in a nonactive disease stage, and what was their likelihood they would stop DMTs.11 Interestingly, only 59.4% of respondents self-assessed their MS as nonactive, and just 11.9% of respondents were willing to discontinue DMTs.11 These results suggest that there may be a need for patient education about nonactive SPMS and the rationale to continue or discontinue DMTs. Thus, before broaching the topic of discontinuation, explaining the nonactive SPMS subtype is important.

Even with a good understanding of nonactive SPMS, patients may be hesitant to stop using DMTs that they previously relied on to keep their MS stable. The 2019 survey ranked physician recommendation as the third highest reason to discontinue DMTs.11 Taking the time to explain the clinical evidence for DMT discontinuation may help patients better understand a clinician’s recommendation and inspire more confidence.

Another important aspect of DMT discontinuation decision making is creating a plan for how the patient will be monitored to provide assurance if they experience a relapse. The 2019 survey asked patients what would be most important to them for their management plan after discontinuing DMT; magnetic resonance imaging and neurologic examination monitoring ranked the highest.11 The plan should include timing for follow-up appointments and imaging, providing the patient comfort in knowing their MS will be monitored and verified for the relapse stability that is expected from nonactive SPMS. In the rare case a relapse does occur, having a contingency plan and noting the possibility of restarting DMTs is an integral part of reassuring the patient that their decision to discontinue DMTs will be treated with the utmost caution and individualized to their needs.

Lastly, highlighting which aspects of MS treatment will continue to be a priority in nonactive SPMS, such as symptomatic medication management and nonpharmacologic therapy, is important for the patient to recognize that there are still opportunities to manage this phase of MS. There are many lifestyle modifications that can be considered complementary to medical management of MS at any stage of the disease. Vascular comorbidities, such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes, have been associated with more rapid disability progression in MS.12 Optimized management of these diseases may slow disability progression, in addition to the benefit of improved outcomes of the vascular comorbidity. Various formats of exercise have been studied in the MS population. A meta-analysis of aerobic, resistance, and combined exercise found benefits in these formats on health-related QOL.13

Many dietary strategies have been studied in MS. A recent network meta-analysis reviewed some of the more commonly studied diets, including low-fat, modified Mediterranean, ketogenic, anti-inflammatory, Paleolithic, intermittent fasting, and calorie restriction vs a usual diet.14 Although the overall quality of evidence was low, the Paleolithic and modified Mediterranean showed greater reductions in fatigue, as well as increased physical and

As with any health care decision, it is important to involve the patient in a joint decision regarding their care. This may mean giving the patient time to think about the information presented, do their own research, talk to family members or other clinicians, etc. The decision to discontinue DMT may not happen at the same appointment it is initially brought up at. It may even be reasonable to revisit the conversation later if discontinuation is not something the patient is amenable to at the time.

Conclusions

There is high-quality evidence that discontinuing DMTs in nonactive SPMS is not a major detriment to the MS disease course. Current literature also suggests that there may be benefits to discontinuation in this MS subtype in terms of QOL and meeting patient values. Additional research particularly in the nonactive SPMS population will continue to improve the knowledge and awareness of this aspect of MS DMT management. The growing evidence in this area may make discontinuation of DMT in nonactive SPMS a less-debatable topic, but it is still a major treatment decision that clinicians must thoroughly discuss with the patient to provide high-quality, patient-centered care.

1. Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Campbell JD, et al. The prevalence of MS in the United States: a population-based estimate using health claims data. Neurology. 2019;92(10):e1029-e1040. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000007035

2. Lunde HMB, Assmus J, Myhr KM, Bø L, Grytten N. Survival and cause of death in multiple sclerosis: a 60-year longitudinal population study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(8):621-625. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2016-315238

3. Rae-Grant A, Day GS, Marrie RA, et al. Practice guideline recommendations summary: disease-modifying therapies for adults with multiple sclerosis: report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2018;90(17):777-788. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000005347

4. Roos I, Leray E, Casey R, et al. Effects of high- and low-efficacy therapy in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2021;97(9):e869-e880. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000012354

5. Bsteh G, Feige J, Ehling R, et al. Discontinuation of disease-modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis - clinical outcome and prognostic factors. Mult Scler. 2017;23(9):1241-1248. doi:10.1177/1352458516675751

6. Musella A, Gentile A, Rizzo FR, et al. Interplay between age and neuroinflammation in multiple sclerosis: effects on motor and cognitive functions. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:238. Published 2018 Aug 8. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2018.00238

7. Weideman AM, Tapia-Maltos MA, Johnson K, Greenwood M, Bielekova B. Meta-analysis of the age-dependent efficacy of multiple sclerosis treatments. Front Neurol. 2017;8:577. Published 2017 Nov 10. doi:10.3389/fneur.2017.00577

8. Hua LH, Harris H, Conway D, Thompson NR. Changes in patient-reported outcomes between continuers and discontinuers of disease modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis over age 60. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;30:252-256. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2019.02.028

9. San-Juan-Rodriguez A, Good CB, Heyman RA, Parekh N, Shrank WH, Hernandez I. Trends in prices, market share, and spending on self-administered disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis in Medicare part D. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(11):1386-1390. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2711

10. Schweitzer F, Laurent S, Fink GR, et al. Age and the risks of high-efficacy disease modifying drugs in multiple sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2019;32(3):305-312. doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000000701

11. McGinley MP, Cola PA, Fox RJ, Cohen JA, Corboy JJ, Miller D. Perspectives of individuals with multiple sclerosis on discontinuation of disease-modifying therapies. Mult Scler. 2020;26(12):1581-1589. doi:10.1177/1352458519867314

12. Marrie RA, Rudick R, Horwitz R, et al. Vascular comorbidity is associated with more rapid disability progression in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2010;74(13):1041-1047. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d6b125

13. Flores VA, Šilic´ P, DuBose NG, Zheng P, Jeng B, Motl RW. Effects of aerobic, resistance, and combined exercise training on health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2023;75:104746. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2023.104746

14. Snetselaar LG, Cheek JJ, Fox SS, et al. Efficacy of diet on fatigue and quality of life in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized trials. Neurology. 2023;100(4):e357-e366. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000201371

1. Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Campbell JD, et al. The prevalence of MS in the United States: a population-based estimate using health claims data. Neurology. 2019;92(10):e1029-e1040. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000007035

2. Lunde HMB, Assmus J, Myhr KM, Bø L, Grytten N. Survival and cause of death in multiple sclerosis: a 60-year longitudinal population study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(8):621-625. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2016-315238

3. Rae-Grant A, Day GS, Marrie RA, et al. Practice guideline recommendations summary: disease-modifying therapies for adults with multiple sclerosis: report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2018;90(17):777-788. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000005347

4. Roos I, Leray E, Casey R, et al. Effects of high- and low-efficacy therapy in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2021;97(9):e869-e880. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000012354

5. Bsteh G, Feige J, Ehling R, et al. Discontinuation of disease-modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis - clinical outcome and prognostic factors. Mult Scler. 2017;23(9):1241-1248. doi:10.1177/1352458516675751

6. Musella A, Gentile A, Rizzo FR, et al. Interplay between age and neuroinflammation in multiple sclerosis: effects on motor and cognitive functions. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:238. Published 2018 Aug 8. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2018.00238

7. Weideman AM, Tapia-Maltos MA, Johnson K, Greenwood M, Bielekova B. Meta-analysis of the age-dependent efficacy of multiple sclerosis treatments. Front Neurol. 2017;8:577. Published 2017 Nov 10. doi:10.3389/fneur.2017.00577

8. Hua LH, Harris H, Conway D, Thompson NR. Changes in patient-reported outcomes between continuers and discontinuers of disease modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis over age 60. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;30:252-256. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2019.02.028

9. San-Juan-Rodriguez A, Good CB, Heyman RA, Parekh N, Shrank WH, Hernandez I. Trends in prices, market share, and spending on self-administered disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis in Medicare part D. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(11):1386-1390. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2711

10. Schweitzer F, Laurent S, Fink GR, et al. Age and the risks of high-efficacy disease modifying drugs in multiple sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2019;32(3):305-312. doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000000701

11. McGinley MP, Cola PA, Fox RJ, Cohen JA, Corboy JJ, Miller D. Perspectives of individuals with multiple sclerosis on discontinuation of disease-modifying therapies. Mult Scler. 2020;26(12):1581-1589. doi:10.1177/1352458519867314

12. Marrie RA, Rudick R, Horwitz R, et al. Vascular comorbidity is associated with more rapid disability progression in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2010;74(13):1041-1047. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d6b125

13. Flores VA, Šilic´ P, DuBose NG, Zheng P, Jeng B, Motl RW. Effects of aerobic, resistance, and combined exercise training on health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2023;75:104746. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2023.104746

14. Snetselaar LG, Cheek JJ, Fox SS, et al. Efficacy of diet on fatigue and quality of life in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized trials. Neurology. 2023;100(4):e357-e366. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000201371

AI model interprets EEGs with near-perfect accuracy

An automated artificial intelligence (AI) model trained to read electroencephalograms (EEGs) in patients with suspected epilepsy is just as accurate as trained neurologists, new data suggest.

Known as SCORE-AI, the technology distinguishes between abnormal and normal EEG recordings and classifies irregular recordings into specific categories crucial for patient decision-making.