User login

Vascular injury common in mild TBI

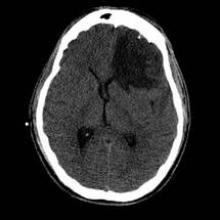

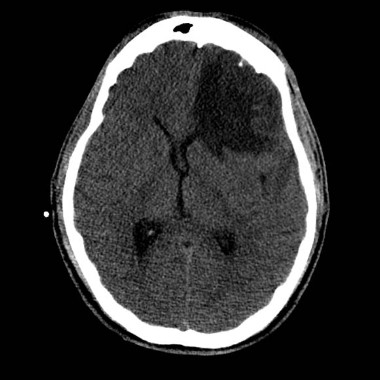

SAN DIEGO – Tube-shaped linear lesions seen on advanced MRI in people admitted to the emergency department for head injuries may not be diffuse axonal injury but rather evidence of bleeding due to mild traumatic brain injury, judging from preliminary results of a novel study.

"Not everything that we’re calling diffuse axonal injury is diffuse axonal injury," Dr. Gunjan Y. Parikh said in an interview during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. "There may be, in fact, evidence under our noses of vascular injury. This has implications, and those patients should be followed very closely. If we can pinpoint that they’re a vascular injury in the acute setting, there are a lot of therapies [we can use] that target the vasculature."

Between October 2010 and October 2012 Dr. Parikh, a neuroimaging fellow at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and his associates prospectively evaluated 256 patients enrolled in the Traumatic Head Injury Neuroimaging Classification (THINC) study who were admitted to the emergency department at Suburban Hospital in Bethesda, Md., and Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center after mild head injuries.

Administered by the Center for Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine at Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, the THINC study protocol includes taking an MRI in subjects within 48 hours of presenting with acute head injury, with or without a positive diagnosis of concussion, and at up to three follow-up visits at 4, 30, and 90 days. The protocol includes T2-weighted MRI, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), and three-dimensional tracking imaging (3-DTI).

The average age of the 256 patients was 50 years. Of these, 104 (41%) had imaging evidence of hemorrhage in the brain (67% reported loss of consciousness and 65% reported amnesia). These 104 patients underwent more detailed brain scans with advanced MRI within an average of 17 hours after the injury. This advanced imaging demonstrated that 20% of the 104 patients had microbleed lesions and 33% had tube-shaped linear lesions suggestive of vascular injury. Microbleeds were distributed throughout the brain, whereas linear lesions, which were found primarily in the anterior corona radiata, were more likely to be associated with injury to adjacent brain tissue.

"I was surprised that one-third of patients are having this linear type of lesion that we may think is vascular injury, and the majority of them – 91% – met the Glasgow Coma Scale criteria for mild TBI," Dr. Parikh commented. "These are patients who are usually sent home [after initial emergency department presentation]. I was also surprised to see so much evidence on other MRI sequences, proving that there is evidence of associated infarct or ischemia."

This type of analysis has not been done previously because "the logistical hurdles to imaging patients after any type of brain injury are so dramatic that it’s difficult to do this type of study," he said, emphasizing the preliminary nature of the work. "It was able to be done because of a unique collaboration between the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Department of Defense. If it weren’t for this collaboration, this would not have happened."

He noted that histopathological studies are "an important next step" to confirm the connection between the imaging markers and the pathology.

The study was supported by the NIH, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the Center for Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine, a collaborative effort among the NIH, the Department of Defense, and Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda. Dr. Parikh reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Tube-shaped linear lesions seen on advanced MRI in people admitted to the emergency department for head injuries may not be diffuse axonal injury but rather evidence of bleeding due to mild traumatic brain injury, judging from preliminary results of a novel study.

"Not everything that we’re calling diffuse axonal injury is diffuse axonal injury," Dr. Gunjan Y. Parikh said in an interview during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. "There may be, in fact, evidence under our noses of vascular injury. This has implications, and those patients should be followed very closely. If we can pinpoint that they’re a vascular injury in the acute setting, there are a lot of therapies [we can use] that target the vasculature."

Between October 2010 and October 2012 Dr. Parikh, a neuroimaging fellow at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and his associates prospectively evaluated 256 patients enrolled in the Traumatic Head Injury Neuroimaging Classification (THINC) study who were admitted to the emergency department at Suburban Hospital in Bethesda, Md., and Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center after mild head injuries.

Administered by the Center for Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine at Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, the THINC study protocol includes taking an MRI in subjects within 48 hours of presenting with acute head injury, with or without a positive diagnosis of concussion, and at up to three follow-up visits at 4, 30, and 90 days. The protocol includes T2-weighted MRI, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), and three-dimensional tracking imaging (3-DTI).

The average age of the 256 patients was 50 years. Of these, 104 (41%) had imaging evidence of hemorrhage in the brain (67% reported loss of consciousness and 65% reported amnesia). These 104 patients underwent more detailed brain scans with advanced MRI within an average of 17 hours after the injury. This advanced imaging demonstrated that 20% of the 104 patients had microbleed lesions and 33% had tube-shaped linear lesions suggestive of vascular injury. Microbleeds were distributed throughout the brain, whereas linear lesions, which were found primarily in the anterior corona radiata, were more likely to be associated with injury to adjacent brain tissue.

"I was surprised that one-third of patients are having this linear type of lesion that we may think is vascular injury, and the majority of them – 91% – met the Glasgow Coma Scale criteria for mild TBI," Dr. Parikh commented. "These are patients who are usually sent home [after initial emergency department presentation]. I was also surprised to see so much evidence on other MRI sequences, proving that there is evidence of associated infarct or ischemia."

This type of analysis has not been done previously because "the logistical hurdles to imaging patients after any type of brain injury are so dramatic that it’s difficult to do this type of study," he said, emphasizing the preliminary nature of the work. "It was able to be done because of a unique collaboration between the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Department of Defense. If it weren’t for this collaboration, this would not have happened."

He noted that histopathological studies are "an important next step" to confirm the connection between the imaging markers and the pathology.

The study was supported by the NIH, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the Center for Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine, a collaborative effort among the NIH, the Department of Defense, and Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda. Dr. Parikh reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Tube-shaped linear lesions seen on advanced MRI in people admitted to the emergency department for head injuries may not be diffuse axonal injury but rather evidence of bleeding due to mild traumatic brain injury, judging from preliminary results of a novel study.

"Not everything that we’re calling diffuse axonal injury is diffuse axonal injury," Dr. Gunjan Y. Parikh said in an interview during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. "There may be, in fact, evidence under our noses of vascular injury. This has implications, and those patients should be followed very closely. If we can pinpoint that they’re a vascular injury in the acute setting, there are a lot of therapies [we can use] that target the vasculature."

Between October 2010 and October 2012 Dr. Parikh, a neuroimaging fellow at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and his associates prospectively evaluated 256 patients enrolled in the Traumatic Head Injury Neuroimaging Classification (THINC) study who were admitted to the emergency department at Suburban Hospital in Bethesda, Md., and Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center after mild head injuries.

Administered by the Center for Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine at Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, the THINC study protocol includes taking an MRI in subjects within 48 hours of presenting with acute head injury, with or without a positive diagnosis of concussion, and at up to three follow-up visits at 4, 30, and 90 days. The protocol includes T2-weighted MRI, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), and three-dimensional tracking imaging (3-DTI).

The average age of the 256 patients was 50 years. Of these, 104 (41%) had imaging evidence of hemorrhage in the brain (67% reported loss of consciousness and 65% reported amnesia). These 104 patients underwent more detailed brain scans with advanced MRI within an average of 17 hours after the injury. This advanced imaging demonstrated that 20% of the 104 patients had microbleed lesions and 33% had tube-shaped linear lesions suggestive of vascular injury. Microbleeds were distributed throughout the brain, whereas linear lesions, which were found primarily in the anterior corona radiata, were more likely to be associated with injury to adjacent brain tissue.

"I was surprised that one-third of patients are having this linear type of lesion that we may think is vascular injury, and the majority of them – 91% – met the Glasgow Coma Scale criteria for mild TBI," Dr. Parikh commented. "These are patients who are usually sent home [after initial emergency department presentation]. I was also surprised to see so much evidence on other MRI sequences, proving that there is evidence of associated infarct or ischemia."

This type of analysis has not been done previously because "the logistical hurdles to imaging patients after any type of brain injury are so dramatic that it’s difficult to do this type of study," he said, emphasizing the preliminary nature of the work. "It was able to be done because of a unique collaboration between the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Department of Defense. If it weren’t for this collaboration, this would not have happened."

He noted that histopathological studies are "an important next step" to confirm the connection between the imaging markers and the pathology.

The study was supported by the NIH, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the Center for Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine, a collaborative effort among the NIH, the Department of Defense, and Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda. Dr. Parikh reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE 2013 AAN ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: In a subset of patients with MRI evidence of hemorrhage in the brain following head injury, more advanced MRI imaging demonstrated that 20% had microbleed lesions and 33% had tube-shaped linear lesions suggestive of vascular injury.

Data source: A prospective study of 256 patients in the Traumatic Head Injury Neuroimaging Classification (THINC) study who were admitted to the emergency department at Suburban Hospital in Bethesda, Md., and Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center after mild head injuries.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the NIH, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the Center for Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine, a collaborative effort among the NIH, the Department of Defense, and Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda. Dr. Parikh reported having no financial disclosures.

New concussion guidelines stress individualized approach

Any athlete with a possible concussion should be immediately removed from play pending an evaluation by a licensed health care provider trained in assessing concussions and traumatic brain injury, according to a new guideline from the American Academy of Neurology.

The guideline for evaluating and managing athletes with concussion was published online in the journal Neurology on March 18 (doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828d57dd) in conjunction with the annual meeting of the AAN. The guideline replaces the Academy’s 1997 recommendations, which stressed using a grading system to try to predict concussion outcomes.

The new guideline takes a more individualized and conservative approach, especially for younger athletes. The new approach comes as many states have enacted legislation regulating when young athletes can return to play following a concussion.

"If in doubt, sit it out," Dr. Jeffrey S. Kutcher, coauthor of the guideline and a neurologist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, said in a statement. "Being seen by a trained professional is extremely important after a concussion. If headaches or other symptoms return with the start of exercise, stop the activity and consult a doctor. You only get one brain; treat it well."

The new guideline calls for athletes to stay off the field until they are asymptomatic off medication. High school athletes and younger players with a concussion should be managed more conservatively since they take longer to recover than older athletes, according to the AAN.

But there is not enough evidence to support complete rest after a concussion. Activities that do not worsen symptoms and don’t pose a risk of another concussion can be part of the management of the injury, according to the guideline.

"We’re moved away from the concussion grading systems we first established in 1997 and are now recommending concussion and return to play be assessed in each athlete individually," Dr. Christopher C. Giza, the co–lead guideline author and a neurologist at Mattel Children’s Hospital at the University of California, Los Angeles, said in a statement. "There is no set timeline for safe return to play."

The AAN expert panel recommends that sideline providers use symptom checklists such as the Standardized Assessment of Concussion to help identify suspected concussion and that the scores be shared with the physicians involved in the athletes’ care off the field. But these checklists should not be the only tool used in making a diagnosis, according to the guidelines. Also, the checklist scores may be more useful if they are compared against preinjury individual scores, especially in younger athletes and those with prior concussions.

CT imaging should not be used to diagnose a suspected sport-related concussion, according to the guideline. But imaging might be used to rule out more serious traumatic brain injuries, such as intracranial hemorrhage in athletes with a suspected concussion who also have a loss of consciousness, posttraumatic amnesia, persistently altered mental status, focal neurologic deficit, evidence of skull fracture, or signs of clinical deterioration.

Athletes are at greater risk of concussion if they have a history of concussion. The first 10 days after a concussion pose the greatest risk for a repeat injury.

The AAN advises physicians to be on the lookout for ongoing symptoms that are linked to a longer recovery, such as continued headache or fogginess. Athletes with a history of concussions and younger players also tend to have a longer recovery.

The guideline also include level C recommendations stating that health care providers "might" develop individualized graded plans for returning to physical and cognitive activity. They might also provide cognitive restructuring counseling in an effort to shorten the duration of symptoms and the likelihood of developing chronic post-concussion syndrome, according to the guideline.

The guideline also included a number of recommendations on areas for future research, including studies of pre–high school age athletes to determine the natural history of concussion and recovery time for this age group, as well as the best assessment tools. The expert panel also called for clinical trials of different postconcussion management strategies and return-to-play protocols.

The guidelines were developed by a multidisciplinary expert committee that included representatives from neurology, athletic training, neuropsychology, epidemiology and biostatistics, neurosurgery, physical medicine and rehabilitation, and sports medicine. Many of the authors reported serving as consultants for professional sports associations, receiving honoraria and funding for travel for lectures on sports concussion, receiving research support from various foundations and organizations, and providing expert testimony in legal cases involving traumatic brain injury or concussion.

One of the most important statements in the new guideline

is that providers should not rely on a single diagnostic test when evaluating

an athlete, said Dr. Barry Jordan, the assistant medical director and attending

neurologist at the Burke Rehabilitation Hospital in White Plains, N.Y. Dr.

Jordan, who is an expert on sports concussions, said he’s seen too many

providers using a single computerized screening tool to assess whether an

athlete is well enough to return to play.

The new

guideline calls on providers to combine screening checklists with clinical

findings when making the determination about whether an athlete is well enough

to return to the field. Dr. Jordan

said this comprehensive approach is the way to go. And physicians who are

knowledgeable about concussions must be involved with that evaluation, he said.

|

| Dr. Barry Jordan |

The new guideline is an important update reflecting

the movement away from grading concussions to a more individualized approach. "You can't grade the severity until the concussion is over," he said.

Dr. Jordan

said the AAN guideline is "clear and easy to follow" and will results in better

care if followed.

Dr.

Barry Jordan is the director of the Brain Injury Program at Burke

Rehabilitation Hospital in White Plains, N.Y. He works with several sports

organizations including the New York State Athletic Commission, U.S.A. Boxing, and the National

Football League Players Association. He also writes a bimonthly column for

Clinical Neurology News called “On the Sidelines.”

One of the most important statements in the new guideline

is that providers should not rely on a single diagnostic test when evaluating

an athlete, said Dr. Barry Jordan, the assistant medical director and attending

neurologist at the Burke Rehabilitation Hospital in White Plains, N.Y. Dr.

Jordan, who is an expert on sports concussions, said he’s seen too many

providers using a single computerized screening tool to assess whether an

athlete is well enough to return to play.

The new

guideline calls on providers to combine screening checklists with clinical

findings when making the determination about whether an athlete is well enough

to return to the field. Dr. Jordan

said this comprehensive approach is the way to go. And physicians who are

knowledgeable about concussions must be involved with that evaluation, he said.

|

| Dr. Barry Jordan |

The new guideline is an important update reflecting

the movement away from grading concussions to a more individualized approach. "You can't grade the severity until the concussion is over," he said.

Dr. Jordan

said the AAN guideline is "clear and easy to follow" and will results in better

care if followed.

Dr.

Barry Jordan is the director of the Brain Injury Program at Burke

Rehabilitation Hospital in White Plains, N.Y. He works with several sports

organizations including the New York State Athletic Commission, U.S.A. Boxing, and the National

Football League Players Association. He also writes a bimonthly column for

Clinical Neurology News called “On the Sidelines.”

One of the most important statements in the new guideline

is that providers should not rely on a single diagnostic test when evaluating

an athlete, said Dr. Barry Jordan, the assistant medical director and attending

neurologist at the Burke Rehabilitation Hospital in White Plains, N.Y. Dr.

Jordan, who is an expert on sports concussions, said he’s seen too many

providers using a single computerized screening tool to assess whether an

athlete is well enough to return to play.

The new

guideline calls on providers to combine screening checklists with clinical

findings when making the determination about whether an athlete is well enough

to return to the field. Dr. Jordan

said this comprehensive approach is the way to go. And physicians who are

knowledgeable about concussions must be involved with that evaluation, he said.

|

| Dr. Barry Jordan |

The new guideline is an important update reflecting

the movement away from grading concussions to a more individualized approach. "You can't grade the severity until the concussion is over," he said.

Dr. Jordan

said the AAN guideline is "clear and easy to follow" and will results in better

care if followed.

Dr.

Barry Jordan is the director of the Brain Injury Program at Burke

Rehabilitation Hospital in White Plains, N.Y. He works with several sports

organizations including the New York State Athletic Commission, U.S.A. Boxing, and the National

Football League Players Association. He also writes a bimonthly column for

Clinical Neurology News called “On the Sidelines.”

Any athlete with a possible concussion should be immediately removed from play pending an evaluation by a licensed health care provider trained in assessing concussions and traumatic brain injury, according to a new guideline from the American Academy of Neurology.

The guideline for evaluating and managing athletes with concussion was published online in the journal Neurology on March 18 (doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828d57dd) in conjunction with the annual meeting of the AAN. The guideline replaces the Academy’s 1997 recommendations, which stressed using a grading system to try to predict concussion outcomes.

The new guideline takes a more individualized and conservative approach, especially for younger athletes. The new approach comes as many states have enacted legislation regulating when young athletes can return to play following a concussion.

"If in doubt, sit it out," Dr. Jeffrey S. Kutcher, coauthor of the guideline and a neurologist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, said in a statement. "Being seen by a trained professional is extremely important after a concussion. If headaches or other symptoms return with the start of exercise, stop the activity and consult a doctor. You only get one brain; treat it well."

The new guideline calls for athletes to stay off the field until they are asymptomatic off medication. High school athletes and younger players with a concussion should be managed more conservatively since they take longer to recover than older athletes, according to the AAN.

But there is not enough evidence to support complete rest after a concussion. Activities that do not worsen symptoms and don’t pose a risk of another concussion can be part of the management of the injury, according to the guideline.

"We’re moved away from the concussion grading systems we first established in 1997 and are now recommending concussion and return to play be assessed in each athlete individually," Dr. Christopher C. Giza, the co–lead guideline author and a neurologist at Mattel Children’s Hospital at the University of California, Los Angeles, said in a statement. "There is no set timeline for safe return to play."

The AAN expert panel recommends that sideline providers use symptom checklists such as the Standardized Assessment of Concussion to help identify suspected concussion and that the scores be shared with the physicians involved in the athletes’ care off the field. But these checklists should not be the only tool used in making a diagnosis, according to the guidelines. Also, the checklist scores may be more useful if they are compared against preinjury individual scores, especially in younger athletes and those with prior concussions.

CT imaging should not be used to diagnose a suspected sport-related concussion, according to the guideline. But imaging might be used to rule out more serious traumatic brain injuries, such as intracranial hemorrhage in athletes with a suspected concussion who also have a loss of consciousness, posttraumatic amnesia, persistently altered mental status, focal neurologic deficit, evidence of skull fracture, or signs of clinical deterioration.

Athletes are at greater risk of concussion if they have a history of concussion. The first 10 days after a concussion pose the greatest risk for a repeat injury.

The AAN advises physicians to be on the lookout for ongoing symptoms that are linked to a longer recovery, such as continued headache or fogginess. Athletes with a history of concussions and younger players also tend to have a longer recovery.

The guideline also include level C recommendations stating that health care providers "might" develop individualized graded plans for returning to physical and cognitive activity. They might also provide cognitive restructuring counseling in an effort to shorten the duration of symptoms and the likelihood of developing chronic post-concussion syndrome, according to the guideline.

The guideline also included a number of recommendations on areas for future research, including studies of pre–high school age athletes to determine the natural history of concussion and recovery time for this age group, as well as the best assessment tools. The expert panel also called for clinical trials of different postconcussion management strategies and return-to-play protocols.

The guidelines were developed by a multidisciplinary expert committee that included representatives from neurology, athletic training, neuropsychology, epidemiology and biostatistics, neurosurgery, physical medicine and rehabilitation, and sports medicine. Many of the authors reported serving as consultants for professional sports associations, receiving honoraria and funding for travel for lectures on sports concussion, receiving research support from various foundations and organizations, and providing expert testimony in legal cases involving traumatic brain injury or concussion.

Any athlete with a possible concussion should be immediately removed from play pending an evaluation by a licensed health care provider trained in assessing concussions and traumatic brain injury, according to a new guideline from the American Academy of Neurology.

The guideline for evaluating and managing athletes with concussion was published online in the journal Neurology on March 18 (doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828d57dd) in conjunction with the annual meeting of the AAN. The guideline replaces the Academy’s 1997 recommendations, which stressed using a grading system to try to predict concussion outcomes.

The new guideline takes a more individualized and conservative approach, especially for younger athletes. The new approach comes as many states have enacted legislation regulating when young athletes can return to play following a concussion.

"If in doubt, sit it out," Dr. Jeffrey S. Kutcher, coauthor of the guideline and a neurologist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, said in a statement. "Being seen by a trained professional is extremely important after a concussion. If headaches or other symptoms return with the start of exercise, stop the activity and consult a doctor. You only get one brain; treat it well."

The new guideline calls for athletes to stay off the field until they are asymptomatic off medication. High school athletes and younger players with a concussion should be managed more conservatively since they take longer to recover than older athletes, according to the AAN.

But there is not enough evidence to support complete rest after a concussion. Activities that do not worsen symptoms and don’t pose a risk of another concussion can be part of the management of the injury, according to the guideline.

"We’re moved away from the concussion grading systems we first established in 1997 and are now recommending concussion and return to play be assessed in each athlete individually," Dr. Christopher C. Giza, the co–lead guideline author and a neurologist at Mattel Children’s Hospital at the University of California, Los Angeles, said in a statement. "There is no set timeline for safe return to play."

The AAN expert panel recommends that sideline providers use symptom checklists such as the Standardized Assessment of Concussion to help identify suspected concussion and that the scores be shared with the physicians involved in the athletes’ care off the field. But these checklists should not be the only tool used in making a diagnosis, according to the guidelines. Also, the checklist scores may be more useful if they are compared against preinjury individual scores, especially in younger athletes and those with prior concussions.

CT imaging should not be used to diagnose a suspected sport-related concussion, according to the guideline. But imaging might be used to rule out more serious traumatic brain injuries, such as intracranial hemorrhage in athletes with a suspected concussion who also have a loss of consciousness, posttraumatic amnesia, persistently altered mental status, focal neurologic deficit, evidence of skull fracture, or signs of clinical deterioration.

Athletes are at greater risk of concussion if they have a history of concussion. The first 10 days after a concussion pose the greatest risk for a repeat injury.

The AAN advises physicians to be on the lookout for ongoing symptoms that are linked to a longer recovery, such as continued headache or fogginess. Athletes with a history of concussions and younger players also tend to have a longer recovery.

The guideline also include level C recommendations stating that health care providers "might" develop individualized graded plans for returning to physical and cognitive activity. They might also provide cognitive restructuring counseling in an effort to shorten the duration of symptoms and the likelihood of developing chronic post-concussion syndrome, according to the guideline.

The guideline also included a number of recommendations on areas for future research, including studies of pre–high school age athletes to determine the natural history of concussion and recovery time for this age group, as well as the best assessment tools. The expert panel also called for clinical trials of different postconcussion management strategies and return-to-play protocols.

The guidelines were developed by a multidisciplinary expert committee that included representatives from neurology, athletic training, neuropsychology, epidemiology and biostatistics, neurosurgery, physical medicine and rehabilitation, and sports medicine. Many of the authors reported serving as consultants for professional sports associations, receiving honoraria and funding for travel for lectures on sports concussion, receiving research support from various foundations and organizations, and providing expert testimony in legal cases involving traumatic brain injury or concussion.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Survey: Most support transfusing to increase organ donation

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – The majority of trauma surgeons would aggressively manage patients with a lethal brain injury for the purposes of organ donation.

Consensus on how best to transfuse these patients to protect their organs appears to be another matter, a survey of Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) members reveals.

"Further investigation is needed to determine what the transfusion triggers and limits should be in order to maximize our donor conversion rates," said Dr. Stancie Rhodes and her colleagues at Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, New Brunswick, N.J.

Many institutions have set up aggressive donor management protocols to help address the worldwide shortage of transplantable organs. At press time, 117,090 candidates were on the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network waiting list, with just 25,785 transplants performed between January and November 2012.

Aggressive donor management (ADM) protocols typically include guidelines for invasive monitoring and correction of metabolic disturbances that follow brain death, but many continue to lack guidelines on when and in what quantity to transfuse potential organ donors, explained Dr. Rhodes, a trauma surgeon at Robert Wood Johnson.

To further develop these guidelines, the investigators electronically surveyed all trauma surgeons in EAST regarding their transfusion practices in patients with nonsurvivable brain injury. In all, 285 members responded (24.5%). Among these respondents, 53.5% currently transfuse these patients.

Almost three-fourths, 72.5%, of respondents agreed with aggressive medical management of patients with lethal brain injury in the hope they could donate organs, while 9.4% strongly disagreed, Dr. Rhodes reported in a poster at the EAST’s annual meeting.

Trauma surgeons practicing in a suburban setting were significantly more likely to agree with transfusion than were those in rural or urban settings (77% vs. 52% vs. 55%; P less than .04).

Before deciding to aggressively manage a potential organ donor, respondents were divided on whether the testing for declaration of brain death must already be underway (111 strongly agree/26 strongly disagree), the patient must be declared brain dead (11 strongly agree/84 strongly disagree), or consent for donation of organs must have been obtained (6 strongly agree/114 strongly disagree, Dr. Rhodes reported.

"I think the important piece is that respondents overwhelmingly agreed that they would not wait for declaration of brain death to begin to aggressively manage these patients," she said in an interview. "This is important, as these patients succumb to hypoperfusion, coagulopathy, and acidosis if their ongoing hemorrhage is uncontrolled early in their course."

The majority of respondents (75%) agreed that they have a limit to the amount of product they would administer.

If the potential donor was in hemorrhagic shock, 6 respondents strongly agreed and 12 agreed they would consider transfusing blood products, while 114 disagreed and 119 strongly disagreed with the practice.

Respondents were more likely to consider transfusing, however, if the potential donor was having coagulopathic bleeding. In all, 47 strongly agreed and 106 agreed with transfusing in this setting, while 30 disagreed and 15 strongly disagreed.

If either hemorrhagic shock or coagulopathic bleeding were present, most respondents would limit packed red blood cells and fresh frozen plasma to no more than 5-8 units, and platelets to no more than 1-4 units, the authors reported.

Of those surgeons surveyed, 42% were between the ages of 40 and 49 years, 10.2% practiced primarily in a rural setting, 15.1% practiced in an suburban setting – defined as a population less than 500,000 – and 45.6% were in an urban setting, defined by a population in excess of 500,000 residents.

Dr. Rhodes and her coauthors have nothing to disclose.

transfuse, survey, Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, EAST, Dr. Stancie Rhodes, aggressive donor management protocols, worldwide shortage of transplantable organs, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network waiting list,

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – The majority of trauma surgeons would aggressively manage patients with a lethal brain injury for the purposes of organ donation.

Consensus on how best to transfuse these patients to protect their organs appears to be another matter, a survey of Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) members reveals.

"Further investigation is needed to determine what the transfusion triggers and limits should be in order to maximize our donor conversion rates," said Dr. Stancie Rhodes and her colleagues at Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, New Brunswick, N.J.

Many institutions have set up aggressive donor management protocols to help address the worldwide shortage of transplantable organs. At press time, 117,090 candidates were on the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network waiting list, with just 25,785 transplants performed between January and November 2012.

Aggressive donor management (ADM) protocols typically include guidelines for invasive monitoring and correction of metabolic disturbances that follow brain death, but many continue to lack guidelines on when and in what quantity to transfuse potential organ donors, explained Dr. Rhodes, a trauma surgeon at Robert Wood Johnson.

To further develop these guidelines, the investigators electronically surveyed all trauma surgeons in EAST regarding their transfusion practices in patients with nonsurvivable brain injury. In all, 285 members responded (24.5%). Among these respondents, 53.5% currently transfuse these patients.

Almost three-fourths, 72.5%, of respondents agreed with aggressive medical management of patients with lethal brain injury in the hope they could donate organs, while 9.4% strongly disagreed, Dr. Rhodes reported in a poster at the EAST’s annual meeting.

Trauma surgeons practicing in a suburban setting were significantly more likely to agree with transfusion than were those in rural or urban settings (77% vs. 52% vs. 55%; P less than .04).

Before deciding to aggressively manage a potential organ donor, respondents were divided on whether the testing for declaration of brain death must already be underway (111 strongly agree/26 strongly disagree), the patient must be declared brain dead (11 strongly agree/84 strongly disagree), or consent for donation of organs must have been obtained (6 strongly agree/114 strongly disagree, Dr. Rhodes reported.

"I think the important piece is that respondents overwhelmingly agreed that they would not wait for declaration of brain death to begin to aggressively manage these patients," she said in an interview. "This is important, as these patients succumb to hypoperfusion, coagulopathy, and acidosis if their ongoing hemorrhage is uncontrolled early in their course."

The majority of respondents (75%) agreed that they have a limit to the amount of product they would administer.

If the potential donor was in hemorrhagic shock, 6 respondents strongly agreed and 12 agreed they would consider transfusing blood products, while 114 disagreed and 119 strongly disagreed with the practice.

Respondents were more likely to consider transfusing, however, if the potential donor was having coagulopathic bleeding. In all, 47 strongly agreed and 106 agreed with transfusing in this setting, while 30 disagreed and 15 strongly disagreed.

If either hemorrhagic shock or coagulopathic bleeding were present, most respondents would limit packed red blood cells and fresh frozen plasma to no more than 5-8 units, and platelets to no more than 1-4 units, the authors reported.

Of those surgeons surveyed, 42% were between the ages of 40 and 49 years, 10.2% practiced primarily in a rural setting, 15.1% practiced in an suburban setting – defined as a population less than 500,000 – and 45.6% were in an urban setting, defined by a population in excess of 500,000 residents.

Dr. Rhodes and her coauthors have nothing to disclose.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – The majority of trauma surgeons would aggressively manage patients with a lethal brain injury for the purposes of organ donation.

Consensus on how best to transfuse these patients to protect their organs appears to be another matter, a survey of Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) members reveals.

"Further investigation is needed to determine what the transfusion triggers and limits should be in order to maximize our donor conversion rates," said Dr. Stancie Rhodes and her colleagues at Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, New Brunswick, N.J.

Many institutions have set up aggressive donor management protocols to help address the worldwide shortage of transplantable organs. At press time, 117,090 candidates were on the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network waiting list, with just 25,785 transplants performed between January and November 2012.

Aggressive donor management (ADM) protocols typically include guidelines for invasive monitoring and correction of metabolic disturbances that follow brain death, but many continue to lack guidelines on when and in what quantity to transfuse potential organ donors, explained Dr. Rhodes, a trauma surgeon at Robert Wood Johnson.

To further develop these guidelines, the investigators electronically surveyed all trauma surgeons in EAST regarding their transfusion practices in patients with nonsurvivable brain injury. In all, 285 members responded (24.5%). Among these respondents, 53.5% currently transfuse these patients.

Almost three-fourths, 72.5%, of respondents agreed with aggressive medical management of patients with lethal brain injury in the hope they could donate organs, while 9.4% strongly disagreed, Dr. Rhodes reported in a poster at the EAST’s annual meeting.

Trauma surgeons practicing in a suburban setting were significantly more likely to agree with transfusion than were those in rural or urban settings (77% vs. 52% vs. 55%; P less than .04).

Before deciding to aggressively manage a potential organ donor, respondents were divided on whether the testing for declaration of brain death must already be underway (111 strongly agree/26 strongly disagree), the patient must be declared brain dead (11 strongly agree/84 strongly disagree), or consent for donation of organs must have been obtained (6 strongly agree/114 strongly disagree, Dr. Rhodes reported.

"I think the important piece is that respondents overwhelmingly agreed that they would not wait for declaration of brain death to begin to aggressively manage these patients," she said in an interview. "This is important, as these patients succumb to hypoperfusion, coagulopathy, and acidosis if their ongoing hemorrhage is uncontrolled early in their course."

The majority of respondents (75%) agreed that they have a limit to the amount of product they would administer.

If the potential donor was in hemorrhagic shock, 6 respondents strongly agreed and 12 agreed they would consider transfusing blood products, while 114 disagreed and 119 strongly disagreed with the practice.

Respondents were more likely to consider transfusing, however, if the potential donor was having coagulopathic bleeding. In all, 47 strongly agreed and 106 agreed with transfusing in this setting, while 30 disagreed and 15 strongly disagreed.

If either hemorrhagic shock or coagulopathic bleeding were present, most respondents would limit packed red blood cells and fresh frozen plasma to no more than 5-8 units, and platelets to no more than 1-4 units, the authors reported.

Of those surgeons surveyed, 42% were between the ages of 40 and 49 years, 10.2% practiced primarily in a rural setting, 15.1% practiced in an suburban setting – defined as a population less than 500,000 – and 45.6% were in an urban setting, defined by a population in excess of 500,000 residents.

Dr. Rhodes and her coauthors have nothing to disclose.

transfuse, survey, Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, EAST, Dr. Stancie Rhodes, aggressive donor management protocols, worldwide shortage of transplantable organs, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network waiting list,

transfuse, survey, Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, EAST, Dr. Stancie Rhodes, aggressive donor management protocols, worldwide shortage of transplantable organs, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network waiting list,

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE EAST ANNUAL MEETING

Major Finding: Among respondents, 72.5% agreed with aggressive medical management of patients with lethal brain injury for the sake of organ donation, but there was less consensus on when and how to manage these patients.

Data Source: Electronic survey of 285 trauma surgeons in the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Disclosures: Dr. Rhodes and her coauthors have nothing to disclose.

Novel hemorrhagic stroke therapy bests medical management

A minimally invasive surgical procedure that enables direct local delivery of tissue plasminogen activator to the blood clot in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage safely resulted in markedly improved functional ability, greater independence, and dramatically lower costs than conventional medical management at 1 year of follow-up, in the randomized multicenter MISTIE trial.

"The procedure is simple, rapid, and easy to generalize. There is now real hope we have a treatment for the last form of stroke that doesn’t have a treatment: brain hemorrhage," Dr. Daniel F. Hanley said at the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Stroke Association.

That being said, MISTIE (Minimally Invasive Surgery plus rTPA for Intracerebral Hemorrhage Evacuation) was a modestly sized, phase II proof-of-concept study, the concept being that reducing clot size should improve outcomes in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). Based on the encouraging 1-year MISTIE results, the plan is to ramp up to a 500-patient definitive phase III trial, said Dr. Hanley, professor of neurology and director of the brain injury outcomes division at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

The trial involved 96 patients with ICH at 26 hospitals who were randomized to the minimally invasive surgical procedure or medical management. The "most startling" finding to emerge from the trial, in Dr. Hanley’s view, was that the benefits of the surgical intervention documented at 6 months’ follow-up and reported at last year’s International Stroke Conference are even greater at 1 year.

"The benefits of surgery are expanding over time," the neurologist observed. "It takes a long time to resolve brain injury, even though we’re getting the majority of the clot out in the first 3 days."

The procedure entails cutting a dime-sized hole in the patient’s skull, snaking a catheter through it and into the bulk of the clot, then delivering a dose of tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) every 8 hours for 2-3 days. As TPA dissolves the clot, the material is evacuated through the catheter. The surgical procedure took an average of 42 minutes compared with 3 hours, typically, for a craniotomy.

Among the key findings from the MISTIE 1-year update:

• Non-ICU hospital length of stay averaged 38 days less in the surgically managed group.

• The cost of acute care averaged $44,000 less per patient, a 35% reduction, compared with medical management.

• At 1 year, 21% of patients in the medically managed group were in a nursing home, compared with just 8% of the surgically managed group.

• The average Stroke Impact Scale mobility score in the surgical group doubled from 40 at 6 months to 80 at 1 year while plateauing at about 20 between days 80 and 90 in the medically managed patients. A score of 80 on this scale means a patient can do what he wants most of the time; a score of 20 means he seldom can

• The average Stroke Impact Scale activities of daily living score similarly showed progressive, roughly linear improvement in the surgical group between 6 months and 1 year while plateauing at a low performance level at 90-180 days in the medically managed group.

• The proportion of patients with functional independence as defined by a modified Rankin score of 0-2 was an absolute 14% greater in surgically managed compared with medically managed patients at 1 year.

The average baseline clot volume was 46 mL. The surgical goal was to remove 60% of the clot volume; this was achieved in 72% of treated patients. On average 28 mL of clot were removed over a period of 3 days.

"The surgeons are consistently able to achieve 20- to 40-mL reductions in clot volume. Twenty-nine surgeons have done the procedure, and we don’t see a learning curve. That’s good. It means this is a pretty simple procedure to do. In point of fact, the training consisted of a single 1-hour conference with the lead neurosurgeon and a short self-learning computer program," according to Dr. Hanley.

Roughly 60% of patients whose clot volume was reduced to less than 10 mL had functional independence as reflected in a modified Rankin score of 0-2 at 180 days, compared with a 10% rate in those with a residual clot volume in excess of 35 mL.

Outcomes were similar regardless of whether the surgery was done within 36 hours after stroke onset or later.

"To me it looks like the time consideration for this surgery is going to be permissive. That’s very important for the 1 million people in the world each year who have an ICH," the neurologist noted.

The MISTIE trial was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Hanley reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

A minimally invasive surgical procedure that enables direct local delivery of tissue plasminogen activator to the blood clot in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage safely resulted in markedly improved functional ability, greater independence, and dramatically lower costs than conventional medical management at 1 year of follow-up, in the randomized multicenter MISTIE trial.

"The procedure is simple, rapid, and easy to generalize. There is now real hope we have a treatment for the last form of stroke that doesn’t have a treatment: brain hemorrhage," Dr. Daniel F. Hanley said at the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Stroke Association.

That being said, MISTIE (Minimally Invasive Surgery plus rTPA for Intracerebral Hemorrhage Evacuation) was a modestly sized, phase II proof-of-concept study, the concept being that reducing clot size should improve outcomes in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). Based on the encouraging 1-year MISTIE results, the plan is to ramp up to a 500-patient definitive phase III trial, said Dr. Hanley, professor of neurology and director of the brain injury outcomes division at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

The trial involved 96 patients with ICH at 26 hospitals who were randomized to the minimally invasive surgical procedure or medical management. The "most startling" finding to emerge from the trial, in Dr. Hanley’s view, was that the benefits of the surgical intervention documented at 6 months’ follow-up and reported at last year’s International Stroke Conference are even greater at 1 year.

"The benefits of surgery are expanding over time," the neurologist observed. "It takes a long time to resolve brain injury, even though we’re getting the majority of the clot out in the first 3 days."

The procedure entails cutting a dime-sized hole in the patient’s skull, snaking a catheter through it and into the bulk of the clot, then delivering a dose of tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) every 8 hours for 2-3 days. As TPA dissolves the clot, the material is evacuated through the catheter. The surgical procedure took an average of 42 minutes compared with 3 hours, typically, for a craniotomy.

Among the key findings from the MISTIE 1-year update:

• Non-ICU hospital length of stay averaged 38 days less in the surgically managed group.

• The cost of acute care averaged $44,000 less per patient, a 35% reduction, compared with medical management.

• At 1 year, 21% of patients in the medically managed group were in a nursing home, compared with just 8% of the surgically managed group.

• The average Stroke Impact Scale mobility score in the surgical group doubled from 40 at 6 months to 80 at 1 year while plateauing at about 20 between days 80 and 90 in the medically managed patients. A score of 80 on this scale means a patient can do what he wants most of the time; a score of 20 means he seldom can

• The average Stroke Impact Scale activities of daily living score similarly showed progressive, roughly linear improvement in the surgical group between 6 months and 1 year while plateauing at a low performance level at 90-180 days in the medically managed group.

• The proportion of patients with functional independence as defined by a modified Rankin score of 0-2 was an absolute 14% greater in surgically managed compared with medically managed patients at 1 year.

The average baseline clot volume was 46 mL. The surgical goal was to remove 60% of the clot volume; this was achieved in 72% of treated patients. On average 28 mL of clot were removed over a period of 3 days.

"The surgeons are consistently able to achieve 20- to 40-mL reductions in clot volume. Twenty-nine surgeons have done the procedure, and we don’t see a learning curve. That’s good. It means this is a pretty simple procedure to do. In point of fact, the training consisted of a single 1-hour conference with the lead neurosurgeon and a short self-learning computer program," according to Dr. Hanley.

Roughly 60% of patients whose clot volume was reduced to less than 10 mL had functional independence as reflected in a modified Rankin score of 0-2 at 180 days, compared with a 10% rate in those with a residual clot volume in excess of 35 mL.

Outcomes were similar regardless of whether the surgery was done within 36 hours after stroke onset or later.

"To me it looks like the time consideration for this surgery is going to be permissive. That’s very important for the 1 million people in the world each year who have an ICH," the neurologist noted.

The MISTIE trial was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Hanley reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

A minimally invasive surgical procedure that enables direct local delivery of tissue plasminogen activator to the blood clot in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage safely resulted in markedly improved functional ability, greater independence, and dramatically lower costs than conventional medical management at 1 year of follow-up, in the randomized multicenter MISTIE trial.

"The procedure is simple, rapid, and easy to generalize. There is now real hope we have a treatment for the last form of stroke that doesn’t have a treatment: brain hemorrhage," Dr. Daniel F. Hanley said at the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Stroke Association.

That being said, MISTIE (Minimally Invasive Surgery plus rTPA for Intracerebral Hemorrhage Evacuation) was a modestly sized, phase II proof-of-concept study, the concept being that reducing clot size should improve outcomes in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). Based on the encouraging 1-year MISTIE results, the plan is to ramp up to a 500-patient definitive phase III trial, said Dr. Hanley, professor of neurology and director of the brain injury outcomes division at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

The trial involved 96 patients with ICH at 26 hospitals who were randomized to the minimally invasive surgical procedure or medical management. The "most startling" finding to emerge from the trial, in Dr. Hanley’s view, was that the benefits of the surgical intervention documented at 6 months’ follow-up and reported at last year’s International Stroke Conference are even greater at 1 year.

"The benefits of surgery are expanding over time," the neurologist observed. "It takes a long time to resolve brain injury, even though we’re getting the majority of the clot out in the first 3 days."

The procedure entails cutting a dime-sized hole in the patient’s skull, snaking a catheter through it and into the bulk of the clot, then delivering a dose of tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) every 8 hours for 2-3 days. As TPA dissolves the clot, the material is evacuated through the catheter. The surgical procedure took an average of 42 minutes compared with 3 hours, typically, for a craniotomy.

Among the key findings from the MISTIE 1-year update:

• Non-ICU hospital length of stay averaged 38 days less in the surgically managed group.

• The cost of acute care averaged $44,000 less per patient, a 35% reduction, compared with medical management.

• At 1 year, 21% of patients in the medically managed group were in a nursing home, compared with just 8% of the surgically managed group.

• The average Stroke Impact Scale mobility score in the surgical group doubled from 40 at 6 months to 80 at 1 year while plateauing at about 20 between days 80 and 90 in the medically managed patients. A score of 80 on this scale means a patient can do what he wants most of the time; a score of 20 means he seldom can

• The average Stroke Impact Scale activities of daily living score similarly showed progressive, roughly linear improvement in the surgical group between 6 months and 1 year while plateauing at a low performance level at 90-180 days in the medically managed group.

• The proportion of patients with functional independence as defined by a modified Rankin score of 0-2 was an absolute 14% greater in surgically managed compared with medically managed patients at 1 year.

The average baseline clot volume was 46 mL. The surgical goal was to remove 60% of the clot volume; this was achieved in 72% of treated patients. On average 28 mL of clot were removed over a period of 3 days.

"The surgeons are consistently able to achieve 20- to 40-mL reductions in clot volume. Twenty-nine surgeons have done the procedure, and we don’t see a learning curve. That’s good. It means this is a pretty simple procedure to do. In point of fact, the training consisted of a single 1-hour conference with the lead neurosurgeon and a short self-learning computer program," according to Dr. Hanley.

Roughly 60% of patients whose clot volume was reduced to less than 10 mL had functional independence as reflected in a modified Rankin score of 0-2 at 180 days, compared with a 10% rate in those with a residual clot volume in excess of 35 mL.

Outcomes were similar regardless of whether the surgery was done within 36 hours after stroke onset or later.

"To me it looks like the time consideration for this surgery is going to be permissive. That’s very important for the 1 million people in the world each year who have an ICH," the neurologist noted.

The MISTIE trial was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Hanley reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

AT THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Major Finding: One year after undergoing a novel minimally invasive surgical procedure for treatment of intracerebral hemorrhage, patients had significantly better outcomes than those randomized to medical management – and the disparity in outcomes was significantly greater than at 6 months’ follow-up.

Data Source: MISTIE, a randomized multicenter trial in which 96 patients with intracerebral hemorrhage were randomized to standard medical management or to a novel surgical procedure.

Disclosures: MISTIE was sponsored by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The study presenter said he had no relevant financial conflicts.

Hemodynamic complications commonly found in veterans after TBI

HONOLULU – Cerebral vasospasm and intracranial hypertension may be frequent secondary insults following wartime traumatic brain injury, according to a retrospective study of 122 consecutive veterans.

Transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasonography signs of mild, moderate, and severe vasospasm involving anterior circulation vessels were observed in 71%, 42%, and 16% of the veterans with traumatic brain injury (TBI), respectively.

TCD signs involving posterior circulation vessels were observed in 57%, 32%, and 14%, respectively.

Intracranial hypertension was recorded in 43% of patients, lead author Alexander Razumovsky, Ph.D., reported at the International Stroke Conference.

"Cerebral blood flow velocity measurements permit detection of early signs of cerebral vasospasm and allow physicians to better define management strategies," he said.

TCD monitoring is routinely used by the U.S. Army, but it has not been fully embraced elsewhere because many physicians are unaware of how it can be used within the continuum of TBI care to help reverse outcomes, said study coauthor Col. Rocco Armonda, MC, USA.

"There’s this lack of drive to change outcomes because people haven’t seen how you can take someone who is in a comatose state and eventually gain functional independence," said Dr. Armonda, who is the director of cerebrovascular surgery and interventional neuroradiology at the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Md.

A recent study from Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:1525-30), however, reported that 63% of veterans with a penetrating TBI and a mean discharge Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 6-8 progressed to functional independence – a number twice as high as would be expected, Dr. Armonda remarked.

Dr. Razumovsky said that simple, noninvasive TCD monitoring should be performed in the daily management of hospitalized TBI patients to complement other monitoring strategies, and it can be used alone in emergency situations when intracranial pressure monitoring is contraindicated or not readily available.

TCD monitoring is not necessary during outpatient follow-up of patients with TBI, with the exception of the subset who’ve undergone hemicraniectomy, Dr. Armonda said.

"In those patients who’ve had hemicraniectomy, some of them suffer prolonged duration from atmospheric pressure of the cranial defect, and TCD has actually been helpful to look at the cerebral blood flow dynamics," he said at a press briefing on the study.

The results confirm earlier data that TBI is associated with a high incidence of cerebral vasospasm, particularly in patients with severe TBI, and are applicable to civilian TBI patients because a significant number will experience post-traumatic bleeding that will lead to vasospasm and intracranial hypertension, said Dr. Razumovsky, director of Sentient NeuroCare Services in Hunt Valley, Md., which provides services to the National Naval Medical Hospital.

In the current study, patients were admitted to Walter Reed a mean of 6.7 days after injury from Oct. 1, 2008, to Nov. 30, 2012. Mean cerebral blood flow velocity (CBFV) of 100-139 cm/s was used to define mild vasospasm, 140-199 cm/s moderate vasospasm, and more than 200 cm/s severe vasospasm.

In all, 88 patients had penetrating head injury, of whom 45 (51%) had a secondary diagnosis of blast injury; and 34 patients had a closed head injury, of whom 15 (44%) had a secondary diagnosis of blast injury. Their mean age was 26 years.

In the mild vasospasm group, the mean anterior circulation CBFV was 122.5 cm/s and mean posterior CBFV was 61 cm/s. Their average GCS score changed from 8 at baseline to 6.1 at discharge, Dr. Razumovsky said.

In the moderate vasospasm group, the mean anterior circulation CBFV was 156.6 cm/s and mean posterior CBFV was 77.5 cm/s. Their average GCS score changed from 5.9 at baseline to 5.3 at discharge.

Patients with severe vasospasm had an average anterior circulation CBFV of 241.9 cm/s and a mean posterior CBFV of 101.8 cm/s. Their average GCS score was 4.8 at both time periods.

Eight patients (7%) underwent transluminal angioplasty for post-traumatic symptomatic vasospasm, he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

Dr. Larry Goldstein, director of the Duke Stroke Center in Durham, N.C., said in an interview that the detection of vasospasm by TCD was potentially important because there is an increased risk of vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage that can lead to delayed ischemic neurological deficits. Although it was unclear from the data how many patients had traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage associated with their brain injury, he noted that the risk of vasospasm seems to be similar for traumatic and nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage.

"In many centers, both groups of patients are routinely monitored with transcranial Dopplers over the first couple of weeks or so, which is when the peak period of vasospasm develops," Dr. Goldstein said. "Showing that monitoring leads to interventions that then change outcome, that’s not so straightforward."

The study was supported in part by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command’s Telemedicine and Advanced Technology Research Center. Dr. Razumovsky and two of his coauthors reported financial remuneration from private practice.

posterior circulation vessels, Alexander Razumovsky, Ph.D., the International Stroke Conference, Cerebral blood flow velocity, U.S. Army, Col. Rocco Armonda, MC, USA,

HONOLULU – Cerebral vasospasm and intracranial hypertension may be frequent secondary insults following wartime traumatic brain injury, according to a retrospective study of 122 consecutive veterans.

Transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasonography signs of mild, moderate, and severe vasospasm involving anterior circulation vessels were observed in 71%, 42%, and 16% of the veterans with traumatic brain injury (TBI), respectively.

TCD signs involving posterior circulation vessels were observed in 57%, 32%, and 14%, respectively.

Intracranial hypertension was recorded in 43% of patients, lead author Alexander Razumovsky, Ph.D., reported at the International Stroke Conference.

"Cerebral blood flow velocity measurements permit detection of early signs of cerebral vasospasm and allow physicians to better define management strategies," he said.

TCD monitoring is routinely used by the U.S. Army, but it has not been fully embraced elsewhere because many physicians are unaware of how it can be used within the continuum of TBI care to help reverse outcomes, said study coauthor Col. Rocco Armonda, MC, USA.

"There’s this lack of drive to change outcomes because people haven’t seen how you can take someone who is in a comatose state and eventually gain functional independence," said Dr. Armonda, who is the director of cerebrovascular surgery and interventional neuroradiology at the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Md.

A recent study from Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:1525-30), however, reported that 63% of veterans with a penetrating TBI and a mean discharge Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 6-8 progressed to functional independence – a number twice as high as would be expected, Dr. Armonda remarked.

Dr. Razumovsky said that simple, noninvasive TCD monitoring should be performed in the daily management of hospitalized TBI patients to complement other monitoring strategies, and it can be used alone in emergency situations when intracranial pressure monitoring is contraindicated or not readily available.

TCD monitoring is not necessary during outpatient follow-up of patients with TBI, with the exception of the subset who’ve undergone hemicraniectomy, Dr. Armonda said.

"In those patients who’ve had hemicraniectomy, some of them suffer prolonged duration from atmospheric pressure of the cranial defect, and TCD has actually been helpful to look at the cerebral blood flow dynamics," he said at a press briefing on the study.

The results confirm earlier data that TBI is associated with a high incidence of cerebral vasospasm, particularly in patients with severe TBI, and are applicable to civilian TBI patients because a significant number will experience post-traumatic bleeding that will lead to vasospasm and intracranial hypertension, said Dr. Razumovsky, director of Sentient NeuroCare Services in Hunt Valley, Md., which provides services to the National Naval Medical Hospital.

In the current study, patients were admitted to Walter Reed a mean of 6.7 days after injury from Oct. 1, 2008, to Nov. 30, 2012. Mean cerebral blood flow velocity (CBFV) of 100-139 cm/s was used to define mild vasospasm, 140-199 cm/s moderate vasospasm, and more than 200 cm/s severe vasospasm.

In all, 88 patients had penetrating head injury, of whom 45 (51%) had a secondary diagnosis of blast injury; and 34 patients had a closed head injury, of whom 15 (44%) had a secondary diagnosis of blast injury. Their mean age was 26 years.

In the mild vasospasm group, the mean anterior circulation CBFV was 122.5 cm/s and mean posterior CBFV was 61 cm/s. Their average GCS score changed from 8 at baseline to 6.1 at discharge, Dr. Razumovsky said.

In the moderate vasospasm group, the mean anterior circulation CBFV was 156.6 cm/s and mean posterior CBFV was 77.5 cm/s. Their average GCS score changed from 5.9 at baseline to 5.3 at discharge.

Patients with severe vasospasm had an average anterior circulation CBFV of 241.9 cm/s and a mean posterior CBFV of 101.8 cm/s. Their average GCS score was 4.8 at both time periods.

Eight patients (7%) underwent transluminal angioplasty for post-traumatic symptomatic vasospasm, he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

Dr. Larry Goldstein, director of the Duke Stroke Center in Durham, N.C., said in an interview that the detection of vasospasm by TCD was potentially important because there is an increased risk of vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage that can lead to delayed ischemic neurological deficits. Although it was unclear from the data how many patients had traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage associated with their brain injury, he noted that the risk of vasospasm seems to be similar for traumatic and nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage.

"In many centers, both groups of patients are routinely monitored with transcranial Dopplers over the first couple of weeks or so, which is when the peak period of vasospasm develops," Dr. Goldstein said. "Showing that monitoring leads to interventions that then change outcome, that’s not so straightforward."

The study was supported in part by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command’s Telemedicine and Advanced Technology Research Center. Dr. Razumovsky and two of his coauthors reported financial remuneration from private practice.

HONOLULU – Cerebral vasospasm and intracranial hypertension may be frequent secondary insults following wartime traumatic brain injury, according to a retrospective study of 122 consecutive veterans.

Transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasonography signs of mild, moderate, and severe vasospasm involving anterior circulation vessels were observed in 71%, 42%, and 16% of the veterans with traumatic brain injury (TBI), respectively.

TCD signs involving posterior circulation vessels were observed in 57%, 32%, and 14%, respectively.

Intracranial hypertension was recorded in 43% of patients, lead author Alexander Razumovsky, Ph.D., reported at the International Stroke Conference.

"Cerebral blood flow velocity measurements permit detection of early signs of cerebral vasospasm and allow physicians to better define management strategies," he said.

TCD monitoring is routinely used by the U.S. Army, but it has not been fully embraced elsewhere because many physicians are unaware of how it can be used within the continuum of TBI care to help reverse outcomes, said study coauthor Col. Rocco Armonda, MC, USA.

"There’s this lack of drive to change outcomes because people haven’t seen how you can take someone who is in a comatose state and eventually gain functional independence," said Dr. Armonda, who is the director of cerebrovascular surgery and interventional neuroradiology at the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Md.

A recent study from Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:1525-30), however, reported that 63% of veterans with a penetrating TBI and a mean discharge Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 6-8 progressed to functional independence – a number twice as high as would be expected, Dr. Armonda remarked.

Dr. Razumovsky said that simple, noninvasive TCD monitoring should be performed in the daily management of hospitalized TBI patients to complement other monitoring strategies, and it can be used alone in emergency situations when intracranial pressure monitoring is contraindicated or not readily available.

TCD monitoring is not necessary during outpatient follow-up of patients with TBI, with the exception of the subset who’ve undergone hemicraniectomy, Dr. Armonda said.

"In those patients who’ve had hemicraniectomy, some of them suffer prolonged duration from atmospheric pressure of the cranial defect, and TCD has actually been helpful to look at the cerebral blood flow dynamics," he said at a press briefing on the study.

The results confirm earlier data that TBI is associated with a high incidence of cerebral vasospasm, particularly in patients with severe TBI, and are applicable to civilian TBI patients because a significant number will experience post-traumatic bleeding that will lead to vasospasm and intracranial hypertension, said Dr. Razumovsky, director of Sentient NeuroCare Services in Hunt Valley, Md., which provides services to the National Naval Medical Hospital.

In the current study, patients were admitted to Walter Reed a mean of 6.7 days after injury from Oct. 1, 2008, to Nov. 30, 2012. Mean cerebral blood flow velocity (CBFV) of 100-139 cm/s was used to define mild vasospasm, 140-199 cm/s moderate vasospasm, and more than 200 cm/s severe vasospasm.

In all, 88 patients had penetrating head injury, of whom 45 (51%) had a secondary diagnosis of blast injury; and 34 patients had a closed head injury, of whom 15 (44%) had a secondary diagnosis of blast injury. Their mean age was 26 years.

In the mild vasospasm group, the mean anterior circulation CBFV was 122.5 cm/s and mean posterior CBFV was 61 cm/s. Their average GCS score changed from 8 at baseline to 6.1 at discharge, Dr. Razumovsky said.

In the moderate vasospasm group, the mean anterior circulation CBFV was 156.6 cm/s and mean posterior CBFV was 77.5 cm/s. Their average GCS score changed from 5.9 at baseline to 5.3 at discharge.

Patients with severe vasospasm had an average anterior circulation CBFV of 241.9 cm/s and a mean posterior CBFV of 101.8 cm/s. Their average GCS score was 4.8 at both time periods.

Eight patients (7%) underwent transluminal angioplasty for post-traumatic symptomatic vasospasm, he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

Dr. Larry Goldstein, director of the Duke Stroke Center in Durham, N.C., said in an interview that the detection of vasospasm by TCD was potentially important because there is an increased risk of vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage that can lead to delayed ischemic neurological deficits. Although it was unclear from the data how many patients had traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage associated with their brain injury, he noted that the risk of vasospasm seems to be similar for traumatic and nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage.

"In many centers, both groups of patients are routinely monitored with transcranial Dopplers over the first couple of weeks or so, which is when the peak period of vasospasm develops," Dr. Goldstein said. "Showing that monitoring leads to interventions that then change outcome, that’s not so straightforward."

The study was supported in part by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command’s Telemedicine and Advanced Technology Research Center. Dr. Razumovsky and two of his coauthors reported financial remuneration from private practice.

posterior circulation vessels, Alexander Razumovsky, Ph.D., the International Stroke Conference, Cerebral blood flow velocity, U.S. Army, Col. Rocco Armonda, MC, USA,

posterior circulation vessels, Alexander Razumovsky, Ph.D., the International Stroke Conference, Cerebral blood flow velocity, U.S. Army, Col. Rocco Armonda, MC, USA,

AT THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Major finding: Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography revealed signs of mild, moderate, and severe vasospasm involving anterior circulation vessels in 71%, 42%, and 16% of patients, respectively, but slightly less often in posterior circulation vessels (57%, 32%, and 14%).

Data source: A retrospective study of 122 consecutive patients with combat-related traumatic brain injury.

Disclosures: The study was supported in part by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command’s Telemedicine and Advanced Technology Research Center. Dr. Razumovsky and two of his coauthors reported financial remuneration from private practice.

Laser ablation rivaled open surgery for epileptogenic lesions

Craniotomies and open resections may soon no longer be necessary to remove focal, well-circumscribed refractory epileptogenic lesions from the brain, two small studies have shown.

Two research teams reported positive, early results for laser ablation, an alternative approach in which a narrow probe is inserted through a small hole in the skull to kill epileptogenic neurons with heat under real-time MRI and EEG guidance.

At the Sutter Neuroscience Institute in Sacramento, "we are having about a 70% [seizure-free] success rate" in the six children and two young adults who have undergone the procedure and been followed for up to a year," said neurologist Michael Chez, director of Sutter’s pediatric and adult epilepsy program. He and his team have treated lesions of the frontal, nonmesial temporal, occipital, and parietal lobes.

"We’ve had some very nice results with a very minimally invasive technique. The outcomes are very promising. We have another six surgeries planned," he said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.