User login

Early surgery for intracerebral bleeds may benefit a select few

LONDON – Approximately 2%-3% of patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage may benefit from early surgical removal of hematoma, according to the results of the second Surgical Trial in Lobar Intracerebral Hemorrhage.

As reported at the annual European Stroke Conference and published simultaneously in the Lancet, patients with superficial lesions and an unfavorable prognostic score appeared to benefit from early surgical intervention, compared with those given conservative medical treatment (odds ratio [OR] = 0.49, P =.02). Conversely, those with a good prognostic score did not seem to benefit (OR = 1.12, P = .57).

The primary analysis showed no significant benefit of early surgery overall, with 41.4% of 297 patients in the early surgery group and 37.7% of 286 patients in the conservative treatment group having a favorable outcome at 6 months, as determined by the 8-point extended Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS-E) (P = .367).

"That’s a 3.7% absolute benefit, which is not enough to change surgical practice on its own," said Dr. A. David Mendelow, professor of neurosurgery at Newcastle University in Newcastle upon Tyne, England. "We were looking for a 12% benefit when we set out to do this trial," he added during a press conference.

A 6% decrease in mortality at 6 months was seen favoring surgery (18% vs. 24% for conservative therapy), but this was not statistically significant (P = .095).

"Intracerebral hemorrhage is not a homogenous condition," Dr. Mendelow said, adding that it can be a difficult decision to operate. Clinical manifestations can range from no apparent effects to severe disability and rapid death. "STICH [Surgical Trial in Lobar Intracerebral Hemorrhage] focused on patients that we are not quite sure about whether to operate or not," he said.

The hypothesis for the trial was based on the findings of the first STICH trial (Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 2006;96:65-8). The results of the trial were again neutral overall, but subgroup analyses showed that some groups of patients did worse with surgery, such as those with deep-seated bleeds, and some may fare better, such as those with superficial lobar hematomas.

STICH II therefore specifically recruited this latter group of patients to see if the effect was real or an artifact of the scientific analysis. In total, 601 conscious ICH patients with a median age of 65 years were recruited at 78 centers in 27 countries. Patients had to have a superficial lesion (1 cm or less from the cortical surface of the brain) that was between 10 mL and 100 mL in volume, and with no sign of intraventricular hemorrhage on CT scanning. Patients had to be recruited within 48 hours of the stroke and surgical intervention had to be performed within 12 hours (Lancet 2013 May 29 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60986-1]). (A total of 6 patients were excluded or withdrew from the study before intervention, and after intervention another 12 withdrew, were lost to follow-up, or were alive but had an unknown status.)

The GOS-E was calculated from the answers to a questionnaire sent out to patients and their relatives 6 months following their stroke. A cutoff score of approximately 27 was used to categorize patients as having a good or bad prognosis. At baseline, about two-thirds of patients had a good prognosis, and the remainder had a poor prognosis.

"The notion that early surgery might be beneficial in this subgroup of patients is supported by the results of the investigator’s updated meta-analysis of 15 trials,"

"One of the reasons, perhaps, for a lack of significance was the [number of] crossovers from initial conservative therapy to surgery," Dr. Mendelow said. Indeed, 21% of patients who were originally randomized to conservative treatment crossed over to the surgical arm. These patients had "clearly deteriorated" prior to having surgery, he said when presenting the findings. Furthermore, only 37% of these crossovers received surgery within the specified 12-hour time limit.

STICH provides the best, albeit insufficient, evidence to date on the role of surgery in ICH, Dr. Oliver Gautschi and Dr. Karl Schaller, both of the University of Geneva, commented in an editorial about the trial (Lancet 2013 May 29 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61087-9]) .

"The notion that early surgery might be beneficial in this subgroup of patients is supported by the results of the investigator’s updated meta-analysis of 15 trials," they wrote. "The overall result of this meta-analysis of patients with different types of intracerebral hemorrhage favors surgery."

The results of two other surgical studies, CLEAR III and MISTIE III, "are eagerly awaited," Dr. Gautschi and Dr. Schaller said, noting that, "decompressive hemicraniectomy might be a[nother] promising surgical procedure."

The U.K. Medical Research Council funded STICH II. Dr. Mendelow reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

LONDON – Approximately 2%-3% of patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage may benefit from early surgical removal of hematoma, according to the results of the second Surgical Trial in Lobar Intracerebral Hemorrhage.

As reported at the annual European Stroke Conference and published simultaneously in the Lancet, patients with superficial lesions and an unfavorable prognostic score appeared to benefit from early surgical intervention, compared with those given conservative medical treatment (odds ratio [OR] = 0.49, P =.02). Conversely, those with a good prognostic score did not seem to benefit (OR = 1.12, P = .57).

The primary analysis showed no significant benefit of early surgery overall, with 41.4% of 297 patients in the early surgery group and 37.7% of 286 patients in the conservative treatment group having a favorable outcome at 6 months, as determined by the 8-point extended Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS-E) (P = .367).

"That’s a 3.7% absolute benefit, which is not enough to change surgical practice on its own," said Dr. A. David Mendelow, professor of neurosurgery at Newcastle University in Newcastle upon Tyne, England. "We were looking for a 12% benefit when we set out to do this trial," he added during a press conference.

A 6% decrease in mortality at 6 months was seen favoring surgery (18% vs. 24% for conservative therapy), but this was not statistically significant (P = .095).

"Intracerebral hemorrhage is not a homogenous condition," Dr. Mendelow said, adding that it can be a difficult decision to operate. Clinical manifestations can range from no apparent effects to severe disability and rapid death. "STICH [Surgical Trial in Lobar Intracerebral Hemorrhage] focused on patients that we are not quite sure about whether to operate or not," he said.

The hypothesis for the trial was based on the findings of the first STICH trial (Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 2006;96:65-8). The results of the trial were again neutral overall, but subgroup analyses showed that some groups of patients did worse with surgery, such as those with deep-seated bleeds, and some may fare better, such as those with superficial lobar hematomas.

STICH II therefore specifically recruited this latter group of patients to see if the effect was real or an artifact of the scientific analysis. In total, 601 conscious ICH patients with a median age of 65 years were recruited at 78 centers in 27 countries. Patients had to have a superficial lesion (1 cm or less from the cortical surface of the brain) that was between 10 mL and 100 mL in volume, and with no sign of intraventricular hemorrhage on CT scanning. Patients had to be recruited within 48 hours of the stroke and surgical intervention had to be performed within 12 hours (Lancet 2013 May 29 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60986-1]). (A total of 6 patients were excluded or withdrew from the study before intervention, and after intervention another 12 withdrew, were lost to follow-up, or were alive but had an unknown status.)

The GOS-E was calculated from the answers to a questionnaire sent out to patients and their relatives 6 months following their stroke. A cutoff score of approximately 27 was used to categorize patients as having a good or bad prognosis. At baseline, about two-thirds of patients had a good prognosis, and the remainder had a poor prognosis.

"The notion that early surgery might be beneficial in this subgroup of patients is supported by the results of the investigator’s updated meta-analysis of 15 trials,"

"One of the reasons, perhaps, for a lack of significance was the [number of] crossovers from initial conservative therapy to surgery," Dr. Mendelow said. Indeed, 21% of patients who were originally randomized to conservative treatment crossed over to the surgical arm. These patients had "clearly deteriorated" prior to having surgery, he said when presenting the findings. Furthermore, only 37% of these crossovers received surgery within the specified 12-hour time limit.

STICH provides the best, albeit insufficient, evidence to date on the role of surgery in ICH, Dr. Oliver Gautschi and Dr. Karl Schaller, both of the University of Geneva, commented in an editorial about the trial (Lancet 2013 May 29 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61087-9]) .

"The notion that early surgery might be beneficial in this subgroup of patients is supported by the results of the investigator’s updated meta-analysis of 15 trials," they wrote. "The overall result of this meta-analysis of patients with different types of intracerebral hemorrhage favors surgery."

The results of two other surgical studies, CLEAR III and MISTIE III, "are eagerly awaited," Dr. Gautschi and Dr. Schaller said, noting that, "decompressive hemicraniectomy might be a[nother] promising surgical procedure."

The U.K. Medical Research Council funded STICH II. Dr. Mendelow reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

LONDON – Approximately 2%-3% of patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage may benefit from early surgical removal of hematoma, according to the results of the second Surgical Trial in Lobar Intracerebral Hemorrhage.

As reported at the annual European Stroke Conference and published simultaneously in the Lancet, patients with superficial lesions and an unfavorable prognostic score appeared to benefit from early surgical intervention, compared with those given conservative medical treatment (odds ratio [OR] = 0.49, P =.02). Conversely, those with a good prognostic score did not seem to benefit (OR = 1.12, P = .57).

The primary analysis showed no significant benefit of early surgery overall, with 41.4% of 297 patients in the early surgery group and 37.7% of 286 patients in the conservative treatment group having a favorable outcome at 6 months, as determined by the 8-point extended Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS-E) (P = .367).

"That’s a 3.7% absolute benefit, which is not enough to change surgical practice on its own," said Dr. A. David Mendelow, professor of neurosurgery at Newcastle University in Newcastle upon Tyne, England. "We were looking for a 12% benefit when we set out to do this trial," he added during a press conference.

A 6% decrease in mortality at 6 months was seen favoring surgery (18% vs. 24% for conservative therapy), but this was not statistically significant (P = .095).

"Intracerebral hemorrhage is not a homogenous condition," Dr. Mendelow said, adding that it can be a difficult decision to operate. Clinical manifestations can range from no apparent effects to severe disability and rapid death. "STICH [Surgical Trial in Lobar Intracerebral Hemorrhage] focused on patients that we are not quite sure about whether to operate or not," he said.

The hypothesis for the trial was based on the findings of the first STICH trial (Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 2006;96:65-8). The results of the trial were again neutral overall, but subgroup analyses showed that some groups of patients did worse with surgery, such as those with deep-seated bleeds, and some may fare better, such as those with superficial lobar hematomas.

STICH II therefore specifically recruited this latter group of patients to see if the effect was real or an artifact of the scientific analysis. In total, 601 conscious ICH patients with a median age of 65 years were recruited at 78 centers in 27 countries. Patients had to have a superficial lesion (1 cm or less from the cortical surface of the brain) that was between 10 mL and 100 mL in volume, and with no sign of intraventricular hemorrhage on CT scanning. Patients had to be recruited within 48 hours of the stroke and surgical intervention had to be performed within 12 hours (Lancet 2013 May 29 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60986-1]). (A total of 6 patients were excluded or withdrew from the study before intervention, and after intervention another 12 withdrew, were lost to follow-up, or were alive but had an unknown status.)

The GOS-E was calculated from the answers to a questionnaire sent out to patients and their relatives 6 months following their stroke. A cutoff score of approximately 27 was used to categorize patients as having a good or bad prognosis. At baseline, about two-thirds of patients had a good prognosis, and the remainder had a poor prognosis.

"The notion that early surgery might be beneficial in this subgroup of patients is supported by the results of the investigator’s updated meta-analysis of 15 trials,"

"One of the reasons, perhaps, for a lack of significance was the [number of] crossovers from initial conservative therapy to surgery," Dr. Mendelow said. Indeed, 21% of patients who were originally randomized to conservative treatment crossed over to the surgical arm. These patients had "clearly deteriorated" prior to having surgery, he said when presenting the findings. Furthermore, only 37% of these crossovers received surgery within the specified 12-hour time limit.

STICH provides the best, albeit insufficient, evidence to date on the role of surgery in ICH, Dr. Oliver Gautschi and Dr. Karl Schaller, both of the University of Geneva, commented in an editorial about the trial (Lancet 2013 May 29 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61087-9]) .

"The notion that early surgery might be beneficial in this subgroup of patients is supported by the results of the investigator’s updated meta-analysis of 15 trials," they wrote. "The overall result of this meta-analysis of patients with different types of intracerebral hemorrhage favors surgery."

The results of two other surgical studies, CLEAR III and MISTIE III, "are eagerly awaited," Dr. Gautschi and Dr. Schaller said, noting that, "decompressive hemicraniectomy might be a[nother] promising surgical procedure."

The U.K. Medical Research Council funded STICH II. Dr. Mendelow reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE EUROPEAN STROKE CONFERENCE

Major finding: A favorable outcome at 6 months was seen in 41% of the early surgery group and 38% of the conservative treatment group (P = .367).

Data source: STICH II, an international, multicenter prospective trial of 601 patients randomized to early surgery (within 12 hours) or medical treatment within 48 hours of a spontaneous superficial intracerebral hemorrhage.

Disclosures: The U.K. Medical Research Council funded STICH II. Dr. Mendelow reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Headgear comes off for amateur boxers

This summer, amateur, elite male boxers are back to competing without headgear after nearly 3 decades of being required to wear it during competition. The headgear rule was put in place by the International Boxing Association (AIBA) before the 1984 Olympics, but now elite, male boxers are beginning to compete in much more professional style.

So what will this mean for concussion rates and concussion risk?

At first glance, it may seem to put boxers at greater risk; however, clinical evidence has shown that headgear does not necessarily reduce the incidence of concussion. The advantage of headgear is that it protects the face and decreases eye injuries, nose injuries, and facial lacerations. It does not stop the head from spinning, the primary cause of concussion in boxers.

There are four ways that boxers can get brain injury, but none of them can be prevented by wearing headgear. These mechanisms include:

• Rotational acceleration. This occurs when the head twists/spins – usually from a blow to the side of the jaw, cheek, or chin – and the brain follows, resulting in the stretching and tearing of axons. (This is why knockouts usually come from a severe blow to the chin.)

• Linear acceleration. This happens when the brain moves forward/backward – usually from a direct blow to the face – and strikes the skull, resulting in the stretching or tearing of neurons in the brain and brain stem.

• Injury to the carotid arteries. This occurs after a sudden flexion of the neck – usually from a direct blow to it – resulting in tears in one or both carotid arteries, causing a stroke.

• Impact deceleration. This is the rapid slowing of the brain inside the skull and is usually caused by hitting an immovable object like the ring floor, resulting in cerebral contusions.

In fact, there is a new, still unpublished AIBA study that suggests the removal of headgear would decrease head injuries, such as concussions. According to the study spearheaded by AIBA medical commission chairman Dr. Charles Butler, the rate of concussion was 0.38% in 7,352 rounds for boxers wearing headgear, compared with 0.17% in 7,545 rounds for those without headgear.

On the other hand, another recent study by the Cleveland Clinic found that headgear can help decrease linear acceleration and the potential for injury from it.

Clearly, there is still much debate on this issue. As amateur boxers start this new phase of competition, experts will be better able to observe changes in concussion rates, if any, and hopefully come to a definitive conclusion as to whether headgear use has any impact at all.

Dr. Jordan is the director of the brain injury program and the memory evaluation treatment service at Burke Rehabilitation Hospital in White Plains, N.Y. He currently serves as the chief medical officer of the New York State Athletic Commission, as a team physician for USA Boxing, and as a member of the NFL Players Association Mackey-White Traumatic Brain Injury Committee and the NFL Neuro-Cognitive Disability Committee.

This summer, amateur, elite male boxers are back to competing without headgear after nearly 3 decades of being required to wear it during competition. The headgear rule was put in place by the International Boxing Association (AIBA) before the 1984 Olympics, but now elite, male boxers are beginning to compete in much more professional style.

So what will this mean for concussion rates and concussion risk?

At first glance, it may seem to put boxers at greater risk; however, clinical evidence has shown that headgear does not necessarily reduce the incidence of concussion. The advantage of headgear is that it protects the face and decreases eye injuries, nose injuries, and facial lacerations. It does not stop the head from spinning, the primary cause of concussion in boxers.

There are four ways that boxers can get brain injury, but none of them can be prevented by wearing headgear. These mechanisms include:

• Rotational acceleration. This occurs when the head twists/spins – usually from a blow to the side of the jaw, cheek, or chin – and the brain follows, resulting in the stretching and tearing of axons. (This is why knockouts usually come from a severe blow to the chin.)

• Linear acceleration. This happens when the brain moves forward/backward – usually from a direct blow to the face – and strikes the skull, resulting in the stretching or tearing of neurons in the brain and brain stem.

• Injury to the carotid arteries. This occurs after a sudden flexion of the neck – usually from a direct blow to it – resulting in tears in one or both carotid arteries, causing a stroke.

• Impact deceleration. This is the rapid slowing of the brain inside the skull and is usually caused by hitting an immovable object like the ring floor, resulting in cerebral contusions.

In fact, there is a new, still unpublished AIBA study that suggests the removal of headgear would decrease head injuries, such as concussions. According to the study spearheaded by AIBA medical commission chairman Dr. Charles Butler, the rate of concussion was 0.38% in 7,352 rounds for boxers wearing headgear, compared with 0.17% in 7,545 rounds for those without headgear.

On the other hand, another recent study by the Cleveland Clinic found that headgear can help decrease linear acceleration and the potential for injury from it.

Clearly, there is still much debate on this issue. As amateur boxers start this new phase of competition, experts will be better able to observe changes in concussion rates, if any, and hopefully come to a definitive conclusion as to whether headgear use has any impact at all.

Dr. Jordan is the director of the brain injury program and the memory evaluation treatment service at Burke Rehabilitation Hospital in White Plains, N.Y. He currently serves as the chief medical officer of the New York State Athletic Commission, as a team physician for USA Boxing, and as a member of the NFL Players Association Mackey-White Traumatic Brain Injury Committee and the NFL Neuro-Cognitive Disability Committee.

This summer, amateur, elite male boxers are back to competing without headgear after nearly 3 decades of being required to wear it during competition. The headgear rule was put in place by the International Boxing Association (AIBA) before the 1984 Olympics, but now elite, male boxers are beginning to compete in much more professional style.

So what will this mean for concussion rates and concussion risk?

At first glance, it may seem to put boxers at greater risk; however, clinical evidence has shown that headgear does not necessarily reduce the incidence of concussion. The advantage of headgear is that it protects the face and decreases eye injuries, nose injuries, and facial lacerations. It does not stop the head from spinning, the primary cause of concussion in boxers.

There are four ways that boxers can get brain injury, but none of them can be prevented by wearing headgear. These mechanisms include:

• Rotational acceleration. This occurs when the head twists/spins – usually from a blow to the side of the jaw, cheek, or chin – and the brain follows, resulting in the stretching and tearing of axons. (This is why knockouts usually come from a severe blow to the chin.)

• Linear acceleration. This happens when the brain moves forward/backward – usually from a direct blow to the face – and strikes the skull, resulting in the stretching or tearing of neurons in the brain and brain stem.

• Injury to the carotid arteries. This occurs after a sudden flexion of the neck – usually from a direct blow to it – resulting in tears in one or both carotid arteries, causing a stroke.

• Impact deceleration. This is the rapid slowing of the brain inside the skull and is usually caused by hitting an immovable object like the ring floor, resulting in cerebral contusions.

In fact, there is a new, still unpublished AIBA study that suggests the removal of headgear would decrease head injuries, such as concussions. According to the study spearheaded by AIBA medical commission chairman Dr. Charles Butler, the rate of concussion was 0.38% in 7,352 rounds for boxers wearing headgear, compared with 0.17% in 7,545 rounds for those without headgear.

On the other hand, another recent study by the Cleveland Clinic found that headgear can help decrease linear acceleration and the potential for injury from it.

Clearly, there is still much debate on this issue. As amateur boxers start this new phase of competition, experts will be better able to observe changes in concussion rates, if any, and hopefully come to a definitive conclusion as to whether headgear use has any impact at all.

Dr. Jordan is the director of the brain injury program and the memory evaluation treatment service at Burke Rehabilitation Hospital in White Plains, N.Y. He currently serves as the chief medical officer of the New York State Athletic Commission, as a team physician for USA Boxing, and as a member of the NFL Players Association Mackey-White Traumatic Brain Injury Committee and the NFL Neuro-Cognitive Disability Committee.

Decompression for malignant stroke in elderly lowers death, disability

LONDON – Decompressive surgery dramatically increased the survival chances of older adult patients who had massive brain swelling after a middle cerebral artery stroke, according to the results of a randomized clinical trial.

After 1 year of follow-up, 57% of patients aged 61 years or older were still alive if they had undergone hemicraniectomy, compared with 24% (P less than .001) of those who received standard intensive care alone in the DESTINY II trial. The increase in survival did not lead to an increase in severe disability, study investigator Dr. Werner Hacke of the University of Heidelberg, Germany, reported at the annual European Stroke Conference.

"Malignant infarction of the middle cerebral artery [MCA] is the deadliest type of ischemic brain infarction," Dr. Hacke noted. It is associated with rapid neurological deterioration caused by cerebral edema (Postgrad. Med. J. 2010;86:235-42) and is responsible for 70%-80% of in-hospital mortality if treated conservatively using mechanical ventilation and intracranial pressure reduction.

Evidence supporting decompressive surgery

Previous pooled research, including the DESTINY I study (Decompressive Surgery for the Treatment of Malignant Infarction of the Middle Cerebral Artery), showed that relieving the pressure on the brain by temporarily removing part of the skull within the first 48 hours of ischemic injury reduces the risk of death and poor clinical outcome by almost 50% in patients under the age of 60 years (Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:215-22). The DESTINY II data now show that older patients also can benefit from decompressive surgery, perhaps as much as their younger counterparts.

A total of 112 patients with malignant MCA infarction aged 61 years and older were recruited into the study and randomized to receive maximum conservative treatment alone or in addition to hemicraniectomy within 48 hours after symptom onset (Int. J. Stroke 2011;6:79-86). The mean age was 70 years, and 60%-67% had infarctions affecting the nondominant cerebral hemisphere. The mean National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was 20-22 at admission.

The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients achieving a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score of 0-4 versus 5-6 at 6 months. A score of 6 on this scale signifies death and a score of 5 represents severe disability, such as being bedridden and incontinent and requiring constant nursing care and attention.

Dr. Hacke noted that the trial’s data and safety monitoring board halted the trial at the 6-month assessment after reviewing data on 82 patients. The exact reasons were undisclosed, but part of the study’s protocol was to stop the trial once statistical significance was reached. At the time the trial has halted, a further 30 patients had already been randomized and were included in the intention-to-treat analysis (ITT).

DESTINY II results

Significantly more patients who underwent surgery had a mRS of 0-4 than did those who had standard intensive care treatment (40.5% vs. 18.6%, P = .039) using the DSMB data set. The percentages of surgically and conservatively treated patients with an mRS of 5 or 6 were 59.5% and 81.4%, respectively. Performing an ITT analysis did not change the findings.

The number needed to treat was just 4, Dr. Hacke reported.

At 12 months in the ITT population, he noted that 38% of surgically and 16% of conservatively managed patients with an mRS of 0-4 were alive, as were 62% versus 84% of those, respectively, who had a mRS of 5-6 (P =.009).

An ITT analysis of multiple secondary endpoints at 1 year – which included the NIHSS score, Barthel Activities of Daily Living Index, Short Form-36 physical and mental domains, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, and the EuroQoL-5D – was also significantly in favor of early hemicraniectomy. This was perhaps a statistical artifact, Dr. Hacke observed, as the significance disappeared when data were examined in only the patients who had survived to 1 year.

Retrospective consent to surgery

When survivors and their caregivers were asked if they would undergo the same procedure again, given the knowledge of the final outcome, the majority of both surgically treated (77%, n = 27) and conservatively managed survivors (73%, n = 15) said that they would.

This finding shows that most patients, including those with moderately severe disability (mRS of 4) would rather have the procedures than be dead.

Dr. Christine Roffe, professor of medicine at Keele University in Stoke-on-Trent, England, commented that a person’s point of view of disability often changes after having a stroke.

"We’ve always assumed that if you asked someone before they had a stroke, ‘Would you rather have a stroke or be dead?’ that people would say, ‘I’d rather be dead,’ " she said in an interview. It’s not unreasonable that most people would probably say they would rather be dead than be severely incapacitated for the rest of their lives, she added.

However, after having a stroke, people often report that they are able to continue to live their lives reasonably happily despite often being quite disabled and having lost their independence.

The DESTINY II data show that people who had surgery were quite happy despite any disability, and this was at a similar level to those who were treated conservatively but with higher survival rates, Dr. Roffe noted.

The ethical implications of this could be considerable, she suggested. It shows that people who have living wills or who decide that they do not want treatment in the event of a stroke could live just as happy a life after the event as before. It therefore begs the question of whether patients should be allowed to decide on this aspect of their care, she added.

The German Research Foundation and the German Ministry of Science and Education financially supported the study. Dr. Hacke had no disclosures. Dr. Roffe was not involved in the study and had no relevant conflicts of interest.

LONDON – Decompressive surgery dramatically increased the survival chances of older adult patients who had massive brain swelling after a middle cerebral artery stroke, according to the results of a randomized clinical trial.

After 1 year of follow-up, 57% of patients aged 61 years or older were still alive if they had undergone hemicraniectomy, compared with 24% (P less than .001) of those who received standard intensive care alone in the DESTINY II trial. The increase in survival did not lead to an increase in severe disability, study investigator Dr. Werner Hacke of the University of Heidelberg, Germany, reported at the annual European Stroke Conference.

"Malignant infarction of the middle cerebral artery [MCA] is the deadliest type of ischemic brain infarction," Dr. Hacke noted. It is associated with rapid neurological deterioration caused by cerebral edema (Postgrad. Med. J. 2010;86:235-42) and is responsible for 70%-80% of in-hospital mortality if treated conservatively using mechanical ventilation and intracranial pressure reduction.

Evidence supporting decompressive surgery

Previous pooled research, including the DESTINY I study (Decompressive Surgery for the Treatment of Malignant Infarction of the Middle Cerebral Artery), showed that relieving the pressure on the brain by temporarily removing part of the skull within the first 48 hours of ischemic injury reduces the risk of death and poor clinical outcome by almost 50% in patients under the age of 60 years (Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:215-22). The DESTINY II data now show that older patients also can benefit from decompressive surgery, perhaps as much as their younger counterparts.

A total of 112 patients with malignant MCA infarction aged 61 years and older were recruited into the study and randomized to receive maximum conservative treatment alone or in addition to hemicraniectomy within 48 hours after symptom onset (Int. J. Stroke 2011;6:79-86). The mean age was 70 years, and 60%-67% had infarctions affecting the nondominant cerebral hemisphere. The mean National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was 20-22 at admission.

The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients achieving a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score of 0-4 versus 5-6 at 6 months. A score of 6 on this scale signifies death and a score of 5 represents severe disability, such as being bedridden and incontinent and requiring constant nursing care and attention.

Dr. Hacke noted that the trial’s data and safety monitoring board halted the trial at the 6-month assessment after reviewing data on 82 patients. The exact reasons were undisclosed, but part of the study’s protocol was to stop the trial once statistical significance was reached. At the time the trial has halted, a further 30 patients had already been randomized and were included in the intention-to-treat analysis (ITT).

DESTINY II results

Significantly more patients who underwent surgery had a mRS of 0-4 than did those who had standard intensive care treatment (40.5% vs. 18.6%, P = .039) using the DSMB data set. The percentages of surgically and conservatively treated patients with an mRS of 5 or 6 were 59.5% and 81.4%, respectively. Performing an ITT analysis did not change the findings.

The number needed to treat was just 4, Dr. Hacke reported.

At 12 months in the ITT population, he noted that 38% of surgically and 16% of conservatively managed patients with an mRS of 0-4 were alive, as were 62% versus 84% of those, respectively, who had a mRS of 5-6 (P =.009).

An ITT analysis of multiple secondary endpoints at 1 year – which included the NIHSS score, Barthel Activities of Daily Living Index, Short Form-36 physical and mental domains, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, and the EuroQoL-5D – was also significantly in favor of early hemicraniectomy. This was perhaps a statistical artifact, Dr. Hacke observed, as the significance disappeared when data were examined in only the patients who had survived to 1 year.

Retrospective consent to surgery

When survivors and their caregivers were asked if they would undergo the same procedure again, given the knowledge of the final outcome, the majority of both surgically treated (77%, n = 27) and conservatively managed survivors (73%, n = 15) said that they would.

This finding shows that most patients, including those with moderately severe disability (mRS of 4) would rather have the procedures than be dead.

Dr. Christine Roffe, professor of medicine at Keele University in Stoke-on-Trent, England, commented that a person’s point of view of disability often changes after having a stroke.

"We’ve always assumed that if you asked someone before they had a stroke, ‘Would you rather have a stroke or be dead?’ that people would say, ‘I’d rather be dead,’ " she said in an interview. It’s not unreasonable that most people would probably say they would rather be dead than be severely incapacitated for the rest of their lives, she added.

However, after having a stroke, people often report that they are able to continue to live their lives reasonably happily despite often being quite disabled and having lost their independence.

The DESTINY II data show that people who had surgery were quite happy despite any disability, and this was at a similar level to those who were treated conservatively but with higher survival rates, Dr. Roffe noted.

The ethical implications of this could be considerable, she suggested. It shows that people who have living wills or who decide that they do not want treatment in the event of a stroke could live just as happy a life after the event as before. It therefore begs the question of whether patients should be allowed to decide on this aspect of their care, she added.

The German Research Foundation and the German Ministry of Science and Education financially supported the study. Dr. Hacke had no disclosures. Dr. Roffe was not involved in the study and had no relevant conflicts of interest.

LONDON – Decompressive surgery dramatically increased the survival chances of older adult patients who had massive brain swelling after a middle cerebral artery stroke, according to the results of a randomized clinical trial.

After 1 year of follow-up, 57% of patients aged 61 years or older were still alive if they had undergone hemicraniectomy, compared with 24% (P less than .001) of those who received standard intensive care alone in the DESTINY II trial. The increase in survival did not lead to an increase in severe disability, study investigator Dr. Werner Hacke of the University of Heidelberg, Germany, reported at the annual European Stroke Conference.

"Malignant infarction of the middle cerebral artery [MCA] is the deadliest type of ischemic brain infarction," Dr. Hacke noted. It is associated with rapid neurological deterioration caused by cerebral edema (Postgrad. Med. J. 2010;86:235-42) and is responsible for 70%-80% of in-hospital mortality if treated conservatively using mechanical ventilation and intracranial pressure reduction.

Evidence supporting decompressive surgery

Previous pooled research, including the DESTINY I study (Decompressive Surgery for the Treatment of Malignant Infarction of the Middle Cerebral Artery), showed that relieving the pressure on the brain by temporarily removing part of the skull within the first 48 hours of ischemic injury reduces the risk of death and poor clinical outcome by almost 50% in patients under the age of 60 years (Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:215-22). The DESTINY II data now show that older patients also can benefit from decompressive surgery, perhaps as much as their younger counterparts.

A total of 112 patients with malignant MCA infarction aged 61 years and older were recruited into the study and randomized to receive maximum conservative treatment alone or in addition to hemicraniectomy within 48 hours after symptom onset (Int. J. Stroke 2011;6:79-86). The mean age was 70 years, and 60%-67% had infarctions affecting the nondominant cerebral hemisphere. The mean National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was 20-22 at admission.

The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients achieving a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score of 0-4 versus 5-6 at 6 months. A score of 6 on this scale signifies death and a score of 5 represents severe disability, such as being bedridden and incontinent and requiring constant nursing care and attention.

Dr. Hacke noted that the trial’s data and safety monitoring board halted the trial at the 6-month assessment after reviewing data on 82 patients. The exact reasons were undisclosed, but part of the study’s protocol was to stop the trial once statistical significance was reached. At the time the trial has halted, a further 30 patients had already been randomized and were included in the intention-to-treat analysis (ITT).

DESTINY II results

Significantly more patients who underwent surgery had a mRS of 0-4 than did those who had standard intensive care treatment (40.5% vs. 18.6%, P = .039) using the DSMB data set. The percentages of surgically and conservatively treated patients with an mRS of 5 or 6 were 59.5% and 81.4%, respectively. Performing an ITT analysis did not change the findings.

The number needed to treat was just 4, Dr. Hacke reported.

At 12 months in the ITT population, he noted that 38% of surgically and 16% of conservatively managed patients with an mRS of 0-4 were alive, as were 62% versus 84% of those, respectively, who had a mRS of 5-6 (P =.009).

An ITT analysis of multiple secondary endpoints at 1 year – which included the NIHSS score, Barthel Activities of Daily Living Index, Short Form-36 physical and mental domains, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, and the EuroQoL-5D – was also significantly in favor of early hemicraniectomy. This was perhaps a statistical artifact, Dr. Hacke observed, as the significance disappeared when data were examined in only the patients who had survived to 1 year.

Retrospective consent to surgery

When survivors and their caregivers were asked if they would undergo the same procedure again, given the knowledge of the final outcome, the majority of both surgically treated (77%, n = 27) and conservatively managed survivors (73%, n = 15) said that they would.

This finding shows that most patients, including those with moderately severe disability (mRS of 4) would rather have the procedures than be dead.

Dr. Christine Roffe, professor of medicine at Keele University in Stoke-on-Trent, England, commented that a person’s point of view of disability often changes after having a stroke.

"We’ve always assumed that if you asked someone before they had a stroke, ‘Would you rather have a stroke or be dead?’ that people would say, ‘I’d rather be dead,’ " she said in an interview. It’s not unreasonable that most people would probably say they would rather be dead than be severely incapacitated for the rest of their lives, she added.

However, after having a stroke, people often report that they are able to continue to live their lives reasonably happily despite often being quite disabled and having lost their independence.

The DESTINY II data show that people who had surgery were quite happy despite any disability, and this was at a similar level to those who were treated conservatively but with higher survival rates, Dr. Roffe noted.

The ethical implications of this could be considerable, she suggested. It shows that people who have living wills or who decide that they do not want treatment in the event of a stroke could live just as happy a life after the event as before. It therefore begs the question of whether patients should be allowed to decide on this aspect of their care, she added.

The German Research Foundation and the German Ministry of Science and Education financially supported the study. Dr. Hacke had no disclosures. Dr. Roffe was not involved in the study and had no relevant conflicts of interest.

AT THE EUROPEAN STROKE CONFERENCE

Major finding: At 1 year, 57% of surgically managed versus 24% of conservatively managed patients were alive (P less than .001).

Data source: DESTINY II, a multicenter, randomized controlled clinical trial of decompressive surgery or conservative intensive care treatment in 112 patients aged 61 years or older with malignant infarction of the middle cerebral artery.

Disclosures: The German Research Foundation and the German Ministry of Science and Education financially supported the study. Dr. Hacke had no disclosures. Dr. Roffe was not involved in the study and had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Improved presurgery impulse control screening needed in Parkinson’s

SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA – Many Parkinson’s disease centers performing deep brain stimulation surgery are not using formal, standardized screening for impulse control disorders in pre- or postsurgical patients, according to a large survey of Parkinson Study Group centers.

Deep brain stimulation surgery is known to increase impulsivity, and standard practice is to identify and treat impulse control disorders in patients before surgery, according to lead author Dr. Nawaz Hack, a junior fellow in movement disorders at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and his colleagues.

"Surgery will improve their motor symptoms, but it may make their impulsivity worse, especially if you don’t screen and appropriately identify it," Dr. Hack said. "But if you catch it early through a standardized screening, you can address it."

The researchers surveyed 48 Parkinson Study Group centers, 97% of which performed deep brain stimulation surgery and 67% of which said they served a population of over 500 patients a year.

The results showed that only 23% of sites employed a formal battery of tests for impulsive and compulsive behavior and that 7% did not report screening for impulse control disorders.

Speaking at a poster session at the international congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders, Dr. Hack said that the majority of sites were employing a more ad-hoc approach to screening for impulse control disorders, using questions that were not necessarily standardized.

The survey found that 80% of responding centers used a neuropsychologist to screen for potential behavioral issues but only 32% used a psychiatrist, suggesting that most are focused on identifying the problem but do not necessarily have the facilities to manage and treat it.

There was also a wide variety of approaches taken to manage impulse control issues in presurgical patients.

Seventy-nine percent of patients with an impulse control disorder were treated with medication reduction, although there were 10 different strategies employed across centers, the survey’s authors reported.

"This is what happens in the centers that understand Parkinson’s disease – these are centers that are knowledgeable – so if we’re deficient there, what’s happening?" Dr. Hack said.

The concern was that patients whose impulsivity becomes exacerbated by surgery were more likely to be lost to follow up because of the potential financial consequences of their behavioral disorder.

"If you’re impulsive before, and you’re not treated or screened, you will be seriously impulsive after, so they’ll leave the operating room, they’ll go home, and they’ll start doing behaviors that are literally destroying their family, their lives, and their finances," Dr. Hack said.

However, he said that identifying patients with impulse control disorders could be difficult because patients were sometimes reluctant to volunteer information on behaviors that might indicate the presence of impulsivity, such as hypersexuality or problem gambling.

Nearly three-quarters of centers (72%) reported observing impulse control disorders among deep brain stimulation surgery patients, and 68% reported it in postoperative patients.

Most centers (79%) did not feel that the choice of brain target, whether subthalamic nucleus or globus pallidus, was influential in behavioral disorders.

Dr. Hack did not declare any financial conflicts of interest with the research.

SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA – Many Parkinson’s disease centers performing deep brain stimulation surgery are not using formal, standardized screening for impulse control disorders in pre- or postsurgical patients, according to a large survey of Parkinson Study Group centers.

Deep brain stimulation surgery is known to increase impulsivity, and standard practice is to identify and treat impulse control disorders in patients before surgery, according to lead author Dr. Nawaz Hack, a junior fellow in movement disorders at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and his colleagues.

"Surgery will improve their motor symptoms, but it may make their impulsivity worse, especially if you don’t screen and appropriately identify it," Dr. Hack said. "But if you catch it early through a standardized screening, you can address it."

The researchers surveyed 48 Parkinson Study Group centers, 97% of which performed deep brain stimulation surgery and 67% of which said they served a population of over 500 patients a year.

The results showed that only 23% of sites employed a formal battery of tests for impulsive and compulsive behavior and that 7% did not report screening for impulse control disorders.

Speaking at a poster session at the international congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders, Dr. Hack said that the majority of sites were employing a more ad-hoc approach to screening for impulse control disorders, using questions that were not necessarily standardized.

The survey found that 80% of responding centers used a neuropsychologist to screen for potential behavioral issues but only 32% used a psychiatrist, suggesting that most are focused on identifying the problem but do not necessarily have the facilities to manage and treat it.

There was also a wide variety of approaches taken to manage impulse control issues in presurgical patients.

Seventy-nine percent of patients with an impulse control disorder were treated with medication reduction, although there were 10 different strategies employed across centers, the survey’s authors reported.

"This is what happens in the centers that understand Parkinson’s disease – these are centers that are knowledgeable – so if we’re deficient there, what’s happening?" Dr. Hack said.

The concern was that patients whose impulsivity becomes exacerbated by surgery were more likely to be lost to follow up because of the potential financial consequences of their behavioral disorder.

"If you’re impulsive before, and you’re not treated or screened, you will be seriously impulsive after, so they’ll leave the operating room, they’ll go home, and they’ll start doing behaviors that are literally destroying their family, their lives, and their finances," Dr. Hack said.

However, he said that identifying patients with impulse control disorders could be difficult because patients were sometimes reluctant to volunteer information on behaviors that might indicate the presence of impulsivity, such as hypersexuality or problem gambling.

Nearly three-quarters of centers (72%) reported observing impulse control disorders among deep brain stimulation surgery patients, and 68% reported it in postoperative patients.

Most centers (79%) did not feel that the choice of brain target, whether subthalamic nucleus or globus pallidus, was influential in behavioral disorders.

Dr. Hack did not declare any financial conflicts of interest with the research.

SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA – Many Parkinson’s disease centers performing deep brain stimulation surgery are not using formal, standardized screening for impulse control disorders in pre- or postsurgical patients, according to a large survey of Parkinson Study Group centers.

Deep brain stimulation surgery is known to increase impulsivity, and standard practice is to identify and treat impulse control disorders in patients before surgery, according to lead author Dr. Nawaz Hack, a junior fellow in movement disorders at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and his colleagues.

"Surgery will improve their motor symptoms, but it may make their impulsivity worse, especially if you don’t screen and appropriately identify it," Dr. Hack said. "But if you catch it early through a standardized screening, you can address it."

The researchers surveyed 48 Parkinson Study Group centers, 97% of which performed deep brain stimulation surgery and 67% of which said they served a population of over 500 patients a year.

The results showed that only 23% of sites employed a formal battery of tests for impulsive and compulsive behavior and that 7% did not report screening for impulse control disorders.

Speaking at a poster session at the international congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders, Dr. Hack said that the majority of sites were employing a more ad-hoc approach to screening for impulse control disorders, using questions that were not necessarily standardized.

The survey found that 80% of responding centers used a neuropsychologist to screen for potential behavioral issues but only 32% used a psychiatrist, suggesting that most are focused on identifying the problem but do not necessarily have the facilities to manage and treat it.

There was also a wide variety of approaches taken to manage impulse control issues in presurgical patients.

Seventy-nine percent of patients with an impulse control disorder were treated with medication reduction, although there were 10 different strategies employed across centers, the survey’s authors reported.

"This is what happens in the centers that understand Parkinson’s disease – these are centers that are knowledgeable – so if we’re deficient there, what’s happening?" Dr. Hack said.

The concern was that patients whose impulsivity becomes exacerbated by surgery were more likely to be lost to follow up because of the potential financial consequences of their behavioral disorder.

"If you’re impulsive before, and you’re not treated or screened, you will be seriously impulsive after, so they’ll leave the operating room, they’ll go home, and they’ll start doing behaviors that are literally destroying their family, their lives, and their finances," Dr. Hack said.

However, he said that identifying patients with impulse control disorders could be difficult because patients were sometimes reluctant to volunteer information on behaviors that might indicate the presence of impulsivity, such as hypersexuality or problem gambling.

Nearly three-quarters of centers (72%) reported observing impulse control disorders among deep brain stimulation surgery patients, and 68% reported it in postoperative patients.

Most centers (79%) did not feel that the choice of brain target, whether subthalamic nucleus or globus pallidus, was influential in behavioral disorders.

Dr. Hack did not declare any financial conflicts of interest with the research.

AT THE 2013 MDS INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS

Major finding: Only 23% of sites employed a formal battery of tests for impulsive and compulsive behavior and 7% did not report screening for impulse control disorders.

Data source: Survey of 48 Parkinson Study Group centers.

Disclosures: Dr. Hack did not declare any financial conflicts of interest.

Concussion recovery takes longer if children have had one before

Children and teenagers take longer to recover from a concussion if they’ve had one before, especially within the past year, Boston Children’s Hospital emergency department physicians found in a study of 280 of their concussed patients published June 10 in Pediatrics.

The median duration of symptoms, assessed by the serial Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire (RPSQ) over a period of 3 months, climbed from 12 days in patients who hadn’t been concussed before to 24 days in those who had. The median symptom duration was 28 days in patients with multiple previous concussions, and 35 days in those who’d been concussed within the previous year, "nearly three times the median duration [for] those who had no previous concussions," according to Dr. Matthew A. Eisenberg and his associates at the hospital (Pediatrics 2013 [doi:10.1542/peds.2013-0432]).

"Similarly, patients with two or more previous concussions had more than double the median symptom duration [of] patients with zero or one previous concussion," they found.

On multivariate analysis, previous concussion, maintaining consciousness, being 13 years or older, and an initial RPSQ of 18 or higher all predicted prolonged recovery. Among all comers, 77% had symptoms at 1 week, 32% at 4 weeks, and 15% at 3 months. The mean age in the trial was 14.3 years (range, 11-22 years).

The findings were statistically significant and have "direct implications on the management of athletes and other at-risk individuals who sustain concussions, supporting the concept that sufficient time to recover from a concussion may improve long-term outcomes," the investigators said.

"However, we did not find an association between physician-advised cognitive or physical rest and duration of symptoms, which may reflect the limitations of our observational study," they added. "A randomized [controlled] trial will likely be necessary to address the utility of this intervention."

Sixty-six percent of the subjects were enrolled the day they were injured; 24.7% were enrolled 1 day later, 7.2% 2 days later, and 1.7% 3 days later. The majority (63.8%) had been injured playing hockey, soccer, football, basketball or some other sport.

The investigators defined concussion broadly to include either altered mental status following blunt head trauma or, within 4 hours of it, any of the following symptoms that were not present before the injury: headache, nausea, vomiting, dizziness/balance problems, fatigue, drowsiness, blurred vision, memory difficulty, or trouble concentrating.

The most common symptoms in the study were headache (85.1%), fatigue (64.7%), and dizziness (63.0%); 4.3% of subjects had altered gait or balance, and 2.4% had altered mental status. There were no abnormalities in the 20.8% of kids who got neuroimaging.

On discharge, 65.9% were prescribed a period of cognitive rest and 92.4% were told to take time off from sports; 63.8% were also told to follow up with their primary care doctor, 45.5% with a sports concussion clinic, and 6.2% with a specialist.

In contrast to prior studies, loss of consciousness seemed to protect against a prolonged recovery (HR, 0.648; P = .02). Maybe the 22% of kids who got knocked out were more likely to follow their doctors’ advice to rest, "thus speeding recovery from their injury. We cannot, however, eliminate the possibility that there is a biological basis to this finding," the team noted.

Subjects who were 13 years or older might have taken longer to recover (HR, 1.404; P = .04) because games "between older children involve more contact and higher-force impacts," although neurobiologic differences between older and younger kids might have played a role, as well, the investigators said.

"Female patients" – about 43% of the study total – "had more severe symptoms at presentation in our study (mean initial RPSQ of 21.3 vs. 17.0 in male patients, P = .02). ... Whether this finding is indicative of the fact that female patients have more severe symptoms from concussion in general, as suggested in several previous studies, or is due to referral bias in which female individuals preferentially present to the ED when symptoms are more severe ... cannot be ascertained from our data," they noted.

Female gender fell out on multivariate analysis as a predictor of prolonged recovery (HR, 1.294; P= 0.11).

The investigators said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

This study is "incredibly interesting. It’s amazing to think that as recently as 5-7 years ago, people were still operating under the advice that 90% of concussion patients get better within a week. You can still find that online every now and then. But clearly, whether they’ve had multiple concussions or not, recovery time is longer for teens and preteens than anyone has expected in the past. This backs up what I see in the clinic," said Dr. Kevin Walter.

So, if kids come to the office a week or 2 after a concussion and say they’re all better, they are "going to be the exception to the rule." More likely, they are not being honest with themselves or are a bit too eager to get back into the game or classroom, he said.

"You don’t want to let the athlete make the decision on their own that they’re better. [Sometimes] ERs [still] send them out saying that ‘if you still feel bad in a week, then go get seen. Otherwise, get back into sport[s],’ " he said.

Follow-up is critical to prevent that from happening. "The gold standard is moving towards multidisciplinary care with physicians and neuropsychologists, with the input of a school athletic trainer. [In my clinic,] the luxury of having a neuropsychologist is wonderful; they’ve got the cognitive function testing" to uncover subtle problems, "and they’ve got more time [to work with patients] and expertise on how to deliver the tests appropriately," Dr. Walter said.

No matter how hard it is for young patients to power down for a bit, "we know without a doubt that kids need some degree of cognitive rest and physical rest from activity and sports" after a concussion. It’s troubling in the study "that only 92% of people who had a concussion were told to refrain from athletics. That should be 100%; that’s the goal we need to shoot for," he said.

For now, it’s unclear if there’s a gap between when kids feel better and when they are truly physiologically recovered, and if they are especially vulnerable to another concussion in between. Also, although it’s been recognized before that kid concussions are different than ones in adults, what exactly that means for treatment is uncertain at this point.

Even so, "for most kids, we need to move a little bit more slowly" than in the past, he said.

Dr. Walter is an associate professor in the departments of orthopedic surgery and pediatrics at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, cofounder of the college’s Sports Concussion Program, and a member of the Institute of Medicine’s Committee on Sports-Related Concussions in Youth. He was lead author of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ clinical report "Sport-Related Concussion in Children and Adolescents."

This study is "incredibly interesting. It’s amazing to think that as recently as 5-7 years ago, people were still operating under the advice that 90% of concussion patients get better within a week. You can still find that online every now and then. But clearly, whether they’ve had multiple concussions or not, recovery time is longer for teens and preteens than anyone has expected in the past. This backs up what I see in the clinic," said Dr. Kevin Walter.

So, if kids come to the office a week or 2 after a concussion and say they’re all better, they are "going to be the exception to the rule." More likely, they are not being honest with themselves or are a bit too eager to get back into the game or classroom, he said.

"You don’t want to let the athlete make the decision on their own that they’re better. [Sometimes] ERs [still] send them out saying that ‘if you still feel bad in a week, then go get seen. Otherwise, get back into sport[s],’ " he said.

Follow-up is critical to prevent that from happening. "The gold standard is moving towards multidisciplinary care with physicians and neuropsychologists, with the input of a school athletic trainer. [In my clinic,] the luxury of having a neuropsychologist is wonderful; they’ve got the cognitive function testing" to uncover subtle problems, "and they’ve got more time [to work with patients] and expertise on how to deliver the tests appropriately," Dr. Walter said.

No matter how hard it is for young patients to power down for a bit, "we know without a doubt that kids need some degree of cognitive rest and physical rest from activity and sports" after a concussion. It’s troubling in the study "that only 92% of people who had a concussion were told to refrain from athletics. That should be 100%; that’s the goal we need to shoot for," he said.

For now, it’s unclear if there’s a gap between when kids feel better and when they are truly physiologically recovered, and if they are especially vulnerable to another concussion in between. Also, although it’s been recognized before that kid concussions are different than ones in adults, what exactly that means for treatment is uncertain at this point.

Even so, "for most kids, we need to move a little bit more slowly" than in the past, he said.

Dr. Walter is an associate professor in the departments of orthopedic surgery and pediatrics at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, cofounder of the college’s Sports Concussion Program, and a member of the Institute of Medicine’s Committee on Sports-Related Concussions in Youth. He was lead author of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ clinical report "Sport-Related Concussion in Children and Adolescents."

This study is "incredibly interesting. It’s amazing to think that as recently as 5-7 years ago, people were still operating under the advice that 90% of concussion patients get better within a week. You can still find that online every now and then. But clearly, whether they’ve had multiple concussions or not, recovery time is longer for teens and preteens than anyone has expected in the past. This backs up what I see in the clinic," said Dr. Kevin Walter.

So, if kids come to the office a week or 2 after a concussion and say they’re all better, they are "going to be the exception to the rule." More likely, they are not being honest with themselves or are a bit too eager to get back into the game or classroom, he said.

"You don’t want to let the athlete make the decision on their own that they’re better. [Sometimes] ERs [still] send them out saying that ‘if you still feel bad in a week, then go get seen. Otherwise, get back into sport[s],’ " he said.

Follow-up is critical to prevent that from happening. "The gold standard is moving towards multidisciplinary care with physicians and neuropsychologists, with the input of a school athletic trainer. [In my clinic,] the luxury of having a neuropsychologist is wonderful; they’ve got the cognitive function testing" to uncover subtle problems, "and they’ve got more time [to work with patients] and expertise on how to deliver the tests appropriately," Dr. Walter said.

No matter how hard it is for young patients to power down for a bit, "we know without a doubt that kids need some degree of cognitive rest and physical rest from activity and sports" after a concussion. It’s troubling in the study "that only 92% of people who had a concussion were told to refrain from athletics. That should be 100%; that’s the goal we need to shoot for," he said.

For now, it’s unclear if there’s a gap between when kids feel better and when they are truly physiologically recovered, and if they are especially vulnerable to another concussion in between. Also, although it’s been recognized before that kid concussions are different than ones in adults, what exactly that means for treatment is uncertain at this point.

Even so, "for most kids, we need to move a little bit more slowly" than in the past, he said.

Dr. Walter is an associate professor in the departments of orthopedic surgery and pediatrics at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, cofounder of the college’s Sports Concussion Program, and a member of the Institute of Medicine’s Committee on Sports-Related Concussions in Youth. He was lead author of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ clinical report "Sport-Related Concussion in Children and Adolescents."

Children and teenagers take longer to recover from a concussion if they’ve had one before, especially within the past year, Boston Children’s Hospital emergency department physicians found in a study of 280 of their concussed patients published June 10 in Pediatrics.

The median duration of symptoms, assessed by the serial Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire (RPSQ) over a period of 3 months, climbed from 12 days in patients who hadn’t been concussed before to 24 days in those who had. The median symptom duration was 28 days in patients with multiple previous concussions, and 35 days in those who’d been concussed within the previous year, "nearly three times the median duration [for] those who had no previous concussions," according to Dr. Matthew A. Eisenberg and his associates at the hospital (Pediatrics 2013 [doi:10.1542/peds.2013-0432]).

"Similarly, patients with two or more previous concussions had more than double the median symptom duration [of] patients with zero or one previous concussion," they found.

On multivariate analysis, previous concussion, maintaining consciousness, being 13 years or older, and an initial RPSQ of 18 or higher all predicted prolonged recovery. Among all comers, 77% had symptoms at 1 week, 32% at 4 weeks, and 15% at 3 months. The mean age in the trial was 14.3 years (range, 11-22 years).

The findings were statistically significant and have "direct implications on the management of athletes and other at-risk individuals who sustain concussions, supporting the concept that sufficient time to recover from a concussion may improve long-term outcomes," the investigators said.

"However, we did not find an association between physician-advised cognitive or physical rest and duration of symptoms, which may reflect the limitations of our observational study," they added. "A randomized [controlled] trial will likely be necessary to address the utility of this intervention."

Sixty-six percent of the subjects were enrolled the day they were injured; 24.7% were enrolled 1 day later, 7.2% 2 days later, and 1.7% 3 days later. The majority (63.8%) had been injured playing hockey, soccer, football, basketball or some other sport.

The investigators defined concussion broadly to include either altered mental status following blunt head trauma or, within 4 hours of it, any of the following symptoms that were not present before the injury: headache, nausea, vomiting, dizziness/balance problems, fatigue, drowsiness, blurred vision, memory difficulty, or trouble concentrating.

The most common symptoms in the study were headache (85.1%), fatigue (64.7%), and dizziness (63.0%); 4.3% of subjects had altered gait or balance, and 2.4% had altered mental status. There were no abnormalities in the 20.8% of kids who got neuroimaging.

On discharge, 65.9% were prescribed a period of cognitive rest and 92.4% were told to take time off from sports; 63.8% were also told to follow up with their primary care doctor, 45.5% with a sports concussion clinic, and 6.2% with a specialist.

In contrast to prior studies, loss of consciousness seemed to protect against a prolonged recovery (HR, 0.648; P = .02). Maybe the 22% of kids who got knocked out were more likely to follow their doctors’ advice to rest, "thus speeding recovery from their injury. We cannot, however, eliminate the possibility that there is a biological basis to this finding," the team noted.

Subjects who were 13 years or older might have taken longer to recover (HR, 1.404; P = .04) because games "between older children involve more contact and higher-force impacts," although neurobiologic differences between older and younger kids might have played a role, as well, the investigators said.

"Female patients" – about 43% of the study total – "had more severe symptoms at presentation in our study (mean initial RPSQ of 21.3 vs. 17.0 in male patients, P = .02). ... Whether this finding is indicative of the fact that female patients have more severe symptoms from concussion in general, as suggested in several previous studies, or is due to referral bias in which female individuals preferentially present to the ED when symptoms are more severe ... cannot be ascertained from our data," they noted.

Female gender fell out on multivariate analysis as a predictor of prolonged recovery (HR, 1.294; P= 0.11).

The investigators said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

Children and teenagers take longer to recover from a concussion if they’ve had one before, especially within the past year, Boston Children’s Hospital emergency department physicians found in a study of 280 of their concussed patients published June 10 in Pediatrics.

The median duration of symptoms, assessed by the serial Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire (RPSQ) over a period of 3 months, climbed from 12 days in patients who hadn’t been concussed before to 24 days in those who had. The median symptom duration was 28 days in patients with multiple previous concussions, and 35 days in those who’d been concussed within the previous year, "nearly three times the median duration [for] those who had no previous concussions," according to Dr. Matthew A. Eisenberg and his associates at the hospital (Pediatrics 2013 [doi:10.1542/peds.2013-0432]).

"Similarly, patients with two or more previous concussions had more than double the median symptom duration [of] patients with zero or one previous concussion," they found.

On multivariate analysis, previous concussion, maintaining consciousness, being 13 years or older, and an initial RPSQ of 18 or higher all predicted prolonged recovery. Among all comers, 77% had symptoms at 1 week, 32% at 4 weeks, and 15% at 3 months. The mean age in the trial was 14.3 years (range, 11-22 years).

The findings were statistically significant and have "direct implications on the management of athletes and other at-risk individuals who sustain concussions, supporting the concept that sufficient time to recover from a concussion may improve long-term outcomes," the investigators said.

"However, we did not find an association between physician-advised cognitive or physical rest and duration of symptoms, which may reflect the limitations of our observational study," they added. "A randomized [controlled] trial will likely be necessary to address the utility of this intervention."

Sixty-six percent of the subjects were enrolled the day they were injured; 24.7% were enrolled 1 day later, 7.2% 2 days later, and 1.7% 3 days later. The majority (63.8%) had been injured playing hockey, soccer, football, basketball or some other sport.

The investigators defined concussion broadly to include either altered mental status following blunt head trauma or, within 4 hours of it, any of the following symptoms that were not present before the injury: headache, nausea, vomiting, dizziness/balance problems, fatigue, drowsiness, blurred vision, memory difficulty, or trouble concentrating.

The most common symptoms in the study were headache (85.1%), fatigue (64.7%), and dizziness (63.0%); 4.3% of subjects had altered gait or balance, and 2.4% had altered mental status. There were no abnormalities in the 20.8% of kids who got neuroimaging.

On discharge, 65.9% were prescribed a period of cognitive rest and 92.4% were told to take time off from sports; 63.8% were also told to follow up with their primary care doctor, 45.5% with a sports concussion clinic, and 6.2% with a specialist.

In contrast to prior studies, loss of consciousness seemed to protect against a prolonged recovery (HR, 0.648; P = .02). Maybe the 22% of kids who got knocked out were more likely to follow their doctors’ advice to rest, "thus speeding recovery from their injury. We cannot, however, eliminate the possibility that there is a biological basis to this finding," the team noted.

Subjects who were 13 years or older might have taken longer to recover (HR, 1.404; P = .04) because games "between older children involve more contact and higher-force impacts," although neurobiologic differences between older and younger kids might have played a role, as well, the investigators said.

"Female patients" – about 43% of the study total – "had more severe symptoms at presentation in our study (mean initial RPSQ of 21.3 vs. 17.0 in male patients, P = .02). ... Whether this finding is indicative of the fact that female patients have more severe symptoms from concussion in general, as suggested in several previous studies, or is due to referral bias in which female individuals preferentially present to the ED when symptoms are more severe ... cannot be ascertained from our data," they noted.

Female gender fell out on multivariate analysis as a predictor of prolonged recovery (HR, 1.294; P= 0.11).

The investigators said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Major finding: The median duration of concussion symptoms was 12 days in children and teens who hadn’t been concussed before, 24 days in those who had, and 35 days in those who had been concussed within the previous year.

Data source: A prospective cohort study of 280 concussed patients aged 11-22 years.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Boston Children’s Hospital, where it was conducted. The investigators said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

Getting back in the game

"When can I go back to play, doc?" is a question you’ll hear often when treating athletes with concussions. For many of them, the answer would be in 7-10 days, but for more moderate or severe cases, that could go up to a month or more. It all depends on the athlete and his or her concussion history. However, there are some general guidelines to follow to determine when an athlete is ready to get back on the field.

First of all, athletes should not be allowed to return to play in the current game or practice in which they were injured. From there, they should be medically managed and given adequate physical and cognitive rest until they are asymptomatic.

This means that all symptoms have resolved, the neurologic examination is normal and their cognitive function has returned to baseline, if this was established prior to injury. They also should not be on any medications for concussion, that is, they should not be popping acetaminophen for headaches.

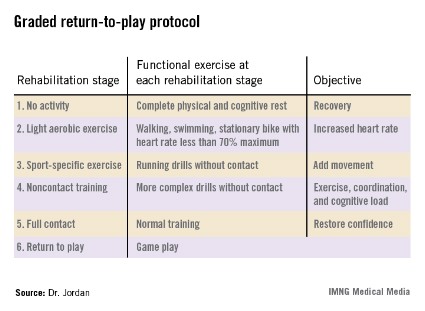

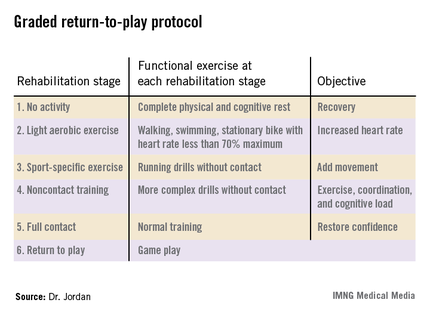

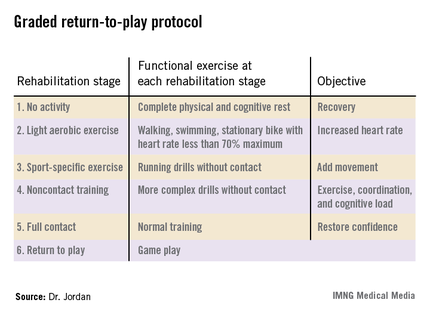

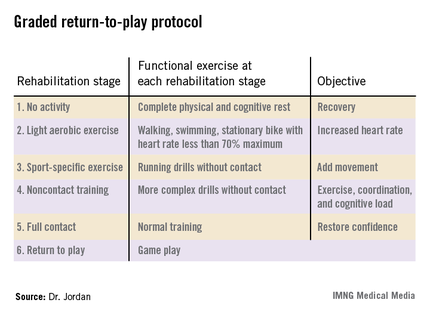

Another way to determine if the athlete is ready to get back in the game is by using the graded return-to-play protocol.

Typically, athletes move up the stages one level a day, although that is not necessary. You can certainly accelerate the process depending on the sport and the athlete. Those who are in noncontact sports like swimming can probably go through the levels quicker than someone who plays soccer.

I would suggest documenting how the athlete is doing throughout the process so everyone has a record of the athlete’s progress. I don’t think you can ever overdocument, and it’s a good habit to get into.

Along with the protocol, there’s also a computerized neuropsychological testing tool that’s fairly short and really focuses on what functions are affected. People tend to rely on this tool but you have to keep in mind that this is only one tool and should not be used alone.

Tools cannot replace a thorough cognitive evaluation. Just as there are no tests that can diagnose a concussion, there’s no tool that’ll say the athlete is ok to return to play. Ultimately, it is up to you to make that call, but the evaluation tools should certainly be used to help.

Dr. Barry Jordan is the director of the brain injury program and the memory evaluation treatment service at Burke Rehabilitation Hospital in White Plains, N.Y. He currently serves as the chief medical officer of the New York State Athletic Commission, a team physician for U.S.A. Boxing, and as a member of the NFL Players Association Mackey-White Traumatic Brain Injury Committee and the NFL Neuro-Cognitive Disability Committee.