User login

How ovarian reserve testing can (and cannot) address your patients’ fertility concerns

CASE Your patient wants ovarian reserve testing. Is her request reasonable?

A 34-year-old woman, recently married, plans to delay attempting pregnancy for a few years. She requests ovarian reserve testing to inform this timeline.

This is not an unreasonable inquiry, given her age (<35 years), after which there is natural acceleration in the rate of decline in the quality of oocytes. Regardless of the results of testing, attempting pregnancy or pursuing fertility preservation as soon as possible (particularly in patients >35 years) is associated with better outcomes.

A woman is born with all the eggs she will ever have. Oocyte atresia occurs throughout a woman’s lifetime, from 1,000,000 eggs at birth to only 1,000 by the time of menopause.1 A woman’s ovarian reserve reflects the number of oocytes present in the ovaries and is the result of complex interactions of age, genetics, and environmental variables.

Ovarian reserve testing, however, only has been consistently shown to predict ovarian response to stimulation with gonadotropins; these tests might reflect in vitro fertilization (IVF) birth outcomes to a lesser degree, but have not been shown to predict natural fecundability.2,3 Essentially, ovarian reserve testing provides a partial view of reproductive potential.

Ovarian reserve testing also does not reflect an age-related decline in oocyte quality, particularly after age 35.4,5 As such, female age is the principal driver of fertility potential, regardless of oocyte number. A woman with abnormal ovarian reserve tests may benefit from referral to a fertility specialist for counseling that integrates her results, age, and medical history, with the caveat that abnormal results do not necessarily mean she needs assisted reproductive technology (ART) to conceive.

In this article, we review 6 common questions about the ovarian reserve, providing current data to support the answers.

Continue to: #1 What tests are part of an ovarian reserve assessment?

#1 What tests are part of an ovarian reserve assessment? What is their utility?

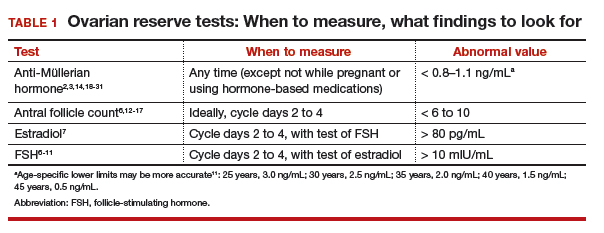

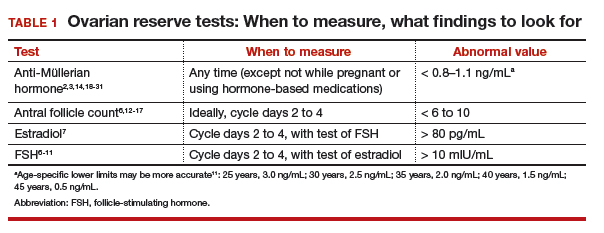

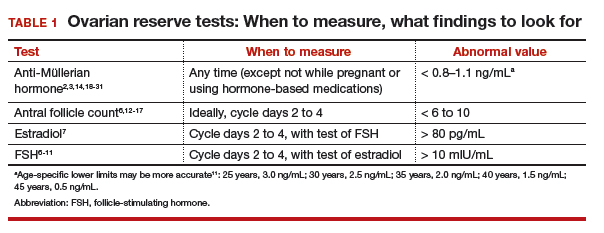

FSH and estradiol

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and estradiol should be checked together in the early follicular phase (days 2 to 4 of the cycle). Elevated levels of one or both hormones suggest diminished ovarian reserve; an FSH level greater than 10 mIU/mL and/or an estradiol level greater than 80 pg/mL represent abnormal results6 (TABLE 1). Because FSH demonstrates significant intercycle variability, a single abnormal result should be confirmed in a subsequent cycle.7

Although the basal FSH level does not reflect egg quality or predict natural fecundity, an elevated FSH level predicts poor ovarian response (<3 or 4 eggs retrieved) to ovarian hyperstimulation, with good specificity.3,6,8,9 In patients younger than age 35 years undergoing IVF, basal FSH levels do not predict live birth or pregnancy loss.10 In older patients undergoing IVF, however, an elevated FSH level is associated with a reduced live birth rate (a 5% reduction in women <40 years to a 26% reduction in women >42 years) and a higher miscarriage rate, reflecting the positive correlation of oocyte aneuploidy and age.

In addition to high intercycle variability, an FSH level is reliable only in the setting of normal hypothalamic and pituitary function.7 Conditions such a prolactinoma (or other causes of hyperprolactinemia), other intracranial masses, prior central radiation, hormone-based medication use, and inadequate energy reserve (as the result of anorexia nervosa, resulting in hypothalamic suppression), might result in a low or inappropriately normal FSH level that does not reflect ovarian function.11

Antral follicle count

Antral follicle count (AFC) is defined as the total number of follicles measuring 2 to 10 mm, in both ovaries, in the early follicular phase (days 2 to 4 of the cycle). A count of fewer than 6 to 10 antral follicles in total is considered consistent with diminished ovarian reserve6,12,13 (TABLE 1). Antral follicle count is not predictive of natural fecundity but, rather, projects ovarian response during IVF. Antral follicle count has been shown to decrease by 5% a year with increasing age among women with or without infertility.14

Studies have highlighted concerns regarding interobserver and intraobserver variability in determining the AFC but, in experienced hands, the AFC is a reliable test of ovarian reserve.15,16 Visualization of antral follicles can be compromised in obese patients.11 Conversely, AFC sometimes also overestimates ovarian reserve, because atretic follicles might be included in the count.11,15 Last, AFC is reduced in patients who take a hormone-based medication but recovers with cessation of the medication.17 Ideally, a woman should stop all hormone-based medications for 2 or 3 months (≥2 or 3 spontaneous cycles) before AFC is measured.

Continue to: Anti-Müllerian hormone

Anti-Müllerian hormone

A transforming growth factor β superfamily peptide produced by preantral and early antral follicles of the ovary, anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) is a direct and quantitative marker of ovarian reserve.18 AMH is detectable at birth; the level rises slowly until puberty, reaching a peak at approximately 16 years of age,19 then remains relatively stable until 25 years, after which AMH and age are inversely correlated, reflecting ongoing oocyte atresia. AMH declines roughly 5% a year with increasing age.14

A low level of AMH (<1 ng/mL) suggests diminished ovarian reserve20,21 (TABLE 1). AMH has been consistently validated only for predicting ovarian response during IVF.2,20 To a lesser extent, AMH might reflect the likelihood of pregnancy following ART, although studies are inconsistent on this point.22 AMH is not predictive of natural fecundity or time to spontaneous conception.3,23 Among 700 women younger than age 40, AMH levels were not significantly different among those with or without infertility, and a similar percentage of women in both groups had what was characterized as a “very low” AMH level (<0.7 ng/mL).14

At the other extreme, a high AMH value (>3.5 ng/mL) predicts a hyper-response to ovarian stimulation with gonadotropins and elevated risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. In conjunction with clinical and other laboratory findings, an elevated level of AMH also can suggest polycystic ovary syndrome. No AMH cutoff for a diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome exists, although a level of greater than 5 to 7.8 ng/mL has been proposed as a point of delineation.24,25

Unlike FSH and AFC, AMH is generally considered to be a valid marker of ovarian reserve throughout the menstrual cycle. AMH levels are higher in the follicular phase of the cycle and lower in the midluteal phase, but the differences are minor and seldom alter the patient’s overall prognosis.26-29 As with FSH and AFC, levels of AMH are significantly lower in patients who are pregnant or taking hormone-based medications: Hormonal contraception lowers AMH level by 30% to 50%.17,30,31 Ideally, patients should stop all hormone-based medications for 2 or 3 months (≥2 or 3 spontaneous cycles) before testing ovarian reserve.

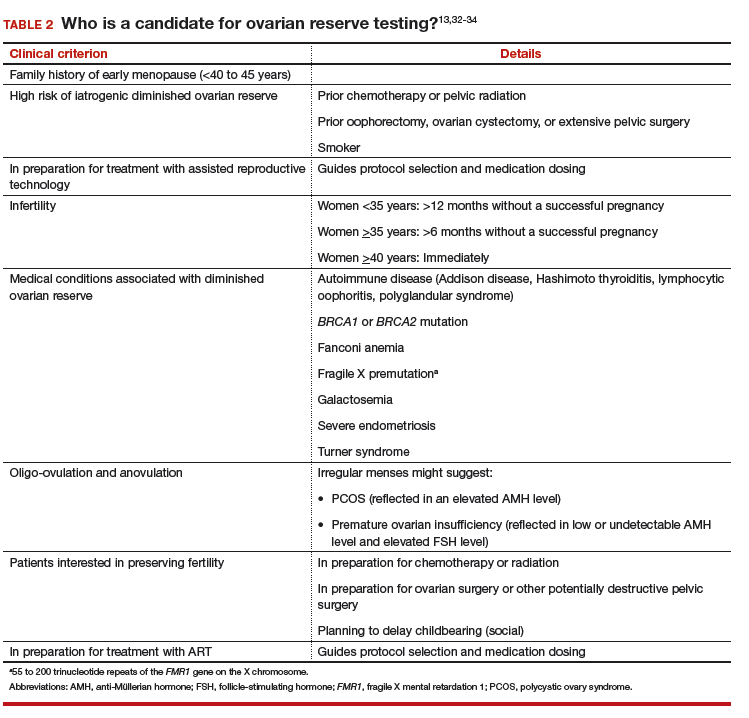

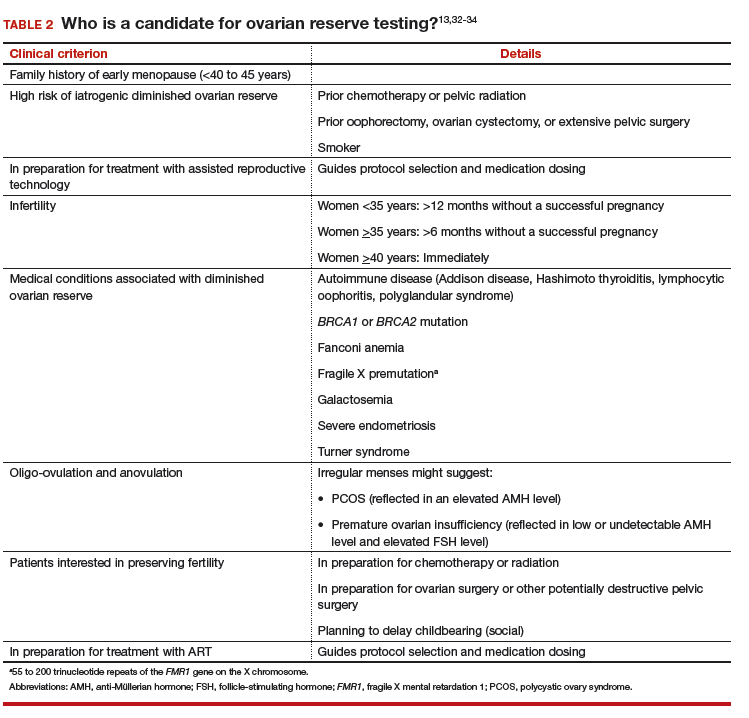

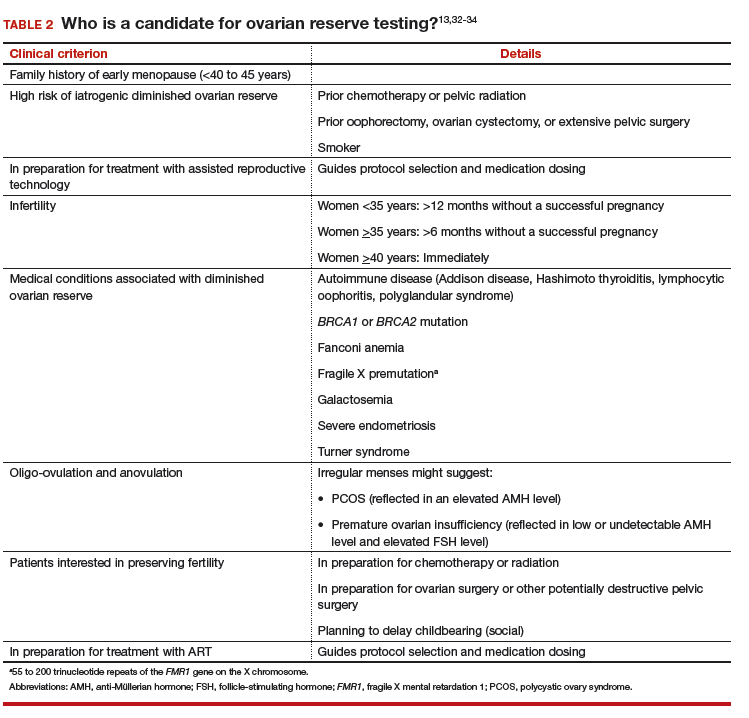

#2 Who should have ovarian reserve testing?

The clinical criteria and specific indications for proceeding with ovarian reserve testing are summarized in TABLE 2.13,32-34 Such testing is not indicated in women who are planning to attempt pregnancy but who do not have risk factors for diminished ovarian reserve. These tests cannot predict their success at becoming pregnant; age is a far more appropriate predictor of pregnancy and risk of miscarriage.3 At most, an abnormal result in a patient who meets one of the clinical criteria for testing could prompt earlier referral to a reproductive specialist for consultation—after it is explained to her that abnormal ovarian reserve tests do not, alone, mean that ART is required.

Continue to: #3 Can I reassure my patient about her reproductive potential using these tests?

#3 Can I reassure my patient about her reproductive potential using these tests?

Normal findings on ovarian reserve testing suggests that a woman might have a normal (that is, commensurate with age-matched peers) number of eggs in her ovaries. But normal test results do not mean she will have an easy time conceiving. Similarly, abnormal results do not mean that she will have difficulty conceiving.

Ovarian reserve testing reflects only the number of oocytes, not their quality, which is primarily determined by maternal age.35 Genetic testing of embryos during IVF shows that the percentage of embryos that are aneuploid (usually resulting from abnormal eggs) rises with advancing maternal age, beginning at 35 years.5 The increasing rate of oocyte aneuploidy is also reflected in the rising rate of loss of clinically recognized pregnancies with advancing maternal age: from 11% in women younger than age 34 to greater than 36% in women older than age 42.4

Furthermore, ovarian reserve testing does not reflect other potential genetic barriers to reproduction, such as a chromosomal translocation that can result in recurrent pregnancy loss. Fallopian tube obstruction and uterine issues, such as fibroids or septa, and male factors are also not reflected in ovarian reserve testing.

#4 My patient is trying to get pregnant and has abnormal ovarian reserve testing results. Will she need IVF?"

Not necessarily. Consultation with a fertility specialist to discuss the nuances of abnormal test results and management options is ideal but, essentially, as the American Society for Reproductive Medicine states, “evidence of [diminished ovarian reserve] does not necessarily equate with inability to conceive.” Furthermore, the Society states, “there is insufficient evidence to recommend that any ovarian reserve test now available should be used as a sole criterion for the use of ART.”

Once counseled, patients might elect to pursue more aggressive treatment, but they might not necessarily need it. Age must figure significantly into treatment decisions, because oocyte quality—regardless of number—begins to decline at 35 years of age, with an associated increasing risk of infertility and miscarriage.

In a recently published study of 750 women attempting pregnancy, women with a low AMH level (<0.7 ng/mL) or high FSH level (>10 mIU/mL), or both, did not have a significantly lower likelihood of achieving spontaneous pregnancy within 1 year, compared with women with normal results of ovarian reserve testing.3

Continue to: #5 My patient is not ready to be pregnant

#5 My patient is not ready to be pregnant. If her results are abnormal, should she freeze eggs?

For patients who might be interested in seeking fertility preservation and ART, earlier referral to a reproductive specialist to discuss risks and benefits of oocyte or embryo cryopreservation is always preferable. The younger a woman is when she undergoes fertility preservation, the better. Among patients planning to delay conception, each one’s decision is driven by her personal calculations of the cost, risk, and benefit of egg or embryo freezing—a picture of which ovarian reserve testing is only one piece.

#6 Can these tests predict menopause?

Menopause is a clinical diagnosis, defined as 12 months without menses (without hormone use or other causes of amenorrhea). In such women, FSH levels are elevated, but biochemical tests are not part of the menopause diagnosis.36 In the years leading to menopause, FSH levels are highly variable and unreliable in predicting time to menopause.

AMH has been shown to correlate with time to menopause. (Once the AMH level becomes undetectable, menopause occurs in a mean of 6 years.37,38) Patients do not typically have serial AMH measurements, however, so it is not usually known when the hormone became undetectable. Therefore, AMH is not a useful test for predicting time to menopause.

Premature ovarian insufficiency (loss of ovarian function in women younger than age 40), should be considered in women with secondary amenorrhea of 4 months or longer. The diagnosis requires confirmatory laboratory assessment,36 and findings include an FSH level greater than 25 mIU/mL on 2 tests performed at least 1 month apart.39,40

Ovarian reserve tests: A partial view of reproductive potential

The answers we have provided highlight several key concepts and conclusions that should guide clinical practice and decisions made by patients:

- Ovarian reserve tests best serve to predict ovarian response during IVF; to a far lesser extent, they might predict birth outcomes from IVF. These tests have not, however, been shown to predict spontaneous pregnancy.

- Ovarian reserve tests should be administered purposefully, with counseling beforehand regarding their limitations.

- Abnormal ovarian reserve test results do not necessitate ART; however, they may prompt a patient to accelerate her reproductive timeline and consult with a reproductive endocrinologist to consider her age and health-related risks of infertility or pregnancy loss.

- Patients should be counseled that, regardless of the results of ovarian reserve testing, attempting conception or pursuing fertility preservation at a younger age (in particular, at <35 years of age) is associated with better outcomes.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Forman MR, Mangini LD, Thelus-Jean R, Hayward MD. Life-course origins of the ages at menarche and menopause. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2013;4:1-21.

- Reichman DE, Goldschlag D, Rosenwaks Z. Value of antimüllerian hormone as a prognostic indicator of in vitro fertilization outcome. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(4):1012-1018.e1.

- Steiner AZ, Pritchard D, Stanczyk FZ, Kesner JS, Meadows JW, Herring AH, et al. Association between biomarkers of ovarian reserve and infertility among older women of reproductive age. JAMA. 2017;318(14):1367-1376.

- Farr SL, Schieve LA, Jamieson DJ. Pregnancy loss among pregnancies conceived through assisted reproductive technology, United States, 1999-2002. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(12):1380-1388.

- Franasiak JM, Forman EJ, Hong KH, Werner MD, Upham KM, Treff NR, et al. The nature of aneuploidy with increasing age of the female partner: a review of 1,169 consecutive trophectoderm biopsies evaluated with comprehensive chromosomal screening. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(3):656-663.e1.

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Testing and interpreting measures of ovarian reserve: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(3):e9-e17.

- Kwee J, Schats R, McDonnell J, Lambalk CB, Schoemaker J. Intercycle variability of ovarian reserve tests: results of a prospective randomized study. Hum Reprod. 2004;19(3):590-595.

- Thum MY, Abdalla HI, Taylor D. Relationship between women’s age and basal follicle-stimulating hormone levels with aneuploidy risk in in vitro fertilization treatment. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(2):315-321.

- Roberts JE, Spandorfer S, Fasouliotis SJ, Kashyap S, Rosenwaks Z. Taking a basal follicle-stimulating hormone history is essential before initiating in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2005;83(1):37-41.

- Bishop LA, Richter KS, Patounakis G, Andriani L, Moon K, Devine K. Diminished ovarian reserve as measured by means of baseline follicle-stimulating hormone and antral follicle count is not associated with pregnancy loss in younger in vitro fertilization patients. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(6):980-987.

- Tal R, Seifer DB. Ovarian reserve testing: a user’s guide. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(2):129-140.

- Ferraretti AP, La Marca L, Fauser BC, Tarlatzis B, Nargund G, Gianaroli L; ESHRE working group on Poor Ovarian Response Definition. ESHRE consensus on the definition of ‘poor response’ to ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization: the Bologna criteria. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(7):1616-1624.

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Diagnostic evaluation of the infertile female: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(6):e44-e50.

- Hvidman HW, Bentzen JG, Thuesen LL, Lauritsen MP, Forman JL, Loft A, et al. Infertile women below the age of 40 have similar anti-Müllerian hormone levels and antral follicle count compared with women of the same age with no history of infertility. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(5):1034-1045.

- Broekmans FJ, Kwee J, Hendriks DJ, Mol BW, Lambalk CB. A systematic review of tests predicting ovarian reserve and IVF outcome. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12(6):685-718.

- Iliodromiti S, Anderson RA, Nelson SM. Technical and performance characteristics of anti-Mullerian hormone and antral follicle count as biomarkers of ovarian response. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21(6):698-710.

- Bentzen JG, Forman JL, Pinborg A, Lidegaard Ø, Larsen EC, Friis-Hansen L, et al. Ovarian reserve parameters: a comparison between users and non-users of hormonal contraception. Reprod Biomed Online. 2012;25(6):612-619.

- Broer SL, Broekmans FJ, Laven JS, Fauser BC. Anti-Müllerian hormone: ovarian reserve testing and its potential clinical implications. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(5):688-701.

- Lie Fong S, Visser JA, Welt CK, de Rijke YB, Eijkemans MJ, Broekmans FJ, et al. Serum anti-müllerian hormone levels in healthy females: a nomogram ranging from infancy to adulthood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(12):4650-4655.

- Hamdine O, Eijkemans MJ, Lentjes EW, Torrance HL, Macklon NS, Fauser BC, et al. Ovarian response prediction in GnRH antagonist treatment for IVF using anti-Müllerian hormone. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(1):170-178.

- Jayaprakasan K, Campbell B, Hopkisson J, Johnson I, Raine-Fenning N. A prospective, comparative analysis of anti-Mullerian hormone, inhibin-B, and three-dimensional ultrasound determinants of ovarian reserve in the prediction of poor response to controlled ovarian stimulation. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(3):855-864.

- Silberstein T, MacLaughlin DT, Shai I, Trimarchi JR, Lambert-Messerlian G, Seifer DB, et al. Mullerian inhibiting substance levels at the time of HCG administration in IVF cycles predict both ovarian reserve and embryo morphology. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(1):159-163.

- Korsholm AS, Petersen KB, Bentzen JG, Hilsted LM, Andersen AN, Hvidman HW. Investigation of anti-Müllerian hormone concentrations in relation to natural conception rate and time to pregnancy. Reprod Biomed Online. 2018;36(5):568-575.

- Quinn MM, Kao CN, Ahmad AK, Haisenleder DJ, Santoro N, Eisenberg E, et al. Age-stratified thresholds of anti-Müllerian hormone improve prediction of polycystic ovary syndrome over a population-based threshold. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf).

- Dewailly D, Gronier H, Poncelet E, Robin G, Leroy M, Pigny P, et al. Diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): revisiting the threshold values of follicle count on ultrasound and of the serum AMH level for the definition of polycystic ovaries. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(11):3123-129.

- Schiffner J, Roos J, Broomhead D, Helden JV, Godehardt E, Fehr D, et al. Relationship between anti-Müllerian hormone and antral follicle count across the menstrual cycle using the Beckman Coulter Access assay in comparison with Gen II manual assay. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2017;55(7):1025-1033.

- Gracia CR, Shin SS, Prewitt M, Chamberlin JS, Lofaro LR, Jones KL, et al. Multi-center clinical evaluation of the Access AMH assay to determine AMH levels in reproductive age women during normal menstrual cycles. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;35(5):777-783.

- Dewailly D, Andersen CY, Balen A, Broekmans F, Dilaver N, Fanchin R, et al. The physiology and clinical utility of anti-Mullerian hormone in women. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(3):370-385.

- Kissell KA, Danaher MR, Schisterman EF, Wactawski-Wende J, Ahrens KA, Schliep K, et al. Biological variability in serum anti-Müllerian hormone throughout the menstrual cycle in ovulatory and sporadic anovulatory cycles in eumenorrheic women. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(8):1764-1772.

- Dólleman M, Verschuren WM, Eijkemans MJ, Dollé ME, Jansen EH, Broekmans FJ, et al. Reproductive and lifestyle determinants of anti-Müllerian hormone in a large population-based study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(5):2106-2115.

- Kallio S, Puurunen J, Ruokonen A, Vaskivuo T, Piltonen T, Tapanainen JS. Antimüllerian hormone levels decrease in women using combined contraception independently of administration route. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(5):1305-1310.

- Kim CW, Shim HS, Jang H, Song YG. The effects of uterine artery embolization on ovarian reserve. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016 ;206:172-176.

- Lin W, Titus S, Moy F, Ginsburg ES, Oktay K. Ovarian aging in women with BRCA germline mutations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(10):3839-3847.

- Nelson LM. Clinical practice. Primary ovarian insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(6):606-614.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice and Practice Committee. Female age-related fertility decline. Committee Opinion No. 589. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(3):633-634.

- National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health (UK). Menopause: Full Guideline. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK); 2015 Nov 12. (NICE Guideline, No. 23). Premature ovarian insufficiency. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK343476/.

- Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Gracia CR. Anti-mullerian hormone as a predictor of time to menopause in late reproductive age women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(5):1673-1680.

- van Rooij IA, den Tonkelaar I, Broekmans FJ, Looman CW, Scheffer GJ, de Jong FH, et al. Anti-müllerian hormone is a promising predictor for the occurrence of the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2004;11(6 Pt 1):601-606.

- European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) Guideline Group on POI, Webber L, Davies M, Anderson R, Bartlett J, Braat D, et al. ESHRE Guideline: management of women with premature ovarian insufficiency. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(5):926-937.

- Committee opinion no. 605: primary ovarian insufficiency in adolescents and young women. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(1):193-197.

CASE Your patient wants ovarian reserve testing. Is her request reasonable?

A 34-year-old woman, recently married, plans to delay attempting pregnancy for a few years. She requests ovarian reserve testing to inform this timeline.

This is not an unreasonable inquiry, given her age (<35 years), after which there is natural acceleration in the rate of decline in the quality of oocytes. Regardless of the results of testing, attempting pregnancy or pursuing fertility preservation as soon as possible (particularly in patients >35 years) is associated with better outcomes.

A woman is born with all the eggs she will ever have. Oocyte atresia occurs throughout a woman’s lifetime, from 1,000,000 eggs at birth to only 1,000 by the time of menopause.1 A woman’s ovarian reserve reflects the number of oocytes present in the ovaries and is the result of complex interactions of age, genetics, and environmental variables.

Ovarian reserve testing, however, only has been consistently shown to predict ovarian response to stimulation with gonadotropins; these tests might reflect in vitro fertilization (IVF) birth outcomes to a lesser degree, but have not been shown to predict natural fecundability.2,3 Essentially, ovarian reserve testing provides a partial view of reproductive potential.

Ovarian reserve testing also does not reflect an age-related decline in oocyte quality, particularly after age 35.4,5 As such, female age is the principal driver of fertility potential, regardless of oocyte number. A woman with abnormal ovarian reserve tests may benefit from referral to a fertility specialist for counseling that integrates her results, age, and medical history, with the caveat that abnormal results do not necessarily mean she needs assisted reproductive technology (ART) to conceive.

In this article, we review 6 common questions about the ovarian reserve, providing current data to support the answers.

Continue to: #1 What tests are part of an ovarian reserve assessment?

#1 What tests are part of an ovarian reserve assessment? What is their utility?

FSH and estradiol

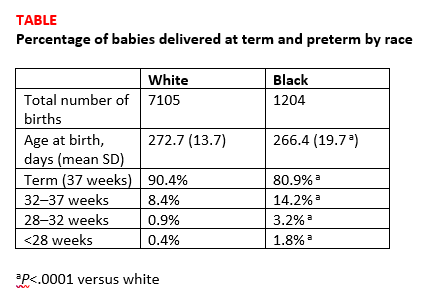

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and estradiol should be checked together in the early follicular phase (days 2 to 4 of the cycle). Elevated levels of one or both hormones suggest diminished ovarian reserve; an FSH level greater than 10 mIU/mL and/or an estradiol level greater than 80 pg/mL represent abnormal results6 (TABLE 1). Because FSH demonstrates significant intercycle variability, a single abnormal result should be confirmed in a subsequent cycle.7

Although the basal FSH level does not reflect egg quality or predict natural fecundity, an elevated FSH level predicts poor ovarian response (<3 or 4 eggs retrieved) to ovarian hyperstimulation, with good specificity.3,6,8,9 In patients younger than age 35 years undergoing IVF, basal FSH levels do not predict live birth or pregnancy loss.10 In older patients undergoing IVF, however, an elevated FSH level is associated with a reduced live birth rate (a 5% reduction in women <40 years to a 26% reduction in women >42 years) and a higher miscarriage rate, reflecting the positive correlation of oocyte aneuploidy and age.

In addition to high intercycle variability, an FSH level is reliable only in the setting of normal hypothalamic and pituitary function.7 Conditions such a prolactinoma (or other causes of hyperprolactinemia), other intracranial masses, prior central radiation, hormone-based medication use, and inadequate energy reserve (as the result of anorexia nervosa, resulting in hypothalamic suppression), might result in a low or inappropriately normal FSH level that does not reflect ovarian function.11

Antral follicle count

Antral follicle count (AFC) is defined as the total number of follicles measuring 2 to 10 mm, in both ovaries, in the early follicular phase (days 2 to 4 of the cycle). A count of fewer than 6 to 10 antral follicles in total is considered consistent with diminished ovarian reserve6,12,13 (TABLE 1). Antral follicle count is not predictive of natural fecundity but, rather, projects ovarian response during IVF. Antral follicle count has been shown to decrease by 5% a year with increasing age among women with or without infertility.14

Studies have highlighted concerns regarding interobserver and intraobserver variability in determining the AFC but, in experienced hands, the AFC is a reliable test of ovarian reserve.15,16 Visualization of antral follicles can be compromised in obese patients.11 Conversely, AFC sometimes also overestimates ovarian reserve, because atretic follicles might be included in the count.11,15 Last, AFC is reduced in patients who take a hormone-based medication but recovers with cessation of the medication.17 Ideally, a woman should stop all hormone-based medications for 2 or 3 months (≥2 or 3 spontaneous cycles) before AFC is measured.

Continue to: Anti-Müllerian hormone

Anti-Müllerian hormone

A transforming growth factor β superfamily peptide produced by preantral and early antral follicles of the ovary, anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) is a direct and quantitative marker of ovarian reserve.18 AMH is detectable at birth; the level rises slowly until puberty, reaching a peak at approximately 16 years of age,19 then remains relatively stable until 25 years, after which AMH and age are inversely correlated, reflecting ongoing oocyte atresia. AMH declines roughly 5% a year with increasing age.14

A low level of AMH (<1 ng/mL) suggests diminished ovarian reserve20,21 (TABLE 1). AMH has been consistently validated only for predicting ovarian response during IVF.2,20 To a lesser extent, AMH might reflect the likelihood of pregnancy following ART, although studies are inconsistent on this point.22 AMH is not predictive of natural fecundity or time to spontaneous conception.3,23 Among 700 women younger than age 40, AMH levels were not significantly different among those with or without infertility, and a similar percentage of women in both groups had what was characterized as a “very low” AMH level (<0.7 ng/mL).14

At the other extreme, a high AMH value (>3.5 ng/mL) predicts a hyper-response to ovarian stimulation with gonadotropins and elevated risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. In conjunction with clinical and other laboratory findings, an elevated level of AMH also can suggest polycystic ovary syndrome. No AMH cutoff for a diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome exists, although a level of greater than 5 to 7.8 ng/mL has been proposed as a point of delineation.24,25

Unlike FSH and AFC, AMH is generally considered to be a valid marker of ovarian reserve throughout the menstrual cycle. AMH levels are higher in the follicular phase of the cycle and lower in the midluteal phase, but the differences are minor and seldom alter the patient’s overall prognosis.26-29 As with FSH and AFC, levels of AMH are significantly lower in patients who are pregnant or taking hormone-based medications: Hormonal contraception lowers AMH level by 30% to 50%.17,30,31 Ideally, patients should stop all hormone-based medications for 2 or 3 months (≥2 or 3 spontaneous cycles) before testing ovarian reserve.

#2 Who should have ovarian reserve testing?

The clinical criteria and specific indications for proceeding with ovarian reserve testing are summarized in TABLE 2.13,32-34 Such testing is not indicated in women who are planning to attempt pregnancy but who do not have risk factors for diminished ovarian reserve. These tests cannot predict their success at becoming pregnant; age is a far more appropriate predictor of pregnancy and risk of miscarriage.3 At most, an abnormal result in a patient who meets one of the clinical criteria for testing could prompt earlier referral to a reproductive specialist for consultation—after it is explained to her that abnormal ovarian reserve tests do not, alone, mean that ART is required.

Continue to: #3 Can I reassure my patient about her reproductive potential using these tests?

#3 Can I reassure my patient about her reproductive potential using these tests?

Normal findings on ovarian reserve testing suggests that a woman might have a normal (that is, commensurate with age-matched peers) number of eggs in her ovaries. But normal test results do not mean she will have an easy time conceiving. Similarly, abnormal results do not mean that she will have difficulty conceiving.

Ovarian reserve testing reflects only the number of oocytes, not their quality, which is primarily determined by maternal age.35 Genetic testing of embryos during IVF shows that the percentage of embryos that are aneuploid (usually resulting from abnormal eggs) rises with advancing maternal age, beginning at 35 years.5 The increasing rate of oocyte aneuploidy is also reflected in the rising rate of loss of clinically recognized pregnancies with advancing maternal age: from 11% in women younger than age 34 to greater than 36% in women older than age 42.4

Furthermore, ovarian reserve testing does not reflect other potential genetic barriers to reproduction, such as a chromosomal translocation that can result in recurrent pregnancy loss. Fallopian tube obstruction and uterine issues, such as fibroids or septa, and male factors are also not reflected in ovarian reserve testing.

#4 My patient is trying to get pregnant and has abnormal ovarian reserve testing results. Will she need IVF?"

Not necessarily. Consultation with a fertility specialist to discuss the nuances of abnormal test results and management options is ideal but, essentially, as the American Society for Reproductive Medicine states, “evidence of [diminished ovarian reserve] does not necessarily equate with inability to conceive.” Furthermore, the Society states, “there is insufficient evidence to recommend that any ovarian reserve test now available should be used as a sole criterion for the use of ART.”

Once counseled, patients might elect to pursue more aggressive treatment, but they might not necessarily need it. Age must figure significantly into treatment decisions, because oocyte quality—regardless of number—begins to decline at 35 years of age, with an associated increasing risk of infertility and miscarriage.

In a recently published study of 750 women attempting pregnancy, women with a low AMH level (<0.7 ng/mL) or high FSH level (>10 mIU/mL), or both, did not have a significantly lower likelihood of achieving spontaneous pregnancy within 1 year, compared with women with normal results of ovarian reserve testing.3

Continue to: #5 My patient is not ready to be pregnant

#5 My patient is not ready to be pregnant. If her results are abnormal, should she freeze eggs?

For patients who might be interested in seeking fertility preservation and ART, earlier referral to a reproductive specialist to discuss risks and benefits of oocyte or embryo cryopreservation is always preferable. The younger a woman is when she undergoes fertility preservation, the better. Among patients planning to delay conception, each one’s decision is driven by her personal calculations of the cost, risk, and benefit of egg or embryo freezing—a picture of which ovarian reserve testing is only one piece.

#6 Can these tests predict menopause?

Menopause is a clinical diagnosis, defined as 12 months without menses (without hormone use or other causes of amenorrhea). In such women, FSH levels are elevated, but biochemical tests are not part of the menopause diagnosis.36 In the years leading to menopause, FSH levels are highly variable and unreliable in predicting time to menopause.

AMH has been shown to correlate with time to menopause. (Once the AMH level becomes undetectable, menopause occurs in a mean of 6 years.37,38) Patients do not typically have serial AMH measurements, however, so it is not usually known when the hormone became undetectable. Therefore, AMH is not a useful test for predicting time to menopause.

Premature ovarian insufficiency (loss of ovarian function in women younger than age 40), should be considered in women with secondary amenorrhea of 4 months or longer. The diagnosis requires confirmatory laboratory assessment,36 and findings include an FSH level greater than 25 mIU/mL on 2 tests performed at least 1 month apart.39,40

Ovarian reserve tests: A partial view of reproductive potential

The answers we have provided highlight several key concepts and conclusions that should guide clinical practice and decisions made by patients:

- Ovarian reserve tests best serve to predict ovarian response during IVF; to a far lesser extent, they might predict birth outcomes from IVF. These tests have not, however, been shown to predict spontaneous pregnancy.

- Ovarian reserve tests should be administered purposefully, with counseling beforehand regarding their limitations.

- Abnormal ovarian reserve test results do not necessitate ART; however, they may prompt a patient to accelerate her reproductive timeline and consult with a reproductive endocrinologist to consider her age and health-related risks of infertility or pregnancy loss.

- Patients should be counseled that, regardless of the results of ovarian reserve testing, attempting conception or pursuing fertility preservation at a younger age (in particular, at <35 years of age) is associated with better outcomes.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE Your patient wants ovarian reserve testing. Is her request reasonable?

A 34-year-old woman, recently married, plans to delay attempting pregnancy for a few years. She requests ovarian reserve testing to inform this timeline.

This is not an unreasonable inquiry, given her age (<35 years), after which there is natural acceleration in the rate of decline in the quality of oocytes. Regardless of the results of testing, attempting pregnancy or pursuing fertility preservation as soon as possible (particularly in patients >35 years) is associated with better outcomes.

A woman is born with all the eggs she will ever have. Oocyte atresia occurs throughout a woman’s lifetime, from 1,000,000 eggs at birth to only 1,000 by the time of menopause.1 A woman’s ovarian reserve reflects the number of oocytes present in the ovaries and is the result of complex interactions of age, genetics, and environmental variables.

Ovarian reserve testing, however, only has been consistently shown to predict ovarian response to stimulation with gonadotropins; these tests might reflect in vitro fertilization (IVF) birth outcomes to a lesser degree, but have not been shown to predict natural fecundability.2,3 Essentially, ovarian reserve testing provides a partial view of reproductive potential.

Ovarian reserve testing also does not reflect an age-related decline in oocyte quality, particularly after age 35.4,5 As such, female age is the principal driver of fertility potential, regardless of oocyte number. A woman with abnormal ovarian reserve tests may benefit from referral to a fertility specialist for counseling that integrates her results, age, and medical history, with the caveat that abnormal results do not necessarily mean she needs assisted reproductive technology (ART) to conceive.

In this article, we review 6 common questions about the ovarian reserve, providing current data to support the answers.

Continue to: #1 What tests are part of an ovarian reserve assessment?

#1 What tests are part of an ovarian reserve assessment? What is their utility?

FSH and estradiol

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and estradiol should be checked together in the early follicular phase (days 2 to 4 of the cycle). Elevated levels of one or both hormones suggest diminished ovarian reserve; an FSH level greater than 10 mIU/mL and/or an estradiol level greater than 80 pg/mL represent abnormal results6 (TABLE 1). Because FSH demonstrates significant intercycle variability, a single abnormal result should be confirmed in a subsequent cycle.7

Although the basal FSH level does not reflect egg quality or predict natural fecundity, an elevated FSH level predicts poor ovarian response (<3 or 4 eggs retrieved) to ovarian hyperstimulation, with good specificity.3,6,8,9 In patients younger than age 35 years undergoing IVF, basal FSH levels do not predict live birth or pregnancy loss.10 In older patients undergoing IVF, however, an elevated FSH level is associated with a reduced live birth rate (a 5% reduction in women <40 years to a 26% reduction in women >42 years) and a higher miscarriage rate, reflecting the positive correlation of oocyte aneuploidy and age.

In addition to high intercycle variability, an FSH level is reliable only in the setting of normal hypothalamic and pituitary function.7 Conditions such a prolactinoma (or other causes of hyperprolactinemia), other intracranial masses, prior central radiation, hormone-based medication use, and inadequate energy reserve (as the result of anorexia nervosa, resulting in hypothalamic suppression), might result in a low or inappropriately normal FSH level that does not reflect ovarian function.11

Antral follicle count

Antral follicle count (AFC) is defined as the total number of follicles measuring 2 to 10 mm, in both ovaries, in the early follicular phase (days 2 to 4 of the cycle). A count of fewer than 6 to 10 antral follicles in total is considered consistent with diminished ovarian reserve6,12,13 (TABLE 1). Antral follicle count is not predictive of natural fecundity but, rather, projects ovarian response during IVF. Antral follicle count has been shown to decrease by 5% a year with increasing age among women with or without infertility.14

Studies have highlighted concerns regarding interobserver and intraobserver variability in determining the AFC but, in experienced hands, the AFC is a reliable test of ovarian reserve.15,16 Visualization of antral follicles can be compromised in obese patients.11 Conversely, AFC sometimes also overestimates ovarian reserve, because atretic follicles might be included in the count.11,15 Last, AFC is reduced in patients who take a hormone-based medication but recovers with cessation of the medication.17 Ideally, a woman should stop all hormone-based medications for 2 or 3 months (≥2 or 3 spontaneous cycles) before AFC is measured.

Continue to: Anti-Müllerian hormone

Anti-Müllerian hormone

A transforming growth factor β superfamily peptide produced by preantral and early antral follicles of the ovary, anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) is a direct and quantitative marker of ovarian reserve.18 AMH is detectable at birth; the level rises slowly until puberty, reaching a peak at approximately 16 years of age,19 then remains relatively stable until 25 years, after which AMH and age are inversely correlated, reflecting ongoing oocyte atresia. AMH declines roughly 5% a year with increasing age.14

A low level of AMH (<1 ng/mL) suggests diminished ovarian reserve20,21 (TABLE 1). AMH has been consistently validated only for predicting ovarian response during IVF.2,20 To a lesser extent, AMH might reflect the likelihood of pregnancy following ART, although studies are inconsistent on this point.22 AMH is not predictive of natural fecundity or time to spontaneous conception.3,23 Among 700 women younger than age 40, AMH levels were not significantly different among those with or without infertility, and a similar percentage of women in both groups had what was characterized as a “very low” AMH level (<0.7 ng/mL).14

At the other extreme, a high AMH value (>3.5 ng/mL) predicts a hyper-response to ovarian stimulation with gonadotropins and elevated risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. In conjunction with clinical and other laboratory findings, an elevated level of AMH also can suggest polycystic ovary syndrome. No AMH cutoff for a diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome exists, although a level of greater than 5 to 7.8 ng/mL has been proposed as a point of delineation.24,25

Unlike FSH and AFC, AMH is generally considered to be a valid marker of ovarian reserve throughout the menstrual cycle. AMH levels are higher in the follicular phase of the cycle and lower in the midluteal phase, but the differences are minor and seldom alter the patient’s overall prognosis.26-29 As with FSH and AFC, levels of AMH are significantly lower in patients who are pregnant or taking hormone-based medications: Hormonal contraception lowers AMH level by 30% to 50%.17,30,31 Ideally, patients should stop all hormone-based medications for 2 or 3 months (≥2 or 3 spontaneous cycles) before testing ovarian reserve.

#2 Who should have ovarian reserve testing?

The clinical criteria and specific indications for proceeding with ovarian reserve testing are summarized in TABLE 2.13,32-34 Such testing is not indicated in women who are planning to attempt pregnancy but who do not have risk factors for diminished ovarian reserve. These tests cannot predict their success at becoming pregnant; age is a far more appropriate predictor of pregnancy and risk of miscarriage.3 At most, an abnormal result in a patient who meets one of the clinical criteria for testing could prompt earlier referral to a reproductive specialist for consultation—after it is explained to her that abnormal ovarian reserve tests do not, alone, mean that ART is required.

Continue to: #3 Can I reassure my patient about her reproductive potential using these tests?

#3 Can I reassure my patient about her reproductive potential using these tests?

Normal findings on ovarian reserve testing suggests that a woman might have a normal (that is, commensurate with age-matched peers) number of eggs in her ovaries. But normal test results do not mean she will have an easy time conceiving. Similarly, abnormal results do not mean that she will have difficulty conceiving.

Ovarian reserve testing reflects only the number of oocytes, not their quality, which is primarily determined by maternal age.35 Genetic testing of embryos during IVF shows that the percentage of embryos that are aneuploid (usually resulting from abnormal eggs) rises with advancing maternal age, beginning at 35 years.5 The increasing rate of oocyte aneuploidy is also reflected in the rising rate of loss of clinically recognized pregnancies with advancing maternal age: from 11% in women younger than age 34 to greater than 36% in women older than age 42.4

Furthermore, ovarian reserve testing does not reflect other potential genetic barriers to reproduction, such as a chromosomal translocation that can result in recurrent pregnancy loss. Fallopian tube obstruction and uterine issues, such as fibroids or septa, and male factors are also not reflected in ovarian reserve testing.

#4 My patient is trying to get pregnant and has abnormal ovarian reserve testing results. Will she need IVF?"

Not necessarily. Consultation with a fertility specialist to discuss the nuances of abnormal test results and management options is ideal but, essentially, as the American Society for Reproductive Medicine states, “evidence of [diminished ovarian reserve] does not necessarily equate with inability to conceive.” Furthermore, the Society states, “there is insufficient evidence to recommend that any ovarian reserve test now available should be used as a sole criterion for the use of ART.”

Once counseled, patients might elect to pursue more aggressive treatment, but they might not necessarily need it. Age must figure significantly into treatment decisions, because oocyte quality—regardless of number—begins to decline at 35 years of age, with an associated increasing risk of infertility and miscarriage.

In a recently published study of 750 women attempting pregnancy, women with a low AMH level (<0.7 ng/mL) or high FSH level (>10 mIU/mL), or both, did not have a significantly lower likelihood of achieving spontaneous pregnancy within 1 year, compared with women with normal results of ovarian reserve testing.3

Continue to: #5 My patient is not ready to be pregnant

#5 My patient is not ready to be pregnant. If her results are abnormal, should she freeze eggs?

For patients who might be interested in seeking fertility preservation and ART, earlier referral to a reproductive specialist to discuss risks and benefits of oocyte or embryo cryopreservation is always preferable. The younger a woman is when she undergoes fertility preservation, the better. Among patients planning to delay conception, each one’s decision is driven by her personal calculations of the cost, risk, and benefit of egg or embryo freezing—a picture of which ovarian reserve testing is only one piece.

#6 Can these tests predict menopause?

Menopause is a clinical diagnosis, defined as 12 months without menses (without hormone use or other causes of amenorrhea). In such women, FSH levels are elevated, but biochemical tests are not part of the menopause diagnosis.36 In the years leading to menopause, FSH levels are highly variable and unreliable in predicting time to menopause.

AMH has been shown to correlate with time to menopause. (Once the AMH level becomes undetectable, menopause occurs in a mean of 6 years.37,38) Patients do not typically have serial AMH measurements, however, so it is not usually known when the hormone became undetectable. Therefore, AMH is not a useful test for predicting time to menopause.

Premature ovarian insufficiency (loss of ovarian function in women younger than age 40), should be considered in women with secondary amenorrhea of 4 months or longer. The diagnosis requires confirmatory laboratory assessment,36 and findings include an FSH level greater than 25 mIU/mL on 2 tests performed at least 1 month apart.39,40

Ovarian reserve tests: A partial view of reproductive potential

The answers we have provided highlight several key concepts and conclusions that should guide clinical practice and decisions made by patients:

- Ovarian reserve tests best serve to predict ovarian response during IVF; to a far lesser extent, they might predict birth outcomes from IVF. These tests have not, however, been shown to predict spontaneous pregnancy.

- Ovarian reserve tests should be administered purposefully, with counseling beforehand regarding their limitations.

- Abnormal ovarian reserve test results do not necessitate ART; however, they may prompt a patient to accelerate her reproductive timeline and consult with a reproductive endocrinologist to consider her age and health-related risks of infertility or pregnancy loss.

- Patients should be counseled that, regardless of the results of ovarian reserve testing, attempting conception or pursuing fertility preservation at a younger age (in particular, at <35 years of age) is associated with better outcomes.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Forman MR, Mangini LD, Thelus-Jean R, Hayward MD. Life-course origins of the ages at menarche and menopause. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2013;4:1-21.

- Reichman DE, Goldschlag D, Rosenwaks Z. Value of antimüllerian hormone as a prognostic indicator of in vitro fertilization outcome. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(4):1012-1018.e1.

- Steiner AZ, Pritchard D, Stanczyk FZ, Kesner JS, Meadows JW, Herring AH, et al. Association between biomarkers of ovarian reserve and infertility among older women of reproductive age. JAMA. 2017;318(14):1367-1376.

- Farr SL, Schieve LA, Jamieson DJ. Pregnancy loss among pregnancies conceived through assisted reproductive technology, United States, 1999-2002. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(12):1380-1388.

- Franasiak JM, Forman EJ, Hong KH, Werner MD, Upham KM, Treff NR, et al. The nature of aneuploidy with increasing age of the female partner: a review of 1,169 consecutive trophectoderm biopsies evaluated with comprehensive chromosomal screening. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(3):656-663.e1.

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Testing and interpreting measures of ovarian reserve: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(3):e9-e17.

- Kwee J, Schats R, McDonnell J, Lambalk CB, Schoemaker J. Intercycle variability of ovarian reserve tests: results of a prospective randomized study. Hum Reprod. 2004;19(3):590-595.

- Thum MY, Abdalla HI, Taylor D. Relationship between women’s age and basal follicle-stimulating hormone levels with aneuploidy risk in in vitro fertilization treatment. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(2):315-321.

- Roberts JE, Spandorfer S, Fasouliotis SJ, Kashyap S, Rosenwaks Z. Taking a basal follicle-stimulating hormone history is essential before initiating in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2005;83(1):37-41.

- Bishop LA, Richter KS, Patounakis G, Andriani L, Moon K, Devine K. Diminished ovarian reserve as measured by means of baseline follicle-stimulating hormone and antral follicle count is not associated with pregnancy loss in younger in vitro fertilization patients. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(6):980-987.

- Tal R, Seifer DB. Ovarian reserve testing: a user’s guide. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(2):129-140.

- Ferraretti AP, La Marca L, Fauser BC, Tarlatzis B, Nargund G, Gianaroli L; ESHRE working group on Poor Ovarian Response Definition. ESHRE consensus on the definition of ‘poor response’ to ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization: the Bologna criteria. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(7):1616-1624.

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Diagnostic evaluation of the infertile female: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(6):e44-e50.

- Hvidman HW, Bentzen JG, Thuesen LL, Lauritsen MP, Forman JL, Loft A, et al. Infertile women below the age of 40 have similar anti-Müllerian hormone levels and antral follicle count compared with women of the same age with no history of infertility. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(5):1034-1045.

- Broekmans FJ, Kwee J, Hendriks DJ, Mol BW, Lambalk CB. A systematic review of tests predicting ovarian reserve and IVF outcome. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12(6):685-718.

- Iliodromiti S, Anderson RA, Nelson SM. Technical and performance characteristics of anti-Mullerian hormone and antral follicle count as biomarkers of ovarian response. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21(6):698-710.

- Bentzen JG, Forman JL, Pinborg A, Lidegaard Ø, Larsen EC, Friis-Hansen L, et al. Ovarian reserve parameters: a comparison between users and non-users of hormonal contraception. Reprod Biomed Online. 2012;25(6):612-619.

- Broer SL, Broekmans FJ, Laven JS, Fauser BC. Anti-Müllerian hormone: ovarian reserve testing and its potential clinical implications. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(5):688-701.

- Lie Fong S, Visser JA, Welt CK, de Rijke YB, Eijkemans MJ, Broekmans FJ, et al. Serum anti-müllerian hormone levels in healthy females: a nomogram ranging from infancy to adulthood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(12):4650-4655.

- Hamdine O, Eijkemans MJ, Lentjes EW, Torrance HL, Macklon NS, Fauser BC, et al. Ovarian response prediction in GnRH antagonist treatment for IVF using anti-Müllerian hormone. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(1):170-178.

- Jayaprakasan K, Campbell B, Hopkisson J, Johnson I, Raine-Fenning N. A prospective, comparative analysis of anti-Mullerian hormone, inhibin-B, and three-dimensional ultrasound determinants of ovarian reserve in the prediction of poor response to controlled ovarian stimulation. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(3):855-864.

- Silberstein T, MacLaughlin DT, Shai I, Trimarchi JR, Lambert-Messerlian G, Seifer DB, et al. Mullerian inhibiting substance levels at the time of HCG administration in IVF cycles predict both ovarian reserve and embryo morphology. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(1):159-163.

- Korsholm AS, Petersen KB, Bentzen JG, Hilsted LM, Andersen AN, Hvidman HW. Investigation of anti-Müllerian hormone concentrations in relation to natural conception rate and time to pregnancy. Reprod Biomed Online. 2018;36(5):568-575.

- Quinn MM, Kao CN, Ahmad AK, Haisenleder DJ, Santoro N, Eisenberg E, et al. Age-stratified thresholds of anti-Müllerian hormone improve prediction of polycystic ovary syndrome over a population-based threshold. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf).

- Dewailly D, Gronier H, Poncelet E, Robin G, Leroy M, Pigny P, et al. Diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): revisiting the threshold values of follicle count on ultrasound and of the serum AMH level for the definition of polycystic ovaries. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(11):3123-129.

- Schiffner J, Roos J, Broomhead D, Helden JV, Godehardt E, Fehr D, et al. Relationship between anti-Müllerian hormone and antral follicle count across the menstrual cycle using the Beckman Coulter Access assay in comparison with Gen II manual assay. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2017;55(7):1025-1033.

- Gracia CR, Shin SS, Prewitt M, Chamberlin JS, Lofaro LR, Jones KL, et al. Multi-center clinical evaluation of the Access AMH assay to determine AMH levels in reproductive age women during normal menstrual cycles. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;35(5):777-783.

- Dewailly D, Andersen CY, Balen A, Broekmans F, Dilaver N, Fanchin R, et al. The physiology and clinical utility of anti-Mullerian hormone in women. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(3):370-385.

- Kissell KA, Danaher MR, Schisterman EF, Wactawski-Wende J, Ahrens KA, Schliep K, et al. Biological variability in serum anti-Müllerian hormone throughout the menstrual cycle in ovulatory and sporadic anovulatory cycles in eumenorrheic women. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(8):1764-1772.

- Dólleman M, Verschuren WM, Eijkemans MJ, Dollé ME, Jansen EH, Broekmans FJ, et al. Reproductive and lifestyle determinants of anti-Müllerian hormone in a large population-based study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(5):2106-2115.

- Kallio S, Puurunen J, Ruokonen A, Vaskivuo T, Piltonen T, Tapanainen JS. Antimüllerian hormone levels decrease in women using combined contraception independently of administration route. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(5):1305-1310.

- Kim CW, Shim HS, Jang H, Song YG. The effects of uterine artery embolization on ovarian reserve. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016 ;206:172-176.

- Lin W, Titus S, Moy F, Ginsburg ES, Oktay K. Ovarian aging in women with BRCA germline mutations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(10):3839-3847.

- Nelson LM. Clinical practice. Primary ovarian insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(6):606-614.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice and Practice Committee. Female age-related fertility decline. Committee Opinion No. 589. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(3):633-634.

- National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health (UK). Menopause: Full Guideline. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK); 2015 Nov 12. (NICE Guideline, No. 23). Premature ovarian insufficiency. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK343476/.

- Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Gracia CR. Anti-mullerian hormone as a predictor of time to menopause in late reproductive age women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(5):1673-1680.

- van Rooij IA, den Tonkelaar I, Broekmans FJ, Looman CW, Scheffer GJ, de Jong FH, et al. Anti-müllerian hormone is a promising predictor for the occurrence of the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2004;11(6 Pt 1):601-606.

- European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) Guideline Group on POI, Webber L, Davies M, Anderson R, Bartlett J, Braat D, et al. ESHRE Guideline: management of women with premature ovarian insufficiency. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(5):926-937.

- Committee opinion no. 605: primary ovarian insufficiency in adolescents and young women. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(1):193-197.

- Forman MR, Mangini LD, Thelus-Jean R, Hayward MD. Life-course origins of the ages at menarche and menopause. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2013;4:1-21.

- Reichman DE, Goldschlag D, Rosenwaks Z. Value of antimüllerian hormone as a prognostic indicator of in vitro fertilization outcome. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(4):1012-1018.e1.

- Steiner AZ, Pritchard D, Stanczyk FZ, Kesner JS, Meadows JW, Herring AH, et al. Association between biomarkers of ovarian reserve and infertility among older women of reproductive age. JAMA. 2017;318(14):1367-1376.

- Farr SL, Schieve LA, Jamieson DJ. Pregnancy loss among pregnancies conceived through assisted reproductive technology, United States, 1999-2002. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(12):1380-1388.

- Franasiak JM, Forman EJ, Hong KH, Werner MD, Upham KM, Treff NR, et al. The nature of aneuploidy with increasing age of the female partner: a review of 1,169 consecutive trophectoderm biopsies evaluated with comprehensive chromosomal screening. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(3):656-663.e1.

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Testing and interpreting measures of ovarian reserve: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(3):e9-e17.

- Kwee J, Schats R, McDonnell J, Lambalk CB, Schoemaker J. Intercycle variability of ovarian reserve tests: results of a prospective randomized study. Hum Reprod. 2004;19(3):590-595.

- Thum MY, Abdalla HI, Taylor D. Relationship between women’s age and basal follicle-stimulating hormone levels with aneuploidy risk in in vitro fertilization treatment. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(2):315-321.

- Roberts JE, Spandorfer S, Fasouliotis SJ, Kashyap S, Rosenwaks Z. Taking a basal follicle-stimulating hormone history is essential before initiating in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2005;83(1):37-41.

- Bishop LA, Richter KS, Patounakis G, Andriani L, Moon K, Devine K. Diminished ovarian reserve as measured by means of baseline follicle-stimulating hormone and antral follicle count is not associated with pregnancy loss in younger in vitro fertilization patients. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(6):980-987.

- Tal R, Seifer DB. Ovarian reserve testing: a user’s guide. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(2):129-140.

- Ferraretti AP, La Marca L, Fauser BC, Tarlatzis B, Nargund G, Gianaroli L; ESHRE working group on Poor Ovarian Response Definition. ESHRE consensus on the definition of ‘poor response’ to ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization: the Bologna criteria. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(7):1616-1624.

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Diagnostic evaluation of the infertile female: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(6):e44-e50.

- Hvidman HW, Bentzen JG, Thuesen LL, Lauritsen MP, Forman JL, Loft A, et al. Infertile women below the age of 40 have similar anti-Müllerian hormone levels and antral follicle count compared with women of the same age with no history of infertility. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(5):1034-1045.

- Broekmans FJ, Kwee J, Hendriks DJ, Mol BW, Lambalk CB. A systematic review of tests predicting ovarian reserve and IVF outcome. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12(6):685-718.

- Iliodromiti S, Anderson RA, Nelson SM. Technical and performance characteristics of anti-Mullerian hormone and antral follicle count as biomarkers of ovarian response. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21(6):698-710.

- Bentzen JG, Forman JL, Pinborg A, Lidegaard Ø, Larsen EC, Friis-Hansen L, et al. Ovarian reserve parameters: a comparison between users and non-users of hormonal contraception. Reprod Biomed Online. 2012;25(6):612-619.

- Broer SL, Broekmans FJ, Laven JS, Fauser BC. Anti-Müllerian hormone: ovarian reserve testing and its potential clinical implications. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(5):688-701.

- Lie Fong S, Visser JA, Welt CK, de Rijke YB, Eijkemans MJ, Broekmans FJ, et al. Serum anti-müllerian hormone levels in healthy females: a nomogram ranging from infancy to adulthood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(12):4650-4655.

- Hamdine O, Eijkemans MJ, Lentjes EW, Torrance HL, Macklon NS, Fauser BC, et al. Ovarian response prediction in GnRH antagonist treatment for IVF using anti-Müllerian hormone. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(1):170-178.

- Jayaprakasan K, Campbell B, Hopkisson J, Johnson I, Raine-Fenning N. A prospective, comparative analysis of anti-Mullerian hormone, inhibin-B, and three-dimensional ultrasound determinants of ovarian reserve in the prediction of poor response to controlled ovarian stimulation. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(3):855-864.

- Silberstein T, MacLaughlin DT, Shai I, Trimarchi JR, Lambert-Messerlian G, Seifer DB, et al. Mullerian inhibiting substance levels at the time of HCG administration in IVF cycles predict both ovarian reserve and embryo morphology. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(1):159-163.

- Korsholm AS, Petersen KB, Bentzen JG, Hilsted LM, Andersen AN, Hvidman HW. Investigation of anti-Müllerian hormone concentrations in relation to natural conception rate and time to pregnancy. Reprod Biomed Online. 2018;36(5):568-575.

- Quinn MM, Kao CN, Ahmad AK, Haisenleder DJ, Santoro N, Eisenberg E, et al. Age-stratified thresholds of anti-Müllerian hormone improve prediction of polycystic ovary syndrome over a population-based threshold. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf).

- Dewailly D, Gronier H, Poncelet E, Robin G, Leroy M, Pigny P, et al. Diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): revisiting the threshold values of follicle count on ultrasound and of the serum AMH level for the definition of polycystic ovaries. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(11):3123-129.

- Schiffner J, Roos J, Broomhead D, Helden JV, Godehardt E, Fehr D, et al. Relationship between anti-Müllerian hormone and antral follicle count across the menstrual cycle using the Beckman Coulter Access assay in comparison with Gen II manual assay. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2017;55(7):1025-1033.

- Gracia CR, Shin SS, Prewitt M, Chamberlin JS, Lofaro LR, Jones KL, et al. Multi-center clinical evaluation of the Access AMH assay to determine AMH levels in reproductive age women during normal menstrual cycles. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;35(5):777-783.

- Dewailly D, Andersen CY, Balen A, Broekmans F, Dilaver N, Fanchin R, et al. The physiology and clinical utility of anti-Mullerian hormone in women. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(3):370-385.

- Kissell KA, Danaher MR, Schisterman EF, Wactawski-Wende J, Ahrens KA, Schliep K, et al. Biological variability in serum anti-Müllerian hormone throughout the menstrual cycle in ovulatory and sporadic anovulatory cycles in eumenorrheic women. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(8):1764-1772.

- Dólleman M, Verschuren WM, Eijkemans MJ, Dollé ME, Jansen EH, Broekmans FJ, et al. Reproductive and lifestyle determinants of anti-Müllerian hormone in a large population-based study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(5):2106-2115.

- Kallio S, Puurunen J, Ruokonen A, Vaskivuo T, Piltonen T, Tapanainen JS. Antimüllerian hormone levels decrease in women using combined contraception independently of administration route. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(5):1305-1310.

- Kim CW, Shim HS, Jang H, Song YG. The effects of uterine artery embolization on ovarian reserve. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016 ;206:172-176.

- Lin W, Titus S, Moy F, Ginsburg ES, Oktay K. Ovarian aging in women with BRCA germline mutations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(10):3839-3847.

- Nelson LM. Clinical practice. Primary ovarian insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(6):606-614.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice and Practice Committee. Female age-related fertility decline. Committee Opinion No. 589. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(3):633-634.

- National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health (UK). Menopause: Full Guideline. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK); 2015 Nov 12. (NICE Guideline, No. 23). Premature ovarian insufficiency. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK343476/.

- Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Gracia CR. Anti-mullerian hormone as a predictor of time to menopause in late reproductive age women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(5):1673-1680.

- van Rooij IA, den Tonkelaar I, Broekmans FJ, Looman CW, Scheffer GJ, de Jong FH, et al. Anti-müllerian hormone is a promising predictor for the occurrence of the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2004;11(6 Pt 1):601-606.

- European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) Guideline Group on POI, Webber L, Davies M, Anderson R, Bartlett J, Braat D, et al. ESHRE Guideline: management of women with premature ovarian insufficiency. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(5):926-937.

- Committee opinion no. 605: primary ovarian insufficiency in adolescents and young women. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(1):193-197.

Subclinical Hypothyroidism in Pregnancy

Vaccine protects against flu-related hospitalizations in pregnancy

A review of more than 1,000 hospitalizations revealed a 40% influenza vaccine effectiveness against laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations during pregnancy, Mark Thompson, MD, said at a meeting of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices in Atlanta.

To date, no study has examined influenza vaccine effectiveness (IVE) against hospitalizations among pregnant women, said Dr. Thompson, of the CDC’s influenza division.

He presented results of a study based on data from the Pregnancy Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (PREVENT), which included public health or health care systems with integrated laboratory, medical, and vaccination records in Australia, Canada (Alberta and Ontario), Israel, and three states (California, Oregon, and Washington). The study included women aged 18-50 years who were pregnant during local influenza seasons from 2010 to 2016. Most of the women were older than 35 years (79%), and in the third trimester (65%), and had no high risk medical conditions (66%). The study was published in Clinical Infectious Diseases (2018 Oct 11. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy737).

The researchers identified 19,450 hospitalizations with an acute respiratory or febrile illness discharge diagnosis and clinician-ordered real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) testing for flu viruses. Of these, 1,030 (6%) of the women underwent rRT-PCR testing, 54% were diagnosed with either influenza or pneumonia, and 58% had detectable influenza A or B virus infections.

Overall, the adjusted IVE was 40%; 13% of rRT-PCR-confirmed influenza-positive pregnant women and 22% of influenza-negative pregnant women were vaccinated; IVE was adjusted for site, season, season timing, and high-risk medical conditions.

“The takeaway is this is the average performance of the vaccine across multiple countries and different seasons,” and the vaccine effectiveness appeared stable across high-risk medical conditions and trimesters of pregnancy, Dr. Thompson said.

The generalizability of the study findings was limited by the lack of data from low- to middle-income countries, he said during the meeting discussion. However, the ICU admission rate is “what we would expect” and similar to results from previous studies. The consistent results showed the need to increase flu vaccination for pregnant women worldwide and to include study populations from lower-income countries in future research.

Dr. Thompson had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A review of more than 1,000 hospitalizations revealed a 40% influenza vaccine effectiveness against laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations during pregnancy, Mark Thompson, MD, said at a meeting of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices in Atlanta.

To date, no study has examined influenza vaccine effectiveness (IVE) against hospitalizations among pregnant women, said Dr. Thompson, of the CDC’s influenza division.

He presented results of a study based on data from the Pregnancy Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (PREVENT), which included public health or health care systems with integrated laboratory, medical, and vaccination records in Australia, Canada (Alberta and Ontario), Israel, and three states (California, Oregon, and Washington). The study included women aged 18-50 years who were pregnant during local influenza seasons from 2010 to 2016. Most of the women were older than 35 years (79%), and in the third trimester (65%), and had no high risk medical conditions (66%). The study was published in Clinical Infectious Diseases (2018 Oct 11. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy737).

The researchers identified 19,450 hospitalizations with an acute respiratory or febrile illness discharge diagnosis and clinician-ordered real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) testing for flu viruses. Of these, 1,030 (6%) of the women underwent rRT-PCR testing, 54% were diagnosed with either influenza or pneumonia, and 58% had detectable influenza A or B virus infections.

Overall, the adjusted IVE was 40%; 13% of rRT-PCR-confirmed influenza-positive pregnant women and 22% of influenza-negative pregnant women were vaccinated; IVE was adjusted for site, season, season timing, and high-risk medical conditions.

“The takeaway is this is the average performance of the vaccine across multiple countries and different seasons,” and the vaccine effectiveness appeared stable across high-risk medical conditions and trimesters of pregnancy, Dr. Thompson said.

The generalizability of the study findings was limited by the lack of data from low- to middle-income countries, he said during the meeting discussion. However, the ICU admission rate is “what we would expect” and similar to results from previous studies. The consistent results showed the need to increase flu vaccination for pregnant women worldwide and to include study populations from lower-income countries in future research.

Dr. Thompson had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A review of more than 1,000 hospitalizations revealed a 40% influenza vaccine effectiveness against laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations during pregnancy, Mark Thompson, MD, said at a meeting of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices in Atlanta.

To date, no study has examined influenza vaccine effectiveness (IVE) against hospitalizations among pregnant women, said Dr. Thompson, of the CDC’s influenza division.

He presented results of a study based on data from the Pregnancy Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (PREVENT), which included public health or health care systems with integrated laboratory, medical, and vaccination records in Australia, Canada (Alberta and Ontario), Israel, and three states (California, Oregon, and Washington). The study included women aged 18-50 years who were pregnant during local influenza seasons from 2010 to 2016. Most of the women were older than 35 years (79%), and in the third trimester (65%), and had no high risk medical conditions (66%). The study was published in Clinical Infectious Diseases (2018 Oct 11. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy737).

The researchers identified 19,450 hospitalizations with an acute respiratory or febrile illness discharge diagnosis and clinician-ordered real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) testing for flu viruses. Of these, 1,030 (6%) of the women underwent rRT-PCR testing, 54% were diagnosed with either influenza or pneumonia, and 58% had detectable influenza A or B virus infections.

Overall, the adjusted IVE was 40%; 13% of rRT-PCR-confirmed influenza-positive pregnant women and 22% of influenza-negative pregnant women were vaccinated; IVE was adjusted for site, season, season timing, and high-risk medical conditions.

“The takeaway is this is the average performance of the vaccine across multiple countries and different seasons,” and the vaccine effectiveness appeared stable across high-risk medical conditions and trimesters of pregnancy, Dr. Thompson said.

The generalizability of the study findings was limited by the lack of data from low- to middle-income countries, he said during the meeting discussion. However, the ICU admission rate is “what we would expect” and similar to results from previous studies. The consistent results showed the need to increase flu vaccination for pregnant women worldwide and to include study populations from lower-income countries in future research.

Dr. Thompson had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM AN ACIP MEETING

Shorter interpregnancy intervals may increase risk of adverse outcomes

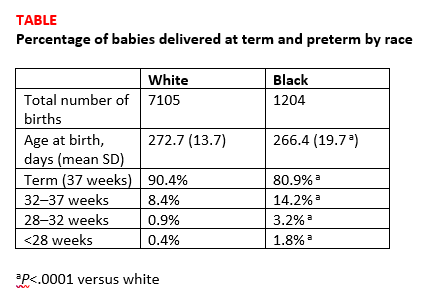

Short interpregnancy intervals carry an increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes for women of all ages and increased adverse fetal and infant outcome risks for women between 20 and 34 years old, according to research published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“This finding may be reassuring particularly for older women who must weigh the competing risks of increasing maternal age with longer interpregnancy intervals (including infertility and chromosomal anomalies) against the risks of short interpregnancy intervals,” wrote Laura Schummers, SD, of the department of epidemiology at Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and her colleagues.

The researchers examined 148,544 pregnancies of women in British Columbia who were younger than 20 years old at the index (5%), 20-34 years at the index birth (83%), and 35 years or older (12%). The women had two or more consecutive singleton pregnancies that resulted in a live birth between 2004 and 2014 and were recorded in the British Columbia Perinatal Data Registry. There was a lower number of short interpregnancy intervals, defined as less than 6 months between the index and second pregnancy, among women in the 35-years-or-older group, compared with the 20- to 34-year-old group (4.4% vs. 5.5%); the 35-years-or-older group instead had a higher number of interpregnancy intervals between 6 and 11 months and between 12 and 17 months, compared with the 20- to 34-year-old group (17.7% vs. 16.6%, and 25.2% vs. 22.5%, respectively).

The risk for maternal mortality or severe morbidity was higher in women who were a minimum 35 years old with 6 months between pregnancies (0.62%), compared with women who had 18 months (0.26%) between pregnancies (adjusted relative risk [aRR], 2.39). There was no significant increase in those aged between 20 and 34 years at 6 months, compared with 18 months (0.23% vs. 0.25%; aRR, 0.92). However, the 20- to 34-year-old group did have an increased risk of fetal and infant adverse outcomes at 6 months, compared with 18 months (2.0% vs. 1.4%; aRR, 1.42) and compared with women in the 35-years-or-older group at 6 months and 18 months (2.1% vs. 1.8%; aRR, 1.15).

There was a 5.3% increased risk at 6 months and a 3.2% increased risk at 18 months of spontaneous preterm delivery in the 20- to 34-year-old group (aRR, 1.65), compared with a 5.0% risk at 6 months and 3.6% at 18 months in the 35-years-or-older group (aRR, 1.40). The researchers noted “modest increases” in newborns who were born small for their gestational age and indicated preterm delivery at short intervals that did not differ by age group.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest. Dr Schummers was supported a National Research Service Award from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and received a grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and the Public Health Agency of Canada Family Planning Public Health Chair Seed Grant. Two of her coauthors were supported by various other awards.

SOURCE: Schummers L et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4696.

While the findings of Schummers et al. appear to encourage pregnancy spacing among women of all ages, women who are 35 or older should be counseled differently than women aged 20-34 years, Stephanie B. Teal, MD, MPH, and Jeanelle Sheeder, MSPH, PhD, wrote in a related editorial.

“Clinicians should understand that women delivering at age 35 years or later may desire more children and may wish to conceive sooner than recommended,” the authors wrote.