User login

Hypertensive crisis of pregnancy must be treated with all urgency

Hypertensive crisis of pregnancy must be treated with all urgency

The following happened approximately 27 years ago when I worked as an attending at a regional level 2 hospital in Puerto Rico. One afternoon I received a call from the emergency department that they had been managing a patient (G4P3) at 33 weeks of gestation for about 4 hours. The patient was consulted for hypertension when she went into a hypertensive encephalopathic coma. The patient was brought back to the birth center. Apresoline was given but did not bring the blood pressure down. Magnesium sulfate also was started at that time. I called a colleague from internal medicine and started to give nitroprusside.

Every time the patient’s blood pressure dropped from 120 mm Hg diastolic, she would become conscious and speak with us. As soon as her blood pressure went up, she would go into a coma. The patient was then transferred to a tertiary center in as stable a condition as possible. Cesarean delivery was performed, and the baby did not survive. The mother had an intracerebral hemorrhage. She was transferred to the supra-tertiary center in San Juan where she later passed away from complications of the hypertensive crisis. If the emergency physician had called me earlier, more could have been done.

This event is always fresh I my mind when I manage my patients in Ohio. Thank God for the newer medications we have available and the protocols to manage hypertensive crisis in pregnancy. I hope this experience heightens awareness of how deadly this condition can be.

David A. Rosado, MD

Celina, Ohio

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Hypertensive crisis of pregnancy must be treated with all urgency

The following happened approximately 27 years ago when I worked as an attending at a regional level 2 hospital in Puerto Rico. One afternoon I received a call from the emergency department that they had been managing a patient (G4P3) at 33 weeks of gestation for about 4 hours. The patient was consulted for hypertension when she went into a hypertensive encephalopathic coma. The patient was brought back to the birth center. Apresoline was given but did not bring the blood pressure down. Magnesium sulfate also was started at that time. I called a colleague from internal medicine and started to give nitroprusside.

Every time the patient’s blood pressure dropped from 120 mm Hg diastolic, she would become conscious and speak with us. As soon as her blood pressure went up, she would go into a coma. The patient was then transferred to a tertiary center in as stable a condition as possible. Cesarean delivery was performed, and the baby did not survive. The mother had an intracerebral hemorrhage. She was transferred to the supra-tertiary center in San Juan where she later passed away from complications of the hypertensive crisis. If the emergency physician had called me earlier, more could have been done.

This event is always fresh I my mind when I manage my patients in Ohio. Thank God for the newer medications we have available and the protocols to manage hypertensive crisis in pregnancy. I hope this experience heightens awareness of how deadly this condition can be.

David A. Rosado, MD

Celina, Ohio

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Hypertensive crisis of pregnancy must be treated with all urgency

The following happened approximately 27 years ago when I worked as an attending at a regional level 2 hospital in Puerto Rico. One afternoon I received a call from the emergency department that they had been managing a patient (G4P3) at 33 weeks of gestation for about 4 hours. The patient was consulted for hypertension when she went into a hypertensive encephalopathic coma. The patient was brought back to the birth center. Apresoline was given but did not bring the blood pressure down. Magnesium sulfate also was started at that time. I called a colleague from internal medicine and started to give nitroprusside.

Every time the patient’s blood pressure dropped from 120 mm Hg diastolic, she would become conscious and speak with us. As soon as her blood pressure went up, she would go into a coma. The patient was then transferred to a tertiary center in as stable a condition as possible. Cesarean delivery was performed, and the baby did not survive. The mother had an intracerebral hemorrhage. She was transferred to the supra-tertiary center in San Juan where she later passed away from complications of the hypertensive crisis. If the emergency physician had called me earlier, more could have been done.

This event is always fresh I my mind when I manage my patients in Ohio. Thank God for the newer medications we have available and the protocols to manage hypertensive crisis in pregnancy. I hope this experience heightens awareness of how deadly this condition can be.

David A. Rosado, MD

Celina, Ohio

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Risk of adverse birth outcomes for singleton infants born to ART-treated or subfertile women

Singleton infants born to mothers who are subfertile or treated with assisted reproductive technology (ART) are at higher risk for multiple adverse health outcomes beyond prematurity, a recent retrospective study shows.

Risks of chromosomal abnormalities, infectious diseases, and cardiovascular and respiratory conditions were all increased, compared with infants born to fertile mothers, in analyses of neonatal outcomes stratified by gestational age.

This population-based study is among the first to show differences in adverse birth outcomes beyond preterm birth and, more specifically, by organ system conditions across gestational age categories, according to Sunah S. Hwang, MD, MPH, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and her coinvestigators.

“With this approach, we offer more detailed associations between maternal fertility and the receipt of treatment along the continuum of fetal organ development and subsequent infant health conditions,” Dr. Hwang and her coauthors wrote in Pediatrics.

The study, which included singleton infants of at least 23 weeks’ gestational age born during 2004-2010, was based on data from a Massachusetts clinical ART database (MOSART) that was linked with state vital records.

Out of 350,123 infants with birth hospitalization records in the study cohort, 336,705 were born to fertile women, while 8,375 were born to women treated with ART, and 5,403 were born to subfertile women.

After adjustment for key maternal and infant characteristics, infants born to subfertile or ART-treated women were more often preterm as compared with infants to fertile mothers. Adjusted odds ratios were 1.39 (95% confidence interval, 1.26-1.54) and 1.72 (95% CI, 1.60-1.85) for infants of subfertile and ART-treated women, respectively, Dr. Hwang and her coinvestigators reported.

Infants born to subfertile or ART-treated women were also more likely to have adverse respiratory, gastrointestinal, or nutritional outcomes, with adjusted ORs ranging from 1.12 to 1.18, they added in the report.

Looking specifically at outcomes stratified by gestational age, they found an increased risk of congenital malformations, infectious diseases, and cardiovascular or respiratory outcomes, with adjusted ORs from 1.30 to 2.61, in the data published in the journal.

By contrast, there were no differences in risks of neonatal mortality, length of hospitalization, low birth weight, or neurologic and hematologic abnormalities for infants of subfertile and ART-treated women, compared with fertile women, according to Dr. Hwang and her coauthors.

These results confirm results of some previous studies that suggested a higher risk of adverse birth outcomes among infants born as singletons, according to the study authors.

“Although it is clearly accepted that multiple gestation is a significant predictor of preterm birth and low birth weight, recent studies have also revealed that, even among singleton births, mothers with infertility without ART treatment along with those who do undergo ART treatment are at higher risk for preterm delivery,” they wrote.

The study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Authors said they had no financial relationships relevant to the study.

SOURCE: Hwang SS et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Aug;142(2):e20174069.

Singleton infants born to mothers who are subfertile or treated with assisted reproductive technology (ART) are at higher risk for multiple adverse health outcomes beyond prematurity, a recent retrospective study shows.

Risks of chromosomal abnormalities, infectious diseases, and cardiovascular and respiratory conditions were all increased, compared with infants born to fertile mothers, in analyses of neonatal outcomes stratified by gestational age.

This population-based study is among the first to show differences in adverse birth outcomes beyond preterm birth and, more specifically, by organ system conditions across gestational age categories, according to Sunah S. Hwang, MD, MPH, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and her coinvestigators.

“With this approach, we offer more detailed associations between maternal fertility and the receipt of treatment along the continuum of fetal organ development and subsequent infant health conditions,” Dr. Hwang and her coauthors wrote in Pediatrics.

The study, which included singleton infants of at least 23 weeks’ gestational age born during 2004-2010, was based on data from a Massachusetts clinical ART database (MOSART) that was linked with state vital records.

Out of 350,123 infants with birth hospitalization records in the study cohort, 336,705 were born to fertile women, while 8,375 were born to women treated with ART, and 5,403 were born to subfertile women.

After adjustment for key maternal and infant characteristics, infants born to subfertile or ART-treated women were more often preterm as compared with infants to fertile mothers. Adjusted odds ratios were 1.39 (95% confidence interval, 1.26-1.54) and 1.72 (95% CI, 1.60-1.85) for infants of subfertile and ART-treated women, respectively, Dr. Hwang and her coinvestigators reported.

Infants born to subfertile or ART-treated women were also more likely to have adverse respiratory, gastrointestinal, or nutritional outcomes, with adjusted ORs ranging from 1.12 to 1.18, they added in the report.

Looking specifically at outcomes stratified by gestational age, they found an increased risk of congenital malformations, infectious diseases, and cardiovascular or respiratory outcomes, with adjusted ORs from 1.30 to 2.61, in the data published in the journal.

By contrast, there were no differences in risks of neonatal mortality, length of hospitalization, low birth weight, or neurologic and hematologic abnormalities for infants of subfertile and ART-treated women, compared with fertile women, according to Dr. Hwang and her coauthors.

These results confirm results of some previous studies that suggested a higher risk of adverse birth outcomes among infants born as singletons, according to the study authors.

“Although it is clearly accepted that multiple gestation is a significant predictor of preterm birth and low birth weight, recent studies have also revealed that, even among singleton births, mothers with infertility without ART treatment along with those who do undergo ART treatment are at higher risk for preterm delivery,” they wrote.

The study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Authors said they had no financial relationships relevant to the study.

SOURCE: Hwang SS et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Aug;142(2):e20174069.

Singleton infants born to mothers who are subfertile or treated with assisted reproductive technology (ART) are at higher risk for multiple adverse health outcomes beyond prematurity, a recent retrospective study shows.

Risks of chromosomal abnormalities, infectious diseases, and cardiovascular and respiratory conditions were all increased, compared with infants born to fertile mothers, in analyses of neonatal outcomes stratified by gestational age.

This population-based study is among the first to show differences in adverse birth outcomes beyond preterm birth and, more specifically, by organ system conditions across gestational age categories, according to Sunah S. Hwang, MD, MPH, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and her coinvestigators.

“With this approach, we offer more detailed associations between maternal fertility and the receipt of treatment along the continuum of fetal organ development and subsequent infant health conditions,” Dr. Hwang and her coauthors wrote in Pediatrics.

The study, which included singleton infants of at least 23 weeks’ gestational age born during 2004-2010, was based on data from a Massachusetts clinical ART database (MOSART) that was linked with state vital records.

Out of 350,123 infants with birth hospitalization records in the study cohort, 336,705 were born to fertile women, while 8,375 were born to women treated with ART, and 5,403 were born to subfertile women.

After adjustment for key maternal and infant characteristics, infants born to subfertile or ART-treated women were more often preterm as compared with infants to fertile mothers. Adjusted odds ratios were 1.39 (95% confidence interval, 1.26-1.54) and 1.72 (95% CI, 1.60-1.85) for infants of subfertile and ART-treated women, respectively, Dr. Hwang and her coinvestigators reported.

Infants born to subfertile or ART-treated women were also more likely to have adverse respiratory, gastrointestinal, or nutritional outcomes, with adjusted ORs ranging from 1.12 to 1.18, they added in the report.

Looking specifically at outcomes stratified by gestational age, they found an increased risk of congenital malformations, infectious diseases, and cardiovascular or respiratory outcomes, with adjusted ORs from 1.30 to 2.61, in the data published in the journal.

By contrast, there were no differences in risks of neonatal mortality, length of hospitalization, low birth weight, or neurologic and hematologic abnormalities for infants of subfertile and ART-treated women, compared with fertile women, according to Dr. Hwang and her coauthors.

These results confirm results of some previous studies that suggested a higher risk of adverse birth outcomes among infants born as singletons, according to the study authors.

“Although it is clearly accepted that multiple gestation is a significant predictor of preterm birth and low birth weight, recent studies have also revealed that, even among singleton births, mothers with infertility without ART treatment along with those who do undergo ART treatment are at higher risk for preterm delivery,” they wrote.

The study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Authors said they had no financial relationships relevant to the study.

SOURCE: Hwang SS et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Aug;142(2):e20174069.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Subfertility, whether treated by ART or not, is associated with adverse health outcomes for infants.

Major finding: Infants of subfertile and ART-treated women were more likely to be born preterm (odds ratios, 1.39 and 1.72, respectively) than were the infants of fertile women.

Study details: Population-based study of 350,123 infants from a Massachusetts clinical database.

Disclosures: The study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. The authors said they had no financial relationships relevant to the study.

Source: Hwang SS et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Aug;142(2):e20174069.

How to differentiate maternal from fetal heart rate patterns on electronic fetal monitoring

Continuous electronic fetal heart rate monitoring (EFM) is used in the vast majority of all labors in the United States. With the use of EFM categories and definitions from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the National Institutes of Health, and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, clinicians can now better define and communicate tracing assessments. Except for reducing neonatal seizure activity, however, EFM use during labor has not been demonstrated to significantly improve fetal and neonatal outcomes, yet EFM is associated with an increase in cesarean deliveries and instrument-assisted vaginal births.1

The negative predictive value of EFM for fetal hypoxia/acidosis is high, but its positive predictive value is only 30%, and the false-positive rate is as high as 60%.2 Although a false-positive assessment may result in a potentially unnecessary operative vaginal or cesarean delivery, a falsely reassuring strip may produce devastating consequences in the newborn and, not infrequently, medical malpractice liability. One etiology associated with falsely reassuring assessments is that of EFM monitoring of the maternal heart rate and the failure to recognize the tracing as maternal.

In this article, I discuss the mechanisms and periods of labor that often are associated with the maternal heart rate masquerading as the fetal heart rate. I review common EFM patterns associated with the maternal heart rate so as to aid in recognizing the maternal heart rate. In addition, I provide 3 case scenarios that illustrate the simple yet critical steps that clinicians can take to remedy the situation. Being aware of the potential for a maternal heart rate recording, investigating the EFM signals, and correcting the monitoring can help prevent significant morbidity.

CASE 1 EFM shows seesaw decelerations and returns to baseline rate

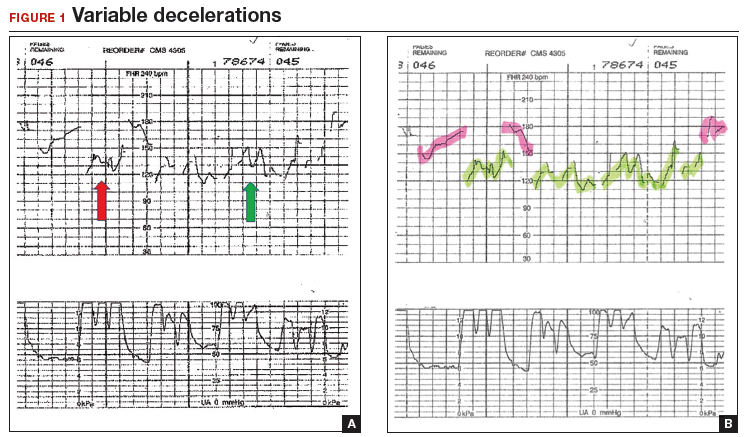

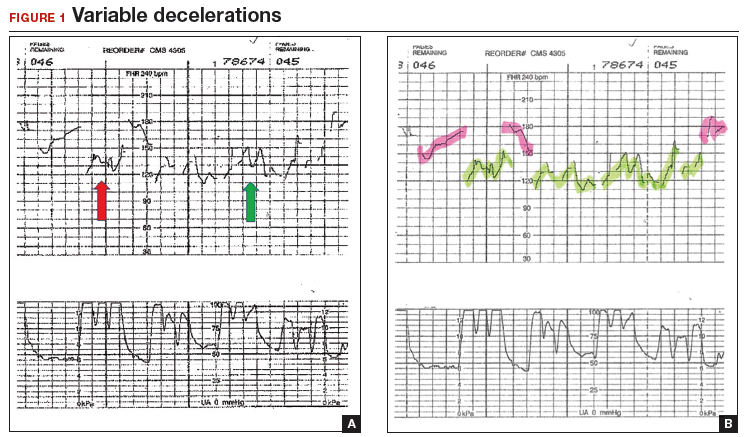

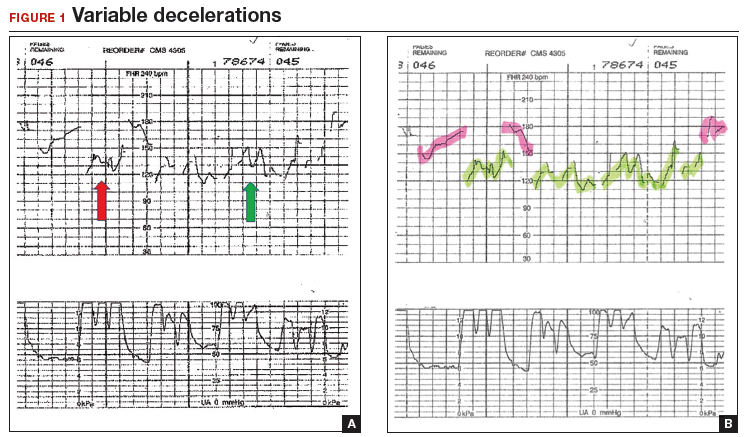

A 29-year-old woman (G3P2) at 39 weeks’ gestation was admitted to the hospital with spontaneous labor. Continuous EFM external monitoring was initiated. After membranes spontaneously ruptured at 4 cm dilation, an epidural was placed. Throughout the active phase of labor, the fetus demonstrated intermittent mild variable decelerations, and the fetal heart rate baseline increased to 180 beats per minute (BPM). With complete dilation, the patient initiated pushing. During the first several pushes, the EFM demonstrated an initial heart rate deceleration, and a loss of signal, but the heart rate returned to a baseline rate of 150 BPM. With the patient’s continued pushing efforts, the EFM baseline increased to 180 BPM, with evidence of variable decelerations to a nadir of 120 BPM, although with some signal gaps (FIGURE 1, red arrow). The tracing then appeared to have a baseline of 120 BPM with variability or accelerations (FIGURE 1, green arrow) before shifting again to 170 to 180 BPM.

What was happening?

Why does the EFM record the maternal heart rate?

Most commonly, EFM recording of the maternal heart rate occurs during the second stage of labor. Early in labor, the normal fetal heart rate (110–160 BPM) typically exceeds the basal maternal heart rate. However, in the presence of chorioamnionitis and maternal fever or with the stress of maternal pushing, the maternal heart rate frequently approaches or exceeds that of the fetal heart rate. The maximum maternal heart rate can be estimated as 220 BPM minus the maternal age. Thus, the heart rate in a 20-year-old gravida may reach rates of 160 to 180 BPM, equivalent to 80% to 90% of her maximum heart rate during second-stage pushing.

The external Doppler fetal monitor, having a somewhat narrow acoustic window, may lose the focus on the fetal heart as a result of descent of the baby, the abdominal shape-altering effect of uterine contractions, and the patient’s pushing. During the second stage, the EFM may record the maternal heart rate from the uterine arteries. Although some clinicians claim to differentiate the maternal from the fetal heart rate by the “whooshing” maternal uterine artery signal as compared with the “thumping” fetal heart rate signal, this auditory assessment is unproven and likely unreliable.

CASE 1 Problem recognized and addressed

In this case, the obstetrician recognized that “slipping” from the fetal to the maternal heart rate recording occurred with the onset of maternal pushing. After the pushing ceased, the maternal heart rate slipped back to the fetal heart rate. With the next several contractions, only the maternal heart rate was recorded. A fetal scalp electrode was then placed, and fetal variable decelerations were recognized. In view of the category II EFM recording, a vacuum procedure was performed from +3 station and a female infant was delivered. She had Apgar scores of 6 and 8 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively, and she did well in the nursery.

Read what happened in Case 2 when the EFM demonstrated breaks in the tracing

CASE 2 EFM tracings belie the clinical situation

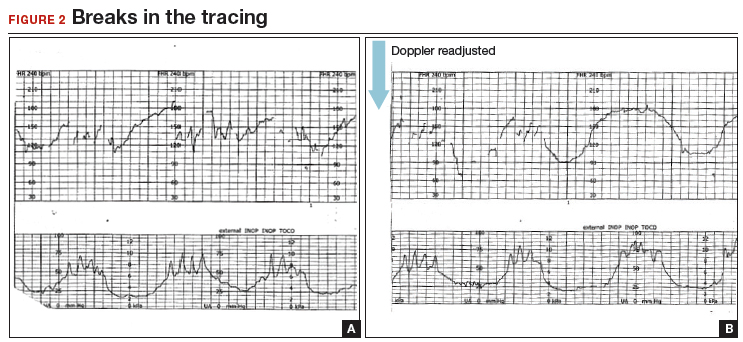

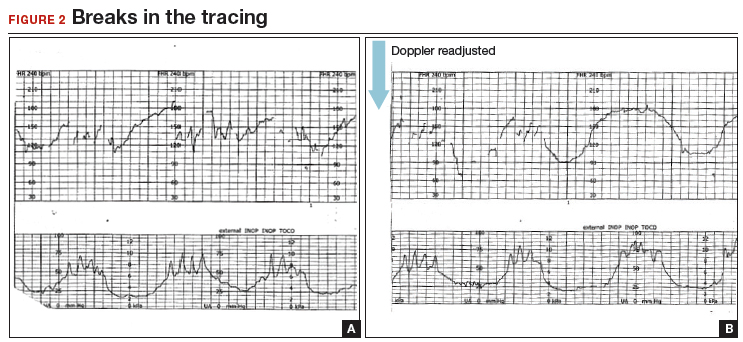

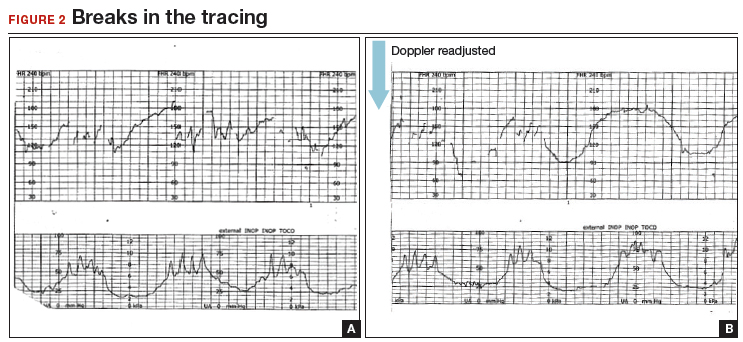

A 20-year-old woman (G1P0) presented for induction of labor at 41 weeks’ gestation. Continuous EFM recording was initiated, and the patient was given dinoprostone and, subsequently, oxytocin. Rupture of membranes at 3 cm demonstrated a small amount of fluid with thick meconium. The patient progressed to complete dilation and developed a temperature of 38.5°C; the EFM baseline increased to 180 BPM. Throughout the first hour of the second stage of labor, the EFM demonstrated breaks in the tracing and a heart rate of 130 to 150 BPM with each pushing effort (FIGURE 2A). The Doppler monitor was subsequently adjusted to focus on the fetal heart and repetitive late decelerations were observed (FIGURE 2B). An emergent cesarean delivery was performed. A depressed newborn male was delivered, with Apgar scores of 2 and 4 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively, and significant metabolic acidosis.

What happened?

Fetal versus maternal responses to pushing

The fetal variable deceleration pattern is well recognized by clinicians. As a result of umbilical cord occlusion (due to compression, stretching, or twisting of the cord), fetal variable decelerations have a typical pattern. An initial acceleration shoulder resulting from umbilical vein occlusion (due to reduced venous return) is followed by an umbilical artery occlusion–induced sharp deceleration. The relief of the occlusion allows the sharp return toward baseline with the secondary shoulder overshoot.

In some cases, partial umbilical cord occlusion that affects only the fetal umbilical vein may result in an acceleration, although these usually resolve or evolve into variable decelerations within 30 minutes. By contrast, the maternal heart rate typically increases with contractions and with maternal pushing efforts. Thus, a repetitive pattern of heart rate accelerations with each contraction should warn of a possible maternal heart rate recording.

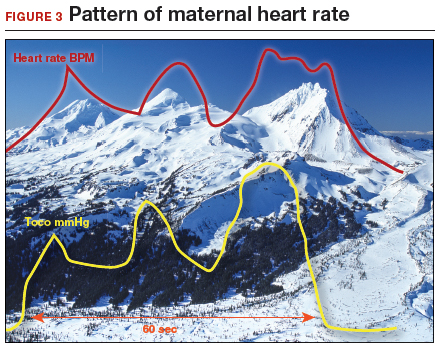

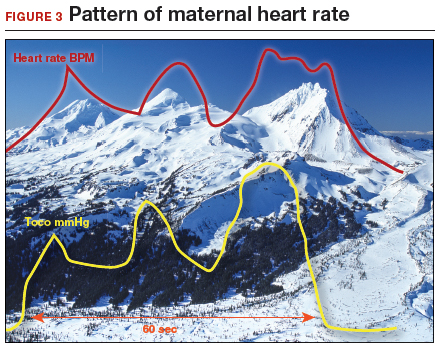

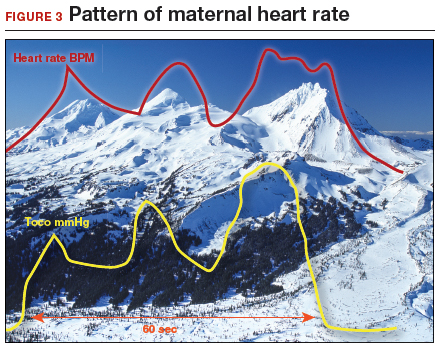

How maternal heart rate responds to pushing. Maternal pushing is a Valsalva maneuver. Although there are 4 classic cardiovascular phases of Valsalva responses, the typical maternal pushing effort results in an increase in the maternal heart rate. With the common sequence of three 10-second pushes during each contraction, the maternal heart rate often exhibits 3 acceleration and deceleration responses. The maternal heart rate tracing looks similar to the shape of the Three Sisters mountain peaks in Oregon (FIGURE 3). Due to Valsalva physiology, the 3 peaks of the Sisters mirror the 3 uterine wave form peaks, although with a 5- to 10-second delay in the heart rate responses (mountain peaks) from the pushing efforts.

Pre- and postcontraction changes offer clues. Several classic findings aid in differentiating the maternal from the fetal heart rate. If the tracing is maternal, typically the heart rate gradually decreases following the end of the contraction/pushing and continues to decrease until the start of the next contraction/pushing, at which time it increases. During the push, the Three Sisters wave form, with the 5- to 10-second offset, should alert the clinician to possible maternal heart rate recordings. By contrast, the fetal heart rate variable deceleration typically increases following the end of the maternal contraction/pushing and is either stable or increases further (variable with slow recovery) prior to the next uterine contraction/pushing effort. These differences in the patterns of precontraction and postcontraction changes can be very valuable in differentiating periods of maternal versus fetal heart rate recordings.

With “slipping” between fetal and maternal recording, it is not uncommon to record fetal heart rate between contractions, slip to the maternal heart rate during the pushing effort, and return again to the fetal heart rate with the end of the contraction. When confounded with the potential for other EFM artifacts, including doubling of a low maternal or fetal heart rate, or halving of a tachycardic signal, it is not surprising that it is challenging to recognize an EFM maternal heart rate recording.

CASE 2 Check the monitor for accurate focus

A retrospective analysis of this case revealed that the maternal heart rate was recorded with each contraction throughout the second stage. The actual fetal heart rate pattern of decelerations was revealed with the refocusing of the Doppler monitor.

Read how subtle slipping manifested in the EFM tracing of Case 3

CASE 3 Low fetal heart rate and variability during contractions

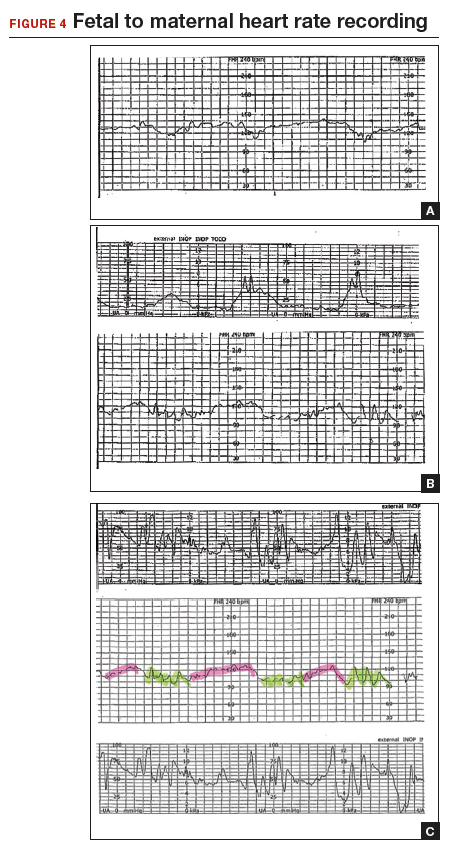

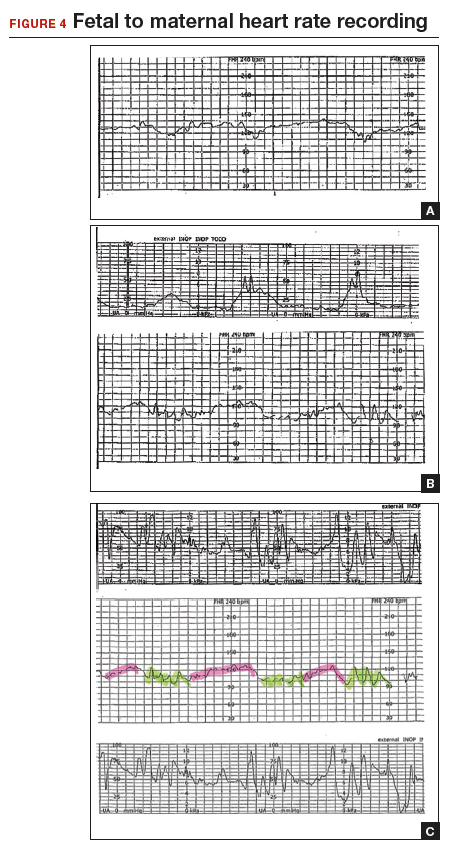

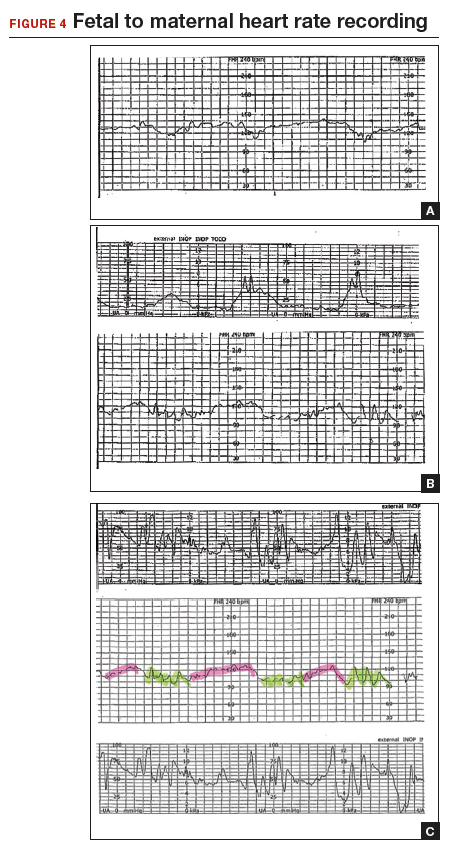

A 22-year-old woman (G2P1) in spontaneous labor at term progressed to complete dilation. Fetal heart rate accelerations occurred for approximately 30 minutes. With the advent of pushing, the fetal heart rate showed a rate of 130 to 140 BPM and mild decelerations with each contraction (FIGURE 4A). As the second stage progressed, the tracing demonstrated an undulating baseline heart rate between 100 and 130 BPM with possible variability during contractions (FIGURE 4B). This pattern continued for an additional 60 minutes. At vaginal delivery, the ObGyn was surprised to deliver a depressed newborn with Apgar scores of 1 and 3 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively.

Slipping from the fetal to the maternal heart rate may be imperceptible

In contrast to the breaks in the tracings seen in Case 1 and Case 2, the EFM tracing in Case 3 appears continuous. Yet, slipping from the fetal to the maternal recording was occurring.

As seen in FIGURE 4C, the maternal heart rate with variability was recorded during pushing efforts, and the fetal heart rate was seen rising back toward a baseline between contractions. Note that the fetal heart rate did not reach a level baseline, but rather decelerated with the next contraction. The slipping to the maternal heart rate occurred without a perceptible break in the recording, making this tracing extremely difficult to interpret.

CASE 3 Be ever vigilant

The lack of recognition that the EFM recording had slipped to the maternal heart rate resulted in fetal and newborn hypoxia and acidosis, accounting for the infant’s low Apgar scores.

Read how using 3 steps can help you distinguish fetal from maternal heart rate patterns

Follow 3 steps to discern fetal vs maternal heart rate

These cases illustrate the difficulties in recognizing maternal heart rate patterns on the fetal monitor tracing. The 3 simple steps described below can aid in differentiating maternal from fetal heart rate patterns.

1 Be aware and alert

Recognize that EFM monitoring of the maternal heart rate may occur during periods of monitoring, particularly in second-stage labor. Often, the recorded tracing is a mix of fetal and maternal patterns. Remember that the maternal heart rate may increase markedly during the second stage and rise even higher during pushing efforts. When presented with a tracing that ostensibly represents the fetus, it may be challenging for the clinician to question that assumption. Thus, be aware that tracings may not represent what they seem to be.

Often, clinicians view only the 10-minute portion of the tracing displayed on the monitor screen. I recommend, however, that clinicians review the tracing over the past 30 to 60 minutes, or since their last EFM assessment, for an understanding of the recent fetal baseline heart rate and decelerations.

2 Investigate

Although it is sometimes challenging to recognize EFM maternal heart rate recordings, this is relatively easy to investigate. Even without a pulse oximeter in place, carefully examine the EFM recording for maternal signs to determine if the maternal heart rate is within the range of the recording. You can confirm that the recording is maternal through 1 of 3 easy measures:

- First, check the maternal radial pulse and correlate it with the heart rate baseline.

- Second, place a maternal electrocardiographic (EKG) heart rate monitor.

- Last, and often the simplest approach for continuous tracings, place a finger pulse oximeter to provide a continuous maternal pulse reading. Should the maternal heart rate superimpose on the EFM recording, maternal patterns are likely being detected. However, since the pulse oximeter and EFM Doppler devices use different technologies, they will provide similar—but not precisely identical—heart rate numerical readings if both are assessing the maternal heart rate. In that case, take steps to assure that the EFM truly is recording the fetal heart rate.

3 Treat and correct

If the EFM is recording a maternal signal or if a significant question remains, place a fetal scalp electrode (unless contraindicated), as this may likely occur during the second stage. Alternatively, place a maternal surface fetal EKG monitor, or use ultrasonography to visually assess the fetal heart rate in real time.

Key point summary

The use of a maternal finger pulse oximeter, combined with a careful assessment of the EFM tracing, and/or a fetal scalp electrode are appropriate measures for confirming a fetal heart rate recording.

The 3 steps described (be aware and alert, investigate, treat and correct) can help you effectively monitor the fetal heart rate and avoid the potentially dangerous outcomes that might occur when the maternal heart rate masquerades as the fetal heart rate.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Alfirevic Z, Devane D, Gyte GM, Cuthbert A. Continuous cardiotocography (CTG) as a form of electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) for fetal assessment during labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017; doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006066.pub3.

- Pinas A, Chandraharan E. Continuous cardiotocography during labour: analysis, classification and management. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;30:33–47.

Continuous electronic fetal heart rate monitoring (EFM) is used in the vast majority of all labors in the United States. With the use of EFM categories and definitions from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the National Institutes of Health, and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, clinicians can now better define and communicate tracing assessments. Except for reducing neonatal seizure activity, however, EFM use during labor has not been demonstrated to significantly improve fetal and neonatal outcomes, yet EFM is associated with an increase in cesarean deliveries and instrument-assisted vaginal births.1

The negative predictive value of EFM for fetal hypoxia/acidosis is high, but its positive predictive value is only 30%, and the false-positive rate is as high as 60%.2 Although a false-positive assessment may result in a potentially unnecessary operative vaginal or cesarean delivery, a falsely reassuring strip may produce devastating consequences in the newborn and, not infrequently, medical malpractice liability. One etiology associated with falsely reassuring assessments is that of EFM monitoring of the maternal heart rate and the failure to recognize the tracing as maternal.

In this article, I discuss the mechanisms and periods of labor that often are associated with the maternal heart rate masquerading as the fetal heart rate. I review common EFM patterns associated with the maternal heart rate so as to aid in recognizing the maternal heart rate. In addition, I provide 3 case scenarios that illustrate the simple yet critical steps that clinicians can take to remedy the situation. Being aware of the potential for a maternal heart rate recording, investigating the EFM signals, and correcting the monitoring can help prevent significant morbidity.

CASE 1 EFM shows seesaw decelerations and returns to baseline rate

A 29-year-old woman (G3P2) at 39 weeks’ gestation was admitted to the hospital with spontaneous labor. Continuous EFM external monitoring was initiated. After membranes spontaneously ruptured at 4 cm dilation, an epidural was placed. Throughout the active phase of labor, the fetus demonstrated intermittent mild variable decelerations, and the fetal heart rate baseline increased to 180 beats per minute (BPM). With complete dilation, the patient initiated pushing. During the first several pushes, the EFM demonstrated an initial heart rate deceleration, and a loss of signal, but the heart rate returned to a baseline rate of 150 BPM. With the patient’s continued pushing efforts, the EFM baseline increased to 180 BPM, with evidence of variable decelerations to a nadir of 120 BPM, although with some signal gaps (FIGURE 1, red arrow). The tracing then appeared to have a baseline of 120 BPM with variability or accelerations (FIGURE 1, green arrow) before shifting again to 170 to 180 BPM.

What was happening?

Why does the EFM record the maternal heart rate?

Most commonly, EFM recording of the maternal heart rate occurs during the second stage of labor. Early in labor, the normal fetal heart rate (110–160 BPM) typically exceeds the basal maternal heart rate. However, in the presence of chorioamnionitis and maternal fever or with the stress of maternal pushing, the maternal heart rate frequently approaches or exceeds that of the fetal heart rate. The maximum maternal heart rate can be estimated as 220 BPM minus the maternal age. Thus, the heart rate in a 20-year-old gravida may reach rates of 160 to 180 BPM, equivalent to 80% to 90% of her maximum heart rate during second-stage pushing.

The external Doppler fetal monitor, having a somewhat narrow acoustic window, may lose the focus on the fetal heart as a result of descent of the baby, the abdominal shape-altering effect of uterine contractions, and the patient’s pushing. During the second stage, the EFM may record the maternal heart rate from the uterine arteries. Although some clinicians claim to differentiate the maternal from the fetal heart rate by the “whooshing” maternal uterine artery signal as compared with the “thumping” fetal heart rate signal, this auditory assessment is unproven and likely unreliable.

CASE 1 Problem recognized and addressed

In this case, the obstetrician recognized that “slipping” from the fetal to the maternal heart rate recording occurred with the onset of maternal pushing. After the pushing ceased, the maternal heart rate slipped back to the fetal heart rate. With the next several contractions, only the maternal heart rate was recorded. A fetal scalp electrode was then placed, and fetal variable decelerations were recognized. In view of the category II EFM recording, a vacuum procedure was performed from +3 station and a female infant was delivered. She had Apgar scores of 6 and 8 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively, and she did well in the nursery.

Read what happened in Case 2 when the EFM demonstrated breaks in the tracing

CASE 2 EFM tracings belie the clinical situation

A 20-year-old woman (G1P0) presented for induction of labor at 41 weeks’ gestation. Continuous EFM recording was initiated, and the patient was given dinoprostone and, subsequently, oxytocin. Rupture of membranes at 3 cm demonstrated a small amount of fluid with thick meconium. The patient progressed to complete dilation and developed a temperature of 38.5°C; the EFM baseline increased to 180 BPM. Throughout the first hour of the second stage of labor, the EFM demonstrated breaks in the tracing and a heart rate of 130 to 150 BPM with each pushing effort (FIGURE 2A). The Doppler monitor was subsequently adjusted to focus on the fetal heart and repetitive late decelerations were observed (FIGURE 2B). An emergent cesarean delivery was performed. A depressed newborn male was delivered, with Apgar scores of 2 and 4 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively, and significant metabolic acidosis.

What happened?

Fetal versus maternal responses to pushing

The fetal variable deceleration pattern is well recognized by clinicians. As a result of umbilical cord occlusion (due to compression, stretching, or twisting of the cord), fetal variable decelerations have a typical pattern. An initial acceleration shoulder resulting from umbilical vein occlusion (due to reduced venous return) is followed by an umbilical artery occlusion–induced sharp deceleration. The relief of the occlusion allows the sharp return toward baseline with the secondary shoulder overshoot.

In some cases, partial umbilical cord occlusion that affects only the fetal umbilical vein may result in an acceleration, although these usually resolve or evolve into variable decelerations within 30 minutes. By contrast, the maternal heart rate typically increases with contractions and with maternal pushing efforts. Thus, a repetitive pattern of heart rate accelerations with each contraction should warn of a possible maternal heart rate recording.

How maternal heart rate responds to pushing. Maternal pushing is a Valsalva maneuver. Although there are 4 classic cardiovascular phases of Valsalva responses, the typical maternal pushing effort results in an increase in the maternal heart rate. With the common sequence of three 10-second pushes during each contraction, the maternal heart rate often exhibits 3 acceleration and deceleration responses. The maternal heart rate tracing looks similar to the shape of the Three Sisters mountain peaks in Oregon (FIGURE 3). Due to Valsalva physiology, the 3 peaks of the Sisters mirror the 3 uterine wave form peaks, although with a 5- to 10-second delay in the heart rate responses (mountain peaks) from the pushing efforts.

Pre- and postcontraction changes offer clues. Several classic findings aid in differentiating the maternal from the fetal heart rate. If the tracing is maternal, typically the heart rate gradually decreases following the end of the contraction/pushing and continues to decrease until the start of the next contraction/pushing, at which time it increases. During the push, the Three Sisters wave form, with the 5- to 10-second offset, should alert the clinician to possible maternal heart rate recordings. By contrast, the fetal heart rate variable deceleration typically increases following the end of the maternal contraction/pushing and is either stable or increases further (variable with slow recovery) prior to the next uterine contraction/pushing effort. These differences in the patterns of precontraction and postcontraction changes can be very valuable in differentiating periods of maternal versus fetal heart rate recordings.

With “slipping” between fetal and maternal recording, it is not uncommon to record fetal heart rate between contractions, slip to the maternal heart rate during the pushing effort, and return again to the fetal heart rate with the end of the contraction. When confounded with the potential for other EFM artifacts, including doubling of a low maternal or fetal heart rate, or halving of a tachycardic signal, it is not surprising that it is challenging to recognize an EFM maternal heart rate recording.

CASE 2 Check the monitor for accurate focus

A retrospective analysis of this case revealed that the maternal heart rate was recorded with each contraction throughout the second stage. The actual fetal heart rate pattern of decelerations was revealed with the refocusing of the Doppler monitor.

Read how subtle slipping manifested in the EFM tracing of Case 3

CASE 3 Low fetal heart rate and variability during contractions

A 22-year-old woman (G2P1) in spontaneous labor at term progressed to complete dilation. Fetal heart rate accelerations occurred for approximately 30 minutes. With the advent of pushing, the fetal heart rate showed a rate of 130 to 140 BPM and mild decelerations with each contraction (FIGURE 4A). As the second stage progressed, the tracing demonstrated an undulating baseline heart rate between 100 and 130 BPM with possible variability during contractions (FIGURE 4B). This pattern continued for an additional 60 minutes. At vaginal delivery, the ObGyn was surprised to deliver a depressed newborn with Apgar scores of 1 and 3 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively.

Slipping from the fetal to the maternal heart rate may be imperceptible

In contrast to the breaks in the tracings seen in Case 1 and Case 2, the EFM tracing in Case 3 appears continuous. Yet, slipping from the fetal to the maternal recording was occurring.

As seen in FIGURE 4C, the maternal heart rate with variability was recorded during pushing efforts, and the fetal heart rate was seen rising back toward a baseline between contractions. Note that the fetal heart rate did not reach a level baseline, but rather decelerated with the next contraction. The slipping to the maternal heart rate occurred without a perceptible break in the recording, making this tracing extremely difficult to interpret.

CASE 3 Be ever vigilant

The lack of recognition that the EFM recording had slipped to the maternal heart rate resulted in fetal and newborn hypoxia and acidosis, accounting for the infant’s low Apgar scores.

Read how using 3 steps can help you distinguish fetal from maternal heart rate patterns

Follow 3 steps to discern fetal vs maternal heart rate

These cases illustrate the difficulties in recognizing maternal heart rate patterns on the fetal monitor tracing. The 3 simple steps described below can aid in differentiating maternal from fetal heart rate patterns.

1 Be aware and alert

Recognize that EFM monitoring of the maternal heart rate may occur during periods of monitoring, particularly in second-stage labor. Often, the recorded tracing is a mix of fetal and maternal patterns. Remember that the maternal heart rate may increase markedly during the second stage and rise even higher during pushing efforts. When presented with a tracing that ostensibly represents the fetus, it may be challenging for the clinician to question that assumption. Thus, be aware that tracings may not represent what they seem to be.

Often, clinicians view only the 10-minute portion of the tracing displayed on the monitor screen. I recommend, however, that clinicians review the tracing over the past 30 to 60 minutes, or since their last EFM assessment, for an understanding of the recent fetal baseline heart rate and decelerations.

2 Investigate

Although it is sometimes challenging to recognize EFM maternal heart rate recordings, this is relatively easy to investigate. Even without a pulse oximeter in place, carefully examine the EFM recording for maternal signs to determine if the maternal heart rate is within the range of the recording. You can confirm that the recording is maternal through 1 of 3 easy measures:

- First, check the maternal radial pulse and correlate it with the heart rate baseline.

- Second, place a maternal electrocardiographic (EKG) heart rate monitor.

- Last, and often the simplest approach for continuous tracings, place a finger pulse oximeter to provide a continuous maternal pulse reading. Should the maternal heart rate superimpose on the EFM recording, maternal patterns are likely being detected. However, since the pulse oximeter and EFM Doppler devices use different technologies, they will provide similar—but not precisely identical—heart rate numerical readings if both are assessing the maternal heart rate. In that case, take steps to assure that the EFM truly is recording the fetal heart rate.

3 Treat and correct

If the EFM is recording a maternal signal or if a significant question remains, place a fetal scalp electrode (unless contraindicated), as this may likely occur during the second stage. Alternatively, place a maternal surface fetal EKG monitor, or use ultrasonography to visually assess the fetal heart rate in real time.

Key point summary

The use of a maternal finger pulse oximeter, combined with a careful assessment of the EFM tracing, and/or a fetal scalp electrode are appropriate measures for confirming a fetal heart rate recording.

The 3 steps described (be aware and alert, investigate, treat and correct) can help you effectively monitor the fetal heart rate and avoid the potentially dangerous outcomes that might occur when the maternal heart rate masquerades as the fetal heart rate.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Continuous electronic fetal heart rate monitoring (EFM) is used in the vast majority of all labors in the United States. With the use of EFM categories and definitions from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the National Institutes of Health, and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, clinicians can now better define and communicate tracing assessments. Except for reducing neonatal seizure activity, however, EFM use during labor has not been demonstrated to significantly improve fetal and neonatal outcomes, yet EFM is associated with an increase in cesarean deliveries and instrument-assisted vaginal births.1

The negative predictive value of EFM for fetal hypoxia/acidosis is high, but its positive predictive value is only 30%, and the false-positive rate is as high as 60%.2 Although a false-positive assessment may result in a potentially unnecessary operative vaginal or cesarean delivery, a falsely reassuring strip may produce devastating consequences in the newborn and, not infrequently, medical malpractice liability. One etiology associated with falsely reassuring assessments is that of EFM monitoring of the maternal heart rate and the failure to recognize the tracing as maternal.

In this article, I discuss the mechanisms and periods of labor that often are associated with the maternal heart rate masquerading as the fetal heart rate. I review common EFM patterns associated with the maternal heart rate so as to aid in recognizing the maternal heart rate. In addition, I provide 3 case scenarios that illustrate the simple yet critical steps that clinicians can take to remedy the situation. Being aware of the potential for a maternal heart rate recording, investigating the EFM signals, and correcting the monitoring can help prevent significant morbidity.

CASE 1 EFM shows seesaw decelerations and returns to baseline rate

A 29-year-old woman (G3P2) at 39 weeks’ gestation was admitted to the hospital with spontaneous labor. Continuous EFM external monitoring was initiated. After membranes spontaneously ruptured at 4 cm dilation, an epidural was placed. Throughout the active phase of labor, the fetus demonstrated intermittent mild variable decelerations, and the fetal heart rate baseline increased to 180 beats per minute (BPM). With complete dilation, the patient initiated pushing. During the first several pushes, the EFM demonstrated an initial heart rate deceleration, and a loss of signal, but the heart rate returned to a baseline rate of 150 BPM. With the patient’s continued pushing efforts, the EFM baseline increased to 180 BPM, with evidence of variable decelerations to a nadir of 120 BPM, although with some signal gaps (FIGURE 1, red arrow). The tracing then appeared to have a baseline of 120 BPM with variability or accelerations (FIGURE 1, green arrow) before shifting again to 170 to 180 BPM.

What was happening?

Why does the EFM record the maternal heart rate?

Most commonly, EFM recording of the maternal heart rate occurs during the second stage of labor. Early in labor, the normal fetal heart rate (110–160 BPM) typically exceeds the basal maternal heart rate. However, in the presence of chorioamnionitis and maternal fever or with the stress of maternal pushing, the maternal heart rate frequently approaches or exceeds that of the fetal heart rate. The maximum maternal heart rate can be estimated as 220 BPM minus the maternal age. Thus, the heart rate in a 20-year-old gravida may reach rates of 160 to 180 BPM, equivalent to 80% to 90% of her maximum heart rate during second-stage pushing.

The external Doppler fetal monitor, having a somewhat narrow acoustic window, may lose the focus on the fetal heart as a result of descent of the baby, the abdominal shape-altering effect of uterine contractions, and the patient’s pushing. During the second stage, the EFM may record the maternal heart rate from the uterine arteries. Although some clinicians claim to differentiate the maternal from the fetal heart rate by the “whooshing” maternal uterine artery signal as compared with the “thumping” fetal heart rate signal, this auditory assessment is unproven and likely unreliable.

CASE 1 Problem recognized and addressed

In this case, the obstetrician recognized that “slipping” from the fetal to the maternal heart rate recording occurred with the onset of maternal pushing. After the pushing ceased, the maternal heart rate slipped back to the fetal heart rate. With the next several contractions, only the maternal heart rate was recorded. A fetal scalp electrode was then placed, and fetal variable decelerations were recognized. In view of the category II EFM recording, a vacuum procedure was performed from +3 station and a female infant was delivered. She had Apgar scores of 6 and 8 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively, and she did well in the nursery.

Read what happened in Case 2 when the EFM demonstrated breaks in the tracing

CASE 2 EFM tracings belie the clinical situation

A 20-year-old woman (G1P0) presented for induction of labor at 41 weeks’ gestation. Continuous EFM recording was initiated, and the patient was given dinoprostone and, subsequently, oxytocin. Rupture of membranes at 3 cm demonstrated a small amount of fluid with thick meconium. The patient progressed to complete dilation and developed a temperature of 38.5°C; the EFM baseline increased to 180 BPM. Throughout the first hour of the second stage of labor, the EFM demonstrated breaks in the tracing and a heart rate of 130 to 150 BPM with each pushing effort (FIGURE 2A). The Doppler monitor was subsequently adjusted to focus on the fetal heart and repetitive late decelerations were observed (FIGURE 2B). An emergent cesarean delivery was performed. A depressed newborn male was delivered, with Apgar scores of 2 and 4 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively, and significant metabolic acidosis.

What happened?

Fetal versus maternal responses to pushing

The fetal variable deceleration pattern is well recognized by clinicians. As a result of umbilical cord occlusion (due to compression, stretching, or twisting of the cord), fetal variable decelerations have a typical pattern. An initial acceleration shoulder resulting from umbilical vein occlusion (due to reduced venous return) is followed by an umbilical artery occlusion–induced sharp deceleration. The relief of the occlusion allows the sharp return toward baseline with the secondary shoulder overshoot.

In some cases, partial umbilical cord occlusion that affects only the fetal umbilical vein may result in an acceleration, although these usually resolve or evolve into variable decelerations within 30 minutes. By contrast, the maternal heart rate typically increases with contractions and with maternal pushing efforts. Thus, a repetitive pattern of heart rate accelerations with each contraction should warn of a possible maternal heart rate recording.

How maternal heart rate responds to pushing. Maternal pushing is a Valsalva maneuver. Although there are 4 classic cardiovascular phases of Valsalva responses, the typical maternal pushing effort results in an increase in the maternal heart rate. With the common sequence of three 10-second pushes during each contraction, the maternal heart rate often exhibits 3 acceleration and deceleration responses. The maternal heart rate tracing looks similar to the shape of the Three Sisters mountain peaks in Oregon (FIGURE 3). Due to Valsalva physiology, the 3 peaks of the Sisters mirror the 3 uterine wave form peaks, although with a 5- to 10-second delay in the heart rate responses (mountain peaks) from the pushing efforts.

Pre- and postcontraction changes offer clues. Several classic findings aid in differentiating the maternal from the fetal heart rate. If the tracing is maternal, typically the heart rate gradually decreases following the end of the contraction/pushing and continues to decrease until the start of the next contraction/pushing, at which time it increases. During the push, the Three Sisters wave form, with the 5- to 10-second offset, should alert the clinician to possible maternal heart rate recordings. By contrast, the fetal heart rate variable deceleration typically increases following the end of the maternal contraction/pushing and is either stable or increases further (variable with slow recovery) prior to the next uterine contraction/pushing effort. These differences in the patterns of precontraction and postcontraction changes can be very valuable in differentiating periods of maternal versus fetal heart rate recordings.

With “slipping” between fetal and maternal recording, it is not uncommon to record fetal heart rate between contractions, slip to the maternal heart rate during the pushing effort, and return again to the fetal heart rate with the end of the contraction. When confounded with the potential for other EFM artifacts, including doubling of a low maternal or fetal heart rate, or halving of a tachycardic signal, it is not surprising that it is challenging to recognize an EFM maternal heart rate recording.

CASE 2 Check the monitor for accurate focus

A retrospective analysis of this case revealed that the maternal heart rate was recorded with each contraction throughout the second stage. The actual fetal heart rate pattern of decelerations was revealed with the refocusing of the Doppler monitor.

Read how subtle slipping manifested in the EFM tracing of Case 3

CASE 3 Low fetal heart rate and variability during contractions

A 22-year-old woman (G2P1) in spontaneous labor at term progressed to complete dilation. Fetal heart rate accelerations occurred for approximately 30 minutes. With the advent of pushing, the fetal heart rate showed a rate of 130 to 140 BPM and mild decelerations with each contraction (FIGURE 4A). As the second stage progressed, the tracing demonstrated an undulating baseline heart rate between 100 and 130 BPM with possible variability during contractions (FIGURE 4B). This pattern continued for an additional 60 minutes. At vaginal delivery, the ObGyn was surprised to deliver a depressed newborn with Apgar scores of 1 and 3 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively.

Slipping from the fetal to the maternal heart rate may be imperceptible

In contrast to the breaks in the tracings seen in Case 1 and Case 2, the EFM tracing in Case 3 appears continuous. Yet, slipping from the fetal to the maternal recording was occurring.

As seen in FIGURE 4C, the maternal heart rate with variability was recorded during pushing efforts, and the fetal heart rate was seen rising back toward a baseline between contractions. Note that the fetal heart rate did not reach a level baseline, but rather decelerated with the next contraction. The slipping to the maternal heart rate occurred without a perceptible break in the recording, making this tracing extremely difficult to interpret.

CASE 3 Be ever vigilant

The lack of recognition that the EFM recording had slipped to the maternal heart rate resulted in fetal and newborn hypoxia and acidosis, accounting for the infant’s low Apgar scores.

Read how using 3 steps can help you distinguish fetal from maternal heart rate patterns

Follow 3 steps to discern fetal vs maternal heart rate

These cases illustrate the difficulties in recognizing maternal heart rate patterns on the fetal monitor tracing. The 3 simple steps described below can aid in differentiating maternal from fetal heart rate patterns.

1 Be aware and alert

Recognize that EFM monitoring of the maternal heart rate may occur during periods of monitoring, particularly in second-stage labor. Often, the recorded tracing is a mix of fetal and maternal patterns. Remember that the maternal heart rate may increase markedly during the second stage and rise even higher during pushing efforts. When presented with a tracing that ostensibly represents the fetus, it may be challenging for the clinician to question that assumption. Thus, be aware that tracings may not represent what they seem to be.

Often, clinicians view only the 10-minute portion of the tracing displayed on the monitor screen. I recommend, however, that clinicians review the tracing over the past 30 to 60 minutes, or since their last EFM assessment, for an understanding of the recent fetal baseline heart rate and decelerations.

2 Investigate

Although it is sometimes challenging to recognize EFM maternal heart rate recordings, this is relatively easy to investigate. Even without a pulse oximeter in place, carefully examine the EFM recording for maternal signs to determine if the maternal heart rate is within the range of the recording. You can confirm that the recording is maternal through 1 of 3 easy measures:

- First, check the maternal radial pulse and correlate it with the heart rate baseline.

- Second, place a maternal electrocardiographic (EKG) heart rate monitor.

- Last, and often the simplest approach for continuous tracings, place a finger pulse oximeter to provide a continuous maternal pulse reading. Should the maternal heart rate superimpose on the EFM recording, maternal patterns are likely being detected. However, since the pulse oximeter and EFM Doppler devices use different technologies, they will provide similar—but not precisely identical—heart rate numerical readings if both are assessing the maternal heart rate. In that case, take steps to assure that the EFM truly is recording the fetal heart rate.

3 Treat and correct

If the EFM is recording a maternal signal or if a significant question remains, place a fetal scalp electrode (unless contraindicated), as this may likely occur during the second stage. Alternatively, place a maternal surface fetal EKG monitor, or use ultrasonography to visually assess the fetal heart rate in real time.

Key point summary

The use of a maternal finger pulse oximeter, combined with a careful assessment of the EFM tracing, and/or a fetal scalp electrode are appropriate measures for confirming a fetal heart rate recording.

The 3 steps described (be aware and alert, investigate, treat and correct) can help you effectively monitor the fetal heart rate and avoid the potentially dangerous outcomes that might occur when the maternal heart rate masquerades as the fetal heart rate.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Alfirevic Z, Devane D, Gyte GM, Cuthbert A. Continuous cardiotocography (CTG) as a form of electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) for fetal assessment during labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017; doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006066.pub3.

- Pinas A, Chandraharan E. Continuous cardiotocography during labour: analysis, classification and management. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;30:33–47.

- Alfirevic Z, Devane D, Gyte GM, Cuthbert A. Continuous cardiotocography (CTG) as a form of electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) for fetal assessment during labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017; doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006066.pub3.

- Pinas A, Chandraharan E. Continuous cardiotocography during labour: analysis, classification and management. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;30:33–47.

2018 Update on infectious disease

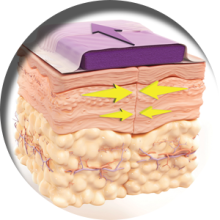

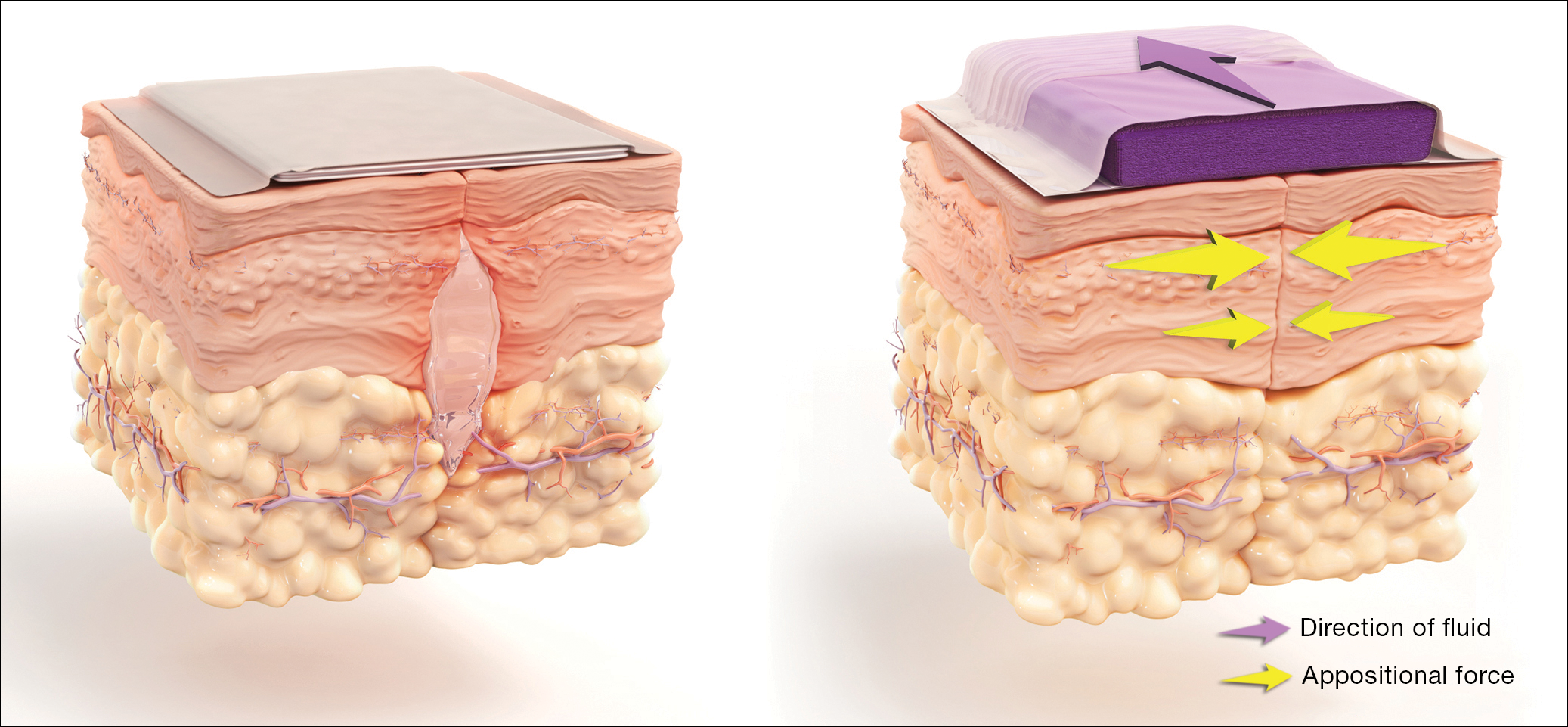

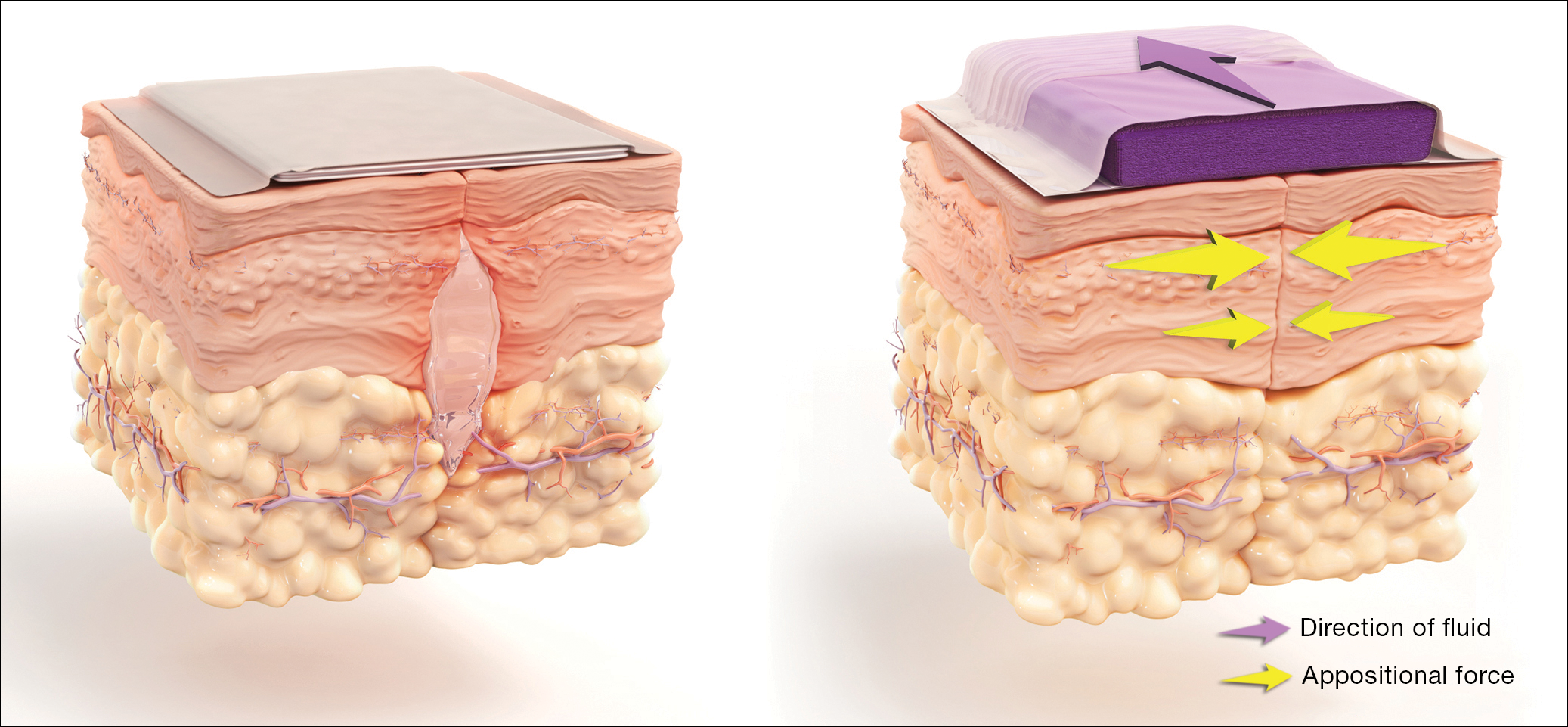

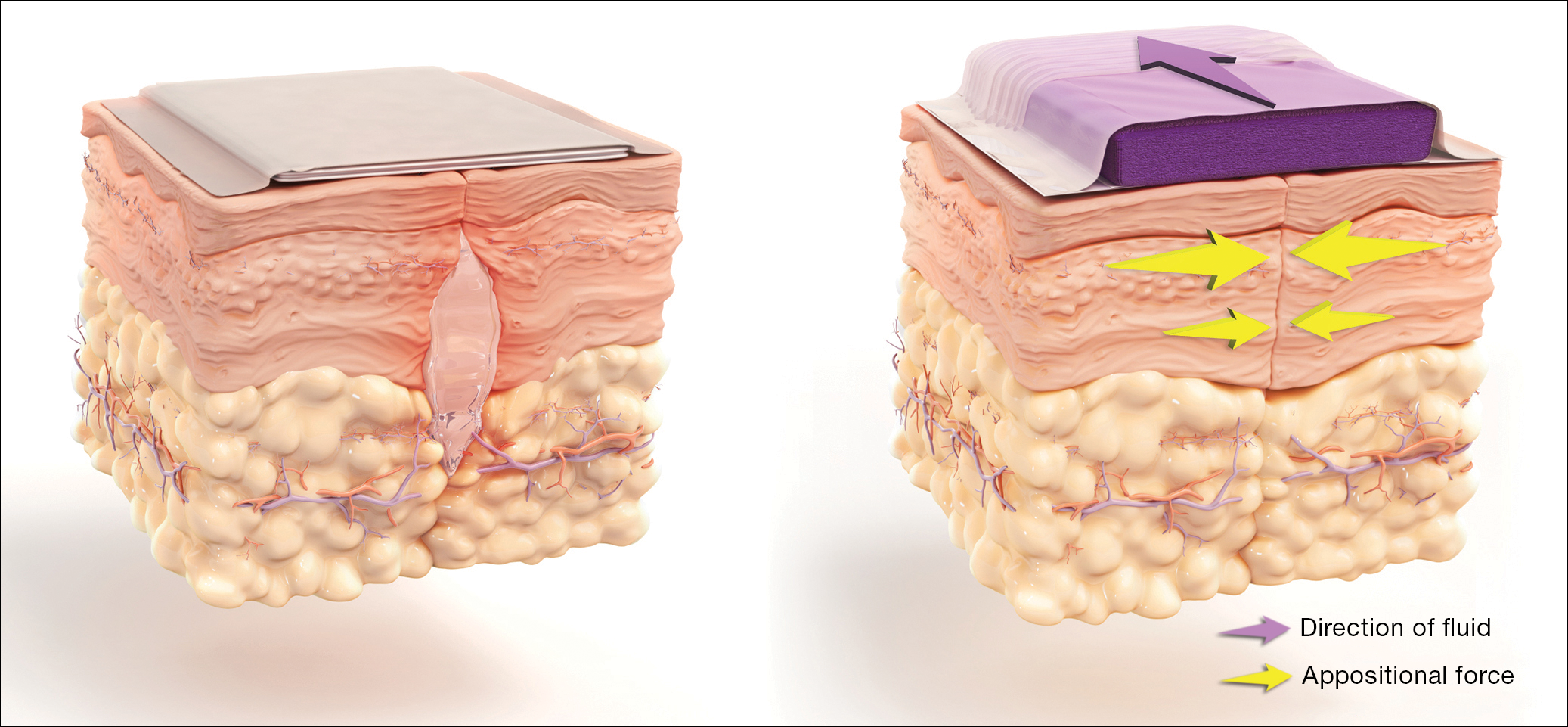

In this Update I highlight 5 interesting investigations on infectious diseases. The first addresses the value of applying prophylactically a negative-pressure wound dressing to prevent surgical site infection (SSI) in obese women having cesarean delivery (CD). The second report assesses the effectiveness of a preoperative vaginal wash in reducing the frequency of postcesarean endometritis. The third investigation examines the role of systemic antibiotics, combined with surgical drainage, for patients who have subcutaneous abscesses ranging in size up to 5 cm. The fourth study presents new information about the major risk factors for Clostridium difficile infections in obstetric patients. The final study presents valuable sobering new data about the risks of congenital Zika virus infection.

Negative-pressure wound therapy after CD shows some benefit in preventing SSI

Yu L, Kronen RJ, Simon LE, Stoll CR, Colditz GA, Tuuli MG. Prophylactic negative-pressure wound therapy after cesarean is associated with reduced risk of surgical site infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(2):200-210.e1.

Yu and colleagues sought to determine if the prophylactic use of negative-pressure devices, compared with standard wound dressing, was effective in reducing the frequency of SSI after CD.

The authors searched multiple databases and initially identified 161 randomized controlled trials and cohort studies for further assessment. After applying rigorous exclusion criteria, they ultimately selected 9 studies for systematic review and meta-analysis. Six studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 2 were retrospective cohort studies, and 1 was a prospective cohort study. Five studies were considered high quality; 4 were of low quality.

Details of the study

Several types of negative-pressure devices were used, but the 2 most common were the Prevena incision management system (KCI, San Antonio, Texas) and PICO negative- pressure wound therapy (Smith & Nephew, St. Petersburg, Florida). The majority of patients in all groups were at high risk for wound complications because of obesity.

The primary outcome of interest was the frequency of SSI. Secondary outcomes included dehiscence, seroma, endometritis, a composite measure for all wound complications, and hospital readmission.

The absolute risk of SSI in the intervention group was 5% (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.0%-7.0%) compared with 11% (95% CI, 7.0%-16.0%) in the standard dressing group. The pooled risk ratio was 0.45 (95% CI, 0.31-0.66). The absolute risk reduction was 6% (95% CI, -10.0% to -3.0%), and the number needed to treat was 17.

There were no significant differences in the rate of any of the secondary outcomes other than the composite of all wound complications. This difference was largely accounted for by the difference in the rate of SSI.

How negative-pressure devices aid wound healing

Yu and colleagues explained that negative-pressure devices exert their beneficial effects in various ways, including:

- shrinking the wound

- inducing cellular stretch

- removing extracellular fluids

- creating a favorable environment for healing

- promoting angiogenesis and neurogenesis.

Multiple studies in nonobstetric patients have shown that prophylactic use of negative-pressure devices is beneficial in reducing the rate of SSI.1 Yu and colleagues' systematic review and meta-analysis confirms those findings in a high-risk population of women having CD.

Study limitations

Before routinely adopting the use of negative-pressure devices for all women having CD, however, obstetricians should consider the following caveats:

- The investigations included in the study by Yu and colleagues did not consistently distinguish between scheduled versus unscheduled CDs.

- The reports did not systematically consider other major risk factors for wound complications besides obesity, and they did not control for these confounders in the statistical analyses.

- The studies included in the meta-analysis did not provide full descriptions of other measures that might influence the rate of SSIs, such as timing and selection of prophylactic antibiotics, selection of suture material, preoperative skin preparation, and closure techniques for the deep subcutaneous tissue and skin.

- None of the included studies systematically considered the cost-effectiveness of the negative-pressure devices. This is an important consideration given that the acquisition cost of these devices ranges from $200 to $500.

Results of the systematic review and meta-analysis by Yu and colleagues suggest that prophylactic negative-pressure wound therapy in high-risk mostly obese women after CD reduces SSI and overall wound complications. The study's limitations, however, must be kept in mind, and more data are needed. It would be most helpful if a large, well-designed RCT was conducted and included 2 groups with comparable multiple major risk factors for wound complications, and in which all women received the following important interventions2-4:

- removal of hair in the surgical site with a clipper, not a razor

- cleansing of the skin with a chlorhexidine rather than an iodophor solution

- closure of the deep subcutaneous tissue if the total subcutaneous layer exceeds 2 cm in depth

- closure of the skin with suture rather than staples

- administration of antibiotic prophylaxis, ideally with a combination of cefazolin plus azithromycin, prior to the surgical incision.

Read about vaginal cleansing’s effect on post-CD endometritis

Vaginal cleansing before CD lowers risk of postop endometritis

Caissutti C, Saccone G, Zullo F, et al. Vaginal cleansing before cesarean delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(3):527-538.

Caissutti and colleagues aimed to determine if cleansing the vagina with an antiseptic solution prior to surgery reduced the frequency of postcesarean endometritis. They included 16 RCTs (4,837 patients) in their systematic review and meta-analysis. The primary outcome was the frequency of postoperative endometritis.

Details of the study

The studies were conducted in several countries and included patients of various socioeconomic classes. Six trials included only patients having a scheduled CD; 9 included both scheduled and unscheduled cesareans; and 1 included only unscheduled cesareans. In 11 studies, povidone-iodine was the antiseptic solution used. Two trials used chlorhexidine diacetate 0.2%, and 1 used chlorhexidine diacetate 0.4%. One trial used metronidazole 0.5% gel, and another used the antiseptic cetrimide, which is a mixture of different quaternary ammonium salts, including cetrimonium bromide.

In all trials, patients received prophylactic antibiotics. The antibiotics were administered prior to the surgical incision in 6 trials; they were given after the umbilical cord was clamped in 6 trials. In 2 trials, the antibiotics were given at varying times, and in the final 2 trials, the timing of antibiotic administration was not reported. Of note, no trials described the method of placenta removal, a factor of considerable significance in influencing the rate of postoperative endometritis.5,6

Endometritis frequency reduced with vaginal cleansing; benefit greater in certain groups. Overall, in the 15 trials in which vaginal cleansing was compared with placebo or with no treatment, women in the treatment group had a significantly lower rate of endometritis (4.5% compared with 8.8%; relative risk [RR], 0.52; 95% CI, 0.37-0.72). When only women in labor were considered, the frequency of endometritis was 8.1% in the intervention group compared with 13.8% in the control group (RR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.28-0.97). In the women who were not in labor, the difference in the incidence of endometritis was not statistically significant (3.5% vs 6.6%; RR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.34-1.15).

In the subgroup analysis of women with ruptured membranes at the time of surgery, the incidence of endometritis was 4.3% in the treatment group compared with 20.1% in the control group (RR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.10-0.52). In women with intact membranes at the time of surgery, the incidence of endometritis was not significantly reduced in the treatment group.

Interestingly, in the subgroup analysis of the 10 trials that used povidone-iodine, the reduction in the frequency of postcesarean endometritis was statistically significant (2.8% vs 6.3%; RR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.25-0.71). However, this same protective effect was not observed in the women treated with chlorhexidine. In the 1 trial that directly compared povidone-iodine with chlorhexidine, there was no statistically significant difference in outcome.

Simple intervention, solid benefit

Endometritis is the most common complication following CD. The infection is polymicrobial, with mixed aerobic and anaerobic organisms. The principal risk factors for postcesarean endometritis are low socioeconomic status, extended duration of labor and ruptured membranes, multiple vaginal examinations, internal fetal monitoring, and pre-existing vaginal infections (principally, bacterial vaginosis and group B streptococcal colonization).

Two interventions are clearly of value in reducing the incidence of endometritis: administration of prophylactic antibiotics prior to the surgical incision and removal of the placenta by traction on the cord as opposed to manual extraction.5,6

The assessment by Caissutti and colleagues confirms that a third measure — preoperative vaginal cleansing — also helps reduce the incidence of postcesarean endometritis. The principal benefit is seen in women who have been in labor with ruptured membranes, although certainly it is not harmful in lower-risk patients. The intervention is simple and straightforward: a 30-second vaginal wash with a povidone-iodine solution just prior to surgery.

From my perspective, the interesting unanswered question is why a chlorhexidine solution with low alcohol content was not more effective than povidone-iodine, given that a chlorhexidine abdominal wash is superior to povidone-iodine in preventing wound infection after cesarean delivery.7 Until additional studies confirm the effectiveness of vaginal cleansing with chlorhexidine, I recommend the routine use of the povidone-iodine solution in all women having CD.

Read about management approaches for skin abscesses

Treat smaller skin abscesses with antibiotics after surgical drainage? Yes.

Daum RS, Miller LG, Immergluck L, et al; for the DMID 07-0051 Team. A placebo-controlled trial of antibiotics for smaller skin abscesses. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(26):2545-2555.

For treatment of subcutaneous abscesses that were 5 cm or smaller in diameter, investigators sought to determine if surgical drainage alone was equivalent to surgical drainage plus systemic antibiotics. After their abscess was drained, patients were randomly assigned to receive either clindamycin (300 mg 3 times daily) or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (80 mg/400 mg twice daily) or placebo for 10 days. The primary outcome was clinical cure 7 to 10 days after treatment.

Details of the study

Daum and colleagues enrolled 786 participants (505 adults, 281 children) in the prospective double-blind study. Staphylococcus aureus was isolated from 527 patients (67.0%); methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) was isolated from 388 (49.4%). The cure rate was similar in patients in the clindamycin group (83.1%) and the trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole group (81.7%), and the cure rate in each antibiotic group was significantly higher than that in the placebo group (68.9%; P<.001 for both comparisons). The difference in treatment effect was specifically limited to patients who had S aureus isolated from their lesions.

Findings at follow-up. At 1 month of follow-up, new infections were less common in the clindamycin group (6.8%) than in the trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole group (13.5%; P = .03) or the placebo group (12.4%; P = .06). However, the highest frequency of adverse effects occurred in the patients who received clindamycin (21.9% vs 11.1% vs 12.5%). No adverse effects were judged to be serious, and all resolved without sequela.

Controversy remains on antibiotic use after drainage

This study is important for 2 major reasons. First, soft tissue infections are quite commonand can evolve into serious problems, especially when the offending pathogen is MRSA. Second, controversy exists about whether systemic antibiotics are indicated if the subcutaneous abscess is relatively small and is adequately drained. For example, Talan and colleagues demonstrated that, in settings with a high prevalence of MRSA, surgical drainage combined with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (1 double-strength tablet orally twice daily) was superior to drainage plus placebo.8 However, Daum and Gold recently debated the issue of drainage plus antibiotics in a case vignette and reached opposite conclusions.9

In my opinion, this investigation by Daum and colleagues supports a role for consistent use of systemic antibiotics following surgical drainage of clinically significant subcutaneous abscesses that have a 5 cm or smaller diameter. Several oral antibiotics are effective against S aureus, including MRSA.10 These drugs include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (1 double-strength tablet orally twice daily), clindamycin (300-450 mg 3 times daily), doxycycline (100 mg twice daily), and minocycline (200 mg initially, then 100 mg every 12 hours).

Of these drugs, I prefer trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, provided that the patient does not have an allergy to sulfonamides. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is significantly less expensive than the other 3 drugs and usually is better tolerated. In particular, compared with clindamycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is less likely to cause antibiotic-associated diarrhea, including Clostridium difficile infection. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole should not be used in the first trimester of pregnancy because of concerns about fetal teratogenicity.

Read how to avoid C difficile infections in pregnant patients

Antibiotic use, common in the obstetric population, raises risk for C difficile infection

Ruiter-Ligeti J, Vincent S, Czuzoj-Shulman N, Abenhaim HA. Risk factors, incidence, and morbidity associated with obstetric Clostridium difficile infection. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(2):387-391.

The objective of this investigation was to identify risk factors for Clostridium difficile infection (previously termed pseudomembranous enterocolitis) in obstetric patients. The authors performed a retrospective cohort study using information from a large database maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. This database provides information about inpatient hospital stays in the United States, and it is the largest repository of its kind. It includes data from a sample of 1,000 US hospitals.

Details of the study

Ruiter-Ligeti and colleagues reviewed 13,881,592 births during 1999-2013 and identified 2,757 (0.02%) admissions for delivery complicated by C difficile infection, a rate of 20 admissions per 100,000 deliveries per year (95% CI, 19.13-20.62). The rate of admissions with this diagnosis doubled from 1999 (15 per 100,000) to 2013 (30 per 100,000, P<.001).

Among these obstetric patients, the principal risk factors for C difficile infection were older age, multiple gestation, long-term antibiotic use (not precisely defined), and concurrent diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. In addition, patients with pyelonephritis, perineal or cesarean wound infections, or pneumonia also were at increased risk, presumably because those patients required longer courses of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Of additional note, when compared with women who did not have C difficile infection, patients with infection were more likely to develop a thromboembolic event (38.4 per 1,000), paralytic ileus (58.0 per 1,000), sepsis (46.4 per 1,000), and death (8.0 per 1,000).

Be on guard for C difficile infection in antibiotic-treated obstetric patients

C difficile infection is an uncommon but potentially very serious complication of antibiotic therapy. Given that approximately half of all women admitted for delivery are exposed to antibiotics because of prophylaxis for group B streptococcus infection, prophylaxis for CD, and treatment of chorioamnionitis and puerperal endometritis, clinicians constantly need to be vigilant for this complication.11

Affected patients typically present with frequent loose, watery stools and lower abdominal cramping. In severe cases, blood may be present in the stool, and signs of intestinal distention and even acute peritonitis may be evident. The diagnosis can be established by documenting a positive culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay for C difficile and a positive cytotoxin assay for toxins A and/or B. In addition, if endoscopy is performed, the characteristic gray membranous plaques can be visualized on the rectal and colonic mucosa.11

Discontinue antibiotic therapy. The first step in managing affected patients is to stop all antibiotics, if possible, or at least the one most likely to be the causative agent of C difficile infection. Patients with relatively mild clinical findings should be treated with oral metronidazole, 500 mg every 8 hours for 10 to 14 days. Patients with severe findings should be treated with oral vancomycin, 500 mg every 6 hours, plus IV metronidazole, 500 mg every 8 hours. The more seriously ill patient must be observed carefully for signs of bowel obstruction, intestinal perforation, peritonitis, and sepsis.

Clearly, clinicians should make every effort to prevent C difficile infection in the first place. The following preventive measures are essential:

- Avoid the use of extremely broad-spectrum antibiotics for prophylaxis for CD.

- When using therapeutic antibiotics, keep the spectrum as narrow as possible, consistent with adequately treating the pathogens causing the infection.