User login

New York City launches initiative to eliminate racial disparities in maternal death

In response to alarming racial disparities, New York City announced a new initiative last week to reduce maternal deaths and complications among women of color. Under the new plan, the city will improve the data collection on maternal deaths and complications, fund implicit bias training for medical staff at private and public hospitals, and launch a public awareness campaign.

Over the next three years, the city will spend $12.8 million on the initiative, with the goal of eliminating the black-white racial disparity in deaths related to pregnancy and childbirth and cutting the number of complications in half within five years.

“We recognize these are ambitious goals, but they are not unrealistic,” said Dr. Herminia Palacio, New York City’s deputy mayor for health and human services. “It’s an explicit recognition of the urgency of this issue and puts the goal posts in front of us.”

The city’s health department is targeting nearly two dozen public and private hospitals over four years, focusing on neighborhoods with the highest complication rates, including the South Bronx, North and Central Brooklyn, and East and Central Harlem. Hospital officials will study data from cases that led to bad outcomes, and staff will participate in drills aimed at helping them recognize and treat those complications.

Health department officials approached SUNY Downstate Medical Center in May to serve as a pilot site for many of the new measures.

The Central Brooklyn hospital was featured in the “Lost Mothers” series published by ProPublica and NPR last year as one of the starkest examples of racial disparities among hospitals in three states, according to our analysis of over 1 million births in Florida, Illinois and New York. In the second half of last year, two women, both black, died shortly after delivering at SUNY Downstate from causes that experts have said are preventable. The public, state-run hospital has one of the highest complication rates for hemorrhage in the city.

“We look forward to working with all of our partners to provide quality maternal health care for expectant mothers,” said hospital spokesperson Dawn Skeete-Walker.

“SUNY Downstate serves a unique and diverse population in Brooklyn where many of our expectant mothers are from a variety of different backgrounds, beliefs, and cultures.”

The city will also specifically target its own public hospitals, which are run by NYC Health + Hospitals, training staff on how to better identify and treat hemorrhage and blood clots, two leading causes of maternal death.

The initiative is “aimed at using an approach that encourages folks to have a sense of accountability without finger pointing or blame, and that encourages hospitals to be active participants to identify practices that would benefit from improvement,” said Palacio.

In addition to training, the city’s public hospitals will hire maternal care coordinators who will assist high-risk pregnant women with their appointments, prescriptions and public health benefits. Public hospitals will also work to strengthen prenatal and postpartum care, including conducting hemorrhage assessments, establishing care plans, and providing contraceptive counselling, breastfeeding support and screening for maternal depression.

Starting in 2019, the health department plans to launch a maternal safety public awareness campaign in partnership with grassroots organizations.

“This is a positive first step in really being able to address the concerns of women of color and pregnant women,” said Chanel Porchia-Albert, founder and executive director of Ancient Song Doula Services, which is based in New York City. “There need to be accountability measures that are put in place that stress the community as an active participant and stakeholder.”

The city’s initiative is the latest in a wave of maternal health reforms following the “Lost Mothers” series. Over the past few months, the U.S. Senate has proposed $50 million in funding to reduce maternal deaths, and several states have launched review committees to examine birth outcomes.

As ProPublica and NPR reported, between 700 and 900 women die from causes related to pregnancy and childbirth in the United States every year, and tens of thousands more experience severe complications. The rate of maternal death is substantially higher in the United States than in other affluent nations, and has climbed over the past decade, mostly driven by the outcomes of women of color.

While poverty and inadequate access to health care explain part of the racial disparity in maternal deaths, research has shown that the quality of care at hospitals where black women deliver plays a significant role as well. ProPublica added to research that has found that women who deliver at disproportionately “black-serving” hospitals are more likely to experience serious complications — from emergency hysterectomies to birth-related blood clots — than mothers who deliver at institutions that serve fewer black women.

In New York City, the racial disparity in maternal outcomes is among the largest in the nation, and it’s growing. According to a recent report from New York City’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, even as the overall maternal mortality rate across the city has decreased, the gap between black and white mothers has widened.

Regardless of their education, obesity or poverty level, black mothers in New York City are at a higher risk of harm than their white counterparts. Black mothers with a college education fare worse than women of all other races who dropped out of high school. Black women of normal weight have higher rates of harm than obese women of all other races. And black women who reside in the wealthiest neighborhoods have worse outcomes than white, Asian and Hispanic mothers in the poorest ones.

“If you are a poor black woman, you don’t have access to quality OBGYN care, and if you are a wealthy black women, like Serena Williams, you get providers who don’t listen to you when you say you can’t breathe,” said Patricia Loftman, a member of the American College of Nurse Midwives Board of Directors who worked for 30 years as a certified nurse-midwife in Harlem. “The components of this initiative are very aggressive and laudable to the extent that they are forcing hospital departments to talk about implicit bias.”

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom.

In response to alarming racial disparities, New York City announced a new initiative last week to reduce maternal deaths and complications among women of color. Under the new plan, the city will improve the data collection on maternal deaths and complications, fund implicit bias training for medical staff at private and public hospitals, and launch a public awareness campaign.

Over the next three years, the city will spend $12.8 million on the initiative, with the goal of eliminating the black-white racial disparity in deaths related to pregnancy and childbirth and cutting the number of complications in half within five years.

“We recognize these are ambitious goals, but they are not unrealistic,” said Dr. Herminia Palacio, New York City’s deputy mayor for health and human services. “It’s an explicit recognition of the urgency of this issue and puts the goal posts in front of us.”

The city’s health department is targeting nearly two dozen public and private hospitals over four years, focusing on neighborhoods with the highest complication rates, including the South Bronx, North and Central Brooklyn, and East and Central Harlem. Hospital officials will study data from cases that led to bad outcomes, and staff will participate in drills aimed at helping them recognize and treat those complications.

Health department officials approached SUNY Downstate Medical Center in May to serve as a pilot site for many of the new measures.

The Central Brooklyn hospital was featured in the “Lost Mothers” series published by ProPublica and NPR last year as one of the starkest examples of racial disparities among hospitals in three states, according to our analysis of over 1 million births in Florida, Illinois and New York. In the second half of last year, two women, both black, died shortly after delivering at SUNY Downstate from causes that experts have said are preventable. The public, state-run hospital has one of the highest complication rates for hemorrhage in the city.

“We look forward to working with all of our partners to provide quality maternal health care for expectant mothers,” said hospital spokesperson Dawn Skeete-Walker.

“SUNY Downstate serves a unique and diverse population in Brooklyn where many of our expectant mothers are from a variety of different backgrounds, beliefs, and cultures.”

The city will also specifically target its own public hospitals, which are run by NYC Health + Hospitals, training staff on how to better identify and treat hemorrhage and blood clots, two leading causes of maternal death.

The initiative is “aimed at using an approach that encourages folks to have a sense of accountability without finger pointing or blame, and that encourages hospitals to be active participants to identify practices that would benefit from improvement,” said Palacio.

In addition to training, the city’s public hospitals will hire maternal care coordinators who will assist high-risk pregnant women with their appointments, prescriptions and public health benefits. Public hospitals will also work to strengthen prenatal and postpartum care, including conducting hemorrhage assessments, establishing care plans, and providing contraceptive counselling, breastfeeding support and screening for maternal depression.

Starting in 2019, the health department plans to launch a maternal safety public awareness campaign in partnership with grassroots organizations.

“This is a positive first step in really being able to address the concerns of women of color and pregnant women,” said Chanel Porchia-Albert, founder and executive director of Ancient Song Doula Services, which is based in New York City. “There need to be accountability measures that are put in place that stress the community as an active participant and stakeholder.”

The city’s initiative is the latest in a wave of maternal health reforms following the “Lost Mothers” series. Over the past few months, the U.S. Senate has proposed $50 million in funding to reduce maternal deaths, and several states have launched review committees to examine birth outcomes.

As ProPublica and NPR reported, between 700 and 900 women die from causes related to pregnancy and childbirth in the United States every year, and tens of thousands more experience severe complications. The rate of maternal death is substantially higher in the United States than in other affluent nations, and has climbed over the past decade, mostly driven by the outcomes of women of color.

While poverty and inadequate access to health care explain part of the racial disparity in maternal deaths, research has shown that the quality of care at hospitals where black women deliver plays a significant role as well. ProPublica added to research that has found that women who deliver at disproportionately “black-serving” hospitals are more likely to experience serious complications — from emergency hysterectomies to birth-related blood clots — than mothers who deliver at institutions that serve fewer black women.

In New York City, the racial disparity in maternal outcomes is among the largest in the nation, and it’s growing. According to a recent report from New York City’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, even as the overall maternal mortality rate across the city has decreased, the gap between black and white mothers has widened.

Regardless of their education, obesity or poverty level, black mothers in New York City are at a higher risk of harm than their white counterparts. Black mothers with a college education fare worse than women of all other races who dropped out of high school. Black women of normal weight have higher rates of harm than obese women of all other races. And black women who reside in the wealthiest neighborhoods have worse outcomes than white, Asian and Hispanic mothers in the poorest ones.

“If you are a poor black woman, you don’t have access to quality OBGYN care, and if you are a wealthy black women, like Serena Williams, you get providers who don’t listen to you when you say you can’t breathe,” said Patricia Loftman, a member of the American College of Nurse Midwives Board of Directors who worked for 30 years as a certified nurse-midwife in Harlem. “The components of this initiative are very aggressive and laudable to the extent that they are forcing hospital departments to talk about implicit bias.”

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom.

In response to alarming racial disparities, New York City announced a new initiative last week to reduce maternal deaths and complications among women of color. Under the new plan, the city will improve the data collection on maternal deaths and complications, fund implicit bias training for medical staff at private and public hospitals, and launch a public awareness campaign.

Over the next three years, the city will spend $12.8 million on the initiative, with the goal of eliminating the black-white racial disparity in deaths related to pregnancy and childbirth and cutting the number of complications in half within five years.

“We recognize these are ambitious goals, but they are not unrealistic,” said Dr. Herminia Palacio, New York City’s deputy mayor for health and human services. “It’s an explicit recognition of the urgency of this issue and puts the goal posts in front of us.”

The city’s health department is targeting nearly two dozen public and private hospitals over four years, focusing on neighborhoods with the highest complication rates, including the South Bronx, North and Central Brooklyn, and East and Central Harlem. Hospital officials will study data from cases that led to bad outcomes, and staff will participate in drills aimed at helping them recognize and treat those complications.

Health department officials approached SUNY Downstate Medical Center in May to serve as a pilot site for many of the new measures.

The Central Brooklyn hospital was featured in the “Lost Mothers” series published by ProPublica and NPR last year as one of the starkest examples of racial disparities among hospitals in three states, according to our analysis of over 1 million births in Florida, Illinois and New York. In the second half of last year, two women, both black, died shortly after delivering at SUNY Downstate from causes that experts have said are preventable. The public, state-run hospital has one of the highest complication rates for hemorrhage in the city.

“We look forward to working with all of our partners to provide quality maternal health care for expectant mothers,” said hospital spokesperson Dawn Skeete-Walker.

“SUNY Downstate serves a unique and diverse population in Brooklyn where many of our expectant mothers are from a variety of different backgrounds, beliefs, and cultures.”

The city will also specifically target its own public hospitals, which are run by NYC Health + Hospitals, training staff on how to better identify and treat hemorrhage and blood clots, two leading causes of maternal death.

The initiative is “aimed at using an approach that encourages folks to have a sense of accountability without finger pointing or blame, and that encourages hospitals to be active participants to identify practices that would benefit from improvement,” said Palacio.

In addition to training, the city’s public hospitals will hire maternal care coordinators who will assist high-risk pregnant women with their appointments, prescriptions and public health benefits. Public hospitals will also work to strengthen prenatal and postpartum care, including conducting hemorrhage assessments, establishing care plans, and providing contraceptive counselling, breastfeeding support and screening for maternal depression.

Starting in 2019, the health department plans to launch a maternal safety public awareness campaign in partnership with grassroots organizations.

“This is a positive first step in really being able to address the concerns of women of color and pregnant women,” said Chanel Porchia-Albert, founder and executive director of Ancient Song Doula Services, which is based in New York City. “There need to be accountability measures that are put in place that stress the community as an active participant and stakeholder.”

The city’s initiative is the latest in a wave of maternal health reforms following the “Lost Mothers” series. Over the past few months, the U.S. Senate has proposed $50 million in funding to reduce maternal deaths, and several states have launched review committees to examine birth outcomes.

As ProPublica and NPR reported, between 700 and 900 women die from causes related to pregnancy and childbirth in the United States every year, and tens of thousands more experience severe complications. The rate of maternal death is substantially higher in the United States than in other affluent nations, and has climbed over the past decade, mostly driven by the outcomes of women of color.

While poverty and inadequate access to health care explain part of the racial disparity in maternal deaths, research has shown that the quality of care at hospitals where black women deliver plays a significant role as well. ProPublica added to research that has found that women who deliver at disproportionately “black-serving” hospitals are more likely to experience serious complications — from emergency hysterectomies to birth-related blood clots — than mothers who deliver at institutions that serve fewer black women.

In New York City, the racial disparity in maternal outcomes is among the largest in the nation, and it’s growing. According to a recent report from New York City’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, even as the overall maternal mortality rate across the city has decreased, the gap between black and white mothers has widened.

Regardless of their education, obesity or poverty level, black mothers in New York City are at a higher risk of harm than their white counterparts. Black mothers with a college education fare worse than women of all other races who dropped out of high school. Black women of normal weight have higher rates of harm than obese women of all other races. And black women who reside in the wealthiest neighborhoods have worse outcomes than white, Asian and Hispanic mothers in the poorest ones.

“If you are a poor black woman, you don’t have access to quality OBGYN care, and if you are a wealthy black women, like Serena Williams, you get providers who don’t listen to you when you say you can’t breathe,” said Patricia Loftman, a member of the American College of Nurse Midwives Board of Directors who worked for 30 years as a certified nurse-midwife in Harlem. “The components of this initiative are very aggressive and laudable to the extent that they are forcing hospital departments to talk about implicit bias.”

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom.

Alcohol use during breastfeeding linked to cognitive harms in children

Risky or higher alcohol consumption while breastfeeding could be associated with poorer cognitive outcomes in children, according to a longitudinal cohort study.

In a paper published in Pediatrics, researchers analyzed data from 5,107 infants who were followed up every 2 years from Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. They also examined other factors, such as information on mothers’ smoking and drinking habits during breastfeeding.

The analysis showed a significant association between increased maternal alcohol consumption and decreased nonverbal reasoning scores in children aged 6-7 years who had been breastfed at any time (95% confidence interval, –0.18 to –0.04; P = .01). The effect was independent of other factors that might have played a role, including prenatal alcohol consumption, maternal age, income, birth weight, head injury, and learning delay.

(95% CI, –0.20 to 0.17; P = .87), which the authors said supported the suggestion that the cognitive effects were the result of alcohol exposure through breast milk.

“This suggests that alcohol exposure through breast milk was responsible for cognitive reductions in breastfed infants rather than psychosocial or environmental factors surrounding maternal alcohol consumption,” wrote Louisa Gibson and Melanie Porter, PhD, of the department of psychology at Macquarie University in Sydney.

However, the association was no longer evident in children aged 8-11 years. The authors said that finding might be attributable to mediation by factors such as increased education.

In addition, Ms. Gibson and Dr. Porter did not find an association between smoking during breastfeeding and cognitive outcomes of the offspring.

The findings on breastfeeding and cognitive reductions in breastfed infants are consistent with animal studies showing that ethanol in breast milk can affect normal brain development.

“Increased cerebral cortex apoptosis and necrosis, for example, may disrupt higher order executive skills relied on in reasoning tasks,” the authors wrote. “Likewise, decreased myelination could reduce the processing speed needed to problem solve quickly.”

Children also might experience reduced cognition as a secondary effect of changes in feeding, nutritional intake, and sleep patterns that could themselves affect brain development, leading to behavioral changes that might “reduce exposure to enriching stimuli.”

However, the authors noted that the frequency and quantity of milk consumed, and the timing of alcohol consumption relative to breastfeeding, were not recorded as part of the study.

“The impact of this is unknown, however, because not all women time their alcohol consumption to limit alcohol exposure, and unpredictable infant feeding patterns can interfere with timing attempts.”

Ms. Gibson and Dr. Porter reported no external funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gibson L et al. Pediatrics 2018 Jul 30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4266.

This study represents an important step toward understanding the neurobiological and developmental risks associated with substance exposure during breastfeeding.

The finding of an association between maternal alcohol consumption during breastfeeding and later negative effects on child development are not surprising, given what already is known harmful effects of alcohol on the developing brain. There is no reason to think that these harmful effects might be limited to prenatal alcohol exposure.

“Previous recommendations that reveal limited alcohol consumption to be compatible with breastfeeding during critical periods of development ... may need to be reconsidered in light of this combined evidence,” wrote Lauren M. Jansson, MD.

Dr. Jansson is affiliated with the department of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. These comments are taken from an editorial (Pediatrics. 2018 Jul 30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1377). She declared having no conflicts of interest.

This study represents an important step toward understanding the neurobiological and developmental risks associated with substance exposure during breastfeeding.

The finding of an association between maternal alcohol consumption during breastfeeding and later negative effects on child development are not surprising, given what already is known harmful effects of alcohol on the developing brain. There is no reason to think that these harmful effects might be limited to prenatal alcohol exposure.

“Previous recommendations that reveal limited alcohol consumption to be compatible with breastfeeding during critical periods of development ... may need to be reconsidered in light of this combined evidence,” wrote Lauren M. Jansson, MD.

Dr. Jansson is affiliated with the department of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. These comments are taken from an editorial (Pediatrics. 2018 Jul 30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1377). She declared having no conflicts of interest.

This study represents an important step toward understanding the neurobiological and developmental risks associated with substance exposure during breastfeeding.

The finding of an association between maternal alcohol consumption during breastfeeding and later negative effects on child development are not surprising, given what already is known harmful effects of alcohol on the developing brain. There is no reason to think that these harmful effects might be limited to prenatal alcohol exposure.

“Previous recommendations that reveal limited alcohol consumption to be compatible with breastfeeding during critical periods of development ... may need to be reconsidered in light of this combined evidence,” wrote Lauren M. Jansson, MD.

Dr. Jansson is affiliated with the department of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. These comments are taken from an editorial (Pediatrics. 2018 Jul 30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1377). She declared having no conflicts of interest.

Risky or higher alcohol consumption while breastfeeding could be associated with poorer cognitive outcomes in children, according to a longitudinal cohort study.

In a paper published in Pediatrics, researchers analyzed data from 5,107 infants who were followed up every 2 years from Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. They also examined other factors, such as information on mothers’ smoking and drinking habits during breastfeeding.

The analysis showed a significant association between increased maternal alcohol consumption and decreased nonverbal reasoning scores in children aged 6-7 years who had been breastfed at any time (95% confidence interval, –0.18 to –0.04; P = .01). The effect was independent of other factors that might have played a role, including prenatal alcohol consumption, maternal age, income, birth weight, head injury, and learning delay.

(95% CI, –0.20 to 0.17; P = .87), which the authors said supported the suggestion that the cognitive effects were the result of alcohol exposure through breast milk.

“This suggests that alcohol exposure through breast milk was responsible for cognitive reductions in breastfed infants rather than psychosocial or environmental factors surrounding maternal alcohol consumption,” wrote Louisa Gibson and Melanie Porter, PhD, of the department of psychology at Macquarie University in Sydney.

However, the association was no longer evident in children aged 8-11 years. The authors said that finding might be attributable to mediation by factors such as increased education.

In addition, Ms. Gibson and Dr. Porter did not find an association between smoking during breastfeeding and cognitive outcomes of the offspring.

The findings on breastfeeding and cognitive reductions in breastfed infants are consistent with animal studies showing that ethanol in breast milk can affect normal brain development.

“Increased cerebral cortex apoptosis and necrosis, for example, may disrupt higher order executive skills relied on in reasoning tasks,” the authors wrote. “Likewise, decreased myelination could reduce the processing speed needed to problem solve quickly.”

Children also might experience reduced cognition as a secondary effect of changes in feeding, nutritional intake, and sleep patterns that could themselves affect brain development, leading to behavioral changes that might “reduce exposure to enriching stimuli.”

However, the authors noted that the frequency and quantity of milk consumed, and the timing of alcohol consumption relative to breastfeeding, were not recorded as part of the study.

“The impact of this is unknown, however, because not all women time their alcohol consumption to limit alcohol exposure, and unpredictable infant feeding patterns can interfere with timing attempts.”

Ms. Gibson and Dr. Porter reported no external funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gibson L et al. Pediatrics 2018 Jul 30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4266.

Risky or higher alcohol consumption while breastfeeding could be associated with poorer cognitive outcomes in children, according to a longitudinal cohort study.

In a paper published in Pediatrics, researchers analyzed data from 5,107 infants who were followed up every 2 years from Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. They also examined other factors, such as information on mothers’ smoking and drinking habits during breastfeeding.

The analysis showed a significant association between increased maternal alcohol consumption and decreased nonverbal reasoning scores in children aged 6-7 years who had been breastfed at any time (95% confidence interval, –0.18 to –0.04; P = .01). The effect was independent of other factors that might have played a role, including prenatal alcohol consumption, maternal age, income, birth weight, head injury, and learning delay.

(95% CI, –0.20 to 0.17; P = .87), which the authors said supported the suggestion that the cognitive effects were the result of alcohol exposure through breast milk.

“This suggests that alcohol exposure through breast milk was responsible for cognitive reductions in breastfed infants rather than psychosocial or environmental factors surrounding maternal alcohol consumption,” wrote Louisa Gibson and Melanie Porter, PhD, of the department of psychology at Macquarie University in Sydney.

However, the association was no longer evident in children aged 8-11 years. The authors said that finding might be attributable to mediation by factors such as increased education.

In addition, Ms. Gibson and Dr. Porter did not find an association between smoking during breastfeeding and cognitive outcomes of the offspring.

The findings on breastfeeding and cognitive reductions in breastfed infants are consistent with animal studies showing that ethanol in breast milk can affect normal brain development.

“Increased cerebral cortex apoptosis and necrosis, for example, may disrupt higher order executive skills relied on in reasoning tasks,” the authors wrote. “Likewise, decreased myelination could reduce the processing speed needed to problem solve quickly.”

Children also might experience reduced cognition as a secondary effect of changes in feeding, nutritional intake, and sleep patterns that could themselves affect brain development, leading to behavioral changes that might “reduce exposure to enriching stimuli.”

However, the authors noted that the frequency and quantity of milk consumed, and the timing of alcohol consumption relative to breastfeeding, were not recorded as part of the study.

“The impact of this is unknown, however, because not all women time their alcohol consumption to limit alcohol exposure, and unpredictable infant feeding patterns can interfere with timing attempts.”

Ms. Gibson and Dr. Porter reported no external funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gibson L et al. Pediatrics 2018 Jul 30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4266.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Alcohol consumption during breastfeeding might affect infants’ later cognitive outcomes.

Major finding: Children exposed to alcohol during breastfeeding showed lower decreased nonverbal reasoning scores (95% confidence interval, –0.18 to –0.04; P = .01).

Study details: A cohort study in 5,107 infants called Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children.

Disclosures: Ms. Gibson and Dr. Porter reported no external funding and no conflicts of interest.

Source: Gibson L et al. Pediatrics 2018 Jul 30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4266.

Preterm birth rate ‘is on the rise again’

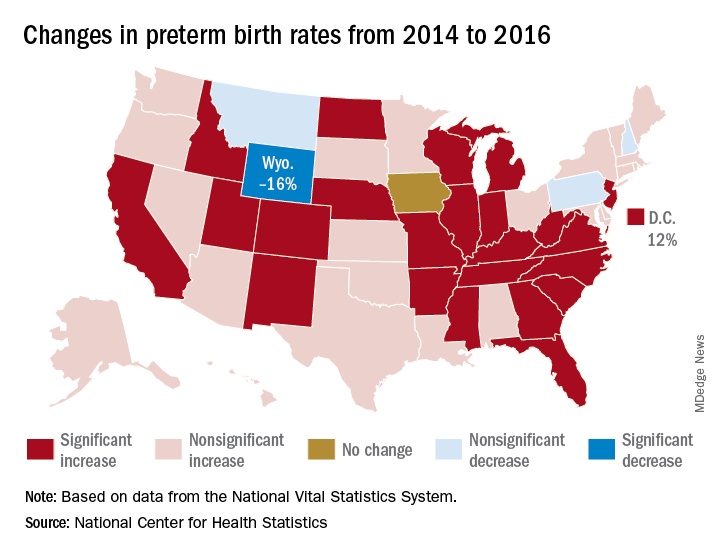

After several years of decline, the incidence of preterm births in the United States “is on the rise again,” according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

That 3% increase was spread pretty evenly: 23 states and the District of Columbia experienced statistically significant increases from 2014 to 2016, and 22 other states also had increases, although these were not statistically significant. One state, Iowa, had no change; three states – Montana, New Hampshire, and Pennsylvania – had nonsignificant declines, and Wyoming was the only state with a statistically significant drop (16%) in preterm birth incidence, they said based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

The largest increase, 12%, was seen in the District of Columbia, followed by Idaho and North Dakota at 10% and Arkansas, New Mexico, and West Virginia at 9%, the researchers reported.

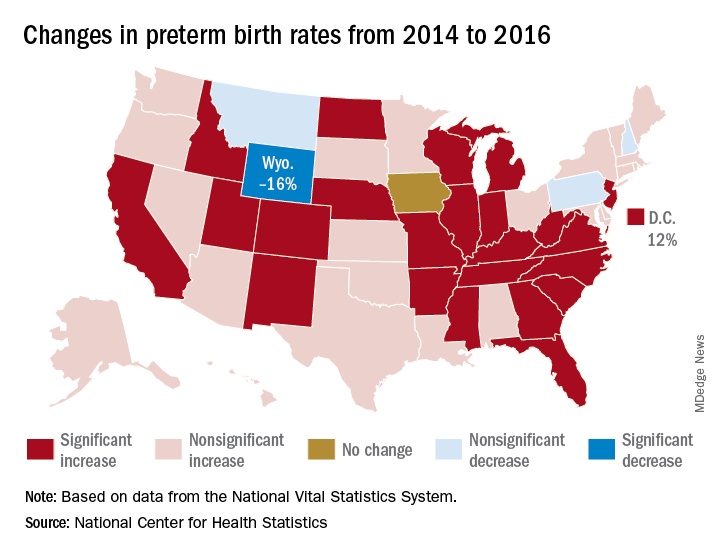

After several years of decline, the incidence of preterm births in the United States “is on the rise again,” according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

That 3% increase was spread pretty evenly: 23 states and the District of Columbia experienced statistically significant increases from 2014 to 2016, and 22 other states also had increases, although these were not statistically significant. One state, Iowa, had no change; three states – Montana, New Hampshire, and Pennsylvania – had nonsignificant declines, and Wyoming was the only state with a statistically significant drop (16%) in preterm birth incidence, they said based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

The largest increase, 12%, was seen in the District of Columbia, followed by Idaho and North Dakota at 10% and Arkansas, New Mexico, and West Virginia at 9%, the researchers reported.

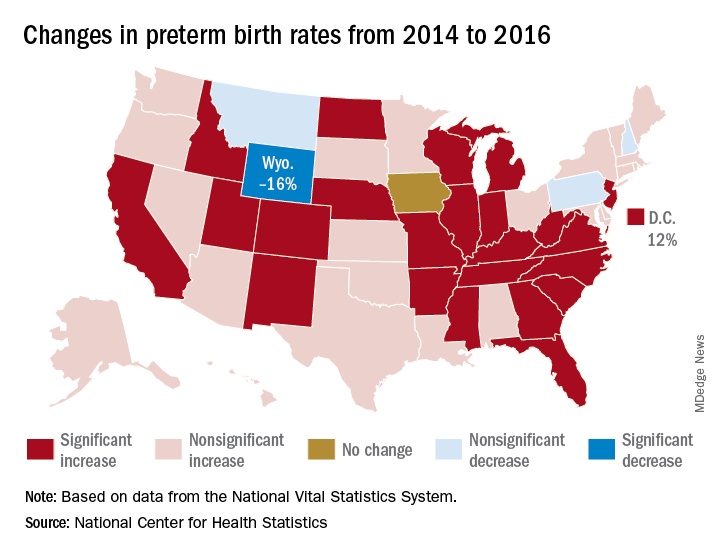

After several years of decline, the incidence of preterm births in the United States “is on the rise again,” according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

That 3% increase was spread pretty evenly: 23 states and the District of Columbia experienced statistically significant increases from 2014 to 2016, and 22 other states also had increases, although these were not statistically significant. One state, Iowa, had no change; three states – Montana, New Hampshire, and Pennsylvania – had nonsignificant declines, and Wyoming was the only state with a statistically significant drop (16%) in preterm birth incidence, they said based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

The largest increase, 12%, was seen in the District of Columbia, followed by Idaho and North Dakota at 10% and Arkansas, New Mexico, and West Virginia at 9%, the researchers reported.

Endocrinologists clash over routine CGM during pregnancy

ORLANDO – Diabetes and pregnancy aren’t a good mix, but what about pregnancy and continuous glucose monitors (CGMs)? In a polite but pointed debate, two endocrinologists used each other’s studies as evidence to support their opposing perspectives about routine GCM use by diabetic women during pregnancy.

“This topic shouldn’t really be debated because the evidence is clear” in favor of CGM, said Denice S. Feig, MD, MSc, FRCPC, of the University of Toronto and Mt. Sinai Hospital, also in Toronto, in a presentation at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

However, Elisabeth R. Mathiesen, MD, DMSc, of Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen, rebutted. She said her own research suggests CGM use may lead to larger babies and more premature births, convincing her to “say no to uncritical use of CGM in pregnancy.”

At issue: What is the best routine treatment for diabetic women before, during, and after pregnancy? As the American Diabetes Association noted in its 2018 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes report, “specific risks of uncontrolled diabetes in pregnancy include spontaneous abortion, fetal anomalies, preeclampsia, fetal demise, macrosomia, neonatal hypoglycemia, and neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, among others. In addition, diabetes in pregnancy may increase the risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes [mellitus] in offspring later in life.”

In her presentation, Dr. Feig pointed to a 2017 study she led that examined the effectiveness of continuous, real-time CGM on women with type 1 diabetes mellitus who were pregnant or planning to become pregnant (Lancet. 2017 Nov 25;390(10110):2347-2359).

“The study, in effect, was two parallel, randomized trials, one in those who planned pregnancy and one in those who were pregnant,” Dr. Feig said.

Participants, aged 18-40 years, from 31 hospitals in seven European and North American nations, had to have hemoglobin A1c levels greater than or equal to 6.5% during pregnancy or greater than or equal to 7% while planning pregnancy to be included in the study.

“We had a run-in phase to make sure they were able and willing to wear the CGM. Then we had 215 women in the pregnancy arm and 110 in the prepregnancy group randomized to real-time continuous CGM or standard care,” Dr. Feig said. The study ran for 34 weeks in the pregnant patients and for 24 weeks or until conception in the other women.

According to Dr. Feig, 70% of pregnant participants used CGM devices for more than 75% of the time. Compared with the control group, HbA1c levels in those who used CGM fell by 0.19% (P = .0207). The researchers also reported that women in the CGM group spent 100 more minutes a day within the glucose target range.

No differences in outcomes such as gestational age at delivery and rate of preterm delivery was found, although incidence of large-for-gestational-age infants, hypoglycemia requiring dextrose infusion, and neonatal ICU admission were lower in the CGM group to a statistically significant degree. “The numbers needed to treat were very small at six to eight women to reduce one of these events,” said Dr. Feig, who added that the numbers suggest the potential for cost savings.

Whatever the case, she said, “what price would you place on your baby avoiding a prolonged stay in the NICU? I think [it’s] priceless.”

She added that 80% of participants reported having trouble with the devices, which she attributed to the technology being old.

As for the planned pregnancy group, the study noted that “it did not have sufficient power to detect the magnitude of differences that were significant in the pregnancy trial.”

However, Dr. Feig said the study showed a trend toward lower HbA1c levels among CGM users in this population in which “tight glycemic control is absolutely paramount,” and that other studies also provide evidence supporting CGM use through the breastfeeding period.

Dr. Feig also pointed to a similar 2013 study coauthored by Dr. Mathiesen, her debate opponent. Dr. Feig said its findings are weakened because participants used CGM intermittently. She also pointed to the low participation (64%) in CGM by women assigned to a CGM group. (Diabetes Care. 2013 Jul;36[7]:1877-83)

In that study, researchers assigned 123 Danish women with type 1 diabetes mellitus and 31 women with type 2 diabetes mellitus to use real-time CGM for 6 days at various points in pregnancy or to only engage in routine care (including self-monitored plasma glucose seven times daily).

Researchers found no difference in HbA1c levels at 33 weeks between the groups, and they found similar rates of severe hypoglycemia and perinatal outcomes such as large-for-gestational-age infants.

These results, Dr. Mathiesen said, make her skeptical of a blanket recommendation to use CGM in pregnancy. Women aren’t eager to upload their glucose readings, making it difficult for doctors to make adjustments. “My women are Vikings. They come from Denmark,” she said, but “even these women don’t upload their glucose data between visits. ... I rarely have women who upload their data and look at their curves themselves. I think that’s a major disadvantage.”

Dr. Mathiesen also pointed to Dr. Feig’s study and noted that many women used CGM less than 75% of the time. In addition, 80% reported problems with the technology. “I’ve seen lots of skin problems with sensors. One lady used CGM during pregnancy; 4 years later, during another pregnancy, she showed me the mark of her sensor.”

Finally, the cost of CGM use is high considering the ongoing expense of the devices and the nurse time needed to upload data in the clinic. “As a rough estimate, the cost of CGM use in about 20 women during their pregnancies is the cost of the salary for one nurse per year,” she said.

Dr. Feig reported speaking fees from Medtronic, which provided CGM devices at reduced cost to her trial. Dr. Mathiesen reported research funding from the Novo Nordisk Foundation and speaker fees from Novo Nordisk, Lilly, AstraZeneca, and Sanofi-Aventis.

ORLANDO – Diabetes and pregnancy aren’t a good mix, but what about pregnancy and continuous glucose monitors (CGMs)? In a polite but pointed debate, two endocrinologists used each other’s studies as evidence to support their opposing perspectives about routine GCM use by diabetic women during pregnancy.

“This topic shouldn’t really be debated because the evidence is clear” in favor of CGM, said Denice S. Feig, MD, MSc, FRCPC, of the University of Toronto and Mt. Sinai Hospital, also in Toronto, in a presentation at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

However, Elisabeth R. Mathiesen, MD, DMSc, of Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen, rebutted. She said her own research suggests CGM use may lead to larger babies and more premature births, convincing her to “say no to uncritical use of CGM in pregnancy.”

At issue: What is the best routine treatment for diabetic women before, during, and after pregnancy? As the American Diabetes Association noted in its 2018 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes report, “specific risks of uncontrolled diabetes in pregnancy include spontaneous abortion, fetal anomalies, preeclampsia, fetal demise, macrosomia, neonatal hypoglycemia, and neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, among others. In addition, diabetes in pregnancy may increase the risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes [mellitus] in offspring later in life.”

In her presentation, Dr. Feig pointed to a 2017 study she led that examined the effectiveness of continuous, real-time CGM on women with type 1 diabetes mellitus who were pregnant or planning to become pregnant (Lancet. 2017 Nov 25;390(10110):2347-2359).

“The study, in effect, was two parallel, randomized trials, one in those who planned pregnancy and one in those who were pregnant,” Dr. Feig said.

Participants, aged 18-40 years, from 31 hospitals in seven European and North American nations, had to have hemoglobin A1c levels greater than or equal to 6.5% during pregnancy or greater than or equal to 7% while planning pregnancy to be included in the study.

“We had a run-in phase to make sure they were able and willing to wear the CGM. Then we had 215 women in the pregnancy arm and 110 in the prepregnancy group randomized to real-time continuous CGM or standard care,” Dr. Feig said. The study ran for 34 weeks in the pregnant patients and for 24 weeks or until conception in the other women.

According to Dr. Feig, 70% of pregnant participants used CGM devices for more than 75% of the time. Compared with the control group, HbA1c levels in those who used CGM fell by 0.19% (P = .0207). The researchers also reported that women in the CGM group spent 100 more minutes a day within the glucose target range.

No differences in outcomes such as gestational age at delivery and rate of preterm delivery was found, although incidence of large-for-gestational-age infants, hypoglycemia requiring dextrose infusion, and neonatal ICU admission were lower in the CGM group to a statistically significant degree. “The numbers needed to treat were very small at six to eight women to reduce one of these events,” said Dr. Feig, who added that the numbers suggest the potential for cost savings.

Whatever the case, she said, “what price would you place on your baby avoiding a prolonged stay in the NICU? I think [it’s] priceless.”

She added that 80% of participants reported having trouble with the devices, which she attributed to the technology being old.

As for the planned pregnancy group, the study noted that “it did not have sufficient power to detect the magnitude of differences that were significant in the pregnancy trial.”

However, Dr. Feig said the study showed a trend toward lower HbA1c levels among CGM users in this population in which “tight glycemic control is absolutely paramount,” and that other studies also provide evidence supporting CGM use through the breastfeeding period.

Dr. Feig also pointed to a similar 2013 study coauthored by Dr. Mathiesen, her debate opponent. Dr. Feig said its findings are weakened because participants used CGM intermittently. She also pointed to the low participation (64%) in CGM by women assigned to a CGM group. (Diabetes Care. 2013 Jul;36[7]:1877-83)

In that study, researchers assigned 123 Danish women with type 1 diabetes mellitus and 31 women with type 2 diabetes mellitus to use real-time CGM for 6 days at various points in pregnancy or to only engage in routine care (including self-monitored plasma glucose seven times daily).

Researchers found no difference in HbA1c levels at 33 weeks between the groups, and they found similar rates of severe hypoglycemia and perinatal outcomes such as large-for-gestational-age infants.

These results, Dr. Mathiesen said, make her skeptical of a blanket recommendation to use CGM in pregnancy. Women aren’t eager to upload their glucose readings, making it difficult for doctors to make adjustments. “My women are Vikings. They come from Denmark,” she said, but “even these women don’t upload their glucose data between visits. ... I rarely have women who upload their data and look at their curves themselves. I think that’s a major disadvantage.”

Dr. Mathiesen also pointed to Dr. Feig’s study and noted that many women used CGM less than 75% of the time. In addition, 80% reported problems with the technology. “I’ve seen lots of skin problems with sensors. One lady used CGM during pregnancy; 4 years later, during another pregnancy, she showed me the mark of her sensor.”

Finally, the cost of CGM use is high considering the ongoing expense of the devices and the nurse time needed to upload data in the clinic. “As a rough estimate, the cost of CGM use in about 20 women during their pregnancies is the cost of the salary for one nurse per year,” she said.

Dr. Feig reported speaking fees from Medtronic, which provided CGM devices at reduced cost to her trial. Dr. Mathiesen reported research funding from the Novo Nordisk Foundation and speaker fees from Novo Nordisk, Lilly, AstraZeneca, and Sanofi-Aventis.

ORLANDO – Diabetes and pregnancy aren’t a good mix, but what about pregnancy and continuous glucose monitors (CGMs)? In a polite but pointed debate, two endocrinologists used each other’s studies as evidence to support their opposing perspectives about routine GCM use by diabetic women during pregnancy.

“This topic shouldn’t really be debated because the evidence is clear” in favor of CGM, said Denice S. Feig, MD, MSc, FRCPC, of the University of Toronto and Mt. Sinai Hospital, also in Toronto, in a presentation at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

However, Elisabeth R. Mathiesen, MD, DMSc, of Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen, rebutted. She said her own research suggests CGM use may lead to larger babies and more premature births, convincing her to “say no to uncritical use of CGM in pregnancy.”

At issue: What is the best routine treatment for diabetic women before, during, and after pregnancy? As the American Diabetes Association noted in its 2018 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes report, “specific risks of uncontrolled diabetes in pregnancy include spontaneous abortion, fetal anomalies, preeclampsia, fetal demise, macrosomia, neonatal hypoglycemia, and neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, among others. In addition, diabetes in pregnancy may increase the risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes [mellitus] in offspring later in life.”

In her presentation, Dr. Feig pointed to a 2017 study she led that examined the effectiveness of continuous, real-time CGM on women with type 1 diabetes mellitus who were pregnant or planning to become pregnant (Lancet. 2017 Nov 25;390(10110):2347-2359).

“The study, in effect, was two parallel, randomized trials, one in those who planned pregnancy and one in those who were pregnant,” Dr. Feig said.

Participants, aged 18-40 years, from 31 hospitals in seven European and North American nations, had to have hemoglobin A1c levels greater than or equal to 6.5% during pregnancy or greater than or equal to 7% while planning pregnancy to be included in the study.

“We had a run-in phase to make sure they were able and willing to wear the CGM. Then we had 215 women in the pregnancy arm and 110 in the prepregnancy group randomized to real-time continuous CGM or standard care,” Dr. Feig said. The study ran for 34 weeks in the pregnant patients and for 24 weeks or until conception in the other women.

According to Dr. Feig, 70% of pregnant participants used CGM devices for more than 75% of the time. Compared with the control group, HbA1c levels in those who used CGM fell by 0.19% (P = .0207). The researchers also reported that women in the CGM group spent 100 more minutes a day within the glucose target range.

No differences in outcomes such as gestational age at delivery and rate of preterm delivery was found, although incidence of large-for-gestational-age infants, hypoglycemia requiring dextrose infusion, and neonatal ICU admission were lower in the CGM group to a statistically significant degree. “The numbers needed to treat were very small at six to eight women to reduce one of these events,” said Dr. Feig, who added that the numbers suggest the potential for cost savings.

Whatever the case, she said, “what price would you place on your baby avoiding a prolonged stay in the NICU? I think [it’s] priceless.”

She added that 80% of participants reported having trouble with the devices, which she attributed to the technology being old.

As for the planned pregnancy group, the study noted that “it did not have sufficient power to detect the magnitude of differences that were significant in the pregnancy trial.”

However, Dr. Feig said the study showed a trend toward lower HbA1c levels among CGM users in this population in which “tight glycemic control is absolutely paramount,” and that other studies also provide evidence supporting CGM use through the breastfeeding period.

Dr. Feig also pointed to a similar 2013 study coauthored by Dr. Mathiesen, her debate opponent. Dr. Feig said its findings are weakened because participants used CGM intermittently. She also pointed to the low participation (64%) in CGM by women assigned to a CGM group. (Diabetes Care. 2013 Jul;36[7]:1877-83)

In that study, researchers assigned 123 Danish women with type 1 diabetes mellitus and 31 women with type 2 diabetes mellitus to use real-time CGM for 6 days at various points in pregnancy or to only engage in routine care (including self-monitored plasma glucose seven times daily).

Researchers found no difference in HbA1c levels at 33 weeks between the groups, and they found similar rates of severe hypoglycemia and perinatal outcomes such as large-for-gestational-age infants.

These results, Dr. Mathiesen said, make her skeptical of a blanket recommendation to use CGM in pregnancy. Women aren’t eager to upload their glucose readings, making it difficult for doctors to make adjustments. “My women are Vikings. They come from Denmark,” she said, but “even these women don’t upload their glucose data between visits. ... I rarely have women who upload their data and look at their curves themselves. I think that’s a major disadvantage.”

Dr. Mathiesen also pointed to Dr. Feig’s study and noted that many women used CGM less than 75% of the time. In addition, 80% reported problems with the technology. “I’ve seen lots of skin problems with sensors. One lady used CGM during pregnancy; 4 years later, during another pregnancy, she showed me the mark of her sensor.”

Finally, the cost of CGM use is high considering the ongoing expense of the devices and the nurse time needed to upload data in the clinic. “As a rough estimate, the cost of CGM use in about 20 women during their pregnancies is the cost of the salary for one nurse per year,” she said.

Dr. Feig reported speaking fees from Medtronic, which provided CGM devices at reduced cost to her trial. Dr. Mathiesen reported research funding from the Novo Nordisk Foundation and speaker fees from Novo Nordisk, Lilly, AstraZeneca, and Sanofi-Aventis.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ADA 2018

Maternal lifestyle affects child obesity

A study published in the British Medical Journal found that women who practiced five healthy habits had children who when they reached adolescence were 75% less likely to be overweight, compared with women who practiced none of the those healthy habits.

The healthy habits were maintaining a healthy weight, eating a nutritious diet, exercising regularly, not smoking, and consuming no more than a moderate amount of alcohol (BMJ 2018;362:k2486). I suspect you aren’t surprised by the core finding of this study of 16,945 female nurses and their 24,289 children. You’ve seen it scores of times. Mothers who lead unhealthy lifestyles seem to have children who are more likely to be obese. Now you have some numbers to support your decades of anecdotal observations. But the question is, what are we supposed to do with this new data? When and with whom should we share this unfortunate truth?

Evidence from previous studies makes it clear that by the time a child enters grade school the die is cast. Baby fat is neither cute nor temporary. This means that our target audience must be mothers-to-be and women whose children are infants and toddlers. On the other hand, telling the mother of an overweight teenager that her own unhealthy habits have probably contributed to her child’s weight problem is cruel and a waste of time. The mother already may have suspected her culpability. She also may feel that it is too late to do anything about it. While there have been some studies looking for an association between paternal body mass index and offspring BMI, I was unable to find any addressing paternal lifestyle and adolescent obesity.

This new study doesn’t address the unusual situation in which a mother of a teenager sheds all five of her unhealthy habits. I guess there may be examples in which a mother’s positive lifestyle change has helped reverse her adolescent child’s path to obesity. But I suspect these cases are rare.

So on one hand but on the other we must be careful to avoid playing the blame game and giving other mothers a one-way ticket on the guilt train. This is just one more example of the tightrope that we have been walking for generations. Every day in our offices we see children whose health is endangered by their parents’ behaviors and lifestyles. In cases in which the parental behavior is creating a serious short-term risk, such as failing to use an appropriate motor vehicle safety restraint system, we have no qualms about speaking out. We aren’t afraid to do a little shaming in hopes of sparing a family a serious guilt trip. When the threat to the child is more abstract and less dramatic – such as vaccine refusal – shaming and education don’t seem to be effective in changing parental behavior.

Obesity presents its own collection of complexities. It is like a car wreck seen in slow motion as the plots on the growth chart accumulate pound by pound. Unfortunately, parents often are among the last to notice or accept the reality. This new study doesn’t tell us whether we can make a difference. But it does suggest that when we first see the warning signs on the growth chart that we should engage the parents in a discussion of their lifestyle and its possible association with the child’s weight gain. The challenge, of course, is how one can cast the discussion without sounding judgmental.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

A study published in the British Medical Journal found that women who practiced five healthy habits had children who when they reached adolescence were 75% less likely to be overweight, compared with women who practiced none of the those healthy habits.

The healthy habits were maintaining a healthy weight, eating a nutritious diet, exercising regularly, not smoking, and consuming no more than a moderate amount of alcohol (BMJ 2018;362:k2486). I suspect you aren’t surprised by the core finding of this study of 16,945 female nurses and their 24,289 children. You’ve seen it scores of times. Mothers who lead unhealthy lifestyles seem to have children who are more likely to be obese. Now you have some numbers to support your decades of anecdotal observations. But the question is, what are we supposed to do with this new data? When and with whom should we share this unfortunate truth?

Evidence from previous studies makes it clear that by the time a child enters grade school the die is cast. Baby fat is neither cute nor temporary. This means that our target audience must be mothers-to-be and women whose children are infants and toddlers. On the other hand, telling the mother of an overweight teenager that her own unhealthy habits have probably contributed to her child’s weight problem is cruel and a waste of time. The mother already may have suspected her culpability. She also may feel that it is too late to do anything about it. While there have been some studies looking for an association between paternal body mass index and offspring BMI, I was unable to find any addressing paternal lifestyle and adolescent obesity.

This new study doesn’t address the unusual situation in which a mother of a teenager sheds all five of her unhealthy habits. I guess there may be examples in which a mother’s positive lifestyle change has helped reverse her adolescent child’s path to obesity. But I suspect these cases are rare.

So on one hand but on the other we must be careful to avoid playing the blame game and giving other mothers a one-way ticket on the guilt train. This is just one more example of the tightrope that we have been walking for generations. Every day in our offices we see children whose health is endangered by their parents’ behaviors and lifestyles. In cases in which the parental behavior is creating a serious short-term risk, such as failing to use an appropriate motor vehicle safety restraint system, we have no qualms about speaking out. We aren’t afraid to do a little shaming in hopes of sparing a family a serious guilt trip. When the threat to the child is more abstract and less dramatic – such as vaccine refusal – shaming and education don’t seem to be effective in changing parental behavior.

Obesity presents its own collection of complexities. It is like a car wreck seen in slow motion as the plots on the growth chart accumulate pound by pound. Unfortunately, parents often are among the last to notice or accept the reality. This new study doesn’t tell us whether we can make a difference. But it does suggest that when we first see the warning signs on the growth chart that we should engage the parents in a discussion of their lifestyle and its possible association with the child’s weight gain. The challenge, of course, is how one can cast the discussion without sounding judgmental.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

A study published in the British Medical Journal found that women who practiced five healthy habits had children who when they reached adolescence were 75% less likely to be overweight, compared with women who practiced none of the those healthy habits.

The healthy habits were maintaining a healthy weight, eating a nutritious diet, exercising regularly, not smoking, and consuming no more than a moderate amount of alcohol (BMJ 2018;362:k2486). I suspect you aren’t surprised by the core finding of this study of 16,945 female nurses and their 24,289 children. You’ve seen it scores of times. Mothers who lead unhealthy lifestyles seem to have children who are more likely to be obese. Now you have some numbers to support your decades of anecdotal observations. But the question is, what are we supposed to do with this new data? When and with whom should we share this unfortunate truth?

Evidence from previous studies makes it clear that by the time a child enters grade school the die is cast. Baby fat is neither cute nor temporary. This means that our target audience must be mothers-to-be and women whose children are infants and toddlers. On the other hand, telling the mother of an overweight teenager that her own unhealthy habits have probably contributed to her child’s weight problem is cruel and a waste of time. The mother already may have suspected her culpability. She also may feel that it is too late to do anything about it. While there have been some studies looking for an association between paternal body mass index and offspring BMI, I was unable to find any addressing paternal lifestyle and adolescent obesity.

This new study doesn’t address the unusual situation in which a mother of a teenager sheds all five of her unhealthy habits. I guess there may be examples in which a mother’s positive lifestyle change has helped reverse her adolescent child’s path to obesity. But I suspect these cases are rare.

So on one hand but on the other we must be careful to avoid playing the blame game and giving other mothers a one-way ticket on the guilt train. This is just one more example of the tightrope that we have been walking for generations. Every day in our offices we see children whose health is endangered by their parents’ behaviors and lifestyles. In cases in which the parental behavior is creating a serious short-term risk, such as failing to use an appropriate motor vehicle safety restraint system, we have no qualms about speaking out. We aren’t afraid to do a little shaming in hopes of sparing a family a serious guilt trip. When the threat to the child is more abstract and less dramatic – such as vaccine refusal – shaming and education don’t seem to be effective in changing parental behavior.

Obesity presents its own collection of complexities. It is like a car wreck seen in slow motion as the plots on the growth chart accumulate pound by pound. Unfortunately, parents often are among the last to notice or accept the reality. This new study doesn’t tell us whether we can make a difference. But it does suggest that when we first see the warning signs on the growth chart that we should engage the parents in a discussion of their lifestyle and its possible association with the child’s weight gain. The challenge, of course, is how one can cast the discussion without sounding judgmental.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Prenatal depression tracked through multiple generations shows increase

Rebecca M. Pearson, PhD, and her associates reported in JAMA Network Open.

The findings come from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), which prospectively followed women who became pregnant between 1990 and 1992 (G0) in a region in southwest England.

In the current analysis, the researchers examined 180 daughters of the original participants, or the female partners of male children (G1). They were recruited during a pregnancy that occurred between June 6, 2012, and Dec. 31, 2016, and had to have completed the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) at 18 weeks of the pregnancy. They were compared to G0 mothers who had become pregnant in the same age range as the G1 subjects (age 19-24 years). Because the G1 participants had all been born in the county of Avon, the G0 subjects were also restricted to 2,390 women who were born there, which represented about 50% of the G0 sample.

Seventeen percent of the G0 women had high depression scores (EPDS greater than or equal to 13) at 18 weeks, compared with 25% of the G1 women. After adjustment for age, body mass index, smoking, parity, and education, the risk ratio for prenatal depression in the later generation of women was 1.77 (95% confidence interval, 1.27-2.46).

There was a strong association between prenatal depression in G1 women and their mothers: Fifty-four percent of women whose mothers had experienced prenatal depression also were positive for prenatal depression, compared with 16% of women whose mothers did not have prenatal depression (RR, 3.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.65-6.67).

An increased incidence of prenatal depression has major implications for service providers and public health efforts. The authors of the study call for more research to confirm this increase and identify potential causes.

The study is the first multigenerational cohort look at prenatal depression, but was limited by the much smaller size of the G1 group. The study also may not be generalizable to older women or ethnic groups other than white European individuals, and selection bias is possible.

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children was supported by the UK Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust, and the University of Bristol. This current study received support from the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at the University Hospitals Bristol National Health Service Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol, the National Institutes of Health, and the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme. Dr. Pearson reported no relevant financial disclosures; a number of the other researchers reported support from a variety of grants.

SOURCE: RM Pearson RM et al. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(3):e180725.

Rebecca M. Pearson, PhD, and her associates reported in JAMA Network Open.

The findings come from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), which prospectively followed women who became pregnant between 1990 and 1992 (G0) in a region in southwest England.

In the current analysis, the researchers examined 180 daughters of the original participants, or the female partners of male children (G1). They were recruited during a pregnancy that occurred between June 6, 2012, and Dec. 31, 2016, and had to have completed the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) at 18 weeks of the pregnancy. They were compared to G0 mothers who had become pregnant in the same age range as the G1 subjects (age 19-24 years). Because the G1 participants had all been born in the county of Avon, the G0 subjects were also restricted to 2,390 women who were born there, which represented about 50% of the G0 sample.

Seventeen percent of the G0 women had high depression scores (EPDS greater than or equal to 13) at 18 weeks, compared with 25% of the G1 women. After adjustment for age, body mass index, smoking, parity, and education, the risk ratio for prenatal depression in the later generation of women was 1.77 (95% confidence interval, 1.27-2.46).

There was a strong association between prenatal depression in G1 women and their mothers: Fifty-four percent of women whose mothers had experienced prenatal depression also were positive for prenatal depression, compared with 16% of women whose mothers did not have prenatal depression (RR, 3.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.65-6.67).

An increased incidence of prenatal depression has major implications for service providers and public health efforts. The authors of the study call for more research to confirm this increase and identify potential causes.

The study is the first multigenerational cohort look at prenatal depression, but was limited by the much smaller size of the G1 group. The study also may not be generalizable to older women or ethnic groups other than white European individuals, and selection bias is possible.

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children was supported by the UK Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust, and the University of Bristol. This current study received support from the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at the University Hospitals Bristol National Health Service Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol, the National Institutes of Health, and the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme. Dr. Pearson reported no relevant financial disclosures; a number of the other researchers reported support from a variety of grants.

SOURCE: RM Pearson RM et al. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(3):e180725.

Rebecca M. Pearson, PhD, and her associates reported in JAMA Network Open.

The findings come from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), which prospectively followed women who became pregnant between 1990 and 1992 (G0) in a region in southwest England.

In the current analysis, the researchers examined 180 daughters of the original participants, or the female partners of male children (G1). They were recruited during a pregnancy that occurred between June 6, 2012, and Dec. 31, 2016, and had to have completed the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) at 18 weeks of the pregnancy. They were compared to G0 mothers who had become pregnant in the same age range as the G1 subjects (age 19-24 years). Because the G1 participants had all been born in the county of Avon, the G0 subjects were also restricted to 2,390 women who were born there, which represented about 50% of the G0 sample.

Seventeen percent of the G0 women had high depression scores (EPDS greater than or equal to 13) at 18 weeks, compared with 25% of the G1 women. After adjustment for age, body mass index, smoking, parity, and education, the risk ratio for prenatal depression in the later generation of women was 1.77 (95% confidence interval, 1.27-2.46).

There was a strong association between prenatal depression in G1 women and their mothers: Fifty-four percent of women whose mothers had experienced prenatal depression also were positive for prenatal depression, compared with 16% of women whose mothers did not have prenatal depression (RR, 3.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.65-6.67).

An increased incidence of prenatal depression has major implications for service providers and public health efforts. The authors of the study call for more research to confirm this increase and identify potential causes.

The study is the first multigenerational cohort look at prenatal depression, but was limited by the much smaller size of the G1 group. The study also may not be generalizable to older women or ethnic groups other than white European individuals, and selection bias is possible.

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children was supported by the UK Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust, and the University of Bristol. This current study received support from the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at the University Hospitals Bristol National Health Service Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol, the National Institutes of Health, and the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme. Dr. Pearson reported no relevant financial disclosures; a number of the other researchers reported support from a variety of grants.

SOURCE: RM Pearson RM et al. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(3):e180725.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Key clinical point: The frequency of prenatal depression increased from one generation to the next in English women.

Major finding: The second generation of mothers had a higher risk of prenatal depression (risk ratio, 1.77).

Study details: Prospective study of 2,390 first-generation mothers and 180 second-generation mothers.

Disclosures: The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children was supported by the UK Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust, and the University of Bristol. This current study received support from the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at the University Hospitals Bristol National Health Service Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol, the National Institutes of Health, and the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme. Dr. Pearson reported no relevant financial disclosures; a number of the other researchers reported support from a variety of grants.

Source: RM Pearson RM et al. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(3):e180725.

New insights into sleep, pregnancy weight gain

BALTIMORE – Pregnant women who are overweight and obese are like the general population in that the less they sleep, the more weight they gain, particularly in the first half of pregnancy. However, unlike in the larger adult population, prolonged daily total eating time was not associated with gestational weight gain in these women, particularly early in pregnancy, according to findings from a small study presented at the Associated Professional Sleep Societies annual meeting.

Those findings point to a need to further study the , said Rachel P. Kolko, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar at the University of Pittsburgh, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic.

“The association with total sleep time was found to be significant, such that if you had less sleep, you had higher amounts of weight gain; we did not find a significant relation with our eating window variable,” Dr. Kolko said.

She reported on research involving 62 pregnant women, 53% of whom were overweight with a body mass index of 25-29.9 kg/m2 and 47% of whom were obese with BMI greater than 30. Forty-seven percent of the study population was nonwhite.

The research grew out of a need to identify potentially modifiable factors to curtail excessive gestational weight gain during pregnancy, she said. The study hypotheses were that both shorter total sleep time and longer total eating time would lead to higher gestational weight gain, but the study confirmed only the former as a contributing factor.

The women in the study were at 12-20 weeks of pregnancy. Gestational weight gain was calculated as the difference between self-reported prepregnancy weight and current weight. Total sleep time was based on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, and total eating time was calculated as the time difference between the day’s first meal or snack of more than 50 calories and the last, as self-reported.

Average total sleep time was 7.8 hours, with total eating time spanning 10.8 hours. On average, study participants gained 9.7 pounds through the first half of pregnancy, Dr. Kolko said. She noted that the Institute of Medicine, now known as the National Academy of Medicine, recommends that women who are overweight women gain 15-25 pounds during pregnancy and women who are obese gain 11-20 pounds (JAMA. 2017;317:2207-25). “Already about 20% of our sample has gained that amount of weight within the first half of pregnancy,” she said.

“Total sleep time was related to a higher early gestational weight in women with overweight and obesity, and it’s possible that addressing this may affect and hopefully improve women’s weight gain during early pregnancy to fit within those guidelines,” she said.

Future research should look at the entire gestational period – possibly targeting sleep patterns during pregnancy – and should expand to include women who are not overweight or obese, Dr. Kolko noted.

Dr. Kolko reported having no financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Kolko RP, et al., SLEEP 2018, Abstract 0692.

BALTIMORE – Pregnant women who are overweight and obese are like the general population in that the less they sleep, the more weight they gain, particularly in the first half of pregnancy. However, unlike in the larger adult population, prolonged daily total eating time was not associated with gestational weight gain in these women, particularly early in pregnancy, according to findings from a small study presented at the Associated Professional Sleep Societies annual meeting.

Those findings point to a need to further study the , said Rachel P. Kolko, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar at the University of Pittsburgh, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic.

“The association with total sleep time was found to be significant, such that if you had less sleep, you had higher amounts of weight gain; we did not find a significant relation with our eating window variable,” Dr. Kolko said.

She reported on research involving 62 pregnant women, 53% of whom were overweight with a body mass index of 25-29.9 kg/m2 and 47% of whom were obese with BMI greater than 30. Forty-seven percent of the study population was nonwhite.

The research grew out of a need to identify potentially modifiable factors to curtail excessive gestational weight gain during pregnancy, she said. The study hypotheses were that both shorter total sleep time and longer total eating time would lead to higher gestational weight gain, but the study confirmed only the former as a contributing factor.

The women in the study were at 12-20 weeks of pregnancy. Gestational weight gain was calculated as the difference between self-reported prepregnancy weight and current weight. Total sleep time was based on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, and total eating time was calculated as the time difference between the day’s first meal or snack of more than 50 calories and the last, as self-reported.

Average total sleep time was 7.8 hours, with total eating time spanning 10.8 hours. On average, study participants gained 9.7 pounds through the first half of pregnancy, Dr. Kolko said. She noted that the Institute of Medicine, now known as the National Academy of Medicine, recommends that women who are overweight women gain 15-25 pounds during pregnancy and women who are obese gain 11-20 pounds (JAMA. 2017;317:2207-25). “Already about 20% of our sample has gained that amount of weight within the first half of pregnancy,” she said.