User login

Take action to prevent maternal mortality

The facts

While other industrialized nations are seeing a decrease in their maternal mortality rates, the United States has noted a 26% increase over a 15-year period. This is especially true for women of color: black women are nearly 4 times as likely to die from pregnancy related causes as compared to non-Hispanic white women. Postpartum hemorrhage and preeclampsia are often the leading causes of maternal death; however, suicide and overdoses are becoming increasingly more common. This information is highlighted in the March 2018 OBG Management article “Factors critical to reducing US maternal mortality and morbidity,” by Lucia DiVenere, MA, Government and Political Affairs, at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).1

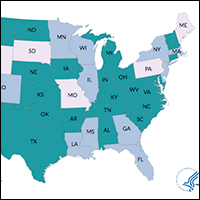

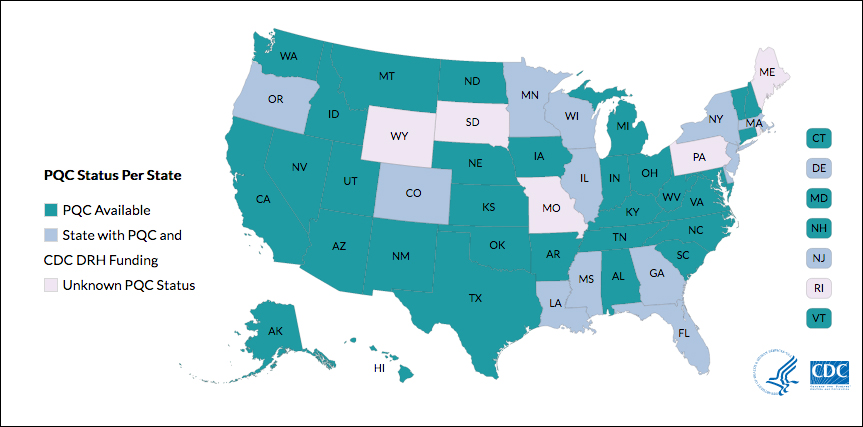

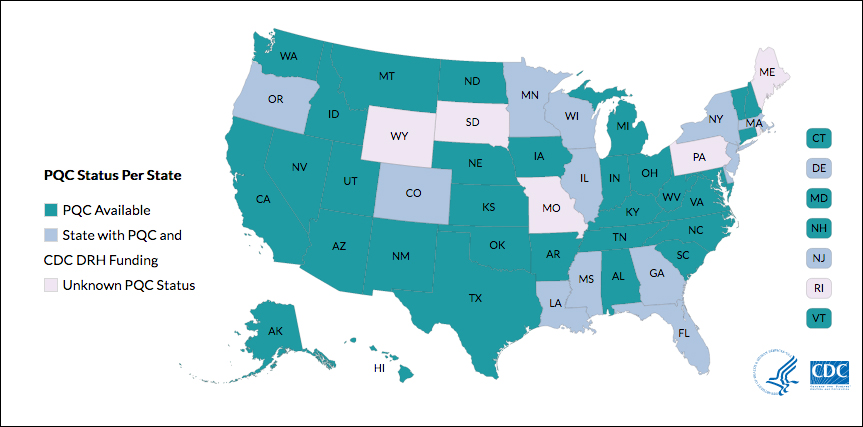

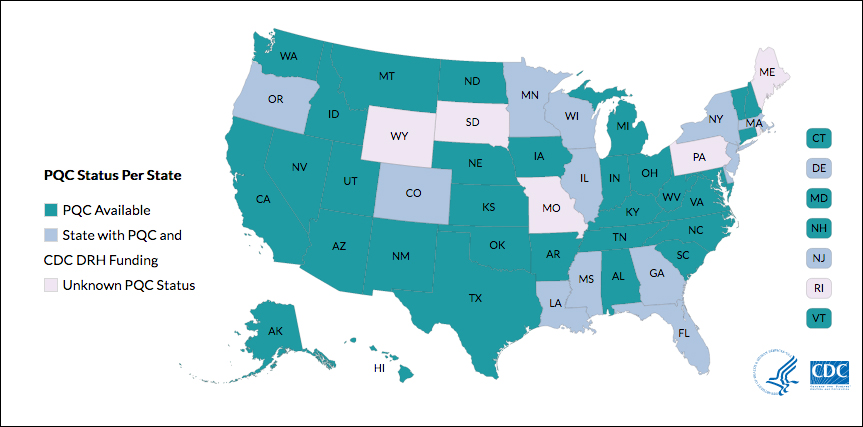

Although there are efforts to improve these outcomes, programs vary by state. One initiative is the perinatal quality collaboratives (PQCs), state or multistate networks of teams working to improve the quality of care for mothers and babies (see “Has your state established a perinatal quality collaborative?”).

Currently, only 33 states have a maternal mortality review committee (MMRC) comprised of an interdisciplinary team of ObGyns, nurses, and other stakeholders. The MMRC reviews each maternal death in their state and provides recommendations and policy changes to help prevent further loss of life.

Many states currently have active collaboratives, and others are in development. The CDC’s Division of Reproductive Health (DRH) currently provides support for state-based PQCs in Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, and Wisconsin. The status of PQCs in Maine, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, Missouri, South Dakota, and Wyoming is unknown.1

The CDC can help people establish a collaborative. Visit: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pqc-states.html.

Reference

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reproductive health: State Perinatal Quality Collaboratives. CDC website. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pqc-states.html Updated October 17, 2017. Accessed April 4, 2018.

The bill

Preventing Maternal Deaths Act/Maternal Health Accountability Act (H.R. 1318/S. 1112) is a bipartisan, bicameral effort to reduce maternal mortality and reduce health care disparities.

The bills authorize the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to help states create or expand state MMRCs through annual grant funding of $7 million through fiscal year 2022. Through the MMRCs, the CDC would have the ability to gather data on maternal mortality and health care disparities, allowing the agency to better understand leading causes of maternal death as well as a state’s successes and pitfalls in interventions.

Currently the House bill (H.R. 1318) has 102 cosponsors (https://cqrcengage.com/acog/app/bill/903056?0) and the Senate bill (S. 1112) has 17 cosponsors (https://cqrcengage.com/acog/app/bill/943204?1). Click these links to see if your representative is a cosponsor.

Not sure who your representative is? Click here to find out: http://cqrcengage.com/acog/app/lookup?1&m=29525.

Take action

Both the Senate and House bills have been referred to health committees. However, no advances have been made since March 2017. In order for the bills to move forward, your representatives need to hear from you.

If your representative is a cosponsor of the bill, thank them for their support, but also ask what we can do to ensure this bill becomes law.

If your representative is not a cosponsor, follow this link to email your representative: http://cqrcengage.com/acog/app/onestep-write-a-letter?0&engagementId=306574. You also can call your representative’s office and speak directly to a staff member.

When calling or emailing, highlight the following:

- I am an ObGyn and I am asking [your Representative/Senator] to support H.R. 1318 or S. 1112.

- While maternal mortality rates are decreasing in other parts of the world, they are increasing in the United States. We have the highest maternal mortality rate in the developing world.

- This bill gives all states the opportunity to have a maternal mortality review committee, allowing health care leaders to review each maternal death and analyze how further deaths can be prevented.

- Congress has invested in programs addressing infant mortality, birth defects, and preterm birth. It is time we put the same investment into saving our nation’s mothers.

- As an ObGyn, I urge you to support this bill.

More from ACOG

Want to know what other advocacy opportunities are available? Check out ACOG action at http://cqrcengage.com/acog/home?3.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- DiVenere L. Factors critical to reducing US maternal mortality and morbidity. OBG Manag. 2018;30(3):30−33.

The facts

While other industrialized nations are seeing a decrease in their maternal mortality rates, the United States has noted a 26% increase over a 15-year period. This is especially true for women of color: black women are nearly 4 times as likely to die from pregnancy related causes as compared to non-Hispanic white women. Postpartum hemorrhage and preeclampsia are often the leading causes of maternal death; however, suicide and overdoses are becoming increasingly more common. This information is highlighted in the March 2018 OBG Management article “Factors critical to reducing US maternal mortality and morbidity,” by Lucia DiVenere, MA, Government and Political Affairs, at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).1

Although there are efforts to improve these outcomes, programs vary by state. One initiative is the perinatal quality collaboratives (PQCs), state or multistate networks of teams working to improve the quality of care for mothers and babies (see “Has your state established a perinatal quality collaborative?”).

Currently, only 33 states have a maternal mortality review committee (MMRC) comprised of an interdisciplinary team of ObGyns, nurses, and other stakeholders. The MMRC reviews each maternal death in their state and provides recommendations and policy changes to help prevent further loss of life.

Many states currently have active collaboratives, and others are in development. The CDC’s Division of Reproductive Health (DRH) currently provides support for state-based PQCs in Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, and Wisconsin. The status of PQCs in Maine, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, Missouri, South Dakota, and Wyoming is unknown.1

The CDC can help people establish a collaborative. Visit: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pqc-states.html.

Reference

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reproductive health: State Perinatal Quality Collaboratives. CDC website. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pqc-states.html Updated October 17, 2017. Accessed April 4, 2018.

The bill

Preventing Maternal Deaths Act/Maternal Health Accountability Act (H.R. 1318/S. 1112) is a bipartisan, bicameral effort to reduce maternal mortality and reduce health care disparities.

The bills authorize the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to help states create or expand state MMRCs through annual grant funding of $7 million through fiscal year 2022. Through the MMRCs, the CDC would have the ability to gather data on maternal mortality and health care disparities, allowing the agency to better understand leading causes of maternal death as well as a state’s successes and pitfalls in interventions.

Currently the House bill (H.R. 1318) has 102 cosponsors (https://cqrcengage.com/acog/app/bill/903056?0) and the Senate bill (S. 1112) has 17 cosponsors (https://cqrcengage.com/acog/app/bill/943204?1). Click these links to see if your representative is a cosponsor.

Not sure who your representative is? Click here to find out: http://cqrcengage.com/acog/app/lookup?1&m=29525.

Take action

Both the Senate and House bills have been referred to health committees. However, no advances have been made since March 2017. In order for the bills to move forward, your representatives need to hear from you.

If your representative is a cosponsor of the bill, thank them for their support, but also ask what we can do to ensure this bill becomes law.

If your representative is not a cosponsor, follow this link to email your representative: http://cqrcengage.com/acog/app/onestep-write-a-letter?0&engagementId=306574. You also can call your representative’s office and speak directly to a staff member.

When calling or emailing, highlight the following:

- I am an ObGyn and I am asking [your Representative/Senator] to support H.R. 1318 or S. 1112.

- While maternal mortality rates are decreasing in other parts of the world, they are increasing in the United States. We have the highest maternal mortality rate in the developing world.

- This bill gives all states the opportunity to have a maternal mortality review committee, allowing health care leaders to review each maternal death and analyze how further deaths can be prevented.

- Congress has invested in programs addressing infant mortality, birth defects, and preterm birth. It is time we put the same investment into saving our nation’s mothers.

- As an ObGyn, I urge you to support this bill.

More from ACOG

Want to know what other advocacy opportunities are available? Check out ACOG action at http://cqrcengage.com/acog/home?3.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The facts

While other industrialized nations are seeing a decrease in their maternal mortality rates, the United States has noted a 26% increase over a 15-year period. This is especially true for women of color: black women are nearly 4 times as likely to die from pregnancy related causes as compared to non-Hispanic white women. Postpartum hemorrhage and preeclampsia are often the leading causes of maternal death; however, suicide and overdoses are becoming increasingly more common. This information is highlighted in the March 2018 OBG Management article “Factors critical to reducing US maternal mortality and morbidity,” by Lucia DiVenere, MA, Government and Political Affairs, at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).1

Although there are efforts to improve these outcomes, programs vary by state. One initiative is the perinatal quality collaboratives (PQCs), state or multistate networks of teams working to improve the quality of care for mothers and babies (see “Has your state established a perinatal quality collaborative?”).

Currently, only 33 states have a maternal mortality review committee (MMRC) comprised of an interdisciplinary team of ObGyns, nurses, and other stakeholders. The MMRC reviews each maternal death in their state and provides recommendations and policy changes to help prevent further loss of life.

Many states currently have active collaboratives, and others are in development. The CDC’s Division of Reproductive Health (DRH) currently provides support for state-based PQCs in Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, and Wisconsin. The status of PQCs in Maine, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, Missouri, South Dakota, and Wyoming is unknown.1

The CDC can help people establish a collaborative. Visit: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pqc-states.html.

Reference

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reproductive health: State Perinatal Quality Collaboratives. CDC website. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pqc-states.html Updated October 17, 2017. Accessed April 4, 2018.

The bill

Preventing Maternal Deaths Act/Maternal Health Accountability Act (H.R. 1318/S. 1112) is a bipartisan, bicameral effort to reduce maternal mortality and reduce health care disparities.

The bills authorize the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to help states create or expand state MMRCs through annual grant funding of $7 million through fiscal year 2022. Through the MMRCs, the CDC would have the ability to gather data on maternal mortality and health care disparities, allowing the agency to better understand leading causes of maternal death as well as a state’s successes and pitfalls in interventions.

Currently the House bill (H.R. 1318) has 102 cosponsors (https://cqrcengage.com/acog/app/bill/903056?0) and the Senate bill (S. 1112) has 17 cosponsors (https://cqrcengage.com/acog/app/bill/943204?1). Click these links to see if your representative is a cosponsor.

Not sure who your representative is? Click here to find out: http://cqrcengage.com/acog/app/lookup?1&m=29525.

Take action

Both the Senate and House bills have been referred to health committees. However, no advances have been made since March 2017. In order for the bills to move forward, your representatives need to hear from you.

If your representative is a cosponsor of the bill, thank them for their support, but also ask what we can do to ensure this bill becomes law.

If your representative is not a cosponsor, follow this link to email your representative: http://cqrcengage.com/acog/app/onestep-write-a-letter?0&engagementId=306574. You also can call your representative’s office and speak directly to a staff member.

When calling or emailing, highlight the following:

- I am an ObGyn and I am asking [your Representative/Senator] to support H.R. 1318 or S. 1112.

- While maternal mortality rates are decreasing in other parts of the world, they are increasing in the United States. We have the highest maternal mortality rate in the developing world.

- This bill gives all states the opportunity to have a maternal mortality review committee, allowing health care leaders to review each maternal death and analyze how further deaths can be prevented.

- Congress has invested in programs addressing infant mortality, birth defects, and preterm birth. It is time we put the same investment into saving our nation’s mothers.

- As an ObGyn, I urge you to support this bill.

More from ACOG

Want to know what other advocacy opportunities are available? Check out ACOG action at http://cqrcengage.com/acog/home?3.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- DiVenere L. Factors critical to reducing US maternal mortality and morbidity. OBG Manag. 2018;30(3):30−33.

- DiVenere L. Factors critical to reducing US maternal mortality and morbidity. OBG Manag. 2018;30(3):30−33.

Pot peaks in breast milk 1 hour after smoking

The levels of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in breast milk peak around 1 hour after smoking, according to a pilot pharmacokinetic study.

Eight mothers who were either occasional or chronic cannabis smokers, and who exclusively breastfed their infants, were directed to smoke a preweighed, standardized amount of “Prezidential Kush” from a preselected Denver dispensary after initially discontinuing for 24 hours. Researchers collected breast milk samples from just before smoking, and at 20 minutes, 1 hour, 2 hours, and 4 hours after smoking, according to a paper published in the May issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

This translated to an estimated relative infant dose of 2.5% of the maternal dose, or 8 mcg per kilogram per day.

“It remains unclear what exposure to cannabis products during this critical neurobehavioral development period will mean for the infant,” wrote Teresa Baker, MD, of Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, and her coauthors. “These questions will require an enormous effort to determine.”

Concentrations of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol metabolites 11-OH-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and 11-Nor-9-carboxy-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol were too low to be detected.

The authors noted that these metabolites are known to be more water soluble and polar than delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol itself, which may make it more difficult for them to enter the breast milk compartment.

Two of the participants had a low but measurable concentration of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol at zero time (the samples collected just before smoking), suggesting some residual accumulation of it from prior heavy use or use close to the start of breast milk collection.

“Although the transfer of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol into the plasma compartment is almost instantaneous, the transfer of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol into breast milk in our study appears to be slightly slower than the transfer into the plasma compartment,” the authors wrote.

The women in the study were all 2-5 months postpartum. The authors noted that in these women who were exclusively breastfeeding, the breast milk compartment, along with drug entry and exit, “remains fairly consistent.”

The researchers also noted that the lack of corresponding plasma samples was a major limitation of the study, but because of the nature of the study, anonymity was important.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Baker T et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:783-8.

The levels of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in breast milk peak around 1 hour after smoking, according to a pilot pharmacokinetic study.

Eight mothers who were either occasional or chronic cannabis smokers, and who exclusively breastfed their infants, were directed to smoke a preweighed, standardized amount of “Prezidential Kush” from a preselected Denver dispensary after initially discontinuing for 24 hours. Researchers collected breast milk samples from just before smoking, and at 20 minutes, 1 hour, 2 hours, and 4 hours after smoking, according to a paper published in the May issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

This translated to an estimated relative infant dose of 2.5% of the maternal dose, or 8 mcg per kilogram per day.

“It remains unclear what exposure to cannabis products during this critical neurobehavioral development period will mean for the infant,” wrote Teresa Baker, MD, of Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, and her coauthors. “These questions will require an enormous effort to determine.”

Concentrations of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol metabolites 11-OH-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and 11-Nor-9-carboxy-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol were too low to be detected.

The authors noted that these metabolites are known to be more water soluble and polar than delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol itself, which may make it more difficult for them to enter the breast milk compartment.

Two of the participants had a low but measurable concentration of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol at zero time (the samples collected just before smoking), suggesting some residual accumulation of it from prior heavy use or use close to the start of breast milk collection.

“Although the transfer of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol into the plasma compartment is almost instantaneous, the transfer of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol into breast milk in our study appears to be slightly slower than the transfer into the plasma compartment,” the authors wrote.

The women in the study were all 2-5 months postpartum. The authors noted that in these women who were exclusively breastfeeding, the breast milk compartment, along with drug entry and exit, “remains fairly consistent.”

The researchers also noted that the lack of corresponding plasma samples was a major limitation of the study, but because of the nature of the study, anonymity was important.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Baker T et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:783-8.

The levels of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in breast milk peak around 1 hour after smoking, according to a pilot pharmacokinetic study.

Eight mothers who were either occasional or chronic cannabis smokers, and who exclusively breastfed their infants, were directed to smoke a preweighed, standardized amount of “Prezidential Kush” from a preselected Denver dispensary after initially discontinuing for 24 hours. Researchers collected breast milk samples from just before smoking, and at 20 minutes, 1 hour, 2 hours, and 4 hours after smoking, according to a paper published in the May issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

This translated to an estimated relative infant dose of 2.5% of the maternal dose, or 8 mcg per kilogram per day.

“It remains unclear what exposure to cannabis products during this critical neurobehavioral development period will mean for the infant,” wrote Teresa Baker, MD, of Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, and her coauthors. “These questions will require an enormous effort to determine.”

Concentrations of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol metabolites 11-OH-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and 11-Nor-9-carboxy-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol were too low to be detected.

The authors noted that these metabolites are known to be more water soluble and polar than delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol itself, which may make it more difficult for them to enter the breast milk compartment.

Two of the participants had a low but measurable concentration of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol at zero time (the samples collected just before smoking), suggesting some residual accumulation of it from prior heavy use or use close to the start of breast milk collection.

“Although the transfer of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol into the plasma compartment is almost instantaneous, the transfer of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol into breast milk in our study appears to be slightly slower than the transfer into the plasma compartment,” the authors wrote.

The women in the study were all 2-5 months postpartum. The authors noted that in these women who were exclusively breastfeeding, the breast milk compartment, along with drug entry and exit, “remains fairly consistent.”

The researchers also noted that the lack of corresponding plasma samples was a major limitation of the study, but because of the nature of the study, anonymity was important.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Baker T et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:783-8.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point: Cannabinoid levels peak in breast milk 1 hour after smoking.

Major finding: Breastfeeding infants ingest around 2.5% of the maternal dose in breast milk.

Study details: A pilot pharmacokinetic study in eight women.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Baker T et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:783-8.

Zika virus: Sexual contact risk may be limited to short window

Shedding of infectious Zika virus in the semen of symptomatic infected men appears to be uncommon and limited to the first few weeks after onset of illness, according to results of a recent prospective study.

Out of all semen samples with detectable Zika virus RNA, the only ones with infectious virus were those that had been obtained within 30 days of illness onset, study authors reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Sexual transmission of Zika virus, first documented in 2011, has now been reported in at least 13 countries, Dr. Mead and his colleagues wrote.

Usually, the cases have involved transmission from a symptomatic man to a woman, they added.

Previously, some investigators had proposed that sexual transmission of Zika virus could pose a greater risk of fetal infection than could mosquito-borne transmission, Dr. Mead and colleagues noted in their report. “If so, the interruption of sexual transmission could play a critical role in preventing the serious complications that have been associated with fetal infection,” they wrote.

To investigate further, Dr. Mead and his colleagues conducted a prospective study of men with symptomatic Zika virus infection. They collected 1,327 semen samples from 184 men and 1,038 urine samples from 183 men, according to the report.

They obtained specimens twice monthly for 6 months. Samples were tested for Zika RNA using real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assay and for infectious Zika virus using Vero cell culture and plaque assay.

Investigators detected Zika virus RNA in the semen of 60 men (33%), including semen samples from 22 of the 36 men (61%) tested within 30 days after illness onset, investigators said in the report.

While Zika virus RNA shedding decreased considerably in the 3 months after illness onset, it did continue for 281 days in one man, they noted.

Men who were older and those who ejaculated less frequently were more likely to have prolonged RNA shedding in semen, results of multivariable analysis showed.

Infectious Zika virus was isolated from just 3 out of the 78 semen samples with detectable Zika virus RNA that were tested by culture, investigators said. Notably, all 3 of the cases were among the 19 of those samples obtained within 30 days of illness onset, they reported.

Detection of Zika virus RNA in urine was rare, occurring in only 7 men (4%), possibly because of the timing of the first specimen collection, according to investigators. They said previous studies suggest a rapid decline in Zika virus shedding in urine during the first few weeks after onset of illness.

Important questions remain regarding sexual transmission of Zika virus, such as whether maternal infection through sex poses similar risks to the fetus as compared with maternal infection via mosquito bite, Dr. Mead and his coauthors said in the report.

“A better understanding of these issues is needed to guide the development of effective prevention strategies,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Mead and his coauthors reported they had no disclosures related to the study.

SOURCE: Mead PS et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(15):1377-85.

This study illustrates the apparent shortcomings of current virus-detection standards in terms of their relevance to public health, according to Heinz Feldmann, MD.

Approximately 4% of Zika virus RNA-positive semen samples were infectious, according to the report, and of those infectious samples, all were obtained within 30 days of the onset of illness. “This finding suggests that there is a short period during which Zika virus–infected men might transmit this virus through sexual contact,” Dr. Feldmann wrote in an editorial.

Current practice in some areas is to test semen samples sequentially until two or more consecutive negative results are obtained; however, that approach is controversial, according to Dr. Feldmann, because the person could be shedding the virus intermittently because of the potential for virus latency and reactivation.

“This also raises the question of whether modern molecular approaches are properly positioned to detect virus latency rather than persistence,” he said in his editorial. The goal, he added, should be to determine infectivity, which is probably best assessed by means of viral isolation – which is believed to be less sensitive than molecular detection.

“Thus, the diagnostic situation is far more complicated than it seems,” he noted.

However, he added, these diagnostic scenarios may be less applicable for public health entities, which have “quickly” disseminated recommendations for safer sex to prevent Zika virus spread and the potentially devastating consequences of fetal infection.

“These recommendations leverage the best data available and have been implemented, but ought to be updated as new data emerge,” Dr. Feldmann wrote.

Dr. Feldmann is with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, and Rocky Mountain Laboratories, Hamilton, Mont. These comments are derived from his editorial N Engl J Med 2018;378:1377-85 . Dr. Feldmann reported that he had nothing to disclose related to the editorial.

This study illustrates the apparent shortcomings of current virus-detection standards in terms of their relevance to public health, according to Heinz Feldmann, MD.

Approximately 4% of Zika virus RNA-positive semen samples were infectious, according to the report, and of those infectious samples, all were obtained within 30 days of the onset of illness. “This finding suggests that there is a short period during which Zika virus–infected men might transmit this virus through sexual contact,” Dr. Feldmann wrote in an editorial.

Current practice in some areas is to test semen samples sequentially until two or more consecutive negative results are obtained; however, that approach is controversial, according to Dr. Feldmann, because the person could be shedding the virus intermittently because of the potential for virus latency and reactivation.

“This also raises the question of whether modern molecular approaches are properly positioned to detect virus latency rather than persistence,” he said in his editorial. The goal, he added, should be to determine infectivity, which is probably best assessed by means of viral isolation – which is believed to be less sensitive than molecular detection.

“Thus, the diagnostic situation is far more complicated than it seems,” he noted.

However, he added, these diagnostic scenarios may be less applicable for public health entities, which have “quickly” disseminated recommendations for safer sex to prevent Zika virus spread and the potentially devastating consequences of fetal infection.

“These recommendations leverage the best data available and have been implemented, but ought to be updated as new data emerge,” Dr. Feldmann wrote.

Dr. Feldmann is with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, and Rocky Mountain Laboratories, Hamilton, Mont. These comments are derived from his editorial N Engl J Med 2018;378:1377-85 . Dr. Feldmann reported that he had nothing to disclose related to the editorial.

This study illustrates the apparent shortcomings of current virus-detection standards in terms of their relevance to public health, according to Heinz Feldmann, MD.

Approximately 4% of Zika virus RNA-positive semen samples were infectious, according to the report, and of those infectious samples, all were obtained within 30 days of the onset of illness. “This finding suggests that there is a short period during which Zika virus–infected men might transmit this virus through sexual contact,” Dr. Feldmann wrote in an editorial.

Current practice in some areas is to test semen samples sequentially until two or more consecutive negative results are obtained; however, that approach is controversial, according to Dr. Feldmann, because the person could be shedding the virus intermittently because of the potential for virus latency and reactivation.

“This also raises the question of whether modern molecular approaches are properly positioned to detect virus latency rather than persistence,” he said in his editorial. The goal, he added, should be to determine infectivity, which is probably best assessed by means of viral isolation – which is believed to be less sensitive than molecular detection.

“Thus, the diagnostic situation is far more complicated than it seems,” he noted.

However, he added, these diagnostic scenarios may be less applicable for public health entities, which have “quickly” disseminated recommendations for safer sex to prevent Zika virus spread and the potentially devastating consequences of fetal infection.

“These recommendations leverage the best data available and have been implemented, but ought to be updated as new data emerge,” Dr. Feldmann wrote.

Dr. Feldmann is with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, and Rocky Mountain Laboratories, Hamilton, Mont. These comments are derived from his editorial N Engl J Med 2018;378:1377-85 . Dr. Feldmann reported that he had nothing to disclose related to the editorial.

Shedding of infectious Zika virus in the semen of symptomatic infected men appears to be uncommon and limited to the first few weeks after onset of illness, according to results of a recent prospective study.

Out of all semen samples with detectable Zika virus RNA, the only ones with infectious virus were those that had been obtained within 30 days of illness onset, study authors reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Sexual transmission of Zika virus, first documented in 2011, has now been reported in at least 13 countries, Dr. Mead and his colleagues wrote.

Usually, the cases have involved transmission from a symptomatic man to a woman, they added.

Previously, some investigators had proposed that sexual transmission of Zika virus could pose a greater risk of fetal infection than could mosquito-borne transmission, Dr. Mead and colleagues noted in their report. “If so, the interruption of sexual transmission could play a critical role in preventing the serious complications that have been associated with fetal infection,” they wrote.

To investigate further, Dr. Mead and his colleagues conducted a prospective study of men with symptomatic Zika virus infection. They collected 1,327 semen samples from 184 men and 1,038 urine samples from 183 men, according to the report.

They obtained specimens twice monthly for 6 months. Samples were tested for Zika RNA using real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assay and for infectious Zika virus using Vero cell culture and plaque assay.

Investigators detected Zika virus RNA in the semen of 60 men (33%), including semen samples from 22 of the 36 men (61%) tested within 30 days after illness onset, investigators said in the report.

While Zika virus RNA shedding decreased considerably in the 3 months after illness onset, it did continue for 281 days in one man, they noted.

Men who were older and those who ejaculated less frequently were more likely to have prolonged RNA shedding in semen, results of multivariable analysis showed.

Infectious Zika virus was isolated from just 3 out of the 78 semen samples with detectable Zika virus RNA that were tested by culture, investigators said. Notably, all 3 of the cases were among the 19 of those samples obtained within 30 days of illness onset, they reported.

Detection of Zika virus RNA in urine was rare, occurring in only 7 men (4%), possibly because of the timing of the first specimen collection, according to investigators. They said previous studies suggest a rapid decline in Zika virus shedding in urine during the first few weeks after onset of illness.

Important questions remain regarding sexual transmission of Zika virus, such as whether maternal infection through sex poses similar risks to the fetus as compared with maternal infection via mosquito bite, Dr. Mead and his coauthors said in the report.

“A better understanding of these issues is needed to guide the development of effective prevention strategies,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Mead and his coauthors reported they had no disclosures related to the study.

SOURCE: Mead PS et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(15):1377-85.

Shedding of infectious Zika virus in the semen of symptomatic infected men appears to be uncommon and limited to the first few weeks after onset of illness, according to results of a recent prospective study.

Out of all semen samples with detectable Zika virus RNA, the only ones with infectious virus were those that had been obtained within 30 days of illness onset, study authors reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Sexual transmission of Zika virus, first documented in 2011, has now been reported in at least 13 countries, Dr. Mead and his colleagues wrote.

Usually, the cases have involved transmission from a symptomatic man to a woman, they added.

Previously, some investigators had proposed that sexual transmission of Zika virus could pose a greater risk of fetal infection than could mosquito-borne transmission, Dr. Mead and colleagues noted in their report. “If so, the interruption of sexual transmission could play a critical role in preventing the serious complications that have been associated with fetal infection,” they wrote.

To investigate further, Dr. Mead and his colleagues conducted a prospective study of men with symptomatic Zika virus infection. They collected 1,327 semen samples from 184 men and 1,038 urine samples from 183 men, according to the report.

They obtained specimens twice monthly for 6 months. Samples were tested for Zika RNA using real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assay and for infectious Zika virus using Vero cell culture and plaque assay.

Investigators detected Zika virus RNA in the semen of 60 men (33%), including semen samples from 22 of the 36 men (61%) tested within 30 days after illness onset, investigators said in the report.

While Zika virus RNA shedding decreased considerably in the 3 months after illness onset, it did continue for 281 days in one man, they noted.

Men who were older and those who ejaculated less frequently were more likely to have prolonged RNA shedding in semen, results of multivariable analysis showed.

Infectious Zika virus was isolated from just 3 out of the 78 semen samples with detectable Zika virus RNA that were tested by culture, investigators said. Notably, all 3 of the cases were among the 19 of those samples obtained within 30 days of illness onset, they reported.

Detection of Zika virus RNA in urine was rare, occurring in only 7 men (4%), possibly because of the timing of the first specimen collection, according to investigators. They said previous studies suggest a rapid decline in Zika virus shedding in urine during the first few weeks after onset of illness.

Important questions remain regarding sexual transmission of Zika virus, such as whether maternal infection through sex poses similar risks to the fetus as compared with maternal infection via mosquito bite, Dr. Mead and his coauthors said in the report.

“A better understanding of these issues is needed to guide the development of effective prevention strategies,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Mead and his coauthors reported they had no disclosures related to the study.

SOURCE: Mead PS et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(15):1377-85.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: While Zika virus RNA is common and may persist for months in the semen of symptomatic infected men, shedding of infectious virus appears to be much less common and limited to the first few weeks after onset of illness.

Major finding: Out of 78 semen samples with detectable Zika virus RNA, 3 had infectious virus, and all 3 were obtained within 30 days of illness onset.

Study details: A prospective study of 1,327 semen samples from 184 men with symptomatic Zika virus infection.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Study authors reported they had nothing to disclose relative to the study.

Source: Mead PS et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Apr 12;378(15):1377-85.

Does measuring episiotomy rates really benefit the quality of care our patients receive?

Like most California institutions performing deliveries, St. Joseph Hospital in Orange, California, started releasing 2016 maternal quality metrics internally at first. Data for the first 9 months of 2016 were distributed in December 2016. These metrics depend on a denominator based on the number of deliveries attributed to each obstetrician.

- I was very pleased to see that I ranked first in the vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) rate at 36.8%.

- I also was pleased that I ranked the fourth lowest, at 15.9%, for my cesarean delivery rate in the low-risk, nulliparous term singleton vertex (NTSV) population.

- I was neither pleased nor displeased that I ranked number 29 of 31 physicians at 59.1% (39/66) for the episiotomy rate. The denominator range was 1 to 287. I knew I would hear about this! Sure enough, a medical director asked me how 2 of my metrics could be so good, yet the third be so abysmal.

After the release of the data and the somewhat humorous chastisement by the medical director, I decided to try complying with the new American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines1 again beginning in January 2017.

A little personal history

Allow me to date myself. I completed my residency in 1981 and was Board Certified in 1984. My wife refers to me as a “Dinosaur!” As an ObGyn in solo practice, I take my own call.

During my training, episiotomies were commonly performed but were not always necessary. We were taught to not perform an episiotomy if the patient could safely and easily deliver without one. However, if clinically indicated, an episiotomy should be performed. If a 3rd- or 4th-degree laceration occurred, we were taught to anatomically repair it. Nowadays in my practice, these lacerations are rare in conjunction with an episiotomy, and with a controlled delivery of the fetal head.

Our nursing staff will tell you that I resist change. However, I usually attempt and often do adapt the latest national guidelines into my practice. Although I did not agree when restrictive episiotomies became a national goal a few years ago, I tried to adhere to the new national episiotomy recommendations.1 I am meticulous: a standard episiotomy repair that does not involve excessive bleeding usually takes 20 minutes to restore normal anatomy with a simple, straightforward, layered closure.

My episiotomy performance record

In 2015, I restricted my use of episiotomies. When I did not perform one, the patient usually experienced lacerations. These were labial or periurethral as well as complex 3-dimensional “Z” or “Y” shaped vaginal/perineal lacerations, not just the 1st- and 2nd-degree perineal lacerations to which the literature refers.

The problems associated with complex, geometric vaginal lacerations are multifactorial:

- Lacerations occur at multiple locations.

- Significant bleeding often occurs. Because the lacerations are in multiple locations, the bleeding cannot be addressed easily, quickly, or at once.

- Visualization is difficult because of the bleeding, thus further prolonging the repair.

- These lacerations are often deeper than an episiotomy would have been and are very friable as all the layers have been stretched to their breaking point before tearing.

- Sometimes the lacerations include avulsion of the hymen with extensive bleeding.

- Difficult-to-repair lacerations can tear upon suturing, requiring layer upon layer of sutures at the same site. Future scarring and vaginal stricture leading to sexual dysfunction are concerns.

- At times, the friability and bleeding is so brisk that once the bleeding is controlled and the episiotomy is partially repaired, I can see that it is has not been an anatomic repair. I then have to take it down and re-do the repair with an obscured field from bleeding again!

- Some repairs are so fragile that when I express retained blood from the uterus and upper vagina after completing the repair, the tissue tears, bleeds, and requires additional restoration.

- These tears usually require an hour to repair and achieve hemostasis. At times, an assistant and a retractor are necessary.

After 2015, when I spent the year complying with the new guidelines, I returned to my original protocol: I performed an episiotomy only when I thought the patient was going to experience a significant laceration. I did not perform an episiotomy if I thought the mother could deliver easily without one. That is how I attained the 59.1% episiotomy rate in 2016.

Another try

After the 2016 hospital data were released, I decided to comply with the new guidelines1 again beginning in January 2017. Here I share the details of 3 deliveries that occurred in 2017:

- A 30-year-old woman (G2P1) planned to have a repeat cesarean delivery. At 38 3/7 weeks’ gestation, she was admitted in active labor with the cervix dilated to 5 cm. She requested a VBAC. After successful vaginal delivery without episiotomy of a 7 lb 5 oz infant, there were bilateral periurethral and right labia minora abrasions/lacerations.

- A 21-year-old woman (G1P0) at 40 4/7 weeks’ gestation was admitted in early labor. The cervix was 2-cm dilated and 70% effaced after spontaneous rupture of membranes. I exercised my clinical judgment and performed a midline episiotomy. A 9 lb 3 oz infant was delivered by vaginal delivery.

- A 16-year-old woman (G1P0) at 41 weeks’ gestation was admitted for induction of labor with an unripe cervix. I was delayed, and the laborist performed a vaginal delivery after 1 attempt at vacuum extraction and no episiotomy. The 7 lb 3 oz baby had Apgar scores of 4 and 9 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively. There was significant bleeding from bilateral vaginal lacerations with bilateral hymeneal avulsions.

What is the benefit?

Are we really benefitting our patients by restricting the use of episiotomy? Consider these questions:

- Should we delay the mother’s bonding with her baby for an hour’s complex repair versus 20 minutes for a simple, layered episiotomy repair?

- In a busy labor and delivery unit, should resources be tied up for this extra time? With all due respect to the national experts advocating this recommendation, are they in the trenches performing deliveries and spending hours repairing complex lacerations?

- Should we not use our clinical judgment instead of allowing the mother to experience an extensive vaginal/perineal laceration after a vaginal delivery of a 9- or 10-lb baby?

- Where are the long-term data showing that it is better for a woman to stretch and attenuate her perineal and vaginal muscles to the breaking point, and then tear?

- Do all the additional sutures lead to vaginal scarring, vaginal stricture, and sexual dysfunction in later years?

- Which protocol better enables the mother to maintain pelvic organ support and avoid pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence?

In Williams Obstetrics, the authors state: “We are of the view that episiotomy should be applied selectively for the appropriate indications. The final rule is that there is no substitute for surgical judgment and common sense.”2

Consider other metrics

Patients might be better served by measuring quality and safety metrics other than episiotomy. These might include, for example, measuring:

- the use of prophylactic oxytocin after the anterior shoulder is delivered in order to decrease the risk of postpartum hemorrhage, as advocated by the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative3

- the number of patients admitted before active labor and those receiving an epidural before active labor (with the aim of decreasing the primary cesarean rate in the NTSV population)

- the number of patients in an advanced stage of labor whose labor pattern has become dysfunctional, in whom no interventions have been instituted to improve the labor pattern, and who subsequently deliver by primary cesarean.

Recommendation

I recommend that performing an episiotomy should be an individual clinical decision for the individual patient by the individual obstetrician, and not a national mandate. We can provide quality care to our patients by performing selective episiotomies when clinically necessary, and not avoid them to an extreme that harms our patients. In my opinion, using the episiotomy rate as a quality metric should be abandoned.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- CambriaAmerican College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 165: Prevention and management of obstetric lacerations at vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(1):e1Times New Roman MT Std–e15.

- Vaginal delivery. In: Cunnigham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, et al, eds. Williams Obstetrics. 24th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2014:550.

- CMQCC: California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative website. https://www.cmqcc.org/. Accessed March 12, 2018.

Like most California institutions performing deliveries, St. Joseph Hospital in Orange, California, started releasing 2016 maternal quality metrics internally at first. Data for the first 9 months of 2016 were distributed in December 2016. These metrics depend on a denominator based on the number of deliveries attributed to each obstetrician.

- I was very pleased to see that I ranked first in the vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) rate at 36.8%.

- I also was pleased that I ranked the fourth lowest, at 15.9%, for my cesarean delivery rate in the low-risk, nulliparous term singleton vertex (NTSV) population.

- I was neither pleased nor displeased that I ranked number 29 of 31 physicians at 59.1% (39/66) for the episiotomy rate. The denominator range was 1 to 287. I knew I would hear about this! Sure enough, a medical director asked me how 2 of my metrics could be so good, yet the third be so abysmal.

After the release of the data and the somewhat humorous chastisement by the medical director, I decided to try complying with the new American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines1 again beginning in January 2017.

A little personal history

Allow me to date myself. I completed my residency in 1981 and was Board Certified in 1984. My wife refers to me as a “Dinosaur!” As an ObGyn in solo practice, I take my own call.

During my training, episiotomies were commonly performed but were not always necessary. We were taught to not perform an episiotomy if the patient could safely and easily deliver without one. However, if clinically indicated, an episiotomy should be performed. If a 3rd- or 4th-degree laceration occurred, we were taught to anatomically repair it. Nowadays in my practice, these lacerations are rare in conjunction with an episiotomy, and with a controlled delivery of the fetal head.

Our nursing staff will tell you that I resist change. However, I usually attempt and often do adapt the latest national guidelines into my practice. Although I did not agree when restrictive episiotomies became a national goal a few years ago, I tried to adhere to the new national episiotomy recommendations.1 I am meticulous: a standard episiotomy repair that does not involve excessive bleeding usually takes 20 minutes to restore normal anatomy with a simple, straightforward, layered closure.

My episiotomy performance record

In 2015, I restricted my use of episiotomies. When I did not perform one, the patient usually experienced lacerations. These were labial or periurethral as well as complex 3-dimensional “Z” or “Y” shaped vaginal/perineal lacerations, not just the 1st- and 2nd-degree perineal lacerations to which the literature refers.

The problems associated with complex, geometric vaginal lacerations are multifactorial:

- Lacerations occur at multiple locations.

- Significant bleeding often occurs. Because the lacerations are in multiple locations, the bleeding cannot be addressed easily, quickly, or at once.

- Visualization is difficult because of the bleeding, thus further prolonging the repair.

- These lacerations are often deeper than an episiotomy would have been and are very friable as all the layers have been stretched to their breaking point before tearing.

- Sometimes the lacerations include avulsion of the hymen with extensive bleeding.

- Difficult-to-repair lacerations can tear upon suturing, requiring layer upon layer of sutures at the same site. Future scarring and vaginal stricture leading to sexual dysfunction are concerns.

- At times, the friability and bleeding is so brisk that once the bleeding is controlled and the episiotomy is partially repaired, I can see that it is has not been an anatomic repair. I then have to take it down and re-do the repair with an obscured field from bleeding again!

- Some repairs are so fragile that when I express retained blood from the uterus and upper vagina after completing the repair, the tissue tears, bleeds, and requires additional restoration.

- These tears usually require an hour to repair and achieve hemostasis. At times, an assistant and a retractor are necessary.

After 2015, when I spent the year complying with the new guidelines, I returned to my original protocol: I performed an episiotomy only when I thought the patient was going to experience a significant laceration. I did not perform an episiotomy if I thought the mother could deliver easily without one. That is how I attained the 59.1% episiotomy rate in 2016.

Another try

After the 2016 hospital data were released, I decided to comply with the new guidelines1 again beginning in January 2017. Here I share the details of 3 deliveries that occurred in 2017:

- A 30-year-old woman (G2P1) planned to have a repeat cesarean delivery. At 38 3/7 weeks’ gestation, she was admitted in active labor with the cervix dilated to 5 cm. She requested a VBAC. After successful vaginal delivery without episiotomy of a 7 lb 5 oz infant, there were bilateral periurethral and right labia minora abrasions/lacerations.

- A 21-year-old woman (G1P0) at 40 4/7 weeks’ gestation was admitted in early labor. The cervix was 2-cm dilated and 70% effaced after spontaneous rupture of membranes. I exercised my clinical judgment and performed a midline episiotomy. A 9 lb 3 oz infant was delivered by vaginal delivery.

- A 16-year-old woman (G1P0) at 41 weeks’ gestation was admitted for induction of labor with an unripe cervix. I was delayed, and the laborist performed a vaginal delivery after 1 attempt at vacuum extraction and no episiotomy. The 7 lb 3 oz baby had Apgar scores of 4 and 9 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively. There was significant bleeding from bilateral vaginal lacerations with bilateral hymeneal avulsions.

What is the benefit?

Are we really benefitting our patients by restricting the use of episiotomy? Consider these questions:

- Should we delay the mother’s bonding with her baby for an hour’s complex repair versus 20 minutes for a simple, layered episiotomy repair?

- In a busy labor and delivery unit, should resources be tied up for this extra time? With all due respect to the national experts advocating this recommendation, are they in the trenches performing deliveries and spending hours repairing complex lacerations?

- Should we not use our clinical judgment instead of allowing the mother to experience an extensive vaginal/perineal laceration after a vaginal delivery of a 9- or 10-lb baby?

- Where are the long-term data showing that it is better for a woman to stretch and attenuate her perineal and vaginal muscles to the breaking point, and then tear?

- Do all the additional sutures lead to vaginal scarring, vaginal stricture, and sexual dysfunction in later years?

- Which protocol better enables the mother to maintain pelvic organ support and avoid pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence?

In Williams Obstetrics, the authors state: “We are of the view that episiotomy should be applied selectively for the appropriate indications. The final rule is that there is no substitute for surgical judgment and common sense.”2

Consider other metrics

Patients might be better served by measuring quality and safety metrics other than episiotomy. These might include, for example, measuring:

- the use of prophylactic oxytocin after the anterior shoulder is delivered in order to decrease the risk of postpartum hemorrhage, as advocated by the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative3

- the number of patients admitted before active labor and those receiving an epidural before active labor (with the aim of decreasing the primary cesarean rate in the NTSV population)

- the number of patients in an advanced stage of labor whose labor pattern has become dysfunctional, in whom no interventions have been instituted to improve the labor pattern, and who subsequently deliver by primary cesarean.

Recommendation

I recommend that performing an episiotomy should be an individual clinical decision for the individual patient by the individual obstetrician, and not a national mandate. We can provide quality care to our patients by performing selective episiotomies when clinically necessary, and not avoid them to an extreme that harms our patients. In my opinion, using the episiotomy rate as a quality metric should be abandoned.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Like most California institutions performing deliveries, St. Joseph Hospital in Orange, California, started releasing 2016 maternal quality metrics internally at first. Data for the first 9 months of 2016 were distributed in December 2016. These metrics depend on a denominator based on the number of deliveries attributed to each obstetrician.

- I was very pleased to see that I ranked first in the vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) rate at 36.8%.

- I also was pleased that I ranked the fourth lowest, at 15.9%, for my cesarean delivery rate in the low-risk, nulliparous term singleton vertex (NTSV) population.

- I was neither pleased nor displeased that I ranked number 29 of 31 physicians at 59.1% (39/66) for the episiotomy rate. The denominator range was 1 to 287. I knew I would hear about this! Sure enough, a medical director asked me how 2 of my metrics could be so good, yet the third be so abysmal.

After the release of the data and the somewhat humorous chastisement by the medical director, I decided to try complying with the new American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines1 again beginning in January 2017.

A little personal history

Allow me to date myself. I completed my residency in 1981 and was Board Certified in 1984. My wife refers to me as a “Dinosaur!” As an ObGyn in solo practice, I take my own call.

During my training, episiotomies were commonly performed but were not always necessary. We were taught to not perform an episiotomy if the patient could safely and easily deliver without one. However, if clinically indicated, an episiotomy should be performed. If a 3rd- or 4th-degree laceration occurred, we were taught to anatomically repair it. Nowadays in my practice, these lacerations are rare in conjunction with an episiotomy, and with a controlled delivery of the fetal head.

Our nursing staff will tell you that I resist change. However, I usually attempt and often do adapt the latest national guidelines into my practice. Although I did not agree when restrictive episiotomies became a national goal a few years ago, I tried to adhere to the new national episiotomy recommendations.1 I am meticulous: a standard episiotomy repair that does not involve excessive bleeding usually takes 20 minutes to restore normal anatomy with a simple, straightforward, layered closure.

My episiotomy performance record

In 2015, I restricted my use of episiotomies. When I did not perform one, the patient usually experienced lacerations. These were labial or periurethral as well as complex 3-dimensional “Z” or “Y” shaped vaginal/perineal lacerations, not just the 1st- and 2nd-degree perineal lacerations to which the literature refers.

The problems associated with complex, geometric vaginal lacerations are multifactorial:

- Lacerations occur at multiple locations.

- Significant bleeding often occurs. Because the lacerations are in multiple locations, the bleeding cannot be addressed easily, quickly, or at once.

- Visualization is difficult because of the bleeding, thus further prolonging the repair.

- These lacerations are often deeper than an episiotomy would have been and are very friable as all the layers have been stretched to their breaking point before tearing.

- Sometimes the lacerations include avulsion of the hymen with extensive bleeding.

- Difficult-to-repair lacerations can tear upon suturing, requiring layer upon layer of sutures at the same site. Future scarring and vaginal stricture leading to sexual dysfunction are concerns.

- At times, the friability and bleeding is so brisk that once the bleeding is controlled and the episiotomy is partially repaired, I can see that it is has not been an anatomic repair. I then have to take it down and re-do the repair with an obscured field from bleeding again!

- Some repairs are so fragile that when I express retained blood from the uterus and upper vagina after completing the repair, the tissue tears, bleeds, and requires additional restoration.

- These tears usually require an hour to repair and achieve hemostasis. At times, an assistant and a retractor are necessary.

After 2015, when I spent the year complying with the new guidelines, I returned to my original protocol: I performed an episiotomy only when I thought the patient was going to experience a significant laceration. I did not perform an episiotomy if I thought the mother could deliver easily without one. That is how I attained the 59.1% episiotomy rate in 2016.

Another try

After the 2016 hospital data were released, I decided to comply with the new guidelines1 again beginning in January 2017. Here I share the details of 3 deliveries that occurred in 2017:

- A 30-year-old woman (G2P1) planned to have a repeat cesarean delivery. At 38 3/7 weeks’ gestation, she was admitted in active labor with the cervix dilated to 5 cm. She requested a VBAC. After successful vaginal delivery without episiotomy of a 7 lb 5 oz infant, there were bilateral periurethral and right labia minora abrasions/lacerations.

- A 21-year-old woman (G1P0) at 40 4/7 weeks’ gestation was admitted in early labor. The cervix was 2-cm dilated and 70% effaced after spontaneous rupture of membranes. I exercised my clinical judgment and performed a midline episiotomy. A 9 lb 3 oz infant was delivered by vaginal delivery.

- A 16-year-old woman (G1P0) at 41 weeks’ gestation was admitted for induction of labor with an unripe cervix. I was delayed, and the laborist performed a vaginal delivery after 1 attempt at vacuum extraction and no episiotomy. The 7 lb 3 oz baby had Apgar scores of 4 and 9 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively. There was significant bleeding from bilateral vaginal lacerations with bilateral hymeneal avulsions.

What is the benefit?

Are we really benefitting our patients by restricting the use of episiotomy? Consider these questions:

- Should we delay the mother’s bonding with her baby for an hour’s complex repair versus 20 minutes for a simple, layered episiotomy repair?

- In a busy labor and delivery unit, should resources be tied up for this extra time? With all due respect to the national experts advocating this recommendation, are they in the trenches performing deliveries and spending hours repairing complex lacerations?

- Should we not use our clinical judgment instead of allowing the mother to experience an extensive vaginal/perineal laceration after a vaginal delivery of a 9- or 10-lb baby?

- Where are the long-term data showing that it is better for a woman to stretch and attenuate her perineal and vaginal muscles to the breaking point, and then tear?

- Do all the additional sutures lead to vaginal scarring, vaginal stricture, and sexual dysfunction in later years?

- Which protocol better enables the mother to maintain pelvic organ support and avoid pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence?

In Williams Obstetrics, the authors state: “We are of the view that episiotomy should be applied selectively for the appropriate indications. The final rule is that there is no substitute for surgical judgment and common sense.”2

Consider other metrics

Patients might be better served by measuring quality and safety metrics other than episiotomy. These might include, for example, measuring:

- the use of prophylactic oxytocin after the anterior shoulder is delivered in order to decrease the risk of postpartum hemorrhage, as advocated by the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative3

- the number of patients admitted before active labor and those receiving an epidural before active labor (with the aim of decreasing the primary cesarean rate in the NTSV population)

- the number of patients in an advanced stage of labor whose labor pattern has become dysfunctional, in whom no interventions have been instituted to improve the labor pattern, and who subsequently deliver by primary cesarean.

Recommendation

I recommend that performing an episiotomy should be an individual clinical decision for the individual patient by the individual obstetrician, and not a national mandate. We can provide quality care to our patients by performing selective episiotomies when clinically necessary, and not avoid them to an extreme that harms our patients. In my opinion, using the episiotomy rate as a quality metric should be abandoned.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- CambriaAmerican College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 165: Prevention and management of obstetric lacerations at vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(1):e1Times New Roman MT Std–e15.

- Vaginal delivery. In: Cunnigham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, et al, eds. Williams Obstetrics. 24th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2014:550.

- CMQCC: California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative website. https://www.cmqcc.org/. Accessed March 12, 2018.

- CambriaAmerican College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 165: Prevention and management of obstetric lacerations at vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(1):e1Times New Roman MT Std–e15.

- Vaginal delivery. In: Cunnigham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, et al, eds. Williams Obstetrics. 24th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2014:550.

- CMQCC: California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative website. https://www.cmqcc.org/. Accessed March 12, 2018.

SSRI exposure in utero may change brain structure and connectivity

Prenatal exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) was associated with fetal brain development in brain regions important in emotional processing, results of an imaging study show.

Compared to controls, SSRI-exposed infants had significant gray matter volume expansion and increased white matter structural connectivity in the amygdala and insula, according to results published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“Our findings suggest a potential association between prenatal SSRI exposure, likely via aberrant serotonin signaling, and the development of the amygdala-insula circuit in the fetal brain,” wrote Claudia Lugo-Candelas, PhD, of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, and her coauthors.

An increasing number of pregnant women are taking SSRIs, in part due to increased awareness of the negative effects of untreated prenatal maternal depression (PMD), the investigators said in their report.

“Because untreated PMD poses risks to both the infant and mother, the decision to initiate, continue, or suspend SSRI treatment remains a clinical dilemma,” they wrote.

Animal studies suggest atypical serotonergic signaling from prenatal SSRI exposure could change fetal brain development and affect function later in life, they explained.

Studies in humans have produced mixed results, but in a recent national registry study including more than 15,000 individuals exposed to SSRIs prenatally, exposure was linked to increased rates of depression.

To evaluate the impact of prenatal SSRI exposure on brain development, Dr. Lugo-Candelas and colleagues used structural and diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to evaluate the brains of 98 infants.

They included 16 infants with in utero exposure to SSRIs, 21 born to mothers with untreated maternal depression, and 61 healthy control subjects, all evaluated between 2011 and 2016.

Infants exposed to SSRIs in utero had significant (P less than .05) gray matter volume expansion versus controls in both the right amygdala (Cohen’s d, 0.65; 95 %CI, 0.06-1.23) and the right insula (Cohen’s d = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.26-1.14).

The SSRI-exposed infants also had a significant (P less than .05) increase in connectivity between the right amygdala and the right insula versus controls (Cohen’s d, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.40-1.57).

Whether these neurodevelopmental changes translate into long-term behavioral or psychological outcomes should be evaluated in subsequent studies, Dr. Lugo-Candelas and colleagues said.

Abnormalities in amygdala-insula circuitry may lead to anxiety or depression, they wrote.

“The structurally primed circuit in the infant brains could lead to maladaptive fear processing in their later life, such as generalization of conditioned fear or negative attention bias,” they added.

Dr. Lugo-Candelas reported no conflicts of interest related to the study. One study coauthor reported research support from Shire Pharmaceuticals and Aevi Genomics.

SOURCE: Lugo-Candelas C, et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Apr 9. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.5227.

Prenatal exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) was associated with fetal brain development in brain regions important in emotional processing, results of an imaging study show.

Compared to controls, SSRI-exposed infants had significant gray matter volume expansion and increased white matter structural connectivity in the amygdala and insula, according to results published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“Our findings suggest a potential association between prenatal SSRI exposure, likely via aberrant serotonin signaling, and the development of the amygdala-insula circuit in the fetal brain,” wrote Claudia Lugo-Candelas, PhD, of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, and her coauthors.

An increasing number of pregnant women are taking SSRIs, in part due to increased awareness of the negative effects of untreated prenatal maternal depression (PMD), the investigators said in their report.

“Because untreated PMD poses risks to both the infant and mother, the decision to initiate, continue, or suspend SSRI treatment remains a clinical dilemma,” they wrote.

Animal studies suggest atypical serotonergic signaling from prenatal SSRI exposure could change fetal brain development and affect function later in life, they explained.

Studies in humans have produced mixed results, but in a recent national registry study including more than 15,000 individuals exposed to SSRIs prenatally, exposure was linked to increased rates of depression.

To evaluate the impact of prenatal SSRI exposure on brain development, Dr. Lugo-Candelas and colleagues used structural and diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to evaluate the brains of 98 infants.

They included 16 infants with in utero exposure to SSRIs, 21 born to mothers with untreated maternal depression, and 61 healthy control subjects, all evaluated between 2011 and 2016.

Infants exposed to SSRIs in utero had significant (P less than .05) gray matter volume expansion versus controls in both the right amygdala (Cohen’s d, 0.65; 95 %CI, 0.06-1.23) and the right insula (Cohen’s d = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.26-1.14).

The SSRI-exposed infants also had a significant (P less than .05) increase in connectivity between the right amygdala and the right insula versus controls (Cohen’s d, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.40-1.57).

Whether these neurodevelopmental changes translate into long-term behavioral or psychological outcomes should be evaluated in subsequent studies, Dr. Lugo-Candelas and colleagues said.

Abnormalities in amygdala-insula circuitry may lead to anxiety or depression, they wrote.

“The structurally primed circuit in the infant brains could lead to maladaptive fear processing in their later life, such as generalization of conditioned fear or negative attention bias,” they added.

Dr. Lugo-Candelas reported no conflicts of interest related to the study. One study coauthor reported research support from Shire Pharmaceuticals and Aevi Genomics.

SOURCE: Lugo-Candelas C, et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Apr 9. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.5227.

Prenatal exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) was associated with fetal brain development in brain regions important in emotional processing, results of an imaging study show.

Compared to controls, SSRI-exposed infants had significant gray matter volume expansion and increased white matter structural connectivity in the amygdala and insula, according to results published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“Our findings suggest a potential association between prenatal SSRI exposure, likely via aberrant serotonin signaling, and the development of the amygdala-insula circuit in the fetal brain,” wrote Claudia Lugo-Candelas, PhD, of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, and her coauthors.

An increasing number of pregnant women are taking SSRIs, in part due to increased awareness of the negative effects of untreated prenatal maternal depression (PMD), the investigators said in their report.

“Because untreated PMD poses risks to both the infant and mother, the decision to initiate, continue, or suspend SSRI treatment remains a clinical dilemma,” they wrote.

Animal studies suggest atypical serotonergic signaling from prenatal SSRI exposure could change fetal brain development and affect function later in life, they explained.

Studies in humans have produced mixed results, but in a recent national registry study including more than 15,000 individuals exposed to SSRIs prenatally, exposure was linked to increased rates of depression.

To evaluate the impact of prenatal SSRI exposure on brain development, Dr. Lugo-Candelas and colleagues used structural and diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to evaluate the brains of 98 infants.

They included 16 infants with in utero exposure to SSRIs, 21 born to mothers with untreated maternal depression, and 61 healthy control subjects, all evaluated between 2011 and 2016.

Infants exposed to SSRIs in utero had significant (P less than .05) gray matter volume expansion versus controls in both the right amygdala (Cohen’s d, 0.65; 95 %CI, 0.06-1.23) and the right insula (Cohen’s d = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.26-1.14).

The SSRI-exposed infants also had a significant (P less than .05) increase in connectivity between the right amygdala and the right insula versus controls (Cohen’s d, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.40-1.57).

Whether these neurodevelopmental changes translate into long-term behavioral or psychological outcomes should be evaluated in subsequent studies, Dr. Lugo-Candelas and colleagues said.

Abnormalities in amygdala-insula circuitry may lead to anxiety or depression, they wrote.

“The structurally primed circuit in the infant brains could lead to maladaptive fear processing in their later life, such as generalization of conditioned fear or negative attention bias,” they added.

Dr. Lugo-Candelas reported no conflicts of interest related to the study. One study coauthor reported research support from Shire Pharmaceuticals and Aevi Genomics.

SOURCE: Lugo-Candelas C, et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Apr 9. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.5227.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Prenatal selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) exposure was associated with fetal brain development, especially in regions of the brain important to emotional processing.

Major finding: Compared to controls, SSRI-exposed infants had significant gray matter volume expansion and increased white matter structural connectivity in the amygdala and insula.

Study details: A two-center cohort study of data collected between 2011 and 2016 for 98 infants, including 16 with in utero exposure to SSRIs.

Disclosures: One study author reported research support from Shire Pharmaceuticals and Aevi Genomics.

Source: Lugo-Candelas C et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Apr 9. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.5227.

Tackling opioids and maternal health in US Congress

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Pregnant women in clinical trials: FDA questions how to include them

Pregnant women are rarely included in clinical drug trials, creating a significant and potentially dangerous gap in knowledge. Now, a new draft guidance from the Food and Drug Administration broadens the discussion about these trials, suggesting issues to consider – including ethics and risks – when testing medications in pregnant women.

“The guidance opens the possibility of ethical conduct of trials in pregnant women but carefully lays out the caveats to be considered,” Christina Chambers, PhD, a perinatal epidemiologist at the University of California, San Diego, said in an interview. “With proper planning and thoughtful consultation with the relevant experts, this change in regulatory limitations will benefit pregnant women and their children.”