User login

Obstacles plague prenatal cell-free DNA testing use

A recent California study examining cell-free DNA (cfDNA) testing suggests that the test generally performs well as a second-line screen for fetal aneuploidy. However, while the test itself is reliable, some physicians say gaps in patient education, limited availability of genetic counseling, and a lack of coordinated research and data collection are all standing in the way of its optimal utilization.

In some of the most recent data presented on cfDNA test performance, researchers in California found that the test had few false positives and was best at predicting Down syndrome, with a positive predictive value of 98.6%.

California offers prenatal screening as a public health program, with a structured system of screening tests and follow-up services, according to Dr. Currier, who is chief of the evaluation section of the state’s Genetic Disease Screening Program. First trimester screening includes screens for trisomies 18 and 21. During the second trimester, the screening adds on checks for neural tube defects and Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, also known as 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase deficiency.

Overall, 20,852 patients were offered cfDNA screening during this period, and 63% (n = 12,960) went on to have the screen. Dr. Currier and his colleagues found that about a third of patients with a first- or second-trimester positive cfDNA test opted for diagnostic testing with either chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis. If patients had a known karyotype, most were in agreement with the trisomy or sex-chromosome aneuploidies that had been picked up by cfDNA testing.

There were a small number of false-positive cfDNA results seen in the California data, Dr. Currier noted. Performance was best for Down syndrome, where cfDNA had a positive predictive value of 98.6%. Here, 214 of the 611 cfDNA positive results received diagnostic confirmation. Of those, 197 were true positives and 3 were false positives, while a karyotype other than trisomy 21 was revealed in 14 cases. Positive predictive values were lower in the less-common aneuploidies, he said.

A small number of test failures also occurred. Of the 148 failures reported, just 40 were followed by successful repeat tests.

“Cell-free DNA is a good second-tier screening test, but it does have false-positive and false-negative results, so pre- and post-test counseling addressing these limitations are essential,” Dr. Currier said.

Nancy Rose, MD, agrees with that assessment of the limitations of the cfDNA test. She helped write the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2015 opinion on cell-free DNA screening for aneuploidy, which states that conventional screening methods “remain the most appropriate choice for first-line screening for most women in the general obstetric population.”

While it is “perfectly reasonable” for general ob.gyns. to offer cfDNA screening, in her practice, “genetic counselors call out all the results for general providers because patients don’t really understand what a screen negative result is,” Dr. Rose said in an interview. “Certainly, screen positive results should go to a genetic counselor for sure.”

However, that level of follow-up may be hard to implement. “One issue that we’re all facing right now is that genetic counselors are a scarce commodity because of the competition with them working for labs or insurance companies,” said Dr. Rose, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist in Salt Lake City.

If the lack of appropriate counseling is an issue, are patients sometimes jumping the gun? The immediate past president of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Mary Norton, MD, said maybe so.

When asked whether she thinks pregnancies are being terminated on the basis of cfDNA results alone, Dr. Norton said, “I absolutely think that is happening. How many is hard to know. I do know that we have many patients that we see who say, ‘My result here says that the chance of Down syndrome is greater than 99%,’ but that is not what that number means, and people don’t understand that.”

She added, “In some cases there are also ultrasound abnormalities, but there is no question that there is misunderstanding leading to the loss of normal fetuses.”

Patient misunderstandings about what’s entailed in first- and second-line screening tests persist, said Dr. Norton, professor of obstetrics and gynecology and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco. One example is ongoing hesitancy about amniocentesis. “Amnio has become very, very safe,” she said. “It’s much safer than it used to be. The miscarriage rate is nearly nonexistent.”

The care team needs to work to find time to educate patients about both older technologies and noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT), Dr. Rose and Dr. Norton stressed.

“Even though ‘NIPT’ is easy to say – it rolls off the tongue – we really shouldn’t call it that. It’s misleading, because all of the other screening tests are noninvasive too,” Dr. Norton said. “I’ve had many patients who declined diagnostic testing, even though they want as much information as possible about what they should do.”

Dr. Rose added, “It’s a screening test; it’s not perfect. But screening tests are really what obstetricians do. They do pap smears; they do breast exams. So I think that isn’t the issue so much as that there is no time in an obstetrician’s office to really educate women about what they are accepting.”

Additional ethical issues revolving around the mother may arise in rare cases. Only about 10% of the DNA sampled is fetal, meaning that the rest is maternal DNA, Dr. Norton explained. “And they’re not separated,” she said. “So, the issue that is coming up is that they are finding things in the mother that are unanticipated, and women aren’t told that ahead of time.”

Some of these thorny – and still evolving – legal and ethical questions were addressed during a workshop at the 2017 Pregnancy Meeting. A working group that met there is developing a summary of their discussion for future publication.

For Dr. Rose, the larger issue is the lack of coordinated data collection and quality initiatives. She pointed out that the California outcomes study may not be generalizable to most of the rest of the country because most states don’t have such a coordinated public health approach to prenatal testing and data collection.

This reality is hampering knowledge advancement in the field, she said. When she was asked about terminations on the basis of cfDNA alone, Dr. Rose said, “Because there’s no outcome data on these patients, because there are no unbiased studies that cross through these companies, we actually don’t really know that on a national level. There are no unbiased outcome data. There may be small studies, but I think there are no national data to answer that question at the moment.”

Overall, Dr. Rose said that cfDNA screening is fairly reliable. “This is no different than what has been done before with serum analyte screening, and it’s probably a little bit better,” she said. “My feeling is the tragedy is really in the lack of companies either being able to work together or to have some unbiased funding so you could really actually know what test performance means.”

Dr. Norton reported receiving research funding from Natera and Ultragenyx. Dr. Rose reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Currier’s study was funded by the California Department of Public Health, where he is employed.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

A recent California study examining cell-free DNA (cfDNA) testing suggests that the test generally performs well as a second-line screen for fetal aneuploidy. However, while the test itself is reliable, some physicians say gaps in patient education, limited availability of genetic counseling, and a lack of coordinated research and data collection are all standing in the way of its optimal utilization.

In some of the most recent data presented on cfDNA test performance, researchers in California found that the test had few false positives and was best at predicting Down syndrome, with a positive predictive value of 98.6%.

California offers prenatal screening as a public health program, with a structured system of screening tests and follow-up services, according to Dr. Currier, who is chief of the evaluation section of the state’s Genetic Disease Screening Program. First trimester screening includes screens for trisomies 18 and 21. During the second trimester, the screening adds on checks for neural tube defects and Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, also known as 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase deficiency.

Overall, 20,852 patients were offered cfDNA screening during this period, and 63% (n = 12,960) went on to have the screen. Dr. Currier and his colleagues found that about a third of patients with a first- or second-trimester positive cfDNA test opted for diagnostic testing with either chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis. If patients had a known karyotype, most were in agreement with the trisomy or sex-chromosome aneuploidies that had been picked up by cfDNA testing.

There were a small number of false-positive cfDNA results seen in the California data, Dr. Currier noted. Performance was best for Down syndrome, where cfDNA had a positive predictive value of 98.6%. Here, 214 of the 611 cfDNA positive results received diagnostic confirmation. Of those, 197 were true positives and 3 were false positives, while a karyotype other than trisomy 21 was revealed in 14 cases. Positive predictive values were lower in the less-common aneuploidies, he said.

A small number of test failures also occurred. Of the 148 failures reported, just 40 were followed by successful repeat tests.

“Cell-free DNA is a good second-tier screening test, but it does have false-positive and false-negative results, so pre- and post-test counseling addressing these limitations are essential,” Dr. Currier said.

Nancy Rose, MD, agrees with that assessment of the limitations of the cfDNA test. She helped write the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2015 opinion on cell-free DNA screening for aneuploidy, which states that conventional screening methods “remain the most appropriate choice for first-line screening for most women in the general obstetric population.”

While it is “perfectly reasonable” for general ob.gyns. to offer cfDNA screening, in her practice, “genetic counselors call out all the results for general providers because patients don’t really understand what a screen negative result is,” Dr. Rose said in an interview. “Certainly, screen positive results should go to a genetic counselor for sure.”

However, that level of follow-up may be hard to implement. “One issue that we’re all facing right now is that genetic counselors are a scarce commodity because of the competition with them working for labs or insurance companies,” said Dr. Rose, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist in Salt Lake City.

If the lack of appropriate counseling is an issue, are patients sometimes jumping the gun? The immediate past president of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Mary Norton, MD, said maybe so.

When asked whether she thinks pregnancies are being terminated on the basis of cfDNA results alone, Dr. Norton said, “I absolutely think that is happening. How many is hard to know. I do know that we have many patients that we see who say, ‘My result here says that the chance of Down syndrome is greater than 99%,’ but that is not what that number means, and people don’t understand that.”

She added, “In some cases there are also ultrasound abnormalities, but there is no question that there is misunderstanding leading to the loss of normal fetuses.”

Patient misunderstandings about what’s entailed in first- and second-line screening tests persist, said Dr. Norton, professor of obstetrics and gynecology and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco. One example is ongoing hesitancy about amniocentesis. “Amnio has become very, very safe,” she said. “It’s much safer than it used to be. The miscarriage rate is nearly nonexistent.”

The care team needs to work to find time to educate patients about both older technologies and noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT), Dr. Rose and Dr. Norton stressed.

“Even though ‘NIPT’ is easy to say – it rolls off the tongue – we really shouldn’t call it that. It’s misleading, because all of the other screening tests are noninvasive too,” Dr. Norton said. “I’ve had many patients who declined diagnostic testing, even though they want as much information as possible about what they should do.”

Dr. Rose added, “It’s a screening test; it’s not perfect. But screening tests are really what obstetricians do. They do pap smears; they do breast exams. So I think that isn’t the issue so much as that there is no time in an obstetrician’s office to really educate women about what they are accepting.”

Additional ethical issues revolving around the mother may arise in rare cases. Only about 10% of the DNA sampled is fetal, meaning that the rest is maternal DNA, Dr. Norton explained. “And they’re not separated,” she said. “So, the issue that is coming up is that they are finding things in the mother that are unanticipated, and women aren’t told that ahead of time.”

Some of these thorny – and still evolving – legal and ethical questions were addressed during a workshop at the 2017 Pregnancy Meeting. A working group that met there is developing a summary of their discussion for future publication.

For Dr. Rose, the larger issue is the lack of coordinated data collection and quality initiatives. She pointed out that the California outcomes study may not be generalizable to most of the rest of the country because most states don’t have such a coordinated public health approach to prenatal testing and data collection.

This reality is hampering knowledge advancement in the field, she said. When she was asked about terminations on the basis of cfDNA alone, Dr. Rose said, “Because there’s no outcome data on these patients, because there are no unbiased studies that cross through these companies, we actually don’t really know that on a national level. There are no unbiased outcome data. There may be small studies, but I think there are no national data to answer that question at the moment.”

Overall, Dr. Rose said that cfDNA screening is fairly reliable. “This is no different than what has been done before with serum analyte screening, and it’s probably a little bit better,” she said. “My feeling is the tragedy is really in the lack of companies either being able to work together or to have some unbiased funding so you could really actually know what test performance means.”

Dr. Norton reported receiving research funding from Natera and Ultragenyx. Dr. Rose reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Currier’s study was funded by the California Department of Public Health, where he is employed.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

A recent California study examining cell-free DNA (cfDNA) testing suggests that the test generally performs well as a second-line screen for fetal aneuploidy. However, while the test itself is reliable, some physicians say gaps in patient education, limited availability of genetic counseling, and a lack of coordinated research and data collection are all standing in the way of its optimal utilization.

In some of the most recent data presented on cfDNA test performance, researchers in California found that the test had few false positives and was best at predicting Down syndrome, with a positive predictive value of 98.6%.

California offers prenatal screening as a public health program, with a structured system of screening tests and follow-up services, according to Dr. Currier, who is chief of the evaluation section of the state’s Genetic Disease Screening Program. First trimester screening includes screens for trisomies 18 and 21. During the second trimester, the screening adds on checks for neural tube defects and Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, also known as 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase deficiency.

Overall, 20,852 patients were offered cfDNA screening during this period, and 63% (n = 12,960) went on to have the screen. Dr. Currier and his colleagues found that about a third of patients with a first- or second-trimester positive cfDNA test opted for diagnostic testing with either chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis. If patients had a known karyotype, most were in agreement with the trisomy or sex-chromosome aneuploidies that had been picked up by cfDNA testing.

There were a small number of false-positive cfDNA results seen in the California data, Dr. Currier noted. Performance was best for Down syndrome, where cfDNA had a positive predictive value of 98.6%. Here, 214 of the 611 cfDNA positive results received diagnostic confirmation. Of those, 197 were true positives and 3 were false positives, while a karyotype other than trisomy 21 was revealed in 14 cases. Positive predictive values were lower in the less-common aneuploidies, he said.

A small number of test failures also occurred. Of the 148 failures reported, just 40 were followed by successful repeat tests.

“Cell-free DNA is a good second-tier screening test, but it does have false-positive and false-negative results, so pre- and post-test counseling addressing these limitations are essential,” Dr. Currier said.

Nancy Rose, MD, agrees with that assessment of the limitations of the cfDNA test. She helped write the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2015 opinion on cell-free DNA screening for aneuploidy, which states that conventional screening methods “remain the most appropriate choice for first-line screening for most women in the general obstetric population.”

While it is “perfectly reasonable” for general ob.gyns. to offer cfDNA screening, in her practice, “genetic counselors call out all the results for general providers because patients don’t really understand what a screen negative result is,” Dr. Rose said in an interview. “Certainly, screen positive results should go to a genetic counselor for sure.”

However, that level of follow-up may be hard to implement. “One issue that we’re all facing right now is that genetic counselors are a scarce commodity because of the competition with them working for labs or insurance companies,” said Dr. Rose, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist in Salt Lake City.

If the lack of appropriate counseling is an issue, are patients sometimes jumping the gun? The immediate past president of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Mary Norton, MD, said maybe so.

When asked whether she thinks pregnancies are being terminated on the basis of cfDNA results alone, Dr. Norton said, “I absolutely think that is happening. How many is hard to know. I do know that we have many patients that we see who say, ‘My result here says that the chance of Down syndrome is greater than 99%,’ but that is not what that number means, and people don’t understand that.”

She added, “In some cases there are also ultrasound abnormalities, but there is no question that there is misunderstanding leading to the loss of normal fetuses.”

Patient misunderstandings about what’s entailed in first- and second-line screening tests persist, said Dr. Norton, professor of obstetrics and gynecology and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco. One example is ongoing hesitancy about amniocentesis. “Amnio has become very, very safe,” she said. “It’s much safer than it used to be. The miscarriage rate is nearly nonexistent.”

The care team needs to work to find time to educate patients about both older technologies and noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT), Dr. Rose and Dr. Norton stressed.

“Even though ‘NIPT’ is easy to say – it rolls off the tongue – we really shouldn’t call it that. It’s misleading, because all of the other screening tests are noninvasive too,” Dr. Norton said. “I’ve had many patients who declined diagnostic testing, even though they want as much information as possible about what they should do.”

Dr. Rose added, “It’s a screening test; it’s not perfect. But screening tests are really what obstetricians do. They do pap smears; they do breast exams. So I think that isn’t the issue so much as that there is no time in an obstetrician’s office to really educate women about what they are accepting.”

Additional ethical issues revolving around the mother may arise in rare cases. Only about 10% of the DNA sampled is fetal, meaning that the rest is maternal DNA, Dr. Norton explained. “And they’re not separated,” she said. “So, the issue that is coming up is that they are finding things in the mother that are unanticipated, and women aren’t told that ahead of time.”

Some of these thorny – and still evolving – legal and ethical questions were addressed during a workshop at the 2017 Pregnancy Meeting. A working group that met there is developing a summary of their discussion for future publication.

For Dr. Rose, the larger issue is the lack of coordinated data collection and quality initiatives. She pointed out that the California outcomes study may not be generalizable to most of the rest of the country because most states don’t have such a coordinated public health approach to prenatal testing and data collection.

This reality is hampering knowledge advancement in the field, she said. When she was asked about terminations on the basis of cfDNA alone, Dr. Rose said, “Because there’s no outcome data on these patients, because there are no unbiased studies that cross through these companies, we actually don’t really know that on a national level. There are no unbiased outcome data. There may be small studies, but I think there are no national data to answer that question at the moment.”

Overall, Dr. Rose said that cfDNA screening is fairly reliable. “This is no different than what has been done before with serum analyte screening, and it’s probably a little bit better,” she said. “My feeling is the tragedy is really in the lack of companies either being able to work together or to have some unbiased funding so you could really actually know what test performance means.”

Dr. Norton reported receiving research funding from Natera and Ultragenyx. Dr. Rose reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Currier’s study was funded by the California Department of Public Health, where he is employed.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Infants’ head circumference larger with PCOS moms on metformin

Women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) who took metformin had newborns with larger heads than the offspring of women with PCOS who took a placebo, though PCOS offspring were, on average, shorter than newborns in a reference population, according to a recent study.

Metformin is commonly prescribed to women with PCOS, and though metformin passes the placental barrier and can reach therapeutic concentrations in the umbilical cord blood, it hasn’t been proven teratogenic, said Anna Hjorth-Hansen, MD, of the internal medicine department at Levanger Hospital, Norway.

The study was a post hoc analysis of data from the PregMet study, which was run from 2005 to 2009, and compared metformin to placebo, in combination with diet and lifestyle changes, for women with PCOS, said Dr. Hjorth-Hansen. The PregMet study tested the hypothesis that women with PCOS who received metformin from the first trimester until delivery had fewer pregnancy complications overall than women who did not.

Though women receiving placebo in the PregMet study had no more eclampsia, preterm delivery, or gestational diabetes than those who received metformin, the newborns who had in utero metformin exposure had significantly larger head circumference.

Dr. Hjorth-Hansen said that the study looked at in utero growth and anthropometric measurements at birth of infants born to women taking metformin, to determine whether metformin could affect fetal growth and newborn anthropometrics.

Ultrasound examination was used to measure crown-rump length, biparietal diameter (BPD), and mean abdominal diameter (MAD). At birth, head circumference (HC), length, and weight were measured.

Maternal characteristics were comparable between the metformin (131 patients) and placebo (127 patients) groups, said Dr. Hjorth-Hansen. Specifically, there were no significant differences between groups in terms of PCOS phenotype, blood glucose levels, and parity.

Infants born to women who took metformin had, on average, a larger BPD at 32 weeks gestation, compared with the infants whose mothers took placebo (86.1 mm versus 85.2 mm, P = .027). This larger head size was also seen at birth (mean HC, metformin, 35.6 cm; placebo, 35.0 cm; P = .007).

There were no significant differences between the groups in MAD or weight, either as assessed by ultrasound at 32 weeks gestation or as measured at birth.

Although the two groups did not differ in length at birth, the aggregate study population of infants born to women with PCOS was shorter than a large Swedish reference population.

When Dr. Hjorth-Hansen and her colleagues stratified the results by maternal body mass index (BMI), looking at babies born to women with BMIs below 25 kg/m2, compared with those with BMI of 25 kg/m2 and greater, they saw no differences in infant anthropometric measurements for women who had taken placebo.

However, when the investigators dichotomized maternal BMI for the metformin group, they found that infants born to the higher BMI group had a larger head size (P = .022), and were heavier (P = .002) and longer (P = .003) than infants born to women with BMIs less than 25.

“Metformin resulted in a larger head size, traceable already in utero,” said Dr. Hjorth-Hansen. However, she said, there’s a “PCOS effect” that results in the offspring of women with the condition to have a shorter body, compared with offspring of women without PCOS.

Dr. Hjorth-Hansen reported no relevant disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

Women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) who took metformin had newborns with larger heads than the offspring of women with PCOS who took a placebo, though PCOS offspring were, on average, shorter than newborns in a reference population, according to a recent study.

Metformin is commonly prescribed to women with PCOS, and though metformin passes the placental barrier and can reach therapeutic concentrations in the umbilical cord blood, it hasn’t been proven teratogenic, said Anna Hjorth-Hansen, MD, of the internal medicine department at Levanger Hospital, Norway.

The study was a post hoc analysis of data from the PregMet study, which was run from 2005 to 2009, and compared metformin to placebo, in combination with diet and lifestyle changes, for women with PCOS, said Dr. Hjorth-Hansen. The PregMet study tested the hypothesis that women with PCOS who received metformin from the first trimester until delivery had fewer pregnancy complications overall than women who did not.

Though women receiving placebo in the PregMet study had no more eclampsia, preterm delivery, or gestational diabetes than those who received metformin, the newborns who had in utero metformin exposure had significantly larger head circumference.

Dr. Hjorth-Hansen said that the study looked at in utero growth and anthropometric measurements at birth of infants born to women taking metformin, to determine whether metformin could affect fetal growth and newborn anthropometrics.

Ultrasound examination was used to measure crown-rump length, biparietal diameter (BPD), and mean abdominal diameter (MAD). At birth, head circumference (HC), length, and weight were measured.

Maternal characteristics were comparable between the metformin (131 patients) and placebo (127 patients) groups, said Dr. Hjorth-Hansen. Specifically, there were no significant differences between groups in terms of PCOS phenotype, blood glucose levels, and parity.

Infants born to women who took metformin had, on average, a larger BPD at 32 weeks gestation, compared with the infants whose mothers took placebo (86.1 mm versus 85.2 mm, P = .027). This larger head size was also seen at birth (mean HC, metformin, 35.6 cm; placebo, 35.0 cm; P = .007).

There were no significant differences between the groups in MAD or weight, either as assessed by ultrasound at 32 weeks gestation or as measured at birth.

Although the two groups did not differ in length at birth, the aggregate study population of infants born to women with PCOS was shorter than a large Swedish reference population.

When Dr. Hjorth-Hansen and her colleagues stratified the results by maternal body mass index (BMI), looking at babies born to women with BMIs below 25 kg/m2, compared with those with BMI of 25 kg/m2 and greater, they saw no differences in infant anthropometric measurements for women who had taken placebo.

However, when the investigators dichotomized maternal BMI for the metformin group, they found that infants born to the higher BMI group had a larger head size (P = .022), and were heavier (P = .002) and longer (P = .003) than infants born to women with BMIs less than 25.

“Metformin resulted in a larger head size, traceable already in utero,” said Dr. Hjorth-Hansen. However, she said, there’s a “PCOS effect” that results in the offspring of women with the condition to have a shorter body, compared with offspring of women without PCOS.

Dr. Hjorth-Hansen reported no relevant disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

Women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) who took metformin had newborns with larger heads than the offspring of women with PCOS who took a placebo, though PCOS offspring were, on average, shorter than newborns in a reference population, according to a recent study.

Metformin is commonly prescribed to women with PCOS, and though metformin passes the placental barrier and can reach therapeutic concentrations in the umbilical cord blood, it hasn’t been proven teratogenic, said Anna Hjorth-Hansen, MD, of the internal medicine department at Levanger Hospital, Norway.

The study was a post hoc analysis of data from the PregMet study, which was run from 2005 to 2009, and compared metformin to placebo, in combination with diet and lifestyle changes, for women with PCOS, said Dr. Hjorth-Hansen. The PregMet study tested the hypothesis that women with PCOS who received metformin from the first trimester until delivery had fewer pregnancy complications overall than women who did not.

Though women receiving placebo in the PregMet study had no more eclampsia, preterm delivery, or gestational diabetes than those who received metformin, the newborns who had in utero metformin exposure had significantly larger head circumference.

Dr. Hjorth-Hansen said that the study looked at in utero growth and anthropometric measurements at birth of infants born to women taking metformin, to determine whether metformin could affect fetal growth and newborn anthropometrics.

Ultrasound examination was used to measure crown-rump length, biparietal diameter (BPD), and mean abdominal diameter (MAD). At birth, head circumference (HC), length, and weight were measured.

Maternal characteristics were comparable between the metformin (131 patients) and placebo (127 patients) groups, said Dr. Hjorth-Hansen. Specifically, there were no significant differences between groups in terms of PCOS phenotype, blood glucose levels, and parity.

Infants born to women who took metformin had, on average, a larger BPD at 32 weeks gestation, compared with the infants whose mothers took placebo (86.1 mm versus 85.2 mm, P = .027). This larger head size was also seen at birth (mean HC, metformin, 35.6 cm; placebo, 35.0 cm; P = .007).

There were no significant differences between the groups in MAD or weight, either as assessed by ultrasound at 32 weeks gestation or as measured at birth.

Although the two groups did not differ in length at birth, the aggregate study population of infants born to women with PCOS was shorter than a large Swedish reference population.

When Dr. Hjorth-Hansen and her colleagues stratified the results by maternal body mass index (BMI), looking at babies born to women with BMIs below 25 kg/m2, compared with those with BMI of 25 kg/m2 and greater, they saw no differences in infant anthropometric measurements for women who had taken placebo.

However, when the investigators dichotomized maternal BMI for the metformin group, they found that infants born to the higher BMI group had a larger head size (P = .022), and were heavier (P = .002) and longer (P = .003) than infants born to women with BMIs less than 25.

“Metformin resulted in a larger head size, traceable already in utero,” said Dr. Hjorth-Hansen. However, she said, there’s a “PCOS effect” that results in the offspring of women with the condition to have a shorter body, compared with offspring of women without PCOS.

Dr. Hjorth-Hansen reported no relevant disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

FROM ENDO 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Infants born to women with PCOS who took metformin during pregnancy had larger head circumferences at birth than those born to women with PCOS who took placebo (35.6 cm versus 35.0 cm, P = .007).

Data source: Retrospective analysis of data from 258 women in the PregMet study.

Disclosures: Dr. Hjorth-Hansen reported no relevant disclosures.

VIDEO: Careful TKI hiatus makes CML pregnancy possible

NEW YORK – The success that tyrosine kinase inhibitors have had in prolonging life and producing deep hematologic and molecular remissions in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia has led to an unexpected bonus for young women living with the disease: an opportunity to safely become pregnant and mother a child.

The approach is not yet routine and poses a level of risk to both the mother and fetus, especially because tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are teratogenic. But with careful planning, close gestational monitoring, and with support from skilled obstetricians, the scenario of a successful pregnancy in women with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) has now played out several dozen times at a handful of U.S. centers, Mrinal S. Patnaik, MD, said in a talk at the conference held by Imedex.

“We make it clear that this is experimental and is associated with risk, and we share the data [from case reports]; but if the woman wants to go forward,” a protocol now exists “to successfully get them to pregnancy,” said Dr. Patnaik, a hematologist oncologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

At Mayo alone, upwards of 20 women with CML have been successfully shepherded through pregnancy, he said in a video interview.

The prospect for a planned pregnancy is reserved for women with their CML well controlled for at least 2 years using a TKI, most often imatinib (Gleevec). In addition to being under complete hematologic control, the candidate patient must also show a deep molecular response, which means a blood level of the BRC-ABL tyrosine kinase that drives CML at least 4 or 4.5 logs (10,000-50,000-fold) below pretreatment levels or molecularly undetectable.

The patient then monitors her ovulatory cycle and stops her medication at the time of ovulation, attempts conception, and then monitors whether pregnancy has actually started. If it has, she needs to stay off her TKI regimen through at least the first 18 weeks of gestation, although an even longer drug holiday is preferred. If not, she resumes the medication and repeats the process later if she wants.

Once the women is pregnant and remains off her TKI regimen Dr. Patnaik and his associates closely follow the woman for signs of a molecular or hematologic relapse, although the latter are unusual. If a resurgence of CML stem cells occurs, the woman receives treatment with pegylated interferon-alpha, which is safe during pregnancy. When possible, TKI treatment remains on hold into the breast-feeding period.

During pregnancy and delivery, the patient requires careful and regular follow-up by a maternal-fetal medicine specialist and has an ongoing risk for high platelet counts causing placental blood clots, fetuses that are small for gestational age, preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, and other complications.

“These are manageable with good obstetrical care,” Dr. Patnaik said. “We have developed a good system to work out the obstetrical complications.

“By and large we can be successful, but it requires a lot of monitoring and a lot of patient compliance with regular follow-ups,” he stressed.

In a video interview at the meeting, Dr. Patnaik discussed the approach he takes with his patients.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

NEW YORK – The success that tyrosine kinase inhibitors have had in prolonging life and producing deep hematologic and molecular remissions in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia has led to an unexpected bonus for young women living with the disease: an opportunity to safely become pregnant and mother a child.

The approach is not yet routine and poses a level of risk to both the mother and fetus, especially because tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are teratogenic. But with careful planning, close gestational monitoring, and with support from skilled obstetricians, the scenario of a successful pregnancy in women with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) has now played out several dozen times at a handful of U.S. centers, Mrinal S. Patnaik, MD, said in a talk at the conference held by Imedex.

“We make it clear that this is experimental and is associated with risk, and we share the data [from case reports]; but if the woman wants to go forward,” a protocol now exists “to successfully get them to pregnancy,” said Dr. Patnaik, a hematologist oncologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

At Mayo alone, upwards of 20 women with CML have been successfully shepherded through pregnancy, he said in a video interview.

The prospect for a planned pregnancy is reserved for women with their CML well controlled for at least 2 years using a TKI, most often imatinib (Gleevec). In addition to being under complete hematologic control, the candidate patient must also show a deep molecular response, which means a blood level of the BRC-ABL tyrosine kinase that drives CML at least 4 or 4.5 logs (10,000-50,000-fold) below pretreatment levels or molecularly undetectable.

The patient then monitors her ovulatory cycle and stops her medication at the time of ovulation, attempts conception, and then monitors whether pregnancy has actually started. If it has, she needs to stay off her TKI regimen through at least the first 18 weeks of gestation, although an even longer drug holiday is preferred. If not, she resumes the medication and repeats the process later if she wants.

Once the women is pregnant and remains off her TKI regimen Dr. Patnaik and his associates closely follow the woman for signs of a molecular or hematologic relapse, although the latter are unusual. If a resurgence of CML stem cells occurs, the woman receives treatment with pegylated interferon-alpha, which is safe during pregnancy. When possible, TKI treatment remains on hold into the breast-feeding period.

During pregnancy and delivery, the patient requires careful and regular follow-up by a maternal-fetal medicine specialist and has an ongoing risk for high platelet counts causing placental blood clots, fetuses that are small for gestational age, preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, and other complications.

“These are manageable with good obstetrical care,” Dr. Patnaik said. “We have developed a good system to work out the obstetrical complications.

“By and large we can be successful, but it requires a lot of monitoring and a lot of patient compliance with regular follow-ups,” he stressed.

In a video interview at the meeting, Dr. Patnaik discussed the approach he takes with his patients.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

NEW YORK – The success that tyrosine kinase inhibitors have had in prolonging life and producing deep hematologic and molecular remissions in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia has led to an unexpected bonus for young women living with the disease: an opportunity to safely become pregnant and mother a child.

The approach is not yet routine and poses a level of risk to both the mother and fetus, especially because tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are teratogenic. But with careful planning, close gestational monitoring, and with support from skilled obstetricians, the scenario of a successful pregnancy in women with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) has now played out several dozen times at a handful of U.S. centers, Mrinal S. Patnaik, MD, said in a talk at the conference held by Imedex.

“We make it clear that this is experimental and is associated with risk, and we share the data [from case reports]; but if the woman wants to go forward,” a protocol now exists “to successfully get them to pregnancy,” said Dr. Patnaik, a hematologist oncologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

At Mayo alone, upwards of 20 women with CML have been successfully shepherded through pregnancy, he said in a video interview.

The prospect for a planned pregnancy is reserved for women with their CML well controlled for at least 2 years using a TKI, most often imatinib (Gleevec). In addition to being under complete hematologic control, the candidate patient must also show a deep molecular response, which means a blood level of the BRC-ABL tyrosine kinase that drives CML at least 4 or 4.5 logs (10,000-50,000-fold) below pretreatment levels or molecularly undetectable.

The patient then monitors her ovulatory cycle and stops her medication at the time of ovulation, attempts conception, and then monitors whether pregnancy has actually started. If it has, she needs to stay off her TKI regimen through at least the first 18 weeks of gestation, although an even longer drug holiday is preferred. If not, she resumes the medication and repeats the process later if she wants.

Once the women is pregnant and remains off her TKI regimen Dr. Patnaik and his associates closely follow the woman for signs of a molecular or hematologic relapse, although the latter are unusual. If a resurgence of CML stem cells occurs, the woman receives treatment with pegylated interferon-alpha, which is safe during pregnancy. When possible, TKI treatment remains on hold into the breast-feeding period.

During pregnancy and delivery, the patient requires careful and regular follow-up by a maternal-fetal medicine specialist and has an ongoing risk for high platelet counts causing placental blood clots, fetuses that are small for gestational age, preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, and other complications.

“These are manageable with good obstetrical care,” Dr. Patnaik said. “We have developed a good system to work out the obstetrical complications.

“By and large we can be successful, but it requires a lot of monitoring and a lot of patient compliance with regular follow-ups,” he stressed.

In a video interview at the meeting, Dr. Patnaik discussed the approach he takes with his patients.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A MEETING ON HEMATOLOGIC MALIGNANCIES

Bundled maternal HIV, well-baby visits boost ART adherence

SEATTLE – When new moms can get their well-baby visits and HIV care together in the same office, they have better antiretroviral adherence, better viral suppression, and breast-feed longer, according to a randomized trial of 472 new moms with HIV in Cape Town, South Africa.

“It’s a simple and highly effective strategy for promoting maternal postpartum engagement” in HIV care, said lead investigator Landon Myer, MD, professor and head of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of Cape Town.

Antiretroviral treatment management is often a routine part of prenatal care, but care splits after birth, with moms generally sent to an adult HIV clinic and babies in follow-up care at the pediatrician’s office. It’s a logistics problem for many, and women tend to prioritize the care of their infants over their own HIV.

“There’s a big push [globally] to identify interventions that can enhance women’s antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence post partum,” Dr. Myer said.

The investigators had a hunch that bundling care would help. They randomized 234 women to centers with combined HIV and pediatric care within a week of birth and 238 to the usual split care approach. In the latter group, the mothers were referred to adult HIV services soon after delivery.

At 12 months, 77% of the women in the integrated-care group had viral loads below 50 copies/mL, versus 56% of women in the split care group. Women in the integrated group breastfed for about 9 months, versus 3 months in the control group. The findings were statistically significant.

“We were surprised by how big the differences were,” Dr. Myer said at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections in partnership with the International Antiviral Society.

Mother-to-child transmission was low, at about 0.55%, and did not differ by arm. Vaccination rates, vitamin use, and other infant outcomes were also similar in both groups. Just a few women in each arm dropped out before the 12-month, postpartum visit.

The mothers were a median of 28 years old, and all had started ART during pregnancy at a median of 21 weeks gestation, with a median pre-ART T-cell count of 354 cells/microL. Three-quarters had viral suppression below 50 copies/mL at randomization. About a quarter were giving birth for the first time. Mothers in the bundled-care group were referred back to adult HIV services at the end of breastfeeding.

Dr. Myer had no disclosures. The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

SEATTLE – When new moms can get their well-baby visits and HIV care together in the same office, they have better antiretroviral adherence, better viral suppression, and breast-feed longer, according to a randomized trial of 472 new moms with HIV in Cape Town, South Africa.

“It’s a simple and highly effective strategy for promoting maternal postpartum engagement” in HIV care, said lead investigator Landon Myer, MD, professor and head of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of Cape Town.

Antiretroviral treatment management is often a routine part of prenatal care, but care splits after birth, with moms generally sent to an adult HIV clinic and babies in follow-up care at the pediatrician’s office. It’s a logistics problem for many, and women tend to prioritize the care of their infants over their own HIV.

“There’s a big push [globally] to identify interventions that can enhance women’s antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence post partum,” Dr. Myer said.

The investigators had a hunch that bundling care would help. They randomized 234 women to centers with combined HIV and pediatric care within a week of birth and 238 to the usual split care approach. In the latter group, the mothers were referred to adult HIV services soon after delivery.

At 12 months, 77% of the women in the integrated-care group had viral loads below 50 copies/mL, versus 56% of women in the split care group. Women in the integrated group breastfed for about 9 months, versus 3 months in the control group. The findings were statistically significant.

“We were surprised by how big the differences were,” Dr. Myer said at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections in partnership with the International Antiviral Society.

Mother-to-child transmission was low, at about 0.55%, and did not differ by arm. Vaccination rates, vitamin use, and other infant outcomes were also similar in both groups. Just a few women in each arm dropped out before the 12-month, postpartum visit.

The mothers were a median of 28 years old, and all had started ART during pregnancy at a median of 21 weeks gestation, with a median pre-ART T-cell count of 354 cells/microL. Three-quarters had viral suppression below 50 copies/mL at randomization. About a quarter were giving birth for the first time. Mothers in the bundled-care group were referred back to adult HIV services at the end of breastfeeding.

Dr. Myer had no disclosures. The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

SEATTLE – When new moms can get their well-baby visits and HIV care together in the same office, they have better antiretroviral adherence, better viral suppression, and breast-feed longer, according to a randomized trial of 472 new moms with HIV in Cape Town, South Africa.

“It’s a simple and highly effective strategy for promoting maternal postpartum engagement” in HIV care, said lead investigator Landon Myer, MD, professor and head of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of Cape Town.

Antiretroviral treatment management is often a routine part of prenatal care, but care splits after birth, with moms generally sent to an adult HIV clinic and babies in follow-up care at the pediatrician’s office. It’s a logistics problem for many, and women tend to prioritize the care of their infants over their own HIV.

“There’s a big push [globally] to identify interventions that can enhance women’s antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence post partum,” Dr. Myer said.

The investigators had a hunch that bundling care would help. They randomized 234 women to centers with combined HIV and pediatric care within a week of birth and 238 to the usual split care approach. In the latter group, the mothers were referred to adult HIV services soon after delivery.

At 12 months, 77% of the women in the integrated-care group had viral loads below 50 copies/mL, versus 56% of women in the split care group. Women in the integrated group breastfed for about 9 months, versus 3 months in the control group. The findings were statistically significant.

“We were surprised by how big the differences were,” Dr. Myer said at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections in partnership with the International Antiviral Society.

Mother-to-child transmission was low, at about 0.55%, and did not differ by arm. Vaccination rates, vitamin use, and other infant outcomes were also similar in both groups. Just a few women in each arm dropped out before the 12-month, postpartum visit.

The mothers were a median of 28 years old, and all had started ART during pregnancy at a median of 21 weeks gestation, with a median pre-ART T-cell count of 354 cells/microL. Three-quarters had viral suppression below 50 copies/mL at randomization. About a quarter were giving birth for the first time. Mothers in the bundled-care group were referred back to adult HIV services at the end of breastfeeding.

Dr. Myer had no disclosures. The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

AT CROI

Key clinical point:

Major finding: At 12 months, 77% of the women in the integrated-care group had viral loads below 50 copies/mL, versus 56% of women in the control arm. Women in the integrated group breastfed for about 9 months, versus 3 months in the split-care group.

Data source: A randomized trial of 472 new moms with HIV and their babies in Cape Town, South Africa.

Disclosures: Dr. Myer had no disclosures. The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

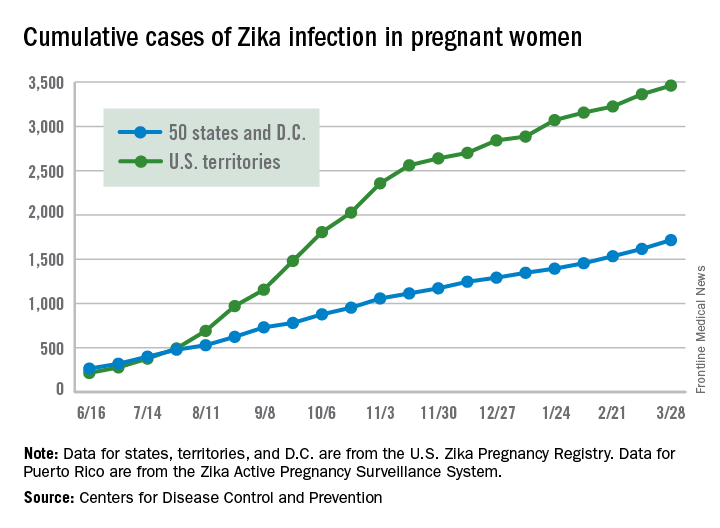

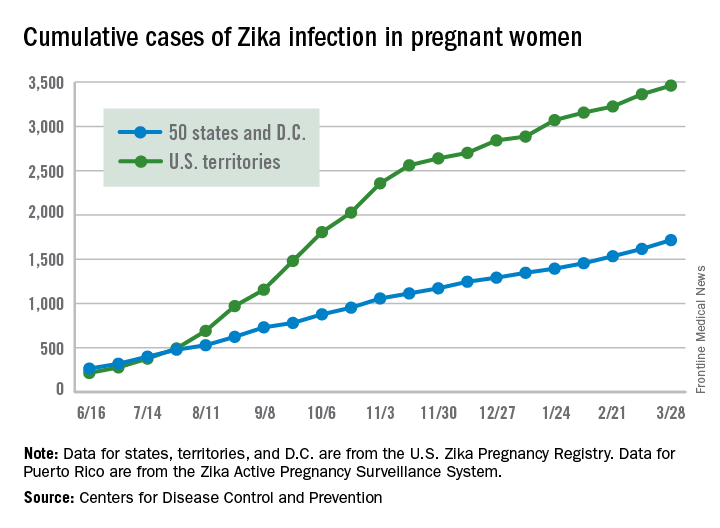

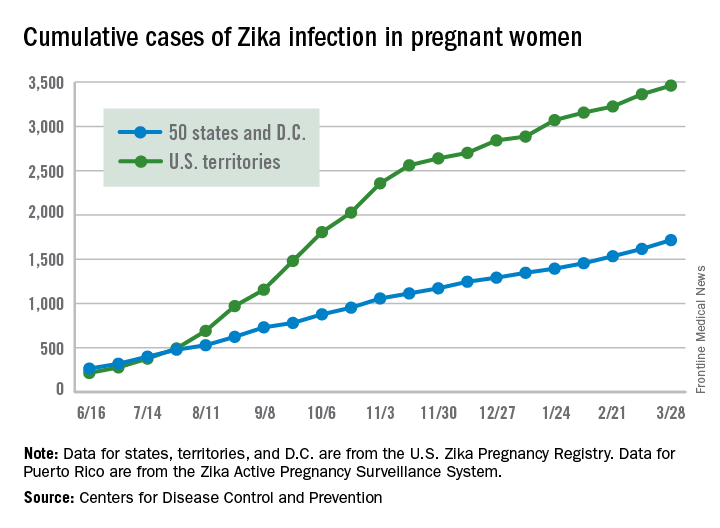

Number of U.S. Zika-infected pregnancies tops 5,100

Almost 200 cases of pregnant women with Zika virus infection were reported in the United States during the 2 weeks ending March 28, with the number split evenly between the territories and the 50 states and Washington, D.C., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

These latest 197 cases – 98 in the territories and 99 in the states/D.C. – bring the U.S. total since the beginning of 2016 to 5,177 pregnant women with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection: 3,461 in the U.S. territories and 1,716 in the states/D.C., the CDC reported on April 6.

Since Jan. 1, 2015, a total of 41,701 cases of Zika virus infection have been reported among all Americans: 5,197 in the states/D.C. and 36,504 in the territories. Almost all of the territorial cases (97%) have occurred in Puerto Rico, while Florida (21%), New York (20%), and California (9%) together have accounted for half of the cases in the states/D.C., the CDC said.

These are not real-time data and reflect only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, although it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes. Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, or termination with evidence of birth defects.

Almost 200 cases of pregnant women with Zika virus infection were reported in the United States during the 2 weeks ending March 28, with the number split evenly between the territories and the 50 states and Washington, D.C., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

These latest 197 cases – 98 in the territories and 99 in the states/D.C. – bring the U.S. total since the beginning of 2016 to 5,177 pregnant women with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection: 3,461 in the U.S. territories and 1,716 in the states/D.C., the CDC reported on April 6.

Since Jan. 1, 2015, a total of 41,701 cases of Zika virus infection have been reported among all Americans: 5,197 in the states/D.C. and 36,504 in the territories. Almost all of the territorial cases (97%) have occurred in Puerto Rico, while Florida (21%), New York (20%), and California (9%) together have accounted for half of the cases in the states/D.C., the CDC said.

These are not real-time data and reflect only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, although it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes. Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, or termination with evidence of birth defects.

Almost 200 cases of pregnant women with Zika virus infection were reported in the United States during the 2 weeks ending March 28, with the number split evenly between the territories and the 50 states and Washington, D.C., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

These latest 197 cases – 98 in the territories and 99 in the states/D.C. – bring the U.S. total since the beginning of 2016 to 5,177 pregnant women with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection: 3,461 in the U.S. territories and 1,716 in the states/D.C., the CDC reported on April 6.

Since Jan. 1, 2015, a total of 41,701 cases of Zika virus infection have been reported among all Americans: 5,197 in the states/D.C. and 36,504 in the territories. Almost all of the territorial cases (97%) have occurred in Puerto Rico, while Florida (21%), New York (20%), and California (9%) together have accounted for half of the cases in the states/D.C., the CDC said.

These are not real-time data and reflect only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, although it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes. Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, or termination with evidence of birth defects.

Birth defects found in 10% of confirmed U.S. Zika pregnancies

FROM MMWR

About 1 in 10 pregnant women with confirmed Zika infection in the United States had a fetus or baby with Zika-related birth defects in 2016, officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

Among 972 completed pregnancies with laboratory evidence of possible recent Zika virus infection – 895 liveborn infants and 77 pregnancy losses – there were 51 fetuses/infants with Zika-related birth defects (5%). Among 250 pregnancies with laboratory-confirmed Zika infection, there were 24 cases of birth defects (10%). Among the 60 pregnancies in which Zika infection was confirmed and onset occurred during the first trimester, there were nine cases of birth defects (15%).

“We are seeing about 30-40 new Zika cases in pregnant women each week in the United States. With the current tally of more than 1,600 pregnant women with evidence of Zika” reported in at least 44 states, mostly from travel to endemic areas, “this devastating outbreak is far from over,” CDC Acting Director Anne Schuchat, MD, said during an April 4 press conference.

But current birth defect estimates may not reflect the full impact of Zika virus in pregnancy, since some Zika-related developmental problems may not become apparent until months after birth. “We recommend babies receive close developmental monitoring and follow-up,” she said.

Despite CDC recommendations, one in three infants with possible congenital Zika infection had no report of Zika testing at birth, and only 1 in 4 had brain imaging (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017 Apr 4. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6613e1).

“Because the full clinical spectrum of congenital Zika virus infection is not yet known, all infants born to women with laboratory evidence of possible recent Zika virus infection during pregnancy should receive postnatal neuroimaging and Zika virus testing in addition to a comprehensive newborn physical exam and hearing screen,” the CDC officials wrote.

Birth defects – most commonly microcephaly or brain abnormalities – were reported in similar proportions of fetuses/infants whose mothers did and did not report Zika symptoms.

Dr. Schuchat noted that Zika virus can cause vision problems, hearing problems, and seizures. Some infants have little or no control over their arms or legs, and cannot reach out to touch things because of their constricted joints. There can be problems reaching developmental milestones, such as sitting up, as well as problems with feeding, swallowing, and breathing. Some babies cry inconsolably. Others may be born with a normal head size but experience slow head growth later on and develop microcephaly.

The study confirms the need for pregnant women to continue taking steps to prevent Zika virus exposure through mosquito bites and sexual transmission.

“We encourage [health care providers] to ask about possible Zika exposure when caring for both pregnant women and their babies, and to follow CDC guidance for evaluation and care of infants with possible Zika infection,” said Peggy Honein, PhD, senior investigator on the review, in a statement.

The mothers of the 51 fetuses or infants with birth defects were exposed to Zika during trips to 16 countries, including Barbados, Belize, Brazil, Cape Verde, Colombia, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Puerto Rico, Republic of Marshall Islands, and Venezuela.

FROM MMWR

About 1 in 10 pregnant women with confirmed Zika infection in the United States had a fetus or baby with Zika-related birth defects in 2016, officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

Among 972 completed pregnancies with laboratory evidence of possible recent Zika virus infection – 895 liveborn infants and 77 pregnancy losses – there were 51 fetuses/infants with Zika-related birth defects (5%). Among 250 pregnancies with laboratory-confirmed Zika infection, there were 24 cases of birth defects (10%). Among the 60 pregnancies in which Zika infection was confirmed and onset occurred during the first trimester, there were nine cases of birth defects (15%).

“We are seeing about 30-40 new Zika cases in pregnant women each week in the United States. With the current tally of more than 1,600 pregnant women with evidence of Zika” reported in at least 44 states, mostly from travel to endemic areas, “this devastating outbreak is far from over,” CDC Acting Director Anne Schuchat, MD, said during an April 4 press conference.

But current birth defect estimates may not reflect the full impact of Zika virus in pregnancy, since some Zika-related developmental problems may not become apparent until months after birth. “We recommend babies receive close developmental monitoring and follow-up,” she said.

Despite CDC recommendations, one in three infants with possible congenital Zika infection had no report of Zika testing at birth, and only 1 in 4 had brain imaging (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017 Apr 4. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6613e1).

“Because the full clinical spectrum of congenital Zika virus infection is not yet known, all infants born to women with laboratory evidence of possible recent Zika virus infection during pregnancy should receive postnatal neuroimaging and Zika virus testing in addition to a comprehensive newborn physical exam and hearing screen,” the CDC officials wrote.

Birth defects – most commonly microcephaly or brain abnormalities – were reported in similar proportions of fetuses/infants whose mothers did and did not report Zika symptoms.

Dr. Schuchat noted that Zika virus can cause vision problems, hearing problems, and seizures. Some infants have little or no control over their arms or legs, and cannot reach out to touch things because of their constricted joints. There can be problems reaching developmental milestones, such as sitting up, as well as problems with feeding, swallowing, and breathing. Some babies cry inconsolably. Others may be born with a normal head size but experience slow head growth later on and develop microcephaly.

The study confirms the need for pregnant women to continue taking steps to prevent Zika virus exposure through mosquito bites and sexual transmission.

“We encourage [health care providers] to ask about possible Zika exposure when caring for both pregnant women and their babies, and to follow CDC guidance for evaluation and care of infants with possible Zika infection,” said Peggy Honein, PhD, senior investigator on the review, in a statement.

The mothers of the 51 fetuses or infants with birth defects were exposed to Zika during trips to 16 countries, including Barbados, Belize, Brazil, Cape Verde, Colombia, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Puerto Rico, Republic of Marshall Islands, and Venezuela.

FROM MMWR

About 1 in 10 pregnant women with confirmed Zika infection in the United States had a fetus or baby with Zika-related birth defects in 2016, officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

Among 972 completed pregnancies with laboratory evidence of possible recent Zika virus infection – 895 liveborn infants and 77 pregnancy losses – there were 51 fetuses/infants with Zika-related birth defects (5%). Among 250 pregnancies with laboratory-confirmed Zika infection, there were 24 cases of birth defects (10%). Among the 60 pregnancies in which Zika infection was confirmed and onset occurred during the first trimester, there were nine cases of birth defects (15%).

“We are seeing about 30-40 new Zika cases in pregnant women each week in the United States. With the current tally of more than 1,600 pregnant women with evidence of Zika” reported in at least 44 states, mostly from travel to endemic areas, “this devastating outbreak is far from over,” CDC Acting Director Anne Schuchat, MD, said during an April 4 press conference.

But current birth defect estimates may not reflect the full impact of Zika virus in pregnancy, since some Zika-related developmental problems may not become apparent until months after birth. “We recommend babies receive close developmental monitoring and follow-up,” she said.

Despite CDC recommendations, one in three infants with possible congenital Zika infection had no report of Zika testing at birth, and only 1 in 4 had brain imaging (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017 Apr 4. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6613e1).

“Because the full clinical spectrum of congenital Zika virus infection is not yet known, all infants born to women with laboratory evidence of possible recent Zika virus infection during pregnancy should receive postnatal neuroimaging and Zika virus testing in addition to a comprehensive newborn physical exam and hearing screen,” the CDC officials wrote.

Birth defects – most commonly microcephaly or brain abnormalities – were reported in similar proportions of fetuses/infants whose mothers did and did not report Zika symptoms.

Dr. Schuchat noted that Zika virus can cause vision problems, hearing problems, and seizures. Some infants have little or no control over their arms or legs, and cannot reach out to touch things because of their constricted joints. There can be problems reaching developmental milestones, such as sitting up, as well as problems with feeding, swallowing, and breathing. Some babies cry inconsolably. Others may be born with a normal head size but experience slow head growth later on and develop microcephaly.

The study confirms the need for pregnant women to continue taking steps to prevent Zika virus exposure through mosquito bites and sexual transmission.

“We encourage [health care providers] to ask about possible Zika exposure when caring for both pregnant women and their babies, and to follow CDC guidance for evaluation and care of infants with possible Zika infection,” said Peggy Honein, PhD, senior investigator on the review, in a statement.

The mothers of the 51 fetuses or infants with birth defects were exposed to Zika during trips to 16 countries, including Barbados, Belize, Brazil, Cape Verde, Colombia, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Puerto Rico, Republic of Marshall Islands, and Venezuela.

Stopping TNF inhibitors for pregnancy may invite flares

Women with rheumatoid arthritis or axial spondyloarthritis who stop treatment with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors when they become pregnant may be inviting disease flares during the pregnancy, according to a report published in Arthritis Research & Therapy.

To examine the frequency of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) flares during pregnancy, researchers prospectively followed 136 women treated at the Center for Pregnancy in Rheumatic Diseases at Inselspital Bern (Switzerland) during a 5-year period. These patients – 75 with RA and 61 with axSpA – were assessed before conception, during each trimester, and 6-8 weeks postpartum for disease activity and medication use, said Stephanie van den Brandt, MD, of the department of rheumatology, immunology, and allergology at the University of Bern, and her associates.

The relative risk of a disease flare was 3.33 among RA patients and 3.08 among axSpA patients who discontinued TNF inhibitors at the time of a positive pregnancy test. In comparison, rheumatic disease remained stable throughout pregnancy in most women who were not taking TNF inhibitors before pregnancy, the investigators said (Arthritis Res Ther. 2017 Mar 20. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1269-1).

Most disease flares occurred in the first trimester among women with RA and in the second half of pregnancy among women with axSpA. Most women with RA who resumed taking TNF inhibitors when their disease flared responded well to the treatment, with CRP levels dropping by 70% and remission being achieved rapidly. In contrast, most women with axSpA who resumed taking TNF inhibitors did not respond as well, with CRP levels dropping by only 35%. Their disease was ameliorated but not controlled by restarting the therapy.

No sponsor was cited for this study. Dr. van den Brandt and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Women with rheumatoid arthritis or axial spondyloarthritis who stop treatment with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors when they become pregnant may be inviting disease flares during the pregnancy, according to a report published in Arthritis Research & Therapy.

To examine the frequency of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) flares during pregnancy, researchers prospectively followed 136 women treated at the Center for Pregnancy in Rheumatic Diseases at Inselspital Bern (Switzerland) during a 5-year period. These patients – 75 with RA and 61 with axSpA – were assessed before conception, during each trimester, and 6-8 weeks postpartum for disease activity and medication use, said Stephanie van den Brandt, MD, of the department of rheumatology, immunology, and allergology at the University of Bern, and her associates.

The relative risk of a disease flare was 3.33 among RA patients and 3.08 among axSpA patients who discontinued TNF inhibitors at the time of a positive pregnancy test. In comparison, rheumatic disease remained stable throughout pregnancy in most women who were not taking TNF inhibitors before pregnancy, the investigators said (Arthritis Res Ther. 2017 Mar 20. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1269-1).

Most disease flares occurred in the first trimester among women with RA and in the second half of pregnancy among women with axSpA. Most women with RA who resumed taking TNF inhibitors when their disease flared responded well to the treatment, with CRP levels dropping by 70% and remission being achieved rapidly. In contrast, most women with axSpA who resumed taking TNF inhibitors did not respond as well, with CRP levels dropping by only 35%. Their disease was ameliorated but not controlled by restarting the therapy.

No sponsor was cited for this study. Dr. van den Brandt and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Women with rheumatoid arthritis or axial spondyloarthritis who stop treatment with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors when they become pregnant may be inviting disease flares during the pregnancy, according to a report published in Arthritis Research & Therapy.

To examine the frequency of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) flares during pregnancy, researchers prospectively followed 136 women treated at the Center for Pregnancy in Rheumatic Diseases at Inselspital Bern (Switzerland) during a 5-year period. These patients – 75 with RA and 61 with axSpA – were assessed before conception, during each trimester, and 6-8 weeks postpartum for disease activity and medication use, said Stephanie van den Brandt, MD, of the department of rheumatology, immunology, and allergology at the University of Bern, and her associates.

The relative risk of a disease flare was 3.33 among RA patients and 3.08 among axSpA patients who discontinued TNF inhibitors at the time of a positive pregnancy test. In comparison, rheumatic disease remained stable throughout pregnancy in most women who were not taking TNF inhibitors before pregnancy, the investigators said (Arthritis Res Ther. 2017 Mar 20. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1269-1).

Most disease flares occurred in the first trimester among women with RA and in the second half of pregnancy among women with axSpA. Most women with RA who resumed taking TNF inhibitors when their disease flared responded well to the treatment, with CRP levels dropping by 70% and remission being achieved rapidly. In contrast, most women with axSpA who resumed taking TNF inhibitors did not respond as well, with CRP levels dropping by only 35%. Their disease was ameliorated but not controlled by restarting the therapy.

No sponsor was cited for this study. Dr. van den Brandt and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The relative risk of a disease flare was 3.33 among RA patients and 3.08 among axSpA patients who discontinued TNF inhibitors at conception.

Data source: A prospective cohort study involving 75 pregnant women with RA and 61 with axial spondyloarthritis treated at one Swiss specialty center in 2000-2015.

Disclosures: No sponsor was cited for this study. Dr. van den Brandt and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Hormonal IUDs have higher expulsion rates immediately postpartum

Hormonal intrauterine devices inserted immediately postpartum had a nearly six times greater likelihood of expulsion compared with copper IUDs, but most women who requested any type of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) postpartum were still using it half a year later, a recent study found.

“With more than eight out of ten women continuing use at 6 months, in-hospital placement of postpartum LARC devices is a worthwhile intervention,” reported Jennifer L. Eggebroten, MD, and her associates at the University of Utah. “More than half of women who experienced IUD expulsion without commencement of another highly effective contraceptive went on to become pregnant within 2 years, highlighting the need for appropriate counseling prior to device placement and backup contraception planning.”

Ninety percent of the patients were Hispanic, 87% had prior children, and 87% had an income below $24,000. Most (77%) had a vaginal delivery. Those who requested the copper IUD tended to be older and have more children compared with those who asked for the hormonal IUD or implant.

Among the 289 patients who completed the 6 months of follow-up, 17% of those with a hormonal IUD had an expulsion, compared with 4% of women with copper IUDs. That translated to a 5.8 times greater risk of expulsion for hormonal IUDs than for copper ones after the researchers accounted for age, mode of delivery, parity, and any breastfeeding. Expulsion rates were statistically similar between those who had vaginal deliveries and those who had cesarean deliveries.

Just 8% of the women requested removal of their device during the 6 months of follow-up. Most (67%) of the 21 women who had expulsions asked for a replacement. Cost of the device delayed or prevented replacement in some cases. Over the next 2 years, 6 of the 11 women who did not get replacement devices became pregnant.

Meanwhile, 81% of women with a hormonal IUD (88% including replacements), 83% with a copper IUD (86% including replacements), and 90% with an implant were still using that device 6 months later. A quarter of the women who completed the study follow-up reported that they did not return to their providers for their postpartum exams.

“For patients at high risk of rapid repeat pregnancy or who may not return for a postpartum visit, the benefit of placement of a highly effective method of contraception in the hospital prior to discharge may outweigh the increased risk of expulsion,” the researchers wrote. “In some states, by 8 weeks, public insurance coverage may expire and women face much more challenging obstacles to affordable, highly effective birth control options.”

The University of Utah and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development funded the research. The University of Utah receives research funding from LARC manufacturers and one of the coauthors reported financial relationships with LARC manufacturers.

Hormonal intrauterine devices inserted immediately postpartum had a nearly six times greater likelihood of expulsion compared with copper IUDs, but most women who requested any type of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) postpartum were still using it half a year later, a recent study found.

“With more than eight out of ten women continuing use at 6 months, in-hospital placement of postpartum LARC devices is a worthwhile intervention,” reported Jennifer L. Eggebroten, MD, and her associates at the University of Utah. “More than half of women who experienced IUD expulsion without commencement of another highly effective contraceptive went on to become pregnant within 2 years, highlighting the need for appropriate counseling prior to device placement and backup contraception planning.”

Ninety percent of the patients were Hispanic, 87% had prior children, and 87% had an income below $24,000. Most (77%) had a vaginal delivery. Those who requested the copper IUD tended to be older and have more children compared with those who asked for the hormonal IUD or implant.

Among the 289 patients who completed the 6 months of follow-up, 17% of those with a hormonal IUD had an expulsion, compared with 4% of women with copper IUDs. That translated to a 5.8 times greater risk of expulsion for hormonal IUDs than for copper ones after the researchers accounted for age, mode of delivery, parity, and any breastfeeding. Expulsion rates were statistically similar between those who had vaginal deliveries and those who had cesarean deliveries.

Just 8% of the women requested removal of their device during the 6 months of follow-up. Most (67%) of the 21 women who had expulsions asked for a replacement. Cost of the device delayed or prevented replacement in some cases. Over the next 2 years, 6 of the 11 women who did not get replacement devices became pregnant.

Meanwhile, 81% of women with a hormonal IUD (88% including replacements), 83% with a copper IUD (86% including replacements), and 90% with an implant were still using that device 6 months later. A quarter of the women who completed the study follow-up reported that they did not return to their providers for their postpartum exams.