User login

FDA, EPA clarify which fish pregnant women and young children should eat

The Food and Drug Administration and the Environmental Protection Agency have issued updated guidance about fish consumption for pregnant women and young children, clarifying which types of fish are recommended and what types of fish to avoid.

In guidance issued Jan. 18, the agencies sort 62 types of fish into three categories based on mercury level: best choices, good choices, and fish to avoid. They recommend that women who are pregnant, women who may become pregnant, breastfeeding mothers, and young children eat two to three servings of fish in the “best choices” category per week. Women and young children are advised to eat one serving per week of fish in the “good choices” category, according to the announcement. Fish in the “best choices” category make up nearly 90% of fish eaten in the United States, according to the FDA.

“Fish are an important source of protein and other nutrients for young children and women who are or may become pregnant or are breastfeeding,” Stephen Ostroff, MD, FDA’s deputy commissioner for Foods and Veterinary Medicine, said in a statement. “This advice clearly shows the great diversity of fish in the U.S. market that they can consume safely. This new, clear and concrete advice is an excellent tool for making safe and healthy choices when buying fish.”

The updated advice cautions pregnant women and others to avoid seven types of fish that generally have higher mercury levels. This includes tilefish from the Gulf of Mexico, shark; swordfish; orange roughy, bigeye tuna; marlin, and king mackerel. Meanwhile, recommended choices lower in mercury include such fish as shrimp, pollock, salmon, canned light tuna, tilapia, catfish, and cod.

Consumers are urged to check local advisories for fish caught recreationally and gauge their fish consumption based on any local and state advisories for those waters. If no information on fishing advisories is available, the FDA recommends eating just one fish meal a week from local waters and to avoid other fish that week.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

The Food and Drug Administration and the Environmental Protection Agency have issued updated guidance about fish consumption for pregnant women and young children, clarifying which types of fish are recommended and what types of fish to avoid.

In guidance issued Jan. 18, the agencies sort 62 types of fish into three categories based on mercury level: best choices, good choices, and fish to avoid. They recommend that women who are pregnant, women who may become pregnant, breastfeeding mothers, and young children eat two to three servings of fish in the “best choices” category per week. Women and young children are advised to eat one serving per week of fish in the “good choices” category, according to the announcement. Fish in the “best choices” category make up nearly 90% of fish eaten in the United States, according to the FDA.

“Fish are an important source of protein and other nutrients for young children and women who are or may become pregnant or are breastfeeding,” Stephen Ostroff, MD, FDA’s deputy commissioner for Foods and Veterinary Medicine, said in a statement. “This advice clearly shows the great diversity of fish in the U.S. market that they can consume safely. This new, clear and concrete advice is an excellent tool for making safe and healthy choices when buying fish.”

The updated advice cautions pregnant women and others to avoid seven types of fish that generally have higher mercury levels. This includes tilefish from the Gulf of Mexico, shark; swordfish; orange roughy, bigeye tuna; marlin, and king mackerel. Meanwhile, recommended choices lower in mercury include such fish as shrimp, pollock, salmon, canned light tuna, tilapia, catfish, and cod.

Consumers are urged to check local advisories for fish caught recreationally and gauge their fish consumption based on any local and state advisories for those waters. If no information on fishing advisories is available, the FDA recommends eating just one fish meal a week from local waters and to avoid other fish that week.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

The Food and Drug Administration and the Environmental Protection Agency have issued updated guidance about fish consumption for pregnant women and young children, clarifying which types of fish are recommended and what types of fish to avoid.

In guidance issued Jan. 18, the agencies sort 62 types of fish into three categories based on mercury level: best choices, good choices, and fish to avoid. They recommend that women who are pregnant, women who may become pregnant, breastfeeding mothers, and young children eat two to three servings of fish in the “best choices” category per week. Women and young children are advised to eat one serving per week of fish in the “good choices” category, according to the announcement. Fish in the “best choices” category make up nearly 90% of fish eaten in the United States, according to the FDA.

“Fish are an important source of protein and other nutrients for young children and women who are or may become pregnant or are breastfeeding,” Stephen Ostroff, MD, FDA’s deputy commissioner for Foods and Veterinary Medicine, said in a statement. “This advice clearly shows the great diversity of fish in the U.S. market that they can consume safely. This new, clear and concrete advice is an excellent tool for making safe and healthy choices when buying fish.”

The updated advice cautions pregnant women and others to avoid seven types of fish that generally have higher mercury levels. This includes tilefish from the Gulf of Mexico, shark; swordfish; orange roughy, bigeye tuna; marlin, and king mackerel. Meanwhile, recommended choices lower in mercury include such fish as shrimp, pollock, salmon, canned light tuna, tilapia, catfish, and cod.

Consumers are urged to check local advisories for fish caught recreationally and gauge their fish consumption based on any local and state advisories for those waters. If no information on fishing advisories is available, the FDA recommends eating just one fish meal a week from local waters and to avoid other fish that week.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Cutaneous eruption reported in pregnant woman with locally acquired Zika virus

Zika presented in a young, pregnant Florida woman as erythematous follicular macules and papules on the trunk and arms, scattered tender pink papules on the palms, and a few petechiae on the hard palate, according to a Jan. 11 report in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The report advises how Zika virus may present during pregnancy. “Medical providers on the front line should be aware of the constellation of symptoms in patients reporting travel to endemic areas, including areas in Southern Florida, where other non–travel-associated cases have been confirmed,” wrote investigators led by Lucy Chen, MD, of the University of Miami (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1610614).

Zika virus RNA was detected in the woman’s urine and serum specimens with the use of reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction and persisted for 2 weeks in urine samples and for 6 weeks in serum samples. On histopathology, skin lesions revealed a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltration in the upper dermis, admixed with some neutrophils. Liver and renal functions were normal.

Fetal ultrasonography performed on the day of presentation showed an estimated fetal weight of 644 g (53rd percentile), an estimated head circumference of 221 mm (63rd percentile), and normal intracranial anatomy. Fevers and rash subsided after 3 days of supportive care. Screening for measles, varicella, rubella, syphilis, Epstein-Barr virus, influenza, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, mumps, and dengue was unrevealing.

An initial IgM test on July 7 was negative; seroconversion occurred 1 week after presentation and remained positive through delivery.

A full-term infant weighing 2,990 g was delivered vaginally. Neonatal ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging of the head showed a normal head size and intracranial anatomy, with no calcifications. Placental tissue was negative for Zika virus, and neonatal laboratory testing revealed no evidence of infection.

The case was confirmed by the Miami-Dade County Department of Health as the first non–travel-associated Zika infection in the United States.

The investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Zika presented in a young, pregnant Florida woman as erythematous follicular macules and papules on the trunk and arms, scattered tender pink papules on the palms, and a few petechiae on the hard palate, according to a Jan. 11 report in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The report advises how Zika virus may present during pregnancy. “Medical providers on the front line should be aware of the constellation of symptoms in patients reporting travel to endemic areas, including areas in Southern Florida, where other non–travel-associated cases have been confirmed,” wrote investigators led by Lucy Chen, MD, of the University of Miami (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1610614).

Zika virus RNA was detected in the woman’s urine and serum specimens with the use of reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction and persisted for 2 weeks in urine samples and for 6 weeks in serum samples. On histopathology, skin lesions revealed a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltration in the upper dermis, admixed with some neutrophils. Liver and renal functions were normal.

Fetal ultrasonography performed on the day of presentation showed an estimated fetal weight of 644 g (53rd percentile), an estimated head circumference of 221 mm (63rd percentile), and normal intracranial anatomy. Fevers and rash subsided after 3 days of supportive care. Screening for measles, varicella, rubella, syphilis, Epstein-Barr virus, influenza, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, mumps, and dengue was unrevealing.

An initial IgM test on July 7 was negative; seroconversion occurred 1 week after presentation and remained positive through delivery.

A full-term infant weighing 2,990 g was delivered vaginally. Neonatal ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging of the head showed a normal head size and intracranial anatomy, with no calcifications. Placental tissue was negative for Zika virus, and neonatal laboratory testing revealed no evidence of infection.

The case was confirmed by the Miami-Dade County Department of Health as the first non–travel-associated Zika infection in the United States.

The investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Zika presented in a young, pregnant Florida woman as erythematous follicular macules and papules on the trunk and arms, scattered tender pink papules on the palms, and a few petechiae on the hard palate, according to a Jan. 11 report in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The report advises how Zika virus may present during pregnancy. “Medical providers on the front line should be aware of the constellation of symptoms in patients reporting travel to endemic areas, including areas in Southern Florida, where other non–travel-associated cases have been confirmed,” wrote investigators led by Lucy Chen, MD, of the University of Miami (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1610614).

Zika virus RNA was detected in the woman’s urine and serum specimens with the use of reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction and persisted for 2 weeks in urine samples and for 6 weeks in serum samples. On histopathology, skin lesions revealed a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltration in the upper dermis, admixed with some neutrophils. Liver and renal functions were normal.

Fetal ultrasonography performed on the day of presentation showed an estimated fetal weight of 644 g (53rd percentile), an estimated head circumference of 221 mm (63rd percentile), and normal intracranial anatomy. Fevers and rash subsided after 3 days of supportive care. Screening for measles, varicella, rubella, syphilis, Epstein-Barr virus, influenza, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, mumps, and dengue was unrevealing.

An initial IgM test on July 7 was negative; seroconversion occurred 1 week after presentation and remained positive through delivery.

A full-term infant weighing 2,990 g was delivered vaginally. Neonatal ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging of the head showed a normal head size and intracranial anatomy, with no calcifications. Placental tissue was negative for Zika virus, and neonatal laboratory testing revealed no evidence of infection.

The case was confirmed by the Miami-Dade County Department of Health as the first non–travel-associated Zika infection in the United States.

The investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Antiplatelet agents reduce preterm birth risk in some groups

The use of antiplatelet agents in pregnant women at risk for preeclampsia reduces the risk of spontaneous preterm birth by about 7%, while moderate to very preterm birth at less than 34 weeks of gestation is reduced by 14%.

Those are key findings from a meta-analysis of data from 17 trials that evaluated the effect of antiplatelet agents to reduce preeclampsia.

In an effort to evaluate the efficacy of low-dose aspirin for the prevention of spontaneous preterm birth in women at risk for preeclampsia and to explore the effect in prespecified subgroups, the researchers assessed results from the Perinatal Antiplatelet Review of International Studies Individual Participant Data meta-analysis, which comprised 31 studies that randomized women to low-dose aspirin/dipyridamole or placebo/no treatment as a primary preventive strategy for preeclampsia.

For the current study, researchers from the Netherlands and Australia analyzed data from 17 of the 31 trials that supplied data on type of delivery (spontaneous, compared with indicated birth), which included a total of 28,797 women. The study’s primary endpoints were spontaneous preterm birth at less than 37 weeks, less than 34 weeks, and less than 28 weeks of gestation (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:327-36).

Compared with women who received placebo/no treatment, women assigned to antiplatelet treatment had a lower risk of spontaneous preterm birth at less than 37 weeks’ gestation (relative risk, 0.93) and at less than 34 weeks of gestation (RR, 0.86). The relative risk of having a spontaneous preterm birth at less than 37 weeks was even lower for those who had a previous pregnancy (RR, 0.83).

The number needed to treat to prevent 1 case of spontaneous preterm birth at less than 37 weeks’ gestation was 139. The number needed to treat was 242 for spontaneous preterm birth at less than 34 weeks’ gestation.

The researchers noted certain limitations of the analysis, including the potential for the possibility of inconsistency in the definition of spontaneous preterm birth between studies. “Because antiplatelet agents in pregnancy are a low-cost and safe intervention, we suggest that antiplatelet agents may also be a promising intervention for women at high risk for a spontaneous preterm birth, especially in high-risk women with a previous pregnancy,” they wrote. “The current study provides clinicians with the best available evidence to counsel women regarding who might benefit from this intervention.”

The researchers reported having no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. van Vliet was supported by a travel grant of the Dutch Ter Meulen Fund of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The use of antiplatelet agents in pregnant women at risk for preeclampsia reduces the risk of spontaneous preterm birth by about 7%, while moderate to very preterm birth at less than 34 weeks of gestation is reduced by 14%.

Those are key findings from a meta-analysis of data from 17 trials that evaluated the effect of antiplatelet agents to reduce preeclampsia.

In an effort to evaluate the efficacy of low-dose aspirin for the prevention of spontaneous preterm birth in women at risk for preeclampsia and to explore the effect in prespecified subgroups, the researchers assessed results from the Perinatal Antiplatelet Review of International Studies Individual Participant Data meta-analysis, which comprised 31 studies that randomized women to low-dose aspirin/dipyridamole or placebo/no treatment as a primary preventive strategy for preeclampsia.

For the current study, researchers from the Netherlands and Australia analyzed data from 17 of the 31 trials that supplied data on type of delivery (spontaneous, compared with indicated birth), which included a total of 28,797 women. The study’s primary endpoints were spontaneous preterm birth at less than 37 weeks, less than 34 weeks, and less than 28 weeks of gestation (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:327-36).

Compared with women who received placebo/no treatment, women assigned to antiplatelet treatment had a lower risk of spontaneous preterm birth at less than 37 weeks’ gestation (relative risk, 0.93) and at less than 34 weeks of gestation (RR, 0.86). The relative risk of having a spontaneous preterm birth at less than 37 weeks was even lower for those who had a previous pregnancy (RR, 0.83).

The number needed to treat to prevent 1 case of spontaneous preterm birth at less than 37 weeks’ gestation was 139. The number needed to treat was 242 for spontaneous preterm birth at less than 34 weeks’ gestation.

The researchers noted certain limitations of the analysis, including the potential for the possibility of inconsistency in the definition of spontaneous preterm birth between studies. “Because antiplatelet agents in pregnancy are a low-cost and safe intervention, we suggest that antiplatelet agents may also be a promising intervention for women at high risk for a spontaneous preterm birth, especially in high-risk women with a previous pregnancy,” they wrote. “The current study provides clinicians with the best available evidence to counsel women regarding who might benefit from this intervention.”

The researchers reported having no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. van Vliet was supported by a travel grant of the Dutch Ter Meulen Fund of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The use of antiplatelet agents in pregnant women at risk for preeclampsia reduces the risk of spontaneous preterm birth by about 7%, while moderate to very preterm birth at less than 34 weeks of gestation is reduced by 14%.

Those are key findings from a meta-analysis of data from 17 trials that evaluated the effect of antiplatelet agents to reduce preeclampsia.

In an effort to evaluate the efficacy of low-dose aspirin for the prevention of spontaneous preterm birth in women at risk for preeclampsia and to explore the effect in prespecified subgroups, the researchers assessed results from the Perinatal Antiplatelet Review of International Studies Individual Participant Data meta-analysis, which comprised 31 studies that randomized women to low-dose aspirin/dipyridamole or placebo/no treatment as a primary preventive strategy for preeclampsia.

For the current study, researchers from the Netherlands and Australia analyzed data from 17 of the 31 trials that supplied data on type of delivery (spontaneous, compared with indicated birth), which included a total of 28,797 women. The study’s primary endpoints were spontaneous preterm birth at less than 37 weeks, less than 34 weeks, and less than 28 weeks of gestation (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:327-36).

Compared with women who received placebo/no treatment, women assigned to antiplatelet treatment had a lower risk of spontaneous preterm birth at less than 37 weeks’ gestation (relative risk, 0.93) and at less than 34 weeks of gestation (RR, 0.86). The relative risk of having a spontaneous preterm birth at less than 37 weeks was even lower for those who had a previous pregnancy (RR, 0.83).

The number needed to treat to prevent 1 case of spontaneous preterm birth at less than 37 weeks’ gestation was 139. The number needed to treat was 242 for spontaneous preterm birth at less than 34 weeks’ gestation.

The researchers noted certain limitations of the analysis, including the potential for the possibility of inconsistency in the definition of spontaneous preterm birth between studies. “Because antiplatelet agents in pregnancy are a low-cost and safe intervention, we suggest that antiplatelet agents may also be a promising intervention for women at high risk for a spontaneous preterm birth, especially in high-risk women with a previous pregnancy,” they wrote. “The current study provides clinicians with the best available evidence to counsel women regarding who might benefit from this intervention.”

The researchers reported having no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. van Vliet was supported by a travel grant of the Dutch Ter Meulen Fund of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Compared with women who received placebo/no treatment, women assigned to antiplatelet treatment had a lower risk of spontaneous preterm birth at less than 37 weeks’ gestation (RR, 0.93) and at less than 34 weeks of gestation (RR, 0.86).

Data source: Results from 17 studies that randomized 28,797 women to low-dose aspirin/dipyridamole or placebo/no treatment as a primary preventive strategy for preeclampsia.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. van Vliet was supported by a travel grant of the Dutch Ter Meulen Fund of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Type 2 risk increases with number of GDM pregnancies

In women with prior mild gestational diabetes, subsequent pregnancies did not increase the frequency of metabolic syndrome but did increase the risk of type 2 diabetes, according to a review of 426 women 5-10 years after a GDM pregnancy.

The risk of diabetes was greatest if additional pregnancies were also complicated by mild gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

The investigators assessed women 5-10 years after they participated in a mild GDM treatment study. The goal was to assess the impact of subsequent pregnancies on cardiometabolic risks. GDM is a known risk factor for type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome, but it hasn’t been clear until know how subsequent pregnancies influence the risk, said investigators led by Michael Varner, MD, a professor at the University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City (Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:273-80).

Echoing previous studies of mild GDM, about a third of the women had metabolic syndrome at follow-up, but the number of subsequent pregnancies didn’t seem to make a difference. Among the 212 women with no additional pregnancies, 34% had metabolic syndrome; among the 143 with one pregnancy, 33% had metabolic syndrome; and among the 71 with two or more, 30% had metabolic syndrome, as defined by American Heart Association and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute criteria.

“Although we observed a high overall frequency of metabolic syndrome in our cohort, our data suggest that subsequent pregnancies do not increase a woman’s risk of developing metabolic syndrome,” Dr. Varner and his colleagues said.

However, subsequent pregnancies did affect diabetes risk; 5.2% of women with no additional pregnancies had diabetes at follow-up, versus 10.5% of women with one additional pregnancy and 11.3% of those with two or more. The risk of diabetes was greatest if a subsequent pregnancy was complicated by GDM (relative risk, 3.75; 95% confidence interval, 1.60-8.82), as was the case for about a third of the women who had additional pregnancies.

“The association with diabetes was driven mostly by subsequent pregnancy complicated with GDM,” the investigators said.

The findings “could be consistent with either a stronger genetic or an environmental predisposition to type II diabetes, [but] could also represent confounders that were not measured in this prospective observational follow-up study. ... Our data are limited ... by the fact that we do not know how many patients had metabolic syndrome at the time of the index pregnancy,” they said.

At follow-up during Feb. 2012-Sept. 2013, women with no additional pregnancies were a median 38 years old; women who had one pregnancy were a median of 35 years, and those with two or more a median of 33 years. The interval from participation in the parent study to participation in the follow-up study was 7 years in women with no or one additional pregnancy, and 8 years for women with two or more. There were no other significant differences among the groups. The average body mass index was about 29 kg/m2; 59% of the women were Hispanic.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The authors had no disclosures.

In women with prior mild gestational diabetes, subsequent pregnancies did not increase the frequency of metabolic syndrome but did increase the risk of type 2 diabetes, according to a review of 426 women 5-10 years after a GDM pregnancy.

The risk of diabetes was greatest if additional pregnancies were also complicated by mild gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

The investigators assessed women 5-10 years after they participated in a mild GDM treatment study. The goal was to assess the impact of subsequent pregnancies on cardiometabolic risks. GDM is a known risk factor for type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome, but it hasn’t been clear until know how subsequent pregnancies influence the risk, said investigators led by Michael Varner, MD, a professor at the University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City (Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:273-80).

Echoing previous studies of mild GDM, about a third of the women had metabolic syndrome at follow-up, but the number of subsequent pregnancies didn’t seem to make a difference. Among the 212 women with no additional pregnancies, 34% had metabolic syndrome; among the 143 with one pregnancy, 33% had metabolic syndrome; and among the 71 with two or more, 30% had metabolic syndrome, as defined by American Heart Association and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute criteria.

“Although we observed a high overall frequency of metabolic syndrome in our cohort, our data suggest that subsequent pregnancies do not increase a woman’s risk of developing metabolic syndrome,” Dr. Varner and his colleagues said.

However, subsequent pregnancies did affect diabetes risk; 5.2% of women with no additional pregnancies had diabetes at follow-up, versus 10.5% of women with one additional pregnancy and 11.3% of those with two or more. The risk of diabetes was greatest if a subsequent pregnancy was complicated by GDM (relative risk, 3.75; 95% confidence interval, 1.60-8.82), as was the case for about a third of the women who had additional pregnancies.

“The association with diabetes was driven mostly by subsequent pregnancy complicated with GDM,” the investigators said.

The findings “could be consistent with either a stronger genetic or an environmental predisposition to type II diabetes, [but] could also represent confounders that were not measured in this prospective observational follow-up study. ... Our data are limited ... by the fact that we do not know how many patients had metabolic syndrome at the time of the index pregnancy,” they said.

At follow-up during Feb. 2012-Sept. 2013, women with no additional pregnancies were a median 38 years old; women who had one pregnancy were a median of 35 years, and those with two or more a median of 33 years. The interval from participation in the parent study to participation in the follow-up study was 7 years in women with no or one additional pregnancy, and 8 years for women with two or more. There were no other significant differences among the groups. The average body mass index was about 29 kg/m2; 59% of the women were Hispanic.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The authors had no disclosures.

In women with prior mild gestational diabetes, subsequent pregnancies did not increase the frequency of metabolic syndrome but did increase the risk of type 2 diabetes, according to a review of 426 women 5-10 years after a GDM pregnancy.

The risk of diabetes was greatest if additional pregnancies were also complicated by mild gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

The investigators assessed women 5-10 years after they participated in a mild GDM treatment study. The goal was to assess the impact of subsequent pregnancies on cardiometabolic risks. GDM is a known risk factor for type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome, but it hasn’t been clear until know how subsequent pregnancies influence the risk, said investigators led by Michael Varner, MD, a professor at the University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City (Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:273-80).

Echoing previous studies of mild GDM, about a third of the women had metabolic syndrome at follow-up, but the number of subsequent pregnancies didn’t seem to make a difference. Among the 212 women with no additional pregnancies, 34% had metabolic syndrome; among the 143 with one pregnancy, 33% had metabolic syndrome; and among the 71 with two or more, 30% had metabolic syndrome, as defined by American Heart Association and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute criteria.

“Although we observed a high overall frequency of metabolic syndrome in our cohort, our data suggest that subsequent pregnancies do not increase a woman’s risk of developing metabolic syndrome,” Dr. Varner and his colleagues said.

However, subsequent pregnancies did affect diabetes risk; 5.2% of women with no additional pregnancies had diabetes at follow-up, versus 10.5% of women with one additional pregnancy and 11.3% of those with two or more. The risk of diabetes was greatest if a subsequent pregnancy was complicated by GDM (relative risk, 3.75; 95% confidence interval, 1.60-8.82), as was the case for about a third of the women who had additional pregnancies.

“The association with diabetes was driven mostly by subsequent pregnancy complicated with GDM,” the investigators said.

The findings “could be consistent with either a stronger genetic or an environmental predisposition to type II diabetes, [but] could also represent confounders that were not measured in this prospective observational follow-up study. ... Our data are limited ... by the fact that we do not know how many patients had metabolic syndrome at the time of the index pregnancy,” they said.

At follow-up during Feb. 2012-Sept. 2013, women with no additional pregnancies were a median 38 years old; women who had one pregnancy were a median of 35 years, and those with two or more a median of 33 years. The interval from participation in the parent study to participation in the follow-up study was 7 years in women with no or one additional pregnancy, and 8 years for women with two or more. There were no other significant differences among the groups. The average body mass index was about 29 kg/m2; 59% of the women were Hispanic.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The authors had no disclosures.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The risk of diabetes was greatest if a subsequent pregnancy was complicated by GDM (RR, 3.75; 95% CI, 1.60-8.82).

Data source: Review of subsequent pregnancies in 426 women 5-10 years after a GDM pregnancy

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The authors had no disclosures.

Diagnosis at a Glance: Partial Hydatidiform Molar Pregnancy

Case

A 26-year-old gravida 3, para 2-0-0-2, aborta 0 whose last menstrual period was 15 weeks 5 days, presented to the ED with complaints of mild vaginal spotting, which she first noted postcoitally the previous day. The patient denied fatigue, lightheadedness, dyspnea, abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting.

Physical examination revealed a well-appearing patient with normal vital signs. The abdomen was soft and nontender, and the fundus was palpable at the level of the umbilicus. A speculum examination was unremarkable, with normal external genitalia, a closed cervical os, no adnexal masses or tenderness, and no blood in the vaginal vault. Laboratory studies were significant for a serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) of 7,442 mIU/mL (reference range for 15 weeks: 12,039-70,971 mIU/mL). The patient was Rh positive with a stable hematocrit.

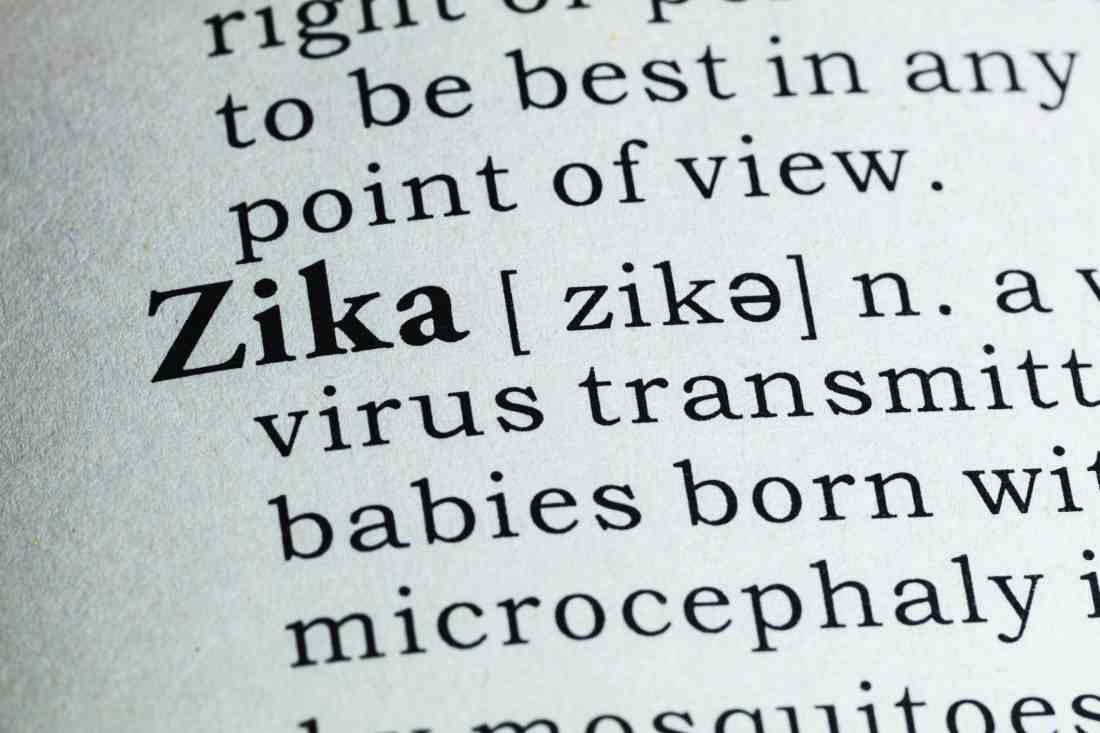

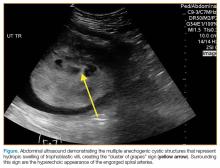

A bedside ultrasound, performed by an ultrasound-]trained emergency physician (EP), was noted to demonstrate a complex intrauterine mass comprised of several small, rounded anechoic clusters (Figure).

An obstetric consultation was made and the patient was taken to the operating room the following day for a dilation and curettage (D&C) procedure. She was discharged home the next day without complications. The products of conception were sent to pathology, and confirmed a triploid karyotype and p57 trophoblastic immunopositivity, diagnostic of a partial hydatidiform mole.

Discussion

Hydatidiform moles are a subset of abnormal pregnancies termed gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD). The two greatest risk factors for GTD are previous GTD and extremis of maternal age.1 Patients often present to the ED because of painless heavy vaginal bleeding, hyperemesis gravidarum, symptoms of hyperthyroidism, or preeclampsia before 20 weeks.2 Clinically, these patients present with an enlarged uterus for gestational age and very high beta-hCG levels, often greater than 100,000 mIU/mL.3 The high beta-hCG levels can lead the patient to present with symptoms of hyperthyroidism, such as severe hypertension, given the similar chemical structures of beta-hCG and thyroid-stimulating hormone.4

After a D&C, interval beta-hCG levels need to be obtained to ensure resolution. A patient with beta-hCG levels that do not fall by 10% after 3 weeks, or are still present after 6 months, should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist.5,6 Furthermore, a chest X-ray is strongly suggested, as the lungs are often the first place of metastasis.7

Partial hydatidiform moles are formed by a dispermic fertilization of a normal ovum leading to a triploid pattern, and are clinically distinguished from complete molar pregnancies because affected patients have a uterus that is often small for gestational age.8 Also, while the beta-hCG is also abnormally elevated, the median value is more modest at approximately 50,000 mIU/mL.3

According to the American College of Radiology’s Appropriateness Criteria, ultrasound is the gold standard for evaluating gestational trophoblastic disease. While the classic sonographic appearance of a molar pregnancy is described as a “snowstorm” appearance, advancement in technology more clearly demonstrates a “cluster of grapes” or “honeycomb” appearance.9 On Doppler mode, increased vascularity peripherally can also be detected due to engorgement of the spiral arteries. While partial moles tend to have more focal lesions, the greatest distinguishing factor is the presence of embryonic or fetal tissue, which is not seen in complete moles. However, due to the heterogeneous appearance of the uterus in all GTD, molar pregnancies can sometimes be misinterpreted as missed abortions or clotted blood, so that pathological confirmation is mandatory for all products of conception in the United States and Canada.2,10

Summary

This case is of particular interest because it demonstrates an atypical presentation of a partial hydatidiform mole. While most classic presentations include older patients with heavy vaginal bleeding, a smaller uterus than expected, significantly elevated beta-hCGs, and hyperemesis gravidarum, our patient was relatively young with no history of molar pregnancies in the past, a larger-than-expected uterus, and no vaginal bleeding noted. Laboratory values also indicated a significantly lower-than-expected beta-hCG level. As such, bedside ultrasound findings were unexpected but resulted in the prompt diagnosis, an emergent obstetric consultation, and confirmatory radiology imaging. The ED bedside ultrasound findings did demonstrate the characteristic “cluster of grapes” appearance surrounded by the hyperechoic appearance of the spiral arteries (Figure). An intrauterine yolk sac was also identified by ultrasound, which strongly suggested a partial rather than a complete hydatidiform molar pregnancy.

While hydatidiform pregnancies are relatively rare, EPs should be aware of the clinical and sonographic features of these diseases. This case, particularly given the atypical clinical presentation for a partial molar pregnancy, highlights the importance of ultrasound in pregnancy, and the utility of bedside ultrasound in the evaluation of the etiology of vaginal bleeding in the early pregnant patient that presents to the ED.

1. Ngan H, Bender H, Benedet JL, et al. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia, FIGO 2000 staging and classification. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83 Suppl 1:175-177.

2. Tie W, Tajnert K, Plavsic SK. Ultrasound imaging of gestational trophoblastic disease. Donald School J Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;7(1):105-112.

3. Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP. Current advances in the management of gestational trophoblastic disease. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128(1):3-5.

4. Cole LA, Butler S. Detection of hCG in trophoblastic disease: The USA hCG reference service experience. J Reprod Med. 2002;47(6):433-444.

5. Lavie I, Rao GG, Castrillon DH, Miller DS, Schorge JO. Duration of human chorionic gonadotropin surveillance for partial hydatidiform moles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5):1362-1364.

6. Kenny L, Seckl MJ. Treatments for gestational trophoblastic disease. Expert Rev of Obstet Gynecol. 2010;5(2):215-225.

7. Soto-Wright V, Bernstein M, Goldstein DP, Berkowitz RS. The changing clinical presentation of complete molar pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86(5):775-779.

8. Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP. Clinical practice. Molar pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(16):1639-1645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0900696.

9. Kirk E, Papageorghiou AT, Condous G, Bottomley C, Bourne T. The accuracy of first trimester ultrasound in the diagnosis of hydatidiform mole. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;29(1):70-75.

10. Wang Y, Zhao S. Vascular Biology of the Placenta. Chapter 4. Cell Types of the Placenta. San Rafael, CA: Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences; 2010.

Case

A 26-year-old gravida 3, para 2-0-0-2, aborta 0 whose last menstrual period was 15 weeks 5 days, presented to the ED with complaints of mild vaginal spotting, which she first noted postcoitally the previous day. The patient denied fatigue, lightheadedness, dyspnea, abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting.

Physical examination revealed a well-appearing patient with normal vital signs. The abdomen was soft and nontender, and the fundus was palpable at the level of the umbilicus. A speculum examination was unremarkable, with normal external genitalia, a closed cervical os, no adnexal masses or tenderness, and no blood in the vaginal vault. Laboratory studies were significant for a serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) of 7,442 mIU/mL (reference range for 15 weeks: 12,039-70,971 mIU/mL). The patient was Rh positive with a stable hematocrit.

A bedside ultrasound, performed by an ultrasound-]trained emergency physician (EP), was noted to demonstrate a complex intrauterine mass comprised of several small, rounded anechoic clusters (Figure).

An obstetric consultation was made and the patient was taken to the operating room the following day for a dilation and curettage (D&C) procedure. She was discharged home the next day without complications. The products of conception were sent to pathology, and confirmed a triploid karyotype and p57 trophoblastic immunopositivity, diagnostic of a partial hydatidiform mole.

Discussion

Hydatidiform moles are a subset of abnormal pregnancies termed gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD). The two greatest risk factors for GTD are previous GTD and extremis of maternal age.1 Patients often present to the ED because of painless heavy vaginal bleeding, hyperemesis gravidarum, symptoms of hyperthyroidism, or preeclampsia before 20 weeks.2 Clinically, these patients present with an enlarged uterus for gestational age and very high beta-hCG levels, often greater than 100,000 mIU/mL.3 The high beta-hCG levels can lead the patient to present with symptoms of hyperthyroidism, such as severe hypertension, given the similar chemical structures of beta-hCG and thyroid-stimulating hormone.4

After a D&C, interval beta-hCG levels need to be obtained to ensure resolution. A patient with beta-hCG levels that do not fall by 10% after 3 weeks, or are still present after 6 months, should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist.5,6 Furthermore, a chest X-ray is strongly suggested, as the lungs are often the first place of metastasis.7

Partial hydatidiform moles are formed by a dispermic fertilization of a normal ovum leading to a triploid pattern, and are clinically distinguished from complete molar pregnancies because affected patients have a uterus that is often small for gestational age.8 Also, while the beta-hCG is also abnormally elevated, the median value is more modest at approximately 50,000 mIU/mL.3

According to the American College of Radiology’s Appropriateness Criteria, ultrasound is the gold standard for evaluating gestational trophoblastic disease. While the classic sonographic appearance of a molar pregnancy is described as a “snowstorm” appearance, advancement in technology more clearly demonstrates a “cluster of grapes” or “honeycomb” appearance.9 On Doppler mode, increased vascularity peripherally can also be detected due to engorgement of the spiral arteries. While partial moles tend to have more focal lesions, the greatest distinguishing factor is the presence of embryonic or fetal tissue, which is not seen in complete moles. However, due to the heterogeneous appearance of the uterus in all GTD, molar pregnancies can sometimes be misinterpreted as missed abortions or clotted blood, so that pathological confirmation is mandatory for all products of conception in the United States and Canada.2,10

Summary

This case is of particular interest because it demonstrates an atypical presentation of a partial hydatidiform mole. While most classic presentations include older patients with heavy vaginal bleeding, a smaller uterus than expected, significantly elevated beta-hCGs, and hyperemesis gravidarum, our patient was relatively young with no history of molar pregnancies in the past, a larger-than-expected uterus, and no vaginal bleeding noted. Laboratory values also indicated a significantly lower-than-expected beta-hCG level. As such, bedside ultrasound findings were unexpected but resulted in the prompt diagnosis, an emergent obstetric consultation, and confirmatory radiology imaging. The ED bedside ultrasound findings did demonstrate the characteristic “cluster of grapes” appearance surrounded by the hyperechoic appearance of the spiral arteries (Figure). An intrauterine yolk sac was also identified by ultrasound, which strongly suggested a partial rather than a complete hydatidiform molar pregnancy.

While hydatidiform pregnancies are relatively rare, EPs should be aware of the clinical and sonographic features of these diseases. This case, particularly given the atypical clinical presentation for a partial molar pregnancy, highlights the importance of ultrasound in pregnancy, and the utility of bedside ultrasound in the evaluation of the etiology of vaginal bleeding in the early pregnant patient that presents to the ED.

Case

A 26-year-old gravida 3, para 2-0-0-2, aborta 0 whose last menstrual period was 15 weeks 5 days, presented to the ED with complaints of mild vaginal spotting, which she first noted postcoitally the previous day. The patient denied fatigue, lightheadedness, dyspnea, abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting.

Physical examination revealed a well-appearing patient with normal vital signs. The abdomen was soft and nontender, and the fundus was palpable at the level of the umbilicus. A speculum examination was unremarkable, with normal external genitalia, a closed cervical os, no adnexal masses or tenderness, and no blood in the vaginal vault. Laboratory studies were significant for a serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) of 7,442 mIU/mL (reference range for 15 weeks: 12,039-70,971 mIU/mL). The patient was Rh positive with a stable hematocrit.

A bedside ultrasound, performed by an ultrasound-]trained emergency physician (EP), was noted to demonstrate a complex intrauterine mass comprised of several small, rounded anechoic clusters (Figure).

An obstetric consultation was made and the patient was taken to the operating room the following day for a dilation and curettage (D&C) procedure. She was discharged home the next day without complications. The products of conception were sent to pathology, and confirmed a triploid karyotype and p57 trophoblastic immunopositivity, diagnostic of a partial hydatidiform mole.

Discussion

Hydatidiform moles are a subset of abnormal pregnancies termed gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD). The two greatest risk factors for GTD are previous GTD and extremis of maternal age.1 Patients often present to the ED because of painless heavy vaginal bleeding, hyperemesis gravidarum, symptoms of hyperthyroidism, or preeclampsia before 20 weeks.2 Clinically, these patients present with an enlarged uterus for gestational age and very high beta-hCG levels, often greater than 100,000 mIU/mL.3 The high beta-hCG levels can lead the patient to present with symptoms of hyperthyroidism, such as severe hypertension, given the similar chemical structures of beta-hCG and thyroid-stimulating hormone.4

After a D&C, interval beta-hCG levels need to be obtained to ensure resolution. A patient with beta-hCG levels that do not fall by 10% after 3 weeks, or are still present after 6 months, should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist.5,6 Furthermore, a chest X-ray is strongly suggested, as the lungs are often the first place of metastasis.7

Partial hydatidiform moles are formed by a dispermic fertilization of a normal ovum leading to a triploid pattern, and are clinically distinguished from complete molar pregnancies because affected patients have a uterus that is often small for gestational age.8 Also, while the beta-hCG is also abnormally elevated, the median value is more modest at approximately 50,000 mIU/mL.3

According to the American College of Radiology’s Appropriateness Criteria, ultrasound is the gold standard for evaluating gestational trophoblastic disease. While the classic sonographic appearance of a molar pregnancy is described as a “snowstorm” appearance, advancement in technology more clearly demonstrates a “cluster of grapes” or “honeycomb” appearance.9 On Doppler mode, increased vascularity peripherally can also be detected due to engorgement of the spiral arteries. While partial moles tend to have more focal lesions, the greatest distinguishing factor is the presence of embryonic or fetal tissue, which is not seen in complete moles. However, due to the heterogeneous appearance of the uterus in all GTD, molar pregnancies can sometimes be misinterpreted as missed abortions or clotted blood, so that pathological confirmation is mandatory for all products of conception in the United States and Canada.2,10

Summary

This case is of particular interest because it demonstrates an atypical presentation of a partial hydatidiform mole. While most classic presentations include older patients with heavy vaginal bleeding, a smaller uterus than expected, significantly elevated beta-hCGs, and hyperemesis gravidarum, our patient was relatively young with no history of molar pregnancies in the past, a larger-than-expected uterus, and no vaginal bleeding noted. Laboratory values also indicated a significantly lower-than-expected beta-hCG level. As such, bedside ultrasound findings were unexpected but resulted in the prompt diagnosis, an emergent obstetric consultation, and confirmatory radiology imaging. The ED bedside ultrasound findings did demonstrate the characteristic “cluster of grapes” appearance surrounded by the hyperechoic appearance of the spiral arteries (Figure). An intrauterine yolk sac was also identified by ultrasound, which strongly suggested a partial rather than a complete hydatidiform molar pregnancy.

While hydatidiform pregnancies are relatively rare, EPs should be aware of the clinical and sonographic features of these diseases. This case, particularly given the atypical clinical presentation for a partial molar pregnancy, highlights the importance of ultrasound in pregnancy, and the utility of bedside ultrasound in the evaluation of the etiology of vaginal bleeding in the early pregnant patient that presents to the ED.

1. Ngan H, Bender H, Benedet JL, et al. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia, FIGO 2000 staging and classification. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83 Suppl 1:175-177.

2. Tie W, Tajnert K, Plavsic SK. Ultrasound imaging of gestational trophoblastic disease. Donald School J Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;7(1):105-112.

3. Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP. Current advances in the management of gestational trophoblastic disease. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128(1):3-5.

4. Cole LA, Butler S. Detection of hCG in trophoblastic disease: The USA hCG reference service experience. J Reprod Med. 2002;47(6):433-444.

5. Lavie I, Rao GG, Castrillon DH, Miller DS, Schorge JO. Duration of human chorionic gonadotropin surveillance for partial hydatidiform moles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5):1362-1364.

6. Kenny L, Seckl MJ. Treatments for gestational trophoblastic disease. Expert Rev of Obstet Gynecol. 2010;5(2):215-225.

7. Soto-Wright V, Bernstein M, Goldstein DP, Berkowitz RS. The changing clinical presentation of complete molar pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86(5):775-779.

8. Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP. Clinical practice. Molar pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(16):1639-1645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0900696.

9. Kirk E, Papageorghiou AT, Condous G, Bottomley C, Bourne T. The accuracy of first trimester ultrasound in the diagnosis of hydatidiform mole. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;29(1):70-75.

10. Wang Y, Zhao S. Vascular Biology of the Placenta. Chapter 4. Cell Types of the Placenta. San Rafael, CA: Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences; 2010.

1. Ngan H, Bender H, Benedet JL, et al. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia, FIGO 2000 staging and classification. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83 Suppl 1:175-177.

2. Tie W, Tajnert K, Plavsic SK. Ultrasound imaging of gestational trophoblastic disease. Donald School J Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;7(1):105-112.

3. Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP. Current advances in the management of gestational trophoblastic disease. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128(1):3-5.

4. Cole LA, Butler S. Detection of hCG in trophoblastic disease: The USA hCG reference service experience. J Reprod Med. 2002;47(6):433-444.

5. Lavie I, Rao GG, Castrillon DH, Miller DS, Schorge JO. Duration of human chorionic gonadotropin surveillance for partial hydatidiform moles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5):1362-1364.

6. Kenny L, Seckl MJ. Treatments for gestational trophoblastic disease. Expert Rev of Obstet Gynecol. 2010;5(2):215-225.

7. Soto-Wright V, Bernstein M, Goldstein DP, Berkowitz RS. The changing clinical presentation of complete molar pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86(5):775-779.

8. Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP. Clinical practice. Molar pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(16):1639-1645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0900696.

9. Kirk E, Papageorghiou AT, Condous G, Bottomley C, Bourne T. The accuracy of first trimester ultrasound in the diagnosis of hydatidiform mole. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;29(1):70-75.

10. Wang Y, Zhao S. Vascular Biology of the Placenta. Chapter 4. Cell Types of the Placenta. San Rafael, CA: Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences; 2010.

USPSTF reaffirms need for folic acid supplements in pregnancy

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force continues to recommend that all women planning or capable of pregnancy should take a daily supplement of 0.4-0.8 mg of folic acid to prevent neural tube defects in their offspring.

The task force “concludes with high certainty” that the benefits of such supplementation are substantial and the harms are minimal, according to the recommendation statement published online Jan. 10 in JAMA (2017;317[2]:183-9). The group based its updated recommendation on a systematic review of 24 studies performed since 2009 and involving 58,860 women. Although some newer studies have suggested that supplementation is no longer needed in this era of folic acid fortification of foods, “the USPSTF found no new substantial evidence ... that would lead to a change in its recommendation from 2009,” the researchers wrote.

The most recent data estimate that folic acid supplementation prevents neural tube defects in approximately 1,300 births each year.

This updated USPSTF recommendation is in accord with recommendations from the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies (formerly the Institute of Medicine), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the U.S. Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Neurology, and the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics.

This work was supported solely by the USPSTF, an independent voluntary group mandated by Congress to assess preventive care services and funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The USPSTF recommendation that all women of childbearing age take folic acid supplements is a prudent one. Ideally, it will educate all women who are planning or capable of pregnancy to follow this recommendation and thereby reduce the risk of these severe birth defects in their infants.

Should the USPSTF recommendation be rejected because fortified food is already providing sufficient folic acid to prevent neural tube defects? No. Too little is known about how folic acid prevents neural tube defects. For example, it is not known whether the tissue stores of folate in the developing embryo or the availability of folate in the serum during the all-important few days of neural tube closure is most important. Habitual use of folic acid supplements is a more reliable method of ensuring adequate levels than is diet. In theory, a woman might not consume sufficient enriched cereal grains during the critical period of approximately 1 week when the neural tube is closing. Exactly when folate must be available also is not known. In addition, some popular diets, such as low carbohydrate or gluten free, may reduce exposure to grains, limiting folic acid intake.

James L. Mills, MD, is in the Division of Intramural Population Health Research at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development in Bethesda, Md. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. These comments are adapted from an editorial accompanying the USPSTF report (JAMA. 2017;317 [2]:144-5).

The USPSTF recommendation that all women of childbearing age take folic acid supplements is a prudent one. Ideally, it will educate all women who are planning or capable of pregnancy to follow this recommendation and thereby reduce the risk of these severe birth defects in their infants.

Should the USPSTF recommendation be rejected because fortified food is already providing sufficient folic acid to prevent neural tube defects? No. Too little is known about how folic acid prevents neural tube defects. For example, it is not known whether the tissue stores of folate in the developing embryo or the availability of folate in the serum during the all-important few days of neural tube closure is most important. Habitual use of folic acid supplements is a more reliable method of ensuring adequate levels than is diet. In theory, a woman might not consume sufficient enriched cereal grains during the critical period of approximately 1 week when the neural tube is closing. Exactly when folate must be available also is not known. In addition, some popular diets, such as low carbohydrate or gluten free, may reduce exposure to grains, limiting folic acid intake.

James L. Mills, MD, is in the Division of Intramural Population Health Research at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development in Bethesda, Md. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. These comments are adapted from an editorial accompanying the USPSTF report (JAMA. 2017;317 [2]:144-5).

The USPSTF recommendation that all women of childbearing age take folic acid supplements is a prudent one. Ideally, it will educate all women who are planning or capable of pregnancy to follow this recommendation and thereby reduce the risk of these severe birth defects in their infants.

Should the USPSTF recommendation be rejected because fortified food is already providing sufficient folic acid to prevent neural tube defects? No. Too little is known about how folic acid prevents neural tube defects. For example, it is not known whether the tissue stores of folate in the developing embryo or the availability of folate in the serum during the all-important few days of neural tube closure is most important. Habitual use of folic acid supplements is a more reliable method of ensuring adequate levels than is diet. In theory, a woman might not consume sufficient enriched cereal grains during the critical period of approximately 1 week when the neural tube is closing. Exactly when folate must be available also is not known. In addition, some popular diets, such as low carbohydrate or gluten free, may reduce exposure to grains, limiting folic acid intake.

James L. Mills, MD, is in the Division of Intramural Population Health Research at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development in Bethesda, Md. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. These comments are adapted from an editorial accompanying the USPSTF report (JAMA. 2017;317 [2]:144-5).

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force continues to recommend that all women planning or capable of pregnancy should take a daily supplement of 0.4-0.8 mg of folic acid to prevent neural tube defects in their offspring.

The task force “concludes with high certainty” that the benefits of such supplementation are substantial and the harms are minimal, according to the recommendation statement published online Jan. 10 in JAMA (2017;317[2]:183-9). The group based its updated recommendation on a systematic review of 24 studies performed since 2009 and involving 58,860 women. Although some newer studies have suggested that supplementation is no longer needed in this era of folic acid fortification of foods, “the USPSTF found no new substantial evidence ... that would lead to a change in its recommendation from 2009,” the researchers wrote.

The most recent data estimate that folic acid supplementation prevents neural tube defects in approximately 1,300 births each year.

This updated USPSTF recommendation is in accord with recommendations from the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies (formerly the Institute of Medicine), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the U.S. Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Neurology, and the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics.

This work was supported solely by the USPSTF, an independent voluntary group mandated by Congress to assess preventive care services and funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force continues to recommend that all women planning or capable of pregnancy should take a daily supplement of 0.4-0.8 mg of folic acid to prevent neural tube defects in their offspring.

The task force “concludes with high certainty” that the benefits of such supplementation are substantial and the harms are minimal, according to the recommendation statement published online Jan. 10 in JAMA (2017;317[2]:183-9). The group based its updated recommendation on a systematic review of 24 studies performed since 2009 and involving 58,860 women. Although some newer studies have suggested that supplementation is no longer needed in this era of folic acid fortification of foods, “the USPSTF found no new substantial evidence ... that would lead to a change in its recommendation from 2009,” the researchers wrote.

The most recent data estimate that folic acid supplementation prevents neural tube defects in approximately 1,300 births each year.

This updated USPSTF recommendation is in accord with recommendations from the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies (formerly the Institute of Medicine), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the U.S. Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Neurology, and the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics.

This work was supported solely by the USPSTF, an independent voluntary group mandated by Congress to assess preventive care services and funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Folic acid supplementation prevents neural tube defects in an estimated 1,300 births each year in the United States.

Data source: A systematic review of 24 studies (involving 58,860 women) that were performed since 2009 regarding the benefits and harms of folic acid supplementation.

Disclosures: This work was supported solely by the USPSTF, an independent voluntary group mandated by Congress to assess preventive care services and funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

United States about to top 40,000 Zika cases

The number of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of Zika infection jumped up a bit at the end of 2016, and the United States approached 40,000 Zika cases among all Americans at the beginning of the new year, according to reports from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There were 187 additional pregnant women with Zika virus infection reported in the 2 weeks ending Dec. 27, compared with the 136 new reports of infected women in each of the two previous comparable periods (Dec. 1-13 and Nov. 18-30). Most of the 187 new cases were reported in the U.S. territories, while 46 were reported in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. There have been delays in reporting, the CDC noted, so these cannot be considered real-time estimates.

For the 2 weeks ending Dec. 27, there were reports of two more infants born with Zika-related birth defects, bringing the total to 36 for the states/D.C. The CDC is no longer reporting adverse pregnancy outcomes for the territories because Puerto Rico is not using the same inclusion criteria. The number of pregnancy losses remains at five in the states/D.C., where it has been since August. Aggregated data from the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry show that there have been 875 completed pregnancies with or without birth defects, the CDC said.

Zika-related birth defects reported by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The number of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of Zika infection jumped up a bit at the end of 2016, and the United States approached 40,000 Zika cases among all Americans at the beginning of the new year, according to reports from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There were 187 additional pregnant women with Zika virus infection reported in the 2 weeks ending Dec. 27, compared with the 136 new reports of infected women in each of the two previous comparable periods (Dec. 1-13 and Nov. 18-30). Most of the 187 new cases were reported in the U.S. territories, while 46 were reported in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. There have been delays in reporting, the CDC noted, so these cannot be considered real-time estimates.

For the 2 weeks ending Dec. 27, there were reports of two more infants born with Zika-related birth defects, bringing the total to 36 for the states/D.C. The CDC is no longer reporting adverse pregnancy outcomes for the territories because Puerto Rico is not using the same inclusion criteria. The number of pregnancy losses remains at five in the states/D.C., where it has been since August. Aggregated data from the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry show that there have been 875 completed pregnancies with or without birth defects, the CDC said.

Zika-related birth defects reported by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The number of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of Zika infection jumped up a bit at the end of 2016, and the United States approached 40,000 Zika cases among all Americans at the beginning of the new year, according to reports from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There were 187 additional pregnant women with Zika virus infection reported in the 2 weeks ending Dec. 27, compared with the 136 new reports of infected women in each of the two previous comparable periods (Dec. 1-13 and Nov. 18-30). Most of the 187 new cases were reported in the U.S. territories, while 46 were reported in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. There have been delays in reporting, the CDC noted, so these cannot be considered real-time estimates.

For the 2 weeks ending Dec. 27, there were reports of two more infants born with Zika-related birth defects, bringing the total to 36 for the states/D.C. The CDC is no longer reporting adverse pregnancy outcomes for the territories because Puerto Rico is not using the same inclusion criteria. The number of pregnancy losses remains at five in the states/D.C., where it has been since August. Aggregated data from the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry show that there have been 875 completed pregnancies with or without birth defects, the CDC said.

Zika-related birth defects reported by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

First-trimester blood glucose predicts congenital heart disease risk

NEW ORLEANS – A single, random, first-trimester maternal plasma glucose measurement is superior to an oral glucose tolerance test later in pregnancy as a predictor of congenital heart disease in newborns, Emmi Helle, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This finding from a large retrospective study, if confirmed in a prospective data set, is likely to be practice changing. At present, a 1-hour oral glucose tolerance test in the second or third trimester is considered the best means of identifying pregnant women who ought to undergo fetal echocardiography for prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease, noted Dr. Helle of Stanford (Calif.) University.

An elevated random plasma glucose value in the first trimester was broadly predictive of increased risk for a variety of congenital heart anomalies, not just, for example, cyanotic conditions.

Fetal heart development is completed during the first trimester, Dr. Helle observed.

Her study received a warm reception. Michael A. Portman, MD, singled it out in his final-day wrap-up of the meeting’s highlights in the field of congenital heart disease.

Several studies have demonstrated that prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease results in improved surgical outcomes in newborns. The question is, how to get the right women – those at increased risk – to diagnostic fetal echocardiography. Guidelines suggest but don’t mandate on the basis of weak evidence that an oral glucose tolerance test performed in the second or early third trimester may be a useful means of screening mothers for fetal imaging. Dr. Helle’s study points to a better way.

“Hopefully we can change our guidelines and make them more scientific for identification of mothers who should undergo fetal echocardiography,” said Dr. Portman, professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington, Seattle, and director of pediatric cardiovascular research at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Dr. Helle and Dr. Portman reported having no relevant financial interests.

NEW ORLEANS – A single, random, first-trimester maternal plasma glucose measurement is superior to an oral glucose tolerance test later in pregnancy as a predictor of congenital heart disease in newborns, Emmi Helle, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This finding from a large retrospective study, if confirmed in a prospective data set, is likely to be practice changing. At present, a 1-hour oral glucose tolerance test in the second or third trimester is considered the best means of identifying pregnant women who ought to undergo fetal echocardiography for prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease, noted Dr. Helle of Stanford (Calif.) University.

An elevated random plasma glucose value in the first trimester was broadly predictive of increased risk for a variety of congenital heart anomalies, not just, for example, cyanotic conditions.

Fetal heart development is completed during the first trimester, Dr. Helle observed.

Her study received a warm reception. Michael A. Portman, MD, singled it out in his final-day wrap-up of the meeting’s highlights in the field of congenital heart disease.

Several studies have demonstrated that prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease results in improved surgical outcomes in newborns. The question is, how to get the right women – those at increased risk – to diagnostic fetal echocardiography. Guidelines suggest but don’t mandate on the basis of weak evidence that an oral glucose tolerance test performed in the second or early third trimester may be a useful means of screening mothers for fetal imaging. Dr. Helle’s study points to a better way.

“Hopefully we can change our guidelines and make them more scientific for identification of mothers who should undergo fetal echocardiography,” said Dr. Portman, professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington, Seattle, and director of pediatric cardiovascular research at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Dr. Helle and Dr. Portman reported having no relevant financial interests.

NEW ORLEANS – A single, random, first-trimester maternal plasma glucose measurement is superior to an oral glucose tolerance test later in pregnancy as a predictor of congenital heart disease in newborns, Emmi Helle, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This finding from a large retrospective study, if confirmed in a prospective data set, is likely to be practice changing. At present, a 1-hour oral glucose tolerance test in the second or third trimester is considered the best means of identifying pregnant women who ought to undergo fetal echocardiography for prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease, noted Dr. Helle of Stanford (Calif.) University.

An elevated random plasma glucose value in the first trimester was broadly predictive of increased risk for a variety of congenital heart anomalies, not just, for example, cyanotic conditions.

Fetal heart development is completed during the first trimester, Dr. Helle observed.

Her study received a warm reception. Michael A. Portman, MD, singled it out in his final-day wrap-up of the meeting’s highlights in the field of congenital heart disease.

Several studies have demonstrated that prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease results in improved surgical outcomes in newborns. The question is, how to get the right women – those at increased risk – to diagnostic fetal echocardiography. Guidelines suggest but don’t mandate on the basis of weak evidence that an oral glucose tolerance test performed in the second or early third trimester may be a useful means of screening mothers for fetal imaging. Dr. Helle’s study points to a better way.

“Hopefully we can change our guidelines and make them more scientific for identification of mothers who should undergo fetal echocardiography,” said Dr. Portman, professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington, Seattle, and director of pediatric cardiovascular research at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Dr. Helle and Dr. Portman reported having no relevant financial interests.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: For every 10-mg/dL increase in maternal plasma glucose on a random first-trimester measurement, the risk of giving birth to a baby with congenital heart disease rose by 8%.

Data source: A retrospective study of 19,197 pregnancies, 811 of which resulted in congenital heart disease in the offspring.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the study.

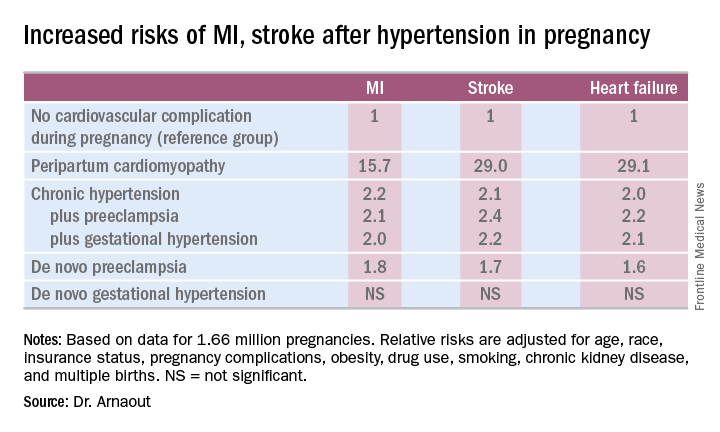

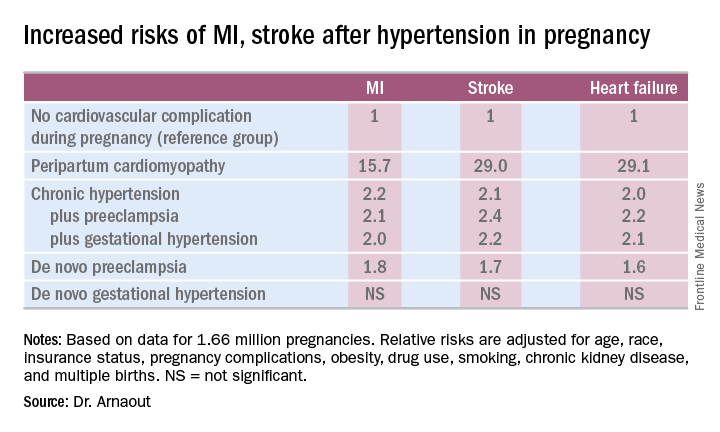

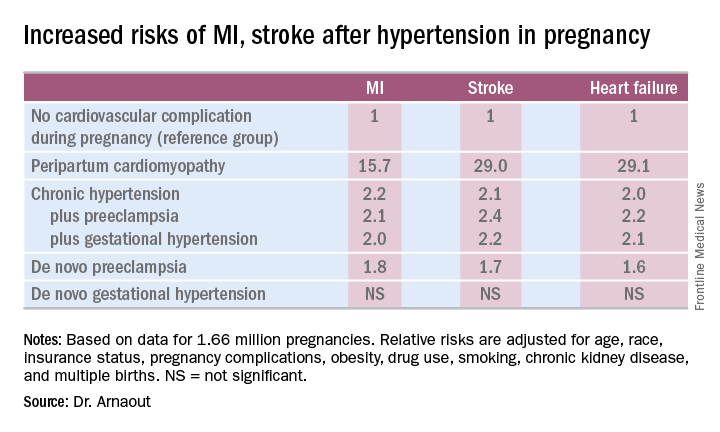

Cardiovascular complications in pregnancy quickly boost future risk

NEW ORLEANS – Women who experience peripartum cardiomyopathy or any of a variety of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy are at sharply increased risk of acute MI, stroke, or new-onset heart failure beginning within just a few years, Rima Arnaout, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“Our study supports the idea that women who have cardiovascular complications in pregnancy really need to be monitored closely for potential primary prevention of cardiovascular events,” said Dr. Arnaout of the University of California, San Francisco.

At a session devoted to “big data” studies in cardiovascular medicine, she presented one of the biggest: a retrospective cohort study of 1.66 million pregnancies during 2005-2009 in California women without any history of congenital or valvular heart disease or prepregnancy cardiovascular events. The California database was created as part of the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s comprehensive Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, which included more than 95% of the state’s hospitals. Women who experienced an MI or a stroke, or who were diagnosed with heart failure, during a median of 2.7 years and a maximum of 6 years of follow-up post pregnancy were identified via ICD-9 codes.

There were 111,202 cases of various forms of hypertension in pregnancy, for a 6.9% incidence. Peripartum cardiomyopathy was diagnosed in 562 women, for a rate of 3.5 cases per 10,000 pregnancies.

Indeed, in a multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis adjusted for numerous potential confounders, peripartum cardiomyopathy was associated with a 16-fold increased risk of acute MI during the relatively short follow-up period, as well as 29-fold increased risks of stroke and heart failure, compared with women with no cardiovascular issues during their pregnancy.

Chronic hypertension, regardless of whether it occurred alone or in combination with preeclampsia or gestational hypertension, was associated with roughly a twofold increased risk of each of the three study outcomes, compared with women who didn’t experience a cardiovascular complication during pregnancy. De novo preeclampsia was also associated with roughly a twofold increased risk of later MI, heart failure, or stroke.

The only form of hypertension in pregnancy that wasn’t associated with a subsequent significantly increased risk of cardiovascular events was de novo gestational hypertension.

Audience member David C. Goff Jr., MD, head of the division of cardiovascular sciences at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in Bethesda, Md., rose to compliment Dr. Arnaout: “Great work and really important.”

He said that her findings are consistent with the notion that pregnancy constitutes a sort of early-life cardiovascular stress test. He said he wondered, however, just how comfortable Dr. Arnaout is in stating that gestational diabetes isn’t associated with increased subsequent cardiovascular risk, given the relatively short follow-up to date in this population of women who still remain several decades away from the age when cardiovascular event rates really start to climb.

“I completely agree with you,” she replied, noting that other investigators utilizing a different registry have reported an increased longer-term risk for women with gestational diabetes.

Dr. Arnaout said she and her coinvestigators plan to continue to follow the women who experienced peripartum cardiomyopathy or hypertension in pregnancy longer term. They’re also in the process of breaking down the data to look at the risks associated with specific subtypes of MI, stroke, and heart failure.

Dr. Arnaout reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, which was supported by the American Heart Association and the Sarnoff Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

NEW ORLEANS – Women who experience peripartum cardiomyopathy or any of a variety of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy are at sharply increased risk of acute MI, stroke, or new-onset heart failure beginning within just a few years, Rima Arnaout, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“Our study supports the idea that women who have cardiovascular complications in pregnancy really need to be monitored closely for potential primary prevention of cardiovascular events,” said Dr. Arnaout of the University of California, San Francisco.