User login

2017 Update on obstetrics

In this Update we discuss several exciting new recommendations for preventive treatments in pregnancy and prenatal diagnostic tests. Our A-to-Z coverage includes:

- antenatal steroids in late preterm pregnancy

- expanded list of high-risk conditions warranting low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prevention

- chromosomal microarray analysis versus karyotype for specific clinical situations

- Zika virus infection evolving information.

Next: New recommendation for timing of late preterm antenatal steroids

New recommendation offered for timing of late preterm antenatal steroids

Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Thom EA, Blackwell SC, et al; for the NICHD Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Antenatal betamethasone for women at risk for late preterm delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(14):1311-1320.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 677. Antenatal corticosteroidtherapy for fetal maturation. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(4):e187-e194.

Kamath-Rayne BD, Rozance PJ, Goldenberg RL, Jobe AH. Antenatal corticosteroids beyond 34 weeks gestation: what do we do now? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(4):423-430.

A dramatic recommendation for obstetric practice change occurred in 2016: the option of administering antenatal steroids for fetal lung maturity after 34 weeks. In the Antenatal Late Preterm Steroids (ALPS) trial of betamethasone in the late preterm period in patients at "high risk" of imminent delivery, Gyamfi-Bannerman and colleagues demonstrated that the treated group had a significant decrease in the rate of neonatal respiratory complications.

The primary outcome, a composite of respiratory morbidities (including transient tachypnea of the newborn, surfactant use, and need for resuscitation at birth) within the first 72 hours of life, had significant differences between groups, occurring in 165 of 1,427 infants (11.6%) in the betamethasone-treated group and 202 of 1,400 (14.4%) in the placebo group (relative risk in the betamethasone group, 0.80; 95% confidence interval, 0.66-0.97; P = .02). However, there was no statistically significant difference in respiratory distress syndrome, apnea, or pneumonia between groups, and the significant difference noted in bronchopulmonary dysplasia was based on a total number of 11 cases.

In response to these findings, both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) released practice advisories and interim updates, culminating in a final recommendation for a single course of betamethasone in patients at high risk of preterm delivery between 34 and 36 6/7 weeks who have not received a previous course.

Related article:

When could use of antenatal corticosteroids in the late preterm birth period be beneficial?

In a thorough review of the literature on antenatal steroid use, Kamath-Rayne and colleagues highlighted several factors that should be considered before adopting universal use of steroids at >34 weeks. These include:

- The definition of "high risk of imminent delivery" as preterm labor with at least 3-cm dilation or 75% effacement, or spontaneous rupture of membranes. The effect of less stringent inclusion criteria in real-world clinical practice is not known, and many patients who will go on to deliver at term will receive steroids unnecessarily.

- Multiple gestation, patients with pre-existing diabetes, women who had previously received a course of steroids, and fetuses with anomalies were excluded from the ALPS study. Use of antenatal steroids in these groups at >34 weeks should be evaluated before universal adoption.

Related article:

What is the ideal gestational age for twin delivery to minimize perinatal deaths?

- The incidence of neonatal hypoglycemia in the treated group was significantly increased. This affects our colleagues in pediatrics considerably from a systems standpoint (need for changes to newborn protocols and communication between services).

- The long-term outcomes of patients exposed to steroids in the late preterm period are yet to be delineated, specifically, the potential neurodevelopmental effects of a medication known to alter preterm brain development as well as cardiovascular and metabolic consequences.

Next: Low-dose aspirin for reducing preeclampsia risk

Low-dose aspirin clearly is effective for reducing the risk of preeclampsia

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1122-1131.

Henderson JT, Whitlock EP, O'Connor E, Senger CA, Thompson JH, Rowland MG. Low-dose aspirin for prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(10):695-703.

LeFevre ML; US Preventive Services Task Force. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(11):819-826.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice advisory on low-dose aspirin and prevention of preeclampsia: updated recommendations. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Practice-Advisories/Practice-Advisory-Low-Dose-Aspirin-and-Prevention-of-Preeclampsia-Updated-Recommendations. Published July 11, 2016. Accessed December 6, 2016.

In the 2013 ACOG Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy report, low-dose aspirin (60-80 mg) was recommended to be initiated in the late first trimester to reduce preeclampsia risk for women with:

- prior early onset preeclampsia with preterm delivery at <34 weeks' gestation, or

- preeclampsia in more than one prior pregnancy.

This recommendation was based on several meta-analyses that demonstrated a 10% to 17% reduction in risk with no increase in bleeding, placental abruption, or other adverse events.

In 2014, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) conducted a systematic evidence review of low-dose aspirin use for prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia. That report revealed a 24% risk reduction of preeclampsia in high-risk women treated with low-dose aspirin, as well as a 14% reduction in preterm birth and a 20% reduction in fetal growth restriction. A final statement from the USPSTF in 2014 recommended low-dose aspirin (60-150 mg) starting between 12 and 28 weeks' gestation for women at "high" risk who have:

- a history of preeclampsia, especially if accompanied by an adverse outcome

- multifetal gestation

- chronic hypertension

- diabetes (type 1 or type 2)

- renal disease

- autoimmune disease (such as systematic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid syndrome).

Related article:

Start offering aspirin to pregnant women at high risk for preeclampsia

As of July 11, 2016, ACOG supports this expanded list of high-risk conditions. Additionally, the USPSTF identified a "moderate" risk group in which low-dose aspirin may be considered if a patient has several risk factors, such as obesity, nulliparity, family history of preeclampsia, age 35 years or older, or another poor pregnancy outcome. ACOG notes, however, that the evidence supporting this practice is uncertain and does not make a recommendation regarding aspirin use in this population. Further study should be conducted to determine the benefit of low-dose aspirin in these patients as well as the long-term effects of treatment on maternal and child outcomes.

Next: CMA for prenatal genetic diagnosis

Chromosomal microarray analysis is preferable to karyotype in certain situations

Pauli JM, Repke JT. Update on obstetrics. OBG Manag. 2013;25(1):28-32.

Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), Dugoff L, Norton ME, Kuller JA. The use of chromosomal microarray for prenatal diagnosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(4):B2-B9.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 682. Microarrays and next- generation sequencing technology: the use of advanced genetic diagnostic tools in obstetrics and gynecology.Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(6):e262-e268.

We previously addressed the use of chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) for prenatal diagnosis in our 2013 "Update on obstetrics," specifically, the question of whether CMA could replace karyotype. The main differences between karyotype and CMA are that 1) only karyotype can detect balanced translocations/inversions and 2) only CMA can detect copy number variants (CNV). There are some differences in the technology and capabilities of the 2 types of CMA currently available as well.

In our 2013 article we concluded that "The total costs of such an approach--test, interpretation, counseling, and long-term follow-up of uncertain results--are unknown at this time and may prove to be unaffordable on a population-wide basis." Today, the cost of CMA is still higher than karyotype, but it is expected to decrease and insurance coverage for this test is expected to increase.

Related article:

Cell-free DNA screening for women at low risk for fetal aneuploidy

Both SMFM and ACOG released recommendations in 2016 regarding the use of CMA in prenatal genetic diagnosis, summarized as follows:

- CMA is recommended over karyotype for fetuses with structural abnormalities on ultrasound

- The detection rate for clinically relevant abnormal CNVs in this population is about 6%

- CMA is recommended for diagnosis for stillbirth specimens

- CMA does not require dividing cells and may be a quicker and more reliable test in this population

- Karotype or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is recommended for fetuses with ultrasound findings suggestive of aneuploidy

- If it is negative, then CMA is recommended

- Karyotype or CMA is recommended for patients desiring prenatal diagnostic testing with a normal fetal ultrasound

- The detection rate for clinically relevant CNVs in this population (advanced maternal age, abnormal serum screening, prior aneuploidy, parental anxiety) is about 1%

- Pretest and posttest counseling about the limitations of CMA and a 2% risk of detection of variants of unknown significance (VUS) should be performed by a provider who has expertise in CMA and who has access to databases with genotype/phenotype information for VUS

- This counseling should also include the possibility of diagnosis of nonpaternity, consanguinity, and adult-onset disease

- Karyotype is recommended for couples with recurrent pregnancy loss

- The identification of balanced translocations in this population is most relevant in this patient population

- Prenatal diagnosis with routine use of whole-genome or whole-exome sequencing is not recommended.

Next: Zika virus: Check for updates

Zika virus infection: Check often for the latest updates

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Practice advisory on Zika virus. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Practice-Advisories/Practice-Advisory-Interim-Guidance-for-Care-of-Obstetric-Patients- During-a-Zika-Virus-Outbreak. Published December 5, 2016. Accessed December 6, 2016.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Zika virus. http://www.cdc.gov/zika/pregnancy/index.html. Updated August 22, 2016. Accessed December 6, 2016.

Petersen EE, Meaney-Delman D, Neblett-Fanfair R, et al. Update: interim guidance for preconception counseling and prevention of sexual transmission of Zika virus for persons with possible Zika virus exposure--United States, September 2016. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(39):1077-1081.

A yearly update on obstetrics would be remiss without mention of the Zika virus and its impact on pregnancy and reproduction. That being said, any recommendations we offer may be out of date by the time this article is published given the rapidly changing picture of Zika virus since it first dominated the headlines in 2016. Here are the basics as summarized from ACOG and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC):

Viral spread. Zika virus may be spread in several ways: by an infected Aedes species mosquito, mother to fetus, sexual contact, blood transfusion, or laboratory exposure.

Symptoms of infection include conjunctivitis, fever, rash, and arthralgia, but most patients (4/5) are asymptomatic.

Sequelae. Zika virus infection during pregnancy is believed to cause fetal and neonatal microcephaly, intracranial calcifications, and brain and eye abnormalities. The rate of these findings in infected individuals, as well as the rate of vertical transmission, is not known.

Travel advisory. Pregnant women should not travel to areas with active Zika infection (the CDC website regularly updates these restricted areas).

Preventive measures. If traveling to an area of active Zika infection, pregnant women should take preventative measures day and night against mosquito bites, such as use of insect repellents approved by the Environmental Protection Agency, clothing that covers exposed skin, and staying indoors.

Safe sex. Abstinence or consistent condom use is recommended for pregnant women with partners who travel to or live in areas of active Zika infection.

Delay conception. Conception should be postponed for at least 6 months in men with Zika infection and at least 8 weeks in women with Zika infection.

Testing recommendations. Pregnant women with Zika virus exposure should be tested, regardless of symptoms. Symptomatic exposed nonpregnant women and all men should be tested.

Prenatal surveillance. High-risk consultation and serial ultrasounds for fetal anatomy and growth should be considered in patients with Zika virus infection during pregnancy. Amniocentesis can be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Related article:

Zika virus update: A rapidly moving target

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

In this Update we discuss several exciting new recommendations for preventive treatments in pregnancy and prenatal diagnostic tests. Our A-to-Z coverage includes:

- antenatal steroids in late preterm pregnancy

- expanded list of high-risk conditions warranting low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prevention

- chromosomal microarray analysis versus karyotype for specific clinical situations

- Zika virus infection evolving information.

Next: New recommendation for timing of late preterm antenatal steroids

New recommendation offered for timing of late preterm antenatal steroids

Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Thom EA, Blackwell SC, et al; for the NICHD Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Antenatal betamethasone for women at risk for late preterm delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(14):1311-1320.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 677. Antenatal corticosteroidtherapy for fetal maturation. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(4):e187-e194.

Kamath-Rayne BD, Rozance PJ, Goldenberg RL, Jobe AH. Antenatal corticosteroids beyond 34 weeks gestation: what do we do now? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(4):423-430.

A dramatic recommendation for obstetric practice change occurred in 2016: the option of administering antenatal steroids for fetal lung maturity after 34 weeks. In the Antenatal Late Preterm Steroids (ALPS) trial of betamethasone in the late preterm period in patients at "high risk" of imminent delivery, Gyamfi-Bannerman and colleagues demonstrated that the treated group had a significant decrease in the rate of neonatal respiratory complications.

The primary outcome, a composite of respiratory morbidities (including transient tachypnea of the newborn, surfactant use, and need for resuscitation at birth) within the first 72 hours of life, had significant differences between groups, occurring in 165 of 1,427 infants (11.6%) in the betamethasone-treated group and 202 of 1,400 (14.4%) in the placebo group (relative risk in the betamethasone group, 0.80; 95% confidence interval, 0.66-0.97; P = .02). However, there was no statistically significant difference in respiratory distress syndrome, apnea, or pneumonia between groups, and the significant difference noted in bronchopulmonary dysplasia was based on a total number of 11 cases.

In response to these findings, both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) released practice advisories and interim updates, culminating in a final recommendation for a single course of betamethasone in patients at high risk of preterm delivery between 34 and 36 6/7 weeks who have not received a previous course.

Related article:

When could use of antenatal corticosteroids in the late preterm birth period be beneficial?

In a thorough review of the literature on antenatal steroid use, Kamath-Rayne and colleagues highlighted several factors that should be considered before adopting universal use of steroids at >34 weeks. These include:

- The definition of "high risk of imminent delivery" as preterm labor with at least 3-cm dilation or 75% effacement, or spontaneous rupture of membranes. The effect of less stringent inclusion criteria in real-world clinical practice is not known, and many patients who will go on to deliver at term will receive steroids unnecessarily.

- Multiple gestation, patients with pre-existing diabetes, women who had previously received a course of steroids, and fetuses with anomalies were excluded from the ALPS study. Use of antenatal steroids in these groups at >34 weeks should be evaluated before universal adoption.

Related article:

What is the ideal gestational age for twin delivery to minimize perinatal deaths?

- The incidence of neonatal hypoglycemia in the treated group was significantly increased. This affects our colleagues in pediatrics considerably from a systems standpoint (need for changes to newborn protocols and communication between services).

- The long-term outcomes of patients exposed to steroids in the late preterm period are yet to be delineated, specifically, the potential neurodevelopmental effects of a medication known to alter preterm brain development as well as cardiovascular and metabolic consequences.

Next: Low-dose aspirin for reducing preeclampsia risk

Low-dose aspirin clearly is effective for reducing the risk of preeclampsia

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1122-1131.

Henderson JT, Whitlock EP, O'Connor E, Senger CA, Thompson JH, Rowland MG. Low-dose aspirin for prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(10):695-703.

LeFevre ML; US Preventive Services Task Force. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(11):819-826.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice advisory on low-dose aspirin and prevention of preeclampsia: updated recommendations. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Practice-Advisories/Practice-Advisory-Low-Dose-Aspirin-and-Prevention-of-Preeclampsia-Updated-Recommendations. Published July 11, 2016. Accessed December 6, 2016.

In the 2013 ACOG Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy report, low-dose aspirin (60-80 mg) was recommended to be initiated in the late first trimester to reduce preeclampsia risk for women with:

- prior early onset preeclampsia with preterm delivery at <34 weeks' gestation, or

- preeclampsia in more than one prior pregnancy.

This recommendation was based on several meta-analyses that demonstrated a 10% to 17% reduction in risk with no increase in bleeding, placental abruption, or other adverse events.

In 2014, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) conducted a systematic evidence review of low-dose aspirin use for prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia. That report revealed a 24% risk reduction of preeclampsia in high-risk women treated with low-dose aspirin, as well as a 14% reduction in preterm birth and a 20% reduction in fetal growth restriction. A final statement from the USPSTF in 2014 recommended low-dose aspirin (60-150 mg) starting between 12 and 28 weeks' gestation for women at "high" risk who have:

- a history of preeclampsia, especially if accompanied by an adverse outcome

- multifetal gestation

- chronic hypertension

- diabetes (type 1 or type 2)

- renal disease

- autoimmune disease (such as systematic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid syndrome).

Related article:

Start offering aspirin to pregnant women at high risk for preeclampsia

As of July 11, 2016, ACOG supports this expanded list of high-risk conditions. Additionally, the USPSTF identified a "moderate" risk group in which low-dose aspirin may be considered if a patient has several risk factors, such as obesity, nulliparity, family history of preeclampsia, age 35 years or older, or another poor pregnancy outcome. ACOG notes, however, that the evidence supporting this practice is uncertain and does not make a recommendation regarding aspirin use in this population. Further study should be conducted to determine the benefit of low-dose aspirin in these patients as well as the long-term effects of treatment on maternal and child outcomes.

Next: CMA for prenatal genetic diagnosis

Chromosomal microarray analysis is preferable to karyotype in certain situations

Pauli JM, Repke JT. Update on obstetrics. OBG Manag. 2013;25(1):28-32.

Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), Dugoff L, Norton ME, Kuller JA. The use of chromosomal microarray for prenatal diagnosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(4):B2-B9.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 682. Microarrays and next- generation sequencing technology: the use of advanced genetic diagnostic tools in obstetrics and gynecology.Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(6):e262-e268.

We previously addressed the use of chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) for prenatal diagnosis in our 2013 "Update on obstetrics," specifically, the question of whether CMA could replace karyotype. The main differences between karyotype and CMA are that 1) only karyotype can detect balanced translocations/inversions and 2) only CMA can detect copy number variants (CNV). There are some differences in the technology and capabilities of the 2 types of CMA currently available as well.

In our 2013 article we concluded that "The total costs of such an approach--test, interpretation, counseling, and long-term follow-up of uncertain results--are unknown at this time and may prove to be unaffordable on a population-wide basis." Today, the cost of CMA is still higher than karyotype, but it is expected to decrease and insurance coverage for this test is expected to increase.

Related article:

Cell-free DNA screening for women at low risk for fetal aneuploidy

Both SMFM and ACOG released recommendations in 2016 regarding the use of CMA in prenatal genetic diagnosis, summarized as follows:

- CMA is recommended over karyotype for fetuses with structural abnormalities on ultrasound

- The detection rate for clinically relevant abnormal CNVs in this population is about 6%

- CMA is recommended for diagnosis for stillbirth specimens

- CMA does not require dividing cells and may be a quicker and more reliable test in this population

- Karotype or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is recommended for fetuses with ultrasound findings suggestive of aneuploidy

- If it is negative, then CMA is recommended

- Karyotype or CMA is recommended for patients desiring prenatal diagnostic testing with a normal fetal ultrasound

- The detection rate for clinically relevant CNVs in this population (advanced maternal age, abnormal serum screening, prior aneuploidy, parental anxiety) is about 1%

- Pretest and posttest counseling about the limitations of CMA and a 2% risk of detection of variants of unknown significance (VUS) should be performed by a provider who has expertise in CMA and who has access to databases with genotype/phenotype information for VUS

- This counseling should also include the possibility of diagnosis of nonpaternity, consanguinity, and adult-onset disease

- Karyotype is recommended for couples with recurrent pregnancy loss

- The identification of balanced translocations in this population is most relevant in this patient population

- Prenatal diagnosis with routine use of whole-genome or whole-exome sequencing is not recommended.

Next: Zika virus: Check for updates

Zika virus infection: Check often for the latest updates

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Practice advisory on Zika virus. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Practice-Advisories/Practice-Advisory-Interim-Guidance-for-Care-of-Obstetric-Patients- During-a-Zika-Virus-Outbreak. Published December 5, 2016. Accessed December 6, 2016.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Zika virus. http://www.cdc.gov/zika/pregnancy/index.html. Updated August 22, 2016. Accessed December 6, 2016.

Petersen EE, Meaney-Delman D, Neblett-Fanfair R, et al. Update: interim guidance for preconception counseling and prevention of sexual transmission of Zika virus for persons with possible Zika virus exposure--United States, September 2016. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(39):1077-1081.

A yearly update on obstetrics would be remiss without mention of the Zika virus and its impact on pregnancy and reproduction. That being said, any recommendations we offer may be out of date by the time this article is published given the rapidly changing picture of Zika virus since it first dominated the headlines in 2016. Here are the basics as summarized from ACOG and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC):

Viral spread. Zika virus may be spread in several ways: by an infected Aedes species mosquito, mother to fetus, sexual contact, blood transfusion, or laboratory exposure.

Symptoms of infection include conjunctivitis, fever, rash, and arthralgia, but most patients (4/5) are asymptomatic.

Sequelae. Zika virus infection during pregnancy is believed to cause fetal and neonatal microcephaly, intracranial calcifications, and brain and eye abnormalities. The rate of these findings in infected individuals, as well as the rate of vertical transmission, is not known.

Travel advisory. Pregnant women should not travel to areas with active Zika infection (the CDC website regularly updates these restricted areas).

Preventive measures. If traveling to an area of active Zika infection, pregnant women should take preventative measures day and night against mosquito bites, such as use of insect repellents approved by the Environmental Protection Agency, clothing that covers exposed skin, and staying indoors.

Safe sex. Abstinence or consistent condom use is recommended for pregnant women with partners who travel to or live in areas of active Zika infection.

Delay conception. Conception should be postponed for at least 6 months in men with Zika infection and at least 8 weeks in women with Zika infection.

Testing recommendations. Pregnant women with Zika virus exposure should be tested, regardless of symptoms. Symptomatic exposed nonpregnant women and all men should be tested.

Prenatal surveillance. High-risk consultation and serial ultrasounds for fetal anatomy and growth should be considered in patients with Zika virus infection during pregnancy. Amniocentesis can be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Related article:

Zika virus update: A rapidly moving target

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

In this Update we discuss several exciting new recommendations for preventive treatments in pregnancy and prenatal diagnostic tests. Our A-to-Z coverage includes:

- antenatal steroids in late preterm pregnancy

- expanded list of high-risk conditions warranting low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prevention

- chromosomal microarray analysis versus karyotype for specific clinical situations

- Zika virus infection evolving information.

Next: New recommendation for timing of late preterm antenatal steroids

New recommendation offered for timing of late preterm antenatal steroids

Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Thom EA, Blackwell SC, et al; for the NICHD Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Antenatal betamethasone for women at risk for late preterm delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(14):1311-1320.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 677. Antenatal corticosteroidtherapy for fetal maturation. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(4):e187-e194.

Kamath-Rayne BD, Rozance PJ, Goldenberg RL, Jobe AH. Antenatal corticosteroids beyond 34 weeks gestation: what do we do now? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(4):423-430.

A dramatic recommendation for obstetric practice change occurred in 2016: the option of administering antenatal steroids for fetal lung maturity after 34 weeks. In the Antenatal Late Preterm Steroids (ALPS) trial of betamethasone in the late preterm period in patients at "high risk" of imminent delivery, Gyamfi-Bannerman and colleagues demonstrated that the treated group had a significant decrease in the rate of neonatal respiratory complications.

The primary outcome, a composite of respiratory morbidities (including transient tachypnea of the newborn, surfactant use, and need for resuscitation at birth) within the first 72 hours of life, had significant differences between groups, occurring in 165 of 1,427 infants (11.6%) in the betamethasone-treated group and 202 of 1,400 (14.4%) in the placebo group (relative risk in the betamethasone group, 0.80; 95% confidence interval, 0.66-0.97; P = .02). However, there was no statistically significant difference in respiratory distress syndrome, apnea, or pneumonia between groups, and the significant difference noted in bronchopulmonary dysplasia was based on a total number of 11 cases.

In response to these findings, both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) released practice advisories and interim updates, culminating in a final recommendation for a single course of betamethasone in patients at high risk of preterm delivery between 34 and 36 6/7 weeks who have not received a previous course.

Related article:

When could use of antenatal corticosteroids in the late preterm birth period be beneficial?

In a thorough review of the literature on antenatal steroid use, Kamath-Rayne and colleagues highlighted several factors that should be considered before adopting universal use of steroids at >34 weeks. These include:

- The definition of "high risk of imminent delivery" as preterm labor with at least 3-cm dilation or 75% effacement, or spontaneous rupture of membranes. The effect of less stringent inclusion criteria in real-world clinical practice is not known, and many patients who will go on to deliver at term will receive steroids unnecessarily.

- Multiple gestation, patients with pre-existing diabetes, women who had previously received a course of steroids, and fetuses with anomalies were excluded from the ALPS study. Use of antenatal steroids in these groups at >34 weeks should be evaluated before universal adoption.

Related article:

What is the ideal gestational age for twin delivery to minimize perinatal deaths?

- The incidence of neonatal hypoglycemia in the treated group was significantly increased. This affects our colleagues in pediatrics considerably from a systems standpoint (need for changes to newborn protocols and communication between services).

- The long-term outcomes of patients exposed to steroids in the late preterm period are yet to be delineated, specifically, the potential neurodevelopmental effects of a medication known to alter preterm brain development as well as cardiovascular and metabolic consequences.

Next: Low-dose aspirin for reducing preeclampsia risk

Low-dose aspirin clearly is effective for reducing the risk of preeclampsia

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1122-1131.

Henderson JT, Whitlock EP, O'Connor E, Senger CA, Thompson JH, Rowland MG. Low-dose aspirin for prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(10):695-703.

LeFevre ML; US Preventive Services Task Force. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(11):819-826.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice advisory on low-dose aspirin and prevention of preeclampsia: updated recommendations. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Practice-Advisories/Practice-Advisory-Low-Dose-Aspirin-and-Prevention-of-Preeclampsia-Updated-Recommendations. Published July 11, 2016. Accessed December 6, 2016.

In the 2013 ACOG Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy report, low-dose aspirin (60-80 mg) was recommended to be initiated in the late first trimester to reduce preeclampsia risk for women with:

- prior early onset preeclampsia with preterm delivery at <34 weeks' gestation, or

- preeclampsia in more than one prior pregnancy.

This recommendation was based on several meta-analyses that demonstrated a 10% to 17% reduction in risk with no increase in bleeding, placental abruption, or other adverse events.

In 2014, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) conducted a systematic evidence review of low-dose aspirin use for prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia. That report revealed a 24% risk reduction of preeclampsia in high-risk women treated with low-dose aspirin, as well as a 14% reduction in preterm birth and a 20% reduction in fetal growth restriction. A final statement from the USPSTF in 2014 recommended low-dose aspirin (60-150 mg) starting between 12 and 28 weeks' gestation for women at "high" risk who have:

- a history of preeclampsia, especially if accompanied by an adverse outcome

- multifetal gestation

- chronic hypertension

- diabetes (type 1 or type 2)

- renal disease

- autoimmune disease (such as systematic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid syndrome).

Related article:

Start offering aspirin to pregnant women at high risk for preeclampsia

As of July 11, 2016, ACOG supports this expanded list of high-risk conditions. Additionally, the USPSTF identified a "moderate" risk group in which low-dose aspirin may be considered if a patient has several risk factors, such as obesity, nulliparity, family history of preeclampsia, age 35 years or older, or another poor pregnancy outcome. ACOG notes, however, that the evidence supporting this practice is uncertain and does not make a recommendation regarding aspirin use in this population. Further study should be conducted to determine the benefit of low-dose aspirin in these patients as well as the long-term effects of treatment on maternal and child outcomes.

Next: CMA for prenatal genetic diagnosis

Chromosomal microarray analysis is preferable to karyotype in certain situations

Pauli JM, Repke JT. Update on obstetrics. OBG Manag. 2013;25(1):28-32.

Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), Dugoff L, Norton ME, Kuller JA. The use of chromosomal microarray for prenatal diagnosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(4):B2-B9.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 682. Microarrays and next- generation sequencing technology: the use of advanced genetic diagnostic tools in obstetrics and gynecology.Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(6):e262-e268.

We previously addressed the use of chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) for prenatal diagnosis in our 2013 "Update on obstetrics," specifically, the question of whether CMA could replace karyotype. The main differences between karyotype and CMA are that 1) only karyotype can detect balanced translocations/inversions and 2) only CMA can detect copy number variants (CNV). There are some differences in the technology and capabilities of the 2 types of CMA currently available as well.

In our 2013 article we concluded that "The total costs of such an approach--test, interpretation, counseling, and long-term follow-up of uncertain results--are unknown at this time and may prove to be unaffordable on a population-wide basis." Today, the cost of CMA is still higher than karyotype, but it is expected to decrease and insurance coverage for this test is expected to increase.

Related article:

Cell-free DNA screening for women at low risk for fetal aneuploidy

Both SMFM and ACOG released recommendations in 2016 regarding the use of CMA in prenatal genetic diagnosis, summarized as follows:

- CMA is recommended over karyotype for fetuses with structural abnormalities on ultrasound

- The detection rate for clinically relevant abnormal CNVs in this population is about 6%

- CMA is recommended for diagnosis for stillbirth specimens

- CMA does not require dividing cells and may be a quicker and more reliable test in this population

- Karotype or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is recommended for fetuses with ultrasound findings suggestive of aneuploidy

- If it is negative, then CMA is recommended

- Karyotype or CMA is recommended for patients desiring prenatal diagnostic testing with a normal fetal ultrasound

- The detection rate for clinically relevant CNVs in this population (advanced maternal age, abnormal serum screening, prior aneuploidy, parental anxiety) is about 1%

- Pretest and posttest counseling about the limitations of CMA and a 2% risk of detection of variants of unknown significance (VUS) should be performed by a provider who has expertise in CMA and who has access to databases with genotype/phenotype information for VUS

- This counseling should also include the possibility of diagnosis of nonpaternity, consanguinity, and adult-onset disease

- Karyotype is recommended for couples with recurrent pregnancy loss

- The identification of balanced translocations in this population is most relevant in this patient population

- Prenatal diagnosis with routine use of whole-genome or whole-exome sequencing is not recommended.

Next: Zika virus: Check for updates

Zika virus infection: Check often for the latest updates

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Practice advisory on Zika virus. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Practice-Advisories/Practice-Advisory-Interim-Guidance-for-Care-of-Obstetric-Patients- During-a-Zika-Virus-Outbreak. Published December 5, 2016. Accessed December 6, 2016.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Zika virus. http://www.cdc.gov/zika/pregnancy/index.html. Updated August 22, 2016. Accessed December 6, 2016.

Petersen EE, Meaney-Delman D, Neblett-Fanfair R, et al. Update: interim guidance for preconception counseling and prevention of sexual transmission of Zika virus for persons with possible Zika virus exposure--United States, September 2016. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(39):1077-1081.

A yearly update on obstetrics would be remiss without mention of the Zika virus and its impact on pregnancy and reproduction. That being said, any recommendations we offer may be out of date by the time this article is published given the rapidly changing picture of Zika virus since it first dominated the headlines in 2016. Here are the basics as summarized from ACOG and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC):

Viral spread. Zika virus may be spread in several ways: by an infected Aedes species mosquito, mother to fetus, sexual contact, blood transfusion, or laboratory exposure.

Symptoms of infection include conjunctivitis, fever, rash, and arthralgia, but most patients (4/5) are asymptomatic.

Sequelae. Zika virus infection during pregnancy is believed to cause fetal and neonatal microcephaly, intracranial calcifications, and brain and eye abnormalities. The rate of these findings in infected individuals, as well as the rate of vertical transmission, is not known.

Travel advisory. Pregnant women should not travel to areas with active Zika infection (the CDC website regularly updates these restricted areas).

Preventive measures. If traveling to an area of active Zika infection, pregnant women should take preventative measures day and night against mosquito bites, such as use of insect repellents approved by the Environmental Protection Agency, clothing that covers exposed skin, and staying indoors.

Safe sex. Abstinence or consistent condom use is recommended for pregnant women with partners who travel to or live in areas of active Zika infection.

Delay conception. Conception should be postponed for at least 6 months in men with Zika infection and at least 8 weeks in women with Zika infection.

Testing recommendations. Pregnant women with Zika virus exposure should be tested, regardless of symptoms. Symptomatic exposed nonpregnant women and all men should be tested.

Prenatal surveillance. High-risk consultation and serial ultrasounds for fetal anatomy and growth should be considered in patients with Zika virus infection during pregnancy. Amniocentesis can be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Related article:

Zika virus update: A rapidly moving target

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Which maternal beta-blockers boost SGA risk?

NEW ORLEANS – The use of labetalol or atenolol in pregnancy is associated with significantly increased risk of having a small-for-gestational-age (SGA) baby; metoprolol and propranolol are not.

And none of these four beta-blockers are associated with increased risk of congenital cardiac anomalies, Angie Ng, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Overall, the average birth weight for babies whose mothers were on a beta-blocker was 2,996 g, significantly less than the 3,353 g in 374,391 controls who weren’t exposed to beta-blockers during pregnancy. But beta-blockers are not a monolithic class of drugs; their pharmacokinetics and physical properties differ. And so did their associated incidence of SGA, according to Dr. Ng of Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles.

The rate of SGA below the 10th percentile was 17.6% in the 3,357 women on labetalol during pregnancy and the same in the 638 women on atenolol. In contrast, the SGA rates in women on metoprolol or propranolol – 10.8% and 10.3%, respectively – weren’t significantly different from the 8.7% incidence in controls.

To deal with the possibility of confounding by indication, Dr. Ng and her coinvestigators performed a multivariate analysis adjusted for maternal age, white race, body mass index, gestational age, diabetes, hypertension, arrhythmias, dyslipidemia, and renal insufficiency. The resultant adjusted risk of having an SGA baby was 2.9-fold greater in women on labetalol and 2.4-fold greater in those on atenolol than in controls. Women on the other two beta-blockers faced no increased risk.

The incidence of congenital cardiac anomalies was 5.1% in women exposed to beta-blockers in pregnancy and 1.9% in controls who weren’t. The most commonly diagnosed anomalies – patent ductus arteriosus, atrial septal defect, and ventricular septal defect – were two- to threefold more frequent in the setting of maternal beta-blocker exposure. However, in a multivariate analysis the use of any beta-blocker was no longer associated with significantly elevated risk of congenital cardiac anomalies.

“This suggests that the initial association we see in the unadjusted analysis is likely due to confounders and not due to the beta-blocker exposure,” Dr. Ng said.

Labetalol and atenolol were prescribed during pregnancy most often for hypertension, while metoprolol and propranolol were typically prescribed to control arrhythmias.

Previous reports by other investigators have yielded conflicting results as to whether maternal beta-blocker therapy is associated with increased risk of SGA. A major limitation of those studies was that they examined beta-blockers as a class rather than assessing the impact of specific agents, according to Dr. Ng.

She reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

NEW ORLEANS – The use of labetalol or atenolol in pregnancy is associated with significantly increased risk of having a small-for-gestational-age (SGA) baby; metoprolol and propranolol are not.

And none of these four beta-blockers are associated with increased risk of congenital cardiac anomalies, Angie Ng, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Overall, the average birth weight for babies whose mothers were on a beta-blocker was 2,996 g, significantly less than the 3,353 g in 374,391 controls who weren’t exposed to beta-blockers during pregnancy. But beta-blockers are not a monolithic class of drugs; their pharmacokinetics and physical properties differ. And so did their associated incidence of SGA, according to Dr. Ng of Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles.

The rate of SGA below the 10th percentile was 17.6% in the 3,357 women on labetalol during pregnancy and the same in the 638 women on atenolol. In contrast, the SGA rates in women on metoprolol or propranolol – 10.8% and 10.3%, respectively – weren’t significantly different from the 8.7% incidence in controls.

To deal with the possibility of confounding by indication, Dr. Ng and her coinvestigators performed a multivariate analysis adjusted for maternal age, white race, body mass index, gestational age, diabetes, hypertension, arrhythmias, dyslipidemia, and renal insufficiency. The resultant adjusted risk of having an SGA baby was 2.9-fold greater in women on labetalol and 2.4-fold greater in those on atenolol than in controls. Women on the other two beta-blockers faced no increased risk.

The incidence of congenital cardiac anomalies was 5.1% in women exposed to beta-blockers in pregnancy and 1.9% in controls who weren’t. The most commonly diagnosed anomalies – patent ductus arteriosus, atrial septal defect, and ventricular septal defect – were two- to threefold more frequent in the setting of maternal beta-blocker exposure. However, in a multivariate analysis the use of any beta-blocker was no longer associated with significantly elevated risk of congenital cardiac anomalies.

“This suggests that the initial association we see in the unadjusted analysis is likely due to confounders and not due to the beta-blocker exposure,” Dr. Ng said.

Labetalol and atenolol were prescribed during pregnancy most often for hypertension, while metoprolol and propranolol were typically prescribed to control arrhythmias.

Previous reports by other investigators have yielded conflicting results as to whether maternal beta-blocker therapy is associated with increased risk of SGA. A major limitation of those studies was that they examined beta-blockers as a class rather than assessing the impact of specific agents, according to Dr. Ng.

She reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

NEW ORLEANS – The use of labetalol or atenolol in pregnancy is associated with significantly increased risk of having a small-for-gestational-age (SGA) baby; metoprolol and propranolol are not.

And none of these four beta-blockers are associated with increased risk of congenital cardiac anomalies, Angie Ng, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Overall, the average birth weight for babies whose mothers were on a beta-blocker was 2,996 g, significantly less than the 3,353 g in 374,391 controls who weren’t exposed to beta-blockers during pregnancy. But beta-blockers are not a monolithic class of drugs; their pharmacokinetics and physical properties differ. And so did their associated incidence of SGA, according to Dr. Ng of Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles.

The rate of SGA below the 10th percentile was 17.6% in the 3,357 women on labetalol during pregnancy and the same in the 638 women on atenolol. In contrast, the SGA rates in women on metoprolol or propranolol – 10.8% and 10.3%, respectively – weren’t significantly different from the 8.7% incidence in controls.

To deal with the possibility of confounding by indication, Dr. Ng and her coinvestigators performed a multivariate analysis adjusted for maternal age, white race, body mass index, gestational age, diabetes, hypertension, arrhythmias, dyslipidemia, and renal insufficiency. The resultant adjusted risk of having an SGA baby was 2.9-fold greater in women on labetalol and 2.4-fold greater in those on atenolol than in controls. Women on the other two beta-blockers faced no increased risk.

The incidence of congenital cardiac anomalies was 5.1% in women exposed to beta-blockers in pregnancy and 1.9% in controls who weren’t. The most commonly diagnosed anomalies – patent ductus arteriosus, atrial septal defect, and ventricular septal defect – were two- to threefold more frequent in the setting of maternal beta-blocker exposure. However, in a multivariate analysis the use of any beta-blocker was no longer associated with significantly elevated risk of congenital cardiac anomalies.

“This suggests that the initial association we see in the unadjusted analysis is likely due to confounders and not due to the beta-blocker exposure,” Dr. Ng said.

Labetalol and atenolol were prescribed during pregnancy most often for hypertension, while metoprolol and propranolol were typically prescribed to control arrhythmias.

Previous reports by other investigators have yielded conflicting results as to whether maternal beta-blocker therapy is associated with increased risk of SGA. A major limitation of those studies was that they examined beta-blockers as a class rather than assessing the impact of specific agents, according to Dr. Ng.

She reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Women on labetalol or atenolol during pregnancy had a 17.6% incidence of small-for-gestational-age babies, a rate more than twice that in women not exposed to a beta-blocker during pregnancy.

Data source: This was a retrospective study of fetal outcomes in nearly 380,000 pregnant women, 4,847 of whom were on beta-blocker therapy during their pregnancy.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

FDA warns of false-positive results with Zika IgM test

, according to a safety alert issued by the Food and Drug Administration.

The ZIKV Detect IgM Capture ELISA test is the first commercially available Zika serological IgM test – it was approved by the FDA in August 2016 and is used by several commercial laboratories. The test reports only presumptive positive results and a sample has to be sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for confirmation. Final results can take up to a month to be delivered. In most instances, the preliminary test results have matched the confirmed sample results.

The FDA recommends that health care providers inform patients that presumptive positive results need to be confirmed and that they not rely on positive IgM test results as the sole basis of patient management. If a patient is pregnant, the FDA recommends contacting the laboratory to expedite the confirmation testing.

FDA officials are working with LabCorp and ZIKV Detect manufacturer InBios International to determine if the false-positive results are related to problems with the test or the commercial testing facility.

Find the full safety alert on the FDA website.

, according to a safety alert issued by the Food and Drug Administration.

The ZIKV Detect IgM Capture ELISA test is the first commercially available Zika serological IgM test – it was approved by the FDA in August 2016 and is used by several commercial laboratories. The test reports only presumptive positive results and a sample has to be sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for confirmation. Final results can take up to a month to be delivered. In most instances, the preliminary test results have matched the confirmed sample results.

The FDA recommends that health care providers inform patients that presumptive positive results need to be confirmed and that they not rely on positive IgM test results as the sole basis of patient management. If a patient is pregnant, the FDA recommends contacting the laboratory to expedite the confirmation testing.

FDA officials are working with LabCorp and ZIKV Detect manufacturer InBios International to determine if the false-positive results are related to problems with the test or the commercial testing facility.

Find the full safety alert on the FDA website.

, according to a safety alert issued by the Food and Drug Administration.

The ZIKV Detect IgM Capture ELISA test is the first commercially available Zika serological IgM test – it was approved by the FDA in August 2016 and is used by several commercial laboratories. The test reports only presumptive positive results and a sample has to be sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for confirmation. Final results can take up to a month to be delivered. In most instances, the preliminary test results have matched the confirmed sample results.

The FDA recommends that health care providers inform patients that presumptive positive results need to be confirmed and that they not rely on positive IgM test results as the sole basis of patient management. If a patient is pregnant, the FDA recommends contacting the laboratory to expedite the confirmation testing.

FDA officials are working with LabCorp and ZIKV Detect manufacturer InBios International to determine if the false-positive results are related to problems with the test or the commercial testing facility.

Find the full safety alert on the FDA website.

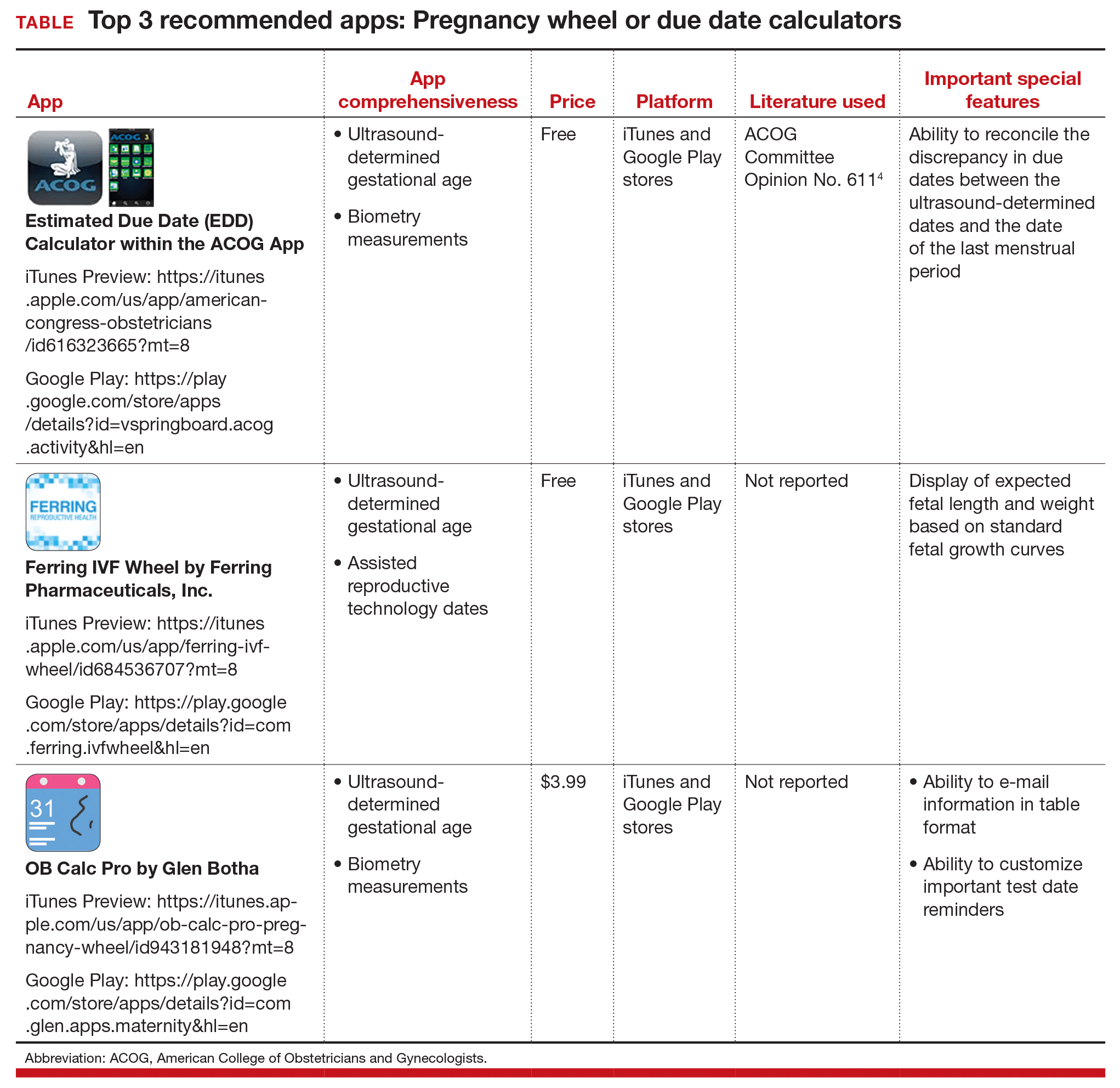

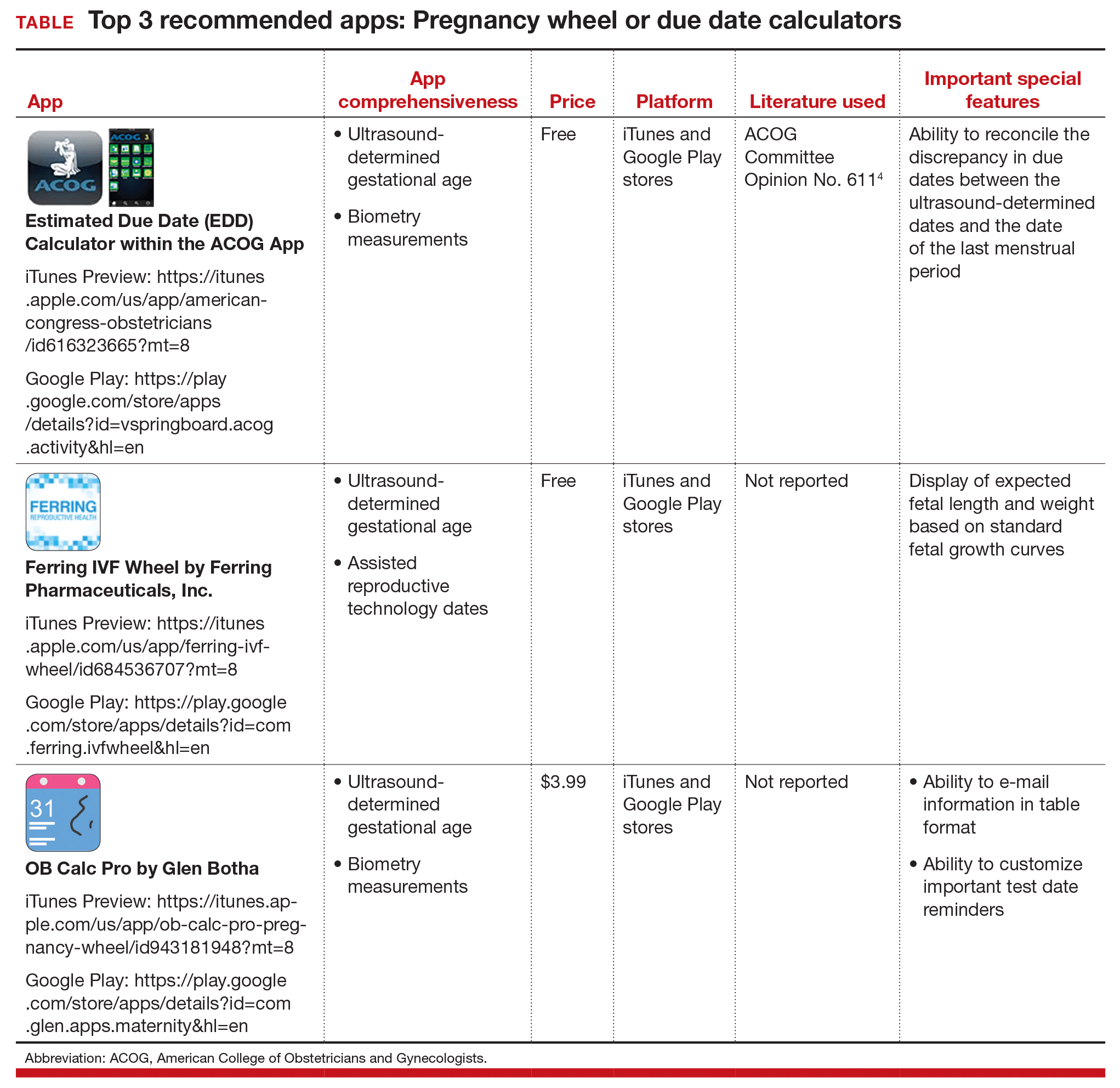

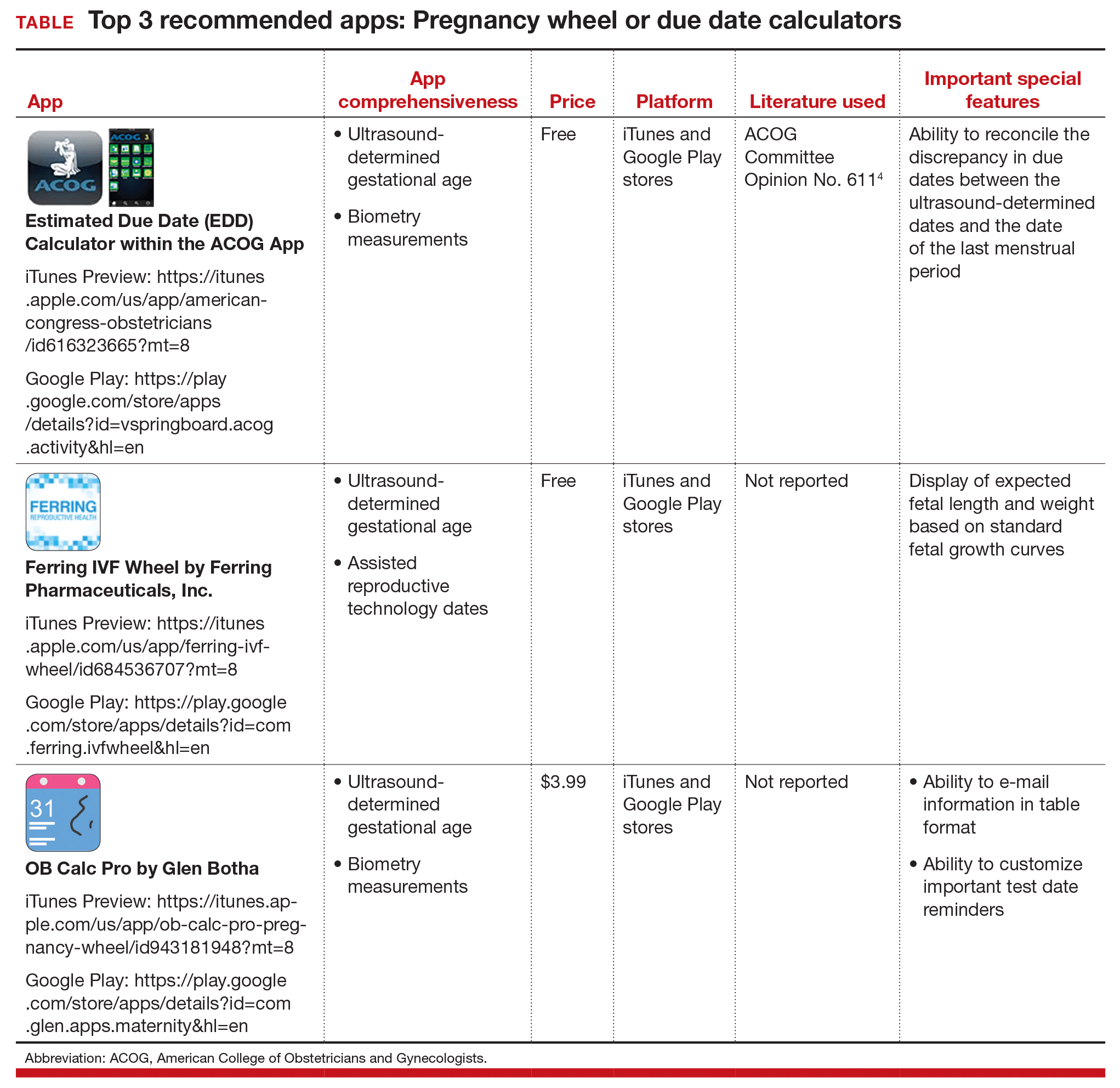

Three good apps for calculating the date of delivery

Technology has changed--and continues to change--the practice of medicine. Health care providers access word processing programs, e-mail, and electronic medical records using desktop and laptop computers. Now, providers are accessing these same tools with handheld devices such as smartphones, tablets, and "phablets" (a class of mobile devices designed to combine the form of a smartphone and a tablet).

Critical to the popularity and functionality of handheld devices are mobile applications, also known as "apps." An app is a self-contained program or piece of software designed to run on handheld devices to perform a specific purpose. App overload and app inaccuracy, however, are major problems. Health care providers do not have the time to search through thousands of medical apps in app stores to find specialty-related apps that might be useful in their practice--or to check the accuracy of those apps.

Vetted apps for ObGyns

My team's research has focused on identifying apps for ObGyns to use in clinical practice.1 In the process, we have developed the APPLICATIONS scoring system, which contains objective and subjective components to help differentiate among the accurate apps.2 This new quarterly "App review" series in OBG Management will showcase recommended apps for the busy ObGyn in the hope of improving work efficiency and the provider-patient relationship.

First up: Apps for calculating the date of delivery. This first app review focuses on pregnancy wheels, or due date calculators. Calculator apps are preferred over other types of apps such as procedure/case documentation apps, as providers use smartphones at point of care to allow rapid decision making.3 Calculating the estimated date of delivery (EDD) and gestational age (GA) is an important, vital task for providers of obstetric care. In fact, new guidelines for calculating EDD were recently developed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM), and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM).4 Notably, pregnancy wheel apps are more accurate than paper wheels.5 My team checked the accuracy of the pregnancy wheel apps by applying strict criteria to ensure the correct EDD and GA and then scored them in a systematic, nonbiased, conflict-of-interest-free manner.2

Related article:

Elective induction of labor at 39 (vs 41) weeks: Caveats and considerations

The TABLE below lists the top 3 recommended pregnancy wheel or due date calculator apps vetted by our research. The apps are listed alphabetically, and details for each app are provided based on a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI--app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature use, and important special features.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Farag S, Chyjek K, Chen KT. Identification of iPhone and iPad applications for obstetrics and gynecology providers. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(5):941-945.

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(6):1478-1483.

- Payne KB, Wharrad H, Watts K. Smartphone and medical related App use among medical students and junior doctors in the United Kingdom (UK): a regional survey. BMC Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:121.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 611. Method for estimating due date. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):863-866.

- Chambliss LR, Clark SL. Paper gestational age wheels are generally inaccurate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(2):145.e1-e4.

Technology has changed--and continues to change--the practice of medicine. Health care providers access word processing programs, e-mail, and electronic medical records using desktop and laptop computers. Now, providers are accessing these same tools with handheld devices such as smartphones, tablets, and "phablets" (a class of mobile devices designed to combine the form of a smartphone and a tablet).

Critical to the popularity and functionality of handheld devices are mobile applications, also known as "apps." An app is a self-contained program or piece of software designed to run on handheld devices to perform a specific purpose. App overload and app inaccuracy, however, are major problems. Health care providers do not have the time to search through thousands of medical apps in app stores to find specialty-related apps that might be useful in their practice--or to check the accuracy of those apps.

Vetted apps for ObGyns

My team's research has focused on identifying apps for ObGyns to use in clinical practice.1 In the process, we have developed the APPLICATIONS scoring system, which contains objective and subjective components to help differentiate among the accurate apps.2 This new quarterly "App review" series in OBG Management will showcase recommended apps for the busy ObGyn in the hope of improving work efficiency and the provider-patient relationship.

First up: Apps for calculating the date of delivery. This first app review focuses on pregnancy wheels, or due date calculators. Calculator apps are preferred over other types of apps such as procedure/case documentation apps, as providers use smartphones at point of care to allow rapid decision making.3 Calculating the estimated date of delivery (EDD) and gestational age (GA) is an important, vital task for providers of obstetric care. In fact, new guidelines for calculating EDD were recently developed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM), and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM).4 Notably, pregnancy wheel apps are more accurate than paper wheels.5 My team checked the accuracy of the pregnancy wheel apps by applying strict criteria to ensure the correct EDD and GA and then scored them in a systematic, nonbiased, conflict-of-interest-free manner.2

Related article:

Elective induction of labor at 39 (vs 41) weeks: Caveats and considerations

The TABLE below lists the top 3 recommended pregnancy wheel or due date calculator apps vetted by our research. The apps are listed alphabetically, and details for each app are provided based on a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI--app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature use, and important special features.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Technology has changed--and continues to change--the practice of medicine. Health care providers access word processing programs, e-mail, and electronic medical records using desktop and laptop computers. Now, providers are accessing these same tools with handheld devices such as smartphones, tablets, and "phablets" (a class of mobile devices designed to combine the form of a smartphone and a tablet).

Critical to the popularity and functionality of handheld devices are mobile applications, also known as "apps." An app is a self-contained program or piece of software designed to run on handheld devices to perform a specific purpose. App overload and app inaccuracy, however, are major problems. Health care providers do not have the time to search through thousands of medical apps in app stores to find specialty-related apps that might be useful in their practice--or to check the accuracy of those apps.

Vetted apps for ObGyns

My team's research has focused on identifying apps for ObGyns to use in clinical practice.1 In the process, we have developed the APPLICATIONS scoring system, which contains objective and subjective components to help differentiate among the accurate apps.2 This new quarterly "App review" series in OBG Management will showcase recommended apps for the busy ObGyn in the hope of improving work efficiency and the provider-patient relationship.

First up: Apps for calculating the date of delivery. This first app review focuses on pregnancy wheels, or due date calculators. Calculator apps are preferred over other types of apps such as procedure/case documentation apps, as providers use smartphones at point of care to allow rapid decision making.3 Calculating the estimated date of delivery (EDD) and gestational age (GA) is an important, vital task for providers of obstetric care. In fact, new guidelines for calculating EDD were recently developed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM), and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM).4 Notably, pregnancy wheel apps are more accurate than paper wheels.5 My team checked the accuracy of the pregnancy wheel apps by applying strict criteria to ensure the correct EDD and GA and then scored them in a systematic, nonbiased, conflict-of-interest-free manner.2

Related article:

Elective induction of labor at 39 (vs 41) weeks: Caveats and considerations

The TABLE below lists the top 3 recommended pregnancy wheel or due date calculator apps vetted by our research. The apps are listed alphabetically, and details for each app are provided based on a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI--app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature use, and important special features.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Farag S, Chyjek K, Chen KT. Identification of iPhone and iPad applications for obstetrics and gynecology providers. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(5):941-945.

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(6):1478-1483.

- Payne KB, Wharrad H, Watts K. Smartphone and medical related App use among medical students and junior doctors in the United Kingdom (UK): a regional survey. BMC Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:121.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 611. Method for estimating due date. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):863-866.

- Chambliss LR, Clark SL. Paper gestational age wheels are generally inaccurate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(2):145.e1-e4.

- Farag S, Chyjek K, Chen KT. Identification of iPhone and iPad applications for obstetrics and gynecology providers. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(5):941-945.

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(6):1478-1483.

- Payne KB, Wharrad H, Watts K. Smartphone and medical related App use among medical students and junior doctors in the United Kingdom (UK): a regional survey. BMC Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:121.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 611. Method for estimating due date. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):863-866.

- Chambliss LR, Clark SL. Paper gestational age wheels are generally inaccurate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(2):145.e1-e4.

Letters to the Editor: Benefit of self-administered vaginal lidocaine gel in IUD placement

“BENEFIT OF SELF-ADMINISTERED VAGINAL LIDOCAINE GEL IN IUD PLACEMENT"

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD (COMMENTARY; DECEMBER 2016)

Use anesthesia for in-office GYN procedures

The recent article by Dr. Kaunitz on the use of self-administered lidocaine gel prior to intrauterine device (IUD) placement was excellent. Having been known as the “lidocaine queen” in the Department of ObGyn at the Mayo Clinic, I feel strongly that gynecologic office procedures should always involve some form of anesthesia, whether with topical lidocaine, intracervical lidocaine, or paracervical block. Such anesthesia often makes the procedure a “nonevent” for the patient. While Dr. Kaunitz describes the use of a fine-toothed tenaculum, I have found that after administration of lidocaine gel, an Allis clamp applied superficially to the cervix provides sufficient traction, is often not detected by the patient, and does not leave any holes. It is unusual for it to slip off.

It is important to teach residents that it is not necessary for women to “tolerate” pain to have good health. I use the above techniques for endometrial biopsy and cervical biopsy as well—there is never a reason for a woman’s biopsy to be done without anesthesia.

Ingrid Carlson, MD

Ponte Vedra, Florida

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“BENEFIT OF SELF-ADMINISTERED VAGINAL LIDOCAINE GEL IN IUD PLACEMENT"

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD (COMMENTARY; DECEMBER 2016)

Use anesthesia for in-office GYN procedures

The recent article by Dr. Kaunitz on the use of self-administered lidocaine gel prior to intrauterine device (IUD) placement was excellent. Having been known as the “lidocaine queen” in the Department of ObGyn at the Mayo Clinic, I feel strongly that gynecologic office procedures should always involve some form of anesthesia, whether with topical lidocaine, intracervical lidocaine, or paracervical block. Such anesthesia often makes the procedure a “nonevent” for the patient. While Dr. Kaunitz describes the use of a fine-toothed tenaculum, I have found that after administration of lidocaine gel, an Allis clamp applied superficially to the cervix provides sufficient traction, is often not detected by the patient, and does not leave any holes. It is unusual for it to slip off.

It is important to teach residents that it is not necessary for women to “tolerate” pain to have good health. I use the above techniques for endometrial biopsy and cervical biopsy as well—there is never a reason for a woman’s biopsy to be done without anesthesia.

Ingrid Carlson, MD

Ponte Vedra, Florida

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“BENEFIT OF SELF-ADMINISTERED VAGINAL LIDOCAINE GEL IN IUD PLACEMENT"

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD (COMMENTARY; DECEMBER 2016)

Use anesthesia for in-office GYN procedures

The recent article by Dr. Kaunitz on the use of self-administered lidocaine gel prior to intrauterine device (IUD) placement was excellent. Having been known as the “lidocaine queen” in the Department of ObGyn at the Mayo Clinic, I feel strongly that gynecologic office procedures should always involve some form of anesthesia, whether with topical lidocaine, intracervical lidocaine, or paracervical block. Such anesthesia often makes the procedure a “nonevent” for the patient. While Dr. Kaunitz describes the use of a fine-toothed tenaculum, I have found that after administration of lidocaine gel, an Allis clamp applied superficially to the cervix provides sufficient traction, is often not detected by the patient, and does not leave any holes. It is unusual for it to slip off.

It is important to teach residents that it is not necessary for women to “tolerate” pain to have good health. I use the above techniques for endometrial biopsy and cervical biopsy as well—there is never a reason for a woman’s biopsy to be done without anesthesia.

Ingrid Carlson, MD

Ponte Vedra, Florida

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Letters to the Editor: Avoid uterine vessels when injecting vasopressin

“DO YOU UTILIZE VASOPRESSIN IN YOUR DIFFICULT CESAREAN DELIVERY SURGERIES?”

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (EDITORIAL; NOVEMBER 2016)

Avoid uterine vessels when injecting vasopressin

Thank you for your recent editorial discussing using vasopressin in difficult cesarean deliveries. I am very interested in using vasopressin for our placenta previa cases.

I reviewed the Kato et al article that Dr. Barbieri referenced, and the authors note a risk of injecting vasopressin into a vessel.1 If you are injecting into the placental bed, how can you confirm you are not in a vessel? (When you withdraw, you will get some blood regardless.)

Sara Garmel, MD

Dearborn, Michigan

REFERENCE

- Kato S, Tanabe A, Kanki K, et al. Local injection of vasopressin reduces the blood loss during cesarean section in placenta previa. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40(5):1249–1256.

Dr. Barbieri responds

I agree with Dr. Garmel that we should avoid the intravascular injection of vasopressin. As I noted in the editorial, “I prefer to inject vasopressin in the subserosa of the uterus rather than inject it in a highly vascular area such as the subendometrium or near the uterine artery and vein.” Subserosal injection creates a depot bleb of vasopressin that is absorbed over a few minutes. You can visualize the reduced blood flow to the uterus following vasopressin injection because the uterus blanches and the diameter of the uterine vessels decreases significantly.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“DO YOU UTILIZE VASOPRESSIN IN YOUR DIFFICULT CESAREAN DELIVERY SURGERIES?”

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (EDITORIAL; NOVEMBER 2016)

Avoid uterine vessels when injecting vasopressin

Thank you for your recent editorial discussing using vasopressin in difficult cesarean deliveries. I am very interested in using vasopressin for our placenta previa cases.

I reviewed the Kato et al article that Dr. Barbieri referenced, and the authors note a risk of injecting vasopressin into a vessel.1 If you are injecting into the placental bed, how can you confirm you are not in a vessel? (When you withdraw, you will get some blood regardless.)

Sara Garmel, MD

Dearborn, Michigan

REFERENCE

- Kato S, Tanabe A, Kanki K, et al. Local injection of vasopressin reduces the blood loss during cesarean section in placenta previa. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40(5):1249–1256.

Dr. Barbieri responds

I agree with Dr. Garmel that we should avoid the intravascular injection of vasopressin. As I noted in the editorial, “I prefer to inject vasopressin in the subserosa of the uterus rather than inject it in a highly vascular area such as the subendometrium or near the uterine artery and vein.” Subserosal injection creates a depot bleb of vasopressin that is absorbed over a few minutes. You can visualize the reduced blood flow to the uterus following vasopressin injection because the uterus blanches and the diameter of the uterine vessels decreases significantly.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“DO YOU UTILIZE VASOPRESSIN IN YOUR DIFFICULT CESAREAN DELIVERY SURGERIES?”

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (EDITORIAL; NOVEMBER 2016)

Avoid uterine vessels when injecting vasopressin

Thank you for your recent editorial discussing using vasopressin in difficult cesarean deliveries. I am very interested in using vasopressin for our placenta previa cases.

I reviewed the Kato et al article that Dr. Barbieri referenced, and the authors note a risk of injecting vasopressin into a vessel.1 If you are injecting into the placental bed, how can you confirm you are not in a vessel? (When you withdraw, you will get some blood regardless.)

Sara Garmel, MD

Dearborn, Michigan

REFERENCE

- Kato S, Tanabe A, Kanki K, et al. Local injection of vasopressin reduces the blood loss during cesarean section in placenta previa. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40(5):1249–1256.

Dr. Barbieri responds

I agree with Dr. Garmel that we should avoid the intravascular injection of vasopressin. As I noted in the editorial, “I prefer to inject vasopressin in the subserosa of the uterus rather than inject it in a highly vascular area such as the subendometrium or near the uterine artery and vein.” Subserosal injection creates a depot bleb of vasopressin that is absorbed over a few minutes. You can visualize the reduced blood flow to the uterus following vasopressin injection because the uterus blanches and the diameter of the uterine vessels decreases significantly.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Letters to the Editor: Patient with a breast mass: Why did she pursue litigation?

“PATIENT WITH A BREAST MASS: WHY DID SHE PURSUE LITIGATION?”

JOSEPH S. SANFILIPPO, MD, MBA, AND STEVEN R. SMITH, JD (WHAT'S THE VERDICT?; DECEMBER 2016)

Clear communication is often key to avoiding litigation

Thank you for the article concerning the patient who commenced action for delay in diagnosis of her breast lesion. In my opinion the gynecologist lost control of the situation because of inadequate communication with the patient either on his or her part and/or on the part of the staff.

J. S. Calabrese, MD, JD

Buffalo, New York

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“PATIENT WITH A BREAST MASS: WHY DID SHE PURSUE LITIGATION?”

JOSEPH S. SANFILIPPO, MD, MBA, AND STEVEN R. SMITH, JD (WHAT'S THE VERDICT?; DECEMBER 2016)

Clear communication is often key to avoiding litigation

Thank you for the article concerning the patient who commenced action for delay in diagnosis of her breast lesion. In my opinion the gynecologist lost control of the situation because of inadequate communication with the patient either on his or her part and/or on the part of the staff.

J. S. Calabrese, MD, JD

Buffalo, New York

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“PATIENT WITH A BREAST MASS: WHY DID SHE PURSUE LITIGATION?”

JOSEPH S. SANFILIPPO, MD, MBA, AND STEVEN R. SMITH, JD (WHAT'S THE VERDICT?; DECEMBER 2016)

Clear communication is often key to avoiding litigation

Thank you for the article concerning the patient who commenced action for delay in diagnosis of her breast lesion. In my opinion the gynecologist lost control of the situation because of inadequate communication with the patient either on his or her part and/or on the part of the staff.

J. S. Calabrese, MD, JD

Buffalo, New York

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Endoscopy during pregnancy increases risk of preterm, SGA birth

Women who undergo an endoscopy during pregnancy are increasing the chances that their baby will be born preterm, or be small for gestational age (SGA), according to research published in the February issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.016).