User login

CDC: Zika virus urine testing preferable to serum

New data showing that Zika virus can be found at higher levels or for longer duration in urine than serum, has prompted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to update its interim diagnostic testing guidance for the virus in public health laboratories.

The CDC now recommends that Zika virus real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) be performed on urine collected less than 14 days after the onset of symptoms in patients with suspected Zika virus disease. The rRT-PCR is the preferred test for Zika infection because it can be performed rapidly and is highly specific, the CDC notes, and currently, the CDC Trioplex rRT-PCR assay is the only diagnostic tool authorized by the Food and Drug Administration for Zika virus testing of urine (MMWR. 2016 May 10. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6518e1).

In most patients, Zika virus RNA is unlikely to be detected in serum after the first week of illness, the CDC said, but adaptations of previously published diagnostic methods suggest that Zika virus RNA can be detected in urine for at least 2 weeks after onset of symptoms. However, the CDC affirmed that Zika virus rRT-PCR testing of urine should be performed in conjunction with serum testing if using specimens collected less than 7 days after symptom onset, and a positive result in either specimen type provides evidence of Zika virus infection.

The CDC added that, because viremia decreases over time and dates of illness onset may not be accurately reported, a negative rRT-PCR does not exclude Zika virus infection, and IgM antibody testing should be performed. The agency also said other laboratory-developed tests will need in-house validations to adequately characterize the performance of the assay and meet Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments requirements.

Read the full report here.

On Twitter @richpizzi

New data showing that Zika virus can be found at higher levels or for longer duration in urine than serum, has prompted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to update its interim diagnostic testing guidance for the virus in public health laboratories.

The CDC now recommends that Zika virus real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) be performed on urine collected less than 14 days after the onset of symptoms in patients with suspected Zika virus disease. The rRT-PCR is the preferred test for Zika infection because it can be performed rapidly and is highly specific, the CDC notes, and currently, the CDC Trioplex rRT-PCR assay is the only diagnostic tool authorized by the Food and Drug Administration for Zika virus testing of urine (MMWR. 2016 May 10. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6518e1).

In most patients, Zika virus RNA is unlikely to be detected in serum after the first week of illness, the CDC said, but adaptations of previously published diagnostic methods suggest that Zika virus RNA can be detected in urine for at least 2 weeks after onset of symptoms. However, the CDC affirmed that Zika virus rRT-PCR testing of urine should be performed in conjunction with serum testing if using specimens collected less than 7 days after symptom onset, and a positive result in either specimen type provides evidence of Zika virus infection.

The CDC added that, because viremia decreases over time and dates of illness onset may not be accurately reported, a negative rRT-PCR does not exclude Zika virus infection, and IgM antibody testing should be performed. The agency also said other laboratory-developed tests will need in-house validations to adequately characterize the performance of the assay and meet Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments requirements.

Read the full report here.

On Twitter @richpizzi

New data showing that Zika virus can be found at higher levels or for longer duration in urine than serum, has prompted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to update its interim diagnostic testing guidance for the virus in public health laboratories.

The CDC now recommends that Zika virus real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) be performed on urine collected less than 14 days after the onset of symptoms in patients with suspected Zika virus disease. The rRT-PCR is the preferred test for Zika infection because it can be performed rapidly and is highly specific, the CDC notes, and currently, the CDC Trioplex rRT-PCR assay is the only diagnostic tool authorized by the Food and Drug Administration for Zika virus testing of urine (MMWR. 2016 May 10. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6518e1).

In most patients, Zika virus RNA is unlikely to be detected in serum after the first week of illness, the CDC said, but adaptations of previously published diagnostic methods suggest that Zika virus RNA can be detected in urine for at least 2 weeks after onset of symptoms. However, the CDC affirmed that Zika virus rRT-PCR testing of urine should be performed in conjunction with serum testing if using specimens collected less than 7 days after symptom onset, and a positive result in either specimen type provides evidence of Zika virus infection.

The CDC added that, because viremia decreases over time and dates of illness onset may not be accurately reported, a negative rRT-PCR does not exclude Zika virus infection, and IgM antibody testing should be performed. The agency also said other laboratory-developed tests will need in-house validations to adequately characterize the performance of the assay and meet Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments requirements.

Read the full report here.

On Twitter @richpizzi

FROM MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

USPSTF recommends daily folic acid supplements for women of childbearing age

All women who are capable of getting pregnant should take a daily supplement containing 400-800 micrograms of folic acid to prevent neural tube defects in early pregnancy, according to a draft recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

The grade A draft recommendation, issued May 10, reaffirms the Task Force’s 2009 recommendation on folic acid supplementation in women of childbearing age.

The critical period for supplementation occurs 1 month before conception and continues through the first 2-3 months of pregnancy, according to the draft recommendation. Although folic acid is found naturally in many fruits and vegetables, and many cereals and breads are fortified with folic acid, most women still fall short of the daily recommended dose of 400 micrograms of folic acid.

In the evidence review, the USPSTF evaluated one randomized controlled trial, two cohort studies, and eight case-control studies for evidence of effectiveness of folic acid supplementation. The Task Force found no substantial new evidence on benefits and harms from folic acid supplementation to change its 2009 recommendation.

“The USPSTF concludes with high certainty that the net benefit of daily folic acid supplementation to prevent neural tube defects in the developing fetus is substantial for women who are planning or capable of pregnancy,” the statement noted.

The draft recommendation is open for public comment on the USPSTF website until June 6.

All women who are capable of getting pregnant should take a daily supplement containing 400-800 micrograms of folic acid to prevent neural tube defects in early pregnancy, according to a draft recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

The grade A draft recommendation, issued May 10, reaffirms the Task Force’s 2009 recommendation on folic acid supplementation in women of childbearing age.

The critical period for supplementation occurs 1 month before conception and continues through the first 2-3 months of pregnancy, according to the draft recommendation. Although folic acid is found naturally in many fruits and vegetables, and many cereals and breads are fortified with folic acid, most women still fall short of the daily recommended dose of 400 micrograms of folic acid.

In the evidence review, the USPSTF evaluated one randomized controlled trial, two cohort studies, and eight case-control studies for evidence of effectiveness of folic acid supplementation. The Task Force found no substantial new evidence on benefits and harms from folic acid supplementation to change its 2009 recommendation.

“The USPSTF concludes with high certainty that the net benefit of daily folic acid supplementation to prevent neural tube defects in the developing fetus is substantial for women who are planning or capable of pregnancy,” the statement noted.

The draft recommendation is open for public comment on the USPSTF website until June 6.

All women who are capable of getting pregnant should take a daily supplement containing 400-800 micrograms of folic acid to prevent neural tube defects in early pregnancy, according to a draft recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

The grade A draft recommendation, issued May 10, reaffirms the Task Force’s 2009 recommendation on folic acid supplementation in women of childbearing age.

The critical period for supplementation occurs 1 month before conception and continues through the first 2-3 months of pregnancy, according to the draft recommendation. Although folic acid is found naturally in many fruits and vegetables, and many cereals and breads are fortified with folic acid, most women still fall short of the daily recommended dose of 400 micrograms of folic acid.

In the evidence review, the USPSTF evaluated one randomized controlled trial, two cohort studies, and eight case-control studies for evidence of effectiveness of folic acid supplementation. The Task Force found no substantial new evidence on benefits and harms from folic acid supplementation to change its 2009 recommendation.

“The USPSTF concludes with high certainty that the net benefit of daily folic acid supplementation to prevent neural tube defects in the developing fetus is substantial for women who are planning or capable of pregnancy,” the statement noted.

The draft recommendation is open for public comment on the USPSTF website until June 6.

Combatting misperceptions in prenatal exposures

It’s clear that for pregnant women and the physicians who care for them, the risk of using medications in pregnancy is a significant issue. Unfortunately, sometimes the perception of that risk is much greater than the reality and drives behavior that can harm women and their babies.

Before the tragedy of thalidomide, the medical community held the general belief that drugs and chemicals do not cross the placenta, so there was no need to fear fetal malformations from medication use in pregnancy. In 1961, thalidomide became a formative event that changed everyone’s perception, with many people adopting the belief that every drug could be dangerous. In reality, though, very few medications prescribed today are known teratogens that cause malformations.

In recent years, an increasing number of drugs have been shown to be “safe.” The issue with the term safe is that there can always be more cases and more studies showing some very small risk that was previously unknown. But, in general, there are more reassuring studies in the literature than ones showing drugs to be dangerous in pregnancy.

The Bendectin example

In the highly charged medicolegal atmosphere in which we practice, physicians are afraid to be sued. If you remember that about 3% of babies are born with malformations just by chance, and that mothers will likely be taking some type of medication, there is always the possibility of a bad outcome that could cast blame on a drug.

In the 1970s, a lot of that litigation centered around the morning sickness drug Bendectin – originally formulated with doxylamine succinate, pyridoxine HCl, and dicyclomine HCl, and later reformulated without the dicyclomine. The drug was taken off the U.S. market by the manufacturer in 1983 because the company couldn’t afford the high cost of litigation and insurance, despite the fact that a panel convened by the Food and Drug Administration said there was no association between Bendectin and human birth defects.

It took nearly 20 years before the FDA declared that the drug had been withdrawn from the market for reasons unrelated to safety and effectiveness. In the meantime, American women remained without an FDA-approved medication to treat morning sickness, and there was a more than twofold increase in hospitalization rates for pregnant women with hyperemesis gravidarum (Can J Public Health. 1995 Jan-Feb;86[1]:66-70). The lesson here is that perceptions in the absence of evidence can lead to grave outcomes.

Exaggeration of risk

Over the years, my colleagues and I have studied how pregnant women perceive drug risk by simply asking them to estimate the risk to their baby from the medication they are currently taking. What we discovered was that women exposed to nonteratogenic drugs consider themselves at a risk of about 25% for having a child with a major malformation. In reality, the risk is between 1% and 3% and has nothing to do with the drug itself. It became clear that there is a huge perception of risk when women are exposed to drugs that should not increase that risk (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989 May;160[5 Pt 1]:1190-4).

The same study also showed that many of the women who gave exaggerated risk assessments said they would consider termination of the pregnancy. Even after hearing the drug is safe, some women were still considering termination.

Sadly, women terminating a pregnancy because of a perceived risk for malformation is not unique to this study. In the 1980s, following the explosion at Chernobyl in the Ukraine, women in Athens were told that they had a high risk for malformation in their children because of radiation exposure. Statistics show that during that month, nearly a quarter of early pregnancies in Athens were terminated (Br Med J [Clin Res Ed] 1987;295:1100).

We have further found that women exposed to radiation for diagnostic purposes estimate a high risk of malformation. This type of estimate is likely influenced by the effects of radiation at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but there is no comparison between the extremely high amounts of radiation in those incidents, compared with the very low amounts in diagnostic tests. Still, we found that women again considered termination because of their perceived risk from radiation.

Social economics are also part of this. Women who are single mothers are more likely to terminate a pregnancy, or consider termination, after exposure to a drug in pregnancy. Women with psychiatric conditions have a similar tendency. On the other hand, women with chronic diseases – who may be used to the effects of a certain medications – are less likely to suggest termination because of perceived risk.

Communicating risk

These are important concepts to consider in the context of the emerging threat of Zika virus and the news from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that it is a definitive cause of microcephaly and other severe fetal malformations. While there is a real risk for pregnant women, both through mosquitoes and sexual contact, women are likely to perceive the highest level of risk. In South America, where therapeutic abortion is often not an option, accurate risk communication is critical.

When medications are prescribed during pregnancy, the first step is determining that a drug is truly needed, often in consultation with a specialist. Once that determination is made, it’s key to ensure that women and their families are familiar with the known risk or the lack of risk based on the best available data. There are resources for physicians to help understand and communicate about drug risks in pregnancy, including information from the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists. It’s also important to note that in every pregnancy, there is a 1%-3% risk of major malformations, even if the drug itself is safe. And it can’t hurt to think defensively and document that conversation and that the patient appears to have understood the concept of risk.

Dr. Koren is professor of pharmacology and pharmacy at the University of Toronto. He is the founding director of the Motherisk Program. He reported having been a paid consultant for Novartis and for Duchesnay, which makes Diclegis to treat nausea and vomiting in pregnancy.

It’s clear that for pregnant women and the physicians who care for them, the risk of using medications in pregnancy is a significant issue. Unfortunately, sometimes the perception of that risk is much greater than the reality and drives behavior that can harm women and their babies.

Before the tragedy of thalidomide, the medical community held the general belief that drugs and chemicals do not cross the placenta, so there was no need to fear fetal malformations from medication use in pregnancy. In 1961, thalidomide became a formative event that changed everyone’s perception, with many people adopting the belief that every drug could be dangerous. In reality, though, very few medications prescribed today are known teratogens that cause malformations.

In recent years, an increasing number of drugs have been shown to be “safe.” The issue with the term safe is that there can always be more cases and more studies showing some very small risk that was previously unknown. But, in general, there are more reassuring studies in the literature than ones showing drugs to be dangerous in pregnancy.

The Bendectin example

In the highly charged medicolegal atmosphere in which we practice, physicians are afraid to be sued. If you remember that about 3% of babies are born with malformations just by chance, and that mothers will likely be taking some type of medication, there is always the possibility of a bad outcome that could cast blame on a drug.

In the 1970s, a lot of that litigation centered around the morning sickness drug Bendectin – originally formulated with doxylamine succinate, pyridoxine HCl, and dicyclomine HCl, and later reformulated without the dicyclomine. The drug was taken off the U.S. market by the manufacturer in 1983 because the company couldn’t afford the high cost of litigation and insurance, despite the fact that a panel convened by the Food and Drug Administration said there was no association between Bendectin and human birth defects.

It took nearly 20 years before the FDA declared that the drug had been withdrawn from the market for reasons unrelated to safety and effectiveness. In the meantime, American women remained without an FDA-approved medication to treat morning sickness, and there was a more than twofold increase in hospitalization rates for pregnant women with hyperemesis gravidarum (Can J Public Health. 1995 Jan-Feb;86[1]:66-70). The lesson here is that perceptions in the absence of evidence can lead to grave outcomes.

Exaggeration of risk

Over the years, my colleagues and I have studied how pregnant women perceive drug risk by simply asking them to estimate the risk to their baby from the medication they are currently taking. What we discovered was that women exposed to nonteratogenic drugs consider themselves at a risk of about 25% for having a child with a major malformation. In reality, the risk is between 1% and 3% and has nothing to do with the drug itself. It became clear that there is a huge perception of risk when women are exposed to drugs that should not increase that risk (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989 May;160[5 Pt 1]:1190-4).

The same study also showed that many of the women who gave exaggerated risk assessments said they would consider termination of the pregnancy. Even after hearing the drug is safe, some women were still considering termination.

Sadly, women terminating a pregnancy because of a perceived risk for malformation is not unique to this study. In the 1980s, following the explosion at Chernobyl in the Ukraine, women in Athens were told that they had a high risk for malformation in their children because of radiation exposure. Statistics show that during that month, nearly a quarter of early pregnancies in Athens were terminated (Br Med J [Clin Res Ed] 1987;295:1100).

We have further found that women exposed to radiation for diagnostic purposes estimate a high risk of malformation. This type of estimate is likely influenced by the effects of radiation at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but there is no comparison between the extremely high amounts of radiation in those incidents, compared with the very low amounts in diagnostic tests. Still, we found that women again considered termination because of their perceived risk from radiation.

Social economics are also part of this. Women who are single mothers are more likely to terminate a pregnancy, or consider termination, after exposure to a drug in pregnancy. Women with psychiatric conditions have a similar tendency. On the other hand, women with chronic diseases – who may be used to the effects of a certain medications – are less likely to suggest termination because of perceived risk.

Communicating risk

These are important concepts to consider in the context of the emerging threat of Zika virus and the news from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that it is a definitive cause of microcephaly and other severe fetal malformations. While there is a real risk for pregnant women, both through mosquitoes and sexual contact, women are likely to perceive the highest level of risk. In South America, where therapeutic abortion is often not an option, accurate risk communication is critical.

When medications are prescribed during pregnancy, the first step is determining that a drug is truly needed, often in consultation with a specialist. Once that determination is made, it’s key to ensure that women and their families are familiar with the known risk or the lack of risk based on the best available data. There are resources for physicians to help understand and communicate about drug risks in pregnancy, including information from the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists. It’s also important to note that in every pregnancy, there is a 1%-3% risk of major malformations, even if the drug itself is safe. And it can’t hurt to think defensively and document that conversation and that the patient appears to have understood the concept of risk.

Dr. Koren is professor of pharmacology and pharmacy at the University of Toronto. He is the founding director of the Motherisk Program. He reported having been a paid consultant for Novartis and for Duchesnay, which makes Diclegis to treat nausea and vomiting in pregnancy.

It’s clear that for pregnant women and the physicians who care for them, the risk of using medications in pregnancy is a significant issue. Unfortunately, sometimes the perception of that risk is much greater than the reality and drives behavior that can harm women and their babies.

Before the tragedy of thalidomide, the medical community held the general belief that drugs and chemicals do not cross the placenta, so there was no need to fear fetal malformations from medication use in pregnancy. In 1961, thalidomide became a formative event that changed everyone’s perception, with many people adopting the belief that every drug could be dangerous. In reality, though, very few medications prescribed today are known teratogens that cause malformations.

In recent years, an increasing number of drugs have been shown to be “safe.” The issue with the term safe is that there can always be more cases and more studies showing some very small risk that was previously unknown. But, in general, there are more reassuring studies in the literature than ones showing drugs to be dangerous in pregnancy.

The Bendectin example

In the highly charged medicolegal atmosphere in which we practice, physicians are afraid to be sued. If you remember that about 3% of babies are born with malformations just by chance, and that mothers will likely be taking some type of medication, there is always the possibility of a bad outcome that could cast blame on a drug.

In the 1970s, a lot of that litigation centered around the morning sickness drug Bendectin – originally formulated with doxylamine succinate, pyridoxine HCl, and dicyclomine HCl, and later reformulated without the dicyclomine. The drug was taken off the U.S. market by the manufacturer in 1983 because the company couldn’t afford the high cost of litigation and insurance, despite the fact that a panel convened by the Food and Drug Administration said there was no association between Bendectin and human birth defects.

It took nearly 20 years before the FDA declared that the drug had been withdrawn from the market for reasons unrelated to safety and effectiveness. In the meantime, American women remained without an FDA-approved medication to treat morning sickness, and there was a more than twofold increase in hospitalization rates for pregnant women with hyperemesis gravidarum (Can J Public Health. 1995 Jan-Feb;86[1]:66-70). The lesson here is that perceptions in the absence of evidence can lead to grave outcomes.

Exaggeration of risk

Over the years, my colleagues and I have studied how pregnant women perceive drug risk by simply asking them to estimate the risk to their baby from the medication they are currently taking. What we discovered was that women exposed to nonteratogenic drugs consider themselves at a risk of about 25% for having a child with a major malformation. In reality, the risk is between 1% and 3% and has nothing to do with the drug itself. It became clear that there is a huge perception of risk when women are exposed to drugs that should not increase that risk (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989 May;160[5 Pt 1]:1190-4).

The same study also showed that many of the women who gave exaggerated risk assessments said they would consider termination of the pregnancy. Even after hearing the drug is safe, some women were still considering termination.

Sadly, women terminating a pregnancy because of a perceived risk for malformation is not unique to this study. In the 1980s, following the explosion at Chernobyl in the Ukraine, women in Athens were told that they had a high risk for malformation in their children because of radiation exposure. Statistics show that during that month, nearly a quarter of early pregnancies in Athens were terminated (Br Med J [Clin Res Ed] 1987;295:1100).

We have further found that women exposed to radiation for diagnostic purposes estimate a high risk of malformation. This type of estimate is likely influenced by the effects of radiation at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but there is no comparison between the extremely high amounts of radiation in those incidents, compared with the very low amounts in diagnostic tests. Still, we found that women again considered termination because of their perceived risk from radiation.

Social economics are also part of this. Women who are single mothers are more likely to terminate a pregnancy, or consider termination, after exposure to a drug in pregnancy. Women with psychiatric conditions have a similar tendency. On the other hand, women with chronic diseases – who may be used to the effects of a certain medications – are less likely to suggest termination because of perceived risk.

Communicating risk

These are important concepts to consider in the context of the emerging threat of Zika virus and the news from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that it is a definitive cause of microcephaly and other severe fetal malformations. While there is a real risk for pregnant women, both through mosquitoes and sexual contact, women are likely to perceive the highest level of risk. In South America, where therapeutic abortion is often not an option, accurate risk communication is critical.

When medications are prescribed during pregnancy, the first step is determining that a drug is truly needed, often in consultation with a specialist. Once that determination is made, it’s key to ensure that women and their families are familiar with the known risk or the lack of risk based on the best available data. There are resources for physicians to help understand and communicate about drug risks in pregnancy, including information from the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists. It’s also important to note that in every pregnancy, there is a 1%-3% risk of major malformations, even if the drug itself is safe. And it can’t hurt to think defensively and document that conversation and that the patient appears to have understood the concept of risk.

Dr. Koren is professor of pharmacology and pharmacy at the University of Toronto. He is the founding director of the Motherisk Program. He reported having been a paid consultant for Novartis and for Duchesnay, which makes Diclegis to treat nausea and vomiting in pregnancy.

US Official Raises Concerns Over Zika Readiness

The ability of the United States to respond to a potential spike in Zika virus infection rates is a cause for concern, according to a top federal health official.

“The big question is will we get local transmission, and my response to that is very likely we will,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told reporters during a joint media briefing with the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) on May 3.

As many as 500 million people in the Americas are at risk for being infected by the Zika virus, PAHO’s Zika incident manager, Dr. Sylvain Aldighieri, said during the briefing.

In the continental United States to date, there have been about 400 travel-related cases of infection. In Puerto Rico, there have been nearly 700 locally reported cases, and one Zika-related death.

Countries at highest risk for Zika include those that have experienced any outbreaks of dengue fever or chikungunya in the past 15 years, Dr. Aldighieri said. Hawaii and U.S. territories in the Caribbean have experienced local dengue outbreaks during that time. Florida has had local outbreaks of both illnesses.

In the United States, Zika is poised to gain a stronger foothold even as funding for the study and prevention of the virus remains stalled in Congress, and a lack of cohesive public health messaging leaves the public vulnerable to misunderstanding the potential threat of the disease, according to Dr. Fauci.

A vaccine to fight Zika virus is currently under development. “Don’t confuse that with readiness,” Dr. Fauci cautioned.

Dr. Fauci said he believes the disbursement by Congress of President Obama’s requested $1.9 billion in Zika-related funds would facilitate a more comprehensive approach to preventing and treating the virus’s spread, but so far, the funding remains stalled.

As a result, Dr. Fauci said he has reallocated funds intended for other infectious disease research needs to cover Zika-related costs, but is concerned that continued congressional inaction could mean he is left with holes across many budgets. “That 1.9 billion dollars is essential,” he said.

Vaccine progress

In April, $589 millionin funds primarily earmarked for the Ebola crisis were redirected by the Obama administration to fight the Zika virus. That money is now being used in part to fund development of a vaccine that is expected to be ready for a phase I study of 80 people by September 2016. If successful, a phase II-b efficacy study of the vaccine would be conducted in the first quarter of 2017 in a country or region that has a high rate of infection.

Dr. Fauci said that although the study is not be as high-powered as would be ideal, researchers might be able to determine the vaccine’s efficacy with several thousand volunteers, taking into consideration that during the 1-3 years needed to gather conclusive data, herd immunity could skew rates of infection downward, bringing into question the vaccine’s actual efficacy.

“That’s just something we have to deal with,” Dr. Fauci said, saying that fewer people being infected is a good thing, either way.

Research gaps

Other pressing Zika research needs to include learning more about the virus’s impact on a developing fetus.

“We don’t know exactly what the percentage is of [infants born with] microcephaly,” Dr. Fauci said. “We don’t know beyond microcephaly what the long-range effects are on babies that look like they were born [without microcephaly] but might have other defects that are more subtle.”

Dr. Fauci said current data are unhelpful in that they show anywhere from 1% to 29% of infected mothers will give birth to children with congenital defects. However, he said that a coalition of nations affected by the virus is currently enrolling thousands of pregnant women in a cohort study to determine risk ratios.

“When we get the data from that study, we will be able to answer precisely what the percentage is, but today in May 2016, we don’t know the answer,” he said.

Predicting which infants are most susceptible, and at what point in utero abnormalities develop, are questions still under investigation, although a study published earlier this year supports the theory that infection during the first trimester poses the highest risk to a developing fetus.

Communicating risk

Another problem facing health officials is how to communicate the potential seriousness of an illness that, if it presents at all, does so only mildly, Dr. Fauci said. “In general, it’s a disease in which 80% of people don’t have any symptoms.”

The World Health Organization advises physicians to suspect Zika – particularly if a person has been in Zika-affected regions – if clinical symptoms include rash, fever, or both, plus at least one of these: arthralgia, arthritis, or conjunctivitis. Aside from bed rest, hydration, and over-the-counter analgesics, there are no specific treatments for the virus.

How to counsel women about avoiding pregnancy where Zika is a concern also poses challenges, particularly if the pregnancy is unintended, as about half of all American pregnancies are, or if, as Dr. Fauci told reporters, pregnancy is “guided by laws and religion.”

Although federal policy has not been to advise persons about whether to delay pregnancy, Dr. Fauci said U.S. officials are unwilling to contradict authorities in local regions such as Puerto Rico where such statements have been issued.

On April 28, the Food and Drug Administration authorized the emergency use of a commercial in vitro diagnostic test for use in individuals with symptoms of the virus, or those who have traveled to affected regions. Earlier this year, the FDA granted emergency authorization for use of a single test that can detect Zika, dengue, and chikungunya. Still, serology tests for Zika are often inconclusive, since the virus can mimic dengue or chikungunya, according to Dr. Aldighieri. “It can be complex to know if there is a Zika or dengue or chikungunya outbreak,” he said.

The ability of the United States to respond to a potential spike in Zika virus infection rates is a cause for concern, according to a top federal health official.

“The big question is will we get local transmission, and my response to that is very likely we will,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told reporters during a joint media briefing with the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) on May 3.

As many as 500 million people in the Americas are at risk for being infected by the Zika virus, PAHO’s Zika incident manager, Dr. Sylvain Aldighieri, said during the briefing.

In the continental United States to date, there have been about 400 travel-related cases of infection. In Puerto Rico, there have been nearly 700 locally reported cases, and one Zika-related death.

Countries at highest risk for Zika include those that have experienced any outbreaks of dengue fever or chikungunya in the past 15 years, Dr. Aldighieri said. Hawaii and U.S. territories in the Caribbean have experienced local dengue outbreaks during that time. Florida has had local outbreaks of both illnesses.

In the United States, Zika is poised to gain a stronger foothold even as funding for the study and prevention of the virus remains stalled in Congress, and a lack of cohesive public health messaging leaves the public vulnerable to misunderstanding the potential threat of the disease, according to Dr. Fauci.

A vaccine to fight Zika virus is currently under development. “Don’t confuse that with readiness,” Dr. Fauci cautioned.

Dr. Fauci said he believes the disbursement by Congress of President Obama’s requested $1.9 billion in Zika-related funds would facilitate a more comprehensive approach to preventing and treating the virus’s spread, but so far, the funding remains stalled.

As a result, Dr. Fauci said he has reallocated funds intended for other infectious disease research needs to cover Zika-related costs, but is concerned that continued congressional inaction could mean he is left with holes across many budgets. “That 1.9 billion dollars is essential,” he said.

Vaccine progress

In April, $589 millionin funds primarily earmarked for the Ebola crisis were redirected by the Obama administration to fight the Zika virus. That money is now being used in part to fund development of a vaccine that is expected to be ready for a phase I study of 80 people by September 2016. If successful, a phase II-b efficacy study of the vaccine would be conducted in the first quarter of 2017 in a country or region that has a high rate of infection.

Dr. Fauci said that although the study is not be as high-powered as would be ideal, researchers might be able to determine the vaccine’s efficacy with several thousand volunteers, taking into consideration that during the 1-3 years needed to gather conclusive data, herd immunity could skew rates of infection downward, bringing into question the vaccine’s actual efficacy.

“That’s just something we have to deal with,” Dr. Fauci said, saying that fewer people being infected is a good thing, either way.

Research gaps

Other pressing Zika research needs to include learning more about the virus’s impact on a developing fetus.

“We don’t know exactly what the percentage is of [infants born with] microcephaly,” Dr. Fauci said. “We don’t know beyond microcephaly what the long-range effects are on babies that look like they were born [without microcephaly] but might have other defects that are more subtle.”

Dr. Fauci said current data are unhelpful in that they show anywhere from 1% to 29% of infected mothers will give birth to children with congenital defects. However, he said that a coalition of nations affected by the virus is currently enrolling thousands of pregnant women in a cohort study to determine risk ratios.

“When we get the data from that study, we will be able to answer precisely what the percentage is, but today in May 2016, we don’t know the answer,” he said.

Predicting which infants are most susceptible, and at what point in utero abnormalities develop, are questions still under investigation, although a study published earlier this year supports the theory that infection during the first trimester poses the highest risk to a developing fetus.

Communicating risk

Another problem facing health officials is how to communicate the potential seriousness of an illness that, if it presents at all, does so only mildly, Dr. Fauci said. “In general, it’s a disease in which 80% of people don’t have any symptoms.”

The World Health Organization advises physicians to suspect Zika – particularly if a person has been in Zika-affected regions – if clinical symptoms include rash, fever, or both, plus at least one of these: arthralgia, arthritis, or conjunctivitis. Aside from bed rest, hydration, and over-the-counter analgesics, there are no specific treatments for the virus.

How to counsel women about avoiding pregnancy where Zika is a concern also poses challenges, particularly if the pregnancy is unintended, as about half of all American pregnancies are, or if, as Dr. Fauci told reporters, pregnancy is “guided by laws and religion.”

Although federal policy has not been to advise persons about whether to delay pregnancy, Dr. Fauci said U.S. officials are unwilling to contradict authorities in local regions such as Puerto Rico where such statements have been issued.

On April 28, the Food and Drug Administration authorized the emergency use of a commercial in vitro diagnostic test for use in individuals with symptoms of the virus, or those who have traveled to affected regions. Earlier this year, the FDA granted emergency authorization for use of a single test that can detect Zika, dengue, and chikungunya. Still, serology tests for Zika are often inconclusive, since the virus can mimic dengue or chikungunya, according to Dr. Aldighieri. “It can be complex to know if there is a Zika or dengue or chikungunya outbreak,” he said.

The ability of the United States to respond to a potential spike in Zika virus infection rates is a cause for concern, according to a top federal health official.

“The big question is will we get local transmission, and my response to that is very likely we will,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told reporters during a joint media briefing with the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) on May 3.

As many as 500 million people in the Americas are at risk for being infected by the Zika virus, PAHO’s Zika incident manager, Dr. Sylvain Aldighieri, said during the briefing.

In the continental United States to date, there have been about 400 travel-related cases of infection. In Puerto Rico, there have been nearly 700 locally reported cases, and one Zika-related death.

Countries at highest risk for Zika include those that have experienced any outbreaks of dengue fever or chikungunya in the past 15 years, Dr. Aldighieri said. Hawaii and U.S. territories in the Caribbean have experienced local dengue outbreaks during that time. Florida has had local outbreaks of both illnesses.

In the United States, Zika is poised to gain a stronger foothold even as funding for the study and prevention of the virus remains stalled in Congress, and a lack of cohesive public health messaging leaves the public vulnerable to misunderstanding the potential threat of the disease, according to Dr. Fauci.

A vaccine to fight Zika virus is currently under development. “Don’t confuse that with readiness,” Dr. Fauci cautioned.

Dr. Fauci said he believes the disbursement by Congress of President Obama’s requested $1.9 billion in Zika-related funds would facilitate a more comprehensive approach to preventing and treating the virus’s spread, but so far, the funding remains stalled.

As a result, Dr. Fauci said he has reallocated funds intended for other infectious disease research needs to cover Zika-related costs, but is concerned that continued congressional inaction could mean he is left with holes across many budgets. “That 1.9 billion dollars is essential,” he said.

Vaccine progress

In April, $589 millionin funds primarily earmarked for the Ebola crisis were redirected by the Obama administration to fight the Zika virus. That money is now being used in part to fund development of a vaccine that is expected to be ready for a phase I study of 80 people by September 2016. If successful, a phase II-b efficacy study of the vaccine would be conducted in the first quarter of 2017 in a country or region that has a high rate of infection.

Dr. Fauci said that although the study is not be as high-powered as would be ideal, researchers might be able to determine the vaccine’s efficacy with several thousand volunteers, taking into consideration that during the 1-3 years needed to gather conclusive data, herd immunity could skew rates of infection downward, bringing into question the vaccine’s actual efficacy.

“That’s just something we have to deal with,” Dr. Fauci said, saying that fewer people being infected is a good thing, either way.

Research gaps

Other pressing Zika research needs to include learning more about the virus’s impact on a developing fetus.

“We don’t know exactly what the percentage is of [infants born with] microcephaly,” Dr. Fauci said. “We don’t know beyond microcephaly what the long-range effects are on babies that look like they were born [without microcephaly] but might have other defects that are more subtle.”

Dr. Fauci said current data are unhelpful in that they show anywhere from 1% to 29% of infected mothers will give birth to children with congenital defects. However, he said that a coalition of nations affected by the virus is currently enrolling thousands of pregnant women in a cohort study to determine risk ratios.

“When we get the data from that study, we will be able to answer precisely what the percentage is, but today in May 2016, we don’t know the answer,” he said.

Predicting which infants are most susceptible, and at what point in utero abnormalities develop, are questions still under investigation, although a study published earlier this year supports the theory that infection during the first trimester poses the highest risk to a developing fetus.

Communicating risk

Another problem facing health officials is how to communicate the potential seriousness of an illness that, if it presents at all, does so only mildly, Dr. Fauci said. “In general, it’s a disease in which 80% of people don’t have any symptoms.”

The World Health Organization advises physicians to suspect Zika – particularly if a person has been in Zika-affected regions – if clinical symptoms include rash, fever, or both, plus at least one of these: arthralgia, arthritis, or conjunctivitis. Aside from bed rest, hydration, and over-the-counter analgesics, there are no specific treatments for the virus.

How to counsel women about avoiding pregnancy where Zika is a concern also poses challenges, particularly if the pregnancy is unintended, as about half of all American pregnancies are, or if, as Dr. Fauci told reporters, pregnancy is “guided by laws and religion.”

Although federal policy has not been to advise persons about whether to delay pregnancy, Dr. Fauci said U.S. officials are unwilling to contradict authorities in local regions such as Puerto Rico where such statements have been issued.

On April 28, the Food and Drug Administration authorized the emergency use of a commercial in vitro diagnostic test for use in individuals with symptoms of the virus, or those who have traveled to affected regions. Earlier this year, the FDA granted emergency authorization for use of a single test that can detect Zika, dengue, and chikungunya. Still, serology tests for Zika are often inconclusive, since the virus can mimic dengue or chikungunya, according to Dr. Aldighieri. “It can be complex to know if there is a Zika or dengue or chikungunya outbreak,” he said.

U.S. official raises concerns over Zika readiness

The ability of the United States to respond to a potential spike in Zika virus infection rates is a cause for concern, according to a top federal health official.

“The big question is will we get local transmission, and my response to that is very likely we will,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told reporters during a joint media briefing with the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) on May 3.

As many as 500 million people in the Americas are at risk for being infected by the Zika virus, PAHO’s Zika incident manager, Dr. Sylvain Aldighieri, said during the briefing.

In the continental United States to date, there have been about 400 travel-related cases of infection. In Puerto Rico, there have been nearly 700 locally reported cases, and one Zika-related death.

Countries at highest risk for Zika include those that have experienced any outbreaks of dengue fever or chikungunya in the past 15 years, Dr. Aldighieri said. Hawaii and U.S. territories in the Caribbean have experienced local dengue outbreaks during that time. Florida has had local outbreaks of both illnesses.

In the United States, Zika is poised to gain a stronger foothold even as funding for the study and prevention of the virus remains stalled in Congress, and a lack of cohesive public health messaging leaves the public vulnerable to misunderstanding the potential threat of the disease, according to Dr. Fauci.

A vaccine to fight Zika virus is currently under development. “Don’t confuse that with readiness,” Dr. Fauci cautioned.

Dr. Fauci said he believes the disbursement by Congress of President Obama’s requested $1.9 billion in Zika-related funds would facilitate a more comprehensive approach to preventing and treating the virus’s spread, but so far, the funding remains stalled.

As a result, Dr. Fauci said he has reallocated funds intended for other infectious disease research needs to cover Zika-related costs, but is concerned that continued congressional inaction could mean he is left with holes across many budgets. “That 1.9 billion dollars is essential,” he said.

Vaccine progress

In April, $589 millionin funds primarily earmarked for the Ebola crisis were redirected by the Obama administration to fight the Zika virus. That money is now being used in part to fund development of a vaccine that is expected to be ready for a phase I study of 80 people by September 2016. If successful, a phase II-b efficacy study of the vaccine would be conducted in the first quarter of 2017 in a country or region that has a high rate of infection.

Dr. Fauci said that although the study is not be as high-powered as would be ideal, researchers might be able to determine the vaccine’s efficacy with several thousand volunteers, taking into consideration that during the 1-3 years needed to gather conclusive data, herd immunity could skew rates of infection downward, bringing into question the vaccine’s actual efficacy.

“That’s just something we have to deal with,” Dr. Fauci said, saying that fewer people being infected is a good thing, either way.

Research gaps

Other pressing Zika research needs to include learning more about the virus’s impact on a developing fetus.

“We don’t know exactly what the percentage is of [infants born with] microcephaly,” Dr. Fauci said. “We don’t know beyond microcephaly what the long-range effects are on babies that look like they were born [without microcephaly] but might have other defects that are more subtle.”

Dr. Fauci said current data are unhelpful in that they show anywhere from 1% to 29% of infected mothers will give birth to children with congenital defects. However, he said that a coalition of nations affected by the virus is currently enrolling thousands of pregnant women in a cohort study to determine risk ratios.

“When we get the data from that study, we will be able to answer precisely what the percentage is, but today in May 2016, we don’t know the answer,” he said.

Predicting which infants are most susceptible, and at what point in utero abnormalities develop, are questions still under investigation, although a study published earlier this year supports the theory that infection during the first trimester poses the highest risk to a developing fetus.

Communicating risk

Another problem facing health officials is how to communicate the potential seriousness of an illness that, if it presents at all, does so only mildly, Dr. Fauci said. “In general, it’s a disease in which 80% of people don’t have any symptoms.”

The World Health Organization advises physicians to suspect Zika – particularly if a person has been in Zika-affected regions – if clinical symptoms include rash, fever, or both, plus at least one of these: arthralgia, arthritis, or conjunctivitis. Aside from bed rest, hydration, and over-the-counter analgesics, there are no specific treatments for the virus.

How to counsel women about avoiding pregnancy where Zika is a concern also poses challenges, particularly if the pregnancy is unintended, as about half of all American pregnancies are, or if, as Dr. Fauci told reporters, pregnancy is “guided by laws and religion.”

Although federal policy has not been to advise persons about whether to delay pregnancy, Dr. Fauci said U.S. officials are unwilling to contradict authorities in local regions such as Puerto Rico where such statements have been issued.

On April 28, the Food and Drug Administration authorized the emergency use of a commercial in vitro diagnostic test for use in individuals with symptoms of the virus, or those who have traveled to affected regions. Earlier this year, the FDA granted emergency authorization for use of a single test that can detect Zika, dengue, and chikungunya. Still, serology tests for Zika are often inconclusive, since the virus can mimic dengue or chikungunya, according to Dr. Aldighieri. “It can be complex to know if there is a Zika or dengue or chikungunya outbreak,” he said.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

The ability of the United States to respond to a potential spike in Zika virus infection rates is a cause for concern, according to a top federal health official.

“The big question is will we get local transmission, and my response to that is very likely we will,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told reporters during a joint media briefing with the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) on May 3.

As many as 500 million people in the Americas are at risk for being infected by the Zika virus, PAHO’s Zika incident manager, Dr. Sylvain Aldighieri, said during the briefing.

In the continental United States to date, there have been about 400 travel-related cases of infection. In Puerto Rico, there have been nearly 700 locally reported cases, and one Zika-related death.

Countries at highest risk for Zika include those that have experienced any outbreaks of dengue fever or chikungunya in the past 15 years, Dr. Aldighieri said. Hawaii and U.S. territories in the Caribbean have experienced local dengue outbreaks during that time. Florida has had local outbreaks of both illnesses.

In the United States, Zika is poised to gain a stronger foothold even as funding for the study and prevention of the virus remains stalled in Congress, and a lack of cohesive public health messaging leaves the public vulnerable to misunderstanding the potential threat of the disease, according to Dr. Fauci.

A vaccine to fight Zika virus is currently under development. “Don’t confuse that with readiness,” Dr. Fauci cautioned.

Dr. Fauci said he believes the disbursement by Congress of President Obama’s requested $1.9 billion in Zika-related funds would facilitate a more comprehensive approach to preventing and treating the virus’s spread, but so far, the funding remains stalled.

As a result, Dr. Fauci said he has reallocated funds intended for other infectious disease research needs to cover Zika-related costs, but is concerned that continued congressional inaction could mean he is left with holes across many budgets. “That 1.9 billion dollars is essential,” he said.

Vaccine progress

In April, $589 millionin funds primarily earmarked for the Ebola crisis were redirected by the Obama administration to fight the Zika virus. That money is now being used in part to fund development of a vaccine that is expected to be ready for a phase I study of 80 people by September 2016. If successful, a phase II-b efficacy study of the vaccine would be conducted in the first quarter of 2017 in a country or region that has a high rate of infection.

Dr. Fauci said that although the study is not be as high-powered as would be ideal, researchers might be able to determine the vaccine’s efficacy with several thousand volunteers, taking into consideration that during the 1-3 years needed to gather conclusive data, herd immunity could skew rates of infection downward, bringing into question the vaccine’s actual efficacy.

“That’s just something we have to deal with,” Dr. Fauci said, saying that fewer people being infected is a good thing, either way.

Research gaps

Other pressing Zika research needs to include learning more about the virus’s impact on a developing fetus.

“We don’t know exactly what the percentage is of [infants born with] microcephaly,” Dr. Fauci said. “We don’t know beyond microcephaly what the long-range effects are on babies that look like they were born [without microcephaly] but might have other defects that are more subtle.”

Dr. Fauci said current data are unhelpful in that they show anywhere from 1% to 29% of infected mothers will give birth to children with congenital defects. However, he said that a coalition of nations affected by the virus is currently enrolling thousands of pregnant women in a cohort study to determine risk ratios.

“When we get the data from that study, we will be able to answer precisely what the percentage is, but today in May 2016, we don’t know the answer,” he said.

Predicting which infants are most susceptible, and at what point in utero abnormalities develop, are questions still under investigation, although a study published earlier this year supports the theory that infection during the first trimester poses the highest risk to a developing fetus.

Communicating risk

Another problem facing health officials is how to communicate the potential seriousness of an illness that, if it presents at all, does so only mildly, Dr. Fauci said. “In general, it’s a disease in which 80% of people don’t have any symptoms.”

The World Health Organization advises physicians to suspect Zika – particularly if a person has been in Zika-affected regions – if clinical symptoms include rash, fever, or both, plus at least one of these: arthralgia, arthritis, or conjunctivitis. Aside from bed rest, hydration, and over-the-counter analgesics, there are no specific treatments for the virus.

How to counsel women about avoiding pregnancy where Zika is a concern also poses challenges, particularly if the pregnancy is unintended, as about half of all American pregnancies are, or if, as Dr. Fauci told reporters, pregnancy is “guided by laws and religion.”

Although federal policy has not been to advise persons about whether to delay pregnancy, Dr. Fauci said U.S. officials are unwilling to contradict authorities in local regions such as Puerto Rico where such statements have been issued.

On April 28, the Food and Drug Administration authorized the emergency use of a commercial in vitro diagnostic test for use in individuals with symptoms of the virus, or those who have traveled to affected regions. Earlier this year, the FDA granted emergency authorization for use of a single test that can detect Zika, dengue, and chikungunya. Still, serology tests for Zika are often inconclusive, since the virus can mimic dengue or chikungunya, according to Dr. Aldighieri. “It can be complex to know if there is a Zika or dengue or chikungunya outbreak,” he said.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

The ability of the United States to respond to a potential spike in Zika virus infection rates is a cause for concern, according to a top federal health official.

“The big question is will we get local transmission, and my response to that is very likely we will,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told reporters during a joint media briefing with the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) on May 3.

As many as 500 million people in the Americas are at risk for being infected by the Zika virus, PAHO’s Zika incident manager, Dr. Sylvain Aldighieri, said during the briefing.

In the continental United States to date, there have been about 400 travel-related cases of infection. In Puerto Rico, there have been nearly 700 locally reported cases, and one Zika-related death.

Countries at highest risk for Zika include those that have experienced any outbreaks of dengue fever or chikungunya in the past 15 years, Dr. Aldighieri said. Hawaii and U.S. territories in the Caribbean have experienced local dengue outbreaks during that time. Florida has had local outbreaks of both illnesses.

In the United States, Zika is poised to gain a stronger foothold even as funding for the study and prevention of the virus remains stalled in Congress, and a lack of cohesive public health messaging leaves the public vulnerable to misunderstanding the potential threat of the disease, according to Dr. Fauci.

A vaccine to fight Zika virus is currently under development. “Don’t confuse that with readiness,” Dr. Fauci cautioned.

Dr. Fauci said he believes the disbursement by Congress of President Obama’s requested $1.9 billion in Zika-related funds would facilitate a more comprehensive approach to preventing and treating the virus’s spread, but so far, the funding remains stalled.

As a result, Dr. Fauci said he has reallocated funds intended for other infectious disease research needs to cover Zika-related costs, but is concerned that continued congressional inaction could mean he is left with holes across many budgets. “That 1.9 billion dollars is essential,” he said.

Vaccine progress

In April, $589 millionin funds primarily earmarked for the Ebola crisis were redirected by the Obama administration to fight the Zika virus. That money is now being used in part to fund development of a vaccine that is expected to be ready for a phase I study of 80 people by September 2016. If successful, a phase II-b efficacy study of the vaccine would be conducted in the first quarter of 2017 in a country or region that has a high rate of infection.

Dr. Fauci said that although the study is not be as high-powered as would be ideal, researchers might be able to determine the vaccine’s efficacy with several thousand volunteers, taking into consideration that during the 1-3 years needed to gather conclusive data, herd immunity could skew rates of infection downward, bringing into question the vaccine’s actual efficacy.

“That’s just something we have to deal with,” Dr. Fauci said, saying that fewer people being infected is a good thing, either way.

Research gaps

Other pressing Zika research needs to include learning more about the virus’s impact on a developing fetus.

“We don’t know exactly what the percentage is of [infants born with] microcephaly,” Dr. Fauci said. “We don’t know beyond microcephaly what the long-range effects are on babies that look like they were born [without microcephaly] but might have other defects that are more subtle.”

Dr. Fauci said current data are unhelpful in that they show anywhere from 1% to 29% of infected mothers will give birth to children with congenital defects. However, he said that a coalition of nations affected by the virus is currently enrolling thousands of pregnant women in a cohort study to determine risk ratios.

“When we get the data from that study, we will be able to answer precisely what the percentage is, but today in May 2016, we don’t know the answer,” he said.

Predicting which infants are most susceptible, and at what point in utero abnormalities develop, are questions still under investigation, although a study published earlier this year supports the theory that infection during the first trimester poses the highest risk to a developing fetus.

Communicating risk

Another problem facing health officials is how to communicate the potential seriousness of an illness that, if it presents at all, does so only mildly, Dr. Fauci said. “In general, it’s a disease in which 80% of people don’t have any symptoms.”

The World Health Organization advises physicians to suspect Zika – particularly if a person has been in Zika-affected regions – if clinical symptoms include rash, fever, or both, plus at least one of these: arthralgia, arthritis, or conjunctivitis. Aside from bed rest, hydration, and over-the-counter analgesics, there are no specific treatments for the virus.

How to counsel women about avoiding pregnancy where Zika is a concern also poses challenges, particularly if the pregnancy is unintended, as about half of all American pregnancies are, or if, as Dr. Fauci told reporters, pregnancy is “guided by laws and religion.”

Although federal policy has not been to advise persons about whether to delay pregnancy, Dr. Fauci said U.S. officials are unwilling to contradict authorities in local regions such as Puerto Rico where such statements have been issued.

On April 28, the Food and Drug Administration authorized the emergency use of a commercial in vitro diagnostic test for use in individuals with symptoms of the virus, or those who have traveled to affected regions. Earlier this year, the FDA granted emergency authorization for use of a single test that can detect Zika, dengue, and chikungunya. Still, serology tests for Zika are often inconclusive, since the virus can mimic dengue or chikungunya, according to Dr. Aldighieri. “It can be complex to know if there is a Zika or dengue or chikungunya outbreak,” he said.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Fistula developed after delivery: $50M verdict

Fistula developed after delivery: $50M verdict

During delivery of a 31-year-old woman's baby, a nuchal cord was encountered. In order to safely deliver the child, the ObGyn performed an episiotomy.

After delivery, the patient reported an odorous vaginal discharge. The ObGyn explained that the condition was a natural byproduct of delivery and suggested that it would resolve without treatment.

The patient became pregnant a second time shortly after her first delivery and was evaluated by a midwife. The patient again reported the odorous discharge, but the condition was not addressed. At delivery of her second child, the ObGyn determined that the patient had a rectovaginal fistula. The patient underwent 13 repair operations.

PATIENT’S CLAIM:

The fistula was a byproduct of the episiotomy performed during the first delivery. The episiotomy should not have been performed. The ObGyn should have diagnosed and treated the fistula prior to delivery of the second child and performed a cesarean delivery.

DEFENDANT'S DEFENSE:

The ObGyn reported that the patient's medical records showed that she did not report the odorous discharge until after her second delivery.

VERDICT:

A New York $50 million verdict was returned.

Related article:

Management of wound complications following obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASIS)

Abdominal wall hematoma during pregnancy: $2.5M award

At 35 weeks' gestation, a 38-year-old woman presented to the emergency department (ED) with right upper abdominal pain. Her pregnancy was at high risk because of her age and the fact that she had thrombophilia involving both factor V and protein S deficiency. During pregnancy she was anticoagulated. She had been coughing from bronchitis, which was treated with antibiotics and an inhaler.

In the ED, laboratory testing determined that her blood was not properly clotting. Upper abdominal ultrasonography (US) showed an abdominal wall hematoma and gall stones. The ED physician, after contacting the on-call ObGyn, told the patient that nothing further could be done until after the baby's birth and prescribed medications for nausea and pain. The patient was discharged.

Thirty-three hours later, the patient was rushed to the hospital after she was found barely responsive, pale, and in severe pain. US results showed that the hematoma had grown extensively. The patient was in hypovolemic shock having lost more than 50% of her blood volume. She was admitted to the intensive care unit.

After induced labor, a stillborn son was delivered. The autopsy report revealed that the child died from either asphyxiation or an hypoxic ischemic event that occurred when the mother went into shock.

PATIENT’S CLAIM:

The ED physician and staff were negligent. Once the hematoma was identified, the standard of care is to monitor the hematoma with regular US. Instead, the ED physician discharged the patient. The ED physician contacted the on-call ObGyn but did not ask for a consult. The patient should have been admitted for monitoring.

DEFENDANT'S DEFENSE:

The ED physician met the standard of care. The mother's condition would likely have been detected during a nonstress test scheduled for the following day but the mother missed the prenatal exam because she had just left the hospital.

VERDICT:

A $2.5 million Missouri verdict was returned.

Incorrect due date, child with brain injuries: $1.2M

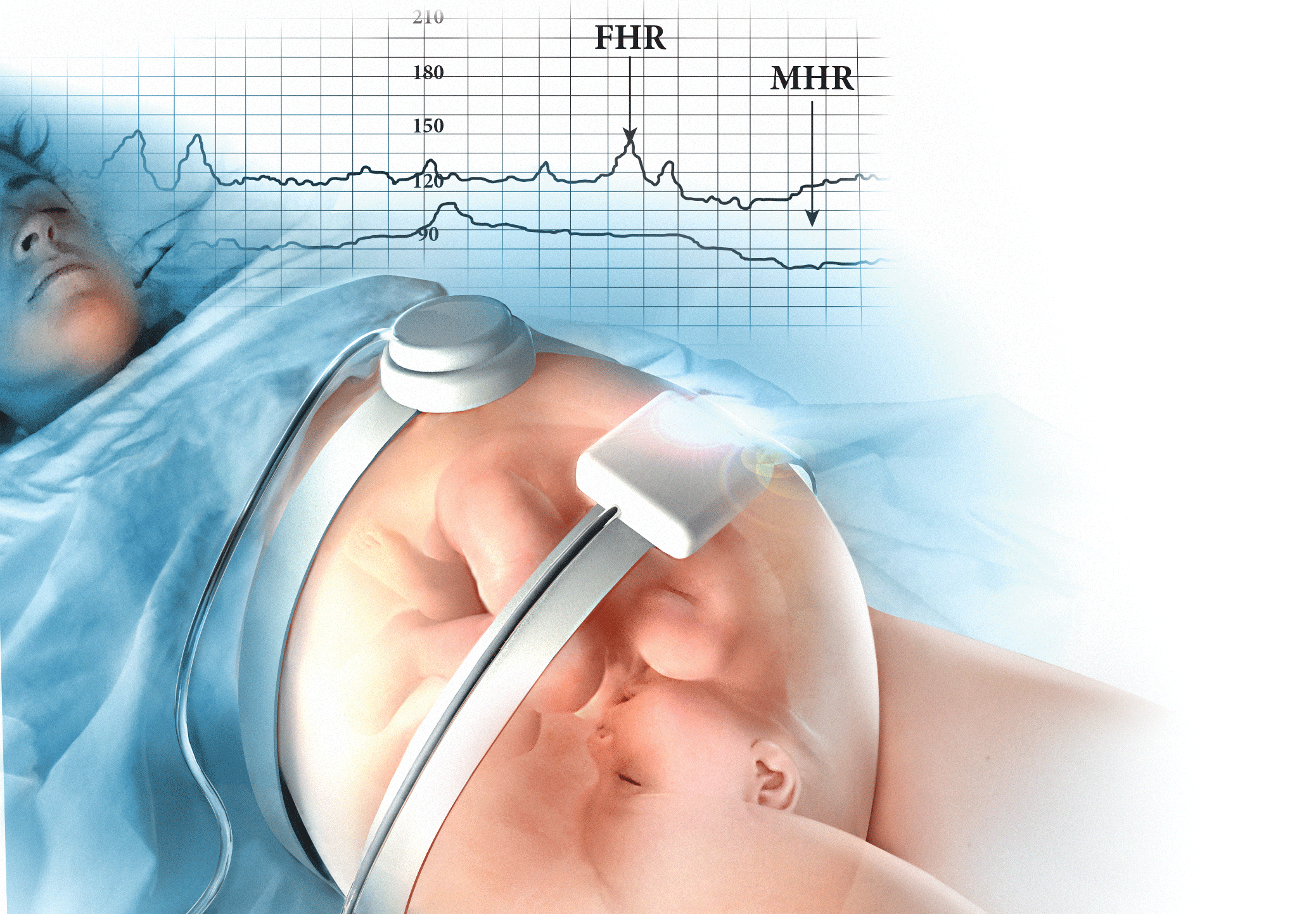

When a pregnant woman presented for her first prenatal visit, she was unsure of the date of her last menstrual period. During subsequent prenatal visits, she underwent 3 ultrasounds.

Labor was induced on August 1 because she reported gastrointestinal reflux. The infant appeared healthy at birth but soon went into respiratory distress. He was slow to meet developmental goals and was believed to be autistic. At age 5 years, he was given a diagnosis of periventricular leukomalacia.

PARENT’S CLAIM:

The child, 11 years old at the time of trial, has permanent brain injuries due to premature delivery. The mother's due date should have been projected as August 25 according to prenatal US measurements. The ObGyn misinterpreted the US data and estimated a due date of August 15. Therefore induction on August 1st caused him to be premature.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE:

The standard of care was met. Gestational age evaluation using US is an estimate based on the child's size at specific time points, not an exact calculation, especially if the mother is not sure about the date of her last menses.

VERDICT:

A $1.2 million New Jersey verdict was returned.

Related article:

Three good apps for calculating the date of delivery

Bacterial infection blamed for birth injury

A woman was at 28 weeks' gestation when her membranes ruptured on September 28. She began to leak amniotic fluid and was put on bed rest. She saw her ObGyn on October 13 with signs of a bacterial infection of her membranes. The ObGyn decided to induce labor; a baby girl was born 11 hours later. The child had meningitis at birth and other infection-related complications including a brain hemorrhage. She continues to have permanent neurologic deficits.

PARENT’S CLAIM:

The ObGyn was negligent in not immediately delivering the child via cesarean delivery on October 13. The delay exposed the baby to infection for 11 more hours; the extended exposure led to her permanent injury.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE:

The patient's treatment met the standard of care.

VERDICT:

A Virginia defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Fistula developed after delivery: $50M verdict

During delivery of a 31-year-old woman's baby, a nuchal cord was encountered. In order to safely deliver the child, the ObGyn performed an episiotomy.

After delivery, the patient reported an odorous vaginal discharge. The ObGyn explained that the condition was a natural byproduct of delivery and suggested that it would resolve without treatment.

The patient became pregnant a second time shortly after her first delivery and was evaluated by a midwife. The patient again reported the odorous discharge, but the condition was not addressed. At delivery of her second child, the ObGyn determined that the patient had a rectovaginal fistula. The patient underwent 13 repair operations.

PATIENT’S CLAIM:

The fistula was a byproduct of the episiotomy performed during the first delivery. The episiotomy should not have been performed. The ObGyn should have diagnosed and treated the fistula prior to delivery of the second child and performed a cesarean delivery.

DEFENDANT'S DEFENSE:

The ObGyn reported that the patient's medical records showed that she did not report the odorous discharge until after her second delivery.

VERDICT:

A New York $50 million verdict was returned.

Related article:

Management of wound complications following obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASIS)

Abdominal wall hematoma during pregnancy: $2.5M award

At 35 weeks' gestation, a 38-year-old woman presented to the emergency department (ED) with right upper abdominal pain. Her pregnancy was at high risk because of her age and the fact that she had thrombophilia involving both factor V and protein S deficiency. During pregnancy she was anticoagulated. She had been coughing from bronchitis, which was treated with antibiotics and an inhaler.

In the ED, laboratory testing determined that her blood was not properly clotting. Upper abdominal ultrasonography (US) showed an abdominal wall hematoma and gall stones. The ED physician, after contacting the on-call ObGyn, told the patient that nothing further could be done until after the baby's birth and prescribed medications for nausea and pain. The patient was discharged.

Thirty-three hours later, the patient was rushed to the hospital after she was found barely responsive, pale, and in severe pain. US results showed that the hematoma had grown extensively. The patient was in hypovolemic shock having lost more than 50% of her blood volume. She was admitted to the intensive care unit.

After induced labor, a stillborn son was delivered. The autopsy report revealed that the child died from either asphyxiation or an hypoxic ischemic event that occurred when the mother went into shock.

PATIENT’S CLAIM:

The ED physician and staff were negligent. Once the hematoma was identified, the standard of care is to monitor the hematoma with regular US. Instead, the ED physician discharged the patient. The ED physician contacted the on-call ObGyn but did not ask for a consult. The patient should have been admitted for monitoring.

DEFENDANT'S DEFENSE:

The ED physician met the standard of care. The mother's condition would likely have been detected during a nonstress test scheduled for the following day but the mother missed the prenatal exam because she had just left the hospital.

VERDICT:

A $2.5 million Missouri verdict was returned.

Incorrect due date, child with brain injuries: $1.2M

When a pregnant woman presented for her first prenatal visit, she was unsure of the date of her last menstrual period. During subsequent prenatal visits, she underwent 3 ultrasounds.

Labor was induced on August 1 because she reported gastrointestinal reflux. The infant appeared healthy at birth but soon went into respiratory distress. He was slow to meet developmental goals and was believed to be autistic. At age 5 years, he was given a diagnosis of periventricular leukomalacia.

PARENT’S CLAIM:

The child, 11 years old at the time of trial, has permanent brain injuries due to premature delivery. The mother's due date should have been projected as August 25 according to prenatal US measurements. The ObGyn misinterpreted the US data and estimated a due date of August 15. Therefore induction on August 1st caused him to be premature.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE:

The standard of care was met. Gestational age evaluation using US is an estimate based on the child's size at specific time points, not an exact calculation, especially if the mother is not sure about the date of her last menses.

VERDICT:

A $1.2 million New Jersey verdict was returned.

Related article:

Three good apps for calculating the date of delivery

Bacterial infection blamed for birth injury

A woman was at 28 weeks' gestation when her membranes ruptured on September 28. She began to leak amniotic fluid and was put on bed rest. She saw her ObGyn on October 13 with signs of a bacterial infection of her membranes. The ObGyn decided to induce labor; a baby girl was born 11 hours later. The child had meningitis at birth and other infection-related complications including a brain hemorrhage. She continues to have permanent neurologic deficits.

PARENT’S CLAIM:

The ObGyn was negligent in not immediately delivering the child via cesarean delivery on October 13. The delay exposed the baby to infection for 11 more hours; the extended exposure led to her permanent injury.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE:

The patient's treatment met the standard of care.

VERDICT:

A Virginia defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Fistula developed after delivery: $50M verdict

During delivery of a 31-year-old woman's baby, a nuchal cord was encountered. In order to safely deliver the child, the ObGyn performed an episiotomy.

After delivery, the patient reported an odorous vaginal discharge. The ObGyn explained that the condition was a natural byproduct of delivery and suggested that it would resolve without treatment.

The patient became pregnant a second time shortly after her first delivery and was evaluated by a midwife. The patient again reported the odorous discharge, but the condition was not addressed. At delivery of her second child, the ObGyn determined that the patient had a rectovaginal fistula. The patient underwent 13 repair operations.

PATIENT’S CLAIM: