User login

RE: Podiatric “Physicians and Surgeons”

On behalf of the California Podiatric Medical Association, we wholeheartedly agree with Dr. Pfeffer’s opinion1 that “The title of physician and surgeon is earned, and should be based on an educational standard established by a recognized accreditation agency, in this case the [Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME)], and not legislative fiat.”

We in podiatric medicine seek to achieve recognition of equivalency by objective proof—not by legislative sleight of hand. Esse quam videri—to be rather than to seem.

Since the initial announcement of the Joint California Podiatric Medical Association, California Medical Association, California Orthopaedic Association (CPMA-CMA-COA) Task Force, which was subsequently joined by Osteopathic Physicians and Surgeons of California (OPSC), the focus has been on objective evaluation of the education and training of podiatric physicians by qualified and unbiased representatives. The addition of an LCME consultant to the Joint Task Force provides greater assurance that an educational standard comparable to that established by LCME is being utilized.

We are sincere in our efforts to prove our equivalency to this Joint Task Force. We do not claim to be identical, just as current holders of the Physicians and Surgeons Certificate are not identical, having trained at differing types of institutions both in the United States and abroad. Rather, we want to show our equivalency in meeting the requirements of the Physician and Surgeon Certificate in California.

We do differ with Dr. Pfeffer’s understanding of the training of podiatric physicians and surgeons in that broadbased medical education not only is, but has been, an

integral part of the podiatric medical education and training since at least the early 1980s. An independent report—the Medio-Nelson Report—prepared for the Medical Board of California and dated October 17, 1993 bears out this fact. Much of this broad-based training is obtained alongside allopathic and osteopathic medical students and residents. As Dr. Pfeffer noted, “Podiatric medical school education

continues to improve in California.” All podiatric medical graduates in California now attend three-year medical and surgical residencies, following four years of podiatric medical school. Some, in addition, go on to attend fellowships in advanced specialties. The limited license that podiatrists obtain reflects the specialty we have chosen and not a limited education.

We are in full agreement with the medical community that all physicians and surgeons, though they may have unrestricted licenses, should practice to their education, training, and experience, which often involves a specialty.

Any significant differences identified by the Joint Task Force will be addressed so that we may take our certified place alongside our allopathic and osteopathic colleagues, as we have on a practical basis for many years and in a myriad of settings, including hospitals, surgical centers, and medical groups across the country.

We are proud to stand together with our allopathic and osteopathic colleagues in creation of the Joint Task Force, and look forward to the culmination of its efforts and realization of its goals.

Karen L. Wrubel, DPM, FACFAS

Dr. Wrubel is President, California Podiatric Medical Association, Hawthorne, California.

Am J Orthop. 2013;42(6):255. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications

Inc. 2013. All rights reserved.

1. Pfeffer GB. Podiatric “Physicians and Surgeons.” Am J Orthop. 2013;42(3):112.

The journal welcomes Letters to the Editor. Letters are not peer reviewed. Opinions expressed in letters published here do not necessarily reflect those of the editorial board or the publishing company and its employees.

On behalf of the California Podiatric Medical Association, we wholeheartedly agree with Dr. Pfeffer’s opinion1 that “The title of physician and surgeon is earned, and should be based on an educational standard established by a recognized accreditation agency, in this case the [Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME)], and not legislative fiat.”

We in podiatric medicine seek to achieve recognition of equivalency by objective proof—not by legislative sleight of hand. Esse quam videri—to be rather than to seem.

Since the initial announcement of the Joint California Podiatric Medical Association, California Medical Association, California Orthopaedic Association (CPMA-CMA-COA) Task Force, which was subsequently joined by Osteopathic Physicians and Surgeons of California (OPSC), the focus has been on objective evaluation of the education and training of podiatric physicians by qualified and unbiased representatives. The addition of an LCME consultant to the Joint Task Force provides greater assurance that an educational standard comparable to that established by LCME is being utilized.

We are sincere in our efforts to prove our equivalency to this Joint Task Force. We do not claim to be identical, just as current holders of the Physicians and Surgeons Certificate are not identical, having trained at differing types of institutions both in the United States and abroad. Rather, we want to show our equivalency in meeting the requirements of the Physician and Surgeon Certificate in California.

We do differ with Dr. Pfeffer’s understanding of the training of podiatric physicians and surgeons in that broadbased medical education not only is, but has been, an

integral part of the podiatric medical education and training since at least the early 1980s. An independent report—the Medio-Nelson Report—prepared for the Medical Board of California and dated October 17, 1993 bears out this fact. Much of this broad-based training is obtained alongside allopathic and osteopathic medical students and residents. As Dr. Pfeffer noted, “Podiatric medical school education

continues to improve in California.” All podiatric medical graduates in California now attend three-year medical and surgical residencies, following four years of podiatric medical school. Some, in addition, go on to attend fellowships in advanced specialties. The limited license that podiatrists obtain reflects the specialty we have chosen and not a limited education.

We are in full agreement with the medical community that all physicians and surgeons, though they may have unrestricted licenses, should practice to their education, training, and experience, which often involves a specialty.

Any significant differences identified by the Joint Task Force will be addressed so that we may take our certified place alongside our allopathic and osteopathic colleagues, as we have on a practical basis for many years and in a myriad of settings, including hospitals, surgical centers, and medical groups across the country.

We are proud to stand together with our allopathic and osteopathic colleagues in creation of the Joint Task Force, and look forward to the culmination of its efforts and realization of its goals.

Karen L. Wrubel, DPM, FACFAS

Dr. Wrubel is President, California Podiatric Medical Association, Hawthorne, California.

Am J Orthop. 2013;42(6):255. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications

Inc. 2013. All rights reserved.

1. Pfeffer GB. Podiatric “Physicians and Surgeons.” Am J Orthop. 2013;42(3):112.

The journal welcomes Letters to the Editor. Letters are not peer reviewed. Opinions expressed in letters published here do not necessarily reflect those of the editorial board or the publishing company and its employees.

On behalf of the California Podiatric Medical Association, we wholeheartedly agree with Dr. Pfeffer’s opinion1 that “The title of physician and surgeon is earned, and should be based on an educational standard established by a recognized accreditation agency, in this case the [Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME)], and not legislative fiat.”

We in podiatric medicine seek to achieve recognition of equivalency by objective proof—not by legislative sleight of hand. Esse quam videri—to be rather than to seem.

Since the initial announcement of the Joint California Podiatric Medical Association, California Medical Association, California Orthopaedic Association (CPMA-CMA-COA) Task Force, which was subsequently joined by Osteopathic Physicians and Surgeons of California (OPSC), the focus has been on objective evaluation of the education and training of podiatric physicians by qualified and unbiased representatives. The addition of an LCME consultant to the Joint Task Force provides greater assurance that an educational standard comparable to that established by LCME is being utilized.

We are sincere in our efforts to prove our equivalency to this Joint Task Force. We do not claim to be identical, just as current holders of the Physicians and Surgeons Certificate are not identical, having trained at differing types of institutions both in the United States and abroad. Rather, we want to show our equivalency in meeting the requirements of the Physician and Surgeon Certificate in California.

We do differ with Dr. Pfeffer’s understanding of the training of podiatric physicians and surgeons in that broadbased medical education not only is, but has been, an

integral part of the podiatric medical education and training since at least the early 1980s. An independent report—the Medio-Nelson Report—prepared for the Medical Board of California and dated October 17, 1993 bears out this fact. Much of this broad-based training is obtained alongside allopathic and osteopathic medical students and residents. As Dr. Pfeffer noted, “Podiatric medical school education

continues to improve in California.” All podiatric medical graduates in California now attend three-year medical and surgical residencies, following four years of podiatric medical school. Some, in addition, go on to attend fellowships in advanced specialties. The limited license that podiatrists obtain reflects the specialty we have chosen and not a limited education.

We are in full agreement with the medical community that all physicians and surgeons, though they may have unrestricted licenses, should practice to their education, training, and experience, which often involves a specialty.

Any significant differences identified by the Joint Task Force will be addressed so that we may take our certified place alongside our allopathic and osteopathic colleagues, as we have on a practical basis for many years and in a myriad of settings, including hospitals, surgical centers, and medical groups across the country.

We are proud to stand together with our allopathic and osteopathic colleagues in creation of the Joint Task Force, and look forward to the culmination of its efforts and realization of its goals.

Karen L. Wrubel, DPM, FACFAS

Dr. Wrubel is President, California Podiatric Medical Association, Hawthorne, California.

Am J Orthop. 2013;42(6):255. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications

Inc. 2013. All rights reserved.

1. Pfeffer GB. Podiatric “Physicians and Surgeons.” Am J Orthop. 2013;42(3):112.

The journal welcomes Letters to the Editor. Letters are not peer reviewed. Opinions expressed in letters published here do not necessarily reflect those of the editorial board or the publishing company and its employees.

The “Canoe” Technique to Insert Lumbar Pedicle Screws: Consistent, Safe, and Simple

Solitary Plasmacytoma of the Medial Clavicle

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus as a Cause of a Quadriceps Tendon Tear

Type IIb Bony Mallet Finger: Is Anatomical Reduction of the Fracture Necessary?

Histologic Analysis of Postmeniscectomy Osteonecrosis

Orthopedic Grand Rounds Can Change Resident Practice

Girl, 13, With a Bump on Her Leg

A girl, age 13 years, 4 months, presented to her primary care provider’s office for a well visit. Among her concerns, she mentioned a “bump” she had had on her right leg “for the past six months, maybe longer.” The area felt irritated when touched or when the patient “ran too much.” She had seen no change in the bump since she first noticed it. The patient knew of no trauma or other preceding factors. She denied any fever or warmth, redness, or ecchymosis to the area.

Medical history was unremarkable except for familial short stature and myopia. The patient was the fifth of eight children born to nonconsanguinous parents. She denied any surgical history or hospitalizations and was premenarcheal. She was up to date on all age-appropriate vaccines, with her meningococcal vaccine administered at that visit.

The patient’s blood pressure was 99/58 mm Hg with an apical pulse rate of 82 beats/min. Her growth parameters were following her curve. Her height was 55” (0.3 percentile); weight, 81 lb (7.5 percentile); and BMI, 18.8 (48.6 percentile).

The physical exam was normal with the exception of the musculoskeletal exam. Examination of the lower extremities revealed a palpable, 4 cm x 5 cm lesion at the right distal medial thigh just proximal to the knee. The lesion could not be visualized but on palpation was tender and firm. There was some question as to whether the lesion itself or inflamed soft tissue overlying the lesion was mobile. No overlying warmth, induration, erythema, or ecchymosis was noted.

Passive and active range of motion was intact at the hip and knee. No lesions to the upper extremities were evident, and no scoliosis was seen.

Blood work was done to rule out certain diagnoses. Results from a complete blood count with differential, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), parathyroid hormone, lipid profiles, thyroid function, and a comprehensive metabolic profile were unremarkable. A low level of vitamin D 25-OH was detected: 21.7 ng/mL (normal range, 32 to 100 ng/mL).

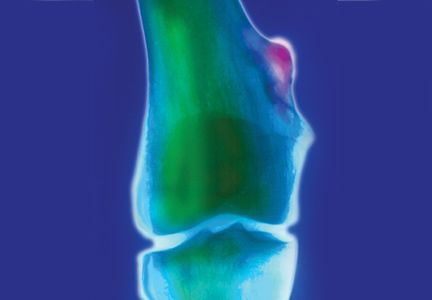

Distal femur x-rays with posteroanterior, lateral, and oblique views were ordered. The imaging revealed a 3 cm x 3 cm lesion projecting from the “distal, somewhat medial” femur, which was diagnosed as a benign femoral osteochondroma. Significant inflammation to the surrounding soft-tissue structures was observed. A questionable old fracture of the osteochondroma was noted. The remaining bony structures and joints appeared normal.

An ultrasound of the lesion was also ordered to investigate soft-tissue swelling. This revealed a hypoechoic collar around the distal end of the osteochondroma, which could represent a fluid collection, hematoma from trauma, or bursitis. The soft tissues were deemed normal.

Because of the extent of inflammation, the radiologist recommended MRI without contrast to rule out bursitis or trauma to the osteochondroma.

DISCUSSION

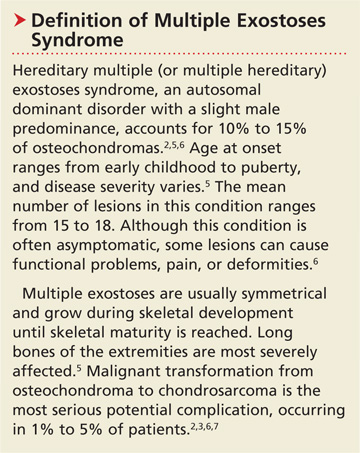

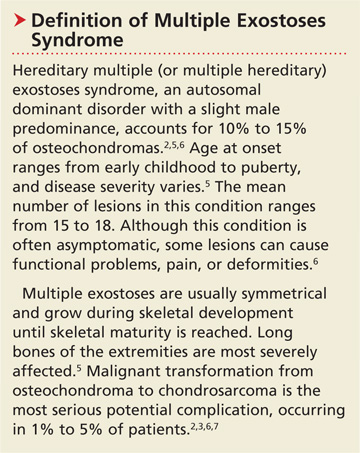

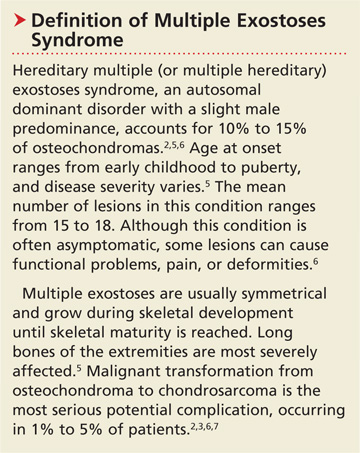

Osteochondromas, which may be present in up to 3% of the general population, are the most common benign bone tumors.1-3 An osteochondroma is a cartilage-capped bony projection that arises on the external surface of the bone; it contains a marrow cavity that is continuous with the underlying bone.2,4 The majority of osteochondromas are solitary, accounting for perhaps 85% to 90% of all such lesions, and they are typically nonhereditary; the remaining 10% to 15% of osteochondromas are hereditary multiple osteochondromas or exostoses1,2 (see “Definition of Multiple Exostoses Syndrome”2,5,6,7).

Most lesions are painless and slow growing, and they usually occur in children and adolescents.2 They typically stop growing at skeletal maturity with the closure of the growth plates.3,8,9 There is no predilection for males or females in single lesions.2

Solitary osteochondromas typically appear in the lower extremities and at long tubular bone metaphyses,1-3,10 especially on the femur, humerus, tibia, spine, and hip. Any part of the skeleton can be affected, but 30% of lesions occur on the femur and 40% at either the proximal metaphysis of the tibia or the distal metaphysis of the femur.2,11

Most osteochondromas are asymptomatic and are found incidentally.1,3 However, some patients present with local pain as a result of irritation to adjacent structures, limitation of joint motion, growth disturbance, or fracture of the pedicle.3,4,9,11,12 A very small proportion of patients (no more than 1%) with solitary osteochondromas experience malignant transformation.2,3,6,7 No particular blood work is recommended for patients with solitary osteochondromas.2

Differential Diagnosis

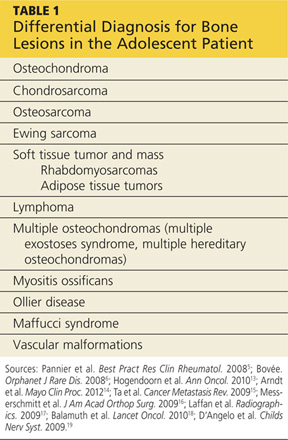

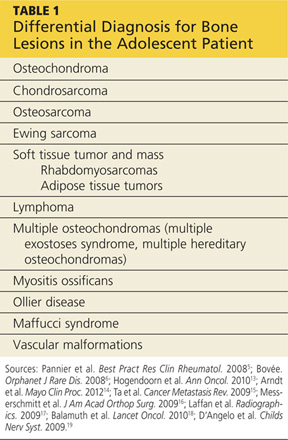

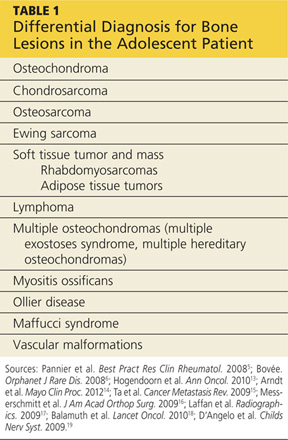

In addition to osteochondromas, several other lesions should be considered in the patient with musculoskeletal lesions (see Table 15,6,13-19).

Cartilaginous tumors. Chondrosarcomas are malignant cartilaginous tumors.20-22 They commonly affect long bones, including the humerus and femur, and some flat bones, such as the pelvic bones.13,22 They are most commonly seen in adults, and have no predisposition by gender.13

Chondrosarcomas can be primary (ie, arising de novo) or secondary (developing on preexisting benign cartilaginous neoplasms, including osteochondromas). The majority of chondrosarcomas are slow growing, and they rarely metastasize. It is difficult to differentiate between a benign lesion (such as an osteochondroma) and a chondrosarcoma by either histology or radiology. However, reliable predictors for malignancy include size exceeding 5 cm and location in the axial skeleton.20

Bone tumors.Osteosarcomas are the most common malignant bone tumors in children and adolescents, with 400 to 560 US patients in this age-group diagnosed each year.14-16 Osteosarcomas are uncommon in children younger than 10; their incidence peaks during the early teenage years (median peak age, 16), then declines rapidly among older patients. They are more common in males than females.15

Osteosarcomas commonly develop during periods of rapid bone turnover, such as the adolescent growth spurt. Common sites include the distal femur, proximal humerus, and proximal tibia,15,16 particularly near the knee.13 Usually, osteosarcomas present with nonspecific symptoms, including strain-related pain of several months’ duration, which may disrupt sleep.16 Laboratory findings in affected patients may include elevations in LDH, alkaline phosphatase, and/or ESR.15,23

Physical exam reveals a visible or palpable mass in the affected area, along with decreased joint motion; localized warmth or erythema may also be present. Late signs of osteosarcoma include weight loss, general malaise, and fever. First-line imaging for the patient with a suspected osteosarcoma is x-ray, which will show ill-defined borders, osteoblastic and/or osteolytic features, and an associated soft tissue mass. Advanced imaging, such as MRI, is warranted.16

Ewing sarcoma, the second most common bone tumor in children and adolescents, is an aggressive form of childhood cancer.14,18 Approximately 25% of all Ewing sarcomas arise in soft tissues rather than bones.18 They are more common in whites than in other ethnic groups and have a slight male predominance.13,18 The median age at diagnosis is 15.13 The most common presenting symptoms are tumor related, such as pain or a noticeable mass. While x-rays are usually ordered first, MRI is preferred.18

Soft tissue tumors and masses.Rhabdomyosarcomas are malignancies that account for more than half of the soft tissue sarcomas in children and adolescents. Less than one-fifth of cases occur in the extremities, and most occur in children younger than 10. These lesions have a slight male predominance and are more common in whites than in other patients.14,17,24

Approximately 6% of childhood soft tissue tumors are adipose tissue tumors, which may be benign (eg, lipomas) or malignant (eg, liposarcomas). Lipomas in children account for nearly 4% of all soft tissue tumors and can be classified as superficial (which are often diagnosed clinically) or deep (frequently requiring imaging).25

Lymphomaaccounts for 7% of cancers in US children and adolescents and more than 25% of newly diagnosed cancers in patients between 15 and 19, making it the most common malignancy in adolescents and the third most common in children.26,27 Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is the fourth leading type of malignancy in US adolescents.27 Rarely, lymphomas present with primary event soft tissue involvement.28

Myositis ossificans (MO) is a rare benign disorder involving formation of heterotrophic bone in skeletal muscles and soft tissues.29 Though possible in patients of any age, MO is most commonly seen in adolescents and young adults. Often the result of soft tissue injury (in which case it is referred to as myositis ossificans circumscripta or traumatic), MO develops in areas that are exposed to trauma, such as the anterior thighs or arms. Lesions can be diagnosed via plain x-ray or CT, although MRI and ultrasound can also be useful evaluation tools.17,29,30

Because MO circumscripta typically presents as a painful soft tissue mass, it can be mistaken for a soft tissue sarcoma or an osteosarcoma; radiologic evaluation is required to make the proper diagnosis. Less common forms of MO are myositis ossificans progressiva and myositis ossificans without a history of trauma.29

Ollier diseaseis a rare, nonfamilial disorder characterized by multiple enchondromas (or enchondromatoses), which are distributed asymmetrically with areas of dysplastic cartilage. Enchondromas are benign cartilage tumors that frequently affect long tubular bones along the metaphyses in proximity to the growth plate. The enchondromas result in significant growth abnormalities. About one in 1 million people are diagnosed yearly.5,19 (Similarly, Maffucci syndrome is represented by multiple enchondromas in association with hemangiomas.5)

Ollier disease typically manifests during childhood5 with bone swelling, local pain, and palpable bony masses, which are often associated with bone deformities.19 Patients generally present with an asymmetric shortening of one extremity and the appearance of palpable bony masses on their fingers or toes, which may or may not be associated with pathologic fractures.5,19 In 20% to 50% of patients with Ollier disease, enchondromas are at risk for malignant transformation into chondrosarcomas.5

Vascular malformations. Certain abnormalities of vascular development cause birthmarks and abnormalities of varying degree in underlying tissues.31 They are usually present at birth and grow proportionally to the child’s growth.25,31 However, they can also be seen in later childhood and adolescence.

Radiologic Investigation

Plain radiography of the affected area is the first-line radiologic study to be performed.13 While most osteochondromas can be diagnosed by plain x-ray, cross-sectional imaging via CT or MRI is recommended in lesions with certain characteristics, such as a broad stalk or location in the axial skeleton. Because MRI involves no radiation exposure, it is a particularly good diagnostic tool for children.32

Ultrasound is a good imaging method for evaluating for complications of osteochondromas, including bursa formation or vascular compromise.32

Treatment and Management

Although usually asymptomatic, osteochondroma can trigger some significant symptoms. Osteochondromas are at risk for fracture and can cause body deformities, mechanical joint problems, weakness of the affected limb, numbness, vascular compression, aneurysm, arterial thrombosis, venous thrombosis, pain, acute ischemia, and nerve compression. Clinical signs of malignant transformation include pain, swelling, and increased lesion size.2

Surgical excision is recommended but should be delayed until after the patient has reached skeletal maturity in order to decrease the risk for recurrence.33

Patient Education and Follow-up

In addition to explaining appropriate pain management (eg, NSAIDs), it is especially important for the pediatric NP or PA to encourage the patient with a solitary osteochondroma to follow up with the pediatric orthopedic surgeon. Reasons include the need to monitor growth of the lesion (which is likely to continue in a patient who has not yet reached skeletal maturity) and assess for associated functional or joint problems. Patients should also be advised to seek the specialist’s attention if such problems develop or if pain increases.

Generally, the pediatric clinician should be sufficiently informed to answer questions about this condition from the patient or family. Any follow-up laboratory work recommended by the specialist can also be performed by the pediatric NP or PA.

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

MRI without contrast, as recommended by the radiologist to rule out a bursa or trauma to the osteochondroma, was considered an important part of the follow-up plan. As the patient had not yet reached skeletal maturity, she was referred to a pediatric orthopedic surgeon for possible excision of the lesion, due to its size and the pain associated with running or other exertion.

CONCLUSION

Solitary osteochondromas are the most common benign bone tumors. Although they are generally asymptomatic, pain and other symptoms can arise as a result of irritation to the adjacent structures. In this case, the patient’s chief complaint was an irritating “bump” that she had had on her right leg for at least six months.

Generally, follow-up monitoring of the osteochondroma and orthopedic follow-up care are warranted, at least until the patient reaches skeletal maturity. At that point, surgical excision of the lesion is recommended.

REFERENCES

1. Florez B, Mönckeberg J, Castillo G, Beguiristain J. Solitary osteochondroma long-term follow-up. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2008;17:91-94.

2. Kitsoulis P, Galani V, Stefanaki K, et al. Osteochondromas: review of the clinical, radiological and pathological features. In Vivo. 2008;22:633-646.

3. Ramos-Pascua LR, Sánchez-Herráez S, Alonso-Barrio JA, Alonso-León A. Solitary proximal end of femur osteochondroma: an indication and result of the en bloc resection without hip luxation [in Spanish]. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2012;56:24-31.

4. Payne WT, Merrell G. Benign bony and soft tissue tumors of the hand. J Hand Surg. 2010;35:1901-1910.

5. Pannier S, Legeai-Mallet L. Hereditary multiple exostoses and enchondromatosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22:45-54.

6. Bovée JV. Multiple osteochondromas. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3(3).

7. Staals EL, Bacchini P, Mercuri M, Bertoni F. Dedifferentiated chondrosarcomas arising in preexisting osteochondromas. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:987-993.

8. Singh R, Jain M, Siwach R, et al. Large para-articular osteochondroma of the knee joint: a case report. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2012;46:139-143.

9. Lee JY, Lee S, Joo KB, et al. Intraarticular osteochondroma of shoulder: a case report. Clin Imaging. 2013;37:379-381.

10. Kim Y-C, Ahn JH, Lee JW. Osteochondroma of the distal tibia complicated by a tibialis posterior tendon tear. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2012;51: 660-663.

11. Allagui M, Amara K, Aloui I, et al. Historical giant near-circumferential osteochondroma of the proximal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:e12-e15.

12. Li M, Luettringhaus T, Walker KR, Cole PA. Operative treatment of femoral neck osteochondroma through a digastric approach in a pediatric patient: a case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2012;21:230-234.

13. Hogendoorn PC, Athanasou N, Bielack S, et al; ESMO/EUROBONET Working Group. Bone sarcomas: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21 suppl 5:v204-v213.

14. Arndt CAS, Rose PS, Folpe AL, Laack NN. Common musculoskeletal tumors of childhood and adolescence. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:475-487.

15. Ta HT, Dass CR, Choong PF, Dunstan DE. Osteosarcoma treatment: state of the art. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:247-263.

16. Messerschmitt PJ, Garcia RM, Abdul-Karim FW, et al. Osteosarcoma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17:515-527.

17. Laffan EE, Ngan B-Y, Navarro OM. Pediatric soft-tissue tumors and pseudotumors: MR imaging features with pathologic correlation: Part 2. Tumors of fibroblastic/myofibroblastic, so-called fibrohistiocytic, muscular, lymphomatous, neurogenic, hair matrix, and uncertain origin. Radiographics. 2009;29:e36.

18. Balamuth NJ, Womer RB. Ewing’s sarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(2):184.

19. D’Angelo L, Massimi L, Narducci A, Di Rocco C. Ollier disease. Childs Nerv Syst. 2009;25:647-653.

20. Gelderblom H, Hogendoorn PC, Dijkstra SD, et al. The clinical approach towards chondrosarcoma. Oncologist. 2008;13:320-329.

21. Nosratzehi T, Pakfetrat A. Chondrosarcoma. Zahedan J Res Med Sci. 2013;15:64-64.

22. Prado FO, Nishimoto IN, Perez DE, et al. Head and neck chondrosarcoma: analysis of 16 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 2009;47:555-557.

23. Kim HJ, Chalmers PN, Morris CD. Pediatric osteogenic sarcoma. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22:61-66.

24. Sultan I, Qaddoumi I, Yaser S, et al. Comparing adult and pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma in the surveillance, epidemiology and end results program, 1973 to 2005: an analysis of 2,600 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3391-3397.

25. Navarro OM, Laffan EE, Ngan B-Y. Pediatric soft-tissue tumors and pseudo-tumors: MR imaging features with pathologic correlation: Part 1. Imaging approach, pseudotumors, vascular lesions, and adipocytic tumors. Radiographics. 2009;29:887-906.

26. Gross TG, Termuhlen AM. Pediatric non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2008;3:167-173.

27. Hochberg J, Waxman IM, Kelly KM, et al. Adolescent non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin lymphoma: state of the science. Br J Haematol. 2009;144:24-40.

28. Derenzini E, Casadei B, Pellegrini C, et al. Non-Hodgkin lymphomas presenting as soft tissue masses: A single center experience and meta-analysis of the published series. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2012 Dec 12. [Epub ahead of print]

29. Micheli A, Trapani S, Brizzi I, et al. Myositis ossificans circumscripta: a paediatric case and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:523-529.

30. McKenzie G, Raby N, Ritchie D. Non-neoplastic soft-tissue masses. Br J Radiol. 2009;82:775-785.

31. Buckmiller LM, Richter GT, Suen JY. Diagnosis and management of hemangiomas and vascular malformations of the head and neck. Oral Dis. 2010;16:405-418.

32. Khanna G, Bennett DL. Pediatric bone lesions: beyond the plain radiographic evaluation. Semin Roentgenol. 2012;47:90-99.

33. Rijal L, Nepal P, Baral S, et al. Solitary diaphyseal exostosis of femur, how common is it? Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2011;21:363-365.

A girl, age 13 years, 4 months, presented to her primary care provider’s office for a well visit. Among her concerns, she mentioned a “bump” she had had on her right leg “for the past six months, maybe longer.” The area felt irritated when touched or when the patient “ran too much.” She had seen no change in the bump since she first noticed it. The patient knew of no trauma or other preceding factors. She denied any fever or warmth, redness, or ecchymosis to the area.

Medical history was unremarkable except for familial short stature and myopia. The patient was the fifth of eight children born to nonconsanguinous parents. She denied any surgical history or hospitalizations and was premenarcheal. She was up to date on all age-appropriate vaccines, with her meningococcal vaccine administered at that visit.

The patient’s blood pressure was 99/58 mm Hg with an apical pulse rate of 82 beats/min. Her growth parameters were following her curve. Her height was 55” (0.3 percentile); weight, 81 lb (7.5 percentile); and BMI, 18.8 (48.6 percentile).

The physical exam was normal with the exception of the musculoskeletal exam. Examination of the lower extremities revealed a palpable, 4 cm x 5 cm lesion at the right distal medial thigh just proximal to the knee. The lesion could not be visualized but on palpation was tender and firm. There was some question as to whether the lesion itself or inflamed soft tissue overlying the lesion was mobile. No overlying warmth, induration, erythema, or ecchymosis was noted.

Passive and active range of motion was intact at the hip and knee. No lesions to the upper extremities were evident, and no scoliosis was seen.

Blood work was done to rule out certain diagnoses. Results from a complete blood count with differential, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), parathyroid hormone, lipid profiles, thyroid function, and a comprehensive metabolic profile were unremarkable. A low level of vitamin D 25-OH was detected: 21.7 ng/mL (normal range, 32 to 100 ng/mL).

Distal femur x-rays with posteroanterior, lateral, and oblique views were ordered. The imaging revealed a 3 cm x 3 cm lesion projecting from the “distal, somewhat medial” femur, which was diagnosed as a benign femoral osteochondroma. Significant inflammation to the surrounding soft-tissue structures was observed. A questionable old fracture of the osteochondroma was noted. The remaining bony structures and joints appeared normal.

An ultrasound of the lesion was also ordered to investigate soft-tissue swelling. This revealed a hypoechoic collar around the distal end of the osteochondroma, which could represent a fluid collection, hematoma from trauma, or bursitis. The soft tissues were deemed normal.

Because of the extent of inflammation, the radiologist recommended MRI without contrast to rule out bursitis or trauma to the osteochondroma.

DISCUSSION

Osteochondromas, which may be present in up to 3% of the general population, are the most common benign bone tumors.1-3 An osteochondroma is a cartilage-capped bony projection that arises on the external surface of the bone; it contains a marrow cavity that is continuous with the underlying bone.2,4 The majority of osteochondromas are solitary, accounting for perhaps 85% to 90% of all such lesions, and they are typically nonhereditary; the remaining 10% to 15% of osteochondromas are hereditary multiple osteochondromas or exostoses1,2 (see “Definition of Multiple Exostoses Syndrome”2,5,6,7).

Most lesions are painless and slow growing, and they usually occur in children and adolescents.2 They typically stop growing at skeletal maturity with the closure of the growth plates.3,8,9 There is no predilection for males or females in single lesions.2

Solitary osteochondromas typically appear in the lower extremities and at long tubular bone metaphyses,1-3,10 especially on the femur, humerus, tibia, spine, and hip. Any part of the skeleton can be affected, but 30% of lesions occur on the femur and 40% at either the proximal metaphysis of the tibia or the distal metaphysis of the femur.2,11

Most osteochondromas are asymptomatic and are found incidentally.1,3 However, some patients present with local pain as a result of irritation to adjacent structures, limitation of joint motion, growth disturbance, or fracture of the pedicle.3,4,9,11,12 A very small proportion of patients (no more than 1%) with solitary osteochondromas experience malignant transformation.2,3,6,7 No particular blood work is recommended for patients with solitary osteochondromas.2

Differential Diagnosis

In addition to osteochondromas, several other lesions should be considered in the patient with musculoskeletal lesions (see Table 15,6,13-19).

Cartilaginous tumors. Chondrosarcomas are malignant cartilaginous tumors.20-22 They commonly affect long bones, including the humerus and femur, and some flat bones, such as the pelvic bones.13,22 They are most commonly seen in adults, and have no predisposition by gender.13

Chondrosarcomas can be primary (ie, arising de novo) or secondary (developing on preexisting benign cartilaginous neoplasms, including osteochondromas). The majority of chondrosarcomas are slow growing, and they rarely metastasize. It is difficult to differentiate between a benign lesion (such as an osteochondroma) and a chondrosarcoma by either histology or radiology. However, reliable predictors for malignancy include size exceeding 5 cm and location in the axial skeleton.20

Bone tumors.Osteosarcomas are the most common malignant bone tumors in children and adolescents, with 400 to 560 US patients in this age-group diagnosed each year.14-16 Osteosarcomas are uncommon in children younger than 10; their incidence peaks during the early teenage years (median peak age, 16), then declines rapidly among older patients. They are more common in males than females.15

Osteosarcomas commonly develop during periods of rapid bone turnover, such as the adolescent growth spurt. Common sites include the distal femur, proximal humerus, and proximal tibia,15,16 particularly near the knee.13 Usually, osteosarcomas present with nonspecific symptoms, including strain-related pain of several months’ duration, which may disrupt sleep.16 Laboratory findings in affected patients may include elevations in LDH, alkaline phosphatase, and/or ESR.15,23

Physical exam reveals a visible or palpable mass in the affected area, along with decreased joint motion; localized warmth or erythema may also be present. Late signs of osteosarcoma include weight loss, general malaise, and fever. First-line imaging for the patient with a suspected osteosarcoma is x-ray, which will show ill-defined borders, osteoblastic and/or osteolytic features, and an associated soft tissue mass. Advanced imaging, such as MRI, is warranted.16

Ewing sarcoma, the second most common bone tumor in children and adolescents, is an aggressive form of childhood cancer.14,18 Approximately 25% of all Ewing sarcomas arise in soft tissues rather than bones.18 They are more common in whites than in other ethnic groups and have a slight male predominance.13,18 The median age at diagnosis is 15.13 The most common presenting symptoms are tumor related, such as pain or a noticeable mass. While x-rays are usually ordered first, MRI is preferred.18

Soft tissue tumors and masses.Rhabdomyosarcomas are malignancies that account for more than half of the soft tissue sarcomas in children and adolescents. Less than one-fifth of cases occur in the extremities, and most occur in children younger than 10. These lesions have a slight male predominance and are more common in whites than in other patients.14,17,24

Approximately 6% of childhood soft tissue tumors are adipose tissue tumors, which may be benign (eg, lipomas) or malignant (eg, liposarcomas). Lipomas in children account for nearly 4% of all soft tissue tumors and can be classified as superficial (which are often diagnosed clinically) or deep (frequently requiring imaging).25

Lymphomaaccounts for 7% of cancers in US children and adolescents and more than 25% of newly diagnosed cancers in patients between 15 and 19, making it the most common malignancy in adolescents and the third most common in children.26,27 Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is the fourth leading type of malignancy in US adolescents.27 Rarely, lymphomas present with primary event soft tissue involvement.28

Myositis ossificans (MO) is a rare benign disorder involving formation of heterotrophic bone in skeletal muscles and soft tissues.29 Though possible in patients of any age, MO is most commonly seen in adolescents and young adults. Often the result of soft tissue injury (in which case it is referred to as myositis ossificans circumscripta or traumatic), MO develops in areas that are exposed to trauma, such as the anterior thighs or arms. Lesions can be diagnosed via plain x-ray or CT, although MRI and ultrasound can also be useful evaluation tools.17,29,30

Because MO circumscripta typically presents as a painful soft tissue mass, it can be mistaken for a soft tissue sarcoma or an osteosarcoma; radiologic evaluation is required to make the proper diagnosis. Less common forms of MO are myositis ossificans progressiva and myositis ossificans without a history of trauma.29

Ollier diseaseis a rare, nonfamilial disorder characterized by multiple enchondromas (or enchondromatoses), which are distributed asymmetrically with areas of dysplastic cartilage. Enchondromas are benign cartilage tumors that frequently affect long tubular bones along the metaphyses in proximity to the growth plate. The enchondromas result in significant growth abnormalities. About one in 1 million people are diagnosed yearly.5,19 (Similarly, Maffucci syndrome is represented by multiple enchondromas in association with hemangiomas.5)

Ollier disease typically manifests during childhood5 with bone swelling, local pain, and palpable bony masses, which are often associated with bone deformities.19 Patients generally present with an asymmetric shortening of one extremity and the appearance of palpable bony masses on their fingers or toes, which may or may not be associated with pathologic fractures.5,19 In 20% to 50% of patients with Ollier disease, enchondromas are at risk for malignant transformation into chondrosarcomas.5

Vascular malformations. Certain abnormalities of vascular development cause birthmarks and abnormalities of varying degree in underlying tissues.31 They are usually present at birth and grow proportionally to the child’s growth.25,31 However, they can also be seen in later childhood and adolescence.

Radiologic Investigation

Plain radiography of the affected area is the first-line radiologic study to be performed.13 While most osteochondromas can be diagnosed by plain x-ray, cross-sectional imaging via CT or MRI is recommended in lesions with certain characteristics, such as a broad stalk or location in the axial skeleton. Because MRI involves no radiation exposure, it is a particularly good diagnostic tool for children.32

Ultrasound is a good imaging method for evaluating for complications of osteochondromas, including bursa formation or vascular compromise.32

Treatment and Management

Although usually asymptomatic, osteochondroma can trigger some significant symptoms. Osteochondromas are at risk for fracture and can cause body deformities, mechanical joint problems, weakness of the affected limb, numbness, vascular compression, aneurysm, arterial thrombosis, venous thrombosis, pain, acute ischemia, and nerve compression. Clinical signs of malignant transformation include pain, swelling, and increased lesion size.2

Surgical excision is recommended but should be delayed until after the patient has reached skeletal maturity in order to decrease the risk for recurrence.33

Patient Education and Follow-up

In addition to explaining appropriate pain management (eg, NSAIDs), it is especially important for the pediatric NP or PA to encourage the patient with a solitary osteochondroma to follow up with the pediatric orthopedic surgeon. Reasons include the need to monitor growth of the lesion (which is likely to continue in a patient who has not yet reached skeletal maturity) and assess for associated functional or joint problems. Patients should also be advised to seek the specialist’s attention if such problems develop or if pain increases.

Generally, the pediatric clinician should be sufficiently informed to answer questions about this condition from the patient or family. Any follow-up laboratory work recommended by the specialist can also be performed by the pediatric NP or PA.

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

MRI without contrast, as recommended by the radiologist to rule out a bursa or trauma to the osteochondroma, was considered an important part of the follow-up plan. As the patient had not yet reached skeletal maturity, she was referred to a pediatric orthopedic surgeon for possible excision of the lesion, due to its size and the pain associated with running or other exertion.

CONCLUSION

Solitary osteochondromas are the most common benign bone tumors. Although they are generally asymptomatic, pain and other symptoms can arise as a result of irritation to the adjacent structures. In this case, the patient’s chief complaint was an irritating “bump” that she had had on her right leg for at least six months.

Generally, follow-up monitoring of the osteochondroma and orthopedic follow-up care are warranted, at least until the patient reaches skeletal maturity. At that point, surgical excision of the lesion is recommended.

REFERENCES

1. Florez B, Mönckeberg J, Castillo G, Beguiristain J. Solitary osteochondroma long-term follow-up. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2008;17:91-94.

2. Kitsoulis P, Galani V, Stefanaki K, et al. Osteochondromas: review of the clinical, radiological and pathological features. In Vivo. 2008;22:633-646.

3. Ramos-Pascua LR, Sánchez-Herráez S, Alonso-Barrio JA, Alonso-León A. Solitary proximal end of femur osteochondroma: an indication and result of the en bloc resection without hip luxation [in Spanish]. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2012;56:24-31.

4. Payne WT, Merrell G. Benign bony and soft tissue tumors of the hand. J Hand Surg. 2010;35:1901-1910.

5. Pannier S, Legeai-Mallet L. Hereditary multiple exostoses and enchondromatosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22:45-54.

6. Bovée JV. Multiple osteochondromas. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3(3).

7. Staals EL, Bacchini P, Mercuri M, Bertoni F. Dedifferentiated chondrosarcomas arising in preexisting osteochondromas. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:987-993.

8. Singh R, Jain M, Siwach R, et al. Large para-articular osteochondroma of the knee joint: a case report. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2012;46:139-143.

9. Lee JY, Lee S, Joo KB, et al. Intraarticular osteochondroma of shoulder: a case report. Clin Imaging. 2013;37:379-381.

10. Kim Y-C, Ahn JH, Lee JW. Osteochondroma of the distal tibia complicated by a tibialis posterior tendon tear. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2012;51: 660-663.

11. Allagui M, Amara K, Aloui I, et al. Historical giant near-circumferential osteochondroma of the proximal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:e12-e15.

12. Li M, Luettringhaus T, Walker KR, Cole PA. Operative treatment of femoral neck osteochondroma through a digastric approach in a pediatric patient: a case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2012;21:230-234.

13. Hogendoorn PC, Athanasou N, Bielack S, et al; ESMO/EUROBONET Working Group. Bone sarcomas: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21 suppl 5:v204-v213.

14. Arndt CAS, Rose PS, Folpe AL, Laack NN. Common musculoskeletal tumors of childhood and adolescence. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:475-487.

15. Ta HT, Dass CR, Choong PF, Dunstan DE. Osteosarcoma treatment: state of the art. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:247-263.

16. Messerschmitt PJ, Garcia RM, Abdul-Karim FW, et al. Osteosarcoma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17:515-527.

17. Laffan EE, Ngan B-Y, Navarro OM. Pediatric soft-tissue tumors and pseudotumors: MR imaging features with pathologic correlation: Part 2. Tumors of fibroblastic/myofibroblastic, so-called fibrohistiocytic, muscular, lymphomatous, neurogenic, hair matrix, and uncertain origin. Radiographics. 2009;29:e36.

18. Balamuth NJ, Womer RB. Ewing’s sarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(2):184.

19. D’Angelo L, Massimi L, Narducci A, Di Rocco C. Ollier disease. Childs Nerv Syst. 2009;25:647-653.

20. Gelderblom H, Hogendoorn PC, Dijkstra SD, et al. The clinical approach towards chondrosarcoma. Oncologist. 2008;13:320-329.

21. Nosratzehi T, Pakfetrat A. Chondrosarcoma. Zahedan J Res Med Sci. 2013;15:64-64.

22. Prado FO, Nishimoto IN, Perez DE, et al. Head and neck chondrosarcoma: analysis of 16 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 2009;47:555-557.

23. Kim HJ, Chalmers PN, Morris CD. Pediatric osteogenic sarcoma. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22:61-66.

24. Sultan I, Qaddoumi I, Yaser S, et al. Comparing adult and pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma in the surveillance, epidemiology and end results program, 1973 to 2005: an analysis of 2,600 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3391-3397.

25. Navarro OM, Laffan EE, Ngan B-Y. Pediatric soft-tissue tumors and pseudo-tumors: MR imaging features with pathologic correlation: Part 1. Imaging approach, pseudotumors, vascular lesions, and adipocytic tumors. Radiographics. 2009;29:887-906.

26. Gross TG, Termuhlen AM. Pediatric non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2008;3:167-173.

27. Hochberg J, Waxman IM, Kelly KM, et al. Adolescent non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin lymphoma: state of the science. Br J Haematol. 2009;144:24-40.

28. Derenzini E, Casadei B, Pellegrini C, et al. Non-Hodgkin lymphomas presenting as soft tissue masses: A single center experience and meta-analysis of the published series. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2012 Dec 12. [Epub ahead of print]

29. Micheli A, Trapani S, Brizzi I, et al. Myositis ossificans circumscripta: a paediatric case and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:523-529.

30. McKenzie G, Raby N, Ritchie D. Non-neoplastic soft-tissue masses. Br J Radiol. 2009;82:775-785.

31. Buckmiller LM, Richter GT, Suen JY. Diagnosis and management of hemangiomas and vascular malformations of the head and neck. Oral Dis. 2010;16:405-418.

32. Khanna G, Bennett DL. Pediatric bone lesions: beyond the plain radiographic evaluation. Semin Roentgenol. 2012;47:90-99.

33. Rijal L, Nepal P, Baral S, et al. Solitary diaphyseal exostosis of femur, how common is it? Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2011;21:363-365.

A girl, age 13 years, 4 months, presented to her primary care provider’s office for a well visit. Among her concerns, she mentioned a “bump” she had had on her right leg “for the past six months, maybe longer.” The area felt irritated when touched or when the patient “ran too much.” She had seen no change in the bump since she first noticed it. The patient knew of no trauma or other preceding factors. She denied any fever or warmth, redness, or ecchymosis to the area.

Medical history was unremarkable except for familial short stature and myopia. The patient was the fifth of eight children born to nonconsanguinous parents. She denied any surgical history or hospitalizations and was premenarcheal. She was up to date on all age-appropriate vaccines, with her meningococcal vaccine administered at that visit.

The patient’s blood pressure was 99/58 mm Hg with an apical pulse rate of 82 beats/min. Her growth parameters were following her curve. Her height was 55” (0.3 percentile); weight, 81 lb (7.5 percentile); and BMI, 18.8 (48.6 percentile).

The physical exam was normal with the exception of the musculoskeletal exam. Examination of the lower extremities revealed a palpable, 4 cm x 5 cm lesion at the right distal medial thigh just proximal to the knee. The lesion could not be visualized but on palpation was tender and firm. There was some question as to whether the lesion itself or inflamed soft tissue overlying the lesion was mobile. No overlying warmth, induration, erythema, or ecchymosis was noted.

Passive and active range of motion was intact at the hip and knee. No lesions to the upper extremities were evident, and no scoliosis was seen.

Blood work was done to rule out certain diagnoses. Results from a complete blood count with differential, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), parathyroid hormone, lipid profiles, thyroid function, and a comprehensive metabolic profile were unremarkable. A low level of vitamin D 25-OH was detected: 21.7 ng/mL (normal range, 32 to 100 ng/mL).

Distal femur x-rays with posteroanterior, lateral, and oblique views were ordered. The imaging revealed a 3 cm x 3 cm lesion projecting from the “distal, somewhat medial” femur, which was diagnosed as a benign femoral osteochondroma. Significant inflammation to the surrounding soft-tissue structures was observed. A questionable old fracture of the osteochondroma was noted. The remaining bony structures and joints appeared normal.

An ultrasound of the lesion was also ordered to investigate soft-tissue swelling. This revealed a hypoechoic collar around the distal end of the osteochondroma, which could represent a fluid collection, hematoma from trauma, or bursitis. The soft tissues were deemed normal.

Because of the extent of inflammation, the radiologist recommended MRI without contrast to rule out bursitis or trauma to the osteochondroma.

DISCUSSION

Osteochondromas, which may be present in up to 3% of the general population, are the most common benign bone tumors.1-3 An osteochondroma is a cartilage-capped bony projection that arises on the external surface of the bone; it contains a marrow cavity that is continuous with the underlying bone.2,4 The majority of osteochondromas are solitary, accounting for perhaps 85% to 90% of all such lesions, and they are typically nonhereditary; the remaining 10% to 15% of osteochondromas are hereditary multiple osteochondromas or exostoses1,2 (see “Definition of Multiple Exostoses Syndrome”2,5,6,7).

Most lesions are painless and slow growing, and they usually occur in children and adolescents.2 They typically stop growing at skeletal maturity with the closure of the growth plates.3,8,9 There is no predilection for males or females in single lesions.2

Solitary osteochondromas typically appear in the lower extremities and at long tubular bone metaphyses,1-3,10 especially on the femur, humerus, tibia, spine, and hip. Any part of the skeleton can be affected, but 30% of lesions occur on the femur and 40% at either the proximal metaphysis of the tibia or the distal metaphysis of the femur.2,11

Most osteochondromas are asymptomatic and are found incidentally.1,3 However, some patients present with local pain as a result of irritation to adjacent structures, limitation of joint motion, growth disturbance, or fracture of the pedicle.3,4,9,11,12 A very small proportion of patients (no more than 1%) with solitary osteochondromas experience malignant transformation.2,3,6,7 No particular blood work is recommended for patients with solitary osteochondromas.2

Differential Diagnosis

In addition to osteochondromas, several other lesions should be considered in the patient with musculoskeletal lesions (see Table 15,6,13-19).

Cartilaginous tumors. Chondrosarcomas are malignant cartilaginous tumors.20-22 They commonly affect long bones, including the humerus and femur, and some flat bones, such as the pelvic bones.13,22 They are most commonly seen in adults, and have no predisposition by gender.13

Chondrosarcomas can be primary (ie, arising de novo) or secondary (developing on preexisting benign cartilaginous neoplasms, including osteochondromas). The majority of chondrosarcomas are slow growing, and they rarely metastasize. It is difficult to differentiate between a benign lesion (such as an osteochondroma) and a chondrosarcoma by either histology or radiology. However, reliable predictors for malignancy include size exceeding 5 cm and location in the axial skeleton.20

Bone tumors.Osteosarcomas are the most common malignant bone tumors in children and adolescents, with 400 to 560 US patients in this age-group diagnosed each year.14-16 Osteosarcomas are uncommon in children younger than 10; their incidence peaks during the early teenage years (median peak age, 16), then declines rapidly among older patients. They are more common in males than females.15

Osteosarcomas commonly develop during periods of rapid bone turnover, such as the adolescent growth spurt. Common sites include the distal femur, proximal humerus, and proximal tibia,15,16 particularly near the knee.13 Usually, osteosarcomas present with nonspecific symptoms, including strain-related pain of several months’ duration, which may disrupt sleep.16 Laboratory findings in affected patients may include elevations in LDH, alkaline phosphatase, and/or ESR.15,23

Physical exam reveals a visible or palpable mass in the affected area, along with decreased joint motion; localized warmth or erythema may also be present. Late signs of osteosarcoma include weight loss, general malaise, and fever. First-line imaging for the patient with a suspected osteosarcoma is x-ray, which will show ill-defined borders, osteoblastic and/or osteolytic features, and an associated soft tissue mass. Advanced imaging, such as MRI, is warranted.16

Ewing sarcoma, the second most common bone tumor in children and adolescents, is an aggressive form of childhood cancer.14,18 Approximately 25% of all Ewing sarcomas arise in soft tissues rather than bones.18 They are more common in whites than in other ethnic groups and have a slight male predominance.13,18 The median age at diagnosis is 15.13 The most common presenting symptoms are tumor related, such as pain or a noticeable mass. While x-rays are usually ordered first, MRI is preferred.18

Soft tissue tumors and masses.Rhabdomyosarcomas are malignancies that account for more than half of the soft tissue sarcomas in children and adolescents. Less than one-fifth of cases occur in the extremities, and most occur in children younger than 10. These lesions have a slight male predominance and are more common in whites than in other patients.14,17,24

Approximately 6% of childhood soft tissue tumors are adipose tissue tumors, which may be benign (eg, lipomas) or malignant (eg, liposarcomas). Lipomas in children account for nearly 4% of all soft tissue tumors and can be classified as superficial (which are often diagnosed clinically) or deep (frequently requiring imaging).25

Lymphomaaccounts for 7% of cancers in US children and adolescents and more than 25% of newly diagnosed cancers in patients between 15 and 19, making it the most common malignancy in adolescents and the third most common in children.26,27 Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is the fourth leading type of malignancy in US adolescents.27 Rarely, lymphomas present with primary event soft tissue involvement.28

Myositis ossificans (MO) is a rare benign disorder involving formation of heterotrophic bone in skeletal muscles and soft tissues.29 Though possible in patients of any age, MO is most commonly seen in adolescents and young adults. Often the result of soft tissue injury (in which case it is referred to as myositis ossificans circumscripta or traumatic), MO develops in areas that are exposed to trauma, such as the anterior thighs or arms. Lesions can be diagnosed via plain x-ray or CT, although MRI and ultrasound can also be useful evaluation tools.17,29,30

Because MO circumscripta typically presents as a painful soft tissue mass, it can be mistaken for a soft tissue sarcoma or an osteosarcoma; radiologic evaluation is required to make the proper diagnosis. Less common forms of MO are myositis ossificans progressiva and myositis ossificans without a history of trauma.29

Ollier diseaseis a rare, nonfamilial disorder characterized by multiple enchondromas (or enchondromatoses), which are distributed asymmetrically with areas of dysplastic cartilage. Enchondromas are benign cartilage tumors that frequently affect long tubular bones along the metaphyses in proximity to the growth plate. The enchondromas result in significant growth abnormalities. About one in 1 million people are diagnosed yearly.5,19 (Similarly, Maffucci syndrome is represented by multiple enchondromas in association with hemangiomas.5)

Ollier disease typically manifests during childhood5 with bone swelling, local pain, and palpable bony masses, which are often associated with bone deformities.19 Patients generally present with an asymmetric shortening of one extremity and the appearance of palpable bony masses on their fingers or toes, which may or may not be associated with pathologic fractures.5,19 In 20% to 50% of patients with Ollier disease, enchondromas are at risk for malignant transformation into chondrosarcomas.5

Vascular malformations. Certain abnormalities of vascular development cause birthmarks and abnormalities of varying degree in underlying tissues.31 They are usually present at birth and grow proportionally to the child’s growth.25,31 However, they can also be seen in later childhood and adolescence.

Radiologic Investigation

Plain radiography of the affected area is the first-line radiologic study to be performed.13 While most osteochondromas can be diagnosed by plain x-ray, cross-sectional imaging via CT or MRI is recommended in lesions with certain characteristics, such as a broad stalk or location in the axial skeleton. Because MRI involves no radiation exposure, it is a particularly good diagnostic tool for children.32

Ultrasound is a good imaging method for evaluating for complications of osteochondromas, including bursa formation or vascular compromise.32

Treatment and Management

Although usually asymptomatic, osteochondroma can trigger some significant symptoms. Osteochondromas are at risk for fracture and can cause body deformities, mechanical joint problems, weakness of the affected limb, numbness, vascular compression, aneurysm, arterial thrombosis, venous thrombosis, pain, acute ischemia, and nerve compression. Clinical signs of malignant transformation include pain, swelling, and increased lesion size.2

Surgical excision is recommended but should be delayed until after the patient has reached skeletal maturity in order to decrease the risk for recurrence.33

Patient Education and Follow-up

In addition to explaining appropriate pain management (eg, NSAIDs), it is especially important for the pediatric NP or PA to encourage the patient with a solitary osteochondroma to follow up with the pediatric orthopedic surgeon. Reasons include the need to monitor growth of the lesion (which is likely to continue in a patient who has not yet reached skeletal maturity) and assess for associated functional or joint problems. Patients should also be advised to seek the specialist’s attention if such problems develop or if pain increases.

Generally, the pediatric clinician should be sufficiently informed to answer questions about this condition from the patient or family. Any follow-up laboratory work recommended by the specialist can also be performed by the pediatric NP or PA.

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

MRI without contrast, as recommended by the radiologist to rule out a bursa or trauma to the osteochondroma, was considered an important part of the follow-up plan. As the patient had not yet reached skeletal maturity, she was referred to a pediatric orthopedic surgeon for possible excision of the lesion, due to its size and the pain associated with running or other exertion.

CONCLUSION

Solitary osteochondromas are the most common benign bone tumors. Although they are generally asymptomatic, pain and other symptoms can arise as a result of irritation to the adjacent structures. In this case, the patient’s chief complaint was an irritating “bump” that she had had on her right leg for at least six months.

Generally, follow-up monitoring of the osteochondroma and orthopedic follow-up care are warranted, at least until the patient reaches skeletal maturity. At that point, surgical excision of the lesion is recommended.

REFERENCES

1. Florez B, Mönckeberg J, Castillo G, Beguiristain J. Solitary osteochondroma long-term follow-up. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2008;17:91-94.

2. Kitsoulis P, Galani V, Stefanaki K, et al. Osteochondromas: review of the clinical, radiological and pathological features. In Vivo. 2008;22:633-646.

3. Ramos-Pascua LR, Sánchez-Herráez S, Alonso-Barrio JA, Alonso-León A. Solitary proximal end of femur osteochondroma: an indication and result of the en bloc resection without hip luxation [in Spanish]. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2012;56:24-31.

4. Payne WT, Merrell G. Benign bony and soft tissue tumors of the hand. J Hand Surg. 2010;35:1901-1910.

5. Pannier S, Legeai-Mallet L. Hereditary multiple exostoses and enchondromatosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22:45-54.

6. Bovée JV. Multiple osteochondromas. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3(3).

7. Staals EL, Bacchini P, Mercuri M, Bertoni F. Dedifferentiated chondrosarcomas arising in preexisting osteochondromas. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:987-993.

8. Singh R, Jain M, Siwach R, et al. Large para-articular osteochondroma of the knee joint: a case report. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2012;46:139-143.

9. Lee JY, Lee S, Joo KB, et al. Intraarticular osteochondroma of shoulder: a case report. Clin Imaging. 2013;37:379-381.

10. Kim Y-C, Ahn JH, Lee JW. Osteochondroma of the distal tibia complicated by a tibialis posterior tendon tear. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2012;51: 660-663.

11. Allagui M, Amara K, Aloui I, et al. Historical giant near-circumferential osteochondroma of the proximal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:e12-e15.

12. Li M, Luettringhaus T, Walker KR, Cole PA. Operative treatment of femoral neck osteochondroma through a digastric approach in a pediatric patient: a case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2012;21:230-234.

13. Hogendoorn PC, Athanasou N, Bielack S, et al; ESMO/EUROBONET Working Group. Bone sarcomas: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21 suppl 5:v204-v213.

14. Arndt CAS, Rose PS, Folpe AL, Laack NN. Common musculoskeletal tumors of childhood and adolescence. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:475-487.

15. Ta HT, Dass CR, Choong PF, Dunstan DE. Osteosarcoma treatment: state of the art. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:247-263.

16. Messerschmitt PJ, Garcia RM, Abdul-Karim FW, et al. Osteosarcoma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17:515-527.

17. Laffan EE, Ngan B-Y, Navarro OM. Pediatric soft-tissue tumors and pseudotumors: MR imaging features with pathologic correlation: Part 2. Tumors of fibroblastic/myofibroblastic, so-called fibrohistiocytic, muscular, lymphomatous, neurogenic, hair matrix, and uncertain origin. Radiographics. 2009;29:e36.

18. Balamuth NJ, Womer RB. Ewing’s sarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(2):184.

19. D’Angelo L, Massimi L, Narducci A, Di Rocco C. Ollier disease. Childs Nerv Syst. 2009;25:647-653.

20. Gelderblom H, Hogendoorn PC, Dijkstra SD, et al. The clinical approach towards chondrosarcoma. Oncologist. 2008;13:320-329.

21. Nosratzehi T, Pakfetrat A. Chondrosarcoma. Zahedan J Res Med Sci. 2013;15:64-64.

22. Prado FO, Nishimoto IN, Perez DE, et al. Head and neck chondrosarcoma: analysis of 16 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 2009;47:555-557.

23. Kim HJ, Chalmers PN, Morris CD. Pediatric osteogenic sarcoma. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22:61-66.

24. Sultan I, Qaddoumi I, Yaser S, et al. Comparing adult and pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma in the surveillance, epidemiology and end results program, 1973 to 2005: an analysis of 2,600 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3391-3397.

25. Navarro OM, Laffan EE, Ngan B-Y. Pediatric soft-tissue tumors and pseudo-tumors: MR imaging features with pathologic correlation: Part 1. Imaging approach, pseudotumors, vascular lesions, and adipocytic tumors. Radiographics. 2009;29:887-906.

26. Gross TG, Termuhlen AM. Pediatric non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2008;3:167-173.

27. Hochberg J, Waxman IM, Kelly KM, et al. Adolescent non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin lymphoma: state of the science. Br J Haematol. 2009;144:24-40.

28. Derenzini E, Casadei B, Pellegrini C, et al. Non-Hodgkin lymphomas presenting as soft tissue masses: A single center experience and meta-analysis of the published series. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2012 Dec 12. [Epub ahead of print]

29. Micheli A, Trapani S, Brizzi I, et al. Myositis ossificans circumscripta: a paediatric case and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:523-529.

30. McKenzie G, Raby N, Ritchie D. Non-neoplastic soft-tissue masses. Br J Radiol. 2009;82:775-785.

31. Buckmiller LM, Richter GT, Suen JY. Diagnosis and management of hemangiomas and vascular malformations of the head and neck. Oral Dis. 2010;16:405-418.

32. Khanna G, Bennett DL. Pediatric bone lesions: beyond the plain radiographic evaluation. Semin Roentgenol. 2012;47:90-99.

33. Rijal L, Nepal P, Baral S, et al. Solitary diaphyseal exostosis of femur, how common is it? Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2011;21:363-365.

Chiropractic Manipulation vs Manipulation Under Anesthesia

I read a very interesting article by Gardner et al1 in the April 2013 issue: “Man, 57, With Dyspnea After Chiropractic Manipulation” (Grand Rounds. 2013;23[4]:23,24,27,28). In the article, a patient with ankylosing spondylitis underwent chiropractic manipulation for 10 years, and subsequently received serial manipulations under anesthesia (MUA) during which the patient sustained thoracic spine fractures and a hemothorax.

What concerned me about this particular article are the generalizations and conclusions made. The title itself is very deceptive in its implication that chiropractic manipulation caused the fractures and hemothorax. Within the article, the authors write “the patient, who had a history of ankylosing spondylitis, had been receiving weekly therapy from a chiropractor for about 10 years.” Although the article does not specifically detail what types of modalities were used for these 10 years, presumably the main modality was spinal manipulation. Following this treatment, the patient received serial manipulations under anesthesia, presumably from the same chiropractor, following which the patient experienced his subsequent dyspnea.

The authors fail to identify that MUA has been around for more than 60 years and was developed by osteopathic physicians.2 Therefore, MUA is not a chiropractic procedure as the authors suggest, but a mainstream medical procedure that specifically trained and credentialed chiropractors can perform. MUA procedures are standardized, no matter what type of clinician is performing them. This insinuation by the authors suggests either an agenda with this communication, or a lack of knowledge and training in this procedure.

As an example, they write “In the chiropractic literature, between 3% and 10% of patients are estimated to be candidates for MUA.” They then reference this statement using a 1973 article from the Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, which was not authored by a chiropractic physician (see reference 14 in the article).

The authors also cite the most extensive safety review of MUA,3 which reported a complication rate of 0.7%. To say that the literature supporting MUA for various indications is “largely anecdotal” is disingenuous, since there have been several textbooks,4,5 textbook chapters,6,7 reviews,3 and guidelines8 developed on the use and appropriateness of MUA. For this particular patient, it is likely that he was not, nor should have been, a candidate for MUA in the first place, as evidenced by published indications and contraindications.3-8 However, this is not a problem with the procedure itself, but a practitioner error in the patient selection process.

The authors devoted the majority of the article to discussion of the utilization and safety of chiropractic manipulation. In this particular patient’s case, chiropractic care was utilized for more than 10 years without incident prior to the MUA being performed. Therefore, the entire discussion section of this article is totally irrelevant from the main point of the communication. The discussion section references only chiropractic manipulation in the typical clinical setting. The authors should have stayed focused on the safety concerns of MUA only. To the objective reader, this looks as if the authors are taking advantage of this platform to further a specific opinion on chiropractic manipulation. This is exemplified by the authors’ assertion that “the clinicians who treated the case patient find it curious that the reported rate of adverse events following this procedure is so low, but they suspect an element of reporting bias in the chiropractic literature.” This is purely a speculative statement, and one that does not belong in the scientific, peer-reviewed literature.

Notwithstanding the authors’ opinions on chiropractic manipulation, the entire study design of this paper limits any possible conclusions. There is no mention of the patient’s bone density status before or after MUA and no discussion of his apparent severe thoracic kyphosis, which also could have accounted for the patient’s fractures.

There are multiple possibilities as to the cause of this fracture, and the authors are making assumptions based purely on timing of diagnosis. In conclusion, this article likely should not have been accepted for publication given the erroneous citations, incorrect descriptions, irrelevant discussion, and a conclusion drawn from pure speculation and inadequate study design. In my opinion, this article lowers the perceived objectivity and quality of this biomedical journal, and may only serve to slant the opinions of readers who likely have minimal experience with chiropractic physicians, chiropractic medicine, or manipulation under anesthesia.

Mark W. Morningstar, DC, PhD

Grand Blanc, MI

The Authors’ Reply

We read with great interest the letter to the editor regarding our case report. We appreciate the author taking the time to make insightful comments. Our replies to his comments and concerns are as follows:

1. The author of the letter is concerned that the title of the article is somewhat misleading. We do concur with this, and would note that the original title of this case report that we submitted to the journal was “Unstable Thoracic Spine Fracture and Massive Hemothorax After Chiropractic Manipulation Under Anesthesia.” The journal itself requested that we change it to fit the format of their case reports.

2. We would respectfully disagree that manipulation under anesthesia (MUA) is a “mainstream medical procedure.”As allopathic clinicians, we acknowledge our error and failure to differentiate between osteopathic physicians and chiropractic care in the discussion. We certainly have no agenda with this communication. The patient mentioned in the case report specifically asked that we not make any negative remarks about his chiropractor and chiropractic care in general, as he had a good relationship with his chiropractor. We also had no reason to defame the individual chiropractor or chiropractic care in general.

3. The specific case in our report involves manipulation under anesthesia, but the same type of complication could happen with any procedure under sedation, performed by any type of clinician. As is stated in the letter, “For this particular patient, it is likely that this patient was not, nor should have been, a candidate for MUA in the first place, as evidenced by published indications and contraindications.” We agree.

4. We do not think that the single paragraph we devoted to general chiropractic manipulation renders our entire discussion section irrelevant. The bulk of our discussion does center on MUA, and we stand by our review of the literature on this subject. Details were abbreviated and discussion limited due to the nature of a case report.

5. As this is a case report, there is really no “study design” to speak of.The hemothorax and spine fracture were temporally associated with MUA. The symptoms began immediately after introduction of the procedure, and there were no other events that had any relation to the symptoms and eventual findings. There was no other obvious cause.

Again, we thank the author of this letter for taking the time to comment on our report, and we appreciate being given the opportunity to respond.

Scott C. Gardner, PA-C, MMSc, DFAAPA, Sarah D. Majercik, MD, MBA, FACS, Don VanBoerum, MD, FACS, John R. Macfarlane, MD

References

1. Gardner SC, Majercik SD, VanBoerum D, Macfarlane JR. Man, 57, with dyspnea after chiropractic manipulation (Grand Rounds). Clinician Reviews. 2013;23(4):23,24,27,28.

2. Siehl D, Bradford WG. Manipulation of the low back under general anesthesia. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1952;52:239-242.

3. Kohlbeck FJ, Haldeman S. Medication-assisted spinal manipulation. Spine J. 2002;2:288-302.

4. Gordon RC, ed. Manipulation Under Anesthesia: Concepts in Theory and Application. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2005.

5. Savitz MH, Chiu JC, Yeung AT. Practice of Minimally Invasive Spinal Technique: Special Millennium Edition. AAMISMS Education, LLC; 2000.

6. Gordon RC, Rogers A, West DT, et al. Manipulation under anesthesia: an anthology of past, present, and future use. In: Weiner RS, ed. Pain Management: A Practical Guide for Clinicians. 6th ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2002.

7. Dagenais S, Mayer J, Haldeman S. Medicine-assisted manipulation therapy. In: Dagenais S, Haldeman S, eds. Evidence-Based Management of Low Back Pain. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, Inc; 2012:248-257.

8. Tain L, Gunderson C, Cremata E, et al; Committee for Manipulation Under Anesthesia. Recommendations to the Industrial Medical Council Work Group of California for manipulation under anesthesia use for injured workers. Sacramento: Industrial Medical Council; 2003.

I read a very interesting article by Gardner et al1 in the April 2013 issue: “Man, 57, With Dyspnea After Chiropractic Manipulation” (Grand Rounds. 2013;23[4]:23,24,27,28). In the article, a patient with ankylosing spondylitis underwent chiropractic manipulation for 10 years, and subsequently received serial manipulations under anesthesia (MUA) during which the patient sustained thoracic spine fractures and a hemothorax.

What concerned me about this particular article are the generalizations and conclusions made. The title itself is very deceptive in its implication that chiropractic manipulation caused the fractures and hemothorax. Within the article, the authors write “the patient, who had a history of ankylosing spondylitis, had been receiving weekly therapy from a chiropractor for about 10 years.” Although the article does not specifically detail what types of modalities were used for these 10 years, presumably the main modality was spinal manipulation. Following this treatment, the patient received serial manipulations under anesthesia, presumably from the same chiropractor, following which the patient experienced his subsequent dyspnea.

The authors fail to identify that MUA has been around for more than 60 years and was developed by osteopathic physicians.2 Therefore, MUA is not a chiropractic procedure as the authors suggest, but a mainstream medical procedure that specifically trained and credentialed chiropractors can perform. MUA procedures are standardized, no matter what type of clinician is performing them. This insinuation by the authors suggests either an agenda with this communication, or a lack of knowledge and training in this procedure.

As an example, they write “In the chiropractic literature, between 3% and 10% of patients are estimated to be candidates for MUA.” They then reference this statement using a 1973 article from the Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, which was not authored by a chiropractic physician (see reference 14 in the article).