User login

Patella Alta: A Comprehensive Review of Current Knowledge

Take-Home Points

- Patella alta has a reduced articular area of PF contact.

- Presence of patella alta depends on the measurement method.

- Patella alta is defined as ISI >1.2 and CDI >1.2 to >1.3.

- On sagittal MRI, PTI is used most often with cutoff values of <0.125 to 0.28.

- Tibial tubercle distalization is most often used to treat patella alta. The desired postoperative patellar height is a CDI of 1.0.

Patella alta is a patella that rides abnormally high in relation to the femur, the femoral trochlea, or the tibia,1 with decreased bony stability requiring increased knee flexion angles to engage the trochlea.2,3 An abnormally high patella may therefore insufficiently engage the proximal trochlea groove both in extension and in the early phase of knee flexion—making it one of the potential risk factors for patellar instability.4-10 Accordingly, patella alta is present in 30% of patients with recurrent patellar dislocation.11 It also occurs in other disorders, such as knee extensor apparatus disorders, in patients with patellofemoral (PF) pain, chondromalacia, Sinding-Larsen-Johansson disease, Osgood-Schlatter disease, patellar tendinopathy, and osteoarthritis.1,7,8,12-18 As such, patella alta represents an important predisposing factor for patellar malalignment and PF-related complaints. On the other hand, patella alta may also be a normal variant of a person’s knee anatomy and may be well tolerated when not combined with other instability factors.4

Despite the importance of patella alta, there is no consensus on a precise definition, the most reliable measurement method, or the factors thought to be important in clinical decisions regarding treatment. To address this issue, we systematically reviewed the patella alta literature for definitions, the most common measurement methods and their patella alta cutoff values, and cutoff values for surgical correction and proposed surgical techniques.

Methods

In February 2017, using the term patella alta, we performed a systematic literature search on PubMed. Inclusion criteria were original study or review articles, publication in peer-reviewed English-language journals between 2000 and 2017, and narrative description or measurement of human patellar height on plain radiographs or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Excluded were abstracts and articles in languages other than English; animal and computational/biomechanical studies; case reports; and knee arthroplasties, knee extensor ruptures, and hereditary and congenital diseases. All evidence levels were included.

We assessed measurement methods, reported cutoff values for patella alta, cutoff values for performing surgical correction, proposed surgical techniques, and postoperative target values. Original study articles and review articles were analyzed separately.

Results

Of 211 articles identified, 92 met the inclusion criteria for original study, and 28 for review. All their abstracts were reviewed, and 91 were excluded: 17 for language other than English, 11 for animal study, 12 for biomechanical/computational study, 20 for case report, 8 for arthroplasty, 13 for hereditary or congenital disease, 1 for extensor apparatus rupture, 3 for editorial letter, and 6 for other reasons. Full text copies of all included articles were obtained and reviewed.

Original Study Articles

Definition. Of the 92 original study articles, 17 (18.5%) defined patella alta by description alone, and 75 (81.5%) used imaging-based measurements. Patella alta was described as a patella that rides abnormally high in relation to the trochlear groove, with a reduced articular area of PF contact1,15,19-21 or decreased patella–trochlea cartilage overlap.22 With this reduced contact area, there is increased PF stress.21

With radiographic measurements, patella alta is defined as a Caton-Deschamps index (CDI) of >1.2 to >1.3, an Insall-Salvati index (ISI) of >1.2, a Blackburne-Peel index (PBI) of >1.0,4,15,18,23-25 and a patellotrochlear index (PTI) of <0.125 to 0.28.6,26

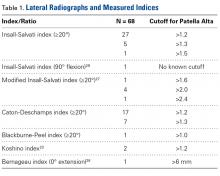

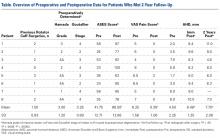

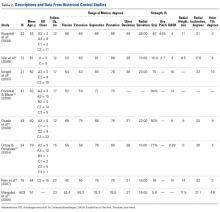

On lateral radiographs, ISI was the most common measurement (33 studies), with patella alta cutoff values ranging from >1.2 to >1.5. The second most common measurement was CDI (24 studies), with cutoff values of >1.2 to >1.3. Other indices, such as the modified ISI (6 studies), the BPI (1 study), and the Koshino index (2 studies), had their cutoff values used more consistently (>1.6 to >2.4, >1.0, and >1.2, respectively) but these indices were rarely reported in the literature (Table 1).27,28,29

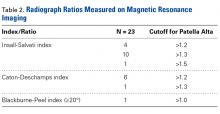

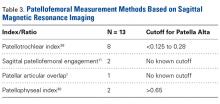

Thirty-six studies defined patella alta with MRI using either the aforementioned radiographic ratios (23 studies, 3 indices, Table 2) or PF indices (13 studies, 4 methods, Table 3).30

On sagittal MRI, PTI was used most often; cutoff values were <0.125 to 0.28.

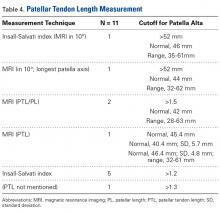

Thirteen studies defined patella alta with PTL: 5 using lateral conventional radiographs and 8 using sagittal MRI. For each type of imaging, the cutoff value was >52 mm to >56 mm. PTL was measured either independently or together with ISI on sagittal MRI (Table 4).

Review Articles

Twenty-eight review articles met the inclusion criteria.35-40 Patella alta was described mostly with ISI (75%) or CDI (64%). In up to 57% of these articles, a patella alta reference value was missing. Only 1 article mentioned different cutoff values for conventional radiographs and MRI. BPI was mentioned in 50% of studies, but only 2 indicated a cutoff value for patella alta. Eleven percent used PTI on sagittal MRI and took patella–trochlea cartilage overlap into account.

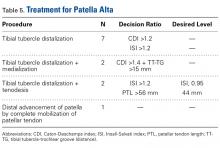

Eight review articles mentioned cutoff values for surgical correction. Only 1 of 4 articles mentioned a cutoff value for correcting patella alta in PF instability, and only 2 articles suggested an ideal postoperative patellar height (Table 6).

No review article relied on PTL to describe patella alta or to advise surgical treatment.

Discussion

Our review revealed many variations in patella alta definitions and descriptions, measurement methods, cutoff values, and treatment options. Interpretation of patellar height and, particularly, patella alta is very heterogeneous. Accordingly, comparing surgical indications, surgical treatment options, and outcomes across studies can be difficult.

Measurement Methods

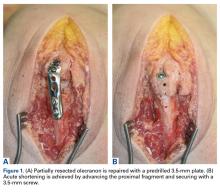

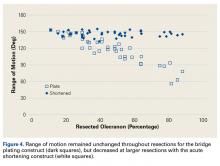

Radiographs. Conventional radiographs were used to describe patella alta in two-thirds of the original study articles. The most common measurement methods marked the position of the patella relative to either the femur (direct assessment) or the tibia (indirect assessment).14,25 All established measurement methods use lateral radiographs, which do not show articular cartilage.11,14 Therefore, lateral radiograph ratios of different and variable bony landmarks do not measure actual PF articular congruence. The widely variable morphologies of patella (distal patellar nose, different articulating surface), femoral trochlea (facet in height and length), proximal tibia (inherited or acquired deformities on tibial tubercle), and slope are all confounding factors that may affect measurement (Figure 1). In addition, specific variations in PF joint morphology (eg, small patellar articular surface, short trochlea) are not well represented by these ratios.11

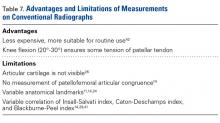

All these methods have advantages, limitations, and different values of interobserver and intraobserver variability, reliability, and reproducibility (Table 7).29,41

Determination of both patellar height and patella alta depends on the measurement method used and is significantly affected by anatomical variants, such as extra-articular patella and femorotibial landmarks.

The ISI method is most commonly used because it does not depend on degree of knee flexion, is thought to measure the relative length of the patellar tendon the best,5 and has established MRI criteria.6 However, ISI has limitations: Its distal bony landmark is the tibial tuberosity, which can be difficult to assess14; the shape of the patella (mainly its inferior point) varies42; and the measurement does not change after distalization of the tibial tubercle.5

CDI is the most accurate diagnostic method because it relies on readily identifiable and reproducible anatomical landmarks; does not depend on radiograph quality, knee size, radiologic enlargement, or position of the tibial tubercle or patellar modification; and is unaffected by degree of knee flexion between 10° and 80°.38,43 CDI is the method that is most useful in describing patellar height after distalization of the tibial tubercle because it assesses the height of the patella relative to the tibial plateau.5 CDI is limited with respect to clear identification of the patellar and tibial articular margin.37

BPI has the lowest interobserver variability and discriminates best among patella alta, norma, and infera.41 Like CDI, BPI assesses patellar height relative to the tibial plateau, and thus is useful in describing patellar height after distalization of the tibial tubercle.5 BPI is limited in that it uses a line drawn along the tibial plateau, where variations in inclination and tibial slope produce inaccuracies,14 and depends highly on projection angles. Clinically, BPI is rarely used.

As the literature shows, the radiologic methods of determining patellar height are variable and unreliable and depend on the ratio used.26,41 These methods do not reveal precise information about the PF articular congruence, the key finding for necessary treatment.

Radiographic Indices on MRI. Some studies measured radiographic indices on sagittal MRI. Radiologic and MRI measurements are described as not significantly different or slightly different, and 0.09 to 0.13 needs to be added with ISI and BP ratios on radiographs, MRI, and computed tomography (CT).17,44-47 ISI is commonly used, and its clinical application is easy. Although classically measured on plain radiographs, ISI is reliably measured on MRI as well.17,30 The traditional 1.2 threshold for defining patella alta was used by Charles and colleagues.44 CDI is equally well measured on radiographs and MRI.47

According to the literature, 3 different measurement methods have been used to describe degree of patella–trochlea cartilage overlap: PTI, sagittal patellofemoral engagement (SPE), and patellar articular overlap (PAO).1,11,26

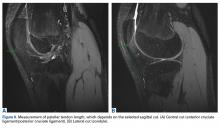

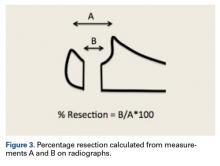

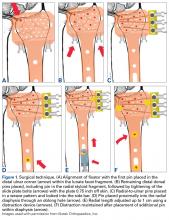

PTI uses the true articular cartilage patella–trochlea relationship for measurement of patellar height on sagittal MRI in extension (Figure 3). If the patellar tendon is fully out to length (no laxity), PTI reliably and precisely determines the exact articular correlation of PF joint and patellar height.6

SPE is similar to percentage of articular coverage.1,11 Patellar overlap of the trochlea is measured on 2 different sagittal MRI images: 1 with the greatest length of patellar cartilage and 1 with the greatest length of femoral trochlear cartilage. This measurement did not correlate with CDI.1 SPE was not evaluated in control studies, and normal and pathologic values are unavailable.

PAO is measured with patients positioned at rest and in standard knee coils.1 MRI was not obtained in full extension or with quadriceps activation, and knee flexion angle values are unavailable. Total patellar articular length was measured on the sagittal MRI that showed the greatest patellar length and articular cartilage thickness. The same image was used to measure articular overlap, or the length of patellar cartilage overlying the trochlear cartilage, as measured parallel to the subchondral surface of the patella. PAO correlates well with conventional patellar height measurements in the sagittal plane and shows promise as a simpler alternative to the conventional indices.1 Normal and pathologic values are unavailable.

So far, PTI is the only method that was controlled in several studies, assessed for its reliability, and compared with other patellar height measurements.6,14

Patellar Tendon Length. PTL can be measured on lateral radiographs or sagittal MRI. Radiologic and MRI measurements are described as not significantly different47 or slightly different, and 0.09 to 0.13 needs to be added with the ISI ratio on radiographs, MRI, and CT.46 PTL is reliably evaluated with ISI.41,50 There is a weak correlation of patient height and PTL: Taller people have normally longer tendons.51-53

PTL measurements revealed that the posterior surface of the patellar tendon was significantly shorter than the anterior surface. Compared with their corresponding posterior fascicles, anterior fascicles are longer; their attachment is more proximal to the patella and more distal to the tibia. In addition, posterior PTL is significantly shorter with the posterior patellar attachment (adheres to posterior aspect of the inferior patellar pole) than with the anterior attachment (adheres to anterior aspect of the inferior patellar pole).56 Moreover, the lateral and medial fascicles are longer than the central fascicles attaching at the most inferior patellar pole. This issue must be considered in image cut selection (Figures 6A, 6B). Furthermore, type of inferior pole of patella (pointed, intermediate, blunt) is important in measurement.56 Overall, mean (SD) PTL was 54.9 (1.2) mm on the anterior surface and 35.0 (0.6) mm on the posterior surface.

It is important to precisely describe the measurement method and location (sagittal cut) and to consider the shape of the inferior patellar pole and the site of the patellar tendon attachment.56

Treatments. For patella alta, the surgical treatment goals are to increase the PF contact area and improve PF articular congruence, and thereby increase PF stability.31-33 Four different procedures were used to treat patella alta (Table 5), but only 11 of the 92 original study articles and 8 of the 28 review articles included in our review mentioned a specific patellar height that required surgical correction (Tables 5, 6). Recommendations were based on CDI (>1.2 to >1.4) and less often on ISI (>1.2 to >1.4) or PTL (>56 mm).

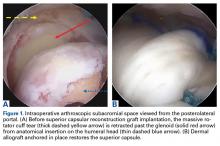

Tibial tubercle distalization is effective in normalizing patellar height to correct the patellar index in patella alta (Figures 7A, 7B).13,18,38,55,57 Tibial tubercle distalization and patellar tendon tenodesis attached to the original insertion normalize PTL and stabilize the PF joint in patients with patella alta.5,47 In a comparison of these surgical procedures, cartilage stress was lower with distalization than with distalization and tenodesis.13

Soft-tissue methods are recommended in children, as bone procedures injure the proximal tibial physis and may cause it to close prematurely.58 The patella can be distally advanced by completely mobilizing the patellar tendon and fixating with sutures through the cartilaginous tibial tubercle. This technique is a satisfactory treatment for skeletally immature patients who present with habitual patellar dislocation associated with patella alta.58,59

CDI and BPI assess patellar height relative to the tibial plateau, and therefore are the most useful measurement methods for patellar height after distalization of the tibial tubercle.5 ISI does not change after distalization of the tibial tubercle and cannot be recommended.5,18 As PF indices (eg, PTI) can trace preoperative and postoperative values, these measurements are valuable.

Controversies

Our review found no consensus on measurement method or cutoff value. No measurement method showed clear clinical or methodologic superiority. Most published patellar height and patella alta data are based on conventional radiographs using a tibial reference point, even though a femoral or even trochlear reference point seems more reproducible, particularly in PF pathologies. Several cutoff values have been reported for each patella alta measurement method. Regarding pathologic thresholds, which might require surgical correction, very little information has been published, and scientific evidence is lacking. Numerous important aspects remain unanswered after this review, and clarification is mandatory.

Five Key Facts

1. In patella alta assessment, different morphologic, biomechanical, and functional aspects must be considered. The most relevant aspect is decreased engagement of the patella and trochlea,4-9,11,26 which results in decreased bony stability in knee extension.1-3 Therefore, patella alta is one of the potential risk factors for patellar instability with a high percentage of recurrent patellar dislocation.4-9 In early knee flexion, the patella translates more distally with better engagement of the patella in the trochlea and better stability. Therefore, measurement in extension, with the patellar tendon out to length, seems to offer a more reliable assessment of the patella–femur relationship.

2. Insufficient engagement of the patella in the trochlea is the most important aspect of patella alta.11 Therefore, direct measurement of this engagement seems logical.

3. As radiographs do not show articular cartilage, they should not be used to assess the articular patella–femur relationship.11,14,26 Patella–trochlea cartilage overlap is the most relevant factor for patella alta and should be measured on MRI.6,14,26,32

4. PTL is an important factor for patellar height and particularly patella alta. The range of normal PTL values is wide: 35 mm to 61 mm. The described cutoff values for patella alta (>52 mm to >56 mm) fall within this normal range. The cause may be the different measurement methods used.33,47,59-61 Therefore, for precise diagnostics, a standardized measurement method that includes the selected cut imaging is mandatory.

Many important aspects remain unanswered, and clarification is mandatory (Table 9).

Conclusion

Our review revealed many variations in patella alta definitions and descriptions, measurement methods, cutoff values, and treatment options. Presence of patella alta depends on measurement method used. Methods cannot be used interchangeably, and they all have their advantages and limitations. Unfortunately, there is no generally accepted consensus on measurement method, patella alta cutoff value, or treatment with ideal correction. Treatment planning and outcomes assessment require clarification of these many issues.

1 Munch JL, Sullivan JP, Nguyen JT, et al. Patellar articular overlap on MRI is a simple alternative to conventional measurements of patellar height. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4(7):2325967116656328.

2. Elias JJ, Soehnlen NT, Guseila LM, Cosgarea AJ. Dynamic tracking influenced by anatomy in patellar instability. Knee. 2016;23(3):450-455.

3. Fabricant PD, Ladenhauf HN, Salvati EA, Green DW. Medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) reconstruction improves radiographic measures of patella alta in children. Knee. 2014;21(6):1180-1184.

4. Askenberger M, Janarv PM, Finnbogason T, Arendt EA. Morphology and anatomic patellar instability risk factors in first-time traumatic lateral patellar dislocations. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(1):50-58.

5. Mayer C, Magnussen RA, Servien E, et al. Patellar tendon tenodesis in association with tibial tubercle distalization for the treatment of episodic patellar dislocation with patella alta. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(2):346-351.

6. Ali SA, Helmer R, Terk MR. Patella alta: lack of correlation between patellotrochlear cartilage congruence and commonly used patellar height ratios. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(5):1361-1366.

7. Lewallen LW, McIntosh AL, Dahm DL. Predictors of recurrent instability after acute patellofemoral dislocation in pediatric and adolescent patients. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(3):575-581.

8. Ward SR, Terk MR, Powers CM. Patella alta: association with patellofemoral alignment and changes in contact area during weight-bearing. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1749-1755.

9. Dejour H, Walch G, Nove-Josserand L, Guier C. Factors of patellar instability: an anatomic radiographic study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1994;2(1):19-26.

10. Arendt EA, Fithian DC, Cohen E. Current concepts of lateral patella dislocation. Clin Sports Med. 2002;21(3):499-519.

11. Dejour D, Ferrua P, Ntagiopoulos PG, et al. The introduction of a new MRI index to evaluate sagittal patellofemoral engagement. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2013;99(8 suppl):S391-S398.

12. Althani S, Shahi A, Tan TL, Al-Belooshi A. Position of the patella among Emirati adult knees. Is Insall-Salvati ratio applicable to Middle-Easterners? Arch Bone Joint Surg. 2016;4(2):137-140.

13. Yin L, Liao TC, Yang L, Powers CM. Does patella tendon tenodesis improve tibial tubercle distalization in treating patella alta? A computational study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(11):2451-2461.

14. Barnett AJ, Prentice M, Mandalia V, Wakeley CJ, Eldridge JD. Patellar height measurement in trochlear dysplasia. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(12):1412-1415.

15. Otsuki S, Nakajima M, Fujiwara K, et al. Influence of age on clinical outcomes of three-dimensional transfer of the tibial tuberosity for patellar instability with patella alta. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(8):2392-2396.

16. Otsuki S, Nakajima M, Oda S, et al. Three-dimensional transfer of the tibial tuberosity for patellar instability with patella alta. J Orthop Sci. 2013;18(3):437-442.

17. Steensen RN, Bentley JC, Trinh TQ, Backes JR, Wiltfong RE. The prevalence and combined prevalences of anatomic factors associated with recurrent patellar dislocation: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(4):921-927.

18. Magnussen RA, De Simone V, Lustig S, Neyret P, Flanigan DC. Treatment of patella alta in patients with episodic patellar dislocation: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(10):2545-2550.

19. Bertollo N, Pelletier MH, Walsh WR. Simulation of patella alta and the implications for in vitro patellar tracking in the ovine stifle joint. J Orthop Res. 2012;30(11):1789-1797.

20. Narkbunnam R, Chareancholvanich K. Effect of patient position on measurement of patellar height ratio. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2015;135(8):1151-1156.

21. Stefanik JJ, Zhu Y, Zumwalt AC, et al. Association between patella alta and the prevalence and worsening of structural features of patellofemoral joint osteoarthritis: the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62(9):1258-1265.

22. Monk AP, Doll HA, Gibbons CL, et al. The patho-anatomy of patellofemoral subluxation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(10):1341-1347.

23. Hirano A, Fukubayashi T, Ishii T, Ochiai N. Relationship between the patellar height and the disorder of the knee extensor mechanism in immature athletes. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21(4):541-544.

24. Ng JP, Cawley DT, Beecher SM, Lee MJ, Bergin D, Shannon FJ. Focal intratendinous radiolucency: a new radiographic method for diagnosing patellar tendon ruptures. Knee. 2016;23(3):482-486.

25. van Duijvenbode D, Stavenuiter M, Burger B, van Dijke C, Spermon J, Hoozemans M. The reliability of four widely used patellar height ratios. Int Orthop. 2016;40(3):493-497.

26. Biedert RM, Albrecht S. The patellotrochlear index: a new index for assessing patellar height. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(8):707-712.

27. Grelsamer RP, Meadows S. The modified Insall-Salvati ratio for assessment of patellar height. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(282):170-176.

28. Thaunat M, Erasmus PJ. The favourable anisometry: an original concept for medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction. Knee. 2007;14(6):424-428.

29. Anagnostakos K, Lorbach O, Reiter S, Kohn D. Comparison of five patellar height measurement methods in 90 degrees knee flexion. Int Orthop. 2011;35(12):1791-1797.

30. Miller TT, Staron RB, Feldman F. Patellar height on sagittal MR imaging of the knee. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167(2):339-341.

31. Dejour D, Le Coultre B. Osteotomies in patello-femoral instabilities. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2007;15(1):39-46.

32. Rhee SJ, Pavlou G, Oakley J, Barlow D, Haddad F. Modern management of patellar instability. Int Orthop. 2012;36(12):2447-2456.

33. Servien E, Verdonk PC, Neyret P. Tibial tuberosity transfer for episodic patellar dislocation. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2007;15(2):61-67.

34. Caton J, Deschamps G, Chambat P, Lerat JL, Dejour H. [Patella infera. Apropos of 128 cases]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1982;68(5):317-325.

35. Meyers AB, Laor T, Sharafinski M, Zbojniewicz AM. Imaging assessment of patellar instability and its treatment in children and adolescents. Pediatr Radiol. 2016;46(5):618-636.

36. Feller JA. Distal realignment (tibial tuberosity transfer). Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2012;20(3):152-161.

37. Dietrich TJ, Fucentese SF, Pfirrmann CW. Imaging of individual anatomical risk factors for patellar instability. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2016;20(1):65-73.

38. Dean CS, Chahla J, Serra Cruz R, Cram TR, LaPrade RF. Patellofemoral joint reconstruction for patellar instability: medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction, trochleoplasty, and tibial tubercle osteotomy. Arthrosc Tech. 2016;5(1):e169-e175.

39. Frosch KH, Schmeling A. A new classification system of patellar instability and patellar maltracking. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2016;136(4):485-497.

40. Weber AE, Nathani A, Dines JS, et al. An algorithmic approach to the management of recurrent lateral patellar dislocation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(5):417-427.

41. Seil R, Muller B, Georg T, Kohn D, Rupp S. Reliability and interobserver variability in radiological patellar height ratios. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8(4):231-236.

42. Laprade J, Culham E. Radiographic measures in subjects who are asymptomatic and subjects with patellofemoral pain syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(414):172-182.

43. Caton JH, Dejour D. Tibial tubercle osteotomy in patello-femoral instability and in patellar height abnormality. Int Orthop. 2010;34(2):305-309.

44. Charles MD, Haloman S, Chen L, Ward SR, Fithian D, Afra R. Magnetic resonance imaging–based topographical differences between control and recurrent patellofemoral instability patients. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(2):374-384.

45. Kurtul Yildiz H, Ekin EE. Patellar malalignment: a new method on knee MRI. Springerplus. 2016;5(1):1500.

46. Lee PP, Chalian M, Carrino JA, Eng J, Chhabra A. Multimodality correlations of patellar height measurement on x-ray, CT, and MRI. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41(10):1309-1314.

47. Neyret P, Robinson AH, Le Coultre B, Lapra C, Chambat P. Patellar tendon length—the factor in patellar instability? Knee. 2002;9(1):3-6.

48. Diederichs G, Issever AS, Scheffler S. MR imaging of patellar instability: injury patterns and assessment of risk factors. Radiographics. 2010;30(4):961-981.

49. Earhart C, Patel DB, White EA, Gottsegen CJ, Forrester DM, Matcuk GR Jr. Transient lateral patellar dislocation: review of imaging findings, patellofemoral anatomy, and treatment options. Emerg Radiol. 2013;20(1):11-23.

50. Aarimaa V, Ranne J, Mattila K, Rahi K, Virolainen P, Hiltunen A. Patellar tendon shortening after treatment of patellar instability with a patellar tendon medialization procedure. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2008;18(4):442-446.

51. Brown DE, Alexander AH, Lichtman DM. The Elmslie-Trillat procedure: evaluation in patellar dislocation and subluxation. Am J Sports Med. 1984;12(2):104-109.

52. Goldstein JL, Verma N, McNickle AG, Zelazny A, Ghodadra N, Bach BR Jr. Avoiding mismatch in allograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: correlation between patient height and patellar tendon length. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(5):643-650.

53. Navali AM, Jafarabadi MA. Is there any correlation between patient height and patellar tendon length? Arch Bone Joint Surg. 2015;3(2):99-103.

54. Park MS, Chung CY, Lee KM, Lee SH, Choi IH. Which is the best method to determine the patellar height in children and adolescents? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(5):1344-1351.

55. Berard JB, Magnussen RA, Bonjean G, et al. Femoral tunnel enlargement after medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction: prevalence, risk factors, and clinical effect. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(2):297-301.

56. Edama M, Kageyama I, Nakamura M, et al. Anatomical study of the inferior patellar pole and patellar tendon [published online ahead of print February 16, 2017]. Scand J Med Sci Sports. doi:10.1111/sms.12858.

57. Al-Sayyad MJ, Cameron JC. Functional outcome after tibial tubercle transfer for the painful patella alta. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;(396):152-162.

58. Benoit B, Laflamme GY, Laflamme GH, Rouleau D, Delisle J, Morin B. Long-term outcome of surgically-treated habitual patellar dislocation in children with coexistent patella alta. Minimum follow-up of 11 years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(9):1172-1177.

59. Simmons E Jr, Cameron JC. Patella alta and recurrent dislocation of the patella. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(274):265-269.

60. Degnan AJ, Maldjian C, Adam RJ, Fu FH, Di Domenica M. Comparison of Insall-Salvati ratios in children with an acute anterior cruciate ligament tear and a matched control population. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204(1):161-166.

61. Wittstein JR, Bartlett EC, Easterbrook J, Byrd JC. Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of patellofemoral malalignment. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(6):643-649.

Take-Home Points

- Patella alta has a reduced articular area of PF contact.

- Presence of patella alta depends on the measurement method.

- Patella alta is defined as ISI >1.2 and CDI >1.2 to >1.3.

- On sagittal MRI, PTI is used most often with cutoff values of <0.125 to 0.28.

- Tibial tubercle distalization is most often used to treat patella alta. The desired postoperative patellar height is a CDI of 1.0.

Patella alta is a patella that rides abnormally high in relation to the femur, the femoral trochlea, or the tibia,1 with decreased bony stability requiring increased knee flexion angles to engage the trochlea.2,3 An abnormally high patella may therefore insufficiently engage the proximal trochlea groove both in extension and in the early phase of knee flexion—making it one of the potential risk factors for patellar instability.4-10 Accordingly, patella alta is present in 30% of patients with recurrent patellar dislocation.11 It also occurs in other disorders, such as knee extensor apparatus disorders, in patients with patellofemoral (PF) pain, chondromalacia, Sinding-Larsen-Johansson disease, Osgood-Schlatter disease, patellar tendinopathy, and osteoarthritis.1,7,8,12-18 As such, patella alta represents an important predisposing factor for patellar malalignment and PF-related complaints. On the other hand, patella alta may also be a normal variant of a person’s knee anatomy and may be well tolerated when not combined with other instability factors.4

Despite the importance of patella alta, there is no consensus on a precise definition, the most reliable measurement method, or the factors thought to be important in clinical decisions regarding treatment. To address this issue, we systematically reviewed the patella alta literature for definitions, the most common measurement methods and their patella alta cutoff values, and cutoff values for surgical correction and proposed surgical techniques.

Methods

In February 2017, using the term patella alta, we performed a systematic literature search on PubMed. Inclusion criteria were original study or review articles, publication in peer-reviewed English-language journals between 2000 and 2017, and narrative description or measurement of human patellar height on plain radiographs or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Excluded were abstracts and articles in languages other than English; animal and computational/biomechanical studies; case reports; and knee arthroplasties, knee extensor ruptures, and hereditary and congenital diseases. All evidence levels were included.

We assessed measurement methods, reported cutoff values for patella alta, cutoff values for performing surgical correction, proposed surgical techniques, and postoperative target values. Original study articles and review articles were analyzed separately.

Results

Of 211 articles identified, 92 met the inclusion criteria for original study, and 28 for review. All their abstracts were reviewed, and 91 were excluded: 17 for language other than English, 11 for animal study, 12 for biomechanical/computational study, 20 for case report, 8 for arthroplasty, 13 for hereditary or congenital disease, 1 for extensor apparatus rupture, 3 for editorial letter, and 6 for other reasons. Full text copies of all included articles were obtained and reviewed.

Original Study Articles

Definition. Of the 92 original study articles, 17 (18.5%) defined patella alta by description alone, and 75 (81.5%) used imaging-based measurements. Patella alta was described as a patella that rides abnormally high in relation to the trochlear groove, with a reduced articular area of PF contact1,15,19-21 or decreased patella–trochlea cartilage overlap.22 With this reduced contact area, there is increased PF stress.21

With radiographic measurements, patella alta is defined as a Caton-Deschamps index (CDI) of >1.2 to >1.3, an Insall-Salvati index (ISI) of >1.2, a Blackburne-Peel index (PBI) of >1.0,4,15,18,23-25 and a patellotrochlear index (PTI) of <0.125 to 0.28.6,26

On lateral radiographs, ISI was the most common measurement (33 studies), with patella alta cutoff values ranging from >1.2 to >1.5. The second most common measurement was CDI (24 studies), with cutoff values of >1.2 to >1.3. Other indices, such as the modified ISI (6 studies), the BPI (1 study), and the Koshino index (2 studies), had their cutoff values used more consistently (>1.6 to >2.4, >1.0, and >1.2, respectively) but these indices were rarely reported in the literature (Table 1).27,28,29

Thirty-six studies defined patella alta with MRI using either the aforementioned radiographic ratios (23 studies, 3 indices, Table 2) or PF indices (13 studies, 4 methods, Table 3).30

On sagittal MRI, PTI was used most often; cutoff values were <0.125 to 0.28.

Thirteen studies defined patella alta with PTL: 5 using lateral conventional radiographs and 8 using sagittal MRI. For each type of imaging, the cutoff value was >52 mm to >56 mm. PTL was measured either independently or together with ISI on sagittal MRI (Table 4).

Review Articles

Twenty-eight review articles met the inclusion criteria.35-40 Patella alta was described mostly with ISI (75%) or CDI (64%). In up to 57% of these articles, a patella alta reference value was missing. Only 1 article mentioned different cutoff values for conventional radiographs and MRI. BPI was mentioned in 50% of studies, but only 2 indicated a cutoff value for patella alta. Eleven percent used PTI on sagittal MRI and took patella–trochlea cartilage overlap into account.

Eight review articles mentioned cutoff values for surgical correction. Only 1 of 4 articles mentioned a cutoff value for correcting patella alta in PF instability, and only 2 articles suggested an ideal postoperative patellar height (Table 6).

No review article relied on PTL to describe patella alta or to advise surgical treatment.

Discussion

Our review revealed many variations in patella alta definitions and descriptions, measurement methods, cutoff values, and treatment options. Interpretation of patellar height and, particularly, patella alta is very heterogeneous. Accordingly, comparing surgical indications, surgical treatment options, and outcomes across studies can be difficult.

Measurement Methods

Radiographs. Conventional radiographs were used to describe patella alta in two-thirds of the original study articles. The most common measurement methods marked the position of the patella relative to either the femur (direct assessment) or the tibia (indirect assessment).14,25 All established measurement methods use lateral radiographs, which do not show articular cartilage.11,14 Therefore, lateral radiograph ratios of different and variable bony landmarks do not measure actual PF articular congruence. The widely variable morphologies of patella (distal patellar nose, different articulating surface), femoral trochlea (facet in height and length), proximal tibia (inherited or acquired deformities on tibial tubercle), and slope are all confounding factors that may affect measurement (Figure 1). In addition, specific variations in PF joint morphology (eg, small patellar articular surface, short trochlea) are not well represented by these ratios.11

All these methods have advantages, limitations, and different values of interobserver and intraobserver variability, reliability, and reproducibility (Table 7).29,41

Determination of both patellar height and patella alta depends on the measurement method used and is significantly affected by anatomical variants, such as extra-articular patella and femorotibial landmarks.

The ISI method is most commonly used because it does not depend on degree of knee flexion, is thought to measure the relative length of the patellar tendon the best,5 and has established MRI criteria.6 However, ISI has limitations: Its distal bony landmark is the tibial tuberosity, which can be difficult to assess14; the shape of the patella (mainly its inferior point) varies42; and the measurement does not change after distalization of the tibial tubercle.5

CDI is the most accurate diagnostic method because it relies on readily identifiable and reproducible anatomical landmarks; does not depend on radiograph quality, knee size, radiologic enlargement, or position of the tibial tubercle or patellar modification; and is unaffected by degree of knee flexion between 10° and 80°.38,43 CDI is the method that is most useful in describing patellar height after distalization of the tibial tubercle because it assesses the height of the patella relative to the tibial plateau.5 CDI is limited with respect to clear identification of the patellar and tibial articular margin.37

BPI has the lowest interobserver variability and discriminates best among patella alta, norma, and infera.41 Like CDI, BPI assesses patellar height relative to the tibial plateau, and thus is useful in describing patellar height after distalization of the tibial tubercle.5 BPI is limited in that it uses a line drawn along the tibial plateau, where variations in inclination and tibial slope produce inaccuracies,14 and depends highly on projection angles. Clinically, BPI is rarely used.

As the literature shows, the radiologic methods of determining patellar height are variable and unreliable and depend on the ratio used.26,41 These methods do not reveal precise information about the PF articular congruence, the key finding for necessary treatment.

Radiographic Indices on MRI. Some studies measured radiographic indices on sagittal MRI. Radiologic and MRI measurements are described as not significantly different or slightly different, and 0.09 to 0.13 needs to be added with ISI and BP ratios on radiographs, MRI, and computed tomography (CT).17,44-47 ISI is commonly used, and its clinical application is easy. Although classically measured on plain radiographs, ISI is reliably measured on MRI as well.17,30 The traditional 1.2 threshold for defining patella alta was used by Charles and colleagues.44 CDI is equally well measured on radiographs and MRI.47

According to the literature, 3 different measurement methods have been used to describe degree of patella–trochlea cartilage overlap: PTI, sagittal patellofemoral engagement (SPE), and patellar articular overlap (PAO).1,11,26

PTI uses the true articular cartilage patella–trochlea relationship for measurement of patellar height on sagittal MRI in extension (Figure 3). If the patellar tendon is fully out to length (no laxity), PTI reliably and precisely determines the exact articular correlation of PF joint and patellar height.6

SPE is similar to percentage of articular coverage.1,11 Patellar overlap of the trochlea is measured on 2 different sagittal MRI images: 1 with the greatest length of patellar cartilage and 1 with the greatest length of femoral trochlear cartilage. This measurement did not correlate with CDI.1 SPE was not evaluated in control studies, and normal and pathologic values are unavailable.

PAO is measured with patients positioned at rest and in standard knee coils.1 MRI was not obtained in full extension or with quadriceps activation, and knee flexion angle values are unavailable. Total patellar articular length was measured on the sagittal MRI that showed the greatest patellar length and articular cartilage thickness. The same image was used to measure articular overlap, or the length of patellar cartilage overlying the trochlear cartilage, as measured parallel to the subchondral surface of the patella. PAO correlates well with conventional patellar height measurements in the sagittal plane and shows promise as a simpler alternative to the conventional indices.1 Normal and pathologic values are unavailable.

So far, PTI is the only method that was controlled in several studies, assessed for its reliability, and compared with other patellar height measurements.6,14

Patellar Tendon Length. PTL can be measured on lateral radiographs or sagittal MRI. Radiologic and MRI measurements are described as not significantly different47 or slightly different, and 0.09 to 0.13 needs to be added with the ISI ratio on radiographs, MRI, and CT.46 PTL is reliably evaluated with ISI.41,50 There is a weak correlation of patient height and PTL: Taller people have normally longer tendons.51-53

PTL measurements revealed that the posterior surface of the patellar tendon was significantly shorter than the anterior surface. Compared with their corresponding posterior fascicles, anterior fascicles are longer; their attachment is more proximal to the patella and more distal to the tibia. In addition, posterior PTL is significantly shorter with the posterior patellar attachment (adheres to posterior aspect of the inferior patellar pole) than with the anterior attachment (adheres to anterior aspect of the inferior patellar pole).56 Moreover, the lateral and medial fascicles are longer than the central fascicles attaching at the most inferior patellar pole. This issue must be considered in image cut selection (Figures 6A, 6B). Furthermore, type of inferior pole of patella (pointed, intermediate, blunt) is important in measurement.56 Overall, mean (SD) PTL was 54.9 (1.2) mm on the anterior surface and 35.0 (0.6) mm on the posterior surface.

It is important to precisely describe the measurement method and location (sagittal cut) and to consider the shape of the inferior patellar pole and the site of the patellar tendon attachment.56

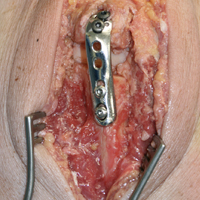

Treatments. For patella alta, the surgical treatment goals are to increase the PF contact area and improve PF articular congruence, and thereby increase PF stability.31-33 Four different procedures were used to treat patella alta (Table 5), but only 11 of the 92 original study articles and 8 of the 28 review articles included in our review mentioned a specific patellar height that required surgical correction (Tables 5, 6). Recommendations were based on CDI (>1.2 to >1.4) and less often on ISI (>1.2 to >1.4) or PTL (>56 mm).

Tibial tubercle distalization is effective in normalizing patellar height to correct the patellar index in patella alta (Figures 7A, 7B).13,18,38,55,57 Tibial tubercle distalization and patellar tendon tenodesis attached to the original insertion normalize PTL and stabilize the PF joint in patients with patella alta.5,47 In a comparison of these surgical procedures, cartilage stress was lower with distalization than with distalization and tenodesis.13

Soft-tissue methods are recommended in children, as bone procedures injure the proximal tibial physis and may cause it to close prematurely.58 The patella can be distally advanced by completely mobilizing the patellar tendon and fixating with sutures through the cartilaginous tibial tubercle. This technique is a satisfactory treatment for skeletally immature patients who present with habitual patellar dislocation associated with patella alta.58,59

CDI and BPI assess patellar height relative to the tibial plateau, and therefore are the most useful measurement methods for patellar height after distalization of the tibial tubercle.5 ISI does not change after distalization of the tibial tubercle and cannot be recommended.5,18 As PF indices (eg, PTI) can trace preoperative and postoperative values, these measurements are valuable.

Controversies

Our review found no consensus on measurement method or cutoff value. No measurement method showed clear clinical or methodologic superiority. Most published patellar height and patella alta data are based on conventional radiographs using a tibial reference point, even though a femoral or even trochlear reference point seems more reproducible, particularly in PF pathologies. Several cutoff values have been reported for each patella alta measurement method. Regarding pathologic thresholds, which might require surgical correction, very little information has been published, and scientific evidence is lacking. Numerous important aspects remain unanswered after this review, and clarification is mandatory.

Five Key Facts

1. In patella alta assessment, different morphologic, biomechanical, and functional aspects must be considered. The most relevant aspect is decreased engagement of the patella and trochlea,4-9,11,26 which results in decreased bony stability in knee extension.1-3 Therefore, patella alta is one of the potential risk factors for patellar instability with a high percentage of recurrent patellar dislocation.4-9 In early knee flexion, the patella translates more distally with better engagement of the patella in the trochlea and better stability. Therefore, measurement in extension, with the patellar tendon out to length, seems to offer a more reliable assessment of the patella–femur relationship.

2. Insufficient engagement of the patella in the trochlea is the most important aspect of patella alta.11 Therefore, direct measurement of this engagement seems logical.

3. As radiographs do not show articular cartilage, they should not be used to assess the articular patella–femur relationship.11,14,26 Patella–trochlea cartilage overlap is the most relevant factor for patella alta and should be measured on MRI.6,14,26,32

4. PTL is an important factor for patellar height and particularly patella alta. The range of normal PTL values is wide: 35 mm to 61 mm. The described cutoff values for patella alta (>52 mm to >56 mm) fall within this normal range. The cause may be the different measurement methods used.33,47,59-61 Therefore, for precise diagnostics, a standardized measurement method that includes the selected cut imaging is mandatory.

Many important aspects remain unanswered, and clarification is mandatory (Table 9).

Conclusion

Our review revealed many variations in patella alta definitions and descriptions, measurement methods, cutoff values, and treatment options. Presence of patella alta depends on measurement method used. Methods cannot be used interchangeably, and they all have their advantages and limitations. Unfortunately, there is no generally accepted consensus on measurement method, patella alta cutoff value, or treatment with ideal correction. Treatment planning and outcomes assessment require clarification of these many issues.

Take-Home Points

- Patella alta has a reduced articular area of PF contact.

- Presence of patella alta depends on the measurement method.

- Patella alta is defined as ISI >1.2 and CDI >1.2 to >1.3.

- On sagittal MRI, PTI is used most often with cutoff values of <0.125 to 0.28.

- Tibial tubercle distalization is most often used to treat patella alta. The desired postoperative patellar height is a CDI of 1.0.

Patella alta is a patella that rides abnormally high in relation to the femur, the femoral trochlea, or the tibia,1 with decreased bony stability requiring increased knee flexion angles to engage the trochlea.2,3 An abnormally high patella may therefore insufficiently engage the proximal trochlea groove both in extension and in the early phase of knee flexion—making it one of the potential risk factors for patellar instability.4-10 Accordingly, patella alta is present in 30% of patients with recurrent patellar dislocation.11 It also occurs in other disorders, such as knee extensor apparatus disorders, in patients with patellofemoral (PF) pain, chondromalacia, Sinding-Larsen-Johansson disease, Osgood-Schlatter disease, patellar tendinopathy, and osteoarthritis.1,7,8,12-18 As such, patella alta represents an important predisposing factor for patellar malalignment and PF-related complaints. On the other hand, patella alta may also be a normal variant of a person’s knee anatomy and may be well tolerated when not combined with other instability factors.4

Despite the importance of patella alta, there is no consensus on a precise definition, the most reliable measurement method, or the factors thought to be important in clinical decisions regarding treatment. To address this issue, we systematically reviewed the patella alta literature for definitions, the most common measurement methods and their patella alta cutoff values, and cutoff values for surgical correction and proposed surgical techniques.

Methods

In February 2017, using the term patella alta, we performed a systematic literature search on PubMed. Inclusion criteria were original study or review articles, publication in peer-reviewed English-language journals between 2000 and 2017, and narrative description or measurement of human patellar height on plain radiographs or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Excluded were abstracts and articles in languages other than English; animal and computational/biomechanical studies; case reports; and knee arthroplasties, knee extensor ruptures, and hereditary and congenital diseases. All evidence levels were included.

We assessed measurement methods, reported cutoff values for patella alta, cutoff values for performing surgical correction, proposed surgical techniques, and postoperative target values. Original study articles and review articles were analyzed separately.

Results

Of 211 articles identified, 92 met the inclusion criteria for original study, and 28 for review. All their abstracts were reviewed, and 91 were excluded: 17 for language other than English, 11 for animal study, 12 for biomechanical/computational study, 20 for case report, 8 for arthroplasty, 13 for hereditary or congenital disease, 1 for extensor apparatus rupture, 3 for editorial letter, and 6 for other reasons. Full text copies of all included articles were obtained and reviewed.

Original Study Articles

Definition. Of the 92 original study articles, 17 (18.5%) defined patella alta by description alone, and 75 (81.5%) used imaging-based measurements. Patella alta was described as a patella that rides abnormally high in relation to the trochlear groove, with a reduced articular area of PF contact1,15,19-21 or decreased patella–trochlea cartilage overlap.22 With this reduced contact area, there is increased PF stress.21

With radiographic measurements, patella alta is defined as a Caton-Deschamps index (CDI) of >1.2 to >1.3, an Insall-Salvati index (ISI) of >1.2, a Blackburne-Peel index (PBI) of >1.0,4,15,18,23-25 and a patellotrochlear index (PTI) of <0.125 to 0.28.6,26

On lateral radiographs, ISI was the most common measurement (33 studies), with patella alta cutoff values ranging from >1.2 to >1.5. The second most common measurement was CDI (24 studies), with cutoff values of >1.2 to >1.3. Other indices, such as the modified ISI (6 studies), the BPI (1 study), and the Koshino index (2 studies), had their cutoff values used more consistently (>1.6 to >2.4, >1.0, and >1.2, respectively) but these indices were rarely reported in the literature (Table 1).27,28,29

Thirty-six studies defined patella alta with MRI using either the aforementioned radiographic ratios (23 studies, 3 indices, Table 2) or PF indices (13 studies, 4 methods, Table 3).30

On sagittal MRI, PTI was used most often; cutoff values were <0.125 to 0.28.

Thirteen studies defined patella alta with PTL: 5 using lateral conventional radiographs and 8 using sagittal MRI. For each type of imaging, the cutoff value was >52 mm to >56 mm. PTL was measured either independently or together with ISI on sagittal MRI (Table 4).

Review Articles

Twenty-eight review articles met the inclusion criteria.35-40 Patella alta was described mostly with ISI (75%) or CDI (64%). In up to 57% of these articles, a patella alta reference value was missing. Only 1 article mentioned different cutoff values for conventional radiographs and MRI. BPI was mentioned in 50% of studies, but only 2 indicated a cutoff value for patella alta. Eleven percent used PTI on sagittal MRI and took patella–trochlea cartilage overlap into account.

Eight review articles mentioned cutoff values for surgical correction. Only 1 of 4 articles mentioned a cutoff value for correcting patella alta in PF instability, and only 2 articles suggested an ideal postoperative patellar height (Table 6).

No review article relied on PTL to describe patella alta or to advise surgical treatment.

Discussion

Our review revealed many variations in patella alta definitions and descriptions, measurement methods, cutoff values, and treatment options. Interpretation of patellar height and, particularly, patella alta is very heterogeneous. Accordingly, comparing surgical indications, surgical treatment options, and outcomes across studies can be difficult.

Measurement Methods

Radiographs. Conventional radiographs were used to describe patella alta in two-thirds of the original study articles. The most common measurement methods marked the position of the patella relative to either the femur (direct assessment) or the tibia (indirect assessment).14,25 All established measurement methods use lateral radiographs, which do not show articular cartilage.11,14 Therefore, lateral radiograph ratios of different and variable bony landmarks do not measure actual PF articular congruence. The widely variable morphologies of patella (distal patellar nose, different articulating surface), femoral trochlea (facet in height and length), proximal tibia (inherited or acquired deformities on tibial tubercle), and slope are all confounding factors that may affect measurement (Figure 1). In addition, specific variations in PF joint morphology (eg, small patellar articular surface, short trochlea) are not well represented by these ratios.11

All these methods have advantages, limitations, and different values of interobserver and intraobserver variability, reliability, and reproducibility (Table 7).29,41

Determination of both patellar height and patella alta depends on the measurement method used and is significantly affected by anatomical variants, such as extra-articular patella and femorotibial landmarks.

The ISI method is most commonly used because it does not depend on degree of knee flexion, is thought to measure the relative length of the patellar tendon the best,5 and has established MRI criteria.6 However, ISI has limitations: Its distal bony landmark is the tibial tuberosity, which can be difficult to assess14; the shape of the patella (mainly its inferior point) varies42; and the measurement does not change after distalization of the tibial tubercle.5

CDI is the most accurate diagnostic method because it relies on readily identifiable and reproducible anatomical landmarks; does not depend on radiograph quality, knee size, radiologic enlargement, or position of the tibial tubercle or patellar modification; and is unaffected by degree of knee flexion between 10° and 80°.38,43 CDI is the method that is most useful in describing patellar height after distalization of the tibial tubercle because it assesses the height of the patella relative to the tibial plateau.5 CDI is limited with respect to clear identification of the patellar and tibial articular margin.37

BPI has the lowest interobserver variability and discriminates best among patella alta, norma, and infera.41 Like CDI, BPI assesses patellar height relative to the tibial plateau, and thus is useful in describing patellar height after distalization of the tibial tubercle.5 BPI is limited in that it uses a line drawn along the tibial plateau, where variations in inclination and tibial slope produce inaccuracies,14 and depends highly on projection angles. Clinically, BPI is rarely used.

As the literature shows, the radiologic methods of determining patellar height are variable and unreliable and depend on the ratio used.26,41 These methods do not reveal precise information about the PF articular congruence, the key finding for necessary treatment.

Radiographic Indices on MRI. Some studies measured radiographic indices on sagittal MRI. Radiologic and MRI measurements are described as not significantly different or slightly different, and 0.09 to 0.13 needs to be added with ISI and BP ratios on radiographs, MRI, and computed tomography (CT).17,44-47 ISI is commonly used, and its clinical application is easy. Although classically measured on plain radiographs, ISI is reliably measured on MRI as well.17,30 The traditional 1.2 threshold for defining patella alta was used by Charles and colleagues.44 CDI is equally well measured on radiographs and MRI.47

According to the literature, 3 different measurement methods have been used to describe degree of patella–trochlea cartilage overlap: PTI, sagittal patellofemoral engagement (SPE), and patellar articular overlap (PAO).1,11,26

PTI uses the true articular cartilage patella–trochlea relationship for measurement of patellar height on sagittal MRI in extension (Figure 3). If the patellar tendon is fully out to length (no laxity), PTI reliably and precisely determines the exact articular correlation of PF joint and patellar height.6

SPE is similar to percentage of articular coverage.1,11 Patellar overlap of the trochlea is measured on 2 different sagittal MRI images: 1 with the greatest length of patellar cartilage and 1 with the greatest length of femoral trochlear cartilage. This measurement did not correlate with CDI.1 SPE was not evaluated in control studies, and normal and pathologic values are unavailable.

PAO is measured with patients positioned at rest and in standard knee coils.1 MRI was not obtained in full extension or with quadriceps activation, and knee flexion angle values are unavailable. Total patellar articular length was measured on the sagittal MRI that showed the greatest patellar length and articular cartilage thickness. The same image was used to measure articular overlap, or the length of patellar cartilage overlying the trochlear cartilage, as measured parallel to the subchondral surface of the patella. PAO correlates well with conventional patellar height measurements in the sagittal plane and shows promise as a simpler alternative to the conventional indices.1 Normal and pathologic values are unavailable.

So far, PTI is the only method that was controlled in several studies, assessed for its reliability, and compared with other patellar height measurements.6,14

Patellar Tendon Length. PTL can be measured on lateral radiographs or sagittal MRI. Radiologic and MRI measurements are described as not significantly different47 or slightly different, and 0.09 to 0.13 needs to be added with the ISI ratio on radiographs, MRI, and CT.46 PTL is reliably evaluated with ISI.41,50 There is a weak correlation of patient height and PTL: Taller people have normally longer tendons.51-53

PTL measurements revealed that the posterior surface of the patellar tendon was significantly shorter than the anterior surface. Compared with their corresponding posterior fascicles, anterior fascicles are longer; their attachment is more proximal to the patella and more distal to the tibia. In addition, posterior PTL is significantly shorter with the posterior patellar attachment (adheres to posterior aspect of the inferior patellar pole) than with the anterior attachment (adheres to anterior aspect of the inferior patellar pole).56 Moreover, the lateral and medial fascicles are longer than the central fascicles attaching at the most inferior patellar pole. This issue must be considered in image cut selection (Figures 6A, 6B). Furthermore, type of inferior pole of patella (pointed, intermediate, blunt) is important in measurement.56 Overall, mean (SD) PTL was 54.9 (1.2) mm on the anterior surface and 35.0 (0.6) mm on the posterior surface.

It is important to precisely describe the measurement method and location (sagittal cut) and to consider the shape of the inferior patellar pole and the site of the patellar tendon attachment.56

Treatments. For patella alta, the surgical treatment goals are to increase the PF contact area and improve PF articular congruence, and thereby increase PF stability.31-33 Four different procedures were used to treat patella alta (Table 5), but only 11 of the 92 original study articles and 8 of the 28 review articles included in our review mentioned a specific patellar height that required surgical correction (Tables 5, 6). Recommendations were based on CDI (>1.2 to >1.4) and less often on ISI (>1.2 to >1.4) or PTL (>56 mm).

Tibial tubercle distalization is effective in normalizing patellar height to correct the patellar index in patella alta (Figures 7A, 7B).13,18,38,55,57 Tibial tubercle distalization and patellar tendon tenodesis attached to the original insertion normalize PTL and stabilize the PF joint in patients with patella alta.5,47 In a comparison of these surgical procedures, cartilage stress was lower with distalization than with distalization and tenodesis.13

Soft-tissue methods are recommended in children, as bone procedures injure the proximal tibial physis and may cause it to close prematurely.58 The patella can be distally advanced by completely mobilizing the patellar tendon and fixating with sutures through the cartilaginous tibial tubercle. This technique is a satisfactory treatment for skeletally immature patients who present with habitual patellar dislocation associated with patella alta.58,59

CDI and BPI assess patellar height relative to the tibial plateau, and therefore are the most useful measurement methods for patellar height after distalization of the tibial tubercle.5 ISI does not change after distalization of the tibial tubercle and cannot be recommended.5,18 As PF indices (eg, PTI) can trace preoperative and postoperative values, these measurements are valuable.

Controversies

Our review found no consensus on measurement method or cutoff value. No measurement method showed clear clinical or methodologic superiority. Most published patellar height and patella alta data are based on conventional radiographs using a tibial reference point, even though a femoral or even trochlear reference point seems more reproducible, particularly in PF pathologies. Several cutoff values have been reported for each patella alta measurement method. Regarding pathologic thresholds, which might require surgical correction, very little information has been published, and scientific evidence is lacking. Numerous important aspects remain unanswered after this review, and clarification is mandatory.

Five Key Facts

1. In patella alta assessment, different morphologic, biomechanical, and functional aspects must be considered. The most relevant aspect is decreased engagement of the patella and trochlea,4-9,11,26 which results in decreased bony stability in knee extension.1-3 Therefore, patella alta is one of the potential risk factors for patellar instability with a high percentage of recurrent patellar dislocation.4-9 In early knee flexion, the patella translates more distally with better engagement of the patella in the trochlea and better stability. Therefore, measurement in extension, with the patellar tendon out to length, seems to offer a more reliable assessment of the patella–femur relationship.

2. Insufficient engagement of the patella in the trochlea is the most important aspect of patella alta.11 Therefore, direct measurement of this engagement seems logical.

3. As radiographs do not show articular cartilage, they should not be used to assess the articular patella–femur relationship.11,14,26 Patella–trochlea cartilage overlap is the most relevant factor for patella alta and should be measured on MRI.6,14,26,32

4. PTL is an important factor for patellar height and particularly patella alta. The range of normal PTL values is wide: 35 mm to 61 mm. The described cutoff values for patella alta (>52 mm to >56 mm) fall within this normal range. The cause may be the different measurement methods used.33,47,59-61 Therefore, for precise diagnostics, a standardized measurement method that includes the selected cut imaging is mandatory.

Many important aspects remain unanswered, and clarification is mandatory (Table 9).

Conclusion

Our review revealed many variations in patella alta definitions and descriptions, measurement methods, cutoff values, and treatment options. Presence of patella alta depends on measurement method used. Methods cannot be used interchangeably, and they all have their advantages and limitations. Unfortunately, there is no generally accepted consensus on measurement method, patella alta cutoff value, or treatment with ideal correction. Treatment planning and outcomes assessment require clarification of these many issues.

1 Munch JL, Sullivan JP, Nguyen JT, et al. Patellar articular overlap on MRI is a simple alternative to conventional measurements of patellar height. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4(7):2325967116656328.

2. Elias JJ, Soehnlen NT, Guseila LM, Cosgarea AJ. Dynamic tracking influenced by anatomy in patellar instability. Knee. 2016;23(3):450-455.

3. Fabricant PD, Ladenhauf HN, Salvati EA, Green DW. Medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) reconstruction improves radiographic measures of patella alta in children. Knee. 2014;21(6):1180-1184.

4. Askenberger M, Janarv PM, Finnbogason T, Arendt EA. Morphology and anatomic patellar instability risk factors in first-time traumatic lateral patellar dislocations. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(1):50-58.

5. Mayer C, Magnussen RA, Servien E, et al. Patellar tendon tenodesis in association with tibial tubercle distalization for the treatment of episodic patellar dislocation with patella alta. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(2):346-351.

6. Ali SA, Helmer R, Terk MR. Patella alta: lack of correlation between patellotrochlear cartilage congruence and commonly used patellar height ratios. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(5):1361-1366.

7. Lewallen LW, McIntosh AL, Dahm DL. Predictors of recurrent instability after acute patellofemoral dislocation in pediatric and adolescent patients. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(3):575-581.

8. Ward SR, Terk MR, Powers CM. Patella alta: association with patellofemoral alignment and changes in contact area during weight-bearing. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1749-1755.

9. Dejour H, Walch G, Nove-Josserand L, Guier C. Factors of patellar instability: an anatomic radiographic study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1994;2(1):19-26.

10. Arendt EA, Fithian DC, Cohen E. Current concepts of lateral patella dislocation. Clin Sports Med. 2002;21(3):499-519.

11. Dejour D, Ferrua P, Ntagiopoulos PG, et al. The introduction of a new MRI index to evaluate sagittal patellofemoral engagement. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2013;99(8 suppl):S391-S398.

12. Althani S, Shahi A, Tan TL, Al-Belooshi A. Position of the patella among Emirati adult knees. Is Insall-Salvati ratio applicable to Middle-Easterners? Arch Bone Joint Surg. 2016;4(2):137-140.

13. Yin L, Liao TC, Yang L, Powers CM. Does patella tendon tenodesis improve tibial tubercle distalization in treating patella alta? A computational study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(11):2451-2461.

14. Barnett AJ, Prentice M, Mandalia V, Wakeley CJ, Eldridge JD. Patellar height measurement in trochlear dysplasia. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(12):1412-1415.

15. Otsuki S, Nakajima M, Fujiwara K, et al. Influence of age on clinical outcomes of three-dimensional transfer of the tibial tuberosity for patellar instability with patella alta. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(8):2392-2396.

16. Otsuki S, Nakajima M, Oda S, et al. Three-dimensional transfer of the tibial tuberosity for patellar instability with patella alta. J Orthop Sci. 2013;18(3):437-442.

17. Steensen RN, Bentley JC, Trinh TQ, Backes JR, Wiltfong RE. The prevalence and combined prevalences of anatomic factors associated with recurrent patellar dislocation: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(4):921-927.

18. Magnussen RA, De Simone V, Lustig S, Neyret P, Flanigan DC. Treatment of patella alta in patients with episodic patellar dislocation: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(10):2545-2550.

19. Bertollo N, Pelletier MH, Walsh WR. Simulation of patella alta and the implications for in vitro patellar tracking in the ovine stifle joint. J Orthop Res. 2012;30(11):1789-1797.

20. Narkbunnam R, Chareancholvanich K. Effect of patient position on measurement of patellar height ratio. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2015;135(8):1151-1156.

21. Stefanik JJ, Zhu Y, Zumwalt AC, et al. Association between patella alta and the prevalence and worsening of structural features of patellofemoral joint osteoarthritis: the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62(9):1258-1265.

22. Monk AP, Doll HA, Gibbons CL, et al. The patho-anatomy of patellofemoral subluxation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(10):1341-1347.

23. Hirano A, Fukubayashi T, Ishii T, Ochiai N. Relationship between the patellar height and the disorder of the knee extensor mechanism in immature athletes. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21(4):541-544.

24. Ng JP, Cawley DT, Beecher SM, Lee MJ, Bergin D, Shannon FJ. Focal intratendinous radiolucency: a new radiographic method for diagnosing patellar tendon ruptures. Knee. 2016;23(3):482-486.

25. van Duijvenbode D, Stavenuiter M, Burger B, van Dijke C, Spermon J, Hoozemans M. The reliability of four widely used patellar height ratios. Int Orthop. 2016;40(3):493-497.

26. Biedert RM, Albrecht S. The patellotrochlear index: a new index for assessing patellar height. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(8):707-712.

27. Grelsamer RP, Meadows S. The modified Insall-Salvati ratio for assessment of patellar height. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(282):170-176.

28. Thaunat M, Erasmus PJ. The favourable anisometry: an original concept for medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction. Knee. 2007;14(6):424-428.

29. Anagnostakos K, Lorbach O, Reiter S, Kohn D. Comparison of five patellar height measurement methods in 90 degrees knee flexion. Int Orthop. 2011;35(12):1791-1797.

30. Miller TT, Staron RB, Feldman F. Patellar height on sagittal MR imaging of the knee. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167(2):339-341.

31. Dejour D, Le Coultre B. Osteotomies in patello-femoral instabilities. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2007;15(1):39-46.

32. Rhee SJ, Pavlou G, Oakley J, Barlow D, Haddad F. Modern management of patellar instability. Int Orthop. 2012;36(12):2447-2456.

33. Servien E, Verdonk PC, Neyret P. Tibial tuberosity transfer for episodic patellar dislocation. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2007;15(2):61-67.

34. Caton J, Deschamps G, Chambat P, Lerat JL, Dejour H. [Patella infera. Apropos of 128 cases]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1982;68(5):317-325.

35. Meyers AB, Laor T, Sharafinski M, Zbojniewicz AM. Imaging assessment of patellar instability and its treatment in children and adolescents. Pediatr Radiol. 2016;46(5):618-636.

36. Feller JA. Distal realignment (tibial tuberosity transfer). Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2012;20(3):152-161.

37. Dietrich TJ, Fucentese SF, Pfirrmann CW. Imaging of individual anatomical risk factors for patellar instability. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2016;20(1):65-73.

38. Dean CS, Chahla J, Serra Cruz R, Cram TR, LaPrade RF. Patellofemoral joint reconstruction for patellar instability: medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction, trochleoplasty, and tibial tubercle osteotomy. Arthrosc Tech. 2016;5(1):e169-e175.

39. Frosch KH, Schmeling A. A new classification system of patellar instability and patellar maltracking. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2016;136(4):485-497.

40. Weber AE, Nathani A, Dines JS, et al. An algorithmic approach to the management of recurrent lateral patellar dislocation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(5):417-427.

41. Seil R, Muller B, Georg T, Kohn D, Rupp S. Reliability and interobserver variability in radiological patellar height ratios. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8(4):231-236.

42. Laprade J, Culham E. Radiographic measures in subjects who are asymptomatic and subjects with patellofemoral pain syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(414):172-182.

43. Caton JH, Dejour D. Tibial tubercle osteotomy in patello-femoral instability and in patellar height abnormality. Int Orthop. 2010;34(2):305-309.

44. Charles MD, Haloman S, Chen L, Ward SR, Fithian D, Afra R. Magnetic resonance imaging–based topographical differences between control and recurrent patellofemoral instability patients. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(2):374-384.

45. Kurtul Yildiz H, Ekin EE. Patellar malalignment: a new method on knee MRI. Springerplus. 2016;5(1):1500.

46. Lee PP, Chalian M, Carrino JA, Eng J, Chhabra A. Multimodality correlations of patellar height measurement on x-ray, CT, and MRI. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41(10):1309-1314.

47. Neyret P, Robinson AH, Le Coultre B, Lapra C, Chambat P. Patellar tendon length—the factor in patellar instability? Knee. 2002;9(1):3-6.

48. Diederichs G, Issever AS, Scheffler S. MR imaging of patellar instability: injury patterns and assessment of risk factors. Radiographics. 2010;30(4):961-981.

49. Earhart C, Patel DB, White EA, Gottsegen CJ, Forrester DM, Matcuk GR Jr. Transient lateral patellar dislocation: review of imaging findings, patellofemoral anatomy, and treatment options. Emerg Radiol. 2013;20(1):11-23.

50. Aarimaa V, Ranne J, Mattila K, Rahi K, Virolainen P, Hiltunen A. Patellar tendon shortening after treatment of patellar instability with a patellar tendon medialization procedure. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2008;18(4):442-446.

51. Brown DE, Alexander AH, Lichtman DM. The Elmslie-Trillat procedure: evaluation in patellar dislocation and subluxation. Am J Sports Med. 1984;12(2):104-109.

52. Goldstein JL, Verma N, McNickle AG, Zelazny A, Ghodadra N, Bach BR Jr. Avoiding mismatch in allograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: correlation between patient height and patellar tendon length. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(5):643-650.

53. Navali AM, Jafarabadi MA. Is there any correlation between patient height and patellar tendon length? Arch Bone Joint Surg. 2015;3(2):99-103.

54. Park MS, Chung CY, Lee KM, Lee SH, Choi IH. Which is the best method to determine the patellar height in children and adolescents? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(5):1344-1351.

55. Berard JB, Magnussen RA, Bonjean G, et al. Femoral tunnel enlargement after medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction: prevalence, risk factors, and clinical effect. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(2):297-301.

56. Edama M, Kageyama I, Nakamura M, et al. Anatomical study of the inferior patellar pole and patellar tendon [published online ahead of print February 16, 2017]. Scand J Med Sci Sports. doi:10.1111/sms.12858.

57. Al-Sayyad MJ, Cameron JC. Functional outcome after tibial tubercle transfer for the painful patella alta. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;(396):152-162.

58. Benoit B, Laflamme GY, Laflamme GH, Rouleau D, Delisle J, Morin B. Long-term outcome of surgically-treated habitual patellar dislocation in children with coexistent patella alta. Minimum follow-up of 11 years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(9):1172-1177.

59. Simmons E Jr, Cameron JC. Patella alta and recurrent dislocation of the patella. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(274):265-269.

60. Degnan AJ, Maldjian C, Adam RJ, Fu FH, Di Domenica M. Comparison of Insall-Salvati ratios in children with an acute anterior cruciate ligament tear and a matched control population. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204(1):161-166.

61. Wittstein JR, Bartlett EC, Easterbrook J, Byrd JC. Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of patellofemoral malalignment. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(6):643-649.

1 Munch JL, Sullivan JP, Nguyen JT, et al. Patellar articular overlap on MRI is a simple alternative to conventional measurements of patellar height. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4(7):2325967116656328.

2. Elias JJ, Soehnlen NT, Guseila LM, Cosgarea AJ. Dynamic tracking influenced by anatomy in patellar instability. Knee. 2016;23(3):450-455.

3. Fabricant PD, Ladenhauf HN, Salvati EA, Green DW. Medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) reconstruction improves radiographic measures of patella alta in children. Knee. 2014;21(6):1180-1184.

4. Askenberger M, Janarv PM, Finnbogason T, Arendt EA. Morphology and anatomic patellar instability risk factors in first-time traumatic lateral patellar dislocations. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(1):50-58.

5. Mayer C, Magnussen RA, Servien E, et al. Patellar tendon tenodesis in association with tibial tubercle distalization for the treatment of episodic patellar dislocation with patella alta. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(2):346-351.

6. Ali SA, Helmer R, Terk MR. Patella alta: lack of correlation between patellotrochlear cartilage congruence and commonly used patellar height ratios. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(5):1361-1366.

7. Lewallen LW, McIntosh AL, Dahm DL. Predictors of recurrent instability after acute patellofemoral dislocation in pediatric and adolescent patients. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(3):575-581.

8. Ward SR, Terk MR, Powers CM. Patella alta: association with patellofemoral alignment and changes in contact area during weight-bearing. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1749-1755.

9. Dejour H, Walch G, Nove-Josserand L, Guier C. Factors of patellar instability: an anatomic radiographic study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1994;2(1):19-26.

10. Arendt EA, Fithian DC, Cohen E. Current concepts of lateral patella dislocation. Clin Sports Med. 2002;21(3):499-519.