User login

Prodrug infusion beats oral Parkinson’s disease therapy for motor symptoms

, according to a new study. The beneficial effects of these phosphate prodrugs of levodopa and carbidopa were most noticeable in the early morning, results of the phase 1B study showed.

As Parkinson’s disease progresses and dosing of oral levodopa/carbidopa (LD/CD) increases, its therapeutic window narrows, resulting in troublesome dyskinesia at peak drug levels and tremors and rigidity when levels fall.

“Foslevodopa/foscarbidopa shows lower ‘off’ time than oral levodopa/carbidopa, and this was statistically significant. Also, foslevodopa/foscarbidopa (fosL/fosC) showed more ‘on’ time without dyskinesia, compared with oral levodopa/carbidopa. This was also statistically significant,” lead author Sven Stodtmann, PhD, of AbbVie GmbH, Ludwigshafen, Germany, reported in his recorded presentation at the Movement Disorders Society’s 23rd International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorder (Virtual) 2020.

Continuous infusion versus oral therapy

The analysis included 20 patients, and all data from these individuals were collected between 4:30 a.m. and 9:30 p.m.

Participants were 12 men and 8 women, aged 30-80 years, with advanced, idiopathic Parkinson’s disease responsive to levodopa but inadequately controlled on their current stable therapy, having a minimum of 2.5 off hours/day. Mean age was 61.3 plus or minus 10.5 years (range 35-77 years).

In this single-arm, open-label study, they received subcutaneous infusions of personalized therapeutic doses of fosL/fosC 24 hours/day for 28 days after a 10- to 30-day screening period during which they recorded LD/CD doses in a diary and had motor symptoms monitored using a wearable device.

Following the screening period, fosL/fosC doses were titrated over up to 5 days, with subsequent weekly study visits, for a total time on fosL/fosC of 28 days. Drug titration was aimed at maximizing functional on time and minimizing the number of off episodes while minimizing troublesome dyskinesia.

Continuous infusion of fosL/fosC performed better than oral LD/CD on all counts.

“The off time is much lower in the morning for people on foslevodopa/foscarbidopa [compared with oral LD/CD] because this is a 24-hour infusion product,” Dr. Stodtmann explained.

The effect was maintained over the course of the day with little fluctuation with fosL/fosC, off periods never exceeding about 25% between 4:30 a.m. and 9 p.m. For LD/CD, off periods were highest in the early morning and peaked at about 50% on a 3- to 4-hour cycle during the course of the day.

Increased on time without dyskinesia varied between about 60% and 80% during the day with fosL/fosC, showing the greatest difference between fosL/fosC and oral LD/CD in the early morning hours.

“On time with nontroublesome dyskinesia was lower for foscarbidopa/foslevodopa, compared to oral levodopa/carbidopa, but this was not statistically significant,” Dr. Stodtmann said. On time with troublesome dyskinesia followed the same pattern, again, not statistically significant.

Looking at the data another way, the investigators calculated the odds ratios of motor symptoms using fosL/fosC, compared with oral LD/CD. Use of fosL/fosC was associated with a 59% lower risk of being in the off state during the day, compared with oral LD/CD (odds ratio, 0.4; 95% confidence interval, 0.2-0.7; P < .01). Similarly, the probability of being in the on state without dyskinesia was much greater with fosL/fosC (OR, 2.75; 95% CI, 1.08-6.99; P < .05).

Encouraging, but more data needed

Indu Subramanian, MD, of the department of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the Parkinson’s Disease Research, Education, and Clinical Center at the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Hospital, commented that the field has been waiting to see data on fosL/fosC.

“It seems like it’s pretty reasonable in terms of what the goals were, which is to improve stability of Parkinson’s symptoms, to improve off time and give on time without troublesome dyskinesia,” she said. “So I think those [goals] have been met.”

Dr. Subramanian, who was not involved with the research, said she would have liked to have seen results concerning safety of this drug formulation, which the presentation lacked, “because historically, there have been issues with nodule formation and skin breakdown, things like that, due to the stability of the product in the subcutaneous form. … So, always to my understanding, there has been this search for things that are tolerated in the subcutaneous delivery.”

If this formulation proves safe and tolerable, Dr. Subramanian sees a potential place for it for some patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease.

“Certainly a subcutaneous formulation will be better than something that requires … deep brain surgery or even a pump insertion like Duopa [carbidopa/levodopa enteral suspension, AbbVie] or something like that,” she said. “I think [it] would be beneficial over something with the gut because the gut historically has been a problem to rely on in advanced Parkinson’s patients due to slower transit times, and the gut itself is affected with Parkinson’s disease.”

Dr. Stodtmann and all coauthors are employees of AbbVie, which was the sponsor of the study and was responsible for all aspects of it. Dr. Subramanian has given talks for Acadia Pharmaceuticals and Acorda Therapeutics in the past.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a new study. The beneficial effects of these phosphate prodrugs of levodopa and carbidopa were most noticeable in the early morning, results of the phase 1B study showed.

As Parkinson’s disease progresses and dosing of oral levodopa/carbidopa (LD/CD) increases, its therapeutic window narrows, resulting in troublesome dyskinesia at peak drug levels and tremors and rigidity when levels fall.

“Foslevodopa/foscarbidopa shows lower ‘off’ time than oral levodopa/carbidopa, and this was statistically significant. Also, foslevodopa/foscarbidopa (fosL/fosC) showed more ‘on’ time without dyskinesia, compared with oral levodopa/carbidopa. This was also statistically significant,” lead author Sven Stodtmann, PhD, of AbbVie GmbH, Ludwigshafen, Germany, reported in his recorded presentation at the Movement Disorders Society’s 23rd International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorder (Virtual) 2020.

Continuous infusion versus oral therapy

The analysis included 20 patients, and all data from these individuals were collected between 4:30 a.m. and 9:30 p.m.

Participants were 12 men and 8 women, aged 30-80 years, with advanced, idiopathic Parkinson’s disease responsive to levodopa but inadequately controlled on their current stable therapy, having a minimum of 2.5 off hours/day. Mean age was 61.3 plus or minus 10.5 years (range 35-77 years).

In this single-arm, open-label study, they received subcutaneous infusions of personalized therapeutic doses of fosL/fosC 24 hours/day for 28 days after a 10- to 30-day screening period during which they recorded LD/CD doses in a diary and had motor symptoms monitored using a wearable device.

Following the screening period, fosL/fosC doses were titrated over up to 5 days, with subsequent weekly study visits, for a total time on fosL/fosC of 28 days. Drug titration was aimed at maximizing functional on time and minimizing the number of off episodes while minimizing troublesome dyskinesia.

Continuous infusion of fosL/fosC performed better than oral LD/CD on all counts.

“The off time is much lower in the morning for people on foslevodopa/foscarbidopa [compared with oral LD/CD] because this is a 24-hour infusion product,” Dr. Stodtmann explained.

The effect was maintained over the course of the day with little fluctuation with fosL/fosC, off periods never exceeding about 25% between 4:30 a.m. and 9 p.m. For LD/CD, off periods were highest in the early morning and peaked at about 50% on a 3- to 4-hour cycle during the course of the day.

Increased on time without dyskinesia varied between about 60% and 80% during the day with fosL/fosC, showing the greatest difference between fosL/fosC and oral LD/CD in the early morning hours.

“On time with nontroublesome dyskinesia was lower for foscarbidopa/foslevodopa, compared to oral levodopa/carbidopa, but this was not statistically significant,” Dr. Stodtmann said. On time with troublesome dyskinesia followed the same pattern, again, not statistically significant.

Looking at the data another way, the investigators calculated the odds ratios of motor symptoms using fosL/fosC, compared with oral LD/CD. Use of fosL/fosC was associated with a 59% lower risk of being in the off state during the day, compared with oral LD/CD (odds ratio, 0.4; 95% confidence interval, 0.2-0.7; P < .01). Similarly, the probability of being in the on state without dyskinesia was much greater with fosL/fosC (OR, 2.75; 95% CI, 1.08-6.99; P < .05).

Encouraging, but more data needed

Indu Subramanian, MD, of the department of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the Parkinson’s Disease Research, Education, and Clinical Center at the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Hospital, commented that the field has been waiting to see data on fosL/fosC.

“It seems like it’s pretty reasonable in terms of what the goals were, which is to improve stability of Parkinson’s symptoms, to improve off time and give on time without troublesome dyskinesia,” she said. “So I think those [goals] have been met.”

Dr. Subramanian, who was not involved with the research, said she would have liked to have seen results concerning safety of this drug formulation, which the presentation lacked, “because historically, there have been issues with nodule formation and skin breakdown, things like that, due to the stability of the product in the subcutaneous form. … So, always to my understanding, there has been this search for things that are tolerated in the subcutaneous delivery.”

If this formulation proves safe and tolerable, Dr. Subramanian sees a potential place for it for some patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease.

“Certainly a subcutaneous formulation will be better than something that requires … deep brain surgery or even a pump insertion like Duopa [carbidopa/levodopa enteral suspension, AbbVie] or something like that,” she said. “I think [it] would be beneficial over something with the gut because the gut historically has been a problem to rely on in advanced Parkinson’s patients due to slower transit times, and the gut itself is affected with Parkinson’s disease.”

Dr. Stodtmann and all coauthors are employees of AbbVie, which was the sponsor of the study and was responsible for all aspects of it. Dr. Subramanian has given talks for Acadia Pharmaceuticals and Acorda Therapeutics in the past.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a new study. The beneficial effects of these phosphate prodrugs of levodopa and carbidopa were most noticeable in the early morning, results of the phase 1B study showed.

As Parkinson’s disease progresses and dosing of oral levodopa/carbidopa (LD/CD) increases, its therapeutic window narrows, resulting in troublesome dyskinesia at peak drug levels and tremors and rigidity when levels fall.

“Foslevodopa/foscarbidopa shows lower ‘off’ time than oral levodopa/carbidopa, and this was statistically significant. Also, foslevodopa/foscarbidopa (fosL/fosC) showed more ‘on’ time without dyskinesia, compared with oral levodopa/carbidopa. This was also statistically significant,” lead author Sven Stodtmann, PhD, of AbbVie GmbH, Ludwigshafen, Germany, reported in his recorded presentation at the Movement Disorders Society’s 23rd International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorder (Virtual) 2020.

Continuous infusion versus oral therapy

The analysis included 20 patients, and all data from these individuals were collected between 4:30 a.m. and 9:30 p.m.

Participants were 12 men and 8 women, aged 30-80 years, with advanced, idiopathic Parkinson’s disease responsive to levodopa but inadequately controlled on their current stable therapy, having a minimum of 2.5 off hours/day. Mean age was 61.3 plus or minus 10.5 years (range 35-77 years).

In this single-arm, open-label study, they received subcutaneous infusions of personalized therapeutic doses of fosL/fosC 24 hours/day for 28 days after a 10- to 30-day screening period during which they recorded LD/CD doses in a diary and had motor symptoms monitored using a wearable device.

Following the screening period, fosL/fosC doses were titrated over up to 5 days, with subsequent weekly study visits, for a total time on fosL/fosC of 28 days. Drug titration was aimed at maximizing functional on time and minimizing the number of off episodes while minimizing troublesome dyskinesia.

Continuous infusion of fosL/fosC performed better than oral LD/CD on all counts.

“The off time is much lower in the morning for people on foslevodopa/foscarbidopa [compared with oral LD/CD] because this is a 24-hour infusion product,” Dr. Stodtmann explained.

The effect was maintained over the course of the day with little fluctuation with fosL/fosC, off periods never exceeding about 25% between 4:30 a.m. and 9 p.m. For LD/CD, off periods were highest in the early morning and peaked at about 50% on a 3- to 4-hour cycle during the course of the day.

Increased on time without dyskinesia varied between about 60% and 80% during the day with fosL/fosC, showing the greatest difference between fosL/fosC and oral LD/CD in the early morning hours.

“On time with nontroublesome dyskinesia was lower for foscarbidopa/foslevodopa, compared to oral levodopa/carbidopa, but this was not statistically significant,” Dr. Stodtmann said. On time with troublesome dyskinesia followed the same pattern, again, not statistically significant.

Looking at the data another way, the investigators calculated the odds ratios of motor symptoms using fosL/fosC, compared with oral LD/CD. Use of fosL/fosC was associated with a 59% lower risk of being in the off state during the day, compared with oral LD/CD (odds ratio, 0.4; 95% confidence interval, 0.2-0.7; P < .01). Similarly, the probability of being in the on state without dyskinesia was much greater with fosL/fosC (OR, 2.75; 95% CI, 1.08-6.99; P < .05).

Encouraging, but more data needed

Indu Subramanian, MD, of the department of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the Parkinson’s Disease Research, Education, and Clinical Center at the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Hospital, commented that the field has been waiting to see data on fosL/fosC.

“It seems like it’s pretty reasonable in terms of what the goals were, which is to improve stability of Parkinson’s symptoms, to improve off time and give on time without troublesome dyskinesia,” she said. “So I think those [goals] have been met.”

Dr. Subramanian, who was not involved with the research, said she would have liked to have seen results concerning safety of this drug formulation, which the presentation lacked, “because historically, there have been issues with nodule formation and skin breakdown, things like that, due to the stability of the product in the subcutaneous form. … So, always to my understanding, there has been this search for things that are tolerated in the subcutaneous delivery.”

If this formulation proves safe and tolerable, Dr. Subramanian sees a potential place for it for some patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease.

“Certainly a subcutaneous formulation will be better than something that requires … deep brain surgery or even a pump insertion like Duopa [carbidopa/levodopa enteral suspension, AbbVie] or something like that,” she said. “I think [it] would be beneficial over something with the gut because the gut historically has been a problem to rely on in advanced Parkinson’s patients due to slower transit times, and the gut itself is affected with Parkinson’s disease.”

Dr. Stodtmann and all coauthors are employees of AbbVie, which was the sponsor of the study and was responsible for all aspects of it. Dr. Subramanian has given talks for Acadia Pharmaceuticals and Acorda Therapeutics in the past.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Telemedicine feasible and reliable in Parkinson’s trial

, a 1-year, phase 3 clinical trial has shown. The trial was an add-on study involving a subset of subjects from the STEADY-PD III trial of isradipine in early Parkinson’s disease.

Although the trial was conducted before SARS-CoV-2 arrived on the scene, the findings have particular relevance for being able to conduct a variety of clinical trials in the face of COVID-19 and the need to limit in-person interactions.

The 40 participants used tablets to complete three remote, video-based assessments during 1 year, with each remote visit planned to be completed within 4 weeks of an in-person visit. It was easy to enroll patients, and they completed about 95% of planned visits, said neurologist Christopher Tarolli, MD, of the University of Rochester (N.Y.).

He presented the study findings at the Movement Disorder Society’s 23rd International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders (Virtual) 2020.

“The visits were clearly feasible, and we were able to do them [84%] within that 4-week time frame around the in-person visit,” he said. “The visits were also reasonably reliable, particularly so for what we call the nonmotor outcomes and the patient-reported outcomes.”

In-person versus remote assessment

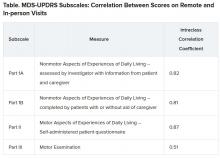

For the remote visits, participants completed primarily the same battery of tests as the in-person visits. Responses on the Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) subscales demonstrated “that there was excellent correlation between patient-reported and nonmotor outcome measures and moderate correlation between in-person and remote-performed motor assessments,” Dr. Tarolli said.

He explained that the study used modified motor assessments (MDS-UPDRS Part III) that excluded testing of rigidity and postural instability, which require hands-on testing by a trained examiner and thus are impossible to do remotely.

Additionally, the somewhat lower correlation on this subscale was probably the result of different investigators conducting in-person versus remote assessments, with a subset of in-person investigators who tended to rate participants more severely driving down the correlation. “I think if these methods were applied in future trials, the in-person and remote investigators would optimally be the same person,” Dr. Tarolli suggested.

Room for error?

Indu Subramanian, MD, of the department of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the Parkinson’s Disease Research, Education, and Clinical Center at the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Hospital, commented that “the reliability of UPDRS [part] III is where I would want to have, for sure, a little bit more of a deep dive. … possibly the same patient be rated by the same person.”

She also noted that doing remote and in-person assessments within 4 weeks of each other leaves a lot of room for variability. “You could see the same patient in the morning and then do UPDRS in the afternoon, and it can be totally different depending on when you meet the person,” she said.

Only so much testing can be done remotely. Nonetheless, she questioned whether it is really a valid UPDRS if rigidity and postural stability measures are eliminated. “[Is] this now a new modified UPDRS that we’re going to use that is as good as the old UPDRS moving forward, a home version of UPDRS or whatever we’re going to call it?”

Dr. Subramanian mentioned that patients have told her that UPDRS part III does not really measure what is most important to them, such as making pastries for their grandchildren rather than rapidly tapping their fingers.

“That speaks a little bit to the fact that we should have more patient-centered outcomes and things that patients can report. … things that are not going to require necessarily an in-person exam as maybe measures that really can be used moving forward in studies,” she suggested.

Patient satisfaction with remote visits

Greater than 90% of the patients were satisfied or very satisfied overall with the remote visits, including the convenience, comfort, and connection (using the devices and Internet connection), with “patients describing enjoying being able to do these visits from the comfort of their own home, not having to travel,” Dr. Tarolli said. Not having to drive in an ‘off’ state “was actually something that some participants identified as a safety benefit from this as well.”

There was also a time benefit to the patients and investigators. The average length of the remote visits was 54.3 minutes each versus 74 minutes of interaction for in-person visits, mainly a result of more efficient hand-offs between the neurologist and the study coordinator during the remote visits, plus being able to pause the remote visit to give a medication dose time to take effect.

For the patient, there was a large amount of time saved when travel time was considered – a total of 190.2 minutes on average for travel and testing for the in-person visits.

About three-quarters (76%) of the study patients said that remote visits would increase their likelihood of participating in future trials. However, that result may be skewed by the fact that these were already people willing to participate in a remote trial, so the generalizability of the result may be affected. Nonetheless, Dr. Tarolli said he thinks that, as technology gets better and older people become more comfortable with it, remote visits within Parkinson’s research studies may become more common.

One caveat he mentioned is that, with remote visits, the neurologist misses a chance to observe a patient’s whole body and construct a global impression of how he or she is moving. On the other hand, remote video gives the investigator the chance to see the living environment of the patient and suggest changes for safety, such as to reduce the risk of falling for a person with unsteadiness of gait living in a crowded house.

“It really allows us to make a more holistic assessment of how our patient is functioning outside the clinic, which I think we’ve traditionally had really no way of doing,” Dr. Tarolli said.

His final suggestion for anyone contemplating conducting studies with remote visits is to develop a team that is comfortable troubleshooting the technological aspects of those visits.

UCLA’s Dr. Subramanian lauded the University of Rochester team for their efforts in moving remote visits forward. “They’re at the cutting edge of these sorts of things,” she said. “So I’m assuming that they’ll come out with more things [for visits] to become better that are going to move this forward, which is exciting.”

Dr. Tarolli has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Subramanian has given talks for Acorda Pharmaceuticals and Acadia Pharmaceuticals in the past. The study had only university, government, foundation, and other nonprofit support.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, a 1-year, phase 3 clinical trial has shown. The trial was an add-on study involving a subset of subjects from the STEADY-PD III trial of isradipine in early Parkinson’s disease.

Although the trial was conducted before SARS-CoV-2 arrived on the scene, the findings have particular relevance for being able to conduct a variety of clinical trials in the face of COVID-19 and the need to limit in-person interactions.

The 40 participants used tablets to complete three remote, video-based assessments during 1 year, with each remote visit planned to be completed within 4 weeks of an in-person visit. It was easy to enroll patients, and they completed about 95% of planned visits, said neurologist Christopher Tarolli, MD, of the University of Rochester (N.Y.).

He presented the study findings at the Movement Disorder Society’s 23rd International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders (Virtual) 2020.

“The visits were clearly feasible, and we were able to do them [84%] within that 4-week time frame around the in-person visit,” he said. “The visits were also reasonably reliable, particularly so for what we call the nonmotor outcomes and the patient-reported outcomes.”

In-person versus remote assessment

For the remote visits, participants completed primarily the same battery of tests as the in-person visits. Responses on the Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) subscales demonstrated “that there was excellent correlation between patient-reported and nonmotor outcome measures and moderate correlation between in-person and remote-performed motor assessments,” Dr. Tarolli said.

He explained that the study used modified motor assessments (MDS-UPDRS Part III) that excluded testing of rigidity and postural instability, which require hands-on testing by a trained examiner and thus are impossible to do remotely.

Additionally, the somewhat lower correlation on this subscale was probably the result of different investigators conducting in-person versus remote assessments, with a subset of in-person investigators who tended to rate participants more severely driving down the correlation. “I think if these methods were applied in future trials, the in-person and remote investigators would optimally be the same person,” Dr. Tarolli suggested.

Room for error?

Indu Subramanian, MD, of the department of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the Parkinson’s Disease Research, Education, and Clinical Center at the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Hospital, commented that “the reliability of UPDRS [part] III is where I would want to have, for sure, a little bit more of a deep dive. … possibly the same patient be rated by the same person.”

She also noted that doing remote and in-person assessments within 4 weeks of each other leaves a lot of room for variability. “You could see the same patient in the morning and then do UPDRS in the afternoon, and it can be totally different depending on when you meet the person,” she said.

Only so much testing can be done remotely. Nonetheless, she questioned whether it is really a valid UPDRS if rigidity and postural stability measures are eliminated. “[Is] this now a new modified UPDRS that we’re going to use that is as good as the old UPDRS moving forward, a home version of UPDRS or whatever we’re going to call it?”

Dr. Subramanian mentioned that patients have told her that UPDRS part III does not really measure what is most important to them, such as making pastries for their grandchildren rather than rapidly tapping their fingers.

“That speaks a little bit to the fact that we should have more patient-centered outcomes and things that patients can report. … things that are not going to require necessarily an in-person exam as maybe measures that really can be used moving forward in studies,” she suggested.

Patient satisfaction with remote visits

Greater than 90% of the patients were satisfied or very satisfied overall with the remote visits, including the convenience, comfort, and connection (using the devices and Internet connection), with “patients describing enjoying being able to do these visits from the comfort of their own home, not having to travel,” Dr. Tarolli said. Not having to drive in an ‘off’ state “was actually something that some participants identified as a safety benefit from this as well.”

There was also a time benefit to the patients and investigators. The average length of the remote visits was 54.3 minutes each versus 74 minutes of interaction for in-person visits, mainly a result of more efficient hand-offs between the neurologist and the study coordinator during the remote visits, plus being able to pause the remote visit to give a medication dose time to take effect.

For the patient, there was a large amount of time saved when travel time was considered – a total of 190.2 minutes on average for travel and testing for the in-person visits.

About three-quarters (76%) of the study patients said that remote visits would increase their likelihood of participating in future trials. However, that result may be skewed by the fact that these were already people willing to participate in a remote trial, so the generalizability of the result may be affected. Nonetheless, Dr. Tarolli said he thinks that, as technology gets better and older people become more comfortable with it, remote visits within Parkinson’s research studies may become more common.

One caveat he mentioned is that, with remote visits, the neurologist misses a chance to observe a patient’s whole body and construct a global impression of how he or she is moving. On the other hand, remote video gives the investigator the chance to see the living environment of the patient and suggest changes for safety, such as to reduce the risk of falling for a person with unsteadiness of gait living in a crowded house.

“It really allows us to make a more holistic assessment of how our patient is functioning outside the clinic, which I think we’ve traditionally had really no way of doing,” Dr. Tarolli said.

His final suggestion for anyone contemplating conducting studies with remote visits is to develop a team that is comfortable troubleshooting the technological aspects of those visits.

UCLA’s Dr. Subramanian lauded the University of Rochester team for their efforts in moving remote visits forward. “They’re at the cutting edge of these sorts of things,” she said. “So I’m assuming that they’ll come out with more things [for visits] to become better that are going to move this forward, which is exciting.”

Dr. Tarolli has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Subramanian has given talks for Acorda Pharmaceuticals and Acadia Pharmaceuticals in the past. The study had only university, government, foundation, and other nonprofit support.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, a 1-year, phase 3 clinical trial has shown. The trial was an add-on study involving a subset of subjects from the STEADY-PD III trial of isradipine in early Parkinson’s disease.

Although the trial was conducted before SARS-CoV-2 arrived on the scene, the findings have particular relevance for being able to conduct a variety of clinical trials in the face of COVID-19 and the need to limit in-person interactions.

The 40 participants used tablets to complete three remote, video-based assessments during 1 year, with each remote visit planned to be completed within 4 weeks of an in-person visit. It was easy to enroll patients, and they completed about 95% of planned visits, said neurologist Christopher Tarolli, MD, of the University of Rochester (N.Y.).

He presented the study findings at the Movement Disorder Society’s 23rd International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders (Virtual) 2020.

“The visits were clearly feasible, and we were able to do them [84%] within that 4-week time frame around the in-person visit,” he said. “The visits were also reasonably reliable, particularly so for what we call the nonmotor outcomes and the patient-reported outcomes.”

In-person versus remote assessment

For the remote visits, participants completed primarily the same battery of tests as the in-person visits. Responses on the Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) subscales demonstrated “that there was excellent correlation between patient-reported and nonmotor outcome measures and moderate correlation between in-person and remote-performed motor assessments,” Dr. Tarolli said.

He explained that the study used modified motor assessments (MDS-UPDRS Part III) that excluded testing of rigidity and postural instability, which require hands-on testing by a trained examiner and thus are impossible to do remotely.

Additionally, the somewhat lower correlation on this subscale was probably the result of different investigators conducting in-person versus remote assessments, with a subset of in-person investigators who tended to rate participants more severely driving down the correlation. “I think if these methods were applied in future trials, the in-person and remote investigators would optimally be the same person,” Dr. Tarolli suggested.

Room for error?

Indu Subramanian, MD, of the department of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the Parkinson’s Disease Research, Education, and Clinical Center at the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Hospital, commented that “the reliability of UPDRS [part] III is where I would want to have, for sure, a little bit more of a deep dive. … possibly the same patient be rated by the same person.”

She also noted that doing remote and in-person assessments within 4 weeks of each other leaves a lot of room for variability. “You could see the same patient in the morning and then do UPDRS in the afternoon, and it can be totally different depending on when you meet the person,” she said.

Only so much testing can be done remotely. Nonetheless, she questioned whether it is really a valid UPDRS if rigidity and postural stability measures are eliminated. “[Is] this now a new modified UPDRS that we’re going to use that is as good as the old UPDRS moving forward, a home version of UPDRS or whatever we’re going to call it?”

Dr. Subramanian mentioned that patients have told her that UPDRS part III does not really measure what is most important to them, such as making pastries for their grandchildren rather than rapidly tapping their fingers.

“That speaks a little bit to the fact that we should have more patient-centered outcomes and things that patients can report. … things that are not going to require necessarily an in-person exam as maybe measures that really can be used moving forward in studies,” she suggested.

Patient satisfaction with remote visits

Greater than 90% of the patients were satisfied or very satisfied overall with the remote visits, including the convenience, comfort, and connection (using the devices and Internet connection), with “patients describing enjoying being able to do these visits from the comfort of their own home, not having to travel,” Dr. Tarolli said. Not having to drive in an ‘off’ state “was actually something that some participants identified as a safety benefit from this as well.”

There was also a time benefit to the patients and investigators. The average length of the remote visits was 54.3 minutes each versus 74 minutes of interaction for in-person visits, mainly a result of more efficient hand-offs between the neurologist and the study coordinator during the remote visits, plus being able to pause the remote visit to give a medication dose time to take effect.

For the patient, there was a large amount of time saved when travel time was considered – a total of 190.2 minutes on average for travel and testing for the in-person visits.

About three-quarters (76%) of the study patients said that remote visits would increase their likelihood of participating in future trials. However, that result may be skewed by the fact that these were already people willing to participate in a remote trial, so the generalizability of the result may be affected. Nonetheless, Dr. Tarolli said he thinks that, as technology gets better and older people become more comfortable with it, remote visits within Parkinson’s research studies may become more common.

One caveat he mentioned is that, with remote visits, the neurologist misses a chance to observe a patient’s whole body and construct a global impression of how he or she is moving. On the other hand, remote video gives the investigator the chance to see the living environment of the patient and suggest changes for safety, such as to reduce the risk of falling for a person with unsteadiness of gait living in a crowded house.

“It really allows us to make a more holistic assessment of how our patient is functioning outside the clinic, which I think we’ve traditionally had really no way of doing,” Dr. Tarolli said.

His final suggestion for anyone contemplating conducting studies with remote visits is to develop a team that is comfortable troubleshooting the technological aspects of those visits.

UCLA’s Dr. Subramanian lauded the University of Rochester team for their efforts in moving remote visits forward. “They’re at the cutting edge of these sorts of things,” she said. “So I’m assuming that they’ll come out with more things [for visits] to become better that are going to move this forward, which is exciting.”

Dr. Tarolli has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Subramanian has given talks for Acorda Pharmaceuticals and Acadia Pharmaceuticals in the past. The study had only university, government, foundation, and other nonprofit support.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Blood biomarker may predict Parkinson’s disease progression

Although the biomarker, neurofilament light chain (NfL), is not especially specific, it is the first blood-based biomarker for Parkinson’s disease.

Neurofilaments are components of the neural cytoskeleton, where they maintain structure along with other functions. Following axonal damage, NfL gets released into extracellular fluids. Previously, NfL has been detected in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in patients with multiple sclerosis and neurodegenerative dementias. NfL in the CSF can distinguish Parkinson’s disease (PD) from multiple system atrophy and progressive supranuclear palsy.

That’s useful, but a serum marker would open new doors. “An easily accessible biomarker that will serve as an indicator of diagnosis, disease state, and progression, as well as a marker of response to therapeutic intervention is needed. A biomarker will strengthen the ability to select patients for inclusion or stratification within clinical trials,” commented Okeanis Vaou, MD, director of the movement disorders program at St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center in Brighton, Mass. Dr. Vaou was not involved in the study, which was published Aug. 15 in Movement Disorders.

A potential biomarker?

To determine if serum NfL levels would correlate with CSF values and had potential as a biomarker, a large, multi-institutional team of researchers led by Brit Mollenhauer, MD, of the University Medical Center Goettingen (Germany), and Danielle Graham, MD, of Biogen, drew data from a prospective, longitudinal, single-center project called the De Novo Parkinson’s disease (DeNoPa) cohort.

The researchers analyzed data from 176 subjects, including drug-naive patients with newly diagnosed PD; age, sex, and education matched healthy controls; and patients who were initially diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease but had their diagnoses changed to a cognate or neurodegenerative disorder (OND). The researchers also drew 514 serum samples from the prospective longitudinal, observational, international multicenter study Parkinson’s Progression Marker Initiative (PPMI) cohort.

In the DeNoPa cohort, OND patients had the highest median CSF NfL levels at baseline (839 pg/mL) followed by PD patients (562 pg/mL) and healthy controls (494 pg/mL; P = .01). There was a strong correlation between CSF and serum NfL levels in a cross-sectional exploratory study with the PPMI cohort.

Age and sex covariates in the PPMI cohort explained 51% of NfL variability. After adjustment for age and sex, baseline median blood NfL levels were highest in the OND group (16.23 pg/mL), followed by the genetic PD group (13.36 pg/mL), prodromal participants (12.20 pg/mL), PD patients (11.73 pg/mL), unaffected mutation carriers (11.63 pg/mL), and healthy controls (11.05 pg/mL; F test P < .0001). Median serum NfL increased by 3.35% per year of age (P < .0001), and median serum NfL was 6.79% higher in women (P = .0002).

Doubling of adjusted serum NfL levels were associated with a median increase in the Movement Disorder Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale total score of 3.45 points (false-discovery rate–adjusted P = .0115), a median decrease in Symbol Digit Modality Test total score of 1.39 (FDR P = .026), a median decrease in Hopkins Verbal Learning Tests with discrimination recognition score of 0.3 (FDR P = .03), and a median decrease in Hopkins Verbal Learning Tests with retention score of 0.029 (FDR P = .04).

More specific markers needed

The findings are intriguing, said Dr Vaou, but “we need to acknowledge that increased NfL levels are not specific enough to Parkinson’s disease and reflect neuronal and axonal damage. Therefore, there is a need for more specific markers to support diagnostic accuracy, rate of progression, and ultimate prognosis. A serum NfL assay may be useful to clinicians evaluating patients with PD or OND diagnosis and mitigate the misdiagnosis of atypical PD. NfL may be particularly useful in differentiating PD from cognate disorders such as multiple system atrophy, progressive supranuclear palsy, and dementia with Lewy bodies.”

The current success is the result of large patient databases containing phenotypic data, imaging, and tests of tissue, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid, along with collaborations between advocacy groups, academia, and industry, according to Dr. Vaou. As that work continues, it could uncover more specific biomarkers “that will allow us not only to help with diagnosis and treatment but with disease progression, inclusion, recruitment and stratification in clinical studies, as well as (be an) indicator of response to therapeutic intervention of an investigational drug.”

The study was funded by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. Dr. Vaou had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Mollenhauer B et al. Mov Disord. 2020 Aug 15. doi: 10.1002/mds.28206.

Although the biomarker, neurofilament light chain (NfL), is not especially specific, it is the first blood-based biomarker for Parkinson’s disease.

Neurofilaments are components of the neural cytoskeleton, where they maintain structure along with other functions. Following axonal damage, NfL gets released into extracellular fluids. Previously, NfL has been detected in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in patients with multiple sclerosis and neurodegenerative dementias. NfL in the CSF can distinguish Parkinson’s disease (PD) from multiple system atrophy and progressive supranuclear palsy.

That’s useful, but a serum marker would open new doors. “An easily accessible biomarker that will serve as an indicator of diagnosis, disease state, and progression, as well as a marker of response to therapeutic intervention is needed. A biomarker will strengthen the ability to select patients for inclusion or stratification within clinical trials,” commented Okeanis Vaou, MD, director of the movement disorders program at St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center in Brighton, Mass. Dr. Vaou was not involved in the study, which was published Aug. 15 in Movement Disorders.

A potential biomarker?

To determine if serum NfL levels would correlate with CSF values and had potential as a biomarker, a large, multi-institutional team of researchers led by Brit Mollenhauer, MD, of the University Medical Center Goettingen (Germany), and Danielle Graham, MD, of Biogen, drew data from a prospective, longitudinal, single-center project called the De Novo Parkinson’s disease (DeNoPa) cohort.

The researchers analyzed data from 176 subjects, including drug-naive patients with newly diagnosed PD; age, sex, and education matched healthy controls; and patients who were initially diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease but had their diagnoses changed to a cognate or neurodegenerative disorder (OND). The researchers also drew 514 serum samples from the prospective longitudinal, observational, international multicenter study Parkinson’s Progression Marker Initiative (PPMI) cohort.

In the DeNoPa cohort, OND patients had the highest median CSF NfL levels at baseline (839 pg/mL) followed by PD patients (562 pg/mL) and healthy controls (494 pg/mL; P = .01). There was a strong correlation between CSF and serum NfL levels in a cross-sectional exploratory study with the PPMI cohort.

Age and sex covariates in the PPMI cohort explained 51% of NfL variability. After adjustment for age and sex, baseline median blood NfL levels were highest in the OND group (16.23 pg/mL), followed by the genetic PD group (13.36 pg/mL), prodromal participants (12.20 pg/mL), PD patients (11.73 pg/mL), unaffected mutation carriers (11.63 pg/mL), and healthy controls (11.05 pg/mL; F test P < .0001). Median serum NfL increased by 3.35% per year of age (P < .0001), and median serum NfL was 6.79% higher in women (P = .0002).

Doubling of adjusted serum NfL levels were associated with a median increase in the Movement Disorder Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale total score of 3.45 points (false-discovery rate–adjusted P = .0115), a median decrease in Symbol Digit Modality Test total score of 1.39 (FDR P = .026), a median decrease in Hopkins Verbal Learning Tests with discrimination recognition score of 0.3 (FDR P = .03), and a median decrease in Hopkins Verbal Learning Tests with retention score of 0.029 (FDR P = .04).

More specific markers needed

The findings are intriguing, said Dr Vaou, but “we need to acknowledge that increased NfL levels are not specific enough to Parkinson’s disease and reflect neuronal and axonal damage. Therefore, there is a need for more specific markers to support diagnostic accuracy, rate of progression, and ultimate prognosis. A serum NfL assay may be useful to clinicians evaluating patients with PD or OND diagnosis and mitigate the misdiagnosis of atypical PD. NfL may be particularly useful in differentiating PD from cognate disorders such as multiple system atrophy, progressive supranuclear palsy, and dementia with Lewy bodies.”

The current success is the result of large patient databases containing phenotypic data, imaging, and tests of tissue, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid, along with collaborations between advocacy groups, academia, and industry, according to Dr. Vaou. As that work continues, it could uncover more specific biomarkers “that will allow us not only to help with diagnosis and treatment but with disease progression, inclusion, recruitment and stratification in clinical studies, as well as (be an) indicator of response to therapeutic intervention of an investigational drug.”

The study was funded by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. Dr. Vaou had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Mollenhauer B et al. Mov Disord. 2020 Aug 15. doi: 10.1002/mds.28206.

Although the biomarker, neurofilament light chain (NfL), is not especially specific, it is the first blood-based biomarker for Parkinson’s disease.

Neurofilaments are components of the neural cytoskeleton, where they maintain structure along with other functions. Following axonal damage, NfL gets released into extracellular fluids. Previously, NfL has been detected in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in patients with multiple sclerosis and neurodegenerative dementias. NfL in the CSF can distinguish Parkinson’s disease (PD) from multiple system atrophy and progressive supranuclear palsy.

That’s useful, but a serum marker would open new doors. “An easily accessible biomarker that will serve as an indicator of diagnosis, disease state, and progression, as well as a marker of response to therapeutic intervention is needed. A biomarker will strengthen the ability to select patients for inclusion or stratification within clinical trials,” commented Okeanis Vaou, MD, director of the movement disorders program at St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center in Brighton, Mass. Dr. Vaou was not involved in the study, which was published Aug. 15 in Movement Disorders.

A potential biomarker?

To determine if serum NfL levels would correlate with CSF values and had potential as a biomarker, a large, multi-institutional team of researchers led by Brit Mollenhauer, MD, of the University Medical Center Goettingen (Germany), and Danielle Graham, MD, of Biogen, drew data from a prospective, longitudinal, single-center project called the De Novo Parkinson’s disease (DeNoPa) cohort.

The researchers analyzed data from 176 subjects, including drug-naive patients with newly diagnosed PD; age, sex, and education matched healthy controls; and patients who were initially diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease but had their diagnoses changed to a cognate or neurodegenerative disorder (OND). The researchers also drew 514 serum samples from the prospective longitudinal, observational, international multicenter study Parkinson’s Progression Marker Initiative (PPMI) cohort.

In the DeNoPa cohort, OND patients had the highest median CSF NfL levels at baseline (839 pg/mL) followed by PD patients (562 pg/mL) and healthy controls (494 pg/mL; P = .01). There was a strong correlation between CSF and serum NfL levels in a cross-sectional exploratory study with the PPMI cohort.

Age and sex covariates in the PPMI cohort explained 51% of NfL variability. After adjustment for age and sex, baseline median blood NfL levels were highest in the OND group (16.23 pg/mL), followed by the genetic PD group (13.36 pg/mL), prodromal participants (12.20 pg/mL), PD patients (11.73 pg/mL), unaffected mutation carriers (11.63 pg/mL), and healthy controls (11.05 pg/mL; F test P < .0001). Median serum NfL increased by 3.35% per year of age (P < .0001), and median serum NfL was 6.79% higher in women (P = .0002).

Doubling of adjusted serum NfL levels were associated with a median increase in the Movement Disorder Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale total score of 3.45 points (false-discovery rate–adjusted P = .0115), a median decrease in Symbol Digit Modality Test total score of 1.39 (FDR P = .026), a median decrease in Hopkins Verbal Learning Tests with discrimination recognition score of 0.3 (FDR P = .03), and a median decrease in Hopkins Verbal Learning Tests with retention score of 0.029 (FDR P = .04).

More specific markers needed

The findings are intriguing, said Dr Vaou, but “we need to acknowledge that increased NfL levels are not specific enough to Parkinson’s disease and reflect neuronal and axonal damage. Therefore, there is a need for more specific markers to support diagnostic accuracy, rate of progression, and ultimate prognosis. A serum NfL assay may be useful to clinicians evaluating patients with PD or OND diagnosis and mitigate the misdiagnosis of atypical PD. NfL may be particularly useful in differentiating PD from cognate disorders such as multiple system atrophy, progressive supranuclear palsy, and dementia with Lewy bodies.”

The current success is the result of large patient databases containing phenotypic data, imaging, and tests of tissue, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid, along with collaborations between advocacy groups, academia, and industry, according to Dr. Vaou. As that work continues, it could uncover more specific biomarkers “that will allow us not only to help with diagnosis and treatment but with disease progression, inclusion, recruitment and stratification in clinical studies, as well as (be an) indicator of response to therapeutic intervention of an investigational drug.”

The study was funded by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. Dr. Vaou had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Mollenhauer B et al. Mov Disord. 2020 Aug 15. doi: 10.1002/mds.28206.

FROM MOVEMENT DISORDERS

Are aging physicians a burden?

The evaluation of physicians with alleged cognitive decline

As forensic evaluators, we are often asked to review and assess the cognition of aging colleagues. The premise often involves a minor mistake, a poor choice of words, or a lapse in judgment. A physician gets reported for having difficulty using a new electronic form, forgetting the dose of a brand new medication, or getting upset in a public setting. Those behaviors often lead to mandatory psychiatric evaluations. Those requirements are often perceived by the provider as an insult, and betrayal by peers despite many years of dedicated work.

Interestingly, we have noticed many independent evaluators and hospital administrators using this opportunity to send many of our colleagues to pasture. There seems to be an unspoken rule among some forensic evaluators that physicians should represent some form of apex of humanity, beyond reproach, and beyond any fault. Those evaluators will point to any mistake on cognitive scales as proof that the aging physician is no longer safe to practice.1 Forgetting that Jill is from Illinois in the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination test or how to copy a three-dimensional cube on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment can cost someone their license.2 We are also aware of some evaluators even taking the step further and opining that physicians not only need to score adequately but also demonstrate cognition significantly above average to maintain their privileges.

There is certainly significant appeal in setting a high bar for physicians. In many ways, physicians are characterized in society by their astuteness, intelligence, and high ethical standards. Patients place their lives in the hands of physicians and should trust that those physicians have the cognitive tools to heal them. It could almost seem evident that physicians should have high IQs, score perfectly on screening tools for dementia, and complete a mandatory psychiatric evaluation without any reproach. Yet the reality is often more complex.

We have two main concerns about the idea that we should be intransigent with aging physicians. The first one is the vast differential diagnosis for minor mistakes. An aging physician refusing to comply with a new form or yelling at a clerk once when asked to learn a new electronic medical record are inappropriate though not specific assessments for dementia. Similarly, having significant difficulty learning a new electronic medical record system more often is a sign of ageism rather than cognitive impairment. Subsequently, when arriving for their evaluation, forgetting the date is a common sign of anxiety. A relatable analogy would be to compare the mistake with a medical student forgetting part of the anatomy while questioning by an attending during surgery. Imagine such medical students being referred to mandatory psychiatric evaluation when failing to answer a question during rounds.

In our practice, the most common reason for those minor mistakes during our clinical evaluation is anxiety. After all, patients who present for problems completely unrelated to cognitive decline make similar mistakes. Psychological stressors in physicians require no introduction. The concept is so prevalent and pervasive that it has its own name, “burnout.” Imagine having dedicated most of one’s life to a profession then being enumerated a list of complaints, having one’s privileges put on hold, then being told to complete an independent psychiatric evaluation. If burnout is in part caused by a lack of control, unclear job expectations, rapidly changing models of health care, and dysfunctional workplace dynamics, imagine the consequence of such a referral.

The militant evaluator will use jargon to vilify the reviewed physician. If the physician complains too voraciously, he will be described as having signs of frontotemporal dementia. If the physician comes with a written list of rebuttals, he will be described as having memory problems requiring aids. If the physician is demoralized and quiet, he will be described as being withdrawn and apathetic. If the physician refuses to use or has difficulty with new forms or electronic systems, he will be described as having “impaired executive function,” an ominous term that surely should not be associated with a practicing physician.

The second concern arises from problems with the validity and use of diagnoses like mild cognitive impairment (MCI). MCI is considered to be a transition stage when one maintains “normal activities of daily living, and normal general cognitive function.”3 The American Psychiatric Association Textbook of Psychiatry mentions that there are “however, many cases of nonprogressive MCI.” Should a disorder with generally normal cognition and unclear progression to a more severe disorder require one to be dispensed of their privileges? Should any disorder trump an assessment of functioning?

It is our experience that many if not most physicians’ practice of medicine is not a job but a profession that defines who they are. As such, their occupational habits are an overly repeated and ingrained series of maneuvers analogous to so-called muscle memory. This kind of ritualistic pattern is precisely the kind of cognition that may persist as one starts to have some deficits. This requires the evaluator to be particularly sensitive and cognizant that one may still be able to perform professionally despite some mild but notable deficits. While it is facile to diagnose someone with MCI and justify removing their license, a review of their actual clinical skills is, despite being more time consuming, more pertinent to the evaluation.

In practice, we find that many cases lie in a gray area, which is hard to define. Physicians may come to our office for an evaluation after having said something odd at work. Maybe they misdosed a medication on one occasion. Maybe they wrote the wrong year on a chart. However, if the physician was 30 years old, would we consider any one of those incidents significant? As a psychiatrist rather than a physician practicing the specialty in review, it is particularly hard and sometimes unwise to condone or sanction individual incidents.

Evaluators find solace in neuropsychological testing. However the relevance to the safety of patients is unclear. Many of those tests end up being a simple proxy for age. A physicians’ ability to sort words or cards at a certain speed might correlate to cognitive performance but has unclear significance to the ability to care for patients. Using such tests becomes a de facto age limit on the practice of medicine. It seems essential to expand and refine our repertoire of evaluation tools for the assessment of physicians. As when we perform capacity evaluation in the hospital, we enlist the assistance of the treating team in understanding the questions being asked for a patient, medical boards could consider creating independent multidisciplinary teams where psychiatry has a seat along with the relevant specialties of the evaluee. Likewise, the assessment would benefit from a broad review of the physicians’ general practice rather than the more typical review of one or two incidents.

We are promoting a more individualized approach by medical boards to the many issues of the aging physician. Retiring is no longer the dream of older physicians, but rather working in the suitable position where their contributions, clinical experience, and wisdom are positive contributions to patient care. Furthermore, we encourage medical boards to consider more nuanced decisions. A binary approach fits few cases that we see. Surgeons are a prime example of this. A surgeon in the early stages of Parkinsonism may be unfit to perform surgery but very capable of continuing to contribute to the well-being of patients in other forms of clinical work, including postsurgical care that doesn’t involve physical dexterity. Similarly, medical boards could consider other forms of partial restrictions, including a ban on procedures, a ban on hospital privileges, as well as required supervision or working in teams. Accumulated clinical wisdom allows older physicians to be excellent mentors and educators for younger doctors. There is no simple method to predict which physicians may have the early stages of a progressive dementia, and which may have a stable MCI. A yearly reevaluation if there are no further complaints, is the best approach to determine progression of cognitive problems.

Few crises like the current COVID-19 pandemic can better remind us of the importance of the place of medicine in society. Many states have encouraged retired physicians to contribute their knowledge and expertise, putting themselves in particular risk because of their age. It is a good time to be reminded that we owe them significant respect and care when deciding to remove their license. We are encouraged by the diligent efforts of medical boards in supervising our colleagues but warn against zealot evaluators who use this opportunity to force physicians into retirement. We also encourage medical boards to expand their tools and approaches when facing such cases, as mislabeled cognitive diagnoses can be an easy scapegoat of a poor understanding of the more important psychological and biological factors in the evaluation.

References

1. Tariq SH et al. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:900-10.

2. Nasreddine Z. mocatest.org. Version 2004 Nov 7.

3. Hales RE et al. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. Washington: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2014.

Dr. Badre is a forensic psychiatrist in San Diego and an expert in correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Among his writings in chapter 7 in the book “Critical Psychiatry: Controversies and Clinical Implications” (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2019). He has no disclosures.

Dr. Abrams is a forensic psychiatrist and attorney in San Diego. He is an expert in addictionology, behavioral toxicology, psychopharmacology and correctional mental health. He holds a teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego. Among his writings are chapters about competency in national textbooks. Dr. Abrams has no disclosures.

The evaluation of physicians with alleged cognitive decline

The evaluation of physicians with alleged cognitive decline

As forensic evaluators, we are often asked to review and assess the cognition of aging colleagues. The premise often involves a minor mistake, a poor choice of words, or a lapse in judgment. A physician gets reported for having difficulty using a new electronic form, forgetting the dose of a brand new medication, or getting upset in a public setting. Those behaviors often lead to mandatory psychiatric evaluations. Those requirements are often perceived by the provider as an insult, and betrayal by peers despite many years of dedicated work.

Interestingly, we have noticed many independent evaluators and hospital administrators using this opportunity to send many of our colleagues to pasture. There seems to be an unspoken rule among some forensic evaluators that physicians should represent some form of apex of humanity, beyond reproach, and beyond any fault. Those evaluators will point to any mistake on cognitive scales as proof that the aging physician is no longer safe to practice.1 Forgetting that Jill is from Illinois in the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination test or how to copy a three-dimensional cube on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment can cost someone their license.2 We are also aware of some evaluators even taking the step further and opining that physicians not only need to score adequately but also demonstrate cognition significantly above average to maintain their privileges.

There is certainly significant appeal in setting a high bar for physicians. In many ways, physicians are characterized in society by their astuteness, intelligence, and high ethical standards. Patients place their lives in the hands of physicians and should trust that those physicians have the cognitive tools to heal them. It could almost seem evident that physicians should have high IQs, score perfectly on screening tools for dementia, and complete a mandatory psychiatric evaluation without any reproach. Yet the reality is often more complex.

We have two main concerns about the idea that we should be intransigent with aging physicians. The first one is the vast differential diagnosis for minor mistakes. An aging physician refusing to comply with a new form or yelling at a clerk once when asked to learn a new electronic medical record are inappropriate though not specific assessments for dementia. Similarly, having significant difficulty learning a new electronic medical record system more often is a sign of ageism rather than cognitive impairment. Subsequently, when arriving for their evaluation, forgetting the date is a common sign of anxiety. A relatable analogy would be to compare the mistake with a medical student forgetting part of the anatomy while questioning by an attending during surgery. Imagine such medical students being referred to mandatory psychiatric evaluation when failing to answer a question during rounds.

In our practice, the most common reason for those minor mistakes during our clinical evaluation is anxiety. After all, patients who present for problems completely unrelated to cognitive decline make similar mistakes. Psychological stressors in physicians require no introduction. The concept is so prevalent and pervasive that it has its own name, “burnout.” Imagine having dedicated most of one’s life to a profession then being enumerated a list of complaints, having one’s privileges put on hold, then being told to complete an independent psychiatric evaluation. If burnout is in part caused by a lack of control, unclear job expectations, rapidly changing models of health care, and dysfunctional workplace dynamics, imagine the consequence of such a referral.

The militant evaluator will use jargon to vilify the reviewed physician. If the physician complains too voraciously, he will be described as having signs of frontotemporal dementia. If the physician comes with a written list of rebuttals, he will be described as having memory problems requiring aids. If the physician is demoralized and quiet, he will be described as being withdrawn and apathetic. If the physician refuses to use or has difficulty with new forms or electronic systems, he will be described as having “impaired executive function,” an ominous term that surely should not be associated with a practicing physician.

The second concern arises from problems with the validity and use of diagnoses like mild cognitive impairment (MCI). MCI is considered to be a transition stage when one maintains “normal activities of daily living, and normal general cognitive function.”3 The American Psychiatric Association Textbook of Psychiatry mentions that there are “however, many cases of nonprogressive MCI.” Should a disorder with generally normal cognition and unclear progression to a more severe disorder require one to be dispensed of their privileges? Should any disorder trump an assessment of functioning?

It is our experience that many if not most physicians’ practice of medicine is not a job but a profession that defines who they are. As such, their occupational habits are an overly repeated and ingrained series of maneuvers analogous to so-called muscle memory. This kind of ritualistic pattern is precisely the kind of cognition that may persist as one starts to have some deficits. This requires the evaluator to be particularly sensitive and cognizant that one may still be able to perform professionally despite some mild but notable deficits. While it is facile to diagnose someone with MCI and justify removing their license, a review of their actual clinical skills is, despite being more time consuming, more pertinent to the evaluation.

In practice, we find that many cases lie in a gray area, which is hard to define. Physicians may come to our office for an evaluation after having said something odd at work. Maybe they misdosed a medication on one occasion. Maybe they wrote the wrong year on a chart. However, if the physician was 30 years old, would we consider any one of those incidents significant? As a psychiatrist rather than a physician practicing the specialty in review, it is particularly hard and sometimes unwise to condone or sanction individual incidents.

Evaluators find solace in neuropsychological testing. However the relevance to the safety of patients is unclear. Many of those tests end up being a simple proxy for age. A physicians’ ability to sort words or cards at a certain speed might correlate to cognitive performance but has unclear significance to the ability to care for patients. Using such tests becomes a de facto age limit on the practice of medicine. It seems essential to expand and refine our repertoire of evaluation tools for the assessment of physicians. As when we perform capacity evaluation in the hospital, we enlist the assistance of the treating team in understanding the questions being asked for a patient, medical boards could consider creating independent multidisciplinary teams where psychiatry has a seat along with the relevant specialties of the evaluee. Likewise, the assessment would benefit from a broad review of the physicians’ general practice rather than the more typical review of one or two incidents.

We are promoting a more individualized approach by medical boards to the many issues of the aging physician. Retiring is no longer the dream of older physicians, but rather working in the suitable position where their contributions, clinical experience, and wisdom are positive contributions to patient care. Furthermore, we encourage medical boards to consider more nuanced decisions. A binary approach fits few cases that we see. Surgeons are a prime example of this. A surgeon in the early stages of Parkinsonism may be unfit to perform surgery but very capable of continuing to contribute to the well-being of patients in other forms of clinical work, including postsurgical care that doesn’t involve physical dexterity. Similarly, medical boards could consider other forms of partial restrictions, including a ban on procedures, a ban on hospital privileges, as well as required supervision or working in teams. Accumulated clinical wisdom allows older physicians to be excellent mentors and educators for younger doctors. There is no simple method to predict which physicians may have the early stages of a progressive dementia, and which may have a stable MCI. A yearly reevaluation if there are no further complaints, is the best approach to determine progression of cognitive problems.

Few crises like the current COVID-19 pandemic can better remind us of the importance of the place of medicine in society. Many states have encouraged retired physicians to contribute their knowledge and expertise, putting themselves in particular risk because of their age. It is a good time to be reminded that we owe them significant respect and care when deciding to remove their license. We are encouraged by the diligent efforts of medical boards in supervising our colleagues but warn against zealot evaluators who use this opportunity to force physicians into retirement. We also encourage medical boards to expand their tools and approaches when facing such cases, as mislabeled cognitive diagnoses can be an easy scapegoat of a poor understanding of the more important psychological and biological factors in the evaluation.

References

1. Tariq SH et al. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:900-10.

2. Nasreddine Z. mocatest.org. Version 2004 Nov 7.

3. Hales RE et al. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. Washington: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2014.

Dr. Badre is a forensic psychiatrist in San Diego and an expert in correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Among his writings in chapter 7 in the book “Critical Psychiatry: Controversies and Clinical Implications” (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2019). He has no disclosures.

Dr. Abrams is a forensic psychiatrist and attorney in San Diego. He is an expert in addictionology, behavioral toxicology, psychopharmacology and correctional mental health. He holds a teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego. Among his writings are chapters about competency in national textbooks. Dr. Abrams has no disclosures.

As forensic evaluators, we are often asked to review and assess the cognition of aging colleagues. The premise often involves a minor mistake, a poor choice of words, or a lapse in judgment. A physician gets reported for having difficulty using a new electronic form, forgetting the dose of a brand new medication, or getting upset in a public setting. Those behaviors often lead to mandatory psychiatric evaluations. Those requirements are often perceived by the provider as an insult, and betrayal by peers despite many years of dedicated work.

Interestingly, we have noticed many independent evaluators and hospital administrators using this opportunity to send many of our colleagues to pasture. There seems to be an unspoken rule among some forensic evaluators that physicians should represent some form of apex of humanity, beyond reproach, and beyond any fault. Those evaluators will point to any mistake on cognitive scales as proof that the aging physician is no longer safe to practice.1 Forgetting that Jill is from Illinois in the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination test or how to copy a three-dimensional cube on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment can cost someone their license.2 We are also aware of some evaluators even taking the step further and opining that physicians not only need to score adequately but also demonstrate cognition significantly above average to maintain their privileges.

There is certainly significant appeal in setting a high bar for physicians. In many ways, physicians are characterized in society by their astuteness, intelligence, and high ethical standards. Patients place their lives in the hands of physicians and should trust that those physicians have the cognitive tools to heal them. It could almost seem evident that physicians should have high IQs, score perfectly on screening tools for dementia, and complete a mandatory psychiatric evaluation without any reproach. Yet the reality is often more complex.

We have two main concerns about the idea that we should be intransigent with aging physicians. The first one is the vast differential diagnosis for minor mistakes. An aging physician refusing to comply with a new form or yelling at a clerk once when asked to learn a new electronic medical record are inappropriate though not specific assessments for dementia. Similarly, having significant difficulty learning a new electronic medical record system more often is a sign of ageism rather than cognitive impairment. Subsequently, when arriving for their evaluation, forgetting the date is a common sign of anxiety. A relatable analogy would be to compare the mistake with a medical student forgetting part of the anatomy while questioning by an attending during surgery. Imagine such medical students being referred to mandatory psychiatric evaluation when failing to answer a question during rounds.

In our practice, the most common reason for those minor mistakes during our clinical evaluation is anxiety. After all, patients who present for problems completely unrelated to cognitive decline make similar mistakes. Psychological stressors in physicians require no introduction. The concept is so prevalent and pervasive that it has its own name, “burnout.” Imagine having dedicated most of one’s life to a profession then being enumerated a list of complaints, having one’s privileges put on hold, then being told to complete an independent psychiatric evaluation. If burnout is in part caused by a lack of control, unclear job expectations, rapidly changing models of health care, and dysfunctional workplace dynamics, imagine the consequence of such a referral.

The militant evaluator will use jargon to vilify the reviewed physician. If the physician complains too voraciously, he will be described as having signs of frontotemporal dementia. If the physician comes with a written list of rebuttals, he will be described as having memory problems requiring aids. If the physician is demoralized and quiet, he will be described as being withdrawn and apathetic. If the physician refuses to use or has difficulty with new forms or electronic systems, he will be described as having “impaired executive function,” an ominous term that surely should not be associated with a practicing physician.

The second concern arises from problems with the validity and use of diagnoses like mild cognitive impairment (MCI). MCI is considered to be a transition stage when one maintains “normal activities of daily living, and normal general cognitive function.”3 The American Psychiatric Association Textbook of Psychiatry mentions that there are “however, many cases of nonprogressive MCI.” Should a disorder with generally normal cognition and unclear progression to a more severe disorder require one to be dispensed of their privileges? Should any disorder trump an assessment of functioning?

It is our experience that many if not most physicians’ practice of medicine is not a job but a profession that defines who they are. As such, their occupational habits are an overly repeated and ingrained series of maneuvers analogous to so-called muscle memory. This kind of ritualistic pattern is precisely the kind of cognition that may persist as one starts to have some deficits. This requires the evaluator to be particularly sensitive and cognizant that one may still be able to perform professionally despite some mild but notable deficits. While it is facile to diagnose someone with MCI and justify removing their license, a review of their actual clinical skills is, despite being more time consuming, more pertinent to the evaluation.