User login

Children may develop prolonged headache after concussion

CHARLOTTE, N.C. – , according to research presented at the annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society. The headache may be migraine, chronic daily headache, tension-type headache, or a combination of these headaches.

“We strongly recommend that individuals who develop persistent headache after a concussion be evaluated and treated by a neurologist with experience in administering treatment for headache,” said Marcus Barissi, Weller Scholar at the Cleveland Clinic, and colleagues. “Using this approach, we hope that their prolonged headaches will be lessened.”

Few studies have examined prolonged pediatric postconcussion headache

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that between 1.6 million and 3.8 million concussions occur annually during athletic and recreational activities in the United States. About 90% of concussions affect children or adolescents. The symptom most often reported after concussion is headache.

Few studies have focused on new persistent postconcussion headache (NPPCH) in children. Mr. Barissi and colleagues did not find any previous study that had examined prolonged headache following concussion in patients without prior chronic headache. They sought to ascertain the prognosis of patients with NPPCH and no history of prior headache, to describe this clinical entity, and to identify beneficial treatment methods.

The investigators retrospectively reviewed charts for approximately 2,000 patients who presented to the Cleveland Clinic pediatric neurology department between June 2017 and August 2018 for headaches. They identified 259 patients who received a diagnosis of concussion, 69 (27%) of whom had headaches for longer than 2 months after injury.

Mr. Barissi and colleagues emailed these patients, and 33 (48%) of them agreed to complete a questionnaire and participate in a 10-minute phone interview. Thirty-one patients (43%) could not be contacted, and eight (11%) declined to participate. All participants confirmed that they had not had consistent headache before the concussion and that chronic headache had arisen after concussion. To determine participants’ medical outcomes, the researchers compared participants’ initial assessment data with posttreatment data collected during the interview process.

Healthy behaviors increased after concussion

Of the 69 eligible participants, 38 (55%) were female. The population’s median age was 17. Twenty-eight (85%) of the 33 patients who completed the questionnaire considered the information and treatment that they had received to be beneficial. Twenty-five (78%) patients continued to have headache after several months, despite treatment.

Participants had withstood a mean of 1.72 concussions, and the mean age at first injury was 12.49 years. The most common cause of injury was a fall for males (36%) and an automobile accident for females (18%).

Forty-eight patients (70%) reported having two types of headache. Fifty-two patients (75%) had migraines, and 65 (94%) had chronic daily headache or tension-type headache. Forty-eight (70%) participants had a family history of headache.

In all, 64 patients (93%) had used a headache medication. The most common headache medications used were amitriptyline, topiramate, and cyproheptadine. Few patients were still taking these medications at several months after evaluation. The most common nonprescription medications used were Migravent (i.e., magnesium, riboflavin, coenzyme Q10, and butterbur), ondansetron, and melatonin. Furthermore, 61 patients (88%) participated in nonmedicinal therapy such as physical therapy, chiropractic therapy, and acupuncture.

After evaluation, patients engaged in several healthy behaviors (e.g., adequate exercise, proper use of over-the-counter medications, and drinking sufficient water) more frequently, but did not get adequate sleep. Sixty-five participants (94%) had undergone CT or MRI imaging, but the results did not improve understanding of headache etiology or treatment. Many patients missed several days of school, but average attendance improved after months of treatment.

Long-term outcomes

Thirty-one survey respondents (94%) reported that their emotional, cognitive, sleep, and somatic postconcussion symptoms had resolved. Nevertheless, a majority of participants still had headache. “The persistence of postconcussion symptoms is uncommon, but lasting headache is not,” said the researchers. “If patients are not properly educated, conditions may deteriorate, extending the duration of disability.” A longer study with a larger sample size could provide valuable information, said the researchers. Future work should examine objectively the efficacy of various medications used to treat NPPCH and determine the best methods of treatment for this syndrome, which “can cause prolonged pain, suffering, and lack of function,” they concluded.

The investigators did not report any study funding or disclosures.

SOURCE: Barissi M et al. CNS 2019, Abstract 95.

CHARLOTTE, N.C. – , according to research presented at the annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society. The headache may be migraine, chronic daily headache, tension-type headache, or a combination of these headaches.

“We strongly recommend that individuals who develop persistent headache after a concussion be evaluated and treated by a neurologist with experience in administering treatment for headache,” said Marcus Barissi, Weller Scholar at the Cleveland Clinic, and colleagues. “Using this approach, we hope that their prolonged headaches will be lessened.”

Few studies have examined prolonged pediatric postconcussion headache

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that between 1.6 million and 3.8 million concussions occur annually during athletic and recreational activities in the United States. About 90% of concussions affect children or adolescents. The symptom most often reported after concussion is headache.

Few studies have focused on new persistent postconcussion headache (NPPCH) in children. Mr. Barissi and colleagues did not find any previous study that had examined prolonged headache following concussion in patients without prior chronic headache. They sought to ascertain the prognosis of patients with NPPCH and no history of prior headache, to describe this clinical entity, and to identify beneficial treatment methods.

The investigators retrospectively reviewed charts for approximately 2,000 patients who presented to the Cleveland Clinic pediatric neurology department between June 2017 and August 2018 for headaches. They identified 259 patients who received a diagnosis of concussion, 69 (27%) of whom had headaches for longer than 2 months after injury.

Mr. Barissi and colleagues emailed these patients, and 33 (48%) of them agreed to complete a questionnaire and participate in a 10-minute phone interview. Thirty-one patients (43%) could not be contacted, and eight (11%) declined to participate. All participants confirmed that they had not had consistent headache before the concussion and that chronic headache had arisen after concussion. To determine participants’ medical outcomes, the researchers compared participants’ initial assessment data with posttreatment data collected during the interview process.

Healthy behaviors increased after concussion

Of the 69 eligible participants, 38 (55%) were female. The population’s median age was 17. Twenty-eight (85%) of the 33 patients who completed the questionnaire considered the information and treatment that they had received to be beneficial. Twenty-five (78%) patients continued to have headache after several months, despite treatment.

Participants had withstood a mean of 1.72 concussions, and the mean age at first injury was 12.49 years. The most common cause of injury was a fall for males (36%) and an automobile accident for females (18%).

Forty-eight patients (70%) reported having two types of headache. Fifty-two patients (75%) had migraines, and 65 (94%) had chronic daily headache or tension-type headache. Forty-eight (70%) participants had a family history of headache.

In all, 64 patients (93%) had used a headache medication. The most common headache medications used were amitriptyline, topiramate, and cyproheptadine. Few patients were still taking these medications at several months after evaluation. The most common nonprescription medications used were Migravent (i.e., magnesium, riboflavin, coenzyme Q10, and butterbur), ondansetron, and melatonin. Furthermore, 61 patients (88%) participated in nonmedicinal therapy such as physical therapy, chiropractic therapy, and acupuncture.

After evaluation, patients engaged in several healthy behaviors (e.g., adequate exercise, proper use of over-the-counter medications, and drinking sufficient water) more frequently, but did not get adequate sleep. Sixty-five participants (94%) had undergone CT or MRI imaging, but the results did not improve understanding of headache etiology or treatment. Many patients missed several days of school, but average attendance improved after months of treatment.

Long-term outcomes

Thirty-one survey respondents (94%) reported that their emotional, cognitive, sleep, and somatic postconcussion symptoms had resolved. Nevertheless, a majority of participants still had headache. “The persistence of postconcussion symptoms is uncommon, but lasting headache is not,” said the researchers. “If patients are not properly educated, conditions may deteriorate, extending the duration of disability.” A longer study with a larger sample size could provide valuable information, said the researchers. Future work should examine objectively the efficacy of various medications used to treat NPPCH and determine the best methods of treatment for this syndrome, which “can cause prolonged pain, suffering, and lack of function,” they concluded.

The investigators did not report any study funding or disclosures.

SOURCE: Barissi M et al. CNS 2019, Abstract 95.

CHARLOTTE, N.C. – , according to research presented at the annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society. The headache may be migraine, chronic daily headache, tension-type headache, or a combination of these headaches.

“We strongly recommend that individuals who develop persistent headache after a concussion be evaluated and treated by a neurologist with experience in administering treatment for headache,” said Marcus Barissi, Weller Scholar at the Cleveland Clinic, and colleagues. “Using this approach, we hope that their prolonged headaches will be lessened.”

Few studies have examined prolonged pediatric postconcussion headache

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that between 1.6 million and 3.8 million concussions occur annually during athletic and recreational activities in the United States. About 90% of concussions affect children or adolescents. The symptom most often reported after concussion is headache.

Few studies have focused on new persistent postconcussion headache (NPPCH) in children. Mr. Barissi and colleagues did not find any previous study that had examined prolonged headache following concussion in patients without prior chronic headache. They sought to ascertain the prognosis of patients with NPPCH and no history of prior headache, to describe this clinical entity, and to identify beneficial treatment methods.

The investigators retrospectively reviewed charts for approximately 2,000 patients who presented to the Cleveland Clinic pediatric neurology department between June 2017 and August 2018 for headaches. They identified 259 patients who received a diagnosis of concussion, 69 (27%) of whom had headaches for longer than 2 months after injury.

Mr. Barissi and colleagues emailed these patients, and 33 (48%) of them agreed to complete a questionnaire and participate in a 10-minute phone interview. Thirty-one patients (43%) could not be contacted, and eight (11%) declined to participate. All participants confirmed that they had not had consistent headache before the concussion and that chronic headache had arisen after concussion. To determine participants’ medical outcomes, the researchers compared participants’ initial assessment data with posttreatment data collected during the interview process.

Healthy behaviors increased after concussion

Of the 69 eligible participants, 38 (55%) were female. The population’s median age was 17. Twenty-eight (85%) of the 33 patients who completed the questionnaire considered the information and treatment that they had received to be beneficial. Twenty-five (78%) patients continued to have headache after several months, despite treatment.

Participants had withstood a mean of 1.72 concussions, and the mean age at first injury was 12.49 years. The most common cause of injury was a fall for males (36%) and an automobile accident for females (18%).

Forty-eight patients (70%) reported having two types of headache. Fifty-two patients (75%) had migraines, and 65 (94%) had chronic daily headache or tension-type headache. Forty-eight (70%) participants had a family history of headache.

In all, 64 patients (93%) had used a headache medication. The most common headache medications used were amitriptyline, topiramate, and cyproheptadine. Few patients were still taking these medications at several months after evaluation. The most common nonprescription medications used were Migravent (i.e., magnesium, riboflavin, coenzyme Q10, and butterbur), ondansetron, and melatonin. Furthermore, 61 patients (88%) participated in nonmedicinal therapy such as physical therapy, chiropractic therapy, and acupuncture.

After evaluation, patients engaged in several healthy behaviors (e.g., adequate exercise, proper use of over-the-counter medications, and drinking sufficient water) more frequently, but did not get adequate sleep. Sixty-five participants (94%) had undergone CT or MRI imaging, but the results did not improve understanding of headache etiology or treatment. Many patients missed several days of school, but average attendance improved after months of treatment.

Long-term outcomes

Thirty-one survey respondents (94%) reported that their emotional, cognitive, sleep, and somatic postconcussion symptoms had resolved. Nevertheless, a majority of participants still had headache. “The persistence of postconcussion symptoms is uncommon, but lasting headache is not,” said the researchers. “If patients are not properly educated, conditions may deteriorate, extending the duration of disability.” A longer study with a larger sample size could provide valuable information, said the researchers. Future work should examine objectively the efficacy of various medications used to treat NPPCH and determine the best methods of treatment for this syndrome, which “can cause prolonged pain, suffering, and lack of function,” they concluded.

The investigators did not report any study funding or disclosures.

SOURCE: Barissi M et al. CNS 2019, Abstract 95.

REPORTING FROM CNS 2019

AVXS-101 may result in long-term motor improvements in SMA

CHARLOTTE, N.C. – AVXS-101, the Food and Drug Administration–approved therapy for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), yields rapid, sustained improvements in CHOP INTEND scores, better survival, and motor function improvements at long-term follow-up, according to an analysis presented at the annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society. The results provide a clinical demonstration of continuous expression of the SMN protein, according to the investigators. In addition, AVXS-101 is associated with reduced health care utilization in treated infants, which could decrease costs, lessen the burden on patients and caregivers, and improve quality of life.

SMA1 is a progressive neurologic disease that causes loss of the lower motor neurons in the spinal cord and brainstem. Patients have increasing muscle weakness that leads to death or the need for permanent ventilation by age 2 years. The disease results from mutations in the SMN1 gene. AVXS-101 replaces the missing or nonfunctional SMN1 with a healthy copy of a human SMN gene.

AveXis, the company that developed the therapy, enrolled 12 patients with SMA1 in a phase 1/2a study between December 2014 and December 2015. All participants received one intravenous infusion of AVXS-101. Omar Dabbous, MD, vice president of global health economics, outcomes research, and real world evidence at AveXis in Bannockburn, Ill., and colleagues evaluated participants’ rates of event-free survival (i.e., absence of death or need for permanent ventilation), pulmonary or nutritional interventions, swallowing, hospitalization, and CHOP INTEND scores, as well as therapeutic safety at 2 years.

At study completion, all patients who had received a therapeutic dose had event-free survival. Seven participants did not need daily noninvasive ventilation. Eleven participants had stable or improved swallowing. All of the latter patients fed orally, and six fed exclusively by mouth. Eleven patients spoke.

Participants had a mean of 1.4 respiratory hospitalizations per year. Mean proportion of time participants spent hospitalized was 4.4%. Mean hospitalization rate per year was 2.1, and mean length of hospital stay was 6.7 days. In addition, participants’ CHOP INTEND scores increased from baseline by 9.8 points at 1 month and by 15.4 points at 3 months. Patients who received a therapeutic dose of AVXS-101 have maintained their motor milestones at long-term follow-up, which suggests that treatment effects persist over the long term. Adverse events included elevated serum aminotransferase levels, which were reduced by prednisolone.

Dr. Dabbous is an employee of AveXis, which developed AVXS-101.

SOURCE: Dabbous O et al. CNS 2019. Abstract 199.

CHARLOTTE, N.C. – AVXS-101, the Food and Drug Administration–approved therapy for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), yields rapid, sustained improvements in CHOP INTEND scores, better survival, and motor function improvements at long-term follow-up, according to an analysis presented at the annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society. The results provide a clinical demonstration of continuous expression of the SMN protein, according to the investigators. In addition, AVXS-101 is associated with reduced health care utilization in treated infants, which could decrease costs, lessen the burden on patients and caregivers, and improve quality of life.

SMA1 is a progressive neurologic disease that causes loss of the lower motor neurons in the spinal cord and brainstem. Patients have increasing muscle weakness that leads to death or the need for permanent ventilation by age 2 years. The disease results from mutations in the SMN1 gene. AVXS-101 replaces the missing or nonfunctional SMN1 with a healthy copy of a human SMN gene.

AveXis, the company that developed the therapy, enrolled 12 patients with SMA1 in a phase 1/2a study between December 2014 and December 2015. All participants received one intravenous infusion of AVXS-101. Omar Dabbous, MD, vice president of global health economics, outcomes research, and real world evidence at AveXis in Bannockburn, Ill., and colleagues evaluated participants’ rates of event-free survival (i.e., absence of death or need for permanent ventilation), pulmonary or nutritional interventions, swallowing, hospitalization, and CHOP INTEND scores, as well as therapeutic safety at 2 years.

At study completion, all patients who had received a therapeutic dose had event-free survival. Seven participants did not need daily noninvasive ventilation. Eleven participants had stable or improved swallowing. All of the latter patients fed orally, and six fed exclusively by mouth. Eleven patients spoke.

Participants had a mean of 1.4 respiratory hospitalizations per year. Mean proportion of time participants spent hospitalized was 4.4%. Mean hospitalization rate per year was 2.1, and mean length of hospital stay was 6.7 days. In addition, participants’ CHOP INTEND scores increased from baseline by 9.8 points at 1 month and by 15.4 points at 3 months. Patients who received a therapeutic dose of AVXS-101 have maintained their motor milestones at long-term follow-up, which suggests that treatment effects persist over the long term. Adverse events included elevated serum aminotransferase levels, which were reduced by prednisolone.

Dr. Dabbous is an employee of AveXis, which developed AVXS-101.

SOURCE: Dabbous O et al. CNS 2019. Abstract 199.

CHARLOTTE, N.C. – AVXS-101, the Food and Drug Administration–approved therapy for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), yields rapid, sustained improvements in CHOP INTEND scores, better survival, and motor function improvements at long-term follow-up, according to an analysis presented at the annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society. The results provide a clinical demonstration of continuous expression of the SMN protein, according to the investigators. In addition, AVXS-101 is associated with reduced health care utilization in treated infants, which could decrease costs, lessen the burden on patients and caregivers, and improve quality of life.

SMA1 is a progressive neurologic disease that causes loss of the lower motor neurons in the spinal cord and brainstem. Patients have increasing muscle weakness that leads to death or the need for permanent ventilation by age 2 years. The disease results from mutations in the SMN1 gene. AVXS-101 replaces the missing or nonfunctional SMN1 with a healthy copy of a human SMN gene.

AveXis, the company that developed the therapy, enrolled 12 patients with SMA1 in a phase 1/2a study between December 2014 and December 2015. All participants received one intravenous infusion of AVXS-101. Omar Dabbous, MD, vice president of global health economics, outcomes research, and real world evidence at AveXis in Bannockburn, Ill., and colleagues evaluated participants’ rates of event-free survival (i.e., absence of death or need for permanent ventilation), pulmonary or nutritional interventions, swallowing, hospitalization, and CHOP INTEND scores, as well as therapeutic safety at 2 years.

At study completion, all patients who had received a therapeutic dose had event-free survival. Seven participants did not need daily noninvasive ventilation. Eleven participants had stable or improved swallowing. All of the latter patients fed orally, and six fed exclusively by mouth. Eleven patients spoke.

Participants had a mean of 1.4 respiratory hospitalizations per year. Mean proportion of time participants spent hospitalized was 4.4%. Mean hospitalization rate per year was 2.1, and mean length of hospital stay was 6.7 days. In addition, participants’ CHOP INTEND scores increased from baseline by 9.8 points at 1 month and by 15.4 points at 3 months. Patients who received a therapeutic dose of AVXS-101 have maintained their motor milestones at long-term follow-up, which suggests that treatment effects persist over the long term. Adverse events included elevated serum aminotransferase levels, which were reduced by prednisolone.

Dr. Dabbous is an employee of AveXis, which developed AVXS-101.

SOURCE: Dabbous O et al. CNS 2019. Abstract 199.

REPORTING FROM CNS 2019

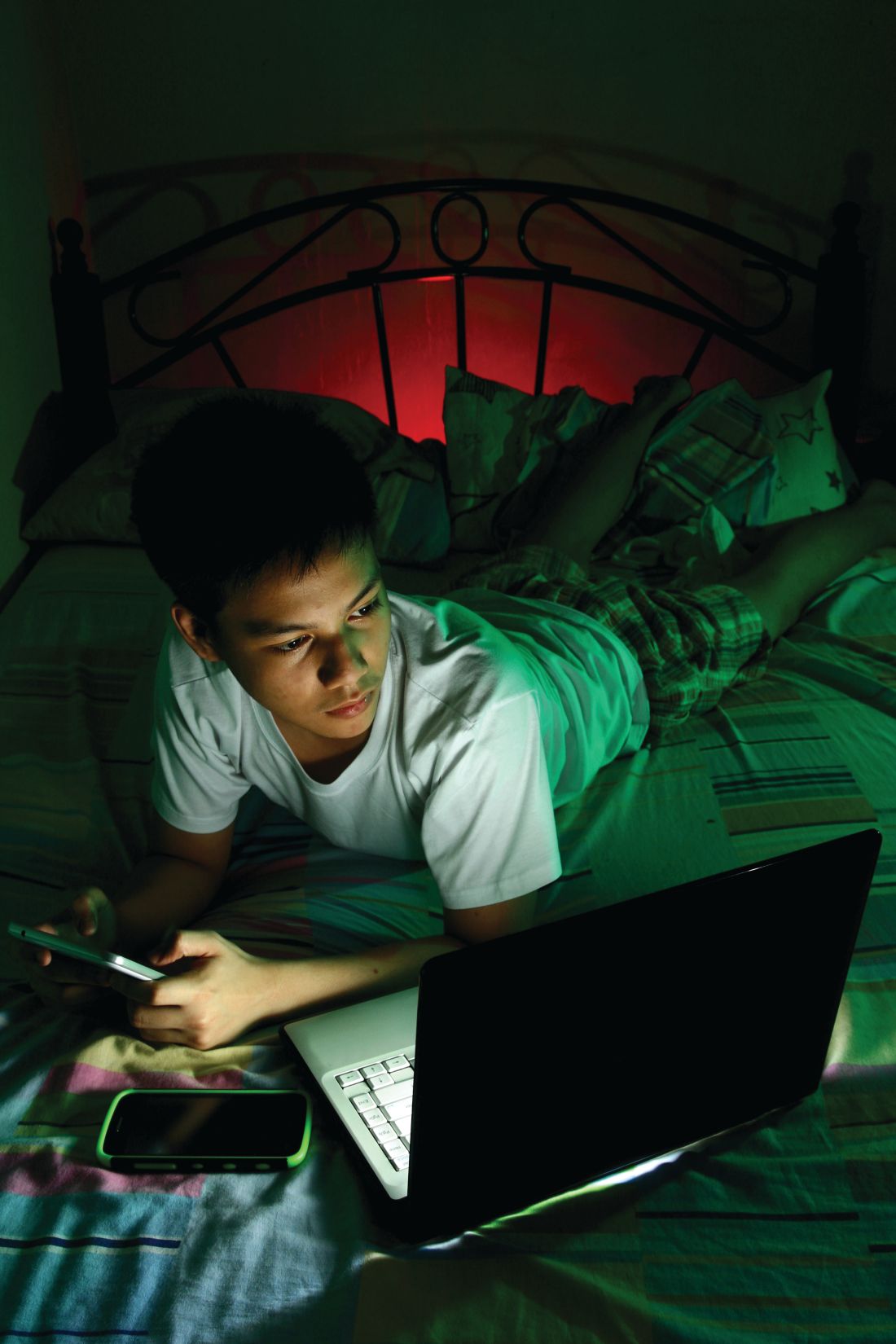

AAP calls for increased attention on unique health needs of adolescents

Adolescence is a critical period of development that brings with it unique health challenges, which has prompted the American Academy of Pediatrics to publish a policy statement addressing those issues.

“The importance of addressing the physical and mental health of adolescents has become more evident, with investigators in recent studies pointing to the fact that unmet health needs during adolescence and in the transition to adulthood predict not only poor health outcomes as adults but also lower quality of life in adulthood,” wrote lead authors Elizabeth M. Alderman, MD, and Cora Collette Breuner, MD, MPH, of the AAP’s Committee on Adolescence.

The first key health risk the authors highlighted was risky and risk-taking behaviors, pointing out that nearly three-quarters of adolescent deaths result from vehicle crashes, injuries from firearms, alcohol and illicit substances, homicide, or suicide. They also cited increased concern about the use of e-cigarettes among adolescents.

Recommendations exist on screening for and counseling on high-risk behaviors, but evidence showing that relatively few adolescents actually receive any kind of preventive counseling or discuss these health risks with pediatricians or primary care physicians suggests that improvement is needed.

“New screening codes for depression, substance use, and alcohol and tobacco use as well as brief intervention services may provide opportunities to receive payment for the services pediatricians are providing to adolescents,” wrote Dr. Alderman of the division of adolescent medicine in the department of pediatrics at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, New York, and Dr. Breuner of the division of adolescent medicine at the University of Washington and Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Thanks to technological advances in pediatric medical care, more adolescents are being identified with chronic medical conditions and developmental challenges. One survey suggested that as many as 31% of adolescents have one moderate to severe chronic health condition, such as asthma, cardiac disease, HIV, and developmental disabilities. Many, however, have unmet health needs that could affect their physical growth and development during adolescence.

, with evidence suggesting this group of adolescents is at risk of depression because of the isolation and discrimination they experience.

Similarly, the statement acknowledged the growing diversity of adolescent populations – for example, adolescents who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender – and the importance of delivering appropriate care to those populations.

“Sexual orientation and behaviors should be assessed by the pediatrician without making assumptions,” the authors wrote. “Adolescents should be allowed to apply and explain the labels they choose to use for sexuality and gender using open-ended questions.”

The authors drew attention to the greater mental health risks of adolescents, pointing out that about one in five adolescents have a diagnosable mental health disorder and one-quarter of adults with mood disorders had their first major depressive episode during adolescence. They also cited the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey of high school students, which showed that adolescents with a parent serving in the military are at increased risk of suicidal ideation.

In addition, Dr. Alderman and Dr. Breuner said, mental health problems experienced by adolescents often are comorbid with eating disorders. Formerly obese adolescents, male teenagers, and young people from lower socioeconomic groups are increasingly developing anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and other disordered eating.

The paper called for more financial, educational, and training support for pediatricians and other health care professionals to enable them to better meet the health and developmental needs of adolescents.

Dr. Alderman and Dr. Breuner declared having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Alderman EM and Breuner CC. Pediatrics. 2019 Nov 18. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3150 .

Adolescence is a critical period of development that brings with it unique health challenges, which has prompted the American Academy of Pediatrics to publish a policy statement addressing those issues.

“The importance of addressing the physical and mental health of adolescents has become more evident, with investigators in recent studies pointing to the fact that unmet health needs during adolescence and in the transition to adulthood predict not only poor health outcomes as adults but also lower quality of life in adulthood,” wrote lead authors Elizabeth M. Alderman, MD, and Cora Collette Breuner, MD, MPH, of the AAP’s Committee on Adolescence.

The first key health risk the authors highlighted was risky and risk-taking behaviors, pointing out that nearly three-quarters of adolescent deaths result from vehicle crashes, injuries from firearms, alcohol and illicit substances, homicide, or suicide. They also cited increased concern about the use of e-cigarettes among adolescents.

Recommendations exist on screening for and counseling on high-risk behaviors, but evidence showing that relatively few adolescents actually receive any kind of preventive counseling or discuss these health risks with pediatricians or primary care physicians suggests that improvement is needed.

“New screening codes for depression, substance use, and alcohol and tobacco use as well as brief intervention services may provide opportunities to receive payment for the services pediatricians are providing to adolescents,” wrote Dr. Alderman of the division of adolescent medicine in the department of pediatrics at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, New York, and Dr. Breuner of the division of adolescent medicine at the University of Washington and Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Thanks to technological advances in pediatric medical care, more adolescents are being identified with chronic medical conditions and developmental challenges. One survey suggested that as many as 31% of adolescents have one moderate to severe chronic health condition, such as asthma, cardiac disease, HIV, and developmental disabilities. Many, however, have unmet health needs that could affect their physical growth and development during adolescence.

, with evidence suggesting this group of adolescents is at risk of depression because of the isolation and discrimination they experience.

Similarly, the statement acknowledged the growing diversity of adolescent populations – for example, adolescents who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender – and the importance of delivering appropriate care to those populations.

“Sexual orientation and behaviors should be assessed by the pediatrician without making assumptions,” the authors wrote. “Adolescents should be allowed to apply and explain the labels they choose to use for sexuality and gender using open-ended questions.”

The authors drew attention to the greater mental health risks of adolescents, pointing out that about one in five adolescents have a diagnosable mental health disorder and one-quarter of adults with mood disorders had their first major depressive episode during adolescence. They also cited the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey of high school students, which showed that adolescents with a parent serving in the military are at increased risk of suicidal ideation.

In addition, Dr. Alderman and Dr. Breuner said, mental health problems experienced by adolescents often are comorbid with eating disorders. Formerly obese adolescents, male teenagers, and young people from lower socioeconomic groups are increasingly developing anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and other disordered eating.

The paper called for more financial, educational, and training support for pediatricians and other health care professionals to enable them to better meet the health and developmental needs of adolescents.

Dr. Alderman and Dr. Breuner declared having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Alderman EM and Breuner CC. Pediatrics. 2019 Nov 18. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3150 .

Adolescence is a critical period of development that brings with it unique health challenges, which has prompted the American Academy of Pediatrics to publish a policy statement addressing those issues.

“The importance of addressing the physical and mental health of adolescents has become more evident, with investigators in recent studies pointing to the fact that unmet health needs during adolescence and in the transition to adulthood predict not only poor health outcomes as adults but also lower quality of life in adulthood,” wrote lead authors Elizabeth M. Alderman, MD, and Cora Collette Breuner, MD, MPH, of the AAP’s Committee on Adolescence.

The first key health risk the authors highlighted was risky and risk-taking behaviors, pointing out that nearly three-quarters of adolescent deaths result from vehicle crashes, injuries from firearms, alcohol and illicit substances, homicide, or suicide. They also cited increased concern about the use of e-cigarettes among adolescents.

Recommendations exist on screening for and counseling on high-risk behaviors, but evidence showing that relatively few adolescents actually receive any kind of preventive counseling or discuss these health risks with pediatricians or primary care physicians suggests that improvement is needed.

“New screening codes for depression, substance use, and alcohol and tobacco use as well as brief intervention services may provide opportunities to receive payment for the services pediatricians are providing to adolescents,” wrote Dr. Alderman of the division of adolescent medicine in the department of pediatrics at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, New York, and Dr. Breuner of the division of adolescent medicine at the University of Washington and Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Thanks to technological advances in pediatric medical care, more adolescents are being identified with chronic medical conditions and developmental challenges. One survey suggested that as many as 31% of adolescents have one moderate to severe chronic health condition, such as asthma, cardiac disease, HIV, and developmental disabilities. Many, however, have unmet health needs that could affect their physical growth and development during adolescence.

, with evidence suggesting this group of adolescents is at risk of depression because of the isolation and discrimination they experience.

Similarly, the statement acknowledged the growing diversity of adolescent populations – for example, adolescents who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender – and the importance of delivering appropriate care to those populations.

“Sexual orientation and behaviors should be assessed by the pediatrician without making assumptions,” the authors wrote. “Adolescents should be allowed to apply and explain the labels they choose to use for sexuality and gender using open-ended questions.”

The authors drew attention to the greater mental health risks of adolescents, pointing out that about one in five adolescents have a diagnosable mental health disorder and one-quarter of adults with mood disorders had their first major depressive episode during adolescence. They also cited the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey of high school students, which showed that adolescents with a parent serving in the military are at increased risk of suicidal ideation.

In addition, Dr. Alderman and Dr. Breuner said, mental health problems experienced by adolescents often are comorbid with eating disorders. Formerly obese adolescents, male teenagers, and young people from lower socioeconomic groups are increasingly developing anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and other disordered eating.

The paper called for more financial, educational, and training support for pediatricians and other health care professionals to enable them to better meet the health and developmental needs of adolescents.

Dr. Alderman and Dr. Breuner declared having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Alderman EM and Breuner CC. Pediatrics. 2019 Nov 18. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3150 .

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: New screening codes for depression, substance use, and other intervention services may make it possible for pediatricians to receive payment for services.

Major finding: Adolescents might have particular health issues around risk-taking behaviors, mental health, and other issues.

Study details: Policy statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Disclosures: No funding or conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Alderman EM and Breuner CC. Pediatrics. 2019 Nov 18. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3150.

Suicide screening crucial in pediatric medical settings

and screening can take as little as 20 seconds, according to Lisa Horowitz, PhD, MPH, a staff scientist and clinical psychologist at the National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, Md.

But clinicians need to use validated screening instruments that are both population specific and site specific, and they need practice guidelines to treat patients screening positive.

Currently, many practitioners use depression screens – such as question #9 on suicide ideation and self harm on the Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents (PHQ-A) – to identify suicide risk, but preliminary data suggest these screens often are inadequate, Dr. Horowitz said. Just one question, especially one without precise language, does not appear to identify as many at-risk youths as more direct questions about suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

A Pathways to Clinical Care suicide risk screening work group therefore designed a three-tiered clinical pathway for suicide risk screenings in emergency departments, inpatient care, and outpatient primary care. It begins with the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ), which takes about 20 seconds and was specifically developed for pediatric patients in the emergency department and validated in both inpatient and outpatient settings.

Dr Horowitz, also the lead principal investigator for development of the ASQ, currently is leading six National Institute of Mental Health studies to validate and implement the screening tool in medical settings. She explained the three-tiered system during a session on youth suicide screening at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting in Baltimore this year.

If a patient screens positive on the ASQ, a trained clinician should conduct a brief suicide safety assessment (BSSA), which takes approximately 10 minutes, Dr Horowitz said. Those who screen positive on the BSSA should receive the Patient Resource List and then be referred for a full mental health and safety evaluation, which takes about 30 minutes. Resources, such as nurse scripts and parent/guardian flyers, are available at the NIMH website, as well as translations of the ASQ in Arabic, Chinese, Dutch, French, Hebrew, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Portuguese, Russian, Somali, Spanish, and Vietnamese.

Acknowledging the importance of suicide screening

During the same session, John V. Campo, MD, an assistant dean for behavioral health and professor of behavioral medicine and psychiatry at West Virginia University in Morgantown, discussed why suicide risk screening is so crucial in general medical settings. As someone who trained as a pediatrician before crossing over to behavioral health, he acknowledged that primary care physicians already have many priorities to cover in short visits, and that the national answer to most public health problems is to deal with it in primary care.

“Anyone who has done primary care pediatrics understands the challenges involved with screening for anything – particularly when you identify someone who is extensively at risk,” he said.

But suicide has a disproportionately high impact on young populations, and “identifying youth at risk for suicide identifies a group of young people who are at risk for a variety of threats to their health and well-being,” he said.

For youth aged 10-19 years in 2016, suicide was the second leading cause of death behind accidents, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018 Jun;67[4]:1-16). In fact, accidents, suicide, and homicide account for three-quarters of deaths among youth aged 10-24 years (Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019 Jun;68[6]:1-77), yet it’s typically the other 25% that most physicians trained for in residency.

“Suicide kills more kids than cancer, heart disease, infections – all kinds, sepsis, meningitis, pneumonia, influenza, HIV, respiratory conditions. Suicide kills more young people every year than all of that [combined],” Dr. Campo said. “And yet, when you walk through a modern emergency department, we see all these specialized programs for those who present with physical trauma or chest pain or all these other things, but zero specialized mental health services. There’s a disconnect.”

There is some good news in the data, he said. Observational data have shown that suicide rates negatively correlate with indicators of better access to health and medical health services, and researchers increasingly are identifying proven strategies that help prevent suicide in young people – once they have been identified.

But that’s the problem, “and we all know it,” Dr. Campo continued. “Most youth who are at risk for suicide aren’t recognized, and those who are recognized most often are untreated or inadequately treated,” he said. Further, “the best predictor of future behavior is past behavior,” but most adolescents die by suicide on their first attempt.

Again, however, Dr. Campo pivoted to the good news. Data also have shown that most youth who die by suicide had at least one health contact in the previous year, which means there are opportunities for screening and intervention.

The most common risk factor for suicide is having a mental health or substance use condition, present in about 90% of completed suicides and affecting approximately one in five youth. Prevalence is even higher in those with physical health conditions and among those with Medicaid or no insurance (J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006 Mar-Apr;47[3-4]372-94).

Yet, “the majority of them have not been treated at all for mental disorder, which seems to be the most important remediable risk factor for suicide, and even fewer are in current treatment at the time of the death,” Dr. Campo said. Suicide also is correlated with a number of other high-risk behaviors or circumstances, such as “vulnerabilities to substance abuse, riding in a car with someone who is intoxicated, carrying a weapon to school, fighting, and meeting criteria for depression” (Pediatrics. 2010 May;125[5]:945-52). Screening for suicide risk therefore allows physicians to identify youth vulnerable to a wide range of risks, conditions, or death.

Overcoming barriers to suicide screening in primary care

Given the high prevalence of suicide and its link to so many other risks for youth, screening in primary care can send the message that suicide screening “really is a part of health care,” Dr. Campo said. Incorporating screening into primary care also can help overcome distrust of behavioral health specialists in the general public and stigma associated with behavioral health disorders.

Primary care screening emphasizes the importance and credibility of mental health and challenges attitudinal barriers to care, he said.

At the same time, however, he acknowledged that providers themselves often are uneasy about addressing behavioral health. Therefore, “having the guideline and the expectation [of suicide risk screening] really drives home the point that this needs to be integrated into the rest of primary care,” he said. “It’s also consistent with the idea of the medical home.” With suicide the second leading cause of death among youth, “if there’s anything that we’re going to be thinking about screening for, one would think suicide would be high on the list.”

In fact, observational evidence has shown that educating and training primary care providers to recognize people with depression or a high risk for suicide can reduce suicide attempts and the suicide rate, Dr. Campo said (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Jun 1;74[6]:563-70). It also can help with the mismatch between where at-risk patients are and where behavioral health specialists are. About 90% of behavioral health specialists work only in specialty settings, and only 5% typically work in general medical settings, he said. Yet “most people who are in mental distress or in crisis don’t present in specialty behavioral health settings. They present in general medical settings.”

More data are needed to demonstrate more definitively whether and how much suicide risk screening changes outcomes, but we know a few things, Dr. Campo said, summing up his key points: “We know suicide’s a major source of mortality in youth that’s been relatively neglected in pediatric health care. Second, we know that suicide risk is associated with risk for other important causes of death, for mental disorders, and for alcohol and substance use.

“We know that most suicide decedents are unrecognized prior to the time of death, and those who are recognized often are not treated. We know that the majority of suicide deaths occur on the very first attempt. We also know that we increasingly have treatments, mental disorders that can be identified, and remediable risk factors, and [that at-risk youth] typically present at general medical settings. Beyond that, focusing on the general medical setting has both conceptual and practical advantages as a site for really helping us to detect patients at risk and then managing them.”

No funding was used for the presentations. Dr. Horowitz and Dr. Campo had no relevant financial disclosures.

and screening can take as little as 20 seconds, according to Lisa Horowitz, PhD, MPH, a staff scientist and clinical psychologist at the National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, Md.

But clinicians need to use validated screening instruments that are both population specific and site specific, and they need practice guidelines to treat patients screening positive.

Currently, many practitioners use depression screens – such as question #9 on suicide ideation and self harm on the Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents (PHQ-A) – to identify suicide risk, but preliminary data suggest these screens often are inadequate, Dr. Horowitz said. Just one question, especially one without precise language, does not appear to identify as many at-risk youths as more direct questions about suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

A Pathways to Clinical Care suicide risk screening work group therefore designed a three-tiered clinical pathway for suicide risk screenings in emergency departments, inpatient care, and outpatient primary care. It begins with the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ), which takes about 20 seconds and was specifically developed for pediatric patients in the emergency department and validated in both inpatient and outpatient settings.

Dr Horowitz, also the lead principal investigator for development of the ASQ, currently is leading six National Institute of Mental Health studies to validate and implement the screening tool in medical settings. She explained the three-tiered system during a session on youth suicide screening at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting in Baltimore this year.

If a patient screens positive on the ASQ, a trained clinician should conduct a brief suicide safety assessment (BSSA), which takes approximately 10 minutes, Dr Horowitz said. Those who screen positive on the BSSA should receive the Patient Resource List and then be referred for a full mental health and safety evaluation, which takes about 30 minutes. Resources, such as nurse scripts and parent/guardian flyers, are available at the NIMH website, as well as translations of the ASQ in Arabic, Chinese, Dutch, French, Hebrew, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Portuguese, Russian, Somali, Spanish, and Vietnamese.

Acknowledging the importance of suicide screening

During the same session, John V. Campo, MD, an assistant dean for behavioral health and professor of behavioral medicine and psychiatry at West Virginia University in Morgantown, discussed why suicide risk screening is so crucial in general medical settings. As someone who trained as a pediatrician before crossing over to behavioral health, he acknowledged that primary care physicians already have many priorities to cover in short visits, and that the national answer to most public health problems is to deal with it in primary care.

“Anyone who has done primary care pediatrics understands the challenges involved with screening for anything – particularly when you identify someone who is extensively at risk,” he said.

But suicide has a disproportionately high impact on young populations, and “identifying youth at risk for suicide identifies a group of young people who are at risk for a variety of threats to their health and well-being,” he said.

For youth aged 10-19 years in 2016, suicide was the second leading cause of death behind accidents, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018 Jun;67[4]:1-16). In fact, accidents, suicide, and homicide account for three-quarters of deaths among youth aged 10-24 years (Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019 Jun;68[6]:1-77), yet it’s typically the other 25% that most physicians trained for in residency.

“Suicide kills more kids than cancer, heart disease, infections – all kinds, sepsis, meningitis, pneumonia, influenza, HIV, respiratory conditions. Suicide kills more young people every year than all of that [combined],” Dr. Campo said. “And yet, when you walk through a modern emergency department, we see all these specialized programs for those who present with physical trauma or chest pain or all these other things, but zero specialized mental health services. There’s a disconnect.”

There is some good news in the data, he said. Observational data have shown that suicide rates negatively correlate with indicators of better access to health and medical health services, and researchers increasingly are identifying proven strategies that help prevent suicide in young people – once they have been identified.

But that’s the problem, “and we all know it,” Dr. Campo continued. “Most youth who are at risk for suicide aren’t recognized, and those who are recognized most often are untreated or inadequately treated,” he said. Further, “the best predictor of future behavior is past behavior,” but most adolescents die by suicide on their first attempt.

Again, however, Dr. Campo pivoted to the good news. Data also have shown that most youth who die by suicide had at least one health contact in the previous year, which means there are opportunities for screening and intervention.

The most common risk factor for suicide is having a mental health or substance use condition, present in about 90% of completed suicides and affecting approximately one in five youth. Prevalence is even higher in those with physical health conditions and among those with Medicaid or no insurance (J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006 Mar-Apr;47[3-4]372-94).

Yet, “the majority of them have not been treated at all for mental disorder, which seems to be the most important remediable risk factor for suicide, and even fewer are in current treatment at the time of the death,” Dr. Campo said. Suicide also is correlated with a number of other high-risk behaviors or circumstances, such as “vulnerabilities to substance abuse, riding in a car with someone who is intoxicated, carrying a weapon to school, fighting, and meeting criteria for depression” (Pediatrics. 2010 May;125[5]:945-52). Screening for suicide risk therefore allows physicians to identify youth vulnerable to a wide range of risks, conditions, or death.

Overcoming barriers to suicide screening in primary care

Given the high prevalence of suicide and its link to so many other risks for youth, screening in primary care can send the message that suicide screening “really is a part of health care,” Dr. Campo said. Incorporating screening into primary care also can help overcome distrust of behavioral health specialists in the general public and stigma associated with behavioral health disorders.

Primary care screening emphasizes the importance and credibility of mental health and challenges attitudinal barriers to care, he said.

At the same time, however, he acknowledged that providers themselves often are uneasy about addressing behavioral health. Therefore, “having the guideline and the expectation [of suicide risk screening] really drives home the point that this needs to be integrated into the rest of primary care,” he said. “It’s also consistent with the idea of the medical home.” With suicide the second leading cause of death among youth, “if there’s anything that we’re going to be thinking about screening for, one would think suicide would be high on the list.”

In fact, observational evidence has shown that educating and training primary care providers to recognize people with depression or a high risk for suicide can reduce suicide attempts and the suicide rate, Dr. Campo said (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Jun 1;74[6]:563-70). It also can help with the mismatch between where at-risk patients are and where behavioral health specialists are. About 90% of behavioral health specialists work only in specialty settings, and only 5% typically work in general medical settings, he said. Yet “most people who are in mental distress or in crisis don’t present in specialty behavioral health settings. They present in general medical settings.”

More data are needed to demonstrate more definitively whether and how much suicide risk screening changes outcomes, but we know a few things, Dr. Campo said, summing up his key points: “We know suicide’s a major source of mortality in youth that’s been relatively neglected in pediatric health care. Second, we know that suicide risk is associated with risk for other important causes of death, for mental disorders, and for alcohol and substance use.

“We know that most suicide decedents are unrecognized prior to the time of death, and those who are recognized often are not treated. We know that the majority of suicide deaths occur on the very first attempt. We also know that we increasingly have treatments, mental disorders that can be identified, and remediable risk factors, and [that at-risk youth] typically present at general medical settings. Beyond that, focusing on the general medical setting has both conceptual and practical advantages as a site for really helping us to detect patients at risk and then managing them.”

No funding was used for the presentations. Dr. Horowitz and Dr. Campo had no relevant financial disclosures.

and screening can take as little as 20 seconds, according to Lisa Horowitz, PhD, MPH, a staff scientist and clinical psychologist at the National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, Md.

But clinicians need to use validated screening instruments that are both population specific and site specific, and they need practice guidelines to treat patients screening positive.

Currently, many practitioners use depression screens – such as question #9 on suicide ideation and self harm on the Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents (PHQ-A) – to identify suicide risk, but preliminary data suggest these screens often are inadequate, Dr. Horowitz said. Just one question, especially one without precise language, does not appear to identify as many at-risk youths as more direct questions about suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

A Pathways to Clinical Care suicide risk screening work group therefore designed a three-tiered clinical pathway for suicide risk screenings in emergency departments, inpatient care, and outpatient primary care. It begins with the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ), which takes about 20 seconds and was specifically developed for pediatric patients in the emergency department and validated in both inpatient and outpatient settings.

Dr Horowitz, also the lead principal investigator for development of the ASQ, currently is leading six National Institute of Mental Health studies to validate and implement the screening tool in medical settings. She explained the three-tiered system during a session on youth suicide screening at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting in Baltimore this year.

If a patient screens positive on the ASQ, a trained clinician should conduct a brief suicide safety assessment (BSSA), which takes approximately 10 minutes, Dr Horowitz said. Those who screen positive on the BSSA should receive the Patient Resource List and then be referred for a full mental health and safety evaluation, which takes about 30 minutes. Resources, such as nurse scripts and parent/guardian flyers, are available at the NIMH website, as well as translations of the ASQ in Arabic, Chinese, Dutch, French, Hebrew, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Portuguese, Russian, Somali, Spanish, and Vietnamese.

Acknowledging the importance of suicide screening

During the same session, John V. Campo, MD, an assistant dean for behavioral health and professor of behavioral medicine and psychiatry at West Virginia University in Morgantown, discussed why suicide risk screening is so crucial in general medical settings. As someone who trained as a pediatrician before crossing over to behavioral health, he acknowledged that primary care physicians already have many priorities to cover in short visits, and that the national answer to most public health problems is to deal with it in primary care.

“Anyone who has done primary care pediatrics understands the challenges involved with screening for anything – particularly when you identify someone who is extensively at risk,” he said.

But suicide has a disproportionately high impact on young populations, and “identifying youth at risk for suicide identifies a group of young people who are at risk for a variety of threats to their health and well-being,” he said.

For youth aged 10-19 years in 2016, suicide was the second leading cause of death behind accidents, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018 Jun;67[4]:1-16). In fact, accidents, suicide, and homicide account for three-quarters of deaths among youth aged 10-24 years (Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019 Jun;68[6]:1-77), yet it’s typically the other 25% that most physicians trained for in residency.

“Suicide kills more kids than cancer, heart disease, infections – all kinds, sepsis, meningitis, pneumonia, influenza, HIV, respiratory conditions. Suicide kills more young people every year than all of that [combined],” Dr. Campo said. “And yet, when you walk through a modern emergency department, we see all these specialized programs for those who present with physical trauma or chest pain or all these other things, but zero specialized mental health services. There’s a disconnect.”

There is some good news in the data, he said. Observational data have shown that suicide rates negatively correlate with indicators of better access to health and medical health services, and researchers increasingly are identifying proven strategies that help prevent suicide in young people – once they have been identified.

But that’s the problem, “and we all know it,” Dr. Campo continued. “Most youth who are at risk for suicide aren’t recognized, and those who are recognized most often are untreated or inadequately treated,” he said. Further, “the best predictor of future behavior is past behavior,” but most adolescents die by suicide on their first attempt.

Again, however, Dr. Campo pivoted to the good news. Data also have shown that most youth who die by suicide had at least one health contact in the previous year, which means there are opportunities for screening and intervention.

The most common risk factor for suicide is having a mental health or substance use condition, present in about 90% of completed suicides and affecting approximately one in five youth. Prevalence is even higher in those with physical health conditions and among those with Medicaid or no insurance (J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006 Mar-Apr;47[3-4]372-94).

Yet, “the majority of them have not been treated at all for mental disorder, which seems to be the most important remediable risk factor for suicide, and even fewer are in current treatment at the time of the death,” Dr. Campo said. Suicide also is correlated with a number of other high-risk behaviors or circumstances, such as “vulnerabilities to substance abuse, riding in a car with someone who is intoxicated, carrying a weapon to school, fighting, and meeting criteria for depression” (Pediatrics. 2010 May;125[5]:945-52). Screening for suicide risk therefore allows physicians to identify youth vulnerable to a wide range of risks, conditions, or death.

Overcoming barriers to suicide screening in primary care

Given the high prevalence of suicide and its link to so many other risks for youth, screening in primary care can send the message that suicide screening “really is a part of health care,” Dr. Campo said. Incorporating screening into primary care also can help overcome distrust of behavioral health specialists in the general public and stigma associated with behavioral health disorders.

Primary care screening emphasizes the importance and credibility of mental health and challenges attitudinal barriers to care, he said.

At the same time, however, he acknowledged that providers themselves often are uneasy about addressing behavioral health. Therefore, “having the guideline and the expectation [of suicide risk screening] really drives home the point that this needs to be integrated into the rest of primary care,” he said. “It’s also consistent with the idea of the medical home.” With suicide the second leading cause of death among youth, “if there’s anything that we’re going to be thinking about screening for, one would think suicide would be high on the list.”

In fact, observational evidence has shown that educating and training primary care providers to recognize people with depression or a high risk for suicide can reduce suicide attempts and the suicide rate, Dr. Campo said (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Jun 1;74[6]:563-70). It also can help with the mismatch between where at-risk patients are and where behavioral health specialists are. About 90% of behavioral health specialists work only in specialty settings, and only 5% typically work in general medical settings, he said. Yet “most people who are in mental distress or in crisis don’t present in specialty behavioral health settings. They present in general medical settings.”

More data are needed to demonstrate more definitively whether and how much suicide risk screening changes outcomes, but we know a few things, Dr. Campo said, summing up his key points: “We know suicide’s a major source of mortality in youth that’s been relatively neglected in pediatric health care. Second, we know that suicide risk is associated with risk for other important causes of death, for mental disorders, and for alcohol and substance use.

“We know that most suicide decedents are unrecognized prior to the time of death, and those who are recognized often are not treated. We know that the majority of suicide deaths occur on the very first attempt. We also know that we increasingly have treatments, mental disorders that can be identified, and remediable risk factors, and [that at-risk youth] typically present at general medical settings. Beyond that, focusing on the general medical setting has both conceptual and practical advantages as a site for really helping us to detect patients at risk and then managing them.”

No funding was used for the presentations. Dr. Horowitz and Dr. Campo had no relevant financial disclosures.

FDA approves treatment for sickle cell pain crises

The Food and Drug Administration has approved crizanlizumab-tmca (Adakveo) to reduce the frequency of vaso-occlusive crisis, a common complication of sickle cell disease.

The drug is approved for patients aged 16 years and older. It was approved on the strength of the SUSTAIN trial, which randomized 198 patients with sickle cell disease and a history of vaso-occlusive crisis to crizanlizumab or placebo. Patients who received crizanlizumab had a median annual rate of 1.63 health care visits for vaso-occlusive crises, compared with patients who received placebo and had a median annual rate of 2.98 visits. The drug also delayed the first vaso-occlusive crisis after starting treatment from 1.4 months to 4.1 months, according to the FDA.

“Adakveo is the first targeted therapy approved for sickle cell disease, specifically inhibiting selectin, a substance that contributes to cells sticking together and leads to vaso-occlusive crisis,” Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, said in a statement. “Vaso-occlusive crisis can be extremely painful and is a frequent reason for emergency department visits and hospitalization for patients with sickle cell disease.”

Common adverse events associated with crizanlizumab included back pain, nausea, pyrexia, and arthralgia. The FDA advised physicians to monitor patients for infusion-related reactions.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved crizanlizumab-tmca (Adakveo) to reduce the frequency of vaso-occlusive crisis, a common complication of sickle cell disease.

The drug is approved for patients aged 16 years and older. It was approved on the strength of the SUSTAIN trial, which randomized 198 patients with sickle cell disease and a history of vaso-occlusive crisis to crizanlizumab or placebo. Patients who received crizanlizumab had a median annual rate of 1.63 health care visits for vaso-occlusive crises, compared with patients who received placebo and had a median annual rate of 2.98 visits. The drug also delayed the first vaso-occlusive crisis after starting treatment from 1.4 months to 4.1 months, according to the FDA.

“Adakveo is the first targeted therapy approved for sickle cell disease, specifically inhibiting selectin, a substance that contributes to cells sticking together and leads to vaso-occlusive crisis,” Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, said in a statement. “Vaso-occlusive crisis can be extremely painful and is a frequent reason for emergency department visits and hospitalization for patients with sickle cell disease.”

Common adverse events associated with crizanlizumab included back pain, nausea, pyrexia, and arthralgia. The FDA advised physicians to monitor patients for infusion-related reactions.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved crizanlizumab-tmca (Adakveo) to reduce the frequency of vaso-occlusive crisis, a common complication of sickle cell disease.

The drug is approved for patients aged 16 years and older. It was approved on the strength of the SUSTAIN trial, which randomized 198 patients with sickle cell disease and a history of vaso-occlusive crisis to crizanlizumab or placebo. Patients who received crizanlizumab had a median annual rate of 1.63 health care visits for vaso-occlusive crises, compared with patients who received placebo and had a median annual rate of 2.98 visits. The drug also delayed the first vaso-occlusive crisis after starting treatment from 1.4 months to 4.1 months, according to the FDA.

“Adakveo is the first targeted therapy approved for sickle cell disease, specifically inhibiting selectin, a substance that contributes to cells sticking together and leads to vaso-occlusive crisis,” Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, said in a statement. “Vaso-occlusive crisis can be extremely painful and is a frequent reason for emergency department visits and hospitalization for patients with sickle cell disease.”

Common adverse events associated with crizanlizumab included back pain, nausea, pyrexia, and arthralgia. The FDA advised physicians to monitor patients for infusion-related reactions.

Without action, every child will be affected by climate change

As wildfires increase the likelihood of respiratory illnesses for residents in California and Queensland, Australia, a new report from the Lancet warns that such health risks will become increasingly common without action to address climate change. But, the authors stressed, it’s still possible to prevent some health effects and mitigate others.

Given the magnitude of the issue, lead author Nick Watts, MBBS, MA, framed the issue in terms of what an individual child born today will face in his or her future. If the world continues on its current trajectory, such a child will eventually live in a world at least 4º C above average preindustrial temperatures.

“We roughly know what that looks like from a climate perspective,” said Dr. Watts, executive director of The Lancet Countdown: Tracking Progress on Health and Climate Change, during a telebriefing on the report.

“We have no idea of what that looks like from a public health perspective, but we know it is catastrophic,” he continued. “We know that it has the potential to undermine the last 50 years of gains in public health and overwhelm the health systems that we rely on.”

Health sector a significant, growing contributor

The report described the changes to which climate change has already contributed and addresses both the health threats and the way institutions and states are currently responding to those threats. It also included policy briefs specific to individual countries and an extensive appendix with projections data.

The authors noted that progress in mitigating fossil fuel combustion – the biggest driver of rising temperatures – is “intermittent at best,” with carbon dioxide emissions continuing to rise in 2018. The past decade has included 8 of the 10 hottest years on record. “Many of the indicators contained in this report suggest the world is following this ‘business as usual’ pathway,” the authors wrote.

In fact, the trend of coal-produced energy that had been declining actually increased 1.7% between 2016 and 2018. Perhaps ironically, given the focus of the report, “the healthcare sector is responsible for about 4.6% of global emissions, a value which is steadily rising across most major economies,” Dr. Watts and colleagues reported.

The potential health risks from climate change range from increased chronic illness, such as asthma and cardiovascular disease, to the increased spread of infectious diseases, especially vector-borne diseases, including dengue fever, malaria, and chikungunya. Increases in the frequency and intensity of severe weather events can lead to increased acute and longer-term morbidity and mortality.

Though children will suffer the brunt of negative health impact from climate change, the effects will touch people at every stage of life, from in utero development through old age, the authors emphasized.

“Downward trends in global yield potential for all major crops tracked since 1960 threaten food production and food security, with infants often the worst affected by the potentially permanent effects of undernutrition,” the authors reported. Children are also most susceptible to diarrheal disease and infectious diseases, particularly dengue.

Mitigating actions available

But the report focused as much on solutions and mitigation strategies as it did on the worst-case scenario without action. Speakers during the telebriefing emphasized the responsibility of all people, including physicians and other health care providers, to play a role in countering the public health disaster that could result from inaction on climate.

“Thankfully, here we have the treatment for climate change, solutions to shift away from the carbon pollution and towards clean energy and working to find the best way to protect ourselves and each other from climate change,” Renee N. Salas, MD, MPH, lead author of the 2019 Lancet Countdown U.S. Policy Brief and a Harvard C-CHANGE Fellow, said during the press briefing. “All we need is political will.”

Salas compared the present moment to that period when a physician still has the ability to save a critically ill patient’s life with fast action.

“If I don’t act quickly, the patient may still die even though that treatment would have saved their life earlier,” she said. “We are in that narrow window.”

Physicians have a responsibility to speak to patients and families frankly about not only specific conditions, such as asthma, but also the climate-related causes of those conditions, such as increasing air pollution, said Gina McCarthy, director of the Harvard Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment and the 13th administrator U.S. Environmental Policy Administration. Physicians are trusted advisers and therefore need to speak up because climate change is “about the health and well-being and the future of children,” she said.

Political polarization is one of the biggest challenges to addressing climate change and stymies efforts to take action, according to Richard Carmona, MD, who served as the 17th U.S. Surgeon General.

“The thing that frustrated me as a surgeon general and continues to frustrate me today is that these very scientifically vetted issues are reduced to political currency that creates divisiveness, and things don’t get done,” he said during the briefing.

“We have to move beyond that and elevate this discussion to one of the survival of our civilization and the health and safety and security of all nations in the world,” continued Dr. Carmona, who is also a professor of public health at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

The report notes that the warming is already “occurring faster than governments are able, or willing, to respond,” likely contributing to the increased outcry across the world from youth about the need to act.

And anyone can take some kind of action, Ms. McCarthy said. Her aim is to make the reality of climate change effects personal so that people understand its impact on them as well as what they can do.

“The report provides a list of actions that policy makers can take today to reduce the threat of climate change” as well as information on “how we can adapt and be more resilient as communities” while facing climate change’s challenges, she said.

Ms. McCarthy encouraged people to pay particular attention to the report’s mitigation and adaptation recommendations, “because I want them to know that climate change isn’t a lost cause,” she said. The actions people can demand of policymakers will not only avoid the worst-case health scenario but can also improve health today, she added.

“We can do better than to dwell on the problem,” Ms. McCarthy said. “We need people now to be hopeful about climate change, to do as others have suggested and demand action and take action in their own lives. We can use that to really drive solutions.”

Annual report assesses numerous indicators

The Lancet Countdown is an annual report supported by the Wellcome Trust that pulls together research from 35 academic institutions and United Nations agencies across the world to provide an update on what the authors described as “41 health indicators across five key domains: climate change impacts, exposures and vulnerability; adaptation, planning, and resilience for health; mitigation action and health cobenefits; economics and finance; [and] public and political engagement.”

Given the complexity of the issue of climate change and the wide range of possible effects and preventive measures, contributing researchers included not just climate scientists but also ecologists, mathematicians, engineers, hydrologists, social and political scientists, physicians and other public health professionals, and experts in energy, food, and transportation.

The research was supported by the Wellcome Trust. Multiple authors also received support from a range of government institutions and public and private foundations and fellowships. No relevant financial relationships were noted.

SOURCE: Watts N et al. Lancet. 2019 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32596-6.

This story first appeared in Medscape.com.

As wildfires increase the likelihood of respiratory illnesses for residents in California and Queensland, Australia, a new report from the Lancet warns that such health risks will become increasingly common without action to address climate change. But, the authors stressed, it’s still possible to prevent some health effects and mitigate others.

Given the magnitude of the issue, lead author Nick Watts, MBBS, MA, framed the issue in terms of what an individual child born today will face in his or her future. If the world continues on its current trajectory, such a child will eventually live in a world at least 4º C above average preindustrial temperatures.

“We roughly know what that looks like from a climate perspective,” said Dr. Watts, executive director of The Lancet Countdown: Tracking Progress on Health and Climate Change, during a telebriefing on the report.

“We have no idea of what that looks like from a public health perspective, but we know it is catastrophic,” he continued. “We know that it has the potential to undermine the last 50 years of gains in public health and overwhelm the health systems that we rely on.”

Health sector a significant, growing contributor

The report described the changes to which climate change has already contributed and addresses both the health threats and the way institutions and states are currently responding to those threats. It also included policy briefs specific to individual countries and an extensive appendix with projections data.

The authors noted that progress in mitigating fossil fuel combustion – the biggest driver of rising temperatures – is “intermittent at best,” with carbon dioxide emissions continuing to rise in 2018. The past decade has included 8 of the 10 hottest years on record. “Many of the indicators contained in this report suggest the world is following this ‘business as usual’ pathway,” the authors wrote.

In fact, the trend of coal-produced energy that had been declining actually increased 1.7% between 2016 and 2018. Perhaps ironically, given the focus of the report, “the healthcare sector is responsible for about 4.6% of global emissions, a value which is steadily rising across most major economies,” Dr. Watts and colleagues reported.

The potential health risks from climate change range from increased chronic illness, such as asthma and cardiovascular disease, to the increased spread of infectious diseases, especially vector-borne diseases, including dengue fever, malaria, and chikungunya. Increases in the frequency and intensity of severe weather events can lead to increased acute and longer-term morbidity and mortality.

Though children will suffer the brunt of negative health impact from climate change, the effects will touch people at every stage of life, from in utero development through old age, the authors emphasized.