User login

Stroke is diagnosed in about one-fifth of children with strokelike symptoms

CHARLOTTE, N.C. – (TIA), according to research presented at the annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society. Ischemic stroke and TIA were the second leading diagnoses among the stroke activations examined in the study, after seizure and Todd’s paralysis. “These data, in conjunction with previous studies, highlight the importance of developing protocols for early recognition and evaluation of children who present with strokelike symptoms,” said Tiffany Barkley, DO, a child neurology resident at Children’s Mercy Hospital in Kansas City, Mo., and colleagues.

Dr. Barkley and colleagues conducted their research to describe the demographic and other characteristics of patients who present with strokelike symptoms to their hospital. They undertook a descriptive, retrospective chart review of patients who came to Children’s Mercy Hospital from Sept. 1, 2016, to August 31, 2018, with concern for acute stroke. The investigators examined only patients for whom the Stroke Alert Process and power plan were activated.

“Power plans were created at Children’s Mercy Hospital to streamline and standardize care for children,” said Dr. Barkley. “While stroke order sets tend to be common practice in many adult hospitals, stroke order sets in pediatric hospitals are new.”

In all, 61 stroke activations occurred during the study period. Twelve patients (20%) had a final diagnosis of ischemic stroke or TIA. Among the patients with a final diagnosis of ischemic stroke, the most common presenting symptom was unilateral weakness. Two of these patients were candidates for intervention with mechanical thrombectomy, and none received tissue plasminogen activator. The average age of patients in all activations was 14 years, and the average age of patients with a final diagnosis of ischemic stroke or TIA was 4 years. About 37 (61%) subjects of activations were female, and the most common racial demographic was Caucasian.

Ischemic stroke or TIA was the second most common diagnosis of all activations (12 patients; 20%). Seizure or Todd’s paralysis (14 patients; 23%) was the leading diagnosis. Other common diagnoses included migraine (18%), psychogenic or conversion disorder (15%), oncologic process (3.0%), and complications of meningitis or encephalitis (1.6%). Children who presented with ischemic stroke secondary to Moyamoya disease were classified separately (two patients or 3%). It can be difficult to distinguish between stroke and stroke mimics based on neurologic examination alone, and imaging such as MRI often is needed, said Dr. Barkley. The researchers did not identify any intracranial hemorrhages in this patient population.

These findings are consistent with current reported literature, said the researchers. “Our study is one of the first to look at the demographics of children who present with strokelike symptoms,” said Dr. Barkley. “We hope that our study will not only help identify children who present with symptoms concerning for stroke, but also help us identify children who may be at risk for ischemic stroke before the stroke happens.”

The investigators did not have funding for this study and did not report any disclosures.

SOURCE: Barkley T et al. CNS 2019. Abstract 235.

CHARLOTTE, N.C. – (TIA), according to research presented at the annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society. Ischemic stroke and TIA were the second leading diagnoses among the stroke activations examined in the study, after seizure and Todd’s paralysis. “These data, in conjunction with previous studies, highlight the importance of developing protocols for early recognition and evaluation of children who present with strokelike symptoms,” said Tiffany Barkley, DO, a child neurology resident at Children’s Mercy Hospital in Kansas City, Mo., and colleagues.

Dr. Barkley and colleagues conducted their research to describe the demographic and other characteristics of patients who present with strokelike symptoms to their hospital. They undertook a descriptive, retrospective chart review of patients who came to Children’s Mercy Hospital from Sept. 1, 2016, to August 31, 2018, with concern for acute stroke. The investigators examined only patients for whom the Stroke Alert Process and power plan were activated.

“Power plans were created at Children’s Mercy Hospital to streamline and standardize care for children,” said Dr. Barkley. “While stroke order sets tend to be common practice in many adult hospitals, stroke order sets in pediatric hospitals are new.”

In all, 61 stroke activations occurred during the study period. Twelve patients (20%) had a final diagnosis of ischemic stroke or TIA. Among the patients with a final diagnosis of ischemic stroke, the most common presenting symptom was unilateral weakness. Two of these patients were candidates for intervention with mechanical thrombectomy, and none received tissue plasminogen activator. The average age of patients in all activations was 14 years, and the average age of patients with a final diagnosis of ischemic stroke or TIA was 4 years. About 37 (61%) subjects of activations were female, and the most common racial demographic was Caucasian.

Ischemic stroke or TIA was the second most common diagnosis of all activations (12 patients; 20%). Seizure or Todd’s paralysis (14 patients; 23%) was the leading diagnosis. Other common diagnoses included migraine (18%), psychogenic or conversion disorder (15%), oncologic process (3.0%), and complications of meningitis or encephalitis (1.6%). Children who presented with ischemic stroke secondary to Moyamoya disease were classified separately (two patients or 3%). It can be difficult to distinguish between stroke and stroke mimics based on neurologic examination alone, and imaging such as MRI often is needed, said Dr. Barkley. The researchers did not identify any intracranial hemorrhages in this patient population.

These findings are consistent with current reported literature, said the researchers. “Our study is one of the first to look at the demographics of children who present with strokelike symptoms,” said Dr. Barkley. “We hope that our study will not only help identify children who present with symptoms concerning for stroke, but also help us identify children who may be at risk for ischemic stroke before the stroke happens.”

The investigators did not have funding for this study and did not report any disclosures.

SOURCE: Barkley T et al. CNS 2019. Abstract 235.

CHARLOTTE, N.C. – (TIA), according to research presented at the annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society. Ischemic stroke and TIA were the second leading diagnoses among the stroke activations examined in the study, after seizure and Todd’s paralysis. “These data, in conjunction with previous studies, highlight the importance of developing protocols for early recognition and evaluation of children who present with strokelike symptoms,” said Tiffany Barkley, DO, a child neurology resident at Children’s Mercy Hospital in Kansas City, Mo., and colleagues.

Dr. Barkley and colleagues conducted their research to describe the demographic and other characteristics of patients who present with strokelike symptoms to their hospital. They undertook a descriptive, retrospective chart review of patients who came to Children’s Mercy Hospital from Sept. 1, 2016, to August 31, 2018, with concern for acute stroke. The investigators examined only patients for whom the Stroke Alert Process and power plan were activated.

“Power plans were created at Children’s Mercy Hospital to streamline and standardize care for children,” said Dr. Barkley. “While stroke order sets tend to be common practice in many adult hospitals, stroke order sets in pediatric hospitals are new.”

In all, 61 stroke activations occurred during the study period. Twelve patients (20%) had a final diagnosis of ischemic stroke or TIA. Among the patients with a final diagnosis of ischemic stroke, the most common presenting symptom was unilateral weakness. Two of these patients were candidates for intervention with mechanical thrombectomy, and none received tissue plasminogen activator. The average age of patients in all activations was 14 years, and the average age of patients with a final diagnosis of ischemic stroke or TIA was 4 years. About 37 (61%) subjects of activations were female, and the most common racial demographic was Caucasian.

Ischemic stroke or TIA was the second most common diagnosis of all activations (12 patients; 20%). Seizure or Todd’s paralysis (14 patients; 23%) was the leading diagnosis. Other common diagnoses included migraine (18%), psychogenic or conversion disorder (15%), oncologic process (3.0%), and complications of meningitis or encephalitis (1.6%). Children who presented with ischemic stroke secondary to Moyamoya disease were classified separately (two patients or 3%). It can be difficult to distinguish between stroke and stroke mimics based on neurologic examination alone, and imaging such as MRI often is needed, said Dr. Barkley. The researchers did not identify any intracranial hemorrhages in this patient population.

These findings are consistent with current reported literature, said the researchers. “Our study is one of the first to look at the demographics of children who present with strokelike symptoms,” said Dr. Barkley. “We hope that our study will not only help identify children who present with symptoms concerning for stroke, but also help us identify children who may be at risk for ischemic stroke before the stroke happens.”

The investigators did not have funding for this study and did not report any disclosures.

SOURCE: Barkley T et al. CNS 2019. Abstract 235.

REPORTING FROM CNS 2019

More adolescents seek medical care for mental health issues

Less than a decade ago, the ED at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego would see maybe one or two young psychiatric patients per day, said Benjamin Maxwell, MD, the hospital’s interim director of child and adolescent psychiatry.

Now, it’s not unusual for the ED to see 10 psychiatric patients in a day, and sometimes even 20, said Dr. Maxwell. “What a lot of times is happening now is kids aren’t getting the care they need, until it gets to the point where it is dangerous.”

EDs throughout California are reporting a sharp increase in adolescents and young adults seeking care for a mental health crisis. In 2018, California EDs treated 84,584 young patients aged 13-21 years who had a primary diagnosis involving mental health. That is up from 59,705 in 2012, a 42% increase, according to data provided by the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development.

By comparison, the number of ED encounters among that age group for all other diagnoses grew by just 4% over the same period. And the number of encounters involving mental health among all other age groups – everyone except adolescents and young adults – rose by about 18%.

The spike in youth mental health visits corresponds with a recent survey that found that members of “Generation Z” – defined in the survey as people born since 1997 – are more likely than other generations to report their mental health as fair or poor. The 2018 polling, done on behalf of the American Psychological Association, also found that members of Generation Z, along with millennials, are more likely to report receiving treatment for mental health issues.

The trend corresponds with another alarming development, as well: a marked increase in suicides among teens and young adults. About 7.5 of every 100,000 young people aged 13-21 in California died by suicide in 2017, up from a rate of 4.9 per 100,000 in 2008, according to the latest figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nationwide, suicides in that age range rose from 7.2 to 11.3 per 100,000 from 2008 to 2017.

Researchers are studying the causes for the surging reports of mental distress among America’s young people. Many recent theories note that the trend parallels the rise of social media, an ever-present window on peer activities that can exacerbate adolescent insecurities and open new avenues of bullying.

“Even though this generation has been raised with social media, youth are feeling more disconnected, judged, bullied, and pressured from their peers,” said Susan Coats, EdD, a school psychologist at Baldwin Park Unified School District near Los Angeles.

“Social media: It’s a blessing and it’s a curse,” Dr. Coats added. “Social media has brought youth together in a forum where maybe they may have felt isolated before, but it also has undermined interpersonal relationships.”

Members of Generation Z also report significant levels of stress about personal debt, housing instability, and hunger, as well as mass shootings and climate change, according to the American Psychological Association survey.

“We’re not doing a great job with … catching things before they devolve into broader problems, and we’re not doing a good job with prevention,” said Lishaun Francis, associate director of health collaborations at Children Now, a nonprofit based in Oakland, Calif.

Many California school districts don’t have enough school psychologists and don’t devote enough resources to teaching students how to cope with depression, anxiety, and other mental health issues, said Ms. Coats, who chairs the mental health and crisis consultation committee of the California Association of School Psychologists.

In the broader community, medical providers also are struggling to keep up. “Many times there aren’t psychiatric beds available for kids in our community,” Dr. Maxwell said.

Most of the adolescents who come into the ED at Rady Children’s Hospital during a mental health crisis are considering suicide, have attempted suicide, or have harmed themselves, said Dr. Maxwell, who is also the hospital’s medical director of inpatient psychiatry.

These patients are triaged and quickly seen by a social worker. Often, a behavioral health assistant is assigned to sit with the patients throughout their stay.

“Suicidal patients – we don’t want them to be alone at all in a busy emergency department,” Dr. Maxwell said. “So that’s a major staffing increase.”

Rady Children’s Hospital plans to open a six-bed, 24-hour psychiatric ED in the spring. Improving emergency care will help, Dr. Maxwell said, but a better solution would be to intervene with young people before they need an ED.

“The ED surge probably represents a failure of the system at large,” Dr. Maxwell said. “They’re ending up in the emergency department because they’re not getting the care they need, when they need it.”

Phillip Reese is a data reporting specialist and an assistant professor of journalism at California State University–Sacramento. This Kaiser Health News story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation. KHN is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Less than a decade ago, the ED at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego would see maybe one or two young psychiatric patients per day, said Benjamin Maxwell, MD, the hospital’s interim director of child and adolescent psychiatry.

Now, it’s not unusual for the ED to see 10 psychiatric patients in a day, and sometimes even 20, said Dr. Maxwell. “What a lot of times is happening now is kids aren’t getting the care they need, until it gets to the point where it is dangerous.”

EDs throughout California are reporting a sharp increase in adolescents and young adults seeking care for a mental health crisis. In 2018, California EDs treated 84,584 young patients aged 13-21 years who had a primary diagnosis involving mental health. That is up from 59,705 in 2012, a 42% increase, according to data provided by the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development.

By comparison, the number of ED encounters among that age group for all other diagnoses grew by just 4% over the same period. And the number of encounters involving mental health among all other age groups – everyone except adolescents and young adults – rose by about 18%.

The spike in youth mental health visits corresponds with a recent survey that found that members of “Generation Z” – defined in the survey as people born since 1997 – are more likely than other generations to report their mental health as fair or poor. The 2018 polling, done on behalf of the American Psychological Association, also found that members of Generation Z, along with millennials, are more likely to report receiving treatment for mental health issues.

The trend corresponds with another alarming development, as well: a marked increase in suicides among teens and young adults. About 7.5 of every 100,000 young people aged 13-21 in California died by suicide in 2017, up from a rate of 4.9 per 100,000 in 2008, according to the latest figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nationwide, suicides in that age range rose from 7.2 to 11.3 per 100,000 from 2008 to 2017.

Researchers are studying the causes for the surging reports of mental distress among America’s young people. Many recent theories note that the trend parallels the rise of social media, an ever-present window on peer activities that can exacerbate adolescent insecurities and open new avenues of bullying.

“Even though this generation has been raised with social media, youth are feeling more disconnected, judged, bullied, and pressured from their peers,” said Susan Coats, EdD, a school psychologist at Baldwin Park Unified School District near Los Angeles.

“Social media: It’s a blessing and it’s a curse,” Dr. Coats added. “Social media has brought youth together in a forum where maybe they may have felt isolated before, but it also has undermined interpersonal relationships.”

Members of Generation Z also report significant levels of stress about personal debt, housing instability, and hunger, as well as mass shootings and climate change, according to the American Psychological Association survey.

“We’re not doing a great job with … catching things before they devolve into broader problems, and we’re not doing a good job with prevention,” said Lishaun Francis, associate director of health collaborations at Children Now, a nonprofit based in Oakland, Calif.

Many California school districts don’t have enough school psychologists and don’t devote enough resources to teaching students how to cope with depression, anxiety, and other mental health issues, said Ms. Coats, who chairs the mental health and crisis consultation committee of the California Association of School Psychologists.

In the broader community, medical providers also are struggling to keep up. “Many times there aren’t psychiatric beds available for kids in our community,” Dr. Maxwell said.

Most of the adolescents who come into the ED at Rady Children’s Hospital during a mental health crisis are considering suicide, have attempted suicide, or have harmed themselves, said Dr. Maxwell, who is also the hospital’s medical director of inpatient psychiatry.

These patients are triaged and quickly seen by a social worker. Often, a behavioral health assistant is assigned to sit with the patients throughout their stay.

“Suicidal patients – we don’t want them to be alone at all in a busy emergency department,” Dr. Maxwell said. “So that’s a major staffing increase.”

Rady Children’s Hospital plans to open a six-bed, 24-hour psychiatric ED in the spring. Improving emergency care will help, Dr. Maxwell said, but a better solution would be to intervene with young people before they need an ED.

“The ED surge probably represents a failure of the system at large,” Dr. Maxwell said. “They’re ending up in the emergency department because they’re not getting the care they need, when they need it.”

Phillip Reese is a data reporting specialist and an assistant professor of journalism at California State University–Sacramento. This Kaiser Health News story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation. KHN is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Less than a decade ago, the ED at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego would see maybe one or two young psychiatric patients per day, said Benjamin Maxwell, MD, the hospital’s interim director of child and adolescent psychiatry.

Now, it’s not unusual for the ED to see 10 psychiatric patients in a day, and sometimes even 20, said Dr. Maxwell. “What a lot of times is happening now is kids aren’t getting the care they need, until it gets to the point where it is dangerous.”

EDs throughout California are reporting a sharp increase in adolescents and young adults seeking care for a mental health crisis. In 2018, California EDs treated 84,584 young patients aged 13-21 years who had a primary diagnosis involving mental health. That is up from 59,705 in 2012, a 42% increase, according to data provided by the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development.

By comparison, the number of ED encounters among that age group for all other diagnoses grew by just 4% over the same period. And the number of encounters involving mental health among all other age groups – everyone except adolescents and young adults – rose by about 18%.

The spike in youth mental health visits corresponds with a recent survey that found that members of “Generation Z” – defined in the survey as people born since 1997 – are more likely than other generations to report their mental health as fair or poor. The 2018 polling, done on behalf of the American Psychological Association, also found that members of Generation Z, along with millennials, are more likely to report receiving treatment for mental health issues.

The trend corresponds with another alarming development, as well: a marked increase in suicides among teens and young adults. About 7.5 of every 100,000 young people aged 13-21 in California died by suicide in 2017, up from a rate of 4.9 per 100,000 in 2008, according to the latest figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nationwide, suicides in that age range rose from 7.2 to 11.3 per 100,000 from 2008 to 2017.

Researchers are studying the causes for the surging reports of mental distress among America’s young people. Many recent theories note that the trend parallels the rise of social media, an ever-present window on peer activities that can exacerbate adolescent insecurities and open new avenues of bullying.

“Even though this generation has been raised with social media, youth are feeling more disconnected, judged, bullied, and pressured from their peers,” said Susan Coats, EdD, a school psychologist at Baldwin Park Unified School District near Los Angeles.

“Social media: It’s a blessing and it’s a curse,” Dr. Coats added. “Social media has brought youth together in a forum where maybe they may have felt isolated before, but it also has undermined interpersonal relationships.”

Members of Generation Z also report significant levels of stress about personal debt, housing instability, and hunger, as well as mass shootings and climate change, according to the American Psychological Association survey.

“We’re not doing a great job with … catching things before they devolve into broader problems, and we’re not doing a good job with prevention,” said Lishaun Francis, associate director of health collaborations at Children Now, a nonprofit based in Oakland, Calif.

Many California school districts don’t have enough school psychologists and don’t devote enough resources to teaching students how to cope with depression, anxiety, and other mental health issues, said Ms. Coats, who chairs the mental health and crisis consultation committee of the California Association of School Psychologists.

In the broader community, medical providers also are struggling to keep up. “Many times there aren’t psychiatric beds available for kids in our community,” Dr. Maxwell said.

Most of the adolescents who come into the ED at Rady Children’s Hospital during a mental health crisis are considering suicide, have attempted suicide, or have harmed themselves, said Dr. Maxwell, who is also the hospital’s medical director of inpatient psychiatry.

These patients are triaged and quickly seen by a social worker. Often, a behavioral health assistant is assigned to sit with the patients throughout their stay.

“Suicidal patients – we don’t want them to be alone at all in a busy emergency department,” Dr. Maxwell said. “So that’s a major staffing increase.”

Rady Children’s Hospital plans to open a six-bed, 24-hour psychiatric ED in the spring. Improving emergency care will help, Dr. Maxwell said, but a better solution would be to intervene with young people before they need an ED.

“The ED surge probably represents a failure of the system at large,” Dr. Maxwell said. “They’re ending up in the emergency department because they’re not getting the care they need, when they need it.”

Phillip Reese is a data reporting specialist and an assistant professor of journalism at California State University–Sacramento. This Kaiser Health News story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation. KHN is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Letters From Maine: An albatross or your identity?

The last time I saw her she was coiled up like a garter snake resting comfortable in the old toiletries travel case that was my “black bag” for more than 40 years. Joining her in peaceful solitude were a couple of ear curettes, an insufflator, and a dead pocket flashlight. The Kermit the Frog sticker on her diaphragm was faded to a barely recognizable blur. The chest piece was frozen in the diaphragm position as it had been for several decades. I never felt comfortable using the bell side.

She was the gift from a drug company back when medical students were more interested in freebies than making a statement about conflicts of interest. I have had to change her tubing several times when cracks at the bifurcation would allow me to hear my own breath sounds better than the patient’s. The ear pieces were the originals that I modified to fit my auditory canals more comfortably.

I suspect that many of you have developed a close relationship with your stethoscope, as I did. We were always close. She was either her coiled up in my pants’ pocket or clasped around my neck where she wore through collars at a costly clip. Her chest piece was kept tucked in my shirt to keep it warm for the patients. I never hung her over my shoulders the way physicians do in publicity photos. I always found that practice pretentious and impractical.

If I decided tomorrow to leave the challenges of retirement behind and reopen my practice would it make any sense to go down to the basement and roust out my old stethoscope from her slumber? There are better ways evaluate hearts and lungs and many of them will fit in my pocket just as well as that old stethoscope. Paul Wallach, MD, an executive associate dean at the Indiana University, Indianapolis, predicts that within a decade hand-held ultrasound devices with become part of a routine part of the physical exam (Lindsey Tanner. “Is the stethoscope dying? High-tech rivals pose a challenge.” Associated Press. 2019 Oct 23). Instruction in the use of these devices has already become part of the curriculum in some medical schools.

There have been several studies demonstrating that chest auscultation is a skill that some of us have lost and many others never successfully mastered. As much as I treasure my old stethoscope, is it time to get rid of those albatrosses hanging around our necks? They do bang against desks with a deafening ring. Cute infants and toddlers yank on them while we are trying to listen to their chests. If there are better ways to auscultate chests that will fit in our pockets shouldn’t we be using them?

Well, there is the cost for one thing. But, inevitably the price will come down and portability will go up. If we allow our stethoscopes to become nothing more than nostalgic museum pieces to sit along with the head mirror, What will photographers drape over our shoulders? With very few of us in office practice wearing white coats or scrub suits, we run the risk of losing our identity.

Sadly, I fear we will have to accept the disappearance of the stethoscope as a natural consequence of the technological march. But, it also is an unfortunate reflection of the fact that the art of doing a physical exam is fading. With auscultation and palpation disappearing from our diagnostic tool kit we must be careful to preserve and improve the one skill that is indispensable to the practice of medicine.

And, that is listening to what the patient has to tell us.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

The last time I saw her she was coiled up like a garter snake resting comfortable in the old toiletries travel case that was my “black bag” for more than 40 years. Joining her in peaceful solitude were a couple of ear curettes, an insufflator, and a dead pocket flashlight. The Kermit the Frog sticker on her diaphragm was faded to a barely recognizable blur. The chest piece was frozen in the diaphragm position as it had been for several decades. I never felt comfortable using the bell side.

She was the gift from a drug company back when medical students were more interested in freebies than making a statement about conflicts of interest. I have had to change her tubing several times when cracks at the bifurcation would allow me to hear my own breath sounds better than the patient’s. The ear pieces were the originals that I modified to fit my auditory canals more comfortably.

I suspect that many of you have developed a close relationship with your stethoscope, as I did. We were always close. She was either her coiled up in my pants’ pocket or clasped around my neck where she wore through collars at a costly clip. Her chest piece was kept tucked in my shirt to keep it warm for the patients. I never hung her over my shoulders the way physicians do in publicity photos. I always found that practice pretentious and impractical.

If I decided tomorrow to leave the challenges of retirement behind and reopen my practice would it make any sense to go down to the basement and roust out my old stethoscope from her slumber? There are better ways evaluate hearts and lungs and many of them will fit in my pocket just as well as that old stethoscope. Paul Wallach, MD, an executive associate dean at the Indiana University, Indianapolis, predicts that within a decade hand-held ultrasound devices with become part of a routine part of the physical exam (Lindsey Tanner. “Is the stethoscope dying? High-tech rivals pose a challenge.” Associated Press. 2019 Oct 23). Instruction in the use of these devices has already become part of the curriculum in some medical schools.

There have been several studies demonstrating that chest auscultation is a skill that some of us have lost and many others never successfully mastered. As much as I treasure my old stethoscope, is it time to get rid of those albatrosses hanging around our necks? They do bang against desks with a deafening ring. Cute infants and toddlers yank on them while we are trying to listen to their chests. If there are better ways to auscultate chests that will fit in our pockets shouldn’t we be using them?

Well, there is the cost for one thing. But, inevitably the price will come down and portability will go up. If we allow our stethoscopes to become nothing more than nostalgic museum pieces to sit along with the head mirror, What will photographers drape over our shoulders? With very few of us in office practice wearing white coats or scrub suits, we run the risk of losing our identity.

Sadly, I fear we will have to accept the disappearance of the stethoscope as a natural consequence of the technological march. But, it also is an unfortunate reflection of the fact that the art of doing a physical exam is fading. With auscultation and palpation disappearing from our diagnostic tool kit we must be careful to preserve and improve the one skill that is indispensable to the practice of medicine.

And, that is listening to what the patient has to tell us.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

The last time I saw her she was coiled up like a garter snake resting comfortable in the old toiletries travel case that was my “black bag” for more than 40 years. Joining her in peaceful solitude were a couple of ear curettes, an insufflator, and a dead pocket flashlight. The Kermit the Frog sticker on her diaphragm was faded to a barely recognizable blur. The chest piece was frozen in the diaphragm position as it had been for several decades. I never felt comfortable using the bell side.

She was the gift from a drug company back when medical students were more interested in freebies than making a statement about conflicts of interest. I have had to change her tubing several times when cracks at the bifurcation would allow me to hear my own breath sounds better than the patient’s. The ear pieces were the originals that I modified to fit my auditory canals more comfortably.

I suspect that many of you have developed a close relationship with your stethoscope, as I did. We were always close. She was either her coiled up in my pants’ pocket or clasped around my neck where she wore through collars at a costly clip. Her chest piece was kept tucked in my shirt to keep it warm for the patients. I never hung her over my shoulders the way physicians do in publicity photos. I always found that practice pretentious and impractical.

If I decided tomorrow to leave the challenges of retirement behind and reopen my practice would it make any sense to go down to the basement and roust out my old stethoscope from her slumber? There are better ways evaluate hearts and lungs and many of them will fit in my pocket just as well as that old stethoscope. Paul Wallach, MD, an executive associate dean at the Indiana University, Indianapolis, predicts that within a decade hand-held ultrasound devices with become part of a routine part of the physical exam (Lindsey Tanner. “Is the stethoscope dying? High-tech rivals pose a challenge.” Associated Press. 2019 Oct 23). Instruction in the use of these devices has already become part of the curriculum in some medical schools.

There have been several studies demonstrating that chest auscultation is a skill that some of us have lost and many others never successfully mastered. As much as I treasure my old stethoscope, is it time to get rid of those albatrosses hanging around our necks? They do bang against desks with a deafening ring. Cute infants and toddlers yank on them while we are trying to listen to their chests. If there are better ways to auscultate chests that will fit in our pockets shouldn’t we be using them?

Well, there is the cost for one thing. But, inevitably the price will come down and portability will go up. If we allow our stethoscopes to become nothing more than nostalgic museum pieces to sit along with the head mirror, What will photographers drape over our shoulders? With very few of us in office practice wearing white coats or scrub suits, we run the risk of losing our identity.

Sadly, I fear we will have to accept the disappearance of the stethoscope as a natural consequence of the technological march. But, it also is an unfortunate reflection of the fact that the art of doing a physical exam is fading. With auscultation and palpation disappearing from our diagnostic tool kit we must be careful to preserve and improve the one skill that is indispensable to the practice of medicine.

And, that is listening to what the patient has to tell us.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Marked increase in psoriasis seen with TNFi use in pediatric inflammatory diseases

ATLANTA – in a review of 4,111 patients at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

The finding confirms a clinical suspicion that biologics can cause psoriasis in children, just as has been shown in adults, said lead investigator Lisa Buckley, MD, a rheumatology fellow at the hospital when she conducted the study, but now a pediatric rheumatologist at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. The study was recently published in Arthritis Care & Research.

“I don’t think this will change my prescribing habits” because tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) are so useful, but “what this will change is how much information I give to families about the risk of psoriasis, especially in kids with a family history,” which also predisposed children in the study to psoriasis, Dr. Buckley said . “Anecdotally, psoriasis has not been part of the traditional risk-benefit conversation with families. This has added that to my” discussion, he added.

TNFi “psoriasis can be a really big deal for these children, especially in adolescence. They don’t want to go to school and things like that. Children and parents often prioritize [it] over the underlying disease,” she said.

For now, how to best manage TNFi psoriasis is uncertain. Children often are in remission when it starts, and a decision has to be made whether to discontinue treatment, reduce the dose, or add something for the psoriasis. There are no clear answers at the moment. “This is the beginning of the beginning of studies looking at this. It just proves that there actually is a problem,” Dr. Buckley said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

About three-quarters of the children had inflammatory bowel disease, and most of the rest had juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Just 2% had chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis. Billing codes were used to confirm diagnosis, new-onset psoriasis, and incident TNFi exposure, defined as at least one prescription for adalimumab, etanercept, or infliximab.

Overall, 1,614 children (39%) were treated with a TNFi and 2,497 (61%) were not. There were 58 cases of psoriasis in the TNFi group for an incidence ratio of 12.3 cases per 1,000 person-years, and a standard IR – observed psoriasis cases over expected cases in the general pediatrics population – of 30.

There were 25 cases among children not treated with a TNFi, for an IR of 3.8 per 1,000 person-years and SIR of 9.3.

In the end, TNFi exposure was associated with a marked increase in psoriasis risk (hazard ratio, 3.84; 95% confidence interval, 2.28-6.47; P less than .001). Family history was positive in 8% of subjects and was a known risk factor; it was the only other independent predictor (HR, 3.11; 95% CI, 1.79-5.41; P less than .001).

Obesity, which was linked in previous studies to psoriasis and was higher in the non-TNFI group, did not influence risk, nor did methotrexate, which was also used more commonly in the TNFi group. “We thought that including patients on methotrexate, which is a treatment for psoriasis, might have altered the outcomes, but it didn’t seem to make any difference in developing psoriasis,” Dr. Buckley said.

It’s possible that children on a TNFi had higher disease activity, and that in itself increased the risk of psoriasis, but there isn’t an association in the literature between high disease activity and psoriasis, she said. In past reports, TNFi-induced psoriasis was most likely to occur in adults who were in disease remission.

Subjects were aged about 11 years on average and about equally split between boys and girls; three-quarters were white. Children previously diagnosed with psoriasis were excluded. Average follow up was about 2 years.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The investigators didn’t report any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Buckley L et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 1816.

ATLANTA – in a review of 4,111 patients at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

The finding confirms a clinical suspicion that biologics can cause psoriasis in children, just as has been shown in adults, said lead investigator Lisa Buckley, MD, a rheumatology fellow at the hospital when she conducted the study, but now a pediatric rheumatologist at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. The study was recently published in Arthritis Care & Research.

“I don’t think this will change my prescribing habits” because tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) are so useful, but “what this will change is how much information I give to families about the risk of psoriasis, especially in kids with a family history,” which also predisposed children in the study to psoriasis, Dr. Buckley said . “Anecdotally, psoriasis has not been part of the traditional risk-benefit conversation with families. This has added that to my” discussion, he added.

TNFi “psoriasis can be a really big deal for these children, especially in adolescence. They don’t want to go to school and things like that. Children and parents often prioritize [it] over the underlying disease,” she said.

For now, how to best manage TNFi psoriasis is uncertain. Children often are in remission when it starts, and a decision has to be made whether to discontinue treatment, reduce the dose, or add something for the psoriasis. There are no clear answers at the moment. “This is the beginning of the beginning of studies looking at this. It just proves that there actually is a problem,” Dr. Buckley said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

About three-quarters of the children had inflammatory bowel disease, and most of the rest had juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Just 2% had chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis. Billing codes were used to confirm diagnosis, new-onset psoriasis, and incident TNFi exposure, defined as at least one prescription for adalimumab, etanercept, or infliximab.

Overall, 1,614 children (39%) were treated with a TNFi and 2,497 (61%) were not. There were 58 cases of psoriasis in the TNFi group for an incidence ratio of 12.3 cases per 1,000 person-years, and a standard IR – observed psoriasis cases over expected cases in the general pediatrics population – of 30.

There were 25 cases among children not treated with a TNFi, for an IR of 3.8 per 1,000 person-years and SIR of 9.3.

In the end, TNFi exposure was associated with a marked increase in psoriasis risk (hazard ratio, 3.84; 95% confidence interval, 2.28-6.47; P less than .001). Family history was positive in 8% of subjects and was a known risk factor; it was the only other independent predictor (HR, 3.11; 95% CI, 1.79-5.41; P less than .001).

Obesity, which was linked in previous studies to psoriasis and was higher in the non-TNFI group, did not influence risk, nor did methotrexate, which was also used more commonly in the TNFi group. “We thought that including patients on methotrexate, which is a treatment for psoriasis, might have altered the outcomes, but it didn’t seem to make any difference in developing psoriasis,” Dr. Buckley said.

It’s possible that children on a TNFi had higher disease activity, and that in itself increased the risk of psoriasis, but there isn’t an association in the literature between high disease activity and psoriasis, she said. In past reports, TNFi-induced psoriasis was most likely to occur in adults who were in disease remission.

Subjects were aged about 11 years on average and about equally split between boys and girls; three-quarters were white. Children previously diagnosed with psoriasis were excluded. Average follow up was about 2 years.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The investigators didn’t report any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Buckley L et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 1816.

ATLANTA – in a review of 4,111 patients at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

The finding confirms a clinical suspicion that biologics can cause psoriasis in children, just as has been shown in adults, said lead investigator Lisa Buckley, MD, a rheumatology fellow at the hospital when she conducted the study, but now a pediatric rheumatologist at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. The study was recently published in Arthritis Care & Research.

“I don’t think this will change my prescribing habits” because tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) are so useful, but “what this will change is how much information I give to families about the risk of psoriasis, especially in kids with a family history,” which also predisposed children in the study to psoriasis, Dr. Buckley said . “Anecdotally, psoriasis has not been part of the traditional risk-benefit conversation with families. This has added that to my” discussion, he added.

TNFi “psoriasis can be a really big deal for these children, especially in adolescence. They don’t want to go to school and things like that. Children and parents often prioritize [it] over the underlying disease,” she said.

For now, how to best manage TNFi psoriasis is uncertain. Children often are in remission when it starts, and a decision has to be made whether to discontinue treatment, reduce the dose, or add something for the psoriasis. There are no clear answers at the moment. “This is the beginning of the beginning of studies looking at this. It just proves that there actually is a problem,” Dr. Buckley said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

About three-quarters of the children had inflammatory bowel disease, and most of the rest had juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Just 2% had chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis. Billing codes were used to confirm diagnosis, new-onset psoriasis, and incident TNFi exposure, defined as at least one prescription for adalimumab, etanercept, or infliximab.

Overall, 1,614 children (39%) were treated with a TNFi and 2,497 (61%) were not. There were 58 cases of psoriasis in the TNFi group for an incidence ratio of 12.3 cases per 1,000 person-years, and a standard IR – observed psoriasis cases over expected cases in the general pediatrics population – of 30.

There were 25 cases among children not treated with a TNFi, for an IR of 3.8 per 1,000 person-years and SIR of 9.3.

In the end, TNFi exposure was associated with a marked increase in psoriasis risk (hazard ratio, 3.84; 95% confidence interval, 2.28-6.47; P less than .001). Family history was positive in 8% of subjects and was a known risk factor; it was the only other independent predictor (HR, 3.11; 95% CI, 1.79-5.41; P less than .001).

Obesity, which was linked in previous studies to psoriasis and was higher in the non-TNFI group, did not influence risk, nor did methotrexate, which was also used more commonly in the TNFi group. “We thought that including patients on methotrexate, which is a treatment for psoriasis, might have altered the outcomes, but it didn’t seem to make any difference in developing psoriasis,” Dr. Buckley said.

It’s possible that children on a TNFi had higher disease activity, and that in itself increased the risk of psoriasis, but there isn’t an association in the literature between high disease activity and psoriasis, she said. In past reports, TNFi-induced psoriasis was most likely to occur in adults who were in disease remission.

Subjects were aged about 11 years on average and about equally split between boys and girls; three-quarters were white. Children previously diagnosed with psoriasis were excluded. Average follow up was about 2 years.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The investigators didn’t report any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Buckley L et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 1816.

REPORTING FROM ACR 2019

Conduct disorder in girls gets overdue research attention

COPENHAGEN – The physiological and emotion-processing abnormalities that underpin conduct disorder in teen girls are essentially the same as in teen boys, although the clinical presentation of conduct disorder in the two groups is often different, according to preliminary results from the large pan-European FemNAT-CD study, the first large study of conduct disorder in girls.

“The main finding of the study, I think, is that we found no major differences in physiology between male and female conduct disorder. There are some differences, mainly related to having less LPE [low prosocial emotions] and more internalizing comorbidity in the girls, but when you look at conduct disorder overall, then you see that the physiological systems are about the same,” Lucres Nauta-Jansen, PhD, commented in presenting some of the early FemNAT-CD findings at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

LPE is a term included in the DSM-5 as a descriptor of individuals with conduct disorder (CD) who exhibit callous-unemotional traits. The LPE specifier was present in 37% of the 296 adolescent girls with CD in FemNAT-CD, significantly less than the 50% prevalence in the 187 adolescent boys with CD in the study. This analysis from the ongoing study, which is being conducted at 13 universities across Europe, also included 363 age-matched girls and 164 age-matched boys without CD as controls. Average participant age was 14 years.

FemNAT-CD is a multidisciplinary study aimed at exploring sex differences between boys and girls with and without CD in terms of brain structure and function, genetics, hormone levels, emotion recognition and regulation, and autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity. At Amsterdam University Medical Center, where Dr. Nauta-Jansen serves as deputy head of the department of child and adolescent psychiatry, she and her coinvestigators have focused on the autonomic activity and emotion-processing portions of FemNAT-CD.

CD is less common in girls than boys, although the prevalence in girls is growing. The importance of FemNAT-CD lies in the fact that virtually all prior studies of CD were conducted in boys. As a result, there is no specific treatment intervention available for girls with CD.

“We actually don’t know anything about girls. There are a few previous studies, but they have small samples and contradictory results. We need to know more about the mechanisms that are involved in this kind of behavior to develop more specific treatments in the future,” Dr. Nauta-Jansen said.

In FemNAT-CD, the girls with CD not only had a lower rate of LPE symptoms than the boys with CD, they also had a significantly higher prevalence of anxiety and other internalizing comorbidities, by a margin of 32% to 22%. These differences are manifested in different expressions of antisocial behavior as described in the model of the neurobiology of CD developed by R. James Blair, PhD, director of the Center for Neurobehavioral Research at the Boys Town National Research Hospital in Omaha, Neb (Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013 Nov;14[11]:786-99).

According to the model’s low psychophysiological arousal theory, boys with the callous-unemotional form of CD have low basal ANS activity and low amygdala responsiveness to stressful events, making them more prone to sensation-seeking behavior.

“This might make them want to do ice climbing or sky diving. Or, in a more negative environment or in a bad neighborhood, it can also lead to aggressive and delinquent behavior,” Dr. Nauta-Jansen said.

The other core impairment that is common in a subset of CD patients as described in the Blair model – again, based upon studies in boys – involves a tendency to engage in threat-based reactive aggression with an increased ANS response to stress and a related difficulty in processing emotions.

Dr. Nauta-Jansen and coinvestigators conducted a series of tests of FemNAT-CD participants which demonstrated, for the first time, that both the callous-unemotional and threat-based reactive aggression forms of CD are present in girls as well as boys, albeit in different proportions.

The investigators found no differences in baseline ANS activity between girls and boys with CD and the controls as measured by heart rate, heart rate variability, and cardiac preejection period. Nor were there any differences in baseline ANS activity between boys and girls with CD and LPE. However, girls with CD and anxiety or other internalizing comorbidity displayed significantly lower heart rate variability than those without internalizing comorbidity or female controls.

Next, the investigators subjected study participants to an emotion provocation task in which they viewed two sadness-inducing film clips, including a heart-rending scene from the 1979 movie, “The Champ,” in which an ex-boxer played by Jon Voight returns to the ring to raise money to support his young son, played by Ricky Shroder. The champ wins by a knockout after taking such a beating that he subsequently dies in his dressing room as his son watches.

Both the girls and boys with CD had an increased heart rate response to “The Champ,” compared with the controls. And those with CD who did not have the LPE specifier showed the biggest ANS response of all. They were highly sensitive to negative emotions.

On a countdown task involving exposure to a loud, startling noise, the girls with CD did not learn to anticipate the pending startle at the autonomic level, whereas the boys with CD reacted no differently from controls.

On the Trier Social Stress Test, which entails public speaking and performing mental math calculations in front of a camera and a live audience of two, both the boys and girls with CD demonstrated a similarly lower heart rate response to the tasks than controls. Those with the LPE specifier had the lowest heart rate response of all.

“The conduct disorder subjects were impaired in their anticipatory response to fear and stress, but their responses to sadness were increased,” Dr. Nauta-Jansen observed.

“I think the main thing with these kids is they are mostly disturbed in their anticipation of bad situations. What you see in the countdown task is they don’t anticipate that there will be a bad event. And you see this also in clinical practice, that they sometimes get overwhelmed by things because they don’t learn from their previous experiences, including bad events. I think they don’t anticipate and therefore are more overwhelmed by bad events – especially the girls,” she said.

The take-home message from this phase of the FemNAT-CD study, she added, is straightforward: “ although you have to be very aware that they show different symptomatology in terms of internalizing comorbidity.”

The FemNAT-CD investigators have developed a multifaceted therapeutic intervention for girls with CD that shows early promise in clinical settings. It includes aggression regulation training, medication in some cases, and emotion-processing training to teach patients how to deal with negative emotions without exploding into aggression.

FemNAT-CD is funded by the European Commission. Dr. Nauta-Jansen reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study.

COPENHAGEN – The physiological and emotion-processing abnormalities that underpin conduct disorder in teen girls are essentially the same as in teen boys, although the clinical presentation of conduct disorder in the two groups is often different, according to preliminary results from the large pan-European FemNAT-CD study, the first large study of conduct disorder in girls.

“The main finding of the study, I think, is that we found no major differences in physiology between male and female conduct disorder. There are some differences, mainly related to having less LPE [low prosocial emotions] and more internalizing comorbidity in the girls, but when you look at conduct disorder overall, then you see that the physiological systems are about the same,” Lucres Nauta-Jansen, PhD, commented in presenting some of the early FemNAT-CD findings at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

LPE is a term included in the DSM-5 as a descriptor of individuals with conduct disorder (CD) who exhibit callous-unemotional traits. The LPE specifier was present in 37% of the 296 adolescent girls with CD in FemNAT-CD, significantly less than the 50% prevalence in the 187 adolescent boys with CD in the study. This analysis from the ongoing study, which is being conducted at 13 universities across Europe, also included 363 age-matched girls and 164 age-matched boys without CD as controls. Average participant age was 14 years.

FemNAT-CD is a multidisciplinary study aimed at exploring sex differences between boys and girls with and without CD in terms of brain structure and function, genetics, hormone levels, emotion recognition and regulation, and autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity. At Amsterdam University Medical Center, where Dr. Nauta-Jansen serves as deputy head of the department of child and adolescent psychiatry, she and her coinvestigators have focused on the autonomic activity and emotion-processing portions of FemNAT-CD.

CD is less common in girls than boys, although the prevalence in girls is growing. The importance of FemNAT-CD lies in the fact that virtually all prior studies of CD were conducted in boys. As a result, there is no specific treatment intervention available for girls with CD.

“We actually don’t know anything about girls. There are a few previous studies, but they have small samples and contradictory results. We need to know more about the mechanisms that are involved in this kind of behavior to develop more specific treatments in the future,” Dr. Nauta-Jansen said.

In FemNAT-CD, the girls with CD not only had a lower rate of LPE symptoms than the boys with CD, they also had a significantly higher prevalence of anxiety and other internalizing comorbidities, by a margin of 32% to 22%. These differences are manifested in different expressions of antisocial behavior as described in the model of the neurobiology of CD developed by R. James Blair, PhD, director of the Center for Neurobehavioral Research at the Boys Town National Research Hospital in Omaha, Neb (Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013 Nov;14[11]:786-99).

According to the model’s low psychophysiological arousal theory, boys with the callous-unemotional form of CD have low basal ANS activity and low amygdala responsiveness to stressful events, making them more prone to sensation-seeking behavior.

“This might make them want to do ice climbing or sky diving. Or, in a more negative environment or in a bad neighborhood, it can also lead to aggressive and delinquent behavior,” Dr. Nauta-Jansen said.

The other core impairment that is common in a subset of CD patients as described in the Blair model – again, based upon studies in boys – involves a tendency to engage in threat-based reactive aggression with an increased ANS response to stress and a related difficulty in processing emotions.

Dr. Nauta-Jansen and coinvestigators conducted a series of tests of FemNAT-CD participants which demonstrated, for the first time, that both the callous-unemotional and threat-based reactive aggression forms of CD are present in girls as well as boys, albeit in different proportions.

The investigators found no differences in baseline ANS activity between girls and boys with CD and the controls as measured by heart rate, heart rate variability, and cardiac preejection period. Nor were there any differences in baseline ANS activity between boys and girls with CD and LPE. However, girls with CD and anxiety or other internalizing comorbidity displayed significantly lower heart rate variability than those without internalizing comorbidity or female controls.

Next, the investigators subjected study participants to an emotion provocation task in which they viewed two sadness-inducing film clips, including a heart-rending scene from the 1979 movie, “The Champ,” in which an ex-boxer played by Jon Voight returns to the ring to raise money to support his young son, played by Ricky Shroder. The champ wins by a knockout after taking such a beating that he subsequently dies in his dressing room as his son watches.

Both the girls and boys with CD had an increased heart rate response to “The Champ,” compared with the controls. And those with CD who did not have the LPE specifier showed the biggest ANS response of all. They were highly sensitive to negative emotions.

On a countdown task involving exposure to a loud, startling noise, the girls with CD did not learn to anticipate the pending startle at the autonomic level, whereas the boys with CD reacted no differently from controls.

On the Trier Social Stress Test, which entails public speaking and performing mental math calculations in front of a camera and a live audience of two, both the boys and girls with CD demonstrated a similarly lower heart rate response to the tasks than controls. Those with the LPE specifier had the lowest heart rate response of all.

“The conduct disorder subjects were impaired in their anticipatory response to fear and stress, but their responses to sadness were increased,” Dr. Nauta-Jansen observed.

“I think the main thing with these kids is they are mostly disturbed in their anticipation of bad situations. What you see in the countdown task is they don’t anticipate that there will be a bad event. And you see this also in clinical practice, that they sometimes get overwhelmed by things because they don’t learn from their previous experiences, including bad events. I think they don’t anticipate and therefore are more overwhelmed by bad events – especially the girls,” she said.

The take-home message from this phase of the FemNAT-CD study, she added, is straightforward: “ although you have to be very aware that they show different symptomatology in terms of internalizing comorbidity.”

The FemNAT-CD investigators have developed a multifaceted therapeutic intervention for girls with CD that shows early promise in clinical settings. It includes aggression regulation training, medication in some cases, and emotion-processing training to teach patients how to deal with negative emotions without exploding into aggression.

FemNAT-CD is funded by the European Commission. Dr. Nauta-Jansen reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study.

COPENHAGEN – The physiological and emotion-processing abnormalities that underpin conduct disorder in teen girls are essentially the same as in teen boys, although the clinical presentation of conduct disorder in the two groups is often different, according to preliminary results from the large pan-European FemNAT-CD study, the first large study of conduct disorder in girls.

“The main finding of the study, I think, is that we found no major differences in physiology between male and female conduct disorder. There are some differences, mainly related to having less LPE [low prosocial emotions] and more internalizing comorbidity in the girls, but when you look at conduct disorder overall, then you see that the physiological systems are about the same,” Lucres Nauta-Jansen, PhD, commented in presenting some of the early FemNAT-CD findings at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

LPE is a term included in the DSM-5 as a descriptor of individuals with conduct disorder (CD) who exhibit callous-unemotional traits. The LPE specifier was present in 37% of the 296 adolescent girls with CD in FemNAT-CD, significantly less than the 50% prevalence in the 187 adolescent boys with CD in the study. This analysis from the ongoing study, which is being conducted at 13 universities across Europe, also included 363 age-matched girls and 164 age-matched boys without CD as controls. Average participant age was 14 years.

FemNAT-CD is a multidisciplinary study aimed at exploring sex differences between boys and girls with and without CD in terms of brain structure and function, genetics, hormone levels, emotion recognition and regulation, and autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity. At Amsterdam University Medical Center, where Dr. Nauta-Jansen serves as deputy head of the department of child and adolescent psychiatry, she and her coinvestigators have focused on the autonomic activity and emotion-processing portions of FemNAT-CD.

CD is less common in girls than boys, although the prevalence in girls is growing. The importance of FemNAT-CD lies in the fact that virtually all prior studies of CD were conducted in boys. As a result, there is no specific treatment intervention available for girls with CD.

“We actually don’t know anything about girls. There are a few previous studies, but they have small samples and contradictory results. We need to know more about the mechanisms that are involved in this kind of behavior to develop more specific treatments in the future,” Dr. Nauta-Jansen said.

In FemNAT-CD, the girls with CD not only had a lower rate of LPE symptoms than the boys with CD, they also had a significantly higher prevalence of anxiety and other internalizing comorbidities, by a margin of 32% to 22%. These differences are manifested in different expressions of antisocial behavior as described in the model of the neurobiology of CD developed by R. James Blair, PhD, director of the Center for Neurobehavioral Research at the Boys Town National Research Hospital in Omaha, Neb (Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013 Nov;14[11]:786-99).

According to the model’s low psychophysiological arousal theory, boys with the callous-unemotional form of CD have low basal ANS activity and low amygdala responsiveness to stressful events, making them more prone to sensation-seeking behavior.

“This might make them want to do ice climbing or sky diving. Or, in a more negative environment or in a bad neighborhood, it can also lead to aggressive and delinquent behavior,” Dr. Nauta-Jansen said.

The other core impairment that is common in a subset of CD patients as described in the Blair model – again, based upon studies in boys – involves a tendency to engage in threat-based reactive aggression with an increased ANS response to stress and a related difficulty in processing emotions.

Dr. Nauta-Jansen and coinvestigators conducted a series of tests of FemNAT-CD participants which demonstrated, for the first time, that both the callous-unemotional and threat-based reactive aggression forms of CD are present in girls as well as boys, albeit in different proportions.

The investigators found no differences in baseline ANS activity between girls and boys with CD and the controls as measured by heart rate, heart rate variability, and cardiac preejection period. Nor were there any differences in baseline ANS activity between boys and girls with CD and LPE. However, girls with CD and anxiety or other internalizing comorbidity displayed significantly lower heart rate variability than those without internalizing comorbidity or female controls.

Next, the investigators subjected study participants to an emotion provocation task in which they viewed two sadness-inducing film clips, including a heart-rending scene from the 1979 movie, “The Champ,” in which an ex-boxer played by Jon Voight returns to the ring to raise money to support his young son, played by Ricky Shroder. The champ wins by a knockout after taking such a beating that he subsequently dies in his dressing room as his son watches.

Both the girls and boys with CD had an increased heart rate response to “The Champ,” compared with the controls. And those with CD who did not have the LPE specifier showed the biggest ANS response of all. They were highly sensitive to negative emotions.

On a countdown task involving exposure to a loud, startling noise, the girls with CD did not learn to anticipate the pending startle at the autonomic level, whereas the boys with CD reacted no differently from controls.

On the Trier Social Stress Test, which entails public speaking and performing mental math calculations in front of a camera and a live audience of two, both the boys and girls with CD demonstrated a similarly lower heart rate response to the tasks than controls. Those with the LPE specifier had the lowest heart rate response of all.

“The conduct disorder subjects were impaired in their anticipatory response to fear and stress, but their responses to sadness were increased,” Dr. Nauta-Jansen observed.

“I think the main thing with these kids is they are mostly disturbed in their anticipation of bad situations. What you see in the countdown task is they don’t anticipate that there will be a bad event. And you see this also in clinical practice, that they sometimes get overwhelmed by things because they don’t learn from their previous experiences, including bad events. I think they don’t anticipate and therefore are more overwhelmed by bad events – especially the girls,” she said.

The take-home message from this phase of the FemNAT-CD study, she added, is straightforward: “ although you have to be very aware that they show different symptomatology in terms of internalizing comorbidity.”

The FemNAT-CD investigators have developed a multifaceted therapeutic intervention for girls with CD that shows early promise in clinical settings. It includes aggression regulation training, medication in some cases, and emotion-processing training to teach patients how to deal with negative emotions without exploding into aggression.

FemNAT-CD is funded by the European Commission. Dr. Nauta-Jansen reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study.

REPORTING FROM ECNP 2019

Unilateral Papules on the Face

The Diagnosis: Mosaic Tuberous Sclerosis

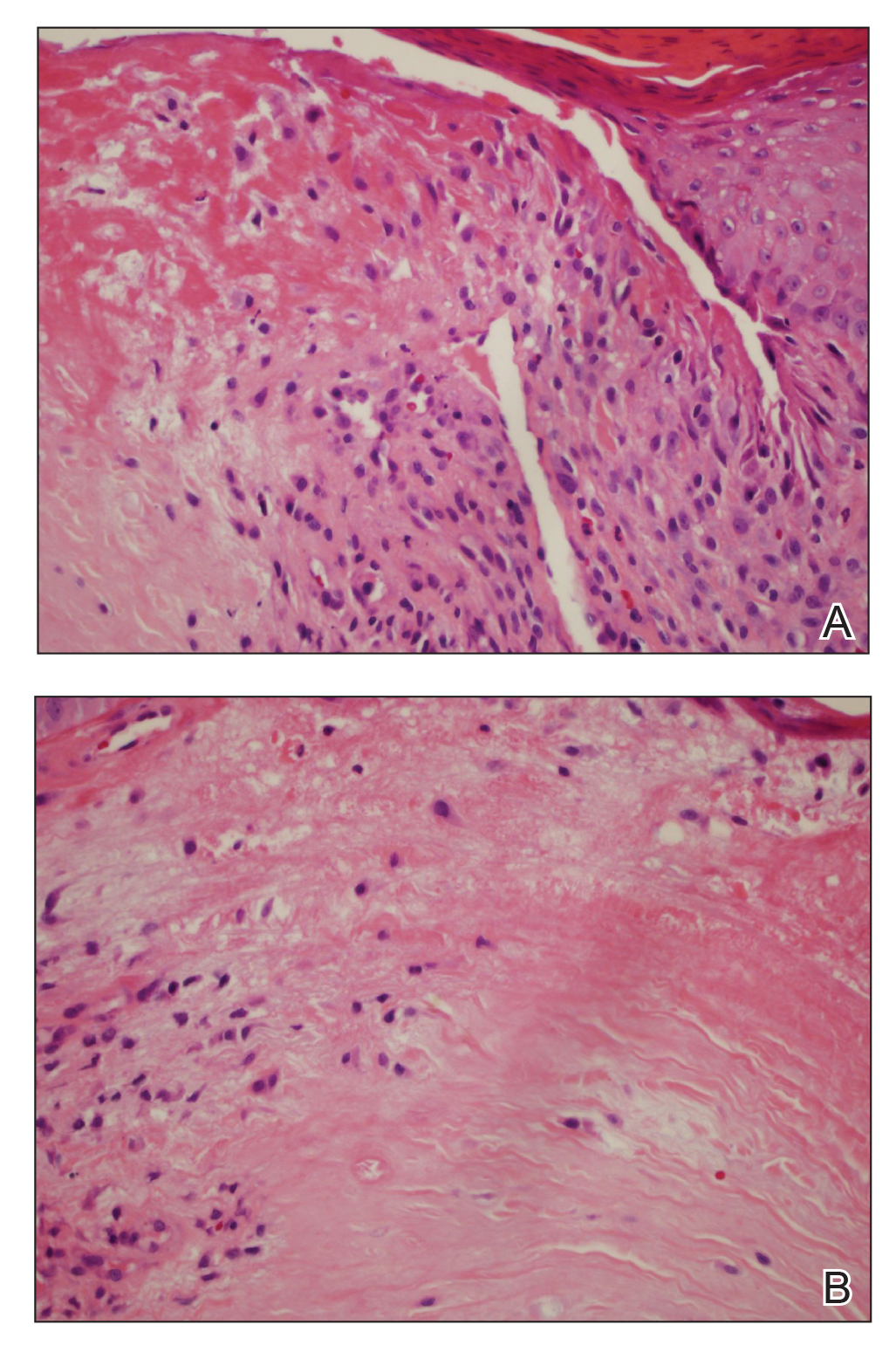

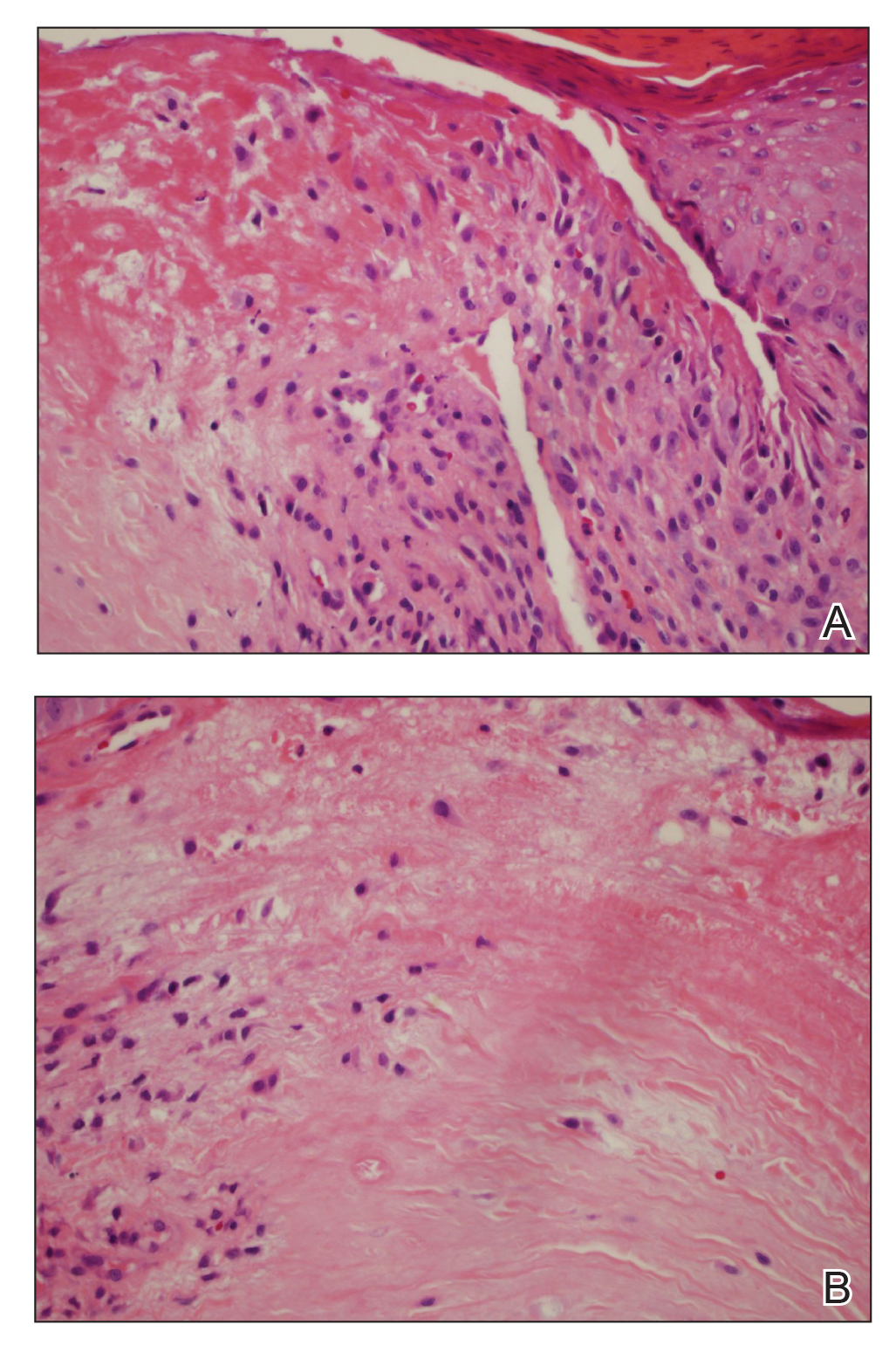

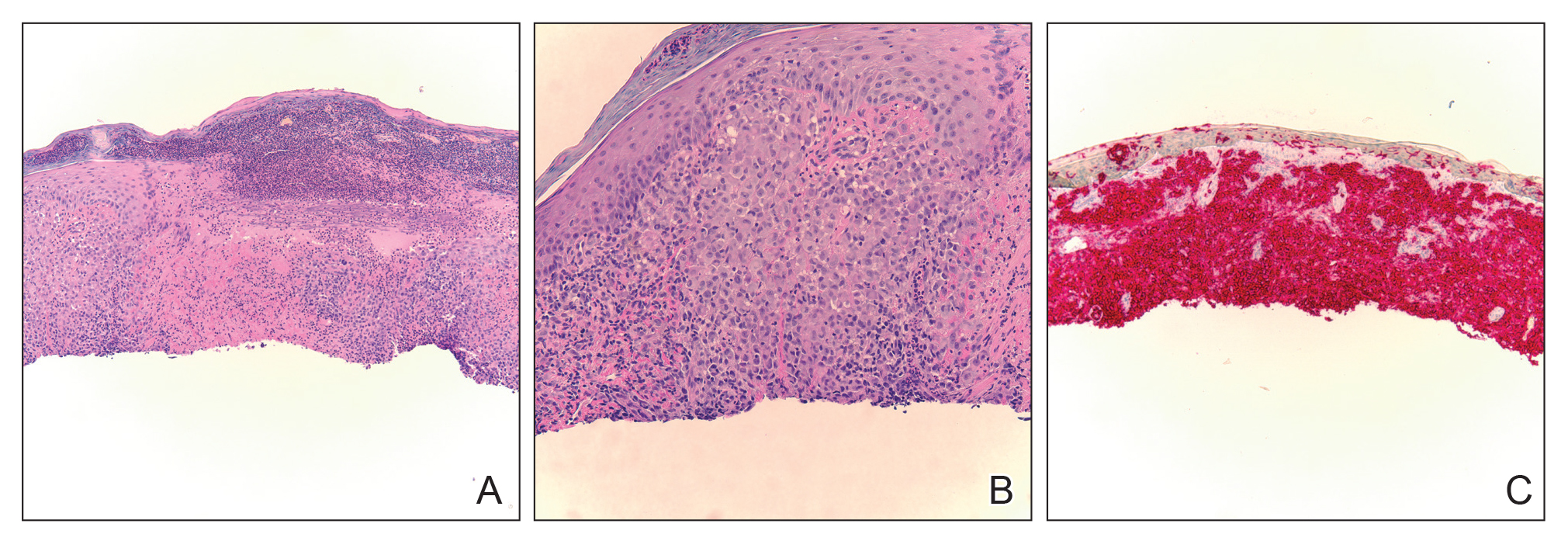

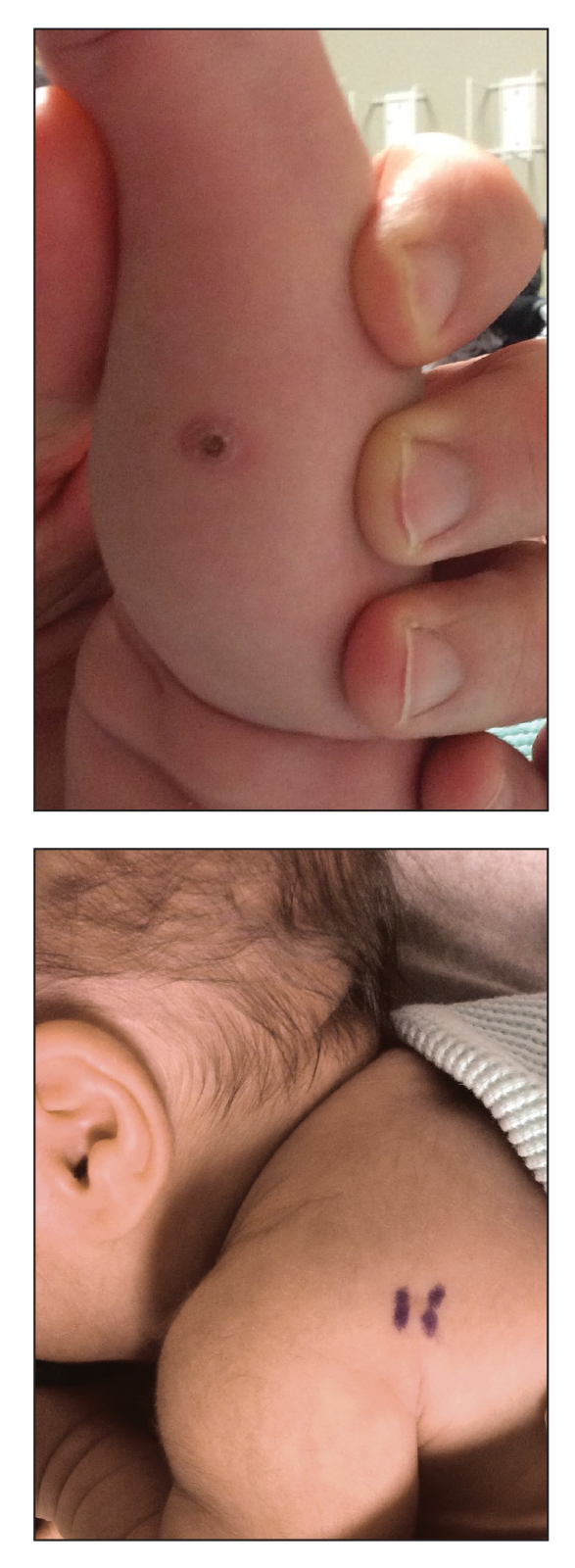

A punch biopsy of the facial lesion was stained with hematoxylin and eosin, which demonstrated spindled and stellate fibroblasts with dilated blood vessels (Figure), consistent with an angiofibroma. Given the clinical presentation and histologic findings, there was concern for a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis (TSC). The patient was referred for genetic workup but tested negative for mutations of the TSC genes in the blood. Because the patient had only unilateral facial lesions, a possible cortical tuber, no other symptoms, and tested negative for TSC gene mutations, mosaic TSC was considered a likely diagnosis. Her facial lesions were treated with pulsed dye vascular laser therapy.

Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disorder caused by inactivation of the genes TSC1 (encoding hamartin) and TSC2 (encoding tuberin). Mutation results in overactivation of the downstream mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway, resulting in abnormal cellular proliferation and hamartomas. These benign tumors can be found in nearly every organ, most often in the central nervous system and skin, and they provide for a highly variable presentation of the disease.1

Tuberous sclerosis affects 1 in 6000 to 10,000 live births and has a prevalence of 1 in 20,000 individuals. Of these individuals, 75% carry sporadic mutations, and 75% to 90% eventually test positive for a TSC gene mutation.2 Genetic mosaicism has been reported in 28% of cases affected by large deletions1 and as few as 1% of cases involving small mutations.3

The dermatologic manifestation of mosaic TSC most often includes unilateral angiofibromas, whereas in nonmosaic cases, angiofibromas cover both cheeks, the forehead, and the eyelids. The other skin lesions of TSC--shagreen patches, forehead plaques, hypomelanotic macules, and ungual fibromas--are seen less frequently.4-6 Additionally, neurologic disease in mosaic patients is notably milder, with 57% of mosaic patients found to have epilepsy compared to 91% of nonmosaic patients.7 Our patient had both unilateral facial angiofibromas and a cortical lesion suspicious for a tuber, prompting a suspected diagnosis of mosaic TSC.

The methods of diagnosis outlined by the International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group pose a challenge in diagnosing mosaic TSC. The clinical criteria require 2 major (eg, multiple angiofibromas, angiomyolipomas, a shagreen patch) and 1 minor feature (eg, dental enamel pit, renal cyst).2 However, case reports detailing unilateral facial angiofibromas have described patients with isolated dermatologic findings.5,6 Further, it has been demonstrated that genetic studies in mosaic TSC can be unreliable depending on the tissue sampled.8 Thus, for patients who have mosaic TSC, establishing a definitive diagnosis is not always possible and may rely solely on the clinical picture.

Considering the differential diagnosis, benign cephalic histiocytosis usually would present with small red-brown macules and papules symmetrically located on the head and neck. The lesions occur at a younger age, usually in the first year or two of life. Fibrofolliculomas present as multiple whitish, slightly larger papules found on the central face. They are a marker for Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, which also is associated with spontaneous pneumothorax.

Agminated means clustering or grouping of lesions. Agminated melanocytic nevi and agminated Spitz nevi are clusters of nevi. These lesions can vary in size and color. They may be elevated or flat. Melanocytic nevi usually are tan-brown or black. Spitz nevi may be pink or pigmented brown or black. To definitively differentiate between these 2 diagnoses and this patient's diagnosis of angiofibroma, a biopsy is needed.

- Curatolo P, Moavero R, Roberto D, et al. Genotype/phenotype correlations in tuberous sclerosis complex. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2015;22:259-273.

- Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243-254.

- Kwiatkowski DJ, Whittemore VH, Thiele EA. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: Genes, Clinical Features and Therapeutics. Weinham, Germany: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

- Alshaiji JM, Spock CR, Connelly EA, et al. Facial angiofibromas in a mosaic pattern tuberous sclerosis: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:8.

- Gutte R, Khopkar U. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a case report with brief review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:159.

- Silvestre JF, Bañuls J, Ramón R, et al. Unilateral multiple facial angiofibromas: a mosaic form of TSC. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(1, pt 1):127-129.

- Kozlowski P, Roberts P, Dabora S, et al. Identification of 54 large deletions/duplications in TSC1 and TSC2 using MLPA, and genotype-phenotype correlations. Hum Genet. 2007;121:389-400.

- Kwiatkowska J, Wigowska-Sowinska J, Napierala D, et al. Mosaicism in TSC as a potential cause of the failure of molecular diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:703-707.

The Diagnosis: Mosaic Tuberous Sclerosis

A punch biopsy of the facial lesion was stained with hematoxylin and eosin, which demonstrated spindled and stellate fibroblasts with dilated blood vessels (Figure), consistent with an angiofibroma. Given the clinical presentation and histologic findings, there was concern for a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis (TSC). The patient was referred for genetic workup but tested negative for mutations of the TSC genes in the blood. Because the patient had only unilateral facial lesions, a possible cortical tuber, no other symptoms, and tested negative for TSC gene mutations, mosaic TSC was considered a likely diagnosis. Her facial lesions were treated with pulsed dye vascular laser therapy.

Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disorder caused by inactivation of the genes TSC1 (encoding hamartin) and TSC2 (encoding tuberin). Mutation results in overactivation of the downstream mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway, resulting in abnormal cellular proliferation and hamartomas. These benign tumors can be found in nearly every organ, most often in the central nervous system and skin, and they provide for a highly variable presentation of the disease.1

Tuberous sclerosis affects 1 in 6000 to 10,000 live births and has a prevalence of 1 in 20,000 individuals. Of these individuals, 75% carry sporadic mutations, and 75% to 90% eventually test positive for a TSC gene mutation.2 Genetic mosaicism has been reported in 28% of cases affected by large deletions1 and as few as 1% of cases involving small mutations.3

The dermatologic manifestation of mosaic TSC most often includes unilateral angiofibromas, whereas in nonmosaic cases, angiofibromas cover both cheeks, the forehead, and the eyelids. The other skin lesions of TSC--shagreen patches, forehead plaques, hypomelanotic macules, and ungual fibromas--are seen less frequently.4-6 Additionally, neurologic disease in mosaic patients is notably milder, with 57% of mosaic patients found to have epilepsy compared to 91% of nonmosaic patients.7 Our patient had both unilateral facial angiofibromas and a cortical lesion suspicious for a tuber, prompting a suspected diagnosis of mosaic TSC.

The methods of diagnosis outlined by the International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group pose a challenge in diagnosing mosaic TSC. The clinical criteria require 2 major (eg, multiple angiofibromas, angiomyolipomas, a shagreen patch) and 1 minor feature (eg, dental enamel pit, renal cyst).2 However, case reports detailing unilateral facial angiofibromas have described patients with isolated dermatologic findings.5,6 Further, it has been demonstrated that genetic studies in mosaic TSC can be unreliable depending on the tissue sampled.8 Thus, for patients who have mosaic TSC, establishing a definitive diagnosis is not always possible and may rely solely on the clinical picture.

Considering the differential diagnosis, benign cephalic histiocytosis usually would present with small red-brown macules and papules symmetrically located on the head and neck. The lesions occur at a younger age, usually in the first year or two of life. Fibrofolliculomas present as multiple whitish, slightly larger papules found on the central face. They are a marker for Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, which also is associated with spontaneous pneumothorax.