User login

The mesh mess, enmeshed in controversy

CASE Complications with mesh placement for SUI

A 47-year-old woman (G4 P3013) presents 5 months posthysterectomy with evidence of urinary tract infection (UTI). Escherichia coli is isolated, and she responds to antibiotic therapy.

Her surgical history includes a mini-sling procedure using a needleless device and mesh placement in order to correct progressive worsening of loss of urine when coughing and sneezing. She also reported slight pelvic pain, dysuria, and urgency upon urination at that time. After subsequent development of pelvic organ prolapse (POP), she underwent the vaginal hysterectomy.

Following her UTI treatment, a host of problems occur for the patient, including pelvic pain and dyspareunia. Her male partner reports “feeling something during sex,” especially at the anterior vaginal wall. A plain radiograph of the abdomen identifies a 2 cm x 2 cm stone over the vaginal mesh. In consultation with female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery subspecialists, lithotripsy is performed, with the stone fragmented. The patient remains symptomatic, however.

The mesh is noted to be eroding through the vaginal wall. An attempt is made to excise the mesh, initially via transuretheral resection, then through a laparoscopic approach. Due to the mesh being embedded in the tissue, however, an open approach is undertaken. Extensive excision of the mesh and stone fragments is performed. Postoperatively, the patient reports “dry vagina,” with no other genitourinary complaints.

The patient sues. She sues the mesh manufacturer. She also seeks to sue the gynecologist who placed the sling and vaginal mesh (as she says she was not informed of “all the risks” of vaginal mesh placement. She is part of a class action lawsuit, along with thousands of other women.

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

The device manufacturer settled out of court with the class action suit. (The gynecologist was never formally a defendant because the patient/plaintiff was advised to “drop the physician from the suit.”) The attorneys representing the class action received 40% of the award plus presented costs for the representation. The class as a whole received a little more than 50% of the negotiated award. The patient in this case received $60,000.

Medical background

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is a prevalent condition; it affects 35% of women.1 Overall, 80% of women aged 80 or younger will undergo some form of surgery for POP during their lifetime.2 The pathophysiology of SUI includes urethral hypermobility and intrinsic sphincter deficiency.3

Surgical correction for urinary incontinence: A timeline

Use of the gracilis muscle flap to surgically correct urinary incontinence was introduced in 1907. This technique has been replaced by today’s more common Burch procedure, which was first described in 1961. Surgical mesh use dates back to the 1950s, when it was primarily used for abdominal hernia repair. Tension-free tape was introduced in 1995.4-6

Continue to: In the late 1990s the US Food and Drug Administration...

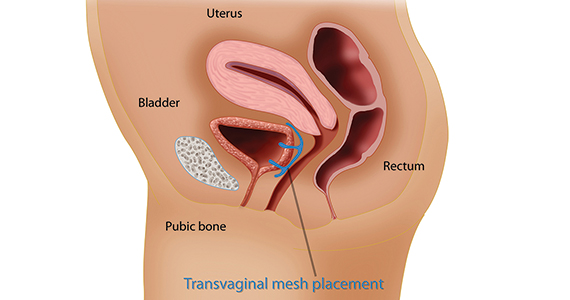

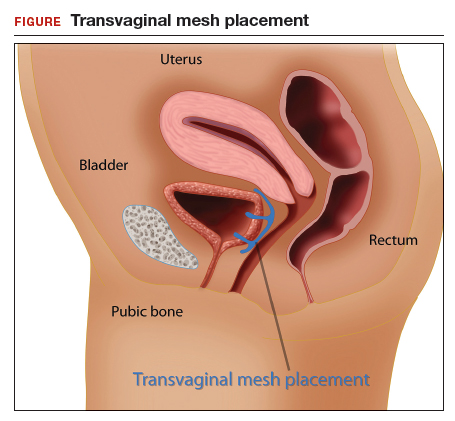

In the late 1990s the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) permitted use of the first transvaginal meshes, which were designed to treat SUI—the midurethral sling. These mesh slings were so successful that similar meshes were developed to treat POP.7 Almost immediately there were problems with the new POP devices, and 3 years later Boston Scientific recalled its device.8 Nonetheless, the FDA cleared more than 150 devices using surgical mesh for urogynecologic indications (FIGURE).9

Mesh complications

Managing complications from intravesical mesh is a clinically challenging problem. Bladder perforation, stone formation, and penetration through the vagina can occur. Bladder-related complications can manifest as recurrent UTIs and obstructive urinary symptoms, especially in association with stone formation. From the gynecologic perspective, the more common complications with mesh utilization are pelvic pain, groin pain, dyspareunia, contracture and scarring of mesh, and narrowing of the vaginal canal.10 Mesh erosion problems will occur in an estimated 10% to 25% of transvaginal mesh POP implants.11

In 2008, a comparison of transvaginal mesh to native tissue repair (suture-based) or other (biologic) grafts was published.12 The bottom line: there is insufficient evidence to suggest that transvaginal mesh significantly improves outcomes for both posterior and apical defects.

Legal background

Mesh used for surgical purposes is a medical device, which legally is a product—a special product to be sure, but a product nonetheless. Products are subject to product liability rules. Mesh is also subject to an FDA regulatory system. We will briefly discuss products liability and the regulation of devices, both of which have played important roles in mesh-related injuries.

Products liability

As a general matter, defective products subject their manufacturer and seller to liability. There are several legal theories regarding product liability: negligence (in which the defect was caused through carelessness), breach of warranty or guarantee (in addition to express warranties, there are a number of implied warranties for products, including that it is fit for its intended purpose), and strict liability (there was a defect in the product, but it may not have been because of negligence). The product may be defective in the way it was designed, manufactured, or packaged, or it may be defective because adequate instructions and warning were not given to consumers.

Of course, not every product involved in an injury is defective—most automobile accidents, for example, are not the result of any defect in the automobile. In medicine, almost no product (device or pharmaceutical) is entirely safe. In some ways they are unavoidably unsafe and bound to cause some injuries. But when injuries are caused by a defect in the product (design or manufacturing defect or failure to warn), then there may be products liability. Most products liability cases arise under state law.

FDA’s device regulations

Both drugs and medical devices are subject to FDA review and ordinarily require some form of FDA clearance before they may be marketed. In the case of devices, the FDA has 3 classes, with an increase in risk to the user from Class I to III. Various levels of FDA review are required before marketing of the device is permitted, again with the intensity of review increasing from I to III as follows:

- Class I devices pose the least risk, have the least regulation, and are subject to general controls (ie, manufacturing and marketing practices).

- Class II devices pose slightly higher risks and are subject to special controls in addition to the criteria for Class I.

- Class III devices pose the most risk to patients and require premarket approval (scientific review and studies are required to ensure efficacy and safety).13

Continue to: There are a number of limits on manufacturer liability for defective devices...

There are a number of limits on manufacturer liability for defective devices. For Class III devices, the thorough FDA review of the safety of a device may limit the ability of an injured patient to sue based on the state product liability laws.14 For the most part, this “preemption” of state law has not played a major role in mesh litigation because they were initially classified as Class II devices which did not require or include a detailed FDA review.15

The duty to warn of the dangers and risk of medical devices means that manufacturers (or sellers) of devices are obligated to inform health care providers and other medical personnel of the risks. Unlike other manufacturers, device manufacturers do not have to directly warn consumers—because physicians deal directly with patients and prescribe the devices. Therefore, the health care providers, rather than the manufacturers, are obligated to inform the patient.16 This is known as the learned intermediary rule. Manufacturers may still be liable for failure to warn if they do not convey to health care providers proper warnings.

Manufacturers and sellers are not the only entities that may be subject to liability caused by medical devices. Hospitals or other entities that stock and care for devices are responsible for maintaining the safety and functionality of devices in their care.

Health care providers also may be responsible for injuries from medical devices. Generally, that liability is based on negligence. Negligence may relate to selecting an improper device, installing or using it incorrectly, or failing to give the patient adequate information (or informed consent) about the device and alternatives to it.17

A look at the mesh mess

There are a lot of distressing problems and professional disappointments in dissecting the “mesh mess,” including a failure of the FDA to regulate effectively, the extended sale and promotion of intrinsic sphincter deficiency mesh products, the improper use of mesh by physicians even after the risks were known, and, in some instances, the taking advantage of injured patients by attorneys and businesses.18 A lot of finger pointing also has occurred.19 We will recount some of the lowlights of this unfortunate tale.

Continue to: The FDA, in the 1990s, classified the first POP and SUI mesh...

The FDA, in the 1990s, classified the first POP and SUI mesh as Class II after deciding these products were “substantially equivalent” to older surgical meshes. This, of course, proved not to be the case.20 The FDA started receiving thousands of reports of adverse events and, in 2008, warned physicians to be vigilant for adverse events from the mesh. The FDA’s notification recommendations regarding mesh included the following13:

- Obtain specialized training for each mesh implantation technique, and be cognizant of risks.

- Be vigilant for potential adverse events from mesh, including erosion and infection.

- Be observant for complications associated with tools of transvaginal placement (ie, bowel, bladder, and vessel perforation).

- Inform patients that implantation of mesh is permanent and complications may require additional surgery for correction.

- Be aware that complications may affect quality of life—eg, pain with intercourse, scarring, and vaginal wall narrowing (POP repair).

- Provide patients with written copy of patient labeling from the surgical mesh manufacturer.

In 2011, the FDA issued a formal warning to providers that transvaginal mesh posed meaningful risks beyond nonmesh surgery. The FDA’s bulletin draws attention to how the mesh is placed more so than the material per se.19,21 Mesh was a Class II device for sacrocolpopexy or midurethral sling and, similarly, the transvaginal kit was also a Class II device. Overall, use of mesh midurethral slings has been well received as treatment for SUI. The FDA also accepted it for POP, however, but with increasingly strong warnings. The FDA’s 2011 communication stated, “This update is to inform you that serious complications associated with surgical mesh for transvaginal repair of POP are not rare….Furthermore, it is not clear that transvaginal POP repair with mesh is more effective than traditional non-mesh repair in all patients with POP and it may expose patients to greater risk.”7,13

In 2014 the FDA proposed reclassifying mesh to a Class III device, which would require that manufacturers obtain approval, based on safety and effectiveness, before selling mesh. Not until 2016 did the FDA actually reclassify the mess as Class III. Of course, during this time, mesh manufacturers were well aware of the substantial problems the products were causing.13

After serious problems with mesh became well known, and especially after FDA warnings, the use of mesh other than as indicated by the FDA was increasingly risky from a legal (as well as a health) standpoint. As long as mesh was still on the market, of course, it was available for use. But use of mesh for POP procedures without good indications in a way that was contrary to the FDA warnings might well be negligent.

Changes to informed consent

The FDA warnings also should have changed the informed consent for the use of mesh.22 Informed consent commonly consists of the following:

- informing the patient of the proposed procedure

- describing risks (and benefits) of the proposed process

- explaining reasonable alternatives

- noting the risks of taking no action.

Information that is material to a decision should be disclosed. If mesh were going to be used, after the problems of mesh were known and identified by the FDA (other than midurethral slings as treatment of SUI), the risks should have been clearly identified for patients, with alternatives outlined. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics has 8 fundamental concepts with regard to informed consent that are worth keeping in mind23:

- Obtaining informed consent for medical treatment and research is an ethical requirement.

- The process expresses respect for the patient as a person.

- It protects patients against unwanted treatment and allows patients’ active involvement in medical planning and care.

- Communication is of paramount importance.

- Informed consent is a process and not a signature on a form.

- A commitment to informed consent and to provision of medical benefit to the patient are linked to provision of care.

- If obtaining informed consent is impossible, a designated surrogate should be identified representing the patient’s best interests.

- Knowledge on the part of the provider regarding state and federal requirements is necessary.

Continue to: Lawsuits line up...

Lawsuits line up

The widespread use of a product with a significant percentage of injuries and eventually with warnings about injuries from use sounds like the formula for a lot of lawsuits. This certainly has happened. A large number of suits—both class actions and individual actions—were filed as a result of mesh injuries.24 These suits were overwhelmingly against the manufacturer, although some included physicians.7 Device makers are more attractive defendants for several reasons. First, they have very deep pockets. In addition, jurors are generally much less sympathetic to large companies than to doctors. Large class actions meant that there were many different patients among the plaintiffs, and medical malpractice claims in most states have a number of trial difficulties not present in other product liability cases. Common defendants have included Johnson & Johnson, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic.

Some of the cases resulted in very large damage awards against manufacturers based on various kinds of product(s) liability. Many other cases were settled or tried with relatively small damages. There were, in addition, a number of instances in which the manufacturers were not liable. Of the 32 plaintiffs who have gone to trial thus far, 24 have obtained verdicts totaling $345 million ($14 million average). The cases that have settled have been for much less—perhaps $60,000 on average. A number of cases remain unresolved. To date, the estimate is that 100,000 women have received almost $8 billion from 7 device manufacturers to resolve claims.25

Some state attorneys general have gotten into the process as well. Attorneys general from California, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Washington have filed lawsuits against Johnson & Johnson, claiming that they deceived doctors and patients about the risks of their pelvic mesh. The states claim that marketing and instructional literature should have contained more information about the risks. Some physicians in these states have expressed concern that these lawsuit risks may do more harm than good because the suits conflate mesh used to treat incontinence with the more risky mesh for POP.26

The “ugly” of class action lawsuits

We have discussed both the sad (the injuries to patients) and the bad (the slow regulatory response and continuing injuries). (The ethics of the marketing by the manufacturers might also be raised as the bad.27) Next, let’s look briefly at the ugly.

Some of the patients affected by mesh injuries have been victimized a second time by medical “lenders” and some of their attorneys. Press reports describe patients with modest awards paying 40% in attorney fees (on the high side for personal injury settlements) plus extravagant costs—leaving modest amounts of actual recovery.25

Worse still, a process of “medical lending” has arisen in mesh cases.28 Medical lenders may contact mesh victims offering to pay up front for surgery to remove mesh, and then place a lien against the settlement for repayment at a much higher rate. They might pay the surgeon $2,500 for the surgery, but place a lien on the settlement amount for $60,000.29,30 In addition, there are allegations that lawyers may recruit the doctors to overstate the injuries or do unnecessary removal surgery because that will likely up the award.31 A quick Google search indicates dozens of offers of cash now for your mesh lawsuit (transvaginal and hernia repair).

The patient in our hypothetical case at the beginning had a fairly typical experience. She was a member of a class filing and received a modest settlement. The attorneys representing the class were allowed by the court to charge substantial attorneys’ fees and costs. The patient had the good sense to avoid medical lenders, although other members of the class did use medical lenders and are now filing complaints about the way they were treated by these lenders.

- Maintain surgical skills and be open to new technology. Medical practice requires constant updating and use of new and improved technology as it comes along. By definition, new technology often requires new skills and understanding. A significant portion of surgeons using mesh indicated that they had not read the instructions for use, or had done so only once.1 CME programs that include surgical education remain of particular value.

- Whether new technology or old, it is essential to keep up to date on all FDA bulletins pertinent to devices and pharmaceuticals that you use and prescribe. For example, in 2016 and 2018 the FDA warned that the use of a very old class of drugs (fluoroquinolones) should be limited. It advised "that the serious side effects associated with fluoroquinolones generally outweigh the benefits for patients with acute sinusitis, acute bronchitis, and uncomplicated urinary tract infections who have other treatment options. For patients with these conditions, fluoroquinolones should be reserved for those who do not have alternative treatment options."2 Continued, unnecessary prescriptions for fluoroquinolones would put a physician at some legal risk whether or not the physician had paid any attention to the warning.

- Informed consent is a very important legal and medical process. Take it seriously, and make sure the patient has the information necessary to make informed decisions about treatment. Document the process and the information provided. In some cases consider directing patients to appropriate literature or websites of the manufacturers.

- As to the use of mesh, if not following FDA advice, it is important to document the reason for this and to document the informed consent especially carefully.

- Follow patients after mesh placement for a minimum of 1 year and emphasize to patients they should convey signs and symptoms of complications from initial placement.3 High-risk patients should be of particular concern and be monitored very closely.

References

- Kirkpatrick G, Faber KD, Fromer DL. Transvaginal mesh placement and the instructions for use: a survey of North American urologists. J Urol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urpr.2018.05.004.

- FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA advises restricting fluoroquinolone antibiotic use for certain uncomplicated infections; warns about disabling side effects that can occur together. July 26, 2016. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm500143.htm. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Karlovsky ME. How to avoid and deal with pelvic mesh litigation. Curr Urol Rep. 2016;17:55.

- Maral I, Ozkardeş H, Peşkircioğlu L, et al. Prevalence of stress urinary incontinence in both sexes at or after age 15 years: a cross-sectional study. J Urol. 2001;165:408-412.

- Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, et al. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501-506.

- Chang J, Lee D. Midurethral slings in the mesh litigation era. Transl Androl Urol. 2017;6(suppl 2): S68-S75.

- Mattingly R, ed. TeLinde's Operative Gynecology, 5th edition. Lippincott, William, and Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA; 1997.

- Burch J. Urethrovaginal fixation to Cooper's ligament for correction of stress incontinence, cystocele, and prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1961;81:281-290.

- Ulmsten U, Falconer C, Johnson P, et al. A multicenter study of tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) for surgical treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1998;9:210-213.

- Kuhlmann-Capek MJ, Kilic GS, Shah AB, et al. Enmeshed in controversy: use of vaginal mesh in the current medicolegal environment. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015;21:241-243.

- Powell SF. Changing our minds: reforming the FDA medical device reclassification process. Food Drug Law J. 2018;73:177-209.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Surgical Mesh for Treatment of Women with Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Stress Urinary Incontinence. September 2011. https://www.thesenatorsfirm.com/documents/OBS.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, et al. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(4):CD004014.

- Ganj FA, Ibeanu OA, Bedestani A, Nolan TE, Chesson RR. Complications of transvaginal monofilament polypropylene mesh in pelvic organ prolapse repair. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:919-925.

- Sung VW, Rogers RG, Schaffer JI, et al. Graft use in transvaginal pelvic organ prolapse repair: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:1131-1142.

- FDA public health notification: serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh in repair of pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence. October 20, 2008. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/PublicHealthNotifications/ucm061976.htm. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- Riegel v. Medtronic, 552 U.S. 312 (2008).

- Whitney DW. Guide to preemption of state-law claims against Class III PMA medical devices. Food Drug Law J. 2010;65:113-139.

- Alam P, Iglesia CB. Informed consent for reconstructive pelvic surgery. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2016;43:131-139.

- Nosti PA, Iglesia CB. Medicolegal issues surrounding devices and mesh for surgical treatment of prolapse and incontinence. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;56:221-228.

- Shepherd CG. Transvaginal mesh litigation: a new opportunity to resolve mass medical device failure claims. Tennessee Law Rev. 2012;80:3:477-94.

- Karlovsky ME. How to avoid and deal with pelvic mesh litigation. Curr Urol Rep. 2016;17:55.

- Cohn JA, Timbrook Brown E, Kowalik CG, et al. The mesh controversy. F1000Research website. https://f1000research.com/articles/5-2423/v1. Accessed June 17, 2019.

- Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel Meeting, February 12, 2019. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/media/122867/download. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Mucowski SJ, Jurnalov C, Phelps JY. Use of vaginal mesh in the face of recent FDA warnings and litigation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:103.e1-e4.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 439: informed consent. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(2 pt 1):401-408.

- Souders CP, Eilber KS, McClelland L, et al. The truth behind transvaginal mesh litigation: devices, timelines, and provider characteristics. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018;24:21-25.

- Goldstein M. As pelvic mesh settlements near $8 billion, women question lawyers' fees. New York Times. February 1, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/01/business/pelvic-mesh-settlements-lawyers.html. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Johnson G. Surgeons fear pelvic mesh lawsuits will spook patients. Associated Press News. January 10, 2019. https://www.apnews.com/25777c3c33e3489283b1dc2ebdde6b55. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Clarke RN. Medical device marketing and the ethics of vaginal mesh kit marketing. In The Innovation and Evolution of Medical Devices. New York, NY: Springer; 2019:103-123.

- Top 5 drug and medical device developments of 2018. Law 360. January 1, 2019. Accessed through LexisNexis.

- Frankel A, Dye J. The Lien Machine. New breed of investor profits by financing surgeries for desperate women patients. Reuters. August 18, 2015. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/usa-litigation-mesh/. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Sullivan T. New report looks at intersection of "medical lending" and pelvic mesh lawsuits. Policy & Medicine. May 5, 2018. https://www.policymed.com/2015/08/medical-lending-and-pelvic-mesh-litigation.html. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Goldstein M, Sliver-Greensberg J. How profiteers lure women into often-unneeded surgery. New York Times. April 14, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/14/business/vaginal-mesh-surgery-lawsuits-financing.html. Accessed June 19, 2019.

CASE Complications with mesh placement for SUI

A 47-year-old woman (G4 P3013) presents 5 months posthysterectomy with evidence of urinary tract infection (UTI). Escherichia coli is isolated, and she responds to antibiotic therapy.

Her surgical history includes a mini-sling procedure using a needleless device and mesh placement in order to correct progressive worsening of loss of urine when coughing and sneezing. She also reported slight pelvic pain, dysuria, and urgency upon urination at that time. After subsequent development of pelvic organ prolapse (POP), she underwent the vaginal hysterectomy.

Following her UTI treatment, a host of problems occur for the patient, including pelvic pain and dyspareunia. Her male partner reports “feeling something during sex,” especially at the anterior vaginal wall. A plain radiograph of the abdomen identifies a 2 cm x 2 cm stone over the vaginal mesh. In consultation with female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery subspecialists, lithotripsy is performed, with the stone fragmented. The patient remains symptomatic, however.

The mesh is noted to be eroding through the vaginal wall. An attempt is made to excise the mesh, initially via transuretheral resection, then through a laparoscopic approach. Due to the mesh being embedded in the tissue, however, an open approach is undertaken. Extensive excision of the mesh and stone fragments is performed. Postoperatively, the patient reports “dry vagina,” with no other genitourinary complaints.

The patient sues. She sues the mesh manufacturer. She also seeks to sue the gynecologist who placed the sling and vaginal mesh (as she says she was not informed of “all the risks” of vaginal mesh placement. She is part of a class action lawsuit, along with thousands of other women.

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

The device manufacturer settled out of court with the class action suit. (The gynecologist was never formally a defendant because the patient/plaintiff was advised to “drop the physician from the suit.”) The attorneys representing the class action received 40% of the award plus presented costs for the representation. The class as a whole received a little more than 50% of the negotiated award. The patient in this case received $60,000.

Medical background

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is a prevalent condition; it affects 35% of women.1 Overall, 80% of women aged 80 or younger will undergo some form of surgery for POP during their lifetime.2 The pathophysiology of SUI includes urethral hypermobility and intrinsic sphincter deficiency.3

Surgical correction for urinary incontinence: A timeline

Use of the gracilis muscle flap to surgically correct urinary incontinence was introduced in 1907. This technique has been replaced by today’s more common Burch procedure, which was first described in 1961. Surgical mesh use dates back to the 1950s, when it was primarily used for abdominal hernia repair. Tension-free tape was introduced in 1995.4-6

Continue to: In the late 1990s the US Food and Drug Administration...

In the late 1990s the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) permitted use of the first transvaginal meshes, which were designed to treat SUI—the midurethral sling. These mesh slings were so successful that similar meshes were developed to treat POP.7 Almost immediately there were problems with the new POP devices, and 3 years later Boston Scientific recalled its device.8 Nonetheless, the FDA cleared more than 150 devices using surgical mesh for urogynecologic indications (FIGURE).9

Mesh complications

Managing complications from intravesical mesh is a clinically challenging problem. Bladder perforation, stone formation, and penetration through the vagina can occur. Bladder-related complications can manifest as recurrent UTIs and obstructive urinary symptoms, especially in association with stone formation. From the gynecologic perspective, the more common complications with mesh utilization are pelvic pain, groin pain, dyspareunia, contracture and scarring of mesh, and narrowing of the vaginal canal.10 Mesh erosion problems will occur in an estimated 10% to 25% of transvaginal mesh POP implants.11

In 2008, a comparison of transvaginal mesh to native tissue repair (suture-based) or other (biologic) grafts was published.12 The bottom line: there is insufficient evidence to suggest that transvaginal mesh significantly improves outcomes for both posterior and apical defects.

Legal background

Mesh used for surgical purposes is a medical device, which legally is a product—a special product to be sure, but a product nonetheless. Products are subject to product liability rules. Mesh is also subject to an FDA regulatory system. We will briefly discuss products liability and the regulation of devices, both of which have played important roles in mesh-related injuries.

Products liability

As a general matter, defective products subject their manufacturer and seller to liability. There are several legal theories regarding product liability: negligence (in which the defect was caused through carelessness), breach of warranty or guarantee (in addition to express warranties, there are a number of implied warranties for products, including that it is fit for its intended purpose), and strict liability (there was a defect in the product, but it may not have been because of negligence). The product may be defective in the way it was designed, manufactured, or packaged, or it may be defective because adequate instructions and warning were not given to consumers.

Of course, not every product involved in an injury is defective—most automobile accidents, for example, are not the result of any defect in the automobile. In medicine, almost no product (device or pharmaceutical) is entirely safe. In some ways they are unavoidably unsafe and bound to cause some injuries. But when injuries are caused by a defect in the product (design or manufacturing defect or failure to warn), then there may be products liability. Most products liability cases arise under state law.

FDA’s device regulations

Both drugs and medical devices are subject to FDA review and ordinarily require some form of FDA clearance before they may be marketed. In the case of devices, the FDA has 3 classes, with an increase in risk to the user from Class I to III. Various levels of FDA review are required before marketing of the device is permitted, again with the intensity of review increasing from I to III as follows:

- Class I devices pose the least risk, have the least regulation, and are subject to general controls (ie, manufacturing and marketing practices).

- Class II devices pose slightly higher risks and are subject to special controls in addition to the criteria for Class I.

- Class III devices pose the most risk to patients and require premarket approval (scientific review and studies are required to ensure efficacy and safety).13

Continue to: There are a number of limits on manufacturer liability for defective devices...

There are a number of limits on manufacturer liability for defective devices. For Class III devices, the thorough FDA review of the safety of a device may limit the ability of an injured patient to sue based on the state product liability laws.14 For the most part, this “preemption” of state law has not played a major role in mesh litigation because they were initially classified as Class II devices which did not require or include a detailed FDA review.15

The duty to warn of the dangers and risk of medical devices means that manufacturers (or sellers) of devices are obligated to inform health care providers and other medical personnel of the risks. Unlike other manufacturers, device manufacturers do not have to directly warn consumers—because physicians deal directly with patients and prescribe the devices. Therefore, the health care providers, rather than the manufacturers, are obligated to inform the patient.16 This is known as the learned intermediary rule. Manufacturers may still be liable for failure to warn if they do not convey to health care providers proper warnings.

Manufacturers and sellers are not the only entities that may be subject to liability caused by medical devices. Hospitals or other entities that stock and care for devices are responsible for maintaining the safety and functionality of devices in their care.

Health care providers also may be responsible for injuries from medical devices. Generally, that liability is based on negligence. Negligence may relate to selecting an improper device, installing or using it incorrectly, or failing to give the patient adequate information (or informed consent) about the device and alternatives to it.17

A look at the mesh mess

There are a lot of distressing problems and professional disappointments in dissecting the “mesh mess,” including a failure of the FDA to regulate effectively, the extended sale and promotion of intrinsic sphincter deficiency mesh products, the improper use of mesh by physicians even after the risks were known, and, in some instances, the taking advantage of injured patients by attorneys and businesses.18 A lot of finger pointing also has occurred.19 We will recount some of the lowlights of this unfortunate tale.

Continue to: The FDA, in the 1990s, classified the first POP and SUI mesh...

The FDA, in the 1990s, classified the first POP and SUI mesh as Class II after deciding these products were “substantially equivalent” to older surgical meshes. This, of course, proved not to be the case.20 The FDA started receiving thousands of reports of adverse events and, in 2008, warned physicians to be vigilant for adverse events from the mesh. The FDA’s notification recommendations regarding mesh included the following13:

- Obtain specialized training for each mesh implantation technique, and be cognizant of risks.

- Be vigilant for potential adverse events from mesh, including erosion and infection.

- Be observant for complications associated with tools of transvaginal placement (ie, bowel, bladder, and vessel perforation).

- Inform patients that implantation of mesh is permanent and complications may require additional surgery for correction.

- Be aware that complications may affect quality of life—eg, pain with intercourse, scarring, and vaginal wall narrowing (POP repair).

- Provide patients with written copy of patient labeling from the surgical mesh manufacturer.

In 2011, the FDA issued a formal warning to providers that transvaginal mesh posed meaningful risks beyond nonmesh surgery. The FDA’s bulletin draws attention to how the mesh is placed more so than the material per se.19,21 Mesh was a Class II device for sacrocolpopexy or midurethral sling and, similarly, the transvaginal kit was also a Class II device. Overall, use of mesh midurethral slings has been well received as treatment for SUI. The FDA also accepted it for POP, however, but with increasingly strong warnings. The FDA’s 2011 communication stated, “This update is to inform you that serious complications associated with surgical mesh for transvaginal repair of POP are not rare….Furthermore, it is not clear that transvaginal POP repair with mesh is more effective than traditional non-mesh repair in all patients with POP and it may expose patients to greater risk.”7,13

In 2014 the FDA proposed reclassifying mesh to a Class III device, which would require that manufacturers obtain approval, based on safety and effectiveness, before selling mesh. Not until 2016 did the FDA actually reclassify the mess as Class III. Of course, during this time, mesh manufacturers were well aware of the substantial problems the products were causing.13

After serious problems with mesh became well known, and especially after FDA warnings, the use of mesh other than as indicated by the FDA was increasingly risky from a legal (as well as a health) standpoint. As long as mesh was still on the market, of course, it was available for use. But use of mesh for POP procedures without good indications in a way that was contrary to the FDA warnings might well be negligent.

Changes to informed consent

The FDA warnings also should have changed the informed consent for the use of mesh.22 Informed consent commonly consists of the following:

- informing the patient of the proposed procedure

- describing risks (and benefits) of the proposed process

- explaining reasonable alternatives

- noting the risks of taking no action.

Information that is material to a decision should be disclosed. If mesh were going to be used, after the problems of mesh were known and identified by the FDA (other than midurethral slings as treatment of SUI), the risks should have been clearly identified for patients, with alternatives outlined. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics has 8 fundamental concepts with regard to informed consent that are worth keeping in mind23:

- Obtaining informed consent for medical treatment and research is an ethical requirement.

- The process expresses respect for the patient as a person.

- It protects patients against unwanted treatment and allows patients’ active involvement in medical planning and care.

- Communication is of paramount importance.

- Informed consent is a process and not a signature on a form.

- A commitment to informed consent and to provision of medical benefit to the patient are linked to provision of care.

- If obtaining informed consent is impossible, a designated surrogate should be identified representing the patient’s best interests.

- Knowledge on the part of the provider regarding state and federal requirements is necessary.

Continue to: Lawsuits line up...

Lawsuits line up

The widespread use of a product with a significant percentage of injuries and eventually with warnings about injuries from use sounds like the formula for a lot of lawsuits. This certainly has happened. A large number of suits—both class actions and individual actions—were filed as a result of mesh injuries.24 These suits were overwhelmingly against the manufacturer, although some included physicians.7 Device makers are more attractive defendants for several reasons. First, they have very deep pockets. In addition, jurors are generally much less sympathetic to large companies than to doctors. Large class actions meant that there were many different patients among the plaintiffs, and medical malpractice claims in most states have a number of trial difficulties not present in other product liability cases. Common defendants have included Johnson & Johnson, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic.

Some of the cases resulted in very large damage awards against manufacturers based on various kinds of product(s) liability. Many other cases were settled or tried with relatively small damages. There were, in addition, a number of instances in which the manufacturers were not liable. Of the 32 plaintiffs who have gone to trial thus far, 24 have obtained verdicts totaling $345 million ($14 million average). The cases that have settled have been for much less—perhaps $60,000 on average. A number of cases remain unresolved. To date, the estimate is that 100,000 women have received almost $8 billion from 7 device manufacturers to resolve claims.25

Some state attorneys general have gotten into the process as well. Attorneys general from California, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Washington have filed lawsuits against Johnson & Johnson, claiming that they deceived doctors and patients about the risks of their pelvic mesh. The states claim that marketing and instructional literature should have contained more information about the risks. Some physicians in these states have expressed concern that these lawsuit risks may do more harm than good because the suits conflate mesh used to treat incontinence with the more risky mesh for POP.26

The “ugly” of class action lawsuits

We have discussed both the sad (the injuries to patients) and the bad (the slow regulatory response and continuing injuries). (The ethics of the marketing by the manufacturers might also be raised as the bad.27) Next, let’s look briefly at the ugly.

Some of the patients affected by mesh injuries have been victimized a second time by medical “lenders” and some of their attorneys. Press reports describe patients with modest awards paying 40% in attorney fees (on the high side for personal injury settlements) plus extravagant costs—leaving modest amounts of actual recovery.25

Worse still, a process of “medical lending” has arisen in mesh cases.28 Medical lenders may contact mesh victims offering to pay up front for surgery to remove mesh, and then place a lien against the settlement for repayment at a much higher rate. They might pay the surgeon $2,500 for the surgery, but place a lien on the settlement amount for $60,000.29,30 In addition, there are allegations that lawyers may recruit the doctors to overstate the injuries or do unnecessary removal surgery because that will likely up the award.31 A quick Google search indicates dozens of offers of cash now for your mesh lawsuit (transvaginal and hernia repair).

The patient in our hypothetical case at the beginning had a fairly typical experience. She was a member of a class filing and received a modest settlement. The attorneys representing the class were allowed by the court to charge substantial attorneys’ fees and costs. The patient had the good sense to avoid medical lenders, although other members of the class did use medical lenders and are now filing complaints about the way they were treated by these lenders.

- Maintain surgical skills and be open to new technology. Medical practice requires constant updating and use of new and improved technology as it comes along. By definition, new technology often requires new skills and understanding. A significant portion of surgeons using mesh indicated that they had not read the instructions for use, or had done so only once.1 CME programs that include surgical education remain of particular value.

- Whether new technology or old, it is essential to keep up to date on all FDA bulletins pertinent to devices and pharmaceuticals that you use and prescribe. For example, in 2016 and 2018 the FDA warned that the use of a very old class of drugs (fluoroquinolones) should be limited. It advised "that the serious side effects associated with fluoroquinolones generally outweigh the benefits for patients with acute sinusitis, acute bronchitis, and uncomplicated urinary tract infections who have other treatment options. For patients with these conditions, fluoroquinolones should be reserved for those who do not have alternative treatment options."2 Continued, unnecessary prescriptions for fluoroquinolones would put a physician at some legal risk whether or not the physician had paid any attention to the warning.

- Informed consent is a very important legal and medical process. Take it seriously, and make sure the patient has the information necessary to make informed decisions about treatment. Document the process and the information provided. In some cases consider directing patients to appropriate literature or websites of the manufacturers.

- As to the use of mesh, if not following FDA advice, it is important to document the reason for this and to document the informed consent especially carefully.

- Follow patients after mesh placement for a minimum of 1 year and emphasize to patients they should convey signs and symptoms of complications from initial placement.3 High-risk patients should be of particular concern and be monitored very closely.

References

- Kirkpatrick G, Faber KD, Fromer DL. Transvaginal mesh placement and the instructions for use: a survey of North American urologists. J Urol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urpr.2018.05.004.

- FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA advises restricting fluoroquinolone antibiotic use for certain uncomplicated infections; warns about disabling side effects that can occur together. July 26, 2016. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm500143.htm. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Karlovsky ME. How to avoid and deal with pelvic mesh litigation. Curr Urol Rep. 2016;17:55.

CASE Complications with mesh placement for SUI

A 47-year-old woman (G4 P3013) presents 5 months posthysterectomy with evidence of urinary tract infection (UTI). Escherichia coli is isolated, and she responds to antibiotic therapy.

Her surgical history includes a mini-sling procedure using a needleless device and mesh placement in order to correct progressive worsening of loss of urine when coughing and sneezing. She also reported slight pelvic pain, dysuria, and urgency upon urination at that time. After subsequent development of pelvic organ prolapse (POP), she underwent the vaginal hysterectomy.

Following her UTI treatment, a host of problems occur for the patient, including pelvic pain and dyspareunia. Her male partner reports “feeling something during sex,” especially at the anterior vaginal wall. A plain radiograph of the abdomen identifies a 2 cm x 2 cm stone over the vaginal mesh. In consultation with female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery subspecialists, lithotripsy is performed, with the stone fragmented. The patient remains symptomatic, however.

The mesh is noted to be eroding through the vaginal wall. An attempt is made to excise the mesh, initially via transuretheral resection, then through a laparoscopic approach. Due to the mesh being embedded in the tissue, however, an open approach is undertaken. Extensive excision of the mesh and stone fragments is performed. Postoperatively, the patient reports “dry vagina,” with no other genitourinary complaints.

The patient sues. She sues the mesh manufacturer. She also seeks to sue the gynecologist who placed the sling and vaginal mesh (as she says she was not informed of “all the risks” of vaginal mesh placement. She is part of a class action lawsuit, along with thousands of other women.

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

The device manufacturer settled out of court with the class action suit. (The gynecologist was never formally a defendant because the patient/plaintiff was advised to “drop the physician from the suit.”) The attorneys representing the class action received 40% of the award plus presented costs for the representation. The class as a whole received a little more than 50% of the negotiated award. The patient in this case received $60,000.

Medical background

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is a prevalent condition; it affects 35% of women.1 Overall, 80% of women aged 80 or younger will undergo some form of surgery for POP during their lifetime.2 The pathophysiology of SUI includes urethral hypermobility and intrinsic sphincter deficiency.3

Surgical correction for urinary incontinence: A timeline

Use of the gracilis muscle flap to surgically correct urinary incontinence was introduced in 1907. This technique has been replaced by today’s more common Burch procedure, which was first described in 1961. Surgical mesh use dates back to the 1950s, when it was primarily used for abdominal hernia repair. Tension-free tape was introduced in 1995.4-6

Continue to: In the late 1990s the US Food and Drug Administration...

In the late 1990s the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) permitted use of the first transvaginal meshes, which were designed to treat SUI—the midurethral sling. These mesh slings were so successful that similar meshes were developed to treat POP.7 Almost immediately there were problems with the new POP devices, and 3 years later Boston Scientific recalled its device.8 Nonetheless, the FDA cleared more than 150 devices using surgical mesh for urogynecologic indications (FIGURE).9

Mesh complications

Managing complications from intravesical mesh is a clinically challenging problem. Bladder perforation, stone formation, and penetration through the vagina can occur. Bladder-related complications can manifest as recurrent UTIs and obstructive urinary symptoms, especially in association with stone formation. From the gynecologic perspective, the more common complications with mesh utilization are pelvic pain, groin pain, dyspareunia, contracture and scarring of mesh, and narrowing of the vaginal canal.10 Mesh erosion problems will occur in an estimated 10% to 25% of transvaginal mesh POP implants.11

In 2008, a comparison of transvaginal mesh to native tissue repair (suture-based) or other (biologic) grafts was published.12 The bottom line: there is insufficient evidence to suggest that transvaginal mesh significantly improves outcomes for both posterior and apical defects.

Legal background

Mesh used for surgical purposes is a medical device, which legally is a product—a special product to be sure, but a product nonetheless. Products are subject to product liability rules. Mesh is also subject to an FDA regulatory system. We will briefly discuss products liability and the regulation of devices, both of which have played important roles in mesh-related injuries.

Products liability

As a general matter, defective products subject their manufacturer and seller to liability. There are several legal theories regarding product liability: negligence (in which the defect was caused through carelessness), breach of warranty or guarantee (in addition to express warranties, there are a number of implied warranties for products, including that it is fit for its intended purpose), and strict liability (there was a defect in the product, but it may not have been because of negligence). The product may be defective in the way it was designed, manufactured, or packaged, or it may be defective because adequate instructions and warning were not given to consumers.

Of course, not every product involved in an injury is defective—most automobile accidents, for example, are not the result of any defect in the automobile. In medicine, almost no product (device or pharmaceutical) is entirely safe. In some ways they are unavoidably unsafe and bound to cause some injuries. But when injuries are caused by a defect in the product (design or manufacturing defect or failure to warn), then there may be products liability. Most products liability cases arise under state law.

FDA’s device regulations

Both drugs and medical devices are subject to FDA review and ordinarily require some form of FDA clearance before they may be marketed. In the case of devices, the FDA has 3 classes, with an increase in risk to the user from Class I to III. Various levels of FDA review are required before marketing of the device is permitted, again with the intensity of review increasing from I to III as follows:

- Class I devices pose the least risk, have the least regulation, and are subject to general controls (ie, manufacturing and marketing practices).

- Class II devices pose slightly higher risks and are subject to special controls in addition to the criteria for Class I.

- Class III devices pose the most risk to patients and require premarket approval (scientific review and studies are required to ensure efficacy and safety).13

Continue to: There are a number of limits on manufacturer liability for defective devices...

There are a number of limits on manufacturer liability for defective devices. For Class III devices, the thorough FDA review of the safety of a device may limit the ability of an injured patient to sue based on the state product liability laws.14 For the most part, this “preemption” of state law has not played a major role in mesh litigation because they were initially classified as Class II devices which did not require or include a detailed FDA review.15

The duty to warn of the dangers and risk of medical devices means that manufacturers (or sellers) of devices are obligated to inform health care providers and other medical personnel of the risks. Unlike other manufacturers, device manufacturers do not have to directly warn consumers—because physicians deal directly with patients and prescribe the devices. Therefore, the health care providers, rather than the manufacturers, are obligated to inform the patient.16 This is known as the learned intermediary rule. Manufacturers may still be liable for failure to warn if they do not convey to health care providers proper warnings.

Manufacturers and sellers are not the only entities that may be subject to liability caused by medical devices. Hospitals or other entities that stock and care for devices are responsible for maintaining the safety and functionality of devices in their care.

Health care providers also may be responsible for injuries from medical devices. Generally, that liability is based on negligence. Negligence may relate to selecting an improper device, installing or using it incorrectly, or failing to give the patient adequate information (or informed consent) about the device and alternatives to it.17

A look at the mesh mess

There are a lot of distressing problems and professional disappointments in dissecting the “mesh mess,” including a failure of the FDA to regulate effectively, the extended sale and promotion of intrinsic sphincter deficiency mesh products, the improper use of mesh by physicians even after the risks were known, and, in some instances, the taking advantage of injured patients by attorneys and businesses.18 A lot of finger pointing also has occurred.19 We will recount some of the lowlights of this unfortunate tale.

Continue to: The FDA, in the 1990s, classified the first POP and SUI mesh...

The FDA, in the 1990s, classified the first POP and SUI mesh as Class II after deciding these products were “substantially equivalent” to older surgical meshes. This, of course, proved not to be the case.20 The FDA started receiving thousands of reports of adverse events and, in 2008, warned physicians to be vigilant for adverse events from the mesh. The FDA’s notification recommendations regarding mesh included the following13:

- Obtain specialized training for each mesh implantation technique, and be cognizant of risks.

- Be vigilant for potential adverse events from mesh, including erosion and infection.

- Be observant for complications associated with tools of transvaginal placement (ie, bowel, bladder, and vessel perforation).

- Inform patients that implantation of mesh is permanent and complications may require additional surgery for correction.

- Be aware that complications may affect quality of life—eg, pain with intercourse, scarring, and vaginal wall narrowing (POP repair).

- Provide patients with written copy of patient labeling from the surgical mesh manufacturer.

In 2011, the FDA issued a formal warning to providers that transvaginal mesh posed meaningful risks beyond nonmesh surgery. The FDA’s bulletin draws attention to how the mesh is placed more so than the material per se.19,21 Mesh was a Class II device for sacrocolpopexy or midurethral sling and, similarly, the transvaginal kit was also a Class II device. Overall, use of mesh midurethral slings has been well received as treatment for SUI. The FDA also accepted it for POP, however, but with increasingly strong warnings. The FDA’s 2011 communication stated, “This update is to inform you that serious complications associated with surgical mesh for transvaginal repair of POP are not rare….Furthermore, it is not clear that transvaginal POP repair with mesh is more effective than traditional non-mesh repair in all patients with POP and it may expose patients to greater risk.”7,13

In 2014 the FDA proposed reclassifying mesh to a Class III device, which would require that manufacturers obtain approval, based on safety and effectiveness, before selling mesh. Not until 2016 did the FDA actually reclassify the mess as Class III. Of course, during this time, mesh manufacturers were well aware of the substantial problems the products were causing.13

After serious problems with mesh became well known, and especially after FDA warnings, the use of mesh other than as indicated by the FDA was increasingly risky from a legal (as well as a health) standpoint. As long as mesh was still on the market, of course, it was available for use. But use of mesh for POP procedures without good indications in a way that was contrary to the FDA warnings might well be negligent.

Changes to informed consent

The FDA warnings also should have changed the informed consent for the use of mesh.22 Informed consent commonly consists of the following:

- informing the patient of the proposed procedure

- describing risks (and benefits) of the proposed process

- explaining reasonable alternatives

- noting the risks of taking no action.

Information that is material to a decision should be disclosed. If mesh were going to be used, after the problems of mesh were known and identified by the FDA (other than midurethral slings as treatment of SUI), the risks should have been clearly identified for patients, with alternatives outlined. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics has 8 fundamental concepts with regard to informed consent that are worth keeping in mind23:

- Obtaining informed consent for medical treatment and research is an ethical requirement.

- The process expresses respect for the patient as a person.

- It protects patients against unwanted treatment and allows patients’ active involvement in medical planning and care.

- Communication is of paramount importance.

- Informed consent is a process and not a signature on a form.

- A commitment to informed consent and to provision of medical benefit to the patient are linked to provision of care.

- If obtaining informed consent is impossible, a designated surrogate should be identified representing the patient’s best interests.

- Knowledge on the part of the provider regarding state and federal requirements is necessary.

Continue to: Lawsuits line up...

Lawsuits line up

The widespread use of a product with a significant percentage of injuries and eventually with warnings about injuries from use sounds like the formula for a lot of lawsuits. This certainly has happened. A large number of suits—both class actions and individual actions—were filed as a result of mesh injuries.24 These suits were overwhelmingly against the manufacturer, although some included physicians.7 Device makers are more attractive defendants for several reasons. First, they have very deep pockets. In addition, jurors are generally much less sympathetic to large companies than to doctors. Large class actions meant that there were many different patients among the plaintiffs, and medical malpractice claims in most states have a number of trial difficulties not present in other product liability cases. Common defendants have included Johnson & Johnson, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic.

Some of the cases resulted in very large damage awards against manufacturers based on various kinds of product(s) liability. Many other cases were settled or tried with relatively small damages. There were, in addition, a number of instances in which the manufacturers were not liable. Of the 32 plaintiffs who have gone to trial thus far, 24 have obtained verdicts totaling $345 million ($14 million average). The cases that have settled have been for much less—perhaps $60,000 on average. A number of cases remain unresolved. To date, the estimate is that 100,000 women have received almost $8 billion from 7 device manufacturers to resolve claims.25

Some state attorneys general have gotten into the process as well. Attorneys general from California, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Washington have filed lawsuits against Johnson & Johnson, claiming that they deceived doctors and patients about the risks of their pelvic mesh. The states claim that marketing and instructional literature should have contained more information about the risks. Some physicians in these states have expressed concern that these lawsuit risks may do more harm than good because the suits conflate mesh used to treat incontinence with the more risky mesh for POP.26

The “ugly” of class action lawsuits

We have discussed both the sad (the injuries to patients) and the bad (the slow regulatory response and continuing injuries). (The ethics of the marketing by the manufacturers might also be raised as the bad.27) Next, let’s look briefly at the ugly.

Some of the patients affected by mesh injuries have been victimized a second time by medical “lenders” and some of their attorneys. Press reports describe patients with modest awards paying 40% in attorney fees (on the high side for personal injury settlements) plus extravagant costs—leaving modest amounts of actual recovery.25

Worse still, a process of “medical lending” has arisen in mesh cases.28 Medical lenders may contact mesh victims offering to pay up front for surgery to remove mesh, and then place a lien against the settlement for repayment at a much higher rate. They might pay the surgeon $2,500 for the surgery, but place a lien on the settlement amount for $60,000.29,30 In addition, there are allegations that lawyers may recruit the doctors to overstate the injuries or do unnecessary removal surgery because that will likely up the award.31 A quick Google search indicates dozens of offers of cash now for your mesh lawsuit (transvaginal and hernia repair).

The patient in our hypothetical case at the beginning had a fairly typical experience. She was a member of a class filing and received a modest settlement. The attorneys representing the class were allowed by the court to charge substantial attorneys’ fees and costs. The patient had the good sense to avoid medical lenders, although other members of the class did use medical lenders and are now filing complaints about the way they were treated by these lenders.

- Maintain surgical skills and be open to new technology. Medical practice requires constant updating and use of new and improved technology as it comes along. By definition, new technology often requires new skills and understanding. A significant portion of surgeons using mesh indicated that they had not read the instructions for use, or had done so only once.1 CME programs that include surgical education remain of particular value.

- Whether new technology or old, it is essential to keep up to date on all FDA bulletins pertinent to devices and pharmaceuticals that you use and prescribe. For example, in 2016 and 2018 the FDA warned that the use of a very old class of drugs (fluoroquinolones) should be limited. It advised "that the serious side effects associated with fluoroquinolones generally outweigh the benefits for patients with acute sinusitis, acute bronchitis, and uncomplicated urinary tract infections who have other treatment options. For patients with these conditions, fluoroquinolones should be reserved for those who do not have alternative treatment options."2 Continued, unnecessary prescriptions for fluoroquinolones would put a physician at some legal risk whether or not the physician had paid any attention to the warning.

- Informed consent is a very important legal and medical process. Take it seriously, and make sure the patient has the information necessary to make informed decisions about treatment. Document the process and the information provided. In some cases consider directing patients to appropriate literature or websites of the manufacturers.

- As to the use of mesh, if not following FDA advice, it is important to document the reason for this and to document the informed consent especially carefully.

- Follow patients after mesh placement for a minimum of 1 year and emphasize to patients they should convey signs and symptoms of complications from initial placement.3 High-risk patients should be of particular concern and be monitored very closely.

References

- Kirkpatrick G, Faber KD, Fromer DL. Transvaginal mesh placement and the instructions for use: a survey of North American urologists. J Urol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urpr.2018.05.004.

- FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA advises restricting fluoroquinolone antibiotic use for certain uncomplicated infections; warns about disabling side effects that can occur together. July 26, 2016. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm500143.htm. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Karlovsky ME. How to avoid and deal with pelvic mesh litigation. Curr Urol Rep. 2016;17:55.

- Maral I, Ozkardeş H, Peşkircioğlu L, et al. Prevalence of stress urinary incontinence in both sexes at or after age 15 years: a cross-sectional study. J Urol. 2001;165:408-412.

- Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, et al. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501-506.

- Chang J, Lee D. Midurethral slings in the mesh litigation era. Transl Androl Urol. 2017;6(suppl 2): S68-S75.

- Mattingly R, ed. TeLinde's Operative Gynecology, 5th edition. Lippincott, William, and Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA; 1997.

- Burch J. Urethrovaginal fixation to Cooper's ligament for correction of stress incontinence, cystocele, and prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1961;81:281-290.

- Ulmsten U, Falconer C, Johnson P, et al. A multicenter study of tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) for surgical treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1998;9:210-213.

- Kuhlmann-Capek MJ, Kilic GS, Shah AB, et al. Enmeshed in controversy: use of vaginal mesh in the current medicolegal environment. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015;21:241-243.

- Powell SF. Changing our minds: reforming the FDA medical device reclassification process. Food Drug Law J. 2018;73:177-209.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Surgical Mesh for Treatment of Women with Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Stress Urinary Incontinence. September 2011. https://www.thesenatorsfirm.com/documents/OBS.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, et al. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(4):CD004014.

- Ganj FA, Ibeanu OA, Bedestani A, Nolan TE, Chesson RR. Complications of transvaginal monofilament polypropylene mesh in pelvic organ prolapse repair. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:919-925.

- Sung VW, Rogers RG, Schaffer JI, et al. Graft use in transvaginal pelvic organ prolapse repair: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:1131-1142.

- FDA public health notification: serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh in repair of pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence. October 20, 2008. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/PublicHealthNotifications/ucm061976.htm. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- Riegel v. Medtronic, 552 U.S. 312 (2008).

- Whitney DW. Guide to preemption of state-law claims against Class III PMA medical devices. Food Drug Law J. 2010;65:113-139.

- Alam P, Iglesia CB. Informed consent for reconstructive pelvic surgery. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2016;43:131-139.

- Nosti PA, Iglesia CB. Medicolegal issues surrounding devices and mesh for surgical treatment of prolapse and incontinence. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;56:221-228.

- Shepherd CG. Transvaginal mesh litigation: a new opportunity to resolve mass medical device failure claims. Tennessee Law Rev. 2012;80:3:477-94.

- Karlovsky ME. How to avoid and deal with pelvic mesh litigation. Curr Urol Rep. 2016;17:55.

- Cohn JA, Timbrook Brown E, Kowalik CG, et al. The mesh controversy. F1000Research website. https://f1000research.com/articles/5-2423/v1. Accessed June 17, 2019.

- Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel Meeting, February 12, 2019. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/media/122867/download. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Mucowski SJ, Jurnalov C, Phelps JY. Use of vaginal mesh in the face of recent FDA warnings and litigation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:103.e1-e4.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 439: informed consent. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(2 pt 1):401-408.

- Souders CP, Eilber KS, McClelland L, et al. The truth behind transvaginal mesh litigation: devices, timelines, and provider characteristics. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018;24:21-25.

- Goldstein M. As pelvic mesh settlements near $8 billion, women question lawyers' fees. New York Times. February 1, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/01/business/pelvic-mesh-settlements-lawyers.html. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Johnson G. Surgeons fear pelvic mesh lawsuits will spook patients. Associated Press News. January 10, 2019. https://www.apnews.com/25777c3c33e3489283b1dc2ebdde6b55. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Clarke RN. Medical device marketing and the ethics of vaginal mesh kit marketing. In The Innovation and Evolution of Medical Devices. New York, NY: Springer; 2019:103-123.

- Top 5 drug and medical device developments of 2018. Law 360. January 1, 2019. Accessed through LexisNexis.

- Frankel A, Dye J. The Lien Machine. New breed of investor profits by financing surgeries for desperate women patients. Reuters. August 18, 2015. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/usa-litigation-mesh/. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Sullivan T. New report looks at intersection of "medical lending" and pelvic mesh lawsuits. Policy & Medicine. May 5, 2018. https://www.policymed.com/2015/08/medical-lending-and-pelvic-mesh-litigation.html. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Goldstein M, Sliver-Greensberg J. How profiteers lure women into often-unneeded surgery. New York Times. April 14, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/14/business/vaginal-mesh-surgery-lawsuits-financing.html. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Maral I, Ozkardeş H, Peşkircioğlu L, et al. Prevalence of stress urinary incontinence in both sexes at or after age 15 years: a cross-sectional study. J Urol. 2001;165:408-412.

- Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, et al. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501-506.

- Chang J, Lee D. Midurethral slings in the mesh litigation era. Transl Androl Urol. 2017;6(suppl 2): S68-S75.

- Mattingly R, ed. TeLinde's Operative Gynecology, 5th edition. Lippincott, William, and Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA; 1997.

- Burch J. Urethrovaginal fixation to Cooper's ligament for correction of stress incontinence, cystocele, and prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1961;81:281-290.

- Ulmsten U, Falconer C, Johnson P, et al. A multicenter study of tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) for surgical treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1998;9:210-213.

- Kuhlmann-Capek MJ, Kilic GS, Shah AB, et al. Enmeshed in controversy: use of vaginal mesh in the current medicolegal environment. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015;21:241-243.

- Powell SF. Changing our minds: reforming the FDA medical device reclassification process. Food Drug Law J. 2018;73:177-209.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Surgical Mesh for Treatment of Women with Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Stress Urinary Incontinence. September 2011. https://www.thesenatorsfirm.com/documents/OBS.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, et al. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(4):CD004014.

- Ganj FA, Ibeanu OA, Bedestani A, Nolan TE, Chesson RR. Complications of transvaginal monofilament polypropylene mesh in pelvic organ prolapse repair. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:919-925.

- Sung VW, Rogers RG, Schaffer JI, et al. Graft use in transvaginal pelvic organ prolapse repair: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:1131-1142.

- FDA public health notification: serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh in repair of pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence. October 20, 2008. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/PublicHealthNotifications/ucm061976.htm. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- Riegel v. Medtronic, 552 U.S. 312 (2008).

- Whitney DW. Guide to preemption of state-law claims against Class III PMA medical devices. Food Drug Law J. 2010;65:113-139.

- Alam P, Iglesia CB. Informed consent for reconstructive pelvic surgery. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2016;43:131-139.

- Nosti PA, Iglesia CB. Medicolegal issues surrounding devices and mesh for surgical treatment of prolapse and incontinence. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;56:221-228.

- Shepherd CG. Transvaginal mesh litigation: a new opportunity to resolve mass medical device failure claims. Tennessee Law Rev. 2012;80:3:477-94.

- Karlovsky ME. How to avoid and deal with pelvic mesh litigation. Curr Urol Rep. 2016;17:55.

- Cohn JA, Timbrook Brown E, Kowalik CG, et al. The mesh controversy. F1000Research website. https://f1000research.com/articles/5-2423/v1. Accessed June 17, 2019.

- Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel Meeting, February 12, 2019. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/media/122867/download. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Mucowski SJ, Jurnalov C, Phelps JY. Use of vaginal mesh in the face of recent FDA warnings and litigation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:103.e1-e4.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 439: informed consent. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(2 pt 1):401-408.

- Souders CP, Eilber KS, McClelland L, et al. The truth behind transvaginal mesh litigation: devices, timelines, and provider characteristics. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018;24:21-25.

- Goldstein M. As pelvic mesh settlements near $8 billion, women question lawyers' fees. New York Times. February 1, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/01/business/pelvic-mesh-settlements-lawyers.html. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Johnson G. Surgeons fear pelvic mesh lawsuits will spook patients. Associated Press News. January 10, 2019. https://www.apnews.com/25777c3c33e3489283b1dc2ebdde6b55. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Clarke RN. Medical device marketing and the ethics of vaginal mesh kit marketing. In The Innovation and Evolution of Medical Devices. New York, NY: Springer; 2019:103-123.

- Top 5 drug and medical device developments of 2018. Law 360. January 1, 2019. Accessed through LexisNexis.

- Frankel A, Dye J. The Lien Machine. New breed of investor profits by financing surgeries for desperate women patients. Reuters. August 18, 2015. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/usa-litigation-mesh/. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Sullivan T. New report looks at intersection of "medical lending" and pelvic mesh lawsuits. Policy & Medicine. May 5, 2018. https://www.policymed.com/2015/08/medical-lending-and-pelvic-mesh-litigation.html. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- Goldstein M, Sliver-Greensberg J. How profiteers lure women into often-unneeded surgery. New York Times. April 14, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/14/business/vaginal-mesh-surgery-lawsuits-financing.html. Accessed June 19, 2019.

SUI cure definition may need updating

TUCSON, ARIZ. – The definition of a surgical cure for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) varies significantly from one clinical trial to another, but the best choice might be an International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire (ICIQ) score of 5 or less, according to a study that correlated a patient’s definition of success with various measures of success or failure.

Adoption of a standard definition could make clinical trial results easier to interpret, as well as improve consistency in clinical practice.

The study was a planned secondary analysis of a randomized, controlled trial that compared midurethral sling to Burch colpopexy in women undergoing abdominal sacrocolpopexy. The original study found no difference in outcomes between the two approaches with respect to stress-specific incontinence rates at 6 months, although the midurethral sling was associated with better secondary, patient-reported outcomes.

That incongruity between objective and subjective outcomes raised questions. “I would frequently have the nurse tell me that a patient didn’t do well [on the stress incontinence test], but you would talk to the patient, and she was happy as could be. She wasn’t using pads, she was perfectly dry. So I thought there was a little bit of a disconnect between the definitions we were using, and what the patients wanted from the procedure,” Emanuel Trabuco, MD, said in an interview.

Dr. Trabuco is a consultant and the chair of the division of urogynecology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He presented the study at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

because as things currently stand, different clinical trials use a range of different outcomes, and as the nurse’s experience shows, an objective outcome might not match patient perception. In fact, objective urinary incontinence tests may not be so objective at all.