User login

Rate of sling removal 9 years after MUS for SUI over 3%

a British study found.

Ipek Gurol-Urganci, PhD, of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and her coauthors said their study comes as a result of safety concerns around the procedure, which resulted in a suspension of the operation in the United Kingdom.

“There is concern about problems that some women experience following MUS insertion, including pain, dyspareunia, persistent urinary incontinence, and exposure or erosion. However, there is little randomized, clinical trial evidence on these longer-term outcomes,” they wrote in JAMA, noting that an estimated 250,000 MUS operations were performed in 2010 in the United States.

The current study involved 95,057 women in England who underwent an MUS insertion procedure for SUI for the first time in a National Health Service hospital between 2006 and 2015. Overall, 60,194 of the women had a retropubic insertion and 34,863 had a transobturator insertion.

At 9 years after the initial insertion, the mesh was removed in 3.3% of women. The risk of removal was higher for women who had a retropubic insertion (3.6%), compared with those who had a transobturator insertion (2.7%).

“The risk of a removal was about 30% lower if the mesh sling had been inserted via the transobturator route, which may be explained by the removal of transobturator sling being a more complicated procedure,” Dr. Gurol-Urganci and her associates noted.

Mesh sling removal risk decreased with age, with the risk at 4.4% for women aged 18-39 years, compared with 2.1% in women aged 70 years and older at 9 years after insertion.

The authors wrote that the risks of removal and any reoperation (mesh removal and/or reoperation for SUI) were higher among women from a white racial/ethnic background. However, it was not possible to “disentangle explanations” for these possible differences in risk seen with patient characteristics, which ranged from higher morbidity to differences in the reasons for surgery.

Results also showed that the risk of reoperation was 4.5% at 9 years after the initial insertion, and was slightly higher for a transobturator insertion at 5.3%, compared with 4.1% for a retropubic insertion.

The risk of any reoperation, including mesh removal and/or reoperation for SUI, following the initial MUS insertion was 6.9% at 9 years (95% confidence interval, 6.7%-7.1%), but no statistically significant difference was observed between retropubic and transobturator insertion.

“The present results demonstrate that removal and reoperation risks were associated with the insertion route and patient factors,” Dr. Gurol-Urganci and her associates wrote.

“These findings may guide women and their surgeons when making decisions about surgical treatment of stress urinary incontinence,” they concluded.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research Programme and several of the authors reported receiving National Institute for Health Research research grants. One author reported providing consultancy services to Cambridge Medical Robotics, Femeda, and Astellas.

SOURCE: Gurol-Urganci I et al. JAMA. 2018 Oct 23. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.14997.

a British study found.

Ipek Gurol-Urganci, PhD, of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and her coauthors said their study comes as a result of safety concerns around the procedure, which resulted in a suspension of the operation in the United Kingdom.

“There is concern about problems that some women experience following MUS insertion, including pain, dyspareunia, persistent urinary incontinence, and exposure or erosion. However, there is little randomized, clinical trial evidence on these longer-term outcomes,” they wrote in JAMA, noting that an estimated 250,000 MUS operations were performed in 2010 in the United States.

The current study involved 95,057 women in England who underwent an MUS insertion procedure for SUI for the first time in a National Health Service hospital between 2006 and 2015. Overall, 60,194 of the women had a retropubic insertion and 34,863 had a transobturator insertion.

At 9 years after the initial insertion, the mesh was removed in 3.3% of women. The risk of removal was higher for women who had a retropubic insertion (3.6%), compared with those who had a transobturator insertion (2.7%).

“The risk of a removal was about 30% lower if the mesh sling had been inserted via the transobturator route, which may be explained by the removal of transobturator sling being a more complicated procedure,” Dr. Gurol-Urganci and her associates noted.

Mesh sling removal risk decreased with age, with the risk at 4.4% for women aged 18-39 years, compared with 2.1% in women aged 70 years and older at 9 years after insertion.

The authors wrote that the risks of removal and any reoperation (mesh removal and/or reoperation for SUI) were higher among women from a white racial/ethnic background. However, it was not possible to “disentangle explanations” for these possible differences in risk seen with patient characteristics, which ranged from higher morbidity to differences in the reasons for surgery.

Results also showed that the risk of reoperation was 4.5% at 9 years after the initial insertion, and was slightly higher for a transobturator insertion at 5.3%, compared with 4.1% for a retropubic insertion.

The risk of any reoperation, including mesh removal and/or reoperation for SUI, following the initial MUS insertion was 6.9% at 9 years (95% confidence interval, 6.7%-7.1%), but no statistically significant difference was observed between retropubic and transobturator insertion.

“The present results demonstrate that removal and reoperation risks were associated with the insertion route and patient factors,” Dr. Gurol-Urganci and her associates wrote.

“These findings may guide women and their surgeons when making decisions about surgical treatment of stress urinary incontinence,” they concluded.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research Programme and several of the authors reported receiving National Institute for Health Research research grants. One author reported providing consultancy services to Cambridge Medical Robotics, Femeda, and Astellas.

SOURCE: Gurol-Urganci I et al. JAMA. 2018 Oct 23. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.14997.

a British study found.

Ipek Gurol-Urganci, PhD, of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and her coauthors said their study comes as a result of safety concerns around the procedure, which resulted in a suspension of the operation in the United Kingdom.

“There is concern about problems that some women experience following MUS insertion, including pain, dyspareunia, persistent urinary incontinence, and exposure or erosion. However, there is little randomized, clinical trial evidence on these longer-term outcomes,” they wrote in JAMA, noting that an estimated 250,000 MUS operations were performed in 2010 in the United States.

The current study involved 95,057 women in England who underwent an MUS insertion procedure for SUI for the first time in a National Health Service hospital between 2006 and 2015. Overall, 60,194 of the women had a retropubic insertion and 34,863 had a transobturator insertion.

At 9 years after the initial insertion, the mesh was removed in 3.3% of women. The risk of removal was higher for women who had a retropubic insertion (3.6%), compared with those who had a transobturator insertion (2.7%).

“The risk of a removal was about 30% lower if the mesh sling had been inserted via the transobturator route, which may be explained by the removal of transobturator sling being a more complicated procedure,” Dr. Gurol-Urganci and her associates noted.

Mesh sling removal risk decreased with age, with the risk at 4.4% for women aged 18-39 years, compared with 2.1% in women aged 70 years and older at 9 years after insertion.

The authors wrote that the risks of removal and any reoperation (mesh removal and/or reoperation for SUI) were higher among women from a white racial/ethnic background. However, it was not possible to “disentangle explanations” for these possible differences in risk seen with patient characteristics, which ranged from higher morbidity to differences in the reasons for surgery.

Results also showed that the risk of reoperation was 4.5% at 9 years after the initial insertion, and was slightly higher for a transobturator insertion at 5.3%, compared with 4.1% for a retropubic insertion.

The risk of any reoperation, including mesh removal and/or reoperation for SUI, following the initial MUS insertion was 6.9% at 9 years (95% confidence interval, 6.7%-7.1%), but no statistically significant difference was observed between retropubic and transobturator insertion.

“The present results demonstrate that removal and reoperation risks were associated with the insertion route and patient factors,” Dr. Gurol-Urganci and her associates wrote.

“These findings may guide women and their surgeons when making decisions about surgical treatment of stress urinary incontinence,” they concluded.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research Programme and several of the authors reported receiving National Institute for Health Research research grants. One author reported providing consultancy services to Cambridge Medical Robotics, Femeda, and Astellas.

SOURCE: Gurol-Urganci I et al. JAMA. 2018 Oct 23. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.14997.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: The findings of this study may inform decision making when choosing treatment for stress urinary incontinence.

Major finding: Within 9 years of a mesh insertion for stress urinary incontinence, the rate of sling removal was 3.3% and the rate of reoperation was 4.5%.

Study details: A prospective, observational study examining long-term mesh removal and reoperations in over 95,000 women who underwent midurethral mesh operations for stress urinary incontinence between 2006 and 2015.

Disclosures: The study was supported by a grant from the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research Programme and several of the authors reported receiving National Institute for Health Research research grants. One author reported providing consultancy services to Cambridge Medical Robotics, Femeda, and Astellas Pharma.

Source: Gurol-Urganci I et al. JAMA. 2018 Oct 23. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.14997.

New and promising GSM treatments, more clinical takeaways from NAMS 2018

Learn more about NAMS: http://www.menopause.org/home

Learn more about NAMS: http://www.menopause.org/home

Learn more about NAMS: http://www.menopause.org/home

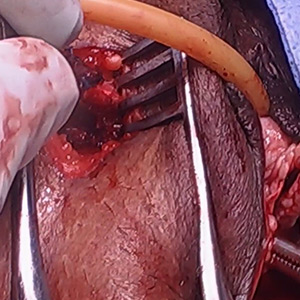

Vaginal and bilateral thigh removal of a transobturator sling

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

- Morcellation at the time of vaginal hysterectomy

- Surgical management of non-tubal ectopic pregnancies

- Size can matter: Laparoscopic hysterectomy for the very large uterus

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

- Morcellation at the time of vaginal hysterectomy

- Surgical management of non-tubal ectopic pregnancies

- Size can matter: Laparoscopic hysterectomy for the very large uterus

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

- Morcellation at the time of vaginal hysterectomy

- Surgical management of non-tubal ectopic pregnancies

- Size can matter: Laparoscopic hysterectomy for the very large uterus

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

This video is brought to you by

2018 Update on pelvic floor dysfunction

Using cystoscopy to evaluate ureteral efflux and bladder integrity following benign gynecologic surgery increases the detection rate of urinary tract injuries.1 Currently, it is standard of care to perform a cystoscopy following anti-incontinence procedures, but there is no consensus among ObGyns regarding the use of universal cystoscopy following benign gynecologic surgery.2 A number of studies, however, have suggested potential best practices for evaluating urinary tract injury during pelvic surgery for benign gynecologic conditions.

Pelvic surgeries for benign gynecologic conditions, including fibroids, menorrhagia, and pelvic organ prolapse (POP), are common. More than 500,000 hysterectomies are performed annually in the United States, and up to 11% of women will undergo at least one surgery for POP or urinary incontinence in their lifetime.3,4 During gynecologic surgery, the urinary tract is at risk, and the injury rate ranges from 0.02% to 2% for ureteral injury and from 1% to 5% for bladder injury.5,6

In a recent large randomized controlled trial, the rate of intraoperative ureteral obstruction following uterosacral ligament suspension (USLS) was 3.2%.7 Vaginal vault suspensions, as well as other vaginal cuff closure techniques, are common procedures associated with urinary tract injury.8 Additionally, ureteral injury during surgery for POP occurs in as many as 2% of anterior vaginal wall repairs.9

It is well documented that a delay in diagnosis of ureteral and/or bladder injuries is associated with increased morbidity, including the need for additional surgery to repair the injury; in addition, significant delay in identifying an injury may lead to subsequent sequela, such as renal injury and fistula formation.8

A large study in California found that 36.5% of hysterectomies performed for POP were performed by general gynecologists.10 General ObGyns performing these surgeries therefore must understand the risk of urinary tract injury during hysterectomy and reconstructive pelvic procedures so that they can appropriately identify, evaluate, and repair injuries in a timely fashion.

The best way to identify urinary tract injury at the time of gynecologic surgery is by cystoscopy, including a bladder survey and ureteral efflux evaluation. When should a cystoscopy be performed, and what is the best method for visualizing ureteral efflux? Can instituting universal cystoscopy for all gynecologic procedures make a difference in the rate of injury detection? In this Update, we summarize the data from 4 studies that help to answer these questions.

Continue to: About 30% of urinary tract injuries...

About 30% of urinary tract injuries identified prior to cystoscopy at hysterectomy (which detected 5 of 6 injuries)

Vakili B, Chesson RR, Kyle BL, et al. The incidence of urinary tract injury during hysterectomy: a prospective analysis based on universal cystoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5):1599–1604.

Vakili and colleagues conducted a multicenter prospective cohort study of women undergoing hysterectomy for benign indications; cystoscopy was performed in all cases. The 3 hospitals involved were all part of the Louisiana State University Health system. The investigators’ goal was to determine the rate of urinary tract injury in this patient population at the time of intraoperative cystoscopy.

Intraoperative cystoscopy beats visual evaluation

Four hundred and seventy-one women underwent hysterectomy and had intraoperative cystoscopy, including evaluation of ureteral patency with administration of intravenous (IV) indigo carmine. Patients underwent abdominal, vaginal, or laparoscopic hysterectomy, and 54 (11.4%) had concurrent POP or anti-incontinence procedures. The majority underwent an abdominal hysterectomy (59%), 31% had a vaginal hysterectomy, and 10% had a laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy or total laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Rate of urinary tract injuries. The total urinary tract injury rate detected by cystoscopy was 4.8%. The ureteral injury rate was 1.7%, and the bladder injury rate was 3.6%. A combined ureteral and bladder injury occurred in 2 women.

Surgery for POP significantly increased the risk of ureteral injury (7.3% vs 1.2%; P = .025). All cases of ureteral injury during POP surgery occurred during USLS. There was a trend toward a higher rate of bladder injury in the group with concurrent anti-incontinence surgery (12.5% vs 3.1%; P = .049). Regarding the route of hysterectomy, the vaginal approach had the highest rate of ureteral injury; however, when prolapse cases were removed from the analysis, there were no differences between the abdominal, vaginal, and laparoscopic approaches for ureteral or bladder injuries.

Injury detection with cystoscopy. Importantly, the authors found that only 30% of injuries were identified prior to performing intraoperative cystoscopy. The majority of these were bladder injuries. In addition, despite visual confirmation of ureteral peristalsis during abdominal hysterectomy, when intraoperative cystoscopy was performed with evaluation for ureteral efflux, 5 of 6 ureteral injury cases were identified. The authors reported 1 postoperative vesicovaginal fistula and concluded that it was likely due to an unrecognized bladder injury. No other undetected injuries were identified.

Notably, no complications occurred as a result of cystoscopy.

Multiple surgical indications reflect real-world scenario

The study included physicians from 3 different hospitals and all routes of hysterectomy for multiple benign gynecologic indications as well as concomitant pelvic reconstructive procedures. While this enhances the generalizability of the study results, all study sites were located in Louisiana at hospitals with resident trainee involvement. Additionally, this study confirms previous retrospective studies that reported higher rates of injury with pelvic reconstructive procedures.

The study is limited by the inability to blind surgeons, which may have resulted in the surgeons altering their techniques and/or having a heightened awareness of the urinary tract. However, their rates of ureteral and bladder injuries were slightly higher than previously reported rates, suggesting that the procedures inherently carry risk. The study is further limited by the lack of a retrospective comparison group of hysterectomy without routine cystoscopy and a longer follow-up period that may have revealed additional missed delayed urologic injuries.

The rate of urinary tract injury, including both bladder and ureteral injuries, was more than 4% at the time of hysterectomy for benign conditions. Using intraoperative peristalsis or normal ureteral caliber could result in a false sense of security since these are not reliable signs of ureteral integrity. The majority of urinary tract injuries will not be identified without cystoscopic evaluation.

Continue to: Universal cystoscopy policy...

Universal cystoscopy policy proves protective, surgeon adherence is high

Chi AM, Curran DS, Morgan DM, Fenner DE, Swenson CW. Universal cystoscopy after benign hysterectomy: examining the effects of an institutional policy. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(2):369–375.

In a retrospective cohort study, Chi and colleagues evaluated urinary tract injuries at the time of hysterectomy before and after the institution of a universal cystoscopy policy. At the time of policy implementation at the University of Michigan, all faculty who performed hysterectomies attended a cystoscopy workshop. Attending physicians without prior cystoscopy training also were proctored in the operating room for 3 sessions and were required to demonstrate competency with bladder survey, visualizing ureteral efflux, and urethral assessment. Indigo carmine was used to visualize ureteral efflux.

Detection of urologic injury almost doubled with cystoscopy

A total of 2,822 hysterectomies were included in the study, with 973 in the pre–universal cystoscopy group and 1,849 in the post–universal cystoscopy group. The study period was 7 years, and data on complications were abstracted for 1 year after the completion of the study period.

The primary outcome had 3 components:

- the rate of urologic injury before and after the policy

- the cystoscopy detection rate of urologic injury

- the adherence rate to the policy.

The overall rate of bladder and ureteral injury was 2.1%; the rate of injury during pre–universal screening was 2.6%, and during post–universal screening was 1.8%. The intraoperative detection rate of injury nearly doubled, from 24% to 47%, when intraoperative cystoscopy was utilized. In addition, the percentage of delayed urologic complications decreased from 28% to 5.9% (P = .03) following implementation of the universal cystoscopy policy. With regard to surgeon adherence, cystoscopy was documented in 86.1% of the hysterectomy cases after the policy was implemented compared with 35.7% of cases before the policy.

The investigators performed a cost analysis and found that hospital costs were nearly twice as much if a delayed urologic injury was diagnosed.

Study had many strengths

This study evaluated aspects of implementing quality initiatives after proper training and proctoring of a procedure. The authors compared very large cohorts from a busy academic medical center in which surgeon adherence with routine cystoscopy was high. The majority of patient outcomes were tracked for an extended period following surgery, thereby minimizing the risk of missing delayed urologic injuries. Notably, however, there was shorter follow-up time for the post–universal cystoscopy group, which could result in underestimating the rate of delayed urologic injuries in this cohort.

Instituting a universal cystoscopy policy for hysterectomy was associated with a significant decrease in delayed postoperative urinary tract complications and an increase in the intraoperative detection rate of urologic injuries. Intraoperative detection and repair of a urinary tract injury is cost-effective compared with a delayed diagnosis.

Continue to: Cystoscopy reveals ureteral obstruction...

Cystoscopy reveals ureteral obstruction during various vaginal POP repair procedures

Gustilo-Ashby AM, Jelovsek JE, Barber MD, Yoo EH, Paraiso MF, Walters MD. The incidence of ureteral obstruction and the value of intraoperative cystoscopy during vaginal surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(5):1478–1485.

To determine the rate of ureteral obstruction and ureteral injury during vaginal surgery for POP and the accuracy of using intraoperative cystoscopy to prevent upper urinary tract morbidity, Gustilo-Ashby and colleagues performed a retrospective review study of a large patient cohort.

Cystoscopy with indigo carmine is highly sensitive

The study included 700 patients who underwent vaginal surgery for anterior and/or apical POP. Patients had 1 or more of the following anterior and apical prolapse repair procedures: USLS (51%), distal McCall culdeplasty (26%), proximal McCall culdeplasty (29%), anterior colporrhaphy (82%), and colpocleisis (1.4%). Of note, distal McCall culdeplasty was defined as incorporation of the “vaginal epithelium into the uterosacral plication,” while proximal McCall culdeplasty involved plication of “the uterosacral ligaments in the midline proximal to the vaginal cuff.” All patients were given IV indigo carmine to aid in visualizing ureteral efflux.

The majority of patients had a hysterectomy (56%). When accounting for rare false-positive and negative cystoscopy results, the overall ureteral obstruction rate was 5.1% and the ureteral injury rate was 0.9%. The majority of obstructions occurred with USLS (5.9%), proximal McCall culdeplasty (4.4%), and colpocleisis (4.2%). Ureteral injuries occurred only in 6 cases: 3 USLS and 3 proximal McCall culdeplasty procedures.

Based on these findings, the authors calculated that cystoscopy at the time of vaginal surgery for anterior and/or apical prolapse has a sensitivity of 94.4% and a specificity of 99.5% for detecting ureteral obstruction. The positive predictive value of cystoscopy with the use of indigo carmine for detection of ureteral obstruction is 91.9% and the negative predictive value is 99.7%.

Impact of indigo carmine’s unavailability

This study’s strengths include its large sample size and the variety of surgical approaches used for repair of anterior vaginal wall and apical prolapse. Its retrospective design, however, is a limitation; this could result in underreporting of ureteral injuries if patients received care at another institution after surgery. Furthermore, it is unclear if cystoscopy would be as predictive of ureteral injury without the use of indigo carmine, which is no longer available at most institutions.

The utility of cystoscopy with IV indigo carmine as a screening test for ureteral obstruction is highlighted by the fact that most obstructions were relieved by intraoperative suture removal following positive cystoscopy. McCall culdeplasty procedures are commonly performed by general ObGyns at the time of vaginal hysterectomy. It is therefore important to note that rates of ureteral obstruction after proximal McCall culdeplasty were only slightly lower than those after USLS.

Continue to: Sodium fluorescein and 10% dextrose...

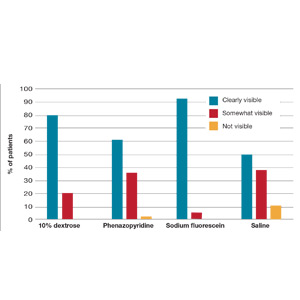

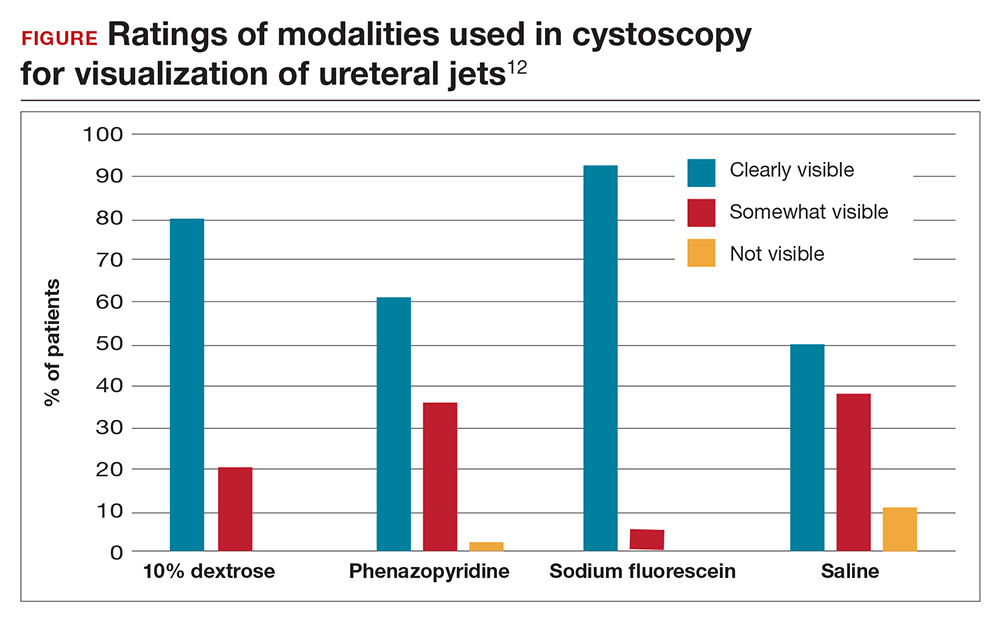

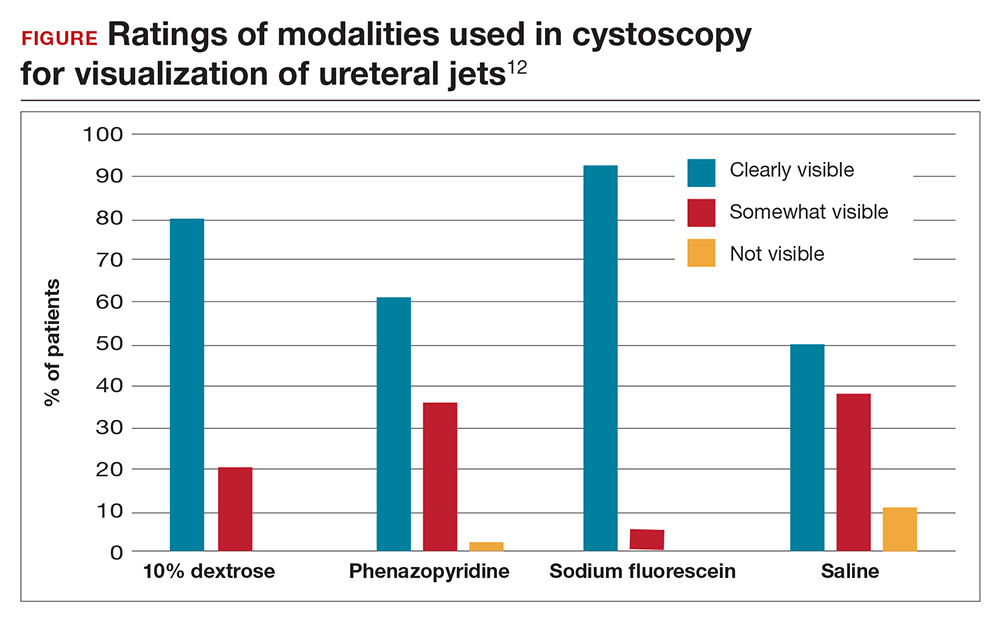

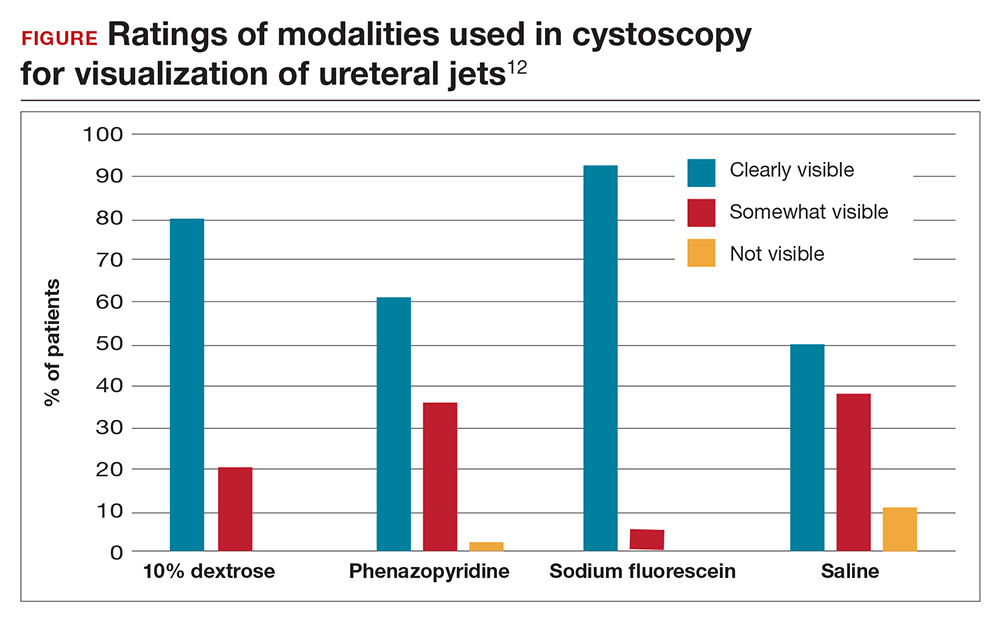

Sodium fluorescein and 10% dextrose provide clear visibility of ureteral jets in cystoscopy

Espaillat-Rijo L, Siff L, Alas AN, et al. Intraoperative cystoscopic evaluation of ureteral patency: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(6):1378–1383.

In a multicenter randomized controlled trial, Espaillat-Rijo and colleagues compared various methods for visualizing ureteral efflux in participants who underwent gynecologic or urogynecologic procedures in which cystoscopy was performed.

Study compared 4 media

The investigators enrolled 176 participants (174 completed the trial) and randomly assigned them to receive 1 of 4 modalities: 1) normal saline as a bladder distention medium (control), 2) 10% dextrose as a bladder distention medium, 3) 200 mg oral phenazopyridine given 30 minutes prior to cystoscopy, or 4) 50 mg IV sodium fluorescein at the start of cystoscopy. Indigo carmine was not included in this study because it has not been routinely available since 2014.

Surgeons were asked to categorize the ureteral jets as “clearly visible,” “somewhat visible,” or “not visible.”

The primary outcome was subjective visibility of the ureteral jet with each modality during cystoscopy. Secondary outcomes included surgeon satisfaction, adverse reactions to the modality used, postoperative urinary tract infection, postoperative urinary retention, and delayed diagnosis of ureteral injury.

Visibility assessment results. Overall, ureteral jets were “clearly visible” in 125 cases (71%) compared with “somewhat visible” in 45 (25.6%) and “not visible” in 4 (2.3%) cases. There was a statistically significant difference between the 4 groups. Use of sodium fluorescein and 10% dextrose resulted in significantly better visualization of ureteral jets (P < .001 and P = .004, respectively) compared with the control group. Visibility with phenazopyridine was not significantly different from that in the control group or in the 10% dextrose group (FIGURE).

Surgeon satisfaction was highest with 10% dextrose and sodium fluorescein. In 6 cases, the surgeon was not satisfied with visualization of the ureteral jets and relied on fluorescein (5 times) or 10% dextrose (1 time) to ultimately see efflux. No significant adverse events occurred; the rate of urinary tract infection was 24.1% and did not differ between groups.

Results are widely generalizable

This was a well-designed randomized multicenter trial that included both benign gynecologic and urogynecologic procedures, thus strengthening the generalizability of the study. The study was timely since proven methods for visualization of ureteral patency became limited with the withdrawal of commercially available indigo carmine, the previous gold standard.

Intravenous sodium fluorescein and 10% dextrose as bladder distention media can both safely be used to visualize ureteral efflux and result in high surgeon satisfaction. Although 10% dextrose has been associated with higher rates of postoperative urinary tract infection,11 this was not found to be the case in this study. Preoperative administration of oral phenazopyridine was no different from the control modality with regard to visibility and surgeon satisfaction.

Continue to: The cost-effectiveness consideration

The cost-effectiveness consideration

The debate around universal cystoscopy following benign gynecologic surgery is ongoing.

The studies discussed in this Update demonstrate that cystoscopy following hysterectomy for benign indications:

- is superior to visualizing ureteral peristalsis

- increases detection of urinary tract injuries, and

- decreases delayed urologic injuries.

Although these articles emphasize the importance of detecting urologic injury, the picture would not be complete without mention of cost-effectiveness. Only one study, from 2001, has evaluated the cost-effectiveness of universal cystoscopy.1 Those authors concluded that universal cystoscopy is cost-effective only when the rate of urologic injury is 1.5% to 2%, but this conclusion, admittedly, was limited by the lack of data on medicolegal settlements, outpatient expenses, and nonmedical-related economic loss from decreased productivity. Given the extensive changes that have occurred in medical practice over the last 17 years and the emphasis on quality metrics and safety, an updated analysis would be needed to make definitive conclusions about cost-effectiveness.

While this Update cannot settle the ongoing debate of universal cystoscopy in gynecology, it is important to remember that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Urogynecologic Society recommend cystoscopy following all surgeries for pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence.2

References

- Visco AG, Taber KH, Weidner AD, Barber MD, Myers ER. Cost-effectiveness of universal cystoscopy to identify ureteral injury at hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(5 pt 1):685–692.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology and the American Urogynecologic Society. Urinary incontinence in women. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015;21(6):304–314.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Ibeanu OA, Chesson RR, Echols KT, Nieves M, Busangu F, Nolan TE. Urinary tract injury during hysterectomy based on universal cystoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(1):6–10.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology and the American Urogynecologic Society. Urinary incontinence in women. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015;21(6):304–314.

- Wilcox LS, Koonin LM, Pokras R, Strauss LT, Xia Z, Peterson HB. Hysterectomy in the United States, 1988–1990. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83(4):549–555.

- Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89(4):501–506.

- Mäkinen J, Johansson J, Tomás C, et al. Morbidity of 10,110 hysterectomies by type of approach. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(7):1473–1478.

- Gilmour DT, Dwyer PL, Carey MP. Lower urinary tract injury during gynecologic surgery and its detection by intraoperative cystoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94(5 pt 2):883–889.

- Barber MD, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, et al; Eunice Kennedy Schriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse: the OPTIMAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1023–1034.

- Brandes S, Coburn M, Armenakas N, McAninch J. Diagnosis and management of ureteric injury: an evidence-based analysis. BJU Int. 2004;94(3):277–289.

- Kwon CH, Goldberg RP, Koduri S, Sand PK. The use of intraoperative cystoscopy in major vaginal and urogynecologic surgeries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(6):1466–1471.

- Adams-Piper ER, Guaderrama NM, Chen Q, Whitcomb EL. Impact of surgical training on the performance of proposed quality measures for hysterectomy for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(6):588.e1–588.e5.

- Siff LN, Unger CA, Jelovsek JE, Paraiso MF, Ridgeway BM Barber MD. Assessing ureteral patency using 10% dextrose cystoscopy fluid: evaluation of urinary tract infection rates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(1):74.e1–74.e6.

- Espaillat-Rijo L, Siff L, Alas AN, et al. Intraoperative cystoscopic evaluation of ureteral patency: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(6):1378–1383.

Using cystoscopy to evaluate ureteral efflux and bladder integrity following benign gynecologic surgery increases the detection rate of urinary tract injuries.1 Currently, it is standard of care to perform a cystoscopy following anti-incontinence procedures, but there is no consensus among ObGyns regarding the use of universal cystoscopy following benign gynecologic surgery.2 A number of studies, however, have suggested potential best practices for evaluating urinary tract injury during pelvic surgery for benign gynecologic conditions.

Pelvic surgeries for benign gynecologic conditions, including fibroids, menorrhagia, and pelvic organ prolapse (POP), are common. More than 500,000 hysterectomies are performed annually in the United States, and up to 11% of women will undergo at least one surgery for POP or urinary incontinence in their lifetime.3,4 During gynecologic surgery, the urinary tract is at risk, and the injury rate ranges from 0.02% to 2% for ureteral injury and from 1% to 5% for bladder injury.5,6

In a recent large randomized controlled trial, the rate of intraoperative ureteral obstruction following uterosacral ligament suspension (USLS) was 3.2%.7 Vaginal vault suspensions, as well as other vaginal cuff closure techniques, are common procedures associated with urinary tract injury.8 Additionally, ureteral injury during surgery for POP occurs in as many as 2% of anterior vaginal wall repairs.9

It is well documented that a delay in diagnosis of ureteral and/or bladder injuries is associated with increased morbidity, including the need for additional surgery to repair the injury; in addition, significant delay in identifying an injury may lead to subsequent sequela, such as renal injury and fistula formation.8

A large study in California found that 36.5% of hysterectomies performed for POP were performed by general gynecologists.10 General ObGyns performing these surgeries therefore must understand the risk of urinary tract injury during hysterectomy and reconstructive pelvic procedures so that they can appropriately identify, evaluate, and repair injuries in a timely fashion.

The best way to identify urinary tract injury at the time of gynecologic surgery is by cystoscopy, including a bladder survey and ureteral efflux evaluation. When should a cystoscopy be performed, and what is the best method for visualizing ureteral efflux? Can instituting universal cystoscopy for all gynecologic procedures make a difference in the rate of injury detection? In this Update, we summarize the data from 4 studies that help to answer these questions.

Continue to: About 30% of urinary tract injuries...

About 30% of urinary tract injuries identified prior to cystoscopy at hysterectomy (which detected 5 of 6 injuries)

Vakili B, Chesson RR, Kyle BL, et al. The incidence of urinary tract injury during hysterectomy: a prospective analysis based on universal cystoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5):1599–1604.

Vakili and colleagues conducted a multicenter prospective cohort study of women undergoing hysterectomy for benign indications; cystoscopy was performed in all cases. The 3 hospitals involved were all part of the Louisiana State University Health system. The investigators’ goal was to determine the rate of urinary tract injury in this patient population at the time of intraoperative cystoscopy.

Intraoperative cystoscopy beats visual evaluation

Four hundred and seventy-one women underwent hysterectomy and had intraoperative cystoscopy, including evaluation of ureteral patency with administration of intravenous (IV) indigo carmine. Patients underwent abdominal, vaginal, or laparoscopic hysterectomy, and 54 (11.4%) had concurrent POP or anti-incontinence procedures. The majority underwent an abdominal hysterectomy (59%), 31% had a vaginal hysterectomy, and 10% had a laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy or total laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Rate of urinary tract injuries. The total urinary tract injury rate detected by cystoscopy was 4.8%. The ureteral injury rate was 1.7%, and the bladder injury rate was 3.6%. A combined ureteral and bladder injury occurred in 2 women.

Surgery for POP significantly increased the risk of ureteral injury (7.3% vs 1.2%; P = .025). All cases of ureteral injury during POP surgery occurred during USLS. There was a trend toward a higher rate of bladder injury in the group with concurrent anti-incontinence surgery (12.5% vs 3.1%; P = .049). Regarding the route of hysterectomy, the vaginal approach had the highest rate of ureteral injury; however, when prolapse cases were removed from the analysis, there were no differences between the abdominal, vaginal, and laparoscopic approaches for ureteral or bladder injuries.

Injury detection with cystoscopy. Importantly, the authors found that only 30% of injuries were identified prior to performing intraoperative cystoscopy. The majority of these were bladder injuries. In addition, despite visual confirmation of ureteral peristalsis during abdominal hysterectomy, when intraoperative cystoscopy was performed with evaluation for ureteral efflux, 5 of 6 ureteral injury cases were identified. The authors reported 1 postoperative vesicovaginal fistula and concluded that it was likely due to an unrecognized bladder injury. No other undetected injuries were identified.

Notably, no complications occurred as a result of cystoscopy.

Multiple surgical indications reflect real-world scenario

The study included physicians from 3 different hospitals and all routes of hysterectomy for multiple benign gynecologic indications as well as concomitant pelvic reconstructive procedures. While this enhances the generalizability of the study results, all study sites were located in Louisiana at hospitals with resident trainee involvement. Additionally, this study confirms previous retrospective studies that reported higher rates of injury with pelvic reconstructive procedures.

The study is limited by the inability to blind surgeons, which may have resulted in the surgeons altering their techniques and/or having a heightened awareness of the urinary tract. However, their rates of ureteral and bladder injuries were slightly higher than previously reported rates, suggesting that the procedures inherently carry risk. The study is further limited by the lack of a retrospective comparison group of hysterectomy without routine cystoscopy and a longer follow-up period that may have revealed additional missed delayed urologic injuries.

The rate of urinary tract injury, including both bladder and ureteral injuries, was more than 4% at the time of hysterectomy for benign conditions. Using intraoperative peristalsis or normal ureteral caliber could result in a false sense of security since these are not reliable signs of ureteral integrity. The majority of urinary tract injuries will not be identified without cystoscopic evaluation.

Continue to: Universal cystoscopy policy...

Universal cystoscopy policy proves protective, surgeon adherence is high

Chi AM, Curran DS, Morgan DM, Fenner DE, Swenson CW. Universal cystoscopy after benign hysterectomy: examining the effects of an institutional policy. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(2):369–375.

In a retrospective cohort study, Chi and colleagues evaluated urinary tract injuries at the time of hysterectomy before and after the institution of a universal cystoscopy policy. At the time of policy implementation at the University of Michigan, all faculty who performed hysterectomies attended a cystoscopy workshop. Attending physicians without prior cystoscopy training also were proctored in the operating room for 3 sessions and were required to demonstrate competency with bladder survey, visualizing ureteral efflux, and urethral assessment. Indigo carmine was used to visualize ureteral efflux.

Detection of urologic injury almost doubled with cystoscopy

A total of 2,822 hysterectomies were included in the study, with 973 in the pre–universal cystoscopy group and 1,849 in the post–universal cystoscopy group. The study period was 7 years, and data on complications were abstracted for 1 year after the completion of the study period.

The primary outcome had 3 components:

- the rate of urologic injury before and after the policy

- the cystoscopy detection rate of urologic injury

- the adherence rate to the policy.

The overall rate of bladder and ureteral injury was 2.1%; the rate of injury during pre–universal screening was 2.6%, and during post–universal screening was 1.8%. The intraoperative detection rate of injury nearly doubled, from 24% to 47%, when intraoperative cystoscopy was utilized. In addition, the percentage of delayed urologic complications decreased from 28% to 5.9% (P = .03) following implementation of the universal cystoscopy policy. With regard to surgeon adherence, cystoscopy was documented in 86.1% of the hysterectomy cases after the policy was implemented compared with 35.7% of cases before the policy.

The investigators performed a cost analysis and found that hospital costs were nearly twice as much if a delayed urologic injury was diagnosed.

Study had many strengths

This study evaluated aspects of implementing quality initiatives after proper training and proctoring of a procedure. The authors compared very large cohorts from a busy academic medical center in which surgeon adherence with routine cystoscopy was high. The majority of patient outcomes were tracked for an extended period following surgery, thereby minimizing the risk of missing delayed urologic injuries. Notably, however, there was shorter follow-up time for the post–universal cystoscopy group, which could result in underestimating the rate of delayed urologic injuries in this cohort.

Instituting a universal cystoscopy policy for hysterectomy was associated with a significant decrease in delayed postoperative urinary tract complications and an increase in the intraoperative detection rate of urologic injuries. Intraoperative detection and repair of a urinary tract injury is cost-effective compared with a delayed diagnosis.

Continue to: Cystoscopy reveals ureteral obstruction...

Cystoscopy reveals ureteral obstruction during various vaginal POP repair procedures

Gustilo-Ashby AM, Jelovsek JE, Barber MD, Yoo EH, Paraiso MF, Walters MD. The incidence of ureteral obstruction and the value of intraoperative cystoscopy during vaginal surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(5):1478–1485.

To determine the rate of ureteral obstruction and ureteral injury during vaginal surgery for POP and the accuracy of using intraoperative cystoscopy to prevent upper urinary tract morbidity, Gustilo-Ashby and colleagues performed a retrospective review study of a large patient cohort.

Cystoscopy with indigo carmine is highly sensitive

The study included 700 patients who underwent vaginal surgery for anterior and/or apical POP. Patients had 1 or more of the following anterior and apical prolapse repair procedures: USLS (51%), distal McCall culdeplasty (26%), proximal McCall culdeplasty (29%), anterior colporrhaphy (82%), and colpocleisis (1.4%). Of note, distal McCall culdeplasty was defined as incorporation of the “vaginal epithelium into the uterosacral plication,” while proximal McCall culdeplasty involved plication of “the uterosacral ligaments in the midline proximal to the vaginal cuff.” All patients were given IV indigo carmine to aid in visualizing ureteral efflux.

The majority of patients had a hysterectomy (56%). When accounting for rare false-positive and negative cystoscopy results, the overall ureteral obstruction rate was 5.1% and the ureteral injury rate was 0.9%. The majority of obstructions occurred with USLS (5.9%), proximal McCall culdeplasty (4.4%), and colpocleisis (4.2%). Ureteral injuries occurred only in 6 cases: 3 USLS and 3 proximal McCall culdeplasty procedures.

Based on these findings, the authors calculated that cystoscopy at the time of vaginal surgery for anterior and/or apical prolapse has a sensitivity of 94.4% and a specificity of 99.5% for detecting ureteral obstruction. The positive predictive value of cystoscopy with the use of indigo carmine for detection of ureteral obstruction is 91.9% and the negative predictive value is 99.7%.

Impact of indigo carmine’s unavailability

This study’s strengths include its large sample size and the variety of surgical approaches used for repair of anterior vaginal wall and apical prolapse. Its retrospective design, however, is a limitation; this could result in underreporting of ureteral injuries if patients received care at another institution after surgery. Furthermore, it is unclear if cystoscopy would be as predictive of ureteral injury without the use of indigo carmine, which is no longer available at most institutions.

The utility of cystoscopy with IV indigo carmine as a screening test for ureteral obstruction is highlighted by the fact that most obstructions were relieved by intraoperative suture removal following positive cystoscopy. McCall culdeplasty procedures are commonly performed by general ObGyns at the time of vaginal hysterectomy. It is therefore important to note that rates of ureteral obstruction after proximal McCall culdeplasty were only slightly lower than those after USLS.

Continue to: Sodium fluorescein and 10% dextrose...

Sodium fluorescein and 10% dextrose provide clear visibility of ureteral jets in cystoscopy

Espaillat-Rijo L, Siff L, Alas AN, et al. Intraoperative cystoscopic evaluation of ureteral patency: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(6):1378–1383.

In a multicenter randomized controlled trial, Espaillat-Rijo and colleagues compared various methods for visualizing ureteral efflux in participants who underwent gynecologic or urogynecologic procedures in which cystoscopy was performed.

Study compared 4 media

The investigators enrolled 176 participants (174 completed the trial) and randomly assigned them to receive 1 of 4 modalities: 1) normal saline as a bladder distention medium (control), 2) 10% dextrose as a bladder distention medium, 3) 200 mg oral phenazopyridine given 30 minutes prior to cystoscopy, or 4) 50 mg IV sodium fluorescein at the start of cystoscopy. Indigo carmine was not included in this study because it has not been routinely available since 2014.

Surgeons were asked to categorize the ureteral jets as “clearly visible,” “somewhat visible,” or “not visible.”

The primary outcome was subjective visibility of the ureteral jet with each modality during cystoscopy. Secondary outcomes included surgeon satisfaction, adverse reactions to the modality used, postoperative urinary tract infection, postoperative urinary retention, and delayed diagnosis of ureteral injury.

Visibility assessment results. Overall, ureteral jets were “clearly visible” in 125 cases (71%) compared with “somewhat visible” in 45 (25.6%) and “not visible” in 4 (2.3%) cases. There was a statistically significant difference between the 4 groups. Use of sodium fluorescein and 10% dextrose resulted in significantly better visualization of ureteral jets (P < .001 and P = .004, respectively) compared with the control group. Visibility with phenazopyridine was not significantly different from that in the control group or in the 10% dextrose group (FIGURE).

Surgeon satisfaction was highest with 10% dextrose and sodium fluorescein. In 6 cases, the surgeon was not satisfied with visualization of the ureteral jets and relied on fluorescein (5 times) or 10% dextrose (1 time) to ultimately see efflux. No significant adverse events occurred; the rate of urinary tract infection was 24.1% and did not differ between groups.

Results are widely generalizable

This was a well-designed randomized multicenter trial that included both benign gynecologic and urogynecologic procedures, thus strengthening the generalizability of the study. The study was timely since proven methods for visualization of ureteral patency became limited with the withdrawal of commercially available indigo carmine, the previous gold standard.

Intravenous sodium fluorescein and 10% dextrose as bladder distention media can both safely be used to visualize ureteral efflux and result in high surgeon satisfaction. Although 10% dextrose has been associated with higher rates of postoperative urinary tract infection,11 this was not found to be the case in this study. Preoperative administration of oral phenazopyridine was no different from the control modality with regard to visibility and surgeon satisfaction.

Continue to: The cost-effectiveness consideration

The cost-effectiveness consideration

The debate around universal cystoscopy following benign gynecologic surgery is ongoing.

The studies discussed in this Update demonstrate that cystoscopy following hysterectomy for benign indications:

- is superior to visualizing ureteral peristalsis

- increases detection of urinary tract injuries, and

- decreases delayed urologic injuries.

Although these articles emphasize the importance of detecting urologic injury, the picture would not be complete without mention of cost-effectiveness. Only one study, from 2001, has evaluated the cost-effectiveness of universal cystoscopy.1 Those authors concluded that universal cystoscopy is cost-effective only when the rate of urologic injury is 1.5% to 2%, but this conclusion, admittedly, was limited by the lack of data on medicolegal settlements, outpatient expenses, and nonmedical-related economic loss from decreased productivity. Given the extensive changes that have occurred in medical practice over the last 17 years and the emphasis on quality metrics and safety, an updated analysis would be needed to make definitive conclusions about cost-effectiveness.

While this Update cannot settle the ongoing debate of universal cystoscopy in gynecology, it is important to remember that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Urogynecologic Society recommend cystoscopy following all surgeries for pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence.2

References

- Visco AG, Taber KH, Weidner AD, Barber MD, Myers ER. Cost-effectiveness of universal cystoscopy to identify ureteral injury at hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(5 pt 1):685–692.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology and the American Urogynecologic Society. Urinary incontinence in women. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015;21(6):304–314.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Using cystoscopy to evaluate ureteral efflux and bladder integrity following benign gynecologic surgery increases the detection rate of urinary tract injuries.1 Currently, it is standard of care to perform a cystoscopy following anti-incontinence procedures, but there is no consensus among ObGyns regarding the use of universal cystoscopy following benign gynecologic surgery.2 A number of studies, however, have suggested potential best practices for evaluating urinary tract injury during pelvic surgery for benign gynecologic conditions.

Pelvic surgeries for benign gynecologic conditions, including fibroids, menorrhagia, and pelvic organ prolapse (POP), are common. More than 500,000 hysterectomies are performed annually in the United States, and up to 11% of women will undergo at least one surgery for POP or urinary incontinence in their lifetime.3,4 During gynecologic surgery, the urinary tract is at risk, and the injury rate ranges from 0.02% to 2% for ureteral injury and from 1% to 5% for bladder injury.5,6

In a recent large randomized controlled trial, the rate of intraoperative ureteral obstruction following uterosacral ligament suspension (USLS) was 3.2%.7 Vaginal vault suspensions, as well as other vaginal cuff closure techniques, are common procedures associated with urinary tract injury.8 Additionally, ureteral injury during surgery for POP occurs in as many as 2% of anterior vaginal wall repairs.9

It is well documented that a delay in diagnosis of ureteral and/or bladder injuries is associated with increased morbidity, including the need for additional surgery to repair the injury; in addition, significant delay in identifying an injury may lead to subsequent sequela, such as renal injury and fistula formation.8

A large study in California found that 36.5% of hysterectomies performed for POP were performed by general gynecologists.10 General ObGyns performing these surgeries therefore must understand the risk of urinary tract injury during hysterectomy and reconstructive pelvic procedures so that they can appropriately identify, evaluate, and repair injuries in a timely fashion.

The best way to identify urinary tract injury at the time of gynecologic surgery is by cystoscopy, including a bladder survey and ureteral efflux evaluation. When should a cystoscopy be performed, and what is the best method for visualizing ureteral efflux? Can instituting universal cystoscopy for all gynecologic procedures make a difference in the rate of injury detection? In this Update, we summarize the data from 4 studies that help to answer these questions.

Continue to: About 30% of urinary tract injuries...

About 30% of urinary tract injuries identified prior to cystoscopy at hysterectomy (which detected 5 of 6 injuries)

Vakili B, Chesson RR, Kyle BL, et al. The incidence of urinary tract injury during hysterectomy: a prospective analysis based on universal cystoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5):1599–1604.

Vakili and colleagues conducted a multicenter prospective cohort study of women undergoing hysterectomy for benign indications; cystoscopy was performed in all cases. The 3 hospitals involved were all part of the Louisiana State University Health system. The investigators’ goal was to determine the rate of urinary tract injury in this patient population at the time of intraoperative cystoscopy.

Intraoperative cystoscopy beats visual evaluation

Four hundred and seventy-one women underwent hysterectomy and had intraoperative cystoscopy, including evaluation of ureteral patency with administration of intravenous (IV) indigo carmine. Patients underwent abdominal, vaginal, or laparoscopic hysterectomy, and 54 (11.4%) had concurrent POP or anti-incontinence procedures. The majority underwent an abdominal hysterectomy (59%), 31% had a vaginal hysterectomy, and 10% had a laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy or total laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Rate of urinary tract injuries. The total urinary tract injury rate detected by cystoscopy was 4.8%. The ureteral injury rate was 1.7%, and the bladder injury rate was 3.6%. A combined ureteral and bladder injury occurred in 2 women.

Surgery for POP significantly increased the risk of ureteral injury (7.3% vs 1.2%; P = .025). All cases of ureteral injury during POP surgery occurred during USLS. There was a trend toward a higher rate of bladder injury in the group with concurrent anti-incontinence surgery (12.5% vs 3.1%; P = .049). Regarding the route of hysterectomy, the vaginal approach had the highest rate of ureteral injury; however, when prolapse cases were removed from the analysis, there were no differences between the abdominal, vaginal, and laparoscopic approaches for ureteral or bladder injuries.

Injury detection with cystoscopy. Importantly, the authors found that only 30% of injuries were identified prior to performing intraoperative cystoscopy. The majority of these were bladder injuries. In addition, despite visual confirmation of ureteral peristalsis during abdominal hysterectomy, when intraoperative cystoscopy was performed with evaluation for ureteral efflux, 5 of 6 ureteral injury cases were identified. The authors reported 1 postoperative vesicovaginal fistula and concluded that it was likely due to an unrecognized bladder injury. No other undetected injuries were identified.

Notably, no complications occurred as a result of cystoscopy.

Multiple surgical indications reflect real-world scenario

The study included physicians from 3 different hospitals and all routes of hysterectomy for multiple benign gynecologic indications as well as concomitant pelvic reconstructive procedures. While this enhances the generalizability of the study results, all study sites were located in Louisiana at hospitals with resident trainee involvement. Additionally, this study confirms previous retrospective studies that reported higher rates of injury with pelvic reconstructive procedures.

The study is limited by the inability to blind surgeons, which may have resulted in the surgeons altering their techniques and/or having a heightened awareness of the urinary tract. However, their rates of ureteral and bladder injuries were slightly higher than previously reported rates, suggesting that the procedures inherently carry risk. The study is further limited by the lack of a retrospective comparison group of hysterectomy without routine cystoscopy and a longer follow-up period that may have revealed additional missed delayed urologic injuries.

The rate of urinary tract injury, including both bladder and ureteral injuries, was more than 4% at the time of hysterectomy for benign conditions. Using intraoperative peristalsis or normal ureteral caliber could result in a false sense of security since these are not reliable signs of ureteral integrity. The majority of urinary tract injuries will not be identified without cystoscopic evaluation.

Continue to: Universal cystoscopy policy...

Universal cystoscopy policy proves protective, surgeon adherence is high

Chi AM, Curran DS, Morgan DM, Fenner DE, Swenson CW. Universal cystoscopy after benign hysterectomy: examining the effects of an institutional policy. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(2):369–375.

In a retrospective cohort study, Chi and colleagues evaluated urinary tract injuries at the time of hysterectomy before and after the institution of a universal cystoscopy policy. At the time of policy implementation at the University of Michigan, all faculty who performed hysterectomies attended a cystoscopy workshop. Attending physicians without prior cystoscopy training also were proctored in the operating room for 3 sessions and were required to demonstrate competency with bladder survey, visualizing ureteral efflux, and urethral assessment. Indigo carmine was used to visualize ureteral efflux.

Detection of urologic injury almost doubled with cystoscopy

A total of 2,822 hysterectomies were included in the study, with 973 in the pre–universal cystoscopy group and 1,849 in the post–universal cystoscopy group. The study period was 7 years, and data on complications were abstracted for 1 year after the completion of the study period.

The primary outcome had 3 components:

- the rate of urologic injury before and after the policy

- the cystoscopy detection rate of urologic injury

- the adherence rate to the policy.

The overall rate of bladder and ureteral injury was 2.1%; the rate of injury during pre–universal screening was 2.6%, and during post–universal screening was 1.8%. The intraoperative detection rate of injury nearly doubled, from 24% to 47%, when intraoperative cystoscopy was utilized. In addition, the percentage of delayed urologic complications decreased from 28% to 5.9% (P = .03) following implementation of the universal cystoscopy policy. With regard to surgeon adherence, cystoscopy was documented in 86.1% of the hysterectomy cases after the policy was implemented compared with 35.7% of cases before the policy.

The investigators performed a cost analysis and found that hospital costs were nearly twice as much if a delayed urologic injury was diagnosed.

Study had many strengths

This study evaluated aspects of implementing quality initiatives after proper training and proctoring of a procedure. The authors compared very large cohorts from a busy academic medical center in which surgeon adherence with routine cystoscopy was high. The majority of patient outcomes were tracked for an extended period following surgery, thereby minimizing the risk of missing delayed urologic injuries. Notably, however, there was shorter follow-up time for the post–universal cystoscopy group, which could result in underestimating the rate of delayed urologic injuries in this cohort.

Instituting a universal cystoscopy policy for hysterectomy was associated with a significant decrease in delayed postoperative urinary tract complications and an increase in the intraoperative detection rate of urologic injuries. Intraoperative detection and repair of a urinary tract injury is cost-effective compared with a delayed diagnosis.

Continue to: Cystoscopy reveals ureteral obstruction...

Cystoscopy reveals ureteral obstruction during various vaginal POP repair procedures

Gustilo-Ashby AM, Jelovsek JE, Barber MD, Yoo EH, Paraiso MF, Walters MD. The incidence of ureteral obstruction and the value of intraoperative cystoscopy during vaginal surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(5):1478–1485.

To determine the rate of ureteral obstruction and ureteral injury during vaginal surgery for POP and the accuracy of using intraoperative cystoscopy to prevent upper urinary tract morbidity, Gustilo-Ashby and colleagues performed a retrospective review study of a large patient cohort.

Cystoscopy with indigo carmine is highly sensitive

The study included 700 patients who underwent vaginal surgery for anterior and/or apical POP. Patients had 1 or more of the following anterior and apical prolapse repair procedures: USLS (51%), distal McCall culdeplasty (26%), proximal McCall culdeplasty (29%), anterior colporrhaphy (82%), and colpocleisis (1.4%). Of note, distal McCall culdeplasty was defined as incorporation of the “vaginal epithelium into the uterosacral plication,” while proximal McCall culdeplasty involved plication of “the uterosacral ligaments in the midline proximal to the vaginal cuff.” All patients were given IV indigo carmine to aid in visualizing ureteral efflux.

The majority of patients had a hysterectomy (56%). When accounting for rare false-positive and negative cystoscopy results, the overall ureteral obstruction rate was 5.1% and the ureteral injury rate was 0.9%. The majority of obstructions occurred with USLS (5.9%), proximal McCall culdeplasty (4.4%), and colpocleisis (4.2%). Ureteral injuries occurred only in 6 cases: 3 USLS and 3 proximal McCall culdeplasty procedures.

Based on these findings, the authors calculated that cystoscopy at the time of vaginal surgery for anterior and/or apical prolapse has a sensitivity of 94.4% and a specificity of 99.5% for detecting ureteral obstruction. The positive predictive value of cystoscopy with the use of indigo carmine for detection of ureteral obstruction is 91.9% and the negative predictive value is 99.7%.

Impact of indigo carmine’s unavailability

This study’s strengths include its large sample size and the variety of surgical approaches used for repair of anterior vaginal wall and apical prolapse. Its retrospective design, however, is a limitation; this could result in underreporting of ureteral injuries if patients received care at another institution after surgery. Furthermore, it is unclear if cystoscopy would be as predictive of ureteral injury without the use of indigo carmine, which is no longer available at most institutions.

The utility of cystoscopy with IV indigo carmine as a screening test for ureteral obstruction is highlighted by the fact that most obstructions were relieved by intraoperative suture removal following positive cystoscopy. McCall culdeplasty procedures are commonly performed by general ObGyns at the time of vaginal hysterectomy. It is therefore important to note that rates of ureteral obstruction after proximal McCall culdeplasty were only slightly lower than those after USLS.

Continue to: Sodium fluorescein and 10% dextrose...

Sodium fluorescein and 10% dextrose provide clear visibility of ureteral jets in cystoscopy

Espaillat-Rijo L, Siff L, Alas AN, et al. Intraoperative cystoscopic evaluation of ureteral patency: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(6):1378–1383.

In a multicenter randomized controlled trial, Espaillat-Rijo and colleagues compared various methods for visualizing ureteral efflux in participants who underwent gynecologic or urogynecologic procedures in which cystoscopy was performed.

Study compared 4 media

The investigators enrolled 176 participants (174 completed the trial) and randomly assigned them to receive 1 of 4 modalities: 1) normal saline as a bladder distention medium (control), 2) 10% dextrose as a bladder distention medium, 3) 200 mg oral phenazopyridine given 30 minutes prior to cystoscopy, or 4) 50 mg IV sodium fluorescein at the start of cystoscopy. Indigo carmine was not included in this study because it has not been routinely available since 2014.

Surgeons were asked to categorize the ureteral jets as “clearly visible,” “somewhat visible,” or “not visible.”

The primary outcome was subjective visibility of the ureteral jet with each modality during cystoscopy. Secondary outcomes included surgeon satisfaction, adverse reactions to the modality used, postoperative urinary tract infection, postoperative urinary retention, and delayed diagnosis of ureteral injury.

Visibility assessment results. Overall, ureteral jets were “clearly visible” in 125 cases (71%) compared with “somewhat visible” in 45 (25.6%) and “not visible” in 4 (2.3%) cases. There was a statistically significant difference between the 4 groups. Use of sodium fluorescein and 10% dextrose resulted in significantly better visualization of ureteral jets (P < .001 and P = .004, respectively) compared with the control group. Visibility with phenazopyridine was not significantly different from that in the control group or in the 10% dextrose group (FIGURE).

Surgeon satisfaction was highest with 10% dextrose and sodium fluorescein. In 6 cases, the surgeon was not satisfied with visualization of the ureteral jets and relied on fluorescein (5 times) or 10% dextrose (1 time) to ultimately see efflux. No significant adverse events occurred; the rate of urinary tract infection was 24.1% and did not differ between groups.

Results are widely generalizable

This was a well-designed randomized multicenter trial that included both benign gynecologic and urogynecologic procedures, thus strengthening the generalizability of the study. The study was timely since proven methods for visualization of ureteral patency became limited with the withdrawal of commercially available indigo carmine, the previous gold standard.

Intravenous sodium fluorescein and 10% dextrose as bladder distention media can both safely be used to visualize ureteral efflux and result in high surgeon satisfaction. Although 10% dextrose has been associated with higher rates of postoperative urinary tract infection,11 this was not found to be the case in this study. Preoperative administration of oral phenazopyridine was no different from the control modality with regard to visibility and surgeon satisfaction.

Continue to: The cost-effectiveness consideration

The cost-effectiveness consideration

The debate around universal cystoscopy following benign gynecologic surgery is ongoing.

The studies discussed in this Update demonstrate that cystoscopy following hysterectomy for benign indications:

- is superior to visualizing ureteral peristalsis

- increases detection of urinary tract injuries, and

- decreases delayed urologic injuries.

Although these articles emphasize the importance of detecting urologic injury, the picture would not be complete without mention of cost-effectiveness. Only one study, from 2001, has evaluated the cost-effectiveness of universal cystoscopy.1 Those authors concluded that universal cystoscopy is cost-effective only when the rate of urologic injury is 1.5% to 2%, but this conclusion, admittedly, was limited by the lack of data on medicolegal settlements, outpatient expenses, and nonmedical-related economic loss from decreased productivity. Given the extensive changes that have occurred in medical practice over the last 17 years and the emphasis on quality metrics and safety, an updated analysis would be needed to make definitive conclusions about cost-effectiveness.

While this Update cannot settle the ongoing debate of universal cystoscopy in gynecology, it is important to remember that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Urogynecologic Society recommend cystoscopy following all surgeries for pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence.2

References

- Visco AG, Taber KH, Weidner AD, Barber MD, Myers ER. Cost-effectiveness of universal cystoscopy to identify ureteral injury at hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(5 pt 1):685–692.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology and the American Urogynecologic Society. Urinary incontinence in women. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015;21(6):304–314.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Ibeanu OA, Chesson RR, Echols KT, Nieves M, Busangu F, Nolan TE. Urinary tract injury during hysterectomy based on universal cystoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(1):6–10.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology and the American Urogynecologic Society. Urinary incontinence in women. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015;21(6):304–314.

- Wilcox LS, Koonin LM, Pokras R, Strauss LT, Xia Z, Peterson HB. Hysterectomy in the United States, 1988–1990. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83(4):549–555.

- Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89(4):501–506.

- Mäkinen J, Johansson J, Tomás C, et al. Morbidity of 10,110 hysterectomies by type of approach. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(7):1473–1478.

- Gilmour DT, Dwyer PL, Carey MP. Lower urinary tract injury during gynecologic surgery and its detection by intraoperative cystoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94(5 pt 2):883–889.

- Barber MD, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, et al; Eunice Kennedy Schriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse: the OPTIMAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1023–1034.

- Brandes S, Coburn M, Armenakas N, McAninch J. Diagnosis and management of ureteric injury: an evidence-based analysis. BJU Int. 2004;94(3):277–289.

- Kwon CH, Goldberg RP, Koduri S, Sand PK. The use of intraoperative cystoscopy in major vaginal and urogynecologic surgeries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(6):1466–1471.

- Adams-Piper ER, Guaderrama NM, Chen Q, Whitcomb EL. Impact of surgical training on the performance of proposed quality measures for hysterectomy for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(6):588.e1–588.e5.

- Siff LN, Unger CA, Jelovsek JE, Paraiso MF, Ridgeway BM Barber MD. Assessing ureteral patency using 10% dextrose cystoscopy fluid: evaluation of urinary tract infection rates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(1):74.e1–74.e6.

- Espaillat-Rijo L, Siff L, Alas AN, et al. Intraoperative cystoscopic evaluation of ureteral patency: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(6):1378–1383.

- Ibeanu OA, Chesson RR, Echols KT, Nieves M, Busangu F, Nolan TE. Urinary tract injury during hysterectomy based on universal cystoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(1):6–10.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology and the American Urogynecologic Society. Urinary incontinence in women. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015;21(6):304–314.

- Wilcox LS, Koonin LM, Pokras R, Strauss LT, Xia Z, Peterson HB. Hysterectomy in the United States, 1988–1990. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83(4):549–555.

- Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89(4):501–506.

- Mäkinen J, Johansson J, Tomás C, et al. Morbidity of 10,110 hysterectomies by type of approach. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(7):1473–1478.

- Gilmour DT, Dwyer PL, Carey MP. Lower urinary tract injury during gynecologic surgery and its detection by intraoperative cystoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94(5 pt 2):883–889.

- Barber MD, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, et al; Eunice Kennedy Schriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse: the OPTIMAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1023–1034.

- Brandes S, Coburn M, Armenakas N, McAninch J. Diagnosis and management of ureteric injury: an evidence-based analysis. BJU Int. 2004;94(3):277–289.

- Kwon CH, Goldberg RP, Koduri S, Sand PK. The use of intraoperative cystoscopy in major vaginal and urogynecologic surgeries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(6):1466–1471.

- Adams-Piper ER, Guaderrama NM, Chen Q, Whitcomb EL. Impact of surgical training on the performance of proposed quality measures for hysterectomy for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(6):588.e1–588.e5.

- Siff LN, Unger CA, Jelovsek JE, Paraiso MF, Ridgeway BM Barber MD. Assessing ureteral patency using 10% dextrose cystoscopy fluid: evaluation of urinary tract infection rates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(1):74.e1–74.e6.

- Espaillat-Rijo L, Siff L, Alas AN, et al. Intraoperative cystoscopic evaluation of ureteral patency: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(6):1378–1383.

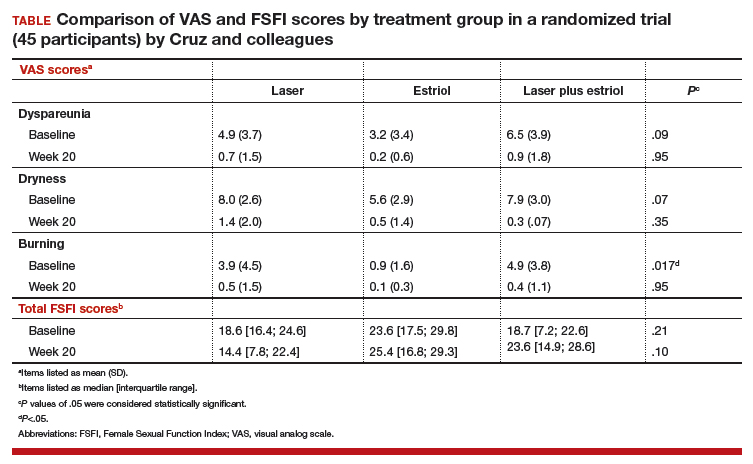

What works best for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: vaginal estrogen, vaginal laser, or combined laser and estrogen therapy?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

GSM encompasses a constellation of symptoms involving the vulva, vagina, urethra, and bladder, and it can affect quality of life in more than half of women by 3 years past menopause.1,2 Local estrogen creams, tablets, and rings are considered the gold standard treatment for GSM.3 The rising cost of many of these pharmacologic treatments has created headlines and concerns over price gouging for drugs used to treat female sexual dysfunction.4 Recent alternatives to local estrogens include vaginal moisturizers and lubricants, vaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) suppositories, oral ospemifene, and vaginal laser therapy.

Laser treatment (with fractionated CO2, erbium, and hybrid lasers) activates heat shock proteins and tissue growth factors to stimulateneocollagenesis and neovascularization within the vaginal epithelium,but it is expensive and not covered by insurance because it is considered a cosmetic procedure.5Most evidence on laser therapy for GSM comes from prospective case series with small numbers and short-term follow-up with no comparison arms.6,7 A recent trial by Cruz and colleagues, however, is notable because it is one of the first published studies that compared vaginal laser with vaginal estrogen alone and with a combination laser plus estrogen arm. We need level 1 comparative data from studies such as this to help us counsel the millions of US women with GSM.

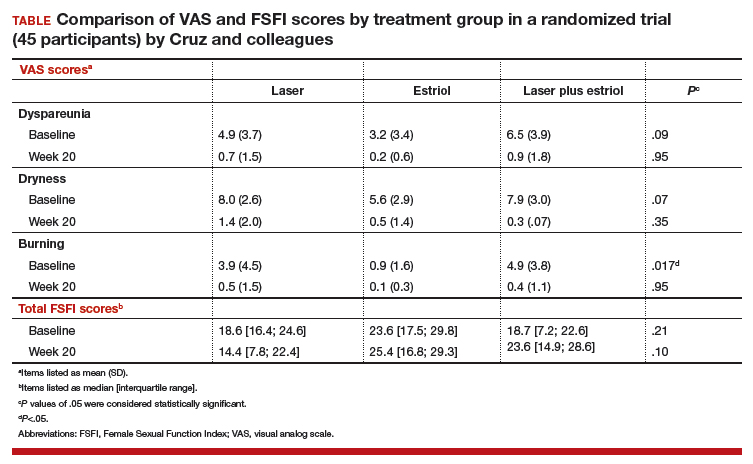

Details of the study

In this single-site randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted in Brazil, postmenopausal women were assigned to 1 of 3 treatment groups (15 per group):

- CO2 laser (MonaLisa Touch, SmartXide 2 system; DEKA Laser; Florence, Italy): 2 treatments total, 1 month apart, plus placebo cream (laser arm)

- estriol cream (1 mg estriol 3 times per week for 20 weeks) plus sham laser (estriol arm)

- CO2 laser plus estriol cream 3 times per week (laser plus estriol combination arm).

The primary outcome included a change in visual analog scale (VAS) score for symptoms related to vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA), including dyspareunia, dryness, and burning (0–10 scale with 0 = no symptoms and 10 = most severe symptoms), and change in the objective Vaginal Health Index (VHI). Assessments were made at baseline and at 8 and 20 weeks. Participants were included if they were menopausal for at least 2 years and had at least 1 moderately bothersome VVA symptom (based on a VAS score of 4 or greater).

Secondary outcomes included the objective FSFI questionnaire evaluating desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. FSFI scores can range from 2 (severe dysfunction) to 36 (no dysfunction). A total FSFI score less than 26 was deemed equivalent to dysfunction. Cytologic smear evaluation using a vaginal maturation index was included in all 3 treatment arms. Sample size calculation of 45 patients (15 per arm) for this trial was based on a 3-point difference in the VHI.

The baseline characteristics for participants in each treatment arm were similar, except that participants in the vaginal estriol group were less symptomatic at baseline. This group had less burning at baseline based on the FSFI and less dyspareunia based on the VAS.