User login

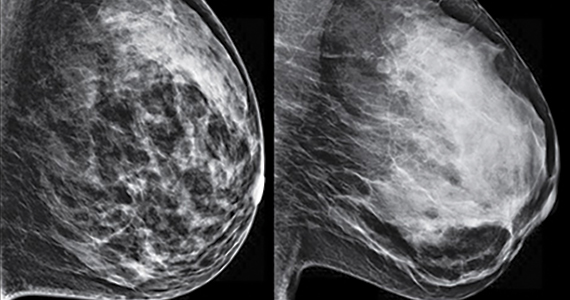

3D vs 2D mammography for detecting cancer in dense breasts

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

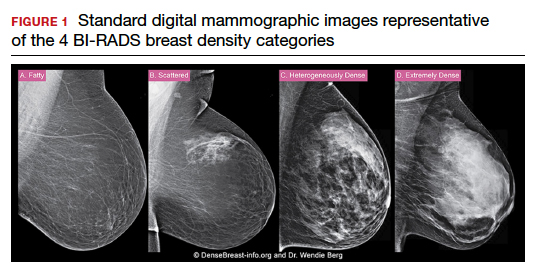

C. Overall, tomosynthesis depicts an additional 1 to 2 cancers per thousand women screened in the first round of screening when added to standard digital mammography;1-3 however, this improvement in cancer detection is only observed in women with fatty breasts (category A), scattered fibroglandular tissue (category B), and heterogeneously dense breasts (category C). Importantly, tomosynthesis does not significantly improve breast cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts (category D).2,4

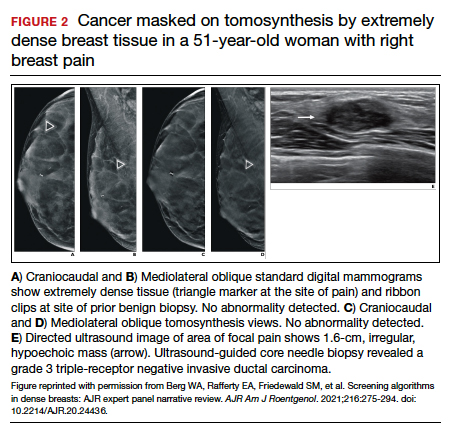

Digital breast tomosynthesis, also referred to as “3-dimensional mammography” (3D mammography) or tomosynthesis, uses a dedicated electronic detector system to obtain multiple projection images that are reconstructed by the computer to create thin slices or slabs of multiple slices of the breast. These slices can be individually “scrolled through” by the radiologist to reduce tissue overlap that may obscure breast cancers on a standard mammogram. While tomosynthesis improves breast cancer detection in women with fatty, scattered fibroglandular density, and heterogeneously dense breasts, there is very little soft tissue contrast in extremely dense breasts due to insufficient fat, and some cancers will remain hidden by dense tissue even on sliced images through the breast.

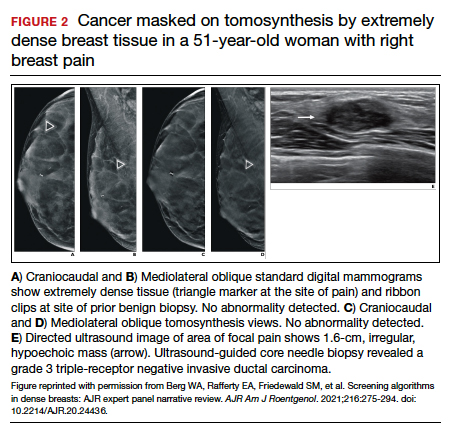

FIGURE 2 shows an example of cancer that was missed on tomosynthesis in a 51-year-old woman with extremely dense breasts and right breast pain. The cancer was masked by extremely dense tissue on standard digital mammography and tomosynthesis; no abnormalities were detected. Ultrasonography showed a 1.6-cm, irregular, hypoechoic mass at the site of pain, and biopsy revealed a grade 3 triple-receptor negative invasive ductal carcinoma.

In women with dense breasts, especially extremely dense breasts, supplemental screening beyond tomosynthesis should be considered. Although tomosynthesis doesn’t improve cancer detection in extremely dense breasts, it does reduce callbacks for additional testing in all breast densities compared with standard digital mammography. Callbacks are reduced from approximately 100‒120 per 1,000 women screened with standard digital mammography alone1,5 to an average of 80 per 1,000 women when tomosynthesis and standard mammography are interpreted together.1-3 ●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

- Conant EF, Zuckerman SP, McDonald ES, et al. Five consecutive years of screening with digital breast tomosynthesis: outcomes by screening year and round. Radiology. 2020;295:285-293.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786.

- Skaane P, Bandos AI, Niklason LT, et al. Digital mammography versus digital mammography plus tomosynthesis in breast cancer screening: the Oslo Tomosynthesis Screening Trial. Radiology. 2019;291:23-30.

- Lowry KP, Coley RY, Miglioretti DL, et al. Screening performance of digital breast tomosynthesis vs digital mammography in community practice by patient age, screening round, and breast density. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2011792.

- Lee CS, Sengupta D, Bhargavan-Chatfield M, et al. Association of patient age with outcomes of current-era, large-scale screening mammography: analysis of data from the National Mammography Database. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1134-1136.

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

C. Overall, tomosynthesis depicts an additional 1 to 2 cancers per thousand women screened in the first round of screening when added to standard digital mammography;1-3 however, this improvement in cancer detection is only observed in women with fatty breasts (category A), scattered fibroglandular tissue (category B), and heterogeneously dense breasts (category C). Importantly, tomosynthesis does not significantly improve breast cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts (category D).2,4

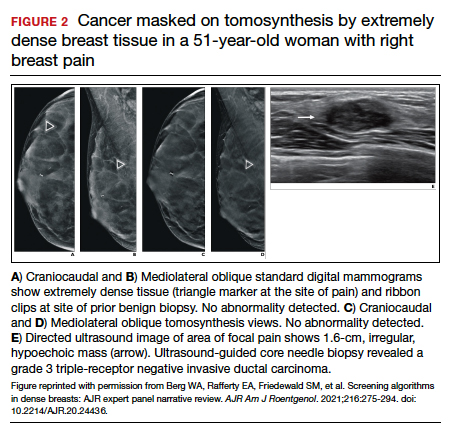

Digital breast tomosynthesis, also referred to as “3-dimensional mammography” (3D mammography) or tomosynthesis, uses a dedicated electronic detector system to obtain multiple projection images that are reconstructed by the computer to create thin slices or slabs of multiple slices of the breast. These slices can be individually “scrolled through” by the radiologist to reduce tissue overlap that may obscure breast cancers on a standard mammogram. While tomosynthesis improves breast cancer detection in women with fatty, scattered fibroglandular density, and heterogeneously dense breasts, there is very little soft tissue contrast in extremely dense breasts due to insufficient fat, and some cancers will remain hidden by dense tissue even on sliced images through the breast.

FIGURE 2 shows an example of cancer that was missed on tomosynthesis in a 51-year-old woman with extremely dense breasts and right breast pain. The cancer was masked by extremely dense tissue on standard digital mammography and tomosynthesis; no abnormalities were detected. Ultrasonography showed a 1.6-cm, irregular, hypoechoic mass at the site of pain, and biopsy revealed a grade 3 triple-receptor negative invasive ductal carcinoma.

In women with dense breasts, especially extremely dense breasts, supplemental screening beyond tomosynthesis should be considered. Although tomosynthesis doesn’t improve cancer detection in extremely dense breasts, it does reduce callbacks for additional testing in all breast densities compared with standard digital mammography. Callbacks are reduced from approximately 100‒120 per 1,000 women screened with standard digital mammography alone1,5 to an average of 80 per 1,000 women when tomosynthesis and standard mammography are interpreted together.1-3 ●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

C. Overall, tomosynthesis depicts an additional 1 to 2 cancers per thousand women screened in the first round of screening when added to standard digital mammography;1-3 however, this improvement in cancer detection is only observed in women with fatty breasts (category A), scattered fibroglandular tissue (category B), and heterogeneously dense breasts (category C). Importantly, tomosynthesis does not significantly improve breast cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts (category D).2,4

Digital breast tomosynthesis, also referred to as “3-dimensional mammography” (3D mammography) or tomosynthesis, uses a dedicated electronic detector system to obtain multiple projection images that are reconstructed by the computer to create thin slices or slabs of multiple slices of the breast. These slices can be individually “scrolled through” by the radiologist to reduce tissue overlap that may obscure breast cancers on a standard mammogram. While tomosynthesis improves breast cancer detection in women with fatty, scattered fibroglandular density, and heterogeneously dense breasts, there is very little soft tissue contrast in extremely dense breasts due to insufficient fat, and some cancers will remain hidden by dense tissue even on sliced images through the breast.

FIGURE 2 shows an example of cancer that was missed on tomosynthesis in a 51-year-old woman with extremely dense breasts and right breast pain. The cancer was masked by extremely dense tissue on standard digital mammography and tomosynthesis; no abnormalities were detected. Ultrasonography showed a 1.6-cm, irregular, hypoechoic mass at the site of pain, and biopsy revealed a grade 3 triple-receptor negative invasive ductal carcinoma.

In women with dense breasts, especially extremely dense breasts, supplemental screening beyond tomosynthesis should be considered. Although tomosynthesis doesn’t improve cancer detection in extremely dense breasts, it does reduce callbacks for additional testing in all breast densities compared with standard digital mammography. Callbacks are reduced from approximately 100‒120 per 1,000 women screened with standard digital mammography alone1,5 to an average of 80 per 1,000 women when tomosynthesis and standard mammography are interpreted together.1-3 ●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

- Conant EF, Zuckerman SP, McDonald ES, et al. Five consecutive years of screening with digital breast tomosynthesis: outcomes by screening year and round. Radiology. 2020;295:285-293.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786.

- Skaane P, Bandos AI, Niklason LT, et al. Digital mammography versus digital mammography plus tomosynthesis in breast cancer screening: the Oslo Tomosynthesis Screening Trial. Radiology. 2019;291:23-30.

- Lowry KP, Coley RY, Miglioretti DL, et al. Screening performance of digital breast tomosynthesis vs digital mammography in community practice by patient age, screening round, and breast density. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2011792.

- Lee CS, Sengupta D, Bhargavan-Chatfield M, et al. Association of patient age with outcomes of current-era, large-scale screening mammography: analysis of data from the National Mammography Database. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1134-1136.

- Conant EF, Zuckerman SP, McDonald ES, et al. Five consecutive years of screening with digital breast tomosynthesis: outcomes by screening year and round. Radiology. 2020;295:285-293.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786.

- Skaane P, Bandos AI, Niklason LT, et al. Digital mammography versus digital mammography plus tomosynthesis in breast cancer screening: the Oslo Tomosynthesis Screening Trial. Radiology. 2019;291:23-30.

- Lowry KP, Coley RY, Miglioretti DL, et al. Screening performance of digital breast tomosynthesis vs digital mammography in community practice by patient age, screening round, and breast density. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2011792.

- Lee CS, Sengupta D, Bhargavan-Chatfield M, et al. Association of patient age with outcomes of current-era, large-scale screening mammography: analysis of data from the National Mammography Database. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1134-1136.

Quiz developed in collaboration with

Boxed warnings: Legal risks that many physicians never see coming

Almost all physicians write prescriptions, and each prescription requires a physician to assess the risks and benefits of the drug. If an adverse drug reaction occurs, physicians may be called on to defend their risk-benefit assessment in court.

The assessment of risk is complicated when there is a boxed warning that describes potentially serious and life-threatening adverse reactions associated with a drug. Some of our most commonly prescribed drugs have boxed warnings, and drugs that were initially approved by the Food and Drug Administration without boxed warnings may have them added years later.

One serious problem with boxed warnings is that there are no reliable mechanisms for making sure that physicians are aware of them. The warnings are typically not seen by physicians as printed product labels, just as physicians often don’t see the pills and capsules that they prescribe. Pharmacists who receive packaged drugs from manufacturers may be the only ones to see an actual printed boxed warning, but even those pharmacists have little reason to read each label and note changes when handling many bulk packages.

This problem is aggravated by misperceptions that many physicians have about boxed warnings and the increasingly intense scrutiny given to them by mass media and the courts. Lawyers can use boxed warnings to make a drug look dangerous, even when it’s not, and to make physicians look reckless when prescribing it. Therefore, it is important for physicians to understand what boxed warnings are, what they are not, the problems they cause, and how to minimize these problems.

What is a ‘boxed warning’?

The marketing and sale of drugs in the United States requires approval by the FDA. Approval requires manufacturers to prepare a document containing “Full Prescribing Information” for the drug and to include a printed copy in every package of the drug that is sold. This document is commonly called a “package insert,” but the FDA designates this document as the manufacturer’s product “label.”

In 1979, the FDA began requiring some labels to appear within thick, black rectangular borders; these have come to be known as boxed warnings. Boxed warnings are usually placed at the beginning of a label. They may be added to the label of a previously approved drug already on the market or included in the product label when first approved and marketed.

The requirement for a boxed warning most often arises when a signal appears during review of postmarketing surveillance data suggesting a possible and plausible association between a drug and an adverse reaction. Warnings may also be initiated in response to petitions from public interest groups, or upon the discovery of serious toxicity in animals. Regardless of their origin, the intent of a boxed warning is to highlight information that may have important therapeutic consequences and warrants heightened awareness among physicians.

What a boxed warning is not

A boxed warning is not “issued” by the FDA; it is merely required by the FDA. Specific wording or a template may be suggested by the FDA, but product labels and boxed warnings are written and issued by the manufacturer. This distinction may seem minor, but extensive litigation has occurred over whether manufacturers have met their duty to warn consumers about possible risks when using their products, and this duty cannot be shifted to the FDA.

A boxed warning may not be added to a product label at the option of a manufacturer. The FDA allows a boxed warning only if it requires the warning, to preserve its impact. It should be noted that some medical information sources (e.g., PDR.net) may include a “BOXED WARNING” in their drug monographs, but monographs not written by a manufacturer are not regulated by the FDA, and the text of their boxed warnings do not always correspond to the boxed warning that was approved by the FDA.

A boxed warning is not an indication that revocation of FDA approval is being considered or that it is likely to be revoked. FDA approval is subject to ongoing review and may be revoked at any time, without a prior boxed warning.

A boxed warning is not the highest level of warning. The FDA may require a manufacturer to send out a “Dear Health Care Provider” (DHCP) letter when an even higher or more urgent level of warning is deemed necessary. DHCP letters are usually accompanied by revisions of the product label, but most label revisions – and even most boxed warnings – are not accompanied by DHCP letters.

A boxed warning is not a statement about causation. Most warnings describe an “association” between a drug and an adverse effect, or “increased risk,” or instances of a particular adverse effect that “have been reported” in persons taking a drug. The words in a boxed warning are carefully chosen and require careful reading; in most cases they refrain from stating that a drug actually causes an adverse effect. The postmarketing surveillance data on which most warnings are based generally cannot provide the kind of evidence required to establish causation, and an association may be nothing more than an uncommon manifestation of the disorder for which the drug has been prescribed.

A boxed warning is not a statement about the probability of an adverse reaction occurring. The requirement for a boxed warning correlates better to the new recognition of a possible association than to the probability of an association. For example, penicillin has long been known to cause fatal anaphylaxis in 1/100,000 first-time administrations, but it does not have a boxed warning. The adverse consequences described in boxed warnings are often far less frequent – so much so that most physicians will never see them.

A boxed warning does not define the standard of care. The warning is a requirement imposed on the manufacturer, not on the practice of medicine. For legal purposes, the “standard of care” for the practice of medicine is defined state by state and is typically cast in terms such as “what most physicians would do in similar circumstances.” Physicians often prescribe drugs in spite of boxed warnings, just as they often prescribe drugs for “off label” indications, always balancing risk versus benefit.

A boxed warning does not constitute a contraindication to the use of a medication. Some warnings state that a drug is contraindicated in some situations, but product labels have another mandated section for listing contraindications, and most boxed warnings have no corresponding entry in that section.

A boxed warning does not necessarily constitute current information, nor is it always updated when new or contrary information becomes available. Revisions to boxed warnings, and to product labels in general, are made only after detailed review at the FDA, and the process of deciding whether an existing boxed warning continues to be appropriate may divert limited regulatory resources from more urgent priorities. Consequently, revisions to a boxed warning may lag behind the data that justify a revision by months or years. Revisions may never occur if softening or eliminating a boxed warning is deemed to be not worth the cost by a manufacturer.

Boxed warning problems for physicians

There is no reliable mechanism for manufacturers or the FDA to communicate boxed warnings directly to physicians, so it’s not clear how physicians are expected to stay informed about the issuance or revision of boxed warnings. They may first learn about new or revised warnings in the mass media, which is paying ever-increasing attention to press releases from the FDA. However, it can be difficult for the media to accurately convey the subtle and complex nature of a boxed warning in nontechnical terms.

Many physicians subscribe to various medical news alerts and attend continuing medical education (CME) programs, which often do an excellent job of highlighting new warnings, while hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies may broadcast news about boxed warnings in newsletters or other notices. But these notifications are ephemeral and may be missed by physicians who are overwhelmed by email, notices, newsletters, and CME programs.

The warnings that pop up in electronic medical records systems are often so numerous that physicians become trained to ignore them. Printed advertisements in professional journals must include mandated boxed warnings, but their visibility is waning as physicians increasingly read journals online.

Another conundrum is how to inform the public about boxed warnings.

Manufacturers are prohibited from direct-to-consumer advertising of drugs with boxed warnings, although the warnings are easily found on the Internet. Some patients expect and welcome detailed information from their physicians, so it’s a good policy to always and repeatedly review this information with them, especially if they are members of an identified risk group. However, that policy may be counterproductive if it dissuades anxious patients from needed therapy despite risk-benefit considerations that strongly favor it. Boxed warnings are well known to have “spillover effects” in which the aspersions cast by a boxed warning for a relatively small subgroup of patients causes use of a drug to decline among all patients.

Compounding this conundrum is that physicians rarely have sufficient information to gauge the magnitude of a risk, given that boxed warnings are often based on information from surveillance systems that cannot accurately quantify the risk or even establish a causal relationship. The text of a boxed warning generally does not provide the information needed for evidence-based clinical practice such as a quantitative estimate of effect, information about source and trustworthiness of the evidence, and guidance on implementation. For these and other reasons, FDA policies about various boxed warnings have been the target of significant criticism.

Medication guides are one mechanism to address the challenge of informing patients about the risks of drugs they are taking. FDA-approved medication guides are available for most drugs dispensed as outpatient prescriptions, they’re written in plain language for the consumer, and they include paraphrased versions of any boxed warning. Ideally, patients review these guides with their physicians or pharmacists, but the guides may be lengthy and raise questions that may not be answerable (e.g., about incidence rates). Patients may decline to review this information when a drug is prescribed or dispensed, and they may discard printed copies given to them without reading.

What can physicians do to minimize boxed warning problems?

Physicians should periodically review the product labels for drugs they commonly prescribe, including drugs they’ve prescribed for a long time. Prescription renewal requests can be used as a prompt to check for changes in a patient’s condition or other medications that might place a patient in the target population of a boxed warning. Physicians can subscribe to newsletters that announce and discuss significant product label changes, including alerts directly from the FDA. Physicians may also enlist their office staff to find and review boxed warnings for drugs being prescribed, noting which ones should require a conversation with any patient who has been or will be receiving this drug. They may want to make explicit mention in their encounter record that a boxed warning, medication guide, or overall risk-benefit assessment has been discussed.

Summary

The nature of boxed warnings, the means by which they are disseminated, and their role in clinical practice are all in great need of improvement. Until that occurs, boxed warnings offer some, but only very limited, help to patients and physicians who struggle to understand the risks of medications.

Dr. Axelsen is professor in the departments of pharmacology, biochemistry, and biophysics, and of medicine, infectious diseases section, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Almost all physicians write prescriptions, and each prescription requires a physician to assess the risks and benefits of the drug. If an adverse drug reaction occurs, physicians may be called on to defend their risk-benefit assessment in court.

The assessment of risk is complicated when there is a boxed warning that describes potentially serious and life-threatening adverse reactions associated with a drug. Some of our most commonly prescribed drugs have boxed warnings, and drugs that were initially approved by the Food and Drug Administration without boxed warnings may have them added years later.

One serious problem with boxed warnings is that there are no reliable mechanisms for making sure that physicians are aware of them. The warnings are typically not seen by physicians as printed product labels, just as physicians often don’t see the pills and capsules that they prescribe. Pharmacists who receive packaged drugs from manufacturers may be the only ones to see an actual printed boxed warning, but even those pharmacists have little reason to read each label and note changes when handling many bulk packages.

This problem is aggravated by misperceptions that many physicians have about boxed warnings and the increasingly intense scrutiny given to them by mass media and the courts. Lawyers can use boxed warnings to make a drug look dangerous, even when it’s not, and to make physicians look reckless when prescribing it. Therefore, it is important for physicians to understand what boxed warnings are, what they are not, the problems they cause, and how to minimize these problems.

What is a ‘boxed warning’?

The marketing and sale of drugs in the United States requires approval by the FDA. Approval requires manufacturers to prepare a document containing “Full Prescribing Information” for the drug and to include a printed copy in every package of the drug that is sold. This document is commonly called a “package insert,” but the FDA designates this document as the manufacturer’s product “label.”

In 1979, the FDA began requiring some labels to appear within thick, black rectangular borders; these have come to be known as boxed warnings. Boxed warnings are usually placed at the beginning of a label. They may be added to the label of a previously approved drug already on the market or included in the product label when first approved and marketed.

The requirement for a boxed warning most often arises when a signal appears during review of postmarketing surveillance data suggesting a possible and plausible association between a drug and an adverse reaction. Warnings may also be initiated in response to petitions from public interest groups, or upon the discovery of serious toxicity in animals. Regardless of their origin, the intent of a boxed warning is to highlight information that may have important therapeutic consequences and warrants heightened awareness among physicians.

What a boxed warning is not

A boxed warning is not “issued” by the FDA; it is merely required by the FDA. Specific wording or a template may be suggested by the FDA, but product labels and boxed warnings are written and issued by the manufacturer. This distinction may seem minor, but extensive litigation has occurred over whether manufacturers have met their duty to warn consumers about possible risks when using their products, and this duty cannot be shifted to the FDA.

A boxed warning may not be added to a product label at the option of a manufacturer. The FDA allows a boxed warning only if it requires the warning, to preserve its impact. It should be noted that some medical information sources (e.g., PDR.net) may include a “BOXED WARNING” in their drug monographs, but monographs not written by a manufacturer are not regulated by the FDA, and the text of their boxed warnings do not always correspond to the boxed warning that was approved by the FDA.

A boxed warning is not an indication that revocation of FDA approval is being considered or that it is likely to be revoked. FDA approval is subject to ongoing review and may be revoked at any time, without a prior boxed warning.

A boxed warning is not the highest level of warning. The FDA may require a manufacturer to send out a “Dear Health Care Provider” (DHCP) letter when an even higher or more urgent level of warning is deemed necessary. DHCP letters are usually accompanied by revisions of the product label, but most label revisions – and even most boxed warnings – are not accompanied by DHCP letters.

A boxed warning is not a statement about causation. Most warnings describe an “association” between a drug and an adverse effect, or “increased risk,” or instances of a particular adverse effect that “have been reported” in persons taking a drug. The words in a boxed warning are carefully chosen and require careful reading; in most cases they refrain from stating that a drug actually causes an adverse effect. The postmarketing surveillance data on which most warnings are based generally cannot provide the kind of evidence required to establish causation, and an association may be nothing more than an uncommon manifestation of the disorder for which the drug has been prescribed.

A boxed warning is not a statement about the probability of an adverse reaction occurring. The requirement for a boxed warning correlates better to the new recognition of a possible association than to the probability of an association. For example, penicillin has long been known to cause fatal anaphylaxis in 1/100,000 first-time administrations, but it does not have a boxed warning. The adverse consequences described in boxed warnings are often far less frequent – so much so that most physicians will never see them.

A boxed warning does not define the standard of care. The warning is a requirement imposed on the manufacturer, not on the practice of medicine. For legal purposes, the “standard of care” for the practice of medicine is defined state by state and is typically cast in terms such as “what most physicians would do in similar circumstances.” Physicians often prescribe drugs in spite of boxed warnings, just as they often prescribe drugs for “off label” indications, always balancing risk versus benefit.

A boxed warning does not constitute a contraindication to the use of a medication. Some warnings state that a drug is contraindicated in some situations, but product labels have another mandated section for listing contraindications, and most boxed warnings have no corresponding entry in that section.

A boxed warning does not necessarily constitute current information, nor is it always updated when new or contrary information becomes available. Revisions to boxed warnings, and to product labels in general, are made only after detailed review at the FDA, and the process of deciding whether an existing boxed warning continues to be appropriate may divert limited regulatory resources from more urgent priorities. Consequently, revisions to a boxed warning may lag behind the data that justify a revision by months or years. Revisions may never occur if softening or eliminating a boxed warning is deemed to be not worth the cost by a manufacturer.

Boxed warning problems for physicians

There is no reliable mechanism for manufacturers or the FDA to communicate boxed warnings directly to physicians, so it’s not clear how physicians are expected to stay informed about the issuance or revision of boxed warnings. They may first learn about new or revised warnings in the mass media, which is paying ever-increasing attention to press releases from the FDA. However, it can be difficult for the media to accurately convey the subtle and complex nature of a boxed warning in nontechnical terms.

Many physicians subscribe to various medical news alerts and attend continuing medical education (CME) programs, which often do an excellent job of highlighting new warnings, while hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies may broadcast news about boxed warnings in newsletters or other notices. But these notifications are ephemeral and may be missed by physicians who are overwhelmed by email, notices, newsletters, and CME programs.

The warnings that pop up in electronic medical records systems are often so numerous that physicians become trained to ignore them. Printed advertisements in professional journals must include mandated boxed warnings, but their visibility is waning as physicians increasingly read journals online.

Another conundrum is how to inform the public about boxed warnings.

Manufacturers are prohibited from direct-to-consumer advertising of drugs with boxed warnings, although the warnings are easily found on the Internet. Some patients expect and welcome detailed information from their physicians, so it’s a good policy to always and repeatedly review this information with them, especially if they are members of an identified risk group. However, that policy may be counterproductive if it dissuades anxious patients from needed therapy despite risk-benefit considerations that strongly favor it. Boxed warnings are well known to have “spillover effects” in which the aspersions cast by a boxed warning for a relatively small subgroup of patients causes use of a drug to decline among all patients.

Compounding this conundrum is that physicians rarely have sufficient information to gauge the magnitude of a risk, given that boxed warnings are often based on information from surveillance systems that cannot accurately quantify the risk or even establish a causal relationship. The text of a boxed warning generally does not provide the information needed for evidence-based clinical practice such as a quantitative estimate of effect, information about source and trustworthiness of the evidence, and guidance on implementation. For these and other reasons, FDA policies about various boxed warnings have been the target of significant criticism.

Medication guides are one mechanism to address the challenge of informing patients about the risks of drugs they are taking. FDA-approved medication guides are available for most drugs dispensed as outpatient prescriptions, they’re written in plain language for the consumer, and they include paraphrased versions of any boxed warning. Ideally, patients review these guides with their physicians or pharmacists, but the guides may be lengthy and raise questions that may not be answerable (e.g., about incidence rates). Patients may decline to review this information when a drug is prescribed or dispensed, and they may discard printed copies given to them without reading.

What can physicians do to minimize boxed warning problems?

Physicians should periodically review the product labels for drugs they commonly prescribe, including drugs they’ve prescribed for a long time. Prescription renewal requests can be used as a prompt to check for changes in a patient’s condition or other medications that might place a patient in the target population of a boxed warning. Physicians can subscribe to newsletters that announce and discuss significant product label changes, including alerts directly from the FDA. Physicians may also enlist their office staff to find and review boxed warnings for drugs being prescribed, noting which ones should require a conversation with any patient who has been or will be receiving this drug. They may want to make explicit mention in their encounter record that a boxed warning, medication guide, or overall risk-benefit assessment has been discussed.

Summary

The nature of boxed warnings, the means by which they are disseminated, and their role in clinical practice are all in great need of improvement. Until that occurs, boxed warnings offer some, but only very limited, help to patients and physicians who struggle to understand the risks of medications.

Dr. Axelsen is professor in the departments of pharmacology, biochemistry, and biophysics, and of medicine, infectious diseases section, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Almost all physicians write prescriptions, and each prescription requires a physician to assess the risks and benefits of the drug. If an adverse drug reaction occurs, physicians may be called on to defend their risk-benefit assessment in court.

The assessment of risk is complicated when there is a boxed warning that describes potentially serious and life-threatening adverse reactions associated with a drug. Some of our most commonly prescribed drugs have boxed warnings, and drugs that were initially approved by the Food and Drug Administration without boxed warnings may have them added years later.

One serious problem with boxed warnings is that there are no reliable mechanisms for making sure that physicians are aware of them. The warnings are typically not seen by physicians as printed product labels, just as physicians often don’t see the pills and capsules that they prescribe. Pharmacists who receive packaged drugs from manufacturers may be the only ones to see an actual printed boxed warning, but even those pharmacists have little reason to read each label and note changes when handling many bulk packages.

This problem is aggravated by misperceptions that many physicians have about boxed warnings and the increasingly intense scrutiny given to them by mass media and the courts. Lawyers can use boxed warnings to make a drug look dangerous, even when it’s not, and to make physicians look reckless when prescribing it. Therefore, it is important for physicians to understand what boxed warnings are, what they are not, the problems they cause, and how to minimize these problems.

What is a ‘boxed warning’?

The marketing and sale of drugs in the United States requires approval by the FDA. Approval requires manufacturers to prepare a document containing “Full Prescribing Information” for the drug and to include a printed copy in every package of the drug that is sold. This document is commonly called a “package insert,” but the FDA designates this document as the manufacturer’s product “label.”

In 1979, the FDA began requiring some labels to appear within thick, black rectangular borders; these have come to be known as boxed warnings. Boxed warnings are usually placed at the beginning of a label. They may be added to the label of a previously approved drug already on the market or included in the product label when first approved and marketed.

The requirement for a boxed warning most often arises when a signal appears during review of postmarketing surveillance data suggesting a possible and plausible association between a drug and an adverse reaction. Warnings may also be initiated in response to petitions from public interest groups, or upon the discovery of serious toxicity in animals. Regardless of their origin, the intent of a boxed warning is to highlight information that may have important therapeutic consequences and warrants heightened awareness among physicians.

What a boxed warning is not

A boxed warning is not “issued” by the FDA; it is merely required by the FDA. Specific wording or a template may be suggested by the FDA, but product labels and boxed warnings are written and issued by the manufacturer. This distinction may seem minor, but extensive litigation has occurred over whether manufacturers have met their duty to warn consumers about possible risks when using their products, and this duty cannot be shifted to the FDA.

A boxed warning may not be added to a product label at the option of a manufacturer. The FDA allows a boxed warning only if it requires the warning, to preserve its impact. It should be noted that some medical information sources (e.g., PDR.net) may include a “BOXED WARNING” in their drug monographs, but monographs not written by a manufacturer are not regulated by the FDA, and the text of their boxed warnings do not always correspond to the boxed warning that was approved by the FDA.

A boxed warning is not an indication that revocation of FDA approval is being considered or that it is likely to be revoked. FDA approval is subject to ongoing review and may be revoked at any time, without a prior boxed warning.

A boxed warning is not the highest level of warning. The FDA may require a manufacturer to send out a “Dear Health Care Provider” (DHCP) letter when an even higher or more urgent level of warning is deemed necessary. DHCP letters are usually accompanied by revisions of the product label, but most label revisions – and even most boxed warnings – are not accompanied by DHCP letters.

A boxed warning is not a statement about causation. Most warnings describe an “association” between a drug and an adverse effect, or “increased risk,” or instances of a particular adverse effect that “have been reported” in persons taking a drug. The words in a boxed warning are carefully chosen and require careful reading; in most cases they refrain from stating that a drug actually causes an adverse effect. The postmarketing surveillance data on which most warnings are based generally cannot provide the kind of evidence required to establish causation, and an association may be nothing more than an uncommon manifestation of the disorder for which the drug has been prescribed.

A boxed warning is not a statement about the probability of an adverse reaction occurring. The requirement for a boxed warning correlates better to the new recognition of a possible association than to the probability of an association. For example, penicillin has long been known to cause fatal anaphylaxis in 1/100,000 first-time administrations, but it does not have a boxed warning. The adverse consequences described in boxed warnings are often far less frequent – so much so that most physicians will never see them.

A boxed warning does not define the standard of care. The warning is a requirement imposed on the manufacturer, not on the practice of medicine. For legal purposes, the “standard of care” for the practice of medicine is defined state by state and is typically cast in terms such as “what most physicians would do in similar circumstances.” Physicians often prescribe drugs in spite of boxed warnings, just as they often prescribe drugs for “off label” indications, always balancing risk versus benefit.

A boxed warning does not constitute a contraindication to the use of a medication. Some warnings state that a drug is contraindicated in some situations, but product labels have another mandated section for listing contraindications, and most boxed warnings have no corresponding entry in that section.

A boxed warning does not necessarily constitute current information, nor is it always updated when new or contrary information becomes available. Revisions to boxed warnings, and to product labels in general, are made only after detailed review at the FDA, and the process of deciding whether an existing boxed warning continues to be appropriate may divert limited regulatory resources from more urgent priorities. Consequently, revisions to a boxed warning may lag behind the data that justify a revision by months or years. Revisions may never occur if softening or eliminating a boxed warning is deemed to be not worth the cost by a manufacturer.

Boxed warning problems for physicians

There is no reliable mechanism for manufacturers or the FDA to communicate boxed warnings directly to physicians, so it’s not clear how physicians are expected to stay informed about the issuance or revision of boxed warnings. They may first learn about new or revised warnings in the mass media, which is paying ever-increasing attention to press releases from the FDA. However, it can be difficult for the media to accurately convey the subtle and complex nature of a boxed warning in nontechnical terms.

Many physicians subscribe to various medical news alerts and attend continuing medical education (CME) programs, which often do an excellent job of highlighting new warnings, while hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies may broadcast news about boxed warnings in newsletters or other notices. But these notifications are ephemeral and may be missed by physicians who are overwhelmed by email, notices, newsletters, and CME programs.

The warnings that pop up in electronic medical records systems are often so numerous that physicians become trained to ignore them. Printed advertisements in professional journals must include mandated boxed warnings, but their visibility is waning as physicians increasingly read journals online.

Another conundrum is how to inform the public about boxed warnings.

Manufacturers are prohibited from direct-to-consumer advertising of drugs with boxed warnings, although the warnings are easily found on the Internet. Some patients expect and welcome detailed information from their physicians, so it’s a good policy to always and repeatedly review this information with them, especially if they are members of an identified risk group. However, that policy may be counterproductive if it dissuades anxious patients from needed therapy despite risk-benefit considerations that strongly favor it. Boxed warnings are well known to have “spillover effects” in which the aspersions cast by a boxed warning for a relatively small subgroup of patients causes use of a drug to decline among all patients.

Compounding this conundrum is that physicians rarely have sufficient information to gauge the magnitude of a risk, given that boxed warnings are often based on information from surveillance systems that cannot accurately quantify the risk or even establish a causal relationship. The text of a boxed warning generally does not provide the information needed for evidence-based clinical practice such as a quantitative estimate of effect, information about source and trustworthiness of the evidence, and guidance on implementation. For these and other reasons, FDA policies about various boxed warnings have been the target of significant criticism.

Medication guides are one mechanism to address the challenge of informing patients about the risks of drugs they are taking. FDA-approved medication guides are available for most drugs dispensed as outpatient prescriptions, they’re written in plain language for the consumer, and they include paraphrased versions of any boxed warning. Ideally, patients review these guides with their physicians or pharmacists, but the guides may be lengthy and raise questions that may not be answerable (e.g., about incidence rates). Patients may decline to review this information when a drug is prescribed or dispensed, and they may discard printed copies given to them without reading.

What can physicians do to minimize boxed warning problems?

Physicians should periodically review the product labels for drugs they commonly prescribe, including drugs they’ve prescribed for a long time. Prescription renewal requests can be used as a prompt to check for changes in a patient’s condition or other medications that might place a patient in the target population of a boxed warning. Physicians can subscribe to newsletters that announce and discuss significant product label changes, including alerts directly from the FDA. Physicians may also enlist their office staff to find and review boxed warnings for drugs being prescribed, noting which ones should require a conversation with any patient who has been or will be receiving this drug. They may want to make explicit mention in their encounter record that a boxed warning, medication guide, or overall risk-benefit assessment has been discussed.

Summary

The nature of boxed warnings, the means by which they are disseminated, and their role in clinical practice are all in great need of improvement. Until that occurs, boxed warnings offer some, but only very limited, help to patients and physicians who struggle to understand the risks of medications.

Dr. Axelsen is professor in the departments of pharmacology, biochemistry, and biophysics, and of medicine, infectious diseases section, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Is telemedicine here to stay?

Dear colleagues and friends,

I am fortunate to receive the baton from Charles Kahi, MD, in facilitating the fascinating and timely debates that have characterized the AGA Perspective series. Favorable reimbursement changes and the need for social distancing fast-tracked telemedicine, a care delivery model that had been slowly evolving.

In this month’s Perspective column, Dr. Hernaez and Dr. Vaughn discuss the pros and cons of telemedicine in GI. Is it the new office visit? Or simply just good enough for when we really need it? I look forward to hearing your thoughts and experiences on the AGA Community forum as well as by email ([email protected]).

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, is assistant professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

It holds promise

BY RUBEN HERNAEZ, MD, MPH, PHD

It was around January 2020, when COVID-19 was something far, far away, and not particularly worrisome. I was performing a routine care visit of one of my out-of-state patients waitlisted for a liver transplant. All was going fine until he stated, “Hey doc, while I appreciate your time and visits, these travels to Houston are quite inconvenient for my family and me: It is a logistical ordeal, and my wife is always afraid of catching something in the airplane. Could you do the same remotely such as a videoconference?” And just like that, it sparked my interest in how to maintain his liver transplant care from a distance. The Federation of State Medical Boards defines telemedicine as “the practice of medicine using electronic communication, information technology, or other means between a physician in one location, and a patient in another location, with or without an intervening health care provider.1 What my patient was asking was to use a mode of telemedicine – a video visit – to receive the same quality of care. He brought up three critical points that I will discuss further: access to specialty care (such as transplant hepatology), reduction of costs (time and money), and improved patient satisfaction.

Arora and colleagues pioneered the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) project, providing complex specialty medical care to underserved populations through a model of team-based interdisciplinary development in hepatitis C infection treatment in underserved communities, with cure rates similar to the university settings.1 The University of Michigan–Veterans Affairs Medical Center used a similar approach, called Specialty Care Access Network–Extension of Community Healthcare Outcome (SCAN‐ECHO). They showed that telemedicine improved survival in 513 patients evaluated in this program compared to regular care (hazard ratio [HR]of 0.54, 95% confidence interval 0.36‐0.81, P = .003).2 So the evidence backs my patient’s request in providing advanced medical care using a telemedicine platform.

An extra benefit of telemedicine in the current climate crisis is reducing the carbon footprint: There’s no need to travel. Telemedicine has been shown to be cost effective: A study of claims data from Jefferson Health reported that patients who received care from an on-demand telemedicine program had net cost savings per telemedicine visit between $19 and $121 per visit compared with traditional in-person visits.3 Using telemonitoring, a form of telemedicine, Bloom et al. showed in 100 simulated patients with cirrhosis and ascites over a 6-month horizon that standard of care was $167,500 more expensive than telemonitoring. The net savings of telemonitoring was always superior in different clinical scenarios.4

Further, our patients significantly decrease travel time (almost instant), improve compliance with medical appointments (more flexibility), and no more headaches related to parking or getting lost around the medical campus. Not surprisingly, these perks from telemedicine are associated with patient-reported outcomes. Reed and colleagues reported patients’ experience with video telemedicine visits in Kaiser Permanente Northern California (n = 1,274) and showed that “67% generally needed to make one or more arrangements to attend an in-person office visit (55% time off from work, 29% coverage for another activity or responsibility, 15% child care or caregiving, and 10% another person to accompany them)”; in contrast, 87% reported a video visit as “more convenient for me,” and 93% stated that “my video visit adequately addressed my needs.”5 In liver transplantation, John et al. showed that, in the Veterans Health Administration, telehealth was associated with a significantly shorter time on the liver transplant waitlist (138.8 vs. 249 days), reduction in the time from referral to evaluation (HR, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.09-0.21; P < .01) and listing (HR, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.12-0.40; P < .01) in a study of 232 patients with advanced cirrhosis.6

So, should I change my approach to patients undergoing care for chronic liver/gastrointestinal diseases? I think so. Telemedicine and its tools provide clear benefits to our patients by increasing access to care, time and money savings, and satisfaction. I am fortunate to work within the largest healthcare network in the Nation – the Veterans Health Administration – and therefore, I can cross state lines to provide medical care/advice using the video-visit tool (VA VideoConnect). One could argue that some patients might find it challenging to access telemedicine appointments, but with adequate coaching or support from our teams, telemedicine visits are a click away.

Going back to my patient, I embraced his request and coached him on using VA VideoConnect. We can continue his waitlist medical care in the following months despite the COVID-19 pandemic using telemedicine. I can assess his asterixis and ascites via his cellphone; his primary care team fills in the vitals and labs to complete a virtual visit. There’s no question in my mind that telemedicine is here to stay and that we will continue to adapt e-health tools into video visits (for example, integrating vitals, measurement of frailty, and remote monitoring). The future of our specialty is here, and I envision we will eventually have home-based hospitalizations with daily virtual rounds.

Dr. Hernaez is with the section of gastroenterology and the Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and in the section of gastroenterology and hepatology in the department of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, both in Houston. He has no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

1. Arora S et al. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jun 9;364(23):2199-207.

2. Su GL et al. Hepatology. 2018 Dec;68(6):2317-24.

3. Nord G et al. Am J Emerg Med. 2019 May;37(5):890-4.

4. Bloom PP et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2021. doi: 10.1007/s10620-021-07013-2.

5. Reed ME et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug;171:222-4.

6. John BV et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jul;18:1822-30.e4.

It has its limits

BY BYRON P. VAUGHN, MD, MS

The post-pandemic world will include telehealth. Technology disrupts business as usual and often brings positive change. But there are consequences. To employ telehealth into routine care equitably and effectively within a gastroenterology practice, we should consider two general questions: “Was the care I provided the same quality as if the patient was seen in person?” and more broadly, “am I satisfied with my practice’s implementation of telehealth?” This perspective will highlight several areas affecting gastroenterology care: lack of physical exam, disproportionate impact on certain populations, development of a patient-provider relationship, impact on physician well-being, and potential financial ramifications. We will all have to adapt to telemedicine to some extent. Understanding the trade-offs of this technology can help us position effectively in a gastroenterology practice.

Perhaps the most obvious limitation of telemedicine is the lack of vital signs and physical exam. Determining if a patient is “sick or not” is often one of the first lessons trainees learn overnight. Vital signs and physical exam are crucial in the complex triaging that occurs when evaluating for diagnoses with potentially urgent interventions. While most outpatient gastroenterology clinics are not evaluating an acute abdomen, in the correct context, the physical exam provides important nuance and often reassurance. My personal estimate is that 90% of a diagnosis is based on the history. But without physical contact, providers may increase costly downstream diagnostic testing or referrals to the emergency department. Increasing use of at-home or wearable health technology could help but requires system investments in infrastructure to implement.

Telemedicine requires a baseline level of equipment and knowledge to participate. A variety of populations will have either a knowledge gap or technology gap. Lack of rural high-speed Internet can lead to poor video quality, inhibiting effective communication and frustrating both provider and patient. In urban areas, there is a drastic wealth divide, and some groups may have difficulty obtaining sufficient equipment to complete a video visit. Even with adequate infrastructure and equipment, certain groups may be disadvantaged because of a lack of the technological savvy or literacy needed to navigate a virtual visit. The addition of interpreter services adds complexity to communication on top of the virtual interaction. These technology and knowledge gaps can produce confusion and potentially lead to worse care.1 Careful selection of appropriate patients for telemedicine is essential. Is the quality of care over a virtual visit the same for a business executive as that of a non-English speaking refugee?

The term “webside manner” precedes the pandemic but will be important in the lexicon of doctor-patient relationships moving forward. We routinely train physicians about the importance of small actions to improve our bedside manner, such as sitting down, reacting to body language, and making eye contact. First impressions matter in relationship building. For many of my established IBD patients, I can easily hop into a comfortable repertoire in person, virtually, or even on the phone. In addition, I know these people well enough to trust that I am providing the same level of care regardless of visit medium. However, a new patient virtual encounter requires nuance. I have met new patients while they are driving (I requested the patient park!), in public places, and at work. Despite instructions given to patients about the appropriate location for a virtual visit, the patient location is not in our control. For some patients this may increase the comfort of the visit. However, for others, it can lead to distractions or potentially limit the amount of information a patient is willing to share. Forming a patient-provider relationship virtually will require a new set of skills and specific training for many practitioners.

Telehealth can contribute to provider burnout. While a busy in-person clinic can be exhausting, I have found I can be more exhausted after a half-day of virtual clinic. There is an element of human connection that is difficult to replace online.2 On top of that loss, video visits are more psychologically demanding than in-person interactions. I also spend more time in a chair, have fewer coffee breaks, and have fewer professional interactions with the clinic staff and professional colleagues. Several other micro-stressors exist in virtual care that may make “Zoom fatigue” a real occupational hazard.3

Lastly, there are implications on reimbursement with telehealth. In Minnesota, a 2015 telemedicine law required private and state employee health plans to provide the same coverage for telemedicine as in-person visits, although patients had to drive to a clinic or facility to use secure telehealth equipment and have vital signs taken. With the pandemic, this stipulation is waived, and it seems likely to become permanent. However, reimbursement questions will arise, as there is a perception that a 30-minute telephone call should not cost as much as a 30-minute in-person visit, regardless of the content of the conversation.

We will have to learn to move forward with telehealth. The strength of telehealth is likely in patients with chronic, well controlled diseases, who have frequent interactions with health care. Examples of this include (although certainly are not limited to) established patients with well-controlled IBD, non-cirrhotic liver disease, and irritable bowel syndrome. Triaging patients who need in-person evaluation, ensuring patient and provider well-being, and creating a financially sustainable model of care are yet unresolved issues. Providers will likely vary in their personal acceptance of telehealth and will need to advocate within their own systems to obtain a hybrid model of telehealth that maximizes quality of care with job satisfaction.

Dr. Vaughn is associate professor of medicine and codirector of the inflammatory bowel disease program in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. He has received consulting fees from Prometheus and research support from Roche, Takeda, Celgene, Diasorin, and Crestovo.

References

1. George S et al. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013;192:946.

2. Blank S. “What’s missing from Zoom reminds us what it means to be human,” 2020 Apr 27, Medium.

3. Williams N. Occup Med (Lond). 2021 Apr. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqab041.

Dear colleagues and friends,

I am fortunate to receive the baton from Charles Kahi, MD, in facilitating the fascinating and timely debates that have characterized the AGA Perspective series. Favorable reimbursement changes and the need for social distancing fast-tracked telemedicine, a care delivery model that had been slowly evolving.

In this month’s Perspective column, Dr. Hernaez and Dr. Vaughn discuss the pros and cons of telemedicine in GI. Is it the new office visit? Or simply just good enough for when we really need it? I look forward to hearing your thoughts and experiences on the AGA Community forum as well as by email ([email protected]).

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, is assistant professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

It holds promise

BY RUBEN HERNAEZ, MD, MPH, PHD

It was around January 2020, when COVID-19 was something far, far away, and not particularly worrisome. I was performing a routine care visit of one of my out-of-state patients waitlisted for a liver transplant. All was going fine until he stated, “Hey doc, while I appreciate your time and visits, these travels to Houston are quite inconvenient for my family and me: It is a logistical ordeal, and my wife is always afraid of catching something in the airplane. Could you do the same remotely such as a videoconference?” And just like that, it sparked my interest in how to maintain his liver transplant care from a distance. The Federation of State Medical Boards defines telemedicine as “the practice of medicine using electronic communication, information technology, or other means between a physician in one location, and a patient in another location, with or without an intervening health care provider.1 What my patient was asking was to use a mode of telemedicine – a video visit – to receive the same quality of care. He brought up three critical points that I will discuss further: access to specialty care (such as transplant hepatology), reduction of costs (time and money), and improved patient satisfaction.

Arora and colleagues pioneered the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) project, providing complex specialty medical care to underserved populations through a model of team-based interdisciplinary development in hepatitis C infection treatment in underserved communities, with cure rates similar to the university settings.1 The University of Michigan–Veterans Affairs Medical Center used a similar approach, called Specialty Care Access Network–Extension of Community Healthcare Outcome (SCAN‐ECHO). They showed that telemedicine improved survival in 513 patients evaluated in this program compared to regular care (hazard ratio [HR]of 0.54, 95% confidence interval 0.36‐0.81, P = .003).2 So the evidence backs my patient’s request in providing advanced medical care using a telemedicine platform.

An extra benefit of telemedicine in the current climate crisis is reducing the carbon footprint: There’s no need to travel. Telemedicine has been shown to be cost effective: A study of claims data from Jefferson Health reported that patients who received care from an on-demand telemedicine program had net cost savings per telemedicine visit between $19 and $121 per visit compared with traditional in-person visits.3 Using telemonitoring, a form of telemedicine, Bloom et al. showed in 100 simulated patients with cirrhosis and ascites over a 6-month horizon that standard of care was $167,500 more expensive than telemonitoring. The net savings of telemonitoring was always superior in different clinical scenarios.4

Further, our patients significantly decrease travel time (almost instant), improve compliance with medical appointments (more flexibility), and no more headaches related to parking or getting lost around the medical campus. Not surprisingly, these perks from telemedicine are associated with patient-reported outcomes. Reed and colleagues reported patients’ experience with video telemedicine visits in Kaiser Permanente Northern California (n = 1,274) and showed that “67% generally needed to make one or more arrangements to attend an in-person office visit (55% time off from work, 29% coverage for another activity or responsibility, 15% child care or caregiving, and 10% another person to accompany them)”; in contrast, 87% reported a video visit as “more convenient for me,” and 93% stated that “my video visit adequately addressed my needs.”5 In liver transplantation, John et al. showed that, in the Veterans Health Administration, telehealth was associated with a significantly shorter time on the liver transplant waitlist (138.8 vs. 249 days), reduction in the time from referral to evaluation (HR, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.09-0.21; P < .01) and listing (HR, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.12-0.40; P < .01) in a study of 232 patients with advanced cirrhosis.6

So, should I change my approach to patients undergoing care for chronic liver/gastrointestinal diseases? I think so. Telemedicine and its tools provide clear benefits to our patients by increasing access to care, time and money savings, and satisfaction. I am fortunate to work within the largest healthcare network in the Nation – the Veterans Health Administration – and therefore, I can cross state lines to provide medical care/advice using the video-visit tool (VA VideoConnect). One could argue that some patients might find it challenging to access telemedicine appointments, but with adequate coaching or support from our teams, telemedicine visits are a click away.

Going back to my patient, I embraced his request and coached him on using VA VideoConnect. We can continue his waitlist medical care in the following months despite the COVID-19 pandemic using telemedicine. I can assess his asterixis and ascites via his cellphone; his primary care team fills in the vitals and labs to complete a virtual visit. There’s no question in my mind that telemedicine is here to stay and that we will continue to adapt e-health tools into video visits (for example, integrating vitals, measurement of frailty, and remote monitoring). The future of our specialty is here, and I envision we will eventually have home-based hospitalizations with daily virtual rounds.

Dr. Hernaez is with the section of gastroenterology and the Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and in the section of gastroenterology and hepatology in the department of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, both in Houston. He has no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

1. Arora S et al. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jun 9;364(23):2199-207.

2. Su GL et al. Hepatology. 2018 Dec;68(6):2317-24.

3. Nord G et al. Am J Emerg Med. 2019 May;37(5):890-4.

4. Bloom PP et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2021. doi: 10.1007/s10620-021-07013-2.

5. Reed ME et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug;171:222-4.

6. John BV et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jul;18:1822-30.e4.

It has its limits

BY BYRON P. VAUGHN, MD, MS

The post-pandemic world will include telehealth. Technology disrupts business as usual and often brings positive change. But there are consequences. To employ telehealth into routine care equitably and effectively within a gastroenterology practice, we should consider two general questions: “Was the care I provided the same quality as if the patient was seen in person?” and more broadly, “am I satisfied with my practice’s implementation of telehealth?” This perspective will highlight several areas affecting gastroenterology care: lack of physical exam, disproportionate impact on certain populations, development of a patient-provider relationship, impact on physician well-being, and potential financial ramifications. We will all have to adapt to telemedicine to some extent. Understanding the trade-offs of this technology can help us position effectively in a gastroenterology practice.

Perhaps the most obvious limitation of telemedicine is the lack of vital signs and physical exam. Determining if a patient is “sick or not” is often one of the first lessons trainees learn overnight. Vital signs and physical exam are crucial in the complex triaging that occurs when evaluating for diagnoses with potentially urgent interventions. While most outpatient gastroenterology clinics are not evaluating an acute abdomen, in the correct context, the physical exam provides important nuance and often reassurance. My personal estimate is that 90% of a diagnosis is based on the history. But without physical contact, providers may increase costly downstream diagnostic testing or referrals to the emergency department. Increasing use of at-home or wearable health technology could help but requires system investments in infrastructure to implement.

Telemedicine requires a baseline level of equipment and knowledge to participate. A variety of populations will have either a knowledge gap or technology gap. Lack of rural high-speed Internet can lead to poor video quality, inhibiting effective communication and frustrating both provider and patient. In urban areas, there is a drastic wealth divide, and some groups may have difficulty obtaining sufficient equipment to complete a video visit. Even with adequate infrastructure and equipment, certain groups may be disadvantaged because of a lack of the technological savvy or literacy needed to navigate a virtual visit. The addition of interpreter services adds complexity to communication on top of the virtual interaction. These technology and knowledge gaps can produce confusion and potentially lead to worse care.1 Careful selection of appropriate patients for telemedicine is essential. Is the quality of care over a virtual visit the same for a business executive as that of a non-English speaking refugee?

The term “webside manner” precedes the pandemic but will be important in the lexicon of doctor-patient relationships moving forward. We routinely train physicians about the importance of small actions to improve our bedside manner, such as sitting down, reacting to body language, and making eye contact. First impressions matter in relationship building. For many of my established IBD patients, I can easily hop into a comfortable repertoire in person, virtually, or even on the phone. In addition, I know these people well enough to trust that I am providing the same level of care regardless of visit medium. However, a new patient virtual encounter requires nuance. I have met new patients while they are driving (I requested the patient park!), in public places, and at work. Despite instructions given to patients about the appropriate location for a virtual visit, the patient location is not in our control. For some patients this may increase the comfort of the visit. However, for others, it can lead to distractions or potentially limit the amount of information a patient is willing to share. Forming a patient-provider relationship virtually will require a new set of skills and specific training for many practitioners.

Telehealth can contribute to provider burnout. While a busy in-person clinic can be exhausting, I have found I can be more exhausted after a half-day of virtual clinic. There is an element of human connection that is difficult to replace online.2 On top of that loss, video visits are more psychologically demanding than in-person interactions. I also spend more time in a chair, have fewer coffee breaks, and have fewer professional interactions with the clinic staff and professional colleagues. Several other micro-stressors exist in virtual care that may make “Zoom fatigue” a real occupational hazard.3

Lastly, there are implications on reimbursement with telehealth. In Minnesota, a 2015 telemedicine law required private and state employee health plans to provide the same coverage for telemedicine as in-person visits, although patients had to drive to a clinic or facility to use secure telehealth equipment and have vital signs taken. With the pandemic, this stipulation is waived, and it seems likely to become permanent. However, reimbursement questions will arise, as there is a perception that a 30-minute telephone call should not cost as much as a 30-minute in-person visit, regardless of the content of the conversation.

We will have to learn to move forward with telehealth. The strength of telehealth is likely in patients with chronic, well controlled diseases, who have frequent interactions with health care. Examples of this include (although certainly are not limited to) established patients with well-controlled IBD, non-cirrhotic liver disease, and irritable bowel syndrome. Triaging patients who need in-person evaluation, ensuring patient and provider well-being, and creating a financially sustainable model of care are yet unresolved issues. Providers will likely vary in their personal acceptance of telehealth and will need to advocate within their own systems to obtain a hybrid model of telehealth that maximizes quality of care with job satisfaction.

Dr. Vaughn is associate professor of medicine and codirector of the inflammatory bowel disease program in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. He has received consulting fees from Prometheus and research support from Roche, Takeda, Celgene, Diasorin, and Crestovo.

References

1. George S et al. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013;192:946.

2. Blank S. “What’s missing from Zoom reminds us what it means to be human,” 2020 Apr 27, Medium.

3. Williams N. Occup Med (Lond). 2021 Apr. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqab041.

Dear colleagues and friends,

I am fortunate to receive the baton from Charles Kahi, MD, in facilitating the fascinating and timely debates that have characterized the AGA Perspective series. Favorable reimbursement changes and the need for social distancing fast-tracked telemedicine, a care delivery model that had been slowly evolving.

In this month’s Perspective column, Dr. Hernaez and Dr. Vaughn discuss the pros and cons of telemedicine in GI. Is it the new office visit? Or simply just good enough for when we really need it? I look forward to hearing your thoughts and experiences on the AGA Community forum as well as by email ([email protected]).

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, is assistant professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

It holds promise

BY RUBEN HERNAEZ, MD, MPH, PHD

It was around January 2020, when COVID-19 was something far, far away, and not particularly worrisome. I was performing a routine care visit of one of my out-of-state patients waitlisted for a liver transplant. All was going fine until he stated, “Hey doc, while I appreciate your time and visits, these travels to Houston are quite inconvenient for my family and me: It is a logistical ordeal, and my wife is always afraid of catching something in the airplane. Could you do the same remotely such as a videoconference?” And just like that, it sparked my interest in how to maintain his liver transplant care from a distance. The Federation of State Medical Boards defines telemedicine as “the practice of medicine using electronic communication, information technology, or other means between a physician in one location, and a patient in another location, with or without an intervening health care provider.1 What my patient was asking was to use a mode of telemedicine – a video visit – to receive the same quality of care. He brought up three critical points that I will discuss further: access to specialty care (such as transplant hepatology), reduction of costs (time and money), and improved patient satisfaction.

Arora and colleagues pioneered the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) project, providing complex specialty medical care to underserved populations through a model of team-based interdisciplinary development in hepatitis C infection treatment in underserved communities, with cure rates similar to the university settings.1 The University of Michigan–Veterans Affairs Medical Center used a similar approach, called Specialty Care Access Network–Extension of Community Healthcare Outcome (SCAN‐ECHO). They showed that telemedicine improved survival in 513 patients evaluated in this program compared to regular care (hazard ratio [HR]of 0.54, 95% confidence interval 0.36‐0.81, P = .003).2 So the evidence backs my patient’s request in providing advanced medical care using a telemedicine platform.

An extra benefit of telemedicine in the current climate crisis is reducing the carbon footprint: There’s no need to travel. Telemedicine has been shown to be cost effective: A study of claims data from Jefferson Health reported that patients who received care from an on-demand telemedicine program had net cost savings per telemedicine visit between $19 and $121 per visit compared with traditional in-person visits.3 Using telemonitoring, a form of telemedicine, Bloom et al. showed in 100 simulated patients with cirrhosis and ascites over a 6-month horizon that standard of care was $167,500 more expensive than telemonitoring. The net savings of telemonitoring was always superior in different clinical scenarios.4