User login

2019-2020 flu season ends with ‘very high’ activity in New Jersey

The 2019-2020 flu season is ending, but not without a revised map to reflect the COVID-induced new world order.

For the week ending April 11, those additions encompass only New Jersey at level 13 and New York City at level 12, the CDC reported April 17.

Eight states, plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, were in the “high” range of flu activity, which runs from level 8 to level 10, for the same week. Those eight states included Connecticut, Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, South Carolina, and Wisconsin.

The CDC’s influenza division included this note with its latest FluView report: “The COVID-19 pandemic is affecting healthcare seeking behavior. The number of persons and their reasons for seeking care in the outpatient and ED settings is changing. These changes impact data from ILINet [Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network] in ways that are difficult to differentiate from changes in illness levels, therefore ILINet data should be interpreted with caution.”

Outpatient visits for influenza-like illness made up 2.9% of all visits to health care providers for the week ending April 11, which is the 23rd consecutive week that it’s been at or above the national baseline level of 2.4%. Twenty-three weeks is longer than this has occurred during any flu season since the CDC started setting a baseline in 2007, according to ILINet data.

Mortality from pneumonia and influenza, at 11.7%, was well above the epidemic threshold of 7.0%, although, again, pneumonia mortality “is being driven primarily by an increase in non-influenza pneumonia deaths due to COVID-19,” the CDC wrote.

The total number of influenza-related deaths in children, with reports of two more added this week, is 168 for the season – higher than two of the last three seasons: 144 in 2018-2019, 188 in 2017-2018, and 110 in 2016-2017, according to the CDC.

The 2019-2020 flu season is ending, but not without a revised map to reflect the COVID-induced new world order.

For the week ending April 11, those additions encompass only New Jersey at level 13 and New York City at level 12, the CDC reported April 17.

Eight states, plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, were in the “high” range of flu activity, which runs from level 8 to level 10, for the same week. Those eight states included Connecticut, Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, South Carolina, and Wisconsin.

The CDC’s influenza division included this note with its latest FluView report: “The COVID-19 pandemic is affecting healthcare seeking behavior. The number of persons and their reasons for seeking care in the outpatient and ED settings is changing. These changes impact data from ILINet [Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network] in ways that are difficult to differentiate from changes in illness levels, therefore ILINet data should be interpreted with caution.”

Outpatient visits for influenza-like illness made up 2.9% of all visits to health care providers for the week ending April 11, which is the 23rd consecutive week that it’s been at or above the national baseline level of 2.4%. Twenty-three weeks is longer than this has occurred during any flu season since the CDC started setting a baseline in 2007, according to ILINet data.

Mortality from pneumonia and influenza, at 11.7%, was well above the epidemic threshold of 7.0%, although, again, pneumonia mortality “is being driven primarily by an increase in non-influenza pneumonia deaths due to COVID-19,” the CDC wrote.

The total number of influenza-related deaths in children, with reports of two more added this week, is 168 for the season – higher than two of the last three seasons: 144 in 2018-2019, 188 in 2017-2018, and 110 in 2016-2017, according to the CDC.

The 2019-2020 flu season is ending, but not without a revised map to reflect the COVID-induced new world order.

For the week ending April 11, those additions encompass only New Jersey at level 13 and New York City at level 12, the CDC reported April 17.

Eight states, plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, were in the “high” range of flu activity, which runs from level 8 to level 10, for the same week. Those eight states included Connecticut, Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, South Carolina, and Wisconsin.

The CDC’s influenza division included this note with its latest FluView report: “The COVID-19 pandemic is affecting healthcare seeking behavior. The number of persons and their reasons for seeking care in the outpatient and ED settings is changing. These changes impact data from ILINet [Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network] in ways that are difficult to differentiate from changes in illness levels, therefore ILINet data should be interpreted with caution.”

Outpatient visits for influenza-like illness made up 2.9% of all visits to health care providers for the week ending April 11, which is the 23rd consecutive week that it’s been at or above the national baseline level of 2.4%. Twenty-three weeks is longer than this has occurred during any flu season since the CDC started setting a baseline in 2007, according to ILINet data.

Mortality from pneumonia and influenza, at 11.7%, was well above the epidemic threshold of 7.0%, although, again, pneumonia mortality “is being driven primarily by an increase in non-influenza pneumonia deaths due to COVID-19,” the CDC wrote.

The total number of influenza-related deaths in children, with reports of two more added this week, is 168 for the season – higher than two of the last three seasons: 144 in 2018-2019, 188 in 2017-2018, and 110 in 2016-2017, according to the CDC.

Flu activity down from its third peak of the season, COVID-19 still a factor

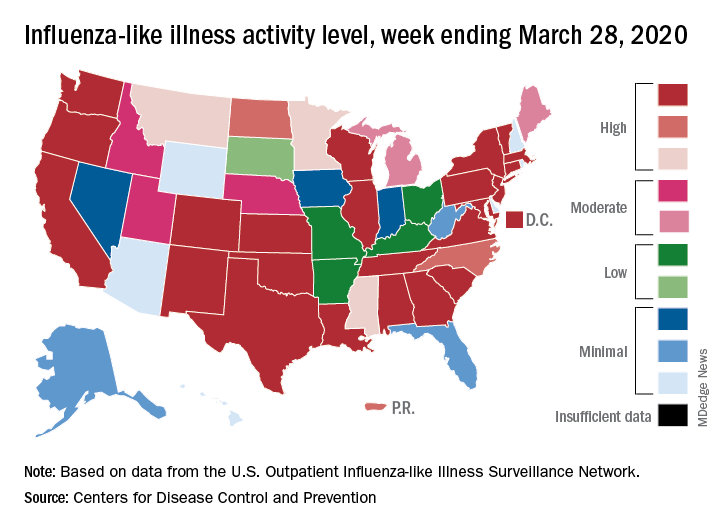

Influenza activity measures dropped during the week ending March 28, but the percentage of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza (P&I) has risen into epidemic territory, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This influenza news, however, needs to be viewed through a COVID-19 lens.

The P&I mortality data are reported together and are always a week behind the other measures, in this case covering the week ending March 21, but they show influenza deaths dropping to 0.8% as the overall P&I rate rose from 7.4% to 8.2%, a pneumonia-fueled increase that was “likely associated with COVID-19 rather than influenza,” the CDC’s influenza division noted.

The two main activity measures, at least, are on the same page for the first time since the end of February.

The rate of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) had been dropping up to that point but then rose for an unprecedented third time this season, a change probably brought about by COVID-related health care–seeking behavior, the influenza division reported in its weekly FluView report.

This corresponding third drop in ILI activity brought the rate down to 5.4% this week from 6.2% the previous week, the CDC reported. The two previous high points occurred during the weeks ending Dec. 28 (7.0%) and Feb. 8 (6.7%)

The COVID-related changes, such as increased use of telemedicine and social distancing, “impact data from [the Outpatient Influenza-Like Illness Surveillance Network] in ways that are difficult to differentiate from changes in illness levels and should be interpreted with caution,” the CDC investigators noted.

The other activity measure, positive tests of respiratory specimens for influenza at clinical laboratories, continued the decline that started in mid-February by falling from 7.3% to 2.1%, its lowest rate since October, CDC data show.

Overall flu-related deaths may be down, but mortality in children continued at a near-record level. Seven such deaths were reported this past week, which brings the total for the 2019-2020 season to 162. “This number is higher than recorded at the same time in every season since reporting began in 2004-05, except for the 2009 pandemic,” the CDC noted.

Influenza activity measures dropped during the week ending March 28, but the percentage of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza (P&I) has risen into epidemic territory, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This influenza news, however, needs to be viewed through a COVID-19 lens.

The P&I mortality data are reported together and are always a week behind the other measures, in this case covering the week ending March 21, but they show influenza deaths dropping to 0.8% as the overall P&I rate rose from 7.4% to 8.2%, a pneumonia-fueled increase that was “likely associated with COVID-19 rather than influenza,” the CDC’s influenza division noted.

The two main activity measures, at least, are on the same page for the first time since the end of February.

The rate of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) had been dropping up to that point but then rose for an unprecedented third time this season, a change probably brought about by COVID-related health care–seeking behavior, the influenza division reported in its weekly FluView report.

This corresponding third drop in ILI activity brought the rate down to 5.4% this week from 6.2% the previous week, the CDC reported. The two previous high points occurred during the weeks ending Dec. 28 (7.0%) and Feb. 8 (6.7%)

The COVID-related changes, such as increased use of telemedicine and social distancing, “impact data from [the Outpatient Influenza-Like Illness Surveillance Network] in ways that are difficult to differentiate from changes in illness levels and should be interpreted with caution,” the CDC investigators noted.

The other activity measure, positive tests of respiratory specimens for influenza at clinical laboratories, continued the decline that started in mid-February by falling from 7.3% to 2.1%, its lowest rate since October, CDC data show.

Overall flu-related deaths may be down, but mortality in children continued at a near-record level. Seven such deaths were reported this past week, which brings the total for the 2019-2020 season to 162. “This number is higher than recorded at the same time in every season since reporting began in 2004-05, except for the 2009 pandemic,” the CDC noted.

Influenza activity measures dropped during the week ending March 28, but the percentage of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza (P&I) has risen into epidemic territory, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This influenza news, however, needs to be viewed through a COVID-19 lens.

The P&I mortality data are reported together and are always a week behind the other measures, in this case covering the week ending March 21, but they show influenza deaths dropping to 0.8% as the overall P&I rate rose from 7.4% to 8.2%, a pneumonia-fueled increase that was “likely associated with COVID-19 rather than influenza,” the CDC’s influenza division noted.

The two main activity measures, at least, are on the same page for the first time since the end of February.

The rate of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) had been dropping up to that point but then rose for an unprecedented third time this season, a change probably brought about by COVID-related health care–seeking behavior, the influenza division reported in its weekly FluView report.

This corresponding third drop in ILI activity brought the rate down to 5.4% this week from 6.2% the previous week, the CDC reported. The two previous high points occurred during the weeks ending Dec. 28 (7.0%) and Feb. 8 (6.7%)

The COVID-related changes, such as increased use of telemedicine and social distancing, “impact data from [the Outpatient Influenza-Like Illness Surveillance Network] in ways that are difficult to differentiate from changes in illness levels and should be interpreted with caution,” the CDC investigators noted.

The other activity measure, positive tests of respiratory specimens for influenza at clinical laboratories, continued the decline that started in mid-February by falling from 7.3% to 2.1%, its lowest rate since October, CDC data show.

Overall flu-related deaths may be down, but mortality in children continued at a near-record level. Seven such deaths were reported this past week, which brings the total for the 2019-2020 season to 162. “This number is higher than recorded at the same time in every season since reporting began in 2004-05, except for the 2009 pandemic,” the CDC noted.

COVID-19 in children, pregnant women: What do we know?

A novel coronavirus, the causative agent of the current pandemic of viral respiratory illness and pneumonia, was first identified in Wuhan, Hubei, China. The disease has been given the name, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The virus at last report has spread to more than 100 countries. Much of what we suspect about this virus comes from work on other severe coronavirus respiratory disease outbreaks – Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). MERS-CoV was a viral respiratory disease, first reported in Saudi Arabia, that was identified in more than 27 additional countries. The disease was characterized by severe acute respiratory illness, including fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Among 2,499 cases, only two patients tested positive for MERS-CoV in the United States. SARS-CoV also caused a severe viral respiratory illness. SARS was first recognized in Asia in 2003 and was subsequently reported in approximately 25 countries. The last case reported was in 2004.

As of March 13, there are 137,066 cases worldwide of COVID-19 and 1,701 in the United States, according to the John Hopkins University Coronavirus COVID-19 resource center.

What about children?

The remarkable observation is how few seriously ill children have been identified in the face of global spread. Unlike the H1N1 influenza epidemic of 2009, where older adults were relatively spared and children were a major target population, COVID-19 appears to be relatively infrequent in children or too mild to come to diagnosis, to date. Specifically, among China’s first approximately 44,000 cases, less than 2% were identified in children less than 20 years of age, and severe disease was uncommon with no deaths in children less than 10 years of age reported. One child, 13 months of age, with acute respiratory distress syndrome and septic shock was reported in China. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention webcast , children present with fever in about 50% of cases, cough, fatigue, and subsequently some (3%-30%) progress to shortness of breath. Some children and adults have presented with gastrointestinal disease initially. Viral RNA has been detected in respiratory secretions, blood, and stool of affected children; however, the samples were not cultured for virus so whether stool is a potential source for transmission is unclear. In adults, the disease appears to be most severe – with development of pneumonia – in the second week of illness. In both children and adults, the chest x-ray findings are an interstitial pneumonitis, ground glass appearance, and/or patchy infiltrates.

Are some children at greater risk? Are children the source of community transmission? Will children become a greater part of the disease pattern as further cases are identified and further testing is available? We cannot answer many of these questions about COVID-19 in children as yet, but as you are aware, data are accumulating daily, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health are providing regular updates.

A report from China gave us some idea about community transmission and infection risk for children. The Shenzhen CDC identified 391 COVID-19 cases and 1,286 close contacts. Household contacts and those persons traveling with a case of the virus were at highest risk of acquisition. The secondary attack rates within households was 15%; children were as likely to become infected as adults (medRxiv preprint. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.03.20028423).

What about pregnant women?

The data on pregnant women are even more limited. The concern about COVID-19 during pregnancy comes from our knowledge of adverse outcomes from other respiratory viral infections. For example, respiratory viral infections such as influenza have been associated with increased maternal risk of severe disease, and adverse neonatal outcomes, including low birth weight and preterm birth. The experience with SARS also is concerning for excess adverse maternal and neonatal complications such as spontaneous miscarriage, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, admission to the ICU, renal failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy all were reported as complications of SARS infection during pregnancy.

Two studies on COVID-19 in pregnancy have been reported to date. In nine pregnant women reported by Chen et al., COVID-19 pneumonia was identified in the third trimester. The women presented with fever, cough, myalgia, sore throat, and/or malaise. Fetal distress was reported in two; all nine infants were born alive. Apgar scores were 8-10 at 1 minute. Five were found to have lymphopenia; three had increases in hepatic enzymes. None of the infants developed severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Amniotic fluid, cord blood, neonatal throat swab, and breast milk samples from six of the nine patients were tested for the novel coronavirus 2019, and all results were negative (Lancet. 2020 Feb 12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[20]30360-3)https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30360-3/fulltext.

In a study by Zhu et al., nine pregnant women with confirmed COVID-19 infection were identified during Jan. 20-Feb. 5, 2020. The onset of clinical symptoms in these women occurred before delivery in four cases, on the day of delivery in two cases, and after delivery in three cases. Of the 10 neonates (one set of twins) many had clinical symptoms, but none were proven to be COVID-19 positive in their pharyngeal swabs. Shortness of breath was observed in six, fever in two, tachycardia in one. GI symptoms such as feeding intolerance, bloating, GI bleed, and vomiting also were observed. Chest radiography showed abnormalities in seven neonates at admission. Thrombocytopenia and/or disseminated intravascular coagulopathy also was reported. Five neonates recovered and were discharged, one died, and four neonates remained in hospital in a stable condition. It is unclear if the illness in these infants was related to COVID-19 (Transl Pediatrics. 2020 Feb. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.02.06)http://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/35919/28274.

In the limited experience to date, no evidence of virus has been found in the breast milk of women with COVID-19, which is consistent with the SARS experience. Current recommendations are to separate the infant from known COVID-19 infected mothers either in a different room or in the mother’s room using a six foot rule, a barrier curtain of some type, and mask and hand washing prior to any contact between mother and infant. If the mother desires to breastfeed her child, the same precautions – mask and hand washing – should be in place.

What about treatment?

There are no proven effective therapies and supportive care has been the mainstay to date. Clinical trials of remdesivir have been initiated both by Gilead (compassionate use, open label) and by the National Institutes of Health (randomized remdesivirhttps://www.drugs.com/history/remdesivir.html vs. placebo) in adults based on in vitro data suggesting activity again COVID-19. Lopinavir/ritonavir (combination protease inhibitors) also have been administered off label, but no results are available as yet.

Keeping up

I suggest several valuable resources to keep yourself abreast of the rapidly changing COVID-19 story. First the CDC website or your local Department of Health. These are being updated frequently and include advisories on personal protective equipment, clusters of cases in your local community, and current recommendations for mitigation of the epidemic. I have listened to Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Robert R. Redfield, MD, the director of the CDC almost daily. I trust their viewpoints and transparency about what is and what is not known, as well as the why and wherefore of their guidance, remembering that each day brings new information and new guidance.

Dr. Pelton is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University and public health and senior attending physician at Boston Medical Center. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

A novel coronavirus, the causative agent of the current pandemic of viral respiratory illness and pneumonia, was first identified in Wuhan, Hubei, China. The disease has been given the name, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The virus at last report has spread to more than 100 countries. Much of what we suspect about this virus comes from work on other severe coronavirus respiratory disease outbreaks – Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). MERS-CoV was a viral respiratory disease, first reported in Saudi Arabia, that was identified in more than 27 additional countries. The disease was characterized by severe acute respiratory illness, including fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Among 2,499 cases, only two patients tested positive for MERS-CoV in the United States. SARS-CoV also caused a severe viral respiratory illness. SARS was first recognized in Asia in 2003 and was subsequently reported in approximately 25 countries. The last case reported was in 2004.

As of March 13, there are 137,066 cases worldwide of COVID-19 and 1,701 in the United States, according to the John Hopkins University Coronavirus COVID-19 resource center.

What about children?

The remarkable observation is how few seriously ill children have been identified in the face of global spread. Unlike the H1N1 influenza epidemic of 2009, where older adults were relatively spared and children were a major target population, COVID-19 appears to be relatively infrequent in children or too mild to come to diagnosis, to date. Specifically, among China’s first approximately 44,000 cases, less than 2% were identified in children less than 20 years of age, and severe disease was uncommon with no deaths in children less than 10 years of age reported. One child, 13 months of age, with acute respiratory distress syndrome and septic shock was reported in China. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention webcast , children present with fever in about 50% of cases, cough, fatigue, and subsequently some (3%-30%) progress to shortness of breath. Some children and adults have presented with gastrointestinal disease initially. Viral RNA has been detected in respiratory secretions, blood, and stool of affected children; however, the samples were not cultured for virus so whether stool is a potential source for transmission is unclear. In adults, the disease appears to be most severe – with development of pneumonia – in the second week of illness. In both children and adults, the chest x-ray findings are an interstitial pneumonitis, ground glass appearance, and/or patchy infiltrates.

Are some children at greater risk? Are children the source of community transmission? Will children become a greater part of the disease pattern as further cases are identified and further testing is available? We cannot answer many of these questions about COVID-19 in children as yet, but as you are aware, data are accumulating daily, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health are providing regular updates.

A report from China gave us some idea about community transmission and infection risk for children. The Shenzhen CDC identified 391 COVID-19 cases and 1,286 close contacts. Household contacts and those persons traveling with a case of the virus were at highest risk of acquisition. The secondary attack rates within households was 15%; children were as likely to become infected as adults (medRxiv preprint. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.03.20028423).

What about pregnant women?

The data on pregnant women are even more limited. The concern about COVID-19 during pregnancy comes from our knowledge of adverse outcomes from other respiratory viral infections. For example, respiratory viral infections such as influenza have been associated with increased maternal risk of severe disease, and adverse neonatal outcomes, including low birth weight and preterm birth. The experience with SARS also is concerning for excess adverse maternal and neonatal complications such as spontaneous miscarriage, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, admission to the ICU, renal failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy all were reported as complications of SARS infection during pregnancy.

Two studies on COVID-19 in pregnancy have been reported to date. In nine pregnant women reported by Chen et al., COVID-19 pneumonia was identified in the third trimester. The women presented with fever, cough, myalgia, sore throat, and/or malaise. Fetal distress was reported in two; all nine infants were born alive. Apgar scores were 8-10 at 1 minute. Five were found to have lymphopenia; three had increases in hepatic enzymes. None of the infants developed severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Amniotic fluid, cord blood, neonatal throat swab, and breast milk samples from six of the nine patients were tested for the novel coronavirus 2019, and all results were negative (Lancet. 2020 Feb 12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[20]30360-3)https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30360-3/fulltext.

In a study by Zhu et al., nine pregnant women with confirmed COVID-19 infection were identified during Jan. 20-Feb. 5, 2020. The onset of clinical symptoms in these women occurred before delivery in four cases, on the day of delivery in two cases, and after delivery in three cases. Of the 10 neonates (one set of twins) many had clinical symptoms, but none were proven to be COVID-19 positive in their pharyngeal swabs. Shortness of breath was observed in six, fever in two, tachycardia in one. GI symptoms such as feeding intolerance, bloating, GI bleed, and vomiting also were observed. Chest radiography showed abnormalities in seven neonates at admission. Thrombocytopenia and/or disseminated intravascular coagulopathy also was reported. Five neonates recovered and were discharged, one died, and four neonates remained in hospital in a stable condition. It is unclear if the illness in these infants was related to COVID-19 (Transl Pediatrics. 2020 Feb. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.02.06)http://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/35919/28274.

In the limited experience to date, no evidence of virus has been found in the breast milk of women with COVID-19, which is consistent with the SARS experience. Current recommendations are to separate the infant from known COVID-19 infected mothers either in a different room or in the mother’s room using a six foot rule, a barrier curtain of some type, and mask and hand washing prior to any contact between mother and infant. If the mother desires to breastfeed her child, the same precautions – mask and hand washing – should be in place.

What about treatment?

There are no proven effective therapies and supportive care has been the mainstay to date. Clinical trials of remdesivir have been initiated both by Gilead (compassionate use, open label) and by the National Institutes of Health (randomized remdesivirhttps://www.drugs.com/history/remdesivir.html vs. placebo) in adults based on in vitro data suggesting activity again COVID-19. Lopinavir/ritonavir (combination protease inhibitors) also have been administered off label, but no results are available as yet.

Keeping up

I suggest several valuable resources to keep yourself abreast of the rapidly changing COVID-19 story. First the CDC website or your local Department of Health. These are being updated frequently and include advisories on personal protective equipment, clusters of cases in your local community, and current recommendations for mitigation of the epidemic. I have listened to Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Robert R. Redfield, MD, the director of the CDC almost daily. I trust their viewpoints and transparency about what is and what is not known, as well as the why and wherefore of their guidance, remembering that each day brings new information and new guidance.

Dr. Pelton is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University and public health and senior attending physician at Boston Medical Center. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

A novel coronavirus, the causative agent of the current pandemic of viral respiratory illness and pneumonia, was first identified in Wuhan, Hubei, China. The disease has been given the name, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The virus at last report has spread to more than 100 countries. Much of what we suspect about this virus comes from work on other severe coronavirus respiratory disease outbreaks – Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). MERS-CoV was a viral respiratory disease, first reported in Saudi Arabia, that was identified in more than 27 additional countries. The disease was characterized by severe acute respiratory illness, including fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Among 2,499 cases, only two patients tested positive for MERS-CoV in the United States. SARS-CoV also caused a severe viral respiratory illness. SARS was first recognized in Asia in 2003 and was subsequently reported in approximately 25 countries. The last case reported was in 2004.

As of March 13, there are 137,066 cases worldwide of COVID-19 and 1,701 in the United States, according to the John Hopkins University Coronavirus COVID-19 resource center.

What about children?

The remarkable observation is how few seriously ill children have been identified in the face of global spread. Unlike the H1N1 influenza epidemic of 2009, where older adults were relatively spared and children were a major target population, COVID-19 appears to be relatively infrequent in children or too mild to come to diagnosis, to date. Specifically, among China’s first approximately 44,000 cases, less than 2% were identified in children less than 20 years of age, and severe disease was uncommon with no deaths in children less than 10 years of age reported. One child, 13 months of age, with acute respiratory distress syndrome and septic shock was reported in China. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention webcast , children present with fever in about 50% of cases, cough, fatigue, and subsequently some (3%-30%) progress to shortness of breath. Some children and adults have presented with gastrointestinal disease initially. Viral RNA has been detected in respiratory secretions, blood, and stool of affected children; however, the samples were not cultured for virus so whether stool is a potential source for transmission is unclear. In adults, the disease appears to be most severe – with development of pneumonia – in the second week of illness. In both children and adults, the chest x-ray findings are an interstitial pneumonitis, ground glass appearance, and/or patchy infiltrates.

Are some children at greater risk? Are children the source of community transmission? Will children become a greater part of the disease pattern as further cases are identified and further testing is available? We cannot answer many of these questions about COVID-19 in children as yet, but as you are aware, data are accumulating daily, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health are providing regular updates.

A report from China gave us some idea about community transmission and infection risk for children. The Shenzhen CDC identified 391 COVID-19 cases and 1,286 close contacts. Household contacts and those persons traveling with a case of the virus were at highest risk of acquisition. The secondary attack rates within households was 15%; children were as likely to become infected as adults (medRxiv preprint. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.03.20028423).

What about pregnant women?

The data on pregnant women are even more limited. The concern about COVID-19 during pregnancy comes from our knowledge of adverse outcomes from other respiratory viral infections. For example, respiratory viral infections such as influenza have been associated with increased maternal risk of severe disease, and adverse neonatal outcomes, including low birth weight and preterm birth. The experience with SARS also is concerning for excess adverse maternal and neonatal complications such as spontaneous miscarriage, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, admission to the ICU, renal failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy all were reported as complications of SARS infection during pregnancy.

Two studies on COVID-19 in pregnancy have been reported to date. In nine pregnant women reported by Chen et al., COVID-19 pneumonia was identified in the third trimester. The women presented with fever, cough, myalgia, sore throat, and/or malaise. Fetal distress was reported in two; all nine infants were born alive. Apgar scores were 8-10 at 1 minute. Five were found to have lymphopenia; three had increases in hepatic enzymes. None of the infants developed severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Amniotic fluid, cord blood, neonatal throat swab, and breast milk samples from six of the nine patients were tested for the novel coronavirus 2019, and all results were negative (Lancet. 2020 Feb 12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[20]30360-3)https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30360-3/fulltext.

In a study by Zhu et al., nine pregnant women with confirmed COVID-19 infection were identified during Jan. 20-Feb. 5, 2020. The onset of clinical symptoms in these women occurred before delivery in four cases, on the day of delivery in two cases, and after delivery in three cases. Of the 10 neonates (one set of twins) many had clinical symptoms, but none were proven to be COVID-19 positive in their pharyngeal swabs. Shortness of breath was observed in six, fever in two, tachycardia in one. GI symptoms such as feeding intolerance, bloating, GI bleed, and vomiting also were observed. Chest radiography showed abnormalities in seven neonates at admission. Thrombocytopenia and/or disseminated intravascular coagulopathy also was reported. Five neonates recovered and were discharged, one died, and four neonates remained in hospital in a stable condition. It is unclear if the illness in these infants was related to COVID-19 (Transl Pediatrics. 2020 Feb. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.02.06)http://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/35919/28274.

In the limited experience to date, no evidence of virus has been found in the breast milk of women with COVID-19, which is consistent with the SARS experience. Current recommendations are to separate the infant from known COVID-19 infected mothers either in a different room or in the mother’s room using a six foot rule, a barrier curtain of some type, and mask and hand washing prior to any contact between mother and infant. If the mother desires to breastfeed her child, the same precautions – mask and hand washing – should be in place.

What about treatment?

There are no proven effective therapies and supportive care has been the mainstay to date. Clinical trials of remdesivir have been initiated both by Gilead (compassionate use, open label) and by the National Institutes of Health (randomized remdesivirhttps://www.drugs.com/history/remdesivir.html vs. placebo) in adults based on in vitro data suggesting activity again COVID-19. Lopinavir/ritonavir (combination protease inhibitors) also have been administered off label, but no results are available as yet.

Keeping up

I suggest several valuable resources to keep yourself abreast of the rapidly changing COVID-19 story. First the CDC website or your local Department of Health. These are being updated frequently and include advisories on personal protective equipment, clusters of cases in your local community, and current recommendations for mitigation of the epidemic. I have listened to Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Robert R. Redfield, MD, the director of the CDC almost daily. I trust their viewpoints and transparency about what is and what is not known, as well as the why and wherefore of their guidance, remembering that each day brings new information and new guidance.

Dr. Pelton is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University and public health and senior attending physician at Boston Medical Center. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

Wuhan case review: COVID-19 characteristics differ in children vs. adults

Pediatric cases of COVID-19 infection are typically mild, but underlying coinfection may be more common in children than in adults, according to an analysis of clinical, laboratory, and chest CT features of pediatric inpatients in Wuhan, China.

The findings point toward a need for early chest CT with corresponding pathogen detection in children with suspected COVID-19 infection, Wei Xia, MD, of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, and colleagues reported in Pediatric Pulmonology.

The most common symptoms in 20 pediatric patients hospitalized between Jan. 23 and Feb. 8, 2020, with COVID-19 infection confirmed by the pharyngeal swab COVID-19 nucleic acid test were fever and cough, which occurred in 60% and 65% of patients, respectively. Coinfection was detected in eight patients (40%), they noted.

Clinical manifestations were similar to those seen in adults, but overall symptoms were relatively mild and overall prognosis was good. Of particular note, 7 of the 20 (35%) patients had a previously diagnosed congenital or acquired diseases, suggesting that children with underlying conditions may be more susceptible, Dr. Xia and colleagues wrote.

Laboratory findings also were notable in that 80% of the children had procalcitonin (PCT) elevations not typically seen in adults with COVID-19. PCT is a marker for bacterial infection and “[this finding] may suggest that routine antibacterial treatment should be considered in pediatric patients,” the investigators wrote.

As for imaging results, chest CT findings in children were similar to those in adults.“The typical manifestations were unilateral or bilateral subpleural ground-glass opacities, and consolidations with surrounding halo signs,” Dr. Xia and associates wrote, adding that consolidations with surrounding halo sign accounted for about half the pediatric cases and should be considered as “typical signs in pediatric patients.”

Pediatric cases were “rather rare” in the early days of the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, where the first cases of infection were reported.

“As a pediatric group is usually susceptible to upper respiratory tract infection, because of their developing immune system, the delayed presence of pediatric patients is confusing,” the investigators wrote, noting that a low detection rate of pharyngeal swab COVID-19 nucleic acid test, distinguishing the virus from other common respiratory tract infectious pathogens in pediatric patients, “is still a problem.”

To better characterize the clinical and imaging features in children versus adults with COVID-19, Dr. Xia and associates reviewed these 20 pediatric cases, including 13 boys and 7 girls with ages ranging from less than 1 month to 14 years, 7 months (median 2 years, 1.5 months). Thirteen had an identified close contact with a COVID-19–diagnosed family member, and all were treated in an isolation ward. A total of 18 children were cured and discharged after an average stay of 13 days, and 2 neonates remained under observation because of positive swab results with negative CT findings. The investigators speculated that the different findings in neonates were perhaps caused by the influence of delivery on sampling or the specific CT manifestations for neonates, adding that more samples are needed for further clarification.

Based on these findings, “the CT imaging of COVID-19 infection should be differentiated with other virus pneumonias such as influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, and adenovirus,” they concluded. It also should “be differentiated from bacterial pneumonia, mycoplasma pneumonia, and chlamydia pneumonia ... the density of pneumonia lesions caused by the latter pathogens is relatively higher.”

However, Dr. Xia and colleagues noted that chest CT manifestations of pneumonia caused by different pathogens overlap, and COVID-19 pneumonia “can be superimposed with serious and complex imaging manifestations, so epidemiological and etiological examinations should be combined.”

The investigators concluded that COVID-19 virus pneumonia in children is generally mild, and that the characteristic changes of subpleural ground-glass opacities and consolidations with surrounding halo on chest CT provide an “effective means for follow-up and evaluating the changes of lung lesions.”

“In the case that the positive rate of COVID-19 nucleic acid test from pharyngeal swab samples is not high, the early detection of lesions by CT is conducive to reasonable management and early treatment for pediatric patients. However, the diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia by CT imaging alone is not sufficient enough, especially in the case of coinfection with other pathogens,” Dr. Xia and associates wrote. “Therefore, early chest CT screening and timely follow-up, combined with corresponding pathogen detection, is a feasible clinical protocol in children.”

An early study

In a separate retrospective analysis described in a letter to the editor of the New England Journal of Medicine, Weiyong Liu, PhD, of Tongji Hospital of Huazhong University of Science and Technology and colleagues found that the most frequently detected pathogens in 366 children under the age of 16 years hospitalized with respiratory infections in Wuhan during Jan. 7-15, 2020, were influenza A virus (6.3% of cases) and influenza B virus (5.5% of cases), whereas COVID-19 was detected in 1.6% of cases.

The median age of the COVID-19 patients in that series was 3 years (range 1-7 years), and in contrast to the findings of Xia et al., all previously had been “completely healthy.” Common characteristics were high fever and cough in all six patients, and vomiting in four patients. Five had pneumonia as assessed by X-ray, and CTs showed typical viral pneumonia patterns.

One patient was admitted to a pediatric ICU. All patients received antiviral agents, antibiotic agents, and supportive therapies; all recovered after a median hospital stay of 7.5 days (median range, 5-13 days).

In contrast with the findings of Xia et al., the findings of Liu et al. showed COVID-19 caused moderate to severe respiratory illness in children, and that infections in children were occurring early in the epidemic.

Some perspective

In an interview regarding the findings by Xia et al., Stephen I. Pelton, MD, professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University, and director of pediatric infectious diseases at Boston Medical Center, noted the absence of fever in 40% of cases.

“This is important, as the criteria for testing by public health departments has been high fever, cough, and shortness of breath,” he said. “The absence of fever is not inconsistent with COVID-19 disease.”

Another important point regarding the findings by Xia et al. is that the highest attack rates appear to be in children under 1 year of age, he said, further noting that the finding of concurrent influenza A, influenza B, or respiratory syncytial virus underscores that “concurrent infection can occur, and the presence of another virus in diagnostic tests does not mean that COVID-19 is not causal.”

As for whether the finding of elevated procalcitonin levels in 80% of cases reflects COVID-19 disease or coinfection with bacteria, the answer is unclear. But none of the children in the study were proven to have bacterial disease, he said, adding that “this marker will need to be interpreted with caution in the setting of COVID-19 disease.”

Dr. Xia and colleagues reported having no disclosures. Dr. Liu and associates also reported having no disclosures. The study by Liu et al. was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China, the National Mega Project on Major Infectious Disease Prevention, and the National Key Research and Development Program of China.

SOURCES: Xia W et al. Ped Pulmonol. 2020 Mar 5. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24718; Liu W et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2003717.

Pediatric cases of COVID-19 infection are typically mild, but underlying coinfection may be more common in children than in adults, according to an analysis of clinical, laboratory, and chest CT features of pediatric inpatients in Wuhan, China.

The findings point toward a need for early chest CT with corresponding pathogen detection in children with suspected COVID-19 infection, Wei Xia, MD, of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, and colleagues reported in Pediatric Pulmonology.

The most common symptoms in 20 pediatric patients hospitalized between Jan. 23 and Feb. 8, 2020, with COVID-19 infection confirmed by the pharyngeal swab COVID-19 nucleic acid test were fever and cough, which occurred in 60% and 65% of patients, respectively. Coinfection was detected in eight patients (40%), they noted.

Clinical manifestations were similar to those seen in adults, but overall symptoms were relatively mild and overall prognosis was good. Of particular note, 7 of the 20 (35%) patients had a previously diagnosed congenital or acquired diseases, suggesting that children with underlying conditions may be more susceptible, Dr. Xia and colleagues wrote.

Laboratory findings also were notable in that 80% of the children had procalcitonin (PCT) elevations not typically seen in adults with COVID-19. PCT is a marker for bacterial infection and “[this finding] may suggest that routine antibacterial treatment should be considered in pediatric patients,” the investigators wrote.

As for imaging results, chest CT findings in children were similar to those in adults.“The typical manifestations were unilateral or bilateral subpleural ground-glass opacities, and consolidations with surrounding halo signs,” Dr. Xia and associates wrote, adding that consolidations with surrounding halo sign accounted for about half the pediatric cases and should be considered as “typical signs in pediatric patients.”

Pediatric cases were “rather rare” in the early days of the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, where the first cases of infection were reported.

“As a pediatric group is usually susceptible to upper respiratory tract infection, because of their developing immune system, the delayed presence of pediatric patients is confusing,” the investigators wrote, noting that a low detection rate of pharyngeal swab COVID-19 nucleic acid test, distinguishing the virus from other common respiratory tract infectious pathogens in pediatric patients, “is still a problem.”

To better characterize the clinical and imaging features in children versus adults with COVID-19, Dr. Xia and associates reviewed these 20 pediatric cases, including 13 boys and 7 girls with ages ranging from less than 1 month to 14 years, 7 months (median 2 years, 1.5 months). Thirteen had an identified close contact with a COVID-19–diagnosed family member, and all were treated in an isolation ward. A total of 18 children were cured and discharged after an average stay of 13 days, and 2 neonates remained under observation because of positive swab results with negative CT findings. The investigators speculated that the different findings in neonates were perhaps caused by the influence of delivery on sampling or the specific CT manifestations for neonates, adding that more samples are needed for further clarification.

Based on these findings, “the CT imaging of COVID-19 infection should be differentiated with other virus pneumonias such as influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, and adenovirus,” they concluded. It also should “be differentiated from bacterial pneumonia, mycoplasma pneumonia, and chlamydia pneumonia ... the density of pneumonia lesions caused by the latter pathogens is relatively higher.”

However, Dr. Xia and colleagues noted that chest CT manifestations of pneumonia caused by different pathogens overlap, and COVID-19 pneumonia “can be superimposed with serious and complex imaging manifestations, so epidemiological and etiological examinations should be combined.”

The investigators concluded that COVID-19 virus pneumonia in children is generally mild, and that the characteristic changes of subpleural ground-glass opacities and consolidations with surrounding halo on chest CT provide an “effective means for follow-up and evaluating the changes of lung lesions.”

“In the case that the positive rate of COVID-19 nucleic acid test from pharyngeal swab samples is not high, the early detection of lesions by CT is conducive to reasonable management and early treatment for pediatric patients. However, the diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia by CT imaging alone is not sufficient enough, especially in the case of coinfection with other pathogens,” Dr. Xia and associates wrote. “Therefore, early chest CT screening and timely follow-up, combined with corresponding pathogen detection, is a feasible clinical protocol in children.”

An early study

In a separate retrospective analysis described in a letter to the editor of the New England Journal of Medicine, Weiyong Liu, PhD, of Tongji Hospital of Huazhong University of Science and Technology and colleagues found that the most frequently detected pathogens in 366 children under the age of 16 years hospitalized with respiratory infections in Wuhan during Jan. 7-15, 2020, were influenza A virus (6.3% of cases) and influenza B virus (5.5% of cases), whereas COVID-19 was detected in 1.6% of cases.

The median age of the COVID-19 patients in that series was 3 years (range 1-7 years), and in contrast to the findings of Xia et al., all previously had been “completely healthy.” Common characteristics were high fever and cough in all six patients, and vomiting in four patients. Five had pneumonia as assessed by X-ray, and CTs showed typical viral pneumonia patterns.

One patient was admitted to a pediatric ICU. All patients received antiviral agents, antibiotic agents, and supportive therapies; all recovered after a median hospital stay of 7.5 days (median range, 5-13 days).

In contrast with the findings of Xia et al., the findings of Liu et al. showed COVID-19 caused moderate to severe respiratory illness in children, and that infections in children were occurring early in the epidemic.

Some perspective

In an interview regarding the findings by Xia et al., Stephen I. Pelton, MD, professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University, and director of pediatric infectious diseases at Boston Medical Center, noted the absence of fever in 40% of cases.

“This is important, as the criteria for testing by public health departments has been high fever, cough, and shortness of breath,” he said. “The absence of fever is not inconsistent with COVID-19 disease.”

Another important point regarding the findings by Xia et al. is that the highest attack rates appear to be in children under 1 year of age, he said, further noting that the finding of concurrent influenza A, influenza B, or respiratory syncytial virus underscores that “concurrent infection can occur, and the presence of another virus in diagnostic tests does not mean that COVID-19 is not causal.”

As for whether the finding of elevated procalcitonin levels in 80% of cases reflects COVID-19 disease or coinfection with bacteria, the answer is unclear. But none of the children in the study were proven to have bacterial disease, he said, adding that “this marker will need to be interpreted with caution in the setting of COVID-19 disease.”

Dr. Xia and colleagues reported having no disclosures. Dr. Liu and associates also reported having no disclosures. The study by Liu et al. was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China, the National Mega Project on Major Infectious Disease Prevention, and the National Key Research and Development Program of China.

SOURCES: Xia W et al. Ped Pulmonol. 2020 Mar 5. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24718; Liu W et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2003717.

Pediatric cases of COVID-19 infection are typically mild, but underlying coinfection may be more common in children than in adults, according to an analysis of clinical, laboratory, and chest CT features of pediatric inpatients in Wuhan, China.

The findings point toward a need for early chest CT with corresponding pathogen detection in children with suspected COVID-19 infection, Wei Xia, MD, of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, and colleagues reported in Pediatric Pulmonology.

The most common symptoms in 20 pediatric patients hospitalized between Jan. 23 and Feb. 8, 2020, with COVID-19 infection confirmed by the pharyngeal swab COVID-19 nucleic acid test were fever and cough, which occurred in 60% and 65% of patients, respectively. Coinfection was detected in eight patients (40%), they noted.

Clinical manifestations were similar to those seen in adults, but overall symptoms were relatively mild and overall prognosis was good. Of particular note, 7 of the 20 (35%) patients had a previously diagnosed congenital or acquired diseases, suggesting that children with underlying conditions may be more susceptible, Dr. Xia and colleagues wrote.

Laboratory findings also were notable in that 80% of the children had procalcitonin (PCT) elevations not typically seen in adults with COVID-19. PCT is a marker for bacterial infection and “[this finding] may suggest that routine antibacterial treatment should be considered in pediatric patients,” the investigators wrote.

As for imaging results, chest CT findings in children were similar to those in adults.“The typical manifestations were unilateral or bilateral subpleural ground-glass opacities, and consolidations with surrounding halo signs,” Dr. Xia and associates wrote, adding that consolidations with surrounding halo sign accounted for about half the pediatric cases and should be considered as “typical signs in pediatric patients.”

Pediatric cases were “rather rare” in the early days of the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, where the first cases of infection were reported.

“As a pediatric group is usually susceptible to upper respiratory tract infection, because of their developing immune system, the delayed presence of pediatric patients is confusing,” the investigators wrote, noting that a low detection rate of pharyngeal swab COVID-19 nucleic acid test, distinguishing the virus from other common respiratory tract infectious pathogens in pediatric patients, “is still a problem.”

To better characterize the clinical and imaging features in children versus adults with COVID-19, Dr. Xia and associates reviewed these 20 pediatric cases, including 13 boys and 7 girls with ages ranging from less than 1 month to 14 years, 7 months (median 2 years, 1.5 months). Thirteen had an identified close contact with a COVID-19–diagnosed family member, and all were treated in an isolation ward. A total of 18 children were cured and discharged after an average stay of 13 days, and 2 neonates remained under observation because of positive swab results with negative CT findings. The investigators speculated that the different findings in neonates were perhaps caused by the influence of delivery on sampling or the specific CT manifestations for neonates, adding that more samples are needed for further clarification.

Based on these findings, “the CT imaging of COVID-19 infection should be differentiated with other virus pneumonias such as influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, and adenovirus,” they concluded. It also should “be differentiated from bacterial pneumonia, mycoplasma pneumonia, and chlamydia pneumonia ... the density of pneumonia lesions caused by the latter pathogens is relatively higher.”

However, Dr. Xia and colleagues noted that chest CT manifestations of pneumonia caused by different pathogens overlap, and COVID-19 pneumonia “can be superimposed with serious and complex imaging manifestations, so epidemiological and etiological examinations should be combined.”

The investigators concluded that COVID-19 virus pneumonia in children is generally mild, and that the characteristic changes of subpleural ground-glass opacities and consolidations with surrounding halo on chest CT provide an “effective means for follow-up and evaluating the changes of lung lesions.”

“In the case that the positive rate of COVID-19 nucleic acid test from pharyngeal swab samples is not high, the early detection of lesions by CT is conducive to reasonable management and early treatment for pediatric patients. However, the diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia by CT imaging alone is not sufficient enough, especially in the case of coinfection with other pathogens,” Dr. Xia and associates wrote. “Therefore, early chest CT screening and timely follow-up, combined with corresponding pathogen detection, is a feasible clinical protocol in children.”

An early study

In a separate retrospective analysis described in a letter to the editor of the New England Journal of Medicine, Weiyong Liu, PhD, of Tongji Hospital of Huazhong University of Science and Technology and colleagues found that the most frequently detected pathogens in 366 children under the age of 16 years hospitalized with respiratory infections in Wuhan during Jan. 7-15, 2020, were influenza A virus (6.3% of cases) and influenza B virus (5.5% of cases), whereas COVID-19 was detected in 1.6% of cases.

The median age of the COVID-19 patients in that series was 3 years (range 1-7 years), and in contrast to the findings of Xia et al., all previously had been “completely healthy.” Common characteristics were high fever and cough in all six patients, and vomiting in four patients. Five had pneumonia as assessed by X-ray, and CTs showed typical viral pneumonia patterns.

One patient was admitted to a pediatric ICU. All patients received antiviral agents, antibiotic agents, and supportive therapies; all recovered after a median hospital stay of 7.5 days (median range, 5-13 days).

In contrast with the findings of Xia et al., the findings of Liu et al. showed COVID-19 caused moderate to severe respiratory illness in children, and that infections in children were occurring early in the epidemic.

Some perspective

In an interview regarding the findings by Xia et al., Stephen I. Pelton, MD, professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University, and director of pediatric infectious diseases at Boston Medical Center, noted the absence of fever in 40% of cases.

“This is important, as the criteria for testing by public health departments has been high fever, cough, and shortness of breath,” he said. “The absence of fever is not inconsistent with COVID-19 disease.”

Another important point regarding the findings by Xia et al. is that the highest attack rates appear to be in children under 1 year of age, he said, further noting that the finding of concurrent influenza A, influenza B, or respiratory syncytial virus underscores that “concurrent infection can occur, and the presence of another virus in diagnostic tests does not mean that COVID-19 is not causal.”

As for whether the finding of elevated procalcitonin levels in 80% of cases reflects COVID-19 disease or coinfection with bacteria, the answer is unclear. But none of the children in the study were proven to have bacterial disease, he said, adding that “this marker will need to be interpreted with caution in the setting of COVID-19 disease.”

Dr. Xia and colleagues reported having no disclosures. Dr. Liu and associates also reported having no disclosures. The study by Liu et al. was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China, the National Mega Project on Major Infectious Disease Prevention, and the National Key Research and Development Program of China.

SOURCES: Xia W et al. Ped Pulmonol. 2020 Mar 5. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24718; Liu W et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2003717.

FROM PEDIATRIC PULMONOLOGY

As novel coronavirus outbreak evolves, critical care providers need to be prepared

ORLANDO – While the impact of the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak on hospitals outside of China remains to be determined, there are several practical points critical care professionals need to know to be prepared in the face of this dynamic and rapidly evolving outbreak, speakers said at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

“Priorities for us in our hospitals are early detection, infection prevention, staff safety, and obviously, taking care of sick people,” said Ryan C. Maves, MD, of the Naval Medical Center San Diego in a special session on the 2019 Novel Coronavirus outbreak.*

Approximately 72,000 cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) had been reported as of Feb. 17, 2020, the day of Dr. Maves’ talk, according to statistics from Johns Hopkins Center for Science and Engineering in Baltimore. A total of 1,775 deaths had been recorded, nearly all of which were in Hubei Province, the central point of the outbreak. In the United States, the number of cases stood at 15, with no deaths reported.

While the dynamics of the 2019 novel coronavirus are still being learned, the estimated range of spread for droplet transmission is 2 meters, according to Dr. Maves. The duration of environmental persistence is not yet known, but he said that other coronaviruses persist in low-humidity conditions for up to 4 days.

The number of secondary cases that arise from a primary infection, or R0, is estimated to be between 1.5 and 3, though it can change as exposure evolves; by comparison, the R0 for H1N1 influenza has been reported as 1.5, while measles is 12-18, indicating that it is “very contagious,” said Dr. Maves. Severe acute respiratory syndrome had an initial R0 of about 3.5, which he said declined rapidly to 0.7 as environmental and policy controls were put into place.

Critical care professionals need to know how to identify patients at risk of having COVID-19 and determine whether they need further work-up, according to Dr. Maves, who highlighted recent criteria released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The highest-risk category, he said, are individuals exposed to a laboratory-confirmed coronavirus case, which along with fever or signs and symptoms of a lower respiratory illness would be sufficient to classify them as a “person of interest” requiring further evaluation for disease. A history of travel from Hubei Province plus fever and signs/symptoms of lower respiratory illness would also meet criteria for evaluation, according to the CDC, while travel to mainland China would also meet the threshold, if those symptoms required hospitalization.

The CDC also published a step-wise flowchart to evaluate patients who may have been exposed to the 2019 novel coronavirus. According to that flowchart, if an individual has traveled to China or had close contact with someone infected with the 2019 Novel Coronavirus within 14 days of symptoms, and that individual has fever or symptoms of lower respiratory illness such as cough or shortness of breath, then providers should isolate that individual and assess clinical status, in addition to contacting the local health department.

Laura E. Evans, MD, MS, FCCM, of New York University, said she might recommend providers “flip the script” on that CDC algorithm when it comes to identifying patients who may have been exposed.

“I think perhaps what we should be doing at sites of entry is not talking about travel as the first question, but rather fever or symptoms of lower respiratory illnesses as the first question, and use that as the opportunity to implement risk mitigation at that stage,” Dr. Evans said in a presentation on preparing for COVID-19.

Even with “substantial uncertainty” about the potential impact of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus, a significant influx of seriously ill patients would put strain the U.S. health care delivery system, she added.

“None of us have tons of extra capacity in our emergency departments, inpatient units, or ICUs, and I think we need to be prepared for that,” she added. “We need to know what our process is for ‘identify, isolate, and inform,’ and we need to be testing that now.”

Dr. Maves and Dr. Evans both reported that they had no financial conflicts of interest to report. Dr. Maves indicated that the views expressed in his presentation did not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the United States government.

*Correction, 2/19/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the location of the naval center.

ORLANDO – While the impact of the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak on hospitals outside of China remains to be determined, there are several practical points critical care professionals need to know to be prepared in the face of this dynamic and rapidly evolving outbreak, speakers said at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

“Priorities for us in our hospitals are early detection, infection prevention, staff safety, and obviously, taking care of sick people,” said Ryan C. Maves, MD, of the Naval Medical Center San Diego in a special session on the 2019 Novel Coronavirus outbreak.*

Approximately 72,000 cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) had been reported as of Feb. 17, 2020, the day of Dr. Maves’ talk, according to statistics from Johns Hopkins Center for Science and Engineering in Baltimore. A total of 1,775 deaths had been recorded, nearly all of which were in Hubei Province, the central point of the outbreak. In the United States, the number of cases stood at 15, with no deaths reported.

While the dynamics of the 2019 novel coronavirus are still being learned, the estimated range of spread for droplet transmission is 2 meters, according to Dr. Maves. The duration of environmental persistence is not yet known, but he said that other coronaviruses persist in low-humidity conditions for up to 4 days.

The number of secondary cases that arise from a primary infection, or R0, is estimated to be between 1.5 and 3, though it can change as exposure evolves; by comparison, the R0 for H1N1 influenza has been reported as 1.5, while measles is 12-18, indicating that it is “very contagious,” said Dr. Maves. Severe acute respiratory syndrome had an initial R0 of about 3.5, which he said declined rapidly to 0.7 as environmental and policy controls were put into place.

Critical care professionals need to know how to identify patients at risk of having COVID-19 and determine whether they need further work-up, according to Dr. Maves, who highlighted recent criteria released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The highest-risk category, he said, are individuals exposed to a laboratory-confirmed coronavirus case, which along with fever or signs and symptoms of a lower respiratory illness would be sufficient to classify them as a “person of interest” requiring further evaluation for disease. A history of travel from Hubei Province plus fever and signs/symptoms of lower respiratory illness would also meet criteria for evaluation, according to the CDC, while travel to mainland China would also meet the threshold, if those symptoms required hospitalization.

The CDC also published a step-wise flowchart to evaluate patients who may have been exposed to the 2019 novel coronavirus. According to that flowchart, if an individual has traveled to China or had close contact with someone infected with the 2019 Novel Coronavirus within 14 days of symptoms, and that individual has fever or symptoms of lower respiratory illness such as cough or shortness of breath, then providers should isolate that individual and assess clinical status, in addition to contacting the local health department.

Laura E. Evans, MD, MS, FCCM, of New York University, said she might recommend providers “flip the script” on that CDC algorithm when it comes to identifying patients who may have been exposed.

“I think perhaps what we should be doing at sites of entry is not talking about travel as the first question, but rather fever or symptoms of lower respiratory illnesses as the first question, and use that as the opportunity to implement risk mitigation at that stage,” Dr. Evans said in a presentation on preparing for COVID-19.

Even with “substantial uncertainty” about the potential impact of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus, a significant influx of seriously ill patients would put strain the U.S. health care delivery system, she added.

“None of us have tons of extra capacity in our emergency departments, inpatient units, or ICUs, and I think we need to be prepared for that,” she added. “We need to know what our process is for ‘identify, isolate, and inform,’ and we need to be testing that now.”

Dr. Maves and Dr. Evans both reported that they had no financial conflicts of interest to report. Dr. Maves indicated that the views expressed in his presentation did not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the United States government.

*Correction, 2/19/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the location of the naval center.

ORLANDO – While the impact of the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak on hospitals outside of China remains to be determined, there are several practical points critical care professionals need to know to be prepared in the face of this dynamic and rapidly evolving outbreak, speakers said at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

“Priorities for us in our hospitals are early detection, infection prevention, staff safety, and obviously, taking care of sick people,” said Ryan C. Maves, MD, of the Naval Medical Center San Diego in a special session on the 2019 Novel Coronavirus outbreak.*

Approximately 72,000 cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) had been reported as of Feb. 17, 2020, the day of Dr. Maves’ talk, according to statistics from Johns Hopkins Center for Science and Engineering in Baltimore. A total of 1,775 deaths had been recorded, nearly all of which were in Hubei Province, the central point of the outbreak. In the United States, the number of cases stood at 15, with no deaths reported.

While the dynamics of the 2019 novel coronavirus are still being learned, the estimated range of spread for droplet transmission is 2 meters, according to Dr. Maves. The duration of environmental persistence is not yet known, but he said that other coronaviruses persist in low-humidity conditions for up to 4 days.

The number of secondary cases that arise from a primary infection, or R0, is estimated to be between 1.5 and 3, though it can change as exposure evolves; by comparison, the R0 for H1N1 influenza has been reported as 1.5, while measles is 12-18, indicating that it is “very contagious,” said Dr. Maves. Severe acute respiratory syndrome had an initial R0 of about 3.5, which he said declined rapidly to 0.7 as environmental and policy controls were put into place.

Critical care professionals need to know how to identify patients at risk of having COVID-19 and determine whether they need further work-up, according to Dr. Maves, who highlighted recent criteria released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The highest-risk category, he said, are individuals exposed to a laboratory-confirmed coronavirus case, which along with fever or signs and symptoms of a lower respiratory illness would be sufficient to classify them as a “person of interest” requiring further evaluation for disease. A history of travel from Hubei Province plus fever and signs/symptoms of lower respiratory illness would also meet criteria for evaluation, according to the CDC, while travel to mainland China would also meet the threshold, if those symptoms required hospitalization.

The CDC also published a step-wise flowchart to evaluate patients who may have been exposed to the 2019 novel coronavirus. According to that flowchart, if an individual has traveled to China or had close contact with someone infected with the 2019 Novel Coronavirus within 14 days of symptoms, and that individual has fever or symptoms of lower respiratory illness such as cough or shortness of breath, then providers should isolate that individual and assess clinical status, in addition to contacting the local health department.

Laura E. Evans, MD, MS, FCCM, of New York University, said she might recommend providers “flip the script” on that CDC algorithm when it comes to identifying patients who may have been exposed.

“I think perhaps what we should be doing at sites of entry is not talking about travel as the first question, but rather fever or symptoms of lower respiratory illnesses as the first question, and use that as the opportunity to implement risk mitigation at that stage,” Dr. Evans said in a presentation on preparing for COVID-19.

Even with “substantial uncertainty” about the potential impact of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus, a significant influx of seriously ill patients would put strain the U.S. health care delivery system, she added.

“None of us have tons of extra capacity in our emergency departments, inpatient units, or ICUs, and I think we need to be prepared for that,” she added. “We need to know what our process is for ‘identify, isolate, and inform,’ and we need to be testing that now.”

Dr. Maves and Dr. Evans both reported that they had no financial conflicts of interest to report. Dr. Maves indicated that the views expressed in his presentation did not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the United States government.

*Correction, 2/19/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the location of the naval center.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM CCC49

An epidemic of fear and misinformation

As I write this, the 2019 novel coronavirus* continues to spread, exceeding 59,000 cases and 1,300 deaths worldwide. With it spreads fear. In the modern world of social media, misinformation spreads even faster than disease.

The news about a novel and deadly illness crowds out more substantial worries. Humans are not particularly good at assessing risk or responding rationally and consistently to it. Risk is hard to fully define. If you look up “risk” in Merriam Webster’s online dictionary, you get the simple definition of “possibility of loss or injury; peril.” If you look up risk in Wikipedia, you get 12 pages of explanation and 8 more pages of links and references.

People handle risk differently. Some people are more risk adverse than others. Some get a pleasurable thrill from risk, whether a slot machine or a parachute jump. Most people really don’t comprehend small probabilities, with tens of billions of dollars spent annually on U.S. lotteries.

Because 98% of people who get COVID-19 are recovering, this is not an extinction-level event or the zombie apocalypse. It is a major health hazard, and one where morbidity and mortality might be assuaged by an early and effective public health response, including the population’s adoption of good habits such as hand washing, cough etiquette, and staying home when ill.

Three key factors may help reduce the fear factor.

One key factor is accurate communication of health information to the public. This has been severely harmed in the last few years by the promotion of gossip on social media, such as Facebook, within newsfeeds without any vetting, along with a smaller component of deliberate misinformation from untraceable sources. Compare this situation with the decision in May 1988 when Surgeon General C. Everett Koop chose to snail mail a brochure on AIDS to every household in America. It was unprecedented. One element of this communication is the public’s belief that government and health care officials will responsibly and timely convey the information. There are accusations that the Chinese government initially impeded early warnings about COVID-19. Dr. Koop, to his great credit and lifesaving leadership, overcame queasiness within the Reagan administration about issues of morality and taste in discussing some of the HIV information. Alas, no similar leadership occurred in the decade of the 2010s when deaths from the opioid epidemic in the United States skyrocketed to claim more lives annually than car accidents or suicide.

A second factor is the credibility of the scientists. Antivaxxers, climate change deniers, and mercenary scientists have severely damaged that credibility of science, compared with the trust in scientists 50 years ago during the Apollo moon shot.

A third factor is perspective. Poor journalism and clickbait can focus excessively on the rare events as news. Airline crashes make the front page while fatal car accidents, claiming a hundred times more lives annually, don’t even merit a story in local media. Someone wins the lottery weekly but few pay attention to those suffering from gambling debts.

Influenza is killing many times more people than the 2019 novel coronavirus, but the news is focused on cruise ships. In the United States, influenza annually will strike tens of millions, with about 10 per 1,000 hospitalized and 0.5 per 1,000 dying. The novel coronavirus is more lethal. SARS (a coronavirus epidemic in 2003) had 8,000 cases with a mortality rate of 96 per 1,000 while the novel 2019 strain so far is killing about 20 per 1,000. That value may be an overestimate, because there may be a significant fraction of COVID-19 patients with symptoms mild enough that they do not seek medical care and do not get tested and counted.