User login

Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy programs: How they can be improved

A Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) is a drug safety program the FDA can require for certain medications with serious safety concerns to help ensure the benefits of the medication outweigh its risks (Box1). The FDA may require medication guides, patient package inserts, communication plans for health care professionals, and/or certain packaging and safe disposal technologies for medications that pose a serious risk of abuse or overdose. The FDA may also require elements to assure safe use and/or an implementation system be included in the REMS. Pharmaceutical manufacturers then develop a proposed REMS for FDA review.2 If the FDA approves the proposed REMS, the manufacturer is responsible for implementing the REMS requirements.

Box

There are many myths and misconceptions surrounding psychiatry, the branch of medicine that deals with the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of mental illness. Some of the most common myths include:

The FDA provides this description of a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS):

“A [REMS] is a drug safety program that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) can require for certain medications with serious safety concerns to help ensure the benefits of the medication outweigh its risks. REMS are designed to reinforce medication use behaviors and actions that support the safe use of that medication. While all medications have labeling that informs health care stakeholders about medication risks, only a few medications require a REMS. REMS are not designed to mitigate all the adverse events of a medication, these are communicated to health care providers in the medication’s prescribing information. Rather, REMS focus on preventing, monitoring and/or managing a specific serious risk by informing, educating and/or reinforcing actions to reduce the frequency and/or severity of the event.”1

The REMS program for clozapine3 has been the subject of much discussion in the psychiatric community. The adverse impact of the 2015 update to the clozapine REMS program was emphasized at meetings of both the American Psychiatric Association and the College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists. A white paper published by the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors shortly after the 2015 update concluded, “clozapine is underused due to a variety of barriers related to the drug and its properties, the health care system, regulatory requirements, and reimbursement issues.”4 After an update to the clozapine REMS program in 2021, the FDA temporarily suspended enforcement of certain requirements due to concerns from health care professionals about patient access to the medication because of problems with implementing the clozapine REMS program.5,6 In November 2022, the FDA issued a second announcement of enforcement discretion related to additional requirements of the REMS program.5 The FDA had previously announced a decision to not take action regarding adherence to REMS requirements for certain laboratory tests in March 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic.7

REMS programs for other psychiatric medications may also present challenges. The REMS programs for esketamine8 and olanzapine for extended-release (ER) injectable suspension9 include certain risks that require postadministration monitoring. Some facilities have had to dedicate additional space and clinician time to ensure REMS requirements are met.

To further understand health care professionals’ perspectives regarding the value and burden of these REMS programs, a collaborative effort of the University of Maryland (College Park and Baltimore campuses) Center of Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation with the FDA was undertaken. The REMS for clozapine, olanzapine for ER injectable suspension, and esketamine were examined to develop recommendations for improving patient access while ensuring safe medication use and limiting the impact on health care professionals.

Assessing the REMS programs

Focus groups were held with health care professionals nominated by professional organizations to gather their perspectives on the REMS requirements. There was 1 focus group for each of the 3 medications. A facilitator’s guide was developed that contained the details of how to conduct the focus group along with the medication-specific questions. The questions were based on the REMS requirements as of May 2021 and assessed the impact of the REMS on patient safety, patient access, and health care professional workload; effects from the COVID-19 pandemic; and suggestions to improve the REMS programs. The University of Maryland Institutional Review Board reviewed the materials and processes and made the determination of exempt.

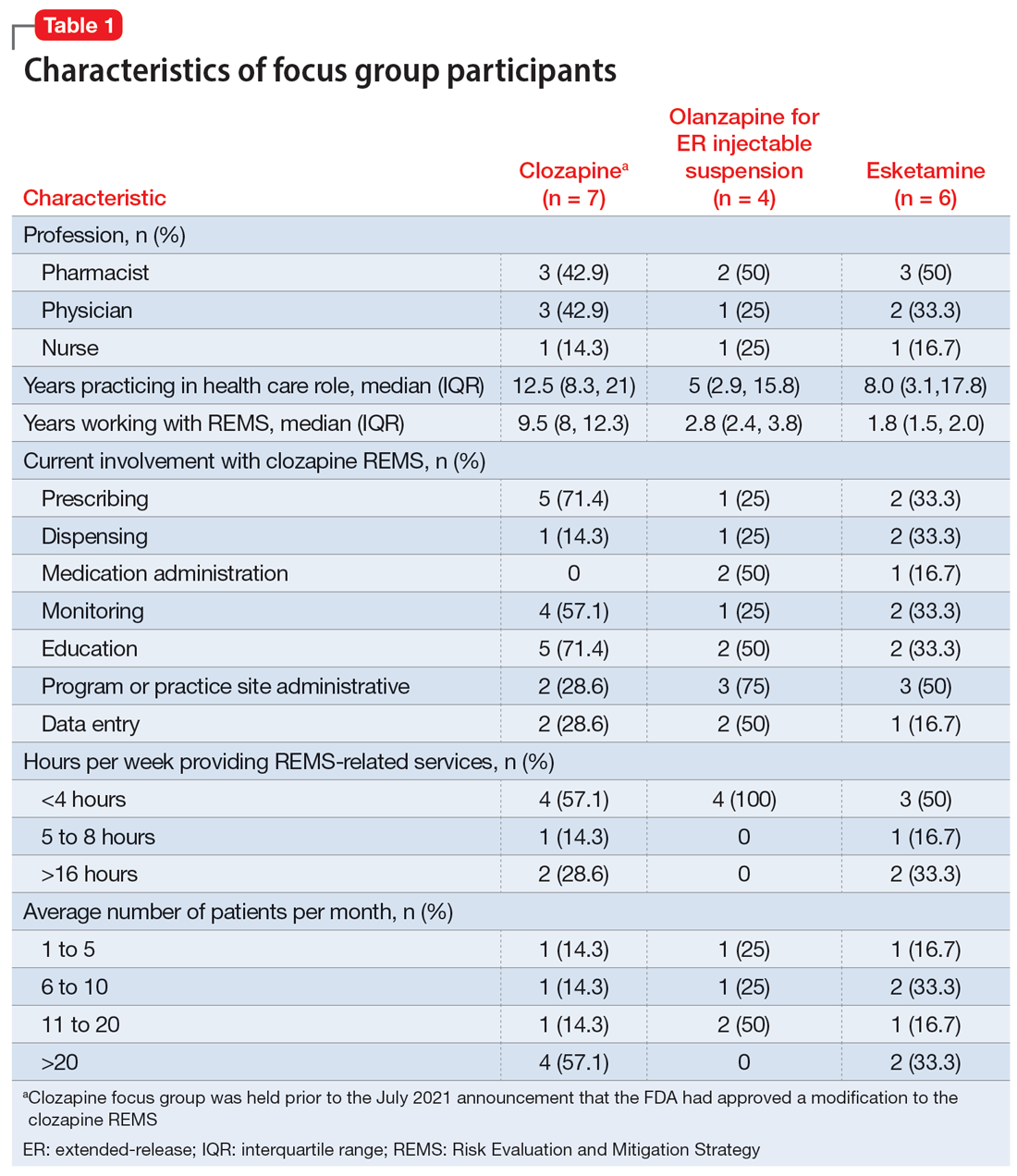

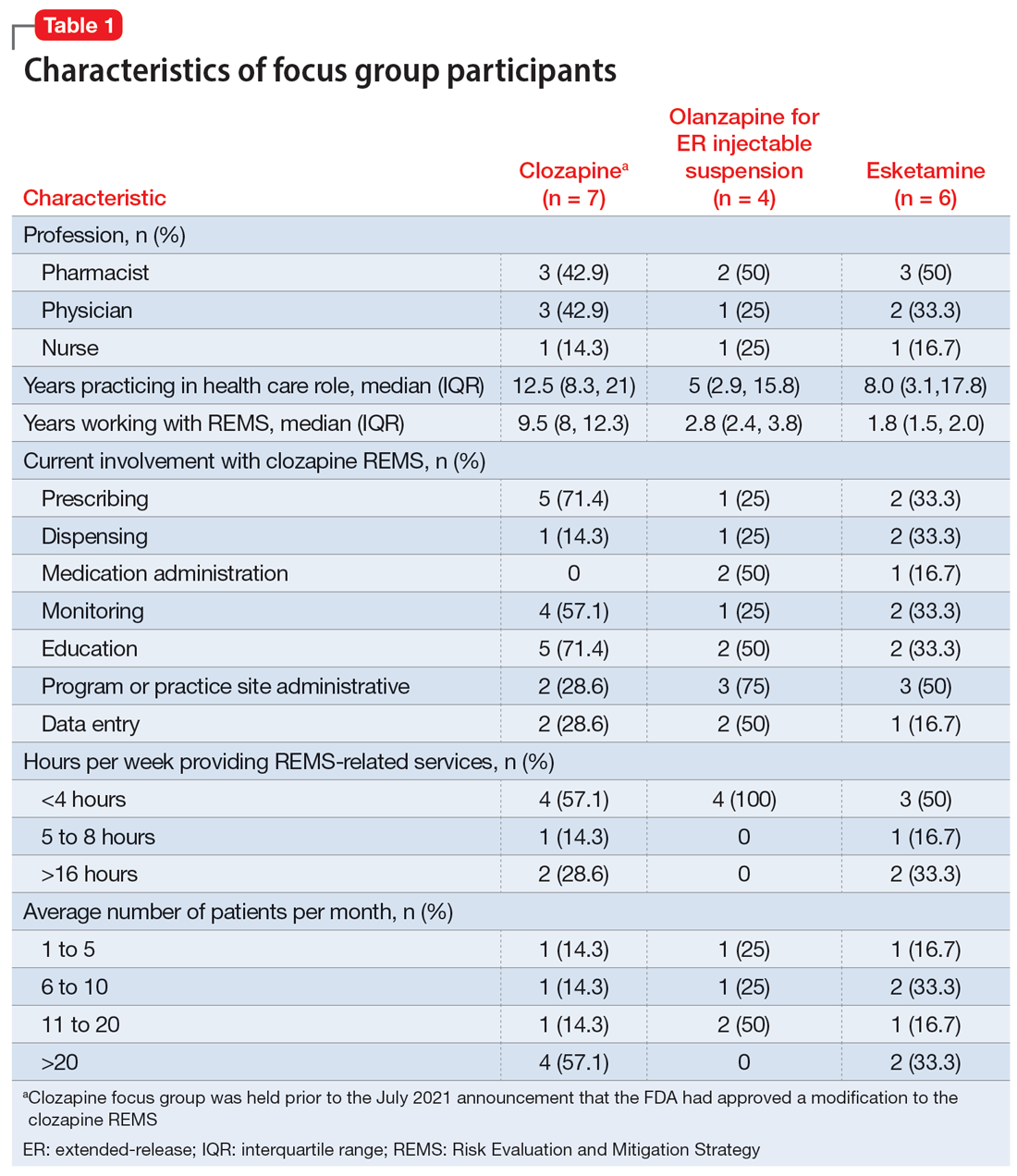

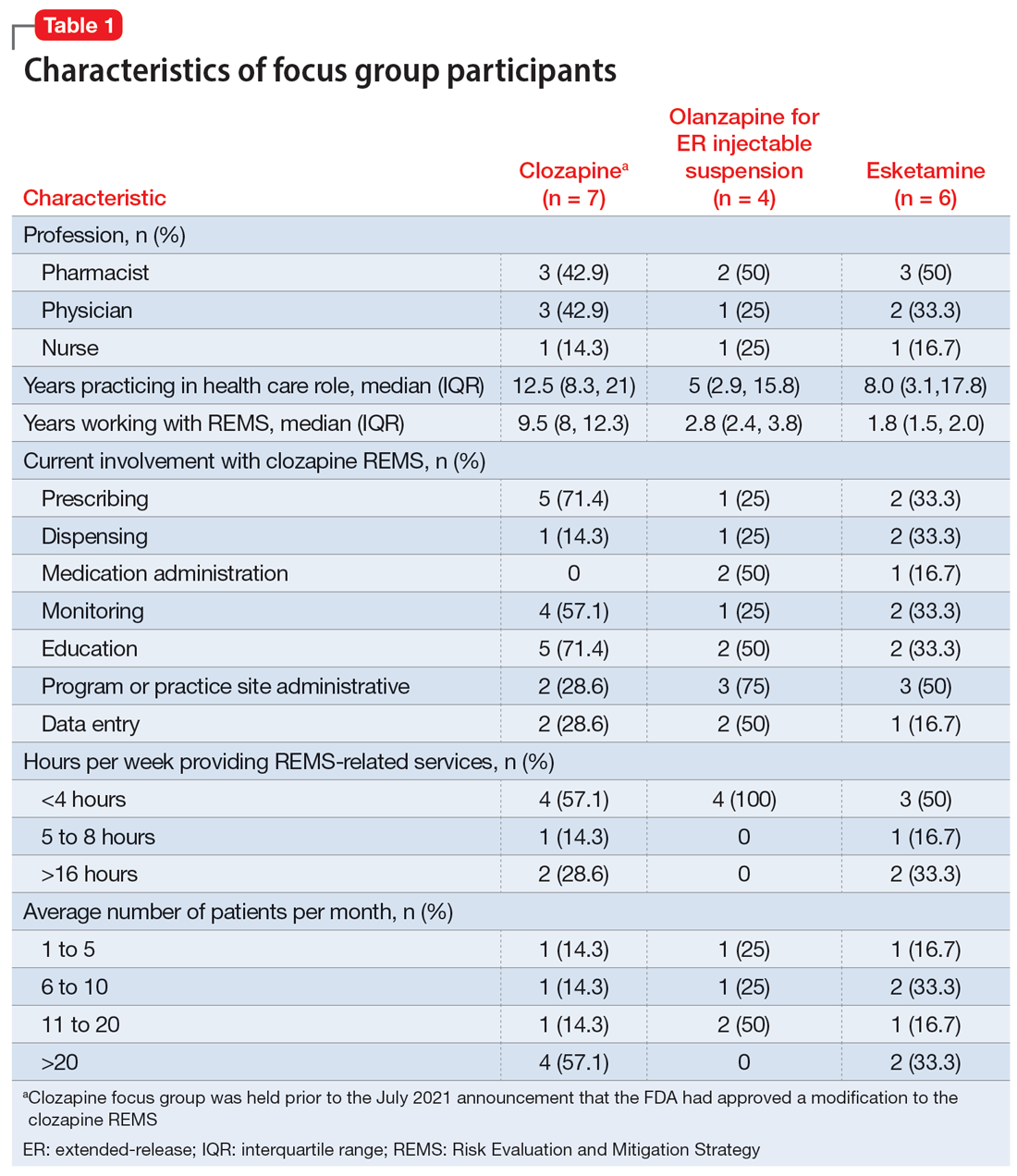

Health care professionals were eligible to participate in a focus group if they had ≥1 year of experience working with patients who use the specific medication and ≥6 months of experience within the past year working with the REMS program for that medication. Participants were excluded if they were employed by a pharmaceutical manufacturer or the FDA. The focus groups were conducted virtually using an online conferencing service during summer 2021 and were scheduled for 90 minutes. Prior to the focus group, participants received information from the “Goals” and “Summary” tabs of the FDA REMS website10 for the specific medication along with patient/caregiver guides, which were available for clozapine and olanzapine for ER injectable suspension. For each focus group, there was a target sample size of 6 to 9 participants. However, there were only 4 participants in the olanzapine for ER injectable suspension focus group, which we believed was due to lower national utilization of this medication. Individuals were only able to participate in 1 focus group, so the unique participant count for all 3 focus groups totaled 17 (Table 1).

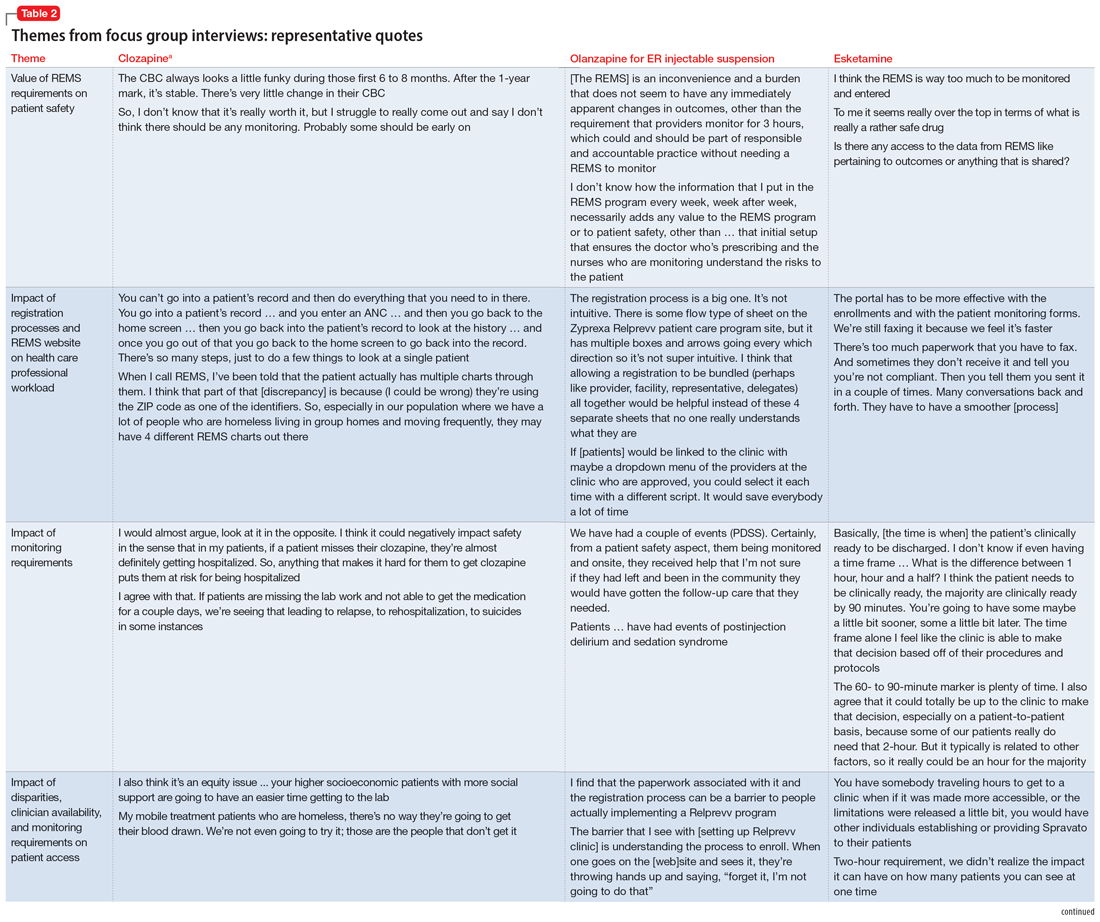

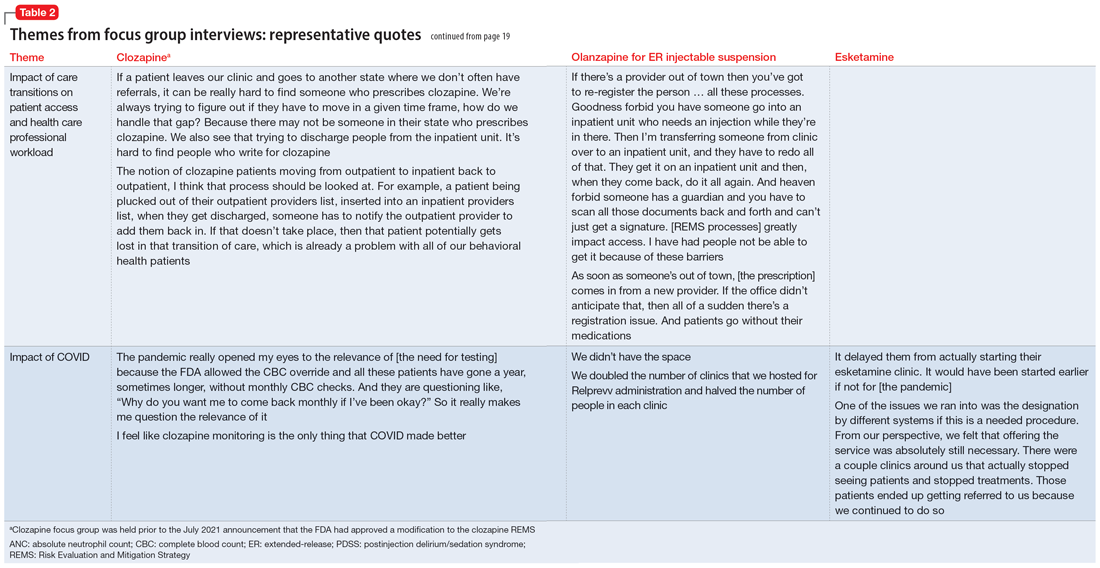

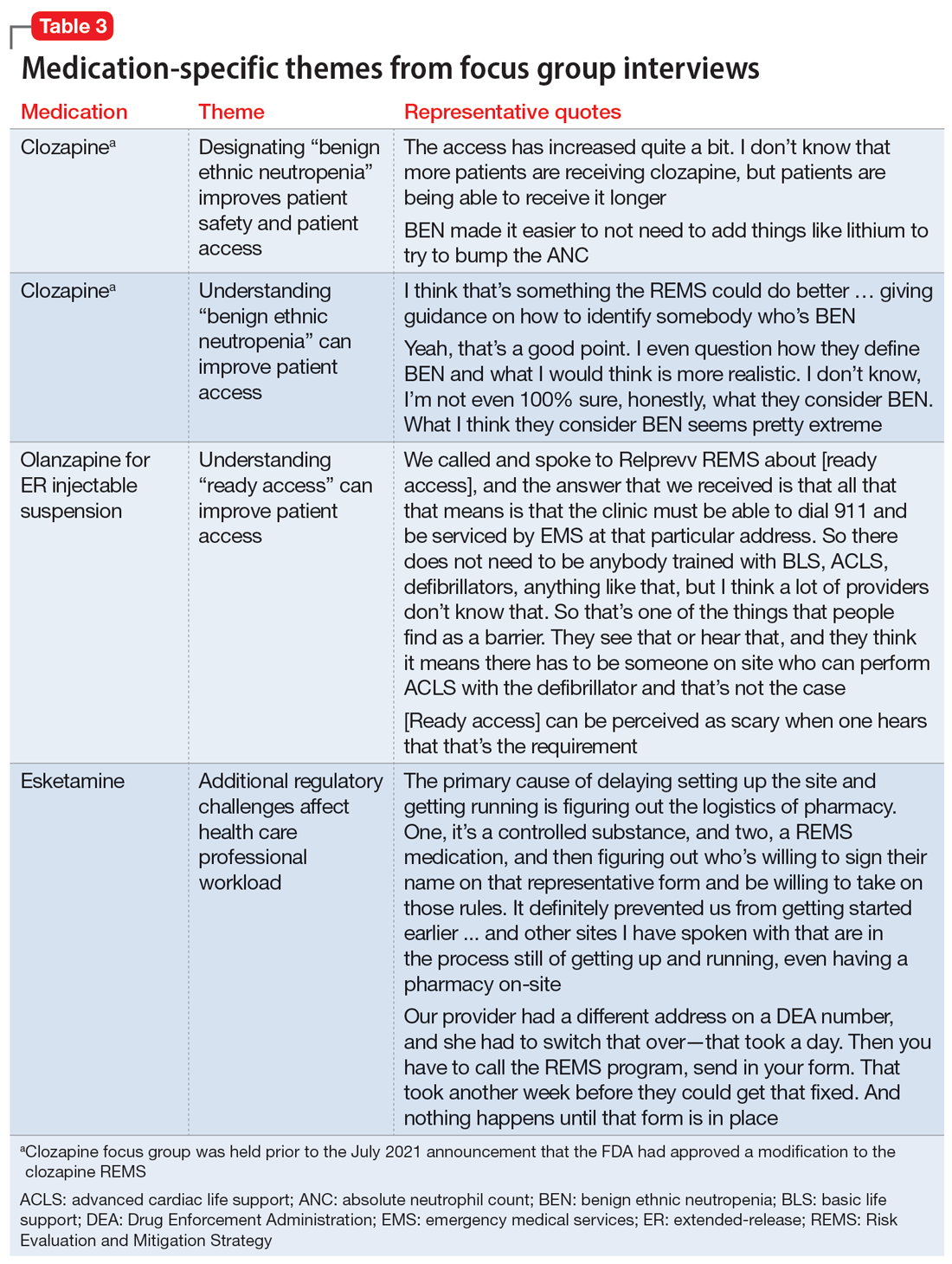

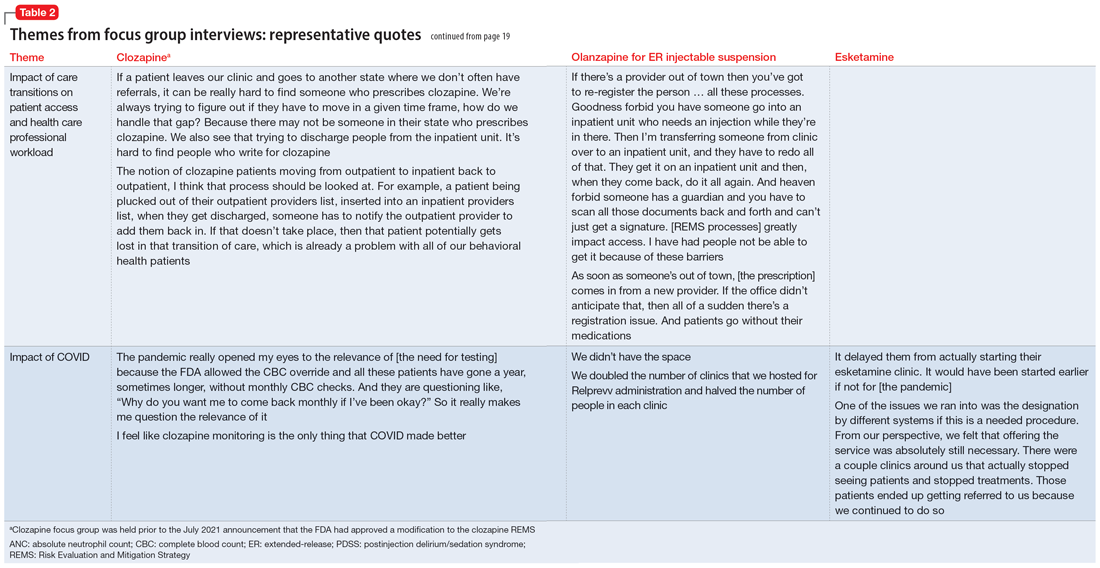

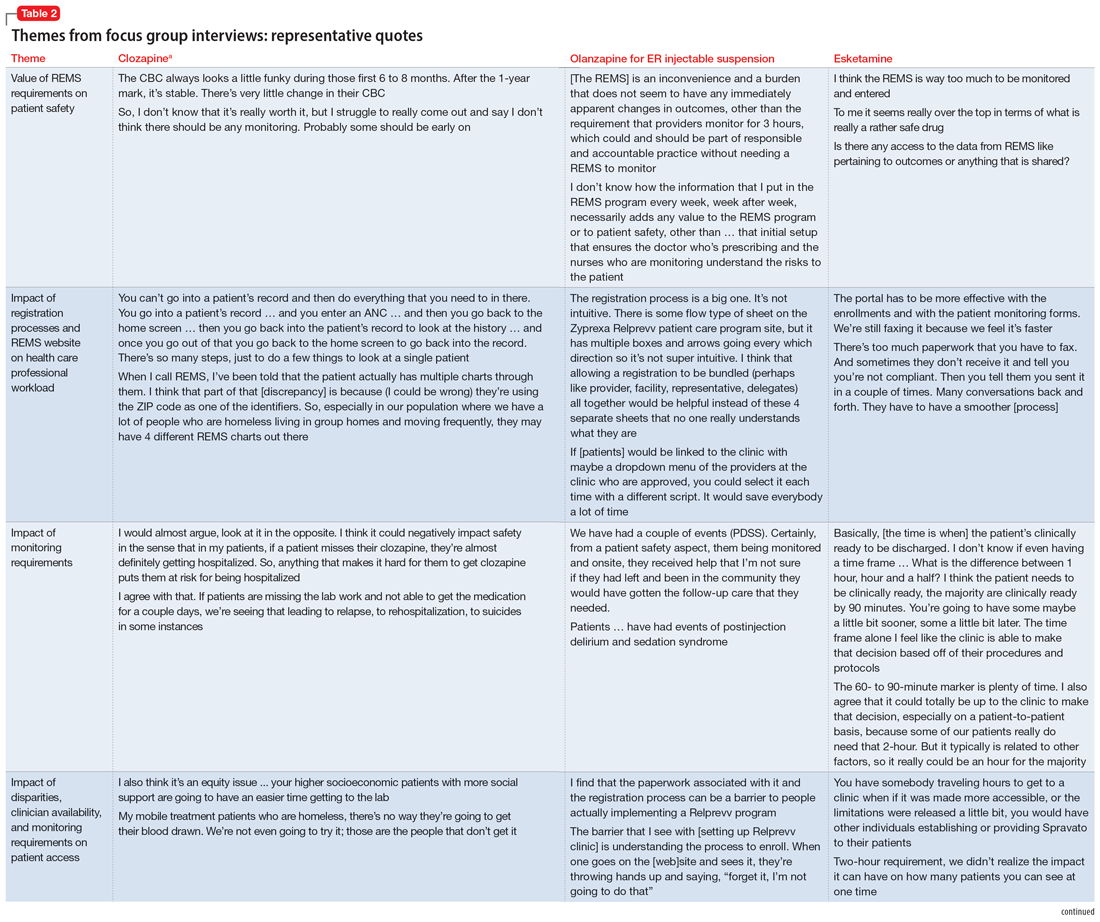

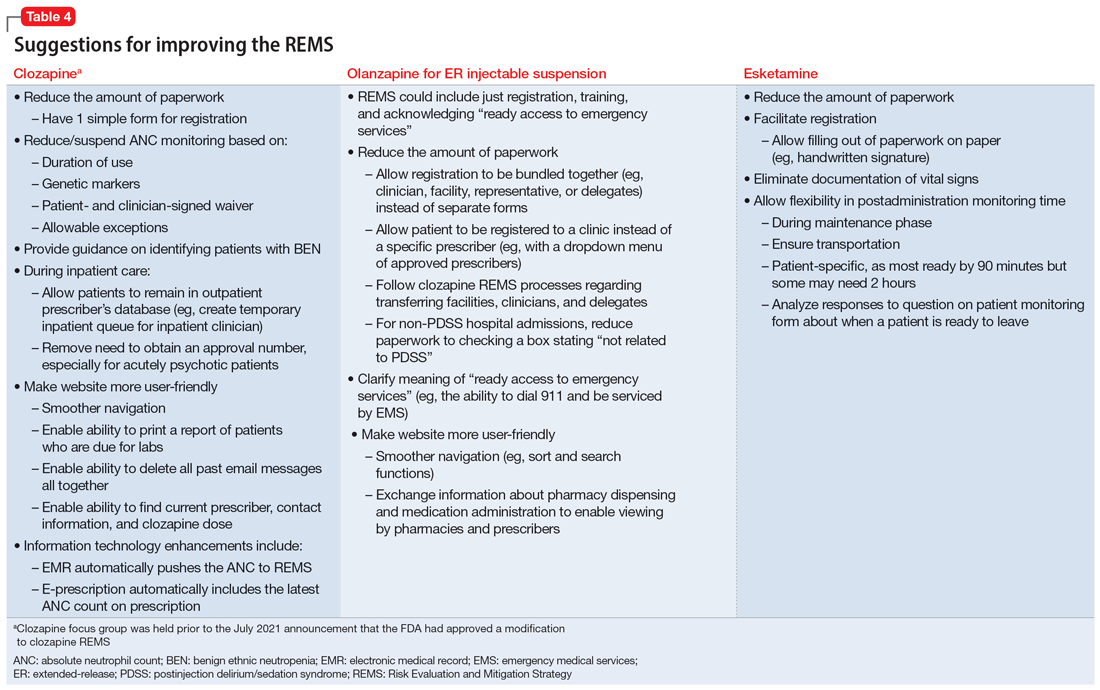

Themes extracted from qualitative analysis of the focus group responses were the value of the REMS programs; registration/enrollment processes and REMS websites; monitoring requirements; care transitions; and COVID considerations (Table 2). While the REMS programs were perceived to increase practitioner and patient awareness of potential harms, discussions centered on the relative cost-to-benefit of the required reporting and other REMS requirements. There were challenges with the registration/enrollment processes and REMS websites that also affected patient care during transitions to different health care settings or clinicians. Patient access was affected by disparities in care related to monitoring requirements and clinician availability.

Continue to: COVID impacted all REMS...

COVID impacted all REMS programs. Physical distancing was an issue for medications that required extensive postadministration monitoring (ie, esketamine and olanzapine for ER injectable suspension). Access to laboratory services was an issue for clozapine.

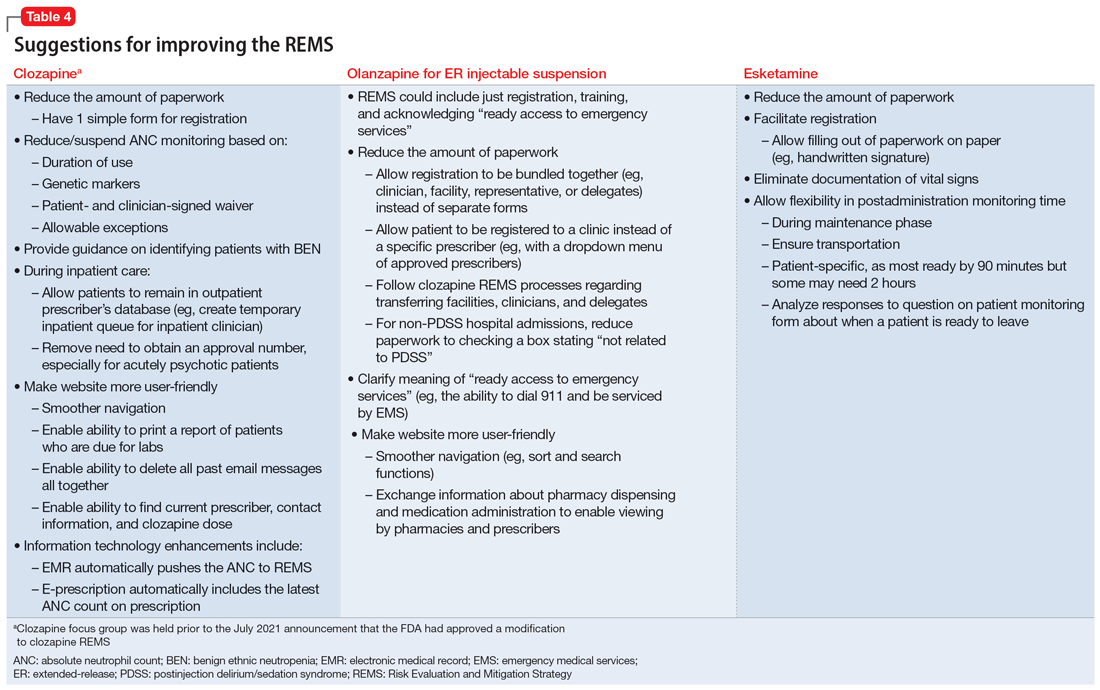

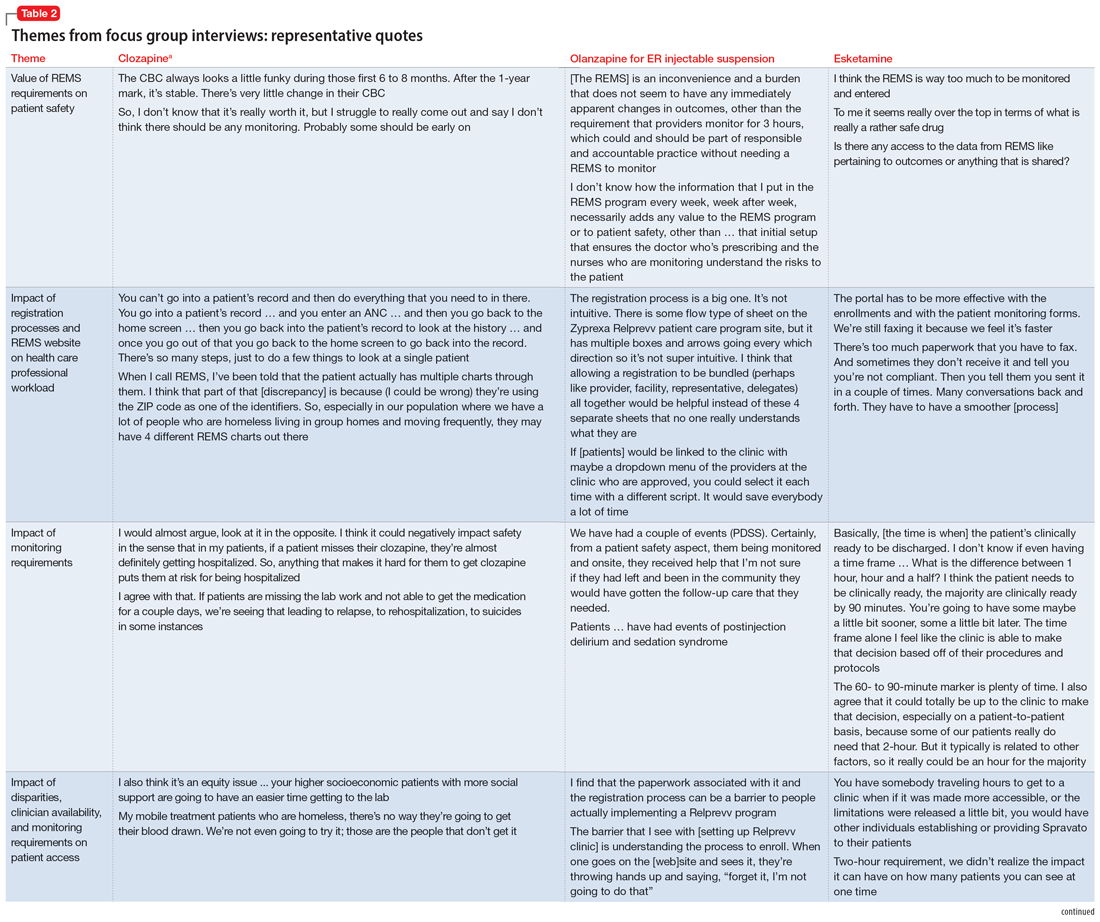

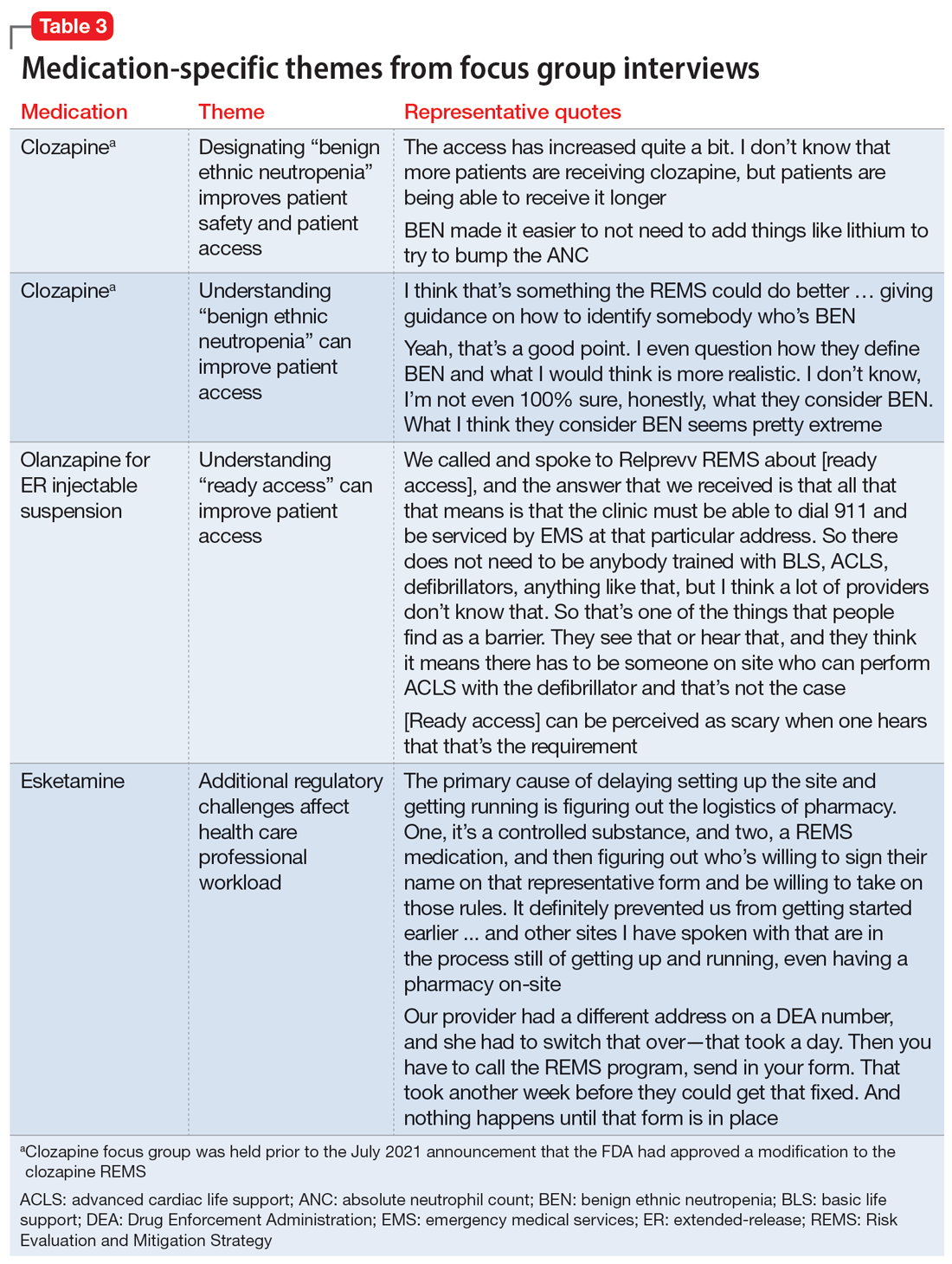

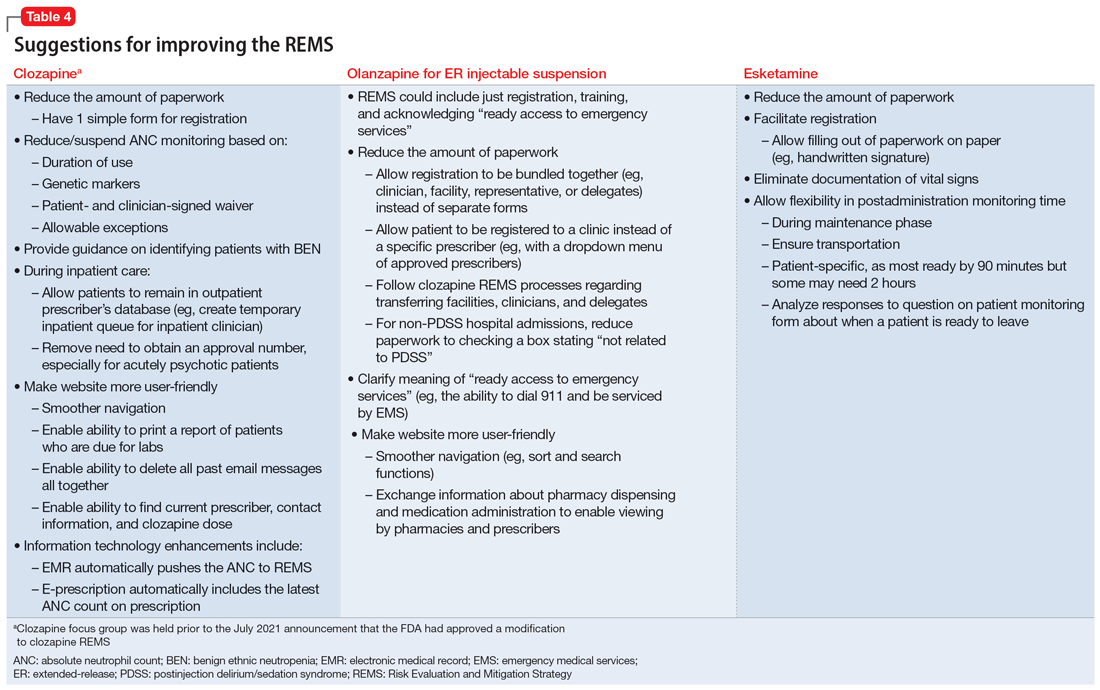

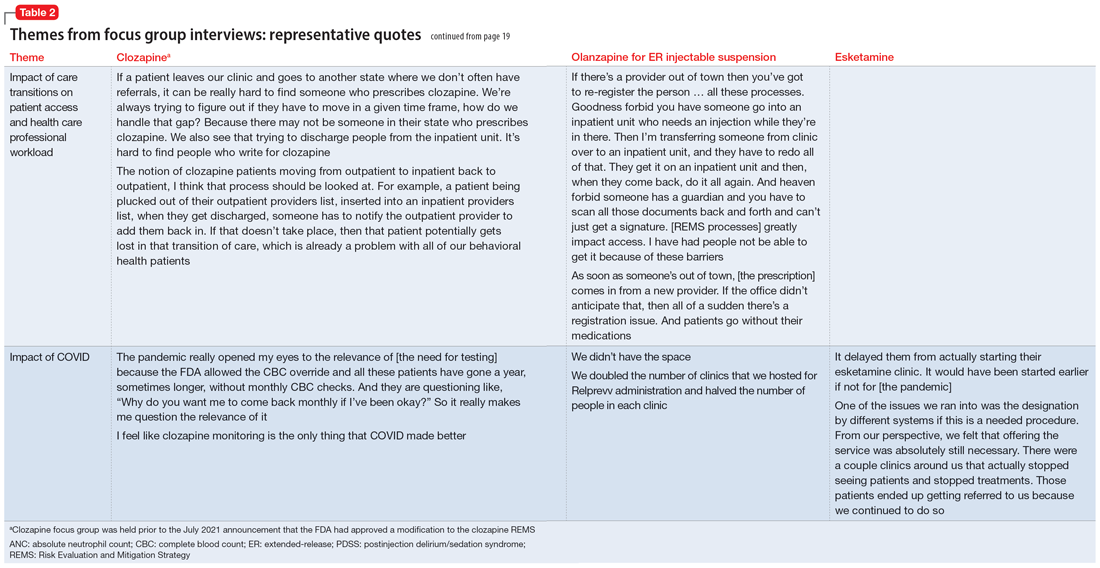

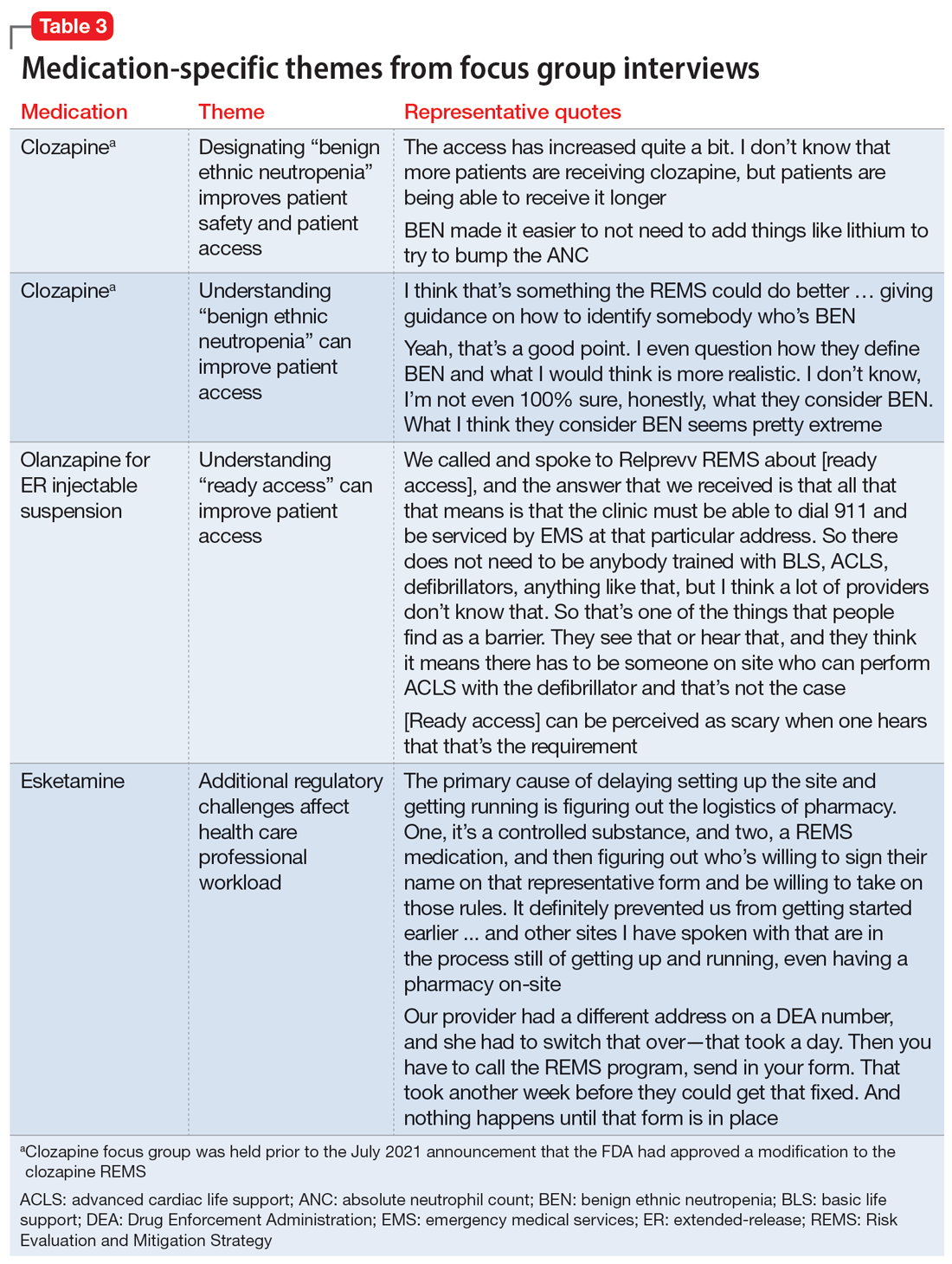

Medication-specific themes are listed in Table 3 and relate to terms and descriptions in the REMS or additional regulatory requirements from the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). Suggestions for improvement to the REMS are presented in Table 4.

Recommendations for improving REMS

A group consisting of health care professionals, policy experts, and mental health advocates reviewed the information provided by the focus groups and developed the following recommendations.

Overarching recommendations

Each REMS should include a section providing justification for its existence, including a risk analysis of the data regarding the risk the REMS is designed to mitigate. This analysis should be repeated on a regular basis as scientific evidence regarding the risk and its epidemiology evolves. This additional section should also explain how the program requirements of the REMS as implemented (or planned) will achieve the aims of the REMS and weigh the potential benefits of the REMS requirements as implemented (or planned) by the manufacturer vs the potential risks of the REMS requirements as implemented (or planned) by the manufacturer.

Each REMS should have specific quantifiable outcomes. For example, it should specify a reduction in occurrence of the rate of the concerned risk by a specified amount.

Continue to: Ensure adequate...

Ensure adequate stakeholder input during the REMS development and real-world testing in multiple environments before implementing the REMS to identify unanticipated consequences that might impact patient access, patient safety, and health care professional burden. Implementation testing should explore issues such as purchasing and procurement, billing and reimbursement, and relevant factors such as other federal regulations or requirements (eg, the DEA or Medicare).

Ensure harmonization of the REMS forms and processes (eg, initiation and monitoring) for different medications where possible. A prescriber, pharmacist, or system should not face additional barriers to participate in a REMS based on REMS-specific intricacies (ie, prescription systems, data submission systems, or ordering systems). This streamlining will likely decrease clinical inertia to initiate care with the REMS medication, decrease health care professional burden, and improve compliance with REMS requirements.

REMS should anticipate the need for care transitions and employ provisions to ensure seamless care. Considerations should be given to transitions that occur due to:

- Different care settings (eg, inpatient, outpatient, or long-term care)

- Different geographies (eg, patient moves)

- Changes in clinicians, including leaves or absences

- Changes in facilities (eg, pharmacies).

REMS should mirror normal health care professional workflow, including how monitoring data are collected and how and with which frequency pharmacies fill prescriptions.Enhanced information technology to support REMS programs is needed. For example, REMS should be integrated with major electronic patient health record and pharmacy systems to reduce the effort required for clinicians to supply data and automate REMS processes.

For medications that are subject to other agencies and their regulations (eg, the CDC, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, or the DEA), REMS should be required to meet all standards of all agencies with a single system that accommodates normal health care professional workflow.

Continue to: REMS should have a...

REMS should have a standard disclaimer that allows the health care professional to waive certain provisions of the REMS in cases when the specific provisions of the REMS pose a greater risk to the patient than the risk posed by waiving the requirement.

Assure the actions implemented by the industry to meet the requirements for each REMS program are based on peer-reviewed evidence and provide a reasonable expectation to achieve the anticipated benefit.

Ensure that manufacturers make all accumulated REMS data available in a deidentified manner for use by qualified scientific researchers. Additionally, each REMS should have a plan for data access upon initiation and termination of the REMS.

Each REMS should collect data on the performance of the centers and/or personnel who operate the REMS and submit this data for review by qualified outside reviewers. Parameters to assess could include:

- timeliness of response

- timeliness of problem resolution

- data availability and its helpfulness to patient care

- adequacy of resources.

Recommendations for clozapine REMS

These comments relate to the clozapine REMS program prior to the July 2021 announcement that FDA had approved a modification.

Provide a clear definition for “benign ethnic neutropenia.”

Ensure the REMS includes patient-specific adjustments to allow flexibility for monitoring. During COVID, the FDA allowed clinicians to “use their best medical judgment in weighing the benefits and risks of continuing treatment in the absence of laboratory testing.”7 This guidance, which allowed flexibility to absolute neutrophil count (ANC) monitoring, was perceived as positive and safe. Before the changes in the REMS requirements, patients with benign ethnic neutropenia were restricted from accessing their medication or encountered harm from additional pharmacotherapy to mitigate ANC levels.

Continue to: Recommendations for olanzapine for ER injectable suspension REMS

Recommendations for olanzapine for ER injectable suspension REMS

Provide clear explicit instructions on what is required to have “ready access to emergency services.”

Ensure the REMS include patient-specific adjustments to allow flexibility for postadministration monitoring (eg, sedation or blood pressure). Specific patient groups may have differential access to certain types of facilities, transportation, or other resources. For example, consider the administration of olanzapine for ER injectable suspension by a mobile treatment team with an adequate protocol (eg, via videoconferencing or phone calls).

Ensure actions with peer-reviewed evidence demonstrating efficacy/effectiveness are included in the REMS. How was the 3-hour cut-point determined? Has it been reevaluated?

Ensure the REMS requirements allow for seamless care during transitions, particularly when clinicians are on vacation.

Continue to: Recommendations for esketamine REMS

Recommendations for esketamine REMS

Ensure the REMS includes patient-specific adjustments to allow flexibility for postadministration monitoring. Specific patient groups may have differential access to certain types of facilities, transportation, or other resources. For example, consider the administration of esketamine by a mobile treatment team with an adequate protocol (eg, via videoconferencing or phone calls).

Ensure actions with peer-reviewed evidence demonstrating efficacy/effectiveness of requirements are included in the REMS. How was the 2-hour cut-point determined? Has it been reevaluated?

Ensure that the REMS meet all standards of the DEA, with a single system that accommodates normal health care professional workflow.

A summary of the findings

Overall, the REMS programs for these 3 medications were positively perceived for raising awareness of safe medication use for clinicians and patients. Monitoring patients for safety concerns is important and REMS requirements provide accountability.

Continue to: The use of a single shared...

The use of a single shared REMS system for documenting requirements for clozapine (compared to separate systems for each manufacturer) was a positive move forward in implementation. The focus group welcomed the increased awareness of benign ethnic neutropenia as a result of this condition being incorporated in the revised monitoring requirements of the clozapine REMS.

Focus group participants raised the issue of the real-world efficiency of the REMS programs (reduced access and increased clinician workload) vs the benefits (patient safety). They noted that excessive workload could lead to clinicians becoming unwilling to use a medication that requires a REMS. Clinician workload may be further compromised when REMS logistics disrupt the normal workflow and transitions of care between clinicians or settings. This latter aspect is of particular concern for clozapine.

The complexities of the registration and reporting system for olanzapine for ER injectable suspension and the lack of clarity about monitoring were noted to have discouraged the opening of treatment sites. This scarcity of sites may make clinicians hesitant to use this medication, and instead opt for alternative treatments in patients who may be appropriate candidates.

There has also been limited growth of esketamine treatment sites, especially in comparison to ketamine treatment sites.11-14 Esketamine is FDA-approved for treatment-resistant depression in adults and for depressive symptoms in adults with major depressive disorder with acute suicidal ideation or behavior. Ketamine is not FDA-approved for treating depression but is being used off-label to treat this disorder.15 The FDA determined that ketamine does not require a REMS to ensure the benefits outweigh the risks for its approved indications as an anesthetic agent, anesthesia-inducing agent, or supplement to anesthesia. Since ketamine has no REMS requirements, there may be a lower burden for its use. Thus, clinicians are treating patients for depression with this medication without needing to comply with a REMS.16

Technology plays a role in workload burden, and integrating health care processes within current workflow systems, such as using electronic patient health records and pharmacy systems, is recommended. The FDA has been exploring technologies to facilitate the completion of REMS requirements, including mandatory education within the prescribers’ and pharmacists’ workflow.17 This is a complex task that requires multiple stakeholders with differing perspectives and incentives to align.

Continue to: The data collected for the REMS...

The data collected for the REMS program belongs to the medication’s manufacturer. Current regulations do not require manufacturers to make this data available to qualified scientific researchers. A regulatory mandate to establish data sharing methods would improve transparency and enhance efforts to better understand the outcomes of the REMS programs.

A few caveats

Both the overarching and medication-specific recommendations were based on a small number of participants’ discussions related to clozapine, olanzapine for ER injectable suspension, and esketamine. These recommendations do not include other medications with REMS that are used to treat psychiatric disorders, such as loxapine, buprenorphine ER, and buprenorphine transmucosal products. Larger-scale qualitative and quantitative research is needed to better understand health care professionals’ perspectives. Lastly, some of the recommendations outlined in this article are beyond the current purview or authority of the FDA and may require legislative or regulatory action to implement.

Bottom Line

Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) programs are designed to help reduce the occurrence and/or severity of serious risks or to inform decision-making. However, REMS requirements may adversely impact patient access to certain REMS medications and clinician burden. Health care professionals can provide informed recommendations for improving the REMS programs for clozapine, olanzapine for extended-release injectable suspension, and esketamine.

Related Resources

- FDA. Frequently asked questions (FAQs) about REMS. www.fda.gov/drugs/risk-evaluation-and-mitigation-strategies-rems/frequently-asked-questions-faqs-about-rems

Drug Brand Names

Buprenorphine extended-release • Sublocade

Buprenorphine transmucosal • Subutex, Suboxone

Clozapine • Clozaril

Esketamine • Spravato

Ketamine • Ketalar

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Loxapine • Adasuve

Olanzapine extended-release injectable suspension • Zyprexa Relprevv

1. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/risk-evaluation-and-mitigation-strategies-rems

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Format and Content of a REMS Document. Guidance for Industry. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/media/77846/download

3. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS), Clozapine. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/index.cfm?event=RemsDetails.page&REMS=351

4. The National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors. Clozapine underutilization: addressing the barriers. Accessed September 30, 2019. https://nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/Assessment%201_Clozapine%20Underutilization.pdf

5. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA is temporarily exercising enforcement discretion with respect to certain clozapine REMS program requirements to ensure continuity of care for patients taking clozapine. Updated November 22, 2022. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-temporarily-exercising-enforcement-discretion-respect-certain-clozapine-rems-program

6. Tanzi M. REMS issues affect clozapine, isotretinoin. Pharmacy Today. 2022;28(3):49.

7. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA provides update on patient access to certain REMS drugs during COVID-19 public health emergency. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-provides-update-patient-access-certain-rems-drugs-during-covid-19

8. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS), Spravato (esketamine). Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/index.cfm?event=IndvRemsDetails.page&REMS=386

9. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS), Zyprexa Relprevv (olanzapine). Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/index.cfm?event=IndvRemsDetails.page&REMS=74

10. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS). Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/index.cfm

11. Parikh SV, Lopez D, Vande Voort JL, et al. Developing an IV ketamine clinic for treatment-resistant depression: a primer. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2021;51(3):109-124.

12. Dodge D. The ketamine cure. The New York Times. November 4, 2021. Updated November 5, 2021. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/04/well/ketamine-therapy-depression.html

13. Burton KW. Time for a national ketamine registry, experts say. Medscape. February 15, 2023. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/988310

14. Wilkinson ST, Howard DH, Busch SH. Psychiatric practice patterns and barriers to the adoption of esketamine. JAMA. 2019;322(11):1039-1040. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.10728

15. Wilkinson ST, Toprak M, Turner MS, et al. A survey of the clinical, off-label use of ketamine as a treatment for psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(7):695-696. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17020239

16. Pai SM, Gries JM; ACCP Public Policy Committee. Off-label use of ketamine: a challenging drug treatment delivery model with an inherently unfavorable risk-benefit profile. J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;62(1):10-13. doi:10.1002/jcph.1983

17. Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) Integration. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://confluence.hl7.org/display/COD/Risk+Evaluation+and+Mitigation+Strategies+%28REMS%29+Integration

A Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) is a drug safety program the FDA can require for certain medications with serious safety concerns to help ensure the benefits of the medication outweigh its risks (Box1). The FDA may require medication guides, patient package inserts, communication plans for health care professionals, and/or certain packaging and safe disposal technologies for medications that pose a serious risk of abuse or overdose. The FDA may also require elements to assure safe use and/or an implementation system be included in the REMS. Pharmaceutical manufacturers then develop a proposed REMS for FDA review.2 If the FDA approves the proposed REMS, the manufacturer is responsible for implementing the REMS requirements.

Box

There are many myths and misconceptions surrounding psychiatry, the branch of medicine that deals with the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of mental illness. Some of the most common myths include:

The FDA provides this description of a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS):

“A [REMS] is a drug safety program that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) can require for certain medications with serious safety concerns to help ensure the benefits of the medication outweigh its risks. REMS are designed to reinforce medication use behaviors and actions that support the safe use of that medication. While all medications have labeling that informs health care stakeholders about medication risks, only a few medications require a REMS. REMS are not designed to mitigate all the adverse events of a medication, these are communicated to health care providers in the medication’s prescribing information. Rather, REMS focus on preventing, monitoring and/or managing a specific serious risk by informing, educating and/or reinforcing actions to reduce the frequency and/or severity of the event.”1

The REMS program for clozapine3 has been the subject of much discussion in the psychiatric community. The adverse impact of the 2015 update to the clozapine REMS program was emphasized at meetings of both the American Psychiatric Association and the College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists. A white paper published by the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors shortly after the 2015 update concluded, “clozapine is underused due to a variety of barriers related to the drug and its properties, the health care system, regulatory requirements, and reimbursement issues.”4 After an update to the clozapine REMS program in 2021, the FDA temporarily suspended enforcement of certain requirements due to concerns from health care professionals about patient access to the medication because of problems with implementing the clozapine REMS program.5,6 In November 2022, the FDA issued a second announcement of enforcement discretion related to additional requirements of the REMS program.5 The FDA had previously announced a decision to not take action regarding adherence to REMS requirements for certain laboratory tests in March 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic.7

REMS programs for other psychiatric medications may also present challenges. The REMS programs for esketamine8 and olanzapine for extended-release (ER) injectable suspension9 include certain risks that require postadministration monitoring. Some facilities have had to dedicate additional space and clinician time to ensure REMS requirements are met.

To further understand health care professionals’ perspectives regarding the value and burden of these REMS programs, a collaborative effort of the University of Maryland (College Park and Baltimore campuses) Center of Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation with the FDA was undertaken. The REMS for clozapine, olanzapine for ER injectable suspension, and esketamine were examined to develop recommendations for improving patient access while ensuring safe medication use and limiting the impact on health care professionals.

Assessing the REMS programs

Focus groups were held with health care professionals nominated by professional organizations to gather their perspectives on the REMS requirements. There was 1 focus group for each of the 3 medications. A facilitator’s guide was developed that contained the details of how to conduct the focus group along with the medication-specific questions. The questions were based on the REMS requirements as of May 2021 and assessed the impact of the REMS on patient safety, patient access, and health care professional workload; effects from the COVID-19 pandemic; and suggestions to improve the REMS programs. The University of Maryland Institutional Review Board reviewed the materials and processes and made the determination of exempt.

Health care professionals were eligible to participate in a focus group if they had ≥1 year of experience working with patients who use the specific medication and ≥6 months of experience within the past year working with the REMS program for that medication. Participants were excluded if they were employed by a pharmaceutical manufacturer or the FDA. The focus groups were conducted virtually using an online conferencing service during summer 2021 and were scheduled for 90 minutes. Prior to the focus group, participants received information from the “Goals” and “Summary” tabs of the FDA REMS website10 for the specific medication along with patient/caregiver guides, which were available for clozapine and olanzapine for ER injectable suspension. For each focus group, there was a target sample size of 6 to 9 participants. However, there were only 4 participants in the olanzapine for ER injectable suspension focus group, which we believed was due to lower national utilization of this medication. Individuals were only able to participate in 1 focus group, so the unique participant count for all 3 focus groups totaled 17 (Table 1).

Themes extracted from qualitative analysis of the focus group responses were the value of the REMS programs; registration/enrollment processes and REMS websites; monitoring requirements; care transitions; and COVID considerations (Table 2). While the REMS programs were perceived to increase practitioner and patient awareness of potential harms, discussions centered on the relative cost-to-benefit of the required reporting and other REMS requirements. There were challenges with the registration/enrollment processes and REMS websites that also affected patient care during transitions to different health care settings or clinicians. Patient access was affected by disparities in care related to monitoring requirements and clinician availability.

Continue to: COVID impacted all REMS...

COVID impacted all REMS programs. Physical distancing was an issue for medications that required extensive postadministration monitoring (ie, esketamine and olanzapine for ER injectable suspension). Access to laboratory services was an issue for clozapine.

Medication-specific themes are listed in Table 3 and relate to terms and descriptions in the REMS or additional regulatory requirements from the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). Suggestions for improvement to the REMS are presented in Table 4.

Recommendations for improving REMS

A group consisting of health care professionals, policy experts, and mental health advocates reviewed the information provided by the focus groups and developed the following recommendations.

Overarching recommendations

Each REMS should include a section providing justification for its existence, including a risk analysis of the data regarding the risk the REMS is designed to mitigate. This analysis should be repeated on a regular basis as scientific evidence regarding the risk and its epidemiology evolves. This additional section should also explain how the program requirements of the REMS as implemented (or planned) will achieve the aims of the REMS and weigh the potential benefits of the REMS requirements as implemented (or planned) by the manufacturer vs the potential risks of the REMS requirements as implemented (or planned) by the manufacturer.

Each REMS should have specific quantifiable outcomes. For example, it should specify a reduction in occurrence of the rate of the concerned risk by a specified amount.

Continue to: Ensure adequate...

Ensure adequate stakeholder input during the REMS development and real-world testing in multiple environments before implementing the REMS to identify unanticipated consequences that might impact patient access, patient safety, and health care professional burden. Implementation testing should explore issues such as purchasing and procurement, billing and reimbursement, and relevant factors such as other federal regulations or requirements (eg, the DEA or Medicare).

Ensure harmonization of the REMS forms and processes (eg, initiation and monitoring) for different medications where possible. A prescriber, pharmacist, or system should not face additional barriers to participate in a REMS based on REMS-specific intricacies (ie, prescription systems, data submission systems, or ordering systems). This streamlining will likely decrease clinical inertia to initiate care with the REMS medication, decrease health care professional burden, and improve compliance with REMS requirements.

REMS should anticipate the need for care transitions and employ provisions to ensure seamless care. Considerations should be given to transitions that occur due to:

- Different care settings (eg, inpatient, outpatient, or long-term care)

- Different geographies (eg, patient moves)

- Changes in clinicians, including leaves or absences

- Changes in facilities (eg, pharmacies).

REMS should mirror normal health care professional workflow, including how monitoring data are collected and how and with which frequency pharmacies fill prescriptions.Enhanced information technology to support REMS programs is needed. For example, REMS should be integrated with major electronic patient health record and pharmacy systems to reduce the effort required for clinicians to supply data and automate REMS processes.

For medications that are subject to other agencies and their regulations (eg, the CDC, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, or the DEA), REMS should be required to meet all standards of all agencies with a single system that accommodates normal health care professional workflow.

Continue to: REMS should have a...

REMS should have a standard disclaimer that allows the health care professional to waive certain provisions of the REMS in cases when the specific provisions of the REMS pose a greater risk to the patient than the risk posed by waiving the requirement.

Assure the actions implemented by the industry to meet the requirements for each REMS program are based on peer-reviewed evidence and provide a reasonable expectation to achieve the anticipated benefit.

Ensure that manufacturers make all accumulated REMS data available in a deidentified manner for use by qualified scientific researchers. Additionally, each REMS should have a plan for data access upon initiation and termination of the REMS.

Each REMS should collect data on the performance of the centers and/or personnel who operate the REMS and submit this data for review by qualified outside reviewers. Parameters to assess could include:

- timeliness of response

- timeliness of problem resolution

- data availability and its helpfulness to patient care

- adequacy of resources.

Recommendations for clozapine REMS

These comments relate to the clozapine REMS program prior to the July 2021 announcement that FDA had approved a modification.

Provide a clear definition for “benign ethnic neutropenia.”

Ensure the REMS includes patient-specific adjustments to allow flexibility for monitoring. During COVID, the FDA allowed clinicians to “use their best medical judgment in weighing the benefits and risks of continuing treatment in the absence of laboratory testing.”7 This guidance, which allowed flexibility to absolute neutrophil count (ANC) monitoring, was perceived as positive and safe. Before the changes in the REMS requirements, patients with benign ethnic neutropenia were restricted from accessing their medication or encountered harm from additional pharmacotherapy to mitigate ANC levels.

Continue to: Recommendations for olanzapine for ER injectable suspension REMS

Recommendations for olanzapine for ER injectable suspension REMS

Provide clear explicit instructions on what is required to have “ready access to emergency services.”

Ensure the REMS include patient-specific adjustments to allow flexibility for postadministration monitoring (eg, sedation or blood pressure). Specific patient groups may have differential access to certain types of facilities, transportation, or other resources. For example, consider the administration of olanzapine for ER injectable suspension by a mobile treatment team with an adequate protocol (eg, via videoconferencing or phone calls).

Ensure actions with peer-reviewed evidence demonstrating efficacy/effectiveness are included in the REMS. How was the 3-hour cut-point determined? Has it been reevaluated?

Ensure the REMS requirements allow for seamless care during transitions, particularly when clinicians are on vacation.

Continue to: Recommendations for esketamine REMS

Recommendations for esketamine REMS

Ensure the REMS includes patient-specific adjustments to allow flexibility for postadministration monitoring. Specific patient groups may have differential access to certain types of facilities, transportation, or other resources. For example, consider the administration of esketamine by a mobile treatment team with an adequate protocol (eg, via videoconferencing or phone calls).

Ensure actions with peer-reviewed evidence demonstrating efficacy/effectiveness of requirements are included in the REMS. How was the 2-hour cut-point determined? Has it been reevaluated?

Ensure that the REMS meet all standards of the DEA, with a single system that accommodates normal health care professional workflow.

A summary of the findings

Overall, the REMS programs for these 3 medications were positively perceived for raising awareness of safe medication use for clinicians and patients. Monitoring patients for safety concerns is important and REMS requirements provide accountability.

Continue to: The use of a single shared...

The use of a single shared REMS system for documenting requirements for clozapine (compared to separate systems for each manufacturer) was a positive move forward in implementation. The focus group welcomed the increased awareness of benign ethnic neutropenia as a result of this condition being incorporated in the revised monitoring requirements of the clozapine REMS.

Focus group participants raised the issue of the real-world efficiency of the REMS programs (reduced access and increased clinician workload) vs the benefits (patient safety). They noted that excessive workload could lead to clinicians becoming unwilling to use a medication that requires a REMS. Clinician workload may be further compromised when REMS logistics disrupt the normal workflow and transitions of care between clinicians or settings. This latter aspect is of particular concern for clozapine.

The complexities of the registration and reporting system for olanzapine for ER injectable suspension and the lack of clarity about monitoring were noted to have discouraged the opening of treatment sites. This scarcity of sites may make clinicians hesitant to use this medication, and instead opt for alternative treatments in patients who may be appropriate candidates.

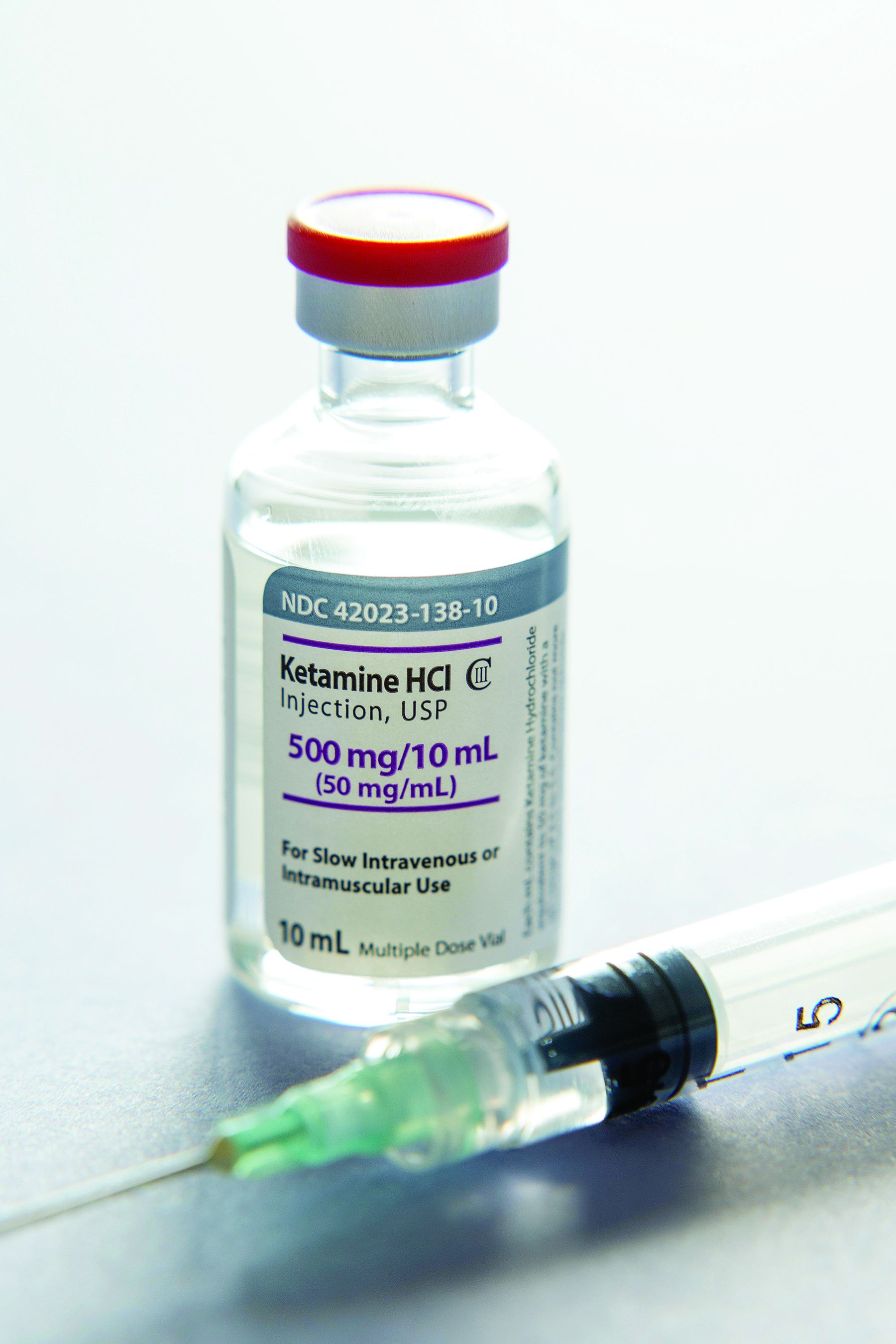

There has also been limited growth of esketamine treatment sites, especially in comparison to ketamine treatment sites.11-14 Esketamine is FDA-approved for treatment-resistant depression in adults and for depressive symptoms in adults with major depressive disorder with acute suicidal ideation or behavior. Ketamine is not FDA-approved for treating depression but is being used off-label to treat this disorder.15 The FDA determined that ketamine does not require a REMS to ensure the benefits outweigh the risks for its approved indications as an anesthetic agent, anesthesia-inducing agent, or supplement to anesthesia. Since ketamine has no REMS requirements, there may be a lower burden for its use. Thus, clinicians are treating patients for depression with this medication without needing to comply with a REMS.16

Technology plays a role in workload burden, and integrating health care processes within current workflow systems, such as using electronic patient health records and pharmacy systems, is recommended. The FDA has been exploring technologies to facilitate the completion of REMS requirements, including mandatory education within the prescribers’ and pharmacists’ workflow.17 This is a complex task that requires multiple stakeholders with differing perspectives and incentives to align.

Continue to: The data collected for the REMS...

The data collected for the REMS program belongs to the medication’s manufacturer. Current regulations do not require manufacturers to make this data available to qualified scientific researchers. A regulatory mandate to establish data sharing methods would improve transparency and enhance efforts to better understand the outcomes of the REMS programs.

A few caveats

Both the overarching and medication-specific recommendations were based on a small number of participants’ discussions related to clozapine, olanzapine for ER injectable suspension, and esketamine. These recommendations do not include other medications with REMS that are used to treat psychiatric disorders, such as loxapine, buprenorphine ER, and buprenorphine transmucosal products. Larger-scale qualitative and quantitative research is needed to better understand health care professionals’ perspectives. Lastly, some of the recommendations outlined in this article are beyond the current purview or authority of the FDA and may require legislative or regulatory action to implement.

Bottom Line

Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) programs are designed to help reduce the occurrence and/or severity of serious risks or to inform decision-making. However, REMS requirements may adversely impact patient access to certain REMS medications and clinician burden. Health care professionals can provide informed recommendations for improving the REMS programs for clozapine, olanzapine for extended-release injectable suspension, and esketamine.

Related Resources

- FDA. Frequently asked questions (FAQs) about REMS. www.fda.gov/drugs/risk-evaluation-and-mitigation-strategies-rems/frequently-asked-questions-faqs-about-rems

Drug Brand Names

Buprenorphine extended-release • Sublocade

Buprenorphine transmucosal • Subutex, Suboxone

Clozapine • Clozaril

Esketamine • Spravato

Ketamine • Ketalar

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Loxapine • Adasuve

Olanzapine extended-release injectable suspension • Zyprexa Relprevv

A Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) is a drug safety program the FDA can require for certain medications with serious safety concerns to help ensure the benefits of the medication outweigh its risks (Box1). The FDA may require medication guides, patient package inserts, communication plans for health care professionals, and/or certain packaging and safe disposal technologies for medications that pose a serious risk of abuse or overdose. The FDA may also require elements to assure safe use and/or an implementation system be included in the REMS. Pharmaceutical manufacturers then develop a proposed REMS for FDA review.2 If the FDA approves the proposed REMS, the manufacturer is responsible for implementing the REMS requirements.

Box

There are many myths and misconceptions surrounding psychiatry, the branch of medicine that deals with the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of mental illness. Some of the most common myths include:

The FDA provides this description of a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS):

“A [REMS] is a drug safety program that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) can require for certain medications with serious safety concerns to help ensure the benefits of the medication outweigh its risks. REMS are designed to reinforce medication use behaviors and actions that support the safe use of that medication. While all medications have labeling that informs health care stakeholders about medication risks, only a few medications require a REMS. REMS are not designed to mitigate all the adverse events of a medication, these are communicated to health care providers in the medication’s prescribing information. Rather, REMS focus on preventing, monitoring and/or managing a specific serious risk by informing, educating and/or reinforcing actions to reduce the frequency and/or severity of the event.”1

The REMS program for clozapine3 has been the subject of much discussion in the psychiatric community. The adverse impact of the 2015 update to the clozapine REMS program was emphasized at meetings of both the American Psychiatric Association and the College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists. A white paper published by the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors shortly after the 2015 update concluded, “clozapine is underused due to a variety of barriers related to the drug and its properties, the health care system, regulatory requirements, and reimbursement issues.”4 After an update to the clozapine REMS program in 2021, the FDA temporarily suspended enforcement of certain requirements due to concerns from health care professionals about patient access to the medication because of problems with implementing the clozapine REMS program.5,6 In November 2022, the FDA issued a second announcement of enforcement discretion related to additional requirements of the REMS program.5 The FDA had previously announced a decision to not take action regarding adherence to REMS requirements for certain laboratory tests in March 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic.7

REMS programs for other psychiatric medications may also present challenges. The REMS programs for esketamine8 and olanzapine for extended-release (ER) injectable suspension9 include certain risks that require postadministration monitoring. Some facilities have had to dedicate additional space and clinician time to ensure REMS requirements are met.

To further understand health care professionals’ perspectives regarding the value and burden of these REMS programs, a collaborative effort of the University of Maryland (College Park and Baltimore campuses) Center of Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation with the FDA was undertaken. The REMS for clozapine, olanzapine for ER injectable suspension, and esketamine were examined to develop recommendations for improving patient access while ensuring safe medication use and limiting the impact on health care professionals.

Assessing the REMS programs

Focus groups were held with health care professionals nominated by professional organizations to gather their perspectives on the REMS requirements. There was 1 focus group for each of the 3 medications. A facilitator’s guide was developed that contained the details of how to conduct the focus group along with the medication-specific questions. The questions were based on the REMS requirements as of May 2021 and assessed the impact of the REMS on patient safety, patient access, and health care professional workload; effects from the COVID-19 pandemic; and suggestions to improve the REMS programs. The University of Maryland Institutional Review Board reviewed the materials and processes and made the determination of exempt.

Health care professionals were eligible to participate in a focus group if they had ≥1 year of experience working with patients who use the specific medication and ≥6 months of experience within the past year working with the REMS program for that medication. Participants were excluded if they were employed by a pharmaceutical manufacturer or the FDA. The focus groups were conducted virtually using an online conferencing service during summer 2021 and were scheduled for 90 minutes. Prior to the focus group, participants received information from the “Goals” and “Summary” tabs of the FDA REMS website10 for the specific medication along with patient/caregiver guides, which were available for clozapine and olanzapine for ER injectable suspension. For each focus group, there was a target sample size of 6 to 9 participants. However, there were only 4 participants in the olanzapine for ER injectable suspension focus group, which we believed was due to lower national utilization of this medication. Individuals were only able to participate in 1 focus group, so the unique participant count for all 3 focus groups totaled 17 (Table 1).

Themes extracted from qualitative analysis of the focus group responses were the value of the REMS programs; registration/enrollment processes and REMS websites; monitoring requirements; care transitions; and COVID considerations (Table 2). While the REMS programs were perceived to increase practitioner and patient awareness of potential harms, discussions centered on the relative cost-to-benefit of the required reporting and other REMS requirements. There were challenges with the registration/enrollment processes and REMS websites that also affected patient care during transitions to different health care settings or clinicians. Patient access was affected by disparities in care related to monitoring requirements and clinician availability.

Continue to: COVID impacted all REMS...

COVID impacted all REMS programs. Physical distancing was an issue for medications that required extensive postadministration monitoring (ie, esketamine and olanzapine for ER injectable suspension). Access to laboratory services was an issue for clozapine.

Medication-specific themes are listed in Table 3 and relate to terms and descriptions in the REMS or additional regulatory requirements from the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). Suggestions for improvement to the REMS are presented in Table 4.

Recommendations for improving REMS

A group consisting of health care professionals, policy experts, and mental health advocates reviewed the information provided by the focus groups and developed the following recommendations.

Overarching recommendations

Each REMS should include a section providing justification for its existence, including a risk analysis of the data regarding the risk the REMS is designed to mitigate. This analysis should be repeated on a regular basis as scientific evidence regarding the risk and its epidemiology evolves. This additional section should also explain how the program requirements of the REMS as implemented (or planned) will achieve the aims of the REMS and weigh the potential benefits of the REMS requirements as implemented (or planned) by the manufacturer vs the potential risks of the REMS requirements as implemented (or planned) by the manufacturer.

Each REMS should have specific quantifiable outcomes. For example, it should specify a reduction in occurrence of the rate of the concerned risk by a specified amount.

Continue to: Ensure adequate...

Ensure adequate stakeholder input during the REMS development and real-world testing in multiple environments before implementing the REMS to identify unanticipated consequences that might impact patient access, patient safety, and health care professional burden. Implementation testing should explore issues such as purchasing and procurement, billing and reimbursement, and relevant factors such as other federal regulations or requirements (eg, the DEA or Medicare).

Ensure harmonization of the REMS forms and processes (eg, initiation and monitoring) for different medications where possible. A prescriber, pharmacist, or system should not face additional barriers to participate in a REMS based on REMS-specific intricacies (ie, prescription systems, data submission systems, or ordering systems). This streamlining will likely decrease clinical inertia to initiate care with the REMS medication, decrease health care professional burden, and improve compliance with REMS requirements.

REMS should anticipate the need for care transitions and employ provisions to ensure seamless care. Considerations should be given to transitions that occur due to:

- Different care settings (eg, inpatient, outpatient, or long-term care)

- Different geographies (eg, patient moves)

- Changes in clinicians, including leaves or absences

- Changes in facilities (eg, pharmacies).

REMS should mirror normal health care professional workflow, including how monitoring data are collected and how and with which frequency pharmacies fill prescriptions.Enhanced information technology to support REMS programs is needed. For example, REMS should be integrated with major electronic patient health record and pharmacy systems to reduce the effort required for clinicians to supply data and automate REMS processes.

For medications that are subject to other agencies and their regulations (eg, the CDC, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, or the DEA), REMS should be required to meet all standards of all agencies with a single system that accommodates normal health care professional workflow.

Continue to: REMS should have a...

REMS should have a standard disclaimer that allows the health care professional to waive certain provisions of the REMS in cases when the specific provisions of the REMS pose a greater risk to the patient than the risk posed by waiving the requirement.

Assure the actions implemented by the industry to meet the requirements for each REMS program are based on peer-reviewed evidence and provide a reasonable expectation to achieve the anticipated benefit.

Ensure that manufacturers make all accumulated REMS data available in a deidentified manner for use by qualified scientific researchers. Additionally, each REMS should have a plan for data access upon initiation and termination of the REMS.

Each REMS should collect data on the performance of the centers and/or personnel who operate the REMS and submit this data for review by qualified outside reviewers. Parameters to assess could include:

- timeliness of response

- timeliness of problem resolution

- data availability and its helpfulness to patient care

- adequacy of resources.

Recommendations for clozapine REMS

These comments relate to the clozapine REMS program prior to the July 2021 announcement that FDA had approved a modification.

Provide a clear definition for “benign ethnic neutropenia.”

Ensure the REMS includes patient-specific adjustments to allow flexibility for monitoring. During COVID, the FDA allowed clinicians to “use their best medical judgment in weighing the benefits and risks of continuing treatment in the absence of laboratory testing.”7 This guidance, which allowed flexibility to absolute neutrophil count (ANC) monitoring, was perceived as positive and safe. Before the changes in the REMS requirements, patients with benign ethnic neutropenia were restricted from accessing their medication or encountered harm from additional pharmacotherapy to mitigate ANC levels.

Continue to: Recommendations for olanzapine for ER injectable suspension REMS

Recommendations for olanzapine for ER injectable suspension REMS

Provide clear explicit instructions on what is required to have “ready access to emergency services.”

Ensure the REMS include patient-specific adjustments to allow flexibility for postadministration monitoring (eg, sedation or blood pressure). Specific patient groups may have differential access to certain types of facilities, transportation, or other resources. For example, consider the administration of olanzapine for ER injectable suspension by a mobile treatment team with an adequate protocol (eg, via videoconferencing or phone calls).

Ensure actions with peer-reviewed evidence demonstrating efficacy/effectiveness are included in the REMS. How was the 3-hour cut-point determined? Has it been reevaluated?

Ensure the REMS requirements allow for seamless care during transitions, particularly when clinicians are on vacation.

Continue to: Recommendations for esketamine REMS

Recommendations for esketamine REMS

Ensure the REMS includes patient-specific adjustments to allow flexibility for postadministration monitoring. Specific patient groups may have differential access to certain types of facilities, transportation, or other resources. For example, consider the administration of esketamine by a mobile treatment team with an adequate protocol (eg, via videoconferencing or phone calls).

Ensure actions with peer-reviewed evidence demonstrating efficacy/effectiveness of requirements are included in the REMS. How was the 2-hour cut-point determined? Has it been reevaluated?

Ensure that the REMS meet all standards of the DEA, with a single system that accommodates normal health care professional workflow.

A summary of the findings

Overall, the REMS programs for these 3 medications were positively perceived for raising awareness of safe medication use for clinicians and patients. Monitoring patients for safety concerns is important and REMS requirements provide accountability.

Continue to: The use of a single shared...

The use of a single shared REMS system for documenting requirements for clozapine (compared to separate systems for each manufacturer) was a positive move forward in implementation. The focus group welcomed the increased awareness of benign ethnic neutropenia as a result of this condition being incorporated in the revised monitoring requirements of the clozapine REMS.

Focus group participants raised the issue of the real-world efficiency of the REMS programs (reduced access and increased clinician workload) vs the benefits (patient safety). They noted that excessive workload could lead to clinicians becoming unwilling to use a medication that requires a REMS. Clinician workload may be further compromised when REMS logistics disrupt the normal workflow and transitions of care between clinicians or settings. This latter aspect is of particular concern for clozapine.

The complexities of the registration and reporting system for olanzapine for ER injectable suspension and the lack of clarity about monitoring were noted to have discouraged the opening of treatment sites. This scarcity of sites may make clinicians hesitant to use this medication, and instead opt for alternative treatments in patients who may be appropriate candidates.

There has also been limited growth of esketamine treatment sites, especially in comparison to ketamine treatment sites.11-14 Esketamine is FDA-approved for treatment-resistant depression in adults and for depressive symptoms in adults with major depressive disorder with acute suicidal ideation or behavior. Ketamine is not FDA-approved for treating depression but is being used off-label to treat this disorder.15 The FDA determined that ketamine does not require a REMS to ensure the benefits outweigh the risks for its approved indications as an anesthetic agent, anesthesia-inducing agent, or supplement to anesthesia. Since ketamine has no REMS requirements, there may be a lower burden for its use. Thus, clinicians are treating patients for depression with this medication without needing to comply with a REMS.16

Technology plays a role in workload burden, and integrating health care processes within current workflow systems, such as using electronic patient health records and pharmacy systems, is recommended. The FDA has been exploring technologies to facilitate the completion of REMS requirements, including mandatory education within the prescribers’ and pharmacists’ workflow.17 This is a complex task that requires multiple stakeholders with differing perspectives and incentives to align.

Continue to: The data collected for the REMS...

The data collected for the REMS program belongs to the medication’s manufacturer. Current regulations do not require manufacturers to make this data available to qualified scientific researchers. A regulatory mandate to establish data sharing methods would improve transparency and enhance efforts to better understand the outcomes of the REMS programs.

A few caveats

Both the overarching and medication-specific recommendations were based on a small number of participants’ discussions related to clozapine, olanzapine for ER injectable suspension, and esketamine. These recommendations do not include other medications with REMS that are used to treat psychiatric disorders, such as loxapine, buprenorphine ER, and buprenorphine transmucosal products. Larger-scale qualitative and quantitative research is needed to better understand health care professionals’ perspectives. Lastly, some of the recommendations outlined in this article are beyond the current purview or authority of the FDA and may require legislative or regulatory action to implement.

Bottom Line

Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) programs are designed to help reduce the occurrence and/or severity of serious risks or to inform decision-making. However, REMS requirements may adversely impact patient access to certain REMS medications and clinician burden. Health care professionals can provide informed recommendations for improving the REMS programs for clozapine, olanzapine for extended-release injectable suspension, and esketamine.

Related Resources

- FDA. Frequently asked questions (FAQs) about REMS. www.fda.gov/drugs/risk-evaluation-and-mitigation-strategies-rems/frequently-asked-questions-faqs-about-rems

Drug Brand Names

Buprenorphine extended-release • Sublocade

Buprenorphine transmucosal • Subutex, Suboxone

Clozapine • Clozaril

Esketamine • Spravato

Ketamine • Ketalar

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Loxapine • Adasuve

Olanzapine extended-release injectable suspension • Zyprexa Relprevv

1. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/risk-evaluation-and-mitigation-strategies-rems

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Format and Content of a REMS Document. Guidance for Industry. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/media/77846/download

3. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS), Clozapine. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/index.cfm?event=RemsDetails.page&REMS=351

4. The National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors. Clozapine underutilization: addressing the barriers. Accessed September 30, 2019. https://nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/Assessment%201_Clozapine%20Underutilization.pdf

5. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA is temporarily exercising enforcement discretion with respect to certain clozapine REMS program requirements to ensure continuity of care for patients taking clozapine. Updated November 22, 2022. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-temporarily-exercising-enforcement-discretion-respect-certain-clozapine-rems-program

6. Tanzi M. REMS issues affect clozapine, isotretinoin. Pharmacy Today. 2022;28(3):49.

7. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA provides update on patient access to certain REMS drugs during COVID-19 public health emergency. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-provides-update-patient-access-certain-rems-drugs-during-covid-19

8. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS), Spravato (esketamine). Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/index.cfm?event=IndvRemsDetails.page&REMS=386

9. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS), Zyprexa Relprevv (olanzapine). Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/index.cfm?event=IndvRemsDetails.page&REMS=74

10. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS). Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/index.cfm

11. Parikh SV, Lopez D, Vande Voort JL, et al. Developing an IV ketamine clinic for treatment-resistant depression: a primer. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2021;51(3):109-124.

12. Dodge D. The ketamine cure. The New York Times. November 4, 2021. Updated November 5, 2021. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/04/well/ketamine-therapy-depression.html

13. Burton KW. Time for a national ketamine registry, experts say. Medscape. February 15, 2023. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/988310

14. Wilkinson ST, Howard DH, Busch SH. Psychiatric practice patterns and barriers to the adoption of esketamine. JAMA. 2019;322(11):1039-1040. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.10728

15. Wilkinson ST, Toprak M, Turner MS, et al. A survey of the clinical, off-label use of ketamine as a treatment for psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(7):695-696. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17020239

16. Pai SM, Gries JM; ACCP Public Policy Committee. Off-label use of ketamine: a challenging drug treatment delivery model with an inherently unfavorable risk-benefit profile. J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;62(1):10-13. doi:10.1002/jcph.1983

17. Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) Integration. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://confluence.hl7.org/display/COD/Risk+Evaluation+and+Mitigation+Strategies+%28REMS%29+Integration

1. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/risk-evaluation-and-mitigation-strategies-rems

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Format and Content of a REMS Document. Guidance for Industry. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/media/77846/download

3. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS), Clozapine. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/index.cfm?event=RemsDetails.page&REMS=351

4. The National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors. Clozapine underutilization: addressing the barriers. Accessed September 30, 2019. https://nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/Assessment%201_Clozapine%20Underutilization.pdf

5. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA is temporarily exercising enforcement discretion with respect to certain clozapine REMS program requirements to ensure continuity of care for patients taking clozapine. Updated November 22, 2022. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-temporarily-exercising-enforcement-discretion-respect-certain-clozapine-rems-program

6. Tanzi M. REMS issues affect clozapine, isotretinoin. Pharmacy Today. 2022;28(3):49.

7. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA provides update on patient access to certain REMS drugs during COVID-19 public health emergency. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-provides-update-patient-access-certain-rems-drugs-during-covid-19

8. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS), Spravato (esketamine). Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/index.cfm?event=IndvRemsDetails.page&REMS=386

9. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS), Zyprexa Relprevv (olanzapine). Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/index.cfm?event=IndvRemsDetails.page&REMS=74

10. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS). Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/index.cfm

11. Parikh SV, Lopez D, Vande Voort JL, et al. Developing an IV ketamine clinic for treatment-resistant depression: a primer. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2021;51(3):109-124.

12. Dodge D. The ketamine cure. The New York Times. November 4, 2021. Updated November 5, 2021. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/04/well/ketamine-therapy-depression.html

13. Burton KW. Time for a national ketamine registry, experts say. Medscape. February 15, 2023. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/988310

14. Wilkinson ST, Howard DH, Busch SH. Psychiatric practice patterns and barriers to the adoption of esketamine. JAMA. 2019;322(11):1039-1040. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.10728

15. Wilkinson ST, Toprak M, Turner MS, et al. A survey of the clinical, off-label use of ketamine as a treatment for psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(7):695-696. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17020239

16. Pai SM, Gries JM; ACCP Public Policy Committee. Off-label use of ketamine: a challenging drug treatment delivery model with an inherently unfavorable risk-benefit profile. J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;62(1):10-13. doi:10.1002/jcph.1983

17. Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) Integration. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://confluence.hl7.org/display/COD/Risk+Evaluation+and+Mitigation+Strategies+%28REMS%29+Integration

Tips for addressing uptick in mental health visits: Primary care providers collaborate, innovate

This growth in the number of patients needing behavioral health–related care is likely driven by multiple factors, including a shortage of mental health care providers, an increasing incidence of psychiatric illness, and destigmatization of mental health in general, suggested Swetha P. Iruku, MD, MPH, associate professor of family medicine and community health at the University of Pennsylvania and Penn Medicine family physician in Philadelphia.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention noted that “the COVID-19 pandemic has been associated with mental health challenges related to the morbidity and mortality caused by the disease and to mitigation activities, including the impact of physical distancing and stay-at-home orders,” in a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

From June 24 to 30, 2020, U.S. adults reported considerably elevated adverse mental health conditions associated with COVID-19, and symptoms of anxiety disorder and depressive disorder climbed during the months of April through June of the same year, compared with the same period in 2019, they wrote.

Even before the pandemic got underway, multiple studies of national data published this year suggested mental issues were on the rise in the United States. For example, the proportion of adult patient visits to primary care providers that addressed mental health concerns rose from 10.7% to 15.9% from 2006 to 2018, according to research published in Health Affairs. Plus, the number and proportion of pediatric acute care hospitalizations because of mental health diagnoses increased significantly between 2009 and 2019, according to a paper published in JAMA.

“I truly believe that we can’t, as primary care physicians, take care of someone’s physical health without also taking care of their mental health,” Dr. Iruku said in an interview. “It’s all intertwined.”

To rise to this challenge, PCPs first need a collaborative mindset, she suggested, as well as familiarity with available resources, both locally and virtually.

This article examines strategies for managing mental illness in primary care, outlines clinical resources, and reviews related educational opportunities.

In addition, clinical pearls are shared by Dr. Iruku and five other clinicians who provide or have provided mental health care to primary care patients or work in close collaboration with a primary care practice, including a clinical psychologist, a nurse practitioner licensed in psychiatric health, a pediatrician, and a licensed clinical social worker.

Build a network

Most of the providers interviewed cited the importance of collaboration in mental health care, particularly for complex cases.

“I would recommend [that primary care providers get] to know the psychiatric providers [in their area],” said Jessica Viton, DNP, FNP, PMHNP, who delivers mental health care through a community-based primary care practice in Colorado which she requested remain anonymous.

Dr. Iruku suggested making an in-person connection first, if possible.

“So much of what we do is ‘see one, do one, teach one,’ so learn a little bit, then go off and trial,” she said. “[It can be valuable] having someone in your back pocket that you can contact in the case of an emergency, or in a situation where you just don’t know how to tackle it.”

Screen for depression and anxiety

William J. Sieber, PhD, a clinical psychologist, director of integrated behavioral health, and professor in the department of family medicine and public health and the department of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, said primary care providers should screen all adult patients for depression and anxiety with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and General Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7), respectively.

To save time, he suggested a cascading approach.

“In primary care, everybody’s in a hurry,” Dr. Sieber said. “[With the cascading approach,] the first two items [from each questionnaire] are given, and if a person endorses either of those items … then they are asked to complete the other items.”

Jennifer Mullally, MD, a pediatrician at Sanford Health in Fargo, N.D., uses this cascading approach to depression and anxiety screening with all her patients aged 13-18. For younger kids, she screens only those who present with signs or symptoms of mental health issues, or if the parent shares a concern.

This approach differs slightly from U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations, which suggest screening for anxiety in patients aged 8-18 years and depression in patients aged 12-18 years.

Use other screening tools only as needed

Dr. Sieber, the research director for the division of family medicine at UC San Diego, collaborates regularly with primary care providers via hallway consultations, by sharing cases, and through providing oversight of psychiatric care at 13 primary care practices within the UC San Diego network. He recommended against routine screening beyond depression and anxiety in the primary care setting.

“There are a lot of screening tools,” Dr. Sieber said. “It depends on what you’re presented with. The challenge in primary care is you’re going to see all kinds of things. It’s not like running a depression clinic.”

Other than the PHQ-9 and GAD-7, he suggested primary care providers establish familiarity with screening tools for posttraumatic stress disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, noting again that these should be used only when one of the conditions is already suspected.

Dr. Mullally follows a similar approach with her pediatric population. In addition to the GAD-7, she investigates whether a patient has anxiety with the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED). For depression, she couples the PHQ-9 with the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale.

While additional screening tools like these are readily available online, Dr. Viton suggested that they should be employed only if the provider is trained to interpret and respond to those findings, and only if they know which tool to use, and when.

For example, she has recently observed PCPs diagnosing adults with ADHD using a three-question test, when in fact a full-length, standardized instrument should be administered by a provider with necessary training.

She also pointed out that bipolar disorder continues to be underdiagnosed, possibly because of providers detecting depression using a questionnaire like the PHQ-9, while failing to inquire about manic episodes.

Leverage online resources

If depression is confirmed, Dr. Iruku often directs the patient to the Mayo Clinic Depression Medication Choice Decision Aid. This website steers patients through medication options based on their answers to a questionnaire. Choices are listed alongside possible adverse effects.

For clinician use, Dr. Iruku recommended The Waco Guide to Psychopharmacology in Primary Care, which aids clinical decision-making for mental illness and substance abuse. The app processes case details to suggest first-, second-, and third-line pharmacotherapies, as well as modifications based on patient needs.

Even with tools like these, however, a referral may be needed.

“[Primary care providers] may not be the best fit for what the patient is looking for, from a mental health or behavioral standpoint,” Dr. Sieber said.

In this case, he encourages patients to visit Psychology Today, a “quite popular portal” that helps patients locate a suitable provider based on location, insurance, driving radius, and mental health concern. This usually generates 10-20 options, Dr. Sieber said, although results can vary.

“It may be discouraging, because maybe only three [providers] pop up based on your criteria, and the closest one is miles away,” he said.

Consider virtual support

If no local psychiatric help is available, Dr. Sieber suggested virtual support, highlighting that “it’s much easier now than it was 3 or 4 years ago” to connect patients with external mental health care.

But this strategy should be reserved for cases of actual need instead of pure convenience, cautioned Dr. Viton, who noted that virtual visits may fail to capture the nuance of an in-person meeting, as body language, mode of dress, and other clues can provide insights into mental health status.

“Occasionally, I think you do have to have an in-person visit, especially when you’re developing a rapport with someone,” Dr. Viton said.

Claire McArdle, a licensed clinical social worker in Fort Collins, Colo., noted that virtual care from an outside provider may also impede the collaboration needed to effectively address mental illness.

In her 11 years in primary care at Associates in Family Medicine, Ms. McArdle had countless interactions with colleagues seeking support when managing a complex case. “I’m coaching providers, front desk staff, and nursing staff on how to interact with patients [with] behavioral health needs,” she said, citing the multitude of nonmedical factors that need to be considered, such as family relationships and patient preferences.

These unscheduled conversations with colleagues throughout the day are impossible to have when sharing a case with an unknown, remote peer.

Ms. McArdle speaks from experience. She recently resigned from Associates in Family Medicine to start her own private therapy practice after her former employer was acquired by VillageMD, a national provider that terminated employment of most other social workers in the practice and began outsourcing mental health care to Mindoula Health, a virtual provider.

Dr. Sieber offered a similar perspective on in-person collaboration as the psychiatric specialist at his center. He routinely offers on-site support for both providers and patients, serving as “another set of eyes and ears” when there is a concern about patient safety or directly managing care when a patient is hospitalized for mental illness.