User login

AHA targets rising prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in children

Obstructive sleep apnea is becoming more common in children and adolescents as the prevalence of obesity increases, but it may also be a preventable risk factor for cardiovascular disease, according to a new scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

The statement focuses on the links between OSA and CVD risk factors in children and adolescents, and reviews diagnostic strategies and treatments. The writing committee reported that 1%-6% of children and adolescents have OSA, as do up to 60% of adolescents considered obese.

The statement was created by the AHA’s Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, and Obesity in the Young subcommittee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young and was published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Carissa M. Baker-Smith, MD, chair of the writing group chair and director of pediatric preventive cardiology at Nemours Cardiac Center, Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, Del., explained the rationale for issuing the statement at this time, noting that the relationship between OSA and CVD in adults is well documented.

“There has been less focus on the importance of recognizing and treating sleep apnea in youth,” she said in an interview. “Thus, we felt that it was vitally important to get the word out to parents and to providers that paying attention to the quality and duration of your child’s sleep is vitally important to a child’s long-term heart health. Risk factors for heart disease, when present in childhood, can persist into adulthood.”

Clarity on polysomnography

For making the diagnosis of OSA in children, the statement provides clarity on the use of polysomnography and the role of the apnea-hypopnea index, which is lower in children with OSA than in adults. “One controversy, or at least as I saw it, was whether or not polysomnography testing is always required to make the diagnosis of OSA and before proceeding with tonsil and adenoid removal among children for whom enlarged tonsils and adenoids are present,” Dr. Baker-Smith said. “Polysomnography testing is not always needed before an ear, nose, and throat surgeon may recommend surgery.”

The statement also noted that history and physical examination may not yield enough reliable information to distinguish OSA from snoring.

In areas where sleep laboratories that work with children aren’t available, alternative tests such as daytime nap polysomnography, nocturnal oximetry, and nocturnal video recording may be used – with a caveat. “These alternative tests have weaker positive and negative predictive values when compared with polysomnography,” the writing committee noted. Home sleep apnea tests aren’t recommended in children. Questionnaires “are useful as screening, but not as diagnostic tools.”

Pediatric patients being evaluated for OSA should also be screened for hypertension and metabolic syndrome, as well as central nervous system and behavioral disorders. Diagnosing OSA in children and adolescents requires “a high index of suspicion,” the committee wrote.

Pediatricians and pediatric cardiologists should exercise that high index of suspicion when receiving referrals for cardiac evaluations for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder medication, Dr. Baker-Smith said. “Take the time to ask about a child’s sleep – snoring, apnea, etc. – especially if the child has obesity, difficulty focusing during the day, and if there is evidence of systemic hypertension or other signs of metabolic syndrome,” she said.

Risk factors for OSA in children

The statement also reviewed risk factors for OSA, among them obesity, particularly among children younger than 6 years. Other risk factors include upper and lower airway disease, hypotonia, parental history of hyperplasia of the adenoids and tonsils, craniofacial malformations, and neuromuscular disorders. However, the committee cited “limited data” to support that children with congenital heart disease may be at greater risk for OSA and sleep-disordered breathing (SDB).

Black children are at significantly greater risk, and socioeconomic factors “may be potential confounders,” the committee stated. Other risk factors include allergic rhinitis and sickle cell disease.

But the statement underscores that “obesity is the main risk factor” for OSA in children and adolescents, and that the presence of increased inflammation may explain this relationship. Steroids may alleviate these symptoms, even in nonobese children, and removal of the adenoids or tonsils is an option to reduce inflammation in children with OSA.

“Obesity is a significant risk factor for sleep disturbances and obstructive sleep apnea, and the severity of sleep apnea may be improved by weight-loss interventions, which then improves metabolic syndrome factors such as insulin sensitivity,” Dr. Baker-Smith said. “We need to increase awareness about how the rising prevalence of obesity may be impacting sleep quality in kids and recognize sleep-disordered breathing as something that could contribute to risks for hypertension and later cardiovascular disease.”

Children in whom OSA is suspected should also undergo screening for metabolic syndrome, and central nervous system and behavioral disorders.

Cardiovascular risks

The statement explores the connection between cardiovascular complications and SDB and OSA in depth.

“Inadequate sleep duration of < 5 hours per night in children and adolescents has been linked to an increased risk of hypertension and is also associated with an increased prevalence of obesity,” the committee wrote.

However, the statement left one question hanging: whether OSA alone or obesity cause higher BP in younger patients with OSA. But the committee concluded that BP levels increase with the severity of OSA, although the effects can vary with age. OSA in children peaks between ages 2 and 8, corresponding to the peak prevalence of hypertrophy of the tonsils and adenoids. Children aged 10-11 with more severe OSA may have BP dysregulation, while older adolescents develop higher sustained BP. Obesity may be a confounder for daytime BP elevations, while nighttime hypertension depends less on obesity and more on OSA severity.

“OSA is associated with abnormal BP in youth and, in particular, higher nighttime blood pressures and loss of the normal decline in BP that should occur during sleep,” Dr. Baker-Smith said. “Children with OSA appear to have higher BP than controls during both sleep and wake times, and BP levels increase with increasing severity of OSA.”

Nonetheless, children with OSA are at greater risk for other cardiovascular problems. Left ventricular hypertrophy may be a secondary outcome. “The presence of obstructive sleep apnea in children is associated with an 11-fold increased risk for LVH in children, a relationship not seen in the presence of primary snoring alone,” Dr. Baker-Smith said.

Dr. Baker-Smith had no relevant disclosures. Coauthor Amal Isaiah, MD, is coinventor of an imaging system for sleep apnea and receives royalties from the University of Maryland. The other coauthors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Obstructive sleep apnea is becoming more common in children and adolescents as the prevalence of obesity increases, but it may also be a preventable risk factor for cardiovascular disease, according to a new scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

The statement focuses on the links between OSA and CVD risk factors in children and adolescents, and reviews diagnostic strategies and treatments. The writing committee reported that 1%-6% of children and adolescents have OSA, as do up to 60% of adolescents considered obese.

The statement was created by the AHA’s Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, and Obesity in the Young subcommittee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young and was published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Carissa M. Baker-Smith, MD, chair of the writing group chair and director of pediatric preventive cardiology at Nemours Cardiac Center, Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, Del., explained the rationale for issuing the statement at this time, noting that the relationship between OSA and CVD in adults is well documented.

“There has been less focus on the importance of recognizing and treating sleep apnea in youth,” she said in an interview. “Thus, we felt that it was vitally important to get the word out to parents and to providers that paying attention to the quality and duration of your child’s sleep is vitally important to a child’s long-term heart health. Risk factors for heart disease, when present in childhood, can persist into adulthood.”

Clarity on polysomnography

For making the diagnosis of OSA in children, the statement provides clarity on the use of polysomnography and the role of the apnea-hypopnea index, which is lower in children with OSA than in adults. “One controversy, or at least as I saw it, was whether or not polysomnography testing is always required to make the diagnosis of OSA and before proceeding with tonsil and adenoid removal among children for whom enlarged tonsils and adenoids are present,” Dr. Baker-Smith said. “Polysomnography testing is not always needed before an ear, nose, and throat surgeon may recommend surgery.”

The statement also noted that history and physical examination may not yield enough reliable information to distinguish OSA from snoring.

In areas where sleep laboratories that work with children aren’t available, alternative tests such as daytime nap polysomnography, nocturnal oximetry, and nocturnal video recording may be used – with a caveat. “These alternative tests have weaker positive and negative predictive values when compared with polysomnography,” the writing committee noted. Home sleep apnea tests aren’t recommended in children. Questionnaires “are useful as screening, but not as diagnostic tools.”

Pediatric patients being evaluated for OSA should also be screened for hypertension and metabolic syndrome, as well as central nervous system and behavioral disorders. Diagnosing OSA in children and adolescents requires “a high index of suspicion,” the committee wrote.

Pediatricians and pediatric cardiologists should exercise that high index of suspicion when receiving referrals for cardiac evaluations for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder medication, Dr. Baker-Smith said. “Take the time to ask about a child’s sleep – snoring, apnea, etc. – especially if the child has obesity, difficulty focusing during the day, and if there is evidence of systemic hypertension or other signs of metabolic syndrome,” she said.

Risk factors for OSA in children

The statement also reviewed risk factors for OSA, among them obesity, particularly among children younger than 6 years. Other risk factors include upper and lower airway disease, hypotonia, parental history of hyperplasia of the adenoids and tonsils, craniofacial malformations, and neuromuscular disorders. However, the committee cited “limited data” to support that children with congenital heart disease may be at greater risk for OSA and sleep-disordered breathing (SDB).

Black children are at significantly greater risk, and socioeconomic factors “may be potential confounders,” the committee stated. Other risk factors include allergic rhinitis and sickle cell disease.

But the statement underscores that “obesity is the main risk factor” for OSA in children and adolescents, and that the presence of increased inflammation may explain this relationship. Steroids may alleviate these symptoms, even in nonobese children, and removal of the adenoids or tonsils is an option to reduce inflammation in children with OSA.

“Obesity is a significant risk factor for sleep disturbances and obstructive sleep apnea, and the severity of sleep apnea may be improved by weight-loss interventions, which then improves metabolic syndrome factors such as insulin sensitivity,” Dr. Baker-Smith said. “We need to increase awareness about how the rising prevalence of obesity may be impacting sleep quality in kids and recognize sleep-disordered breathing as something that could contribute to risks for hypertension and later cardiovascular disease.”

Children in whom OSA is suspected should also undergo screening for metabolic syndrome, and central nervous system and behavioral disorders.

Cardiovascular risks

The statement explores the connection between cardiovascular complications and SDB and OSA in depth.

“Inadequate sleep duration of < 5 hours per night in children and adolescents has been linked to an increased risk of hypertension and is also associated with an increased prevalence of obesity,” the committee wrote.

However, the statement left one question hanging: whether OSA alone or obesity cause higher BP in younger patients with OSA. But the committee concluded that BP levels increase with the severity of OSA, although the effects can vary with age. OSA in children peaks between ages 2 and 8, corresponding to the peak prevalence of hypertrophy of the tonsils and adenoids. Children aged 10-11 with more severe OSA may have BP dysregulation, while older adolescents develop higher sustained BP. Obesity may be a confounder for daytime BP elevations, while nighttime hypertension depends less on obesity and more on OSA severity.

“OSA is associated with abnormal BP in youth and, in particular, higher nighttime blood pressures and loss of the normal decline in BP that should occur during sleep,” Dr. Baker-Smith said. “Children with OSA appear to have higher BP than controls during both sleep and wake times, and BP levels increase with increasing severity of OSA.”

Nonetheless, children with OSA are at greater risk for other cardiovascular problems. Left ventricular hypertrophy may be a secondary outcome. “The presence of obstructive sleep apnea in children is associated with an 11-fold increased risk for LVH in children, a relationship not seen in the presence of primary snoring alone,” Dr. Baker-Smith said.

Dr. Baker-Smith had no relevant disclosures. Coauthor Amal Isaiah, MD, is coinventor of an imaging system for sleep apnea and receives royalties from the University of Maryland. The other coauthors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Obstructive sleep apnea is becoming more common in children and adolescents as the prevalence of obesity increases, but it may also be a preventable risk factor for cardiovascular disease, according to a new scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

The statement focuses on the links between OSA and CVD risk factors in children and adolescents, and reviews diagnostic strategies and treatments. The writing committee reported that 1%-6% of children and adolescents have OSA, as do up to 60% of adolescents considered obese.

The statement was created by the AHA’s Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, and Obesity in the Young subcommittee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young and was published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Carissa M. Baker-Smith, MD, chair of the writing group chair and director of pediatric preventive cardiology at Nemours Cardiac Center, Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, Del., explained the rationale for issuing the statement at this time, noting that the relationship between OSA and CVD in adults is well documented.

“There has been less focus on the importance of recognizing and treating sleep apnea in youth,” she said in an interview. “Thus, we felt that it was vitally important to get the word out to parents and to providers that paying attention to the quality and duration of your child’s sleep is vitally important to a child’s long-term heart health. Risk factors for heart disease, when present in childhood, can persist into adulthood.”

Clarity on polysomnography

For making the diagnosis of OSA in children, the statement provides clarity on the use of polysomnography and the role of the apnea-hypopnea index, which is lower in children with OSA than in adults. “One controversy, or at least as I saw it, was whether or not polysomnography testing is always required to make the diagnosis of OSA and before proceeding with tonsil and adenoid removal among children for whom enlarged tonsils and adenoids are present,” Dr. Baker-Smith said. “Polysomnography testing is not always needed before an ear, nose, and throat surgeon may recommend surgery.”

The statement also noted that history and physical examination may not yield enough reliable information to distinguish OSA from snoring.

In areas where sleep laboratories that work with children aren’t available, alternative tests such as daytime nap polysomnography, nocturnal oximetry, and nocturnal video recording may be used – with a caveat. “These alternative tests have weaker positive and negative predictive values when compared with polysomnography,” the writing committee noted. Home sleep apnea tests aren’t recommended in children. Questionnaires “are useful as screening, but not as diagnostic tools.”

Pediatric patients being evaluated for OSA should also be screened for hypertension and metabolic syndrome, as well as central nervous system and behavioral disorders. Diagnosing OSA in children and adolescents requires “a high index of suspicion,” the committee wrote.

Pediatricians and pediatric cardiologists should exercise that high index of suspicion when receiving referrals for cardiac evaluations for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder medication, Dr. Baker-Smith said. “Take the time to ask about a child’s sleep – snoring, apnea, etc. – especially if the child has obesity, difficulty focusing during the day, and if there is evidence of systemic hypertension or other signs of metabolic syndrome,” she said.

Risk factors for OSA in children

The statement also reviewed risk factors for OSA, among them obesity, particularly among children younger than 6 years. Other risk factors include upper and lower airway disease, hypotonia, parental history of hyperplasia of the adenoids and tonsils, craniofacial malformations, and neuromuscular disorders. However, the committee cited “limited data” to support that children with congenital heart disease may be at greater risk for OSA and sleep-disordered breathing (SDB).

Black children are at significantly greater risk, and socioeconomic factors “may be potential confounders,” the committee stated. Other risk factors include allergic rhinitis and sickle cell disease.

But the statement underscores that “obesity is the main risk factor” for OSA in children and adolescents, and that the presence of increased inflammation may explain this relationship. Steroids may alleviate these symptoms, even in nonobese children, and removal of the adenoids or tonsils is an option to reduce inflammation in children with OSA.

“Obesity is a significant risk factor for sleep disturbances and obstructive sleep apnea, and the severity of sleep apnea may be improved by weight-loss interventions, which then improves metabolic syndrome factors such as insulin sensitivity,” Dr. Baker-Smith said. “We need to increase awareness about how the rising prevalence of obesity may be impacting sleep quality in kids and recognize sleep-disordered breathing as something that could contribute to risks for hypertension and later cardiovascular disease.”

Children in whom OSA is suspected should also undergo screening for metabolic syndrome, and central nervous system and behavioral disorders.

Cardiovascular risks

The statement explores the connection between cardiovascular complications and SDB and OSA in depth.

“Inadequate sleep duration of < 5 hours per night in children and adolescents has been linked to an increased risk of hypertension and is also associated with an increased prevalence of obesity,” the committee wrote.

However, the statement left one question hanging: whether OSA alone or obesity cause higher BP in younger patients with OSA. But the committee concluded that BP levels increase with the severity of OSA, although the effects can vary with age. OSA in children peaks between ages 2 and 8, corresponding to the peak prevalence of hypertrophy of the tonsils and adenoids. Children aged 10-11 with more severe OSA may have BP dysregulation, while older adolescents develop higher sustained BP. Obesity may be a confounder for daytime BP elevations, while nighttime hypertension depends less on obesity and more on OSA severity.

“OSA is associated with abnormal BP in youth and, in particular, higher nighttime blood pressures and loss of the normal decline in BP that should occur during sleep,” Dr. Baker-Smith said. “Children with OSA appear to have higher BP than controls during both sleep and wake times, and BP levels increase with increasing severity of OSA.”

Nonetheless, children with OSA are at greater risk for other cardiovascular problems. Left ventricular hypertrophy may be a secondary outcome. “The presence of obstructive sleep apnea in children is associated with an 11-fold increased risk for LVH in children, a relationship not seen in the presence of primary snoring alone,” Dr. Baker-Smith said.

Dr. Baker-Smith had no relevant disclosures. Coauthor Amal Isaiah, MD, is coinventor of an imaging system for sleep apnea and receives royalties from the University of Maryland. The other coauthors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION

Managing sleep in the elderly

Sleep problems are prevalent in older adults, and overmedication is a common cause. Insomnia is a concern, and it might not look the same in older adults as it does in younger populations, especially when neurodegenerative disorders may be present. “There’s often not only the inability to get to sleep and stay asleep in older adults but also changes in their biological rhythms, which is why treatments really need to be focused on both,” Ruth M. Benca, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Dr. Benca spoke on the topic of insomnia in the elderly at a virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists. She is chair of psychiatry at Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Sleep issues strongly affect quality of life and health outcomes in the elderly, and there isn’t a lot of clear guidance for physicians to manage these issues. who spoke at the meeting presented by MedscapeLive. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Behavioral approaches are important, because quality of sleep is often affected by daytime activities, such as exercise and light exposure, according to Dr. Benca, who said that those factors can and should be addressed by behavioral interventions. Medications should be used as an adjunct to those treatments. “When we do need to use medications, we need to use ones that have been tested and found to be more helpful than harmful in older adults,” Dr. Benca said.

Many Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs should be used with caution or avoided in the elderly. The Beers criteria provide a useful list of potentially problematic drugs, and removing those drugs from consideration leaves just a few options, including the melatonin receptor agonist ramelteon, low doses of the tricyclic antidepressant doxepin, and dual orexin receptor antagonists, which are being tested in older adults, including some with dementia, Dr. Benca said.

Other drugs like benzodiazepines and related “Z” drugs can cause problems like amnesia, confusion, and psychomotor issues. “They’re advised against because there are some concerns about those side effects,” Dr. Benca said.

Sleep disturbance itself can be the result of polypharmacy. Even something as simple as a diuretic can interrupt slumber because of nocturnal bathroom visits. Antihypertensives and drugs that affect the central nervous system, including antidepressants, can affect sleep. “I’ve had patients get horrible dreams and nightmares from antihypertensive drugs. So there’s a very long laundry list of drugs that can affect sleep in a negative way,” said Dr. Benca.

Physicians have a tendency to prescribe more drugs to a patient without eliminating any, which can result in complex situations. “We see this sort of chasing the tail: You give a drug, it may have a positive effect on the primary thing you want to treat, but it has a side effect. When you give another drug to treat that side effect, it in turn has its own side effect. We keep piling on drugs,” Dr. Benca said.

“So if [a patient is] on medications for an indication, and particularly for sleep or other things, and the patient isn’t getting better, what we might want to do is slowly to withdraw things. Even for older adults who are on sleeping medications and maybe are doing better, sometimes we can decrease the dose [of the other drugs], or get them off those drugs or put them on something that might be less likely to have side effects,” Dr. Benca said.

To do that, she suggests taking a history to determine when the sleep problem began, and whether it coincided with adding or changing a medication. Another approach is to look at the list of current medications, and look for drugs that are prescribed for a problem and where the problem still persists. “You might want to take that away first, before you start adding something else,” said Dr. Benca.

Another challenge is that physicians are often unwilling to investigate sleep disorders, which are more common in older adults. Physicians can be reluctant to prescribe sleep medications, and may also be unfamiliar with behavioral interventions. “For a lot of providers, getting into sleep issues is like opening a Pandora’s Box. I think mostly physicians are taught: Don’t do this, and don’t do that. They’re not as well versed in the things that they can and should do,” said Dr. Benca.

If attempts to treat insomnia don’t succeed, or if the physician suspects a movement disorder or primary sleep disorder like sleep apnea, then the patients should be referred to a sleep specialist, according to Dr. Benca.

During the question-and-answer period following her talk, a questioner brought up the increasingly common use of cannabis to improve sleep. That can be tricky because it can be difficult to stop cannabis use, because of the rebound insomnia that may persist. She noted that there are ongoing studies on the potential impact of cannabidiol oil.

Dr. Benca was also asked about patients who take sedatives chronically and seem to be doing well. She emphasized the need for finding the lowest effective dose of a short-acting medication. “Patients should be monitored frequently, at least every 6 months. Just monitor your patient carefully.”

Dr. Benca is a consultant for Eisai, Genomind, Idorsia, Jazz, Merck, Sage, and Sunovion.

Sleep problems are prevalent in older adults, and overmedication is a common cause. Insomnia is a concern, and it might not look the same in older adults as it does in younger populations, especially when neurodegenerative disorders may be present. “There’s often not only the inability to get to sleep and stay asleep in older adults but also changes in their biological rhythms, which is why treatments really need to be focused on both,” Ruth M. Benca, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Dr. Benca spoke on the topic of insomnia in the elderly at a virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists. She is chair of psychiatry at Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Sleep issues strongly affect quality of life and health outcomes in the elderly, and there isn’t a lot of clear guidance for physicians to manage these issues. who spoke at the meeting presented by MedscapeLive. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Behavioral approaches are important, because quality of sleep is often affected by daytime activities, such as exercise and light exposure, according to Dr. Benca, who said that those factors can and should be addressed by behavioral interventions. Medications should be used as an adjunct to those treatments. “When we do need to use medications, we need to use ones that have been tested and found to be more helpful than harmful in older adults,” Dr. Benca said.

Many Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs should be used with caution or avoided in the elderly. The Beers criteria provide a useful list of potentially problematic drugs, and removing those drugs from consideration leaves just a few options, including the melatonin receptor agonist ramelteon, low doses of the tricyclic antidepressant doxepin, and dual orexin receptor antagonists, which are being tested in older adults, including some with dementia, Dr. Benca said.

Other drugs like benzodiazepines and related “Z” drugs can cause problems like amnesia, confusion, and psychomotor issues. “They’re advised against because there are some concerns about those side effects,” Dr. Benca said.

Sleep disturbance itself can be the result of polypharmacy. Even something as simple as a diuretic can interrupt slumber because of nocturnal bathroom visits. Antihypertensives and drugs that affect the central nervous system, including antidepressants, can affect sleep. “I’ve had patients get horrible dreams and nightmares from antihypertensive drugs. So there’s a very long laundry list of drugs that can affect sleep in a negative way,” said Dr. Benca.

Physicians have a tendency to prescribe more drugs to a patient without eliminating any, which can result in complex situations. “We see this sort of chasing the tail: You give a drug, it may have a positive effect on the primary thing you want to treat, but it has a side effect. When you give another drug to treat that side effect, it in turn has its own side effect. We keep piling on drugs,” Dr. Benca said.

“So if [a patient is] on medications for an indication, and particularly for sleep or other things, and the patient isn’t getting better, what we might want to do is slowly to withdraw things. Even for older adults who are on sleeping medications and maybe are doing better, sometimes we can decrease the dose [of the other drugs], or get them off those drugs or put them on something that might be less likely to have side effects,” Dr. Benca said.

To do that, she suggests taking a history to determine when the sleep problem began, and whether it coincided with adding or changing a medication. Another approach is to look at the list of current medications, and look for drugs that are prescribed for a problem and where the problem still persists. “You might want to take that away first, before you start adding something else,” said Dr. Benca.

Another challenge is that physicians are often unwilling to investigate sleep disorders, which are more common in older adults. Physicians can be reluctant to prescribe sleep medications, and may also be unfamiliar with behavioral interventions. “For a lot of providers, getting into sleep issues is like opening a Pandora’s Box. I think mostly physicians are taught: Don’t do this, and don’t do that. They’re not as well versed in the things that they can and should do,” said Dr. Benca.

If attempts to treat insomnia don’t succeed, or if the physician suspects a movement disorder or primary sleep disorder like sleep apnea, then the patients should be referred to a sleep specialist, according to Dr. Benca.

During the question-and-answer period following her talk, a questioner brought up the increasingly common use of cannabis to improve sleep. That can be tricky because it can be difficult to stop cannabis use, because of the rebound insomnia that may persist. She noted that there are ongoing studies on the potential impact of cannabidiol oil.

Dr. Benca was also asked about patients who take sedatives chronically and seem to be doing well. She emphasized the need for finding the lowest effective dose of a short-acting medication. “Patients should be monitored frequently, at least every 6 months. Just monitor your patient carefully.”

Dr. Benca is a consultant for Eisai, Genomind, Idorsia, Jazz, Merck, Sage, and Sunovion.

Sleep problems are prevalent in older adults, and overmedication is a common cause. Insomnia is a concern, and it might not look the same in older adults as it does in younger populations, especially when neurodegenerative disorders may be present. “There’s often not only the inability to get to sleep and stay asleep in older adults but also changes in their biological rhythms, which is why treatments really need to be focused on both,” Ruth M. Benca, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Dr. Benca spoke on the topic of insomnia in the elderly at a virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists. She is chair of psychiatry at Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Sleep issues strongly affect quality of life and health outcomes in the elderly, and there isn’t a lot of clear guidance for physicians to manage these issues. who spoke at the meeting presented by MedscapeLive. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Behavioral approaches are important, because quality of sleep is often affected by daytime activities, such as exercise and light exposure, according to Dr. Benca, who said that those factors can and should be addressed by behavioral interventions. Medications should be used as an adjunct to those treatments. “When we do need to use medications, we need to use ones that have been tested and found to be more helpful than harmful in older adults,” Dr. Benca said.

Many Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs should be used with caution or avoided in the elderly. The Beers criteria provide a useful list of potentially problematic drugs, and removing those drugs from consideration leaves just a few options, including the melatonin receptor agonist ramelteon, low doses of the tricyclic antidepressant doxepin, and dual orexin receptor antagonists, which are being tested in older adults, including some with dementia, Dr. Benca said.

Other drugs like benzodiazepines and related “Z” drugs can cause problems like amnesia, confusion, and psychomotor issues. “They’re advised against because there are some concerns about those side effects,” Dr. Benca said.

Sleep disturbance itself can be the result of polypharmacy. Even something as simple as a diuretic can interrupt slumber because of nocturnal bathroom visits. Antihypertensives and drugs that affect the central nervous system, including antidepressants, can affect sleep. “I’ve had patients get horrible dreams and nightmares from antihypertensive drugs. So there’s a very long laundry list of drugs that can affect sleep in a negative way,” said Dr. Benca.

Physicians have a tendency to prescribe more drugs to a patient without eliminating any, which can result in complex situations. “We see this sort of chasing the tail: You give a drug, it may have a positive effect on the primary thing you want to treat, but it has a side effect. When you give another drug to treat that side effect, it in turn has its own side effect. We keep piling on drugs,” Dr. Benca said.

“So if [a patient is] on medications for an indication, and particularly for sleep or other things, and the patient isn’t getting better, what we might want to do is slowly to withdraw things. Even for older adults who are on sleeping medications and maybe are doing better, sometimes we can decrease the dose [of the other drugs], or get them off those drugs or put them on something that might be less likely to have side effects,” Dr. Benca said.

To do that, she suggests taking a history to determine when the sleep problem began, and whether it coincided with adding or changing a medication. Another approach is to look at the list of current medications, and look for drugs that are prescribed for a problem and where the problem still persists. “You might want to take that away first, before you start adding something else,” said Dr. Benca.

Another challenge is that physicians are often unwilling to investigate sleep disorders, which are more common in older adults. Physicians can be reluctant to prescribe sleep medications, and may also be unfamiliar with behavioral interventions. “For a lot of providers, getting into sleep issues is like opening a Pandora’s Box. I think mostly physicians are taught: Don’t do this, and don’t do that. They’re not as well versed in the things that they can and should do,” said Dr. Benca.

If attempts to treat insomnia don’t succeed, or if the physician suspects a movement disorder or primary sleep disorder like sleep apnea, then the patients should be referred to a sleep specialist, according to Dr. Benca.

During the question-and-answer period following her talk, a questioner brought up the increasingly common use of cannabis to improve sleep. That can be tricky because it can be difficult to stop cannabis use, because of the rebound insomnia that may persist. She noted that there are ongoing studies on the potential impact of cannabidiol oil.

Dr. Benca was also asked about patients who take sedatives chronically and seem to be doing well. She emphasized the need for finding the lowest effective dose of a short-acting medication. “Patients should be monitored frequently, at least every 6 months. Just monitor your patient carefully.”

Dr. Benca is a consultant for Eisai, Genomind, Idorsia, Jazz, Merck, Sage, and Sunovion.

FROM FOCUS ON NEUROPSYCHIATRY 2021

Brain memory signals appear to regulate metabolism

Rhythmic brain signals that help encode memories also appear to influence blood sugar levels and may regulate the timing of the release of hormones, early, pre-clinical research shows.

“Our study is the first to show how clusters of brain cell firing in the hippocampus may directly regulate metabolism,” senior author György Buzsáki, MD, PhD, professor, department of neuroscience and physiology, NYU Grossman School of Medicine and NYU Langone Health, said in a news release.

“Evidence suggests that the brain evolved, for reasons of efficiency, to use the same signals to achieve two very different functions in terms of memory and hormonal regulation,” added corresponding author David Tingley, PhD, a post-doctoral scholar in Dr. Buzsáki’s lab.

The study was published online August 11 in Nature.

It’s recently been discovered that populations of hippocampal neurons fire within milliseconds of each other in cycles. This firing pattern is called a “sharp wave ripple” for the shape it takes when captured graphically by electroencephalogram.

In their study, Dr. Buzsáki, Dr. Tingley, and colleagues observed that clusters of sharp wave ripples recorded from the hippocampus of rats were “reliably” and rapidly, followed by decreases in blood sugar concentrations in the animals.

“This correlation was not dependent on circadian, ultradian, or meal-triggered fluctuations; it could be mimicked with optogenetically induced ripples in the hippocampus, but not in the parietal cortex, and was attenuated to chance levels by pharmacogenetically suppressing activity of the lateral septum (LS), the major conduit between the hippocampus and hypothalamus,” the researchers report.

These observations suggest that hippocampal sharp wave ripples may regulate the timing of the release of hormones, possibly including insulin, by the pancreas and liver, as well as other hormones by the pituitary gland, the researchers note.

As sharp wave ripples mostly occur during non-rapid eye movement sleep, the impact of sleep disturbance on sharp wave ripples may provide a mechanistic link between poor sleep and high blood sugar levels seen in type 2 diabetes, they suggest.

“There are a couple of experimental studies showing that if you deprive a young healthy person from sleep [for 48 hours], their glucose tolerance resembles” that of a person with diabetes, Dr. Buzsáki noted in an interview.

Moving forward, the researchers will seek to extend their theory that several hormones could be affected by nightly sharp wave ripples.

The research was funded by National Institutes of Health. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Rhythmic brain signals that help encode memories also appear to influence blood sugar levels and may regulate the timing of the release of hormones, early, pre-clinical research shows.

“Our study is the first to show how clusters of brain cell firing in the hippocampus may directly regulate metabolism,” senior author György Buzsáki, MD, PhD, professor, department of neuroscience and physiology, NYU Grossman School of Medicine and NYU Langone Health, said in a news release.

“Evidence suggests that the brain evolved, for reasons of efficiency, to use the same signals to achieve two very different functions in terms of memory and hormonal regulation,” added corresponding author David Tingley, PhD, a post-doctoral scholar in Dr. Buzsáki’s lab.

The study was published online August 11 in Nature.

It’s recently been discovered that populations of hippocampal neurons fire within milliseconds of each other in cycles. This firing pattern is called a “sharp wave ripple” for the shape it takes when captured graphically by electroencephalogram.

In their study, Dr. Buzsáki, Dr. Tingley, and colleagues observed that clusters of sharp wave ripples recorded from the hippocampus of rats were “reliably” and rapidly, followed by decreases in blood sugar concentrations in the animals.

“This correlation was not dependent on circadian, ultradian, or meal-triggered fluctuations; it could be mimicked with optogenetically induced ripples in the hippocampus, but not in the parietal cortex, and was attenuated to chance levels by pharmacogenetically suppressing activity of the lateral septum (LS), the major conduit between the hippocampus and hypothalamus,” the researchers report.

These observations suggest that hippocampal sharp wave ripples may regulate the timing of the release of hormones, possibly including insulin, by the pancreas and liver, as well as other hormones by the pituitary gland, the researchers note.

As sharp wave ripples mostly occur during non-rapid eye movement sleep, the impact of sleep disturbance on sharp wave ripples may provide a mechanistic link between poor sleep and high blood sugar levels seen in type 2 diabetes, they suggest.

“There are a couple of experimental studies showing that if you deprive a young healthy person from sleep [for 48 hours], their glucose tolerance resembles” that of a person with diabetes, Dr. Buzsáki noted in an interview.

Moving forward, the researchers will seek to extend their theory that several hormones could be affected by nightly sharp wave ripples.

The research was funded by National Institutes of Health. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Rhythmic brain signals that help encode memories also appear to influence blood sugar levels and may regulate the timing of the release of hormones, early, pre-clinical research shows.

“Our study is the first to show how clusters of brain cell firing in the hippocampus may directly regulate metabolism,” senior author György Buzsáki, MD, PhD, professor, department of neuroscience and physiology, NYU Grossman School of Medicine and NYU Langone Health, said in a news release.

“Evidence suggests that the brain evolved, for reasons of efficiency, to use the same signals to achieve two very different functions in terms of memory and hormonal regulation,” added corresponding author David Tingley, PhD, a post-doctoral scholar in Dr. Buzsáki’s lab.

The study was published online August 11 in Nature.

It’s recently been discovered that populations of hippocampal neurons fire within milliseconds of each other in cycles. This firing pattern is called a “sharp wave ripple” for the shape it takes when captured graphically by electroencephalogram.

In their study, Dr. Buzsáki, Dr. Tingley, and colleagues observed that clusters of sharp wave ripples recorded from the hippocampus of rats were “reliably” and rapidly, followed by decreases in blood sugar concentrations in the animals.

“This correlation was not dependent on circadian, ultradian, or meal-triggered fluctuations; it could be mimicked with optogenetically induced ripples in the hippocampus, but not in the parietal cortex, and was attenuated to chance levels by pharmacogenetically suppressing activity of the lateral septum (LS), the major conduit between the hippocampus and hypothalamus,” the researchers report.

These observations suggest that hippocampal sharp wave ripples may regulate the timing of the release of hormones, possibly including insulin, by the pancreas and liver, as well as other hormones by the pituitary gland, the researchers note.

As sharp wave ripples mostly occur during non-rapid eye movement sleep, the impact of sleep disturbance on sharp wave ripples may provide a mechanistic link between poor sleep and high blood sugar levels seen in type 2 diabetes, they suggest.

“There are a couple of experimental studies showing that if you deprive a young healthy person from sleep [for 48 hours], their glucose tolerance resembles” that of a person with diabetes, Dr. Buzsáki noted in an interview.

Moving forward, the researchers will seek to extend their theory that several hormones could be affected by nightly sharp wave ripples.

The research was funded by National Institutes of Health. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA approves first drug for idiopathic hypersomnia

, the company announced in a news release.

It marks the second approval for Xywav. The FDA approved it last year for the treatment of cataplexy or excessive daytime sleepiness in patients with narcolepsy as young as 7 years of age.

This recent approval is the first for a treatment for idiopathic hypersomnia.

“Idiopathic hypersomnia can have a significant impact on the social, educational, and occupational functioning of people living with the condition,” Diane Powell, board chair and CEO of the Hypersomnia Foundation, noted in the release.

This FDA approval “is a major milestone for the entire idiopathic hypersomnia community as Xywav becomes the first medicine approved to manage this chronic sleep disorder,” said Ms. Powell.

Low sodium oxybate product

Xywav is a novel oxybate product with a unique composition of cations. It contains 92% less sodium than sodium oxybate (Xyrem) at the recommended adult dosage range of 6 to 9 g, the company noted in a news release.

An estimated 37,000 people in the United States have been diagnosed with idiopathic hypersomnia, a neurologic sleep disorder characterized by chronic excessive daytime sleepiness.

Other symptoms of the disorder may include severe sleep inertia or sleep drunkenness (prolonged difficulty waking with frequent re-entries into sleep, confusion, and irritability), as well as prolonged, nonrestorative night-time sleep, cognitive impairment, and long and unrefreshing naps.

The approval was based on findings from a phase 3, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled, randomized withdrawal study.

Results showed “statistically significant and clinically meaningful” differences compared with placebo in change in the primary endpoint of Epworth Sleepiness Scale score (P < .0001) and the secondary endpoints of Patient Global Impression of Change (P < .0001) and the Idiopathic Hypersomnia Severity Scale (P < .0001), the company reported.

The most common adverse reactions were nausea, headache, dizziness, anxiety, insomnia, decreased appetite, hyperhidrosis, vomiting, diarrhea, dry mouth, parasomnia, somnolence, fatigue, and tremor.

The novel agent can be administered once or twice nightly for the treatment of idiopathic hypersomnia in adults.

“To optimize response, a patient’s health care provider may consider prescribing a twice-nightly regimen in equally or unequally divided doses at bedtime and 2.5 to 4 hours later and gradually titrate Xywav so that a patient may receive an individualized dose and regimen based on efficacy and tolerability,” the company said.

Xywav carries a boxed warning because it is a central nervous system depressant and because there is potential for abuse and misuse. The drug is only available through a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) program.

The company plans to make Xywav available to patients with idiopathic hypersomnia later this year following implementation of the REMS program.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, the company announced in a news release.

It marks the second approval for Xywav. The FDA approved it last year for the treatment of cataplexy or excessive daytime sleepiness in patients with narcolepsy as young as 7 years of age.

This recent approval is the first for a treatment for idiopathic hypersomnia.

“Idiopathic hypersomnia can have a significant impact on the social, educational, and occupational functioning of people living with the condition,” Diane Powell, board chair and CEO of the Hypersomnia Foundation, noted in the release.

This FDA approval “is a major milestone for the entire idiopathic hypersomnia community as Xywav becomes the first medicine approved to manage this chronic sleep disorder,” said Ms. Powell.

Low sodium oxybate product

Xywav is a novel oxybate product with a unique composition of cations. It contains 92% less sodium than sodium oxybate (Xyrem) at the recommended adult dosage range of 6 to 9 g, the company noted in a news release.

An estimated 37,000 people in the United States have been diagnosed with idiopathic hypersomnia, a neurologic sleep disorder characterized by chronic excessive daytime sleepiness.

Other symptoms of the disorder may include severe sleep inertia or sleep drunkenness (prolonged difficulty waking with frequent re-entries into sleep, confusion, and irritability), as well as prolonged, nonrestorative night-time sleep, cognitive impairment, and long and unrefreshing naps.

The approval was based on findings from a phase 3, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled, randomized withdrawal study.

Results showed “statistically significant and clinically meaningful” differences compared with placebo in change in the primary endpoint of Epworth Sleepiness Scale score (P < .0001) and the secondary endpoints of Patient Global Impression of Change (P < .0001) and the Idiopathic Hypersomnia Severity Scale (P < .0001), the company reported.

The most common adverse reactions were nausea, headache, dizziness, anxiety, insomnia, decreased appetite, hyperhidrosis, vomiting, diarrhea, dry mouth, parasomnia, somnolence, fatigue, and tremor.

The novel agent can be administered once or twice nightly for the treatment of idiopathic hypersomnia in adults.

“To optimize response, a patient’s health care provider may consider prescribing a twice-nightly regimen in equally or unequally divided doses at bedtime and 2.5 to 4 hours later and gradually titrate Xywav so that a patient may receive an individualized dose and regimen based on efficacy and tolerability,” the company said.

Xywav carries a boxed warning because it is a central nervous system depressant and because there is potential for abuse and misuse. The drug is only available through a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) program.

The company plans to make Xywav available to patients with idiopathic hypersomnia later this year following implementation of the REMS program.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, the company announced in a news release.

It marks the second approval for Xywav. The FDA approved it last year for the treatment of cataplexy or excessive daytime sleepiness in patients with narcolepsy as young as 7 years of age.

This recent approval is the first for a treatment for idiopathic hypersomnia.

“Idiopathic hypersomnia can have a significant impact on the social, educational, and occupational functioning of people living with the condition,” Diane Powell, board chair and CEO of the Hypersomnia Foundation, noted in the release.

This FDA approval “is a major milestone for the entire idiopathic hypersomnia community as Xywav becomes the first medicine approved to manage this chronic sleep disorder,” said Ms. Powell.

Low sodium oxybate product

Xywav is a novel oxybate product with a unique composition of cations. It contains 92% less sodium than sodium oxybate (Xyrem) at the recommended adult dosage range of 6 to 9 g, the company noted in a news release.

An estimated 37,000 people in the United States have been diagnosed with idiopathic hypersomnia, a neurologic sleep disorder characterized by chronic excessive daytime sleepiness.

Other symptoms of the disorder may include severe sleep inertia or sleep drunkenness (prolonged difficulty waking with frequent re-entries into sleep, confusion, and irritability), as well as prolonged, nonrestorative night-time sleep, cognitive impairment, and long and unrefreshing naps.

The approval was based on findings from a phase 3, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled, randomized withdrawal study.

Results showed “statistically significant and clinically meaningful” differences compared with placebo in change in the primary endpoint of Epworth Sleepiness Scale score (P < .0001) and the secondary endpoints of Patient Global Impression of Change (P < .0001) and the Idiopathic Hypersomnia Severity Scale (P < .0001), the company reported.

The most common adverse reactions were nausea, headache, dizziness, anxiety, insomnia, decreased appetite, hyperhidrosis, vomiting, diarrhea, dry mouth, parasomnia, somnolence, fatigue, and tremor.

The novel agent can be administered once or twice nightly for the treatment of idiopathic hypersomnia in adults.

“To optimize response, a patient’s health care provider may consider prescribing a twice-nightly regimen in equally or unequally divided doses at bedtime and 2.5 to 4 hours later and gradually titrate Xywav so that a patient may receive an individualized dose and regimen based on efficacy and tolerability,” the company said.

Xywav carries a boxed warning because it is a central nervous system depressant and because there is potential for abuse and misuse. The drug is only available through a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) program.

The company plans to make Xywav available to patients with idiopathic hypersomnia later this year following implementation of the REMS program.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Late-onset, treatment-resistant anxiety and depression

CASE Anxious and can’t sleep

Mr. A, age 41, presents to his primary care physician (PCP) with anxiety and insomnia. He describes having generalized anxiety with initial and middle insomnia, and says he is sleeping an average of 2 hours per night. He denies any other psychiatric symptoms. Mr. A has no significant psychiatric or medical history.

Mr. A is initiated on zolpidem tartrate, 12.5 mg every night at bedtime, and paroxetine, 20 mg every night at bedtime, for anxiety and insomnia, but these medications result in little to no improvement.

During a 4-month period, he is treated with trials of alprazolam, 0.5 mg every 8 hours as needed; diazepam 5 mg twice a day as needed; diphenhydramine, 50 mg at bedtime; and eszopiclone, 3 mg at bedtime. Despite these treatments, he experiences increased anxiety and insomnia, and develops depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, poor concentration, general malaise, extreme fatigue, a 15-pound unintentional weight loss, erectile dysfunction, and decreased libido. Mr. A denies having suicidal or homicidal ideations. Additionally, he typically goes to the gym approximately 3 times per week, and has noticed that the amount of weight he is able to lift has decreased, which is distressing. Previously, he had been able to lift 300 pounds, but now he can only lift 200 pounds.

[polldaddy:10891920]

The authors’ observations

Insomnia, anxiety, and depression are common chief complaints in medical settings. However, some psychiatric presentations may have an underlying medical etiology.

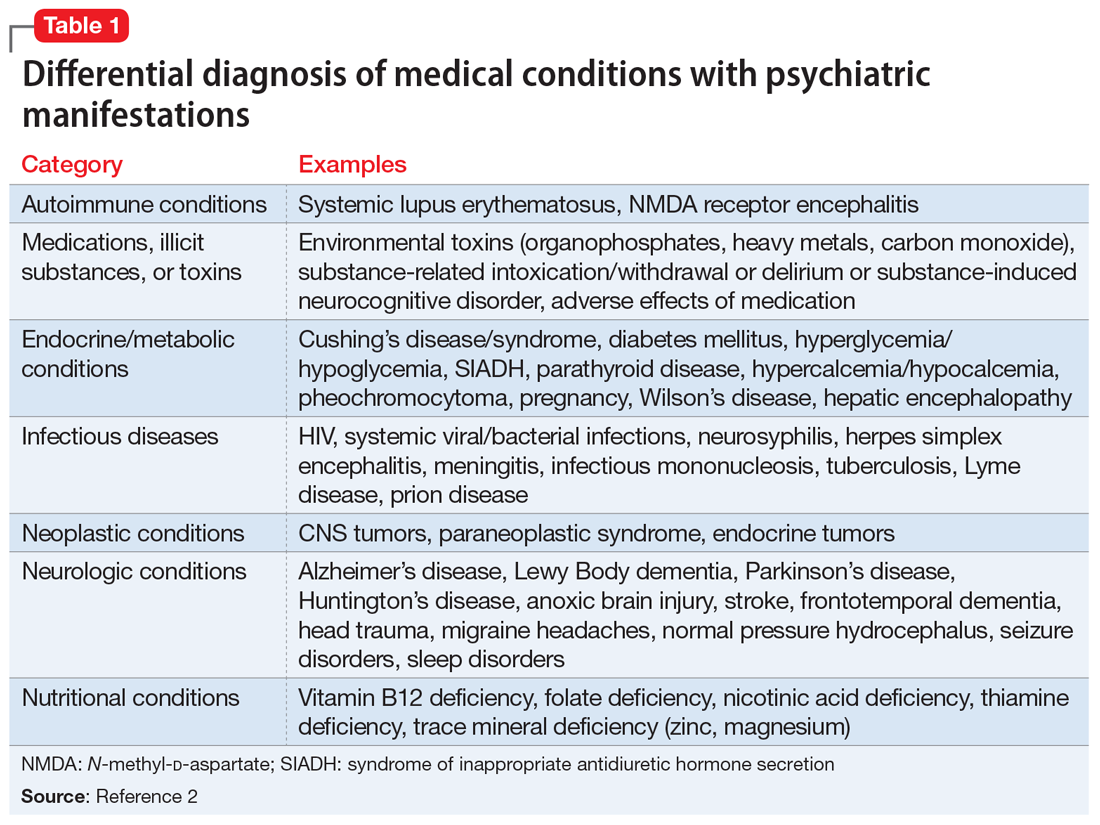

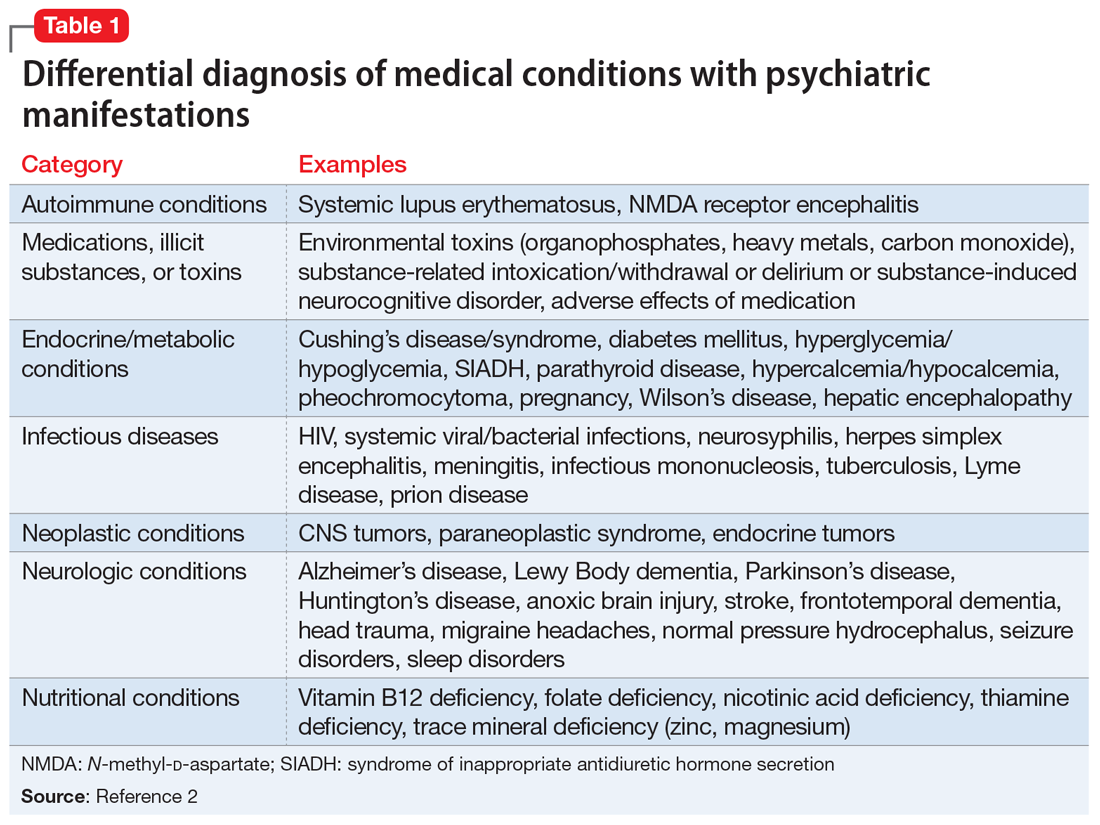

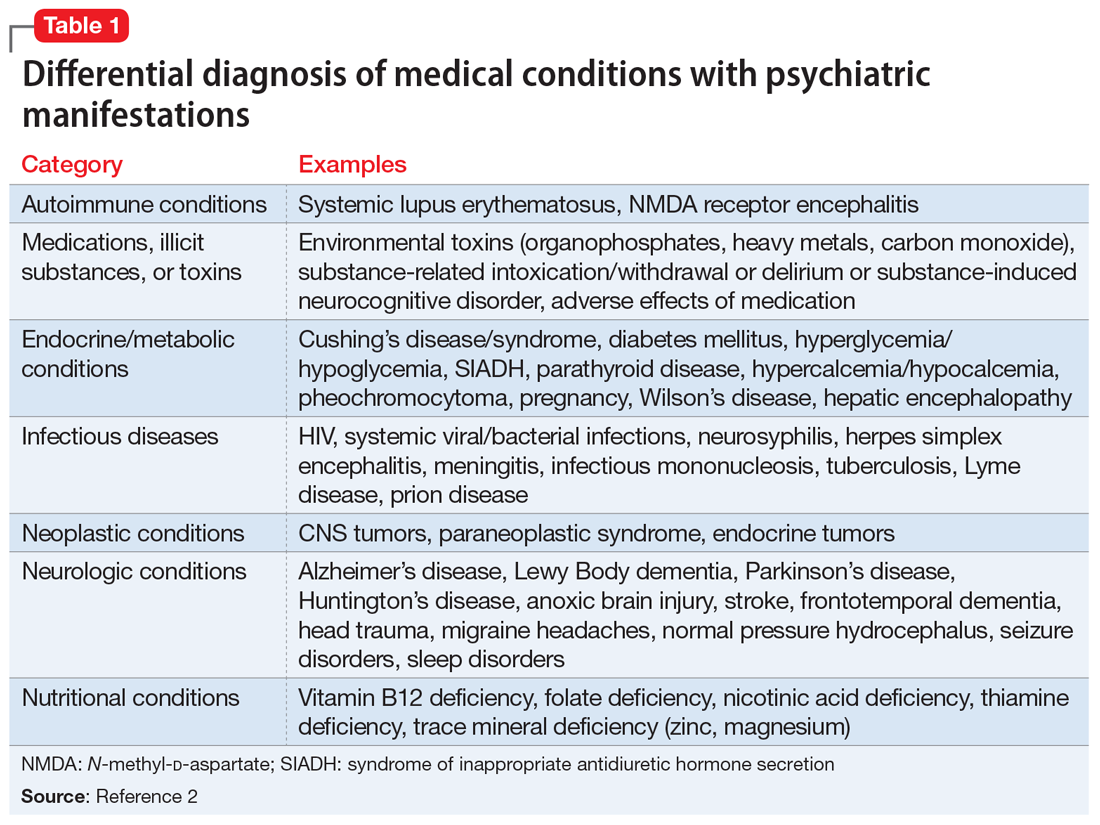

DSM-5 requires that medical conditions be ruled out in order for a patient to meet criteria for a psychiatric diagnosis.1 Medical differential diagnoses for patients with psychiatric symptoms can include autoimmune, drug/toxin, metabolic, infectious, neoplastic, neurologic, and nutritional etiologies (Table 12). To rule out the possibility of an underlying medical etiology, general screening guidelines include complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, urinalysis, and urine drug screen with alcohol. Human immunodeficiency virus testing and thyroid hormone testing are also commonly ordered.3 Further laboratory testing and imaging is typically not warranted in the absence of historical or physical findings because they are not advocated as cost-effective, so health care professionals must use their clinical judgment to determine appropriate further evaluation. The onset of anxiety most commonly occurs in late adolescence early and adulthood, but Mr. A experienced his first symptoms of anxiety at age 41.2 Mr. A’s age, lack of psychiatric or family history of mental illness, acute onset of symptoms, and failure of symptoms to abate with standard psychiatric treatments warrant a more extensive workup.

EVALUATION Imaging reveals an important finding

Because Mr. A’s symptoms do not improve with standard psychiatric treatments, his PCP orders standard laboratory bloodwork to investigate a possible medical etiology; however, his results are all within normal range.

After the PCP’s niece is coincidentally diagnosed with a pituitary macroadenoma, the PCP orders brain imaging for Mr. A. Results of an MRI show that Mr. A has a 1.6-cm macroadenoma of the pituitary. He is referred to an endocrinologist, who orders additional laboratory tests that show an elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol level of 73 μg/24 h (normal range: 3.5 to 45 μg/24 h), suggesting that Mr. A’s anxiety may be due to Cushing’s disease or that his anxiety caused falsely elevated urinary cortisol levels. Four weeks later, bloodwork is repeated and shows an abnormal dexamethasone suppression test, and 2 more elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol levels of 76 μg/24 h and 150 μg/24 h. A repeat MRI shows a 1.8-cm, mostly cystic sellar mass, indicating the need for surgical intervention. Although the tumor is large and shows optic nerve compression, Mr. A does not complain of headaches or changes in vision.

Continue to: Two months later...

Two months later, Mr. A undergoes a transsphenoidal tumor resection of the pituitary adenoma, and biopsy results confirm an adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-secreting pituitary macroadenoma, which is consistent with Cushing’s disease. Following surgery, steroid treatment with dexamethasone is discontinued due to a persistently elevated

[polldaddy:10891923]

The authors’ observations

Chronic excess glucocorticoid production is the underlying pathophysiology of Cushing’s disease, which is most commonly caused by an ACTH-producing adenoma.4,5 When these hormones become dysregulated, the result can be over- or underproduction of cortisol, which can lead to physical and psychiatric manifestations.6

Cushing’s disease most commonly manifests with the physical symptoms of centripetal fat deposition, abdominal striae, facial plethora, muscle atrophy, bone density loss, immunosuppression, and cardiovascular complications.5

Hypercortisolism can precipitate anxiety (12% to 79%), mood disorders (50% to 70%), and (less commonly) psychotic disorders; however, in a clinical setting, if a patient presented with one of these as a chief complaint, they would likely first be treated psychiatrically rather than worked up medically for a rare medical condition.5,7-13

Mr. A’s initial bloodwork was unremarkable, but cortisol levels were not obtained at that time because testing for cortisol levels to rule out an underlying medical condition is not routine in patients with depression and anxiety. In Mr. A’s case, a neuroendocrine workup was only ordered once his PCP’s niece coincidentally was diagnosed with a pituitary adenoma.

Continue to: For Mr. A...

For Mr. A, Cushing’s disease presented as a psychiatric disorder with anxiety and insomnia that were resistant to numerous psychiatric medications during an 8-month period. If Mr. A’s PCP had not ordered a brain MRI, he may have continued to receive ineffective psychiatric treatment for some time. Many of Mr. A’s physical symptoms were consistent with Cushing’s disease and mental illness, including erectile dysfunction, fatigue, and muscle weakness; however, his 15-pound weight loss pointed more toward psychiatric illness and further disguised his underlying medical diagnosis, because sudden weight gain is commonly seen in Cushing’s disease (Table 24,5,7,9).

TREATMENT Persistent psychiatric symptoms, then finally relief

Four weeks after surgery, Mr. A’s psychiatric symptoms gradually intensify, which prompts him to see a psychiatrist. A mental status examination (MSE) shows that he is well-nourished, with normal activity, appropriate behavior, and coherent thought process, but depressed mood and flat affect. He denies suicidal or homicidal ideation. He reports that despite being advised to have realistic expectations, he had high hopes that the surgery would lead to remission of all his symptoms, and expresses disappointment that he does not feel “back to normal.”

Six days later, Mr. A’s wife takes him to the hospital. His MSE shows that he has a tense appearance, fidgety activity, depressed and anxious mood, restricted affect, circumstantial thought process, and paranoid delusions that his wife was plotting against him. He says he still is experiencing insomnia. He also discloses having suicidal ideations with a plan and intent to overdose on medication, as well as homicidal ideations about killing his wife and children. Mr. A provides reasons for why he would want to hurt his family, and does not appear to be bothered by these thoughts.

Mr. A is admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit and is prescribed quetiapine, 100 mg every night at bedtime. During the next 2 days, quetiapine is titrated to 300 mg every night at bedtime. On hospital Day 3, Mr. A says he is feeling worse than the previous days. He is still having vague suicidal thoughts and feels agitated, guilty, and depressed. To treat these persistent symptoms, quetiapine is further increased to 400 mg every night at bedtime, and he is initiated on bupropion XL, 150 mg, to treat persistent symptoms.

After 1 week of hospitalization, the treatment team meets with Mr. A and his wife, who has been supportive throughout her husband’s hospitalization. During the meeting, they both agree that Mr. A has experienced some improvement because he is no longer having suicidal or homicidal thoughts, but he is still feeling depressed and frustrated by his continued insomnia. Following the meeting, Mr. A’s quetiapine is further increased to 450 mg every night at bedtime to address continued insomnia, and bupropion XL is increased to 300 mg/d to address continued depressive symptoms. During the next few days, his affective symptoms improve; however, his initial insomnia continues, and quetiapine is further increased to 500 mg every night at bedtime.

Continue to: On hospital Day 20...

On hospital Day 20, Mr. A is discharged back to his outpatient psychiatrist and receives quetiapine, 500 mg every night at bedtime, and bupropion XL, 300 mg/d. Although Mr. A’s depression and anxiety continue to be well controlled, his insomnia persists. Sleep hygiene is addressed, and alprazolam, 0.5 mg every night at bedtime, is added to his regimen, which proves to be effective.

OUTCOME A slow remission

After a year of treatment, Mr. A is slowly tapered off of all medications. Two years later, he is in complete remission of all psychiatric symptoms and no longer requires any psychotropic medications.

The authors’ observations

Treatment for hypercortisolism in patients with psychiatric symptoms triggered by glucocorticoid imbalance has typically resulted in a decrease in the severity of their psychiatric symptoms.9,11 A prospective longitudinal study examining 33 patients found that correction of hypercortisolism in patients with Cushing’s syndrome often led to resolution of their psychiatric symptoms, with 87.9% of patients back to baseline within 1 year.14 However, to our knowledge, few reports have described the management of patients whose symptoms are resistant to treatment of hypercortisolism.

In our case, after transsphenoidal resection of an adenoma, Mr. A became suicidal and paranoid, and his anxiety and insomnia also persisted. A possible explanation for the worsening of Mr. A’s symptoms after surgery could be the slow recovery of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and therefore a temporary deficiency in glucocorticoid, which caused an increase in catecholamines, leading to an increase in stress.14 This concept of a “slow recovery” is supported by the fact that Mr. A was successfully weaned off all medication after 1 year of treatment, and achieved complete remission of psychiatric symptoms for >2 years. Furthermore, the severity of Mr. A’s symptoms appeared to correlate with his 24-hour urine cortisol and

Future research should evaluate the utility of screening all patients with treatment-resistant anxiety and/or insomnia for hypercortisolism. Even without other clues to endocrinopathies, serum cortisol levels can be used as a screening tool for diagnosing underlying medical causes in patients with anxiety and depression.2 A greater understanding of the relationship between medical and psychiatric manifestations will allow clinicians to better care for patients. Further research is needed to elucidate the quantitative relationship between cortisol levels and anxiety to evaluate severity, guide treatment planning, and follow treatment response for patients with anxiety. It may be useful to determine the threshold between elevated cortisol levels due to anxiety vs elevated cortisol due to an underlying medical pathology such as Cushing’s disease. Additionally, little research has been conducted to compare how psychiatric symptoms respond to pituitary macroadenoma resection alone, pharmaceutical intervention alone, or a combination of these approaches. It would be beneficial to evaluate these treatment strategies to elucidate the most effective method to reduce psychiatric symptoms in patients with hypercortisolism, and perhaps to reduce the incidence of post-resection worsening of psychiatric symptoms.

Continue to: This case was challenging...

This case was challenging because Mr. A did not initially respond to psychiatric intervention, his psychiatric symptoms worsened after transsphenoidal resection of the pituitary adenoma, and his symptoms were alleviated only after psychiatric medications were re-initiated following surgery. This case highlights the importance of considering an underlying medically diagnosable and treatable cause of psychiatric illness, and illustrates the complex ongoing management that may be necessary to help a patient with this condition achieve their baseline. Further, Mr. A’s case shows that the absence of response to standard psychiatric therapies should warrant earlier laboratory and/or imaging evaluation prior to or in conjunction with psychiatric referral. Additionally, testing for cortisol levels is not typically done for a patient with treatment-resistant anxiety, and this case highlights the importance of considering hypercortisolism in such circumstances.

Bottom Line

Consider testing cortisol levels in patients with treatment-resistant anxiety and insomnia, because cortisol plays a role in Cushing’s disease and anxiety. The severity of psychiatric manifestations of Cushing’s disease may correlate with cortisol levels. Treatment should focus on symptomatic management and underlying etiology.

Related Resources

- Roberts LW, Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, ed. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. 7th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019.

- Rotham J. Cushing’s syndrome: a tale of frequent misdiagnosis. National Center for Health Research. 2020. www.center4research.org/cushings-syndrome-frequent-misdiagnosis/

- Middleman D. Psychiatric issues of Cushing’s patients: coping with Cushing’s. Cushing’s Support and Research Foundation. www.csrf.net/coping-with-cushings/psychiatric-issues-of-cushings-patients/

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Dexamethasone • Decadron

Diazepam • Valium

Eszopiclone • Lunesta

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Zolpidem tartrate • Ambien CR

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, et al. Neural sciences. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, et al. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

3. Anfinson TJ, Kathol RG. Screening laboratory evaluation in psychiatric patients: a review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1992;14(4):248-257.

4. Fehm HL, Voigt KH. Pathophysiology of Cushing’s disease. Pathobiol Annu. 1979;9:225-255.

5. Fujii Y, Mizoguchi Y, Masuoka J, et al. Cushing’s syndrome and psychosis: a case report and literature review. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(5):18.

6. Raff H, Sharma ST, Nieman LK. Physiological basis for the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of adrenal disorders: Cushing’s syndrome, adrenal insufficiency, and congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Compr Physiol. 2011;4(2):739-769.

7. Santos A, Resimini E, Pascual JC, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in patients with Cushing’s syndrome: prevalence diagnosis, and management. Drugs. 2017;77(8):829-842.

8. Arnaldi G, Angeli A, Atkinson B, et al. Diagnosis and complications of Cushing’s syndrome: a consensus statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(12):5593-5602.

9. Sonino N, Fava GA. Psychosomatic aspects of Cushing’s disease. Psychother Psychosom. 1998;67(3):140-146.

10. Loosen PT, Chambliss B, DeBold CR, et al. Psychiatric phenomenology in Cushing’s disease. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1992;25(4):192-198.

11. Kelly WF, Kelly MJ, Faragher B. A prospective study of psychiatric and psychological aspects of Cushing’s syndrome. Clin Endocrinol. 1996;45(6):715-720.

12. Katho RG, Delahunt JW, Hannah L. Transition from bipolar affective disorder to intermittent Cushing’s syndrome: case report. J Clin Psychiatry. 1985;46(5):194-196.

13. Hirsh D, Orr G, Kantarovich V, et al. Cushing’s syndrome presenting as a schizophrenia-like psychotic state. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2000;37(1):46-50.

14. Dorn LD, Burgess ES, Friedman TC, et al. The longitudinal course of psychopathology in Cushing’s syndrome after correction of hypercortisolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(3):912-919.

15. Starkman MN, Schteingart DE, Schork MA. Cushing’s syndrome after treatment: changes in cortisol and ACTH levels, and amelioration of the depressive syndrome. Psychiatry Res. 1986;19(3):177-178.

CASE Anxious and can’t sleep

Mr. A, age 41, presents to his primary care physician (PCP) with anxiety and insomnia. He describes having generalized anxiety with initial and middle insomnia, and says he is sleeping an average of 2 hours per night. He denies any other psychiatric symptoms. Mr. A has no significant psychiatric or medical history.

Mr. A is initiated on zolpidem tartrate, 12.5 mg every night at bedtime, and paroxetine, 20 mg every night at bedtime, for anxiety and insomnia, but these medications result in little to no improvement.

During a 4-month period, he is treated with trials of alprazolam, 0.5 mg every 8 hours as needed; diazepam 5 mg twice a day as needed; diphenhydramine, 50 mg at bedtime; and eszopiclone, 3 mg at bedtime. Despite these treatments, he experiences increased anxiety and insomnia, and develops depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, poor concentration, general malaise, extreme fatigue, a 15-pound unintentional weight loss, erectile dysfunction, and decreased libido. Mr. A denies having suicidal or homicidal ideations. Additionally, he typically goes to the gym approximately 3 times per week, and has noticed that the amount of weight he is able to lift has decreased, which is distressing. Previously, he had been able to lift 300 pounds, but now he can only lift 200 pounds.

[polldaddy:10891920]

The authors’ observations

Insomnia, anxiety, and depression are common chief complaints in medical settings. However, some psychiatric presentations may have an underlying medical etiology.

DSM-5 requires that medical conditions be ruled out in order for a patient to meet criteria for a psychiatric diagnosis.1 Medical differential diagnoses for patients with psychiatric symptoms can include autoimmune, drug/toxin, metabolic, infectious, neoplastic, neurologic, and nutritional etiologies (Table 12). To rule out the possibility of an underlying medical etiology, general screening guidelines include complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, urinalysis, and urine drug screen with alcohol. Human immunodeficiency virus testing and thyroid hormone testing are also commonly ordered.3 Further laboratory testing and imaging is typically not warranted in the absence of historical or physical findings because they are not advocated as cost-effective, so health care professionals must use their clinical judgment to determine appropriate further evaluation. The onset of anxiety most commonly occurs in late adolescence early and adulthood, but Mr. A experienced his first symptoms of anxiety at age 41.2 Mr. A’s age, lack of psychiatric or family history of mental illness, acute onset of symptoms, and failure of symptoms to abate with standard psychiatric treatments warrant a more extensive workup.

EVALUATION Imaging reveals an important finding

Because Mr. A’s symptoms do not improve with standard psychiatric treatments, his PCP orders standard laboratory bloodwork to investigate a possible medical etiology; however, his results are all within normal range.

After the PCP’s niece is coincidentally diagnosed with a pituitary macroadenoma, the PCP orders brain imaging for Mr. A. Results of an MRI show that Mr. A has a 1.6-cm macroadenoma of the pituitary. He is referred to an endocrinologist, who orders additional laboratory tests that show an elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol level of 73 μg/24 h (normal range: 3.5 to 45 μg/24 h), suggesting that Mr. A’s anxiety may be due to Cushing’s disease or that his anxiety caused falsely elevated urinary cortisol levels. Four weeks later, bloodwork is repeated and shows an abnormal dexamethasone suppression test, and 2 more elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol levels of 76 μg/24 h and 150 μg/24 h. A repeat MRI shows a 1.8-cm, mostly cystic sellar mass, indicating the need for surgical intervention. Although the tumor is large and shows optic nerve compression, Mr. A does not complain of headaches or changes in vision.

Continue to: Two months later...

Two months later, Mr. A undergoes a transsphenoidal tumor resection of the pituitary adenoma, and biopsy results confirm an adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-secreting pituitary macroadenoma, which is consistent with Cushing’s disease. Following surgery, steroid treatment with dexamethasone is discontinued due to a persistently elevated

[polldaddy:10891923]

The authors’ observations

Chronic excess glucocorticoid production is the underlying pathophysiology of Cushing’s disease, which is most commonly caused by an ACTH-producing adenoma.4,5 When these hormones become dysregulated, the result can be over- or underproduction of cortisol, which can lead to physical and psychiatric manifestations.6

Cushing’s disease most commonly manifests with the physical symptoms of centripetal fat deposition, abdominal striae, facial plethora, muscle atrophy, bone density loss, immunosuppression, and cardiovascular complications.5

Hypercortisolism can precipitate anxiety (12% to 79%), mood disorders (50% to 70%), and (less commonly) psychotic disorders; however, in a clinical setting, if a patient presented with one of these as a chief complaint, they would likely first be treated psychiatrically rather than worked up medically for a rare medical condition.5,7-13

Mr. A’s initial bloodwork was unremarkable, but cortisol levels were not obtained at that time because testing for cortisol levels to rule out an underlying medical condition is not routine in patients with depression and anxiety. In Mr. A’s case, a neuroendocrine workup was only ordered once his PCP’s niece coincidentally was diagnosed with a pituitary adenoma.

Continue to: For Mr. A...

For Mr. A, Cushing’s disease presented as a psychiatric disorder with anxiety and insomnia that were resistant to numerous psychiatric medications during an 8-month period. If Mr. A’s PCP had not ordered a brain MRI, he may have continued to receive ineffective psychiatric treatment for some time. Many of Mr. A’s physical symptoms were consistent with Cushing’s disease and mental illness, including erectile dysfunction, fatigue, and muscle weakness; however, his 15-pound weight loss pointed more toward psychiatric illness and further disguised his underlying medical diagnosis, because sudden weight gain is commonly seen in Cushing’s disease (Table 24,5,7,9).

TREATMENT Persistent psychiatric symptoms, then finally relief