User login

Sleep, chronic pain, and OUD have a complex relationship

MILWAUKEE – Individuals with chronic pain frequently have disrupted sleep and also may be at risk for opioid use disorder. However, even with advanced monitoring, it’s not clear how sleep modulates pain and opioid cravings.

Sleep has an impact on positive and negative affect, but new research shows that the link between sleep and mood states that may contribute to opioid use disorder is not straightforward. At the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society, Patrick Finan, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, discussed how sleep and mood affect cravings for opioids among those in treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD).

said Dr. Finan, who told attendees that one key question he and his colleagues were seeking to answer was whether those with OUD and chronic pain had more disturbed sleep than those with OUD alone. Also, the researchers wanted to know whether the ups and downs of sleep on a day-to-day basis were reflected in pain scores among those with OUD, as would be predicted by prevailing models.

Finally, two “proximal indicators” of relapse risk, affect and heroin craving, might be affected by both sleep and pain, and Dr. Finan and collaborators sought to explore that association.

The work was part of a larger study looking at the natural history of OUD and OUD with comorbid chronic pain. To participate in this parent study, adults with OUD had to be seeking treatment or currently enrolled in methadone or buprenorphine maintenance treatment, and without current major depressive disorder. Also, patients could not have a history of significant mental illness, cognitive impairment, or a medical condition that would interfere with study participation. A total of 56 patients participated, and 20 of these individuals also had chronic pain.

Those with OUD and chronic pain qualified if they had pain (not related to opioid withdrawal) averaging above 3 on a 0-10 pain rating scale over the past week; additional criteria included pain for at least the past 3 months, with 10 or more days per month of pain.

Pain ratings were captured via a smartphone app that prompted participants to enter a pain rating at three random times during each day. Each evening, patients also completed a sleep diary giving information about bedtime, sleep onset latency, waking after sleep onset, and wake time for the preceding day.

A self-applied ambulatory electroencephalogram applied to the forehead was used for up to 7 consecutive nights to capture sleep continuity estimates; the device has been validated against polysomnography data in other work. Participants were given incentives to use the device, and this “yielded strong adherence,” with an average of 5 nights of use per participant, Dr. Finan said.

Patients were an average age of about 49 years, and were 75% male. African American participants made up just over half of the cohort, and 43% were white. Participants were roughly evenly divided in the type of maintenance therapy they were taking. Overall, 39% of participants had a positive urine toxicology screen.

For patients with chronic pain, 45% of all momentary pain reports had a pain score over zero, with a mean of 32 days of pain. Looking at the data another way, 58% of all patient-days had at least one momentary report of pain greater than zero, said Dr. Finan. On average, participants recorded a pain score of 2.27.

Brief Pain Inventory scores at baseline showed a mean severity of 5, and a pain interference score of 5.07.

Participants with OUD and chronic pain did not differ across any EEG-recorded sleep measures, compared with those with OUD alone. However, subjective reports of sleep were actually better overall for those with chronic pain than the objective EEG reports. The EEG recordings captured an average of 9.11 minutes more of waking after sleep onset (P less than .001). Also, total sleep time was 10.37 minutes shorter as recorded by the EEG than by self-report (P less than .001). Overall sleep efficiency was also worse by 5.96 minutes according to the EEG, compared with self-report (P less than .001).

“Sleep is objectively poor but subjectively ‘normal’ and variable in opioid use disorder patients,” Dr. Finan said. In aggregate, however, neither diary-based subjective nor EEG-based objective sleep measures differed between those with and without chronic pain in the research cohort. This phenomenon of sleep efficiency being self-reported as higher than objective measures capture sleep has also been seen in those newly abstinent from cocaine, Dr. Finan said, adding that it’s possible individuals with substance use disorder who are new to treatment simply feel better than they have in some time along many dimensions, with sleep being one such domain.

Pain on a given day didn’t predict poor sleep on that night, except that sleep onset took slightly longer (P = .01), said Dr. Finan. He noted that “there was no substantive effect on other sleep continuity parameters.”

Looking at how negative affect mediated craving for heroin, Dr. Finan and colleagues found that negative affect–related craving was significantly greater for those with chronic pain (P less than .001). Unlike findings in patients without OUD, having disrupted sleep continuity was more associated with increased daily negative affect, rather than decreased positive affect. And this increased negative affect was associated with heroin cravings, said Dr. Finan. “In the past few years, we’ve seen quite a few studies that have found some abnormalities in the reward system in patients with chronic pain.” Whether poor sleep is a mediator of these abnormalities deserves further study.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Finan reported no outside sources of funding.

MILWAUKEE – Individuals with chronic pain frequently have disrupted sleep and also may be at risk for opioid use disorder. However, even with advanced monitoring, it’s not clear how sleep modulates pain and opioid cravings.

Sleep has an impact on positive and negative affect, but new research shows that the link between sleep and mood states that may contribute to opioid use disorder is not straightforward. At the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society, Patrick Finan, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, discussed how sleep and mood affect cravings for opioids among those in treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD).

said Dr. Finan, who told attendees that one key question he and his colleagues were seeking to answer was whether those with OUD and chronic pain had more disturbed sleep than those with OUD alone. Also, the researchers wanted to know whether the ups and downs of sleep on a day-to-day basis were reflected in pain scores among those with OUD, as would be predicted by prevailing models.

Finally, two “proximal indicators” of relapse risk, affect and heroin craving, might be affected by both sleep and pain, and Dr. Finan and collaborators sought to explore that association.

The work was part of a larger study looking at the natural history of OUD and OUD with comorbid chronic pain. To participate in this parent study, adults with OUD had to be seeking treatment or currently enrolled in methadone or buprenorphine maintenance treatment, and without current major depressive disorder. Also, patients could not have a history of significant mental illness, cognitive impairment, or a medical condition that would interfere with study participation. A total of 56 patients participated, and 20 of these individuals also had chronic pain.

Those with OUD and chronic pain qualified if they had pain (not related to opioid withdrawal) averaging above 3 on a 0-10 pain rating scale over the past week; additional criteria included pain for at least the past 3 months, with 10 or more days per month of pain.

Pain ratings were captured via a smartphone app that prompted participants to enter a pain rating at three random times during each day. Each evening, patients also completed a sleep diary giving information about bedtime, sleep onset latency, waking after sleep onset, and wake time for the preceding day.

A self-applied ambulatory electroencephalogram applied to the forehead was used for up to 7 consecutive nights to capture sleep continuity estimates; the device has been validated against polysomnography data in other work. Participants were given incentives to use the device, and this “yielded strong adherence,” with an average of 5 nights of use per participant, Dr. Finan said.

Patients were an average age of about 49 years, and were 75% male. African American participants made up just over half of the cohort, and 43% were white. Participants were roughly evenly divided in the type of maintenance therapy they were taking. Overall, 39% of participants had a positive urine toxicology screen.

For patients with chronic pain, 45% of all momentary pain reports had a pain score over zero, with a mean of 32 days of pain. Looking at the data another way, 58% of all patient-days had at least one momentary report of pain greater than zero, said Dr. Finan. On average, participants recorded a pain score of 2.27.

Brief Pain Inventory scores at baseline showed a mean severity of 5, and a pain interference score of 5.07.

Participants with OUD and chronic pain did not differ across any EEG-recorded sleep measures, compared with those with OUD alone. However, subjective reports of sleep were actually better overall for those with chronic pain than the objective EEG reports. The EEG recordings captured an average of 9.11 minutes more of waking after sleep onset (P less than .001). Also, total sleep time was 10.37 minutes shorter as recorded by the EEG than by self-report (P less than .001). Overall sleep efficiency was also worse by 5.96 minutes according to the EEG, compared with self-report (P less than .001).

“Sleep is objectively poor but subjectively ‘normal’ and variable in opioid use disorder patients,” Dr. Finan said. In aggregate, however, neither diary-based subjective nor EEG-based objective sleep measures differed between those with and without chronic pain in the research cohort. This phenomenon of sleep efficiency being self-reported as higher than objective measures capture sleep has also been seen in those newly abstinent from cocaine, Dr. Finan said, adding that it’s possible individuals with substance use disorder who are new to treatment simply feel better than they have in some time along many dimensions, with sleep being one such domain.

Pain on a given day didn’t predict poor sleep on that night, except that sleep onset took slightly longer (P = .01), said Dr. Finan. He noted that “there was no substantive effect on other sleep continuity parameters.”

Looking at how negative affect mediated craving for heroin, Dr. Finan and colleagues found that negative affect–related craving was significantly greater for those with chronic pain (P less than .001). Unlike findings in patients without OUD, having disrupted sleep continuity was more associated with increased daily negative affect, rather than decreased positive affect. And this increased negative affect was associated with heroin cravings, said Dr. Finan. “In the past few years, we’ve seen quite a few studies that have found some abnormalities in the reward system in patients with chronic pain.” Whether poor sleep is a mediator of these abnormalities deserves further study.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Finan reported no outside sources of funding.

MILWAUKEE – Individuals with chronic pain frequently have disrupted sleep and also may be at risk for opioid use disorder. However, even with advanced monitoring, it’s not clear how sleep modulates pain and opioid cravings.

Sleep has an impact on positive and negative affect, but new research shows that the link between sleep and mood states that may contribute to opioid use disorder is not straightforward. At the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society, Patrick Finan, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, discussed how sleep and mood affect cravings for opioids among those in treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD).

said Dr. Finan, who told attendees that one key question he and his colleagues were seeking to answer was whether those with OUD and chronic pain had more disturbed sleep than those with OUD alone. Also, the researchers wanted to know whether the ups and downs of sleep on a day-to-day basis were reflected in pain scores among those with OUD, as would be predicted by prevailing models.

Finally, two “proximal indicators” of relapse risk, affect and heroin craving, might be affected by both sleep and pain, and Dr. Finan and collaborators sought to explore that association.

The work was part of a larger study looking at the natural history of OUD and OUD with comorbid chronic pain. To participate in this parent study, adults with OUD had to be seeking treatment or currently enrolled in methadone or buprenorphine maintenance treatment, and without current major depressive disorder. Also, patients could not have a history of significant mental illness, cognitive impairment, or a medical condition that would interfere with study participation. A total of 56 patients participated, and 20 of these individuals also had chronic pain.

Those with OUD and chronic pain qualified if they had pain (not related to opioid withdrawal) averaging above 3 on a 0-10 pain rating scale over the past week; additional criteria included pain for at least the past 3 months, with 10 or more days per month of pain.

Pain ratings were captured via a smartphone app that prompted participants to enter a pain rating at three random times during each day. Each evening, patients also completed a sleep diary giving information about bedtime, sleep onset latency, waking after sleep onset, and wake time for the preceding day.

A self-applied ambulatory electroencephalogram applied to the forehead was used for up to 7 consecutive nights to capture sleep continuity estimates; the device has been validated against polysomnography data in other work. Participants were given incentives to use the device, and this “yielded strong adherence,” with an average of 5 nights of use per participant, Dr. Finan said.

Patients were an average age of about 49 years, and were 75% male. African American participants made up just over half of the cohort, and 43% were white. Participants were roughly evenly divided in the type of maintenance therapy they were taking. Overall, 39% of participants had a positive urine toxicology screen.

For patients with chronic pain, 45% of all momentary pain reports had a pain score over zero, with a mean of 32 days of pain. Looking at the data another way, 58% of all patient-days had at least one momentary report of pain greater than zero, said Dr. Finan. On average, participants recorded a pain score of 2.27.

Brief Pain Inventory scores at baseline showed a mean severity of 5, and a pain interference score of 5.07.

Participants with OUD and chronic pain did not differ across any EEG-recorded sleep measures, compared with those with OUD alone. However, subjective reports of sleep were actually better overall for those with chronic pain than the objective EEG reports. The EEG recordings captured an average of 9.11 minutes more of waking after sleep onset (P less than .001). Also, total sleep time was 10.37 minutes shorter as recorded by the EEG than by self-report (P less than .001). Overall sleep efficiency was also worse by 5.96 minutes according to the EEG, compared with self-report (P less than .001).

“Sleep is objectively poor but subjectively ‘normal’ and variable in opioid use disorder patients,” Dr. Finan said. In aggregate, however, neither diary-based subjective nor EEG-based objective sleep measures differed between those with and without chronic pain in the research cohort. This phenomenon of sleep efficiency being self-reported as higher than objective measures capture sleep has also been seen in those newly abstinent from cocaine, Dr. Finan said, adding that it’s possible individuals with substance use disorder who are new to treatment simply feel better than they have in some time along many dimensions, with sleep being one such domain.

Pain on a given day didn’t predict poor sleep on that night, except that sleep onset took slightly longer (P = .01), said Dr. Finan. He noted that “there was no substantive effect on other sleep continuity parameters.”

Looking at how negative affect mediated craving for heroin, Dr. Finan and colleagues found that negative affect–related craving was significantly greater for those with chronic pain (P less than .001). Unlike findings in patients without OUD, having disrupted sleep continuity was more associated with increased daily negative affect, rather than decreased positive affect. And this increased negative affect was associated with heroin cravings, said Dr. Finan. “In the past few years, we’ve seen quite a few studies that have found some abnormalities in the reward system in patients with chronic pain.” Whether poor sleep is a mediator of these abnormalities deserves further study.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Finan reported no outside sources of funding.

REPORTING FROM APS 2019

Sleep apnea is linked with tau accumulation in the brain

PHILADELPHIA – according to data that will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. Tau accumulation is a biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease, and the finding suggests a possible explanation for the apparent association between sleep disruption and dementia.

“Our research results raise the possibility that sleep apnea affects tau accumulation,” said Diego Z. Carvalho, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., in a press release. “But it is also possible that higher levels of tau in other regions may predispose a person to sleep apnea, so longer studies are now needed to solve this chicken-and-egg problem.”

Previous research had suggested an association between sleep disruption and increased risk of dementia. Obstructive sleep apnea in particular has been associated with this increased risk. The pathological processes that account for this association are unknown, however.

Dr. Carvalho and colleagues decided to evaluate whether apneas during sleep, reported by the patient or an informant, were associated with high levels of tau in cognitively normal elderly individuals. The investigators identified 288 participants in the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging for their analysis. Eligible participants were aged 65 years or older, had no cognitive impairment, had undergone tau PET and amyloid PET scans, and had completed a questionnaire that solicited information about witnessed apneas during sleep (either from patients or bed partners). Dr. Carvalho’s group took the entorhinal cortex as its region of interest because it is highly susceptible to tau accumulation. The entorhinal cortex is involved in memory, navigation, and the perception of time. They chose the cerebellum crus as their reference region.

The investigators created a linear model to evaluate the association between tau in the entorhinal cortex and witnessed apneas. They controlled the data for age, sex, years of education, body mass index, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, reduced sleep, excessive daytime sleepiness, and global amyloid.

In all, 43 participants (15%) had witnessed apneas during sleep. Witnessed apneas were significantly associated with tau in the entorhinal cortex. After controlling for potential confounders, Dr. Carvalho and colleagues estimated a 0.049 elevation in the entorhinal cortex tau standardized uptake value ratio (95% confidence interval, 0.011–0.087; P = 0.012).

The study had a relatively small sample size, and its results require validation. Other important limitations include the absence of sleep studies to confirm the presence and severity of sleep apnea and a lack of information about whether participants already were receiving treatment for sleep apnea.

The National Institutes of Health supported the study.

SOURCE: Carvalho D et al. AAN 2019, Abstract P3.6-021.

PHILADELPHIA – according to data that will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. Tau accumulation is a biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease, and the finding suggests a possible explanation for the apparent association between sleep disruption and dementia.

“Our research results raise the possibility that sleep apnea affects tau accumulation,” said Diego Z. Carvalho, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., in a press release. “But it is also possible that higher levels of tau in other regions may predispose a person to sleep apnea, so longer studies are now needed to solve this chicken-and-egg problem.”

Previous research had suggested an association between sleep disruption and increased risk of dementia. Obstructive sleep apnea in particular has been associated with this increased risk. The pathological processes that account for this association are unknown, however.

Dr. Carvalho and colleagues decided to evaluate whether apneas during sleep, reported by the patient or an informant, were associated with high levels of tau in cognitively normal elderly individuals. The investigators identified 288 participants in the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging for their analysis. Eligible participants were aged 65 years or older, had no cognitive impairment, had undergone tau PET and amyloid PET scans, and had completed a questionnaire that solicited information about witnessed apneas during sleep (either from patients or bed partners). Dr. Carvalho’s group took the entorhinal cortex as its region of interest because it is highly susceptible to tau accumulation. The entorhinal cortex is involved in memory, navigation, and the perception of time. They chose the cerebellum crus as their reference region.

The investigators created a linear model to evaluate the association between tau in the entorhinal cortex and witnessed apneas. They controlled the data for age, sex, years of education, body mass index, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, reduced sleep, excessive daytime sleepiness, and global amyloid.

In all, 43 participants (15%) had witnessed apneas during sleep. Witnessed apneas were significantly associated with tau in the entorhinal cortex. After controlling for potential confounders, Dr. Carvalho and colleagues estimated a 0.049 elevation in the entorhinal cortex tau standardized uptake value ratio (95% confidence interval, 0.011–0.087; P = 0.012).

The study had a relatively small sample size, and its results require validation. Other important limitations include the absence of sleep studies to confirm the presence and severity of sleep apnea and a lack of information about whether participants already were receiving treatment for sleep apnea.

The National Institutes of Health supported the study.

SOURCE: Carvalho D et al. AAN 2019, Abstract P3.6-021.

PHILADELPHIA – according to data that will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. Tau accumulation is a biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease, and the finding suggests a possible explanation for the apparent association between sleep disruption and dementia.

“Our research results raise the possibility that sleep apnea affects tau accumulation,” said Diego Z. Carvalho, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., in a press release. “But it is also possible that higher levels of tau in other regions may predispose a person to sleep apnea, so longer studies are now needed to solve this chicken-and-egg problem.”

Previous research had suggested an association between sleep disruption and increased risk of dementia. Obstructive sleep apnea in particular has been associated with this increased risk. The pathological processes that account for this association are unknown, however.

Dr. Carvalho and colleagues decided to evaluate whether apneas during sleep, reported by the patient or an informant, were associated with high levels of tau in cognitively normal elderly individuals. The investigators identified 288 participants in the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging for their analysis. Eligible participants were aged 65 years or older, had no cognitive impairment, had undergone tau PET and amyloid PET scans, and had completed a questionnaire that solicited information about witnessed apneas during sleep (either from patients or bed partners). Dr. Carvalho’s group took the entorhinal cortex as its region of interest because it is highly susceptible to tau accumulation. The entorhinal cortex is involved in memory, navigation, and the perception of time. They chose the cerebellum crus as their reference region.

The investigators created a linear model to evaluate the association between tau in the entorhinal cortex and witnessed apneas. They controlled the data for age, sex, years of education, body mass index, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, reduced sleep, excessive daytime sleepiness, and global amyloid.

In all, 43 participants (15%) had witnessed apneas during sleep. Witnessed apneas were significantly associated with tau in the entorhinal cortex. After controlling for potential confounders, Dr. Carvalho and colleagues estimated a 0.049 elevation in the entorhinal cortex tau standardized uptake value ratio (95% confidence interval, 0.011–0.087; P = 0.012).

The study had a relatively small sample size, and its results require validation. Other important limitations include the absence of sleep studies to confirm the presence and severity of sleep apnea and a lack of information about whether participants already were receiving treatment for sleep apnea.

The National Institutes of Health supported the study.

SOURCE: Carvalho D et al. AAN 2019, Abstract P3.6-021.

FROM AAN 2019

PAP may reduce mortality in patients with obesity and severe OSA

according to the results of a cohort study published in JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery.

The association becomes evident several years after positive airway pressure (PAP) initiation, according to the researchers. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is among the top 10 modifiable cardiovascular risk factors, and is associated with increased risks of coronary artery disease, stroke, and death. PAP is the most effective treatment for OSA, but this treatment’s effect on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality is uncertain. Randomized trials have yielded inconclusive answers to this question, and evidence from observational studies has been weak.

To investigate the association between PAP prescription and mortality in patients with obesity and severe OSA, Quentin Lisan, MD, of the Paris Cardiovascular Research Center and his colleagues conducted a multicenter, population-based cohort study. The researchers examined data for 392 participants in the Sleep Heart Health Study, in which adult men and women age 40 years or older were recruited from nine population-based studies between 1995 and 1998 and followed for a mean of 11.1 years. With each participant who had been prescribed PAP, the investigators matched as many as four participants who had not been prescribed PAP, on the basis of age, sex, and apnea-hypopnea index. Of this sample, 81 patients were prescribed PAP, and 311 were not.

All participants had a clinic visit and underwent overnight polysomnography at baseline. At 2-3 years, participants had a follow-up visit or phone call, during which they were asked whether their physicians had prescribed PAP. Participants were monitored for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality.

In all, 319 of the 392 participants were men; the population’s mean age was 63 years. Patients who had received a PAP prescription had a higher body mass index and more education, compared with patients who had not received a prescription. Mean follow-up duration was 11.6 years in the PAP-prescribed group and 10.9 years in the nonprescribed group.

A total of 96 deaths occurred during follow-up: 12 in the PAP-prescribed group and 84 in the nonprescribed PAP group. The crude incidence rate of mortality was 24.7 deaths per 1,000 person-years in the nonprescribed group and 12.8 deaths per 1,000 person-years in the PAP-prescribed group. The difference in survival between the prescribed and nonprescribed groups was evident in survival curves after 6-7 years of follow-up. After adjustments for prevalent cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, body mass index, education level, smoking status, and alcohol consumption, the hazard ratio of all-cause mortality for the prescribed group was 0.38, compared with the nonprescribed group.

Dr. Lisan and his colleagues identified 27 deaths of cardiovascular origin, one of which occurred in the prescribed group. After adjusting for prevalent cardiovascular disease, the hazard ratio of cardiovascular mortality for the prescribed group was 0.06, compared with the nonprescribed group.

One reason that the reduction in mortality associated with PAP was not found in previous randomized, controlled trials could be that their mean length of follow-up was not long enough, the researchers wrote. For example, the mean length of follow-up in the SAVE trial was 3.7 years, but the survival benefit was not apparent in the present analysis until 6-7 years after treatment initiation.

These results are exploratory and require confirmation in future research, Dr. Lisan and his colleagues wrote. No information on adherence to PAP was available, and the researchers could not account for initiation and interruption of PAP therapy. Nevertheless, “prescribing PAP in patients with OSA should be pursued and encouraged, given its potential major public health implication,” they concluded.

The Sleep Heart Health Study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Lisan Q et al. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 Apr 11. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.0281.

Further confirmation of the benefits of positive airway pressure (PAP) on mortality in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) may follow the results published by Lisan et al., wrote Clete A. Kushida, MD, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. Dr. Kushida is a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University. “Of the study limitations described by Lisan et al., a major factor is the participants’ use of PAP therapy: The participants self-reported if they were prescribed PAP therapy, but their PAP adherence data (i.e., duration and frequency of PAP use) were unknown. Discrepancies exist between self-reported versus objective PAP adherence, as well as between patterns of PAP adherence over time, and the lack of adherence data would be expected to limit our understanding of the effects of PAP therapy on mortality.” A further limitation is that the study’s findings are restricted to patients with obesity and severe OSA.

“Even taking into consideration the technological improvement in size, comfort, and convenience of these devices since PAP was first tried on patients with OSA, every knowledgeable sleep specialist has had difficulty in convincing some patients of the need to treat their OSA with these devices, and/or the need to improve their use of the devices once they have been prescribed,” Dr. Kushida continued. “Although at this point experienced sleep specialists cannot say with certainty that use of PAP improves survival, the study by Lisan et al. will undoubtedly make these clinicians’ jobs a little easier by enabling them to present to their patients evidence that PAP may be associated with reduced mortality, particularly in those with severe OSA and comorbid obesity.”

Dr. Kushida receives salary support from a contract between Stanford University and Philips-Respironics for the conduct of a clinical trial. These comments are from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 April 11. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.0345).

Further confirmation of the benefits of positive airway pressure (PAP) on mortality in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) may follow the results published by Lisan et al., wrote Clete A. Kushida, MD, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. Dr. Kushida is a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University. “Of the study limitations described by Lisan et al., a major factor is the participants’ use of PAP therapy: The participants self-reported if they were prescribed PAP therapy, but their PAP adherence data (i.e., duration and frequency of PAP use) were unknown. Discrepancies exist between self-reported versus objective PAP adherence, as well as between patterns of PAP adherence over time, and the lack of adherence data would be expected to limit our understanding of the effects of PAP therapy on mortality.” A further limitation is that the study’s findings are restricted to patients with obesity and severe OSA.

“Even taking into consideration the technological improvement in size, comfort, and convenience of these devices since PAP was first tried on patients with OSA, every knowledgeable sleep specialist has had difficulty in convincing some patients of the need to treat their OSA with these devices, and/or the need to improve their use of the devices once they have been prescribed,” Dr. Kushida continued. “Although at this point experienced sleep specialists cannot say with certainty that use of PAP improves survival, the study by Lisan et al. will undoubtedly make these clinicians’ jobs a little easier by enabling them to present to their patients evidence that PAP may be associated with reduced mortality, particularly in those with severe OSA and comorbid obesity.”

Dr. Kushida receives salary support from a contract between Stanford University and Philips-Respironics for the conduct of a clinical trial. These comments are from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 April 11. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.0345).

Further confirmation of the benefits of positive airway pressure (PAP) on mortality in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) may follow the results published by Lisan et al., wrote Clete A. Kushida, MD, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. Dr. Kushida is a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University. “Of the study limitations described by Lisan et al., a major factor is the participants’ use of PAP therapy: The participants self-reported if they were prescribed PAP therapy, but their PAP adherence data (i.e., duration and frequency of PAP use) were unknown. Discrepancies exist between self-reported versus objective PAP adherence, as well as between patterns of PAP adherence over time, and the lack of adherence data would be expected to limit our understanding of the effects of PAP therapy on mortality.” A further limitation is that the study’s findings are restricted to patients with obesity and severe OSA.

“Even taking into consideration the technological improvement in size, comfort, and convenience of these devices since PAP was first tried on patients with OSA, every knowledgeable sleep specialist has had difficulty in convincing some patients of the need to treat their OSA with these devices, and/or the need to improve their use of the devices once they have been prescribed,” Dr. Kushida continued. “Although at this point experienced sleep specialists cannot say with certainty that use of PAP improves survival, the study by Lisan et al. will undoubtedly make these clinicians’ jobs a little easier by enabling them to present to their patients evidence that PAP may be associated with reduced mortality, particularly in those with severe OSA and comorbid obesity.”

Dr. Kushida receives salary support from a contract between Stanford University and Philips-Respironics for the conduct of a clinical trial. These comments are from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 April 11. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.0345).

according to the results of a cohort study published in JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery.

The association becomes evident several years after positive airway pressure (PAP) initiation, according to the researchers. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is among the top 10 modifiable cardiovascular risk factors, and is associated with increased risks of coronary artery disease, stroke, and death. PAP is the most effective treatment for OSA, but this treatment’s effect on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality is uncertain. Randomized trials have yielded inconclusive answers to this question, and evidence from observational studies has been weak.

To investigate the association between PAP prescription and mortality in patients with obesity and severe OSA, Quentin Lisan, MD, of the Paris Cardiovascular Research Center and his colleagues conducted a multicenter, population-based cohort study. The researchers examined data for 392 participants in the Sleep Heart Health Study, in which adult men and women age 40 years or older were recruited from nine population-based studies between 1995 and 1998 and followed for a mean of 11.1 years. With each participant who had been prescribed PAP, the investigators matched as many as four participants who had not been prescribed PAP, on the basis of age, sex, and apnea-hypopnea index. Of this sample, 81 patients were prescribed PAP, and 311 were not.

All participants had a clinic visit and underwent overnight polysomnography at baseline. At 2-3 years, participants had a follow-up visit or phone call, during which they were asked whether their physicians had prescribed PAP. Participants were monitored for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality.

In all, 319 of the 392 participants were men; the population’s mean age was 63 years. Patients who had received a PAP prescription had a higher body mass index and more education, compared with patients who had not received a prescription. Mean follow-up duration was 11.6 years in the PAP-prescribed group and 10.9 years in the nonprescribed group.

A total of 96 deaths occurred during follow-up: 12 in the PAP-prescribed group and 84 in the nonprescribed PAP group. The crude incidence rate of mortality was 24.7 deaths per 1,000 person-years in the nonprescribed group and 12.8 deaths per 1,000 person-years in the PAP-prescribed group. The difference in survival between the prescribed and nonprescribed groups was evident in survival curves after 6-7 years of follow-up. After adjustments for prevalent cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, body mass index, education level, smoking status, and alcohol consumption, the hazard ratio of all-cause mortality for the prescribed group was 0.38, compared with the nonprescribed group.

Dr. Lisan and his colleagues identified 27 deaths of cardiovascular origin, one of which occurred in the prescribed group. After adjusting for prevalent cardiovascular disease, the hazard ratio of cardiovascular mortality for the prescribed group was 0.06, compared with the nonprescribed group.

One reason that the reduction in mortality associated with PAP was not found in previous randomized, controlled trials could be that their mean length of follow-up was not long enough, the researchers wrote. For example, the mean length of follow-up in the SAVE trial was 3.7 years, but the survival benefit was not apparent in the present analysis until 6-7 years after treatment initiation.

These results are exploratory and require confirmation in future research, Dr. Lisan and his colleagues wrote. No information on adherence to PAP was available, and the researchers could not account for initiation and interruption of PAP therapy. Nevertheless, “prescribing PAP in patients with OSA should be pursued and encouraged, given its potential major public health implication,” they concluded.

The Sleep Heart Health Study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Lisan Q et al. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 Apr 11. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.0281.

according to the results of a cohort study published in JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery.

The association becomes evident several years after positive airway pressure (PAP) initiation, according to the researchers. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is among the top 10 modifiable cardiovascular risk factors, and is associated with increased risks of coronary artery disease, stroke, and death. PAP is the most effective treatment for OSA, but this treatment’s effect on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality is uncertain. Randomized trials have yielded inconclusive answers to this question, and evidence from observational studies has been weak.

To investigate the association between PAP prescription and mortality in patients with obesity and severe OSA, Quentin Lisan, MD, of the Paris Cardiovascular Research Center and his colleagues conducted a multicenter, population-based cohort study. The researchers examined data for 392 participants in the Sleep Heart Health Study, in which adult men and women age 40 years or older were recruited from nine population-based studies between 1995 and 1998 and followed for a mean of 11.1 years. With each participant who had been prescribed PAP, the investigators matched as many as four participants who had not been prescribed PAP, on the basis of age, sex, and apnea-hypopnea index. Of this sample, 81 patients were prescribed PAP, and 311 were not.

All participants had a clinic visit and underwent overnight polysomnography at baseline. At 2-3 years, participants had a follow-up visit or phone call, during which they were asked whether their physicians had prescribed PAP. Participants were monitored for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality.

In all, 319 of the 392 participants were men; the population’s mean age was 63 years. Patients who had received a PAP prescription had a higher body mass index and more education, compared with patients who had not received a prescription. Mean follow-up duration was 11.6 years in the PAP-prescribed group and 10.9 years in the nonprescribed group.

A total of 96 deaths occurred during follow-up: 12 in the PAP-prescribed group and 84 in the nonprescribed PAP group. The crude incidence rate of mortality was 24.7 deaths per 1,000 person-years in the nonprescribed group and 12.8 deaths per 1,000 person-years in the PAP-prescribed group. The difference in survival between the prescribed and nonprescribed groups was evident in survival curves after 6-7 years of follow-up. After adjustments for prevalent cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, body mass index, education level, smoking status, and alcohol consumption, the hazard ratio of all-cause mortality for the prescribed group was 0.38, compared with the nonprescribed group.

Dr. Lisan and his colleagues identified 27 deaths of cardiovascular origin, one of which occurred in the prescribed group. After adjusting for prevalent cardiovascular disease, the hazard ratio of cardiovascular mortality for the prescribed group was 0.06, compared with the nonprescribed group.

One reason that the reduction in mortality associated with PAP was not found in previous randomized, controlled trials could be that their mean length of follow-up was not long enough, the researchers wrote. For example, the mean length of follow-up in the SAVE trial was 3.7 years, but the survival benefit was not apparent in the present analysis until 6-7 years after treatment initiation.

These results are exploratory and require confirmation in future research, Dr. Lisan and his colleagues wrote. No information on adherence to PAP was available, and the researchers could not account for initiation and interruption of PAP therapy. Nevertheless, “prescribing PAP in patients with OSA should be pursued and encouraged, given its potential major public health implication,” they concluded.

The Sleep Heart Health Study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Lisan Q et al. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 Apr 11. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.0281.

FROM JAMA OTOLARYNGOLOGY–HEAD & NECK SURGERY

New sleep apnea guidelines offer evidence-based recommendations

New guidelines on treating obstructive sleep apnea with positive airway pressure include recommendations for using positive airway pressure (PAP) versus no therapy, using either continuous PAP (CPAP) or automatic PAP (APAP) for ongoing treatment, and providing educational interventions to patients starting PAP. The complete guidelines, issued by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, were published in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine.

The guidelines were driven by improvements in PAP adherence and device technology, wrote lead author Susheel P. Patil, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his colleagues.

The guidelines begin with a pair of Good Practice Statements to ensure effective and appropriate management of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in adults. First, “Treatment of OSA with PAP therapy should be based on a diagnosis of OSA established using objective sleep apnea testing.” Second, “Adequate follow-up, including troubleshooting and monitoring of objective efficacy and usage data to ensure adequate treatment and adherence, should occur following PAP therapy initiation and during treatment of OSA.”

The nine recommendations, approved by the AASM board of directors, include four strong recommendations that clinicians should follow under most circumstances, and five conditional recommendations that are suggested but lack strong clinical support for their appropriateness for all patients in all circumstances.

The first of the strong recommendations, for using PAP versus no therapy to treat adults with OSA and excessive sleepiness, was based on a high level of evidence from a meta-analysis of 38 randomized, controlled trials and the conclusion that the benefits of PAP outweighed the harms.

The second strong recommendation for using either CPAP or APAP for ongoing treatment was based on data from 26 trials that showed no clinically significant difference between the two. The third strong recommendation that PAP therapy be initiated using either APAP at home or in-laboratory PAP titration in adults with OSA and no significant comorbidities was supported by a meta-analysis of 10 trials that showed no clinically significant difference between at-home and laboratory initiation, and that each option has its benefits. The authors noted that “the majority of well-informed adult patients with OSA and without significant comorbidities would prefer initiation of PAP using the most rapid, convenient, and cost-effective strategy.” This comment supports the fourth strong recommendation for providing educational interventions to patients starting PAP.

The conditional recommendations include using PAP versus no therapy for adults with OSA and impaired quality of life related to poor sleep, such as insomnia, snoring, morning headaches, and daytime fatigue. Other conditional recommendations include using PAP versus no therapy for adults with OSA and comorbid hypertension, choosing CPAP or APAP over bilateral PAP for routine treatment of OSA in adults, providing behavioral interventions or troubleshooting during patients’ initial use of PAP, and using telemonitoring-guided interventions to monitor patients during their initial use of PAP.

“The ultimate judgment regarding any specific care must be made by the treating clinician and the patient, taking into consideration the individual circumstances of the patient, available treatment options, and resources,” the authors noted.

“When implementing the recommendations, providers should consider additional strategies that will maximize the individual patient’s comfort and adherence such as nasal/intranasal over oronasal mask interface and heated humidification,” they added.

The guidelines were developed by a task force commissioned by the AASM that included board-certified sleep specialists and experts in PAP use, and will be reviewed and updated as new information surfaces, the authors wrote.

Dr. Patil reported no financial conflicts; several coauthors reported conflicts that were managed by their not voting on guidelines related to those conflicts.

SOURCE: Patil SP et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018 Feb 15;15(2):335-43.

Octavian C. Ioachimescu, MD, FCCP, comments: The last guidelines and practice parameters for the use of positive airway pressure (PAP) as therapy for adult patients with obstructive sleep apnea, were published in 2006 and 2008, respectively. Since then, new technological advances, an ever-growing body of literature, and shifting practice patterns led to an acute need for a thorough reassessment, a comprehensive update of the previous recommendations, and the potential of issuing new ones for emerging areas. As such, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine commissioned a task force of content experts to review the existing evidence, to issue new guidelines and to publish an associated systematic review and a meta-analysis of the literature on this topic.

A welcome recommendation is the endorsement by the task force of the use of telemedicine capabilities in monitoring patients’ adherence to PAP therapy. Another interesting aspect is that, while our literature is represented by a mix of both randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials, occasionally there seems to be an interesting dichotomy in the results: Randomized trials tend to point in one direction, while nonrandomized studies pooled in the meta-analysis seem to point to the contrary or to give the impression of more definitive effects. While this is clearly not the place to make an extensive analysis of the strengths and the potential pitfalls of randomized versus nonrandomized studies, this clearly raises some issues. One is that our randomized studies are typically small, underpowered, and hence with nonconvincing risk or hazard reduction assessments. Second, the dichotomy in the results may be driven by publication bias, expense, and difficulty in performing adequately-powered, long-term trials that essentially may be studying small effects.

Guidelines are not intended to be used in an Occam’s razor approach, but in a fashion that would allow individualization of therapy while critically appraising the existing evidence for various interventions in specific conditions and maintaining a very stringent and critical view on generalizability, expected results, and adequate management of reasonable expectations. In addition, the areas that are unclear, with conflicting evidence or in which the guidelines allow “too much” latitude to the treating clinician, may be seen as either an invitation to remain “creative,” or one for abstaining from action in the name of equipoise. I would advise that both extremes are to be avoided.

Octavian C. Ioachimescu, MD, FCCP, comments: The last guidelines and practice parameters for the use of positive airway pressure (PAP) as therapy for adult patients with obstructive sleep apnea, were published in 2006 and 2008, respectively. Since then, new technological advances, an ever-growing body of literature, and shifting practice patterns led to an acute need for a thorough reassessment, a comprehensive update of the previous recommendations, and the potential of issuing new ones for emerging areas. As such, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine commissioned a task force of content experts to review the existing evidence, to issue new guidelines and to publish an associated systematic review and a meta-analysis of the literature on this topic.

A welcome recommendation is the endorsement by the task force of the use of telemedicine capabilities in monitoring patients’ adherence to PAP therapy. Another interesting aspect is that, while our literature is represented by a mix of both randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials, occasionally there seems to be an interesting dichotomy in the results: Randomized trials tend to point in one direction, while nonrandomized studies pooled in the meta-analysis seem to point to the contrary or to give the impression of more definitive effects. While this is clearly not the place to make an extensive analysis of the strengths and the potential pitfalls of randomized versus nonrandomized studies, this clearly raises some issues. One is that our randomized studies are typically small, underpowered, and hence with nonconvincing risk or hazard reduction assessments. Second, the dichotomy in the results may be driven by publication bias, expense, and difficulty in performing adequately-powered, long-term trials that essentially may be studying small effects.

Guidelines are not intended to be used in an Occam’s razor approach, but in a fashion that would allow individualization of therapy while critically appraising the existing evidence for various interventions in specific conditions and maintaining a very stringent and critical view on generalizability, expected results, and adequate management of reasonable expectations. In addition, the areas that are unclear, with conflicting evidence or in which the guidelines allow “too much” latitude to the treating clinician, may be seen as either an invitation to remain “creative,” or one for abstaining from action in the name of equipoise. I would advise that both extremes are to be avoided.

Octavian C. Ioachimescu, MD, FCCP, comments: The last guidelines and practice parameters for the use of positive airway pressure (PAP) as therapy for adult patients with obstructive sleep apnea, were published in 2006 and 2008, respectively. Since then, new technological advances, an ever-growing body of literature, and shifting practice patterns led to an acute need for a thorough reassessment, a comprehensive update of the previous recommendations, and the potential of issuing new ones for emerging areas. As such, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine commissioned a task force of content experts to review the existing evidence, to issue new guidelines and to publish an associated systematic review and a meta-analysis of the literature on this topic.

A welcome recommendation is the endorsement by the task force of the use of telemedicine capabilities in monitoring patients’ adherence to PAP therapy. Another interesting aspect is that, while our literature is represented by a mix of both randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials, occasionally there seems to be an interesting dichotomy in the results: Randomized trials tend to point in one direction, while nonrandomized studies pooled in the meta-analysis seem to point to the contrary or to give the impression of more definitive effects. While this is clearly not the place to make an extensive analysis of the strengths and the potential pitfalls of randomized versus nonrandomized studies, this clearly raises some issues. One is that our randomized studies are typically small, underpowered, and hence with nonconvincing risk or hazard reduction assessments. Second, the dichotomy in the results may be driven by publication bias, expense, and difficulty in performing adequately-powered, long-term trials that essentially may be studying small effects.

Guidelines are not intended to be used in an Occam’s razor approach, but in a fashion that would allow individualization of therapy while critically appraising the existing evidence for various interventions in specific conditions and maintaining a very stringent and critical view on generalizability, expected results, and adequate management of reasonable expectations. In addition, the areas that are unclear, with conflicting evidence or in which the guidelines allow “too much” latitude to the treating clinician, may be seen as either an invitation to remain “creative,” or one for abstaining from action in the name of equipoise. I would advise that both extremes are to be avoided.

New guidelines on treating obstructive sleep apnea with positive airway pressure include recommendations for using positive airway pressure (PAP) versus no therapy, using either continuous PAP (CPAP) or automatic PAP (APAP) for ongoing treatment, and providing educational interventions to patients starting PAP. The complete guidelines, issued by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, were published in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine.

The guidelines were driven by improvements in PAP adherence and device technology, wrote lead author Susheel P. Patil, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his colleagues.

The guidelines begin with a pair of Good Practice Statements to ensure effective and appropriate management of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in adults. First, “Treatment of OSA with PAP therapy should be based on a diagnosis of OSA established using objective sleep apnea testing.” Second, “Adequate follow-up, including troubleshooting and monitoring of objective efficacy and usage data to ensure adequate treatment and adherence, should occur following PAP therapy initiation and during treatment of OSA.”

The nine recommendations, approved by the AASM board of directors, include four strong recommendations that clinicians should follow under most circumstances, and five conditional recommendations that are suggested but lack strong clinical support for their appropriateness for all patients in all circumstances.

The first of the strong recommendations, for using PAP versus no therapy to treat adults with OSA and excessive sleepiness, was based on a high level of evidence from a meta-analysis of 38 randomized, controlled trials and the conclusion that the benefits of PAP outweighed the harms.

The second strong recommendation for using either CPAP or APAP for ongoing treatment was based on data from 26 trials that showed no clinically significant difference between the two. The third strong recommendation that PAP therapy be initiated using either APAP at home or in-laboratory PAP titration in adults with OSA and no significant comorbidities was supported by a meta-analysis of 10 trials that showed no clinically significant difference between at-home and laboratory initiation, and that each option has its benefits. The authors noted that “the majority of well-informed adult patients with OSA and without significant comorbidities would prefer initiation of PAP using the most rapid, convenient, and cost-effective strategy.” This comment supports the fourth strong recommendation for providing educational interventions to patients starting PAP.

The conditional recommendations include using PAP versus no therapy for adults with OSA and impaired quality of life related to poor sleep, such as insomnia, snoring, morning headaches, and daytime fatigue. Other conditional recommendations include using PAP versus no therapy for adults with OSA and comorbid hypertension, choosing CPAP or APAP over bilateral PAP for routine treatment of OSA in adults, providing behavioral interventions or troubleshooting during patients’ initial use of PAP, and using telemonitoring-guided interventions to monitor patients during their initial use of PAP.

“The ultimate judgment regarding any specific care must be made by the treating clinician and the patient, taking into consideration the individual circumstances of the patient, available treatment options, and resources,” the authors noted.

“When implementing the recommendations, providers should consider additional strategies that will maximize the individual patient’s comfort and adherence such as nasal/intranasal over oronasal mask interface and heated humidification,” they added.

The guidelines were developed by a task force commissioned by the AASM that included board-certified sleep specialists and experts in PAP use, and will be reviewed and updated as new information surfaces, the authors wrote.

Dr. Patil reported no financial conflicts; several coauthors reported conflicts that were managed by their not voting on guidelines related to those conflicts.

SOURCE: Patil SP et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018 Feb 15;15(2):335-43.

New guidelines on treating obstructive sleep apnea with positive airway pressure include recommendations for using positive airway pressure (PAP) versus no therapy, using either continuous PAP (CPAP) or automatic PAP (APAP) for ongoing treatment, and providing educational interventions to patients starting PAP. The complete guidelines, issued by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, were published in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine.

The guidelines were driven by improvements in PAP adherence and device technology, wrote lead author Susheel P. Patil, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his colleagues.

The guidelines begin with a pair of Good Practice Statements to ensure effective and appropriate management of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in adults. First, “Treatment of OSA with PAP therapy should be based on a diagnosis of OSA established using objective sleep apnea testing.” Second, “Adequate follow-up, including troubleshooting and monitoring of objective efficacy and usage data to ensure adequate treatment and adherence, should occur following PAP therapy initiation and during treatment of OSA.”

The nine recommendations, approved by the AASM board of directors, include four strong recommendations that clinicians should follow under most circumstances, and five conditional recommendations that are suggested but lack strong clinical support for their appropriateness for all patients in all circumstances.

The first of the strong recommendations, for using PAP versus no therapy to treat adults with OSA and excessive sleepiness, was based on a high level of evidence from a meta-analysis of 38 randomized, controlled trials and the conclusion that the benefits of PAP outweighed the harms.

The second strong recommendation for using either CPAP or APAP for ongoing treatment was based on data from 26 trials that showed no clinically significant difference between the two. The third strong recommendation that PAP therapy be initiated using either APAP at home or in-laboratory PAP titration in adults with OSA and no significant comorbidities was supported by a meta-analysis of 10 trials that showed no clinically significant difference between at-home and laboratory initiation, and that each option has its benefits. The authors noted that “the majority of well-informed adult patients with OSA and without significant comorbidities would prefer initiation of PAP using the most rapid, convenient, and cost-effective strategy.” This comment supports the fourth strong recommendation for providing educational interventions to patients starting PAP.

The conditional recommendations include using PAP versus no therapy for adults with OSA and impaired quality of life related to poor sleep, such as insomnia, snoring, morning headaches, and daytime fatigue. Other conditional recommendations include using PAP versus no therapy for adults with OSA and comorbid hypertension, choosing CPAP or APAP over bilateral PAP for routine treatment of OSA in adults, providing behavioral interventions or troubleshooting during patients’ initial use of PAP, and using telemonitoring-guided interventions to monitor patients during their initial use of PAP.

“The ultimate judgment regarding any specific care must be made by the treating clinician and the patient, taking into consideration the individual circumstances of the patient, available treatment options, and resources,” the authors noted.

“When implementing the recommendations, providers should consider additional strategies that will maximize the individual patient’s comfort and adherence such as nasal/intranasal over oronasal mask interface and heated humidification,” they added.

The guidelines were developed by a task force commissioned by the AASM that included board-certified sleep specialists and experts in PAP use, and will be reviewed and updated as new information surfaces, the authors wrote.

Dr. Patil reported no financial conflicts; several coauthors reported conflicts that were managed by their not voting on guidelines related to those conflicts.

SOURCE: Patil SP et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018 Feb 15;15(2):335-43.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL SLEEP MEDICINE

Depression, antidepressant use may be common among patients with OSA

About a quarter of patients with obstructive sleep apnea also had clinical depression and used antidepressants, recent research has shown.

Although patients in the study associated their sleep disorder with poorer quality of life as well as symptoms of anxiety and depression, it is unclear whether treating their obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) would alleviate these symptoms, said Melinda L. Jackson, PhD, from Monash University in Clayton, Victoria, Australia, and her colleagues.

“OSA is a modifiable factor that, if treated, may reduce the economic, health care, and personal burden of depression,” Dr. Jackson and her colleagues wrote in their study, recently published in the journal Sleep Medicine. “Findings from the treatment phase of this study will help us determine whether clinical depression is alleviated with CPAP use, taking into account antidepressant use; whether there are subgroups of patients who respond better to treatment; and what are the characteristics of patients who respond compared to those who remain depressed.”

The researchers used baseline data from 109 patients in the CPAP for OSA and Depression trial who were diagnosed with OSA. Participants (mean age, 52.6 years; 43.1% female) consecutively presented to a sleep laboratory where they answered interview questions to assess clinical depression and sleep habits. Data were collected using the structured clinical interview for depression (SCID-IV), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ), Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and Assessment of Quality of Life questionnaire. In addition, the researchers performed a meta-analysis of seven studies, including the current study, to determine the prevalence of clinical depression among patients with untreated OSA.

Overall, SCID-IV scores identified clinical depression in 25 participants (22.7%), and these participants said they had greater sleep disturbance and reported higher depressive, anxiety and stress as well as lower quality of life as a result of their clinical depression. Researchers found these participants also had significantly worse quality of sleep (P less than .05) and daytime dysfunction (P less than .05) as identified by PSQI scores, while FOSQ results showed participants with clinical depression had significantly lower activity levels, social outcomes, and general productivity, compared with patients without clinical depression (P less than .05). In a meta-analysis, Dr. Jackson and her colleagues found a pooled prevalence of 23% for clinical depression among participants with OSA.

Participants using antidepressants were examined separately from participants who had clinical depression. The researchers found 27 participants (24.8%) using antidepressants who also had reported higher symptoms of anxiety, depression and stress, lower quality of life, and poorer sleep outcomes. Participants using antidepressants also were more likely to have bipolar disorder or a condition such as hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, high cholesterol, or type 2 diabetes, and 75% of these participants reported having some type of comorbid condition.

Dr. Jackson and her colleagues noted they were uncertain whether depression or OSA occurred first, or whether depression exacerbated symptoms of OSA through other factors such as weight gain, sleep disruption, inactivity, or alcohol use. Depression and OSA may also present independently of one another, they added.

“Development of scales to better capture information about when symptoms commenced and the length of time an individual has experienced OSA will provide a clearer understanding of the consequences of OSA on psychological and medical conditions,” the researchers said.

This study was funded by the Austin Medical Research Fund, and one authors reported support from an National Health and Medical Research Council Early Career Fellowship. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Jackson ML et al. Sleep Med. 2019 Mar 27. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.03.011.

About a quarter of patients with obstructive sleep apnea also had clinical depression and used antidepressants, recent research has shown.

Although patients in the study associated their sleep disorder with poorer quality of life as well as symptoms of anxiety and depression, it is unclear whether treating their obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) would alleviate these symptoms, said Melinda L. Jackson, PhD, from Monash University in Clayton, Victoria, Australia, and her colleagues.

“OSA is a modifiable factor that, if treated, may reduce the economic, health care, and personal burden of depression,” Dr. Jackson and her colleagues wrote in their study, recently published in the journal Sleep Medicine. “Findings from the treatment phase of this study will help us determine whether clinical depression is alleviated with CPAP use, taking into account antidepressant use; whether there are subgroups of patients who respond better to treatment; and what are the characteristics of patients who respond compared to those who remain depressed.”

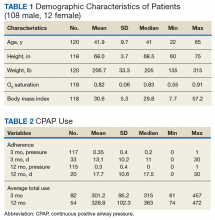

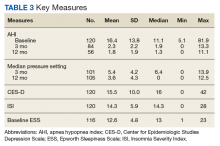

The researchers used baseline data from 109 patients in the CPAP for OSA and Depression trial who were diagnosed with OSA. Participants (mean age, 52.6 years; 43.1% female) consecutively presented to a sleep laboratory where they answered interview questions to assess clinical depression and sleep habits. Data were collected using the structured clinical interview for depression (SCID-IV), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ), Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and Assessment of Quality of Life questionnaire. In addition, the researchers performed a meta-analysis of seven studies, including the current study, to determine the prevalence of clinical depression among patients with untreated OSA.

Overall, SCID-IV scores identified clinical depression in 25 participants (22.7%), and these participants said they had greater sleep disturbance and reported higher depressive, anxiety and stress as well as lower quality of life as a result of their clinical depression. Researchers found these participants also had significantly worse quality of sleep (P less than .05) and daytime dysfunction (P less than .05) as identified by PSQI scores, while FOSQ results showed participants with clinical depression had significantly lower activity levels, social outcomes, and general productivity, compared with patients without clinical depression (P less than .05). In a meta-analysis, Dr. Jackson and her colleagues found a pooled prevalence of 23% for clinical depression among participants with OSA.

Participants using antidepressants were examined separately from participants who had clinical depression. The researchers found 27 participants (24.8%) using antidepressants who also had reported higher symptoms of anxiety, depression and stress, lower quality of life, and poorer sleep outcomes. Participants using antidepressants also were more likely to have bipolar disorder or a condition such as hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, high cholesterol, or type 2 diabetes, and 75% of these participants reported having some type of comorbid condition.

Dr. Jackson and her colleagues noted they were uncertain whether depression or OSA occurred first, or whether depression exacerbated symptoms of OSA through other factors such as weight gain, sleep disruption, inactivity, or alcohol use. Depression and OSA may also present independently of one another, they added.

“Development of scales to better capture information about when symptoms commenced and the length of time an individual has experienced OSA will provide a clearer understanding of the consequences of OSA on psychological and medical conditions,” the researchers said.

This study was funded by the Austin Medical Research Fund, and one authors reported support from an National Health and Medical Research Council Early Career Fellowship. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Jackson ML et al. Sleep Med. 2019 Mar 27. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.03.011.

About a quarter of patients with obstructive sleep apnea also had clinical depression and used antidepressants, recent research has shown.

Although patients in the study associated their sleep disorder with poorer quality of life as well as symptoms of anxiety and depression, it is unclear whether treating their obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) would alleviate these symptoms, said Melinda L. Jackson, PhD, from Monash University in Clayton, Victoria, Australia, and her colleagues.

“OSA is a modifiable factor that, if treated, may reduce the economic, health care, and personal burden of depression,” Dr. Jackson and her colleagues wrote in their study, recently published in the journal Sleep Medicine. “Findings from the treatment phase of this study will help us determine whether clinical depression is alleviated with CPAP use, taking into account antidepressant use; whether there are subgroups of patients who respond better to treatment; and what are the characteristics of patients who respond compared to those who remain depressed.”

The researchers used baseline data from 109 patients in the CPAP for OSA and Depression trial who were diagnosed with OSA. Participants (mean age, 52.6 years; 43.1% female) consecutively presented to a sleep laboratory where they answered interview questions to assess clinical depression and sleep habits. Data were collected using the structured clinical interview for depression (SCID-IV), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ), Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and Assessment of Quality of Life questionnaire. In addition, the researchers performed a meta-analysis of seven studies, including the current study, to determine the prevalence of clinical depression among patients with untreated OSA.

Overall, SCID-IV scores identified clinical depression in 25 participants (22.7%), and these participants said they had greater sleep disturbance and reported higher depressive, anxiety and stress as well as lower quality of life as a result of their clinical depression. Researchers found these participants also had significantly worse quality of sleep (P less than .05) and daytime dysfunction (P less than .05) as identified by PSQI scores, while FOSQ results showed participants with clinical depression had significantly lower activity levels, social outcomes, and general productivity, compared with patients without clinical depression (P less than .05). In a meta-analysis, Dr. Jackson and her colleagues found a pooled prevalence of 23% for clinical depression among participants with OSA.

Participants using antidepressants were examined separately from participants who had clinical depression. The researchers found 27 participants (24.8%) using antidepressants who also had reported higher symptoms of anxiety, depression and stress, lower quality of life, and poorer sleep outcomes. Participants using antidepressants also were more likely to have bipolar disorder or a condition such as hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, high cholesterol, or type 2 diabetes, and 75% of these participants reported having some type of comorbid condition.

Dr. Jackson and her colleagues noted they were uncertain whether depression or OSA occurred first, or whether depression exacerbated symptoms of OSA through other factors such as weight gain, sleep disruption, inactivity, or alcohol use. Depression and OSA may also present independently of one another, they added.

“Development of scales to better capture information about when symptoms commenced and the length of time an individual has experienced OSA will provide a clearer understanding of the consequences of OSA on psychological and medical conditions,” the researchers said.

This study was funded by the Austin Medical Research Fund, and one authors reported support from an National Health and Medical Research Council Early Career Fellowship. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Jackson ML et al. Sleep Med. 2019 Mar 27. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.03.011.

FROM SLEEP MEDICINE

Long-term CPAP use not linked to weight gain

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) over several years did not lead to clinically concerning levels of weight gain among patients with obstructive sleep apnea and comorbid cardiovascular disease enrolled in a large international trial, findings from a large, multicenter trial show.

No differences in weight, body mass index (BMI), or other body measurements were found when comparing CPAP and control groups in a post hoc analysis of the Sleep Apnea Cardiovascular Endpoints (SAVE) trial, which included 2,483 adults enrolled at 89 centers in seven countries.

In a subanalysis, there was a small but statistically significant weight gain of less than 400 g in men who used CPAP at least 4 hours per night as compared to matched controls. However, there were no differences in BMI or neck and waist circumferences for these men, and no such changes were observed in women, according to the investigators, led by Qiong Ou, MD, of Guangdong (China) General Hospital and R. Doug McEvoy, MD, of the Adelaide Institute for Sleep Health at Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia.

“Such a small change in weight, even with good adherence over several years, is highly unlikely to have any serious clinical ramifications,” wrote the investigators of the study published in Chest.

“Taken together, these results indicate that long-term CPAP treatment is unlikely to exacerbate the problems of overweight and obesity that are common among patients with OSA,” they added.

In a previous meta-analysis of randomized trials, investigators concluded that CPAP promoted significant increases in BMI and weight. However, the median study duration was only 3 months.

In contrast, the analysis of the SAVE trial included adults who had regular body measurements over a mean follow-up of nearly 4 years.

That long-term follow-up provided an “ideal opportunity” to assess whether CPAP treatment promotes weight gain in OSA patients over the course of several years, the authors of the SAVE trial analysis wrote.