User login

A ‘crisis’ of suicidal thoughts, attempts in transgender youth

Transgender youth are significantly more likely to consider suicide and attempt it, compared with their cisgender peers, new research shows.

In a large population-based study, investigators found the increased risk of suicidality is partly because of bullying and cyberbullying experienced by transgender teens.

The findings are “extremely concerning and should be a wake-up call,” Ian Colman, PhD, with the University of Ottawa School of Epidemiology and Public Health, said in an interview.

Young people who are exploring their sexual identities may suffer from depression and anxiety, both about the reactions of their peers and families, as well as their own sense of self.

“These youth are highly marginalized and stigmatized in many corners of our society, and these findings highlight just how distressing these experiences can be,” Dr. Colman said.

The study was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Sevenfold increased risk of attempted suicide

The risk of suicidal thoughts and actions is not well studied in transgender and nonbinary youth.

To expand the evidence base, the researchers analyzed data for 6,800 adolescents aged 15-17 years from the 2019 Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth.

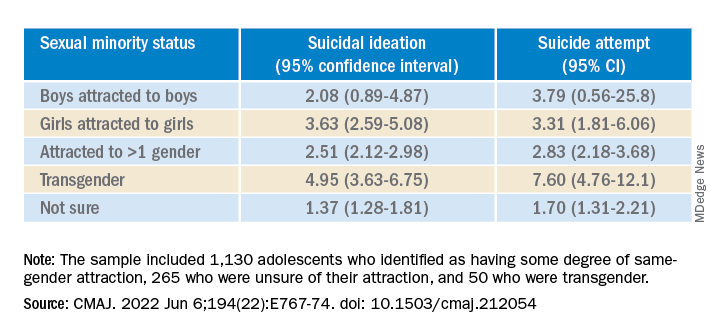

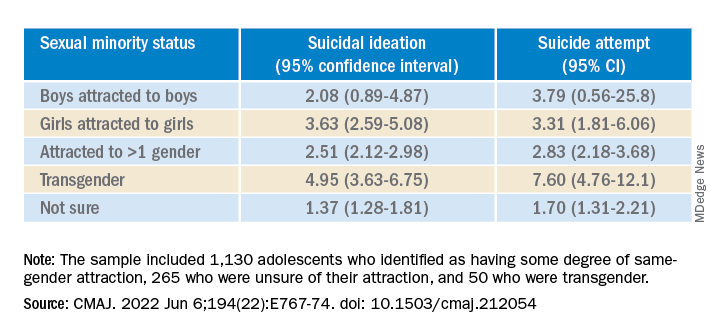

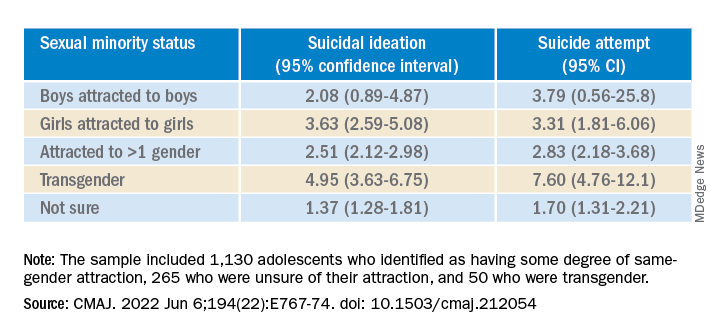

The sample included 1,130 (16.5%) adolescents who identified as having some degree of same-gender attraction, 265 (4.3%) who were unsure of their attraction (“questioning”), and 50 (0.6%) who were transgender, meaning they identified as being of a gender different from that assigned at birth.

Overall, 980 (14.0%) adolescents reported having thoughts of suicide in the prior year, and 480 (6.8%) had attempted suicide in their life.

Transgender youth were five times more likely to think about suicide and more than seven times more likely to have ever attempted suicide than cisgender, heterosexual peers.

Among cisgender adolescents, girls who were attracted to girls had 3.6 times the risk of suicidal ideation and 3.3 times the risk of having ever attempted suicide, compared with their heterosexual peers.

Teens attracted to multiple genders had more than twice the risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt. Youth who were questioning their sexual orientation had twice the risk of having attempted suicide in their lifetime.

A crisis – with reason for hope

“This is a crisis, and it shows just how much more needs to be done to support transgender young people,” co-author Fae Johnstone, MSW, executive director, Wisdom2Action, who is a trans woman herself, said in the news release.

“Suicide prevention programs specifically targeted to transgender, nonbinary, and sexual minority adolescents, as well as gender-affirming care for transgender adolescents, may help reduce the burden of suicidality among this group,” Ms. Johnstone added.

“The most important thing that parents, teachers, and health care providers can do is to be supportive of these youth,” Dr. Colman told this news organization.

“Providing a safe place where gender and sexual minorities can explore and express themselves is crucial. The first step is to listen and to be compassionate,” Dr. Colman added.

Reached for comment, Jess Ting, MD, director of surgery at the Mount Sinai Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery, New York, said the data from this study on suicidal thoughts and actions among sexual minority and transgender adolescents “mirror what we see and what we know” about suicidality in trans and nonbinary adults.

“The reasons for this are complex, and it’s hard for someone who doesn’t have a lived experience as a trans or nonbinary person to understand the reasons for suicidality,” he told this news organization.

“But we also know that there are higher rates of anxiety and depression and self-image issues and posttraumatic stress disorder, not to mention outside factors – marginalization, discrimination, violence, abuse. When you add up all these intrinsic and extrinsic factors, it’s not hard to believe that there is a high rate of suicidality,” Dr. Ting said.

“There have been studies that have shown that in children who are supported in their gender identity, the rates of depression and anxiety decreased to almost the same levels as non-trans and nonbinary children, so I think that gives cause for hope,” Dr. Ting added.

The study was funded in part by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme and by a Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship Doctoral Award. Ms. Johnstone reports consulting fees from Spectrum Waterloo and volunteer participation with the Youth Suicide Prevention Leadership Committee of Ontario. No other competing interests were declared. Dr. Ting has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transgender youth are significantly more likely to consider suicide and attempt it, compared with their cisgender peers, new research shows.

In a large population-based study, investigators found the increased risk of suicidality is partly because of bullying and cyberbullying experienced by transgender teens.

The findings are “extremely concerning and should be a wake-up call,” Ian Colman, PhD, with the University of Ottawa School of Epidemiology and Public Health, said in an interview.

Young people who are exploring their sexual identities may suffer from depression and anxiety, both about the reactions of their peers and families, as well as their own sense of self.

“These youth are highly marginalized and stigmatized in many corners of our society, and these findings highlight just how distressing these experiences can be,” Dr. Colman said.

The study was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Sevenfold increased risk of attempted suicide

The risk of suicidal thoughts and actions is not well studied in transgender and nonbinary youth.

To expand the evidence base, the researchers analyzed data for 6,800 adolescents aged 15-17 years from the 2019 Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth.

The sample included 1,130 (16.5%) adolescents who identified as having some degree of same-gender attraction, 265 (4.3%) who were unsure of their attraction (“questioning”), and 50 (0.6%) who were transgender, meaning they identified as being of a gender different from that assigned at birth.

Overall, 980 (14.0%) adolescents reported having thoughts of suicide in the prior year, and 480 (6.8%) had attempted suicide in their life.

Transgender youth were five times more likely to think about suicide and more than seven times more likely to have ever attempted suicide than cisgender, heterosexual peers.

Among cisgender adolescents, girls who were attracted to girls had 3.6 times the risk of suicidal ideation and 3.3 times the risk of having ever attempted suicide, compared with their heterosexual peers.

Teens attracted to multiple genders had more than twice the risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt. Youth who were questioning their sexual orientation had twice the risk of having attempted suicide in their lifetime.

A crisis – with reason for hope

“This is a crisis, and it shows just how much more needs to be done to support transgender young people,” co-author Fae Johnstone, MSW, executive director, Wisdom2Action, who is a trans woman herself, said in the news release.

“Suicide prevention programs specifically targeted to transgender, nonbinary, and sexual minority adolescents, as well as gender-affirming care for transgender adolescents, may help reduce the burden of suicidality among this group,” Ms. Johnstone added.

“The most important thing that parents, teachers, and health care providers can do is to be supportive of these youth,” Dr. Colman told this news organization.

“Providing a safe place where gender and sexual minorities can explore and express themselves is crucial. The first step is to listen and to be compassionate,” Dr. Colman added.

Reached for comment, Jess Ting, MD, director of surgery at the Mount Sinai Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery, New York, said the data from this study on suicidal thoughts and actions among sexual minority and transgender adolescents “mirror what we see and what we know” about suicidality in trans and nonbinary adults.

“The reasons for this are complex, and it’s hard for someone who doesn’t have a lived experience as a trans or nonbinary person to understand the reasons for suicidality,” he told this news organization.

“But we also know that there are higher rates of anxiety and depression and self-image issues and posttraumatic stress disorder, not to mention outside factors – marginalization, discrimination, violence, abuse. When you add up all these intrinsic and extrinsic factors, it’s not hard to believe that there is a high rate of suicidality,” Dr. Ting said.

“There have been studies that have shown that in children who are supported in their gender identity, the rates of depression and anxiety decreased to almost the same levels as non-trans and nonbinary children, so I think that gives cause for hope,” Dr. Ting added.

The study was funded in part by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme and by a Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship Doctoral Award. Ms. Johnstone reports consulting fees from Spectrum Waterloo and volunteer participation with the Youth Suicide Prevention Leadership Committee of Ontario. No other competing interests were declared. Dr. Ting has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transgender youth are significantly more likely to consider suicide and attempt it, compared with their cisgender peers, new research shows.

In a large population-based study, investigators found the increased risk of suicidality is partly because of bullying and cyberbullying experienced by transgender teens.

The findings are “extremely concerning and should be a wake-up call,” Ian Colman, PhD, with the University of Ottawa School of Epidemiology and Public Health, said in an interview.

Young people who are exploring their sexual identities may suffer from depression and anxiety, both about the reactions of their peers and families, as well as their own sense of self.

“These youth are highly marginalized and stigmatized in many corners of our society, and these findings highlight just how distressing these experiences can be,” Dr. Colman said.

The study was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Sevenfold increased risk of attempted suicide

The risk of suicidal thoughts and actions is not well studied in transgender and nonbinary youth.

To expand the evidence base, the researchers analyzed data for 6,800 adolescents aged 15-17 years from the 2019 Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth.

The sample included 1,130 (16.5%) adolescents who identified as having some degree of same-gender attraction, 265 (4.3%) who were unsure of their attraction (“questioning”), and 50 (0.6%) who were transgender, meaning they identified as being of a gender different from that assigned at birth.

Overall, 980 (14.0%) adolescents reported having thoughts of suicide in the prior year, and 480 (6.8%) had attempted suicide in their life.

Transgender youth were five times more likely to think about suicide and more than seven times more likely to have ever attempted suicide than cisgender, heterosexual peers.

Among cisgender adolescents, girls who were attracted to girls had 3.6 times the risk of suicidal ideation and 3.3 times the risk of having ever attempted suicide, compared with their heterosexual peers.

Teens attracted to multiple genders had more than twice the risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt. Youth who were questioning their sexual orientation had twice the risk of having attempted suicide in their lifetime.

A crisis – with reason for hope

“This is a crisis, and it shows just how much more needs to be done to support transgender young people,” co-author Fae Johnstone, MSW, executive director, Wisdom2Action, who is a trans woman herself, said in the news release.

“Suicide prevention programs specifically targeted to transgender, nonbinary, and sexual minority adolescents, as well as gender-affirming care for transgender adolescents, may help reduce the burden of suicidality among this group,” Ms. Johnstone added.

“The most important thing that parents, teachers, and health care providers can do is to be supportive of these youth,” Dr. Colman told this news organization.

“Providing a safe place where gender and sexual minorities can explore and express themselves is crucial. The first step is to listen and to be compassionate,” Dr. Colman added.

Reached for comment, Jess Ting, MD, director of surgery at the Mount Sinai Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery, New York, said the data from this study on suicidal thoughts and actions among sexual minority and transgender adolescents “mirror what we see and what we know” about suicidality in trans and nonbinary adults.

“The reasons for this are complex, and it’s hard for someone who doesn’t have a lived experience as a trans or nonbinary person to understand the reasons for suicidality,” he told this news organization.

“But we also know that there are higher rates of anxiety and depression and self-image issues and posttraumatic stress disorder, not to mention outside factors – marginalization, discrimination, violence, abuse. When you add up all these intrinsic and extrinsic factors, it’s not hard to believe that there is a high rate of suicidality,” Dr. Ting said.

“There have been studies that have shown that in children who are supported in their gender identity, the rates of depression and anxiety decreased to almost the same levels as non-trans and nonbinary children, so I think that gives cause for hope,” Dr. Ting added.

The study was funded in part by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme and by a Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship Doctoral Award. Ms. Johnstone reports consulting fees from Spectrum Waterloo and volunteer participation with the Youth Suicide Prevention Leadership Committee of Ontario. No other competing interests were declared. Dr. Ting has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE CANADIAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION JOURNAL

New studies show growing number of trans, nonbinary youth in U.S.

Two new studies point to an ever-increasing number of young people in the United States who identify as transgender and nonbinary, with the figures doubling among 18- to 24-year-olds in one institute’s research – from 0.66% of the population in 2016 to 1.3% (398,900) in 2022.

In addition, 1.4% (300,100) of 13- to 17-year-olds identify as trans or nonbinary, according to the report from that group, the Williams Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles, School of Law.

Williams, which conducts independent research on sexual orientation and gender identity law and public policy, did not contain data on 13- to 17-year-olds in its 2016 study, so the growth in that group over the past 5+ years is not as well documented.

Overall, some 1.6 million Americans older than age 13 now identify as transgender, reported the Williams researchers.

And in a new Pew Research Center survey, 2% of adults aged 18-29 identify as transgender and 3% identify as nonbinary, a far greater number than in other age cohorts.

These reports are likely underestimates. The Human Rights Campaign estimates that some 2 million Americans of all ages identify as transgender.

The Pew survey is weighted to be representative but still has limitations, said the organization. The Williams analysis, based on responses to two CDC surveys – the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) and Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) – is incomplete, say researchers, because not every state collects data on gender identity.

Transgender identities more predominant among youth

The Williams researchers report that 18.3% of those who identified as trans were 13- to 17-year-olds; that age group makes up 7.6% of the United States population 13 and older.

And despite not having firm figures from earlier reports, they comment: “Youth ages 13-17 comprise a larger share of the transgender-identified population than we previously estimated, currently comprising about 18% of the transgender-identified population in the United State, up from 10% previously.”

About one-quarter of those who identified as trans in the new 2022 report were aged 18-24; that age cohort accounts for 11% of Americans.

The number of older Americans who identify as trans are more proportionate to their representation in the population, according to Williams. Overall, about half of those who said they were trans were aged 25-64; that group accounts for 62% of the overall American population. Some 10% of trans-identified individuals were over age 65. About 20% of Americans are 65 or older, said the researchers.

The Pew research – based on the responses of 10,188 individuals surveyed in May – also found growing numbers of young people who identify as trans. “The share of U.S. adults who are transgender is particularly high among adults younger than 25,” reported Pew in a blog post.

In the 18- to 25-year-old group, 3.1% identified as a trans man or a trans woman, compared with just 0.5% of those ages 25-29.

That compares to 0.3% of those aged 30-49 and 0.2% of those older than 50.

Racial and state-by-state variation

Similar percentages of youth aged 13-17 of all races and ethnicities in the Williams study report they are transgender, ranging from 1% of those who are Asian, to 1.3% of White youth, 1.4% of Black youth, 1.8% of American Indian or Alaska Native, and 1.8% of Latinx youth. The institute reported that 1.5% of biracial and multiracial youth identified as transgender.

The researchers said, however, that “transgender-identified youth and adults appear more likely to report being Latinx and less likely to report being White, as compared to the United States population.”

Transgender individuals live in every state, with the greatest percentage of both youth and adults in the Northeast and West, and lesser percentages in the Midwest and South, reported the Williams Institute.

Williams estimates as many as 3% of 13- to 17-year-olds in New York identify as trans, while just 0.6% of that age group in Wyoming is transgender. A total of 2%-2.5% of those aged 13-17 are transgender in Hawaii, New Mexico, Maryland, and Washington, D.C.

Among the states with higher percentages of trans-identifying 18- to 24-year-olds: Arizona (1.9%), Arkansas (3.6%), Colorado (2%), Delaware (2.4%), Illinois (1.9%), Maryland (1.9%), North Carolina (2.5%), Oklahoma (2.5%), Massachusetts (2.3%), Rhode Island (2.1%), and Washington (2%).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two new studies point to an ever-increasing number of young people in the United States who identify as transgender and nonbinary, with the figures doubling among 18- to 24-year-olds in one institute’s research – from 0.66% of the population in 2016 to 1.3% (398,900) in 2022.

In addition, 1.4% (300,100) of 13- to 17-year-olds identify as trans or nonbinary, according to the report from that group, the Williams Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles, School of Law.

Williams, which conducts independent research on sexual orientation and gender identity law and public policy, did not contain data on 13- to 17-year-olds in its 2016 study, so the growth in that group over the past 5+ years is not as well documented.

Overall, some 1.6 million Americans older than age 13 now identify as transgender, reported the Williams researchers.

And in a new Pew Research Center survey, 2% of adults aged 18-29 identify as transgender and 3% identify as nonbinary, a far greater number than in other age cohorts.

These reports are likely underestimates. The Human Rights Campaign estimates that some 2 million Americans of all ages identify as transgender.

The Pew survey is weighted to be representative but still has limitations, said the organization. The Williams analysis, based on responses to two CDC surveys – the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) and Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) – is incomplete, say researchers, because not every state collects data on gender identity.

Transgender identities more predominant among youth

The Williams researchers report that 18.3% of those who identified as trans were 13- to 17-year-olds; that age group makes up 7.6% of the United States population 13 and older.

And despite not having firm figures from earlier reports, they comment: “Youth ages 13-17 comprise a larger share of the transgender-identified population than we previously estimated, currently comprising about 18% of the transgender-identified population in the United State, up from 10% previously.”

About one-quarter of those who identified as trans in the new 2022 report were aged 18-24; that age cohort accounts for 11% of Americans.

The number of older Americans who identify as trans are more proportionate to their representation in the population, according to Williams. Overall, about half of those who said they were trans were aged 25-64; that group accounts for 62% of the overall American population. Some 10% of trans-identified individuals were over age 65. About 20% of Americans are 65 or older, said the researchers.

The Pew research – based on the responses of 10,188 individuals surveyed in May – also found growing numbers of young people who identify as trans. “The share of U.S. adults who are transgender is particularly high among adults younger than 25,” reported Pew in a blog post.

In the 18- to 25-year-old group, 3.1% identified as a trans man or a trans woman, compared with just 0.5% of those ages 25-29.

That compares to 0.3% of those aged 30-49 and 0.2% of those older than 50.

Racial and state-by-state variation

Similar percentages of youth aged 13-17 of all races and ethnicities in the Williams study report they are transgender, ranging from 1% of those who are Asian, to 1.3% of White youth, 1.4% of Black youth, 1.8% of American Indian or Alaska Native, and 1.8% of Latinx youth. The institute reported that 1.5% of biracial and multiracial youth identified as transgender.

The researchers said, however, that “transgender-identified youth and adults appear more likely to report being Latinx and less likely to report being White, as compared to the United States population.”

Transgender individuals live in every state, with the greatest percentage of both youth and adults in the Northeast and West, and lesser percentages in the Midwest and South, reported the Williams Institute.

Williams estimates as many as 3% of 13- to 17-year-olds in New York identify as trans, while just 0.6% of that age group in Wyoming is transgender. A total of 2%-2.5% of those aged 13-17 are transgender in Hawaii, New Mexico, Maryland, and Washington, D.C.

Among the states with higher percentages of trans-identifying 18- to 24-year-olds: Arizona (1.9%), Arkansas (3.6%), Colorado (2%), Delaware (2.4%), Illinois (1.9%), Maryland (1.9%), North Carolina (2.5%), Oklahoma (2.5%), Massachusetts (2.3%), Rhode Island (2.1%), and Washington (2%).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two new studies point to an ever-increasing number of young people in the United States who identify as transgender and nonbinary, with the figures doubling among 18- to 24-year-olds in one institute’s research – from 0.66% of the population in 2016 to 1.3% (398,900) in 2022.

In addition, 1.4% (300,100) of 13- to 17-year-olds identify as trans or nonbinary, according to the report from that group, the Williams Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles, School of Law.

Williams, which conducts independent research on sexual orientation and gender identity law and public policy, did not contain data on 13- to 17-year-olds in its 2016 study, so the growth in that group over the past 5+ years is not as well documented.

Overall, some 1.6 million Americans older than age 13 now identify as transgender, reported the Williams researchers.

And in a new Pew Research Center survey, 2% of adults aged 18-29 identify as transgender and 3% identify as nonbinary, a far greater number than in other age cohorts.

These reports are likely underestimates. The Human Rights Campaign estimates that some 2 million Americans of all ages identify as transgender.

The Pew survey is weighted to be representative but still has limitations, said the organization. The Williams analysis, based on responses to two CDC surveys – the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) and Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) – is incomplete, say researchers, because not every state collects data on gender identity.

Transgender identities more predominant among youth

The Williams researchers report that 18.3% of those who identified as trans were 13- to 17-year-olds; that age group makes up 7.6% of the United States population 13 and older.

And despite not having firm figures from earlier reports, they comment: “Youth ages 13-17 comprise a larger share of the transgender-identified population than we previously estimated, currently comprising about 18% of the transgender-identified population in the United State, up from 10% previously.”

About one-quarter of those who identified as trans in the new 2022 report were aged 18-24; that age cohort accounts for 11% of Americans.

The number of older Americans who identify as trans are more proportionate to their representation in the population, according to Williams. Overall, about half of those who said they were trans were aged 25-64; that group accounts for 62% of the overall American population. Some 10% of trans-identified individuals were over age 65. About 20% of Americans are 65 or older, said the researchers.

The Pew research – based on the responses of 10,188 individuals surveyed in May – also found growing numbers of young people who identify as trans. “The share of U.S. adults who are transgender is particularly high among adults younger than 25,” reported Pew in a blog post.

In the 18- to 25-year-old group, 3.1% identified as a trans man or a trans woman, compared with just 0.5% of those ages 25-29.

That compares to 0.3% of those aged 30-49 and 0.2% of those older than 50.

Racial and state-by-state variation

Similar percentages of youth aged 13-17 of all races and ethnicities in the Williams study report they are transgender, ranging from 1% of those who are Asian, to 1.3% of White youth, 1.4% of Black youth, 1.8% of American Indian or Alaska Native, and 1.8% of Latinx youth. The institute reported that 1.5% of biracial and multiracial youth identified as transgender.

The researchers said, however, that “transgender-identified youth and adults appear more likely to report being Latinx and less likely to report being White, as compared to the United States population.”

Transgender individuals live in every state, with the greatest percentage of both youth and adults in the Northeast and West, and lesser percentages in the Midwest and South, reported the Williams Institute.

Williams estimates as many as 3% of 13- to 17-year-olds in New York identify as trans, while just 0.6% of that age group in Wyoming is transgender. A total of 2%-2.5% of those aged 13-17 are transgender in Hawaii, New Mexico, Maryland, and Washington, D.C.

Among the states with higher percentages of trans-identifying 18- to 24-year-olds: Arizona (1.9%), Arkansas (3.6%), Colorado (2%), Delaware (2.4%), Illinois (1.9%), Maryland (1.9%), North Carolina (2.5%), Oklahoma (2.5%), Massachusetts (2.3%), Rhode Island (2.1%), and Washington (2%).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Trans teens less likely to commit acts of sexual violence, says new study

Transgender and nonbinary adolescents are twice as likely to experience sexual violence as their cisgendered peers but are less likely to attempt rape or commit sexual assault, researchers have found.

The study, which was published online in JAMA Network Open, is among the first on the sexual violence that trans, nonbinary, and other gender nonconforming adolescents experience. Previous studies have focused on adults.

“In the busy world of clinical care, it is essential that clinicians be aware of potential disparities their patients are navigating,” said Michele Ybarra, PhD, MPH, president and research director of the Center for Innovative Public Health Research, San Clemente, California, who led the study. “This includes sexual violence victimization for gender minority youth and the need to talk about consent and boundaries for youth of all genders.”

Dr. Ybarra said that while clinicians may be aware that transgender young people face stigma, discrimination, and bullying, they may not be aware that trans youth are also the targets of sexual violence.

Studies indicate that health care providers and communities have significant misconceptions about sexually explicit behavior among trans and nonbinary teens. Misconceptions can lead to discrimination, resulting in higher rates of drug abuse, dropping out of school, suicide, and homelessness.

Dr. Ybarra and her colleagues surveyed 911 trans, nonbinary, or questioning youth on Instagram and Facebook through a collaboration with Growing Up With Media, a national longitudinal survey designed to investigate sexual violence during adolescence.

They also surveyed 3,282 cisgender persons aged 14-16 years who were recruited to the study between June 2018 and March 2020. The term “cisgender” refers to youth who identify with their gender at birth.

The questionnaires asked teens about gender identity, race, economic status, and support systems at home. Factors associated with not experiencing sexual violence included having a strong network of friends, family, and educators; involvement in the community; and having people close who affirm their gender identity.

More than three-fourths (78%) of youth surveyed identified as cisgender, 13.9% identified as questioning, and 7.9% identified as transgender.

Roughly two-thirds (67%) of transgender adolescents said they had experienced serious sexual violence, 73% reported experiencing violence in their communities, and 63% said they had been exposed to aggressive behavior. In contrast, 6.7% of trans youth said they had ever committed sexual violence, while 7.4% of cisgender teens surveyed, or 243 students, said they had done so.

“The relative lack of visibility of gender minority youth in sexual violence research is unacceptable,” Dr. Ybarra told this news organization. “To be counted, one needs to be seen. We aimed to start addressing this exclusion with the current study.”

The findings provide a lens into the levels of sexual violence that LGBTQIA+ youth experience and an opportunity to provide more inclusive care, according to Elizabeth Miller, MD, PhD, FSAHM, Distinguished Professor of Pediatrics, director of the Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine, and medical director of community and population health at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, who was not involved in the study.

“There are unfortunately pervasive and harmful stereotypes in our society about the ‘sexual deviancy’ attributed to LGBTQIA+ individuals,” Dr. Miller told this news organization. “This study adds to the research literature that counters and challenges these harmful – and inaccurate – perceptions.”

Dr. Miller said clinicians can help this population by offering youth accurate information about relevant support and services, including how to help a friend.

Programs that providers could incorporate include gender transformative approaches, which guide youth to examine gender norms and inequities and that develop leadership skills.

Such programs are more common outside the United States and have been shown to decrease LGBTQIA+ youth exposure to sexual violence, she said.

Dr. Miller said more research is needed to understand the contexts in which gender minority youth experience sexual violence to guide prevention efforts: “We need to move beyond individual-focused interventions to considering community-level interventions to create safer and more inclusive spaces for all youth.”

Dr. Miller has received royalties for writing content for UptoDate Wolters Kluwer outside of the current study. Dr. Ybarra has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transgender and nonbinary adolescents are twice as likely to experience sexual violence as their cisgendered peers but are less likely to attempt rape or commit sexual assault, researchers have found.

The study, which was published online in JAMA Network Open, is among the first on the sexual violence that trans, nonbinary, and other gender nonconforming adolescents experience. Previous studies have focused on adults.

“In the busy world of clinical care, it is essential that clinicians be aware of potential disparities their patients are navigating,” said Michele Ybarra, PhD, MPH, president and research director of the Center for Innovative Public Health Research, San Clemente, California, who led the study. “This includes sexual violence victimization for gender minority youth and the need to talk about consent and boundaries for youth of all genders.”

Dr. Ybarra said that while clinicians may be aware that transgender young people face stigma, discrimination, and bullying, they may not be aware that trans youth are also the targets of sexual violence.

Studies indicate that health care providers and communities have significant misconceptions about sexually explicit behavior among trans and nonbinary teens. Misconceptions can lead to discrimination, resulting in higher rates of drug abuse, dropping out of school, suicide, and homelessness.

Dr. Ybarra and her colleagues surveyed 911 trans, nonbinary, or questioning youth on Instagram and Facebook through a collaboration with Growing Up With Media, a national longitudinal survey designed to investigate sexual violence during adolescence.

They also surveyed 3,282 cisgender persons aged 14-16 years who were recruited to the study between June 2018 and March 2020. The term “cisgender” refers to youth who identify with their gender at birth.

The questionnaires asked teens about gender identity, race, economic status, and support systems at home. Factors associated with not experiencing sexual violence included having a strong network of friends, family, and educators; involvement in the community; and having people close who affirm their gender identity.

More than three-fourths (78%) of youth surveyed identified as cisgender, 13.9% identified as questioning, and 7.9% identified as transgender.

Roughly two-thirds (67%) of transgender adolescents said they had experienced serious sexual violence, 73% reported experiencing violence in their communities, and 63% said they had been exposed to aggressive behavior. In contrast, 6.7% of trans youth said they had ever committed sexual violence, while 7.4% of cisgender teens surveyed, or 243 students, said they had done so.

“The relative lack of visibility of gender minority youth in sexual violence research is unacceptable,” Dr. Ybarra told this news organization. “To be counted, one needs to be seen. We aimed to start addressing this exclusion with the current study.”

The findings provide a lens into the levels of sexual violence that LGBTQIA+ youth experience and an opportunity to provide more inclusive care, according to Elizabeth Miller, MD, PhD, FSAHM, Distinguished Professor of Pediatrics, director of the Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine, and medical director of community and population health at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, who was not involved in the study.

“There are unfortunately pervasive and harmful stereotypes in our society about the ‘sexual deviancy’ attributed to LGBTQIA+ individuals,” Dr. Miller told this news organization. “This study adds to the research literature that counters and challenges these harmful – and inaccurate – perceptions.”

Dr. Miller said clinicians can help this population by offering youth accurate information about relevant support and services, including how to help a friend.

Programs that providers could incorporate include gender transformative approaches, which guide youth to examine gender norms and inequities and that develop leadership skills.

Such programs are more common outside the United States and have been shown to decrease LGBTQIA+ youth exposure to sexual violence, she said.

Dr. Miller said more research is needed to understand the contexts in which gender minority youth experience sexual violence to guide prevention efforts: “We need to move beyond individual-focused interventions to considering community-level interventions to create safer and more inclusive spaces for all youth.”

Dr. Miller has received royalties for writing content for UptoDate Wolters Kluwer outside of the current study. Dr. Ybarra has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transgender and nonbinary adolescents are twice as likely to experience sexual violence as their cisgendered peers but are less likely to attempt rape or commit sexual assault, researchers have found.

The study, which was published online in JAMA Network Open, is among the first on the sexual violence that trans, nonbinary, and other gender nonconforming adolescents experience. Previous studies have focused on adults.

“In the busy world of clinical care, it is essential that clinicians be aware of potential disparities their patients are navigating,” said Michele Ybarra, PhD, MPH, president and research director of the Center for Innovative Public Health Research, San Clemente, California, who led the study. “This includes sexual violence victimization for gender minority youth and the need to talk about consent and boundaries for youth of all genders.”

Dr. Ybarra said that while clinicians may be aware that transgender young people face stigma, discrimination, and bullying, they may not be aware that trans youth are also the targets of sexual violence.

Studies indicate that health care providers and communities have significant misconceptions about sexually explicit behavior among trans and nonbinary teens. Misconceptions can lead to discrimination, resulting in higher rates of drug abuse, dropping out of school, suicide, and homelessness.

Dr. Ybarra and her colleagues surveyed 911 trans, nonbinary, or questioning youth on Instagram and Facebook through a collaboration with Growing Up With Media, a national longitudinal survey designed to investigate sexual violence during adolescence.

They also surveyed 3,282 cisgender persons aged 14-16 years who were recruited to the study between June 2018 and March 2020. The term “cisgender” refers to youth who identify with their gender at birth.

The questionnaires asked teens about gender identity, race, economic status, and support systems at home. Factors associated with not experiencing sexual violence included having a strong network of friends, family, and educators; involvement in the community; and having people close who affirm their gender identity.

More than three-fourths (78%) of youth surveyed identified as cisgender, 13.9% identified as questioning, and 7.9% identified as transgender.

Roughly two-thirds (67%) of transgender adolescents said they had experienced serious sexual violence, 73% reported experiencing violence in their communities, and 63% said they had been exposed to aggressive behavior. In contrast, 6.7% of trans youth said they had ever committed sexual violence, while 7.4% of cisgender teens surveyed, or 243 students, said they had done so.

“The relative lack of visibility of gender minority youth in sexual violence research is unacceptable,” Dr. Ybarra told this news organization. “To be counted, one needs to be seen. We aimed to start addressing this exclusion with the current study.”

The findings provide a lens into the levels of sexual violence that LGBTQIA+ youth experience and an opportunity to provide more inclusive care, according to Elizabeth Miller, MD, PhD, FSAHM, Distinguished Professor of Pediatrics, director of the Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine, and medical director of community and population health at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, who was not involved in the study.

“There are unfortunately pervasive and harmful stereotypes in our society about the ‘sexual deviancy’ attributed to LGBTQIA+ individuals,” Dr. Miller told this news organization. “This study adds to the research literature that counters and challenges these harmful – and inaccurate – perceptions.”

Dr. Miller said clinicians can help this population by offering youth accurate information about relevant support and services, including how to help a friend.

Programs that providers could incorporate include gender transformative approaches, which guide youth to examine gender norms and inequities and that develop leadership skills.

Such programs are more common outside the United States and have been shown to decrease LGBTQIA+ youth exposure to sexual violence, she said.

Dr. Miller said more research is needed to understand the contexts in which gender minority youth experience sexual violence to guide prevention efforts: “We need to move beyond individual-focused interventions to considering community-level interventions to create safer and more inclusive spaces for all youth.”

Dr. Miller has received royalties for writing content for UptoDate Wolters Kluwer outside of the current study. Dr. Ybarra has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Urinary incontinence in transfeminine patients

Whether your patient is a cisgender female or a transfeminine patient, urinary incontinence is unfortunately common and can have a significant negative effect on a person’s quality of life. While the incidence of incontinence is relatively well established in the cisgender population, these statistics remain elusive among transfeminine individuals. Many studies today currently examine cosmetic results, sexual function, and major complications rates, and are now starting to explore the long-term effects of these surgeries on the urinary tract.1

As gender-affirming surgery increases in prevalence, our knowledge regarding long-term outcomes impacting quality of life needs to subsequently improve. A few small studies have examined the rates of incontinence and urinary dysfunction among transfeminine patients. In one study, changes in voiding were reported in 32% of patients, with 19% reporting worse voiding and 19% reporting some degree of incontinence.2 A small series of 52 transgender female patients found rates of urinary urgency to be 24.6% and stress incontinence 23%.1,3 Another study of only 18 patients demonstrated a significant rate of incontinence at 33%, which was due to stress urinary incontinence and overactive bladder.1,4 Other studies noted postvoid dribbling to be as high as 79%.1,2

Obtaining a thorough history is essential in evaluating patients with incontinence. Compared with cisgender females, risk factors for urinary incontinence in cisgender males are naturally different. For example, increasing age, parity, vaginal delivery, history of hysterectomy, and obesity are some risk factors for incontinence in cisgender women.1,6 However, in men, overall rates are lower and tend to be associated with factors such as a history of stroke, diabetes, and injury to the urethral sphincter – which can occur in radical prostatectomy.1

In addition to asking standard questions, such as caffeine use, beverage consumption, medication changes, physical activity, etc., the relationship of a patient’s symptoms to her vaginoplasty is crucial. Providers should elucidate whether patients experienced urinary symptoms prior to surgery, note the type of vaginoplasty performed, and determine if any temporal relationship exists with dilation or intercourse.

Communicating with the original surgeon and obtaining operative reports is often necessary to understand the flaps utilized and the current anatomic structures that were altered during surgery. Creation of the neovagina involves dissection through the levator ani, which can lead to neurologic injury and subsequently predispose patients to incontinence. The surgeon must be meticulous in their creation of the neovaginal space, particularly between the rectum and the prostatic urethra. As the dissection continues in a cephalad direction to the peritoneal reflection, the bladder can also suffer an iatrogenic injury.

In cases of the penile inversion vaginoplasty, a skin graft is typically used to line the neovaginal canal. If this graft fails to take appropriately it can prolapse and can contribute to urinary incontinence symptoms. Some surgeons will suspend the apical portion of the neovagina; however, the effect on rates of incontinence is mixed.

The physical exam of a transfeminine patient should consist of a general health assessment, neurological, abdominal, and genitourinary examinations. Palpation of the prostate is performed through the neovaginal canal if patent. During the urinary exam, the provider should make note of stenosis at the urethral meatus or urethral hypermobility. For patients reporting symptoms of stress incontinence, a cough stress test is useful. The neovagina should be carefully examined for fistula formation or any other structural abnormality.

Testing for urinary incontinence is similar to the evaluation in cisgender females in that every patient should undergo a urinalysis and a postvoid residual volume measurement, and should maintain a voiding diary. Indications for urodynamic testing are the same for transfeminine women and cisgender women – symptoms do not correlate with objective findings, failure to improve with treatment, prior incontinence from pelvic floor surgery, difficult diagnostic evaluation with unclear diagnosis.5,6 Cystoscopy is useful for patients experiencing hematuria, before anti-incontinence surgery, or prior to transurethral prostate intervention.1

Treatment is tailored to the type of incontinence diagnosed; however, there are no specific guidelines that are evidence-based for transfeminine patients after vaginoplasty. The therapies available are extrapolated from the general patient population. All patients can benefit from dietary modifications such as avoiding bladder irritants, monitoring fluid and caffeine intake, timed voiding, and pelvic floor exercises.1,6 If patients do not experience improvement from conservative measures, the mainstay treatment for overactive bladder is antimuscarinic agents. However, in cisgender male patients who have a prostate, these agents can lead to urinary retention related to bladder outlet obstruction, although the rates of urinary retention are low.1 Overall, these agents are relatively safe and effective in cisgender men with a prostate and by extension should be utilized in transfeminine patients when indicated.

In patients diagnosed with stress urinary incontinence, conservative options with weight loss, smoking cessation, and pelvic floor exercises should be attempted. If these measures fail in cisgender women, surgical treatment is often recommended. However, surgical treatment in transfeminine patients is significantly less straightforward and beyond the scope of this article.

Obstetrician/gynecologists are familiar with assessing and treating cisgender female patients reporting incontinence and should use this same knowledge for diagnosing and treating transfeminine patients. In addition, providers should be aware of complications of these procedures in evaluating patients presenting for symptoms of incontinence, as these complications directly contribute to incontinence in this patient population.1

Dr. Brandt is an ob.gyn. and fellowship-trained gender-affirming surgeon in West Reading, Pa. Email her at [email protected] .

References

1. Ginzburg N. Care of transgender patients: Incontinence. In: Nikolavsky D, Blakley SA, eds. Urological Care for the Transgender Patient: A Comprehensive Guide. Syracuse, NY: Springer, 2021:203-17.

2. Hoebeke P et al. Eur Urol. 2005;47(3):398-402.

3. Kuhn A et al. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(7):2379-82.

4. Kuhn A et al. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;131(2):226-30.

5. Winters JC et al. J Urol. 2012;188(6s):2464-72.

6. Practice Bulletin No. 155. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:e66-81.

Whether your patient is a cisgender female or a transfeminine patient, urinary incontinence is unfortunately common and can have a significant negative effect on a person’s quality of life. While the incidence of incontinence is relatively well established in the cisgender population, these statistics remain elusive among transfeminine individuals. Many studies today currently examine cosmetic results, sexual function, and major complications rates, and are now starting to explore the long-term effects of these surgeries on the urinary tract.1

As gender-affirming surgery increases in prevalence, our knowledge regarding long-term outcomes impacting quality of life needs to subsequently improve. A few small studies have examined the rates of incontinence and urinary dysfunction among transfeminine patients. In one study, changes in voiding were reported in 32% of patients, with 19% reporting worse voiding and 19% reporting some degree of incontinence.2 A small series of 52 transgender female patients found rates of urinary urgency to be 24.6% and stress incontinence 23%.1,3 Another study of only 18 patients demonstrated a significant rate of incontinence at 33%, which was due to stress urinary incontinence and overactive bladder.1,4 Other studies noted postvoid dribbling to be as high as 79%.1,2

Obtaining a thorough history is essential in evaluating patients with incontinence. Compared with cisgender females, risk factors for urinary incontinence in cisgender males are naturally different. For example, increasing age, parity, vaginal delivery, history of hysterectomy, and obesity are some risk factors for incontinence in cisgender women.1,6 However, in men, overall rates are lower and tend to be associated with factors such as a history of stroke, diabetes, and injury to the urethral sphincter – which can occur in radical prostatectomy.1

In addition to asking standard questions, such as caffeine use, beverage consumption, medication changes, physical activity, etc., the relationship of a patient’s symptoms to her vaginoplasty is crucial. Providers should elucidate whether patients experienced urinary symptoms prior to surgery, note the type of vaginoplasty performed, and determine if any temporal relationship exists with dilation or intercourse.

Communicating with the original surgeon and obtaining operative reports is often necessary to understand the flaps utilized and the current anatomic structures that were altered during surgery. Creation of the neovagina involves dissection through the levator ani, which can lead to neurologic injury and subsequently predispose patients to incontinence. The surgeon must be meticulous in their creation of the neovaginal space, particularly between the rectum and the prostatic urethra. As the dissection continues in a cephalad direction to the peritoneal reflection, the bladder can also suffer an iatrogenic injury.

In cases of the penile inversion vaginoplasty, a skin graft is typically used to line the neovaginal canal. If this graft fails to take appropriately it can prolapse and can contribute to urinary incontinence symptoms. Some surgeons will suspend the apical portion of the neovagina; however, the effect on rates of incontinence is mixed.

The physical exam of a transfeminine patient should consist of a general health assessment, neurological, abdominal, and genitourinary examinations. Palpation of the prostate is performed through the neovaginal canal if patent. During the urinary exam, the provider should make note of stenosis at the urethral meatus or urethral hypermobility. For patients reporting symptoms of stress incontinence, a cough stress test is useful. The neovagina should be carefully examined for fistula formation or any other structural abnormality.

Testing for urinary incontinence is similar to the evaluation in cisgender females in that every patient should undergo a urinalysis and a postvoid residual volume measurement, and should maintain a voiding diary. Indications for urodynamic testing are the same for transfeminine women and cisgender women – symptoms do not correlate with objective findings, failure to improve with treatment, prior incontinence from pelvic floor surgery, difficult diagnostic evaluation with unclear diagnosis.5,6 Cystoscopy is useful for patients experiencing hematuria, before anti-incontinence surgery, or prior to transurethral prostate intervention.1

Treatment is tailored to the type of incontinence diagnosed; however, there are no specific guidelines that are evidence-based for transfeminine patients after vaginoplasty. The therapies available are extrapolated from the general patient population. All patients can benefit from dietary modifications such as avoiding bladder irritants, monitoring fluid and caffeine intake, timed voiding, and pelvic floor exercises.1,6 If patients do not experience improvement from conservative measures, the mainstay treatment for overactive bladder is antimuscarinic agents. However, in cisgender male patients who have a prostate, these agents can lead to urinary retention related to bladder outlet obstruction, although the rates of urinary retention are low.1 Overall, these agents are relatively safe and effective in cisgender men with a prostate and by extension should be utilized in transfeminine patients when indicated.

In patients diagnosed with stress urinary incontinence, conservative options with weight loss, smoking cessation, and pelvic floor exercises should be attempted. If these measures fail in cisgender women, surgical treatment is often recommended. However, surgical treatment in transfeminine patients is significantly less straightforward and beyond the scope of this article.

Obstetrician/gynecologists are familiar with assessing and treating cisgender female patients reporting incontinence and should use this same knowledge for diagnosing and treating transfeminine patients. In addition, providers should be aware of complications of these procedures in evaluating patients presenting for symptoms of incontinence, as these complications directly contribute to incontinence in this patient population.1

Dr. Brandt is an ob.gyn. and fellowship-trained gender-affirming surgeon in West Reading, Pa. Email her at [email protected] .

References

1. Ginzburg N. Care of transgender patients: Incontinence. In: Nikolavsky D, Blakley SA, eds. Urological Care for the Transgender Patient: A Comprehensive Guide. Syracuse, NY: Springer, 2021:203-17.

2. Hoebeke P et al. Eur Urol. 2005;47(3):398-402.

3. Kuhn A et al. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(7):2379-82.

4. Kuhn A et al. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;131(2):226-30.

5. Winters JC et al. J Urol. 2012;188(6s):2464-72.

6. Practice Bulletin No. 155. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:e66-81.

Whether your patient is a cisgender female or a transfeminine patient, urinary incontinence is unfortunately common and can have a significant negative effect on a person’s quality of life. While the incidence of incontinence is relatively well established in the cisgender population, these statistics remain elusive among transfeminine individuals. Many studies today currently examine cosmetic results, sexual function, and major complications rates, and are now starting to explore the long-term effects of these surgeries on the urinary tract.1

As gender-affirming surgery increases in prevalence, our knowledge regarding long-term outcomes impacting quality of life needs to subsequently improve. A few small studies have examined the rates of incontinence and urinary dysfunction among transfeminine patients. In one study, changes in voiding were reported in 32% of patients, with 19% reporting worse voiding and 19% reporting some degree of incontinence.2 A small series of 52 transgender female patients found rates of urinary urgency to be 24.6% and stress incontinence 23%.1,3 Another study of only 18 patients demonstrated a significant rate of incontinence at 33%, which was due to stress urinary incontinence and overactive bladder.1,4 Other studies noted postvoid dribbling to be as high as 79%.1,2

Obtaining a thorough history is essential in evaluating patients with incontinence. Compared with cisgender females, risk factors for urinary incontinence in cisgender males are naturally different. For example, increasing age, parity, vaginal delivery, history of hysterectomy, and obesity are some risk factors for incontinence in cisgender women.1,6 However, in men, overall rates are lower and tend to be associated with factors such as a history of stroke, diabetes, and injury to the urethral sphincter – which can occur in radical prostatectomy.1

In addition to asking standard questions, such as caffeine use, beverage consumption, medication changes, physical activity, etc., the relationship of a patient’s symptoms to her vaginoplasty is crucial. Providers should elucidate whether patients experienced urinary symptoms prior to surgery, note the type of vaginoplasty performed, and determine if any temporal relationship exists with dilation or intercourse.

Communicating with the original surgeon and obtaining operative reports is often necessary to understand the flaps utilized and the current anatomic structures that were altered during surgery. Creation of the neovagina involves dissection through the levator ani, which can lead to neurologic injury and subsequently predispose patients to incontinence. The surgeon must be meticulous in their creation of the neovaginal space, particularly between the rectum and the prostatic urethra. As the dissection continues in a cephalad direction to the peritoneal reflection, the bladder can also suffer an iatrogenic injury.

In cases of the penile inversion vaginoplasty, a skin graft is typically used to line the neovaginal canal. If this graft fails to take appropriately it can prolapse and can contribute to urinary incontinence symptoms. Some surgeons will suspend the apical portion of the neovagina; however, the effect on rates of incontinence is mixed.

The physical exam of a transfeminine patient should consist of a general health assessment, neurological, abdominal, and genitourinary examinations. Palpation of the prostate is performed through the neovaginal canal if patent. During the urinary exam, the provider should make note of stenosis at the urethral meatus or urethral hypermobility. For patients reporting symptoms of stress incontinence, a cough stress test is useful. The neovagina should be carefully examined for fistula formation or any other structural abnormality.

Testing for urinary incontinence is similar to the evaluation in cisgender females in that every patient should undergo a urinalysis and a postvoid residual volume measurement, and should maintain a voiding diary. Indications for urodynamic testing are the same for transfeminine women and cisgender women – symptoms do not correlate with objective findings, failure to improve with treatment, prior incontinence from pelvic floor surgery, difficult diagnostic evaluation with unclear diagnosis.5,6 Cystoscopy is useful for patients experiencing hematuria, before anti-incontinence surgery, or prior to transurethral prostate intervention.1

Treatment is tailored to the type of incontinence diagnosed; however, there are no specific guidelines that are evidence-based for transfeminine patients after vaginoplasty. The therapies available are extrapolated from the general patient population. All patients can benefit from dietary modifications such as avoiding bladder irritants, monitoring fluid and caffeine intake, timed voiding, and pelvic floor exercises.1,6 If patients do not experience improvement from conservative measures, the mainstay treatment for overactive bladder is antimuscarinic agents. However, in cisgender male patients who have a prostate, these agents can lead to urinary retention related to bladder outlet obstruction, although the rates of urinary retention are low.1 Overall, these agents are relatively safe and effective in cisgender men with a prostate and by extension should be utilized in transfeminine patients when indicated.

In patients diagnosed with stress urinary incontinence, conservative options with weight loss, smoking cessation, and pelvic floor exercises should be attempted. If these measures fail in cisgender women, surgical treatment is often recommended. However, surgical treatment in transfeminine patients is significantly less straightforward and beyond the scope of this article.

Obstetrician/gynecologists are familiar with assessing and treating cisgender female patients reporting incontinence and should use this same knowledge for diagnosing and treating transfeminine patients. In addition, providers should be aware of complications of these procedures in evaluating patients presenting for symptoms of incontinence, as these complications directly contribute to incontinence in this patient population.1

Dr. Brandt is an ob.gyn. and fellowship-trained gender-affirming surgeon in West Reading, Pa. Email her at [email protected] .

References

1. Ginzburg N. Care of transgender patients: Incontinence. In: Nikolavsky D, Blakley SA, eds. Urological Care for the Transgender Patient: A Comprehensive Guide. Syracuse, NY: Springer, 2021:203-17.

2. Hoebeke P et al. Eur Urol. 2005;47(3):398-402.

3. Kuhn A et al. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(7):2379-82.

4. Kuhn A et al. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;131(2):226-30.

5. Winters JC et al. J Urol. 2012;188(6s):2464-72.

6. Practice Bulletin No. 155. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:e66-81.

Few children with early social gender transition change their minds

Approximately 7% of youth who chose gender identity social transition in early childhood had retransitioned 5 years later, based on data from 317 individuals.

“Increasing numbers of children are socially transitioning to live in line with their gender identity, rather than the gender assumed by their sex at birth – a process that typically involves changing a child’s pronouns, first name, hairstyle, and clothing,” wrote Kristina R. Olson, PhD, of Princeton (N.J.) University, and colleagues.

The question of whether early childhood social transitions will result in high rates of retransition continues to be a subject for debate, and long-term data on retransition rates and identity outcomes in children who transition are limited, they said.

To examine retransition in early-transitioning children, the researchers identified 317 binary socially transitioned transgender children to participate in a longitudinal study known as the Trans Youth Project (TYP) between July 2013 and December 2017. The study was published in Pediatrics. The mean age at baseline was 8 years. At study entry, participants had to have made a complete binary social transition, including changing their pronouns from those used at birth. During the 5-year follow-up period, children and parents were asked about use of puberty blockers and/or gender-affirming hormones. At study entry, 37 children had begun some type of puberty blockers. A total of 124 children initially socially transitioned before 6 years of age, and 193 initially socially transitioned at 6 years or older.

The study did not evaluate whether the participants met the DSM-5 criteria for gender dysphoria in childhood, the researchers noted. “Based on data collected at their initial visit, we do know that these participants showed signs of gender identification and gender-typed preferences commonly associated with their gender, not their sex assigned at birth,” they wrote.

Participants were classified as binary transgender, nonbinary, or cisgender based on their pronouns at follow-up. Binary transgender pronouns were associated with the other binary assigned sex, nonbinary pronouns were they/them or a mix of they/them and binary pronouns, and cisgender pronouns were those associated with assigned sex.

Overall, 7.3% of the participants had retransitioned at least once by 5 years after their initial binary social transition. The majority (94%) were living as binary transgender youth, including 1.3% who retransitioned to cisgender or nonbinary and then back to binary transgender during the follow-up period. A total of 2.5% were living as cisgender youth and 3.5% were living as nonbinary youth. These rates were similar across the initial population, as well as the 291 participants who continue to be in contact with the researchers, the 200 who had gone at least 5 years since their initial social transition, and the 280 participants who began the study before starting puberty blockers.

The researchers found no differences in retransition rates related to participant sex at birth. Rates of retransition were slightly higher among participants who made their initial social transition before 6 years of age, but these rates were low, the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of a volunteer community sample, with the potential for bias that may not generalize to the population at large, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the use of pronouns as the main criteria for retransition, and the classification of a change from binary transgender to nonbinary as a transition, they said. “Many nonbinary people consider themselves to be transgender,” they noted.

“If we had used a stricter criterion of retransition, more similar to the common use of terms like “detransition” or “desistence,” referring only to youth who are living as cisgender, then our retransition rate would have been lower (2.5%),” the researchers explained. Another limitation was the disproportionate number of trans girls, the researchers said. However, because no significant gender effect appeared in terms of retransition rates, “we do not predict any change in pattern of results if we had a different ratio of participants by sex at birth,” they said.

The researchers stated that they intend to follow the cohort through adolescence and into adulthood.

“As more youth are coming out and being supported in their transitions early in development, it is increasingly critical that clinicians understand the experiences of this cohort and not make assumptions about them as a function of older data from youth who lived under different circumstances,” the researchers emphasized. “Though we can never predict the exact gender trajectory of any child, these data suggest that many youth who identify as transgender early, and are supported through a social transition, will continue to identify as transgender 5 years after initial social transition.” They concluded that more research is needed to determine how best to support initial and later gender transitions in youth.

Study offers support for family discussions

“This study is important to help provide more data regarding the experiences of gender-diverse youth,” M. Brett Cooper, MD, of UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, said in an interview. “The results of a study like this can be used by clinicians to help provide advice and guidance to parents and families as they support their children through their gender journey,” said Dr. Cooper, who was not involved in the study. The current study “also provides evidence to support that persistent, insistent, and consistent youth have an extremely low rate of retransition to a gender that aligns with their sex assigned at birth. This refutes suggestions by politicians and others that those who seek medical care have a high rate of regret or retransition,” Dr. Cooper emphasized.

“I was not surprised at all by their findings,” said Dr. Cooper. “These are very similar to what I have seen in my own panel of gender-diverse patients and what has been seen in other studies,” he noted.

The take-home message of the current study does not suggest any change in clinical practice, Dr. Cooper said. “Guidance already suggests supporting these youth on their gender journey and that for some youth, this may mean retransitioning to identify with their sex assigned at birth,” he explained.

The study was supported in part by grants to the researchers from the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the Arcus Foundation, and the MacArthur Foundation. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Approximately 7% of youth who chose gender identity social transition in early childhood had retransitioned 5 years later, based on data from 317 individuals.

“Increasing numbers of children are socially transitioning to live in line with their gender identity, rather than the gender assumed by their sex at birth – a process that typically involves changing a child’s pronouns, first name, hairstyle, and clothing,” wrote Kristina R. Olson, PhD, of Princeton (N.J.) University, and colleagues.

The question of whether early childhood social transitions will result in high rates of retransition continues to be a subject for debate, and long-term data on retransition rates and identity outcomes in children who transition are limited, they said.

To examine retransition in early-transitioning children, the researchers identified 317 binary socially transitioned transgender children to participate in a longitudinal study known as the Trans Youth Project (TYP) between July 2013 and December 2017. The study was published in Pediatrics. The mean age at baseline was 8 years. At study entry, participants had to have made a complete binary social transition, including changing their pronouns from those used at birth. During the 5-year follow-up period, children and parents were asked about use of puberty blockers and/or gender-affirming hormones. At study entry, 37 children had begun some type of puberty blockers. A total of 124 children initially socially transitioned before 6 years of age, and 193 initially socially transitioned at 6 years or older.

The study did not evaluate whether the participants met the DSM-5 criteria for gender dysphoria in childhood, the researchers noted. “Based on data collected at their initial visit, we do know that these participants showed signs of gender identification and gender-typed preferences commonly associated with their gender, not their sex assigned at birth,” they wrote.

Participants were classified as binary transgender, nonbinary, or cisgender based on their pronouns at follow-up. Binary transgender pronouns were associated with the other binary assigned sex, nonbinary pronouns were they/them or a mix of they/them and binary pronouns, and cisgender pronouns were those associated with assigned sex.

Overall, 7.3% of the participants had retransitioned at least once by 5 years after their initial binary social transition. The majority (94%) were living as binary transgender youth, including 1.3% who retransitioned to cisgender or nonbinary and then back to binary transgender during the follow-up period. A total of 2.5% were living as cisgender youth and 3.5% were living as nonbinary youth. These rates were similar across the initial population, as well as the 291 participants who continue to be in contact with the researchers, the 200 who had gone at least 5 years since their initial social transition, and the 280 participants who began the study before starting puberty blockers.

The researchers found no differences in retransition rates related to participant sex at birth. Rates of retransition were slightly higher among participants who made their initial social transition before 6 years of age, but these rates were low, the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of a volunteer community sample, with the potential for bias that may not generalize to the population at large, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the use of pronouns as the main criteria for retransition, and the classification of a change from binary transgender to nonbinary as a transition, they said. “Many nonbinary people consider themselves to be transgender,” they noted.

“If we had used a stricter criterion of retransition, more similar to the common use of terms like “detransition” or “desistence,” referring only to youth who are living as cisgender, then our retransition rate would have been lower (2.5%),” the researchers explained. Another limitation was the disproportionate number of trans girls, the researchers said. However, because no significant gender effect appeared in terms of retransition rates, “we do not predict any change in pattern of results if we had a different ratio of participants by sex at birth,” they said.

The researchers stated that they intend to follow the cohort through adolescence and into adulthood.

“As more youth are coming out and being supported in their transitions early in development, it is increasingly critical that clinicians understand the experiences of this cohort and not make assumptions about them as a function of older data from youth who lived under different circumstances,” the researchers emphasized. “Though we can never predict the exact gender trajectory of any child, these data suggest that many youth who identify as transgender early, and are supported through a social transition, will continue to identify as transgender 5 years after initial social transition.” They concluded that more research is needed to determine how best to support initial and later gender transitions in youth.

Study offers support for family discussions

“This study is important to help provide more data regarding the experiences of gender-diverse youth,” M. Brett Cooper, MD, of UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, said in an interview. “The results of a study like this can be used by clinicians to help provide advice and guidance to parents and families as they support their children through their gender journey,” said Dr. Cooper, who was not involved in the study. The current study “also provides evidence to support that persistent, insistent, and consistent youth have an extremely low rate of retransition to a gender that aligns with their sex assigned at birth. This refutes suggestions by politicians and others that those who seek medical care have a high rate of regret or retransition,” Dr. Cooper emphasized.

“I was not surprised at all by their findings,” said Dr. Cooper. “These are very similar to what I have seen in my own panel of gender-diverse patients and what has been seen in other studies,” he noted.

The take-home message of the current study does not suggest any change in clinical practice, Dr. Cooper said. “Guidance already suggests supporting these youth on their gender journey and that for some youth, this may mean retransitioning to identify with their sex assigned at birth,” he explained.

The study was supported in part by grants to the researchers from the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the Arcus Foundation, and the MacArthur Foundation. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Approximately 7% of youth who chose gender identity social transition in early childhood had retransitioned 5 years later, based on data from 317 individuals.

“Increasing numbers of children are socially transitioning to live in line with their gender identity, rather than the gender assumed by their sex at birth – a process that typically involves changing a child’s pronouns, first name, hairstyle, and clothing,” wrote Kristina R. Olson, PhD, of Princeton (N.J.) University, and colleagues.

The question of whether early childhood social transitions will result in high rates of retransition continues to be a subject for debate, and long-term data on retransition rates and identity outcomes in children who transition are limited, they said.

To examine retransition in early-transitioning children, the researchers identified 317 binary socially transitioned transgender children to participate in a longitudinal study known as the Trans Youth Project (TYP) between July 2013 and December 2017. The study was published in Pediatrics. The mean age at baseline was 8 years. At study entry, participants had to have made a complete binary social transition, including changing their pronouns from those used at birth. During the 5-year follow-up period, children and parents were asked about use of puberty blockers and/or gender-affirming hormones. At study entry, 37 children had begun some type of puberty blockers. A total of 124 children initially socially transitioned before 6 years of age, and 193 initially socially transitioned at 6 years or older.

The study did not evaluate whether the participants met the DSM-5 criteria for gender dysphoria in childhood, the researchers noted. “Based on data collected at their initial visit, we do know that these participants showed signs of gender identification and gender-typed preferences commonly associated with their gender, not their sex assigned at birth,” they wrote.

Participants were classified as binary transgender, nonbinary, or cisgender based on their pronouns at follow-up. Binary transgender pronouns were associated with the other binary assigned sex, nonbinary pronouns were they/them or a mix of they/them and binary pronouns, and cisgender pronouns were those associated with assigned sex.