User login

Click for Credit: Roux-en-Y for diabetes; Exercise & fall prevention; more

Here are 5 articles from the July issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Cloud of inconsistency hangs over cannabis data

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NfjaDS

Expires February 6, 2020

2. Roux-en-Y achieves diabetes remission in majority of patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2x9hLnE

Expires February 6, 2020

3. Socioeconomic status, race found to impact CPAP compliance

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2RBpLa9

Expires February 8, 2020

4. Exercise type matters for fall prevention among elderly

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2X26OUh

Expires February 12, 2020

5. Adult HIV patients should receive standard vaccinations, with caveats

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2X1S7LV

Expires February 12, 2020

Here are 5 articles from the July issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Cloud of inconsistency hangs over cannabis data

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NfjaDS

Expires February 6, 2020

2. Roux-en-Y achieves diabetes remission in majority of patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2x9hLnE

Expires February 6, 2020

3. Socioeconomic status, race found to impact CPAP compliance

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2RBpLa9

Expires February 8, 2020

4. Exercise type matters for fall prevention among elderly

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2X26OUh

Expires February 12, 2020

5. Adult HIV patients should receive standard vaccinations, with caveats

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2X1S7LV

Expires February 12, 2020

Here are 5 articles from the July issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Cloud of inconsistency hangs over cannabis data

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NfjaDS

Expires February 6, 2020

2. Roux-en-Y achieves diabetes remission in majority of patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2x9hLnE

Expires February 6, 2020

3. Socioeconomic status, race found to impact CPAP compliance

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2RBpLa9

Expires February 8, 2020

4. Exercise type matters for fall prevention among elderly

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2X26OUh

Expires February 12, 2020

5. Adult HIV patients should receive standard vaccinations, with caveats

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2X1S7LV

Expires February 12, 2020

ACIP approves meningococcal booster for persons at increased risk

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

The committee voted unanimously in favor of a booster dose of MenB vaccine 1 year after completion of the primary series, with additional boosters every 2-3 years “for as long as risk remains” for high-risk persons, including microbiologists and persons with complement deficiency, complement inhibitor use, or asplenia.

The committee also voted unanimously in favor of a one-time MenB booster for individuals aged 10 years and older who are at least a year beyond completion of a MenB primary series and deemed at increased risk by public health officials in an outbreak situation.

In addition, “a booster dose interval of 6 months or more may be considered by public health officials depending on the specific outbreak, vaccine strategy, and projected duration of elevated risk” according to the language, which was included in the unanimously approved statement “Meningococcal Vaccination: Recommendations of The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.”

The updated statement on meningococcal vaccination was developed in 2019 “to consolidate all existing ACIP recommendations for MenACWY and MenB vaccines in a single document,” said Sarah Mbaeyi, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, who presented immunogenicity data and the proposed recommendations.

The statement includes the recommendation of a MenB primary series for individuals aged 16-23 years based on shared clinical decision making. Kelly Moore, MD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., noted the importance of ongoing data collection, and said clinicians must make clear to patients that, “if they want protection, they need the booster.”

Approximately 7% of serogroup B cases in the United States are related to disease outbreaks, mainly among college students, Dr. Mbaeyi said. All 13 universities that experienced outbreaks between 2013 and 2019 have implemented a MenB primary series, and one university has implemented an off-label booster program.

The work group concluded that a MenB booster dose is necessary to sustain protection against serogroup B disease in persons at increased risk during an outbreak, and that the potential benefits outweighed the harms given the seriousness of meningococcal disease.

Paul Hunter, MD, of the City of Milwaukee Health Department, noted that “the booster recommendation gives more flexibility” in an outbreak response.

The committee also voted unanimously to approve the Vaccines for Children resolution for the meningococcal vaccine that updates language to align with the new recommendations.

The ACIP members had no financial conflicts to disclose.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

The committee voted unanimously in favor of a booster dose of MenB vaccine 1 year after completion of the primary series, with additional boosters every 2-3 years “for as long as risk remains” for high-risk persons, including microbiologists and persons with complement deficiency, complement inhibitor use, or asplenia.

The committee also voted unanimously in favor of a one-time MenB booster for individuals aged 10 years and older who are at least a year beyond completion of a MenB primary series and deemed at increased risk by public health officials in an outbreak situation.

In addition, “a booster dose interval of 6 months or more may be considered by public health officials depending on the specific outbreak, vaccine strategy, and projected duration of elevated risk” according to the language, which was included in the unanimously approved statement “Meningococcal Vaccination: Recommendations of The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.”

The updated statement on meningococcal vaccination was developed in 2019 “to consolidate all existing ACIP recommendations for MenACWY and MenB vaccines in a single document,” said Sarah Mbaeyi, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, who presented immunogenicity data and the proposed recommendations.

The statement includes the recommendation of a MenB primary series for individuals aged 16-23 years based on shared clinical decision making. Kelly Moore, MD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., noted the importance of ongoing data collection, and said clinicians must make clear to patients that, “if they want protection, they need the booster.”

Approximately 7% of serogroup B cases in the United States are related to disease outbreaks, mainly among college students, Dr. Mbaeyi said. All 13 universities that experienced outbreaks between 2013 and 2019 have implemented a MenB primary series, and one university has implemented an off-label booster program.

The work group concluded that a MenB booster dose is necessary to sustain protection against serogroup B disease in persons at increased risk during an outbreak, and that the potential benefits outweighed the harms given the seriousness of meningococcal disease.

Paul Hunter, MD, of the City of Milwaukee Health Department, noted that “the booster recommendation gives more flexibility” in an outbreak response.

The committee also voted unanimously to approve the Vaccines for Children resolution for the meningococcal vaccine that updates language to align with the new recommendations.

The ACIP members had no financial conflicts to disclose.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

The committee voted unanimously in favor of a booster dose of MenB vaccine 1 year after completion of the primary series, with additional boosters every 2-3 years “for as long as risk remains” for high-risk persons, including microbiologists and persons with complement deficiency, complement inhibitor use, or asplenia.

The committee also voted unanimously in favor of a one-time MenB booster for individuals aged 10 years and older who are at least a year beyond completion of a MenB primary series and deemed at increased risk by public health officials in an outbreak situation.

In addition, “a booster dose interval of 6 months or more may be considered by public health officials depending on the specific outbreak, vaccine strategy, and projected duration of elevated risk” according to the language, which was included in the unanimously approved statement “Meningococcal Vaccination: Recommendations of The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.”

The updated statement on meningococcal vaccination was developed in 2019 “to consolidate all existing ACIP recommendations for MenACWY and MenB vaccines in a single document,” said Sarah Mbaeyi, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, who presented immunogenicity data and the proposed recommendations.

The statement includes the recommendation of a MenB primary series for individuals aged 16-23 years based on shared clinical decision making. Kelly Moore, MD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., noted the importance of ongoing data collection, and said clinicians must make clear to patients that, “if they want protection, they need the booster.”

Approximately 7% of serogroup B cases in the United States are related to disease outbreaks, mainly among college students, Dr. Mbaeyi said. All 13 universities that experienced outbreaks between 2013 and 2019 have implemented a MenB primary series, and one university has implemented an off-label booster program.

The work group concluded that a MenB booster dose is necessary to sustain protection against serogroup B disease in persons at increased risk during an outbreak, and that the potential benefits outweighed the harms given the seriousness of meningococcal disease.

Paul Hunter, MD, of the City of Milwaukee Health Department, noted that “the booster recommendation gives more flexibility” in an outbreak response.

The committee also voted unanimously to approve the Vaccines for Children resolution for the meningococcal vaccine that updates language to align with the new recommendations.

The ACIP members had no financial conflicts to disclose.

REPORTING FROM AN ACIP MEETING

ACIP approves flu vaccine recommendations for 2019-2020 season

All individuals aged 6 months and older should receive the influenza vaccine by the end of October next season, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Committee on Immunization Practices. The committee voted unanimously to accept minor updates to the ACIP flu recommendations for the 2019-2020 season, but no major changes were made from recent years.

The past flu season was moderate overall, but notable for two waves of viral infections of similar magnitude, one with H1N1 and another with H3N2, said Lynette Brewer of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, who presented data on last year’s flu activity.

Last year’s vaccine likely prevented between 40,000 and 90,000 hospitalizations, but mostly reduced the burden of H1N1 disease and provided no real protection against H3N2, she said.

The recommended H3N2 component for next season is A/Kansas/14/2017–like virus, which is genetically similar to the H3N2 that circulated last year.

Lisa Grohskopf, MD, of the CDC’s influenza division, presented the minor adjustments that included the changes in vaccine composition for next year, some licensure changes, and a new table summarizing dose volumes. Also, language was changed to advise vaccination for all eligible individuals by the end of October, and individuals who need two doses should have the first one as soon as it becomes available, in July or August if possible. The updated language also clarified that 8 year olds who need two doses should receive the second dose, even if they turn 9 between the two doses.

Additional guidance updates approved by the committee included harmonizing language on groups that should be the focus of vaccination in the event of limited supply to be more consistent with the 2011 ACIP Recommendations for the Immunization of Health Care Personnel.

The committee also voted unanimously to accept the proposed influenza vaccine in the Vaccines for Children program; there were no changes in recommended dosing intervals, dosages, contraindications, or precautions, according to Frank Whitlach of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, who presented the Vaccines for Children information.

The ACIP members had no financial conflicts to disclose.

All individuals aged 6 months and older should receive the influenza vaccine by the end of October next season, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Committee on Immunization Practices. The committee voted unanimously to accept minor updates to the ACIP flu recommendations for the 2019-2020 season, but no major changes were made from recent years.

The past flu season was moderate overall, but notable for two waves of viral infections of similar magnitude, one with H1N1 and another with H3N2, said Lynette Brewer of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, who presented data on last year’s flu activity.

Last year’s vaccine likely prevented between 40,000 and 90,000 hospitalizations, but mostly reduced the burden of H1N1 disease and provided no real protection against H3N2, she said.

The recommended H3N2 component for next season is A/Kansas/14/2017–like virus, which is genetically similar to the H3N2 that circulated last year.

Lisa Grohskopf, MD, of the CDC’s influenza division, presented the minor adjustments that included the changes in vaccine composition for next year, some licensure changes, and a new table summarizing dose volumes. Also, language was changed to advise vaccination for all eligible individuals by the end of October, and individuals who need two doses should have the first one as soon as it becomes available, in July or August if possible. The updated language also clarified that 8 year olds who need two doses should receive the second dose, even if they turn 9 between the two doses.

Additional guidance updates approved by the committee included harmonizing language on groups that should be the focus of vaccination in the event of limited supply to be more consistent with the 2011 ACIP Recommendations for the Immunization of Health Care Personnel.

The committee also voted unanimously to accept the proposed influenza vaccine in the Vaccines for Children program; there were no changes in recommended dosing intervals, dosages, contraindications, or precautions, according to Frank Whitlach of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, who presented the Vaccines for Children information.

The ACIP members had no financial conflicts to disclose.

All individuals aged 6 months and older should receive the influenza vaccine by the end of October next season, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Committee on Immunization Practices. The committee voted unanimously to accept minor updates to the ACIP flu recommendations for the 2019-2020 season, but no major changes were made from recent years.

The past flu season was moderate overall, but notable for two waves of viral infections of similar magnitude, one with H1N1 and another with H3N2, said Lynette Brewer of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, who presented data on last year’s flu activity.

Last year’s vaccine likely prevented between 40,000 and 90,000 hospitalizations, but mostly reduced the burden of H1N1 disease and provided no real protection against H3N2, she said.

The recommended H3N2 component for next season is A/Kansas/14/2017–like virus, which is genetically similar to the H3N2 that circulated last year.

Lisa Grohskopf, MD, of the CDC’s influenza division, presented the minor adjustments that included the changes in vaccine composition for next year, some licensure changes, and a new table summarizing dose volumes. Also, language was changed to advise vaccination for all eligible individuals by the end of October, and individuals who need two doses should have the first one as soon as it becomes available, in July or August if possible. The updated language also clarified that 8 year olds who need two doses should receive the second dose, even if they turn 9 between the two doses.

Additional guidance updates approved by the committee included harmonizing language on groups that should be the focus of vaccination in the event of limited supply to be more consistent with the 2011 ACIP Recommendations for the Immunization of Health Care Personnel.

The committee also voted unanimously to accept the proposed influenza vaccine in the Vaccines for Children program; there were no changes in recommended dosing intervals, dosages, contraindications, or precautions, according to Frank Whitlach of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, who presented the Vaccines for Children information.

The ACIP members had no financial conflicts to disclose.

REPORTING FROM AN ACIP MEETING

ACIP endorses catch-up hepatitis A vaccinations

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Committee on Immunization Practices voted unanimously in support of three recommendations for the use of hepatitis A vaccines.

The committee recommended catch-up vaccination at any age for all children aged 2-18 years who had not previously received hepatitis A vaccination, recommended that all persons with HIV aged 1 year and older should be vaccinated with the hepatitis A vaccine, and approved updating the language in the full hepatitis A vaccine statement, “Prevention of Hepatitis A Virus Infection in The United States: Recommendations of The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.”

Catch-up vaccination will expand coverage to adolescents who might have missed it, and data show that the vaccine effectiveness is high, and the rates of adverse events are low in the child and adolescent population, said Noele Nelson, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, who presented the recommendations to the committee. “Recent outbreaks are occurring primarily among adults,” and many cases are among persons who use drugs or are homeless, she added.

Several committee members noted that the specific recommendations for catch-up in children and teens and for vaccination of HIV patients offer more opportunities for protection than risk-based recommendations. Catching up with vaccinating adolescents is “more effective than tracking down high-risk adults later in life,” noted Grace Lee, MD, of Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford, Calif.

The committee also recommended that all persons with HIV aged 1 year and older should be vaccinated with the hepatitis A vaccine. Data on persons with HIV show that approximately 60% have at least one risk factor for hepatitis A, such as men who have sex with men or individuals engaged in intravenous drug use, said Dr. Nelson. Data also show that individuals with HIV are at increased risk for complications if they get hepatitis A.

The committee’s approval of the full hepatitis A vaccine statement included one notable change – the removal of clotting factor disorders as a high-risk group. The risk has decreased over time based on improvements such as better screening of source plasma, and this group is now at no greater risk than the general population, according to work group chair Kelly Moore, MD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

The ACIP members had no financial conflicts to disclose.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Committee on Immunization Practices voted unanimously in support of three recommendations for the use of hepatitis A vaccines.

The committee recommended catch-up vaccination at any age for all children aged 2-18 years who had not previously received hepatitis A vaccination, recommended that all persons with HIV aged 1 year and older should be vaccinated with the hepatitis A vaccine, and approved updating the language in the full hepatitis A vaccine statement, “Prevention of Hepatitis A Virus Infection in The United States: Recommendations of The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.”

Catch-up vaccination will expand coverage to adolescents who might have missed it, and data show that the vaccine effectiveness is high, and the rates of adverse events are low in the child and adolescent population, said Noele Nelson, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, who presented the recommendations to the committee. “Recent outbreaks are occurring primarily among adults,” and many cases are among persons who use drugs or are homeless, she added.

Several committee members noted that the specific recommendations for catch-up in children and teens and for vaccination of HIV patients offer more opportunities for protection than risk-based recommendations. Catching up with vaccinating adolescents is “more effective than tracking down high-risk adults later in life,” noted Grace Lee, MD, of Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford, Calif.

The committee also recommended that all persons with HIV aged 1 year and older should be vaccinated with the hepatitis A vaccine. Data on persons with HIV show that approximately 60% have at least one risk factor for hepatitis A, such as men who have sex with men or individuals engaged in intravenous drug use, said Dr. Nelson. Data also show that individuals with HIV are at increased risk for complications if they get hepatitis A.

The committee’s approval of the full hepatitis A vaccine statement included one notable change – the removal of clotting factor disorders as a high-risk group. The risk has decreased over time based on improvements such as better screening of source plasma, and this group is now at no greater risk than the general population, according to work group chair Kelly Moore, MD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

The ACIP members had no financial conflicts to disclose.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Committee on Immunization Practices voted unanimously in support of three recommendations for the use of hepatitis A vaccines.

The committee recommended catch-up vaccination at any age for all children aged 2-18 years who had not previously received hepatitis A vaccination, recommended that all persons with HIV aged 1 year and older should be vaccinated with the hepatitis A vaccine, and approved updating the language in the full hepatitis A vaccine statement, “Prevention of Hepatitis A Virus Infection in The United States: Recommendations of The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.”

Catch-up vaccination will expand coverage to adolescents who might have missed it, and data show that the vaccine effectiveness is high, and the rates of adverse events are low in the child and adolescent population, said Noele Nelson, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, who presented the recommendations to the committee. “Recent outbreaks are occurring primarily among adults,” and many cases are among persons who use drugs or are homeless, she added.

Several committee members noted that the specific recommendations for catch-up in children and teens and for vaccination of HIV patients offer more opportunities for protection than risk-based recommendations. Catching up with vaccinating adolescents is “more effective than tracking down high-risk adults later in life,” noted Grace Lee, MD, of Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford, Calif.

The committee also recommended that all persons with HIV aged 1 year and older should be vaccinated with the hepatitis A vaccine. Data on persons with HIV show that approximately 60% have at least one risk factor for hepatitis A, such as men who have sex with men or individuals engaged in intravenous drug use, said Dr. Nelson. Data also show that individuals with HIV are at increased risk for complications if they get hepatitis A.

The committee’s approval of the full hepatitis A vaccine statement included one notable change – the removal of clotting factor disorders as a high-risk group. The risk has decreased over time based on improvements such as better screening of source plasma, and this group is now at no greater risk than the general population, according to work group chair Kelly Moore, MD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

The ACIP members had no financial conflicts to disclose.

REPORTING FROM AN ACIP MEETING

ACIP adds hexavalent vaccine to VFC program

The pediatric hexavalent vaccine (DTaP-[inactivated poliovirus] IPV-[hepatitis B] HepB-[Haemophilis influenzae type b] Hib) should be included as an option in the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program for the infant series at ages 2, 4, and 6 months, according to unanimous votes at a meeting of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

The addition of the vaccine to the VFC program required no motions on the part of the committee, but involved separate votes on each component of the vaccine.

Combination vaccination has been associated with increased coverage and more likely completion of the full infant vaccine series, said Sara Oliver, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

The new vaccine is being developed jointly by Sanofi and Merck, and has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in children through age 4 years.

Dr. Oliver presented evidence that the safety profile of the combination vaccine is consistent with that of the component vaccines. In addition, “use of combination vaccines can reduce the number of injections patient receive and alleviate concern associated with the number of injections,” she said. However, “considerations should include provider assessment, patient preference, and the potential for adverse events.”

although it will not be available until 2021 in order to ensure sufficient supply, Dr. Oliver noted.

The combination vaccination work group considered whether the new vaccine should be preferentially recommended for American Indian and Alaskan Native populations, but they concluded that post–dose one immunogenicity data are needed before such a preferential recommendation can be made.

The ACIP members had no financial conflicts to disclose.

The pediatric hexavalent vaccine (DTaP-[inactivated poliovirus] IPV-[hepatitis B] HepB-[Haemophilis influenzae type b] Hib) should be included as an option in the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program for the infant series at ages 2, 4, and 6 months, according to unanimous votes at a meeting of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

The addition of the vaccine to the VFC program required no motions on the part of the committee, but involved separate votes on each component of the vaccine.

Combination vaccination has been associated with increased coverage and more likely completion of the full infant vaccine series, said Sara Oliver, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

The new vaccine is being developed jointly by Sanofi and Merck, and has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in children through age 4 years.

Dr. Oliver presented evidence that the safety profile of the combination vaccine is consistent with that of the component vaccines. In addition, “use of combination vaccines can reduce the number of injections patient receive and alleviate concern associated with the number of injections,” she said. However, “considerations should include provider assessment, patient preference, and the potential for adverse events.”

although it will not be available until 2021 in order to ensure sufficient supply, Dr. Oliver noted.

The combination vaccination work group considered whether the new vaccine should be preferentially recommended for American Indian and Alaskan Native populations, but they concluded that post–dose one immunogenicity data are needed before such a preferential recommendation can be made.

The ACIP members had no financial conflicts to disclose.

The pediatric hexavalent vaccine (DTaP-[inactivated poliovirus] IPV-[hepatitis B] HepB-[Haemophilis influenzae type b] Hib) should be included as an option in the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program for the infant series at ages 2, 4, and 6 months, according to unanimous votes at a meeting of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

The addition of the vaccine to the VFC program required no motions on the part of the committee, but involved separate votes on each component of the vaccine.

Combination vaccination has been associated with increased coverage and more likely completion of the full infant vaccine series, said Sara Oliver, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

The new vaccine is being developed jointly by Sanofi and Merck, and has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in children through age 4 years.

Dr. Oliver presented evidence that the safety profile of the combination vaccine is consistent with that of the component vaccines. In addition, “use of combination vaccines can reduce the number of injections patient receive and alleviate concern associated with the number of injections,” she said. However, “considerations should include provider assessment, patient preference, and the potential for adverse events.”

although it will not be available until 2021 in order to ensure sufficient supply, Dr. Oliver noted.

The combination vaccination work group considered whether the new vaccine should be preferentially recommended for American Indian and Alaskan Native populations, but they concluded that post–dose one immunogenicity data are needed before such a preferential recommendation can be made.

The ACIP members had no financial conflicts to disclose.

REPORTING FROM AN ACIP MEETING

ACIP favors shared decision on pneumococcal vaccine for older adults

Pneumococcal vaccination with the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) based on shared clinical decision making is recommended for immunocompetent adults aged 65 years and older who have not previously received PCV13, and all adults aged 65 years and older should continue to receive the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23), according to a vote at a meeting of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

The motion passed with an 11-1 vote after members voted down two other options to either discontinue or continue the current recommendation of PCV13 for all immunocompetent adults aged 65 years and older. The current recommendation for PCV13 for adults aged 65 years and older has been in place since 2014.

The pneumococcal work group assessed indirect effects of the pediatric PCV vaccination on older adults prior to 2014 and since 2014, and what additional benefits might be expected if routine vaccination of older adults continued.

“Indirect effects have been observed in all age groups” said Almea Matanock, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. Although there were no safety concerns, the public health impact of continued vaccination of adults was minimal.

Although PCV13 resulted in a 75% reduction in vaccine-type invasive pneumococcal disease and a 45% reduction in vaccine-type nonbacteremic pneumonia in 2014, the annual number needed to vaccinate to prevent a single case of outpatient pneumonia was 2,600, said Dr. Matanock.

Dr. Matanock presented key issues from the Evidence to Recommendations Framework for and against the recommendation for PCV13 in older adults. Work group comments in favor of continuing the recommendation for PCV13 in older adults included effective disease prevention and the potential negative impact on the importance of adult vaccines if the vaccine was no longer recommended. However, some work group members and committee members expressed concern about resource allocation and steering vaccines away from younger age groups in whom they have been more consistently effective.

Paul Hunter, MD, of the City of Milwaukee Health Department, voted against the shared clinical decision making, and instead favored discontinuing the recommendation for PCV13 for older adults. “I think clinicians need a clear message,” he said, adding that “the public health bang for the buck is with the kids.”

“I think there was a recognition that the population level benefit is minimal,” said work group chair Grace Lee, MD.

Although the work group recognized some benefit for older adults, the burden of disease for PCV-specific disease is low, compared with all-cause pneumonia, said Dr. Lee of Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford, Calif. However, the recommendation for shared clinical decision making allows for potential insurance coverage of the vaccine for adults who decide after discussion with their health care provider that they would benefit.

“We are still unpacking this construct” of shared clinical decision making, which in this case applies to adults without immunocompromising conditions, and is more of a provider assessment than a risk assessment, she said.

The ACIP members had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Pneumococcal vaccination with the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) based on shared clinical decision making is recommended for immunocompetent adults aged 65 years and older who have not previously received PCV13, and all adults aged 65 years and older should continue to receive the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23), according to a vote at a meeting of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

The motion passed with an 11-1 vote after members voted down two other options to either discontinue or continue the current recommendation of PCV13 for all immunocompetent adults aged 65 years and older. The current recommendation for PCV13 for adults aged 65 years and older has been in place since 2014.

The pneumococcal work group assessed indirect effects of the pediatric PCV vaccination on older adults prior to 2014 and since 2014, and what additional benefits might be expected if routine vaccination of older adults continued.

“Indirect effects have been observed in all age groups” said Almea Matanock, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. Although there were no safety concerns, the public health impact of continued vaccination of adults was minimal.

Although PCV13 resulted in a 75% reduction in vaccine-type invasive pneumococcal disease and a 45% reduction in vaccine-type nonbacteremic pneumonia in 2014, the annual number needed to vaccinate to prevent a single case of outpatient pneumonia was 2,600, said Dr. Matanock.

Dr. Matanock presented key issues from the Evidence to Recommendations Framework for and against the recommendation for PCV13 in older adults. Work group comments in favor of continuing the recommendation for PCV13 in older adults included effective disease prevention and the potential negative impact on the importance of adult vaccines if the vaccine was no longer recommended. However, some work group members and committee members expressed concern about resource allocation and steering vaccines away from younger age groups in whom they have been more consistently effective.

Paul Hunter, MD, of the City of Milwaukee Health Department, voted against the shared clinical decision making, and instead favored discontinuing the recommendation for PCV13 for older adults. “I think clinicians need a clear message,” he said, adding that “the public health bang for the buck is with the kids.”

“I think there was a recognition that the population level benefit is minimal,” said work group chair Grace Lee, MD.

Although the work group recognized some benefit for older adults, the burden of disease for PCV-specific disease is low, compared with all-cause pneumonia, said Dr. Lee of Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford, Calif. However, the recommendation for shared clinical decision making allows for potential insurance coverage of the vaccine for adults who decide after discussion with their health care provider that they would benefit.

“We are still unpacking this construct” of shared clinical decision making, which in this case applies to adults without immunocompromising conditions, and is more of a provider assessment than a risk assessment, she said.

The ACIP members had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Pneumococcal vaccination with the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) based on shared clinical decision making is recommended for immunocompetent adults aged 65 years and older who have not previously received PCV13, and all adults aged 65 years and older should continue to receive the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23), according to a vote at a meeting of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

The motion passed with an 11-1 vote after members voted down two other options to either discontinue or continue the current recommendation of PCV13 for all immunocompetent adults aged 65 years and older. The current recommendation for PCV13 for adults aged 65 years and older has been in place since 2014.

The pneumococcal work group assessed indirect effects of the pediatric PCV vaccination on older adults prior to 2014 and since 2014, and what additional benefits might be expected if routine vaccination of older adults continued.

“Indirect effects have been observed in all age groups” said Almea Matanock, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. Although there were no safety concerns, the public health impact of continued vaccination of adults was minimal.

Although PCV13 resulted in a 75% reduction in vaccine-type invasive pneumococcal disease and a 45% reduction in vaccine-type nonbacteremic pneumonia in 2014, the annual number needed to vaccinate to prevent a single case of outpatient pneumonia was 2,600, said Dr. Matanock.

Dr. Matanock presented key issues from the Evidence to Recommendations Framework for and against the recommendation for PCV13 in older adults. Work group comments in favor of continuing the recommendation for PCV13 in older adults included effective disease prevention and the potential negative impact on the importance of adult vaccines if the vaccine was no longer recommended. However, some work group members and committee members expressed concern about resource allocation and steering vaccines away from younger age groups in whom they have been more consistently effective.

Paul Hunter, MD, of the City of Milwaukee Health Department, voted against the shared clinical decision making, and instead favored discontinuing the recommendation for PCV13 for older adults. “I think clinicians need a clear message,” he said, adding that “the public health bang for the buck is with the kids.”

“I think there was a recognition that the population level benefit is minimal,” said work group chair Grace Lee, MD.

Although the work group recognized some benefit for older adults, the burden of disease for PCV-specific disease is low, compared with all-cause pneumonia, said Dr. Lee of Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford, Calif. However, the recommendation for shared clinical decision making allows for potential insurance coverage of the vaccine for adults who decide after discussion with their health care provider that they would benefit.

“We are still unpacking this construct” of shared clinical decision making, which in this case applies to adults without immunocompromising conditions, and is more of a provider assessment than a risk assessment, she said.

The ACIP members had no financial conflicts to disclose.

REPORTING FROM AN ACIP MEETING

ACIP extends HPV vaccine coverage

according to a unanimous vote at a meeting of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

This change affects males aged 22 through 26 years; the HPV vaccine is currently recommended for males and females aged 11 or 12 years, with catch-up vaccination through age 21 for males and age 26 for females.

The change was supported in part by increased interest in simplifying and harmonizing the vaccine schedule, said Lauri Markowitz, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), who presented the HPV work group’s considerations.

In addition, the committee voted 10-4 in favor of catch-up HPV vaccination, based on shared clinical decision making, for all adults aged 27 through 45 years.

Although the current program of HPV vaccination for youth has demonstrated effectiveness, data from multiple models suggest that widespread HPV vaccination for adults older than 26 years is much less cost effective, and would yield relatively small additional health benefits, Dr. Markowitz said.

The HPV work group reviewed data from a range of clinical trials, epidemiology, and natural history, as well as results from five different health economic models. They concluded that an assessment of benefits and harms favors expanding the catch-up vaccination to all individuals through 26 years, said Elissa Meites, MD, of the CDC, who presented the official work group opinion. The group’s opinion on the second question was that the additional population level benefit of expanding HPV vaccination to all adults would be minimal and not a reasonable and effective allocation of resources, but that shared clinical decision making would allow flexibility.

The committee expressed strong opinions about the potential for shared clinical decision making as a policy for vaccination for adults older than 26 years. Some felt that this option was a way to include adults at risk for HPV, such as divorced women with new partners, or women getting married for the first time later in life who might not have been exposed to HPV through other relationships. In addition, supporters noted that the shared clinical decision-making option would allow for potential insurance coverage, and would involve discussion between doctors and patients to assess risk.

However, other committee members felt that any recommendation for older adult vaccination would distract clinicians from the importance and value of HPV vaccination for the target age group of 11- and 12-year-olds, and might divert resources from the younger age group in whom it has shown the most benefit.

Resource allocation was a concern voiced by many committee members. Kelly Moore, MD, MPH, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., said she voted no on expanding vaccination to older adults because “we didn’t have details on shared clinical decision making, in the absence of information on what that meant, and in the presence of supply questions, I didn’t feel comfortable expanding vaccination to a huge population,” she said.

Paul Hunter, MD, of the City of Milwaukee Health Department, also voted no, and expressed concern that expanding the HPV vaccination recommendations to older adults would send the message that vaccination for children and teens is not effective or important.

The text of the new recommendations for routine and catch-up vaccination states that the recommendations “also apply to MSM [men who have sex with men], transgender people, and people with immunocompromising conditions.”

The ACIP members had no financial conflicts to disclose.

according to a unanimous vote at a meeting of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

This change affects males aged 22 through 26 years; the HPV vaccine is currently recommended for males and females aged 11 or 12 years, with catch-up vaccination through age 21 for males and age 26 for females.

The change was supported in part by increased interest in simplifying and harmonizing the vaccine schedule, said Lauri Markowitz, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), who presented the HPV work group’s considerations.

In addition, the committee voted 10-4 in favor of catch-up HPV vaccination, based on shared clinical decision making, for all adults aged 27 through 45 years.

Although the current program of HPV vaccination for youth has demonstrated effectiveness, data from multiple models suggest that widespread HPV vaccination for adults older than 26 years is much less cost effective, and would yield relatively small additional health benefits, Dr. Markowitz said.

The HPV work group reviewed data from a range of clinical trials, epidemiology, and natural history, as well as results from five different health economic models. They concluded that an assessment of benefits and harms favors expanding the catch-up vaccination to all individuals through 26 years, said Elissa Meites, MD, of the CDC, who presented the official work group opinion. The group’s opinion on the second question was that the additional population level benefit of expanding HPV vaccination to all adults would be minimal and not a reasonable and effective allocation of resources, but that shared clinical decision making would allow flexibility.

The committee expressed strong opinions about the potential for shared clinical decision making as a policy for vaccination for adults older than 26 years. Some felt that this option was a way to include adults at risk for HPV, such as divorced women with new partners, or women getting married for the first time later in life who might not have been exposed to HPV through other relationships. In addition, supporters noted that the shared clinical decision-making option would allow for potential insurance coverage, and would involve discussion between doctors and patients to assess risk.

However, other committee members felt that any recommendation for older adult vaccination would distract clinicians from the importance and value of HPV vaccination for the target age group of 11- and 12-year-olds, and might divert resources from the younger age group in whom it has shown the most benefit.

Resource allocation was a concern voiced by many committee members. Kelly Moore, MD, MPH, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., said she voted no on expanding vaccination to older adults because “we didn’t have details on shared clinical decision making, in the absence of information on what that meant, and in the presence of supply questions, I didn’t feel comfortable expanding vaccination to a huge population,” she said.

Paul Hunter, MD, of the City of Milwaukee Health Department, also voted no, and expressed concern that expanding the HPV vaccination recommendations to older adults would send the message that vaccination for children and teens is not effective or important.

The text of the new recommendations for routine and catch-up vaccination states that the recommendations “also apply to MSM [men who have sex with men], transgender people, and people with immunocompromising conditions.”

The ACIP members had no financial conflicts to disclose.

according to a unanimous vote at a meeting of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

This change affects males aged 22 through 26 years; the HPV vaccine is currently recommended for males and females aged 11 or 12 years, with catch-up vaccination through age 21 for males and age 26 for females.

The change was supported in part by increased interest in simplifying and harmonizing the vaccine schedule, said Lauri Markowitz, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), who presented the HPV work group’s considerations.

In addition, the committee voted 10-4 in favor of catch-up HPV vaccination, based on shared clinical decision making, for all adults aged 27 through 45 years.

Although the current program of HPV vaccination for youth has demonstrated effectiveness, data from multiple models suggest that widespread HPV vaccination for adults older than 26 years is much less cost effective, and would yield relatively small additional health benefits, Dr. Markowitz said.

The HPV work group reviewed data from a range of clinical trials, epidemiology, and natural history, as well as results from five different health economic models. They concluded that an assessment of benefits and harms favors expanding the catch-up vaccination to all individuals through 26 years, said Elissa Meites, MD, of the CDC, who presented the official work group opinion. The group’s opinion on the second question was that the additional population level benefit of expanding HPV vaccination to all adults would be minimal and not a reasonable and effective allocation of resources, but that shared clinical decision making would allow flexibility.

The committee expressed strong opinions about the potential for shared clinical decision making as a policy for vaccination for adults older than 26 years. Some felt that this option was a way to include adults at risk for HPV, such as divorced women with new partners, or women getting married for the first time later in life who might not have been exposed to HPV through other relationships. In addition, supporters noted that the shared clinical decision-making option would allow for potential insurance coverage, and would involve discussion between doctors and patients to assess risk.

However, other committee members felt that any recommendation for older adult vaccination would distract clinicians from the importance and value of HPV vaccination for the target age group of 11- and 12-year-olds, and might divert resources from the younger age group in whom it has shown the most benefit.

Resource allocation was a concern voiced by many committee members. Kelly Moore, MD, MPH, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., said she voted no on expanding vaccination to older adults because “we didn’t have details on shared clinical decision making, in the absence of information on what that meant, and in the presence of supply questions, I didn’t feel comfortable expanding vaccination to a huge population,” she said.

Paul Hunter, MD, of the City of Milwaukee Health Department, also voted no, and expressed concern that expanding the HPV vaccination recommendations to older adults would send the message that vaccination for children and teens is not effective or important.

The text of the new recommendations for routine and catch-up vaccination states that the recommendations “also apply to MSM [men who have sex with men], transgender people, and people with immunocompromising conditions.”

The ACIP members had no financial conflicts to disclose.

REPORTING FROM AN ACIP MEETING

Substantial reductions in HPV infections, CIN2+ after vaccination

The introduction of the human papillomavirus according to a meta-analysis of data from more than 60 million individuals worldwide.

Mélanie Drolet, PhD, from the Centre de recherche du CHU de Québec–Université Laval, and coauthors of the HPV Vaccination Impact Study Group reported the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis of 65 studies showing pre- and postvaccination frequency of at least one HPV-related endpoint published in the Lancet. The studies were conducted in 14 high-income countries, 12 of which were vaccinating only women and girls, with the results at 5-8 years published in the Lancet.

At 5-8 years after a vaccination program was implemented, there was a significant 83% reduction in the prevalence of HPV 16 and 18, both of which are targeted by the vaccine, among girls aged 13-19 years; a 66% reduction among women aged 20-24 years; and a 37% reduction in women aged 25-29 years, even though most of these women were unvaccinated.

There also were significant decreases at 5-8 years in the prevalence of HPV subtypes 31, 33, and 45, which are not included in the vaccine but against which the vaccine appears to offer cross-protection. Among girls aged 13-19 years, there was a significant 54% reduction in the prevalence of these subtypes, among women aged 20-24 years there was a nonsignificant 28% decrease, but among women aged 25-29 years, there was no significant decrease.

The analysis also found significant declines in the prevalence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasias (CINs) of grade 2 or above. At 5-9 years after vaccination was introduced, CIN2+ decreased by 51% among girls aged 15-19 years who also were screened for cervical cancer, and by 31% among women aged 20-24 years.

However, over the same time period, the rates of CIN2+ increased by a significant 19% among mostly unvaccinated women aged 25-29 years and 23% among mostly unvaccinated women aged 30-39 years, despite both groups being screened for cervical abnormalities.

While most of the countries in the study vaccinated only girls and women, two studies did find nonsignificant decreases in the prevalence of HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, and 45 among boys aged 16-19 years, but not among men aged 20-24 years.

HPV vaccination also was associated with significant declines in the incidence of anogenital warts among both males and females. In the first 4 years alone, vaccination was associated with significant reductions in anogenital wart diagnoses among females aged 15-29 years, as well as nonsignificant but “substantial” reductions in unvaccinated boys aged 15-19 years.

After 5-8 years, anogenital wart diagnoses decreased by 67% among girls aged 15-19 years, significantly by 54% among women aged 20-24 years, and 31% among women aged 25-29 years – all significant changes. Among boys aged 15-19 years, anogenital wart diagnoses decreased by a significant 48%, and among men aged 20-24 years they decreased by a significant 32%.

The decreases in anogenital wart diagnoses were even greater in countries that implemented vaccination among multiple cohorts simultaneously and achieved high vaccination coverage, compared with countries that vaccinated only one cohort at a time or had low routine vaccination coverage.

“Our study is the first to show the real-world additional benefit of multicohort HPV vaccination and high routine vaccination coverage, and the fast and substantial herd effects of vaccination in countries which implement these measures,” wrote Dr. Drolet and coauthors. “The greater impact of multicohort vaccination was similar when restricting the analyses to countries with high routine vaccination coverage.”

They pointed to the World Health Organization’s recently revised position on HPV vaccination, which now recommends vaccination of multiple cohorts of girls aged 9-14 years, although they raised the question of what might be the optimal number of age cohorts. “Number needed to vaccinate and cost-effectiveness analyses in high-income countries suggest that vaccinating multiple cohorts of individuals up to 18 years of age is highly efficient and cost effective.”

This analysis by Drolet et al. “provides compelling evidence for HPV vaccine efficacy on all outcomes explored and for almost all age strata,” Dr. Silvia de Sanjose, of PATH in Seattle, and Dr. Sinead Delany-Moretlwe of the Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, said in an accompanying editorial (Lancet. 2019 Jun 26. doi: 10.1016/ S0140-6736[19]30549-5). This study shows just how effective HPV vaccination can be across a range of outcomes and ages, and also demonstrates the herd immunity benefits, particularly when multiple cohorts are vaccinated and there is high vaccination coverage.

One key limitation of this analysis is the lack of data from low- and middle-income countries. The data by Drolet et al. “emphasise the importance of redoubling our efforts to tackle the fiscal, supply, and programmatic barriers that currently limit HPV vaccine programmes; with these efforts, HPV vaccination could become a hallmark investment of cancer prevention in the 21st century,” Dr. de Sanjose and Dr. Delany-Moretlwe concluded.

The study was funded by WHO, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and Fonds de recherche du Québec–Santé. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Dr. de Sanjose declared previous institutional support from Merck.

SOURCE: Drolet M et al. Lancet 2019 Jun 26. doi: 10.1016/ S0140-6736(19)30298-3.

The introduction of the human papillomavirus according to a meta-analysis of data from more than 60 million individuals worldwide.

Mélanie Drolet, PhD, from the Centre de recherche du CHU de Québec–Université Laval, and coauthors of the HPV Vaccination Impact Study Group reported the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis of 65 studies showing pre- and postvaccination frequency of at least one HPV-related endpoint published in the Lancet. The studies were conducted in 14 high-income countries, 12 of which were vaccinating only women and girls, with the results at 5-8 years published in the Lancet.

At 5-8 years after a vaccination program was implemented, there was a significant 83% reduction in the prevalence of HPV 16 and 18, both of which are targeted by the vaccine, among girls aged 13-19 years; a 66% reduction among women aged 20-24 years; and a 37% reduction in women aged 25-29 years, even though most of these women were unvaccinated.

There also were significant decreases at 5-8 years in the prevalence of HPV subtypes 31, 33, and 45, which are not included in the vaccine but against which the vaccine appears to offer cross-protection. Among girls aged 13-19 years, there was a significant 54% reduction in the prevalence of these subtypes, among women aged 20-24 years there was a nonsignificant 28% decrease, but among women aged 25-29 years, there was no significant decrease.

The analysis also found significant declines in the prevalence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasias (CINs) of grade 2 or above. At 5-9 years after vaccination was introduced, CIN2+ decreased by 51% among girls aged 15-19 years who also were screened for cervical cancer, and by 31% among women aged 20-24 years.

However, over the same time period, the rates of CIN2+ increased by a significant 19% among mostly unvaccinated women aged 25-29 years and 23% among mostly unvaccinated women aged 30-39 years, despite both groups being screened for cervical abnormalities.

While most of the countries in the study vaccinated only girls and women, two studies did find nonsignificant decreases in the prevalence of HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, and 45 among boys aged 16-19 years, but not among men aged 20-24 years.

HPV vaccination also was associated with significant declines in the incidence of anogenital warts among both males and females. In the first 4 years alone, vaccination was associated with significant reductions in anogenital wart diagnoses among females aged 15-29 years, as well as nonsignificant but “substantial” reductions in unvaccinated boys aged 15-19 years.

After 5-8 years, anogenital wart diagnoses decreased by 67% among girls aged 15-19 years, significantly by 54% among women aged 20-24 years, and 31% among women aged 25-29 years – all significant changes. Among boys aged 15-19 years, anogenital wart diagnoses decreased by a significant 48%, and among men aged 20-24 years they decreased by a significant 32%.

The decreases in anogenital wart diagnoses were even greater in countries that implemented vaccination among multiple cohorts simultaneously and achieved high vaccination coverage, compared with countries that vaccinated only one cohort at a time or had low routine vaccination coverage.

“Our study is the first to show the real-world additional benefit of multicohort HPV vaccination and high routine vaccination coverage, and the fast and substantial herd effects of vaccination in countries which implement these measures,” wrote Dr. Drolet and coauthors. “The greater impact of multicohort vaccination was similar when restricting the analyses to countries with high routine vaccination coverage.”

They pointed to the World Health Organization’s recently revised position on HPV vaccination, which now recommends vaccination of multiple cohorts of girls aged 9-14 years, although they raised the question of what might be the optimal number of age cohorts. “Number needed to vaccinate and cost-effectiveness analyses in high-income countries suggest that vaccinating multiple cohorts of individuals up to 18 years of age is highly efficient and cost effective.”

This analysis by Drolet et al. “provides compelling evidence for HPV vaccine efficacy on all outcomes explored and for almost all age strata,” Dr. Silvia de Sanjose, of PATH in Seattle, and Dr. Sinead Delany-Moretlwe of the Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, said in an accompanying editorial (Lancet. 2019 Jun 26. doi: 10.1016/ S0140-6736[19]30549-5). This study shows just how effective HPV vaccination can be across a range of outcomes and ages, and also demonstrates the herd immunity benefits, particularly when multiple cohorts are vaccinated and there is high vaccination coverage.

One key limitation of this analysis is the lack of data from low- and middle-income countries. The data by Drolet et al. “emphasise the importance of redoubling our efforts to tackle the fiscal, supply, and programmatic barriers that currently limit HPV vaccine programmes; with these efforts, HPV vaccination could become a hallmark investment of cancer prevention in the 21st century,” Dr. de Sanjose and Dr. Delany-Moretlwe concluded.

The study was funded by WHO, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and Fonds de recherche du Québec–Santé. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Dr. de Sanjose declared previous institutional support from Merck.

SOURCE: Drolet M et al. Lancet 2019 Jun 26. doi: 10.1016/ S0140-6736(19)30298-3.

The introduction of the human papillomavirus according to a meta-analysis of data from more than 60 million individuals worldwide.

Mélanie Drolet, PhD, from the Centre de recherche du CHU de Québec–Université Laval, and coauthors of the HPV Vaccination Impact Study Group reported the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis of 65 studies showing pre- and postvaccination frequency of at least one HPV-related endpoint published in the Lancet. The studies were conducted in 14 high-income countries, 12 of which were vaccinating only women and girls, with the results at 5-8 years published in the Lancet.

At 5-8 years after a vaccination program was implemented, there was a significant 83% reduction in the prevalence of HPV 16 and 18, both of which are targeted by the vaccine, among girls aged 13-19 years; a 66% reduction among women aged 20-24 years; and a 37% reduction in women aged 25-29 years, even though most of these women were unvaccinated.

There also were significant decreases at 5-8 years in the prevalence of HPV subtypes 31, 33, and 45, which are not included in the vaccine but against which the vaccine appears to offer cross-protection. Among girls aged 13-19 years, there was a significant 54% reduction in the prevalence of these subtypes, among women aged 20-24 years there was a nonsignificant 28% decrease, but among women aged 25-29 years, there was no significant decrease.

The analysis also found significant declines in the prevalence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasias (CINs) of grade 2 or above. At 5-9 years after vaccination was introduced, CIN2+ decreased by 51% among girls aged 15-19 years who also were screened for cervical cancer, and by 31% among women aged 20-24 years.

However, over the same time period, the rates of CIN2+ increased by a significant 19% among mostly unvaccinated women aged 25-29 years and 23% among mostly unvaccinated women aged 30-39 years, despite both groups being screened for cervical abnormalities.

While most of the countries in the study vaccinated only girls and women, two studies did find nonsignificant decreases in the prevalence of HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, and 45 among boys aged 16-19 years, but not among men aged 20-24 years.

HPV vaccination also was associated with significant declines in the incidence of anogenital warts among both males and females. In the first 4 years alone, vaccination was associated with significant reductions in anogenital wart diagnoses among females aged 15-29 years, as well as nonsignificant but “substantial” reductions in unvaccinated boys aged 15-19 years.

After 5-8 years, anogenital wart diagnoses decreased by 67% among girls aged 15-19 years, significantly by 54% among women aged 20-24 years, and 31% among women aged 25-29 years – all significant changes. Among boys aged 15-19 years, anogenital wart diagnoses decreased by a significant 48%, and among men aged 20-24 years they decreased by a significant 32%.

The decreases in anogenital wart diagnoses were even greater in countries that implemented vaccination among multiple cohorts simultaneously and achieved high vaccination coverage, compared with countries that vaccinated only one cohort at a time or had low routine vaccination coverage.

“Our study is the first to show the real-world additional benefit of multicohort HPV vaccination and high routine vaccination coverage, and the fast and substantial herd effects of vaccination in countries which implement these measures,” wrote Dr. Drolet and coauthors. “The greater impact of multicohort vaccination was similar when restricting the analyses to countries with high routine vaccination coverage.”

They pointed to the World Health Organization’s recently revised position on HPV vaccination, which now recommends vaccination of multiple cohorts of girls aged 9-14 years, although they raised the question of what might be the optimal number of age cohorts. “Number needed to vaccinate and cost-effectiveness analyses in high-income countries suggest that vaccinating multiple cohorts of individuals up to 18 years of age is highly efficient and cost effective.”

This analysis by Drolet et al. “provides compelling evidence for HPV vaccine efficacy on all outcomes explored and for almost all age strata,” Dr. Silvia de Sanjose, of PATH in Seattle, and Dr. Sinead Delany-Moretlwe of the Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, said in an accompanying editorial (Lancet. 2019 Jun 26. doi: 10.1016/ S0140-6736[19]30549-5). This study shows just how effective HPV vaccination can be across a range of outcomes and ages, and also demonstrates the herd immunity benefits, particularly when multiple cohorts are vaccinated and there is high vaccination coverage.

One key limitation of this analysis is the lack of data from low- and middle-income countries. The data by Drolet et al. “emphasise the importance of redoubling our efforts to tackle the fiscal, supply, and programmatic barriers that currently limit HPV vaccine programmes; with these efforts, HPV vaccination could become a hallmark investment of cancer prevention in the 21st century,” Dr. de Sanjose and Dr. Delany-Moretlwe concluded.

The study was funded by WHO, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and Fonds de recherche du Québec–Santé. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Dr. de Sanjose declared previous institutional support from Merck.

SOURCE: Drolet M et al. Lancet 2019 Jun 26. doi: 10.1016/ S0140-6736(19)30298-3.

FROM THE LANCET

Key clinical point: Significant declines in HPV infections, CIN2+, and anogenital warts have occurred after the introduction of HPV vaccine programs, some because of herd effects.

Major finding: The HPV vaccination program is associated with a significant 83% reduction in the prevalence of HPV 16 and 18 among girls aged 13-19 years in 14 high-income countries.

Study details: Systematic review and meta-analysis of 65 studies involving more than 60 million individuals in 14 countries.

Disclosures: The study was funded by World Health Organization, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Drolet M et al. Lancet 2019 Jun 26. doi: 10.1016/ S0140-6736(19)30298-3.

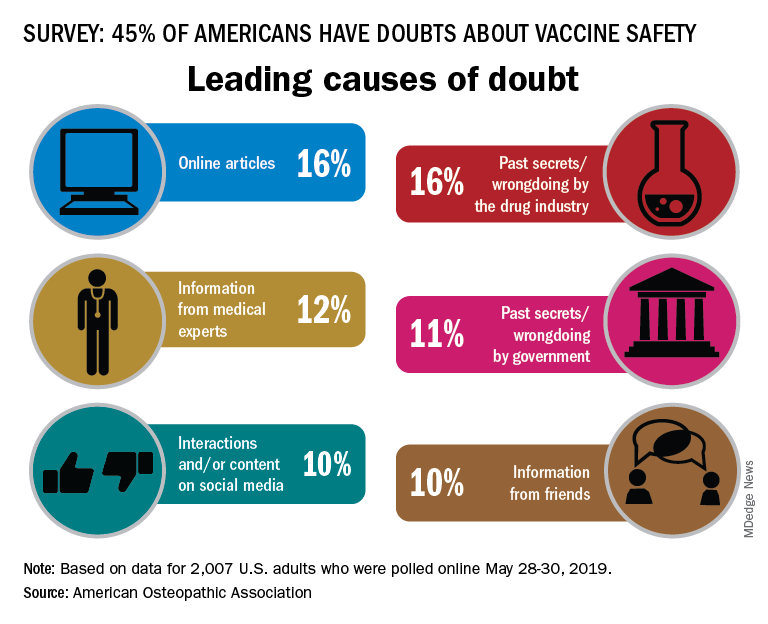

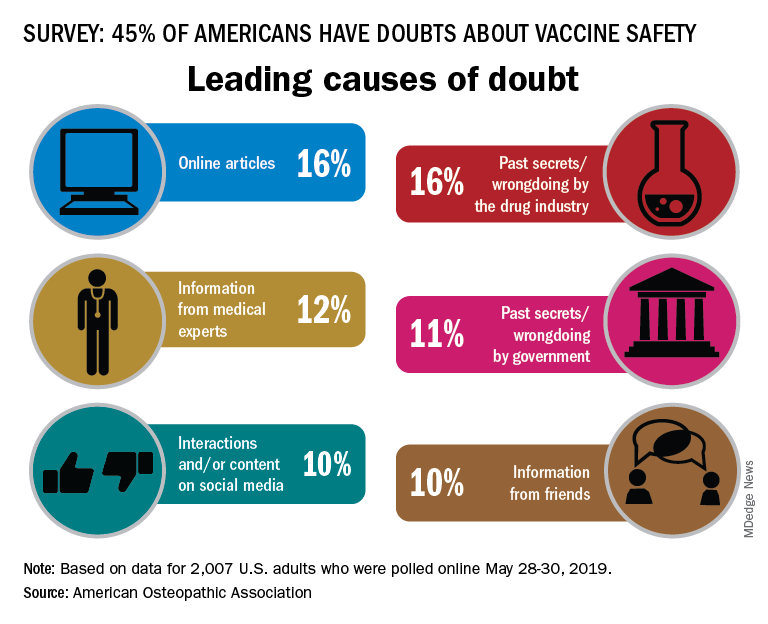

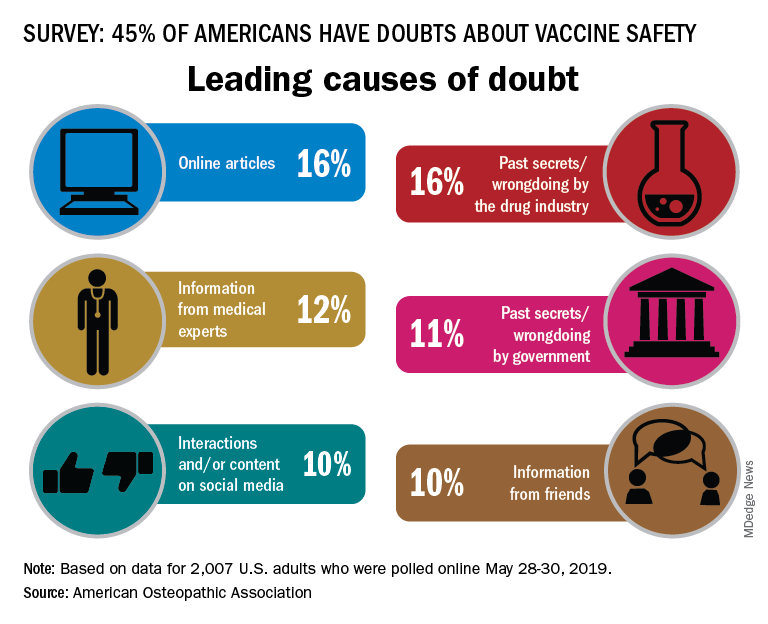

Almost half of Americans express doubts about vaccines

according to the American Osteopathic Association.

In a survey conducted by the Harris Poll on behalf of the AOA, 45% of the 2,007 respondents expressed a negative attitude towards vaccine safety, with online articles (16%) and past secrets/wrongdoings by the pharmaceutical industry (16%) cited as the leading causes, the AOA said.

There was no difference in negative attitude between men and women, but age, region, and parental status each had a notable effect. Doubts of vaccine safety were highest in those aged 18-34 years (55%) and lowest in those aged 65 and older (29%). Those living in the West had the highest rate at 50%, while residents of the Midwest were lowest at 39%, and the negative attitude rate was 55% for adults who had children under age 18 years and 40% for those who did not, the AOA reported.

Respondents to the survey, conducted May 28-30, 2019, also were asked to choose one of five statements that best expressed their view of vaccines, and those data paint a somewhat different picture:

- 2% said vaccines are unsafe and ineffective.

- 6% said that the side-effect risks outweigh the benefits.

- 9% said they were not sure if vaccines are safe and effective.

- 31% said that the benefits outweigh the risks.

- 51% said that vaccines are safe and effective.

Social media were another important source of doubt among respondents, but they have not been effective at countering the spread of vaccine misinformation, said psychiatrist Rachel Shmuts, DO, of Cherry Hill, N.J.

Confirmation bias makes it difficult to convince someone vaccines are safe, effective, and necessary once they believe they are not. “The number of people who believe vaccines are dangerous and refuse to get them is still relatively small. However, online support groups seem to solidify their beliefs, making them less susceptible to influence from their neighbors and real-world communities,” she said in the AOA statement.

Osteopathic family physician Paul Ehrmann, DO, said in the statement, “People know that a lot of practices won’t accept patients who don’t vaccinate, so when they find one that will, they spread the word to their community that it’s a safe place. Whether intentional or not, those doctors are often seen as endorsing anti-vaxxer beliefs.”

In 2017, his home state of Michigan, with other partners, put on a public information campaign. It has “significantly improved vaccination rates across demographics,” according to the statement.

“Beliefs are hard to change especially when they’re based in fear,” Dr. Ehrmann, of Royal Oak, Mich., said in the statement. “But, being responsible for our patients’ health and the public’s health, we can’t afford to give in to those fears. We must insist on evidence-based medicine.”

according to the American Osteopathic Association.

In a survey conducted by the Harris Poll on behalf of the AOA, 45% of the 2,007 respondents expressed a negative attitude towards vaccine safety, with online articles (16%) and past secrets/wrongdoings by the pharmaceutical industry (16%) cited as the leading causes, the AOA said.

There was no difference in negative attitude between men and women, but age, region, and parental status each had a notable effect. Doubts of vaccine safety were highest in those aged 18-34 years (55%) and lowest in those aged 65 and older (29%). Those living in the West had the highest rate at 50%, while residents of the Midwest were lowest at 39%, and the negative attitude rate was 55% for adults who had children under age 18 years and 40% for those who did not, the AOA reported.

Respondents to the survey, conducted May 28-30, 2019, also were asked to choose one of five statements that best expressed their view of vaccines, and those data paint a somewhat different picture:

- 2% said vaccines are unsafe and ineffective.

- 6% said that the side-effect risks outweigh the benefits.

- 9% said they were not sure if vaccines are safe and effective.

- 31% said that the benefits outweigh the risks.

- 51% said that vaccines are safe and effective.

Social media were another important source of doubt among respondents, but they have not been effective at countering the spread of vaccine misinformation, said psychiatrist Rachel Shmuts, DO, of Cherry Hill, N.J.

Confirmation bias makes it difficult to convince someone vaccines are safe, effective, and necessary once they believe they are not. “The number of people who believe vaccines are dangerous and refuse to get them is still relatively small. However, online support groups seem to solidify their beliefs, making them less susceptible to influence from their neighbors and real-world communities,” she said in the AOA statement.

Osteopathic family physician Paul Ehrmann, DO, said in the statement, “People know that a lot of practices won’t accept patients who don’t vaccinate, so when they find one that will, they spread the word to their community that it’s a safe place. Whether intentional or not, those doctors are often seen as endorsing anti-vaxxer beliefs.”

In 2017, his home state of Michigan, with other partners, put on a public information campaign. It has “significantly improved vaccination rates across demographics,” according to the statement.

“Beliefs are hard to change especially when they’re based in fear,” Dr. Ehrmann, of Royal Oak, Mich., said in the statement. “But, being responsible for our patients’ health and the public’s health, we can’t afford to give in to those fears. We must insist on evidence-based medicine.”

according to the American Osteopathic Association.

In a survey conducted by the Harris Poll on behalf of the AOA, 45% of the 2,007 respondents expressed a negative attitude towards vaccine safety, with online articles (16%) and past secrets/wrongdoings by the pharmaceutical industry (16%) cited as the leading causes, the AOA said.

There was no difference in negative attitude between men and women, but age, region, and parental status each had a notable effect. Doubts of vaccine safety were highest in those aged 18-34 years (55%) and lowest in those aged 65 and older (29%). Those living in the West had the highest rate at 50%, while residents of the Midwest were lowest at 39%, and the negative attitude rate was 55% for adults who had children under age 18 years and 40% for those who did not, the AOA reported.

Respondents to the survey, conducted May 28-30, 2019, also were asked to choose one of five statements that best expressed their view of vaccines, and those data paint a somewhat different picture:

- 2% said vaccines are unsafe and ineffective.

- 6% said that the side-effect risks outweigh the benefits.

- 9% said they were not sure if vaccines are safe and effective.

- 31% said that the benefits outweigh the risks.

- 51% said that vaccines are safe and effective.

Social media were another important source of doubt among respondents, but they have not been effective at countering the spread of vaccine misinformation, said psychiatrist Rachel Shmuts, DO, of Cherry Hill, N.J.

Confirmation bias makes it difficult to convince someone vaccines are safe, effective, and necessary once they believe they are not. “The number of people who believe vaccines are dangerous and refuse to get them is still relatively small. However, online support groups seem to solidify their beliefs, making them less susceptible to influence from their neighbors and real-world communities,” she said in the AOA statement.

Osteopathic family physician Paul Ehrmann, DO, said in the statement, “People know that a lot of practices won’t accept patients who don’t vaccinate, so when they find one that will, they spread the word to their community that it’s a safe place. Whether intentional or not, those doctors are often seen as endorsing anti-vaxxer beliefs.”

In 2017, his home state of Michigan, with other partners, put on a public information campaign. It has “significantly improved vaccination rates across demographics,” according to the statement.

“Beliefs are hard to change especially when they’re based in fear,” Dr. Ehrmann, of Royal Oak, Mich., said in the statement. “But, being responsible for our patients’ health and the public’s health, we can’t afford to give in to those fears. We must insist on evidence-based medicine.”

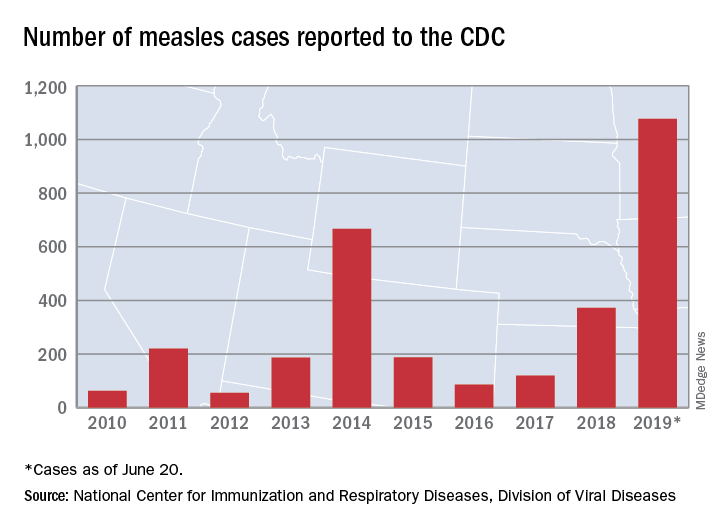

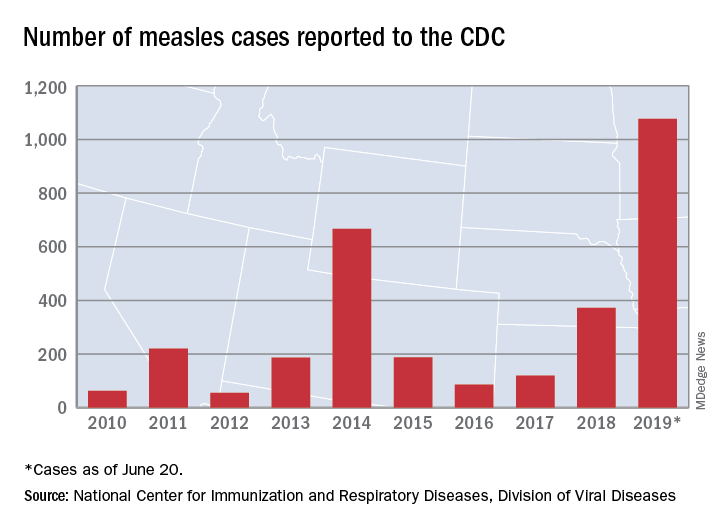

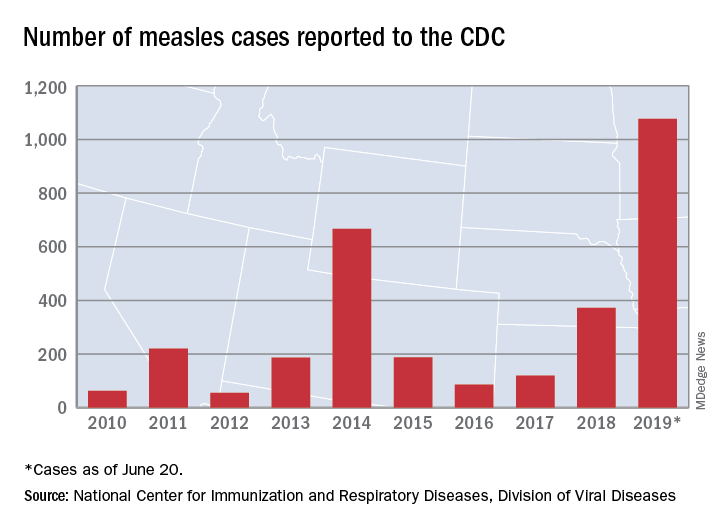

Measles incidence has slowed as summer begins

There were 33 new measles cases reported last week, bringing the U.S. total to 1,077 for the year through June 20, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The number of new cases is an increase from the 22 reported the week before, but weekly incidence has been trending downward since hitting a high of 90 in mid-April, CDC data show.