User login

Medtronic recalls HawkOne directional atherectomy system

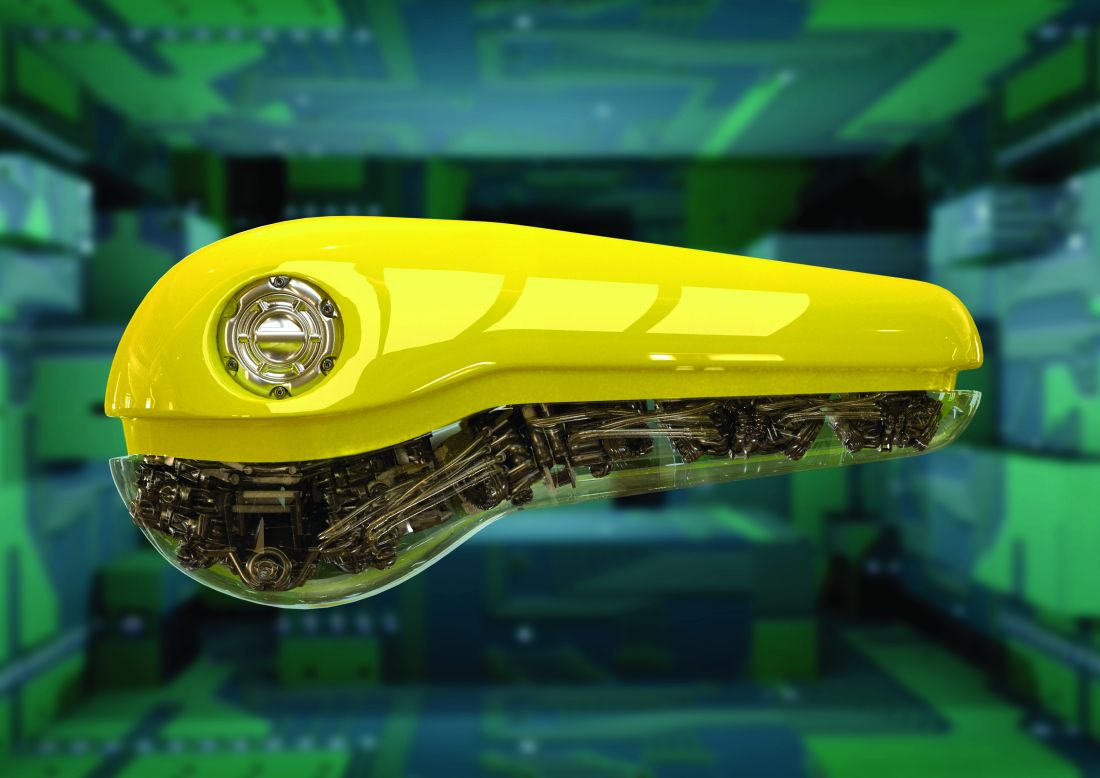

Medtronic has recalled 95,110 HawkOne Directional Atherectomy Systems because of the risk of the guidewire within the catheter moving downward or prolapsing during use, which may damage the tip of the catheter.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has identified this as a Class I recall, the most serious type, because of the potential for serious injury or death.

The HawkOne Directional Atherectomy system is used during procedures intended to remove blockage from peripheral arteries and improve blood flow.

If the guideline moves downward or prolapses during use, the “catheter tip may break off or separate, and this could lead to serious adverse events, including a tear along the inside wall of an artery (arterial dissection), a rupture or breakage of an artery (arterial rupture), decrease in blood flow to a part of the body because of a blocked artery (ischemia), and/or blood vessel complications that could require surgical repair and additional procedures to capture and remove the detached and/or migrated (embolized) tip,” the FDA says in a recall notice posted today on its website.

To date, there have been 55 injuries, no deaths, and 163 complaints reported for this device.

The recalled devices were distributed in the United States between Jan. 22, 2018 and Oct. 4, 2021. Product codes and lot numbers pertaining to the devices are listed on the FDA website.

Medtronic sent an urgent field safety notice to customers Dec. 6, 2021, requesting that they alert parties of the defect, review the instructions for use before using the device, and note the warnings and precautions listed in the letter.

Customers were also asked to complete the enclosed confirmation form and email to [email protected].

Health care providers can report adverse reactions or quality problems they experience using these devices to the FDA’s MedWatch program.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medtronic has recalled 95,110 HawkOne Directional Atherectomy Systems because of the risk of the guidewire within the catheter moving downward or prolapsing during use, which may damage the tip of the catheter.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has identified this as a Class I recall, the most serious type, because of the potential for serious injury or death.

The HawkOne Directional Atherectomy system is used during procedures intended to remove blockage from peripheral arteries and improve blood flow.

If the guideline moves downward or prolapses during use, the “catheter tip may break off or separate, and this could lead to serious adverse events, including a tear along the inside wall of an artery (arterial dissection), a rupture or breakage of an artery (arterial rupture), decrease in blood flow to a part of the body because of a blocked artery (ischemia), and/or blood vessel complications that could require surgical repair and additional procedures to capture and remove the detached and/or migrated (embolized) tip,” the FDA says in a recall notice posted today on its website.

To date, there have been 55 injuries, no deaths, and 163 complaints reported for this device.

The recalled devices were distributed in the United States between Jan. 22, 2018 and Oct. 4, 2021. Product codes and lot numbers pertaining to the devices are listed on the FDA website.

Medtronic sent an urgent field safety notice to customers Dec. 6, 2021, requesting that they alert parties of the defect, review the instructions for use before using the device, and note the warnings and precautions listed in the letter.

Customers were also asked to complete the enclosed confirmation form and email to [email protected].

Health care providers can report adverse reactions or quality problems they experience using these devices to the FDA’s MedWatch program.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medtronic has recalled 95,110 HawkOne Directional Atherectomy Systems because of the risk of the guidewire within the catheter moving downward or prolapsing during use, which may damage the tip of the catheter.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has identified this as a Class I recall, the most serious type, because of the potential for serious injury or death.

The HawkOne Directional Atherectomy system is used during procedures intended to remove blockage from peripheral arteries and improve blood flow.

If the guideline moves downward or prolapses during use, the “catheter tip may break off or separate, and this could lead to serious adverse events, including a tear along the inside wall of an artery (arterial dissection), a rupture or breakage of an artery (arterial rupture), decrease in blood flow to a part of the body because of a blocked artery (ischemia), and/or blood vessel complications that could require surgical repair and additional procedures to capture and remove the detached and/or migrated (embolized) tip,” the FDA says in a recall notice posted today on its website.

To date, there have been 55 injuries, no deaths, and 163 complaints reported for this device.

The recalled devices were distributed in the United States between Jan. 22, 2018 and Oct. 4, 2021. Product codes and lot numbers pertaining to the devices are listed on the FDA website.

Medtronic sent an urgent field safety notice to customers Dec. 6, 2021, requesting that they alert parties of the defect, review the instructions for use before using the device, and note the warnings and precautions listed in the letter.

Customers were also asked to complete the enclosed confirmation form and email to [email protected].

Health care providers can report adverse reactions or quality problems they experience using these devices to the FDA’s MedWatch program.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘We just have to keep them alive’: Transitioning youth with type 1 diabetes

“No one has asked young people what they want,” said Tabitha Randell, MBChB, an endocrinologist with Nottingham (England) University Hospitals NHS Trust, who specializes in treating teenagers with type 1 diabetes as they transition to adult care.

Dr. Randell, who has set up a very successful specialist service in her hospital for such patients, said: “We consistently have the best, or the second best, outcomes in this country for our diabetes patients.” She believes this is one of the most important issues in modern endocrinology today.

Speaking at the Diabetes Professional Care conference in London at the end of 2021, and sharing her thoughts afterward with this news organization, she noted that in general there are “virtually no published outcomes” on how best to transition a patient with type 1 diabetes from pediatric to adult care.

“If you actually get them to transition – because some just drop out and disengage and there’s nothing you can do – none of them get lost. Some of them disengage in the adult clinic, but if you’re in the young diabetes service [in England] the rules are that if you miss a diabetes appointment you do not get discharged, as compared with the adult clinic, where if you miss an appointment, you are discharged.”

In the young diabetes clinic, doctors will “carry on trying to contact you, and get you back,” she explained. “And the patients do eventually come back in – it might be a year or 2, but they do come back. We’ve just got to keep them alive in the meantime!”

This issue needs tackling all over the world. Dr. Randell said she’s not aware of any one country – although there may be “pockets” of good care within a given country – that is doing this perfectly.

Across the pond, Grazia Aleppo, MD, division of endocrinology at Northwestern University, Chicago, agreed that transitioning pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes to adult care presents “unique challenges.”

Challenges when transitioning from pediatric to adult care

During childhood, type 1 diabetes management is largely supervised by patients’ parents and members of the pediatric diabetes care team, which may include diabetes educators, psychologists, or social workers, as well as pediatric endocrinologists.

When the patient with type 1 diabetes becomes a young adult and takes over management of their own health, Dr. Aleppo said, the care team may diminish along with the time spent in provider visits.

The adult endocrinology setting focuses more on self-management and autonomous functioning of the individual with diabetes.

Adult appointments are typically shorter, and the patient is usually expected to follow doctors’ suggestions independently, she noted. They are also expected to manage the practical aspects of their diabetes care, including prescriptions, diabetes supplies, laboratory tests, scheduling, and keeping appointments.

At the same time that the emerging adult needs to start asserting independence over their health care, they will also be going through a myriad of other important lifestyle changes, such as attending college, living on their own for the first time, and starting a career.

“With these fundamental differences and challenges, competing priorities, such as college, work and relationships, medical care may become of secondary importance and patients may become disengaged,” Dr. Aleppo explained.

As Dr. Randell has said, loss to follow-up is a big problem with this patient population, with disengagement from specialist services and worsening A1c across the transition, Dr. Aleppo noted. This makes addressing these patients’ specific needs extremely important.

Engage with kid, not disease; don’t palm them off on new recruits

“The really key thing these kids say is, ‘I do not want to be a disease,’” Dr. Randell said. “They want you to know that they are a person. Engage these kids!” she suggested. “Ask them: ‘How is your exam revision going?’ Find something positive to say, even if it’s just: ‘I’m glad you came today.’ ”

“If the first thing that you do is tell them off [for poor diabetes care], you are never going to see them again,” she cautioned.

Dr. Randell also said that role models with type 1 diabetes, such as Lila Moss – daughter of British supermodel Kate Moss – who was recently pictured wearing an insulin pump on her leg on the catwalk, are helping youngsters not feel so self-conscious about their diabetes.

“Let them know it’s not the end of the world, having [type 1] diabetes,” she emphasized.

And Partha Kar, MBBS, OBE, national specialty advisor, diabetes with NHS England, agreed wholeheartedly with Dr. Randall.

Reminiscing about his early days as a newly qualified endocrinologist, Dr. Kar, who works at Portsmouth (England) Hospital NHS Trust, noted that as a new member of staff he was given the youth with type 1 diabetes – those getting ready to transition to adult care – to look after.

But this is the exact opposite of what should be happening, he emphasized. “If you don’t think transition care is important, you shouldn’t be treating type 1 diabetes.”

He believes that every diabetes center “must have a young-adult team lead” and this job must not be given to the least experienced member of staff.

This lead “doesn’t need to be a doctor,” Dr. Kar stressed. “It can be a psychologist, or a diabetes nurse, or a pharmacist, or a dietician.”

In short, it must be someone experienced who loves working with this age group.

Dr. Randell agreed: “Make sure the team is interested in young people. It shouldn’t be the last person in who gets the job no one else wants.” Teens “are my favorite group to work with. They don’t take any nonsense.”

And she explained: “Young people like to get to know the person who’s going to take care of them. So, stay with them for their young adult years.” This can be “quite a fluid period,” with it normally extending to age 25, but in some cases, “it can be up to 32 years old.”

Preparing for the transition

To ease pediatric patients into the transition to adult care, Dr. Aleppo recommended that the pediatric diabetes team provide enough time so that any concerns the patient and their family may have can be addressed.

This should also include transferring management responsibilities to the young adult rather than their parent.

The pediatric provider should discuss with the patient available potential adult colleagues, personalizing these options to their needs, she said.

And the adult and pediatric clinicians should collaborate and provide important information beyond medical records or health summaries.

Adult providers should guide young adults on how to navigate the new practices, from scheduling follow-up appointments to policies regarding medication refills or supplies, to providing information about urgent numbers or email addresses for after-hours communications.

Dr. Kar reiterated that there are too few published outcomes in this patient group to guide the establishment of good transition services.

“Without data, we are dead on the ground. Without data, it’s all conjecture, anecdotes,” he said.

What he does know is that, in the latest national type 1 diabetes audit for England, “Diabetic ketoacidosis admissions ... are up in this age group,” which suggests these patients are not receiving adequate care.

Be a guide, not a gatekeeper

Dr. Kar stressed that, of the 8,760 hours in a year, the average patient with type 1 diabetes in the United Kingdom gets just “1-2 hours with you as a clinician, based on four appointments per year of 30 minutes each.”

“So you spend 0.02% of their time with individuals with type 1 diabetes. So, what’s the one thing you can do with that minimal contact? Be nice!”

Dr. Kar said he always has his email open to his adult patients and they are very respectful of his time. “They don’t email you at 1 a.m. That means every one of my patients has got support [from me]. Don’t be a barrier.”

“We have to fundamentally change the narrative. Doctors must have more empathy,” he said, stating that the one thing adolescents have constantly given feedback on has been, “Why don’t appointments start with: ‘How are you?’

“For a teenager, if you throw type 1 diabetes into the loop, it’s not easy,” he stressed. “Talk to them about something else. As a clinician, be a guide, not a gatekeeper. Give people the tools to self-manage better.”

Adult providers can meet these young adult patients “at their level,” Dr. Aleppo agreed.

“Pay attention to their immediate needs and focus on their present circumstances – whether how to get through their next semester in college, navigating job interviews, or handling having diabetes in the workplace.”

Paying attention to the mental health needs of these young patients is equally “paramount,” Dr. Aleppo said.

While access to mental health professionals may be challenging in the adult setting, providers should bring it up with their patients and offer counseling referrals.

“Diabetes impacts everything, and office appointments and conversations carry weight on these patients’ lives as a whole, not just on their diabetes,” she stressed. “A patient told me recently: ‘We’re learning to be adults,’ which can be hard enough, and with diabetes it can be even more challenging. Adult providers need to be aware of the patient’s ‘diabetes language’ in that often it is not what a patient is saying, rather how they are saying it that gives us information on what they truly need.

“As adult providers, we need to also train and teach our young patients to advocate for themselves on where to find resources that can help them navigate adulthood with diabetes,” she added.

One particularly helpful resource in the United States is the College Diabetes Network, a not-for-profit organization whose mission is to equip young adults with type 1 diabetes to successfully manage the challenging transition to independence at college and beyond.

“The sweetest thing that can happen to us as adult diabetes providers is when a patient – seen as an emerging adult during college – returns to your practice 10 years later after moving back and seeks you out for their diabetes care because of the relationship and trust you developed in those transitioning years,” Dr. Aleppo said.

Another resource is a freely available comic book series cocreated by Dr. Kar and colleague Mayank Patel, MBBS, an endocrinologist from University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust.

As detailed by this news organization in 2021, the series consists of three volumes: the first, Type 1: Origins, focuses on actual experiences of patients who have type 1 diabetes; the second, Type 1: Attack of the Ketones, is aimed at professionals who may provide care but have limited understanding of type 1 diabetes; and the third, Type 1 Mission 3: S.T.I.G.M.A., addresses the stigmas and misconceptions that patients with type 1 diabetes may face.

The idea for the first comic was inspired by a patient who compared having diabetes to being like the Marvel character The Hulk, said Dr. Kar, and has been expanded to include the additional volumes.

Dr. Kar and Dr. Patel have also just launched the fourth comic in the series, Type 1: Generations, to mark the 100-year anniversary since insulin was first given to a human.

“This is high priority”

Dr. Kar said the NHS in England has just appointed a national lead for type 1 diabetes in youth, Fulya Mehta, MD, of Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust, Liverpool, England.

“If you have a plan, bring it to us,” he told the audience at the DPC conference, and “tell us, what is the one thing you would change? This is not a session we are doing just to tick a box. This is high priority.

“Encourage your colleagues to think about transition services. This is an absolute priority. We will be asking every center [in England] who is your transitioning lead?”

And he once again stressed that “a lead of transition service does not have to be a medic. This should be a multidisciplinary team. But they do need to be comfortable in that space. To that teenager, your job title means nothing. Give them time and space.”

Dr. Randell summed it up: “If we can work together, it’s only going to result in better outcomes. We need to blaze the trail for young people.”

Dr. Aleppo has reported serving as a consultant to Dexcom and Insulet and receiving support to Northwestern University from AstraZeneca, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Fractyl Health, Insulet, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Randell and Dr. Kar have no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“No one has asked young people what they want,” said Tabitha Randell, MBChB, an endocrinologist with Nottingham (England) University Hospitals NHS Trust, who specializes in treating teenagers with type 1 diabetes as they transition to adult care.

Dr. Randell, who has set up a very successful specialist service in her hospital for such patients, said: “We consistently have the best, or the second best, outcomes in this country for our diabetes patients.” She believes this is one of the most important issues in modern endocrinology today.

Speaking at the Diabetes Professional Care conference in London at the end of 2021, and sharing her thoughts afterward with this news organization, she noted that in general there are “virtually no published outcomes” on how best to transition a patient with type 1 diabetes from pediatric to adult care.

“If you actually get them to transition – because some just drop out and disengage and there’s nothing you can do – none of them get lost. Some of them disengage in the adult clinic, but if you’re in the young diabetes service [in England] the rules are that if you miss a diabetes appointment you do not get discharged, as compared with the adult clinic, where if you miss an appointment, you are discharged.”

In the young diabetes clinic, doctors will “carry on trying to contact you, and get you back,” she explained. “And the patients do eventually come back in – it might be a year or 2, but they do come back. We’ve just got to keep them alive in the meantime!”

This issue needs tackling all over the world. Dr. Randell said she’s not aware of any one country – although there may be “pockets” of good care within a given country – that is doing this perfectly.

Across the pond, Grazia Aleppo, MD, division of endocrinology at Northwestern University, Chicago, agreed that transitioning pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes to adult care presents “unique challenges.”

Challenges when transitioning from pediatric to adult care

During childhood, type 1 diabetes management is largely supervised by patients’ parents and members of the pediatric diabetes care team, which may include diabetes educators, psychologists, or social workers, as well as pediatric endocrinologists.

When the patient with type 1 diabetes becomes a young adult and takes over management of their own health, Dr. Aleppo said, the care team may diminish along with the time spent in provider visits.

The adult endocrinology setting focuses more on self-management and autonomous functioning of the individual with diabetes.

Adult appointments are typically shorter, and the patient is usually expected to follow doctors’ suggestions independently, she noted. They are also expected to manage the practical aspects of their diabetes care, including prescriptions, diabetes supplies, laboratory tests, scheduling, and keeping appointments.

At the same time that the emerging adult needs to start asserting independence over their health care, they will also be going through a myriad of other important lifestyle changes, such as attending college, living on their own for the first time, and starting a career.

“With these fundamental differences and challenges, competing priorities, such as college, work and relationships, medical care may become of secondary importance and patients may become disengaged,” Dr. Aleppo explained.

As Dr. Randell has said, loss to follow-up is a big problem with this patient population, with disengagement from specialist services and worsening A1c across the transition, Dr. Aleppo noted. This makes addressing these patients’ specific needs extremely important.

Engage with kid, not disease; don’t palm them off on new recruits

“The really key thing these kids say is, ‘I do not want to be a disease,’” Dr. Randell said. “They want you to know that they are a person. Engage these kids!” she suggested. “Ask them: ‘How is your exam revision going?’ Find something positive to say, even if it’s just: ‘I’m glad you came today.’ ”

“If the first thing that you do is tell them off [for poor diabetes care], you are never going to see them again,” she cautioned.

Dr. Randell also said that role models with type 1 diabetes, such as Lila Moss – daughter of British supermodel Kate Moss – who was recently pictured wearing an insulin pump on her leg on the catwalk, are helping youngsters not feel so self-conscious about their diabetes.

“Let them know it’s not the end of the world, having [type 1] diabetes,” she emphasized.

And Partha Kar, MBBS, OBE, national specialty advisor, diabetes with NHS England, agreed wholeheartedly with Dr. Randall.

Reminiscing about his early days as a newly qualified endocrinologist, Dr. Kar, who works at Portsmouth (England) Hospital NHS Trust, noted that as a new member of staff he was given the youth with type 1 diabetes – those getting ready to transition to adult care – to look after.

But this is the exact opposite of what should be happening, he emphasized. “If you don’t think transition care is important, you shouldn’t be treating type 1 diabetes.”

He believes that every diabetes center “must have a young-adult team lead” and this job must not be given to the least experienced member of staff.

This lead “doesn’t need to be a doctor,” Dr. Kar stressed. “It can be a psychologist, or a diabetes nurse, or a pharmacist, or a dietician.”

In short, it must be someone experienced who loves working with this age group.

Dr. Randell agreed: “Make sure the team is interested in young people. It shouldn’t be the last person in who gets the job no one else wants.” Teens “are my favorite group to work with. They don’t take any nonsense.”

And she explained: “Young people like to get to know the person who’s going to take care of them. So, stay with them for their young adult years.” This can be “quite a fluid period,” with it normally extending to age 25, but in some cases, “it can be up to 32 years old.”

Preparing for the transition

To ease pediatric patients into the transition to adult care, Dr. Aleppo recommended that the pediatric diabetes team provide enough time so that any concerns the patient and their family may have can be addressed.

This should also include transferring management responsibilities to the young adult rather than their parent.

The pediatric provider should discuss with the patient available potential adult colleagues, personalizing these options to their needs, she said.

And the adult and pediatric clinicians should collaborate and provide important information beyond medical records or health summaries.

Adult providers should guide young adults on how to navigate the new practices, from scheduling follow-up appointments to policies regarding medication refills or supplies, to providing information about urgent numbers or email addresses for after-hours communications.

Dr. Kar reiterated that there are too few published outcomes in this patient group to guide the establishment of good transition services.

“Without data, we are dead on the ground. Without data, it’s all conjecture, anecdotes,” he said.

What he does know is that, in the latest national type 1 diabetes audit for England, “Diabetic ketoacidosis admissions ... are up in this age group,” which suggests these patients are not receiving adequate care.

Be a guide, not a gatekeeper

Dr. Kar stressed that, of the 8,760 hours in a year, the average patient with type 1 diabetes in the United Kingdom gets just “1-2 hours with you as a clinician, based on four appointments per year of 30 minutes each.”

“So you spend 0.02% of their time with individuals with type 1 diabetes. So, what’s the one thing you can do with that minimal contact? Be nice!”

Dr. Kar said he always has his email open to his adult patients and they are very respectful of his time. “They don’t email you at 1 a.m. That means every one of my patients has got support [from me]. Don’t be a barrier.”

“We have to fundamentally change the narrative. Doctors must have more empathy,” he said, stating that the one thing adolescents have constantly given feedback on has been, “Why don’t appointments start with: ‘How are you?’

“For a teenager, if you throw type 1 diabetes into the loop, it’s not easy,” he stressed. “Talk to them about something else. As a clinician, be a guide, not a gatekeeper. Give people the tools to self-manage better.”

Adult providers can meet these young adult patients “at their level,” Dr. Aleppo agreed.

“Pay attention to their immediate needs and focus on their present circumstances – whether how to get through their next semester in college, navigating job interviews, or handling having diabetes in the workplace.”

Paying attention to the mental health needs of these young patients is equally “paramount,” Dr. Aleppo said.

While access to mental health professionals may be challenging in the adult setting, providers should bring it up with their patients and offer counseling referrals.

“Diabetes impacts everything, and office appointments and conversations carry weight on these patients’ lives as a whole, not just on their diabetes,” she stressed. “A patient told me recently: ‘We’re learning to be adults,’ which can be hard enough, and with diabetes it can be even more challenging. Adult providers need to be aware of the patient’s ‘diabetes language’ in that often it is not what a patient is saying, rather how they are saying it that gives us information on what they truly need.

“As adult providers, we need to also train and teach our young patients to advocate for themselves on where to find resources that can help them navigate adulthood with diabetes,” she added.

One particularly helpful resource in the United States is the College Diabetes Network, a not-for-profit organization whose mission is to equip young adults with type 1 diabetes to successfully manage the challenging transition to independence at college and beyond.

“The sweetest thing that can happen to us as adult diabetes providers is when a patient – seen as an emerging adult during college – returns to your practice 10 years later after moving back and seeks you out for their diabetes care because of the relationship and trust you developed in those transitioning years,” Dr. Aleppo said.

Another resource is a freely available comic book series cocreated by Dr. Kar and colleague Mayank Patel, MBBS, an endocrinologist from University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust.

As detailed by this news organization in 2021, the series consists of three volumes: the first, Type 1: Origins, focuses on actual experiences of patients who have type 1 diabetes; the second, Type 1: Attack of the Ketones, is aimed at professionals who may provide care but have limited understanding of type 1 diabetes; and the third, Type 1 Mission 3: S.T.I.G.M.A., addresses the stigmas and misconceptions that patients with type 1 diabetes may face.

The idea for the first comic was inspired by a patient who compared having diabetes to being like the Marvel character The Hulk, said Dr. Kar, and has been expanded to include the additional volumes.

Dr. Kar and Dr. Patel have also just launched the fourth comic in the series, Type 1: Generations, to mark the 100-year anniversary since insulin was first given to a human.

“This is high priority”

Dr. Kar said the NHS in England has just appointed a national lead for type 1 diabetes in youth, Fulya Mehta, MD, of Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust, Liverpool, England.

“If you have a plan, bring it to us,” he told the audience at the DPC conference, and “tell us, what is the one thing you would change? This is not a session we are doing just to tick a box. This is high priority.

“Encourage your colleagues to think about transition services. This is an absolute priority. We will be asking every center [in England] who is your transitioning lead?”

And he once again stressed that “a lead of transition service does not have to be a medic. This should be a multidisciplinary team. But they do need to be comfortable in that space. To that teenager, your job title means nothing. Give them time and space.”

Dr. Randell summed it up: “If we can work together, it’s only going to result in better outcomes. We need to blaze the trail for young people.”

Dr. Aleppo has reported serving as a consultant to Dexcom and Insulet and receiving support to Northwestern University from AstraZeneca, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Fractyl Health, Insulet, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Randell and Dr. Kar have no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“No one has asked young people what they want,” said Tabitha Randell, MBChB, an endocrinologist with Nottingham (England) University Hospitals NHS Trust, who specializes in treating teenagers with type 1 diabetes as they transition to adult care.

Dr. Randell, who has set up a very successful specialist service in her hospital for such patients, said: “We consistently have the best, or the second best, outcomes in this country for our diabetes patients.” She believes this is one of the most important issues in modern endocrinology today.

Speaking at the Diabetes Professional Care conference in London at the end of 2021, and sharing her thoughts afterward with this news organization, she noted that in general there are “virtually no published outcomes” on how best to transition a patient with type 1 diabetes from pediatric to adult care.

“If you actually get them to transition – because some just drop out and disengage and there’s nothing you can do – none of them get lost. Some of them disengage in the adult clinic, but if you’re in the young diabetes service [in England] the rules are that if you miss a diabetes appointment you do not get discharged, as compared with the adult clinic, where if you miss an appointment, you are discharged.”

In the young diabetes clinic, doctors will “carry on trying to contact you, and get you back,” she explained. “And the patients do eventually come back in – it might be a year or 2, but they do come back. We’ve just got to keep them alive in the meantime!”

This issue needs tackling all over the world. Dr. Randell said she’s not aware of any one country – although there may be “pockets” of good care within a given country – that is doing this perfectly.

Across the pond, Grazia Aleppo, MD, division of endocrinology at Northwestern University, Chicago, agreed that transitioning pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes to adult care presents “unique challenges.”

Challenges when transitioning from pediatric to adult care

During childhood, type 1 diabetes management is largely supervised by patients’ parents and members of the pediatric diabetes care team, which may include diabetes educators, psychologists, or social workers, as well as pediatric endocrinologists.

When the patient with type 1 diabetes becomes a young adult and takes over management of their own health, Dr. Aleppo said, the care team may diminish along with the time spent in provider visits.

The adult endocrinology setting focuses more on self-management and autonomous functioning of the individual with diabetes.

Adult appointments are typically shorter, and the patient is usually expected to follow doctors’ suggestions independently, she noted. They are also expected to manage the practical aspects of their diabetes care, including prescriptions, diabetes supplies, laboratory tests, scheduling, and keeping appointments.

At the same time that the emerging adult needs to start asserting independence over their health care, they will also be going through a myriad of other important lifestyle changes, such as attending college, living on their own for the first time, and starting a career.

“With these fundamental differences and challenges, competing priorities, such as college, work and relationships, medical care may become of secondary importance and patients may become disengaged,” Dr. Aleppo explained.

As Dr. Randell has said, loss to follow-up is a big problem with this patient population, with disengagement from specialist services and worsening A1c across the transition, Dr. Aleppo noted. This makes addressing these patients’ specific needs extremely important.

Engage with kid, not disease; don’t palm them off on new recruits

“The really key thing these kids say is, ‘I do not want to be a disease,’” Dr. Randell said. “They want you to know that they are a person. Engage these kids!” she suggested. “Ask them: ‘How is your exam revision going?’ Find something positive to say, even if it’s just: ‘I’m glad you came today.’ ”

“If the first thing that you do is tell them off [for poor diabetes care], you are never going to see them again,” she cautioned.

Dr. Randell also said that role models with type 1 diabetes, such as Lila Moss – daughter of British supermodel Kate Moss – who was recently pictured wearing an insulin pump on her leg on the catwalk, are helping youngsters not feel so self-conscious about their diabetes.

“Let them know it’s not the end of the world, having [type 1] diabetes,” she emphasized.

And Partha Kar, MBBS, OBE, national specialty advisor, diabetes with NHS England, agreed wholeheartedly with Dr. Randall.

Reminiscing about his early days as a newly qualified endocrinologist, Dr. Kar, who works at Portsmouth (England) Hospital NHS Trust, noted that as a new member of staff he was given the youth with type 1 diabetes – those getting ready to transition to adult care – to look after.

But this is the exact opposite of what should be happening, he emphasized. “If you don’t think transition care is important, you shouldn’t be treating type 1 diabetes.”

He believes that every diabetes center “must have a young-adult team lead” and this job must not be given to the least experienced member of staff.

This lead “doesn’t need to be a doctor,” Dr. Kar stressed. “It can be a psychologist, or a diabetes nurse, or a pharmacist, or a dietician.”

In short, it must be someone experienced who loves working with this age group.

Dr. Randell agreed: “Make sure the team is interested in young people. It shouldn’t be the last person in who gets the job no one else wants.” Teens “are my favorite group to work with. They don’t take any nonsense.”

And she explained: “Young people like to get to know the person who’s going to take care of them. So, stay with them for their young adult years.” This can be “quite a fluid period,” with it normally extending to age 25, but in some cases, “it can be up to 32 years old.”

Preparing for the transition

To ease pediatric patients into the transition to adult care, Dr. Aleppo recommended that the pediatric diabetes team provide enough time so that any concerns the patient and their family may have can be addressed.

This should also include transferring management responsibilities to the young adult rather than their parent.

The pediatric provider should discuss with the patient available potential adult colleagues, personalizing these options to their needs, she said.

And the adult and pediatric clinicians should collaborate and provide important information beyond medical records or health summaries.

Adult providers should guide young adults on how to navigate the new practices, from scheduling follow-up appointments to policies regarding medication refills or supplies, to providing information about urgent numbers or email addresses for after-hours communications.

Dr. Kar reiterated that there are too few published outcomes in this patient group to guide the establishment of good transition services.

“Without data, we are dead on the ground. Without data, it’s all conjecture, anecdotes,” he said.

What he does know is that, in the latest national type 1 diabetes audit for England, “Diabetic ketoacidosis admissions ... are up in this age group,” which suggests these patients are not receiving adequate care.

Be a guide, not a gatekeeper

Dr. Kar stressed that, of the 8,760 hours in a year, the average patient with type 1 diabetes in the United Kingdom gets just “1-2 hours with you as a clinician, based on four appointments per year of 30 minutes each.”

“So you spend 0.02% of their time with individuals with type 1 diabetes. So, what’s the one thing you can do with that minimal contact? Be nice!”

Dr. Kar said he always has his email open to his adult patients and they are very respectful of his time. “They don’t email you at 1 a.m. That means every one of my patients has got support [from me]. Don’t be a barrier.”

“We have to fundamentally change the narrative. Doctors must have more empathy,” he said, stating that the one thing adolescents have constantly given feedback on has been, “Why don’t appointments start with: ‘How are you?’

“For a teenager, if you throw type 1 diabetes into the loop, it’s not easy,” he stressed. “Talk to them about something else. As a clinician, be a guide, not a gatekeeper. Give people the tools to self-manage better.”

Adult providers can meet these young adult patients “at their level,” Dr. Aleppo agreed.

“Pay attention to their immediate needs and focus on their present circumstances – whether how to get through their next semester in college, navigating job interviews, or handling having diabetes in the workplace.”

Paying attention to the mental health needs of these young patients is equally “paramount,” Dr. Aleppo said.

While access to mental health professionals may be challenging in the adult setting, providers should bring it up with their patients and offer counseling referrals.

“Diabetes impacts everything, and office appointments and conversations carry weight on these patients’ lives as a whole, not just on their diabetes,” she stressed. “A patient told me recently: ‘We’re learning to be adults,’ which can be hard enough, and with diabetes it can be even more challenging. Adult providers need to be aware of the patient’s ‘diabetes language’ in that often it is not what a patient is saying, rather how they are saying it that gives us information on what they truly need.

“As adult providers, we need to also train and teach our young patients to advocate for themselves on where to find resources that can help them navigate adulthood with diabetes,” she added.

One particularly helpful resource in the United States is the College Diabetes Network, a not-for-profit organization whose mission is to equip young adults with type 1 diabetes to successfully manage the challenging transition to independence at college and beyond.

“The sweetest thing that can happen to us as adult diabetes providers is when a patient – seen as an emerging adult during college – returns to your practice 10 years later after moving back and seeks you out for their diabetes care because of the relationship and trust you developed in those transitioning years,” Dr. Aleppo said.

Another resource is a freely available comic book series cocreated by Dr. Kar and colleague Mayank Patel, MBBS, an endocrinologist from University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust.

As detailed by this news organization in 2021, the series consists of three volumes: the first, Type 1: Origins, focuses on actual experiences of patients who have type 1 diabetes; the second, Type 1: Attack of the Ketones, is aimed at professionals who may provide care but have limited understanding of type 1 diabetes; and the third, Type 1 Mission 3: S.T.I.G.M.A., addresses the stigmas and misconceptions that patients with type 1 diabetes may face.

The idea for the first comic was inspired by a patient who compared having diabetes to being like the Marvel character The Hulk, said Dr. Kar, and has been expanded to include the additional volumes.

Dr. Kar and Dr. Patel have also just launched the fourth comic in the series, Type 1: Generations, to mark the 100-year anniversary since insulin was first given to a human.

“This is high priority”

Dr. Kar said the NHS in England has just appointed a national lead for type 1 diabetes in youth, Fulya Mehta, MD, of Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust, Liverpool, England.

“If you have a plan, bring it to us,” he told the audience at the DPC conference, and “tell us, what is the one thing you would change? This is not a session we are doing just to tick a box. This is high priority.

“Encourage your colleagues to think about transition services. This is an absolute priority. We will be asking every center [in England] who is your transitioning lead?”

And he once again stressed that “a lead of transition service does not have to be a medic. This should be a multidisciplinary team. But they do need to be comfortable in that space. To that teenager, your job title means nothing. Give them time and space.”

Dr. Randell summed it up: “If we can work together, it’s only going to result in better outcomes. We need to blaze the trail for young people.”

Dr. Aleppo has reported serving as a consultant to Dexcom and Insulet and receiving support to Northwestern University from AstraZeneca, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Fractyl Health, Insulet, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Randell and Dr. Kar have no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Artificial pancreas’ life-changing in kids with type 1 diabetes

A semiautomated insulin delivery system improved glycemic control in young children with type 1 diabetes aged 1-7 years without increasing hypoglycemia.

“Hybrid closed-loop” systems – comprising an insulin pump, a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), and software enabling communication that semiautomates insulin delivery based on glucose levels – have been shown to improve glucose control in older children and adults.

The technology, also known as an artificial pancreas, has been less studied in very young children even though it may uniquely benefit them, said the authors of the new study, led by Julia Ware, MD, of the Wellcome Trust–Medical Research Council Institute of Metabolic Science and the University of Cambridge (England). The findings were published online Jan. 19, 2022, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Very young children are extremely vulnerable to changes in their blood sugar levels. High levels in particular can have potentially lasting consequences to their brain development. On top of that, diabetes is very challenging to manage in this age group, creating a huge burden for families,” she said in a University of Cambridge statement.

There is “high variability of insulin requirements, marked insulin sensitivity, and unpredictable eating and activity patterns,” Dr. Ware and colleagues noted.

“Caregiver fear of hypoglycemia, particularly overnight, is common and, coupled with young children’s unawareness that hypoglycemia is occurring, contributes to children not meeting the recommended glycemic targets or having difficulty maintaining recommended glycemic control unless caregivers can provide constant monitoring. These issues often lead to ... reduced quality of life for the whole family,” they added.

Except for mealtimes, device is fully automated

The new multicenter, randomized, crossover trial was conducted at seven centers across Austria, Germany, Luxembourg, and the United Kingdom in 2019-2020.

The trial compared the safety and efficacy of hybrid closed-loop therapy with sensor-augmented pump therapy (that is, without the device communication, as a control). All 74 children used the CamAPS FX hybrid closed-loop system for 16 weeks, and then used the control treatment for 16 weeks. The children were a mean age of 5.6 years and had a baseline hemoglobin A1c of 7.3% (56.6 mmol/mol).

The hybrid closed-loop system consisted of components that are commercially available in Europe: the Sooil insulin pump (Dana Diabecare RS) and the Dexcom G6 CGM, along with an unlocked Samsung Galaxy 8 smartphone housing an app (CamAPS FX, CamDiab) that runs the Cambridge proprietary model predictive control algorithm.

The smartphone communicates wirelessly with both the pump and the CGM transmitter and automatically adjusts the pump’s insulin delivery based on real-time sensor glucose readings. It also issues alarms if glucose levels fall below or rise above user-specified thresholds. This functionality was disabled during the study control periods.

Senior investigator Roman Hovorka, PhD, who developed the CamAPS FX app, explained in the University of Cambridge statement that the app “makes predictions about what it thinks is likely to happen next based on past experience. It learns how much insulin the child needs per day and how this changes at different times of the day.

“It then uses this [information] to adjust insulin levels to help achieve ideal blood sugar levels. Other than at mealtimes, it is fully automated, so parents do not need to continually monitor their child’s blood sugar levels.”

Indeed, the time spent in target glucose range (70-180 mg/dL) during the 16-week closed-loop period was 8.7 percentage points higher than during the control period (P < .001).

That difference translates to “a clinically meaningful 125 minutes per day,” and represented around three-quarters of their day (71.6%) in the target range, the investigators wrote.

The mean adjusted difference in time spent above 180 mg/dL was 8.5 percentage points lower with the closed-loop, also a significant difference (P < .001). Time spent below 70 mg/dL did not differ significantly between the two interventions (P = .74).

At the end of the study periods, the mean adjusted between-treatment difference in A1c was –0.4 percentage points, significantly lower following the closed-loop, compared with the control period (P < .001).

That percentage point difference (equivalent to 3.9 mmol/mol) “is important in a population of patients who had tight glycemic control at baseline. This result was observed without an increase in the time spent in a hypoglycemic state,” Dr. Ware and colleagues noted.

Median glucose sensor use was 99% during the closed-loop period and 96% during the control periods. During the closed-loop periods, the system was in closed-loop mode 95% of the time.

This finding supports longer-term usability in this age group and compares well with use in older children, they said.

One serious hypoglycemic episode, attributed to parental error rather than system malfunction, occurred during the closed-loop period. There were no episodes of diabetic ketoacidosis. Rates of other adverse events didn’t differ between the two periods.

“CamAPS FX led to improvements in several measures, including hyperglycemia and average blood sugar levels, without increasing the risk of hypos. This is likely to have important benefits for those children who use it,” Dr. Ware summarized.

Sleep quality could improve for children and caregivers

Reductions in time spent in hyperglycemia without increasing hypoglycemia could minimize the risk for neurocognitive deficits that have been reported among young children with type 1 diabetes, the authors speculated.

In addition, they noted that because 80% of overnight sensor readings were within target range and less than 3% were below 70 mg/dL, sleep quality could improve for both the children and their parents. This, in turn, “would confer associated quality of life benefits.”

“Parents have described our artificial pancreas as ‘life changing’ as it meant they were able to relax and spend less time worrying about their child’s blood sugar levels, particularly at nighttime. They tell us it gives them more time to do what any ‘normal’ family can do, to play and do fun things with their children,” observed Dr. Ware.

The CamAPS FX has been commercialized by CamDiab, a spin-out company set up by Dr. Hovorka. It is currently available through several NHS trusts across the United Kingdom, including Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and is expected to be more widely available soon.

The study was supported by the European Commission within the Horizon 2020 Framework Program, the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, and JDRF. Dr. Ware had no further disclosures. Dr. Hovorka has reported acting as consultant for Abbott Diabetes Care, BD, Dexcom, being a speaker for Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, and receiving royalty payments from B. Braun for software. He is director of CamDiab.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A semiautomated insulin delivery system improved glycemic control in young children with type 1 diabetes aged 1-7 years without increasing hypoglycemia.

“Hybrid closed-loop” systems – comprising an insulin pump, a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), and software enabling communication that semiautomates insulin delivery based on glucose levels – have been shown to improve glucose control in older children and adults.

The technology, also known as an artificial pancreas, has been less studied in very young children even though it may uniquely benefit them, said the authors of the new study, led by Julia Ware, MD, of the Wellcome Trust–Medical Research Council Institute of Metabolic Science and the University of Cambridge (England). The findings were published online Jan. 19, 2022, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Very young children are extremely vulnerable to changes in their blood sugar levels. High levels in particular can have potentially lasting consequences to their brain development. On top of that, diabetes is very challenging to manage in this age group, creating a huge burden for families,” she said in a University of Cambridge statement.

There is “high variability of insulin requirements, marked insulin sensitivity, and unpredictable eating and activity patterns,” Dr. Ware and colleagues noted.

“Caregiver fear of hypoglycemia, particularly overnight, is common and, coupled with young children’s unawareness that hypoglycemia is occurring, contributes to children not meeting the recommended glycemic targets or having difficulty maintaining recommended glycemic control unless caregivers can provide constant monitoring. These issues often lead to ... reduced quality of life for the whole family,” they added.

Except for mealtimes, device is fully automated

The new multicenter, randomized, crossover trial was conducted at seven centers across Austria, Germany, Luxembourg, and the United Kingdom in 2019-2020.

The trial compared the safety and efficacy of hybrid closed-loop therapy with sensor-augmented pump therapy (that is, without the device communication, as a control). All 74 children used the CamAPS FX hybrid closed-loop system for 16 weeks, and then used the control treatment for 16 weeks. The children were a mean age of 5.6 years and had a baseline hemoglobin A1c of 7.3% (56.6 mmol/mol).

The hybrid closed-loop system consisted of components that are commercially available in Europe: the Sooil insulin pump (Dana Diabecare RS) and the Dexcom G6 CGM, along with an unlocked Samsung Galaxy 8 smartphone housing an app (CamAPS FX, CamDiab) that runs the Cambridge proprietary model predictive control algorithm.

The smartphone communicates wirelessly with both the pump and the CGM transmitter and automatically adjusts the pump’s insulin delivery based on real-time sensor glucose readings. It also issues alarms if glucose levels fall below or rise above user-specified thresholds. This functionality was disabled during the study control periods.

Senior investigator Roman Hovorka, PhD, who developed the CamAPS FX app, explained in the University of Cambridge statement that the app “makes predictions about what it thinks is likely to happen next based on past experience. It learns how much insulin the child needs per day and how this changes at different times of the day.

“It then uses this [information] to adjust insulin levels to help achieve ideal blood sugar levels. Other than at mealtimes, it is fully automated, so parents do not need to continually monitor their child’s blood sugar levels.”

Indeed, the time spent in target glucose range (70-180 mg/dL) during the 16-week closed-loop period was 8.7 percentage points higher than during the control period (P < .001).

That difference translates to “a clinically meaningful 125 minutes per day,” and represented around three-quarters of their day (71.6%) in the target range, the investigators wrote.

The mean adjusted difference in time spent above 180 mg/dL was 8.5 percentage points lower with the closed-loop, also a significant difference (P < .001). Time spent below 70 mg/dL did not differ significantly between the two interventions (P = .74).

At the end of the study periods, the mean adjusted between-treatment difference in A1c was –0.4 percentage points, significantly lower following the closed-loop, compared with the control period (P < .001).

That percentage point difference (equivalent to 3.9 mmol/mol) “is important in a population of patients who had tight glycemic control at baseline. This result was observed without an increase in the time spent in a hypoglycemic state,” Dr. Ware and colleagues noted.

Median glucose sensor use was 99% during the closed-loop period and 96% during the control periods. During the closed-loop periods, the system was in closed-loop mode 95% of the time.

This finding supports longer-term usability in this age group and compares well with use in older children, they said.

One serious hypoglycemic episode, attributed to parental error rather than system malfunction, occurred during the closed-loop period. There were no episodes of diabetic ketoacidosis. Rates of other adverse events didn’t differ between the two periods.

“CamAPS FX led to improvements in several measures, including hyperglycemia and average blood sugar levels, without increasing the risk of hypos. This is likely to have important benefits for those children who use it,” Dr. Ware summarized.

Sleep quality could improve for children and caregivers

Reductions in time spent in hyperglycemia without increasing hypoglycemia could minimize the risk for neurocognitive deficits that have been reported among young children with type 1 diabetes, the authors speculated.

In addition, they noted that because 80% of overnight sensor readings were within target range and less than 3% were below 70 mg/dL, sleep quality could improve for both the children and their parents. This, in turn, “would confer associated quality of life benefits.”

“Parents have described our artificial pancreas as ‘life changing’ as it meant they were able to relax and spend less time worrying about their child’s blood sugar levels, particularly at nighttime. They tell us it gives them more time to do what any ‘normal’ family can do, to play and do fun things with their children,” observed Dr. Ware.

The CamAPS FX has been commercialized by CamDiab, a spin-out company set up by Dr. Hovorka. It is currently available through several NHS trusts across the United Kingdom, including Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and is expected to be more widely available soon.

The study was supported by the European Commission within the Horizon 2020 Framework Program, the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, and JDRF. Dr. Ware had no further disclosures. Dr. Hovorka has reported acting as consultant for Abbott Diabetes Care, BD, Dexcom, being a speaker for Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, and receiving royalty payments from B. Braun for software. He is director of CamDiab.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A semiautomated insulin delivery system improved glycemic control in young children with type 1 diabetes aged 1-7 years without increasing hypoglycemia.

“Hybrid closed-loop” systems – comprising an insulin pump, a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), and software enabling communication that semiautomates insulin delivery based on glucose levels – have been shown to improve glucose control in older children and adults.

The technology, also known as an artificial pancreas, has been less studied in very young children even though it may uniquely benefit them, said the authors of the new study, led by Julia Ware, MD, of the Wellcome Trust–Medical Research Council Institute of Metabolic Science and the University of Cambridge (England). The findings were published online Jan. 19, 2022, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Very young children are extremely vulnerable to changes in their blood sugar levels. High levels in particular can have potentially lasting consequences to their brain development. On top of that, diabetes is very challenging to manage in this age group, creating a huge burden for families,” she said in a University of Cambridge statement.

There is “high variability of insulin requirements, marked insulin sensitivity, and unpredictable eating and activity patterns,” Dr. Ware and colleagues noted.

“Caregiver fear of hypoglycemia, particularly overnight, is common and, coupled with young children’s unawareness that hypoglycemia is occurring, contributes to children not meeting the recommended glycemic targets or having difficulty maintaining recommended glycemic control unless caregivers can provide constant monitoring. These issues often lead to ... reduced quality of life for the whole family,” they added.

Except for mealtimes, device is fully automated

The new multicenter, randomized, crossover trial was conducted at seven centers across Austria, Germany, Luxembourg, and the United Kingdom in 2019-2020.

The trial compared the safety and efficacy of hybrid closed-loop therapy with sensor-augmented pump therapy (that is, without the device communication, as a control). All 74 children used the CamAPS FX hybrid closed-loop system for 16 weeks, and then used the control treatment for 16 weeks. The children were a mean age of 5.6 years and had a baseline hemoglobin A1c of 7.3% (56.6 mmol/mol).

The hybrid closed-loop system consisted of components that are commercially available in Europe: the Sooil insulin pump (Dana Diabecare RS) and the Dexcom G6 CGM, along with an unlocked Samsung Galaxy 8 smartphone housing an app (CamAPS FX, CamDiab) that runs the Cambridge proprietary model predictive control algorithm.

The smartphone communicates wirelessly with both the pump and the CGM transmitter and automatically adjusts the pump’s insulin delivery based on real-time sensor glucose readings. It also issues alarms if glucose levels fall below or rise above user-specified thresholds. This functionality was disabled during the study control periods.

Senior investigator Roman Hovorka, PhD, who developed the CamAPS FX app, explained in the University of Cambridge statement that the app “makes predictions about what it thinks is likely to happen next based on past experience. It learns how much insulin the child needs per day and how this changes at different times of the day.

“It then uses this [information] to adjust insulin levels to help achieve ideal blood sugar levels. Other than at mealtimes, it is fully automated, so parents do not need to continually monitor their child’s blood sugar levels.”

Indeed, the time spent in target glucose range (70-180 mg/dL) during the 16-week closed-loop period was 8.7 percentage points higher than during the control period (P < .001).

That difference translates to “a clinically meaningful 125 minutes per day,” and represented around three-quarters of their day (71.6%) in the target range, the investigators wrote.

The mean adjusted difference in time spent above 180 mg/dL was 8.5 percentage points lower with the closed-loop, also a significant difference (P < .001). Time spent below 70 mg/dL did not differ significantly between the two interventions (P = .74).

At the end of the study periods, the mean adjusted between-treatment difference in A1c was –0.4 percentage points, significantly lower following the closed-loop, compared with the control period (P < .001).

That percentage point difference (equivalent to 3.9 mmol/mol) “is important in a population of patients who had tight glycemic control at baseline. This result was observed without an increase in the time spent in a hypoglycemic state,” Dr. Ware and colleagues noted.

Median glucose sensor use was 99% during the closed-loop period and 96% during the control periods. During the closed-loop periods, the system was in closed-loop mode 95% of the time.

This finding supports longer-term usability in this age group and compares well with use in older children, they said.

One serious hypoglycemic episode, attributed to parental error rather than system malfunction, occurred during the closed-loop period. There were no episodes of diabetic ketoacidosis. Rates of other adverse events didn’t differ between the two periods.

“CamAPS FX led to improvements in several measures, including hyperglycemia and average blood sugar levels, without increasing the risk of hypos. This is likely to have important benefits for those children who use it,” Dr. Ware summarized.

Sleep quality could improve for children and caregivers

Reductions in time spent in hyperglycemia without increasing hypoglycemia could minimize the risk for neurocognitive deficits that have been reported among young children with type 1 diabetes, the authors speculated.

In addition, they noted that because 80% of overnight sensor readings were within target range and less than 3% were below 70 mg/dL, sleep quality could improve for both the children and their parents. This, in turn, “would confer associated quality of life benefits.”

“Parents have described our artificial pancreas as ‘life changing’ as it meant they were able to relax and spend less time worrying about their child’s blood sugar levels, particularly at nighttime. They tell us it gives them more time to do what any ‘normal’ family can do, to play and do fun things with their children,” observed Dr. Ware.

The CamAPS FX has been commercialized by CamDiab, a spin-out company set up by Dr. Hovorka. It is currently available through several NHS trusts across the United Kingdom, including Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and is expected to be more widely available soon.

The study was supported by the European Commission within the Horizon 2020 Framework Program, the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, and JDRF. Dr. Ware had no further disclosures. Dr. Hovorka has reported acting as consultant for Abbott Diabetes Care, BD, Dexcom, being a speaker for Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, and receiving royalty payments from B. Braun for software. He is director of CamDiab.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Advances in Diabetes and Cardiovascular Care

Real-World Experience With Automated Insulin Pumps

Continuous Blood Glucose Monitoring for T2DM

Statin-Induced Adverse Effects

Long QT and Cardiac Arrest After Pulmonary Edema

And more online

• Clinical Impact of U-500 Insulin Initiation

• Diabetes Self-Management Education

• SGLT2 Inhibitors, T2DM, and Heart Failure

• Alirocumab Use in Statin-Intolerant Veterans

• K Pneumoniae-Induced Aortitis

Real-World Experience With Automated Insulin Pumps

Continuous Blood Glucose Monitoring for T2DM

Statin-Induced Adverse Effects

Long QT and Cardiac Arrest After Pulmonary Edema

And more online

• Clinical Impact of U-500 Insulin Initiation

• Diabetes Self-Management Education

• SGLT2 Inhibitors, T2DM, and Heart Failure

• Alirocumab Use in Statin-Intolerant Veterans

• K Pneumoniae-Induced Aortitis

Real-World Experience With Automated Insulin Pumps

Continuous Blood Glucose Monitoring for T2DM

Statin-Induced Adverse Effects

Long QT and Cardiac Arrest After Pulmonary Edema

And more online

• Clinical Impact of U-500 Insulin Initiation

• Diabetes Self-Management Education

• SGLT2 Inhibitors, T2DM, and Heart Failure

• Alirocumab Use in Statin-Intolerant Veterans

• K Pneumoniae-Induced Aortitis

Program targets preschoolers to promote heart health

Creators of a pilot program that educates preschoolers about good heart health have validated a template for successful early childhood intervention that, they claim, provides a pathway for translating scientific evidence into the community and classroom for educational purposes to encourage long-lasting lifestyle changes.

That validation supports the creators' plans to take the program into more schools.

They reported key lessons in crafting the program, known as the SI! Program (for Salud Integral-Comprehensive Health), online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“This is a research-based program that uses randomized clinical trial evidence with implementation strategies to design educational health promotion programs,” senior author Valentin Fuster, MD, PhD, founder and trustees chairman of the Foundation for Science, Health, and Education (SHE) based in Barcelona, under whose aegis the SI! Program was implemented, said in an interview. Dr. Fuster is also director of Mount Sinai Heart and physician-in-chief at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, and general director of the National Center for Cardiovascular Investigation (CNIC) in Madrid, Spain’s equivalent of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

“There are specific times in a child’s life when improvements can be made to enhance long-term cardiovascular health status,” said Rodrigo Fernández-Jiménez, MD, PhD, group leader of the cardiovascular health and imaging lab at CNIC and study coauthor. “Our review, and previous studies, suggest that 4-5 years of age is the most favorable time to start a school-based intervention focused on healthy habits.”

A key piece of the SI! Program used a Sesame Street character, known as Dr. Ruster, a Muppet based on Dr. Fuster, to introduce and convey most messages and activities to the preschool children. The program also used a heart-shaped mascot named “Cardio” to teach about healthy behaviors. Other components include video segments, a colorful storybook, an interactive board game, flash cards, and a teacher’s guide. The activities and messages were tailored based on the country in which the program was implemented.

A decade of experience

The review evaluated 10 years of experience with the preschool-based program, drawing upon cluster-randomized clinical trials of the program in three countries with different socioeconomic conditions: Colombia, Spain, and the United States. The studies randomized schools to receive the SI! Program for 4 months or to a control group and included more than 3,800 children from 50 schools, along with their parents or caregivers and teachers. The studies found significant increases in preschoolers’ knowledge, attitudes, and habits toward healthy eating and living an active lifestyle. Now, the SI! Program is expanding into more than 250 schools in Spain and more than 40 schools in all five boroughs of New York City.

“This is a multidimensional program,” Dr. Fuster said. The review identified five stages for implementing the program: dissemination; adoption; implementation; evaluation; and institutionalization.

Dissemination involves three substages for intervention: components, design, and strategy. With regard to the components, said Dr. Fuster, “We’re targeting children to educate them in four topics: how the body works; nutritional and dietary requirements; physical activity; and the need to control emotions – to say no in the future when they’re confronted with alcohol, drugs, and tobacco.”

Design involved a multidisciplinary team of experts to develop the intervention, Dr. Fuster said. The strategy itself enlists parents and teachers in the implementation, but goes beyond that. “This is a community,” Dr. Fuster said. Hence, the school environment and classroom itself are also engaged to support the message of the four topics.

Dr. Fuster said future research should look at knowledge, attitude, and habits and biological outcomes in children who’ve been in the SI! Program when they reach adolescence. “Our hypothesis is that we can do this in older children, but when they reach age 10 we want to reintervene in them,” Dr. Fuster said. “Humans need reintervention. Our findings don’t get into sustainability.” He added that further research should also identify socioeconomic factors that influence child health.

Expanding the program across the New York City’s five boroughs “offers a unique opportunity to explore which socioeconomic factors, at both the family and borough level, and may eventually affect children’s health, how they are implicated in the intervention’s effectiveness, and how they can be addressed to reduce the gap in health inequalities,” he said.

Karalyn Kinsella, MD, a pediatrician affiliated with Yale New Haven (Conn.) Medical Center, noted the program’s multidimensional nature is an important element. “I think what is so important about this intervention is that it is not one single intervention but a curriculum that takes a significant amount of time (up to 50 hours) that allows for repetition of the information, which allows it to become remembered,” she said in an interview. “I also think incorporating families in the intervention is key as that is where change often has to happen.”

While she said the program may provide a template for a mental health curriculum, she added, “My concern is that teachers are already feeling overwhelmed and this may be viewed as another burden.”

The American Heart Association provided funding for the study in the United States. Dr Fernández-Jiménez has received funding from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria–Instituto de Salud Carlos III, which is cofunded by the European Regional Development Fund/European Social Fund. Dr. Fuster and Dr. Kinsella have no relevant disclosures.

Creators of a pilot program that educates preschoolers about good heart health have validated a template for successful early childhood intervention that, they claim, provides a pathway for translating scientific evidence into the community and classroom for educational purposes to encourage long-lasting lifestyle changes.

That validation supports the creators' plans to take the program into more schools.

They reported key lessons in crafting the program, known as the SI! Program (for Salud Integral-Comprehensive Health), online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“This is a research-based program that uses randomized clinical trial evidence with implementation strategies to design educational health promotion programs,” senior author Valentin Fuster, MD, PhD, founder and trustees chairman of the Foundation for Science, Health, and Education (SHE) based in Barcelona, under whose aegis the SI! Program was implemented, said in an interview. Dr. Fuster is also director of Mount Sinai Heart and physician-in-chief at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, and general director of the National Center for Cardiovascular Investigation (CNIC) in Madrid, Spain’s equivalent of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

“There are specific times in a child’s life when improvements can be made to enhance long-term cardiovascular health status,” said Rodrigo Fernández-Jiménez, MD, PhD, group leader of the cardiovascular health and imaging lab at CNIC and study coauthor. “Our review, and previous studies, suggest that 4-5 years of age is the most favorable time to start a school-based intervention focused on healthy habits.”

A key piece of the SI! Program used a Sesame Street character, known as Dr. Ruster, a Muppet based on Dr. Fuster, to introduce and convey most messages and activities to the preschool children. The program also used a heart-shaped mascot named “Cardio” to teach about healthy behaviors. Other components include video segments, a colorful storybook, an interactive board game, flash cards, and a teacher’s guide. The activities and messages were tailored based on the country in which the program was implemented.

A decade of experience

The review evaluated 10 years of experience with the preschool-based program, drawing upon cluster-randomized clinical trials of the program in three countries with different socioeconomic conditions: Colombia, Spain, and the United States. The studies randomized schools to receive the SI! Program for 4 months or to a control group and included more than 3,800 children from 50 schools, along with their parents or caregivers and teachers. The studies found significant increases in preschoolers’ knowledge, attitudes, and habits toward healthy eating and living an active lifestyle. Now, the SI! Program is expanding into more than 250 schools in Spain and more than 40 schools in all five boroughs of New York City.

“This is a multidimensional program,” Dr. Fuster said. The review identified five stages for implementing the program: dissemination; adoption; implementation; evaluation; and institutionalization.

Dissemination involves three substages for intervention: components, design, and strategy. With regard to the components, said Dr. Fuster, “We’re targeting children to educate them in four topics: how the body works; nutritional and dietary requirements; physical activity; and the need to control emotions – to say no in the future when they’re confronted with alcohol, drugs, and tobacco.”

Design involved a multidisciplinary team of experts to develop the intervention, Dr. Fuster said. The strategy itself enlists parents and teachers in the implementation, but goes beyond that. “This is a community,” Dr. Fuster said. Hence, the school environment and classroom itself are also engaged to support the message of the four topics.

Dr. Fuster said future research should look at knowledge, attitude, and habits and biological outcomes in children who’ve been in the SI! Program when they reach adolescence. “Our hypothesis is that we can do this in older children, but when they reach age 10 we want to reintervene in them,” Dr. Fuster said. “Humans need reintervention. Our findings don’t get into sustainability.” He added that further research should also identify socioeconomic factors that influence child health.

Expanding the program across the New York City’s five boroughs “offers a unique opportunity to explore which socioeconomic factors, at both the family and borough level, and may eventually affect children’s health, how they are implicated in the intervention’s effectiveness, and how they can be addressed to reduce the gap in health inequalities,” he said.

Karalyn Kinsella, MD, a pediatrician affiliated with Yale New Haven (Conn.) Medical Center, noted the program’s multidimensional nature is an important element. “I think what is so important about this intervention is that it is not one single intervention but a curriculum that takes a significant amount of time (up to 50 hours) that allows for repetition of the information, which allows it to become remembered,” she said in an interview. “I also think incorporating families in the intervention is key as that is where change often has to happen.”

While she said the program may provide a template for a mental health curriculum, she added, “My concern is that teachers are already feeling overwhelmed and this may be viewed as another burden.”

The American Heart Association provided funding for the study in the United States. Dr Fernández-Jiménez has received funding from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria–Instituto de Salud Carlos III, which is cofunded by the European Regional Development Fund/European Social Fund. Dr. Fuster and Dr. Kinsella have no relevant disclosures.