User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

SLN mapping is most cost-effective in low-risk endometrial carcinoma

Researchers conducting a cost-utility analysis of sentinel lymph node (SLN) mapping and lymph node dissection (LND), both selective and routine, for low-risk endometrial carcinoma (clinical stage 1 disease with grade 1-2 endometrioid histology on preoperative endometrial biopsy), found that the SLN mapping had the lowest costs and the highest quality-adjusted survival of the three strategies.

Between the two strategies of LND, selective LND based on intraoperative frozen section was more cost-effective than routine LND.

The researchers created a model using data from past studies and clinical estimates. “Our biggest assumption was that sentinel lymph node mapping is associated with a decreased risk of lymphedema compared with lymph node dissection ... [from] several studies showing that having less than five lymph nodes excised was associated with a much smaller risk of developing lymphedema,” wrote Rudy S. Suidan, MD, of the MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and his coauthors. Lymphedema was the main factor affecting quality of life in the analysis.

The analysis included estimates of rates of lymphadenectomy, bilateral mapping, and unilateral mapping, 3-year disease-specific survival, and overall survival, all of which were compared with third-party reimbursement costs at 2016 Medicare rates.

SLN mapping cost $16,401 per patient, while selective LND cost $17,036 per patient and routine LND cost $18,041 per patient. These strategies had quality-adjusted life years of 2.87, 2.81, and 2.79, respectively.

The superior cost-effectiveness of SLN mapping held, even when the researchers altered several of the variables in the model, including assuming open surgery instead of minimally invasive, and altering the assumed risk of lymphedema.

In addition to the possible limitation of making assumptions about SLN mapping and lymphedema, the researchers also pointed to the 3-year survival rates as shorter-term than preferable, driven by the available literature. The quality-adjusted life years did not differ much between the strategies because “most patients with low-risk cancer tend to have good clinical outcomes,” they wrote.

“This adds to the body of literature evaluating the clinical benefits of this strategy and may help health care providers in the decision-making process as they consider which approach to use,” the researchers wrote.

Dr. Suidan is supported by an NIH grant. Three coauthors reported other grants and fellowships. Five coauthors reported research support from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Clovis Oncology, and several other companies.

SOURCE: Suidan RS et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jun 11;132:52-8.

Researchers conducting a cost-utility analysis of sentinel lymph node (SLN) mapping and lymph node dissection (LND), both selective and routine, for low-risk endometrial carcinoma (clinical stage 1 disease with grade 1-2 endometrioid histology on preoperative endometrial biopsy), found that the SLN mapping had the lowest costs and the highest quality-adjusted survival of the three strategies.

Between the two strategies of LND, selective LND based on intraoperative frozen section was more cost-effective than routine LND.

The researchers created a model using data from past studies and clinical estimates. “Our biggest assumption was that sentinel lymph node mapping is associated with a decreased risk of lymphedema compared with lymph node dissection ... [from] several studies showing that having less than five lymph nodes excised was associated with a much smaller risk of developing lymphedema,” wrote Rudy S. Suidan, MD, of the MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and his coauthors. Lymphedema was the main factor affecting quality of life in the analysis.

The analysis included estimates of rates of lymphadenectomy, bilateral mapping, and unilateral mapping, 3-year disease-specific survival, and overall survival, all of which were compared with third-party reimbursement costs at 2016 Medicare rates.

SLN mapping cost $16,401 per patient, while selective LND cost $17,036 per patient and routine LND cost $18,041 per patient. These strategies had quality-adjusted life years of 2.87, 2.81, and 2.79, respectively.

The superior cost-effectiveness of SLN mapping held, even when the researchers altered several of the variables in the model, including assuming open surgery instead of minimally invasive, and altering the assumed risk of lymphedema.

In addition to the possible limitation of making assumptions about SLN mapping and lymphedema, the researchers also pointed to the 3-year survival rates as shorter-term than preferable, driven by the available literature. The quality-adjusted life years did not differ much between the strategies because “most patients with low-risk cancer tend to have good clinical outcomes,” they wrote.

“This adds to the body of literature evaluating the clinical benefits of this strategy and may help health care providers in the decision-making process as they consider which approach to use,” the researchers wrote.

Dr. Suidan is supported by an NIH grant. Three coauthors reported other grants and fellowships. Five coauthors reported research support from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Clovis Oncology, and several other companies.

SOURCE: Suidan RS et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jun 11;132:52-8.

Researchers conducting a cost-utility analysis of sentinel lymph node (SLN) mapping and lymph node dissection (LND), both selective and routine, for low-risk endometrial carcinoma (clinical stage 1 disease with grade 1-2 endometrioid histology on preoperative endometrial biopsy), found that the SLN mapping had the lowest costs and the highest quality-adjusted survival of the three strategies.

Between the two strategies of LND, selective LND based on intraoperative frozen section was more cost-effective than routine LND.

The researchers created a model using data from past studies and clinical estimates. “Our biggest assumption was that sentinel lymph node mapping is associated with a decreased risk of lymphedema compared with lymph node dissection ... [from] several studies showing that having less than five lymph nodes excised was associated with a much smaller risk of developing lymphedema,” wrote Rudy S. Suidan, MD, of the MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and his coauthors. Lymphedema was the main factor affecting quality of life in the analysis.

The analysis included estimates of rates of lymphadenectomy, bilateral mapping, and unilateral mapping, 3-year disease-specific survival, and overall survival, all of which were compared with third-party reimbursement costs at 2016 Medicare rates.

SLN mapping cost $16,401 per patient, while selective LND cost $17,036 per patient and routine LND cost $18,041 per patient. These strategies had quality-adjusted life years of 2.87, 2.81, and 2.79, respectively.

The superior cost-effectiveness of SLN mapping held, even when the researchers altered several of the variables in the model, including assuming open surgery instead of minimally invasive, and altering the assumed risk of lymphedema.

In addition to the possible limitation of making assumptions about SLN mapping and lymphedema, the researchers also pointed to the 3-year survival rates as shorter-term than preferable, driven by the available literature. The quality-adjusted life years did not differ much between the strategies because “most patients with low-risk cancer tend to have good clinical outcomes,” they wrote.

“This adds to the body of literature evaluating the clinical benefits of this strategy and may help health care providers in the decision-making process as they consider which approach to use,” the researchers wrote.

Dr. Suidan is supported by an NIH grant. Three coauthors reported other grants and fellowships. Five coauthors reported research support from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Clovis Oncology, and several other companies.

SOURCE: Suidan RS et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jun 11;132:52-8.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Azar blames PBMs for no drop in prescription prices

“The president said that, in reaction to the release of the drug pricing blueprint, drug companies would be ‘announcing voluntary massive drops in prices within 2 weeks,’ ” Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) said during a hearing of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee to review the administration’s plan to lower drug costs.

Sen. Warren said she, along with Sen. Tina Smith (D-Minn.), sent letters to the top 10 drug manufacturers to get a pricing update and see what products were going to be the recipient of price cuts in response to the blueprint.

She then asked Alex Azar, Health & Human Services secretary and the hearing’s only witness, which manufacturers the president was referring to when he said drug companies would be reducing prices.

“There are actually several drug companies that are looking at substantial and material decreases of drug prices in competitive classes and actually competing with each other and looking to do that,” Mr. Azar testified. “They are working right now with the pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and distributors.”

He went on to blame the PBMs for the inability to lower prices.

“What they are trying to do is work to ensure they are not discriminated against,” he said. “Oddly, the fear is that they would be discriminated against for decreasing their price.”

He noted during the hearing that PBMs get paid based on the rebates they negotiate and could retaliate against manufacturers by placing products on a higher tier or dropping them from formularies in total if manufacturers were to impact the PBM bottom line by dropping prices. He added that one of the options in the blueprint was to ban any financial transactions between the manufacturer and the PBM to ensure there is no conflict of interest and that the PBM is working on behalf of the insurers only to negotiate the best prices for drugs.

Panel Democrats used the hearing to hammer the administration for not following up on President Trump’s campaign promise to allow the government to negotiate Medicare Part D drug pricing. Part of that discussion focused on using government leverage to get “best price” contracts using prices for drugs in other countries, an exercise that Mr. Azar said would theoretically result in manufacturers yanking their drugs out of foreign markets and jacking the prices even more in the United States.

When pressed to try it on a pilot basis with one or two drugs, he pushed back, suggesting that even a pilot trial of it could result in “irreparable harm.”

“The president said that, in reaction to the release of the drug pricing blueprint, drug companies would be ‘announcing voluntary massive drops in prices within 2 weeks,’ ” Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) said during a hearing of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee to review the administration’s plan to lower drug costs.

Sen. Warren said she, along with Sen. Tina Smith (D-Minn.), sent letters to the top 10 drug manufacturers to get a pricing update and see what products were going to be the recipient of price cuts in response to the blueprint.

She then asked Alex Azar, Health & Human Services secretary and the hearing’s only witness, which manufacturers the president was referring to when he said drug companies would be reducing prices.

“There are actually several drug companies that are looking at substantial and material decreases of drug prices in competitive classes and actually competing with each other and looking to do that,” Mr. Azar testified. “They are working right now with the pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and distributors.”

He went on to blame the PBMs for the inability to lower prices.

“What they are trying to do is work to ensure they are not discriminated against,” he said. “Oddly, the fear is that they would be discriminated against for decreasing their price.”

He noted during the hearing that PBMs get paid based on the rebates they negotiate and could retaliate against manufacturers by placing products on a higher tier or dropping them from formularies in total if manufacturers were to impact the PBM bottom line by dropping prices. He added that one of the options in the blueprint was to ban any financial transactions between the manufacturer and the PBM to ensure there is no conflict of interest and that the PBM is working on behalf of the insurers only to negotiate the best prices for drugs.

Panel Democrats used the hearing to hammer the administration for not following up on President Trump’s campaign promise to allow the government to negotiate Medicare Part D drug pricing. Part of that discussion focused on using government leverage to get “best price” contracts using prices for drugs in other countries, an exercise that Mr. Azar said would theoretically result in manufacturers yanking their drugs out of foreign markets and jacking the prices even more in the United States.

When pressed to try it on a pilot basis with one or two drugs, he pushed back, suggesting that even a pilot trial of it could result in “irreparable harm.”

“The president said that, in reaction to the release of the drug pricing blueprint, drug companies would be ‘announcing voluntary massive drops in prices within 2 weeks,’ ” Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) said during a hearing of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee to review the administration’s plan to lower drug costs.

Sen. Warren said she, along with Sen. Tina Smith (D-Minn.), sent letters to the top 10 drug manufacturers to get a pricing update and see what products were going to be the recipient of price cuts in response to the blueprint.

She then asked Alex Azar, Health & Human Services secretary and the hearing’s only witness, which manufacturers the president was referring to when he said drug companies would be reducing prices.

“There are actually several drug companies that are looking at substantial and material decreases of drug prices in competitive classes and actually competing with each other and looking to do that,” Mr. Azar testified. “They are working right now with the pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and distributors.”

He went on to blame the PBMs for the inability to lower prices.

“What they are trying to do is work to ensure they are not discriminated against,” he said. “Oddly, the fear is that they would be discriminated against for decreasing their price.”

He noted during the hearing that PBMs get paid based on the rebates they negotiate and could retaliate against manufacturers by placing products on a higher tier or dropping them from formularies in total if manufacturers were to impact the PBM bottom line by dropping prices. He added that one of the options in the blueprint was to ban any financial transactions between the manufacturer and the PBM to ensure there is no conflict of interest and that the PBM is working on behalf of the insurers only to negotiate the best prices for drugs.

Panel Democrats used the hearing to hammer the administration for not following up on President Trump’s campaign promise to allow the government to negotiate Medicare Part D drug pricing. Part of that discussion focused on using government leverage to get “best price” contracts using prices for drugs in other countries, an exercise that Mr. Azar said would theoretically result in manufacturers yanking their drugs out of foreign markets and jacking the prices even more in the United States.

When pressed to try it on a pilot basis with one or two drugs, he pushed back, suggesting that even a pilot trial of it could result in “irreparable harm.”

6 ways to reduce liability by improving doc-nurse teams

Positive relationships between physicians and nurses not only make for a smoother work environment, they also may reduce medical errors and lower the risk of lawsuits.

A recent study of closed claims by national medical malpractice insurer The Doctors Company found that poor physician oversight is a key contributor to lawsuits against nurses. Investigators analyzed 67 nurse practitioner (NP) claims from January 2011 to December 2016 and compared them with 1,358 claims against primary care physicians during the same time period.

Diagnostic and medication errors were the most common allegations against NPs, the study found, a trend that matched the most frequent allegations against primary care (internal medicine and family medicine) doctors. Top administrative factors that prompted lawsuits against nurses included inadequate physician supervision, failure to adhere to scope of practice, and absence of or deviation from written protocols.

The findings illustrate the importance of effective collaboration between physicians and NPs, said Darrell Ranum, vice president for patient safety and risk management for The Doctors Co. Below, legal experts share six ways to strengthen the physician-nurse relationship and at the same time, reduce liability:

1. Foster open dialogue. Cultivating a comfortable environment where nurses and physicians feel at ease sharing concerns and problems is a key step, says Louise B. Andrew, MD, JD, a physician and attorney who specializes in litigation stress management. A common scenario is a nurse who notices an abnormal vital sign but fails to mention it to the supervising physician because they feel they can handle it themselves or because they believe the doctor is too busy or too tired to be bothered, she said. The patient’s condition then worsens, resulting in a poor outcome that could have been avoided with better communication among providers. Delayed/wrong diagnosis accounted for 41% of claims against primary care physicians and 48% of claims against NPs in The Doctors Company study.

Set the tone early by exemplifying positive and clear communication, practicing good listening, and remaining empathetic, yet firm when making your needs known, Dr. Andrew advised.

“In the medical setting, you are always communicating for the benefit of the patient, and it is good to both keep this in mind, and to say it out loud,” she said.

2. Stick to the scope. When hiring an NP, make sure their scope of practice is clearly understood by all parties and respect their limitations, said Melanie L. Balestra, a Newport Beach, Calif., attorney and nurse practitioner who represents health providers.

Nurses practitioners must refrain from overstepping their authority, but physicians also must be careful not to ask too much of their NPs, experts stress. Ms. Balestra notes there is frequent confusion among doctors and NPs over how and whether scope of practice can be expanded as needed.

“This happens all the time,” Ms. Balestra said. “I get at least two questions on this every week [from nurses] asking, ‘Can I do this? Can I do that?’ ”

The answer depends on the circumstances, the nurse’s training, and the type of practice being broadened, Ms. Balestra said. For example, an NP in cardiology care may be allowed to perform more procedures in that field after internal training, but an NP who is trained in the care of adults can see pediatric patients only by going back to school.

“Know who you’re hiring, where their expertise lies, and where they feel comfortable,” she emphasized.

3. Preplan reviews. Early in the doctor-NP relationship, discuss and decide what type of medical cases warrant physician review, Mr. Ranum said. This includes agreeing on the type of patient conditions that will require a physician review and determining the types and percentage of medical records the doctor will evaluate, he said.

“The numbers should be higher at the beginning of the relationship until the physician gains an understanding of the NP’s experience and competence,” Mr. Ranum said. “Setting expectations will open the door to more frequent and more effective communication.”

NPs, meanwhile, should feel confident in requesting the physician’s assistance when a patient’s presentation is complex or a patient has returned with the same complaints, he added.

4. Convene regularly. Schedule regular meetings to catch up and discuss patient cases – not just when something goes awry, said Ms. Balestra. During weekly or monthly meetings, physicians, NPs, and other team members can converse in a more relaxed atmosphere and share any concerns or ideas for improvements.

“Have a meeting, whether by phone or in person, just to see how things are going,” she said. “That way, the NP may be able to take some things off the plate for the physician and the physician can see how [he or she] can assist the NP.”

Short huddles at the start of each day also help clinicians and staff prepare for patients and discuss approaches to managing complex conditions or challenging patient personalities, Mr. Ranum said.

“It is often helpful to debrief on patients who were seen during that day and who represent complex conditions,” he said. “Physicians may see opportunities to improve care following the NP’s assessment and diagnosis.”

5. Consider noncompliant policy. Create a noncompliant patient policy and work together to address uncooperative patients. Noncompliant patients are a top lawsuit risk, Ms. Balestra said. A noncompliant patient for instance, may provide conflicting information to different health professionals or attempt to blame providers for adverse events, she said.

“Your noncompliant patient is your easiest patient for a lawsuit because they’re not following [instructions] and then something happens, and they say, ‘It’s your fault, you didn’t treat me right.’”

Physician and NPs should be on the same page about noncompliant patients, including taking time to discuss when and how to terminate them from the practice if necessary, she said. Consistent documentation about patients by both physician and NPs is also critical, experts emphasize. Insufficient or lack of documentation led to patient injuries in 17% of cases against primary care doctors and in 19% of cases against NPs in The Doctors Company study.

6. Keep patients out of it. When disagreements or grievances occur, discuss the problem in private and ensure all staff members do the same, Dr. Andrew said. Refrain from letting anger or annoyance with another team member carry into patient care or worse, trigger a negative comment about a staff member in front of a patient, she said.

“All it takes is for something to go wrong and a patient or family who has heard such sentiments is tuned into the fact there may be some culpability,” she said. “This is probably a key factor in many a claimant’s decision to seek redress for a bad outcome.”

Instead, address problems or differences as soon as possible and work toward a resolution. It may help to create a conflict resolution policy that outlines behavioral expectations from all team members and suggested solutions when concerns arise.

“We have to put our egos aside,” Ms. Balestra said. “The ultimate goal is the best care of the patient.”

Positive relationships between physicians and nurses not only make for a smoother work environment, they also may reduce medical errors and lower the risk of lawsuits.

A recent study of closed claims by national medical malpractice insurer The Doctors Company found that poor physician oversight is a key contributor to lawsuits against nurses. Investigators analyzed 67 nurse practitioner (NP) claims from January 2011 to December 2016 and compared them with 1,358 claims against primary care physicians during the same time period.

Diagnostic and medication errors were the most common allegations against NPs, the study found, a trend that matched the most frequent allegations against primary care (internal medicine and family medicine) doctors. Top administrative factors that prompted lawsuits against nurses included inadequate physician supervision, failure to adhere to scope of practice, and absence of or deviation from written protocols.

The findings illustrate the importance of effective collaboration between physicians and NPs, said Darrell Ranum, vice president for patient safety and risk management for The Doctors Co. Below, legal experts share six ways to strengthen the physician-nurse relationship and at the same time, reduce liability:

1. Foster open dialogue. Cultivating a comfortable environment where nurses and physicians feel at ease sharing concerns and problems is a key step, says Louise B. Andrew, MD, JD, a physician and attorney who specializes in litigation stress management. A common scenario is a nurse who notices an abnormal vital sign but fails to mention it to the supervising physician because they feel they can handle it themselves or because they believe the doctor is too busy or too tired to be bothered, she said. The patient’s condition then worsens, resulting in a poor outcome that could have been avoided with better communication among providers. Delayed/wrong diagnosis accounted for 41% of claims against primary care physicians and 48% of claims against NPs in The Doctors Company study.

Set the tone early by exemplifying positive and clear communication, practicing good listening, and remaining empathetic, yet firm when making your needs known, Dr. Andrew advised.

“In the medical setting, you are always communicating for the benefit of the patient, and it is good to both keep this in mind, and to say it out loud,” she said.

2. Stick to the scope. When hiring an NP, make sure their scope of practice is clearly understood by all parties and respect their limitations, said Melanie L. Balestra, a Newport Beach, Calif., attorney and nurse practitioner who represents health providers.

Nurses practitioners must refrain from overstepping their authority, but physicians also must be careful not to ask too much of their NPs, experts stress. Ms. Balestra notes there is frequent confusion among doctors and NPs over how and whether scope of practice can be expanded as needed.

“This happens all the time,” Ms. Balestra said. “I get at least two questions on this every week [from nurses] asking, ‘Can I do this? Can I do that?’ ”

The answer depends on the circumstances, the nurse’s training, and the type of practice being broadened, Ms. Balestra said. For example, an NP in cardiology care may be allowed to perform more procedures in that field after internal training, but an NP who is trained in the care of adults can see pediatric patients only by going back to school.

“Know who you’re hiring, where their expertise lies, and where they feel comfortable,” she emphasized.

3. Preplan reviews. Early in the doctor-NP relationship, discuss and decide what type of medical cases warrant physician review, Mr. Ranum said. This includes agreeing on the type of patient conditions that will require a physician review and determining the types and percentage of medical records the doctor will evaluate, he said.

“The numbers should be higher at the beginning of the relationship until the physician gains an understanding of the NP’s experience and competence,” Mr. Ranum said. “Setting expectations will open the door to more frequent and more effective communication.”

NPs, meanwhile, should feel confident in requesting the physician’s assistance when a patient’s presentation is complex or a patient has returned with the same complaints, he added.

4. Convene regularly. Schedule regular meetings to catch up and discuss patient cases – not just when something goes awry, said Ms. Balestra. During weekly or monthly meetings, physicians, NPs, and other team members can converse in a more relaxed atmosphere and share any concerns or ideas for improvements.

“Have a meeting, whether by phone or in person, just to see how things are going,” she said. “That way, the NP may be able to take some things off the plate for the physician and the physician can see how [he or she] can assist the NP.”

Short huddles at the start of each day also help clinicians and staff prepare for patients and discuss approaches to managing complex conditions or challenging patient personalities, Mr. Ranum said.

“It is often helpful to debrief on patients who were seen during that day and who represent complex conditions,” he said. “Physicians may see opportunities to improve care following the NP’s assessment and diagnosis.”

5. Consider noncompliant policy. Create a noncompliant patient policy and work together to address uncooperative patients. Noncompliant patients are a top lawsuit risk, Ms. Balestra said. A noncompliant patient for instance, may provide conflicting information to different health professionals or attempt to blame providers for adverse events, she said.

“Your noncompliant patient is your easiest patient for a lawsuit because they’re not following [instructions] and then something happens, and they say, ‘It’s your fault, you didn’t treat me right.’”

Physician and NPs should be on the same page about noncompliant patients, including taking time to discuss when and how to terminate them from the practice if necessary, she said. Consistent documentation about patients by both physician and NPs is also critical, experts emphasize. Insufficient or lack of documentation led to patient injuries in 17% of cases against primary care doctors and in 19% of cases against NPs in The Doctors Company study.

6. Keep patients out of it. When disagreements or grievances occur, discuss the problem in private and ensure all staff members do the same, Dr. Andrew said. Refrain from letting anger or annoyance with another team member carry into patient care or worse, trigger a negative comment about a staff member in front of a patient, she said.

“All it takes is for something to go wrong and a patient or family who has heard such sentiments is tuned into the fact there may be some culpability,” she said. “This is probably a key factor in many a claimant’s decision to seek redress for a bad outcome.”

Instead, address problems or differences as soon as possible and work toward a resolution. It may help to create a conflict resolution policy that outlines behavioral expectations from all team members and suggested solutions when concerns arise.

“We have to put our egos aside,” Ms. Balestra said. “The ultimate goal is the best care of the patient.”

Positive relationships between physicians and nurses not only make for a smoother work environment, they also may reduce medical errors and lower the risk of lawsuits.

A recent study of closed claims by national medical malpractice insurer The Doctors Company found that poor physician oversight is a key contributor to lawsuits against nurses. Investigators analyzed 67 nurse practitioner (NP) claims from January 2011 to December 2016 and compared them with 1,358 claims against primary care physicians during the same time period.

Diagnostic and medication errors were the most common allegations against NPs, the study found, a trend that matched the most frequent allegations against primary care (internal medicine and family medicine) doctors. Top administrative factors that prompted lawsuits against nurses included inadequate physician supervision, failure to adhere to scope of practice, and absence of or deviation from written protocols.

The findings illustrate the importance of effective collaboration between physicians and NPs, said Darrell Ranum, vice president for patient safety and risk management for The Doctors Co. Below, legal experts share six ways to strengthen the physician-nurse relationship and at the same time, reduce liability:

1. Foster open dialogue. Cultivating a comfortable environment where nurses and physicians feel at ease sharing concerns and problems is a key step, says Louise B. Andrew, MD, JD, a physician and attorney who specializes in litigation stress management. A common scenario is a nurse who notices an abnormal vital sign but fails to mention it to the supervising physician because they feel they can handle it themselves or because they believe the doctor is too busy or too tired to be bothered, she said. The patient’s condition then worsens, resulting in a poor outcome that could have been avoided with better communication among providers. Delayed/wrong diagnosis accounted for 41% of claims against primary care physicians and 48% of claims against NPs in The Doctors Company study.

Set the tone early by exemplifying positive and clear communication, practicing good listening, and remaining empathetic, yet firm when making your needs known, Dr. Andrew advised.

“In the medical setting, you are always communicating for the benefit of the patient, and it is good to both keep this in mind, and to say it out loud,” she said.

2. Stick to the scope. When hiring an NP, make sure their scope of practice is clearly understood by all parties and respect their limitations, said Melanie L. Balestra, a Newport Beach, Calif., attorney and nurse practitioner who represents health providers.

Nurses practitioners must refrain from overstepping their authority, but physicians also must be careful not to ask too much of their NPs, experts stress. Ms. Balestra notes there is frequent confusion among doctors and NPs over how and whether scope of practice can be expanded as needed.

“This happens all the time,” Ms. Balestra said. “I get at least two questions on this every week [from nurses] asking, ‘Can I do this? Can I do that?’ ”

The answer depends on the circumstances, the nurse’s training, and the type of practice being broadened, Ms. Balestra said. For example, an NP in cardiology care may be allowed to perform more procedures in that field after internal training, but an NP who is trained in the care of adults can see pediatric patients only by going back to school.

“Know who you’re hiring, where their expertise lies, and where they feel comfortable,” she emphasized.

3. Preplan reviews. Early in the doctor-NP relationship, discuss and decide what type of medical cases warrant physician review, Mr. Ranum said. This includes agreeing on the type of patient conditions that will require a physician review and determining the types and percentage of medical records the doctor will evaluate, he said.

“The numbers should be higher at the beginning of the relationship until the physician gains an understanding of the NP’s experience and competence,” Mr. Ranum said. “Setting expectations will open the door to more frequent and more effective communication.”

NPs, meanwhile, should feel confident in requesting the physician’s assistance when a patient’s presentation is complex or a patient has returned with the same complaints, he added.

4. Convene regularly. Schedule regular meetings to catch up and discuss patient cases – not just when something goes awry, said Ms. Balestra. During weekly or monthly meetings, physicians, NPs, and other team members can converse in a more relaxed atmosphere and share any concerns or ideas for improvements.

“Have a meeting, whether by phone or in person, just to see how things are going,” she said. “That way, the NP may be able to take some things off the plate for the physician and the physician can see how [he or she] can assist the NP.”

Short huddles at the start of each day also help clinicians and staff prepare for patients and discuss approaches to managing complex conditions or challenging patient personalities, Mr. Ranum said.

“It is often helpful to debrief on patients who were seen during that day and who represent complex conditions,” he said. “Physicians may see opportunities to improve care following the NP’s assessment and diagnosis.”

5. Consider noncompliant policy. Create a noncompliant patient policy and work together to address uncooperative patients. Noncompliant patients are a top lawsuit risk, Ms. Balestra said. A noncompliant patient for instance, may provide conflicting information to different health professionals or attempt to blame providers for adverse events, she said.

“Your noncompliant patient is your easiest patient for a lawsuit because they’re not following [instructions] and then something happens, and they say, ‘It’s your fault, you didn’t treat me right.’”

Physician and NPs should be on the same page about noncompliant patients, including taking time to discuss when and how to terminate them from the practice if necessary, she said. Consistent documentation about patients by both physician and NPs is also critical, experts emphasize. Insufficient or lack of documentation led to patient injuries in 17% of cases against primary care doctors and in 19% of cases against NPs in The Doctors Company study.

6. Keep patients out of it. When disagreements or grievances occur, discuss the problem in private and ensure all staff members do the same, Dr. Andrew said. Refrain from letting anger or annoyance with another team member carry into patient care or worse, trigger a negative comment about a staff member in front of a patient, she said.

“All it takes is for something to go wrong and a patient or family who has heard such sentiments is tuned into the fact there may be some culpability,” she said. “This is probably a key factor in many a claimant’s decision to seek redress for a bad outcome.”

Instead, address problems or differences as soon as possible and work toward a resolution. It may help to create a conflict resolution policy that outlines behavioral expectations from all team members and suggested solutions when concerns arise.

“We have to put our egos aside,” Ms. Balestra said. “The ultimate goal is the best care of the patient.”

Fundoplication works best for true PPI-refractory heartburn

WASHINGTON – Less than a quarter of patients with heartburn that appears refractory to proton pump inhibitor treatment truly have reflux-related, drug-refractory heartburn with a high symptom–related probability, but patients who fall into this select subgroup often have significant symptom relief from surgical fundoplication, based on results from a randomized, multicenter, Department of Veterans Affairs study with 78 patients.

Although laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication relieved the heartburn symptoms of just two-thirds of patients who met the study’s definition of having true proton pump inhibitor (PPI)–refractory heartburn, this level of efficacy far exceeded the impact of drug therapy with baclofen or desipramine, which was little better than placebo, Stuart J. Spechler, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

“Fundoplication fell out of favor because of the success of PPI treatment, and because of complications from the surgery, but what our results show is that there is a subgroup of patients who can benefit from fundoplication. The challenge is identifying them,” said Dr. Spechler, a gastroenterologist and professor of medicine at the University of Texas, Dallas. “If you go through a careful work-up you will find the patients who have true PPI-refractory acid reflux and heartburn, and in the end we don’t have good medical treatments for these patients,” leaving fundoplication as their best hope for symptom relief.

The study he ran included 366 patients seen at about 30 VA Medical Centers across the United States who had been referred to his center because of presumed PPI-refractory heartburn. The careful work-up that Dr. Spechler and his associates ran included a closely supervised, 2-week trial of a standardized PPI regimen with omeprazole, careful symptom scoring on this treatment with a reflux-specific, health-related quality of life questionnaire, endoscopic esophageal manometry, and esophageal pH monitoring while on omeprazole.

This process placed patients into several distinct subgroups: About 19% dropped out of the study during this assessment, and another 15% left the study because of their intolerance of various stages of the work-up. Nearly 12% of patients wound up being responsive to the PPI regimen, about 6% had organic disorders not related to gastroesophageal reflux disease, and 27% had functional heartburn with a normal level of acid reflux, which left 78 patients (21%) who demonstrated true reflux-related, PPI-refractory heartburn symptoms.

The researchers then randomized this 78-patient subgroup into three treatment arms, with one group of 27 underwent fundoplication surgery. A group of 25 underwent active medical therapy with 20 mg omeprazole b.i.d. plus baclofen, which was started at 5 mg t.i.d. and increased to 20 mg t.i.d. In baclofen-intolerant or nonresponding patients, this treatment was followed up with desipramine, increasing from a starting dosage of 25 mg/day to 100 mg/day. A third group of 26 control patients received active omeprazole at the same dosage but placebo in place of the baclofen and desipramine. These three subgroups showed no statistically significant differences at baseline for all demographic and clinical parameters recorded.

The study’s primary endpoint was the percentage of patients in each treatment arm who had a “successful” outcome, defined as at least a 50% improvement in their gastroesophageal reflux health-related quality of life score (J Gastrointest Surg. 1998 Mar-Apr;2[2]:141-5) after 1 year on treatment, which occurred in 67% of the fundoplication patients, 28% in the active medical arm, and 12% in the control arm. The fundoplication-treated patients had a significantly higher rate of a successful outcome, compared with patients in each of the other two treatment groups, while the success rates among patients in the active medical group and the control group did not differ significantly, Dr. Spechler said.

Dr. Spechler had no disclosures to report.

WASHINGTON – Less than a quarter of patients with heartburn that appears refractory to proton pump inhibitor treatment truly have reflux-related, drug-refractory heartburn with a high symptom–related probability, but patients who fall into this select subgroup often have significant symptom relief from surgical fundoplication, based on results from a randomized, multicenter, Department of Veterans Affairs study with 78 patients.

Although laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication relieved the heartburn symptoms of just two-thirds of patients who met the study’s definition of having true proton pump inhibitor (PPI)–refractory heartburn, this level of efficacy far exceeded the impact of drug therapy with baclofen or desipramine, which was little better than placebo, Stuart J. Spechler, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

“Fundoplication fell out of favor because of the success of PPI treatment, and because of complications from the surgery, but what our results show is that there is a subgroup of patients who can benefit from fundoplication. The challenge is identifying them,” said Dr. Spechler, a gastroenterologist and professor of medicine at the University of Texas, Dallas. “If you go through a careful work-up you will find the patients who have true PPI-refractory acid reflux and heartburn, and in the end we don’t have good medical treatments for these patients,” leaving fundoplication as their best hope for symptom relief.

The study he ran included 366 patients seen at about 30 VA Medical Centers across the United States who had been referred to his center because of presumed PPI-refractory heartburn. The careful work-up that Dr. Spechler and his associates ran included a closely supervised, 2-week trial of a standardized PPI regimen with omeprazole, careful symptom scoring on this treatment with a reflux-specific, health-related quality of life questionnaire, endoscopic esophageal manometry, and esophageal pH monitoring while on omeprazole.

This process placed patients into several distinct subgroups: About 19% dropped out of the study during this assessment, and another 15% left the study because of their intolerance of various stages of the work-up. Nearly 12% of patients wound up being responsive to the PPI regimen, about 6% had organic disorders not related to gastroesophageal reflux disease, and 27% had functional heartburn with a normal level of acid reflux, which left 78 patients (21%) who demonstrated true reflux-related, PPI-refractory heartburn symptoms.

The researchers then randomized this 78-patient subgroup into three treatment arms, with one group of 27 underwent fundoplication surgery. A group of 25 underwent active medical therapy with 20 mg omeprazole b.i.d. plus baclofen, which was started at 5 mg t.i.d. and increased to 20 mg t.i.d. In baclofen-intolerant or nonresponding patients, this treatment was followed up with desipramine, increasing from a starting dosage of 25 mg/day to 100 mg/day. A third group of 26 control patients received active omeprazole at the same dosage but placebo in place of the baclofen and desipramine. These three subgroups showed no statistically significant differences at baseline for all demographic and clinical parameters recorded.

The study’s primary endpoint was the percentage of patients in each treatment arm who had a “successful” outcome, defined as at least a 50% improvement in their gastroesophageal reflux health-related quality of life score (J Gastrointest Surg. 1998 Mar-Apr;2[2]:141-5) after 1 year on treatment, which occurred in 67% of the fundoplication patients, 28% in the active medical arm, and 12% in the control arm. The fundoplication-treated patients had a significantly higher rate of a successful outcome, compared with patients in each of the other two treatment groups, while the success rates among patients in the active medical group and the control group did not differ significantly, Dr. Spechler said.

Dr. Spechler had no disclosures to report.

WASHINGTON – Less than a quarter of patients with heartburn that appears refractory to proton pump inhibitor treatment truly have reflux-related, drug-refractory heartburn with a high symptom–related probability, but patients who fall into this select subgroup often have significant symptom relief from surgical fundoplication, based on results from a randomized, multicenter, Department of Veterans Affairs study with 78 patients.

Although laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication relieved the heartburn symptoms of just two-thirds of patients who met the study’s definition of having true proton pump inhibitor (PPI)–refractory heartburn, this level of efficacy far exceeded the impact of drug therapy with baclofen or desipramine, which was little better than placebo, Stuart J. Spechler, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

“Fundoplication fell out of favor because of the success of PPI treatment, and because of complications from the surgery, but what our results show is that there is a subgroup of patients who can benefit from fundoplication. The challenge is identifying them,” said Dr. Spechler, a gastroenterologist and professor of medicine at the University of Texas, Dallas. “If you go through a careful work-up you will find the patients who have true PPI-refractory acid reflux and heartburn, and in the end we don’t have good medical treatments for these patients,” leaving fundoplication as their best hope for symptom relief.

The study he ran included 366 patients seen at about 30 VA Medical Centers across the United States who had been referred to his center because of presumed PPI-refractory heartburn. The careful work-up that Dr. Spechler and his associates ran included a closely supervised, 2-week trial of a standardized PPI regimen with omeprazole, careful symptom scoring on this treatment with a reflux-specific, health-related quality of life questionnaire, endoscopic esophageal manometry, and esophageal pH monitoring while on omeprazole.

This process placed patients into several distinct subgroups: About 19% dropped out of the study during this assessment, and another 15% left the study because of their intolerance of various stages of the work-up. Nearly 12% of patients wound up being responsive to the PPI regimen, about 6% had organic disorders not related to gastroesophageal reflux disease, and 27% had functional heartburn with a normal level of acid reflux, which left 78 patients (21%) who demonstrated true reflux-related, PPI-refractory heartburn symptoms.

The researchers then randomized this 78-patient subgroup into three treatment arms, with one group of 27 underwent fundoplication surgery. A group of 25 underwent active medical therapy with 20 mg omeprazole b.i.d. plus baclofen, which was started at 5 mg t.i.d. and increased to 20 mg t.i.d. In baclofen-intolerant or nonresponding patients, this treatment was followed up with desipramine, increasing from a starting dosage of 25 mg/day to 100 mg/day. A third group of 26 control patients received active omeprazole at the same dosage but placebo in place of the baclofen and desipramine. These three subgroups showed no statistically significant differences at baseline for all demographic and clinical parameters recorded.

The study’s primary endpoint was the percentage of patients in each treatment arm who had a “successful” outcome, defined as at least a 50% improvement in their gastroesophageal reflux health-related quality of life score (J Gastrointest Surg. 1998 Mar-Apr;2[2]:141-5) after 1 year on treatment, which occurred in 67% of the fundoplication patients, 28% in the active medical arm, and 12% in the control arm. The fundoplication-treated patients had a significantly higher rate of a successful outcome, compared with patients in each of the other two treatment groups, while the success rates among patients in the active medical group and the control group did not differ significantly, Dr. Spechler said.

Dr. Spechler had no disclosures to report.

REPORTING FROM DDW 2018

Key clinical point: Fundoplication produces the best outcomes in patients with true proton pump inhibitor–refractory heartburn.

Major finding: Two-thirds of patients treated with fundoplication had successful outcomes, compared with 28% in medical controls and 12% in placebo controls.

Study details: A multicenter, randomized study with 78 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Spechler had no disclosures to report.

Honors Committee Accepting Nominations for Prestigious ACS Awards

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) Honors Committee is soliciting nominations for several prestigious awards and honors. These include the Distinguished Service Award; the Rodman E. and Thomas G. Sheen Award; the Jacobson Innovation Award; the Lifetime Achievement Award; candidates for Honorary Fellowship (from countries outside of the U.S. and Canada); and potential innovative speakers for the Martin Memorial Lecture, delivered at the Opening Ceremony of the annual ACS Clinical Congress.

Nominations are accepted all year long; however, Honorary Fellowship nominees are selected each October for induction at the following year’s Clinical Congress.

Visit the Honors Committee web page at www.facs.org/about-acs/governance/acs-committees/honors-committee for additional details about the criteria for nominations. Specific questions may be directed to Donna Coulombe, Honors Committee Staff Liaison, at [email protected] or 312-202-5203.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) Honors Committee is soliciting nominations for several prestigious awards and honors. These include the Distinguished Service Award; the Rodman E. and Thomas G. Sheen Award; the Jacobson Innovation Award; the Lifetime Achievement Award; candidates for Honorary Fellowship (from countries outside of the U.S. and Canada); and potential innovative speakers for the Martin Memorial Lecture, delivered at the Opening Ceremony of the annual ACS Clinical Congress.

Nominations are accepted all year long; however, Honorary Fellowship nominees are selected each October for induction at the following year’s Clinical Congress.

Visit the Honors Committee web page at www.facs.org/about-acs/governance/acs-committees/honors-committee for additional details about the criteria for nominations. Specific questions may be directed to Donna Coulombe, Honors Committee Staff Liaison, at [email protected] or 312-202-5203.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) Honors Committee is soliciting nominations for several prestigious awards and honors. These include the Distinguished Service Award; the Rodman E. and Thomas G. Sheen Award; the Jacobson Innovation Award; the Lifetime Achievement Award; candidates for Honorary Fellowship (from countries outside of the U.S. and Canada); and potential innovative speakers for the Martin Memorial Lecture, delivered at the Opening Ceremony of the annual ACS Clinical Congress.

Nominations are accepted all year long; however, Honorary Fellowship nominees are selected each October for induction at the following year’s Clinical Congress.

Visit the Honors Committee web page at www.facs.org/about-acs/governance/acs-committees/honors-committee for additional details about the criteria for nominations. Specific questions may be directed to Donna Coulombe, Honors Committee Staff Liaison, at [email protected] or 312-202-5203.

NAPRC Awards accredited John Muir Health Rectal Cancer Program

The National Accreditation Program for Rectal Cancer (NAPRC), recently launched by the American College of Surgeons (ACS), has awarded its first accreditation to the John Muir Health Rectal Cancer Program, Walnut Creek and Concord, CA. To earn the voluntary accreditation, the John Muir Health Rectal Cancer Program met 19 standards, including the establishment of a rectal cancer multidisciplinary team (RC-MDT) with clinical representatives from surgery, pathology, radiology, radiation oncology, and medical oncology.

Thirteen of those standards address clinical services that the program was required to provide, including carcinoembryonic antigen testing and magnetic resonance and computed tomography imaging for cancer staging, and ensuring a process whereby the patient starts treatment within a defined time frame. One of the most important clinical standards requires all rectal cancer patients to be present at both pre- and post-treatment RC-MDT meetings.

“When a cancer center achieves this type of specialized accreditation, it means that their rectal cancer patients will receive streamlined, modern evaluation and treatment for the disease. Compliance with our standards will assure optimal care for these patients,” said David P. Winchester, MD, FACS, Medical Director of ACS Cancer Programs.

The NAPRC was developed through a collaboration between the Optimizing the Surgical Treatment of Rectal Cancer Consortium and the ACS Commission on Cancer. It is based on successful international models that emphasize program structure, patient care processes, performance improvement, and performance measures. Its goal is to ensure that rectal cancer patients receive appropriate care using a multidisciplinary approach.

Read more in the ACS press release at www.facs.org/media/press-releases/2018/naprc052218. For more information about the program and instructions on how to apply for accreditation, visit the NAPRC website at www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/naprc, or contact [email protected].

The National Accreditation Program for Rectal Cancer (NAPRC), recently launched by the American College of Surgeons (ACS), has awarded its first accreditation to the John Muir Health Rectal Cancer Program, Walnut Creek and Concord, CA. To earn the voluntary accreditation, the John Muir Health Rectal Cancer Program met 19 standards, including the establishment of a rectal cancer multidisciplinary team (RC-MDT) with clinical representatives from surgery, pathology, radiology, radiation oncology, and medical oncology.

Thirteen of those standards address clinical services that the program was required to provide, including carcinoembryonic antigen testing and magnetic resonance and computed tomography imaging for cancer staging, and ensuring a process whereby the patient starts treatment within a defined time frame. One of the most important clinical standards requires all rectal cancer patients to be present at both pre- and post-treatment RC-MDT meetings.

“When a cancer center achieves this type of specialized accreditation, it means that their rectal cancer patients will receive streamlined, modern evaluation and treatment for the disease. Compliance with our standards will assure optimal care for these patients,” said David P. Winchester, MD, FACS, Medical Director of ACS Cancer Programs.

The NAPRC was developed through a collaboration between the Optimizing the Surgical Treatment of Rectal Cancer Consortium and the ACS Commission on Cancer. It is based on successful international models that emphasize program structure, patient care processes, performance improvement, and performance measures. Its goal is to ensure that rectal cancer patients receive appropriate care using a multidisciplinary approach.

Read more in the ACS press release at www.facs.org/media/press-releases/2018/naprc052218. For more information about the program and instructions on how to apply for accreditation, visit the NAPRC website at www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/naprc, or contact [email protected].

The National Accreditation Program for Rectal Cancer (NAPRC), recently launched by the American College of Surgeons (ACS), has awarded its first accreditation to the John Muir Health Rectal Cancer Program, Walnut Creek and Concord, CA. To earn the voluntary accreditation, the John Muir Health Rectal Cancer Program met 19 standards, including the establishment of a rectal cancer multidisciplinary team (RC-MDT) with clinical representatives from surgery, pathology, radiology, radiation oncology, and medical oncology.

Thirteen of those standards address clinical services that the program was required to provide, including carcinoembryonic antigen testing and magnetic resonance and computed tomography imaging for cancer staging, and ensuring a process whereby the patient starts treatment within a defined time frame. One of the most important clinical standards requires all rectal cancer patients to be present at both pre- and post-treatment RC-MDT meetings.

“When a cancer center achieves this type of specialized accreditation, it means that their rectal cancer patients will receive streamlined, modern evaluation and treatment for the disease. Compliance with our standards will assure optimal care for these patients,” said David P. Winchester, MD, FACS, Medical Director of ACS Cancer Programs.

The NAPRC was developed through a collaboration between the Optimizing the Surgical Treatment of Rectal Cancer Consortium and the ACS Commission on Cancer. It is based on successful international models that emphasize program structure, patient care processes, performance improvement, and performance measures. Its goal is to ensure that rectal cancer patients receive appropriate care using a multidisciplinary approach.

Read more in the ACS press release at www.facs.org/media/press-releases/2018/naprc052218. For more information about the program and instructions on how to apply for accreditation, visit the NAPRC website at www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/naprc, or contact [email protected].

NCDB-Sourced Study Focuses on Post-Treatment Surveillance for Colorectal Cancer Patients

The first findings from a collaborative study within the American College of Surgeons (ACS) Cancer Programs—and published earlier this week in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA)—showed no significant association between frequency of surveillance testing and the time to detection of recurrence for colorectal cancer patients.

The study is an effort of the ACS Clinical Research Program and the Commission on Cancer and uses data from the National Cancer Database (NCDB), which is jointly sponsored by the ACS and the American Cancer Society. It focuses on post-treatment surveillance for breast, colon, and lung cancers and was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

This portion of the study included more than 8,500 patients and was the first of eight manuscripts accepted for publication from a larger study conducted in 2015. The corresponding author is George J. Chang, MD, FACS, chief, section of colon and rectal surgery; professor of surgical oncology and health services research; and director of clinical operations, minimally invasive and new technologies in oncologic surgery program, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

View the full text article on the JAMA website at https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2681746/.

The first findings from a collaborative study within the American College of Surgeons (ACS) Cancer Programs—and published earlier this week in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA)—showed no significant association between frequency of surveillance testing and the time to detection of recurrence for colorectal cancer patients.

The study is an effort of the ACS Clinical Research Program and the Commission on Cancer and uses data from the National Cancer Database (NCDB), which is jointly sponsored by the ACS and the American Cancer Society. It focuses on post-treatment surveillance for breast, colon, and lung cancers and was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

This portion of the study included more than 8,500 patients and was the first of eight manuscripts accepted for publication from a larger study conducted in 2015. The corresponding author is George J. Chang, MD, FACS, chief, section of colon and rectal surgery; professor of surgical oncology and health services research; and director of clinical operations, minimally invasive and new technologies in oncologic surgery program, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

View the full text article on the JAMA website at https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2681746/.

The first findings from a collaborative study within the American College of Surgeons (ACS) Cancer Programs—and published earlier this week in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA)—showed no significant association between frequency of surveillance testing and the time to detection of recurrence for colorectal cancer patients.

The study is an effort of the ACS Clinical Research Program and the Commission on Cancer and uses data from the National Cancer Database (NCDB), which is jointly sponsored by the ACS and the American Cancer Society. It focuses on post-treatment surveillance for breast, colon, and lung cancers and was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

This portion of the study included more than 8,500 patients and was the first of eight manuscripts accepted for publication from a larger study conducted in 2015. The corresponding author is George J. Chang, MD, FACS, chief, section of colon and rectal surgery; professor of surgical oncology and health services research; and director of clinical operations, minimally invasive and new technologies in oncologic surgery program, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

View the full text article on the JAMA website at https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2681746/.

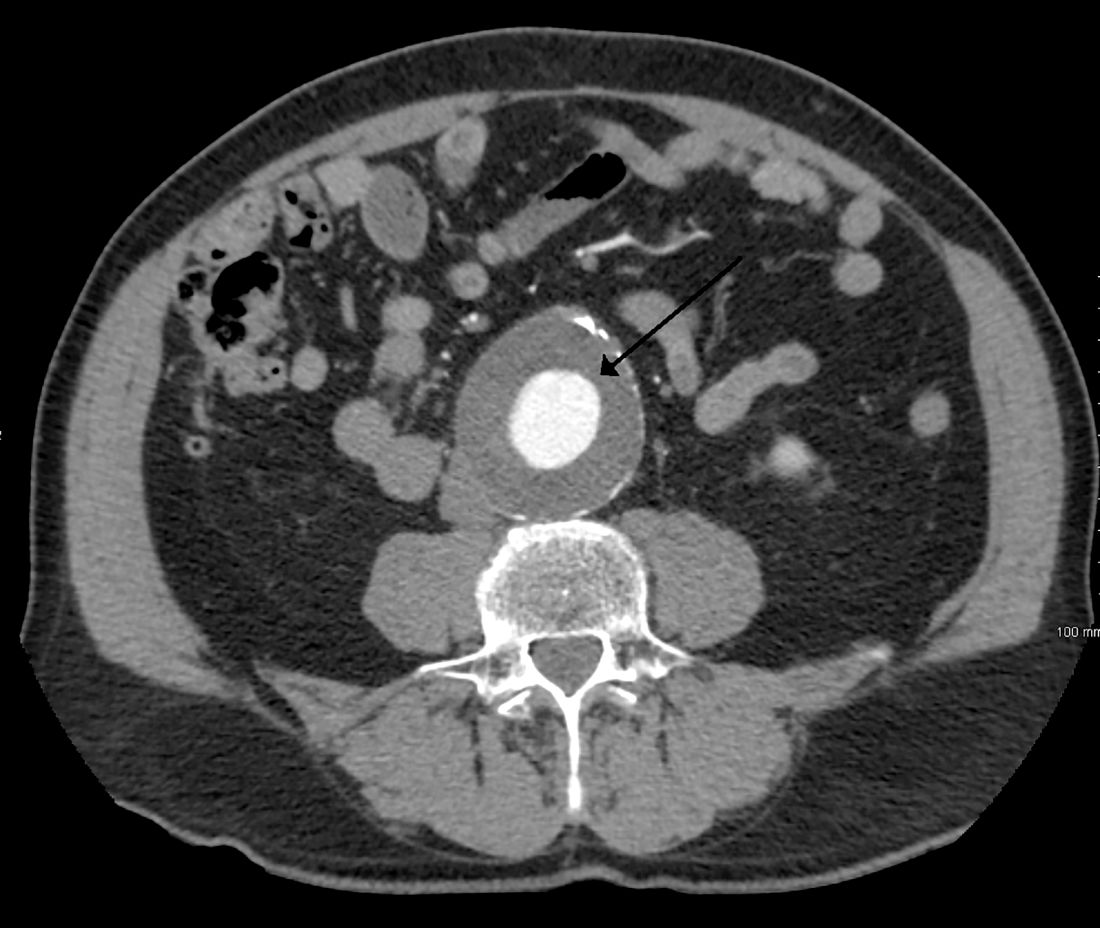

Routine screening for AAA in older men may harm more than help

Deaths from abdominal aortic aneurysm among Swedish men are going down – but not because they’re being screened for the potentially fatal condition.

Although the death rate has decreased by 70% since the early 2000s, screening only saved 2 lives per 10,000 men screened. It did, however, increase by 59% the risk of unnecessary surgery, Minna Johansson, MD, and colleagues wrote in the June 16 issue of the Lancet.

“Screening had only a minor effect on AAA mortality,” wrote Dr. Johansson of the University of Gothenburg (Sweden). “In absolute numbers, only 7% of the benefit estimated in the largest trial of AAA screening was observed. The observed large reductions in AAA mortality were present in both the screened and nonscreened cohorts and were thus mainly caused by other factors – probably reduced smoking. … Our results call the continued justification of AAA screening into question.”

In Sweden, all men aged 65 years are invited to a one-time ultrasound abdominal aorta screening. Most participate. Anyone with an aneurysm is followed up at a vascular surgery clinic, with surgery considered if the aortic diameter is 55 mm or larger.

Dr. Johansson and her colleagues plumbed national health records to estimate the risks and benefits of this routine screening. The study comprised 25,265 men invited to join the AAA screening program in Sweden from 2006 to 2009. Mortality data were compared with those from a contemporaneous cohort of 106,087 men of similar age who were not invited to screen. Finally, the mortality data were compared with national trends in AAA mortality in all Swedish men aged 40-99 years from 1987 to 2015.

A multivariate analysis adjusted for cohort year, marital status, educational level, income, and whether the patient already had an AAA diagnosis at baseline.

From the early 2000s to 2015, AAA mortality among men aged 65-74 years declined from 36 to10 deaths per 100,000. This 70% reduction was similar in both screened and unscreened populations; in fact, the decline began about a decade before population-based screening was introduced and continued to decrease at a steady rate afterward.

After 6 years of screening, there was a 30% reduction of AAA mortality in the screened population, compared with the unscreened, translating to an absolute mortality reduction of two deaths per 10,000 men offered screening.

Screening increased by 52% the number of AAAs detected. The absolute difference in incidence after 6 years of screening translated to an additional 49 overdiagnoses per 10,000 screened men.

Looking back into the mid-1990s, the investigators saw the numbers of elective AAA surgeries rise steadily. In the adjusted model, screened men were 59% more likely to have this procedure than unscreened. The increased risk didn’t come with an equally increased benefit, though. There was a 10% decrease in AAA ruptures, “rendering a risk of overtreatment of 19%, or 19 potentially avoidable elective surgeries per 10,000 men,” the team noted. “Sixty-three percent of all additional elective surgeries for AAA might therefore have constituted overtreat.”

The findings are at odds with large published studies that found a consistent benefit to screening.

“Compared with results at 7-year follow-up of the largest trial of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm [Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS)], we found about half of the benefit in terms of a relative effect and 7% of the estimated benefit in terms of absolute numbers [2 vs. 27 avoided deaths from AAA per 10,000 invited men]. Compared with previous estimates of overdiagnosis and overtreatment, we found a lower absolute number of over-diagnosed cases [49 vs.176 per 10,000 invited men] and fewer overtreated cases [19 vs. 37 per 10,000 invited men]. However, since the harms of screening decreased less than the benefit, the balance between benefits and harms seems much less appealing in today’s setting.”

None of the authors had any financial disclosures.

The study by Johansson et al. indicates a significant risk of overdiagnosis associated with routine screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: Those risks may not be as clinically harmful as might be assumed, Stefan Acosta, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Lancet 2018; 391: 2394-95).

“Although I agree that having a small AAA that needs long-term follow-up might be associated with negative psychological consequences, there could also be a window of opportunity [eg. with statins, antiplatelet therapy, and blood pressure reduction], for individuals with increased burden of cardiovascular disease. Indeed, screening for AAA, peripheral artery disease, and hypertension, with the initiation of relevant pharmacotherapy, if positive, reduces all-cause mortality and some evidence suggests that this approach of multifaceted vascular screening instead of isolated AAA screening should be considered.”

When performed according to the established criteria for elective AAA surgery, the procedure is associated with less than 1% postoperative mortality, “mainly because of wide implementation of endovascular aneurysm repair, a minimally invasive method.”

The 6-year follow-up time, as the authors noted, is relatively short. A 2016 review of the Swedish Nationwide Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening Program determined that significant mortality benefit could take 10 years to materialize(Circ 2016;134:1141-8).

The full impact of Sweden’s remarkable decrease in smoking is almost certainly making itself known in these outcomes – smoking is implicated in 75% of AAA cases.

“The decreased prevalence of smoking in Sweden, from 44% of the population in 1970 to 15% in 2010, should be viewed as the main cause of the decreasing incidence and mortality of AAA. Every percent drop in the prevalence of smoking will have a huge effect on smoking-related diseases, such as cancer and AAA.”

Dr. Stefan is a vascular disease researcher at Lund (Sweden) University. He had no financial disclosures.

The study by Johansson et al. indicates a significant risk of overdiagnosis associated with routine screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: Those risks may not be as clinically harmful as might be assumed, Stefan Acosta, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Lancet 2018; 391: 2394-95).

“Although I agree that having a small AAA that needs long-term follow-up might be associated with negative psychological consequences, there could also be a window of opportunity [eg. with statins, antiplatelet therapy, and blood pressure reduction], for individuals with increased burden of cardiovascular disease. Indeed, screening for AAA, peripheral artery disease, and hypertension, with the initiation of relevant pharmacotherapy, if positive, reduces all-cause mortality and some evidence suggests that this approach of multifaceted vascular screening instead of isolated AAA screening should be considered.”

When performed according to the established criteria for elective AAA surgery, the procedure is associated with less than 1% postoperative mortality, “mainly because of wide implementation of endovascular aneurysm repair, a minimally invasive method.”

The 6-year follow-up time, as the authors noted, is relatively short. A 2016 review of the Swedish Nationwide Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening Program determined that significant mortality benefit could take 10 years to materialize(Circ 2016;134:1141-8).

The full impact of Sweden’s remarkable decrease in smoking is almost certainly making itself known in these outcomes – smoking is implicated in 75% of AAA cases.

“The decreased prevalence of smoking in Sweden, from 44% of the population in 1970 to 15% in 2010, should be viewed as the main cause of the decreasing incidence and mortality of AAA. Every percent drop in the prevalence of smoking will have a huge effect on smoking-related diseases, such as cancer and AAA.”

Dr. Stefan is a vascular disease researcher at Lund (Sweden) University. He had no financial disclosures.

The study by Johansson et al. indicates a significant risk of overdiagnosis associated with routine screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: Those risks may not be as clinically harmful as might be assumed, Stefan Acosta, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Lancet 2018; 391: 2394-95).

“Although I agree that having a small AAA that needs long-term follow-up might be associated with negative psychological consequences, there could also be a window of opportunity [eg. with statins, antiplatelet therapy, and blood pressure reduction], for individuals with increased burden of cardiovascular disease. Indeed, screening for AAA, peripheral artery disease, and hypertension, with the initiation of relevant pharmacotherapy, if positive, reduces all-cause mortality and some evidence suggests that this approach of multifaceted vascular screening instead of isolated AAA screening should be considered.”

When performed according to the established criteria for elective AAA surgery, the procedure is associated with less than 1% postoperative mortality, “mainly because of wide implementation of endovascular aneurysm repair, a minimally invasive method.”

The 6-year follow-up time, as the authors noted, is relatively short. A 2016 review of the Swedish Nationwide Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening Program determined that significant mortality benefit could take 10 years to materialize(Circ 2016;134:1141-8).

The full impact of Sweden’s remarkable decrease in smoking is almost certainly making itself known in these outcomes – smoking is implicated in 75% of AAA cases.

“The decreased prevalence of smoking in Sweden, from 44% of the population in 1970 to 15% in 2010, should be viewed as the main cause of the decreasing incidence and mortality of AAA. Every percent drop in the prevalence of smoking will have a huge effect on smoking-related diseases, such as cancer and AAA.”

Dr. Stefan is a vascular disease researcher at Lund (Sweden) University. He had no financial disclosures.

Deaths from abdominal aortic aneurysm among Swedish men are going down – but not because they’re being screened for the potentially fatal condition.

Although the death rate has decreased by 70% since the early 2000s, screening only saved 2 lives per 10,000 men screened. It did, however, increase by 59% the risk of unnecessary surgery, Minna Johansson, MD, and colleagues wrote in the June 16 issue of the Lancet.

“Screening had only a minor effect on AAA mortality,” wrote Dr. Johansson of the University of Gothenburg (Sweden). “In absolute numbers, only 7% of the benefit estimated in the largest trial of AAA screening was observed. The observed large reductions in AAA mortality were present in both the screened and nonscreened cohorts and were thus mainly caused by other factors – probably reduced smoking. … Our results call the continued justification of AAA screening into question.”

In Sweden, all men aged 65 years are invited to a one-time ultrasound abdominal aorta screening. Most participate. Anyone with an aneurysm is followed up at a vascular surgery clinic, with surgery considered if the aortic diameter is 55 mm or larger.

Dr. Johansson and her colleagues plumbed national health records to estimate the risks and benefits of this routine screening. The study comprised 25,265 men invited to join the AAA screening program in Sweden from 2006 to 2009. Mortality data were compared with those from a contemporaneous cohort of 106,087 men of similar age who were not invited to screen. Finally, the mortality data were compared with national trends in AAA mortality in all Swedish men aged 40-99 years from 1987 to 2015.

A multivariate analysis adjusted for cohort year, marital status, educational level, income, and whether the patient already had an AAA diagnosis at baseline.

From the early 2000s to 2015, AAA mortality among men aged 65-74 years declined from 36 to10 deaths per 100,000. This 70% reduction was similar in both screened and unscreened populations; in fact, the decline began about a decade before population-based screening was introduced and continued to decrease at a steady rate afterward.

After 6 years of screening, there was a 30% reduction of AAA mortality in the screened population, compared with the unscreened, translating to an absolute mortality reduction of two deaths per 10,000 men offered screening.

Screening increased by 52% the number of AAAs detected. The absolute difference in incidence after 6 years of screening translated to an additional 49 overdiagnoses per 10,000 screened men.

Looking back into the mid-1990s, the investigators saw the numbers of elective AAA surgeries rise steadily. In the adjusted model, screened men were 59% more likely to have this procedure than unscreened. The increased risk didn’t come with an equally increased benefit, though. There was a 10% decrease in AAA ruptures, “rendering a risk of overtreatment of 19%, or 19 potentially avoidable elective surgeries per 10,000 men,” the team noted. “Sixty-three percent of all additional elective surgeries for AAA might therefore have constituted overtreat.”

The findings are at odds with large published studies that found a consistent benefit to screening.

“Compared with results at 7-year follow-up of the largest trial of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm [Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS)], we found about half of the benefit in terms of a relative effect and 7% of the estimated benefit in terms of absolute numbers [2 vs. 27 avoided deaths from AAA per 10,000 invited men]. Compared with previous estimates of overdiagnosis and overtreatment, we found a lower absolute number of over-diagnosed cases [49 vs.176 per 10,000 invited men] and fewer overtreated cases [19 vs. 37 per 10,000 invited men]. However, since the harms of screening decreased less than the benefit, the balance between benefits and harms seems much less appealing in today’s setting.”

None of the authors had any financial disclosures.

Deaths from abdominal aortic aneurysm among Swedish men are going down – but not because they’re being screened for the potentially fatal condition.

Although the death rate has decreased by 70% since the early 2000s, screening only saved 2 lives per 10,000 men screened. It did, however, increase by 59% the risk of unnecessary surgery, Minna Johansson, MD, and colleagues wrote in the June 16 issue of the Lancet.

“Screening had only a minor effect on AAA mortality,” wrote Dr. Johansson of the University of Gothenburg (Sweden). “In absolute numbers, only 7% of the benefit estimated in the largest trial of AAA screening was observed. The observed large reductions in AAA mortality were present in both the screened and nonscreened cohorts and were thus mainly caused by other factors – probably reduced smoking. … Our results call the continued justification of AAA screening into question.”

In Sweden, all men aged 65 years are invited to a one-time ultrasound abdominal aorta screening. Most participate. Anyone with an aneurysm is followed up at a vascular surgery clinic, with surgery considered if the aortic diameter is 55 mm or larger.