User login

Medication-Nonadherent Hypothyroidism Requiring Frequent Primary Care Visits to Achieve Euthyroidism

Nonadherence to medications is an issue across health care. In endocrinology, hypothyroidism, a deficiency of thyroid hormones, is most often treated with levothyroxine and if left untreated can lead to myxedema coma, which can lead to death due to multiorgan dysfunction.1 Therefore, adherence to levothyroxine is very important in preventing fatal complications.

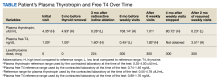

We present the case of a patient with persistent primary hypothyroidism who was suspected to be nonadherent to levothyroxine, although the patient consistently claimed adherence. The patient’s plasma thyrotropin (TSH) level improved to reference range after 6 weeks of weekly primary care clinic visits. After stopping the visits, his plasma TSH level increased again, so 9 more weeks of visits resumed, which again helped bring down his plasma TSH levels.

Case Presentation

A male patient aged 67 years presented to the Dayton Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) endocrinology clinic for evaluation of thyroid nodules. The patient reported no history of neck irradiation and a physical examination was unremarkable. At that time, laboratory results showed a slightly elevated plasma TSH level of 4.35 uIU/mL (reference range, 0.35-4.00 uIU/mL) and normal free thyroxine (T4) of 1.00 ng/dL (reference range, 0.74-1.46 ng/dL). Later that year, the patient underwent a total thyroidectomy at the Cincinnati VAMC for Hurthle cell variant papillary thyroid carcinoma that was noted on biopsy at the Dayton VAMC. After surgical pathology results were available, the patient started levothyroxine 200 mcg daily, although 224 mcg would have been more appropriate based on his 142 kg weight. Due to a history of arrhythmia, the goal plasma TSH level was 0.10 to 0.50 uIU/mL. The patient subsequently underwent radioactive iodine ablation. After levothyroxine dose adjustments, the patient’s plasma TSH level was noted to be within his target range at 0.28 uIU/mL 3 months postablation.

Over the next 5 years the patient had regular laboratory tests during which his plasma TSH level rose and were typically high despite adjusting levothyroxine doses between 200 mcg and 325 mcg. The patient received counseling on taking the medication in the morning on an empty stomach and waiting at least 1 hour before consuming anything, and he went to many follow-up visits at the Dayton VAMC endocrinology clinic. He reported no vomiting or diarrhea but endorsed weight gain once. The patient also had high free T4 at times and did not take extra levothyroxine before undergoing laboratory tests.

Nonadherence to levothyroxine was suspected, but the patient insisted he was adherent. He received the medication in the mail regularly, generally had 90-day refills unless a dose change was made, used a pill box, and had social support from his son, but he did not use a phone alarm to remind him to take it. A home care nurse made weekly visits to make sure the remaining levothyroxine pill counts were correct; however, the patient continued to have difficulty maintaining daily adherence at home as indicated by the nurse’s pill counts not aligning with the number of pills which should have been left if the patient was talking the pills daily.

The patient was asked to visit a local community-based outpatient clinic (CBOC) weekly (to avoid patient travel time to Dayton VAMC > 1 hour) to check pill counts and assess adherence. The patient went to the CBOC clinic for these visits, during which pill counts indicated much better but not 100% adherence. After 6 weeks of clinic visits, his plasma TSH decreased to 1.01 uIU/mL, which was within the reference range, and the patient stopped coming to the weekly clinic visits (Table). Four months later, the patient's plasma TSH levels increased to 80.72 uIU/mL. Nonadherence to levothyroxine was suspected again. He was asked to resume weekly clinic visits, and the life-threatening effects of hypothyroidism and not taking levothyroxine were discussed with the patient and his son. The patient made CBOC clinic visits for 9 weeks, after which his plasma TSH level was low at 0.23 uIU/mL.

Discussion

There are multiple important causes to consider in patients with persistent hypothyroidism. One is medication nonadherence, which was most likely seen in the patient in this case. Missing even 1 day of levothyroxine can affect TSH and thyroid hormone levels for several days due to the long half-life of the medication.2 Hepp and colleagues found that patients with hypothyroidism were significantly more likely to be nonadherent to levothyroxine if they had comorbid conditions such as type 2 diabetes or were obese.3 Another study of levothyroxine adherence found that the most common reason for missing doses was forgetfulness.4 However, memory and cognition impairments can also be symptoms of hypothyroidism itself; Haskard-Zolnierek and colleagues found a significant association between nonadherence to levothyroxine and self-reported brain fog in patients with hypothyroidism.5

Another cause of persistent hypothyroidism is malabsorption. Absorption of levothyroxine can be affected by intestinal malabsorption due to inflammatory bowel disease, lactose intolerance, or gastrointestinal infection, as well as several foods, drinks (eg, coffee), medications, vitamins, and supplements (eg, proton-pump inhibitors and calcium).2,6 Levothyroxine is absorbed mainly at the jejunum and upper ileum, so any pathologies or ingested items that would directly or indirectly affect absorption at those sites can affect levothyroxine absorption.2

A liquid levothyroxine formulation can help with malabsorption.2 Alternatively, weight gain may lead to a need for increasing the dosage of levothyroxine.2,6 Other factors that can affect TSH levels include Addison disease, dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis, and TSH heterophile antibodies.2

Research describes methods that have effectively treated hypothyroidism in patients struggling with levothyroxine adherence. Two case reports describe weekly visits for levothyroxine administration successfully treating uncontrolled hypothyroidism.7,8 A meta-analysis found that while weekly levothyroxine tablets led to a higher mean TSH level than daily use, weekly use still led to reference-range TSH levels, suggesting that weekly levothyroxine may be a helpful alternative for nonadherent patients.9 Alternatively, patients taking levothyroxine tablets have been shown to forget to take their medication more frequently compared to those taking the liquid formulation.10,11 Additionally, a study by El Helou and colleagues found that adherence to levothyroxine was significantly improved when patients had endocrinology visits once a month and when the endocrinologist provided information about hypothyroidism.12

Another method that may improve adherence to levothyroxine is telehealth visits. This would be especially helpful for patients who live far from the clinic or do not have the time, transportation, or financial means to visit the clinic for weekly visits to assess medication adherence. Additionally, patients may be afraid of admitting to a health care professional that they are nonadherent. Clinicians must be tactful when asking about adherence to make the patient feel comfortable with admitting to nonadherence if their cognition is not impaired. Then, a patient-led conversation can occur regarding realistic ways the patient feels they can work toward adherence.

To our knowledge, the patient in this case report had no symptoms of intestinal malabsorption, and weight gain was not thought to be the issue, as levothyroxine dosage was adjusted multiple times. His plasma TSH levels returned to reference range after weekly pill count visits for 6 weeks and after weekly pill count visits for 9 weeks. Therefore, nonadherence to levothyroxine was suspected to be the cause of frequently elevated plasma TSH levels despite the patient’s insistence on adherence. While the patient did not report memory issues, cognitive impairments due to hypothyroidism may have been contributing to his probable nonadherence. Additionally, he had comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity, which may have made adherence more difficult.

Levothyroxine was also only prescribed in daily tablet form, so the frequency and formulation may have also contributed to nonadherence. While the home nurse was originally sent to assess the patient’s adherence, the care team could have had the nurse start giving the patient weekly levothyroxine once nonadherence was determined to be a likely issue. The patient’s adherence only improved when he went to the clinic for pill counts but not when the home nurse came to his house weekly; this could be because the patient knew he had to invest the time to physically go to clinic visits for pill checks, motivating him to increase adherence.

Conclusions

This case reports a patient with frequently high plasma TSH levels achieving normalization of plasma TSH levels after weekly medication adherence checks at a primary care clinic. Weekly visits to a clinic seem impractical compared to weekly dosing with a visiting nurse; however, after review of the literature, this may be an approach to consider in the future. This strategy may especially help in cases of persistent abnormal plasma TSH levels in which no etiology can be found other than suspected medication nonadherence. Knowing their medication use will be checked at weekly clinic visits may motivate patients to be adherent.

1. Chaker L, Bianco AC, Jonklaas J, Peeters RP. Hypothyroidism. Lancet. 2017;390(10101):1550-1562. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30703-1

2. Centanni M, Benvenga S, Sachmechi I. Diagnosis and management of treatment-refractory hypothyroidism: an expert consensus report. J Endocrinol Invest. 2017;40(12):1289-1301. doi:10.1007/s40618-017-0706-y

3. Hepp Z, Lage MJ, Espaillat R, Gossain VV. The association between adherence to levothyroxine and economic and clinical outcomes in patients with hypothyroidism in the US. J Med Econ. 2018;21(9):912-919. doi:10.1080/13696998.2018.1484749

4. Shakya Shrestha S, Risal K, Shrestha R, Bhatta RD. Medication Adherence to Levothyroxine Therapy among Hypothyroid Patients and their Clinical Outcomes with Special Reference to Thyroid Function Parameters. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2018;16(62):129-137.

5. Haskard-Zolnierek K, Wilson C, Pruin J, Deason R, Howard K. The Relationship Between Brain Fog and Medication Adherence for Individuals With Hypothyroidism. Clin Nurs Res. 2022;31(3):445-452. doi:10.1177/10547738211038127

6. McNally LJ, Ofiaeli CI, Oyibo SO. Treatment-refractory hypothyroidism. BMJ. 2019;364:l579. Published 2019 Feb 25. doi:10.1136/bmj.l579

7. Nakano Y, Hashimoto K, Ohkiba N, et al. A Case of Refractory Hypothyroidism due to Poor Compliance Treated with the Weekly Intravenous and Oral Levothyroxine Administration. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2019;2019:5986014. Published 2019 Feb 5. doi:10.1155/2019/5986014

8. Kiran Z, Shaikh KS, Fatima N, Tariq N, Baloch AA. Levothyroxine absorption test followed by directly observed treatment on an outpatient basis to address long-term high TSH levels in a hypothyroid patient: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2023;17(1):24. Published 2023 Jan 25. doi:10.1186/s13256-023-03760-0

9. Chiu HH, Larrazabal R Jr, Uy AB, Jimeno C. Weekly Versus Daily Levothyroxine Tablet Replacement in Adults with Hypothyroidism: A Meta-Analysis. J ASEAN Fed Endocr Soc. 2021;36(2):156-160. doi:10.15605/jafes.036.02.07

10. Cappelli C, Castello R, Marini F, et al. Adherence to Levothyroxine Treatment Among Patients With Hypothyroidism: A Northeastern Italian Survey. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;9:699. Published 2018 Nov 23. doi:10.3389/fendo.2018.00699

11. Bocale R, Desideri G, Barini A, et al. Long-Term Adherence to Levothyroxine Replacement Therapy in Thyroidectomized Patients. J Clin Med. 2022;11(15):4296. Published 2022 Jul 24. doi:10.3390/jcm11154296

12. El Helou S, Hallit S, Awada S, et al. Adherence to levothyroxine among patients with hypothyroidism in Lebanon. East Mediterr Health J. 2019;25(3):149-159. Published 2019 Apr 25. doi:10.26719/emhj.18.022

Nonadherence to medications is an issue across health care. In endocrinology, hypothyroidism, a deficiency of thyroid hormones, is most often treated with levothyroxine and if left untreated can lead to myxedema coma, which can lead to death due to multiorgan dysfunction.1 Therefore, adherence to levothyroxine is very important in preventing fatal complications.

We present the case of a patient with persistent primary hypothyroidism who was suspected to be nonadherent to levothyroxine, although the patient consistently claimed adherence. The patient’s plasma thyrotropin (TSH) level improved to reference range after 6 weeks of weekly primary care clinic visits. After stopping the visits, his plasma TSH level increased again, so 9 more weeks of visits resumed, which again helped bring down his plasma TSH levels.

Case Presentation

A male patient aged 67 years presented to the Dayton Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) endocrinology clinic for evaluation of thyroid nodules. The patient reported no history of neck irradiation and a physical examination was unremarkable. At that time, laboratory results showed a slightly elevated plasma TSH level of 4.35 uIU/mL (reference range, 0.35-4.00 uIU/mL) and normal free thyroxine (T4) of 1.00 ng/dL (reference range, 0.74-1.46 ng/dL). Later that year, the patient underwent a total thyroidectomy at the Cincinnati VAMC for Hurthle cell variant papillary thyroid carcinoma that was noted on biopsy at the Dayton VAMC. After surgical pathology results were available, the patient started levothyroxine 200 mcg daily, although 224 mcg would have been more appropriate based on his 142 kg weight. Due to a history of arrhythmia, the goal plasma TSH level was 0.10 to 0.50 uIU/mL. The patient subsequently underwent radioactive iodine ablation. After levothyroxine dose adjustments, the patient’s plasma TSH level was noted to be within his target range at 0.28 uIU/mL 3 months postablation.

Over the next 5 years the patient had regular laboratory tests during which his plasma TSH level rose and were typically high despite adjusting levothyroxine doses between 200 mcg and 325 mcg. The patient received counseling on taking the medication in the morning on an empty stomach and waiting at least 1 hour before consuming anything, and he went to many follow-up visits at the Dayton VAMC endocrinology clinic. He reported no vomiting or diarrhea but endorsed weight gain once. The patient also had high free T4 at times and did not take extra levothyroxine before undergoing laboratory tests.

Nonadherence to levothyroxine was suspected, but the patient insisted he was adherent. He received the medication in the mail regularly, generally had 90-day refills unless a dose change was made, used a pill box, and had social support from his son, but he did not use a phone alarm to remind him to take it. A home care nurse made weekly visits to make sure the remaining levothyroxine pill counts were correct; however, the patient continued to have difficulty maintaining daily adherence at home as indicated by the nurse’s pill counts not aligning with the number of pills which should have been left if the patient was talking the pills daily.

The patient was asked to visit a local community-based outpatient clinic (CBOC) weekly (to avoid patient travel time to Dayton VAMC > 1 hour) to check pill counts and assess adherence. The patient went to the CBOC clinic for these visits, during which pill counts indicated much better but not 100% adherence. After 6 weeks of clinic visits, his plasma TSH decreased to 1.01 uIU/mL, which was within the reference range, and the patient stopped coming to the weekly clinic visits (Table). Four months later, the patient's plasma TSH levels increased to 80.72 uIU/mL. Nonadherence to levothyroxine was suspected again. He was asked to resume weekly clinic visits, and the life-threatening effects of hypothyroidism and not taking levothyroxine were discussed with the patient and his son. The patient made CBOC clinic visits for 9 weeks, after which his plasma TSH level was low at 0.23 uIU/mL.

Discussion

There are multiple important causes to consider in patients with persistent hypothyroidism. One is medication nonadherence, which was most likely seen in the patient in this case. Missing even 1 day of levothyroxine can affect TSH and thyroid hormone levels for several days due to the long half-life of the medication.2 Hepp and colleagues found that patients with hypothyroidism were significantly more likely to be nonadherent to levothyroxine if they had comorbid conditions such as type 2 diabetes or were obese.3 Another study of levothyroxine adherence found that the most common reason for missing doses was forgetfulness.4 However, memory and cognition impairments can also be symptoms of hypothyroidism itself; Haskard-Zolnierek and colleagues found a significant association between nonadherence to levothyroxine and self-reported brain fog in patients with hypothyroidism.5

Another cause of persistent hypothyroidism is malabsorption. Absorption of levothyroxine can be affected by intestinal malabsorption due to inflammatory bowel disease, lactose intolerance, or gastrointestinal infection, as well as several foods, drinks (eg, coffee), medications, vitamins, and supplements (eg, proton-pump inhibitors and calcium).2,6 Levothyroxine is absorbed mainly at the jejunum and upper ileum, so any pathologies or ingested items that would directly or indirectly affect absorption at those sites can affect levothyroxine absorption.2

A liquid levothyroxine formulation can help with malabsorption.2 Alternatively, weight gain may lead to a need for increasing the dosage of levothyroxine.2,6 Other factors that can affect TSH levels include Addison disease, dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis, and TSH heterophile antibodies.2

Research describes methods that have effectively treated hypothyroidism in patients struggling with levothyroxine adherence. Two case reports describe weekly visits for levothyroxine administration successfully treating uncontrolled hypothyroidism.7,8 A meta-analysis found that while weekly levothyroxine tablets led to a higher mean TSH level than daily use, weekly use still led to reference-range TSH levels, suggesting that weekly levothyroxine may be a helpful alternative for nonadherent patients.9 Alternatively, patients taking levothyroxine tablets have been shown to forget to take their medication more frequently compared to those taking the liquid formulation.10,11 Additionally, a study by El Helou and colleagues found that adherence to levothyroxine was significantly improved when patients had endocrinology visits once a month and when the endocrinologist provided information about hypothyroidism.12

Another method that may improve adherence to levothyroxine is telehealth visits. This would be especially helpful for patients who live far from the clinic or do not have the time, transportation, or financial means to visit the clinic for weekly visits to assess medication adherence. Additionally, patients may be afraid of admitting to a health care professional that they are nonadherent. Clinicians must be tactful when asking about adherence to make the patient feel comfortable with admitting to nonadherence if their cognition is not impaired. Then, a patient-led conversation can occur regarding realistic ways the patient feels they can work toward adherence.

To our knowledge, the patient in this case report had no symptoms of intestinal malabsorption, and weight gain was not thought to be the issue, as levothyroxine dosage was adjusted multiple times. His plasma TSH levels returned to reference range after weekly pill count visits for 6 weeks and after weekly pill count visits for 9 weeks. Therefore, nonadherence to levothyroxine was suspected to be the cause of frequently elevated plasma TSH levels despite the patient’s insistence on adherence. While the patient did not report memory issues, cognitive impairments due to hypothyroidism may have been contributing to his probable nonadherence. Additionally, he had comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity, which may have made adherence more difficult.

Levothyroxine was also only prescribed in daily tablet form, so the frequency and formulation may have also contributed to nonadherence. While the home nurse was originally sent to assess the patient’s adherence, the care team could have had the nurse start giving the patient weekly levothyroxine once nonadherence was determined to be a likely issue. The patient’s adherence only improved when he went to the clinic for pill counts but not when the home nurse came to his house weekly; this could be because the patient knew he had to invest the time to physically go to clinic visits for pill checks, motivating him to increase adherence.

Conclusions

This case reports a patient with frequently high plasma TSH levels achieving normalization of plasma TSH levels after weekly medication adherence checks at a primary care clinic. Weekly visits to a clinic seem impractical compared to weekly dosing with a visiting nurse; however, after review of the literature, this may be an approach to consider in the future. This strategy may especially help in cases of persistent abnormal plasma TSH levels in which no etiology can be found other than suspected medication nonadherence. Knowing their medication use will be checked at weekly clinic visits may motivate patients to be adherent.

Nonadherence to medications is an issue across health care. In endocrinology, hypothyroidism, a deficiency of thyroid hormones, is most often treated with levothyroxine and if left untreated can lead to myxedema coma, which can lead to death due to multiorgan dysfunction.1 Therefore, adherence to levothyroxine is very important in preventing fatal complications.

We present the case of a patient with persistent primary hypothyroidism who was suspected to be nonadherent to levothyroxine, although the patient consistently claimed adherence. The patient’s plasma thyrotropin (TSH) level improved to reference range after 6 weeks of weekly primary care clinic visits. After stopping the visits, his plasma TSH level increased again, so 9 more weeks of visits resumed, which again helped bring down his plasma TSH levels.

Case Presentation

A male patient aged 67 years presented to the Dayton Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) endocrinology clinic for evaluation of thyroid nodules. The patient reported no history of neck irradiation and a physical examination was unremarkable. At that time, laboratory results showed a slightly elevated plasma TSH level of 4.35 uIU/mL (reference range, 0.35-4.00 uIU/mL) and normal free thyroxine (T4) of 1.00 ng/dL (reference range, 0.74-1.46 ng/dL). Later that year, the patient underwent a total thyroidectomy at the Cincinnati VAMC for Hurthle cell variant papillary thyroid carcinoma that was noted on biopsy at the Dayton VAMC. After surgical pathology results were available, the patient started levothyroxine 200 mcg daily, although 224 mcg would have been more appropriate based on his 142 kg weight. Due to a history of arrhythmia, the goal plasma TSH level was 0.10 to 0.50 uIU/mL. The patient subsequently underwent radioactive iodine ablation. After levothyroxine dose adjustments, the patient’s plasma TSH level was noted to be within his target range at 0.28 uIU/mL 3 months postablation.

Over the next 5 years the patient had regular laboratory tests during which his plasma TSH level rose and were typically high despite adjusting levothyroxine doses between 200 mcg and 325 mcg. The patient received counseling on taking the medication in the morning on an empty stomach and waiting at least 1 hour before consuming anything, and he went to many follow-up visits at the Dayton VAMC endocrinology clinic. He reported no vomiting or diarrhea but endorsed weight gain once. The patient also had high free T4 at times and did not take extra levothyroxine before undergoing laboratory tests.

Nonadherence to levothyroxine was suspected, but the patient insisted he was adherent. He received the medication in the mail regularly, generally had 90-day refills unless a dose change was made, used a pill box, and had social support from his son, but he did not use a phone alarm to remind him to take it. A home care nurse made weekly visits to make sure the remaining levothyroxine pill counts were correct; however, the patient continued to have difficulty maintaining daily adherence at home as indicated by the nurse’s pill counts not aligning with the number of pills which should have been left if the patient was talking the pills daily.

The patient was asked to visit a local community-based outpatient clinic (CBOC) weekly (to avoid patient travel time to Dayton VAMC > 1 hour) to check pill counts and assess adherence. The patient went to the CBOC clinic for these visits, during which pill counts indicated much better but not 100% adherence. After 6 weeks of clinic visits, his plasma TSH decreased to 1.01 uIU/mL, which was within the reference range, and the patient stopped coming to the weekly clinic visits (Table). Four months later, the patient's plasma TSH levels increased to 80.72 uIU/mL. Nonadherence to levothyroxine was suspected again. He was asked to resume weekly clinic visits, and the life-threatening effects of hypothyroidism and not taking levothyroxine were discussed with the patient and his son. The patient made CBOC clinic visits for 9 weeks, after which his plasma TSH level was low at 0.23 uIU/mL.

Discussion

There are multiple important causes to consider in patients with persistent hypothyroidism. One is medication nonadherence, which was most likely seen in the patient in this case. Missing even 1 day of levothyroxine can affect TSH and thyroid hormone levels for several days due to the long half-life of the medication.2 Hepp and colleagues found that patients with hypothyroidism were significantly more likely to be nonadherent to levothyroxine if they had comorbid conditions such as type 2 diabetes or were obese.3 Another study of levothyroxine adherence found that the most common reason for missing doses was forgetfulness.4 However, memory and cognition impairments can also be symptoms of hypothyroidism itself; Haskard-Zolnierek and colleagues found a significant association between nonadherence to levothyroxine and self-reported brain fog in patients with hypothyroidism.5

Another cause of persistent hypothyroidism is malabsorption. Absorption of levothyroxine can be affected by intestinal malabsorption due to inflammatory bowel disease, lactose intolerance, or gastrointestinal infection, as well as several foods, drinks (eg, coffee), medications, vitamins, and supplements (eg, proton-pump inhibitors and calcium).2,6 Levothyroxine is absorbed mainly at the jejunum and upper ileum, so any pathologies or ingested items that would directly or indirectly affect absorption at those sites can affect levothyroxine absorption.2

A liquid levothyroxine formulation can help with malabsorption.2 Alternatively, weight gain may lead to a need for increasing the dosage of levothyroxine.2,6 Other factors that can affect TSH levels include Addison disease, dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis, and TSH heterophile antibodies.2

Research describes methods that have effectively treated hypothyroidism in patients struggling with levothyroxine adherence. Two case reports describe weekly visits for levothyroxine administration successfully treating uncontrolled hypothyroidism.7,8 A meta-analysis found that while weekly levothyroxine tablets led to a higher mean TSH level than daily use, weekly use still led to reference-range TSH levels, suggesting that weekly levothyroxine may be a helpful alternative for nonadherent patients.9 Alternatively, patients taking levothyroxine tablets have been shown to forget to take their medication more frequently compared to those taking the liquid formulation.10,11 Additionally, a study by El Helou and colleagues found that adherence to levothyroxine was significantly improved when patients had endocrinology visits once a month and when the endocrinologist provided information about hypothyroidism.12

Another method that may improve adherence to levothyroxine is telehealth visits. This would be especially helpful for patients who live far from the clinic or do not have the time, transportation, or financial means to visit the clinic for weekly visits to assess medication adherence. Additionally, patients may be afraid of admitting to a health care professional that they are nonadherent. Clinicians must be tactful when asking about adherence to make the patient feel comfortable with admitting to nonadherence if their cognition is not impaired. Then, a patient-led conversation can occur regarding realistic ways the patient feels they can work toward adherence.

To our knowledge, the patient in this case report had no symptoms of intestinal malabsorption, and weight gain was not thought to be the issue, as levothyroxine dosage was adjusted multiple times. His plasma TSH levels returned to reference range after weekly pill count visits for 6 weeks and after weekly pill count visits for 9 weeks. Therefore, nonadherence to levothyroxine was suspected to be the cause of frequently elevated plasma TSH levels despite the patient’s insistence on adherence. While the patient did not report memory issues, cognitive impairments due to hypothyroidism may have been contributing to his probable nonadherence. Additionally, he had comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity, which may have made adherence more difficult.

Levothyroxine was also only prescribed in daily tablet form, so the frequency and formulation may have also contributed to nonadherence. While the home nurse was originally sent to assess the patient’s adherence, the care team could have had the nurse start giving the patient weekly levothyroxine once nonadherence was determined to be a likely issue. The patient’s adherence only improved when he went to the clinic for pill counts but not when the home nurse came to his house weekly; this could be because the patient knew he had to invest the time to physically go to clinic visits for pill checks, motivating him to increase adherence.

Conclusions

This case reports a patient with frequently high plasma TSH levels achieving normalization of plasma TSH levels after weekly medication adherence checks at a primary care clinic. Weekly visits to a clinic seem impractical compared to weekly dosing with a visiting nurse; however, after review of the literature, this may be an approach to consider in the future. This strategy may especially help in cases of persistent abnormal plasma TSH levels in which no etiology can be found other than suspected medication nonadherence. Knowing their medication use will be checked at weekly clinic visits may motivate patients to be adherent.

1. Chaker L, Bianco AC, Jonklaas J, Peeters RP. Hypothyroidism. Lancet. 2017;390(10101):1550-1562. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30703-1

2. Centanni M, Benvenga S, Sachmechi I. Diagnosis and management of treatment-refractory hypothyroidism: an expert consensus report. J Endocrinol Invest. 2017;40(12):1289-1301. doi:10.1007/s40618-017-0706-y

3. Hepp Z, Lage MJ, Espaillat R, Gossain VV. The association between adherence to levothyroxine and economic and clinical outcomes in patients with hypothyroidism in the US. J Med Econ. 2018;21(9):912-919. doi:10.1080/13696998.2018.1484749

4. Shakya Shrestha S, Risal K, Shrestha R, Bhatta RD. Medication Adherence to Levothyroxine Therapy among Hypothyroid Patients and their Clinical Outcomes with Special Reference to Thyroid Function Parameters. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2018;16(62):129-137.

5. Haskard-Zolnierek K, Wilson C, Pruin J, Deason R, Howard K. The Relationship Between Brain Fog and Medication Adherence for Individuals With Hypothyroidism. Clin Nurs Res. 2022;31(3):445-452. doi:10.1177/10547738211038127

6. McNally LJ, Ofiaeli CI, Oyibo SO. Treatment-refractory hypothyroidism. BMJ. 2019;364:l579. Published 2019 Feb 25. doi:10.1136/bmj.l579

7. Nakano Y, Hashimoto K, Ohkiba N, et al. A Case of Refractory Hypothyroidism due to Poor Compliance Treated with the Weekly Intravenous and Oral Levothyroxine Administration. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2019;2019:5986014. Published 2019 Feb 5. doi:10.1155/2019/5986014

8. Kiran Z, Shaikh KS, Fatima N, Tariq N, Baloch AA. Levothyroxine absorption test followed by directly observed treatment on an outpatient basis to address long-term high TSH levels in a hypothyroid patient: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2023;17(1):24. Published 2023 Jan 25. doi:10.1186/s13256-023-03760-0

9. Chiu HH, Larrazabal R Jr, Uy AB, Jimeno C. Weekly Versus Daily Levothyroxine Tablet Replacement in Adults with Hypothyroidism: A Meta-Analysis. J ASEAN Fed Endocr Soc. 2021;36(2):156-160. doi:10.15605/jafes.036.02.07

10. Cappelli C, Castello R, Marini F, et al. Adherence to Levothyroxine Treatment Among Patients With Hypothyroidism: A Northeastern Italian Survey. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;9:699. Published 2018 Nov 23. doi:10.3389/fendo.2018.00699

11. Bocale R, Desideri G, Barini A, et al. Long-Term Adherence to Levothyroxine Replacement Therapy in Thyroidectomized Patients. J Clin Med. 2022;11(15):4296. Published 2022 Jul 24. doi:10.3390/jcm11154296

12. El Helou S, Hallit S, Awada S, et al. Adherence to levothyroxine among patients with hypothyroidism in Lebanon. East Mediterr Health J. 2019;25(3):149-159. Published 2019 Apr 25. doi:10.26719/emhj.18.022

1. Chaker L, Bianco AC, Jonklaas J, Peeters RP. Hypothyroidism. Lancet. 2017;390(10101):1550-1562. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30703-1

2. Centanni M, Benvenga S, Sachmechi I. Diagnosis and management of treatment-refractory hypothyroidism: an expert consensus report. J Endocrinol Invest. 2017;40(12):1289-1301. doi:10.1007/s40618-017-0706-y

3. Hepp Z, Lage MJ, Espaillat R, Gossain VV. The association between adherence to levothyroxine and economic and clinical outcomes in patients with hypothyroidism in the US. J Med Econ. 2018;21(9):912-919. doi:10.1080/13696998.2018.1484749

4. Shakya Shrestha S, Risal K, Shrestha R, Bhatta RD. Medication Adherence to Levothyroxine Therapy among Hypothyroid Patients and their Clinical Outcomes with Special Reference to Thyroid Function Parameters. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2018;16(62):129-137.

5. Haskard-Zolnierek K, Wilson C, Pruin J, Deason R, Howard K. The Relationship Between Brain Fog and Medication Adherence for Individuals With Hypothyroidism. Clin Nurs Res. 2022;31(3):445-452. doi:10.1177/10547738211038127

6. McNally LJ, Ofiaeli CI, Oyibo SO. Treatment-refractory hypothyroidism. BMJ. 2019;364:l579. Published 2019 Feb 25. doi:10.1136/bmj.l579

7. Nakano Y, Hashimoto K, Ohkiba N, et al. A Case of Refractory Hypothyroidism due to Poor Compliance Treated with the Weekly Intravenous and Oral Levothyroxine Administration. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2019;2019:5986014. Published 2019 Feb 5. doi:10.1155/2019/5986014

8. Kiran Z, Shaikh KS, Fatima N, Tariq N, Baloch AA. Levothyroxine absorption test followed by directly observed treatment on an outpatient basis to address long-term high TSH levels in a hypothyroid patient: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2023;17(1):24. Published 2023 Jan 25. doi:10.1186/s13256-023-03760-0

9. Chiu HH, Larrazabal R Jr, Uy AB, Jimeno C. Weekly Versus Daily Levothyroxine Tablet Replacement in Adults with Hypothyroidism: A Meta-Analysis. J ASEAN Fed Endocr Soc. 2021;36(2):156-160. doi:10.15605/jafes.036.02.07

10. Cappelli C, Castello R, Marini F, et al. Adherence to Levothyroxine Treatment Among Patients With Hypothyroidism: A Northeastern Italian Survey. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;9:699. Published 2018 Nov 23. doi:10.3389/fendo.2018.00699

11. Bocale R, Desideri G, Barini A, et al. Long-Term Adherence to Levothyroxine Replacement Therapy in Thyroidectomized Patients. J Clin Med. 2022;11(15):4296. Published 2022 Jul 24. doi:10.3390/jcm11154296

12. El Helou S, Hallit S, Awada S, et al. Adherence to levothyroxine among patients with hypothyroidism in Lebanon. East Mediterr Health J. 2019;25(3):149-159. Published 2019 Apr 25. doi:10.26719/emhj.18.022

Clinical Implications of a Formulary Conversion From Budesonide/formoterol to Fluticasone/salmeterol at a VA Medical Center

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a respiratory disorder associated with slowly progressive systemic inflammation. It includes emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and small airway disease. Patients with COPD have an incomplete reversibility of airway obstruction, the key differentiating factor between it and asthma.1

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines recommend a combination inhaler consisting of a long-acting β-2 agonist (LABA) and inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) for patients with a history of COPD exacerbations.2 Blood eosinophil count is another marker for the initiation of an ICS in patients with COPD. According to the 2023 GOLD Report, ICS therapy is appropriate for patients who experience frequent exacerbations and have a blood eosinophil count > 100 cells/μL, while on maximum tolerated inhaler therapy.3 A 2019 meta-analysis found an overall reduction in the risk of exacerbations in patients with blood eosinophil counts ≥ 100 cells/µL after initiating an ICS.4

Common ICS-LABA inhalers include the combination of budesonide/formoterol as well as fluticasone/salmeterol. Though these combinations are within the same therapeutic class, they have different delivery systems: budesonide/formoterol is a metered dose inhaler, while fluticasone/salmeterol is a dry powder inhaler. The PATHOS study compared the exacerbation rates for the 2 inhalers in primary care patients with COPD. Patients treated long-term with the budesonide/formoterol inhaler were significantly less likely to experience a COPD exacerbation than those treated with the fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler.5

In 2021, The Veteran Health Administration transitioned patients from budesonide/formoterol inhalers to fluticasone/salmeterol inhalers through a formulary conversion. The purpose of this study was to examine the outcomes for patients undergoing the transition.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was conducted on patients at the Hershel “Woody” Williams Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Huntington, West Virginia, with COPD and prescriptions for both budesonide/formoterol and fluticasone/salmeterol inhalers between February 1, 2021, and May 30, 2022. In 2018, the prevalence of COPD in West Virginia was 13.9%, highest in the US.6 Data was obtained through the US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) Corporate Data Warehouse and stored on a VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure server. Patients were randomly selected from this cohort and included if they were aged 18 to 89 years, prescribed both inhalers, and had a confirmed COPD diagnosis. Patients were excluded if they also had an asthma diagnosis, if they had an interstitial lung disease, or any tracheostomy tubes. The date of transition from a budesonide/formoterol inhaler to a fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler was collected to establish a timeline of 6 months before and 6 months after the transition.

The primary endpoint was to assess clinical outcomes such as the number of COPD exacerbations and hospitalizations within 6 months of the transition for patients affected by the formulary conversion. Secondary outcomes included the incidence of adverse effects (AEs), treatment failure, tobacco use, and systemic corticosteroid/antimicrobial utilization.

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA v.15. Numerical data was analyzed using a Wilcoxon signed rank test. Categorical data was analyzed by a logistic regression analysis.

Results

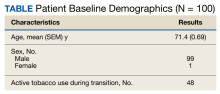

Of 1497 included patients who transitioned from budesonide/formoterol to fluticasone/salmeterol inhalers, 165 were randomly selected and 100 patients were included in this analysis. Of the 100 patients, 99 were male with a mean (SEM) age of 71 (0.69) years (range, 54-87) (Table).

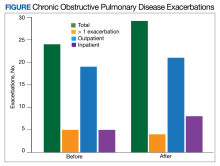

The transition from budesonide/formoterol to fluticasone/salmeterol inhalers did not have a statistically significant impact on exacerbations (P = .56). Thirty patients had ≥ 1 exacerbation: 12 had an exacerbation before the transition, 10 had an exacerbation after the transition, and 8 had exacerbations before and after the transition. In the 6 months prior to the transition while on a budesonide/formoterol inhaler, there were 24 exacerbations among 20 patients. Five patients had > 1 exacerbation, accounting for 11 of the 24 exacerbations. There were 29 exacerbations among 19 patients while on a fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler in the 6 months after the transition. Four of these patients had > 1 exacerbation, accounting for 14 of 29 exacerbations (Figure).

Secondary endpoints showed 3 patients experienced an AE related to fluticasone/salmeterol, including thrush, coughing and throat irritation, and dyspnea. Eighteen fluticasone/salmeterol therapeutic failures were indicated by related prior authorization medication requests in the electronic health record. Twelve of 18 patients experienced no difference in exacerbations before vs after the transition to budesonide/formoterol. Twenty-three patients transitioned from fluticasone/salmeterol to a different ICS-LABA therapy; 20 of those 23 patients transitioned back to a budesonide/formoterol inhaler.

There were 48 documented active tobacco users in the study. There was no statistically significant correlation (P = .52) when comparing tobacco use at time of conversion and exacerbation frequency, although the coefficient showed a negative correlation of -0.387. In the 6 months prior to the transition, there were 17 prescriptions for systemic corticosteroids and 24 for antibiotics to treat COPD exacerbations. Following the transition, there were only 12 prescriptions for systemic corticosteroids and 23 for antibiotics. Fifty-two patients had an active prescription for a fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler at the time of the data review (November to December 2022); of the 48 patients who did not, 10 were no longer active due to patient death between the study period and data retrieval.

Discussion

Patients who transitioned from budesonide/formoterol to fluticasone/salmeterol inhalers did not show a significant difference in clinical COPD outcomes. While the total number of exacerbations increased after switching to the fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler, fewer patients had exacerbations during fluticasone/salmeterol therapy when compared with budesonide/fluticasone therapy. The number of patients receiving systemic corticosteroids and antibiotics to treat exacerbations before and after the transition were similar.

The frequency of treatment failures and AEs to the fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler could be due to the change of the inhaler delivery systems. Budesonide/formoterol is a metered dose inhaler (MDI). It is equipped with a pressurized canister that allows a spacer to be used to maximize benefit. Spacers can assist in preventing oral candidiasis by reducing the amount of medication that touches the back of the throat. Spacers are an option for patients, but not all use them for their MDIs, which can result in a less effective administered dose. Fluticasone/salmeterol is a dry powder inhaler, which requires a deep, fast breath to maximize the benefit, and spacers cannot be used with them. MDIs have been shown to be responsible for a negative impact on climate change, which can be reduced by switching to a dry powder inhaler.7

Tobacco cessation is very important in limiting the progression of COPD. As shown with the negative coefficient correlation, not being an active tobacco user at the time of transition correlated (although not significantly) with less frequent exacerbations. When comparing this study to similar research, such as the PATHOS study, several differences are observed.5 The PATHOS study compared long term treatment (> 1 year) of budesonide/formoterol or fluticasone/salmeterol, a longer period than this study. It regarded similar outcomes for the definition of an exacerbation, such as antibiotic/steroid use or hospital admission. While the current study showed no significant difference between the 2 inhalers and their effect on exacerbations, the PATHOS study found that those treated with a budesonide/formoterol inhaler were less likely to experience COPD-related exacerbations than those treated with the fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler. The PATHOS study had a larger mainly Scandinavian sample (N = 5500). This population could exhibit baseline differences from a study of US veterans.5 A similar Canadian matched cohort study of 2262 patients compared the 2 inhalers to assess their relative effectiveness. It found that COPD exacerbations did not differ between the 2 groups, but the budesonide/formoterol group was significantly less likely to have an emergency department visit compared to the fluticasone salmeterol group.8 Like the PATHOS study, the Canadian study had a larger sample size and longer timeframe than did our study.

Limitations

There are various limitations to this study. It was a retrospective, single-center study and the patient population was relatively homogenous, with only 1 female and a mean age of 71 years. As a study conducted in a veteran population in West Virginia, the findings may not be representative of the general population with COPD, which includes more women and more racial diversity.9 The American Lung Association discusses how environmental exposures to hazardous conditions increase the risks of pulmonary diseases for veterans.10 It has been reported that the prevalence of COPD is higher among veterans compared to the general population, but it is not different in terms of disease manifestation.10

Another limitation is the short time frame. Clinical guidelines, including the GOLD Report, typically track the number of exacerbations for 1 year to escalate therapy.3 Six months was a relatively short time frame, and it is possible that more exacerbations may have occurred beyond the study time frame. Ten patients in the sample died between the end of the study period and data retrieval, which might have been caught by a longer study period. An additional limitation was the inability to measure adherence. As this was a formulary conversion, many patients had been mailed a 30- or 90-day prescription of the budesonide/formoterol inhaler when transitioned to the fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler. There was no way to accurately determine when the patient made the switch to the fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler. This study also had a small sample group (a pre-post analysis of the same group), a limitation when evaluating the impact of this formulary change on a small percentage of the population transitioned.

This formulary conversion occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, and some exacerbations could have been the result of a misdiagnosed COVID-19 infection. Respiratory infections, including COVID-19, are common causes of exacerbations. It is also possible that some patients elected not to receive medical care for symptoms of an exacerbation during the pandemic.11

Conclusions

Switching from the budesonide/formoterol inhaler to the fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler through formulary conversion did not have a significant impact on the clinical outcomes in patients with COPD. This study found that although the inhalers contain different active ingredients, products within the same therapeutic class yielded nonsignificant changes. When conducting formulary conversions, intolerances and treatment failures should be expected when switching from different inhaler delivery systems. This study further justifies the ability to be cost effective by making formulary conversions within the same therapeutic class within a veterans population.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge James Brown, PharmD, PhD.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA/DOD Clinical Practice Guideline. Management of Outpatient Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2021. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/cd/copd/

2. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD Report. 2022. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://goldcopd.org/2022-gold-reports/

3. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 2023 report. Accessed January 26, 2024. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/GOLD-2023-ver-1.3-17Feb2023_WMV.pdf

4. Oshagbemi OA, Odiba JO, Daniel A, Yunusa I. Absolute blood eosinophil counts to guide inhaled corticosteroids therapy among patients with COPD: systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Drug Targets. 2019;20(16):1670-1679. doi:10.2174/1389450120666190808141625

5. Larsson K, Janson C, Lisspers K, et al. Combination of budesonide/formoterol more effective than fluticasone/salmeterol in preventing exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the PATHOS study. J Intern Med. 2013;273(6):584-594. doi:10.1111/joim.12067

6. West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources, Division of Health Promotion and Chronic Disease. Statistics about the population of West Virginia. 2018. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://dhhr.wv.gov/hpcd/data_reports/ Pages/Fast-Facts.aspx

7. Fidler L, Green S, Wintemute K. Pressurized metered-dose inhalers and their impact on climate change. CMAJ. 2022;194(12):E460. doi:10.1503/cmaj.211747

8. Blais L, Forget A, Ramachandran S. Relative effectiveness of budesonide/formoterol and fluticasone propionate/salmeterol in a 1-year, population-based, matched cohort study of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): Effect on COPD-related exacerbations, emergency department visits and hospitalizations, medication utilization, and treatment adherence. Clin Ther. 2010;32(7):1320-1328. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.06.022

9. Wheaton AG, Cunningham TJ, Ford ES, Croft JB; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Employment and activity limitations among adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease — United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015:64(11):289-295.

10. Bamonti PM, Robinson SA, Wan ES, Moy ML. Improving physiological, physical, and psychological health outcomes: a narrative review in US veterans with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:1269-1283. doi:10.2147/COPD.S339323

11. Czeisler MÉ, Marynak K, Clarke KEN, et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19–related concerns - United States, June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(36):1250-1257. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6936a4

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a respiratory disorder associated with slowly progressive systemic inflammation. It includes emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and small airway disease. Patients with COPD have an incomplete reversibility of airway obstruction, the key differentiating factor between it and asthma.1

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines recommend a combination inhaler consisting of a long-acting β-2 agonist (LABA) and inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) for patients with a history of COPD exacerbations.2 Blood eosinophil count is another marker for the initiation of an ICS in patients with COPD. According to the 2023 GOLD Report, ICS therapy is appropriate for patients who experience frequent exacerbations and have a blood eosinophil count > 100 cells/μL, while on maximum tolerated inhaler therapy.3 A 2019 meta-analysis found an overall reduction in the risk of exacerbations in patients with blood eosinophil counts ≥ 100 cells/µL after initiating an ICS.4

Common ICS-LABA inhalers include the combination of budesonide/formoterol as well as fluticasone/salmeterol. Though these combinations are within the same therapeutic class, they have different delivery systems: budesonide/formoterol is a metered dose inhaler, while fluticasone/salmeterol is a dry powder inhaler. The PATHOS study compared the exacerbation rates for the 2 inhalers in primary care patients with COPD. Patients treated long-term with the budesonide/formoterol inhaler were significantly less likely to experience a COPD exacerbation than those treated with the fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler.5

In 2021, The Veteran Health Administration transitioned patients from budesonide/formoterol inhalers to fluticasone/salmeterol inhalers through a formulary conversion. The purpose of this study was to examine the outcomes for patients undergoing the transition.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was conducted on patients at the Hershel “Woody” Williams Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Huntington, West Virginia, with COPD and prescriptions for both budesonide/formoterol and fluticasone/salmeterol inhalers between February 1, 2021, and May 30, 2022. In 2018, the prevalence of COPD in West Virginia was 13.9%, highest in the US.6 Data was obtained through the US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) Corporate Data Warehouse and stored on a VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure server. Patients were randomly selected from this cohort and included if they were aged 18 to 89 years, prescribed both inhalers, and had a confirmed COPD diagnosis. Patients were excluded if they also had an asthma diagnosis, if they had an interstitial lung disease, or any tracheostomy tubes. The date of transition from a budesonide/formoterol inhaler to a fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler was collected to establish a timeline of 6 months before and 6 months after the transition.

The primary endpoint was to assess clinical outcomes such as the number of COPD exacerbations and hospitalizations within 6 months of the transition for patients affected by the formulary conversion. Secondary outcomes included the incidence of adverse effects (AEs), treatment failure, tobacco use, and systemic corticosteroid/antimicrobial utilization.

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA v.15. Numerical data was analyzed using a Wilcoxon signed rank test. Categorical data was analyzed by a logistic regression analysis.

Results

Of 1497 included patients who transitioned from budesonide/formoterol to fluticasone/salmeterol inhalers, 165 were randomly selected and 100 patients were included in this analysis. Of the 100 patients, 99 were male with a mean (SEM) age of 71 (0.69) years (range, 54-87) (Table).

The transition from budesonide/formoterol to fluticasone/salmeterol inhalers did not have a statistically significant impact on exacerbations (P = .56). Thirty patients had ≥ 1 exacerbation: 12 had an exacerbation before the transition, 10 had an exacerbation after the transition, and 8 had exacerbations before and after the transition. In the 6 months prior to the transition while on a budesonide/formoterol inhaler, there were 24 exacerbations among 20 patients. Five patients had > 1 exacerbation, accounting for 11 of the 24 exacerbations. There were 29 exacerbations among 19 patients while on a fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler in the 6 months after the transition. Four of these patients had > 1 exacerbation, accounting for 14 of 29 exacerbations (Figure).

Secondary endpoints showed 3 patients experienced an AE related to fluticasone/salmeterol, including thrush, coughing and throat irritation, and dyspnea. Eighteen fluticasone/salmeterol therapeutic failures were indicated by related prior authorization medication requests in the electronic health record. Twelve of 18 patients experienced no difference in exacerbations before vs after the transition to budesonide/formoterol. Twenty-three patients transitioned from fluticasone/salmeterol to a different ICS-LABA therapy; 20 of those 23 patients transitioned back to a budesonide/formoterol inhaler.

There were 48 documented active tobacco users in the study. There was no statistically significant correlation (P = .52) when comparing tobacco use at time of conversion and exacerbation frequency, although the coefficient showed a negative correlation of -0.387. In the 6 months prior to the transition, there were 17 prescriptions for systemic corticosteroids and 24 for antibiotics to treat COPD exacerbations. Following the transition, there were only 12 prescriptions for systemic corticosteroids and 23 for antibiotics. Fifty-two patients had an active prescription for a fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler at the time of the data review (November to December 2022); of the 48 patients who did not, 10 were no longer active due to patient death between the study period and data retrieval.

Discussion

Patients who transitioned from budesonide/formoterol to fluticasone/salmeterol inhalers did not show a significant difference in clinical COPD outcomes. While the total number of exacerbations increased after switching to the fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler, fewer patients had exacerbations during fluticasone/salmeterol therapy when compared with budesonide/fluticasone therapy. The number of patients receiving systemic corticosteroids and antibiotics to treat exacerbations before and after the transition were similar.

The frequency of treatment failures and AEs to the fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler could be due to the change of the inhaler delivery systems. Budesonide/formoterol is a metered dose inhaler (MDI). It is equipped with a pressurized canister that allows a spacer to be used to maximize benefit. Spacers can assist in preventing oral candidiasis by reducing the amount of medication that touches the back of the throat. Spacers are an option for patients, but not all use them for their MDIs, which can result in a less effective administered dose. Fluticasone/salmeterol is a dry powder inhaler, which requires a deep, fast breath to maximize the benefit, and spacers cannot be used with them. MDIs have been shown to be responsible for a negative impact on climate change, which can be reduced by switching to a dry powder inhaler.7

Tobacco cessation is very important in limiting the progression of COPD. As shown with the negative coefficient correlation, not being an active tobacco user at the time of transition correlated (although not significantly) with less frequent exacerbations. When comparing this study to similar research, such as the PATHOS study, several differences are observed.5 The PATHOS study compared long term treatment (> 1 year) of budesonide/formoterol or fluticasone/salmeterol, a longer period than this study. It regarded similar outcomes for the definition of an exacerbation, such as antibiotic/steroid use or hospital admission. While the current study showed no significant difference between the 2 inhalers and their effect on exacerbations, the PATHOS study found that those treated with a budesonide/formoterol inhaler were less likely to experience COPD-related exacerbations than those treated with the fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler. The PATHOS study had a larger mainly Scandinavian sample (N = 5500). This population could exhibit baseline differences from a study of US veterans.5 A similar Canadian matched cohort study of 2262 patients compared the 2 inhalers to assess their relative effectiveness. It found that COPD exacerbations did not differ between the 2 groups, but the budesonide/formoterol group was significantly less likely to have an emergency department visit compared to the fluticasone salmeterol group.8 Like the PATHOS study, the Canadian study had a larger sample size and longer timeframe than did our study.

Limitations

There are various limitations to this study. It was a retrospective, single-center study and the patient population was relatively homogenous, with only 1 female and a mean age of 71 years. As a study conducted in a veteran population in West Virginia, the findings may not be representative of the general population with COPD, which includes more women and more racial diversity.9 The American Lung Association discusses how environmental exposures to hazardous conditions increase the risks of pulmonary diseases for veterans.10 It has been reported that the prevalence of COPD is higher among veterans compared to the general population, but it is not different in terms of disease manifestation.10

Another limitation is the short time frame. Clinical guidelines, including the GOLD Report, typically track the number of exacerbations for 1 year to escalate therapy.3 Six months was a relatively short time frame, and it is possible that more exacerbations may have occurred beyond the study time frame. Ten patients in the sample died between the end of the study period and data retrieval, which might have been caught by a longer study period. An additional limitation was the inability to measure adherence. As this was a formulary conversion, many patients had been mailed a 30- or 90-day prescription of the budesonide/formoterol inhaler when transitioned to the fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler. There was no way to accurately determine when the patient made the switch to the fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler. This study also had a small sample group (a pre-post analysis of the same group), a limitation when evaluating the impact of this formulary change on a small percentage of the population transitioned.

This formulary conversion occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, and some exacerbations could have been the result of a misdiagnosed COVID-19 infection. Respiratory infections, including COVID-19, are common causes of exacerbations. It is also possible that some patients elected not to receive medical care for symptoms of an exacerbation during the pandemic.11

Conclusions

Switching from the budesonide/formoterol inhaler to the fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler through formulary conversion did not have a significant impact on the clinical outcomes in patients with COPD. This study found that although the inhalers contain different active ingredients, products within the same therapeutic class yielded nonsignificant changes. When conducting formulary conversions, intolerances and treatment failures should be expected when switching from different inhaler delivery systems. This study further justifies the ability to be cost effective by making formulary conversions within the same therapeutic class within a veterans population.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge James Brown, PharmD, PhD.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a respiratory disorder associated with slowly progressive systemic inflammation. It includes emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and small airway disease. Patients with COPD have an incomplete reversibility of airway obstruction, the key differentiating factor between it and asthma.1

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines recommend a combination inhaler consisting of a long-acting β-2 agonist (LABA) and inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) for patients with a history of COPD exacerbations.2 Blood eosinophil count is another marker for the initiation of an ICS in patients with COPD. According to the 2023 GOLD Report, ICS therapy is appropriate for patients who experience frequent exacerbations and have a blood eosinophil count > 100 cells/μL, while on maximum tolerated inhaler therapy.3 A 2019 meta-analysis found an overall reduction in the risk of exacerbations in patients with blood eosinophil counts ≥ 100 cells/µL after initiating an ICS.4

Common ICS-LABA inhalers include the combination of budesonide/formoterol as well as fluticasone/salmeterol. Though these combinations are within the same therapeutic class, they have different delivery systems: budesonide/formoterol is a metered dose inhaler, while fluticasone/salmeterol is a dry powder inhaler. The PATHOS study compared the exacerbation rates for the 2 inhalers in primary care patients with COPD. Patients treated long-term with the budesonide/formoterol inhaler were significantly less likely to experience a COPD exacerbation than those treated with the fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler.5

In 2021, The Veteran Health Administration transitioned patients from budesonide/formoterol inhalers to fluticasone/salmeterol inhalers through a formulary conversion. The purpose of this study was to examine the outcomes for patients undergoing the transition.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was conducted on patients at the Hershel “Woody” Williams Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Huntington, West Virginia, with COPD and prescriptions for both budesonide/formoterol and fluticasone/salmeterol inhalers between February 1, 2021, and May 30, 2022. In 2018, the prevalence of COPD in West Virginia was 13.9%, highest in the US.6 Data was obtained through the US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) Corporate Data Warehouse and stored on a VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure server. Patients were randomly selected from this cohort and included if they were aged 18 to 89 years, prescribed both inhalers, and had a confirmed COPD diagnosis. Patients were excluded if they also had an asthma diagnosis, if they had an interstitial lung disease, or any tracheostomy tubes. The date of transition from a budesonide/formoterol inhaler to a fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler was collected to establish a timeline of 6 months before and 6 months after the transition.

The primary endpoint was to assess clinical outcomes such as the number of COPD exacerbations and hospitalizations within 6 months of the transition for patients affected by the formulary conversion. Secondary outcomes included the incidence of adverse effects (AEs), treatment failure, tobacco use, and systemic corticosteroid/antimicrobial utilization.

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA v.15. Numerical data was analyzed using a Wilcoxon signed rank test. Categorical data was analyzed by a logistic regression analysis.

Results

Of 1497 included patients who transitioned from budesonide/formoterol to fluticasone/salmeterol inhalers, 165 were randomly selected and 100 patients were included in this analysis. Of the 100 patients, 99 were male with a mean (SEM) age of 71 (0.69) years (range, 54-87) (Table).

The transition from budesonide/formoterol to fluticasone/salmeterol inhalers did not have a statistically significant impact on exacerbations (P = .56). Thirty patients had ≥ 1 exacerbation: 12 had an exacerbation before the transition, 10 had an exacerbation after the transition, and 8 had exacerbations before and after the transition. In the 6 months prior to the transition while on a budesonide/formoterol inhaler, there were 24 exacerbations among 20 patients. Five patients had > 1 exacerbation, accounting for 11 of the 24 exacerbations. There were 29 exacerbations among 19 patients while on a fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler in the 6 months after the transition. Four of these patients had > 1 exacerbation, accounting for 14 of 29 exacerbations (Figure).

Secondary endpoints showed 3 patients experienced an AE related to fluticasone/salmeterol, including thrush, coughing and throat irritation, and dyspnea. Eighteen fluticasone/salmeterol therapeutic failures were indicated by related prior authorization medication requests in the electronic health record. Twelve of 18 patients experienced no difference in exacerbations before vs after the transition to budesonide/formoterol. Twenty-three patients transitioned from fluticasone/salmeterol to a different ICS-LABA therapy; 20 of those 23 patients transitioned back to a budesonide/formoterol inhaler.

There were 48 documented active tobacco users in the study. There was no statistically significant correlation (P = .52) when comparing tobacco use at time of conversion and exacerbation frequency, although the coefficient showed a negative correlation of -0.387. In the 6 months prior to the transition, there were 17 prescriptions for systemic corticosteroids and 24 for antibiotics to treat COPD exacerbations. Following the transition, there were only 12 prescriptions for systemic corticosteroids and 23 for antibiotics. Fifty-two patients had an active prescription for a fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler at the time of the data review (November to December 2022); of the 48 patients who did not, 10 were no longer active due to patient death between the study period and data retrieval.

Discussion

Patients who transitioned from budesonide/formoterol to fluticasone/salmeterol inhalers did not show a significant difference in clinical COPD outcomes. While the total number of exacerbations increased after switching to the fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler, fewer patients had exacerbations during fluticasone/salmeterol therapy when compared with budesonide/fluticasone therapy. The number of patients receiving systemic corticosteroids and antibiotics to treat exacerbations before and after the transition were similar.

The frequency of treatment failures and AEs to the fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler could be due to the change of the inhaler delivery systems. Budesonide/formoterol is a metered dose inhaler (MDI). It is equipped with a pressurized canister that allows a spacer to be used to maximize benefit. Spacers can assist in preventing oral candidiasis by reducing the amount of medication that touches the back of the throat. Spacers are an option for patients, but not all use them for their MDIs, which can result in a less effective administered dose. Fluticasone/salmeterol is a dry powder inhaler, which requires a deep, fast breath to maximize the benefit, and spacers cannot be used with them. MDIs have been shown to be responsible for a negative impact on climate change, which can be reduced by switching to a dry powder inhaler.7

Tobacco cessation is very important in limiting the progression of COPD. As shown with the negative coefficient correlation, not being an active tobacco user at the time of transition correlated (although not significantly) with less frequent exacerbations. When comparing this study to similar research, such as the PATHOS study, several differences are observed.5 The PATHOS study compared long term treatment (> 1 year) of budesonide/formoterol or fluticasone/salmeterol, a longer period than this study. It regarded similar outcomes for the definition of an exacerbation, such as antibiotic/steroid use or hospital admission. While the current study showed no significant difference between the 2 inhalers and their effect on exacerbations, the PATHOS study found that those treated with a budesonide/formoterol inhaler were less likely to experience COPD-related exacerbations than those treated with the fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler. The PATHOS study had a larger mainly Scandinavian sample (N = 5500). This population could exhibit baseline differences from a study of US veterans.5 A similar Canadian matched cohort study of 2262 patients compared the 2 inhalers to assess their relative effectiveness. It found that COPD exacerbations did not differ between the 2 groups, but the budesonide/formoterol group was significantly less likely to have an emergency department visit compared to the fluticasone salmeterol group.8 Like the PATHOS study, the Canadian study had a larger sample size and longer timeframe than did our study.

Limitations

There are various limitations to this study. It was a retrospective, single-center study and the patient population was relatively homogenous, with only 1 female and a mean age of 71 years. As a study conducted in a veteran population in West Virginia, the findings may not be representative of the general population with COPD, which includes more women and more racial diversity.9 The American Lung Association discusses how environmental exposures to hazardous conditions increase the risks of pulmonary diseases for veterans.10 It has been reported that the prevalence of COPD is higher among veterans compared to the general population, but it is not different in terms of disease manifestation.10

Another limitation is the short time frame. Clinical guidelines, including the GOLD Report, typically track the number of exacerbations for 1 year to escalate therapy.3 Six months was a relatively short time frame, and it is possible that more exacerbations may have occurred beyond the study time frame. Ten patients in the sample died between the end of the study period and data retrieval, which might have been caught by a longer study period. An additional limitation was the inability to measure adherence. As this was a formulary conversion, many patients had been mailed a 30- or 90-day prescription of the budesonide/formoterol inhaler when transitioned to the fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler. There was no way to accurately determine when the patient made the switch to the fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler. This study also had a small sample group (a pre-post analysis of the same group), a limitation when evaluating the impact of this formulary change on a small percentage of the population transitioned.

This formulary conversion occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, and some exacerbations could have been the result of a misdiagnosed COVID-19 infection. Respiratory infections, including COVID-19, are common causes of exacerbations. It is also possible that some patients elected not to receive medical care for symptoms of an exacerbation during the pandemic.11

Conclusions

Switching from the budesonide/formoterol inhaler to the fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler through formulary conversion did not have a significant impact on the clinical outcomes in patients with COPD. This study found that although the inhalers contain different active ingredients, products within the same therapeutic class yielded nonsignificant changes. When conducting formulary conversions, intolerances and treatment failures should be expected when switching from different inhaler delivery systems. This study further justifies the ability to be cost effective by making formulary conversions within the same therapeutic class within a veterans population.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge James Brown, PharmD, PhD.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA/DOD Clinical Practice Guideline. Management of Outpatient Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2021. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/cd/copd/

2. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD Report. 2022. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://goldcopd.org/2022-gold-reports/

3. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 2023 report. Accessed January 26, 2024. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/GOLD-2023-ver-1.3-17Feb2023_WMV.pdf

4. Oshagbemi OA, Odiba JO, Daniel A, Yunusa I. Absolute blood eosinophil counts to guide inhaled corticosteroids therapy among patients with COPD: systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Drug Targets. 2019;20(16):1670-1679. doi:10.2174/1389450120666190808141625

5. Larsson K, Janson C, Lisspers K, et al. Combination of budesonide/formoterol more effective than fluticasone/salmeterol in preventing exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the PATHOS study. J Intern Med. 2013;273(6):584-594. doi:10.1111/joim.12067

6. West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources, Division of Health Promotion and Chronic Disease. Statistics about the population of West Virginia. 2018. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://dhhr.wv.gov/hpcd/data_reports/ Pages/Fast-Facts.aspx

7. Fidler L, Green S, Wintemute K. Pressurized metered-dose inhalers and their impact on climate change. CMAJ. 2022;194(12):E460. doi:10.1503/cmaj.211747

8. Blais L, Forget A, Ramachandran S. Relative effectiveness of budesonide/formoterol and fluticasone propionate/salmeterol in a 1-year, population-based, matched cohort study of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): Effect on COPD-related exacerbations, emergency department visits and hospitalizations, medication utilization, and treatment adherence. Clin Ther. 2010;32(7):1320-1328. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.06.022

9. Wheaton AG, Cunningham TJ, Ford ES, Croft JB; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Employment and activity limitations among adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease — United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015:64(11):289-295.

10. Bamonti PM, Robinson SA, Wan ES, Moy ML. Improving physiological, physical, and psychological health outcomes: a narrative review in US veterans with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:1269-1283. doi:10.2147/COPD.S339323

11. Czeisler MÉ, Marynak K, Clarke KEN, et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19–related concerns - United States, June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(36):1250-1257. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6936a4

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA/DOD Clinical Practice Guideline. Management of Outpatient Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2021. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/cd/copd/

2. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD Report. 2022. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://goldcopd.org/2022-gold-reports/

3. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 2023 report. Accessed January 26, 2024. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/GOLD-2023-ver-1.3-17Feb2023_WMV.pdf

4. Oshagbemi OA, Odiba JO, Daniel A, Yunusa I. Absolute blood eosinophil counts to guide inhaled corticosteroids therapy among patients with COPD: systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Drug Targets. 2019;20(16):1670-1679. doi:10.2174/1389450120666190808141625

5. Larsson K, Janson C, Lisspers K, et al. Combination of budesonide/formoterol more effective than fluticasone/salmeterol in preventing exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the PATHOS study. J Intern Med. 2013;273(6):584-594. doi:10.1111/joim.12067

6. West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources, Division of Health Promotion and Chronic Disease. Statistics about the population of West Virginia. 2018. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://dhhr.wv.gov/hpcd/data_reports/ Pages/Fast-Facts.aspx