User login

Plaquelike Syringoma Mimicking Microcystic Adnexal Carcinoma: A Potential Histologic Pitfall

To the Editor:

Plaquelike or plaque-type syringoma is a lesser-known variant of syringoma that can appear histologically indistinguishable from the superficial portion of microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC). The plaquelike variant of syringoma holds a benign clinical course, and no treatment is necessary. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is distinguished from plaquelike syringoma by an aggressive growth pattern with a high risk for local invasion and recurrence if inadequately treated. Thus, treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has been recommended as the mainstay for MAC. If superficial biopsy specimens reveal suspicion for MAC and patients are referred for MMS, careful consideration should be made to differentiate MAC and plaquelike syringoma early to prevent unnecessary morbidity.

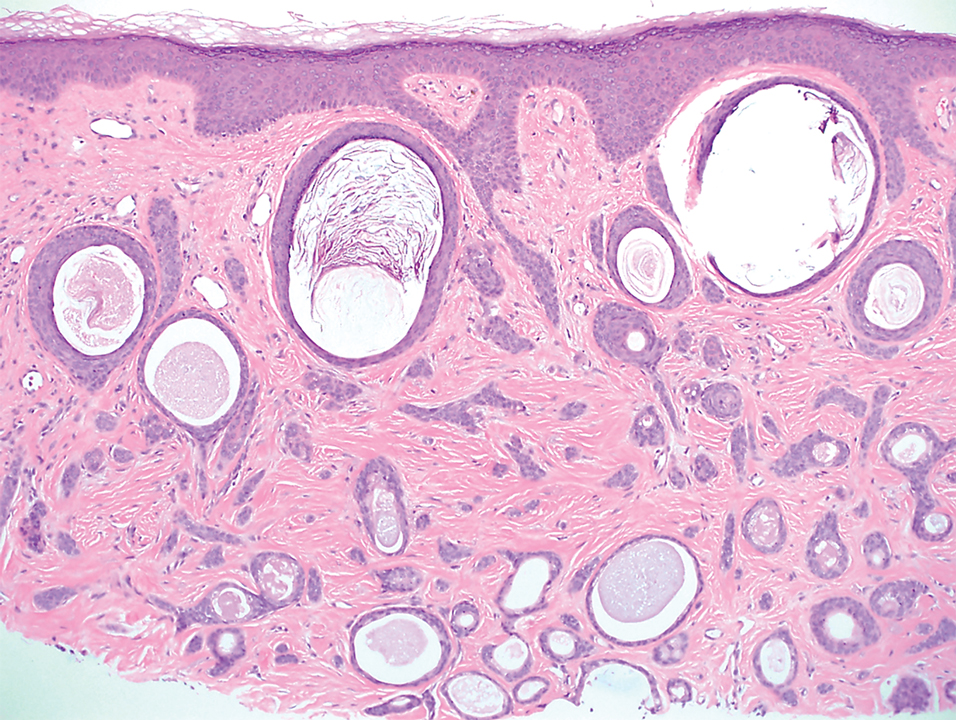

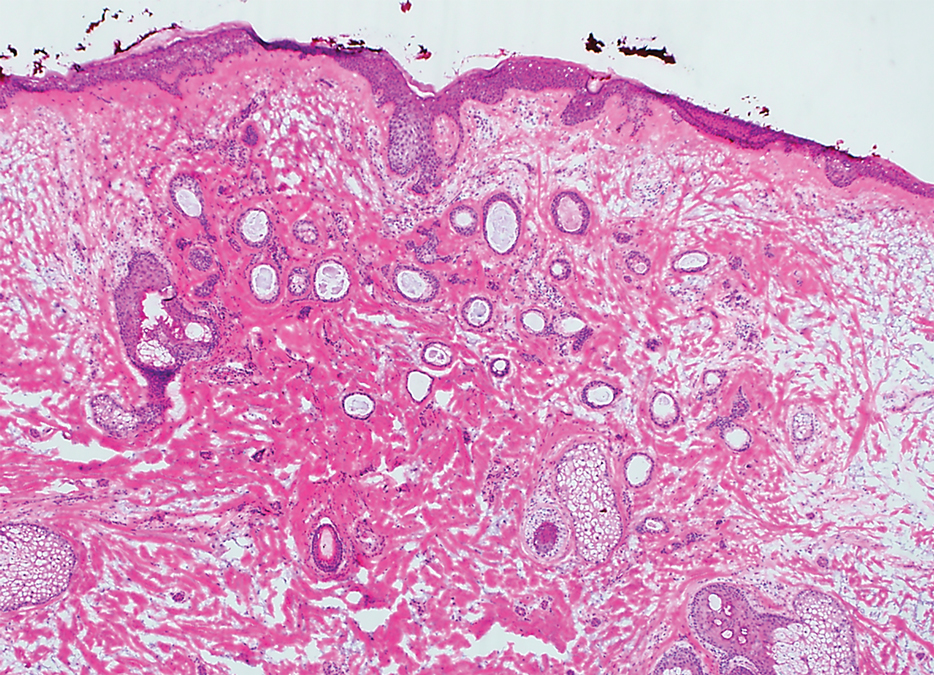

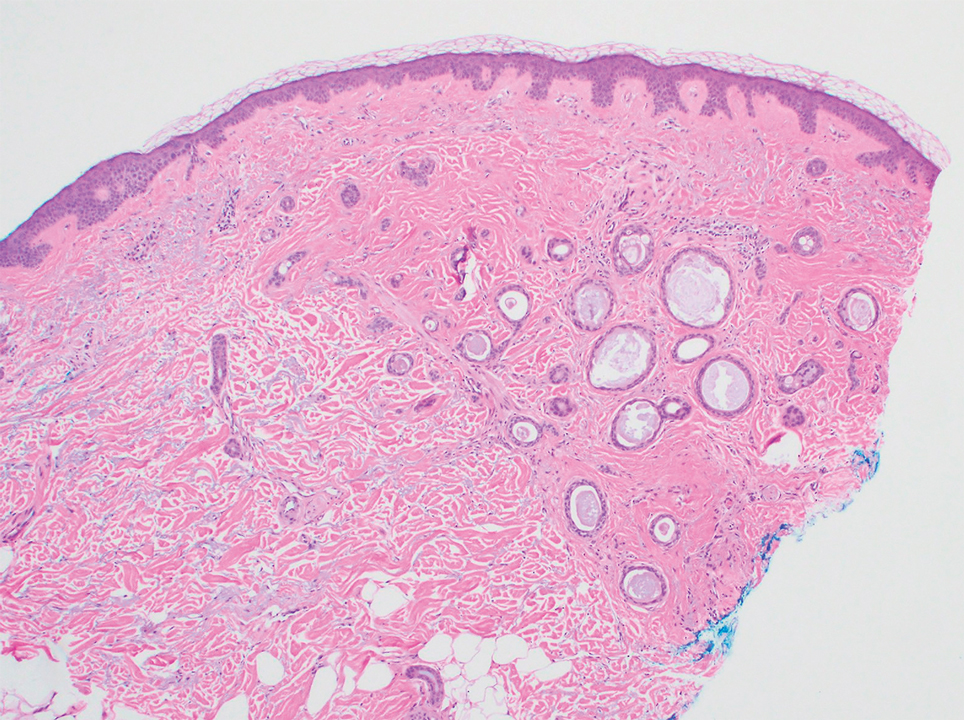

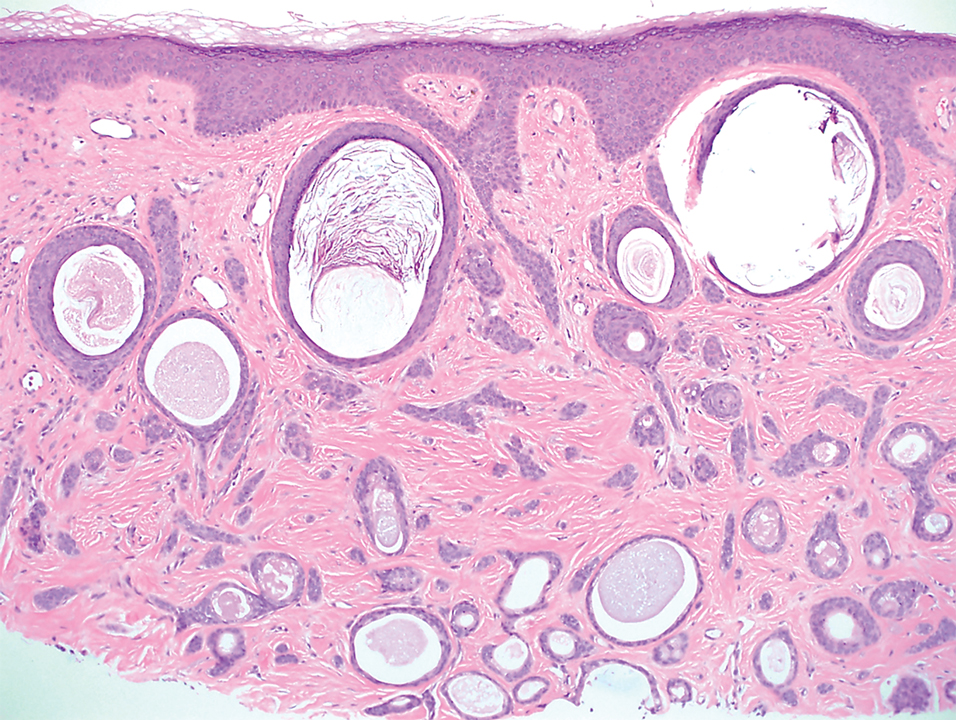

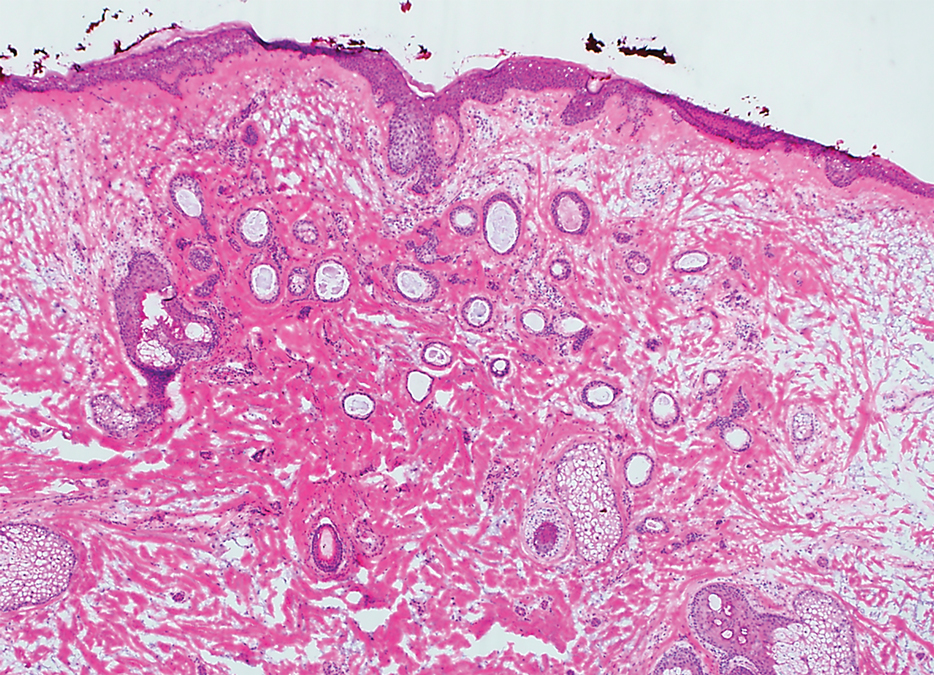

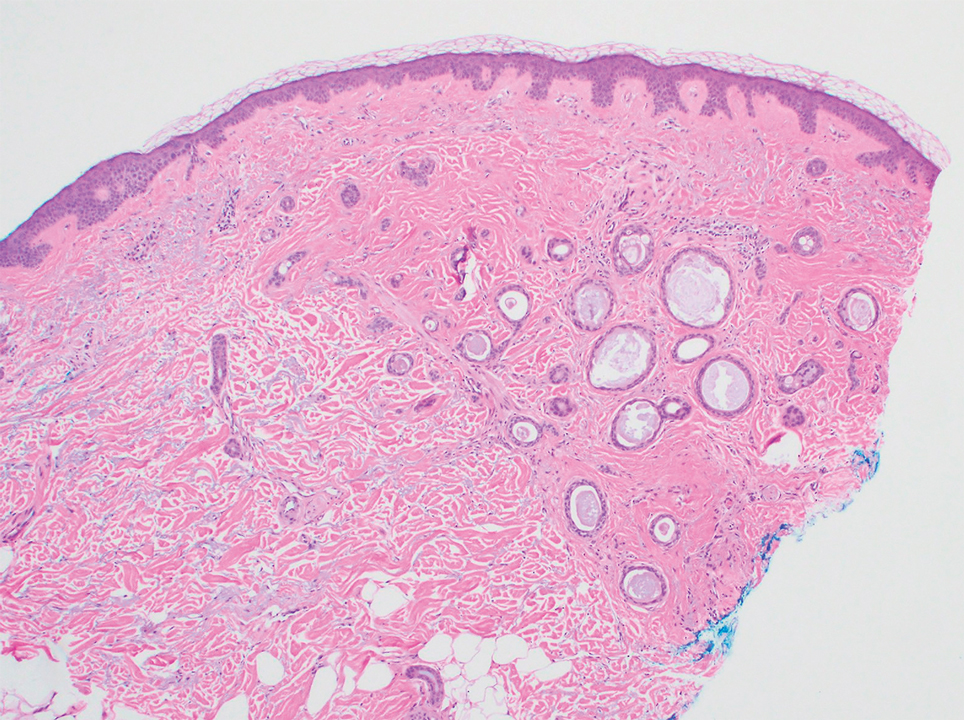

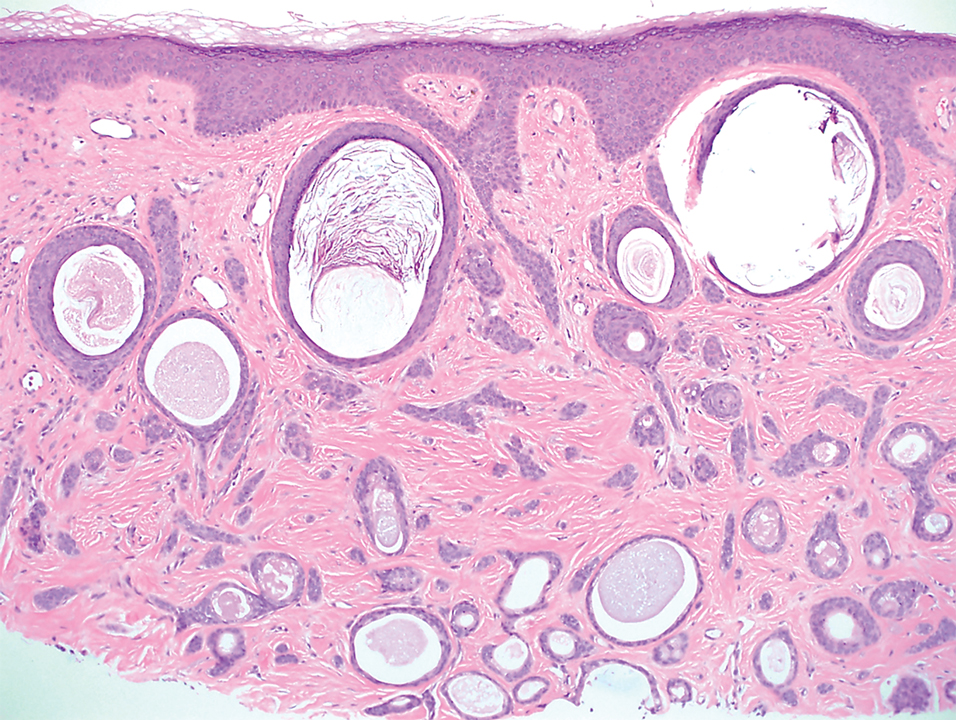

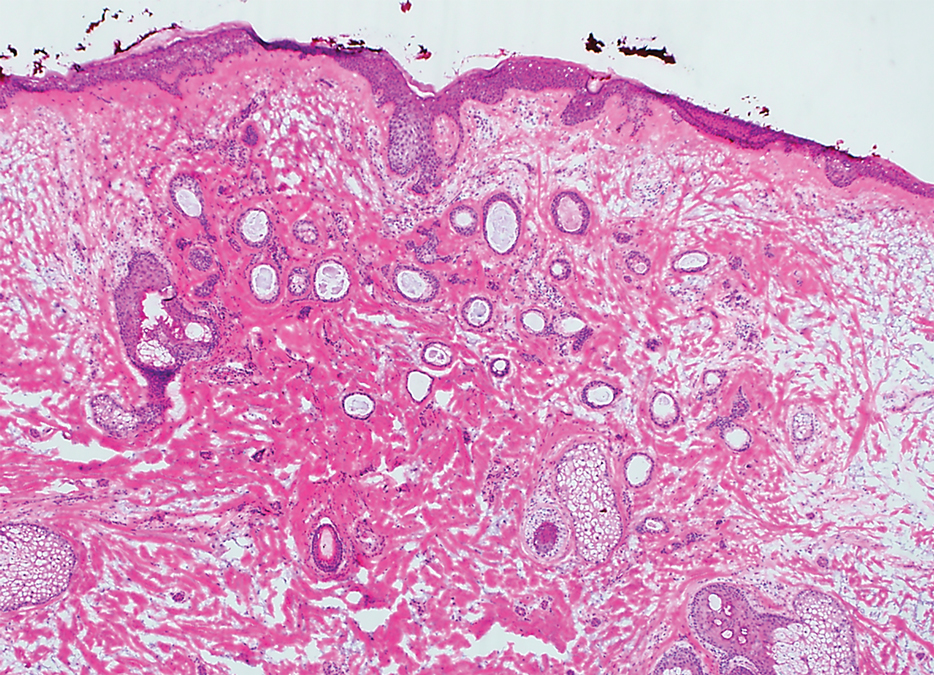

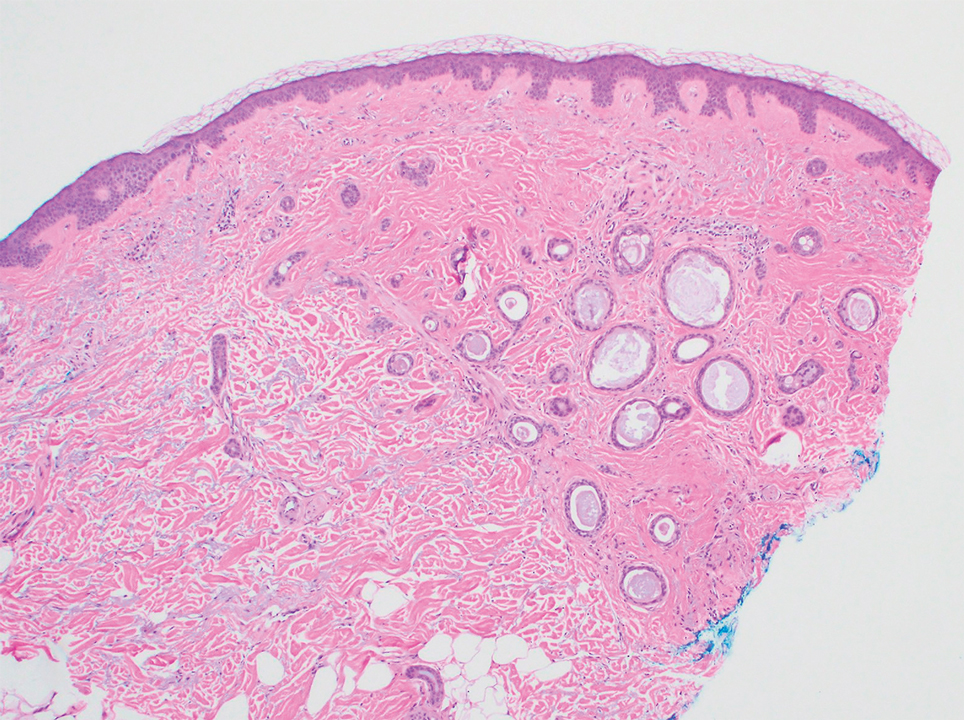

A 78-year-old woman was referred for MMS for a left forehead lesion that was diagnosed via shave biopsy as a desmoplastic and cystic adnexal neoplasm with suspicion for desmoplastic trichoepithelioma or MAC (Figure 1). Upon presentation for MMS, a well-healed, 1.0×0.9-cm scar at the biopsy site on the left forehead was observed (Figure 2A). One stage was obtained by standard MMS technique and sent for intraoperative processing (Figure 2B). Frozen section examination of the first stage demonstrated peripheral margin involvement with syringomatous change confined to the superficial and mid dermis (Figure 3). Before proceeding further, these findings were reviewed with an in-house dermatopathologist, and it was determined that no infiltrative tumor, perineural involvement, or other features to indicate malignancy were noted. A decision was made to refrain from obtaining any additional layers and to send excised Burow triangles for permanent section analysis. A primary linear closure was performed without complication, and the patient was discharged from the ambulatory surgery suite. Histopathologic examination of the Burow triangles later confirmed findings consistent with plaquelike syringoma with no evidence of malignancy (Figure 4).

Syringomas present as small flesh-colored papules in the periorbital areas. These benign neoplasms previously have been classified into 4 major clinical variants: localized, generalized, Down syndrome associated, and familial.1 The lesser-known plaquelike variant of syringoma was first described by Kikuchi et al2 in 1979. Aside from our report, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms plaquelike or plaque-type syringoma yielded 16 cases in the literature.2-14 Of these, 6 were referred to or encountered in the MMS setting.8,9,11,12,14 Plaquelike syringoma can be solitary or multiple in presentation.6 It most commonly involves the head and neck but also can present on the trunk, arms, legs, and groin areas. The clinical size of plaquelike syringoma is variable, with the largest reported cases extending several centimeters in diameter.2,6 Similar to reported associations with conventional syringoma, the plaquelike subtype of syringoma has been reported in association with Down syndrome.13

Histopathologically, plaquelike syringoma shares features with MAC as well as desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and desmoplastic basal cell carcinoma. Plaquelike syringoma demonstrates broad proliferations of small tubules morphologically reminiscent of tadpoles confined within the dermis. Ducts typically are lined with 2 or 3 layers of small cuboidal cells. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma typically features asymmetric ductal structures lined with single cells extending from the dermis into the subcutis and even underlying muscle, cartilage, or bone.8 There are no reliable immunohistochemical stains to differentiate between these 2 entities; thus, the primary distinction lies in the depth of involvement. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma is composed of narrow cords and nests of basaloid cells of follicular origin commonly admixed with small cornifying cysts appearing in the dermis.8 Colonizing Merkel cells positive for cytokeratin 20 often are present in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and not in syringoma or MAC.15 Desmoplastic basal cell carcinoma demonstrates narrow strands of basaloid cells of follicular origin appearing in the dermis. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and desmoplastic basal cell carcinoma are each fundamentally differentiated from plaquelike syringoma in that proliferations of cords and nests are not of eccrine or apocrine origin.

Several cases of plaquelike syringoma have been challenging to distinguish from MAC in performing MMS.8,9,11 Underlying extension of this syringoma variant can be far-reaching, extending to several centimeters in size and involving multiple cosmetic subunits.6,11,14 Inadvertent overtreatment with multiple MMS stages can be avoided with careful recognition of the differentiating histopathologic features. Syringomatous lesions commonly are encountered in MMS and may even be present at the edge of other tumor types. Plaquelike syringoma has been reported as a coexistent entity with nodular basal cell carcinoma.12 Boos et al16 similarly reported the presence of deceptive ductal proliferations along the immediate peripheral margin of MAC, which prompted multiple re-excisions. Pursuit of permanent section analysis in these cases revealed the appearance of small syringomas, and a diagnosis of benign subclinical syringomatous proliferations was made, averting further intervention.16

Our case sheds light on the threat of commission bias in dermatologic surgery, which is the tendency for action rather than inaction.17 In this context, it is important to avoid the perspective that harm to the patient can only be prevented by active intervention. Cognitive bias has been increasingly recognized as a source of medical error, and methods to mitigate bias in medical practice have been well described.17 Microcystic adnexal carcinoma and plaquelike syringoma can be hard to differentiate especially initially, as demonstrated in our case, which particularly illustrates the importance of slowing down a surgical case at the appropriate time, considering and revisiting alternative diagnoses, implementing checklists, and seeking histopathologic collaboration with colleagues when necessary. Our attempted implementation of these principles, especially early collaboration with colleagues, led to intraoperative recognition of plaquelike syringoma within the first stage of MMS.

We seek to raise the index of suspicion for plaquelike syringoma among dermatologists and dermatologic surgeons, especially when syringomatous structures are limited to the superficial dermis. We encourage familiarity with the plaquelike syringoma entity as well as careful consideration of further investigation via scouting biopsies or permanent section analysis when other characteristic features of MAC are unclear or lacking. Adequate sampling as well as collaboration with a dermatopathologist in cases of suspected syringoma can help to reduce the susceptibility to commission bias and prevent histopathologic pitfalls and unwarranted surgical morbidity.

- Friedman SJ, Butler DF. Syringoma presenting as milia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:310-314.

- Kikuchi I, Idemori M, Okazaki M. Plaque type syringoma. J Dermatol. 1979;6:329-331.

- Dekio S, Jidoi J. Submammary syringoma—report of a case. J Dermatol. 1988;15:351-352.

- Patrizi A, Neri I, Marzaduri S, et al. Syringoma: a review of twenty-nine cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:460-462.

- Nguyen DB, Patterson JW, Wilson BB. Syringoma of the moustache area. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:337-339.

- Rongioletti F, Semino MT, Rebora A. Unilateral multiple plaque-like syringomas. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:623-625.

- Chi HI. A case of unusual syringoma: unilateral linear distribution and plaque formation. J Dermatol. 1996;23:505-506.

- Suwatee P, McClelland MC, Huiras EE, et al. Plaque-type syringoma: two cases misdiagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:570-574.

- Wallace JS, Bond JS, Seidel GD, et al. An important mimicker: plaque-type syringoma mistakenly diagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:810-812.

- Mitkov M, Balagula Y, Taube JM, et al. Plaque-like syringoma with involvement of deep reticular dermis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E206-E207.

- Schleich C, Ferringer T, Petrick M. Plaque type syringoma mimicking a microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(suppl 1):AB287.

- Yang Y, Srivastava D. Plaque-type syringoma coexisting with basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1464-1466.

- Motegi SI, Sekiguchi A, Fujiwara C, et al. Milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis and plaque-type syringoma in a girl with Down syndrome. J Dermatol. 2019;46:E136-E137.

- Clark M, Duprey C, Sutton A, et al. Plaque-type syringoma masquerading as microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of the literature and description of a novel technique that emphasizes lesion architecture to help make the diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:E98-E101.

- Abesamis-Cubillan E, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, LeBoit PE. Merkel cells and sclerosing epithelial neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:311-315.

- Boos MD, Elenitsas R, Seykora J, et al. Benign subclinical syringomatous proliferations adjacent to a microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a tumor mimic with significant patient implications. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:174-178.

- O’Sullivan ED, Schofield SJ. Cognitive bias in clinical medicine. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2018;48:225-232.

To the Editor:

Plaquelike or plaque-type syringoma is a lesser-known variant of syringoma that can appear histologically indistinguishable from the superficial portion of microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC). The plaquelike variant of syringoma holds a benign clinical course, and no treatment is necessary. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is distinguished from plaquelike syringoma by an aggressive growth pattern with a high risk for local invasion and recurrence if inadequately treated. Thus, treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has been recommended as the mainstay for MAC. If superficial biopsy specimens reveal suspicion for MAC and patients are referred for MMS, careful consideration should be made to differentiate MAC and plaquelike syringoma early to prevent unnecessary morbidity.

A 78-year-old woman was referred for MMS for a left forehead lesion that was diagnosed via shave biopsy as a desmoplastic and cystic adnexal neoplasm with suspicion for desmoplastic trichoepithelioma or MAC (Figure 1). Upon presentation for MMS, a well-healed, 1.0×0.9-cm scar at the biopsy site on the left forehead was observed (Figure 2A). One stage was obtained by standard MMS technique and sent for intraoperative processing (Figure 2B). Frozen section examination of the first stage demonstrated peripheral margin involvement with syringomatous change confined to the superficial and mid dermis (Figure 3). Before proceeding further, these findings were reviewed with an in-house dermatopathologist, and it was determined that no infiltrative tumor, perineural involvement, or other features to indicate malignancy were noted. A decision was made to refrain from obtaining any additional layers and to send excised Burow triangles for permanent section analysis. A primary linear closure was performed without complication, and the patient was discharged from the ambulatory surgery suite. Histopathologic examination of the Burow triangles later confirmed findings consistent with plaquelike syringoma with no evidence of malignancy (Figure 4).

Syringomas present as small flesh-colored papules in the periorbital areas. These benign neoplasms previously have been classified into 4 major clinical variants: localized, generalized, Down syndrome associated, and familial.1 The lesser-known plaquelike variant of syringoma was first described by Kikuchi et al2 in 1979. Aside from our report, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms plaquelike or plaque-type syringoma yielded 16 cases in the literature.2-14 Of these, 6 were referred to or encountered in the MMS setting.8,9,11,12,14 Plaquelike syringoma can be solitary or multiple in presentation.6 It most commonly involves the head and neck but also can present on the trunk, arms, legs, and groin areas. The clinical size of plaquelike syringoma is variable, with the largest reported cases extending several centimeters in diameter.2,6 Similar to reported associations with conventional syringoma, the plaquelike subtype of syringoma has been reported in association with Down syndrome.13

Histopathologically, plaquelike syringoma shares features with MAC as well as desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and desmoplastic basal cell carcinoma. Plaquelike syringoma demonstrates broad proliferations of small tubules morphologically reminiscent of tadpoles confined within the dermis. Ducts typically are lined with 2 or 3 layers of small cuboidal cells. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma typically features asymmetric ductal structures lined with single cells extending from the dermis into the subcutis and even underlying muscle, cartilage, or bone.8 There are no reliable immunohistochemical stains to differentiate between these 2 entities; thus, the primary distinction lies in the depth of involvement. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma is composed of narrow cords and nests of basaloid cells of follicular origin commonly admixed with small cornifying cysts appearing in the dermis.8 Colonizing Merkel cells positive for cytokeratin 20 often are present in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and not in syringoma or MAC.15 Desmoplastic basal cell carcinoma demonstrates narrow strands of basaloid cells of follicular origin appearing in the dermis. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and desmoplastic basal cell carcinoma are each fundamentally differentiated from plaquelike syringoma in that proliferations of cords and nests are not of eccrine or apocrine origin.

Several cases of plaquelike syringoma have been challenging to distinguish from MAC in performing MMS.8,9,11 Underlying extension of this syringoma variant can be far-reaching, extending to several centimeters in size and involving multiple cosmetic subunits.6,11,14 Inadvertent overtreatment with multiple MMS stages can be avoided with careful recognition of the differentiating histopathologic features. Syringomatous lesions commonly are encountered in MMS and may even be present at the edge of other tumor types. Plaquelike syringoma has been reported as a coexistent entity with nodular basal cell carcinoma.12 Boos et al16 similarly reported the presence of deceptive ductal proliferations along the immediate peripheral margin of MAC, which prompted multiple re-excisions. Pursuit of permanent section analysis in these cases revealed the appearance of small syringomas, and a diagnosis of benign subclinical syringomatous proliferations was made, averting further intervention.16

Our case sheds light on the threat of commission bias in dermatologic surgery, which is the tendency for action rather than inaction.17 In this context, it is important to avoid the perspective that harm to the patient can only be prevented by active intervention. Cognitive bias has been increasingly recognized as a source of medical error, and methods to mitigate bias in medical practice have been well described.17 Microcystic adnexal carcinoma and plaquelike syringoma can be hard to differentiate especially initially, as demonstrated in our case, which particularly illustrates the importance of slowing down a surgical case at the appropriate time, considering and revisiting alternative diagnoses, implementing checklists, and seeking histopathologic collaboration with colleagues when necessary. Our attempted implementation of these principles, especially early collaboration with colleagues, led to intraoperative recognition of plaquelike syringoma within the first stage of MMS.

We seek to raise the index of suspicion for plaquelike syringoma among dermatologists and dermatologic surgeons, especially when syringomatous structures are limited to the superficial dermis. We encourage familiarity with the plaquelike syringoma entity as well as careful consideration of further investigation via scouting biopsies or permanent section analysis when other characteristic features of MAC are unclear or lacking. Adequate sampling as well as collaboration with a dermatopathologist in cases of suspected syringoma can help to reduce the susceptibility to commission bias and prevent histopathologic pitfalls and unwarranted surgical morbidity.

To the Editor:

Plaquelike or plaque-type syringoma is a lesser-known variant of syringoma that can appear histologically indistinguishable from the superficial portion of microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC). The plaquelike variant of syringoma holds a benign clinical course, and no treatment is necessary. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is distinguished from plaquelike syringoma by an aggressive growth pattern with a high risk for local invasion and recurrence if inadequately treated. Thus, treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has been recommended as the mainstay for MAC. If superficial biopsy specimens reveal suspicion for MAC and patients are referred for MMS, careful consideration should be made to differentiate MAC and plaquelike syringoma early to prevent unnecessary morbidity.

A 78-year-old woman was referred for MMS for a left forehead lesion that was diagnosed via shave biopsy as a desmoplastic and cystic adnexal neoplasm with suspicion for desmoplastic trichoepithelioma or MAC (Figure 1). Upon presentation for MMS, a well-healed, 1.0×0.9-cm scar at the biopsy site on the left forehead was observed (Figure 2A). One stage was obtained by standard MMS technique and sent for intraoperative processing (Figure 2B). Frozen section examination of the first stage demonstrated peripheral margin involvement with syringomatous change confined to the superficial and mid dermis (Figure 3). Before proceeding further, these findings were reviewed with an in-house dermatopathologist, and it was determined that no infiltrative tumor, perineural involvement, or other features to indicate malignancy were noted. A decision was made to refrain from obtaining any additional layers and to send excised Burow triangles for permanent section analysis. A primary linear closure was performed without complication, and the patient was discharged from the ambulatory surgery suite. Histopathologic examination of the Burow triangles later confirmed findings consistent with plaquelike syringoma with no evidence of malignancy (Figure 4).

Syringomas present as small flesh-colored papules in the periorbital areas. These benign neoplasms previously have been classified into 4 major clinical variants: localized, generalized, Down syndrome associated, and familial.1 The lesser-known plaquelike variant of syringoma was first described by Kikuchi et al2 in 1979. Aside from our report, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms plaquelike or plaque-type syringoma yielded 16 cases in the literature.2-14 Of these, 6 were referred to or encountered in the MMS setting.8,9,11,12,14 Plaquelike syringoma can be solitary or multiple in presentation.6 It most commonly involves the head and neck but also can present on the trunk, arms, legs, and groin areas. The clinical size of plaquelike syringoma is variable, with the largest reported cases extending several centimeters in diameter.2,6 Similar to reported associations with conventional syringoma, the plaquelike subtype of syringoma has been reported in association with Down syndrome.13

Histopathologically, plaquelike syringoma shares features with MAC as well as desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and desmoplastic basal cell carcinoma. Plaquelike syringoma demonstrates broad proliferations of small tubules morphologically reminiscent of tadpoles confined within the dermis. Ducts typically are lined with 2 or 3 layers of small cuboidal cells. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma typically features asymmetric ductal structures lined with single cells extending from the dermis into the subcutis and even underlying muscle, cartilage, or bone.8 There are no reliable immunohistochemical stains to differentiate between these 2 entities; thus, the primary distinction lies in the depth of involvement. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma is composed of narrow cords and nests of basaloid cells of follicular origin commonly admixed with small cornifying cysts appearing in the dermis.8 Colonizing Merkel cells positive for cytokeratin 20 often are present in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and not in syringoma or MAC.15 Desmoplastic basal cell carcinoma demonstrates narrow strands of basaloid cells of follicular origin appearing in the dermis. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and desmoplastic basal cell carcinoma are each fundamentally differentiated from plaquelike syringoma in that proliferations of cords and nests are not of eccrine or apocrine origin.

Several cases of plaquelike syringoma have been challenging to distinguish from MAC in performing MMS.8,9,11 Underlying extension of this syringoma variant can be far-reaching, extending to several centimeters in size and involving multiple cosmetic subunits.6,11,14 Inadvertent overtreatment with multiple MMS stages can be avoided with careful recognition of the differentiating histopathologic features. Syringomatous lesions commonly are encountered in MMS and may even be present at the edge of other tumor types. Plaquelike syringoma has been reported as a coexistent entity with nodular basal cell carcinoma.12 Boos et al16 similarly reported the presence of deceptive ductal proliferations along the immediate peripheral margin of MAC, which prompted multiple re-excisions. Pursuit of permanent section analysis in these cases revealed the appearance of small syringomas, and a diagnosis of benign subclinical syringomatous proliferations was made, averting further intervention.16

Our case sheds light on the threat of commission bias in dermatologic surgery, which is the tendency for action rather than inaction.17 In this context, it is important to avoid the perspective that harm to the patient can only be prevented by active intervention. Cognitive bias has been increasingly recognized as a source of medical error, and methods to mitigate bias in medical practice have been well described.17 Microcystic adnexal carcinoma and plaquelike syringoma can be hard to differentiate especially initially, as demonstrated in our case, which particularly illustrates the importance of slowing down a surgical case at the appropriate time, considering and revisiting alternative diagnoses, implementing checklists, and seeking histopathologic collaboration with colleagues when necessary. Our attempted implementation of these principles, especially early collaboration with colleagues, led to intraoperative recognition of plaquelike syringoma within the first stage of MMS.

We seek to raise the index of suspicion for plaquelike syringoma among dermatologists and dermatologic surgeons, especially when syringomatous structures are limited to the superficial dermis. We encourage familiarity with the plaquelike syringoma entity as well as careful consideration of further investigation via scouting biopsies or permanent section analysis when other characteristic features of MAC are unclear or lacking. Adequate sampling as well as collaboration with a dermatopathologist in cases of suspected syringoma can help to reduce the susceptibility to commission bias and prevent histopathologic pitfalls and unwarranted surgical morbidity.

- Friedman SJ, Butler DF. Syringoma presenting as milia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:310-314.

- Kikuchi I, Idemori M, Okazaki M. Plaque type syringoma. J Dermatol. 1979;6:329-331.

- Dekio S, Jidoi J. Submammary syringoma—report of a case. J Dermatol. 1988;15:351-352.

- Patrizi A, Neri I, Marzaduri S, et al. Syringoma: a review of twenty-nine cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:460-462.

- Nguyen DB, Patterson JW, Wilson BB. Syringoma of the moustache area. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:337-339.

- Rongioletti F, Semino MT, Rebora A. Unilateral multiple plaque-like syringomas. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:623-625.

- Chi HI. A case of unusual syringoma: unilateral linear distribution and plaque formation. J Dermatol. 1996;23:505-506.

- Suwatee P, McClelland MC, Huiras EE, et al. Plaque-type syringoma: two cases misdiagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:570-574.

- Wallace JS, Bond JS, Seidel GD, et al. An important mimicker: plaque-type syringoma mistakenly diagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:810-812.

- Mitkov M, Balagula Y, Taube JM, et al. Plaque-like syringoma with involvement of deep reticular dermis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E206-E207.

- Schleich C, Ferringer T, Petrick M. Plaque type syringoma mimicking a microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(suppl 1):AB287.

- Yang Y, Srivastava D. Plaque-type syringoma coexisting with basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1464-1466.

- Motegi SI, Sekiguchi A, Fujiwara C, et al. Milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis and plaque-type syringoma in a girl with Down syndrome. J Dermatol. 2019;46:E136-E137.

- Clark M, Duprey C, Sutton A, et al. Plaque-type syringoma masquerading as microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of the literature and description of a novel technique that emphasizes lesion architecture to help make the diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:E98-E101.

- Abesamis-Cubillan E, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, LeBoit PE. Merkel cells and sclerosing epithelial neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:311-315.

- Boos MD, Elenitsas R, Seykora J, et al. Benign subclinical syringomatous proliferations adjacent to a microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a tumor mimic with significant patient implications. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:174-178.

- O’Sullivan ED, Schofield SJ. Cognitive bias in clinical medicine. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2018;48:225-232.

- Friedman SJ, Butler DF. Syringoma presenting as milia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:310-314.

- Kikuchi I, Idemori M, Okazaki M. Plaque type syringoma. J Dermatol. 1979;6:329-331.

- Dekio S, Jidoi J. Submammary syringoma—report of a case. J Dermatol. 1988;15:351-352.

- Patrizi A, Neri I, Marzaduri S, et al. Syringoma: a review of twenty-nine cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:460-462.

- Nguyen DB, Patterson JW, Wilson BB. Syringoma of the moustache area. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:337-339.

- Rongioletti F, Semino MT, Rebora A. Unilateral multiple plaque-like syringomas. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:623-625.

- Chi HI. A case of unusual syringoma: unilateral linear distribution and plaque formation. J Dermatol. 1996;23:505-506.

- Suwatee P, McClelland MC, Huiras EE, et al. Plaque-type syringoma: two cases misdiagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:570-574.

- Wallace JS, Bond JS, Seidel GD, et al. An important mimicker: plaque-type syringoma mistakenly diagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:810-812.

- Mitkov M, Balagula Y, Taube JM, et al. Plaque-like syringoma with involvement of deep reticular dermis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E206-E207.

- Schleich C, Ferringer T, Petrick M. Plaque type syringoma mimicking a microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(suppl 1):AB287.

- Yang Y, Srivastava D. Plaque-type syringoma coexisting with basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1464-1466.

- Motegi SI, Sekiguchi A, Fujiwara C, et al. Milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis and plaque-type syringoma in a girl with Down syndrome. J Dermatol. 2019;46:E136-E137.

- Clark M, Duprey C, Sutton A, et al. Plaque-type syringoma masquerading as microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of the literature and description of a novel technique that emphasizes lesion architecture to help make the diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:E98-E101.

- Abesamis-Cubillan E, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, LeBoit PE. Merkel cells and sclerosing epithelial neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:311-315.

- Boos MD, Elenitsas R, Seykora J, et al. Benign subclinical syringomatous proliferations adjacent to a microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a tumor mimic with significant patient implications. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:174-178.

- O’Sullivan ED, Schofield SJ. Cognitive bias in clinical medicine. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2018;48:225-232.

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should familiarize themselves with the plaquelike subtype of syringoma, which can histologically mimic the superficial portion of microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC).

- Careful recognition of plaquelike syringoma in the Mohs micrographic surgery setting may prevent unnecessary surgical morbidity.

- Further diagnostic investigation is warranted for superficial biopsies suggestive of MAC or when other characteristic features are lacking.

Blue Nodules on the Forearms in an Active-Duty Military Servicemember

The Diagnosis: Glomangiomyoma

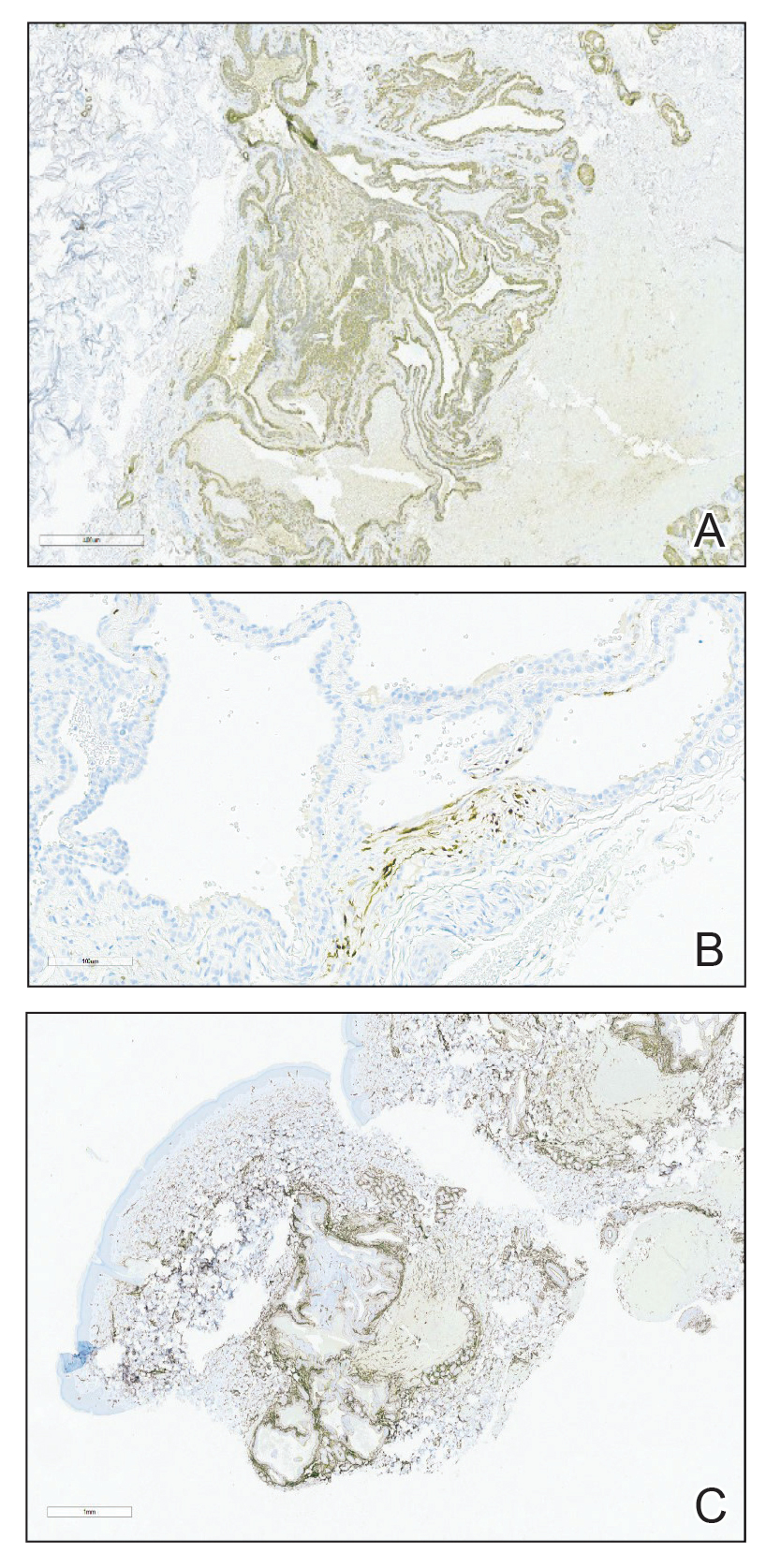

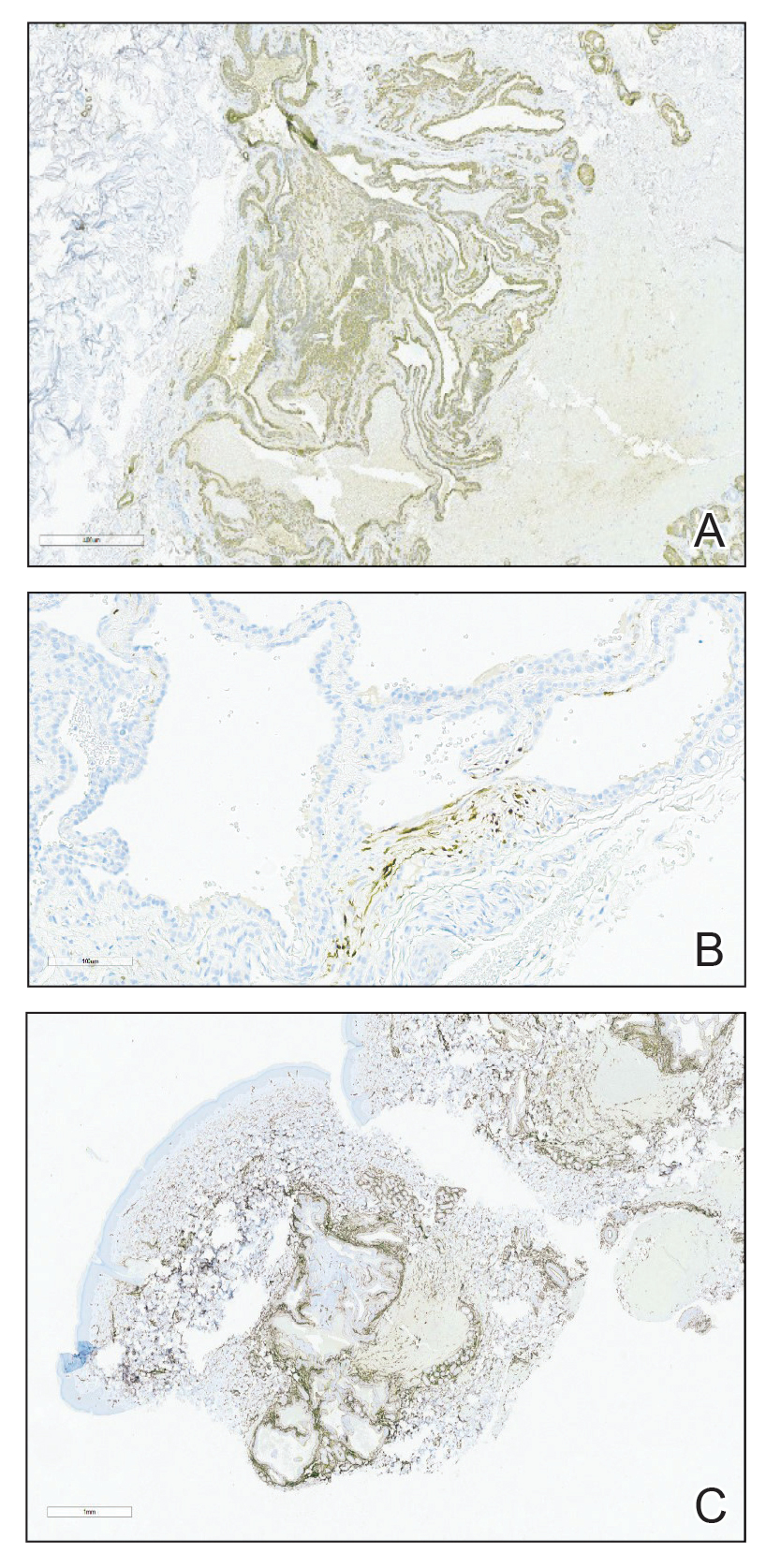

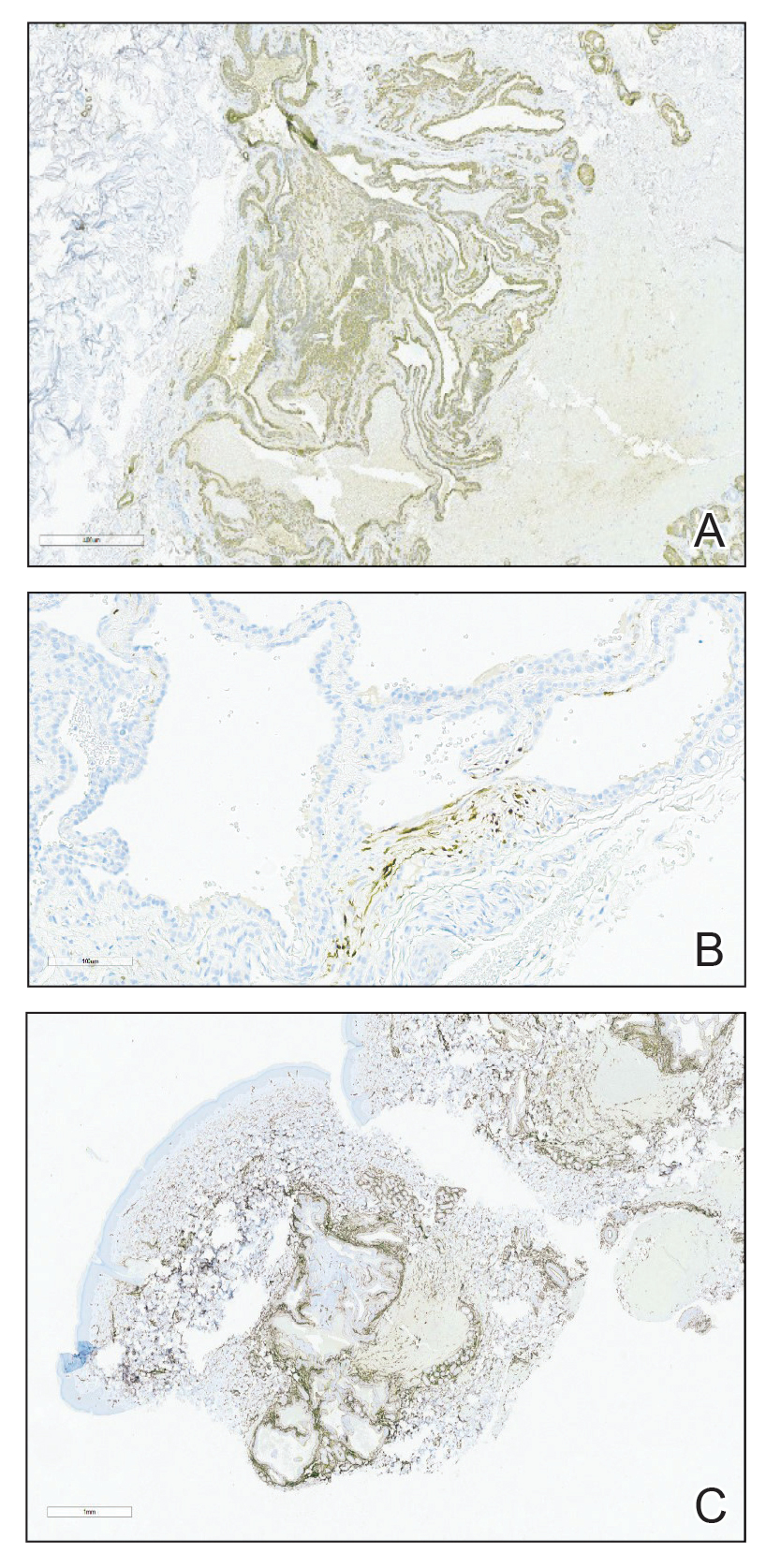

A punch biopsy of the right forearm revealed a collection of vascular and smooth muscle components with small and spindled bland cells containing minimal eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 1), confirming the diagnosis of glomangiomyoma. Immunohistochemical stains also supported the diagnosis and were positive for smooth muscle actin, desmin, and CD34 (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance imaging from a prior attempt at treatment with sclerotherapy demonstrated scattered vascular malformations with no notable internal derangement. There was no improvement with sclerotherapy. Given the number and vascular nature of the lesions, a trial of pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy was administered and tolerated by the patient. He subsequently moved to a new military duty station. On follow-up, he reported no noticeable clinical improvement in the lesions after PDL and opted not to continue with laser treatment.

Glomangiomyoma is a rare and benign glomus tumor variant that demonstrates differentiation into the smooth muscle and potentially can result in substantial complications.1 Glomus tumors generally are benign neoplasms of the glomus apparatus, and glomus cells function as thermoregulators in the reticular dermis.2 Glomus tumors comprise less than 2% of soft tissue neoplasms and generally are solitary nodules; only 10% of glomus tumors occur with multiple lesions, and among them, glomangiomyoma is the rarest subtype, presenting in only 15% of cases.2,3 The 3 main subtypes of glomus tumors are solid, glomangioma, and glomangiomyoma.4 Clinically, the lesions may present as small blue nodules with associated pain and cold or pressure sensitivity. Although there appears to be variation of the nomenclature depending on the source in the literature, glomangiomas are characterized by their predominant vascular malformations on biopsy. Glomangiomyomas are a subset of glomus tumors with distinct smooth muscle differentiation.4 Given their pathologic presentation, our patient’s lesions were most consistent with the diagnosis of glomangiomyoma.

The small size of the lesions may result in difficulty establishing a clinical diagnosis, particularly if there is no hand involvement, where lesions most commonly occur.2 Therefore, histopathologic evaluation is essential and is the best initial step in evaluating glomangiomyomas.4 Biopsy is the most reliable means of confirming a diagnosis2,4,5; however, diagnostic imaging such as a computed tomography also should be performed if considering blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome due to the primary site of involvement. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice after confirming the diagnosis in most cases of symptomatic glomangiomyomas, particularly with painful lesions.6

Neurilemmomas (also known as schwannomas) are benign lesions that generally present as asymptomatic, soft, smooth nodules most often on the neck; however, they also may present on the flexor extremities or in internal organs. Although primarily asymptomatic, the tumors may be associated with pain and paresthesia as they enlarge and affect surrounding structures. Neurilemmomas may occur spontaneously or as part of a syndrome, such as neurofibromatosis type 2 or Carney complex.7

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (formerly known as Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome) is an autosomal-dominant disease that presents with arteriovenous malformations and telangiectases. Patients generally present in the third decade of life, with the main concern generally being epistaxis.8

Kaposi sarcoma is a viral infection secondary to human herpesvirus 8 that results in red-purple lesions commonly on mucocutaneous sites. Kaposi sarcoma can be AIDS associated and non-HIV associated. Although clinically indistinguishable, a few subtle histologic features can assist in differentiating the 2 etiologies. In addition to a potential history of immunodeficiency, evaluating for involvement of the lymphatic system, respiratory tract, or gastrointestinal tract can aid in differentiating this entity from glomus tumors.9

Leiomyomas are smooth muscle lesions divided into 3 subcategories: angioleiomyoma, piloleiomyoma, and genital leiomyoma. The clinical presentation and histopathology will vary depending on the subcategory. Although cutaneous leiomyomas are benign, further workup for piloleiomyoma may be required given the reported association with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (Reed syndrome).10

Imaging can be helpful when the clinical diagnosis of a glomus tumor vs other painful neoplasms of the skin is unclear, such as in blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome, angioleiomyomas, neuromas, glomus tumors, leiomyomas, eccrine spiradenomas, congenital vascular malformations, schwannomas, or hemangiomas.4 Radiologic findings for glomus tumors may demonstrate cortical or cystic osseous defects. Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasonography can help provide additional information on the lesion size and depth of involvement.1 Additionally, deeper glomangiomyomas have been associated with malignancy,2 potentially highlighting the benefit of early incorporation of imaging in the workup for this condition. Malignant transformation is rare and has been reported in less than 1% of cases.6

Treatment of glomus tumors predominantly is directed to the patient’s symptoms; asymptomatic lesions may be monitored.4 For symptomatic lesions, therapeutic options include wide local excision; sclerotherapy; and incorporation of various lasers, including Nd:YAG, CO2, and flashlamp tunable dye laser.4,5 One case report documented use of a PDL that successfully eliminated the pain associated with glomangiomyoma; however, the lesion in that report was not biopsy proven.11

Our case highlights the need to consider glomus tumors in patients presenting with multiple small nodules given the potential for misdiagnosis, impact on quality of life with associated psychological distress, and potential utility of incorporating PDL in treatment. Although our patient did not report clinical improvement in the appearance of the lesions with PDL therapy, additional treatment sessions may have helped,11 but he opted to discontinue. Follow-up for persistently symptomatic or changing lesions is necessary, given the minimal risk for malignant transformation.6

- Lee DY, Hwang SC, Jeong ST, et al. The value of diagnostic ultrasonography in the assessment of a glomus tumor of the subcutaneous layer of the forearm mimicking a hemangioma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2015;9:191. doi:10.1186/s13256-015-0672-y

- Li L, Bardsley V, Grainger A, et al. Extradigital glomangiomyoma of the forearm mimicking peripheral nerve sheath tumour and thrombosed varicose vein. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14:E241221. doi: 10.1136 /bcr-2020-241221

- Calduch L, Monteagudo C, Martínez-Ruiz E, et al. Familial generalized multiple glomangiomyoma: report of a new family, with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:402-408. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.2002.00114.x

- Mohammadi O, Suarez M. Glomus cancer. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Maxey ML, Houghton CC, Mastriani KS, et al. Large prepatellar glomangioma: a case report [published online July 10, 2015]. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;14:80-84. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.07.002

- Brathwaite CD, Poppiti RJ Jr. Malignant glomus tumor. a case report of widespread metastases in a patient with multiple glomus body hamartomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:233-238. doi:10.1097/00000478-199602000-00012

- Davis DD, Kane SM. Neurilemmoma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Kühnel T, Wirsching K, Wohlgemuth W, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2018;51:237-254. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2017.09.017

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294. doi:10.5858/arpa.2012-0101-RS

- Bernett CN, Mammino JJ. Cutaneous leiomyomas. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Antony FC, Cliff S, Cowley N. Complete pain relief following treatment of a glomangiomyoma with the pulsed dye laser. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:617-619. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01403.x

The Diagnosis: Glomangiomyoma

A punch biopsy of the right forearm revealed a collection of vascular and smooth muscle components with small and spindled bland cells containing minimal eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 1), confirming the diagnosis of glomangiomyoma. Immunohistochemical stains also supported the diagnosis and were positive for smooth muscle actin, desmin, and CD34 (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance imaging from a prior attempt at treatment with sclerotherapy demonstrated scattered vascular malformations with no notable internal derangement. There was no improvement with sclerotherapy. Given the number and vascular nature of the lesions, a trial of pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy was administered and tolerated by the patient. He subsequently moved to a new military duty station. On follow-up, he reported no noticeable clinical improvement in the lesions after PDL and opted not to continue with laser treatment.

Glomangiomyoma is a rare and benign glomus tumor variant that demonstrates differentiation into the smooth muscle and potentially can result in substantial complications.1 Glomus tumors generally are benign neoplasms of the glomus apparatus, and glomus cells function as thermoregulators in the reticular dermis.2 Glomus tumors comprise less than 2% of soft tissue neoplasms and generally are solitary nodules; only 10% of glomus tumors occur with multiple lesions, and among them, glomangiomyoma is the rarest subtype, presenting in only 15% of cases.2,3 The 3 main subtypes of glomus tumors are solid, glomangioma, and glomangiomyoma.4 Clinically, the lesions may present as small blue nodules with associated pain and cold or pressure sensitivity. Although there appears to be variation of the nomenclature depending on the source in the literature, glomangiomas are characterized by their predominant vascular malformations on biopsy. Glomangiomyomas are a subset of glomus tumors with distinct smooth muscle differentiation.4 Given their pathologic presentation, our patient’s lesions were most consistent with the diagnosis of glomangiomyoma.

The small size of the lesions may result in difficulty establishing a clinical diagnosis, particularly if there is no hand involvement, where lesions most commonly occur.2 Therefore, histopathologic evaluation is essential and is the best initial step in evaluating glomangiomyomas.4 Biopsy is the most reliable means of confirming a diagnosis2,4,5; however, diagnostic imaging such as a computed tomography also should be performed if considering blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome due to the primary site of involvement. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice after confirming the diagnosis in most cases of symptomatic glomangiomyomas, particularly with painful lesions.6

Neurilemmomas (also known as schwannomas) are benign lesions that generally present as asymptomatic, soft, smooth nodules most often on the neck; however, they also may present on the flexor extremities or in internal organs. Although primarily asymptomatic, the tumors may be associated with pain and paresthesia as they enlarge and affect surrounding structures. Neurilemmomas may occur spontaneously or as part of a syndrome, such as neurofibromatosis type 2 or Carney complex.7

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (formerly known as Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome) is an autosomal-dominant disease that presents with arteriovenous malformations and telangiectases. Patients generally present in the third decade of life, with the main concern generally being epistaxis.8

Kaposi sarcoma is a viral infection secondary to human herpesvirus 8 that results in red-purple lesions commonly on mucocutaneous sites. Kaposi sarcoma can be AIDS associated and non-HIV associated. Although clinically indistinguishable, a few subtle histologic features can assist in differentiating the 2 etiologies. In addition to a potential history of immunodeficiency, evaluating for involvement of the lymphatic system, respiratory tract, or gastrointestinal tract can aid in differentiating this entity from glomus tumors.9

Leiomyomas are smooth muscle lesions divided into 3 subcategories: angioleiomyoma, piloleiomyoma, and genital leiomyoma. The clinical presentation and histopathology will vary depending on the subcategory. Although cutaneous leiomyomas are benign, further workup for piloleiomyoma may be required given the reported association with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (Reed syndrome).10

Imaging can be helpful when the clinical diagnosis of a glomus tumor vs other painful neoplasms of the skin is unclear, such as in blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome, angioleiomyomas, neuromas, glomus tumors, leiomyomas, eccrine spiradenomas, congenital vascular malformations, schwannomas, or hemangiomas.4 Radiologic findings for glomus tumors may demonstrate cortical or cystic osseous defects. Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasonography can help provide additional information on the lesion size and depth of involvement.1 Additionally, deeper glomangiomyomas have been associated with malignancy,2 potentially highlighting the benefit of early incorporation of imaging in the workup for this condition. Malignant transformation is rare and has been reported in less than 1% of cases.6

Treatment of glomus tumors predominantly is directed to the patient’s symptoms; asymptomatic lesions may be monitored.4 For symptomatic lesions, therapeutic options include wide local excision; sclerotherapy; and incorporation of various lasers, including Nd:YAG, CO2, and flashlamp tunable dye laser.4,5 One case report documented use of a PDL that successfully eliminated the pain associated with glomangiomyoma; however, the lesion in that report was not biopsy proven.11

Our case highlights the need to consider glomus tumors in patients presenting with multiple small nodules given the potential for misdiagnosis, impact on quality of life with associated psychological distress, and potential utility of incorporating PDL in treatment. Although our patient did not report clinical improvement in the appearance of the lesions with PDL therapy, additional treatment sessions may have helped,11 but he opted to discontinue. Follow-up for persistently symptomatic or changing lesions is necessary, given the minimal risk for malignant transformation.6

The Diagnosis: Glomangiomyoma

A punch biopsy of the right forearm revealed a collection of vascular and smooth muscle components with small and spindled bland cells containing minimal eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 1), confirming the diagnosis of glomangiomyoma. Immunohistochemical stains also supported the diagnosis and were positive for smooth muscle actin, desmin, and CD34 (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance imaging from a prior attempt at treatment with sclerotherapy demonstrated scattered vascular malformations with no notable internal derangement. There was no improvement with sclerotherapy. Given the number and vascular nature of the lesions, a trial of pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy was administered and tolerated by the patient. He subsequently moved to a new military duty station. On follow-up, he reported no noticeable clinical improvement in the lesions after PDL and opted not to continue with laser treatment.

Glomangiomyoma is a rare and benign glomus tumor variant that demonstrates differentiation into the smooth muscle and potentially can result in substantial complications.1 Glomus tumors generally are benign neoplasms of the glomus apparatus, and glomus cells function as thermoregulators in the reticular dermis.2 Glomus tumors comprise less than 2% of soft tissue neoplasms and generally are solitary nodules; only 10% of glomus tumors occur with multiple lesions, and among them, glomangiomyoma is the rarest subtype, presenting in only 15% of cases.2,3 The 3 main subtypes of glomus tumors are solid, glomangioma, and glomangiomyoma.4 Clinically, the lesions may present as small blue nodules with associated pain and cold or pressure sensitivity. Although there appears to be variation of the nomenclature depending on the source in the literature, glomangiomas are characterized by their predominant vascular malformations on biopsy. Glomangiomyomas are a subset of glomus tumors with distinct smooth muscle differentiation.4 Given their pathologic presentation, our patient’s lesions were most consistent with the diagnosis of glomangiomyoma.

The small size of the lesions may result in difficulty establishing a clinical diagnosis, particularly if there is no hand involvement, where lesions most commonly occur.2 Therefore, histopathologic evaluation is essential and is the best initial step in evaluating glomangiomyomas.4 Biopsy is the most reliable means of confirming a diagnosis2,4,5; however, diagnostic imaging such as a computed tomography also should be performed if considering blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome due to the primary site of involvement. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice after confirming the diagnosis in most cases of symptomatic glomangiomyomas, particularly with painful lesions.6

Neurilemmomas (also known as schwannomas) are benign lesions that generally present as asymptomatic, soft, smooth nodules most often on the neck; however, they also may present on the flexor extremities or in internal organs. Although primarily asymptomatic, the tumors may be associated with pain and paresthesia as they enlarge and affect surrounding structures. Neurilemmomas may occur spontaneously or as part of a syndrome, such as neurofibromatosis type 2 or Carney complex.7

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (formerly known as Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome) is an autosomal-dominant disease that presents with arteriovenous malformations and telangiectases. Patients generally present in the third decade of life, with the main concern generally being epistaxis.8

Kaposi sarcoma is a viral infection secondary to human herpesvirus 8 that results in red-purple lesions commonly on mucocutaneous sites. Kaposi sarcoma can be AIDS associated and non-HIV associated. Although clinically indistinguishable, a few subtle histologic features can assist in differentiating the 2 etiologies. In addition to a potential history of immunodeficiency, evaluating for involvement of the lymphatic system, respiratory tract, or gastrointestinal tract can aid in differentiating this entity from glomus tumors.9

Leiomyomas are smooth muscle lesions divided into 3 subcategories: angioleiomyoma, piloleiomyoma, and genital leiomyoma. The clinical presentation and histopathology will vary depending on the subcategory. Although cutaneous leiomyomas are benign, further workup for piloleiomyoma may be required given the reported association with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (Reed syndrome).10

Imaging can be helpful when the clinical diagnosis of a glomus tumor vs other painful neoplasms of the skin is unclear, such as in blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome, angioleiomyomas, neuromas, glomus tumors, leiomyomas, eccrine spiradenomas, congenital vascular malformations, schwannomas, or hemangiomas.4 Radiologic findings for glomus tumors may demonstrate cortical or cystic osseous defects. Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasonography can help provide additional information on the lesion size and depth of involvement.1 Additionally, deeper glomangiomyomas have been associated with malignancy,2 potentially highlighting the benefit of early incorporation of imaging in the workup for this condition. Malignant transformation is rare and has been reported in less than 1% of cases.6

Treatment of glomus tumors predominantly is directed to the patient’s symptoms; asymptomatic lesions may be monitored.4 For symptomatic lesions, therapeutic options include wide local excision; sclerotherapy; and incorporation of various lasers, including Nd:YAG, CO2, and flashlamp tunable dye laser.4,5 One case report documented use of a PDL that successfully eliminated the pain associated with glomangiomyoma; however, the lesion in that report was not biopsy proven.11

Our case highlights the need to consider glomus tumors in patients presenting with multiple small nodules given the potential for misdiagnosis, impact on quality of life with associated psychological distress, and potential utility of incorporating PDL in treatment. Although our patient did not report clinical improvement in the appearance of the lesions with PDL therapy, additional treatment sessions may have helped,11 but he opted to discontinue. Follow-up for persistently symptomatic or changing lesions is necessary, given the minimal risk for malignant transformation.6

- Lee DY, Hwang SC, Jeong ST, et al. The value of diagnostic ultrasonography in the assessment of a glomus tumor of the subcutaneous layer of the forearm mimicking a hemangioma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2015;9:191. doi:10.1186/s13256-015-0672-y

- Li L, Bardsley V, Grainger A, et al. Extradigital glomangiomyoma of the forearm mimicking peripheral nerve sheath tumour and thrombosed varicose vein. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14:E241221. doi: 10.1136 /bcr-2020-241221

- Calduch L, Monteagudo C, Martínez-Ruiz E, et al. Familial generalized multiple glomangiomyoma: report of a new family, with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:402-408. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.2002.00114.x

- Mohammadi O, Suarez M. Glomus cancer. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Maxey ML, Houghton CC, Mastriani KS, et al. Large prepatellar glomangioma: a case report [published online July 10, 2015]. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;14:80-84. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.07.002

- Brathwaite CD, Poppiti RJ Jr. Malignant glomus tumor. a case report of widespread metastases in a patient with multiple glomus body hamartomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:233-238. doi:10.1097/00000478-199602000-00012

- Davis DD, Kane SM. Neurilemmoma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Kühnel T, Wirsching K, Wohlgemuth W, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2018;51:237-254. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2017.09.017

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294. doi:10.5858/arpa.2012-0101-RS

- Bernett CN, Mammino JJ. Cutaneous leiomyomas. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Antony FC, Cliff S, Cowley N. Complete pain relief following treatment of a glomangiomyoma with the pulsed dye laser. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:617-619. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01403.x

- Lee DY, Hwang SC, Jeong ST, et al. The value of diagnostic ultrasonography in the assessment of a glomus tumor of the subcutaneous layer of the forearm mimicking a hemangioma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2015;9:191. doi:10.1186/s13256-015-0672-y

- Li L, Bardsley V, Grainger A, et al. Extradigital glomangiomyoma of the forearm mimicking peripheral nerve sheath tumour and thrombosed varicose vein. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14:E241221. doi: 10.1136 /bcr-2020-241221

- Calduch L, Monteagudo C, Martínez-Ruiz E, et al. Familial generalized multiple glomangiomyoma: report of a new family, with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:402-408. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.2002.00114.x

- Mohammadi O, Suarez M. Glomus cancer. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Maxey ML, Houghton CC, Mastriani KS, et al. Large prepatellar glomangioma: a case report [published online July 10, 2015]. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;14:80-84. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.07.002

- Brathwaite CD, Poppiti RJ Jr. Malignant glomus tumor. a case report of widespread metastases in a patient with multiple glomus body hamartomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:233-238. doi:10.1097/00000478-199602000-00012

- Davis DD, Kane SM. Neurilemmoma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Kühnel T, Wirsching K, Wohlgemuth W, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2018;51:237-254. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2017.09.017

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294. doi:10.5858/arpa.2012-0101-RS

- Bernett CN, Mammino JJ. Cutaneous leiomyomas. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Antony FC, Cliff S, Cowley N. Complete pain relief following treatment of a glomangiomyoma with the pulsed dye laser. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:617-619. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01403.x

A 31-year-old active-duty military servicemember presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of 0.3- to 2-cm, tender, blue nodules on the wrists and forearms. The lesions first appeared on the right volar wrist secondary to a presumed injury sustained approximately 10 years prior to presentation and spread to the proximal forearm as well as the left wrist and forearm. He denied fevers, chills, chest pain, hematochezia, hematuria, or other skin findings. Physical examination revealed blue-violaceous, firm nodules on the right volar wrist and forearm that were tender to palpation. Blue-violaceous, papulonodular lesions on the left volar wrist and dorsal hand were not tender to palpation. A punch biopsy was performed.

Frustrating facial lesions

These tender nodules are classic for cystic acne and are common in women older than 20 years. Instead of outgrowing acne in their teenage years, some people (such as this patient) develop frequent tender cystic acne lesions that often heal with hyperpigmented scars.

Acne is the most prevalent chronic skin condition in the United States, affecting up to 50 million people.1 Approximately 12% of adult women are affected.2 The main contributing factors include increased sebum production, follicular hyperkeratinization, microbial follicular colonization with Propionibacterium acnes, and an inflammatory reaction.3

Treatment is available in both topical and oral forms. Topical antibiotics are used predominantly for treating mild-to-moderate inflammatory acne. They are not recommended as monotherapy due to the risk for bacterial resistance; this can be prevented by adding benzoyl peroxide, which exfoliates and acts as an antibacterial agent. Clindamycin 1% solution or gel is the preferred topical antibiotic for treatment of acne.4

Topical retinoids can be used as monotherapy or in combination with antibiotics. They also can be used for maintenance after treatment goals are reached and systemic antibiotics are discontinued. Retinoids generally are applied in the evening because the sun weakens their effect. Patients on retinoids also are more sensitive to the sun and should be counseled to use sunscreen daily. Counseling on pregnancy risks and appropriate use of contraception also should be offered to patients using retinoids. It is advisable to consider the use of combination oral contraceptives, particularly in women who have adult-onset acne or experience flare-ups around the time of their menstrual cycle.3

Azelaic acid has anticomedonal, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory properties and may be effective in treating mild-to-moderate inflammatory acne and hyperpigmentation. Salicylic acid also has comedolytic properties, although there have been limited studies examining its effectiveness. Both azelaic and salicylic acid are considered safe for use in pregnancy.

Oral antibiotics are recommended in the treatment of moderate-to-severe acne. Both doxycycline and minocycline are more effective than tetracycline for treating acne, with no clear superiority between the two.4 Macrolides also can be effective in treating acne, although their use should be limited to those who cannot tolerate tetracyclines. Systemic antibiotic use should be limited to 3 to 4 months due to decreasing efficacy over time and to minimize the development of bacterial resistance. If treatment goals are attained, the antibiotics can be replaced with retinoids.

Oral isotretinoin is reserved for treatment of severe nodular acne or moderate acne that is treatment resistant. Patients should be counseled on contraceptive methods, as isotretinoin is highly teratogenic and therefore prescribed through the iPLEDGE program.3,4

Given this patient’s persistent symptoms despite use of topical antibiotics and topical tretinoin, she decided to try oral antibiotics (doxycycline 100 mg twice daily) for 3 months and to start long-term oral contraceptives. If her symptoms continue, she will enroll in the iPLEDGE program and start treatment with oral isotretinoin.

Photo courtesy of Ayo Sorunke, MD. Text courtesy of Ayo Sorunke, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University, Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. White GM. Recent findings in the epidemiologic evidence, classification, and subtypes of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:S34-S37. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70442-6

2. Goulden V, Stables GI, Cunliffe WJ. Prevalence of facial acne in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:577-580.

3. Titus S, Hodge J. Diagnosis and treatment of acne. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:734-740.

4. Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037

These tender nodules are classic for cystic acne and are common in women older than 20 years. Instead of outgrowing acne in their teenage years, some people (such as this patient) develop frequent tender cystic acne lesions that often heal with hyperpigmented scars.

Acne is the most prevalent chronic skin condition in the United States, affecting up to 50 million people.1 Approximately 12% of adult women are affected.2 The main contributing factors include increased sebum production, follicular hyperkeratinization, microbial follicular colonization with Propionibacterium acnes, and an inflammatory reaction.3

Treatment is available in both topical and oral forms. Topical antibiotics are used predominantly for treating mild-to-moderate inflammatory acne. They are not recommended as monotherapy due to the risk for bacterial resistance; this can be prevented by adding benzoyl peroxide, which exfoliates and acts as an antibacterial agent. Clindamycin 1% solution or gel is the preferred topical antibiotic for treatment of acne.4

Topical retinoids can be used as monotherapy or in combination with antibiotics. They also can be used for maintenance after treatment goals are reached and systemic antibiotics are discontinued. Retinoids generally are applied in the evening because the sun weakens their effect. Patients on retinoids also are more sensitive to the sun and should be counseled to use sunscreen daily. Counseling on pregnancy risks and appropriate use of contraception also should be offered to patients using retinoids. It is advisable to consider the use of combination oral contraceptives, particularly in women who have adult-onset acne or experience flare-ups around the time of their menstrual cycle.3

Azelaic acid has anticomedonal, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory properties and may be effective in treating mild-to-moderate inflammatory acne and hyperpigmentation. Salicylic acid also has comedolytic properties, although there have been limited studies examining its effectiveness. Both azelaic and salicylic acid are considered safe for use in pregnancy.

Oral antibiotics are recommended in the treatment of moderate-to-severe acne. Both doxycycline and minocycline are more effective than tetracycline for treating acne, with no clear superiority between the two.4 Macrolides also can be effective in treating acne, although their use should be limited to those who cannot tolerate tetracyclines. Systemic antibiotic use should be limited to 3 to 4 months due to decreasing efficacy over time and to minimize the development of bacterial resistance. If treatment goals are attained, the antibiotics can be replaced with retinoids.

Oral isotretinoin is reserved for treatment of severe nodular acne or moderate acne that is treatment resistant. Patients should be counseled on contraceptive methods, as isotretinoin is highly teratogenic and therefore prescribed through the iPLEDGE program.3,4

Given this patient’s persistent symptoms despite use of topical antibiotics and topical tretinoin, she decided to try oral antibiotics (doxycycline 100 mg twice daily) for 3 months and to start long-term oral contraceptives. If her symptoms continue, she will enroll in the iPLEDGE program and start treatment with oral isotretinoin.

Photo courtesy of Ayo Sorunke, MD. Text courtesy of Ayo Sorunke, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University, Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

These tender nodules are classic for cystic acne and are common in women older than 20 years. Instead of outgrowing acne in their teenage years, some people (such as this patient) develop frequent tender cystic acne lesions that often heal with hyperpigmented scars.

Acne is the most prevalent chronic skin condition in the United States, affecting up to 50 million people.1 Approximately 12% of adult women are affected.2 The main contributing factors include increased sebum production, follicular hyperkeratinization, microbial follicular colonization with Propionibacterium acnes, and an inflammatory reaction.3

Treatment is available in both topical and oral forms. Topical antibiotics are used predominantly for treating mild-to-moderate inflammatory acne. They are not recommended as monotherapy due to the risk for bacterial resistance; this can be prevented by adding benzoyl peroxide, which exfoliates and acts as an antibacterial agent. Clindamycin 1% solution or gel is the preferred topical antibiotic for treatment of acne.4

Topical retinoids can be used as monotherapy or in combination with antibiotics. They also can be used for maintenance after treatment goals are reached and systemic antibiotics are discontinued. Retinoids generally are applied in the evening because the sun weakens their effect. Patients on retinoids also are more sensitive to the sun and should be counseled to use sunscreen daily. Counseling on pregnancy risks and appropriate use of contraception also should be offered to patients using retinoids. It is advisable to consider the use of combination oral contraceptives, particularly in women who have adult-onset acne or experience flare-ups around the time of their menstrual cycle.3

Azelaic acid has anticomedonal, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory properties and may be effective in treating mild-to-moderate inflammatory acne and hyperpigmentation. Salicylic acid also has comedolytic properties, although there have been limited studies examining its effectiveness. Both azelaic and salicylic acid are considered safe for use in pregnancy.

Oral antibiotics are recommended in the treatment of moderate-to-severe acne. Both doxycycline and minocycline are more effective than tetracycline for treating acne, with no clear superiority between the two.4 Macrolides also can be effective in treating acne, although their use should be limited to those who cannot tolerate tetracyclines. Systemic antibiotic use should be limited to 3 to 4 months due to decreasing efficacy over time and to minimize the development of bacterial resistance. If treatment goals are attained, the antibiotics can be replaced with retinoids.

Oral isotretinoin is reserved for treatment of severe nodular acne or moderate acne that is treatment resistant. Patients should be counseled on contraceptive methods, as isotretinoin is highly teratogenic and therefore prescribed through the iPLEDGE program.3,4

Given this patient’s persistent symptoms despite use of topical antibiotics and topical tretinoin, she decided to try oral antibiotics (doxycycline 100 mg twice daily) for 3 months and to start long-term oral contraceptives. If her symptoms continue, she will enroll in the iPLEDGE program and start treatment with oral isotretinoin.

Photo courtesy of Ayo Sorunke, MD. Text courtesy of Ayo Sorunke, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University, Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. White GM. Recent findings in the epidemiologic evidence, classification, and subtypes of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:S34-S37. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70442-6

2. Goulden V, Stables GI, Cunliffe WJ. Prevalence of facial acne in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:577-580.

3. Titus S, Hodge J. Diagnosis and treatment of acne. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:734-740.

4. Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037

1. White GM. Recent findings in the epidemiologic evidence, classification, and subtypes of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:S34-S37. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70442-6

2. Goulden V, Stables GI, Cunliffe WJ. Prevalence of facial acne in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:577-580.

3. Titus S, Hodge J. Diagnosis and treatment of acne. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:734-740.

4. Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037

Ultrasound assessment of flexor retinacula can help¬ distinguish PsA from RA in patients with ankle pain

Key clinical point: Ultrasound assessment of individuals with painful ankles revealed that abnormalities of the flexor retinacula (FR) were more common in patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) vs rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Major finding: The FR were thicker in patients with PsA vs patients with RA and control individuals (0.96 vs 0.64 and 0.56, respectively; both P < .001), with abnormalities, such as retinaculitis (39.0% vs 2.7%), hypoechogenicity (46.0% vs 6.8%), power Doppler positivity (43.0% vs 8.1%), and periostosis (43.0% vs 8.1%), being significantly more prevalent in patients with PsA vs RA (all P < .001).

Study details: Findings are from a cross-sectional observational study including patients with PsA (n = 23) and RA (n = 37) who reported painful ankles and control individuals (n = 20) without rheumatic disease or ankle pain.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Forien M et al. Ankle retinacula abnormalities as features of psoriatic arthritis: An ultrasound study. Joint Bone Spine. 2023 (Oct 4). doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2023.105649

Key clinical point: Ultrasound assessment of individuals with painful ankles revealed that abnormalities of the flexor retinacula (FR) were more common in patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) vs rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Major finding: The FR were thicker in patients with PsA vs patients with RA and control individuals (0.96 vs 0.64 and 0.56, respectively; both P < .001), with abnormalities, such as retinaculitis (39.0% vs 2.7%), hypoechogenicity (46.0% vs 6.8%), power Doppler positivity (43.0% vs 8.1%), and periostosis (43.0% vs 8.1%), being significantly more prevalent in patients with PsA vs RA (all P < .001).

Study details: Findings are from a cross-sectional observational study including patients with PsA (n = 23) and RA (n = 37) who reported painful ankles and control individuals (n = 20) without rheumatic disease or ankle pain.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Forien M et al. Ankle retinacula abnormalities as features of psoriatic arthritis: An ultrasound study. Joint Bone Spine. 2023 (Oct 4). doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2023.105649

Key clinical point: Ultrasound assessment of individuals with painful ankles revealed that abnormalities of the flexor retinacula (FR) were more common in patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) vs rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Major finding: The FR were thicker in patients with PsA vs patients with RA and control individuals (0.96 vs 0.64 and 0.56, respectively; both P < .001), with abnormalities, such as retinaculitis (39.0% vs 2.7%), hypoechogenicity (46.0% vs 6.8%), power Doppler positivity (43.0% vs 8.1%), and periostosis (43.0% vs 8.1%), being significantly more prevalent in patients with PsA vs RA (all P < .001).

Study details: Findings are from a cross-sectional observational study including patients with PsA (n = 23) and RA (n = 37) who reported painful ankles and control individuals (n = 20) without rheumatic disease or ankle pain.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Forien M et al. Ankle retinacula abnormalities as features of psoriatic arthritis: An ultrasound study. Joint Bone Spine. 2023 (Oct 4). doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2023.105649

No causal association between PsA and the genetic risk for skin cancer

Key clinical point: This Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis established that there exists no causal association between psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and the genetic risk for skin cancer.

Major finding: PsA did not increase the genetic susceptibility to cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (odds ratio [OR] 1.00; P = .214) and cutaneous melanoma (OR 1.00; P = .477). Although PsA decreased the genetic risk for basal cell carcinoma (OR 0.94; P = .016), the association disappeared when skin cancer risk factors like skin tanning, radiation-related disorders, and telomere length were considered.

Study details: Findings are from a multivariate MR analysis including 3186 patients with PsA and 240,862 control individuals without PsA.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China and the Youth Science Foundation of Xiangya Hospital. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Yu N et al. Multivariate Mendelian randomization provides no evidence for causal associations among both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, and skin cancer. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1252720 (Sep 19). doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1252720

Key clinical point: This Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis established that there exists no causal association between psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and the genetic risk for skin cancer.

Major finding: PsA did not increase the genetic susceptibility to cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (odds ratio [OR] 1.00; P = .214) and cutaneous melanoma (OR 1.00; P = .477). Although PsA decreased the genetic risk for basal cell carcinoma (OR 0.94; P = .016), the association disappeared when skin cancer risk factors like skin tanning, radiation-related disorders, and telomere length were considered.

Study details: Findings are from a multivariate MR analysis including 3186 patients with PsA and 240,862 control individuals without PsA.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China and the Youth Science Foundation of Xiangya Hospital. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Yu N et al. Multivariate Mendelian randomization provides no evidence for causal associations among both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, and skin cancer. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1252720 (Sep 19). doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1252720

Key clinical point: This Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis established that there exists no causal association between psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and the genetic risk for skin cancer.

Major finding: PsA did not increase the genetic susceptibility to cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (odds ratio [OR] 1.00; P = .214) and cutaneous melanoma (OR 1.00; P = .477). Although PsA decreased the genetic risk for basal cell carcinoma (OR 0.94; P = .016), the association disappeared when skin cancer risk factors like skin tanning, radiation-related disorders, and telomere length were considered.

Study details: Findings are from a multivariate MR analysis including 3186 patients with PsA and 240,862 control individuals without PsA.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China and the Youth Science Foundation of Xiangya Hospital. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Yu N et al. Multivariate Mendelian randomization provides no evidence for causal associations among both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, and skin cancer. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1252720 (Sep 19). doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1252720

Identifying characteristics of difficult-to-treat PsA in real-world conditions

Key clinical point: Difficult-to-treat (D2T) psoriatic arthritis (PsA), a condition characterized by the failure of ≥2 targeted synthetic or biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (ts/bDMARD), is associated with a higher prevalence of axial involvement, structural damage, and treatment discontinuation.

Major finding: Peripheral structural damage (odds ratio [OR] 2.57; P = .020), axial involvement (OR 2.37; P = .035), and the discontinuation of bDMARD due to poor dermatological control (OR 2.99; P = .008) were more prevalent in patients with D2T PsA vs non-D2T PsA.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective cohort study including 150 patients with PsA who initiated treatment with ts/bDMARD and were followed up for ≥2 years, of whom 49 patients had D2T PsA.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. Three authors declared receiving honorary fees or research grants or serving as advisory board members for various sources.

Source: Philippoteaux C et al. Characteristics of difficult-to-treat psoriatic arthritis: A comparative analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2023;63:152275 (Oct 5). doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2023.152275

Key clinical point: Difficult-to-treat (D2T) psoriatic arthritis (PsA), a condition characterized by the failure of ≥2 targeted synthetic or biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (ts/bDMARD), is associated with a higher prevalence of axial involvement, structural damage, and treatment discontinuation.

Major finding: Peripheral structural damage (odds ratio [OR] 2.57; P = .020), axial involvement (OR 2.37; P = .035), and the discontinuation of bDMARD due to poor dermatological control (OR 2.99; P = .008) were more prevalent in patients with D2T PsA vs non-D2T PsA.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective cohort study including 150 patients with PsA who initiated treatment with ts/bDMARD and were followed up for ≥2 years, of whom 49 patients had D2T PsA.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. Three authors declared receiving honorary fees or research grants or serving as advisory board members for various sources.

Source: Philippoteaux C et al. Characteristics of difficult-to-treat psoriatic arthritis: A comparative analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2023;63:152275 (Oct 5). doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2023.152275

Key clinical point: Difficult-to-treat (D2T) psoriatic arthritis (PsA), a condition characterized by the failure of ≥2 targeted synthetic or biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (ts/bDMARD), is associated with a higher prevalence of axial involvement, structural damage, and treatment discontinuation.

Major finding: Peripheral structural damage (odds ratio [OR] 2.57; P = .020), axial involvement (OR 2.37; P = .035), and the discontinuation of bDMARD due to poor dermatological control (OR 2.99; P = .008) were more prevalent in patients with D2T PsA vs non-D2T PsA.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective cohort study including 150 patients with PsA who initiated treatment with ts/bDMARD and were followed up for ≥2 years, of whom 49 patients had D2T PsA.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. Three authors declared receiving honorary fees or research grants or serving as advisory board members for various sources.

Source: Philippoteaux C et al. Characteristics of difficult-to-treat psoriatic arthritis: A comparative analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2023;63:152275 (Oct 5). doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2023.152275

What factors are responsible for a delayed diagnosis of PsA?

Key clinical point: Approximately one-third of patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) reported a diagnostic delay of >2 years, which can be attributed to a number of clinical and demographic factors.

Major finding: The mean diagnostic delay period was 35.1 months. A diagnostic delay of >2 years was seen in 32.98% of patients, with the occurrence of arthritis symptoms before skin manifestations (odds ratio [OR] 1.72; 95% CI 1.20-2.46) and low back pain at first visit (OR 1.60; 95% CI 1.21-2.11) being significant factors associated with this delay. However, generalized-type psoriasis was negatively associated with the diagnostic delay of >2 years (OR 0.25; 95% CI 0.07-0.98).

Study details: Findings are from a cross-sectional study including 1134 patients with PsA.

Disclosures: This study did not disclose any funding source. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Kılıç G et al. Diagnostic delay in psoriatic arthritis: Insights from a nationwide multicenter study. Rheumatol Int. 2023 (Oct 8). doi: 10.1007/s00296-023-05479-z

Key clinical point: Approximately one-third of patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) reported a diagnostic delay of >2 years, which can be attributed to a number of clinical and demographic factors.