User login

Real-world effectiveness of T2T and routine care in abatacept-treated moderate-to-severe RA

Key clinical point: Abatacept improved disease activity in patients with moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA), with those managed with treat-to-target (T2T) approach being more likely to achieve low disease activity (LDA) compared with routine care (RC).

Major finding: In each treatment group, abatacept treatment led to early and sustained improvement in disease activity (P < .0001). However, the odds of achieving Clinical Disease Activity Index LDA were significantly higher with T2T vs RC approach (odds ratio 1.33; P = .0263).

Study details: Findings are from the 12-month prospective, randomized Abatacept Best Care trial including 284 patients with moderate-to-severely active RA who initiated abatacept as first- or second-line biologic therapy and were randomly assigned to the T2T (n = 130) or RC (n = 154) group.

Disclosures: This study was managed by JSS Medical Research, and the trial was funded by Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS). Three authors declared being employees of or holding stock or stock options in BMS or JSS Medical Research. Several authors declared ties with various sources, including BMS.

Source: Bessette L et al. Effectiveness of a treat-to-target strategy in patients with moderate to severely active rheumatoid arthritis treated with abatacept. Arthritis Res Ther. 2023;25:183 (Sep 28). doi: 10.1186/s13075-023-03151-2

Key clinical point: Abatacept improved disease activity in patients with moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA), with those managed with treat-to-target (T2T) approach being more likely to achieve low disease activity (LDA) compared with routine care (RC).

Major finding: In each treatment group, abatacept treatment led to early and sustained improvement in disease activity (P < .0001). However, the odds of achieving Clinical Disease Activity Index LDA were significantly higher with T2T vs RC approach (odds ratio 1.33; P = .0263).

Study details: Findings are from the 12-month prospective, randomized Abatacept Best Care trial including 284 patients with moderate-to-severely active RA who initiated abatacept as first- or second-line biologic therapy and were randomly assigned to the T2T (n = 130) or RC (n = 154) group.

Disclosures: This study was managed by JSS Medical Research, and the trial was funded by Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS). Three authors declared being employees of or holding stock or stock options in BMS or JSS Medical Research. Several authors declared ties with various sources, including BMS.

Source: Bessette L et al. Effectiveness of a treat-to-target strategy in patients with moderate to severely active rheumatoid arthritis treated with abatacept. Arthritis Res Ther. 2023;25:183 (Sep 28). doi: 10.1186/s13075-023-03151-2

Key clinical point: Abatacept improved disease activity in patients with moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA), with those managed with treat-to-target (T2T) approach being more likely to achieve low disease activity (LDA) compared with routine care (RC).

Major finding: In each treatment group, abatacept treatment led to early and sustained improvement in disease activity (P < .0001). However, the odds of achieving Clinical Disease Activity Index LDA were significantly higher with T2T vs RC approach (odds ratio 1.33; P = .0263).

Study details: Findings are from the 12-month prospective, randomized Abatacept Best Care trial including 284 patients with moderate-to-severely active RA who initiated abatacept as first- or second-line biologic therapy and were randomly assigned to the T2T (n = 130) or RC (n = 154) group.

Disclosures: This study was managed by JSS Medical Research, and the trial was funded by Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS). Three authors declared being employees of or holding stock or stock options in BMS or JSS Medical Research. Several authors declared ties with various sources, including BMS.

Source: Bessette L et al. Effectiveness of a treat-to-target strategy in patients with moderate to severely active rheumatoid arthritis treated with abatacept. Arthritis Res Ther. 2023;25:183 (Sep 28). doi: 10.1186/s13075-023-03151-2

Prevalence and risk factors for fibrotic progression in patients with RA-ILD

Key clinical point: Nearly half of the patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) showed radiographic progression of fibrosis, and the presence of diabetes mellitus, high disease activity, and advanced high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scores significantly increased the fibrotic progression risk.

Major finding: HRCT-based radiographic progression of fibrosis was observed in 51.0% of patients with RA-ILD, with diabetes mellitus (hazard ratio [HR] 2.47; P < .01), Disease Activity Scores in 28 Joints-Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate > 5.1 (HR 2.32; P = .04), and baseline HRCT scores > 5 (HR 3.04; P < .01) being significant risk factors for fibrotic progression.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective cohort study including 371 patients with RA, of which 32.3% had RA-ILD.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Chai D et al. Progression of radiographic fibrosis in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1265355 (Sep 22). doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1265355

Key clinical point: Nearly half of the patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) showed radiographic progression of fibrosis, and the presence of diabetes mellitus, high disease activity, and advanced high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scores significantly increased the fibrotic progression risk.

Major finding: HRCT-based radiographic progression of fibrosis was observed in 51.0% of patients with RA-ILD, with diabetes mellitus (hazard ratio [HR] 2.47; P < .01), Disease Activity Scores in 28 Joints-Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate > 5.1 (HR 2.32; P = .04), and baseline HRCT scores > 5 (HR 3.04; P < .01) being significant risk factors for fibrotic progression.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective cohort study including 371 patients with RA, of which 32.3% had RA-ILD.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Chai D et al. Progression of radiographic fibrosis in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1265355 (Sep 22). doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1265355

Key clinical point: Nearly half of the patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) showed radiographic progression of fibrosis, and the presence of diabetes mellitus, high disease activity, and advanced high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scores significantly increased the fibrotic progression risk.

Major finding: HRCT-based radiographic progression of fibrosis was observed in 51.0% of patients with RA-ILD, with diabetes mellitus (hazard ratio [HR] 2.47; P < .01), Disease Activity Scores in 28 Joints-Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate > 5.1 (HR 2.32; P = .04), and baseline HRCT scores > 5 (HR 3.04; P < .01) being significant risk factors for fibrotic progression.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective cohort study including 371 patients with RA, of which 32.3% had RA-ILD.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Chai D et al. Progression of radiographic fibrosis in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1265355 (Sep 22). doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1265355

Encouraging evidence to consider glucocorticoid tapering and discontinuation in RA

Key clinical point: The findings demonstrate the feasibility of glucocorticoid discontinuation in patients with long-standing rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and inadequate response to methotrexate (MTX-IR) treated with tofacitinib, highlighting the steroid-sparing effect of tofacitinib.

Major finding: Overall, 30% and 40% of patients completely discontinued prednisone by weeks 12 and 24-48 of initiating tofacitinib, respectively. The median prednisone dose was reduced from 5 to 2.5 mg/day at week 12 (P < .00001), with nine patients further reducing the glucocorticoid dose to 1.25 mg/day from week 12 to week 48 (P < .00001).

Study details: This prospective, open-label, pilot study included 30 patients with moderate-to-severe RA and MTX-IR receiving a stable dose of glucocorticoids who initiated 5 mg tofacitinib twice daily, of which those who achieved at least a moderate European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology response initiated glucocorticoid tapering until complete discontinuation.

Disclosures: This study was supported by a Pfizer Grant Award. FR Spinelli declared receiving a research grant from Pfizer. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Spinelli FR et al. Tapering and discontinuation of glucocorticoids in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tofacitinib. Sci Rep. 2023;13:15537 (Sep 20). doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-42371-z

Key clinical point: The findings demonstrate the feasibility of glucocorticoid discontinuation in patients with long-standing rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and inadequate response to methotrexate (MTX-IR) treated with tofacitinib, highlighting the steroid-sparing effect of tofacitinib.

Major finding: Overall, 30% and 40% of patients completely discontinued prednisone by weeks 12 and 24-48 of initiating tofacitinib, respectively. The median prednisone dose was reduced from 5 to 2.5 mg/day at week 12 (P < .00001), with nine patients further reducing the glucocorticoid dose to 1.25 mg/day from week 12 to week 48 (P < .00001).

Study details: This prospective, open-label, pilot study included 30 patients with moderate-to-severe RA and MTX-IR receiving a stable dose of glucocorticoids who initiated 5 mg tofacitinib twice daily, of which those who achieved at least a moderate European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology response initiated glucocorticoid tapering until complete discontinuation.

Disclosures: This study was supported by a Pfizer Grant Award. FR Spinelli declared receiving a research grant from Pfizer. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Spinelli FR et al. Tapering and discontinuation of glucocorticoids in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tofacitinib. Sci Rep. 2023;13:15537 (Sep 20). doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-42371-z

Key clinical point: The findings demonstrate the feasibility of glucocorticoid discontinuation in patients with long-standing rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and inadequate response to methotrexate (MTX-IR) treated with tofacitinib, highlighting the steroid-sparing effect of tofacitinib.

Major finding: Overall, 30% and 40% of patients completely discontinued prednisone by weeks 12 and 24-48 of initiating tofacitinib, respectively. The median prednisone dose was reduced from 5 to 2.5 mg/day at week 12 (P < .00001), with nine patients further reducing the glucocorticoid dose to 1.25 mg/day from week 12 to week 48 (P < .00001).

Study details: This prospective, open-label, pilot study included 30 patients with moderate-to-severe RA and MTX-IR receiving a stable dose of glucocorticoids who initiated 5 mg tofacitinib twice daily, of which those who achieved at least a moderate European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology response initiated glucocorticoid tapering until complete discontinuation.

Disclosures: This study was supported by a Pfizer Grant Award. FR Spinelli declared receiving a research grant from Pfizer. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Spinelli FR et al. Tapering and discontinuation of glucocorticoids in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tofacitinib. Sci Rep. 2023;13:15537 (Sep 20). doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-42371-z

Microscopic colitis raises risk for incident RA

Key clinical point: Patients with microscopic colitis (MC) were at nearly 2-fold higher risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis (RA) compared with the general population, with a significant risk persisting up to 5 years after MC diagnosis.

Major finding: The risk for RA was significantly higher in patients with MC compared with matched reference individuals (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.83; 95% CI 1.39-2.41) and full siblings without MC (aHR 2.04; 95% CI 1.18-3.56). The risk was highest during the first year of follow-up (aHR 2.31; 95% CI 1.08-4.97) and remained significantly high up to 5 years after MC diagnosis (aHR 2.16; 95% CI 1.42-3.30).

Study details: Findings are from a population-based matched cohort study including 8179 patients with biopsy-verified MC, 36,400 matched reference individuals, and 8202 full siblings without MC.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Karolinska Institutet and other sources. Some authors declared serving as study coordinators or advisory board members for, receiving financial support from, and reporting agreements between various sources.

Source: Bergman D et al. Microscopic colitis and risk of incident rheumatoid arthritis: A nationwide population-based matched cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2023 (Sep 20). D+oi: 10.1111/apt.17708

Key clinical point: Patients with microscopic colitis (MC) were at nearly 2-fold higher risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis (RA) compared with the general population, with a significant risk persisting up to 5 years after MC diagnosis.

Major finding: The risk for RA was significantly higher in patients with MC compared with matched reference individuals (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.83; 95% CI 1.39-2.41) and full siblings without MC (aHR 2.04; 95% CI 1.18-3.56). The risk was highest during the first year of follow-up (aHR 2.31; 95% CI 1.08-4.97) and remained significantly high up to 5 years after MC diagnosis (aHR 2.16; 95% CI 1.42-3.30).

Study details: Findings are from a population-based matched cohort study including 8179 patients with biopsy-verified MC, 36,400 matched reference individuals, and 8202 full siblings without MC.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Karolinska Institutet and other sources. Some authors declared serving as study coordinators or advisory board members for, receiving financial support from, and reporting agreements between various sources.

Source: Bergman D et al. Microscopic colitis and risk of incident rheumatoid arthritis: A nationwide population-based matched cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2023 (Sep 20). D+oi: 10.1111/apt.17708

Key clinical point: Patients with microscopic colitis (MC) were at nearly 2-fold higher risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis (RA) compared with the general population, with a significant risk persisting up to 5 years after MC diagnosis.

Major finding: The risk for RA was significantly higher in patients with MC compared with matched reference individuals (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.83; 95% CI 1.39-2.41) and full siblings without MC (aHR 2.04; 95% CI 1.18-3.56). The risk was highest during the first year of follow-up (aHR 2.31; 95% CI 1.08-4.97) and remained significantly high up to 5 years after MC diagnosis (aHR 2.16; 95% CI 1.42-3.30).

Study details: Findings are from a population-based matched cohort study including 8179 patients with biopsy-verified MC, 36,400 matched reference individuals, and 8202 full siblings without MC.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Karolinska Institutet and other sources. Some authors declared serving as study coordinators or advisory board members for, receiving financial support from, and reporting agreements between various sources.

Source: Bergman D et al. Microscopic colitis and risk of incident rheumatoid arthritis: A nationwide population-based matched cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2023 (Sep 20). D+oi: 10.1111/apt.17708

Oral contraceptives protective against rheumatoid arthritis

Key clinical point: The use of oral contraceptives (OC) appeared to be protective against rheumatoid arthritis (RA), whereas the use of menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) increased the risk for late-onset RA.

Major finding: Compared with never-use, ever-use (hazard ratio [HR] 0.89; 95% CI 0.82-0.96) and current-use (HR 0.81; 95% CI 0.73-0.91) of OC decreased the risk for RA, whereas ever-use (HR 1.16; 95% CI 1.06-1.26) and former-use (HR 1.13; 95% CI 1.03-1.24) of MHT increased the risk for late-onset RA.

Study details: This prospective cohort study included 239,785 British women whose data were evaluated for the effect of OC (n = 236,602) or MHT (age ≥ 60 years, n = 102,466) on RA risk.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Agnes and Mac Rudbergs Foundation (Sweden), the Åke Wiberg Foundation (Sweden), the Marcus Borgström Foundation (Sweden), and various other sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Hadizadeh F et al. Effects of oral contraceptives and menopausal hormone therapy on the risk of rheumatoid arthritis: A prospective cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2023 (Sep 29). doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kead513

Key clinical point: The use of oral contraceptives (OC) appeared to be protective against rheumatoid arthritis (RA), whereas the use of menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) increased the risk for late-onset RA.

Major finding: Compared with never-use, ever-use (hazard ratio [HR] 0.89; 95% CI 0.82-0.96) and current-use (HR 0.81; 95% CI 0.73-0.91) of OC decreased the risk for RA, whereas ever-use (HR 1.16; 95% CI 1.06-1.26) and former-use (HR 1.13; 95% CI 1.03-1.24) of MHT increased the risk for late-onset RA.

Study details: This prospective cohort study included 239,785 British women whose data were evaluated for the effect of OC (n = 236,602) or MHT (age ≥ 60 years, n = 102,466) on RA risk.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Agnes and Mac Rudbergs Foundation (Sweden), the Åke Wiberg Foundation (Sweden), the Marcus Borgström Foundation (Sweden), and various other sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Hadizadeh F et al. Effects of oral contraceptives and menopausal hormone therapy on the risk of rheumatoid arthritis: A prospective cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2023 (Sep 29). doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kead513

Key clinical point: The use of oral contraceptives (OC) appeared to be protective against rheumatoid arthritis (RA), whereas the use of menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) increased the risk for late-onset RA.

Major finding: Compared with never-use, ever-use (hazard ratio [HR] 0.89; 95% CI 0.82-0.96) and current-use (HR 0.81; 95% CI 0.73-0.91) of OC decreased the risk for RA, whereas ever-use (HR 1.16; 95% CI 1.06-1.26) and former-use (HR 1.13; 95% CI 1.03-1.24) of MHT increased the risk for late-onset RA.

Study details: This prospective cohort study included 239,785 British women whose data were evaluated for the effect of OC (n = 236,602) or MHT (age ≥ 60 years, n = 102,466) on RA risk.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Agnes and Mac Rudbergs Foundation (Sweden), the Åke Wiberg Foundation (Sweden), the Marcus Borgström Foundation (Sweden), and various other sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Hadizadeh F et al. Effects of oral contraceptives and menopausal hormone therapy on the risk of rheumatoid arthritis: A prospective cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2023 (Sep 29). doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kead513

Commentary: Axillary Surgery, PM2.5, and Treatment With Tucatinib in Breast Cancer, November 2023

Hormone receptor–positive breast cancer is the most common subtype, with established risk factors including exposure to exogenous hormones, reproductive history, and lifestyle components (alcohol intake, obesity). There are also less-recognized environmental influences that may disrupt endocrine pathways and, as a result, affect tumor development. Fine particulate matter (PM2.5), produced by combustion processes (vehicles, industrial facilities), burning wood, and fires, among other sources, is composed of various airborne pollutants (metals, organic compounds, ammonium, nitrate, ozone, sulfate, etc.). Prior studies evaluating the association of PM2.5 and breast cancer development have shown mixed results.3,4 A prospective US cohort study including 196,905 women without a prior history of breast cancer estimated historical annual average PM2.5 concentrations between 1980 and 1984 (10 years prior to enrollment) (White et al). A total of 15,870 breast cancer cases were identified, and a 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 was associated with an 8% increase in overall breast cancer incidence (HR 1.08; 95% CI 1.02-1.13). The association was observed for estrogen-receptor (ER)-positive (HR 1.10; 95% CI 1.04-1.17) but not ER-negative tumors. Future studies focusing on historic exposures, investigating geographic differences and the resultant effect on cancer development, are of interest.

HER2CLIMB was a pivotal phase 3 randomized, double-blinded trial that demonstrated significant improvement in survival outcomes with the combination of tucatinib/trastuzumab/capecitabine vs tucatinib/trastuzumab/placebo among patients with previously treated human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive metastatic breast cancer.5 Real-world data help inform our daily practice because patients enrolled in clinical trials do not always accurately represent the general population. A retrospective cohort study including 3449 patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer evaluated outcomes with tucatinib in a real-world setting, demonstrating results similar to those seen in HER2CLIMB. Among all patients who received tucatinib (n = 216), median real-world time to treatment discontinuation was 6.5 months (95% CI 5.4-8.8), median real-world time to next treatment (which can serve as a proxy for progression-free survival) was 8.7 months (95% CI 6.8-10.7), and real-world overall survival was 26.6 months (95% CI 20.2–not reached). Median real-world time to treatment discontinuation was 8.1 months (95% CI 5.7-9.5) for patients who received the approved tucatinib triplet combination after one or more HER2-directed regimens in the metastatic setting and 9.4 months (95% CI 6.3-14.1) for those receiving it in the second- or third-line setting (Kaufman et al). These results support the efficacy of tucatinib in a real-world population, suggesting that earlier use (second or third line) may result in better outcomes. Future studies will continue to address the positioning of tucatinib in the treatment algorithm for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer, including the evaluation of novel combinations.

Additional References

- Giuliano AE et al. Effect of axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection on 10-year overall survival among women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: The ACOSOG Z0011 (Alliance) randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:918-926. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11470

- Bartels SAL, Donker M, et al. Radiotherapy or surgery of the axilla after a positive sentinel node in breast cancer: 10-year results of the randomized controlled EORTC 10981-22023 AMAROS Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:2159-2165. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.01565

- Gabet S, Lemarchand C, Guénel P, Slama R. Breast cancer risk in association with atmospheric pollution exposure: A meta-analysis of effect estimates followed by a health impact assessment. Environ Health Perspect. 2021;129:57012. doi: 10.1289/EHP8419

- Hvidtfeldt UA et al. Breast cancer incidence in relation to long-term low-level exposure to air pollution in the ELAPSE pooled cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2023;32:105-113. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-22-0720

- Murthy RK et al. Tucatinib, trastuzumab, and capecitabine for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:597-609. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1914609

Hormone receptor–positive breast cancer is the most common subtype, with established risk factors including exposure to exogenous hormones, reproductive history, and lifestyle components (alcohol intake, obesity). There are also less-recognized environmental influences that may disrupt endocrine pathways and, as a result, affect tumor development. Fine particulate matter (PM2.5), produced by combustion processes (vehicles, industrial facilities), burning wood, and fires, among other sources, is composed of various airborne pollutants (metals, organic compounds, ammonium, nitrate, ozone, sulfate, etc.). Prior studies evaluating the association of PM2.5 and breast cancer development have shown mixed results.3,4 A prospective US cohort study including 196,905 women without a prior history of breast cancer estimated historical annual average PM2.5 concentrations between 1980 and 1984 (10 years prior to enrollment) (White et al). A total of 15,870 breast cancer cases were identified, and a 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 was associated with an 8% increase in overall breast cancer incidence (HR 1.08; 95% CI 1.02-1.13). The association was observed for estrogen-receptor (ER)-positive (HR 1.10; 95% CI 1.04-1.17) but not ER-negative tumors. Future studies focusing on historic exposures, investigating geographic differences and the resultant effect on cancer development, are of interest.

HER2CLIMB was a pivotal phase 3 randomized, double-blinded trial that demonstrated significant improvement in survival outcomes with the combination of tucatinib/trastuzumab/capecitabine vs tucatinib/trastuzumab/placebo among patients with previously treated human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive metastatic breast cancer.5 Real-world data help inform our daily practice because patients enrolled in clinical trials do not always accurately represent the general population. A retrospective cohort study including 3449 patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer evaluated outcomes with tucatinib in a real-world setting, demonstrating results similar to those seen in HER2CLIMB. Among all patients who received tucatinib (n = 216), median real-world time to treatment discontinuation was 6.5 months (95% CI 5.4-8.8), median real-world time to next treatment (which can serve as a proxy for progression-free survival) was 8.7 months (95% CI 6.8-10.7), and real-world overall survival was 26.6 months (95% CI 20.2–not reached). Median real-world time to treatment discontinuation was 8.1 months (95% CI 5.7-9.5) for patients who received the approved tucatinib triplet combination after one or more HER2-directed regimens in the metastatic setting and 9.4 months (95% CI 6.3-14.1) for those receiving it in the second- or third-line setting (Kaufman et al). These results support the efficacy of tucatinib in a real-world population, suggesting that earlier use (second or third line) may result in better outcomes. Future studies will continue to address the positioning of tucatinib in the treatment algorithm for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer, including the evaluation of novel combinations.

Additional References

- Giuliano AE et al. Effect of axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection on 10-year overall survival among women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: The ACOSOG Z0011 (Alliance) randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:918-926. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11470

- Bartels SAL, Donker M, et al. Radiotherapy or surgery of the axilla after a positive sentinel node in breast cancer: 10-year results of the randomized controlled EORTC 10981-22023 AMAROS Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:2159-2165. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.01565

- Gabet S, Lemarchand C, Guénel P, Slama R. Breast cancer risk in association with atmospheric pollution exposure: A meta-analysis of effect estimates followed by a health impact assessment. Environ Health Perspect. 2021;129:57012. doi: 10.1289/EHP8419

- Hvidtfeldt UA et al. Breast cancer incidence in relation to long-term low-level exposure to air pollution in the ELAPSE pooled cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2023;32:105-113. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-22-0720

- Murthy RK et al. Tucatinib, trastuzumab, and capecitabine for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:597-609. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1914609

Hormone receptor–positive breast cancer is the most common subtype, with established risk factors including exposure to exogenous hormones, reproductive history, and lifestyle components (alcohol intake, obesity). There are also less-recognized environmental influences that may disrupt endocrine pathways and, as a result, affect tumor development. Fine particulate matter (PM2.5), produced by combustion processes (vehicles, industrial facilities), burning wood, and fires, among other sources, is composed of various airborne pollutants (metals, organic compounds, ammonium, nitrate, ozone, sulfate, etc.). Prior studies evaluating the association of PM2.5 and breast cancer development have shown mixed results.3,4 A prospective US cohort study including 196,905 women without a prior history of breast cancer estimated historical annual average PM2.5 concentrations between 1980 and 1984 (10 years prior to enrollment) (White et al). A total of 15,870 breast cancer cases were identified, and a 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 was associated with an 8% increase in overall breast cancer incidence (HR 1.08; 95% CI 1.02-1.13). The association was observed for estrogen-receptor (ER)-positive (HR 1.10; 95% CI 1.04-1.17) but not ER-negative tumors. Future studies focusing on historic exposures, investigating geographic differences and the resultant effect on cancer development, are of interest.

HER2CLIMB was a pivotal phase 3 randomized, double-blinded trial that demonstrated significant improvement in survival outcomes with the combination of tucatinib/trastuzumab/capecitabine vs tucatinib/trastuzumab/placebo among patients with previously treated human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive metastatic breast cancer.5 Real-world data help inform our daily practice because patients enrolled in clinical trials do not always accurately represent the general population. A retrospective cohort study including 3449 patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer evaluated outcomes with tucatinib in a real-world setting, demonstrating results similar to those seen in HER2CLIMB. Among all patients who received tucatinib (n = 216), median real-world time to treatment discontinuation was 6.5 months (95% CI 5.4-8.8), median real-world time to next treatment (which can serve as a proxy for progression-free survival) was 8.7 months (95% CI 6.8-10.7), and real-world overall survival was 26.6 months (95% CI 20.2–not reached). Median real-world time to treatment discontinuation was 8.1 months (95% CI 5.7-9.5) for patients who received the approved tucatinib triplet combination after one or more HER2-directed regimens in the metastatic setting and 9.4 months (95% CI 6.3-14.1) for those receiving it in the second- or third-line setting (Kaufman et al). These results support the efficacy of tucatinib in a real-world population, suggesting that earlier use (second or third line) may result in better outcomes. Future studies will continue to address the positioning of tucatinib in the treatment algorithm for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer, including the evaluation of novel combinations.

Additional References

- Giuliano AE et al. Effect of axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection on 10-year overall survival among women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: The ACOSOG Z0011 (Alliance) randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:918-926. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11470

- Bartels SAL, Donker M, et al. Radiotherapy or surgery of the axilla after a positive sentinel node in breast cancer: 10-year results of the randomized controlled EORTC 10981-22023 AMAROS Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:2159-2165. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.01565

- Gabet S, Lemarchand C, Guénel P, Slama R. Breast cancer risk in association with atmospheric pollution exposure: A meta-analysis of effect estimates followed by a health impact assessment. Environ Health Perspect. 2021;129:57012. doi: 10.1289/EHP8419

- Hvidtfeldt UA et al. Breast cancer incidence in relation to long-term low-level exposure to air pollution in the ELAPSE pooled cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2023;32:105-113. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-22-0720

- Murthy RK et al. Tucatinib, trastuzumab, and capecitabine for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:597-609. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1914609

Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy With Ocular Involvement

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an uncommon microangiopathy that presents with progressive telangiectases on the lower extremities that can eventually spread to involve the upper extremities and trunk. Systemic involvement is uncommon. The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy, which demonstrates dilated capillaries and postcapillary venules with eosinophilic hyalinized walls. Treatment generally has focused on the use of vascular lasers.1 We report a patient with advanced CCV and ocular involvement that responded to a combination of pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy and sclerotherapy for cutaneous lesions.

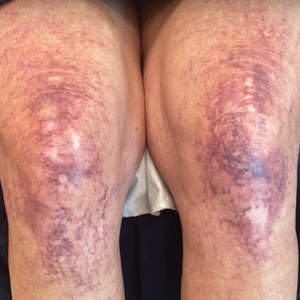

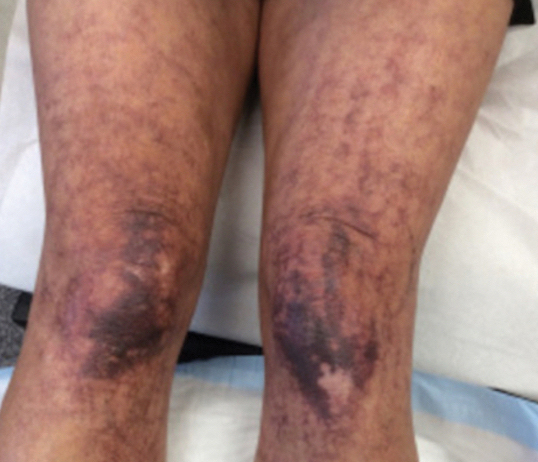

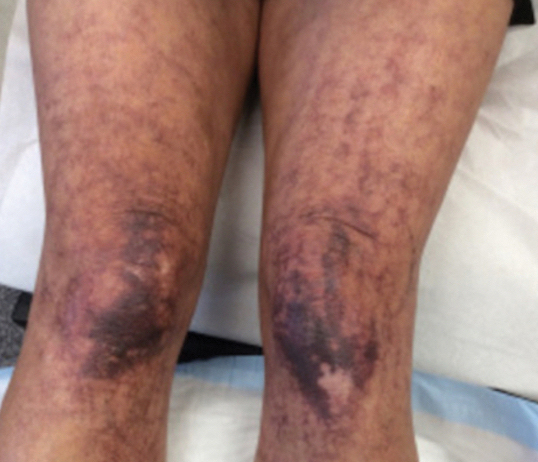

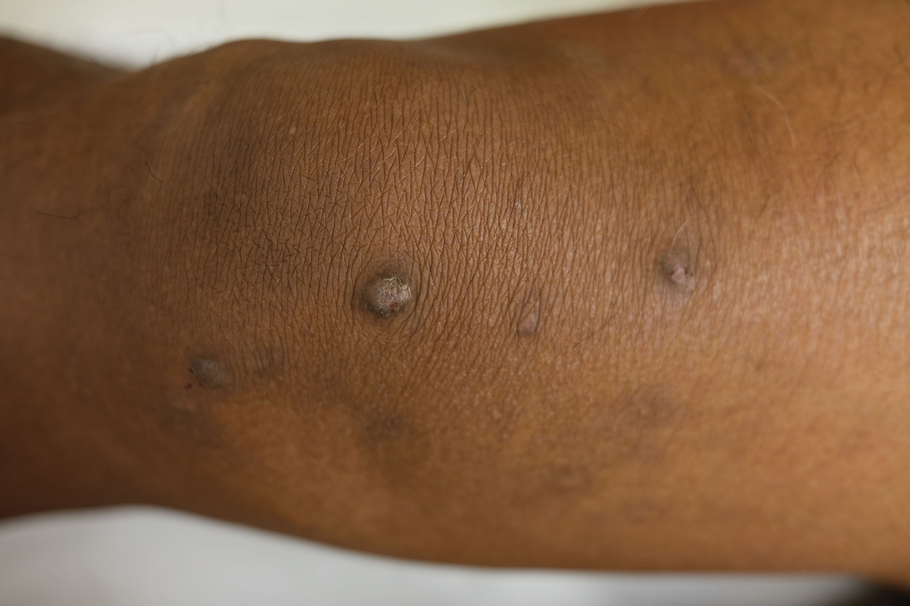

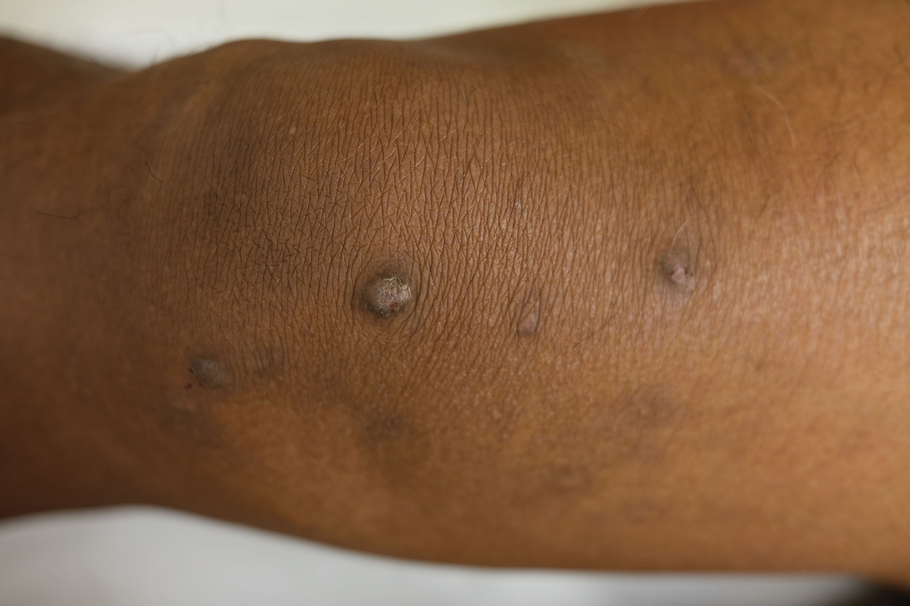

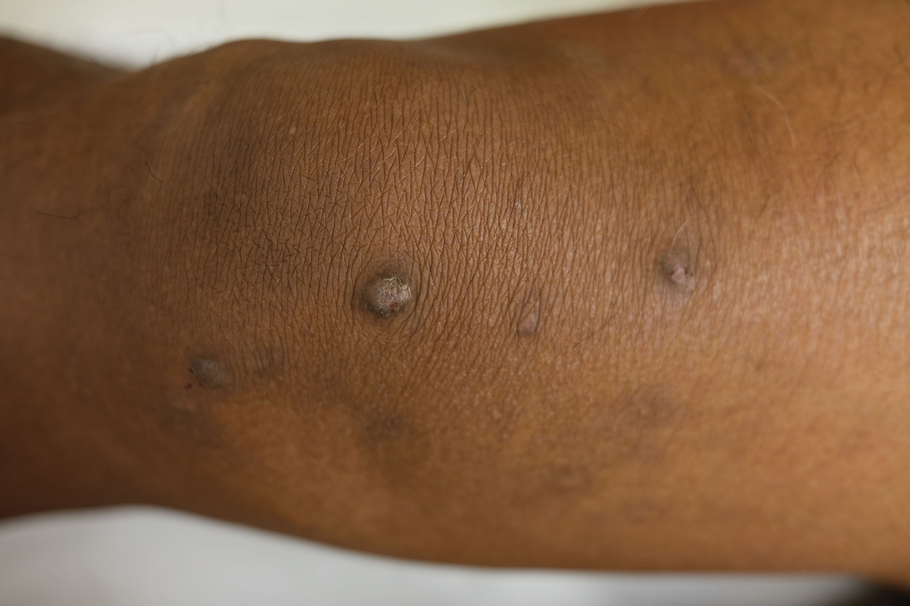

A 63-year-old woman presented with partially blanchable, purple-black patches on the lower extremities (Figure 1). The upper extremities had minimal involvement at the time of presentation. A medical history revealed the lesions presented on the legs 10 years prior but were beginning to form on the arms. She had a history of hypertension and bleeding in the retina.

Histopathology revealed prominent dilation of postcapillary venules with eosinophilic collagenous materials in the vessel walls that was positive on periodic acid–Schiff stain, confirming the diagnosis of CCV. The perivascular collagenous material failed to stain with Congo red. Laboratory testing for serum protein electrophoresis, antinuclear antibodies, and baseline hematologic and metabolic panels revealed no abnormalities.

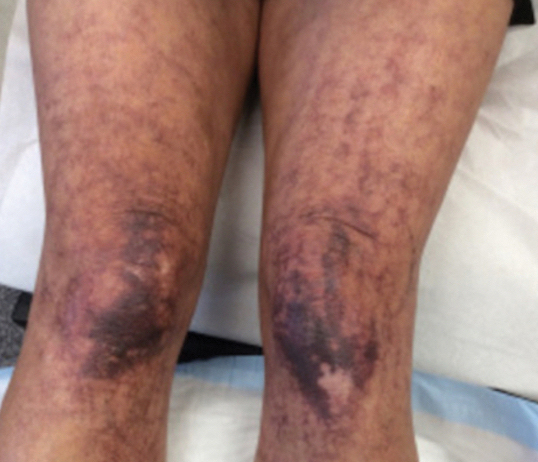

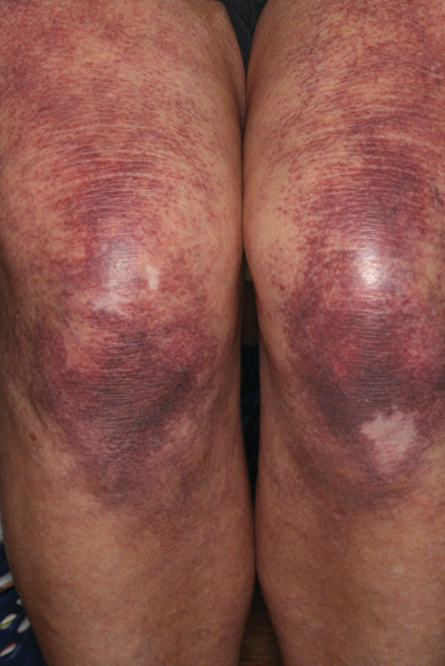

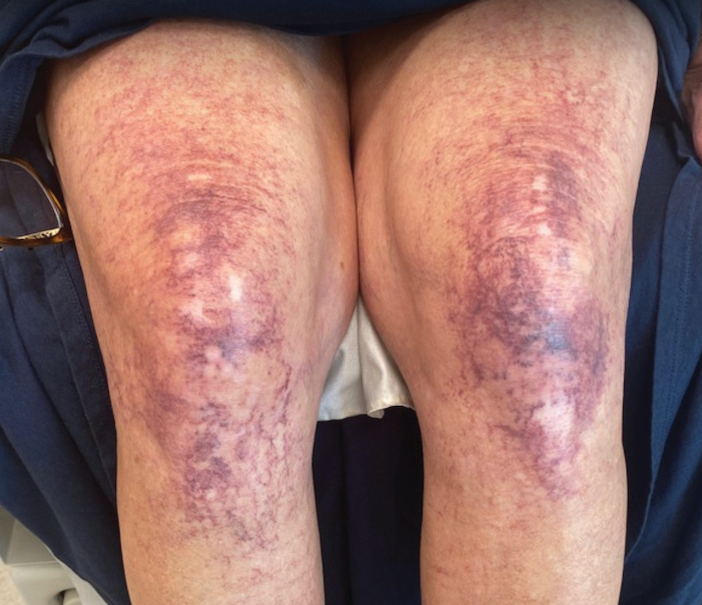

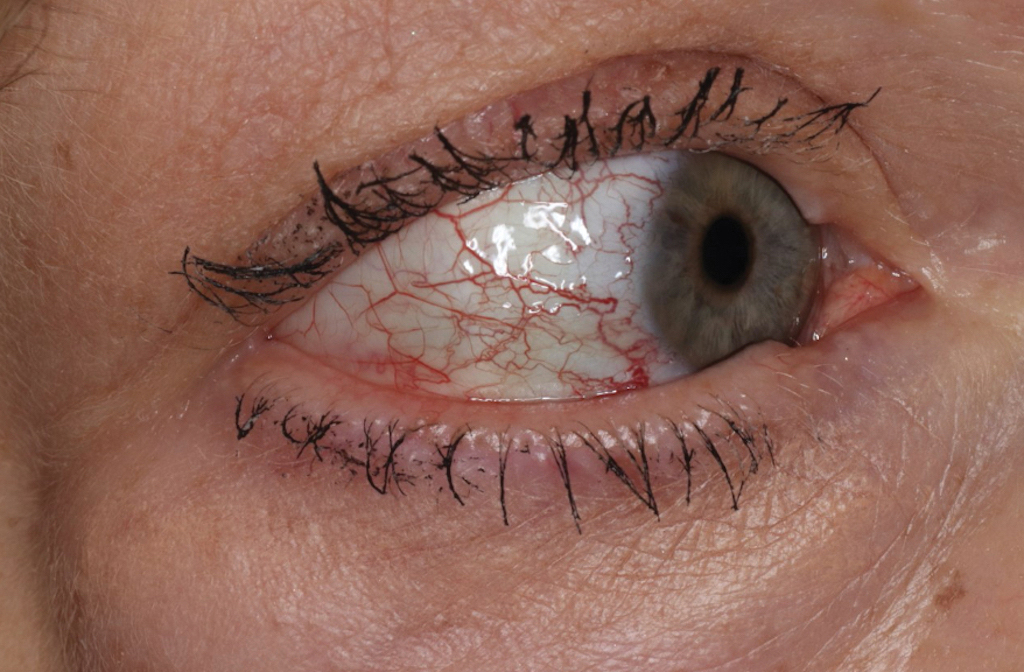

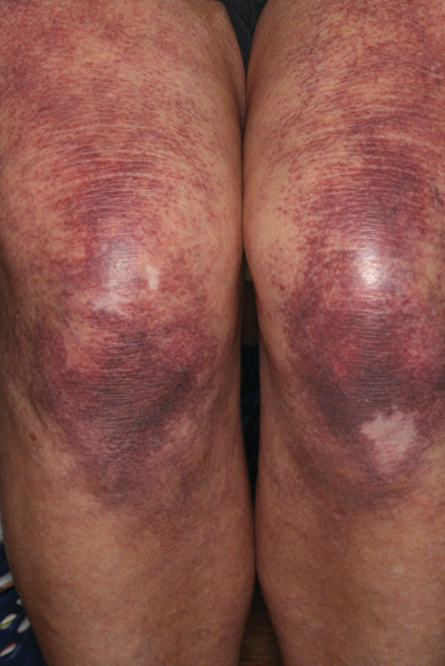

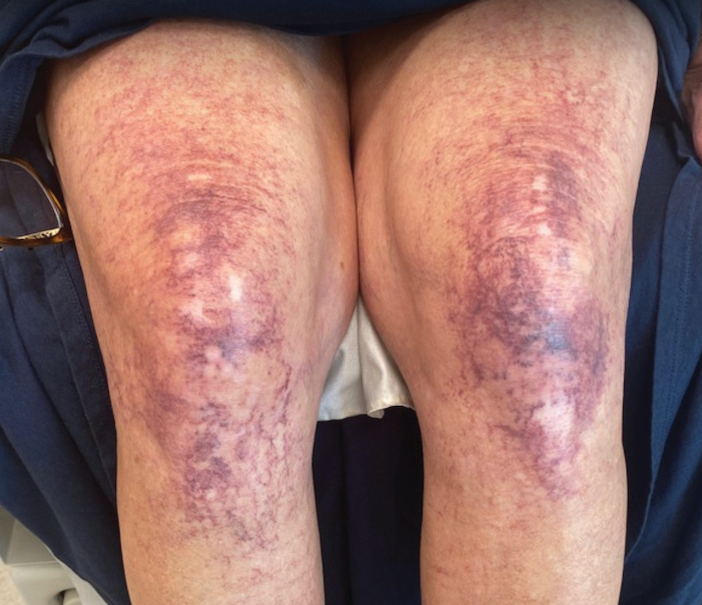

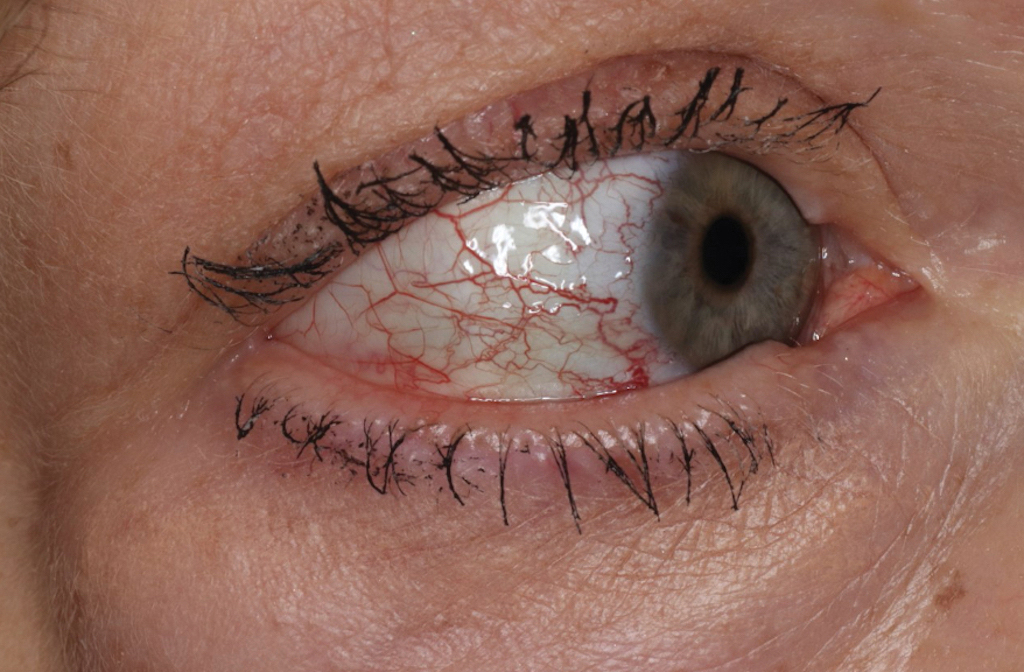

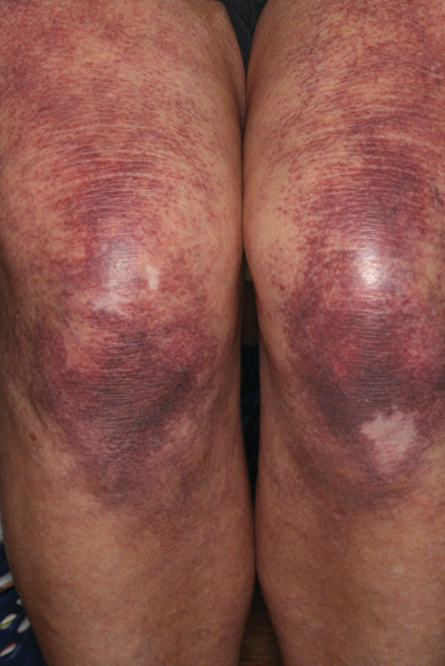

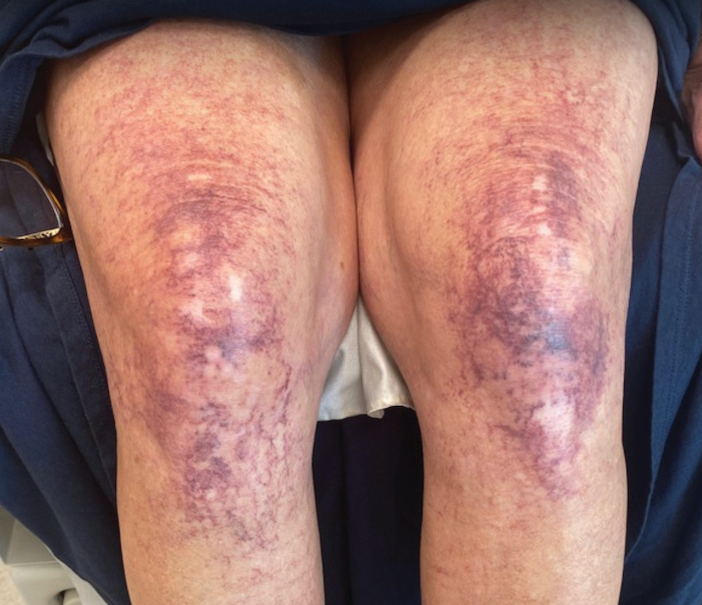

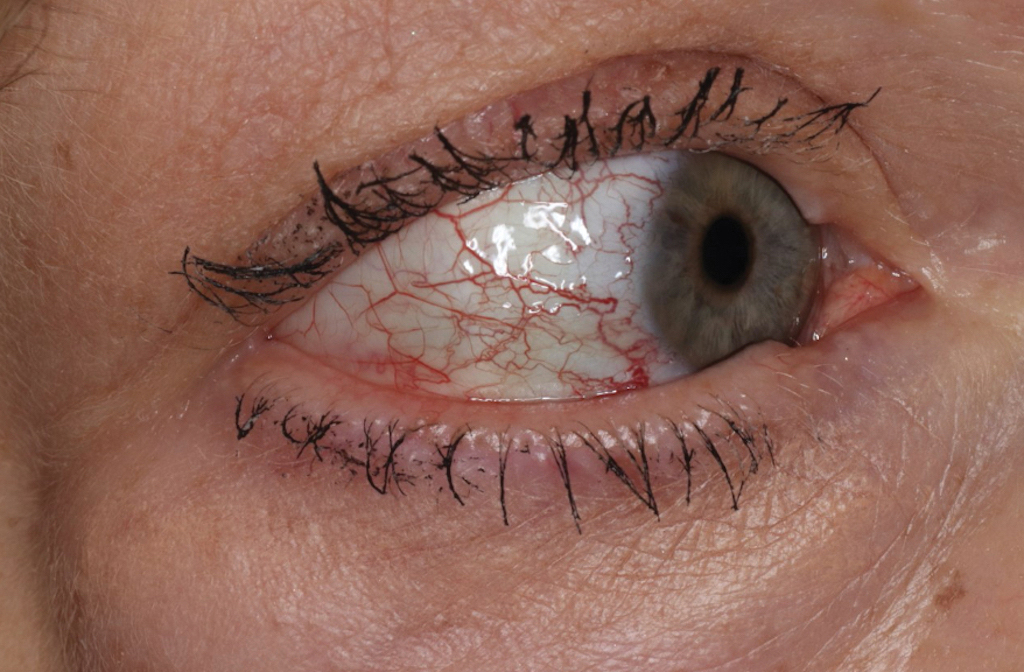

Over 3 years of treatment with PDL, most of the black patches resolved, but prominent telangiectatic vessels remained (Figure 2). Sclerotherapy with polidocanol (10 mg/mL) resulted in clearance of the majority of telangiectatic vessels. After each sclerotherapy treatment, Unna boots were applied for a minimum of 24 hours. The patient had no adverse effects from either PDL or sclerotherapy and was pleased with the results (Figure 3). An ophthalmologist had attributed the retinal bleeding to central serous chorioretinopathy, but tortuosity of superficial scleral and episcleral vessels progressed, suggesting CCV as the more likely cause (Figure 4). Currently, she is being followed for visual changes and further retinal bleeding.

Early CCV typically appears as blanchable pink or red macules, telangiectases, or petechiae on the lower extremities, progressing to involve the trunk and upper extremity.1-3 In rare cases, CCV presents in a papular or annular variant instead of the typical telangiectatic form.4,5 As the lesions progress, they often darken in appearance. Bleeding can occur, and the progressive patches are disfiguring.6,7 Middle-aged to older adults typically present with CCV (range, 16–83 years), with a mean age of 62 years.1,2,6 This disease affects both males and females, predominantly in White individuals.1 Extracutaneous manifestations are rare.1,2,6 One case of mucosal involvement was described in a patient with glossitis and oral erosions.8 We found no prior reports of nail or eye changes.1,2

The etiology of CCV is unknown, but different theories have been proposed. One is that CCV is due to a genetic defect that changes collagen synthesis in the cutaneous microvasculature. Another more widely held belief is that CCV originates from an injury that occurs to the microvasculature endothelial cells. Regardless of the cause of the triggering injury, the result is induced intravascular occlusive microthrombi that cause perivascular fibrosis and endothelial hyperplasia.2,6,7,9

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be influenced by systemic diseases. The most common comorbidities are hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia.1,3,6-8 The presentation of CCV with a malignancy is rare; 1 patient was diagnosed with multiple myeloma 18 months after CCV, and another patient’s cutaneous presentation led to discovery of pancreatic cancer with metastasis.8,10 In this setting, the increased growth factors or hypercoagulability of malignancy may play a role in endothelial cell damage and hyperplasia. Autoimmune vascular injury also has been suggested to trigger CCV; 1 case involved antiribonucleoprotein antibodies, while another case involved anti–endothelial cell antibody assays.11 In addition, CCV has been reported in hypercoagulable patients, demonstrating another route for endothelial damage, with 1 patient being heterozygous for prothrombin G20210A, a report of CCV in a patient with cryofibrinogenemia, and another patient being found positive for lupus anticoagulant.11,12 Drugs also have been thought to influence CCV, including corticosteroids, lithium, thiothixene, interferon, isotretinoin, calcium channel blockers, antibiotics, hydroxyurea, and antidepressants.7,11

The diagnosis of CCV is confirmed using light microscopy and collagen-specific immunostaining. Examination shows hyaline eosinophilic deposition of type IV collagen around the affected vessels, with the postcapillary venules showing characteristic duplication of the basal lamina.3,9 The material stains positive with periodic acid-Schiff and Masson trichrome.3

Underreporting may contribute to the low incidence of CCV. The clinical presentation of CCV is similar to generalized essential telangiectasia, with biopsy distinguishing the two. Other diagnoses in the differential include hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, which typically would have mucosal involvement; radiating telangiectatic mats and a strong family history; and hereditary benign telangiectasia, which typically presents in younger patients aged 1 year to adolescence.1

Treatment with vascular lasers has been the main focus, using either the 595-nm PDL or the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.6,13 Pulsed dye laser or intense pulsed light devices can improve patient well-being1,2; intense pulsed light allows for a larger spot size and may be preferred in patients with a larger body surface area involved.13 However, a few other treatments have been proposed. One case report noted poor response to sclerotherapy.1 In another case, a patient treated with a chemotherapy agent, bortezomib, for their concurrent multiple myeloma showed notable CCV cutaneous improvement. The proposed mechanism for bortezomib improving CCV is through its antiproliferative effect on endothelial cells of the superficial dermal vessels.8 Our patient did not achieve an adequate response with PDL, but the addition of sclerotherapy with polidocanol induced a successful response.

Patients should be examined for evidence of ocular involvement and referred to an ophthalmologist for appropriate care. Although there is no definite association with systemic illnesses or mediation, recent associations with an autoimmune disorder or underlying malignancy have been noted.8,10,11 Age-appropriate cancer screening and attention to associated signs and symptoms are recommended.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52. https://doi.org/10.1097/dad.0000000000000194

- Castiñeiras-Mato I, Rodríguez-Lojo R, Fernández-Díaz ML, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:444-447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2015.11.006

- Rambhia KD, Hadawale SD, Khopkar US. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare case report. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:40-42. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5178.174327

- Conde-Ferreirós A, Roncero-Riesco M, Cañueto J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: papular form [published online August 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. https://doi.org/10.5070/d3258045128

- García-Martínez P, Gomez-Martin I, Lloreta J, et al. Multiple progressive annular telangiectasias: a clinicopathological variant of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy? J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:982-985. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13029

- Sartori DS, de Almeida Jr HL, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213. https://doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198166

- Basso D, Ribero S, Blazek C, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare form of microangiopathy successfully treated with a combination of multiplex laser and optimized pulsed light with a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232:107-111. https://doi.org/10.1159/000439126

- Dura M, Pock L, Cetkovska P, et al. A case of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with multiple myeloma and with a pathogenic variant of the glucocerebrosidase gene. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:717-721. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14227

- Salama S, Chorneyko K, Belovic B. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with intravascular occlusive fibrin thrombi. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:386-393. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.12285

- Holder E, Schreckenberg C, Lipsker D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy leading to the diagnosis of an advanced pancreatic cancer. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E699-E701. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18152

- Grossman ME, Cohen M, Ravits M, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:491-495. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14192

- Eldik H, Leisenring NH, Al-Rohil RN, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy in a middle-aged woman with a history of prothrombin G20210A thrombophilia. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:679-682. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13895

- Weiss E, Lazzara DR. Commentary on clinical improvement of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with intense pulsed light therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1412. https://doi.org/10.1097/DSS.0000000000003209

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an uncommon microangiopathy that presents with progressive telangiectases on the lower extremities that can eventually spread to involve the upper extremities and trunk. Systemic involvement is uncommon. The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy, which demonstrates dilated capillaries and postcapillary venules with eosinophilic hyalinized walls. Treatment generally has focused on the use of vascular lasers.1 We report a patient with advanced CCV and ocular involvement that responded to a combination of pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy and sclerotherapy for cutaneous lesions.

A 63-year-old woman presented with partially blanchable, purple-black patches on the lower extremities (Figure 1). The upper extremities had minimal involvement at the time of presentation. A medical history revealed the lesions presented on the legs 10 years prior but were beginning to form on the arms. She had a history of hypertension and bleeding in the retina.

Histopathology revealed prominent dilation of postcapillary venules with eosinophilic collagenous materials in the vessel walls that was positive on periodic acid–Schiff stain, confirming the diagnosis of CCV. The perivascular collagenous material failed to stain with Congo red. Laboratory testing for serum protein electrophoresis, antinuclear antibodies, and baseline hematologic and metabolic panels revealed no abnormalities.

Over 3 years of treatment with PDL, most of the black patches resolved, but prominent telangiectatic vessels remained (Figure 2). Sclerotherapy with polidocanol (10 mg/mL) resulted in clearance of the majority of telangiectatic vessels. After each sclerotherapy treatment, Unna boots were applied for a minimum of 24 hours. The patient had no adverse effects from either PDL or sclerotherapy and was pleased with the results (Figure 3). An ophthalmologist had attributed the retinal bleeding to central serous chorioretinopathy, but tortuosity of superficial scleral and episcleral vessels progressed, suggesting CCV as the more likely cause (Figure 4). Currently, she is being followed for visual changes and further retinal bleeding.

Early CCV typically appears as blanchable pink or red macules, telangiectases, or petechiae on the lower extremities, progressing to involve the trunk and upper extremity.1-3 In rare cases, CCV presents in a papular or annular variant instead of the typical telangiectatic form.4,5 As the lesions progress, they often darken in appearance. Bleeding can occur, and the progressive patches are disfiguring.6,7 Middle-aged to older adults typically present with CCV (range, 16–83 years), with a mean age of 62 years.1,2,6 This disease affects both males and females, predominantly in White individuals.1 Extracutaneous manifestations are rare.1,2,6 One case of mucosal involvement was described in a patient with glossitis and oral erosions.8 We found no prior reports of nail or eye changes.1,2

The etiology of CCV is unknown, but different theories have been proposed. One is that CCV is due to a genetic defect that changes collagen synthesis in the cutaneous microvasculature. Another more widely held belief is that CCV originates from an injury that occurs to the microvasculature endothelial cells. Regardless of the cause of the triggering injury, the result is induced intravascular occlusive microthrombi that cause perivascular fibrosis and endothelial hyperplasia.2,6,7,9

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be influenced by systemic diseases. The most common comorbidities are hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia.1,3,6-8 The presentation of CCV with a malignancy is rare; 1 patient was diagnosed with multiple myeloma 18 months after CCV, and another patient’s cutaneous presentation led to discovery of pancreatic cancer with metastasis.8,10 In this setting, the increased growth factors or hypercoagulability of malignancy may play a role in endothelial cell damage and hyperplasia. Autoimmune vascular injury also has been suggested to trigger CCV; 1 case involved antiribonucleoprotein antibodies, while another case involved anti–endothelial cell antibody assays.11 In addition, CCV has been reported in hypercoagulable patients, demonstrating another route for endothelial damage, with 1 patient being heterozygous for prothrombin G20210A, a report of CCV in a patient with cryofibrinogenemia, and another patient being found positive for lupus anticoagulant.11,12 Drugs also have been thought to influence CCV, including corticosteroids, lithium, thiothixene, interferon, isotretinoin, calcium channel blockers, antibiotics, hydroxyurea, and antidepressants.7,11

The diagnosis of CCV is confirmed using light microscopy and collagen-specific immunostaining. Examination shows hyaline eosinophilic deposition of type IV collagen around the affected vessels, with the postcapillary venules showing characteristic duplication of the basal lamina.3,9 The material stains positive with periodic acid-Schiff and Masson trichrome.3

Underreporting may contribute to the low incidence of CCV. The clinical presentation of CCV is similar to generalized essential telangiectasia, with biopsy distinguishing the two. Other diagnoses in the differential include hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, which typically would have mucosal involvement; radiating telangiectatic mats and a strong family history; and hereditary benign telangiectasia, which typically presents in younger patients aged 1 year to adolescence.1

Treatment with vascular lasers has been the main focus, using either the 595-nm PDL or the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.6,13 Pulsed dye laser or intense pulsed light devices can improve patient well-being1,2; intense pulsed light allows for a larger spot size and may be preferred in patients with a larger body surface area involved.13 However, a few other treatments have been proposed. One case report noted poor response to sclerotherapy.1 In another case, a patient treated with a chemotherapy agent, bortezomib, for their concurrent multiple myeloma showed notable CCV cutaneous improvement. The proposed mechanism for bortezomib improving CCV is through its antiproliferative effect on endothelial cells of the superficial dermal vessels.8 Our patient did not achieve an adequate response with PDL, but the addition of sclerotherapy with polidocanol induced a successful response.

Patients should be examined for evidence of ocular involvement and referred to an ophthalmologist for appropriate care. Although there is no definite association with systemic illnesses or mediation, recent associations with an autoimmune disorder or underlying malignancy have been noted.8,10,11 Age-appropriate cancer screening and attention to associated signs and symptoms are recommended.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an uncommon microangiopathy that presents with progressive telangiectases on the lower extremities that can eventually spread to involve the upper extremities and trunk. Systemic involvement is uncommon. The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy, which demonstrates dilated capillaries and postcapillary venules with eosinophilic hyalinized walls. Treatment generally has focused on the use of vascular lasers.1 We report a patient with advanced CCV and ocular involvement that responded to a combination of pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy and sclerotherapy for cutaneous lesions.

A 63-year-old woman presented with partially blanchable, purple-black patches on the lower extremities (Figure 1). The upper extremities had minimal involvement at the time of presentation. A medical history revealed the lesions presented on the legs 10 years prior but were beginning to form on the arms. She had a history of hypertension and bleeding in the retina.

Histopathology revealed prominent dilation of postcapillary venules with eosinophilic collagenous materials in the vessel walls that was positive on periodic acid–Schiff stain, confirming the diagnosis of CCV. The perivascular collagenous material failed to stain with Congo red. Laboratory testing for serum protein electrophoresis, antinuclear antibodies, and baseline hematologic and metabolic panels revealed no abnormalities.

Over 3 years of treatment with PDL, most of the black patches resolved, but prominent telangiectatic vessels remained (Figure 2). Sclerotherapy with polidocanol (10 mg/mL) resulted in clearance of the majority of telangiectatic vessels. After each sclerotherapy treatment, Unna boots were applied for a minimum of 24 hours. The patient had no adverse effects from either PDL or sclerotherapy and was pleased with the results (Figure 3). An ophthalmologist had attributed the retinal bleeding to central serous chorioretinopathy, but tortuosity of superficial scleral and episcleral vessels progressed, suggesting CCV as the more likely cause (Figure 4). Currently, she is being followed for visual changes and further retinal bleeding.

Early CCV typically appears as blanchable pink or red macules, telangiectases, or petechiae on the lower extremities, progressing to involve the trunk and upper extremity.1-3 In rare cases, CCV presents in a papular or annular variant instead of the typical telangiectatic form.4,5 As the lesions progress, they often darken in appearance. Bleeding can occur, and the progressive patches are disfiguring.6,7 Middle-aged to older adults typically present with CCV (range, 16–83 years), with a mean age of 62 years.1,2,6 This disease affects both males and females, predominantly in White individuals.1 Extracutaneous manifestations are rare.1,2,6 One case of mucosal involvement was described in a patient with glossitis and oral erosions.8 We found no prior reports of nail or eye changes.1,2

The etiology of CCV is unknown, but different theories have been proposed. One is that CCV is due to a genetic defect that changes collagen synthesis in the cutaneous microvasculature. Another more widely held belief is that CCV originates from an injury that occurs to the microvasculature endothelial cells. Regardless of the cause of the triggering injury, the result is induced intravascular occlusive microthrombi that cause perivascular fibrosis and endothelial hyperplasia.2,6,7,9

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be influenced by systemic diseases. The most common comorbidities are hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia.1,3,6-8 The presentation of CCV with a malignancy is rare; 1 patient was diagnosed with multiple myeloma 18 months after CCV, and another patient’s cutaneous presentation led to discovery of pancreatic cancer with metastasis.8,10 In this setting, the increased growth factors or hypercoagulability of malignancy may play a role in endothelial cell damage and hyperplasia. Autoimmune vascular injury also has been suggested to trigger CCV; 1 case involved antiribonucleoprotein antibodies, while another case involved anti–endothelial cell antibody assays.11 In addition, CCV has been reported in hypercoagulable patients, demonstrating another route for endothelial damage, with 1 patient being heterozygous for prothrombin G20210A, a report of CCV in a patient with cryofibrinogenemia, and another patient being found positive for lupus anticoagulant.11,12 Drugs also have been thought to influence CCV, including corticosteroids, lithium, thiothixene, interferon, isotretinoin, calcium channel blockers, antibiotics, hydroxyurea, and antidepressants.7,11

The diagnosis of CCV is confirmed using light microscopy and collagen-specific immunostaining. Examination shows hyaline eosinophilic deposition of type IV collagen around the affected vessels, with the postcapillary venules showing characteristic duplication of the basal lamina.3,9 The material stains positive with periodic acid-Schiff and Masson trichrome.3

Underreporting may contribute to the low incidence of CCV. The clinical presentation of CCV is similar to generalized essential telangiectasia, with biopsy distinguishing the two. Other diagnoses in the differential include hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, which typically would have mucosal involvement; radiating telangiectatic mats and a strong family history; and hereditary benign telangiectasia, which typically presents in younger patients aged 1 year to adolescence.1

Treatment with vascular lasers has been the main focus, using either the 595-nm PDL or the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.6,13 Pulsed dye laser or intense pulsed light devices can improve patient well-being1,2; intense pulsed light allows for a larger spot size and may be preferred in patients with a larger body surface area involved.13 However, a few other treatments have been proposed. One case report noted poor response to sclerotherapy.1 In another case, a patient treated with a chemotherapy agent, bortezomib, for their concurrent multiple myeloma showed notable CCV cutaneous improvement. The proposed mechanism for bortezomib improving CCV is through its antiproliferative effect on endothelial cells of the superficial dermal vessels.8 Our patient did not achieve an adequate response with PDL, but the addition of sclerotherapy with polidocanol induced a successful response.

Patients should be examined for evidence of ocular involvement and referred to an ophthalmologist for appropriate care. Although there is no definite association with systemic illnesses or mediation, recent associations with an autoimmune disorder or underlying malignancy have been noted.8,10,11 Age-appropriate cancer screening and attention to associated signs and symptoms are recommended.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52. https://doi.org/10.1097/dad.0000000000000194

- Castiñeiras-Mato I, Rodríguez-Lojo R, Fernández-Díaz ML, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:444-447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2015.11.006

- Rambhia KD, Hadawale SD, Khopkar US. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare case report. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:40-42. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5178.174327

- Conde-Ferreirós A, Roncero-Riesco M, Cañueto J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: papular form [published online August 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. https://doi.org/10.5070/d3258045128

- García-Martínez P, Gomez-Martin I, Lloreta J, et al. Multiple progressive annular telangiectasias: a clinicopathological variant of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy? J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:982-985. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13029

- Sartori DS, de Almeida Jr HL, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213. https://doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198166

- Basso D, Ribero S, Blazek C, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare form of microangiopathy successfully treated with a combination of multiplex laser and optimized pulsed light with a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232:107-111. https://doi.org/10.1159/000439126

- Dura M, Pock L, Cetkovska P, et al. A case of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with multiple myeloma and with a pathogenic variant of the glucocerebrosidase gene. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:717-721. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14227

- Salama S, Chorneyko K, Belovic B. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with intravascular occlusive fibrin thrombi. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:386-393. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.12285

- Holder E, Schreckenberg C, Lipsker D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy leading to the diagnosis of an advanced pancreatic cancer. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E699-E701. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18152

- Grossman ME, Cohen M, Ravits M, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:491-495. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14192

- Eldik H, Leisenring NH, Al-Rohil RN, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy in a middle-aged woman with a history of prothrombin G20210A thrombophilia. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:679-682. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13895

- Weiss E, Lazzara DR. Commentary on clinical improvement of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with intense pulsed light therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1412. https://doi.org/10.1097/DSS.0000000000003209

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52. https://doi.org/10.1097/dad.0000000000000194

- Castiñeiras-Mato I, Rodríguez-Lojo R, Fernández-Díaz ML, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:444-447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2015.11.006

- Rambhia KD, Hadawale SD, Khopkar US. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare case report. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:40-42. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5178.174327

- Conde-Ferreirós A, Roncero-Riesco M, Cañueto J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: papular form [published online August 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. https://doi.org/10.5070/d3258045128

- García-Martínez P, Gomez-Martin I, Lloreta J, et al. Multiple progressive annular telangiectasias: a clinicopathological variant of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy? J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:982-985. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13029

- Sartori DS, de Almeida Jr HL, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213. https://doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198166

- Basso D, Ribero S, Blazek C, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare form of microangiopathy successfully treated with a combination of multiplex laser and optimized pulsed light with a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232:107-111. https://doi.org/10.1159/000439126

- Dura M, Pock L, Cetkovska P, et al. A case of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with multiple myeloma and with a pathogenic variant of the glucocerebrosidase gene. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:717-721. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14227

- Salama S, Chorneyko K, Belovic B. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with intravascular occlusive fibrin thrombi. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:386-393. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.12285

- Holder E, Schreckenberg C, Lipsker D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy leading to the diagnosis of an advanced pancreatic cancer. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E699-E701. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18152

- Grossman ME, Cohen M, Ravits M, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:491-495. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14192

- Eldik H, Leisenring NH, Al-Rohil RN, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy in a middle-aged woman with a history of prothrombin G20210A thrombophilia. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:679-682. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13895

- Weiss E, Lazzara DR. Commentary on clinical improvement of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with intense pulsed light therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1412. https://doi.org/10.1097/DSS.0000000000003209

Practice Points

- Collagenous vasculopathy is an underrecognized entity.

- Although most patients exhibit only cutaneous disease, systemic involvement also should be assessed.

Commentary: Diagnostic Delay and Optimal Treatments for PsA, November 2023

There is steady advance in the treatment of PsA. Bimekizumab is a novel monoclonal antibody that, by binding to similar sites on interleukin (IL)-17A and IL-17F, inhibits these cytokines. Ritchlin and colleagues recently reported the 52-week results from the phase 3 BE OPTIMAL study including 852 biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD)-naive patients with active PsA who were randomly assigned to receive bimekizumab, adalimumab, or placebo. At week 16, 43.9% of patients receiving bimekizumab achieved ≥ 50% improvement in the American College of Rheumatology scores (ACR50), with the response being maintained up to week 52 (54.5%). Among patients who switched from placebo to bimekizumab at week 16, a similar proportion (53.0%) achieved ACR50 at week 52. No new safety signals were observed. Thus, bimekizumab led to sustained improvements in clinical response up to week 52 and probably will soon be available to patients with PsA.

The optimal management of axial PsA continues to be investigated. One major question is whether IL-23 inhibitors, which are not efficacious in axial spondyloarthritis, have efficacy in axial PsA. A post hoc analysis of the DISCOVER-2 study included 246 biologic-naive patients with active PsA and sacroiliitis who were randomly assigned to guselkumab every 4 weeks (Q4W; n = 82), guselkumab every 8 weeks (Q8W; n = 68), or placebo with crossover to guselkumab Q4W at week 24 (n = 96), Mease and colleagues report that at week 24, guselkumab Q4W and Q8W vs placebo showed significantly greater scores in the total Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) as well as Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS), with further improvements noted at week 100. Thus, in patients with active PsA and imaging-confirmed sacroiliitis, 100 mg guselkumab Q4W and Q8W yielded clinically meaningful and sustained improvements in axial symptoms through 2 years.

Finally, attention is currently being paid to patients with refractory or difficult-to-treat (D2T) PsA. These patients are generally characterized as having active disease despite treatment with two or more targeted DMARD (tDMARD). Philippoteaux and colleagues have reported results from their retrospective cohort study that included 150 patients with PsA who initiated treatment with tDMARD and were followed for at least 2 years, of whom 49 patients had D2T PsA. They found that peripheral structural damage, axial involvement, and the discontinuation of bDMARD due to poor skin psoriasis control were more prevalent in patients with D2T PsA compared with in non-D2T PsA. Thus, patients with D2T PsA are more likely to have more structural damage. Early diagnosis and treatment to reduce structural damage might reduce the prevalence of D2T PsA.

There is steady advance in the treatment of PsA. Bimekizumab is a novel monoclonal antibody that, by binding to similar sites on interleukin (IL)-17A and IL-17F, inhibits these cytokines. Ritchlin and colleagues recently reported the 52-week results from the phase 3 BE OPTIMAL study including 852 biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD)-naive patients with active PsA who were randomly assigned to receive bimekizumab, adalimumab, or placebo. At week 16, 43.9% of patients receiving bimekizumab achieved ≥ 50% improvement in the American College of Rheumatology scores (ACR50), with the response being maintained up to week 52 (54.5%). Among patients who switched from placebo to bimekizumab at week 16, a similar proportion (53.0%) achieved ACR50 at week 52. No new safety signals were observed. Thus, bimekizumab led to sustained improvements in clinical response up to week 52 and probably will soon be available to patients with PsA.

The optimal management of axial PsA continues to be investigated. One major question is whether IL-23 inhibitors, which are not efficacious in axial spondyloarthritis, have efficacy in axial PsA. A post hoc analysis of the DISCOVER-2 study included 246 biologic-naive patients with active PsA and sacroiliitis who were randomly assigned to guselkumab every 4 weeks (Q4W; n = 82), guselkumab every 8 weeks (Q8W; n = 68), or placebo with crossover to guselkumab Q4W at week 24 (n = 96), Mease and colleagues report that at week 24, guselkumab Q4W and Q8W vs placebo showed significantly greater scores in the total Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) as well as Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS), with further improvements noted at week 100. Thus, in patients with active PsA and imaging-confirmed sacroiliitis, 100 mg guselkumab Q4W and Q8W yielded clinically meaningful and sustained improvements in axial symptoms through 2 years.

Finally, attention is currently being paid to patients with refractory or difficult-to-treat (D2T) PsA. These patients are generally characterized as having active disease despite treatment with two or more targeted DMARD (tDMARD). Philippoteaux and colleagues have reported results from their retrospective cohort study that included 150 patients with PsA who initiated treatment with tDMARD and were followed for at least 2 years, of whom 49 patients had D2T PsA. They found that peripheral structural damage, axial involvement, and the discontinuation of bDMARD due to poor skin psoriasis control were more prevalent in patients with D2T PsA compared with in non-D2T PsA. Thus, patients with D2T PsA are more likely to have more structural damage. Early diagnosis and treatment to reduce structural damage might reduce the prevalence of D2T PsA.

There is steady advance in the treatment of PsA. Bimekizumab is a novel monoclonal antibody that, by binding to similar sites on interleukin (IL)-17A and IL-17F, inhibits these cytokines. Ritchlin and colleagues recently reported the 52-week results from the phase 3 BE OPTIMAL study including 852 biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD)-naive patients with active PsA who were randomly assigned to receive bimekizumab, adalimumab, or placebo. At week 16, 43.9% of patients receiving bimekizumab achieved ≥ 50% improvement in the American College of Rheumatology scores (ACR50), with the response being maintained up to week 52 (54.5%). Among patients who switched from placebo to bimekizumab at week 16, a similar proportion (53.0%) achieved ACR50 at week 52. No new safety signals were observed. Thus, bimekizumab led to sustained improvements in clinical response up to week 52 and probably will soon be available to patients with PsA.

The optimal management of axial PsA continues to be investigated. One major question is whether IL-23 inhibitors, which are not efficacious in axial spondyloarthritis, have efficacy in axial PsA. A post hoc analysis of the DISCOVER-2 study included 246 biologic-naive patients with active PsA and sacroiliitis who were randomly assigned to guselkumab every 4 weeks (Q4W; n = 82), guselkumab every 8 weeks (Q8W; n = 68), or placebo with crossover to guselkumab Q4W at week 24 (n = 96), Mease and colleagues report that at week 24, guselkumab Q4W and Q8W vs placebo showed significantly greater scores in the total Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) as well as Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS), with further improvements noted at week 100. Thus, in patients with active PsA and imaging-confirmed sacroiliitis, 100 mg guselkumab Q4W and Q8W yielded clinically meaningful and sustained improvements in axial symptoms through 2 years.

Finally, attention is currently being paid to patients with refractory or difficult-to-treat (D2T) PsA. These patients are generally characterized as having active disease despite treatment with two or more targeted DMARD (tDMARD). Philippoteaux and colleagues have reported results from their retrospective cohort study that included 150 patients with PsA who initiated treatment with tDMARD and were followed for at least 2 years, of whom 49 patients had D2T PsA. They found that peripheral structural damage, axial involvement, and the discontinuation of bDMARD due to poor skin psoriasis control were more prevalent in patients with D2T PsA compared with in non-D2T PsA. Thus, patients with D2T PsA are more likely to have more structural damage. Early diagnosis and treatment to reduce structural damage might reduce the prevalence of D2T PsA.

Skin in the Game: Inadequate Photoprotection Among Olympic Athletes

The XXXIII Olympic Summer Games will take place in Paris, France, from July 26 to August 11, 2024, and a variety of outdoor sporting events (eg, surfing, cycling, beach volleyball) will be included. Participation in the Olympic Games is a distinct honor for athletes selected to compete at the highest level in their sports.

Because of their training regimens and lifestyles, Olympic athletes face unique health risks. One such risk appears to be skin cancer, a substantial contributor to the global burden of disease. Taken together, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma account for 6.7 million cases of skin cancer worldwide. Squamous cell carcinoma and malignant skin melanoma were attributed to 1.2 million and 1.7 million life-years lost to disability, respectively.1

Olympic athletes are at increased risk for sunburn from UVA and UVB radiation, placing them at higher risk for both melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers.2,3 Sweating increases skin photosensitivity, sportswear often offers inadequate sun protection, and sustained high-intensity exercise itself has an immunosuppressive effect. Athletes competing in skiing and snowboarding events also receive radiation reflected off snow and ice at high altitudes.3 In fact, skiing without sunscreen at 11,000-feet above sea level can induce sunburn after only 6 minutes of exposure.4 Moreover, sweat, water immersion, and friction can decrease the effectiveness of topical sunscreens.5

World-class athletes appear to be exposed to UV radiation to a substantially higher degree than the general public. In an analysis of 144 events at the 2020 XXXII Olympic Summer Games in Tokyo, Japan, the highest exposure assessments were for women’s tennis, men’s golf, and men’s road cycling.6 In a 2020 study (N=240), the rates of sunburn were as high as 76.7% among Olympic sailors, elite surfers, and windsurfers, with more than one-quarter of athletes reporting sunburn that lasted longer than 24 hours.7 An earlier study reported that professional cyclists were exposed to UV radiation during a single race that exceeded the personal exposure limit by 30 times.8

Regrettably, the high level of sun exposure experienced by elite athletes is compounded by their low rate of sunscreen use. In a 2020 survey of 95 Olympians and super sprint triathletes, approximately half rarely used sunscreen, with 1 in 5 athletes never using sunscreen during training.9 In another study of 246 elite athletes in surfing, windsurfing, and sailing, nearly half used inadequate sun protection and nearly one-quarter reported never using sunscreen.10 Surprisingly, as many as 90% of Olympic athletes and super sprint competitors understood the importance of using sunscreen.9

What can we learn from these findings?

First, elite athletes remain at high risk for skin cancer because of training regimens, occupational environmental hazards, and other requirements of their sport. Second, despite awareness of the risks of UV radiation exposure, Olympic athletes utilize inadequate photoprotection. Athletes with darker skin are still at risk for skin cancer, photoaging, and pigmentation disorders—indicating a need for photoprotective behaviors in athletes of all skin types.11

Therefore, efforts to promote adequate sunscreen use and understanding of the consequences of UV radiation may need to be prioritized earlier in athletes’ careers and implemented according to evidence-based guidelines. For example, the Stanford University Network for Sun Protection, Outreach, Research and Teamwork (Sunsport) provided information about skin cancer risk and prevention by educating student-athletes, coaches, and trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Association in the United States. The Sunsport initiative led to a dramatic increase in sunscreen use by student-athletes as well as increased knowledge and discussion of skin cancer risk.12

- Zhang W, Zeng W, Jiang A, et al. Global, regional and national incidence, mortality and disability-adjusted life-years of skin cancers and trend analysis from 1990 to 2019: an analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Cancer Med. 2021;10:4905-4922. doi:10.1002/cam4.4046

- De Luca JF, Adams BB, Yosipovitch G. Skin manifestations of athletes competing in the summer Olympics: what a sports medicine physician should know. Sports Med. 2012;42:399-413. doi:10.2165/11599050-000000000-00000

- Moehrle M. Outdoor sports and skin cancer. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:12-15. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.10.001

- Rigel DS, Rigel EG, Rigel AC. Effects of altitude and latitude on ambient UVB radiation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:114-116. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70542-6

- Harrison SC, Bergfeld WF. Ultraviolet light and skin cancer in athletes. Sports Health. 2009;1:335-340. doi:10.1177/19417381093338923

- Downs NJ, Axelsen T, Schouten P, et al. Biologically effective solar ultraviolet exposures and the potential skin cancer risk for individual gold medalists of the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympic Games. Temperature (Austin). 2019;7:89-108. doi:10.1080/23328940.2019.1581427

- De Castro-Maqueda G, Gutierrez-Manzanedo JV, Ponce-González JG, et al. Sun protection habits and sunburn in elite aquatics athletes: surfers, windsurfers and Olympic sailors. J Cancer Educ. 2020;35:312-320. doi:10.1007/s13187-018-1466-x

- Moehrle M, Heinrich L, Schmid A, et al. Extreme UV exposure of professional cyclists. Dermatology. 2000;201:44-45. doi:10.1159/000018428

- Buljan M, Kolic´ M, Šitum M, et al. Do athletes practicing outdoors know and care enough about the importance of photoprotection? Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2020;28:41-42.

- De Castro-Maqueda G, Gutierrez-Manzanedo JV, Lagares-Franco C. Sun exposure during water sports: do elite athletes adequately protect their skin against skin cancer? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:800. doi:10.3390/ijerph18020800

- Tsai J, Chien AL. Photoprotection for skin of color. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:195-205. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00670-z

- Ally MS, Swetter SM, Hirotsu KE, et al. Promoting sunscreen use and sun-protective practices in NCAA athletes: impact of SUNSPORT educational intervention for student-athletes, athletic trainers, and coaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:289-292.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.050

The XXXIII Olympic Summer Games will take place in Paris, France, from July 26 to August 11, 2024, and a variety of outdoor sporting events (eg, surfing, cycling, beach volleyball) will be included. Participation in the Olympic Games is a distinct honor for athletes selected to compete at the highest level in their sports.

Because of their training regimens and lifestyles, Olympic athletes face unique health risks. One such risk appears to be skin cancer, a substantial contributor to the global burden of disease. Taken together, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma account for 6.7 million cases of skin cancer worldwide. Squamous cell carcinoma and malignant skin melanoma were attributed to 1.2 million and 1.7 million life-years lost to disability, respectively.1

Olympic athletes are at increased risk for sunburn from UVA and UVB radiation, placing them at higher risk for both melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers.2,3 Sweating increases skin photosensitivity, sportswear often offers inadequate sun protection, and sustained high-intensity exercise itself has an immunosuppressive effect. Athletes competing in skiing and snowboarding events also receive radiation reflected off snow and ice at high altitudes.3 In fact, skiing without sunscreen at 11,000-feet above sea level can induce sunburn after only 6 minutes of exposure.4 Moreover, sweat, water immersion, and friction can decrease the effectiveness of topical sunscreens.5

World-class athletes appear to be exposed to UV radiation to a substantially higher degree than the general public. In an analysis of 144 events at the 2020 XXXII Olympic Summer Games in Tokyo, Japan, the highest exposure assessments were for women’s tennis, men’s golf, and men’s road cycling.6 In a 2020 study (N=240), the rates of sunburn were as high as 76.7% among Olympic sailors, elite surfers, and windsurfers, with more than one-quarter of athletes reporting sunburn that lasted longer than 24 hours.7 An earlier study reported that professional cyclists were exposed to UV radiation during a single race that exceeded the personal exposure limit by 30 times.8