User login

Can We Successfully Adapt to Changes in Direction and Support for Acne?

Can We Successfully Adapt to Changes in Direction and Support for Acne?

How did I develop a strong interest in acne and rosacea? Interest on a personal level was with me throughout my adolescence and post-teen years as I suffered with very severe facial acne from ages 13 through 23 (1967-1977). I was sometimes called “pizza face” in high school, and biweekly trips to a dermatology office that always had a packed waiting room were of little help that I could appreciate visibly. Six straight years of extractions, intralesional injections, draining of fluctuant cysts, UVC light treatments, oral tetracycline, irritating topical formulations of benzoyl peroxide and tretinoin, and topical sulfacetamide-sulfur products resulted in minimal improvement. However, maybe all of this did something to what was happening underneath the skin surface, as I have no residual acne scars. I do recall vividly that I walked the halls in high school and college consistently affected by a very red face from the topical agents and smelling like rotten eggs from the topical sulfur application. I fortunately handled it well emotionally and socially, for which I am very thankful. Many people affected with acne do not.

In dermatology, I have always had a strong interest in pathophysiology and therapeutics, rooted I am sure in my background as a pharmacist. Although I was always interested in acne therapy, I was fully captivated by a presentation given by Dr. Jim Leyden many years ago at a small meeting in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. He brought the subject of acne to life in a way that more than grabbed my complete attention and ignited an interest in learning everything I could about it. Over time, I was fortunate enough to work alongside Dr. Leyden and many other household names in acne at meetings and publications to further education on one of the most common disease states seen in ambulatory dermatology practices worldwide. The rest is history, leading to almost 4 decades of work in acne on many levels in dermatology, all being efforts that I am grateful for.

What I have observed to date is that we have had few revolutionary advances in acne therapy, the major one being oral isotretinoin, which was first brought to market in 1982. We are still utilizing many of the same therapeutic agents that I used back when I was treated for acne. A few new topical compounds have emerged, such as dapsone and clascoterone, and a narrow-spectrum tetracycline agent, sarecycline, also was developed. These agents do represent important advances with some specific benefits. There have been many major improvements in drug delivery formulations, including several vehicle technologies that allow augmented skin tolerability, increased efficacy, and improved stability, allowing for combination therapy products containing 2 or 3 active ingredients. A recent example is the first triple-combination topical acne therapy with excellent supporting data on speed of onset, efficacy, and safety.1

Technological advances also have aided in the development of modified- or extended-release formulations of oral antibiotics, such as doxycycline and minocycline, which allow for reduced adverse effects and lower daily dosages. Lidose formulations of isotretinoin have circumvented the need for concurrent ingestion of a high-fat meal to facilitate its absorption in the gastrointestinal tract (as required with conventional formulations). Many hours also have been spent on delivery devices and vehicles such as pumps, foams, and aqueous-based gels. Let us not forget the efforts and myriad products directed at skin care, cosmeceuticals, and physical devices (lasers and lights) for acne. Regardless of the above, we have not seen the monumental therapeutic and research revolution for acne that we have experienced more recently with biologic agents, Janus kinase inhibitors, and other modes of action for many common disease states such as atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, hidradenitis suppurativa, prurigo nodularis, and chronic spontaneous urticaria.

Unfortunately, the slow development of advances in treatments for acne has been compounded further by the widespread availability of generic equivalents of most topical and oral therapies along with several over-the- counter topical medications. The expanded skin care and cosmeceutical product world has further diluted the perceived value of topical prescription therapies for acne. The marked difficulty in achieving and sustaining total clearance of acne, with the exception of many individuals treated with oral isotretinoin, results in many patients searching for other options, often through sources beyond dermatology practices (eg, the internet). While some of these sources may provide valid suggestions, they often are not truly substantiated by valid clinical research and are not formally regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration.

All of the above, in addition to the barriers to medication coverage put in place by third-party organizations such as pharmacy benefit managers, have contributed to the extreme slowdown in the development of new prescription therapies for acne. What this leads me to believe is that until there is a true meeting of the minds of all stakeholders on policies that facilitate access to both established and newly available acne therapies, there will be an enduring diminished incentive to support the development of newer acne treatments that will continue to spiral progressively downward. Some research on acne will always continue, such as the search for an acne vaccine and cutaneous microbiome alterations that are in progress.2,3 However, I do not see much happening in the foreseeable future. I am not inherently a pessimist or a “prophet of doom,” so I sincerely hope I am wrong.

- Stein Gold L, Baldwin H, Kircik LH, et al. Efficacy and safety of a fixed-dose clindamycin phosphate 1.2%, benzoyl peroxide 3.1%, and adapalene 0.15% gel for moderate-to-severe acne: a randomized phase II study of the first triple-combination drug. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:93-104. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00650-3

- Keshari S, Kumar M, Balasubramaniam A, et al. Prospects of acne vaccines targeting secreted virulence factors of Cutibacterium acnes. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2019;18:433-437. doi:10.1080/14760584

- Dreno B, Dekio I, Baldwin H, et al. Acne microbiome: from phyla to phylotypes. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024;38:657- 664. doi:10.1111/jdv.19540 .2019.1593830

How did I develop a strong interest in acne and rosacea? Interest on a personal level was with me throughout my adolescence and post-teen years as I suffered with very severe facial acne from ages 13 through 23 (1967-1977). I was sometimes called “pizza face” in high school, and biweekly trips to a dermatology office that always had a packed waiting room were of little help that I could appreciate visibly. Six straight years of extractions, intralesional injections, draining of fluctuant cysts, UVC light treatments, oral tetracycline, irritating topical formulations of benzoyl peroxide and tretinoin, and topical sulfacetamide-sulfur products resulted in minimal improvement. However, maybe all of this did something to what was happening underneath the skin surface, as I have no residual acne scars. I do recall vividly that I walked the halls in high school and college consistently affected by a very red face from the topical agents and smelling like rotten eggs from the topical sulfur application. I fortunately handled it well emotionally and socially, for which I am very thankful. Many people affected with acne do not.

In dermatology, I have always had a strong interest in pathophysiology and therapeutics, rooted I am sure in my background as a pharmacist. Although I was always interested in acne therapy, I was fully captivated by a presentation given by Dr. Jim Leyden many years ago at a small meeting in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. He brought the subject of acne to life in a way that more than grabbed my complete attention and ignited an interest in learning everything I could about it. Over time, I was fortunate enough to work alongside Dr. Leyden and many other household names in acne at meetings and publications to further education on one of the most common disease states seen in ambulatory dermatology practices worldwide. The rest is history, leading to almost 4 decades of work in acne on many levels in dermatology, all being efforts that I am grateful for.

What I have observed to date is that we have had few revolutionary advances in acne therapy, the major one being oral isotretinoin, which was first brought to market in 1982. We are still utilizing many of the same therapeutic agents that I used back when I was treated for acne. A few new topical compounds have emerged, such as dapsone and clascoterone, and a narrow-spectrum tetracycline agent, sarecycline, also was developed. These agents do represent important advances with some specific benefits. There have been many major improvements in drug delivery formulations, including several vehicle technologies that allow augmented skin tolerability, increased efficacy, and improved stability, allowing for combination therapy products containing 2 or 3 active ingredients. A recent example is the first triple-combination topical acne therapy with excellent supporting data on speed of onset, efficacy, and safety.1

Technological advances also have aided in the development of modified- or extended-release formulations of oral antibiotics, such as doxycycline and minocycline, which allow for reduced adverse effects and lower daily dosages. Lidose formulations of isotretinoin have circumvented the need for concurrent ingestion of a high-fat meal to facilitate its absorption in the gastrointestinal tract (as required with conventional formulations). Many hours also have been spent on delivery devices and vehicles such as pumps, foams, and aqueous-based gels. Let us not forget the efforts and myriad products directed at skin care, cosmeceuticals, and physical devices (lasers and lights) for acne. Regardless of the above, we have not seen the monumental therapeutic and research revolution for acne that we have experienced more recently with biologic agents, Janus kinase inhibitors, and other modes of action for many common disease states such as atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, hidradenitis suppurativa, prurigo nodularis, and chronic spontaneous urticaria.

Unfortunately, the slow development of advances in treatments for acne has been compounded further by the widespread availability of generic equivalents of most topical and oral therapies along with several over-the- counter topical medications. The expanded skin care and cosmeceutical product world has further diluted the perceived value of topical prescription therapies for acne. The marked difficulty in achieving and sustaining total clearance of acne, with the exception of many individuals treated with oral isotretinoin, results in many patients searching for other options, often through sources beyond dermatology practices (eg, the internet). While some of these sources may provide valid suggestions, they often are not truly substantiated by valid clinical research and are not formally regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration.

All of the above, in addition to the barriers to medication coverage put in place by third-party organizations such as pharmacy benefit managers, have contributed to the extreme slowdown in the development of new prescription therapies for acne. What this leads me to believe is that until there is a true meeting of the minds of all stakeholders on policies that facilitate access to both established and newly available acne therapies, there will be an enduring diminished incentive to support the development of newer acne treatments that will continue to spiral progressively downward. Some research on acne will always continue, such as the search for an acne vaccine and cutaneous microbiome alterations that are in progress.2,3 However, I do not see much happening in the foreseeable future. I am not inherently a pessimist or a “prophet of doom,” so I sincerely hope I am wrong.

How did I develop a strong interest in acne and rosacea? Interest on a personal level was with me throughout my adolescence and post-teen years as I suffered with very severe facial acne from ages 13 through 23 (1967-1977). I was sometimes called “pizza face” in high school, and biweekly trips to a dermatology office that always had a packed waiting room were of little help that I could appreciate visibly. Six straight years of extractions, intralesional injections, draining of fluctuant cysts, UVC light treatments, oral tetracycline, irritating topical formulations of benzoyl peroxide and tretinoin, and topical sulfacetamide-sulfur products resulted in minimal improvement. However, maybe all of this did something to what was happening underneath the skin surface, as I have no residual acne scars. I do recall vividly that I walked the halls in high school and college consistently affected by a very red face from the topical agents and smelling like rotten eggs from the topical sulfur application. I fortunately handled it well emotionally and socially, for which I am very thankful. Many people affected with acne do not.

In dermatology, I have always had a strong interest in pathophysiology and therapeutics, rooted I am sure in my background as a pharmacist. Although I was always interested in acne therapy, I was fully captivated by a presentation given by Dr. Jim Leyden many years ago at a small meeting in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. He brought the subject of acne to life in a way that more than grabbed my complete attention and ignited an interest in learning everything I could about it. Over time, I was fortunate enough to work alongside Dr. Leyden and many other household names in acne at meetings and publications to further education on one of the most common disease states seen in ambulatory dermatology practices worldwide. The rest is history, leading to almost 4 decades of work in acne on many levels in dermatology, all being efforts that I am grateful for.

What I have observed to date is that we have had few revolutionary advances in acne therapy, the major one being oral isotretinoin, which was first brought to market in 1982. We are still utilizing many of the same therapeutic agents that I used back when I was treated for acne. A few new topical compounds have emerged, such as dapsone and clascoterone, and a narrow-spectrum tetracycline agent, sarecycline, also was developed. These agents do represent important advances with some specific benefits. There have been many major improvements in drug delivery formulations, including several vehicle technologies that allow augmented skin tolerability, increased efficacy, and improved stability, allowing for combination therapy products containing 2 or 3 active ingredients. A recent example is the first triple-combination topical acne therapy with excellent supporting data on speed of onset, efficacy, and safety.1

Technological advances also have aided in the development of modified- or extended-release formulations of oral antibiotics, such as doxycycline and minocycline, which allow for reduced adverse effects and lower daily dosages. Lidose formulations of isotretinoin have circumvented the need for concurrent ingestion of a high-fat meal to facilitate its absorption in the gastrointestinal tract (as required with conventional formulations). Many hours also have been spent on delivery devices and vehicles such as pumps, foams, and aqueous-based gels. Let us not forget the efforts and myriad products directed at skin care, cosmeceuticals, and physical devices (lasers and lights) for acne. Regardless of the above, we have not seen the monumental therapeutic and research revolution for acne that we have experienced more recently with biologic agents, Janus kinase inhibitors, and other modes of action for many common disease states such as atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, hidradenitis suppurativa, prurigo nodularis, and chronic spontaneous urticaria.

Unfortunately, the slow development of advances in treatments for acne has been compounded further by the widespread availability of generic equivalents of most topical and oral therapies along with several over-the- counter topical medications. The expanded skin care and cosmeceutical product world has further diluted the perceived value of topical prescription therapies for acne. The marked difficulty in achieving and sustaining total clearance of acne, with the exception of many individuals treated with oral isotretinoin, results in many patients searching for other options, often through sources beyond dermatology practices (eg, the internet). While some of these sources may provide valid suggestions, they often are not truly substantiated by valid clinical research and are not formally regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration.

All of the above, in addition to the barriers to medication coverage put in place by third-party organizations such as pharmacy benefit managers, have contributed to the extreme slowdown in the development of new prescription therapies for acne. What this leads me to believe is that until there is a true meeting of the minds of all stakeholders on policies that facilitate access to both established and newly available acne therapies, there will be an enduring diminished incentive to support the development of newer acne treatments that will continue to spiral progressively downward. Some research on acne will always continue, such as the search for an acne vaccine and cutaneous microbiome alterations that are in progress.2,3 However, I do not see much happening in the foreseeable future. I am not inherently a pessimist or a “prophet of doom,” so I sincerely hope I am wrong.

- Stein Gold L, Baldwin H, Kircik LH, et al. Efficacy and safety of a fixed-dose clindamycin phosphate 1.2%, benzoyl peroxide 3.1%, and adapalene 0.15% gel for moderate-to-severe acne: a randomized phase II study of the first triple-combination drug. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:93-104. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00650-3

- Keshari S, Kumar M, Balasubramaniam A, et al. Prospects of acne vaccines targeting secreted virulence factors of Cutibacterium acnes. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2019;18:433-437. doi:10.1080/14760584

- Dreno B, Dekio I, Baldwin H, et al. Acne microbiome: from phyla to phylotypes. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024;38:657- 664. doi:10.1111/jdv.19540 .2019.1593830

- Stein Gold L, Baldwin H, Kircik LH, et al. Efficacy and safety of a fixed-dose clindamycin phosphate 1.2%, benzoyl peroxide 3.1%, and adapalene 0.15% gel for moderate-to-severe acne: a randomized phase II study of the first triple-combination drug. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:93-104. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00650-3

- Keshari S, Kumar M, Balasubramaniam A, et al. Prospects of acne vaccines targeting secreted virulence factors of Cutibacterium acnes. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2019;18:433-437. doi:10.1080/14760584

- Dreno B, Dekio I, Baldwin H, et al. Acne microbiome: from phyla to phylotypes. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024;38:657- 664. doi:10.1111/jdv.19540 .2019.1593830

Can We Successfully Adapt to Changes in Direction and Support for Acne?

Can We Successfully Adapt to Changes in Direction and Support for Acne?

Benzoyl Peroxide, Benzene, and Lots of Unanswered Questions: Where Are We Now?

March 2024 proved to be a busy month for benzoyl peroxide in the media! We are now at almost 4 months since Valisure, an independent analytical laboratory located in Connecticut, filed a Citizen Petition on benzene in benzoyl peroxide drug products with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on March 5, 2024.1 This petition was filed shortly before the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology was held in San Diego, California, creating quite a stir of concern in the dermatology world. Further information on the degradation of benzoyl peroxide with production of benzene was published in the medical literature in March 2024.2 As benzene is recognized as a human carcinogen, manufacturing regulations exist to assure that it does not appear in topical products either through contamination or degradation over the course of a product’s shelf-life.3

As anticipated, several opinions and commentaries appeared quickly, both on video and in various articles. The American Acne & Rosacea Society (AARS) released a statement on this issue on March 20, 2024.4 The safety of the public is the overarching primary concern. This AARS statement does include some general suggestions related to benzoyl peroxide use based on the best assessment to date while awaiting further guidance from the FDA on this issue. Benzoyl peroxide is approved for use by the FDA as an over-the-counter (OTC) topical product for acne and also is in several FDA-approved prescription topical products.5,6

The following reflects my personal viewpoint as both a dermatologist and a grandfather who has grandchildren who use acne products. My views are not necessarily those of AARS. Since early March 2024, I have read several documents and spoken to several dermatologists, scientists, and formulators with knowledge in this area, including contacts at Valisure. I was hoping to get to some reasonable definitive answer but have not been able to achieve this to my full satisfaction. There are many opinions and concerns, and each one makes sense based on the vantage point of the presenter. However, several unanswered questions remain related to what testing and data are currently required of companies to gain FDA approval of a benzoyl peroxide product, including:

- assessment of stability and degradation products (including benzene),

- validation of testing methods,

- the issue of benzoyl peroxide stability in commercial products, and

- the relevant magnitude of resultant benzene exposures, especially as we are all exposed to benzene from several sources each day.

I am certain that companies with benzoyl peroxide products will evaluate their already-approved products and also do further testing. However, in this situation, which impacts millions of people on so many levels, I feel there needs to be an organized approach to evaluate and resolve the issue, otherwise the likelihood of continued confusion and uncertainty is high. As the FDA is the approval body, I am hoping it will provide definitive guidance within a reasonable timeline so that clinicians, patients, and manufacturers of benzoyl peroxide can proceed with full confidence. Right now, we all remain in a state of limbo. It is time for less talk and more definitive action to sort out this issue.

- Valisure Citizen Petition on Benzene in Benzoyl Peroxide Products. March 5, 2024. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://assets-global.website-files.com/6215052733f8bb8fea016220/65e8560962ed23f744902a7b_Valisure%20Citizen%20Petition%20on%20Benzene%20in%20Benzoyl%20Peroxide%20Drug%20Products.pdf

- Kucera K, Zenzola N, Hudspeth A, et al. Benzoyl peroxide drug products form benzene. Environ Health Perspect. 2024;132:37702. doi:10.1289/EHP13984

- US Food and Drug Administration. Reformulating drug products that contain carbomers manufactured with benzene. December 2023. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/reformulating-drug-products-contain-carbomers-manufactured-benzene

- American Acne & Rosacea Society. Response Statement from the AARS to the Valisure Citizen Petition on Benzene in Benzoyl Peroxide Drug Products. March 20, 2024. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.einpresswire.com/article/697481595/response-statement-from-the-aars-to-the-valisure-citizen-petition-on-benzene-in-benzoyl-peroxide-drug-products

- Department of Health and Human Services. Classification of benzoyl peroxide as safe and effective and revision of labeling to drug facts format; topical acne drug products for over-the-counter human use; Final Rule. Fed Registr. 2010;75:9767-9777.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Topical acne drug products for over-the-counter human use—revision of labeling and classification of benzoyl peroxide as safe and effective. June 2011. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/topical-acne-drug-products-over-counter-human-use-revision-labeling-and-classification-benzoyl

March 2024 proved to be a busy month for benzoyl peroxide in the media! We are now at almost 4 months since Valisure, an independent analytical laboratory located in Connecticut, filed a Citizen Petition on benzene in benzoyl peroxide drug products with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on March 5, 2024.1 This petition was filed shortly before the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology was held in San Diego, California, creating quite a stir of concern in the dermatology world. Further information on the degradation of benzoyl peroxide with production of benzene was published in the medical literature in March 2024.2 As benzene is recognized as a human carcinogen, manufacturing regulations exist to assure that it does not appear in topical products either through contamination or degradation over the course of a product’s shelf-life.3

As anticipated, several opinions and commentaries appeared quickly, both on video and in various articles. The American Acne & Rosacea Society (AARS) released a statement on this issue on March 20, 2024.4 The safety of the public is the overarching primary concern. This AARS statement does include some general suggestions related to benzoyl peroxide use based on the best assessment to date while awaiting further guidance from the FDA on this issue. Benzoyl peroxide is approved for use by the FDA as an over-the-counter (OTC) topical product for acne and also is in several FDA-approved prescription topical products.5,6

The following reflects my personal viewpoint as both a dermatologist and a grandfather who has grandchildren who use acne products. My views are not necessarily those of AARS. Since early March 2024, I have read several documents and spoken to several dermatologists, scientists, and formulators with knowledge in this area, including contacts at Valisure. I was hoping to get to some reasonable definitive answer but have not been able to achieve this to my full satisfaction. There are many opinions and concerns, and each one makes sense based on the vantage point of the presenter. However, several unanswered questions remain related to what testing and data are currently required of companies to gain FDA approval of a benzoyl peroxide product, including:

- assessment of stability and degradation products (including benzene),

- validation of testing methods,

- the issue of benzoyl peroxide stability in commercial products, and

- the relevant magnitude of resultant benzene exposures, especially as we are all exposed to benzene from several sources each day.

I am certain that companies with benzoyl peroxide products will evaluate their already-approved products and also do further testing. However, in this situation, which impacts millions of people on so many levels, I feel there needs to be an organized approach to evaluate and resolve the issue, otherwise the likelihood of continued confusion and uncertainty is high. As the FDA is the approval body, I am hoping it will provide definitive guidance within a reasonable timeline so that clinicians, patients, and manufacturers of benzoyl peroxide can proceed with full confidence. Right now, we all remain in a state of limbo. It is time for less talk and more definitive action to sort out this issue.

March 2024 proved to be a busy month for benzoyl peroxide in the media! We are now at almost 4 months since Valisure, an independent analytical laboratory located in Connecticut, filed a Citizen Petition on benzene in benzoyl peroxide drug products with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on March 5, 2024.1 This petition was filed shortly before the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology was held in San Diego, California, creating quite a stir of concern in the dermatology world. Further information on the degradation of benzoyl peroxide with production of benzene was published in the medical literature in March 2024.2 As benzene is recognized as a human carcinogen, manufacturing regulations exist to assure that it does not appear in topical products either through contamination or degradation over the course of a product’s shelf-life.3

As anticipated, several opinions and commentaries appeared quickly, both on video and in various articles. The American Acne & Rosacea Society (AARS) released a statement on this issue on March 20, 2024.4 The safety of the public is the overarching primary concern. This AARS statement does include some general suggestions related to benzoyl peroxide use based on the best assessment to date while awaiting further guidance from the FDA on this issue. Benzoyl peroxide is approved for use by the FDA as an over-the-counter (OTC) topical product for acne and also is in several FDA-approved prescription topical products.5,6

The following reflects my personal viewpoint as both a dermatologist and a grandfather who has grandchildren who use acne products. My views are not necessarily those of AARS. Since early March 2024, I have read several documents and spoken to several dermatologists, scientists, and formulators with knowledge in this area, including contacts at Valisure. I was hoping to get to some reasonable definitive answer but have not been able to achieve this to my full satisfaction. There are many opinions and concerns, and each one makes sense based on the vantage point of the presenter. However, several unanswered questions remain related to what testing and data are currently required of companies to gain FDA approval of a benzoyl peroxide product, including:

- assessment of stability and degradation products (including benzene),

- validation of testing methods,

- the issue of benzoyl peroxide stability in commercial products, and

- the relevant magnitude of resultant benzene exposures, especially as we are all exposed to benzene from several sources each day.

I am certain that companies with benzoyl peroxide products will evaluate their already-approved products and also do further testing. However, in this situation, which impacts millions of people on so many levels, I feel there needs to be an organized approach to evaluate and resolve the issue, otherwise the likelihood of continued confusion and uncertainty is high. As the FDA is the approval body, I am hoping it will provide definitive guidance within a reasonable timeline so that clinicians, patients, and manufacturers of benzoyl peroxide can proceed with full confidence. Right now, we all remain in a state of limbo. It is time for less talk and more definitive action to sort out this issue.

- Valisure Citizen Petition on Benzene in Benzoyl Peroxide Products. March 5, 2024. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://assets-global.website-files.com/6215052733f8bb8fea016220/65e8560962ed23f744902a7b_Valisure%20Citizen%20Petition%20on%20Benzene%20in%20Benzoyl%20Peroxide%20Drug%20Products.pdf

- Kucera K, Zenzola N, Hudspeth A, et al. Benzoyl peroxide drug products form benzene. Environ Health Perspect. 2024;132:37702. doi:10.1289/EHP13984

- US Food and Drug Administration. Reformulating drug products that contain carbomers manufactured with benzene. December 2023. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/reformulating-drug-products-contain-carbomers-manufactured-benzene

- American Acne & Rosacea Society. Response Statement from the AARS to the Valisure Citizen Petition on Benzene in Benzoyl Peroxide Drug Products. March 20, 2024. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.einpresswire.com/article/697481595/response-statement-from-the-aars-to-the-valisure-citizen-petition-on-benzene-in-benzoyl-peroxide-drug-products

- Department of Health and Human Services. Classification of benzoyl peroxide as safe and effective and revision of labeling to drug facts format; topical acne drug products for over-the-counter human use; Final Rule. Fed Registr. 2010;75:9767-9777.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Topical acne drug products for over-the-counter human use—revision of labeling and classification of benzoyl peroxide as safe and effective. June 2011. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/topical-acne-drug-products-over-counter-human-use-revision-labeling-and-classification-benzoyl

- Valisure Citizen Petition on Benzene in Benzoyl Peroxide Products. March 5, 2024. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://assets-global.website-files.com/6215052733f8bb8fea016220/65e8560962ed23f744902a7b_Valisure%20Citizen%20Petition%20on%20Benzene%20in%20Benzoyl%20Peroxide%20Drug%20Products.pdf

- Kucera K, Zenzola N, Hudspeth A, et al. Benzoyl peroxide drug products form benzene. Environ Health Perspect. 2024;132:37702. doi:10.1289/EHP13984

- US Food and Drug Administration. Reformulating drug products that contain carbomers manufactured with benzene. December 2023. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/reformulating-drug-products-contain-carbomers-manufactured-benzene

- American Acne & Rosacea Society. Response Statement from the AARS to the Valisure Citizen Petition on Benzene in Benzoyl Peroxide Drug Products. March 20, 2024. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.einpresswire.com/article/697481595/response-statement-from-the-aars-to-the-valisure-citizen-petition-on-benzene-in-benzoyl-peroxide-drug-products

- Department of Health and Human Services. Classification of benzoyl peroxide as safe and effective and revision of labeling to drug facts format; topical acne drug products for over-the-counter human use; Final Rule. Fed Registr. 2010;75:9767-9777.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Topical acne drug products for over-the-counter human use—revision of labeling and classification of benzoyl peroxide as safe and effective. June 2011. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/topical-acne-drug-products-over-counter-human-use-revision-labeling-and-classification-benzoyl

The Growing Pains of Changing Times for Acne and Rosacea Pathophysiology: Where Will It All End Up?

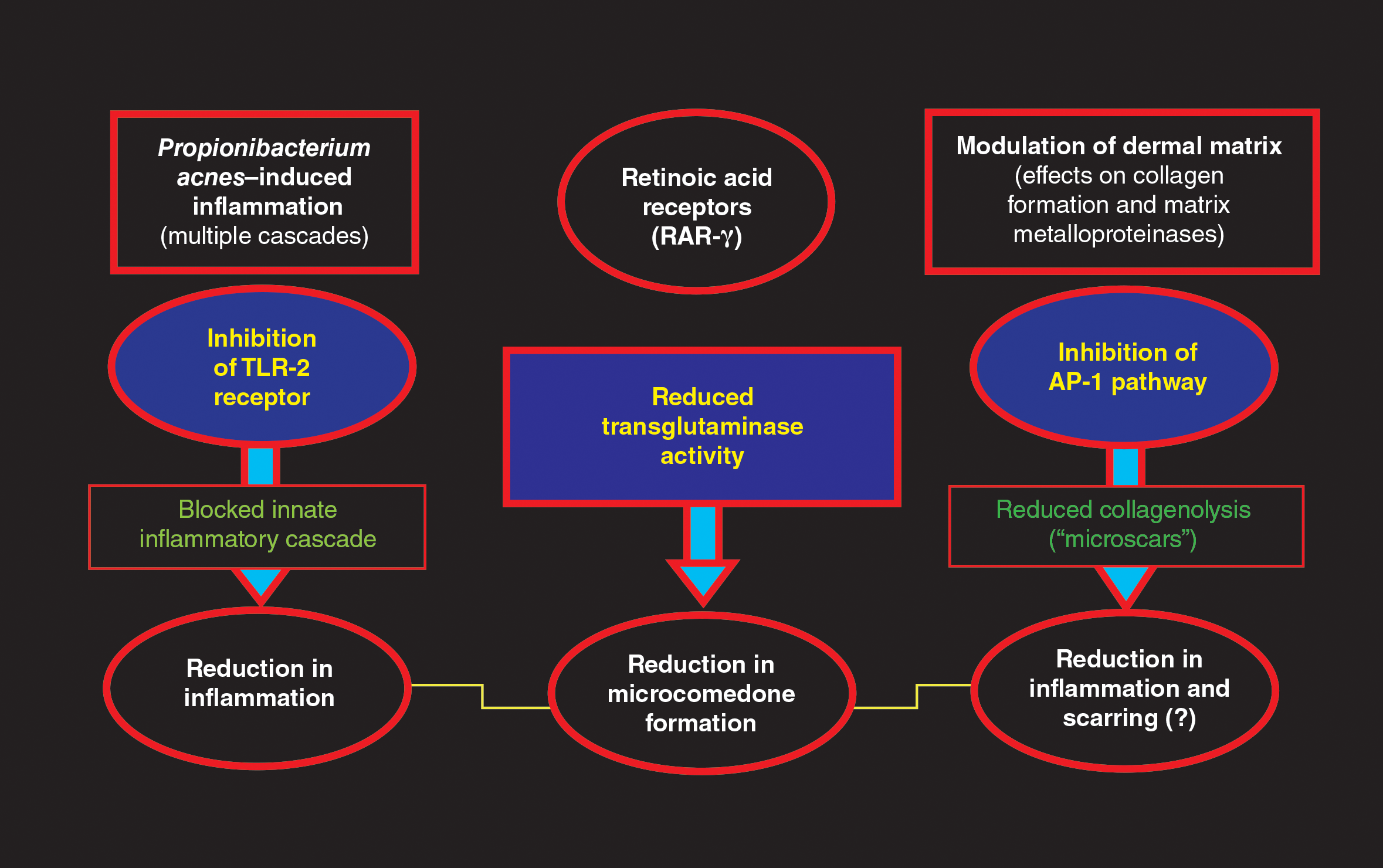

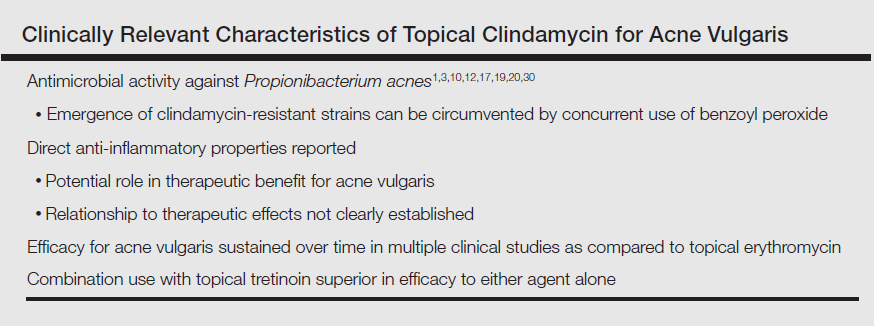

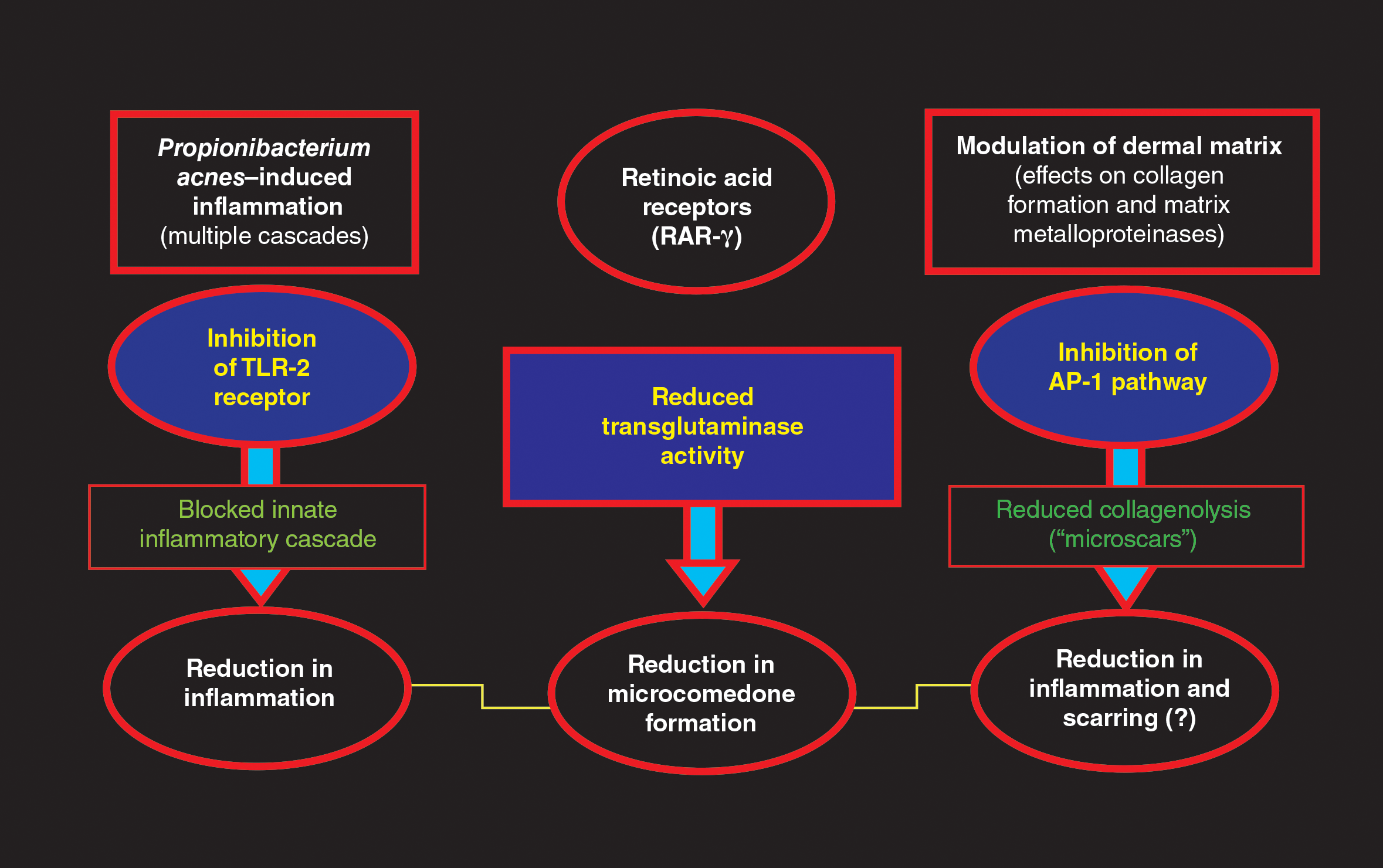

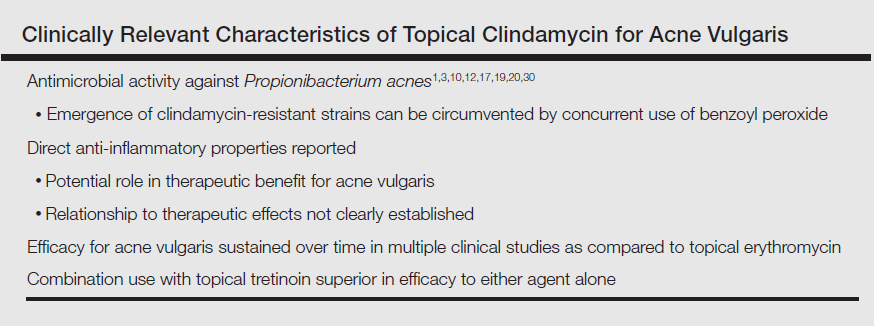

It is interesting to observe the changes in dermatology that have occurred over the last 1 to 2 decades, especially as major advances in basic science research techniques have rapidly expanded our current understanding of the pathophysiology of many disease states—psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, atopic dermatitis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, hidradenitis suppurativa, and lichen planus.1 Although acne vulgaris (AV) and rosacea do not make front-page news quite as often as some of these other aforementioned disease states in the pathophysiology arena, advances still have been made in understanding the pathophysiology, albeit slower and often less popularized in dermatology publications and other forms of media.2-4

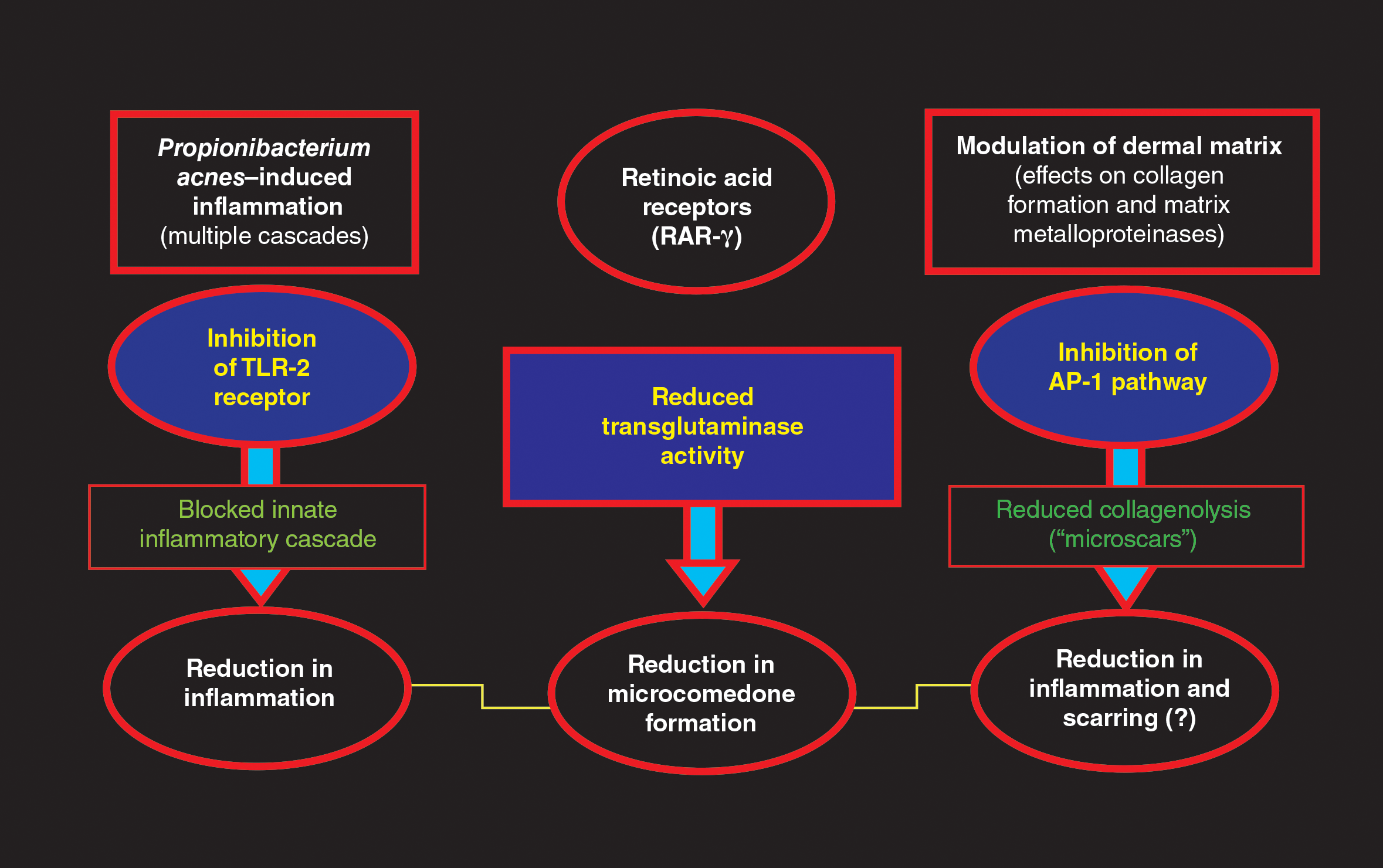

If one looks at our fundamental understanding of AV, most of the discussion over multiple decades has been driven by new treatments and in some cases new formulations and packaging differences with topical agents. Although we understood that adrenarche, a subsequent increase in androgen synthesis, and the ensuing sebocyte development with formation of sebum were prerequisites for the development of AV, the absence of therapeutic options to address these vital components of AV—especially US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapies—resulted in limited discussion about this specific area.5 Rather, the discussion was dominated by the notable role of Propionibacterium acnes (now called Cutibacterium acnes) in AV pathophysiology, as we had therapies such as benzoyl peroxide and antibiotics that improved AV in direct correlation with reductions in P acnes.6 This was soon coupled with an advanced understanding of how to reduce follicular hyperkeratinization with the development of topical tretinoin, followed by 3 other topical retinoids over time—adapalene, tazarotene, and trifarotene. Over subsequent years, slowly emerging basic science developments and collective data reviews added to our understanding of AV and how different therapies appear to work, including the role of toll-like receptors, anti-inflammatory properties of tetracyclines, and inflammasomes.7-9 Without a doubt, the availability of oral isotretinoin revolutionized AV therapy, especially in patients with severe refractory disease, with advanced formulations allowing for optimization of sustained remission without the need for high dietary fat intake.10-12

Progress in the pathophysiology of rosacea has been slower to develop, with the first true discussion of specific clinical presentations published after the new millennium.13 This was followed by more advanced basic science and clinical research, which led to an improved ability to understand modes of action of various therapies and to correlate treatment selection with specific visible manifestations of rosacea, including incorporation of physical devices.14-16 A newer perspective on evaluation and management of rosacea moved away from the “buckets” of rosacea subtypes to phenotypes observed at the time of clinical presentation.17,18

I could elaborate on research advancements with both diseases, but the bottom line is that information, developments, and current perspectives change over time. Keeping up is a challenge for all who study and practice dermatology. It is human nature to revert to what we already believe and do, which sometimes remains valid and other times is quite outdated and truly replaced by more optimal approaches. With AV and rosacea, progress is much slower in availability of newer agents. With AV, new agents have included topical dapsone, oral sarecycline, and topical clascoterone, with the latter being the first FDA-approved topical agent to mitigate the effects of androgens and sebum in both males and females. For rosacea, the 2 most recent FDA-approved therapies are minocycline foam and microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide. All of these therapies are proven to be effective for the modes of action and skin manifestations they specifically manage. Over the upcoming year, we are hoping to see the first triple-combination topical product come to market for AV, which will prompt our minds to consider if and how 3 established agents can work together to further augment treatment efficacy with favorable tolerability and safety.

Where will all of this end up? It is hard to say. We still have several other areas to tackle with both disease states, including establishing a well-substantiated understanding of the pathophysiologic role of the microbiome, sorting out the role of antibiotic use due to concerns about bacterial resistance, integration of FDA-approved physical devices in AV, and data on both diet and optimized skin care, to name a few.19-21

There is a lot on the plate to accomplish and digest. I have remained very involved in this subject matter for almost 3 decades and am still feeling the growing pains. Fortunately, the satisfaction of being part of a process so important to the lives of millions of patients makes this worth every moment. Stay tuned—more valuable information is to come.

- Wu J, Fang Z, Liu T, et al. Maximizing the utility of transcriptomics data in inflammatory skin diseases. Front Immunol. 2021;12:761890.

- Firlej E, Kowalska W, Szymaszek K, et al. The role of skin immune system in acne. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1579.

- Mias C, Mengeaud V, Bessou-Touya S, et al. Recent advances in understanding inflammatory acne: deciphering the relationship between Cutibacterium acnes and Th17 inflammatory pathway. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;(37 suppl 2):3-11.

- Buddenkotte J, Steinhoff M. Recent advances in understanding and managing rosacea. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1885. doi:10.12688/f1000research.16537.1

- Platsidaki E, Dessinioti C. Recent advances in understanding Propionibacterium acnes (Cutibacterium acnes) in acne. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1953. doi:10.12688/f1000research.15659.1

- Leyden JJ. The evolving role of Propionibacterium acnes in acne. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2001;20:139-143.

- Kim J. Review of the innate immune response in acne vulgaris: activation of toll-like receptor 2 in acne triggers inflammatory cytokine responses. Dermatology. 2005;211:193-198.

- Del Rosso JQ, Webster G, Weiss JS, et al. Nonantibiotic properties of tetracyclines in rosacea and their clinical implications. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:14-21.

- Zhu W, Wang HL, Bu XL, et al. A narrative review of research progress on the role of NLRP3 inflammasome in acne vulgaris. Ann Transl Med. 2022;10:645.

- Leyden JJ, Del Rosso JQ, Baum EW. The use of isotretinoin in the treatment of acne vulgaris: clinical considerations and future directions. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7(2 suppl):S3-S21.

- Webster GF, Leyden JJ, Gross JA. Comparative pharmacokinetic profiles of a novel isotretinoin formulation (isotretinoin-Lidose) and the innovator isotretinoin formulation: a randomized, treatment, crossover study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:762-767.

- Del Rosso JQ, Stein Gold L, Seagal J, et al. An open-label, phase IV study evaluating Lidose-isotretinoin administered without food in patients with severe recalcitrant nodular acne: low relapse rates observed over the 104-week post-treatment period. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12:13-18.

- Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard classification of rosacea: report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the classification and staging of rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:584-587.

- Steinhoff M, Buddenkotte J, Aubert J, et al. Clinical, cellular, and molecular aspects in the pathophysiology of rosacea. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;15:2-11.

- Yamasaki K, Gallo RL. The molecular pathology of rosacea. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;55:77-81.

- Tanghetti E, Del Rosso JQ, Thiboutot D, et al. Consensus recommendations from the American Acne & Rosacea Society on the management of rosacea, part 4: a status report on physical modalities and devices. Cutis. 2014;93:71-76.

- Del Rosso JQ, Gallo RL, Tanghetti E, et al. An evaluation of potential correlations between pathophysiologic mechanisms, clinical manifestations, and management of rosacea. Cutis. 2013;91(3 suppl):1-8.

- Schaller M, Almeida LMC, Bewley A, et al. Recommendations for rosacea diagnosis, classification and management: update from the global ROSacea COnsensus 2019 panel. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:1269-1276.

- Xu H, Li H. Acne, the skin microbiome, and antibiotic treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:335-344.

- Daou H, Paradiso M, Hennessy K. Rosacea and the microbiome: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1-12.

- Kayiran MA, Karadag AS, Al-Khuzaei S, et al. Antibiotic resistance in acne: mechanisms, complications and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:813-819.

It is interesting to observe the changes in dermatology that have occurred over the last 1 to 2 decades, especially as major advances in basic science research techniques have rapidly expanded our current understanding of the pathophysiology of many disease states—psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, atopic dermatitis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, hidradenitis suppurativa, and lichen planus.1 Although acne vulgaris (AV) and rosacea do not make front-page news quite as often as some of these other aforementioned disease states in the pathophysiology arena, advances still have been made in understanding the pathophysiology, albeit slower and often less popularized in dermatology publications and other forms of media.2-4

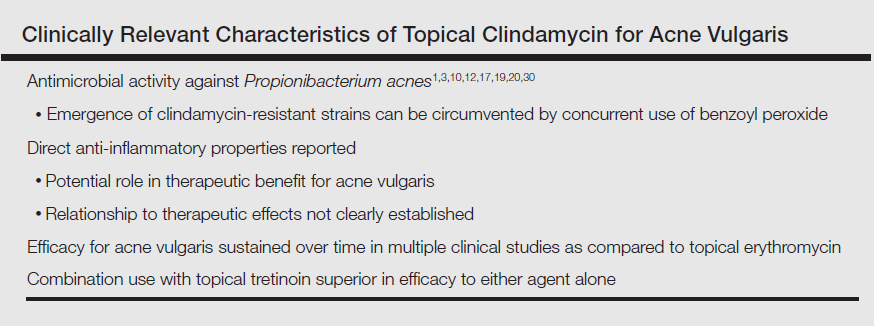

If one looks at our fundamental understanding of AV, most of the discussion over multiple decades has been driven by new treatments and in some cases new formulations and packaging differences with topical agents. Although we understood that adrenarche, a subsequent increase in androgen synthesis, and the ensuing sebocyte development with formation of sebum were prerequisites for the development of AV, the absence of therapeutic options to address these vital components of AV—especially US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapies—resulted in limited discussion about this specific area.5 Rather, the discussion was dominated by the notable role of Propionibacterium acnes (now called Cutibacterium acnes) in AV pathophysiology, as we had therapies such as benzoyl peroxide and antibiotics that improved AV in direct correlation with reductions in P acnes.6 This was soon coupled with an advanced understanding of how to reduce follicular hyperkeratinization with the development of topical tretinoin, followed by 3 other topical retinoids over time—adapalene, tazarotene, and trifarotene. Over subsequent years, slowly emerging basic science developments and collective data reviews added to our understanding of AV and how different therapies appear to work, including the role of toll-like receptors, anti-inflammatory properties of tetracyclines, and inflammasomes.7-9 Without a doubt, the availability of oral isotretinoin revolutionized AV therapy, especially in patients with severe refractory disease, with advanced formulations allowing for optimization of sustained remission without the need for high dietary fat intake.10-12

Progress in the pathophysiology of rosacea has been slower to develop, with the first true discussion of specific clinical presentations published after the new millennium.13 This was followed by more advanced basic science and clinical research, which led to an improved ability to understand modes of action of various therapies and to correlate treatment selection with specific visible manifestations of rosacea, including incorporation of physical devices.14-16 A newer perspective on evaluation and management of rosacea moved away from the “buckets” of rosacea subtypes to phenotypes observed at the time of clinical presentation.17,18

I could elaborate on research advancements with both diseases, but the bottom line is that information, developments, and current perspectives change over time. Keeping up is a challenge for all who study and practice dermatology. It is human nature to revert to what we already believe and do, which sometimes remains valid and other times is quite outdated and truly replaced by more optimal approaches. With AV and rosacea, progress is much slower in availability of newer agents. With AV, new agents have included topical dapsone, oral sarecycline, and topical clascoterone, with the latter being the first FDA-approved topical agent to mitigate the effects of androgens and sebum in both males and females. For rosacea, the 2 most recent FDA-approved therapies are minocycline foam and microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide. All of these therapies are proven to be effective for the modes of action and skin manifestations they specifically manage. Over the upcoming year, we are hoping to see the first triple-combination topical product come to market for AV, which will prompt our minds to consider if and how 3 established agents can work together to further augment treatment efficacy with favorable tolerability and safety.

Where will all of this end up? It is hard to say. We still have several other areas to tackle with both disease states, including establishing a well-substantiated understanding of the pathophysiologic role of the microbiome, sorting out the role of antibiotic use due to concerns about bacterial resistance, integration of FDA-approved physical devices in AV, and data on both diet and optimized skin care, to name a few.19-21

There is a lot on the plate to accomplish and digest. I have remained very involved in this subject matter for almost 3 decades and am still feeling the growing pains. Fortunately, the satisfaction of being part of a process so important to the lives of millions of patients makes this worth every moment. Stay tuned—more valuable information is to come.

It is interesting to observe the changes in dermatology that have occurred over the last 1 to 2 decades, especially as major advances in basic science research techniques have rapidly expanded our current understanding of the pathophysiology of many disease states—psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, atopic dermatitis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, hidradenitis suppurativa, and lichen planus.1 Although acne vulgaris (AV) and rosacea do not make front-page news quite as often as some of these other aforementioned disease states in the pathophysiology arena, advances still have been made in understanding the pathophysiology, albeit slower and often less popularized in dermatology publications and other forms of media.2-4

If one looks at our fundamental understanding of AV, most of the discussion over multiple decades has been driven by new treatments and in some cases new formulations and packaging differences with topical agents. Although we understood that adrenarche, a subsequent increase in androgen synthesis, and the ensuing sebocyte development with formation of sebum were prerequisites for the development of AV, the absence of therapeutic options to address these vital components of AV—especially US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapies—resulted in limited discussion about this specific area.5 Rather, the discussion was dominated by the notable role of Propionibacterium acnes (now called Cutibacterium acnes) in AV pathophysiology, as we had therapies such as benzoyl peroxide and antibiotics that improved AV in direct correlation with reductions in P acnes.6 This was soon coupled with an advanced understanding of how to reduce follicular hyperkeratinization with the development of topical tretinoin, followed by 3 other topical retinoids over time—adapalene, tazarotene, and trifarotene. Over subsequent years, slowly emerging basic science developments and collective data reviews added to our understanding of AV and how different therapies appear to work, including the role of toll-like receptors, anti-inflammatory properties of tetracyclines, and inflammasomes.7-9 Without a doubt, the availability of oral isotretinoin revolutionized AV therapy, especially in patients with severe refractory disease, with advanced formulations allowing for optimization of sustained remission without the need for high dietary fat intake.10-12

Progress in the pathophysiology of rosacea has been slower to develop, with the first true discussion of specific clinical presentations published after the new millennium.13 This was followed by more advanced basic science and clinical research, which led to an improved ability to understand modes of action of various therapies and to correlate treatment selection with specific visible manifestations of rosacea, including incorporation of physical devices.14-16 A newer perspective on evaluation and management of rosacea moved away from the “buckets” of rosacea subtypes to phenotypes observed at the time of clinical presentation.17,18

I could elaborate on research advancements with both diseases, but the bottom line is that information, developments, and current perspectives change over time. Keeping up is a challenge for all who study and practice dermatology. It is human nature to revert to what we already believe and do, which sometimes remains valid and other times is quite outdated and truly replaced by more optimal approaches. With AV and rosacea, progress is much slower in availability of newer agents. With AV, new agents have included topical dapsone, oral sarecycline, and topical clascoterone, with the latter being the first FDA-approved topical agent to mitigate the effects of androgens and sebum in both males and females. For rosacea, the 2 most recent FDA-approved therapies are minocycline foam and microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide. All of these therapies are proven to be effective for the modes of action and skin manifestations they specifically manage. Over the upcoming year, we are hoping to see the first triple-combination topical product come to market for AV, which will prompt our minds to consider if and how 3 established agents can work together to further augment treatment efficacy with favorable tolerability and safety.

Where will all of this end up? It is hard to say. We still have several other areas to tackle with both disease states, including establishing a well-substantiated understanding of the pathophysiologic role of the microbiome, sorting out the role of antibiotic use due to concerns about bacterial resistance, integration of FDA-approved physical devices in AV, and data on both diet and optimized skin care, to name a few.19-21

There is a lot on the plate to accomplish and digest. I have remained very involved in this subject matter for almost 3 decades and am still feeling the growing pains. Fortunately, the satisfaction of being part of a process so important to the lives of millions of patients makes this worth every moment. Stay tuned—more valuable information is to come.

- Wu J, Fang Z, Liu T, et al. Maximizing the utility of transcriptomics data in inflammatory skin diseases. Front Immunol. 2021;12:761890.

- Firlej E, Kowalska W, Szymaszek K, et al. The role of skin immune system in acne. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1579.

- Mias C, Mengeaud V, Bessou-Touya S, et al. Recent advances in understanding inflammatory acne: deciphering the relationship between Cutibacterium acnes and Th17 inflammatory pathway. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;(37 suppl 2):3-11.

- Buddenkotte J, Steinhoff M. Recent advances in understanding and managing rosacea. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1885. doi:10.12688/f1000research.16537.1

- Platsidaki E, Dessinioti C. Recent advances in understanding Propionibacterium acnes (Cutibacterium acnes) in acne. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1953. doi:10.12688/f1000research.15659.1

- Leyden JJ. The evolving role of Propionibacterium acnes in acne. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2001;20:139-143.

- Kim J. Review of the innate immune response in acne vulgaris: activation of toll-like receptor 2 in acne triggers inflammatory cytokine responses. Dermatology. 2005;211:193-198.

- Del Rosso JQ, Webster G, Weiss JS, et al. Nonantibiotic properties of tetracyclines in rosacea and their clinical implications. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:14-21.

- Zhu W, Wang HL, Bu XL, et al. A narrative review of research progress on the role of NLRP3 inflammasome in acne vulgaris. Ann Transl Med. 2022;10:645.

- Leyden JJ, Del Rosso JQ, Baum EW. The use of isotretinoin in the treatment of acne vulgaris: clinical considerations and future directions. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7(2 suppl):S3-S21.

- Webster GF, Leyden JJ, Gross JA. Comparative pharmacokinetic profiles of a novel isotretinoin formulation (isotretinoin-Lidose) and the innovator isotretinoin formulation: a randomized, treatment, crossover study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:762-767.

- Del Rosso JQ, Stein Gold L, Seagal J, et al. An open-label, phase IV study evaluating Lidose-isotretinoin administered without food in patients with severe recalcitrant nodular acne: low relapse rates observed over the 104-week post-treatment period. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12:13-18.

- Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard classification of rosacea: report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the classification and staging of rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:584-587.

- Steinhoff M, Buddenkotte J, Aubert J, et al. Clinical, cellular, and molecular aspects in the pathophysiology of rosacea. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;15:2-11.

- Yamasaki K, Gallo RL. The molecular pathology of rosacea. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;55:77-81.

- Tanghetti E, Del Rosso JQ, Thiboutot D, et al. Consensus recommendations from the American Acne & Rosacea Society on the management of rosacea, part 4: a status report on physical modalities and devices. Cutis. 2014;93:71-76.

- Del Rosso JQ, Gallo RL, Tanghetti E, et al. An evaluation of potential correlations between pathophysiologic mechanisms, clinical manifestations, and management of rosacea. Cutis. 2013;91(3 suppl):1-8.

- Schaller M, Almeida LMC, Bewley A, et al. Recommendations for rosacea diagnosis, classification and management: update from the global ROSacea COnsensus 2019 panel. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:1269-1276.

- Xu H, Li H. Acne, the skin microbiome, and antibiotic treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:335-344.

- Daou H, Paradiso M, Hennessy K. Rosacea and the microbiome: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1-12.

- Kayiran MA, Karadag AS, Al-Khuzaei S, et al. Antibiotic resistance in acne: mechanisms, complications and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:813-819.

- Wu J, Fang Z, Liu T, et al. Maximizing the utility of transcriptomics data in inflammatory skin diseases. Front Immunol. 2021;12:761890.

- Firlej E, Kowalska W, Szymaszek K, et al. The role of skin immune system in acne. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1579.

- Mias C, Mengeaud V, Bessou-Touya S, et al. Recent advances in understanding inflammatory acne: deciphering the relationship between Cutibacterium acnes and Th17 inflammatory pathway. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;(37 suppl 2):3-11.

- Buddenkotte J, Steinhoff M. Recent advances in understanding and managing rosacea. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1885. doi:10.12688/f1000research.16537.1

- Platsidaki E, Dessinioti C. Recent advances in understanding Propionibacterium acnes (Cutibacterium acnes) in acne. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1953. doi:10.12688/f1000research.15659.1

- Leyden JJ. The evolving role of Propionibacterium acnes in acne. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2001;20:139-143.

- Kim J. Review of the innate immune response in acne vulgaris: activation of toll-like receptor 2 in acne triggers inflammatory cytokine responses. Dermatology. 2005;211:193-198.

- Del Rosso JQ, Webster G, Weiss JS, et al. Nonantibiotic properties of tetracyclines in rosacea and their clinical implications. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:14-21.

- Zhu W, Wang HL, Bu XL, et al. A narrative review of research progress on the role of NLRP3 inflammasome in acne vulgaris. Ann Transl Med. 2022;10:645.

- Leyden JJ, Del Rosso JQ, Baum EW. The use of isotretinoin in the treatment of acne vulgaris: clinical considerations and future directions. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7(2 suppl):S3-S21.

- Webster GF, Leyden JJ, Gross JA. Comparative pharmacokinetic profiles of a novel isotretinoin formulation (isotretinoin-Lidose) and the innovator isotretinoin formulation: a randomized, treatment, crossover study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:762-767.

- Del Rosso JQ, Stein Gold L, Seagal J, et al. An open-label, phase IV study evaluating Lidose-isotretinoin administered without food in patients with severe recalcitrant nodular acne: low relapse rates observed over the 104-week post-treatment period. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12:13-18.

- Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard classification of rosacea: report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the classification and staging of rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:584-587.

- Steinhoff M, Buddenkotte J, Aubert J, et al. Clinical, cellular, and molecular aspects in the pathophysiology of rosacea. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;15:2-11.

- Yamasaki K, Gallo RL. The molecular pathology of rosacea. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;55:77-81.

- Tanghetti E, Del Rosso JQ, Thiboutot D, et al. Consensus recommendations from the American Acne & Rosacea Society on the management of rosacea, part 4: a status report on physical modalities and devices. Cutis. 2014;93:71-76.

- Del Rosso JQ, Gallo RL, Tanghetti E, et al. An evaluation of potential correlations between pathophysiologic mechanisms, clinical manifestations, and management of rosacea. Cutis. 2013;91(3 suppl):1-8.

- Schaller M, Almeida LMC, Bewley A, et al. Recommendations for rosacea diagnosis, classification and management: update from the global ROSacea COnsensus 2019 panel. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:1269-1276.

- Xu H, Li H. Acne, the skin microbiome, and antibiotic treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:335-344.

- Daou H, Paradiso M, Hennessy K. Rosacea and the microbiome: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1-12.

- Kayiran MA, Karadag AS, Al-Khuzaei S, et al. Antibiotic resistance in acne: mechanisms, complications and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:813-819.

Adapting to Changes in Acne Management: Take One Step at a Time

After most dermatology residents graduate from their programs, they go out into practice and will often carry with them what they learned from their teachers, especially clinicians. Everyone else in their dermatology residency programs approaches disease management and the use of different therapies in the same way, right?

It does not take very long before these same dermatology residents realize that things are different in real-world clinical practice in many ways. Most clinicians develop a range of fairly predictable patterns in how they approach and treat common skin disorders such as acne, rosacea, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis/eczema, and seborrheic dermatitis. These patterns often include what testing is performed at baseline and at follow-up.

Recently, I have been giving thought to how clinicians—myself included—change their approaches to management of specific skin diseases over time, especially as new information and therapies emerge. Are we fast adopters, or are we slow adopters? How much evidence do we need to see before we consider adjusting our approach? Is the needle moving too fast or not fast enough?

I would like to use an example that relates to acne treatment, especially as this is one of the most common skin disorders encountered in outpatient dermatologic practice. Despite lack of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for use in acne, oral spironolactone commonly is used in females, especially adults, with acne vulgaris and has a long history as an acceptable approach in dermatology.1 Because spironolactone is a potassium-sparing diuretic, one question that commonly arises is: Do we monitor serum potassium levels at baseline and periodically during treatment with spironolactone? There has never been a definitive consensus on which approach to take. However, there has been evidence to suggest that such monitoring is not necessary in young healthy women due to a negligible risk for clinically relevant hyperkalemia.2,3

In fact, the suggestion that there is a very low risk for clinically significant hyperkalemia in healthy young women treated with spironolactone is accurate based on population-based studies. Nevertheless, the clinician is faced with confirming the patient is in fact healthy rather than assuming this is the case due to her “young” age. In addition, it is important to exclude potential drug-drug interactions that can increase the risk for hyperkalemia when coadministered with spironolactone and also to exclude an unknown underlying decrease in renal function.1 At the end of the day, I support the continued research that is being done to evaluate questions that can challenge the recycled dogma on how we manage patients, and I do not fault those who follow what they believe to be new cogent evidence. However, in the case of oral spironolactone use, I also could never fault a clinician for monitoring renal function and electrolytes including serum potassium levels in a female patient treated for acne, especially with a drug that has the known potential to cause hyperkalemia in certain clinical situations and is not FDA approved for the indication of acne (ie, the guidance that accompanies the level of investigation needed for such FDA approval is missing). The clinical judgment of the clinician who is responsible for the individual patient trumps the results from population-based studies completed thus far. Ultimately, it is the responsibility of that clinician to assure the safety of their patient in a manner that they are comfortable with.

It takes time to make changes in our approaches to patient management, and in the majority of cases, that is rightfully so. There are several potential limitations to how certain data are collected, and a reasonable verification of results over time is what tends to change behavior patterns. Ultimately, the common goal is to do what is in the best interest of our patients. No one can argue successfully against that.

- Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Oral spironolactone in post-teenage female patients with acne vulgaris: practical considerations for the clinician based on current data and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:37-50.

- Plovanich M, Weng QY, Arash Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:941-944.

- Barbieri JS, Margolis DJ, Mostaghimi A. Temporal trends and clinician variability in potassium monitoring of healthy young women treated for acne with spironolactone. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:296-300.

After most dermatology residents graduate from their programs, they go out into practice and will often carry with them what they learned from their teachers, especially clinicians. Everyone else in their dermatology residency programs approaches disease management and the use of different therapies in the same way, right?

It does not take very long before these same dermatology residents realize that things are different in real-world clinical practice in many ways. Most clinicians develop a range of fairly predictable patterns in how they approach and treat common skin disorders such as acne, rosacea, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis/eczema, and seborrheic dermatitis. These patterns often include what testing is performed at baseline and at follow-up.

Recently, I have been giving thought to how clinicians—myself included—change their approaches to management of specific skin diseases over time, especially as new information and therapies emerge. Are we fast adopters, or are we slow adopters? How much evidence do we need to see before we consider adjusting our approach? Is the needle moving too fast or not fast enough?

I would like to use an example that relates to acne treatment, especially as this is one of the most common skin disorders encountered in outpatient dermatologic practice. Despite lack of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for use in acne, oral spironolactone commonly is used in females, especially adults, with acne vulgaris and has a long history as an acceptable approach in dermatology.1 Because spironolactone is a potassium-sparing diuretic, one question that commonly arises is: Do we monitor serum potassium levels at baseline and periodically during treatment with spironolactone? There has never been a definitive consensus on which approach to take. However, there has been evidence to suggest that such monitoring is not necessary in young healthy women due to a negligible risk for clinically relevant hyperkalemia.2,3

In fact, the suggestion that there is a very low risk for clinically significant hyperkalemia in healthy young women treated with spironolactone is accurate based on population-based studies. Nevertheless, the clinician is faced with confirming the patient is in fact healthy rather than assuming this is the case due to her “young” age. In addition, it is important to exclude potential drug-drug interactions that can increase the risk for hyperkalemia when coadministered with spironolactone and also to exclude an unknown underlying decrease in renal function.1 At the end of the day, I support the continued research that is being done to evaluate questions that can challenge the recycled dogma on how we manage patients, and I do not fault those who follow what they believe to be new cogent evidence. However, in the case of oral spironolactone use, I also could never fault a clinician for monitoring renal function and electrolytes including serum potassium levels in a female patient treated for acne, especially with a drug that has the known potential to cause hyperkalemia in certain clinical situations and is not FDA approved for the indication of acne (ie, the guidance that accompanies the level of investigation needed for such FDA approval is missing). The clinical judgment of the clinician who is responsible for the individual patient trumps the results from population-based studies completed thus far. Ultimately, it is the responsibility of that clinician to assure the safety of their patient in a manner that they are comfortable with.

It takes time to make changes in our approaches to patient management, and in the majority of cases, that is rightfully so. There are several potential limitations to how certain data are collected, and a reasonable verification of results over time is what tends to change behavior patterns. Ultimately, the common goal is to do what is in the best interest of our patients. No one can argue successfully against that.

After most dermatology residents graduate from their programs, they go out into practice and will often carry with them what they learned from their teachers, especially clinicians. Everyone else in their dermatology residency programs approaches disease management and the use of different therapies in the same way, right?

It does not take very long before these same dermatology residents realize that things are different in real-world clinical practice in many ways. Most clinicians develop a range of fairly predictable patterns in how they approach and treat common skin disorders such as acne, rosacea, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis/eczema, and seborrheic dermatitis. These patterns often include what testing is performed at baseline and at follow-up.

Recently, I have been giving thought to how clinicians—myself included—change their approaches to management of specific skin diseases over time, especially as new information and therapies emerge. Are we fast adopters, or are we slow adopters? How much evidence do we need to see before we consider adjusting our approach? Is the needle moving too fast or not fast enough?

I would like to use an example that relates to acne treatment, especially as this is one of the most common skin disorders encountered in outpatient dermatologic practice. Despite lack of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for use in acne, oral spironolactone commonly is used in females, especially adults, with acne vulgaris and has a long history as an acceptable approach in dermatology.1 Because spironolactone is a potassium-sparing diuretic, one question that commonly arises is: Do we monitor serum potassium levels at baseline and periodically during treatment with spironolactone? There has never been a definitive consensus on which approach to take. However, there has been evidence to suggest that such monitoring is not necessary in young healthy women due to a negligible risk for clinically relevant hyperkalemia.2,3

In fact, the suggestion that there is a very low risk for clinically significant hyperkalemia in healthy young women treated with spironolactone is accurate based on population-based studies. Nevertheless, the clinician is faced with confirming the patient is in fact healthy rather than assuming this is the case due to her “young” age. In addition, it is important to exclude potential drug-drug interactions that can increase the risk for hyperkalemia when coadministered with spironolactone and also to exclude an unknown underlying decrease in renal function.1 At the end of the day, I support the continued research that is being done to evaluate questions that can challenge the recycled dogma on how we manage patients, and I do not fault those who follow what they believe to be new cogent evidence. However, in the case of oral spironolactone use, I also could never fault a clinician for monitoring renal function and electrolytes including serum potassium levels in a female patient treated for acne, especially with a drug that has the known potential to cause hyperkalemia in certain clinical situations and is not FDA approved for the indication of acne (ie, the guidance that accompanies the level of investigation needed for such FDA approval is missing). The clinical judgment of the clinician who is responsible for the individual patient trumps the results from population-based studies completed thus far. Ultimately, it is the responsibility of that clinician to assure the safety of their patient in a manner that they are comfortable with.

It takes time to make changes in our approaches to patient management, and in the majority of cases, that is rightfully so. There are several potential limitations to how certain data are collected, and a reasonable verification of results over time is what tends to change behavior patterns. Ultimately, the common goal is to do what is in the best interest of our patients. No one can argue successfully against that.

- Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Oral spironolactone in post-teenage female patients with acne vulgaris: practical considerations for the clinician based on current data and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:37-50.

- Plovanich M, Weng QY, Arash Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:941-944.

- Barbieri JS, Margolis DJ, Mostaghimi A. Temporal trends and clinician variability in potassium monitoring of healthy young women treated for acne with spironolactone. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:296-300.

- Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Oral spironolactone in post-teenage female patients with acne vulgaris: practical considerations for the clinician based on current data and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:37-50.

- Plovanich M, Weng QY, Arash Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:941-944.

- Barbieri JS, Margolis DJ, Mostaghimi A. Temporal trends and clinician variability in potassium monitoring of healthy young women treated for acne with spironolactone. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:296-300.

Just Like Rock and Roll, Topical Medications for Psoriasis Are Here to Stay

When I finished my dermatology training in 1986, the only moving parts in the skin that I recall were keratinocytes moving upward from the basal layer of the epidermis until they were desquamated 4 or 5 weeks later and hairs growing within their follicles until they were shed. Now we are learning about countless cytokines, chemokines, interleukins, antibodies, receptors, enzymes, and cell types, as well as their associated pathways, at an endless pace. Every day I am looking in my inbox to sign up for the “Cytokine of the Month” club! Despite the challenges of sorting through what is relevant clinically, it is a very exciting time. Coupled with this myriad of fundamental science is the emergence of newer therapies that are more directly targeting specific disease states and dramatically changing the lives of patients. We see prominent examples of these therapeutic results every day in patients we treat, especially with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Importantly, there also is hope for patients with notoriously refractory skin disorders, such as hidradenitis suppurativa, alopecia areata, and vitiligo, as newer therapies are being thoroughly studied in clinical trials.

Despite the best advances in therapy that we currently have available and those anticipated in the foreseeable future, patients with chronic dermatoses such as psoriasis and atopic dermatitis still require prolonged constant or frequently used intermittent therapies to adequately control their disease. Fortunately, as dermatologists we understand the importance of proper skin care and topical medications as well as how to incorporate them in the management plan. To date, specifically with psoriasis, we have a variety of brand and generic topical corticosteroids, calcipotriene (vitamin D analogue), and tazarotene (retinoid), as well as combination formulations, in our toolbox to help manage localized areas of involvement.1 This includes both patients with more limited psoriasis and those responding favorably to systemic therapy but who still develop some new or persistent areas of localized psoriatic lesions. New data with the brand formulation of calcipotriene–betamethasone dipropionate (Cal-BDP) foam applied once daily shows that after adequate control is achieved, continued application to the affected sites twice weekly is superior to vehicle in preventing relapse of psoriasis.2 A highly cosmetically acceptable Cal-BDP cream incorporating a unique vehicle technology has been US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for once-daily use for plaque psoriasis, overcoming the compatibility difficulties encountered in combining both active ingredients in an aqueous-based formulation and also optimizing the delivery of the active ingredients into the skin. This Cal-BDP cream demonstrated efficacy superior to a brand Cal-BDP suspension, rapid reduction in pruritus, and favorable tolerability and safety.3 Another combination formulation that is FDA approved for plaque psoriasis with once-daily application that has been shown to be effective and safe is halobetasol propionate–tazarotene lotion. This formulation contains lower concentrations of both active ingredients than those normally used in a barrier-friendly polymeric emulsion vehicle, allowing for augmented delivery of both active ingredients into the skin than with the individual agents applied separately and sequentially.4,5 In the best of circumstances, most patients with psoriasis still require use of topical therapy and appreciate its availability. Just like on any menu, it is good to have multiple good options.

What else does this psoriasis management story need? A pipeline! I am happy to tell you that with topical therapy, 2 nonsteroidal agents are under development with completion of phase 2 and phase 3 trials submitted to the FDA to evaluate for approval for psoriasis. They are tapinarof cream, an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist, and roflumilast cream, a phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor. Both of these modes of action involve intracellular pathways that are highly conserved in humans and are ubiquitously present in structural and hematopoietic cells.