User login

Clindamycin Phosphate–Tretinoin Combination Gel Revisited: Status Report on a Specific Formulation Used for Acne Treatment

Topical management of acne vulgaris (AV) incorporates a variety of agents with diverse modes of action (MOAs), including retinoids and antibiotics.1-3 The first topical retinoid developed for acne therapy was tretinoin, available in the United States since 1971.2,4 Topical retinoids, including tretinoin, exhibit multiple pharmacologic effects that are believed to correlate with efficacy for acne treatment,1,2,4,5 such as the reduction of inflammatory and comedonal lesions and contribution to dermal matrix remodeling.1,2,4-9 The predominant topical antibiotic used for acne treatment, often in combination with benzoyl peroxide (BP) and/or a topical retinoid, is clindamycin. Clindamycin is a lincosamide antibiotic that is closely related to erythromycin, a member of the macrolide antibiotic category.1,3,10 Available data support that over time topical clindamycin has sustained greater efficacy in reducing AV lesions than topical erythromycin; the latter also has been shown to exhibit a greater prevalence of Propionibacterium acnes resistance than clindamycin.1,3,10-12

Combination gel formulations of clindamycin phosphate 1.2%–tretinoin 0.025% (CP-Tret) are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and available in the United States for once-daily treatment of AV in patients 12 years of age and older.13-15 Large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated both efficacy and safety for these formulations.16,17 This article reviews important considerations related to both individual active ingredients (clindamycin phosphate [CP] and tretinoin [Tret]), formulation characteristics, and data from pivotal RCTs with a CP-Tret gel that has more recently been reintroduced into the US marketplace for acne therapy (Veltin, Aqua Pharmaceuticals).

What is the rationale behind combining CP and Tret in a single combination formulation?

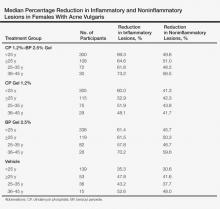

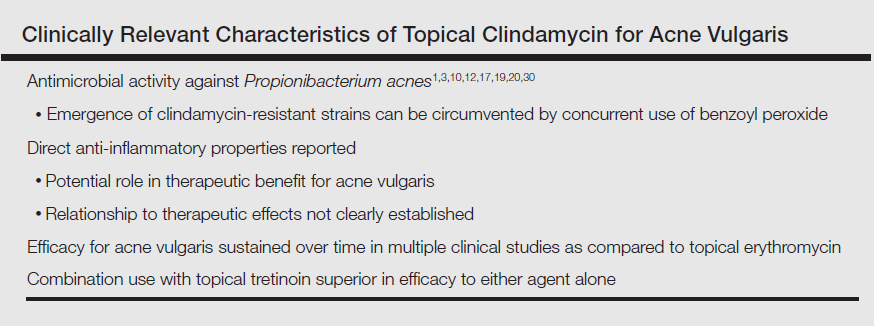

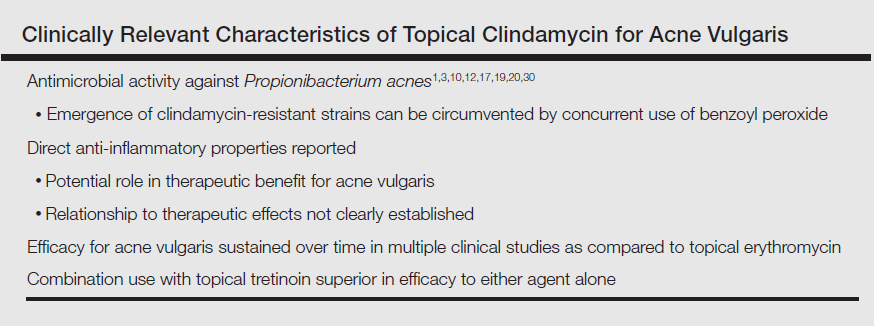

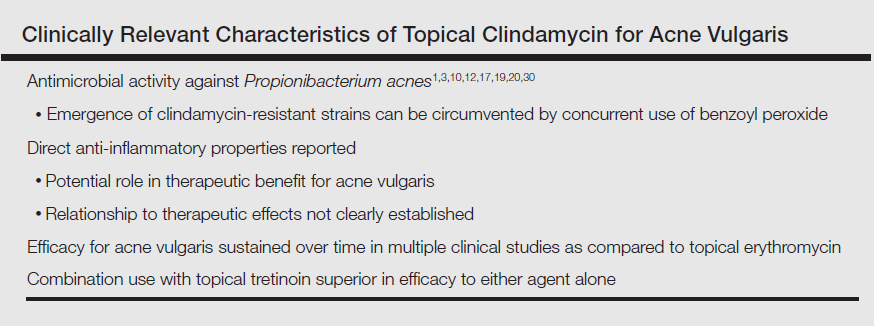

Clindamycin is a lincosamide antibiotic that has been used for the treatment of AV for approximately 5 decades.1,3,10,17 The main MOA of clindamycin in the treatment of AV is believed to be reduction of P acnes; however, anti-inflammatory effects maypotentially play some role in AV lesion reduction.3,10,12,17-19 Multiple RCTs completed over approximately 3 decades and inclusive of more than 2000 participants treated topically with clindamycin as monotherapy have shown that the efficacy of this agent in reducing AV lesions has remained consistent overall,3,20-24 unlike topical erythromycin, which did not sustain its efficacy over a similar comparative time period.20 Importantly, these data are based on RCTs designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of individual agents, including topical clindamycin; however, topical antibiotic therapy is not recommended as monotherapy for AV treatment due to emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains.1,3,11,12,25-28 Although the prevalence of resistant strains of P acnes is lower in the United States and many other countries for clindamycin versus erythromycin, the magnitude of clindamycin-resistant P acnes strains increases and response to clindamycin therapy may decrease when this agent is used alone.12,25-27,29,30 Therefore, it is recommended that a BP formulation that exhibits the ability to adequately reduce P acnes counts be used concurrently with antibiotic therapy for AV to reduce the emergence and proliferation of antibiotic-resistant P acnes organisms; short-contact BP therapy using a high-concentration (9.8%) emollient foam formulation and sufficient contact time (ie, 2 minutes) prior to washing off also has been shown to markedly reduce truncal P acnes organism counts.1,3,10-12,25-33 The Table depicts the major characteristics of clindamycin related to its use for treatment of AV.

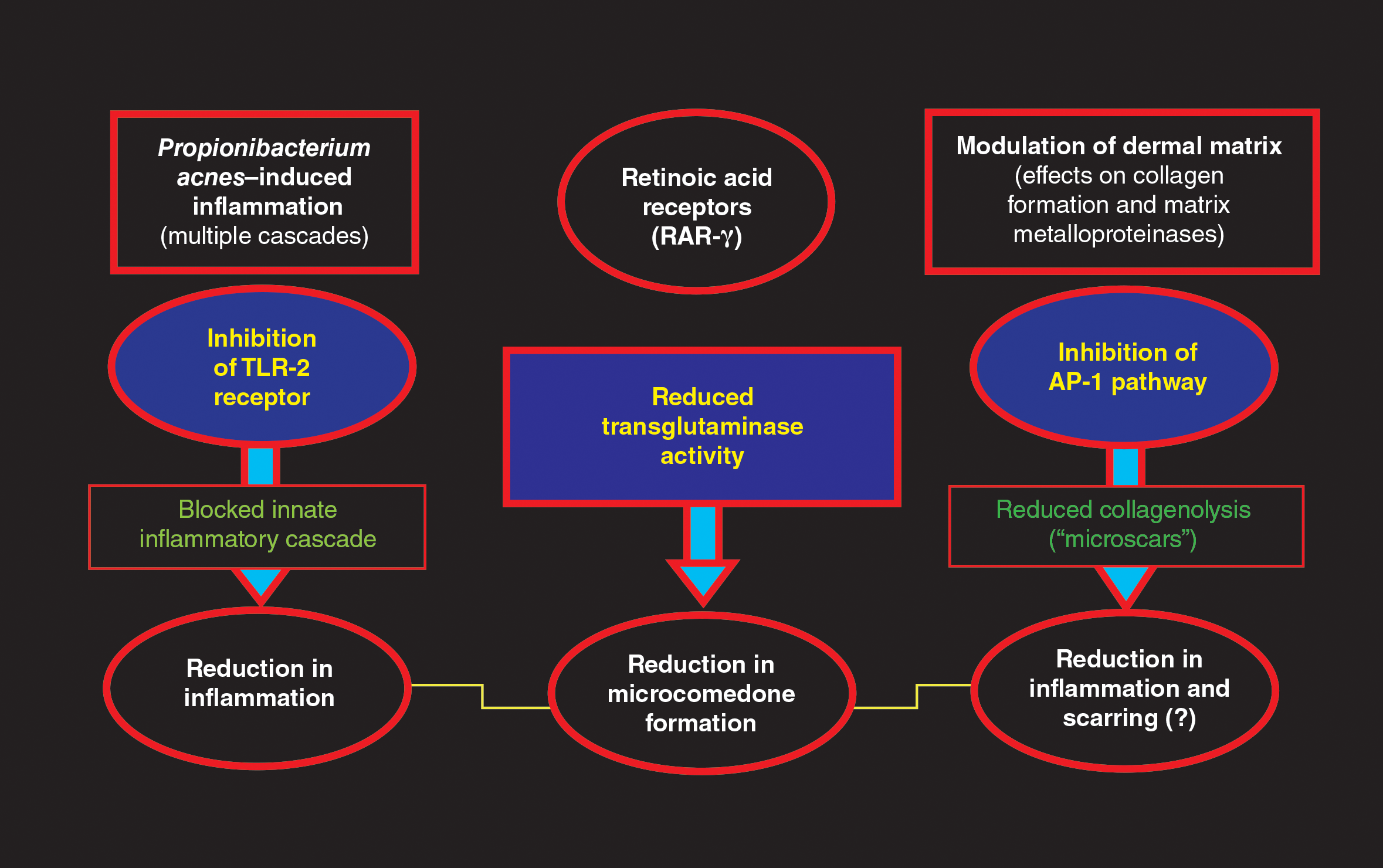

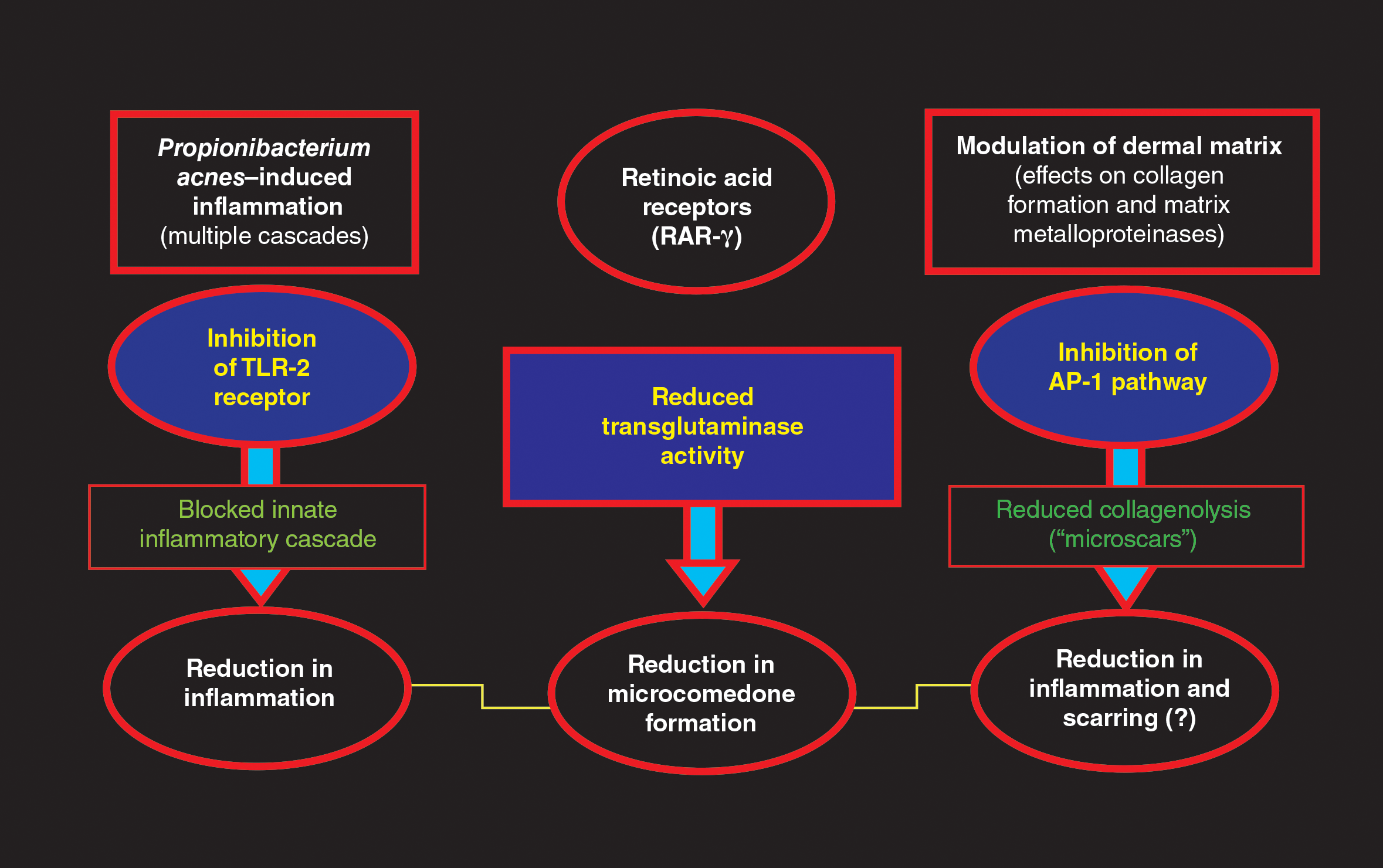

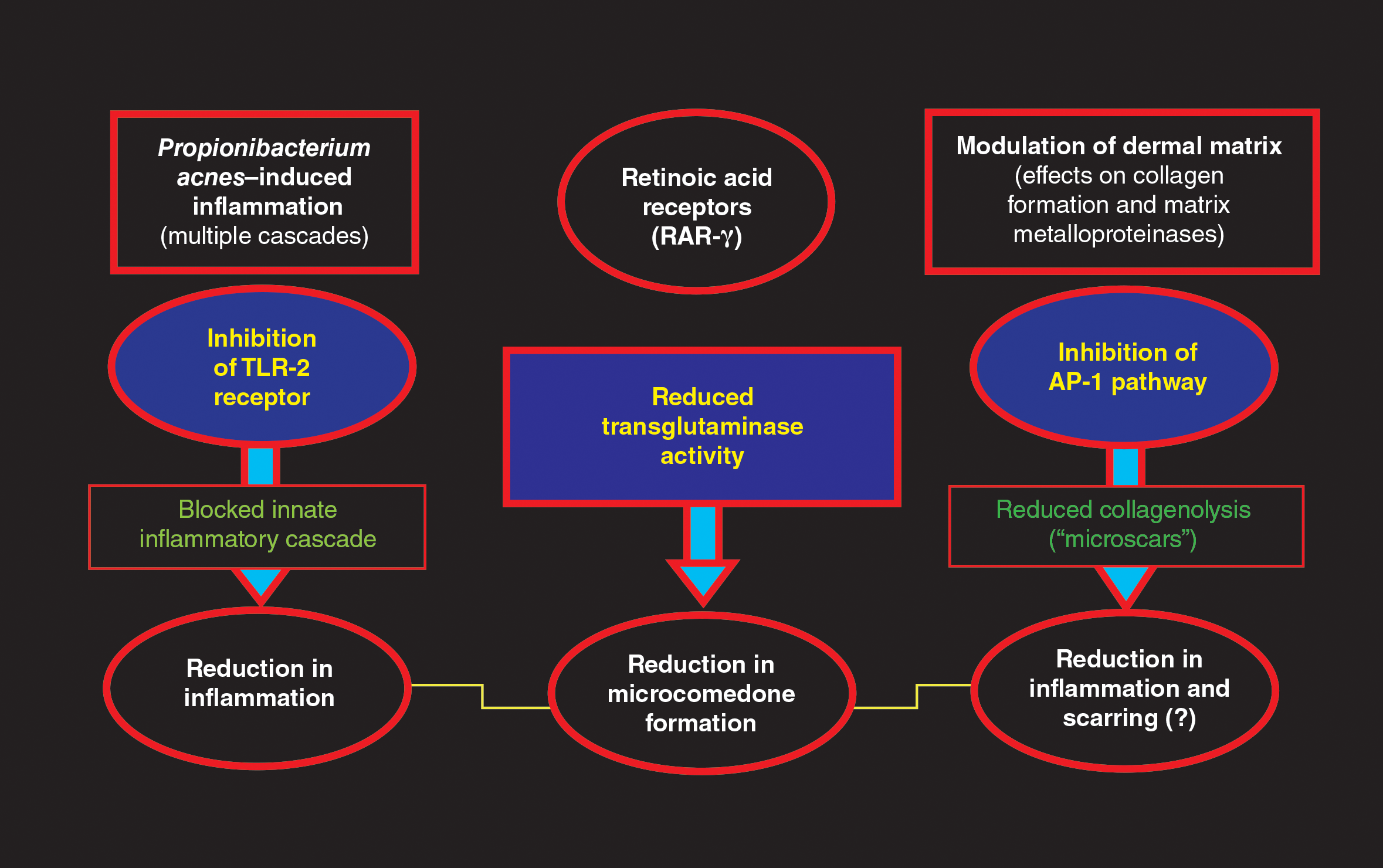

Tretinoin has been used extensively for the treatment of AV since its introduction in the United States in 1971.1,2,4,5 The proposed MOAs of topical retinoids, including tretinoin, based on available data include a variety of pharmacologic effects such as inhibition of follicular hyperkeratosis (decreased microcomedone formation), modulation of keratinocyte differentiation, anti-inflammatory properties, and inhibition of dermal matrix degradation (Figure).1,2,4,5,14,34,35 Topical retinoids, including tretinoin, have been shown to reduce both inflammatory and comedonal acne lesions, likely due to multiple MOAs, and are devoid of antibiotic properties.2,4-8,16 Available data support that topical combination therapy for AV with a retinoid and a topical antimicrobial agent augments the therapeutic benefit as compared to use of either agent alone.1-4,12,15,16,28,31,32

The rationale for incorporating both clindamycin and tretinoin together into one topical formulation includes combining different MOAs that appear to correlate with suppression of AV lesion formation and to improve patient adherence through once-daily application of a single topical product.16,31,32,36 Importantly, formulation researchers were able to combine CP-Tret into a specific aqueous gel formulation that maintained the stability of both active ingredients and proved to be effective and safe in preliminary studies completed in participants with AV.16,23,37-39 This aqueous formulation incorporated a limited number of excipients with low to negligible potential for cutaneous irritation or allergenicity, including anhydrous citric acid (chelating agent, preservative, emulsifier, acidulent), butylated hydroxytoluene (antioxidant), carbomer homopolymer type C (thickening agent, dispersing agent, biocompatible gel matrix), edetate disodium (chelating agent), laureth 4 (emulsifier, dissolution agent), methylparaben (preservative), propylene glycol (low-concentration humectant), purified water (diluent), and tromethamine (buffer, permeability enhancer).14

What are the clinical data evaluating the efficacy and tolerability/safety of the specific aqueous-based gel formulation of CP-Tret?

An aqueous-based gel formulation (referred to in the literature as a hydrogel) of CP-Tret is devoid of alcohol and contains the excipients described above.14 This formulation was shown to be efficacious, well tolerated, and safe in smaller clinical studies of participants with AV.23,37-39 Two large-scale phase 3 studies were completed (N=2219), powered to compare the efficacy and tolerability/safety of CP-Tret hydrogel (n=634) versus CP hydrogel (n=635), Tret hydrogel (n=635), and vehicle hydrogel (n=315) in participants with facial AV. All 4 study drug formulations in both studies—CP-Tret, CP, Tret, vehicle—used the same hydrogel vehicle, hereafter referred to simply as gel.16

In both trials, participants 12 years of age and older with AV were randomized to active drug groups versus vehicle (2:2:2:1 randomization), each applied once daily at bedtime for 12 weeks.16 The baseline demographics among all 4 study groups were well matched, with approximately two-thirds of white participants and one-third Asian (2%–3%), black (19%–21%), or Hispanic (9%–10%). Approximately half of enrolled participants were 16 years of age or younger (mean age [range], 19.0–20.2 years). Enrolled participants in each study group presented at baseline predominantly with facial AV of mild (grade 2 [20%–23% of enrolled participants]) or moderate (grade 3 [60%–62% of enrolled participants]) severity based on a protocol-mandated, 6-point investigator static global assessment scale. Investigator static global assessment scores and acne lesion counts, including noninflammatory (comedonal), inflammatory (papules, pustules), and total AV lesions, were evaluated at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 (end of study [EOS]). Among the 4 study groups at baseline, the range of mean lesion counts was 27.7 to 29.3 for noninflammatory lesions, 26.0 to 26.4 for inflammatory lesions, and 76.4 to 78.3 for total lesions. All enrolled participants met protocol-mandated, standardized, inclusion, exclusion, and prestudy washout period criteria.16

The primary efficacy end points determined based on intention-to-treat analysis were the percentage reduction in all 3 lesion counts at EOS compared to baseline and the proportion of participants who achieved scores of clear (grade 0) or almost clear (grade 1) at EOS. The secondary end point parameter was time to 50% reduction in total lesion counts.16

The study efficacy outcomes were as follows: The mean percentage reduction in inflammatory lesions at EOS versus baseline was significantly higher in the CP-Tret group than in each of the other 3 groups (CP-Tret, 53.4%; CP, 47.5%; Tret, 43.3%; vehicle, 30.3%)(P<.005).16 The mean percentage reduction in noninflammatory lesions at EOS versus baseline was significantly higher in the CP-Tret group than in each of the other 3 groups (CP-Tret, 45.2%; CP, 31.6%; Tret, 37.9%; vehicle, 18.5%)(P≤.0004). The mean percentage reduction in total AV lesions at EOS versus baseline was significantly higher in the CP-Tret group than in each of the other 3 groups (CP-Tret, 48.7%; CP, 38.3%; Tret, 40.3%; vehicle, 23.2%)(P≤.0001). The median time to 50% reduction in total AV lesion counts was significantly faster with CP-Tret (8 weeks) compared to the other 3 groups (CP, 12 weeks [P<.0001]; Tret, 12 weeks [P<.001]; vehicle, not reached by EOS [P<.0001]). The consistency of results, methodologies, and overall study characteristics between the 2 phase 3 RCTs allowed for accurate pooling of data.16

Tolerability and safety assessments were completed at each visit for all enrolled participants. No adverse events (AEs) were noted in approximately 90% of enrolled participants.16 The most common AEs noted over the course of the study were mild to moderate application-site reactions (eg, dryness, erythema, burning, pruritus, desquamation), mostly correlated with the 2 groups containing tretinoin—CP-Tret and Tret—which is not unanticipated with topical retinoid use; 1.2% of these participants withdrew from the study due to such application-site AEs. No serious AEs or systemic safety signals emerged during the study.16

What summarizing statements can be made about CP-Tret gel from these study results that may be helpful to clinicians treating patients with AV?

The gel formulation of CP-Tret incorporates active ingredients that target different pathophysiologic cascades in AV, providing antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and anticomedonal effects.

Applied once daily, CP-Tret gel demonstrated the ability to achieve complete or near-complete clearance of comedonal and papulopustular facial AV lesions of mild to moderate severity in approximately 40% of participants within 12 weeks of use in 2 large-scale RCTs.16 The ability to achieve a median 50% reduction in total lesions by 8 weeks of use provides relevant information for patients regarding reasonable expectations with therapy.

The favorable cutaneous tolerability profile and low number of AEs demonstrated with CP-Tret gel are major considerations, especially as skin tolerability reactions can impede patient adherence with treatment. Any issues that interfere with achieving a favorable therapeutic outcome can lead to patients giving up with their therapy.

The large number of patients with skin of color treated with CP-Tret gel (n=209) in the 2 phase 3 RCTs is important, as the spectrum of racial origins, skin types, and skin colors seen in dermatology practices is diversifying across the United States. Both clinicians and patients with skin of color are often concerned about the sequelae of medication-induced skin irritation, which can lead to ensuing dyschromia.

Concerns related to potential development of clindamycin-resistant P acnes with CP-Tret gel may be addressed by concurrent use of BP, including with leave-on or short-contact therapy.

Although phase 3 RCTs evaluate therapeutic agents as monotherapy, in real world clinical practice, combination topical regimens using different individual products are common to optimize therapeutic outcomes. Advantages of the CP-Tret gel formulation, if a clinician desires to use it along with another topical product, are once-daily use and the low risk for cutaneous irritation.

- Gollnick H, Cunliffe W, Berson D, et al. Management of acne: a report from the Global Alliance to improve outcomes in acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(suppl 1):S1-S37.

- Hui AM, Shalita AR. Topical retinoids. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:86-94.

- Del Rosso JQ. Topical antibiotics. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:95-104.

- Sami N. Topical retinoids. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:505-517.

- Baldwin HE, Nighland M, Kendall C, et al. 40 years of topical tretinoin use in review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:638-642.

- Retin-A Micro [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Valeant Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

- Tazorac [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2014.

- Differin [package insert]. Fort Worth, TX: Galderma Laboratories, LP; 2011.

- Kang S. The mechanism of action of topical retinoids. Cutis. 2005;75(suppl 2):10-13; discussion 13.

- Motaparthi K, Hsu S. Topical antibacterial agents. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:445-459.

- Leyden JJ. The evolving role of Propionibacterium acnes in acne. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2001;20:139-143.

- Leyden JJ, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF. Clinical considerations in the treatment of acne vulgaris and other inflammatory skin disorders: focus on antibiotic resistance. Cutis. 2007;79(suppl 6):9-25.

- Ziana [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Valeant Pharmaceuticals; 2016.

- Veltin [package insert]. Exton, PA: Aqua Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

- Ochsendorf F. Clindamycin phosphate 1.2%/tretinoin 0.025%: a novel fixed-dose combination treatment for acne vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(suppl 5):8-13.

- Leyden JJ, Krochmal L, Yaroshinsky A. Two randomized, double-blind, controlled trials of 2219 subjects to compare the combination clindamycin/tretinoin hydrogel with each agent alone and vehicle for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:73-81.

- Del Rosso JQ. Topical and oral antibiotics for acne vulgaris. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2016;35:57-61.

- Leyden JJ. Open-label evaluation of topical antimicrobial and anti-acne preparations for effectiveness versus Propionibacterium acnes in vivo. Cutis. 1992;49(suppl 6A):8-11.

- Del Rosso JQ, Schmidt NF. A review of the anti-inflammatory properties of clindamycin in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Cutis. 2010;85:15-24.

- Simonart T, Dramaix M. Treatment of acne with topical antibiotics: lessons from clinical studies. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:395-403.

- Schlessinger J, Menter A, Gold M, et al. Clinical safety and efficacy studies of a novel formulation combining 1.2% clindamycin phosphate and 0.025% tretinoin for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:607-615.

- Thiboutot D, Zaenglein A, Weiss J, et al. An aqueous gel fixed combination of clindamycin phosphate 1.2% and benzoyl peroxide 2.5% for the once-daily treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris: assessment of efficacy and safety in 2813 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:792-800.

- Zouboulis CC, Derumeaux L, Decroix J, et al. A multicentre, single-blind, randomized comparison of a fixed clindamycin phosphate/tretinoin gel formulation (Velac) applied once daily and a clindamycin lotion formulation (Dalacin T) applied twice daily in the topical treatment of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:498-505.

- Del Rosso JQ. Topical therapy for acne in women: is there a role for clindamycin phosphate-benzoyl peroxide gel? Cutis. 2014;94:177-182.

- Del Rosso JQ, Zeichner JA. The clinical relevance of antibiotic resistance: thirteen principles that every dermatologist needs to consider when prescribing antibiotic therapy. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:167-173.

- Leyden JJ. Antibiotic resistance in the topical treatment of acne vulgaris. Cutis. 2004;73(6 suppl):6-10.

- Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, Rosen T, et al. Status report from the Scientific Panel on Antibiotic Use in Dermatology of the American Acne and Rosacea Society: part 1: antibiotic prescribing patterns, sources of antibiotic exposure, antibiotic consumption and emergence of antibiotic resistance, impact of alterations in antibiotic prescribing, and clinical sequelae of antibiotic use. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9:18-24.

- Layton AM. Top ten list of clinical pearls in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:147-157.

- Leyden JJ. In vivo antibacterial effects of tretinoin-clindamycin and clindamycin alone on Propionibacterium acnes with varying clindamycin minimum inhibitory. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:1434-1438.

- Cunliffe WJ, Holland KT, Bojar R, et al. A randomized, double-blind comparison of a clindamycin phosphate/benzoyl peroxide gel formulation and a matching clindamycin gel with respect to microbiologic activity and clinical efficacy in the topical treatment of acne vulgaris. Clin Ther. 2002;24:1117-1133.

- Villasenor J, Berson DS, Kroshinsky D. Combination therapy. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:105-112.

- Feneran A, Kaufman WS, Dabade TS, et al. Retinoid plus antimicrobial combination treatments for acne. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2011;4:79-92.

- Leyden JJ, Del Rosso JQ. The effect of benzoyl peroxide 9.8% emollient foam on reduction of Propionibacterium acnes on the back using a short contact therapy approach. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:830-833.

- Bikowski JB. Mechanisms of the comedolytic and anti-inflammatory properties of topical retinoids. J Drugs Dermatol. 2005;4:41-47.

- Del Rosso JQ. Retinoic acid receptors and topical acne therapy: establishing the link between gene expression and drug efficacy. Cutis. 2002;70:127-129.

- Zaghloul SS, Cunliffe WJ, Goodfield MJ. Objective assessment of compliance with treatments in acne. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1015-1021.

- Richter JR, Bousema MT, DeBoulle KLVM, et al. Efficacy of fixed clindamycin 1.2%, tretinoin 0.025% gel formulation (Velac) in topical control of facial acne lesions. J Dermatol Treat. 1998;9:81-90.

- Richter JR, Fӧrstrӧm LR, Kiistala UO, et al. Efficacy of fixed 1.2% clindamycin phosphate, 0.025% tretinoin gel formulation (Velac) and a proprietary 0.025% tretinoin gel formulation (Aberela) in the topical control of facial acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1998;11:227-233.

- Cambazard F. Clinical efficacy of Velac, a new tretinoin and clindamycin gel in acne vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1998;11(suppl 1):S20-S27; discussion S28-S29.

Topical management of acne vulgaris (AV) incorporates a variety of agents with diverse modes of action (MOAs), including retinoids and antibiotics.1-3 The first topical retinoid developed for acne therapy was tretinoin, available in the United States since 1971.2,4 Topical retinoids, including tretinoin, exhibit multiple pharmacologic effects that are believed to correlate with efficacy for acne treatment,1,2,4,5 such as the reduction of inflammatory and comedonal lesions and contribution to dermal matrix remodeling.1,2,4-9 The predominant topical antibiotic used for acne treatment, often in combination with benzoyl peroxide (BP) and/or a topical retinoid, is clindamycin. Clindamycin is a lincosamide antibiotic that is closely related to erythromycin, a member of the macrolide antibiotic category.1,3,10 Available data support that over time topical clindamycin has sustained greater efficacy in reducing AV lesions than topical erythromycin; the latter also has been shown to exhibit a greater prevalence of Propionibacterium acnes resistance than clindamycin.1,3,10-12

Combination gel formulations of clindamycin phosphate 1.2%–tretinoin 0.025% (CP-Tret) are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and available in the United States for once-daily treatment of AV in patients 12 years of age and older.13-15 Large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated both efficacy and safety for these formulations.16,17 This article reviews important considerations related to both individual active ingredients (clindamycin phosphate [CP] and tretinoin [Tret]), formulation characteristics, and data from pivotal RCTs with a CP-Tret gel that has more recently been reintroduced into the US marketplace for acne therapy (Veltin, Aqua Pharmaceuticals).

What is the rationale behind combining CP and Tret in a single combination formulation?

Clindamycin is a lincosamide antibiotic that has been used for the treatment of AV for approximately 5 decades.1,3,10,17 The main MOA of clindamycin in the treatment of AV is believed to be reduction of P acnes; however, anti-inflammatory effects maypotentially play some role in AV lesion reduction.3,10,12,17-19 Multiple RCTs completed over approximately 3 decades and inclusive of more than 2000 participants treated topically with clindamycin as monotherapy have shown that the efficacy of this agent in reducing AV lesions has remained consistent overall,3,20-24 unlike topical erythromycin, which did not sustain its efficacy over a similar comparative time period.20 Importantly, these data are based on RCTs designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of individual agents, including topical clindamycin; however, topical antibiotic therapy is not recommended as monotherapy for AV treatment due to emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains.1,3,11,12,25-28 Although the prevalence of resistant strains of P acnes is lower in the United States and many other countries for clindamycin versus erythromycin, the magnitude of clindamycin-resistant P acnes strains increases and response to clindamycin therapy may decrease when this agent is used alone.12,25-27,29,30 Therefore, it is recommended that a BP formulation that exhibits the ability to adequately reduce P acnes counts be used concurrently with antibiotic therapy for AV to reduce the emergence and proliferation of antibiotic-resistant P acnes organisms; short-contact BP therapy using a high-concentration (9.8%) emollient foam formulation and sufficient contact time (ie, 2 minutes) prior to washing off also has been shown to markedly reduce truncal P acnes organism counts.1,3,10-12,25-33 The Table depicts the major characteristics of clindamycin related to its use for treatment of AV.

Tretinoin has been used extensively for the treatment of AV since its introduction in the United States in 1971.1,2,4,5 The proposed MOAs of topical retinoids, including tretinoin, based on available data include a variety of pharmacologic effects such as inhibition of follicular hyperkeratosis (decreased microcomedone formation), modulation of keratinocyte differentiation, anti-inflammatory properties, and inhibition of dermal matrix degradation (Figure).1,2,4,5,14,34,35 Topical retinoids, including tretinoin, have been shown to reduce both inflammatory and comedonal acne lesions, likely due to multiple MOAs, and are devoid of antibiotic properties.2,4-8,16 Available data support that topical combination therapy for AV with a retinoid and a topical antimicrobial agent augments the therapeutic benefit as compared to use of either agent alone.1-4,12,15,16,28,31,32

The rationale for incorporating both clindamycin and tretinoin together into one topical formulation includes combining different MOAs that appear to correlate with suppression of AV lesion formation and to improve patient adherence through once-daily application of a single topical product.16,31,32,36 Importantly, formulation researchers were able to combine CP-Tret into a specific aqueous gel formulation that maintained the stability of both active ingredients and proved to be effective and safe in preliminary studies completed in participants with AV.16,23,37-39 This aqueous formulation incorporated a limited number of excipients with low to negligible potential for cutaneous irritation or allergenicity, including anhydrous citric acid (chelating agent, preservative, emulsifier, acidulent), butylated hydroxytoluene (antioxidant), carbomer homopolymer type C (thickening agent, dispersing agent, biocompatible gel matrix), edetate disodium (chelating agent), laureth 4 (emulsifier, dissolution agent), methylparaben (preservative), propylene glycol (low-concentration humectant), purified water (diluent), and tromethamine (buffer, permeability enhancer).14

What are the clinical data evaluating the efficacy and tolerability/safety of the specific aqueous-based gel formulation of CP-Tret?

An aqueous-based gel formulation (referred to in the literature as a hydrogel) of CP-Tret is devoid of alcohol and contains the excipients described above.14 This formulation was shown to be efficacious, well tolerated, and safe in smaller clinical studies of participants with AV.23,37-39 Two large-scale phase 3 studies were completed (N=2219), powered to compare the efficacy and tolerability/safety of CP-Tret hydrogel (n=634) versus CP hydrogel (n=635), Tret hydrogel (n=635), and vehicle hydrogel (n=315) in participants with facial AV. All 4 study drug formulations in both studies—CP-Tret, CP, Tret, vehicle—used the same hydrogel vehicle, hereafter referred to simply as gel.16

In both trials, participants 12 years of age and older with AV were randomized to active drug groups versus vehicle (2:2:2:1 randomization), each applied once daily at bedtime for 12 weeks.16 The baseline demographics among all 4 study groups were well matched, with approximately two-thirds of white participants and one-third Asian (2%–3%), black (19%–21%), or Hispanic (9%–10%). Approximately half of enrolled participants were 16 years of age or younger (mean age [range], 19.0–20.2 years). Enrolled participants in each study group presented at baseline predominantly with facial AV of mild (grade 2 [20%–23% of enrolled participants]) or moderate (grade 3 [60%–62% of enrolled participants]) severity based on a protocol-mandated, 6-point investigator static global assessment scale. Investigator static global assessment scores and acne lesion counts, including noninflammatory (comedonal), inflammatory (papules, pustules), and total AV lesions, were evaluated at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 (end of study [EOS]). Among the 4 study groups at baseline, the range of mean lesion counts was 27.7 to 29.3 for noninflammatory lesions, 26.0 to 26.4 for inflammatory lesions, and 76.4 to 78.3 for total lesions. All enrolled participants met protocol-mandated, standardized, inclusion, exclusion, and prestudy washout period criteria.16

The primary efficacy end points determined based on intention-to-treat analysis were the percentage reduction in all 3 lesion counts at EOS compared to baseline and the proportion of participants who achieved scores of clear (grade 0) or almost clear (grade 1) at EOS. The secondary end point parameter was time to 50% reduction in total lesion counts.16

The study efficacy outcomes were as follows: The mean percentage reduction in inflammatory lesions at EOS versus baseline was significantly higher in the CP-Tret group than in each of the other 3 groups (CP-Tret, 53.4%; CP, 47.5%; Tret, 43.3%; vehicle, 30.3%)(P<.005).16 The mean percentage reduction in noninflammatory lesions at EOS versus baseline was significantly higher in the CP-Tret group than in each of the other 3 groups (CP-Tret, 45.2%; CP, 31.6%; Tret, 37.9%; vehicle, 18.5%)(P≤.0004). The mean percentage reduction in total AV lesions at EOS versus baseline was significantly higher in the CP-Tret group than in each of the other 3 groups (CP-Tret, 48.7%; CP, 38.3%; Tret, 40.3%; vehicle, 23.2%)(P≤.0001). The median time to 50% reduction in total AV lesion counts was significantly faster with CP-Tret (8 weeks) compared to the other 3 groups (CP, 12 weeks [P<.0001]; Tret, 12 weeks [P<.001]; vehicle, not reached by EOS [P<.0001]). The consistency of results, methodologies, and overall study characteristics between the 2 phase 3 RCTs allowed for accurate pooling of data.16

Tolerability and safety assessments were completed at each visit for all enrolled participants. No adverse events (AEs) were noted in approximately 90% of enrolled participants.16 The most common AEs noted over the course of the study were mild to moderate application-site reactions (eg, dryness, erythema, burning, pruritus, desquamation), mostly correlated with the 2 groups containing tretinoin—CP-Tret and Tret—which is not unanticipated with topical retinoid use; 1.2% of these participants withdrew from the study due to such application-site AEs. No serious AEs or systemic safety signals emerged during the study.16

What summarizing statements can be made about CP-Tret gel from these study results that may be helpful to clinicians treating patients with AV?

The gel formulation of CP-Tret incorporates active ingredients that target different pathophysiologic cascades in AV, providing antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and anticomedonal effects.

Applied once daily, CP-Tret gel demonstrated the ability to achieve complete or near-complete clearance of comedonal and papulopustular facial AV lesions of mild to moderate severity in approximately 40% of participants within 12 weeks of use in 2 large-scale RCTs.16 The ability to achieve a median 50% reduction in total lesions by 8 weeks of use provides relevant information for patients regarding reasonable expectations with therapy.

The favorable cutaneous tolerability profile and low number of AEs demonstrated with CP-Tret gel are major considerations, especially as skin tolerability reactions can impede patient adherence with treatment. Any issues that interfere with achieving a favorable therapeutic outcome can lead to patients giving up with their therapy.

The large number of patients with skin of color treated with CP-Tret gel (n=209) in the 2 phase 3 RCTs is important, as the spectrum of racial origins, skin types, and skin colors seen in dermatology practices is diversifying across the United States. Both clinicians and patients with skin of color are often concerned about the sequelae of medication-induced skin irritation, which can lead to ensuing dyschromia.

Concerns related to potential development of clindamycin-resistant P acnes with CP-Tret gel may be addressed by concurrent use of BP, including with leave-on or short-contact therapy.

Although phase 3 RCTs evaluate therapeutic agents as monotherapy, in real world clinical practice, combination topical regimens using different individual products are common to optimize therapeutic outcomes. Advantages of the CP-Tret gel formulation, if a clinician desires to use it along with another topical product, are once-daily use and the low risk for cutaneous irritation.

Topical management of acne vulgaris (AV) incorporates a variety of agents with diverse modes of action (MOAs), including retinoids and antibiotics.1-3 The first topical retinoid developed for acne therapy was tretinoin, available in the United States since 1971.2,4 Topical retinoids, including tretinoin, exhibit multiple pharmacologic effects that are believed to correlate with efficacy for acne treatment,1,2,4,5 such as the reduction of inflammatory and comedonal lesions and contribution to dermal matrix remodeling.1,2,4-9 The predominant topical antibiotic used for acne treatment, often in combination with benzoyl peroxide (BP) and/or a topical retinoid, is clindamycin. Clindamycin is a lincosamide antibiotic that is closely related to erythromycin, a member of the macrolide antibiotic category.1,3,10 Available data support that over time topical clindamycin has sustained greater efficacy in reducing AV lesions than topical erythromycin; the latter also has been shown to exhibit a greater prevalence of Propionibacterium acnes resistance than clindamycin.1,3,10-12

Combination gel formulations of clindamycin phosphate 1.2%–tretinoin 0.025% (CP-Tret) are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and available in the United States for once-daily treatment of AV in patients 12 years of age and older.13-15 Large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated both efficacy and safety for these formulations.16,17 This article reviews important considerations related to both individual active ingredients (clindamycin phosphate [CP] and tretinoin [Tret]), formulation characteristics, and data from pivotal RCTs with a CP-Tret gel that has more recently been reintroduced into the US marketplace for acne therapy (Veltin, Aqua Pharmaceuticals).

What is the rationale behind combining CP and Tret in a single combination formulation?

Clindamycin is a lincosamide antibiotic that has been used for the treatment of AV for approximately 5 decades.1,3,10,17 The main MOA of clindamycin in the treatment of AV is believed to be reduction of P acnes; however, anti-inflammatory effects maypotentially play some role in AV lesion reduction.3,10,12,17-19 Multiple RCTs completed over approximately 3 decades and inclusive of more than 2000 participants treated topically with clindamycin as monotherapy have shown that the efficacy of this agent in reducing AV lesions has remained consistent overall,3,20-24 unlike topical erythromycin, which did not sustain its efficacy over a similar comparative time period.20 Importantly, these data are based on RCTs designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of individual agents, including topical clindamycin; however, topical antibiotic therapy is not recommended as monotherapy for AV treatment due to emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains.1,3,11,12,25-28 Although the prevalence of resistant strains of P acnes is lower in the United States and many other countries for clindamycin versus erythromycin, the magnitude of clindamycin-resistant P acnes strains increases and response to clindamycin therapy may decrease when this agent is used alone.12,25-27,29,30 Therefore, it is recommended that a BP formulation that exhibits the ability to adequately reduce P acnes counts be used concurrently with antibiotic therapy for AV to reduce the emergence and proliferation of antibiotic-resistant P acnes organisms; short-contact BP therapy using a high-concentration (9.8%) emollient foam formulation and sufficient contact time (ie, 2 minutes) prior to washing off also has been shown to markedly reduce truncal P acnes organism counts.1,3,10-12,25-33 The Table depicts the major characteristics of clindamycin related to its use for treatment of AV.

Tretinoin has been used extensively for the treatment of AV since its introduction in the United States in 1971.1,2,4,5 The proposed MOAs of topical retinoids, including tretinoin, based on available data include a variety of pharmacologic effects such as inhibition of follicular hyperkeratosis (decreased microcomedone formation), modulation of keratinocyte differentiation, anti-inflammatory properties, and inhibition of dermal matrix degradation (Figure).1,2,4,5,14,34,35 Topical retinoids, including tretinoin, have been shown to reduce both inflammatory and comedonal acne lesions, likely due to multiple MOAs, and are devoid of antibiotic properties.2,4-8,16 Available data support that topical combination therapy for AV with a retinoid and a topical antimicrobial agent augments the therapeutic benefit as compared to use of either agent alone.1-4,12,15,16,28,31,32

The rationale for incorporating both clindamycin and tretinoin together into one topical formulation includes combining different MOAs that appear to correlate with suppression of AV lesion formation and to improve patient adherence through once-daily application of a single topical product.16,31,32,36 Importantly, formulation researchers were able to combine CP-Tret into a specific aqueous gel formulation that maintained the stability of both active ingredients and proved to be effective and safe in preliminary studies completed in participants with AV.16,23,37-39 This aqueous formulation incorporated a limited number of excipients with low to negligible potential for cutaneous irritation or allergenicity, including anhydrous citric acid (chelating agent, preservative, emulsifier, acidulent), butylated hydroxytoluene (antioxidant), carbomer homopolymer type C (thickening agent, dispersing agent, biocompatible gel matrix), edetate disodium (chelating agent), laureth 4 (emulsifier, dissolution agent), methylparaben (preservative), propylene glycol (low-concentration humectant), purified water (diluent), and tromethamine (buffer, permeability enhancer).14

What are the clinical data evaluating the efficacy and tolerability/safety of the specific aqueous-based gel formulation of CP-Tret?

An aqueous-based gel formulation (referred to in the literature as a hydrogel) of CP-Tret is devoid of alcohol and contains the excipients described above.14 This formulation was shown to be efficacious, well tolerated, and safe in smaller clinical studies of participants with AV.23,37-39 Two large-scale phase 3 studies were completed (N=2219), powered to compare the efficacy and tolerability/safety of CP-Tret hydrogel (n=634) versus CP hydrogel (n=635), Tret hydrogel (n=635), and vehicle hydrogel (n=315) in participants with facial AV. All 4 study drug formulations in both studies—CP-Tret, CP, Tret, vehicle—used the same hydrogel vehicle, hereafter referred to simply as gel.16

In both trials, participants 12 years of age and older with AV were randomized to active drug groups versus vehicle (2:2:2:1 randomization), each applied once daily at bedtime for 12 weeks.16 The baseline demographics among all 4 study groups were well matched, with approximately two-thirds of white participants and one-third Asian (2%–3%), black (19%–21%), or Hispanic (9%–10%). Approximately half of enrolled participants were 16 years of age or younger (mean age [range], 19.0–20.2 years). Enrolled participants in each study group presented at baseline predominantly with facial AV of mild (grade 2 [20%–23% of enrolled participants]) or moderate (grade 3 [60%–62% of enrolled participants]) severity based on a protocol-mandated, 6-point investigator static global assessment scale. Investigator static global assessment scores and acne lesion counts, including noninflammatory (comedonal), inflammatory (papules, pustules), and total AV lesions, were evaluated at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 (end of study [EOS]). Among the 4 study groups at baseline, the range of mean lesion counts was 27.7 to 29.3 for noninflammatory lesions, 26.0 to 26.4 for inflammatory lesions, and 76.4 to 78.3 for total lesions. All enrolled participants met protocol-mandated, standardized, inclusion, exclusion, and prestudy washout period criteria.16

The primary efficacy end points determined based on intention-to-treat analysis were the percentage reduction in all 3 lesion counts at EOS compared to baseline and the proportion of participants who achieved scores of clear (grade 0) or almost clear (grade 1) at EOS. The secondary end point parameter was time to 50% reduction in total lesion counts.16

The study efficacy outcomes were as follows: The mean percentage reduction in inflammatory lesions at EOS versus baseline was significantly higher in the CP-Tret group than in each of the other 3 groups (CP-Tret, 53.4%; CP, 47.5%; Tret, 43.3%; vehicle, 30.3%)(P<.005).16 The mean percentage reduction in noninflammatory lesions at EOS versus baseline was significantly higher in the CP-Tret group than in each of the other 3 groups (CP-Tret, 45.2%; CP, 31.6%; Tret, 37.9%; vehicle, 18.5%)(P≤.0004). The mean percentage reduction in total AV lesions at EOS versus baseline was significantly higher in the CP-Tret group than in each of the other 3 groups (CP-Tret, 48.7%; CP, 38.3%; Tret, 40.3%; vehicle, 23.2%)(P≤.0001). The median time to 50% reduction in total AV lesion counts was significantly faster with CP-Tret (8 weeks) compared to the other 3 groups (CP, 12 weeks [P<.0001]; Tret, 12 weeks [P<.001]; vehicle, not reached by EOS [P<.0001]). The consistency of results, methodologies, and overall study characteristics between the 2 phase 3 RCTs allowed for accurate pooling of data.16

Tolerability and safety assessments were completed at each visit for all enrolled participants. No adverse events (AEs) were noted in approximately 90% of enrolled participants.16 The most common AEs noted over the course of the study were mild to moderate application-site reactions (eg, dryness, erythema, burning, pruritus, desquamation), mostly correlated with the 2 groups containing tretinoin—CP-Tret and Tret—which is not unanticipated with topical retinoid use; 1.2% of these participants withdrew from the study due to such application-site AEs. No serious AEs or systemic safety signals emerged during the study.16

What summarizing statements can be made about CP-Tret gel from these study results that may be helpful to clinicians treating patients with AV?

The gel formulation of CP-Tret incorporates active ingredients that target different pathophysiologic cascades in AV, providing antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and anticomedonal effects.

Applied once daily, CP-Tret gel demonstrated the ability to achieve complete or near-complete clearance of comedonal and papulopustular facial AV lesions of mild to moderate severity in approximately 40% of participants within 12 weeks of use in 2 large-scale RCTs.16 The ability to achieve a median 50% reduction in total lesions by 8 weeks of use provides relevant information for patients regarding reasonable expectations with therapy.

The favorable cutaneous tolerability profile and low number of AEs demonstrated with CP-Tret gel are major considerations, especially as skin tolerability reactions can impede patient adherence with treatment. Any issues that interfere with achieving a favorable therapeutic outcome can lead to patients giving up with their therapy.

The large number of patients with skin of color treated with CP-Tret gel (n=209) in the 2 phase 3 RCTs is important, as the spectrum of racial origins, skin types, and skin colors seen in dermatology practices is diversifying across the United States. Both clinicians and patients with skin of color are often concerned about the sequelae of medication-induced skin irritation, which can lead to ensuing dyschromia.

Concerns related to potential development of clindamycin-resistant P acnes with CP-Tret gel may be addressed by concurrent use of BP, including with leave-on or short-contact therapy.

Although phase 3 RCTs evaluate therapeutic agents as monotherapy, in real world clinical practice, combination topical regimens using different individual products are common to optimize therapeutic outcomes. Advantages of the CP-Tret gel formulation, if a clinician desires to use it along with another topical product, are once-daily use and the low risk for cutaneous irritation.

- Gollnick H, Cunliffe W, Berson D, et al. Management of acne: a report from the Global Alliance to improve outcomes in acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(suppl 1):S1-S37.

- Hui AM, Shalita AR. Topical retinoids. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:86-94.

- Del Rosso JQ. Topical antibiotics. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:95-104.

- Sami N. Topical retinoids. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:505-517.

- Baldwin HE, Nighland M, Kendall C, et al. 40 years of topical tretinoin use in review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:638-642.

- Retin-A Micro [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Valeant Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

- Tazorac [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2014.

- Differin [package insert]. Fort Worth, TX: Galderma Laboratories, LP; 2011.

- Kang S. The mechanism of action of topical retinoids. Cutis. 2005;75(suppl 2):10-13; discussion 13.

- Motaparthi K, Hsu S. Topical antibacterial agents. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:445-459.

- Leyden JJ. The evolving role of Propionibacterium acnes in acne. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2001;20:139-143.

- Leyden JJ, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF. Clinical considerations in the treatment of acne vulgaris and other inflammatory skin disorders: focus on antibiotic resistance. Cutis. 2007;79(suppl 6):9-25.

- Ziana [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Valeant Pharmaceuticals; 2016.

- Veltin [package insert]. Exton, PA: Aqua Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

- Ochsendorf F. Clindamycin phosphate 1.2%/tretinoin 0.025%: a novel fixed-dose combination treatment for acne vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(suppl 5):8-13.

- Leyden JJ, Krochmal L, Yaroshinsky A. Two randomized, double-blind, controlled trials of 2219 subjects to compare the combination clindamycin/tretinoin hydrogel with each agent alone and vehicle for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:73-81.

- Del Rosso JQ. Topical and oral antibiotics for acne vulgaris. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2016;35:57-61.

- Leyden JJ. Open-label evaluation of topical antimicrobial and anti-acne preparations for effectiveness versus Propionibacterium acnes in vivo. Cutis. 1992;49(suppl 6A):8-11.

- Del Rosso JQ, Schmidt NF. A review of the anti-inflammatory properties of clindamycin in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Cutis. 2010;85:15-24.

- Simonart T, Dramaix M. Treatment of acne with topical antibiotics: lessons from clinical studies. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:395-403.

- Schlessinger J, Menter A, Gold M, et al. Clinical safety and efficacy studies of a novel formulation combining 1.2% clindamycin phosphate and 0.025% tretinoin for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:607-615.

- Thiboutot D, Zaenglein A, Weiss J, et al. An aqueous gel fixed combination of clindamycin phosphate 1.2% and benzoyl peroxide 2.5% for the once-daily treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris: assessment of efficacy and safety in 2813 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:792-800.

- Zouboulis CC, Derumeaux L, Decroix J, et al. A multicentre, single-blind, randomized comparison of a fixed clindamycin phosphate/tretinoin gel formulation (Velac) applied once daily and a clindamycin lotion formulation (Dalacin T) applied twice daily in the topical treatment of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:498-505.

- Del Rosso JQ. Topical therapy for acne in women: is there a role for clindamycin phosphate-benzoyl peroxide gel? Cutis. 2014;94:177-182.

- Del Rosso JQ, Zeichner JA. The clinical relevance of antibiotic resistance: thirteen principles that every dermatologist needs to consider when prescribing antibiotic therapy. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:167-173.

- Leyden JJ. Antibiotic resistance in the topical treatment of acne vulgaris. Cutis. 2004;73(6 suppl):6-10.

- Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, Rosen T, et al. Status report from the Scientific Panel on Antibiotic Use in Dermatology of the American Acne and Rosacea Society: part 1: antibiotic prescribing patterns, sources of antibiotic exposure, antibiotic consumption and emergence of antibiotic resistance, impact of alterations in antibiotic prescribing, and clinical sequelae of antibiotic use. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9:18-24.

- Layton AM. Top ten list of clinical pearls in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:147-157.

- Leyden JJ. In vivo antibacterial effects of tretinoin-clindamycin and clindamycin alone on Propionibacterium acnes with varying clindamycin minimum inhibitory. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:1434-1438.

- Cunliffe WJ, Holland KT, Bojar R, et al. A randomized, double-blind comparison of a clindamycin phosphate/benzoyl peroxide gel formulation and a matching clindamycin gel with respect to microbiologic activity and clinical efficacy in the topical treatment of acne vulgaris. Clin Ther. 2002;24:1117-1133.

- Villasenor J, Berson DS, Kroshinsky D. Combination therapy. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:105-112.

- Feneran A, Kaufman WS, Dabade TS, et al. Retinoid plus antimicrobial combination treatments for acne. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2011;4:79-92.

- Leyden JJ, Del Rosso JQ. The effect of benzoyl peroxide 9.8% emollient foam on reduction of Propionibacterium acnes on the back using a short contact therapy approach. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:830-833.

- Bikowski JB. Mechanisms of the comedolytic and anti-inflammatory properties of topical retinoids. J Drugs Dermatol. 2005;4:41-47.

- Del Rosso JQ. Retinoic acid receptors and topical acne therapy: establishing the link between gene expression and drug efficacy. Cutis. 2002;70:127-129.

- Zaghloul SS, Cunliffe WJ, Goodfield MJ. Objective assessment of compliance with treatments in acne. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1015-1021.

- Richter JR, Bousema MT, DeBoulle KLVM, et al. Efficacy of fixed clindamycin 1.2%, tretinoin 0.025% gel formulation (Velac) in topical control of facial acne lesions. J Dermatol Treat. 1998;9:81-90.

- Richter JR, Fӧrstrӧm LR, Kiistala UO, et al. Efficacy of fixed 1.2% clindamycin phosphate, 0.025% tretinoin gel formulation (Velac) and a proprietary 0.025% tretinoin gel formulation (Aberela) in the topical control of facial acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1998;11:227-233.

- Cambazard F. Clinical efficacy of Velac, a new tretinoin and clindamycin gel in acne vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1998;11(suppl 1):S20-S27; discussion S28-S29.

- Gollnick H, Cunliffe W, Berson D, et al. Management of acne: a report from the Global Alliance to improve outcomes in acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(suppl 1):S1-S37.

- Hui AM, Shalita AR. Topical retinoids. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:86-94.

- Del Rosso JQ. Topical antibiotics. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:95-104.

- Sami N. Topical retinoids. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:505-517.

- Baldwin HE, Nighland M, Kendall C, et al. 40 years of topical tretinoin use in review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:638-642.

- Retin-A Micro [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Valeant Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

- Tazorac [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2014.

- Differin [package insert]. Fort Worth, TX: Galderma Laboratories, LP; 2011.

- Kang S. The mechanism of action of topical retinoids. Cutis. 2005;75(suppl 2):10-13; discussion 13.

- Motaparthi K, Hsu S. Topical antibacterial agents. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:445-459.

- Leyden JJ. The evolving role of Propionibacterium acnes in acne. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2001;20:139-143.

- Leyden JJ, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF. Clinical considerations in the treatment of acne vulgaris and other inflammatory skin disorders: focus on antibiotic resistance. Cutis. 2007;79(suppl 6):9-25.

- Ziana [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Valeant Pharmaceuticals; 2016.

- Veltin [package insert]. Exton, PA: Aqua Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

- Ochsendorf F. Clindamycin phosphate 1.2%/tretinoin 0.025%: a novel fixed-dose combination treatment for acne vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(suppl 5):8-13.

- Leyden JJ, Krochmal L, Yaroshinsky A. Two randomized, double-blind, controlled trials of 2219 subjects to compare the combination clindamycin/tretinoin hydrogel with each agent alone and vehicle for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:73-81.

- Del Rosso JQ. Topical and oral antibiotics for acne vulgaris. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2016;35:57-61.

- Leyden JJ. Open-label evaluation of topical antimicrobial and anti-acne preparations for effectiveness versus Propionibacterium acnes in vivo. Cutis. 1992;49(suppl 6A):8-11.

- Del Rosso JQ, Schmidt NF. A review of the anti-inflammatory properties of clindamycin in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Cutis. 2010;85:15-24.

- Simonart T, Dramaix M. Treatment of acne with topical antibiotics: lessons from clinical studies. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:395-403.

- Schlessinger J, Menter A, Gold M, et al. Clinical safety and efficacy studies of a novel formulation combining 1.2% clindamycin phosphate and 0.025% tretinoin for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:607-615.

- Thiboutot D, Zaenglein A, Weiss J, et al. An aqueous gel fixed combination of clindamycin phosphate 1.2% and benzoyl peroxide 2.5% for the once-daily treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris: assessment of efficacy and safety in 2813 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:792-800.

- Zouboulis CC, Derumeaux L, Decroix J, et al. A multicentre, single-blind, randomized comparison of a fixed clindamycin phosphate/tretinoin gel formulation (Velac) applied once daily and a clindamycin lotion formulation (Dalacin T) applied twice daily in the topical treatment of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:498-505.

- Del Rosso JQ. Topical therapy for acne in women: is there a role for clindamycin phosphate-benzoyl peroxide gel? Cutis. 2014;94:177-182.

- Del Rosso JQ, Zeichner JA. The clinical relevance of antibiotic resistance: thirteen principles that every dermatologist needs to consider when prescribing antibiotic therapy. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:167-173.

- Leyden JJ. Antibiotic resistance in the topical treatment of acne vulgaris. Cutis. 2004;73(6 suppl):6-10.

- Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, Rosen T, et al. Status report from the Scientific Panel on Antibiotic Use in Dermatology of the American Acne and Rosacea Society: part 1: antibiotic prescribing patterns, sources of antibiotic exposure, antibiotic consumption and emergence of antibiotic resistance, impact of alterations in antibiotic prescribing, and clinical sequelae of antibiotic use. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9:18-24.

- Layton AM. Top ten list of clinical pearls in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:147-157.

- Leyden JJ. In vivo antibacterial effects of tretinoin-clindamycin and clindamycin alone on Propionibacterium acnes with varying clindamycin minimum inhibitory. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:1434-1438.

- Cunliffe WJ, Holland KT, Bojar R, et al. A randomized, double-blind comparison of a clindamycin phosphate/benzoyl peroxide gel formulation and a matching clindamycin gel with respect to microbiologic activity and clinical efficacy in the topical treatment of acne vulgaris. Clin Ther. 2002;24:1117-1133.

- Villasenor J, Berson DS, Kroshinsky D. Combination therapy. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:105-112.

- Feneran A, Kaufman WS, Dabade TS, et al. Retinoid plus antimicrobial combination treatments for acne. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2011;4:79-92.

- Leyden JJ, Del Rosso JQ. The effect of benzoyl peroxide 9.8% emollient foam on reduction of Propionibacterium acnes on the back using a short contact therapy approach. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:830-833.

- Bikowski JB. Mechanisms of the comedolytic and anti-inflammatory properties of topical retinoids. J Drugs Dermatol. 2005;4:41-47.

- Del Rosso JQ. Retinoic acid receptors and topical acne therapy: establishing the link between gene expression and drug efficacy. Cutis. 2002;70:127-129.

- Zaghloul SS, Cunliffe WJ, Goodfield MJ. Objective assessment of compliance with treatments in acne. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1015-1021.

- Richter JR, Bousema MT, DeBoulle KLVM, et al. Efficacy of fixed clindamycin 1.2%, tretinoin 0.025% gel formulation (Velac) in topical control of facial acne lesions. J Dermatol Treat. 1998;9:81-90.

- Richter JR, Fӧrstrӧm LR, Kiistala UO, et al. Efficacy of fixed 1.2% clindamycin phosphate, 0.025% tretinoin gel formulation (Velac) and a proprietary 0.025% tretinoin gel formulation (Aberela) in the topical control of facial acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1998;11:227-233.

- Cambazard F. Clinical efficacy of Velac, a new tretinoin and clindamycin gel in acne vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1998;11(suppl 1):S20-S27; discussion S28-S29.

Practice Points

- Clindamycin phosphate (CP)–tretinoin (Tret) formulated in an aqueous gel is effective based on clinical trials of the management of acne vulgaris (AV).

- The favorable tolerability of CP-Tret gel is advantageous, as topical agents often are used in combination with other therapies to treat AV, especially with a benzoyl peroxide–containing product.

- The availability of 2 active agents in 1 formulation is likely to optimize compliance.

When Do Efficacy Outcomes in Clinical Trials Correlate With Clinical Relevance? Analysis of Clindamycin Phosphate 1.2%–Benzoyl Peroxide 3.75% Gel in Moderate to Severe Acne Vulgaris

Acne vulgaris (AV) is a common skin disease that usually presents in adolescence and can persist into adulthood. Some cases may start in adulthood, especially in women. Acne vulgaris remains a challenge to treat successfully, both in teenagers and adults. Unrealistic expectations that therapy will rapidly clear and sustain clearance of AV completely can lead to incomplete adherence or complete cessation of treatment.1-4 Local tolerability reactions also may decrease adherence to topical medications. Suboptimal adherence to medications for AV is one of the major reasons for treatment failure.5 Acne vulgaris can strongly influence psychological well-being and self-esteem.6 In general, severe AV causes more psychological distress, but the adverse emotional impact of AV can be independent of its severity.7

An effective relationship between the patient and his/her physician and staff is believed to be important in setting realistic expectations, optimizing adherence, and achieving a positive therapeutic outcome. One component related to setting reasonable expectations is the discussion about when the patient may begin to visibly perceive that the treatment regimen is working. This article evaluates the time course of a clinically meaningful response using pivotal trial data with clindamycin phosphate 1.2%–benzoyl peroxide 3.75% (clindamycin-BP 3.75%) gel for treatment of AV.

Are data available that evaluate the time course of a clinically relevant response to treatment of AV?

Unfortunately, data on what might be perceived as a clinically meaningful improvement in AV and how long it might take to achieve this treatment effect are limited. A meta-analysis of more than 4000 patients with moderate to severe AV suggested that a 10% to 20% difference in acne lesion counts from baseline as compared to a subsequent designated time point was clinically relevant.8 A review of 24 comparative studies of patients with mild to moderate AV used a primary outcome parameter of a 25% reduction in mean inflammatory lesion count to evaluate time to onset of action (TOA) to achieve a clinically meaningful benefit.9 This outcome was based on a previously identified threshold of clinical relevance and the authors’ clinical experience in a patient population with milder AV. In this same analysis, a difference of greater than 4 days between the active group and the vehicle group was considered to be relevant to the patient.9

A faster onset of visible improvement as perceived by the patient should be more desirable and is likely to improve treatment adherence, as long as it is not counterbalanced by an increase in adverse events.

What is meant by TOA?

Time to onset of action refers to the duration required to achieve a 25% mean lesion count reduction from baseline, which is believed to correlate with the time point at which many patients would be able to perceive visible improvement when viewing their full face. Therefore, TOA represents an attempt to correlate data that is quantitative (based on lesion count reduction) with what is likely to be the average time that a patient may qualitatively observe an initial visible improvement in their AV. This concept may be useful as a tool when communicating with AV patients but should not be used in a way that will overpromise and underdeliver; rather, it is a guide for discussion with the patient and with a parent or guardian when applicable.

Consistent with the comparative AV study analysis that evaluated TOA, a linear course of lesion reductions between the provided time intervals was assumed. In this linear model, the TOA was calculated using the 2 extracted lesion count values between which the 25% lesion reduction was achieved as well as their corresponding given time points.9 Differences between the results in the active and vehicle study arms were calculated for a number of determinants.

How was pivotal trial data with clindamycin-BP 3.75% gel used to assess TOA?

A total of 498 patients with moderate to severe AV were randomized (1:1) to receive clindamycin-BP 3.75% gel or vehicle in a multicenter, double-blind, controlled, 12-week, 2-arm study.10 Before randomization, patients were stratified by acne severity based on a static Evaluator’s Global Severity Score (EGSS) ranging from 0 (clear) to 5 (very severe). Specifically, moderate AV (EGSS of 3) was described as predominantly noninflammatory lesions with evidence of multiple inflammatory lesions; several to many comedones, papules, and pustules; and no more than 1 small nodulocystic lesion. Severe AV (EGSS of 4) was characterized by inflammatory lesions; numerous comedones, papules, and pustules; and possibly a few nodulocystic lesions.10

Male and female patients aged 12 to 40 years with moderate to severe AV—defined as 20 to 40 inflammatory lesions (papules, pustules, nodules), 20 to 100 noninflammatory lesions (comedones), and no more than 2 nodules—were included in the study. Standard washout periods were required for patients using prior prescription and over-the-counter acne treatments.10

Efficacy evaluations included inflammatory and noninflammatory lesion counts and EGSS at screening, baseline, and during treatment (weeks 4, 8, and 12).10 Primary efficacy end points included absolute change in mean inflammatory and noninflammatory lesion counts and the proportion of patients who achieved at least a 2-grade reduction in EGSS from baseline to week 12 (treatment success at end of study). Secondary efficacy end points included mean percentage change from baseline to week 12 in inflammatory and noninflammatory lesion counts and the proportion of patients who considered themselves clear or almost clear at week 12.10

After 12 weeks of daily treatment, inflammatory and noninflammatory lesion counts decreased by a mean of 60.4% and 51.8%, respectively, with clindamycin-BP 3.75% gel compared to 31.3% and 27.6%, respectively, with vehicle (both P<.001). At weeks 4, 8, and 12, the difference in inflammatory and noninflammatory lesion counts for the active treatment was 17.4%, 24.8%, and 29.1%, respectively, and 8.1%, 19.8%, and 24.2%, respectively, for vehicle.10

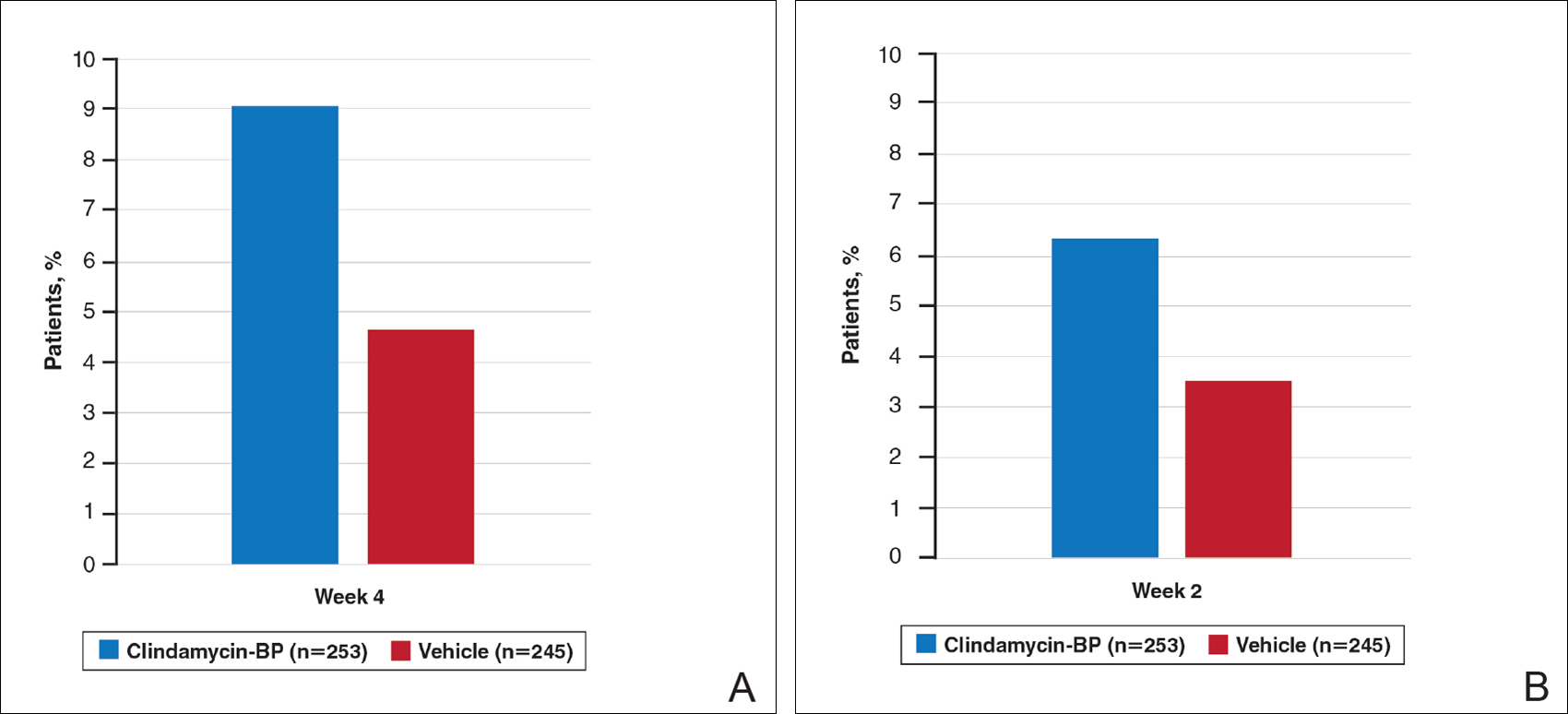

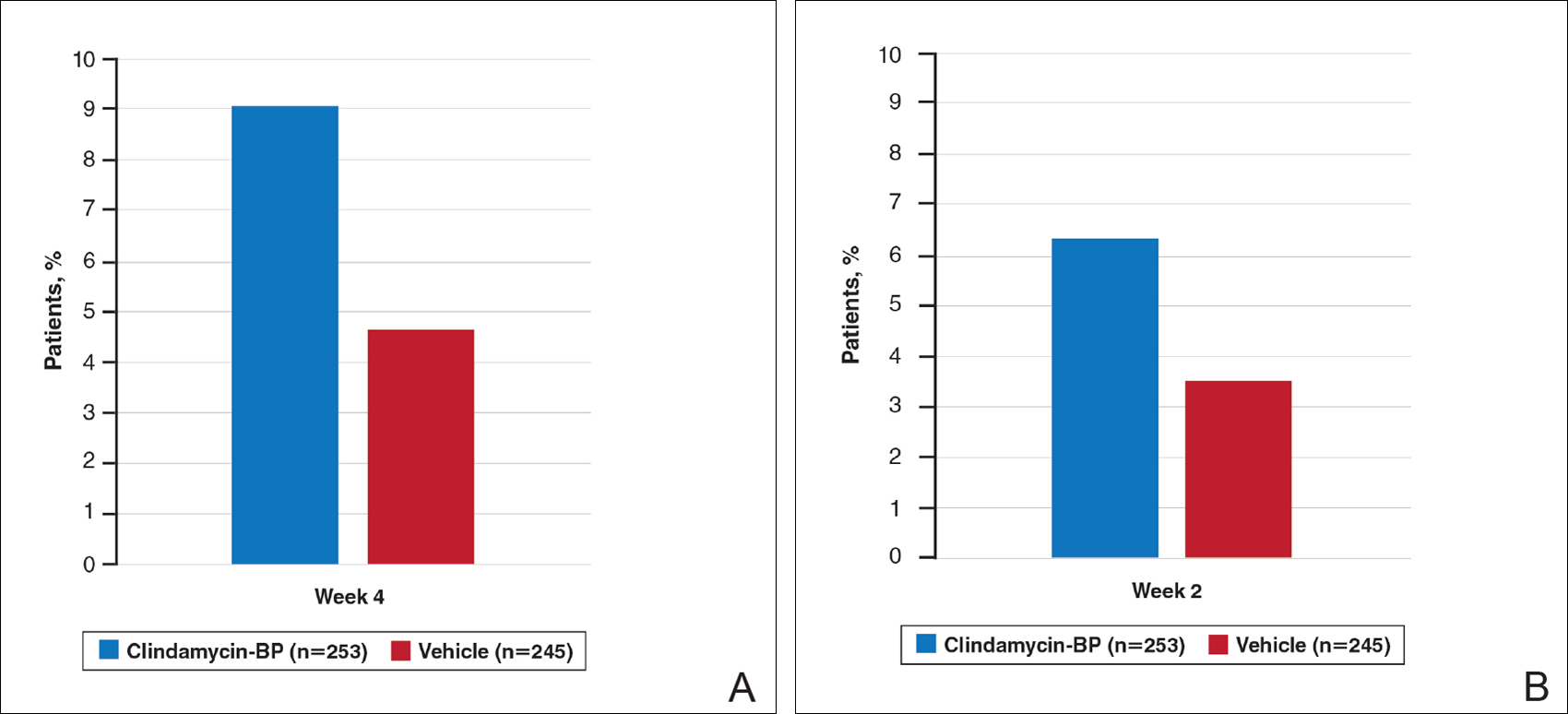

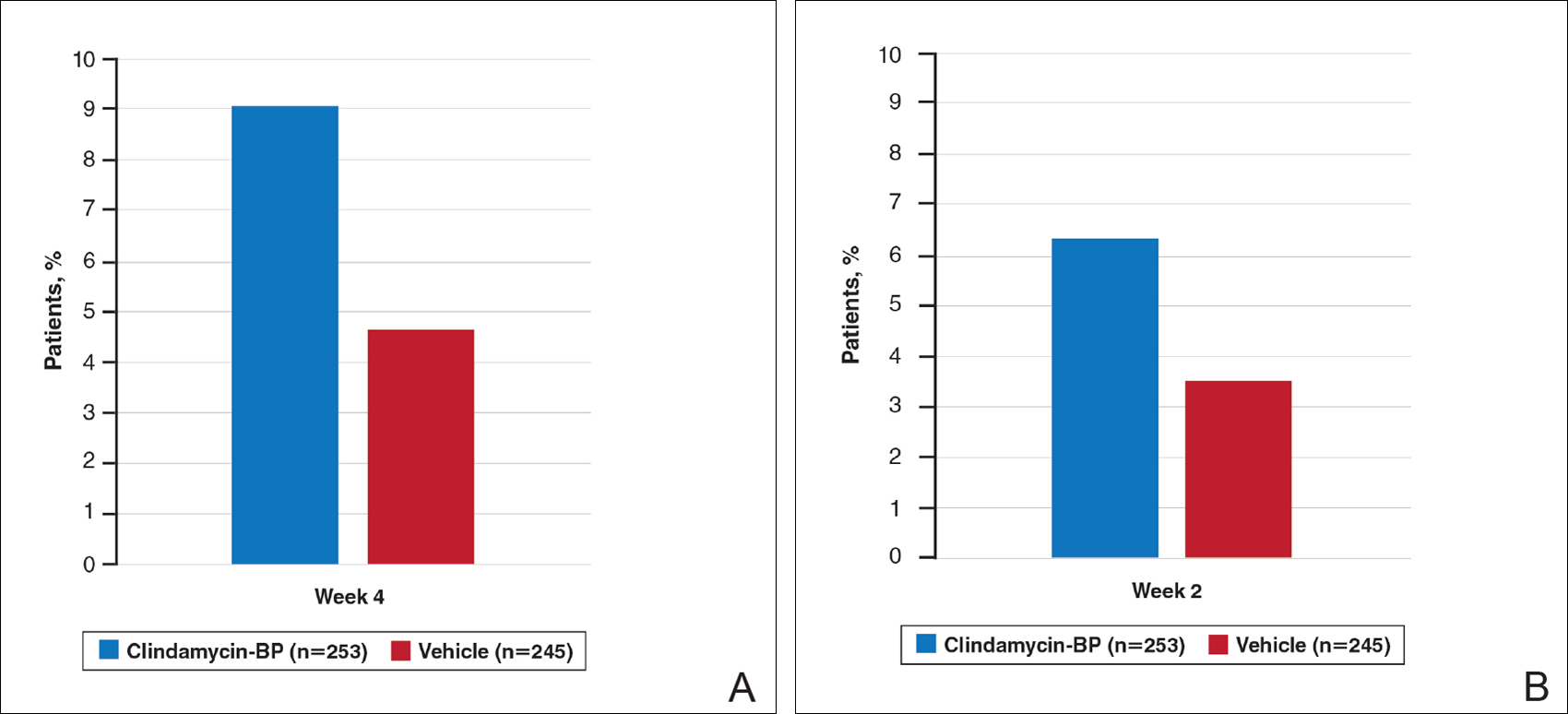

Treatment success (at least a 2-grade improvement in EGSS) was achieved by 9.1% of patients using clindamycin-BP 3.75% gel compared to 4.6% using vehicle by week 4. Additionally, 6.3% of patients considered their AV as clear or almost clear compared to 3.5% with vehicle at week 2 (Figure 1).10

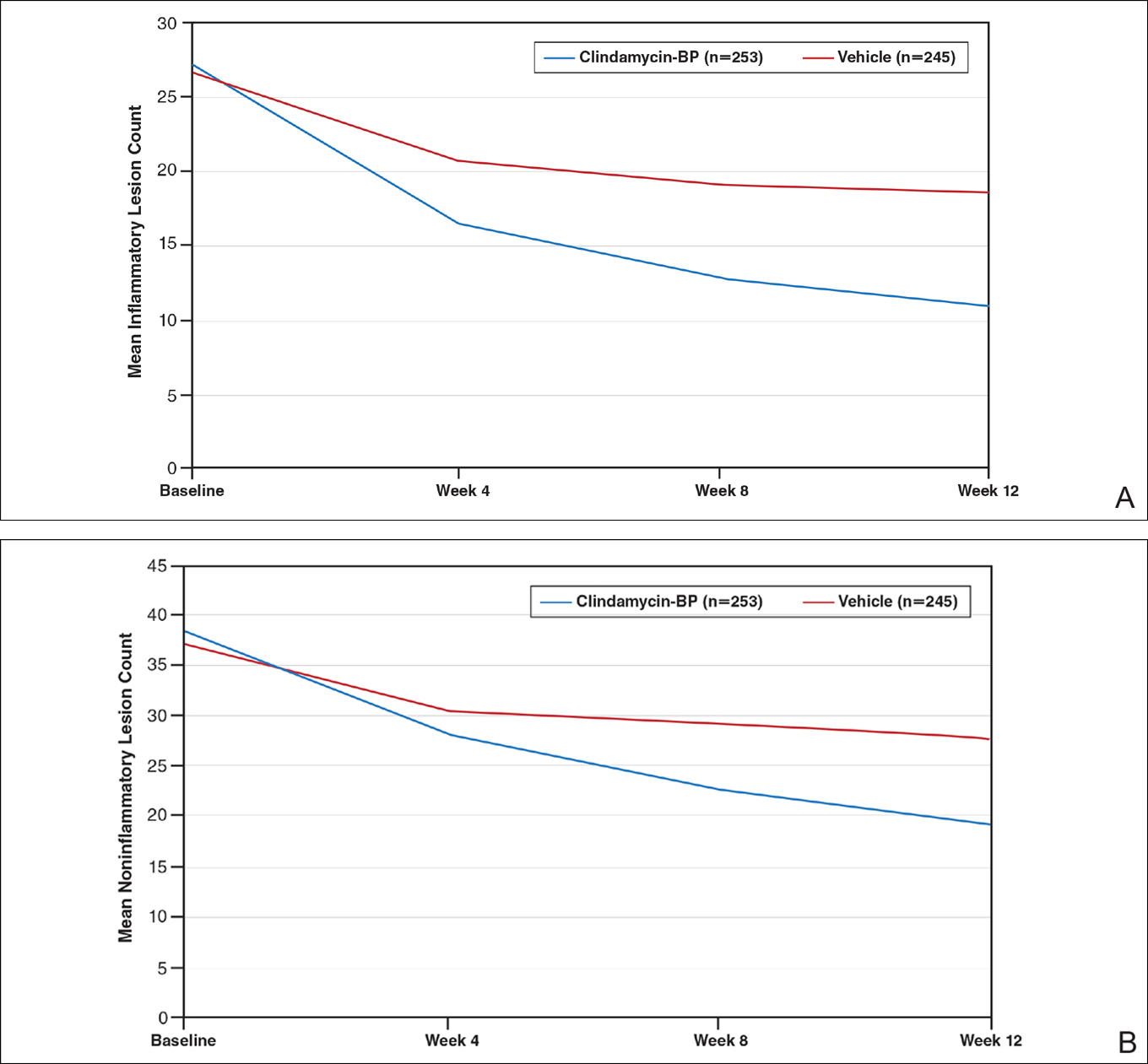

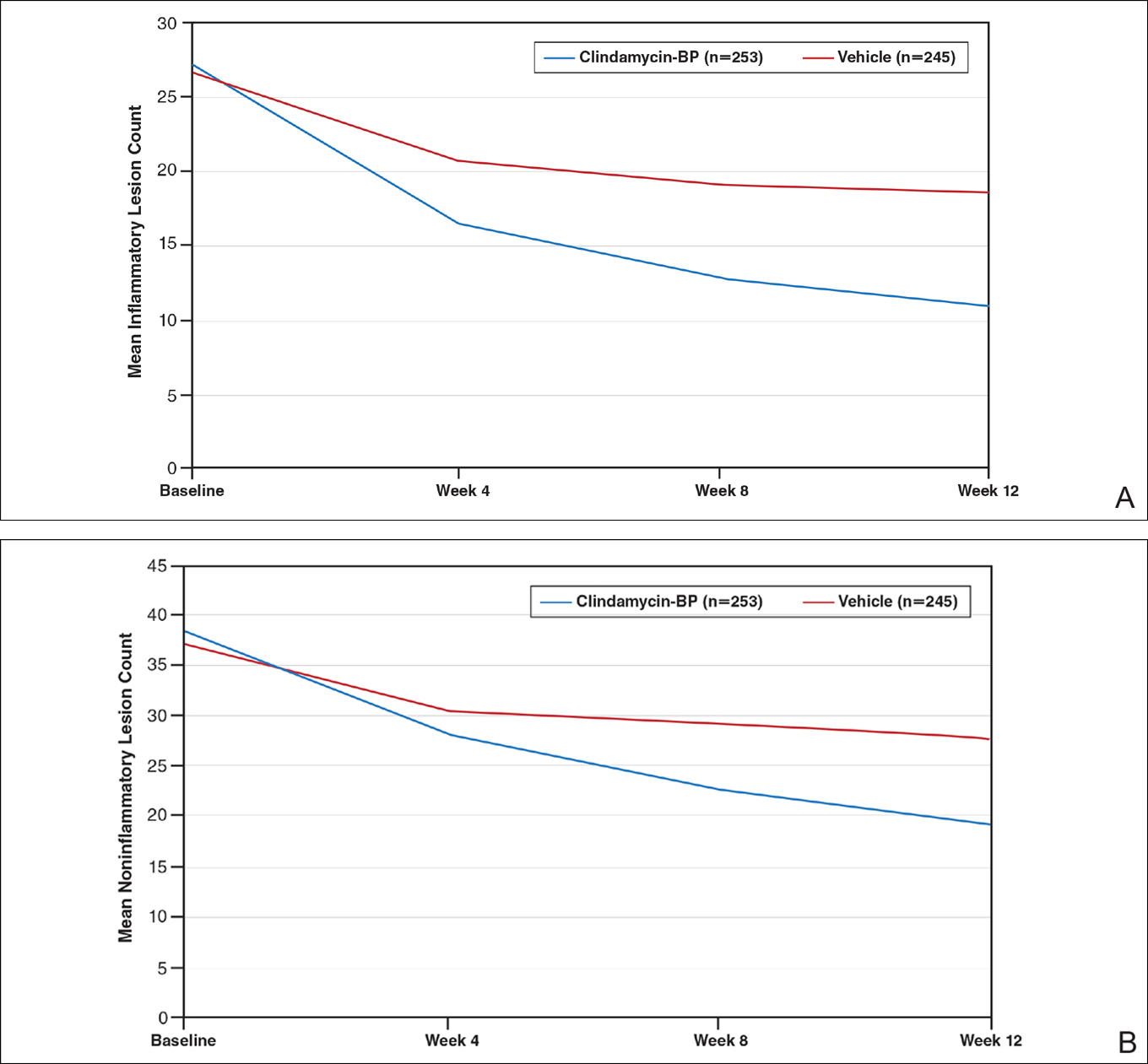

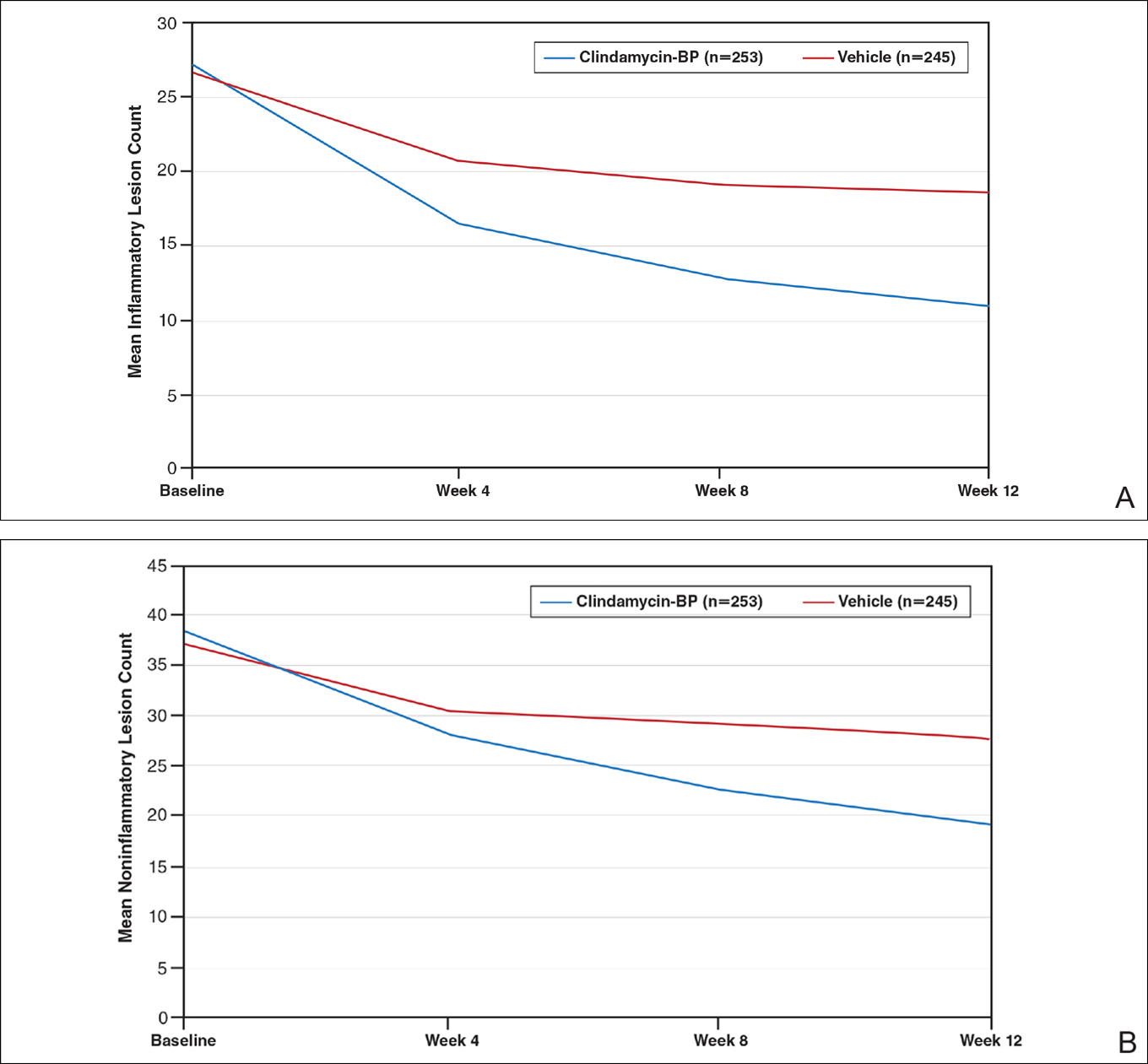

This analysis represents the first attempt to evaluate and report TOA results with clindamycin-BP 3.75% gel. Time to onset of action for inflammatory lesions treated with clindamycin-BP 3.75% gel was calculated as 2.5 weeks versus 6.2 weeks for vehicle (Figure 2A). Time to onset of action for noninflammatory lesions was 3.7 weeks with clindamycin-BP 3.75% gel versus 8.6 weeks with vehicle (Figure 2B). The difference in TOA between the active and vehicle study groups was 3.7 weeks and 4.9 weeks, respectively. In addition, among actively treated patients, TOA was shorter in females (2.1 weeks) than in males (2.6 weeks) and in moderate AV (2.5 weeks) compared to severe AV (3.0 weeks).

Comment

Differences in lesion counts between clindamycin-BP 3.75% gel and vehicle suggest a clinically relevant benefit in favor of active treatment with both inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions. Nearly twice as many patients were rated as treatment successes using EGSS by week 4 or clear or almost clear as early as week 2 compared to the vehicle group.10 However, these data are suggested as an overall guide but do not provide adequate guidance on when visible improvement may start to be evident in a given patient.

The analysis reported here shows a TOA of 2.5 weeks with clindamycin-BP 3.75% gel for inflammatory lesions, approximately 4 weeks faster than with the vehicle. In most cases, a reduction in inflammatory lesions is more likely to have a greater impact on patient perception of TOA. Unless a patient is aware or focused enough to actively distinguish visibly between inflammatory and noninflammatory (comedonal) AV lesions, their eye is more likely to be drawn initially to reduction in inflammatory lesions, which are erythematous and more visible at a greater viewing distance. Although noninflammatory AV lesions usually require closer inspection to visualize them (especially closed comedones), they are often slower to respond to treatment. Analysis of the pivotal trial data reports a longer TOA with clindamycin-BP 3.75% gel for noninflammatory lesions (3.7 weeks) versus inflammatory lesions (2.5 weeks).

As expected, TOA was shorter in patients with moderate AV than severe AV (2.5 weeks vs 3.0 weeks). Time to onset of action also was shorter in females overall. It is unclear why we see gender differences in acne studies. A number of reasons have been suggested, including differences in AV pathophysiology and/or treatment adherence.11,12 Greater efficacy of clindamycin-BP 3.75% gel in females compared with males has already been reported, and better overall efficacy leading to a shorter TOA has been noted by others.13

There are limitations with this analysis. First, it is not possible to assess the contributions from each of the monads to the efficacy of clindamycin-BP 3.75% gel or TOA. Also, the data extraction method used assumes a linear progression model during the provided time points and was used to provide some comparison with calculations for other combination products.9 Although no strong deviations from the linear model are likely, calculations of TOA using other methodologies may give different results. The definition of a clinically meaningful benefit, defined here as a 25% reduction in the mean lesion count, has been used as a guide, but it has not been validated in clinical practice. It also is important to recognize that the initial visible perception of improvement of AV is likely to differ based on interpatient variability; that is, how different individuals perceive improvement. It also may be affected by differences in baseline severity of AV among different patients. Additionally, the TOA reflects an average duration of time, so it should not be described to patients as a suggestion of when they will definitely see visible improvement in their AV.

Conclusion

Unrealistic expectations of acne therapy or poor tolerability can lead to low adherence and poor clinical outcomes.1-4 The data on TOA reported here suggests that a clinically meaningful benefit with clindamycin-BP 3.75% gel may be seen in some patients within 2 to 3 weeks and maybe sooner in females or those with milder disease; however, longer durations may be required in some patients. This information can help clinicians and their staff in providing reasonable expectations and stress the importance of encouraging patients about the need to adhere to treatment.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Brian Bulley, MSc (Inergy Limited, Lindfield, West Sussex, United Kingdom), for publication support. Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America, LLC, funded Inergy’s activities pertaining to this analysis. The author did not receive funding or any form of compensation for authorship of this publication.

- Krakowski AC, Stendardo S, Eichenfield LF. Practical considerations in acne treatment and the clinical impact of topical combination therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25(suppl 1):1-14.

- Yentzer BA, Ade RA, Fountain JM, et al. Simplifying regimens promotes greater adherence and outcomes with topical acne medications: a randomized controlled trial. Cutis. 2010;86:103-108.

- Zaghloul SS, Cunliffe WJ, Goodfield MJ. Objective assessment of compliance with treatments in acne. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1015-1021.

- Snyder S, Crandell I, Davis SA, et al. Medical adherence to acne therapy: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:87-94.

- Miyachi Y, Hayashi N, Furukawa F, et al. Acne management in Japan: study of patient adherence. Dermatology. 2011;223:174-181.

- Zauli S, Caracciolo S, Borghi A, et al. Which factors influence quality of life in acne patients? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:46-50.

- Mulder MM, Sigurdsson V, van Zuuren EJ, et al. Psychosocial impact of acne vulgaris. evaluation of the relation between a change in clinical acne severity and psychosocial state. Dermatology. 2001;203:124-130.

- Gerlinger C, Stadtler G, Gotzelmann R, et al. A noninferiority margin for acne lesion counts. Drug Inf J. 2008;42:607-615.

- Jacobs A, Starke G, Rosumeck S, et al. Systematic review on the rapidity of the onset of action of topical treatments in the therapy of mild-to-moderate acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:557-564.

- Pariser DM, Rich P, Cook-Bolden FE, et al. An aqueous gel fixed combination of clindamycin phosphate 1.2% and benzoyl peroxide 3.75% for the once-daily treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:611-617.

- Tanghetti E, Harper JC, Oefelein MG. The efficacy and tolerability of dapsone 5% gel in female vs male patients with facial acne vulgaris: gender as a clinically relevant outcome variable. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:1417-1421.

- Lott R, Taylor SL, O’Neill JL, et al. Medication adherence among acne patients: a review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2010;9:160-166.

- Harper JC. The efficacy and tolerability of a fixed combination clindamycin (1.2%) and benzoyl peroxide (3.75%) aqueous gel in patients with facial acne vulgaris: gender as a clinically relevant outcome variable. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:381-384.

Acne vulgaris (AV) is a common skin disease that usually presents in adolescence and can persist into adulthood. Some cases may start in adulthood, especially in women. Acne vulgaris remains a challenge to treat successfully, both in teenagers and adults. Unrealistic expectations that therapy will rapidly clear and sustain clearance of AV completely can lead to incomplete adherence or complete cessation of treatment.1-4 Local tolerability reactions also may decrease adherence to topical medications. Suboptimal adherence to medications for AV is one of the major reasons for treatment failure.5 Acne vulgaris can strongly influence psychological well-being and self-esteem.6 In general, severe AV causes more psychological distress, but the adverse emotional impact of AV can be independent of its severity.7

An effective relationship between the patient and his/her physician and staff is believed to be important in setting realistic expectations, optimizing adherence, and achieving a positive therapeutic outcome. One component related to setting reasonable expectations is the discussion about when the patient may begin to visibly perceive that the treatment regimen is working. This article evaluates the time course of a clinically meaningful response using pivotal trial data with clindamycin phosphate 1.2%–benzoyl peroxide 3.75% (clindamycin-BP 3.75%) gel for treatment of AV.

Are data available that evaluate the time course of a clinically relevant response to treatment of AV?

Unfortunately, data on what might be perceived as a clinically meaningful improvement in AV and how long it might take to achieve this treatment effect are limited. A meta-analysis of more than 4000 patients with moderate to severe AV suggested that a 10% to 20% difference in acne lesion counts from baseline as compared to a subsequent designated time point was clinically relevant.8 A review of 24 comparative studies of patients with mild to moderate AV used a primary outcome parameter of a 25% reduction in mean inflammatory lesion count to evaluate time to onset of action (TOA) to achieve a clinically meaningful benefit.9 This outcome was based on a previously identified threshold of clinical relevance and the authors’ clinical experience in a patient population with milder AV. In this same analysis, a difference of greater than 4 days between the active group and the vehicle group was considered to be relevant to the patient.9

A faster onset of visible improvement as perceived by the patient should be more desirable and is likely to improve treatment adherence, as long as it is not counterbalanced by an increase in adverse events.

What is meant by TOA?

Time to onset of action refers to the duration required to achieve a 25% mean lesion count reduction from baseline, which is believed to correlate with the time point at which many patients would be able to perceive visible improvement when viewing their full face. Therefore, TOA represents an attempt to correlate data that is quantitative (based on lesion count reduction) with what is likely to be the average time that a patient may qualitatively observe an initial visible improvement in their AV. This concept may be useful as a tool when communicating with AV patients but should not be used in a way that will overpromise and underdeliver; rather, it is a guide for discussion with the patient and with a parent or guardian when applicable.

Consistent with the comparative AV study analysis that evaluated TOA, a linear course of lesion reductions between the provided time intervals was assumed. In this linear model, the TOA was calculated using the 2 extracted lesion count values between which the 25% lesion reduction was achieved as well as their corresponding given time points.9 Differences between the results in the active and vehicle study arms were calculated for a number of determinants.

How was pivotal trial data with clindamycin-BP 3.75% gel used to assess TOA?

A total of 498 patients with moderate to severe AV were randomized (1:1) to receive clindamycin-BP 3.75% gel or vehicle in a multicenter, double-blind, controlled, 12-week, 2-arm study.10 Before randomization, patients were stratified by acne severity based on a static Evaluator’s Global Severity Score (EGSS) ranging from 0 (clear) to 5 (very severe). Specifically, moderate AV (EGSS of 3) was described as predominantly noninflammatory lesions with evidence of multiple inflammatory lesions; several to many comedones, papules, and pustules; and no more than 1 small nodulocystic lesion. Severe AV (EGSS of 4) was characterized by inflammatory lesions; numerous comedones, papules, and pustules; and possibly a few nodulocystic lesions.10

Male and female patients aged 12 to 40 years with moderate to severe AV—defined as 20 to 40 inflammatory lesions (papules, pustules, nodules), 20 to 100 noninflammatory lesions (comedones), and no more than 2 nodules—were included in the study. Standard washout periods were required for patients using prior prescription and over-the-counter acne treatments.10

Efficacy evaluations included inflammatory and noninflammatory lesion counts and EGSS at screening, baseline, and during treatment (weeks 4, 8, and 12).10 Primary efficacy end points included absolute change in mean inflammatory and noninflammatory lesion counts and the proportion of patients who achieved at least a 2-grade reduction in EGSS from baseline to week 12 (treatment success at end of study). Secondary efficacy end points included mean percentage change from baseline to week 12 in inflammatory and noninflammatory lesion counts and the proportion of patients who considered themselves clear or almost clear at week 12.10

After 12 weeks of daily treatment, inflammatory and noninflammatory lesion counts decreased by a mean of 60.4% and 51.8%, respectively, with clindamycin-BP 3.75% gel compared to 31.3% and 27.6%, respectively, with vehicle (both P<.001). At weeks 4, 8, and 12, the difference in inflammatory and noninflammatory lesion counts for the active treatment was 17.4%, 24.8%, and 29.1%, respectively, and 8.1%, 19.8%, and 24.2%, respectively, for vehicle.10

Treatment success (at least a 2-grade improvement in EGSS) was achieved by 9.1% of patients using clindamycin-BP 3.75% gel compared to 4.6% using vehicle by week 4. Additionally, 6.3% of patients considered their AV as clear or almost clear compared to 3.5% with vehicle at week 2 (Figure 1).10

This analysis represents the first attempt to evaluate and report TOA results with clindamycin-BP 3.75% gel. Time to onset of action for inflammatory lesions treated with clindamycin-BP 3.75% gel was calculated as 2.5 weeks versus 6.2 weeks for vehicle (Figure 2A). Time to onset of action for noninflammatory lesions was 3.7 weeks with clindamycin-BP 3.75% gel versus 8.6 weeks with vehicle (Figure 2B). The difference in TOA between the active and vehicle study groups was 3.7 weeks and 4.9 weeks, respectively. In addition, among actively treated patients, TOA was shorter in females (2.1 weeks) than in males (2.6 weeks) and in moderate AV (2.5 weeks) compared to severe AV (3.0 weeks).

Comment

Differences in lesion counts between clindamycin-BP 3.75% gel and vehicle suggest a clinically relevant benefit in favor of active treatment with both inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions. Nearly twice as many patients were rated as treatment successes using EGSS by week 4 or clear or almost clear as early as week 2 compared to the vehicle group.10 However, these data are suggested as an overall guide but do not provide adequate guidance on when visible improvement may start to be evident in a given patient.