User login

Acne Treatment: Analysis of Acne-Related Social Media Posts and the Impact on Patient Care

Social media has become a prominent source of medical information for patients, including those with dermatologic conditions.1,2 Physicians, patients, and pharmaceutical companies can use social media platforms to communicate with each other and share knowledge and advertisements related to conditions. Social media can influence patients’ perceptions of their disease and serve as a modality to acquire medical treatments.3 Furthermore, social media posts from illicit pharmacies can result in patients buying harmful medications without physician oversight.4,5 Examination of the content and sources of social media posts related to acne may be useful in determining those who are primarily utilizing social media and for what purpose. The goal of this systematic review was to identify sources of acne-related social media posts to determine communication trends to gain a better understanding of the potential impact social media may have on patient care.

Methods

Social media posts were identified (May 2008 to May 2016) using the search terms acne and treatment across all social media platforms available through a commercial social media data aggregating software (Crimson Hexagon). Information from relevant posts was extracted and compiled into a spreadsheet that included the content, post date, social media platform, and hyperlink. To further analyze the data, the first 100 posts on acne treatment from May 2008 to May 2016 were selected and manually classified by the following types of communication: (1) patient-to-patient (eg, testimonies of patients’ medical experiences); (2) professional-to-patient (eg, clinical knowledge or experience provided by a medical provider and/or cited article in reference to relevant treatments); (3) pharmaceutical company–to-patient (eg, information from reputable drug manufacturers regarding drug activity and adverse effects); (4) illicit pharmacy–to-patient (eg, pharmacies with advertisements calling patients to buy a drug online or offering discrete shipping without a prescription)4,5; or (5) other-to-patient (eg, posts that did not contain enough detail to be classified).

Results

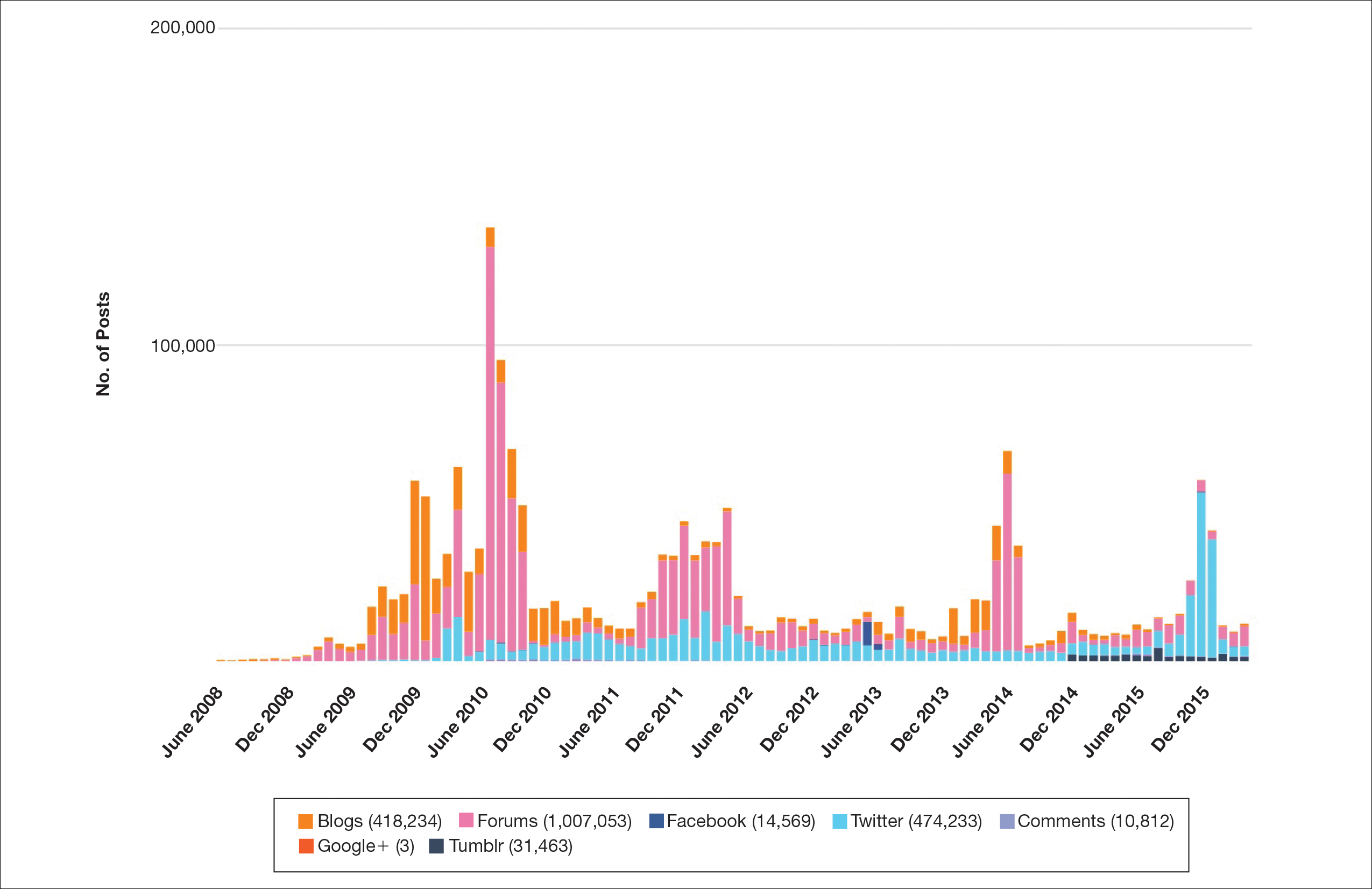

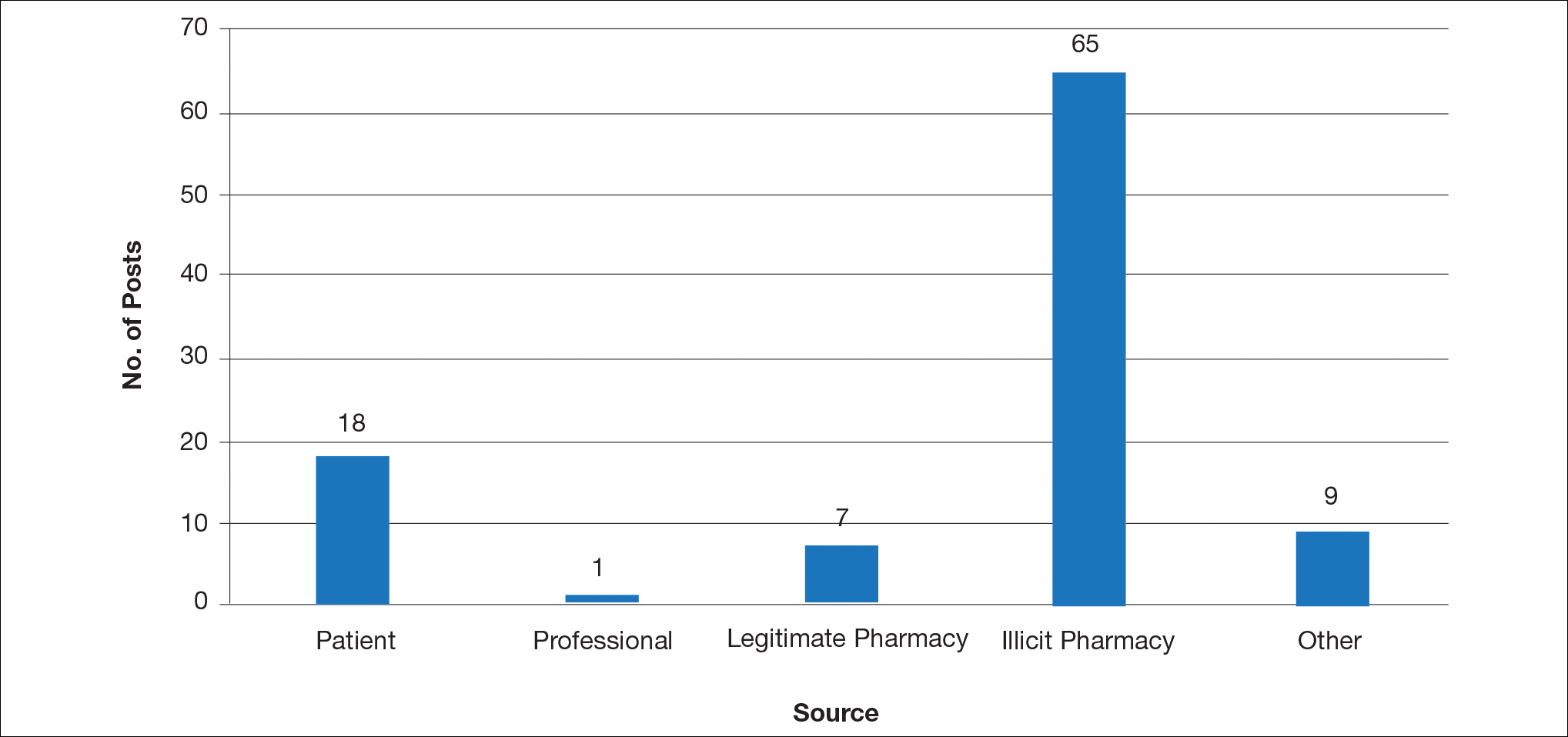

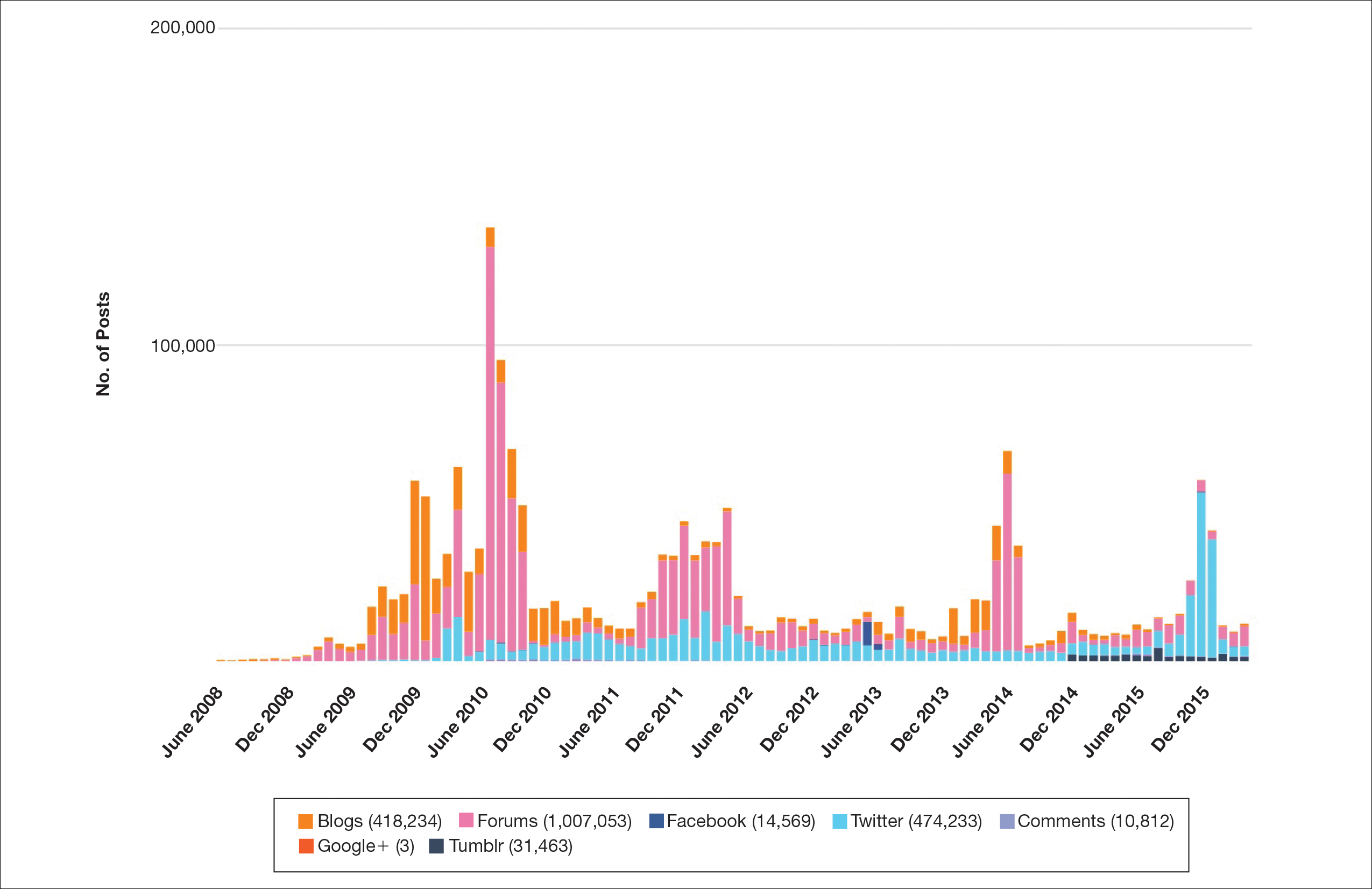

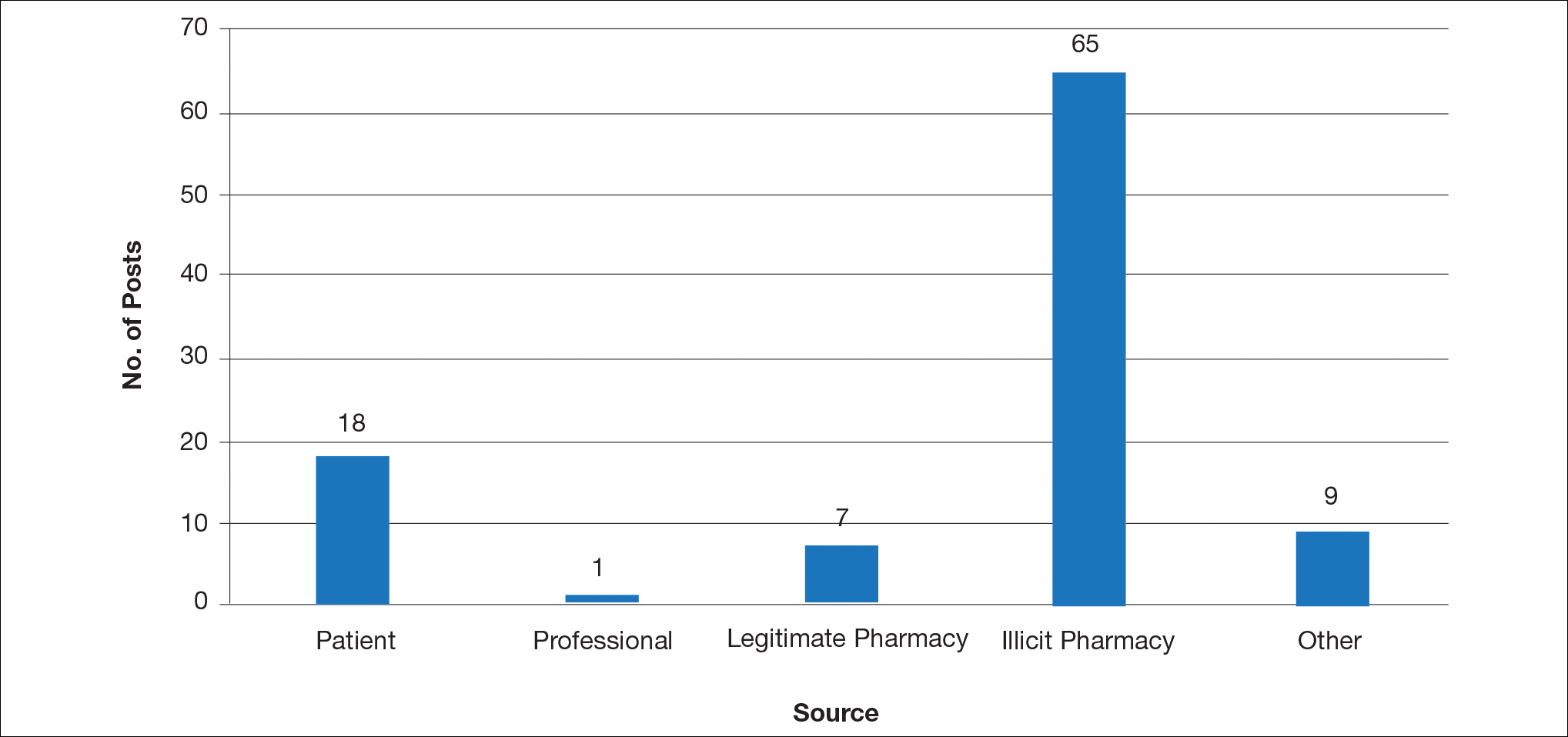

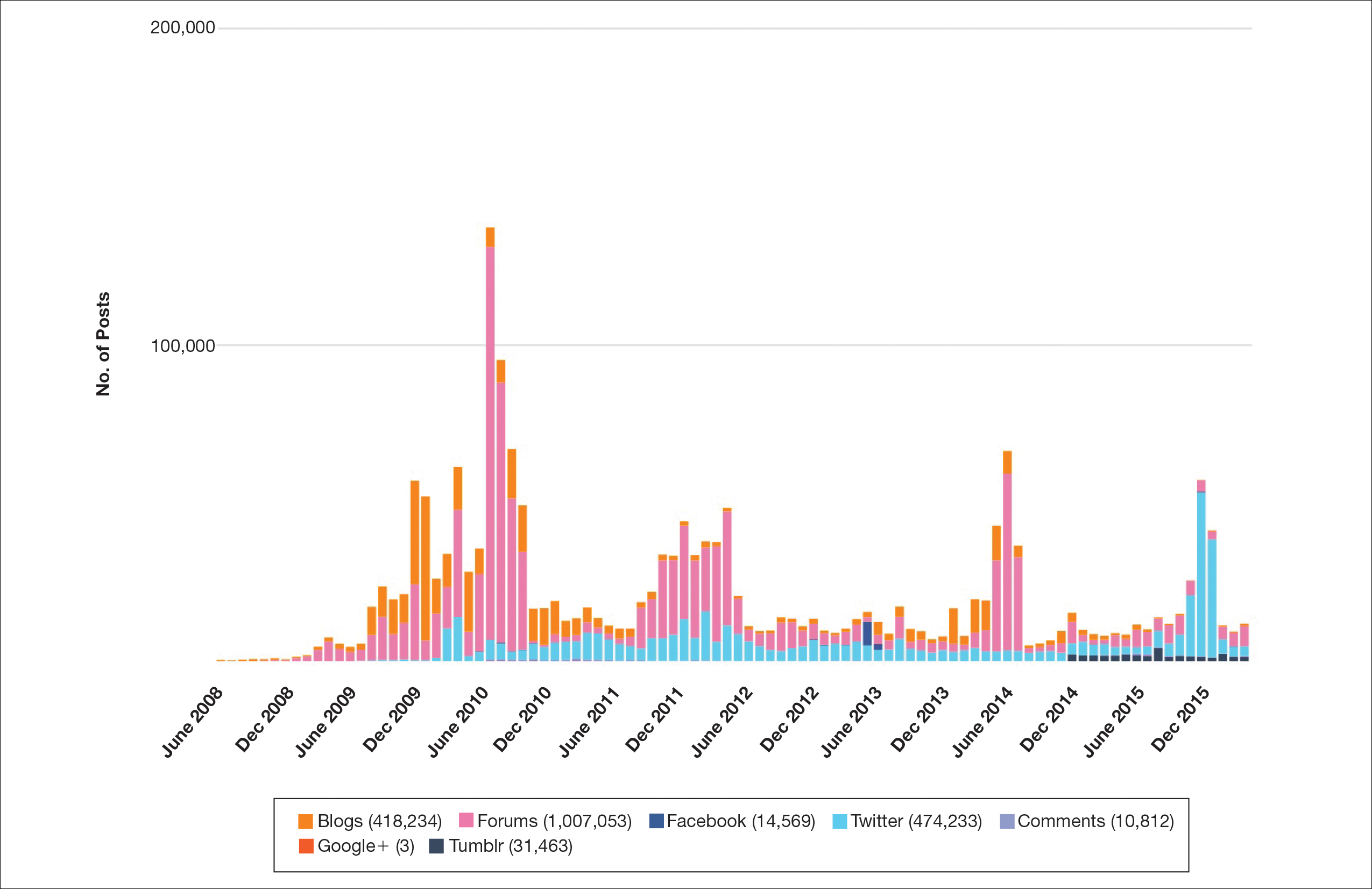

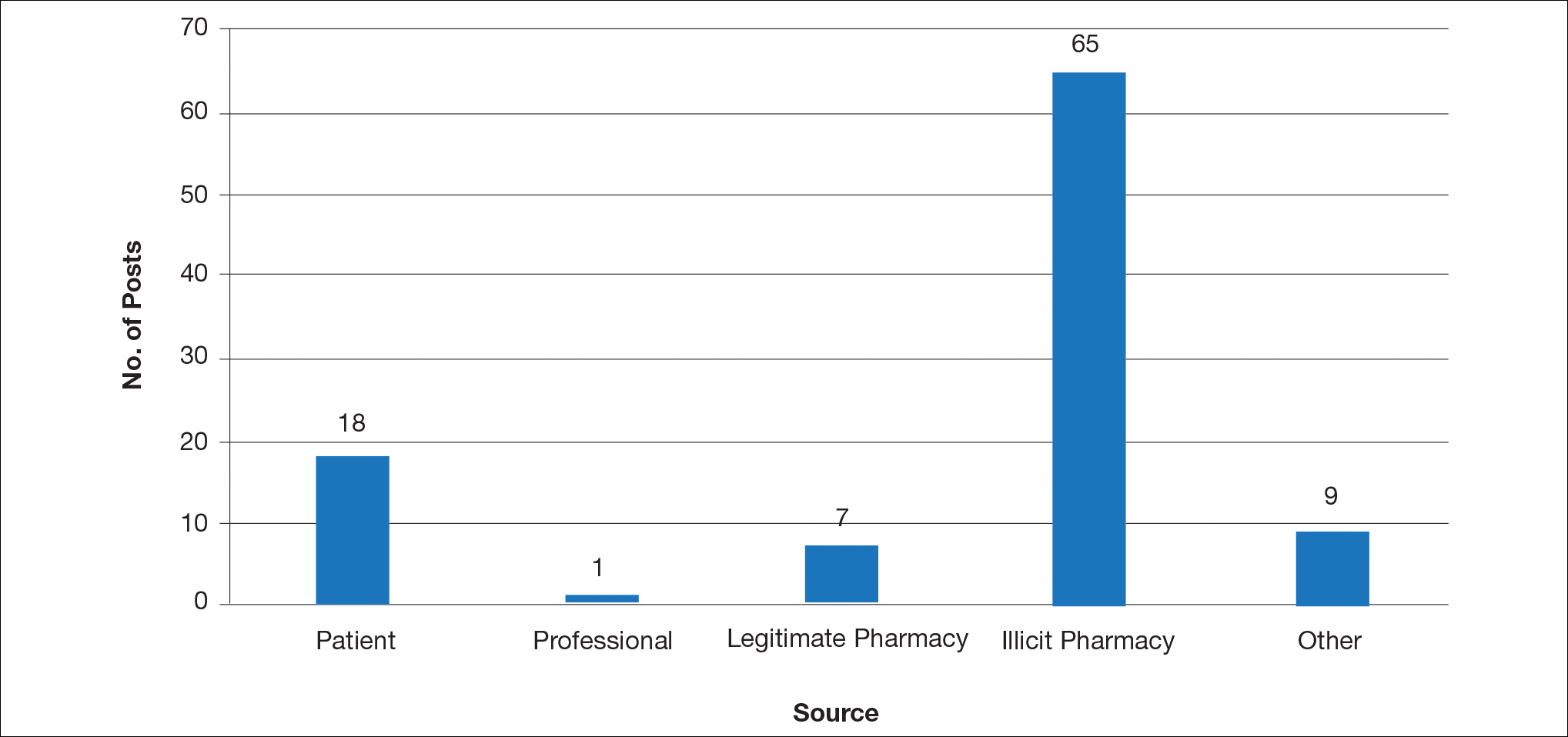

Hundreds of thousands of social media posts discussing acne treatment were identified over the 8-year study period (Figure 1). The social media data aggregator extracted posts from various blogs, website comment sections, and online forums, as well as major social media platforms (ie, Facebook, Twitter, Google+, Tumblr). The first 100 posts selected for further analysis included 0 from 2008, 6 from 2009, 36 from 2010, 15 from 2011, 7 from 2012, 8 from 2013, 12 from 2014, 11 from 2015, and 5 from 2016. From this sample, 65 posts were considered to have an illicit source; conversely, 18 posts were from patients and 7 posts were from pharmaceutical companies (Figure 2).

Comment

This study demonstrated that discussion of acne treatment is prevalent in social media. Although our research underrepresents the social media interest in specific acne treatments, as only posts mentioning the terms acne and treatment were evaluated to gain insights into how social media platforms are being used by individuals with cutaneous disease. As such, even with this potential underrepresentation, our study demonstrated a high incidence of illicit marketing of prescription acne medications across multiple social media platforms (Figure 2). The sale of dermatologic pharmaceuticals (eg, isotretinoin) without a prescription is recognized by the US Government as a problem that is rapidly growing.4,5 Illicit pharmacies pose as legitimate pharmacies that can provide prescription medications to consumers without a prescription.5,6 The fact that these illicit pharmacy–to-patient posts were the most abundant in our study may speak to their relative success on social media platforms in encouraging patients to purchase prescription medications without physician oversight. These findings should concern health care providers, as the procurement of prescription medications without a prescription may put patients at risk.

- Alinia H, Moradi Tuchayi S, Farhangian ME, et al. Rosacea patients seeking advice: qualitative analysis of patients’ posts on a rosacea support forum. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:99-102.

- Karimkhani C, Connett J, Boyers L, et al. Dermatology on Instagram. Dermatology Online J. 2014:20. pii:13030/qt71g178w9.

- Smailhodzic E, Hooijsma W, Boonstra A, et al. Social media use in healthcare: a systematic review of effects on patients and on their relationship with healthcare professionals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:442.

- Lagan BM, Dolk H, White B, et al. Assessing the availability of the teratogenic drug isotretinoin outside the pregnancy prevention programme: a survey of e-pharmacies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23:411-418.

- Lott JP, Kovarik CL. Availability of oral isotretinoin and terbinafine on the Internet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:153-154.

- Mahé E, Beauchet A. Dermatologists and the Internet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:908.

Social media has become a prominent source of medical information for patients, including those with dermatologic conditions.1,2 Physicians, patients, and pharmaceutical companies can use social media platforms to communicate with each other and share knowledge and advertisements related to conditions. Social media can influence patients’ perceptions of their disease and serve as a modality to acquire medical treatments.3 Furthermore, social media posts from illicit pharmacies can result in patients buying harmful medications without physician oversight.4,5 Examination of the content and sources of social media posts related to acne may be useful in determining those who are primarily utilizing social media and for what purpose. The goal of this systematic review was to identify sources of acne-related social media posts to determine communication trends to gain a better understanding of the potential impact social media may have on patient care.

Methods

Social media posts were identified (May 2008 to May 2016) using the search terms acne and treatment across all social media platforms available through a commercial social media data aggregating software (Crimson Hexagon). Information from relevant posts was extracted and compiled into a spreadsheet that included the content, post date, social media platform, and hyperlink. To further analyze the data, the first 100 posts on acne treatment from May 2008 to May 2016 were selected and manually classified by the following types of communication: (1) patient-to-patient (eg, testimonies of patients’ medical experiences); (2) professional-to-patient (eg, clinical knowledge or experience provided by a medical provider and/or cited article in reference to relevant treatments); (3) pharmaceutical company–to-patient (eg, information from reputable drug manufacturers regarding drug activity and adverse effects); (4) illicit pharmacy–to-patient (eg, pharmacies with advertisements calling patients to buy a drug online or offering discrete shipping without a prescription)4,5; or (5) other-to-patient (eg, posts that did not contain enough detail to be classified).

Results

Hundreds of thousands of social media posts discussing acne treatment were identified over the 8-year study period (Figure 1). The social media data aggregator extracted posts from various blogs, website comment sections, and online forums, as well as major social media platforms (ie, Facebook, Twitter, Google+, Tumblr). The first 100 posts selected for further analysis included 0 from 2008, 6 from 2009, 36 from 2010, 15 from 2011, 7 from 2012, 8 from 2013, 12 from 2014, 11 from 2015, and 5 from 2016. From this sample, 65 posts were considered to have an illicit source; conversely, 18 posts were from patients and 7 posts were from pharmaceutical companies (Figure 2).

Comment

This study demonstrated that discussion of acne treatment is prevalent in social media. Although our research underrepresents the social media interest in specific acne treatments, as only posts mentioning the terms acne and treatment were evaluated to gain insights into how social media platforms are being used by individuals with cutaneous disease. As such, even with this potential underrepresentation, our study demonstrated a high incidence of illicit marketing of prescription acne medications across multiple social media platforms (Figure 2). The sale of dermatologic pharmaceuticals (eg, isotretinoin) without a prescription is recognized by the US Government as a problem that is rapidly growing.4,5 Illicit pharmacies pose as legitimate pharmacies that can provide prescription medications to consumers without a prescription.5,6 The fact that these illicit pharmacy–to-patient posts were the most abundant in our study may speak to their relative success on social media platforms in encouraging patients to purchase prescription medications without physician oversight. These findings should concern health care providers, as the procurement of prescription medications without a prescription may put patients at risk.

Social media has become a prominent source of medical information for patients, including those with dermatologic conditions.1,2 Physicians, patients, and pharmaceutical companies can use social media platforms to communicate with each other and share knowledge and advertisements related to conditions. Social media can influence patients’ perceptions of their disease and serve as a modality to acquire medical treatments.3 Furthermore, social media posts from illicit pharmacies can result in patients buying harmful medications without physician oversight.4,5 Examination of the content and sources of social media posts related to acne may be useful in determining those who are primarily utilizing social media and for what purpose. The goal of this systematic review was to identify sources of acne-related social media posts to determine communication trends to gain a better understanding of the potential impact social media may have on patient care.

Methods

Social media posts were identified (May 2008 to May 2016) using the search terms acne and treatment across all social media platforms available through a commercial social media data aggregating software (Crimson Hexagon). Information from relevant posts was extracted and compiled into a spreadsheet that included the content, post date, social media platform, and hyperlink. To further analyze the data, the first 100 posts on acne treatment from May 2008 to May 2016 were selected and manually classified by the following types of communication: (1) patient-to-patient (eg, testimonies of patients’ medical experiences); (2) professional-to-patient (eg, clinical knowledge or experience provided by a medical provider and/or cited article in reference to relevant treatments); (3) pharmaceutical company–to-patient (eg, information from reputable drug manufacturers regarding drug activity and adverse effects); (4) illicit pharmacy–to-patient (eg, pharmacies with advertisements calling patients to buy a drug online or offering discrete shipping without a prescription)4,5; or (5) other-to-patient (eg, posts that did not contain enough detail to be classified).

Results

Hundreds of thousands of social media posts discussing acne treatment were identified over the 8-year study period (Figure 1). The social media data aggregator extracted posts from various blogs, website comment sections, and online forums, as well as major social media platforms (ie, Facebook, Twitter, Google+, Tumblr). The first 100 posts selected for further analysis included 0 from 2008, 6 from 2009, 36 from 2010, 15 from 2011, 7 from 2012, 8 from 2013, 12 from 2014, 11 from 2015, and 5 from 2016. From this sample, 65 posts were considered to have an illicit source; conversely, 18 posts were from patients and 7 posts were from pharmaceutical companies (Figure 2).

Comment

This study demonstrated that discussion of acne treatment is prevalent in social media. Although our research underrepresents the social media interest in specific acne treatments, as only posts mentioning the terms acne and treatment were evaluated to gain insights into how social media platforms are being used by individuals with cutaneous disease. As such, even with this potential underrepresentation, our study demonstrated a high incidence of illicit marketing of prescription acne medications across multiple social media platforms (Figure 2). The sale of dermatologic pharmaceuticals (eg, isotretinoin) without a prescription is recognized by the US Government as a problem that is rapidly growing.4,5 Illicit pharmacies pose as legitimate pharmacies that can provide prescription medications to consumers without a prescription.5,6 The fact that these illicit pharmacy–to-patient posts were the most abundant in our study may speak to their relative success on social media platforms in encouraging patients to purchase prescription medications without physician oversight. These findings should concern health care providers, as the procurement of prescription medications without a prescription may put patients at risk.

- Alinia H, Moradi Tuchayi S, Farhangian ME, et al. Rosacea patients seeking advice: qualitative analysis of patients’ posts on a rosacea support forum. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:99-102.

- Karimkhani C, Connett J, Boyers L, et al. Dermatology on Instagram. Dermatology Online J. 2014:20. pii:13030/qt71g178w9.

- Smailhodzic E, Hooijsma W, Boonstra A, et al. Social media use in healthcare: a systematic review of effects on patients and on their relationship with healthcare professionals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:442.

- Lagan BM, Dolk H, White B, et al. Assessing the availability of the teratogenic drug isotretinoin outside the pregnancy prevention programme: a survey of e-pharmacies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23:411-418.

- Lott JP, Kovarik CL. Availability of oral isotretinoin and terbinafine on the Internet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:153-154.

- Mahé E, Beauchet A. Dermatologists and the Internet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:908.

- Alinia H, Moradi Tuchayi S, Farhangian ME, et al. Rosacea patients seeking advice: qualitative analysis of patients’ posts on a rosacea support forum. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:99-102.

- Karimkhani C, Connett J, Boyers L, et al. Dermatology on Instagram. Dermatology Online J. 2014:20. pii:13030/qt71g178w9.

- Smailhodzic E, Hooijsma W, Boonstra A, et al. Social media use in healthcare: a systematic review of effects on patients and on their relationship with healthcare professionals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:442.

- Lagan BM, Dolk H, White B, et al. Assessing the availability of the teratogenic drug isotretinoin outside the pregnancy prevention programme: a survey of e-pharmacies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23:411-418.

- Lott JP, Kovarik CL. Availability of oral isotretinoin and terbinafine on the Internet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:153-154.

- Mahé E, Beauchet A. Dermatologists and the Internet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:908.

Practice Points

- Social media content can influence patients’ perceptions of their disease and serve as a modality to acquire medical treatments, though the source often is unknown.

- This study aimed to identify sources of acne-related social media posts to determine communication trends to gain a better understanding of the potential impact social media may have on patient care.

- Due to the potential for illicit marketing of prescription acne medications across multiple social media platforms, it is important to ask your patients what resources they use to learn about acne and offer to answer any questions regarding acne and its treatment.

Perceptions of Tanning Risk Among Melanoma Patients With a History of Indoor Tanning

The incidence of melanoma is increasing at a rate greater than any other cancer,1 possibly due to the increasing use of indoor tanning devices. These devices emit unnaturally high levels of UVA and low levels of UVA and UVB rays.2 The risks of using these devices include increased incidence of melanoma (3438 cases attributed to indoor tanning in 2008) and keratinocytes cancer (increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma by 67% and basal cell carcinoma by 29%), severe sunburns (61.1% of female users and 44.6% of male users have reported sunburns), and aggravation of underlying disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus.3-5

The literature varies in its explanation of how indoor tanning increases the risk of developing melanoma. Some authors suggest it is due to increased frequency of use, duration of sessions, and years of using tanning devices.1,6 Others suggest the increased cancer risk is the result of starting to tan at an earlier age.2,3,6-10 There is conflicting literature on the level of increased risk of melanoma in those who tan indoors at a young age (<35 years). Although the estimated rate of increased skin cancer risk varies, with rates up to 75% compared to nonusers, nearly all sources support an increased rate.6 Despite the growing body of knowledge that indoor tanning is dangerous, as well as the academic publication of these risks (eg, carcinogenesis, short-term and long-term eye injury, burns, UV sensitivity when combined with certain medications), teenagers in the United States and affluent countries appear to disregard the risks of tanning.11

Tanning companies have promoted the misconception that only UVB rays cause cell damage and UVA rays, which the devices emit, result in “damage-free” or “safe” tans.2,3 Until 2013, indoor tanning devices were classified by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as class I, indicating that they are safe in terms of electrical shock. Many indoor tanning facilities have promoted the FDA “safe” label without clarifying that the safety indications only referred to electrical-shock potential. Nonetheless, it is known now that these devices, which emit high UVA and low UVB rays, promote melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancers, and severe sunburns, as well as aggravate existing conditions (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus).4 As a result of an unacceptably high incidence of these disease complications, a 2014 FDA regulation categorized tanning beds as class II, requiring that tanning bed users be informed of the risk of skin cancer in an effort to reverse the growing trend of indoor tanning.12 Despite these regulatory interventions, it is not clear if this knowledge of cancer risk deters patients from indoor tanning.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the patients’ perspective on indoor tanning behaviors as associated with the severity of their melanoma and the time frame in which they were diagnosed as well as their perceived views on the safety of indoor tanning and the frequency in which they continue to tan indoors. This information is highly relevant in helping to determine if requiring a warning of the risk of skin cancer will deter patients from this unhealthy habit, especially given recent reclassification of sunbeds as class II by the FDA. Additional insights from these data may clarify if indoor tanning decreases the time frame in which melanoma is diagnosed or increases the severity of the resulting melanoma. Moreover, it will help elucidate whether or not the age at which indoor tanning is initiated affects the time frame to melanoma onset and corresponding severity.

Methods

An original unvalidated online survey was conducted worldwide via a link distributed to the following supporting institutions: Advanced Dermatology & Cosmetic Surgery, Ameriderm Research, Melanoma Research Foundation (a melanoma patient advocacy group), Florida State University Department of Dermatology, Moffitt Cancer Center Cutaneous Oncology Program, Cleveland Clinic, Ohio State University Division of Medical Oncology, Harvard Medical School Department of Dermatology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Department of Dermatology, University of Colorado Department of Dermatology, and Northwestern University Department of Dermatology. However, there was not confirmation that all of these institutions promoted the survey. Additionally, respondents were recruited through patient advocacy groups and social media sites including Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Tumblr, and Instagram. The patient advocacy groups and social media sites invited participation through recruitment announcements, including DermNetNZ (a global dermatology patient information site), with additional help from the International Federation of Dermatology Clinical Trial Network.

The survey was restricted to those who were self-identified as 18 years or older and who self-reported a diagnosis of melanoma following the use of indoor tanning devices. The survey was hosted by SurveyMonkey, which allowed consent to be obtained and responses to remain anonymous. Access to the survey was sponsored by the Basal Cell Carcinoma Nevus Syndrome Life Support Network. The University of Central Florida (Orlando, Florida) institutional review board reviewed and approved this study as exempt human research.

Survey responses collected from January 2014 to June 2015 were analyzed herein. The survey contained 58 questions and was divided into different topics including indoor tanning background (eg, states/countries in which participants tanned indoors, age when they first tanned, frequency of tanning), consenting process (eg, length, did someone review the consent with participants, what was contained in the consent), indoor tanning and melanoma (eg, how long after tanning did melanoma develop, age at development, location of melanoma), indoor tanning postmelanoma (eg, did participants tan after diagnosis and why), and other risk factors (eg, did participants smoke or drink pre- or postmelanoma).

Statistical Analysis

The data consist of both categorical and continuous variables. The categorical variables included age (<35 years or ≥35 years), frequency of indoor tanning (≤1 time weekly or >1 time weekly), and onset of melanoma diagnosis (within or after 5 years

Difference in proportions among groups, age, frequency of tanning, onset of melanoma diagnosis within or after 5 years of starting indoor tanning, and knowledge of cancer risks was tested for significance using the χ² test. Reported P values were 2-tailed, corresponding with a significance level of P<.05. All data were analyzed using SPSS (version 21.0). All statistical analyses were conducted independent of the participants’ sex.

Results

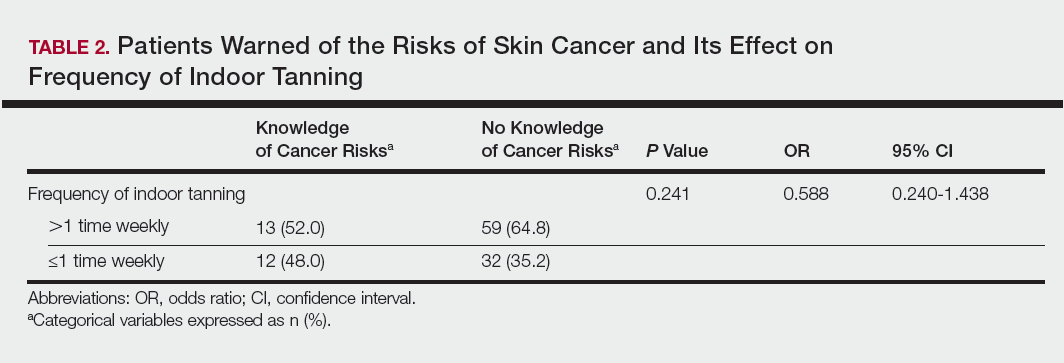

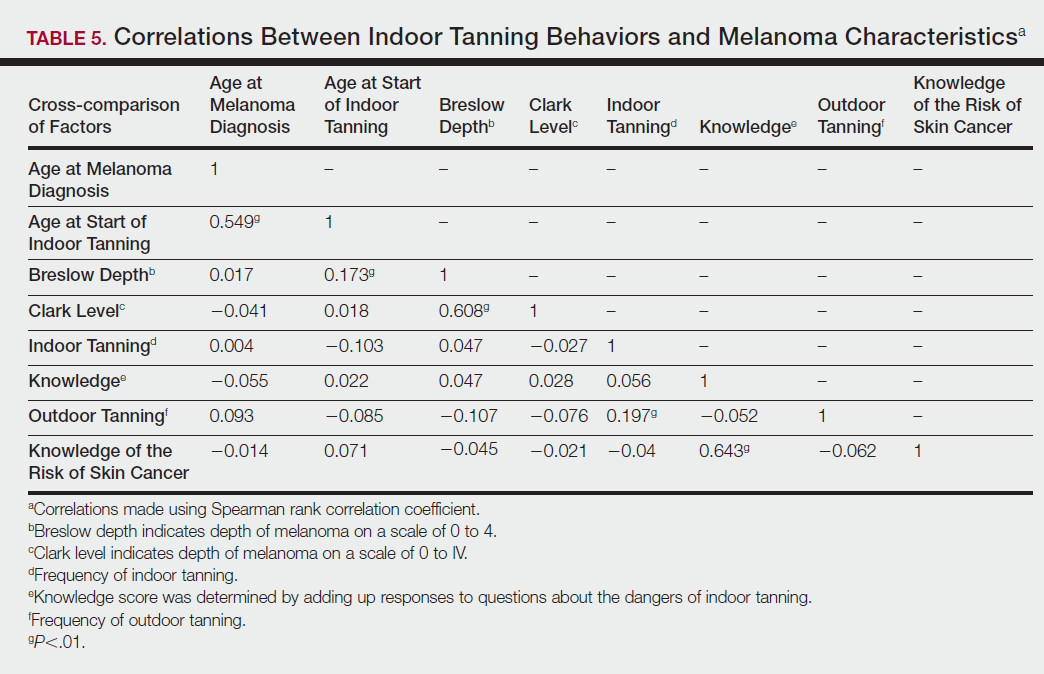

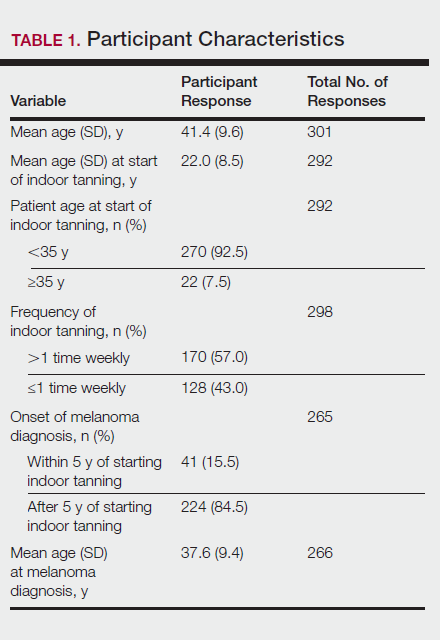

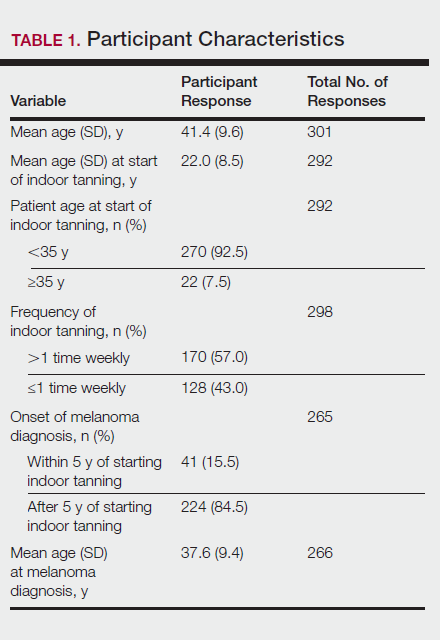

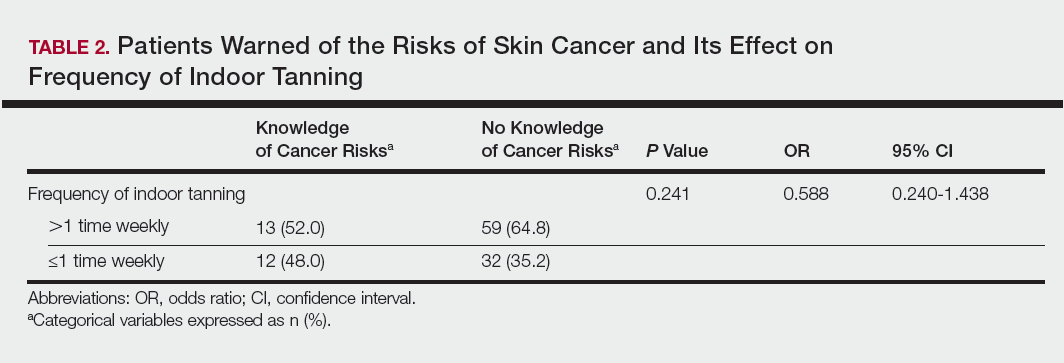

Of the 454 participants who accessed the survey, 448 were analyzed in this study; 6 participants did not complete the questionnaire. Both males and females were analyzed: 289 females, 12 males, and 153 who did not report gender. The age range of participants was 18 to 69 years. The age at start of indoor tanning ranged from 8 to 54 years, with a mean of 22 years. Additional participant characteristics are described in Table 1. The mean frequency of indoor tanning was reported as 2 times weekly. When participants were asked if they were warned of the risk of skin cancer, 21.5% reported yes while 78.4% reported not being told of the risk. This knowledge was compared to their frequency of indoor tanning. Having the knowledge of the risk of skin cancer had no influence on their frequency of indoor tanning (Table 2).

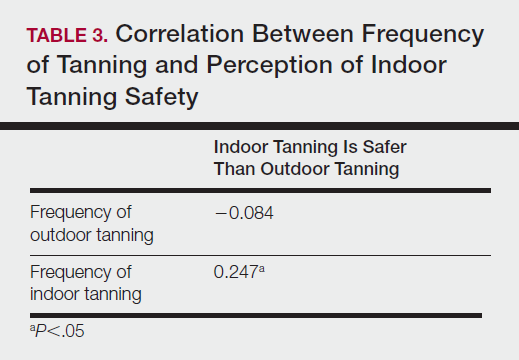

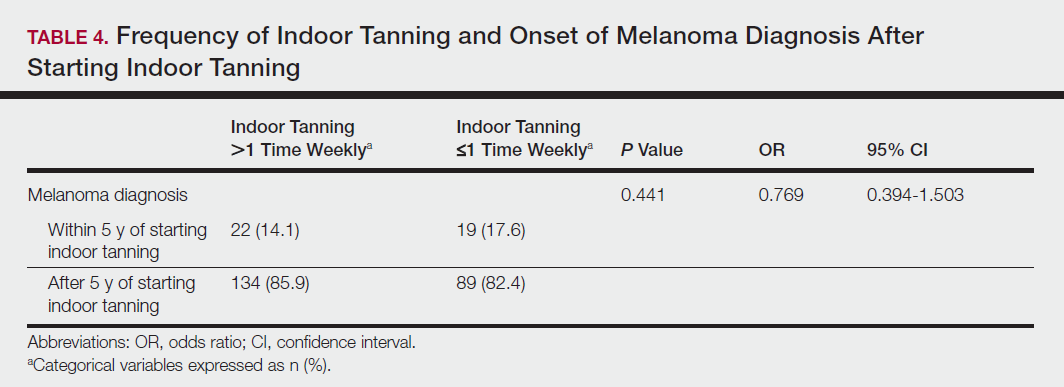

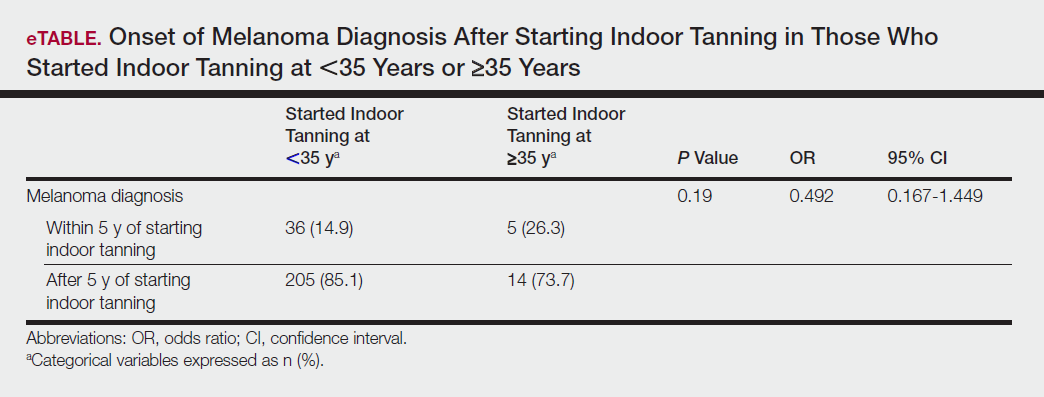

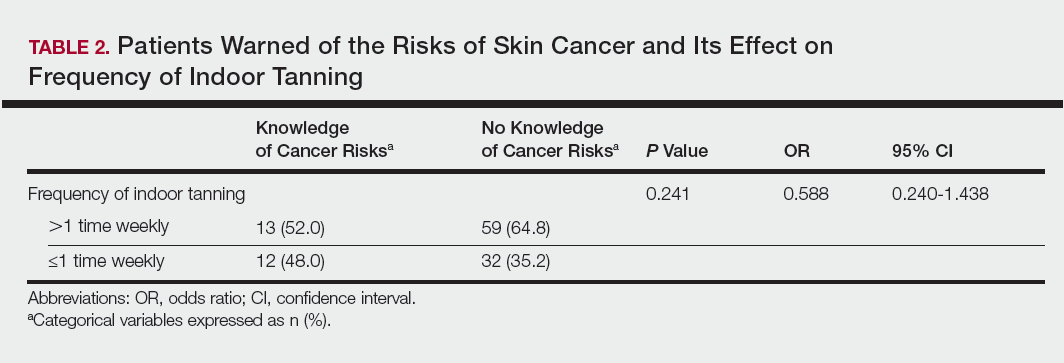

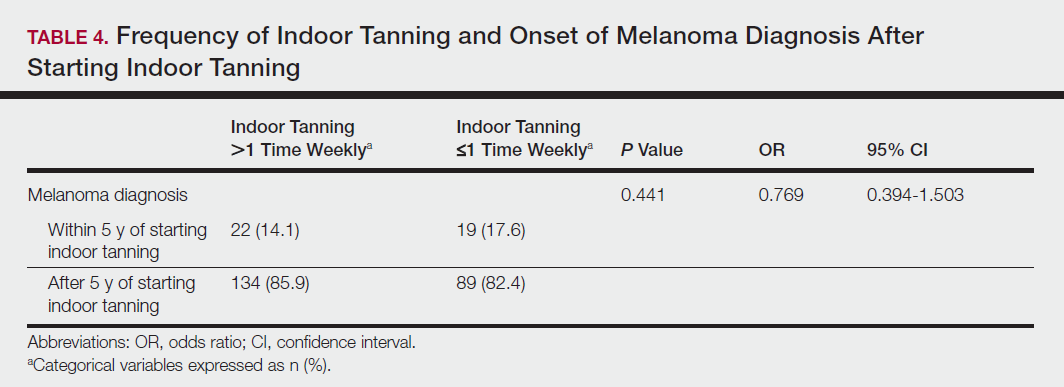

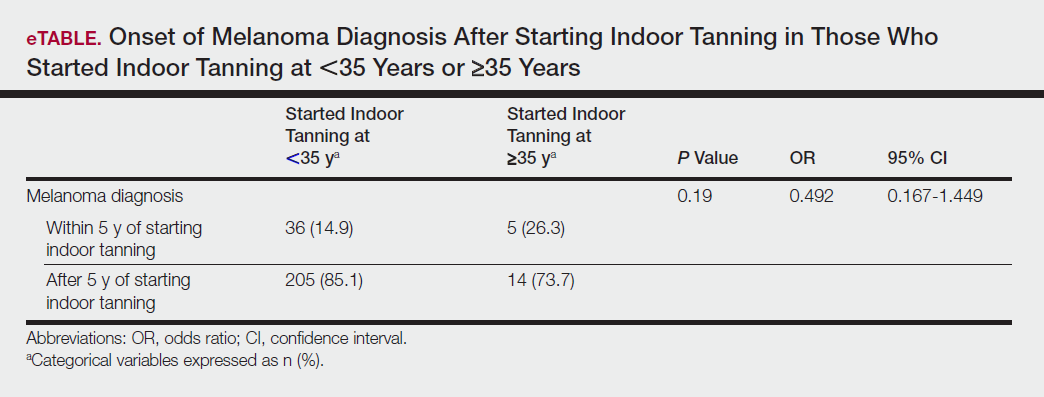

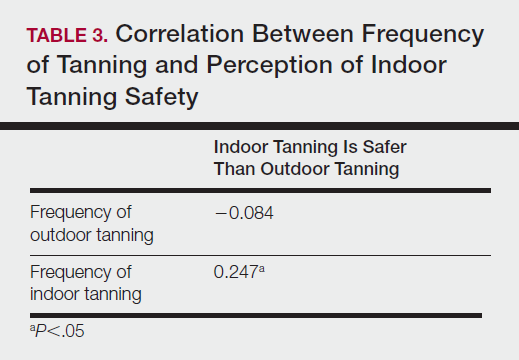

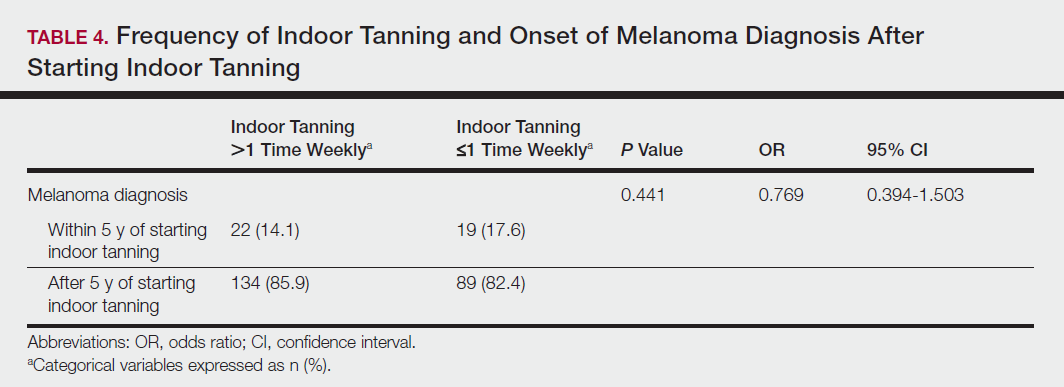

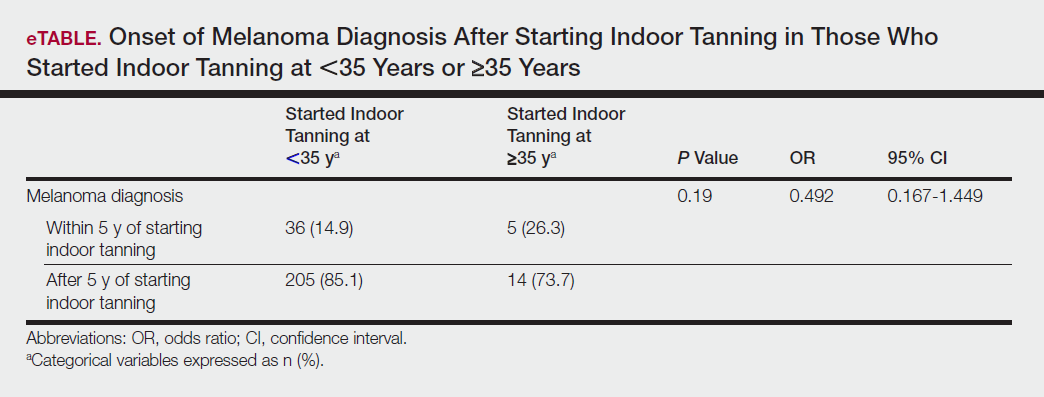

Among responders, those who perceived indoor tanning as safer than outdoor tanning tanned indoors more frequently than those who do not (Spearman r=−0.224; P<.05)(Table 3). The frequency of indoor tanning was divided into those who tanned indoors more than once weekly and those who tanned indoors once a week or less. This study showed that the frequency of indoor tanning had no effect on the latency time between the commencement of indoor tanning and diagnosis of melanoma (Table 4). The time frame from the onset of melanoma diagnosis also was compared to the age at which the participants started to tan indoors. Age was divided into those younger than 35 years and those 35 years and older. There was no correlation between the age when indoor tanning began and the time frame in which the melanoma was diagnosed (eTable).

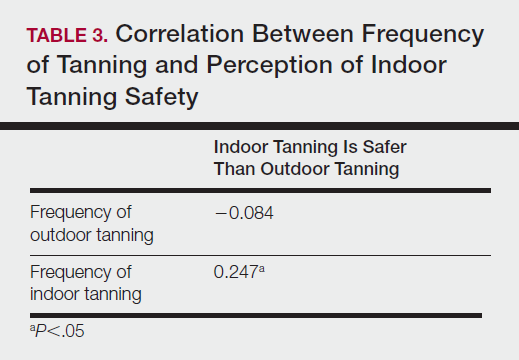

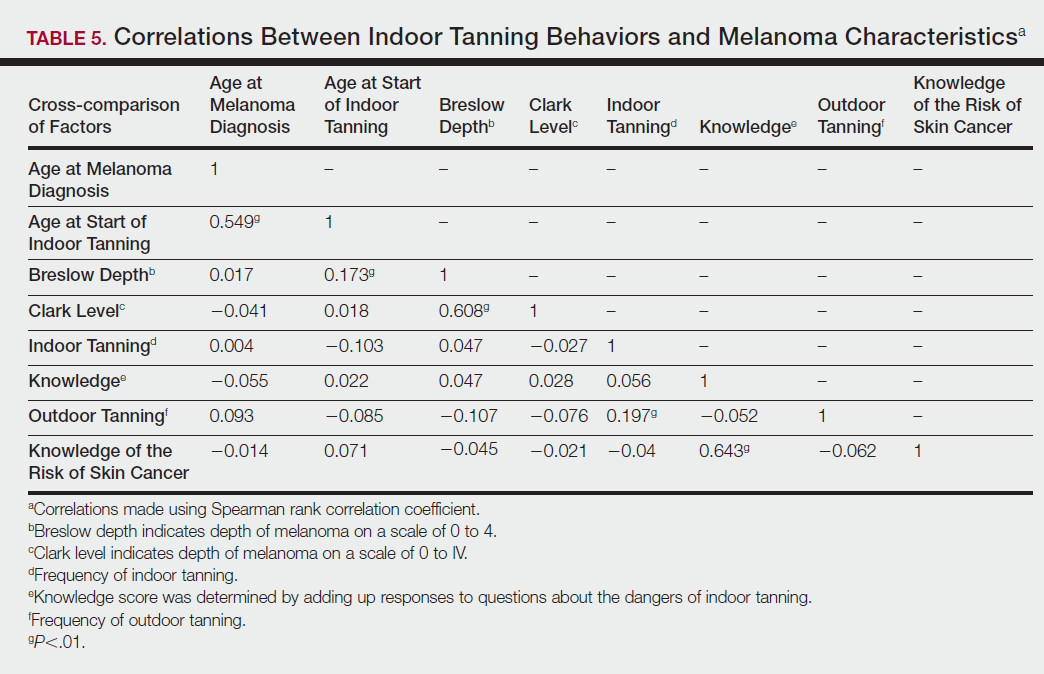

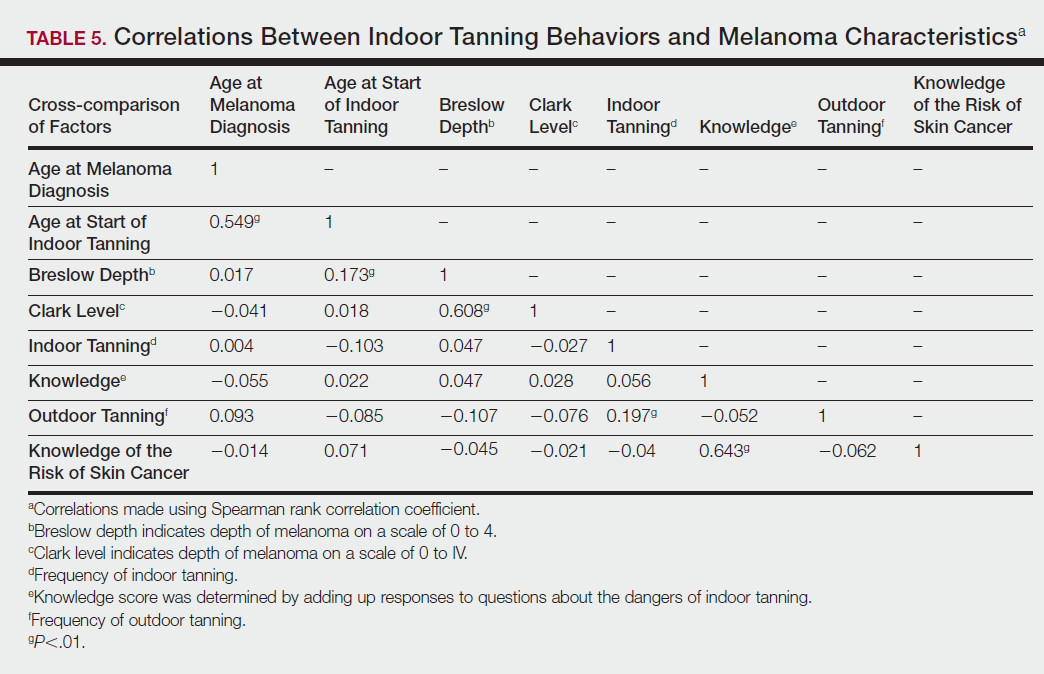

Table 5 shows the correlations between indoor tanning behaviors and melanoma characteristics. Those who started indoor tanning at an earlier age were diagnosed with melanoma at an earlier age compared to those who started indoor tanning later in life (r=0.549; P<.01). Moreover, those who started indoor tanning at a later age reported being diagnosed with a melanoma of greater Breslow depth (r=0.173; P<.01). Those who reported being diagnosed with a greater Breslow depth also reported a higher Clark level (r=0.608; P<.01). Among responders, those who more frequently tanned indoors also reported greater frequency of outdoor tanning (r=0.197; P<.01). This study showed no correlation between the age at melanoma diagnosis and the frequency of indoor (r=0.004; P>.05 not significant) or outdoor (r=0.093; P>.05 not significant) tanning. Having the knowledge of the risk of skin cancer had no relationship on the frequency of indoor tanning (r=−0.04; P>.05 not significant).

Comment

Thirty million Americans utilize indoor tanning devices at least once a year.13 UVA light comprises the majority of the spectrum used by indoor tanning devices, with a fraction (<5%) being UVB light. Until recently, UVB light was the only solar spectrum considered carcinogenic. In 2009, the International Agency for Research on Cancer classified the whole spectrum as carcinogenic to humans.5,11 Despite this evidence, indoor tanning facilities have promoted indoor tanning as damage free.3 The goal of this study was to collect the patient perspective on the safety of indoor tanning, indoor tanning behaviors, time frame of onset of melanoma, and the severity (ie, Breslow depth) of those melanomas.

Melanoma is the most prevalent cancer in females aged 25 to 29 years.3 The median age of diagnosis of melanoma (with and without the use of indoor tanning devices) is approximately 60 years14 versus our study, which found the average age at diagnosis was 37.6 years. Our findings are consistent with other literature in that those who start indoor tanning earlier (<35 years of age) develop melanoma at an earlier age.14,15 Cust et al14 also promoted the idea that patients develop melanoma earlier because younger individuals are more biologically susceptible to the carcinogenic effects of artificial UV light. However, our study found that those who started indoor tanning at an older age reported being diagnosed with a melanoma of greater Breslow depth, seemingly incongruent with the aforementioned hypothesis. One limitation is the age range for this research sample (18–69 years). The young age range may be attributable to the recruitment through social media, which is geared toward a younger population. Additionally, indoor tanning is a relatively new phenomenon practiced since the 1980s,2 which may contribute to the younger sample size. However, 2.7 billion individuals use social media worldwide with 40% of those older than 65 years on social media.16

Prior research has shown that those who start indoor tanning before the age of 35 years have a 75% increased risk of developing melanoma.14 Another study also has suggested that UVA-rich sunlamps may shorten the latency period for induction of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers.3 Our study used similar age cutoffs in concluding that there was no earlier onset of melanoma diagnosis between those who started indoor tanning before the age of 35 years and those who started at the age of 35 years or older. Limitations include that our study is cross-sectional, and therefore time course cannot be established. Also, survey responses were self-reported, allowing the possibility of recall bias.

A plethora of research has been conducted to determine if there is a connection between the use of indoor tanning devices and developing melanoma. Cust et al14 suggested the risk of melanoma was 41% higher for those who had ever used a sunbed in comparison to those who had not. Other studies describe the difficulty in making the connection between indoor tanning and melanoma, as those who more frequently tan indoors also more frequently tan outdoors,11 as suggested by this study. However, there is a paucity of literature on the patients’ perspectives on the safety of indoor tanning. This study determined that those who more frequently tan indoors believed that indoor tanning is safer than outdoor tanning. With this altered perception promoted by the indoor tanning industry, the FDA has added a warning label to all indoor tanning devices about the risk of skin cancer. Our study revealed that having the knowledge of the risk of skin cancer had no influence on the frequency of indoor tanning. This concerning finding highlights a pressing need for an alternative approach to increase awareness of the harmful consequences that accompany indoor tanning. Further studies may elaborate on potential effective methods and messages to relate to an indoor tanning population comprised mostly of young females.

Acknowledgments

Supported and funded by the Basal Cell Carcinoma Nevus Syndrome Life Support Network. This research project was completed as part of the FIRE Module at the University of Central Florida, College of Medicine. We thank the FIRE Module faculty and staff for their assistance with this project.

- Fisher DE, James WD. Indoor tanning—science, behavior, and policy. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:901-903.

- Boniol M, Autier P, Boyle P, et al. Cutaneous melanoma attributable to sunbed use: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e4757.

- Coelho SG, Hearing VJ. UVA tanning is involved in the increased incidence of skin cancers in fair-skinned young women. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010;23:57-63.

- Klein RS, Sayre RM, Dowdy JC, et al. The risk of ultraviolet radiation exposure from indoor lamps in lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8:320-324.

- O’Sullivan NA, Tait CP. Tanning bed and nail lamp use and the risk of cutaneous malignancy: a review of the literature. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:99-106.

- Schmidt CW. UV radiation and skin cancer: the science behind age restrictions for tanning beds. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:a308-a313.

- Lazovich D, Vogel RI, Berwick M, et al. Indoor tanning and risk of melanoma: a case-control study in a highly exposed population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1557-1568.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of indoor tanning devices by adults—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:323-326.

- Nielsen K, Masback A, Olsson H, et al. A prospective, population-based study of 40,000 women regarding host factors, UV exposure and sunbed use in relation to risk and anatomic site of cutaneous melanoma. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:706-715.

- Gandini S, Autier P, Boniol M. Reviews on sun exposure and artificial light and melanoma. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2011;107:362-366.

- Indoor tanning: the risks of ultraviolet rays. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm186687.htm. Updated September 11, 2017. Accessed November 2, 2017.

- Food and Drug Administration, HHS. General and plastic surgery devices: reclassification of ultraviolet lamps for tanning, henceforth to be known as sunlamp products and ultraviolet lamps intended for use in sunlamp products. Fed Regist. 2014;79:31205-31214.

- Brady MS. Public health and the tanning bed controversy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1571-1573.

- Cust AE, Armstrong BK, Goumas C, et al. Sunbed use during adolescence and early adulthood is associated with increased risk of early-onset melanoma. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:2425-2435.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer Working Group on artificial ultraviolet (UV) light and skin cancer. The association of use of sunbeds with cutaneous malignant melanoma and other skin cancers: a systematic review. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:1116-1122.

- Greenwood S, Perrin A, Duggan M. Social media update 2016. Pew Research Center website. http://www.pewinternet.org/2016/11/11/social-media-update-2016/. Published November 11, 2016. Accessed December 12, 2017.

The incidence of melanoma is increasing at a rate greater than any other cancer,1 possibly due to the increasing use of indoor tanning devices. These devices emit unnaturally high levels of UVA and low levels of UVA and UVB rays.2 The risks of using these devices include increased incidence of melanoma (3438 cases attributed to indoor tanning in 2008) and keratinocytes cancer (increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma by 67% and basal cell carcinoma by 29%), severe sunburns (61.1% of female users and 44.6% of male users have reported sunburns), and aggravation of underlying disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus.3-5

The literature varies in its explanation of how indoor tanning increases the risk of developing melanoma. Some authors suggest it is due to increased frequency of use, duration of sessions, and years of using tanning devices.1,6 Others suggest the increased cancer risk is the result of starting to tan at an earlier age.2,3,6-10 There is conflicting literature on the level of increased risk of melanoma in those who tan indoors at a young age (<35 years). Although the estimated rate of increased skin cancer risk varies, with rates up to 75% compared to nonusers, nearly all sources support an increased rate.6 Despite the growing body of knowledge that indoor tanning is dangerous, as well as the academic publication of these risks (eg, carcinogenesis, short-term and long-term eye injury, burns, UV sensitivity when combined with certain medications), teenagers in the United States and affluent countries appear to disregard the risks of tanning.11

Tanning companies have promoted the misconception that only UVB rays cause cell damage and UVA rays, which the devices emit, result in “damage-free” or “safe” tans.2,3 Until 2013, indoor tanning devices were classified by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as class I, indicating that they are safe in terms of electrical shock. Many indoor tanning facilities have promoted the FDA “safe” label without clarifying that the safety indications only referred to electrical-shock potential. Nonetheless, it is known now that these devices, which emit high UVA and low UVB rays, promote melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancers, and severe sunburns, as well as aggravate existing conditions (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus).4 As a result of an unacceptably high incidence of these disease complications, a 2014 FDA regulation categorized tanning beds as class II, requiring that tanning bed users be informed of the risk of skin cancer in an effort to reverse the growing trend of indoor tanning.12 Despite these regulatory interventions, it is not clear if this knowledge of cancer risk deters patients from indoor tanning.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the patients’ perspective on indoor tanning behaviors as associated with the severity of their melanoma and the time frame in which they were diagnosed as well as their perceived views on the safety of indoor tanning and the frequency in which they continue to tan indoors. This information is highly relevant in helping to determine if requiring a warning of the risk of skin cancer will deter patients from this unhealthy habit, especially given recent reclassification of sunbeds as class II by the FDA. Additional insights from these data may clarify if indoor tanning decreases the time frame in which melanoma is diagnosed or increases the severity of the resulting melanoma. Moreover, it will help elucidate whether or not the age at which indoor tanning is initiated affects the time frame to melanoma onset and corresponding severity.

Methods

An original unvalidated online survey was conducted worldwide via a link distributed to the following supporting institutions: Advanced Dermatology & Cosmetic Surgery, Ameriderm Research, Melanoma Research Foundation (a melanoma patient advocacy group), Florida State University Department of Dermatology, Moffitt Cancer Center Cutaneous Oncology Program, Cleveland Clinic, Ohio State University Division of Medical Oncology, Harvard Medical School Department of Dermatology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Department of Dermatology, University of Colorado Department of Dermatology, and Northwestern University Department of Dermatology. However, there was not confirmation that all of these institutions promoted the survey. Additionally, respondents were recruited through patient advocacy groups and social media sites including Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Tumblr, and Instagram. The patient advocacy groups and social media sites invited participation through recruitment announcements, including DermNetNZ (a global dermatology patient information site), with additional help from the International Federation of Dermatology Clinical Trial Network.

The survey was restricted to those who were self-identified as 18 years or older and who self-reported a diagnosis of melanoma following the use of indoor tanning devices. The survey was hosted by SurveyMonkey, which allowed consent to be obtained and responses to remain anonymous. Access to the survey was sponsored by the Basal Cell Carcinoma Nevus Syndrome Life Support Network. The University of Central Florida (Orlando, Florida) institutional review board reviewed and approved this study as exempt human research.

Survey responses collected from January 2014 to June 2015 were analyzed herein. The survey contained 58 questions and was divided into different topics including indoor tanning background (eg, states/countries in which participants tanned indoors, age when they first tanned, frequency of tanning), consenting process (eg, length, did someone review the consent with participants, what was contained in the consent), indoor tanning and melanoma (eg, how long after tanning did melanoma develop, age at development, location of melanoma), indoor tanning postmelanoma (eg, did participants tan after diagnosis and why), and other risk factors (eg, did participants smoke or drink pre- or postmelanoma).

Statistical Analysis

The data consist of both categorical and continuous variables. The categorical variables included age (<35 years or ≥35 years), frequency of indoor tanning (≤1 time weekly or >1 time weekly), and onset of melanoma diagnosis (within or after 5 years

Difference in proportions among groups, age, frequency of tanning, onset of melanoma diagnosis within or after 5 years of starting indoor tanning, and knowledge of cancer risks was tested for significance using the χ² test. Reported P values were 2-tailed, corresponding with a significance level of P<.05. All data were analyzed using SPSS (version 21.0). All statistical analyses were conducted independent of the participants’ sex.

Results

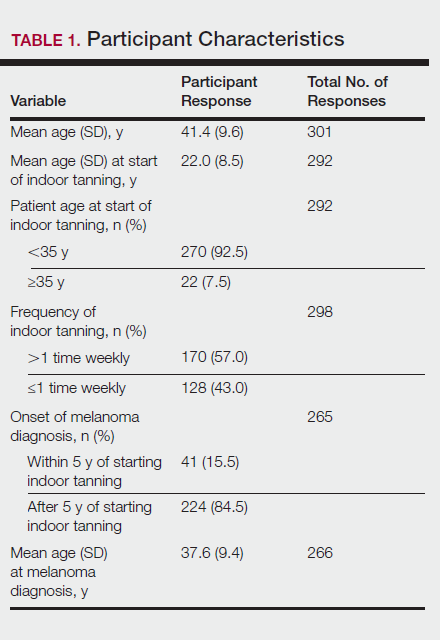

Of the 454 participants who accessed the survey, 448 were analyzed in this study; 6 participants did not complete the questionnaire. Both males and females were analyzed: 289 females, 12 males, and 153 who did not report gender. The age range of participants was 18 to 69 years. The age at start of indoor tanning ranged from 8 to 54 years, with a mean of 22 years. Additional participant characteristics are described in Table 1. The mean frequency of indoor tanning was reported as 2 times weekly. When participants were asked if they were warned of the risk of skin cancer, 21.5% reported yes while 78.4% reported not being told of the risk. This knowledge was compared to their frequency of indoor tanning. Having the knowledge of the risk of skin cancer had no influence on their frequency of indoor tanning (Table 2).

Among responders, those who perceived indoor tanning as safer than outdoor tanning tanned indoors more frequently than those who do not (Spearman r=−0.224; P<.05)(Table 3). The frequency of indoor tanning was divided into those who tanned indoors more than once weekly and those who tanned indoors once a week or less. This study showed that the frequency of indoor tanning had no effect on the latency time between the commencement of indoor tanning and diagnosis of melanoma (Table 4). The time frame from the onset of melanoma diagnosis also was compared to the age at which the participants started to tan indoors. Age was divided into those younger than 35 years and those 35 years and older. There was no correlation between the age when indoor tanning began and the time frame in which the melanoma was diagnosed (eTable).

Table 5 shows the correlations between indoor tanning behaviors and melanoma characteristics. Those who started indoor tanning at an earlier age were diagnosed with melanoma at an earlier age compared to those who started indoor tanning later in life (r=0.549; P<.01). Moreover, those who started indoor tanning at a later age reported being diagnosed with a melanoma of greater Breslow depth (r=0.173; P<.01). Those who reported being diagnosed with a greater Breslow depth also reported a higher Clark level (r=0.608; P<.01). Among responders, those who more frequently tanned indoors also reported greater frequency of outdoor tanning (r=0.197; P<.01). This study showed no correlation between the age at melanoma diagnosis and the frequency of indoor (r=0.004; P>.05 not significant) or outdoor (r=0.093; P>.05 not significant) tanning. Having the knowledge of the risk of skin cancer had no relationship on the frequency of indoor tanning (r=−0.04; P>.05 not significant).

Comment

Thirty million Americans utilize indoor tanning devices at least once a year.13 UVA light comprises the majority of the spectrum used by indoor tanning devices, with a fraction (<5%) being UVB light. Until recently, UVB light was the only solar spectrum considered carcinogenic. In 2009, the International Agency for Research on Cancer classified the whole spectrum as carcinogenic to humans.5,11 Despite this evidence, indoor tanning facilities have promoted indoor tanning as damage free.3 The goal of this study was to collect the patient perspective on the safety of indoor tanning, indoor tanning behaviors, time frame of onset of melanoma, and the severity (ie, Breslow depth) of those melanomas.

Melanoma is the most prevalent cancer in females aged 25 to 29 years.3 The median age of diagnosis of melanoma (with and without the use of indoor tanning devices) is approximately 60 years14 versus our study, which found the average age at diagnosis was 37.6 years. Our findings are consistent with other literature in that those who start indoor tanning earlier (<35 years of age) develop melanoma at an earlier age.14,15 Cust et al14 also promoted the idea that patients develop melanoma earlier because younger individuals are more biologically susceptible to the carcinogenic effects of artificial UV light. However, our study found that those who started indoor tanning at an older age reported being diagnosed with a melanoma of greater Breslow depth, seemingly incongruent with the aforementioned hypothesis. One limitation is the age range for this research sample (18–69 years). The young age range may be attributable to the recruitment through social media, which is geared toward a younger population. Additionally, indoor tanning is a relatively new phenomenon practiced since the 1980s,2 which may contribute to the younger sample size. However, 2.7 billion individuals use social media worldwide with 40% of those older than 65 years on social media.16

Prior research has shown that those who start indoor tanning before the age of 35 years have a 75% increased risk of developing melanoma.14 Another study also has suggested that UVA-rich sunlamps may shorten the latency period for induction of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers.3 Our study used similar age cutoffs in concluding that there was no earlier onset of melanoma diagnosis between those who started indoor tanning before the age of 35 years and those who started at the age of 35 years or older. Limitations include that our study is cross-sectional, and therefore time course cannot be established. Also, survey responses were self-reported, allowing the possibility of recall bias.

A plethora of research has been conducted to determine if there is a connection between the use of indoor tanning devices and developing melanoma. Cust et al14 suggested the risk of melanoma was 41% higher for those who had ever used a sunbed in comparison to those who had not. Other studies describe the difficulty in making the connection between indoor tanning and melanoma, as those who more frequently tan indoors also more frequently tan outdoors,11 as suggested by this study. However, there is a paucity of literature on the patients’ perspectives on the safety of indoor tanning. This study determined that those who more frequently tan indoors believed that indoor tanning is safer than outdoor tanning. With this altered perception promoted by the indoor tanning industry, the FDA has added a warning label to all indoor tanning devices about the risk of skin cancer. Our study revealed that having the knowledge of the risk of skin cancer had no influence on the frequency of indoor tanning. This concerning finding highlights a pressing need for an alternative approach to increase awareness of the harmful consequences that accompany indoor tanning. Further studies may elaborate on potential effective methods and messages to relate to an indoor tanning population comprised mostly of young females.

Acknowledgments

Supported and funded by the Basal Cell Carcinoma Nevus Syndrome Life Support Network. This research project was completed as part of the FIRE Module at the University of Central Florida, College of Medicine. We thank the FIRE Module faculty and staff for their assistance with this project.

The incidence of melanoma is increasing at a rate greater than any other cancer,1 possibly due to the increasing use of indoor tanning devices. These devices emit unnaturally high levels of UVA and low levels of UVA and UVB rays.2 The risks of using these devices include increased incidence of melanoma (3438 cases attributed to indoor tanning in 2008) and keratinocytes cancer (increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma by 67% and basal cell carcinoma by 29%), severe sunburns (61.1% of female users and 44.6% of male users have reported sunburns), and aggravation of underlying disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus.3-5

The literature varies in its explanation of how indoor tanning increases the risk of developing melanoma. Some authors suggest it is due to increased frequency of use, duration of sessions, and years of using tanning devices.1,6 Others suggest the increased cancer risk is the result of starting to tan at an earlier age.2,3,6-10 There is conflicting literature on the level of increased risk of melanoma in those who tan indoors at a young age (<35 years). Although the estimated rate of increased skin cancer risk varies, with rates up to 75% compared to nonusers, nearly all sources support an increased rate.6 Despite the growing body of knowledge that indoor tanning is dangerous, as well as the academic publication of these risks (eg, carcinogenesis, short-term and long-term eye injury, burns, UV sensitivity when combined with certain medications), teenagers in the United States and affluent countries appear to disregard the risks of tanning.11

Tanning companies have promoted the misconception that only UVB rays cause cell damage and UVA rays, which the devices emit, result in “damage-free” or “safe” tans.2,3 Until 2013, indoor tanning devices were classified by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as class I, indicating that they are safe in terms of electrical shock. Many indoor tanning facilities have promoted the FDA “safe” label without clarifying that the safety indications only referred to electrical-shock potential. Nonetheless, it is known now that these devices, which emit high UVA and low UVB rays, promote melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancers, and severe sunburns, as well as aggravate existing conditions (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus).4 As a result of an unacceptably high incidence of these disease complications, a 2014 FDA regulation categorized tanning beds as class II, requiring that tanning bed users be informed of the risk of skin cancer in an effort to reverse the growing trend of indoor tanning.12 Despite these regulatory interventions, it is not clear if this knowledge of cancer risk deters patients from indoor tanning.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the patients’ perspective on indoor tanning behaviors as associated with the severity of their melanoma and the time frame in which they were diagnosed as well as their perceived views on the safety of indoor tanning and the frequency in which they continue to tan indoors. This information is highly relevant in helping to determine if requiring a warning of the risk of skin cancer will deter patients from this unhealthy habit, especially given recent reclassification of sunbeds as class II by the FDA. Additional insights from these data may clarify if indoor tanning decreases the time frame in which melanoma is diagnosed or increases the severity of the resulting melanoma. Moreover, it will help elucidate whether or not the age at which indoor tanning is initiated affects the time frame to melanoma onset and corresponding severity.

Methods

An original unvalidated online survey was conducted worldwide via a link distributed to the following supporting institutions: Advanced Dermatology & Cosmetic Surgery, Ameriderm Research, Melanoma Research Foundation (a melanoma patient advocacy group), Florida State University Department of Dermatology, Moffitt Cancer Center Cutaneous Oncology Program, Cleveland Clinic, Ohio State University Division of Medical Oncology, Harvard Medical School Department of Dermatology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Department of Dermatology, University of Colorado Department of Dermatology, and Northwestern University Department of Dermatology. However, there was not confirmation that all of these institutions promoted the survey. Additionally, respondents were recruited through patient advocacy groups and social media sites including Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Tumblr, and Instagram. The patient advocacy groups and social media sites invited participation through recruitment announcements, including DermNetNZ (a global dermatology patient information site), with additional help from the International Federation of Dermatology Clinical Trial Network.

The survey was restricted to those who were self-identified as 18 years or older and who self-reported a diagnosis of melanoma following the use of indoor tanning devices. The survey was hosted by SurveyMonkey, which allowed consent to be obtained and responses to remain anonymous. Access to the survey was sponsored by the Basal Cell Carcinoma Nevus Syndrome Life Support Network. The University of Central Florida (Orlando, Florida) institutional review board reviewed and approved this study as exempt human research.

Survey responses collected from January 2014 to June 2015 were analyzed herein. The survey contained 58 questions and was divided into different topics including indoor tanning background (eg, states/countries in which participants tanned indoors, age when they first tanned, frequency of tanning), consenting process (eg, length, did someone review the consent with participants, what was contained in the consent), indoor tanning and melanoma (eg, how long after tanning did melanoma develop, age at development, location of melanoma), indoor tanning postmelanoma (eg, did participants tan after diagnosis and why), and other risk factors (eg, did participants smoke or drink pre- or postmelanoma).

Statistical Analysis

The data consist of both categorical and continuous variables. The categorical variables included age (<35 years or ≥35 years), frequency of indoor tanning (≤1 time weekly or >1 time weekly), and onset of melanoma diagnosis (within or after 5 years

Difference in proportions among groups, age, frequency of tanning, onset of melanoma diagnosis within or after 5 years of starting indoor tanning, and knowledge of cancer risks was tested for significance using the χ² test. Reported P values were 2-tailed, corresponding with a significance level of P<.05. All data were analyzed using SPSS (version 21.0). All statistical analyses were conducted independent of the participants’ sex.

Results

Of the 454 participants who accessed the survey, 448 were analyzed in this study; 6 participants did not complete the questionnaire. Both males and females were analyzed: 289 females, 12 males, and 153 who did not report gender. The age range of participants was 18 to 69 years. The age at start of indoor tanning ranged from 8 to 54 years, with a mean of 22 years. Additional participant characteristics are described in Table 1. The mean frequency of indoor tanning was reported as 2 times weekly. When participants were asked if they were warned of the risk of skin cancer, 21.5% reported yes while 78.4% reported not being told of the risk. This knowledge was compared to their frequency of indoor tanning. Having the knowledge of the risk of skin cancer had no influence on their frequency of indoor tanning (Table 2).

Among responders, those who perceived indoor tanning as safer than outdoor tanning tanned indoors more frequently than those who do not (Spearman r=−0.224; P<.05)(Table 3). The frequency of indoor tanning was divided into those who tanned indoors more than once weekly and those who tanned indoors once a week or less. This study showed that the frequency of indoor tanning had no effect on the latency time between the commencement of indoor tanning and diagnosis of melanoma (Table 4). The time frame from the onset of melanoma diagnosis also was compared to the age at which the participants started to tan indoors. Age was divided into those younger than 35 years and those 35 years and older. There was no correlation between the age when indoor tanning began and the time frame in which the melanoma was diagnosed (eTable).

Table 5 shows the correlations between indoor tanning behaviors and melanoma characteristics. Those who started indoor tanning at an earlier age were diagnosed with melanoma at an earlier age compared to those who started indoor tanning later in life (r=0.549; P<.01). Moreover, those who started indoor tanning at a later age reported being diagnosed with a melanoma of greater Breslow depth (r=0.173; P<.01). Those who reported being diagnosed with a greater Breslow depth also reported a higher Clark level (r=0.608; P<.01). Among responders, those who more frequently tanned indoors also reported greater frequency of outdoor tanning (r=0.197; P<.01). This study showed no correlation between the age at melanoma diagnosis and the frequency of indoor (r=0.004; P>.05 not significant) or outdoor (r=0.093; P>.05 not significant) tanning. Having the knowledge of the risk of skin cancer had no relationship on the frequency of indoor tanning (r=−0.04; P>.05 not significant).

Comment

Thirty million Americans utilize indoor tanning devices at least once a year.13 UVA light comprises the majority of the spectrum used by indoor tanning devices, with a fraction (<5%) being UVB light. Until recently, UVB light was the only solar spectrum considered carcinogenic. In 2009, the International Agency for Research on Cancer classified the whole spectrum as carcinogenic to humans.5,11 Despite this evidence, indoor tanning facilities have promoted indoor tanning as damage free.3 The goal of this study was to collect the patient perspective on the safety of indoor tanning, indoor tanning behaviors, time frame of onset of melanoma, and the severity (ie, Breslow depth) of those melanomas.

Melanoma is the most prevalent cancer in females aged 25 to 29 years.3 The median age of diagnosis of melanoma (with and without the use of indoor tanning devices) is approximately 60 years14 versus our study, which found the average age at diagnosis was 37.6 years. Our findings are consistent with other literature in that those who start indoor tanning earlier (<35 years of age) develop melanoma at an earlier age.14,15 Cust et al14 also promoted the idea that patients develop melanoma earlier because younger individuals are more biologically susceptible to the carcinogenic effects of artificial UV light. However, our study found that those who started indoor tanning at an older age reported being diagnosed with a melanoma of greater Breslow depth, seemingly incongruent with the aforementioned hypothesis. One limitation is the age range for this research sample (18–69 years). The young age range may be attributable to the recruitment through social media, which is geared toward a younger population. Additionally, indoor tanning is a relatively new phenomenon practiced since the 1980s,2 which may contribute to the younger sample size. However, 2.7 billion individuals use social media worldwide with 40% of those older than 65 years on social media.16

Prior research has shown that those who start indoor tanning before the age of 35 years have a 75% increased risk of developing melanoma.14 Another study also has suggested that UVA-rich sunlamps may shorten the latency period for induction of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers.3 Our study used similar age cutoffs in concluding that there was no earlier onset of melanoma diagnosis between those who started indoor tanning before the age of 35 years and those who started at the age of 35 years or older. Limitations include that our study is cross-sectional, and therefore time course cannot be established. Also, survey responses were self-reported, allowing the possibility of recall bias.

A plethora of research has been conducted to determine if there is a connection between the use of indoor tanning devices and developing melanoma. Cust et al14 suggested the risk of melanoma was 41% higher for those who had ever used a sunbed in comparison to those who had not. Other studies describe the difficulty in making the connection between indoor tanning and melanoma, as those who more frequently tan indoors also more frequently tan outdoors,11 as suggested by this study. However, there is a paucity of literature on the patients’ perspectives on the safety of indoor tanning. This study determined that those who more frequently tan indoors believed that indoor tanning is safer than outdoor tanning. With this altered perception promoted by the indoor tanning industry, the FDA has added a warning label to all indoor tanning devices about the risk of skin cancer. Our study revealed that having the knowledge of the risk of skin cancer had no influence on the frequency of indoor tanning. This concerning finding highlights a pressing need for an alternative approach to increase awareness of the harmful consequences that accompany indoor tanning. Further studies may elaborate on potential effective methods and messages to relate to an indoor tanning population comprised mostly of young females.

Acknowledgments

Supported and funded by the Basal Cell Carcinoma Nevus Syndrome Life Support Network. This research project was completed as part of the FIRE Module at the University of Central Florida, College of Medicine. We thank the FIRE Module faculty and staff for their assistance with this project.

- Fisher DE, James WD. Indoor tanning—science, behavior, and policy. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:901-903.

- Boniol M, Autier P, Boyle P, et al. Cutaneous melanoma attributable to sunbed use: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e4757.

- Coelho SG, Hearing VJ. UVA tanning is involved in the increased incidence of skin cancers in fair-skinned young women. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010;23:57-63.

- Klein RS, Sayre RM, Dowdy JC, et al. The risk of ultraviolet radiation exposure from indoor lamps in lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8:320-324.

- O’Sullivan NA, Tait CP. Tanning bed and nail lamp use and the risk of cutaneous malignancy: a review of the literature. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:99-106.

- Schmidt CW. UV radiation and skin cancer: the science behind age restrictions for tanning beds. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:a308-a313.

- Lazovich D, Vogel RI, Berwick M, et al. Indoor tanning and risk of melanoma: a case-control study in a highly exposed population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1557-1568.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of indoor tanning devices by adults—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:323-326.

- Nielsen K, Masback A, Olsson H, et al. A prospective, population-based study of 40,000 women regarding host factors, UV exposure and sunbed use in relation to risk and anatomic site of cutaneous melanoma. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:706-715.

- Gandini S, Autier P, Boniol M. Reviews on sun exposure and artificial light and melanoma. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2011;107:362-366.

- Indoor tanning: the risks of ultraviolet rays. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm186687.htm. Updated September 11, 2017. Accessed November 2, 2017.

- Food and Drug Administration, HHS. General and plastic surgery devices: reclassification of ultraviolet lamps for tanning, henceforth to be known as sunlamp products and ultraviolet lamps intended for use in sunlamp products. Fed Regist. 2014;79:31205-31214.

- Brady MS. Public health and the tanning bed controversy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1571-1573.

- Cust AE, Armstrong BK, Goumas C, et al. Sunbed use during adolescence and early adulthood is associated with increased risk of early-onset melanoma. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:2425-2435.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer Working Group on artificial ultraviolet (UV) light and skin cancer. The association of use of sunbeds with cutaneous malignant melanoma and other skin cancers: a systematic review. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:1116-1122.

- Greenwood S, Perrin A, Duggan M. Social media update 2016. Pew Research Center website. http://www.pewinternet.org/2016/11/11/social-media-update-2016/. Published November 11, 2016. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Fisher DE, James WD. Indoor tanning—science, behavior, and policy. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:901-903.

- Boniol M, Autier P, Boyle P, et al. Cutaneous melanoma attributable to sunbed use: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e4757.

- Coelho SG, Hearing VJ. UVA tanning is involved in the increased incidence of skin cancers in fair-skinned young women. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010;23:57-63.

- Klein RS, Sayre RM, Dowdy JC, et al. The risk of ultraviolet radiation exposure from indoor lamps in lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8:320-324.

- O’Sullivan NA, Tait CP. Tanning bed and nail lamp use and the risk of cutaneous malignancy: a review of the literature. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:99-106.

- Schmidt CW. UV radiation and skin cancer: the science behind age restrictions for tanning beds. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:a308-a313.

- Lazovich D, Vogel RI, Berwick M, et al. Indoor tanning and risk of melanoma: a case-control study in a highly exposed population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1557-1568.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of indoor tanning devices by adults—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:323-326.

- Nielsen K, Masback A, Olsson H, et al. A prospective, population-based study of 40,000 women regarding host factors, UV exposure and sunbed use in relation to risk and anatomic site of cutaneous melanoma. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:706-715.

- Gandini S, Autier P, Boniol M. Reviews on sun exposure and artificial light and melanoma. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2011;107:362-366.

- Indoor tanning: the risks of ultraviolet rays. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm186687.htm. Updated September 11, 2017. Accessed November 2, 2017.

- Food and Drug Administration, HHS. General and plastic surgery devices: reclassification of ultraviolet lamps for tanning, henceforth to be known as sunlamp products and ultraviolet lamps intended for use in sunlamp products. Fed Regist. 2014;79:31205-31214.

- Brady MS. Public health and the tanning bed controversy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1571-1573.

- Cust AE, Armstrong BK, Goumas C, et al. Sunbed use during adolescence and early adulthood is associated with increased risk of early-onset melanoma. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:2425-2435.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer Working Group on artificial ultraviolet (UV) light and skin cancer. The association of use of sunbeds with cutaneous malignant melanoma and other skin cancers: a systematic review. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:1116-1122.

- Greenwood S, Perrin A, Duggan M. Social media update 2016. Pew Research Center website. http://www.pewinternet.org/2016/11/11/social-media-update-2016/. Published November 11, 2016. Accessed December 12, 2017.

Practice Points

- Despite US Food and Drug Administration reclassification and publicity of the risks of skin cancer, many patients continue to use sunbeds.

- It is important to assess how patients are obtaining information regarding sunbed safety, as indoor tanning companies are promoting sunbeds as “safe” tans.

- The increased combination of sunbed use and outdoor tanning is putting people at greater risk for the development of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer.

Patient-Reported Outcomes of Azelaic Acid Foam 15% for Patients With Papulopustular Rosacea: Secondary Efficacy Results From a Randomized, Controlled, Double-blind, Phase 3 Trial

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory disorder that may negatively impact patients’ quality of life (QOL).1,2 Papulopustular rosacea (PPR) is characterized by centrofacial inflammatory lesions and erythema as well as burning and stinging secondary to skin barrier dysfunction.3-5 Increasing rosacea severity is associated with greater rates of anxiety and depression and lower QOL6 as well as low self-esteem and feelings of embarrassment.7,8 Accordingly, assessing patient perceptions of rosacea treatments is necessary for understanding its impact on patient health.6,9

The Rosacea International Expert Group has emphasized the need to incorporate patient assessments of disease severity and QOL when developing therapeutic strategies for rosacea.7 Ease of use, sensory experience, and patient preference also are important dimensions in the evaluation of topical medications, as attributes of specific formulations may affect usability, adherence, and efficacy.10,11

An azelaic acid (AzA) 15% foam formulation, which was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2015, was developed to deliver AzA in a vehicle designed to improve treatment experience in patients with mild to moderate PPR.12 Results from a clinical trial demonstrated superiority of AzA foam to vehicle foam for primary end points that included therapeutic success rate and change in inflammatory lesion count.13,14 Secondary end points assessed in the current analysis included patient perception of product usability, efficacy, and effect on QOL. These patient-reported outcome (PRO) results are reported here.

Methods

Study Design

The design of this phase 3 multicenter, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, parallel-group clinical trial was described in more detail in an earlier report.13 This study was approved by all appropriate institutional review boards. Eligible participants were 18 years and older with moderate or severe PPR, 12 to 50 inflammatory lesions, and persistent erythema with or without telangiectasia. Exclusion criteria included known nonresponse to AzA, current or prior use (within 6 weeks of randomization) of noninvestigational products to treat rosacea, and presence of other dermatoses that could interfere with rosacea evaluation.

Participants were randomized into the AzA foam or vehicle group (1:1 ratio). The study medication (0.5 g) or vehicle foam was applied twice daily to the entire face until the end of treatment (EoT) at 12 weeks. Efficacy and safety parameters were evaluated at baseline and at 4, 8, and 12 weeks of treatment, and at a follow-up visit 4 weeks after EoT (week 16).

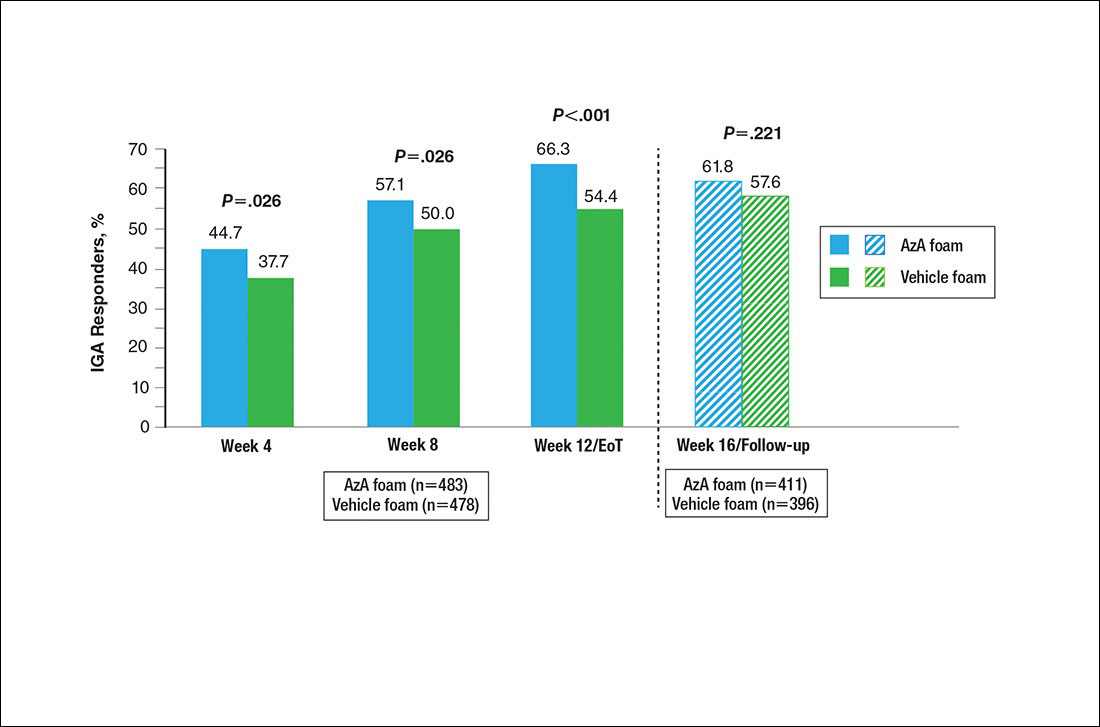

Results for the coprimary efficacy end points—therapeutic success rate according to investigator global assessment and nominal change in inflammatory lesion count—were previously reported,13 as well as secondary efficacy outcomes including change in inflammatory lesion count, therapeutic response rate, and change in erythema rating.14

Patient-Reported Secondary Efficacy Outcomes

The secondary PRO end points were patient-reported global assessment of treatment response (rated as excellent, good, fair, none, or worse), global assessment of tolerability (rated as excellent, good, acceptable despite minor irritation, less acceptable due to continuous irritation, not acceptable, or no opinion), and opinion on cosmetic acceptability and practicability of product use in areas adjacent to the hairline (rated as very good, good, satisfactory, poor, or no opinion).

Additionally, QOL was measured by 3 validated standardized PRO tools, including the Rosacea Quality of Life Index (RosaQOL),15 the EuroQOL 5-dimension 5-level questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L),16 and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). The RosaQOL is a rosacea-specific instrument assessing 3 constructs: (1) symptom, (2) emotion, and (3) function. The EQ-5D-5L questionnaire measures overall health status and comprises 5 constructs: (1) mobility, (2) self-care, (3) usual activities, (4) pain/discomfort, and (5) anxiety/depression. The DLQI is a general, dermatology-oriented instrument categorized into 6 constructs: (1) symptoms and feelings, (2) daily activities, (3) leisure, (4) work and school, (5) personal relationships, and (6) treatment.

Statistical Analyses

Patient-reported outcomes were analyzed in an exploratory manner and evaluated at EoT relative to baseline. Self-reported global assessment of treatment response and change in RosaQOL, EQ-5D-5L, and DLQI scores between AzA foam and vehicle foam groups were evaluated using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Categorical change in the number of participants achieving an increase of 5 or more points in overall DLQI score was evaluated using a χ2 test.

Safety

Safety was analyzed for all randomized patients who were dispensed any study medication. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2.

Results

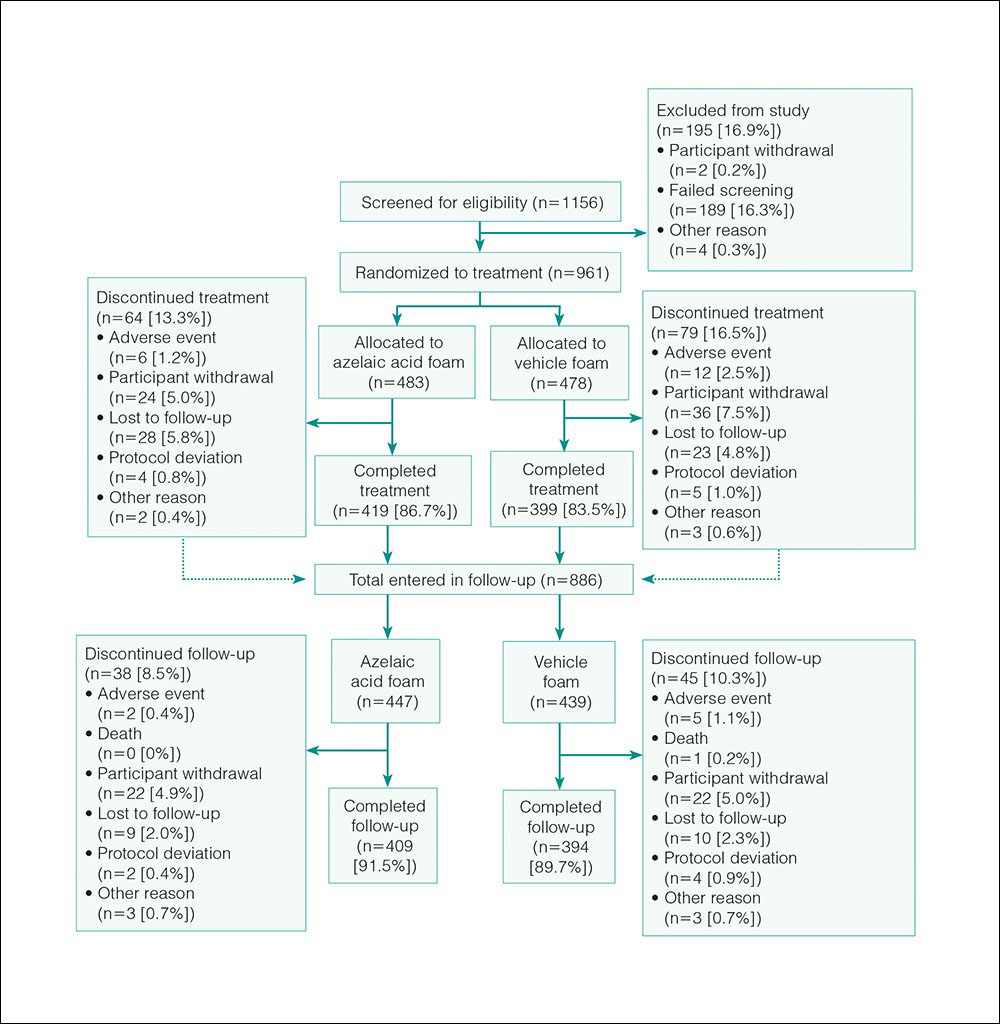

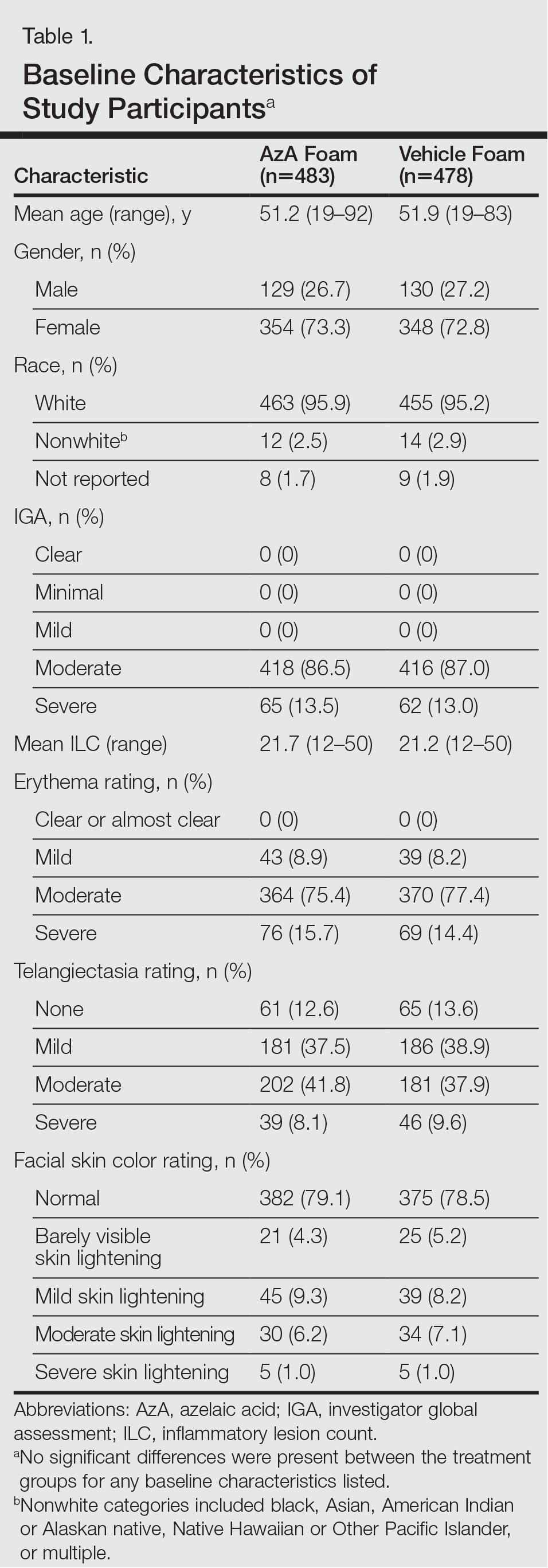

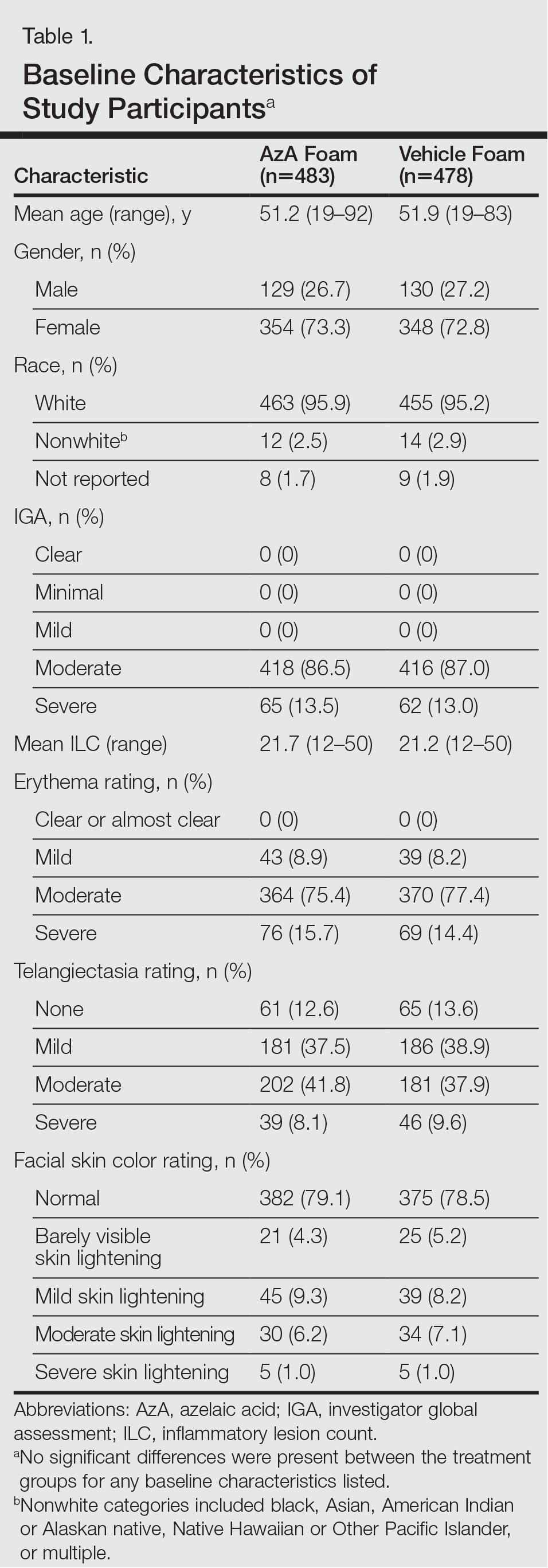

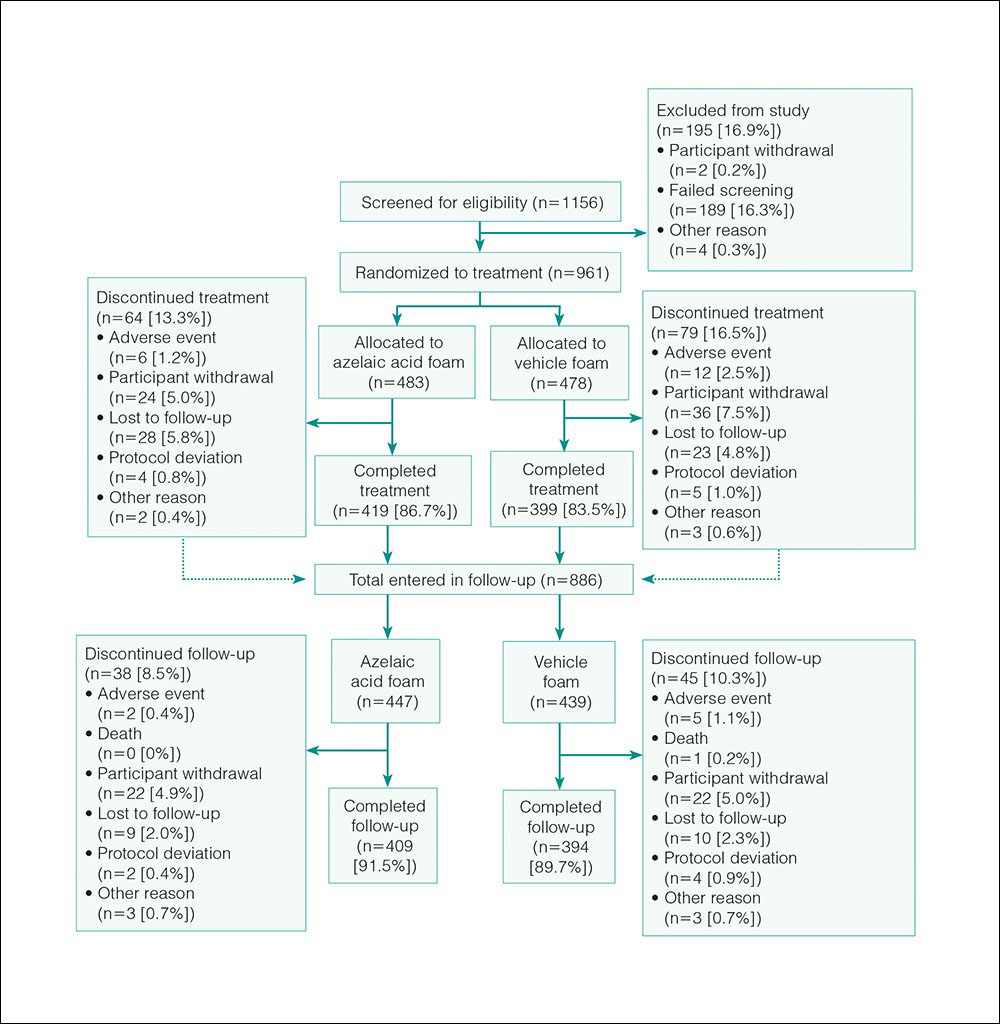

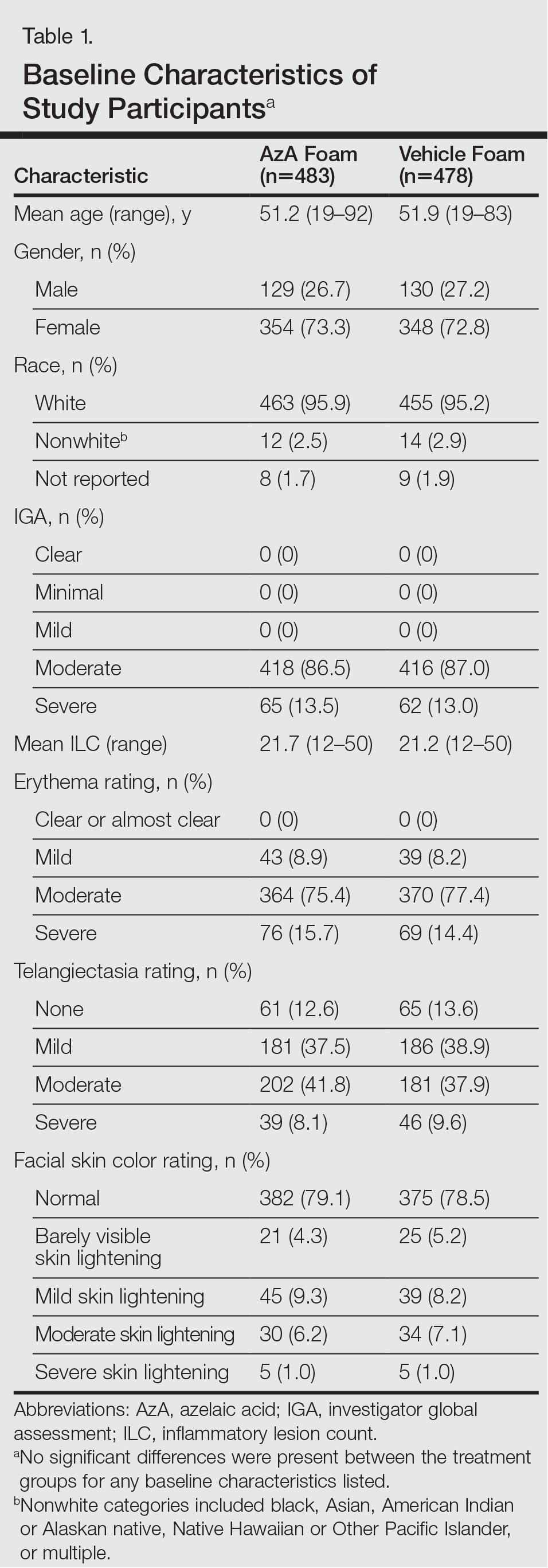

Of the 961 participants included in the study, 483 were randomized to receive AzA foam and 478 were randomized to receive vehicle foam. The mean age was 51.5 years, and the majority of participants were female (73.0%) and white (95.5%)(Table). At baseline, 834 (86.8%) participants had moderate PPR and 127 (13.2%) had severe PPR. The mean inflammatory lesion count (SD) was 21.4 (8.9). No significant differences in baseline characteristics were observed between treatment groups.

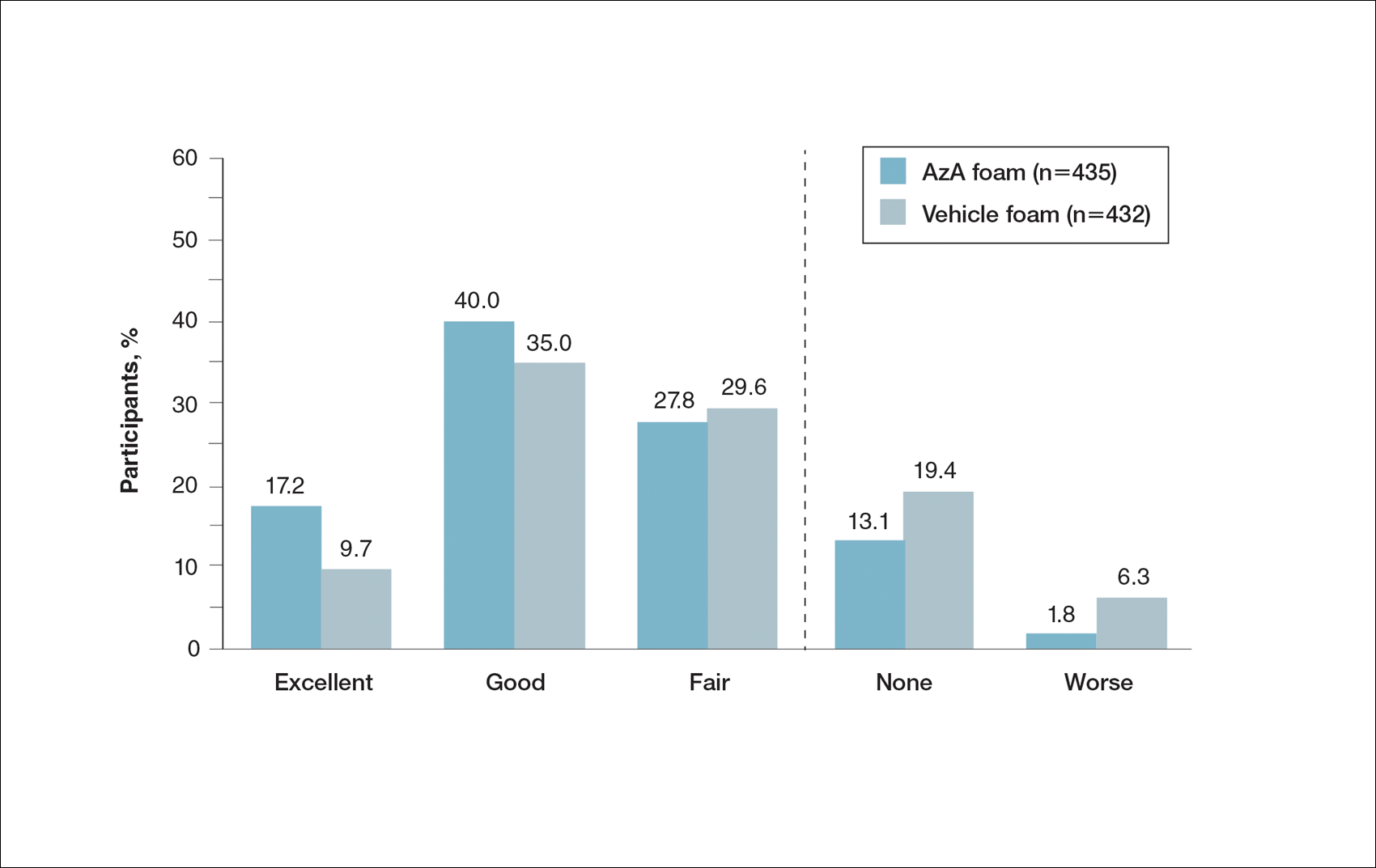

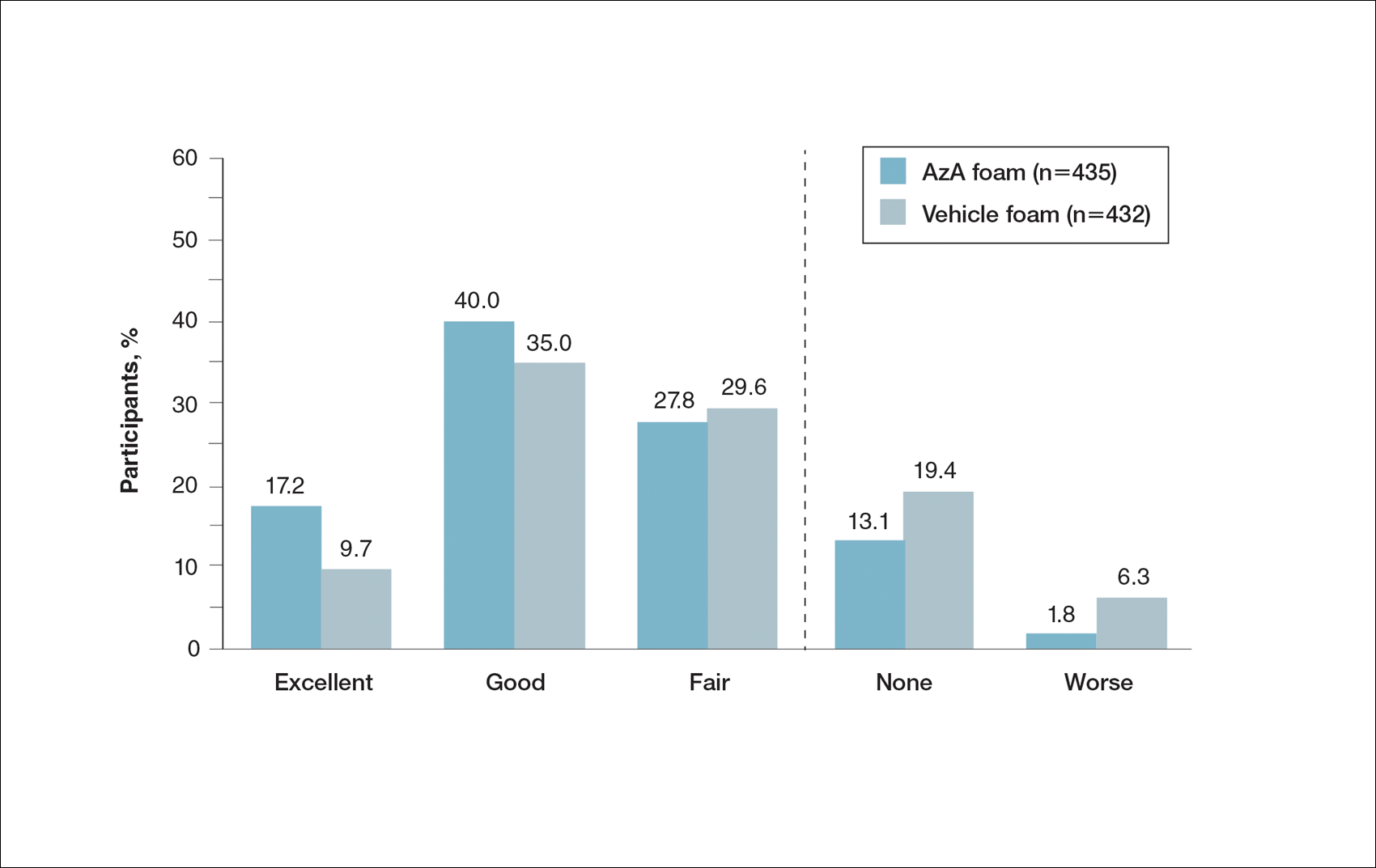

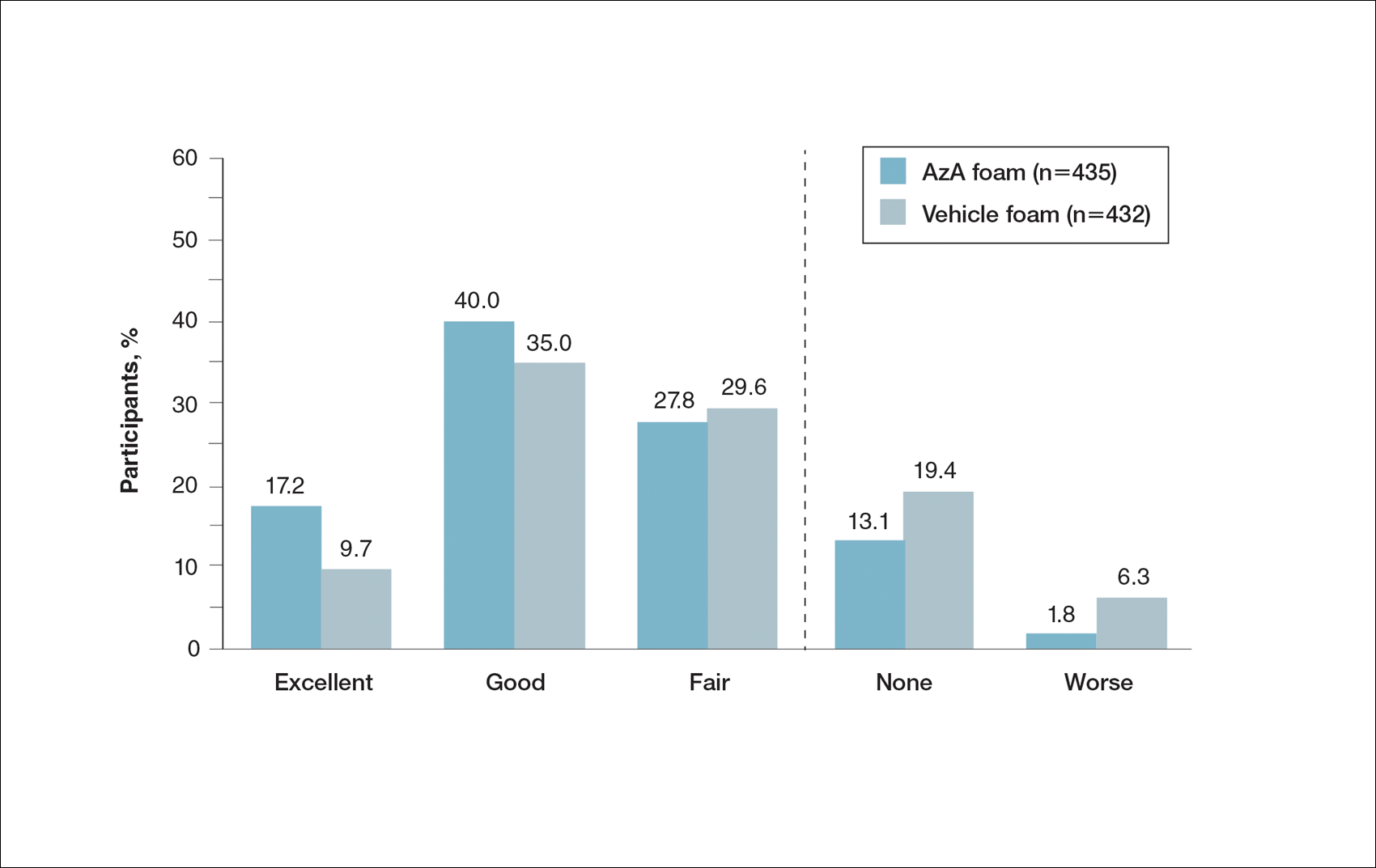

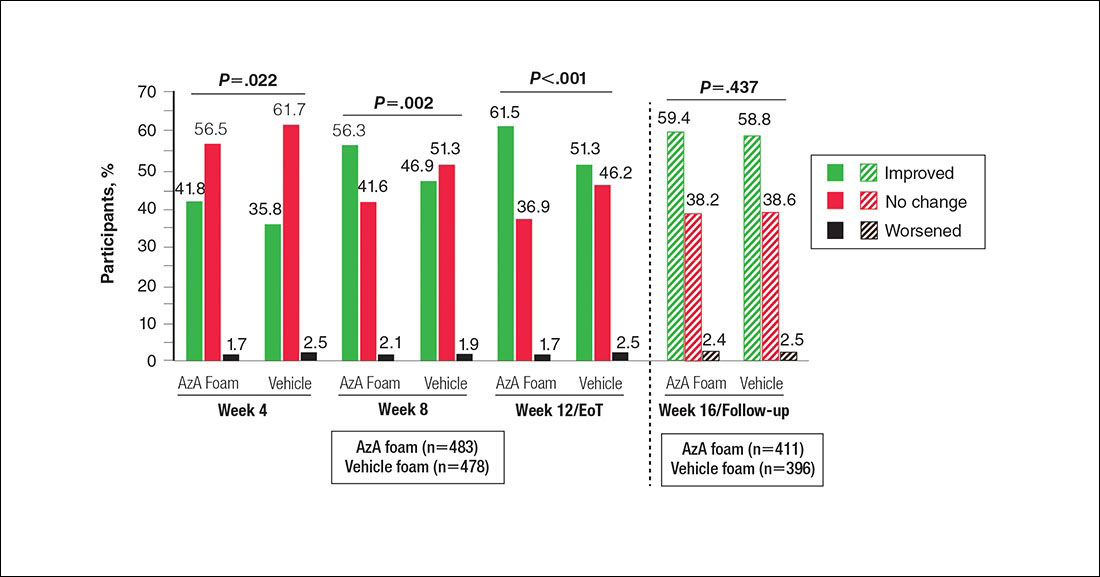

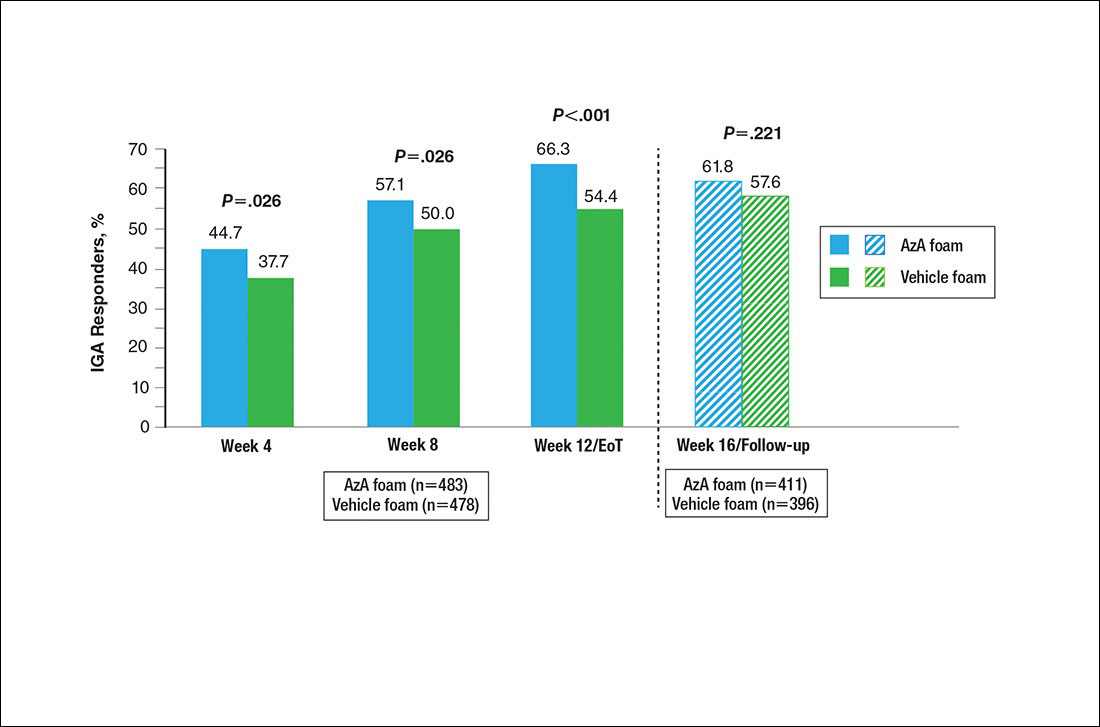

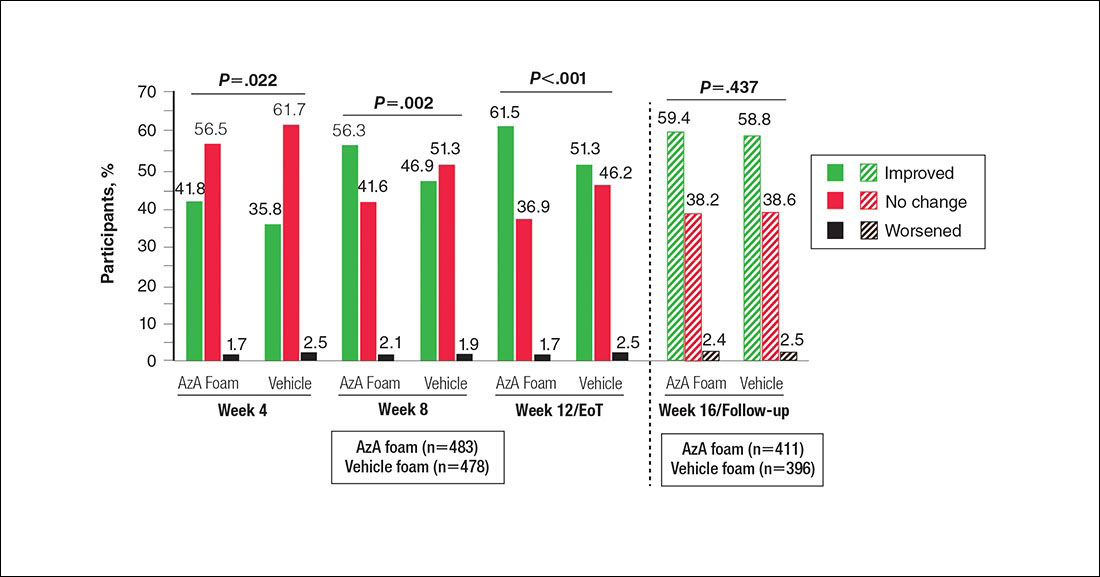

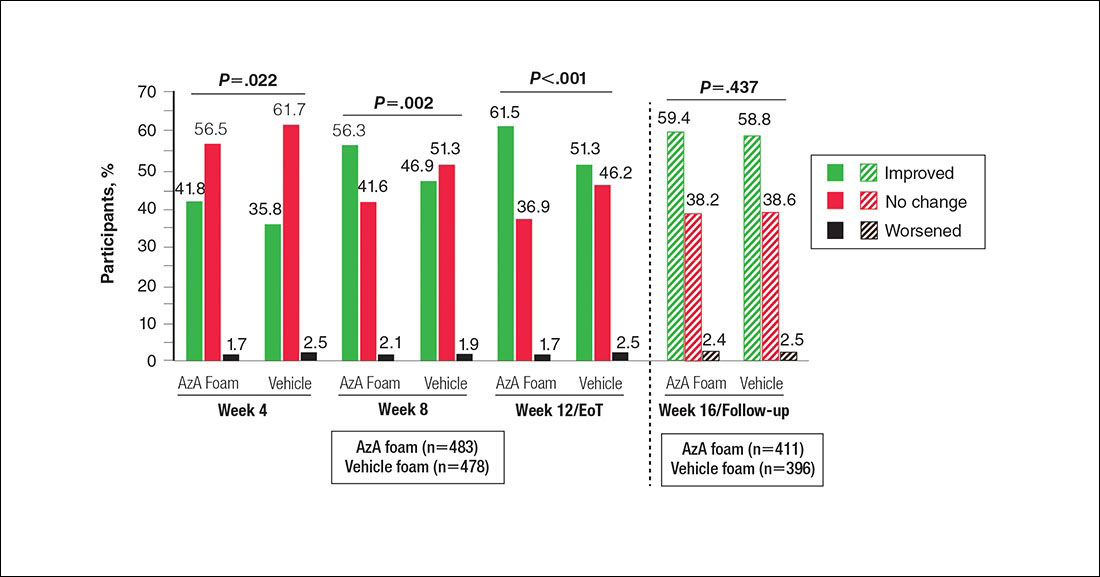

Patient-reported global assessment of treatment response differed between treatment groups at EoT (P<.001)(Figure 1). Higher ratings of treatment response were reported among the AzA foam group (excellent, 17.2%; good, 40.0%) versus vehicle foam (excellent, 9.7%; good, 35.0%). The number of participants reporting no treatment response was 13.1% in the AzA foam group, with 1.8% reporting worsening of their condition, while 19.4% of participants in the vehicle foam group reported no response, with 6.3% reporting worsening of their condition (Figure 1).

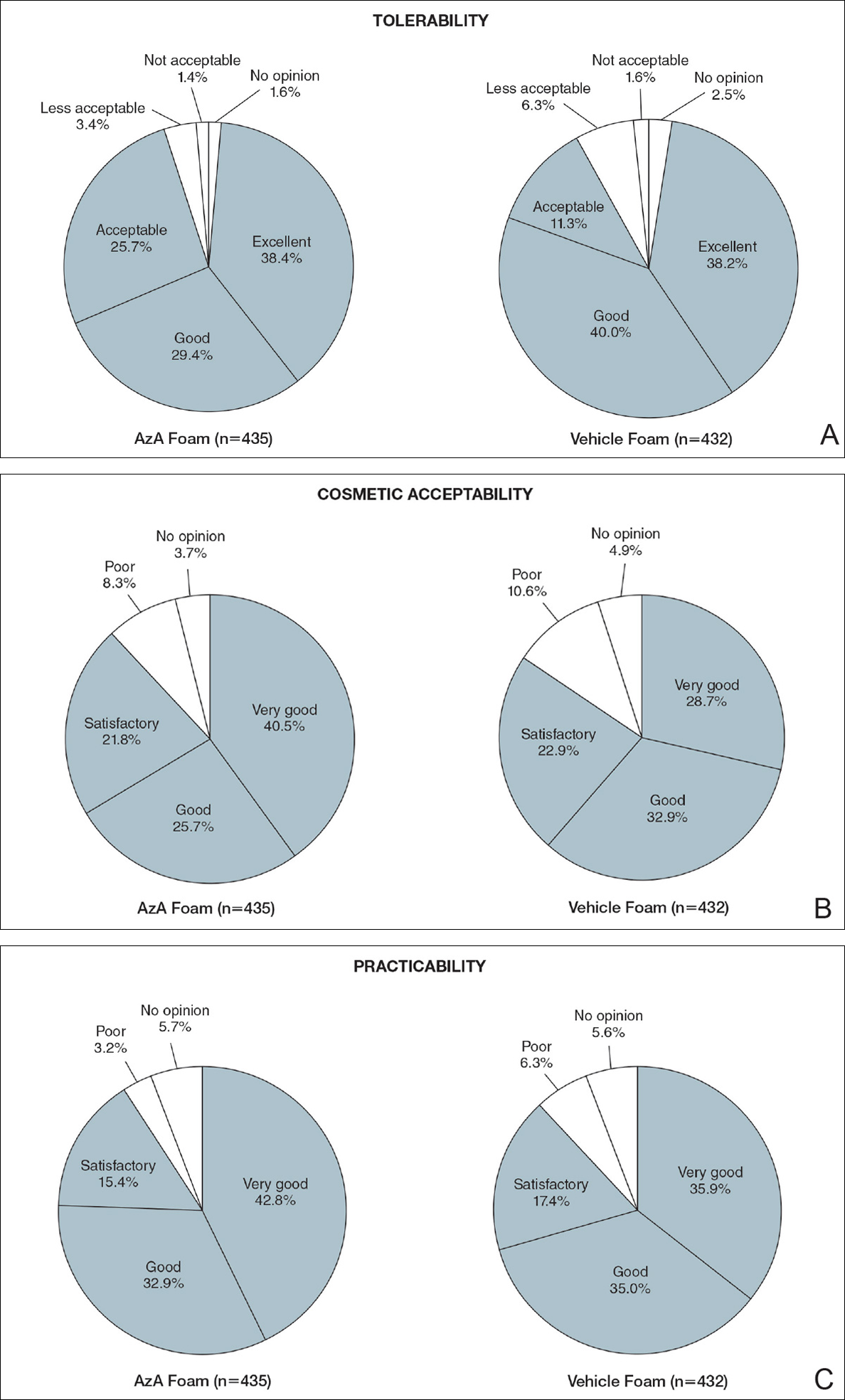

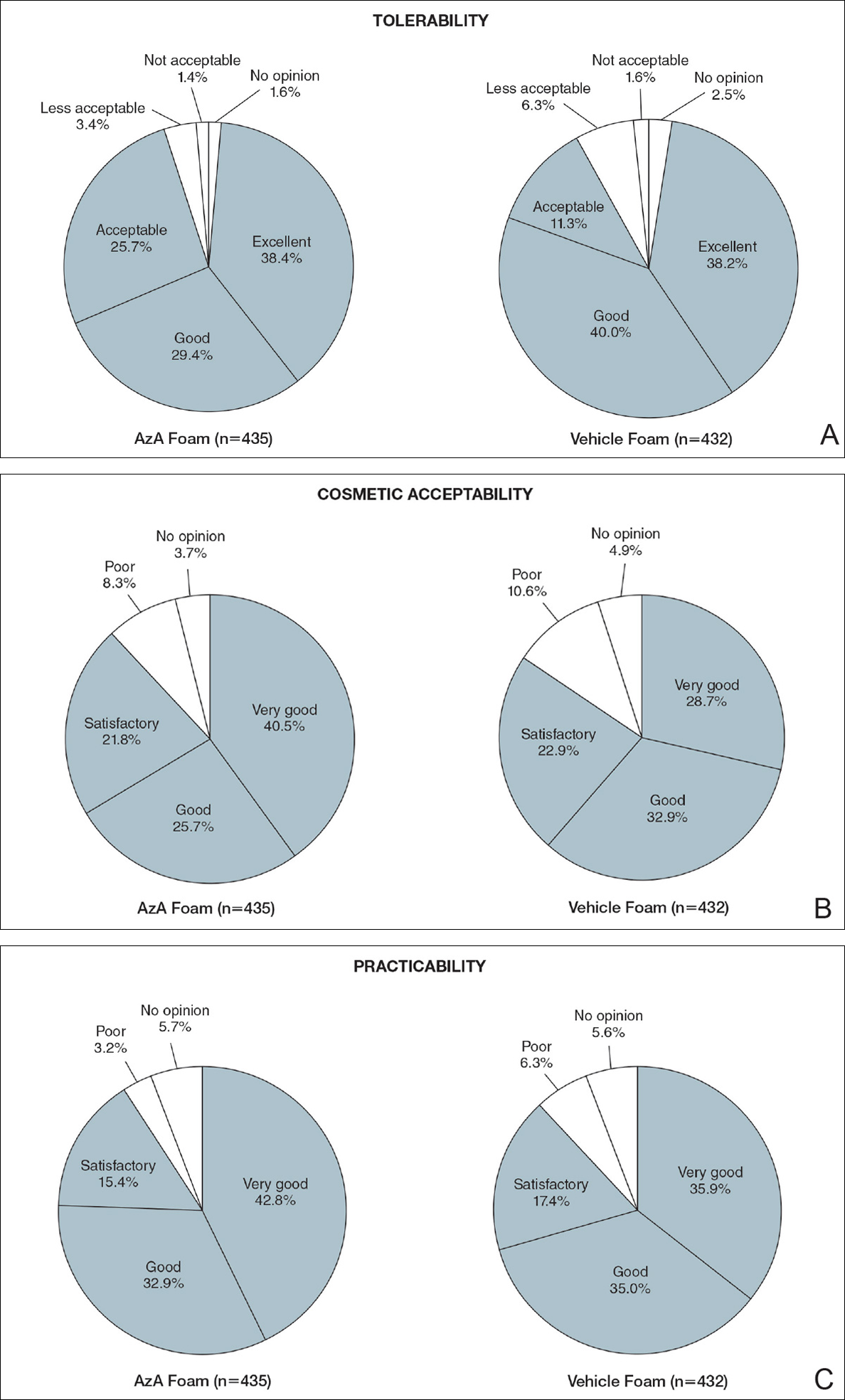

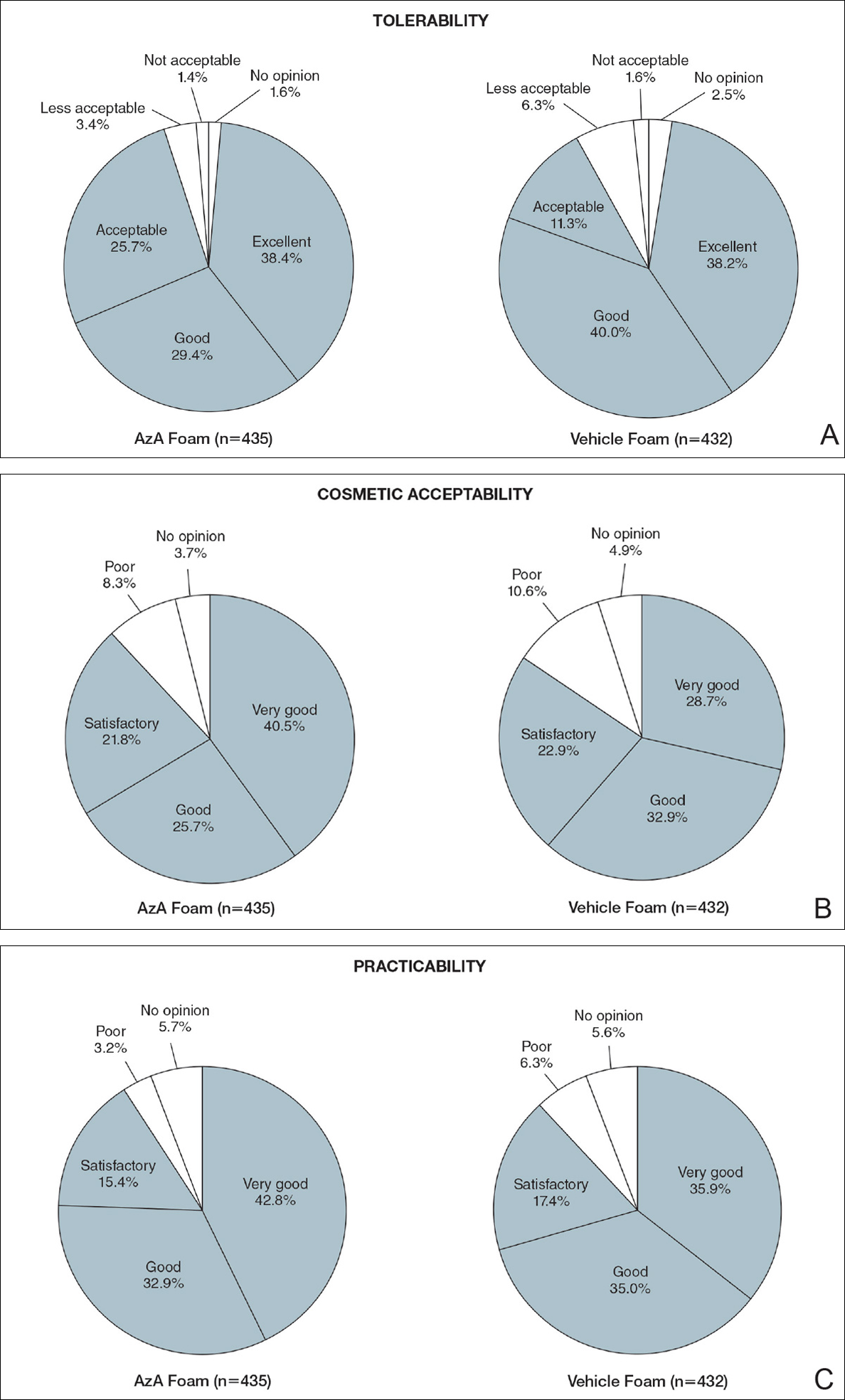

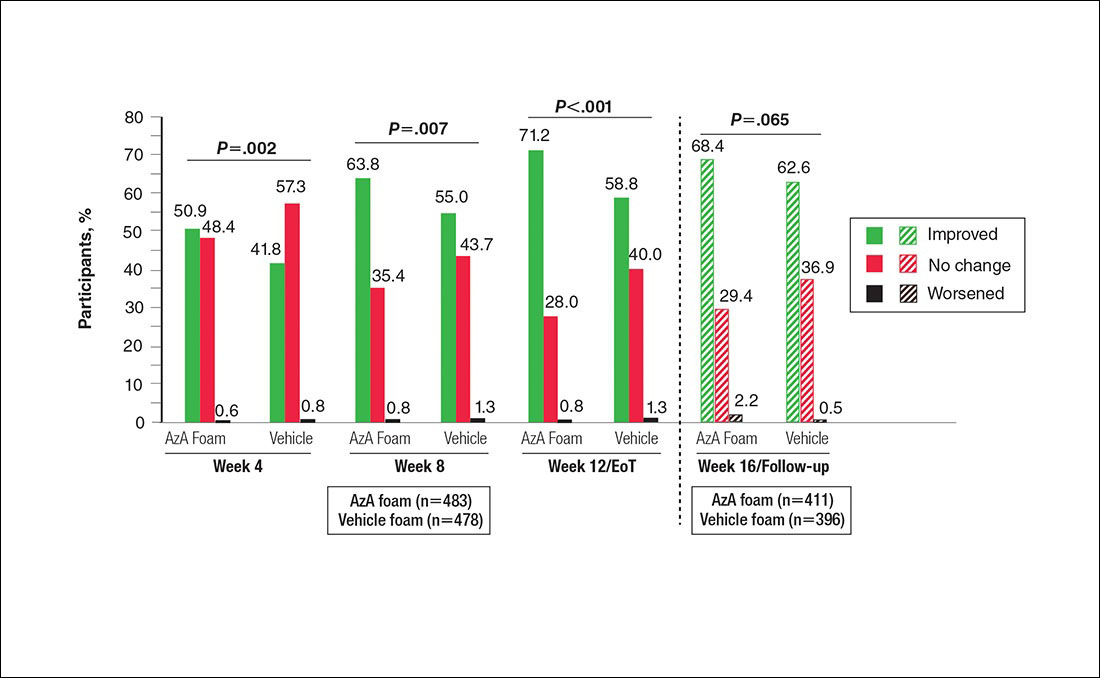

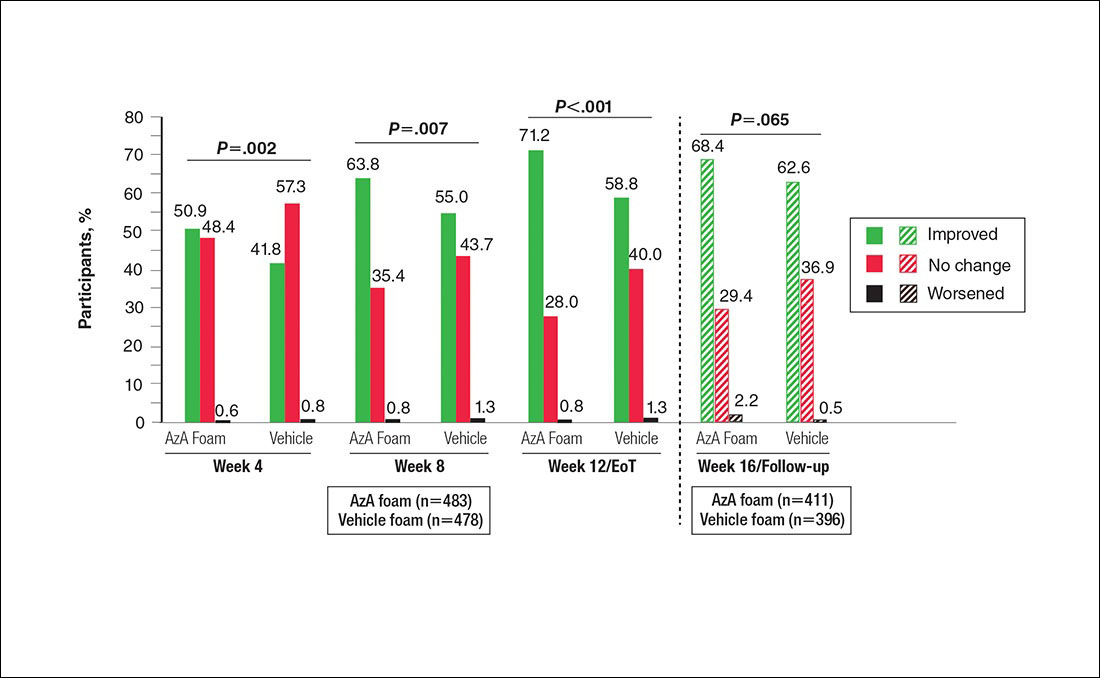

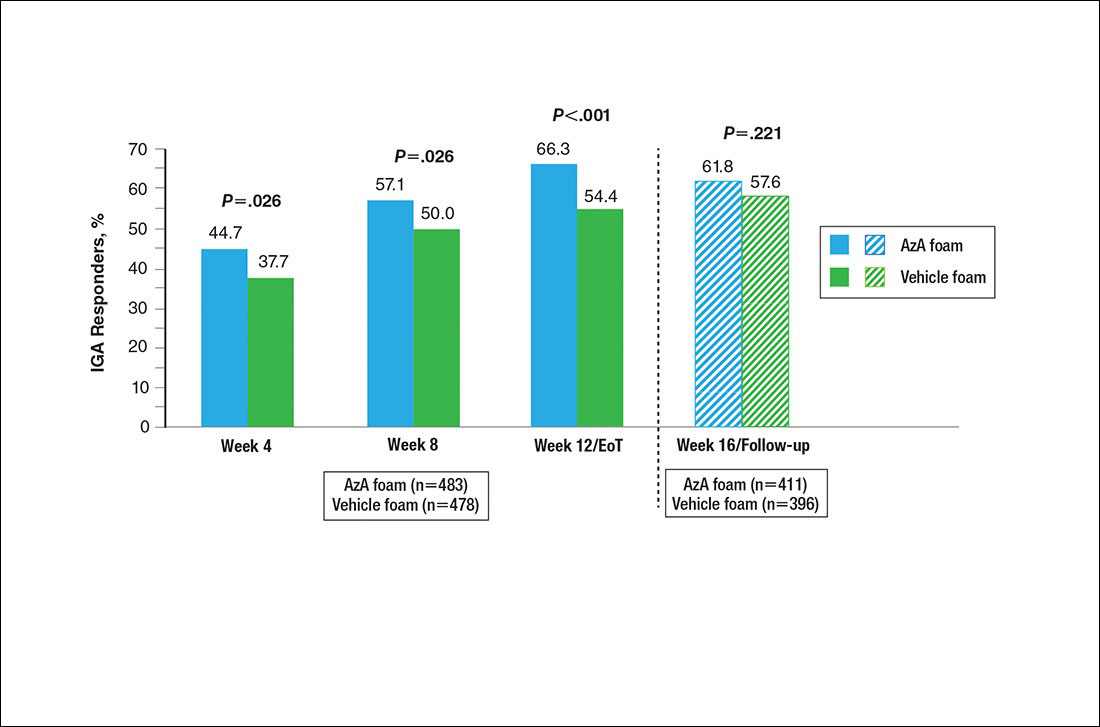

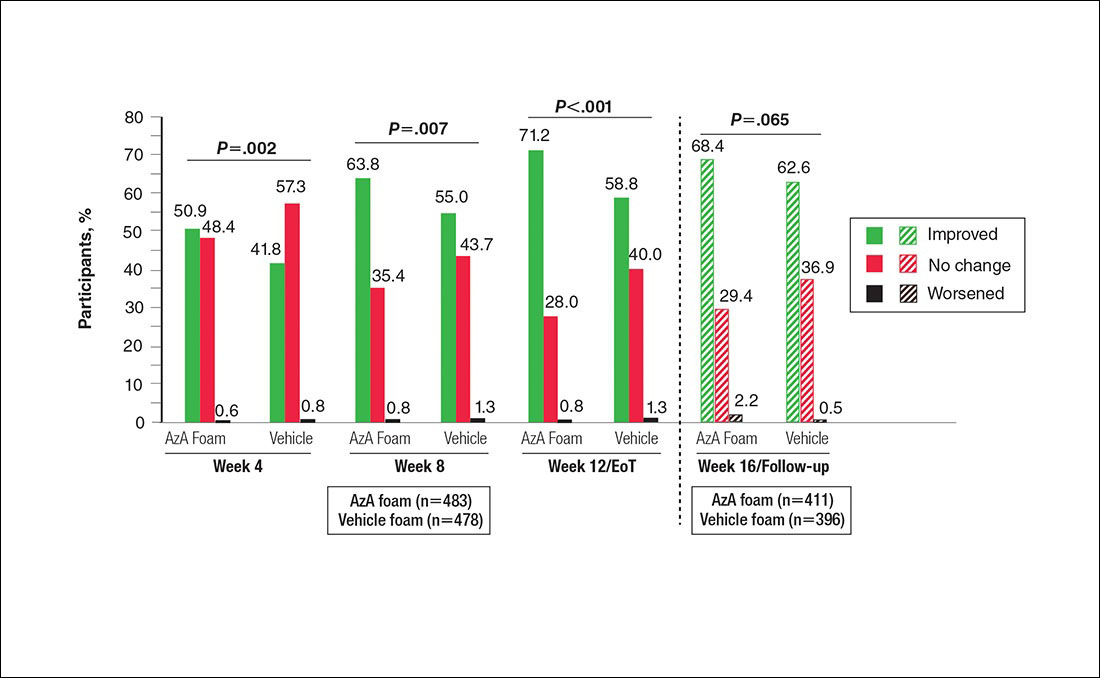

Tolerability was rated excellent or good in 67.8% of the AzA foam group versus 78.2% of the vehicle foam group (Figure 2A). Approximately 38.4% of the AzA foam group versus 38.2% of the vehicle foam group rated treatment tolerability as excellent, while 93.5% of the AzA foam group rated tolerability as acceptable, good, or excellent compared with 89.5% of the vehicle foam group. Only 1.4% of participants in the AzA foam group indicated that treatment was not acceptable due to irritation. In addition, a greater proportion of the AzA foam group reported cosmetic acceptability as very good versus the vehicle foam group (40.5% vs 28.7%)(Figure 2B), with two-thirds reporting cosmetic acceptability as very good or good. Practicability of product use in areas adjacent to the hairline was rated very good by substantial proportions of both the AzA foam and vehicle foam groups (42.8% vs 35.9%)(Figure 2C).

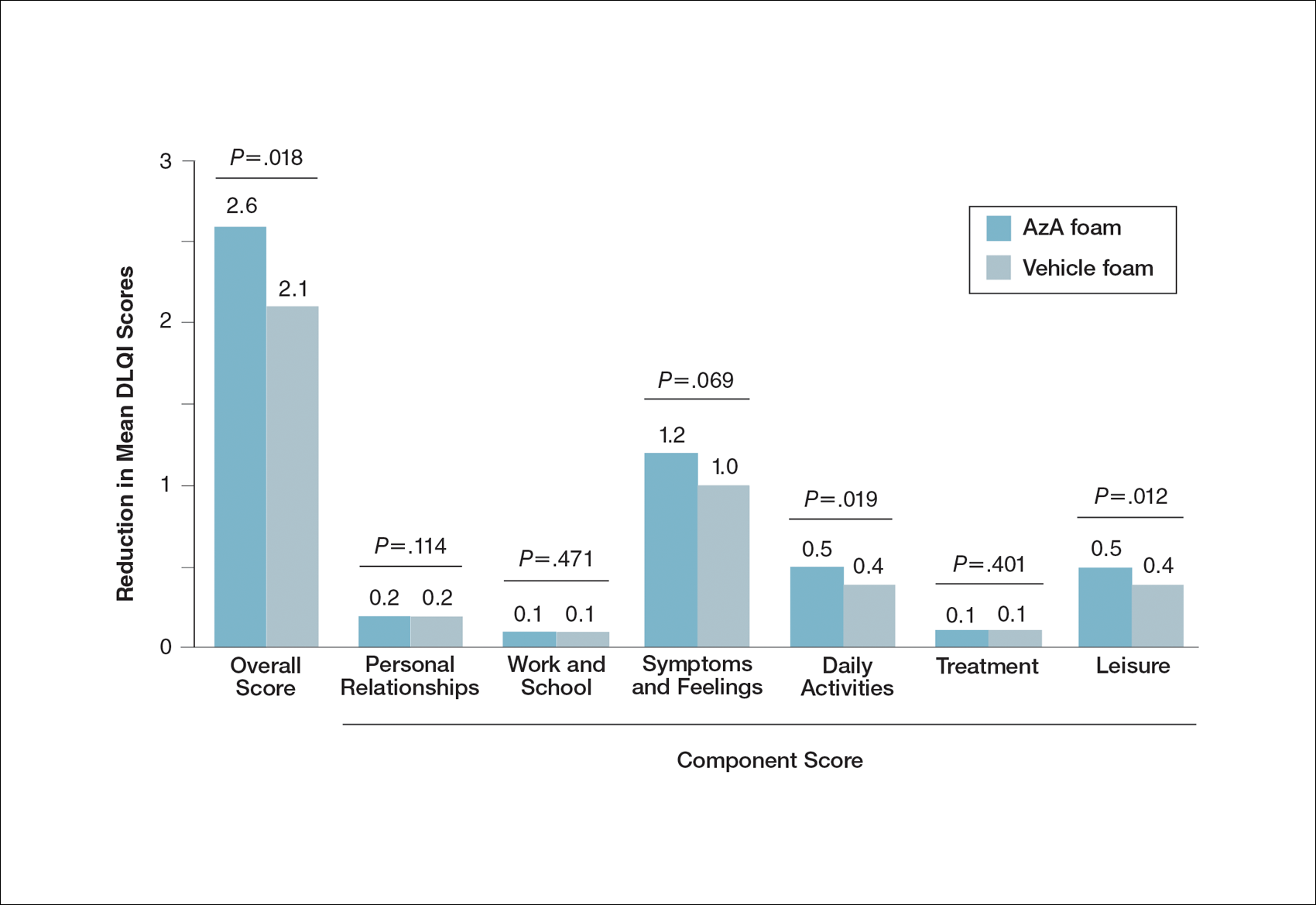

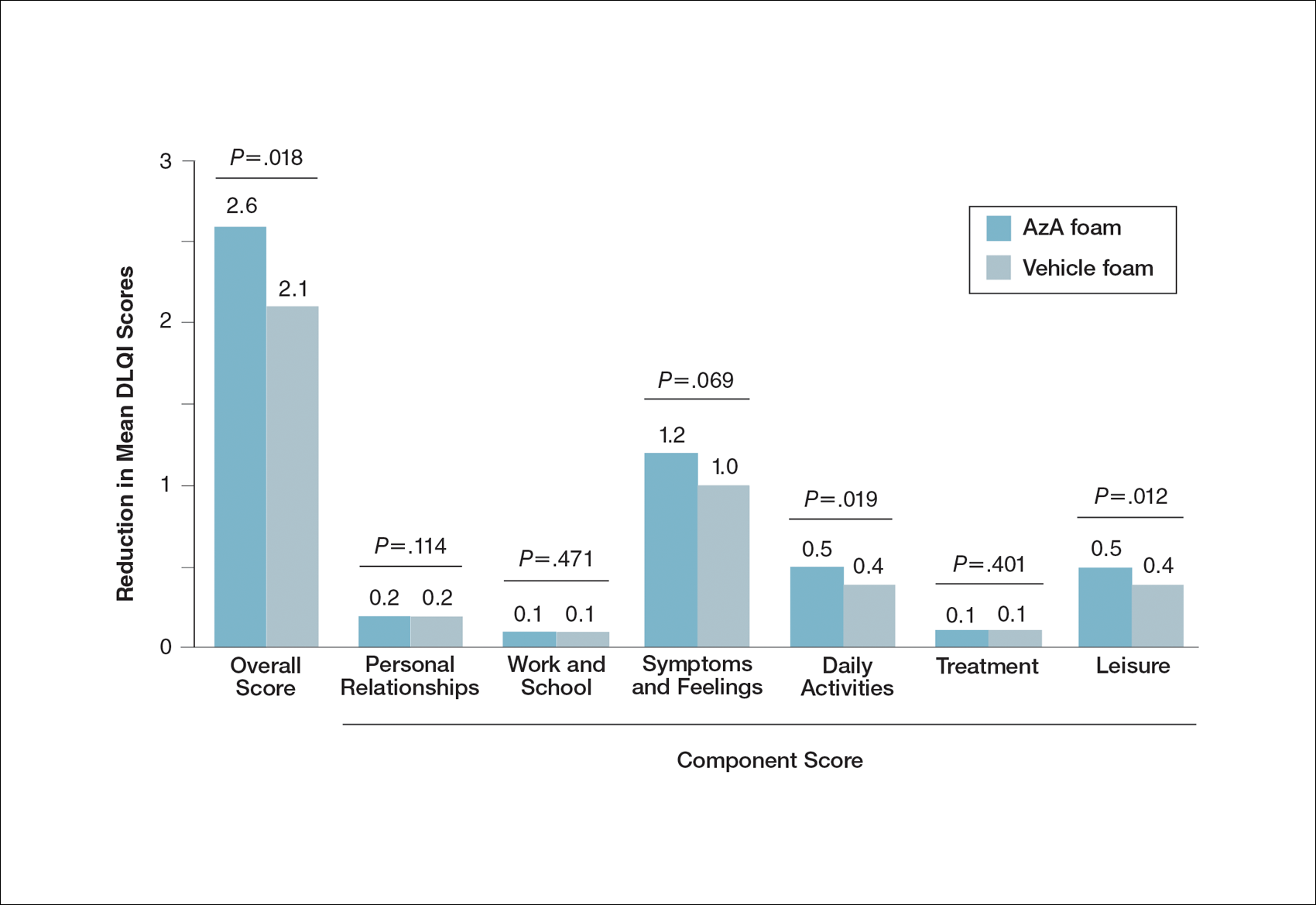

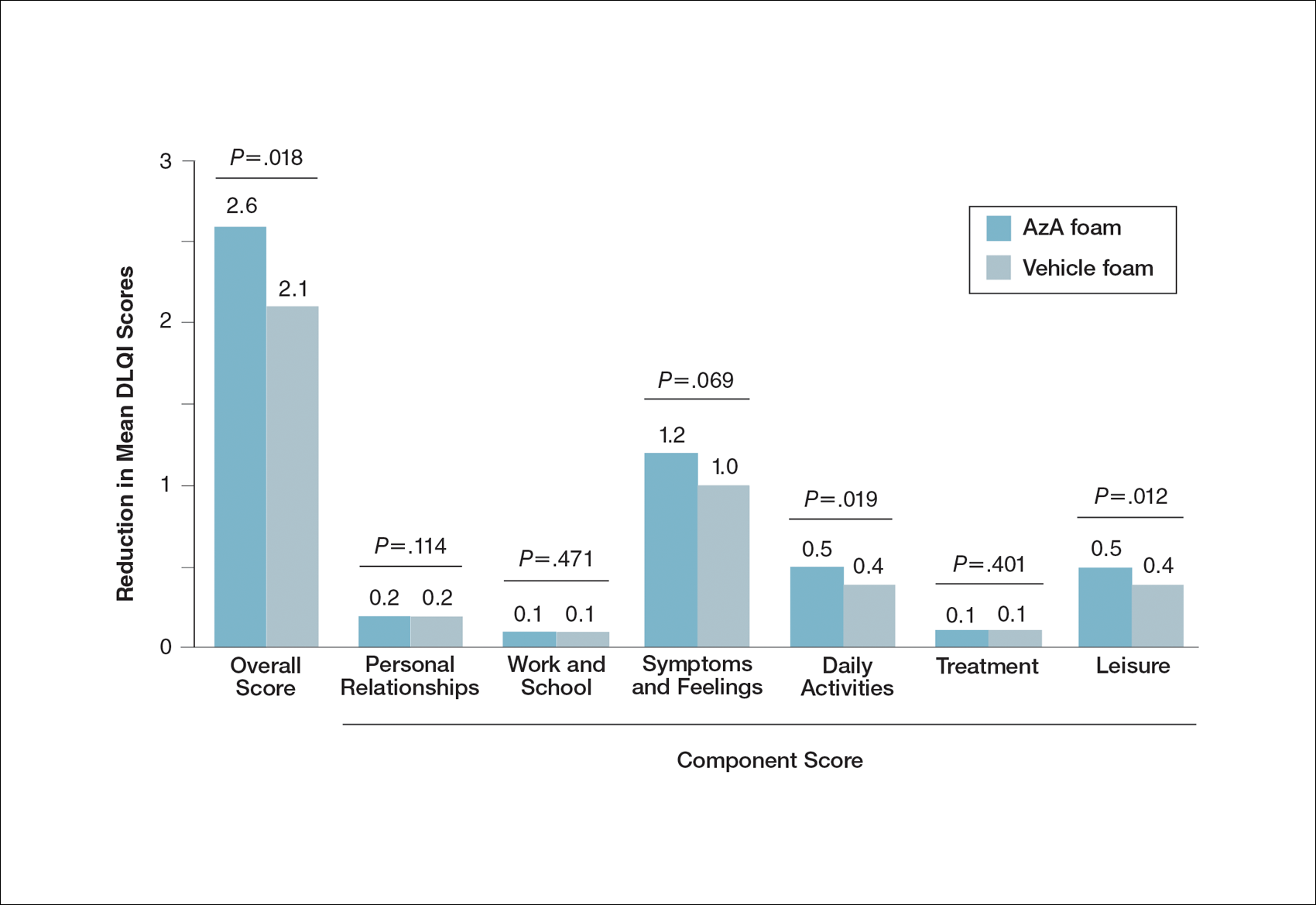

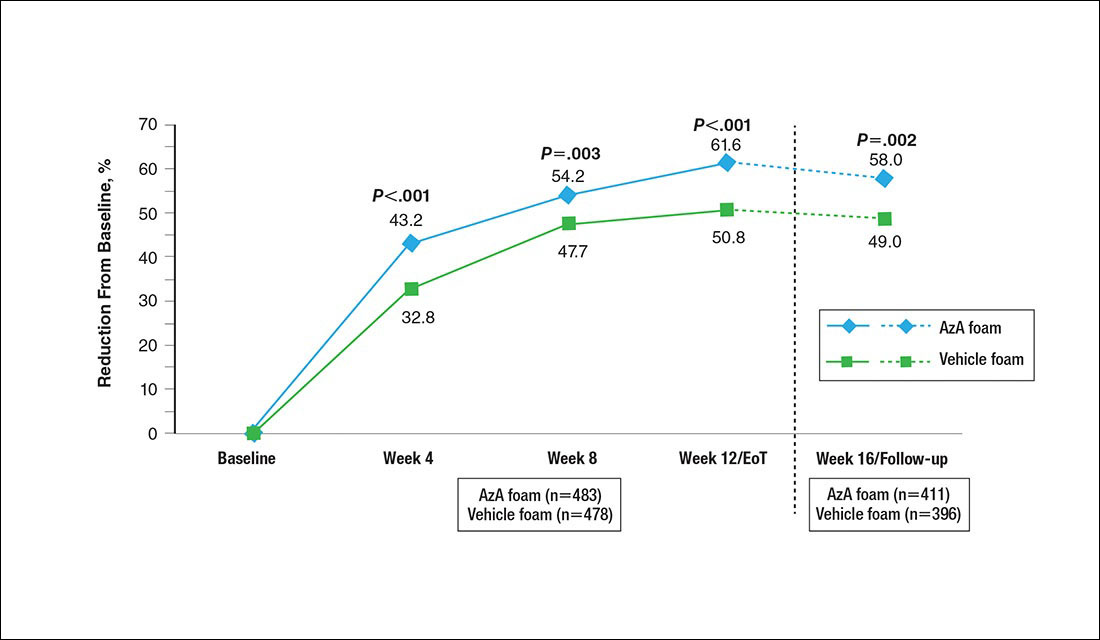

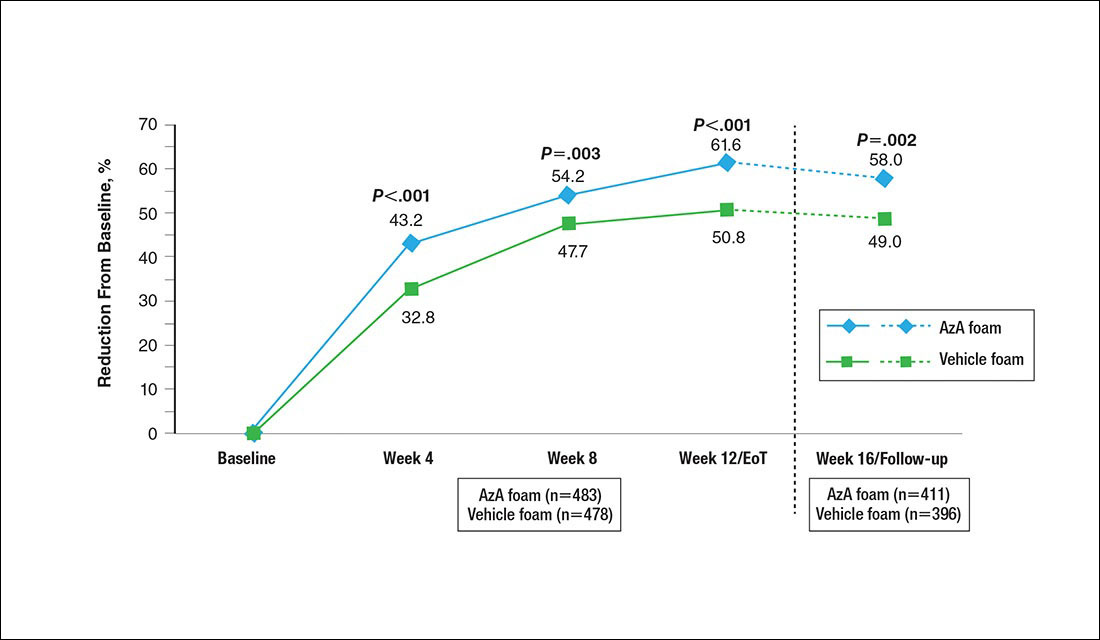

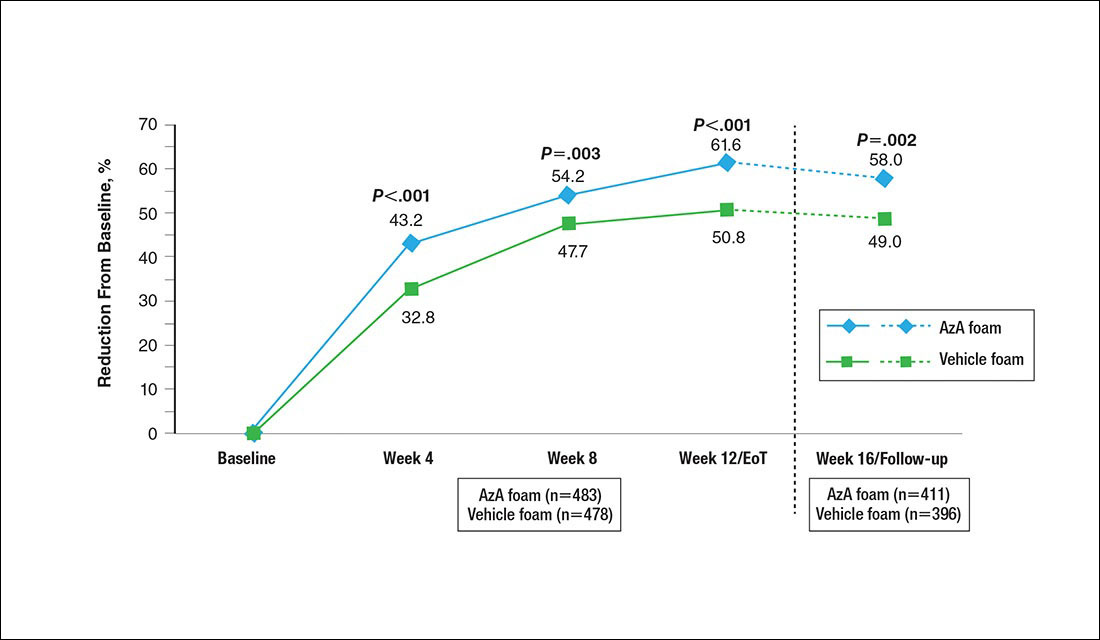

At baseline, average disease burden was moderate according to mean overall DLQI scores (SD) for the AzA foam (5.4 [4.8]) and vehicle foam (5.4 [4.9]) groups. Mean overall DLQI scores improved at EoT, with greater improvement occurring in the AzA foam group (2.6 vs 2.1; P=.018)(Figure 3). A larger proportion of participants in the AzA foam group versus the vehicle foam group also achieved a 5-point or more improvement in overall DLQI score (24.6% vs 19.0%; P=.047). Changes in specific DLQI subscore components were either balanced or in favor of the AzA foam group, including daily activities (0.5 vs 0.4; P=.019), symptoms and feelings (1.2 vs 1.0; P=.069), and leisure (0.5 vs 0.4; P=.012). Specific DLQI items with differences in scores between treatment groups from baseline included the following questions: Over the last week, how embarrassed or self-conscious have you been because of your skin? (P<.001); Over the last week, how much has your skin interfered with you going shopping or looking after your home or garden? (P=.005); Over the last week, how much has your skin affected any social or leisure activities? (P=.040); Over the last week, how much has your skin created problems with your partner or any of your close friends or relatives? (P=.001). Differences between treatment groups favored the AzA foam group for each of these items.

Participants in the AzA foam and vehicle foam groups also showed improvement in RosaQOL scores at EoT (6.8 vs 6.4; P=.67), while EQ-5D-5L scores changed minimally from baseline (0.006 vs 0.007; P=.50).

Safety

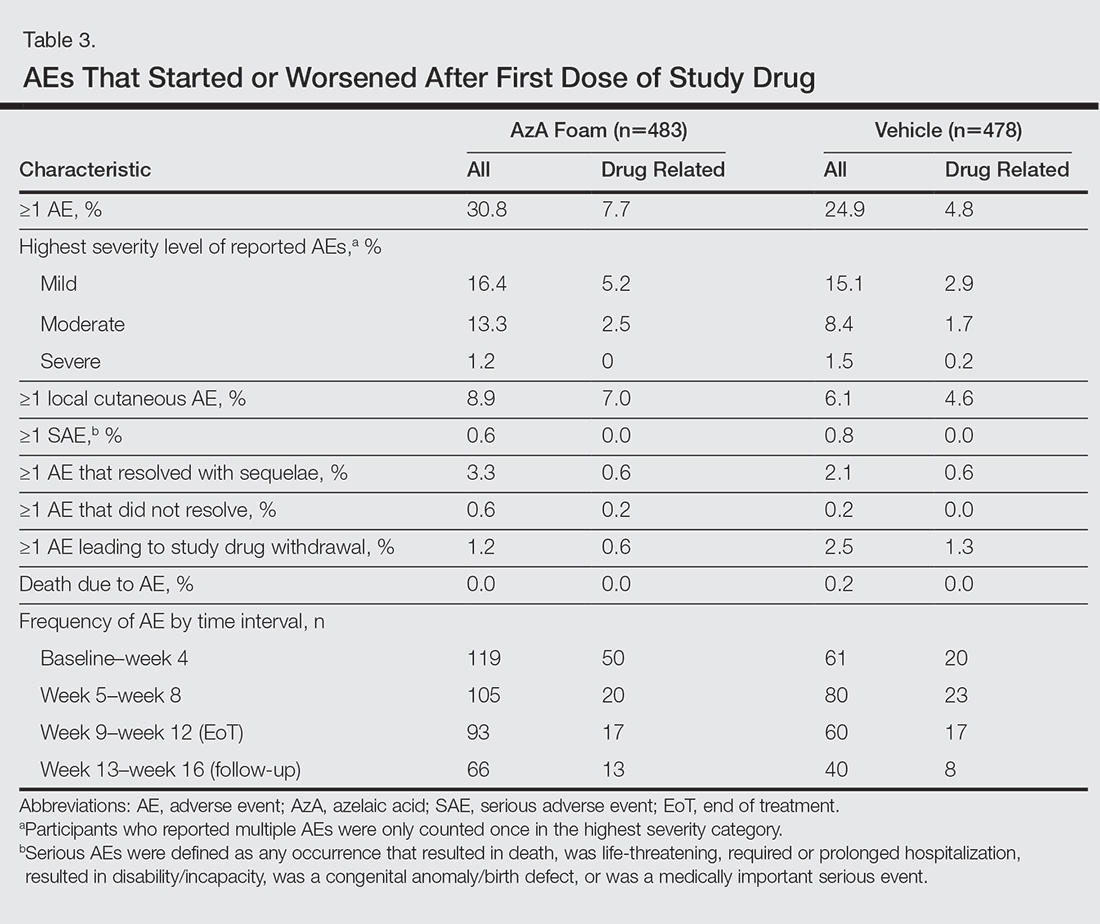

The incidence of drug-related adverse events (AEs) was greater in the AzA foam group versus the vehicle foam group (7.7% vs 4.8%). Drug-related AEs occurring in 1% of the AzA foam group were application-site pain including tenderness, stinging, and burning (3.5% for AzA foam vs 1.3% for vehicle foam); application-site pruritus (1.4% vs 0.4%); and application-site dryness (1.0% vs 0.6%). One drug-related AE of severe intensity—application-site dermatitis—occurred in the vehicle foam group; all other drug-related AEs were mild or moderate.14 More detailed safety results are described in a previous report.13

Comment

The PRO outcome data reported here are consistent with previously reported statistically significant improvements in investigator-assessed primary end points for the treatment of PPR with AzA foam.13,14 The data demonstrate that AzA foam benefits both clinical and patient-oriented dimensions of rosacea disease burden and suggest an association between positive treatment response and improved QOL.

Specifically, patient evaluation of treatment response to AzA foam was highly favorable, with 57.2% reporting excellent or good response and 85.1% reporting positive response overall. Recognizing the relapsing-remitting course of PPR, only 1.8% of the AzA foam group experienced worsening of disease at EoT.

The DLQI and RosaQOL instruments revealed notable improvements in QOL from baseline for both treatment groups. Although no significant differences in RosaQOL scores were observed between groups at EoT, significant differences in DLQI scores were detected. Almost one-quarter of participants in the AzA foam group achieved at least a 5-point improvement in DLQI score, exceeding the 4-point threshold for clinically meaningful change.17 Although little change in EQ-5D-5L scores was observed at EoT for both groups with no between-group differences, this finding is not unexpected, as this instrument assesses QOL dimensions such as loss of function, mobility, and ability to wash or dress, which are unlikely to be compromised in most rosacea patients.

Our results also underscore the importance of vehicle in the treatment of compromised skin. Studies of topical treatments for other dermatoses suggest that vehicle properties may reduce disease severity and improve QOL independent of active ingredients.10,18 For example, ease of application, minimal residue, and less time spent in application may explain the superiority of foam to other vehicles in the treatment of psoriasis.18 Our data demonstrating high cosmetic favorability of AzA foam are consistent with these prior observations. Increased tolerability of foam formulations also may affect response to treatment, in part by supporting adherence.18 Most participants receiving AzA foam described tolerability as excellent or good, and the discontinuation rate was low (1.2% of participants in the AzA foam group left the study due to AEs) in the setting of near-complete dosage administration (97% of expected doses applied).13

Conclusion

These results indicate that use of AzA foam as well as its novel vehicle results in high patient satisfaction and improved QOL. Although additional research is necessary to further delineate the relationship between PROs and other measures of clinical efficacy, our data demonstrate a positive treatment experience as perceived by patients that parallels the clinical efficacy of AzA foam for the treatment of PPR.13,14

Acknowledgment

Editorial support through inVentiv Medical Communications (New York, New York) was provided by Bayer Pharmaceuticals.

- Cardwell LA, Farhangian ME, Alinia H, et al. Psychological disorders associated with rosacea: analysis of unscripted comments. J Dermatol Surg. 2015;19:99-103.

- Moustafa F, Lewallen RS, Feldman SR. The psychological impact of rosacea and the influence of current management options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:973-980.

- Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard classification of rosacea: report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:584-587.

- Yamasaki K, Gallo RL. The molecular pathology of rosacea. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;55:77-81.

- Del Rosso JQ. Advances in understanding and managing rosacea: part 1: connecting the dots between pathophysiological mechanisms and common clinical features of rosacea with emphasis on vascular changes and facial erythema. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:16-25.