User login

Jeff Evans has been editor of Rheumatology News/MDedge Rheumatology and the EULAR Congress News since 2013. He started at Frontline Medical Communications in 2001 and was a reporter for 8 years before serving as editor of Clinical Neurology News and World Neurology, and briefly as editor of GI & Hepatology News. He graduated cum laude from Cornell University (New York) with a BA in biological sciences, concentrating in neurobiology and behavior.

Neurologists weigh in on rising drug prices

Neurologists will tackle the issues surrounding rising prices for neurological drug treatments in a set of presentations during the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology in Boston.

During the Contemporary Clinical Issues Plenary Session on April 24, Dennis N. Bourdette, MD, of Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, will give his presentation, “High Drug Prices: The Elephant in the Clinic.”

Dr. Bourdette will also address the problem on April 26 in a session called “Section Topic Controversies,” in which he and Dennis W. Choi, MD, PhD, of the State University of New York at Stony Brook will offer their opinions on how “Neurologists Should Take a Position Regarding the Cost of Neurological Treatments.” Dr. Bourdette is set to illustrate how “Neurologists Should More Vocally Protest Some of the Marked Price Increases Involving Neurological Treatments,” while Dr. Choi will provide rationale for his argument on why “Neurologists Should Influence Policies that Allow Companies to Commit More Resources to R&D for Neurological Diseases While Not Allowing for Rapacious Pricing Practices.” Following the discussion, Dr. Bourdette, Dr. Choi, and session moderators will have a panel discussion on the ways in which AAN members can work most productively for the benefit of their patients.

Sure to be discussed in the series of talks is a recent AAN position paper on prescription drug prices released in March that identified three distinct drug pricing challenges:

- Massive increase in the pricing of previously low-cost generic drugs used to treat common disorders without obvious increases in cost of production or distribution.

- Massive increase in the pricing for high-priced generic and brand name drugs used to treat serious disorders that are not protected by the Orphan Drug Act.

- The high cost of new medications used to treat rare disorders as defined by the Orphan Drug Act.

Neurologists will tackle the issues surrounding rising prices for neurological drug treatments in a set of presentations during the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology in Boston.

During the Contemporary Clinical Issues Plenary Session on April 24, Dennis N. Bourdette, MD, of Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, will give his presentation, “High Drug Prices: The Elephant in the Clinic.”

Dr. Bourdette will also address the problem on April 26 in a session called “Section Topic Controversies,” in which he and Dennis W. Choi, MD, PhD, of the State University of New York at Stony Brook will offer their opinions on how “Neurologists Should Take a Position Regarding the Cost of Neurological Treatments.” Dr. Bourdette is set to illustrate how “Neurologists Should More Vocally Protest Some of the Marked Price Increases Involving Neurological Treatments,” while Dr. Choi will provide rationale for his argument on why “Neurologists Should Influence Policies that Allow Companies to Commit More Resources to R&D for Neurological Diseases While Not Allowing for Rapacious Pricing Practices.” Following the discussion, Dr. Bourdette, Dr. Choi, and session moderators will have a panel discussion on the ways in which AAN members can work most productively for the benefit of their patients.

Sure to be discussed in the series of talks is a recent AAN position paper on prescription drug prices released in March that identified three distinct drug pricing challenges:

- Massive increase in the pricing of previously low-cost generic drugs used to treat common disorders without obvious increases in cost of production or distribution.

- Massive increase in the pricing for high-priced generic and brand name drugs used to treat serious disorders that are not protected by the Orphan Drug Act.

- The high cost of new medications used to treat rare disorders as defined by the Orphan Drug Act.

Neurologists will tackle the issues surrounding rising prices for neurological drug treatments in a set of presentations during the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology in Boston.

During the Contemporary Clinical Issues Plenary Session on April 24, Dennis N. Bourdette, MD, of Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, will give his presentation, “High Drug Prices: The Elephant in the Clinic.”

Dr. Bourdette will also address the problem on April 26 in a session called “Section Topic Controversies,” in which he and Dennis W. Choi, MD, PhD, of the State University of New York at Stony Brook will offer their opinions on how “Neurologists Should Take a Position Regarding the Cost of Neurological Treatments.” Dr. Bourdette is set to illustrate how “Neurologists Should More Vocally Protest Some of the Marked Price Increases Involving Neurological Treatments,” while Dr. Choi will provide rationale for his argument on why “Neurologists Should Influence Policies that Allow Companies to Commit More Resources to R&D for Neurological Diseases While Not Allowing for Rapacious Pricing Practices.” Following the discussion, Dr. Bourdette, Dr. Choi, and session moderators will have a panel discussion on the ways in which AAN members can work most productively for the benefit of their patients.

Sure to be discussed in the series of talks is a recent AAN position paper on prescription drug prices released in March that identified three distinct drug pricing challenges:

- Massive increase in the pricing of previously low-cost generic drugs used to treat common disorders without obvious increases in cost of production or distribution.

- Massive increase in the pricing for high-priced generic and brand name drugs used to treat serious disorders that are not protected by the Orphan Drug Act.

- The high cost of new medications used to treat rare disorders as defined by the Orphan Drug Act.

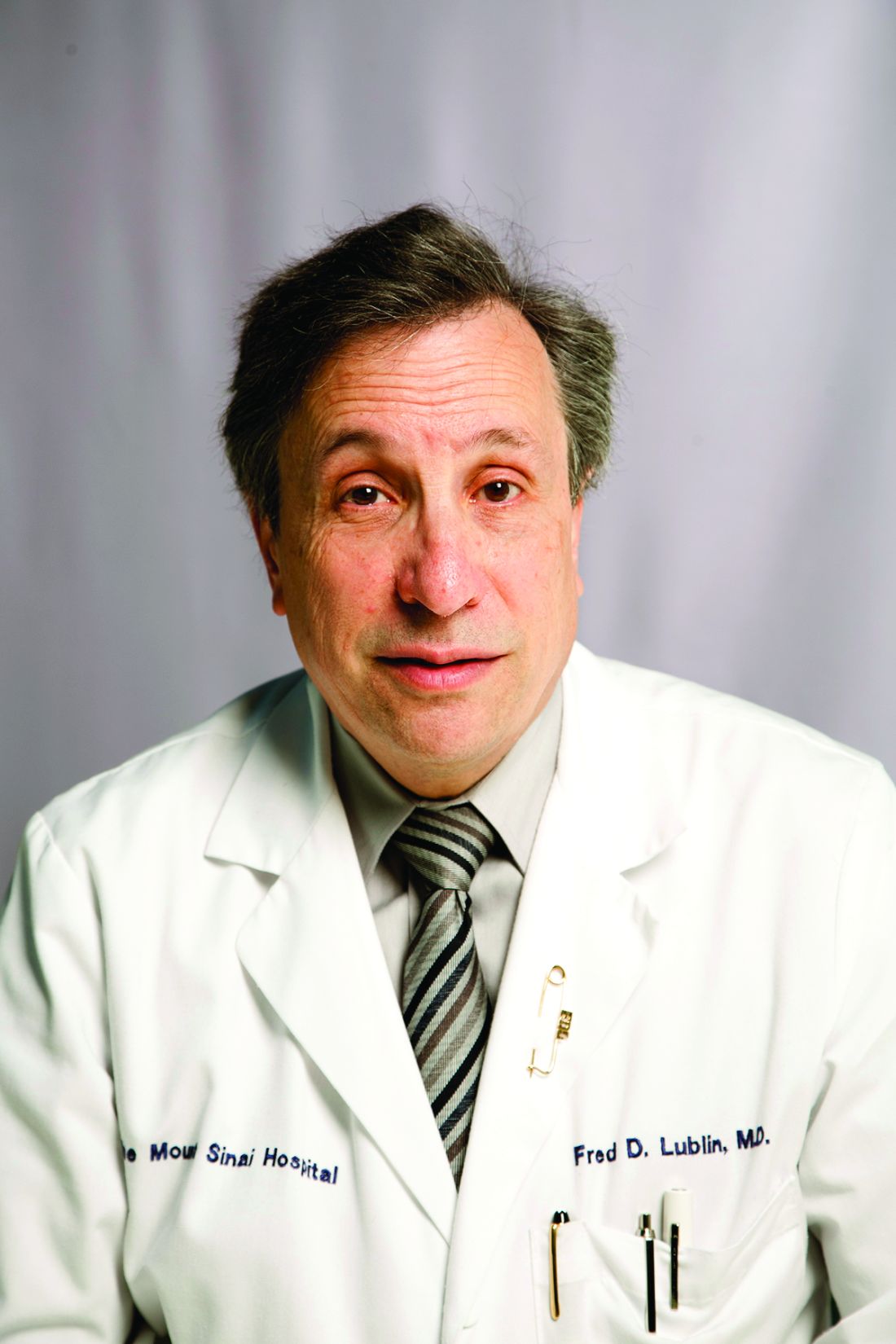

Ocrelizumab gets first-ever FDA approval for primary progressive MS

The humanized monoclonal antibody ocrelizumab became the first drug to receive approval from the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of primary progressive multiple sclerosis in adults, according to a March 29 announcement from the agency that also said it is approved for relapsing-remitting disease in adults.

The drug has a mechanism of action similar to rituximab (Rituxan) through its selective targeting of CD20-positive B cells, which depletes them from circulation. CD20-positive B cells are thought to be a key contributor to myelin and axonal damage.

Although the effect of ocrelizumab on primary progressive MS patients was modest, its stature as the only drug approved for the indication represents “a start for being able to treat progressive MS,” Fred Lublin, MD, a member of the steering committee that designed and monitored the phase III ocrelizumab trials, said in an interview.

In the ORATORIO trial that randomized 732 patients with primary progressive MS in a 2:1 ratio to infusions of either 600 mg ocrelizumab or placebo every 24 weeks for 120 weeks, ocrelizumab reduced the risk of progression in clinical disability by 24% at 12 weeks (the primary end point), 25% at 24 weeks, and 24% at 120 weeks, compared with placebo (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 19;376[3]:209-20).

Over 120 weeks, the antibody also reduced the volume of hyperintense T2 lesions by 3.4%, whereas patients taking placebo experienced a 7.4% increase. The rate of whole brain volume loss was also significantly reduced from week 24 to 120 (–0.9% with ocrelizumab vs. –1.1% for placebo).

The group of patients who participated in ORATORIO was younger and had more activity on MRI, but it’s unclear if there is a progressive MS patient population who will respond best to the biologic, said Dr. Lublin, director of the Corinne Goldsmith Dickinson Center for Multiple Sclerosis at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

“The safety was acceptable, and so I think it will get a lot of use. There are always some who like to wait until a drug has been out for a while, but there is considerable experience with this type of drug based on off-label use of rituximab” in relapsing-remitting patients, including phase II trial data (but not phase III), he said. There’s potential for ocrelizumab to be used as a first-line treatment for relapsing-remitting disease to the same extent as natalizumab (Tysabri), he added.

In two identical phase III trials, OPERA I and OPERA II, investigators randomized 1,656 relapsing-remitting MS patients to intravenous ocrelizumab 600 mg every 24 weeks plus placebo subcutaneous injections three times weekly or to subcutaneous interferon beta-1a 44 mcg (Rebif) three times weekly plus placebo IV infusions every 24 weeks over 96 weeks (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 19;376[3]:221-34).

Compared with interferon beta-1a, ocrelizumab reduced the annualized relapse rate by 46% in OPERA 1 and 47% in OPERA 2. In a pooled analysis of both trials, the risk of confirmed disability progression was 40% lower for ocrelizumab at both 12 and 24 weeks. Ocrelizumab conferred a 94% and 95% reduction in the total number of T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions and a 77% and 83% reduction in the total number of new and/or enlarging hyperintense T2 lesions. An exploratory analysis also suggested that the drug reduced the rate of whole brain volume loss, compared with interferon beta-1a.

At 96 weeks, 47.9% and 47.5% of ocrelizumab patients versus 29.2% and 25.1% of interferon patients had no evidence of disease activity (NEDA) in the two studies. NEDA is a composite score defined as no relapses, no confirmed disability progression, and no new or enlarging T2 or gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesions.

Across both studies, relapses occurred in about 20% of ocrelizumab patients versus about 35% of interferon patients. About 10% of ocrelizumab patients had clinical disease progression, compared with about 15% of interferon patients. Similarly, about 10% of ocrelizumab patients developed new gadolinium-enhancing lesions, compared with about 35% in the interferon groups. New or enlarging T2 lesions were found in about 40% in the ocrelizumab groups but in more than 60% in the interferon arms.

Safety results at 24 weeks in the OPERA trials showed that infusion reactions were significantly more common with ocrelizumab than with interferon beta-1a (34% vs. 9.7%), and most of these were mild to moderate in severity. Otherwise, there were similar rates of serious adverse events, including serious infections.

In ORATORIO, infusion reaction occurred in 40% of ocrelizumab patients and 26% of placebo patients. Most of the reactions were mild to moderate in severity. Among all patients in ORATORIO, 13 malignancies occurred over 3 years, and they occurred more than twice as often in the ocrelizumab arm than in the placebo arm (2.3% vs. 0.8%). These included four breast cancers in the active arm and none in the placebo arm.

No cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) have been reported in association with ocrelizumab, although the risk of PML with long-term use is unknown.

The FDA said in its announcement that ocrelizumab should not be used in patients with hepatitis B infection or a history of life-threatening infusion-related reactions to the drug. Ocrelizumab is required to be dispensed with a patient Medication Guide that describes important information about the drug’s uses and risks. The agency also advised that vaccination with live or live attenuated vaccines is not recommended in patients receiving the drug.

Genentech says it plans to offer patient assistance programs through Genentech Access Solutions.

Dr. Lublin reported receiving fees for serving on an advisory board from Genentech/Roche and from many other companies investigating or marketing drugs for MS.

The humanized monoclonal antibody ocrelizumab became the first drug to receive approval from the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of primary progressive multiple sclerosis in adults, according to a March 29 announcement from the agency that also said it is approved for relapsing-remitting disease in adults.

The drug has a mechanism of action similar to rituximab (Rituxan) through its selective targeting of CD20-positive B cells, which depletes them from circulation. CD20-positive B cells are thought to be a key contributor to myelin and axonal damage.

Although the effect of ocrelizumab on primary progressive MS patients was modest, its stature as the only drug approved for the indication represents “a start for being able to treat progressive MS,” Fred Lublin, MD, a member of the steering committee that designed and monitored the phase III ocrelizumab trials, said in an interview.

In the ORATORIO trial that randomized 732 patients with primary progressive MS in a 2:1 ratio to infusions of either 600 mg ocrelizumab or placebo every 24 weeks for 120 weeks, ocrelizumab reduced the risk of progression in clinical disability by 24% at 12 weeks (the primary end point), 25% at 24 weeks, and 24% at 120 weeks, compared with placebo (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 19;376[3]:209-20).

Over 120 weeks, the antibody also reduced the volume of hyperintense T2 lesions by 3.4%, whereas patients taking placebo experienced a 7.4% increase. The rate of whole brain volume loss was also significantly reduced from week 24 to 120 (–0.9% with ocrelizumab vs. –1.1% for placebo).

The group of patients who participated in ORATORIO was younger and had more activity on MRI, but it’s unclear if there is a progressive MS patient population who will respond best to the biologic, said Dr. Lublin, director of the Corinne Goldsmith Dickinson Center for Multiple Sclerosis at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

“The safety was acceptable, and so I think it will get a lot of use. There are always some who like to wait until a drug has been out for a while, but there is considerable experience with this type of drug based on off-label use of rituximab” in relapsing-remitting patients, including phase II trial data (but not phase III), he said. There’s potential for ocrelizumab to be used as a first-line treatment for relapsing-remitting disease to the same extent as natalizumab (Tysabri), he added.

In two identical phase III trials, OPERA I and OPERA II, investigators randomized 1,656 relapsing-remitting MS patients to intravenous ocrelizumab 600 mg every 24 weeks plus placebo subcutaneous injections three times weekly or to subcutaneous interferon beta-1a 44 mcg (Rebif) three times weekly plus placebo IV infusions every 24 weeks over 96 weeks (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 19;376[3]:221-34).

Compared with interferon beta-1a, ocrelizumab reduced the annualized relapse rate by 46% in OPERA 1 and 47% in OPERA 2. In a pooled analysis of both trials, the risk of confirmed disability progression was 40% lower for ocrelizumab at both 12 and 24 weeks. Ocrelizumab conferred a 94% and 95% reduction in the total number of T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions and a 77% and 83% reduction in the total number of new and/or enlarging hyperintense T2 lesions. An exploratory analysis also suggested that the drug reduced the rate of whole brain volume loss, compared with interferon beta-1a.

At 96 weeks, 47.9% and 47.5% of ocrelizumab patients versus 29.2% and 25.1% of interferon patients had no evidence of disease activity (NEDA) in the two studies. NEDA is a composite score defined as no relapses, no confirmed disability progression, and no new or enlarging T2 or gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesions.

Across both studies, relapses occurred in about 20% of ocrelizumab patients versus about 35% of interferon patients. About 10% of ocrelizumab patients had clinical disease progression, compared with about 15% of interferon patients. Similarly, about 10% of ocrelizumab patients developed new gadolinium-enhancing lesions, compared with about 35% in the interferon groups. New or enlarging T2 lesions were found in about 40% in the ocrelizumab groups but in more than 60% in the interferon arms.

Safety results at 24 weeks in the OPERA trials showed that infusion reactions were significantly more common with ocrelizumab than with interferon beta-1a (34% vs. 9.7%), and most of these were mild to moderate in severity. Otherwise, there were similar rates of serious adverse events, including serious infections.

In ORATORIO, infusion reaction occurred in 40% of ocrelizumab patients and 26% of placebo patients. Most of the reactions were mild to moderate in severity. Among all patients in ORATORIO, 13 malignancies occurred over 3 years, and they occurred more than twice as often in the ocrelizumab arm than in the placebo arm (2.3% vs. 0.8%). These included four breast cancers in the active arm and none in the placebo arm.

No cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) have been reported in association with ocrelizumab, although the risk of PML with long-term use is unknown.

The FDA said in its announcement that ocrelizumab should not be used in patients with hepatitis B infection or a history of life-threatening infusion-related reactions to the drug. Ocrelizumab is required to be dispensed with a patient Medication Guide that describes important information about the drug’s uses and risks. The agency also advised that vaccination with live or live attenuated vaccines is not recommended in patients receiving the drug.

Genentech says it plans to offer patient assistance programs through Genentech Access Solutions.

Dr. Lublin reported receiving fees for serving on an advisory board from Genentech/Roche and from many other companies investigating or marketing drugs for MS.

The humanized monoclonal antibody ocrelizumab became the first drug to receive approval from the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of primary progressive multiple sclerosis in adults, according to a March 29 announcement from the agency that also said it is approved for relapsing-remitting disease in adults.

The drug has a mechanism of action similar to rituximab (Rituxan) through its selective targeting of CD20-positive B cells, which depletes them from circulation. CD20-positive B cells are thought to be a key contributor to myelin and axonal damage.

Although the effect of ocrelizumab on primary progressive MS patients was modest, its stature as the only drug approved for the indication represents “a start for being able to treat progressive MS,” Fred Lublin, MD, a member of the steering committee that designed and monitored the phase III ocrelizumab trials, said in an interview.

In the ORATORIO trial that randomized 732 patients with primary progressive MS in a 2:1 ratio to infusions of either 600 mg ocrelizumab or placebo every 24 weeks for 120 weeks, ocrelizumab reduced the risk of progression in clinical disability by 24% at 12 weeks (the primary end point), 25% at 24 weeks, and 24% at 120 weeks, compared with placebo (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 19;376[3]:209-20).

Over 120 weeks, the antibody also reduced the volume of hyperintense T2 lesions by 3.4%, whereas patients taking placebo experienced a 7.4% increase. The rate of whole brain volume loss was also significantly reduced from week 24 to 120 (–0.9% with ocrelizumab vs. –1.1% for placebo).

The group of patients who participated in ORATORIO was younger and had more activity on MRI, but it’s unclear if there is a progressive MS patient population who will respond best to the biologic, said Dr. Lublin, director of the Corinne Goldsmith Dickinson Center for Multiple Sclerosis at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

“The safety was acceptable, and so I think it will get a lot of use. There are always some who like to wait until a drug has been out for a while, but there is considerable experience with this type of drug based on off-label use of rituximab” in relapsing-remitting patients, including phase II trial data (but not phase III), he said. There’s potential for ocrelizumab to be used as a first-line treatment for relapsing-remitting disease to the same extent as natalizumab (Tysabri), he added.

In two identical phase III trials, OPERA I and OPERA II, investigators randomized 1,656 relapsing-remitting MS patients to intravenous ocrelizumab 600 mg every 24 weeks plus placebo subcutaneous injections three times weekly or to subcutaneous interferon beta-1a 44 mcg (Rebif) three times weekly plus placebo IV infusions every 24 weeks over 96 weeks (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 19;376[3]:221-34).

Compared with interferon beta-1a, ocrelizumab reduced the annualized relapse rate by 46% in OPERA 1 and 47% in OPERA 2. In a pooled analysis of both trials, the risk of confirmed disability progression was 40% lower for ocrelizumab at both 12 and 24 weeks. Ocrelizumab conferred a 94% and 95% reduction in the total number of T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions and a 77% and 83% reduction in the total number of new and/or enlarging hyperintense T2 lesions. An exploratory analysis also suggested that the drug reduced the rate of whole brain volume loss, compared with interferon beta-1a.

At 96 weeks, 47.9% and 47.5% of ocrelizumab patients versus 29.2% and 25.1% of interferon patients had no evidence of disease activity (NEDA) in the two studies. NEDA is a composite score defined as no relapses, no confirmed disability progression, and no new or enlarging T2 or gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesions.

Across both studies, relapses occurred in about 20% of ocrelizumab patients versus about 35% of interferon patients. About 10% of ocrelizumab patients had clinical disease progression, compared with about 15% of interferon patients. Similarly, about 10% of ocrelizumab patients developed new gadolinium-enhancing lesions, compared with about 35% in the interferon groups. New or enlarging T2 lesions were found in about 40% in the ocrelizumab groups but in more than 60% in the interferon arms.

Safety results at 24 weeks in the OPERA trials showed that infusion reactions were significantly more common with ocrelizumab than with interferon beta-1a (34% vs. 9.7%), and most of these were mild to moderate in severity. Otherwise, there were similar rates of serious adverse events, including serious infections.

In ORATORIO, infusion reaction occurred in 40% of ocrelizumab patients and 26% of placebo patients. Most of the reactions were mild to moderate in severity. Among all patients in ORATORIO, 13 malignancies occurred over 3 years, and they occurred more than twice as often in the ocrelizumab arm than in the placebo arm (2.3% vs. 0.8%). These included four breast cancers in the active arm and none in the placebo arm.

No cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) have been reported in association with ocrelizumab, although the risk of PML with long-term use is unknown.

The FDA said in its announcement that ocrelizumab should not be used in patients with hepatitis B infection or a history of life-threatening infusion-related reactions to the drug. Ocrelizumab is required to be dispensed with a patient Medication Guide that describes important information about the drug’s uses and risks. The agency also advised that vaccination with live or live attenuated vaccines is not recommended in patients receiving the drug.

Genentech says it plans to offer patient assistance programs through Genentech Access Solutions.

Dr. Lublin reported receiving fees for serving on an advisory board from Genentech/Roche and from many other companies investigating or marketing drugs for MS.

Methotrexate use justified for early RA, disease prevention

Efforts to delay or prevent rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in individuals at high risk for the disease received a boost from the findings of a subgroup analysis of an older Dutch prevention trial involving methotrexate that were published recently in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

However, while the 22-patient subgroup analysis of the 2007 trial, called PROMPT (Probable RA: Methotrexate Versus Placebo Treatment), showed that 1 year of methotrexate prevented the development of rheumatoid arthritis in significantly more individuals at high risk for the disease than did placebo, hindsight has shown that most of these high-risk individuals actually had RA at baseline as defined by the 2010 American College or Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria.

Even though the “landscape of RA has changed since this study was conceived, enrolled, and performed,” Dr. Sparks noted that the study provides evidence that today’s “standard of care really works” by making use of data that are unobtainable today.

“Nowadays, we wouldn’t be able to do a placebo-controlled trial in early RA because those patients need to be treated, but at the time, it was perfectly fine, based on the treatment landscape, to put these patients in a [placebo-controlled] trial,” he said in an interview.

“It also demonstrates that you really need to find high-risk individuals, because, if you recruit people who are never going to develop RA, you’re just diluting your effect, and you’re not going to find the difference in the groups based on that diluted effect when there could be a true effect in that special subgroup,” he added.

Senior study author Annette van der Helm-van Mil, MD, PhD, and her colleagues at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center performed the reanalysis after the initial finding that methotrexate had no preventative effect may have been falsely negative because the study included patients with a low risk of progressing to RA (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Feb 19. doi: 10.1002/art.40062).

In the reanalysis, the investigators defined 22 out of the trial’s 110 participants as high risk based on their score of 8 or higher on the Leiden prediction rule at baseline. Of those 22, 18 also fulfilled the 2010 classification criteria for RA.

This “definition of high risk [in the trial] very much coincided with the new classification criteria and reinforces the standard of care that patients with new diagnosed RA should be treated with DMARDs [disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs] front line,” Dr. Sparks said.

The Leiden prediction rule score is based on ACPA statuses, as well as age, sex, distribution of involved joints, number of swollen and tender joints, severity of morning stiffness, C-reactive protein level, and rheumatoid factor. In previous studies of patients with undifferentiated arthritis, a score of 8 or higher with the prediction rule had a positive predictive value of 84% in patients with undifferentiated arthritis, according to the investigators.

Based on a primary outcome of fulfilling the 1987 classification criteria for RA after 5 years of follow-up, the investigators found that 6 of 11 (55%) in the methotrexate arm developed RA, compared with all 11 patients in the placebo arm (P = .011). “A 1-year course of methotrexate was associated with an absolute risk reduction of 45% on RA development, resulting in a number needed to treat of 2.2 (95% [confidence interval], 1.3-6.2),” the authors wrote.

Furthermore, the time to the development of RA based on the 1987 criteria was longer with methotrexate than with placebo (median of 22.5 months vs. 3 months; P less than .001).

Drug-free remission was also achieved by 4 of 11 (36%) patients taking methotrexate, compared with none of the patients taking placebo (P = .027).

The beneficial effects of methotrexate were seen in ACPA-positive and ACPA-negative high-risk patients but not in patients without a high risk of RA.

For the patients who did not fulfill the 2010 RA criteria at baseline, only one of four of those in the placebo arm did go on to develop RA based on 1987 criteria, whereas only one of three who received methotrexate did.

Overall, the reanalysis of PROMPT trial data illustrates how “noninformative inclusions can blur highly relevant study outcomes, such as prevention of RA,” the study authors concluded.

“As trials are now being conducted to evaluate the efficacy of treatment initiated in the phase of arthralgia, the development of adequate risk prediction models are of importance in order to prevent false-negative study results in the future,” they added.

The PROMPT trial was supported by the Dutch Arthritis Foundation and the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research.

Small numbers not withstanding, the findings of this reanalysis of the PROMPT trial are exciting, and they address the importance of identifying the right individuals to include in any type of prevention study in RA.

Given the temporal limits of clinical trials, inclusion criteria will need to incorporate both the likelihood of an important outcome and the timing of that outcome – right individuals, right time, right drug/intervention.

It is hoped that investigators will be able to demonstrate conclusively that preventive interventions work for rheumatic disease once these issues are addressed.

Kevin D. Deane, MD, PhD, and his coauthors are with the division of rheumatology at the University of Colorado, Denver, and made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the PROMPT trial reanalysis (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Feb 19. doi: 10.1002/art.40061).

Small numbers not withstanding, the findings of this reanalysis of the PROMPT trial are exciting, and they address the importance of identifying the right individuals to include in any type of prevention study in RA.

Given the temporal limits of clinical trials, inclusion criteria will need to incorporate both the likelihood of an important outcome and the timing of that outcome – right individuals, right time, right drug/intervention.

It is hoped that investigators will be able to demonstrate conclusively that preventive interventions work for rheumatic disease once these issues are addressed.

Kevin D. Deane, MD, PhD, and his coauthors are with the division of rheumatology at the University of Colorado, Denver, and made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the PROMPT trial reanalysis (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Feb 19. doi: 10.1002/art.40061).

Small numbers not withstanding, the findings of this reanalysis of the PROMPT trial are exciting, and they address the importance of identifying the right individuals to include in any type of prevention study in RA.

Given the temporal limits of clinical trials, inclusion criteria will need to incorporate both the likelihood of an important outcome and the timing of that outcome – right individuals, right time, right drug/intervention.

It is hoped that investigators will be able to demonstrate conclusively that preventive interventions work for rheumatic disease once these issues are addressed.

Kevin D. Deane, MD, PhD, and his coauthors are with the division of rheumatology at the University of Colorado, Denver, and made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the PROMPT trial reanalysis (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Feb 19. doi: 10.1002/art.40061).

Efforts to delay or prevent rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in individuals at high risk for the disease received a boost from the findings of a subgroup analysis of an older Dutch prevention trial involving methotrexate that were published recently in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

However, while the 22-patient subgroup analysis of the 2007 trial, called PROMPT (Probable RA: Methotrexate Versus Placebo Treatment), showed that 1 year of methotrexate prevented the development of rheumatoid arthritis in significantly more individuals at high risk for the disease than did placebo, hindsight has shown that most of these high-risk individuals actually had RA at baseline as defined by the 2010 American College or Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria.

Even though the “landscape of RA has changed since this study was conceived, enrolled, and performed,” Dr. Sparks noted that the study provides evidence that today’s “standard of care really works” by making use of data that are unobtainable today.

“Nowadays, we wouldn’t be able to do a placebo-controlled trial in early RA because those patients need to be treated, but at the time, it was perfectly fine, based on the treatment landscape, to put these patients in a [placebo-controlled] trial,” he said in an interview.

“It also demonstrates that you really need to find high-risk individuals, because, if you recruit people who are never going to develop RA, you’re just diluting your effect, and you’re not going to find the difference in the groups based on that diluted effect when there could be a true effect in that special subgroup,” he added.

Senior study author Annette van der Helm-van Mil, MD, PhD, and her colleagues at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center performed the reanalysis after the initial finding that methotrexate had no preventative effect may have been falsely negative because the study included patients with a low risk of progressing to RA (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Feb 19. doi: 10.1002/art.40062).

In the reanalysis, the investigators defined 22 out of the trial’s 110 participants as high risk based on their score of 8 or higher on the Leiden prediction rule at baseline. Of those 22, 18 also fulfilled the 2010 classification criteria for RA.

This “definition of high risk [in the trial] very much coincided with the new classification criteria and reinforces the standard of care that patients with new diagnosed RA should be treated with DMARDs [disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs] front line,” Dr. Sparks said.

The Leiden prediction rule score is based on ACPA statuses, as well as age, sex, distribution of involved joints, number of swollen and tender joints, severity of morning stiffness, C-reactive protein level, and rheumatoid factor. In previous studies of patients with undifferentiated arthritis, a score of 8 or higher with the prediction rule had a positive predictive value of 84% in patients with undifferentiated arthritis, according to the investigators.

Based on a primary outcome of fulfilling the 1987 classification criteria for RA after 5 years of follow-up, the investigators found that 6 of 11 (55%) in the methotrexate arm developed RA, compared with all 11 patients in the placebo arm (P = .011). “A 1-year course of methotrexate was associated with an absolute risk reduction of 45% on RA development, resulting in a number needed to treat of 2.2 (95% [confidence interval], 1.3-6.2),” the authors wrote.

Furthermore, the time to the development of RA based on the 1987 criteria was longer with methotrexate than with placebo (median of 22.5 months vs. 3 months; P less than .001).

Drug-free remission was also achieved by 4 of 11 (36%) patients taking methotrexate, compared with none of the patients taking placebo (P = .027).

The beneficial effects of methotrexate were seen in ACPA-positive and ACPA-negative high-risk patients but not in patients without a high risk of RA.

For the patients who did not fulfill the 2010 RA criteria at baseline, only one of four of those in the placebo arm did go on to develop RA based on 1987 criteria, whereas only one of three who received methotrexate did.

Overall, the reanalysis of PROMPT trial data illustrates how “noninformative inclusions can blur highly relevant study outcomes, such as prevention of RA,” the study authors concluded.

“As trials are now being conducted to evaluate the efficacy of treatment initiated in the phase of arthralgia, the development of adequate risk prediction models are of importance in order to prevent false-negative study results in the future,” they added.

The PROMPT trial was supported by the Dutch Arthritis Foundation and the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research.

Efforts to delay or prevent rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in individuals at high risk for the disease received a boost from the findings of a subgroup analysis of an older Dutch prevention trial involving methotrexate that were published recently in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

However, while the 22-patient subgroup analysis of the 2007 trial, called PROMPT (Probable RA: Methotrexate Versus Placebo Treatment), showed that 1 year of methotrexate prevented the development of rheumatoid arthritis in significantly more individuals at high risk for the disease than did placebo, hindsight has shown that most of these high-risk individuals actually had RA at baseline as defined by the 2010 American College or Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria.

Even though the “landscape of RA has changed since this study was conceived, enrolled, and performed,” Dr. Sparks noted that the study provides evidence that today’s “standard of care really works” by making use of data that are unobtainable today.

“Nowadays, we wouldn’t be able to do a placebo-controlled trial in early RA because those patients need to be treated, but at the time, it was perfectly fine, based on the treatment landscape, to put these patients in a [placebo-controlled] trial,” he said in an interview.

“It also demonstrates that you really need to find high-risk individuals, because, if you recruit people who are never going to develop RA, you’re just diluting your effect, and you’re not going to find the difference in the groups based on that diluted effect when there could be a true effect in that special subgroup,” he added.

Senior study author Annette van der Helm-van Mil, MD, PhD, and her colleagues at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center performed the reanalysis after the initial finding that methotrexate had no preventative effect may have been falsely negative because the study included patients with a low risk of progressing to RA (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Feb 19. doi: 10.1002/art.40062).

In the reanalysis, the investigators defined 22 out of the trial’s 110 participants as high risk based on their score of 8 or higher on the Leiden prediction rule at baseline. Of those 22, 18 also fulfilled the 2010 classification criteria for RA.

This “definition of high risk [in the trial] very much coincided with the new classification criteria and reinforces the standard of care that patients with new diagnosed RA should be treated with DMARDs [disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs] front line,” Dr. Sparks said.

The Leiden prediction rule score is based on ACPA statuses, as well as age, sex, distribution of involved joints, number of swollen and tender joints, severity of morning stiffness, C-reactive protein level, and rheumatoid factor. In previous studies of patients with undifferentiated arthritis, a score of 8 or higher with the prediction rule had a positive predictive value of 84% in patients with undifferentiated arthritis, according to the investigators.

Based on a primary outcome of fulfilling the 1987 classification criteria for RA after 5 years of follow-up, the investigators found that 6 of 11 (55%) in the methotrexate arm developed RA, compared with all 11 patients in the placebo arm (P = .011). “A 1-year course of methotrexate was associated with an absolute risk reduction of 45% on RA development, resulting in a number needed to treat of 2.2 (95% [confidence interval], 1.3-6.2),” the authors wrote.

Furthermore, the time to the development of RA based on the 1987 criteria was longer with methotrexate than with placebo (median of 22.5 months vs. 3 months; P less than .001).

Drug-free remission was also achieved by 4 of 11 (36%) patients taking methotrexate, compared with none of the patients taking placebo (P = .027).

The beneficial effects of methotrexate were seen in ACPA-positive and ACPA-negative high-risk patients but not in patients without a high risk of RA.

For the patients who did not fulfill the 2010 RA criteria at baseline, only one of four of those in the placebo arm did go on to develop RA based on 1987 criteria, whereas only one of three who received methotrexate did.

Overall, the reanalysis of PROMPT trial data illustrates how “noninformative inclusions can blur highly relevant study outcomes, such as prevention of RA,” the study authors concluded.

“As trials are now being conducted to evaluate the efficacy of treatment initiated in the phase of arthralgia, the development of adequate risk prediction models are of importance in order to prevent false-negative study results in the future,” they added.

The PROMPT trial was supported by the Dutch Arthritis Foundation and the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Main finding: In people deemed to be at high risk for RA, a 1-year course of methotrexate was associated with an absolute risk reduction of 45% of RA development, resulting in a number needed to treat of 2.2 (95% CI, 1.3-6.2).

Data source: A reanalysis of the PROMPT trial involving 110 patients with undifferentiated arthritis randomized to a 1-year course of methotrexate or placebo.

Disclosures: The PROMPT trial was supported by the Dutch Arthritis Foundation and the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research.

Opinions vary considerably on withdrawing drugs in clinically inactive JIA

A wide range of attitudes and practices for the process of withdrawing medications in pediatric patients with clinically inactive juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) exist among clinician members of the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA), according to findings from an anonymous survey.

The cross-sectional, electronic survey found that respondents varied in the amount of time they thought was necessary to spend in clinically inactive disease before beginning withdrawal of medications and in the amount of time to spend during tapering or stopping medications, for both methotrexate and biologics.

To better understand how clinicians care for patients with clinically inactive disease, the investigators emailed the survey to 388 clinician members of the CARRA in the United States and Canada over a 4-week period during November-December 2015 (J Rheumatol. 2017 Feb 1. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.161078).

The survey, which the investigators thought to be “the first comprehensive evaluation of influential factors and approaches for the clinical management of children with clinically inactive JIA,” did not include questions about systemic JIA, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, and uveitis in order “to simplify responses and encourage participation, because in practice, the manifestations and outcomes of these diseases could substantially influence treatment decisions for children with JIA.”

They received complete responses from 124 of the 132 clinicians who responded to the survey email. Of the 121 respondents who reported taking clinical care of patients with JIA, 87% were physicians, and the same number reported taking care of pediatric patients only. About three-quarters spent half of their professional time in clinical care, and about half had more than 10 years of post-training clinical experience.

When deciding about withdrawing JIA medications, more than one-half of respondents said that the time that a patient spent in clinically inactive disease and a history of drug toxicity are very important factors. Most participants ranked those two factors most highly and most often among their top five factors for decision making.

Respondents also commonly ranked these factors as important:

- JIA duration before attaining clinically inactive disease.

- Patient/family preferences.

- Presence of JIA-related damage.

- JIA category.

The factors that consistently appeared in responses fit into three clusters that included JIA features and time spent in clinically inactive disease (JIA category and total disease duration), JIA severity and resistance to treatment (disease duration before clinically inactive disease, number of drugs needed to attain inactivity, joint damage, and a history of sacroiliac or temporomandibular disease), and the patient’s experience (drug toxicity and family preference).

The respondents indicated that they would be least likely to stop medications for children with rheumatoid factor (RF)–positive polyarthritis (85%), which is “consistent with prior studies showing that RF-positive polyarthritis is associated with higher rates of flares than other JIA categories,” the investigators wrote. However, respondents said they would be most likely to stop medications for children with persistent oligoarthritis (87%) “even though rates of flares in this category appear similar to other JIA types. This method may reflect a belief that flares in children with persistent oligoarticular JIA will be less severe and easier to control.”

When patients met all criteria for clinically inactive disease for a “sufficient amount of time” and families were interested in stopping medications, some factors continued to make respondents reluctant to withdraw medications. These factors were most often a history of erosions (81%), asymptomatic joint abnormalities on ultrasound or MRI (72%), and failure of multiple prior disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs or biologics to control disease (64%). The definition of clinically inactive disease is a composite of no active arthritis, uveitis, or systemic JIA symptoms; the best possible clinical global assessment; inflammatory markers normal or elevated for reasons other than JIA; and no more than 15 minutes of joint stiffness.

A little over half of respondents said they would wait until clinically inactive disease had lasted 12 months before considering stopping or tapering methotrexate or biologic monotherapy, but a substantial minority said they would wait for only 6 months for methotrexate (31%) or biologic monotherapy (23%). A smaller number would wait for 18 months for methotrexate (13%) or biologics (18%), and another 3%-5% said they could not give a time frame.

The strategies varied for how actual withdrawing of medications occurred. Most methotrexate monotherapy withdrawals involved tapering over 2-6 months, one-third over longer periods, and the fewest reported tapering for less than 2 months (7%) or immediate withdrawal (17%).

Withdrawal of biologics was generally said to occur more gradually than with methotrexate, with one-third of respondents citing over 2-6 months, a quarter more slowly, and another 29% in less than 2 months or immediately. Some wrote that they preferred spacing out the interval between doses, but none decreased the dose. When children took combination therapy with methotrexate plus a biologic, 63% said that they began tapering or stopping methotrexate first, but a quarter said that the order was strongly context dependent, and the most commonly cited reason for deciding was history of toxicity or intolerance.

Imaging played a role in less than half of the decisions to withdraw medications, with it being used often by 9% and sometimes by 36%. And while it’s assumed that patients and family consideration played an important role in decision making, only 25% of respondents reported using specific patient-reported outcomes in deciding to withdraw medications.

The study was funded by grants from Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

A wide range of attitudes and practices for the process of withdrawing medications in pediatric patients with clinically inactive juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) exist among clinician members of the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA), according to findings from an anonymous survey.

The cross-sectional, electronic survey found that respondents varied in the amount of time they thought was necessary to spend in clinically inactive disease before beginning withdrawal of medications and in the amount of time to spend during tapering or stopping medications, for both methotrexate and biologics.

To better understand how clinicians care for patients with clinically inactive disease, the investigators emailed the survey to 388 clinician members of the CARRA in the United States and Canada over a 4-week period during November-December 2015 (J Rheumatol. 2017 Feb 1. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.161078).

The survey, which the investigators thought to be “the first comprehensive evaluation of influential factors and approaches for the clinical management of children with clinically inactive JIA,” did not include questions about systemic JIA, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, and uveitis in order “to simplify responses and encourage participation, because in practice, the manifestations and outcomes of these diseases could substantially influence treatment decisions for children with JIA.”

They received complete responses from 124 of the 132 clinicians who responded to the survey email. Of the 121 respondents who reported taking clinical care of patients with JIA, 87% were physicians, and the same number reported taking care of pediatric patients only. About three-quarters spent half of their professional time in clinical care, and about half had more than 10 years of post-training clinical experience.

When deciding about withdrawing JIA medications, more than one-half of respondents said that the time that a patient spent in clinically inactive disease and a history of drug toxicity are very important factors. Most participants ranked those two factors most highly and most often among their top five factors for decision making.

Respondents also commonly ranked these factors as important:

- JIA duration before attaining clinically inactive disease.

- Patient/family preferences.

- Presence of JIA-related damage.

- JIA category.

The factors that consistently appeared in responses fit into three clusters that included JIA features and time spent in clinically inactive disease (JIA category and total disease duration), JIA severity and resistance to treatment (disease duration before clinically inactive disease, number of drugs needed to attain inactivity, joint damage, and a history of sacroiliac or temporomandibular disease), and the patient’s experience (drug toxicity and family preference).

The respondents indicated that they would be least likely to stop medications for children with rheumatoid factor (RF)–positive polyarthritis (85%), which is “consistent with prior studies showing that RF-positive polyarthritis is associated with higher rates of flares than other JIA categories,” the investigators wrote. However, respondents said they would be most likely to stop medications for children with persistent oligoarthritis (87%) “even though rates of flares in this category appear similar to other JIA types. This method may reflect a belief that flares in children with persistent oligoarticular JIA will be less severe and easier to control.”

When patients met all criteria for clinically inactive disease for a “sufficient amount of time” and families were interested in stopping medications, some factors continued to make respondents reluctant to withdraw medications. These factors were most often a history of erosions (81%), asymptomatic joint abnormalities on ultrasound or MRI (72%), and failure of multiple prior disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs or biologics to control disease (64%). The definition of clinically inactive disease is a composite of no active arthritis, uveitis, or systemic JIA symptoms; the best possible clinical global assessment; inflammatory markers normal or elevated for reasons other than JIA; and no more than 15 minutes of joint stiffness.

A little over half of respondents said they would wait until clinically inactive disease had lasted 12 months before considering stopping or tapering methotrexate or biologic monotherapy, but a substantial minority said they would wait for only 6 months for methotrexate (31%) or biologic monotherapy (23%). A smaller number would wait for 18 months for methotrexate (13%) or biologics (18%), and another 3%-5% said they could not give a time frame.

The strategies varied for how actual withdrawing of medications occurred. Most methotrexate monotherapy withdrawals involved tapering over 2-6 months, one-third over longer periods, and the fewest reported tapering for less than 2 months (7%) or immediate withdrawal (17%).

Withdrawal of biologics was generally said to occur more gradually than with methotrexate, with one-third of respondents citing over 2-6 months, a quarter more slowly, and another 29% in less than 2 months or immediately. Some wrote that they preferred spacing out the interval between doses, but none decreased the dose. When children took combination therapy with methotrexate plus a biologic, 63% said that they began tapering or stopping methotrexate first, but a quarter said that the order was strongly context dependent, and the most commonly cited reason for deciding was history of toxicity or intolerance.

Imaging played a role in less than half of the decisions to withdraw medications, with it being used often by 9% and sometimes by 36%. And while it’s assumed that patients and family consideration played an important role in decision making, only 25% of respondents reported using specific patient-reported outcomes in deciding to withdraw medications.

The study was funded by grants from Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

A wide range of attitudes and practices for the process of withdrawing medications in pediatric patients with clinically inactive juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) exist among clinician members of the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA), according to findings from an anonymous survey.

The cross-sectional, electronic survey found that respondents varied in the amount of time they thought was necessary to spend in clinically inactive disease before beginning withdrawal of medications and in the amount of time to spend during tapering or stopping medications, for both methotrexate and biologics.

To better understand how clinicians care for patients with clinically inactive disease, the investigators emailed the survey to 388 clinician members of the CARRA in the United States and Canada over a 4-week period during November-December 2015 (J Rheumatol. 2017 Feb 1. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.161078).

The survey, which the investigators thought to be “the first comprehensive evaluation of influential factors and approaches for the clinical management of children with clinically inactive JIA,” did not include questions about systemic JIA, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, and uveitis in order “to simplify responses and encourage participation, because in practice, the manifestations and outcomes of these diseases could substantially influence treatment decisions for children with JIA.”

They received complete responses from 124 of the 132 clinicians who responded to the survey email. Of the 121 respondents who reported taking clinical care of patients with JIA, 87% were physicians, and the same number reported taking care of pediatric patients only. About three-quarters spent half of their professional time in clinical care, and about half had more than 10 years of post-training clinical experience.

When deciding about withdrawing JIA medications, more than one-half of respondents said that the time that a patient spent in clinically inactive disease and a history of drug toxicity are very important factors. Most participants ranked those two factors most highly and most often among their top five factors for decision making.

Respondents also commonly ranked these factors as important:

- JIA duration before attaining clinically inactive disease.

- Patient/family preferences.

- Presence of JIA-related damage.

- JIA category.

The factors that consistently appeared in responses fit into three clusters that included JIA features and time spent in clinically inactive disease (JIA category and total disease duration), JIA severity and resistance to treatment (disease duration before clinically inactive disease, number of drugs needed to attain inactivity, joint damage, and a history of sacroiliac or temporomandibular disease), and the patient’s experience (drug toxicity and family preference).

The respondents indicated that they would be least likely to stop medications for children with rheumatoid factor (RF)–positive polyarthritis (85%), which is “consistent with prior studies showing that RF-positive polyarthritis is associated with higher rates of flares than other JIA categories,” the investigators wrote. However, respondents said they would be most likely to stop medications for children with persistent oligoarthritis (87%) “even though rates of flares in this category appear similar to other JIA types. This method may reflect a belief that flares in children with persistent oligoarticular JIA will be less severe and easier to control.”

When patients met all criteria for clinically inactive disease for a “sufficient amount of time” and families were interested in stopping medications, some factors continued to make respondents reluctant to withdraw medications. These factors were most often a history of erosions (81%), asymptomatic joint abnormalities on ultrasound or MRI (72%), and failure of multiple prior disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs or biologics to control disease (64%). The definition of clinically inactive disease is a composite of no active arthritis, uveitis, or systemic JIA symptoms; the best possible clinical global assessment; inflammatory markers normal or elevated for reasons other than JIA; and no more than 15 minutes of joint stiffness.

A little over half of respondents said they would wait until clinically inactive disease had lasted 12 months before considering stopping or tapering methotrexate or biologic monotherapy, but a substantial minority said they would wait for only 6 months for methotrexate (31%) or biologic monotherapy (23%). A smaller number would wait for 18 months for methotrexate (13%) or biologics (18%), and another 3%-5% said they could not give a time frame.

The strategies varied for how actual withdrawing of medications occurred. Most methotrexate monotherapy withdrawals involved tapering over 2-6 months, one-third over longer periods, and the fewest reported tapering for less than 2 months (7%) or immediate withdrawal (17%).

Withdrawal of biologics was generally said to occur more gradually than with methotrexate, with one-third of respondents citing over 2-6 months, a quarter more slowly, and another 29% in less than 2 months or immediately. Some wrote that they preferred spacing out the interval between doses, but none decreased the dose. When children took combination therapy with methotrexate plus a biologic, 63% said that they began tapering or stopping methotrexate first, but a quarter said that the order was strongly context dependent, and the most commonly cited reason for deciding was history of toxicity or intolerance.

Imaging played a role in less than half of the decisions to withdraw medications, with it being used often by 9% and sometimes by 36%. And while it’s assumed that patients and family consideration played an important role in decision making, only 25% of respondents reported using specific patient-reported outcomes in deciding to withdraw medications.

The study was funded by grants from Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A little over half of respondents said they would wait until clinically inactive disease had lasted 12 months before considering stopping or tapering methotrexate or biologic monotherapy.

Data source: A survey of 121 of 388 CARRA members involved in clinical care of JIA patients.

Disclosures: The study was funded by grants from Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

Lyme arthritis changes its immune response profile if it persists after antibiotics

The persistence of Lyme arthritis after treatment with antibiotics comes with a shift from an immune response expected for bacterial infection to one characterized by chronic inflammation, synovial proliferation, and breakdown of wound repair processes, according to an analysis of microRNA expression in patients before, during, and after infection.

Based on the findings, investigators led by Robert B. Lochhead, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said that they “suspect that, in humans, genetic variables determine whether the response to B. burgdorferi infection elicits an appropriate wound repair response … or a maladaptive inflammatory cellular response and arrest of wound repair processes.”

The investigators studied synovial fluid or tissue from 32 patients with LA who were representative of the spectrum of disease severity and treatment responses seen in this disease. In 18 patients for whom synovial fluid samples were available, 5 illustrated the differences in miRNA expression that occur from the time before any antibiotic treatment to the time after antibiotic treatment that successfully resolves arthritis symptoms, and 13 showed how an incomplete response to antibiotic treatment can affect miRNA expression. The expression profile of miRNA in synovial tissue samples from another 14 patients who underwent arthroscopic synovectomies 4-48 months after oral and intravenous antibiotics demonstrated the change in immune response seen in postinfectious LA.

The group of five patients with synovial fluid samples who were referred prior to antibiotic therapy when they had active B. burgdorferi infection (group 1) had a history of mild to severe knee swelling and pain for a median duration of 1 month prior to evaluation and the start of antibiotic treatment. A 1-month course of oral doxycycline resolved arthritis in three of the patients, and the other two continued to have marked knee swelling that later resolved after 1 month of IV ceftriaxone. Of six different miRNAs that the investigators measured, five were at low levels in these patients. The lone exception was a hematopoietic-specific miRNA, miR-223, which is abundantly expressed in polymorphonuclear lymphocytes (PMNs) and is associated with downregulation of acute inflammation and tissue remodeling.

In the group of 13 who still had joint swelling despite oral or IV antibiotics (group 2), only 2 had resolution of their swelling after IV antibiotics. Most of the remaining 11 had successful treatment with methotrexate. The synovial fluid samples for seven patients were collected after oral antibiotics but before IV antibiotics, and in the other six the samples were collected after both therapies. These 13 patients had significantly lower white blood cell counts in synovial fluid, fewer PMNs, and greater percentages of lymphocytes and monocytes than did group 1 patients. The five miRNAs that were found at low levels among the patients in group 1 were higher in these patients, which “suggested that the nature of the arthritis had changed after spirochetal killing.” The higher miR-223 levels seen in group 1 also occurred in group 2.

A separate analysis of synovial fluid samples from four patients with osteoarthritis and six patients with RA showed that levels of the six miRNAs from RA patients were similar to those of patients from group 2, and the low levels that were observed for most of the miRNAs in group 1 were similar to those seen in OA patients.

The investigators found that the five miRNAs with elevated levels in group 2 patients, but not miR-223, were positively correlated with arthritis duration after start of oral antibiotic therapy. B. burgdorferi IgG antibody titers negatively correlated with some of the elevated miRNAs in group 2.

The investigators analyzed a larger set of miRNAs in the synovial tissue samples obtained from 14 patients who underwent synovectomies for treatment of persistent synovitis a median of 15.5 months after they had undergone 2-3 months of antibiotic therapy (group 3). Some of the miRNAs overexpressed in these postinfectious LA samples, relative to samples from five OA patients, were associated with proliferative, tumor-associated responses and regulation of inflammatory processes. However, miRNAs overexpressed in tissues from OA patients relative to postinfectious LA patients were thought to affect genes that control tissue remodeling and cell proliferation, but not inflammation. The “distinct oncogenic miRNA profile” exhibited by postinfectious synovial tissue, according to the investigators, showed that “in these patients, the transition to the postinfectious phase was blocked by chronic inflammation, which stalled the wound repair process.”

The investigators concluded that “miRNAs hold promise as potential biomarkers to identify LA patients who are developing maladaptive immune responses during the period of infection. In such patients, it will be important to learn whether simultaneous treatment with antibiotics and DMARDs, rather than sequential treatment with these medications, will reduce the period of therapy and improve outcome, creating a new paradigm in treatment of this form of chronic inflammatory arthritis.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Lucius N. Littauer Foundation, the Roland Foundation, the Lyme Disease and Arthritis Research Fund at Massachusetts General Hospital, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, and the English, Bonter, Mitchell Foundation.

The persistence of Lyme arthritis after treatment with antibiotics comes with a shift from an immune response expected for bacterial infection to one characterized by chronic inflammation, synovial proliferation, and breakdown of wound repair processes, according to an analysis of microRNA expression in patients before, during, and after infection.

Based on the findings, investigators led by Robert B. Lochhead, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said that they “suspect that, in humans, genetic variables determine whether the response to B. burgdorferi infection elicits an appropriate wound repair response … or a maladaptive inflammatory cellular response and arrest of wound repair processes.”

The investigators studied synovial fluid or tissue from 32 patients with LA who were representative of the spectrum of disease severity and treatment responses seen in this disease. In 18 patients for whom synovial fluid samples were available, 5 illustrated the differences in miRNA expression that occur from the time before any antibiotic treatment to the time after antibiotic treatment that successfully resolves arthritis symptoms, and 13 showed how an incomplete response to antibiotic treatment can affect miRNA expression. The expression profile of miRNA in synovial tissue samples from another 14 patients who underwent arthroscopic synovectomies 4-48 months after oral and intravenous antibiotics demonstrated the change in immune response seen in postinfectious LA.

The group of five patients with synovial fluid samples who were referred prior to antibiotic therapy when they had active B. burgdorferi infection (group 1) had a history of mild to severe knee swelling and pain for a median duration of 1 month prior to evaluation and the start of antibiotic treatment. A 1-month course of oral doxycycline resolved arthritis in three of the patients, and the other two continued to have marked knee swelling that later resolved after 1 month of IV ceftriaxone. Of six different miRNAs that the investigators measured, five were at low levels in these patients. The lone exception was a hematopoietic-specific miRNA, miR-223, which is abundantly expressed in polymorphonuclear lymphocytes (PMNs) and is associated with downregulation of acute inflammation and tissue remodeling.

In the group of 13 who still had joint swelling despite oral or IV antibiotics (group 2), only 2 had resolution of their swelling after IV antibiotics. Most of the remaining 11 had successful treatment with methotrexate. The synovial fluid samples for seven patients were collected after oral antibiotics but before IV antibiotics, and in the other six the samples were collected after both therapies. These 13 patients had significantly lower white blood cell counts in synovial fluid, fewer PMNs, and greater percentages of lymphocytes and monocytes than did group 1 patients. The five miRNAs that were found at low levels among the patients in group 1 were higher in these patients, which “suggested that the nature of the arthritis had changed after spirochetal killing.” The higher miR-223 levels seen in group 1 also occurred in group 2.

A separate analysis of synovial fluid samples from four patients with osteoarthritis and six patients with RA showed that levels of the six miRNAs from RA patients were similar to those of patients from group 2, and the low levels that were observed for most of the miRNAs in group 1 were similar to those seen in OA patients.

The investigators found that the five miRNAs with elevated levels in group 2 patients, but not miR-223, were positively correlated with arthritis duration after start of oral antibiotic therapy. B. burgdorferi IgG antibody titers negatively correlated with some of the elevated miRNAs in group 2.

The investigators analyzed a larger set of miRNAs in the synovial tissue samples obtained from 14 patients who underwent synovectomies for treatment of persistent synovitis a median of 15.5 months after they had undergone 2-3 months of antibiotic therapy (group 3). Some of the miRNAs overexpressed in these postinfectious LA samples, relative to samples from five OA patients, were associated with proliferative, tumor-associated responses and regulation of inflammatory processes. However, miRNAs overexpressed in tissues from OA patients relative to postinfectious LA patients were thought to affect genes that control tissue remodeling and cell proliferation, but not inflammation. The “distinct oncogenic miRNA profile” exhibited by postinfectious synovial tissue, according to the investigators, showed that “in these patients, the transition to the postinfectious phase was blocked by chronic inflammation, which stalled the wound repair process.”

The investigators concluded that “miRNAs hold promise as potential biomarkers to identify LA patients who are developing maladaptive immune responses during the period of infection. In such patients, it will be important to learn whether simultaneous treatment with antibiotics and DMARDs, rather than sequential treatment with these medications, will reduce the period of therapy and improve outcome, creating a new paradigm in treatment of this form of chronic inflammatory arthritis.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Lucius N. Littauer Foundation, the Roland Foundation, the Lyme Disease and Arthritis Research Fund at Massachusetts General Hospital, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, and the English, Bonter, Mitchell Foundation.

The persistence of Lyme arthritis after treatment with antibiotics comes with a shift from an immune response expected for bacterial infection to one characterized by chronic inflammation, synovial proliferation, and breakdown of wound repair processes, according to an analysis of microRNA expression in patients before, during, and after infection.

Based on the findings, investigators led by Robert B. Lochhead, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said that they “suspect that, in humans, genetic variables determine whether the response to B. burgdorferi infection elicits an appropriate wound repair response … or a maladaptive inflammatory cellular response and arrest of wound repair processes.”

The investigators studied synovial fluid or tissue from 32 patients with LA who were representative of the spectrum of disease severity and treatment responses seen in this disease. In 18 patients for whom synovial fluid samples were available, 5 illustrated the differences in miRNA expression that occur from the time before any antibiotic treatment to the time after antibiotic treatment that successfully resolves arthritis symptoms, and 13 showed how an incomplete response to antibiotic treatment can affect miRNA expression. The expression profile of miRNA in synovial tissue samples from another 14 patients who underwent arthroscopic synovectomies 4-48 months after oral and intravenous antibiotics demonstrated the change in immune response seen in postinfectious LA.

The group of five patients with synovial fluid samples who were referred prior to antibiotic therapy when they had active B. burgdorferi infection (group 1) had a history of mild to severe knee swelling and pain for a median duration of 1 month prior to evaluation and the start of antibiotic treatment. A 1-month course of oral doxycycline resolved arthritis in three of the patients, and the other two continued to have marked knee swelling that later resolved after 1 month of IV ceftriaxone. Of six different miRNAs that the investigators measured, five were at low levels in these patients. The lone exception was a hematopoietic-specific miRNA, miR-223, which is abundantly expressed in polymorphonuclear lymphocytes (PMNs) and is associated with downregulation of acute inflammation and tissue remodeling.

In the group of 13 who still had joint swelling despite oral or IV antibiotics (group 2), only 2 had resolution of their swelling after IV antibiotics. Most of the remaining 11 had successful treatment with methotrexate. The synovial fluid samples for seven patients were collected after oral antibiotics but before IV antibiotics, and in the other six the samples were collected after both therapies. These 13 patients had significantly lower white blood cell counts in synovial fluid, fewer PMNs, and greater percentages of lymphocytes and monocytes than did group 1 patients. The five miRNAs that were found at low levels among the patients in group 1 were higher in these patients, which “suggested that the nature of the arthritis had changed after spirochetal killing.” The higher miR-223 levels seen in group 1 also occurred in group 2.

A separate analysis of synovial fluid samples from four patients with osteoarthritis and six patients with RA showed that levels of the six miRNAs from RA patients were similar to those of patients from group 2, and the low levels that were observed for most of the miRNAs in group 1 were similar to those seen in OA patients.

The investigators found that the five miRNAs with elevated levels in group 2 patients, but not miR-223, were positively correlated with arthritis duration after start of oral antibiotic therapy. B. burgdorferi IgG antibody titers negatively correlated with some of the elevated miRNAs in group 2.

The investigators analyzed a larger set of miRNAs in the synovial tissue samples obtained from 14 patients who underwent synovectomies for treatment of persistent synovitis a median of 15.5 months after they had undergone 2-3 months of antibiotic therapy (group 3). Some of the miRNAs overexpressed in these postinfectious LA samples, relative to samples from five OA patients, were associated with proliferative, tumor-associated responses and regulation of inflammatory processes. However, miRNAs overexpressed in tissues from OA patients relative to postinfectious LA patients were thought to affect genes that control tissue remodeling and cell proliferation, but not inflammation. The “distinct oncogenic miRNA profile” exhibited by postinfectious synovial tissue, according to the investigators, showed that “in these patients, the transition to the postinfectious phase was blocked by chronic inflammation, which stalled the wound repair process.”

The investigators concluded that “miRNAs hold promise as potential biomarkers to identify LA patients who are developing maladaptive immune responses during the period of infection. In such patients, it will be important to learn whether simultaneous treatment with antibiotics and DMARDs, rather than sequential treatment with these medications, will reduce the period of therapy and improve outcome, creating a new paradigm in treatment of this form of chronic inflammatory arthritis.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Lucius N. Littauer Foundation, the Roland Foundation, the Lyme Disease and Arthritis Research Fund at Massachusetts General Hospital, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, and the English, Bonter, Mitchell Foundation.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: miRNAs overexpressed in synovial tissue samples from 14 patients with postinfectious Lyme arthritis, relative to samples from five OA patients, were associated with proliferative, tumor-associated responses and regulation of inflammatory processes.

Data source: A retrospective study of synovial fluid or tissue samples from 32 patients with Lyme arthritis.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Lucius N. Littauer Foundation, the Roland Foundation, the Lyme Disease and Arthritis Research Fund at Massachusetts General Hospital, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, and the English, Bonter, Mitchell Foundation.

New histopathologic marker may aid dermatomyositis diagnosis

The detection of sarcoplasmic myxovirus resistance A expression in immunohistochemical analysis of muscle biopsy in patients suspected of having dermatomyositis may add greater sensitivity for the diagnosis when compared with conventional pathologic hallmarks of the disease, according to findings from a retrospective cohort study.

Myxovirus resistance A (MxA) is one of the type 1 interferon–inducible proteins whose overexpression is believed to play a role in the pathogenesis of dermatomyositis, and MxA expression has rarely been observed in other idiopathic inflammatory myopathies, said first author Akinori Uruha, MD, PhD, of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Tokyo, and his colleagues. They compared MxA expression in muscle biopsy samples from definite, probable, and possible dermatomyositis cases as well as other idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and other control conditions to assess its value against other muscle pathologic markers of dermatomyositis, such as the presence of perifascicular atrophy (PFA) and capillary membrane attack complex (MAC) deposition (Neurology. 2016 Dec 30. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003568).