User login

Psoriasis Cohort Reveals High Arthritis Risk

Psoriatic arthritis may occur more frequently among people with psoriasis than previously reported, and risk factors include having severe psoriasis, nail pitting, low education levels, and uveitis, according to findings from a Canadian cohort study.

Beginning in 2006, Dr. Lihi Eder of the University of Toronto and coinvestigators recruited 464 patients (mean age 47, 56% male, 77% white) mainly from phototherapy and dermatology outpatient clinics in Toronto, and followed them 8 years. All had psoriasis of varying type and severity at baseline, but not inflammatory arthritis or spondylitis (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Nov 10 doi: 10.1002/art.39494).

During the 8-year follow-up, 51 patients developed rheumatologist-confirmed psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Dr. Eder and colleagues reported an annual incidence rate of 2.7 confirmed cases of psoriatic arthritis per 100 psoriasis patients per year, which is considerably higher than previous published estimates, the investigators noted. The independent predictors of confirmed psoriatic arthritis were severe psoriasis (relative risk, 5.4; P = .006), not finishing high school (vs. finishing college RR, 4.5, P = .005; and vs. finishing high school RR, 3.3; P = .049), and use of systemic retinoids (RR, 3.4; P = .02). Time-dependent predictive variables included psoriatic nail pitting (RR, 2.5; P = .002) and uveitis (RR, 31.5; P = .001). Disease severity and nail pitting have been found in previous studies to be associated with a higher risk of psoriatic arthritis.

This study confirmed this association and also identified low education levels and uveitis as predictors. Low education is a marker of socioeconomic status that has been associated with lifestyle habits and possibly occupations that may increase PsA risk, the study authors noted, but the link requires further investigation. The authors cautioned that only three uveitis cases occurred in the cohort and that confidence intervals were wide. They also noted as a limitation that most participants were recruited from dermatology clinics, leading to overrepresentation of moderate-severe psoriasis and possibly patients with longer disease duration. Nevertheless, it “is likely that the true incidence of PsA in patients with psoriasis, particularly those attending dermatology clinics, is higher than previously reported,” the investigators wrote. “This highlights the role of dermatologists as key players in identifying psoriasis patients who are at higher risk of developing PsA.”

Krembil Foundation, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and The Arthritis Society supported the study.

Psoriatic arthritis may occur more frequently among people with psoriasis than previously reported, and risk factors include having severe psoriasis, nail pitting, low education levels, and uveitis, according to findings from a Canadian cohort study.

Beginning in 2006, Dr. Lihi Eder of the University of Toronto and coinvestigators recruited 464 patients (mean age 47, 56% male, 77% white) mainly from phototherapy and dermatology outpatient clinics in Toronto, and followed them 8 years. All had psoriasis of varying type and severity at baseline, but not inflammatory arthritis or spondylitis (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Nov 10 doi: 10.1002/art.39494).

During the 8-year follow-up, 51 patients developed rheumatologist-confirmed psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Dr. Eder and colleagues reported an annual incidence rate of 2.7 confirmed cases of psoriatic arthritis per 100 psoriasis patients per year, which is considerably higher than previous published estimates, the investigators noted. The independent predictors of confirmed psoriatic arthritis were severe psoriasis (relative risk, 5.4; P = .006), not finishing high school (vs. finishing college RR, 4.5, P = .005; and vs. finishing high school RR, 3.3; P = .049), and use of systemic retinoids (RR, 3.4; P = .02). Time-dependent predictive variables included psoriatic nail pitting (RR, 2.5; P = .002) and uveitis (RR, 31.5; P = .001). Disease severity and nail pitting have been found in previous studies to be associated with a higher risk of psoriatic arthritis.

This study confirmed this association and also identified low education levels and uveitis as predictors. Low education is a marker of socioeconomic status that has been associated with lifestyle habits and possibly occupations that may increase PsA risk, the study authors noted, but the link requires further investigation. The authors cautioned that only three uveitis cases occurred in the cohort and that confidence intervals were wide. They also noted as a limitation that most participants were recruited from dermatology clinics, leading to overrepresentation of moderate-severe psoriasis and possibly patients with longer disease duration. Nevertheless, it “is likely that the true incidence of PsA in patients with psoriasis, particularly those attending dermatology clinics, is higher than previously reported,” the investigators wrote. “This highlights the role of dermatologists as key players in identifying psoriasis patients who are at higher risk of developing PsA.”

Krembil Foundation, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and The Arthritis Society supported the study.

Psoriatic arthritis may occur more frequently among people with psoriasis than previously reported, and risk factors include having severe psoriasis, nail pitting, low education levels, and uveitis, according to findings from a Canadian cohort study.

Beginning in 2006, Dr. Lihi Eder of the University of Toronto and coinvestigators recruited 464 patients (mean age 47, 56% male, 77% white) mainly from phototherapy and dermatology outpatient clinics in Toronto, and followed them 8 years. All had psoriasis of varying type and severity at baseline, but not inflammatory arthritis or spondylitis (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Nov 10 doi: 10.1002/art.39494).

During the 8-year follow-up, 51 patients developed rheumatologist-confirmed psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Dr. Eder and colleagues reported an annual incidence rate of 2.7 confirmed cases of psoriatic arthritis per 100 psoriasis patients per year, which is considerably higher than previous published estimates, the investigators noted. The independent predictors of confirmed psoriatic arthritis were severe psoriasis (relative risk, 5.4; P = .006), not finishing high school (vs. finishing college RR, 4.5, P = .005; and vs. finishing high school RR, 3.3; P = .049), and use of systemic retinoids (RR, 3.4; P = .02). Time-dependent predictive variables included psoriatic nail pitting (RR, 2.5; P = .002) and uveitis (RR, 31.5; P = .001). Disease severity and nail pitting have been found in previous studies to be associated with a higher risk of psoriatic arthritis.

This study confirmed this association and also identified low education levels and uveitis as predictors. Low education is a marker of socioeconomic status that has been associated with lifestyle habits and possibly occupations that may increase PsA risk, the study authors noted, but the link requires further investigation. The authors cautioned that only three uveitis cases occurred in the cohort and that confidence intervals were wide. They also noted as a limitation that most participants were recruited from dermatology clinics, leading to overrepresentation of moderate-severe psoriasis and possibly patients with longer disease duration. Nevertheless, it “is likely that the true incidence of PsA in patients with psoriasis, particularly those attending dermatology clinics, is higher than previously reported,” the investigators wrote. “This highlights the role of dermatologists as key players in identifying psoriasis patients who are at higher risk of developing PsA.”

Krembil Foundation, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and The Arthritis Society supported the study.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Psoriasis cohort reveals high arthritis risk

Psoriatic arthritis may occur more frequently among people with psoriasis than previously reported, and risk factors include having severe psoriasis, nail pitting, low education levels, and uveitis, according to findings from a Canadian cohort study.

Beginning in 2006, Dr. Lihi Eder of the University of Toronto and coinvestigators recruited 464 patients (mean age 47, 56% male, 77% white) mainly from phototherapy and dermatology outpatient clinics in Toronto, and followed them 8 years. All had psoriasis of varying type and severity at baseline, but not inflammatory arthritis or spondylitis (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Nov 10 doi: 10.1002/art.39494).

During the 8-year follow-up, 51 patients developed rheumatologist-confirmed psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Dr. Eder and colleagues reported an annual incidence rate of 2.7 confirmed cases of psoriatic arthritis per 100 psoriasis patients per year, which is considerably higher than previous published estimates, the investigators noted. The independent predictors of confirmed psoriatic arthritis were severe psoriasis (relative risk, 5.4; P = .006), not finishing high school (vs. finishing college RR, 4.5, P = .005; and vs. finishing high school RR, 3.3; P = .049), and use of systemic retinoids (RR, 3.4; P = .02). Time-dependent predictive variables included psoriatic nail pitting (RR, 2.5; P = .002) and uveitis (RR, 31.5; P = .001). Disease severity and nail pitting have been found in previous studies to be associated with a higher risk of psoriatic arthritis.

This study confirmed this association and also identified low education levels and uveitis as predictors. Low education is a marker of socioeconomic status that has been associated with lifestyle habits and possibly occupations that may increase PsA risk, the study authors noted, but the link requires further investigation. The authors cautioned that only three uveitis cases occurred in the cohort and that confidence intervals were wide. They also noted as a limitation that most participants were recruited from dermatology clinics, leading to overrepresentation of moderate-severe psoriasis and possibly patients with longer disease duration. Nevertheless, it “is likely that the true incidence of PsA in patients with psoriasis, particularly those attending dermatology clinics, is higher than previously reported,” the investigators wrote. “This highlights the role of dermatologists as key players in identifying psoriasis patients who are at higher risk of developing PsA.”

Krembil Foundation, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and The Arthritis Society supported the study.

Psoriatic arthritis may occur more frequently among people with psoriasis than previously reported, and risk factors include having severe psoriasis, nail pitting, low education levels, and uveitis, according to findings from a Canadian cohort study.

Beginning in 2006, Dr. Lihi Eder of the University of Toronto and coinvestigators recruited 464 patients (mean age 47, 56% male, 77% white) mainly from phototherapy and dermatology outpatient clinics in Toronto, and followed them 8 years. All had psoriasis of varying type and severity at baseline, but not inflammatory arthritis or spondylitis (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Nov 10 doi: 10.1002/art.39494).

During the 8-year follow-up, 51 patients developed rheumatologist-confirmed psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Dr. Eder and colleagues reported an annual incidence rate of 2.7 confirmed cases of psoriatic arthritis per 100 psoriasis patients per year, which is considerably higher than previous published estimates, the investigators noted. The independent predictors of confirmed psoriatic arthritis were severe psoriasis (relative risk, 5.4; P = .006), not finishing high school (vs. finishing college RR, 4.5, P = .005; and vs. finishing high school RR, 3.3; P = .049), and use of systemic retinoids (RR, 3.4; P = .02). Time-dependent predictive variables included psoriatic nail pitting (RR, 2.5; P = .002) and uveitis (RR, 31.5; P = .001). Disease severity and nail pitting have been found in previous studies to be associated with a higher risk of psoriatic arthritis.

This study confirmed this association and also identified low education levels and uveitis as predictors. Low education is a marker of socioeconomic status that has been associated with lifestyle habits and possibly occupations that may increase PsA risk, the study authors noted, but the link requires further investigation. The authors cautioned that only three uveitis cases occurred in the cohort and that confidence intervals were wide. They also noted as a limitation that most participants were recruited from dermatology clinics, leading to overrepresentation of moderate-severe psoriasis and possibly patients with longer disease duration. Nevertheless, it “is likely that the true incidence of PsA in patients with psoriasis, particularly those attending dermatology clinics, is higher than previously reported,” the investigators wrote. “This highlights the role of dermatologists as key players in identifying psoriasis patients who are at higher risk of developing PsA.”

Krembil Foundation, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and The Arthritis Society supported the study.

Psoriatic arthritis may occur more frequently among people with psoriasis than previously reported, and risk factors include having severe psoriasis, nail pitting, low education levels, and uveitis, according to findings from a Canadian cohort study.

Beginning in 2006, Dr. Lihi Eder of the University of Toronto and coinvestigators recruited 464 patients (mean age 47, 56% male, 77% white) mainly from phototherapy and dermatology outpatient clinics in Toronto, and followed them 8 years. All had psoriasis of varying type and severity at baseline, but not inflammatory arthritis or spondylitis (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Nov 10 doi: 10.1002/art.39494).

During the 8-year follow-up, 51 patients developed rheumatologist-confirmed psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Dr. Eder and colleagues reported an annual incidence rate of 2.7 confirmed cases of psoriatic arthritis per 100 psoriasis patients per year, which is considerably higher than previous published estimates, the investigators noted. The independent predictors of confirmed psoriatic arthritis were severe psoriasis (relative risk, 5.4; P = .006), not finishing high school (vs. finishing college RR, 4.5, P = .005; and vs. finishing high school RR, 3.3; P = .049), and use of systemic retinoids (RR, 3.4; P = .02). Time-dependent predictive variables included psoriatic nail pitting (RR, 2.5; P = .002) and uveitis (RR, 31.5; P = .001). Disease severity and nail pitting have been found in previous studies to be associated with a higher risk of psoriatic arthritis.

This study confirmed this association and also identified low education levels and uveitis as predictors. Low education is a marker of socioeconomic status that has been associated with lifestyle habits and possibly occupations that may increase PsA risk, the study authors noted, but the link requires further investigation. The authors cautioned that only three uveitis cases occurred in the cohort and that confidence intervals were wide. They also noted as a limitation that most participants were recruited from dermatology clinics, leading to overrepresentation of moderate-severe psoriasis and possibly patients with longer disease duration. Nevertheless, it “is likely that the true incidence of PsA in patients with psoriasis, particularly those attending dermatology clinics, is higher than previously reported,” the investigators wrote. “This highlights the role of dermatologists as key players in identifying psoriasis patients who are at higher risk of developing PsA.”

Krembil Foundation, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and The Arthritis Society supported the study.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Incidence of psoriatic arthritis is higher among psoriasis patients than previously estimated.

Major finding: Annual incidence rate was 2.7 (95% confidence interval 2.1, 3.6) PsA cases per 100 psoriasis patients; significant predictors included disease severity, nail pitting, low education, and uveitis.

Data source: A prospective cohort study of 464 psoriasis patients without arthritis at baseline, followed for 8 years.

Disclosures: Krembil Foundation, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and The Arthritis Society sponsored the study.

Higher anemia risk for children with atopic disease

Children with a history of atopic disease (AD) are at a significantly higher risk for an anemia diagnosis than are children without AD, according to an analysis of two large U.S. population-based studies.

In addition, the risk of anemia increased with the number of caregiver-reported atopic disorders, reported the investigators, Dr. Jonathan I. Silverberg and his associates in the department of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago. A current diagnosis of eczema or asthma was associated with a significantly increased risk of anemia, particularly microcytic anemia, in the study, published online on Nov. 30 in JAMA Pediatrics (doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3065).

The authors evaluated data from the U.S. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) on about 207,000 children and adolescents collected between 1997 and 2013, and from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) on nearly 31,000 children and adolescents between 1999 and 2012.

Data from the NHIS cohort found a significantly elevated anemia risk among children with a caregiver-reported history of hay fever, eczema, asthma, and food allergy (P less than .001 for all 4 disorders). After adjustments for age, sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic factors, the anemia risk for a child with any single atopic disorder was modestly elevated (adjusted odds ratio, 1.84; 95% confidence interval, 1.60-2.11; P less than .001). The adjusted risk among those with all four disorders was markedly elevated (adjusted OR, 7.87; 95% CI, 5.17-12.00; P less than .001).

In the NHANES cohort, the investigators found a current asthma or eczema diagnosis associated with anemia, as defined by laboratory assessment (adjusted OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.04-1.70; P = .02 for asthma; and an adjusted OR 1.93; 95% CI, 1.04-3.59; P = .04 for eczema).

In the NHANES cohort, asthma was associated with an increased risk for microcytic anemia (adjusted OR, 1.61; 95% CI 1.09-2.38 P = .02). In the 2005-2006 NHANES cohort, a history of eczema was associated with an increased risk of microcytic anemia (adjusted OR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.20-3.46; P = .009). But no significant associations for hay fever and any type of anemia were noted.

While the reasons for the observed association between atopic disease and anemia remain unknown and are probably multifactorial, physicians “should be aware that fatigue may be related to unrecognized anemia and not merely sleep loss owing to atopic dermatitis or airway disease,” the investigators wrote. Moreover, they noted, restricted diets to treat atopic disorders could play a role. “This finding underscores the importance of properly evaluating and ruling out suspected food allergy in children rather than placing them on empirical avoidance diets that might contribute to anemia,” they said.

The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Dermatology Foundation. Dr. Silverberg and his coauthors, Kerry E. Drury and Matt Schaeffer, declared no conflicts of interest.

Children with a history of atopic disease (AD) are at a significantly higher risk for an anemia diagnosis than are children without AD, according to an analysis of two large U.S. population-based studies.

In addition, the risk of anemia increased with the number of caregiver-reported atopic disorders, reported the investigators, Dr. Jonathan I. Silverberg and his associates in the department of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago. A current diagnosis of eczema or asthma was associated with a significantly increased risk of anemia, particularly microcytic anemia, in the study, published online on Nov. 30 in JAMA Pediatrics (doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3065).

The authors evaluated data from the U.S. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) on about 207,000 children and adolescents collected between 1997 and 2013, and from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) on nearly 31,000 children and adolescents between 1999 and 2012.

Data from the NHIS cohort found a significantly elevated anemia risk among children with a caregiver-reported history of hay fever, eczema, asthma, and food allergy (P less than .001 for all 4 disorders). After adjustments for age, sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic factors, the anemia risk for a child with any single atopic disorder was modestly elevated (adjusted odds ratio, 1.84; 95% confidence interval, 1.60-2.11; P less than .001). The adjusted risk among those with all four disorders was markedly elevated (adjusted OR, 7.87; 95% CI, 5.17-12.00; P less than .001).

In the NHANES cohort, the investigators found a current asthma or eczema diagnosis associated with anemia, as defined by laboratory assessment (adjusted OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.04-1.70; P = .02 for asthma; and an adjusted OR 1.93; 95% CI, 1.04-3.59; P = .04 for eczema).

In the NHANES cohort, asthma was associated with an increased risk for microcytic anemia (adjusted OR, 1.61; 95% CI 1.09-2.38 P = .02). In the 2005-2006 NHANES cohort, a history of eczema was associated with an increased risk of microcytic anemia (adjusted OR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.20-3.46; P = .009). But no significant associations for hay fever and any type of anemia were noted.

While the reasons for the observed association between atopic disease and anemia remain unknown and are probably multifactorial, physicians “should be aware that fatigue may be related to unrecognized anemia and not merely sleep loss owing to atopic dermatitis or airway disease,” the investigators wrote. Moreover, they noted, restricted diets to treat atopic disorders could play a role. “This finding underscores the importance of properly evaluating and ruling out suspected food allergy in children rather than placing them on empirical avoidance diets that might contribute to anemia,” they said.

The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Dermatology Foundation. Dr. Silverberg and his coauthors, Kerry E. Drury and Matt Schaeffer, declared no conflicts of interest.

Children with a history of atopic disease (AD) are at a significantly higher risk for an anemia diagnosis than are children without AD, according to an analysis of two large U.S. population-based studies.

In addition, the risk of anemia increased with the number of caregiver-reported atopic disorders, reported the investigators, Dr. Jonathan I. Silverberg and his associates in the department of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago. A current diagnosis of eczema or asthma was associated with a significantly increased risk of anemia, particularly microcytic anemia, in the study, published online on Nov. 30 in JAMA Pediatrics (doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3065).

The authors evaluated data from the U.S. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) on about 207,000 children and adolescents collected between 1997 and 2013, and from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) on nearly 31,000 children and adolescents between 1999 and 2012.

Data from the NHIS cohort found a significantly elevated anemia risk among children with a caregiver-reported history of hay fever, eczema, asthma, and food allergy (P less than .001 for all 4 disorders). After adjustments for age, sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic factors, the anemia risk for a child with any single atopic disorder was modestly elevated (adjusted odds ratio, 1.84; 95% confidence interval, 1.60-2.11; P less than .001). The adjusted risk among those with all four disorders was markedly elevated (adjusted OR, 7.87; 95% CI, 5.17-12.00; P less than .001).

In the NHANES cohort, the investigators found a current asthma or eczema diagnosis associated with anemia, as defined by laboratory assessment (adjusted OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.04-1.70; P = .02 for asthma; and an adjusted OR 1.93; 95% CI, 1.04-3.59; P = .04 for eczema).

In the NHANES cohort, asthma was associated with an increased risk for microcytic anemia (adjusted OR, 1.61; 95% CI 1.09-2.38 P = .02). In the 2005-2006 NHANES cohort, a history of eczema was associated with an increased risk of microcytic anemia (adjusted OR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.20-3.46; P = .009). But no significant associations for hay fever and any type of anemia were noted.

While the reasons for the observed association between atopic disease and anemia remain unknown and are probably multifactorial, physicians “should be aware that fatigue may be related to unrecognized anemia and not merely sleep loss owing to atopic dermatitis or airway disease,” the investigators wrote. Moreover, they noted, restricted diets to treat atopic disorders could play a role. “This finding underscores the importance of properly evaluating and ruling out suspected food allergy in children rather than placing them on empirical avoidance diets that might contribute to anemia,” they said.

The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Dermatology Foundation. Dr. Silverberg and his coauthors, Kerry E. Drury and Matt Schaeffer, declared no conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Children with atopic disorders are at a higher risk of anemia, which may be underrecognized in this population, and could be related to a restricted diet.

Major finding: Children with history of eczema, asthma, hay fever, or food allergy were at an increased risk of anemia, compared with children without these disorders (P less than .001 for all).

Data source: The study evaluated data on children and adolescents in the population-based U.S. National Health Interview Survey (207,007) and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (30,673 children).

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Dermatology Foundation; the authors reported no conflicts.

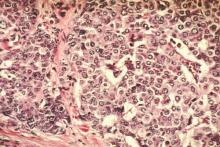

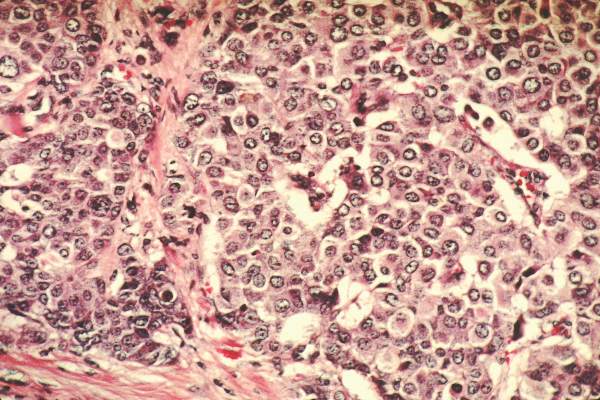

Racial differences found in neoadjuvant chemo, pCR rates for breast cancer

Chemotherapy and neoadjuvant chemotherapy are given more often to non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and Asian women than to non-Hispanic white women with breast cancer, while black women saw a lower rate of pathological complete response (pCR), according to the results of a new study.

Dr. Brigid Killelea of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and her colleagues looked at records from nearly 280,000 patients in the National Cancer Data Base who received treatment for stage I-III disease in 2010 and 2011.

In the cohort as a whole, 46% of women received chemotherapy, and, among the majority of patients for whom information on the timing of chemotherapy was available, 23% received neoadjuvant therapy, with non-white women receiving chemotherapy and neoadjuvant chemotherapy more frequently (P less than .001). This could mainly be explained by the advanced age, higher-grade tumors and a larger share of triple-negative and human epidermal growth factor receptor–positive tumors in the non-white women, the investigators said (J Clin Oncol. 2015 Nov. 23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.7801).

Of about 18,000 patients in the cohort with known outcomes, 33% had a pathological complete response, Dr. Killelea and her colleagues found. Black women in the study had a lower rate of pCR, compared with white women for estrogen receptor/progesterone receptor–negative, human epidermal growth factor receptor2–positive tumors (43% vs. 54%, P = .001) and for triple-negative tumors (37% vs. 43%, P less than .001) despite adjustment for a large number of clinical and socioeconomic factors. Racial disparities in breast cancer incidence, treatment, and survival have been long reported, and racial disparities in neoadjuvant chemotherapy are important to measure, the investigators wrote, as neoadjuvant chemotherapy allows for initiation of systemic therapy before surgery in patients with locally advanced and/or node-positive disease, among other potential advantages. Meanwhile, pCR has been shown in recent years to be a key prognostic indicator for certain breast cancer subtypes and therefore is also important to measure with regard to race. Dr. Killelea and colleagues concluded that the reasons for the lower pCR rates seen among black women in the study could not be determined, and may involve differences in treatment, chemosensitivity, or socioeconomic factors that they could not control for, but that warranted investigation in future studies. “One hypothesis is that the lower pCR rate reflects undertreatment,” the investigators wrote in their analysis. “Women who were unable to complete chemotherapy or had dose reduction, treatment delays, or less-aggressive chemotherapy regimens would be less likely to have a pCR.”

Chemotherapy and neoadjuvant chemotherapy are given more often to non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and Asian women than to non-Hispanic white women with breast cancer, while black women saw a lower rate of pathological complete response (pCR), according to the results of a new study.

Dr. Brigid Killelea of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and her colleagues looked at records from nearly 280,000 patients in the National Cancer Data Base who received treatment for stage I-III disease in 2010 and 2011.

In the cohort as a whole, 46% of women received chemotherapy, and, among the majority of patients for whom information on the timing of chemotherapy was available, 23% received neoadjuvant therapy, with non-white women receiving chemotherapy and neoadjuvant chemotherapy more frequently (P less than .001). This could mainly be explained by the advanced age, higher-grade tumors and a larger share of triple-negative and human epidermal growth factor receptor–positive tumors in the non-white women, the investigators said (J Clin Oncol. 2015 Nov. 23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.7801).

Of about 18,000 patients in the cohort with known outcomes, 33% had a pathological complete response, Dr. Killelea and her colleagues found. Black women in the study had a lower rate of pCR, compared with white women for estrogen receptor/progesterone receptor–negative, human epidermal growth factor receptor2–positive tumors (43% vs. 54%, P = .001) and for triple-negative tumors (37% vs. 43%, P less than .001) despite adjustment for a large number of clinical and socioeconomic factors. Racial disparities in breast cancer incidence, treatment, and survival have been long reported, and racial disparities in neoadjuvant chemotherapy are important to measure, the investigators wrote, as neoadjuvant chemotherapy allows for initiation of systemic therapy before surgery in patients with locally advanced and/or node-positive disease, among other potential advantages. Meanwhile, pCR has been shown in recent years to be a key prognostic indicator for certain breast cancer subtypes and therefore is also important to measure with regard to race. Dr. Killelea and colleagues concluded that the reasons for the lower pCR rates seen among black women in the study could not be determined, and may involve differences in treatment, chemosensitivity, or socioeconomic factors that they could not control for, but that warranted investigation in future studies. “One hypothesis is that the lower pCR rate reflects undertreatment,” the investigators wrote in their analysis. “Women who were unable to complete chemotherapy or had dose reduction, treatment delays, or less-aggressive chemotherapy regimens would be less likely to have a pCR.”

Chemotherapy and neoadjuvant chemotherapy are given more often to non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and Asian women than to non-Hispanic white women with breast cancer, while black women saw a lower rate of pathological complete response (pCR), according to the results of a new study.

Dr. Brigid Killelea of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and her colleagues looked at records from nearly 280,000 patients in the National Cancer Data Base who received treatment for stage I-III disease in 2010 and 2011.

In the cohort as a whole, 46% of women received chemotherapy, and, among the majority of patients for whom information on the timing of chemotherapy was available, 23% received neoadjuvant therapy, with non-white women receiving chemotherapy and neoadjuvant chemotherapy more frequently (P less than .001). This could mainly be explained by the advanced age, higher-grade tumors and a larger share of triple-negative and human epidermal growth factor receptor–positive tumors in the non-white women, the investigators said (J Clin Oncol. 2015 Nov. 23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.7801).

Of about 18,000 patients in the cohort with known outcomes, 33% had a pathological complete response, Dr. Killelea and her colleagues found. Black women in the study had a lower rate of pCR, compared with white women for estrogen receptor/progesterone receptor–negative, human epidermal growth factor receptor2–positive tumors (43% vs. 54%, P = .001) and for triple-negative tumors (37% vs. 43%, P less than .001) despite adjustment for a large number of clinical and socioeconomic factors. Racial disparities in breast cancer incidence, treatment, and survival have been long reported, and racial disparities in neoadjuvant chemotherapy are important to measure, the investigators wrote, as neoadjuvant chemotherapy allows for initiation of systemic therapy before surgery in patients with locally advanced and/or node-positive disease, among other potential advantages. Meanwhile, pCR has been shown in recent years to be a key prognostic indicator for certain breast cancer subtypes and therefore is also important to measure with regard to race. Dr. Killelea and colleagues concluded that the reasons for the lower pCR rates seen among black women in the study could not be determined, and may involve differences in treatment, chemosensitivity, or socioeconomic factors that they could not control for, but that warranted investigation in future studies. “One hypothesis is that the lower pCR rate reflects undertreatment,” the investigators wrote in their analysis. “Women who were unable to complete chemotherapy or had dose reduction, treatment delays, or less-aggressive chemotherapy regimens would be less likely to have a pCR.”

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Non-white Hispanic, Asian, and black women are likelier to receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy than are white women for breast cancers, while black women had lower rates of pathological complete response, compared with white women for some types of cancers.

Major finding: Black women had a lower rate of pCR than did white women for ER/PR-negative, HER2-positive (43% vs. 54%; P = .001) and triple-negative tumors (37% vs. 43%; P less than .001).

Data source: 278,815 women identified in the National Cancer Database diagnosed with stage I-III breast cancer in 2010 and 2011, for whom ethnicity was recorded.

Disclosures: Two authors disclosed relationships with various pharma companies, while the majority reported no relationships to disclose.

No racial disparity in appropriate use of Oncotype DX

Black women with node-positive breast cancer were less likely to receive tumor gene profiling for treatment decision making compared with women of other ethnicities, according to a new study. However, black women who were node negative were just as likely to receive the test as were other women, suggesting that testing protocols for black women are kept closer to guidelines than for other groups.

The genetic test, known as Oncotype DX (ODX), came into wide use a decade ago as a chemotherapy decision-making tool for patients with estrogen receptor–positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2–negative breast cancer, stage I or II, with tumors of 0.5 cm or larger. Current guidelines used by public and private insurers, including Medicare, incorporate ODX testing for these patients who are node negative. Still, there is some evidence suggesting a role for ODX for women with up to three positive nodes, and one major clinical trial is underway to determine whether ODX testing is helpful in these patients.

Megan C. Roberts, Ph.D., of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and her colleagues, looked at data for 1,468 women (609 black) from the population-based, phase III Carolina Breast Cancer Study.

Overall in the cohort, 42% of women received ODX testing, and no racial disparities were seen in the likelihood of ODX testing in node-negative women. For patients with node-positive disease, black women were 46% less likely to receive ODX testing than were nonblack women (adjusted risk ratio 0.54, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.84; P = .006).

“Current medical guidelines do not recommend ODX testing in patients with node-positive, early-stage, ER+ breast cancer,” Dr. Roberts and colleagues wrote in their analysis (J Clin Oncol. 2015 Nov 23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.2489).

“Therefore, lower rates of ODX testing among black women in our sample reflect their receipt of more guideline-concordant care than nonblack women with node-positive breast cancer. Thus, differential receipt of ODX testing does not necessarily reflect a racial disparity in the quality of care. This paradox illustrates challenges that will accompany the measurement of disparities in the early adoption of new genetic technologies into clinical practice,” the researchers wrote.

They noted as a study limitations the fact that patient preferences regarding ODX could not be accounted for, and that previous studies have suggested these could differ by race.

Black women with node-positive breast cancer were less likely to receive tumor gene profiling for treatment decision making compared with women of other ethnicities, according to a new study. However, black women who were node negative were just as likely to receive the test as were other women, suggesting that testing protocols for black women are kept closer to guidelines than for other groups.

The genetic test, known as Oncotype DX (ODX), came into wide use a decade ago as a chemotherapy decision-making tool for patients with estrogen receptor–positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2–negative breast cancer, stage I or II, with tumors of 0.5 cm or larger. Current guidelines used by public and private insurers, including Medicare, incorporate ODX testing for these patients who are node negative. Still, there is some evidence suggesting a role for ODX for women with up to three positive nodes, and one major clinical trial is underway to determine whether ODX testing is helpful in these patients.

Megan C. Roberts, Ph.D., of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and her colleagues, looked at data for 1,468 women (609 black) from the population-based, phase III Carolina Breast Cancer Study.

Overall in the cohort, 42% of women received ODX testing, and no racial disparities were seen in the likelihood of ODX testing in node-negative women. For patients with node-positive disease, black women were 46% less likely to receive ODX testing than were nonblack women (adjusted risk ratio 0.54, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.84; P = .006).

“Current medical guidelines do not recommend ODX testing in patients with node-positive, early-stage, ER+ breast cancer,” Dr. Roberts and colleagues wrote in their analysis (J Clin Oncol. 2015 Nov 23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.2489).

“Therefore, lower rates of ODX testing among black women in our sample reflect their receipt of more guideline-concordant care than nonblack women with node-positive breast cancer. Thus, differential receipt of ODX testing does not necessarily reflect a racial disparity in the quality of care. This paradox illustrates challenges that will accompany the measurement of disparities in the early adoption of new genetic technologies into clinical practice,” the researchers wrote.

They noted as a study limitations the fact that patient preferences regarding ODX could not be accounted for, and that previous studies have suggested these could differ by race.

Black women with node-positive breast cancer were less likely to receive tumor gene profiling for treatment decision making compared with women of other ethnicities, according to a new study. However, black women who were node negative were just as likely to receive the test as were other women, suggesting that testing protocols for black women are kept closer to guidelines than for other groups.

The genetic test, known as Oncotype DX (ODX), came into wide use a decade ago as a chemotherapy decision-making tool for patients with estrogen receptor–positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2–negative breast cancer, stage I or II, with tumors of 0.5 cm or larger. Current guidelines used by public and private insurers, including Medicare, incorporate ODX testing for these patients who are node negative. Still, there is some evidence suggesting a role for ODX for women with up to three positive nodes, and one major clinical trial is underway to determine whether ODX testing is helpful in these patients.

Megan C. Roberts, Ph.D., of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and her colleagues, looked at data for 1,468 women (609 black) from the population-based, phase III Carolina Breast Cancer Study.

Overall in the cohort, 42% of women received ODX testing, and no racial disparities were seen in the likelihood of ODX testing in node-negative women. For patients with node-positive disease, black women were 46% less likely to receive ODX testing than were nonblack women (adjusted risk ratio 0.54, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.84; P = .006).

“Current medical guidelines do not recommend ODX testing in patients with node-positive, early-stage, ER+ breast cancer,” Dr. Roberts and colleagues wrote in their analysis (J Clin Oncol. 2015 Nov 23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.2489).

“Therefore, lower rates of ODX testing among black women in our sample reflect their receipt of more guideline-concordant care than nonblack women with node-positive breast cancer. Thus, differential receipt of ODX testing does not necessarily reflect a racial disparity in the quality of care. This paradox illustrates challenges that will accompany the measurement of disparities in the early adoption of new genetic technologies into clinical practice,” the researchers wrote.

They noted as a study limitations the fact that patient preferences regarding ODX could not be accounted for, and that previous studies have suggested these could differ by race.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: ODX testing is more likely to be administered to nonblack women with node-positive disease than to black women.

Major finding: Black patients with node-positive tumors were 46% less likely to receive ODX testing than were nonblack women (adjusted RR 0.54; 95% CI, 0.35 to 0.84; P = .006).

Data source: Review of data from nearly 1,500 patients from a longitudinal population-based study of 3,000 women with breast cancer in North Carolina, diagnosed from 2008 to 2014.

Disclosures: One author disclosed a consultancy with Salix. All other authors reported no conflicts.

rTMS Investigated in Autism Spectrum Disorder

SAN ANTONIO– Results from a pilot randomized double-blind trial suggest that repetitive transcranial stimulation, or rTMS, a technology currently approved to treat depression that is being investigated in a range of psychiatric disorders, might be a viable treatment strategy to improve executive function in young people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

The findings were presented by Dr. Stephanie Ameis of the Campbell Family Mental Health Research Institute in Toronto at the annual meeting American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Impairments in executive function are common among higher functioning people with ASD. Previous studies have found executive function impairments to have common neurobiologic underpinnings. No studies to date have investigated rTMS on executive function in autism, but previous research by Dr. Ameis’s colleague and coauthor on the study, Dr. Z. Jeff Daskalakis, found that a course of rTMS significantly improved executive function among people with schizophrenia (Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73[6]:510-7).

Dr. Ameis and her colleagues hypothesized that a similar treatment approach might be feasible in people with ASD with known executive function impairment.

The researchers randomized 18 patients aged 16-35 years to 4 weeks of rTMS (20Hz) to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex or sham treatment. All subjects were clinically stable, with an IQ greater than 70 (mean 95) and a qualifying measure of disability on the BRIEF (Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functions) assessment tool used to measure real-world impairment.

MRI and cognitive assessment were performed at baseline and 1 month after the treatment period ended. Baseline analysis of diffusion MRI indicated a trend toward a significant positive association between working memory scores on the BRIEF and white matter structures along the anterior thalamic radiation. Though white matter integrity in this part of the brain has been linked to executive function in other disorders, Dr. Ameis cautioned that the MRI findings in her study were preliminary and that it was too early to draw conclusions from them.

Mean age in the study was 23 years. Dr. Ameis said she hopes to continue to recruit a younger cohort, but that recruitment challenges led the group to expand an initial targeted age range of 16-25 years up to 35 years.

“We want to focus our intervention on the transition period to adulthood, as this is a time where effective interventions can really make an impact on individuals’ successful transition to work and school as young adults.”

The goal, Dr. Ameis said, “is to see if rTMS is feasible for this particular indication or treatment target, and so it’s the first study that’s really used a rigorous sham study design for this indication. We’re seeing whether people are interested and able to tolerate the 4-week protocol, as well as the other aspects of our study and secondarily, whether we are changing things with regard to [executive function].”

The protocol was well tolerated, the researchers found, with the time commitment – about 30 minutes a day, 5 days a week – being the biggest demand on subjects. rTMS was associated with no adverse effects except headaches around treatment times.

The pilot study established tolerability and feasibility in this patient group, Dr. Ameis said. Now the investigators will measure differences in executive function after a second year of recruitment to double the current sample size.

Dr. Ameis reported no conflicts of interest related to the findings. A coauthor on the study, Dr. Paul E. Croarkin, reported funding from Pfizer, and study supplies and genotyping from Assurex. Dr. Daskalakis acknowledged funding from Neuronetics.

SAN ANTONIO– Results from a pilot randomized double-blind trial suggest that repetitive transcranial stimulation, or rTMS, a technology currently approved to treat depression that is being investigated in a range of psychiatric disorders, might be a viable treatment strategy to improve executive function in young people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

The findings were presented by Dr. Stephanie Ameis of the Campbell Family Mental Health Research Institute in Toronto at the annual meeting American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Impairments in executive function are common among higher functioning people with ASD. Previous studies have found executive function impairments to have common neurobiologic underpinnings. No studies to date have investigated rTMS on executive function in autism, but previous research by Dr. Ameis’s colleague and coauthor on the study, Dr. Z. Jeff Daskalakis, found that a course of rTMS significantly improved executive function among people with schizophrenia (Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73[6]:510-7).

Dr. Ameis and her colleagues hypothesized that a similar treatment approach might be feasible in people with ASD with known executive function impairment.

The researchers randomized 18 patients aged 16-35 years to 4 weeks of rTMS (20Hz) to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex or sham treatment. All subjects were clinically stable, with an IQ greater than 70 (mean 95) and a qualifying measure of disability on the BRIEF (Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functions) assessment tool used to measure real-world impairment.

MRI and cognitive assessment were performed at baseline and 1 month after the treatment period ended. Baseline analysis of diffusion MRI indicated a trend toward a significant positive association between working memory scores on the BRIEF and white matter structures along the anterior thalamic radiation. Though white matter integrity in this part of the brain has been linked to executive function in other disorders, Dr. Ameis cautioned that the MRI findings in her study were preliminary and that it was too early to draw conclusions from them.

Mean age in the study was 23 years. Dr. Ameis said she hopes to continue to recruit a younger cohort, but that recruitment challenges led the group to expand an initial targeted age range of 16-25 years up to 35 years.

“We want to focus our intervention on the transition period to adulthood, as this is a time where effective interventions can really make an impact on individuals’ successful transition to work and school as young adults.”

The goal, Dr. Ameis said, “is to see if rTMS is feasible for this particular indication or treatment target, and so it’s the first study that’s really used a rigorous sham study design for this indication. We’re seeing whether people are interested and able to tolerate the 4-week protocol, as well as the other aspects of our study and secondarily, whether we are changing things with regard to [executive function].”

The protocol was well tolerated, the researchers found, with the time commitment – about 30 minutes a day, 5 days a week – being the biggest demand on subjects. rTMS was associated with no adverse effects except headaches around treatment times.

The pilot study established tolerability and feasibility in this patient group, Dr. Ameis said. Now the investigators will measure differences in executive function after a second year of recruitment to double the current sample size.

Dr. Ameis reported no conflicts of interest related to the findings. A coauthor on the study, Dr. Paul E. Croarkin, reported funding from Pfizer, and study supplies and genotyping from Assurex. Dr. Daskalakis acknowledged funding from Neuronetics.

SAN ANTONIO– Results from a pilot randomized double-blind trial suggest that repetitive transcranial stimulation, or rTMS, a technology currently approved to treat depression that is being investigated in a range of psychiatric disorders, might be a viable treatment strategy to improve executive function in young people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

The findings were presented by Dr. Stephanie Ameis of the Campbell Family Mental Health Research Institute in Toronto at the annual meeting American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Impairments in executive function are common among higher functioning people with ASD. Previous studies have found executive function impairments to have common neurobiologic underpinnings. No studies to date have investigated rTMS on executive function in autism, but previous research by Dr. Ameis’s colleague and coauthor on the study, Dr. Z. Jeff Daskalakis, found that a course of rTMS significantly improved executive function among people with schizophrenia (Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73[6]:510-7).

Dr. Ameis and her colleagues hypothesized that a similar treatment approach might be feasible in people with ASD with known executive function impairment.

The researchers randomized 18 patients aged 16-35 years to 4 weeks of rTMS (20Hz) to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex or sham treatment. All subjects were clinically stable, with an IQ greater than 70 (mean 95) and a qualifying measure of disability on the BRIEF (Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functions) assessment tool used to measure real-world impairment.

MRI and cognitive assessment were performed at baseline and 1 month after the treatment period ended. Baseline analysis of diffusion MRI indicated a trend toward a significant positive association between working memory scores on the BRIEF and white matter structures along the anterior thalamic radiation. Though white matter integrity in this part of the brain has been linked to executive function in other disorders, Dr. Ameis cautioned that the MRI findings in her study were preliminary and that it was too early to draw conclusions from them.

Mean age in the study was 23 years. Dr. Ameis said she hopes to continue to recruit a younger cohort, but that recruitment challenges led the group to expand an initial targeted age range of 16-25 years up to 35 years.

“We want to focus our intervention on the transition period to adulthood, as this is a time where effective interventions can really make an impact on individuals’ successful transition to work and school as young adults.”

The goal, Dr. Ameis said, “is to see if rTMS is feasible for this particular indication or treatment target, and so it’s the first study that’s really used a rigorous sham study design for this indication. We’re seeing whether people are interested and able to tolerate the 4-week protocol, as well as the other aspects of our study and secondarily, whether we are changing things with regard to [executive function].”

The protocol was well tolerated, the researchers found, with the time commitment – about 30 minutes a day, 5 days a week – being the biggest demand on subjects. rTMS was associated with no adverse effects except headaches around treatment times.

The pilot study established tolerability and feasibility in this patient group, Dr. Ameis said. Now the investigators will measure differences in executive function after a second year of recruitment to double the current sample size.

Dr. Ameis reported no conflicts of interest related to the findings. A coauthor on the study, Dr. Paul E. Croarkin, reported funding from Pfizer, and study supplies and genotyping from Assurex. Dr. Daskalakis acknowledged funding from Neuronetics.

AT THE AACAP ANNUAL MEETING

rTMS investigated in autism spectrum disorder

SAN ANTONIO– Results from a pilot randomized double-blind trial suggest that repetitive transcranial stimulation, or rTMS, a technology currently approved to treat depression that is being investigated in a range of psychiatric disorders, might be a viable treatment strategy to improve executive function in young people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

The findings were presented by Dr. Stephanie Ameis of the Campbell Family Mental Health Research Institute in Toronto at the annual meeting American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Impairments in executive function are common among higher functioning people with ASD. Previous studies have found executive function impairments to have common neurobiologic underpinnings. No studies to date have investigated rTMS on executive function in autism, but previous research by Dr. Ameis’s colleague and coauthor on the study, Dr. Z. Jeff Daskalakis, found that a course of rTMS significantly improved executive function among people with schizophrenia (Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73[6]:510-7).

Dr. Ameis and her colleagues hypothesized that a similar treatment approach might be feasible in people with ASD with known executive function impairment.

The researchers randomized 18 patients aged 16-35 years to 4 weeks of rTMS (20Hz) to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex or sham treatment. All subjects were clinically stable, with an IQ greater than 70 (mean 95) and a qualifying measure of disability on the BRIEF (Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functions) assessment tool used to measure real-world impairment.

MRI and cognitive assessment were performed at baseline and 1 month after the treatment period ended. Baseline analysis of diffusion MRI indicated a trend toward a significant positive association between working memory scores on the BRIEF and white matter structures along the anterior thalamic radiation. Though white matter integrity in this part of the brain has been linked to executive function in other disorders, Dr. Ameis cautioned that the MRI findings in her study were preliminary and that it was too early to draw conclusions from them.

Mean age in the study was 23 years. Dr. Ameis said she hopes to continue to recruit a younger cohort, but that recruitment challenges led the group to expand an initial targeted age range of 16-25 years up to 35 years.

“We want to focus our intervention on the transition period to adulthood, as this is a time where effective interventions can really make an impact on individuals’ successful transition to work and school as young adults.”

The goal, Dr. Ameis said, “is to see if rTMS is feasible for this particular indication or treatment target, and so it’s the first study that’s really used a rigorous sham study design for this indication. We’re seeing whether people are interested and able to tolerate the 4-week protocol, as well as the other aspects of our study and secondarily, whether we are changing things with regard to [executive function].”

The protocol was well tolerated, the researchers found, with the time commitment – about 30 minutes a day, 5 days a week – being the biggest demand on subjects. rTMS was associated with no adverse effects except headaches around treatment times.

The pilot study established tolerability and feasibility in this patient group, Dr. Ameis said. Now the investigators will measure differences in executive function after a second year of recruitment to double the current sample size.

Dr. Ameis reported no conflicts of interest related to the findings. A coauthor on the study, Dr. Paul E. Croarkin, reported funding from Pfizer, and study supplies and genotyping from Assurex. Dr. Daskalakis acknowledged funding from Neuronetics.

SAN ANTONIO– Results from a pilot randomized double-blind trial suggest that repetitive transcranial stimulation, or rTMS, a technology currently approved to treat depression that is being investigated in a range of psychiatric disorders, might be a viable treatment strategy to improve executive function in young people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

The findings were presented by Dr. Stephanie Ameis of the Campbell Family Mental Health Research Institute in Toronto at the annual meeting American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Impairments in executive function are common among higher functioning people with ASD. Previous studies have found executive function impairments to have common neurobiologic underpinnings. No studies to date have investigated rTMS on executive function in autism, but previous research by Dr. Ameis’s colleague and coauthor on the study, Dr. Z. Jeff Daskalakis, found that a course of rTMS significantly improved executive function among people with schizophrenia (Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73[6]:510-7).

Dr. Ameis and her colleagues hypothesized that a similar treatment approach might be feasible in people with ASD with known executive function impairment.

The researchers randomized 18 patients aged 16-35 years to 4 weeks of rTMS (20Hz) to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex or sham treatment. All subjects were clinically stable, with an IQ greater than 70 (mean 95) and a qualifying measure of disability on the BRIEF (Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functions) assessment tool used to measure real-world impairment.

MRI and cognitive assessment were performed at baseline and 1 month after the treatment period ended. Baseline analysis of diffusion MRI indicated a trend toward a significant positive association between working memory scores on the BRIEF and white matter structures along the anterior thalamic radiation. Though white matter integrity in this part of the brain has been linked to executive function in other disorders, Dr. Ameis cautioned that the MRI findings in her study were preliminary and that it was too early to draw conclusions from them.

Mean age in the study was 23 years. Dr. Ameis said she hopes to continue to recruit a younger cohort, but that recruitment challenges led the group to expand an initial targeted age range of 16-25 years up to 35 years.

“We want to focus our intervention on the transition period to adulthood, as this is a time where effective interventions can really make an impact on individuals’ successful transition to work and school as young adults.”

The goal, Dr. Ameis said, “is to see if rTMS is feasible for this particular indication or treatment target, and so it’s the first study that’s really used a rigorous sham study design for this indication. We’re seeing whether people are interested and able to tolerate the 4-week protocol, as well as the other aspects of our study and secondarily, whether we are changing things with regard to [executive function].”

The protocol was well tolerated, the researchers found, with the time commitment – about 30 minutes a day, 5 days a week – being the biggest demand on subjects. rTMS was associated with no adverse effects except headaches around treatment times.

The pilot study established tolerability and feasibility in this patient group, Dr. Ameis said. Now the investigators will measure differences in executive function after a second year of recruitment to double the current sample size.

Dr. Ameis reported no conflicts of interest related to the findings. A coauthor on the study, Dr. Paul E. Croarkin, reported funding from Pfizer, and study supplies and genotyping from Assurex. Dr. Daskalakis acknowledged funding from Neuronetics.

SAN ANTONIO– Results from a pilot randomized double-blind trial suggest that repetitive transcranial stimulation, or rTMS, a technology currently approved to treat depression that is being investigated in a range of psychiatric disorders, might be a viable treatment strategy to improve executive function in young people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

The findings were presented by Dr. Stephanie Ameis of the Campbell Family Mental Health Research Institute in Toronto at the annual meeting American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Impairments in executive function are common among higher functioning people with ASD. Previous studies have found executive function impairments to have common neurobiologic underpinnings. No studies to date have investigated rTMS on executive function in autism, but previous research by Dr. Ameis’s colleague and coauthor on the study, Dr. Z. Jeff Daskalakis, found that a course of rTMS significantly improved executive function among people with schizophrenia (Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73[6]:510-7).

Dr. Ameis and her colleagues hypothesized that a similar treatment approach might be feasible in people with ASD with known executive function impairment.

The researchers randomized 18 patients aged 16-35 years to 4 weeks of rTMS (20Hz) to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex or sham treatment. All subjects were clinically stable, with an IQ greater than 70 (mean 95) and a qualifying measure of disability on the BRIEF (Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functions) assessment tool used to measure real-world impairment.

MRI and cognitive assessment were performed at baseline and 1 month after the treatment period ended. Baseline analysis of diffusion MRI indicated a trend toward a significant positive association between working memory scores on the BRIEF and white matter structures along the anterior thalamic radiation. Though white matter integrity in this part of the brain has been linked to executive function in other disorders, Dr. Ameis cautioned that the MRI findings in her study were preliminary and that it was too early to draw conclusions from them.

Mean age in the study was 23 years. Dr. Ameis said she hopes to continue to recruit a younger cohort, but that recruitment challenges led the group to expand an initial targeted age range of 16-25 years up to 35 years.

“We want to focus our intervention on the transition period to adulthood, as this is a time where effective interventions can really make an impact on individuals’ successful transition to work and school as young adults.”

The goal, Dr. Ameis said, “is to see if rTMS is feasible for this particular indication or treatment target, and so it’s the first study that’s really used a rigorous sham study design for this indication. We’re seeing whether people are interested and able to tolerate the 4-week protocol, as well as the other aspects of our study and secondarily, whether we are changing things with regard to [executive function].”

The protocol was well tolerated, the researchers found, with the time commitment – about 30 minutes a day, 5 days a week – being the biggest demand on subjects. rTMS was associated with no adverse effects except headaches around treatment times.

The pilot study established tolerability and feasibility in this patient group, Dr. Ameis said. Now the investigators will measure differences in executive function after a second year of recruitment to double the current sample size.

Dr. Ameis reported no conflicts of interest related to the findings. A coauthor on the study, Dr. Paul E. Croarkin, reported funding from Pfizer, and study supplies and genotyping from Assurex. Dr. Daskalakis acknowledged funding from Neuronetics.

AT THE AACAP ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: rTMS, a brain stimulation technology, might help improve executive function in older teens and young adults with autism spectrum disorder.

Major finding: rTMS can be successfully studied in autistic patients; MRI data suggest that executive function in autism might be associated with white matter patterns known to affect executive function in other disorders.

Data source: A double-blind clinical trial randomizing 18 patients with ASD to rTMS or sham treatment for 20 sessions over 4 weeks.

Disclosures: Two coauthors disclosed industry funding.

Phelan-McDermid syndrome behaviors close to those in autism

SAN ANTONIO – New models of autism research and treatment are increasingly looking to study specific genetic causes, including Phelan-McDermid syndrome.

Phelan-McDermid Syndrome, or PMS, is caused by deletion or mutation of the SHANK3 gene and is characterized by intellectual disability, delayed or absent speech, hypotonia, and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Children with PMS also often have an uneven gait and other motor difficulties.

SHANK3 deletions and mutations are thought responsible for up to 2% of ASD cases; however, aberrant behavior, such as irritability, lethargy, stereotypy, hyperactivity, and inappropriate speech have not been thoroughly investigated in PMS.

Erin Li, a 4th-year medical student, presented findings at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry from a study in children with PMS that sought to discern whether a caregiver checklist for aberrant behavior used in diagnosing ASD and intellectual disabilities could pinpoint differences in aberrant behaviors between PMS and idiopathic ASD.

The study looked at two cohorts of children, 24 with ASD caused by PMS (mean age, 7.2 years; 14 males) and 23 with idiopathic ASD (mean age, 6.4 years;15 males) using the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC) developed by Michael G. Aman, Ph.D., and his colleagues. Children in both cohorts had intellectual disability, reported Ms. Li, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

The ABC is a 58-item parent-reported checklist, and Ms. Li and her colleagues did not find significant differences in the severity of aberrant behavior between groups. The results suggest that, similar to idiopathic ASD, aberrant behavior in PMS can be measured using the ABC.

However, only genetic screening can detect PMS, Ms. Li noted in an interview. The best tool is the chromosomal microarray (CMA) test.

Ms. Li’s research was conducted at the Seaver Autism Center at Mount Sinai, a clinical research group headed by Dr. Alexander Kolevzon. The team also is investigating several treatments for children with PMS, including with insulinlike growth factor–1 (IGF-1), which was seen in a small pilot study (n = 9) to be associated with significant improvement in social impairment and restrictive behaviors (Mol Autism. 2014 Dec 12;5[1]:54).

A larger study with IGF-1 is currently underway, and the group is beginning to investigate treatment of PMS with oxytocin, after results from an animal study suggested that it could improve social deficits in mice with SHANK3 deletions.

Ms. Li and her coauthors disclosed no conflicts of interest related to their findings. The director of the Seaver Autism Center, Joseph Buxbaum, Ph.D., and Mount Sinai hold a shared patent for the use of IGF-1 in PMS.

SAN ANTONIO – New models of autism research and treatment are increasingly looking to study specific genetic causes, including Phelan-McDermid syndrome.

Phelan-McDermid Syndrome, or PMS, is caused by deletion or mutation of the SHANK3 gene and is characterized by intellectual disability, delayed or absent speech, hypotonia, and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Children with PMS also often have an uneven gait and other motor difficulties.

SHANK3 deletions and mutations are thought responsible for up to 2% of ASD cases; however, aberrant behavior, such as irritability, lethargy, stereotypy, hyperactivity, and inappropriate speech have not been thoroughly investigated in PMS.

Erin Li, a 4th-year medical student, presented findings at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry from a study in children with PMS that sought to discern whether a caregiver checklist for aberrant behavior used in diagnosing ASD and intellectual disabilities could pinpoint differences in aberrant behaviors between PMS and idiopathic ASD.

The study looked at two cohorts of children, 24 with ASD caused by PMS (mean age, 7.2 years; 14 males) and 23 with idiopathic ASD (mean age, 6.4 years;15 males) using the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC) developed by Michael G. Aman, Ph.D., and his colleagues. Children in both cohorts had intellectual disability, reported Ms. Li, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

The ABC is a 58-item parent-reported checklist, and Ms. Li and her colleagues did not find significant differences in the severity of aberrant behavior between groups. The results suggest that, similar to idiopathic ASD, aberrant behavior in PMS can be measured using the ABC.

However, only genetic screening can detect PMS, Ms. Li noted in an interview. The best tool is the chromosomal microarray (CMA) test.

Ms. Li’s research was conducted at the Seaver Autism Center at Mount Sinai, a clinical research group headed by Dr. Alexander Kolevzon. The team also is investigating several treatments for children with PMS, including with insulinlike growth factor–1 (IGF-1), which was seen in a small pilot study (n = 9) to be associated with significant improvement in social impairment and restrictive behaviors (Mol Autism. 2014 Dec 12;5[1]:54).

A larger study with IGF-1 is currently underway, and the group is beginning to investigate treatment of PMS with oxytocin, after results from an animal study suggested that it could improve social deficits in mice with SHANK3 deletions.

Ms. Li and her coauthors disclosed no conflicts of interest related to their findings. The director of the Seaver Autism Center, Joseph Buxbaum, Ph.D., and Mount Sinai hold a shared patent for the use of IGF-1 in PMS.

SAN ANTONIO – New models of autism research and treatment are increasingly looking to study specific genetic causes, including Phelan-McDermid syndrome.

Phelan-McDermid Syndrome, or PMS, is caused by deletion or mutation of the SHANK3 gene and is characterized by intellectual disability, delayed or absent speech, hypotonia, and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Children with PMS also often have an uneven gait and other motor difficulties.

SHANK3 deletions and mutations are thought responsible for up to 2% of ASD cases; however, aberrant behavior, such as irritability, lethargy, stereotypy, hyperactivity, and inappropriate speech have not been thoroughly investigated in PMS.

Erin Li, a 4th-year medical student, presented findings at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry from a study in children with PMS that sought to discern whether a caregiver checklist for aberrant behavior used in diagnosing ASD and intellectual disabilities could pinpoint differences in aberrant behaviors between PMS and idiopathic ASD.

The study looked at two cohorts of children, 24 with ASD caused by PMS (mean age, 7.2 years; 14 males) and 23 with idiopathic ASD (mean age, 6.4 years;15 males) using the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC) developed by Michael G. Aman, Ph.D., and his colleagues. Children in both cohorts had intellectual disability, reported Ms. Li, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

The ABC is a 58-item parent-reported checklist, and Ms. Li and her colleagues did not find significant differences in the severity of aberrant behavior between groups. The results suggest that, similar to idiopathic ASD, aberrant behavior in PMS can be measured using the ABC.

However, only genetic screening can detect PMS, Ms. Li noted in an interview. The best tool is the chromosomal microarray (CMA) test.

Ms. Li’s research was conducted at the Seaver Autism Center at Mount Sinai, a clinical research group headed by Dr. Alexander Kolevzon. The team also is investigating several treatments for children with PMS, including with insulinlike growth factor–1 (IGF-1), which was seen in a small pilot study (n = 9) to be associated with significant improvement in social impairment and restrictive behaviors (Mol Autism. 2014 Dec 12;5[1]:54).

A larger study with IGF-1 is currently underway, and the group is beginning to investigate treatment of PMS with oxytocin, after results from an animal study suggested that it could improve social deficits in mice with SHANK3 deletions.

Ms. Li and her coauthors disclosed no conflicts of interest related to their findings. The director of the Seaver Autism Center, Joseph Buxbaum, Ph.D., and Mount Sinai hold a shared patent for the use of IGF-1 in PMS.

AT THE AACAP MEETING

Key clinical point: Behavioral screening did not reveal significant differences between children with idiopathic autism spectrum disorder and Phelan-McDermid syndrome.

Major finding: Using a checklist of aberrant behavioral symptoms seen in iASD, no differences were seen in cohorts of PMS and iASD children with intellectual disability; however, the checklist was used successfully in minimally verbal children.

Data source: Cohorts of children with iASD (n = 23) and PMS (n = 24) matched for cognitive functioning underwent a caregiver questionnaire on irritability, lethargy, stereotypy, hyperactivity, and inappropriate speech.

Disclosures: The researchers’ institution and its director hold a patent for an investigational treatment for PMS.

Daily cookie makes no dent in ADHD diet effect

SAN ANTONIO – Though restriction and elimination diets have been studied for decades in the treatment of children with attention deficit hyperactive disorder, their therapeutic role and level of efficacy remain controversial in part because of blinding difficulties in dietary studies.

In a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry Dr. Steven Pliszka of the University of Texas Health Center in San Antonio reported that among children with ADHD on a gluten- and additive-free diet, those given a daily snack inconsistent with the prescribed diet still showed behavioral improvement over 5 weeks.

In the study, Dr. Pliszka and colleagues randomized 29 children with ADHD, ages 8-12, to a restricted diet with a daily cookie or with a snack consistent with the diet. Stimulants were the only psychotropic medications allowed in the study. “The hypothesis was that if you’re on the restriction diet and getting better, and you get a snack that has gluten in it, you ought to deteriorate,” Dr. Pliszka said in an interview. “What we thought we would see was only one group would improve, but we saw improvement across the board.” This could mean that one cookie was not enough to corrupt the beneficial effects of the diet, he said, or that something besides the diet, such as a placebo effect, was responsible for the children’s improvement.

ADHD behavioral rating scores for both groups of children improved over the course of the 5 weeks; however, neither group improved faster. Children were also screened on functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) at baseline and 5 weeks to evaluate activity in the ventral striatum related to images of high and low-calorie foods. Because not enough children were available for fMRI screening at the study’s end, Dr. Pliszka and colleagues combined the cohorts for analysis. Both groups also showed imaging evidence of increased activity in the ventral striatum, the part of the brain associated with reward response, and where activity is known to be lower in children with ADHD.

The researchers found regional activation within the ventral striatum to be significantly greater at follow-up than baseline for the cohort as a whole.

Dr. Pliszka said that the findings required more follow-up to understand.

“What we need to do for a follow-up study is get these groups to separate. If it is a low-calorie gluten free [diet], then probably we need to get the snack to be even more inconsistent than it was in this study, or give it several times a day, for example.”

If more snacks produced different results, “we could say it’s a dose-response issue. If there’s still no difference, we’d be able to say the diet’s not working. Because you give people all the bad stuff, but they think they’re getting the good stuff and they do ok, it’s clearly not the diet. “

Dr. Pliszka disclosed research support from Shire and Purdue Pharma and a consulting relationship with Ironshore Pharma. His co-authors in the study disclosed no conflicts of interest.