User login

Distinguishing Generalized Bullous Fixed Drug Eruption From SJS/TEN: A Retrospective Study on Clinical and Demographic Features

To the Editor:

Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption (GBFDE) is a rare subtype of fixed drug eruption (FDE) that manifests as widespread blisters and erosions following exposure to a causative drug.1 Diagnostic criteria include involvement of at least 3 to 6 anatomic sites—head and neck, anterior trunk, posterior trunk, upper extremities, lower extremities, or genitalia—and more than 10% of the body surface area. It can be challenging to differentiate GBFDE from severe drug rashes such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) due to extensive body surface area involvement of blisters and erosions. Specific features distinguishing GBFDE from SJS/TEN include primary lesions consisting of larger erythematous to dusky, circular plaques that progress to bullae and coalesce into widespread erosions; history of FDE; lack of severe mucosal involvement; and better overall prognosis.2 Treatment typically involves discontinuation of the culprit medication and supportive care; evidence for systemic therapies is not well established.

Our study aimed to characterize the clinical and demographic features of GBFDE in our institution to highlight potential key differences between this diagnosis and SJS/TEN. An electronic medical record search was performed to identify patients who were clinically diagnosed with GBFDE at New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center (New York, New York) in both outpatient and inpatient settings from January 2015 to December 2022. This retrospective study was approved by the Weill Cornell Medicine institutional review board (#22-05024777).

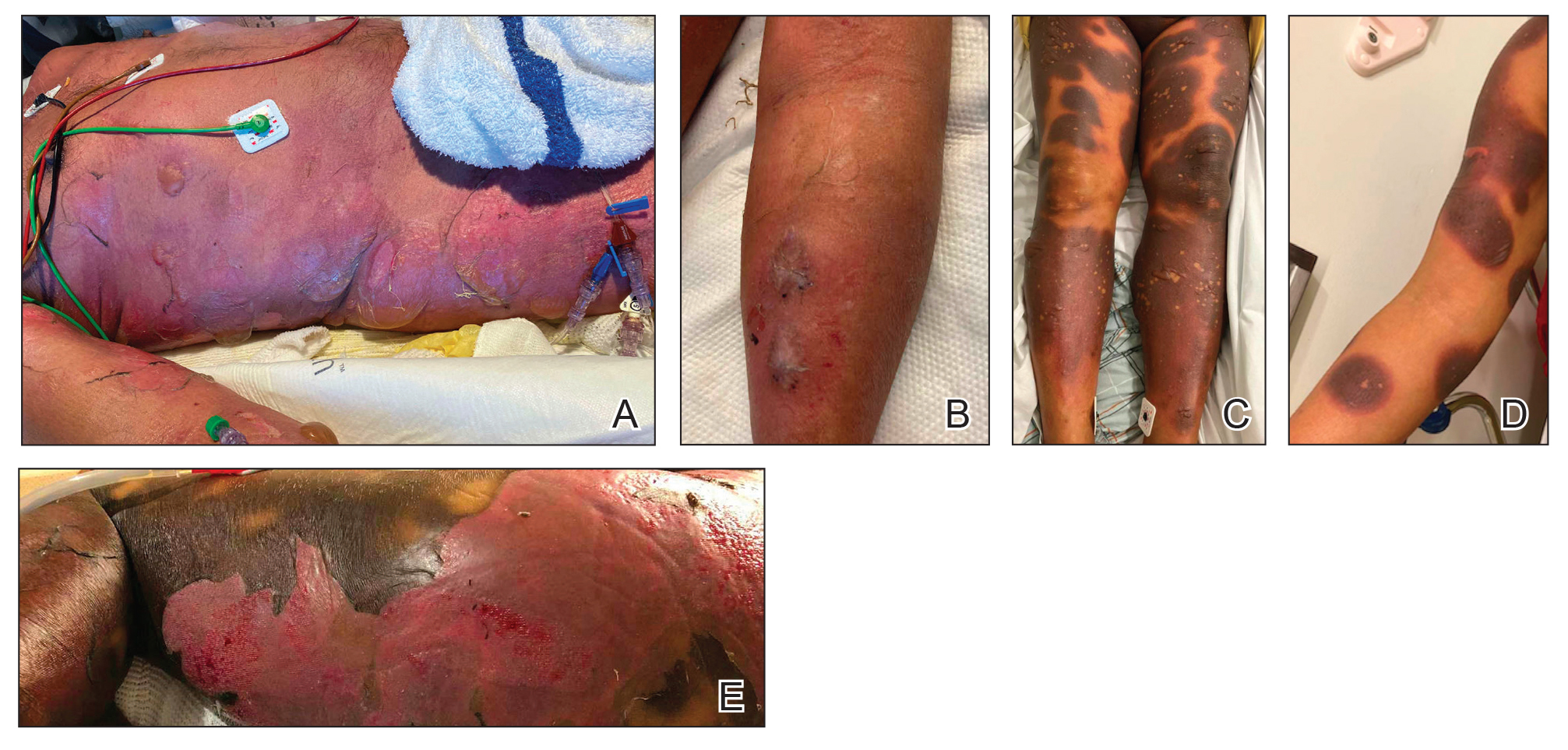

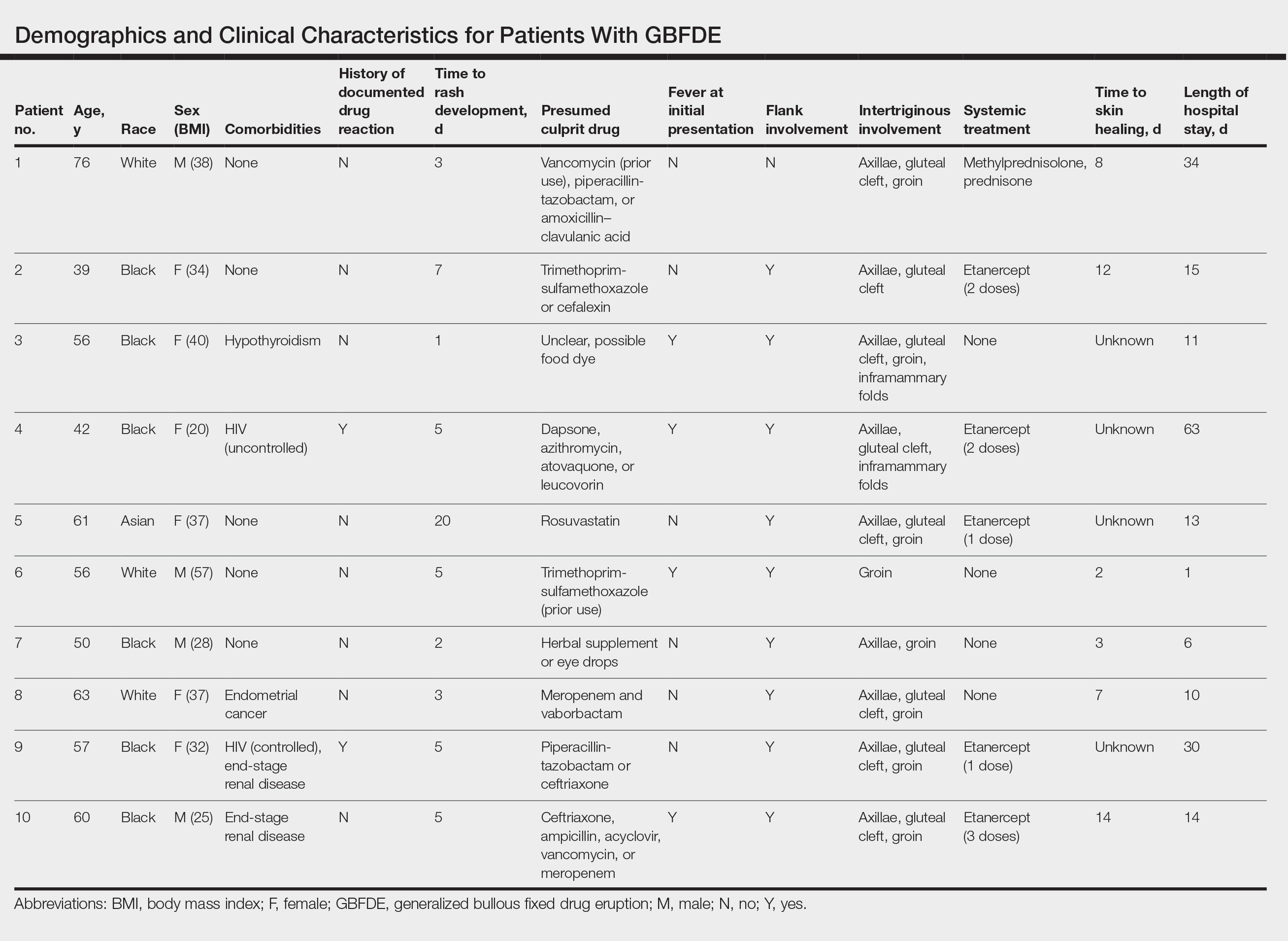

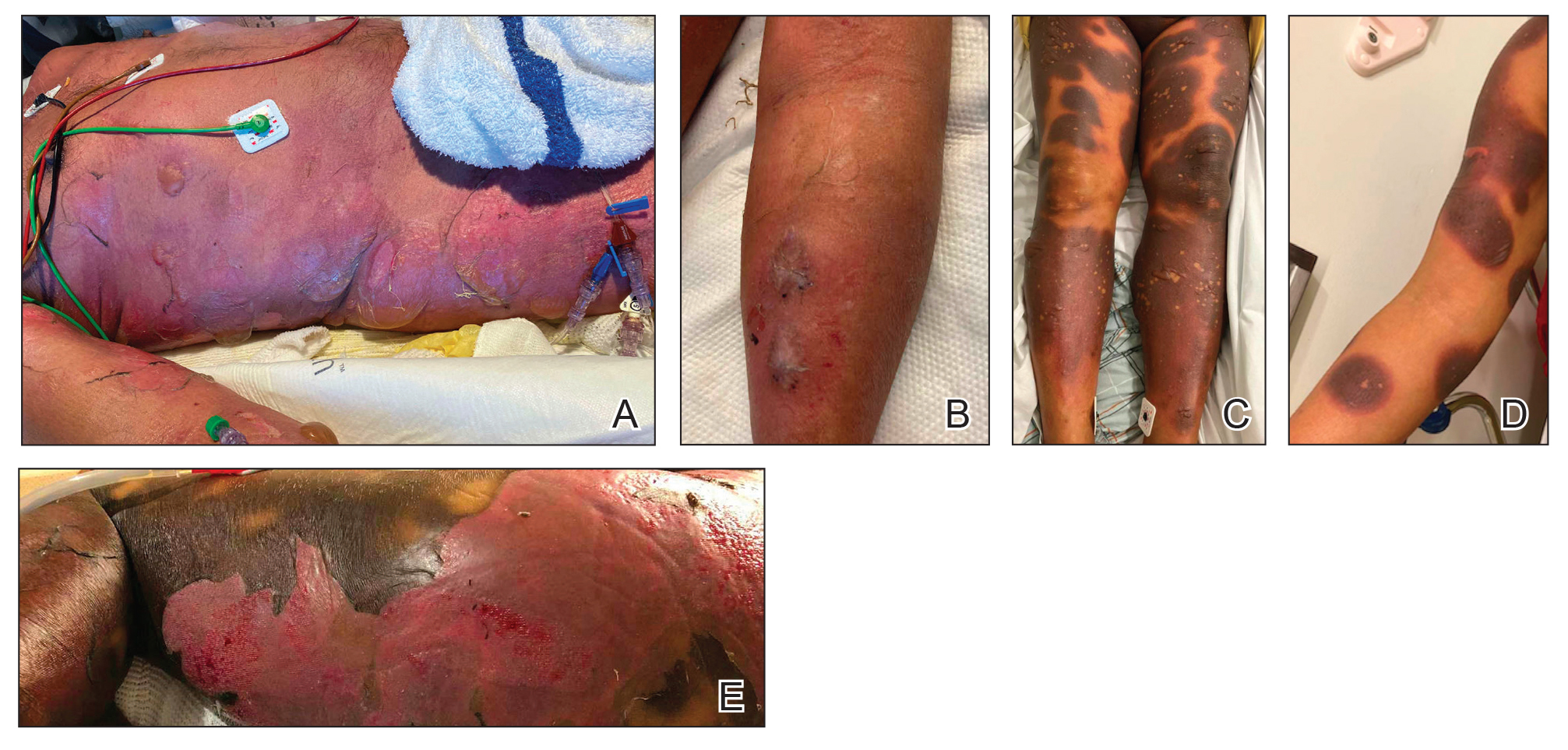

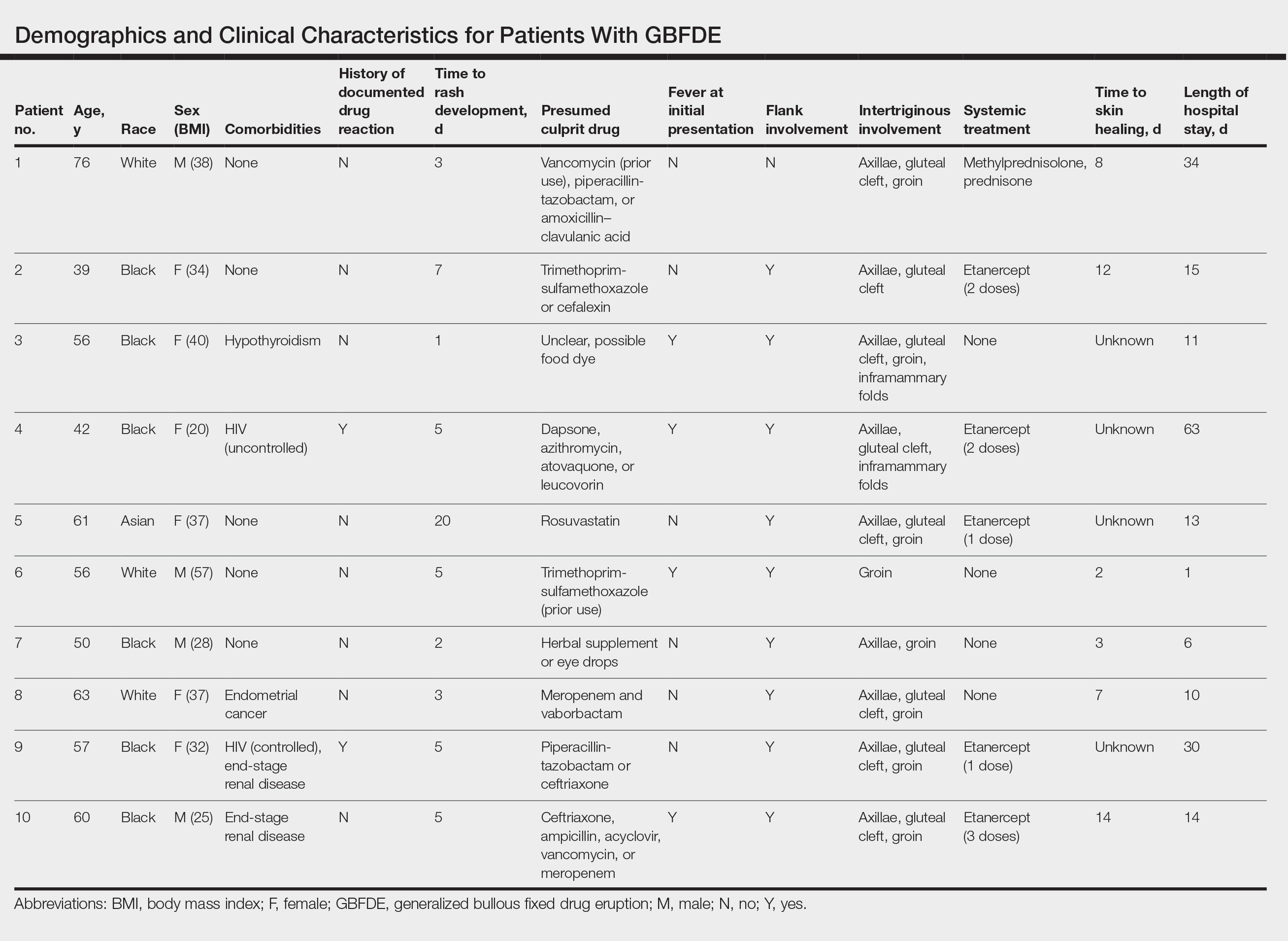

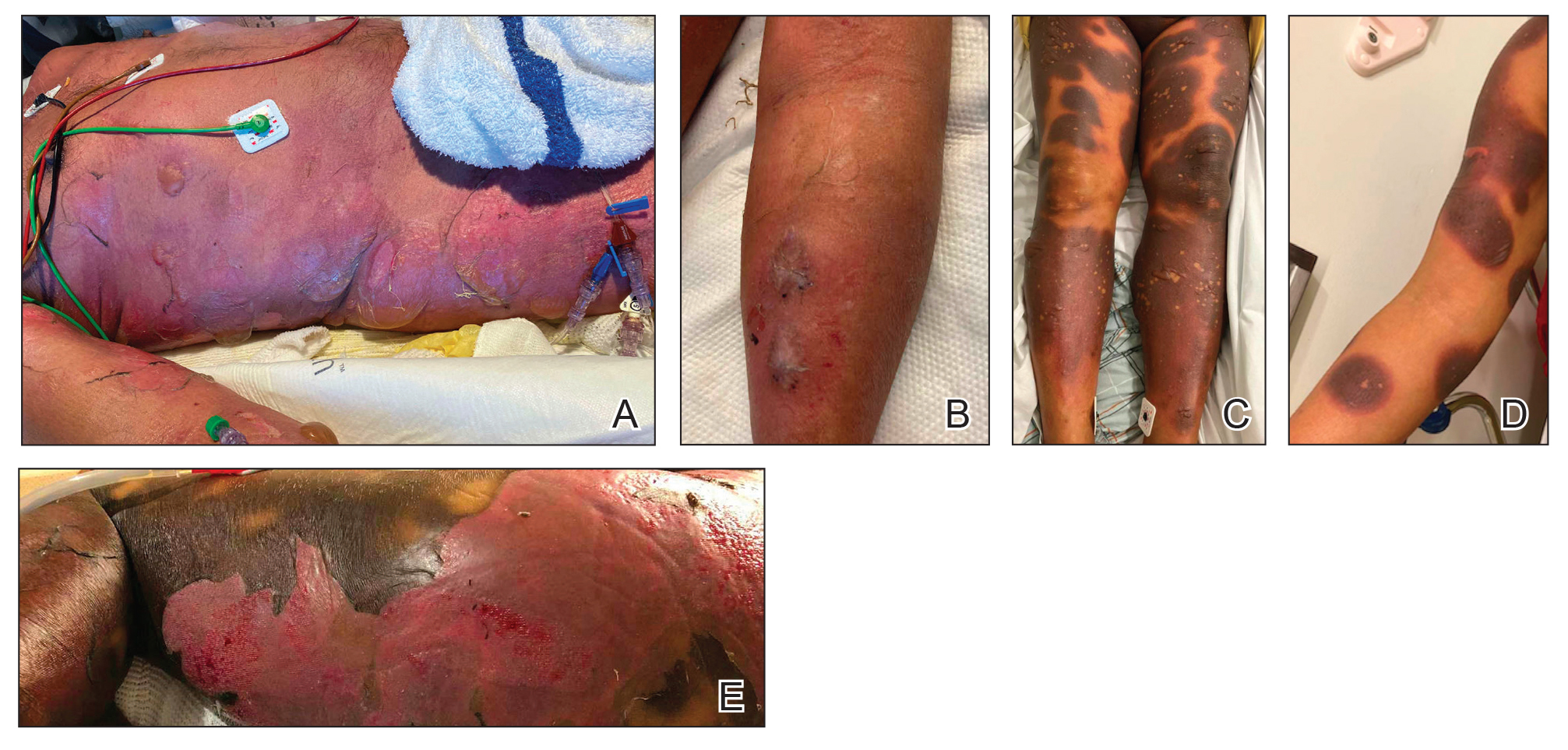

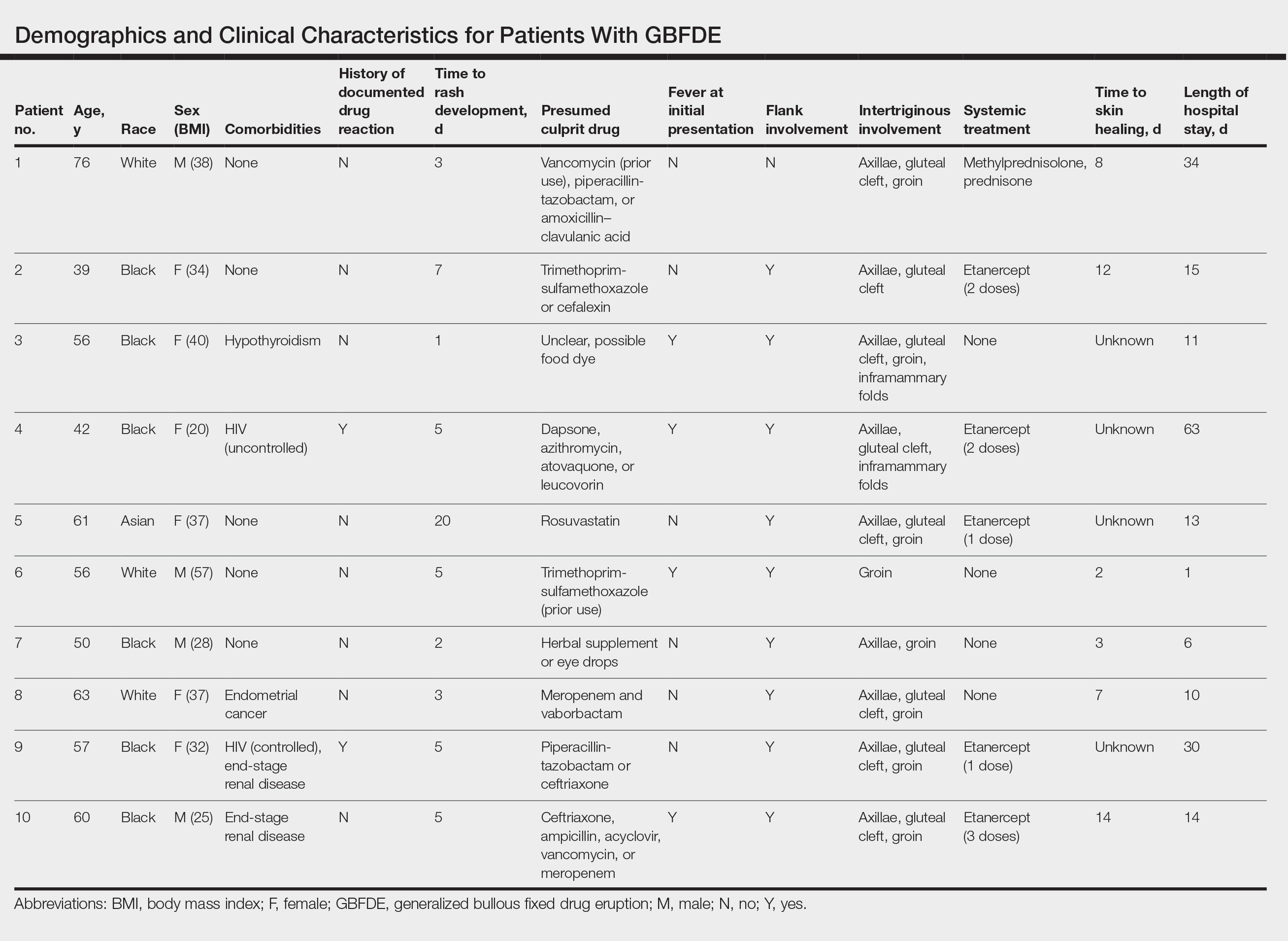

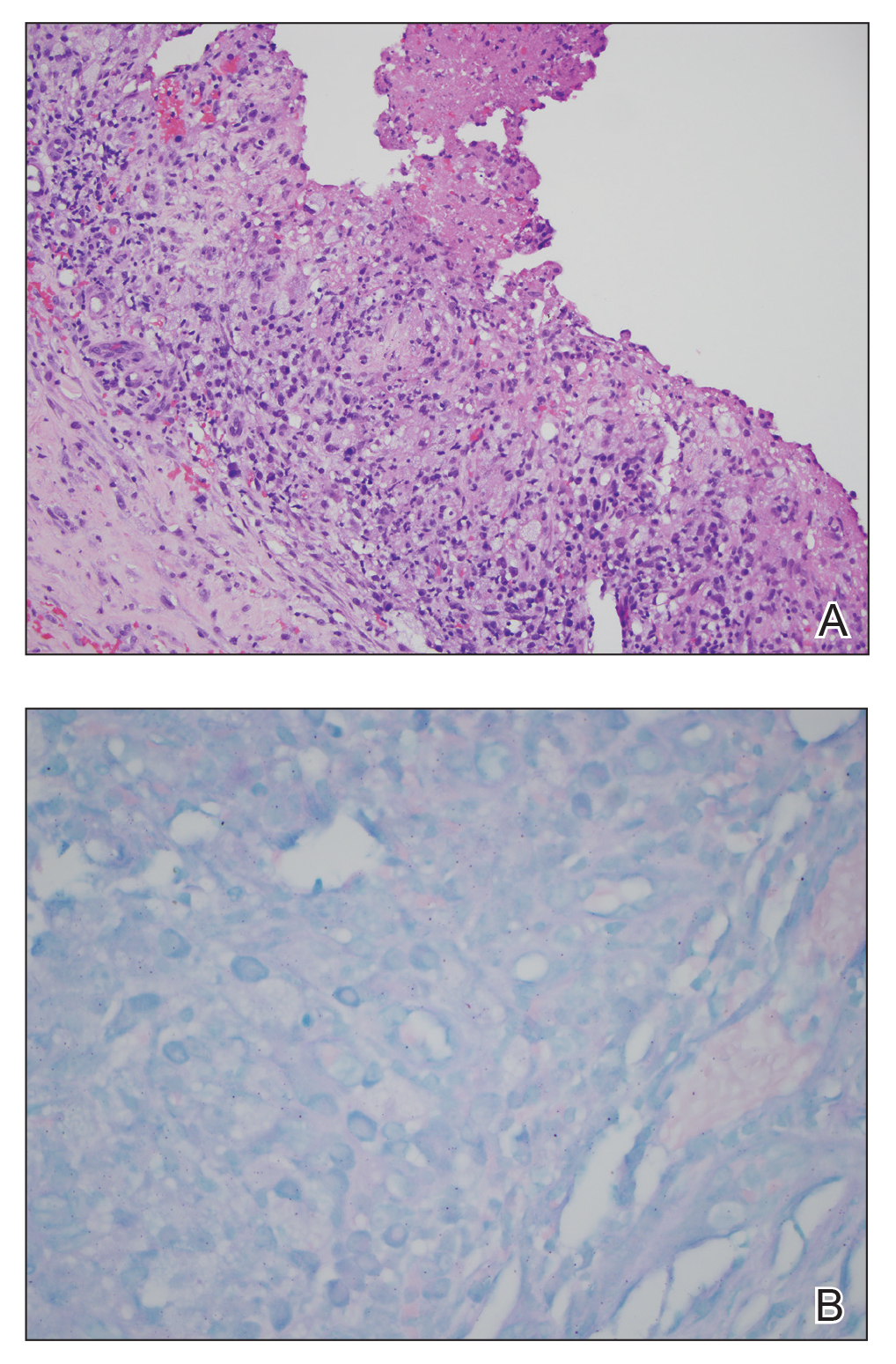

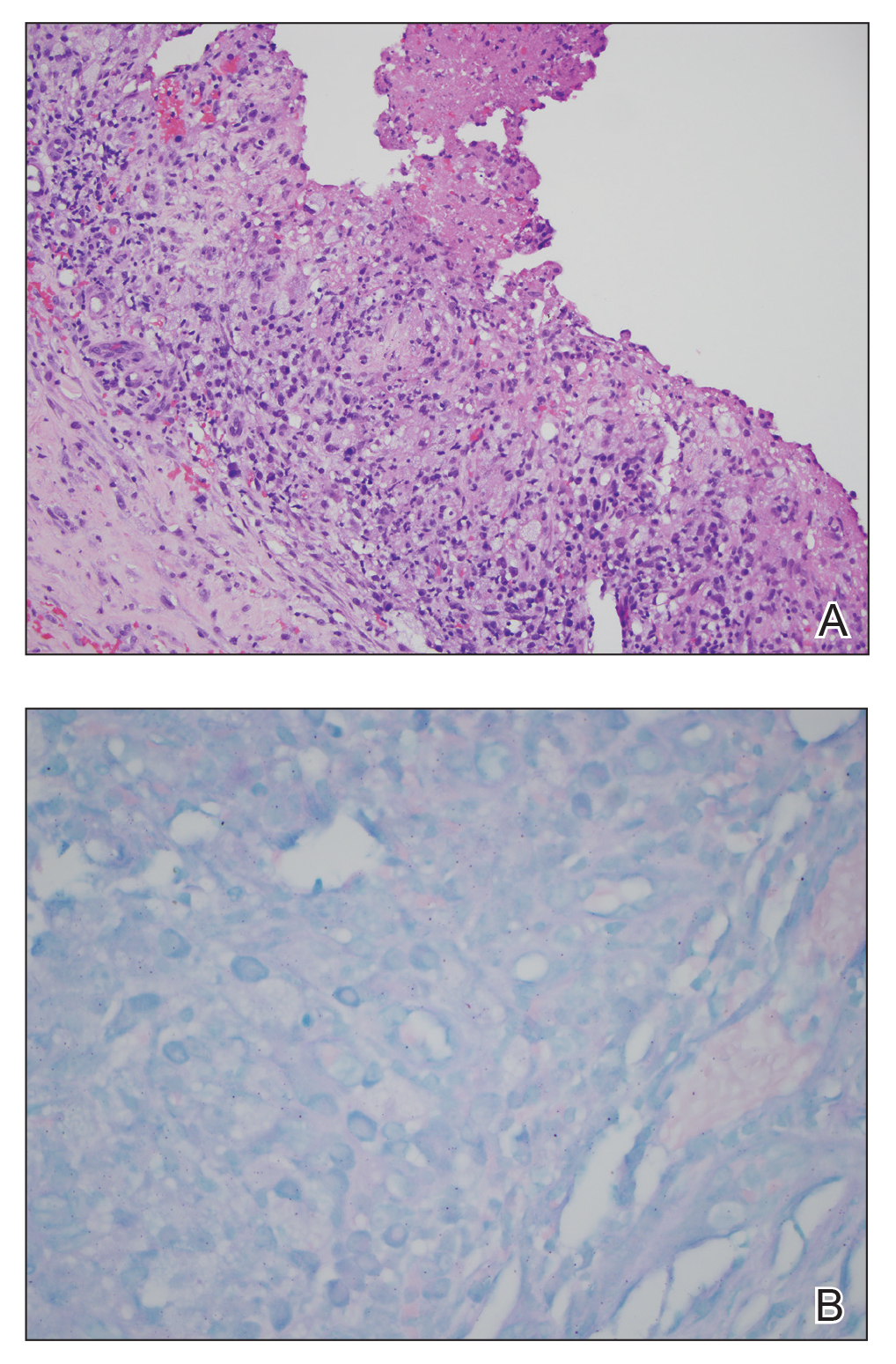

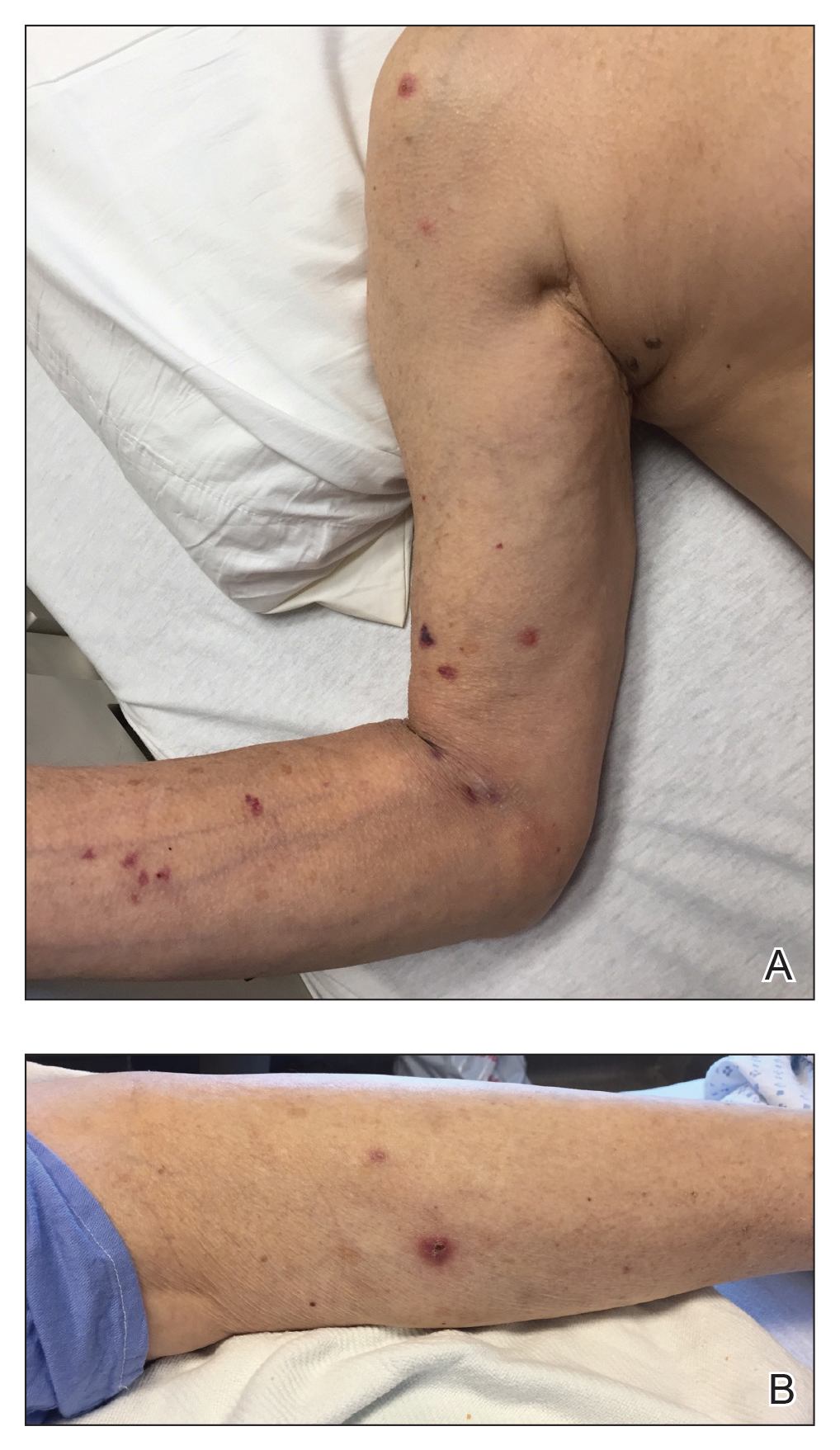

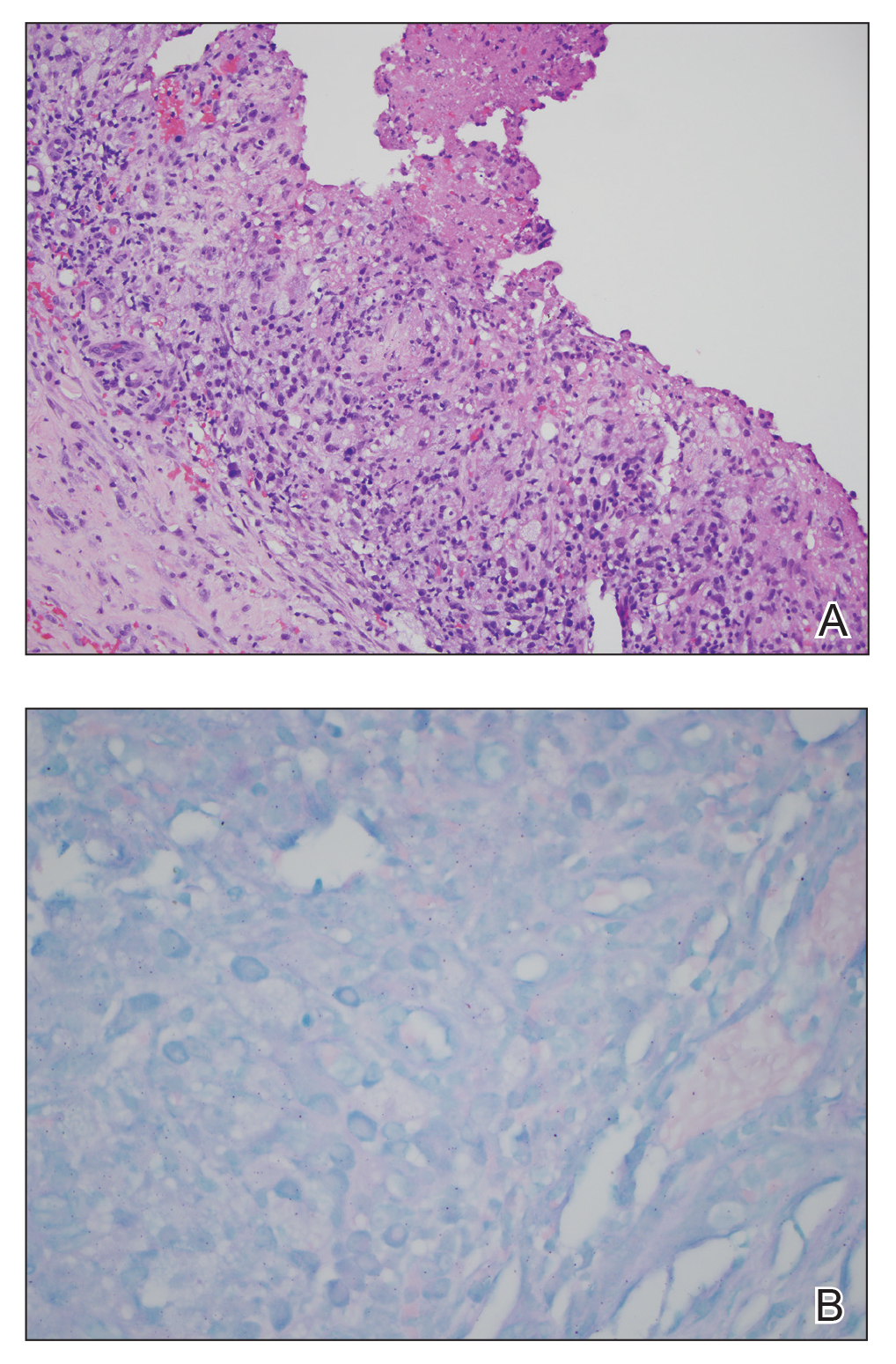

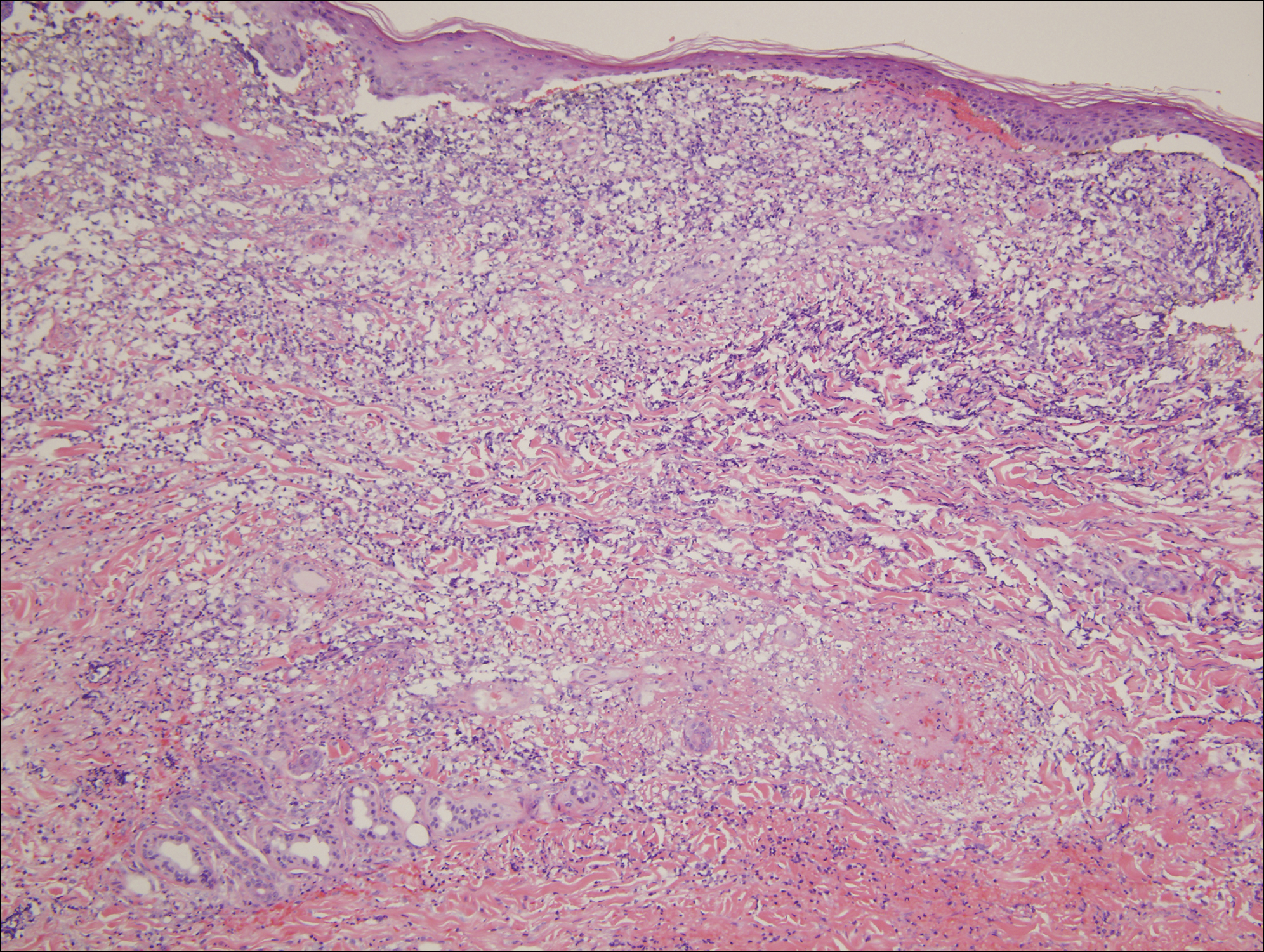

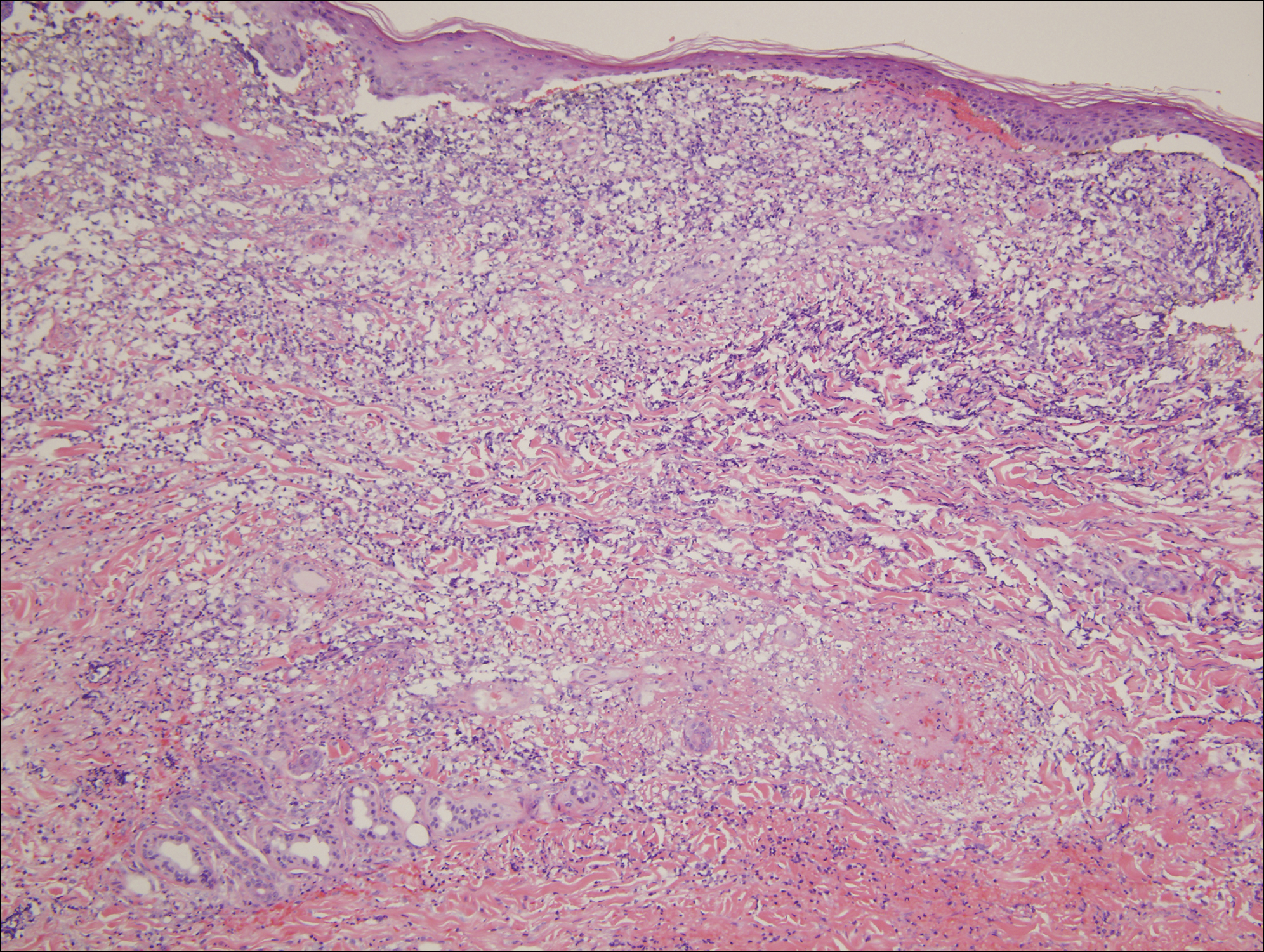

Ten patients were identified and included in the analysis (eTable). The mean age of the patients was 56 years (range, 39–76 years). Seven (70%) patients had skin of color (non-White) and 6 (60%) were female. The mean body mass index was 35 (range, 20–57), and 7 (70%) patients were clinically obese (body mass index >30). Only 2 (20%) patients had a history of a documented drug eruption (hives and erythema multiforme), and no patients had a history of FDE. Erythematous dusky patches followed by rapid development of blisters were noted within 3 days of drug initiation in 40% (4/10) and within 5 days in 80% (8/10) of patients. Antibiotics were identified as likely inciting agents in 8 (80%) patients. Biopsies were obtained in 3 (30%) patients and all 3 demonstrated cytotoxic CD8+ interface dermatitis with marked epithelial necrosis, neutrophilia, eosinophilia, and melanophage accumulation. Fever was present at initial presentation in only 4 (40%) patients, and only 1 (10%) patient had oral mucosal involvement. All 10 patients had intertriginous involvement (axillae, 90% [9/10]; gluteal cleft, 80% [8/10]; groin, 80% [8/10]; inframammary folds, 20% [2/10]), and there was considerable flank involvement in 9 (90%) patients. All 10 patients had initial erythematous to dusky, circular patches on the trunk and proximal extremities that then denuded most dramatically in the intertriginous areas (Figure). Six (60%) patients received systemic therapy, including 5 patients treated with a single dose of etanercept 50 mg. In patients with continued progression, 1 or 2 additional doses of etanercept 50 mg were administered at 48- to 72-hour intervals until blistering halted. Treatment with etanercept resulted in clinical improvement in all 5 patients, and there were no identifiable adverse events. The mean hospital stay was 19.7 days (range, 1–63 days).

This study highlights notable demographic and clinical features of GBFDE that have not been widely described in the literature. Large erythematous and dusky patches with broad zones of blistering with particular localization to the neck, intertriginous areas, and flanks typically are not described in SJS/TEN and may be helpful in distinguishing these conditions from GBFDE. Mild or complete lack of mucosal and facial involvement as well as more rapid time from drug initiation to rash (as rapid as 1 day) were key factors that aided in distinguishing GBFDE from SJS/TEN in our patients. Although a history of FDE is considered a key characteristic in the diagnosis of GBFDE, none of our patients had a known history of FDE, suggesting GBFDE may be the initial manifestation of FDE in some patients. Histopathology showed similar findings consistent with FDE in the 3 patients in whom a biopsy was performed. The remaining patients were diagnosed clinically based on the presence of distinctive, perfectly circular, dusky plaques present at the periphery of larger denuded areas, which are characteristic of GBFDE. Lower levels of serum granulysin3 have been shown to help distinguish GBFDE from SJS/TEN, but this test is not readily available with time-sensitive results at most institutions, and exact diagnostic ranges for GBFDE vs SJS/TEN are not yet known.

Our study was limited by a small number of patients at a single institution. Another limitation was the retrospective design.

Interestingly, a high proportion of our patients were non-White and clinically obese, which are factors that should be considered for future research. Sixty percent (6/10) of the patients in our study were Black, which is a notable difference from our hospital’s general admission demographics with Black individuals constituting 12% of patients.4 Our study also highlighted the utility of etanercept, which has reported mortality benefits and decreased time to re-epithelialization in other severe blistering cutaneous drug reactions including SJS/TEN,5 as a potential therapeutic option in GBFDE.

It is imperative that clinicians recognize the differences between GBFDE and SJS/TEN, as correct diagnosis is crucial for identifying the most likely causative drug as well as providing accurate prognostic information and may have future therapeutic implications as we further understand the immunologic profiles of these severe blistering drug reactions.

- Patel S, John AM, Handler MZ, et al. Fixed drug eruptions: an update, emphasizing the potentially lethal generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:393-399. doi:10.1007/s40257-020-00505-3

- Anderson HJ, Lee JB. A review of fixed drug eruption with a special focus on generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:925. doi:10.3390/medicina57090925

- Cho YT, Lin JW, Chen YC, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption is distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis by immunohistopathological features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:539-548. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.015

- Tran T, Shapiro A. New York-Presbyterian 2022 Health Equity Report. New York-Presbyterian; 2023. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://nyp.widen.net/s/jqfbrvrf9p/dalio-center-2022-health-equity-report

- Dreyer SD, Torres J, Stoddard M, et al. Efficacy of etanercept in the treatment of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Cutis. 2021;107:E22-E28. doi:10.12788/cutis.0288

To the Editor:

Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption (GBFDE) is a rare subtype of fixed drug eruption (FDE) that manifests as widespread blisters and erosions following exposure to a causative drug.1 Diagnostic criteria include involvement of at least 3 to 6 anatomic sites—head and neck, anterior trunk, posterior trunk, upper extremities, lower extremities, or genitalia—and more than 10% of the body surface area. It can be challenging to differentiate GBFDE from severe drug rashes such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) due to extensive body surface area involvement of blisters and erosions. Specific features distinguishing GBFDE from SJS/TEN include primary lesions consisting of larger erythematous to dusky, circular plaques that progress to bullae and coalesce into widespread erosions; history of FDE; lack of severe mucosal involvement; and better overall prognosis.2 Treatment typically involves discontinuation of the culprit medication and supportive care; evidence for systemic therapies is not well established.

Our study aimed to characterize the clinical and demographic features of GBFDE in our institution to highlight potential key differences between this diagnosis and SJS/TEN. An electronic medical record search was performed to identify patients who were clinically diagnosed with GBFDE at New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center (New York, New York) in both outpatient and inpatient settings from January 2015 to December 2022. This retrospective study was approved by the Weill Cornell Medicine institutional review board (#22-05024777).

Ten patients were identified and included in the analysis (eTable). The mean age of the patients was 56 years (range, 39–76 years). Seven (70%) patients had skin of color (non-White) and 6 (60%) were female. The mean body mass index was 35 (range, 20–57), and 7 (70%) patients were clinically obese (body mass index >30). Only 2 (20%) patients had a history of a documented drug eruption (hives and erythema multiforme), and no patients had a history of FDE. Erythematous dusky patches followed by rapid development of blisters were noted within 3 days of drug initiation in 40% (4/10) and within 5 days in 80% (8/10) of patients. Antibiotics were identified as likely inciting agents in 8 (80%) patients. Biopsies were obtained in 3 (30%) patients and all 3 demonstrated cytotoxic CD8+ interface dermatitis with marked epithelial necrosis, neutrophilia, eosinophilia, and melanophage accumulation. Fever was present at initial presentation in only 4 (40%) patients, and only 1 (10%) patient had oral mucosal involvement. All 10 patients had intertriginous involvement (axillae, 90% [9/10]; gluteal cleft, 80% [8/10]; groin, 80% [8/10]; inframammary folds, 20% [2/10]), and there was considerable flank involvement in 9 (90%) patients. All 10 patients had initial erythematous to dusky, circular patches on the trunk and proximal extremities that then denuded most dramatically in the intertriginous areas (Figure). Six (60%) patients received systemic therapy, including 5 patients treated with a single dose of etanercept 50 mg. In patients with continued progression, 1 or 2 additional doses of etanercept 50 mg were administered at 48- to 72-hour intervals until blistering halted. Treatment with etanercept resulted in clinical improvement in all 5 patients, and there were no identifiable adverse events. The mean hospital stay was 19.7 days (range, 1–63 days).

This study highlights notable demographic and clinical features of GBFDE that have not been widely described in the literature. Large erythematous and dusky patches with broad zones of blistering with particular localization to the neck, intertriginous areas, and flanks typically are not described in SJS/TEN and may be helpful in distinguishing these conditions from GBFDE. Mild or complete lack of mucosal and facial involvement as well as more rapid time from drug initiation to rash (as rapid as 1 day) were key factors that aided in distinguishing GBFDE from SJS/TEN in our patients. Although a history of FDE is considered a key characteristic in the diagnosis of GBFDE, none of our patients had a known history of FDE, suggesting GBFDE may be the initial manifestation of FDE in some patients. Histopathology showed similar findings consistent with FDE in the 3 patients in whom a biopsy was performed. The remaining patients were diagnosed clinically based on the presence of distinctive, perfectly circular, dusky plaques present at the periphery of larger denuded areas, which are characteristic of GBFDE. Lower levels of serum granulysin3 have been shown to help distinguish GBFDE from SJS/TEN, but this test is not readily available with time-sensitive results at most institutions, and exact diagnostic ranges for GBFDE vs SJS/TEN are not yet known.

Our study was limited by a small number of patients at a single institution. Another limitation was the retrospective design.

Interestingly, a high proportion of our patients were non-White and clinically obese, which are factors that should be considered for future research. Sixty percent (6/10) of the patients in our study were Black, which is a notable difference from our hospital’s general admission demographics with Black individuals constituting 12% of patients.4 Our study also highlighted the utility of etanercept, which has reported mortality benefits and decreased time to re-epithelialization in other severe blistering cutaneous drug reactions including SJS/TEN,5 as a potential therapeutic option in GBFDE.

It is imperative that clinicians recognize the differences between GBFDE and SJS/TEN, as correct diagnosis is crucial for identifying the most likely causative drug as well as providing accurate prognostic information and may have future therapeutic implications as we further understand the immunologic profiles of these severe blistering drug reactions.

To the Editor:

Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption (GBFDE) is a rare subtype of fixed drug eruption (FDE) that manifests as widespread blisters and erosions following exposure to a causative drug.1 Diagnostic criteria include involvement of at least 3 to 6 anatomic sites—head and neck, anterior trunk, posterior trunk, upper extremities, lower extremities, or genitalia—and more than 10% of the body surface area. It can be challenging to differentiate GBFDE from severe drug rashes such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) due to extensive body surface area involvement of blisters and erosions. Specific features distinguishing GBFDE from SJS/TEN include primary lesions consisting of larger erythematous to dusky, circular plaques that progress to bullae and coalesce into widespread erosions; history of FDE; lack of severe mucosal involvement; and better overall prognosis.2 Treatment typically involves discontinuation of the culprit medication and supportive care; evidence for systemic therapies is not well established.

Our study aimed to characterize the clinical and demographic features of GBFDE in our institution to highlight potential key differences between this diagnosis and SJS/TEN. An electronic medical record search was performed to identify patients who were clinically diagnosed with GBFDE at New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center (New York, New York) in both outpatient and inpatient settings from January 2015 to December 2022. This retrospective study was approved by the Weill Cornell Medicine institutional review board (#22-05024777).

Ten patients were identified and included in the analysis (eTable). The mean age of the patients was 56 years (range, 39–76 years). Seven (70%) patients had skin of color (non-White) and 6 (60%) were female. The mean body mass index was 35 (range, 20–57), and 7 (70%) patients were clinically obese (body mass index >30). Only 2 (20%) patients had a history of a documented drug eruption (hives and erythema multiforme), and no patients had a history of FDE. Erythematous dusky patches followed by rapid development of blisters were noted within 3 days of drug initiation in 40% (4/10) and within 5 days in 80% (8/10) of patients. Antibiotics were identified as likely inciting agents in 8 (80%) patients. Biopsies were obtained in 3 (30%) patients and all 3 demonstrated cytotoxic CD8+ interface dermatitis with marked epithelial necrosis, neutrophilia, eosinophilia, and melanophage accumulation. Fever was present at initial presentation in only 4 (40%) patients, and only 1 (10%) patient had oral mucosal involvement. All 10 patients had intertriginous involvement (axillae, 90% [9/10]; gluteal cleft, 80% [8/10]; groin, 80% [8/10]; inframammary folds, 20% [2/10]), and there was considerable flank involvement in 9 (90%) patients. All 10 patients had initial erythematous to dusky, circular patches on the trunk and proximal extremities that then denuded most dramatically in the intertriginous areas (Figure). Six (60%) patients received systemic therapy, including 5 patients treated with a single dose of etanercept 50 mg. In patients with continued progression, 1 or 2 additional doses of etanercept 50 mg were administered at 48- to 72-hour intervals until blistering halted. Treatment with etanercept resulted in clinical improvement in all 5 patients, and there were no identifiable adverse events. The mean hospital stay was 19.7 days (range, 1–63 days).

This study highlights notable demographic and clinical features of GBFDE that have not been widely described in the literature. Large erythematous and dusky patches with broad zones of blistering with particular localization to the neck, intertriginous areas, and flanks typically are not described in SJS/TEN and may be helpful in distinguishing these conditions from GBFDE. Mild or complete lack of mucosal and facial involvement as well as more rapid time from drug initiation to rash (as rapid as 1 day) were key factors that aided in distinguishing GBFDE from SJS/TEN in our patients. Although a history of FDE is considered a key characteristic in the diagnosis of GBFDE, none of our patients had a known history of FDE, suggesting GBFDE may be the initial manifestation of FDE in some patients. Histopathology showed similar findings consistent with FDE in the 3 patients in whom a biopsy was performed. The remaining patients were diagnosed clinically based on the presence of distinctive, perfectly circular, dusky plaques present at the periphery of larger denuded areas, which are characteristic of GBFDE. Lower levels of serum granulysin3 have been shown to help distinguish GBFDE from SJS/TEN, but this test is not readily available with time-sensitive results at most institutions, and exact diagnostic ranges for GBFDE vs SJS/TEN are not yet known.

Our study was limited by a small number of patients at a single institution. Another limitation was the retrospective design.

Interestingly, a high proportion of our patients were non-White and clinically obese, which are factors that should be considered for future research. Sixty percent (6/10) of the patients in our study were Black, which is a notable difference from our hospital’s general admission demographics with Black individuals constituting 12% of patients.4 Our study also highlighted the utility of etanercept, which has reported mortality benefits and decreased time to re-epithelialization in other severe blistering cutaneous drug reactions including SJS/TEN,5 as a potential therapeutic option in GBFDE.

It is imperative that clinicians recognize the differences between GBFDE and SJS/TEN, as correct diagnosis is crucial for identifying the most likely causative drug as well as providing accurate prognostic information and may have future therapeutic implications as we further understand the immunologic profiles of these severe blistering drug reactions.

- Patel S, John AM, Handler MZ, et al. Fixed drug eruptions: an update, emphasizing the potentially lethal generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:393-399. doi:10.1007/s40257-020-00505-3

- Anderson HJ, Lee JB. A review of fixed drug eruption with a special focus on generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:925. doi:10.3390/medicina57090925

- Cho YT, Lin JW, Chen YC, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption is distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis by immunohistopathological features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:539-548. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.015

- Tran T, Shapiro A. New York-Presbyterian 2022 Health Equity Report. New York-Presbyterian; 2023. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://nyp.widen.net/s/jqfbrvrf9p/dalio-center-2022-health-equity-report

- Dreyer SD, Torres J, Stoddard M, et al. Efficacy of etanercept in the treatment of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Cutis. 2021;107:E22-E28. doi:10.12788/cutis.0288

- Patel S, John AM, Handler MZ, et al. Fixed drug eruptions: an update, emphasizing the potentially lethal generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:393-399. doi:10.1007/s40257-020-00505-3

- Anderson HJ, Lee JB. A review of fixed drug eruption with a special focus on generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:925. doi:10.3390/medicina57090925

- Cho YT, Lin JW, Chen YC, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption is distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis by immunohistopathological features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:539-548. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.015

- Tran T, Shapiro A. New York-Presbyterian 2022 Health Equity Report. New York-Presbyterian; 2023. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://nyp.widen.net/s/jqfbrvrf9p/dalio-center-2022-health-equity-report

- Dreyer SD, Torres J, Stoddard M, et al. Efficacy of etanercept in the treatment of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Cutis. 2021;107:E22-E28. doi:10.12788/cutis.0288

PRACTICE POINTS

- Distinguishing features of generalized bullous fixed

drug eruption (GBFDE) may include truncal and proximal predilection with early intertriginous blistering. - Etanercept is a viable treatment option for GBFDE.

Retiform Purpura on the Buttocks in 6 Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients

To the Editor:

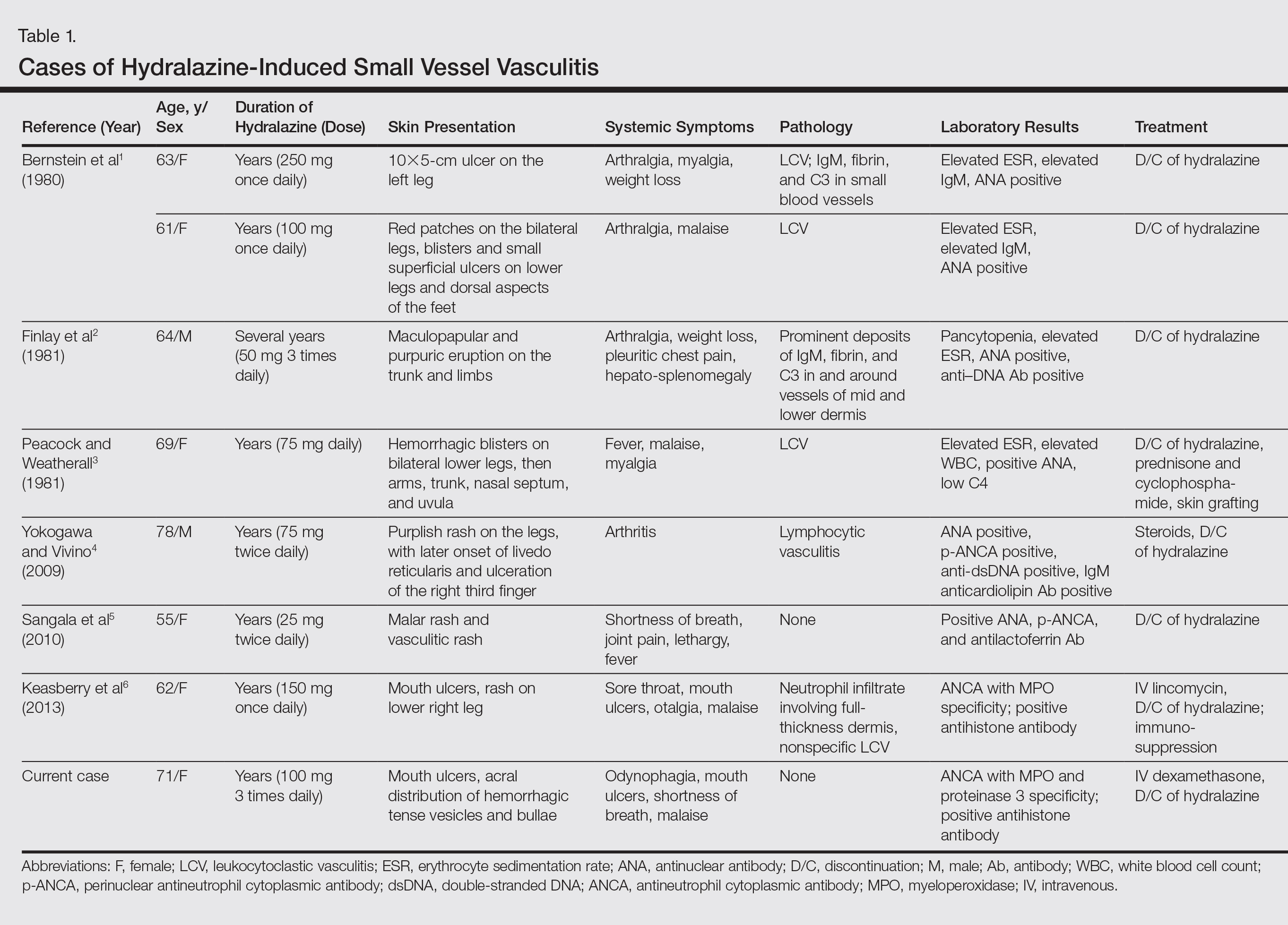

There is emerging evidence of skin findings in patients with COVID-19, including perniolike changes of the toes as well as urticarial and vesicular eruptions.1 Magro et al2 reported 3 cases of livedoid and purpuric skin eruptions in critically ill COVID-19 patients with evidence of thrombotic vasculopathy on skin biopsy, including a 32-year-old man with striking buttocks retiform purpura. Histopathologic analysis revealed thrombotic vasculopathy and pressure-induced ischemic necrosis. Since that patient was first evaluated (March 2020), we identified 6 more cases of critically ill COVID-19 patients from a single academic hospital in New York City with essentially identical clinical findings. Herein, we report those 6 cases of critically ill and intubated patients with COVID-19 who developed retiform purpura on the buttocks only, approximately 11 to 21 days after onset of COVID-19 symptoms.

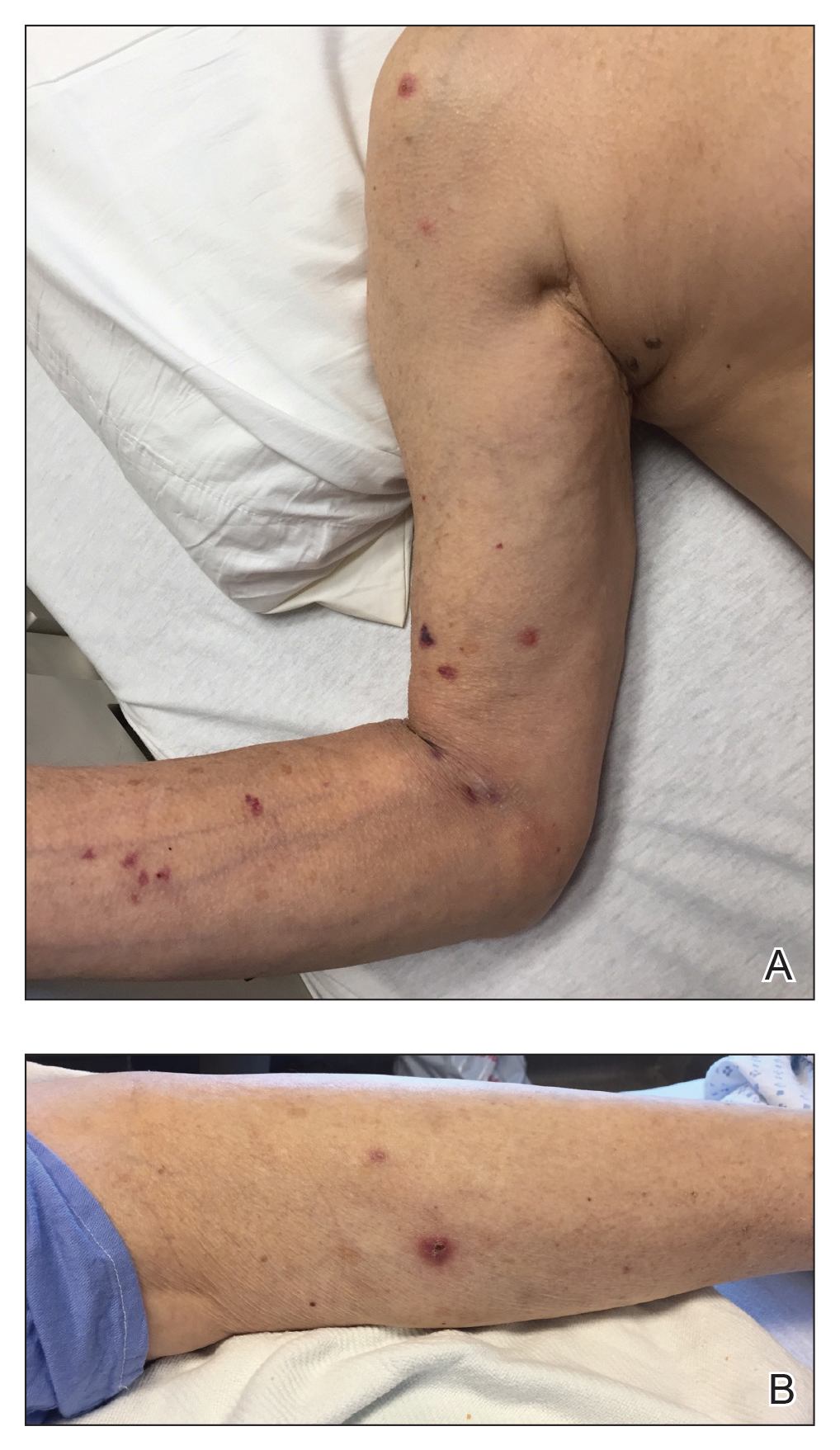

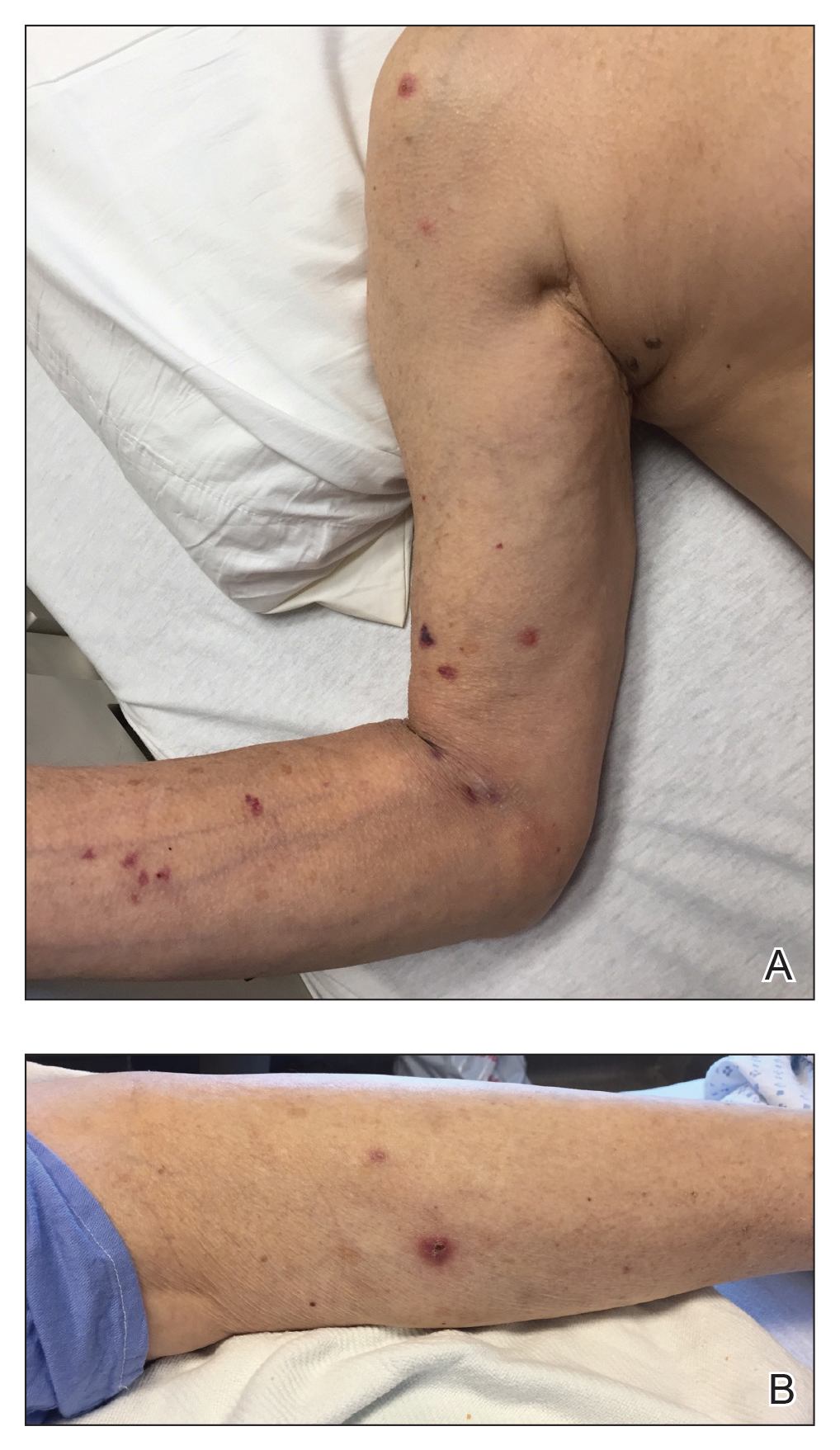

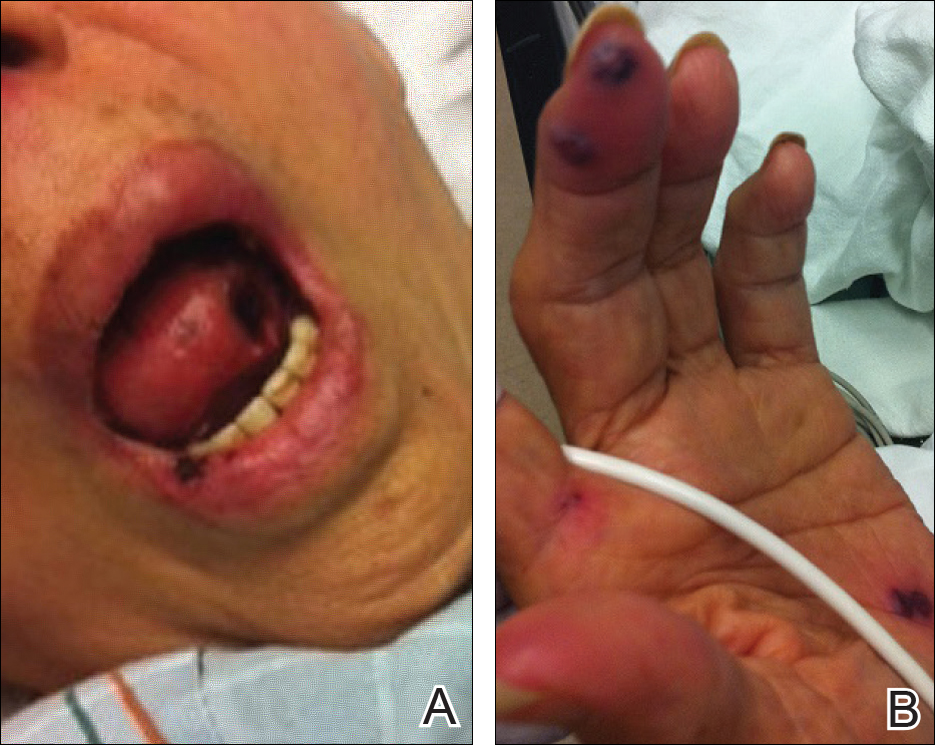

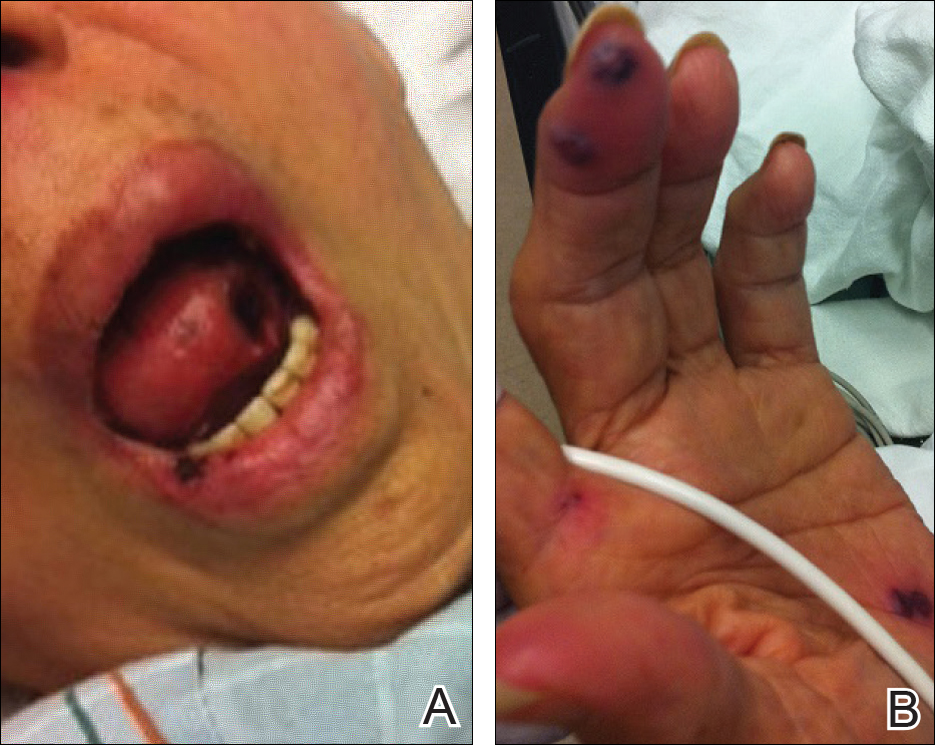

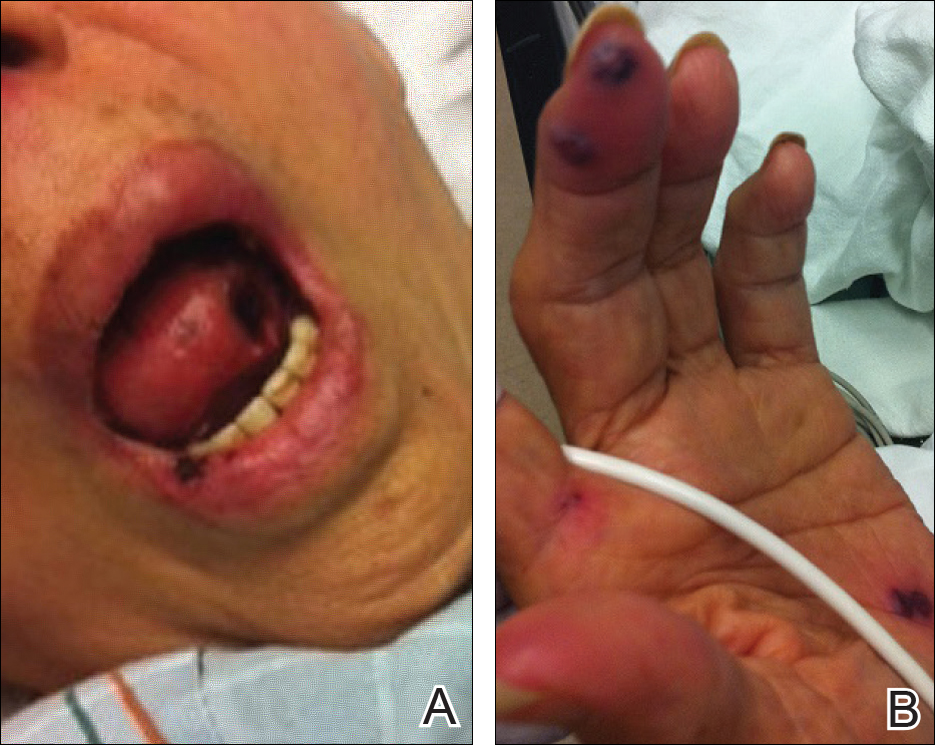

We provided consultation for 5 men and 1 woman (age range, 42–78 years) who were critically ill with COVID-19 and developed retiform purpura on the buttocks (Figures 1 and 2). All had an elevated D-dimer concentration: 2 patients, >700 ng/mL; 2 patients, >2000 ng/mL; 2 patients, >6000 ng/mL (reference, 229 ng/mL). Three patients experienced a peak D-dimer concentration on the day retiform purpura was reported.

Further evidence of coagulopathy in these patients included 1 patient with a newly diagnosed left popliteal deep vein thrombosis and 1 patient with a known history of protein C deficiency and deep vein thromboses. Five patients were receiving anticoagulation on the day the skin changes were documented; anticoagulation was contraindicated in the sixth patient because of oropharyngeal bleeding. Anticoagulation was continued at the treatment dosage (enoxaparin 80 mg twice daily) in 3 patients, and in 2 patients receiving a prophylactic dose (enoxaparin 40 mg daily), anticoagulation was escalated to treatment dose due to rising D-dimer levels and newly diagnosed retiform purpura. Skin biopsy was deferred for all patients due to positional and ventilatory restrictions. At that point in their care, 3 patients remained admitted on medicine floors, 2 were in the intensive care unit, and 1 had died.

Although the differential diagnosis for retiform purpura is broad and should be fully considered in any patient with this finding, based on the elevated D-dimer concentration, critical illness secondary to COVID-19, and striking similarity to earlier reported case of buttocks retiform purpura with thrombotic vasculopathy and pressure injury noted histopathologically,2 we suspect the buttocks retiform purpura in our 6 cases also represent a combination of cutaneous thrombosis and pressure injury. In addition to acral livedoid eruptions (also reported by Magro and colleagues2), we suspect that this cutaneous manifestation might be associated with a hypercoagulable state in some patients, especially in the setting of a rising D-dimer concentration. One study found that 31% of 184 patients with severe COVID-19 had thrombotic complications,3 a clinical picture that portends a poor prognosis.4

COVID-19 patients presenting with retiform purpura should be fully evaluated based on the broad differential for this morphology. We present 6 cases of buttocks retiform purpura in critically ill COVID-19 patients—all with strikingly similar morphologic findings, an elevated D-dimer concentration, and critical illness due to COVID-19—to alert clinicians to this constellation of findings and propose that this cutaneous manifestation could indicate an associated hypercoaguable state and should prompt a hematology consultation. Additionally, biopsy of this skin finding should be considered, especially if biopsy results might serve to guide management; however, obtaining a biopsy specimen can be technically difficult because of ventilatory requirements.

Given the magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic and the propensity of these patients to experience thrombotic events, recognition of this skin finding in COVID-19 is important and might allow timely intervention.

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:e212-e213. doi:10.1111/jdv.16387

- Magro C, Mulvey JJ, Berlin D, et al. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res. 2020;220:1-13. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007

- Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145-147. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013

- Tang N, Li D, Wang X, et al. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:844-847. doi:10.1111/jth.14768

To the Editor:

There is emerging evidence of skin findings in patients with COVID-19, including perniolike changes of the toes as well as urticarial and vesicular eruptions.1 Magro et al2 reported 3 cases of livedoid and purpuric skin eruptions in critically ill COVID-19 patients with evidence of thrombotic vasculopathy on skin biopsy, including a 32-year-old man with striking buttocks retiform purpura. Histopathologic analysis revealed thrombotic vasculopathy and pressure-induced ischemic necrosis. Since that patient was first evaluated (March 2020), we identified 6 more cases of critically ill COVID-19 patients from a single academic hospital in New York City with essentially identical clinical findings. Herein, we report those 6 cases of critically ill and intubated patients with COVID-19 who developed retiform purpura on the buttocks only, approximately 11 to 21 days after onset of COVID-19 symptoms.

We provided consultation for 5 men and 1 woman (age range, 42–78 years) who were critically ill with COVID-19 and developed retiform purpura on the buttocks (Figures 1 and 2). All had an elevated D-dimer concentration: 2 patients, >700 ng/mL; 2 patients, >2000 ng/mL; 2 patients, >6000 ng/mL (reference, 229 ng/mL). Three patients experienced a peak D-dimer concentration on the day retiform purpura was reported.

Further evidence of coagulopathy in these patients included 1 patient with a newly diagnosed left popliteal deep vein thrombosis and 1 patient with a known history of protein C deficiency and deep vein thromboses. Five patients were receiving anticoagulation on the day the skin changes were documented; anticoagulation was contraindicated in the sixth patient because of oropharyngeal bleeding. Anticoagulation was continued at the treatment dosage (enoxaparin 80 mg twice daily) in 3 patients, and in 2 patients receiving a prophylactic dose (enoxaparin 40 mg daily), anticoagulation was escalated to treatment dose due to rising D-dimer levels and newly diagnosed retiform purpura. Skin biopsy was deferred for all patients due to positional and ventilatory restrictions. At that point in their care, 3 patients remained admitted on medicine floors, 2 were in the intensive care unit, and 1 had died.

Although the differential diagnosis for retiform purpura is broad and should be fully considered in any patient with this finding, based on the elevated D-dimer concentration, critical illness secondary to COVID-19, and striking similarity to earlier reported case of buttocks retiform purpura with thrombotic vasculopathy and pressure injury noted histopathologically,2 we suspect the buttocks retiform purpura in our 6 cases also represent a combination of cutaneous thrombosis and pressure injury. In addition to acral livedoid eruptions (also reported by Magro and colleagues2), we suspect that this cutaneous manifestation might be associated with a hypercoagulable state in some patients, especially in the setting of a rising D-dimer concentration. One study found that 31% of 184 patients with severe COVID-19 had thrombotic complications,3 a clinical picture that portends a poor prognosis.4

COVID-19 patients presenting with retiform purpura should be fully evaluated based on the broad differential for this morphology. We present 6 cases of buttocks retiform purpura in critically ill COVID-19 patients—all with strikingly similar morphologic findings, an elevated D-dimer concentration, and critical illness due to COVID-19—to alert clinicians to this constellation of findings and propose that this cutaneous manifestation could indicate an associated hypercoaguable state and should prompt a hematology consultation. Additionally, biopsy of this skin finding should be considered, especially if biopsy results might serve to guide management; however, obtaining a biopsy specimen can be technically difficult because of ventilatory requirements.

Given the magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic and the propensity of these patients to experience thrombotic events, recognition of this skin finding in COVID-19 is important and might allow timely intervention.

To the Editor:

There is emerging evidence of skin findings in patients with COVID-19, including perniolike changes of the toes as well as urticarial and vesicular eruptions.1 Magro et al2 reported 3 cases of livedoid and purpuric skin eruptions in critically ill COVID-19 patients with evidence of thrombotic vasculopathy on skin biopsy, including a 32-year-old man with striking buttocks retiform purpura. Histopathologic analysis revealed thrombotic vasculopathy and pressure-induced ischemic necrosis. Since that patient was first evaluated (March 2020), we identified 6 more cases of critically ill COVID-19 patients from a single academic hospital in New York City with essentially identical clinical findings. Herein, we report those 6 cases of critically ill and intubated patients with COVID-19 who developed retiform purpura on the buttocks only, approximately 11 to 21 days after onset of COVID-19 symptoms.

We provided consultation for 5 men and 1 woman (age range, 42–78 years) who were critically ill with COVID-19 and developed retiform purpura on the buttocks (Figures 1 and 2). All had an elevated D-dimer concentration: 2 patients, >700 ng/mL; 2 patients, >2000 ng/mL; 2 patients, >6000 ng/mL (reference, 229 ng/mL). Three patients experienced a peak D-dimer concentration on the day retiform purpura was reported.

Further evidence of coagulopathy in these patients included 1 patient with a newly diagnosed left popliteal deep vein thrombosis and 1 patient with a known history of protein C deficiency and deep vein thromboses. Five patients were receiving anticoagulation on the day the skin changes were documented; anticoagulation was contraindicated in the sixth patient because of oropharyngeal bleeding. Anticoagulation was continued at the treatment dosage (enoxaparin 80 mg twice daily) in 3 patients, and in 2 patients receiving a prophylactic dose (enoxaparin 40 mg daily), anticoagulation was escalated to treatment dose due to rising D-dimer levels and newly diagnosed retiform purpura. Skin biopsy was deferred for all patients due to positional and ventilatory restrictions. At that point in their care, 3 patients remained admitted on medicine floors, 2 were in the intensive care unit, and 1 had died.

Although the differential diagnosis for retiform purpura is broad and should be fully considered in any patient with this finding, based on the elevated D-dimer concentration, critical illness secondary to COVID-19, and striking similarity to earlier reported case of buttocks retiform purpura with thrombotic vasculopathy and pressure injury noted histopathologically,2 we suspect the buttocks retiform purpura in our 6 cases also represent a combination of cutaneous thrombosis and pressure injury. In addition to acral livedoid eruptions (also reported by Magro and colleagues2), we suspect that this cutaneous manifestation might be associated with a hypercoagulable state in some patients, especially in the setting of a rising D-dimer concentration. One study found that 31% of 184 patients with severe COVID-19 had thrombotic complications,3 a clinical picture that portends a poor prognosis.4

COVID-19 patients presenting with retiform purpura should be fully evaluated based on the broad differential for this morphology. We present 6 cases of buttocks retiform purpura in critically ill COVID-19 patients—all with strikingly similar morphologic findings, an elevated D-dimer concentration, and critical illness due to COVID-19—to alert clinicians to this constellation of findings and propose that this cutaneous manifestation could indicate an associated hypercoaguable state and should prompt a hematology consultation. Additionally, biopsy of this skin finding should be considered, especially if biopsy results might serve to guide management; however, obtaining a biopsy specimen can be technically difficult because of ventilatory requirements.

Given the magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic and the propensity of these patients to experience thrombotic events, recognition of this skin finding in COVID-19 is important and might allow timely intervention.

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:e212-e213. doi:10.1111/jdv.16387

- Magro C, Mulvey JJ, Berlin D, et al. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res. 2020;220:1-13. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007

- Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145-147. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013

- Tang N, Li D, Wang X, et al. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:844-847. doi:10.1111/jth.14768

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:e212-e213. doi:10.1111/jdv.16387

- Magro C, Mulvey JJ, Berlin D, et al. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res. 2020;220:1-13. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007

- Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145-147. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013

- Tang N, Li D, Wang X, et al. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:844-847. doi:10.1111/jth.14768

Practice Points

- Retiform purpura in a severely ill patient with COVID-19 and a markedly elevated D-dimer concentration might be a cutaneous sign of systemic coagulopathy.

- This constellation of findings should prompt consideration of skin biopsy and hematology consultation.

Cutaneous Manifestations of COVID-19: Characteristics, Pathogenesis, and the Role of Dermatology in the Pandemic

The virus that causes COVID-19—SARS-CoV-2—has infected more than 128 million individuals, resulting in more than 2.8 million deaths worldwide between December 2019 and April 2021. Disease mortality primarily is driven by hypoxemic respiratory failure and systemic hypercoagulability, resulting in multisystem organ failure.1 With more than 17 million Americans infected, the virus is estimated to have impacted someone within the social circle of nearly every American.2

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted resource limitations, delayed elective and preventive care, and rapidly increased the adoption of telemedicine, presenting a host of new challenges to providers in every medical specialty, including dermatology. Although COVID-19 primarily is a respiratory disease, clinical manifestations have been observed in nearly every organ, including the skin. The cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 provide insight into disease diagnosis, prognosis, and pathophysiology. In this article, we review the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 and explore the state of knowledge regarding their pathophysiology and clinical significance. Finally, we discuss the role of dermatology consultants in the care of patients with COVID-19, and the impact of the pandemic on the field of dermatology.

Prevalence of Cutaneous Findings in COVID-19

Early reports characterizing the clinical presentation of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 suggested skin findings associated with the disease were rare. Cohort studies from Europe, China, and New York City in January through March 2020 reported a low prevalence or made no mention of rash.3-7 However, reports from dermatologists in Italy that emerged in May 2020 indicated a substantially higher proportion of cutaneous disease: 18 of 88 (20.4%) hospitalized patients were found to have cutaneous involvement, primarily consisting of erythematous rash, along with some cases of urticarial and vesicular lesions.8 In October 2020, a retrospective cohort study from Spain examining 2761 patients presenting to the emergency department or admitted to the hospital for COVID-19 found that 58 (2.1%) patients had skin lesions attributed to COVID-19.9

The wide range in reported prevalence of skin lesions may be due to variable involvement of dermatologic specialists in patient care, particularly in China.10 Some variation also may be due to variability in the timing of clinical examination, as well as demographic and clinical differences in patient populations. Of note, a multisystem inflammatory disease seen in US children subsequent to infection with COVID-19 has been associated with rash in as many as 74% of cases.11 Although COVID-19 disproportionately impacts people with skin of color, there are few reports of cutaneous manifestations in that population,12 highlighting the challenges of the dermatologic examination in individuals with darker skin and suggesting the prevalence of dermatologic disease in COVID-19 may be greater than reported.

Morphologic Patterns of Cutaneous Involvement in COVID-19

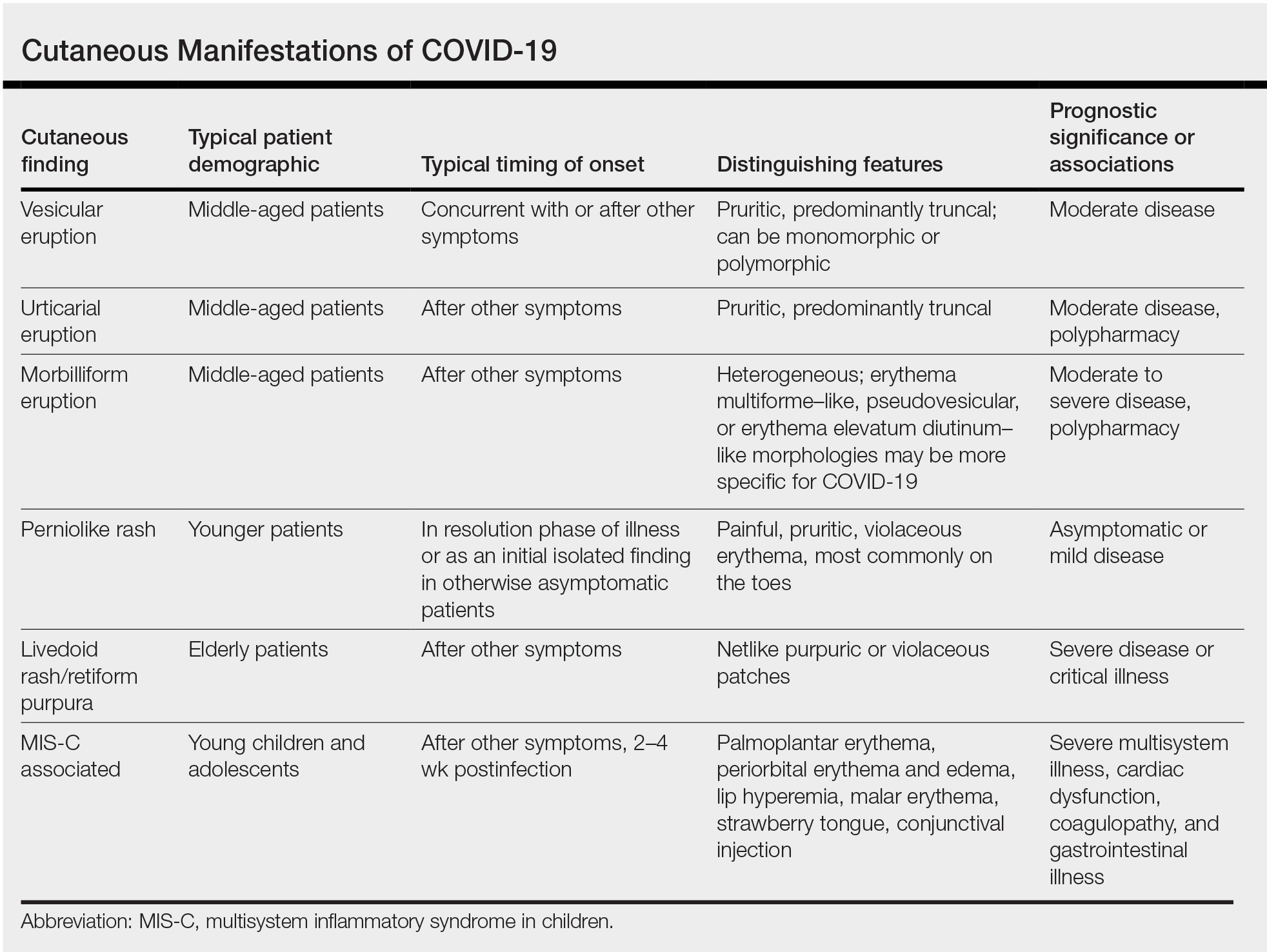

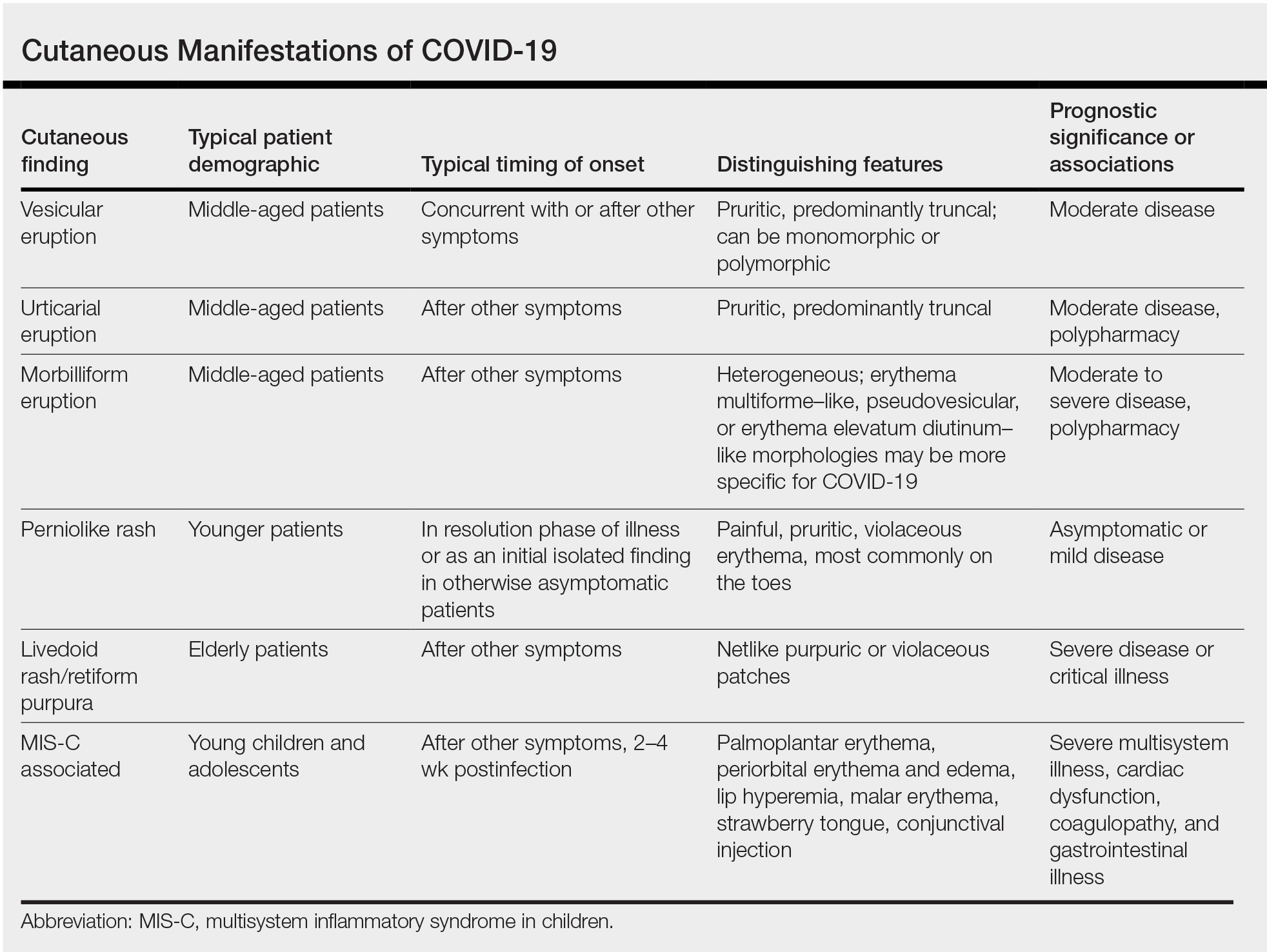

Researchers in Europe and the United States have attempted to classify the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19. A registry established through the American Academy of Dermatology published a compilation of reports from 31 countries, totaling 716 patient profiles.13 A prospective Spanish study detailed the cutaneous involvement of 375 patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19.14 Together, these efforts have revealed several distinct patterns of cutaneous involvement associated with COVID-19 (Table).9,15-18

Vesicular Rash

Vesicular rash associated with COVID-19 has been described in several studies and case series8,13,14 and is considered, along with the pseudopernio (or pseudochilblains) morphology, to be one of the more disease-specific patterns in COVID-19.14,18 Vesicular rash appears to comprise roughly one-tenth of all COVID-19–associated rashes.13,14 It usually is described as pruritic, with 72% to 83% of patients reporting itch.13,16

Small monomorphic or polymorphic vesicles predominantly on the trunk and to a lesser extent the extremities and head have been described by multiple authors.14,16 Vesicular rash is most common among middle-aged individuals, with studies reporting median and mean ages ranging from 40.5 to 55 years.9,13,14,16

Vesicular rash develops concurrent with or after other presenting symptoms of COVID-19; in 2 studies, vesicular rash preceded development of other symptoms in only 15% and 5.6% of cases, respectively.13,14 Prognostically, vesicular rash is associated with moderate disease severity.14,16 It may persist for an average of 8 to 10 days.14,16,18

Histopathologic examination reveals basal layer vacuolar degeneration, hyperchromatic keratinocytes, acantholysis, and dyskeratosis.9,16,18

Urticarial Rash

Urticarial lesions represent approximately 7% to 19% of reported COVID-19–associated rashes.9,13,14 Urticarial rashes in patients testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 primarily occur on the trunk.14 The urticaria, which typically last about 1 week,14 are seen most frequently in middle-aged patients (mean/median age, 42–48 years)13,14 and are associated with pruritus, which has been reported in 74% to 92% of patients.13,14 Urticarial lesions typically do not precede other symptoms of COVID-19 and are nonspecific, making them less useful diagnostically.14

Urticaria appears to be associated with more severe COVID-19 illness in several studies, but this finding may be confounded by several factors, including older age, increased tobacco use, and polypharmacy. Of 104 patients with reported urticarial rash and suspected or confirmed COVID-19 across 3 studies, only 1 death was reported.9,13,14

The histopathologic appearance is that of typical hives, demonstrating a perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils with edema of the upper dermis.9,19

Morbilliform Eruption

Morbilliform eruption is a commonly reported morphology associated with COVID-19, accounting for 20% to 47% of rashes.9,13,14 This categorization may have limited utility from a diagnostic and prognostic perspective, given that morbilliform eruptions are common, nonspecific, and heterogenous and can arise from many causes.9,13,14 Onset of morbilliform eruption appears to coincide with14 or follow13,20,21 the development of other COVID-19–related symptoms, with 5% of patients reporting morbilliform rash as the initial manifestation of infection.13,14 Morbilliform eruptions have been observed to occur in patients with more severe disease.9,13,14

Certain morphologic subtypes, such as erythema multiforme–like, erythema elevatum diutinum–like, or pseudovesicular, may be more specific to COVID-19 infection.14 A small case series highlighted 4 patients with erythema multiforme–like eruptions, 3 of whom also were found to have petechial enanthem occurring after COVID-19 diagnosis; however, the investigators were unable to exclude drug reaction as a potential cause of rash in these patients.22 Another case series of 21 patients with COVID-19 and skin rash described a (primarily) petechial enanthem on the palate in 6 (28.5%) patients.23 It is unclear to what extent oral enanthem may be underrecognized given that some physicians may be disinclined to remove the masks of known COVID-19–positive patients to examine the oral cavity.

The histologic appearance of morbilliform rash seen in association with COVID-19 has been described as spongiotic with interface dermatitis with perivascular lymphocytic inflammation.9,21

COVID Toes, Pseudochilblains Rash, Perniolike Rash, and Acral Erythema/Edema

Of all the rashes associated with COVID-19, COVID toes, or pseudochilblains rash, has perhaps attracted the most attention. The characteristic violaceous erythema on the fingers and/or toes may be itchy or painful, presenting similar to idiopathic cases of pernio (Figure 1).14 The entity has been controversial because of an absence of a clear correlation with a positive SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction test or antibodies to the virus in a subset of reported cases.24,25 Onset of the rash late in the disease course, generally after symptom resolution in mild or asymptomatic cases, may explain the absence of viral DNA in the nasopharynx by the time of lesion appearance.14,26 Seronegative patients may have cleared SARS-CoV-2 infection before humoral immunity could occur via a strong type 1 interferon response.25

Across 3 studies, perniolike skin lesions constituted 18% to 29% of COVID-19–associated skin findings9,13,14 and persisted for an average of 12 to 14 days.13,14 Perniolike lesions portend a favorable outcome; patients with COVID toes rarely present with systemic symptoms or laboratory or imaging abnormalities9 and less commonly require hospitalization for severe illness. Perniolike lesions have been reported most frequently in younger patients, with a median or mean age of 32 to 35 years.13,14

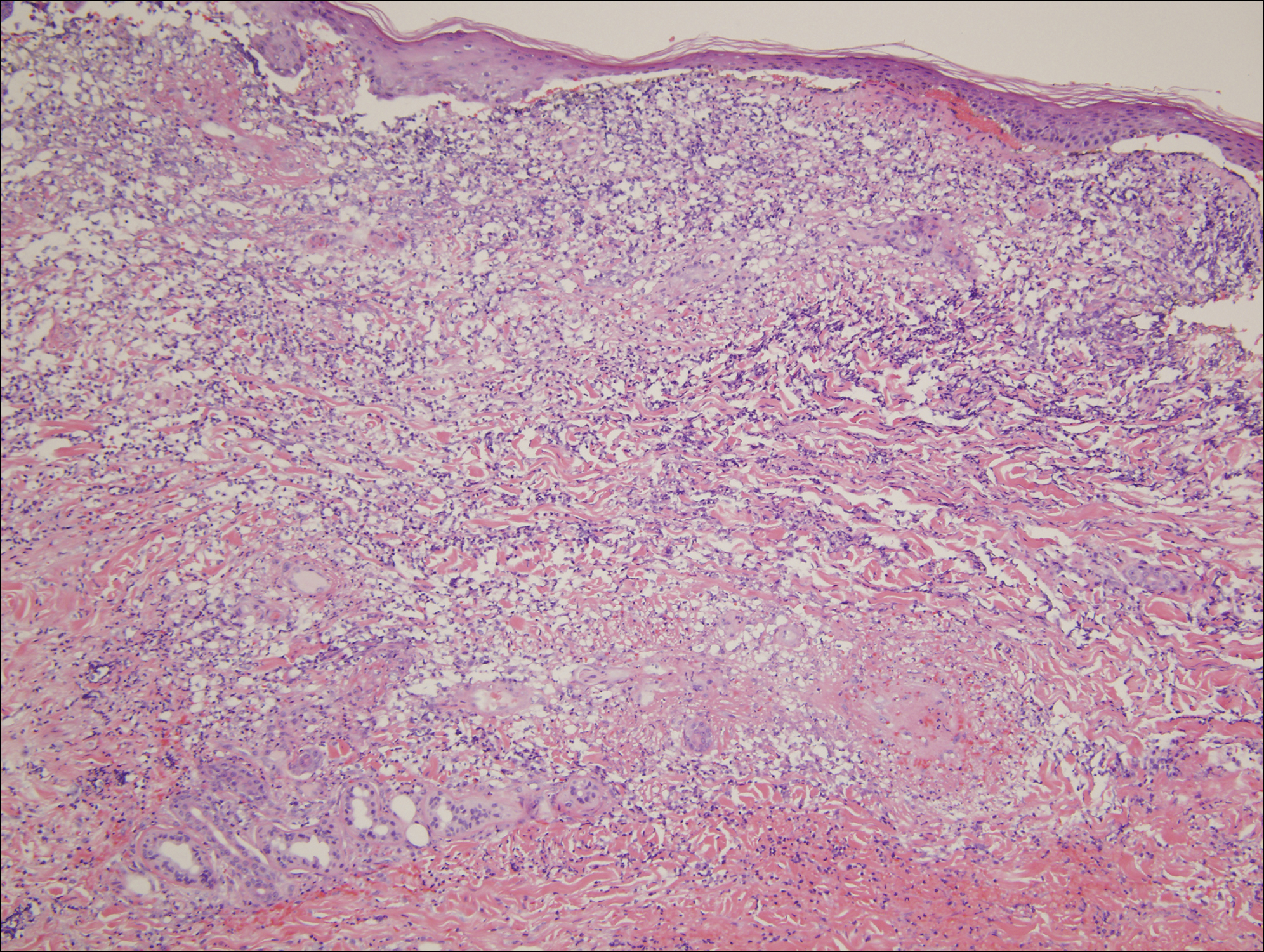

Histology demonstrates lichenoid dermatitis with perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates.9 Notably, one study observed interface dermatitis of the intraepidermal portion of the acrosyringium, a rare finding in chilblain lupus, in 83% of patients (N=40).25 Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates a vasculopathic pattern, with some patients showing deposition of IgM or IgG, C3, and fibrinogen in dermal blood vessels. Vascular C9 deposits also have been demonstrated on immunohistochemistry.9 Biopsies of perniolike lesions in COVID-19 patients have demonstrated the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA,27 have identified SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in endothelial cells on immunohistochemistry, and have visualized intracytoplasmic viral particles in vascular endothelium on electron microscopy.28

Livedoid Rash/Retiform Purpura

Netlike purpuric or violaceous patches signifying vessel damage or occlusion have been seen in association with COVID-19, constituting approximately 6% of COVID-19–associated skin findings in 2 studies.13,14 Livedoid rash (Figure 2) and retiform purpura (Figure 3) are associated with older age and occur primarily in severely ill patients, including those requiring intensive care. In a registry of 716 patients with COVID-19, 100% of patients with retiform purpura were hospitalized, and 82% had acute respiratory distress syndrome.13 In another study, 33% (7/21) of patients with livedoid and necrotic lesions required intensive care, and 10% (2/21) died.14

Livedoid lesions and retiform purpura represent thrombotic disease in the skin due to vasculopathy/coagulopathy. Dermatopathology available through the American Academy of Dermatology registry revealed thrombotic vasculopathy.13 A case series of 4 patients with livedo racemosa and retiform purpura demonstrated pauci-inflammatory thrombogenic vasculopathy involving capillaries, venules, and arterioles with complement deposition.29 Livedoid and retiform lesions in the skin may be associated with a COVID-19–induced coagulopathy, a propensity for systemic clotting including pulmonary embolism, which mostly occurs in hospitalized patients with severe illness.30

Multisystem Inflammatory Disease in Children

A hyperinflammatory syndrome similar to Kawasaki disease and toxic shock syndrome associated with mucocutaneous, cardiac, and gastrointestinal manifestations has been reported following COVID-19 infection.31 This syndrome, known as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), predominantly affects adolescents and children older than 5 years,11 typically occurs 2 to 4 weeks after infection, and appears to be at least 100-times less common than COVID-19 infection among the same age group.31 Sixty percent31 to 74%11 of affected patients have mucocutaneous involvement, with the most common clinical findings being conjunctival injection, palmoplantar erythema, lip hyperemia, periorbital erythema and edema, strawberry tongue, and malar erythema, respectively.32

Because this condition appears to reflect an immune response to the virus, the majority of cases demonstrate negative SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction and positive antibody testing.33 Although cutaneous findings are similar to those seen in Kawasaki disease, certain findings have been noted in MIS-C that are not typical of Kawasaki disease, including heliotrope rash–like periorbital edema and erythema as well as erythema infectiosum–like malar erythema and reticulated erythematous eruptions.32

The course of MIS-C can be severe; in one case series of patients presenting with MIS-C, 80% (79/99) required intensive care unit admission, with 10% requiring mechanical ventilation and 2% of patients dying during admission.31 Cardiac dysfunction, coagulopathy, and gastrointestinal symptoms are common.11,31 It has been postulated that a superantigenlike region of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, similar to that of staphylococcal enterotoxin B, may underlie MIS-C and account for its similarities to toxic shock syndrome.34 Of note, a similar multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with COVID-19 also has been described in adults, and it too may present with rash as a cardinal feature.35

Pathophysiology of COVID-19: What the Skin May Reveal About the Disease

The diverse range of cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19 reflects a spectrum of host immunologicresponses to SARS-CoV-2 and may inform the pathophysiology of the disease as well as potential treatment modalities.

Host Response to SARS-CoV-2

The body’s response to viral infection is 2-pronged, involving activation of cellular antiviral defenses mediated by type I and III interferons, as well as recruitment of leukocytes, mobilized by cytokines and chemokines.36,37 Infection with SARS-CoV-2 results in a unique inflammatory response characterized by suppression of interferons, juxtaposed with a rampant proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine response, reminiscent of a cytokine storm. Reflective of this imbalance, a study of 50 COVID-19 patients and 20 healthy controls found decreased natural killer cells and CD3+ T cells in COVID-19 patients, particularly severely or critically ill patients, with an increase in B cells and monocytes.38 This distinctive immune imbalance positions SARS-CoV-2 to thrive in the absence of inhibitory interferon activity while submitting the host to the deleterious effects of a cytokine surge.36

Type I Interferons

The perniolike lesions associated with mild COVID-19 disease14 may represent a robust immune response via effective stimulation of type I interferons (IFN-1). Similar perniolike lesions are observed in Aicardi-Goutières syndrome37 and familial chilblain lupus, hereditary interferonopathies associated with mutations in the TREX1 (three prime repair exonuclease 1) gene and characterized by inappropriate upregulation of IFN-1,39 resulting in chilblains. It has been suggested that perniolike lesions in COVID-19 result from IFN-1 activation—a robust effective immunologic response to the virus.14,26,40

On the other end of the spectrum, patients with severe COVID-19 may have a blunted IFN-1 response and reduced IFN-1–stimulated gene expression.36,38 Notably, low IFN-1 response preceded clinical deterioration and was associated with increased risk for evolution to critical illness.38 Severe disease from COVID-19 also is more commonly observed in older patients and those with comorbidities,1 both of which are known factors associated with depressed IFN-1 function.38,41 Reflective of this disparate IFN-1 response, biopsies of COVID-19 perniosis have demonstrated striking expression of myxovirus resistance protein A (MXA), a marker for IFN-1 signaling in tissue, whereas its expression is absent in COVID-19 livedo/retiform purpura.27

Familial chilblain lupus may be effectively treated by the Janus kinase inhibitor baricitinib,39 which inhibits IFN-1 signaling. Baricitinib recently received emergency use authorization by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of severe COVID-19 pneumonia,42,43 hinting to disordered IFN-1 signaling in the COVID-19 pathophysiology.

The impaired IFN-1 response in COVID-19 patients may be due to a unique characteristic of SARS-CoV-2: its ORF3b gene is a potent IFN-1 antagonist. In a series of experiments comparing SARS-CoV-2 to the related virus severe acute respiratory disease coronavirus (which was responsible for an epidemic in 2002), Konno et al44 found that SARS-CoV-2 is more effectively able to downregulate host IFN-1, likely due to premature stop codons on ORF3b that produce a truncated version of the gene with amplified anti–IFN-1 activity.

Cytokine Storm and Coagulation Cascade

This dulled interferon response is juxtaposed with a surge of inflammatory chemokines and cytokines, including IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and tumor necrosis factor α, impairing innate immunity and leading to end-organ damage. This inflammatory response is associated with the influx of innate immune cells, specifically neutrophils and monocytes, which likely contribute to lung injury in COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome.38 It also is thought to lead to downstream activation of coagulation, with a high incidence of thrombotic events observed in patients with severe COVID-19.1 In a retrospective study of 184 intensive care patients with COVID-19 receiving at least standard doses of thromboprophylaxis, venous thromboembolism occurred in 27% and arterial thrombotic events occurred in 3.7%.45

Livedo racemosa and retiform purpura are cutaneous markers of hypercoagulability, which indicate an increased risk for systemic clotting in COVID-19. A positive feedback loop between the complement and coagulation cascades appears to be important.13,14,29,46-48 In addition, a few studies have reported antiphospholipid antibody positivity in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.49,50

The high incidence of coagulopathy in severe COVID-19 has prompted many institutions to develop aggressive prophylactic anticoagulation protocols. Elevation of proinflammatory cytokines and observation of terminal complement activation in the skin and other organs has led to therapeutic trials of IL-6 inhibitors such as tocilizumab,51 complement inhibitors such as eculizumab, and Janus kinase inhibitors such as ruxolitinib and baricitinib.42,48

COVID Long-Haulers

The long-term effects of immune dysregulation in COVID-19 patients remain to be seen. Viral triggering of autoimmune disease is a well-established phenomenon, seen in DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome and other dermatologic diseases, raising the possibility that dermatologists will see a rising incidence of cutaneous autoimmune disease in the aftermath of the pandemic. Disordered interferon stimulation could lead to increased incidence of interferon-mediated disorders, such as sarcoidosis and other granulomatous diseases. Vasculitislike skin lesions could persist beyond the acute infectious period. Recent data from a registry of 990 COVID-19 cases from 39 countries suggest that COVID-19 perniolike lesions may persist as long as 150 days.52 In a time of many unknowns, these questions serve as a call to action for rigorous data collection, contribution to existing registries for dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19, and long-term follow-up of COVID-19 patients by the dermatology community.

Pandemic Dermatology

The pandemic has posed unprecedented challenges for patient care. The use of hydroxychloroquine as a popular but unproven treatment for COVID-19, 53 particularly early in the pandemic, has resulted in drug shortages for patients with lupus and other autoimmune skin diseases. Meanwhile, the need for patients with complex dermatologic conditions to receive systemic immunosuppression has had to be balanced against the associated risks during a global pandemic. To help dermatologists navigate this dilemma, various subspecialty groups have issued guidelines, including the COVID-19 Task Force of the Medical Dermatology Society and Society of Dermatology Hospitalists, which recommends a stepwise approach to shared decision-making with the goal of minimizing both the risk for disease flare and that of infection. The use of systemic steroids and rituximab, as well as the dose of immunosuppression—particularly broad-acting immunosuppression—should be limited where permitted. 54

Rapid adoption of telemedicine and remote monitoring strategies has enabled dermatologists to provide safe and timely care when in-person visits have not been possible, including for patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19, as well as for hospitalized patients. 55-57 Use of telemedicine has facilitated preservation of personal protective equipment at a time when these important resources have been scarce. For patients with transportation or scheduling barriers, telemedicine has even expanded access to care.

However, this strategy cannot completely replace comprehensive in-person evaluation. Variability in video and photographic quality limits evaluation, while in-person physical examination can reveal subtle morphologic clues necessary for diagnosis. 5 8 Additionally, unequal access to technology may disadvantage some patients. For dermatologists to provide optimal care and continue to contribute accurate and insightful observations into COVID-19, it is essential to be physically present in the clinic and in the hospital when necessary, caring for patients in need of dermatologic expertise. Creative management strategies developed during this time will benefit patients and expand the reach of the specialty . 5 8

Final Thoughts

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly challenged the medical community and dermatology is no exception. By documenting and characterizing the diverse cutaneous manifestations of this novel disease, dermatologists have furthered understanding of its pathophysiology and management. By adapting quickly and developing creative ways to deliver care, dermatologists have found ways to contribute, both large and small. As we take stock at this juncture of the pandemic, it is clear there remains much to learn. We hope dermatologists will continue to take an active role in meeting the challenges of this time.

- Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, et al. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA . 2020;324:782-793. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.12839

- New York Times . Updated December 23, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/15/us/coronavirus-us-cases-deaths.html

- Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med . 2020;382:1708-1720. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2002032

- Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, Place S, et al. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of 1420 European patients with mild-to-moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Intern Med . 2020;288:335-344. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.13089

- Wu J, Liu J, Zhao X, et al. Clinical characteristics of imported cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Jiangsu province: a multicenter descriptive study. Clin Infect Dis . 2020;71:706-712. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa199

- Goyal P, Choi JJ, Pinheiro LC, et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in New York City. N Engl J Med . 2020;382:2372-2374. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2010419

- Sun L, Shen L, Fan J, et al. Clinical features of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 from a designated hospital in Beijing, China. J Med Virol . 2020;92:2055-2066. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25966

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol . 2020;34:E212-E213. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.16387

- Giavedoni P, Podlipnik S, Pericàs JM, et al. Skin manifestations in COVID-19: prevalence and relationship with disease severity. J Clin Med . 2020;9:3261. doi:10.3390/jcm9103261

- Jimenez-Cauhe J, Ortega-Quijano D, Prieto-Barrios M, et al. Reply to “COVID-19 can present with a rash and be mistaken for dengue”: petechial rash in a patient with COVID-19 infection. J Am Acad Dermatol . 2020;83:E141-E142. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.016

- Feldstein LR, Rose EB, Horwitz SM, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med . 2020;383:334-346. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2021680

- Shinkai K, Bruckner AL. Dermatology and COVID-19. JAMA . 2020;324:1133-1134. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.15276

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, et al. The spectrum of COVID-19-associated dermatologic manifestations: an international registry of 716 patients from 31 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol . 2020;83:1118-1129. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1016

- Galván Casas C, Català A, Carretero Hernández G, et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases. Br J Dermatol . 2020;183:71-77. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.19163

- Bouaziz JD, Duong TA, Jachiet M, et al. Vascular skin symptoms in COVID-19: a French observational study. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol . 2020;34:E451-E452. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.16544

- Fernandez-Nieto D, Ortega-Quijano D, Jimenez-Cauhe J, et al. Clinical and histological characterization of vesicular COVID-19 rashes: a prospective study in a tertiary care hospital. Clin Exp Dermatol . 2020;45:872-875. https://doi.org/10.1111/ced.14277

- Fernandez-Nieto D, Jimenez-Cauhe J, Suarez-Valle A, et al. Characterization of acute acral skin lesions in nonhospitalized patients: a case series of 132 patients during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Am Acad Dermatol . 2020;83:E61-E63. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.093

- Marzano AV, Genovese G, Fabbrocini G, et al. Varicella-like exanthem as a specific COVID-19-associated skin manifestation: Multicenter case series of 22 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol . 2020;83:280-285. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.044

- Fernandez-Nieto D, Ortega-Quijano D, Segurado-Miravalles G, et al. Comment on: cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. safety concerns of clinical images and skin biopsies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol . 2020;34:E252-E254. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.16470

- Herrero-Moyano M, Capusan TM, Andreu-Barasoain M, et al. A clinicopathological study of eight patients with COVID-19 pneumonia and a late-onset exanthema. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol . 2020;34:E460-E464. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.16631

- Rubio-Muniz CA, Puerta-Peñ a M, Falkenhain-L ópez D, et al. The broad spectrum of dermatological manifestations in COVID-19: clinical and histopathological features learned from a series of 34 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol . 2020;34:E574-E576. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.16734

- Jimenez-Cauhe J, Ortega-Quijano D, Carretero-Barrio I, et al. Erythema multiforme-like eruption in patients with COVID-19 infection: clinical and histological findings. Clin Exp Dermatol . 2020;45:892-895. https://doi.org/10.1111/ced.14281

- Jimenez-Cauhe J, Ortega-Quijano D, de Perosanz-Lobo D, et al. Enanthem in patients with COVID-19 and skin rash. JAMA Dermatol . 2020;156:1134-1136. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2550

- Le Cleach L, Dousset L, Assier H, et al. Most chilblains observed during the COVID-19 outbreak occur in patients who are negative for COVID-19 on polymerase chain reaction and serology testing. Br J Dermatol . 2020;183:866-874. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.19377

- Hubiche T, Cardot-Leccia N, Le Duff F, et al. Clinical, laboratory, and interferon-alpha response characteristics of patients with chilblain-like lesions during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online November 25, 2020]. JAMA Dermatol . doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.4324

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, et al. Pernio-like skin lesions associated with COVID-19: a case series of 318 patients from 8 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol . 2020;83:486-492. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.109

- Magro CM, Mulvey JJ, Laurence J, et al. The differing pathophysiologies that underlie COVID-19-associated perniosis and thrombotic retiform purpura: a case series. Br J Dermatol . 2021;184:141-150. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.19415

- Colmenero I, Santonja C, Alonso-Riaño M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 endothelial infection causes COVID-19 chilblains: histopathological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study of seven paediatric cases. Br J Dermatol . 2020;183:729-737. doi:10.1111/bjd.19327

- Droesch C, Do MH, DeSancho M, et al. Livedoid and purpuric skin eruptions associated with coagulopathy in severe COVID-19. JAMA Dermatol . 2020;156:1-3. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2800

- Asakura H, Ogawa H. COVID-19-associated coagulopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Int J Hematol . 2021;113:45-57. doi:10.1007/s12185-020-03029-y

- Dufort EM, Koumans EH, Chow EJ, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children in New York State. N Engl J Med . 2020;383:347-358. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2021756

- Young TK, Shaw KS, Shah JK, et al. Mucocutaneous manifestations of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Dermatol . 2021;157:207-212. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.4779

- Whittaker E, Bamford A, Kenny J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 58 children with a pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2020;324:259-269. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.10369

- Cheng MH, Zhang S, Porritt RA, et al. Superantigenic character of an insert unique to SARS-CoV-2 spike supported by skewed TCR repertoire in patients with hyperinflammation.

- Morris SB, Schwartz NG, Patel P, et al. Case series of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults associated with SARS-CoV-2 Infection—United Kingdom and United States, March–August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1450-1456. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6940e1

- Blanco-Melo D, Nilsson-Payant BE, Liu W-C, et al. Imbalanced host response to SARS-CoV-2 drives development of COVID-19. Cell. 2020;181:1036.e9-1045.e9. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.026

- Crow YJ, Manel N. Aicardi–Goutières syndrome and the type I interferonopathies. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:429-440. doi:10.1038/nri3850

- Hadjadj J, Yatim N, Barnabei L, et al. Impaired type I interferon activity and inflammatory responses in severe COVID-19 patients. Science. 2020;369:718-724. doi:10.1126/science.abc6027

- Zimmermann N, Wolf C, Schwenke R, et al. Assessment of clinical response to janus kinase inhibition in patients with familial chilblain lupus and TREX1 mutation. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:342-346. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5077

- Hubiche T, Le Duff F, Chiaverini C, et al. Negative SARS-CoV-2 PCR in patients with chilblain-like lesions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:315-316. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30518-1

- Agrawal A. Mechanisms and implications of age-associated impaired innate interferon secretion by dendritic cells: a mini-review. Gerontology. 2013;59:421-426. doi:10.1159/000350536

- Kalil AC, Patterson TF, Mehta AK, et al. Baricitinib plus remdesivir for hospitalized adults with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:795-807. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2031994

- US Food and Drug Administration. Fact sheet for healthcare providers: emergency use authorization (EUA) of baricitinib. Accessed March 29, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/143823/download

- Konno Y, Kimura I, Uriu K, et al. SARS-CoV-2 ORF3b is a potent interferon antagonist whose activity is increased by a naturally occurring elongation variant. Cell Rep. 2020;32:108185. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108185

- Sacks D, Baxter B, Campbell BCV, et al. Multisociety consensus quality improvement revised consensus statement for endovascular therapy of acute ischemic stroke: from the American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS), American Society of Neuroradiology (ASNR), Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology Society of Europe (CIRSE), Canadian Interventional Radiology Association (CIRA), Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS), European Society of Minimally Invasive Neurological Therapy (ESMINT), European Society of Neuroradiology (ESNR), European Stroke Organization (ESO), Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI), Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR), Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery (SNIS), and World Stroke Organization (WSO). J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2018;29:441-453. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2017.11.026

- Lo MW, Kemper C, Woodruff TM. COVID-19: complement, coagulation, and collateral damage. J Immunol. 2020;205:1488-1495. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.2000644

- Magro C, Mulvey JJ, Berlin D, et al. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res. 2020;220:1-13. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007

- Yan B, Freiwald T, Chauss D, et al. SARS-CoV2 drives JAK1/2-dependent local and systemic complement hyper-activation [published online June 9, 2020]. Res Sq. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-33390/v1

- Marietta M, Coluccio V, Luppi M. COVID-19, coagulopathy and venous thromboembolism: more questions than answers. Intern Emerg Med. 2020;15:1375-1387. doi:10.1007/s11739-020-02432-x

- Zuo Y, Estes SK, Ali RA, et al. Prothrombotic antiphospholipid antibodies in COVID-19 [published online June 17, 2020]. medRxiv. doi:10.1101/2020.06.15.20131607

- Lan S-H, Lai C-C, Huang H-T, et al. Tocilizumab for severe COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;56:106103. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106103

- McMahon D, Gallman A, Hruza G, et al. COVID-19 “long-haulers” in dermatology? duration of dermatologic symptoms in an international registry from 39 countries. Abstract presented at: 29th EADV Congress; October 29, 2020. Accessed March 29, 2020. https://eadvdistribute.m-anage.com/from.storage?image=PXQEdDtICIihN3sM_8nAmh7p_y9AFijhQlf2-_KjrtYgOsOXNVwGxDdti95GZ2Yh0

- Saag MS. Misguided use of hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19: the infusion of politics into science. JAMA. 2020;324:2161-2162. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.22389

- Zahedi Niaki O, Anadkat MJ, Chen ST, et al. Navigating immunosuppression in a pandemic: a guide for the dermatologist from the COVID Task Force of the Medical Dermatology Society and Society of Dermatology Hospitalists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1150-1159. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.051

- Hammond MI, Sharma TR, Cooper KD, et al. Conducting inpatient dermatology consultations and maintaining resident education in the COVID-19 telemedicine era. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E317-E318. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.008

- Brunasso AMG, Massone C. Teledermatologic monitoring for chronic cutaneous autoimmune diseases with smartworking during COVID-19 emergency in a tertiary center in Italy. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13495-E13495. doi:10.1111/dth.13695

- Trinidad J, Kroshinsky D, Kaffenberger BH, et al. Telemedicine for inpatient dermatology consultations in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E69-E71. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.096

- Madigan LM, Micheletti RG, Shinkai K. How dermatologists can learn and contribute at the leading edge of the COVID-19 global pandemic. JAMA Dermatology. 2020;156:733-734. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1438

The virus that causes COVID-19—SARS-CoV-2—has infected more than 128 million individuals, resulting in more than 2.8 million deaths worldwide between December 2019 and April 2021. Disease mortality primarily is driven by hypoxemic respiratory failure and systemic hypercoagulability, resulting in multisystem organ failure.1 With more than 17 million Americans infected, the virus is estimated to have impacted someone within the social circle of nearly every American.2

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted resource limitations, delayed elective and preventive care, and rapidly increased the adoption of telemedicine, presenting a host of new challenges to providers in every medical specialty, including dermatology. Although COVID-19 primarily is a respiratory disease, clinical manifestations have been observed in nearly every organ, including the skin. The cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 provide insight into disease diagnosis, prognosis, and pathophysiology. In this article, we review the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 and explore the state of knowledge regarding their pathophysiology and clinical significance. Finally, we discuss the role of dermatology consultants in the care of patients with COVID-19, and the impact of the pandemic on the field of dermatology.

Prevalence of Cutaneous Findings in COVID-19

Early reports characterizing the clinical presentation of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 suggested skin findings associated with the disease were rare. Cohort studies from Europe, China, and New York City in January through March 2020 reported a low prevalence or made no mention of rash.3-7 However, reports from dermatologists in Italy that emerged in May 2020 indicated a substantially higher proportion of cutaneous disease: 18 of 88 (20.4%) hospitalized patients were found to have cutaneous involvement, primarily consisting of erythematous rash, along with some cases of urticarial and vesicular lesions.8 In October 2020, a retrospective cohort study from Spain examining 2761 patients presenting to the emergency department or admitted to the hospital for COVID-19 found that 58 (2.1%) patients had skin lesions attributed to COVID-19.9

The wide range in reported prevalence of skin lesions may be due to variable involvement of dermatologic specialists in patient care, particularly in China.10 Some variation also may be due to variability in the timing of clinical examination, as well as demographic and clinical differences in patient populations. Of note, a multisystem inflammatory disease seen in US children subsequent to infection with COVID-19 has been associated with rash in as many as 74% of cases.11 Although COVID-19 disproportionately impacts people with skin of color, there are few reports of cutaneous manifestations in that population,12 highlighting the challenges of the dermatologic examination in individuals with darker skin and suggesting the prevalence of dermatologic disease in COVID-19 may be greater than reported.

Morphologic Patterns of Cutaneous Involvement in COVID-19

Researchers in Europe and the United States have attempted to classify the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19. A registry established through the American Academy of Dermatology published a compilation of reports from 31 countries, totaling 716 patient profiles.13 A prospective Spanish study detailed the cutaneous involvement of 375 patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19.14 Together, these efforts have revealed several distinct patterns of cutaneous involvement associated with COVID-19 (Table).9,15-18

Vesicular Rash

Vesicular rash associated with COVID-19 has been described in several studies and case series8,13,14 and is considered, along with the pseudopernio (or pseudochilblains) morphology, to be one of the more disease-specific patterns in COVID-19.14,18 Vesicular rash appears to comprise roughly one-tenth of all COVID-19–associated rashes.13,14 It usually is described as pruritic, with 72% to 83% of patients reporting itch.13,16

Small monomorphic or polymorphic vesicles predominantly on the trunk and to a lesser extent the extremities and head have been described by multiple authors.14,16 Vesicular rash is most common among middle-aged individuals, with studies reporting median and mean ages ranging from 40.5 to 55 years.9,13,14,16

Vesicular rash develops concurrent with or after other presenting symptoms of COVID-19; in 2 studies, vesicular rash preceded development of other symptoms in only 15% and 5.6% of cases, respectively.13,14 Prognostically, vesicular rash is associated with moderate disease severity.14,16 It may persist for an average of 8 to 10 days.14,16,18

Histopathologic examination reveals basal layer vacuolar degeneration, hyperchromatic keratinocytes, acantholysis, and dyskeratosis.9,16,18

Urticarial Rash

Urticarial lesions represent approximately 7% to 19% of reported COVID-19–associated rashes.9,13,14 Urticarial rashes in patients testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 primarily occur on the trunk.14 The urticaria, which typically last about 1 week,14 are seen most frequently in middle-aged patients (mean/median age, 42–48 years)13,14 and are associated with pruritus, which has been reported in 74% to 92% of patients.13,14 Urticarial lesions typically do not precede other symptoms of COVID-19 and are nonspecific, making them less useful diagnostically.14

Urticaria appears to be associated with more severe COVID-19 illness in several studies, but this finding may be confounded by several factors, including older age, increased tobacco use, and polypharmacy. Of 104 patients with reported urticarial rash and suspected or confirmed COVID-19 across 3 studies, only 1 death was reported.9,13,14

The histopathologic appearance is that of typical hives, demonstrating a perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils with edema of the upper dermis.9,19

Morbilliform Eruption

Morbilliform eruption is a commonly reported morphology associated with COVID-19, accounting for 20% to 47% of rashes.9,13,14 This categorization may have limited utility from a diagnostic and prognostic perspective, given that morbilliform eruptions are common, nonspecific, and heterogenous and can arise from many causes.9,13,14 Onset of morbilliform eruption appears to coincide with14 or follow13,20,21 the development of other COVID-19–related symptoms, with 5% of patients reporting morbilliform rash as the initial manifestation of infection.13,14 Morbilliform eruptions have been observed to occur in patients with more severe disease.9,13,14

Certain morphologic subtypes, such as erythema multiforme–like, erythema elevatum diutinum–like, or pseudovesicular, may be more specific to COVID-19 infection.14 A small case series highlighted 4 patients with erythema multiforme–like eruptions, 3 of whom also were found to have petechial enanthem occurring after COVID-19 diagnosis; however, the investigators were unable to exclude drug reaction as a potential cause of rash in these patients.22 Another case series of 21 patients with COVID-19 and skin rash described a (primarily) petechial enanthem on the palate in 6 (28.5%) patients.23 It is unclear to what extent oral enanthem may be underrecognized given that some physicians may be disinclined to remove the masks of known COVID-19–positive patients to examine the oral cavity.